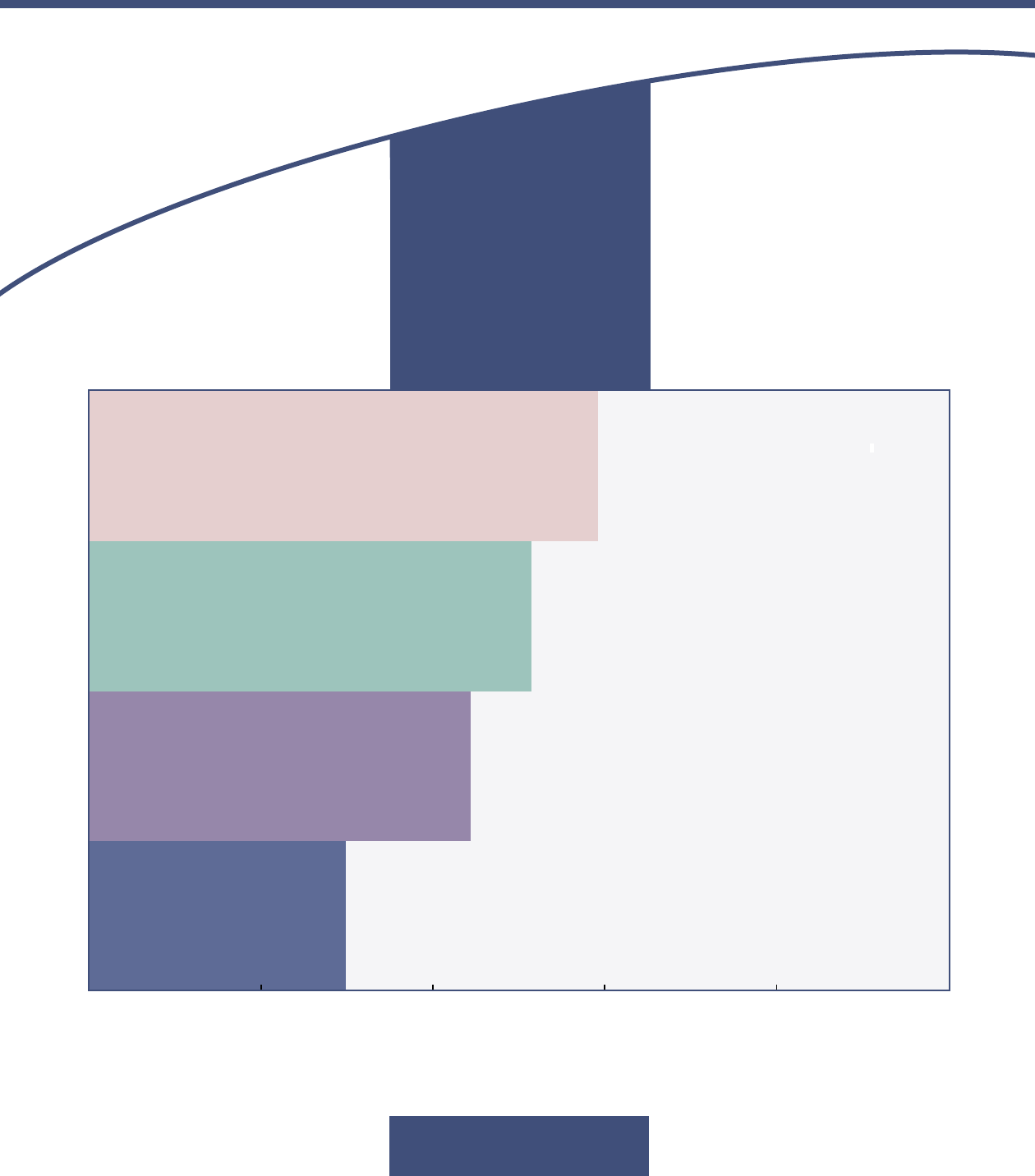

Percentage of People Eligible for Full Benefits from

Medicare and Medicaid Who Have Various Characteristics

Elderly

Originally Qualified for

Medicare Because of

Disability or Kidney Disease

Rather Than Age

Diagnosed With a Mental Illness

Receiving Long-Term

Services and Supports

0 20 40 60 80 100

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE

CBO

Dual-Eligible

Beneficiaries of

Medicare and

Medicaid:

Characteristics, Health

Care Spending, and

Evolv

ing Policies

JUNE 2013

CBO

Notes

Unless otherwise indicated, all of the calculations in this report are based on analysis by the

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and reflect spending by Medicare (by the federal

government) and Medicaid (by the federal and state governments). CBO does not have access

to data on spending by other payers. Out-of-pocket payments by Medicare and Medicaid

enrollees are excluded from the analysis. Most cost sharing incurred under Medicare for

dual-eligible beneficiaries is paid by Medicaid, and those payments are counted as Medicaid

spending. However, payments by Medicaid to cover the Medicare premiums of dual-eligible

beneficiaries are not included in estimates of Medicaid spending in this report because of data

constraints. Information about the data used in the analysis appears in the appendix.

Numbers in the text, tables, and figures may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Definitions of various terms used in this report appear in the glossary at the end of the report.

Correction:

On March 27, 2014, CBO reposted this document with various small corrections.

Misclassifying some people as eligible beneficiaries of Medicaid and misclassifying the reason

for some others’ eligibility affected the results of various calculations, which are reported

mostly in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 3 and in the passages in the text that discuss those results.

Corrections are noted on the pages where they occurred.

Pub. No. 4374

Contents

CBO

Summary 1

Why Are Policymakers Concerned About Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries? 1

What Characteristics and Spending Patterns Distinguish the Dual-Eligible Population? 2

What Strategies Are States and the Federal Government Pursuing to Reduce Costs and

Improve the Quality of Care for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries? 2

What Actions Might Federal Lawmakers Take and How Might They Affect the Budget? 2

Characteristics of Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries That Affect Health Care Needs and Spending 4

Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Risks 4

BOX: PARTIAL DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES 6

Use of Long-Term Care and Related Services 6

Diversity of Services Needed 8

Spending by Medicare and Medicaid for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries 8

Medicare’s and Medicaid’s Current Payment Systems for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries 11

Managed Care Plans in Medicare and Medicaid 11

BOX: ADJUSTING MEDICARE’S PAYMENTS FOR THE HEALTH RISKS OF BENEFICIARIES 12

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries’ Enrollment in Different Service-Delivery Systems 12

Efforts to Integrate Medicare’s and Medicaid’s Financing and Coordinate Care for

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries 15

Multipayer Medical-Home Programs 17

Fully Integrated Dual-Eligible Special-Needs Plans 17

Initiatives to Integrate Behavioral and Physical Health Care 17

Managed Long-Term Services and Supports 19

Financial Alignment Demonstration Projects 20

Challenges Facing Efforts to Integrate Financing and Coordinate Care 25

Potential Legislative Actions Targeting Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries and Their

Impact on the Federal Budget 28

Potential Legislative Changes 28

Possible Budgetary Effects of Legislative Changes 29

Appendix: Data Used in This Analysis 31

List of Tables and Figures 38

About This Document 39

Glossary 41

CBO

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries of

Medicare and Medicaid:

Characteristics, Health Care Spending, and

Evolving Policies

Summary

In 2009, the federal and state governments spent a total

of more than $250 billion on health care benefits for the

9 million low-income elderly or disabled people who

are jointly enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare

is a federal program that provides health insurance cover-

age to people who have disabilities, are diagnosed with

certain medical conditions, or are age 65 or older (50 mil-

lion people in 2009). Medicaid, which is funded jointly

by the federal government and the states, provides health

care coverage to low-income people who meet specific

requirements for income and assets and other eligibility

criteria (65 million in 2009).

1

People who are eligible to

receive benefits from both programs at the same time are

known as “dual-eligible beneficiaries.” All of those benefi-

ciaries qualify for full Medicare benefits, but they differ in

the amount of Medicaid benefits for which they are eligi-

ble. Seven million are “full duals,” who qualify for full

benefits from both programs. The other 2 million are

“partial duals,” who do not meet the eligibility require-

ments for full Medicaid benefits but qualify to have

Medicaid pay some of the costs they incur under

Medicare.

This report examines the characteristics and costs of dual-

eligible beneficiaries, focusing on 2009, the most recent

year for which comprehensive data were available when

the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) began this

analysis. The report also examines the different payment

systems that Medicare and Medicaid use to fund care for

dual-eligible beneficiaries and recent efforts at the federal

and state levels to integrate those payment systems and to

coordinate the care that such beneficiaries receive from

the two programs.

Why Are Policymakers Concerned About

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries?

Federal and state policymakers have growing concerns

about the high costs of dual-eligible beneficiaries—par-

ticularly full duals—as well as about the appropriateness

of the care they receive and the ways in which the sepa-

rate structures of Medicare and Medicaid may affect their

costs and care. Medicare generally pays for acute care

(hospitalization and other short-term care) and postacute

care (services provided in skilled nursing facilities or

elsewhere to help people recover from an acute illness

or surgery). Medicaid pays for long-term services and

supports (LTSS)—which includes long-term care as well

as social support services designed to help people stay in

their homes rather than move to institutions—and other

benefits that Medicare does not cover, such as dental and

vision services.

Those separate funding streams, and the different

payment rates and coverage rules within them, create

conflicting financial incentives for the federal and state

governments and for health care providers, potentially

increasing the costs of care. In addition, receiving care

through separate programs with different payment

and approval procedures increases the likelihood that

full duals—especially those who have many chronic

1. Those enrollment figures are based on total annual enrollment

rather than on average monthly enrollment or enrollment at a

particular point in time.

2 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

conditions and functional limitations—will be treated by

a variety of health care providers who are not coordinat-

ing their care, potentially increasing costs and worsening

outcomes.

What Characteristics and Spending Patterns

Distinguish the Dual-Eligible Population?

Dual-eligible beneficiaries are a varied group, but many

have extensive health care needs, stemming from multiple

illnesses and disabilities. In the case of full duals, for

example, half initially qualified for Medicare because of

disability rather than age, and nearly one-fifth have three

or more chronic conditions (see Figure 1). Consequently,

a sizable share of full duals, more than 40 percent, use

long-term services and supports—a far greater percentage

than for other Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries.

Although some full duals are fairly healthy and have rela-

tively low health care costs, full duals as a group account

for a disproportionate share of federal and state spending

for Medicare and Medicaid. Full duals make up 13 per-

cent of the combined population of Medicare enrollees

and aged, blind, or disabled Medicaid enrollees (the cate-

gories of Medicaid participants who might also qualify

for Medicare), but they account for 34 percent of the two

programs’ total spending on those enrollees.

2

What Strategies Are States and the Federal

Government Pursuing to Reduce Costs and Improve

the Quality of Care for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries?

Many states are working to eliminate differences in the

financial incentives that health care providers face under

Medicare and Medicaid and to improve the coordination

and quality of care for dual-eligible beneficiaries within

the scope of current law. States’ efforts include establish-

ing initiatives under which Medicare, Medicaid, and

private insurers pay fees to the same primary care practice

to manage care for patients; contracting with plans in

Medicare’s managed care program (Medicare Advantage)

to provide services covered by Medicaid; coordinating

physical and behavioral health care for dual-eligible

beneficiaries who have chronic mental illnesses; and

developing managed LTSS programs.

3

At the same time,

the federal government, through the Medicare Advantage

program, has encouraged the establishment of special

health plans for full duals that target their particular

needs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created new options for

addressing financing and quality-of-care issues for dual-

eligible beneficiaries.

4

The largest initiative in that area

under the new law is a three-year demonstration project

to integrate Medicare’s and Medicaid’s financing for full

duals, which 26 states applied to participate in. The first

state projects are due to begin this summer.

What Actions Might Federal Lawmakers Take and

How Might They Affect the Budget?

Various restrictions exist under current law that impede

efforts to reduce costs and improve the quality of care for

dual-eligible beneficiaries by more fully integrating that

care. For example, participation in Medicare’s managed

care program is optional for dual-eligible beneficiaries, as

it is for other Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, states

generally have little information about, and limited con-

trol over, the provision of services covered by Medicare.

Moreover, Medicare and Medicaid contract separately

with managed care organizations even if a beneficiary

receives services from both programs through the same

managed care organization.

5

Federal lawmakers might

choose to relax those and other restrictions—or enact

broader program changes—in an effort to more fully

integrate the care provided to full duals.

The impact of such policy changes on the federal budget

would be likely to depend on multiple factors, such as

how payment rates to providers would compare with the

rates under current law, whether certain complex services

(such as behavioral health care) would be included in

2. Age and blindness or disability are two of the eligibility categories

for Medicaid; the dual-eligible population is a subset of those

categories of beneficiaries. (The remaining Medicaid population

consists largely of children and their parents as well as pregnant

women. In addition, a new category of participants—non-

disabled, nonelderly, childless adults—will begin enrolling in

Medicaid in 2014 because eligibility for that group is expanding

under current law. Those other populations tend to have lower

health care costs than the aged, blind, or disabled.)

3. Behavioral health care includes mental health and substance

abuse services.

4. The ACA comprises the Patient Protection and Affordable

Care Act (Public Law 111-148), the health care provisions of

the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010

(P.L. 111-152), and, in the case of this report, the effects of subse-

quent related judicial decisions, statutory changes, and adminis-

trative actions.

5. One exception is PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the

Elderly) programs, which can use combined Medicaid and

Medicare funds for the full set of services they provide.

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 3

CBO

Figure 1.

Characteristics of Full Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries, 2009

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Notes: Dual-eligible beneficiaries are people who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid at the same time and who are eligible to receive

benefits from both programs. “Full duals” qualify for full benefits from both programs.

ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

a. Includes federal and state spending for Medicaid but excludes Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

b. The Medicare program consists of three parts: Hospital Insurance (Part A), Medical Insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage

(Part D). Medicare Part C (known as Medicare Advantage) specifies the rules under which private health care plans can assume

responsibility for, and be compensated for, providing benefits covered under Parts A, B, and D.

Distribution of Full Duals and Spending for Them, by Health Status

(Percent)

0123–45+

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Full-Dual Population

Total Medicare and

Medicaid Spending for

Full-Duals

0 102030405060708090100

Elderly

Originally Enrolled in Medicare

Because of a Disability or ESRD

Receiving Any Long-Term

Services and Supports

Diagnosed With a

Mental Illness

Share of Full Duals With Selected Characteristics

Number of Chronic Conditions Percent

All Full Duals Full Duals in

Top 10 Percent of

Medicaid Spending

per Beneficiary

Full Duals in

Top 10 Percent of

Medicare Spending

per Beneficiary

Full Duals in

Top 10 Percent of

Combined Spending

per Beneficiary

Full Duals in

Bottom 33 Percent of

Combined Spending

per Beneficiary

Full Duals in

Bottom 50 Percent of

Combined Spending

per Beneficiary

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

15,200

14,400

3,800

80,500

17,900

5,300

21,700

75,700

7,400

63,000

60,300

6,900

1,000

1,600

1,500

1,900

3,100

2,000

Medicaid

a

Medicare Parts A and B

b

Medicare Part D

b

Average Spending Per Beneficiary, by Program and Spending Group

(2009 dollars)

*

*

*

[* Value corrected]

4 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

overall payment rates or be paid for separately, and

whether beneficiaries’ participation in new models for

delivering care would be voluntary or mandatory.

Characteristics of Dual-Eligible

Beneficiaries That Affect Health Care

Needs and Spending

Both Medicare and Medicaid serve a broad range of

elderly and disabled beneficiaries. Some of them (full

duals) receive full benefits from both programs. Others

(partial duals) receive full Medicare benefits but limited

assistance from Medicaid, and the remainder (nonduals)

receive benefits only from Medicare or only from Medic-

aid. The need for health care services varies widely both

within and among those groups of beneficiaries, reflect-

ing differences in the prevalence of disabilities and health

conditions. Those differences lead to large variation in

average spending per beneficiary: In 2009, total Medicare

and Medicaid spending per beneficiary (including both

state and federal spending) ranged from an average of

about $8,300 for nondual Medicare beneficiaries to

$33,400* for full duals (see Table 1).

This report focuses on full duals, who are the main target

of recent policy initiatives and who account for a signifi-

cant share of spending by Medicare and Medicaid. Partial

duals share some of the characteristics of full duals, but

they are much less likely to use nursing facilities and

other types of long-term services and supports. That dif-

ference causes average Medicaid spending for them to be

much lower—and average Medicare spending to be

somewhat lower—than for full duals. (More information

about the partial-dual population is presented in Box 1.)

A detailed analysis of the ways in which people become

dual-eligible beneficiaries is beyond the scope of this

report. However, one large group of dual-eligible benefi-

ciaries consists of Medicare enrollees who became eligible

for Medicaid by spending down their resources, in many

cases while they were in nursing facilities. In general, such

beneficiaries have high health care costs. Other dual-

eligible beneficiaries are Medicare enrollees who gained

Medicaid coverage because they had low income and met

Medicaid’s specific eligibility criteria for age, blindness, or

disability; that group may not initially incur large medical

expenses. Still other dual-eligible beneficiaries became

disabled and had low income; they usually qualified for

Medicaid quickly and became eligible for Medicare later

(because a waiting period exists between qualifying for

Social Security’s Disability Insurance program and

qualifying for Medicare coverage).

6

Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Risks

Full duals are much more likely than other Medicare ben-

eficiaries to have initially qualified for Medicare because

of physical or mental disabilities—factors that increase

people’s need for health care, rehabilitation services, and

long-term care and that may reduce their ability to navi-

gate the health care system.

7

Specifically, just over half of

the people who were full duals in 2009 originally became

eligible for Medicare on the basis of disability or end-

stage renal disease (ESRD) rather than age, compared

with just 17 percent of nondual Medicare beneficiaries.

Reflecting that reason for Medicare eligibility, 41 percent

of full duals in 2009 were under age 65, compared with

only 11 percent of nondual Medicare beneficiaries.

Looked at another way, disabled Medicare beneficiaries

were more than three times as likely as elderly Medicare

beneficiaries to be full duals.

In conjunction with higher rates of disability, full duals

were about twice as likely as nondual Medicare beneficia-

ries to have at least three chronic conditions, and they

were nearly three times as likely to have been diagnosed

with a mental illness.

8

Consequently, medical risk

scores—which indicate differences in expected spending

by Parts A and B of Medicare for different beneficiaries

based on diagnosed conditions and demographic charac-

teristics—were about 55 percent higher for full duals, on

average, than for nondual Medicare beneficiaries.

6. People who receive benefits from the Disability Insurance pro-

gram are eligible for Medicare coverage after two years of receiving

disability benefits, regardless of their age. In certain cases, such as

with a diagnosis of end-stage renal disease, the waiting period

depends on the stage of the illness. In addition, some people with

end-stage renal disease are eligible for Medicare without partici-

pating in the Disability Insurance program.

7. See, for example, Linda P. Fried and others, “Untangling the

Concepts of Disability, Frailty, and Comorbidity: Implications for

Improved Targeting and Care,” Journals of Gerontology: Medical

Sciences, vol. 59, no. 3 (March 2004), pp. M255–M263,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255.

8. CBO identified mental illness using risk-adjustment data

(described in the appendix). Medicare enrollees were classified for

this analysis as having a mental illness if they were listed as having

a diagnosis from the previous year of schizophrenia; major depres-

sive, bipolar, and paranoid disorders; or other major psychiatric

disorders.

[* Value corrected]

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 5

CBO

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries, Compared With

Those of Certain Other Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries, 2009

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Note: n.a. = not applicable; N.A. = not available; * = between zero and 0.5 percent.

a. Dual-eligible beneficiaries are people who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid at the same time and who are eligible to receive benefits

from both programs. “Full duals” qualify for full benefits from both programs; “partial duals” qualify for full benefits from Medicare but

only partial benefits from Medicaid (meaning that Medicaid pays some of the expenses they incur under Medicare, such as premiums,

but does not cover additional health care services, such as long-term services and supports). “Nonduals” qualify for benefits only from

Medicare or only from Medicaid. (For more details, see the glossary.)

b. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services calculates a risk score for each Medicare enrollee on the basis of his or her medical

diagnoses and demographic characteristics. The scores are used to adjust Medicare’s payments to managed care plans to reflect

enrollees’ expected costs for Parts A and B of Medicare. Risk scores are normalized such that the average assigned risk score for enrollees

in fee-for-service Medicare is 1.0. In order to use a common framework for comparing the health status of various beneficiaries, CBO only

reports risk scores from the community version of the CMS-HCC model (see the appendix for details). For that reason and because CBO

includes people enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (not just fee-for-service Medicare), the average risk score for the whole Medicare

population, as reported above, will not equal 1.0.

c. Includes federal and state spending for Medicaid but excludes Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

d. The Medicare program consists of three parts: Hospital Insurance (Part A), Medical Insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage

(Part D). Medicare Part C (known as Medicare Advantage) specifies the rules under which private health care plans can assume

responsibility for, and be compensated for, providing benefits covered under Parts A, B, and D.

7.1 2.1 39.6 6.3 **

41 40 11 88 **

59 60 89 12 **

Percentage With Various Characteristics

Female 62 61 54 51

Black 20 22 8 30 **

Hispanic 8 4 1 14 **

Living in a rural area 21 29 20 20

Originally enrolled in Medicare because of a disability

or end-stage renal disease 52 54 17 n.a.

Diagnosed with three or more chronic conditions 19 14 9 N.A.

Institutionalized 15 * 1 4

Receiving any long-term services and supports 44 14 9 18 **

Diagnosed with a mental illness 30 25 11 N.A.

Average Community Medical Risk Score

b

1.5 1.3 1.0 n.a.

15,200 ** 800 n.a. 15,500 **

Medicare

d

14,400 11,800 7,800 n.a.

3,800 3,200 400 n.a.

_

______

_

______

_

_____ ______

Total Average Spending by Medicaid and Medicare

c

33,400 ** 15,700 8,300 15,500

**

Parts A and B

Part D

Nonelderly (Under age 65)

Elderly (Age 65 or older)

Number of Beneficiaries (Millions)

Duals Duals

Beneficiaries

a

Beneficiaries Medicaid Beneficiaries

Medicaid

c

Dual-Eligible

PartialFull Medicare

Nondual

Blind, or Disabled

Nondual Aged,

Average Spending per Beneficiary, by Program (Dollars)

Distribution by Age (Percent)

[** Value corrected]

6 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

Among both full duals and nondual Medicare beneficia-

ries, those age 65 or older were much more likely than

younger beneficiaries to have been diagnosed with

three or more chronic conditions, and they had corre-

spondingly higher average medical risk scores (see

Table 2). Those differences between age groups were

larger, however, for the full-dual population. By contrast,

beneficiaries under age 65 in both groups were more

likely than elderly beneficiaries to have been diagnosed

with a mental illness.

Use of Long-Term Care and Related Services

One notable characteristic that distinguishes full duals

from their nondual counterparts in Medicare and Medic-

aid is their high rate of use of both community-based and

institutional long-term services and supports.

9

LTSS

Box 1.

Partial Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries

Partial duals are eligible for complete benefits from

Medicare but only limited benefits from Medicaid.

Those limited benefits consist of having Medicaid

pay some of the expenses they incur under Medicare,

such as premiums and, in many cases, cost sharing for

services covered by Medicare. The extent of the assis-

tance that partial duals receive from Medicaid varies

with their income and assets and, to some extent,

with differences in state policies. (Some states’ Medic-

aid programs have higher ceilings on income and

assets for both full and partial duals than the federal

government requires.)

In certain ways, partial duals are very similar to full

duals: About 40 percent of both populations are

under age 65, roughly 60 percent of both populations

are female, and just over half of both populations

qualified for Medicare because of a disability or

end-stage renal disease (see Table 1 on page 5). On

average, however, partial duals tend to be healthier

and have less need for services than full duals. For

example, fewer of them have at least three chronic

conditions (14 percent of partial duals, compared

with 19 percent of full duals), and their average med-

ical risk score is nearly 15 percent lower than that of

full duals. (Medical risk scores, which the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services calculate to adjust

Medicare’s payments to managed care and prescrip-

tion drug plans, reflect enrollees’ expected costs for

Parts A and B of Medicare.) That difference in aver-

age risk scores, and thus in the predicted use of acute

and postacute care services, is reflected in the fact that

Medicare spent an average of $15,000 per beneficiary

for partial duals in 2009 but $18,200 for full duals.

The key difference in use of services, however,

between those two groups involves long-term services

and supports: Partial duals are 70 percent less likely

to use those services than full duals are.

1

In addition,

less than 0.5 percent of partial duals are institutional-

ized, compared with 15 percent of full duals. To some

extent, differences between the two groups in the use

of nursing facilities reflect the factors that make

someone a full or partial dual-eligible beneficiary.

Partial duals may become eligible for full Medicaid

benefits—and thus become full duals—if they

develop the need for long-term nursing home care,

which is very expensive. Specifically, such beneficia-

ries may gain full Medicaid eligibility because of

spending down their assets or because of higher ceil-

ings on income and assets for people living in nursing

facilities, depending on states’ eligibility rules for

Medicaid.

1. In fact, a comparison of full duals and partial duals who do

not use long-term services and supports shows that those two

populations are similar; the partial duals have slightly more

chronic conditions, somewhat higher medical risk scores, and

somewhat higher Medicare spending, on average. Those dif-

ferences may stem from the fact that partial duals who do not

use long-term services and supports are more likely than their

full-dual counterparts to be elderly.

9. All discussion in this report of use of services refers to services cov-

ered by Medicare or Medicaid; CBO does not have access to data

on beneficiaries’ use of other services. Therefore, this analysis may

underestimate LTSS use by partial duals and nondual Medicare

beneficiaries if those services are paid for by the beneficiary or by

another payer other than Medicare.

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 7

CBO

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries, Compared With

Those of Certain Other Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries, 2009, by Age

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Note: n.a. = not applicable; N.A. = not available; * = between zero and 0.5 percent.

a. Dual-eligible beneficiaries are people who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid at the same time and who are eligible to receive benefits

from both programs. “Full duals” qualify for full benefits from both programs; “partial duals” qualify for full benefits from Medicare but

only partial benefits from Medicaid (meaning that Medicaid pays some of the expenses they incur under Medicare, such as premiums,

but does not cover additional health care services, such as long-term services and supports). “Nonduals” qualify for benefits only from

Medicare or only from Medicaid. (For more details, see the glossary.)

b. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services calculates a risk score for each Medicare enrollee on the basis of his or her medical

diagnoses and demographic characteristics. The scores are used to adjust Medicare’s payments to managed care plans to reflect

enrollees’ expected costs for Parts A and B of Medicare. Risk scores are normalized such that the average assigned risk score for enrollees

in fee-for-service Medicare is 1.0. In order to use a common framework for comparing the health status of various beneficiaries, CBO only

reports risk scores from the community version of the CMS-HCC model (see the appendix for details). For that reason and because CBO

includes people enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (not just fee-for-service Medicare), the average risk score for the whole Medicare

population, as reported above, will not equal 1.0.

c. Includes federal and state spending for Medicaid but excludes Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

d. The Medicare program consists of three parts: Hospital Insurance (Part A), Medical Insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage

(Part D). Medicare Part C (known as Medicare Advantage) specifies the rules under which private health care plans can assume

responsibility for, and be compensated for, providing benefits covered under Parts A, B, and D.

2.9 4.2 0.8 1.2 4.3 35.3 5.6 0.8 **

Percentage With Various Characteristics

Female 52 69 51 68 44 55 49 66

Black 23 17 26 20 16 7 31 18

Hispanic 69 3 4311322

Living in a rural area 22 20 29 29 22 20 20 14

Originally enrolled in Medicare because of a disability

or end-stage renal disease 100 18 100 23 100 8 n.a. n.a.

Diagnosed with three or more chronic conditions 8 26 10 17 6 10 N.A. N.A.

Institutionalized 4 23 * 1 * 1 2 17

Receiving any long-term services and supports 31 54 10 16 4 9 16 28

Diagnosed with a mental illness 37 25 37 17 19 10 N.A. N.A.

Average Community Medical Risk Score

b

1.2 1.8 1.2 1.4 0.8 1.0 n.a. n.a.

14,600 15,500 1,100 600 n.a. n.a. 16,200 9,900 **

Medicare

d

12,100 16,100 11,100 12,200 6,600 8,000 n.a. n.a.

4,500 3,300 4,200 2,500 800 400 n.a. n.a.

_____

_

____

_

____

_

____

_

____ _____ _____

_

____

Total Average Spending by Medicaid and

Medicare

c

31,100 34,800 16,400 15,300 7,400 8,400 16,200 9,900

**

Nondual Medicare

Nondual Aged,

Blind, or Disabled

Medicaid

or Older

Beneficiaries

Under Age 65 Under Age 65Age 65

Age 65 or Older

Beneficiaries

Age 65

Part D

Number of Beneficiaries (Millions)

Average Spending per Beneficiary, by Program (Dollars)

Medicaid

c

Parts A and B

Age 65 or Older

Full Duals

a

Age 65 or Older

Partial Duals

a

Under Age 65 Under

**

**

**

**

**

**

[** Value corrected]

8 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

includes long-term care provided in nursing homes and

skilled nursing facilities, as well as hospice care, home

health care, and other social support services that enable

beneficiaries to continue living in the community (that is,

outside institutions).

10

In 2009, full duals were about

five times as likely to use LTSS as nondual Medicare

beneficiaries (44 percent versus 9 percent) and more than

twice as likely to use those services as nondual aged,

blind, or disabled (ABD) Medicaid beneficiaries (44 per-

cent versus 18 percent).* Those differences were reflected

in the various groups’ rates of institutionalization: 15 per-

cent for full duals, compared with 1 percent for nondual

Medicare beneficiaries and 4 percent for nondual ABD

Medicaid beneficiaries. Use of LTSS was particularly high

among elderly full duals, more than half of whom used

such services. Likewise, nearly one-quarter of elderly full

duals lived in an institution.

Diversity of Services Needed

Designing cost-effective programs to provide care for full

duals is challenging in part because those beneficiaries

vary widely in their needs for medical treatment, long-

term care, and social services. For example, 85 percent of

full duals lived outside nursing homes in 2009. Of them,

35 percent received community-based long-term services

and supports, 14 percent had multiple chronic conditions

but did not use such services, and the other 51 percent

had no more than one chronic condition and also did not

use any of those services.

11

The need for services can also vary considerably within

such subgroups. For instance, more than half of full duals

who used community-based LTSS in 2009—and one-

third of those in institutions—had no more than one

chronic condition. (However, some disabling conditions

for which beneficiaries may need nursing home care or

community-based services, such as physical, intellectual,

or developmental disabilities, may not be represented in

data on chronic conditions.) In addition, some beneficia-

ries with multiple chronic conditions have behavioral

health problems, cognitive impairments, or developmen-

tal disabilities that compound the effects of other chronic

illnesses and complicate the management of their care.

Given that diversity of needs, using any single approach

to deliver care to all dual-eligible beneficiaries may be

infeasible. An alternative would be to target subgroups

with the particular services they need, using the models of

care that are most appropriate for them.

12

Such targeting

might require more resources and data than a “one size

fits all” approach, however, which would increase the

administrative costs of providing care.

Spending by Medicare and Medicaid for

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries

Among full duals, Medicare is the primary payer for acute

care services (such as inpatient and outpatient hospital

services, physicians’ services, and prescription drugs) and

for postacute care (such as care in skilled nursing facilities

and home health services).

13

Medicaid is the primary

payer for full duals’ long-term services and supports

(including nursing home care), and it also pays for some

of their acute care costs, such as cost sharing under Medi-

care and some acute care services that Medicare does not

cover (such as dental and vision care). That division of

responsibilities, and the health status and service needs of

full duals, are reflected in the amount that each program

pays per full dual-eligible beneficiary.

In part because full duals have higher-than-average health

risks, they cost Medicare much more, per person, than

other Medicare beneficiaries did in 2009: an average of

about $18,200 (including spending by all parts of the

program), compared with about $8,300 for nondual

Medicare beneficiaries (see Table 1 on page 5). Likewise,

because full duals use long-term services and supports at a

relatively high rate, state and federal Medicaid spending

was almost as high for that population as it was for the

nondual aged, blind, or disabled Medicaid population:

10. Medicare covers care in skilled nursing facilities, hospice care, and

home health services under certain circumstances when a benefi-

ciary meets the requirement for Medicare’s postacute care benefits.

That Medicare coverage is typically short term in nature and is

intended to help beneficiaries recover from acute conditions for

which they are also receiving medical care. Medicaid’s provision of

nursing home, hospice, and home health services could substitute

for those postacute care services for full duals if the Medicare

benefit was not available.

11. That breakdown of beneficiaries follows one used in Randall

Brown and David R. Mann, Best Bets for Reducing Medicare Costs

for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries: Assessing the Evidence (Kaiser Family

Foundation, October 2012), www.kff.org/medicare/8353.cfm.

12. Ibid.

13. The primary payer of a health care bill is the first organization to

pay what it owes for that bill; secondary and other payers make

payments based on any remaining amount owed beyond what the

primary payer covered.

[* Sentence corrected]

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 9

CBO

about $15,200 per beneficiary, on average, versus

$15,500.

14

* That difference is particularly notable

because it means that Medicaid is spending about as

much for only a portion of the health care services that

full duals receive (its share) as for all of the services that

nondual ABD beneficiaries receive.*

Together, Medicare and Medicaid paid an average of

$33,400* per full dual in 2009, with Medicare’s share

being slightly more than half (see Table 3). Of that

amount, 61 percent was for acute care services, 6 percent

was for postacute care, and 33 percent was for long-term

care (including both institutional care and community-

based services).

15

That average for the entire full-dual

population masks wide variation in spending for individ-

uals. For the most costly 10 percent of full duals,

Medicare and Medicaid paid a combined $130,200 per

beneficiary, on average. At the other end of the cost spec-

trum, a substantial share of full duals used relatively few

services: Medicare and Medicaid paid a combined $4,100

per beneficiary, on average, for people in the least costly

33 percent of full duals (see Figure 1 on page 3).

The distribution of spending between the two programs

also varied by beneficiary. In general, dual-eligible benefi-

ciaries for whom Medicaid spent especially large amounts

in 2009 had much lower spending by Medicare, and vice

versa. For example, Medicaid was responsible for nearly

80 percent of the combined spending for full duals who

were in the top 10 percent of Medicaid spending per

beneficiary—people who typically had high long-term

care expenses but close-to-average acute care costs (see

Table 3). Similarly, Medicare covered nearly 80 percent of

total spending for full duals who were in the top 10 per-

cent of Medicare spending—individuals whose average

acute care costs were high but whose long-term care

expenses were relatively low. Spending for full duals who

were in the top 10 percent of combined spending per

beneficiary was more evenly distributed between the two

programs (averaging $63,000 for Medicaid and $67,200

for Medicare in 2009) and among the types of services

paid for. About 54 percent of spending for that costliest

group was for acute care, 38 percent was for long-term

care, and the other 8 percent was for postacute care.

Differences in spending and service use among subgroups

of the full-dual population are partly attributable to dif-

ferences in the prevalence of various chronic conditions.

Among full duals who were in the top 10 percent of Med-

icaid spending in 2009, for instance, 41 percent had

dementia, compared with 14 percent of the overall full-

dual population. Likewise, although full duals in the top

10 percent of Medicare spending or the top 10 percent of

combined spending had much the same set of common

chronic conditions as the total full-dual population, the

prevalence of specific conditions varied substantially

among those groups. Almost half of full duals in the

top 10 percent of Medicare spending had diabetes, and

39 percent had congestive heart failure—roughly twice

the prevalence of those conditions among all full duals.

Other factors drive differences in spending as well. For

example, average spending for elderly and nonelderly full

duals was much closer in 2009 than might be expected,

given how much the two age groups differ in prevalence

of chronic conditions, average medical risk scores, and

use of LTSS (see Table 2 on page 7). Medicaid spending

for the two groups was especially close, partly because

Medicaid spends more on non-LTSS services for the non-

elderly population than for the elderly population, but

also because average Medicaid spending on LTSS among

users of those services is about 40 percent higher for the

nonelderly than for the elderly (not shown in Table 2).

That pattern suggests that chronic conditions may be less

useful predictors of spending for the disabled population

than for the elderly and that other factors also contribute

to disabled beneficiaries’ use of services.

Spending on dual-eligible beneficiaries also varies sub-

stantially among states. That variation may result from

differences in the payment rates, covered services, and eli-

gibility rules of state Medicaid programs as well as from

differences in the share of beneficiaries who have multiple

chronic conditions.

14. All figures for Medicaid spending in this report include both

the state and federal shares of Medicaid spending but exclude

Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

15. Spending for long-term care includes only the long-term

care portion of LTSS. Notably, Medicaid’s institutional and

community-based long-term care is included in this category,

but Medicare’s skilled nursing and home health services are

included in the postacute care category. Hospice care—provided

through both Medicare and Medicaid—is included in the acute

care category. See the appendix for more details.

[* Sentence or value corrected]

10 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

Table 3.

Spending for Full Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries, by Program and

Type of Service, 2009

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Notes: Dual-eligible beneficiaries are people who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid at the same time and who are eligible to receive

benefits from both programs. “Full duals” qualify for full benefits from both programs.

* = between zero and 0.5 percent; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

a. Includes federal and state spending for Medicaid but excludes Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

b. The Medicare program consists of three parts: Hospital Insurance (Part A), Medical Insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage

(Part D). Medicare Part C (known as Medicare Advantage) specifies the rules under which private health care plans can assume

responsibility for, and be compensated for, providing benefits covered under Parts A, B, and D.

c. For details about what types of services are included in these categories, see the appendix.

15,200 ** 80,500 21,700 63,000

14,400 17,900 75,700 60,300

3,800 5,300 7,400 6,900

_

____

_

_____

_

_____ ______

Total Average Spending by Medicaid and Medicare

a

33,400 ** 103,700 104,800 130,200

61 33 74 54

1683524

1571913

12676

18 12 13 12

62 13 8

4296

2* 4 2

33 65 13 38

Institutional care 21 45 9 25

Community-based long-term care 12 20 4 13

Most common

Second most common

Third most common

Fourth most common

Fifth most common

Acute care

Postacute care

Long-term care

Five Most Common Chronic Conditions

(Percentage with that condition)

Home health care

Inpatient care

Ambulatory care

Prescription drugs

Other (Includes capitation payments)

Skilled nursing facility care

Average Spending per Beneficiary, by Program (Dollars)

Medicaid

a

Medicare

b

Distribution of Spending by Type of Service (Percent)

c

Parts A and B

Part D

Full Duals in

Top 10 Percent of

Dementia (14)

Osteoporosis (10)

Full Duals inFull Duals in

COPD (17)

Depression (14)

Dementia (24)

Ischemic heart

All Full Duals per Beneficiary

Medicaid Spending

Top 10 Percent of

per Beneficiary

Medicare Spending

Top 10 Percent of

Diabetes (29) Dementia (41) Diabetes (49) Diabetes (42)

per Beneficiary

Combined Spending

COPD (27)

Ischemic heart

Congestive heartCongestive heartDiabetes (31)

Congestive heart COPD (33) Dementia (31)

failure (33)

disease (21) disease (16)

COPD (17)

failure (39)

failure (15) failure (22)

Congestive heart

[** Value corrected]

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 11

CBO

Medicare’s and Medicaid’s Current

Payment Systems for Dual-Eligible

Beneficiaries

The Medicare and Medicaid programs use two types of

payment systems—fee for service (FFS) and risk-based

managed care—to pay for covered benefits for their

enrollees. Under FFS, the programs pay health care

providers a fee for each service performed, whereas under

risk-based managed care, the programs contract with

health plans, most of which are sponsored by private

insurance companies, to provide a set of covered benefits

for a fixed amount per beneficiary. (Those amounts may

be adjusted to reflect the health risks of beneficiaries, as

explained in Box 2.) Both programs have encouraged

managed care systems in an effort to reduce spending and

improve the quality of care by improving beneficiaries’

access to services and increasing the management of their

care.

Managed Care Plans in Medicare and Medicaid

A minority of Medicare beneficiaries and of aged, blind,

or disabled Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in risk-

based managed care plans, and the percentages are lower

among dual-eligible beneficiaries.

16

In Medicare, about

25 percent of beneficiaries in 2009 were enrolled in

Medicare Advantage plans—private health plans that

assume the responsibility and financial risk for providing

Medicare benefits. A smaller share of full duals, about

17 percent, were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans,

and 60 percent of those beneficiaries were enrolled in

special-needs plans (SNPs)—Medicare Advantage plans

that specialize in dual-eligible beneficiaries, people in

institutions, or those with certain chronic conditions.

In Medicaid, enrollment in risk-based managed care

plans has been more common among children and non-

disabled adults than among other beneficiaries; in 2009,

about 35 percent* of nondual aged, blind, or disabled

Medicaid beneficiaries and 15 percent of full duals were

enrolled in such plans. Unlike Medicare’s managed care

plans, which are responsible for providing the full set

of benefits covered by Parts A and B of that program,

Medicaid’s risk-based managed care plans are often not

required to cover certain Medicaid benefits, such as

behavioral health care or long-term care. Medicaid may

cover those “carved-out” services on a fee-for-service basis

or in special managed care arrangements.

Plans that participate in Medicare Advantage submit bids

indicating the per-enrollee payment they are willing to

accept in return for providing all Medicare benefits to an

average Medicare beneficiary enrolling in their plan in

each region where they operate. Medicare makes a

capitated payment to each participating plan (a single

payment that covers all care within a specified set of ben-

efits) on the basis of the plan’s bid and an administratively

determined benchmark that varies geographically with

fee-for-service spending per beneficiary.

17

Payments to

Medicare Advantage plans are adjusted for the risk profile

of a plan’s enrollees, which reflects their expected relative

costs (see Box 2).

18

In addition, since 2012, plans that

reach a certain quality threshold (based on a star rating

system) are eligible for bonuses in the form of higher

benchmarks.

Medicaid’s contracts with risk-based managed care plans

vary considerably by state. In most cases, a state either

sets a payment rate for all plans operating in the state or

negotiates a payment rate with each plan individually.

16. Some states’ Medicaid programs use primary care case manage-

ment or prepaid health plans as an alternative form of managed

care. Enrollment in primary care case management is counted as

part of fee-for-service Medicaid in this analysis because states

continue to pay providers for each claim, in addition to making a

fixed payment for management activities. Enrollment in prepaid

health plans is also counted under fee-for-service Medicaid

because those plans cover only a limited set of services.

17. Before 2012, Medicare Advantage benchmarks were, on average,

roughly 13 percent higher than average FFS spending. The

Affordable Care Act changed how benchmarks are set beginning

in 2012, with those changes phased in until 2017; at that point,

the new benchmarks will range from 95 percent to 115 percent of

average FFS spending. See Medicare Payment Advisory Commis-

sion, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (March

2011), http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar11_EntireReport.pdf

(6 MB).

18. That payment system does not apply to two types of Medicare

Advantage plans: PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the

Elderly) and cost plans, neither of which submits bids. PACE

programs are paid on the basis of risk scores, benchmarks, and an

adjustment for the frailty of their enrollees, and cost plans are paid

on the basis of submitted claims (that is, they are reimbursed

according to the costs they incur in delivering covered benefits).

The benchmark revisions enacted in the ACA do not apply to

PACE programs; thus, if those revisions were fully implemented

for Medicare Advantage plans in 2013 (rather than being phased

in until 2017), benchmarks for PACE programs would be about

8 percent to 18 percent higher than benchmarks for Medicare

Advantage plans, depending on the county. (That difference does

not include quality adjustments for Medicare Advantage plans

through the star rating system.)

[* Value corrected]

12 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

Continued

Those rates must be certified by the Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services (CMS) as being adequate to cover

average expected costs for the covered population

(including administrative expenses).

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries’ Enrollment in

Different Service-Delivery Systems

The mix of fee-for-service care and risk-based managed

care used in both Medicare and Medicaid means that

full duals receive covered benefits through an array of

fee-for-service and capitated payment systems, with

major differences both within and among states. Those

differences reflect several factors: variation in the avail-

ability of Medicare and Medicaid managed care plans;

state policies governing whether full duals can enroll in

risk-based managed care for Medicaid and, if so, whether

enrollment is mandatory or voluntary; states’ use of mul-

tiple waivers and authority for demonstration projects

Box 2.

Adjusting Medicare’s Payments for the Health Risks of Beneficiaries

Health care costs vary substantially among Medicare

beneficiaries. Some of that variation comes from

unexpected medical problems, and some reflects dif-

ferences in the prevalence of chronic conditions. The

process by which beneficiaries choose health care

plans in Medicare is unlikely to spread costs evenly

among plans—both because some plans may attract

sicker beneficiaries than others do and because unex-

pected health events may not be distributed evenly

among different plans’ enrollees. Thus, to help ensure

that some Medicare Advantage (managed care) and

Medicare Part D (prescription drug) plans do not end

up leaving the market because they had to cover a

more expensive population—and, similarly, to make

sure that plans are not overpaid for a less expensive

population—Medicare adjusts payments to plans

to account for the likely health care costs of their

enrollees.

To do that, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) has developed two models: the Hier-

archical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) model,

which is used for Medicare Advantage plans, and the

Prescription Drug Hierarchical Condition Category

(CMS-RxHCC) model, which is used for Part D

plans. The output of each model is a risk score for

every beneficiary that depends on the person’s set of

diagnoses and demographic characteristics. Payments

to plans are adjusted with those risk scores to account

for differences in expected spending for different

beneficiaries.

CMS calculates the parameters of the models using a

statistical analysis that relates spending by Parts A and

B of Medicare (for the CMS-HCC model) or Part D

(for the CMS-RxHCC model) for a given year to a

set of characteristics of fee-for-service or Part D bene-

ficiaries from the previous year. Those characteristics

include demographic indicators (such as age group

and sex), indicators of chronic conditions, and a set

of interaction terms. The interaction terms involve

either two demographic indicators, two chronic con-

ditions, or a chronic condition and a demographic

indicator. The CMS-HCC model currently includes

70 chronic conditions—called hierarchical condition

categories—and the CMS-RxHCC model includes

78 prescription drug hierarchical condition catego-

ries.

1

As the name implies, some categories include

1. For more information about the two models, see Gregory C.

Pope and others, Evaluation of the CMS-HCC Risk Adjust-

ment Model: Final Report (prepared by RTI International for

the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, March 2011),

http://go.usa.gov/TpRV (pdf, 1 MB); Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services, “Advance Notice of Methodological

Changes for Calendar Year (CY) 2014 for Medicare Advan-

tage (MA) Capitation Rates, Part C and Part D Payment

Policies and 2014 Call Letter” (February 15, 2013),

http://go.usa.gov/TuQG (pdf, 1 MB), and “Advance Notice

of Methodological Changes for Calendar Year (CY) 2011

for Medicare Advantage (MA) Capitation Rates, Part C and

Part D Payment Policies and 2011 Call Letter” (February 19,

2010), http://go.usa.gov/TuUR (pdf, 813 KB); John Robst,

Jesse M. Levy, and Melvin J. Ingber, “Diagnosis-Based Risk

Adjustment for Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Payments,”

Health Care Financing Review, vol. 28, no. 4 (Summer 2007),

pp. 15–30, http://go.usa.gov/TpRH (pdf, 483 KB).

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 13

CBO

granted by Medicare and Medicaid to integrate the deliv-

ery of services under the two programs; and the capacity

of local Medicaid managed care plans to manage the ser-

vices needed by full duals in addition to those used by

other subsets of the Medicaid population.

In 2009, nearly three-quarters of full duals received

Medicare and Medicaid services through the FFS delivery

systems in both programs (see Table 4). Only about

5 percent were enrolled in risk-based managed care plans

for both programs (which may have been the same or

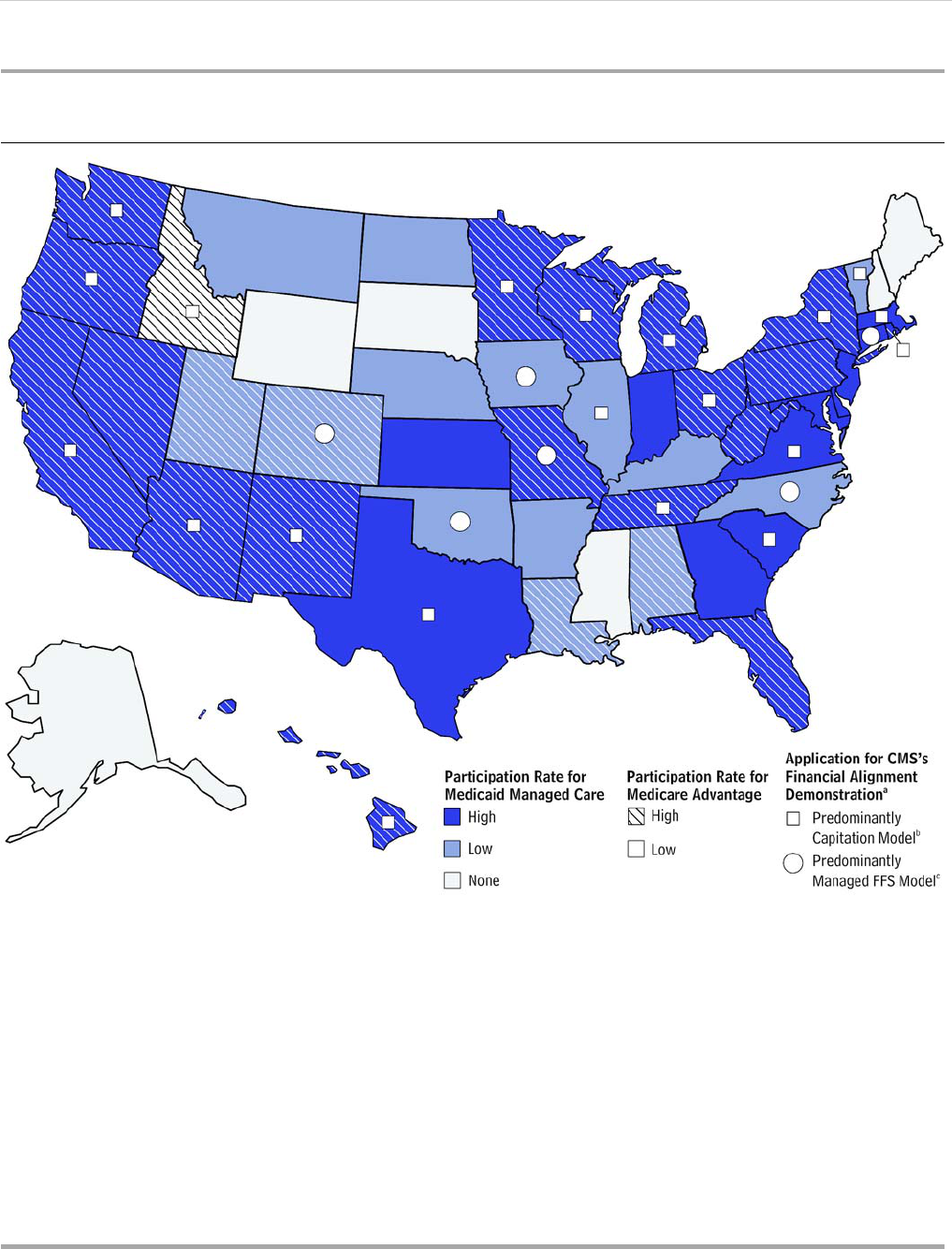

separate plans) or in PACE (Program of All-Inclusive

Care for the Elderly) programs, which receive a combined

Medicare and Medicaid payment for full duals who need

the degree of care typically provided in nursing homes.

19

The other 21 percent of full duals were enrolled in either

risk-based Medicaid plans with FFS Medicare, or FFS

Medicaid with Medicare managed care.

Box 2. Continued

Adjusting Medicare’s Payments for the Health Risks of Beneficiaries

a hierarchy of conditions, and only the most severe

condition in the hierarchy that a beneficiary has

is included in the risk score. (For instance, if someone

has been diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction

as well as with unstable angina or other acute

ischemic heart disease, only the more severe condi-

tion, acute myocardial infarction, is included for that

person.) Other conditions are not part of a hierarchy

and are not subject to being overridden by another

condition. The relationships between spending and

the various condition categories, demographic char-

acteristics, and interactions used in the model are

recalibrated periodically as the relationship between

chronic conditions and fee-for-service spending

changes over time.

For Medicare Advantage, CMS maintains two ver-

sions of the CMS-HCC model: the “community”

version described above and an “institutional” version

that is intended to reflect the fact that nursing facili-

ties often take on some of the care delivered by

medical professionals. The institutional CMS-HCC

model includes the same set of hierarchical condition

categories, demographic characteristics, and inter-

actions as the community model, but it uses different

model parameters, which are based on the relation-

ships between those characteristics and spending that

are calculated for institutionalized beneficiaries. In

addition, because CMS does not have diagnostic

information for new Medicare enrollees, it uses “new

enrollee” models to create Medicare Advantage and

Part D risk scores that reflect the relationship

between spending and demographic characteristics

(but not chronic conditions).

Besides their use in adjusting payments, medical risk

scores are also helpful tools for characterizing the

average health status of various groups. For example,

in 2009, the average risk score from the community

version of the CMS-HCC model was 1.534 for full

dual-eligible beneficiaries, compared with 0.985 for

nondual Medicare beneficiaries (see Table 1 on

page 5). That difference suggests that full duals are in

much worse health, on average, than other Medicare

beneficiaries.

1

1. CMS normalizes risk scores such that the average assigned

risk score for the fee-for-service Medicare population is 1.0.

In this analysis, the Congressional Budget Office reports risk

scores only from the community version of the CMS-HCC

model in order to use a common framework for comparing

the health status of various groups. In addition, the average

risk scores reported here include Medicare Advantage enroll-

ees as well as enrollees in fee-for-service Medicare. For those

reasons, the risk scores reported here do not average 1.0.

19. PACE programs receive capitated payments from Medicare and

Medicaid that are combined into a single payment to provide all

services for both programs—including LTSS—to beneficiaries

who are age 55 or older and not living in institutions at the time

of enrollment but who meet the standards of need for institutional

care. PACE programs also receive a frailty adjustment from Medi-

care to account for the additional service needs of their enrollees.

Less than 1 percent of full duals nationwide are enrolled in PACE

programs. For more details, see Dana B. Mukamel and others,

“Program Characteristics and Enrollees’ Outcomes in the Program

of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE),” Milbank Quarterly,

vol. 85, no. 3 (September 2007), pp. 499–531, http://dx.doi.org/

10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00497.x; and California HealthCare

Foundation, Aging in PACE: The Case for California Expansion

(July 2010), http://tinyurl.com/clbqrm8.

14 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

Table 4.

Demographic Characteristics of and Spending for Full Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries,

by Type of Medicare and Medicaid Payment System Enrolled in, 2009

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Notes: Dual-eligible beneficiaries are people who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid at the same time and who are eligible to receive

benefits from both programs. “Full duals” qualify for full benefits from both programs.

PACE = Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly; * = between zero and 0.5 percent; N.A. = not available; LTSS = long-term

services and supports.

a. For Medicaid, includes only people enrolled in comprehensive risk-based managed care plans. Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in other

types of managed care, such as primary care case management, or enrolled in service-specific managed care plans that are not

comprehensive are counted with the fee-for-service Medicaid population.

b. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services calculates a risk score for each Medicare enrollee on the basis of his or her medical

diagnoses and demographic characteristics. The scores are used to adjust Medicare’s payments to managed care plans to reflect

enrollees’ expected costs for Parts A and B of Medicare.

c. Use of LTSS is based on fee-for-service claims; thus, any use of LTSS within Medicare Advantage or Medicaid managed care (including

PACE programs) is not included in this table.

d. Includes federal and state spending for Medicaid but excludes Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.

e. The Medicare program consists of three parts: Hospital Insurance (Part A), Medical Insurance (Part B), and prescription drug coverage

(Part D). Medicare Part C (known as Medicare Advantage) specifies the rules under which private health care plans can assume

responsibility for, and be compensated for, providing benefits covered under Parts A, B, and D.

73 9 12 5 *

Distribution by Age (Percent)

Nonelderly (Under age 65) 42 51 29 38 3

Elderly (Age 65 or older) 58 49 71 62 97

38 56 31 42 14

43 32 47 43 46

15 10 18 12 30

32429

** 1*1

1.5 1.3 1.6 1.4 2.1

17 6 15 7 14

49 28 38 23 N.A.

31 20 31 27 42

16,700 9,900 11,200 10,200 30,600

Parts A and B 14,500 11,500 16,700 13,000 20,700

Part D 4,000 3,000 3,300 3,100 3,100

1,800 3,000 6,400 ** 7,400 12,600

18,200 11,700 19,100 17,500 54,400

86,300 61,600 75,100 ** 58,300 97,200

Medicare and

(Medicare

Than PACE

Plans Other

Managed Care

PACE

Medicaid Managed Care

Medicaid

Fee-for-Service

Advantage) and

Managed Care

Medicare

Fee-for-Service

Managed Care

a

Medicaid

Medicare and

Fee-for-Service

Percentage of Full Duals

Medicaid

Medicare and

Distribution by Number of Chronic Conditions (Percent)

None

1–2

Medicaid

d

10th percentile

50th percentile

90th percentile

Medicare

e

Various Points in the Distribution of Spending (Dollars)

Total Medicaid and Medicare Spending per Beneficiary at

Percentage Receiving Any LTSS

c

Percentage With a Mental Illness

3–4

5–6

More than 6

Average Community Medical Risk Score

b

Percentage Who Are Institutionalized

Average Spending per Beneficiary, by Program (Dollars)

[** Value corrected]

JUNE 2013 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID 15

CBO

Considerable diversity exists within those groups as well.

For example, some of the full duals enrolled in FFS

Medicaid have their care managed by a primary care case

manager, a medical home (a team-based care delivery

model, led by a primary care provider, that coordinates

care), or another type of care manager, with those differ-

ent approaches sometimes used in the same state. In other

cases, full duals receive most of their Medicaid-covered

services from FFS providers but are enrolled in managed

care plans for specific services, such as dental care or

behavioral health care. Similarly, states’ Medicaid man-

aged care programs may include carve-outs (separate

payment arrangements) for behavioral health care,

long-term care, or other services—in many cases, when

the Medicaid managed care plans in a state have little

experience with those services. In Medicare, full duals

may be enrolled in managed care through regular Medi-

care Advantage plans or special-needs plans. For full duals

who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid risk-

based plans, the degree of integration between those

plans—administrative, financial, and care-related—also

varies from state to state.

20

Among the many possible combinations of Medicare and

Medicaid payment systems, full duals enrolled in risk-

based managed care for Medicaid—and either FFS or

managed care for Medicare—are less likely than other full

duals to be institutionalized or to receive long-term ser-

vices and supports (see Table 4).

21

Those enrolled in risk-

based Medicaid managed care and FFS Medicare also

have the lowest average risk score, the lowest prevalence

of chronic conditions, and the lowest combined spending

by Medicare and Medicaid among full duals (a median of

$11,700 in 2009). In contrast, spending was highest for

the small share of full duals enrolled in PACE programs

(a median of $54,400). That group, which receives LTSS

by definition, has the highest average risk score, reflecting

a population with a large burden of chronic disease—

40 percent have at least three chronic conditions, and

more than 40 percent have mental illness.

Such variation in spending and health status reflects, at

least in part, the differences between the beneficiary pop-

ulations enrolled in managed care and FFS. Enrollment

in Medicare Advantage is voluntary—as is enrollment in

Medicaid managed care for many dual-eligible beneficia-

ries—and healthier beneficiaries appear to be more likely

to enroll in managed care plans. Recent evidence about

whether risk scores fully adjust for that difference is

mixed.

22

(Special-needs plans and PACE programs are

exceptions, in that their eligibility requirements cause

them to enroll less healthy beneficiaries.) Because differ-

ences in spending are related to differences in health

status that also affect beneficiaries’ enrollment decisions,

it is difficult to tell from the relationship between spend-

ing and health status alone whether one managed care

arrangement would produce lower costs for a given

beneficiary than another arrangement would.

Efforts to Integrate Medicare’s and

Medicaid’s Financing and Coordinate

Care for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries

To reduce spending on dual-eligible beneficiaries and

improve the quality of their care, federal and state policy-

makers are focusing on two interrelated approaches:

integrating Medicare’s and Medicaid’s financing for those

beneficiaries, and having some entity coordinate the care

that dual-eligible beneficiaries receive from multiple

health care providers. Coordinating care effectively may

be difficult as long as payers and providers face different

financial incentives under the two programs, but aligning

20. See Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medic-

aid and Managed Care: Key Data, Trends, and Issues (Kaiser Family

Foundation, February 2012), www.kff.org/medicaid/8046.cfm.

21. LTSS use is based on fee-for-service claims; thus, any use of LTSS

within Medicare Advantage or Medicaid managed care (including

PACE programs) is not captured in Table 4. However, Medicaid

provides most LTSS, and those services are often carved out of

Medicaid’s managed care contracts (and are usually provided by

fee-for-service Medicaid).

22. See, for example, Sherry Glied and others, Selection, Marketing,

and Medicaid Managed Care, Working Paper 6164 (National

Bureau of Economic Research, September 1997), www.nber.org/

papers/w6164; Jason Brown and others, How Does Risk Selection

Respond to Risk Adjustment? Evidence From the Medicare Advantage

Program, Working Paper 16977 (National Bureau of Economic

Research, April 2011), www.nber.org/papers/w16977; Joseph P.

Newhouse and others, “Steps to Reduce Favorable Risk Selection

in Medicare Advantage Largely Succeeded, Boding Well for

Health Insurance Exchanges,” Health Affairs, vol. 31, no. 12

(December 2012), pp. 2618–2628, http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/

hlthaff.2012.0345; J. Michael McWilliams, John Hsu, and Joseph

P. Newhouse, “New Risk-Adjustment System Was Associated

With Reduced Favorable Selection in Medicare Advantage,”

Health Affairs, vol. 31, no. 12 (December 2012), pp. 2630–2640,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1344; and Gerald F.

Riley, “Impact of Continued Biased Disenrollment from the

Medicare Advantage Program to Fee-For-Service,” Medicare and

Medicaid Research Review, vol. 2, no. 4 (2012), pp. E1–E16,

http://go.usa.gov/b8M4.

16 DUAL-ELIGIBLE BENEFICIARIES OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID JUNE 2013

CBO

those incentives alone is no guarantee that such coordi-

nation will occur. Successfully implementing both

approaches could improve the quality of care and

decrease spending by reducing duplication of services,

minimizing the extent to which beneficiaries are shifted

between acute and institutional sites of care, and reducing

the provision of conflicting services that may result in

complications and other health problems.

For full duals, although Medicare primarily covers acute

care and Medicaid primarily covers long-term services

and supports, the distinction between the two programs

is not absolute: Some of the services covered by Medicare

and Medicaid overlap, and some may be substituted for

one another. In addition, payment rates for such services

are generally lower in Medicaid than in Medicare. Those

factors—combined with the fact that Medicare is funded

entirely by the federal government whereas Medicaid is

funded partly by the states—create conflicting financial

incentives under the two programs for the federal and

state governments and for health care providers.

23

States, for example, do not have a strong financial

incentive to reduce spending on acute care for full duals

because that spending is largely covered by the federal

government through Medicare (although the states,

through Medicaid, generally contribute to paying dual-

eligible beneficiaries’ cost-sharing amounts for acute

care).

24

Moreover, both programs cover home health care

services, so states may try to maximize the share of such

services paid by Medicare. In addition, Medicare’s pay-

ment rates for postacute care in skilled nursing facilities

(SNFs) are typically higher than Medicaid’s payment

rates to nursing homes. Therefore, nursing homes that

are certified SNFs have a financial incentive for their full-

dual residents to be hospitalized for at least three days,

thereby triggering eligibility for up to 100 days of SNF

benefits provided by Medicare, for which the nursing

home can receive the higher Medicare payment rates. As a

result, nursing home residents may be inappropriately

hospitalized, again shifting financial responsibility from

Medicaid to Medicare.

Recently, both the federal government and state Medicaid

programs have been looking for ways to integrate Medi-

care’s and Medicaid’s financing and service delivery for

dual-eligible beneficiaries to lessen financial incentives

that can lead to inappropriate care—or care in inappro-

priate settings—and thereby reduce unnecessary program

spending. But full duals with multiple chronic or

disabling conditions might continue to be at risk for

lower-quality, fragmented care, stemming from a lack of

communication between health care providers that better

financial integration might not solve. Poor coordination

among providers can cause full duals to receive duplica-

tive services, contradictory advice or procedures for a par-

ticular diagnosis, or poor transitions between settings for

care, all of which reduce the overall quality of their care.

As a result, state Medicaid programs and the federal gov-

ernment are also looking to design care coordination

programs—either in conjunction with or separate from

efforts to align financial incentives—using a variety of

options available under current law.

25

Many care coordi-

nation initiatives include elements to improve the flow of

information among providers, assist patients in making

the transition from one care setting to another (such as

when they are discharged from a hospital to another facil-

ity or to their home), and help patients gain access to

medical and social support services.

26

Spurred in part by new opportunities authorized under

the Affordable Care Act, care and financing arrangements