COMPACTS OF

FREE ASSOCIATION

Populations in U.S.

Areas Have Grown,

with Varying Reported

Effects

Report to the Chairman of the

Committee on Energy and Natural

Resources, U.S. Senate

June 2020

GAO-20-491

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-20-491, a report to the

Chairman of the Committee on Energy and

Natural Resources, U.S. Senate

June 2020

COMPACTS OF FREE ASSOCIATION

Populations in U.S. Areas Have Grown,

with Varying

Reported

Effects

What GAO Found

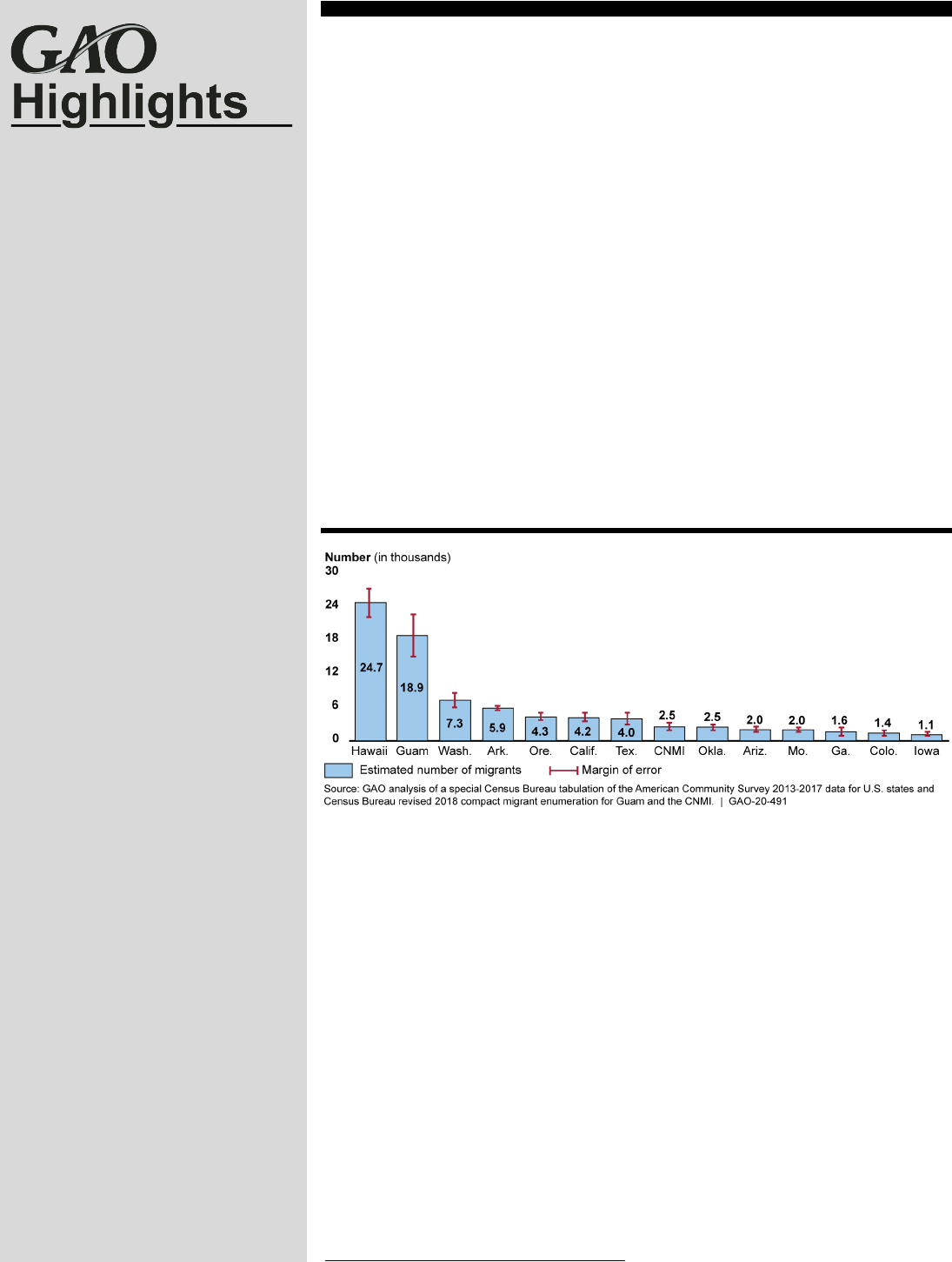

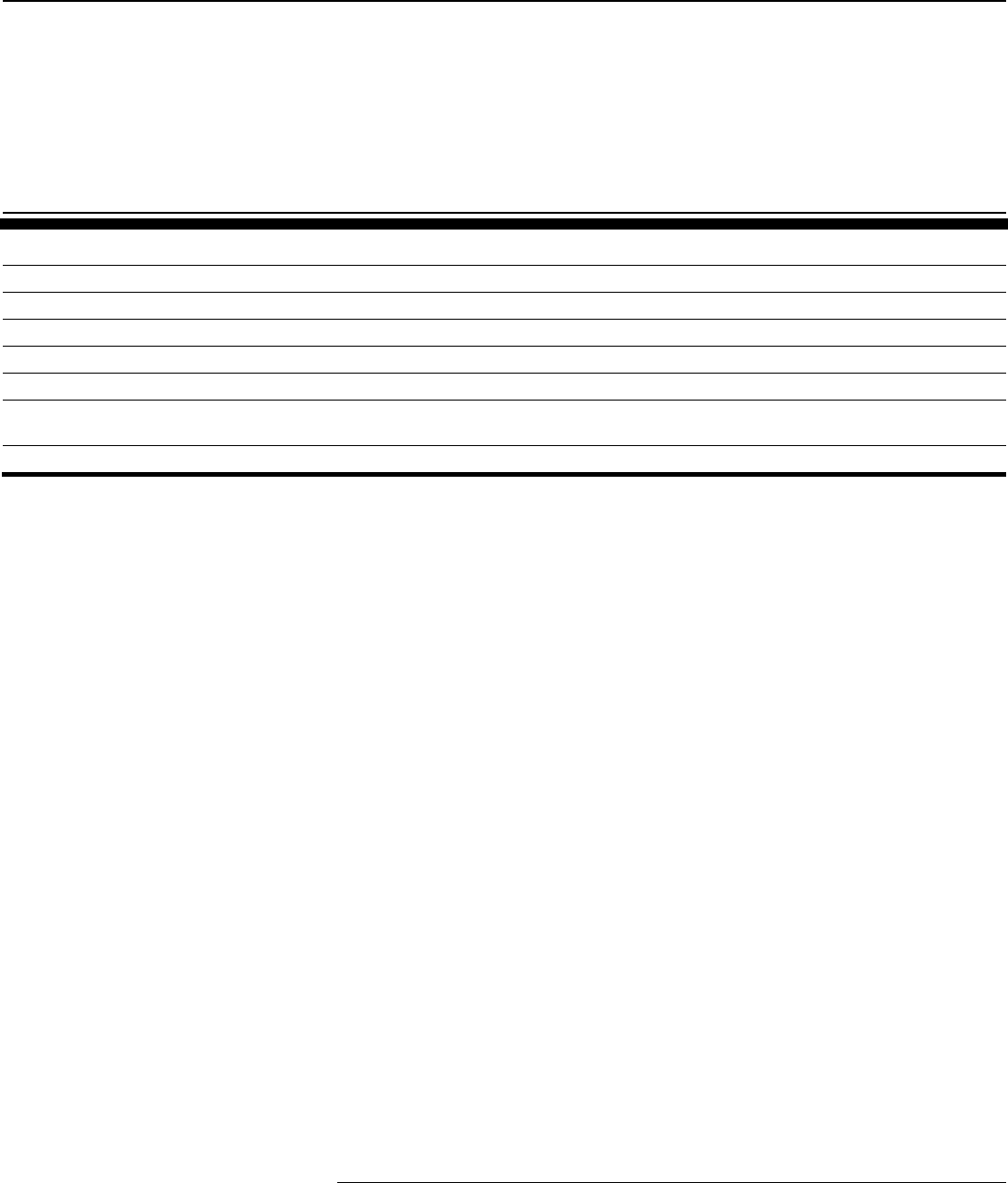

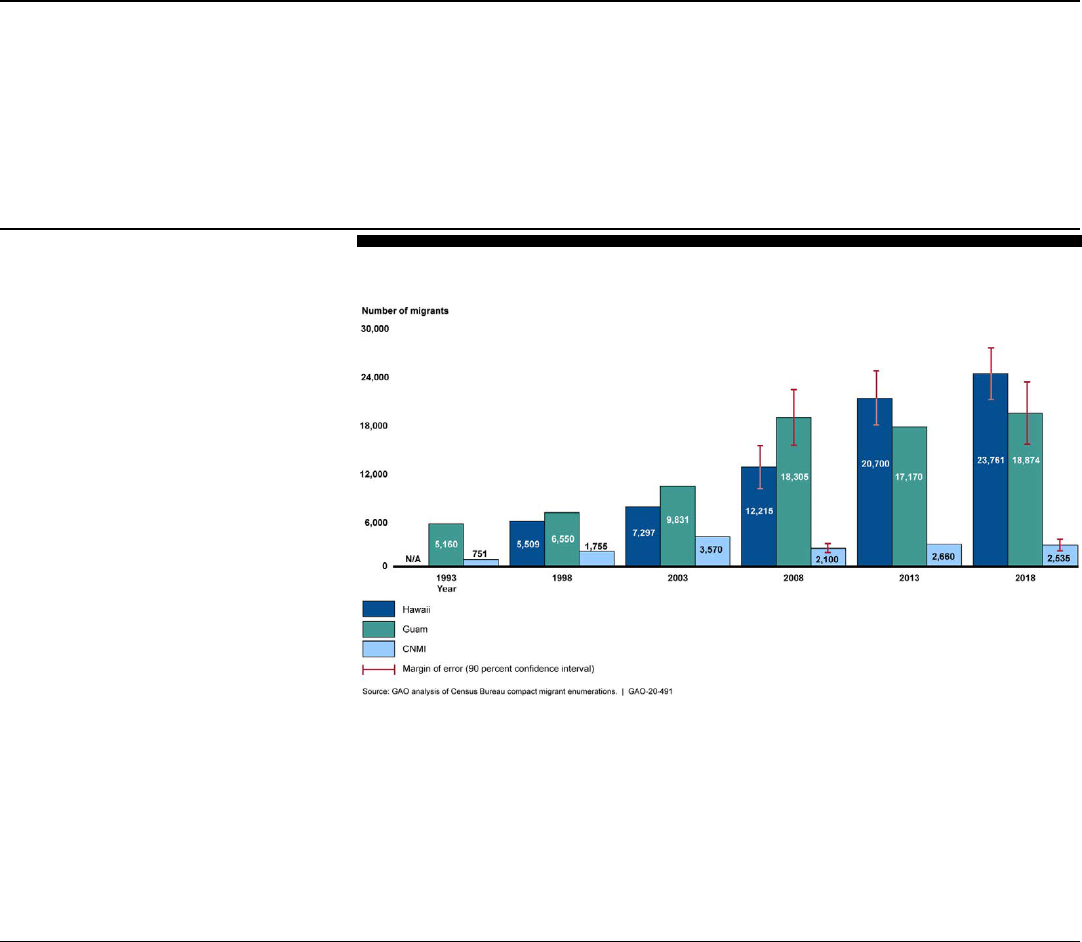

More than 94,000 compact migrants—that is, citizens of the Federated States of

Micronesia (Micronesia), the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Marshall Islands),

and the Republic of Palau (Palau) as well as their U.S.-born children and

grandchildren younger than 18 years—live and work in the United States and its

territories, according to Census Bureau data. Data from Census Bureau surveys

covering the periods 2005-2009 and 2013-2017 and an enumeration in 2018

show that the combined compact migrant populations in U.S. areas grew by an

estimated 68 percent, from about 56,000 to about 94,000. Historically, many

compact migrants have lived in Hawaii, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the

Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). From 2013 to 2018, an estimated 50 percent

of compact migrants lived on the U.S. mainland.

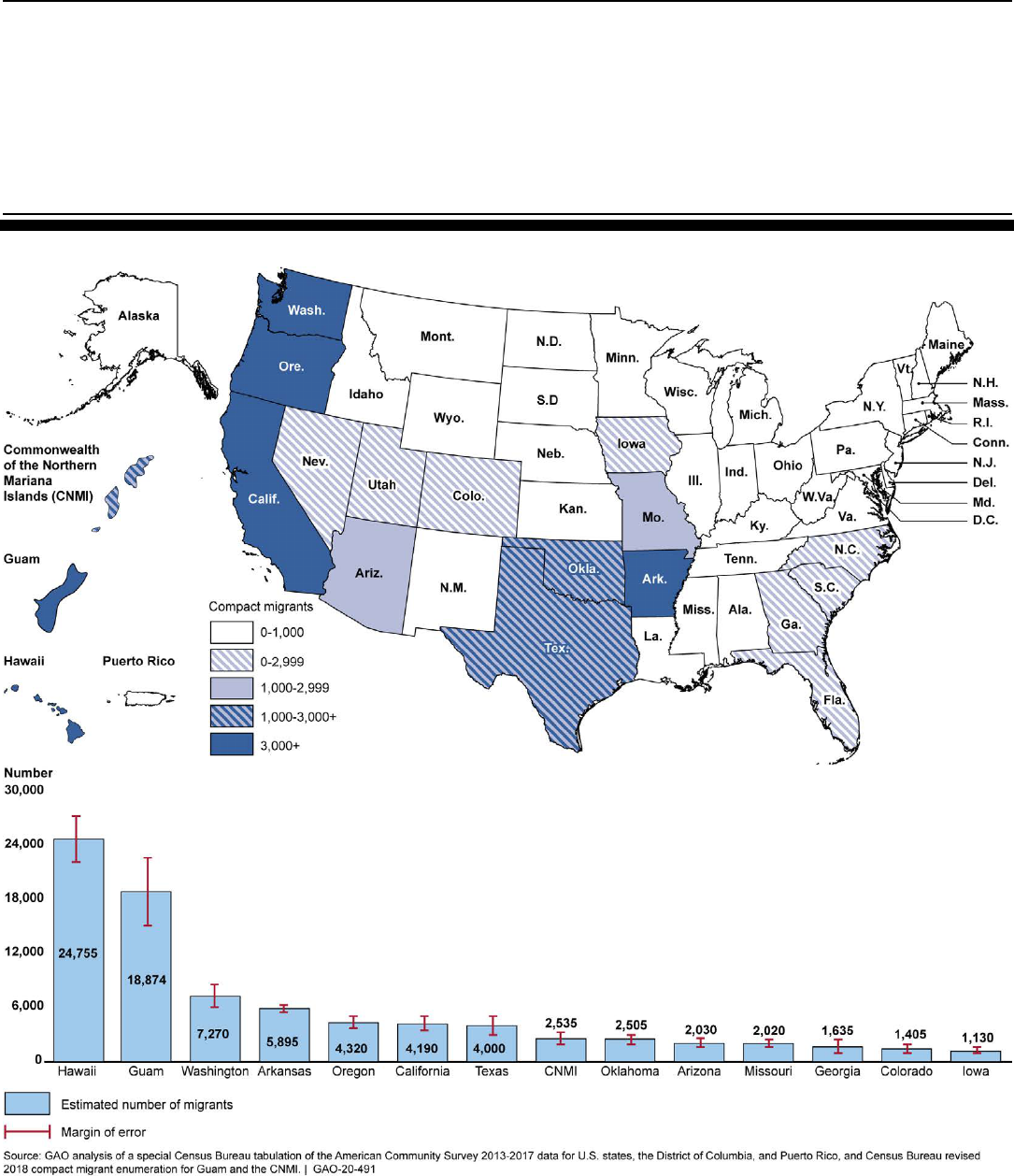

Estimated Compact Migrant Populations in Selected U.S. Areas, 2013-2018

Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI track and report the financial costs related to

compact migration, or compact impact, for their state or territory. These areas

reported estimated costs totaling $3.2 billion during the period fiscal years 2004

through 2018. In fiscal years 2004 through 2019, Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI

received a combined total of approximately $509 million in federal grants to help

defray the costs of providing services to compact migrants.

In the U.S. areas GAO visited—Arkansas, the CNMI, Guam, Hawaii, Oregon,

and Washington—state and territorial officials identified effects of providing public

education and health care services to compact migrants. Some area

governments use a combination of federal and state or territorial funds to extend

health care coverage to compact migrants. For example, some states help

compact migrants pay for coverage through health insurance exchanges, created

under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, by covering the cost

of premiums not covered by advanced premium tax credits available to eligible

compact migrants. Effects of compact migration in these U.S. areas also include

compact migrants’ budgetary contributions through payment of taxes and fees as

well as their workforce contributions—for example, through jobs in hotels,

manufacturing, the U.S. military, poultry processing, caregiving, and government.

View GAO-20-491. For more information,

contact

David Gootnick at (202) 512-3149

or

Why GAO Did This Study

The

U.S. compacts of free association

permit

eligible citizens from the freely

associated states

(FAS), including

Micronesia

, the Marshall Islands, and

Palau,

to migrate to the United States

and its territories

without visa and

labor certification requirements.

In

fiscal year 2004, Congress

authorized

and

appropriated $30 million annually

for 20 years to help defray

costs

associated with compact migration in

affected jurisdictions

, particularly

H

awaii, Guam, and the CNMI. This

funding ends in 2023, though

migration to U.S. areas is permitted

to

continue

and is expected to grow.

GAO was asked to

review topics

related to

compact migration. This

report describes (1)

estimated

compact migrant

populations and

recent trends in compact migration

;

(2)

reported costs related to compact

migration

in Hawaii, Guam, and the

CNMI

; and (3) effects of compact

migration on governments,

workforces, and societies

in these and

other

U.S. areas. GAO reviewed

C

ensus Bureau data to determine the

number

s of compact migrants in U.S.

areas.

In addition, GAO interviewed

federal, state, and territory

government officials

; representatives

of private sector and nonprofit groups

employing or serving compact

migrants

; FAS embassy and consular

officials; and members of compact

migrant communities

.

In commenting on a draft of th

is

report, U.S. area governments and

FAS Ambassadors to the United

States identified areas for additional

study related to compact migration

and impact. Some also discussed

policy considerations, including

restor

ation of Medicaid benefits to

compact migrants.

Page i GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Letter 1

Background 3

Compact Migrant Population Has Grown, with About Half Residing

on U.S. Mainland 13

Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI Have Reported Compact Impact

Costs and Received Annual Grants to Defray Them 21

Compact Migration Affects Government Programs, Workforces,

and Societies 30

Agency Comments, Third-Party Views, and Our Evaluation 47

Comments from U.S. Areas 47

Comments from Freely Associated States 50

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 53

Appendix II Estimates of Compact Migrants in U.S. Areas 58

Appendix III Federal Travel Data Showing Compact Migration to U.S. Areas 65

Appendix IV Demographics and Characteristics of Compact Migrants in the 50

U.S. States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico 67

Appendix V Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii, Guam, and the

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands 74

Appendix VI Compact Migrant Enumeration Methods, Definitions, and Error 76

Appendix VII Stakeholder Suggestions to Address Challenges Related to Compact

Migration 82

Contents

Page ii GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Appendix VIII Nonprofit and Private Sector Organizations Supporting Compact

Migrants 89

Appendix IX Review of Academic Studies of the Workforce Effects of Migration

Similar to Compact Migration 94

Appendix X Compact Migrant Eligibility for, and Access to, REAL ID–Compliant

Identification 98

Appendix XI Comments from the Government of Hawaii 101

Appendix XII Comments from the Government of Guam 102

Appendix XIII Comments from the Government of the Commonwealth of the

Northern Mariana Islands 105

Appendix XIV Comments from the Government of Arkansas 107

Appendix XV Comments from the Government of Oregon 111

Appendix XVI Comments from the Government of Washington 117

Appendix XVII Comments from the Government of the Federated States of

Micronesia 122

Page iii GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Appendix XVIII Comments from the Government of the Republic of the Marshall

Islands 136

Appendix XIX Comments from the Government of the Republic of Palau 140

Appendix XX GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgements 144

Tables

Table 1: Compact Migrant Eligibility for Selected U.S. Federal

Programs as of November 2019 12

Table 2: Estimated Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii,

Guam, and the CNMI, by Sector, Fiscal Year 2017 23

Table 3: Compact Impact Grant Funding to Hawaii, Guam, and the

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI),

Fiscal Years 2004-2019 25

Table 4: Total Underpayment and Overpayment of Compact

Impact Grant Funding to Affected Jurisdictions Resulting

from Enumeration Error, Fiscal Years 2015-2020 28

Table 5: Original and Corrected Allocations of Compact Impact

Grant Funding and Proposed Grant Amounts for Affected

Jurisdictions for Fiscal Years 2021-2023 30

Table 6: Estimated Number of Compact Migrant Students in State

and Territorial Public Schools in Selected U.S. Areas 31

Table 7: Examples of Industries Employing Compact Migrants in

Selected U.S. Areas 41

Table 8: U.S. Areas and FAS Communities Where We Interviewed

Compact Migrants 56

Table 9: Estimated Compact Migrant Populations in Selected U.S.

Areas and Percentage Changes in Populations from

2005-2009 to 2013-2018 58

Table 10: Estimated Compact Migrant Populations, by U.S. Area

of Residence, 2013-2017 60

Table 11: Estimated Compact Migrant Populations, by U.S. Area

of Residence and Freely Associated State (FAS)

Birthplace, 2013-2017 62

Page iv GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Table 12: Demographic Estimates of the Compact Migrant

Populations in the 50 U.S. States, the District of

Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2013-2017 67

Table 13: Demographic Estimates of Compact Migrants in Hawaii,

2013-2017 70

Table 14: Estimated Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii,

Guam, and the CNMI, 1986-2018 74

Table 15: Census Bureau Methods Used to Enumerate Compact

Migrants in Affected Jurisdictions, 1993-2018 77

Table 16: Definitions of “Compact Migrant” Used in Census

Bureau Enumerations, 1993-2018 79

Table 17: Original and Corrected Enumeration Counts, 2013 and

2018 81

Figures

Figure 1: Locations of the Freely Associated States and Affected

Jurisdictions 10

Figure 2: Compact Migrant Populations in U.S. Areas, 2013-2018 16

Figure 3: Estimated Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii,

Guam, and the CNMI, Fiscal Years 2004-2018 22

Figure 4: Guam Schools Built through Leaseback Program

Funded by Compact Impact Grants 27

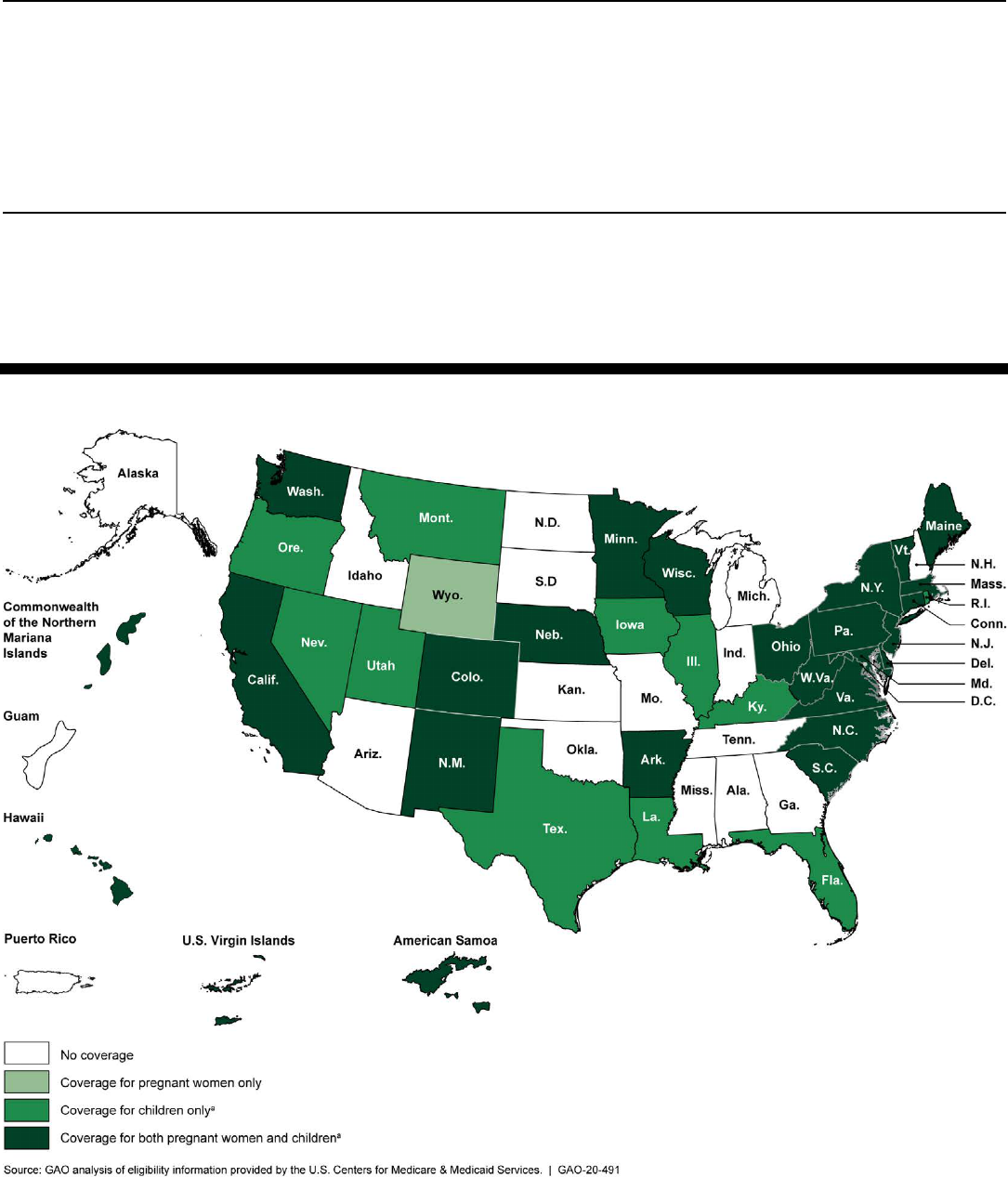

Figure 5: States and Territories That Had Extended Coverage to

Lawfully Residing Children or Pregnant Women under the

Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act

of 2009 as of February 2020 33

Figure 6: Washington State Health Care Authority Advertisement

with Information in English and Six Other Languages

Spoken by Compact Migrants 36

Figure 7: Federally Qualified Health Center Offering Services to

Compact Migrants in Honolulu, Hawaii 38

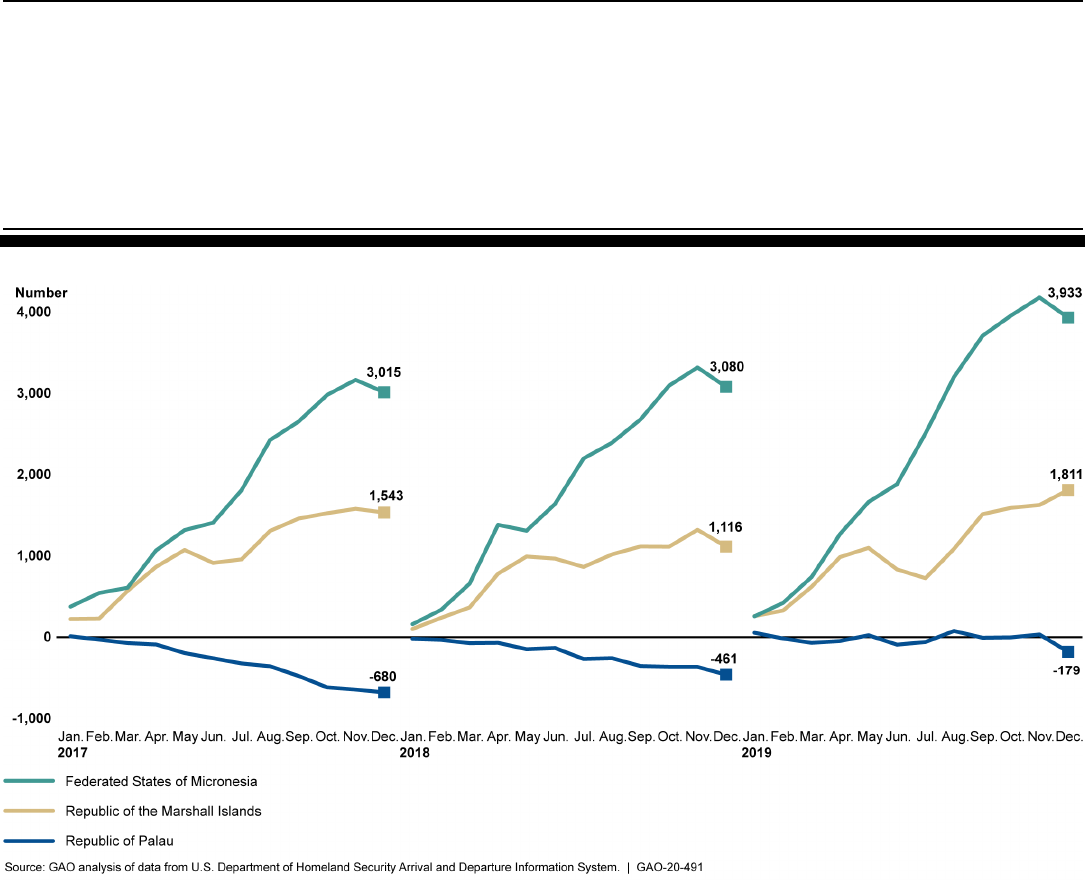

Figure 8: Cumulative Monthly Net Migration of Migrants from the

Freely Associated States to U.S. Areas, 2017-2019 66

Figure 9: Estimates of Compact Migrant Populations in Hawaii,

Guam, and the CNMI, 1993-2018 80

Figure 10: We Are Oceania One-Stop Shop for Compact Migrants

in Hawaii 90

Figure 11: Charity Organization That Provides Services to

Compact Migrants on Saipan, Commonwealth of the

Northern Mariana Islands 92

Page v GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Abbreviations

ACS American Community Survey

ADIS Arrival and Departure Information System

CBP Customs and Border Protection, Department of

Homeland Security

CHIP Children’s Health Insurance Program

CNMI Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

DHS Department of Homeland Security

EAD employment authorization document

FAS freely associated state

Interior Department of the Interior

Marshall Islands Republic of the Marshall Islands

Micronesia Federated States of Micronesia

OIA Office of Insular Affairs, Department of the Interior

Palau Republic of Palau

PPACA Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

PRWORA Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity

Reconciliation Act of 1996

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

June 15, 2020

The Honorable Lisa Murkowski

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

United States Senate

Dear Madam Chairman:

In May 2019, the Presidents of the United States, the Federated States of

Micronesia (Micronesia), the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Marshall

Islands), and the Republic of Palau (Palau) reaffirmed their countries’

commitments to the compacts of free association between the United

States and each of the three other nations. These agreements provide,

among other things, for U.S. economic assistance to these three freely

associated states (FAS), exclusive U.S. military use rights and defense

responsibilities in the FASs, and the ability of eligible FAS citizens to

enter the United States without a visa and reside indefinitely in U.S.

areas—the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S.

territories. Since the compacts went into effect—in 1986 for Micronesia

and the Marshall Islands and in 1994 for Palau—tens of thousands of

migrants from these countries have established residence in U.S. areas.

While many compact provisions are ongoing, certain economic

assistance to Micronesia and the Marshall Islands ends in fiscal year

2023 and assistance to Palau ends in fiscal year 2024.

1

In addition,

certain annual federal grants to designated U.S. areas to defray costs

resulting from migration under the compacts (compact migration) from the

three FASs to these areas are set to end in fiscal year 2023. Legislation

defines these designated areas—Hawaii, Guam, the Commonwealth of

the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), and American Samoa—as affected

jurisdictions.

2

Migration from the FASs to U.S. areas can be expected to

1

Many compact provisions, including some related to defense and migration, last in

perpetuity or until terminated in accordance with the terms of the compacts, according to

officials at the Department of State.

2

Compact of Free Association Amendments Act of 2003, Pub. L. No.108-188 (2003). In

this report, we refer to the act as “the amended compacts’ implementing legislation.” The

act included provisions in addition to those necessary to implement the compacts,

including provisions authorizing and appropriating grants for the affected jurisdictions until

2023.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

continue beyond the expiration of these grants to the affected

jurisdictions. In September 2019, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State

for Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands testified that the

Department of State is coordinating an interagency group to evaluate a

range of options to promote the United States’ continued relationship with

Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau.

3

You asked us to review topics related to compact migration in advance of

upcoming discussions regarding the expiration of certain assistance

under the compacts in 2023. This report (1) presents estimates of

compact migrant populations and describes recent trends in compact

migration; (2) summarizes the reported costs related to compact

migration (compact impact costs) in three affected jurisdictions—Hawaii,

Guam, and the CNMI; and (3) describes effects of compact migration on

governments, workforces, and societies in these and other U.S. areas.

4

As part of this review, we obtained special tabulations of data from the

Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey for the 50 U.S.

states, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. For the U.S. territories

included in this review that are not covered by the survey (Guam and the

CNMI), we used the revised 2018 Census Bureau enumeration of

compact migrants in these areas. We also obtained compact impact cost

information that the affected jurisdictions reported annually to the

Department of the Interior (Interior) and information about grants that they

received to defray these costs.

Additionally, we traveled to, and interviewed stakeholders in, six U.S.

states and territories with compact migrant populations, including three

affected jurisdictions (Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI) and three mainland

states (Arkansas, Oregon, and Washington). We selected these areas on

the basis of previously reported compact migrant populations and the

locations of consulates or Honorary Consuls for Micronesia, the Marshall

3

Sandra Oudkirk, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific

Islands, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Department of State, testimony before

the U.S. House of Representatives Committees on Foreign Affairs and Natural Resources,

Sept. 26, 2019.

4

Because of American Samoa’s small reported FAS population—estimated by the Census

Bureau at 25 in 2018—this report does not address compact migrants in American

Samoa. For information about American Samoa minimum wage increases, see GAO,

American Samoa: Economic Trends, Status of the Tuna Canning Industry, and

Stakeholders' Views on Minimum Wage Increases, GAO-20-467 (Washington, D.C.: June

11, 2020).

Page 3 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Islands, and Palau. Stakeholders whom we interviewed for this review

included federal officials from agencies such as Interior, the Department

of State, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS); state and

territorial government officials in areas we visited; representatives of

private sector and nonprofit organizations such as chambers of

commerce, employers of compact migrants, and nonprofit service

providers; FAS embassy and consulate officials or Honorary Consuls; and

compact migrants living in the areas we visited.

5

We also obtained data from DHS Customs and Border Protection’s Arrival

and Departure Information System to determine net migration to U.S.

areas. To assess the reliability of the data, we spoke with DHS officials to

identify potential data reliability concerns and other limitations, and we

validated the data by checking it against publicly available passenger

data from the Department of Transportation. We found that the data were

sufficiently reliable to describe net compact migration from 2017 through

2019.

For more details of our objectives, scope, and methodology, see

appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2019 through June

2020 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau are among the smallest

countries in the world. In fiscal year 2017, the three FASs had a

combined resident population of approximately 175,000 (102,622 in

5

Consular officials and local community members helped us promote and organize

meetings with compact migrants in areas we visited. The approximately 280 individuals

we met with do not represent a generalizable sample of compact migrants, and the

challenges they discussed are not comprehensive.

Background

Page 4 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Micronesia; 54,354 in the Marshall Islands; and 17,901 in Palau).

6

Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) has primary responsibility for

monitoring and coordinating U.S. assistance to the FASs, and State is

responsible for government-to-government relations.

The U.S. relationship with the FASs began when American forces

liberated the islands from Japanese control near the end of World War II.

In 1947, the United States entered into a trusteeship with the United

Nations and became the administering authority over Micronesia, the

Marshall Islands, and Palau.

7

Voters approved the Constitution of the

Federated States of Micronesia in 1978 and approved the Constitution of

the Marshall Islands in 1979. Both Micronesia and the Marshall Islands

remained subject to the authority of the United States until 1986, when a

compact of free association went into effect between the United States

and the two nations.

8

The Palau constitution took effect in 1981, and

Palau entered into a compact of free association with the United States in

1994.

9

Micronesia and Marshall Islands became members of the United

Nations in 1991, while Palau joined the organization in 1994.

Under its compacts with Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau, the

United States provided economic assistance that includes access to

certain federal services and programs, among other things, for defined

time periods.

6

These population estimates were developed by the Economic Monitoring and Analysis

Program of the Graduate School USA with funding assistance from Interior’s Office of

Insular Affairs. See Graduate School USA, Economic Monitoring and Analysis Program,

FSM FY 2018 Economic Brief (August 2019), RMI FY 2018 Economic Brief (August

2019), and Palau FY 2018 Economic Brief (June 2019).

7

Under the United Nations trusteeship agreement, the United States was the

administering authority for the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: Micronesia, the

Marshall Islands, Palau, and the Northern Mariana Islands. In 1975, the Northern

Marianas became a commonwealth in political union with the United States.

8

Compact of Free Association Act of 1985, Pub. L. No. 99-239 (Jan. 14, 1986).

9

See Proclamation 6726, Placing into Full Force and Effect the Compact of Free

Association with the Republic of Palau, 59 Fed. Reg. 49777 (Sept. 27, 1994) and Palau

Compact of Free Association, Pub. L. No. 99-658 (Nov. 14, 1986).

Compacts of Free

Association

Economic Assistance

Provisions

Page 5 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

• Economic assistance to Micronesia and the Marshall Islands. The

1986 compact of free association between the United States and

Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, respectively, provided about

$2.6 billion in funding for fiscal years 1987 through 2003.

10

In 2003,

the United States approved amended compacts of free association

with the two countries. According to Interior, economic assistance

under the amended compacts is projected to total $3.6 billion,

including payments for compact sector grants and trust fund

contributions for both countries in fiscal years 2004 through 2023.

11

Funding under the original compact and amended compacts has been

provided to Micronesia and the Marshall Islands through Interior.

• Economic assistance to Palau. The compact of free association

between the United States and Palau entered into force in 1994 and

provided $574 million in funding through Interior for fiscal years 1995

through 2009 for assistance to the government, contributions to a trust

fund, construction of a road, and federal services.

12

In September

2010, the United States and Palau signed an agreement that would,

among other things, provide for additional assistance to Palau,

10

See Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs, Budget Justifications and

Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2021. For more information about the compacts with

Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, see GAO, Foreign Assistance: U.S. Funds to Two

Micronesian Nations Had Little Impact on Economic Development, GAO/NSIAD-00-216

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 22, 2000). In addition to receiving funding through Interior,

Micronesia and the Marshall Islands received funding through other federal agencies. For

further information on selected federal programs, loans, and services, see GAO, Foreign

Assistance: Effectiveness and Accountability Problems Common in U.S. Programs to

Assist Two Micronesian Nations, GAO-02-70 (Washington D.C.: Jan. 22, 2002).

11

See Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs, Budget Justifications and

Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2021. For more information about the amended

compacts and the sector grants and trust funds, see GAO, Compacts of Free Association:

Actions Needed to Prepare for the Transition of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands to

Trust Fund Income, GAO-18-415 (Washington, D.C.: May 17, 2018). Under the amended

compacts with Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, economic assistance includes sector

grants in annually decreasing amounts for 2004 through 2023. The amended compacts

require that the sector grants be targeted to sectors such as education, health care, the

environment, public sector capacity building, private sector development, and public

infrastructure or to other sectors as mutually agreed, with priority given to education and

health. See GAO-18-415, appendix IV, for information about U.S. grants and programs

that end, or do not end, in 2023.

12

See Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs, Budget Justifications and

Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2021. For more information about the Palau

compact, see GAO, Compact of Free Association: Palau's Use of and Accountability for

U.S. Assistance and Prospects for Economic Self-Sufficiency, GAO-08-732 (Washington,

D.C.: June 10, 2008). In addition to receiving funding through Interior, Palau received

funding through other federal agencies; see GAO-08-732, appendix VI.

Page 6 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

including contributions to its trust fund.

13

The 2010 agreement and

subsequent amendments entered into force in September 2018.

14

According to Interior, direct assistance to Palau under the compact

will total $229 million for fiscal years 2010 through 2024, including

$105 million that Congress provided in annual appropriations in fiscal

years 2010 through 2017.

15

Under the compacts, the United States has responsibility for defense and

security matters in, and relating to, each of the FASs, and subsidiary

agreements pursuant to the compacts provide for U.S. military use and

operating rights in these countries. According to the Department of

Defense, the compacts have enabled it to maintain a critical strategic

position in the Indo–Pacific region.

16

The compact with the Marshall

Islands also provided for a separate agreement that constituted a full and

final settlement of all claims resulting from U.S. nuclear tests conducted in

13

The Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the

Government of the Republic of Palau Following the Compact of Free Association Section

432 Review, September 3, 2010. For more information about U.S. assistance to Palau,

see GAO, Compact of Free Association: Proposed U.S. Assistance to Palau and Its Likely

Impact, GAO-11-559T (Washington, D.C.: June 16, 2011).

14

See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-141, Div. G, title I, § 114,

132 Stat. 348, 660 (2018).

15

See Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs, Budget Justifications and

Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2021. For more information about the 2010 Palau

agreement, see GAO, Compact of Free Association: Proposed U.S. Assistance to Palau

for Fiscal Years 2016 to 2024, GAO-16-788T (Washington, D.C.: July 6, 2016).

16

See testimony before the House Committees on Foreign Affairs and Natural Resources

of Randall G. Schriver, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs,

Office of the Secretary of Defense, September 26, 2019.

Defense-Related Provisions

Page 7 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

the Marshall Islands during the period 1946 through 1958.

17

In addition, a

subsidiary agreement with the Marshall Islands secured the United

States’ access to the U.S. military facilities on Kwajalein Atoll, which are

used for missile testing and space tracking activities.

Under the compacts, eligible FAS citizens are exempt from certain visa

and labor certification requirements of the Immigration and Nationality Act

as amended.

18

The migration provisions of the compacts allow eligible

FAS citizens to enter the United States (including all states, territories,

and possessions) and to lawfully work and reside in the United States

indefinitely.

19

The implementing legislation for the 1986 compact with Micronesia and

the Marshall Islands stated that it was not Congress’s intent to cause any

17

The United States conducted nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands from 1946 to 1958.

Under the agreement for the implementation of Section 177 of the Compact (Section 177

Agreement), the U.S. government provided $150 million to the Marshall Islands to

establish a nuclear claims fund and an independent Nuclear Claims Tribunal to adjudicate

all claims. While the Section 177 Agreement constituted a full and final settlement of all

claims resulting from the U.S. nuclear testing program, Article IX of the Section 177

Agreement, entitled “Changed Circumstances,” provides for the government of the

Marshall Islands to request the U.S. Congress to consider the provision of additional

compensation for injuries resulting from the U.S. nuclear testing program in the

circumstances specified. Article IX provides that “[i]f loss or damage to property and

person of the citizens of the Marshall Islands, resulting from the Nuclear Testing Program,

arises or is discovered after the effective date of this Agreement, and such injuries were

not and could not reasonably have been identified as of the effective date of this

Agreement, and if such injuries render the provisions of this Agreement manifestly

inadequate," the government of the Marshall Islands may request that the U.S.

government provide additional compensation for such injuries by submitting such a

request to the U.S. Congress. Article IX explicitly states that it is understood that it does

not commit the Congress to authorize and appropriate funds. The government of the

Marshall Islands submitted such a petition in September 2000. In November 2004, the

Executive Branch provided a report evaluating this petition. The report advised that the

facts did not constitute changed circumstances warranting compensation beyond the $150

million contained in the compact.

18

The compacts of free association use the term “immigration” when referring to these

provisions. For the purposes of this report, we refer to them as migration provisions.

19

Under the amended compacts, compact migrants from Micronesia and the Marshall

Islands must have a valid machine-readable passport to be admitted into the United

States. While the compacts allow eligible FAS citizens to work in the United States,

documentation issued by the U.S. government may be required to demonstrate work

authorization to employers. For example, an FAS citizen from Micronesia or the Marshall

Islands may present an unexpired FAS passport and Form I-94 Arrival/Departure Record

(known as Form I-94) to employers to demonstrate identity and employment authorization.

Migration-Related Provisions

Page 8 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

adverse consequences for U.S. territories and commonwealths and the

state of Hawaii.

20

The legislation further declared that Congress would act

sympathetically and expeditiously to redress any adverse consequences.

In addition, the legislation authorized compensation to be appropriated for

these areas that might experience increased demands on their

educational and social services from compact migrants from Micronesia,

the Marshall Islands, and Palau.

21

The legislation required the President to report and make

recommendations annually to Congress regarding adverse consequences

resulting from the compact and provide statistics on compact migration. In

November 2000, Congress made the submission of annual reports about

the impact of compact migration in affected jurisdictions—that is, compact

impact reports—optional and shifted the responsibility for preparing these

reports from the President to the governors of Hawaii and the territories.

22

In December 2003, Congress took steps in the amended compacts’

implementing legislation to address compact impact in designated U.S.

areas. The legislation restated Congress’s intent not to cause any

adverse consequences for the areas defined as affected jurisdictions—

Hawaii, Guam, the CNMI, and American Samoa. In addition, the

legislation authorized and appropriated funding for compact impact grants

to the affected jurisdictions, to be allocated on the basis of the proportion

of compact migrants living in each jurisdiction. Further, the legislation

required an enumeration of compact migrants to be undertaken at least

every 5 years. The legislation also permitted affected jurisdictions to

submit compact impact reports to the Secretary of the Interior.

The implementing legislation for the amended compacts authorized and

appropriated $30 million for each fiscal year from 2004 through 2023 for

grants to the affected jurisdictions. According to the legislation, the grants

are provided to aid in defraying costs incurred by these jurisdictions as a

result of increased demand for services due to the residence of compact

20

Compact of Free Association Act of 1985, Pub. L. No. 99-239, § 104(e) (1986).

21

Financial compensation was provided to Guam and the CNMI in some years during the

period 1986 through 2001.

22

See Pub. L. No. 106-504, § 2 (2000).

Legislative Actions to

Address Compact Impact

Compact Impact Grants to

Affected Jurisdictions

Page 9 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

migrants.

23

OIA reviews the affected jurisdictions’ annual proposals for

the use of the funds and provides the funds to the jurisdictions as

compact impact grants. The grants are to be used only for health,

educational, social, or public safety services or for infrastructure related to

such services.

24

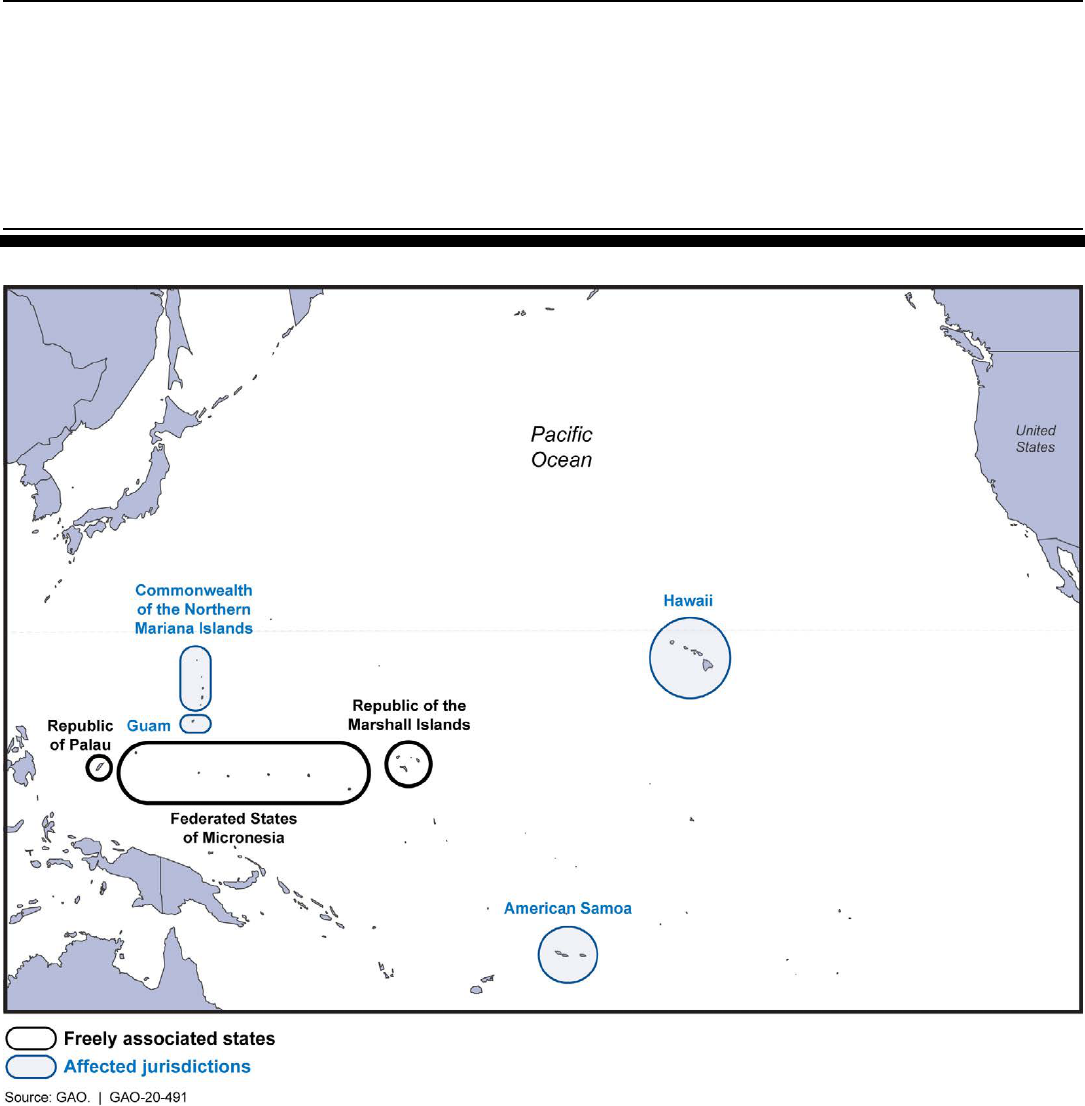

Figure 1 shows the locations of the FASs and the affected jurisdictions.

23

The amended compacts’ implementing legislation, Sec. 104 (e)(6), also “authorized to

be appropriated to the Secretary of the Interior such sums as may be necessary to

reimburse health care institutions in the affected jurisdictions for costs resulting from the

migration of citizens of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of

Micronesia and the Republic of Palau to the affected jurisdictions as a result of the

implementation of the [compacts].” The amended compacts’ implementing legislation,

Sec. 104 (e)(7), requires the Secretary of Defense to make Department of Defense

medical facilities available to properly referred citizens of Micronesia and the Marshall

Islands on a space-available and reimbursable basis.

24

The amended compacts’ implementing legislation, Sec. 104 (e)(10), authorized

additional appropriations to the Secretary of the Interior for each of fiscal years 2004

through 2023 “as may be necessary for grants to the governments of Guam, the State of

Hawaii, the [CNMI], and American Samoa, as a result of increased demands placed on

educational, social, or public safety services or infrastructure related to service due to the

presence in Guam, Hawaii, the [CNMI], and American Samoa” of compact migrants from

the three FASs. Sec. 104 (e)(9) authorized the President to reduce, release, or waive

amounts owed by the governments of Guam and the CNMI to the United States to

address previously accrued and unreimbursed impact expenses, at the request of the

Governor of Guam or the Governor of the CNMI. Guam requested, but did not receive,

such debt relief. The authority granted in Sec. 104 (e)(9)(A) expired on February 28, 2005.

Page 10 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Figure 1: Locations of the Freely Associated States and Affected Jurisdictions

Note: The line around each freely associated state or affected jurisdiction illustrates the general

vicinity of the island area but does not correspond to a territorial boundary or any exclusive economic

zone.

The implementing legislation for the amended compacts requires Interior

to conduct an enumeration of compact migrants, which is to be

supervised by the Census Bureau or another organization selected by

Interior, at least every 5 years beginning in fiscal year 2003. On the basis

of these enumerations, each affected jurisdiction is to receive a portion of

Required Enumerations of

Compact Migrants

Page 11 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

the annual $30 million appropriation in proportion to the number of

compact migrants living there. The legislation permits Interior to use up to

$300,000, adjusted for inflation, of the annual appropriation for compact

impact to conduct each enumeration.

25

The amended compacts’ implementing legislation defines a compact

migrant, for the purposes of the enumeration, as “a person, or their

children under the age of 18, admitted or resident pursuant to [the

compacts] who as of a date referenced in the most recently published

enumeration is a resident of an affected jurisdiction.”

Compact migrants have varying eligibility for certain U.S. federal

government programs. Eligibility for some federal programs changed as a

result of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity

Reconciliation Act.

26

For example, when the compacts were signed, FAS

citizens were eligible for Medicaid; however, the act removed this

eligibility.

27

Table 1 shows compact migrants’ eligibility status for selected

federal benefit programs as of November 2019.

25

Under the agreement between the Census Bureau and Interior, Interior reimbursed the

bureau for these enumerations. In 2008, the enumeration cost approximately $1.3 million,

including headquarters and field costs as well as the cost of final reporting. In 2013 and

2018, the enumerations cost $9,700 and $1.5 million, respectively, according to Interior

officials. The officials noted that the costs of the enumerations ranged widely because the

Census Bureau used existing 2010 Census data in 2013 but collected new data through

special surveys in 2008 and 2018.

26

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996

(PRWORA), Pub. L. No. 104-193, § 401 (1996).

27

Section 401 of PRWORA, codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1611, provides that aliens who are not

considered “qualified aliens” under the definition provided in section 431 of PRWORA,

codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1641, are ineligible for certain federal public benefits. Compact

migrants are not considered qualified aliens under that definition.

Compact Migrant Eligibility

for Selected Federal

Programs

Page 12 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Table 1: Compact Migrant Eligibility for Selected U.S. Federal Programs as of November 2019

Federal program

Eligible

a

Ineligible

Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance

b

Supplemental Security Income

c

Medicaid

d

e

Emergency Medicaid

f

Medicare

g

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

d

e

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

National School Lunch Program/School Breakfast Program

h

Housing and Urban Development rental assistance

i

Federal Emergency Management Agency Individuals and Households Program

j

Enrollment in Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) exchanges

k

Financial assistance through PPACA exchanges

k

Source: GAO analysis of relevant laws and regulations and discussions with agency officials. | GAO-20-491

Note: This information applies to compact migrants who are not U.S. citizens.

a

Eligibility status shown is based solely on compact migrant status. Other eligibility requirements

apply, and a compact migrant may be deemed eligible or ineligible for a benefit on the basis of other

criteria.

b

Eligibility for Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (commonly known as Social Security) is

based on work history.

c

While compact migrants are generally ineligible for Supplemental Security Income, a compact

migrant may be eligible if he or she was receiving such benefits on August 22, 1996.

d

Section 401 of The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996

(PRWORA), Pub. L. No. 104-193, § 401 (1996), codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1611, provides that aliens who

are not considered “qualified aliens” under the definition provided in section 431 of PRWORA,

codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1641, are ineligible for certain federal public benefits, including Medicaid and

CHIP. Compact migrants are not considered qualified aliens under that definition. However, the

Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-3 permits states

to elect to cover children younger than 21 years and pregnant women in both Medicaid and CHIP

who are “lawfully residing in the United States”—a definition that includes compact migrants—and

who are otherwise eligible under the states’ plans. As of February 2020, 38 states and territories and

the District of Columbia had extended coverage under Medicaid or under both Medicaid and CHIP to

lawfully residing non–U.S. citizen pregnant women, children, or both, including compact migrants who

meet all other eligibility requirements.

e

Compact migrants are generally ineligible for Medicaid and CHIP, although some exceptions apply.

See note d for more detail. States can elect to cover children younger than 21 years and pregnant

women who are lawfully residing in the United States and otherwise eligible under the state plan.

f

Medicaid provides payment for treatment of an emergency medical condition for a compact migrant if

he or she satisfies all other Medicaid eligibility requirements in the state, such as income and state

residency standards.

g

Compact migrants are eligible for Medicare parts A, B, C, and D.

h

In addition to administering the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program,

the Department of Agriculture administers other child nutrition programs, including the Child and Adult

Care Food Program, Summer Food Service Program, the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, and

the Special Milk Program. While individuals who are eligible to receive free public education benefits

Page 13 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

under state or local law may not be deemed ineligible to receive benefits in National School Lunch

Program or School Breakfast Program on the basis of citizenship, alienage, or immigration status,

states have some flexibility with regard to citizenship requirements for some of the other programs.

According to the department, no states limit these other programs’ provision of services to U.S.

citizens.

i

”Housing and Urban Development rental assistance” refers to public housing, Section 8 Housing

Choice Vouchers, Project-based Section 8, and certain other smaller programs (Section 236 and

Rent Supplement program).

j

According to officials of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, compact migrants are

ineligible for disaster assistance programs, such as the Individuals and Households Program, that are

considered to be federal public benefits and are thus subject to citizenship requirements; however,

they may be eligible to receive certain types of short-term, noncash, in-kind emergency relief. For

example, compact migrants may receive Public Assistance Emergency Assistance services such as

search and rescue; emergency medical care; emergency mass care; emergency shelter; and

provision of food, water, medicine, and other essential needs.

k

Compact migrants are eligible to apply for coverage in qualified health plans through the

marketplace. They may also be eligible for financial assistance through the marketplace in the form of

premium tax credits or cost-sharing reductions, if they meet the income and other eligibility

requirements.

From 2009 to 2018, the number of compact migrants living in U.S. states

and territories rose by an estimated 68 percent, from about 56,000 to

about 94,000.

28

• In 2011, we reported that combined data from the Census Bureau’s

2005-2009 American Community Survey and 2008 enumeration

28

All Census Bureau data in our report have a confidence interval and margin of error at

the 90 percent confidence level (i.e., the Census Bureau is 90 percent confident that the

true number falls within the given range or margin of error). The estimated increase in the

compact migrant population has a margin of error of 11 percentage points. See

GAO-12-64.

Compact Migrant

Population Has

Grown, with About

Half Residing on U.S.

Mainland

Total Compact Migrant

Population in U.S. Areas

Grew by 68 Percent over 9

Years

Page 14 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

showed an estimated 56,345 compact migrants

29

living in U.S.

areas.

30

• During the period 2013 to 2018, an estimated 94,399 compact

migrants lived in U.S. areas, according to combined data from the

Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey and 2018

required enumeration in Guam, the CNMI, and American Samoa.

31

This estimate includes Micronesian and Marshallese citizens who

entered the United States after 1986, Palauan citizens who entered

the United States after 1994, and certain U.S.-born children younger

than 18 years.

32

Data from the 2013-2017 American Community Survey and the 2018

enumeration indicate that an estimated 50 percent of compact migrants

lived on the U.S. mainland and an estimated 49 percent lived in the

29

The Census Bureau’s 2005-2009 American Community Survey and 2008 enumeration

estimated the total number of compact migrants in U.S. states, the District of Columbia,

Puerto Rico, Guam, and the CNMI as ranging from 51,925 to 60,795. Some assumptions

differ from our 2011 analysis, which did not include American Samoa’s estimated

population of 15 compact migrants.

30

GAO-12-64. The data we reported in 2011 did not include grandchildren.

31

These U.S. areas included the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, American

Samoa, the CNMI, Guam and Puerto Rico. The American Community Survey does not

cover the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Census Bureau does not perform a special territorial

enumeration of compact migrants in that territory. Therefore, this estimate and other data

in this report do not count any compact migrants who may live in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

32

This estimate includes FAS citizens who entered the United States after 1986 (from

Micronesia and the Marshall Islands) or 1994 (from Palau) and their U.S.-born children

(biological, adopted, and step-) and grandchildren younger than 18 years. Because the

Census Bureau also included grandchildren of compact migrants in this estimate, it may

comprise some U.S.-born grandchildren of compact migrants (first- or second-generation

U.S. citizens). In contrast to a census, which produces a population count, the American

Community Survey is a statistical survey and produces estimates with a range of

uncertainty. The Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey for the U.S.

states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico and its 2018 enumeration for Guam, the

CNMI, and American Samoa estimated the total number of compact migrants as ranging

from 89,171 to 99,627. According to Census Bureau officials, because of disclosure

considerations, after providing us with data that include grandchildren, the bureau could

not provide us with data that do not include grandchildren.

About Half of All Compact

Migrants Resided on U.S.

Mainland in 2013-2018

Page 15 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

affected jurisdictions during this period

33

: 26 percent in Hawaii, 20 percent

in Guam, and 3 percent in the CNMI.

34

This estimate indicates growth in

the number of compact migrants on the U.S. mainland since 2011, when

we reported that the Census Bureau estimated 58 percent of compact

migrants lived in the affected jurisdictions.

35

The Census Bureau estimated that 11 states in the U.S. mainland, in

addition to three of the four affected jurisdictions—Hawaii, Guam, and the

CNMI—had compact migrant populations of more than 1,000, according

to the 2013-2017 American Community Survey and the 2018

enumeration (see fig. 2).

36

33

All Census Bureau data in our report have a confidence interval and margin of error at

the 90 percent confidence level. The estimated percentages of compact migrants living on

the U.S. mainland and in the affected jurisdictions each have a margin of error of 4

percentage points. Because of rounding, the percentages do not sum precisely to 100.

The U.S. mainland estimate excludes Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico in addition to

Guam and the CNMI.

34

Data from the 2013-2017 American Community Survey and the 2018 enumeration

indicate that an estimated 25 compact migrants—less than 0.1 percent of all compact

migrants—were living in American Samoa, the fourth affected jurisdiction.

35

The Census Bureau’s estimate had a margin of error of 8 percentage points.

36

See appendix II for more information about compact migrant populations by state and

territory.

Page 16 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Figure 2: Compact Migrant Populations in U.S. Areas, 2013-2018

Notes: For U.S. areas shown with solid shading, the 90 percent confidence interval for the population

point estimate falls entirely in one category (i.e., 0-1,000; 1,000-2,999; or 3,000+). For U.S. areas

shown with variegated shading, the 90 percent confidence interval for the population point estimate

spans the two categories indicated by the shading.

Page 17 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Estimates shown for Guam and the CNMI are from the Census Bureau’s revised 2018 compact

migrant enumeration. Estimates for U.S. states are from the bureau’s 2013-2017 American

Community Survey. The estimate for Hawaii, using 2013-2017 data, differs from the revised 2018

compact migrant enumeration, which used 2015-2017 data.

All estimates shown represent citizens of the freely associated states—the Federated States of

Micronesia (Micronesia), the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Marshall Islands), and the Republic of

Palau—who entered the United States after 1986 (from Micronesia and the Marshall Islands) or 1994

(from Palau) and their U.S.-born children (biological, adopted, and step-) and grandchildren younger

than 18 years.

Stakeholders we interviewed—including FAS embassy and consular

officials, FAS community members, state government officials, and

representatives of private sector and nonprofit organizations—expressed

concerns about the Census Bureau’s prior estimates of compact

migrants. Some Arkansas stakeholders cited other, higher estimates of

the FAS population in their state. Moreover, some stakeholders said that

compact migrant populations are apprehensive or distrustful about being

formally counted through surveys or the census. Stakeholders also noted

that some compact migrant communities have felt frustrated at having

been encouraged to respond to surveys and be counted but not

experiencing any benefit from these efforts, according to a nonprofit

official and FAS community members.

37

Marshallese consular officials

said that they believed the 2010 census undercounted their citizens,

noting that the Census Bureau did not employ any Marshallese surveyors

in the Arkansas counties with Marshallese populations.

Stakeholders also expressed concern about the decennial census to be

conducted in 2020, which, like the 2010 decennial census, will collect

information on race.

38

Nonprofit organization officials whom we

interviewed expressed concern that the 2020 census could result in an

undercounting of compact migrants because of language barriers and

compact migrants’ difficulty accessing the census form online. Arkansas

health care and private sector representatives and the Marshallese

consulate described plans to address barriers to obtaining a more

accurate count of the population in the 2020 census. Hawaii is making a

statewide effort to ensure that compact migrants are counted in the 2020

census, according to Hawaii state officials. According to Guam officials,

an outreach effort in Guam has leveraged “trusted voices,” or parties

37

Other sources of federal data on compact migration may be available. For example,

Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Arrival and Departure Information System

contains arrival and departure data associated with FAS passports; for more information

about these data and estimated net migration to U.S. areas, see appendix III.

38

FAS respondents to the 2020 decennial census can select “Other Pacific Islander,”

among other options, and can also add a race (e.g., Marshallese).

Stakeholders Expressed

Concerns about

Undercounting of Compact

Migrants

Page 18 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

known to compact migrant communities there, to communicate the

importance of responding to the 2020 census.

Data from the American Community Survey showed an estimated 72,965

compact migrants living in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and

Puerto Rico in 2013 through 2017.

39

• An estimated 31,425 compact migrants living in these areas (43

percent) were U.S. citizens.

40

The remaining estimated 41,540 (57

percent) were not U.S. citizens.

41

The U.S. citizens who were counted

included naturalized citizens and minor-age U.S. citizen children of

compact migrants, who would no longer be counted as compact

migrants after reaching 18 years of age.

• An estimated 25,555 compact migrants living in these areas were

born in Micronesia; 20,545 were born in the Marshall Islands; and

3,435 were born in Palau.

42

These totals do not include compact

39

All Census Bureau data in our report have a confidence interval and margin of error at

the 90 percent confidence level. The 2018 enumeration of compact migrants did not

provide detailed information about Guam, the CNMI, and American Samoa, and the

American Community Survey does not cover these three territories. The 2013-2017

American Community Survey estimated the number of compact migrants in the 50 U.S.

states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico as ranging from 69,474 to 76,456. See

appendix II for the Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey estimates of

compact migrants, by U.S. area (table 10) and place of birth (table 11). The American

Community Survey also collects data on self-identified ethnicity, age, gender, and

educational attainment, among other things. See appendix IV for additional demographic

information on compact migrants living in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and

Puerto Rico.

40

The Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey estimated the number of

compact migrants living in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico who are

U.S. citizens (including those born in U.S. areas, born abroad to U.S. parents, or

naturalized) as ranging from 29,583 to 33,267. This estimate has a margin of error of 1

percentage point. This estimate may include individuals younger than 18 years who held

dual citizenship in the United States and one of the FASs. For example, an FAS official

noted that U.S.-born children of Micronesian citizens hold Micronesian citizenship until

they reach 18 years of age, at which point they have 3 years to decide whether to retain

either their U.S. citizenship or their Micronesian citizenship.

41

The Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey estimated the number of

compact migrants living in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico who are

not U.S. citizens as ranging from 39,064 to 44,016. This estimate has a margin of error of

2 percentage points.

42

The Census Bureau estimated the number of compact migrants living in U.S. areas who

were born in Micronesia as ranging from 23,573 to 27,537; in the Marshall Islands, from

19,074 to 22,016; and in Palau, from 2,728 to 4,142.

Census Data Provide

Additional Information

about Compact Migrants

in the States, the District

of Columbia, and Puerto

Rico

Page 19 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

migrants born in the FAS and living in Guam, the CNMI, or American

Samoa, because the American Community Survey does not cover

these territories.

43

• An estimated 27,735 compact migrants living in these areas who were

18 years and older (69 percent) were in the civilian labor force.

44

Of

those, 24,540 (89 percent) were employed and 3,195 (12 percent)

were unemployed.

45

• An estimated 1,660 compact migrants living in these areas—4 percent

of compact migrants 17 years and older—were on active duty in the

U.S. military or had served on active duty in the past.

46

For additional American Community Survey data on compact migrant

demographics, see appendix IV.

Compact migrants move to U.S. areas for a range of reasons, including

greater economic and educational opportunities, better access to health

care, a desire to join family members in the United States, and a wish for

greater personal freedom. In some communities we visited, stakeholders

noted that FAS citizens had come to the United States for school or work

before the compact with Micronesia and the Marshall Islands and the

compact with Palau went into effect but that the compacts had opened

the option of migration to a broader range of individuals.

• Economic opportunities. Compact migrants described moving to

U.S. areas for better, more reliable jobs and higher wages. Having a

better-paying job in the United States sometimes allows individuals to

43

The totals also do not include compact migrants with FAS citizenship born outside the

FASs.

44

The Census Bureau estimated the number of compact migrants 18 years and older in

the civilian labor force (which includes people classified as employed or unemployed) as

ranging from 26,215 to 29,255. This estimate has a margin of error of 1 percentage point.

45

The Census Bureau estimated the number of employed compact migrants 18 years and

older in the civilian labor force as ranging from 23,168 to 25,912. This estimate has a

margin of error of 1 percentage point. The Census Bureau estimated the number of

unemployed compact migrants 18 years and older in the civilian labor force as ranging

from 2,701 to 3,689. This estimate has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

46

The Census Bureau estimated the number of compact migrants 17 years and older who

were on active duty at some point as ranging from 1,369 to 1,951, with a margin of error of

0.7 percentage points. The Census Bureau has also estimated that 7.7 percent of the total

U.S. population who are 18 years and older have been on active duty at some point. This

estimate has a margin of error of 0.1 percentage point.

Reasons for Migration to

U.S. Areas Vary

Page 20 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

send remittances or consumer goods to family members living in an

FAS. Other compact migrants move to U.S. areas to join the military.

• Educational opportunities. Compact migrant families often move to

U.S. areas so that their children will have access to improved primary

and secondary education, according to compact migrants. Some

compact migrants travel to U.S. areas to attend college and choose to

stay to work, including to pay off their student loans, according to

consular officials and compact migrants.

• Health care access. Compact migrants sometimes migrate to U.S.

areas to obtain medical treatment for themselves or family members,

according to FAS community members and consular officials. Some

medical procedures or treatments, such as dialysis or access to

specialists, are not available in the FASs, according to federal and

nonprofit officials.

• Family. Many compact migrants relocate to the United States to join

family members and communities already living there, according to

consular and nonprofit officials.

• Personal freedom. Some compact migrants said that they have more

personal, social, and cultural freedom in the United States than in

their more traditional home country.

Changes in the natural environment in the FASs have also prompted

migration from those areas, according to FAS representatives. Depleted

food resources and effects of climate change—including more-frequent

typhoons, coral reef bleaching, and depletion of fishing stocks—have

contributed to migration, according to an FAS official. In addition,

members of Marshallese communities cited rising sea levels and frequent

tidal flooding as reasons for migrating from the Marshall Islands to U.S.

areas. Some Marshallese community members also noted that the legacy

of U.S. nuclear testing had contributed to their decision or need to

move.

47

Compact migrants cited varied reasons for choosing to migrate to specific

locations. For example, representatives of FAS communities in Guam and

the CNMI noted the FASs’ closer proximity to those territories than to the

U.S. mainland as well as the similarity of Guam’s and the CNMI’s island

47

U.S. nuclear weapons tests were conducted in the Marshall Islands in the 1940s and

1950s. To conduct these tests, the U.S. government moved 167 people from Bikini Atoll

and 142 people from Enewetak Atoll to other locations. In addition, during a test code-

named Castle Bravo, the residents of Rongelap Atoll and Utrik Atoll were exposed to

radioactive fallout and subsequently were moved from their homes.

Page 21 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

cultures to those of their home countries. Also, some compact migrants in

Arkansas and Oregon cited the lower cost of living and a perception of

less discrimination or greater safety there than in Hawaii. Marshallese

community members often migrate to Arkansas for jobs in the poultry

industry.

Consular officials noted that, because of comparatively lower wages and

fewer housing options in the FASs, returning to their countries after living

in U.S. areas can be difficult for some compact migrants. Some compact

migrants said that it is also difficult to find a good job in their home

countries without family or political connections. According to an FAS

official, some compact migrants retire to their home countries. However,

several compact migrants we spoke with said they planned to stay in U.S.

areas to be close to medical care or to children and grandchildren born

there.

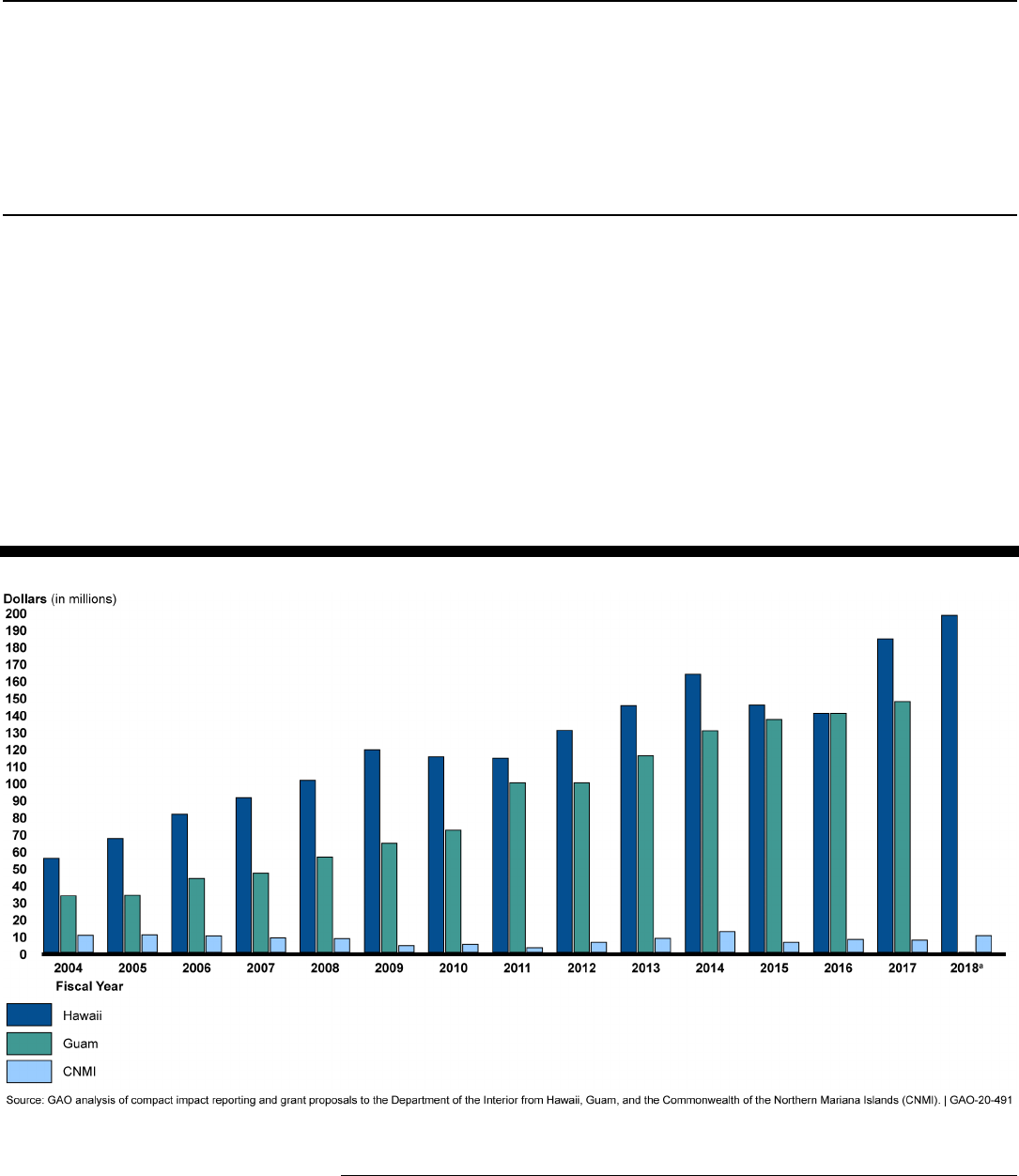

The affected jurisdictions of Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI reported

estimated compact impact costs (i.e., costs incurred as a result of

increased demands on public services from compact migrants) that

totaled $3.2 billion during the period fiscal years 2004 through 2018 and

increased over time for Hawaii and Guam. Interior has provided compact

impact grants totaling more than $30 million annually to the affected

jurisdictions, each of which uses the funds differently. In October 2019,

Census discovered an error in the 2013 and 2018 enumerations, which

Interior had used to determine the distribution of compact impact grant

funds and which resulted in misallocation of these funds for fiscal years

2015 through 2020. In February 2020, Interior officials told us that the

department had developed a modified plan for compact impact grants in

fiscal years 2021 through 2023 that, according to the officials, is intended

to correct the misallocation.

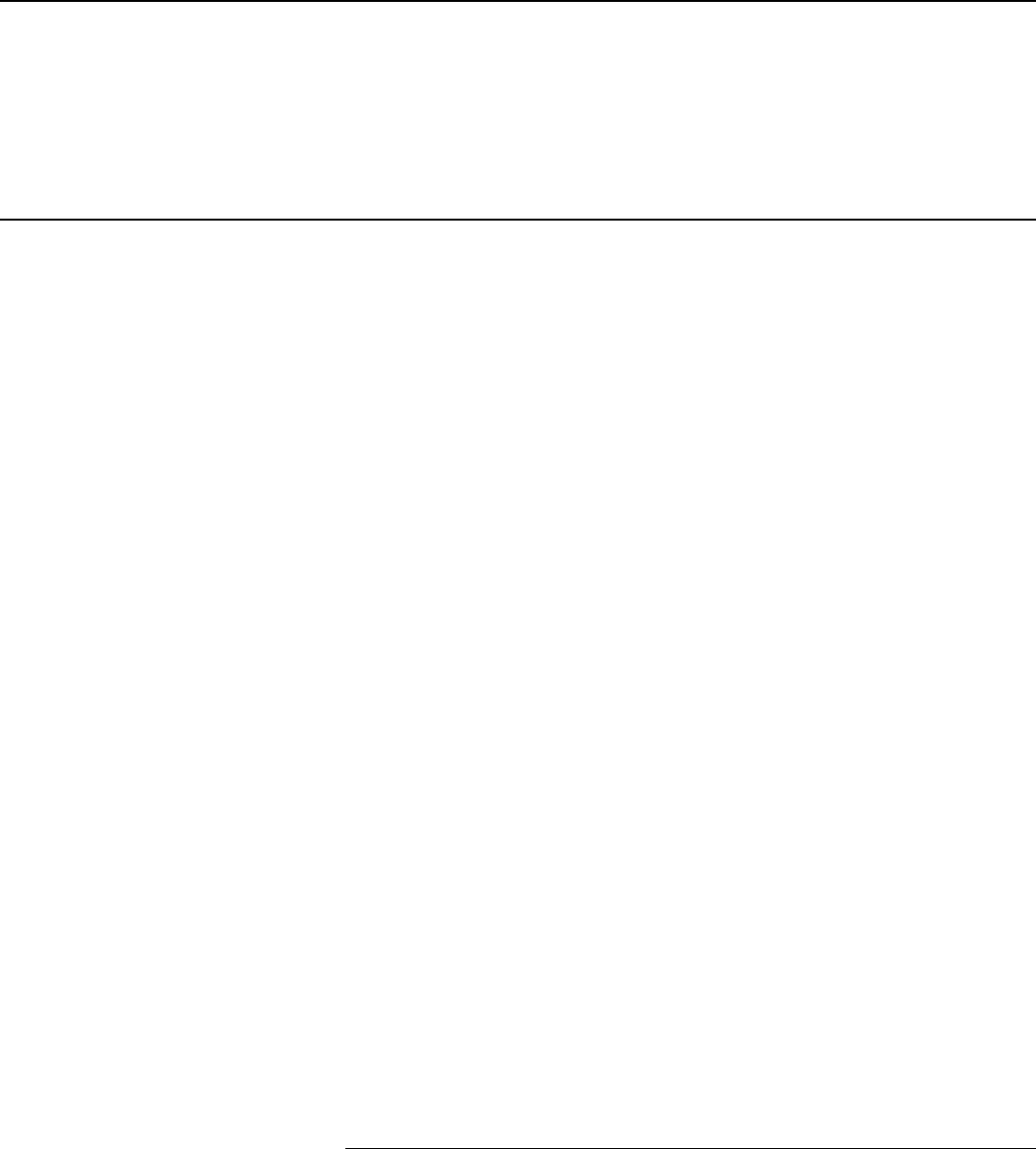

Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI reported a total of $3.2 billion in estimated

compact impact costs during the period fiscal years 2004 through 2018,

with estimated annual costs increasing over time for Hawaii and Guam

and fluctuating for the CNMI.

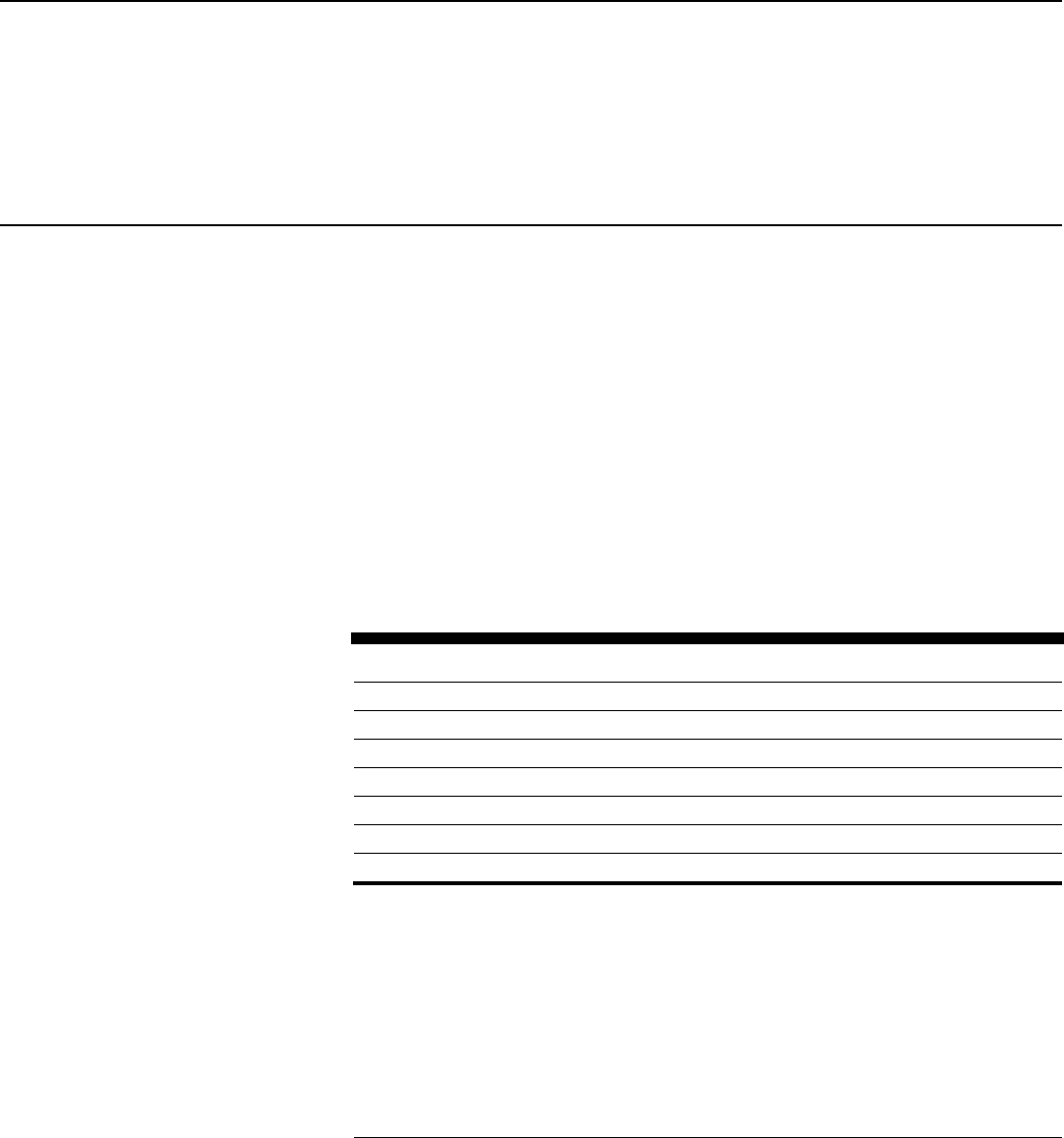

• Hawaii reported $1.8 billion in total estimated compact impact costs.

Hawaii’s reported annual costs increased from $55 million in fiscal

year 2004 to $198 million in fiscal year 2018.

Hawaii, Guam, and

the CNMI Have

Reported Compact

Impact Costs and

Received Annual

Grants to Defray

Them

Hawaii’s and Guam’s

Reported Compact Impact

Costs Have Risen, while

the CNMI’s Have Varied

Page 22 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

• Guam reported $1.2 billion in total estimated compact impact costs.

Guam’s reported annual costs increased from $33 million in fiscal

year 2004 to $147 million in fiscal year 2017.

48

• The CNMI reported $116 million in total estimated compact impact

costs. The CNMI’s reported annual costs amounted to $10 million in

both fiscal year 2004 and fiscal year 2018 but fluctuated over time,

ranging from a low of about $3 million in fiscal year 2011 to a high of

$12 million in fiscal year 2014.

For a summary of the estimated compact impact costs reported by the

three affected jurisdictions, see figure 3.

49

For more details of their

compact impact reporting, see appendix V.

Figure 3: Estimated Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI, Fiscal Years 2004-2018

48

Guam did not report compact impact costs for fiscal year 2018.

49

Hawaii’s Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism separately

reported estimated compact impact costs of $246.1 million to the state for 2017.

Page 23 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

Note: Compact impact costs are costs that Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI reported having incurred as

a result of increased demands on public services from compact migrants from the Federated States

of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau.

a

Guam did not report compact impact costs for fiscal year 2018.

The three affected jurisdictions reported compact impact costs for

education, health, public safety, and social services (see table 2). As the

table shows, the highest total costs in fiscal year 2017 were for education

and health services.

Table 2: Estimated Compact Impact Costs Reported by Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI, by Sector, Fiscal Year 2017

Dollars

Sector

Hawaii

Guam

CNMI

Total

Educational services

117,870,113

72,586,977

775,832

191,232,922

Health services

22,954,383

31,718,391

2,818,223

57,490,997

Public safety

1,009,460

35,277,650

3,487,420

39,774,530

Social services

42,028,662

7,749,290

194,061

49,972,013

Total

183,862,618

147,332,308

7,275,536

338,470,462

Source: GAO analysis of compact impact reporting and grant proposals from Hawaii, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). | GAO-20-491

In November 2011, we found that Interior’s reporting to Congress on

compact impact had been limited, and we identified weaknesses in

existing compact impact reporting.

50

We found that some jurisdictions did

not accurately define compact migrants, account for federal funding that

supplemented local expenditures, or include revenue received from

compact migrants. Our November 2011 report recommended that the

Secretary of the Interior disseminate guidelines to the affected

jurisdictions that adequately addressed concepts essential to producing

reliable impact estimates and that the Secretary call for the use of these

guidelines in developing compact impact reports.

51

Although Interior

developed a draft of compact impact reporting guidelines in 2014, it had

50

GAO-12-64.

51

GAO-12-64.

Page 24 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

not disseminated such guidelines to the affected jurisdictions as of

February 2020.

52

In 2019, Interior awarded the Guam government a technical assistance

grant for $280,000 to conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine

compact migrants’ economic contribution to the local economy. The effort

will reportedly also seek to address weaknesses and methodological

concerns related to compact impact costs calculated by Hawaii, Guam,

and the CNMI. Guam officials said that the grant application was

prepared in response to our prior critique of their compact impact

estimation methodology.

53

The grant was awarded to the Guam Bureau of

Statistics and Plans, which contracted with University of Guam

consultants to carry out the work beginning in October 2019. Guam

officials expected this work to result in two reports—one identifying

economic contributions by compact migrants (expected September 2021)

and another proposing a methodology for determining compact impact

costs (expected August 2022).

During fiscal years 2004 through 2019, Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI

received a combined total of approximately $509 million in compact

impact grant funding. This total includes (1) annual compact impact grant

funding allocated from $30 million authorized and appropriated in the

52

Since 2011, Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI have reported on compact impacts to Interior

with varying frequency. For example, Hawaii submitted a report for fiscal year 2010 but

combined its reporting for fiscal years 2011 through 2014 in a single document submitted

in 2015. Guam submitted a report for each fiscal year through 2017 but did not submit a

report for fiscal year 2018. The CNMI did not submit formal reports, instead embedding

some compact impact data in annual grant applications to Interior. The amended

compacts’ implementing legislation permits, but does not require, affected jurisdictions to

report on compact migrant impact. These reports, which are made publicly available on

OIA’s website, do not affect the allocation of compact impact grants, which OIA bases on

the most recent enumeration. If Interior receives such reports from an affected jurisdiction,

Interior must submit reports to Congress that include, among other things, comments from

the jurisdiction’s governor and from the administration.

53

GAO-12-64.

Hawaii, Guam, and the

CNMI Have Received

Grants to Defray Compact

Impact Costs

Compact Impact Grant

Funding

Page 25 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

amended compacts’ implementing legislation and (2) additional compact

impact grant funding allocated from annual appropriations.

• In fiscal years 2004 through 2019, Interior made annual allocations of

the $30 million of compact impact grant funds authorized and

appropriated in the amended compacts’ implementing legislation.

Interior provided these allocations as compact impact grants to each

affected jurisdiction to defray their costs due to the residence of

compact migrants. Interior used the four most recent enumerations—

conducted in 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018—as the basis for these

annual allocations.

54

• Since fiscal year 2012, Interior has provided additional compact

impact grant funding to the affected jurisdictions from annual

appropriations. This additional funding has ranged from approximately

$3 million to $5 million per year since fiscal year 2012. Interior has

allocated the additional funding on the basis of the 2013 and 2018

enumerations.

Table 3 shows the total amounts that Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI

received as compact impact grant funding in fiscal years 2004 through

2019.

Table 3: Compact Impact Grant Funding to Hawaii, Guam, and the Commonwealth

of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Fiscal Years 2004-2019

Dollars (in millions)

Affected

jurisdiction

Compact impact

grant funding

a

Additional compact

impact grant funding

b

Total

Hawaii

183.5

12.1

195.7

Guam

244.0

15.7

259.7

CNMI

51.8

2.1

53.9

Total

479.3

30.0

509.3

Source: GAO analysis of data from the U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs. | GAO-20-491

Notes: Numbers in columns and rows may not sum precisely to totals because of rounding. The

additional compact impact grant funding was provided in annual appropriations in fiscal years 2012

through 2019. In 2019, the Census Bureau notified the Department of the Interior that the bureau had

miscounted the compact migrant population in Hawaii, which would affect the department’s

allocations based on the 2013 and 2018 compact migrant enumerations.

a

Compact impact grant funding consists of funding authorized and appropriated by the implementing

legislation for the amended compacts between the United States and the Federated States of

Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, respectively.

54

For more information about the methods and definitions used in compact migrant

enumerations, see appendix VI.

Page 26 GAO-20-491 Compacts of Free Association

b

Additional compact impact grant funding consists of additional funding authorized by the amended

compacts’ implementing legislation and appropriated through annual appropriations.

Affected jurisdictions use their compact impact grant funding in varying

ways and report on their use of the funds to Interior. Hawaii allocates the

entirety of its compact impact grant—approximately $13 million annually

since fiscal year 2015—to the state’s MedQuest division to defray costs of

providing medical services to compact migrants. Guam has used some of

its approximately $15 million of compact impact funding each year for

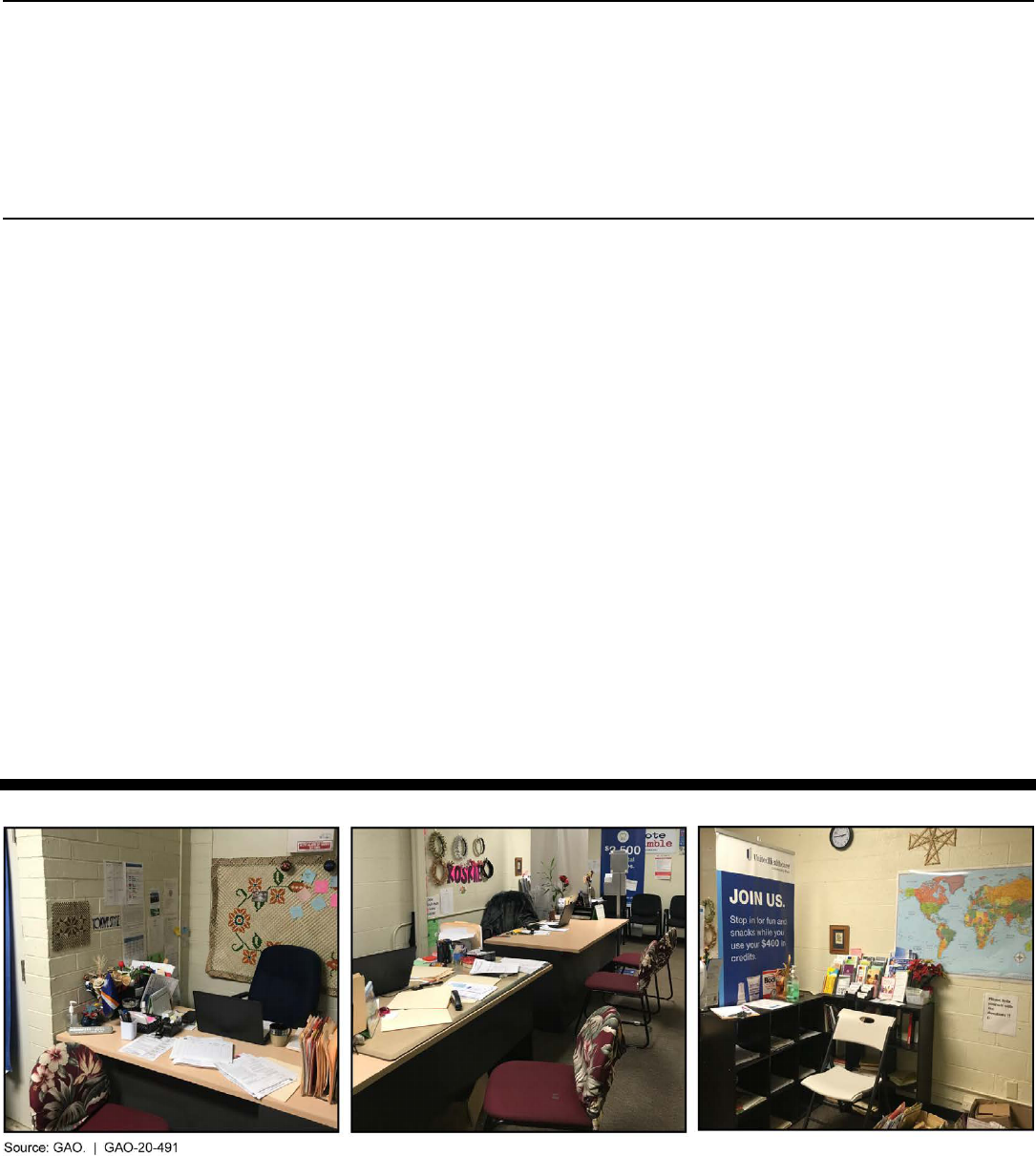

new schools constructed through leasebacks (see fig. 4 for photos of

several schools built by the Guam government with compact impact

funds). The CNMI allocates its approximately $2 million of compact

impact funding each year across the education, health care, public safety,

and social service sectors. Hawaii, Guam, and CNMI officials have

emphasized that compact impact funding does not fully compensate for

the expenses associated with compact migration. For stakeholder