NEW MEXICO

HUMAN SERVICES

DEPARTMENT

5

-

YEAR

STRATEGIC

PLAN

NEW MEXICO

PRIMARY CARE

COUNCIL

2023

Version

2

: Updated from

2022

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 1 of 48

Contents

Honor Native Land ........................................................................................................................................ 2

Letter from the Primary Care Council Chair .................................................................................................. 3

Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4

Background and Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5

New Mexico Overview .................................................................................................................................. 5

Primary Care Council Overview .................................................................................................................... 6

Primary Care Council Timeline of Strategic Activities ................................................................................... 7

Medicaid Primary Care Payment Reforms .................................................................................................. 21

Primary Care Residency Expansion ............................................................................................................. 23

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 25

Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................... 26

Appendix ..................................................................................................................................................... 27

Primary Care Return on Investment ....................................................................................................... 27

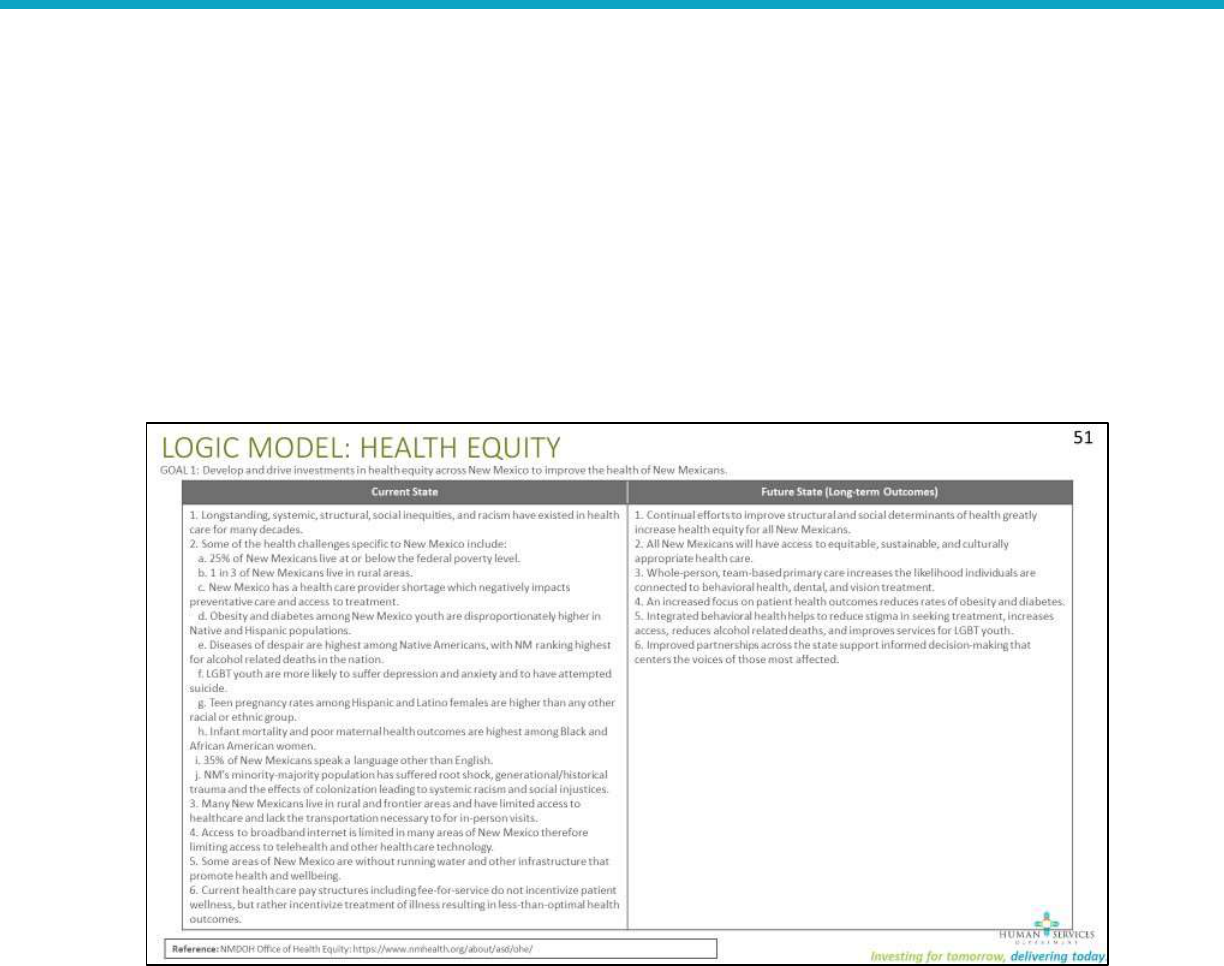

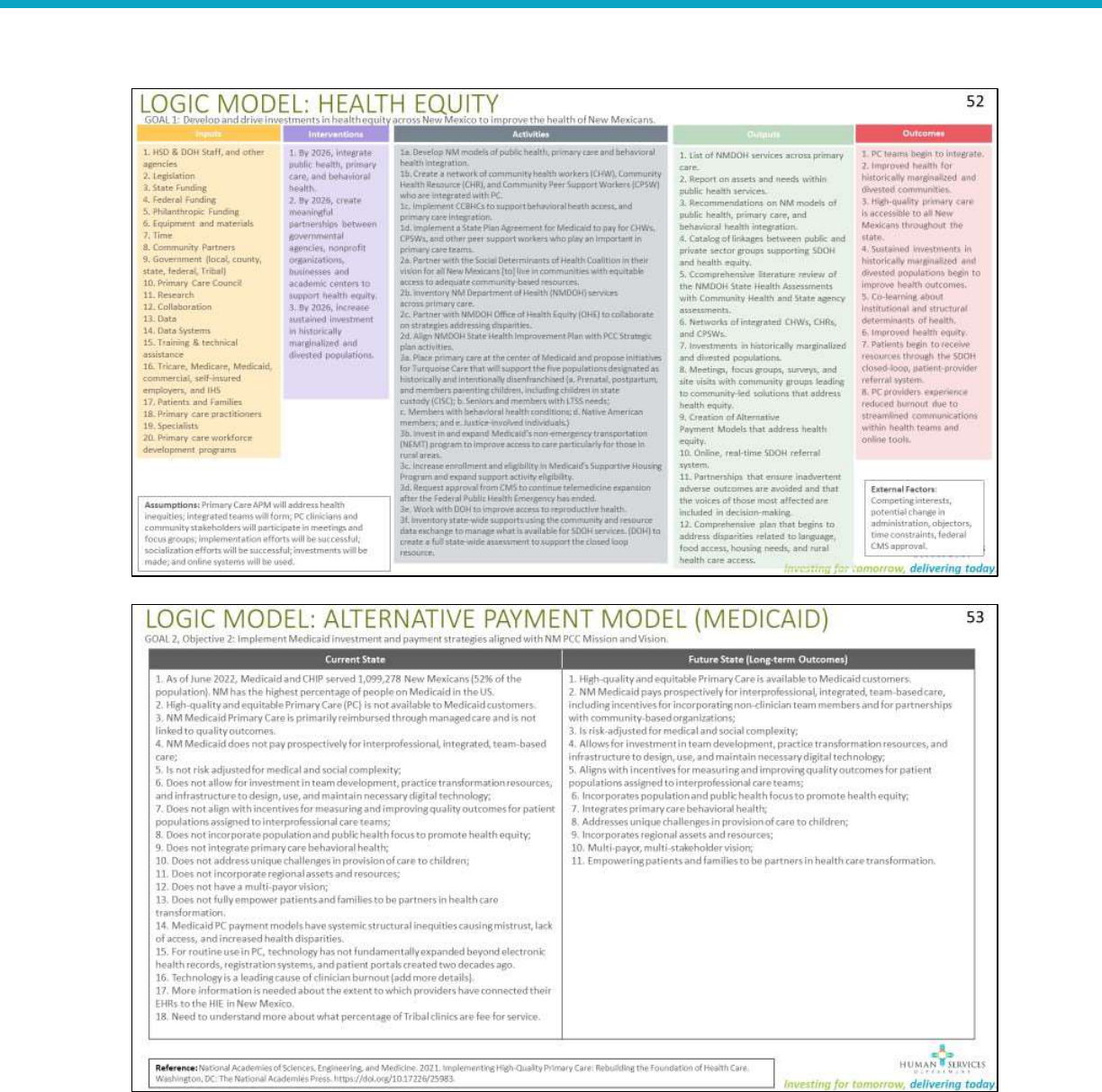

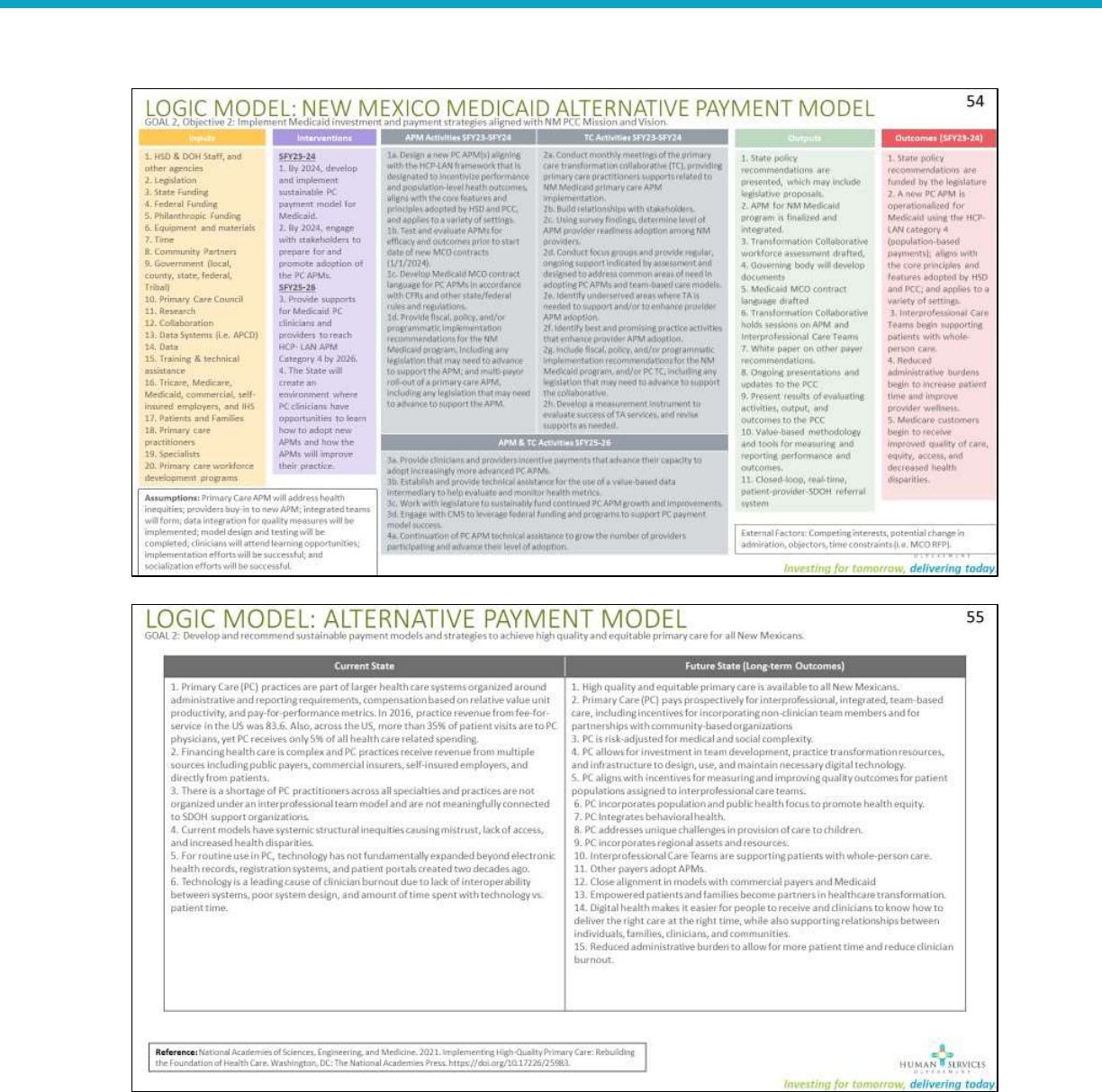

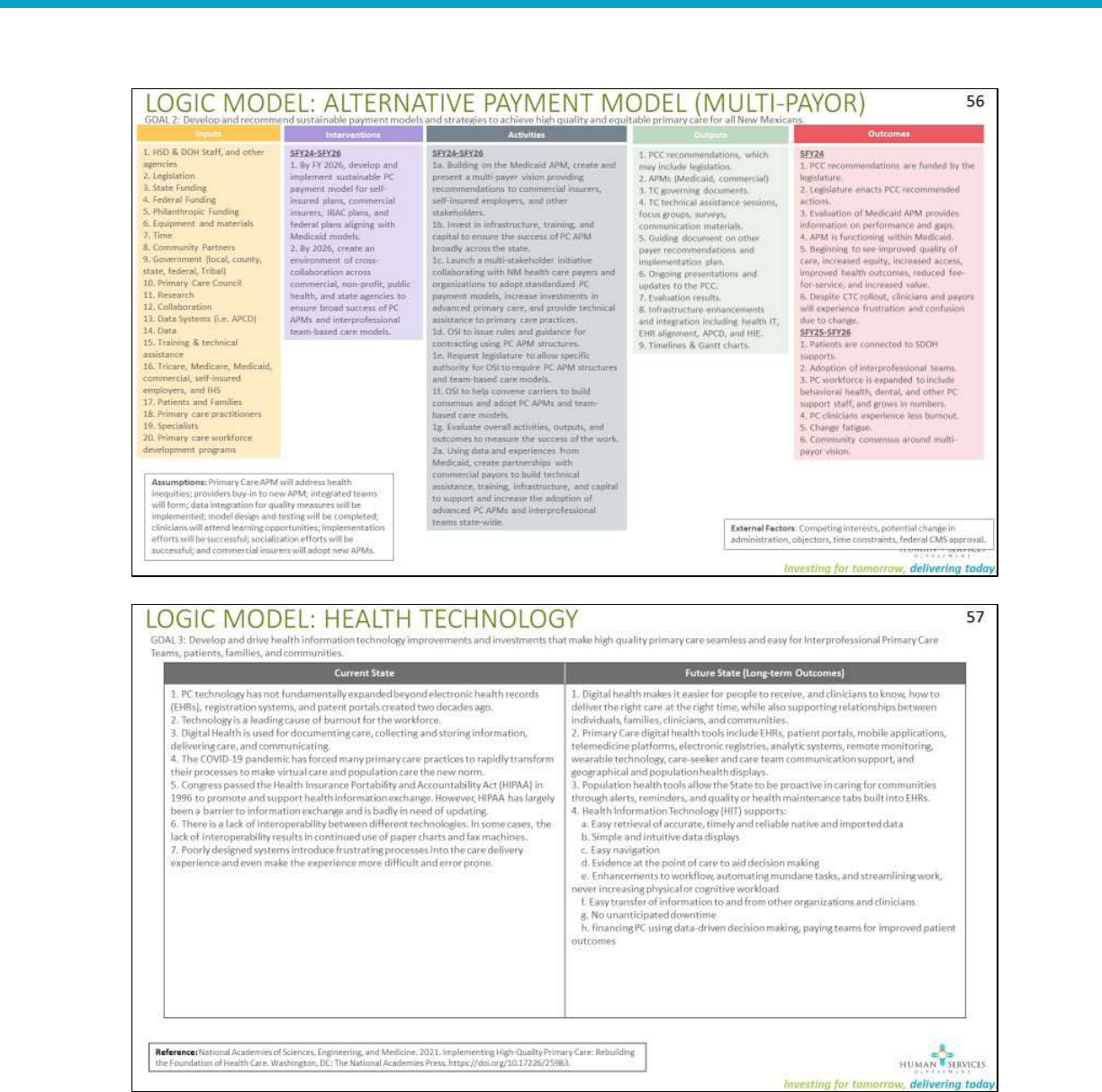

Primary Care Logic Models ..................................................................................................................... 28

Primary Care Best and Promising Practices ............................................................................................ 33

References .................................................................................................................................................. 44

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 2 of 48

Honor Native Land

On behalf of all colleagues at the Human Services Department, we

humbly acknowledge we are on the unceded ancestral lands of the

original peoples of the Pueblo, Apache, and Diné past, present, and

future.

With gratitude we pay our respects to the land, the people and the

communities that contribute to what today is known as the State of

New Mexico.

Evening drive through Corrales, NM in October 2021.

By HSD Employee, Marisa Vigil

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 3 of 48

Letter from the Primary Care Council Chair

Welcome to New Mexico's Primary Care Council.

In 2019, providers, clinicians, and primary care advocates across New Mexico urged the state legislature

to form the New Mexico State Primary Care Council (PCC). Passed as House Bill 67 in 2021, the PCC is

tasked with addressing the immediate and urgent issues plaguing primary care.

I have the honor of serving as chair of the Primary Care Council since its formation. The PCC understands

the urgent need for a primary care revolution to ensure health equity for patients, families,

communities, and primary care workforce; initiate payment strategies to support high-quality primary

care; make health technology investments and improvements; and build a sustainable workforce. At the

heart of our work, is a desire to:

revolutionize primary care through innovation and creativity;

ensure primary care data is valid, reliable, and specific to understand our system;

develop equitable interprofessional primary care teams who value and honor every member of

the team equally and provide person-centered care;

use an intersectional approach to ensure primary care is fairly and justly provided for all New

Mexicans;

support holistic primary care, factoring in a unique array of ancestral approaches to living and

healing;

ensure healthy communities through partnerships designed with the needs of community at

the center.

Over the past year, the Council has focused on developing primary care payment and care delivery

reforms for Medicaid. In 2023, we will announce the new payment models which were developed in

collaboration with, and to meet the needs of, providers and clinicians across the state. I look forward to

sharing and learning together with you as we provide technical assistance and training for the adoption

of these reforms.

Revolutionizing, reimagining, and investing in primary care in is an enormous, yet essential task, for

ensuring the health of all New Mexicans. As you review the Primary Care Council’s 2023 Strategic Plan, I

hope you see a future where New Mexico exemplifies same-day access to high-quality, equitable,

primary care for all persons, families, and communities.

With sincere gratitude,

Jennifer K. Phillips, M.D.

Family Medicine Physician

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 4 of 48

Executive Summary

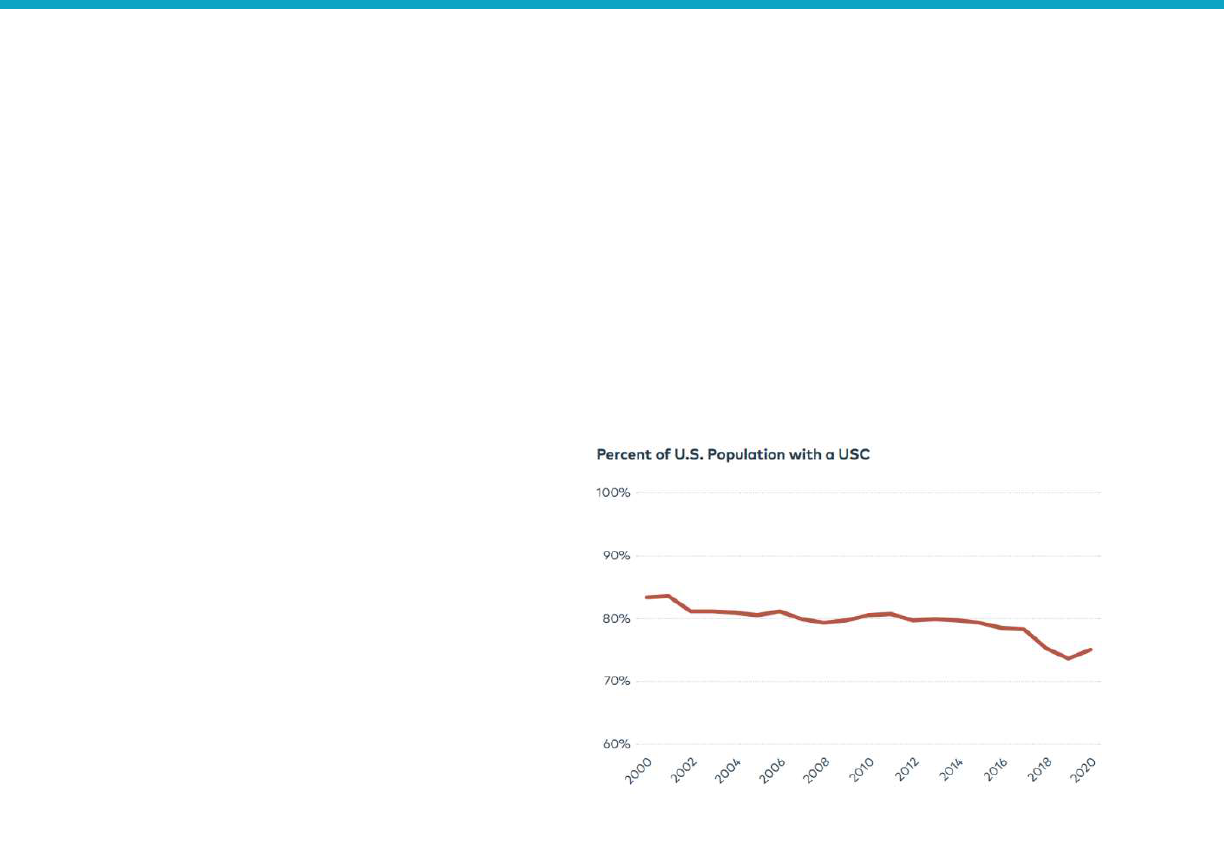

Over the past twenty years, there has been a significant shift in health care resulting in only one in five

Americans having access to a routine or usual source of care. [1] In New Mexico we refer to this usual

source of care as “primary care.” The COVID-19 crisis has brought to the forefront shortcomings in the

current primary care system including a declining workforce experiencing severe burnout; a decline in

patient-physician relationships; profound societal health inequities; and an overall underinvestment in

Primary Care. [2] [3] [4] [5]

A wealth of research shows primary care helps prevent illness and death, and findings in both national

and international studies illustrate primary care results in a more equitable distribution of community

health. [6] Primary care is the only health care component where an increased supply results in

improved population health and more equitable outcomes. Primary care is a common good, which

makes the strength and quality of the country’s primary care services a public concern.

[7]

The primary

care workforce is also key in the promotion of health equity by supporting patients and families in

attaining their full health potential, while ensuring neither social position nor other socially determined

circumstances disadvantages them from achieving their potential.

[8]

In 2022, the Primary Care Council (PCC) and New Mexico Human Services Department (HSD) led a state-

wide collaborative process in to establish new primary care payment models for Medicaid that will

launch on January 1, 2024. Stakeholders across all aspects of primary care were engaged in listening

sessions, surveys, focus groups, and individual conversations. These payment reforms are built to

support the needs of the New Mexico primary care workforce, patients, families, communities, and

payors. Medicaid Turquoise Care Managed Care Organizations (MCO) will be required to adhere to any

payment reform recommendations promulgated by the New Mexico Primary Care Council. The work of

the PCC is also reflected in the State of New Mexico Medicaid federal 1115 waiver demonstration

including:

Expanded Centennial Home Visiting Pilot Programs

Expanded Access to Supportive Housing

Medicaid Services for High-Need Justice-involved Populations 30 Days Before Release

Member-Directed Traditional Healing Benefits for Native Americans

Home-Delivered Meals Pilot Programs

Addition of a Closed-Loop Referral System

Medical Respite for Members Experiencing Homelessness

Primary Care Residency Expansion funding and program technical assistance

In 2023, the PCC will continue their work to revolutionize primary care across the four goals of the

council. Health Equity and wellness for the primary care workforce will continue to be at the center of

the work of the PCC. We will partner with NM Department of Health in the increasing the Community

Health Worker workforce, collaborate on strategies to address health disparities in the state, and begin

to modernize the state’s health IT systems.

HSD, in collaboration with members of the community-based PCC, worked together to develop this

strategic plan. This strategic plan outlines a thoughtful, achievable, and bold plan to improve the many

elements of primary care throughout New Mexico; and the PCC will update it annually over the next

four years.

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 5 of 48

Background and Introduction

The 2021 House Bill 67 (Primary Care Council Act)

[9]

charges HSD to establish an unpaid, statewide PCC

to advise the State in finding means to increase New Mexicans’ access to primary healthcare while

improving overall health and lowering total healthcare costs. As enacted, the statute outlines eight

duties for the Council, which are outlined below:

1. Develop a shared description of primary care practitioners and services;

2. Analyze annually the proportion of health care delivery expenditures allocated to primary care

statewide;

3. Review national and state models of primary care investment with the objectives of increasing

access to primary care, improving the quality of primary care services and lowering the cost of

primary care delivery statewide;

4. Review New Mexico state and county

data and information about barriers to

accessing primary care services faced by

New Mexico residents;

5. Recommend policies, regulations and

legislation to increase access to primary

care, improve the quality of primary

care services and reduce overall health

care costs;

6. Coordinate efforts with the graduate

medical education expansion review

board and other primary care workforce

development initiatives to devise a plan

that addresses primary care workforce

shortages within the state;

7. Report annually to the interim legislative health and human services committee and the legislative

finance committee on ways that primary care investment could increase access to primary care,

improve the quality of primary care services, lower the cost of primary care delivery, address the

shortage of primary care providers and reduce overall health care costs; and,

8. Develop and present to the [Human Services Department] secretary a five-year plan to determine

how primary care investment could increase access to primary care, improve the quality of primary

care services, lower the cost of primary care delivery, address the shortage of primary care

providers and reduce overall health care costs.

New Mexico Overview

Prior to their encounter with the Spanish in 1540, the Pueblo, Navajo, Ute, and Apache communities

(including the Fort Sill, Jicarilla and the Mescalero) lived on the land known today as the state of New

Mexico.

In 2021, the New Mexico state population is 2,106,319

[10], with over 68% identifying as racial or ethnic

minorities.

[10] Though the State’s population centers are in urban areas, New Mexico is a rural and

frontier state, with an average population density of 17.5 persons/square mile. [11] Further 18.5% [10]

FIGURE 1: PERCENT OF POPULATION WITH A USUAL SOURCE OF

(PRIMARY) CARE

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 6 of 48

of state residents in 2020 were 65 years or older, and is projected to reach 26.5% by 2030, making it the

third oldest state in the U.S. [12] This older population, low population density combined with long

distances make the provision of healthcare particularly challenging. New Mexico has a shortage of

healthcare providers across all specialties, including in primary care. One estimate projects a national

primary care physician shortage of over 20,000 by 2033.

[13] Another estimate lists New Mexico among

three states with the largest shortage of registered nurses by 2030. [14] This healthcare workforce

shortage means healthcare access is challenging, as many New Mexicans cannot access timely primary

care, especially rural and frontier communities.

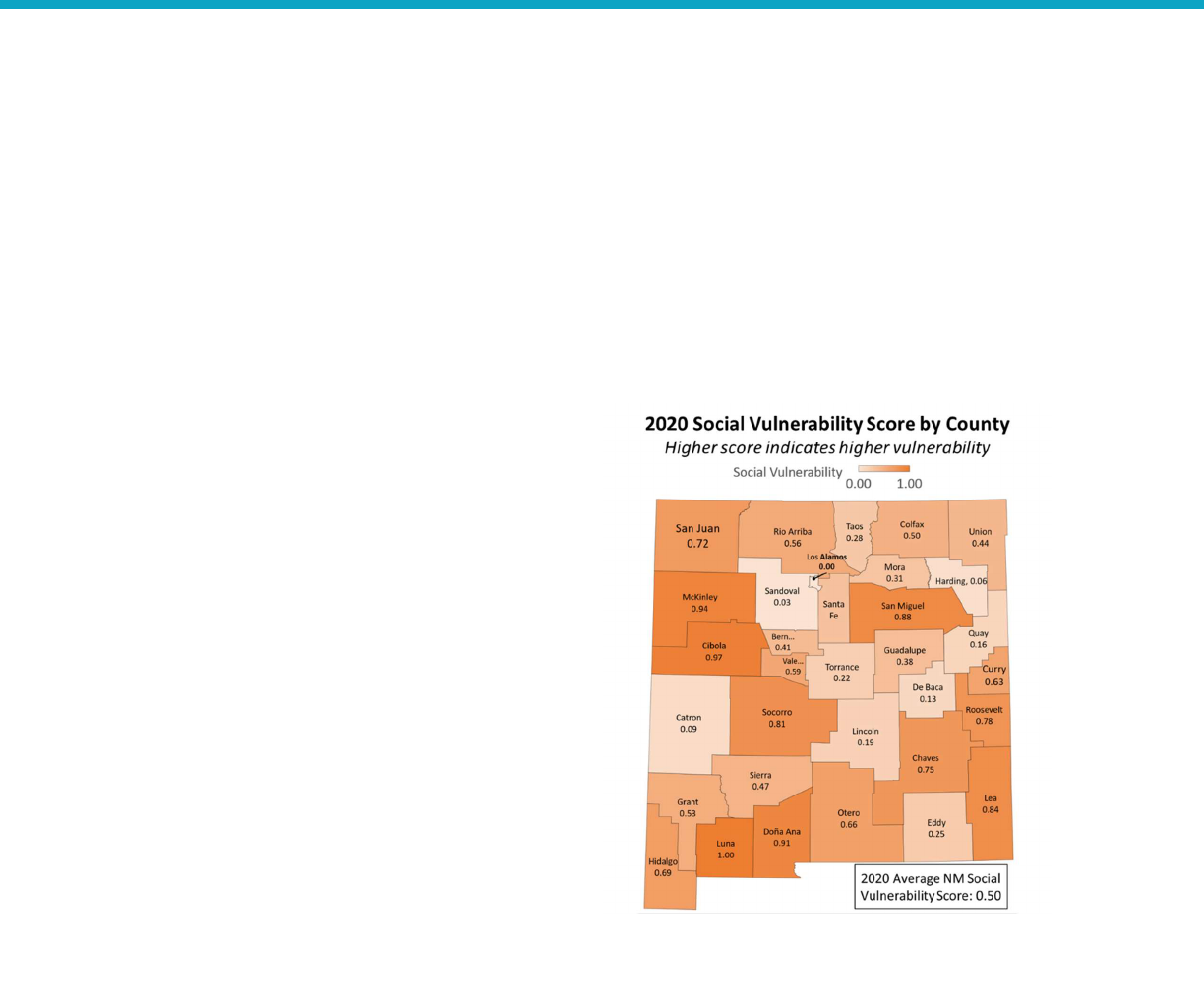

In many health and socioeconomic indicators, New Mexico fares worse when compared to other states

such as per capita personal income ($50,311 4

th

lowest). [15] New Mexico ranks third in U.S. child

poverty (24%), and third in the U.S. in elder

poverty (12.8%). [16] The substantial enrollment

in the Medicaid program reflects the extent of the

state’s poverty: 984,335 New Mexicans enrolled

in the Medicaid public health insurance program

in December 2022, (45% of the State’s

population).

[17]

Although NM has lower death

rates than the national average for heart disease

and cancer, it has much higher death rates for

unintentional injuries, specifically overdose,

motor vehicle injuries, and falls.

The PCC has outlined several activities to support

health equity in New Mexico. Care coordination

and Community Health Workers (CHWs) are

particularly important for achieving access to care

and connection to social supports such as healthy

food, housing, employment, and transportation.

Additionally, HSD is requesting funding for a

closed-loop referral service to connect patents to

social services in their community.

Primary Care Council Overview

The following definition of primary care (adapted from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering

and Medicine) guides the work of the PCC, setting the stage for the PCC’s mission, vision, and goals:

“High-quality primary care is the provision of whole-person, integrated, accessible, and equitable

healthcare by inter-professional teams and community partners who are accountable for addressing the

majority of individuals’ health and well-being across settings and through sustained relationships with

patients, families, and communities.” [7]

FIGURE 2: NM SOCIAL VULNERABILITY BY COUNTY.

SOURCE, U.S. CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND

PREVENTION [66]

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 7 of 48

The PCC definition of high-quality primary care is not a description of the current state of primary care in

New Mexico. It is aspirational and defines what the foundation of the health care system can, should,

and must be for all New Mexicans. Thus, the PCC mission is to revolutionize—to change radically and

fundamentally—how we deliver primary care; to transform primary care into a team-based approach

that values and rewards equitable, accessible, comprehensive, coordinated, high-quality, and cost-

efficient care.

As outlined in statute, [9] the PCC is a public-private body that includes nine voting members and

thirteen advisory members, appointed by the Human Services Department (HSD) Secretary. Members

include representatives from HSD, Department of Health, Office of Superintendent of Insurance, and the

NM Primary Care Association. In 2022, the PCC expanded to include community partners who

participate in quarterly meetings and workgroups to provide additional perspectives.

Primary Care Council Timeline of Strategic Activities

In 2022, the PCC developed and adopted the list of strategic activities below designed to be

accomplished in the next several years. These activities align with the eight duties outlined in House Bill

67. The PCC will annually publish updates in subsequent strategic plans.

FIGURE 3: PRIMARY CARE COUNCIL MISSION, VISION, AND GOALS

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 8 of 48

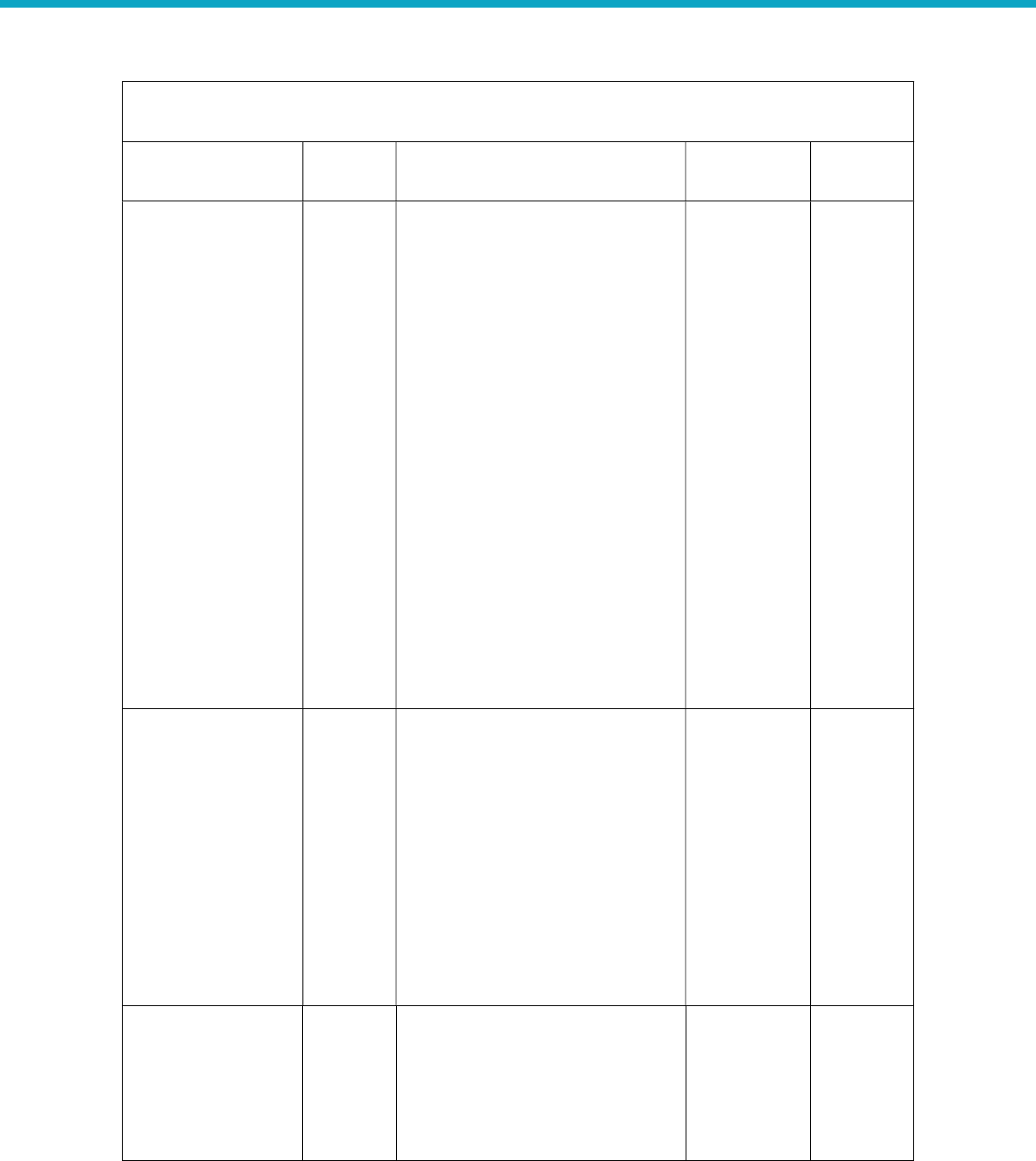

GOAL 1: Develop and drive investments in

health

equity across New Mexico to improve the health of

New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1.

By 2026,

establish a

standard for

health equity in

New Mexico that

includes the

expectations,

tools, and

resources are

available for

Primary Care.

1,

4,

8

1

a

.

In partnership with

the

Department of Health (DOH),

develop a framework for equity at

the clinic level, community,

patient, and family levels.

1b. DOH in partnership with state

agencies, tribal, and community

stakeholders, will identify and

implement strategies to improve

primary care and health equity in

the State Health Improvement

Plan (SHIP).

1c. Submit a 5-year 1115 waiver

renewal application to CMS that

includes strategies to address

health equity in the state’s

Medicaid program with an

anticipated effective date of

January 1, 2024.

1d. Implement strategies in Goal 3

(Health Equity) of the 1115 waiver

to identify groups that have been

historically and intentionally

disenfranchised and address

health disparities through strategic

program changes to enable an

equitable chance at living healthy

lives.

HSD

(1

c

,e

)

DOH (1b)

HSD & DOH (1a,d)

SFY2

3

(1c)

SFY23 (1a,c)

SFY23-26

(1b)

SFY24-26

(1d)

2. By 2026,

integrate public

health, primary

care, and

behavioral health.

4,5

2a.

In coordination and alignment

with payment reforms, develop

models for interprofessional team-

based care with an emphasis on

behavioral health integration.

2b. In coordination and alignment

with payment reforms, provide

technical assistance and training

for clinics to succeed under

models of interprofessional team-

HSD

(

2a

,b,

c)

DOH (2d,f)

HSD & DOH (2g)

New Mexico

Primary Care

Association

(NMPCA) (2e)

SFY23

(2a,d,e)

SFY23-SFY26

(2b,c,f,g)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 9 of 48

GOAL 1: Develop and drive investments in

health

equity across New Mexico to improve the health of

New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

based

care with an emphasis on

behavioral health.

2c. Implement Certified

Community Behavioral Health

Clinics (CCBHCs) to support

behavioral health access; care

coordination including services

provided to assist and support

individuals in developing their

skills to gain access to needed

medical, behavioral health,

housing, employment, social,

educational, and other services

and help advance primary care

integration. [18]

2d. Inventory DOH services across

New Mexico primary care settings,

including staff presence, grants,

and contracts for services.

2e. Conduct needs and

assets assessment for public

health services in primary

care settings across New Mexico.

2f. Develop and implement

strategies to build out co-located

public health in primary care

settings.

2g. Invest in public health and the

public health workforce to

improve disease surveillance

systems and expand and diversify

the public health workforce so we

can address the impacts of the

social and structural determinants

of health, health inequities,

counter spread of health

misinformation and

disinformation, strengthen

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 10 of 48

GOAL 1: Develop and drive investments in

health

equity across New Mexico to improve the health of

New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

partnerships across clinical and

community settings and consider

other societal factors that shape

well-being.

3. By 2026, create

meaningful

partnerships

between

governmental

agencies,

nonprofit

organizations,

businesses, and

academic centers

to support health

equity.

4,5

3a.

A

lign efforts

and

develop

partnerships with social support

organizations who will provide

social services to patients

connected to the closed-loop

referral system.

3b. Align efforts and develop

partnerships with state agencies

and community groups to

establish Accountable

Communities of Health (ACH). [19]

New Mexico

CONNECT

Collaborative (3a,

b)

SFY

23

-

26

(3a,b)

4

. By 2026,

establish

networks of care

coordinators who

support patients

in equitable

access to care,

connection to

social services,

and facilitate

action between

interdisciplinary

care teams.

4,5

4

a.

Improve linkages between

Community Health Workers

(CHW), Community Health

Representatives (CHR), and

Community Peer Support Workers

(CPSW) with primary care clinics to

support integrated team-based

models in primary care.

4b. Standardize training and

certification for CHWs.

4c. Provide training and technical

assistance to CHWs and other care

coordinators on how to use tools,

support equity, connect patients

to social resources, and facilitate

connections and conversations

with interdisciplinary care teams.

4d. Submit a Medicaid state plan

amendment to allow

reimbursement for CHWs and

other care coordinators.

HSD (

4

d

)

DOH (4b,c)

HSD & DOH (4a)

SFY23 (

4

b,

d

)

SFY24-26

(2a,c)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 11 of 48

GOAL 1: Develop and drive investments in

health

equity across New Mexico to improve the health of

New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

5. Analyze

proportion of

health care

delivery

expenditures

allocated to

primary care.

2

5a. In alignment with HB67 duty 2,

annually analyze the proportion of

health care delivery expenditures

allocated to primary care.

5b. Identify and implement policy

changes that can increase the

proportion of health care delivery

expenditures allocated to primary

care.

5c. Once available, utilize the All-

Payer Claims Database to calculate

percentage of primary care spend.

HSD (5a

,b

,c

)

SFY2

4

-

26

(5a,c)

SFY25-26

(5b)

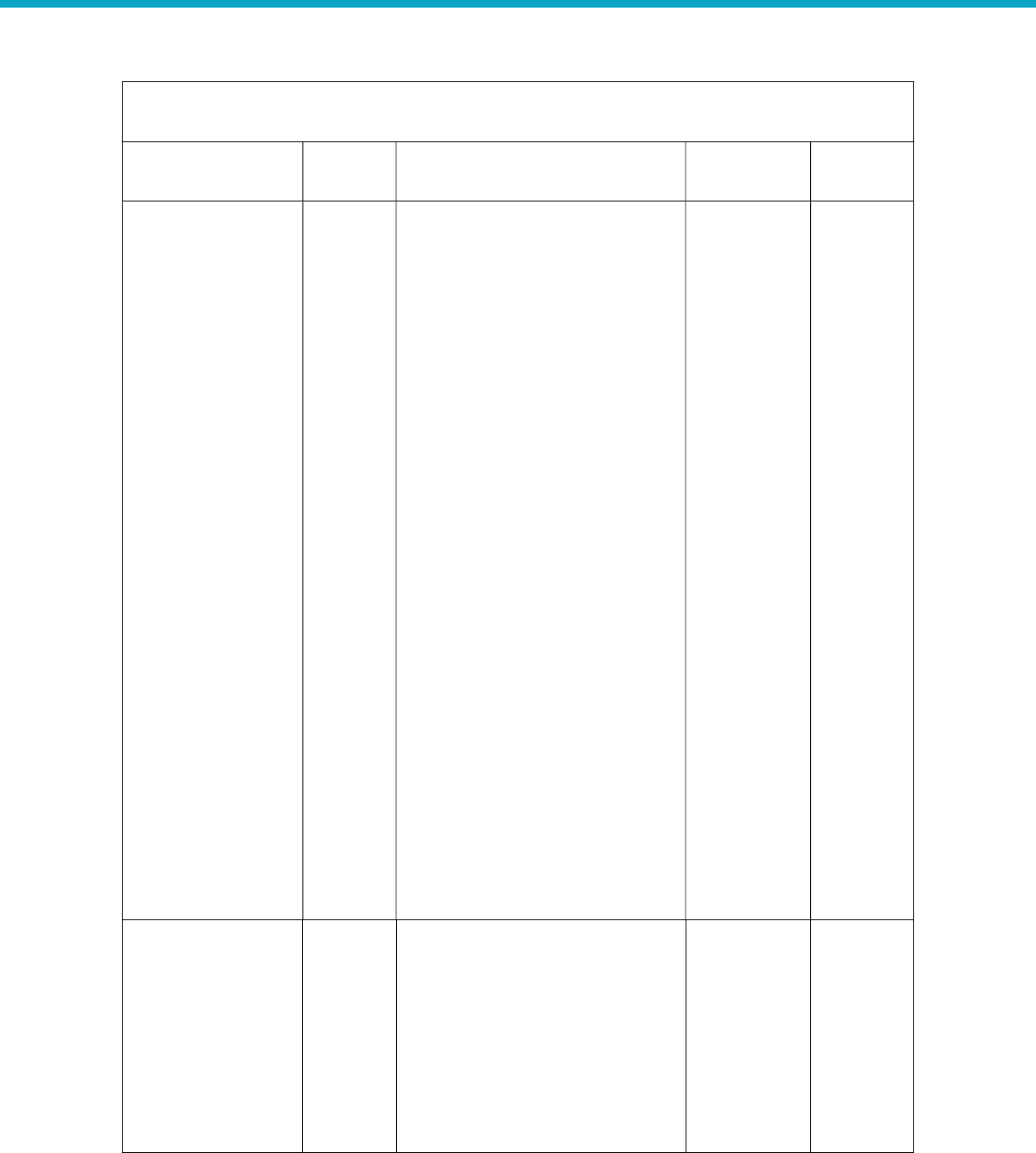

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1. By 2024, develop

and implement

sustainable primary

care payment

model(s) for

Medicaid that move

away from fee-for-

service and volume

to payment for

quality, health

outcomes, and

patient wellness.

3,

4,

5

1a. Design a new

primary care

payment model(s) that aligns with

the Health Care Payment Learning

and Action Network (HCP-LAN)

[20] framework to incentivizing

performance and population-level

health outcomes, aligns with the

core features and principles

adopted by HSD and PCC, and

applies to a variety of settings.

1b. Test and evaluate primary care

payment model(s) for efficacy and

outcomes prior to start date of

new Medicaid MCO contracts

(1/1/2024).

1c. Develop Medicaid MCO

contract language for primary care

payment reforms in accordance

with the Code of Federal

Regulations (CFRs) and other

HSD

(1a,b,c,e,h,I,j,k)

HSD & DOH (f)

OSI (1d)

NMFA & DOH

(1g)

SFY2

3

(1a,b,c,e,k)

SFY23-26

(1d,f,g,h,i,j)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 12 of 48

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

state/federal rules and

regulations.

1d. Provide fiscal, policy, and/or

legislation that may be needed to

advance and support primary care

payment reform; and a multi-

payor roll-out of primary care

payment reform.

1e. Develop and define the quality

metrics (including health equity)

that will be a part of the Medicaid

payment model and harmonized

across the different Medicaid

MCOs.

1f. Create investment

opportunities that support

practices engaged in Medicaid

payment reform implementation

and progression from tier 1 to 4

(e.g., PMPM investments for a

year before moving to additional

tier, up-front investment in

staffing, tech, training, resources).

1g. Through its Primary Care and

Behavioral Health Capital Fund,

the State will provide capital

project financing to community-

based nonprofit clinics located in

rural and underserved areas of

New Mexico.

1h. Work with MCOs to create

consistency across administrative

processes and reduce

administrative burden.

1i. Work with legislature to

sustainably fund continued

primary care payment reform

growth and improvements.

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 13 of 48

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1

j

.

Engage with CMS to leverage

federal funding and programs to

support primary care payment

model success.

1k. Participate in the Center for

Health Care Strategies “Medicaid

Primary Care Population-Based

Payment Learning Collaborative”

to receive technical assistance

focused on developing,

implementing, and improving

primary care population-based

payment models within Medicaid.

2. Build the

foundation for long-

term engagement

with stakeholders

that began in 2022

to prepare for and

promote adoption of

primary care

payment reforms in

Medicaid.

3,4,5

,8

2a. Conduct meetings of the

Primary Care Transformation

Collaborative (TC), providing

primary care practitioners

supports related to NM Medicaid

primary care payment model

implementation.

2b. Continue to build relationships

with stakeholders through

listening sessions, webinars, and

ongoing support to address

common areas of need to support

the adoption and success for

clinics in adopting primary care

payment reforms.

2c. Publish survey findings and

recommendations for clinician and

provider readiness in adopting

primary care payment reforms.

2d. Identify underserved areas

where additional technical

assistance is needed to support

and/or to enhance provider and

clinician adoption of primary care

payment reforms.

HSD

(2a,b,c,d,e,f)

SFY22 (2c

,e

)

SFY22-23

(2f)

SFY23 (2d)

SFY23-26

(2a,b)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 14 of 48

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

2e.

Identify and distribute best

and promising practice activities

that enhance provider and

clinician primary care payment

reform adoption.

2f. Develop a measurement

instrument and evaluate success

of technical assistance services,

and revise supports as needed.

3. Provide supports

for Medicaid primary

care clinicians and

providers to reach

HCP-LAN Category 4

by 2026.

3,5,8

3a. Provide clinicians and

providers incentive payments that

advance their capacity to adopt

increasingly more advanced

primary care payment reforms.

3b. Establish a value-based data

intermediary to help evaluate and

monitor population health

metrics.

3c. Provide technical assistance for

the use of a value-based data

intermediary to help evaluate and

monitor population health

metrics.

3d. Provide technical assistance to

providers and clinicians in

supporting adoption of

increasingly more advanced

primary care payment and

interprofessional-team models.

HSD (3a

,b,c,

d

)

SFY

23

-

26

(3d)

SFY24 (3b)

SFY23-26

(3a,c)

4. By

2026

,

create an

environment where

primary care

providers and

clinicians have

opportunities to

learn how to adopt

new payment and

interprofessional

5,

8

4a. Contin

ue

primary care

payment and interprofessional

technical assistance to grow the

number of providers and clinicians

participating in advanced primary

care in the state.

HSD (4a)

SFY2

3

-

26

(4a)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 15 of 48

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

team

-

based models

and how those

models will improve

their practice.

5. By FY 2026,

develop and

implement

sustainable payment

reforms for self-

insured plans,

commercial insurers,

IBAC plans, and

federal plans

aligning with

Medicaid models.

3,5,8

5

a. Building on Medicaid

payment

reforms, create and present a

multi-payer vision providing

recommendations to commercial

insurers, self-insured employers,

and other stakeholders.

5b. Invest in infrastructure,

training, and capital to ensure the

success of multi-payor primary

care payment reforms broadly

across the state.

5c. Launch a multi-stakeholder

initiative collaborating with NM

health care payers and

organizations to adopt

standardized advanced primary

care payment models, increase

investments in advanced primary

care, and provide technical

assistance to primary care

practices.

5d. Issue rules and guidance for

contracting using PC APM

structures.

5e. Request legislature to allow

specific authority for OSI to

require advanced primary care

payment structures and team-

based care models.

5f. OSI to help convene carriers to

build consensus and adopt PC

APMs and team-based care

models.

HSD

(

5

a

,b,

c,g)

OSI (5d,e,f)

SFY24

(5

a,

c

)

SFY25-26

(5b,d,e,f)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 16 of 48

GOAL 2: Develop and recommend sustainable payment models and strategies to achieve high quality

and equitable primary care for all New Mexicans.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

6

.

Measure the

improvements in

health outcomes

and system-wide

cost savings of

improving an

innovative and

integrated system

that encourages care

coordination,

optimally designed

care management,

and care transition.

3,5,8

6

a. Create state

-

level metrics to

measure population health

outcomes and system-wide health

care savings under primary care

payment reforms.

HSD

, DOH

(

6a

)

SFY2

5

(6a)

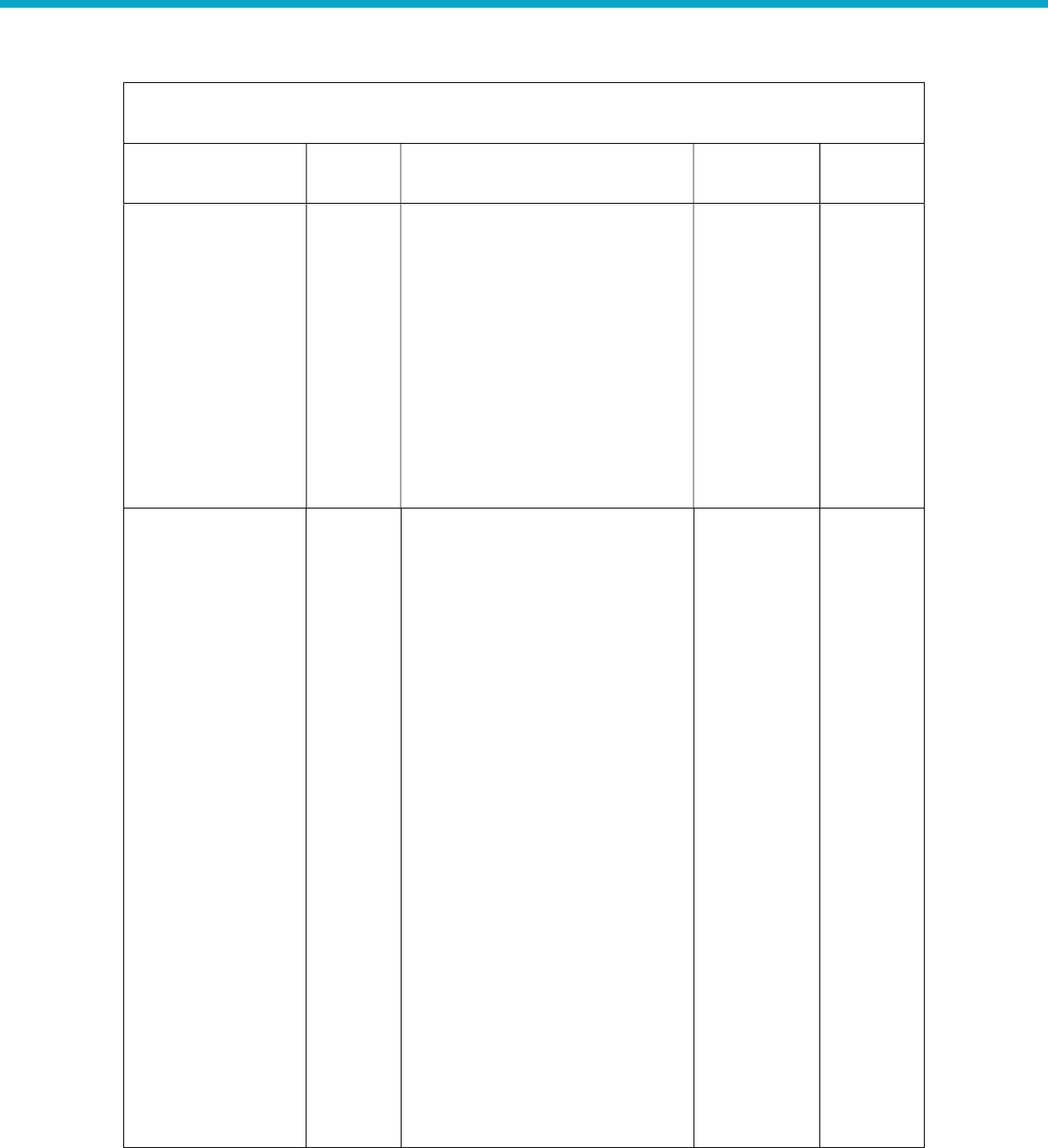

GOAL 3: Develop and drive health information technology improvements and investments that make

high quality primary care seamless and easy for Interprofessional Primary Care Teams, patients,

families, and communities.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1. By 2026, develop,

invest in, and

implement health IT

improvements to

support advanced PC

practice, payment,

and interprofessional

teams.

2,3,4,8

1a. Assess the needs for providers to

connect their EHRs to the HIE to adopt

advanced primary care payment in their

practice.

1b. Contract with business analysts and

project managers to revalidate

requirements for EHRs and modernize

current DOH systems and begin

implementation.

1c. Establish an Office of Informatics to

help manage data and information

exchange between systems.

1d. The All Payor Claims Database

(APCD) will begin collecting data from

various data submitters throughout the

state with an implementation date in 4Q

SFY23.

HSD (1a

,e,i

)

DOH

(1b,c,d,e,f)

Syncronys

(1g,h)

SFY

23

(1a,b,d,f)

SFY24

(1c,e,h)

SFY24-26

(1g)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 17 of 48

GOAL 3: Develop and drive health information technology improvements and investments that make

high quality primary care seamless and easy for Interprofessional Primary Care Teams, patients,

families, and communities.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1e.

Create a collaborative plan for

implementation of health technologies

across multi-payors to reduce

administrative burdens, enable

successful PC APM implementation, and

team-based care models that include

patient and provider identity

management, attribution, care

management and coordination, financial

benchmarking and management, quality

reporting, and feedback.

1f. Collect data from various data

submitters throughout the state with an

implementation date in 4Q SFY23.

1g. If funding becomes available, partner

with HSD on a Social and Structural

Determinants of Health (SDOH) referral

system which is designed to better

connect patients who need social

services with the resources through

creating HIE data collection and

reporting capabilities.

1h. Expand operability of the Healthcare

Information Exchange (HIE) to support

advanced primary care payment models

including risk stratification and

population management.

1i. Receive Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services (CMS) certification to

be a modular system which will allow

the HIE to be a National Committee for

Quality Assurance (NCQA) data

aggregator validator.

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 18 of 48

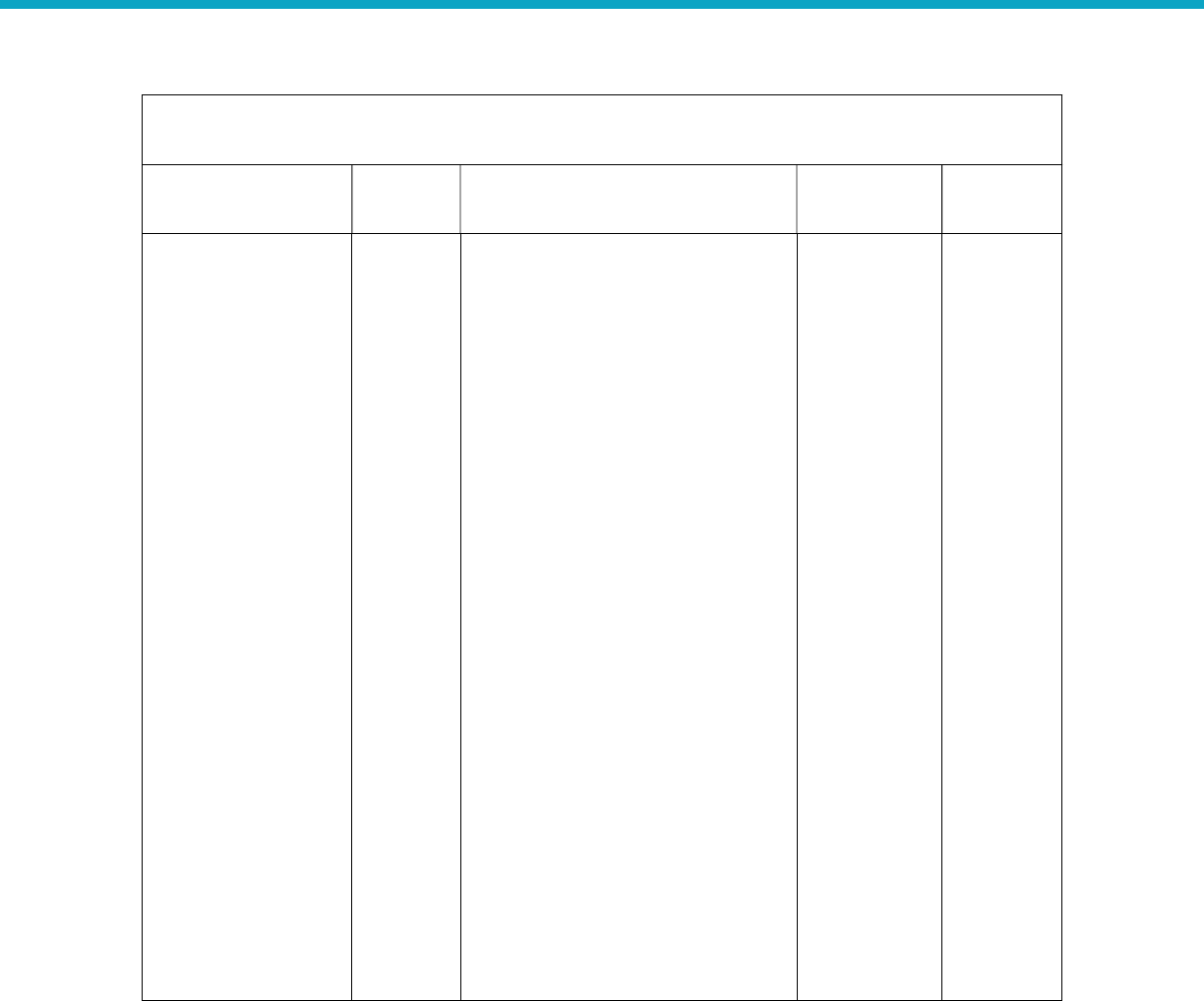

GOAL 4: Create a sustainable workforce, financial model, and budget to support our mission and

secure necessary state and federal funding.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

1. By 2026, develop

a

system for data and

monitoring of the

heath care workforce

across state and

private entities

responsible for

collecting workforce

data.

1,

3,5,6

1a. Conduct a comprehensive,

statewide primary care workforce

analysis to determine the current

provider-to-population ratios,

provider demographics, utilization

of primary care interprofessional

teams.

1b. Understand effectiveness of

loan repayment programs

in recruitment and retention in

rural areas, understand the current

state of provider well-being, and

healthcare career programs that

will inform tactics to address

workforce shortages and

sustainability.

1c. Collaborate with primary care

licensure boards to improve data

collection and analyses.

HSD

(1a

,b,

c

)

SFY2

3

-

26

(1a)

SFY24 (1b)

SFY23-26

(1c)

2. By 2024,

implement

sustainable Medicaid

PC rate adjustments.

2,5

2a.

Develop fair and

equitable

methodology for Medicaid provider

rate reimbursements that support

the healthcare workforce.

2b. Raise Medicaid reimbursement

rates for primary care, behavioral

health, and maternal and child

health to 120% of Medicare.

2c. Raise Medicaid reimbursement

rates for all other services to 100%

of Medicare.

HSD (2a

,b,

c

)

SFY2

3

(2a,b,c)

3. By 2024, develop

plans to expand

existing workforce

capacity and future

workforce

development.

3,5,6

3a. Expand the capacity of

C

ertified

Peer Support Workers (CPSWs)

through training and certification of

existing and future workforces.

3b. Expand the capacity of and

community health workers (CHWs)

HSD (3a

,c

-

g

)

DOH (3b)

SFY24 (

3

c

)

SFY24-26

(3a,b,d)

SFY26 (3e-

g)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 19 of 48

GOAL 4: Create a sustainable workforce, financial model, and budget to support our mission and

secure necessary state and federal funding.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

through training and certification of

existing and future workforces.

3c. Identify strategies the State can

take to promote healthcare

providers and clinicians practice at

the top of their license.

3d. Promote the New Mexico

Health Service Corps (NMHSC) to

recruit, place, and offer financial

assistance to designated health

professionals in rural and medically

underserved areas of the state.

3e. Expand the number of

accredited primary care residency

programs from 8 to 16.

3f. Increase the number of

community primary care residency

positions (from 142 to 264) in NM

by 2025 through expansion of

existing residency programs and

development of new programs,

especially in rural areas.

3g. A minimum of 60% of primary

care residents who complete an

HSD-affiliated residency program

remain in NM and practice primary

care by 2025, reaching 70% by

2030.

4.

By 2024,

expand

and make

improvements to

current recruitment

and retention

efforts.

4a. Make financial incentives and

assistance opportunities for the

health care workforce clear,

transparent, and easy to find.

4b. Identify financial and

nonfinancial barriers to the

recruitment and retention of the

non-licensed primary care

workforce.

DOH (4

a,d)

HSD (4b)

HSD & DOH

(4c)

SFY24

(4a,b,c)

SFY23-26

(4d)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 20 of 48

GOAL 4: Create a sustainable workforce, financial model, and budget to support our mission and

secure necessary state and federal funding.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

4c.

Examine NM state policies that

may be punitive for health care

workers seeking mental health

care, advancing legislation to

protect health workers seeking

help if appropriate.

4d. Provide financial assistance to

rural primary care clinics to sustain

a minimum level of delivery of

primary care services pursuant to

the provisions of the Rural Primary

Health Care Act (RPHCA). [21]

5.

B

y

2026,

implement

recommendations

provided by the US

Surgeon General on

addressing health

worker burnout and

implement programs

relevant needs in

NM. [2]

5

a

.

Examine state health

professional licensing board

questions in applications and

renewal forms for licensure so that

health workers are only asked

about “conditions that currently

impair the clinicians’ ability to

perform the job,” as recommended

by The Joint Commission in 2020,

Federation of State Medical

Boards, and aligned with the

American with Disabilities Act.

5b. Determine extent of workplace

violence against health workers,

and pass legislation to address it if

needed.

5c. Ensure that state boards and

legislatures approach burnout from

a nonpunitive lens by considering

offering options for “safe haven”

non-reporting for clinicians and

providers receiving appropriate

treatment for mental health or

substance use.

5d. Increase access to quality,

confidential mental health, and

HSD

(5a,b,c,d,e,

f,g,h,i)

SFY23

(5,d,e,f)

SFY24

(5a,b,c,g,h)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 21 of 48

GOAL 4: Create a sustainable workforce, financial model, and budget to support our mission and

secure necessary state and federal funding.

Objectives

HB 67

Duty Activities Lead Timeframe

substance use care for all health

workers.

5e. Track timeframes for Medicaid

provider enrollment, simplify

enrollment process and develop a

manual on how to enroll.

5f. Propose updates to the current

MCO credentialling process to

make the process more

streamlined.

5g. Engage with NM Health

Professional Wellness Program

(NMHPWP) to re-design Physician

Health Programs and wellness

programs to provide early

intervention and destigmatize

seeking help.

5h. Analyze licensure questions

about diagnoses and treatment and

determine how to limit questions

to only those necessary for safety,

lowering barriers to seeking

treatment, and easing physician

concerns about their medical

license being suspended or

revoked.

Medicaid Primary Care Payment Reforms

The PCC is beginning its payment reform efforts with the Medicaid program, shifting primary care

financing from a fee-for-service to payments that drive population and patient wellness. This new

payment model will begin January 2024 aligning with the launch of New Mexico Medicaid Turquoise

Care.

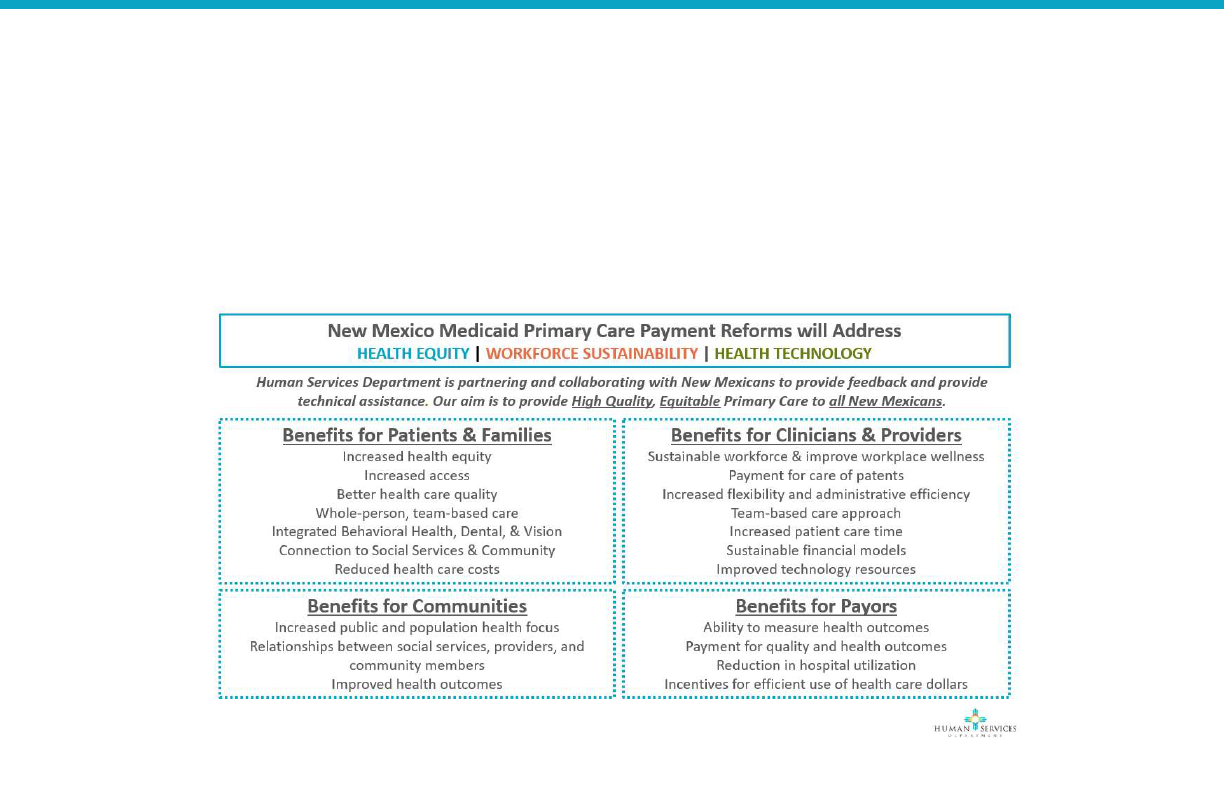

Designing the parameters of the new payment model

HSD has begun the preliminary work to develop the framework for the payment model, and the

approach is strongly influenced by the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network’s alternative

payment model framework. The framework will enable primary care providers and clinicians to engage

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 22 of 48

in value-based payment at a level of risk that is appropriate for their organizations and to move to more

advanced levels of payment over time, in phases. As part of the analysis, HSD and the PCC identified the

benefits of the payment model to patients and providers, including designing a preliminary tiered

measurement framework to create appropriate incentives to improve patient health outcomes and

minimize provider burden. The PCC team will continue to refine the payment model and determine

appropriate incentives and quality measures, and other performance metrics.

Building a new payment model built on community wisdom

Throughout 2022 HSD has met with providers, clinicians, professional societies and associations, and

community-based organizations to obtain input on considerations for payment reform design and

implementation, including provider associations such as:

New Mexico Medical Society

Native American Technical Advisory Committee

New Mexico Pediatrics Association

New Mexico Primary Care Association

New Mexico Medical Society

New Mexico Behavioral Health Providers Association

This engagement was a precursor to conducting a primary care payment reform provider and clinician

readiness survey, where we received 70 responses across the state. The purpose of this survey was to

better understand clinical organizations’ capacity to accept risk, barriers and facilitators to payment

reform implementation, actionable information on primary care providers’ readiness to succeed in

payment reforms, and to identify critical gaps that need to be addressed. The survey was coupled with

four focus groups with representatives of federally qualified health centers, small and medium-sized

physician practices, hospitals, and interprofessional teams (i.e., behavioral health providers, oral health

FIGURE 4: NEW MEXICO MEDICAID PRIMARY CARE PAYMENT REFORM BENEFITS

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 23 of 48

providers, and pharmacies). The findings from the survey and focus groups are presented in the

readiness assessment report included in this strategic plan.

Finally, in 2022 the PCC established the Primary Care Clinician and Provider Transformation

Collaborative and its Governing Council and Collaborative Cohort as a mechanism to provide input to

payment reform development and implementation and to bidirectionally communicate with

communities and constituencies.

During 2023, the PCC will continue to refine the new, primary care payment model, meet with

community members and stakeholders, and offer training and technical assistance to primary care

clinical organizations to help them succeed in preparation for the launch of the new payment model in

2024.

Primary Care Residency Expansion

A key strategy to PCC Goal 4 is the expansion of primary care physician residency programs. Pursuant to

2019 House Bill 480 (Graduate Medical Education Expansion Program Act), HSD provides funding to

new and expanded primary care residency programs (Family Medicine, General Pediatrics, General

Internal Medicine, and General Psychiatry). The statute also creates a governing body to oversee the

program and make funding recommendations to the HSD Secretary.

Since 2019, HSD, in collaboration with members of the community-based Primary Care Residency

Expansion Board & Advisory Group, have worked together to develop a strategic plan for residency

expansion throughout the state by:

Financially supporting new residency development and expansion of existing residencies,

particularly in rural and frontier communities. (Since FY 2019, 6 programs have received

development funding, totaling $1,554,811).

Increasing in-state retention post-residency.

Developing a statewide technical assistance resource center that supports programs with

resident recruitment and retention, staff and faculty development, curriculum development etc.

Amending state Medicaid policies, rules, and regulations to incentivize primary care residency

development.

As a result of these activities and the dedicated work of residency program leaders, over a 5-year period,

starting in 2019, primary care residencies are expected to grow from 8 to 16 (a 100% increase) in New

Mexico. At program maturity, this is expected to result in an increase in the number of primary care

residents in training from 142 to 264 (86% increase), and an increase in the number of graduates each

year will grow from 48 to 82, a 71% increase.

5-Year Timeline of Primary Care Residency Expansion in NM

Number of New First-Year Residents

Program 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 Total new

Residents

New

Graduates per

Year

Family Medicine 3 9 11 12 14 12 61 14

General Psychiatry 0 0 0 5 10 10 25 10

General Pediatrics 0 5 5 5 5 0 20 5

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 24 of 48

General Internal Medicine 2 2 2 0 5 5 16 5

Total Residents per Year 5 16 18 22 34 27 122 34

The organizations outlined below have consulted with the New Mexico Primary Care Training

Consortium (NMPCTC) and HSD to begin developing or expanding their programs. Access to necessary

resources may impact projected start dates. Table 1 provides a high-level overview of residency

expansion and Tables 2 and 3 describes expansion in more detail (by program and specialty).

Sponsoring

Institution

Type Location Specialty

Resident

Capacity

Status Notes

NMPCTC New Las Cruces

Gen.

Psychiatry

3 2024

ACGME application under

development

NMPCTC New Española

Family

Medicine

(FM)

4 2023

ACGME application

submitted, awaiting site

visit

Covenant

Health Hospital

New Hobbs FM 6 2024 Early Development

Covenant

Health Hospital

New Hobbs

Gen.

Psychiatry

2 2024 Early Development

Covenant

Health Hospital

New Hobbs

Internal

Medicine

TBD TBD Early Development

San Juan

Regional

New Farmington FM TBD TBD Early Stages

Three Crosses

Regional

Hospital

New Las Cruces IM 5 2024 Early Development

Hidalgo

Medical

Services

Reaccreditation Silver City FM 2 2024

Actively recruiting to re-

establish program

5

-

Year Timeline of New or Expanded Primary Care Residency Programs in NM (detailed)

Number of New First

-

Year Residents

Program 2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

Total

new

Residents

Family Medicine (3 Year Program)

TABLE 1: 5-YEAR TIMELINE OF PRIMARY CARE RESIDENCY EXPANSION IN NM

TABLE 2: 5-YEAR TIMELINE OF PRIMARY CARE RESIDENCY EXPANSION IN NM

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 25 of 48

Memorial Medical

Center (MMC)

& Gerald Champion

3

3

3

-

-

-

9

MMC & La Clínica de Familia

-

4

4

4

-

-

12

UNM & Shiprock

-

-

2

2

2

-

6

CHRISTUS St. Vincent

-

2

2

2

-

-

6

El Centro Family Health

-

-

-

4

4

4

12

Covenant Health Hospital

-

-

-

-

6

6

12

Hidalgo

Medical Services

-

-

-

-

2

2

4

General Psychiatry (4 Year Program)

UNM (expansion)

-

-

-

5

5

5

15

DAC Psychiatry

-

-

-

-

3

3

6

Covenant Health Hospital

-

-

-

-

2

2

4

General Pediatrics (3 Year Program)

UNM (expansion)

-

5

5

5

5

-

20

General

Internal Medicine (3 Year Program)

UNM (expansion)

2

2

2

-

-

-

6

Three Crosses Regional Hospital

-

-

-

-

5

5

10

Total Residents

Per Year

5

16

18

22

34

27

Total

new

residents

trained

=122

Conclusion

The NM Primary Care Council was established because the legislature listened to providers and clinicians

who demanded an urgent response to the crises in primary care. The current work of the council is in

response to that need. Payment reforms for Medicaid that will go live on January 1, 2024, have been

created in collaboration with providers and clinicians, and was built for the specific needs of New

Mexicans. As we prepare for these payment reforms, HSD and the PCC will offer technical assistance

and training. Establishing payment reforms will lay a foundation for future initiatives of the PCC in

supporting workforce sustainability, health equity, and health technology.

TABLE 3: 5-YEAR TIMELINE OF NEW OR EXPANDED PRIMARY CARE RESIDENCY PROGRAMS IN NM (DETAILED)

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 26 of 48

Acknowledgments

The contributions, wisdom, and talents of our esteemed colleagues make this five-year strategic plan

designed to improve primary care in New Mexico possible:

Primary Care Council Board and Advisory Members

1. Eileen Goode, RN: CEO, NM Primary Care Association

2. Jennifer K. Phillips, MD: CMO UNM Medical Group, Professor, Family Medicine, UNM School of

Medicine

3. Kathy R. Fresquez-Chavez, NP: CEO, Bella Vida Healthcare

4. Aaron Jacobs, MD: Physician, Associate Professor, Pediatrics Critical Care, UNM Health Sciences

5. Matthew Probst, PA: Chief Quality Officer, El Centro Family Health

6. Valory Wangler, MD: Founding Executive Director, Gallop Community Health

7. Deputy Secretary Laura Parajon, M.D.: NM Department of Health

8. Julie Weinberg: Director, Life and Health Division, NM Office of Superintendent of Insurance

9. Alisha Parada, MD: Chief Division of General Internal Medicine, Geriatrics and Integrative Medicine,

UNM Health Sciences Center

10. Anjali Taneja, MD: Executive Director, Casa de Salud

11. Keenan Ryan, PhC: Pharmacist, UNM Health

12. Jason Mitchell, MD: Senior Vice President, Chief Medical and Clinical Transformation Officer,

Presbyterian Healthcare Services

13. Jon Helm, RN: Nurse Flow Manager, First Choice Community Healthcare

14. Maggie McCowen, LISW: Executive Director, NM Behavioral Health Provider Association

15. Rohini McKee, MD: Chief Quality & Safety Officer, UNM Hospital

16. Ruby Ann Esquibel: Health Policy Coordinator, NM Legislative Finance Committee

17. Mercy Jones: Patient Advocate, Senior, College of Population Health UNM Health Sciences Center

18. Susan Wilson: Executive Director, NM Coalition for Healthcare Value

19. Pamela Blackwell: Director, Government Relations & Communications, NM Hospital Association

20. Wei-Ann Bay, MD: Retired

21. Carolyn Thomas Morris, PhD: Psychiatrist

22. Alanna Dancis, MSN, CNP, Medicaid Medical Director, New Mexico Human Services Department

Community Partners

1. Pamela Stanley, LPCC, Consultant, Caraway Solutions

2. Dan Otero, DBA: Chief Executive Officer, Hidalgo Medical Services

3. Jessica Osenbrügge, Community Initiatives Manager – Health & Nutrition, Road Runner Food Bank

4. Nancy Rodriguez, Executive Director, NM Alliance for School-Based Health Care

Primary Care Council Staff

1. Secretary David R. Scrase, M.D.: Secretary, Human Services Department

2. Nicole Comeaux: State Medicaid Director, Human Services Department

3. Alex Castillo Smith: Acting Deputy Cabinet Secretary, Human Services Department

4. Tim Lopez: Director, Office of Primary Care and Rural Health, New Mexico Department of Health

5. Roberto Martinez, M.D., MPH: Interim Health Equity Director, New Mexico Department of Health,

Public Health Division

6. Elisa Wrede: Project Manager, Food Security & Primary Care, New Mexico Human Services

Department

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 27 of 48

Appendix

Primary Care Return on Investment

Healthcare System Savings

A 2019 analysis from The Commonwealth Fund [22]

found several rigorous studies that incorporate a

variety of care management models — which link high-risk patients to needed medical and nonmedical

community supports — reduce utilization of costly health care services, lower costs of care, and produce

a return on investment (ROI). A few programs provided care management through multidisciplinary

teams made up of social workers, case managers, nurses, or physicians and connected patients with

community-based resources as needed. These demonstrated reduced ED visits, hospitalizations, home

health episodes, and skilled nursing home admissions. Several studies also evaluated the impact of

community health workers (CHWs) that connected at-risk patients with social services. A subset of these

studies showed CHWs contributed to a higher follow-up visit show rate, lower ED visits, reduced

Medicaid spending, and an ROI as high as $2.92 for every $1 spent.

Return on Investment: Local Economies

We can consider the economic value of increasing the primary care workforce in several ways. For

example, we can estimate the direct and indirect economic impact of physicians across medical

revenues generated during patient care (output), jobs, wages and benefits, and state and local tax

revenue. We calculate the direct impact from physician activity, and the indirect economic impact from

the industries supported by physicians. On average, each physician supports $3,166,901 in output, an

average of 17.07 jobs, approximately $1.4 million in total wages and benefits, and $126,000 in state and

local tax revenues.

[23]

Primary care dividends are not limited to physicians. Research shows other members of the primary care

interprofessional team produce economic savings. For example, a systematic review of 37 studies found

consistent evidence that cost-related outcomes such as length of stay, emergency visits and

hospitalizations for nurse practitioner care are equivalent to those of physicians.

[24]

Primary care generates additional revenue into the healthcare economy. A study of the economic

impact of a family practice clinic illustrated that for every $1 billed for ambulatory primary care, there

was $6.40 billed elsewhere in the healthcare system. Each full-time equivalent family physician

generated a calculated sum of $784,752 in direct, billed charges for local hospitals and $241,276 in

professional fees for other specialists. [25]

Return on Investment: Population Health

Research has shown the availability of a primary care physician in a rural area to lead to better health

outcomes, such as those relating to all-cause mortality (including cancer) and heart disease. An increase

in one primary care physician per 10,000 individuals results in: 1) an 11% decrease in emergency room

visits; 2) 6% decrease in hospital inpatient admissions; and, 3) 7% decrease in surgery utilization. [6] [26]

These improvements persist after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. Ultimately, people

who identify a primary care physician as their primary source of care are healthier, regardless of health

status or demographics.

New Mexico had the 12

th

highest drug overdose death rate in 2019 (30.4 per 100,000 population), and

the highest alcohol-related death rate in the U.S. (73.8 deaths per 100,000 population). [27]

Addressing

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 28 of 48

the many and complex behavioral health needs of New Mexicans through a fully integrated behavioral

health primary care model is paramount. It is possible to deliver behavioral health services that are

integrated with primary care at relatively low cost, of high quality, and result in improved access.

[28]

Integrating behavioral healthcare in primary care settings provides opportunities to address concerns

before they escalate to crises: screenings to diagnosis an illness; warm handoffs to reduce barriers to

transitioning into behavioral healthcare; guidance from behavioral health specialists acting as

consultants rather than direct service providers; and assessment and triage to short-term therapy or

coaching.

[28] [29]

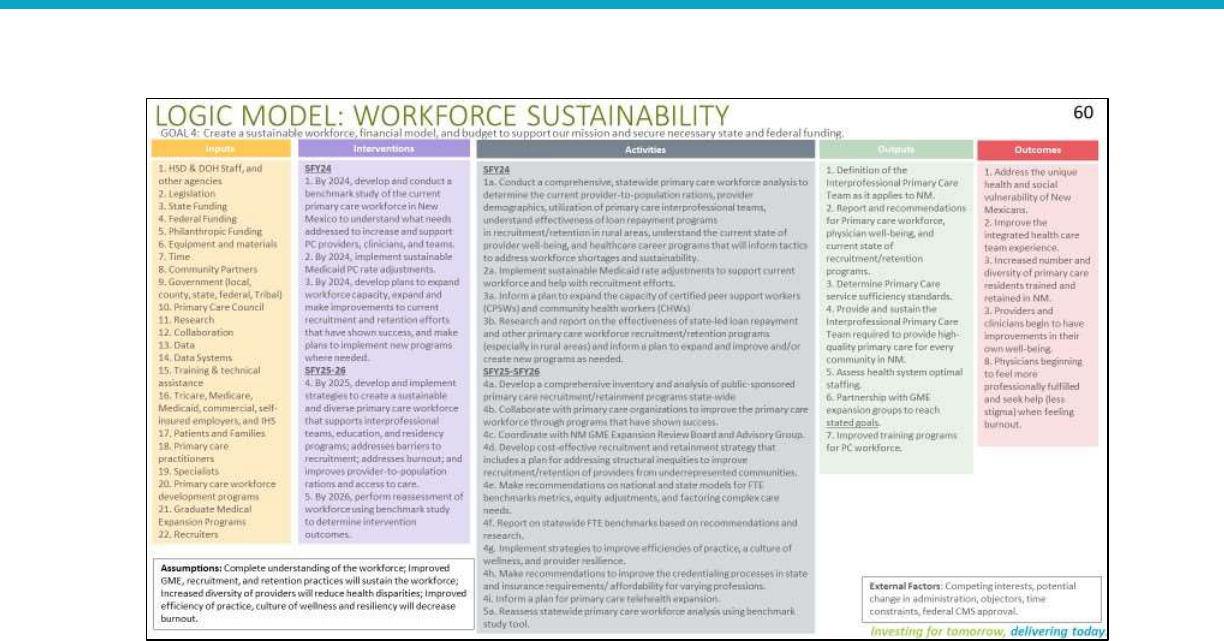

Primary Care Logic Models

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 29 of 48

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 30 of 48

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 31 of 48

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 32 of 48

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 33 of 48

Primary Care Best and Promising Practices

Topic: Dental Medicaid Managed Care

State: Oklahoma

Description: The Oklahoma Health Care Authority (OHCA) released on September 1, 2022, a request for

proposals (RFP) seeking at least two Medicaid dental managed care plans to serve 919,000 members.

[30] [31] Contracts will run from the award date, which is expected to be between January and June

2023, with six one-year renewal options. Enrollment will begin on October 1, 2023, and proposals are

due by October 31, 2022. Current dental benefit plans are DentaQuest, Liberty Dental Plan of Oklahoma,

and MCNA Dental.

Performance measures and outcome measures are on pp. 289-291 of the RFP. The quality measures are:

Percentage of children receiving an oral evaluation

Percentage of children receiving fluoride treatments

Percentage of children who receive sealants on their first molars

Percentage of all members who receive an annual dental visit

Percentage of periodontal evaluations for adults with periodontitis

Each of the measures includes specifications for data source, improvement targets, and the payment

incentive (withholds from the capitation rate).

State: New Hampshire

Description: The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services released on August 25,

2022, an RFP for a Medicaid dental managed care organization to serve approximately 88,000 adults.

[32]The program will be implemented on April 1, 2023, and run through March 31, 2026, with an

additional two-year option. Proposals are due September 30, 2022. The contract does not specify quality

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 34 of 48

measures but rather asks the bidders to propose their quality management plan metrics, APM strategy,

and quality expectations for the bidders’ provider network.

Relevance/applicability to New Mexico:

These three states’ RFPs for managed Medicaid dental care could help inform New Mexico’s alternative

payment model and how oral health is integrated into primary care. The Oklahoma performance metrics

seem to be particularly useful as a starting point for New Mexico’s performance measures for oral

health services.

Topic: Behavioral Health

State: Colorado

Description: Since 2019, CMS has worked with six states – Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, New Mexico,

Oregon, and South Dakota – to add additional behavioral health services to their state “benchmark”

plan. [33] Colorado recently created a Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) led by a cabinet-level

commissioner. [34] The BHA will lead a statewide behavioral health strategy, coordinating policy,

payment, and system design through the networked government with other state agencies. This

includes leading policy for children and youth behavioral health strategy with a senior child and youth

advisor working with the commissioner to ensure a coherent child and youth system of care. The BHA’s

governance structure includes an advisory council that will raise individual and community voice in the

state and a commitment to ensuring community-centered practices. The BHA intends to establish a

system for addressing complaints and grievances with behavioral health care; a system for monitoring

the performance of behavioral health providers; a comprehensive behavioral health safety-net system,

including emergency care, outpatient services, and case management; and a new system for licensing

behavioral health organizations and providers.

State: Minnesota

Description: The Minnesota Department of Human Services released on August 15, 2022, an RFP seeking

a current Minnesota Health Care Programs provider agency to provide school-linked substance use

disorder (SUD) services to students and families. [35] The contract is anticipated to begin on January 1,

2023 and run through June 30, 2026. Proposals are due on October 17, 2022. The detailed obligations

and additional measures of performance will be defined in the final negotiated contract.

Relevance/applicability to New Mexico:

The Colorado beneficiary advisory council may be a worthwhile model to emulate for engaging

members with lived experience and obtaining their input on quality measures and benchmarks.

The Minnesota school-based SUD model may help inform primary care SUD performance measures,

particularly once the contracts are awarded, and the performance measures are established.

Topic: Benchmarks for Health Equity

States: (multiple; Massachusetts)

A Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted in 2021 found that 12 states are measuring health

disparities as a focus for financial incentives: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa,

Massachusetts, Michigan, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. This is an increase from

only two states doing so just two years previously. [36]

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 35 of 48

Massachusetts is requesting a new Section 1115 waiver amendment to provide incentive payments to

provider networks and hospitals that collect accurate social risk factor data, identify and monitor

inequities through stratified data reporting, and achieve measurable reductions in health disparities.

[37]

Relevance/applicability to New Mexico:

Focusing on these 12 states’ – and in particular, Massachusetts’s – health equity benchmarks and

performance measures could help inform the development of health equity measures in New Mexico.

Topic: Behavioral Health Integration with Primary Care

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Health Resources

and Services Administration (HRSA) created a framework for progressive levels of integration between

behavioral health (BH) and primary care providers (PCPs). The three levels are:

1. Coordinated Care: Screen & Consultation | Minimal Collaboration

Care is provided in geographically disparate facilities. Providers communicate about shared patients.

BH providers work to meet care goals established by PCPs.

Examples of this approach include:

PCPs refer BH patients to services: Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

(SBIRT) [38]

BH providers work with patients to meet goals identified by PCPs: Vermont’s Hub and Spoke

Model

2. Co-Located Care: Co-Located | Better Collaboration

BH providers and PCPs share the same facility, aiding in better coordination.

Examples of this approach include:

BH providers are embedded with primary care practices, provide treatment, and monitor

progress: Collaborative Care Model and Comprehensive Primary Care Plus Model

PCPs and BH providers are embedded in the same facility: Common in FQHCs, [39] like the

Cherokee Heath Systems [40] and Golden Valley Health Centers. [41]

3. Integrated Care: Fully Transformed Care (also see: National Center of Excellence for Integrated

Health Solutions) [42]

Close collaboration in partly integrated practices or comprehensive partnerships in fully merged

practices. Integrated, patient-centered care plans, coordination, complex care management, SDoH

considerations, shared information systems, measurement of patient outcomes, and shared

decision-making.

Examples of this approach include:

Ongoing complex care management, treatment, and referrals: Medicaid Health Homes [43]

PCPs and BH providers operate under one management system: Intermountain Healthcare [44]

State: Colorado

Sustaining Healthcare Across Integrated Primary Care Efforts (SHAPE) aimed to examine the integration

of behavioral health and primary care through a global payment system. Practices that received global

payments showed a 4.8% lower total cost of care for attributed patients. [45]

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 36 of 48

State: Texas

The Harris County Hospital District Community Behavioral Health Program (CBHP) program integrates

behavioral health services into 12 Harris County (Houston suburbs) community primary care centers,

two school-based clinics, and a homeless services program. Services include evaluation and treatment of

scheduled patients and walk-in services for patients in crisis, including “curbside” consultations with

PCPs to support psychiatric care. CBHP expanded its capacity to address acute psychiatric service

shortages, reducing average wait times for new appointments from seven months to three weeks, and

admissions to hospital psychiatric emergency centers by 18%. [46]

State: Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP) is an interdisciplinary healthcare initiative

that assists PCPs who treat children and adolescents for psychiatric conditions. [47] MCPAP’s goal is to

expand access to BH treatment across the Commonwealth by making child psychiatry services available

to all PCPs. The model staffs each program team with two full-time child and adolescent psychiatrists,

licensed behavioral health clinicians, resource and referral specialists, and program coordinators. The

team aligns with and assists PCPs with the following integrated BH services:

Screening, identification, and assessment.

Treating mild to moderate cases of behavioral health disorders.

Making effective referrals and coordinating care for patients who need community-based specialty

behavioral health services.

State: Utah

Intermountain Healthcare, a non-profit healthcare system serving metropolitan Salt Lake City, launched

a project to integrate mental healthcare services into primary care practices. [48] Early results showed

that patients with depression treated in integrated clinics were 54% less likely to visit the emergency

department. In addition, patients treated in the integrated clinics had a 27% lower growth in the total

cost of care.

Relevance/Applicability to New Mexico:

Integrated care is crucial for expanding access to and improving the quality of behavioral health services

in New Mexico. Given the widespread barriers to accessing behavioral healthcare, especially with an

acute shortage of behavioral health providers, primary care practitioners may be seen as the default for

seeking behavioral health services. Integrated care becomes necessary to enable comprehensively

managed and optimally coordinated care, in addition to giving New Mexico primary care practitioners

practical tools for diagnosis and treatment. It also expands a culturally and linguistically tailored

workforce, including community health workers or peer support specialists who offer counseling, care

management, and social support. This approach has empirical support in improved behavioral health

access and outcomes across age groups and diagnoses. The approaches of other states may be useful

models for HSD payment systems and/or provider operations.

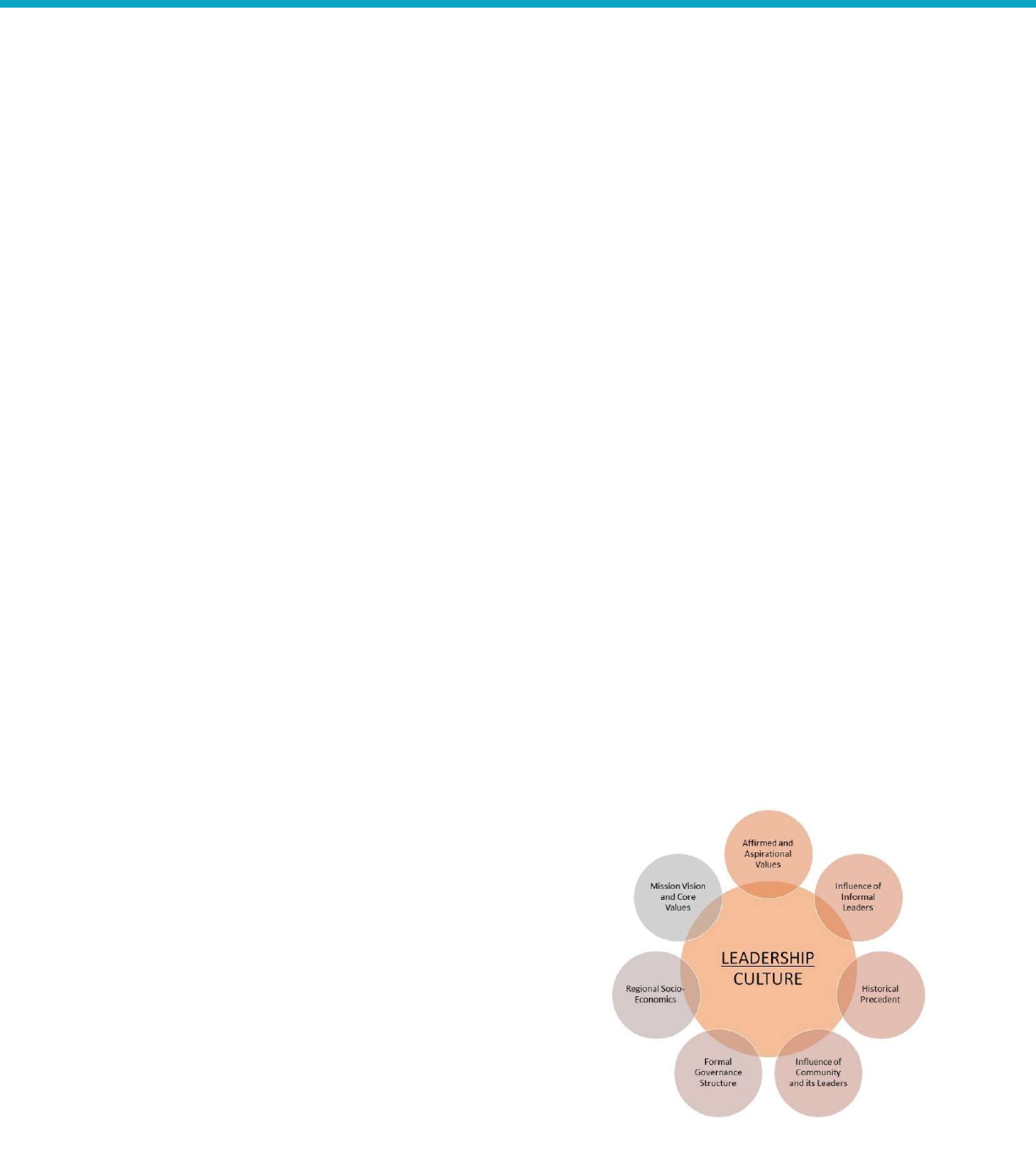

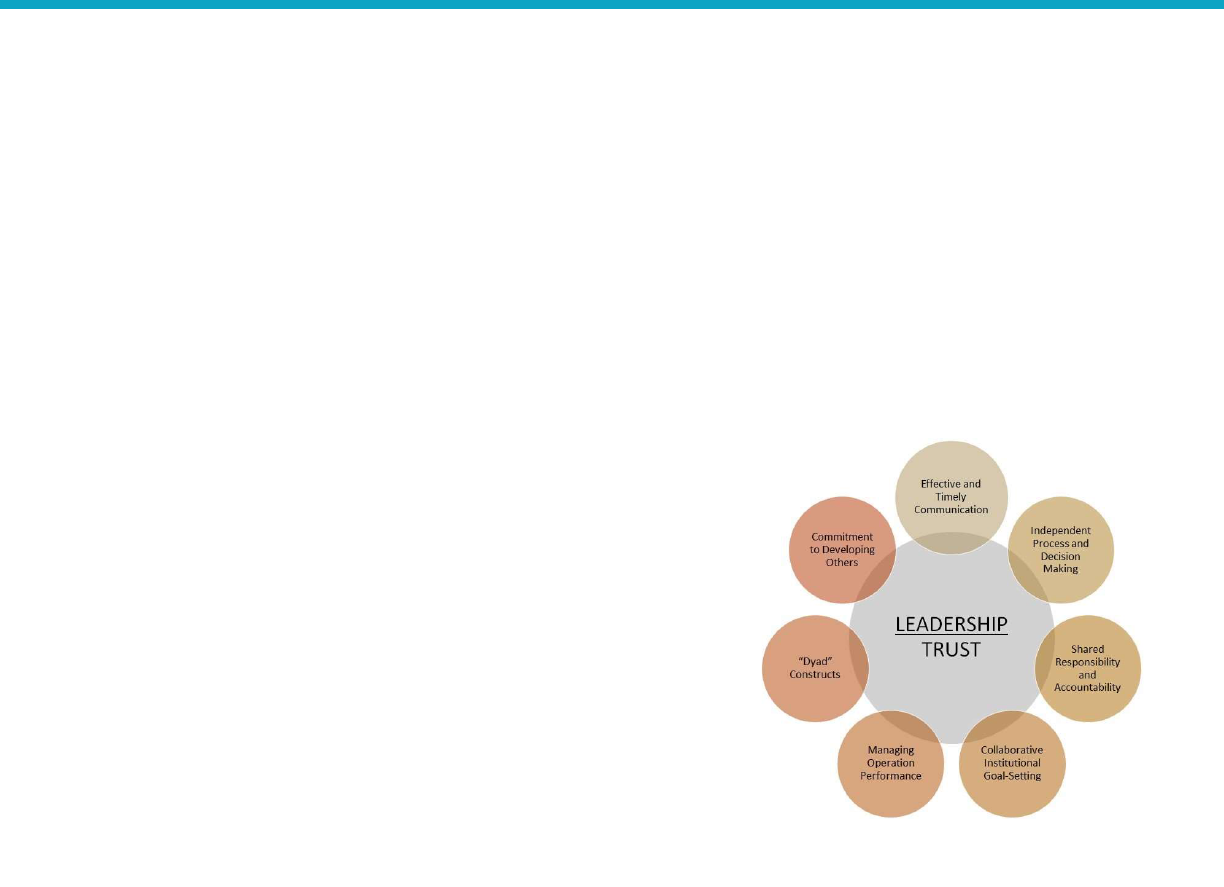

Topic: Leadership and Governance Considerations for Movement Toward Value-Based Care

Leadership must be committed to pursuing value-based care (VBC) and payment (VBP). There needs to

be a clear VBP strategy that includes the “why” and the “how” and it must be communicated

throughout the organization. A multidisciplinary committee structure charged with in-depth analysis and

making recommendations to the leadership governance board is often pivotal, where healthy discussion

and debate can occur to inform critical strategic decisions.

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 37 of 48

The framework for these recommendations is primarily based on the Accountable Care Learning

Collaborative Atlas framework, [49] evidence-based practices from large clinically integrated networks

that operate in risk contracts across lines of business, [50]

and models of leadership principles.

Success factors for operating a high-performing value-based organization:

1. Experienced and respected leadership governance board with an established track record of growth

and success.

2. Broad representation on the leadership board, including physicians.

3. Mix of young emerging leaders with more senior leadership.

4. Shared leadership and organizational vision for pursuing advanced alternative payment models.

5. Leaders engaged in rigorous analysis and debate of recommendations; these conversations should

be viewed as a constructive exercise.

6. The decision to pursue risk should be based on rigorous analysis of historical claims data,

identification of opportunities for improvement, a strategic and operational plan to address these

opportunities, and a financial pro forma that estimates cost and probability for profitability.

7. Leaders should be guided by performance metrics, timelines, and targets to monitor the successful

management of risk.

8. Leadership incentive structure should be aligned with key performance indicators to succeed in

global risk.

9. The leadership group should focus on success in value-based care and payment, including global risk

and a committee structure (clinical, operational, information technology, and finance) to feed

recommendations to this group.

10. Achieve consensus among leadership and staff in pursuing global risk.

Applicability to New Mexico

The New Mexico HSD and New Mexico Medicaid provider organizations are now at an inflection point

where they must pivot from the fee-for-service environment into a value-based environment with

delegation, capitation, upside, and downside risk. Organizations must accept that the healthcare

landscape is an environment of continual change, so the leadership of primary care provider

organizations must guide their staff and teams to embrace and benefit from a changing environment

rather than resist change. Marginal improvements, multiplied by time and teamwork, can magnify

actions, and these modest successes can catalyze the momentum for organizational change. Harnessing

the power of small incremental changes will gradually transform the organization and position it to

succeed under APMs.

Governance Structure

The following leadership governance structure designed for larger clinical organizations can serve as a

broad recommendation for more tailored governance within individual healthcare entities. Smaller

organizations will not need as elaborate a structure, but the critical processes and measures to track are

similar.

1. Establish an Executive Leadership Team (ELT) responsible for the vision and setting of the strategic

priorities and a multidisciplinary Operations Leadership Team (OLT) comprised of clinical and non-

clinical staff to execute the strategic priorities.

2. The ELT should comprise the senior executive leadership. The ELT will identify the organization's

strategic priorities and allocate resources. The ELT must align in the pursuit of value-based care and

payment timelines. Once the strategy is identified, they need to articulate the rationale and

methodology to the entire organization and review performance across the organization. This could

New Mexico Primary Care Council 2023

Page 38 of 48

include dashboards with membership trends, quality, and utilization trends for the practice and