E

NDOCRINOLOGY

U

PDATE

E

NDOCRINOLOGY NEWS FROM

M

AYO

C

LINIC

volume 1

number 4

2006

Adrenal Incidentalomas: An Approach to Uncertainty

Adrenal incidentaloma is defined as an adrenal

mass 1 cm or more in diameter that is discovered

serendipitously by radiologic examination, in the

absence of symptoms or clinical findings sug-

gestive of adrenal disease. As imaging techniques

have improved and computed imaging has become

accepted practice in medicine, the identification of

adrenal incidentalomas has become more

frequent.

William F. Young, Jr, MD, of the Division of

Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and

Nutrition at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, says:

“Adrenal incidentalomas are not new. Instead of

finding them at autopsy, we are now finding them

during life with computed imaging. There is an

age-dependent occurrence of adrenal cortical

adenomas found at autopsy. Thus, the probability

of finding an unsuspected adrenal adenoma on

computed abdominal imaging in a 20- to 29-year-

old person is approximately 0.2%, compared with

7% in a person older than 70 years.” The majority

of adrenal incidentalomas are clinically nonhyper-

secretory benign adrenal cortical adenomas.

However, more than 45 different diagnoses have

been reported in patients with incidentally

discovered adrenal masses (Table on page 2).

An adrenal incidentaloma should be charac-

terized with respect to both functional status, with

a medical history, physical examination, and

hormonal assessment, and malignant potential,

with an assessment of the imaging phenotype and

mass size.

Hormonal Evaluation

The term “subclinical Cushing’s syndrome”

describes adrenal incidentaloma with autonomous

cortisol-secreting cortical adenomas in patients

who lack the typical signs and symptoms of

hypercortisolism. Subclinical Cushing’s syndrome

affects 8% of all adrenal incidentaloma patients.

Although these patients lack the usual obvious

signs of Cushing’s syndrome, they may have the

adverse effects of continuous endogenous cortisol

secretion, including hypertension, obesity,

diabetes, and osteoporosis. Because their 24-hour

urinary cortisol secretion may be normal, all

adrenal incidentaloma patients should undergo a

1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test.

Of all patients with adrenal incidentalomas,

approximately 5% prove to have pheochromo-

cytomas. Even though clinically silent, pheochro-

mocytomas can be lethal. In evaluation of an

adrenal incidentaloma patient, the clinician has a

powerful predictor of pheochromocytoma, the

“imaging phenotype.” Dr Young says: “The imaging

phenotype is so powerful that, even when

biochemical testing for pheochromocytoma is

normal but the imaging phenotype is typical of

pheochromocytoma, these patients should be

treated with Ȋ-adrenergic and ȋ-adrenergic

blockade and tumor resection. At Mayo Clinic, the

most reliable biochemical method for identifying

adrenal pheochromocytoma is measuring

fractionated metanephrines and catecholamines in

a 24-hour urine collection, the sensitivity and

specificity of which are both 98%.”

All patients with adrenal incidentalomas who

have hypertension should be evaluated for

primary aldosteronism. A reasonable screening

test is determination of the ambulatory morning

plasma aldosterone concentration–to–plasma

renin activity ratio (PAC/PRA ratio, where PAC is

reported in ng/dL and PRA is reported in ng/mL

per hour). The PAC/PRA ratio can be obtained

while the patient is treated with any antihy-

pertensive drug except spironolactone, epleren-

one, or high-dose amiloride. A PAC/PRA ratio of

20 or higher and a PAC of 15 ng/dL or higher

Geoffrey B. Thompson, MD, and William F. Young, Jr, MD

Inside This Issue

A Clinical Conundrum: The

Diagnosis and Treatment of

Androgen Deficiency in

Older Men . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Bariatric Surgery: Important

Considerations for the

Clinician and Patient . . . . . 4

A Practical Approach to

the Patient With Subclinical

Hypothyroidism . . . . . . . . . . 6

constitute a positive screening test

result; however, the cutoff for

a positive test is laboratory

dependent.

Assessment of

Malignant Potential

Computed imaging is the most

powerful tool available to the

clinician to guide the management

of patients with adrenal inci-

dentaloma. Geoffrey B. Thompson,

MD, of the Department of Surgery

at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, notes:

“The lipid-rich nature of cortical

adenomas is helpful in dis-

tinguishing these benign neo-

plasms from malignancy.” Imaging

characteristics consistent with

a benign cortical adenoma

include round and homogeneous

density, smooth contour and

sharp margination, diameter

usually less than 4 cm; unilateral

location, low unenhanced CT

attenuation values, and marked

CT contrast medium washout

(Figure 1). The imaging pheno-

type consistent with pheochromo-

cytoma includes delayed contrast

medium washout on CT, high

signal intensity on T2-weighted

MRI, cystic and hemorrhagic

changes, and variable size (Figure

2). Adrenocortical carcinoma

imaging characteristics include

irregular shape, inhomogeneous

density because of central areas

of low attenuation due to tumor

necrosis, tumor calcification,

diameter usually more than 4 cm,

unilateral location, high

unenhanced CT atten-

uation values, and inhomo-

geneous enhancement on

CT with intravenous con-

trast medium. The imaging

phenotype of metastases

includes irregular shape

and inhomogeneous nature,

tendency to be bilateral,

high unenhanced CT atten-

uation values, and delayed

intravenous contrast med-

ium washout on CT.

The greatest lesion

diameter of the adrenal mass is predictive of

malignancy. In 1 study, a 4-cm cutoff was 90%

sensitive for detecting adreno-cortical carcinoma,

even though 76% of lesions more than 4 cm in

diameter were benign. Dr Thompson cautions:

“Clearly, adrenal mass size should not be used as

the only variable to guide treatment. The primary

role of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is to

differentiate adrenal from nonadrenal tissues

(eg, metastases or infection); FNA biopsy cannot

distinguish between primary adrenal benign and

malignant lesions. Pheochromocytoma should

always be excluded with normal biochemistry

before attempting FNA biopsy of an adrenal

mass.”

Frequency and Duration of Follow-up

An area of uncertainty in the management of a

patient with adrenal incidentaloma is the

frequency and duration of follow-up evaluations.

Autonomous function (glucocorticoid and

catecholamine) not present at baseline can be

detected with longer-term follow-up (eg, 4 years).

Repeat imaging at 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years

may be helpful in excluding primary and

metastatic malignancy.

Endocrinology Consultation 800-313-5077 www.mayoclinic.org

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 2

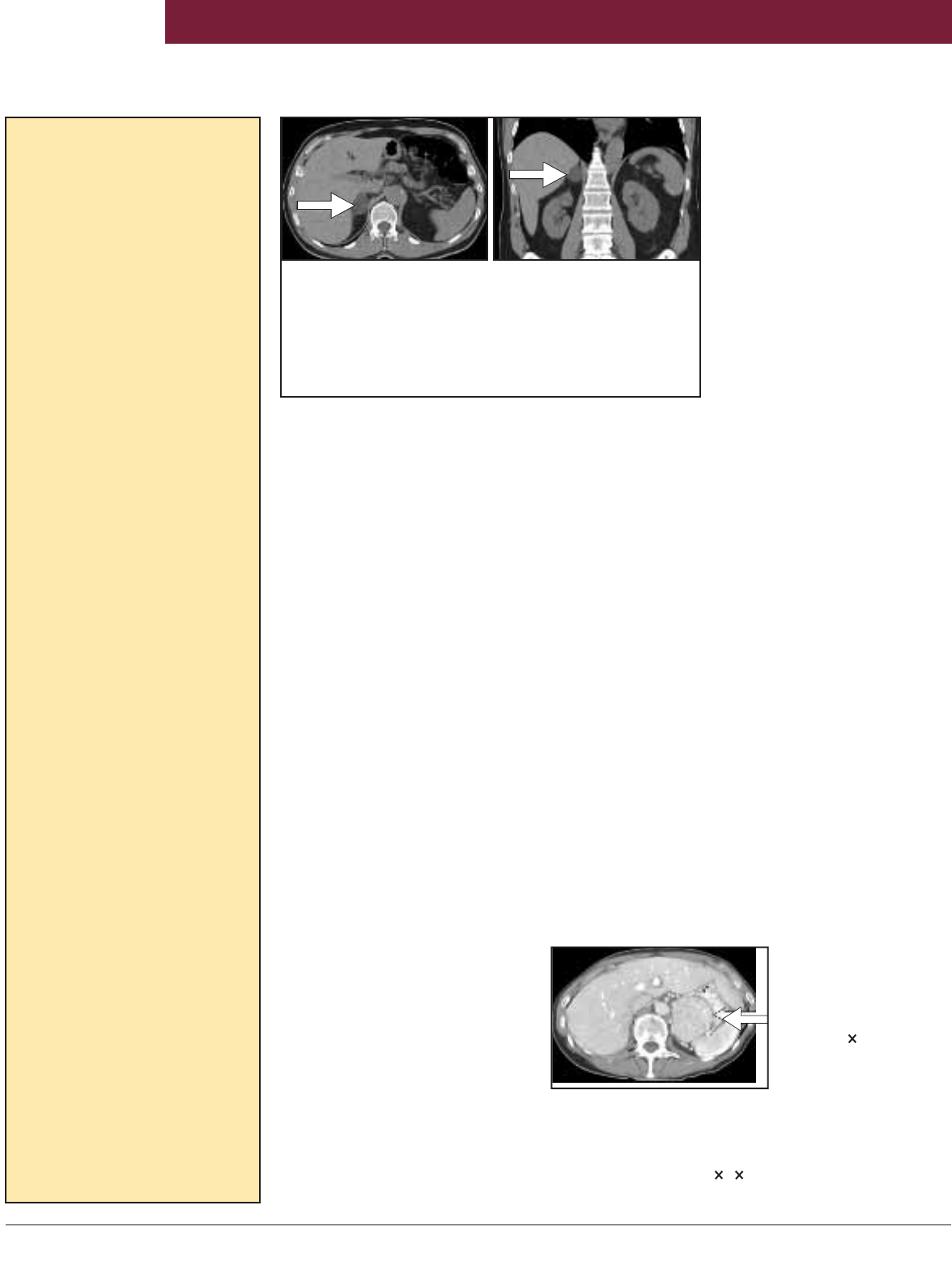

Figure 2. An ab-

dominal CT scan

obtained to eval-

uate bilateral leg

swelling shows a

dense 6.5 5.4-cm,

heterogeneously en-

hancing mass in

the left adrenal

gland (arrow). Results of hormonal testing in this 61-

year-old normotensive woman were positive for

pheochromocytoma. The patient was treated with

Ȋ-

and ȋ-adrenergic blockade followed by laparoscopic

adrenalectomy where a 7 5 5-cm pheochromocytoma

was removed.

Table. Differential Diagnosis

of Asymptomatic Adrenal

Incidentalomas

Benign nonfunctioning mass

Adenoma

Adenomatoid tumor

Adrenolipoma

Amyloidosis

Cyst

Ganglioneuroma

Granuloma

Hamartoma

Hematoma

Hemangioma

Infection (fungal, tuberculosis,

echinococcosis, cryptococcosis,

nocardiosis)

Leiomyoma

Lipoma

Lymphangioma

Myelolipoma

Neurofibroma

Oncocytoma

Pseudocyst

Teratoma

Malignant nonfunctioning mass

Adrenocortical carcinoma

Angiosarcoma

Ganglioneuroblastoma

Leiomyosarcoma

Liposarcoma

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumor

Metastatic carcinoma (eg, breast,

lung, kidney, stomach, pancreas,

ovary, colon, esophagus)

Primary malignancy

Primary malignant melanoma

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor

Subclinical hyperfunctioning mass

Composite pheochromocytoma

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Androgen- and estrogen-secreting

neoplasms

Massive macronodular hyperplasia

Nodular hyperplasia

Pheochromocytoma

Primary aldosteronism

Primary malignancy

Sex cord-stromal tumor

Subclinical Cushing’s syndrome

Pseudoadrenal mass

Mistaken vasculature

Liver

Lymph nodes

Pancreatic mass

Renal mass

Spleen

Stomach mass

Technical artifact

Adapted from Young WF Jr. Management

approaches to adrenal incidentalomas: a

view from Rochester, Minnesota. Endocrinol

Metab Clin North Am. 2000;29:159-85.

Figure 1. An abdominal CT scan (A, axial image; B, coronal

image) obtained to evaluate nonspecific abdominal pain shows

a round, uniform, low-density 2-cm right adrenal mass (arrows).

Results of hormonal testing in this 66-year-old hypertensive

man for subclinical Cushing’s syndrome, primary aldosteronism,

and pheochromocytoma were normal. The patient is being

followed with repeat imaging and hormonal testing.

A

B

Testosterone replacement in young men with hypo-

gonadism maintains or improves bone mineral

density, body composition, virilization, libido, sexual

function, and sense of well-being. As men age,

however, it is difficult to differentiate true hypo-

gonadism from the changes of normal aging. There

is uncertainty if the physiologic changes of aging

are due to testosterone deficiency and if treating

normal older men with testosterone is beneficial.

Because testosterone-dependent diseases such as

benign and malignant prostate growth become

very common as men age, the risk/benefit ratio for

testosterone replacement in older men is more

difficult to define than it is in young men.

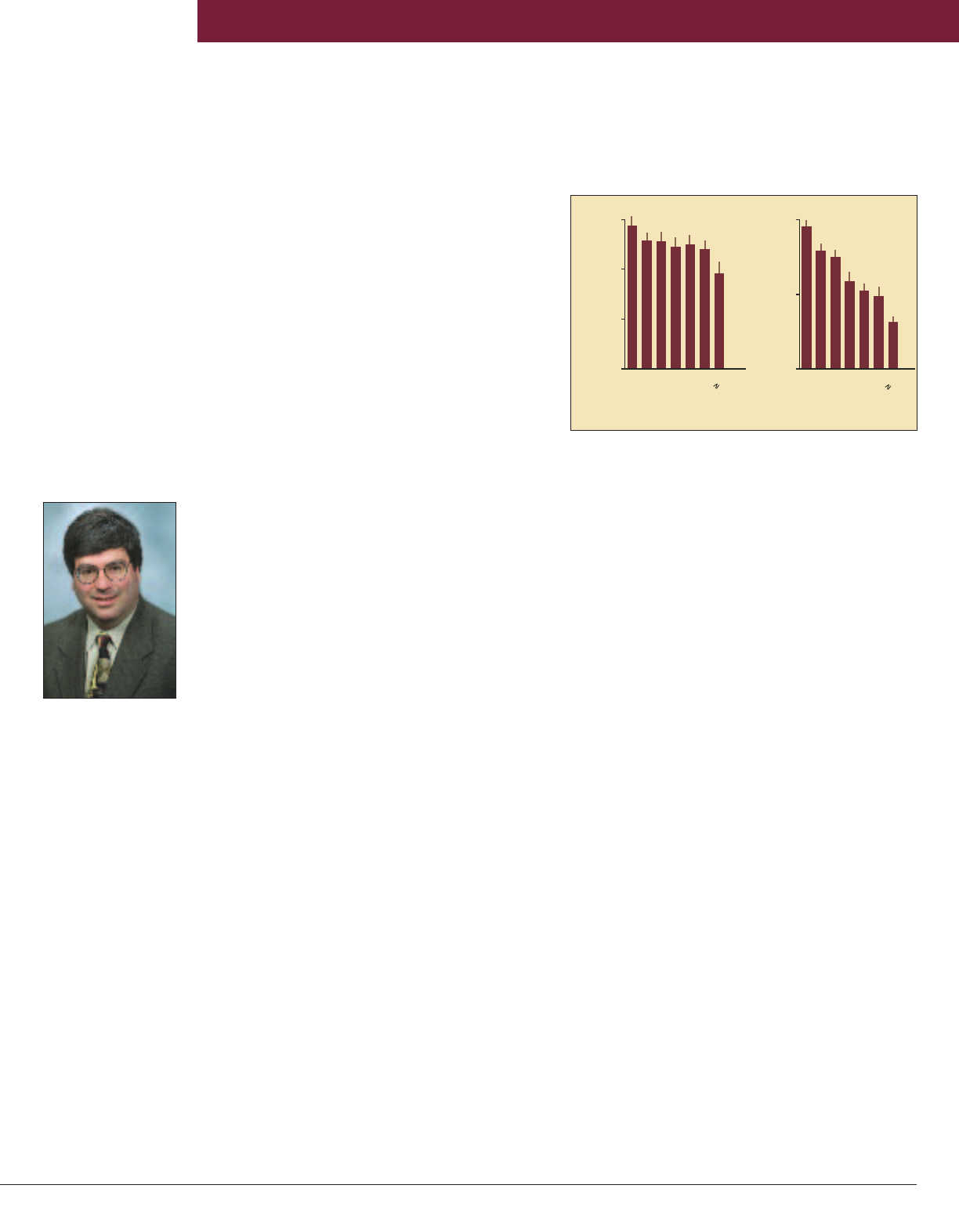

Large epidemiologic studies document a decline

in testosterone production and an increase in sex

hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) as men age,

resulting in a much greater decline in the active

fraction, measured as free or bioavailable

testosterone (Figure). Most studies testing the

effects of testosterone administration in normal

elderly men included men older than 60 years

whose baseline total testosterone levels were in the

low-normal to mildly low range (eg, <350 ng/dL)

or had bioavailable testosterone levels less than 70

ng/dL. These studies, most of which were

published between 1990 and 2002, have been of

short duration and included relatively small

numbers of subjects. Although the results from the

various studies are not entirely consistent, a

composite of the changes seen with testosterone

treatment in older men is shown in the Table on

page 4. Todd B. Nippoldt, MD, of the Division

of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and

Nutrition at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, cautions: “It

is important to emphasize that there are no data on

clinically important end points, such as bone

fracture risk, cardiovascular events, development

of malignancy, or mortality, for testosterone

treatment in normal elderly men.”

Men with gynecomastia, osteoporosis,

diminished libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of

muscle mass, beard, or body hair, or hot flashes

warrant an evaluation for hypogonadism. Because

of the increased level of SHBG with aging, the

laboratory evaluation in older men should start

with a measurement of total testosterone along

with free or bioavailable testosterone. Dr Nippoldt

notes: “It is important to determine the etiology of

a low testosterone level before starting replace-

ment therapy. Blood levels of luteinizing hormone

(LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and

prolactin should be measured in all men with low

testosterone levels. Elevated serum LH and FSH

concentrations indicate primary testicular failure,

and no further studies are needed. Elevated serum

prolactin levels, in the absence of prolactin-

increasing drugs, should dictate computed

imaging of the sellar region.”

Low (or “inappropriately normal”) LH and FSH

imply a central cause for hypogonadism, which

may be functional or structural. A functional

abnormality in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis is

more common. This functional abnormality may

be idiopathic or due to “normal aging,” but several

medical conditions should be considered as well:

obstructive sleep apnea, recent illness or surgery

(eugonadal sick syndrome), extreme emotional

distress, or adverse effects of medications (eg,

high-dose glucocorticoids, narcotic pain relievers,

or drugs that increase prolactin). The only way to

definitively exclude a structural lesion is by sellar

computed imaging. The decision to obtain sellar

MRI depends on the severity of the deficiency, the

patient’s age, and the potential presence of other

pituitary dysfunction or mass effect (eg, headaches

or vision disturbance).

The decision on whether to begin testosterone

replacement in an elderly man may be difficult.

There are no definitive data regarding the level of

testosterone required to prevent osteopenia and

maintain muscle mass. However, values of total

testosterone less than 200 ng/dL or bioavailable

testosterone less than 70 ng/dL are probably

Endocrine Surgery Consultation 507-284-2166 www.mayoclinic.org

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 3

Todd B. Nippoldt, MD

A Clinical Conundrum: The Diagnosis and

Treatment of Androgen Deficiency in Older Men

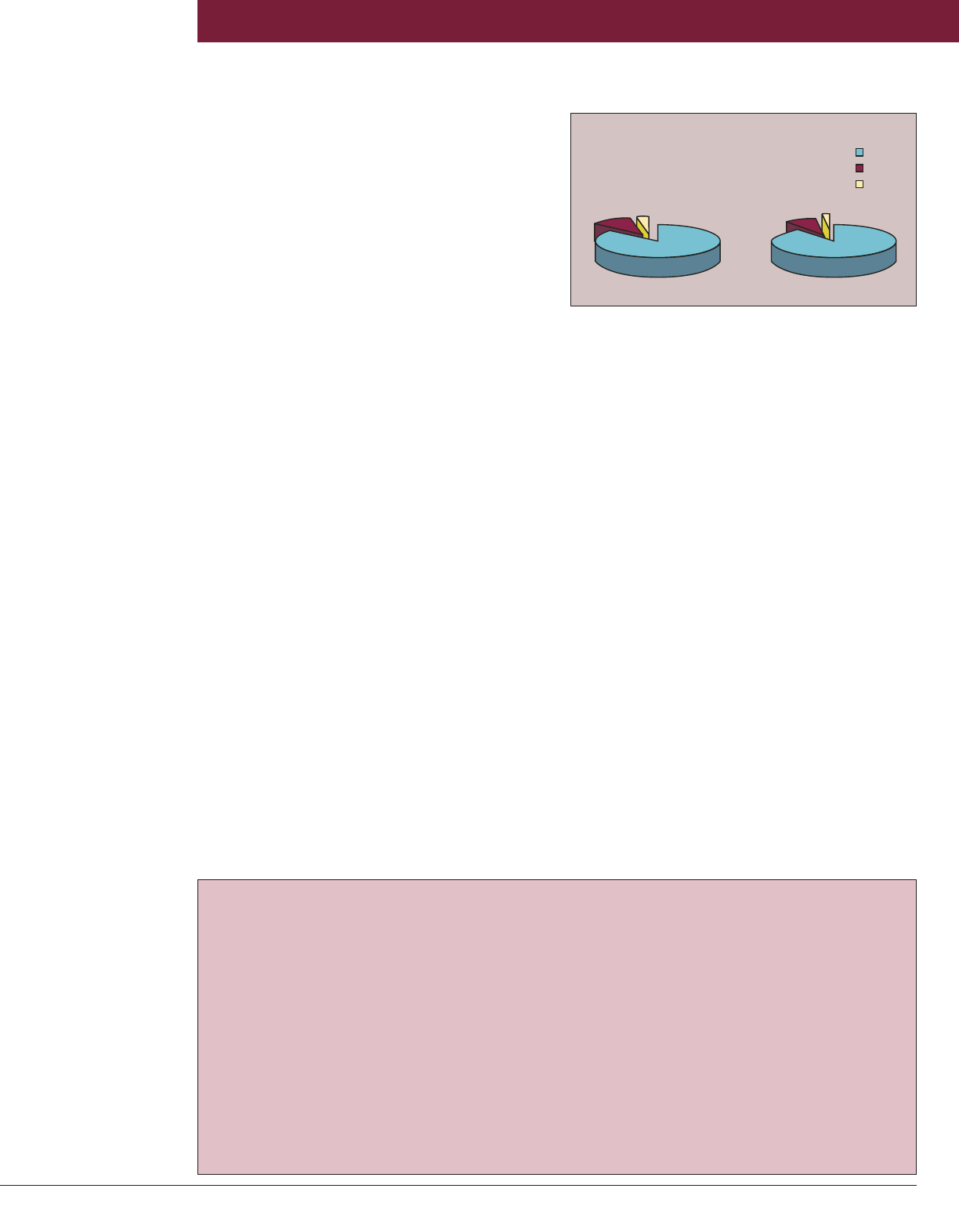

Figure. Total and bioavailable testosterone (T) levels

from 346 men in Rochester, Minnesota, stratified by

age. (Data from Khosla S, et al. Relationship of serum

sex steroid levels and bone turnover markers with bone

mineral density in men and women: a key role for

bioavailable estrogen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

1998;83:2266-74. Copyright 1998, The Endocrine

Society. Reprinted with permission.)

0

200

400

600

0

100

200

<

3

0

30

-

39

40

-

49

50

-

59

60

-

69

70

-

79

80

<30

30

-

39

40

-

49

50

-

59

60

-

69

70

-

79

80

Total T, ng/dL

Bioavailable T, ng/dL

Age, y

Age, y

inadequate, and patients

with these levels should be

considered for replacement,

even in the absence of hypo-

gonadal symptoms. Many

men have symptoms compat-

ible with hypogonadism with

testosterone values at the

lower end of the normal range

or just mildly diminished, and

it is difficult to know if this is

the cause for these symp-

toms. Dr Nippoldt says: “In

this situation, a therapeutic

trial of testosterone replace-

ment is warranted. Replacing

testosterone in doses ade-

quate to bring the total testos-

terone level to the mid-normal

range and bioavailable testos-

terone level higher than 80

ng/dL for at least 3 months is

usually an adequate trial.

Elderly men metabolize testos-

terone at a slower rate than

younger men and usually require lower doses than

those typically used for young hypogonadal men.

If the testosterone replacement trial has no impact

on the symptoms, testosterone replacement should

be discontinued.”

Potential risks for parenteral testosterone

replacement include exacerbating or unmasking

benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer,

obstructive sleep apnea, and polycythemia. No

studies have defined the incidence of these

potential risks or the cost-effectiveness of pre-

treatment screening or monitoring. Dr Nippoldt

advises: “In the absence of these data, it is

reasonable to obtain baseline digital rectal

examination, prostate-specific antigen level,

complete blood cell count, and a history regarding

the potential for obstructive sleep apnea. The

frequency of rechecking these studies during

therapy depends on the patient’s age, family

history, and baseline values. Any new symptom

should be investigated. If polycythemia develops,

overnight polysomnography should be considered

to exclude obstructive sleep apnea.”

Table. Changes Seen With Testosterone Treatment in Older Men

Lean body mass No change or increases (0%-5%)

Fat mass No change or decreases (0%-25%)

Strength No change or modest increase

Physical functioning No change

Sense of well-being Improves

Libido Increases

Erectile dysfunction No change (improves in those with very low T)

Spatial cognition Improves

Memory No effect

Bone resorption/

formation markers Improves or no change

Bone mineral density No change (increases in those with very low T)

Total cholesterol Declines (9%-12%)

HDL cholesterol No change

LDL cholesterol Declines (11%)

Insulin sensitivity No change or improves (equivocal)

IGF-1 level Increases

PSA No change or increases (remains in normal range)

Prostate volume Minimal increase

Hematocrit Increases (0%-7%), more if sleep apnea is present

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 4

Endocrinology Consultation 800-313-5077 www.mayoclinic.org

Bariatric Surgery: Important Considerations

for the Clinician and Patient

The number of bariatric operations per-

formed in the United States is increasing

each year. Several factors have contributed

to this trend: the continued rise in the

prevalence of severe obesity, the lack of

effective medical therapies for obesity, and

a growing body of literature reporting

multiple health benefits in patients who

have undergone bariatric procedures. As a

result, patients, physicians, and third-party

payers have become more receptive to this

therapy.

Counseling the patient interested in

bariatric surgery presents many challenges.

Maria L. Collazo-Clavell, MD, of the Division

of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and

Nutrition at Mayo Clinic in Rochester,

comments: “Several bariatric operations are

offered that vary in their mechanisms of weight

loss, effects on medical comorbidities, and

perioperative and long-term risks. Adding to the

complexity, institution-specific outcomes may

not always reflect the published results achieved

by more established and experienced centers.”

Bariatric operations are categorized by their

mechanism of weight loss, restriction of dietary

Maria L. Collazo-Clavell, MD, and

Michael L. Kendrick, MD

intake, and induction of maldigestion/malab-

sorption of calories. The restrictive procedures

available are the vertical banded gastroplasty

(VBG) and the laparoscopic adjustable gastric

band (LAGB). The VGB consists of a stapled

proximal gastric pouch with a fixed (nonadjustable)

outlet created by a mesh band or silicone rubber

ring. Lower perioperative morbidity and an

acceptable early weight loss compared with

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) were

encouraging, but several randomized trials have

demonstrated inferior weight loss compared with

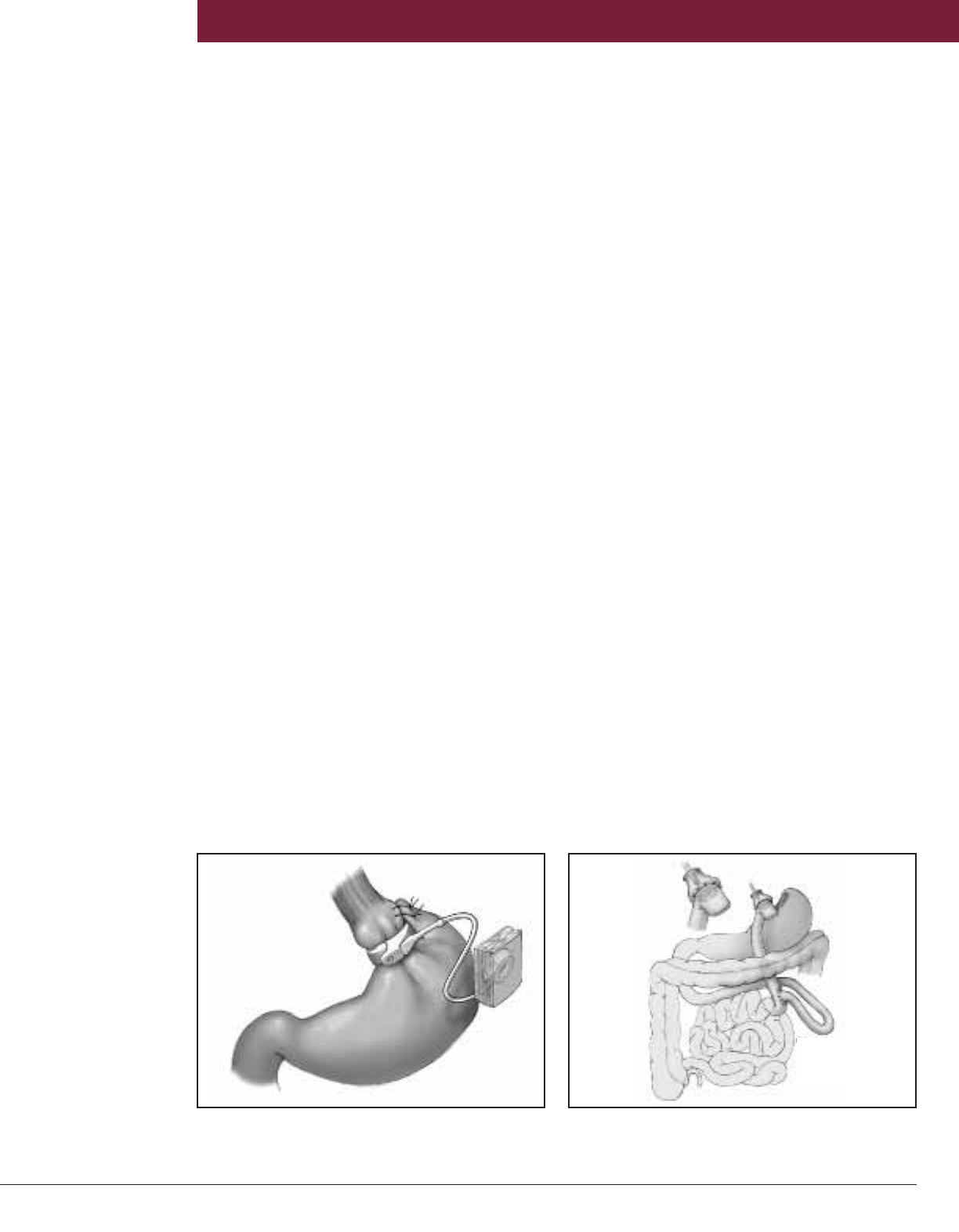

RYGB. The LAGB procedure has 2 components—

a silicone band with an inner inflatable cuff and a

reservoir connected by tubing (Figure 1). The

band is placed around the gastric cardia to create

a small (15 mL) proximal gastric pouch

with an adjustable restrictive outlet that

limits the amount of food that can be consumed.

The reservoir is implanted in the subcutaneous

tissue of the abdominal wall where it can be

accessed percutaneously to either add or remove

saline to adjust the inflatable cuff (Figure 1).

Michael L. Kendrick, MD, of the Department of

Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, comments:

“This adjustable feature provides the ability to

fine-tune the desired effect of restriction. The

absence of any bowel transection or anastomosis

leads to lower perioperative risks. Disadvantages

include less weight loss and lower resolution of

weight-related comorbid conditions compared

with RYGB and lack of long-term outcome

data. Intermediate and long-term complications

can be substantial, with reoperation required in

up to 20% of patients. At Mayo Clinic Rochester,

we no longer offer the VBG and offer the LAGB

only in limited clinical circumstances.”

Dr Kendrick explains: “RYGB is the most

common bariatric surgery performed at our

institution and nationwide. The current

procedure consists of a small proximal cardia

pouch (10-30 mL) and a 75- to 150-cm Roux limb

(Figure 2). The length of the Roux limb can vary,

influencing the weight loss observed and risk

for nutritional sequelae. In several series, RYGB

has provided greater initial and sustained weight

loss than purely restrictive operations and has

demonstrated long-term effectiveness with

reduction of comorbidities and minimal risk for

long-term nutritional complications.”

Several malabsorptive procedures are

available. Modifications to the RYGB, with

lengthening of the Roux limb and shortening of

the common channel, promote a malabsorptive

rather than maldigestive physiology (long-limb

RYGB, the very, very long-limb RYGB [VVLL-

RYGB], and the distal RYGB). Biliopancreatic

diversion (BPD) is a short common channel

procedure combined with a distal gastrectomy,

capable of achieving marked and sustained

weight loss. The increased incidence of stomal

ulceration, severe protein-calorie malnutrition,

diarrhea, and dumping has limited its broad

acceptance. The duodenal switch (DS) involves

transection of the first portion of the duodenum

with resection of the greater curvature of the

stomach leaving a 100- to 150-mL lesser

curvature-based gastric sleeve with an intact

antrum and pylorus. The proximal ileum is

divided 250 cm from the ileocecal junction,

and the biliopancreatic limb is anastomosed to

the distal ileum, creating a short (100 cm)

common channel. A duodenoileostomy is then

constructed, bringing the Roux limb up to the

gastric sleeve. Advantages of the DS include

reduced stomal complications, absence of

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 5

Endocrine Surgery Consultation 507-284-2166 www.mayoclinic.org

Figure 1. The LAGB bariatric operation. The LAGB

consists of a silicone band with an inner inflatable cuff

and a reservoir connected by tubing.

Figure 2. The RYGB procedure consists of a small

proximal cardia pouch (10-30 mL) and a 75- to 150-cm

Roux limb.

Roux limb =

150 cm

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 6

Endocrinology Consultation 800-313-5077 www.mayoclinic.org

Subclinical hypothyroidism occurs when the

serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level

rises above the upper limit of normal (ULN)

despite a normal serum free thyroxine (FT4)

concentration. Subclinical hypothyroidism or mild

thyroid failure is a common problem with a

prevalence of 4% to 8.5% in the adult population.

The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism

increases with advancing age and is higher in

women (Figure on page 7).

Because serum TSH has a log-linear relation-

ship with circulating thyroid hormone levels (eg, a

2-fold change in FT4 produces a 100-fold change

in TSH), it is the key test for the diagnosis of

subclinical hypothyroidism. Vahab Fatourechi,

MD, of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes,

Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic in

Rochester, notes: “The laboratory reference ranges

for TSH and FT4 may not be representative of a

given individual’s personal normal range. That is,

the laboratory reference ranges are wider than the

ranges of thyroid hormones that are typically

observed in an individual over time. For the

diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism, other

causes of elevated serum TSH, such as recovery

from nonthyroidal illness, assay variability,

heterophil antibodies, central hypothyroidism with

biologically inactive TSH, and thyroid hormone

resistance, should be excluded. However, the most

common cause of elevated serum TSH is auto-

immune thyroid disease.”

What Is the Upper Limit of Normal for TSH?

The ULN for serum TSH is the subject of hot

debate. The reference range used by Mayo

Medical Laboratories is 0.3 to 5.0 mIU/L. However,

data that support a move to lower the ULN of

TSH to 3.0 mIU/L

and possibly 2.5

mIU/L have been

published. These lower

ULN cutoffs are ob-

tained if individuals

at risk of thyroid

disease are excluded

from the reference

range population. The

strongest argument

for lowering the ULN

of TSH is the higher

rate of positive antithyroid antibodies (reflecting

underlying autoimmune thyroid disease) for

individuals with TSH concentrations between 3

and 5 mIU/L and the higher rate of progression to

clinical thyroid disease for this subgroup. The

argument against lowering the ULN for serum

TSH is that 22 million to 28 million additional

individuals in the United States would be

considered hypothyroid if the ULN of the TSH

range were decreased to 2.5 to 3.0 mIU/L. Dr

Fatourechi cautions: “Our own data show that

decreasing the ULN of the TSH reference range to

3.0 mIU/L results in a 3-fold increase in the diag-

nosis of hypothyroidism in patients without a history

of thyroid disease. Yet there is no evidence that

intervention at these levels of TSH is beneficial. In

fact, some evidence shows that lowering serum

TSH to the proposed new normal range by adjust-

ment of the thyroxine dose does not improve

patients’ well-being or their nonspecific complaints.”

Dr Fatourechi continues: “Obviously for patients

with TSH levels between 3 and 5 mIU/L, follow-

up and possibly measurement of thyroperoxidase

(TPO) antibody may be considered.”

A Practical Approach to the

Patient With Subclinical Hypothyroidism

dumping, excellent long-term maintenance of

weight loss, and decreased incidence of severe

protein-calorie malnutrition with the DS

compared with BPD. At Mayo Clinic Rochester,

the VVLL-RYGB and the DS are offered to

individuals with body mass index (calculated as

weight in kilograms divided by the square of

height in meters) greater than 55 in whom

malabsorptive procedures are associated with

superior weight loss.

Dr Collazo-Clavell notes: “A patient’s decision

to consider bariatric surgery is not an easy one.

Which bariatric procedure is best for an

individual depends on multiple factors—amount

of weight loss desired, preexisting medical

comorbidities, and preference, to name a few.”

Each year, more than 300 bariatric procedures are

performed at Mayo Clinic Rochester and Mayo

Clinic Arizona. Multidisciplinary teams of

nutritionists and specialists from the fields of

surgery, internal medicine, psychology, and

psychiatry work in an integrated fashion to

evaluate, educate, and prepare patients in hopes

of maximizing success and minimizing short-

and long-term complications of bariatric surgery

for weight loss.

Vahab Fatourechi, MD

Should All Patients With Subclinical

Hypothyroidism Be Treated With Thyroid

Hormone Replacement?

There is consensus for initiating thyroxine

replacement therapy for all patients with elevated

TSH higher than 10 mIU/L, even if FT4 is within

the normal laboratory range. However, con-

troversy continues concerning whether patients

with serum TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L

should be treated. The argument in favor of

replacement therapy is based on numerous

proposed consequences of untreated subclinical

hypothyroidism: progression to clinical hypo-

thyroidism, subtle systemic symptoms of hypo-

thyroidism, lipid abnormalities, adverse cardiac

end points, cardiac dysfunction, adverse fetal

effects and pregnancy outcomes, possible contri-

bution to infertility, neuromuscular dysfunction,

psychiatric dysfunction, and cognitive dysfunction.

Dr Fatourechi explains: “If studies show that

mildly elevated serum TSH has adverse cardiac

effects, then therapy of all cases of subclinical

hypothyroidism will make sense. Several

investigators have demonstrated subtle cardio-

vascular dysfunction in subclinical hypo-

thyroidism, but clinical significance is ques-

tionable. However, to date, most studies have

shown a lack of association of subclinical hypo-

thyroidism with cardiac events and cardiovascular

mortality. Surprisingly, the results of an epidem-

iologic study suggested that for individuals older

than 80 years a slightly higher-than-normal TSH

had survival benefit. Because of the large number

of individuals potentially impacted, there is an

urgent need for settling this controversy. Until

guidance from carefully designed randomized

trials becomes available, individuals with serum

TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L should be

treated selectively. Thyroxine replacement therapy

should be reserved for patients who have goiter,

women who are anticipating pregnancy or are

pregnant, or patients with depression or bipolar

disorder. Patient preference, clinical circumstance,

age, presence of symptoms of hypothyroidism,

TPO antibody positivity, and level of and

progression of TSH over time should also be

considered. We also suggest that subclinical hypo-

thyroidism associated with autoimmune thyroid-

itis of children and adolescents should be treated.

Our data show that patients with serum TSH levels

above 8 mIU/L have a high likelihood of progres-

sion to TSH above 10 mIU/L in 4 years and may be

considered for thyroxine replacement therapy.

“Improvement in serum lipid levels with

thyroxine replacement therapy is more likely for

patients who have baseline TSH levels higher than

10 mIU/L. If hyperlipidemia is encountered in a

patient with a serum TSH between 5 and 10

mIU/L, specific lipid-directed therapy or lifestyle

changes are needed. Some of these recom-

mendations do not have definitive evidence-based

support; however, we believe a practical approach

is needed until more evidence becomes available.”

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 7

Endocrine Surgery Consultation 507-284-2166 www.mayoclinic.org

8%

2%

<5.0

5.1- 10

>10

0

Female

11%

3%

TSH, mIU/L

Male

90%86%

Figure. Serum TSH levels in 123,958 patients aged 50

years or older seen at Mayo Clinic, 1995-1997.

Endocrinology Update

Produced by

Mayo Clinic

200 1st Street SW

Rochester, MN 55905

Medical Editor

William F. Young, Jr, MD

Editorial Board

M. Regina Castro, MD

Bart L. Clarke, MD

Maria L. Collazo-Clavell, MD

Clive S. Grant, MD

Publication Manager

Elizabeth M. Rice

Art Director

Ron O. Stucki

Production Designer

Connie S. Lindstrom

Manuscript Editor

Jane C. Wiggs

Media Support Services

Contributing Artists

Joseph M. Kane

Siddiqi Ray

Endocrinology Update is written for

physicians and should be relied upon

for medical education purposes only.

It does not provide a complete

overview of the topics covered and

should not replace the independent

judgment of a physician about the

appropriateness or risks of a

procedure for a given patient.

Endocrinology Update

Education Opportunities

Please call 800-323-2688 or visit www.mayo.edu

/cme/endocrinology.html for more information

about these courses or to register.

10th Mayo Clinic Endocrine Course

The 10th Mayo Clinic Endocrine Course will be

held March 18-23, 2007, on the Big Island of

Hawaii. This course, created for endocrinologists

and interested internists and surgeons, will

present the latest material on the diagnosis and

treatment of endocrine disorders. This 5-day

course (7:30 AM to 12:30 PM daily) will span the

full spectrum of endocrinology through short

lectures, case-based debates, clinicopathologic

sessions, clinical pearls sessions, and small group

discussions with experts. The digital audience

response system will be used extensively, and

there will be many opportunities for interaction

with the course faculty. Optional sessions on

thyroid ultrasonography and technology in

diabetes will be offered.

Mayo Clinic Nutrition in Health and Disease

Mayo Clinic Nutrition in Health and Disease will

be held November 8-9, 2007, at the Hilton San

Francisco Financial District in San Francisco,

California. This course, designed for physicians,

dietitians, nurses, and pharmacists, will provide

an in-depth overview of challenging nutritional

issues that clinicians encounter in the ambulatory

and hospital settings.

MAYO CLINIC ENDOCRINOLOGY UPDATE 8

NON-PROFIT

ORGANIZATION

U.S. POSTAGE PAID

ROCHESTER, MN

PERMIT NO. 259

To make an

appointment for

a patient through

the Referring

Physicians

Service, use

these toll-free

numbers:

Mayo Clinic

Rochester

800-533-1564

Mayo Clinic

Arizona

866-629-6362

Mayo Clinic

Jacksonville

800-634-1417

MC5810-1206

200 First Street SW

Rochester, Minnesota 55905

www.mayoclinic.org

© 2006, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved.

MAYO, MAYO CLINIC and the tri

p

le-shield Mayo logo are trademarks and service marks of MFMER.

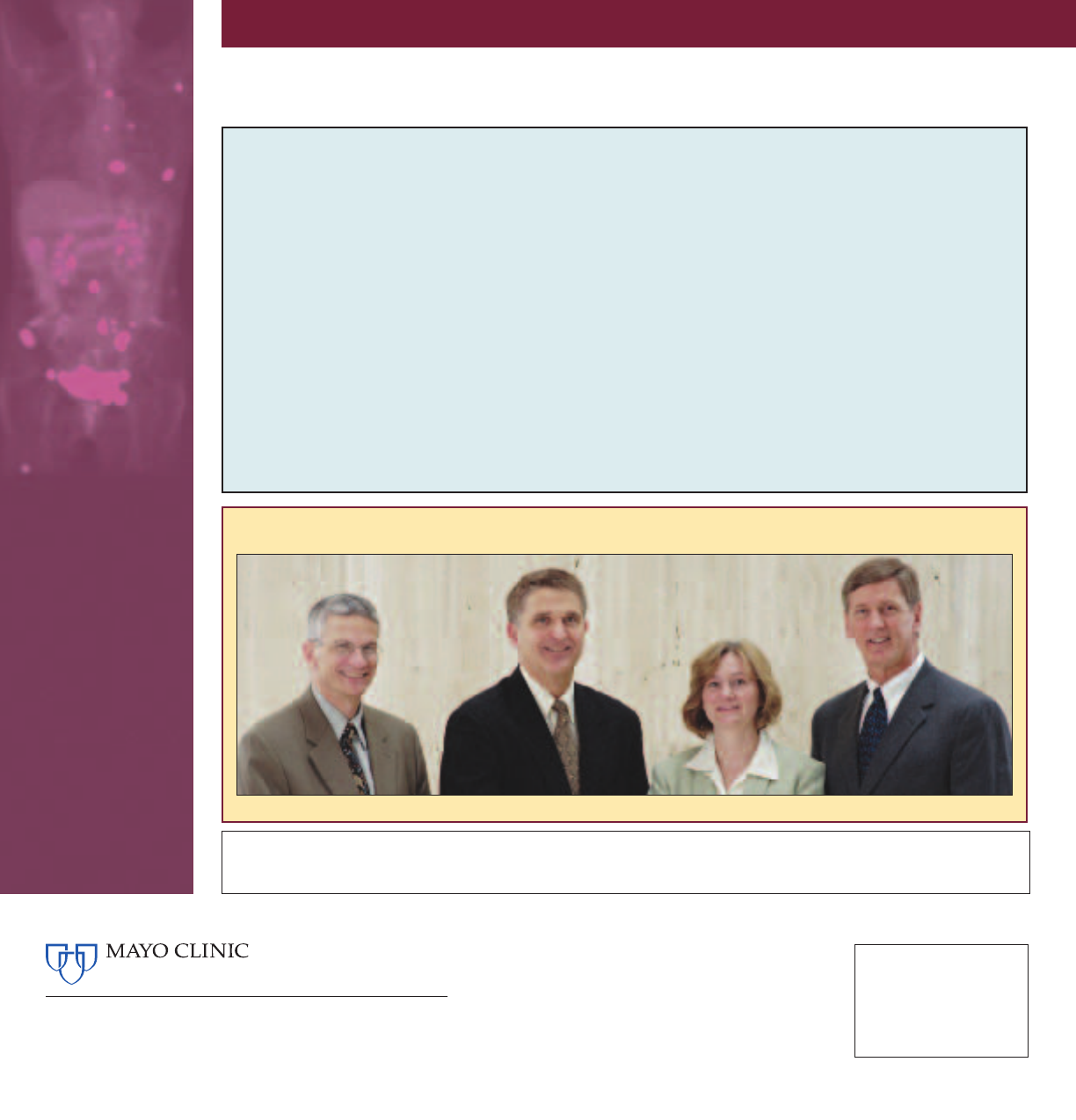

Geoffrey B. Thompson, MD, David R. Farley, MD, Melanie L. Richards, MD, and Clive S. Grant, MD

Mayo Clinic Rochester Endocrine Surgeons

If you would like to be removed from the Mayo Clinic Endocrinology Update mailing list, please send an e-mail with your request

to [email protected]. However, please note this opt-out only applies to Mayo Clinic Endocrinology Update. You may

continue to receive other mailings from Mayo Clinic in the future. Thank you.