1

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Association between person- centred

care and healthcare providers’ job

satisfaction and work- related health: a

scoping review

Cornelia van Diepen ,

1,2,3

Andreas Fors ,

1,2

Inger Ekman,

1,2

Gunnel Hensing

4

To cite: van DiepenC, ForsA,

EkmanI, etal. Association

between person- centred

care and healthcare

providers’ job satisfaction

and work- related health: a

scoping review. BMJ Open

2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2020-042658

► Prepublication history and

additional material for this paper

is available online. To view these

les, please visit the journal

online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10.

1136/ bmjopen- 2020- 042658).

Received 10 July 2020

Revised 20 November 2020

Accepted 24 November 2020

1

Institute of Health and Care

Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy,

University of Gothenburg,

Goteborg, Sweden

2

Centre for Person- Centred

Care (GPCC), University of

Gothenburg, Gothenburg,

Sweden

3

Erasmus School of Health

Policy & Management,

Erasmus University Rotterdam,

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

4

School of Public Health

and Community Medicine,

Sahlgrenska Academy,

University of Gothenburg,

Gothenburg, Sweden

Correspondence to

Dr Cornelia van Diepen;

cornelia. van. diepen@ gu. se

Original research

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2020. Re- use

permitted under CC BY- NC. No

commercial re- use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

ABSTRACT

Objective This scoping review aimed to explore and

describe the research on associations between person-

centred care (PCC) and healthcare provider outcomes, for

example, job satisfaction and work- related health.

Design Scoping review.

Eligibility criteria Studies were included if they were

empirical studies that analysed associations between PCC

measurement tools and healthcare providers outcomes.

Search strategy Searches in PubMed, CINAHL, Psychinfo

and SCOPUS databases were conducted to identify

relevant studies published between 2001 and 2019. Two

authors independently screened studies for inclusion.

Results Eighteen studies fullled the inclusion criteria.

Twelve studies were cross- sectional, four quasi-

experimental, one longitudinal and one randomised

controlled trial. The studies were carried out in Sweden,

The Netherlands, the USA, Australia, Norway and Germany

in residential care, nursing homes, safety net clinics, a

hospital and community care. The healthcare provider

outcomes consisted of job satisfaction, burnout, stress of

conscience, psychosocial work environment, job strain

and intent to leave. The cross- sectional studies found

signicant associations, whereas the longitudinal studies

revealed no signicant effects of PCC on healthcare

provider outcomes over time.

Conclusion Most studies established a positive

association between PCC and healthcare provider

outcomes. However, due to the methodological variation, a

robust conclusion could not be generated. Further research

is required to establish the viability of implementing PCC

for the improvement of job satisfaction and work- related

health outcomes through rigorous and consistent research.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare providers play a key role in the

development of a sustainable population

health. The WHO has repeatedly high-

lighted the importance of well- educated

and trained healthcare workers at a relevant

level of density and distribution geographi-

cally and over professional specialities. The

WHO emphasise the recruitment and reten-

tion of healthcare workers as particularly

important in low- income and middle- income

countries, and countries where competing

labour markets have led to both recruitment

and retention challenges.

1

It is noteworthy

that the United Nations has pointed out

healthcare workers as essential to reaching

the sustainable development goal three to

‘ensure healthy lives and promote well- being

for all at all ages’.

2

The quality of the provided care is influ-

enced by the attraction and retention of

qualified and committed healthcare staff.

3

However, the work environment for health-

care staff is currently characterised by high

demands, low control, ethical stress, sched-

uled working hours, low salary and for most

groups, limited possibilities for career devel-

opment.

4–6

The healthcare providers experi-

ence increased stress and dissatisfaction due

to high expectations and job pride coupled

with insufficient time, skills and social support

at work.

3 6

According to two systematic reviews, inter-

ventions containing changes in working

conditions, organising support, changing

care, increasing communication skills and

changing work schedules are most effective

for improving the work environment.

6 7

In a

recent review, a good work environment was

found a defining factor for higher patient satis-

faction with the provided care.

5

Therefore,

Strengths and limitations of this study

► A transparent and rigorous search strategy was

employed.

► The person- centred care measurement tool un-

derwent scrutinisation for applicability in affecting

healthcare provider outcomes.

► We applied a range of healthcare provider outcome

possibilities.

► The included studies were only written in English.

► We did not assess the quality of the outcome

measures.

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

2

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

interventions focused on improving patient safety and

satisfaction should first consider improving employees’

health and creating safer work environments.

8 9

The Model of Care (MoC) provided by the healthcare

staff can largely influence the work environment for

healthcare personnel.

10

An MoC can be defined most

broadly as ‘the way health services are delivered as it aims

to ensure people get the right care, at the right time, by

the right team and in the right place’ (p3).

11

Improved

patient outcomes and cost- effectiveness are the general

objectives in implementing MoCs, according to a recent

review of systematic reviews on MoC interventions.

12

This same review revealed that only 13% of the included

reviews had healthcare provider outcomes (eg, well-

being, fatigue, stress and satisfaction). However, health-

care professionals should be considered defining factors

in the effects of implementing an MoC as the model

governs how healthcare personnel execute their work,

which directly affects patients’ treatment and health.

There is a growing interest in the model of person-

centred care (PCC) since authorities, such as the WHO,

have called for enabling patients to engage in their

healthcare.

13

PCC has also been endorsed by professional

and patient organisations.

14 15

The concept of PCC is

based on ethical principles and has its roots in the holistic

paradigm, which highlight the importance of knowing

the patient also as a capable human being with needs and

resources.

16–19

PCC is an approach to care in which rela-

tionships are formed and fostered with healthcare profes-

sionals, care providers and patients (often with relatives)

and is supported by values of respect for the person, indi-

vidual right to self- determination, mutual respect and

understanding.

20

Application of PCC in practice contains

core components such as: inclusion of patients narra-

tives, cocreating a health plan, and documentation and

follow- up of the health plan.

19 21

PCC can form a critical

component for effective change in the work environmet

of healthcare professionals.

22

The work environment

often suffers under ethical conflicts and lack of support

and control in daily tasks,

4 5 23

which could be abated

by working in a person- centred manner. Thus, there is

reason to look closer into how implementing PCC influ-

ences the work environment for healthcare professionals.

Although person- centred and patient- centred care

differ, they are often used interchangeably in the liter-

ature.

18 24

Patient- centred care is more focused on the

need of care patients have in common regarding their

disease and treatment while PCC, besides needs, empha-

sises the capabilities and strengths that each person

possess as valuable resources in a collaborative partner-

ship between the patient (often including relatives) and

healthcare professionals.

17

A concept review of the differ-

ence has highlighted how PCC differed to patient- centred

care on a deeper level of a meaningful (person) versus

a functional (patient) life.

25

Certain contexts require

specific types of ‘centredness’ such as family- centred,

relationship- centred, client- centred, patient- focused and

person- focused care.

26

Therefore, this scoping review

accepted all concepts when they followed the PCC prop-

erties highlighted earlier.

Most studies of PCC analysed patients’ point of view

and showed positive results such as shorter hospital stay,

reduced symptoms, improved care experiences and

increased self- efficacy.

27–30

Three reviews have focused

on PCC and healthcare provider outcomes.

31–33

The

reviews found limited indications of a positive associa-

tion between PCC and healthcare provider outcomes.

However, these reviews only focused on the association in

nursing homes and among elderly care.

31–33

There have

been PCC implementations across healthcare sectors,

and there is a need for an overview of how PCC and staff

outcomes are connected.

Aim

This scoping review aimed to explore and describe the

research on associations between PCC and healthcare

provider outcomes.

METHODS

A scoping review methodology was applied to allow for

mapping of the main concepts and a way to give an idea

of what evidence is available for the research area.

34

This

methodology was chosen over a systematic review as the

study aimed to clarify the PCC concept and identify its

relation to key characteristics within healthcare provider

outcomes rather than answer a clinically meaningful

question.

35

Search strategy

The search engines PubMed, CINAHL, Psychinfo and

SCOPUS were accessed in February 2020 for studies

published in academic journals between 2001 and 2019.

The search terms included “person centred” OR

“person centredness” OR “client centred” OR “patient

centred” OR “relationship centred” OR “family centred”

“patient focused” OR “person focused”. AND “Job Satis-

faction” OR “Absenteeism” OR “presentism” OR “Occu-

pational Stress” OR “Personnel Turnover” OR “Sick

Leave” OR “Stress, Psychological” OR “Dyssomnias” OR

“sleep disorder” OR “sleep disturbances” OR “occupa-

tional health” OR “moral stress”. Most terms were overar-

ching concepts (MESH terms), and the search captured

both British and American spellings. See online supple-

mental appendix 1 for the entire search strategy.

Selection of studies

There is no established consensus on the operationali-

sation of PCC.

16 36

To prevent an array of related terms

and to increase the possibility to compare, we applied

a more narrow definition than those used in earlier

reviews. The eligibility criteria in this scoping review were

guided by the six PCC dimensions created in 2001 by the

Institute of Medicine, now called National Academy of

Medicine. These six dimensions are respect for patients’

values, preferences and expressed needs; coordination

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

3

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

and integration of care; information, communication

and education; physical comfort; emotional support—

relieving fear and anxiety; involvement of family and

friends.

37

The relevant studies needed to display a connec-

tion to these dimensions of PCC.

Types of participants included all healthcare personnel

in contact with patients such as registered nurses (RNs),

licenced practical nurses and physicians.

Types of outcomes included healthcare provider

outcomes such as job satisfaction and work- related health

outcomes.

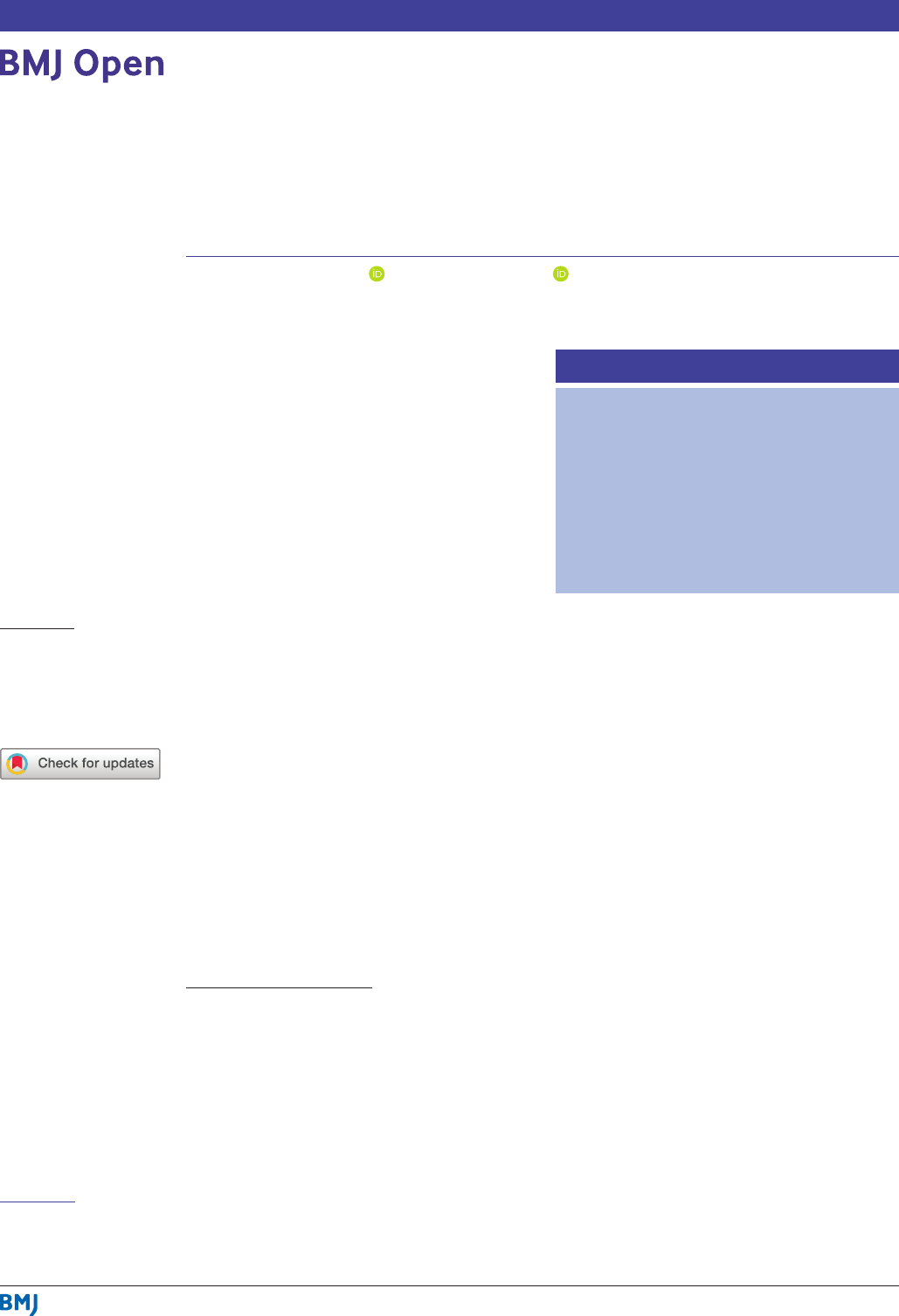

Data extraction and synthesis of results

The data extraction and synthesis of results are presented

in the flowchart (figure 1). The results obtained from

the online search engines were collected and duplicates

removed by the first author (CvD). The search and collec-

tion yielded 1263 titles and abstracts, which were subse-

quently screened for relevance by two authors (CvD and

AF) through the research software program for systematic

reviews ‘Rayyan’.

38

All studies with one author deeming

possible relevance were discussed, and a selection of 45

studies for full- text review was created in agreement by

both authors.

The full text of the potentially relevant studies was

obtained and first reviewed based on the PCC measure-

ment tool to be associated with any healthcare provider

outcome in the results. Disagreements were resolved by

consensus between the two authors. Second, the six dimen-

sions of PCC were compared with the PCC measurement

tool used in the studies. The first dimension ‘respect for

patients’ values, preferences and expressed needs’ is the

core of PCC and needed to be addressed in the tool. PCC

is a broad concept affecting different elements to care,

39

and that needed to be reflected in the PCC measurement

tool. Therefore, the authors decided that at least two of

the other five dimensions needed to be present in order

for the tool to be considered to measure a model of PCC

that could affect healthcare provider outcomes. The two

authors did this inclusion process together. When a PCC

dimension was present in the PCC measurement tool, a ‘+’

sign was inserted, and a ‘−’ was inserted when that partic-

ular dimension was absent. As a result, table 1 shows the

included studies and their reference to the six dimensions.

Figure 1 Flow chart for study inclusion.

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

4

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Table 1 The presence of the six dimensions of person- centred care

37

within the person- centred care measurement tools in the included studies

Dimensions*

Person- centred care

measurement tool Tool subscales Authors

Respect for

patients’ values,

preferences and

expressed needs

Coordination

and

integration of

care

Information,

communication

and education

Physical

comfort

Emotional

support—

relieving fear and

anxiety

Involvement

of family

and friends

Person- centred Care

Assessment Tool (P-

CAT)

13 items

► Personalising care.

► Organisational

support.

► Environmental

accessibility.

Edvardsson et al,

53

Wallin et al,

44

Røen et

al,

55

Schaap et al,

48

Silén et al,

42

Sjögren et al,

43

Vassbø et al

57

+ + + + + –

Person- entred Climate

Questionnaire- Staff

version (PCQ- S)

14 items

► Safety.

► Everydayness.

► Hospitality.

Edvardsson et al,

40

Lehuluante et al,

41

Wallin et al,

44

Sjögren et al,

43

Vassbø et al,

57

Åhlin et al

45

+ – + + + +

Patient Centred

Medical Homes

(PCMH) rating

24 items

► Access to care and

communication

with patients.

► Communication

with other

providers.

► Tracking data.

► Care management.

► Quality

improvement.

► Work environment.

Lewis et al,

51

Nocon et al

52

+ + + – – –

The subscale

‘recognition of

personhood’ of the

Approach to Dementia

Questionnaire (ADQ)

11- items

Dichter et al,

56

Willemse et al

50

+ – + + + –

Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

5

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Dimensions*

Person- centred care

measurement tool Tool subscales Authors

Respect for

patients’ values,

preferences and

expressed needs

Coordination

and

integration of

care

Information,

communication

and education

Physical

comfort

Emotional

support—

relieving fear and

anxiety

Involvement

of family

and friends

8 dimensions

Person- Centred Care

Questionnaire

35 items

► Respect for clients’

values, preferences

and expressed

needs.

► Provision of

information and

education.

► Access to care.

► Emotional support.

► Involvement of

family and friends.

► Continuity and

secure transition of

care.

► Physical comfort.

► Coordination of

care.

van der Meer et al

49

+ + + + + +

Patient- Centred Care

Questionnaire

35 items

► Taking patients’

preferences into

account.

► Coordination of

care.

► Information and

education provided

to patients.

► Level of patient’s

physical comfort.

► Emotional support

for patients.

► Involvement of

patient’s family and

friends.

► Continuity and

transition.

► Access to care.

den Boer et al

47

+ + + + + +

Table 1 Continued

Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

6

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

After scrutinising the full- text of 45 studies for relevance,

five studies did not have a healthcare provider outcome

connected to a PCC measurement tool. Seventeen studies

were excluded for not following our set criteria for PCC.

Three studies were reviews, and two were excluded due to

language. Finally, all four authors confirmed the decision

to include or exclude a study.

The following details of the included studies were

extracted and summarised: authors, year of publication,

country, study design, setting and participants, PCC

measurement tool, staff outcome measures, and main

results (see table 2). Given the variability of the study

designs that are included in this scoping review, a qual-

itative analysis was used to synthesise the results, and the

results are presented in a narrative form.

Patient and public involvement statement

This research was designed without patient involvement.

However, patient care and healthcare organisations were

involved in the interpretation of the results through a

workshop.

RESULTS

This scoping review aimed to explore and describe the

research on associations between PCC and healthcare

provider outcomes. Eighteen studies fulfilled the inclu-

sion criteria (table 2).

Characteristics of the included studies

Seven studies were conducted in Sweden,

40–46

four in the

Netherlands,

47–50

two in the USA,

51 52

two in Australia,

53 54

one in Norway,

55

one in Germany

56

and one study was

conducted in three countries (ie, Sweden, Norway and

Australia).

57

The included studies consisted of twelve cross- sectional

studies,

41–44 46 47 49–51 53 55 57

four quasi- experiments,

40 48 52 56

one longitudinal study

45

and one randomised controlled

trial (RCT).

54

The six studies with a longitudinal design

had a follow- up duration between 8 months in the RCT

54

and 4 years in a quasi- experimental study.

52

The setting for the studies was residential care (homes

with care availability) for eight studies,

40 43–45 48 49 53 54

nursing homes (homes with 24 hours medical care) for

six studies,

42 46 50 55–57

safety net clinics (primary care for

uninsured persons) for two studies,

51 52

hospital for one

study

41

and community care (care for independent living

persons) for the last study.

47

In 12 studies, the participants were all healthcare

staff.

40 42 43 46 48–54 57

In the other studies, participants were

specified as RNs,

41 47

managers, unit head nurses, and

staff,

55

caregivers,

56

nurse assistants and nurse’s aides,

44

and RNs and nurse assistants.

45

Measurement for PCC

The rationale for measuring PCC and healthcare

provider outcomes was for 13 studies to examine the

extent to which staff members rated their provided care

Dimensions*

Person- centred care

measurement tool Tool subscales Authors

Respect for

patients’ values,

preferences and

expressed needs

Coordination

and

integration of

care

Information,

communication

and education

Physical

comfort

Emotional

support—

relieving fear and

anxiety

Involvement

of family

and friends

Individualized Care

Inventory (ICI)

43 items

► Knowing the

person.

► Resident autonomy.

► Staff- to- resident

communication.

► Staff- to- staff

communication.

Elfstrand Corlin and

Kazemi

46

+ + + + + +

The Bradford

University’s Dementia

Care Mapping and

Person- Centred Care

training manual

Jeon et al

54

+ + + – + –

*‘+’ indicates the presence and ‘−’ indicates the absence of this person- centred care (PCC) dimension within the PCC measurement tool.

Table 1 Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

7

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Table 2 Characteristics and results of included studies

Authors (country) Study design Setting, participants Person- centred care measure

Staff outcomes: measurement

tool Results

den Boer et al

47

(Netherlands)

Cross- sectional Community care,

registered nurses (RNs)

n=153

Adapted version of the Patient-

Centred Care Questionnaire 35

items

Job satisfaction: a 38- item job

satisfaction questionnaire

Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Dichter et al

56

(Germany) Quasi-

experimental

6- month and

18- month follow-

up

Nursing home,

caregivers

n=201

The subscale ‘recognition of

personhood’ of the Approach to

Dementia Questionnaire (ADQ) 11

items

Job satisfaction: Copenhagen

Psychosocial Questionnaire

4- items

Burnout: Copenhagen Burnout

Inventory (CBI) 6- items

Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

effect of PCC

intervention

Burnout: no signicant

effect of PCC

intervention

Edvardsson et al

53

(Australia)

Cross- sectional Residential aged care,

all staff

n=297

Person- Centred Care Assessment

Tool (P- CAT), 13 items

Job satisfaction: measure of job

satisfaction (MJS)

22 items

Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Edvardsson et al

40

(Sweden)

Quasi-

experimental

12 months follow-

up

Residential aged care,

all staff

n=171 (baseline)

n=143 (follow- up)

P- CAT 13 items

Person- Centred Climate

Questionnaire- Staff version (PCQ- S)

14 items

Stress of conscience: Stress of

Conscience questionnaire (SCQ)

9 items

Job strain: Demand- Control-

Support Questionnaire (DCSQ)

11 items

Stress of conscience:

signicant negative

effect of PCC

intervention

Job strain: no

signicant effect of

PCC intervention

Elfstrand Corlin and

Kazemi

46

(Sweden)

Cross- sectional Nursing homes,

all staff

n=322

Individualized Care Inventory (ICI)

43 items

Job satisfaction: a single

question

Job satisfaction:

signicant association

to subscales of PCC

Jeon et al

54

(Australia) Cluster

randomised

controlled trial

8 months follow-

up

Residential aged care,

all staff

n=194

Burnout: Maslach Burnout

Inventory (MBI) 22 items

Burnout: signicant

effect of DCM

intervention but not the

PCC intervention

Lehuluante et al

41

(Sweden)

Cross- sectional Hospital,

RNs

n=206

PCQ- S 14 items Job satisfaction: satisfaction with

nursing care and work scale 34

items

Job satisfaction:

signicant association

to subscales of PCC

Lewis et al

51

(USA) Cross- sectional Safety net clinic,

all staff

n=603

5 PCMH subscales 22 items Job satisfaction: a single

question

Burnout: a single question

Job satisfaction:

signicant association

to subscales of PCC

Burnout: signicant

association to

subscales of PCC

Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

8

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Authors (country) Study design Setting, participants Person- centred care measure

Staff outcomes: measurement

tool Results

Nocon et al

52

(USA) Quasi-

experimental

4- year follow- up

Safety net clinic,

all staff

n=536 (baseline)

n=589 (postintervention)

5 PCMH subscales 24 items Job satisfaction: a single

question

Burnout: a single question

Job Satisfaction: no

signicant effect of

PCC intervention

Burnout: no signicant

effect of PCC

intervention

Wallin et al

44

(Sweden) Cross- sectional Residential aged care,

nurse assistants and

nurse’s aides

n=225

P- CAT 13 items, PCQ- S 14 items Job satisfaction: Job Satisfaction

Questionnaire

20 items

Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Røen et al

55

(Norway) Cross- sectional Nursing homes,

managers, unit head

nurses and staff

n=175

P- CAT 13 items Job satisfaction: a single

question

work- related psychosocial

factors: the General Nordic

Questionnaire for Psychosocial

and Social Factors at Work

32 items

Job satisfaction:

signicant association

to PCC

Work- related

psychosocial factors:

signicant association

to PCC

Schaap et al

48

(Netherlands)

Quasi-

experimental

14 months follow-

up

Residential aged care,

all staff

n=227

P- CAT 13 items Job satisfaction: the Maastricht

Work Satisfaction Scale in Health

Care 21 items

Burnout: MBI 6 items

Job satisfaction: no

signicant effect of

PCC intervention

Burnout: no signicant

effect of PCC

intervention

Silén et al

42

(Sweden) Cross- sectional Nursing home,

all staff

n=212

P- CAT 13 items, PCQ- S 14 items Work- related psychosocial

factors: Swedish version of the

Conditions of Work Effectiveness

Questionnaire 19 items

Work- related

psychosocial factors:

signicant association

with PCC

Sjögren et al

43

(Sweden) Cross- sectional Residential aged care,

all staff

n=1169

P- CAT 13 items, PCQ- S 14 items Job satisfaction: Satisfaction with

Nursing Care and Work Scale 34

items

Stress of Conscience: SCQ 9

items

Job strain: DCSQ 11 items

Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Stress of conscience:

signicant negative

association with PCC

Job stress: signicant

negative association

with PCC

Van der Meer et al

49

(Netherlands)

Cross- sectional Residential aged care,

all staff

n=466

8 dimensions Person- Centred Care

Questionnaire 35 items

Job satisfaction: MJS 38 items Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Table 2 Continued

Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

9

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

as person- centred.

41–47 49–51 53 55 57

The other four quasi-

experimental studies and the RCT analysed the effect of

specific interventions designed to increase the level of

PCC.

40 48 52 54 56

Three out of these five invention studies

measured the effect of the Dementia Care Mapping

(DCM) intervention.

48 54 56

DCM is an internationally

recognised complex intervention in dementia research

and care containing a developmental evaluation cycle

to monitor and revise action plans.

48

The RCT

54

applied

the Bradford University’s PCC training manual in addi-

tion to the DCM training manual as the intervention

model. The study from the USA

52

measured PCC after the

Patient- Centred Medical Home (PCMH) intervention.

Core components of the PCMH include comprehensive

primary care, quality improvement, care management

and enhanced access.

51

Finally, the implementation of

the Swedish national guidelines was tested for PCC prop-

erties in combination with the effect of the implementa-

tion on staff.

40

The PCC measurement tool differed, as there were seven

questionnaires and one intervention. The most applied

tool in the included studies was the Person- centred Care

Assessment Tool (P- CAT), which was used on its own in

two quasi- experimental studies

40 48

and two cross- sectional

studies.

53 55

Four studies combined the P- CAT with the

Person- centred Climate Questionnaire–Staff version

(PCQ- S).

42–44 57

The PCQ- S was used by itself in one cross-

sectional

41

and one longitudinal study.

45

The other seven

studies applied different PCC measurement tools: PCMH

subscales questionnaire,

51 52

the subscale ‘recognition of

personhood’ of the Approach to Dementia Question-

naire,

50 56

eight dimensions of PCC measure,

49

an adapted

version of the Patient- Centred Care Questionnaire

47

and

Individualized Care Inventory (ICI).

46

The Bradford

University’s DCM and PCC training manual was applied

as the PCC measurement tool in the RCT.

54

Six PCC measurement tools were constructed of

subscales. The eight dimensions PCC questionnaire

and Patient- Centred Care Questionnaire had subscales

that followed the Picker Institute dimensions of PCC,

58

but with different subscale titles. The other four tools

followed their own subscales, which varied in number and

concepts. All tools with the subscales and reference to the

six dimensions of PCC are presented in table 1.

Measurement of staff outcomes

The included studies contained six healthcare provider

outcomes: job satisfaction, burnout, psychosocial work

environment, stress of conscience, job strain and intent

to leave.

Job satisfaction was estimated in 14 studies with 10

different measurement tools. Three out of these used

the Measure of Job Satisfaction.

49 53 57

In two studies,

job satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with

Nursing Care and Work Scale.

41 43

Four studies applied

a single question approach: ‘Overall, I am satisfied with

my current job’,

51 52

‘How will you describe your general

experience of your job satisfaction?’

55

or ‘I am happy at

Authors (country) Study design Setting, participants Person- centred care measure

Staff outcomes: measurement

tool Results

Vassbø et al

57

(Sweden,

Norway, Australia)

Cross- sectional Nursing homes,

all staff

n=341

P- CAT 13 items, PCQ- S 14 items Job satisfaction: MJS 37 items Job satisfaction:

signicant positive

association with PCC

Willemse et al

50

(Netherlands)

Cross- sectional Nursing homes,

all staff

n=1147

The subscale ‘recognition of

personhood’ of ADQ 11 items

Job satisfaction: 3- item scale

derived from the Leiden Quality

of Work Questionnaire.

Burnout: MBI 8 items.

Intent to leave: Subscale Leiden

Quality of Work Questionnaire 3

items

Job satisfaction:

signicant association

to PCC

Burnout: signicant

association to PCC

Intent to leave:

signicant association

to PCC

Åhlin et al

45

(Sweden) Longitudinal

cohort study

1- year follow- up

Residential aged care,

RNs and nurse assistants

n=488

PCQ- S 14 items Stress of conscience: SCQ 9

items

Stress of conscience:

no signicant

association to PCC

PCC, person- centred care.

Table 2 Continued

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

10

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

work’.

46

Five studies used different job satisfaction ques-

tionnaires: Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire,

56

a

38- item job satisfaction questionnaire,

47

the Maastricht

Work Satisfaction Scale in Health Care.

48

3- item scale

derived from the Leiden Quality of Work Questionnaire

(LQWQ)

50

and Job Satisfaction Questionnaire.

44

Six studies estimated burnout. Three studies applied

the Maslach Burnout Inventory or a setting- appropriate

version.

48 50 54

The two studies from the USA had their

measure stated as ‘Using your own definition of burnout,

please check one’ with a 5- option scale.

51 52

The German

study used the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.

56

Three studies

40 43 45

assessed stress of conscience. All

these studies were set in Sweden and applied the Stress of

Conscience Questionnaire.

Psychosocial work environment was measured in two

studies, which applied different constructs: the General

Nordic Questionnaire for Psychosocial and Social Factors

at Work

55

and a Swedish version of the Conditions of

Work Effectiveness Questionnaire.

42

Job strain was estimated in two studies and measured

in both through the Demand- Control- Support Question-

naire.

40 43

Finally, intent to leave was assessed in one study

50

by a

3- item scale that was derived from the LQWQ.

Results from the included studies

This section presents the results based on the six health-

care provider outcomes and their association with PCC

and is a synthesis of the results presented in table 2.

Job satisfaction was positively associated with PCC in

eight studies.

41 43 44 47 49 50 55 57

Three cross- sectional studies

by Edvardsson et al,

53

Elfstrand Corlin and Kazami

46

and

Lewis et al

51

showed an association between job satisfac-

tion and only subscales of PCC, that is, ‘personalising

care’ and ‘organisational support’,

53

‘knowing the person’

and ‘resident autonomy’

46

and ‘quality improvement

subscale’ and ‘work environment covariate’.

51

Three

quasi- experiment studies by Dichter et al

56

, Nocon et al

52

and Schaap et al

48

found no significant improvement in

job satisfaction after the PCC implementation.

There were mixed results in the association between

burnout and PCC. Two cross- sectional studies by Lewis

et al

51

and Willemse et al

50

found negative associations

between PCC and burnout levels. The quasi- experimental

studies by Nocon et al

52

and Schaap et al

48

found no signif-

icant results. The quasi- experimental study by Dichter et

al,

56

the longitudinal study by Åhlin et al

45

and the RCT by

Jeon et al

54

found non- significant results but nonetheless

an increase in burnout levels over time.

The stress of conscience was negatively associated with

PCC in the cross- sectional study by Sjögren et al.

43

In the

quasi- experimental study by Edvardsson et al,

40

the PCC

intervention significantly reduced stress of conscience.

However, the longitudinal study by Åhlin et al

45

found no

significant results.

The association between PCC and the psychosocial

work environment was analysed in two cross- sectional

studies. Røen et al

55

found that PCC was positively asso-

ciated with most psychosocial and social factors included

in the study, except for the subscale of decision demands.

Silén et al

42

found that PCC mediated the association

between higher access to structural empowerment and

higher psychological empowerment, which improved the

psychosocial work environment significantly.

Job strain was not affected by the intervention in the

quasi- experimental study by Edvardsson et al.

40

The cross-

sectional study by Sjögren et al

43

did find a negative asso-

ciation between job strain and PCC.

The one study that measured intent to leave by Willemse

et al

50

showed a negative association with PCC, meaning

that staff were less likely to leave with higher perceived

PCC.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review explored and described the research

performed to assess the associations between PCC and

healthcare provider outcomes. Eighteen studies fulfilled

the inclusion criteria. The healthcare provider outcomes

measured in the studies were job satisfaction, burnout,

stress of conscience, psychosocial work environment,

job strain and intent to leave. The main findings of this

review support an association between PCC and health-

care provider outcomes as the cross- sectional studies

had mostly significant results. However, the longitu-

dinal studies showed, with two exceptions, no significant

improvement in the healthcare provider outcomes.

The review identified eight PCC measurement tools

that were scrutinised through the six PCC dimensions

and only included if they addressed the first and at least

two other dimensions. The quality assessment of the PCC

tools was applied to capture PCC as a multifaceted frame-

work, which is necessary when there is the expectation of

an improvement in the work environment.

6 7

A strength in this study is the approach applied here,

which might have restricted the number of included

studies, but created a quality assessment of the tools that

ensured the results could be compared within the health-

care provider outcomes. To confirm the occurrence

of the PCC dimensions in the tools and interventions,

additional research needed to be performed to find the

complete questionnaires or details on the interventions,

as the included studies did not disclose more on the PCC

measurement tool beyond the subscales.

This scoping review did not exclude studies based on

the healthcare facility. Many healthcare facilities, partic-

ularly nursing homes and residential care, have incorpo-

rated elements of PCC.

22 59

Thus far, there is no golden

standard for PCC, and previous studies have stressed the

importance of being aware of the normative relations

and cultural aspects as well as practical hinders such as

routines for documentation and suitable premises when

implementing more PCC.

60 61

This review provided an

overview of the research done across healthcare settings,

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

11

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

and interestingly, similar results were found across the

incorporated healthcare facilities and type of participants.

A limitation of the included studies was the occurrence

of a ‘ceiling effect’. A ‘ceiling effect’ occurs when only

well- functioning healthcare facilities want to implement

PCC and participate in research.

62

The baseline measure-

ments in the included intervention studies were already

considerably high, which made a substantial improve-

ment unachievable. Moreover, the cross- sectional studies

were, with one exception,

51

performed in healthcare

facilities that did not undergo an intervention.

Additionally, all PCC measurement questionnaires

were self- reported, and the included studies revealed a

‘perceived’ occurrence of PCC. This occurrence could be

overestimated as with the growing interest in PCC health-

care providers might want to appear more person- centred

in their work than they are, which was also considered a

possibility in other PCC studies.

19 40 49

PCC is based on

ethics that can be summarised as ‘aiming at the good life

with and for others in just institutions’.

63

This implies

that also managers in their leadership form a partnership

with their staff and listen to their narratives and formu-

late a plan, aiming at good working conditions for them.

Operationalisation of person- centred ethics in health-

care is not a quick fix, but rather a process of developing

the professional role and changing the clinical mind set

through reflection on theory and practice.

19

Healthcare providers experience job pride and high

expectations of being a healthcare professional.

3 6

This

makes it likely that there is an overestimation of PCC and

job satisfaction, and an underestimation of job strain,

ethical stress and burnout. These overestimations have

the consequence that in the cross- sectional studies, the

PCC and healthcare provider outcomes were signifi-

cant and, for the quasi- experimental studies, with high

baseline measurements, a significant improvement was

unattainable.

The scoping review approach allowed for all possible

job satisfaction and occupational health- related outcomes

to be included. Still, the results only provided a limited

range of six healthcare provider outcomes. Moreover, the

lack of quality assessment of these outcomes formed a

limitation to the review. The six outcomes with different

measurement tools among them impeded the compar-

ison of the importance of the results of the included

studies. For example, 14 studies had job satisfaction as a

measure in their studies, and 10 different measures were

used. This variation suggests that the healthcare provider

outcomes do not have an established measurement tool

which makes the relative importance of one measure

compared with another unclear in this context.

7 33

The variation in measures caused difficulty in asserting

if PCC could be an MoC that can attract and retain

qualified healthcare professionals, as was suggested by

McCormack and McCance.

22

Similar to the results of the

scoping review by Jessup et al,

12

most research focused on

the patients and financial gain rather than the health-

care provider outcomes. This is despite the healthcare

providers being a defining factor in ensuring patient

safety and hospital care quality.

4

Interventions should

aim at improving both patient and healthcare provider

outcomes,

5 8

which can be achieved with PCC as one

of its cornerstones is the collaboration between profes-

sionals and staff and respect for each other’s knowledge

and experiences.

19

Other reviews on the improvement

of healthcare provider outcomes emphasised that the

intervention needs to be well- defined and continue for

an extended period.

6 7

When research into healthcare

providers becomes more established in the area of MoC

interventions, more consistent scrutinisation can be

achieved, and a better prediction can be made into the

benefits of implementing an MoC, such as PCC, on the

entire healthcare system.

CONCLUSION

This scoping review showed, to a limited extent, a posi-

tive association between PCC and healthcare provider

outcomes. With a significant variation of measurement

tools and conflicting findings across the studies, it is diffi-

cult to provide an overall conclusion.

The implications for future research is the necessity for

increasing the focus on healthcare providers in analysing

the effect of implementing PCC. More specifically, a better

understanding of the impact of the different dimensions

of PCC on staff and how PCC can contribute to improving

the healthcare work environment.

Twitter Cornelia van Diepen @kim24501

Contributors The authors developed and conceived the review together. CvD

and AF completed screening and extraction of data. CvD drafted rst version of

the manuscript including design of the tables with feedback from all authors. The

manuscript was then revised in different steps by AF, GH and IE with CvD taking the

main responsibility for writing. All authors approved the nal version of the review.

Funding The Centre for Person- Centred Care at the University of Gothenburg

(GPCC), Sweden. GPCC is funded by the Swedish Government's grant for Strategic

Research Areas, Care Sciences (Application to Swedish Research Council no.

2009-1088).

Disclaimer All authors had access to the data (literature identied and tables) in

the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy

of the data analysis. The lead author afrms that this manuscript is an honest,

accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important

aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study

as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data sharing not applicable as no datasets were

generated and/or analysed for this study.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has

not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been

peer- reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those

of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and

responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content

includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability

of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines,

terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error

and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

12

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

Open access This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which

permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially,

and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is

properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use

is non- commercial. See:http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

ORCID iDs

Corneliavan Diepen http:// orcid. org/ 0000- 0001- 6991- 9443

AndreasFors http:// orcid. org/ 0000- 0001- 8980- 0538

REFERENCES

1 World Health Organization. Working for health and growth: investing

in the health workforce. Report of the high- level Commission on

health employment and economic growth.; 2016. 978 92 4 151130 8.

2 United Nations. Sustainable development goals. Available: https://

sust aina bled evel opment. un. org/ sdg3 [Accessed 01-12-2020].

3 Castle NG, Engberg J. Organizational characteristics associated with

staff turnover in nursing homes. Gerontologist 2006;46:62–73.

4 Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, etal. Nurses’ reports of working

conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. Int J

Nurs Stud 2013;50:143–53.

5 Copanitsanou P, Fotos N, Brokalaki H. Effects of work environment

on patient and nurse outcomes. Br J Nurs 2017;26:172–6.

6 Marine A, Ruotsalainen J, Serra C, etal. Preventing occupational

stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2006:CD002892.

7 Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, etal. Preventing

occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2015;184.

8 Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, etal. Healthcare staff wellbeing,

burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One

2016;11:e0159015–12.

9 Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, etal. Patient safety,

satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of

nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States.

BMJ 2012;344:e1717.

10 Davidson P, Halcomb E, Hickman L, etal. Beyond the rhetoric: what

do we mean by a 'model of care'? Aust J Adv Nurs 2006;23:47–55.

11 ACI. Understanding the process to develop a model of care: an ACI

framework. Chatswood NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation; 2013.

www. aci. health. nsw. gov. au. 978 1 74187 862 2.

12 Jessup R, Putrik P, Buchbinder R, etal. Identifying alternative models

of healthcare service delivery to inform health system improvement:

Scoping review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2020;10:e036112.

13 WHO. Who global strategy on people- centred and integrated health

services: interim report, 2015. Available: http://www. who. int/ serv iced

eliv erys afety/ areas/ people- centred- care/ global- strategy/ en/

14 EPF. Manifesto 2019: putting what matters to patients at the heart of

EU health policy, 2019. Available: https://www. epp. eu/ les/ uploads/

2019/ 05/ EPP- MANIFESTO- 2019. pdf

15 Bartz CC. International council of nurses and person- centered care.

Int J Integr Care 2010;10 Suppl:29–31.

16 Olsson L- E, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, etal. Efcacy of person-

centred care as an intervention in controlled trials - a systematic

review. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:456–65.

17 Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, etal. Person- centered care- ready for

prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011;10:248–51.

18 Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, etal. Person- centredness: conceptual

and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1555–65.

19 Britten N, Moore L, Lydahl D, etal. Elaboration of the Gothenburg

model of person- centred care. Health Expect 2017;20:407–18.

20 McCance T, McCormack B, Dewing J. An exploration of person-

centredness in practice. Online J Issues Nurs 2011;16:1.

21 Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, etal. Personalised care planning

for adults with chronic or long- term health conditions. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2015;85.

22 McCormack B, McCance TV. Development of a framework for

person- centred nursing. J Adv Nurs 2006;56:472–9.

23 Bégat I, Ellefsen B, Severinsson E. Nurses' satisfaction with their

work environment and the outcomes of clinical nursing supervision

on nurses' experiences of well- being -- a Norwegian study. J Nurs

Manag 2005;13:221–30.

24 Edvardsson D, Innes A. Measuring person- centered care: a

critical comparative review of published tools. Gerontologist

2010;50:834–46.

25 Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, etal. Patient

Education and Counseling “ Same same or different ? ” A review of

reviews of person- centered and patient- centered care. Patient Educ

Couns 2018;102:3–11.

26 Hughes JC, Bamford C, May C. Types of centredness in health care:

themes and concepts. Med Health Care Philos 2008;11:455–63.

27 Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson L- E, etal. Effects of person- centred care

in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC- HF study. Eur Heart J

2012;33:1112–9.

28 Brännström M, Boman K. Effects of person- centred and integrated

chronic heart failure and palliative home care. prefer: a randomized

controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:1142–51.

29 Fors A, Ekman I, Taft C, etal. Person- centred care after acute

coronary syndrome, from hospital to primary care - A randomised

controlled trial. Int J Cardiol 2015;187:693–9.

30 Wolf A, Vella R, Fors A. The impact of person- centred care

on patients' care experiences in relation to educational level

after acute coronary syndrome: secondary outcome analysis

of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs

2019;18:299–308.

31 Barbosa A, Sousa L, Nolan M, etal. Effects of person- centered care

approaches to dementia care on staff: a systematic review. Am J

Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015;30:713–22.

32 Rajamohan S, Porock D, Chang Y- P. Understanding the relationship

between staff and job satisfaction, stress, turnover, and staff

outcomes in the Person- Centered care nursing home arena. J Nurs

Scholarsh 2019;51:560–8.

33 van den Pol- Grevelink A, Jukema JS, Smits CHM. Person-

centred care and job satisfaction of caregivers in nursing homes:

a systematic review of the impact of different forms of person-

centred care on various dimensions of job satisfaction. Int J Geriatr

Psychiatry 2012;27:219–29.

34 Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological

framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32.

35 Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, etal. Systematic review or scoping

review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic

or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:1–7.

36 Harding E, Wait S, Scutton J. Report summary: the state of play in

person- centred care. London, United Kingdom The Health Policy

Partnership; 2015. http://www. heal thpo licy part nership. com/ person-

centred- care/

37 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health

system for the 21th century. Washington, DC: National Academies

Press, 2001.

38 Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, etal. Rayyan—a web and

mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:1–10.

39 McCormack B, McCance T. Person- Centred nursing theory and

practice. Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell, 2010.

40 Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Borell L. Implementing national

guidelines for person- centered care of people with dementia in

residential aged care: effects on perceived person- centeredness,

staff strain, and stress of conscience. Int Psychogeriatr

2014;26:1171–9.

41 Lehuluante A, Nilsson A, Edvardsson D. The inuence of a person-

centred psychosocial unit climate on satisfaction with care and work.

J Nurs Manag 2012;20:319–25.

42 Silén M, Skytt B, Engström M. Relationships between structural

and psychological empowerment, mediated by person- centred

processes and thriving for nursing home staff. Geriatr Nurs

2019;40:67–71.

43 Sjögren K, Lindkvist M, Sandman P- O, etal. To what extent is the

work environment of staff related to person- centred care? A cross-

sectional study of residential aged care. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1310–9.

44 Wallin AO, Jakobsson U, Edberg A- K. Job satisfaction and

associated variables among nurse assistants working in residential

care. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1904–18.

45 Åhlin J, Ericson- Lidman E, Eriksson S, etal. Longitudinal

relationships between stress of conscience and concepts of

importance. Nurs Ethics 2013;20:927–42.

46 Elfstrand Corlin T, Kazemi A. Accounting for job satisfaction:

examining the interplay of person and situation. Scand J Psychol

2017;58:436–42.

47 den Boer J, Nieboer AP, Cramm JM. A cross- sectional study

investigating patient- centred care, co- creation of care, well- being

and job satisfaction among nurses. J Nurs Manag 2017;25:577–84.

48 Schaap FD, Finnema EJ, Stewart RE, etal. Effects of dementia care

mapping on job satisfaction and caring skills of staff caring for older

people with intellectual disabilities: a quasi- experimental study. J

Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2019;32:1228–40.

49 van der Meer L, Nieboer AP, Finkenügel H, etal. The importance of

person- centred care and co- creation of care for the well- being and

job satisfaction of professionals working with people with intellectual

disabilities. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:76–81.

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from

13

van DiepenC, etal. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658

Open access

50 Willemse BM, De Jonge J, Smit D, etal. Staff's person- centredness

in dementia care in relation to job characteristics and job- related

well- being: a cross- sectional survey in nursing homes. J Adv Nurs

2015;71:404–16.

51 Lewis SE, Nocon RS, Tang H, etal. Patient- Centered medical home

characteristics and staff morale in safety net clinics. Arch Intern Med

2012;172:23–31.

52 Nocon RS, Fairchild PC, Gao Y, etal. Provider and staff morale, job

satisfaction, and burnout over a 4- year medical home intervention. J

Gen Intern Med 2019;34:952–9.

53 Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, McAuliffe L, etal. Job

satisfaction amongst aged care staff: exploring the inuence

of person- centered care provision. Int Psychogeriatr

2011;23:1205–12.

54 Jeon Y- H, Luscombe G, Chenoweth L, etal. Staff outcomes from the

caring for aged dementia care resident study (CADRES): a cluster

randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:508–18.

55 Røen I, Kirkevold Øyvind, Testad I, etal. Person- centered care in

Norwegian nursing homes and its relation to organizational factors

and staff characteristics: a cross- sectional survey. Int Psychogeriatr

2018;30:1279–90.

56 Dichter MN, Trutschel D, Schwab CGG, etal. Dementia care

mapping in nursing homes: effects on caregiver attitudes,

job satisfaction, and burnout. A quasi- experimental trial. Int

Psychogeriatr 2017;29:1993–2006.

57 Vassbø TK, Kirkevold M, Edvardsson D, etal. Associations between

job satisfaction, person- centredness, and ethically difcult situations in

nursing homes- A cross- sectional study. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:979–88.

58 Picker Institute. Principles of patient- centered care, 1987. Available:

http:// pickerinstitute. org/ about/ picker- principles/

59 Sjögren K, Lindkvist M, Sandman P- O, etal. Organisational and

environmental characteristics of residential aged care units providing

highly person- centred care: a cross sectional study. BMC Nurs

2017;16:1–9.

60 Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, etal. Barriers and facilitators to the

implementation of person- centred care in different healthcare

contexts. Scand J Caring Sci 2017;31:662–73.

61 Dellenborg L, Wikström E, Andersson Erichsen A. Factors that may

promote the learning of person- centred care: an ethnographic

study of an implementation programme for healthcare

professionals in a medical emergency ward in Sweden. Adv in

Health Sci Educ 2019;24:353–81.

62 Cramer D, Howitt DL. The SAGE dictionary of statistics: a practical

resource for students in the social sciences. 3rd ed. New Delhi: Sage,

2005.

63 Ricoeur P. Oneself as another (originally published in French under

the title soi- meme comme un autre, 1990). London: The University of

Chicago Press, 1992.

44147171. Protected by copyright.

on December 7, 2020 at Swets Subscription Service REF:http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042658 on 7 December 2020. Downloaded from