BrewersAssociation.org

Craft Brewers Guide to

Building a Sensory Panel

All photos credited to Allagash Brewing Company

BrewersAssociation.org

Introduction

Brewers know their beer intimately, because they

regularly taste the product at every stage of the

brewing process. A brewer’s evaluation of his or

her beer can be biased, however, and can be

skewed in a way that prevents objective sensory

analysis. The sensory attributes of beer require

a methodical and deliberate approach to be fully

characterized. Consistently producing beer that

is free of off avors and true-to-brand is of para-

mount importance to the success of any brewery.

The marketplace is competitive and quality has

never been more important to the overall suc-

cess of a brewery. A trained human palate is a

powerful tool and a sensory panel is an essential

process to include in a quality program. Microbi-

ological, chemical, and physical tests can help

ensure that beer meets certain specications, but

if a beer’s avor is not aligned with the brewer’s

intent and the beer drinker’s expectations, then

all other measurements are of very limited use.

Beer is one of the most widely consumed and

historically relevant beverages our civilization has

created and is therefore subject to the inuence

of our emotions, biases, and other personal pref-

erences. Sensory program managers must ac-

knowledge, understand, and account for human

biases and do everything possible to diminish

their inuence on beer evaluation.

This guidance is designed to assist breweries of

all sizes implement sensory evaluation as part of

their quality management efforts. Like the variety

of your beer offerings, your sensory methods will

continue to develop based upon growing capabili-

ties, knowledge, size and business complexity.

Sensory evaluation is often dened as: “the sci-

entic discipline used to evoke, measure, ana-

lyze and interpret responses to products that are

perceived by the senses of sight, smell, touch,

taste and hearing.” (Stone, H and Sidel, JL. 1993.

Sensory Evaluation Practices. 2nd ed. Academic

Press: San Diego.) This denition is useful for

understanding individual roles, tasting methods,

impacts of panel setting, and outcomes of em-

ploying a trained sensory panel.

The Evoker –

Sensory Scientist/Technician/Specialist

The evoker’s role is to elicit a measurable and

relevant response from panelists. It is ideal to

hire a trained sensory scientist, but it is not nec-

essary. Educate yourself, or designate someone

internally to lead the program. There are a host of

classes, books and communities out there to help

you gain knowledge, many of which are included

in the Appendix.

The Evokees – Sensory Panelists

Who should participate?

Anyone willing to put in the time to be trained and

participate on a regular basis, should be

considered for a panel. This can include

brewers, managers, accountants, and human

resources. Anyone who is committed,

regularly available and enthusiastic to learn can

lend their palates in the pursuit of quality.

BrewersAssociation.org

How many panelists should participate?

To obtain rigorous data which can be interpreted

with a high degree of condence, you need at

least 10 highly-trained and validated panelists to

sit on your panel. Depending on the sensory eval-

uation method, more panelists may be required.

Small breweries should get as many trained and

valid panelists as possible to participate in the

panel. Small panels can be used to nd mean-

ingful pieces of data, but be cautious of making

claims about statistical signicance. Start by

using the resources available, but never depend

upon only a single palate. The “brewmaster

panel of one” can be misleading because brew-

ers spend a lot of time in the brewery and can

become desensitized to DMS and other volatile

aromas. Brewers are also prone to bias, and may

not be objective enough when informally tasting

beer. Remember, there is no such thing as a

good panelist, only good panels!

Measuring a response

Training sensory panelists is analogous to cal-

ibrating an analytical instrument. You can have

the most enthusiastic panel, but if they are not

calibrated, they will enthusiastically lead you

astray! For this reason, training must be the foun-

dation of any sensory program. First, the panel

needs to be speaking the same language and

trained on specic attributes. This can be done by

spiking product samples with known quantities of

avor-active chemical standards and measuring

responses. Including spiked samples randomly

into the panel can help validate attribute sensitivi-

ty and alignment with standard descriptors.

Develop a lexicon of standard descriptors to

ensure everyone is speaking the same language.

Tools like the Beer Flavor Map help evaluators

hone-in on their experience, and more specically

describe the beer’s avor. Lexicon development

comes through exposure to various avors, be it

in attribute training or by evaluating competitor’s

beers alongside your brewery’s products. This

process gets your panelist talking and associating

words with their avor experience in a consistent

manner.

Standardize the lexicon by spiking attributes

into beer at known concentrations. Multiple com-

mercial spikes are available on the market rang-

ing in price and quality. You can also make your

own using the ASBC Flavor Standard Calculator.

Please note that some attribute spikes are aroma

based and should not be consumed. Be sure to

read and understand manufacturer’s instructions

and warnings! Care must be taken to ensure the

safety of all panelists. Best practice is to pur-

chase food-safe spike kits.

Train panelists regularly. Evaluating beer is not

like riding a bike! Panelists must be trained and

refreshed regularly if their palates are used as

analytical instruments. Regular exposure to

specic avors at known concentrations is

essential to maintain valid panels. Weekly

refresher training is recommended as best prac-

tice. Find a consistent time and place that is free

from distractions and make training a priority!

Exercises can be geared toward training tasters

to detect avor changes changes and identify off

avors, which gives the panel leader the ability to

recognize the potential source of variation when

running future tests.

BrewersAssociation.org

Training can take many forms, but the most

common and effective method is to spike

samples with pure and food-safe standards. Most

people have never been taught to master their

sensory skills, so it is important to remain patient

and persistent and run attribute trainings on a

regular basis.

Track progress and document individual

panelist’s performance. The only way to know if

a panel is valid is by tracking their progress. As

the sensory program grows, both in numbers and

acuity, you need to have the ability to measure

their improvement; otherwise, you may just be

measuring noise in your data set. For example, if

panelists cannot consistently identify diacetyl in

training but they continue identifying diacetyl in

panel sessions, you may react to a problem that

either doesn’t exist, or is attributable to an entirely

different problem.

Getting Started with Sensory Evaluation

Set a target based on brand descriptions.

The rst thing you need is a target. Each beer

has to have a specic description that denes its

avor. This description will be your guiding star

to compare all subsequent batches of the same

brand. First, generate descriptions, get alignment

to ensure the target matches the brewer’s intent,

and validate that the target is consistent by

testing multiple batches against the target.

Setting visual, aroma, taste and mouthfeel

specications will take the guess work out of

determining if a batch is consistent.

Dedicate an appropriate space to conduct

the panel.

Now that you have a trained panel, and targets

for your brands, nd a time and place where you

can consistently hold panel in a controlled room

that is free from noise, aromas and other dis-

tractions. Late morning tends to work well, after

coffee and before lunch.

Sample preparation room with access to sensory booths.

Sensory booths help reduce distraction.

Utilize the best space available to get started.

BrewersAssociation.org

Determine the initial focus of the

sensory program.

Start by mitigating your greatest risk – releasing

beer that is not consistent with the brand prole

and/or full of off-avors. You can do this using a

production release panel where you simply ask

the panelists: “Is this beer consistent with the

target description? Yes or no? If not, why?” Keep

it simple, elegant and powerful!

Infrastructure for starting up:

It is helpful to get organized before starting a pan-

el. Gather and organize necessary supplies and

create the type of documentation used to best

track data and have guidelines in place for action

based on results.

Glassware can inuence the evaluation of the

beer’s appearance, aroma, taste and mouthfeel,

so it should always be of standardized size, clean

and clear with no scratches or defects. Beer

evaluation glassware should be washed with hot

water and occasionally acid washed. Beware of

detergents or soaps, because they can inuence

the foam quality and other sensory attributes.

Document panel and training results using either

pen and paper or a computer. Even if you do not

brew the same beer twice, having relational data

between batches can help detect process anom-

alies or systemic issues in the brewery. Pen and

paper can be used as long as there is a mecha-

nism to track batch-to-batch variation using excel

or other sensory software packages. The ultimate

goal is to build a body of knowledge that is easily

referenced on an ongoing basis.

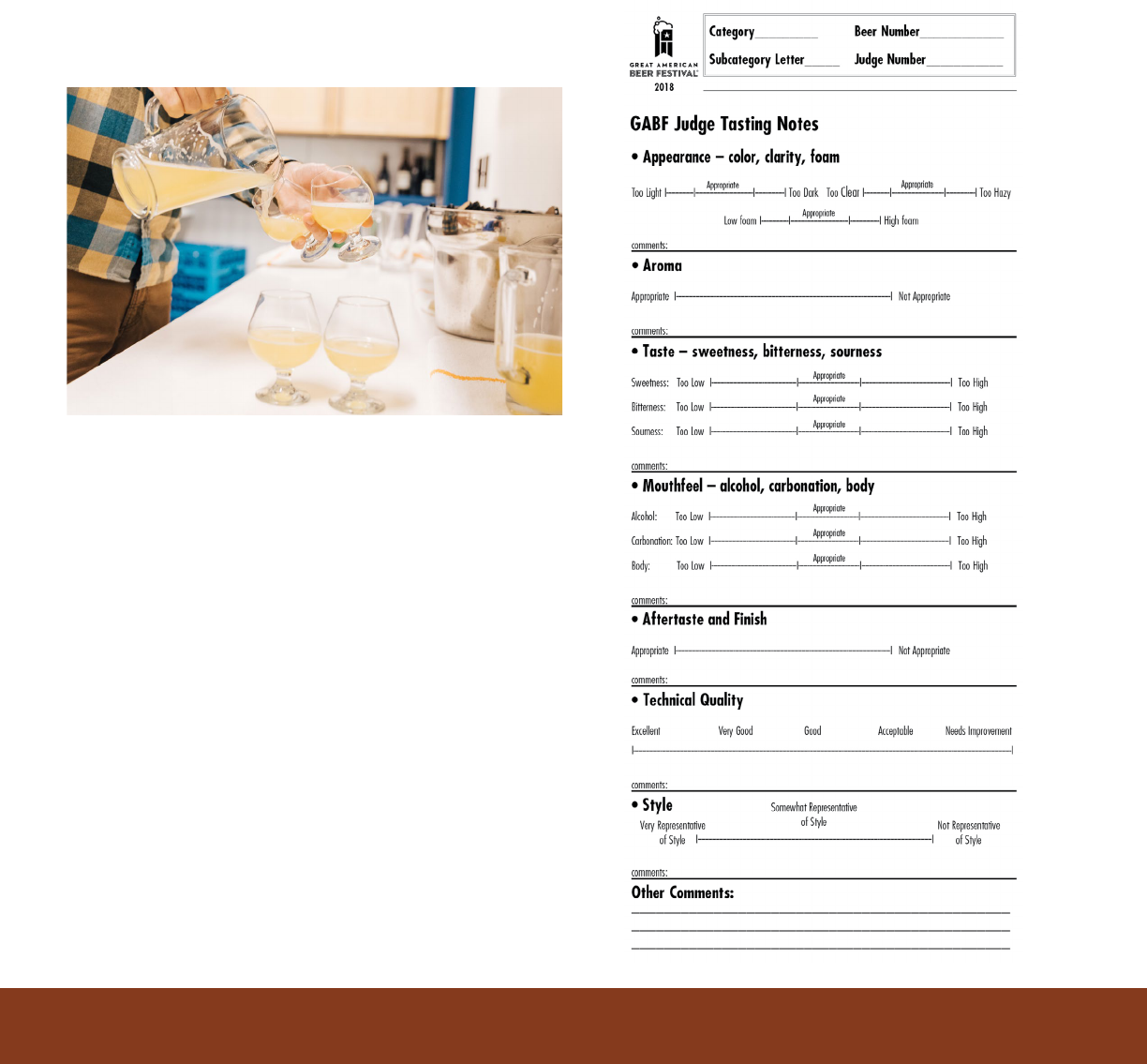

Develop a standard ballot for use in every

panel. Use of scales are seldom appropriate

when the question is whether or not a beer’s

avor prole is within the limits of normal process

variation. Once a avor target is locked in,

simply ask if the beer’s avor is in line with the

set target. The GABF judge form is a good place

to start as it simply asks if the beer adheres to its

set guidelines while allowing for comments.

BrewersAssociation.org

Beer Evaluation Technique:

The method employed to evaluate beers can in-

uence avor perception, so a standardized eval-

uation method is required to enable evaluators to

utilize their senses effectively. The following steps

provide a roadmap to successful evaluation, but

there are many variations, some of which are out-

lined in the additional resources in the Appendix.

1. Hold the taster glass: The glass used to

evaluate beer can inuence the biases and

perceptions of the sample. Make sure to choose

glassware that is consistent and easy to clean.

Glassware that is scratched or not cleaned prop-

erly will have less visual appeal and potentially

impact avor.

2. Visual: Look at the beer for inputs about the

color, clarity, head formation and retention.

3. Distance: Look through glass from a

distance for the same visual clues. Distance can

help with making distinctions in hue, tint, and clar-

ity by examining the beer from

multiple perspectives.

4. Olfaction Wake Up: Take the glass and quick-

ly pass it under your nose, inhaling as it passes.

The olfactory system makes up a tremendous

amount of the data your brain gets in avor and

aroma perception. This just “wakes up” the olfac-

tory system to know it is about to do its job.

5. 1-Second Sniff: Inhale briey through your

nose to take in the volatiles from the beer. Car-

bonation in the beer helps release volatiles out

of solution. Swirling a beer can also help release

volatile compounds. This rst smell should give

the indication of the type of beer being tasted in

terms whether it is an ale or lager, malty or hop-

py, or has added avors like chocolate, fruit, etc.

6. 2-Second Sniff: Inhale deeply with a

longer sniff, to analyze quality of aromas

present and identify any notes that are not de-

sired by the brewer.

7. Cover: You can cover the sample with some

neutral material, which helps build volatiles in

the glass. This can help capture and concentrate

certain aromas between sniffs.

BrewersAssociation.org

8. Taste: This step adds gustation (through

activation of the taste buds, e.g. salty, sweet,

sour, bitter, and umami) and trigeminal sensa-

tions (through activation of the trigeminal nerve

in the mouth, e.g. cold, hot, prickle, tickle) to our

olfaction perceptions to create a complete sense

of avor. Take a sip of the beer, allowing it to coat

the tongue and sit in contact with the mouth for a

moment, then swallow.

9. Retro-nasal Evaluation: For this method, sip

the sample while holding your nose, then exhale

through your nose. This technique helps isolate

sample aromas from the outside world, and en-

ables the taster to identify specic hop varieties,

esters, potential attribute defects and other nu-

ances.

10. Mouthfeel: Beer is carbonated to a

specication level and must be swallowed for

proper mouthfeel evaluation. Beer can also have

thin to full body viscosity, nish dry or sweet, or

be smooth or astringent. Take a taste while focus-

ing on the mouthfeel and nish of the beer.

Collecting Data and Analyzing Product

The appropriate method of data analysis depends

on the test objective and the type of sensory data

produced.

1. Collect only actionable data! Collecting

nonactionable data takes time and does not help

in making decisions about what beer is suitable

for sale to the public. Create an action plan for

responding to unintended attribute avors and

aromas in the beer. Advanced sensory programs

should include decision trees to standardize reac-

tions.

2. Use descriptive testing for research and de-

velopment, pilot batches and new products.

a. The brewer should set descriptive

targets that can be analyzed by panelists. Use

a standard lexicon to describe the avors and

aromas of the beer.

b. Once the descriptive targets have been set,

the panel can determine whether a batch is “true-

to-brand” based on the agreed descriptions and

specs.

3. True-to-brand analysis is the ultimate goal of

a trained panel. Once targets have been agreed

upon, descriptions of beers are formalized, and

panelists are aligned on meaning. This method is

used to track consistency between batches of the

same brand. Good test design will provide current

and trending data that helps keep beer consistent

as ingredients change, processes evolve,

or palate creep emerges.

“Palate creep” can present itself in many forms.

A beer can change over time as result of process

changes, equipment changes, raw ingredient

changes and sensory panelists can develop

either false attribute identication habits or bias

for beers, which can affect the sensory program.

Care must be taken to be proactively aware of

this potential and work continually to hone the

panel’s awareness.

BrewersAssociation.org

4. Shelf-life testing can help the brewery de-

termine what the sales window is for every beer.

Beer is a biological product that changes over

time. Oxidation will also change the avor of the

beer over time. This type of screening is even

more important when breweries sell beer in cans

or bottles. Wholesale partners want to know

how long they can sell the beer before signi-

cant change is noticed by customers. Breweries

should maintain an archive of individual batches,

and compare different batches to determine if

acceptable avor is maintained over the stated

shelf-life of a product.

5. Batch tracking should be done using date

codes on packaging, and documentation through-

out the process, including malt and hop lots, ves-

sel status, process aids and packaging informa-

tion. If there is a problem with a beer in the eld,

a sensory panel can help identify what happened

to that beer, when combined with process doc-

umentation. A recall plan should also be imple-

mented to ensure that a brewery can isolate and

retrieve any batches which need to be removed

from the market.

Interpreting Results

Raw data needs to be put to use, otherwise it is

useless. Numerous techniques can be used to

interpret data, but it’s important to keep it simple

to start.

1. Spreadsheets: Spreadsheets allow for data to

be captured in rows and columns. Data is entered

into cells which can provide an organized visual

look at the data. The data can then be used in

formulas to create relational changes to a data

set. Most spreadsheet programs have additional

abilities to chart data visually in easily workable

formats such as bar graphs, pivot charts, and pie

charts.

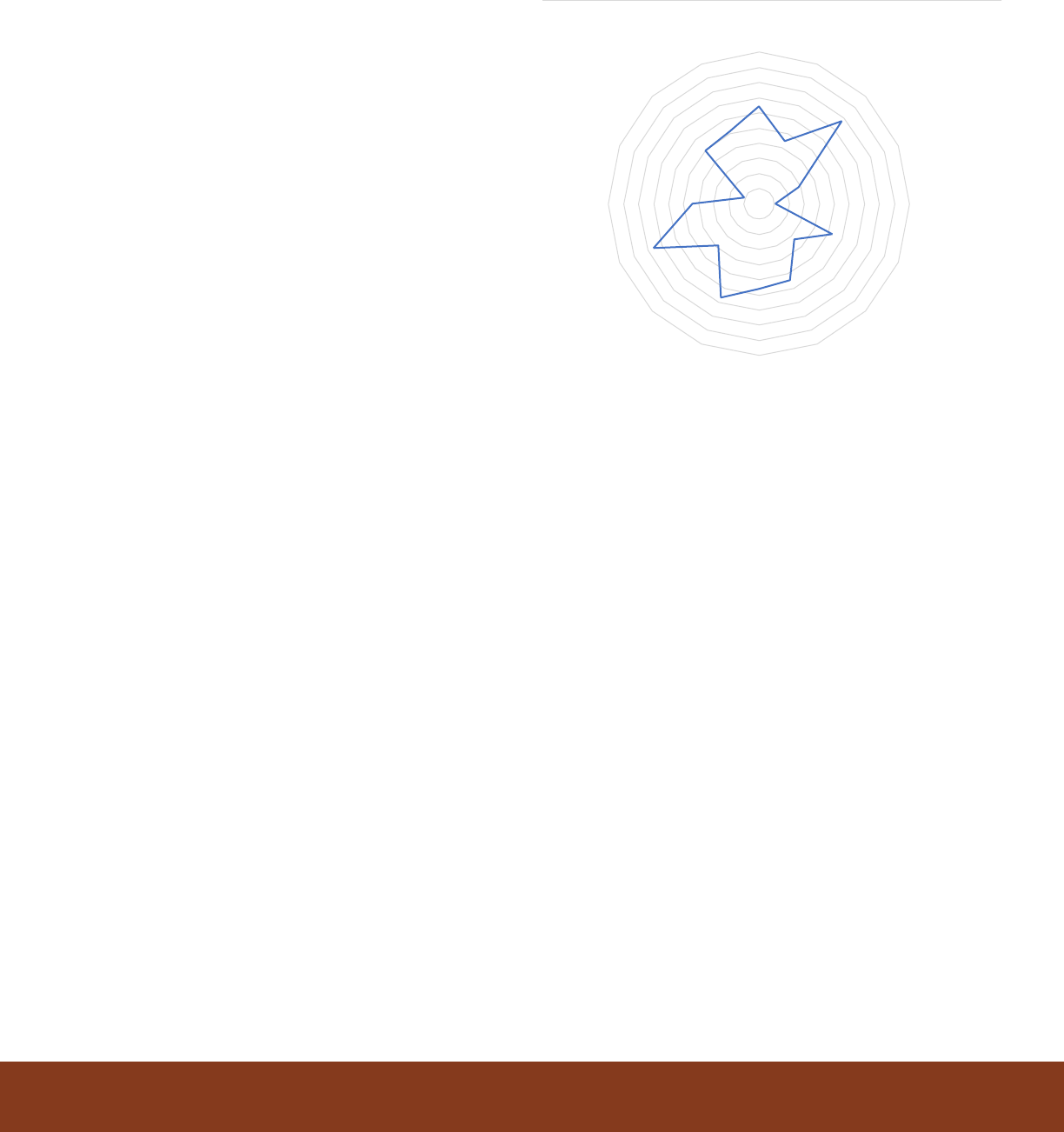

2. Spider Charts: Spider charts record multi-vari-

ate data into a two-dimensional plot of 3 or more

variables. There is a single foci in the middle and

variables record outward in a web-like line away

from the center. Connecting plots with lines cre-

ates a star shape that can be compared to other

samples recorded in this format, which is use-

ful for comparing attributes in various samples.

These charts can also be used to compare hops,

grains or other raw ingredients.

Reacting to Information

Data can be used to track long term variances

in beer consistency as well as make decisions in

the moment; however, a sensory program must

be fully integrated into the company’s quality pro-

gram to be effective.

1. Standard operating procedures are the

foundation of any quality program. Step-by-step

instructions for common procedures or tasks

allow for uniformity, safety, quality and account-

ability. Establishing SOPs for sensory panels

ensures that data is produced and collected in a

standardized form.

a. Recall Plan: Brewers need to be prepared for

voluntary or mandatory recall of packaged beer.

Date codes and other forms of traceability will

help keep consumers safe if a recall is warranted.

A written plan will also help with any FDA audit

and prepare a brewery to respond when action is

needed.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Ci tru s Aroma

F lor al A ro ma

Tropica l Fruit Aroma

Bi scuit Aro ma

Caramel Aroma

Frui ty Esters Aroma

Alco hol Aroma

Sweetness

Bitter ness

Citrus Flavor

Floral Flavor

Tro pical Fruit Flavor

Biscuit Flavor

Caramel Flavor

Car bonat ion

Alco holi c Warmt h

Example Sensory Attribute Spider Chart

BrewersAssociation.org

b. Decision trees are owchart-like maps that

show the various outcomes of a set of related

outcomes. In sensory programs they can chart

go/no-go decision making, recall protocol, and

other decisions that should be data driven. De-

cision trees can help prevent biased decisions

when determining whether to release a particular

product, or initiate a recall.

Total Company Buy-In

Total company buy-in is critical to the success of

any sensory program. Quality is not just done by

a team member or two - it is a philosophy that the

whole company embodies and to which all team

members can contribute. Success for sensory

panels can be hard to dene and investment

can be hard to justify, but the problems sensory

panels can help prevent need to be outlined and

advocated for regularly. Ample resources must be

provided to keep the program going.

An agreement must be made regarding the

program’s value before starting, so that there is

not pushback during time that it takes for this pro-

gram to be developed. If there are managers who

do not believe in the program, those team mem-

bers push back against the program, and some-

times actually get in the way of its implementation

and success. Panelists will be giving valuable

time to the help the sensory program manager

produce data and they need to have the support

of their managers to be able to leave their other

work to make panel times and classes. Managers

who are not supportive can make it hard for a

panelist to participate. Senior management needs

to have unied support of

the program to make sure it is budgeted for and

supported appropriately.

Once validated data is collected, there is an

opportunity for decision making around whether

a beer is true-to-brand and up to quality speci-

cations, which may affect the release of a beer.

Without senior management buy-in, decisions

may be made solely with emotional bias, the bot-

tom line, or retail and wholesale partner supply in

mind. Guidelines for the release of beer need to

be set and agreed upon at the highest levels of

the organization, if a sensory panel is going to be

successful and useful.

It is also important for sales and marketing teams

need to have an understanding of the program,

regardless of whether they participate. There may

be times when a beer is not released due to qual-

ity issues found by the sensory panel, which may

result in wholesale and retail partners not getting

orders fullled. Sensory and quality programs

must be a part of the company culture to have the

best chance of success.

BrewersAssociation.org

Bibliography

Brewers Association Brewing Elements Series:

Hieronymus, S. (2012) For the love of hops: the practical guide to aroma, bitterness, and the culture

of hops. Brewers Publications, Boulder, CO.

Mallett, J. (2014) Malt: a practical guide from eld to brewhouse. Brewers Publications, Boulder, CO.

Palmer, J. J., and Kaminski, C. (2013) Water: a comprehensive guide for brewers. Brewers Publica-

tions, Boulder, CO

White, C., and Zainasheff, J. (2010) Yeast: the practical guide to beer fermentation. Brewers Publica-

tions, Boulder, CO.

Sensory Evaluation Texts:

Bamforth, C. W. (2014) Flavor: practical guides for beer quality. ASBC handbook series American

Society of Brewing Chemists, St. Paul, MN.

Civille, G. V., Carr, B. T., and Meilgaard, M. (2015) Sensory Evaluation Techniques, Fifth Edition. CRC

Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Lawless, H.T. and Heymann, H., (2010) Sensory evaluation of food: principles and practices. Springer

Science & Business Media.

O’Mahony, M., (1986) Sensory evaluation of food: statistical methods and procedures (Vol. 16). CRC

Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Additional Resources:

Pellettieri, M., (2015) Quality Management: Essential Planning for Breweries. Brewers Publications,

Boulder, CO.

Bamforth, C. W. (2002) Standards of brewing: a practical approach to consistency and excellence.

Brewers Publications, Boulder, CO.

Available Coursework:

• University of California Davis, Applied Sensory and Consumer Science Certicate Program

• Siebel Institute, Sensory Panel Management course

• Beer Judge Certication Program

• Cicerone Certication Program Sensory Evaluation Standards:

• American Society of Brewing Chemists, Methods of Analysis, Sensory Methods of Analysis

• ASTM International, Sensory Evaluation Standards, Standard Guide for Sensory Evaluation of

Beverages Containing Alcohol