OXFORD MEDICAL PUBLICATIONS

Oxford Handbook of

Emergency

Medicine

Published and forthcoming Oxford Handbooks

Oxford Handbook for the Foundation Programme 3e

Oxford Handbook of Acute Medicine 3e

Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia 3e

Oxford Handbook of Applied Dental Sciences

Oxford Handbook of Cardiology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 3e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Dentistry 5e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Haematology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Immunology and Allergy 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine - Mini Edition 8e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine 8e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Pharmacy

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Rehabilitation 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties 8e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery 3e

Oxford Handbook of Complementary Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Critical Care 3e

Oxford Handbook of Dental Patient Care 2e

Oxford Handbook of Dialysis 3e

Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine 4e

Oxford Handbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes 2e

Oxford Handbook of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery

Oxford Handbook of Expedition and Wilderness Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Forensic Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2e

Oxford Handbook of General Practice 3e

Oxford Handbook of Genetics

Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV and AIDS 2e

Oxford Handbook of Geriatric Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology

Oxford Handbook of Key Clinical Evidence

Oxford Handbook of Medical Dermatology

Oxford Handbook of Medical Sciences

Oxford Handbook of Medical Statistics

Oxford Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension

Oxford Handbook of Neurology

Oxford Handbook of Nutrition and Dietetics

Oxford Handbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Occupational Health

Oxford Handbook of Oncology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics

Oxford Handbook of Pain Management

Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care 2e

Oxford Handbook of Practical Drug Therapy 2e

Oxford Handbook of Pre-Hospital Care

Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry 2e

Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice 2e

Oxford Handbook of Reproductive Medicine & Family Planning

Oxford Handbook of Respiratory Medicine 2e

Oxford Handbook of Rheumatology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine 3e

Oxford Handbook of Urology 2e

Oxford Handbook of

Emergency

Medicine

Fourth edition

Jonathan P. Wyatt

Consultant in Emergency Medicine and

Forensic Physician

Royal Cornwall Hospital, Truro, UK

Robin N. Illingworth

Consultant in Emergency Medicine

St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK

Colin A. Graham

Professor of Emergency Medicine

Chinese University of Hong Kong,

Hong Kong SAR, China

Kerstin Hogg

Clinical Research Fellow,

The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada

with senior international advisors:

Michael J. Clancy

Consultant in Emergency Medicine

Southampton General Hospital,

Southampton, UK

Colin E. Robertson

Professor of Emergency Medicine

Royal Infi rmary, Edinburgh, UK

1

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offi ces in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

© Oxford University Press, 2012

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First edition published 1999

Second edition published 2005

Third edition published 2006

Fourth edition published 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data

Data available

Typeset by Cenveo, Bangalore, India

Printed in Italy

on acid-free paper by

L.E.G.O. S.p.A.—Lavis TN

ISBN 978–0–19–958956–2

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the

drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the

product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published

product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most

recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and publishers do not

accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or

misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

Dedicated to Dr Robin Mitchell (1964–2010)

Emergency Physician in Christchurch, Edinburgh and Auckland.

Outstanding clinician and teacher, tremendous colleague and friend.

This page intentionally left blank

vii

Abbreviations and symbols

ix

Normal values xvii

Acknowledgements xix

1 General approach

1

2 Life-threatening emergencies

41

3 Medicine

62

4 Toxicology

179

5 Infectious diseases

219

6 Environmental emergencies

253

7 Analgesia and anaesthesia

271

8 Major trauma

319

9 Wounds, fractures, orthopaedics

401

10 Surgery

503

11 Ophthalmology

533

12 Ear, nose and throat

545

13 Obstetrics and gynaecology

563

14 Psychiatry

601

15 Paediatric emergencies

630

Index

737

Contents

This page intentionally left blank

ix

° degrees

8 approximately

+ve positive

–ve negative

± plus or minus

i increase(d)

d decrease(d)

ABC airway, breathing, circulation

ABG arterial blood gas

AC acromio-clavicular

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone

ACS acute coronary syndrome

AF atrial fi brillation

AIDS acquired immune defi ciency syndrome

AIO Ambulance incident offi cer

AIS abbreviated injury scale

ALS advanced life support

ALT alanine aminotransferase

ALTE apparently life-threatening event

AP antero-posterior

APLS Advanced Paediatric Life Support

APTT activated partial thromboplastin time

ARDS adult respiratory distress syndrome

ARF acute renal failure

AST aspartate transaminase

ATLS advanced trauma life support

AV atrio-ventricular

bd twice daily

BKPOP below knee Plaster of Paris

BKWPOP below knee walking Plaster of Paris

BLS basic life support

BMG bedside strip measurement of venous/capillary blood glucose

BNF British National Formulary

BNFC British National Formulary for Children

Abbreviations and symbols

x

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

BP blood pressure

BTS British Thoracic Society

BZP benzylpiperazine

CBRN chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear

CCU critical care unit

CK creatine kinase

cm centimetre(s)

CMV cytomegalovirus

CN chloroacetophenone

CNS central nervous system

CO carbon monoxide

CO

2

carbon dioxide

COHb carboxyhaemoglobin

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CPAP continuous positive airways pressure

CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CRF chronic renal failure

CRP C-reactive protein

CSF cerebrospinal fl uid

CT computed tomography

CTPA computed tomography pulmonary angiography

CVP central venous pressure

CVS cardiovascular system

CXR chest X-ray

DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIPJ distal interphalangeal joint

DKA diabetic ketoacidosis

dL decilitre

DPL diagnostic peritoneal lavage

DPT diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus

DSH deliberate self-harm

DVT deep venous thrombosis

EBV Epstein–Barr virus

ECG electrocardiogram

ECT electroconvulsive therapy

ED emergency department

EEG electroencephalogram

EMLA eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics

ENT ear, nose and throat

EPAP expiratory positive airway pressure

xi

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ET endotracheal

ETCO

2

end-tidal carbon dioxide

FAST focused assessment with sonography for trauma

FB foreign body

FBC full blood count

FFP fresh frozen plasma

FG French Gauge

FiO

2

inspired oxygen concentration

FOB faecal occult blood

G6-PD glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase

g gram(s)

G gauge

GA general anaesthetic

GCS Glasgow Coma Score

GFR glomerular fi ltration rate

GI gastrointestinal

GHB gammahydroxybutyrate

GMC General Medical Council

GP general practitioner

GTN glyceryl trinitrate

GU genitourinary

5HT 5-hydroxytryptamine

HATI human anti-tetanus immunoglobulin

Hb haemoglobin

HCG human chorionic gonadotrophin

HCM hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hct haematocrit

HDU high dependency unit

HHS hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state

HIV human immunodefi ciency virus

HONK hyperosmolar non-ketotic hyperglycaemia

hr hour/s

HTLV human T-cell lymphotropic virus

ICP intracranial pressure

ICU intensive care unit

IDDM insulin dependent diabetes mellitus

IHD ischaemic heart disease

IM intramuscular

INR international normalized ratio (of prothrombin time)

xii

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

IO intra-osseous

IPAP inspiratory positive airway pressure

IPg interphalangeal

IPPV intermittent positive pressure ventilation

ISS injury severity score

ITP idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

IUCD intrauterine contraceptive device

IV intravenous

IVI intravenous infusion

IVRA intravenous regional anaesthesia

IVU intravenous urography

JVP jugular venous pressure

KE kinetic energy

kPa kiloPascal(s) pressure

KUB X-ray covering the area of kidneys, ureters and bladder

L litre(s)

LA local anaesthetic

LAD left axis deviation

LBBB left bundle branch block

LDH lactate dehydrogenase

LET lidocaine epinephrine tetracaine

LFTs liver function tests

LMA laryngeal mask airway

LMP last menstrual period

LMWH low molecular weight heparin

LP lumbar puncture

LSD lysergic acid diethylamide

LV left ventricular

LVF left ventricular failure

LVH left venticular hypertrophy

m metre(s)

MAOI monoamine oxidase inhibitor

MAST military anti-shock trousers

max maximum

MC metacarpal

MCA Mental Capacity Act

MCPJ metacarpophalangeal joint

MDU Medical Defence Union

MI myocardial infarction

min minute/s

xiii

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

MIO medical incident offi cer

mL millilitre(s)

mmHg millimetres of mercury pressure

mmol millimoles

MMR mumps, measles, and rubella

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

MRSA meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MS multiple sclerosis

MSU mid-stream specimen of urine

MT metatarsal

MTPJ metatarsophalangeal joint

MUA manipulation under anaesthetic

NAC N -acetyl cysteine

NAI non-accidental injury

ND notifi able disease

NG nasogastric

NHS National Health Service

NIV non-invasive ventilation

NO nitrous oxide

NSAID non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drug

NSTEMI non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

NWBPOP non-weight-bearing Plaster of Paris

O

2

oxygen

OA osteoarthritis

OCP oral contraceptive pill

od once daily

OPG orthopantomogram

ORIF open reduction and internal fi xation

ORT oral replacement therapy

PA postero-anterior

PACS picture archiving and communication system

PAN polyarteritis nodosa

PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

pCO

2

arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PE pulmonary embolus

PEA pulseless electrical activity

PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure

PEFR peak expiratory fl ow rate

PGL persistent generalized lymphadenopathy

xiv

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

PICU paediatric intensive care unit

PID pelvic infl ammatory disease

PIPJ proximal interphalangeal joint

PO per os (orally/by mouth)

pO

2

arterial partial pressure of oxygen

POP plaster of Paris

PPE personal protective equipment

PPI proton pump inhibitor

PR per rectum

PRF patient report form

PRN pro re nata (as required)

PSP primary spontaneous pneumothorax

PV per vaginam

qds four times a day

RA rheumatoid arthritis

RAD right axis deviation

RBBB right bundle branch block

RBC red blood cells

Rh Rhesus

ROSC restoration of spontaneous circulation

RR respiratory rate

RSI rapid sequence induction/intubation

RSV respiratory syncytial virus

rtPA recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

RTS revised trauma score

RV right ventricular

SA sino-atrial

SARS severe acute respiratory syndrome

SC subcutaneous

SCIWORA spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality

sec second(s)

SIDS sudden infant death syndrome

SIGN Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

SIRS systemic infl ammatory response syndrome

SL sublingual

SLE systemic lupus erythematosus

SpO

2

arterial oxygen saturation

SSP secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

SSRI selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor

STD sexually transmitted disease

xv

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

SVT supraventricular tachycardia

T ° temperature

T

3

tri-iodothyronine

T

4

thyroxine

TAC tetracaine, adrenaline and cocaine

TB tuberculosis

tds three times a day

TFTs thyroid function tests

TIA transient ischaemic attack

TIMI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

tPA tissue plasminogen actvator

TSH thyroid stimulating hormone

u/U unit(s)

U&E urea and electrolytes

URTI upper respiratory tract infection

USS ultrasound scan

UTI urinary tract infection

V volts

VA visual acuity

VF ventricular fi brillation

VHF viral hemorrhagic fever

V/Q ventilation/perfusion (scan)

VT ventricular tachycardia

WB weight-bear(ing)

WBC white blood cells

WCC white cell count

WHO World Health Organization

WPW Wolff Parkinson White (syndrome)

This page intentionally left blank

xvii

Note that ‘normal’ values in adults may vary slightly between labs.

Normal values in pregnancy are shown in b The pregnant patient, p.576.

Arterial blood gas analysis

Biochemistry

Normal values

H

+

35–45 nanomol/L

pH 7.35–7.45

pO

2

(on air) >10.6 kPa, 75–100 mmHg

pCO

2

4.5–6.0 kPa, 35–45 mmHg

bicarbonate 24–28 mmol/L

base excess

± 2 mmol/L

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 5–35 iu/L

albumin 35–50 g/L

alkaline phosphatase 30–300 iu/L

amylase 0–180 Somogyi U/dL

aspartate transaminase (AST) 5–35 iu/L

bicarbonate 24–30 mmol/L

bilirubin 3–17 micromol/L

calcium (total) 2.12–2.65 mmol/L

calcium (ionized) 1–1.25 mmol/L

chloride 95–105 mmol/L

creatine kinase (CK) 25–195 iu/L

creatinine 70–150 micromol/L

C-reactive protein (CRP) <10 mg/L

glucose (fasting) 3.5–5.5 mmol/L

G glutamyl transpeptidase (4)

11–51 IU/L

(5)

7–33 IU/L

magnesium 0.75–1.05 mmol/L

osmolality 278–305 mosmol/kg

potassium 3.5–5.0 mmol/L

sodium 135–145 mmol/L

urea 2.5–6.7 mmol/L

urate (5)

150–390 micromol/L

(4)

210–480 micromol/L

xviii

NORMAL VALUES

Haematology

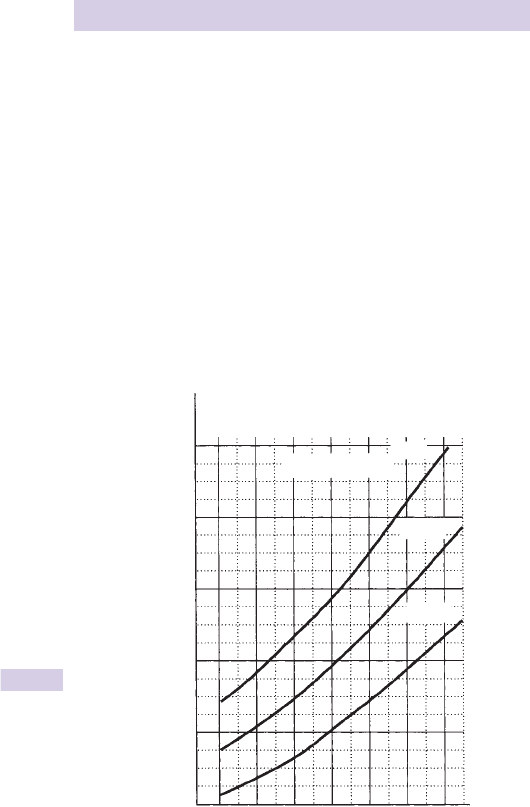

Metric conversion

Length

Weight

Volume

1 L = 1.76 UK pints = 2.11 US liquid pints

1 UK pint = 20 fl uid ounces = 0.568 L

1 US liquid pint = 16 fl uid ounces = 0.473 L

1 teaspoon 8 5mL

1 tablespoon 8 15mL

Temperature

T ° in °C = ( T ° in Fahrenheit – 32) ×

9

5

–

Pressure

1kPa = 7.5mmHg

RBC (women)

3.9–5.6 × 10

12

/L

(men)

4.5–6.5 × 10

12

/L

Hb (women) 11.5–16.0g/dL

(men) 13.5–18.0g/dL

Hct (women) 0.37–0.47

(men) 0.40–0.54

MCV 76–96 femtoL

WCC

4.0–11.0 × 10

9

/L

neutrophils

2.0–7.5 × 10

9

/L (40–75 % of WCC)

lymphocytes

1.5–4.0 × 10

9

/L (20–40 % of WCC)

monocytes

0.2–0.8 × 10

9

/L (2–10 % of WCC)

eosinophils

0.04–0.40 × 10

9

/L (1–6 % of WCC)

basophils

<0.1 × 10

9

/L (<1 % of WCC)

platelets

150–400 × 10

9

/L

prothrombin time

(factors I, II, VII, X) 12–15sec

APTT (factors VII,

IX, XI, XII) 23–42sec

International Normalized Ratio (INR) therapeutic targets

2.0–3.0 (for treating DVT, pulmonary embolism)

2.5–3.5 (embolism prophylaxis for AF)

3.0–4.5 (recurrent thrombo-embolic disease,

arterial grafts & prosthetic valves)

ESR (women) <

(age in years+10)

/

2

mm/hr

(men) <

(age in years)

/

2

mm/hr

1m = 3 feet 3.4 inches 1 foot = 0.3048m

1cm = 0.394 inch 1 inch = 25.4mm

1kg = 2.20 pounds 1 stone = 6.35kg

1g = 15.4 grains 1 pound = 0.454kg

1 ounce = 28.4g

xix

A number of people provided comments, help and moral support. Special

thanks are due to Dr Phil Munro. We also wish to thank:

Miss Sehlah Abassi, Mr David Alao, Dr Matt Baker, Dr Joan Barber, Dr Ruth

Beach, Mr Dewald Behrens, Dr Ash Bhatia, Dr Angela Bonnar, Dr Rachel

Broadley, Dr Chris Brown, Mrs Debra Clayton, Mr Jon Davies, Dr Kate

Evans, Dr James Falconer, Miss Paula Fitzpatrick, Mrs Jennifer Flemen,

Dr Adrian Flynn, Dr Debbie Galbraith, Mr Blair Graham, Dr Catherine

Guly, Mr Chris Hadfi eld, Dr Steve Halford, Mr Andrew Harrower, Miss

Emily Hotton, Mr Jim Huntley, Mrs Eileen Hutchison, Mr Nicholas Hyatt,

Dr Karen Illingworth, Mr Ian Kelly, Mr Jacques Kerr, Dr Alastair Kidd,

Dr Paul Leonard, Mr Malcolm Lewis, Mr AF Mabrook, Dr Simon Mardel,

Dr Nick Mathiew, Ms Carolyn Meikle, Dr Louisa Mitchell, Dr Claudia

Murton, Dr Louisa Pieterse, Dr Stephanie Prince, Dr Laura Robertson, Miss

Katharine Robinson, Dr Andrew Sampson, Mr Tom Scott, Dr Simon Scott-

Hayward, Ms Karen Sim, Mr Toby Slade, Dr Timothy Squires, Mr Ashleigh

Stone, Dr Luke Summers, Dr Rob Taylor, Dr Ross Vanstone, Ms Fiona

Wardlaw, Dr Mike Wells, Mr Ken Woodburn, Mrs Polly Wyatt.

Acknowledgements

This page intentionally left blank

1

The emergency department 2

Note keeping 4

Radiological requests 6

Triage 7

Discharge, referral, and handover 8

Liaising with GPs 10

Telephone advice 11

Liaising with the ambulance crew 12

Coping as a junior doctor 14

Inappropriate attenders 16

The patient with a label 17

The patient you dislike 18

Special patient groups 19

Discharging the elderly patient 20

The patient with learning diffi culties 21

Patient transfer 22

Breaking bad news 24

What to do after a death 26

Medicolegal aspects: avoiding trouble 28

Medicolegal aspects: the law 30

Infection control and prevention 32

What to carry in your car 34

At the roadside 36

Major incidents 38

General approach

Chapter 1

2 CHAPTER 1 General approach

The emergency department

The role of the emergency department

The emergency department (ED) occupies a key position in terms of the

interface between primary and secondary care. It has a high public profi le.

Many patients attend without referral, but some are referred by NHS

Direct, minor injury units, general practitioners (GPs), and other medical

practitioners. The ED manages patients with a huge variety of medical

problems. Many of the patients who attend have painful and/or distressing

disorders of recent origin.

Priorities are:

• To make life-saving interventions.

• To provide analgesia.

• To identify relevant issues, investigations, and commence treatment.

• To decide upon need for admission or discharge.

ED staff work as a team. Traditional roles are often blurred, with the

important issue being what clinical skills a member of staff is capable of.

ED staff include:

• Nurses (including nurse practitioners, nurse consultants, health care

assistants).

• Doctors (permanent and fi xed-term).

• Reception and administrative staff (receptionists, secretaries,

managers).

• Radiographers, including reporting radiographers.

• Other specialist staff (eg psychiatric liaison nurses, plaster technicians,

physiotherapists, paramedic practitioners, physician assistants,

occupational therapists, clinic/ED ward staff).

• Supporting staff (security, porters, cleaners, police).

Physical resources

A principal focus of the ED is to provide immediate resuscitation for

patients who present with emergency conditions. In terms of sheer

numbers, more patients attend with minor conditions and injuries, often

presenting quite a challenge for them to be seen and treated in a timely

fashion. Different departments have systems to suit their own particular

needs, but most have a resuscitation room, an area for patients on trolleys,

and an area for ambulant patients with less serious problems or injuries.

Paediatric patients are seen in a separate area from adults. In addition,

every ED requires facilities for applying casts, exploring and suturing

wounds, obtaining X-rays, and examining patients with eye problems.

Discharge from the ED

To work effi ciently, the overall hospital system needs to enable easy fl ow

of patients out of the ED. Options available for continuing care of patients

who leave the ED, include:

• Discharge home with no follow-up.

• Discharge home with GP and/or other community support/follow-up.

• Discharge with hospital clinic follow-up arranged.

• Admission to hospital for further investigation and treatment.

• Transfer to another hospital with more specialist facilities.

3

THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Emergency department staff beyond the emergency

department

In addition to their roles in providing direct clinical care in their

departments, many ED staff provide related clinical care in other settings

and ways:

• Short stay wards (sometimes called clinical decision units) where

emergency care can be continued by ED staff. The intention is for

admissions to these units to be short: most of the patients admitted

to such wards are observed for relatively short periods (<24hr) and

undergo assessments at an early stage to decide about the need for

discharge or longer-term admission.

• Outpatient clinics enable patients with a variety of clinical problems (eg

burns, soft tissue injuries, and infections) to be followed up by ED staff.

• Planned theatre lists run by ED specialists are used by some hospitals to

manage some simple fractures (eg angulated distal radial fractures).

• Telemedicine advice to satellite and minor injury units.

Emergency medicine in other settings

As the delivery of emergency care continues to develop, patients with

emergency problems are now receiving assessment and treatment in a

variety of settings. These include minor injury units, acute medical assessment

units and walk-in centres. Traditional distinctions between emergency

medicine, acute medicine, and primary care have become blurred.

4 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Note keeping

General aspects

It is impossible to over-emphasize the importance of note keeping.

Doctors and nurse practitioners each treat hundreds of patients every

month. With the passage of time, it is impossible to remember all aspects

relating to these cases, yet it may be necessary to give evidence in court

about them years after the event. The only reference will be the notes

made much earlier. Medicolegally, the ED record is the prime source

of evidence in negligence cases. If the notes are defi cient, it may not be

feasible to defend a claim even if negligence has not occurred. A court

may consider that the standard of the notes refl ects the general standard

of care. Sloppy, illegible, or incomplete notes refl ect badly on the

individual. In contrast, if notes are neat, legible, appropriate, and detailed,

those reviewing the case will naturally expect the general standards of

care, in terms of history taking, examination, and level of knowledge, to

be competent.

The Data Protection and Access to Medical Records Acts give patients right

of access to their medical notes. Remember, whenever writing notes, that

the patient may in the future read exactly what has been written. Follow

the basic general rules listed below.

Layout

Follow a standard outline:

Presenting complaint Indicate from whom the history has been obtained

(eg the patient, a relative, or ambulance personnel). Avoid attributing

events to certain individuals (eg patient was struck by ‘Joe Bloggs’).

Previous relevant history Note recent ED attendances. Include family and

social history. An elderly woman with a Colles’ fracture of her dominant

hand may be able to manage at home with routine follow-up provided

she is normally in good health, and has good family or other support, but

if she lives alone in precarious social conditions without such support,

then admission on ‘social grounds’ may be required.

Current medications Remember to ask about non-prescribed drugs

(including recreational, herbal, and homeopathic). Women may not

volunteer the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) as ‘medication’ unless

specifi cally asked. Enquire about allergies to medications and document

the nature of this reaction.

Examination fi ndings As well as + ve features, document relevant –ve

fi ndings (eg the absence of neck stiffness in a patient with headache and

pyrexia). Always document the side of the patient which has been injured.

For upper limb injuries, note whether the patient is left or right handed.

Use ‘left’ and ‘right’, not ‘L’ and ‘R’. Document if a patient is abusive or

aggressive, but avoid non-medical, judgemental terms (eg ‘drunk’).

Investigation fi ndings Record clearly.

Working diagnosis For patients being admitted, this may be a differential

diagnostic list. Sometimes a problem list can help.

5

NOTE KEEPING

Treatment given Document drugs, including dose, time, and route of

administration (see current British National Formulary ( BNF ) for guidance).

Include medications given in the ED, as well as therapy to be continued

(eg course of antibiotics). Note the number and type of sutures or staples

used for wound closure (eg ‘5 × 6/0 nylon sutures’).

Advice and follow-up arrangements Document if the patient and/or

relative is given preprinted instructions (eg ‘POP care’). Indicate when/

if the patient needs to be reviewed (eg ‘see GP in 5 days for suture

removal’) or other arrangement (eg ‘Fracture clinic in one week’).

Record advice about when/why the patient should return for review,

especially if there is a risk of a rare but serious complication (eg for low

back pain ‘see GP if not better in 1 week. Return to the ED at once if

bladder/bowel problem or numb groin/bottom’ that might be features of

cauda equina syndrome).

Basic rules

• Write legibly in ballpoint pen, ideally black, which photocopies well.

• Always date and time the notes.

• Sign the notes, and print your name and status below.

• Make your notes concise and to the point.

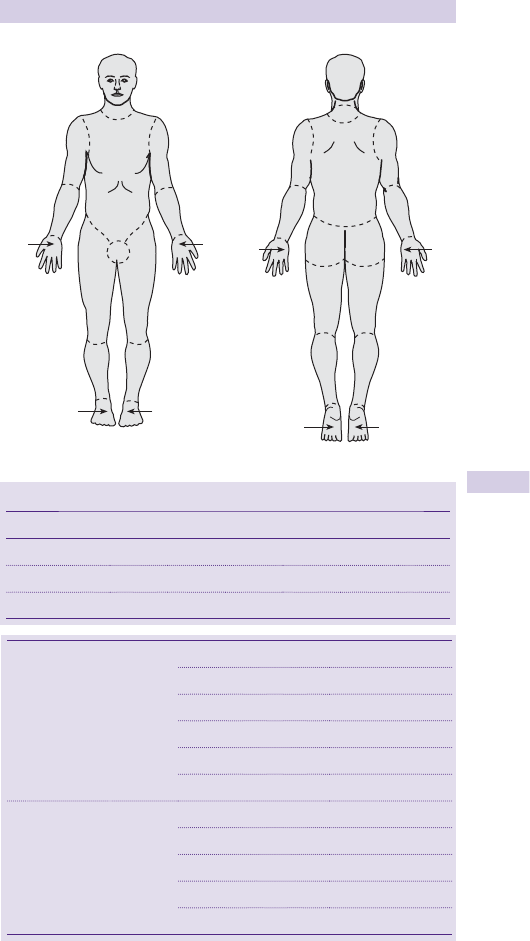

• Use simple line drawings or preprinted sheets for wound/injury

descriptions.

• Avoid idiosyncratic abbreviations.

• Never make rude or judgemental comments .

• Always document the name, grade, and specialty of any doctor from

whom you have received advice.

• When referring or handing a patient over, always document the time of

referral/handover, together with the name, grade, and specialty of the

receiving doctor.

• Inform the GP by letter ( b Liaising with GPs, p.10), even if the patient

is admitted. Most EDs have computerized systems that generate such

letters. In complex cases, send also a copy of ED notes, with results of

investigations.

Pro formas

Increasing emphasis on evidence-based guidelines and protocols has

been associated with the introduction of protocols for many patient

presentations and conditions. Bear in mind the fact that, for some patients,

satisfactory completion of a pro forma may not adequately capture all of

the information required.

Electronic records

In an electronic age, there has been an understandable move towards

trying to introduce electronic patient records. The potential advantages

are obvious, particularly in relation to rapidly ascertaining past medical

history. When completing electronic records, practitioners need to follow

the same principles as those outlined above for written records.

Access to old records can make a huge contribution to decision making.

One potential advantage of electronic records is that they can be accessed

rapidly (compared with older systems requiring a porter to search through

the medical records store and retrieve paper-based notes).

6 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Radiological requests

‘I am glad to say that in this country there is no need to carry out

unnecessary tests as a form of insurance. It is not in this country desirable,

or indeed necessary, that over protective and over examination work

should be done, merely and purely and simply as I say to protect oneself

against possible litigation’ — Judge Fallon, quoted by Oscar Craig, Chairman

Cases Committee, Medical Protection Society.

Requesting investigations

The Royal College of Radiologists’ booklet ‘ Making the Best Use of a

Department of Clinical Radiology: Guidelines for Doctors ’ (6th edn, London,

RCR, 2007) contains very useful information and is strongly recommended.

General aspects

• An X-ray is no substitute for careful, thorough clinical examination. It is

usually unnecessary to request X-rays to confi rm the clinical diagnosis

of uncomplicated fractures of the nose, coccyx, a single rib, or toes

(other than the big toe).

• If in doubt about the need for X-rays or the specifi c test required,

consider relevant guidelines (eg Ottawa rules for ankle injuries,

b p.484) and/or discuss with senior ED staff or radiologist.

• When requesting X-rays, describe the indication/mechanism of injury,

clinical fi ndings, including the side involved (right or left — spelt out

in full, not abbreviated) and the suspected clinical diagnosis. This is

important for the radiologist reporting the fi lms without the advantage

of being able to examine the patient.

• Do not worry about specifying exactly which X-ray views are required.

The radiographer will know the standard views that are needed, based

on the information provided (eg AP + simplifi ed apical oblique views for

a patient with suspected anterior shoulder dislocation). In unusual cases,

discuss with senior ED staff, radiographer, or radiologist.

• Always consider the possibility of pregnancy in women of child-bearing

age before requesting an X-ray of the abdomen, pelvis, lumbar spine,

hips, or thighs. If the clinical indication for X-ray is overriding, tell the

radiographer, who will attempt to shield the foetus/gonads. If the risks/

benefi ts of X-rays in pregnant or possibly pregnant women are not

obvious, consult senior ED or radiology staff.

X-ray reporting system

Many hospitals have systems so that all ED X-rays are reported by a

specialist within 24hr. Reports of any missed abnormalities are returned

with the X-rays to the ED for the attention of senior staff, so that

appropriate action can be taken.

System for identifying abnormalities

In addition to the formal reporting system described above, a system is

commonly used whereby the radiographer taking the fi lms applies a sticky

‘red dot’ to hard copy X-ray fi lms and/or request card or to the equivalent

electronic image if they identify an abnormality. This alerts other clinical

staff to the possibility of abnormal fi ndings.

7

TRIAGE

Triage

The nature of ED work means that a sorting system is required to ensure

that patients with the most immediately life-threatening conditions are seen

fi rst. A triage process aims to categorize patients based on their medical

need and the available departmental resources. One most commonly used

process in the UK is the National Triage Scale (Table 1.1 ).

As soon as a patient arrives in the ED he/she should be assessed by a

dedicated triage nurse (a senior, experienced individual with considerable

common sense). This nurse should provide any immediate interventions

needed (eg elevating injured limbs, applying ice packs or splints, and giving

analgesia) and initiate investigations to speed the patient’s journey through

the department (eg ordering appropriate X-rays). Patients should not

have to wait to be triaged. It is a brief assessment which should take no

more than a few minutes.

Three points require emphasis:

• Triage is a dynamic process. The urgency (and hence triage category)

with which a patient requires to be seen may change with time. For

example a middle-aged man who hobbles in with an inversion ankle

injury is likely to be placed in triage category 4 (green). If in the waiting

room he becomes pale, sweaty, and complains of chest discomfort, he

would require prompt re-triage into category 2 (orange).

• Placement in a triage category does not imply a diagnosis, or even the

lethality of a condition (eg an elderly patient with colicky abdominal

discomfort, vomiting, and absolute constipation would normally

be placed in category 3 (yellow) and a possible diagnosis would be

bowel obstruction). The cause may be a neoplasm which has already

metastasized and is hence likely to be ultimately fatal.

• Triage has its own problems. In particular, patients in non-urgent

categories may wait inordinately long periods of time, whilst patients

who have presented later, but with conditions perceived to be more

urgent, are seen before them. Patients need to be aware of this and to

be informed of likely waiting times. Uncomplaining elderly patients can

often be poorly served by the process.

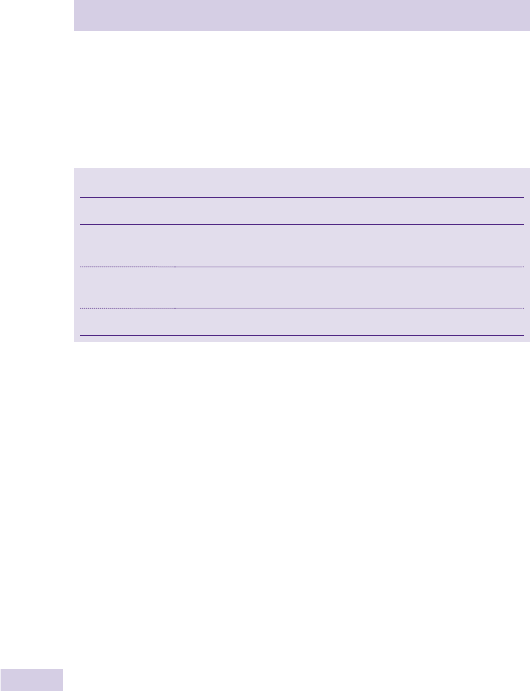

Table 1.1

National Triage Scale Colour Time to be seen by doctor

1 Immediate Red Immediately

2 Very urgent Orange Within 5–10 min

3 Urgent Yellow Within 1 hr

4 Standard Green Within 2 hr

5 Non-urgent Blue Within 4 hr

8 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Discharge, referral, and handover

Most patients seen in the ED are examined, investigated, treated, and

discharged home, either with no follow-up, or advice to see their GP (for

suture removal, wound checks, etc.). Give these patients (and/or attending

relative/friend) clear instructions on when to attend the GP’s surgery and

an indication of the likely course of events, as well as any features that

they should look out for to prompt them to seek medical help prior to

this. Formal written instructions are particularly useful for patients with

minor head injury ( b p.367) and those with limbs in POP or other forms

of cast immobilization ( b Casts and their problems, p.424).

The referral of patients to an inpatient team can cause considerable

anxiety, misunderstanding, and potential confl ict between ED staff and

other disciplines. Before making the referral the following should be

considered.

Is it appropriate to refer this patient to the inpatient team?

Usually, this will be obvious. For example, a middle-aged man with a

history of crushing chest pain and an ECG showing an acute MI clearly

requires urgent management in the ED, and rapid admission for further

investigation and treatment. Similarly, an elderly lady who has fallen, is

unable to weight-bear and has a fractured neck of femur will require

analgesia, inpatient care and surgery.

However, diffi cult situations occur where the clinical situation is less clear;

for example, if a man experienced 4–5min of atypical chest pain, has a

normal ECG and chest X-ray (CXR), and is anxious to go home. Or a lady

has no apparent fracture on X-ray, but cannot weight-bear.

Is there appropriate information to make this decision?

This requires a balance between availability, time, and appropriateness.

In general, simple investigations which rapidly give the diagnosis, or clues

to it, are all that are needed. These include electrocardiogram (ECGs),

arterial blood gas (ABG), and plain X-rays. It is relatively unusual to have

to wait for the results of investigations such as full blood count (FBC), urea

& electrolytes (U&E), and liver function tests (LFTs) before referring a

patient, since these rarely alter the immediate management. Simple trolley-

side investigations are often of great value, for example, stix estimations

of blood glucose (BMG) and urinalysis. If complicated investigations are

needed, then referral for inpatient or outpatient specialist care is often

required.

Has the patient had appropriate treatment pending the admission?

Do not forget, or delay, analgesia. Treat every patient in pain appropriately

as soon as possible. A patient does not have to ‘earn’ analgesia. Never

delay analgesia to allow further examination or investigation. Concern

regarding masking of signs or symptoms (for example, in a patient with an

acute abdomen) is inhumane and incorrect.

9

DISCHARGE, REFERRAL, AND HANDOVER

How to refer patients

Referral is often by telephone, and this can create problems:

• Introduce yourself and ask for the name and grade of the specialist.

• Give a clear, concise summary of the history, investigations, and

treatment that you have already undertaken.

• Early in the discussion say clearly whether you are making a referral for

admission or a request for a specialist opinion. With ever increasing

pressure on hospital beds, inpatient teams can be reluctant to come

and see patients, and may appear to be happier to give advice over

the phone to avoid admission. If, in your view, the patient needs to

be admitted, then clearly indicate this. If, for whatever reason, this is

declined, do not get cross, rude, or aggressive, but contact senior ED

medical staff to speak to the specialist team.

• When the specialist team comes to see the patient, or the patient is

admitted directly to a ward, the ED notes need to be complete and

legible. Make sure that there is a list of the investigations already

performed, together with the available results and crucially, a list of

investigations whose results remain outstanding. The latter is essential

to ensure continuity of care and to prevent an important result ‘falling

through the net’. Similarly, summarize treatment already given and the

response. In an emergency, do not delay referral or treatment merely

to complete the notes, but complete them at the earliest opportunity.

• Encourage inpatient specialists who attend patients to write their

fi ndings and management plan in the notes, adding a signature and the

time/date.

Handing over patients

Dangers of handing over

Handing over a patient to a colleague, because your shift has ended and

you are going home, is fraught with danger. It is easy for patients to be

neglected, or receive sub-optimal or delayed treatment. It is safest

to complete to the point of discharge or referral to an inpatient team

every patient that you are seeing at the end of a shift. Occasionally this

may not be possible (eg if there is a delay in obtaining an X-ray or other

investigation). In these situations, hand over the patient carefully to the

doctor who is taking over and inform the nursing staff of this.

How to hand over

Include in the handover relevant aspects of history and examination

performed, the investigation results, and the treatment undertaken. Sign

and aim to complete records on the patient as soon as possible. Note the

time of hand over, and the name of the doctor or nurse handed over to.

When accepting a ‘handed-over patient’ at the start of a shift, spend time

establishing exactly what has happened so far. Finally, it is courteous (and

will prevent problems) to tell the patient that their further care will be

performed by another doctor or nurse.

10 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Liaising with GPs

Despite changes in the way that care (particularly out of hours) is delivered,

GPs still have a pivotal role in co-ordinating medical care. Often the GP will

know more than anyone about the past history, social and family situation,

and recent events of their patient’s management. Therefore, contact the

GP when these aspects are relevant to the patient’s ED attendance, or

where considerations of admission or discharge are concerned.

Every attendance is followed routinely by a letter to the GP detailing the

reason(s) for presentation, clinical fi ndings and relevant investigations,

treatment given, and follow-up arrangements.

If a patient dies, contact the GP without delay — to provide a medical

contact and assistance to the bereaved family, to prevent embarrassing

experiences (eg letters requesting clinic attendances), and out of courtesy,

because the GP is the patient’s primary medical attendant. Finally, the GP

may be asked to issue a death certifi cate by the Coroner (in Scotland, the

Procurator Fiscal) following further enquiries.

Always contact the GP prior to the discharge of a patient where early

follow-up (ie within the next 24–72hr) is required. This may occur with

elderly patients where there is uncertainty about the home situation and

their ability to manage. A typical example is an elderly lady with a Colles’

fracture of her dominant wrist who lives alone. The ED management of

this patient is relatively simple ( b p.444). However, merely manipulating

a Colles’ fracture into a good position, supporting it in an adequate

cast, and providing analgesia, is only one facet of care. The GP may know

that the lady has supportive relatives or neighbours who will help with

shopping and cooking, and will help her to bath and dress. The GP and

the primary care team may be able to supplement existing support and

check that the patient is coping. Equally, the GP may indicate that with

additional home support (eg home helps, meals, district nurses), the

patient could manage. Alternatively, the GP may indicate that the Colles’

fracture merely represents the fi nal event in an increasingly fragile home

situation and that the patient will require hospital admission, at least in the

short-term.

For the same reasons, a GP who refers a patient to the ED and indicates

that the patient requires admission does so in the full knowledge of that

patient’s circumstances. Always contact the GP if it is contemplated

that the patient is to be discharged — preferably after senior medical

consultation.

Finally, remember that GPs are also under considerable pressure.

Some situations may appear to refl ect the fact that a patient has been

referred inappropriately or the patient may report that they have tried

to contact their GP unsuccessfully. Rather than irately ringing the practice

and antagonizing them, inform the ED consultant who can raise this

constructively and appropriately in a suitable environment.

11

TELEPHONE ADVICE

Telephone advice

Many departments receive calls from patients, parents, and other carers

for advice. Approach these calls in exactly the same way as a face-to-face

consultation. Formally document details of the call, including:

• Date and time of the call.

• The caller’s telephone number.

• The caller’s relationship to the patient.

• The patient’s name, age, and sex.

• The nature of the problem.

• The advice given.

As with all notes, date, time, and sign these notes.

NHS Direct

In England and Wales NHS Direct provides a 24-hr, 7-day a week telephone

service providing information and advice on health matters. It is staffed by

nurses who respond according to protocols.

The telephone number for NHS Direct is 0845 4647.

The equivalent service in Scotland is NHS24 tel. 08454 242424.

These services have internet websites at www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk and

www.nhs24.com

Telephone advice calls from other health professionals

Occasionally, other health professionals request advice regarding the

management of patients in their care. Such advice should be given by

experienced ED staff.

Telemedicine

Increasingly, emergency health care is provided by integrated networks,

which include EDs, minor injuries units, radiology departments, and GP

surgeries connected by telemedicine links. This has advantages in remote

or rural settings, enabling a wide range of injuries and other emergencies

to be diagnosed and treated locally. The combination of video and

teleradiology may allow a decision to be made and explained directly

to the patient. A typical example is whether a patient with an isolated

Colles’ fracture needs to have a manipulation of the fracture. Expertise

is required to undertake telemedicine consultations safely. This specialist

advice should be given by senior ED staff, and careful documentation is

crucial.

12 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Liaising with the ambulance crew

Paramedics and ED staff have a close professional relationship. Paramedics

and ambulance staff are professionals who work in conditions that are

often diffi cult and sometimes dangerous. It is worth taking an off-duty day

to accompany a crew during their shift to see the problems they face.

A benefi t of paramedic training has been to bring ambulance staff into the

ED to work with medical and nursing staff, and to foster the communication

and rapport essential for good patient management.

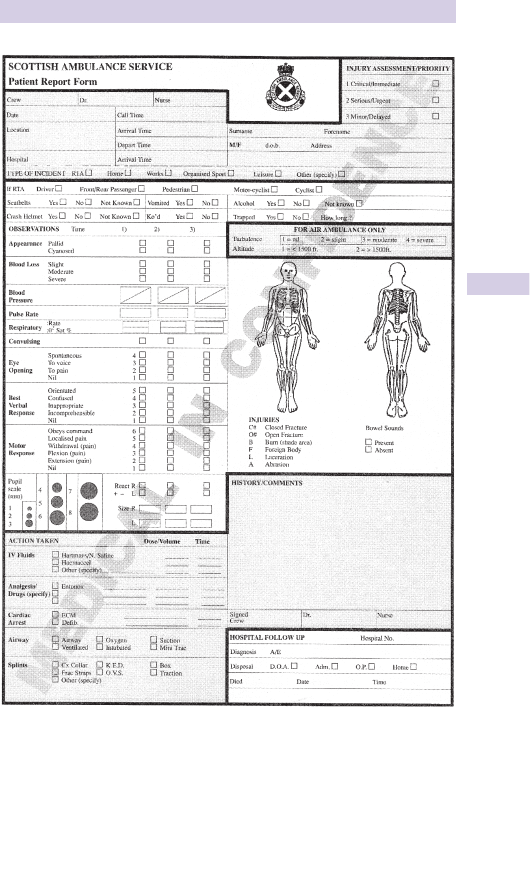

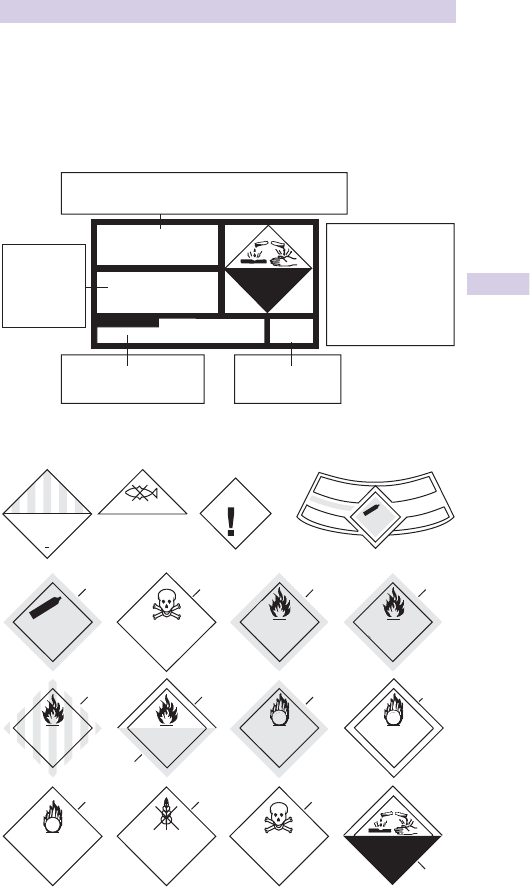

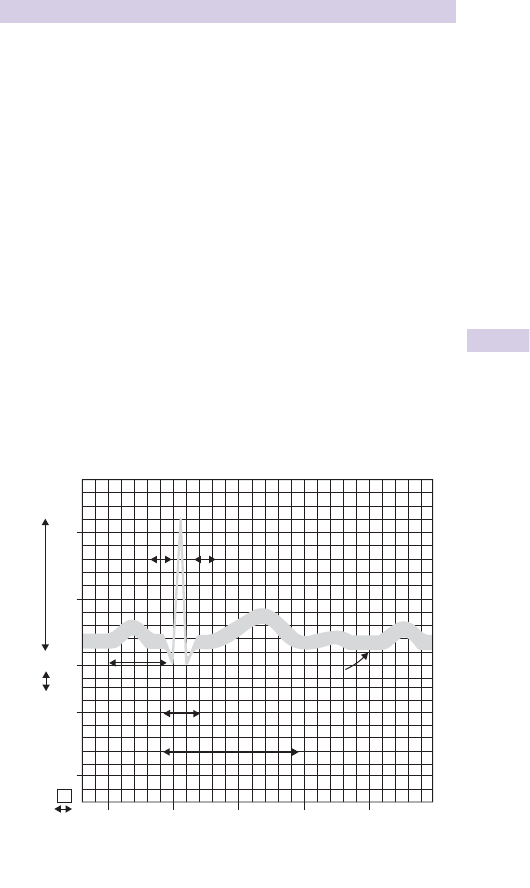

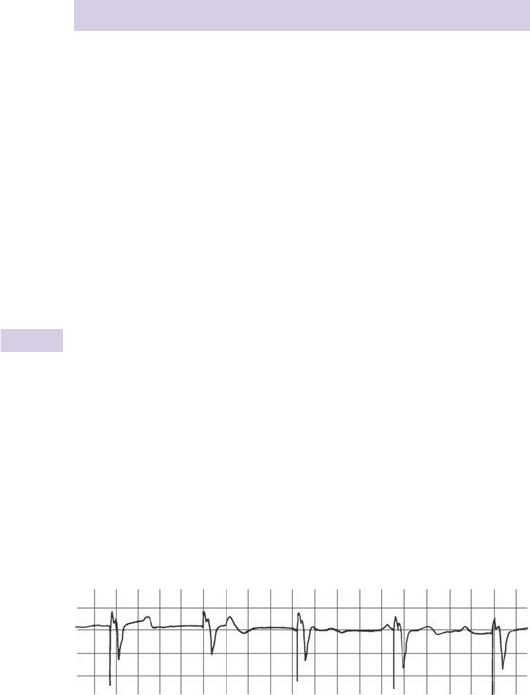

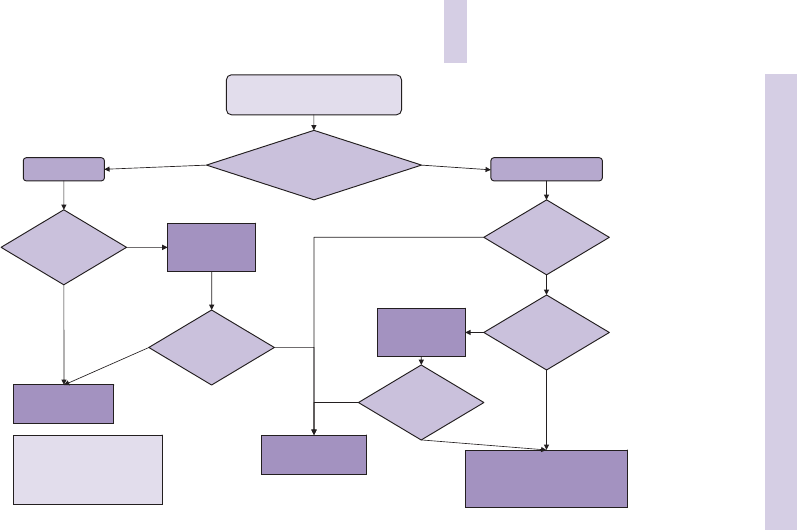

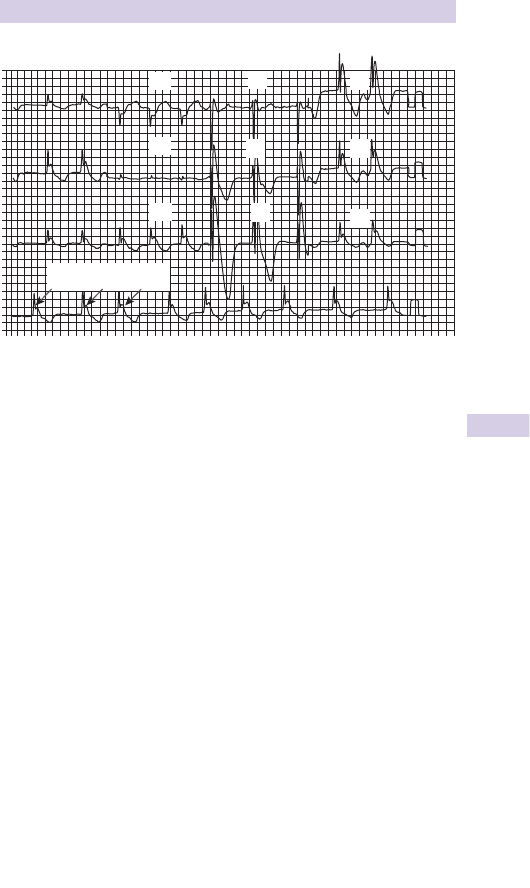

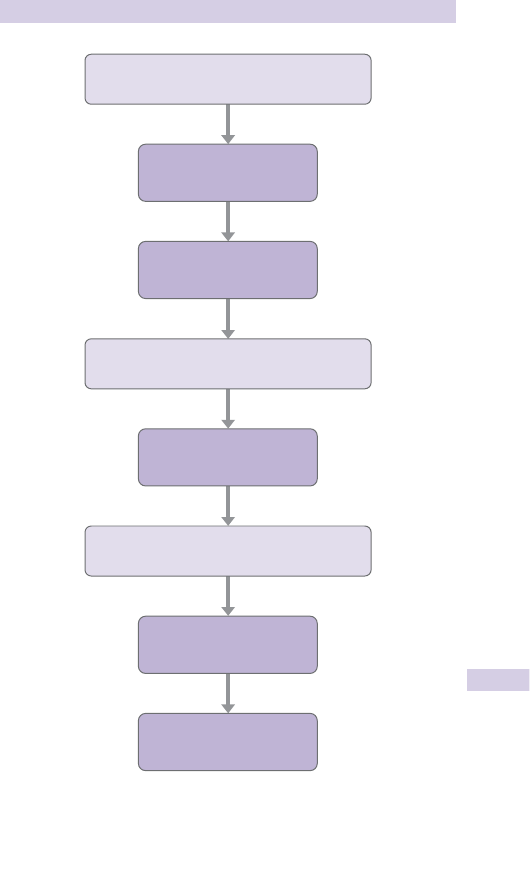

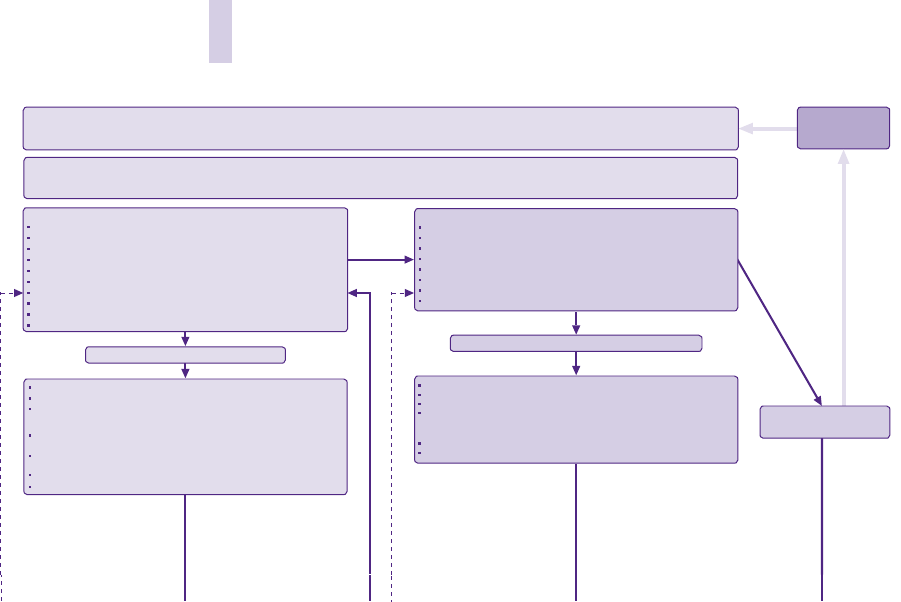

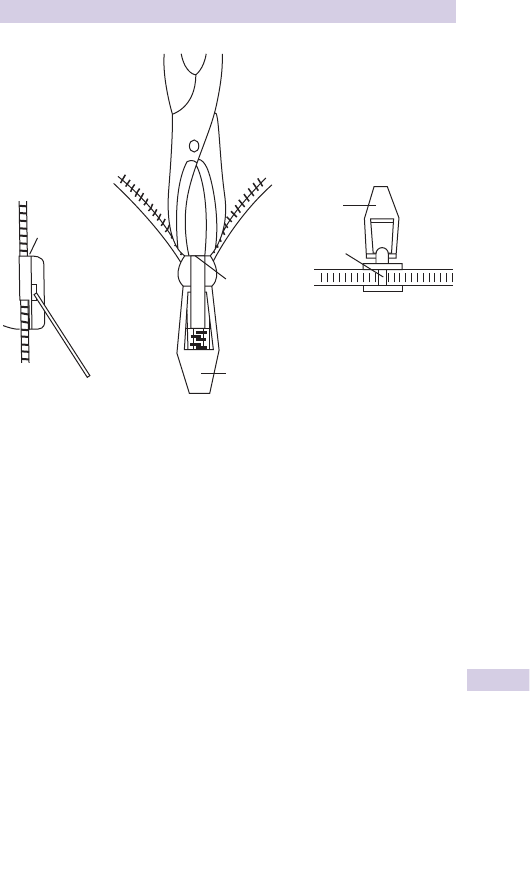

In the UK, a patient brought to an ED by ambulance will routinely have a

patient report form (PRF) (see Fig. 1.1 ). This is completed by the crew at

the scene and in transit, and given to reception or nursing staff on arrival.

The information on these forms can be invaluable. In particular, the time

intervals between the receipt of the 999 call, and arrival at the scene and

at hospital, provide a time framework within which changes in the patient’s

clinical condition can be placed and interpreted.

The initial at-scene assessment will include details of the use of seat belts,

airbags, crash helmets, etc., and is particularly valuable when amplifi ed by

specifi cally asking the crew about their interpretation of the event, likely

speeds involved, types of vehicle, etc.

The clinical features of the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) , pulse rate, blood

pressure (BP), and respiratory rate form baseline values from which trends

and response to treatment can be judged. Useful aspects in the history/

comments section include previous complaints, current medications, etc.,

which the crew may have obtained from the patient, relatives, or friends.

The PRF will also contain important information about oxygen, drugs, IV

fl uids administered, and the response to these interventions. Before the

crew leave the department, confi rm that they have provided all relevant

information.

Do not be judgemental about the crew’s performance. Remember the

constraints under which they operate. Without the benefi ts of a warm

environment, good lighting, and sophisticated equipment, it can be

exceedingly diffi cult to make accurate assessments of illness or injury

severity, or to perform otherwise simple tasks (eg airway management

and intravenous (IV) cannulation).

Do not dismiss the overall assessment of a patient made by an experienced

crew. While the ultimate diagnosis may not be clear (a situation which

pertains equally in the ED), their evaluation of the potential for life-

threatening events is often extremely perceptive. Equally, take heed of

their description of crash scenes. They will have seen far more than most

ED staff, so accept their greater experience.

Most ambulance staff are keen to obtain feedback, both about specifi c cases

and general aspects of medical care. Like everyone, they are interested

in their patients. A few words as to what happened to Mrs Smith who

was brought in last week and her subsequent clinical course is a friendly

and easy way of providing informal feedback, and helps to cement the

professional relationship between the ambulance service and the ED.

13

LIAISING WITH THE AMBULANCE CREW

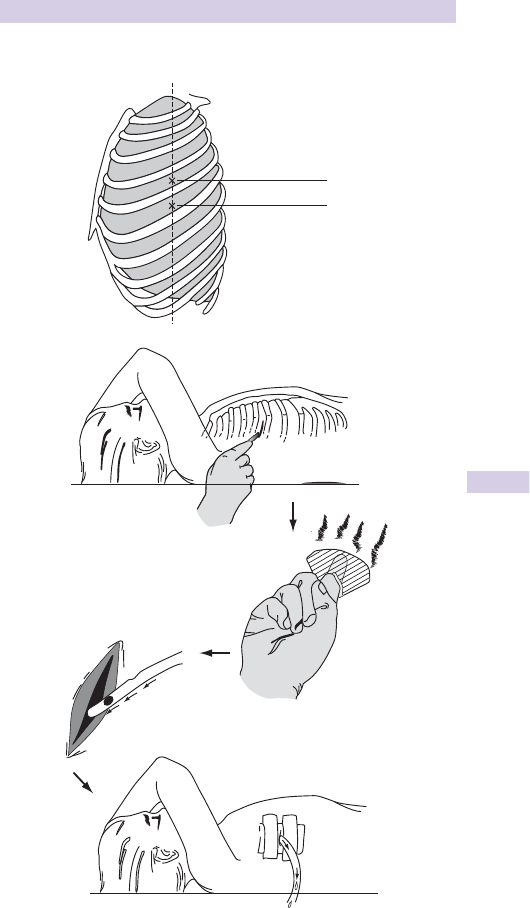

Fig. 1.1 An example of a patient reporting form. Reproduced with kind permission

from the Scottish Ambulance Service.

14 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Coping as a junior doctor

Although many junior doctors coming to the ED have completed more

than 12 months of work since qualifi cation, the prospect of working at the

‘sharp end’ can be accompanied by trepidation. As with many potentially

worrying situations in life, reality is not as terrifying as its anticipation. The

number of hours worked may not appear long in comparison with other

posts, but do not assume that this makes an ED job ‘easy’. Being on duty

inevitably involves much time standing, walking, working, thinking, and making

decisions. It is unusual to come off-shift without feeling physically tired.

Active young doctors can usually cope with these physical demands, but a

demanding professional life and demanding social life are rarely compatible.

Make the most of time off and try to relax from the pressures of the job.

One function of relaxation is to enable you to face work refreshed and

invigorated. You are mistaken if you believe that you can stay out all night

and then work unimpaired the next day. Tired doctors make mistakes.

They also tend to have less patience and, as a consequence, interpersonal

confl icts are more likely.

A greater problem is the mental aspect of the job. Doctors often fi nd that

the ED is the fi rst time in their careers when they have to make unequiv-

ocal decisions based on their own assessment and investigations. This is

one of the great challenges and excitements of emergency medicine. It is

also a worry. Decision-making is central to ED practice and, with experi-

ence, the process becomes easier. Developing a structured approach can

pre-empt many problems and simplify your life. After taking an appropriate

history and completing the relevant clinical examination of a patient, ask

yourself a series of questions such as:

• Do I know what is likely to be wrong with this patient?

• What investigations are required to confi rm the diagnosis?

• Do I know what treatment is needed and have I got the skills needed?

• Does this patient require referral to an inpatient team ( b p.8)?

• If not, do they need to be reviewed in the ED or another specialist clinic?

The wide spectrum of problems with which ED patients can present

means that no individual can be expert in every possible condition. It

is therefore as important to recognize and accept when you are out of

your depth as it is to make decisions and treat patients whom you know

you can manage. Seek help appropriately and do not just try to muddle

through. Help may be readily available from senior ED staff, but in some

departments direct contact with a specialist team is required. One of

the most diffi cult situations is where a specialist either refuses to come

to see the patient or gives telephone advice that is clearly inappropriate.

You must always act as the patient’s advocate. If you refer a patient with

a fractured neck of femur, and the telephone message from the inpatient

team is ‘bring him back to the Fracture Clinic in one week’, it is clearly

wrong to carry this out. First, check that the doctor has understood the

details of the patient’s condition and your concerns. More confl ict and

aggravation is caused by communication errors (usually involving second-

hand telephone messages) than by anything else. If the situation remains

unresolved, consult senior ED staff. Whatever happens, never lose your

cool in public and always put your patient’s interests fi rst.

15

COPING AS A JUNIOR DOCTOR

Learning in the ED

Try to learn something new every day. Keep a note of patients with

interesting or unusual problems, and later check what happened to them.

Ask senior staff for advice. Use the ED reference books. Try to note all

new conditions seen during a shift and read about them later.

Staff interaction

The nature of the job, the patients, and the diversity of staff involved

means that a considerable degree of camaraderie exists. For an outsider,

this can initially be daunting. Junior medical staff are likely to work for

4 − 12 months in the department. Other staff may have spent a lifetime

there with long-established friendships (or sometimes animosities).

Respect their position and experience, learn from them.

The nub of this is an understanding that the role of one individual and that

of other individuals in the department are inextricably linked. Any junior

(or senior) doctor who feels that they are the most important individual

in their working environment will have an extremely uncomfortable

professional existence. In the ED, every member of staff has a role. Your

professionalism should dictate that you respect this. Only in this way will

you gain reciprocal respect from other staff members.

Never consider any job ‘beneath you’ or someone else’s responsibility.

Patients come before pride. So, if portering staff are rushed off their

feet and you are unoccupied, wheel a patient to X-ray yourself — it will

improve your standing with your colleagues and help the patient.

Shifts

Rule 1 Never be late for your shift.

Rule 2 If, for whatever reason, you are unable to work a shift, let the

senior staff in the ED know as soon as possible.

Ensure that you take a break. Two or three short breaks in an 8-hr shift

are better than one long one. Remember to eat and maintain your fl uid

intake. Shift working may mean that you will work sometimes with familiar

faces and perhaps occasionally with individuals with whom you fi nd social

contact uncomfortable. Put these considerations aside while you are at

work, for the sake of the patients and your peace of mind.

If you can’t cope

Finally, if you feel that you are unable to manage or that the pressure

of the job is too great — tell someone . Don’t bottle it up, try to ignore it,

or assume that it refl ects inadequacy. It doesn’t. Everyone, at some time,

has feelings of inability to cope. Trying to disguise or deny the situation

is unfair to yourself, your colleagues, and your patients. You need to tell

someone and discuss things. Do it now. Talk to your consultant. If you

cannot face him or her, talk to your GP or another senior member of

staff — but talk to someone who can help you.

The BMA Counselling Service for Doctors (tel: 08459 200169) provides a

confi dential counselling service 24 hr a day, 365 days of the year to discuss

personal, emotional, and work-related problems. The Doctors’ Support

Network ( www.dsn.org.uk ) and Doctors’ Support Line (tel: 0844 395

3010) are also useful resources.

16 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Inappropriate attenders

This is an emotive and ill-defi ned term. Depending upon the department,

such patients could comprise 4–20 % of attendances.

The perception as to whether it is appropriate to go to an ED or attend a

GP will vary between the patient, GP, and ED staff. Appropriateness is not

simply related to the symptoms, diagnosis, or the time interval involved. It

may not necessarily be related to the need for investigation. For example,

not all patients who require an X-ray necessarily have to attend an ED.

Further blurring of ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ groups relates to the

geographical location of the ED. In rural areas, GPs frequently perform

procedures such as suturing. In urban areas, these arrangements are less

common. For ill-defi ned reasons, patients often perceive that they should

only contact their GP during ‘offi ce’ hours, and outside these times may

attend an ED with primary care complaints.

It is clearly inappropriate to come to an ED simply because of a real or

perceived diffi culty in accessing primary care. Nevertheless, the term

‘inappropriate attendance’ is a pejorative one — it is better to use the

phrase ‘primary care patients’. It must be recognized that primary care

problems are best dealt with by GPs. Many departments try to prevent

this primary care workload presenting to the ED. Some departments

tackle the problem by having GPs working alongside ED staff.

Managing inappropriate attenders

Only through a continual process of patient education will these problems

be resolved. Initiatives include nurse practitioner minor injury units and

hospital-based primary care services. Evaluations are underway but, to

function effectively, such services require adequate funding and staffi ng.

It can sometimes be diffi cult to deal with primary care problems in the

ED. After an appropriate history and examination, it may be necessary to

explain to patients that they will have to attend their own GP. This may

need direct contact between the ED and the practice to facilitate this.

Inappropriate referrals

Sometimes, it may appear that another health professional (eg GP,

emergency nurse practitioner, nurse at NHS Direct) has referred a patient

to the ED inappropriately. Avoid making such judgements. Treat patients

on their merits, but mention the issue to your consultant. Remember

that the information available to the referring clinician at the time of the

prehospital consultation is likely to have been different to that available at

the time of ED attendance.

17

THE PATIENT WITH A LABEL

The patient with a label

Some patients will have been referred by another medical practitioner,

usually a GP. The accompanying letter may include a presumptive diagnosis.

The details in the letter are often extremely helpful, but do not assume

the diagnosis is necessarily correct. Take particular care with patients who

re-attend following an earlier attendance. The situation may have changed

since the previous doctor saw the patient. Clinical signs may have developed

or regressed. The patient may have not given the referring doctor and

ED staff the same history. Do not pre-judge the problem: start with an

open mind. Apply common sense, however. Keep any previous history in

mind. For example, assume that a patient with a known abdominal aortic

aneurysm who collapses with sudden, severe, abdominal pain, signs of

hypovolaemic shock, and a tender pulsatile mass in the abdomen, to have a

ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, rather than intestinal obstruction. The

patient’s

previous ED and hospital case notes are invaluable and will often

give useful information and allow, for example, ECG comparisons, aiding

the diagnostic process. A call to the GP can also provide useful background,

which they may not have had time to include in their referral letter or may

have excluded for confi dentiality or other reasons.

Self-labelled patients

Take care with patients who label themselves. Those with chronic or

unusual diseases often know signifi cantly more about their conditions than

ED staff! In such situations, take special notice of comments and advice

from the patient and/or their relatives. Do not resent this or see it as a

professional affront — rapport with the patient will increase markedly and

management will usually be easier.

Regular attenders

Every ED has a group of ‘regular’ patients who , with time, become physically

and sometimes emotionally attached to the department. Some have

underlying psychiatric illnesses, often with ‘inadequate’ personalities. Some

are homeless. Regular attenders frequently use the ED as a source

of primary care. As outlined above, make attempts to direct them to

appropriate facilities, because the ED is unsuited to the management of

chronic illness, and is unable to provide the continuing medical and nursing

support that these patients require.

Repeated presentations with apparently trivial complaints or with the

same complaint often tax the patience of ED staff. This is heightened if the

presentations are provoked or aggravated by alcohol intake. Remember,

however, that these patients can and do suffer from the same acute events

as everyone else. Keep an open mind, diagnostically and in attitude to the

patient. Just because he/she has returned for the third time in as many

days complaining of chest pain, does not mean that on this occasion he

does not have an acute MI! Maintain adequate documentation for each

attendance. Occasionally, especially with intractable re-attenders, a joint

meeting between the social work team, GP, ED consultant and psychiatric

services is required to provide a defi nitive framework for both the patient

and the medical services. For some patients, it will be possible to follow a

plan of action for ED presentations with a particular complaint.

18 CHAPTER 1 General approach

The patient you dislike

General approach

Accept the patient as he or she is, regardless of behaviour, class, religion,

social lifestyle, or colour. Given human nature, there will inevitably be

some patients whom you immediately dislike or fi nd diffi cult. The feeling

is often mutual. Many factors that cause patients to present to the ED may

aggravate the situation. These include their current medical condition, their

past experiences in hospitals, their social situation, and any concurrent use

of alcohol and/or other drugs. Your approach and state of mind during

the consultation play a major role. This will be infl uenced by whether the

department is busy, how much sleep you have had recently, and when you

last had a break for coffee or food.

Given the nature of ED workload and turnover, confl ict slows down

the process and makes it more likely that you will make clinical errors.

Many potential confl icts can be avoided by an open, pleasant approach.

Introduce yourself politely to the patient. Use body language to reduce a

potentially aggressive response.

The patient’s perspective

Put yourself in the patient’s position. Any patient marched up to by a

doctor who has their hands on hips, a glaring expression, and the demand

‘Well, what’s wrong with you now?’ will retort aggressively.

Defusing a volatile situation

Most complaints and aggression occur when the department is busy and

waiting times are long. Patients understand the pressures medical and

nursing staff have to work under, and a simple, ‘I am sorry you have had to

wait so long, but we have had a number of emergencies elsewhere in the

department’, does much to diffuse potential confl ict and will often mean

that the patient starts to sympathize with you as a young, overworked

practitioner!

There is never any excuse for rude, abusive, or aggressive behaviour

to a patient. If you are rude, complaints will invariably follow and more

importantly, the patient will not have received the appropriate treatment

for their condition. It may be necessary to hand care of a patient to a

colleague if an unresolvable confl ict has arisen.

Management of the violent patient is considered in detail on b p.610.

19

SPECIAL PATIENT GROUPS

Special patient groups

Attending the ED is diffi cult enough, but can be even more so for certain

‘special’ patient groups. It is important that ED staff are sensitive to the

needs of these groups and that there are systems in place to help them

in what may be regarded as an intimidating atmosphere. The following list

is far from exhaustive, but includes some important groups who require

particular consideration:

• Children : they are such an ‘obvious’ and large ‘minority’ group that they

receive special attention to suit their particular needs (see b Paediatric

emergencies, p.630).

• Pregnant women : see b Obstetrics and gynaecology, p.563.

• Those with mental health problems : see b Psychiatry, p.601.

• The elderly : who often have multiple medical problems and live in

socially precarious circumstances.

• Patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other states associated with

chronic confusion.

• Those with learning diffi culties : b p.21.

• Patients with hearing problems.

• The visually impaired.

• Those who do not speak or understand English : arrangements should be in

place to enable the use of interpreters.

• Patients with certain cultural or religious beliefs (particularly amongst

‘minority groups’) : these can impact signifi cantly upon a variety of

situations (eg after unsuccessful resuscitation for cardiac arrest—

b Breaking bad news, p.24).

• Those who are homeless or are away from home, friends, and family

(eg holiday makers).

• Those who have drug/alcohol dependency.

Isn’t everyone special?

Taken at face value, the concept that certain groups of patients are

‘special’ and so require special attention does not meet with universal

approval. There is a good argument that every patient deserves the best

possible care. Whilst this is true, it is also obvious that certain patients

do have additional needs that need to be considered. Many of these

additional needs relate to effective communication. There are some

tremendous resources available that can help practitioners to overcome

communication diffi culties (eg www.communicationpeople.co.uk ).

20 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Discharging the elderly patient

There are no set predisposing factors that determine patients most at risk

following discharge. Those that affect the chance of diffi culties at home

include the current medical problem, underlying functional and social factors.

Risk indicators

Multiple pathologies and atypical symptoms render this group more vulnerable

to the physical, functional, and social effects of acute illness. Past medical

history and pre-admission status are especially important determinants

for patients with dementia or psychiatric illness. There may be evidence of

recently changed circumstances, a recent bereavement, a change in medical or

physical condition, increasing confusion, or unusual behaviour. The patient may

not be able to afford adequate food or heating. Community services may not

be aware that support is needed or help may have been offered, but refused.

Other important indicators are:

• Those living alone.

• Absence of close family support or community services.

• Unsuitable home circumstances (eg external or internal stairs).

• Diffi culty with mobility.

Determining those unable to cope

Look for evidence of self-neglect that suggests that the elderly person

is having diffi culty coping at home (eg poor personal hygiene, unclean or

unsuitable clothing). Evidence of recent weight loss may suggest diffi culties

with food preparation or eating, unavailability of food, or may be due to

serious pathology, such as a malignancy or tuberculosis. Signs of old bruising

or other minor injuries may be consistent with frequent falls. Shortness of

breath and any condition producing impaired mobility are important factors.

Falls are a common problem of old age and require careful analysis, perhaps

at a special ‘Falls’ clinic. Correctable factors include damaged walking aids,

loose rugs, poor lighting, or unsuitable footwear or glasses. Common medical

causes include cerebrovascular disease, arthritis, and side-effects of drugs.

Many elderly people claim that they can cope at home when they are unable

to do so. If in doubt, ask relatives, the GP, and community support agencies.

They may give helpful insight into the patient’s mental state, which can be

investigated/assessed further, whether it be a cognitive or reactive condition.

The decision to discharge

Hospital admission for an elderly person is a frightening experience and

can lead to confusion and disorientation. If circumstances allow, discharge

home is often a more appropriate outcome. If there are concerns regarding

their functional ability and mobility, ask for an occupational therapy and/

or physiotherapy assessment with, if appropriate, a home assessment.

The elderly person is best seen in their home environment with familiar

surroundings, especially if there is evidence of cognitive defi cit. The provision

of equipment and recommendations for adaptations can be made at this

point if required. A wide range of community services including district

nurse, health visitor, home help, crisis care, social work, hospital discharge,

and rapid response therapy teams can be contacted to provide immediate

follow-up and support and play a crucial role in preventing later breakdowns

in home circumstances and unnecessary admissions for social reasons.

21

THE PATIENT WITH LEARNING DIFFICULTIES

The patient with learning diffi culties

Patients with learning diffi culties use the healthcare system more than the

general population. Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have

little experience with these patients. However, understanding common

illness patterns and using different techniques in communication can result

in a successful consultation. Patients with learning diffi culties often have

complex health needs. There are many barriers to assessing health care,

which may lead to later presentations of illness. Patients may have a high

tolerance of pain — take this into consideration when examining them.

Associated health problems

Patients with learning diffi culties have a higher incidence of certain problems:

• Visual and hearing impairment.

• Poor dental health.

• Swallowing problems.

• Gastro-oesophageal refl ux disease.

• Constipation.

• Urinary tract and other infections.

• Epilepsy.

• Mental health problems ( i incidence of depression, anxiety disorders,

schizophrenia, delirium, and dementia), with specifi c syndromes

having their own particular associations (eg Down’s is associated with

depression and dementia; Prader–Willi with affective psychosis).

• Behavioural problems (eg Prader–Willi, Angelman syndrome).

Leading causes of death

These include pneumonia (relating to refl ux, aspiration, swallowing, and

feeding problems) and congenital heart disease.

The patient’s perspective

Past experiences of hospital are likely to have a big impact on the patient’s

reaction to his/her current situation. Most patients have problems with

expression, comprehension, and social communication. They fi nd it diffi cult

to describe symptoms — behavioural change may the best indication that

something is wrong.

Tips for communication

• Explain the consultation process before starting.

• Speak fi rst to the patient, then to the carer.

• Use open questions, then re-phrase to check again.

• Aim to use language that the patient understands, modifying this

according to comprehension.

• Patients may have diffi culties with time, so try to relate symptoms to

real life temporal events (eg ‘did the pain start before lunch?’)

• They may not make a connection between something that they have

done and feeling ill (eg several questions may be required in order to

establish that they have ingested something).

• Take particular note of what the carer has to say — information from

someone who knows the patient well is invaluable.

22 CHAPTER 1 General approach

Patient transfer

The need to transfer

When patients have problems that exceed the capabilities of a hospital

and/or its personnel, transfer to another hospital may be needed.

Timing the transfer

Do not commence any transfer until life-threatening problems have been

identifi ed and managed, and a secondary survey has been completed.

Once the decision to transfer has been made, do not waste time

performing non-essential diagnostic procedures that do not change the

immediate plan of care. First, secure the airway (with tracheal intubation

if necessary). Ensure that patients with pneumothoraces and chest injuries

likely to be associated with pneumothoraces have intercostal drains

inserted prior to transfer. This is particularly important before sending a

patient by helicopter or fi xed wing transfer. Consider the need to insert a

urinary catheter and a gastric tube.

Arranging the transfer

Speak directly to the doctor at the receiving hospital. Provide the following

details by telephone or telemedicine link: