Sustainability Impact Assessment in Support

of the Association Agreement Negotiations

between the European Union and Mercosur

Final Report

▪ December 2020

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

Authors: Max Mendez-Parra (ODI), Elitsa Garnizova (LSE), Daniela Baeza Breinbauer (LSE),

Stefania Lovo (University of Reading), Jean-Baptiste Velut (Université Paris III - Sorbonne

Nouvelle), Badri Narayanan (Infinite Sum Modelling), Matthias Bauer (LSE), Philipp Lamprecht

(LSE), Ken Shadlen (LSE), Valeria Arza (CENIT-Argentina), Martin Obaya (CENIT-Argentina),

Linda Calabrese (ODI), Karishma Banga (ODI), Neil Balchin (ODI)

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European

Union, 2020

© European Union (*), 2020

ISBN: 978-92-76-26958-8

DOI:

10.2781/54752

Catalogue number: NG-03-20-817-EN-N

This report is commissioned via LSE Consulting

which was set up by the London School of

Economics and Political Science to enable and

facilitate the application of its academic expertise

and intellectual resources.

LSE Enterprise Ltd, trading as LSE Consulting, is a

wholly owned subsidiary of the London School of

Economics and Political Science.

The LSE

trademark is used under licence from The London

School of Economics and Political Science.

LSE Consulting

LSE Enterprise Ltd

London School of Economics and Political Science

Houghton Street

London, WC2A 2AE

(T) +44 (0)20 7106 1198

(W) lse.ac.uk/consultancy

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

3

Table of Contents

List of Tables 5

Executive Summary 12

1. Introduction 17

1.1. Research Aims and Objectives 17

1.2. Background 18

2. Economic Analysis 20

2.1. Methodology 20

2.2. Literature Review 24

2.3. Scenario Results 29

2.4. Fiscal Impacts 35

2.5. Policy Recommendations 36

3. Social Analysis 37

3.1. Methodology 37

3.2. Baseline 37

3.3. Analysis 54

3.4. Conclusion 62

3.5. Policy Recommendations 62

4. Environmental Analysis 65

4.1. Methodology 65

4.2. Baseline 65

4.3. Analysis of Impact 86

4.4. Conclusion 103

4.5. Policy Recommendations 104

5. Human Rights Analysis 106

5.1. Methodology 106

5.2. Baseline 109

5.3. Analysis 157

5.4. Conclusion 172

5.5. Policy Recommendations 173

6. Sectoral Analysis 175

6.1. Qualitative Analysis 175

6.2. Cross-Cutting Issues 176

6.3. Sectoral Analysis: Agriculture 178

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

4

6.4. Sectoral Analysis: Manufacturing 233

6.5. Sectoral Analysis: Services 281

7. Consultation Process 327

7.1. Roundtables 327

7.2. Civil Society Dialogue Meetings 329

7.3. Written Comments 330

7.4. Questionnaires 333

7.5. Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires Workshops and Consultation Activities 333

8. Policy Recommendations 335

8.1. Recommendations based on the Economic Analysis 335

8.2. Recommendations based on the Social Analysis 335

8.3. Recommendations based on the Environmental Analysis 337

8.4. Recommendations based on the Human Rights Analysis 338

8.5. Recommendations for the Agriculture Sector 340

8.6. Recommendations for the Manufacturing Sector 342

8.7. Recommendations for the Services Sector 343

Bibliography 345

Annex 1. Indicators and Data Sources 358

Annex 2. Roundtable Summaries 361

Annex 3. Civil Society Dialogue Minutes 382

Annex 4: Economic Modelling Results 393

Annex 5: Summary of Comments to Draft Final Report Received by email 404

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

5

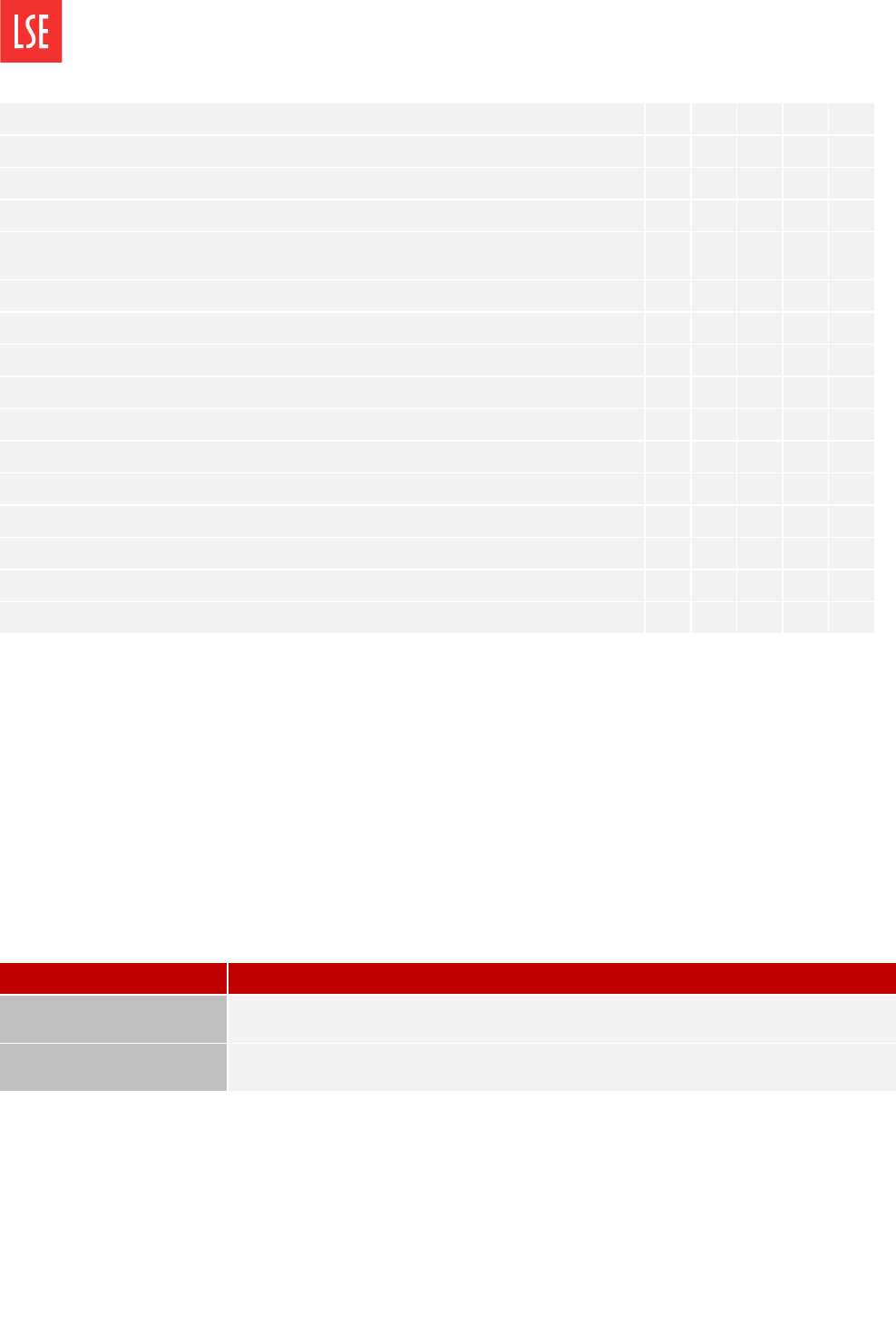

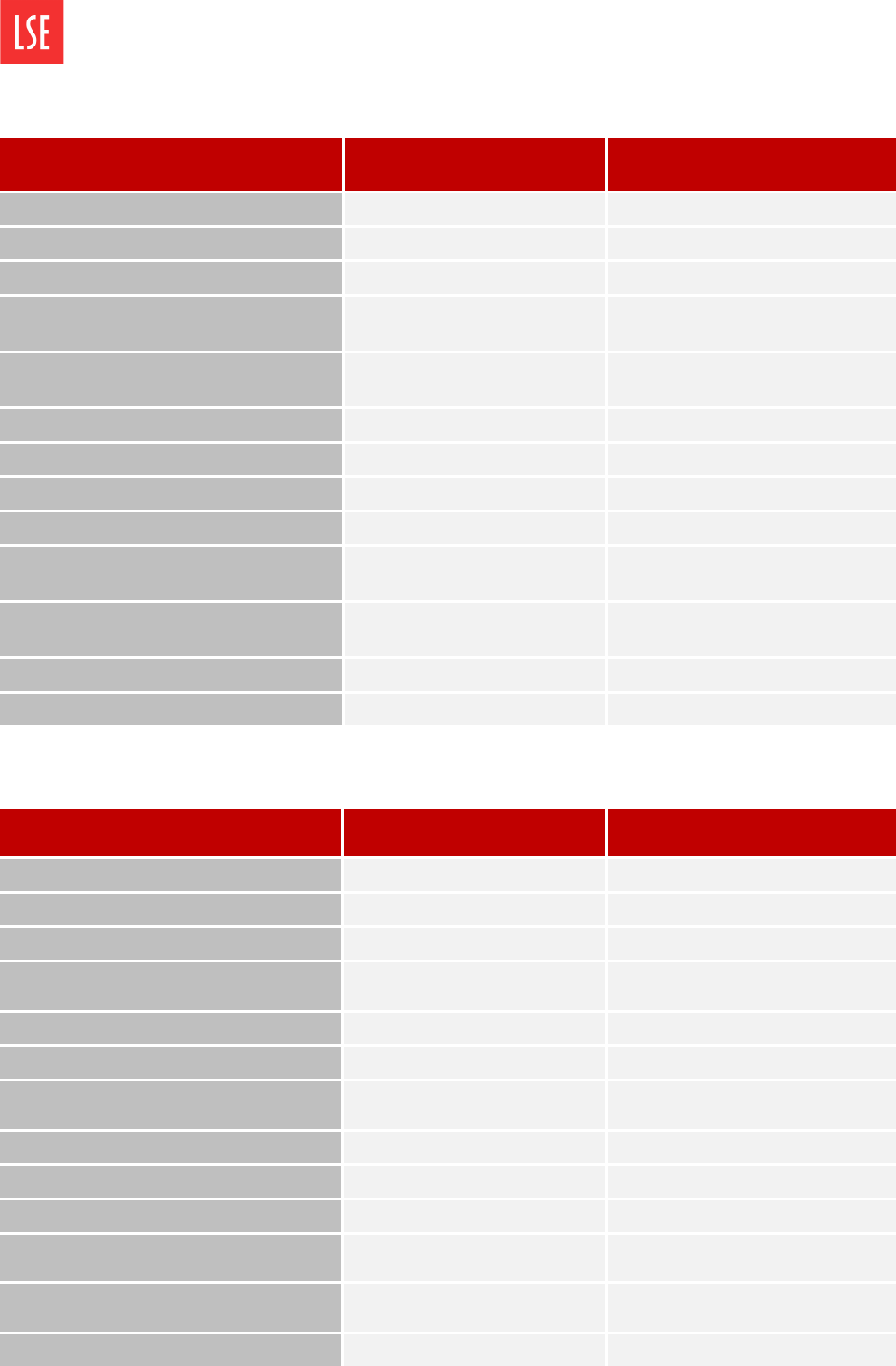

List of Tables

Table 1: Mercosur countries overview 19

Table 2: Sectors included 21

Table 3: Regions 22

Table 4: NTB cuts in EU and Mercosur 24

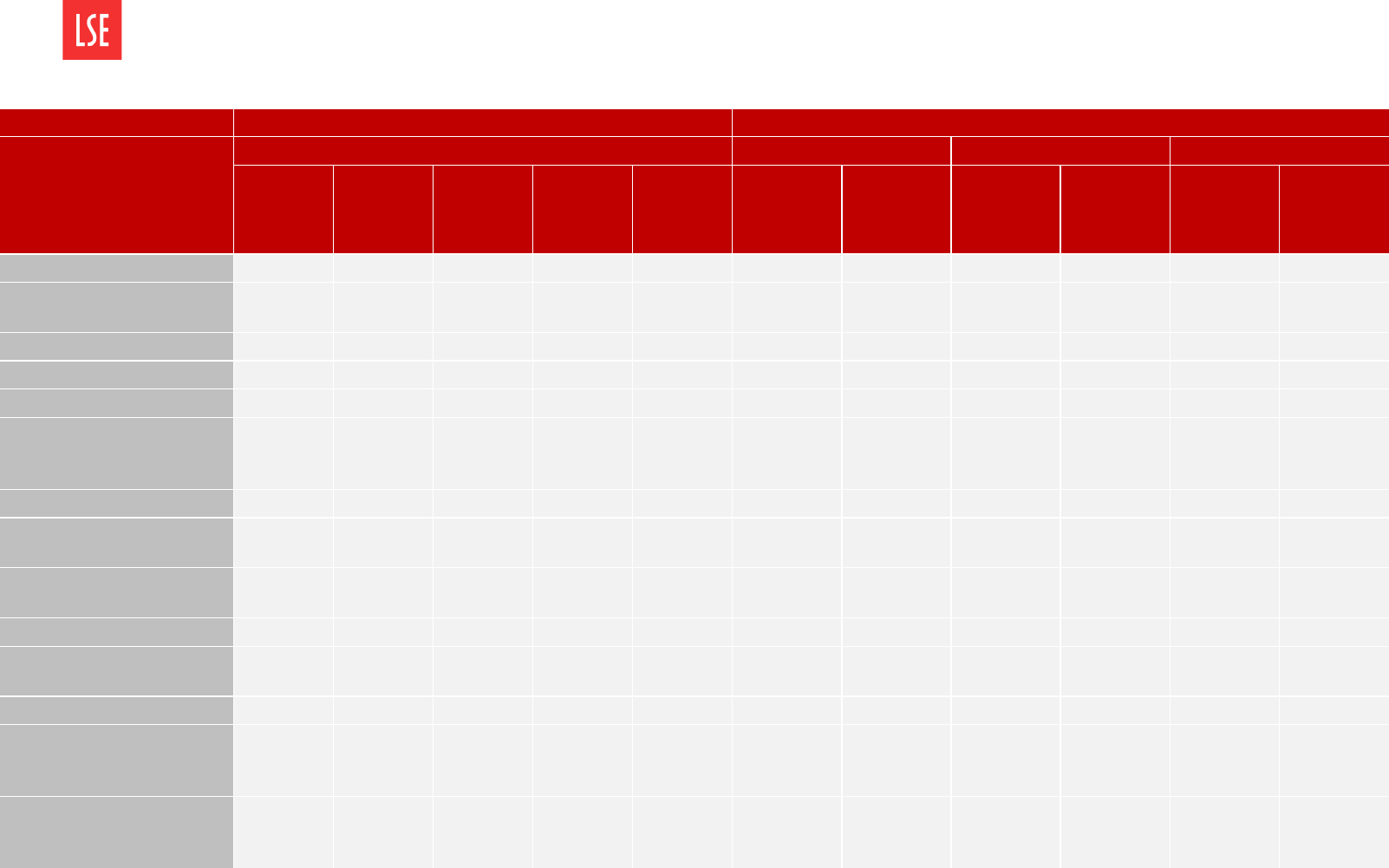

Table 5: Macroeconomic Results for the Conservative scenario 29

Table 6: Macroeconomic Results for the Ambitious scenario 30

Table 7: Sectoral Output changes in the Conservative Scenario 31

Table 8: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade changes by sector in the conservative scenario 32

Table 9: Sectoral Output changes in the Ambitious Scenario 33

Table 10: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade changes by sector in the ambitious scenario 34

Table 11: The incidence of tariff revenue in the Mercosur imports from the EU (2018) 35

Table 12: Union density and concentration among Mercosur members 47

Table 13: Convention 87 and 98 cases brought to CEACR in Mercosur19F 49

Table 14: CEACR cases related to forced labour in Mercosur22F 50

Table 15: CEACR cases related to child labour in Mercosur27F 52

Table 16: CEACR cases related to discrimination in Mercosur30F 54

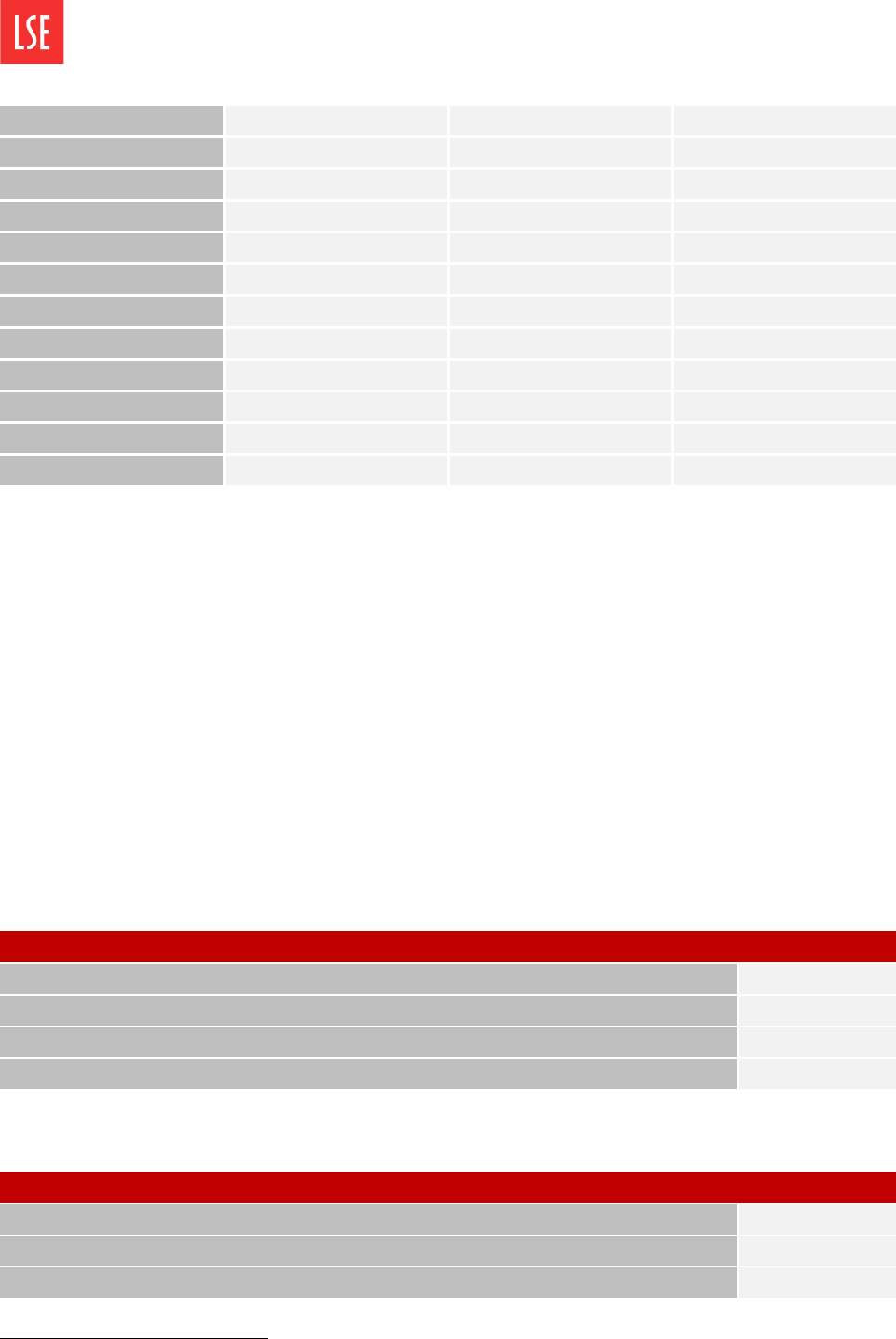

Table 17: Welfare, real wage and price effects on EU and MERCOSUR Members 56

Table 18: Trade-related MEAs signed by the EU and Mercosur 69

Table 19: CO2 Emissions by sector in Mercosur countries and the EU (%) 74

Table 20: Climate change targets in NDC content and laws 75

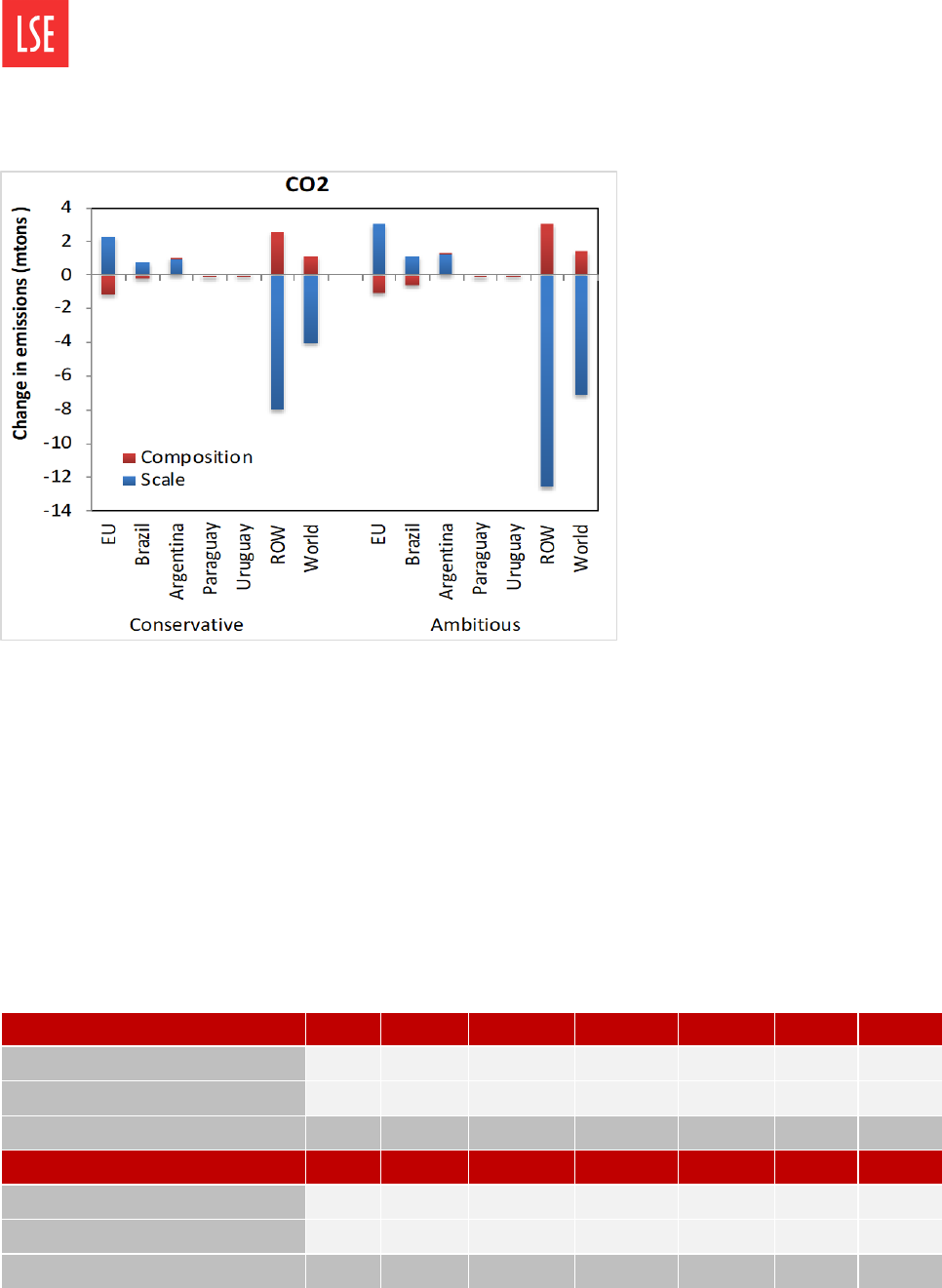

Table 21: Electricity sources in Mercosur countries and the EU 77

Table 22: Top 10 countries in terms of annual forest cover loss in the period 2010-15 (plus EU) 78

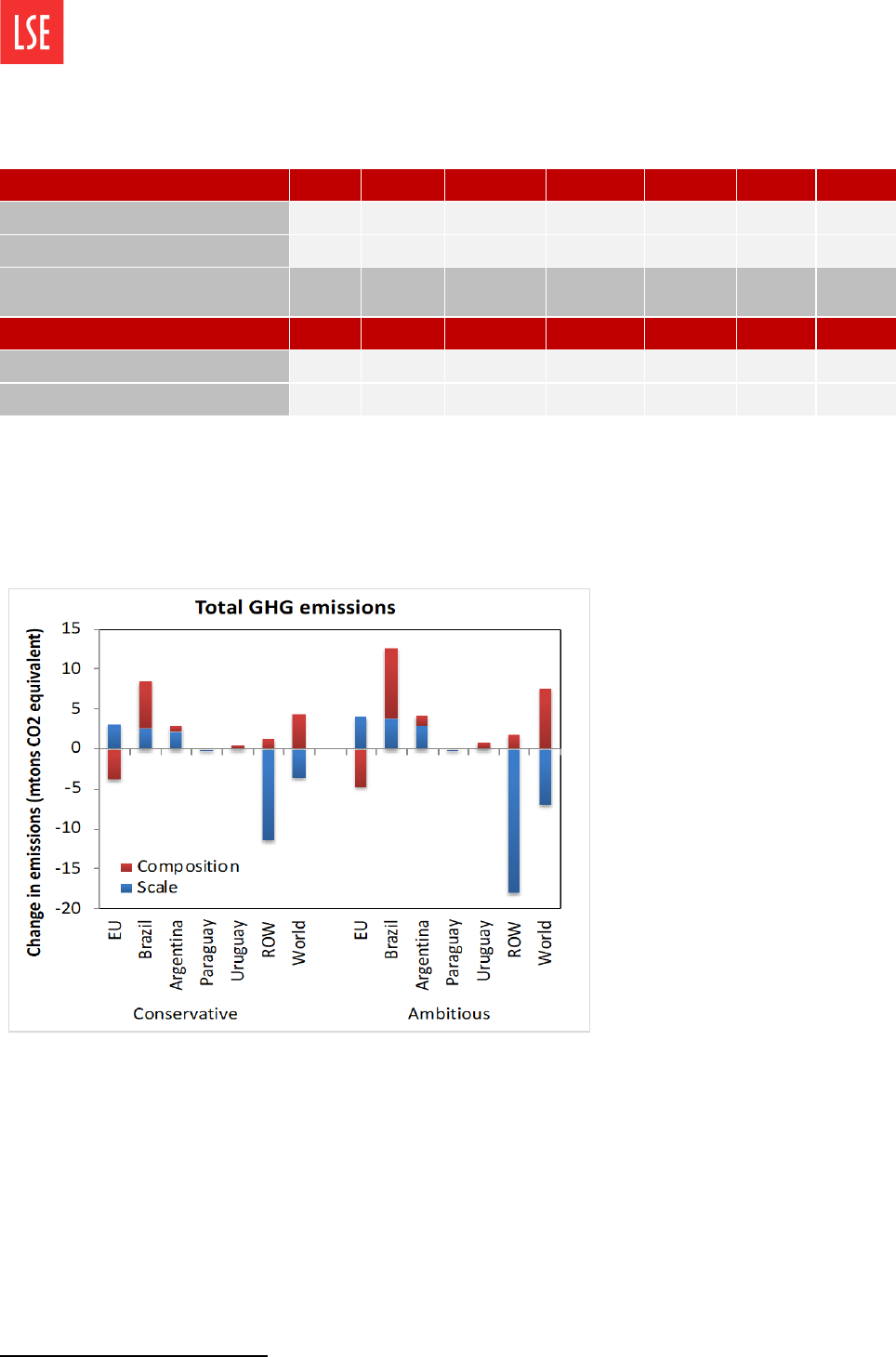

Table 23: Change in CO2 emissions in the two scenarios (long term impact, % change) 86

Table 24: Percentage Change in other GHG emissions in the two scenarios 87

Table 25: Change in total GHG emissions and GDP in the two scenarios (long term impact, % change) 89

Table 26: Percentage of international partnership by co-inventor country (average 2007-2014) – All patents 96

Table 27: Impact of the EU-Mercosur AA on MEA enforcement 97

Table 28: Selected Human Rights 107

Table 29: Identification of sectoral effects and possible human rights linkages 107

Table 30: Human Rights Indicators 108

Table 31: Commitments to the Right to an Adequate Standard of Living 110

Table 32: Right to an Adequate Standard of Living indicators 110

Table 33: Commitments to the Right to Health 120

Table 34: Right to Health indicators 120

Table 35: Commitments to the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 134

Table 36: Commitments to Gender Equality 148

Table 37: Gender Equality Indicators 149

Table 38: Macroeconomic impacts of the AA in the ambitious scenario 171

Table 39: Beef balance in the EU (in thousands of tonnes carcass weight equivalent) 179

Table 40: Beef balance in Mercosur (in thousands of tonnes carcass weight equivalent) 179

Table 41: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade (in billions of Euros) 180

Table 42: Imports of beef products from Mercosur (in millions of Euros) 182

Table 43: Mercosur beef exports to the EU (in millions of Euros) 182

Table 44: MFN tariff applied by the EU on beef products (2016) 183

Table 45: Animal protection regulation in Mercosur countries 185

Table 46: Bovine meat results in the CGE Model 186

Table 47: Land use in Mercosur and the EU (2015) in millions of hectares 189

Table 48: Share of beef in average household consumption in Mercosur 193

Table 49: Least Developed Countries exports of beef (in millions of Euros) 193

Table 50: Balance sheet of dairy products (in thousands of tonnes) 195

Table 51: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade of dairy products (in millions of Euros) 196

Table 52: EU dairy exports to Mercosur (in thousands of Euros) 198

Table 53: Total Mercosur exports of dairy products (including intra-Mercosur, in millions of Euros) 199

Table 54: EU and Mercosur MFN tariffs applied to dairy products in 2016 (%) 200

Table 55: Summary of results in the dairy sector in CGE analysis (million EUR) 203

Table 56: Greenhouse gases emissions in Mercosur and the EU in the production of milk (2012-13) (in mton) 204

Table 57: EU Sugar Market Balance (Million Tonnes) 209

Table 58: EU Ethanol balance (Million Tonnes) 209

Table 59: Sugar and ethanol production in Brazil (million tonnes) 210

Table 60: Revealed Comparative Advantage of EU and Mercosur in sugar and ethanol 211

Table 61: Share of Mercosur in EU trade 212

Table 62: Top five products imported by EU from Mercosur in the sugar sector 213

Table 63: Top exported products by the EU to Mercosur 213

Table 64: Applied MFN tariffs imposed by Mercosur on sugar and ethanol products 215

Table 65: Share of beverages in total EU-Mercosur trade in 2016 220

Table 66: Top 10 beverage products exported from the EU to Mercosur countries, by total value of exports between

2012 and 2016 221

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

6

Table 67: Top 10 beverage products imported by the EU from Mercosur countries, by total value of imports between

2012 and 2016 222

Table 68: EU shares of total beverage imports of Mercosur countries in 2016 223

Table 69: Mercosur countries’ shares in total EU beverage imports in 2016 224

Table 70: Mercosur countries’ applied MFN tariffs on beverage imports from the EU, by HS 6-digit product, 2016 226

Table 71: EU applied MFN tariffs on beverage imports from Mercosur countries, by HS 6-digit product, 2016 227

Table 72: LDC total and selected LDCs with significant beverage exports to the EU (based on the average export value

from 2012-2016), by product 232

Table 73: EU exports to Mercosur, top 20 most exported T&G products, 2016 236

Table 74: EU imports from Mercosur, top 20 most imported T&G products, 2016 238

Table 75: Top 20 Pharmaceutical and Chemical Exports from the EU to Mercosur 248

Table 76: Top 20 Pharmaceutical and Chemical Imports from Mercosur to the EU 250

Table 77: Extra-EU Exports of SMEs and Large Companies, Pharmaceutical and Chemical 252

Table 78: Extra-EU Imports of SMEs and Large Companies, Pharmaceutical and Chemical 253

Table 79: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade on electronic equipment and machinery (2015-18) (in thousands of Euros) 255

Table 80: Mercosur trade on Machinery and electronic equipment (2015-18) (in millions of Euros) 256

Table 81: Top EU exports to Mercosur average 2015-18 (in thousands of Euros) 258

Table 82: Top EU imports from Mercosur average 2015-18 (in thousands of Euros) 260

Table 83: EU-Mercosur bilateral trade changes in the machinery and electronic equipment and manufactures nec 262

Table 84: Output and total trade changes in the machinery and electronic equipment and manufactures nec 263

Table 85. Labour demand changes in the machinery and electronic equipment and manufactures nec 265

Table 86: Applied tariffs in the automotive industry (selected countries, %, 2016) 268

Table 87: Changes in the Motor Vehicle Sector 279

Table 88: Changes in private consumption 281

Table 89: Composition of EU exports to Mercosur by service type 284

Table 90: Composition of EU imports from Mercosur by service type 284

Table 91: Service Trade Barriers for Selected Service Types 285

Table 92: National composition of GDP, Argentina 286

Table 93: National composition of GDP, Brazil 286

Table 94: Other business services trade between the EU and individual Mercosur countries: EU exports 290

Table 95: Other business services trade between the EU and individual Mercosur countries: EU imports 292

Table 96: CGE-model results in the communication and business services sector in the conservative scenario 295

Table 97: CGE-model results in the communication and business services sector in the ambitious scenario 295

Table 98: Argentina’s current commitments under the WTO GATS agreement in business services240F 296

Table 99: Brazil’s current commitments under the WTO GATS agreement in business services241F 298

Table 100: Uruguay’s current commitments under the WTO GATS agreement in business services242F 301

Table 101: Composition of EU services exports to Mercosur by service type 305

Table 102: Composition of EU services imports from Mercosur by service type 305

Table 103: Service Trade Barriers for Selected Service Types 306

Table 104: National composition of GDP, Argentina 306

Table 105: National composition of GDP, Brazil 307

Table 106: Financial and insurance services trade between the EU and individual Mercosur countries: EU exports 309

Table 107: Financial and insurance services trade between the EU and individual Mercosur countries: EU imports 310

Table 108: CGE-model results in the financial services and insurance sector in the conservative scenario 312

Table 109: CGE-model results in the financial services and insurance sector in the ambitious scenario 312

Table 110: Current commitments under the WTO GTAS agreement, financial services, Argentina 314

Table 111: Current commitments under the WTO GTAS agreement, financial services, Brazil 317

Table 112: Current commitments under the WTO GATS agreement, financial services, Paraguay 320

Table 113: Current commitments under the WTO GTAS agreement, financial services, Uruguay 322

Table 114: Stakeholder Consultation Brussels Roundtables - Findings 327

Table 115: Stakeholder Consultation Partner Country Roundtables – Findings 328

Table 116: Civil Society Dialogue Meetings - Findings 329

Table 117: Online Consultation responses to the Interim Report CSD 330

Table 118: In-country activities - Main Findings 334

Table 119: Selected indicators 358

Table 120: Primary and secondary data sources 359

Table 121: Sectoral Private Consumption changes in the Conservative Scenario 393

Table 122: Sectoral Exports changes in the Conservative Scenario 395

Table 123: Sectoral Imports changes in the Conservative Scenario 396

Table 124: Sectoral Private Consumption changes in the Ambitious Scenario 397

Table 125: Sectoral Exports changes in the Ambitious Scenario 398

Table 126: Sectoral Imports changes in the Ambitious Scenario 399

Table 127: Sectoral Unskilled Employment changes in the Conservative Scenario 400

Table 128: Sectoral Skilled Employment changes in the Conservative Scenario 401

Table 129: Sectoral Unskilled Employment changes in the Ambitious Scenario 402

Table 130: Sectoral Skilled Employment changes in the Ambitious Scenario 403

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

7

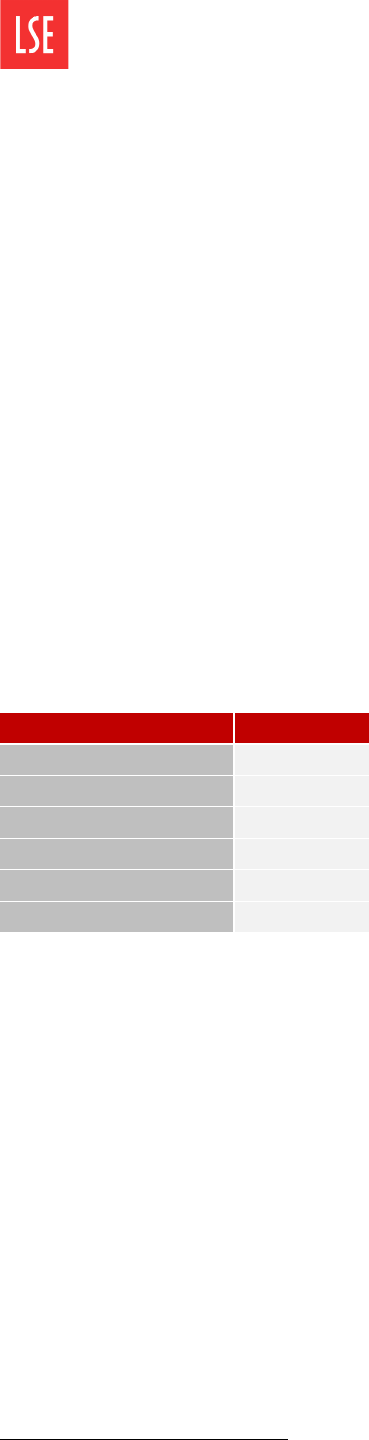

List of Figures

Figure 1: Map of Mercosur 18

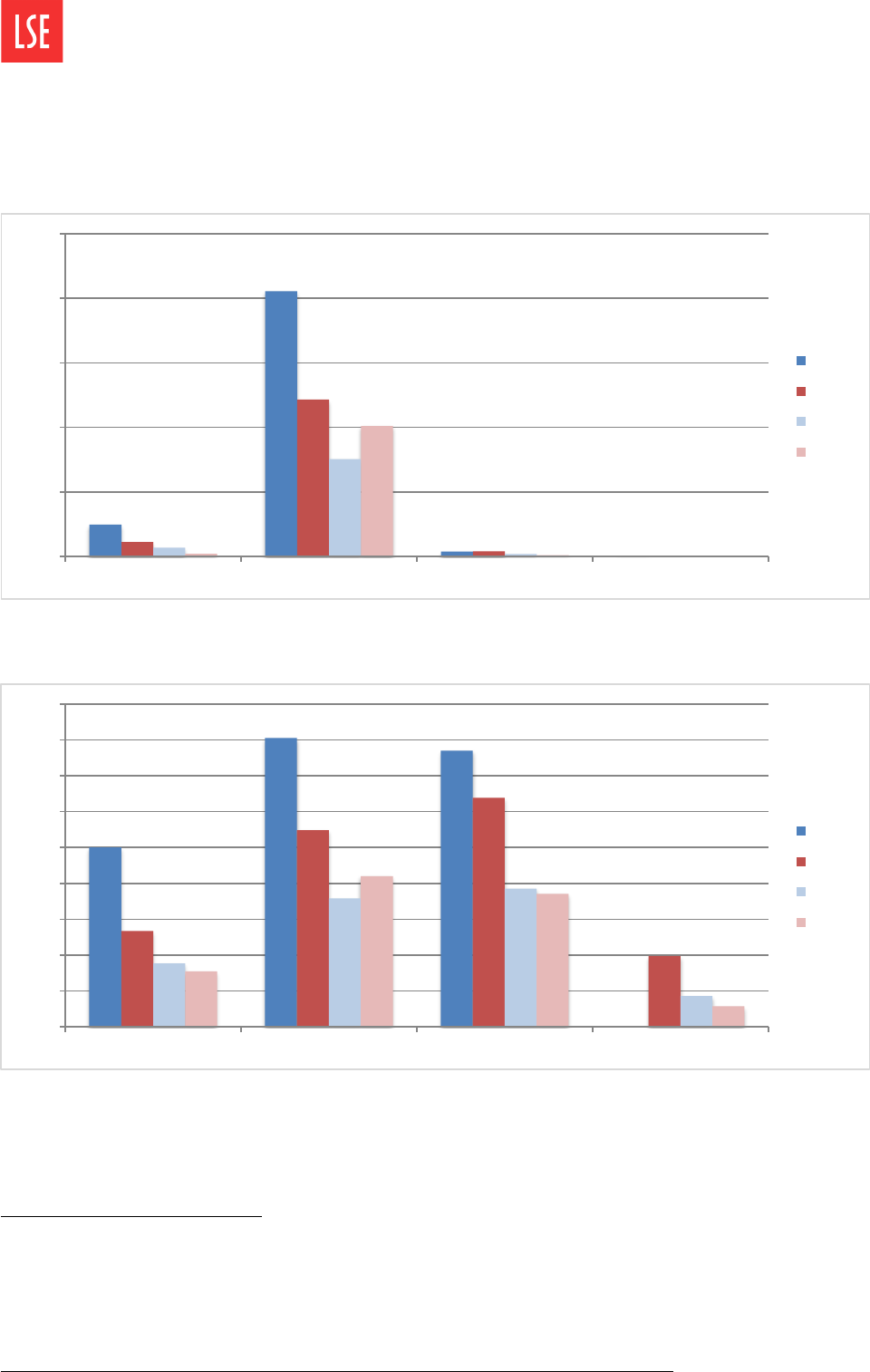

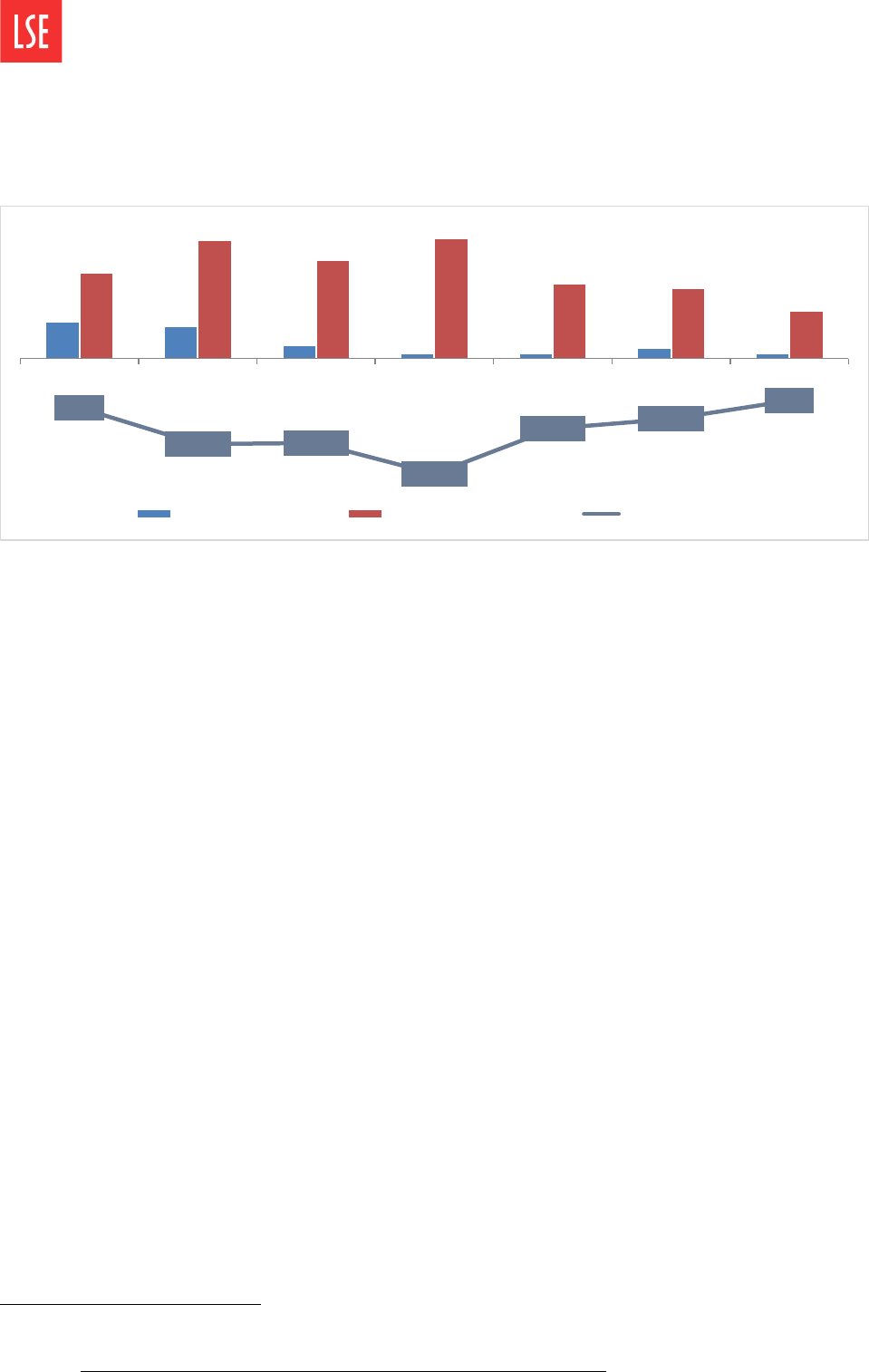

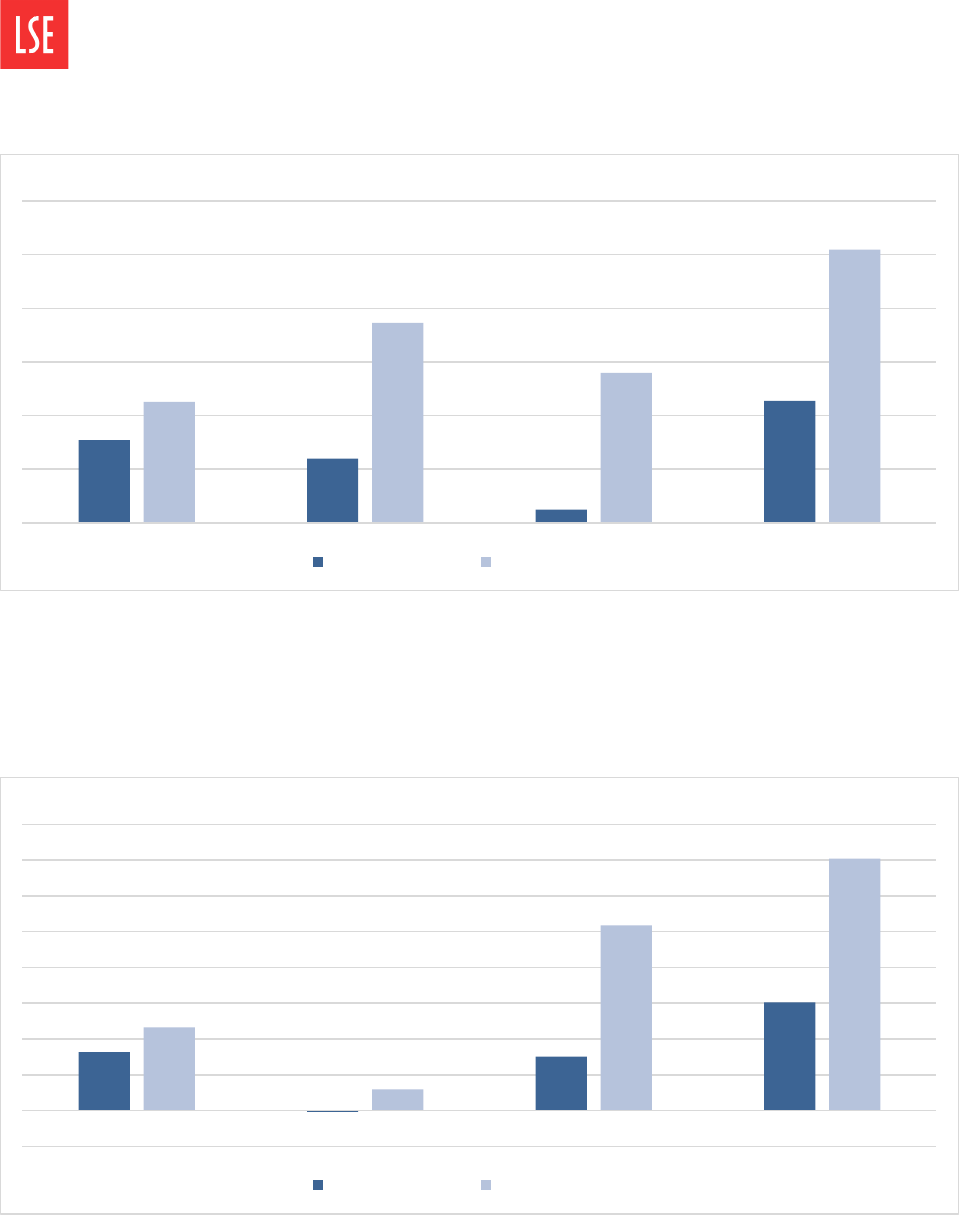

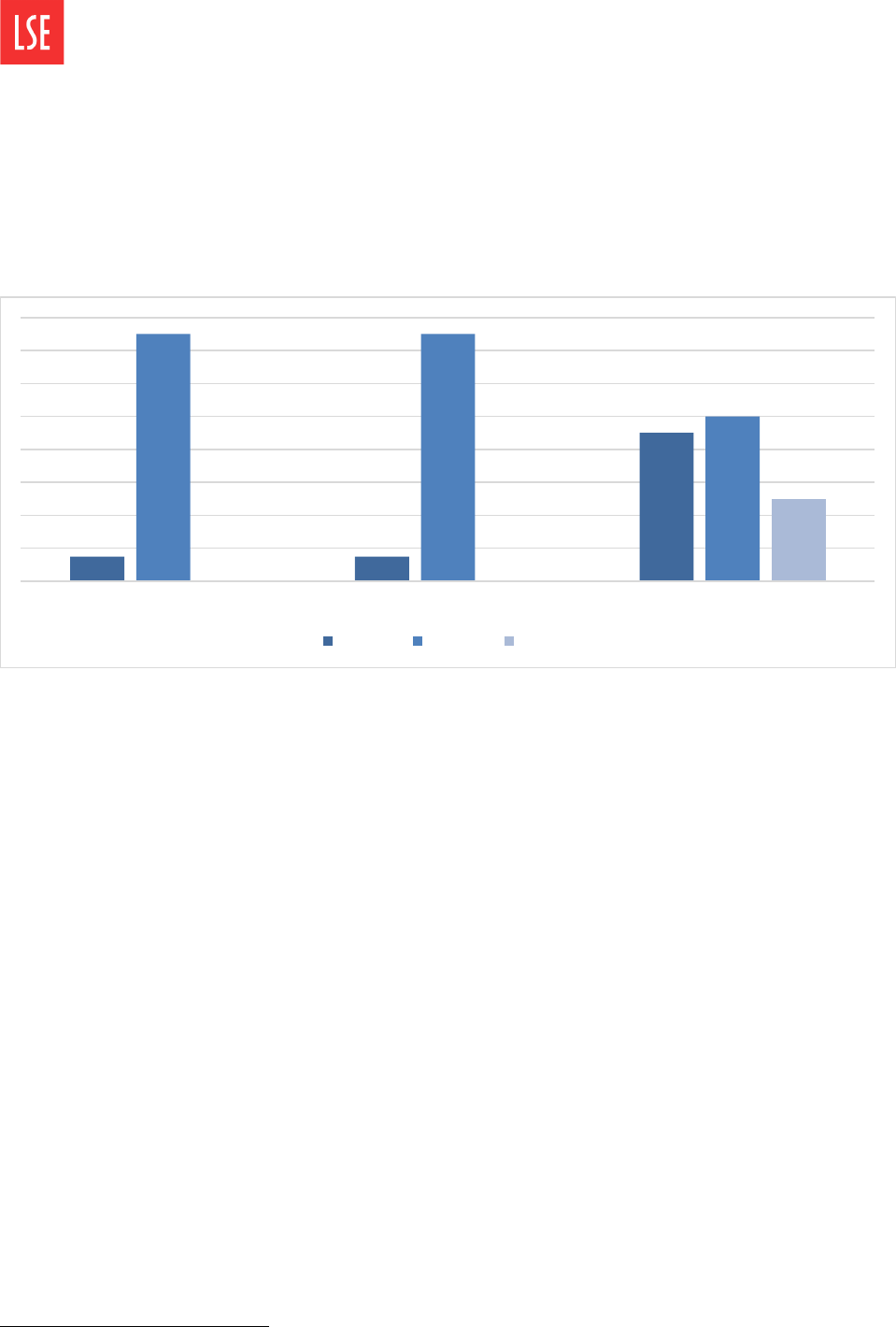

Figure 2: EU and Mercosur unemployment trends (2000-2019) 38

Figure 3: Informal employment and informal sector in Mercosur countries as a percent of employment (%) 39

Figure 4: Number of people living with less than $1.90 a day (millions, 2011 PPP) 40

Figure 5: Number of people living with less than $1.90 a day (millions, 2011 PPP) 41

Figure 6: Percentage of people living with less than $5.50 a day, 2011 PPP 41

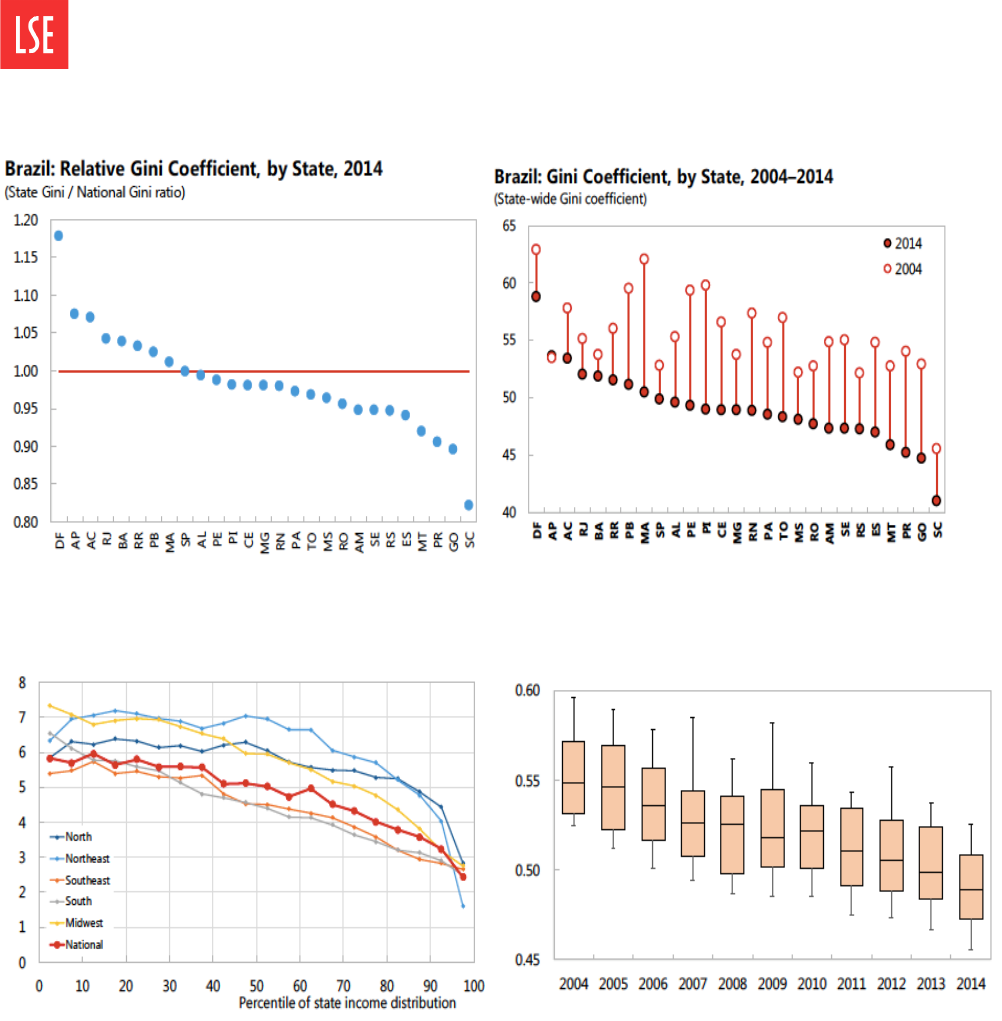

Figure 7: Income inequality in Mercosur (Gini coefficient) 42

Figure 8: Brazil: Convergence in Access to Durable Goods by Households (% of Brazilian households) 42

Figure 9: Income convergence between and within Brazilian states and regions 44

Figure 10: Measures of freedom of association and labour rights protection in Mercosur (2019)* 48

Figure 11: EU employment supported by extra-EU exports: number of jobs in millions 55

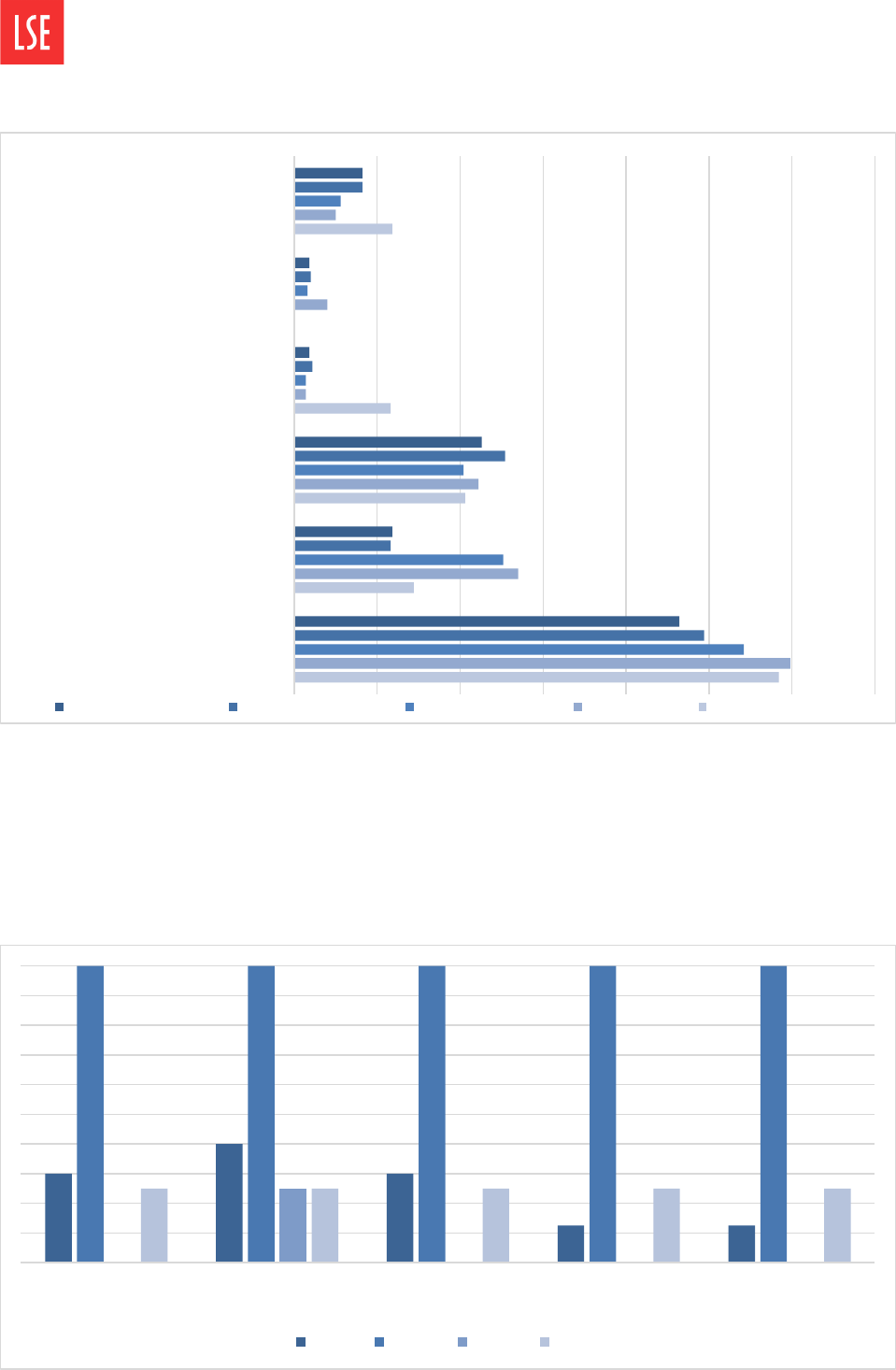

Figure 12: EPI for Mercosur and the EU 70

Figure 13: EPI score over time 70

Figure 14: Scores in EPI sub-categories. EU and Mercosur countries in 2018 71

Figure 15: Climate Laws, Institutions and Measures Index and GDP per capita 72

Figure 16: Total GHG Emissions and emissions per capita in Mercosur countries and the EU (2015) 73

Figure 17: Total GHG Emissions by type of gas in Mercosur countries and the EU (2015) 73

Figure 18: Levels of CO2 per capita in 2015 (left) and trends in CO2 per capita since 1970 (right) 73

Figure 19: Levels of methane per capita in 2015 (left); trends since 1970 (right) 74

Figure 20: Levels of Nitrous Oxide per capita in 2015 (left) and trends since 1970 (right) 75

Figure 21: Deforestation in the Legal Amazon states (left) and Cerrado (right) 79

Figure 22: Wood production for Brazil (left) & other Mercosur countries (right) 81

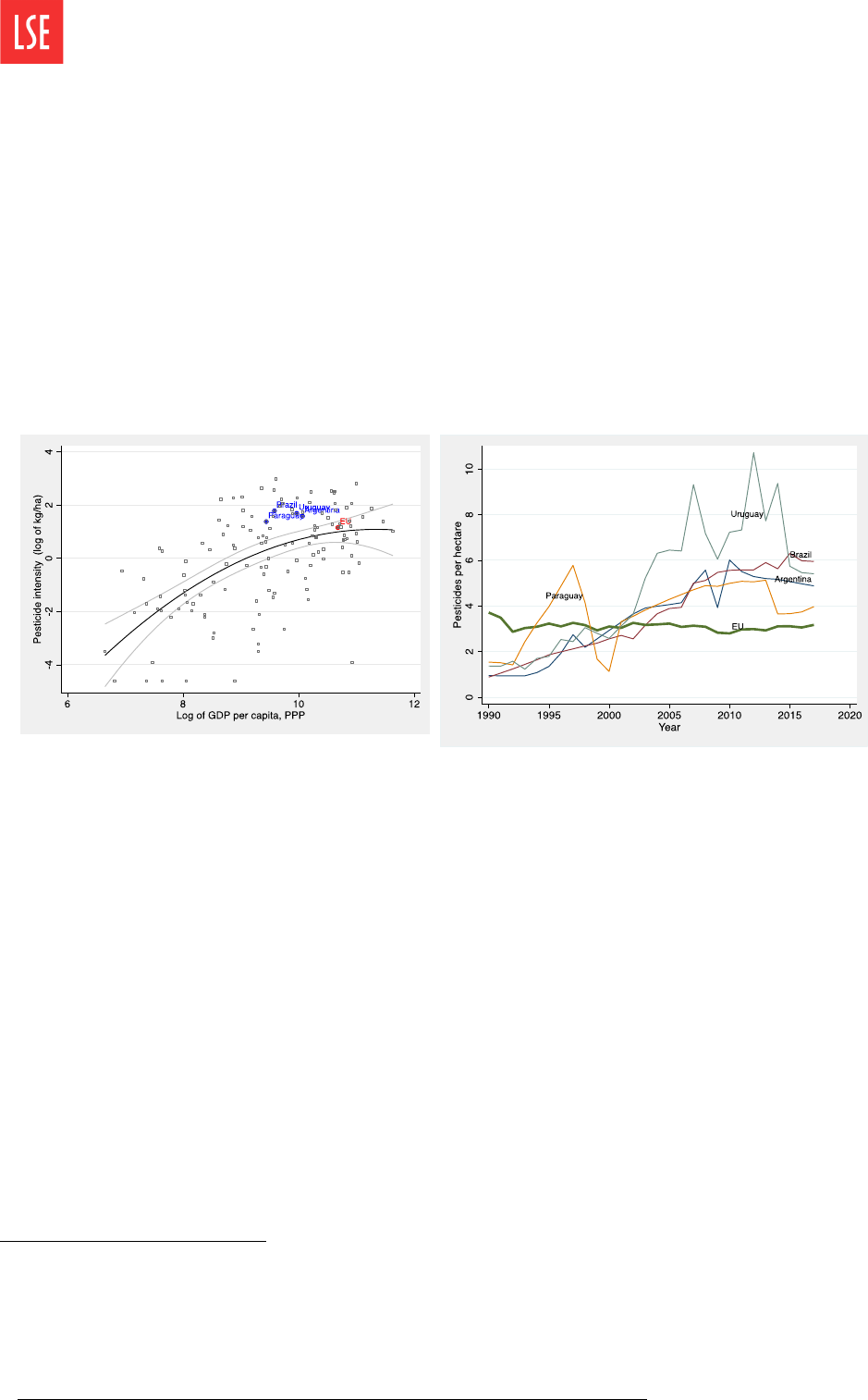

Figure 23: Pesticide use by income levels (2017) and over time (1990-2017) 83

Figure 24: Fertiliser use by income levels (2017) and over time (2002-2017) 84

Figure 25: Exposure to PM2.5 85

Figure 26: Waste generation and collection 85

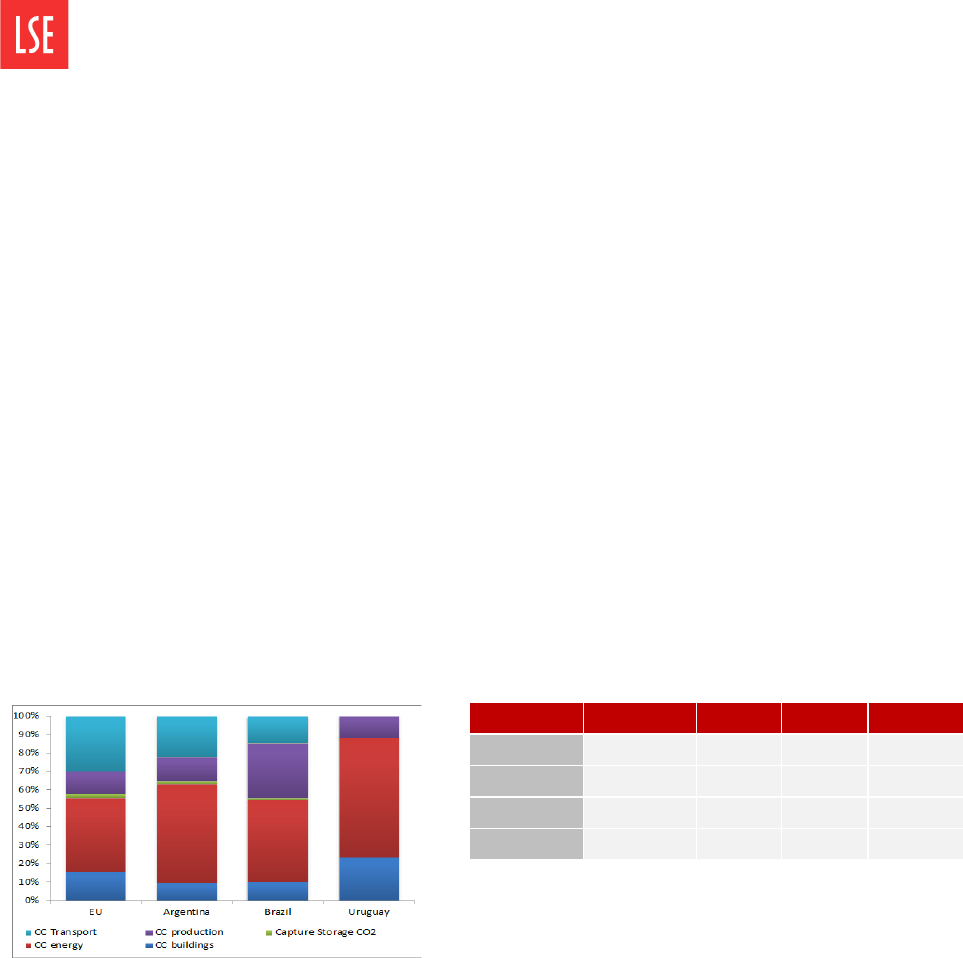

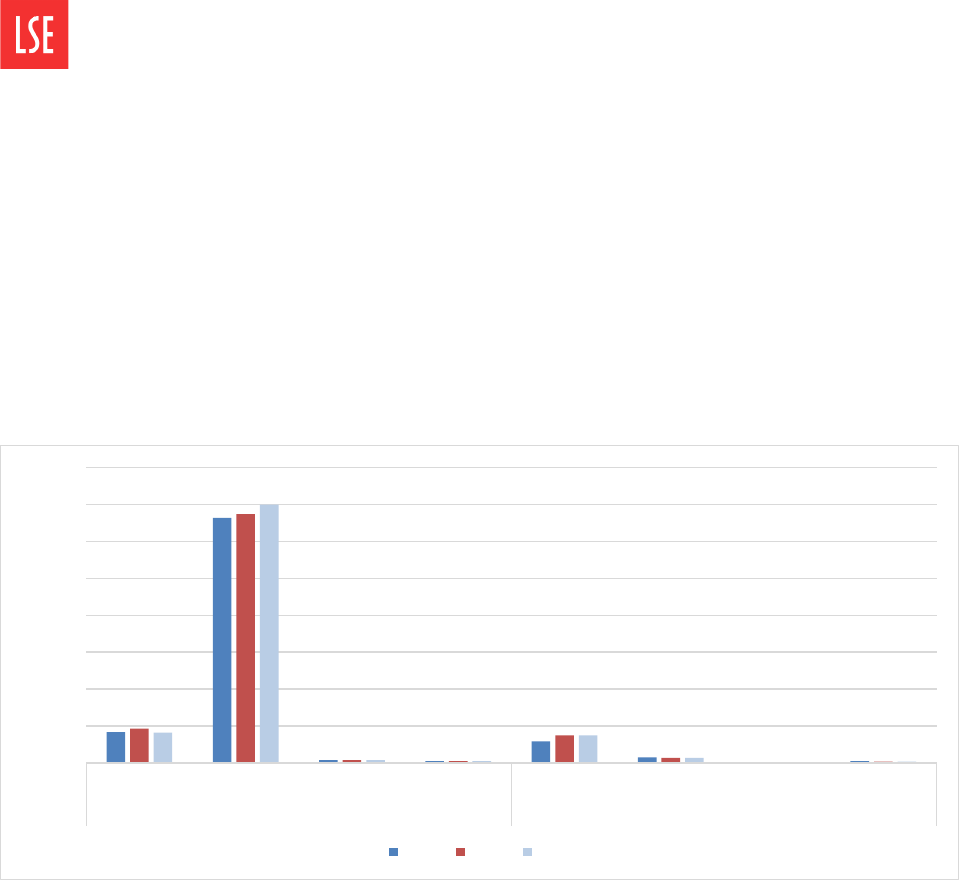

Figure 27: Decomposition of impact on CO2 emissions: conservative scenario (left) and ambitious scenario (right) 87

Figure 28: Decomposition of impact on GHG emissions: methane (left) and nitrous oxide (right) 88

Figure 29: Decomposition of impact on total GHG emissions: conservative scenario and ambitious scenario 89

Figure 30: Patents applications related to climate change mitigation by applicant’s country (accumulated 2005-15) 96

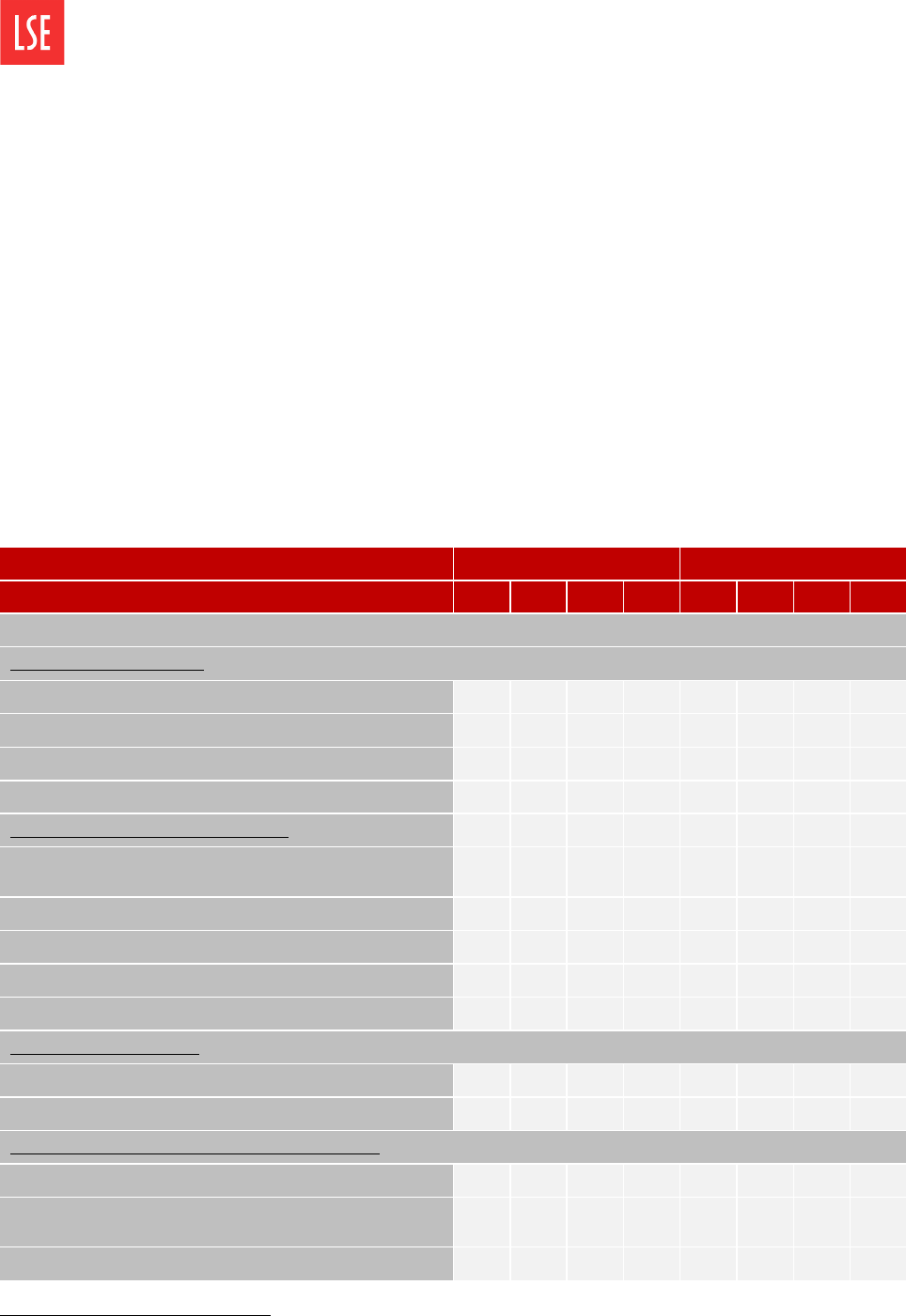

Figure 31: Poverty Headcount Ratio at $1.90 a day in Northern, Eastern, Western, and Southern EU MS 111

Figure 32: Percentage of population with access to basic sanitation facilities (left) electricity (middle) and

information/communication technologies (right) in the EU 112

Figure 33: Percentage of population undernourished (left) lacking access to basic drinking water services (middle) and

lacking access to clean cooking technologies (right) in the EU 113

Figure 34: Poverty Headcount Ratio at $1.90 a day (% of population) 114

Figure 35: Population living in slums (% of urban) (top left); Access to basic sanitation facilities (top right) % of

population with access to electricity (bottom left); and information/communication technologies (bottom right) 116

Figure 36: Percentage of population undernourished (left) lacking access to basic drinking water services (middle) and

lacking access to clean cooking technologies (right) in Argentina 118

Figure 37: Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP); Universal Health Coverage Index score 121

Figure 38: Nurses and midwives, physicians, and specialist surgeons per 100,000 people (left); Hospital beds per 1,000

people (right) 121

Figure 39: Proportion of population spending more than 10% and more than 25% of household consumption on out of

pocket payments 122

Figure 40: Medicine Price Index across EU MS 123

Figure 41: Cause of death (left); mortality rate due to inadequate living conditions per 1000,000 people (right); and

prevalence of anemia (right) 123

Figure 42: Prevalence and Incidence of Mental Disorders (l), and suicide mortality rate per 100,000 people (r) 124

Figure 43: Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP) (top left) and Universal Health Coverage Index

ranking (top right) Nurses, midwives, physicians, and specialist surgeons per 100,000 people (bottom left); Hospital

beds per 100,000 people (bottom right) 125

Figure 44: Proportion of population spending more than 10% and more than 25% of household consumption on out of

pocket payments (left) and Risk of impoverishing expenditure for surgical care (right) 127

Figure 45: Medicine Price Index in Argentina and Brazil (top); prevalence and treatment of HIV (bottom left); and rates

of immunisation (bottom right) 128

Figure 46: Cause of death (left) and mortality rate due to inadequate living conditions per 100,000 people (middle) and

suicide mortality rate per 100,000 people (right) 130

Figure 47: Prevalence of underweight children (l); overweight children (r); anemia among children and women (bl); and

stunting (br) 131

Figure 48: Map of Indigenous Communities in Argentina (left); Brazil (middle); and Paraguay (right) 137

Figure 49: Square kilometres of newly demarcated land in Brazil 139

Figure 50: Indigenous Occupational Structure by Sector 140

Figure 51: Percentage of population unemployed 141

Figure 52: Infant Mortality Rate 142

Figure 53: Access to Adequate Living Conditions for Indigenous Peoples 143

Figure 54: Rates of Illiteracy among Indigenous Populations 145

Figure 55: Average years of study among Indigenous Populations 145

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

8

Figure 56: School Attendance 146

Figure 57: Percentage of Indigenous Population Fluent in traditional Language in Paraguay 147

Figure 58: Gender Inequality Index scores among EU Member States 150

Figure 59: Mortality rate (left); Life expectancy (middle); progression to secondary school (right) 150

Figure 60: Unemployment (top left); % of women in wage employment (top right); % of population in vulnerable

employment (bottom left); time spent on unpaid work (bottom right) 151

Figure 61: Employment by Gender and Sector 152

Figure 62: Gender Inequality Index scores among Mercosur partner countries 153

Figure 63: Mortality rate (left); Life expectancy (middle); progression to secondary school (right) 154

Figure 64: Unemployment (top left), % of women in wage employment (top right); % in vulnerable employment (bottom

left); % of time spent on unpaid work (bottom right) 154

Figure 65: Percentage of Female Employment (left) and Male Employment (right) by Sector, 2017 156

Figure 66: Share of sugar & ethanol imports in total imports from Mercosur (%) 212

Figure 67: Applied MFN tariffs imposed by the EU in 2016 (AVE) 214

Figure 68: Tariffs on sugar products 214

Figure 69: Tariffs on Ethanol products 214

Figure 70: EU-Mercosur trade in alcoholic & non-alcoholic beverages, 2012-2016 220

Figure 71: EU beverage production in € billions, by beverage type, 2012-2014 224

Figure 72: Beer & wine production (million tonnes) in Mercosur, 2012-2014 225

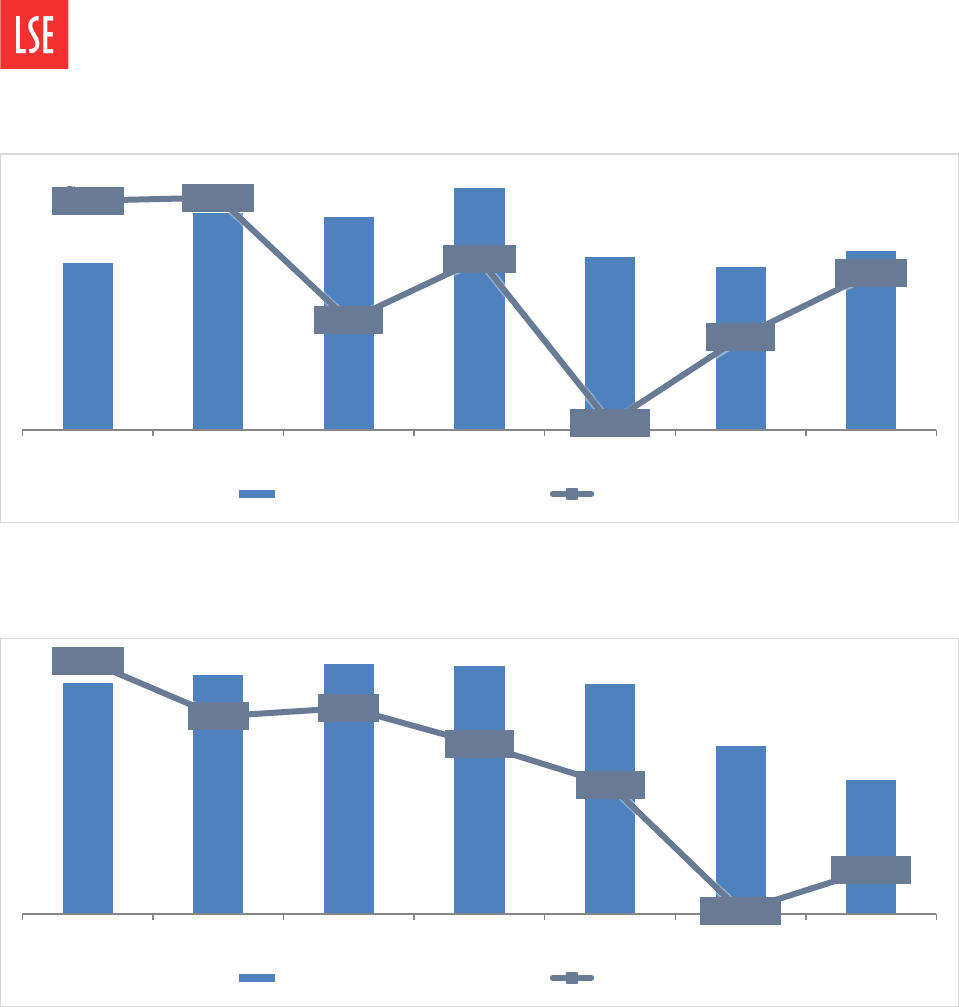

Figure 73: EU exports of garment and textile to Mercosur by country, 2012-2016 234

Figure 74: EU exports of garment and textile to Mercosur by type, 2012-2016 235

Figure 75: EU imports of garment and textile from Mercosur, 2012-2016 237

Figure 76: EU import of garment and textile from Mercosur by type, 2012-2016 237

Figure 77: EU net export of T&G to Mercosur, 2012-2016 239

Figure 78: Mercosur average applied tariff by country, HS 50-62, 2005-2016 239

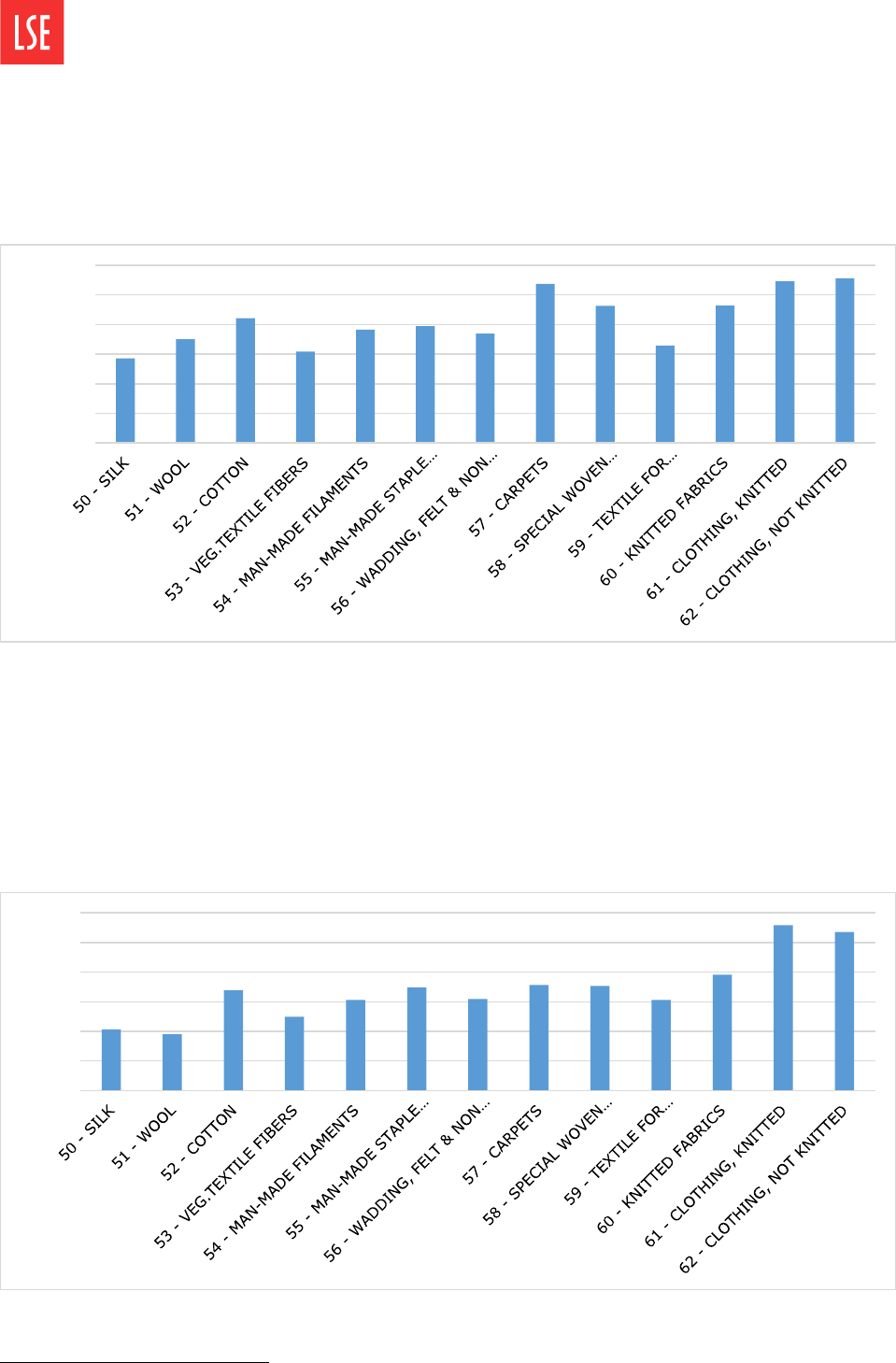

Figure 79: Mercosur average applied tariff by HS code, HS 50-62, 2016 240

Figure 80: EU average applied tariff by HS code, HS 50-62, 2015 240

Figure 81: EU and Mercosur average applied tariff, HS 50-62, 2007-2015 241

Figure 82: EU28 Chemical and Pharmaceutical Exports and Imports 246

Figure 83: EU28 Trade in Chemical and Pharmaceutical Products with Mercosur (Total), in € million 247

Figure 84: EU28 Trade in Chemical and Pharmaceutical Products with Mercosur (% of total extra-EU28 chemical and

pharmaceutical trade) 247

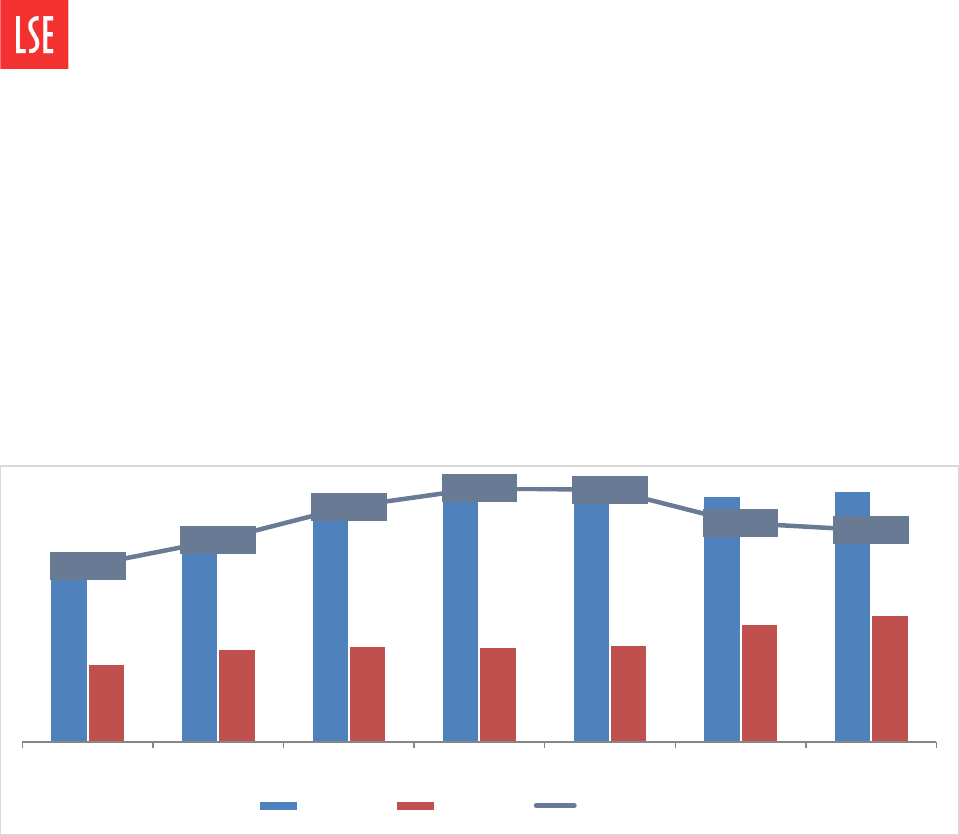

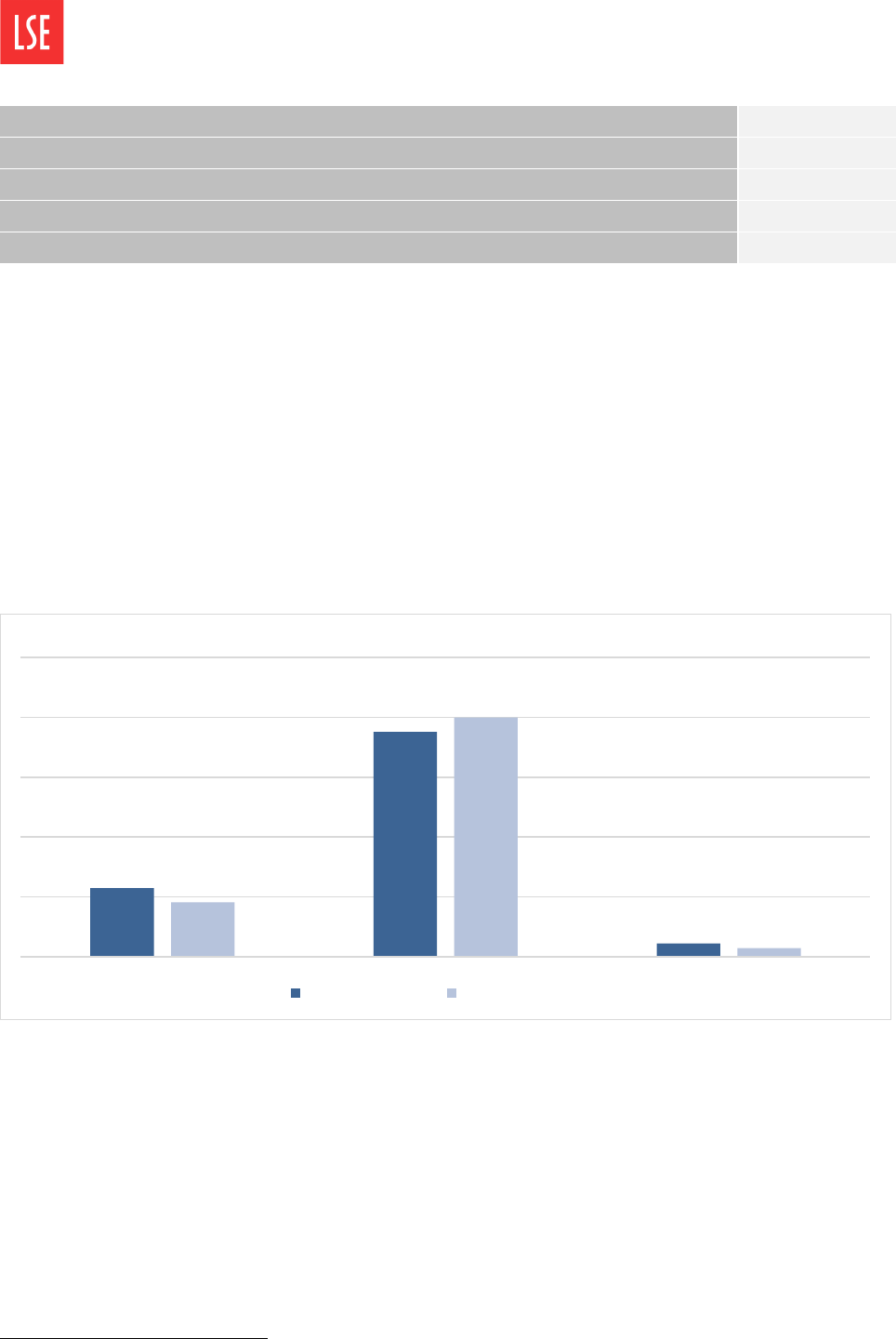

Figure 85: Automotive Intra-Regional Trade Index in EU-28 269

Figure 86: Automotive Intra-Regional Trade Index in Mercosur 270

Figure 87: EU-28 - Motor Vehicle Production 270

Figure 88: Argentina - Motor Vehicle Production 271

Figure 89: Brazil - Motor Vehicle Production 271

Figure 90: Motor Vehicle Production by Type 272

Figure 91: EU-28 - Motor Vehicle Registrations 272

Figure 92: Argentina - Motor Vehicle Sales 273

Figure 93: Brazil - Motor Vehicle Sales 273

Figure 94: EU-28 External Trade in Motor Vehicles (excluding intra-regional trade), EUR mn 274

Figure 95: Mercosur - External Trade in Motor Vehicles (excluding intra-regional trade), EUR mn 274

Figure 96: EU-28 External Trade in Auto Parts (excl. intra-regional trade), EUR mn 275

Figure 97: Argentina, External & intra-regional Trade in Auto Parts, EUR mn 276

Figure 98: Brazil - External Trade in Auto Parts,* EUR mn 276

Figure 99: Bi-regional Trade of Mercosur and EU-28 in Motor Vehicles, EUR mn 277

Figure 100: EU service exports and imports to/from Mercosur 282

Figure 101: EU service exports to selected countries 282

Figure 102: EU service imports from selected countries 283

Figure 103: Importance of the EU as trading partner for Mercosur (services) 283

Figure 104: Share in total Extra-EU28, exports, other business services, 2015 287

Figure 105: Share in total Extra-EU28 imports by sector, 2015 288

Figure 106: Average annual growth rate of EU services exports, 2010 - 2015 289

Figure 107: Average annual growth rate of EU services imports, 2010 - 2015 289

Figure 108: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for professional services in Argentina 297

Figure 109: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for professional services in Brazil 299

Figure 110: Brazil’s services trade restrictiveness in the business services sector 300

Figure 111. Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for professional services in Paraguay 300

Figure 112: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for professional services in Uruguay 302

Figure 113: Share in total Extra-EU28 exports, financial and insurance services, 2015 307

Figure 114: Share in total Extra-EU28 imports, financial and insurance services, 2015 307

Figure 115: Average annual growth rate of EU exports, 2010 - 2015 308

Figure 116: Average annual growth rate of EU imports, 2010 - 2015 308

Figure 117: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for banking services in Argentina 315

Figure 118: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for insurance services in Argentina 316

Figure 119: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for banking services in Brazil 318

Figure 120: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for insurance services in Brazil 319

Figure 121: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for banking services in Paraguay 321

Figure 122: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for insurance services in Paraguay 321

Figure 123: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for Banking services in Uruguay 323

Figure 124: Services trade restrictiveness (STRI) for insurance services in Uruguay 323

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

9

List of Abbreviations

AA

ACP

Association Agreement

African,

Caribbean and Pacific Countries

ARG

Argentina

AVE

Ad Valorem Equivalents

BEC

BNDES

Broad Economic Categories

Brazilian Development Bank

BRA

Brazil

CAP

Common Automobile Policy

CDE

Constant Difference Elasticity

CEDAW

Convention on the Elimination on All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

CERD

CET

Convention on Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination

Common External Tariff

CETA

EU-Canada Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement

CETM

Copenhagen Economic and Trade Model

CGE

CLIMI

Computable General Equilibrium

Climate Laws, Institutions and Measures Index

CLS

Core Labour Standards

CMC

Consejo Mercado Comun

CMPED

Centro Mercosur de Promocion de Estado de Derecho

CO2

Carbon Dioxide

CSD

CSR

Civil Society Dialogue

Corporate

Social Responsibility

DDA

Doha Development Agenda

DG

Directorate General

DOM

Domestic

EBA

Everything But Arms

EBRD

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EC

European Commission

ECA

European Consumer Agenda

EFTA

European Free Trade Association

EIDHR

EPO

ESAF

European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights

European Patent Office

Economic and Social Advisory Forum

EU

European Union

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

FBD

Food Borne Illness

FDI

Foreign Direct Investment

FK

Finger-Kreinin

FIDH

FMD

International Federation for Human Rights

Foo

t-and-Mouth Disease

FTA

Free Trade Agreement

FTIS

Foreign Trade Information System

GATS

General Agreement on Trade in Services

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GDyn Model

Dynamic GTAP Model

GHG

Green House Gas

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

10

GPGC

Global Public Goods and Challenges

GSP

Generalized System of Preferences

GTAP

Global Trade Analysis Project

HR

Human Rights

HRC

Human Rights Council

HRIA

Human Rights Impact Assessment

HS6

IA

Harmonized System at 6 Digits

Impact Assessment

ICCPR

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

IEA

International Energy Agency

ICESCR

International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

ILO

International Labor Organization

INADI

National Institute Against Discrimination, Racism, and Xenophobia

IMF

International Monetary Fund

IPPDH

Instituto de Politicas Publicas en Derechos Humanos

ITUC

International Trade Union Confederation

I2E

Import to Export

JRC

Joint Research Centre

LDC

Least Developed Country

LES

Linear Expenditure System

LMDI

Log Mean Divisia Index

LSE

LULUCF

London School of Economics and Political Science

Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry

MEA

Multilateral Environmental Agreements

Mercosur

Mercado Comun del Sur

MFN

Most Favoured Nation

NAMA

Non-Agricultural Market Access

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

NTB

Non-Tariff Barriers

NTM

Non-Tariff Measures

NUTS2

Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics Level 2

ODM

Observatorio de la Democracia del Mercosur

OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

PCT

Patent Cooperation Treaty

PE

Partial Equilibrium

PRY

Paraguay

RAADH

Reunión de Ministras y Altas Autoridades de DDHH y Cancillerías del Mercosur y Estados Asociados

RAFRO

Reunión de Ministros y Altas Autoridades Sobre los Derechos de los Afrodescendientes

RAPEX

Rapid Exchange of Information System

RAPIM

RBC

Reunión de Autoridades Sobre Pueblos Indígenas

Responsible Business Conduct

RCA

Revealed Comparative Advantage

R&D

Research and Development

RAAM

Reunión de Altas Autoridades de la Mujer

RoW

Rest of World

RTA

Regional Trade Agreements

SADC

South Africa Development Community

SDT

Special Differential Treatment

SIA

Sustainability Impact Assessment

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

11

SENAF

SENASA

National Secretariat of Childhood, Adolescence, and Family

Servicio Nacional de Sanidad

SITC

Standard International Trade Classification

SME

Small Medium Enterprise

SPS

Sanitary & Phytosanitary

STRI

Service Trade Restrictiveness Index

TBTs

Technical Barriers to Trade

TEU

Treaty on European Union

TiVA

Trade in Value Added

ToR

Terms of Reference

TPP

Trans-Pacific Partnership

TRQ

Tariff Rate Quotas

UNCTAD

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNDRIP

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

UNEP

United Nations Environmental Program

UNESCAP

UNFCCC

UNAI

UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

United Nations Academic Impact

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organization

UN UPR

UN Universal Periodic Review

URY

USPTO

Uruguay

United

States Patent and Trademark Office

VAT

Value Added Tax

WDI

World Development Index

WIOD

World Input-Output Database

WTO

World Trade Organization

WTO MC

World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

12

Executive Summary

The trade relations between the EU and Mercosur are essential for both blocs, given that the EU

is the second trading partner for Mercosur and Mercosur the eleventh trading partner for the EU.

An inter-regional Framework Cooperation Agreement from 1999 currently forms the basis for

EU-Mercosur trade relations. Following negotiations since 2000, in June 2019 the EU and

Mercosur reached a political agreement for an Association Agreement including a trade

component.

This Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) provides an examination of the potential economic,

social, human rights and environmental impact of the trade component of an Association

Agreement between the EU and Mercosur, specifically Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.

This analysis lays the basis for designing flanking and mitigating measures, a number of which

are proposed throughout the study.

The report employs the dynamic version of the GTAP Model known as GDyn to study the impacts

of two scenarios, one conservative and one more ambitious, with respect to the outcome of the

negotiations in terms of tariff and non-tariff measures reductions by both parties. For Mercosur,

the conservative scenario assumes the elimination of tariffs in 90% of the industrial products

and 80% in agricultural products. In the ambitious scenario, Mercosur eliminates tariffs in 100%

of products. The EU eliminates tariffs in all industrial products in both scenarios, applies partial

tariff cuts of 15% in the conservative scenario and 30% in the ambitious scenario in rice, sugar,

ruminant meat and other meat sectors. For the cereals and the dairy sector, cuts of 15% are

applied in the conservative scenario and cuts of 100% in the ambitious scenario.

Quantitative methods are then combined with qualitative approaches to address social,

environmental and human rights impacts of the free trade agreement as well as the specific

economic impacts on ten important sectors.

1

This qualitative analysis draws on extensive

consultation with stakeholders in both regions through workshops, civil society dialogues,

questionnaires and interviews.

In the conservative scenario, GDP in the EU expands by 10.9 billion Euros (0.1%) and in

Mercosur by 7.4 billion Euros (0.3%) by 2032, in comparison to the modelling baseline without

the FTA. In the ambitious scenario, GDP in the EU expands by 15 billion Euros (0.1%) and in

Mercosur by 11.4 billion Euros.

EU total exports to the world (extra-EU) expand by 0.4% in the conservative scenario and by

0.6% in the ambitious scenario. In Mercosur, total exports to the world expand between 0.5%

in Paraguay and 4.5% in Brazil in the conservative scenario and between 0.7% in Uruguay and

6.1% in Brazil in the ambitious scenario. EU imports increase by 0.9% (1.1% in the ambitious

scenario). In Mercosur, imports expand between 0.1% in Paraguay and 1.3% in Brazil in the

conservative scenario and between 0.0% in Paraguay and 1.4% in Brazil in the ambitious

scenario.

The modelling results provide also some valuable insights for the social analysis. In the

conservative scenario, the agreement reduces consumer prices in Mercosur between 0.4% in

Paraguay and 1.5% in Brazil (between 0.5% and 2.1% in the ambitious scenario in the same

1

The sectors for in-depth analysis were selected in consultation with the EC.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

13

countries). In the EU, they increase by 0.2% (0.3% in the ambitious scenario). Real wages for

both skilled and unskilled workers in Mercosur increase slightly in the EU, Argentina, Paraguay

and Uruguay and remain the same in Brazil. The increase in real wages for unskilled workers’

income suggests a positive impact in terms of poverty reduction, although its effect is small in

the conservative scenario and only marginally larger in the ambitious scenario.

Employment reductions in certain manufacturing sectors in Mercosur are offset by increases in

the agriculture and food production sectors. The impact on the EU sectoral employment patterns

is much less significant.

Labour standards in Mercosur are, in general, in line with those observed in countries at a similar

level of development. There are higher levels of informality, which is a product of poor

enforcement of and compliance with national legislation that tends to follow international

conventions. The chapter about social aspects examines freedom of association, forced labour,

child labour and discrimination in the EU and Mercosur countries and assesses the potential

impact of the Agreement on these issues. The trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapter

of the Agreement brings an opportunity to engage and cooperate between both parties to help

to lock in or help renew the social achievements of the twenty-first century in the Mercosur

region. The SIA includes a discussion of the value-added of EU policies on trade and labour

linkage and their efficacy.

The environmental chapter addresses issues such as environmental regulations, greenhouse

gases, deforestation and pollution. Environmental policies in Mercosur (like in many other

developing regions) are, in general, less stringent than in the EU. Yet, Mercosur’s current share

of global greenhouse gas emissions is a third of the EU’s, in large part because Mercosur

countries have on average a cleaner energy mix than EU countries. Brazil and Paraguay have

lower per capita emissions than the EU, whereas Argentina and Uruguay’s emissions per capita

are about the same as the EU’s.

The quantitative analysis presented in the report predicts diversion of emissions resulting from

diversion of production. The overall result is a small decrease in global CO2 emissions offset by

a small increase in emissions of other greenhouse gases. Emissions intensity of economic activity

decreases marginally for the world economy as a whole, i.e. world economies produce less

greenhouse gas emissions for a given amount of GDP, with a small increase in emissions

intensity in Mercosur offset by a small decrease in the EU.

The expansion of animal production (associated with beef production), sugar cane production

and other agricultural products in Mercosur seen in the model is small. Consequently, the

analysis does not anticipate an increase in the use and contamination of water or an

intensification of the use of pesticides.

For the same reason, no significant expansion of the agricultural frontier would be expected as

a result of the Agreement according to the modelling results. This seems realistic especially when

we look at past and current productivity trends. Deforestation in Brazil has been on the increase

since 2012 having previously declined very sharply in the period 2004-2012, while meat

production continued to increase. This period 2004-2012 demonstrates that it is possible to

increase agricultural and meat production without increasing pressure on forests. But such a

positive outcome will be dependent on the choice of flanking policies as set out in the

environmental chapter.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

14

The human rights chapter assesses the likely impacts of the free trade agreement on human

rights. It covers in detail the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to the enjoyment

of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, the rights of indigenous people

and gender equality. The moderate increases in GDP, income and consumption that the

agreement generates in Mercosur in both scenarios can contribute to improving standards of

living. The limited increase in agricultural production is not expected to impact indigenous rights

substantially and it is not expected to raise further conflicts. Nevertheless, this situation and the

consequent risks should be monitored carefully following the implementation of the agreement.

For the same and additional reasons, the agreement will bring limited benefits to the female

workforce in rural areas. However, it may bring benefits to women in urban areas by expanding

their participation in the labour force, especially the workforce allocated to the service sector.

The sectoral chapter builds on the modelling results while also drawing on other sources to

provide a more in-depth analysis of the impacts on ten important sectors:

In the beef sector, EU imports from Mercosur will increase in both scenarios (30% and

64%, respectively). EU output will fall by 0.7% (conservative) and 1.2% (ambitious). The

sectoral analysis examines the expected impact in the beef sector in more detail, taking

account of the segmentation of the beef market and existing patterns of in-quota and

out-of-quota trade. The section also assesses the potential impact on animal welfare,

taking account of current legislation in the countries concerned and the existing

framework for EU-Mercosur dialogue and cooperation.

EU dairy exports to Mercosur increase by 91% (conservative) and 121% (ambitious) as

a result of a reduction of high import duties in Mercosur. The recognition of denomination

of origin by Mercosur countries may expand exports of cheese further. For Mercosur

exporters, the agreement expands dairy exports to the EU by 18% (conservative) and

165% (ambitious) but from a low base; and further expansion will depend on more

Mercosur exporters improving sanitary conditions, animal welfare and other quality

features in production.

EU exports of beverages to Mercosur expand by 36% (38% in the ambitious scenario)

and exports from Mercosur by 28% (35% in the ambitious scenario). In the case of the

EU exports, this is expected to be concentrated in wine and spirits and it will be primarily

attributed to the tariff reduction. In the case of Mercosur, the expansion is likely to be

concentrated in wine. Effects on output and consumption in both Mercosur and the EU

are very small in both scenarios. The potential impact of the Agreement on fruit juices,

which are not covered by the same aggregate as alcoholic beverages and soft drinks in

the model, is addressed in the sectoral analysis regarding historic tariffs and trade flows.

The agreement will bring an increase of 32% (36% in the ambitious scenario) in the

Mercosur exports to the EU of textiles and clothing. At the same time, EU exports to

Mercosur will expand by 311% (424% in the ambitious scenario). This is the result of the

reduction of very high tariffs in Mercosur on EU exports. Nevertheless, these changes in

bilateral trade fail to translate into important changes in output and consumption in both

the EU and Mercosur. Consequently, the social effects associated with employment in a

sector with a high degree of informality and a large share of women employed tend to be

minimum.

The reduction of tariffs and non-tariff barriers applied to pharmaceutical and chemical

products in both Mercosur and the EU will expand EU exports to Mercosur by 47% and

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

15

imports by 13% in the conservative scenario. Output in the EU will expand by 0.2%. In

Brazil, it remains unchanged in the conservative scenario and increases by 0.2% in the

ambitious scenario and Argentina, it contracts by 0.2% in both scenarios. In Brazil, both

skilled and unskilled employment fall by 0.5% in both scenarios. In Argentina, they fall

by 0.7%-0.9% depending on the scenario. However, the increase in the trade and lower

import prices generated by the lower tariffs is likely to benefit other manufacturing

sectors and the agricultural sector.

EU exports to Mercosur of machinery expand by 78% in the conservative scenario and

by 100% in the ambitious scenario. EU imports from Mercosur expand by 17% in the

conservative scenario and by 22% in the ambitious scenario. In Mercosur, the agreement

generates a contraction of production between 1.4% and 3.2% in the conservative

scenario (between 1.4% and 5.1% in the ambitious scenario). Both skilled and unskilled

employment fall by corresponding amounts. However, this increase in trade is likely to

benefit other sectors, both agricultural and industrial, due to improvement in the access

to capital goods. EU exports to Mercosur of electronic equipment will expand by 109% in

the conservative and 149% in the ambitious scenario. EU imports will expand by 16%

(conservative) and 24% (ambitious). In Mercosur, output will increase between 0.4%

and 2.1% (conservative) and between 0.8% and 2.6% (ambitious).

There will be significant increases in trade in vehicles and vehicle parts between the two

parties with EU exports increasing by 95% and imports by 41% in the conservative

scenario. EU exports increase by 114% and imports by 47% in the ambitious scenario.

EU will expand its output by 0.5%/0.6% in the conservative/ambitious scenario and

Mercosur will contract its output by 1.7%/1.8% (Brazil) and 2.8%/3.2% (Argentina) in

both scenarios. The agreement may lead to reform of the current Mercosur Common

Automobile Policy which may have additional effects on the sector in the region in a more

liberal direction.

The agreement generates small changes in the trade of business and professional

services with EU imports from Mercosur growing by 6.5% in the conservative scenario

(by 9.2% in the ambitious one) and exports decreasing by 3.4% in the conservative

scenario (and increasing by 1.4% in the ambitious scenario). This is the result of relatively

lower barriers to investment and trade in the sector (in both parties). Nevertheless, in

both scenarios, the agreement generates increases in output in Mercosur which are

associated with the supply of services to other sectors that may see their output

expanded by the agreement.

The financial sector also experiences modest increases in Mercosur exports to the EU in

both scenarios and output in Mercosur. In the EU financial services output contracts

marginally in both scenarios. EU financial services exports to Mercosur decrease slightly

in the conservative and increase slightly in the ambitious.

There are no significant effects on the outermost regions of the EU or least developed countries

(LDCs). This is the case given the limited impacts on the sugar sector and because Mercosur is

not a major exporter of bananas. Although in relative terms the increases in the textiles and

apparel trade of Mercosur appear large, in absolute terms they are small.

Consumers may experience benefits as a result of lower prices. In the EU, the impact on

consumption tends to be small, although positive in all products. In Mercosur, consumers will

experience larger changes notably as regards vehicles consumption, which increases by

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

16

1.7%/2.2% in Argentina and 0.6%/0.8% in Brazil in the conservative/ambitious scenario with

many other sectors seeing a marginal decline driven in large part by an increase in exports.

Finally, this study formulates recommendations for flanking measures to mitigate any potential

risk of negative impact and to maximise potential benefits.

The main recommendations derived from the economic and sectorial analyses are to gradually

introduce tariff changes in Mercosur, particularly in economic sectors that are more vulnerable

to negative economic impacts (for instance vehicles and machinery). In the same vein, retraining

and upskilling programmes are suggested to support the transition of workers between sectors.

On the EU side, the use of quotas and partial liberalisation measures should be considered for

sensitive agricultural products.

Measures to protect workers (e.g. labour inspection programmes, labour formalisation policies

and supporting freedom of association), together with redistributive programmes, should be

considered to mitigate social impacts and drive benefit from the FTA. Due diligence measures

for businesses at the EU-level would also strengthen potential social benefits.

Recommendations for the environment highlight measures to decrease deforestation and

contamination of water resources in Mercosur countries, as well as fulfilling the Paris Agreement

commitments and fostering the development of green technology and sharing good practices

between parties.

Finally, recommendations for the Human Rights area stress the strengthening of accountability

measures and implementation of institutional frameworks that address changes in labour

conditions, use of land that affects indigenous peoples, access to health and development of

medicine, and gender equality issues.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

17

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Aims and Objectives

The Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) provides an examination of the potential economic,

social, human rights and environmental impact of the trade component of an Association

Agreement (AA) between the EU and Mercosur. This analysis lays the basis for designing flanking

and mitigating measures, a number of which are proposed throughout the study.

Overall, the SIA consists of two complementary components, notably:

(i) Robust analysis of the economic, social, human rights and environmental impacts,

that the association agreement under negotiation could have, in the EU, in the partner

countries and other relevant countries; and

(ii) A wide consultation process involving stakeholders both in the EU and in the partner

countries, which provides opportunities for information-gathering and dissemination

results.

The analysis starts with a screening and scoping exercise, and is then followed by overall and

sectoral impact analyses which lead to conclusions and recommendations.

The SIA comprises of the following elements:

An overall analysis of the sustainability impacts arising from the negotiations: While

several key sustainability issues to be analysed in the SIA are cross-cutting and

mainstreamed in the analysis, the identified impacts on small and medium enterprises

(SMEs), consumers, least developed countries (LDCs), and the EU’s outermost regions

(OMRs) are summarised in specific sub-sections.

Economic analysis: Impact of removing tariff and non-tariff measures (NTMs) and the

wider economic impact of the possible effects of the AA.

Social analysis: Analysis of the social impact, direct and indirect, of the potential

agreement; analysis of the impact of trade opening on employment, working conditions,

and distributional impacts, as well as interaction between the envisaged agreement and

effective implementation of international conventions inter alia Core Labour Standards

(CLS) and fundamental Conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Environmental analysis: Detailed analysis of potential environmental impacts, both direct

and indirect, of the agreement; analysis of the impact of trade opening on the

environment by identifying scale, technology, and product effects, as well as the potential

interaction between the AA and multilateral environmental agreements.

Human rights analysis: Detailed analysis of potential impacts of the trade part of the

future AA on HR; analysis of the impact of particular measures in the agreement and

their potential impact on the enjoyment of human rights; assess the impact on vulnerable

groups and gender equality.

Detailed analysis of the specific sectors identified in the inception report.

Consultation process: the qualitative and quantitative analysis is complemented by

detailed input from stakeholders through the consultation process.

Policy recommendations and accompanying measures.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

18

The scope of the project focuses on the Mercosur-4 (Argentina (ARG), Brazil (BRA), Paraguay

(PRY), and Uruguay (URY)). Our analysis uses all relevant data encompassing the period from

2009, when the last SIA was conducted, to the start of the project (September 2017).

1.2. Background

The EU ranks as the second trade in goods partner for Mercosur while Mercosur ranks as the

eleventh trade in goods partner for the EU (Eurostat). In 2018, the majority of exports from the

EU to Mercosur were in the machinery and transport equipment, chemicals and manufactured

goods sectors. Food and live animals, raw materials as well as mineral fuels and lubricants were

the most-featured sectors in EU imports from Mercosur (Eurostat).

In 2015 for Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay), the EU represented nearly 17%

of its exports and 19% of its imports in trade in goods.

2

On the other hand, Mercosur received

2.6% of EU exports and generated 2.7% of the imports. However, this trade takes place

primarily under the most-favoured-nation (MFN) basis where average tariffs applied by Mercosur

are 13% and by the EU are 6%.

3

There are also significant tariffs peaks in both schedules.

Moreover, in addition to the tariff barriers, there are numerous and high non-tariff barriers (NTBs)

affecting trade. Multiple regulations exist that affect the trade in services in all provision modes,

especially related to the movement of natural persons as well as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Figure 1: Map of Mercosur

2

UN Comtrade database.

3

Non-ad valorem duties excluded.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

19

Thus, despite both parties having some defensive concerns, the two sides are expected to gain

from an AA. In agriculture, Mercosur has an interest in improved access for its competitive

agriculture sectors where the EU remains defensive. It should be noted, however, that in this

area there are also offensive interests on the EU side associated with inter alia dairy, beverages,

processed agricultural products and the protection of EU geographical indications. Given the

European influence in the region, there are certain conflicts with products from, for example,

Spain and Italy. These issues are addressed both in the overall economic analysis of the AA and

in the analysis of specific sectors.

On the industrial side, some sectors where the EU industry is competitive are considered

defensive by Mercosur countries. The Mercosur manufacturing sector remains heavily protected

across the board using tariffs as well as administrative measures to slow down the flow of imports.

The car manufacturing sectors in Argentina and Brazil are seen as key in their economic

transformation strategies. In fact, the sector is not liberalised within Mercosur and there is a

Common Automobile Policy that regulates the trade within the bloc and protects it from foreign

competition (Brambilla, 2005; Garriz and Panigo, 2015). However, there is also an important

value chain activity involving SMEs and large firms in both countries as well as European firms

(i.e. a significant share of the car manufactures are of European origin). Thus, Mercosur is on

the one hand vigilant as to how the agreement may affect this sector while also alive to the

opportunities that may arise to integrate further into European value chains. Issues pertaining

to the sector of car and car parts are dealt with in a separate section of our report. The machinery

sector, which also figures prominently in the EU's exports, is also addressed in a separate section.

There is no common services policy in Mercosur, as levels of protection differ between members,

beyond some liberalisation existent within the bloc (Quijano, 2009). However, there are barriers,

which hinder the provision of foreign services in key sectors (e.g. financial, communications,

transportation, etc.) in almost every relevant provision mode. The regulatory frameworks in

some sectors tend to be burdensome, affecting the provision and the investments regardless of

the origin (Rozemberg and Gayá, 2015; Gayá, 2017). The existing arrangements within

Mercosur and possible scope for cooperation with the EU in the area of business services are

reviewed in the final sections of this report.

For the EU, the AA presents the opportunity to secure and increase trade and investment with a

region with which it has important cultural and economic links. For Mercosur, an agreement with

the EU will help to address the relative loss of market access that Mercosur faces (i.e. Mercosur’s

competitors gaining better market access through free trade agreements (FTAs) with the EU) as

well as the chronic trade diversion, affecting productivity, competitiveness and poverty in

Mercosur countries due to intra-Mercosur protection (Chang and Winters, 1999; Bohara et al.

2004).

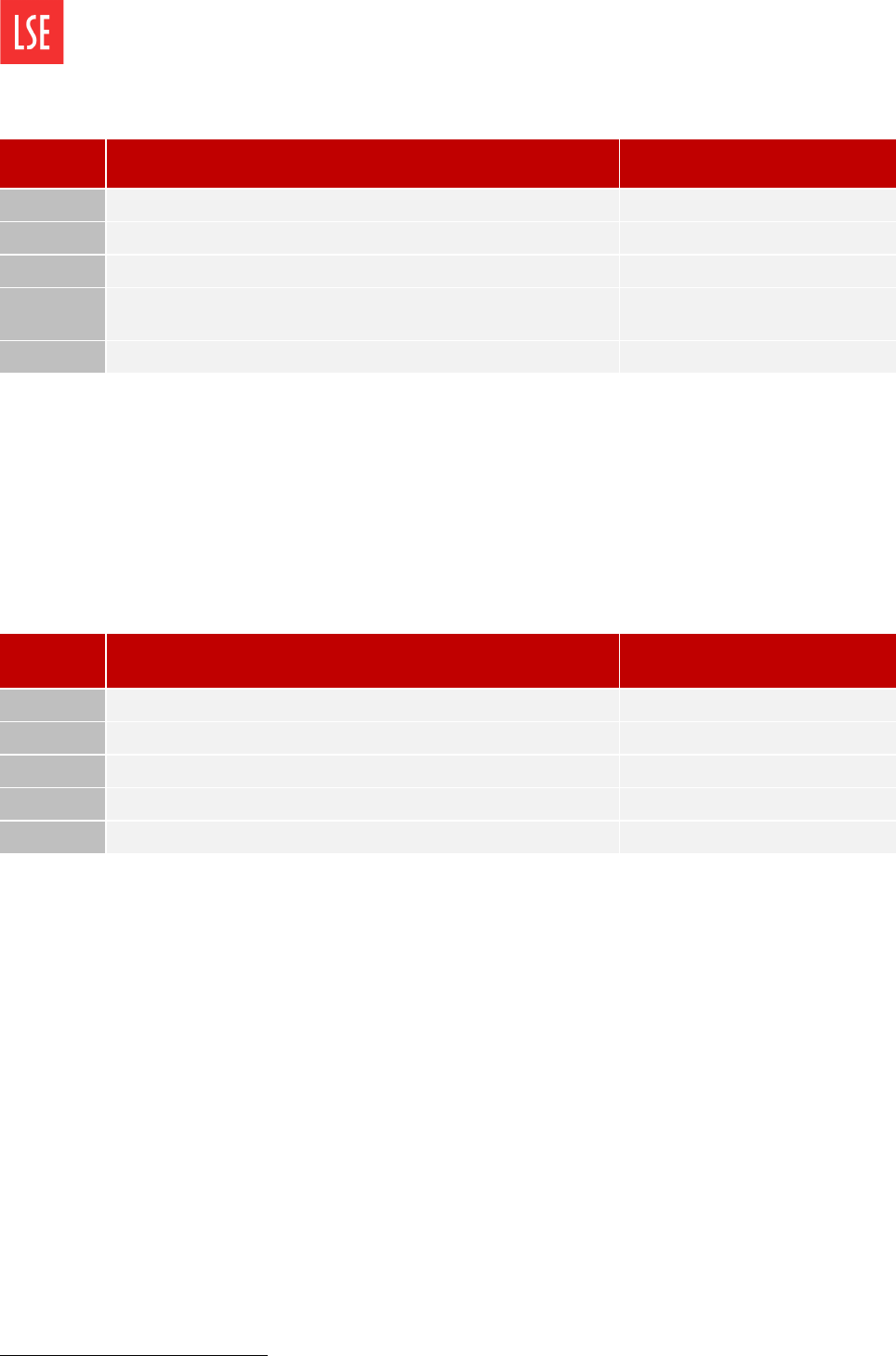

Table 1: Mercosur countries overview

Country Population (total) Surface area (sq. km) GDP (current US$)

Brazil 209,469,333 8,515,770 1,885,482,534,238

Argentina 44,494,502 2,780,400 519,871,519,808

Paraguay 6,956,071 406,752 40,496,953,779

Uruguay 3,449,299 176,220 59,596,885,024

Source: World Bank, 2018 World Development Indicators.

https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&country=BRA,ARG,PRY,URY

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

20

2. Economic Analysis

This chapter provides the results for the computable general equilibrium (CGE) analysis of the

trade aspects of the Association Agreement between the EU and Mercosur. The chapter first

provides a review of the existing literature on EU-Mercosur trade relations as well as EU relations

with other Latin American countries, providing contextual analysis. The CGE results feed into all

other chapters of the report.

2.1. Methodology

This section describes how the LSE Consulting team reaches the specific objectives of the SIA;

an overview of analytical methods to address the tasks and structuring of the work. The analysis

provides the potential economic, human rights, social and environmental effects of the trade-

related parts of the anticipated association agreement between the EU and Mercosur. The study

also covers relevant third countries, in particular LDCs, as well as Turkey which is linked to the

EU by a customs union agreement. Each of the sections on economic, sectoral, social,

environmental, and human rights analysis outlines the methodology and tools used. Below we

expand on our approach to the quantitative analysis to be incorporated across all areas, noting

its limitations to account for all deep integration elements (e.g. government procurement).

Moreover, we highlight how the different methodological tools link to the aims of the analysis

and the components of the work.

2.1.1. CGE Modelling

The CGE analysis carried out by the LSE Consulting team is used to assess the economy-wide

effects in the EU, Mercosur and other relevant partners (e.g. LDCs) of the tariff reductions and

some deep integration elements. For example, it is possible to assess the effect of some trade

costs reductions associated with trade facilitation provisions included in the agreement and/or

harmonisation of standards. In addition, the CGE enables us to view - although with limitations

- the effects of the agreement on services. Additionally, potential impacts on the services sector

are demonstrated through descriptive statistical analysis. CGE helps to assess the FTA’s effect

on the domestic economies. In addition to trade effects, CGE allows us to quantify the effects

on production, consumption, consumer prices and income. The results from the CGE analysis

feed into the social, environmental, human rights, and sectoral analysis, as well as cross-cutting

issues (LDCs, SMEs and consumers).

We employ the dynamic version of the GTAP Model, which is known as GDyn. As regards closure

choices, the labour market is assumed to be in equilibrium, i.e. full employment, where

adjustments are made by changes in real wages. Similarly, land supply is fixed and sluggish

among sectors and adjustments are by rent, i.e. land use increases or decreases as value. Factor

productivity is exogenous. However, when a baseline is updated, the total factor productivity

adjusts to GDP.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

21

2.1.2. CGE Baseline Development

Table 2 and Table 3 show the sectoral and regional aggregations we employ in this model,

starting from the 57 sectors and 140 regions in Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) 9.2 Data

Base with 2011 as a base year.

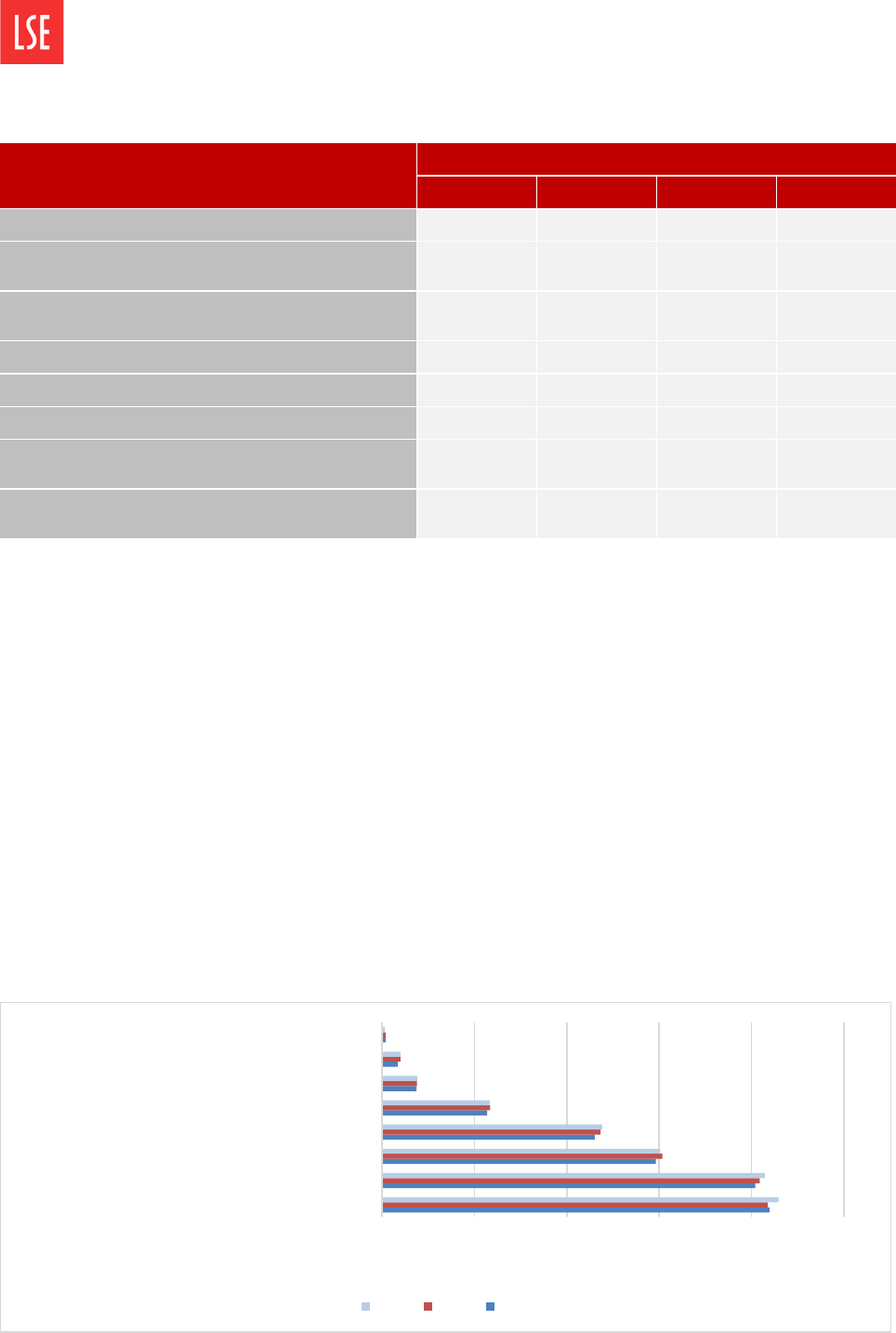

Table 2: Sectors included

Sector number Sector name Notes (GTAP sectors)

1 Cereals 2, 3

2 Rice 1, 23

3 Vegetables, fruits, nuts 4

4 Oilseeds, vegetable oils & fats 5, 21

5 Sugar 6, 24

6 Plant & animal fibres and other crops 7, 8, 12, 14

7 Other food products 25

8 Bovine and other ruminant meats 9, 19

9 Other meats (poultry, pig) 20

10 Other animal products 10

11 Beverages and tobacco 26

12 Dairy products 11, 22

13 Wood and paper products 13, 30. 31

14 Coal 15

15 Oil 16

16 Gas 17, 44

17 Minerals 18

18 Textile, apparel, leather 27, 28, 29

19 Chemicals, rubber, plastic 33

20 Petroleum, coal products 32

21 Metal products 35, 36, 37

22 Non-metallic minerals 34

23 Motor vehicles & transport equipment 38, 39

24 Machinery 41

25 Electronic equipment and other manufacture 40, 42

26 Electricity 43

27 Utility (construction, water) 46, 45

28 Transport 48, 49, 50

29 Communication and business service 51, 54,

30 Financial service and insurance 52, 53

31 Recreational and other services 55, 56, 57, 47

Source: GTAP 9 Data Base.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

22

Table 3: Regions

Region Observations

1 EU28

2 Turkey

3 Brazil

4 Argentina

5 Uruguay

6 Paraguay

7 Mexico

8 Central America

9 Andean Colombia, Peru, Ecuador

10 Latin America Except for countries mentioned elsewhere

11 USA

12 Other high-income countries

Canada, Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand,

13

LDCs

4

14 China (and Hong Kong)

15 Other developing countries

16 Rest of the World (RoW)

Source: GTAP 9 Data Base. Note: the outcome of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union is not

included in the baseline and all results treat EU28 as a single region.

The baseline scenario constitutes the situation without an agreement and provides a

counterfactual scenario to evaluate the effects of the agreement. The baseline outlines the main

policies (economic, social and environmental) expected in both the EU and Mercosur until the

year 2032 without the implementation of the EU-Mercosur FTA. Concerning the main policy

elements of the baseline scenario, it is difficult to determine whether many of the initiatives

currently discussed will be implemented or not. Thus the baseline includes all trade agreements

concluded by the EU and Mercosur at the time of the inception of this project (September 2017),

i.e. those that were already in force or for which negotiations are finalised for the EU and

Mercosur. The GTAP model already includes FTAs up to 2011. Therefore only the FTAs not

included in the GTAP model need to be added separately. We exclude agreements with countries

whose share in EU overall trade or Mercosur overall trade is below 1% (except for those with

Latin American countries) or which cannot for technical reasons be included in the agreed

regional aggregation. These criteria result in the following list of agreements to be added:

For Mercosur:

No FTAs concluded in the relevant period and therefore we do not make any changes

herein.

4

The following GTAP regions were aggregated as LDCs: Rest of Oceania, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Rest of Southeast Asia

(Myanmar and Timor-Leste), Bangladesh, Nepal, Rest of South Asia (Afghanistan, Bhutan and Maldives), Rest of North

Africa (Algeria, Libya and Western Sahara), Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo, Rest of Western Africa (Cape Verde,

Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Saint Helena, Sierra Leone), Rest of Central Africa (Central

African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Sao Tome and Principe), South Central Africa (Angola and

Democratic Republic of Congo), Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, United Republic of

Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

23

For the EU:

Several agreements have been in force since the recent past. FTA with Canada (CETA),

Korea, Southern African Development Community Economic Partnership Agreement

(SADC EPA), West Africa EPA, Central America, Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, which have

already been dealt with by other SIAs and studies.

The GTAP Data Base is based on 2011 data and therefore omits many recent policy developments.

To avoid shortcomings arising from such omissions, we make the following broad changes to the

data set:

Corrections on tariffs for sugar and beef to ensure that the baseline accurately reflects

the various tariff regimes (e.g. WTO quotas) under which these products enter the EU;

Export subsidies from the EU are removed since they are erroneously included in GTAP 9

Data Base.

We employ a macroeconomic baseline comprising Gross Domestic Product (GDP), unskilled

labour, skilled labour and population developed by the modelling team at DG Trade of the EU.

Specifically, the rate of GPD growth is from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), using a

constant annual price rate. The rate of population growth is taken from the ILO. The labour force,

divided into skilled and unskilled labour, is updated using data from CEPII. Since labour is

expressed in terms of value instead than quantity, percentage rates need to be adjusted in order

to shock the baseline figures correctly. We make further adjustments within the baseline, for

the following:

Introduction of FTAs signed by the EU after 2011 and already in force;

Taking into account the NAMA custom Union with Turkey;

Russian import ban and consequences.

In addition, after macro shocks are introduced to update GDP, population and the labour force,

a calibration has to be performed. Input-output tables and policies refer to the year of the

database, 2011. When the shock is applied, sectoral outputs and trade flows must be checked

and calibrated to reflect data for subsequent years.

2.1.3. Policy Scenario

We apply specific assumptions in terms of tariff and NTB reductions in the policy scenario. Full

liberalisation for all industrial goods sectors on the EU side is assumed for both the conservative

and ambitious scenario. For Mercosur, we assume full liberalisation of 90% of industrial goods

in the conservative scenario, 100% in the ambitious scenario.

As regards agricultural goods, for the EU, partial tariff cuts will apply for rice, sugar, ruminant

meat, other meat of 15% in the conservative scenario and 30% in the ambitious scenario. For

cereals and dairy, a partial tariff cut of 15% will apply in the conservative scenario, whereas

100% cuts will apply in the ambitious scenario. For the remaining products, 100% tariff cuts

would apply. For Mercosur, full liberalisation for 80% of tariff lines takes place under the

conservative scenario and 100% under the ambitious scenario.

The scenarios also take into account trade cost reductions to non-tariff barriers to goods and

services trade. For NTBs, we use the variable ‘ams’ in GTAP Data Base, which captures import-

augmented technological change. The base NTBs for non-agricultural goods is based on existing

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

24

estimates by the World Bank

5

. The NTB values available are at Harmonized System at 6 Digits

(HS6) level. The following will be assumed:

EU: No NTB reduction assumed at this stage;

Mercosur:

o Conservative: 5% of impact of non-agricultural NTBs eliminated;

o Ambitious: 10% of impact of non-agricultural NTBs eliminated.

This study does not model NTB cuts in agriculture. The reason is that given the lack of robust

ad-valorem-equivalents (AVE) estimates on agricultural trade to and from the EU, the available

AVE estimates greatly exaggerate the perceived NTBs imposed within the EU in relation to the

agricultural sector and would result in strongly (and artificially) negative results. Instead, we

carry out a qualitative analysis of agricultural NTBs in the SIA.

Table 4: NTB cuts in EU and Mercosur

Sectors / NTB cuts

Conservative Ambitious

EU Mercosur EU Mercosur

Agriculture 0% 0% 0% 0%

Non-agriculture 0% 5% 0% 10%

Source: Terms of Reference.

Regarding services barriers, the starting point for the approach used in this SIA is the

observation that FTA negotiations usually lead to binding of the existing level of liberalisation in

services trade (for the cases where this level is more ambitious than the GATS commitments)

as opposed to achieving new market access. However, the insurance policy effect of binding

current levels of liberalisation has in itself had a positive effect on services trade. The

methodology applied for this and other simulations aim to translate this insurance effect into a

liberalisation parameter for CGE modelling. The 3% AVE cut used in the modelling for trade in

services is an assumption introduced in an earlier study by Decreux and Fontagné (2011).

2.2. Literature review

In this literature review, we discuss key studies which focus on EU FTAs with either Mercosur or

other Latin American countries, briefly setting out their broad assumptions and results.

Estrades (2012) examines the EU-Mercosur FTA impact on both economies, especially at the

household level. The study uses a multi-sector, multi-region computable general equilibrium

model (MIRAGE) to calculate the impact on households after the FTA is implemented by looking

at the comparable data of Mercosur (especially Uruguay) and EU using GTAP 7 Data Base by

looking at parameters like consumption, consumer price index, Gini index, tax etc. The

methodology assumes that the only easily mobile factor of production is labour in comparison to

the immobile natural resource and land. It includes 4 Mercosur countries, 30 European countries

and 30 sectors. It includes one complete EU-Mercosur tariff elimination (2011-2015) scenario,

and has three more sensitivity scenarios namely sensitive products in both the regions, sensitive

products in Mercosur and sensitive products in EU; in each of the scenarios, the sensitive

5

As published in the 2012 update of Kee, Nicita and Olarreaga (2008) Import Demand Elasticities and Trade Distortions.

Review of Economics and Statistics 90(4), 666-682.

SIA in support of the association agreement

negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur

25

products were exempt from the liberalisation shocks. For the EU, the sensitive products are

assumed to be the ones offered by the EU to Mercosur in 2004, while for Mercosur, the authors

assume the formula given by Jean et al. (2010), which defines the sensitive products based on

initial tariffs, share in aggregate imports and tariff cuts proposed. EU sensitive products mostly

include food and agricultural commodities. Among the 55 tariff lines proposed herein, 44% are

meat products, 24% are dairy products and 10% are cereal products. For Mercosur, they include

motor vehicles and parts, beverages and tobacco products and other food products. The paper

tries to explain the impact of the FTA on a low-income country like Uruguay with parameters

such as poverty, income, consumption, transfer benefits, inequalities etc.

Due to the FTA, income inequality tends to decrease in the Mercosur countries due to the

increase in the demand for unskilled labour and wages while the real income increases and

poverty tend to decrease. The study, which focusses in detail on Uruguay, assesses the impact

on different categories of Uruguayan household. Almost all (over 99%) of households in Uruguay

tend to benefit from the FTA in comparison to the baseline. The FTA affects manufacturing in

the EU and agriculture in Mercosur countries positively.

Secondly, we look at the results of the previous SIA of the AA between the EU and Mercosur (EC,

2007). The SIA uses CGE and econometric techniques for the trade agreement analysis. The

database used is GTAP 6.2 and the baseline is taken as the commodity/services price across the

world. The study also considers the full trade agreement hence no barrier to the trade between

the two blocs. The methodology takes into considerations major trading commodity/products

like grains, vegetables, fruits, chemicals, automobiles, pharmaceuticals etc.

The results from the study, which models full liberalisation without taking account of the partial

liberalisation treatment that tends to be applied to sensitive agricultural products, suggest that

the Mercosur countries will benefit by $9 billion while the EU will benefit by $4 billion. Hence the

study shows that given the removal of barriers and the effect of full trade liberalisation between

the blocs, a sizable amount of the economy can be freed up and both the blocs will benefit. The

previous SIA finds relative per capita increase in the income, consumption, GDP and decreases

in poverty and inequality, especially in Mercosur countries.

The follow-up position paper assesses the economic impact of the FTA to be positive both for

the EU and for Mercosur countries (EC, 2010). In the EU, the manufacturing and services sectors

are predicted to benefit most from an FTA. The EU could reap some benefits from better market

access to Mercosur for some vegetable products via an FTA, as well as from better protection of

geographical indications. In Mercosur, the economic benefits of an FTA are expected to be felt

throughout the whole economy and especially in the agricultural sector. In the EU, the only

sector where a negative social impact would be felt is in agriculture and rural areas where short

to medium term social adjustment costs could occur during a transition period and could add to

the underlying downward trend in baseline agricultural sector employment in the EU. For

Mercosur, the social impacts are expected to be positive over the long term while some

adjustment costs on the short term could occur in the manufacturing sector.

The 2007 SIA also suggests that the expansion of agriculture in Mercosur in response to full

liberalisation could cause social problems to the "traditional agriculture" and result in the loss of

livelihoods for indigenous people. The environmental impact of the FTA in EU countries is not

significant. In Mercosur, the 2007 study finds that full trade liberalisation in the agriculture and

the forestry sector could result in added pressure and potentially significant adverse impacts on