A T R A U M A - I N F O R M E D A P P R O A C H

F O R M A R Y L A N D S C H O O L S

The Maryland State Department of Education

MARCH 2021

200 WEST BALTIMORE STREET BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 21201

1

Karen B. Salmon, Ph.D.

State Superintendent of Schools

Clarence C. Crawford

President, Maryland State Board of Education

Larry Hogan

Governor

Sylvia A. Lawson, Ph.D.

Chief Performance Officer

Office of the Deputy for School Effectiveness

Mary L. Gable

Assistant State Superintendent of Schools

Division of Student Support, Academic Enrichment, and Educational Policy

Walter J. Sallee, MPA

Director, Student Services & Strategic Planning

Division of Student Support, Academic Enrichment, and Educational Policy

Kimberly A. Buckheit

Section Chief, School Safety & Climate

Division of Student Support, Academic Enrichment, and Educational Policy

Marone L. Brown, Ph.D.

Lead Specialist for School Safety, Project Director, Grants to States for School Emergency

Management (GSEM)

Division of Student Support, Academic Enrichment, and Educational Policy

Terrell L. Sample, MPA, MSOL

Education Specialist, Project Director, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and

MD-Project AWARE

Division of Student Support, Academic Enrichment, and Educational Policy

The Maryland State Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of age, ancestry/national origin,

color, disability, gender identity/expression, marital status, race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation in matters

affecting employment or in providing access to programs and activities and provides equal access to the Boy Scouts

and other designated youth groups.

For inquiries related to Department policy, please contact:

Equity Assurance and Compliance Office

Office of the Deputy State Superintendent for Finance and Administration

Maryland State Department of Education

200 W. Baltimore Street – 6

th

Floor

Baltimore, Maryland 21201-2595

410-767-0426 – voice

410-767- 0431 – fax

410-333-6442 – TTY/TDD

2

CONTRIBUTORS

Marone L. Brown, Ph.D.

Lead Specialist for School Safety, Maryland State Department of Education

Heather Chapman, LCSW-C

Vice President, Neighborhood Zones United Way of Central Maryland

Kari Gorkos

Sr. Director, Public Education and Programs, Mental Health Association of Maryland

Kelly Gorman

Handle with Care Coordinator, Maryland Governor’s Office Crime Control and Prevention

Courtnay Hatcher, Ed.S., NCSP, BCBA

School Psychologist, Frederick County Public Schools

Sharon Hoover, Ph.D.

Director, Center for School Mental Health

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Tim Morrow

School Principal, Antietam Academy

Kimberly A. Muniz, M.A. /CAS, NCSP

Supervisor of Student Services Behavioral and Mental Health, Carroll County Public Schools

Kelly Parsons, Psy.D.

Clinical Psychologist, Maryland Department of Health

David Rose, MD, MBA

Chief Medical Director, Maryland Department of Human Services

Terrell L. Sample, MPA, MSOL

Director, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and MD-AWARE, Maryland State Department of

Education

Joan B. Smith, MSW, LCSW

Chair, Eastern Shore School Mental Health Coalition

D’Lisa Worthy, M.Ed.

Chief, Early Childhood Services, Maryland Department of Health

3

Contents

CONTRIBUTORS ........................................................................................................................................ 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 4

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5

Trauma-Informed Schools .......................................................................................................... 7

The Logic Model .................................................................................................................................... 7

Creating Safe Spaces and Staff Well-Being ................................................................................. 8

Creating Safe Spaces ............................................................................................................................. 8

Staff Well-Being .................................................................................................................................. 10

Empowerment: Voice and Choice ............................................................................................ 11

Equity and Resilience ................................................................................................................ 11

Equity .................................................................................................................................................. 11

Resilience ............................................................................................................................................ 12

Positive Relationships ............................................................................................................... 13

Family and Community Engagement ........................................................................................ 14

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................................... 17

GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................................................... 18

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................................... 20

RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................................. 22

4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Pursuant to MD Education Article §7-427.1 Trauma-Informed Approach, the Maryland State

Department of Education (MSDE) is required to expand the use of trauma informed approaches

in schools and intensively train schools on becoming trauma informed.

The Trauma-Informed Approach Guidance was developed to provide a framework to Local

School Systems (LSSs) in establishing a holistic approach to education in which all teachers,

school administrators, staff, students, families, and community members recognize and

effectively respond to the behavioral, emotional, relational, and academic impact of stress on

those within the school system. The purpose of this guide is to assist LSSs in implementing

trauma-informed approaches through a multi-tiered system of support.

Research has long supported the critical roles that schools can and do play in supporting

development beyond academic instruction. Schools most often provide a safe haven where

children build relationships with trusted adults who contribute to their healthy development. At

the same time, the demands and expectations of school can be especially challenging for students

who experience traumatic stress, and factors such as negative school climate and poor teacher-

student relationships can make school a place that worsens symptoms of trauma or even re-

traumatizes an individual.

In June 2020, MSDE established a trauma-informed approach work group to accomplish the

tasks outlined in the aforementioned legislation. The work group consisted of representative

from varying agencies across Maryland, including but not limited to, the Maryland Department

of Health, and the Maryland Department of Human Services with a range of expertise in the

areas of trauma, trauma-informed practices, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), multi-tiered

systems of support, resilience, and childhood development. The goal of the workgroup was to

establish a shared vision and definition for a trauma-informed approach for LSSs in Maryland.

The work group would also create guidelines for trauma-informed approaches to assist school

systems with:

(a) Implementing a comprehensive trauma-informed policy at school;

(b) The identification of a student, teacher, or staff member who has experienced trauma;

(c) For schools participating with the “Handle with Care” program the appropriate manner for

responding to a student who is identified as a “Handle with Care” student; and

(d) Becoming a Trauma-Informed School that promotes healing.

For guidance questions and/or assistance, please contact:

Marone L. Brown

Division of Student Support, Educational Policy and Academic Enrichment

Email: [email protected] Phone: (410) 767-0481

Terrell L. Sample

Division of Student Support, Educational Policy and Academic Enrichment

Email: [email protected] Phone: (410) 767-0305

5

INTRODUCTION

Adversity and trauma have a significant impact on the learning and lives of individuals. During

the last decade, there has been an increase in public awareness of the impact of trauma on the

lives of individuals. Addressing trauma early in life through trauma-informed approaches can

improve outcomes for individuals. MD Education Article §7-427.1) directed the MSDE to

develop guidance in support of schools implementing a trauma-informed approach. Trauma

affects a person’s quality of life across all domains (behavioral, emotional, and psychological).

In the United States, 90 percent of students attend public schools where most remain for 13

crucial years of development. Public schools are the ideal place to mitigate the impact of

childhood trauma by creating a healthy school ecosystem that addresses the needs of the whole

child.

Adverse childhood experiences refer to a set of experiences a young person may go through,

such as parental substance abuse or incarceration, divorce, or exposure to violence. The concept

of ACEs has broadened to include other social influencers of physical and mental health such as

housing and food insecurity and poverty. A large body of research indicates that the more ACE’s

a child goes through, the more likely they are to suffer negative or damaging health and

academic outcomes. Some ACE’s constitute traumatic events that can lead young people to

experience post-traumatic stress. According to research, before the age of four, approximately 26

percent of students experience trauma with almost 80 percent of the trauma occurring in the

home by their parents. Traumatic stress is multi-generational. Parents and caretakers who

experienced trauma as children and especially those whose trauma has gone unaddressed are at

risk of repeating a cycle within their own families. The forthcoming strategies and approaches

outlined within this guidance document are designed to ensure that students have the support

needed to graduate and live productive lives through the implementation of trauma-informed

approaches that impact all individuals, students, caregivers, and school staff.

Being trauma-informed is not enough, being trauma-responsive is the goal. Children are exposed

to different degrees of trauma and have their own unique set of circumstances that can protect

them against that trauma. The other half of the equation is resiliency. Resiliency is defined as the

ability to overcome and be successful despite exposure to risk. Some children need protective

factors strengthened to help buffer against risk. As such, there is a current shift to trauma-

responsive education in classrooms and schools across the country. Being trauma-responsive

requires the integration of trauma-informed principles into staff behaviors and practices that

improves their interactions with all students. Additionally, this includes mental health support

provided by school psychologists, school counselors, and other school employed staff, as well as

community partners who provide trauma specific supports and treatment.

Research shows that responding to trauma early increases the likelihood of success as behaviors

due to trauma histories intensify as students get older, including the use of alcohol, drugs, and

other risky behaviors. The trauma-responsive approach is inclusive of a strength-based approach

that promotes healing. Interventions focus not just on “what happened to you” as an individual,

but also “what is right with you” and capitalizes upon individuals’ strengths.

6

Interventions must focus on the systematic factors (e.g., racism, poverty) that contribute to

adversity and trauma, and on the collective impacts of adversity and trauma on communities.

Strengths-based and healing-centered approaches can leverage community assets, including the

cultural and social factors that strengthen individual and community identities and connections.

This is sometimes referred to as the “fix injustices, not kids” principle.

Individuals embracing a growth mindset setting high expectations focused on achievement,

despite existing and prior circumstances, will advance efforts toward equitable opportunities and

positive lifestyle outcomes. The shift in mindset from one of “learned helplessness to learned

optimism” pertains to ALL, not just those subjected to trauma. At the same time, approaches to

address trauma must consider system factors (and not just individual factors) that contribute to

the negative impacts of trauma. It is not enough to ask our children to adopt a “growth mindset”

or to establish greater social emotional competencies if they are not simultaneously supported by

system interventions that reduce or eliminate toxic and stressful environmental factors that lead

to adversity and trauma.

The MSDE recognizes that building and maintaining trauma-informed approaches in schools

requires systems to first build an awareness of trauma among stakeholders, then design, support

and engage stakeholders in the implementation of practices that are trauma-responsive. The

trauma-informed work must include the supporting of adults who serve these students ensuring

self-care to prevent and mitigate proximal trauma (i.e., secondary trauma) and compassion

fatigue.

A trauma-informed approach will interrupt the school to prison pipeline and disparate

disciplinary practices of marginalized students. Research has established that the use of a trauma-

informed approach in schools increases equitable student engagement and creates protective

factors which support graduation and future employment. This guide will provide common

language understanding of trauma to help schools successfully implement trauma-informed

approaches. The forthcoming information leverages the expertise and practices from local and

national experts to advance the essential components of implementing a trauma-informed

approach in schools.

7

Trauma-Informed Schools

Trauma-informed approaches cannot depend on the vision of a single individual but must be

institutionalized or embedded within the fabric of a system. Studies have shown that complex

trauma greatly affects behavior, academic performance, and dropout rates in schools. As such, it

is important to make trauma-informed practices the norm, not the exception. Democratizing

trauma-informed schools (making it available to all) will provide individuals with trauma a more

adequate level of support to educational opportunities that:

• Realize both the widespread impact of trauma and the role of schools in promoting

resiliency.

• Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in students, staff, and families.

• Respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and

practices.

• Resist re-traumatization of students and staff and fosters resiliency.

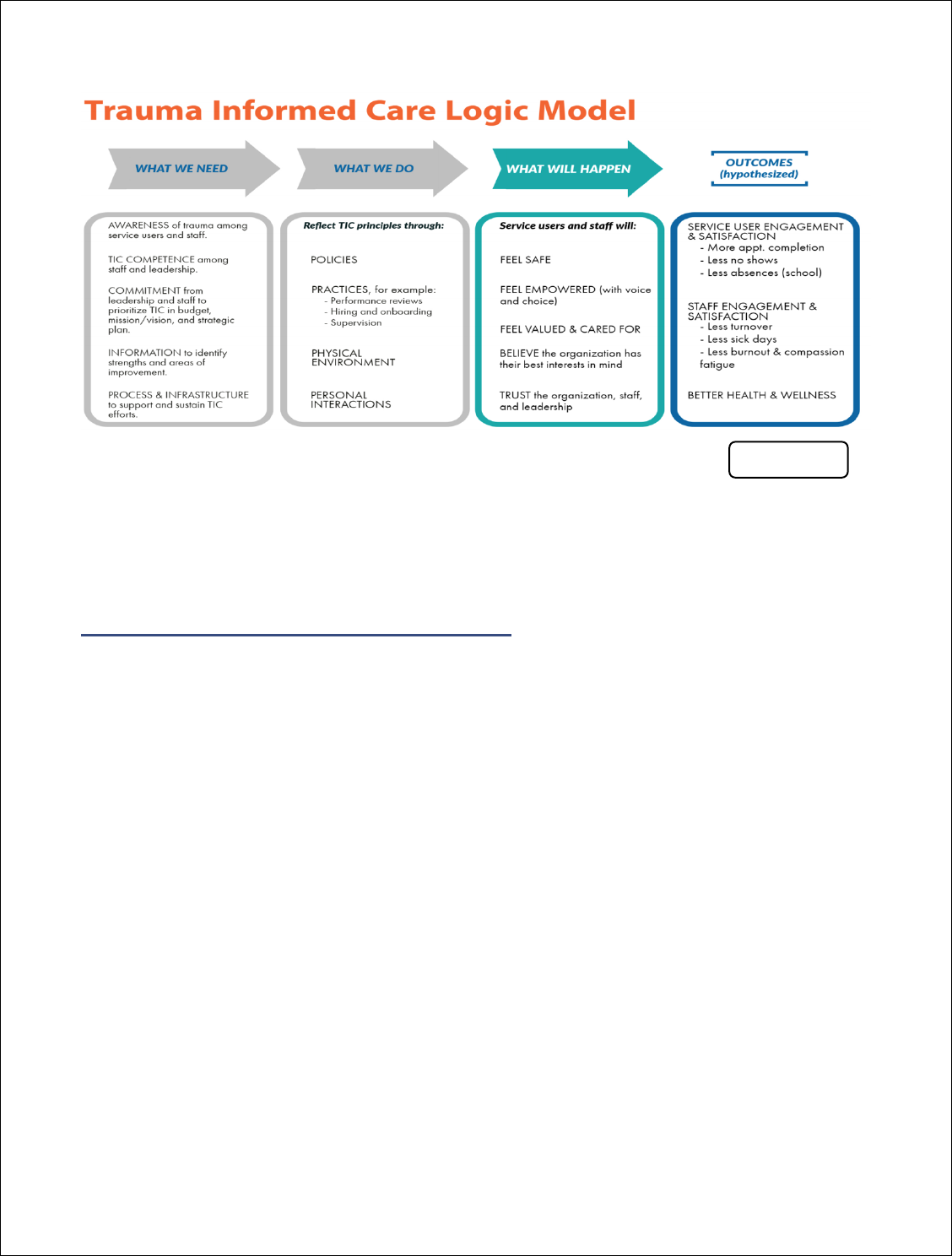

The Logic Model

A trauma-sensitive school can expect an increase in retention, decrease in suspension, expulsion,

dropout rates, arrests, and disparate disciplinary practices. As students develop a feeling of safety

in their school environment and school personnel build trust, students with trauma history will be

able to get their needs met in appropriate ways. This document is not meant to present an

exhaustive list, as the trauma-informed research continues to emerge, but to instead provide

some guidance on how schools can utilize trauma-informed approaches to change social,

emotional, and academic outcomes for students.

The Logic Model provides local school systems with a comprehensive framework for the

establishment of a healthy school ecosystem. There are five core components of trauma-

informed schools that must be included in every model: (1) training faculty and staff on the

impact of trauma, (2) adopting a school wide perspective shift, (3) creating healing relationships

among staff, caregivers, and students, (4) maximizing caregiver capacity, and (5) facilitating

student empowerment and resiliency https://traumainformedoregon.org/.

8

The core of this guidance document is outfitted into five key domains that align within the

framework of the Trauma-Informed Care Logic Model. The domains are as follows: (1) Creating

Safe Spaces and Staff Well-being, (2) Empowerment: Voice, and Choice, (3) Equity and

Resilience (4) Positive Relationships and (5) Parent and Community Engagement.

Creating Safe Spaces and Staff Well-Being

Advancements in neurology provide educators with important information related to optimal

conditions for learning. Safety is a basic human need, second only to food, water and shelter and

is a fundamental condition for the acquisition of knowledge. For LSSs, creating safe spaces is a

complex, multi-faceted issue that requires specific attention to several factors. Safety involves

not only the physical environment, but also emotional and psychological well-being, which are

critical aspects of feeling safe. Safety is particularly important for individuals experiencing

trauma because of violence, trauma, daily challenges in meeting basic needs, strained

relationships, and the high prevalence of behavioral health disorders. Safety is critical for

students and staff experiencing trauma. As such, creating a safe environment in which to learn

requires acknowledging the interaction of the person(s) and their environment. The focus should

be on developing nurturing environments that cultivate respect among individuals and minimize

conditions such as loud and crowded spaces, overly bright or dim lighting, bullying and other

harmful behaviors.

Creating Safe Spaces

A “safe space” is not just a physical location. It can also be something as simple as a group of

people who hold similar values and commit to consistently provide each other with a supportive,

respectful environment. Trauma most often changes the way children and young people view

their world, the people in it, and how and where they belong. They can develop distorted rules

about relationships – rules built from mistrust, terror and betrayal. Safe spaces can provide a

break from judgement, void of unsolicited opinions, and allow for freedom to detach from their

inauthentic selves. Safe spaces allow people to feel supported as their authentic self. This is

Figure 1

9

especially important for minorities, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and other

marginalized groups.

Conversations about safety must be grounded in trauma-informed approaches that foster values

of dignity, equity, and compassion that set the tone for behaviors, policies, structures, and

environments. The acronym S.P.A.C.E. can be used to represents five key dimensions that when

incorporated into approaches offer significant potential to establish effective opportunities for

schools to anticipate and respond to the needs of traumatized individuals.

• Staged- Sophisticated functions of the brain-body only emerge after basic functions have

been developed and consolidated with rehearsal and practice. For example, skills like

reading increase in complexity through repetition and rehearsal, building on basic blocks

of letters, syllables, words, sentences, and paragraphs. Strategies aimed at resourcing

traumatized children need to follow this staged pattern of conceptualization and

implementation for them to succeed.

• Predictable- The brain-body systems of traumatized young children maintain itself in a

state of arousal readiness in preparation for the re-occurrence of a threat. Unpredictable

routines and reactions from others amplify the stress response used by traumatized

children and young people. The opposite is also true. Strategies, which promote stability

and familiarity, reduce the need for the stress system to be engaged. This releases the

energy that children and young people use to lock down their experiences and avoid

change. Safe spaces allow traumatized children and young people to experience

themselves as more flexible and more able to tolerate small degrees of change in the

environment.

• Adaptive- The intensity and challenging behavior of traumatized children and young

people can lead to unitary explanations being applied to their motivations and drives.

The options for traumatized children and young people can be increasingly focused on

discipline and behavior management. Punitive systems restrain flexibility. As such,

strategies which promote adaptability in children and young people are those which are

able to maintain multiple meanings for behavior and remain open to multiple options for

intervention.

• Connected- Traumatized children and young people develop insecure and unstable

templates for forming, maintaining, and being in relationships. In a school context where

relationships are constantly negotiated and renegotiated, traumatized children experience

social exchanges as sources of stress which maintain the need for trauma-based

behavioral routines. Relationships become the primary vehicle through which new

meanings about feelings, beliefs, behaviors, and identity are resourced to emerge.

Connected children and young people are calmer and more able to access their internal

systems to learn.

• Enabled- Traumatized children and young people find the process of understanding

themselves difficult. They are challenged in their capacity to identify their feelings,

understand them, and communicate them to others. Effective strategies for responding to

traumatized children in the school context will enable them to make linkages between

and give meaning to their experiences in their past and present, the feelings and their

behavior, their thoughts and their actions.

10

Staff Well-Being

Relationships are dyadic-it takes two. Adults most often recognize the student’s contribution to

these interactions, but less often is time taken to consider the teachers contribution to the dyad.

Frequently, educators do not have the knowledge, skill, or capacity to care for themselves and

the student with ACEs. This most often leads to undesirable interactions that exacerbate negative

outcomes. As such, it is important to offer trainings to all school staff, including cafeteria, and

janitorial staff on trauma and its impact on health and behavior. Because school support

personnel, including front desk reception area workers, security officers, and drivers often

interact with students, they play an important role in making students feel safe and welcome and

should be included in the awareness building events or trainings. In addition, trauma-informed

trainings can better help staff understand student behavior and thereby improve student staff

interactions.

Teacher temperament and emotionality daily and over time is a major contributor to the

classroom and school climate. The ever-expanding burden upon educators further complicates

the dynamic. Most educators are truly phenomenal, self-sacrificing individuals who greatly

extend themselves to meet the needs of their students and families. However, it is important to

note that school personnel are not exempt from traumatic stress and adverse childhood

experiences. Most all adults enter the workplace every day with personal baggage, existing or

historical which colors their perceptions and impacts interactions with others. For this reason, it

is important that educators be provided with, and encouraged to use tools that allow them to

engage in ongoing self-reflection and self-care to successfully meet the demands of their job and

to better equip themselves for the job.

All personnel have the power to direct major climate control in the school by committing to

being a thermostat. It is important to recognize that placing full onus on individual staff members

to support their well-being considering known effects of secondary trauma is not sufficient.

SAMSHA (2014) recommends that educational school leaders take action to promote

organizational, cultural, policies and practices to support staff. These include:

• Redesigning school and/or district wide policies around training and scheduling;

• Focus on prevention by being proactive in supporting stress management;

• Shifting to a reflective supervision model that relies upon a supportive teacher;

supervisor relationship moving away from adversarial models of supervision;

• Building and reinforcing school and/or district wide natural support systems for

local school system employees; and

• Evaluating school and/or district wide efforts in the aforementioned areas.

It is of equal importance for schools to be a safe space for staff to learn and grow both personally

and professionally. Expanding trauma-informed approaches developed and implemented for

students to include similar opportunities for staff is advantageous. An example of this type of

extension would be providing a mindfulness space and procedures for staff to use when the need

arises. This strategy has proven helpful in increasing staff morale and decreasing the use of

punitive student discipline measures.

11

Empowerment: Voice and Choice

A large part of establishing a trauma-informed culture within LSSs include creating engagement

opportunities for traumatized students to share their thoughts and experiences with policy

makers, administrators, teachers, and other school personnel. This approach can be effective in

uncovering the lived experiences of those who have encountered trauma through their sharing of

thoughts and experiences. Student empowerment is when students gain the authority and agency

to make decisions about their school experience and implement change through their ideas. The

incorporation of student voice and choice early in the planning and awareness-building process is

critical to soliciting ongoing student member feedback.

Empowerment entails acknowledging and using students’ strengths early in the treatment process

rather than overemphasizing diagnoses, weaknesses, or victim status. The empowerment process

can impact students in several ways, including promoting individual and social development,

demonstrating the importance of student rights, promoting youth connection, increasing

confidence, and enhancing decision-making skills. Interventions designed to improve school

climate and instructional methods should be guided by empowering youth strategies, culturally

relevant pedagogy, varied teaching methods, theory driven choices, and positive relationships

with well-trained professionals to ensure students are ready to learn. Using an empowerment

perspective to address problems within the school means:

• Creating opportunities for collaboration with students.

• Encouraging students to identify what problems exists.

• Including youth voice in creating solutions and taking action.

Equity and Resilience

To address trauma in all of its forms and manifestations it is necessary to look at high level

systemic reform, this approach is akin to a public health-oriented model that says, “if you shape

the environment so that ALL kids regardless of level of risk are treated in a way conducive to

mental health, healing, resilience, and well-being, you can do a better job at addressing trauma

for all students.” – Dr. Todd Herren Kohl. The MSDE is committed to this systemic change

through distribution of this guidance document and technical assistance efforts, while also

promoting equity, resilience, and the well-being of school personnel.

Equity

Trauma is an issue of equity; it impedes educational attainment on its own, and

disproportionately targets students of color, students with disabilities, those living in poverty,

LGBTQ+ students, and others who experience marginalization. Specific to race, policies aimed

at providing “color-blind” equitable outcomes for all students fail to enact compensatory

remedies for a long history of racial inequality and injustice. The vision of color blindness as a

means of eliminating racial discrimination is founded on a seemingly paradoxical notion that it is

noble to ignore race while simultaneously honoring diversity. Being trauma-responsive requires

integration of trauma-informed principles into staff behaviors, policies and practices, and

partnership with professionals who provide traumatic specific treatment.

12

As such, implementing transformation is difficult, especially if faced with significant resistance.

It is not however more difficult than navigating oppressive barriers, which many students,

families, and educators of marginalized groups endure. In consideration of this, it is important

for LSSs to consider the following “Basic Principles of Equity Literacy” that can help avoid

equity detours and maximize the impact of our equity efforts:

• Direct Confrontation Principle – The path of equity requires direct confrontations with

inequity- with interpersonal, institutional, cultural, and structural racism, and other forms

of oppression. “Equity” approaches that fail to directly identify and confront inequity

play a significant role in sustaining inequity.

• Equity Ideology Principle- Equity is more than a list of practical strategies. It is a lens

and an ideological commitment. There are no practical strategies that will help develop

equitable institutions if individuals are unwilling to deepen their understanding of equity

and inequity and reject ideologies that are not compatible with equity.

• Prioritization Principle – In order to achieve equity, the interest of students and families

whose interests historically have not been prioritized, must now be prioritized. Every

policy, practice, and program decision should be considered through the questions, “What

impact is this going to have on the most marginalized students and families?” “How are

we prioritizing their interests?”

• Redistribution Principle – Equity requires the redistribution of material, cultural, social

access, and opportunity. This is done by changing inequitable policies, eliminating

oppressive aspects of institutional culture, and examining how practices and programs

might advantage some students over others. If systems and individuals cannot explain

how equity initiatives redistribute access and opportunity, they should be reconsidered.

• Fix Injustice, Not Kids Principle – Educational outcome disparities are not the result of

deficiencies in marginalized communities’ cultures, mindsets, or grittiness, but rather of

inequities. Equity initiatives focus, not on “fixing” students and families who are

marginalized, but on transforming the conditions that marginalize students and families.

• One Size, Fits Few Principle – No individual identity group shares a single mindset,

value system, learning style, or communication style. Identity-specific equity frameworks

(like group level “learning styles”) almost always are based on simplicity and

stereotypes, not equity.

• Evidence-Informed Equity Principle – Equity approaches should be based on evidence

for what works rather than trendiness. “Evidence” can mean quantitative research, but it

can also mean the stories and experiences of people who are marginalized in your

institution.

Resilience

Schools have the capacity to promote resilience in children and young people. Resilience is the

ability to cope and thrive in the face of negative events, challenges, or adversity. Key attributes

of resilience in children and young people include social competence, a sense of agency or

responsibility, optimism, a sense of purpose or hope for the future, attachment to family, to

school and to learning, problem solving skills, effective coping style, pro-social values, a sense

of self-efficacy, and positive self-regard. Schools can enhance resilience through programs like

restorative practices, which build positive social norms and generate a sense of connectedness to

teachers, peers, and the academic goals of the school.

13

Trauma and adversity disrupt the development of healthy attachment bonds that children need to

fulfill their full potential. As such, there are three important factors associated with building

resilience among all children and teens: (1) A strong parent-child relationship, or a strong

relationship with a surrogate caregiver who serves as a mentor if a parent is unavailable, (2)

Good cognitive skills which are predictors of academic success and lead to pro-social behavior;

and (3) The ability to self-regulate emotions, attention, and disruptive behaviors.

Positive Relationships

Research has substantially proven the significant impact of even one positive relationship in a

child’s life. Positive relationships and support are directly related to establishing resiliency,

quicker recovery rates, and lower incidents of relapse. Participating in a reparative experience

can often reduce the negative symptoms of trauma as well as reduce the likelihood of a trauma to

occur again. It is crucial for students to have not only positive relationships with their peers, but

also with adults. Children and young people who have had traumatic experiences inflicted upon

them have a difficult time trusting adults.

In educational settings, where power and control are present, it becomes increasingly difficult

but imperative to establish positive relationships. When adults are transparent, consistent, and

trustworthy, these relationships show the student that the staff member is safe, someone they can

confide in, and someone to rely on. This is accomplished by way of Unconditional Positive

Regard, which requires administrators, teachers, and staff to value a student regardless of his or

her behaviors, affect, or presentation. Unconditional Positive Regard facilitates an environment

of where the individual feels valued regardless of their presenting behaviors, affect, or

cognitions; rather than looking to others for identity and approval, the individual is encouraged

to learn and listen to themselves. Some examples are as follows:

• Personal greetings- Provide each student with a personal greeting using their name and

positive statement each day. Research supports that personal greetings can increase

cooperative behavior in students.

• Praise in public, correct in private- Trauma responses are often exacerbated when a

student feels threatened. Students who are corrected in front of an audience of their peers

may react negatively. Trust is maintained and corrective feedback is more effective when

delivered privately.

• Get to know your students outside the classroom- Try to get to know students, their

families, and their lives outside of school. Getting to know students during times of

baseline as well as when experiencing joy, fear, and anger can help staff identify when

they are in crisis.

The human condition makes it likely relationships will be harmed through simple day to day

interactions, with students experiencing trauma this harm may be more frequent and more

intense. It is advantageous if schools have created as part of a whole school structure, methods

to repair harm to relationships. When the expectation across school environments, and ideally

across community environments, is that all individuals engage in the reparation process than

those with a history of discarding damaged relationships are more likely to comply with the

14

expectation. Those facilitating the reparation process with individuals experiencing trauma must

be mindful of scheduling the event at a time when emotions have diminished as much as

possible; preparing all members in advance of a meeting; reviewing and reinforcing procedures

of conduct before, during, and after the process; and ensuring the process remains safe and

productive for all members. The process of damage and repair to a valued relationship is a

valuable therapeutic experience for individuals experiencing trauma.

Family and Community Engagement

Countless students and educational staff encounter traumatic experiences each day either directly

or vicariously through interactions with others. The prevalence of trauma has increasingly

become recognized as a significant public health concern adversely impacting the communities

we serve. Direct and indirect traumatic experiences or events can have immediate and long-term

adverse effects on an individual’s social, emotional, and physical well-being. As trauma-

informed practices evolve within schools, school mental health providers, and school personnel

recognize the importance of establishing proactive vs. reactive approaches to assist students and

staff affected by trauma. Healthy relationships are the foundation for effectively responding to

students and staff experiencing trauma and can be achieved when individuals immerse

themselves in cultivating robust partnerships inclusive of families and communities.

The goal of a trauma-informed school system is to: (1) recognize and respond to trauma as it

affects students, staff, and families; (2) to act in partnership with individuals impacted; (3) to

make resources available; (4) to address student and staff trauma, and to strengthen resilience

through family and community engagement. Family and community engagement is the means

through which essential relationships can be built, and through which policies, best practices, and

organizational culture can be shifted to create a trauma-informed system.

Figure 2

15

Collaboration enables students, staff, and families to work together to respond to trauma as it

impacts the student and staff members. This can include practical matters as the individual

sharing information about trauma(s) that have affected them or their family, as well as providing

background on their strengths and deficits. Effective engagement assists individuals and families

in understanding the impact of trauma, especially on student behavior. This approach

acknowledges that healing occurs in collaborative, trusting relationships, and the significance of

sharing power to make decisions. Families intertwined with accessible and nurturing

communities are vital supports that can stimulate a sense of identity and belonging for students

and staff. In an effort to overcome trauma and actively build resilience and protective factors to

resist re-traumatization, families and school staff need to be transparent about their source(s) of

trauma and receptive to the available support offered by schools and community organizations

seeking to implement trauma-based services in their respective settings.

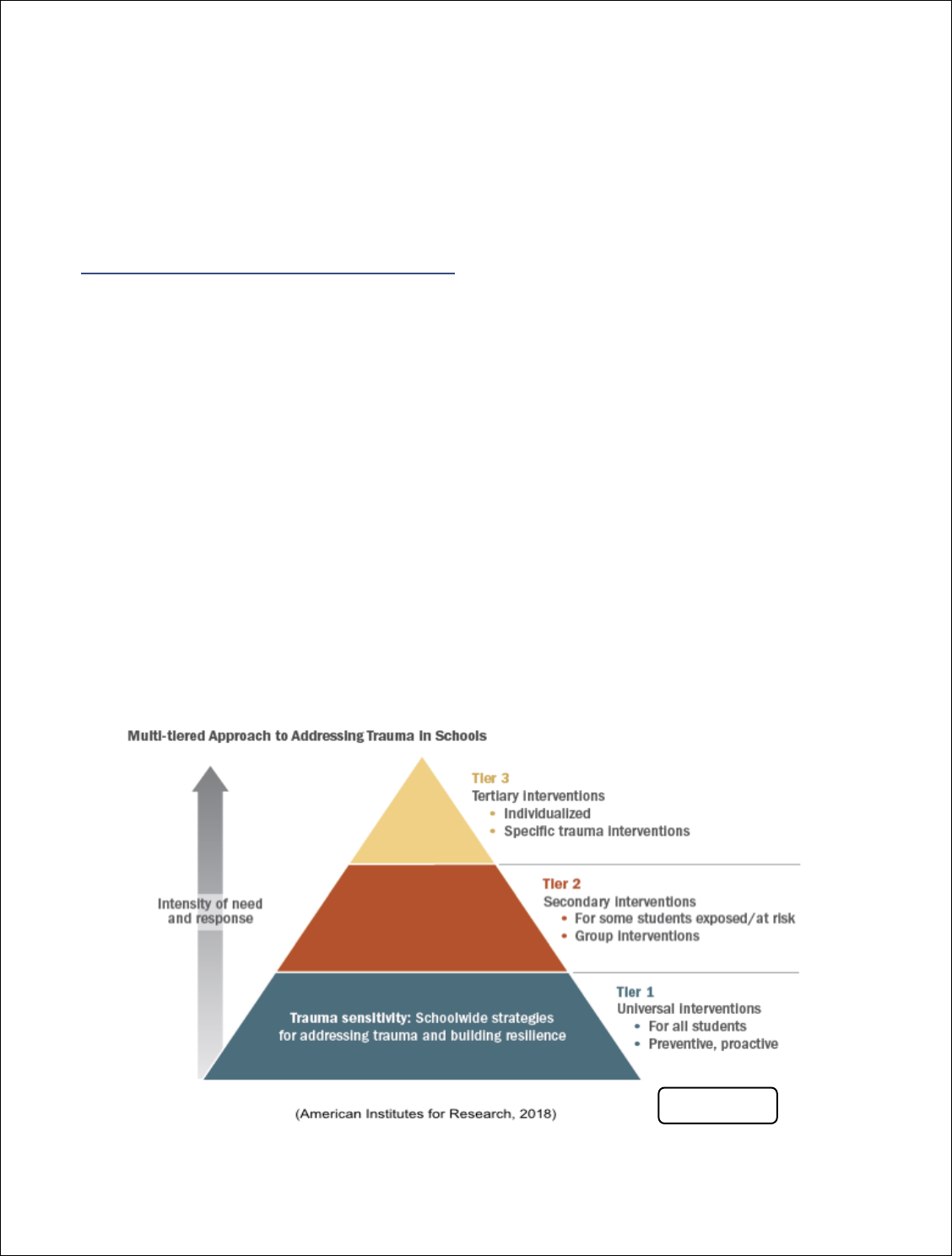

The nucleus of a trauma-informed approach is about connections and connectedness; thus, it

cannot be effectively delivered in seclusion but rather through the framework of a multi-tiered

system of supports (MTSS) (Figure 2) which focuses on the overall needs of individual students

in alignment with existing school practices. Interventions and supports found in MTSS assist in

relationship building and promoting a positive school climate which are significant factors in

fostering student achievement and affording students the opportunity to navigate through their

challenges. Defined tiers of intervention for academic and behavioral challenges, which may

differ from system to system, enable systems to address student needs individually or as a group.

In order to equalize power inequities, schools need to level the playing field by equipping staff

with trauma education, training and resources.

16

Trauma-informed strategies like Handle with Care in schools include educating all school staff

about trauma and its effects; supporting physical and emotional safety in relationships and in

the environment; taking a proactive stance to reducing trauma-related triggers within the

school environment and excluding potential re-traumatizing practices; making trauma-specific

clinical services accessible to students with more intensive needs and addressing the secondary

effects of trauma.

Activities surrounding parent and community engagement within trauma-informed schools

should occur universally within a multi-tiered system of support and increase in scale and

intensity to meet the needs of students and staff who have experienced varying levels of

trauma. Initiatives could lead to modifications or enhancements to school policies, best practices,

professional development, and support to connect students, families and staff to needed school-

based and community trauma-informed services building and fostering resilience.

Handle with Care provides the school or childcare agency with a “heads

up” when a child has been identified at the scene of a traumatic event.

It could be a meth lab explosion, a domestic violence situation, a

shooting in the neighborhood, witnessing a malicious wounding, a drug

raid at the home, etc. Police are trained to identify children at the

scene, find out where they go to school and send the school or agency a

confidential email or fax that simply says: “Handle Johnny with care.”

That’s it. No other details

17

CONCLUSION

Being “trauma-informed” is just as much about a “way of being” than “a way of doing”. A

trauma-informed care model is encouraged as a standard of care across not only health

professions but school settings, regardless of whether a given individual has reported or

experienced trauma and without requiring school staff to know whether a specific individual has

a trauma history. Effective implementation of trauma-informed approaches within systems,

schools and communities requires the participation of all adults and should be approached in a

way that provides information to all and defines clear expectations of conduct by all. Students of

all ages interact with multiple adults over the course of their day. Inconsistent implementation of

approaches by adults is counterproductive to the intended effort of a trauma-informed teaching

and learning environment.

Students must be given opportunities to nurture multiple strengths and assets. However, many of

the current trauma-informed approaches have failed to explicitly focus attention on identifying

and increasing student strengths. As such, existing trauma-informed approaches are not reaching

the full potential of healing that is possible within the school context because they focus only on

repairing negatives and have not given sufficient emphasis on growth building upon the strengths

of trauma-affected students. Cultural context and conceptualization of self, whether

individualistic or collectivist, shape how a person experiences, perceives, makes meaning of, and

eventually heals from trauma. Rather than operating from the assumption that individuals need

special treatment because they come from a given culture or social context, school staff should

consider that students’ culture may serve as a source of strength and a resource for healing.

Achieving a trauma-informed teaching and learning environment occurs over time through a

variety of intentional practices. The use of professional development events to provide

information and teach approaches is only the beginning and should not be considered an

adequate strategy to ensure adult use of trauma-informed approaches. Schools who successfully

make the shift to being trauma-informed invest time into continuous dialogue amongst all staff

through book studies, individual student planning meetings, and honest, courageous reflection

upon past and current events. It is the intent of this guidance document to provide systems and

schools information to inform their journey toward becoming trauma-informed environments

where all students succeed. MSDE seeks to collaborate with all stakeholders in making the

content of this document a reality in Maryland schools.

18

GLOSSARY

Acute trauma- Results from a single stressful or dangerous situation or event.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE’s)- Adverse Childhood Experiences include emotional,

physical, or sexual abuse; emotional or physical neglect; domestic violence; parental substance

use; parental mental illness; parental separation or divorce; death of a parent; incarcerated

household member; poverty or community violence These experiences are linked to long term

health outcomes in a series of studies (Felitti et al, 1998).

Child Traumatic Stress- Child traumatic stress (CTS) refers to the intense fear and stress

response occurring when children are exposed to traumatic events, which overwhelm their ability

to cope with what they have experienced. Children who experience CTS may also be diagnosed

with PTSD, depression, anxiety, or behavioral disorders.

Chronic trauma- Results from repeated and prolonged exposure to highly stressful situations or

events. Examples of chronic trauma include bullying, child abuse, and domestic violence.

Complex trauma- Results from exposure to multiple traumatic events.

Culture- An integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications,

languages, practices, beliefs, value, customs, rituals, manners of interesting, roles, relationships

and expected behaviors of a racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups; the ability to transmit the

above to succeeding generations.

Cultural Awareness- Being cognizant, observant, and conscious of similarities and differences

among cultural groups.

Cultural Competence-The ability to interact effectively with people of different cultures, helps

to ensure the needs of all community members are addressed.

Equity- Giving individuals what they specifically need to achieve health, success and positive

well-being.

Resilience- Is the ability and process of being able to adapt well in the face of adversity.

Re-traumatization- Is a conscious or unconscious reminder of past trauma that results in re-

experiencing of the initial trauma or traumatic event.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) - Is a mental health condition that is triggered by a

terrifying event, either experiencing it or by witnessing it.

Stress- Stress is a feeling of emotional or physical tension. It can evolve from any event or

thought that makes a person feel angry, anxious, frustrated, or nervous.

19

The Logic Model- Logic models and theories of change can help trauma-informed initiatives

conceptualize and operationalize the work to help build the capacity for trauma-informed

approaches to occur.

Trauma- Trauma is an emotional response to a terrible event that can have long-term effects on

a person’s well-being.

Trauma-informed care- Recognizes the presence of trauma symptoms and acknowledges the

role trauma plays in an individual’s life.

Trauma-sensitive school- Is a school in which all students feel safe, welcomed, and supported.

A school where addressing trauma’s impact on learning occurs schoolwide.

20

REFERENCES

Cahill, H., Beadle, S., Forster, R., Smith, K., & Farrelly, A. (1970, January 01). Building

resilience in children and young people: A literature review for the Department of education and

early childhood Development (deecd). Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/scholarlywork/970213-building-resilience-in-children-and

young-people--a-literature-review-for-the-department-of-education-and-early-childhood

development-(deecd).

CDC. (2019). Adverse Childhood Experiences. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/index.html.

Developing and - center for early childhood mental health ... (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2021,

from https://www.ecmhc.org/documents/CECMHC_AdministratorsToolkit.pdf

From trauma-aware to trauma-informed. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://traumainformedde.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Trauma-BluePrint.pdf

Gorski, P. (n.d.). Avoiding racial equity detours. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://www.academia.edu/38727480/Avoiding_Racial_Equity_Detours

Gorski, P. (n.d.). Educational equity: Equity literacy framework. Retrieved November 19, 2020,

from https://www.equityliteracy.org/equity-literacy

Hollingworth, L. (n.d.). Complicated conversations: Exploring race and ideology in an

elementary classroom - Liz Hollingworth, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0042085907312496

J; M. (n.d.). What is equitable resilience? Retrieved January 28, 2021, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30177865/

Journal of Juvenile Justice, 5(1), spring. (2016). www.journalofjuvjustice.org

Kerri Ullucci, D. (n.d.). Exposing color Blindness/Grounding Color Consciousness: Challenges

for teacher education - kerri ULLUCCI, Dan Battey, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042085911413150

Pbis. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2021, from https://www.resa.net/teaching-learning/pbis

Pisapia, J. (1994, October 31). Developing resilient schools and Resilient Students. research brief

#19. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED411343

Plumb, J. L., Kersevich, S. E., & Bush, K. A. (2016, Spring). Trauma-sensitive schools: An

evidence-based approach. Retrieved November 25, 2020, from

http://www.communityschools.org/assets/1/AssetManager/TSS.pdf

21

SAMHSA's concept of trauma and guidance for a Trauma ... (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2021,

from https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Trauma-informed practices for postsecondary education: A guide. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28,

2021, from https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/resources/trauma-informed

practices-postsecondary-508.pdf.

Temkin, D., Harper, K., Stratford, B., Sacks, V., Rodriguez, Y., & Bartlett, J. (2020, November

12). Moving policy toward a whole school, whole community, whole child approach to support

children who have experienced trauma. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/josh.12957.

Trauma informed practice in schools - act group. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2021, from

https://theactgroup.com.au/documents/makingspaceforlearning-traumainschools.pdf.

Using logic models grounded in theory of change to support ... (n.d.). Retrieved February 28,

2021, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262051/trauma-informed-logic-models.pdf.

10 steps to create a Trauma-Informed School. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2021, from

https://starr.org/wp-content/uploads/10-Steps-to-Create-a-Trauma-Informed-School

Whitepaper.pdf.

22

RESOURCES

The follow list is not intended to be inclusive of all resources on the topic of trauma, rather it is merely a sample of

the plethora of media, literature, and research tools available.

What is Trauma This video will give a basic understanding of Trauma Informed Care

Informed Care? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWken5DsJcw

3:33

What is Trauma? This video will give you an understanding of the different types of trauma.

4:01 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6BdW6tAb-5M

(ACE’s) Take the Survey

Adverse

Childhood

Experiences

Empathy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDDWvj_q-o8

Cleveland Clinic

Trauma-Sensitive School Checklist

The National Child. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Traumatic Stress

Network (NCTS)

Ted Talk (Video) What Trauma Taught Me About Resilience