Recommendations from the 2023

International Evidence-based

Guideline for the Assessment and

Management of Polycystic

Ovary Syndromey

Helena J. Teede,

a,b

Chau Thien Tay,

a,b

Joop Laven,

b,c

Anuja Dokras,

d

Lisa J. Moran,

a,b

Terhi T. Piltonen,

e

Michael F. Costello,

b,f

Jacky Boivin,

g

Leanne M. Redman,

h

Jacqueline A. Boyle,

b,i

Robert. J. Norman,

b,j

Aya Mousa,

a

and Anju E. Joham

a,b

on behalf of the International PCOS Network

#

a

Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University and Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria,

Australia;

b

National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence in Women’s Health in

Reproductive Life, Australia;

c

Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands;

d

Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.;

e

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medical Research Center

Oulu, Research Unit of Clinical Medicine, University of Oulu and Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland;

f

University of

New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia;

g

Cymru Fertility and Reproductive Research, School of Psychology,

Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom;

h

Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State

University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S.A.;

i

Eastern Health Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria,

Australia;

j

Robinson Research Institute, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Abstract

STUDY QUESTION: What is the recommended assessment and management of those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), based

on the best available evidence, clinical expertise, and consumer preference?

SUMMARY ANSWER: International evidence-based guidelines address prioritized questions and outcomes and include 254

recommendations and practice points, to promote consistent, evidence-based care and improve the experience and health outcomes

in PCOS.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY: The 2018 International PCOS Guideline was independently evaluated as high quality and integrated

multidisciplinary and consumer perspectives from six continents; it is now used in 196 countries and is widely cited. It was based

on best available, but generally very low to low quality, evidence. It applied robust methodological processes and addressed shared pri-

orities. The guideline transitioned from consensus based to evidence-based diagnostic criteria and enhanced accuracy of diagnosis,

whilst promoting consistency of care. However, diagnosis is still delayed, the needs of those with PCOS are not being adequately

met, evidence quality was low and evidence-practice gaps persist.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION: The 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline update reengaged the 2018 network across

professional societies and consumer organizations with multidisciplinary experts and women with PCOS directly involved at all

stages. Extensive evidence synthesis was completed. Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation-II (AGREEII)-compliant

processes were followed. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was

applied across evidence quality, feasibility, acceptability, cost, implementation and ultimately recommendation strength and

diversity and inclusion were considered throughout.

PARTICIPANTS/ MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS: This summary should be read in conjunction with the full Guideline for

detailed participants and methods. Governance included a six-continent international advisory and management committee, five

guideline development groups, and paediatric, consumer, and translation committees. Extensive consumer engagement and

guideline experts informed the update scope and priorities. Engaged international society-nominated panels included paediatrics,

endocrinology, gynaecology, primary care, reproductive endocrinology, obstetrics, psychiatry, psychology, dietetics, exercise

y

This article is simultaneously published in Fertility and Sterility, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, European Journal of Endocrinology and

Human Reproduction.

#

Participants of the International PCOS Network are listed in the Appendix.

Correspondence: Helena J. Teede, Locked Bag 29, Clayton, Australia, 3168, VIC, Australia (E-mail: helena.teede@ monash.edu).

Fertility and Sterility® Vol. -, No. -, - 2023 0015-0282/$36.00

This article has been co-published with permission in Fertility and Sterility, Human Reproduction, European Journal of Endocrinology, and The Journal of

Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. © The Author(s) 2023. Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine.

This is an open access article under the CC-BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). The articles are identical except for minor

stylistic and spelling differences in keeping with each journal's style.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.07.025

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 1

physiology, obesity care, public health and other experts, alongside consumers, project management, evidence synthesis, statisticians

and translation experts. Thirty-nine professional and consumer organizations covering 71 countries engaged in the process. Twenty

meetings and five face-to-face forums over 12 months addressed 58 prioritized clinical questions involving 52 systematic and 3

narrative reviews. Evidence-based recommendations were developed and approved via consensus across five guideline panels,

modified based on international feedback and peer review, independently reviewed for methodological rigour, and approved by the

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE: The evidence in the assessment and management of PCOS has generally improved in

the past five years, but remains of low to moderate quality. The technical evidence report and analyses (6000 pages) underpins 77

evidence-based and 54 consensus recommendations, with 123 practice points. Key updates include: i) further refinement of

individual diagnostic criteria, a simplified diagnostic algorithm and inclusion of anti-M

€

ullerian hormone (AMH) levels as an

alternative to ultrasound in adults only; ii) strengthening recognition of broader features of PCOS including metabolic risk factors,

cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, very high prevalence of psychological features, and high risk status for adverse outcomes

during pregnancy; iii) emphasizing the poorly recognized, diverse burden of disease and the need for greater healthcare professional

education, evidence-based patient information, improved models of care and shared decision making to improve patient experience,

alongside greater research; iv) maintained emphasis on healthy lifestyle, emotional wellbeing and quality of life, with awareness

and consideration of weight stigma; and v) emphasizing evidence-based medical therapy and cheaper and safer fertility management.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION: Overall, recommendations are strengthened and evidence is improved, but remain gener-

ally low to moderate quality. Significantly greater research is now needed in this neglected, yet common condition. Regional health

system variation was considered and acknowledged, with a further process for guideline and translation resource adaptation provided.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS: The 2023 International Guideline for the Assessment and Management of PCOS provides

clinicians and patients with clear advice on best practice, based on the best available evidence, expert multidisciplinary input and con-

sumer preferences. Research recommendations have been generated and a comprehensive multifaceted dissemination and translation

programme supports the Guideline with an integrated evaluation program.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S): This effort was primarily funded by the Australian Government via the National

Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (APP1171592), supported by a partnership with American Society for Reproductive Med-

icine, Endocrine Society, European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology, and the Society for Endocrinology. The

Commonwealth Government of Australia also supported Guideline translation through the Medical Research Future Fund

(MRFCRI000266). HJT and AM are funded by NHMRC fellowships. JT is funded by a Royal Australasian College of Physicians

(RACP) fellowship. Guideline development group members were volunteers. Travel expenses were covered by the sponsoring organi-

zations. Disclosures of interest were strictly managed according to NHMRC policy and are available with the full guideline, technical

evidence report, peer review and responses (www.monash.edu/medicine/mchri/pcos). Of named authors HJT, CTT, AD, LM, LR, JBoyle,

AM have no conflicts of interest to declare. JL declares grant from Ferring and Merck; consulting fees from Ferring and Titus Health

Care; speaker’s fees from Ferring; unpaid consultancy for Ferring, Roche Diagnostics and Ansh Labs; and sits on advisory boards

for Ferring, Roche Diagnostics, Ansh Labs, and Gedeon Richter. TP declares a grant from Roche; consulting fees from Gedeon Richter

and Organon; speaker’s fees from Gedeon Richter and Exeltis; travel support from Gedeon Richter and Exeltis; unpaid consultancy for

Roche Diagnostics; and sits on advisory boards for Roche Diagnostics. MC declares travels support from Merck; and sits on an advisory

board for Merck. JBoivin declares grants from Merck Serono Ltd.; consulting fees from Ferring B.V; speaker’s fees from Ferring Arz-

neimittell GmbH; travel support from Organon; and sits on an advisory board for the Office of Health Economics. RJN has received

speaker’s fees from Merck and sits on an advisory board for Ferring. AJoham has received speaker’s fees from Novo Nordisk and Boeh-

ringer Ingelheim. The guideline was peer reviewed by special interest groups across our 39 partner and collaborating organizations, was

independently methodologically assessed against AGREEII criteria and was approved by all members of the guideline development

groups and by the NHMRC. (Fertil Steril

2023;-:-–-. This article has been co-published with permission in Fertility and Sterility,

Human Reproduction, European Journal of Endocrinology, and The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. The Author(s)

2023. Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. This is an open access article under the

CC-BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). The articles are identical except for minor stylistic and spelling

differences in keeping with each journal's style.

Key Words: Polycystic ovary syndrome, guideline, evidence-based, assessment, management, GRADE

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR THOSE WITH

PCOS?

Building on the 2018 International Evidence-based Guideline

for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary

Syndrome (PCOS), this Guideline updates and expands clin-

ical questions, aiming to ensure that women with PCOS

receive optimal, evidence-based care that meets their needs

and improves health outcomes. The guideline and translation

program were developed with full consumer participation at

all stages including priority topics and outcomes for those

with PCOS. The aim is to support women and their healthcare

providers to optimize diagnosis, assessment and management

of PCOS. There is an emphasis on improved education and

awareness of healthcare professionals, partnership in care,

and empowerment of women with PCOS. Personal character-

istics, preferences, culture and values are considered, in addi-

tion to resource availability across different settings. With

effective translation, the Guideline will address priorities

identified by women with PCOS, upskill healthcare

professionals, empower consumers, improve care and out-

comes, identify key research gaps, and promote vital future

research.

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endo-

crinopathy affecting reproductive-aged women, with impacts

across the lifespan from adolescence to post menopause.

PCOS prevalence is between 10 to 13% as demonstrated in

2 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

the guideline process.

1,2

PCOS aetiology is complex; clinical

presentation is heterogeneous with reproductive, metabolic,

and psychological features.

1,2

Women internationally experi-

ence delayed diagnosis and dissatisfaction with care.

3-5

Clinical practice in the assessment and management of

PCOS remains inconsistent, with ongoing key practice

evidence gaps. Following on from the 2018 International

Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Manage-

ment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome,

6,7

independently evalu-

ated as high quality, this extensive update integrates current

literature with previous systematic reviews and extends to

new clinical questions prioritized by consumers. Ultimately,

we aim to update, extend and translate rigorous, comprehen-

sive evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis, assessment and

treatment, to improve the lives of those with PCOS worldwide.

To do so, the Guideline leverages substantive government

and society investment and brings together extensive con-

sumer engagement and international collaboration with lead-

ing societies and organizations, multidisciplinary experts, and

primary care representatives. This comprehensive evidence-

based Guideline is constructed from a rigorous, Appraisal of

Guidelines for Research and Evaluation-II (AGREEII)-

compliant, evidence-based guideline development process. It

provides a single source of international evidence-based rec-

ommendations to guide clinical practice with the opportunity

for adaptation in relevant health systems. Together with an

extensive translation program, the aim is to reduce worldwide

variation in care and promote high quality clinical service pro-

vision to improve health outcomes and quality of life in women

with PCOS. The Guideline is supported by a multifaceted inter-

national translation programme with co-designed resources to

enhance the skills of healthcare professionals and to empower

women with PCOS, with an integrated comprehensive evalua-

tion program. Here, we summarize recommendations from the

2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assess-

ment and Management of PCOS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Best practice evidence-based guideline development methods

were applied and are detailed in the full Guideline and the tech-

nical reports, which are available online (www.monash.edu/

medicine/mchri/pcos).

8

In brief, extensive healthcare profes-

sional and consumer or patient engagement informed the

Guideline priority areas. International society-nominated

panels from across three leading entities, four partner organiza-

tions and thirty-two collaborating entities included consumers

and experts in paediatrics, endocrinology, gynaecology, pri-

mary care, reproductive endocrinology, psychology, dietetics,

exercise physiology, sleep, bariatric/ metabolic surgery, public

health, other co-opted experts, project management, evidence

synthesis and translation. Governance included an interna-

tional advisory and a management committee, five guideline

development groups (GDGs) with 56 members, and paediatric,

consumer, and translation committees. The five GDGs covered

i) Screening, diagnostic and risk assessment and life stage; ii)

Psychological features and models of care; iii) Lifestyle man-

agement; iv) Management of nonfertility features; and v)

Assessment and management of infertility. The leading en-

tities; the Australian National Health and Medical Research

Council (NHMRC) Centres for Research Excellence in Women’s

Health in Reproductive Life and in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome,

led by Monash University, partnered with the American Society

for Reproductive Medicine, the Endocrine Society, the Euro-

pean Society of Endocrinology and the European Society of

Human Reproduction and Embryology and collaborated with

32 other entities. With international meetings over 12 months

fifty-five prioritized clinical questions involved 52 systematic

and three narrative reviews, generating evidence-based and

consensus recommendations with accompanying practice

points. Committee members nominated by partner and collab-

orator organizations provided international peer review, and

independent experts reviewed methods which were then sub-

mitted to NHMRC for independent review. The target audience

includes multidisciplinary healthcare professionals, consumers

or patients, policy makers, and educators. The Guideline in-

cludes a focus on equity, cultural and ethnic diversity, avoid-

ance of stigma and inclusivity (see full guideline for details).

Processes aligned with all elements of the AGREE-II tool

for quality guideline assessment,

9

with extensive evidence syn-

thesis and meta-analysis. Integrity assessment was integrated

into guideline evidence synthesis processes and followed the

Research Integrity in Guideline Development (RIGID) frame-

work, with studies assessed against criteria from the Research

Integrity Assessment (RIA) tool and the Trustworthiness in

RAndomised Controlled Trials (TRACT) checklist.

10-12

Evidence synthesis methods are outlined in the full guideline

and followed best practice

9,13,14

Guideline recommendations

are presented by category, terms used, evidence quality and

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and

Evaluation (GRADE) framework considerations. Category

includes evidence-based (sufficient evidence in PCOS) or

consensus (insufficient evidence in PCOS, hence evidence in

general or relevant populations was considered) recommenda-

tions and accompanying practice points (implementation con-

siderations) (Table 1).

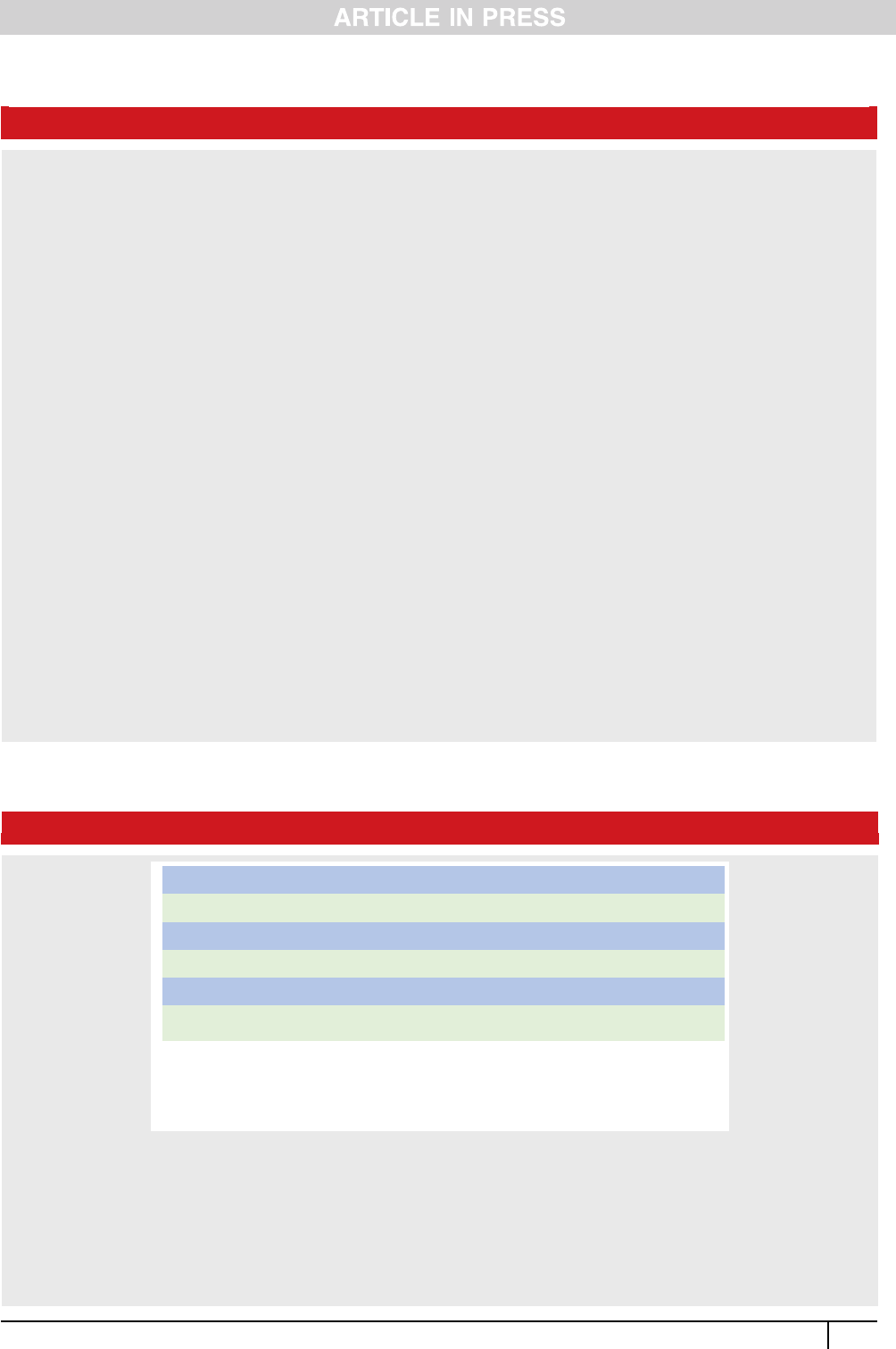

TABLE 1

Categories of PCOS guideline recommendations

EBR Evidence Based Recommendations:

Evidence sufficient to inform a

recommendation made by the

guideline development group.

CR Consensus Recommendations: In

the absence of adequate

evidence, a consensus

recommendation has been

made by the guideline

development group, also

informed by evidence from the

general population.

PP Practice Points: Evidence not

sought. A practice point has

been made by the guideline

development group where

important issues arose from

discussion of evidence-based or

consensus recommendations.

PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Teede. International PCOS Guideline 2023. Fertil Steril 2023.

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 3

Fertility and Sterility®

The terms include ‘‘ should’’, ‘‘could’’ and ‘‘ should not’’ ,

which are informed by the nature of the recommendation (ev-

idence or consensus), the GRADE framework and the evidence

quality and are independent descriptors reflecting GDG

judgement. They refer to overall interpretation and practical

application of the recommendation, balancing benefits and

harms. ‘‘Should’’ is used where benefits of the recommenda-

tion exceed harms and where the recommendation can be

trusted to guide practice. Conditional recommendations are

reflected using the terms ‘‘ could’’ or ‘‘ should/could consider’’

which are used where evidence quality was limited or avail-

able studies demonstrate little clear advantage of one

approach over another, or the balance of benefits to harms

was unclear. ‘‘ Should not’’ applies when there is a lack of

appropriate evidence, or harms may outweigh benefits.

Evidence quality was categorized according to the GRADE

framework, with judgments about the quality of the included

studies and/or synthesized evidence incorporating risk of

bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and any other

considerations (e.g., publication bias) that may influence evi-

dence quality. These judgments considered study number and

design, statistical data and importance of outcomes (Table 2).

The quality of evidence reflects the confidence that the estimate

of the effect is adequate to support each recommendation,

13

largely determined by the expert evidence synthesis team.

GRADE acknowledges that evidence quality is a continuum;

any discrete categorization involves some arbitrary decisions;

nevertheless, the advantages of simplicity, transparency, and

clarity outweigh these limitations.

13

The GRADE framework enabled structured and trans-

parent consideration across evidence quality, feasibility,

acceptability, cost, implementation, and ultimately recom-

mendation strength

13

and was completed at face to face

guideline group meetings for all clinical questions (Table 3).

15

Notably, certainty of evidence varied across outcomes

within each question. Here evidence certainty reflects the

lowest certainty for the critical outcomes. Evidence was often

stronger for the top ranked outcome, and high quality

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were often present,

despite overall low quality of evidence. These nuances were

considered by the GDG for all question as per the technical

report, with any apparent discrepancy between recommenda-

tion strength and evidence certainty justified in the full

Guideline. Finally, we note that this is a living Guideline

with annual evidence review in rapidly evolving areas.

The recommendations (Table 4) apply the category, descrip-

tive terms, GRADE of the recommendations and the quality of

the evidence. The full Guideline, technical evidence and admin-

istrativereportsareavailableonline(www.monash.edu/

medicine/mchri/pcos). The Guideline outlines the clinical need

for the question, the clinical question, the evidence summary,

the recommendations and practice points, and a summary of

the justification developed by the GDGs using the GRADE

framework. Extensive international peer review from across

the39organizationswasthenconsideredbyeachGDGandrec-

ommendations were reconsidered applying the GRADE frame-

work if justified. The comprehensive evidence reviews,

profiles, and GRADE frameworks supporting each recommenda-

tion can be found in the Technical Report. The administrative

report on guideline development, disclosure of interest process

and declarations, peer review feedback and responses can also

be found online. Here, we present the evidence-based and

consensus recommendations and practice points (Table 4). This

summary, the full Guideline and technical reports are supported

by a comprehensiv e co-des igned trans lation program to

optimize dissemination and impact with resources freely avai l-

able online (www.monash.edu/med icine/ mchri/p cos).

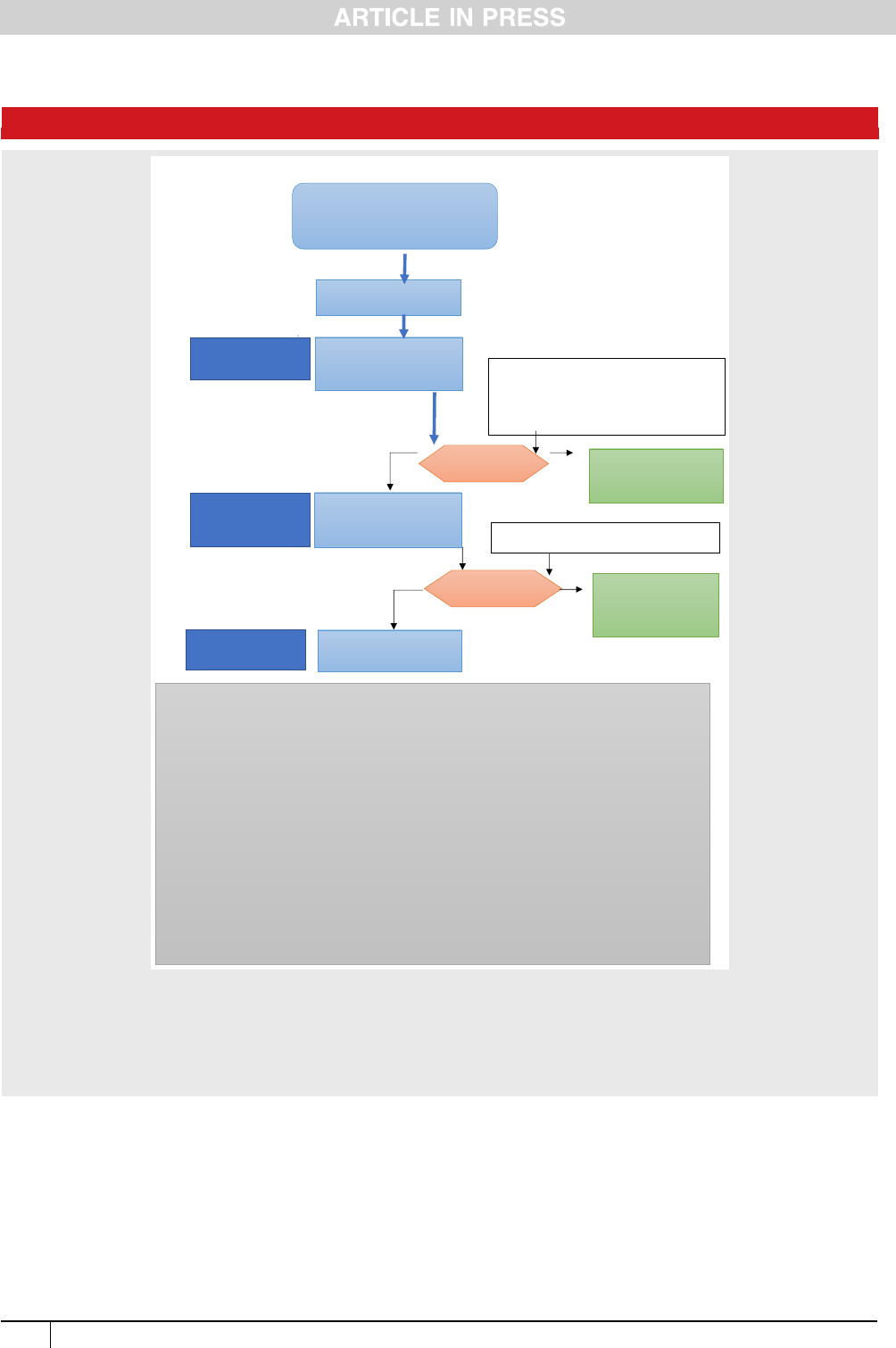

Two algorithms are provided to support recommenda-

tions on diagnosis (Figure 1) and infertility management

(Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment

and Management of PCOS and the related translation program

aims to provide a high quality, reliable source of international

evidence-based recommendations to guide consistent clinical

practice and to empower women with evidence-based informa-

tion. All recommendationswere formulated after an assessment

of the best available evidence, multidisciplinary clinical exper-

tise, consumer preferences and structured review by five GDGs.

The guideline provides 77 evidence-based and 54 consensus

recommendations, with 123 practice points underpinned by a

technical report on evidence synthesis and GRADE detailed

TABLE 2

Quality (certainty) of evidence categories (adapted from GRADE)

High 4444 Very confident that the true

effect lies close to that of the

estimate of the effect.

Moderate 444 Moderate confidence in the

effect estimate. The true

effect is likely to be close to

the estimate of the effect,

but there is a possibility that

it is different.

Low 44 Limited confidence in the effect

estimate. The true effect may

be substantially different

from the estimate of the

effect.

Very Low 4 Very little confidence in the

effect estimate. The true

effect is likely to be

substantially different from

the estimate of the effect.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Teede. International PCOS Guideline 2023. Fertil Steril 2023.

TABLE 3

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and

Evaluation (GRADE) framework recommendation strength

❖ Conditional recommendation against the

option.

❖❖ Conditional recommendation for either the

option or the comparison.

❖❖❖ Conditional recommendation for the

option.

❖❖❖❖ Strong recommendation for the option.

Teede. International PCOS Guideline 2023. Fertil Steril 2023.

4 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Recommendations for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Monash University on behalf of the NHMRC

Centre for Research Excellence in Women's Health in Reproductive Life, 2023.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

1 Screening, diagnostic and risk assessment and life-stages

General principles

PP All diagnostic assessments are recommended for use in accordance with the

diagnostic algorithm (Algorithm 1).

1.1 Irregular cycles and ovulatory dysfunction

1.1.1 CR Irregular menstrual cycles are defined as:

Normal in the first year post menarche as part of the pubertal transition.

1to< 3 years post menarche: < 21 or > 45 days.

3 years post menarche to perimenopause: < 21 or > 35 days or < 8 cycles

per year.

1 year post menarche > 90 days for any one cycle.

Primary amenorrhea by age 15 or > 3 years post thelarche (breast devel-

opment).

When irregular menstrual cycles are present a diagnosis of PCOS should be

considered and assessed according to these PCOS Guidelines.

❖❖❖❖

1.1.2 PP The mean age of menarche may differ across populations.

1.1.3 PP In adolescents with irregular menstrual cycles, the value and optimal timing of

assessment and diagnosis of PCOS should be discussed with the patient

and their parent/s or guardian/s, considering diagnostic challenges at this

life stage and psychosocial and cultural factors.

1.1.4 PP For adolescents who have features of PCOS, but do not meet diagnostic

criteria, an ‘‘ increased risk’’ could be considered and reassessment advised

at or before full reproductive maturity, 8 years post menarche. This

includes those with PCOS features before combined oral contraceptive pill

(COCP) commencement, those with persisting features and those with

significant weight gain in adolescence.

1.1.5 PP Ovulatory dysfunction can still occur with regular cycles and if anovulation

needs to be confirmed serum progesterone levels can be measured.

1.2 Biochemical hyperandrogenism

1.2.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should use total and free testosterone to assess

biochemical hyperandrogenism in the diagnosis of PCOS; free

testosterone can be estimated by the calculated free androgen index.

❖❖❖❖

4

1.2.2 EBR If testosterone or free testosterone is not elevated, healthcare professionals

could consider measuring androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone

sulfate (DHEAS), noting their poorer specificity and greater age associated

decrease in DHEAS.

❖❖❖

4

1.2.3 EBR Laboratories should use validated, highly accurate tandem mass spectrometry

(LC-MS/MS) assays for measuring total testosterone and if needed, for

androstenedione and DHEAS. Free testosterone should be assessed by

calculation, equilibrium dialysis or ammonium sulfate precipitation.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.2.4 EBR Laboratories should use LC-MS/MS assays over direct immunoassays (e.g.,

radiometric, enzyme-linked, etc.) for assessing total or free testosterone,

which have limited accuracy and demonstrate poor sensitivity and

precision for diagnosing hyperandrogenism in PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.2.5 PP For the detection of hyperandrogenism in PCOS, the assessment of

biochemical hyperandrogenism is of greatest value in patients with

minimal or no clinical signs of hyperandrogenism (i.e., hirsutism).

1.2.6 PP It is very difficult to reliably assess for biochemical hyperandrogenism in

women on the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) as the pill

increases sex hormone-binding globulin and reduces gonadotrophin-

dependent androgen production. If already on the COCP, and assessment

of biochemical androgens is imperative, the pill should be withdrawn for a

minimum of three months and contraception should be managed

otherwise during this time.

1.2.7 PP Repeated androgen measures for the ongoing assessment of PCOS in adults

have a limited role.

1.2.8 PP In most adolescents, androgen levels reach adult ranges at 12-15 years of age

1.2.9 PP If androgen levels are markedly above laboratory reference ranges, causes of

hyperandrogenaemia other than PCOS, including ovarian and adrenal

neoplastic growths, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome,

ovarian hyperthecosis (after menopause), iatrogenic causes, and

syndromes of severe insulin resistance, should be considered. However,

some androgen-secreting neoplasms are associated with only mild to

moderate increases in androgen levels. The clinical history of time of onset

and/or rapid progression of symptoms is critical in assessing for an

androgen-secreting tumour.

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 5

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

1.2.10 PP Reference ranges for different methods and laboratories vary widely, and are

often based on an arbitrary percentile or variances of the mean from a

population that has not been fully characterized and is highly likely to

include women with PCOS. Normal values should be determined either by

the range of values in a well characterized healthy control population or by

cluster analysis of general population values.

1.2.11 PP Laboratories involved in androgen measurements in females should consider:

Determining laboratory normal values by either the range of values in a well

characterized healthy control population or by cluster analysis of the values

of a large general population.

Applying the most accurate methods where available.

Using extraction/chromatography immunoassays as an alternative to mass

spectrometry only where adequate expertise is available.

Future improvements may arise from measurement of 11-oxygenated

androgens, and from establishing cut-off levels or thresholds based on

large-scale validation in populations of different ages and ethnicities.

1.3 Clinical hyperandrogenism

1.3.1 EBR The presence of hirsutism alone should be considered predictive of

biochemical hyperandrogenism and PCOS in adults.

❖❖❖

4

1.3.2 EBR Healthcare professionals could recognize that female pattern hair loss and

acne in isolation (without hirsutism) are relatively weak predictors of

biochemical hyperandrogenism.

❖❖❖

4

1.3.3 CR A comprehensive history and physical examination should be completed for

symptoms and signs of clinical hyperandrogenism, including acne, female

pattern hair loss and hirsutism in adults, and severe acne and hirsutism in

adolescents.

❖❖❖❖

1.3.4 CR Healthcare professionals should be aware of the potential negative

psychosocial impact of clinical hyperandrogenism and should consider the

reporting of unwanted excess hair growth and/or female pattern hair loss

as being important, regardless of apparent clinical severity.

❖❖❖

1.3.5 CR A modified Ferriman Gallwey score (mFG) of 4 – 6 should be used to detect

hirsutism, depending on ethnicity, acknowledging that self-treatment is

common and can limit clinical assessment.

❖❖❖❖

1.3.6 CR Healthcare professionals should consider that the severity of hirsutism may

vary by ethnicity but the prevalence of hirsutism appears similar across

ethnicities.

❖❖❖

1.3.7 PP Healthcare professionals should:

Be aware that standardized visual scales are preferred when assessing hir-

sutism, such as the mFG scale in combination with a photographic atlas.

Consider the Ludwig or Olsen visual scales for assessing female pattern hair

loss.

Note that there are no universally accepted visual instruments for assessing

the presence of acne.

Recognize that women commonly treat clinical hyperandrogenism

cosmetically, diminishing their apparent clinical severity.

Appreciate that self-assessment of unwanted excess hair growth, and

possibly acne and female pattern hair loss, has a high degree of validity and

merits close evaluation, even if overt clinical signs of hyperandrogenism are

not readily evident on examination.

Note that only terminal hairs need to be considered in defining hirsutism,

and these can reach >5 mm if untreated, vary in shape and texture, and are

generally pigmented.

Note that new-onset severe or worsening hyperandrogenism, including

hirsutism, requires further investigation to rule out androgen-secreting

tumours and ovarian hyperthecosis.

Monitor clinical signs of hyperandrogenism, including hirsutism, acne and

female pattern hair loss, for improvement or treatment adjustment during

therapy.

1.4 Ultrasound and polycystic ovarian morphology

1.4.1 EBR Follicle number per ovary (FNPO) should be considered the most effective

ultrasound marker to detect polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) in

adults.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.4.2 EBR Follicle number per ovary (FNPO), follicle number per cross-section (FNPS) and

ovarian volume (OV) should be considered accurate ultrasound markers

for PCOM in adults.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.4.3 CR PCOM criteria should be based on follicle excess (FNPO, FNPS) and/or ovarian

enlargement.

❖❖❖❖

6 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

1.4.4 CR Follicle number per ovary (FNPO) R 20 in at least one ovary should be

considered the threshold for PCOM in adults.

❖❖❖❖

1.4.5 CR Ovarian volume (OV) R 10ml or follicle number per section (FNPS) R 10 in at

least one ovary in adults should be considered the threshold for PCOM if

using older technology or image quality is insufficient to allow for an

accurate assessment of follicle counts throughout the entire ovary.

❖❖❖❖

1.4.6 PP There are no definitive criteria to define polycystic ovary morphology (PCOM)

on ultrasound in adolescents, hence it is not recommended in adolescents.

1.4.7 PP When an ultrasound is indicated, if acceptable to the individual, the

transvaginal approach is the most accurate for the diagnosis of PCOM.

1.4.8 PP Transabdominal ultrasound should primarily report ovarian volume (OV) with

a threshold of R 10 ml or follicle number per section (FNPS) R 10 in either

ovary in adults given the difficulty of assessing follicle counts throughout

the entire ovary with this approach.

1.4.9 PP In patients with irregular menstrual cycles and hyperandrogenism, an ovarian

ultrasound is not necessary for PCOS diagnosis.

1.4.10 PP Thresholds for PCOM should be revised regularly with advancing ultrasound

technology, and age-specific cut-off values for PCOM should be defined.

1.4.11 PP There is a need for training in careful and meticulous follicle counting per

ovary and clear standardized protocols are recommended for PCOM

reporting on ultrasound including at a minimum:

Last menstrual period (or stage of cycle).

Transducer bandwidth frequency.

Approach/route assessed.

Total number of 2 – 9 mm follicles per ovary.

Measurements in three dimensions (in cm) or volume of each ovary.

Other ovarian features and/or pathology including ovarian cysts, corpus

lutea, dominant follicles (R10 mm) (which should not be included in

ovarian volume calculations).

Reliance on the contralateral ovary FNPO for diagnosis of PCOM, where a

dominant follicle is noted.

Uterine features and/or pathology including endometrial thickness and

pattern.

1.5 Anti-M

€

ullerian Hormone in the diagnosis of PCOS

1.5.1 EBR Serum anti-M

€

ullerian hormone (AMH) could be used for defining PCOM in

adults.

❖❖❖

444

1.5.2 EBR Serum AMH should only be used in accordance with the diagnostic algorithm,

noting that in patients with irregular menstrual cycles and

hyperandrogenism, an AMH level is not necessary for PCOS diagnosis.

❖❖❖❖

444

1.5.3 EBR We recommend that serum AMH should not be used as a single test for the

diagnosis of PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

444

1.5.4 EBR Serum AMH should not yet be used in adolescents. ❖❖❖❖

444

1.5.5 PP Either serum AMH or ultrasound may be used to define PCOM; however, both

tests should not be performed to limit overdiagnosis.

1.5.6 PP Laboratories and healthcare professionals need to be aware of factors that

influence AMH in the general population including:

Age: Serum AMH generally peaks between the ages of 20-25 years in the

general population.

Body mass index (BMI): Serum AMH is lower in those with higher BMI in the

general population.

Hormonal contraception and ovarian surgery: Serum AMH may be sup-

pressed by current or recent COCP use.

Menstrual cycle day: Serum AMH may vary across the menstrual cycle.

1.5.7 PP Laboratories involved in AMH measurements in females should use

population and assay specific cut-offs.

1.6 Ethnic variation

1.6.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware of the high prevalence of PCOS in

all ethnicities and across world regions, ranging from 10-13% globally

using the Rotterdam criteria.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.6.2 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware that PCOS prevalence is broadly

similar across world regions, but may be higher in South East Asian and

Eastern Mediterranean regions.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.6.3 PP Healthcare professionals should be aware that the presentation of PCOS may

vary across ethnic groups.

1.7 Menopause life stage

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 7

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

1.7.1 CR A diagnosis of PCOS could be considered as enduring / lifelong. ❖❖❖

1.7.2 CR Healthcare professionals could consider that both clinical and biochemical

hyperandrogenism persist in the postmenopause for women with PCOS.

❖❖❖

1.7.3 CR PCOS diagnosis could be considered postmenopause if there is a past

diagnosis, or a long-term history of oligo-amenorrhoea with

hyperandrogenism and/or PCOM, during the earlier reproductive years

(age 20-40).

❖❖❖

1.7.4 CR Further investigations should be considered to rule out androgen-secreting

tumours and ovarian hyperthecosis in postmenopausal women presenting

with new-onset, severe or worsening hyperandrogenism including

hirsutism.

❖❖❖

1.8 Cardiovascular disease risk

1.8.1 EBR Women with PCOS should be considered at increased risk of cardiovascular

disease and potentially of cardiovascular mortality, acknowledging that

the overall risk of cardiovascular disease in pre-menopausal women is low.

❖❖❖

4

1.8.2 EBR All women with PCOS should be assessed for cardiovascular disease risk

factors.

❖❖❖❖

4

1.8.3 CR All women with PCOS, regardless of age and BMI, should have a lipid profile

(cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein

cholesterol and triglyceride level) at diagnosis. Thereafter, frequency of

measurement should be based on the presence of hyperlipidaemia and

additional risk factors or global cardiovascular risk.

❖❖❖❖

1.8.4 CR All women with PCOS should have blood pressure measured annually and

when planning pregnancy or seeking fertility treatment, given the high

risk of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and the associated

comorbidities.

❖❖❖❖

1.8.5 CR Funding bodies should recognize that PCOS is highly prevalent with

multisystem effects including cardiometabolic disease and should diversify

and increase research support accordingly.

❖❖❖❖

1.8.6 CR Cardiovascular general population guidelines could consider the inclusion of

PCOS as a cardiovascular risk factor.

❖❖❖

1.8.7 CR Healthcare professionals, women with PCOS and other stakeholders should

all prioritize preventative strategies to reduce cardiovascular risk.

❖❖❖❖

1.8.8 PP Consideration should be given to the differences in cardiovascular risk factors,

and cardiovascular disease, across ethnicities (see 1.6.1) and age, when

determining frequency of risk assessment.

1.9 Impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes risk

1.9.1 EBR Healthcare professionals and women with PCOS should be aware that,

regardless of age and BMI, women with PCOS have an increased risk of

impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.9.2 EBR Glycaemic status should be assessed at diagnosis in all adults and adolescents

with PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

44

1.9.3 CR Glycaemic status should be reassessed every one to three years, based on

additional individual risk factors for diabetes.

❖❖❖❖

1.9.4 CR Healthcare professionals, women with PCOS and other stakeholders should

prioritize preventative strategies to reduce type 2 diabetes risk.

❖❖❖❖

1.9.5 CR Funding bodies should recognize that PCOS is highly prevalent, has

significantly higher risk for diabetes, and should be funded accordingly.

❖❖❖❖

1.9.6 CR Diabetes general population guidelines should consider the inclusion of PCOS

as an independent risk factor for diabetes.

❖❖❖❖

1.9.7 PP Healthcare professionals, adults and adolescents with PCOS and their first-

degree relatives, should be aware of the increased risk of diabetes and the

need for regular glycaemic assessment.

1.9.8 PP Women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes have an increased risk of PCOS and

screening should be considered in individuals with diabetes.

Glycaemic testing

1.9.9 EBR Healthcare professionals and women with PCOS should recommend the 75-g

oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) as the most accurate test to assess

glycaemic status in PCOS, regardless of BMI.

❖❖❖❖

4

1.9.10 EBR If an OGTT cannot be performed, fasting plasma glucose and/or glycated

haemoglobin (HbA1c) could be considered, noting significantly reduced

accuracy.

❖❖❖

4

8 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

1.9.11 EBR An OGTT should be considered in all women with PCOS and without pre-

existing diabetes, when planning pregnancy or seeking fertility treatment,

given the high risk of hyperglycaemia and the associated comorbidities in

pregnancy. If not performed preconception, an OGTT could be offered at

the first prenatal visit and all women with PCOS should be offered the test

at 24-28 weeks gestation.

❖❖❖

4

1.9.12 PP Insulin resistance is a pathophysiological factor in PCOS, however, clinically

available insulin assays are of limited clinical relevance and are not

recommended in routine care (refer to 3.1.10).

1.10 Obstructive Sleep Apnea

1.10.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware that women with PCOS have

significantly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea compared to

women without PCOS, independent of BMI.

❖❖❖❖

444

1.10.2 EBR Women with PCOS should be assessed for symptoms of obstructive sleep

apnea (i.e., snoring in combination with waking unrefreshed from sleep,

daytime sleepiness or fatigue) and if present, screen with validated tools or

refer for assessment.

❖❖❖❖

444

1.10.3 PP Simple obstructive sleep apnea screening questionnaires (such as the Berlin

questionnaire, validated in the general population) can assist in identifying

obstructive sleep apnea in women with PCOS, noting that diagnosis

requires a formal sleep study.

1.10.4 PP Goals of treatment should target obstructive sleep apnea related symptom

burden.

1.11 Endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

1.11.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware that premenopausal women with

PCOS have markedly higher risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia

and endometrial cancer.

❖❖❖❖

4

1.11.2 PP Women with PCOS should be informed about the increased risk of

endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, acknowledging that the

overall chance of developing endometrial cancer is low, therefore routine

screening is not recommended.

1.11.3 PP Long-standing untreated amenorrhea, higher weight, type 2 diabetes and

persistent thickened endometrium are additional to PCOS as risk factors

for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.

1.11.4 PP Women with PCOS should be informed of preventative strategies including

weight management, cycle regulation and regular progestogen therapy.

1.11.5 PP When excessive endometrial thickness is detected, consideration of a biopsy

with histological analysis and withdrawal bleed is indicated.

1.12 Risks in first degree relatives

1.12.1 EBR Healthcare professionals could consider that fathers and brothers of women

with PCOS may have an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome, type

2 diabetes, and hypertension.

❖❖❖

4

1.12.2 PP The cardiometabolic risk in female first degree relatives of women with PCOS

remains inconclusive.

2 Prevalence, screening and management of psychological features and

models of care

General principles

PP Psychological features are common and important component of PCOS that

all healthcare professionals should be aware of.

PP Funding bodies should recognize that PCOS is highly prevalent, has

significantly higher psychological disorders which should be prioritized

and funded accordingly.

2.1 Quality of Life

2.1.1 EBR Healthcare professionals and women should recognize the adverse impact of

PCOS and/or PCOS features on quality of life in adults.

❖❖❖❖

44

2.1.2 PP Women with PCOS should be asked about their perception of PCOS related-

symptoms, impact on quality of life, key concerns, and priorities for

management.

2.2 Depression and Anxiety

2.2.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware of the high prevalence of moderate

to severe depressive symptoms and depression in adults and adolescents

with PCOS and should screen for depression in all adults and adolescents

with PCOS, using regionally validated screening tools.

❖❖❖❖

4444

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 9

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

2.2.2 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware of the high prevalence of moderate

to severe anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in adults and should

screen for anxiety in all adults with PCOS, using regionally validated

screening tools.

❖❖❖❖

4444

2.2.3 CR If moderate or severe depressive or anxiety symptoms are detected,

practitioners should further assess, refer appropriately, or offer treatment.

❖❖❖❖

2.2.4 PP Severity of symptoms and clinical diagnosis of depression or anxiety should

guide management.

The optimal interval for anxiety and depression screening is not known. A

pragmatic approach could include screening at diagnosis with repeat

screening based on clinical judgement, risk factors, comorbidities, and life

events, including the perinatal period.

Screening for mental health disorders comprises assessment of risk factors,

symptoms, and risk of self-harm and suicidal intent.

2.3 Psychosexual function

2.3.1 CR Healthcare professionals could consider the multiple factors that can influence

psychosexual function in PCOS including higher weight, hirsutism, mood

disorders, infertility and PCOS medications.

❖❖❖

2.3.2 CR Permission to discuss psychosexual function should be sought noting that the

diagnosis of psychosexual dysfunction requires both low psychosexual

function combined with related distress.

❖❖❖❖

2.4 Body Image

2.4.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should be aware that features of PCOS can have a

negative impact on body image.

❖❖❖❖

44

2.5 Eating disorders

2.5.1 EBR Eating disorders and disordered eating should be considered in PCOS,

regardless of weight, especially in the context of weight management and

lifestyle interventions (see sections 2.4 and 3.6).

❖❖❖

44

2.5.2 PP If disordered eating or eating disorders are suspected, appropriately qualified

practitioners should further assess via a full diagnostic interview.

If an eating disorder or disordered eating is detected, appropriate

management and support should be offered.

2.6 Information resources, models of care, cultural and linguistic

considerations

2.6.1 Information needs

2.6.1.1 EBR Tailored information, education and resources that are high-quality, culturally

appropriate and inclusive should be provided to all with PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

444

2.6.1.2 EBR Information, education and resources are a high priority for patients with

PCOS and should be provided in a respectful and empathic manner.

❖❖❖❖

444

2.6.1.3 CR Entities responsible for healthcare professional education should ensure that

information and education on PCOS is systemically embedded at all levels

of healthcare professional training to address knowledge gaps.

❖❖❖❖

2.6.1.4 PP The diversity of the population should be considered when adapting practice

paradigms.

Healthcare professional education opportunities should be optimised at all

stages of graduate and postgraduate training and continuing professional

development and in practice support resources.

2.6.1.5 PP Women should be counselled on the risk of misinformation and guided to

evidence-based resources.

2.6.2 Models of care

2.6.2.1 CR Models of care should prioritize equitable access to evidence-based primary

care with pathways for escalation to integrated specialist and

multidisciplinary services as required.

❖❖❖❖

2.6.2.2 PP Strategies to deliver optimal models of care could include healthcare

professional education, care pathways, virtual care, broader health

professional engagement (e.g., nurse practitioners) and coordination

tools.

2.6.3 Support to manage PCOS

2.6.3.1 CR Public health actors should consider increasing societal awareness and

education on PCOS to reduce stigma and marginalization.

❖❖❖

2.6.3.2 PP Culturally appropriate resources and education on PCOS across the life span

for families of those with the condition should be considered.

10 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

2.6.4 Patient care

2.6.4.1 EBR Healthcare professionals should employ shared decision-making and support

patient agency or ability to take independent actions to manage their

health and care.

❖❖❖❖

444

2.6.4.2 EBR The importance of being knowledgeable about PCOS, of applying evidence-

based practices when sharing news on diagnosis, treatment, and health

implications, and of ascertaining and focusing on patient priorities, should

be recognized.

❖❖❖❖

444

2.6.4.3 CR Healthcare system leaders should enable system wide changes to support

healthcare professional training, knowledge and practice in sharing news

optimally, shared decision making and patient agency, including ensuring

adequate consultation time and accessible resources.

❖❖❖❖

2.6.4.4 PP Evidence-based strategies for shared decision making and for sharing news

(such as the SPIKES framework) are readily available and should be used to

inform PCOS care.

All healthcare professionals partnering with women with PCOS should be

knowledgeable in sharing news, in shared decision-making, and in

supporting patient self-management.

Evidence-based strategies and resources can be used to support patient

activation, which refers to modifiable knowledge, skills, ability,

confidence, and willingness to self-manage one’s own health and care.

2.7 Psychological therapy

2.7.1 CR Women with PCOS diagnosed with depression, anxiety, and/or eating

disorders should be offered psychological therapy guided by regional

general population guidelines and the preference of the woman with

PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

2.7.2 CR Women with PCOS with disordered eating, body image distress, low self-

esteem, problems with feminine identity, or psychosexual dysfunction

should be offered evidence-based treatments (e.g., cognitive behaviour

therapy) where appropriate.

❖❖❖❖

2.8 Antidepressant and anxiolytic treatment

2.8.1 CR Psychological therapy could be considered first-line management, and

antidepressant medications considered in adults where mental health

disorders are clearly documented and persistent, or if suicidal symptoms

are present, based on general population guidelines.

❖❖❖

2.8.2 PP Lifestyle intervention and other therapies (e.g., COCP, metformin, laser hair

removal) that target PCOS features should be considered, given their

potential to improve psychological symptoms.

Where pharmacological treatment for anxiety and depression is offered in

PCOS, healthcare professionals should apply caution:

to avoid inappropriate treatment with antidepressants or anxiolytics.

to limit use of agents that exacerbate PCOS symptoms, including weight

gain.

Healthcare professionals should be aware that not managing anxiety and

depression may impact adherence to PCOS treatment / management.

3 Lifestyle management

3.1 Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions

3.1.1 EBR Lifestyle intervention (exercise alone or multicomponent diet combined with

exercise and behavioural strategies) should be recommended for all

women with PCOS, for improving metabolic health including central

adiposity and lipid profile.

❖❖❖❖

4

3.1.2 CR Healthy lifestyle behaviours encompassing healthy eating and/or physical

activity should be recommended in all women with PCOS to optimize

general health, quality of life, body composition and weight management

(maintaining weight, preventing weight gain and/or modest weight loss).

❖❖❖❖

3.1.3 PP Healthcare professionals should be aware that lifestyle management is a core

focus in PCOS management.

3.1.4 PP Lifestyle management goals and priorities should be co-developed in

partnership with women with PCOS, and value women’s individualized

preferences.

3.1.5 PP There are benefits to a healthy lifestyle even in the absence of weight loss.

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 11

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

3.1.6 PP In those with higher weight, weight management can be associated with

significant clinical improvements and the following key points need to be

considered including:

A lifelong focus on prevention of further weight gain.

If the goal is to achieve weight loss, a tailored energy deficit could be pre-

scribed for women, considering individual energy requirements, body

weight and physical activity levels.

The value of improvement in central adiposity (e.g., waist circumference,

waist-hip ratio) or metabolic health.

The need for ongoing assessment and support.

3.1.7 PP Healthcare professionals should be aware of weight stigma when discussing

lifestyle management with women with PCOS (see 3.6).

3.1.8 PP Healthy lifestyle and optimal weight management, in the context of

structured, intensive, and ongoing clinical support, appears equally

effective in PCOS as in the general population.

3.1.9 PP In those who are not overweight, in the adolescent and at key life points, the

focus should be on healthy lifestyle and the prevention of excess weight

gain.

3.1.10 PP Insulin resistance is a pathophysiological factor in PCOS, however, clinically

available insulin assays are of limited clinical relevance and should not be

used in routine care (refer to 1.9.12).

3.2 Behavioural Strategies

3.2.1 CR Lifestyle interventions could include behavioural strategies such as goal-

setting, self-monitoring, problem solving, assertiveness training,

reinforcing changes, and relapse prevention, to optimize weight

management, healthy lifestyle and emotional wellbeing in women with

PCOS.

❖❖❖

3.2.2 PP Behavioural support could include: goal-setting, problem solving, self-

monitoring and reviewing, or SMART goals (Specific, Measurable,

Achievable, Realistic and Timely).

3.2.3 PP Comprehensive healthy behavioural or cognitive behavioural interventions

could be considered to increase support, engagement, retention,

adherence, and maintenance of healthy lifestyle and improve health

outcomes in women with PCOS.

3.3 Dietary Intervention

3.3.1 EBR Healthcare professionals and women should consider that there is no

evidence to support any one type of diet composition over another for

anthropometric, metabolic, hormonal, reproductive or psychological

outcomes.

❖❖❖

4

3.3.2 CR Any diet composition consistent with population guidelines for healthy eating

will have health benefits and, within this, healthcare professionals should

advise sustainable healthy eating tailored to individual preferences and

goals.

❖❖❖❖

3.3.3 PP Tailoring of dietary changes to food preferences, allowing for a flexible,

individual and co-developed approach to achieving nutritional goals, and

avoiding unduly restrictive and nutritionally unbalanced diets, are

important, as per general population guidelines.

3.3.4 PP Barriers and facilitators to optimize engagement and adherence to dietary

change should be discussed, including psychological factors, physical

limitations, socioeconomic and sociocultural factors, as well as personal

motivators for change. The value of broader family engagement should be

considered. Referral to suitably trained allied healthcare professionals

needs to be considered when women with PCOS need support with

optimizing their diet.

3.4 Exercise Intervention

3.4.1 EBR Healthcare professionals and women could consider that there is a lack of

evidence supporting any one type and intensity of exercise being better

than another for anthropometric, metabolic, hormonal, reproductive or

psychological outcomes.

❖❖❖

4

3.4.2 CR Any physical activity consistent with population guidelines will have health

benefits and, within this, healthcare professionals should advise

sustainable physical activity based on individual preferences and goals.

❖❖❖❖

12 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

3.4.3 CR Healthcare professionals should encourage and advise the following in

concordance with general population physical activity guidelines:

All adults should undertake physical activity as doing some physical activity

is better than none.

Adults should limit the amount of time spent being sedentary (e.g., sitting,

screen time) as replacing sedentary time with physical activity of any in-

tensity (including light intensity) provides health benefits.

For the prevention of weight gain and maintenance of health, adults (18-64

years) should aim for a minimum of 150 to 300 minutes of moderate in-

tensity activities or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic activity

per week or an equivalent combination of both spread throughout the

week, plus muscle strengthening activities (e.g., resistance/flexibility) on

two non-consecutive days per week.

For promotion of greater health benefits including modest weight-loss and

prevention of weight-regain, adults (18-64 years) should aim for a

minimum of 250 min/week of moderate intensity activities or 150 min/

week of vigorous intensities or an equivalent combination of both, plus

muscle strengthening activities (e.g., resistance/flexibility) ideally on two

non-consecutive days per week.

Adolescents should aim for at least 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-

intensity physical activity per day, including activities that strengthen muscle

and bone at least three times per week.

❖❖❖❖

3.4.4 PP Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that

requires energy expenditure. It includes leisure time physical activity,

transportation (e.g., walking or cycling), occupational (i.e., work),

household chores, playing games, sports or planned exercise, or activities

in the context of daily, family and community activities.

3.4.5 PP Aerobic activity is best performed in bouts of at least 10 minutes duration,

aiming to achieve at least 30 minutes daily on most days.

3.4.6 PP Barriers and facilitators to optimize engagement and adherence to physical

activity should be discussed, including psychological factors (e.g., body

image concerns, fear of injury, fear of failure, mental health), personal

safety concerns, environmental factors, physical limitations,

socioeconomic factors, sociocultural factors, and personal motivators for

change. The value of broader family engagement should be considered.

Referral to suitably trained allied healthcare professionals needs to be

considered for optimizing physical activity in women with PCOS.

3.4.7 PP Self-monitoring, including with fitness tracking devices and technologies for

step count and exercise intensity, could be considered as an adjunct to

support and promote active lifestyles and minimize sedentary behaviours.

3.5 Factors affecting weight gain in PCOS

3.5.1 EBR Healthcare professionals and women with PCOS could consider that there is a

lack of consistent evidence of physiological or behavioural lifestyle

differences, related to weight, in women with PCOS compared to women

without PCOS.

❖❖❖

4

3.5.2 PP Whilst the specific mechanisms are unclear, it is recognized that many women

with PCOS will have underlying mechanisms that drive greater

longitudinal weight gain and higher BMI which may:

Underpin greater challenges with weight management.

Highlight the importance of lifelong healthy lifestyle strategies and pre-

vention of excess weight gain.

Assist women with PCOS and healthcare professionals in forming realistic,

tailored lifestyle goals.

3.6 Weight Stigma

3.6.1 EBR Many women with PCOS experience weight stigma in healthcare and other

settings and the negative biopsychosocial impacts of this should be

recognized.

❖❖❖❖

44

3.6.2 CR Healthcare professionals should be aware of their weight biases and the

impact this has on their professional practice and on women with PCOS.

❖❖❖❖

3.6.3 CR Health policy makers, managers and educators should promote awareness of

weight stigma and invest in weight stigma education and minimization

strategies.

❖❖❖❖

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 13

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

NO. TYPE RECOMMENDATION GRADE/QUAITY

3.6.4 PP Healthcare professionals should be aware of weight-inclusive practices which

promote acceptance of and respect for body size diversity and focus on

improvement of health behaviours and health outcomes for people of all

sizes. In PCOS this includes:

Acknowledging that whilst higher weight is a risk factor for PCOS and its

complications, it is only one indicator of health and broader factors should

be assessed.

Asking permission to discuss and measure weight and using strategies to

minimize discomfort (e.g., blind weighing).

Recognizing that the terms ‘‘overweight’’ and ‘‘obese/obesity’’ can be

stigmatizing with suggested alternatives including ‘‘ higher weight’’ .

If weighing, explaining how weight information will be used to inform risks,

prevention and treatment and how not knowing may impact on

recommendations.

Ensuring appropriate equipment is available for women of all sizes.

Offering options of weight-centric care (promoting intentional weight loss)

or weight-inclusive care (promoting healthy lifestyle change without

focusing on intentional weight loss) tailored to individual goals and

preferences.

Offering all women best practice assessment, treatment and support

regardless of weight, acknowledging that weight may be a non-modifiable

risk factor when using lifestyle modification alone.

3.6.5 PP Increasing awareness of weight stigma among family members of women

and adolescents with PCOS should be considered.

4 Management of non-fertility features

4.1 Pharmacology treatment principles in PCOS

PP Shared decision making between the patient (and parent/s or guardian/s, if

the patient is a child) and the healthcare professional is required.

PP An individual’s characteristics, preferences and values must be elicited and

considered when recommending any intervention alone or in

combination.

PP Understanding how individual adults and adolescents value treatment

outcomes is essential when prescribing medications.

PP Medical therapy is generally not approved for use specifically in PCOS and

recommended use is therefore evidence-based, but off-label. Healthcare

professionals need to inform adults, adolescents and their parents/s or

guardian/s and discuss the evidence, possible concerns and side effects.

Regulatory agencies should consider approval of evidence-based

medications for use in PCOS.

4.2 Combined Oral Contraceptive Pills

4.2.1 EBR Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP) could be recommended in

reproductive age adults with PCOS for management of hirsutism and/or

irregular menstrual cycles.

❖❖❖

4

4.2.2 EBR The COCP could be considered in adolescents at risk or with a clear diagnosis

of PCOS for management of hirsutism and/or irregular menstrual cycles.

❖❖❖

4

4.2.3 EBR Healthcare professionals could consider that there is no clinical advantage of

using high dose ethinylestradiol (R 30 mg) versus low dose

ethinylestradiol (< 30mg) when treating hirsutism in adults with PCOS.

❖❖❖

4

4.2.4 EBR General population guidelines should be considered when prescribing COCP

in adults and adolescents with PCOS as specific types or doses of

progestins, estrogens or combinations of COCP cannot currently be

recommended.

❖❖❖

4

4.2.5 EBR The 35mg ethinyl estradiol plus cyproterone acetate preparations should be

considered as second-line therapy over other COCPs, balancing benefits

and adverse effects, including venous thromboembolic risks.

❖❖❖

4

4.2.6 EBR Progestin only oral contraceptives may be considered for endometrial

protection, based on general population guidelines, acknowledging that

evidence in women with PCOS is limited.

❖❖❖

4

14 VOL. - NO. - / - 2023

TABLE 4

Continued.

4.2.7 PP When prescribing COCPs in adults and adolescents with PCOS, and

adolescents at risk of PCOS

It is important to address main presenting symptoms and consider other

treatments such as cosmetic therapies.

Shared decision-making (including accurate information and reassurance

on the efficacy and safety of COCP) is recommended and likely to improve

adherence.

Natural estrogen preparations and the lowest effective estrogen doses

(such as 20-30mg of ethinyl estradiol or equivalent), need consideration,

balancing efficacy, metabolic risk profile, side effects, cost, and availability.

The relatively limited evidence on COCPs specifically in PCOS needs to be

appreciated with practice informed by general population guidelines.

The relative and absolute contraindications and side effects of COCPs

need to be considered and be the subject of individualized discussion.

PCOS specific features, such as higher weight and cardiovascular risk

factors, need to be considered.

4.3 Metformin

4.3.1 EBR Metformin alone should be considered in adults with PCOS and a BMI R 25

kg/m2 for anthropometric, and metabolic outcomes including insulin

resistance, glucose, and lipid profiles.

❖❖❖

4

4.3.2 EBR Metformin alone could be considered in adolescents at risk of or with PCOS

for cycle regulation, acknowledging limited evidence.

❖❖❖

4

4.3.3 CR Metformin alone may be considered in adults with PCOS and BMI < 25 kg/

m2, acknowledging limited evidence.

❖❖❖

4.3.4 PP Where metformin is prescribed the following need to be considered:

Shared decision making needs to consider feasibility and effectiveness of

active lifestyle intervention. Women should be informed that metformin

and active lifestyle intervention have similar efficacy.

Mild adverse effects, including gastrointestinal side-effects are generally

dose dependent and self-limiting.

Starting at a low dose, with 500mg increments 1-2 weekly and extended-

release preparations may minimize side effects and improve adherence.

Suggested maximum daily dose is 2.5g in adults and 2g in adolescents.

Use appears safe long-term, based on use in other populations, however

indications for ongoing requirement needs to be considered.

Use may be associated with low vitamin B12 levels, especially in those with

risk factors for low vitamin B12 (e.g., diabetes, post bariatric / metabolic

surgery, pernicious anaemia, vegan diet etc.), where monitoring should be

considered.

4.4 Metformin and combined oral contraceptive pills

4.4.1 EBR COCP could be used over metformin for management of hirsutism in

irregular menstrual cycles in PCOS.

❖❖❖

4

4.4.2 EBR Metformin could be used over COCP for metabolic indications in PCOS. ❖❖❖

4

4.4.3 EBR The combination of COCP and metformin could be considered to offer

little additional clinical benefit over COCP or metformin alone, in

adults with PCOS with a BMI % 30 kg/m

2

.

❖❖❖

4

4.4.4. PP In combination with the COCP, metformin may be most beneficial in high

metabolic risk groups including those with a BMI >30 kg/m

2

, diabetes

risk factors, impaired glucose tolerance or high-risk ethnic groups.

4.4.5 PP Where COCP is contraindicated, not accepted or not tolerated, metformin

may be considered for irregular menstrual cycles. For hirsutism, other

interventions may be needed.

4.5 Anti-obesity pharmacological agents

4.5.1 CR Anti-obesity medications including liraglutide, semaglutide, both glucagon-

like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and orlistat, could be considered,

in addition to active lifestyle intervention, for the management of higher

weight in adults with PCOS as per general population guidelines.

❖❖❖

4.5.2 PP Healthcare professionals should ensure concurrent effective contraception

when pregnancy is possible for women who take GLP-1 receptor

agonists, as pregnancy safety data are lacking.

4.5.3 PP Gradual dose escalation for GLP-1 receptor agonists is recommended to

reduce gastrointestinal adverse effects.

4.5.4 PP Shared decision making, when discussing GLP-1 receptor agonist use with

women with PCOS, needs to consider side effects, and the potential need

for long-term use in weight management, given the high risk for weight

regain after discontinuation, and the lack of long-term safety data.

4.6 Anti-androgen pharmacological agents

VOL. - NO. - / - 2023 15

Fertility and Sterility®

TABLE 4

Continued.

4.6.1 EBR In combination with effective contraception, anti-androgens could be

considered to treat hirsutism in women with PCOS, if there is a

suboptimal response after a minimum of six months of COCP and/or

cosmetic therapy.

❖❖❖

4

4.6.2 CR Given the negative psychological impact of female pattern hair loss, anti-

androgens in combination with COCP could be trialed, acknowledging

the lack of evidence in the PCOS population.

❖❖❖

4.6.3 PP Whenever pregnancy is possible, healthcare professionals must educate and

counsel women and adolescents, parents/s or guardian/s, regarding the

risks of incomplete development of external genital structures of male

fetuses (undervirilization) when anti-androgens are used. To prevent this,

women who can get pregnant should be strongly counselled to use

effective contraception (e.g., intrauterine device or COCPs).

4.6.4 PP Anti-androgens could be considered to treat hirsutism, in the presence of

another effective form of contraception, for women with

contraindications for COCP therapy or when COCPs are poorly tolerated.

4.6.5 PP

When prescribing anti-androgens, based on general population

recommendations, healthcare professionals should consider that:

Spironolactone at 25-100mg / day appears to have lower risks of adverse

effects.

Cyproterone acetate at doses R 10mg is not advised due to an increased

risk including for meningioma.

Finasteride has an increased risk of liver toxicity.

Flutamide and bicalutamide have an increased risk of severe liver toxicity.

The relatively limited evidence on anti-androgens in PCOS needs to be

appreciated with small numbers of studies and limited numbers of

participants.

4.7 Inositol

4.7.1 EBR Inositol (in any form) could be considered in women with PCOS based on

individual preferences and values, noting limited harm, potential for

improvement in metabolic measures, yet with limited clinical benefits

including in ovulation, hirsutism or weight.

❖❖❖

4

4.7.2 EBR Metformin should be considered over inositol for hirsutism and central

adiposity, noting that metformin has more gastrointestinal side effects

than inositol.

❖❖❖

4

4.7.3 PP Women taking inositol and other complementary therapies are encouraged

to advise their healthcare professional.

4.7.4 PP Specific types, doses or combinations of inositol cannot currently be

recommended in adults and adolescents with PCOS, due to a lack of

quality evidence.

4.7.5 PP Shared decision making should include discussion that regulatory status and

quality control of inositol in any form (like other nutrient supplements) can