Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

The University of Nebraska Public Policy Center provides assistance to

policymakers in all three branches of government and researchers on a wide

range of public policy issues. The mission of the PPC is to actively inform

public policy by facilitating, developing, and making available objective

research and analyses of issues for elected and appointed officials; state and

local agency staff; the public at large; and others who represent policy

interests.

215 Centennial Mall South, Suite 401, Lincoln, NE 68588-0228

Ph: 402-472-5678 | Fax: 402-472-5679

www.ppc.nebraska.edu

®

The University of Nebraska does not discriminate based on gender, age, disability, race,

color, religion, marital status, veteran’s status, national or ethnic origin, or sexual

orientation.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

Contents

................................................................................................. 1

........................................................................................ 3

....................... 4

..................................................... 5

................................................................................. 19

........................................................................................................................................... 24

.................................................................................................................... 32

...................... 45

...................................................................................................................... 108

................... 127

...................................................................................................................... 151

........... 175

...................................................................................................................... 178

................................................................................................................. 205

................................................................................................................ 234

............................................................................ 245

...................................................... 335

.................. 342

................................................................. 352

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

1 | P a g e

From March 2010 through December 2011, the University of Nebraska Public Policy

Center conducted an evaluation of Nebraska’s problem solving courts. Main findings

include the following:

Nebraska’s problem solving courts are effectively operated, following the ten key

components for drug courts, thereby reducing crime and addiction and improving

the lives of participants

Graduation rates for Nebraska drug courts match or exceed national drug court

rates

Costs for Nebraska programs are comparable to costs for drug courts across the

country

Nebraska drug court programs are cost efficient, saving between $2,609,235 and

$9,722,920 in tax dollars per year

Problem solving courts in Nebraska are serving moderate to high need offenders,

the type of offenders most appropriate for drug court services

Nebraska drug courts are serving a diversity of offenders, with few disparities

based on race, ethnicity, and gender

Education and employment skills are emphasized in problem solving courts,

which lead to successful outcomes for participants

Although the evaluation found Nebraska problem solving courts are operating

effectively and efficiently, there are areas that can be improved:

Participants with higher criminal history risk could be accepted and

effectively served in drug courts

Increased training in the 10 key drug court components and the

Standardized Model for Delivery of Substance Abuse Services could

benefit problem solving courts, particularly family drug courts

Review of admissions procedures for select courts could identify causes

for racial/ethnic disparities; culturally competent approaches could

improve services

Improvements could be made by ensuring full participation of county

attorneys, defense attorneys, judges, law enforcement, and treatment

provides in problem solving court teams

Drug court teams could benefit from additional training and team building

Additional funding would enhance key supports for drug courts including

participant incentives, access to day reporting centers, and enhanced

treatment

Programs could be improved through standardized procedures for

reporting treatment progress and fidelity to evidence based practices

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

2 | P a g e

Time between arrest and drug court admission could be reduced, thereby

improving outcomes for participants

The quality of problem solving courts could be improved through ongoing

program evaluation

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

3 | P a g e

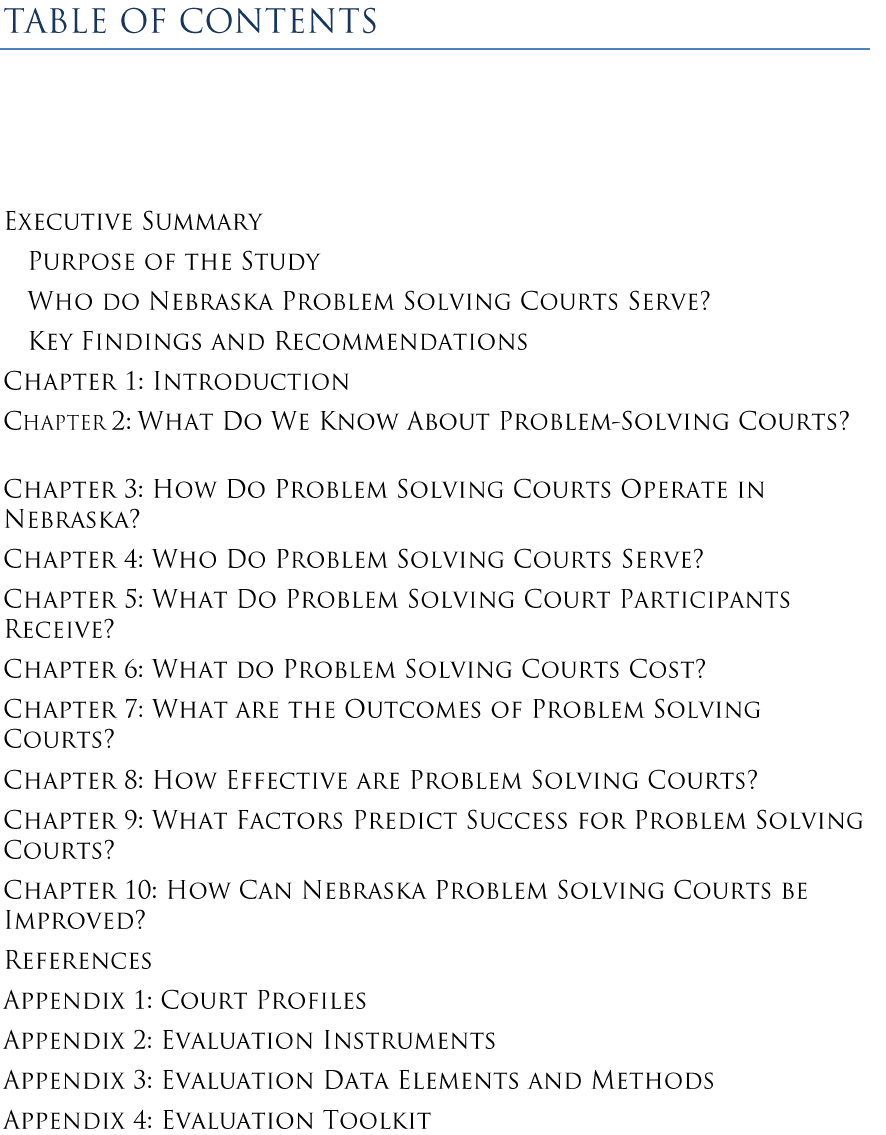

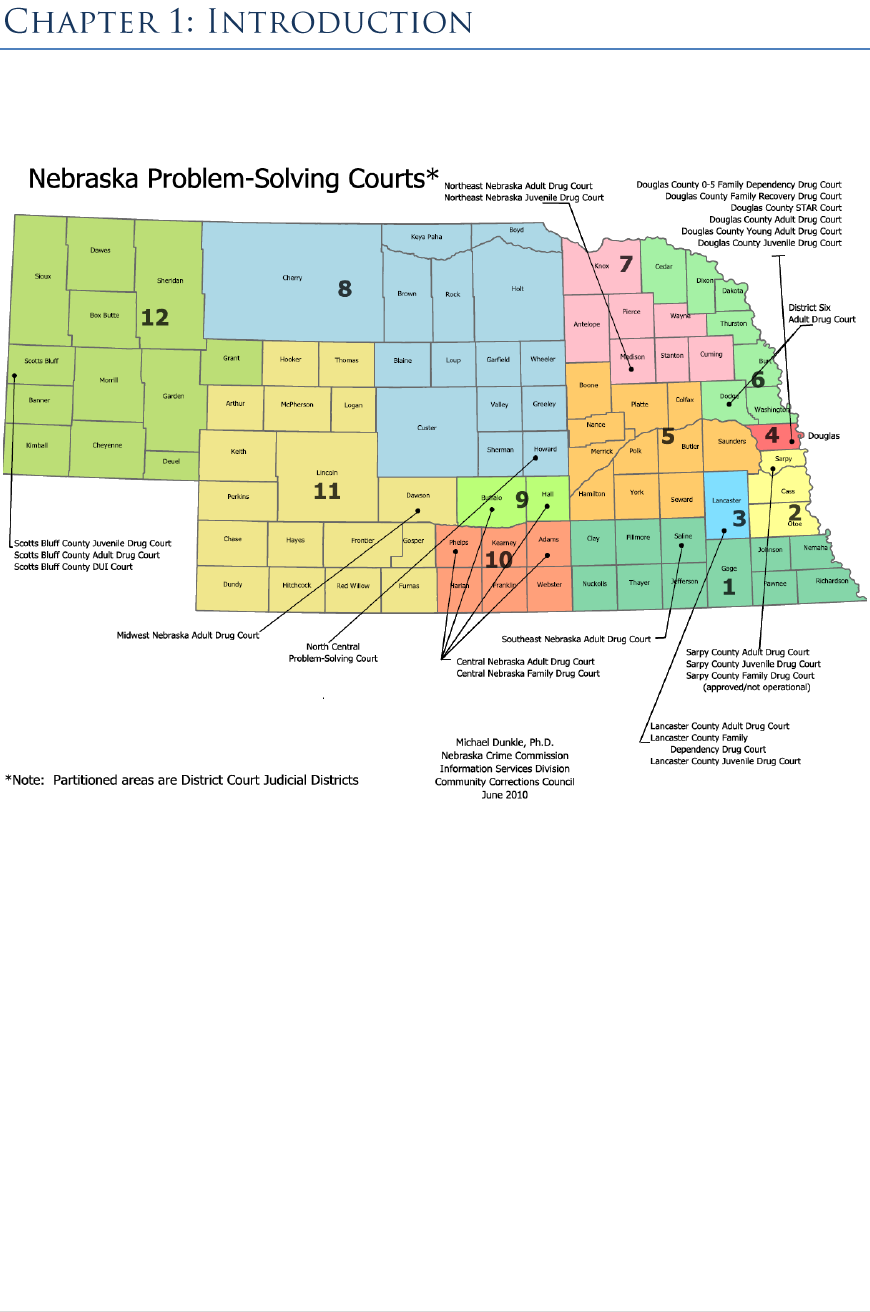

The program evaluation was conducted by the University of Nebraska Public Policy

Center under a contract with the state of Nebraska. There are 22 problem solving courts

in Nebraska (10 adult courts, five juvenile courts, five family courts, one young adult

court, and one Driving Under the Influence (DUI) Court).

The purposes of the study included the following:

Understand what is working well and what can be improved in Nebraska’s

problem solving courts

Understand who is being served through problem solving courts

Understand how problem solving courts operate

Understand what problem solving courts cost

Understand how effective problem solving courts are in Nebraska and what

factors are associated with positive outcomes

Understand how problem solving courts can continuously evaluate and improve

their services

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

4 | P a g e

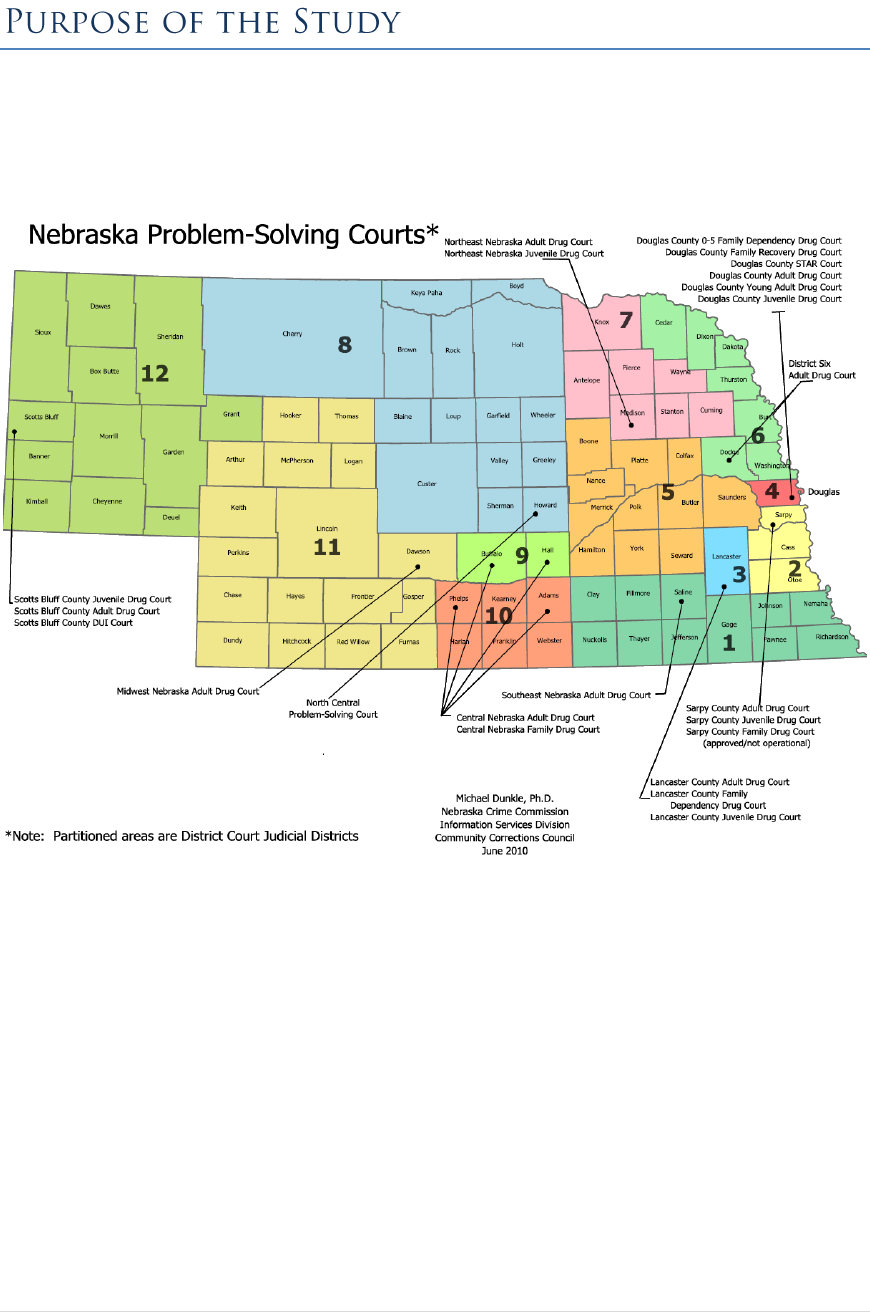

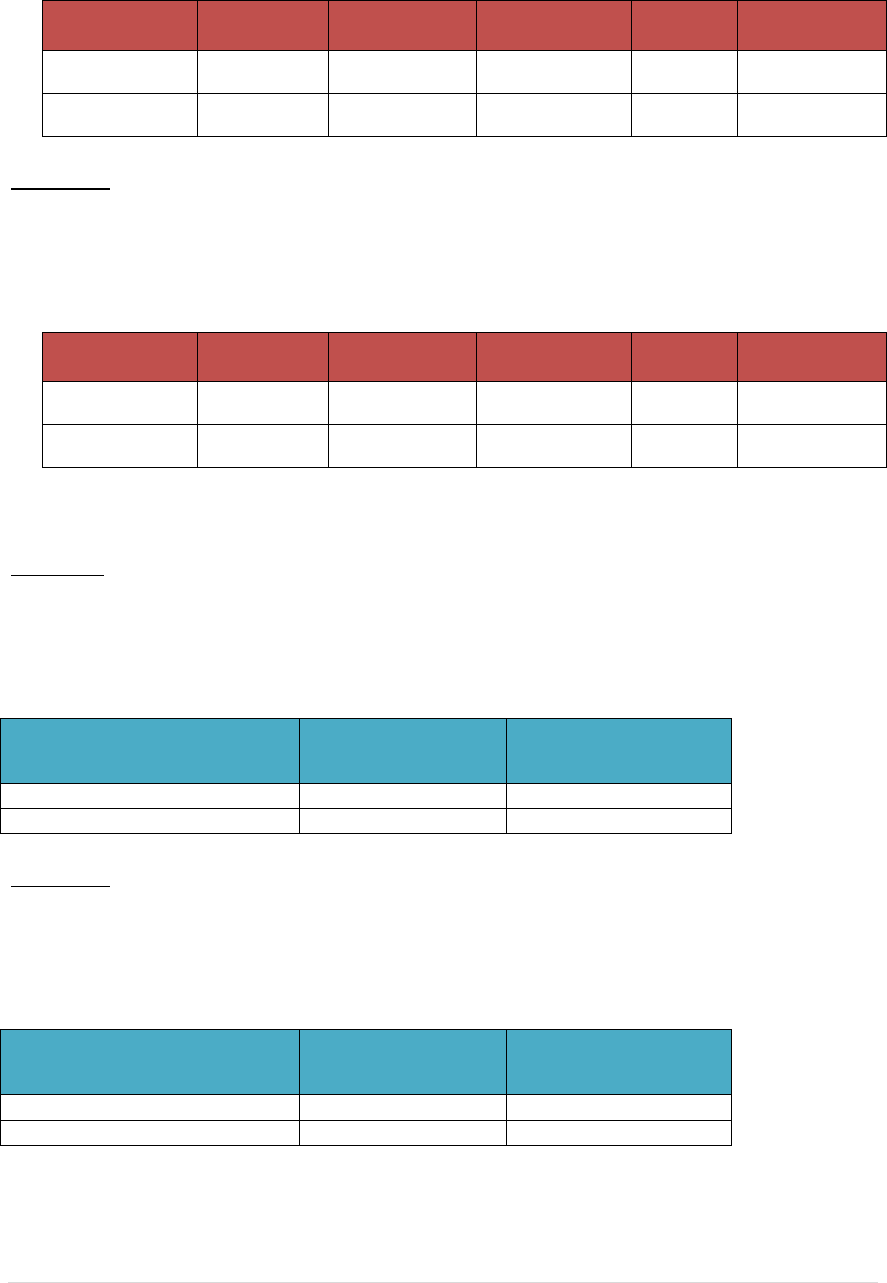

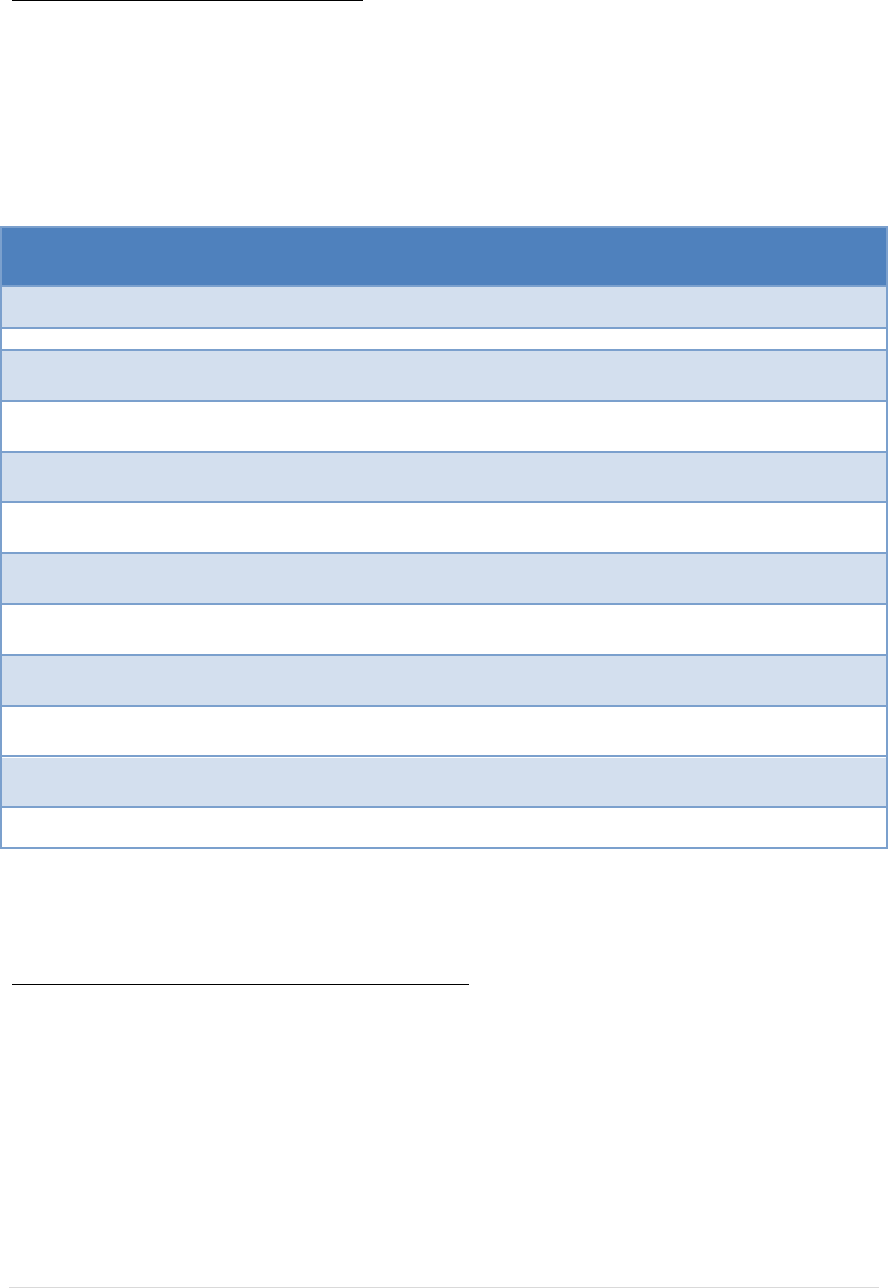

The evaluation focused on offenders who were

served in Nebraska problem solving courts from

January 2007 through April 2011. During this time

period, at least 1862 individuals were served by

Nebraska problems solving courts. About 80%

were served in adult drug courts. Only one of the

family dependency drug courts reported numbers

served. As of July 30, 2011, 726 participants had

graduated from drug court, 609 participants had

been terminated, and 527 were currently active. The

average age for adult drug court participants is 30.3

years of age, and the average for juveniles is 16.6.

The average age for the young adult drug court is

19.7 years.

Participants in Nebraska’s problem solving

courts are predominately male: 63% of

adult drug court participants and nearly

80% of juvenile court participants are male.

Participants in the young adult court (65%)

and DUI court (78.3%) are also mostly

male, while participants in family court are

mostly female (97%).

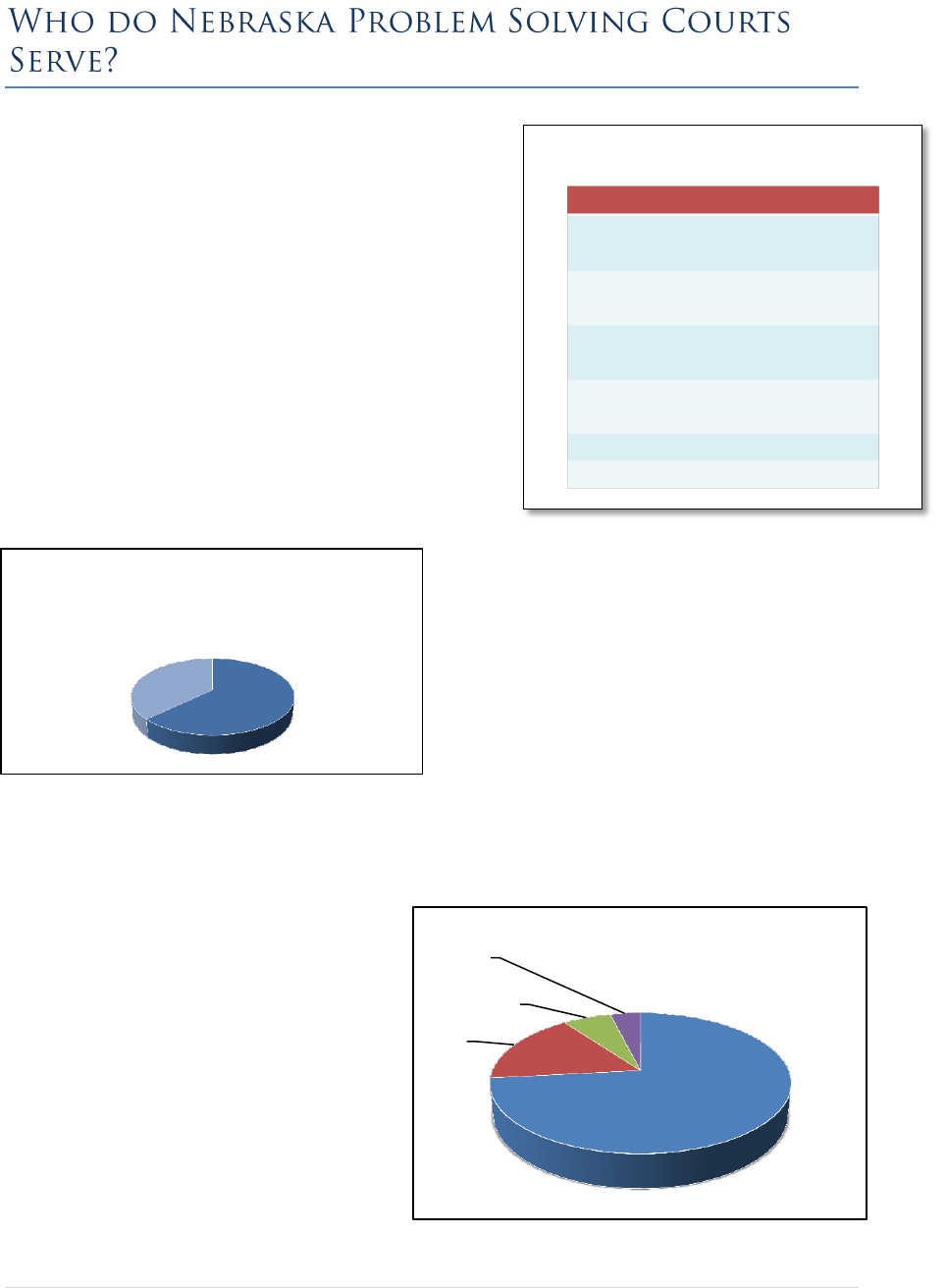

Most participants were white, although there were substantial racial/ethnic differences

across courts, reflecting unique demographics across Nebraska communities. A

comparison of drug court participants to probation participants revealed few racial/ethnic

disparities, although one adult drug court included fewer racial minorities than

anticipated. Nearly all juvenile and

young adult court participants were

single. Most adult court participants

were also single (64%), while 14% were

divorced, 12% were married, 7% were

separated, 4% were cohabitating, and

9% were widowed. Most adult drug

court participants were charged with a

class 2 through 4 felony, while the

majority of juvenile drug court

participants were charged with juvenile

offenses. Cannabis was the most

common primary drug of choice for participants in both adult and juvenile drug courts.

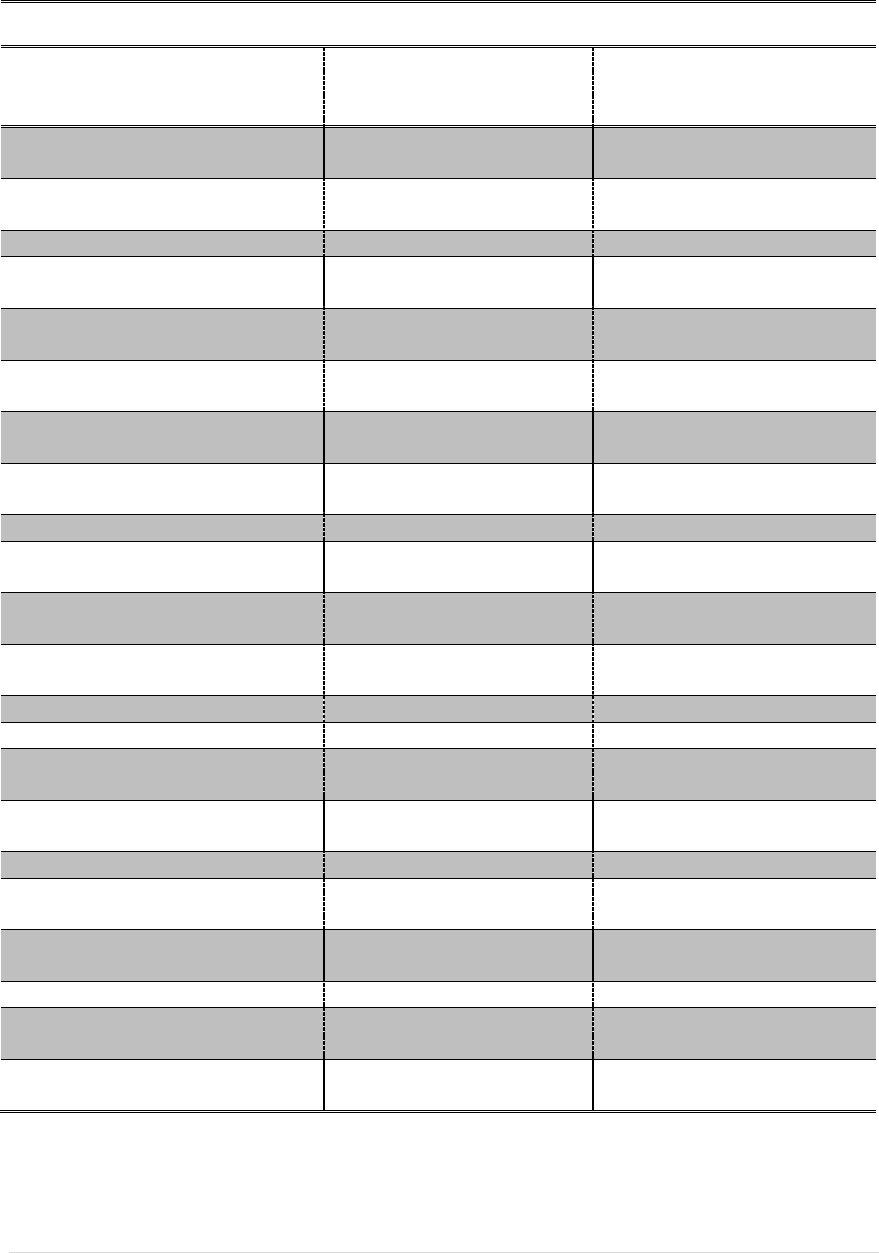

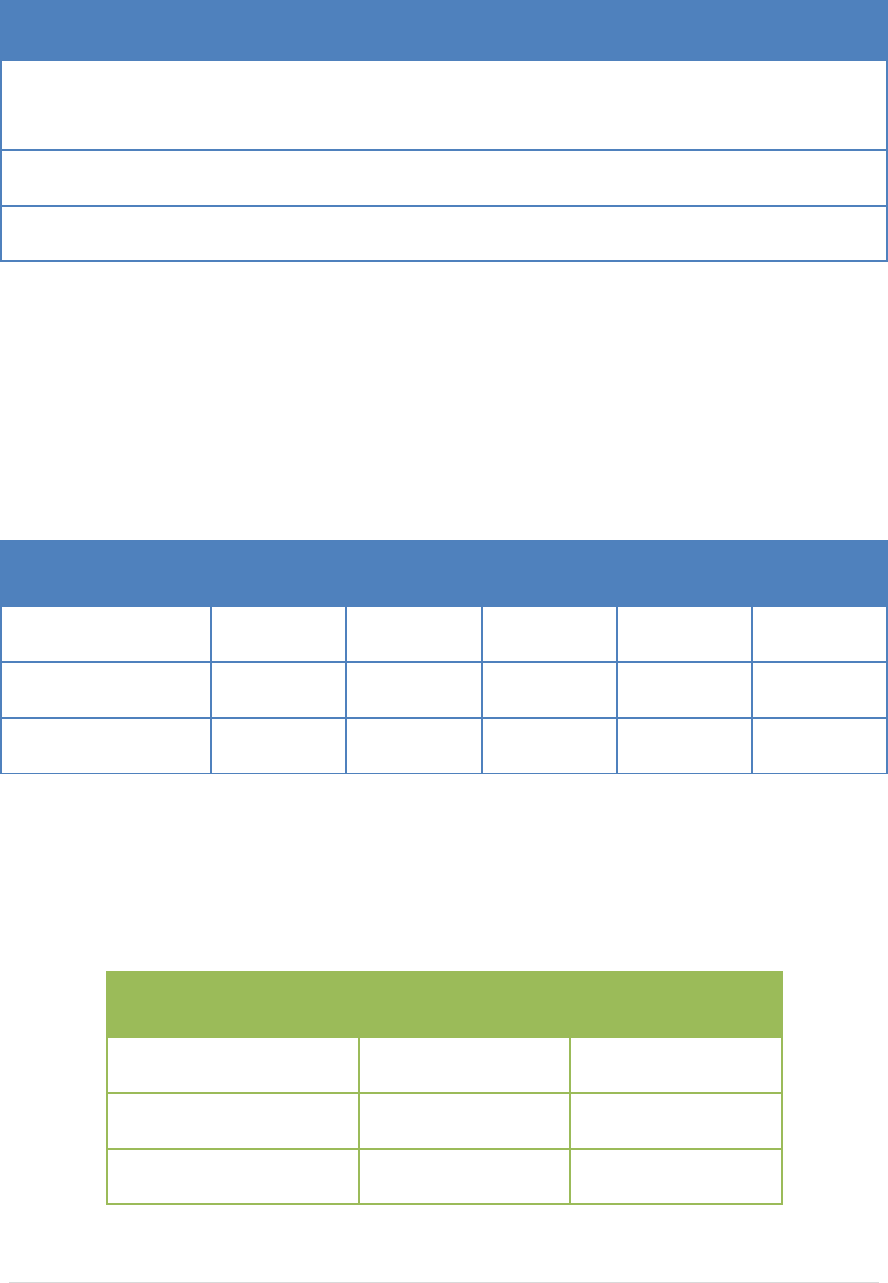

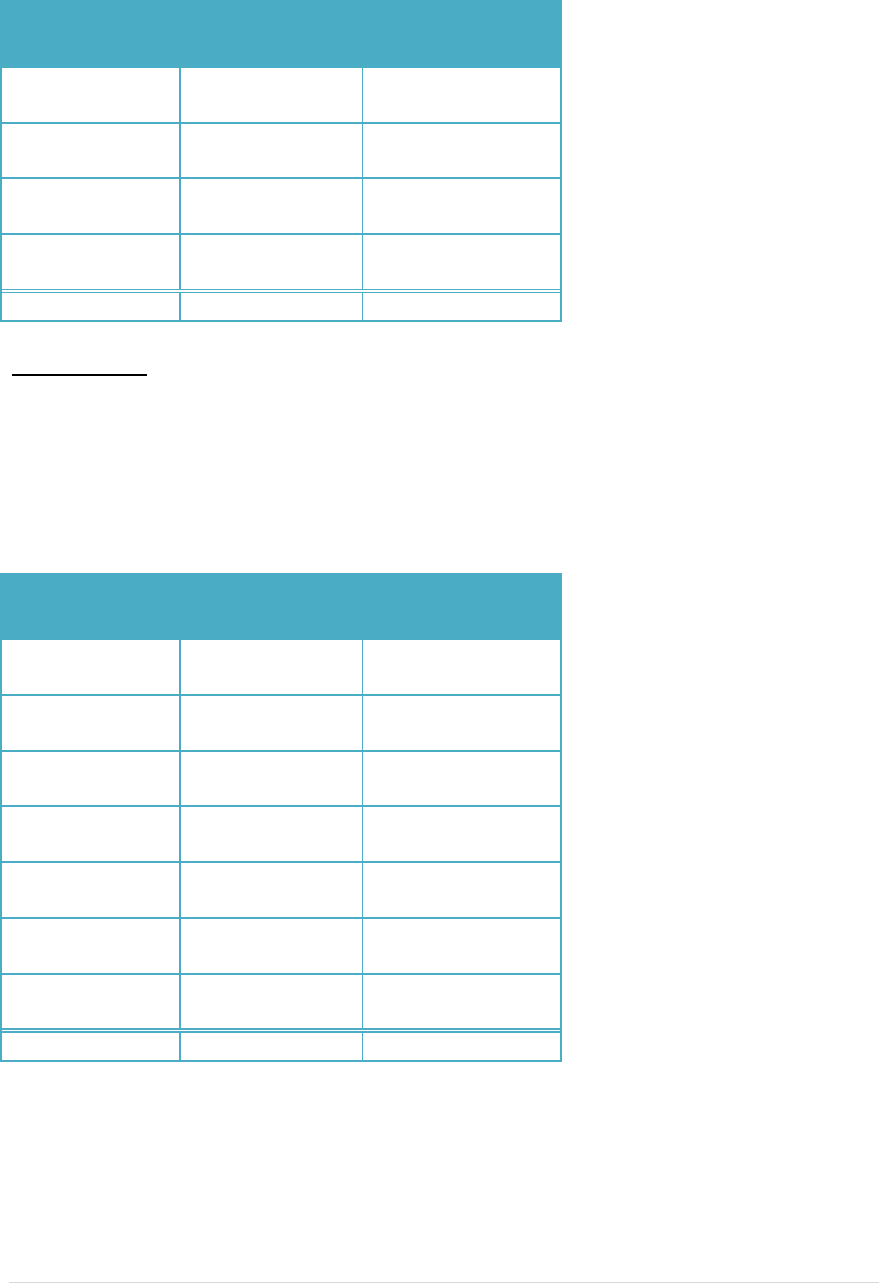

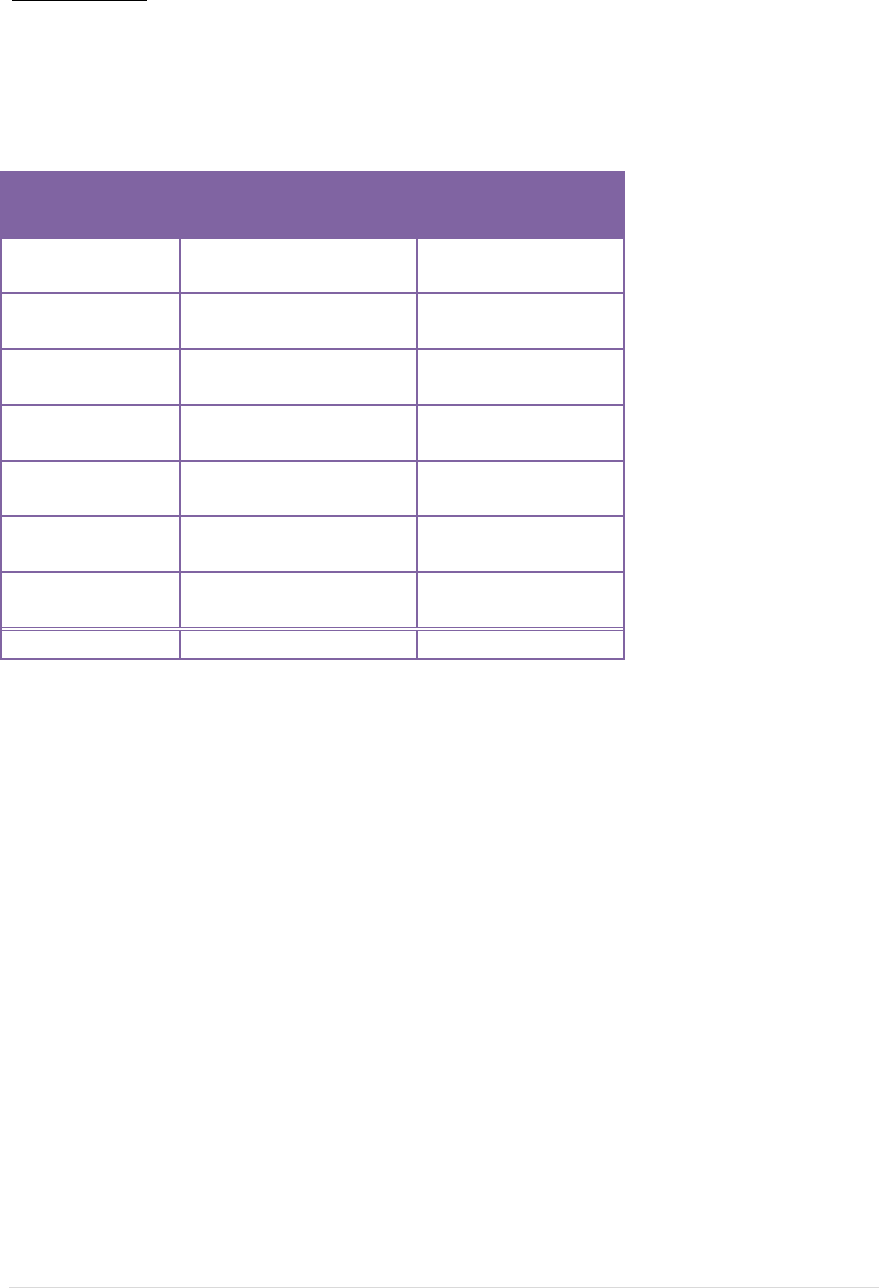

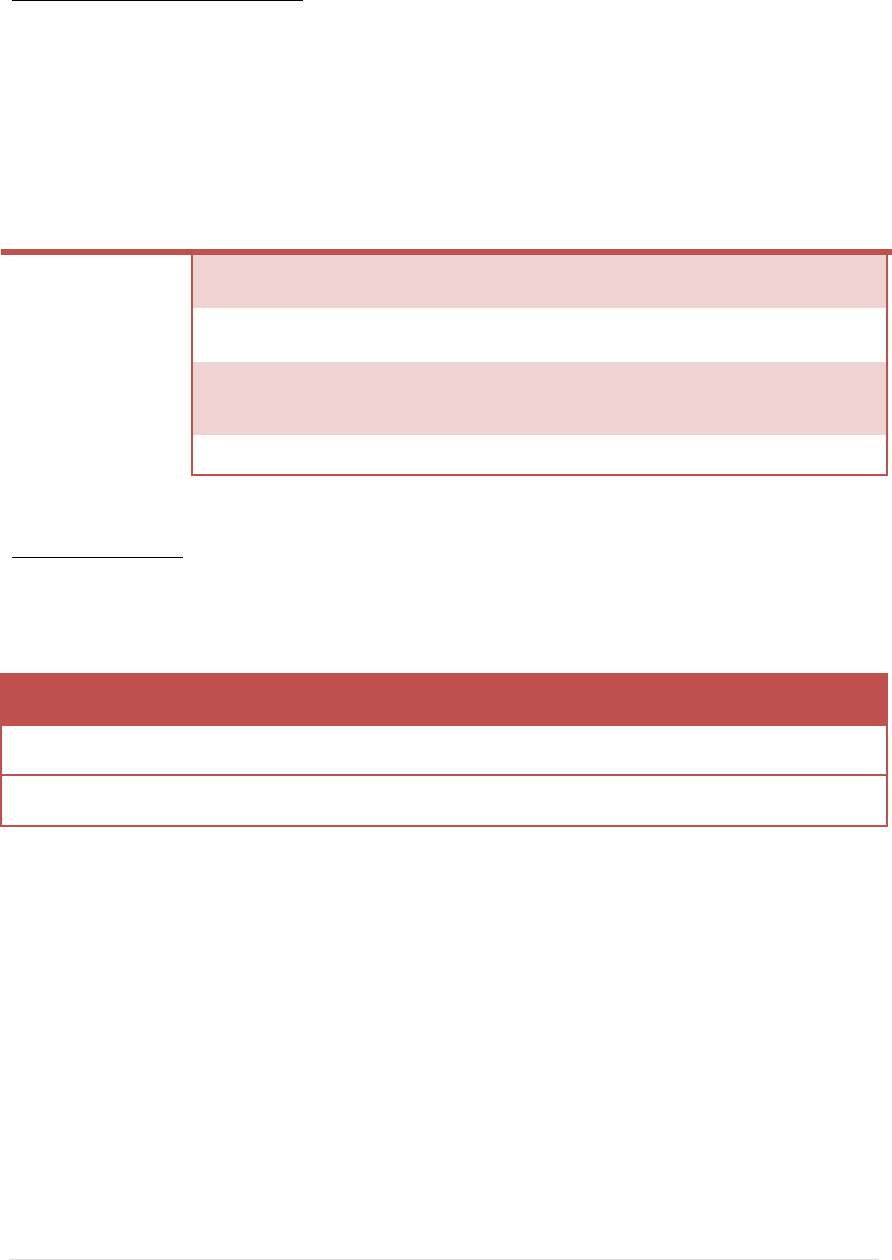

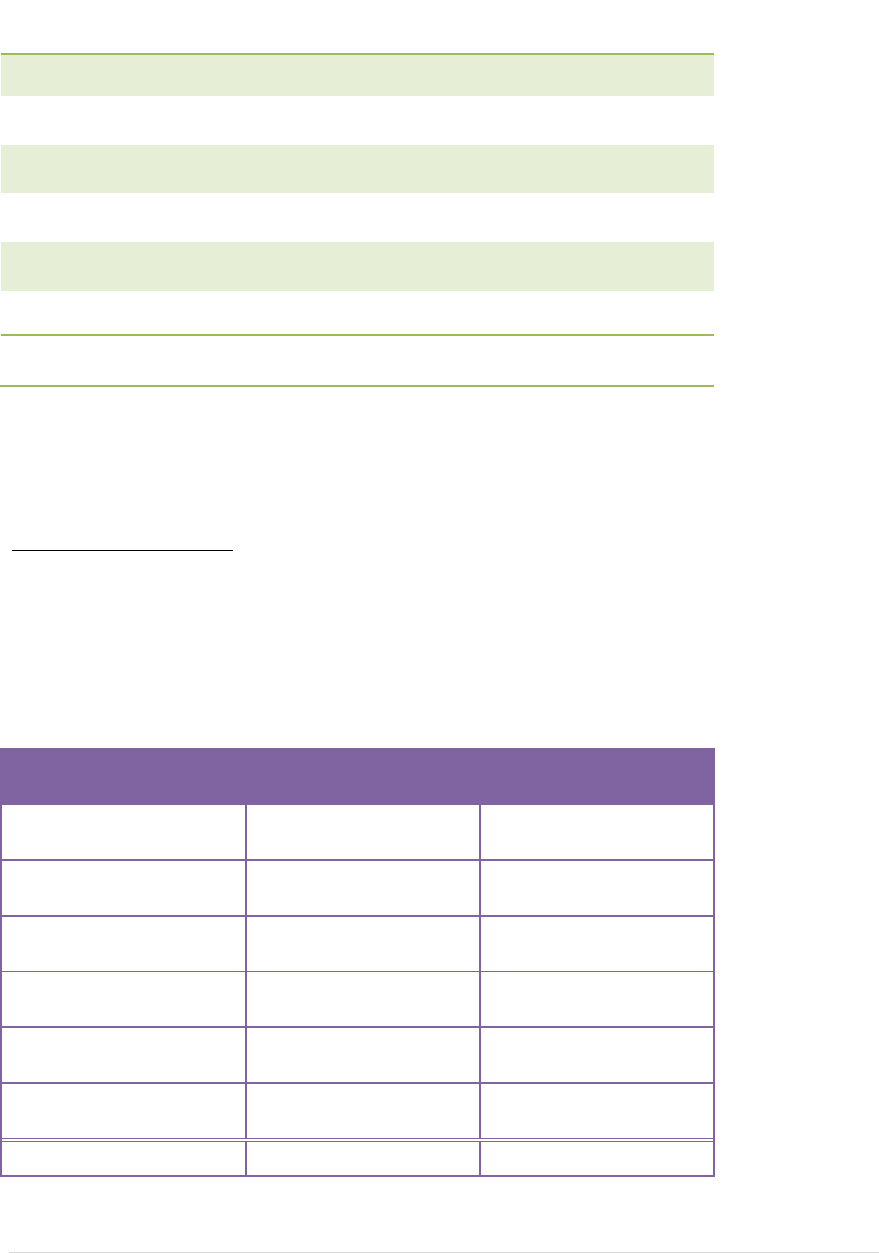

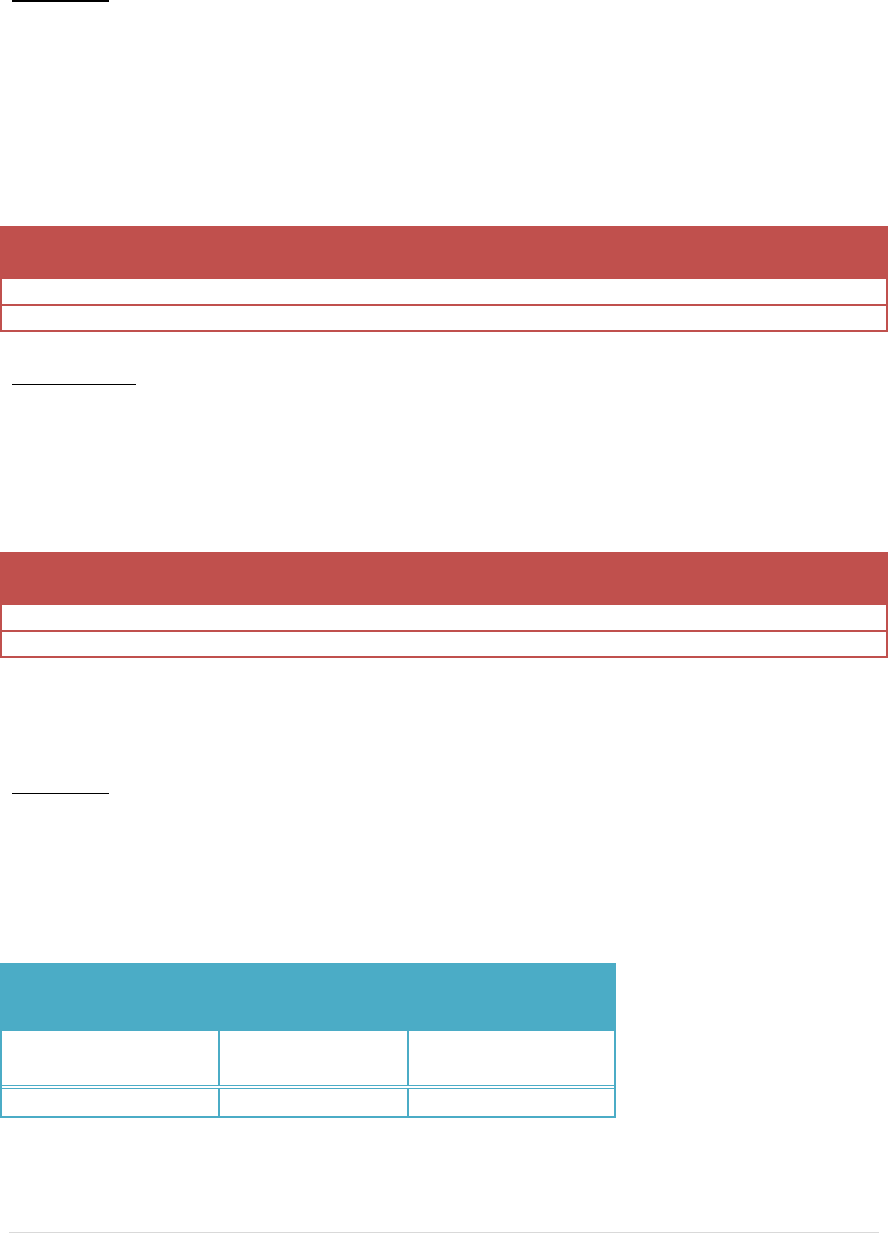

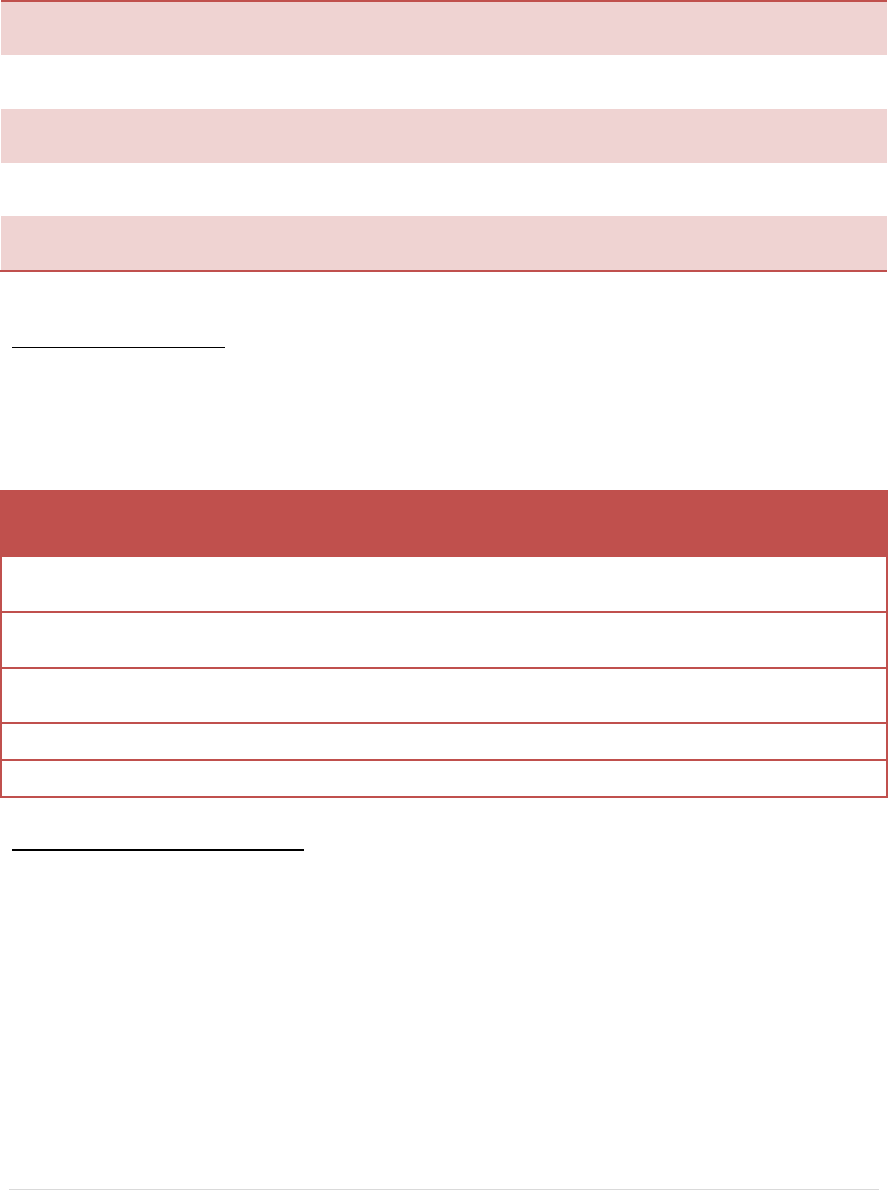

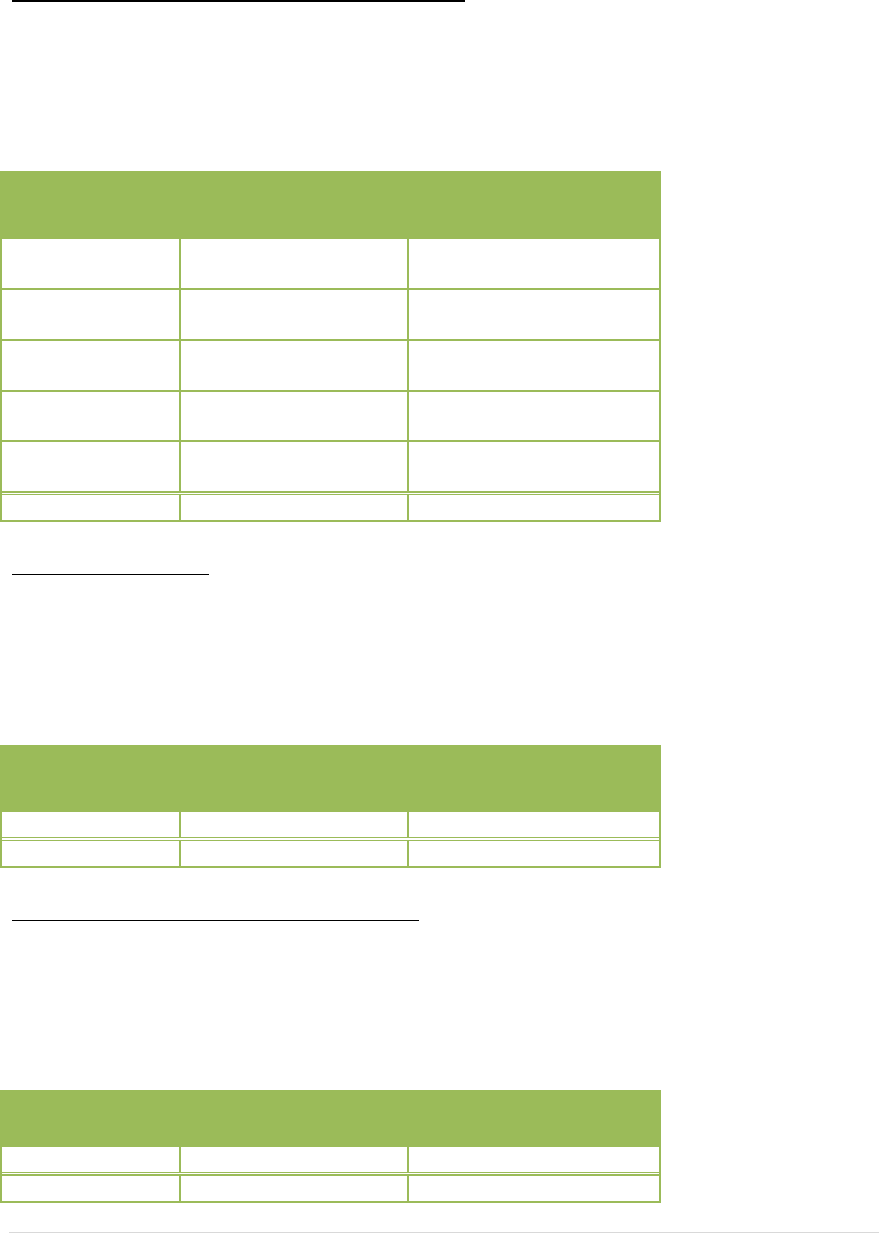

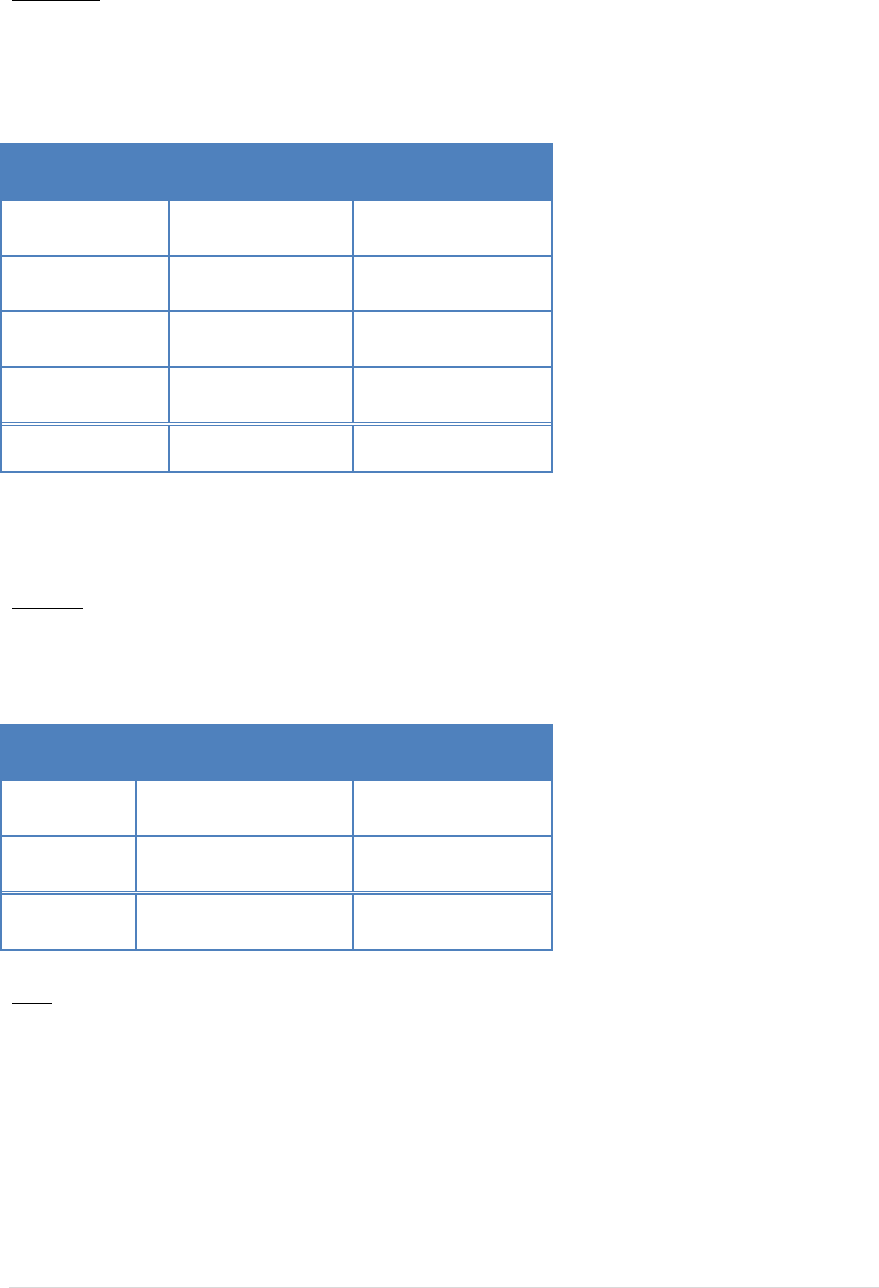

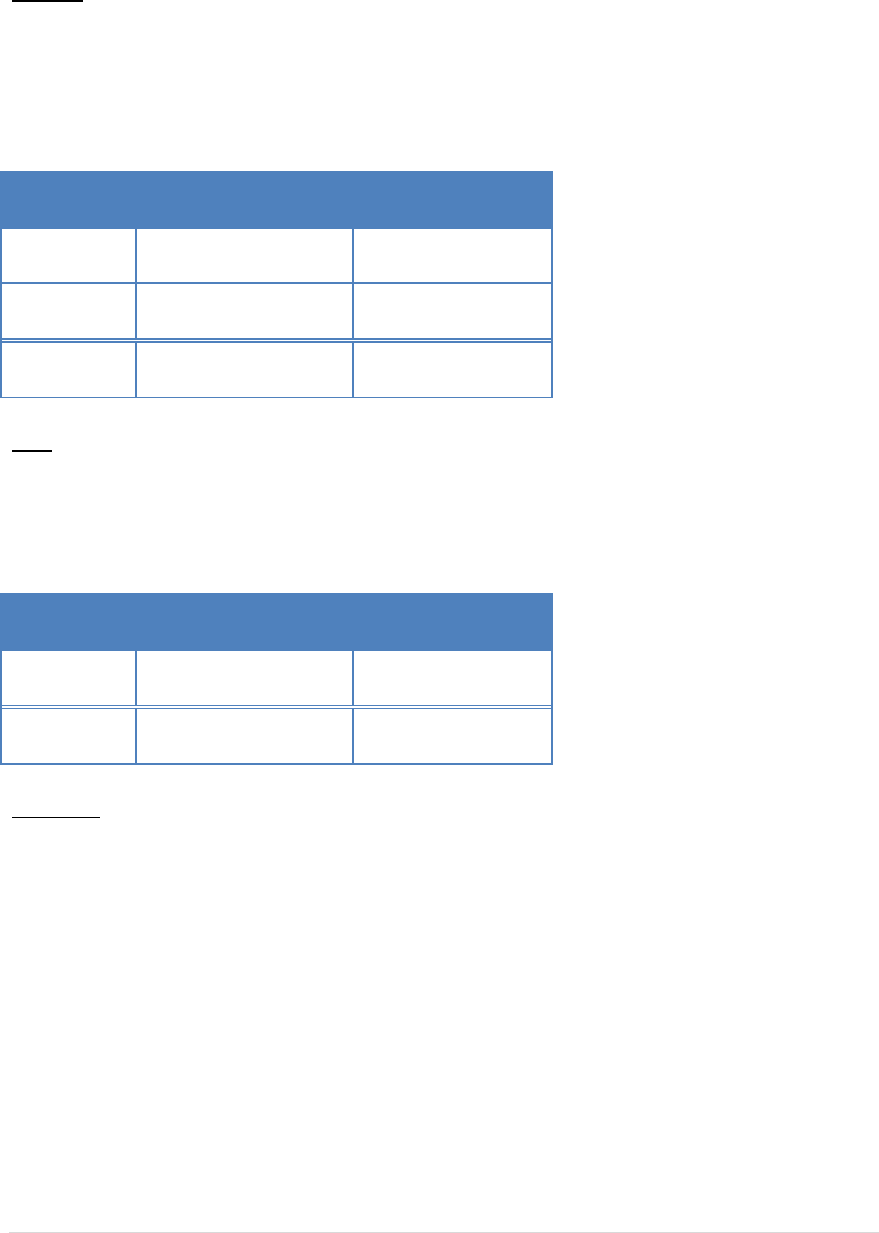

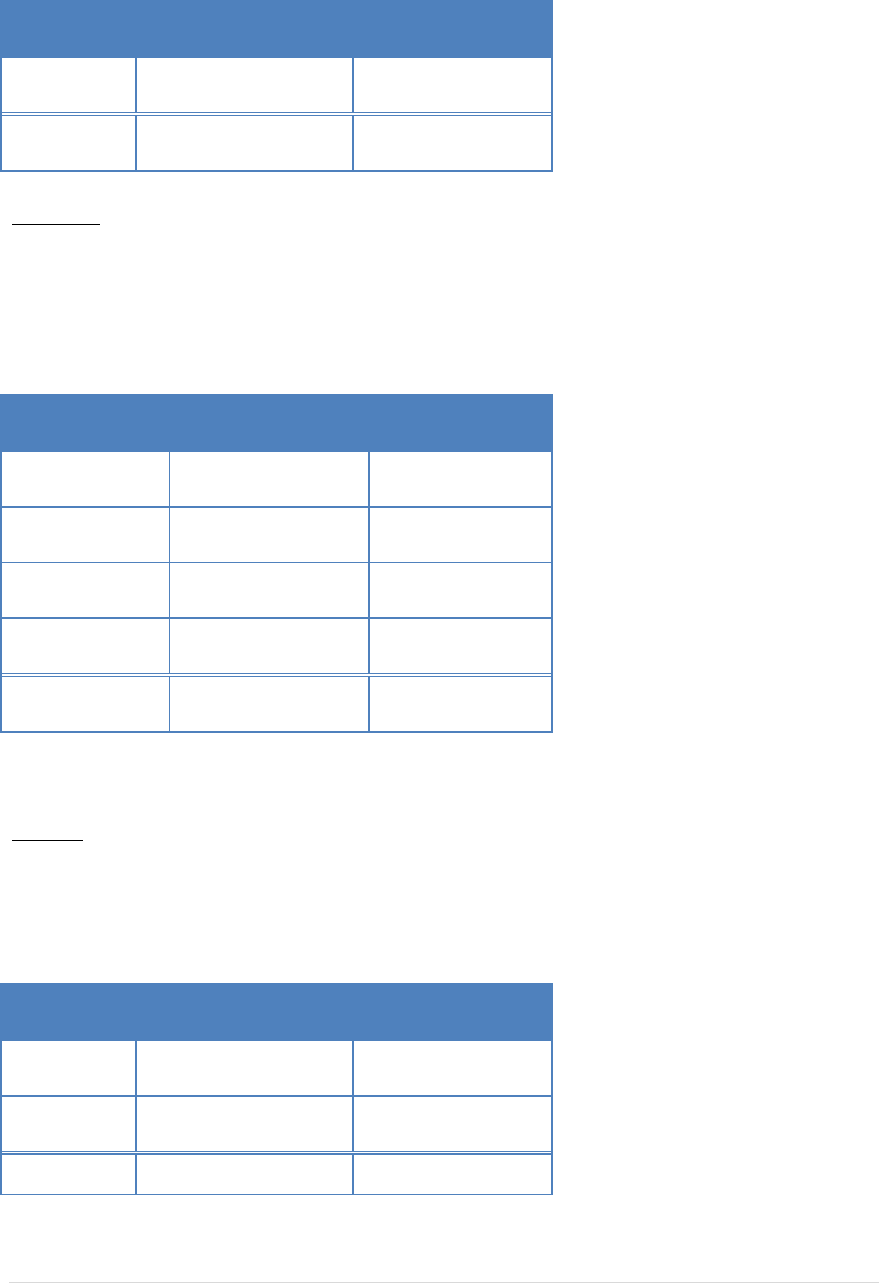

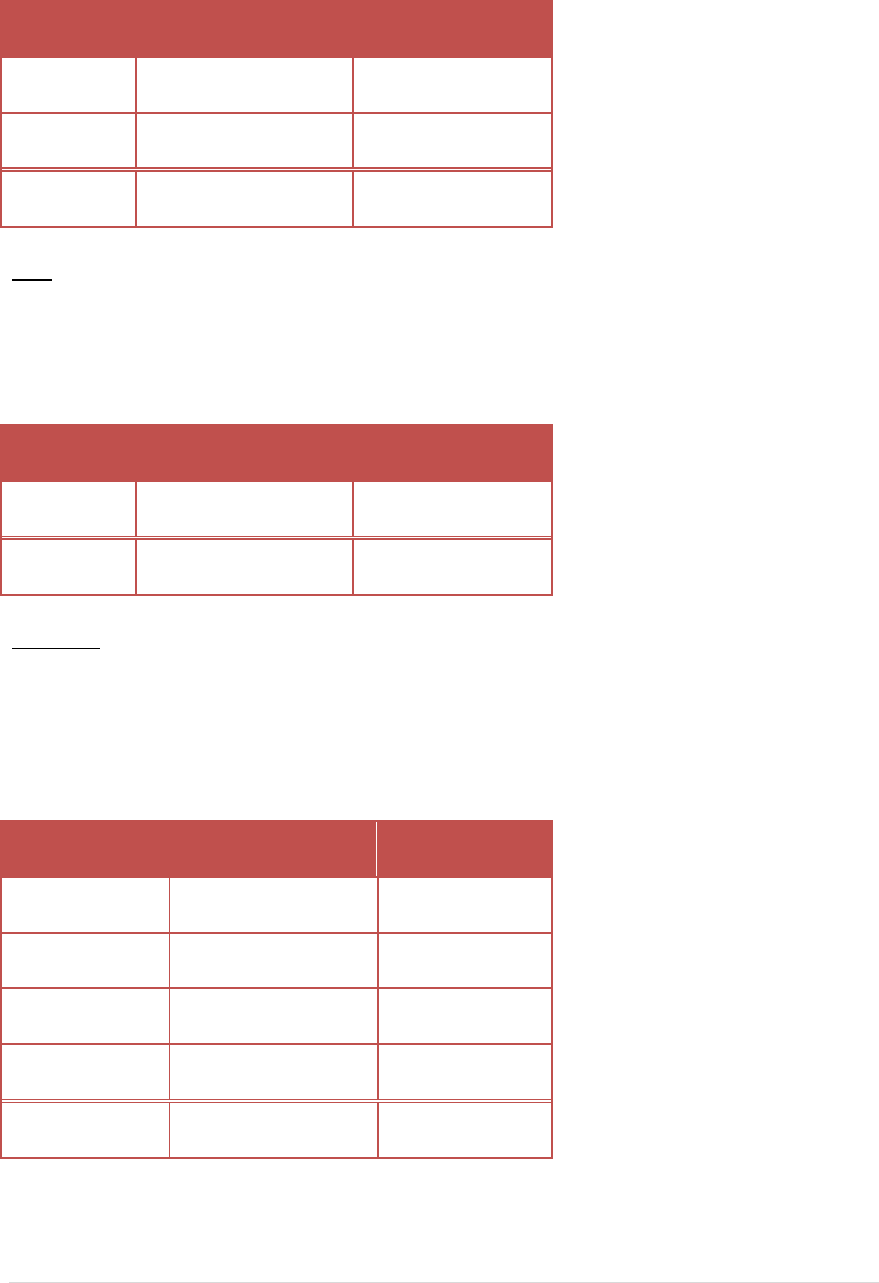

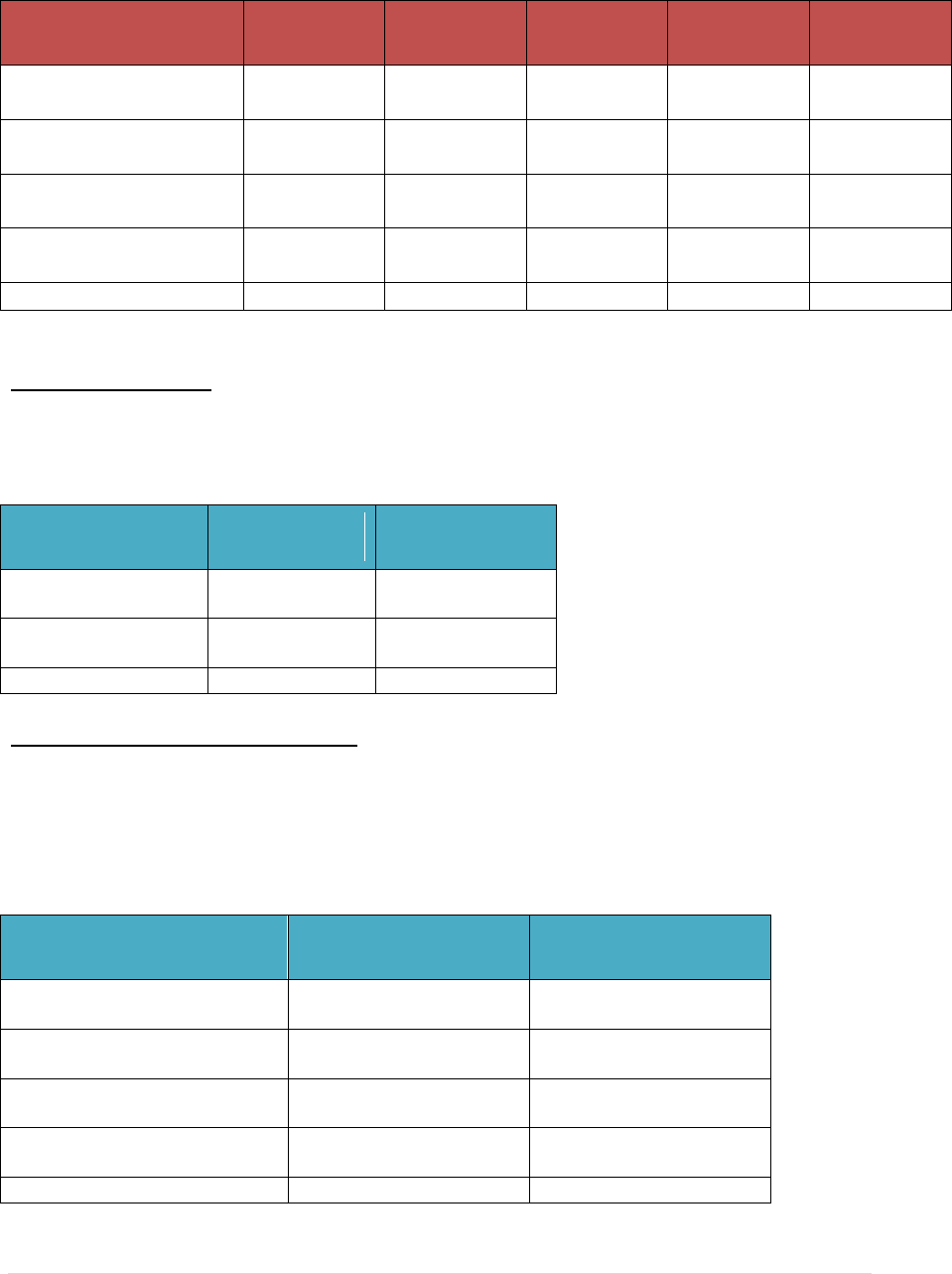

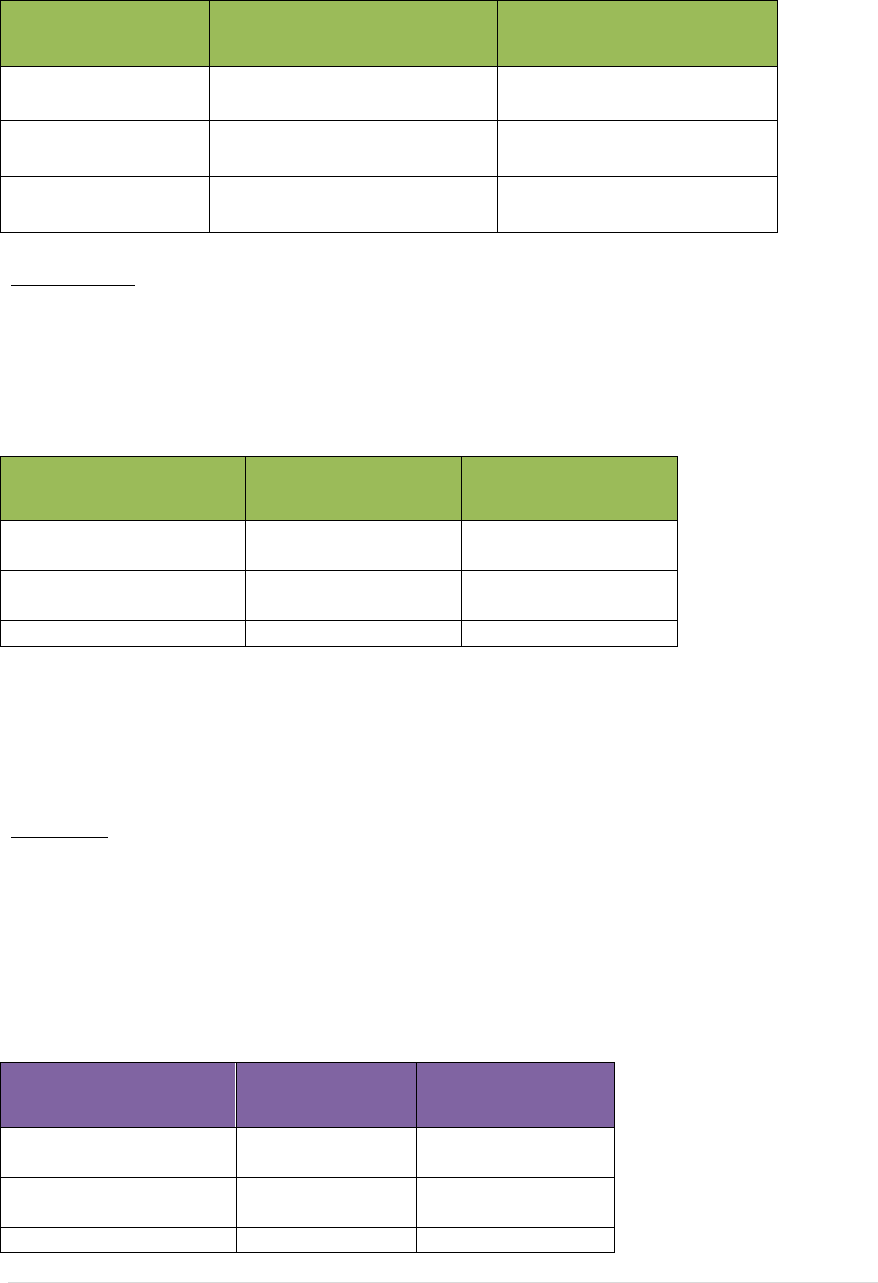

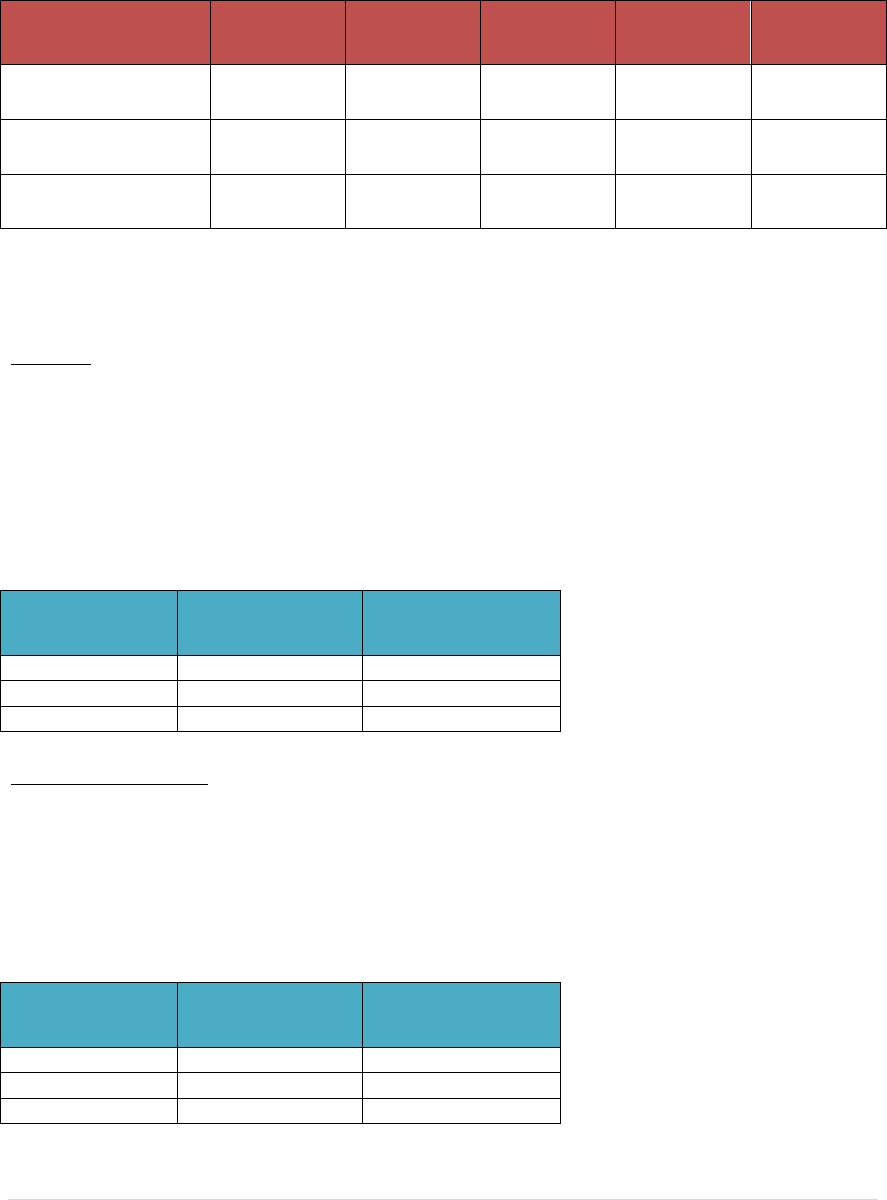

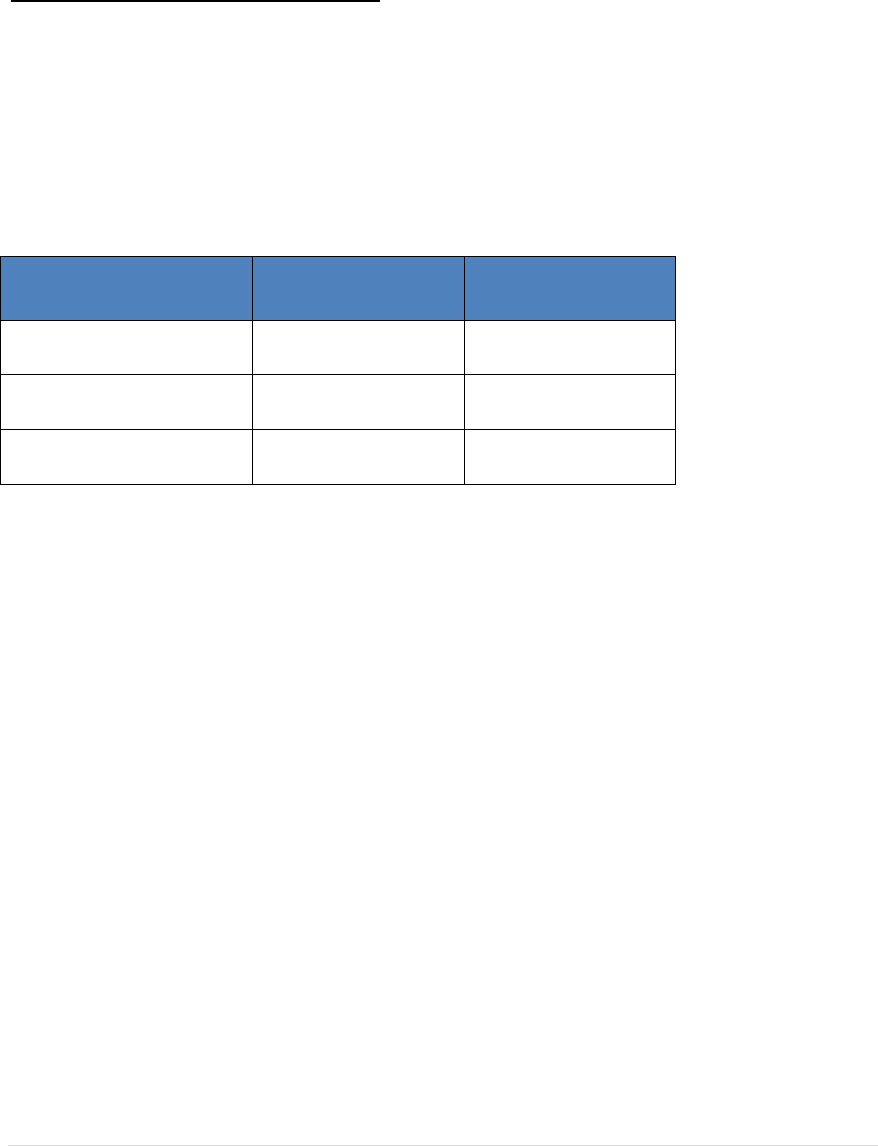

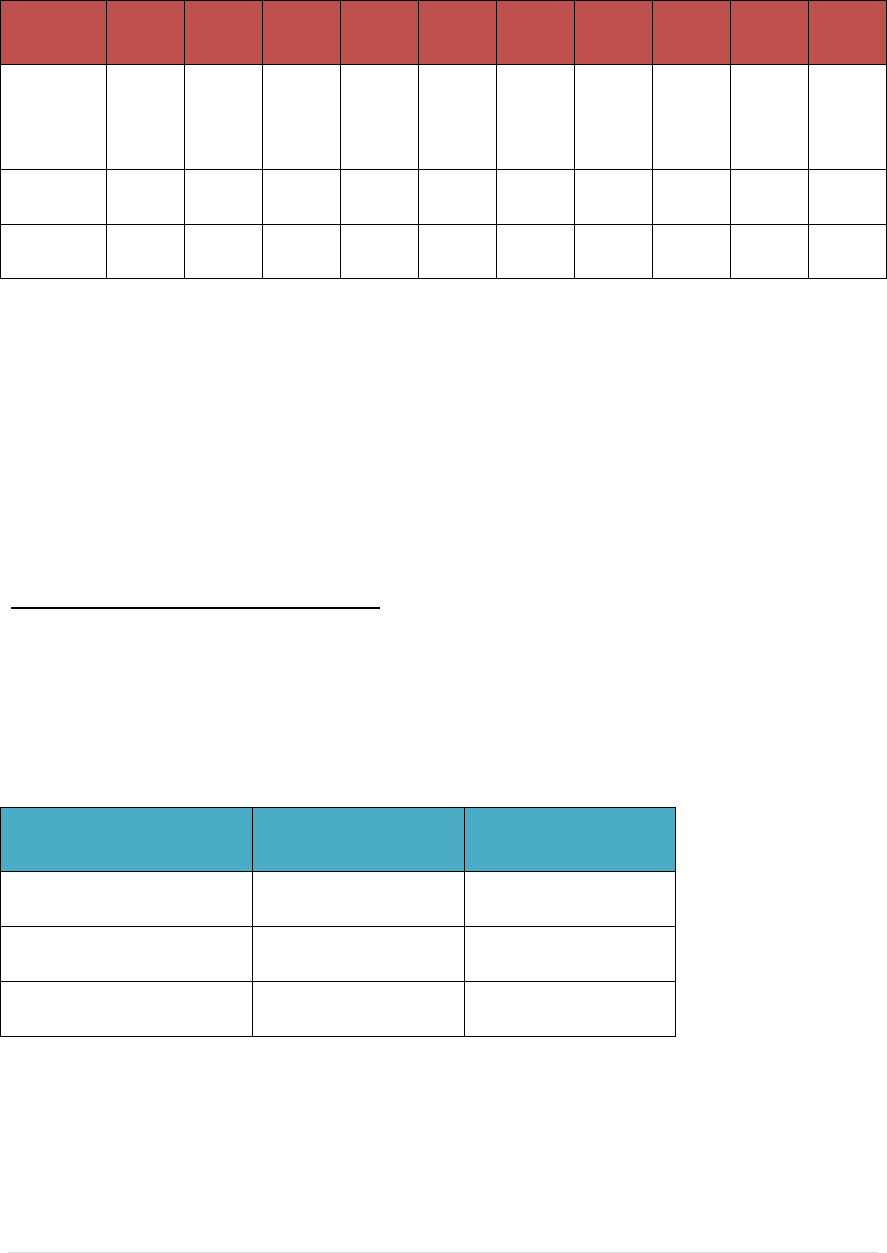

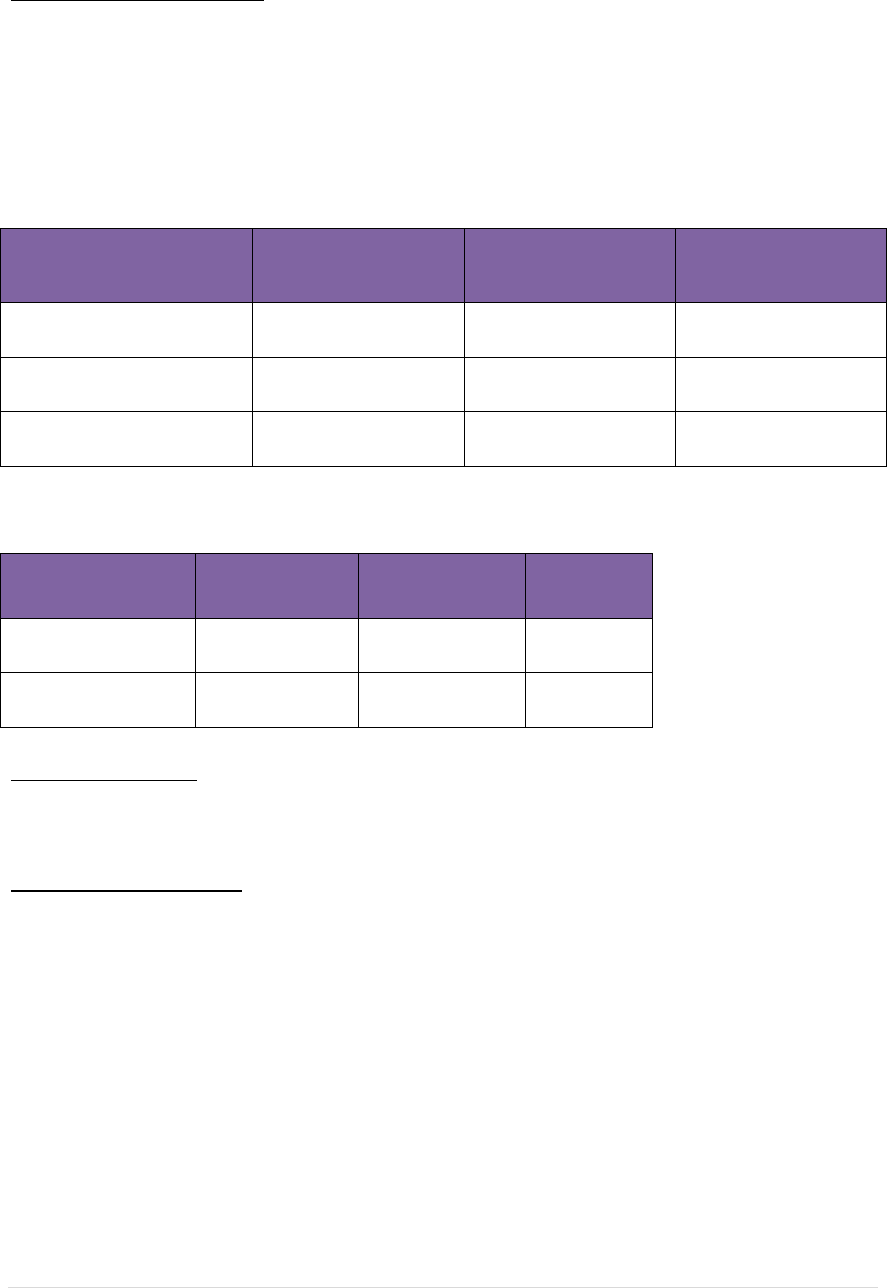

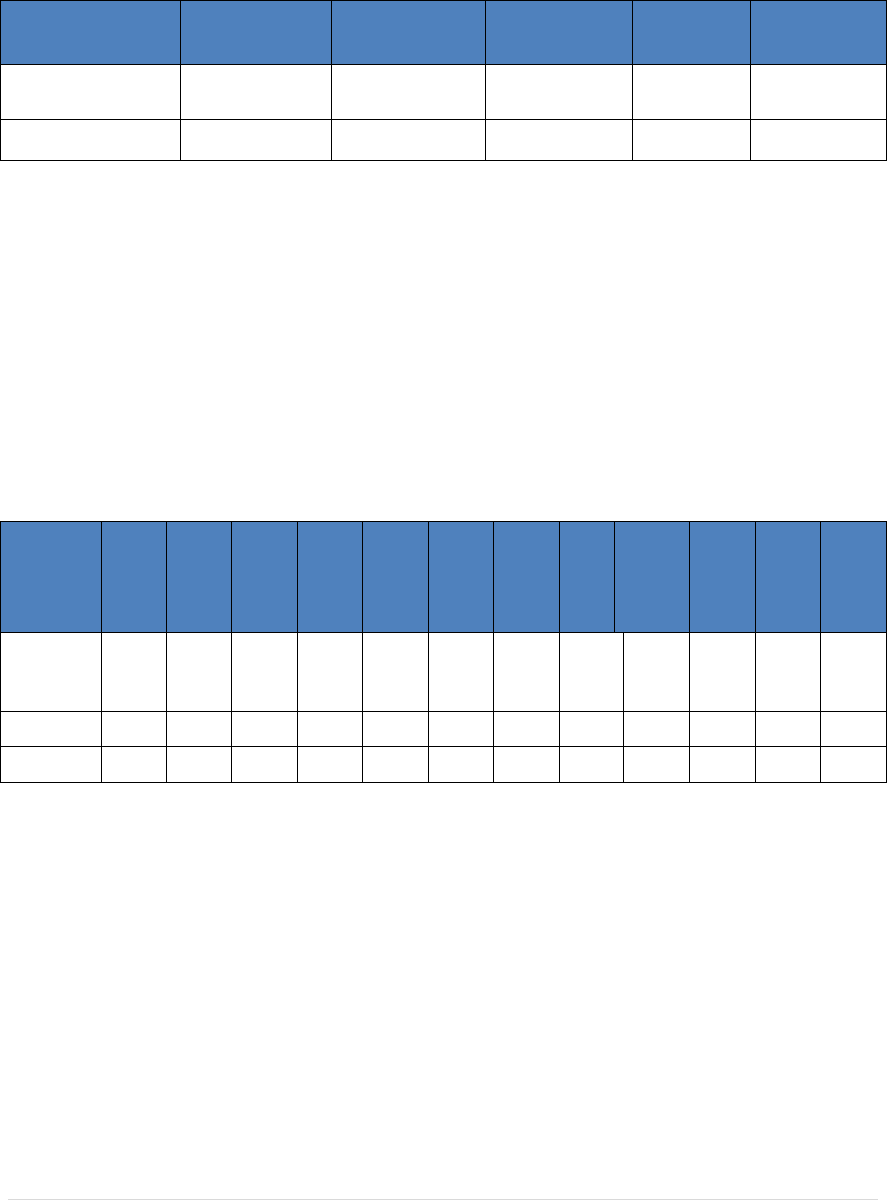

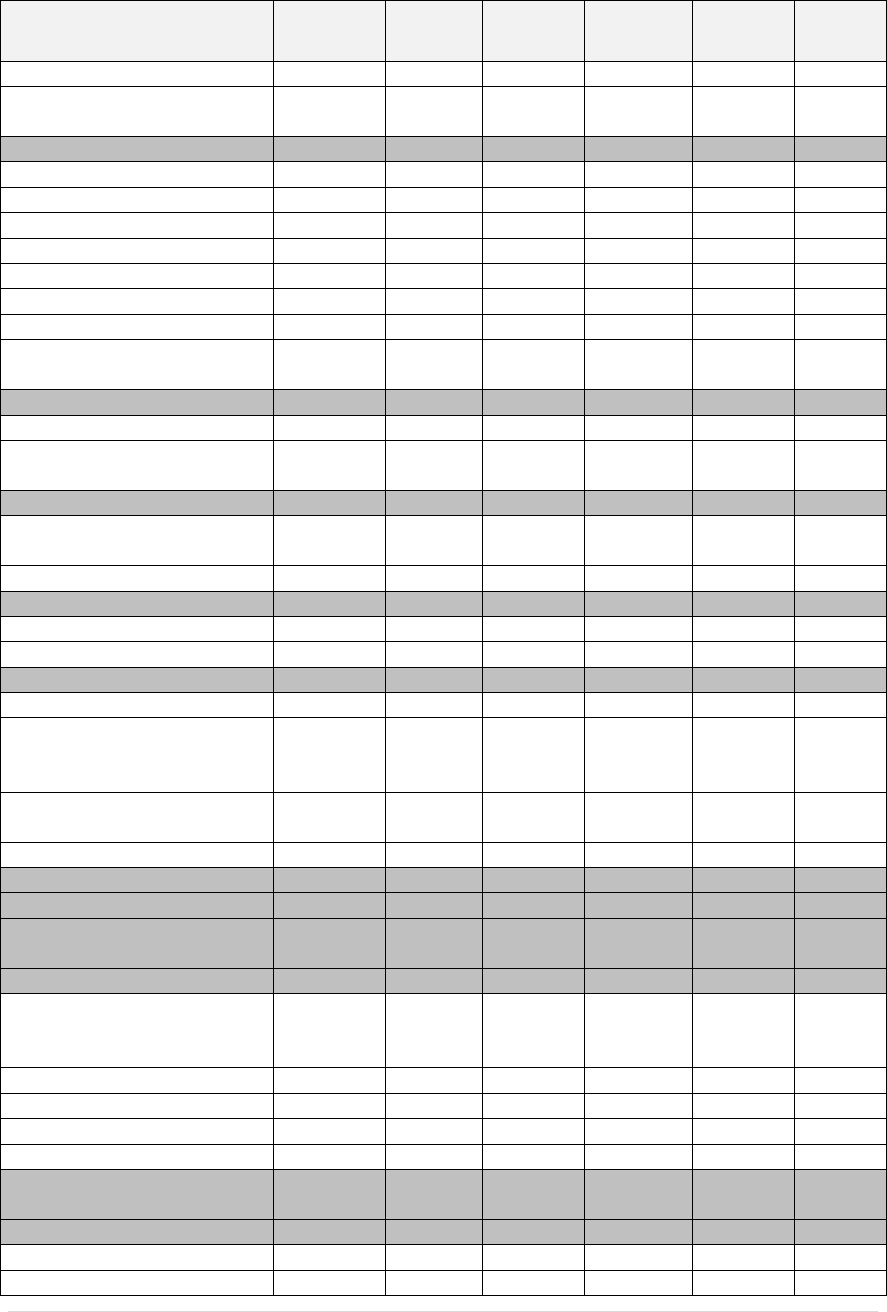

Number of Participants by Court

Type Jan 2007 – April 2011

Type of Court

#

Adult Drug

Courts

1482

Juvenile Drug

Courts

292

Lancaster Family

Court

34

Young Adult

Court

31

DUI Court

23

Total

1862

Male

63%

Female

37%

Adult Drug Court

Participants by Gender

White

73%

Black

17%

Hispanic

6%

Other

4%

Race Ethnicity of

Participants

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

5 | P a g e

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Reduce Crime, Addiction and Costs

In this evaluation, we found Nebraska problem

solving courts are following best practices for drug

courts. National research has shown programs using

best practices are effective in reducing recidivism

and the effects of addiction for participants.

Rigorous studies have clearly demonstrated the

effectiveness of adult drug courts in reducing crime

and alcohol/drug use and in improving the lives of

drug court participants (e.g., Lowenkamp,

Holsinger, & Latessa, 2005). Preliminary findings also suggest juvenile drug courts and

family dependency drug courts that adhere to best practices are likely effective in

preventing recidivism (e.g., Boles, Young, Moore, & DiPirro-Beard, 2007; Henggeler, et.

al, 2006).

In this evaluation we reviewed the operations of problem solving courts in Nebraska and

found courts are following best practice standards and principles for drug courts, thereby

operating effectively.

Problem solving courts have regular, often interdisciplinary team meetings in

which cases are reviewed, determinations are made about sanctions, incentives, or

graduations, and new applications are reviewed. Team meetings regularly

comprise prosecuting and defense attorneys, treatment representatives, law

enforcement, the program coordinator and supervisors, and the judge. The judge

usually presides over and manages all team meetings as the leader, but there were

exceptions in some programs.

During team meetings, judges showed an understanding and appreciation of

treatment considerations for participants. Although judges may not have formal

training in behavioral health or drug/alcohol treatment, they did show a significant

understanding of the treatment process and valued the input of treatment

professionals.

Judges play the central role in hearings procedures. The judges discuss the

progress of each participant on a one-on-one basis and with attorneys. The judges

direct sanctions or incentives to individuals, and showed a good understanding of

the importance of providing both positive and negative feedback to participants.

Direct interaction during hearings with participants ranged from a few minutes

per participant in some of the larger courts, to up to ten or more minutes in

smaller programs; research indicates the more time judges interact with

participants, the better the outcomes. In the juvenile court programs, judges also

interacted with parents on a regular basis.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

6 | P a g e

Both case supervisors/probation officers and representatives from treatment

providers play a critical role in team meetings by informing the rest of the team of

the day to day progress of program participants. In all the team meetings

observed, the judge and attorneys listened carefully to what supervisors and

treatment representatives had to say about individual cases.

Prosecuting attorneys were present in all hearings observed, and played a regular

role in discussing the case progress of individual participants during actual

hearings. Public defenders were not regularly present in hearings. In roughly half

of the site visits we conducted, public defenders were not present during hearings.

Interviews conducted with program coordinators indicated that most programs

were aware of the ten key components of drug courts, and actively striving to

incorporate those principles into regular activities. In practice, program

coordinators indicated that structural issues sometimes impeded full

implementation of all components. For example, a number of programs indicated

that they needed more support and knowledge with evaluation (Key Component 8

- Monitoring and evaluation measure the achievement of program goals and

gauge effectiveness).

Most programs were in compliance with the Standardized Model for Delivery of

Substance Abuse. A small minority of programs indicated they were unaware of

specifics regarding this requirement.

Although Nebraska program are generally operating according to the ten key

components, there are opportunities for improvement:

Problem solving courts across the state vary considerably in terms of team

dynamics, judicial interaction styles, the use of incentives and sanctions, and

program admission characteristics. However, all programs adhere to core

principles of problem solving courts. There is a balance that needs to be

maintained between preserving the local characteristics of individual courts to

ensure buy-in and participation by judges, attorneys, and communities; versus the

importance of mandating a foundation of common principles and operational

processes across all problem solving programs in Nebraska.

There are a number of practices that have been found to improve outcomes for

problem solving court participants. These practices include the amount of time the

judge spends talking to each participant (outcomes are improved if the judge

spends at least three minutes with each participant), the length of time participants

spend in the problem solving court program (outcomes are improved if

participants spend at least 12 months in problem solving court and have at least 90

days of clean drug tests before graduation), and the types of individuals on the

problem solving court team (outcomes are improved if teams include law

enforcement and treatment providers) (Carey, Finigan, & Mackin, 2011).

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

7 | P a g e

Ongoing evaluation can help assure Nebraska problem solving courts adhere to

these evidence based practices.

Efforts should be made to re-orient problem solving court team members to the

requirements of the Standardized Model for Delivery of Substance Abuse

Services, particularly with the family drug programs.

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Yield Effective Outcomes

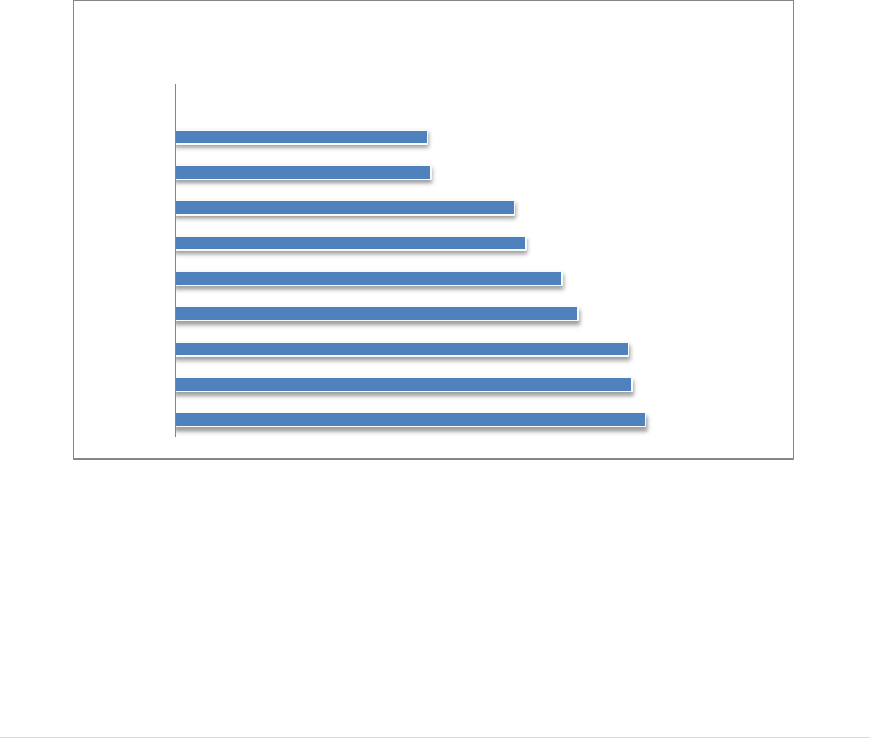

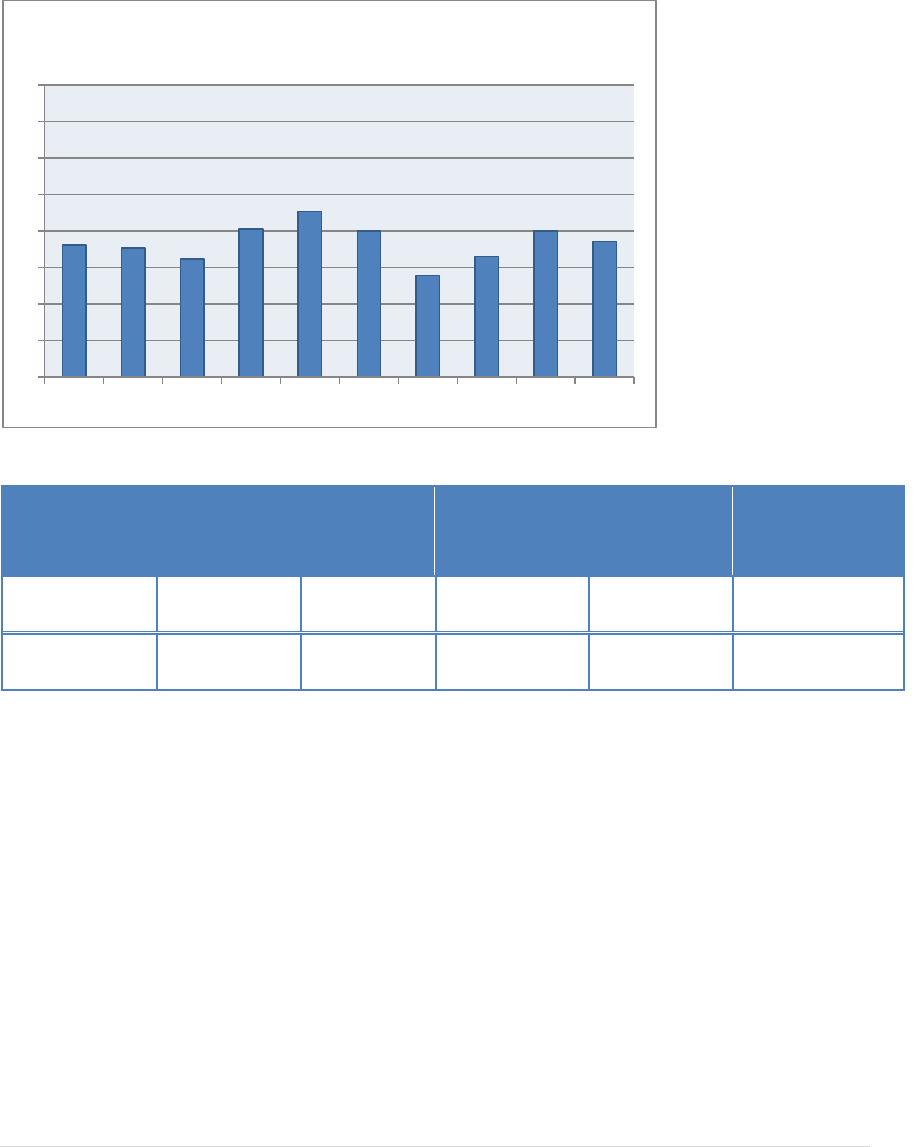

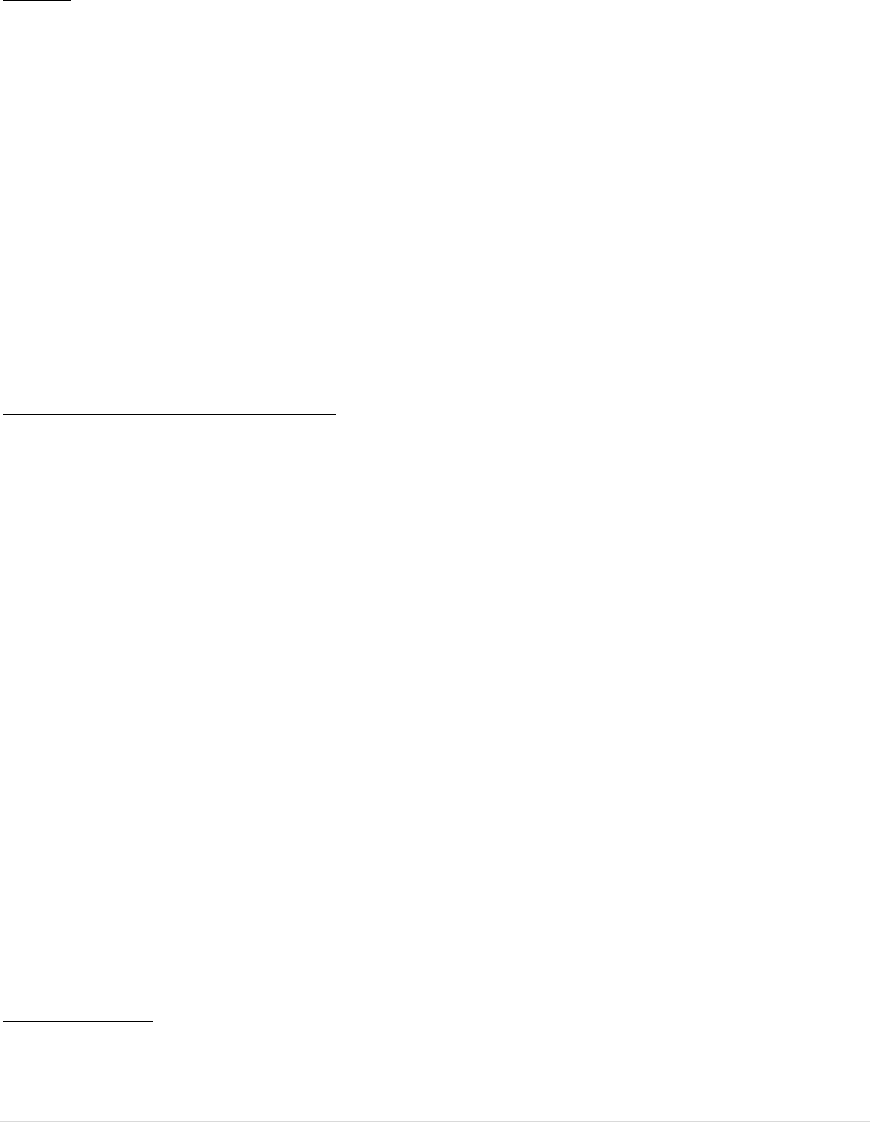

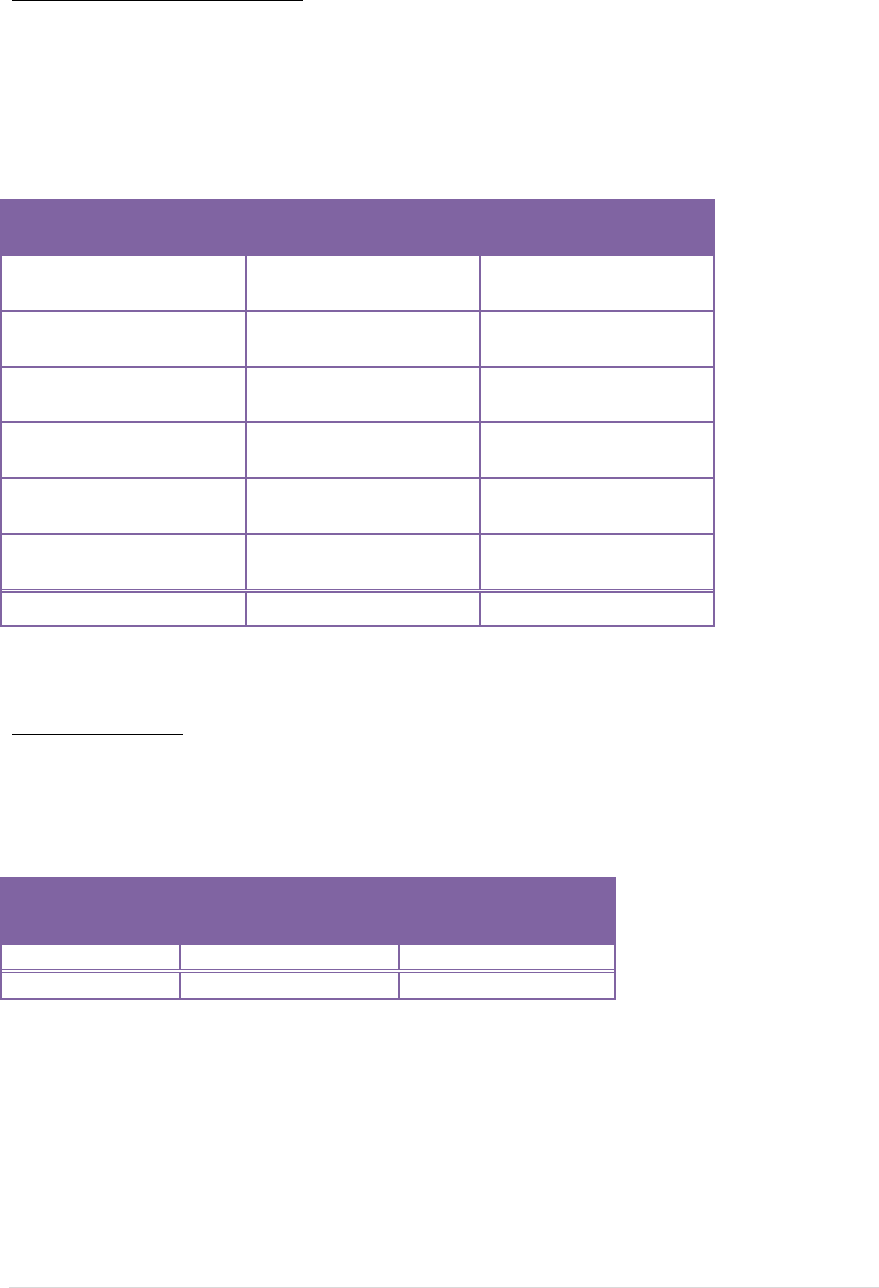

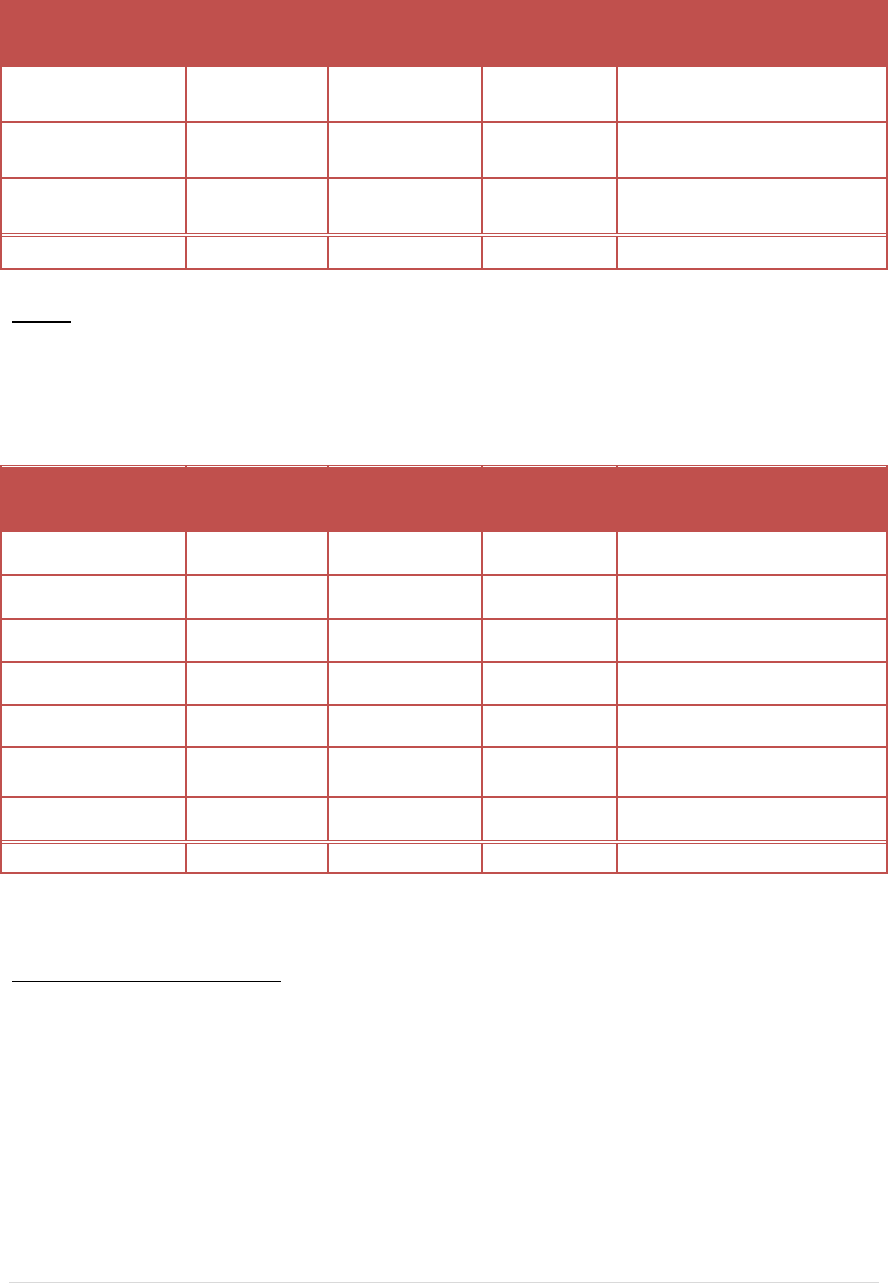

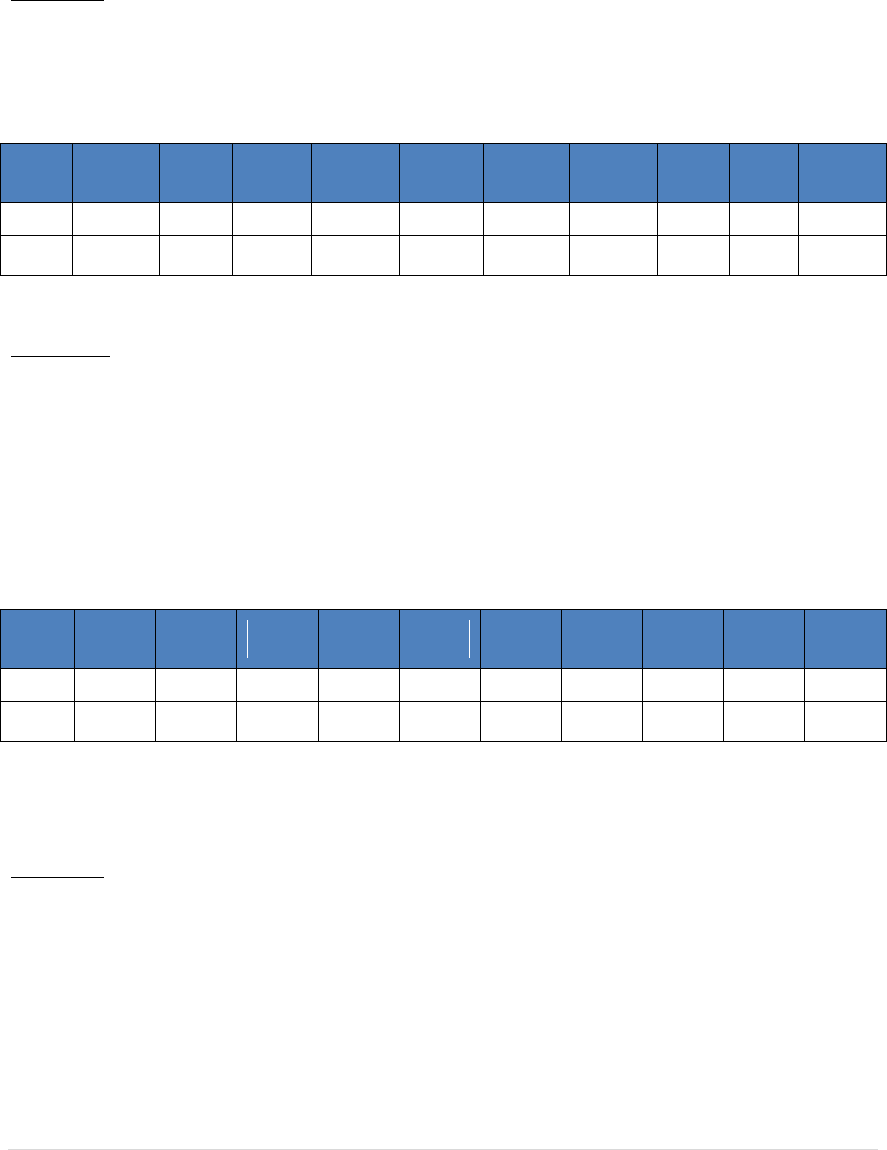

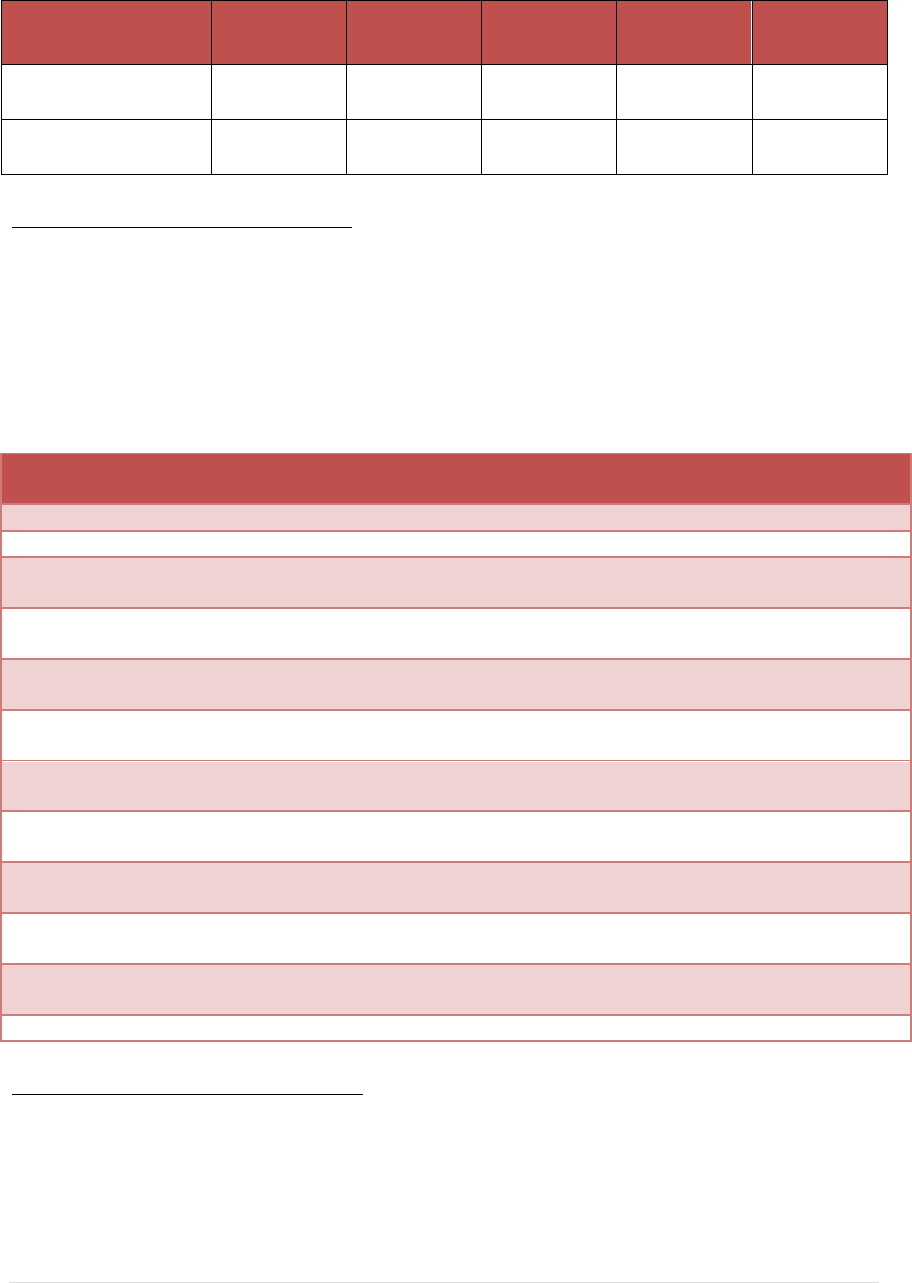

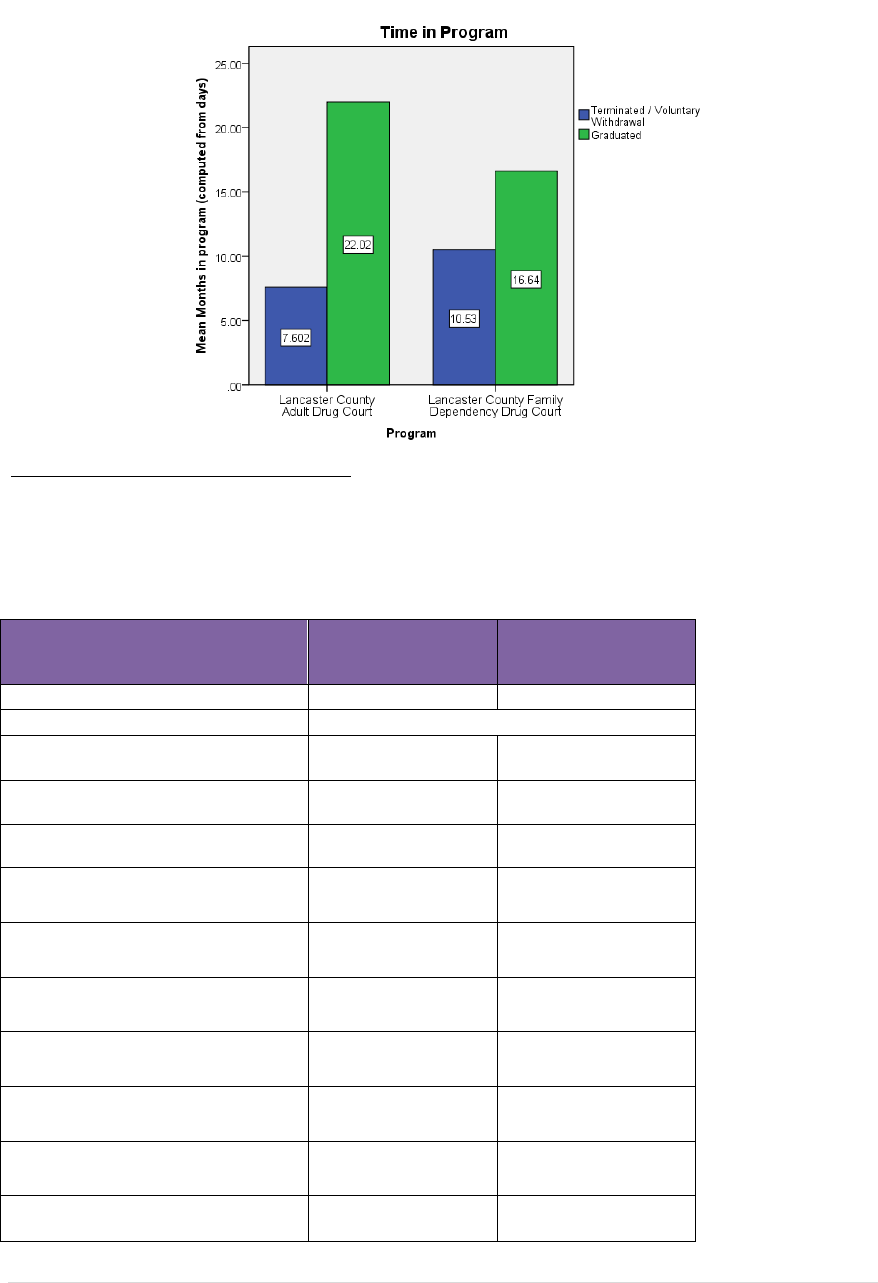

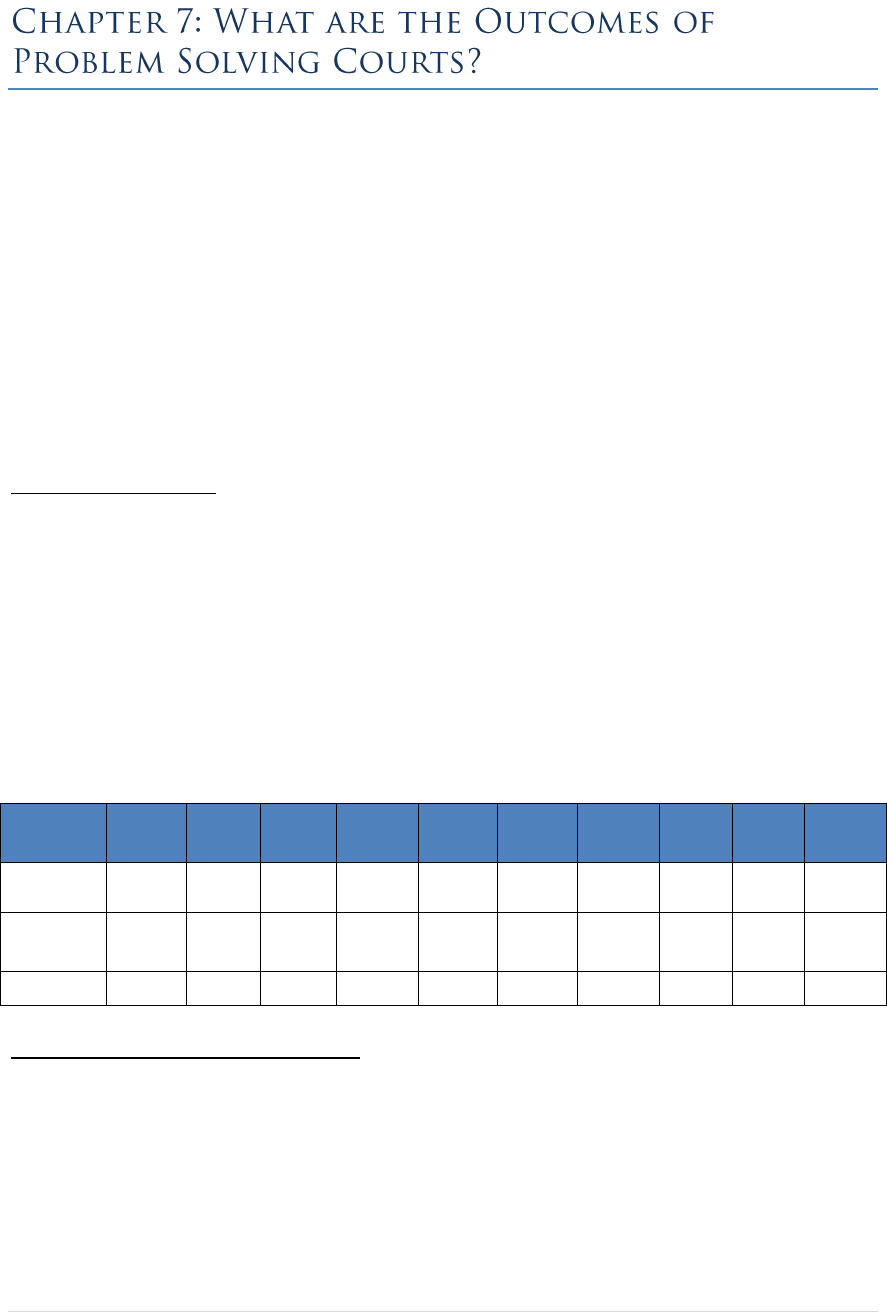

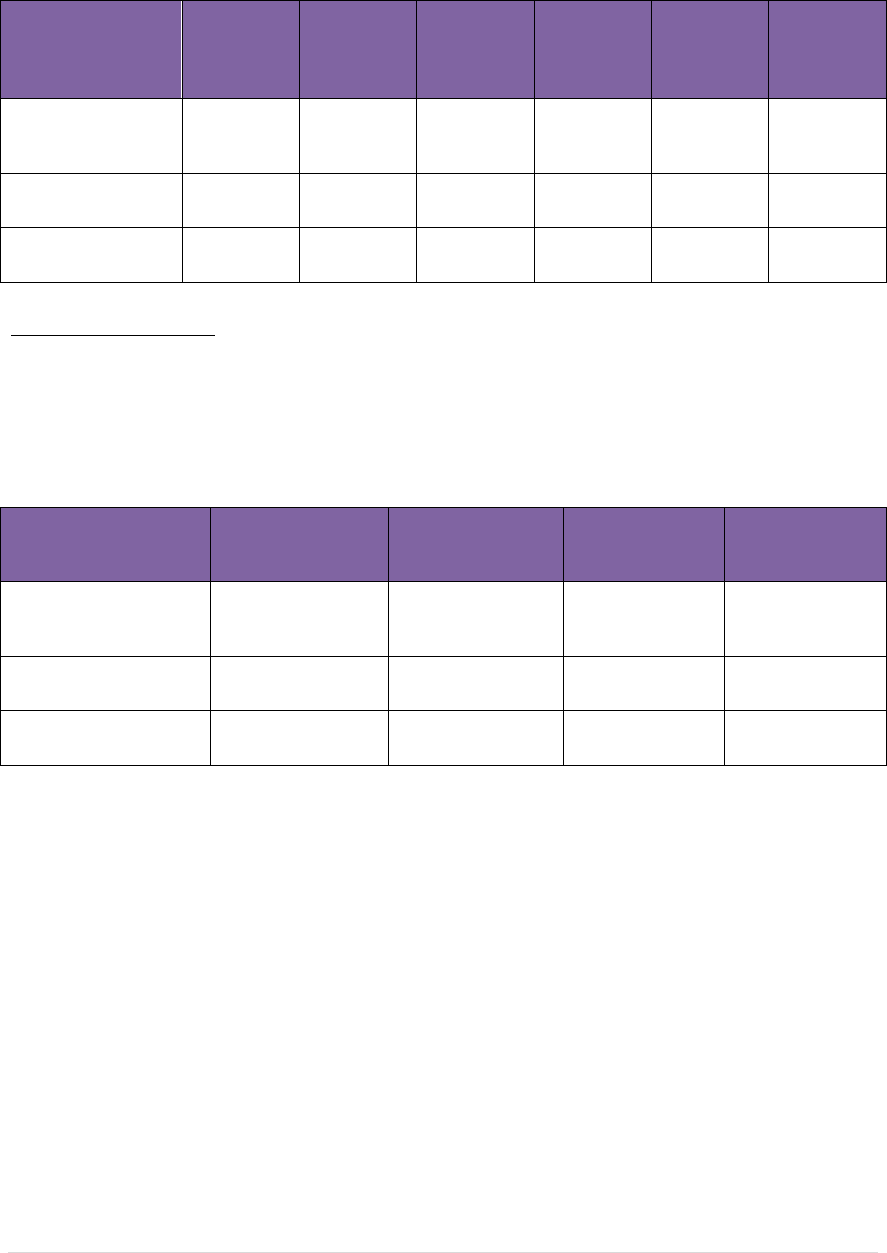

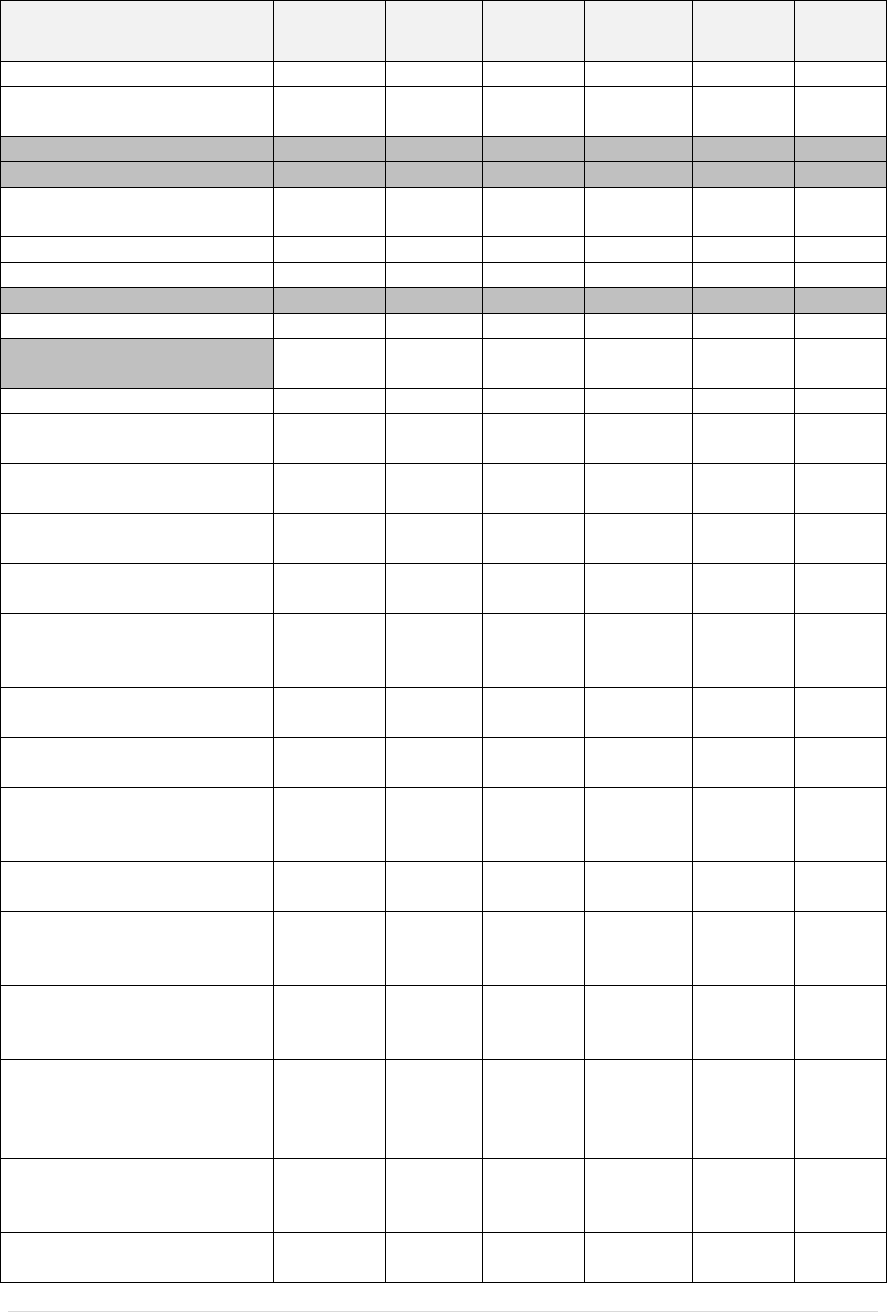

The evaluation examined graduation rates and recidivism rates for Nebraska’s problem

solving courts. The rates for Nebraska programs meet or exceed national averages. Apart

from one rural drug court with no graduations during the study period, Nebraska adult

court graduation rates range from 42.3% to 78.9%. Nationally, graduation rates range

from about 40% to 65%, with an average rate of 57% (Huddleston & Marlowe, 2011).

Graduation rates for Nebraska juvenile drug courts are lower than for adult drug courts,

ranging from 18.2% to 57.6%, consistent with national averages. There were significant

differences in graduation rates across courts; these graduation rate differences are likely

due to differences in participant level of risk accepted by the programs rather than an

indicator of quality.

78.90%

76.60%

76.00%

67.60%

64.90%

58.80%

56.90%

42.90%

42.30%

0.00%

Court 1

Court 2

Court 3

Court 4

Court 5

Court 6

Court 7

Court 8

Court 9

Court 10

Adult Court Graduation Rates

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

8 | P a g e

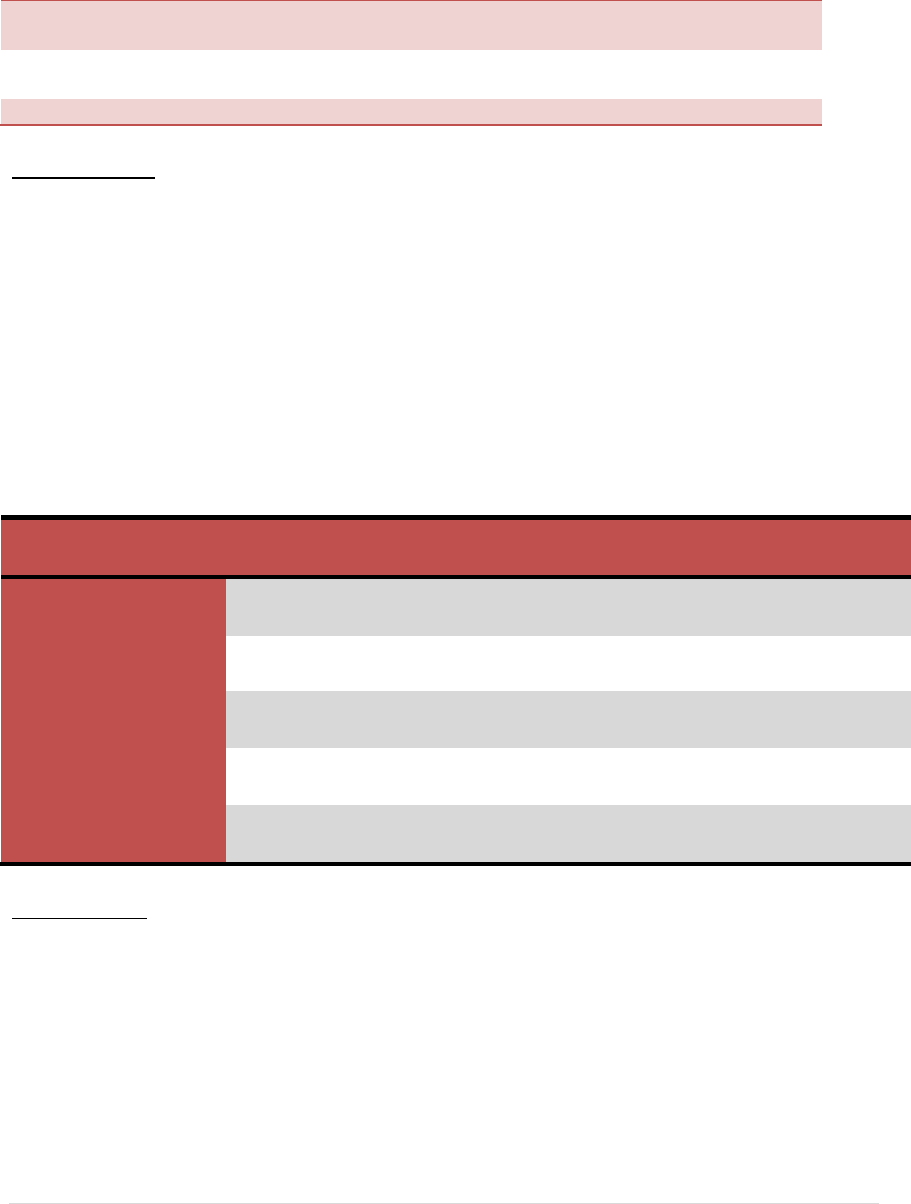

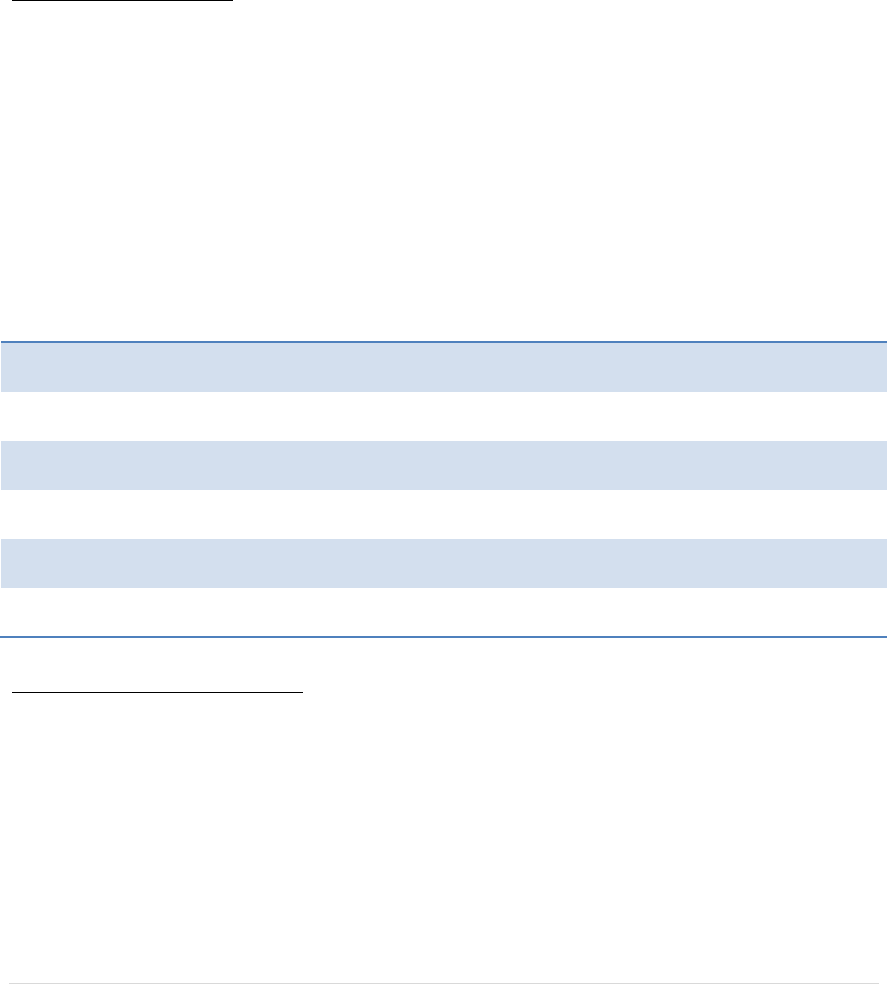

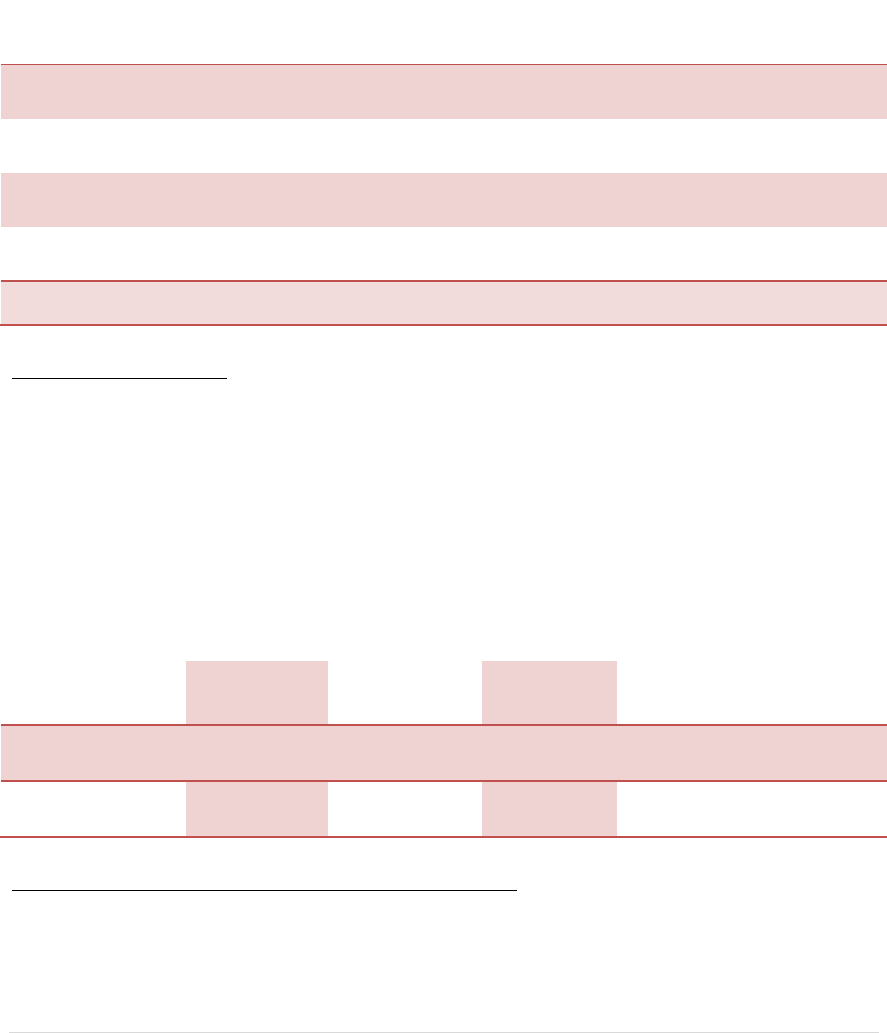

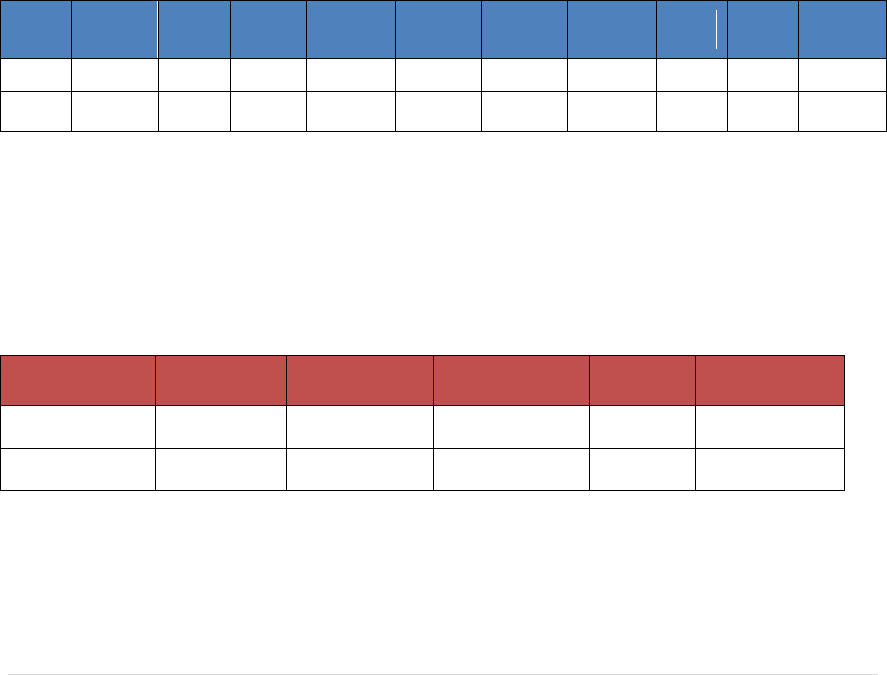

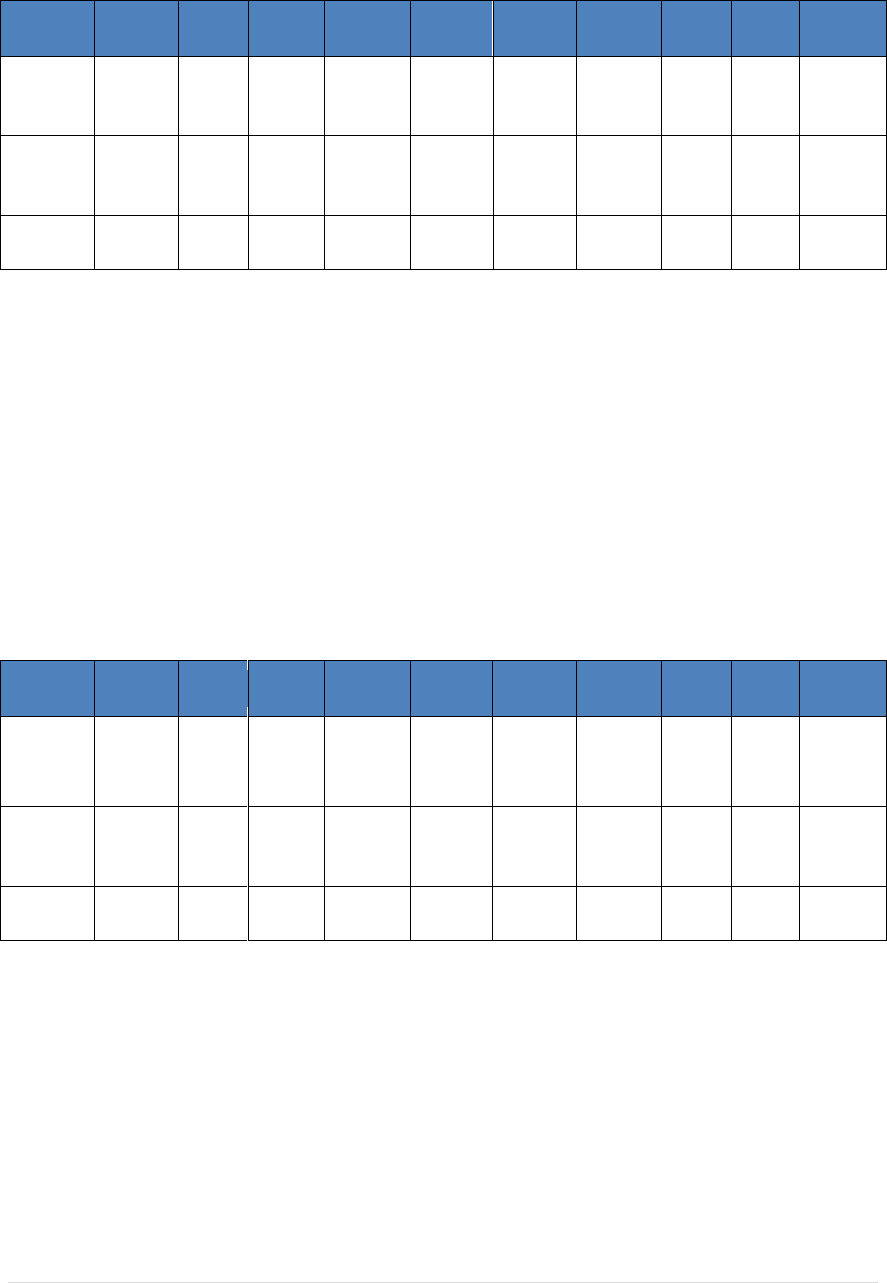

Nebraska problem solving courts also have a relatively low rate of recidivism. As shown

in the table below, the recidivism rate for adult drug court graduates is 4.5%. Problem

solving court graduates are significantly less likely to recidivate than participants who do

not complete the program, indicating drug courts are working in Nebraska.

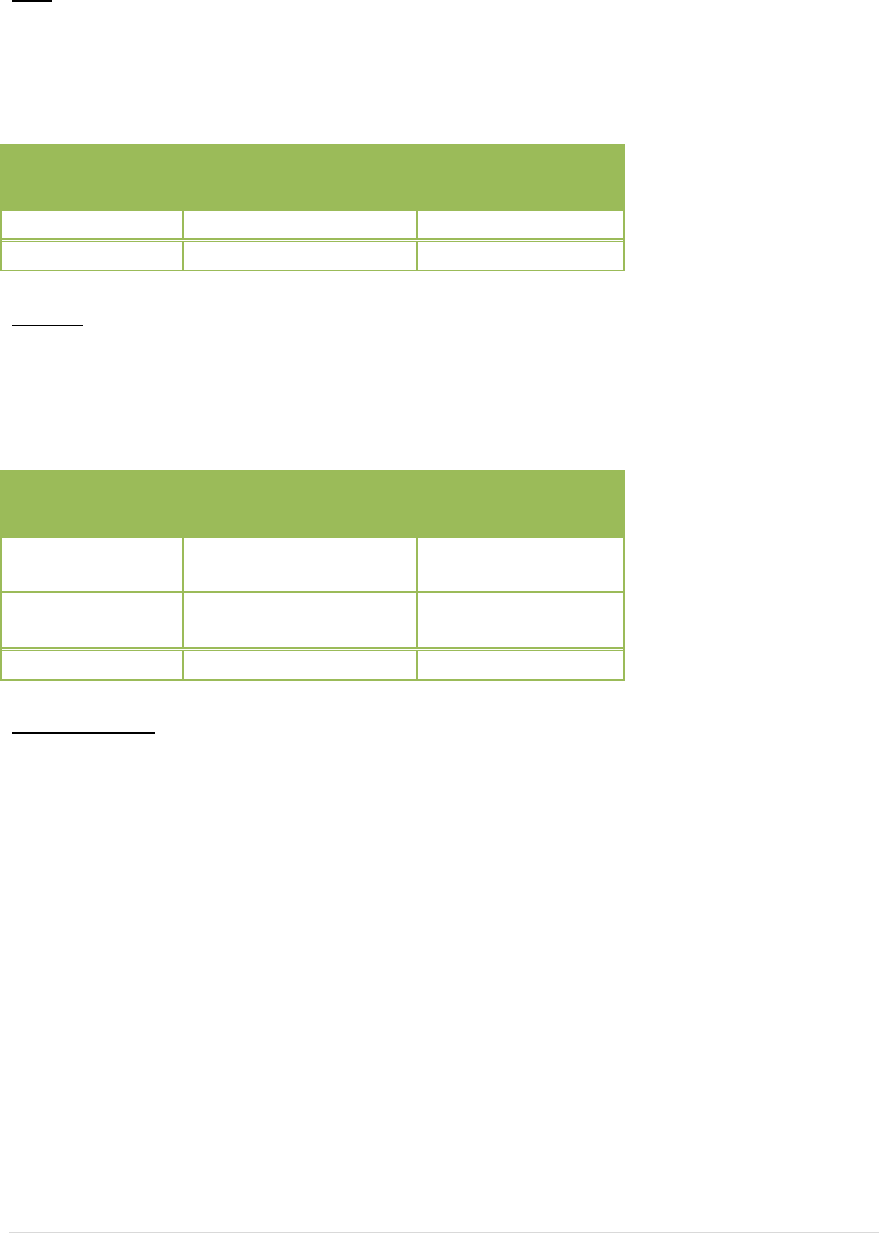

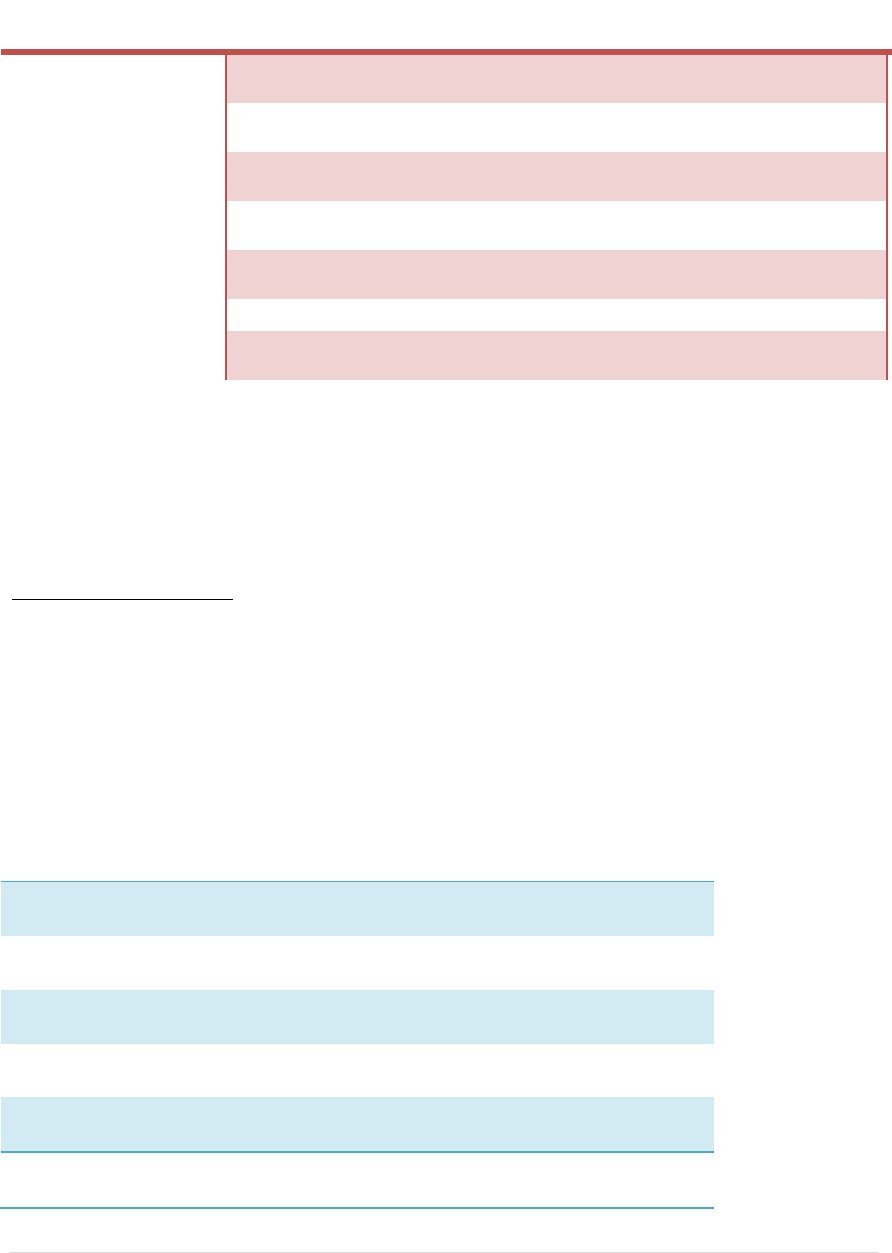

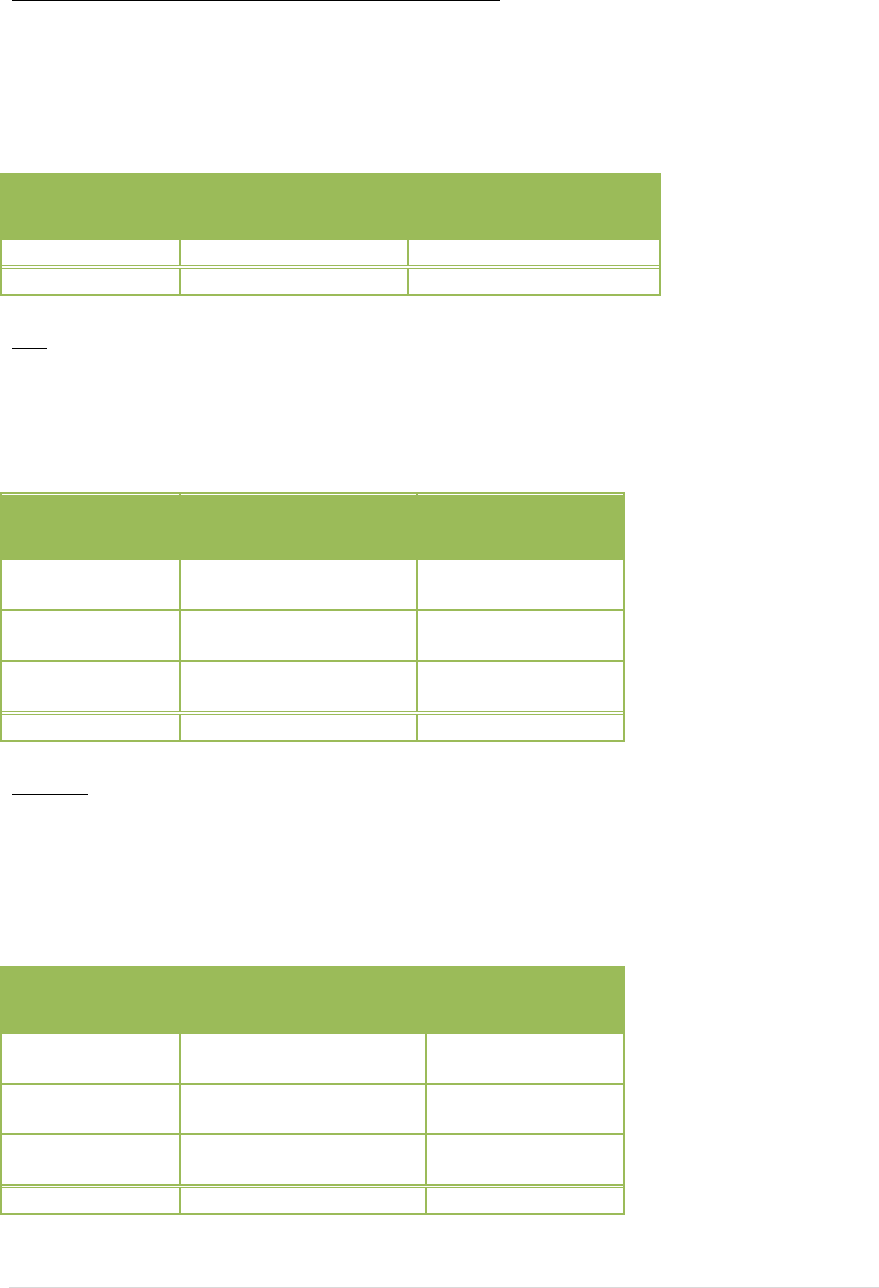

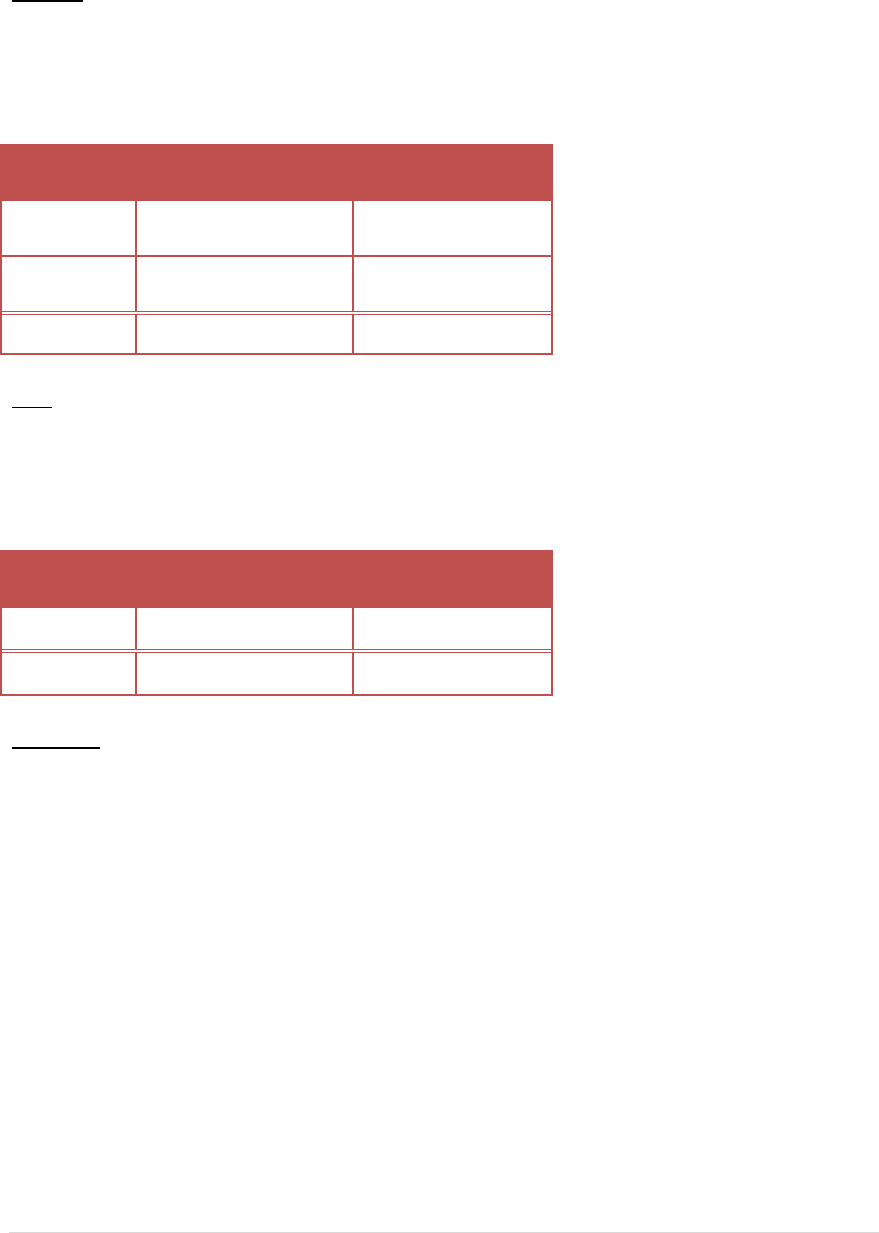

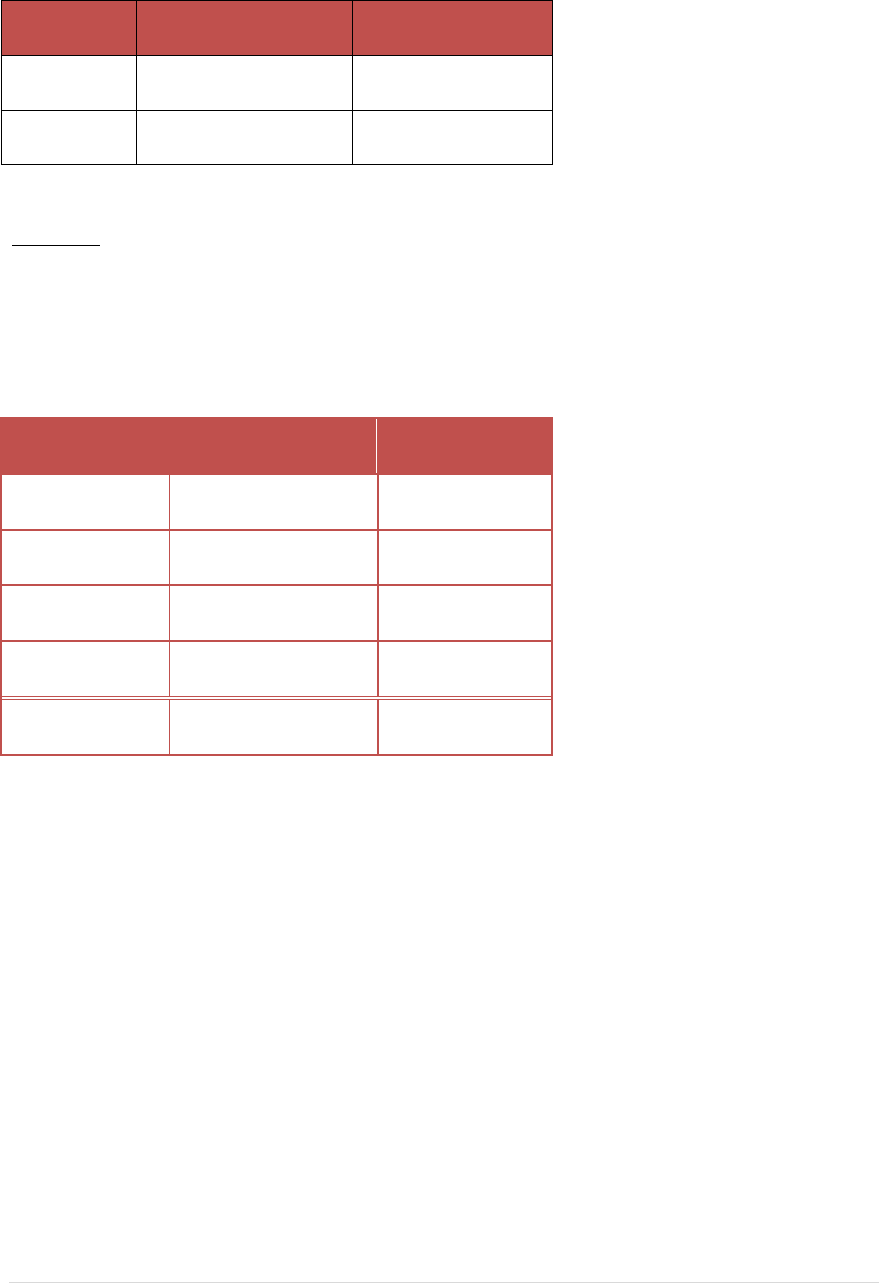

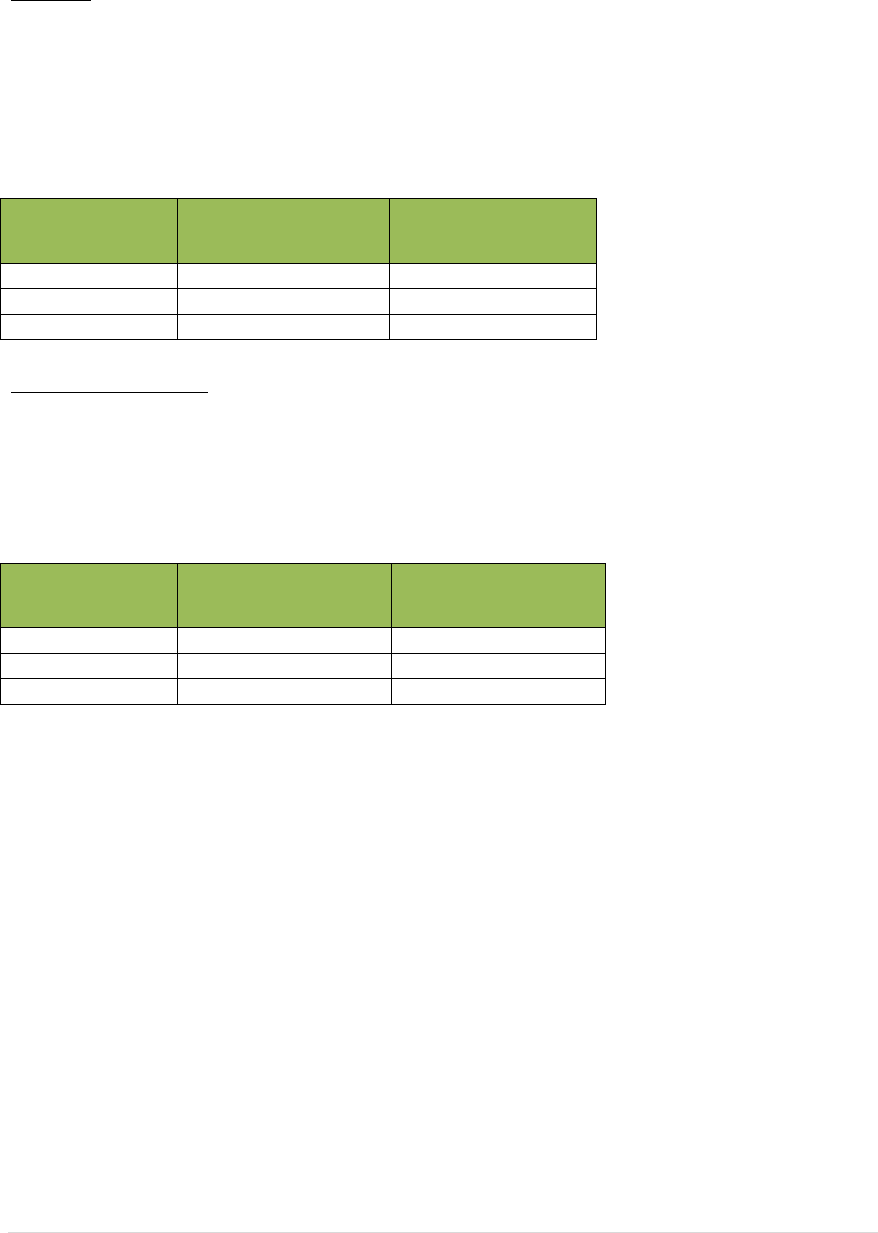

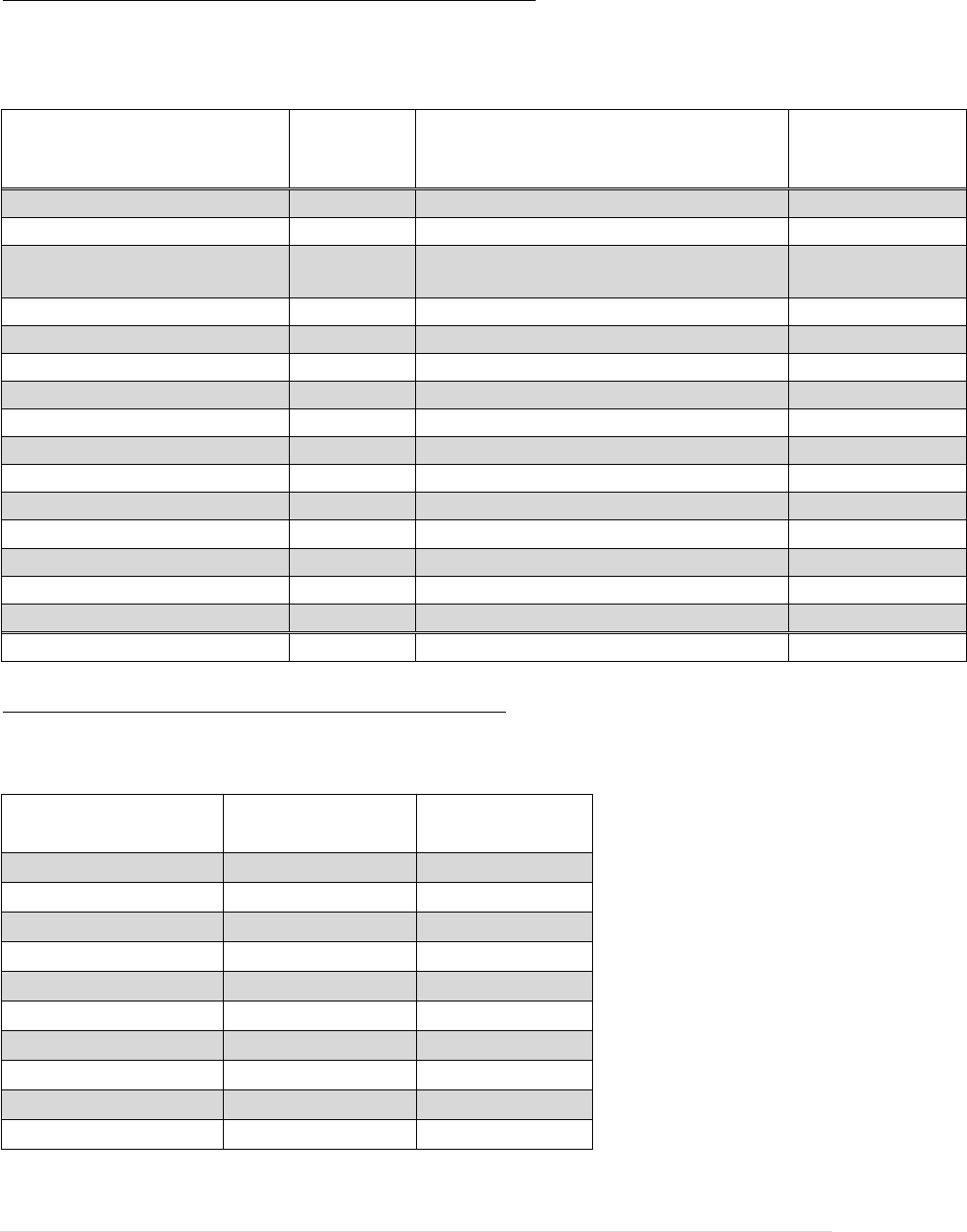

Recidivism* Rates for Graduated

and Terminated Participants in

Nebraska Adult Drug Courts

Adult Drug Courts

Successful Completion

(Graduated)

Unsuccessful Completion

(Terminated)

Recidivated

27

4.5%

33

7.3%

Did Not Recidivate

577

95.5%

417

92.7%

Sample Size

604

450

* For adult courts, post-program recidivism is defined as an arrest that occurs after program exit for a new

offense if, and only if, that arrest eventually results in a conviction for a felony, drug/alcohol-related

misdemeanor, or DUI offense (excluding traffic offenses other than DUI). Participants were tracked for

one year after drug court.

57.60%

55.60%

38.10%

26.00%

18.20%

Court 1

Court 2

Court 3

Court 4

Court 5

Juvenile Court Graduation Rates

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

9 | P a g e

Adult Drug Courts save

between $2,609,235 and

$9,722,920 in tax dollars

per year in Nebraska.

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Save Tax Dollars

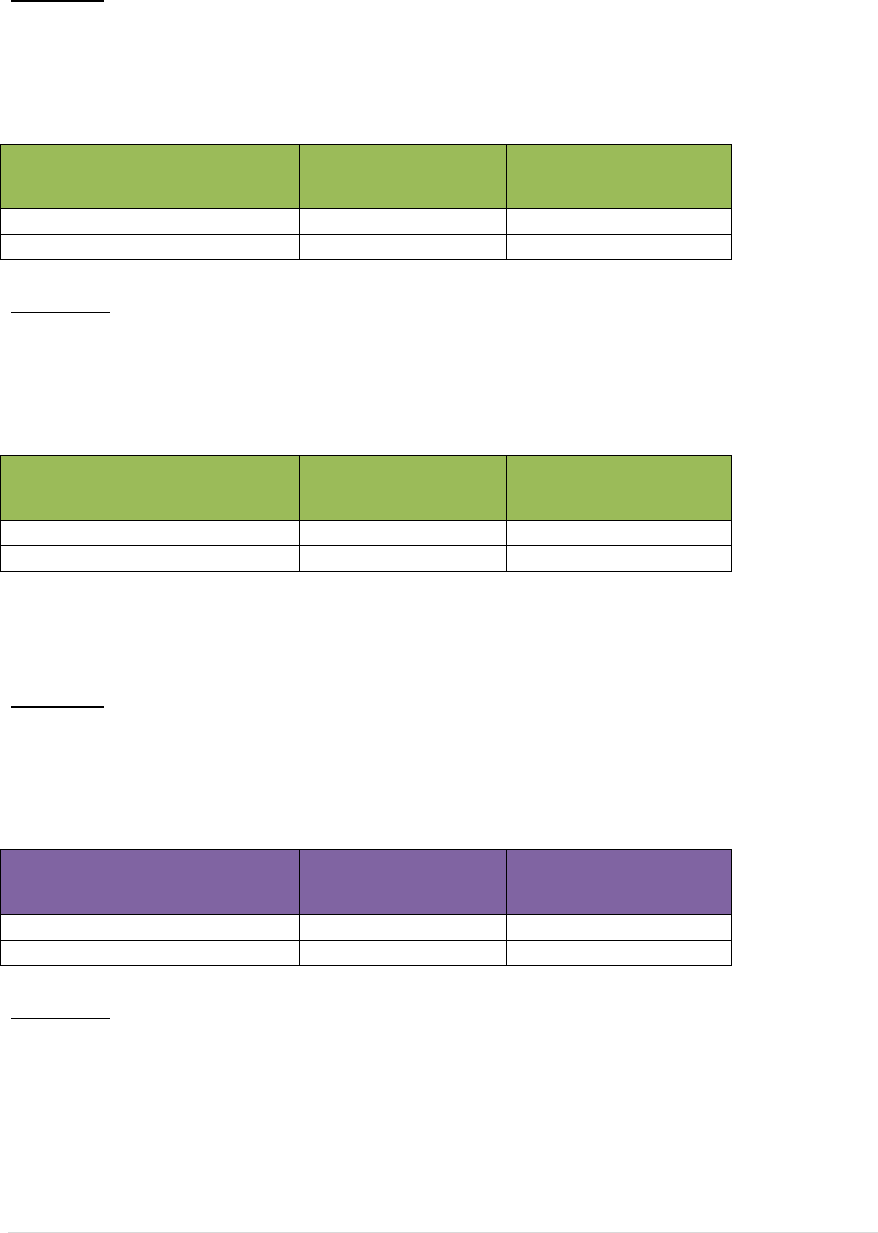

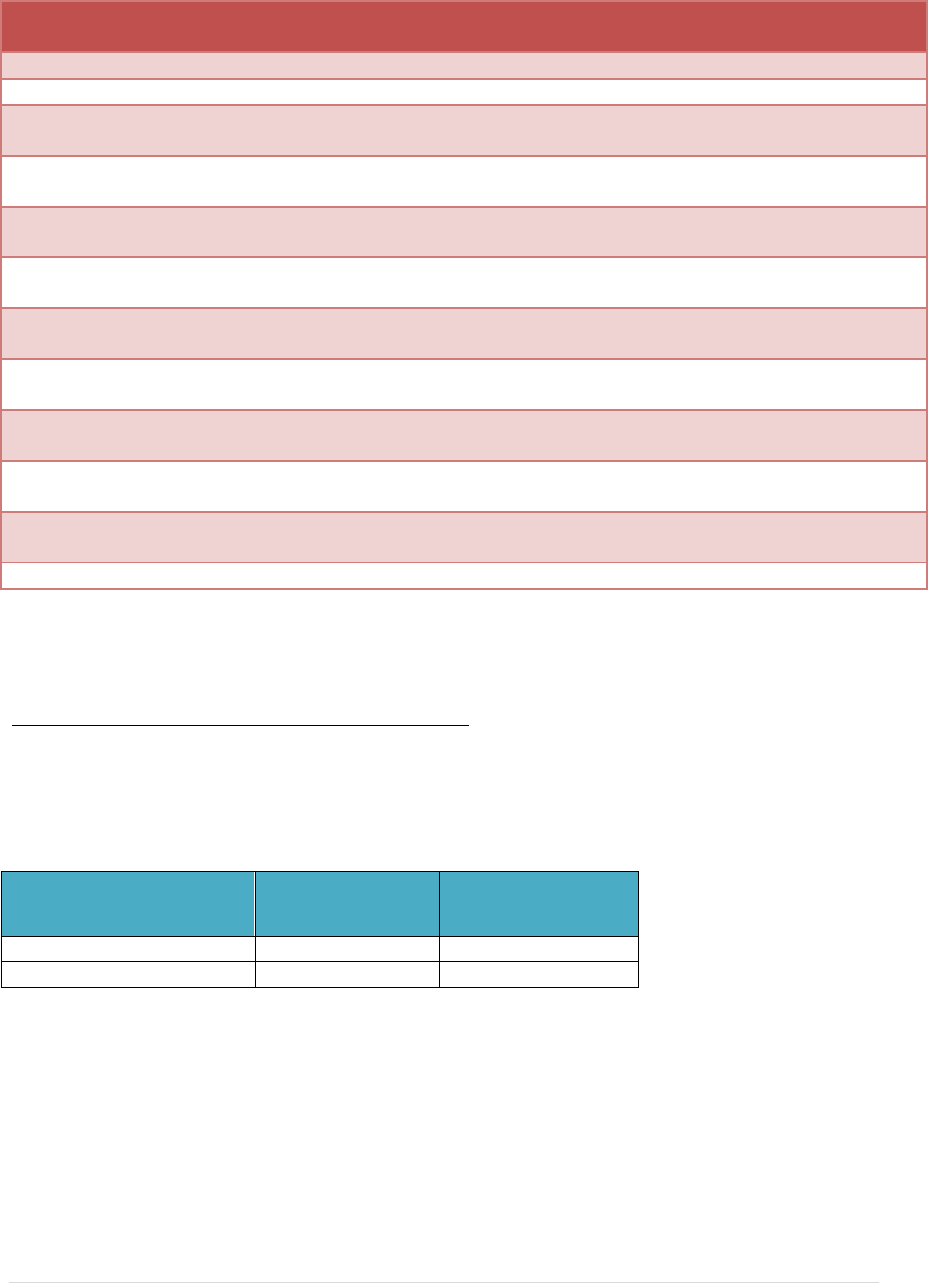

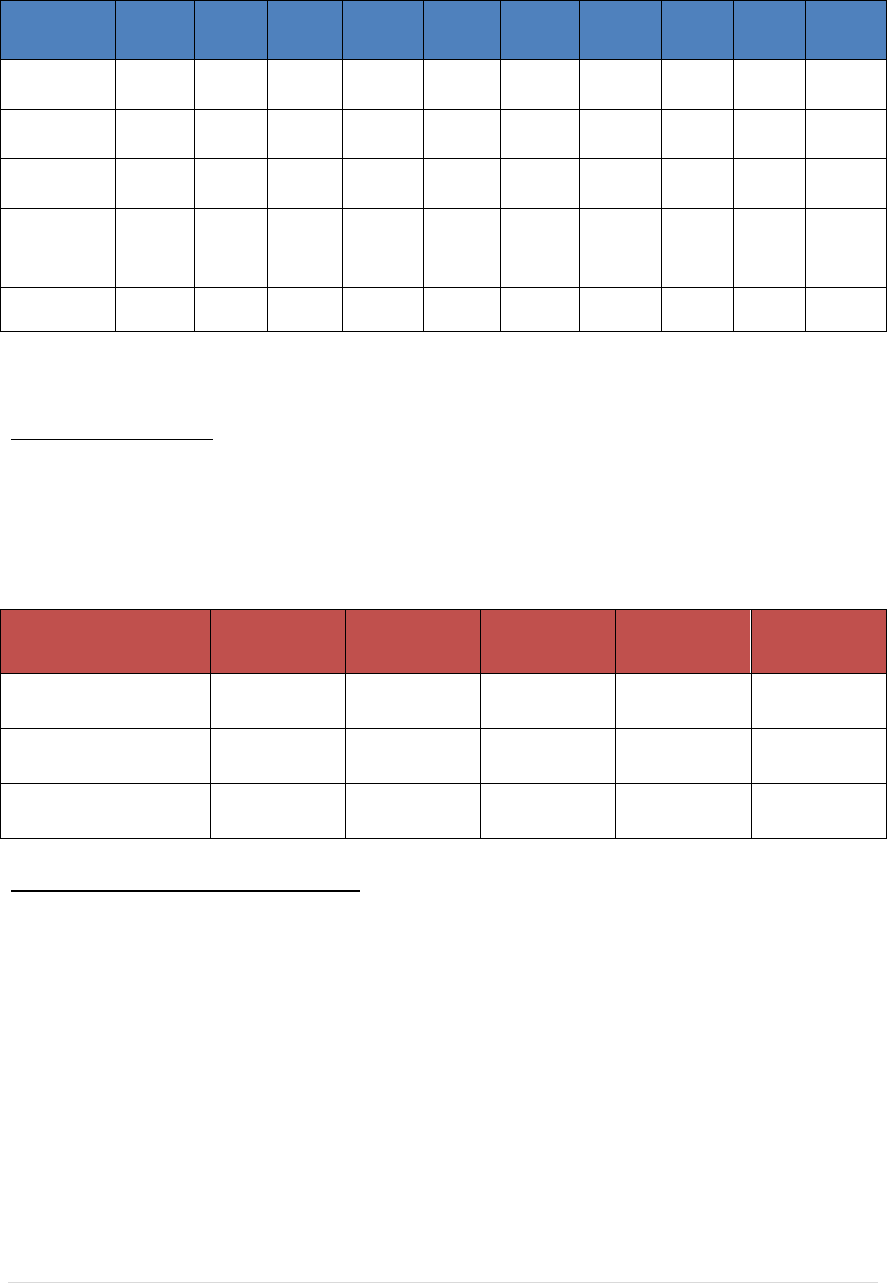

The study included an estimate of costs for each

problem solving court. For each program, we obtained

costs for salaries, benefits and operations for the

program, estimates of costs for judges and attorneys

who participate in problem solving courts, program

costs associated with client fees, treatment costs, and

cost for time participants spent incarcerated. The

average estimated per day cost for each drug court

participant (including case management, treatment, fees and jail/detention) ranged from

$12.08 to $45.81 for adult courts and from $37.19 to $88.19 for juvenile courts. The per

participant average cost (per day cost multiplied by Average Length of Service in the

program (ALOS)) ranges from $7,707 to $25,643 for adult drug courts and from $15,545

to $45,082 for juvenile courts.

It is difficult to meaningfully compare costs for Nebraska problem solving courts to

national averages because of different methodologies used in different studies. Many of

the national studies exclude treatment costs and the costs associated with judges and

attorneys. However, relative to other studies using comparable methods and study

parameters, Nebraska’s problem solving courts were either similar in cost or less costly

that programs in other jurisdictions (Carey & Finigan, 2003; Carey et al., 2009; Mackin

et al., 2009).

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

10 | P a g e

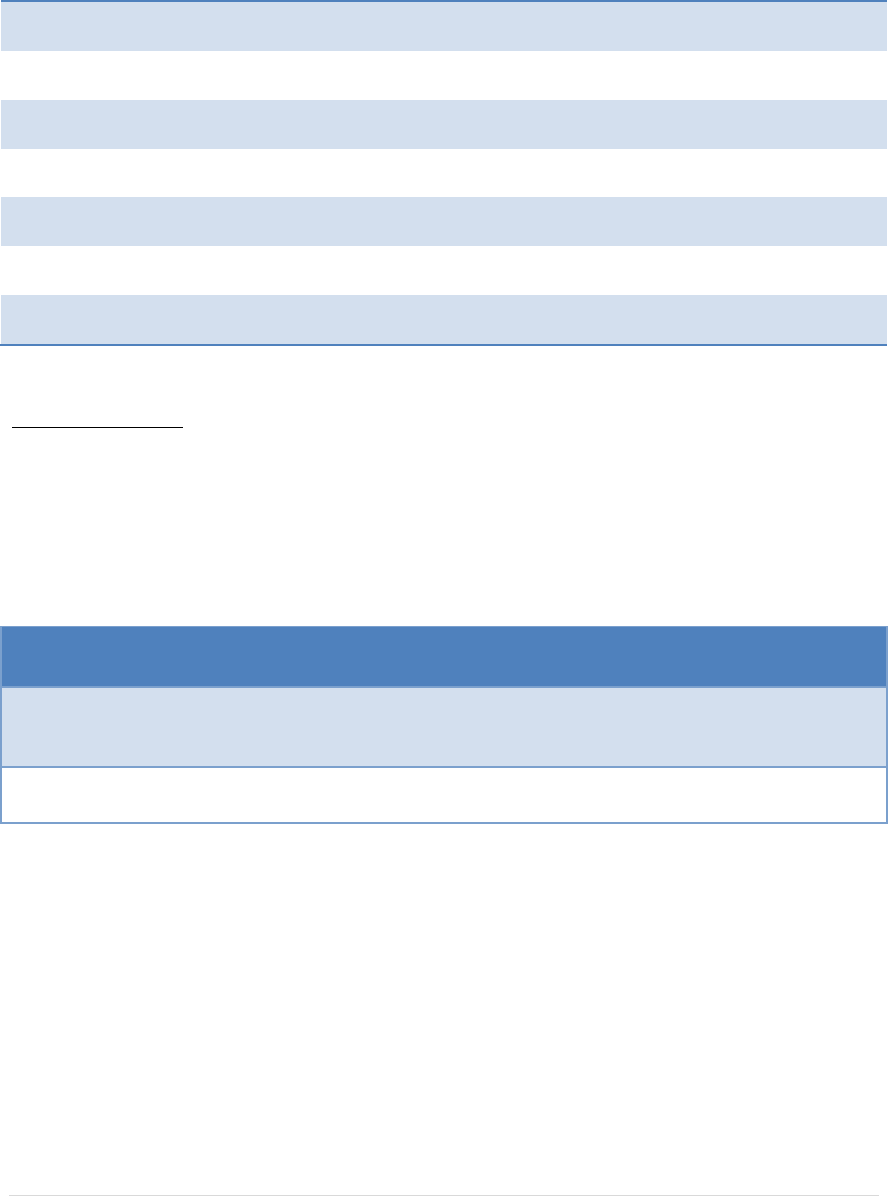

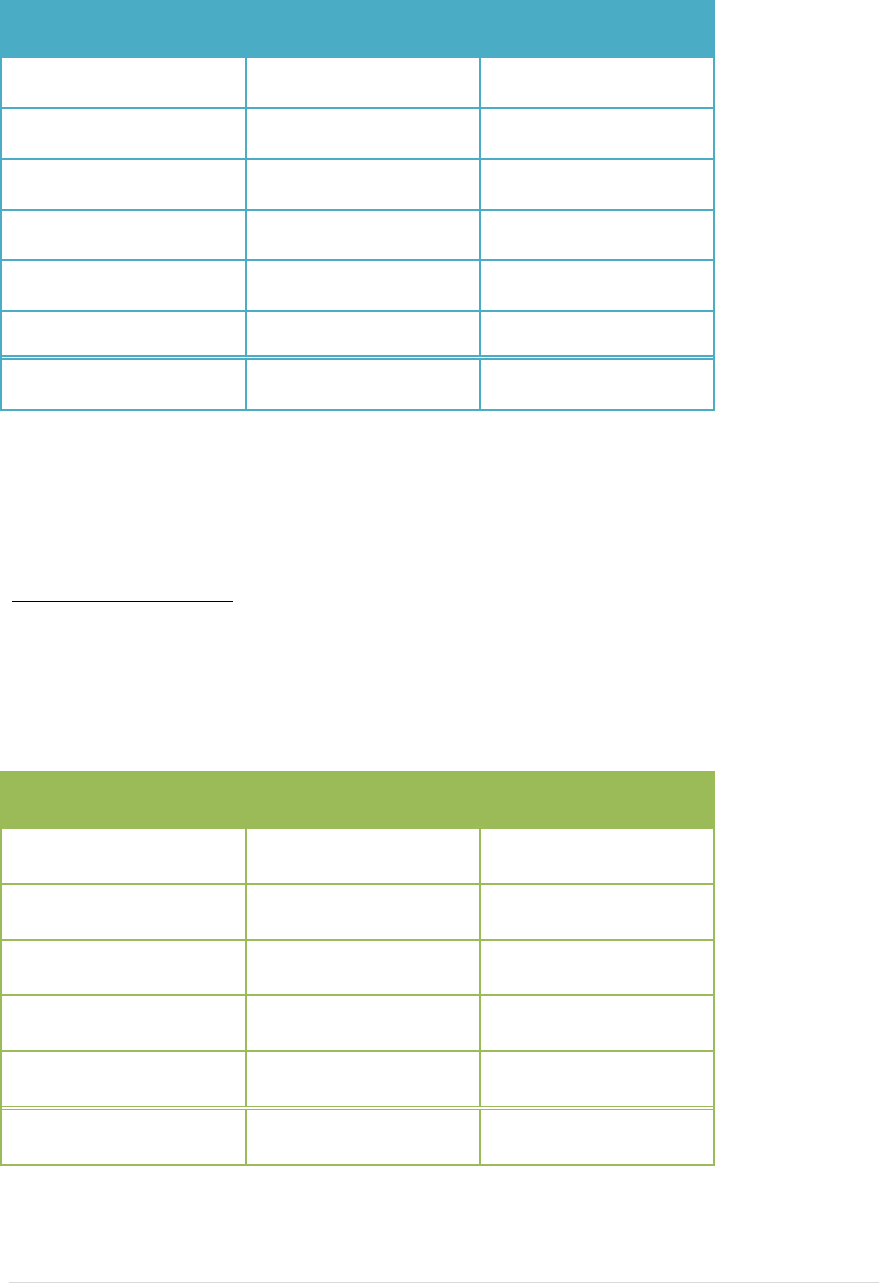

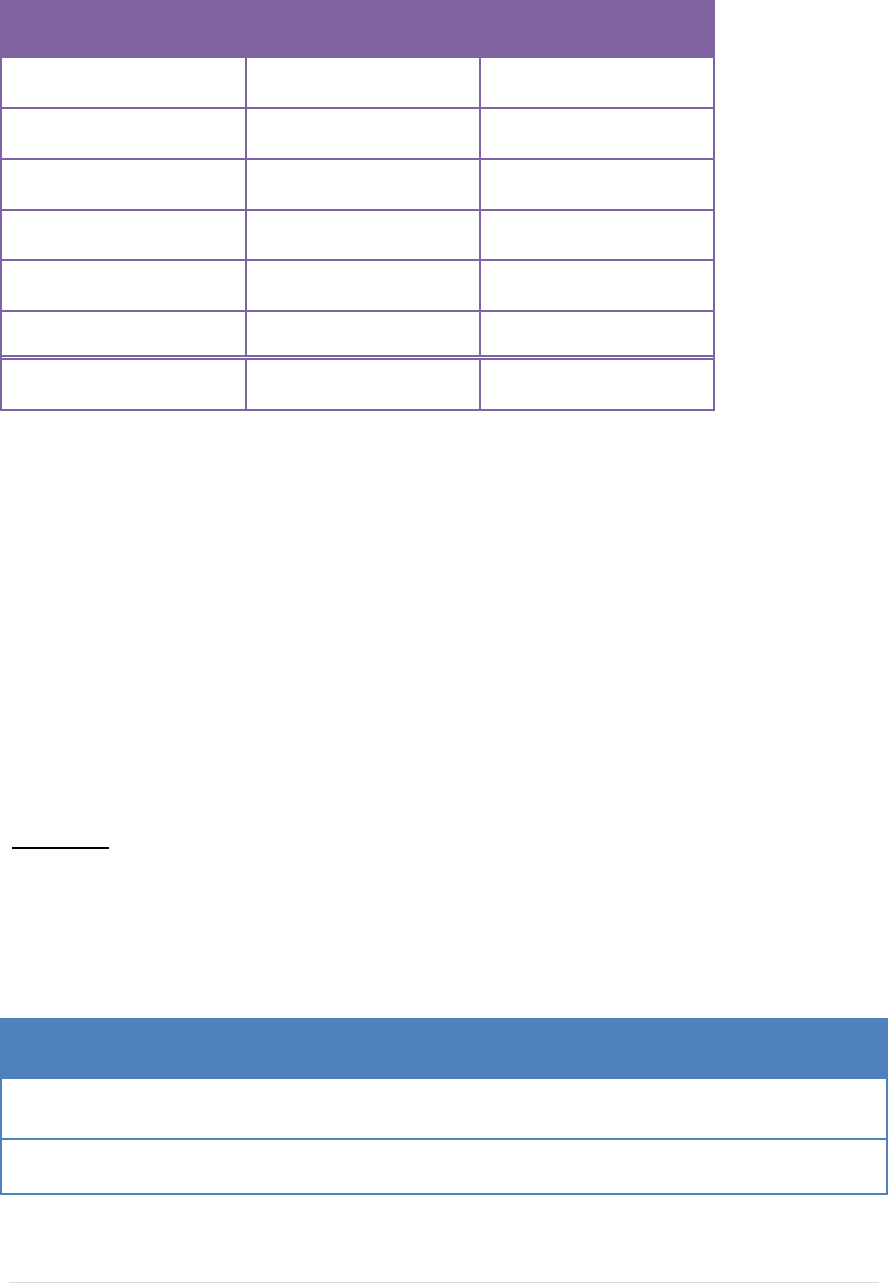

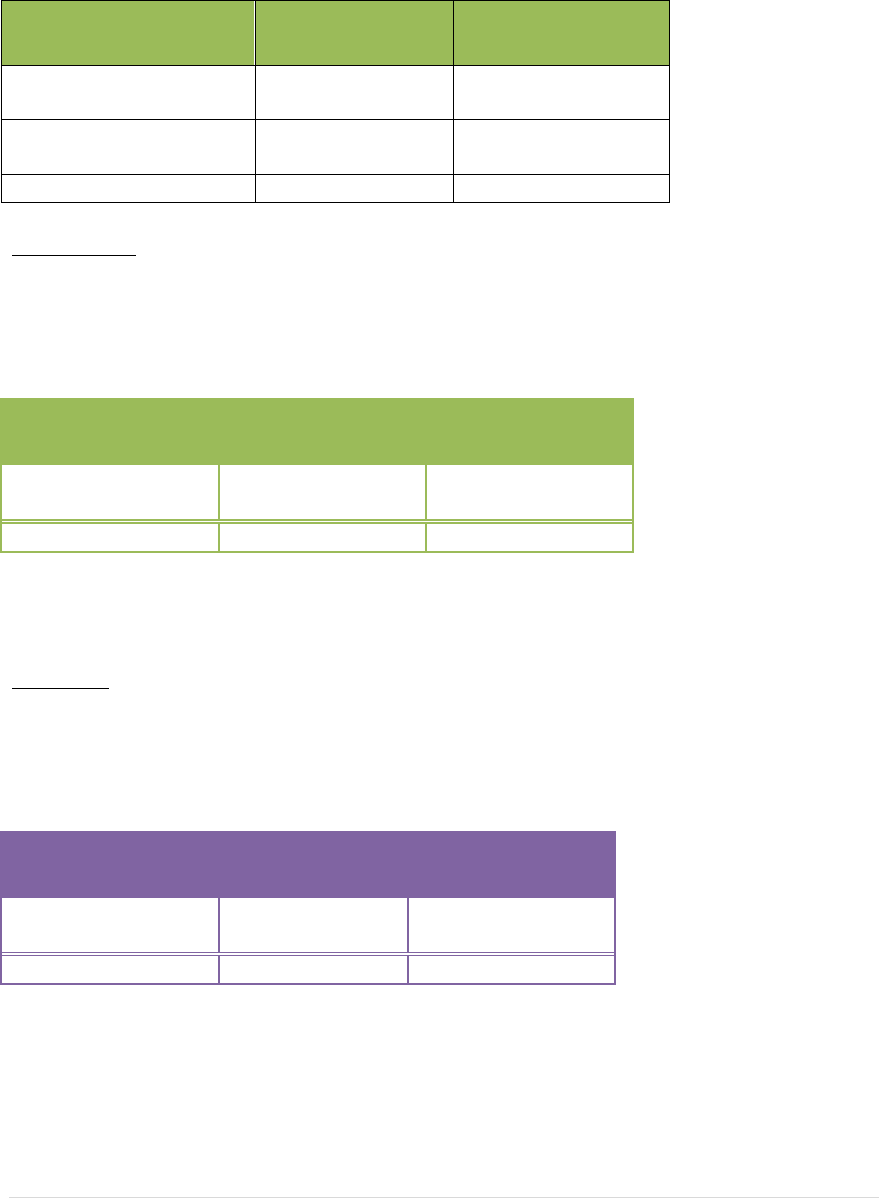

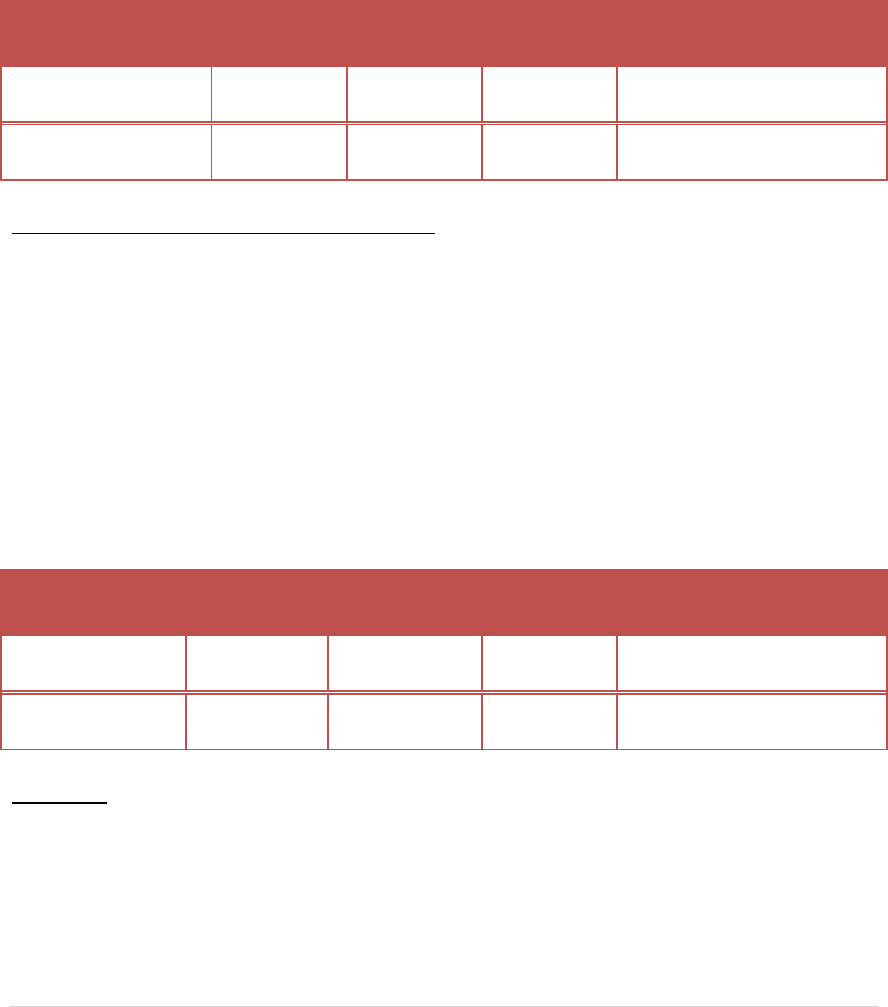

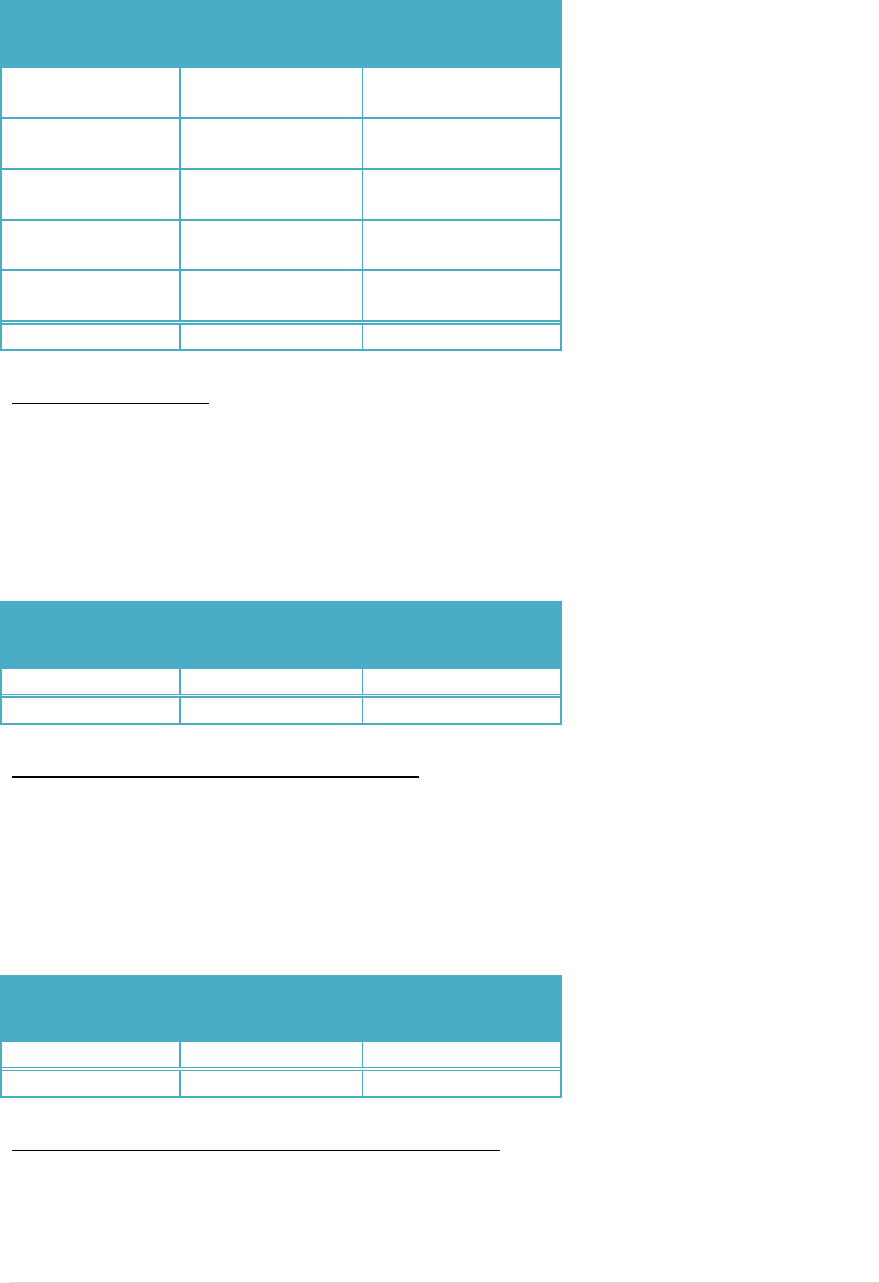

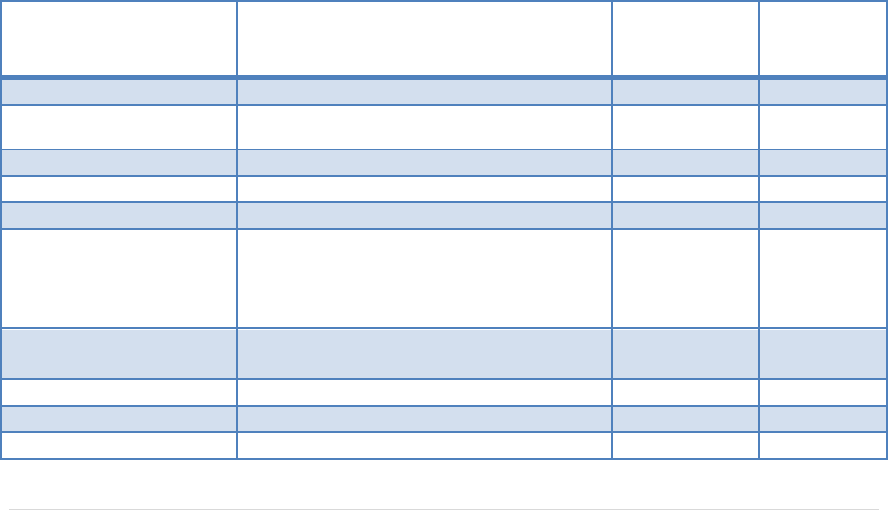

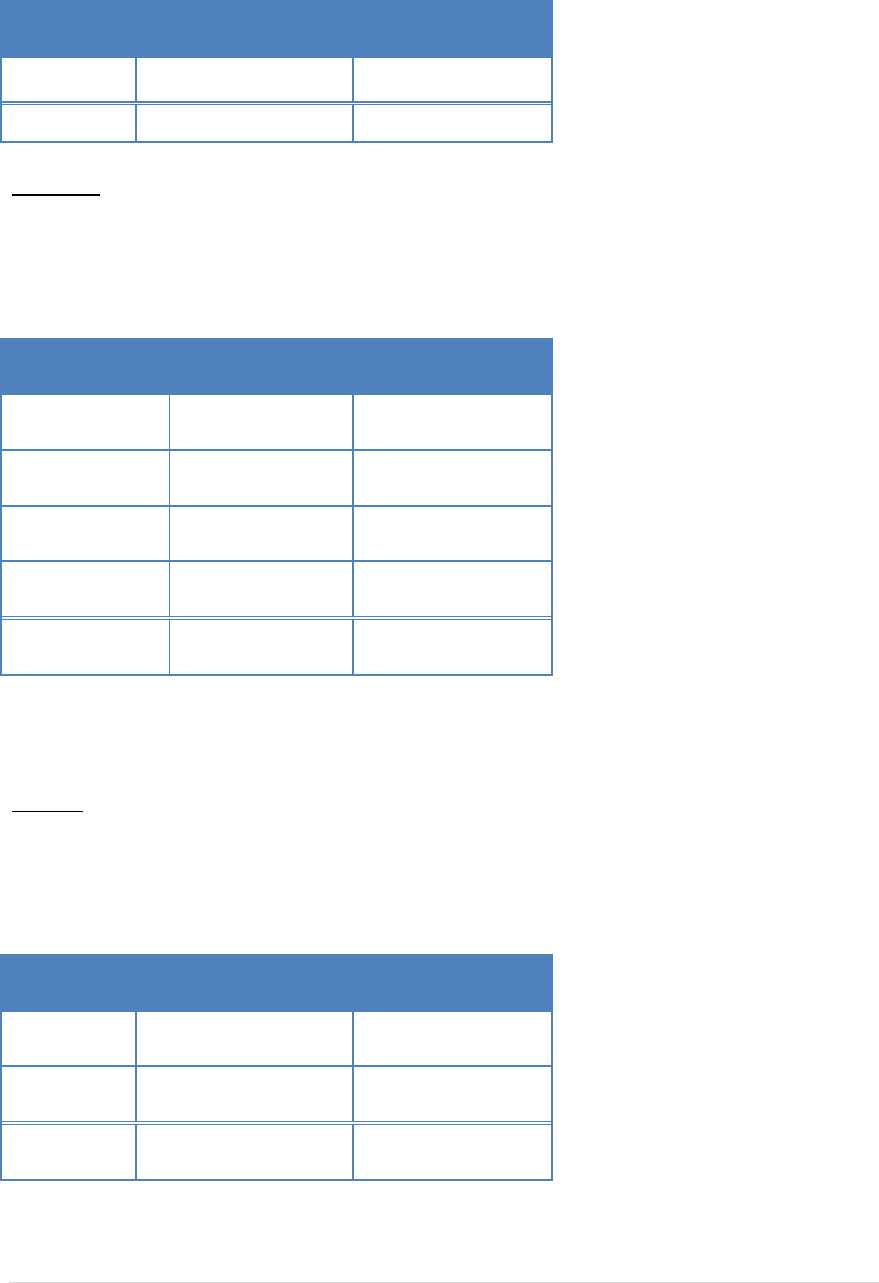

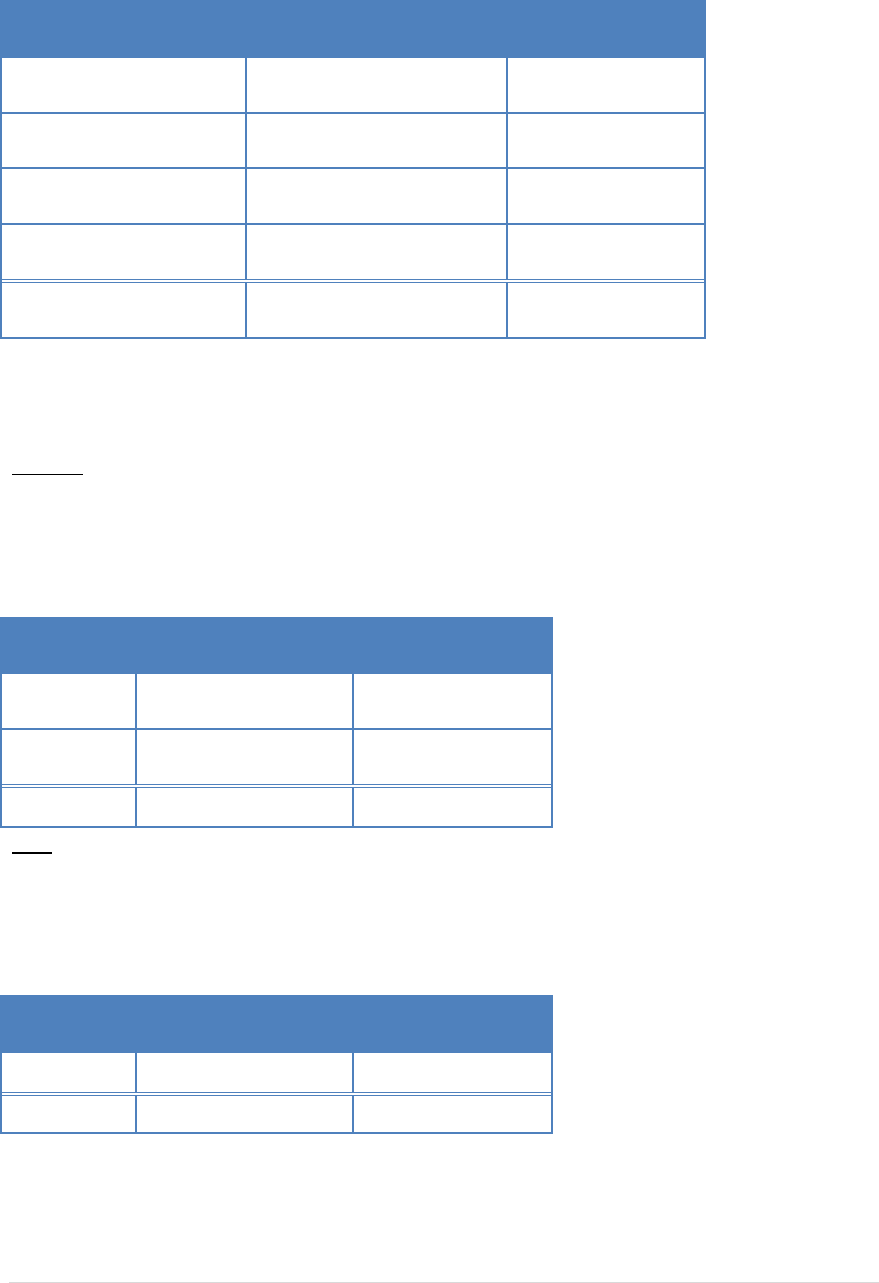

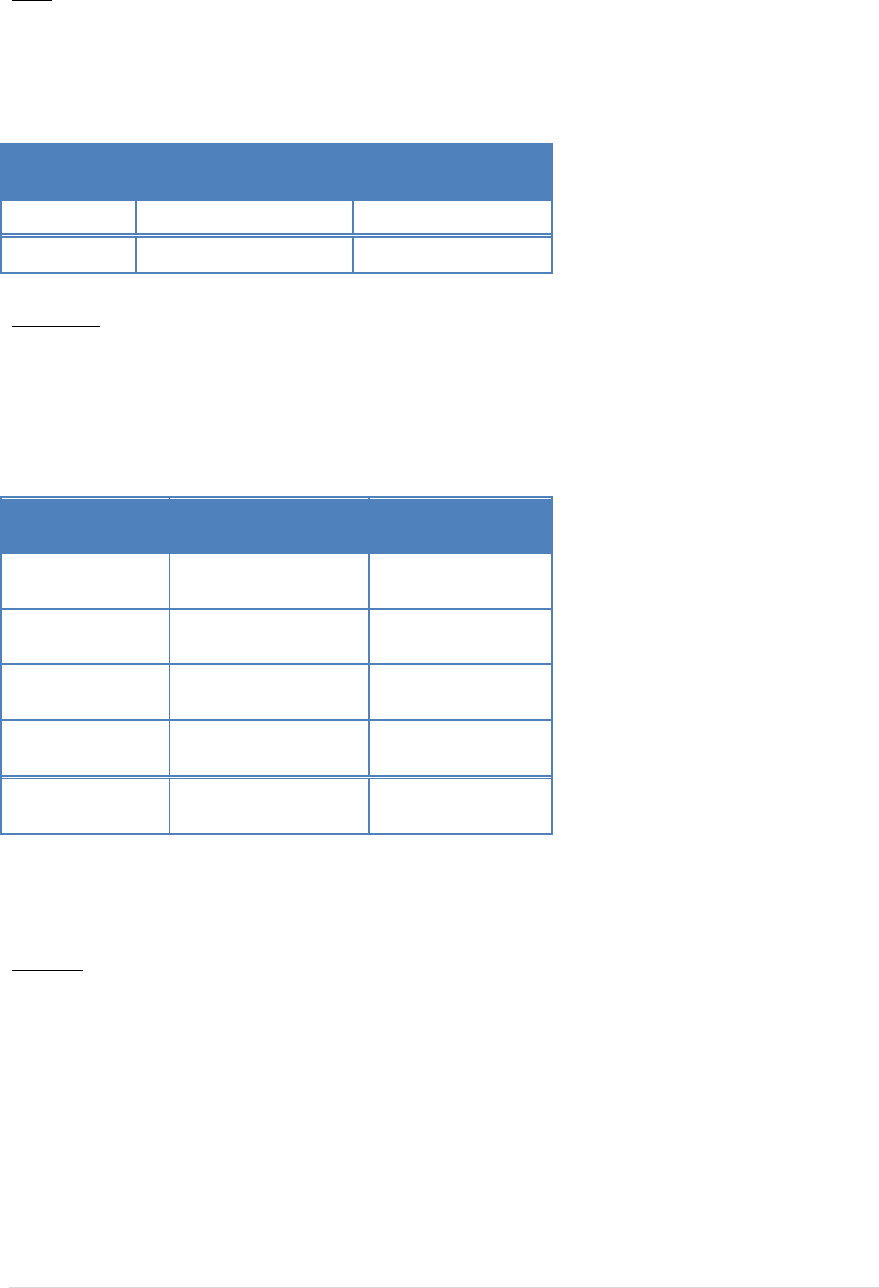

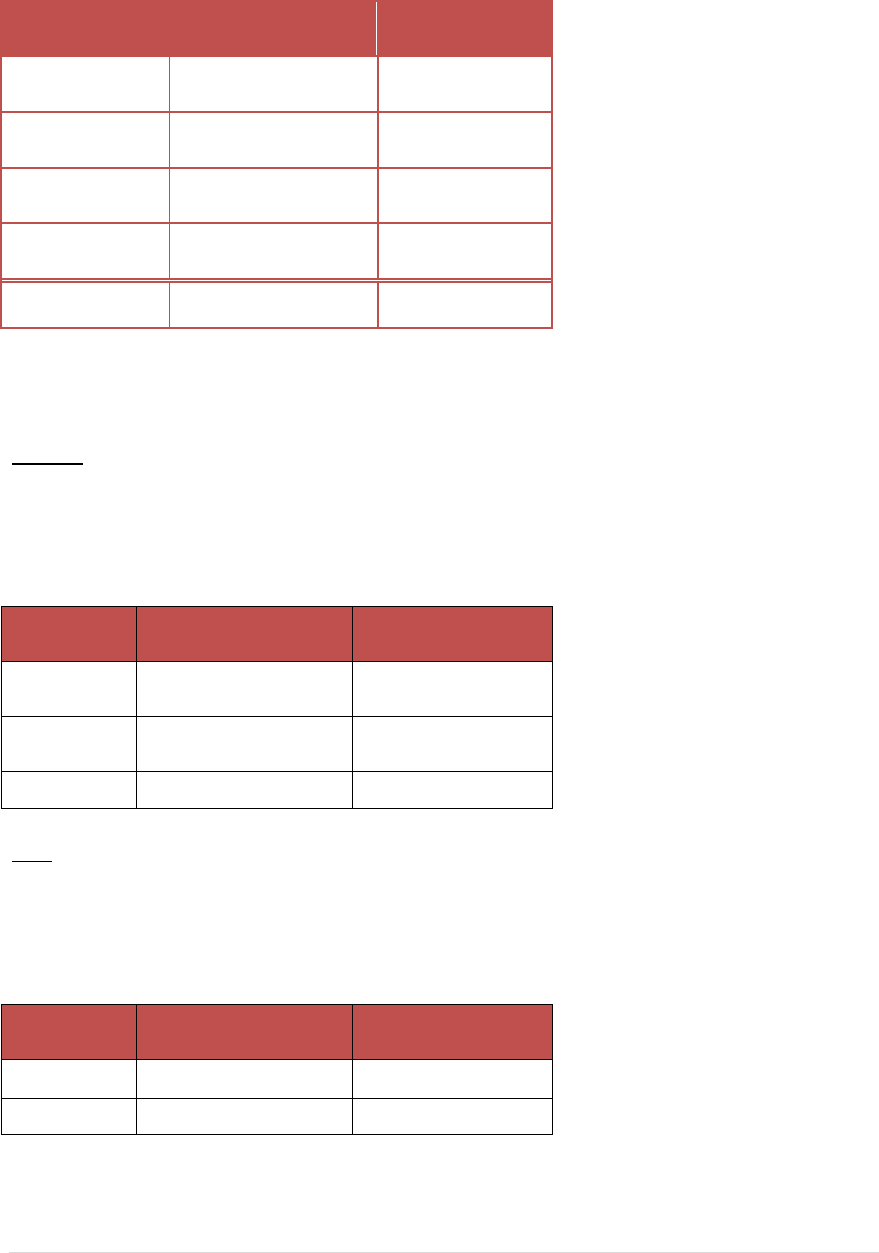

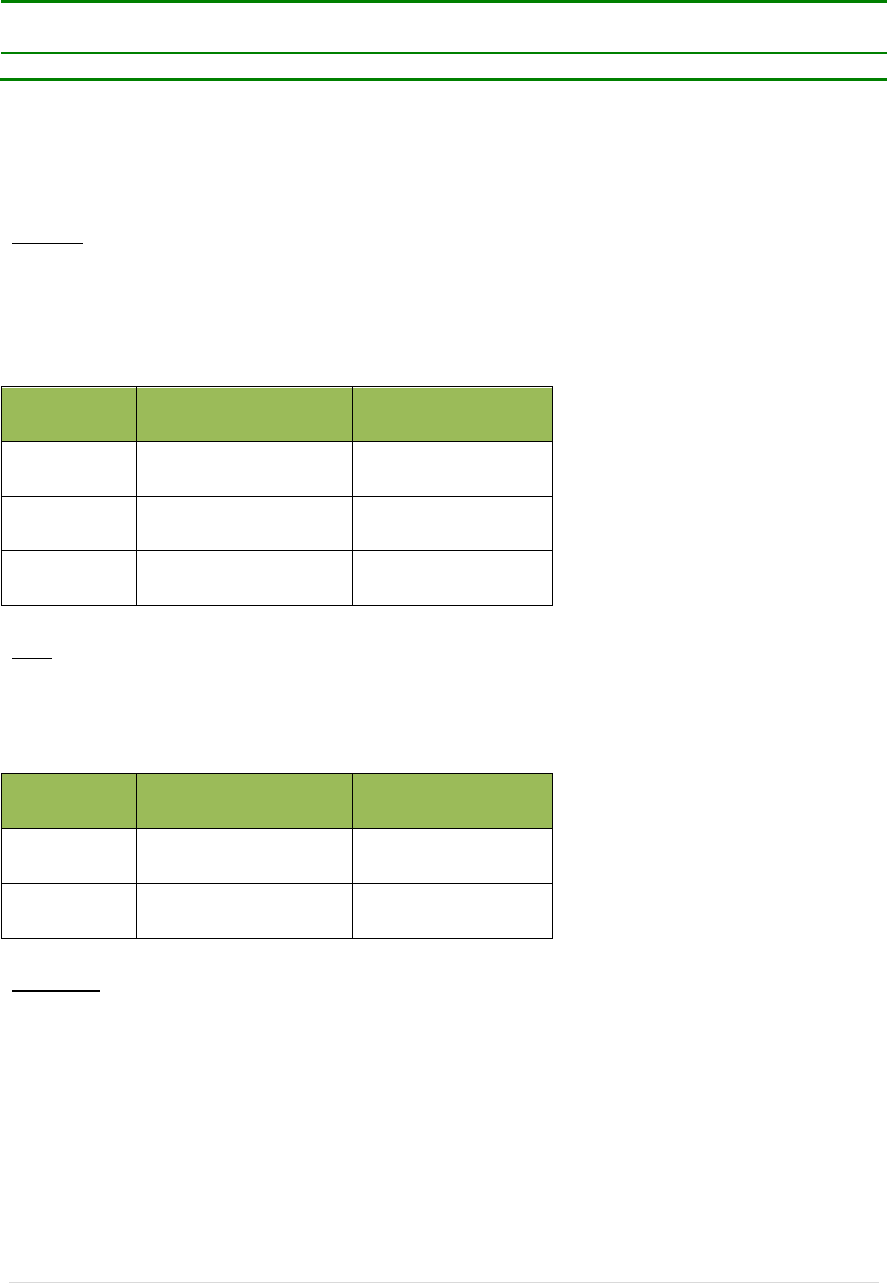

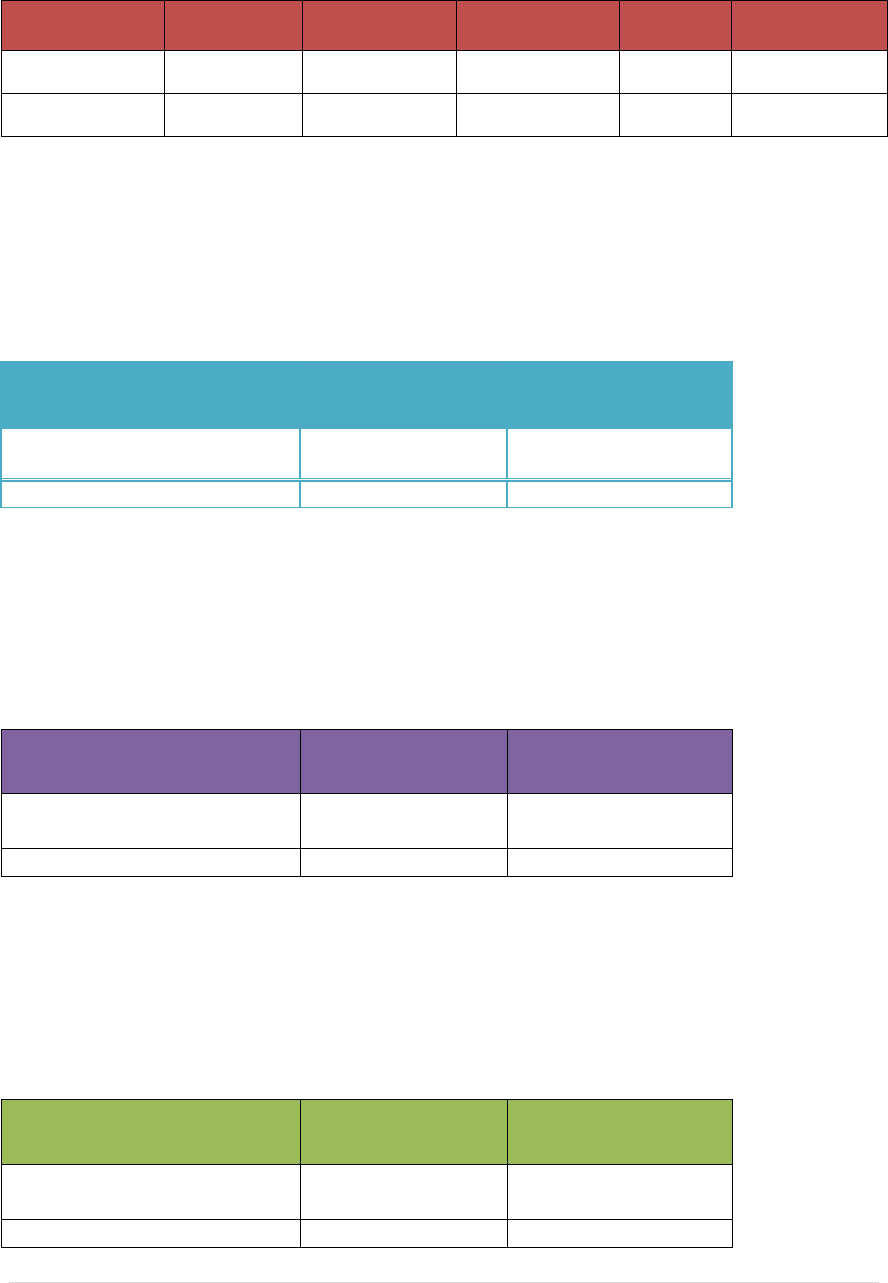

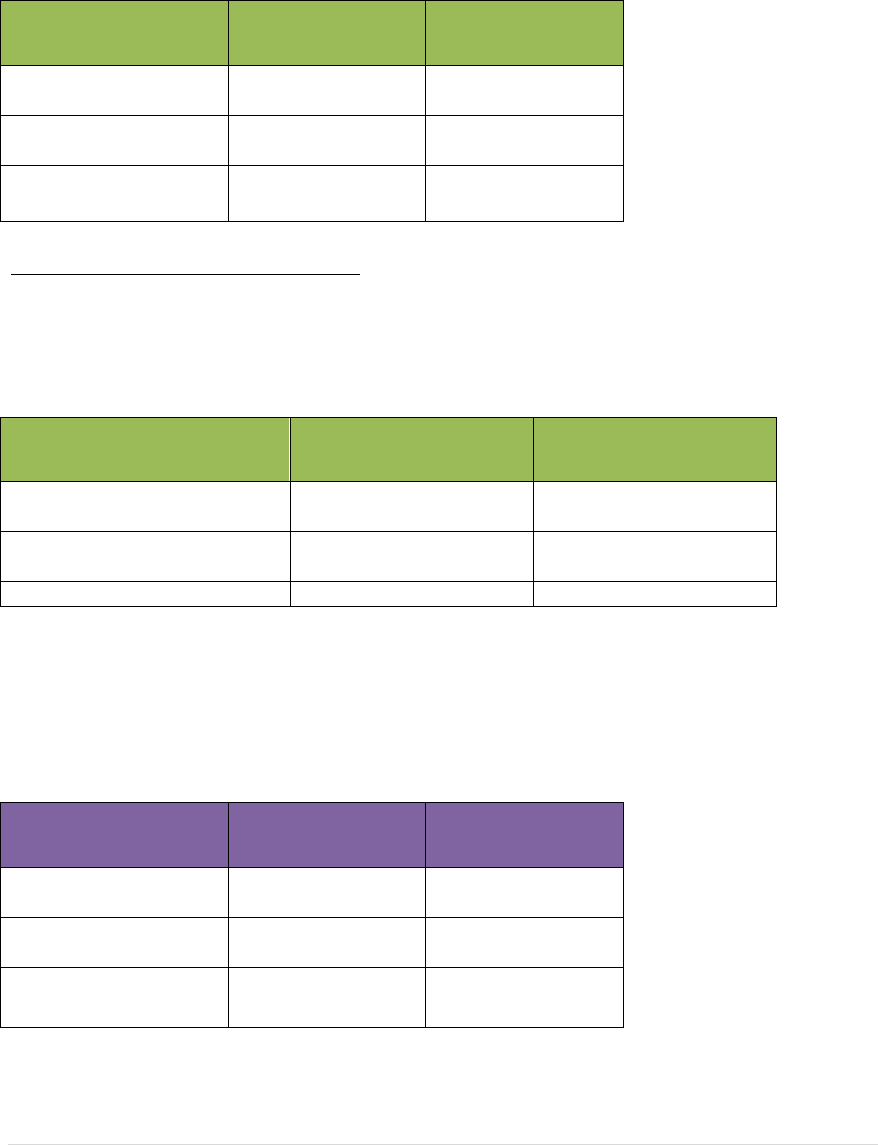

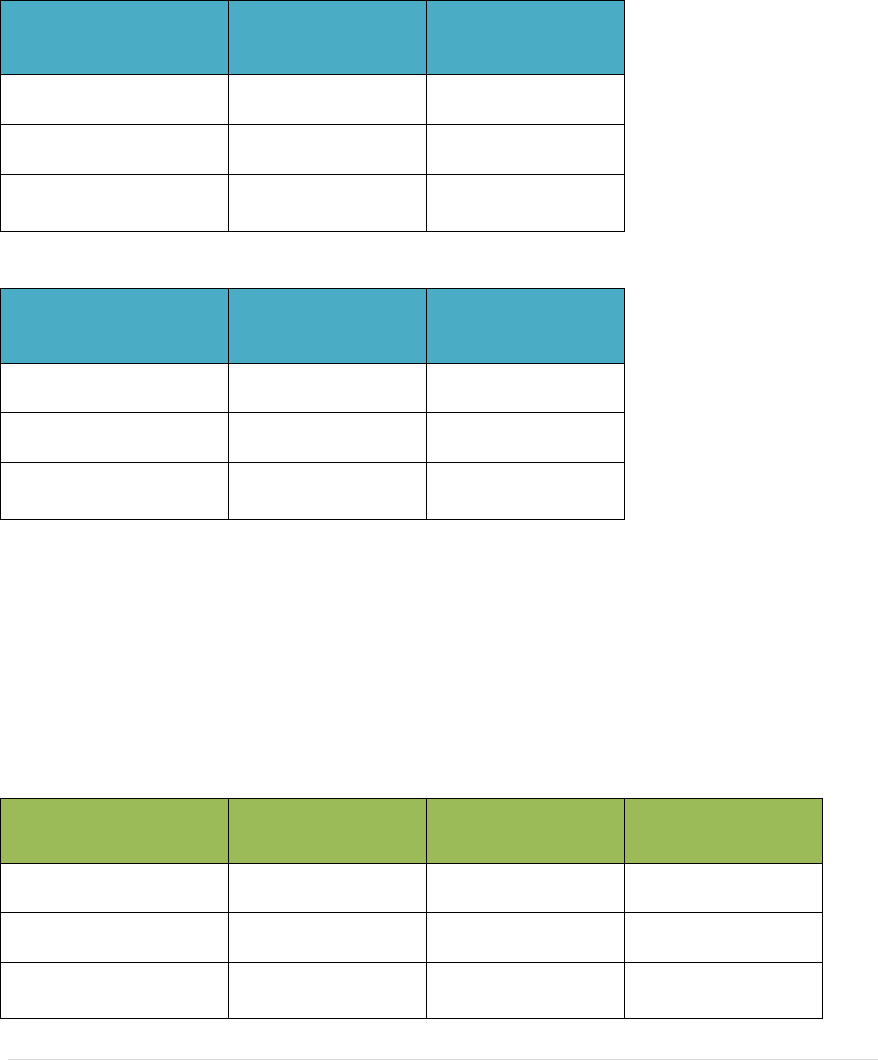

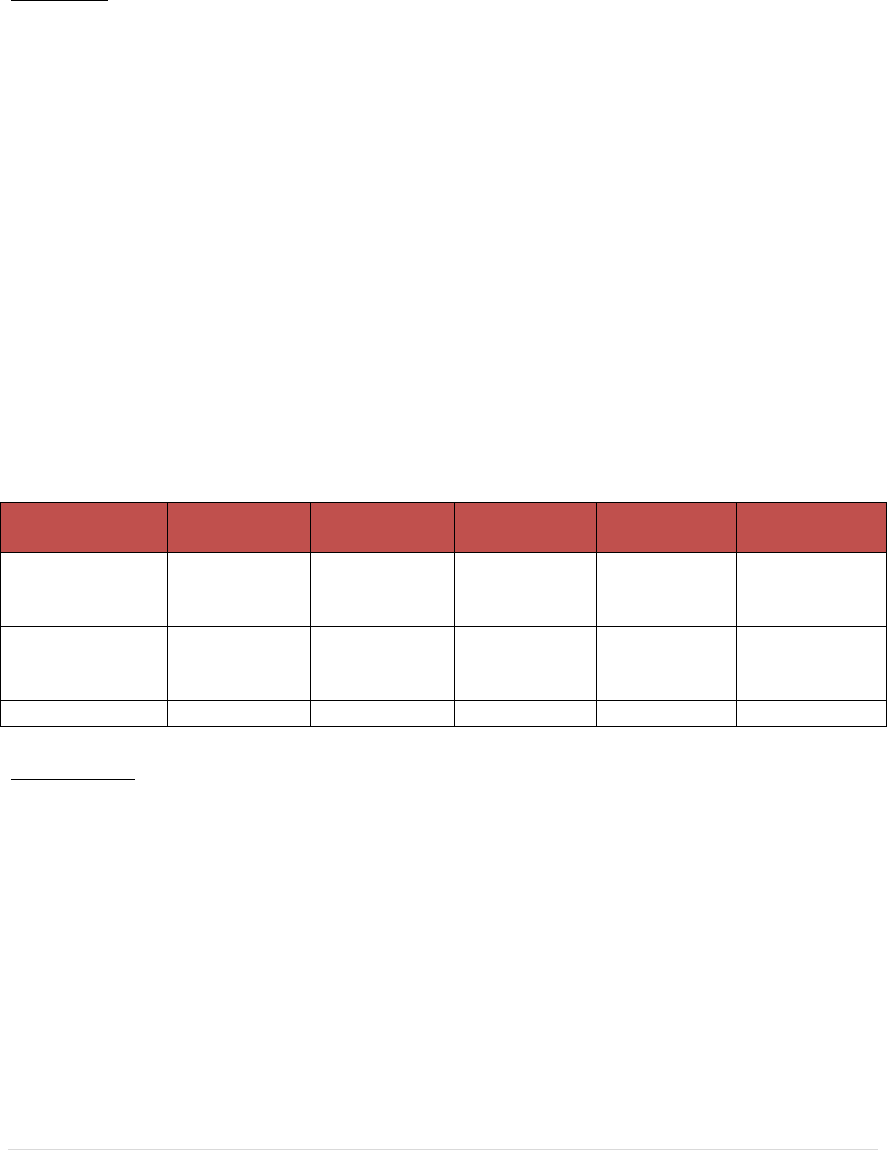

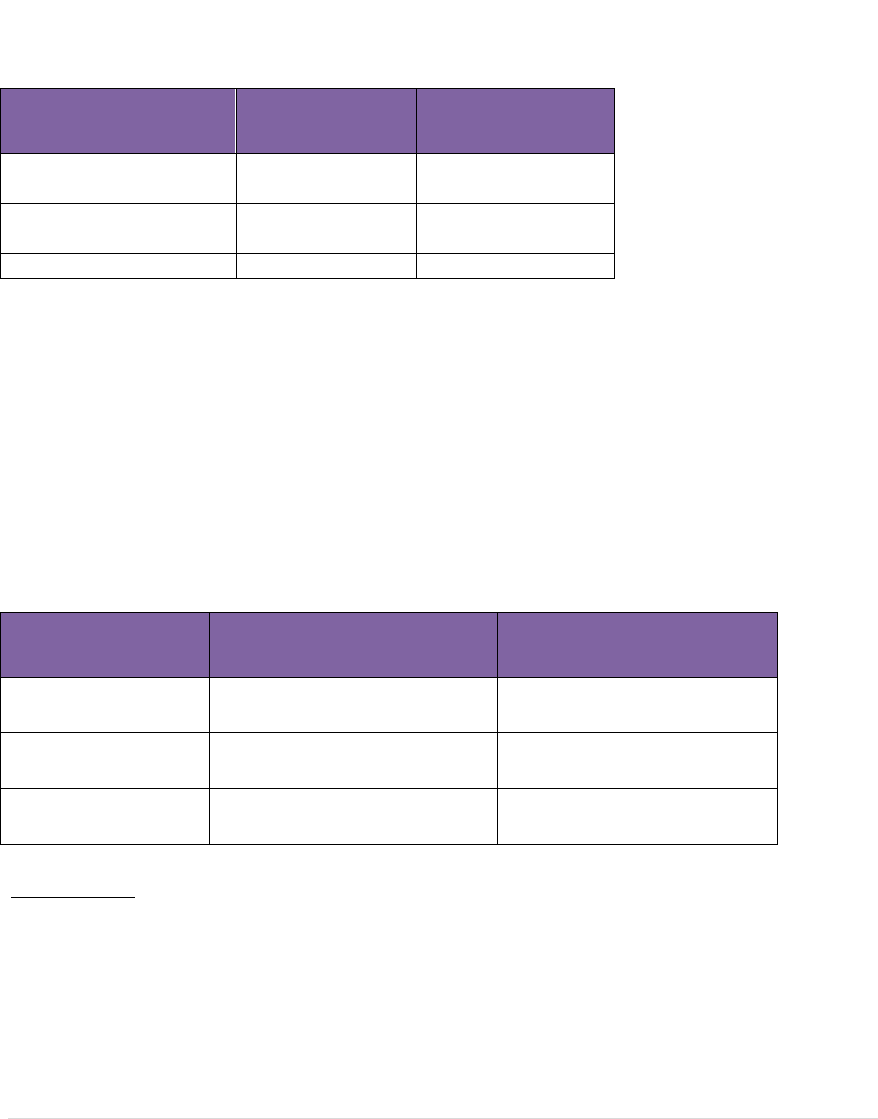

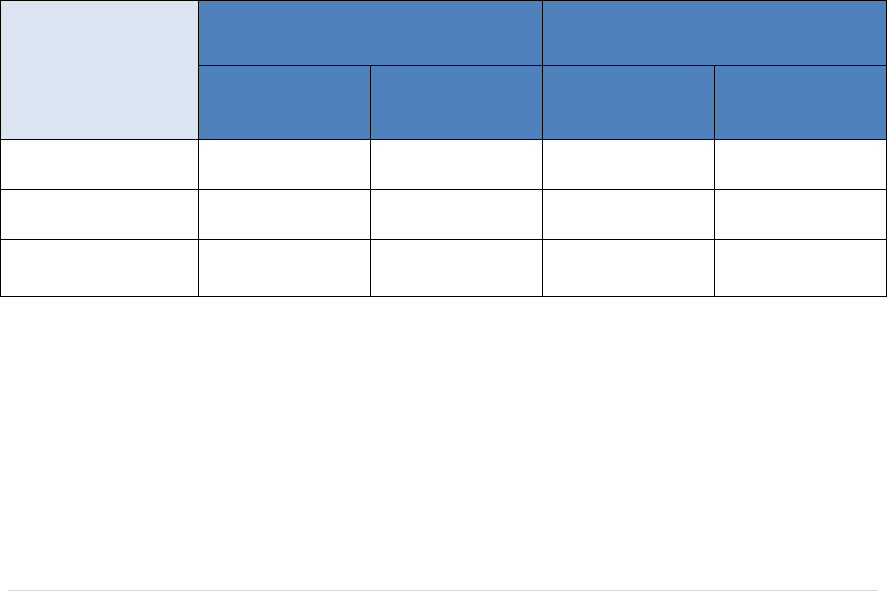

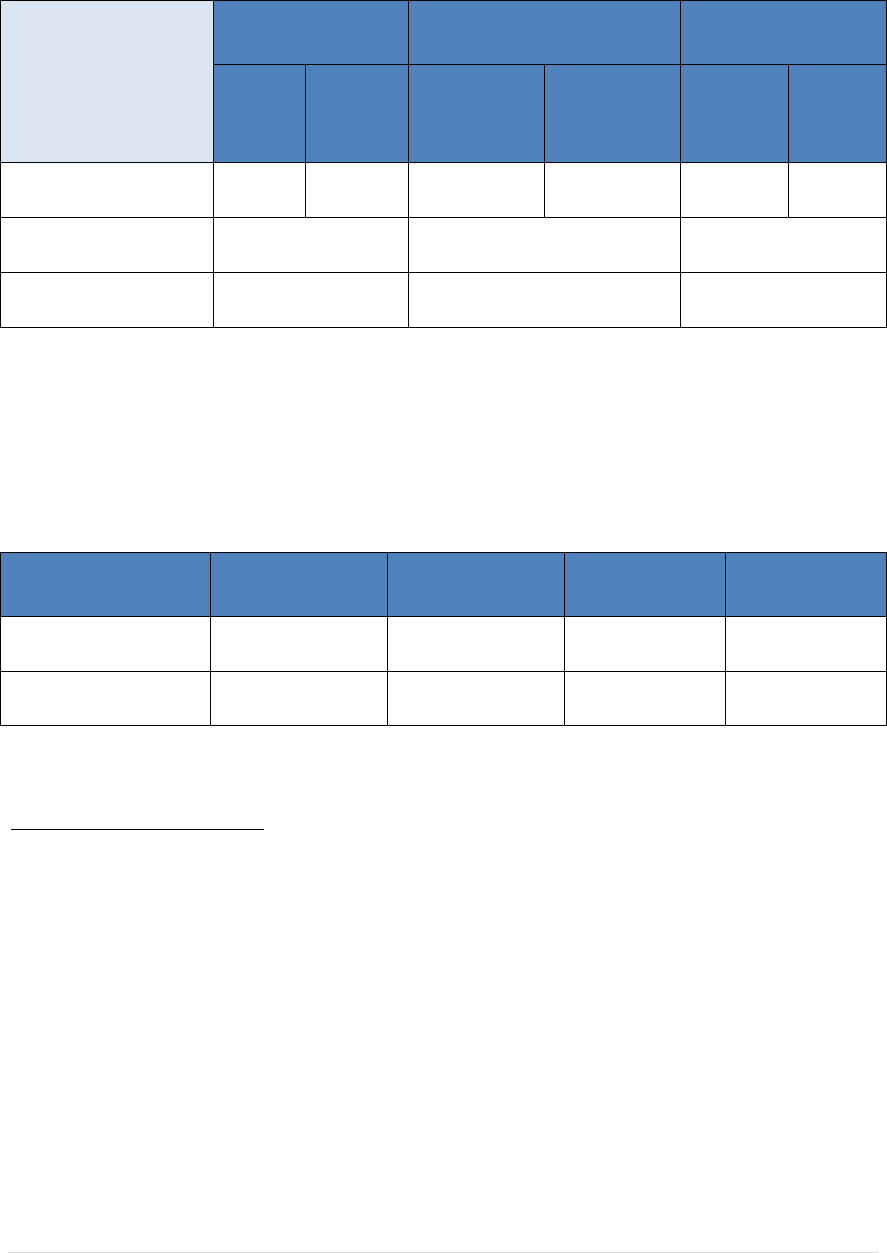

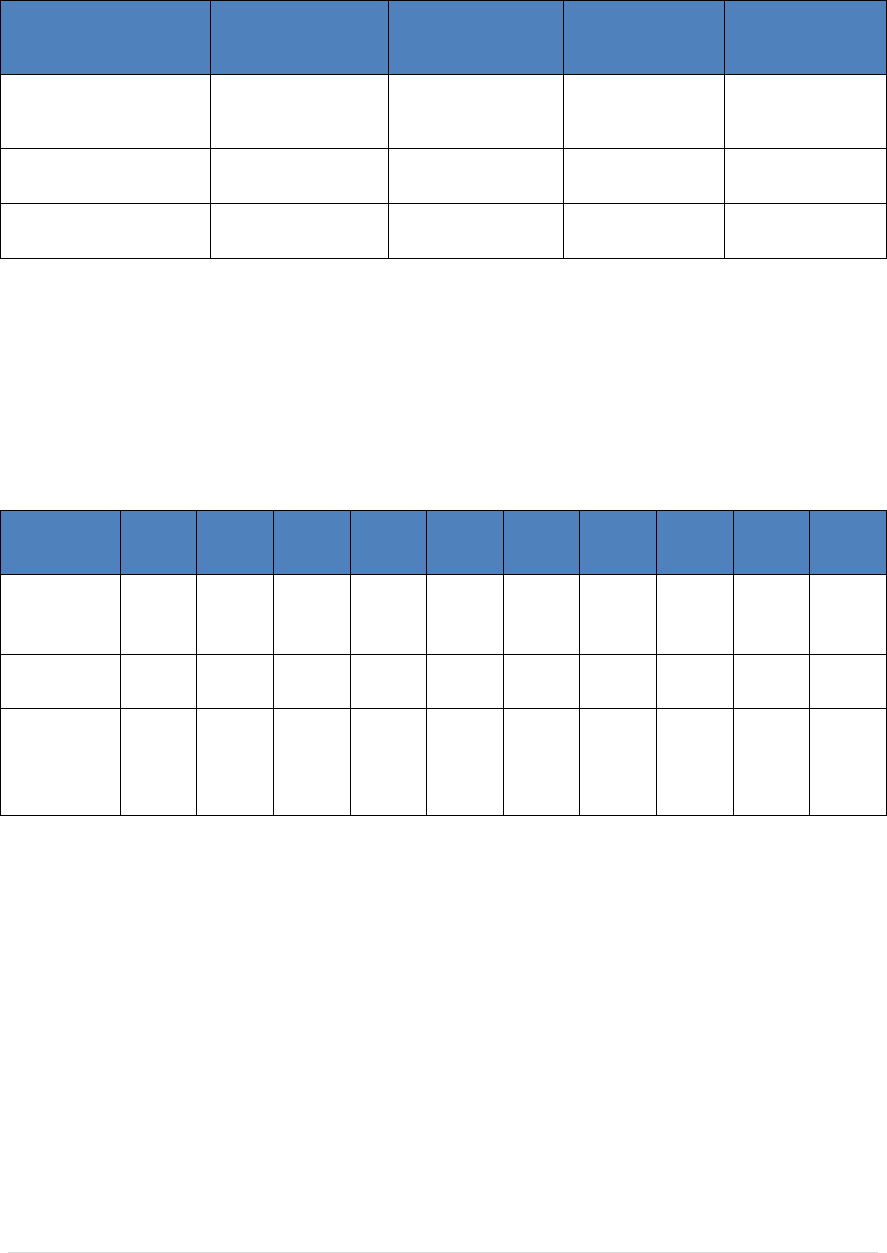

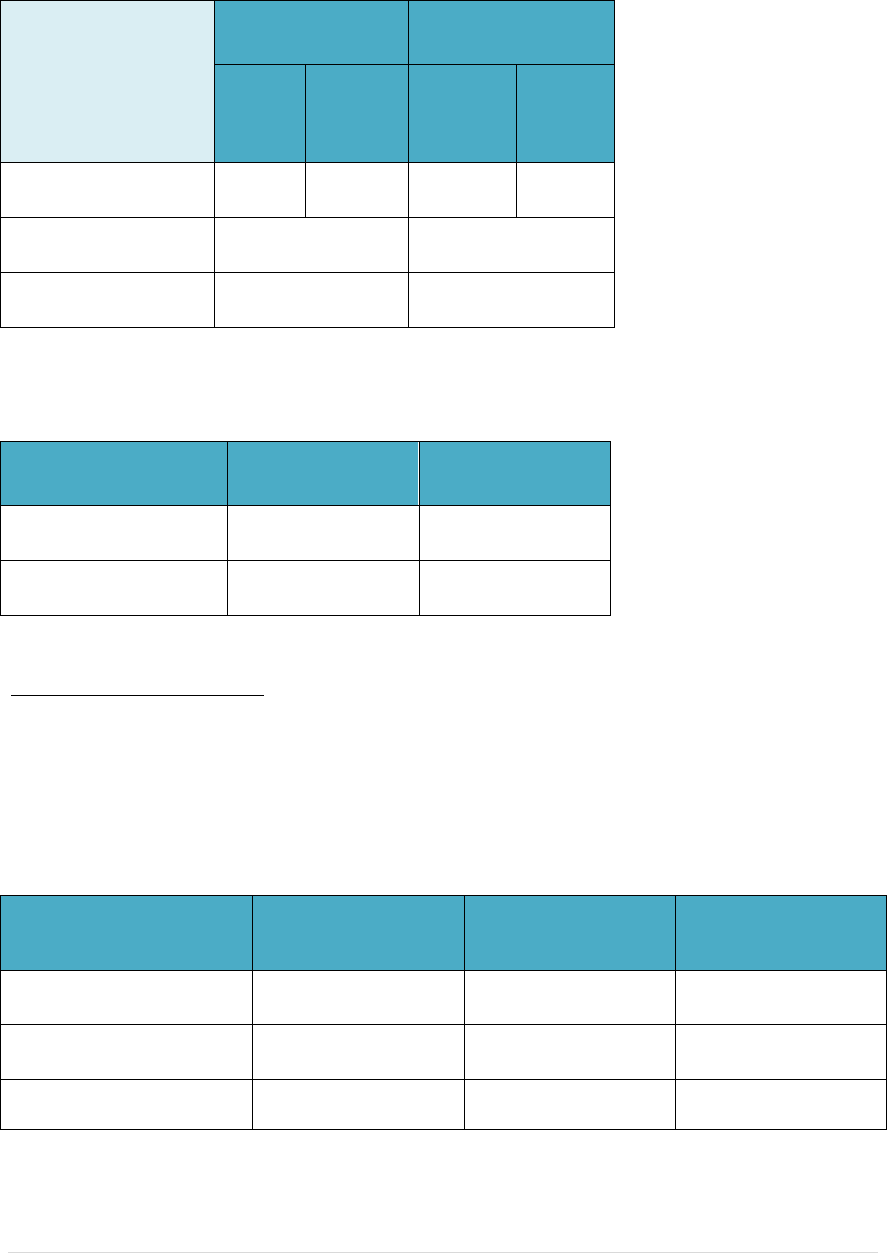

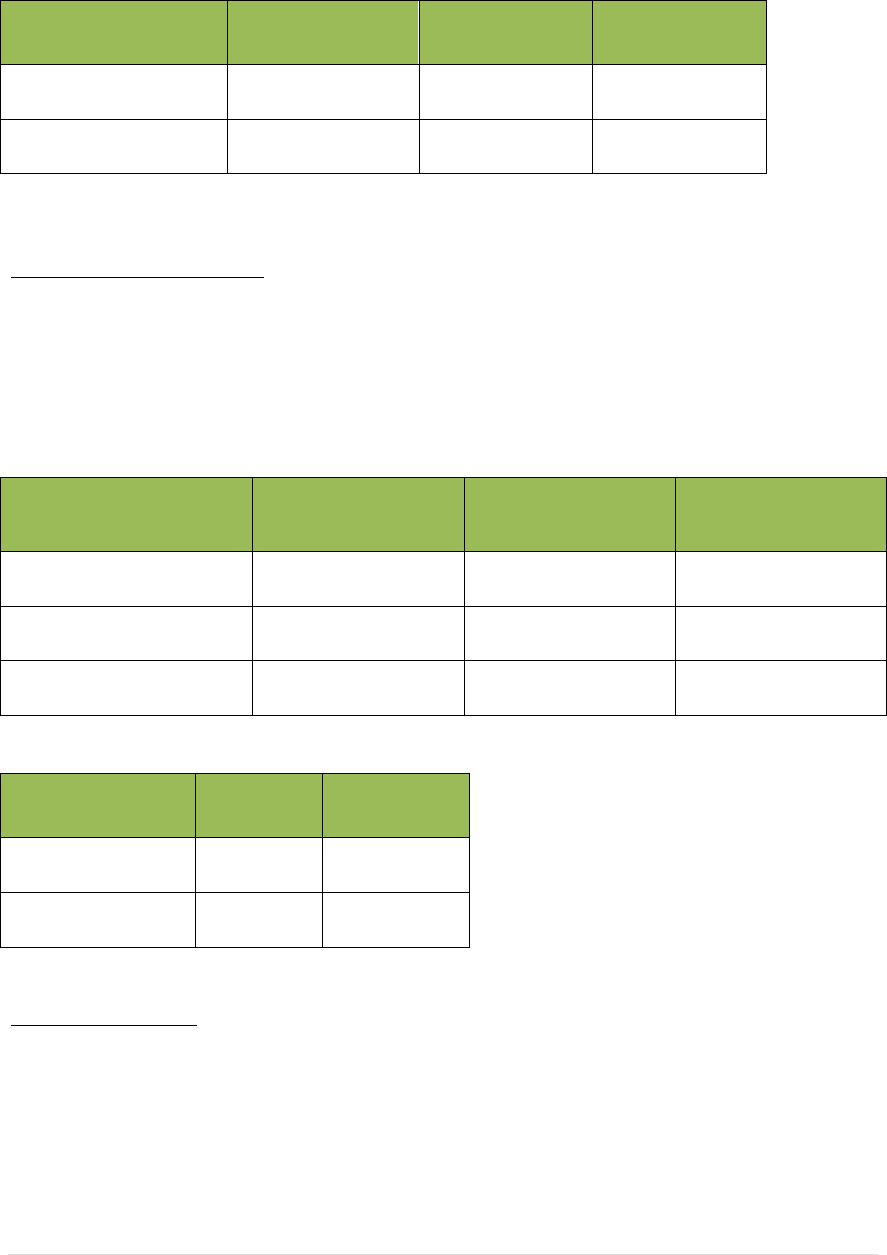

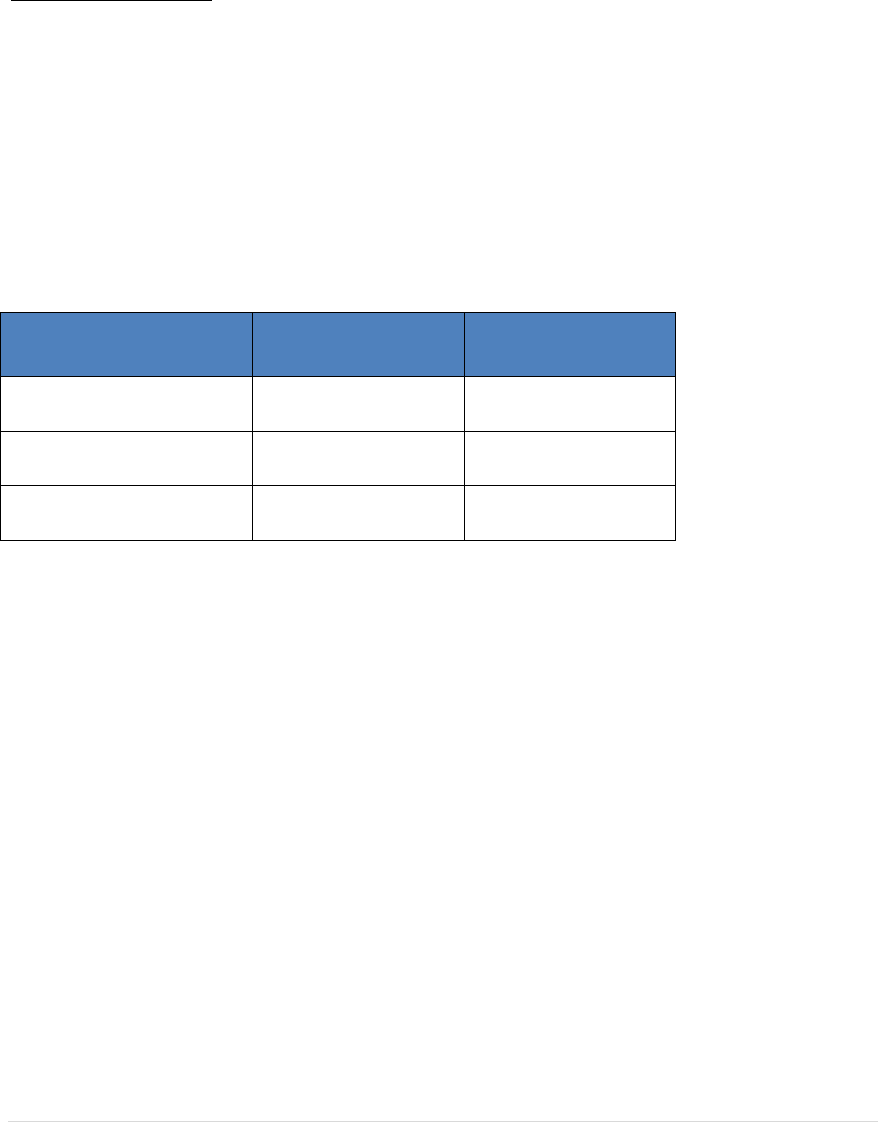

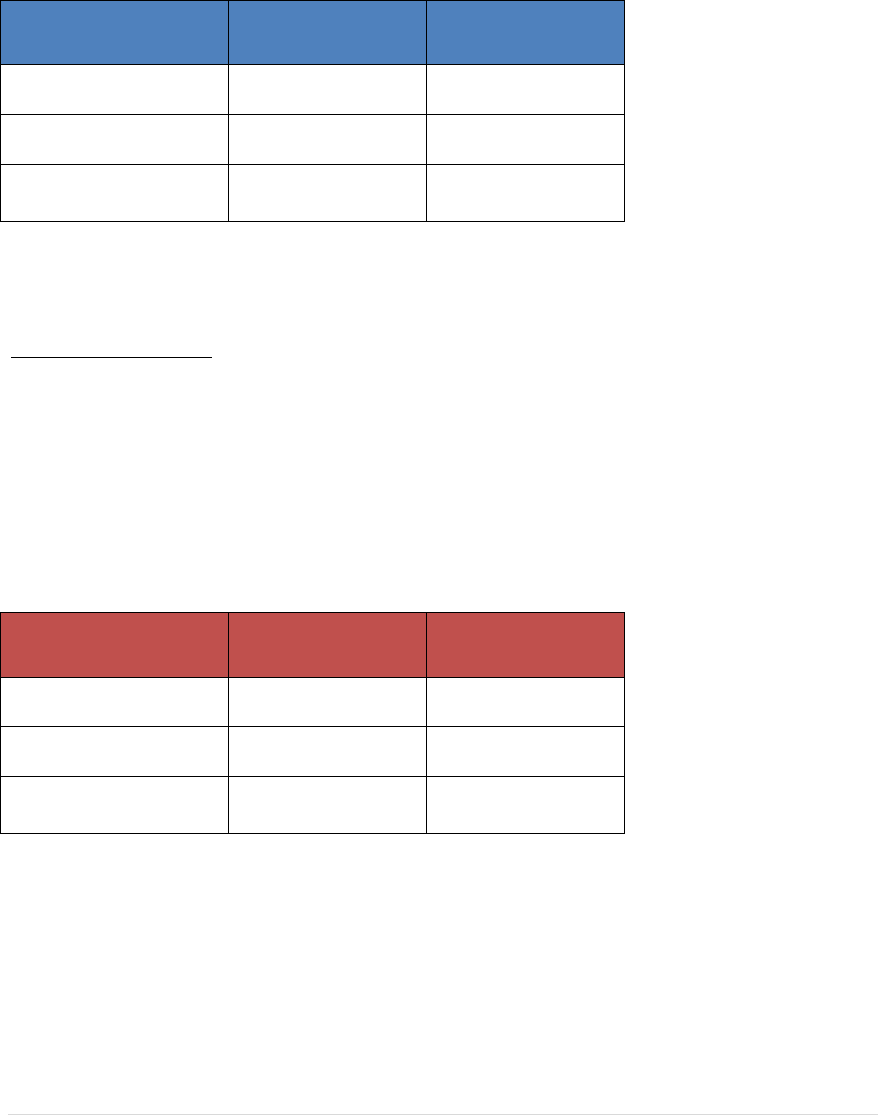

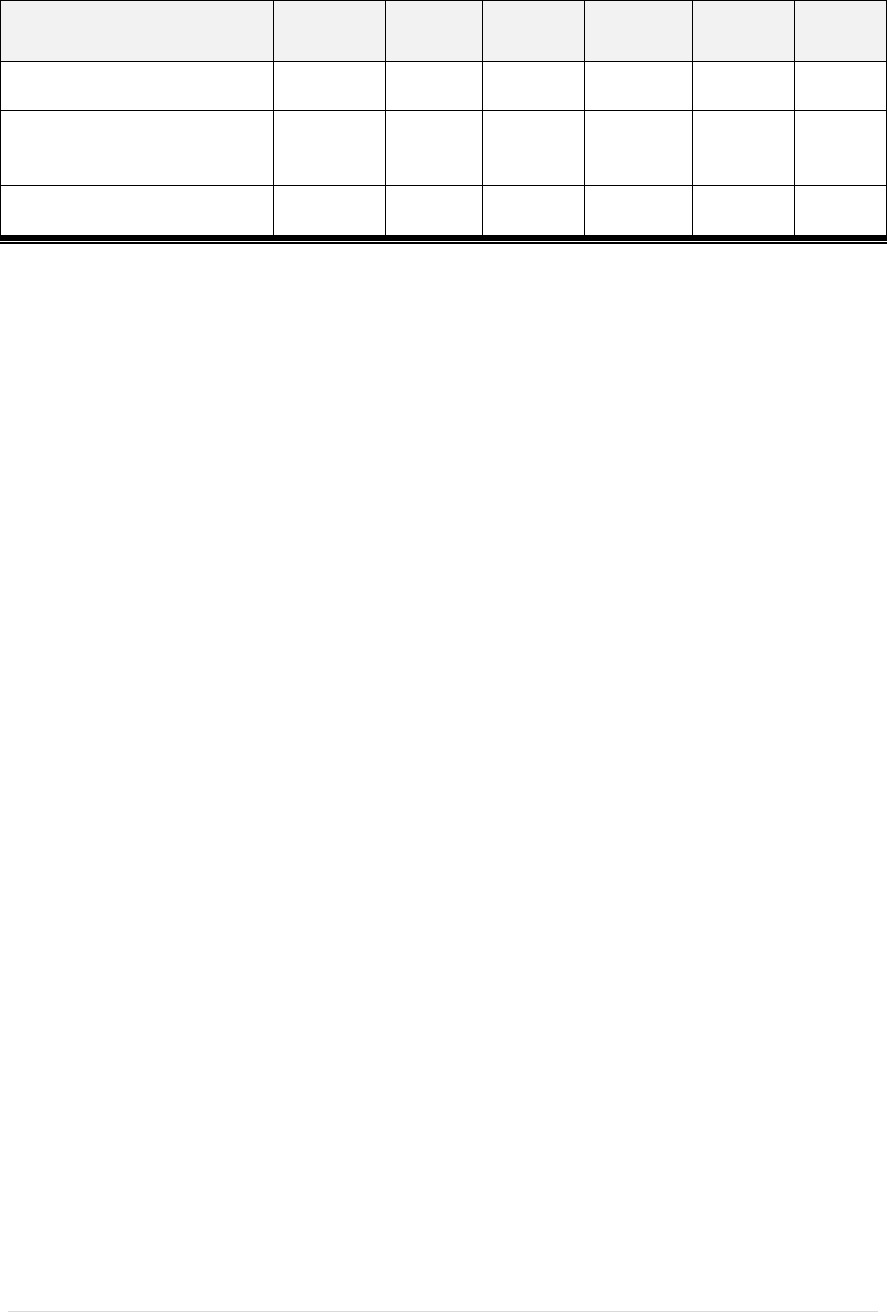

Average Costs for Adult Drug Courts

(including DUI and Young Adult Courts)

Per day

ALOS

Per Person Cost

Court 1

$12.08

638

$7,707.04

Court 2

$18.30

536

$9,808.80

Court 3

$20.56

830

$17,064.80

Court 4

$21.48

661

$14,198.28

Court 5

$21.97

N/A

N/A*

Court 6

$23.22

665

$15,441.30

Court 7

$23.72

765

$18,145.80

Court 8

$27.26

572

$15,592.72

Court 9

$30.34

790

$23,968.60

Court

10

$39.26

628

$24,655.28

Court

11

$40.13

639

$25,643.07

Court

12

$45.81

476

$21,805.56

Average Costs for Juvenile Drug Courts

Per

Day

ALOS

Per Person

Cost

Court 1

$37.19

418

$15,545.42

Court 2

$42.11

394

$16,591.34

Court 3

$85.06

530

$45,081.80

Court 4

$88.19

378

$33,335.82

Although the costs for Nebraska problem solving courts are estimates, these approximate

costs can be used to provide a general idea of cost savings produced through these

programs. For the 10 adult drug courts, the one young adult problem solving court and

the DUI court, the estimated costs for one year are $4,201,740. For the types of

participants served through problem solving courts, the alternative if these programs were

not available would be jail or prison. The estimate for serving the same number of

individuals for one year in jail is $6,810,975 (based on $45/day) and the estimate for

serving them in prison is $13,924,660 (based on $92/day). Hence, it is reasonable to

estimate these 12 problem solving courts save between $2,609,235 and $9,722,920 per

year. These are likely conservative estimates since the jail costs may not include ancillary

costs such as treatment services. In addition, these savings estimates do not account for

the reduction in future victim and societal costs resulting from lower recidivism rates.

While the cost study provided some general estimates for cost savings, we believe more

thorough cost benefit and cost effectiveness studies could be conducted if better data

collection processes were in place. A major challenge in collecting cost information is the

lack of financial data maintained and reported by treatment providers. Many providers

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

11 | P a g e

had difficulty matching cost to individual drug court participants. A standardized,

ongoing process for collecting this information would ensure a better understanding of

the complete costs of problem solving courts and allow an evaluation of how cost are

related to outcomes. The minimum financial data that should be collected for each

problem solving court includes the following:

1. Operations costs including salaries and benefits of staff, rent/utilities,

supplies/equipment, travel, training, and other operational costs

2. Costs of incentives and sanctions including costs of incarceration when used as a

sanction

3. A systematic method to document the amount and cost of time dedicated by drug

court team members who are not funded through the operational budget (e.g.,

judges, attorneys, law enforcement)

4. Costs of treatment and support services including substance abuse and mental

health treatment, employment training services, educational services, parent

training services, etc.

5. We recommend that costs be collected by funding source for each of the above

categories.

Nebraska problem solving courts are a valuable resource in Nebraska that lead to

improved outcomes and reduced criminal and juvenile justice costs. Additional funding

could be used to enhance programs across the state by training new team members; often

federal grant resources allowed initial team members to be trained, but as the original

team members left, new team members have not had the same opportunities. Additional

funding could also be used for incentives for problem solving court participants. In many

programs, the judge or coordinator use their personal resources to purchase incentives.

Day reporting centers are considered an important resource that improves drug court

outcomes; however, in rural areas, these centers are lacking. In addition, treatment

resources are lacking, particularly in rural areas; additional resources would provide for

an increase in availability and accessibility of services. As shown in the cost analysis,

investments in problem solving courts save resources over time.

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Serve High Risk Offenders

There is an emerging national consensus that

problem solving courts should be serving

high risk/high need offenders. If drug courts

are considered a scarce resource, they

should be used for those offenders who

receive the most benefit and produce the

most cost savings. Cost effectiveness studies

have shown these are offenders who have

high need for substance abuse intervention

and are at high risk for reoffending.

“Research has clearly demonstrated that

intensive treatment services should be

reserved for individuals with the most severe

drug use problems. Providing intensive

services to those with less severe problems is

not only a waste of valuable resources

(particularly since these individuals tend to do

as well with less intensive intervention), but

may actually make their drug use problem

worse.”

- Knight et al. (2008)

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

12 | P a g e

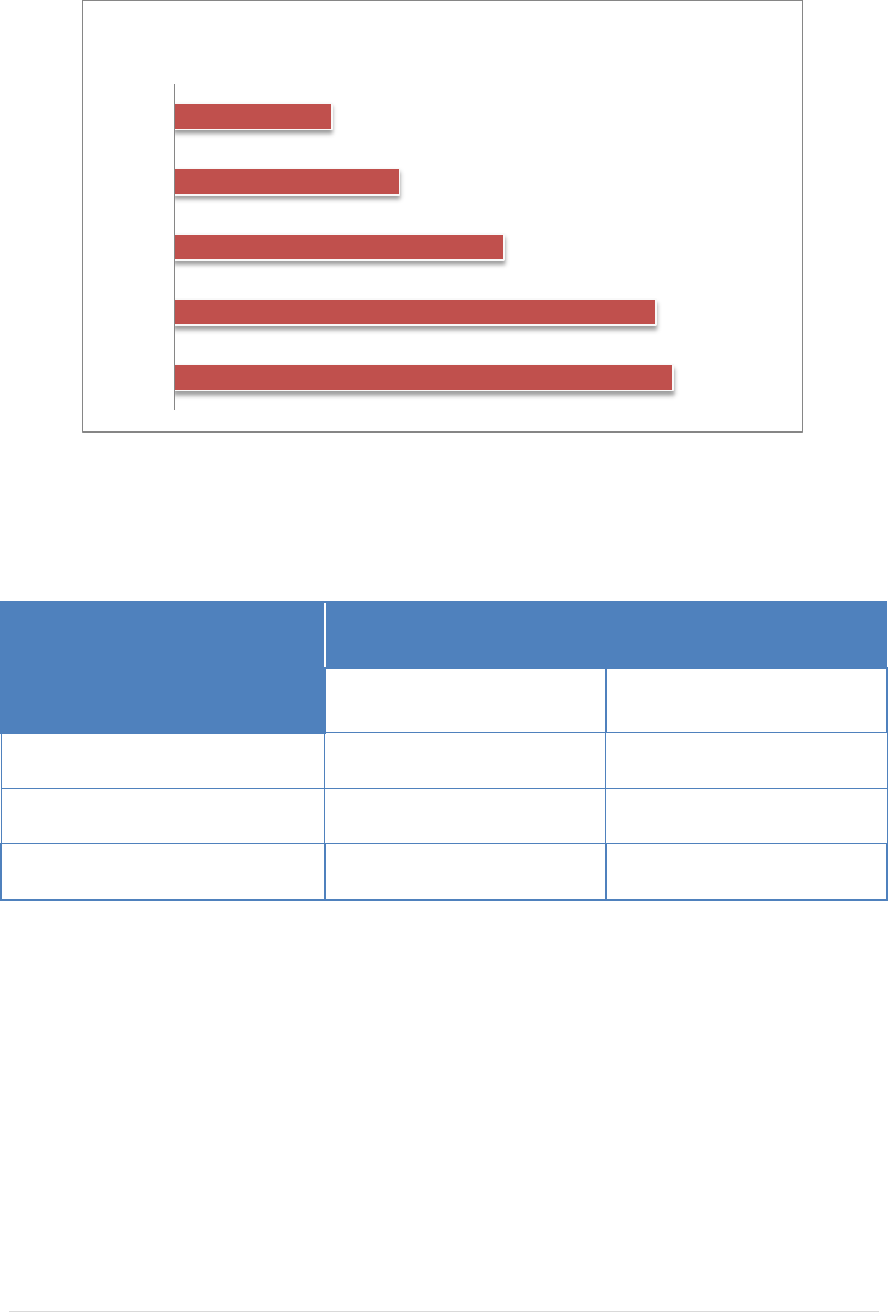

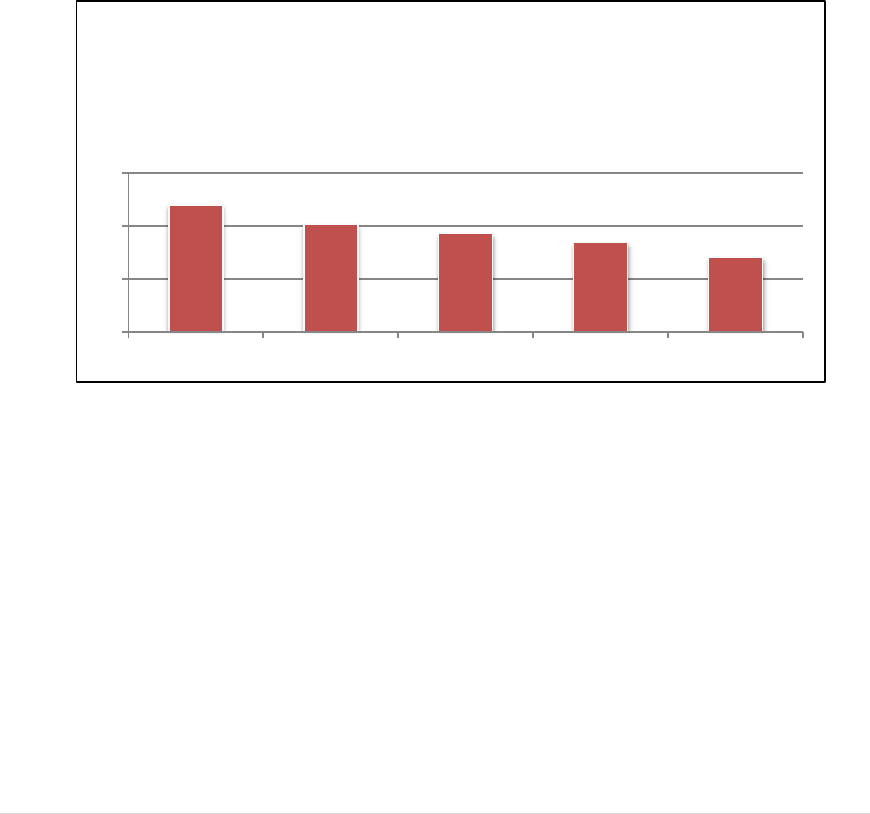

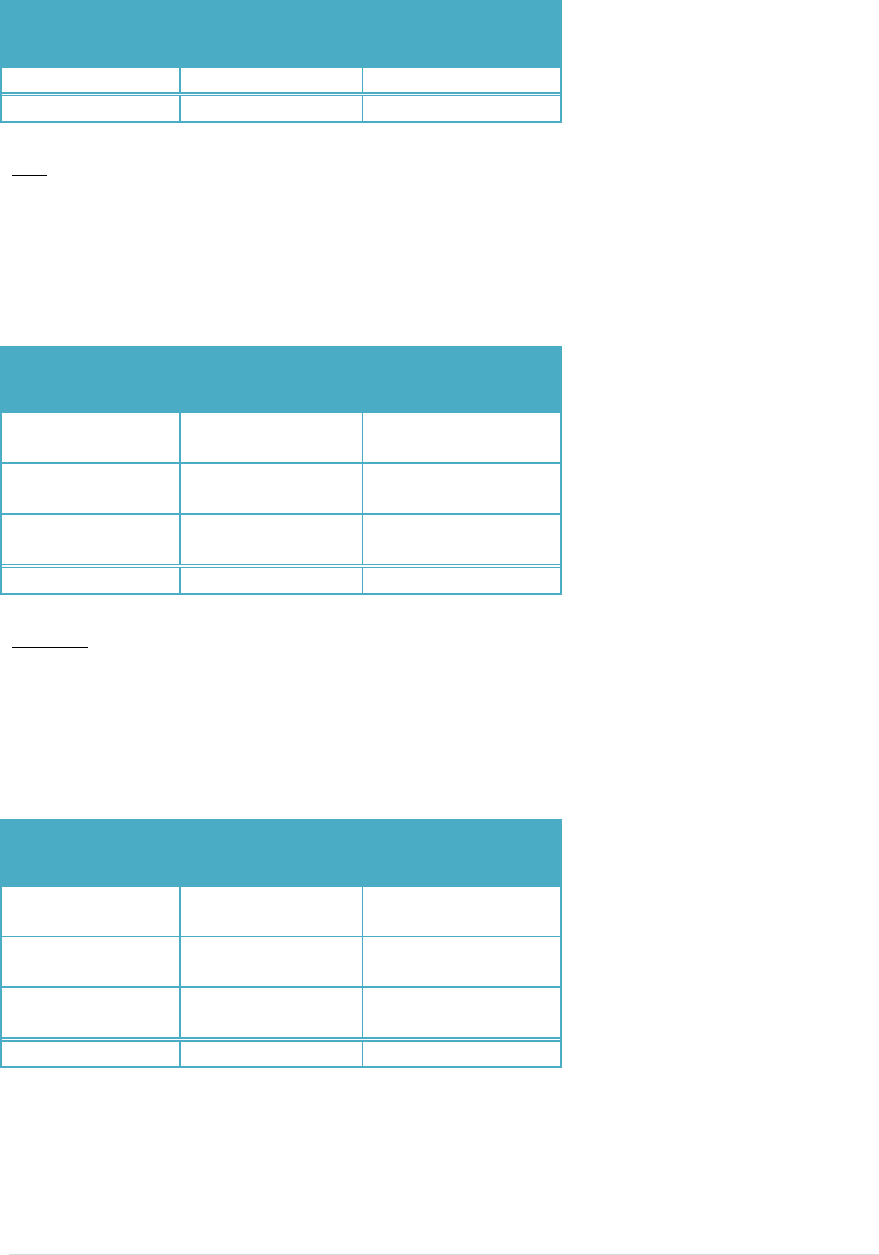

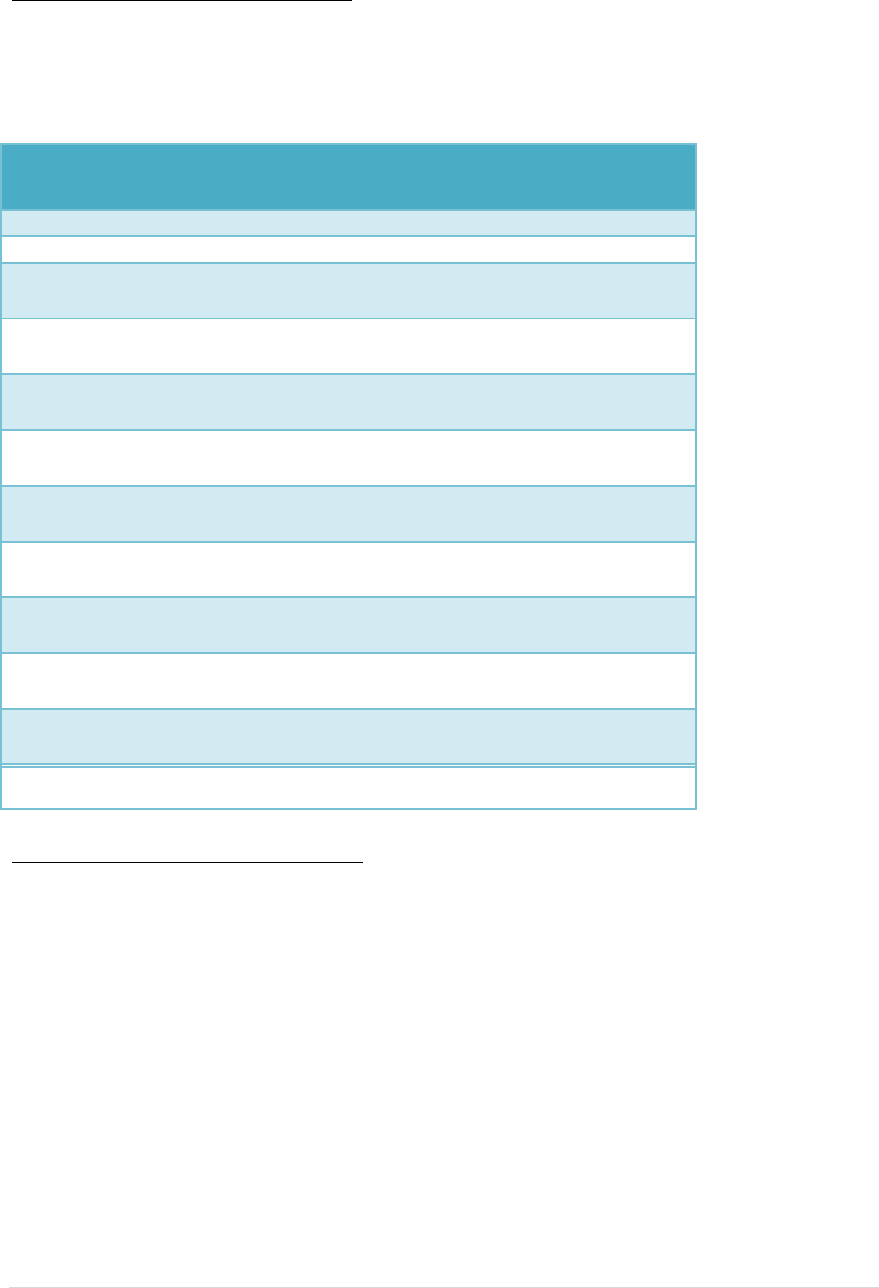

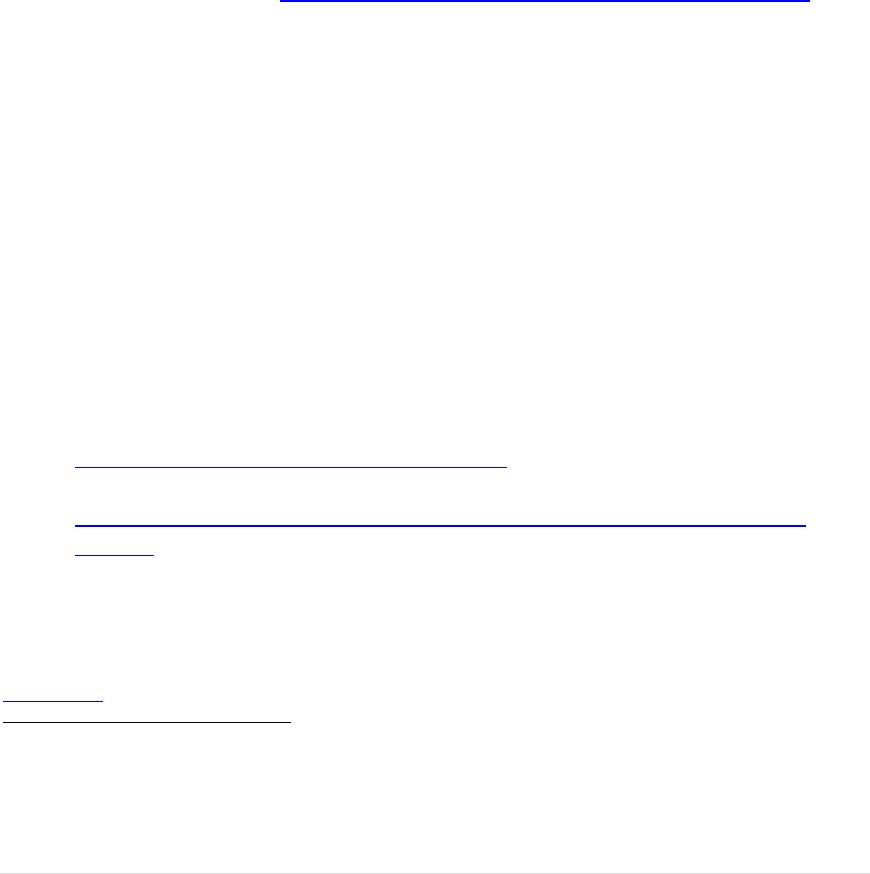

Nebraska problem solving courts are serving a high risk population. For example, adult

drug courts are serving high to very high risk population based on the Alcohol/Drug

Abuse Subscale of the Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI), and

juvenile drug courts serve participants with a moderate to high level of risk based on the

Youth Level of Risk/Case Management Inventory (YLS/CMI).

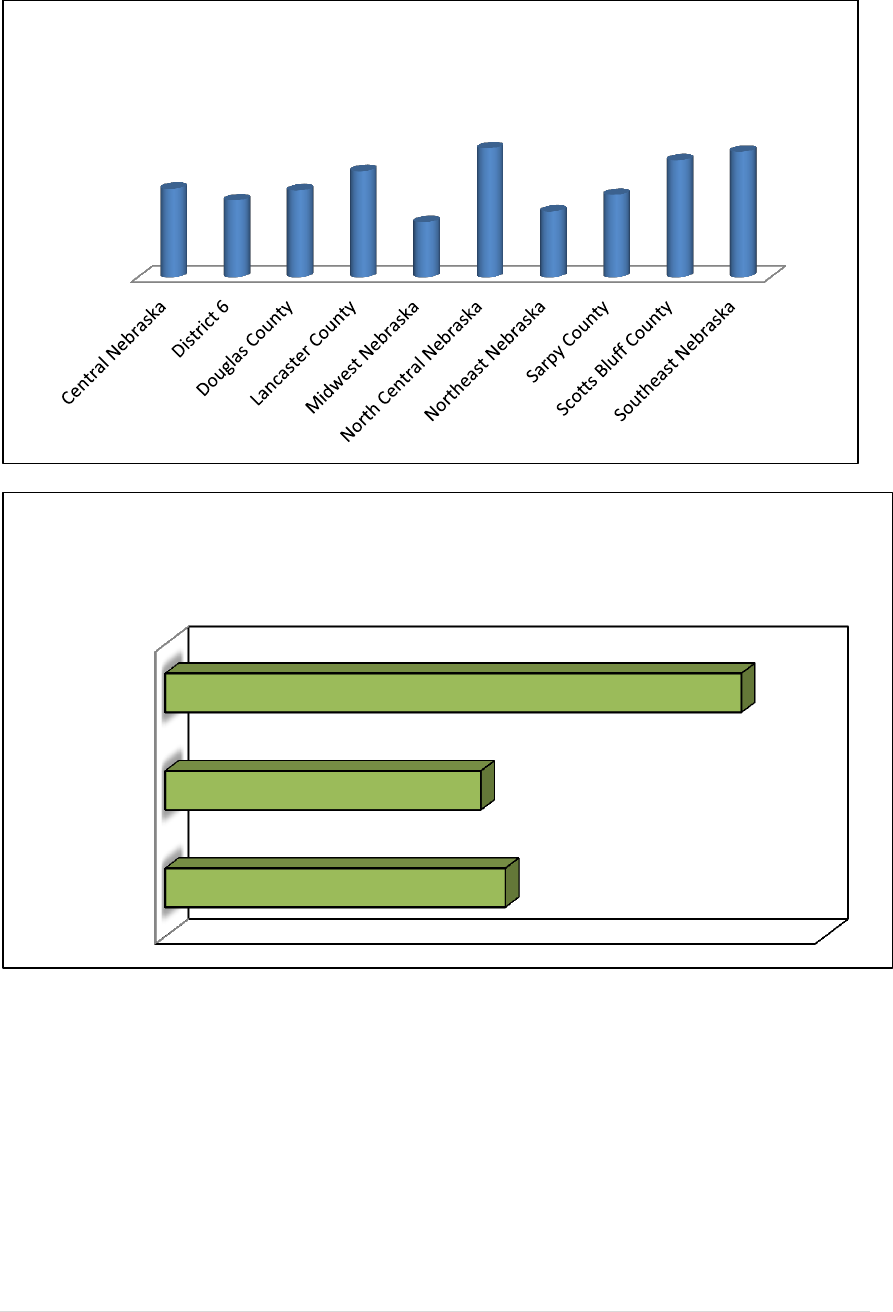

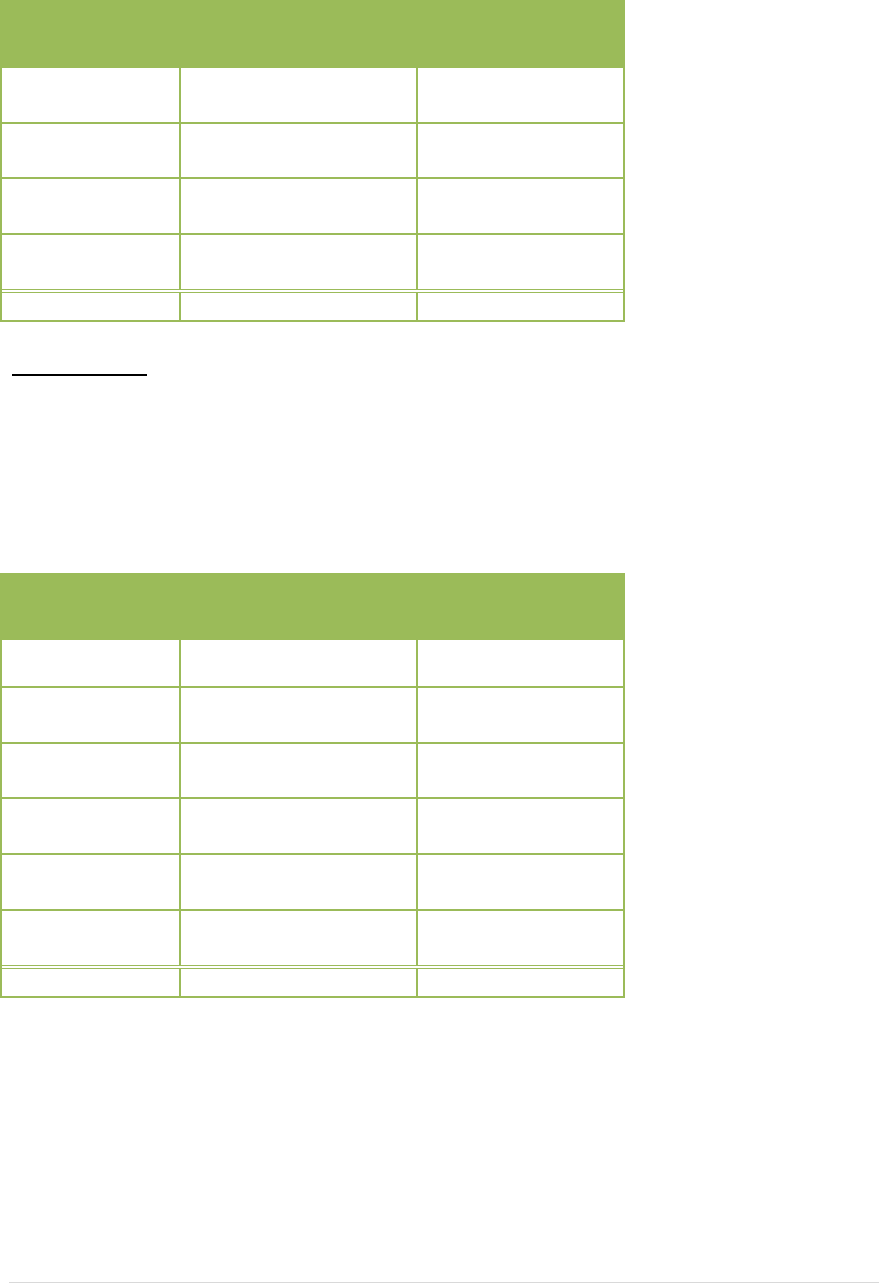

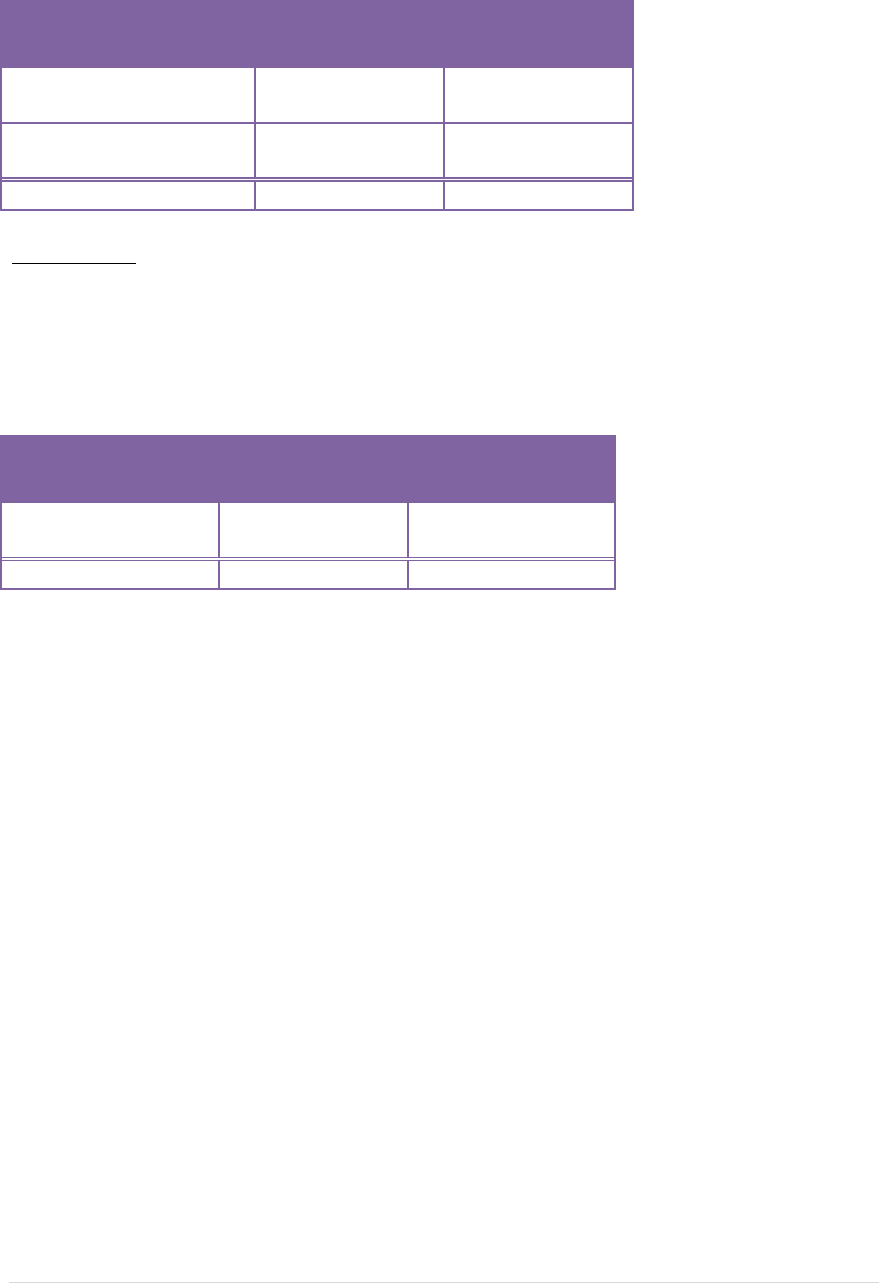

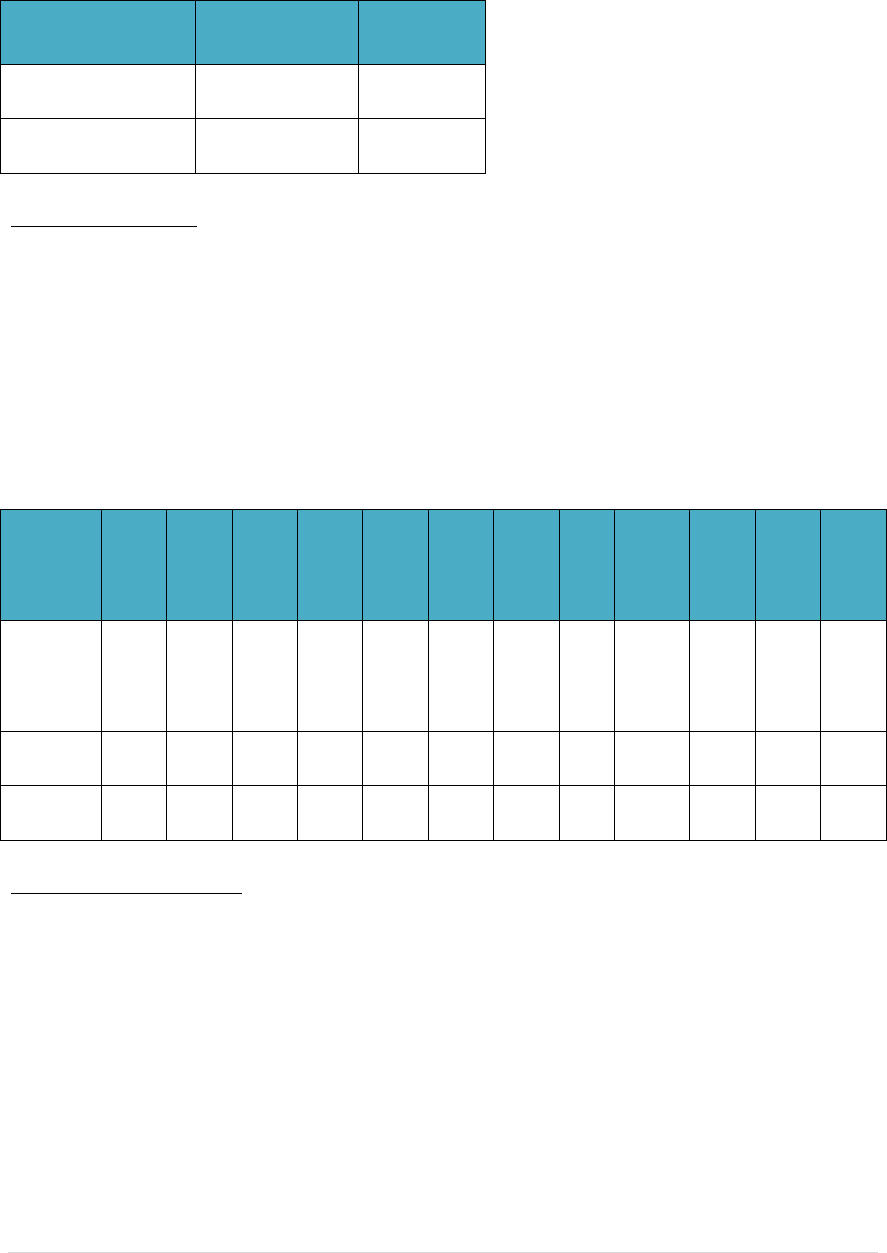

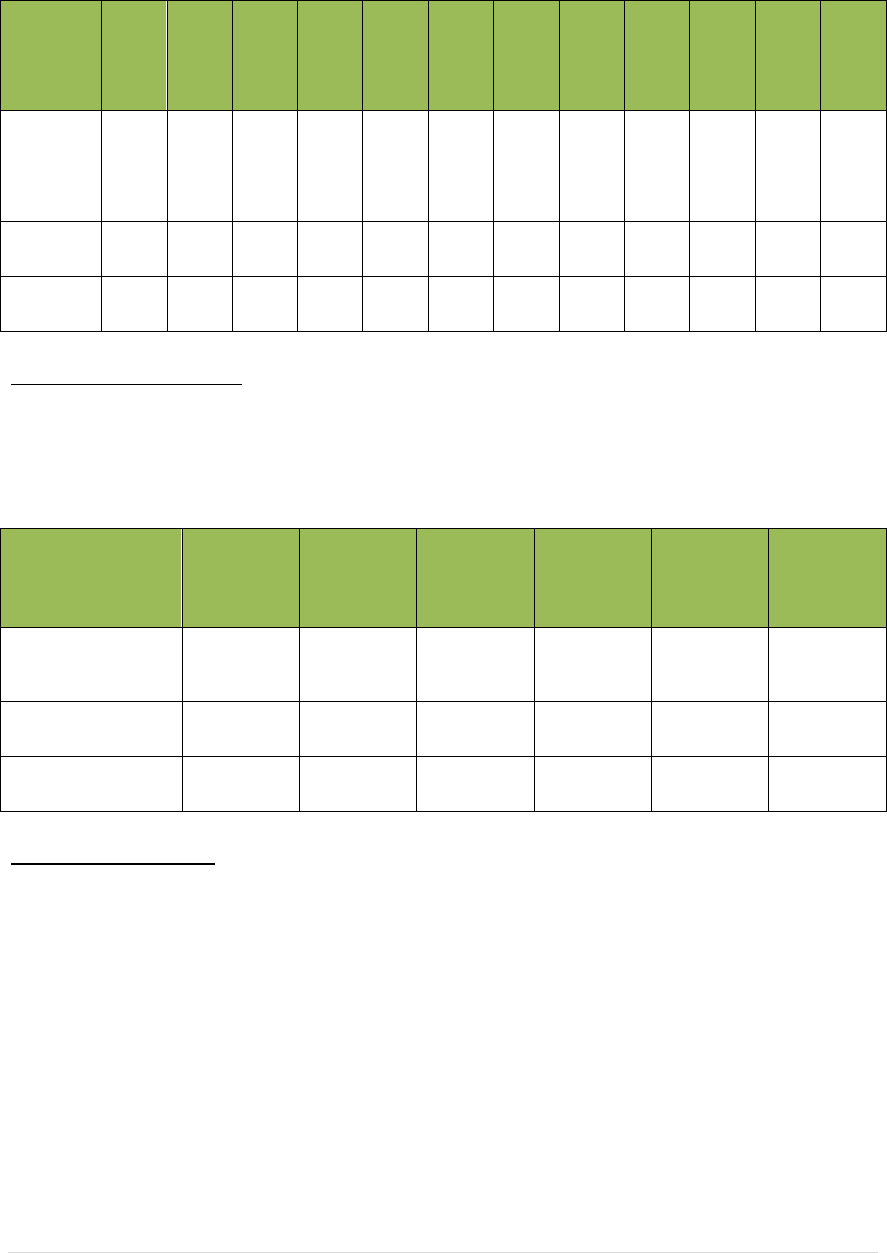

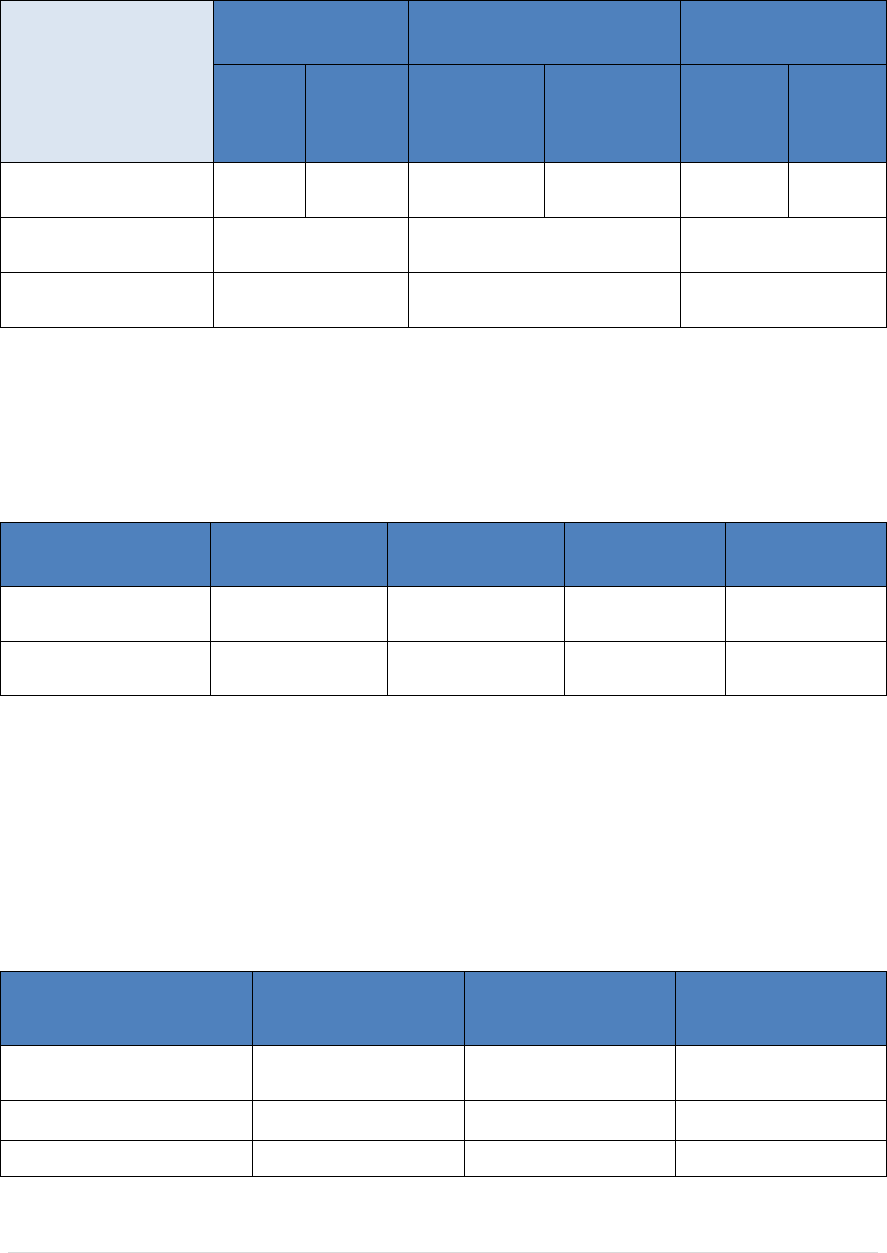

*Adult Alcohol/Drug Problem scores range from 1-8 with 1=very low and 7-8= very high. Juvenile

Substance Abuse scores range from 0-5 with 0=low, 1-2=moderate, and 5= high.

6.14

6.72

6.37

6.91

6.41

6.13

5.92

5.85

5

6.31

Central Nebraska

District 6

Douglas County

Lancaster County

Midwest Nebraska

North Central Nebraska

Northeast Nebraska

Sarpy County

Scotts Bluff County

Southeast Nebraska

Adult Drug Court LS/CMI

Alcohol/Substance Abuse Scores*

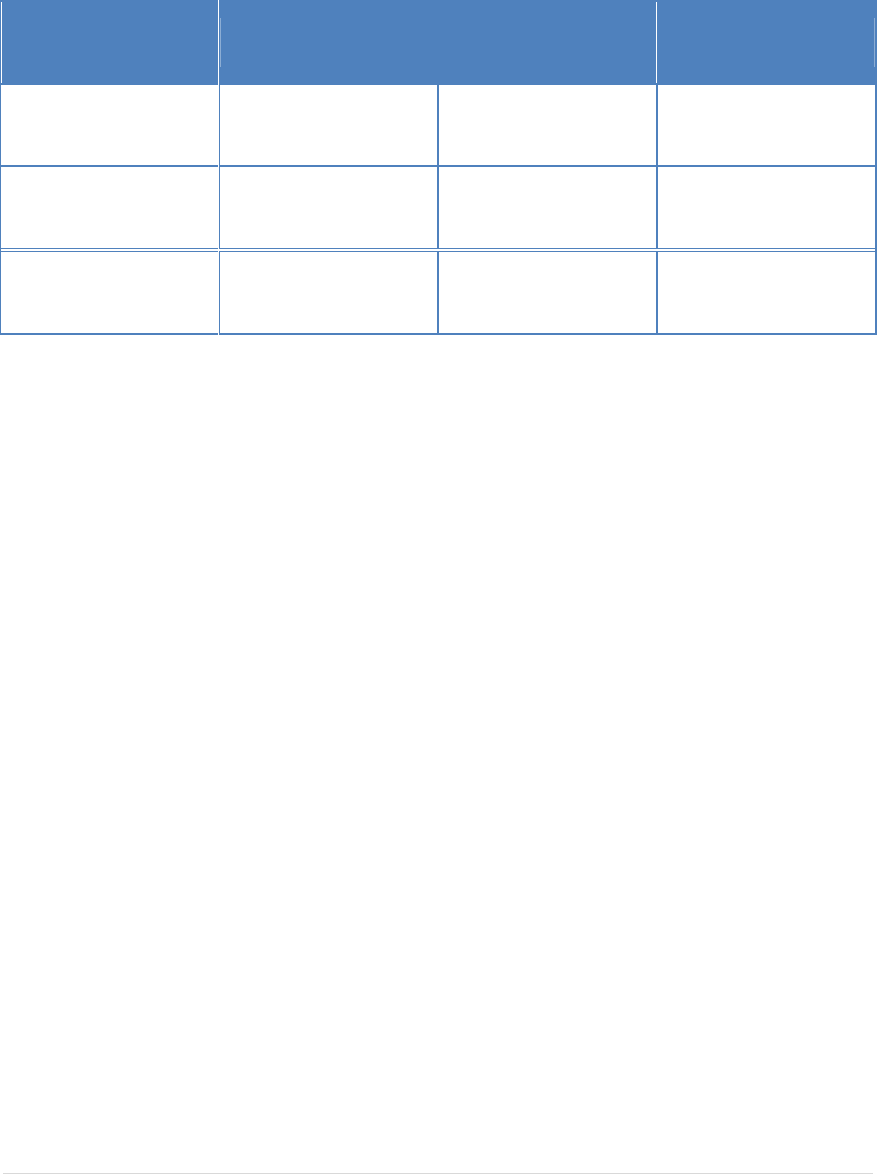

3.27

2.04

2

3.32

2.5

Douglas County

Lancaster County

Northeast Nebraska

Sarpy County

Scotts Bluff County

Juvenile Drug Court YLS/CMI

Substance Abuse Scores*

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

13 | P a g e

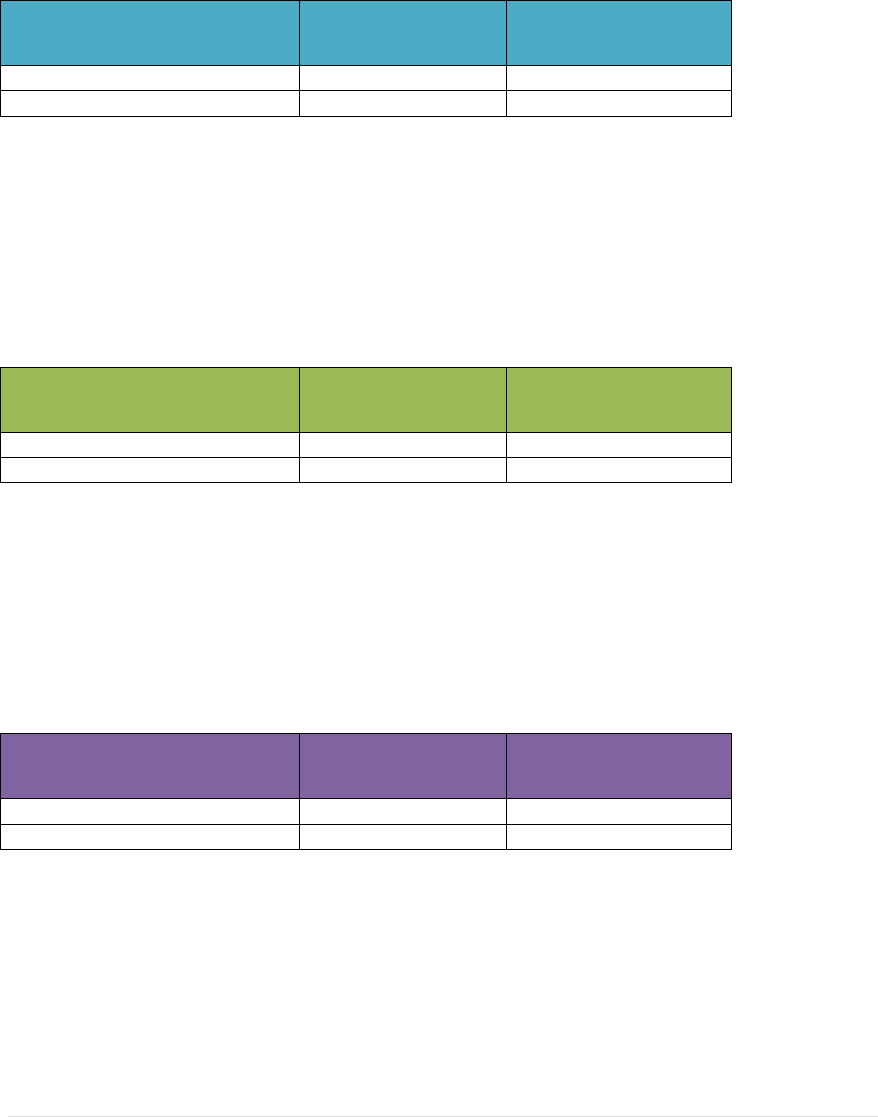

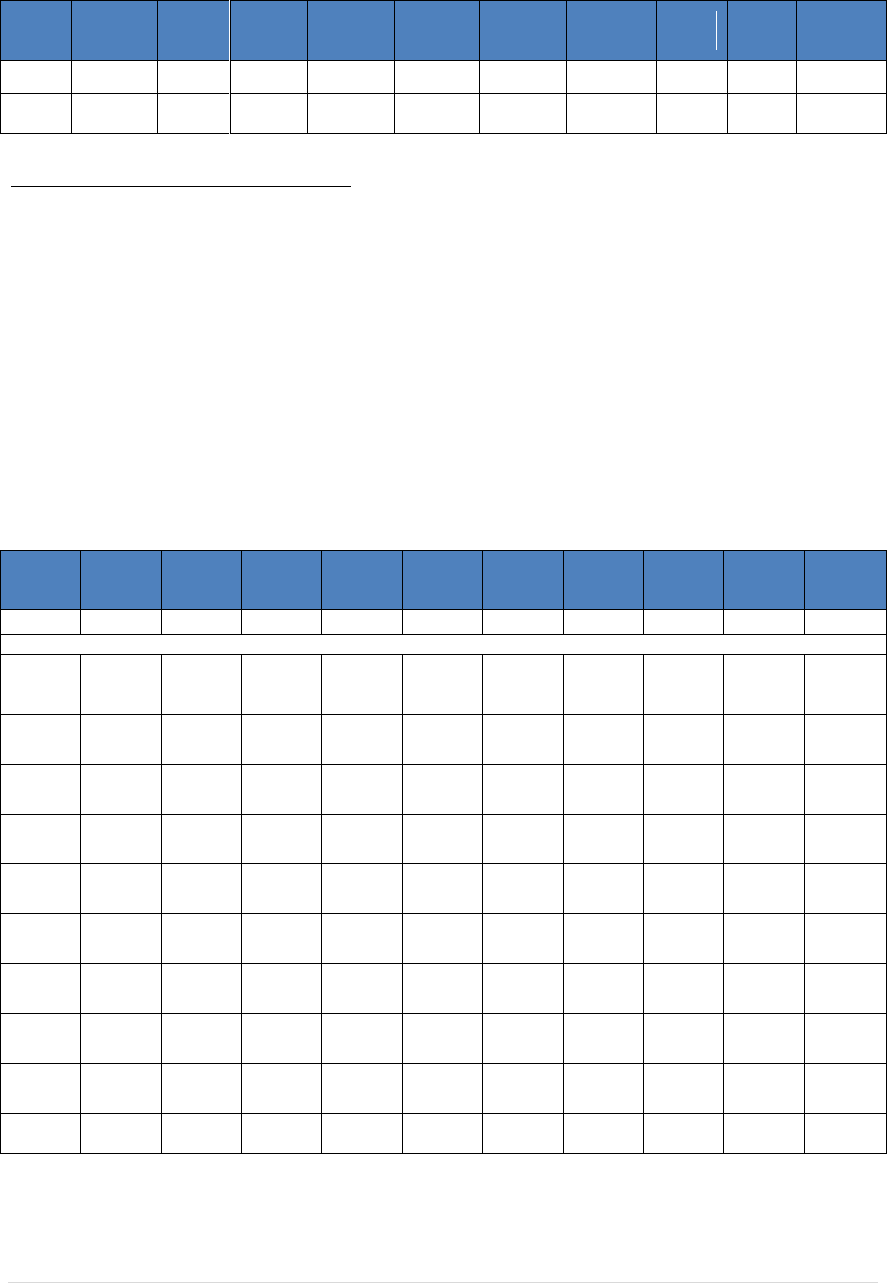

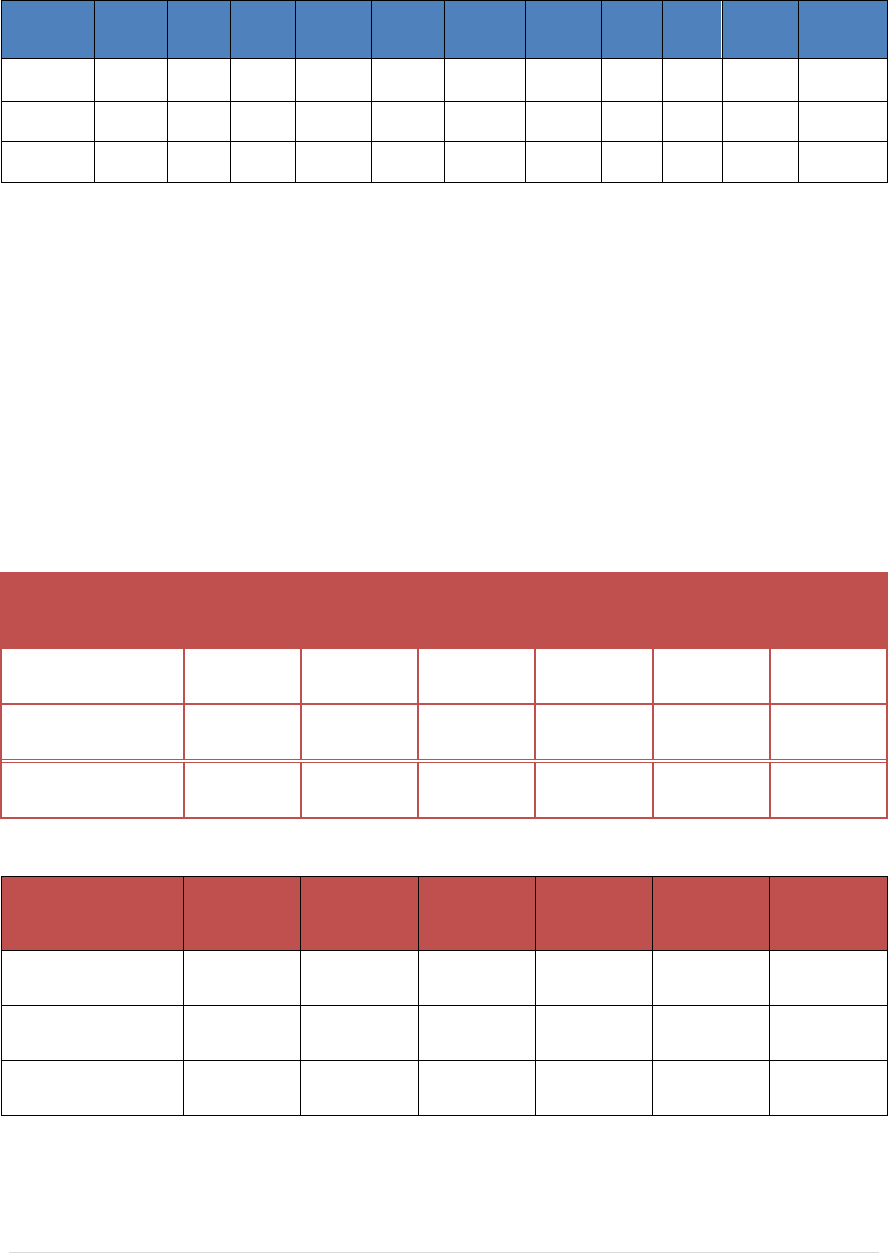

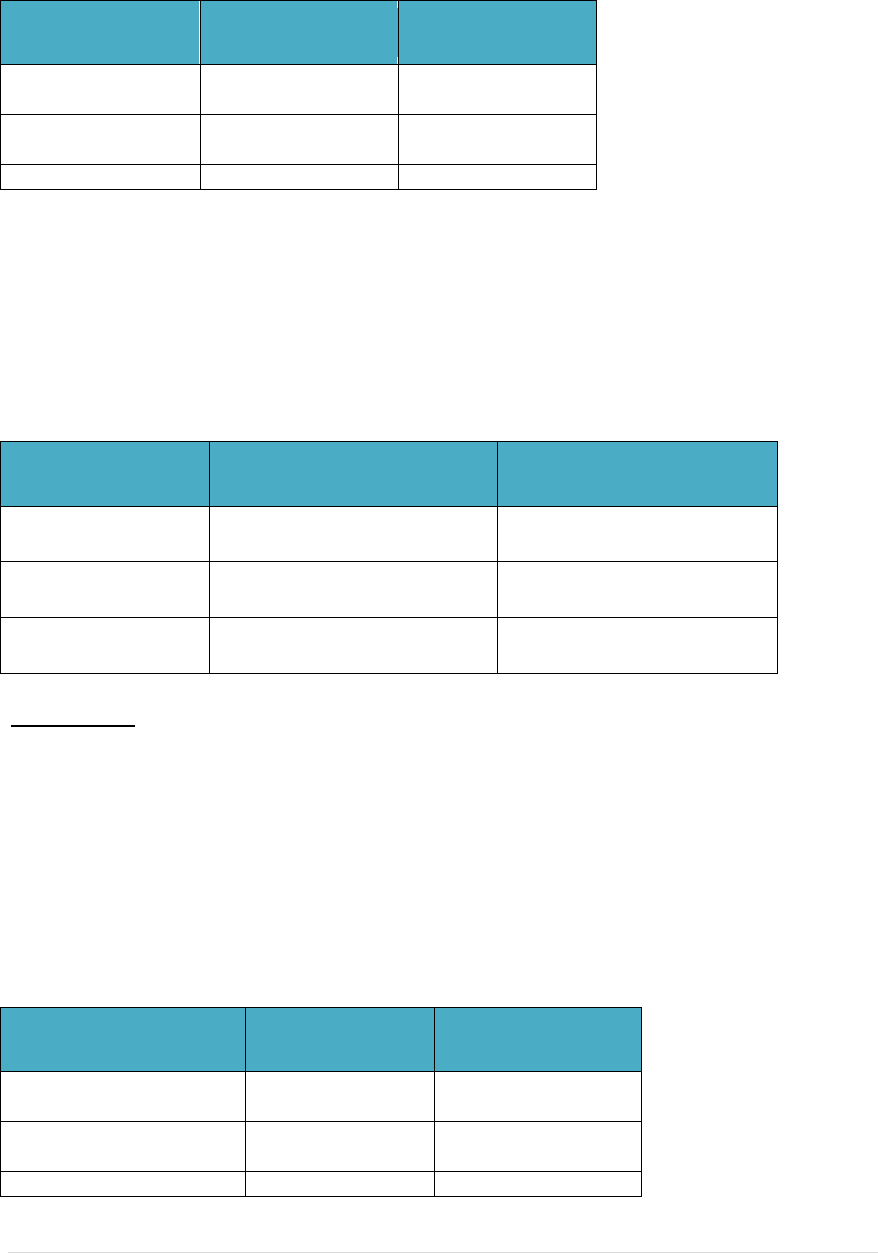

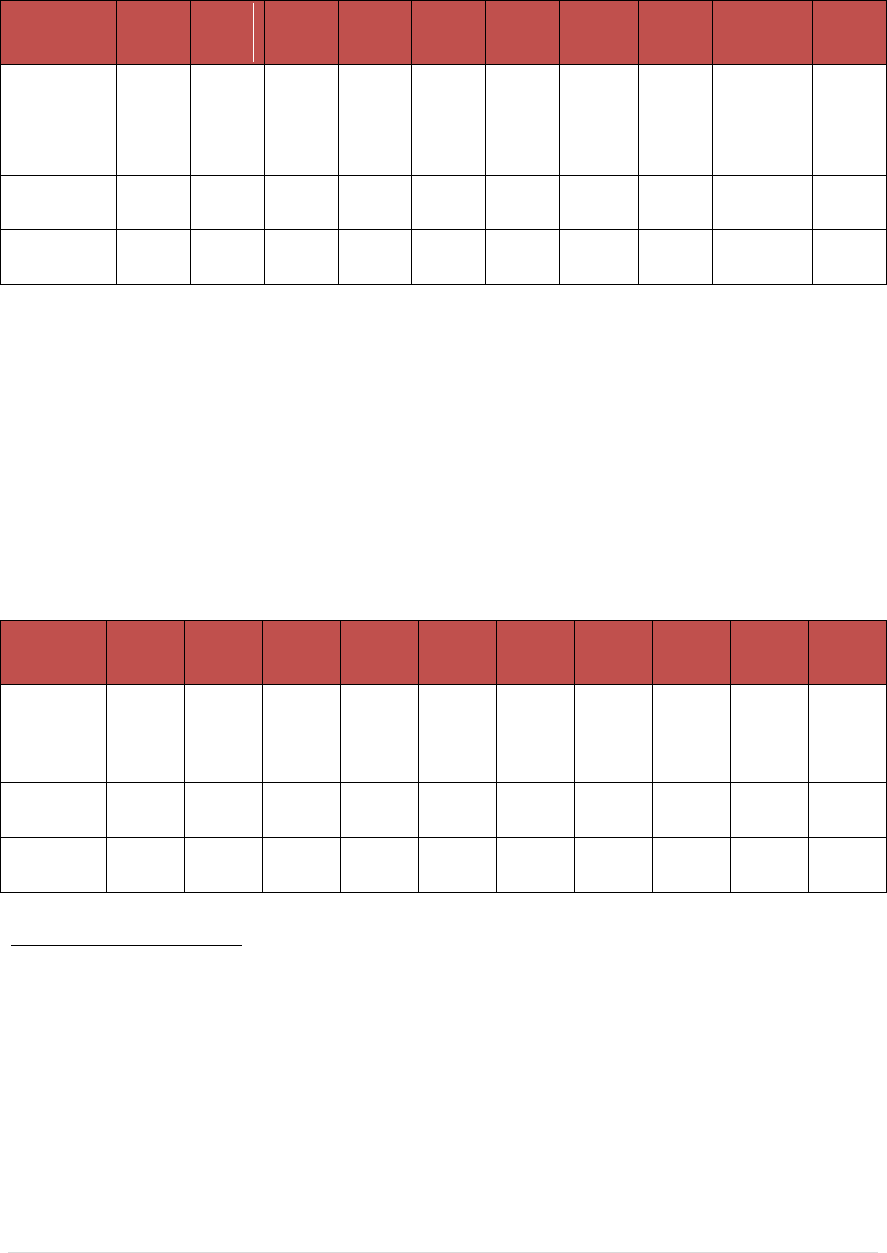

Although Nebraska problem solving courts generally serve high risk population based on

substance abuse risk, participants tend to score lower on criminal history risk. For

example, participants in adult drug courts tend to be low to medium risk on the LS/CMI

criminal history scale, and participants in juvenile drug courts tended to be in the low to

moderate range of the Prior Criminal Offenses Scale of the YLS/CMI.

YLS/CMI Prior

Criminal

Offense

Douglas

County

Lancaster

County

Northeast

Nebraska

Sarpy County

Scotts Bluff

County

Mean

0.81

0.85

2.14

0.88

1.75

Sample Size

64

26

7

66

8

A number of coordinators thought their courts could serve higher risk offenders, but often

other problem solving court team members were reluctant to serve offenders with high

risk levels. Some team members, particularly prosecutors and law enforcement, believe

the appropriate risk level for problem solving court is “moderate.” It would be useful to

develop briefing materials to share with team members regarding the risk level of

participants most appropriate for problem solving courts. Understanding that taking high

risk offenders is the most cost effective approach may help team members in selecting

participants. It may also be useful to administer screening tools prior to drug court

acceptance to more thoroughly understand the risk level of potential candidates.

0

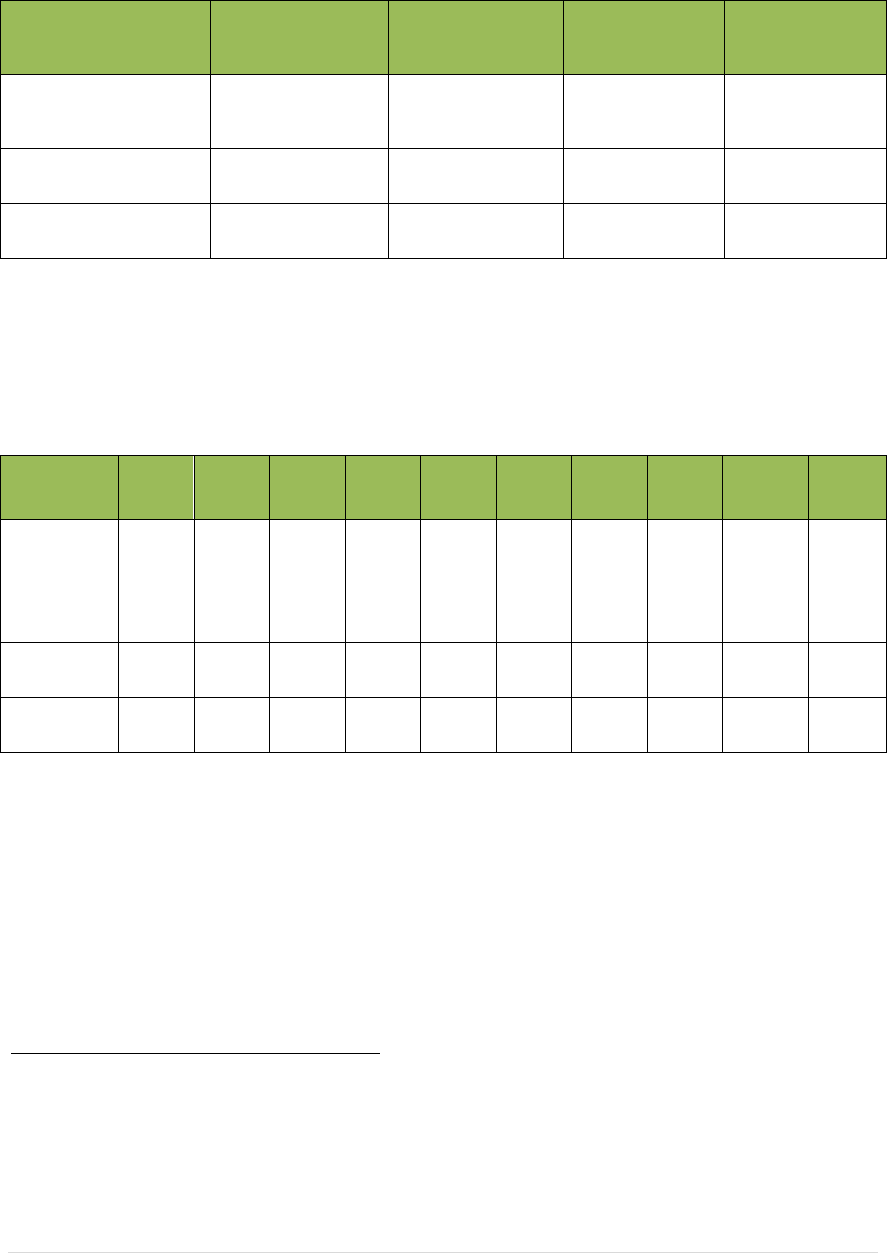

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Ct 1 Ct 2 Ct 3 Ct 4 Ct 5 Ct 6 Ct 7 Ct 8 Ct 9 Ct 10

Adult Court Criminal History Risk

8 = Very High

6-7 = High

4-5 = Medium

2-3 = Low

0-1 = Very Low

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

14 | P a g e

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Should Reduce the Length of Time

Between Arrest and Enrollment

One of the key components of problem solving courts is, “eligible participants are

identified early and promptly placed in the drug court program.” Best practices suggest

that a shorter length of time between arrest and enrollment is important to ensure success

of participants, and research suggests the time between entering drug court and receiving

court-ordered services impacts graduation rates (Colorado Department of Public Safety,

1999; Meyer & Ritter, 2002).

Although there are differences across courts, the evaluation indicates participants have to

wait many months from the time they are arrested until they are enrolled in problem

solving courts. This is true for all types of problem solving courts. Likely reasons for this

delay include lack of resources for drug courts to accept all offenders who are eligible,

procedural issues that delay the time for a person to be referred to problem solving courts,

and trying alternative programs (e.g., probation, diversion) first before offenders are sent

to drug court.

It may be useful both at the state level and at the local court level to examine the

Nebraska juvenile and criminal justice processes to determine if there are ways to

decrease the time between arrest and enrollment.

0

20

40

60

Ct 1 Ct 2 Ct 3 Ct 4 Ct 5

Nebraska Juvenile Drug Courts:

Average Weeks from Arrest to

Participation

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

15 | P a g e

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Should Enhance Educational and

Employment Opportunities for Participants

Problem solving courts in Nebraska have emphasized the development of education and

employment skills for participants. Currently, Nebraska problem solving courts

emphasize education and employment skills for participants, and the evaluation confirms

the need to continue this focus. The evaluation revealed that persons who are employed

more hours and have higher levels of education tend to be more successful in problem

solving courts, and increases in level of education predict success. Individuals with less

26.72

23.19

26.18

32.04

16.65

38.9

19.84

24.89

35.32

37.89

Nebraska Adult Drug Courts: Average Weeks

from Arrest to Participation

Young Adult

DUI

Family

30.9

28.7

52.39

Other Problem Solving Courts: Average Weeks

from Arrest to Participation

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

16 | P a g e

education and who work fewer hours at entry into problem solving court, tend to be less

successful. These results suggest special emphasis is warranted to engage these types of

participants and to develop strategies to raise education levels and to create successful

employment experiences.

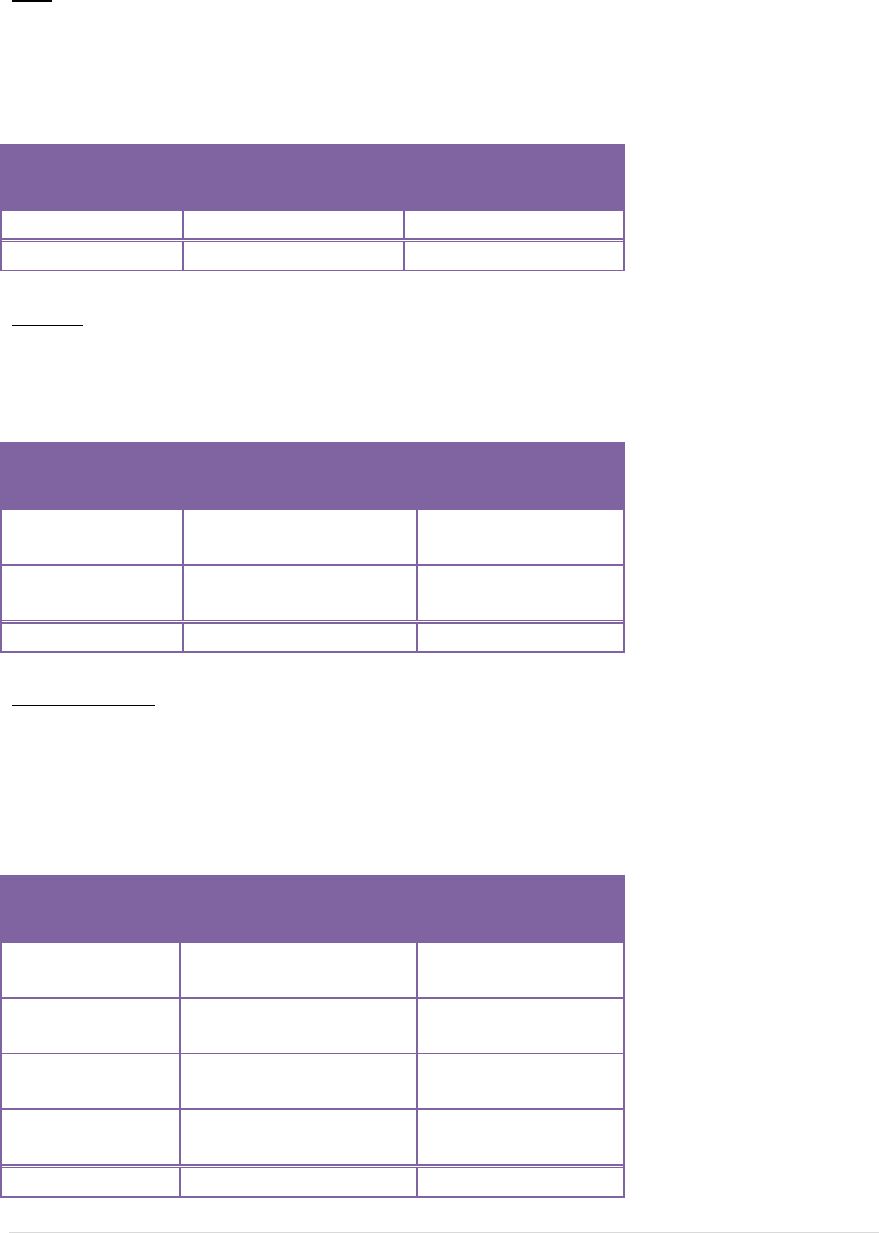

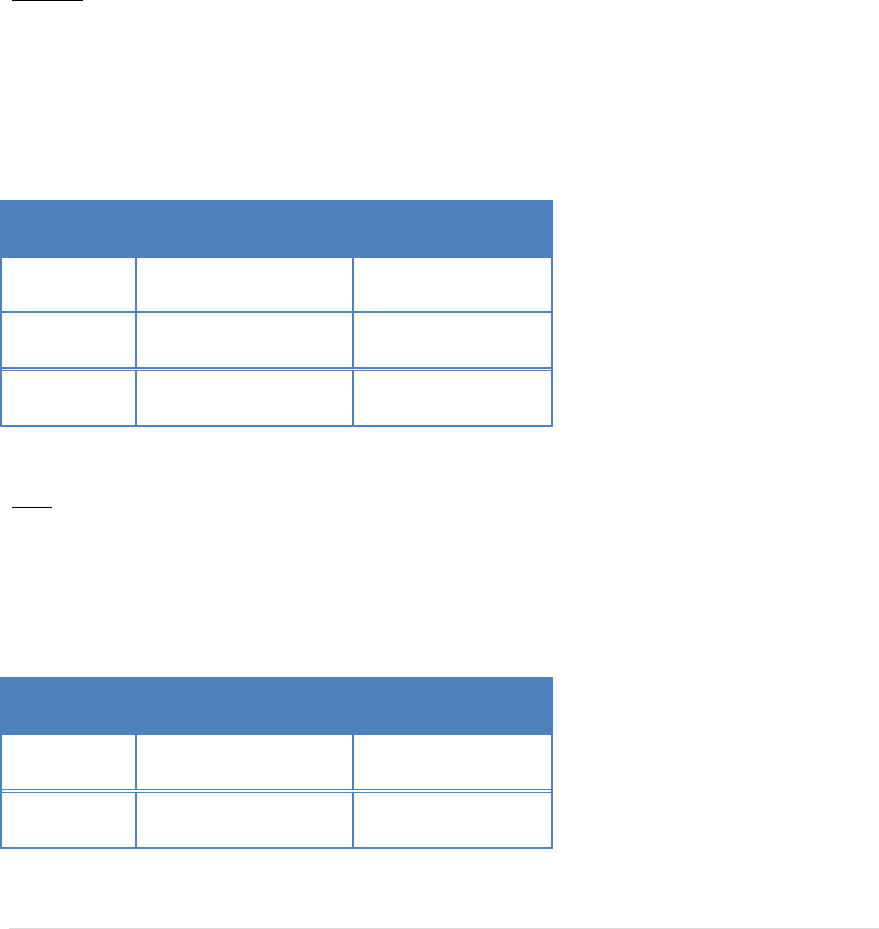

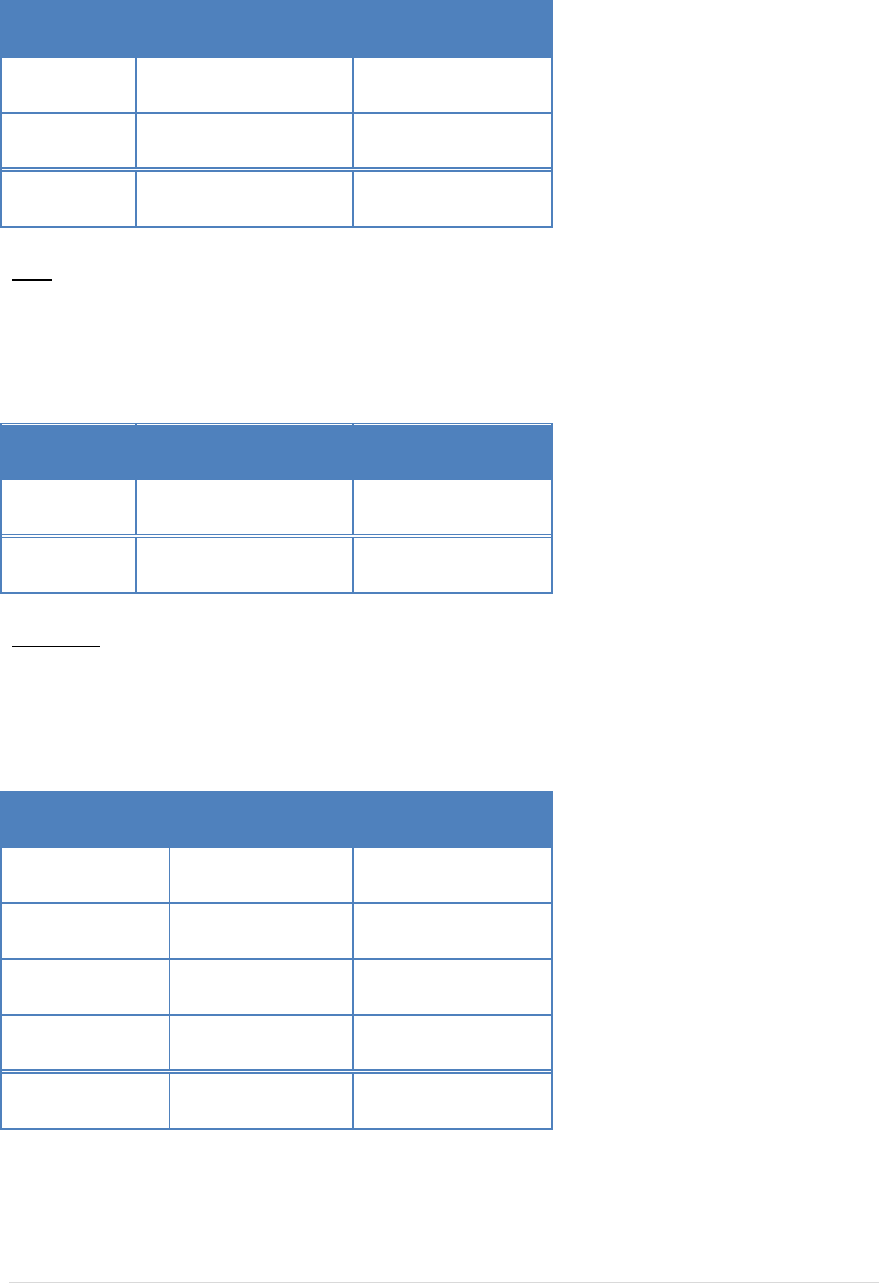

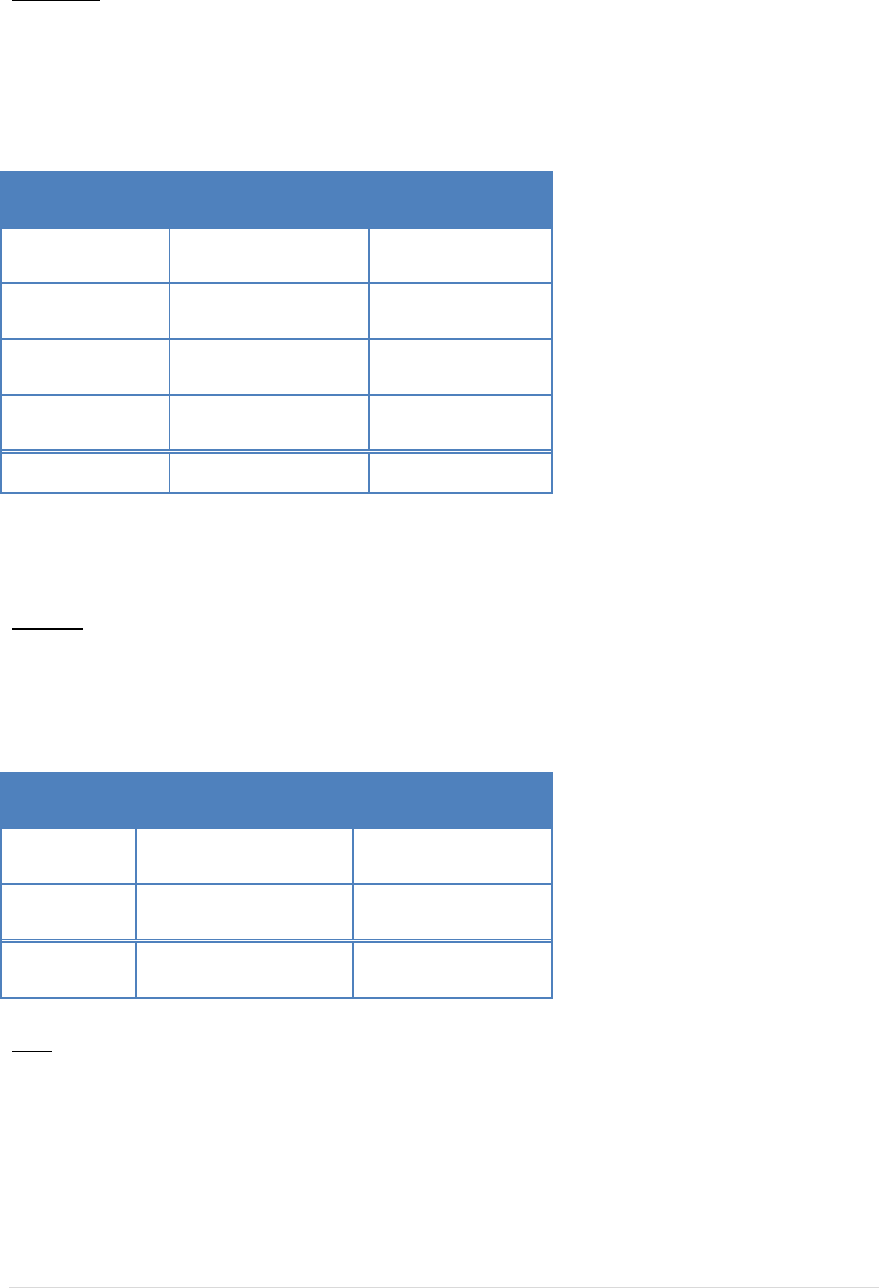

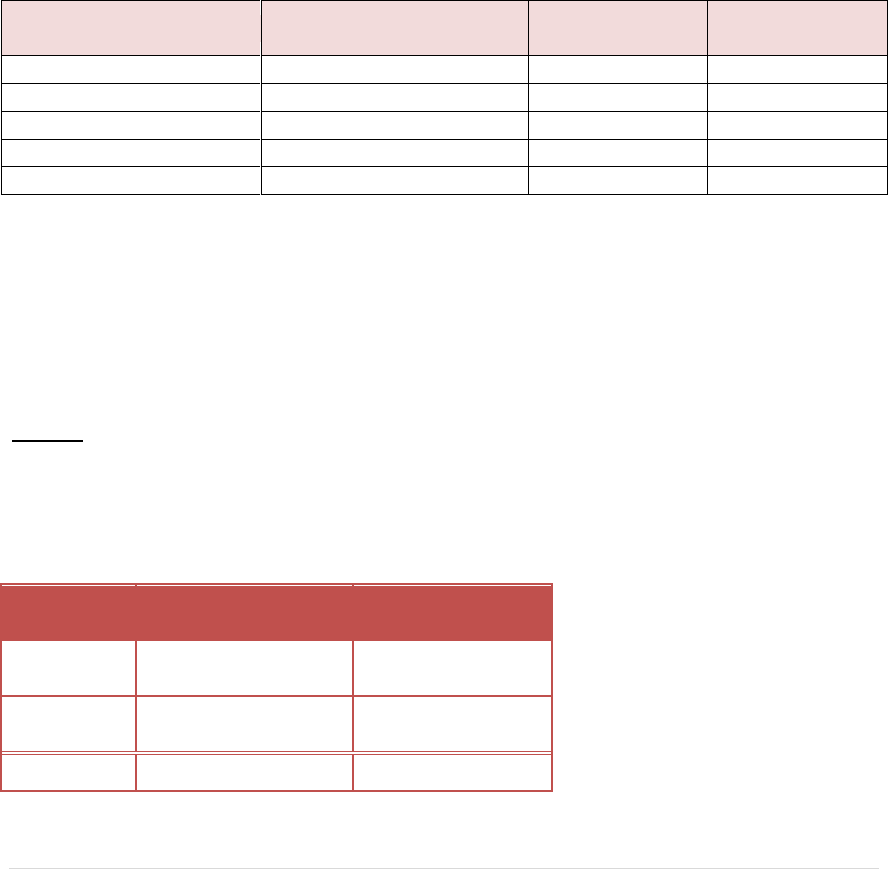

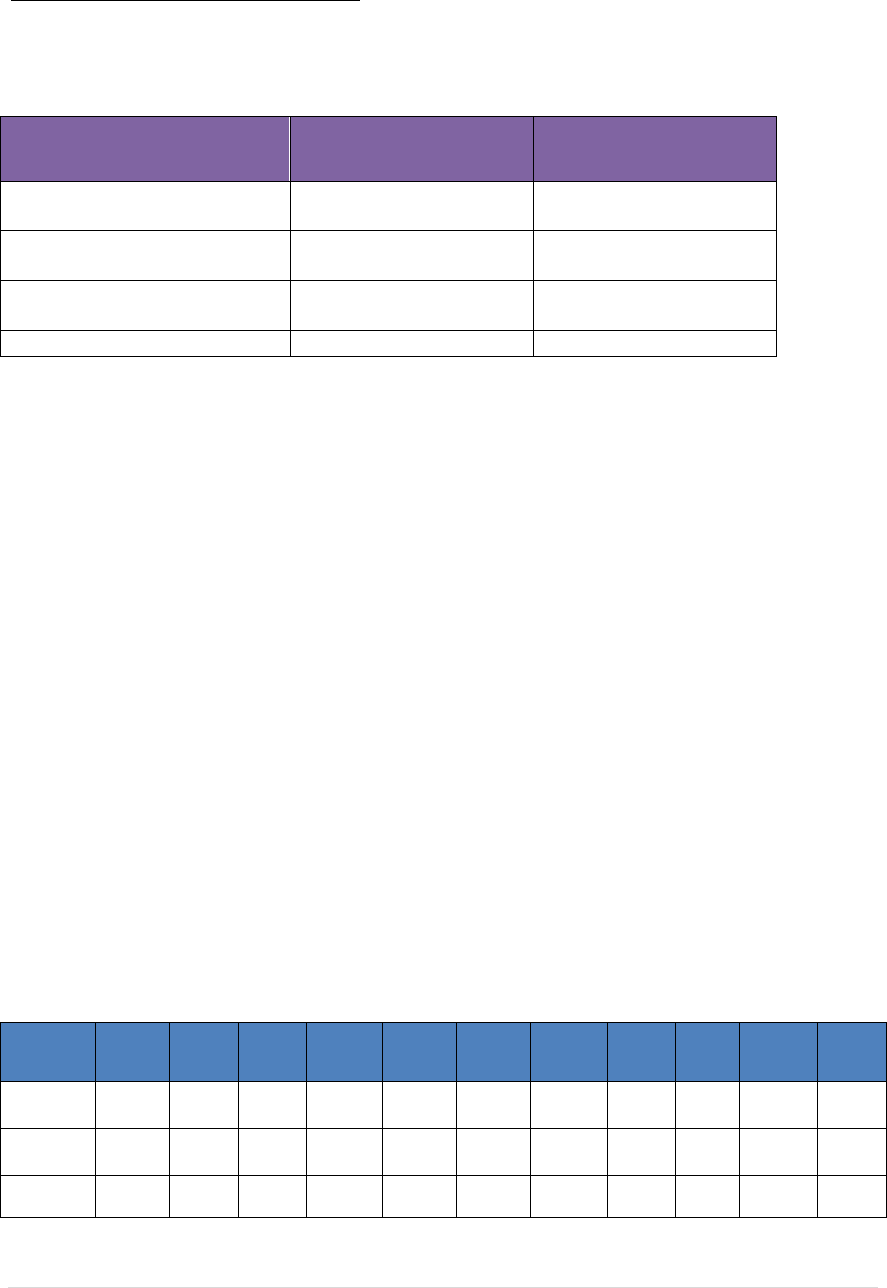

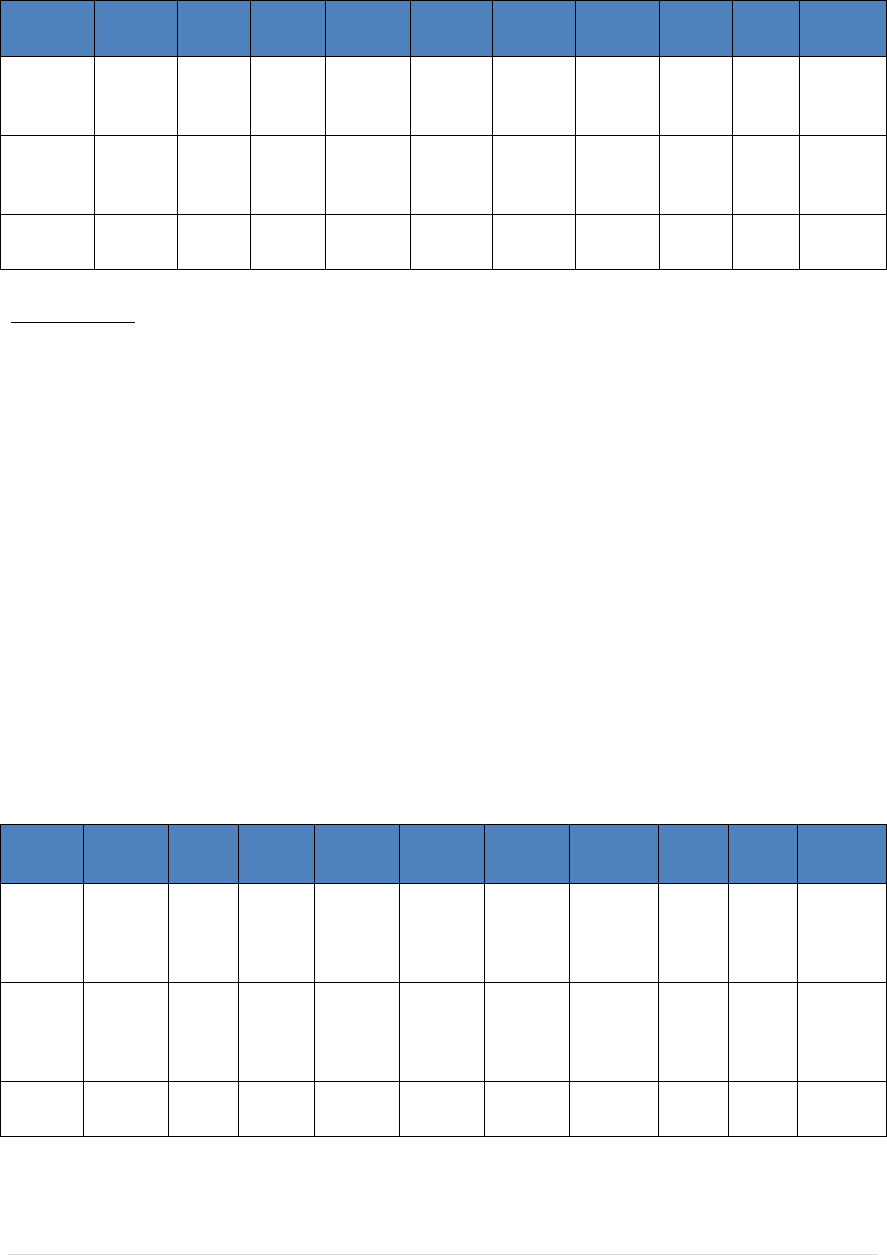

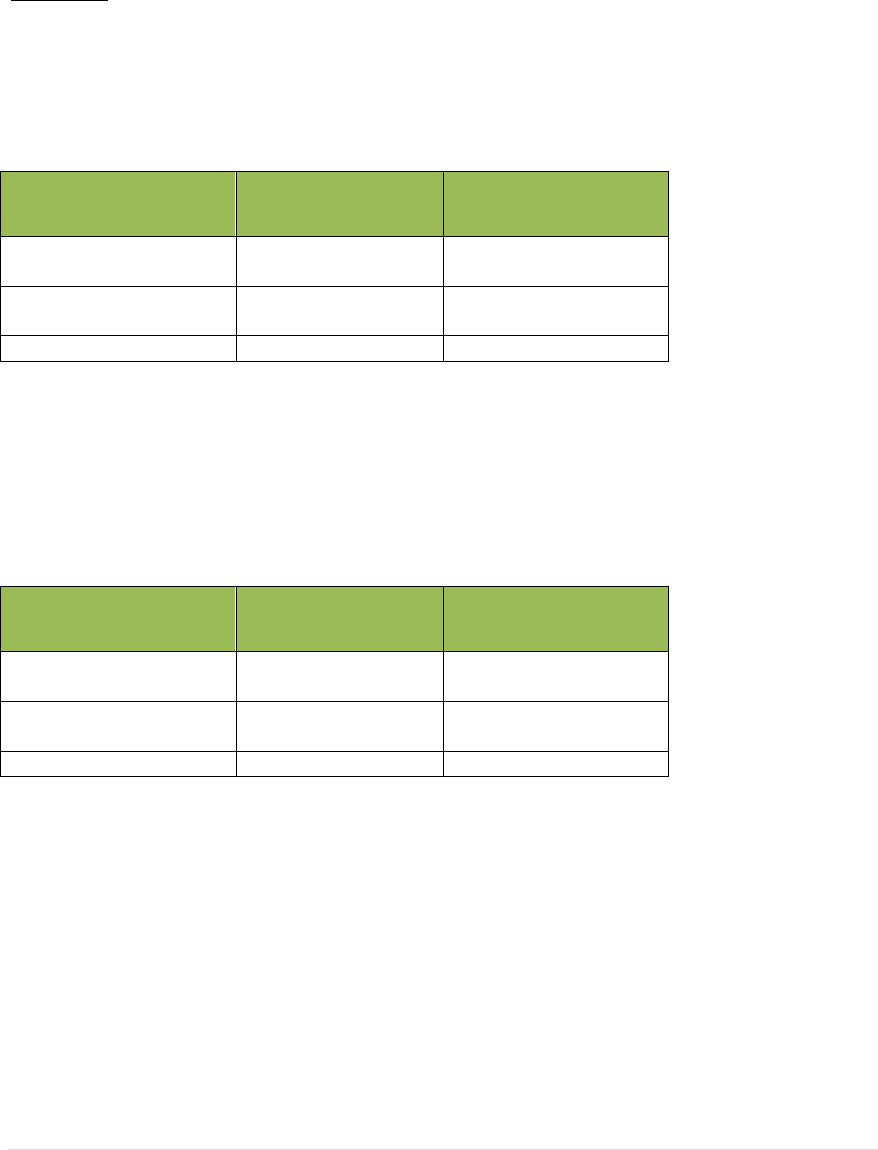

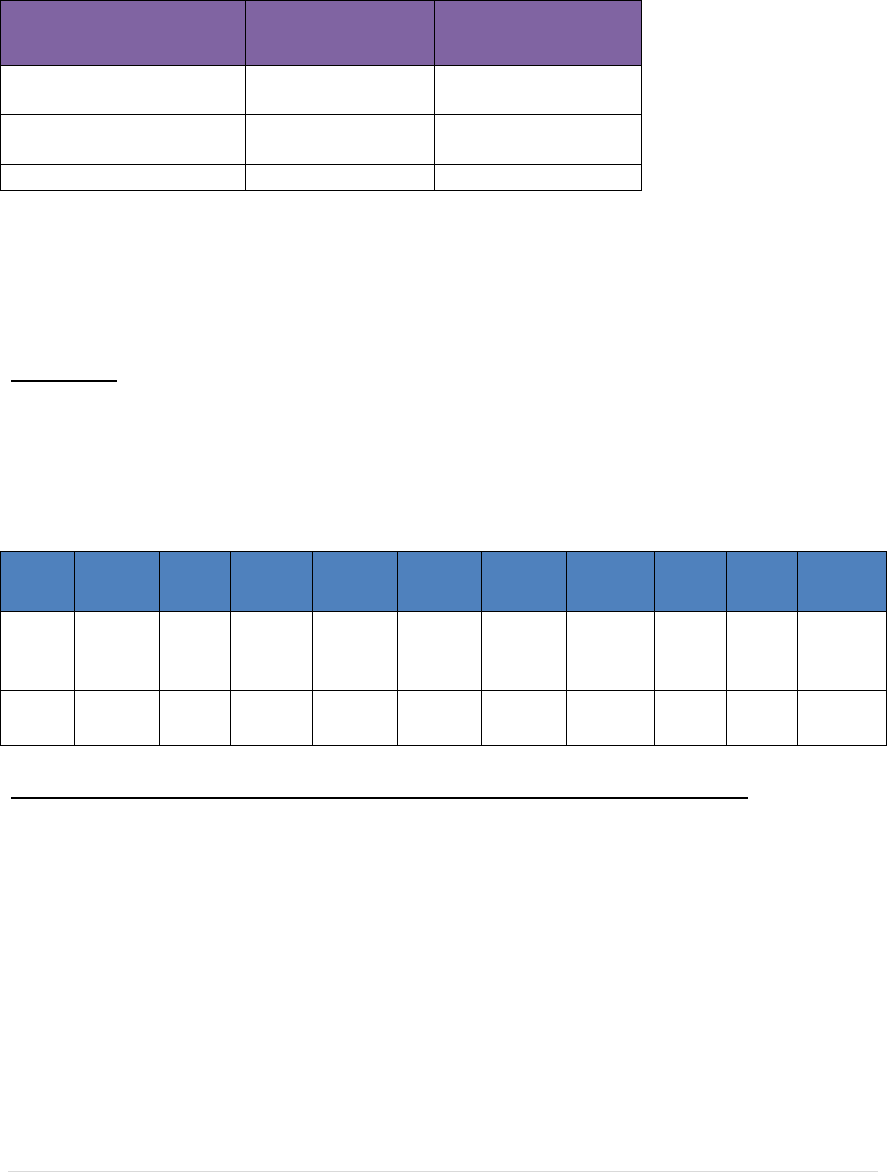

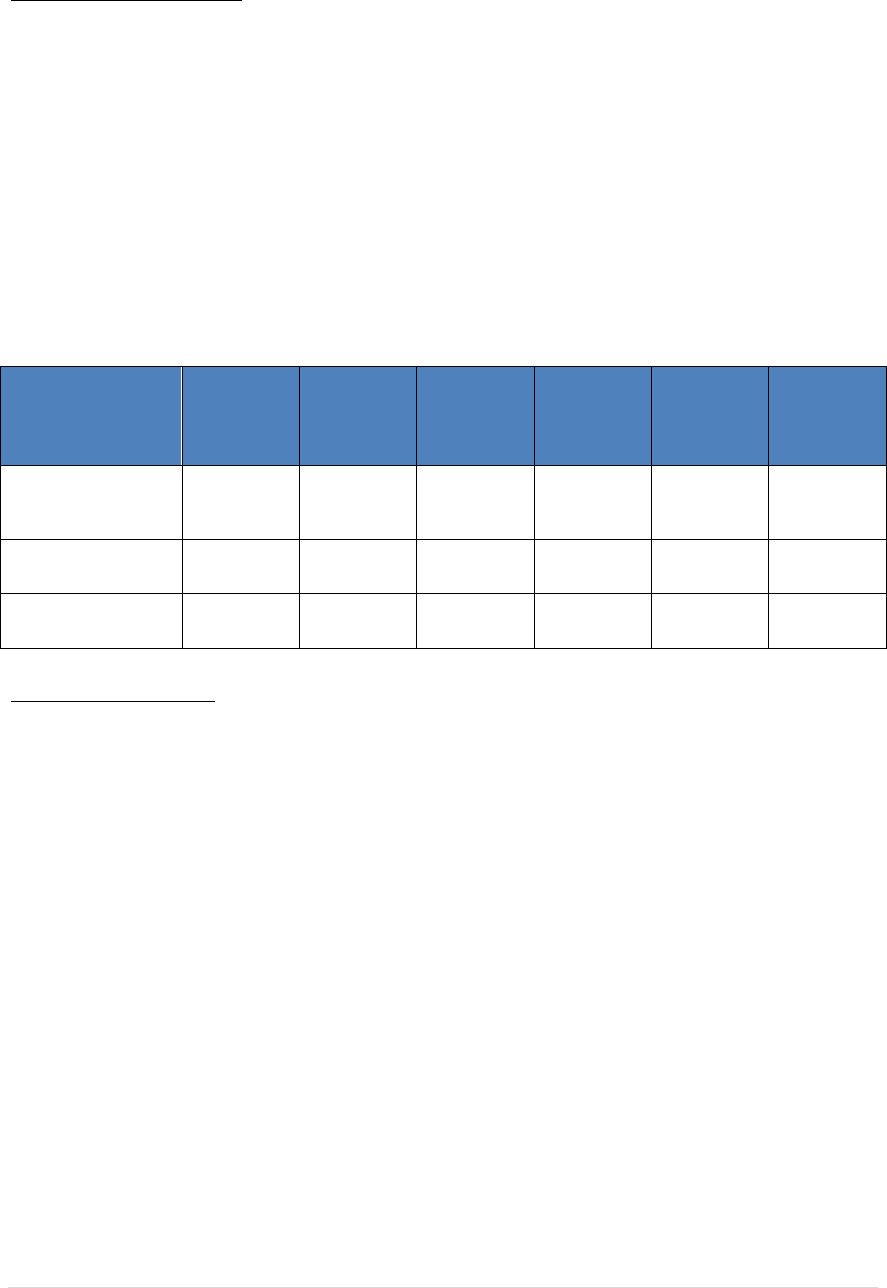

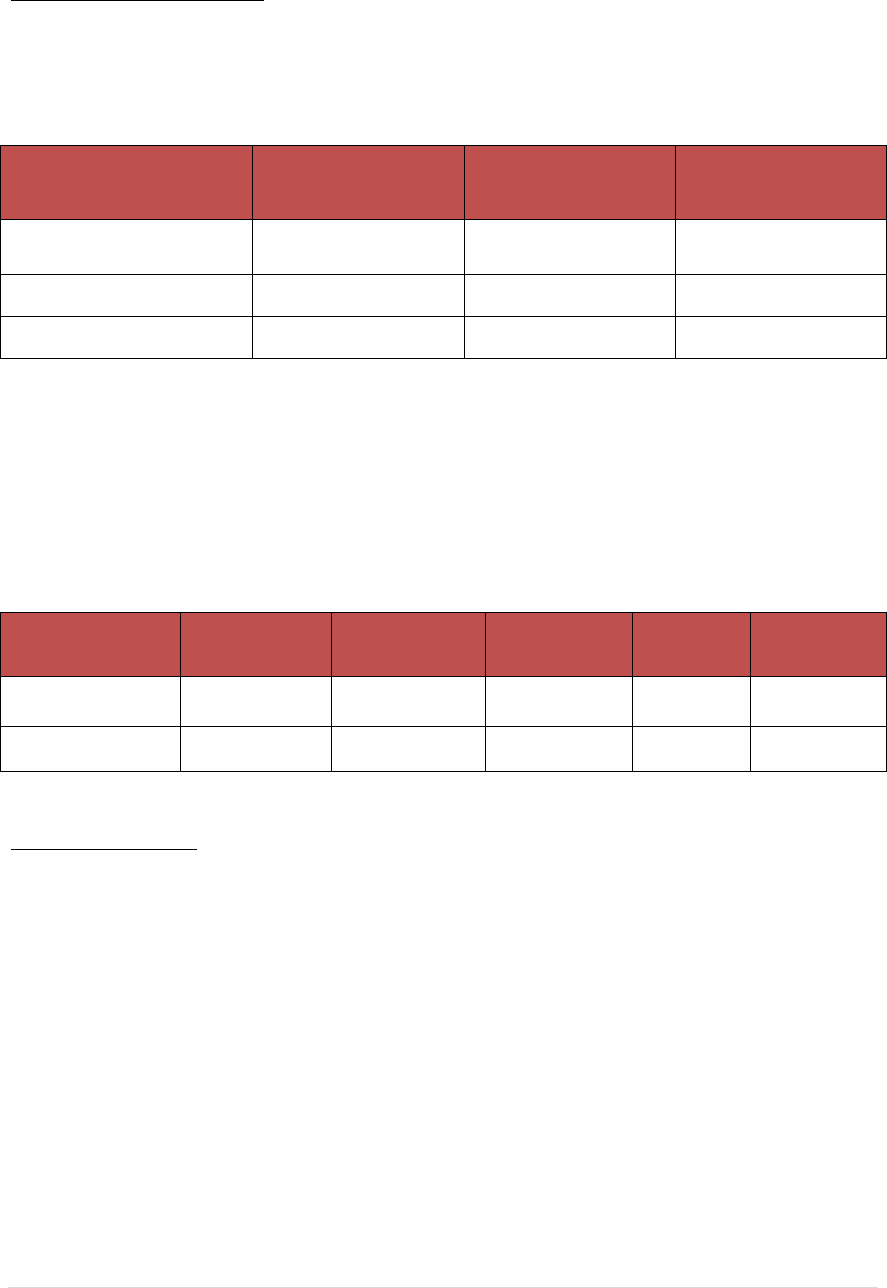

Adult Drug Court

Age at

Program Start

Hours Worked

Per Week

Education Level

Correlation with Program

Completion Status

0.152*

0.114*

10.750*

(Chi Square)

p-value

< .001

< .001

<.001

Sample size

1032

1006

945

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Should Enhance Drug and Alcohol

Treatment for Participants in Problem Solving Court

Treatment is an invaluable component to the drug court process. Based on the evaluation,

there are a number of ways to enhance substance abuse treatment for participants:

We found the number of drugs participants used was a significant factor in

predicting graduation. It is important then for service providers to use evidence

based practices, particularly those practices shown to be effective in addressing

poly-drug use.

Coordinators, particularly in rural parts of the state, identified the lack of service

providers as a major barrier to success for problem solving court participants. To

address this issue, it is important for programs to work with state partners to

increase the availability and accessibility of quality substance abuse services.

A number of coordinators indicated that not all service providers were of the

same quality. Some also expressed frustration that some providers provided

minimal information about progress in treatment. It would be helpful to develop

guidelines for providers to clearly report what evidence based practices they are

using, why the practice is appropriate for the needs of particular individuals, how

they are monitoring fidelity to the practice, and what objective measures they are

using to track progress and improvement for participants.

Most coordinators believe day reporting is a valuable component to participants;

however, some programs, particularly in rural areas, have less access to and

resources for, day reporting centers. As with many services in Nebraska, rural

areas often have fewer treatment or community services available. So it is not

surprising that rural problem solving courts have less access to day reporting

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

17 | P a g e

centers than urban courts. To enhance the availability of this important service, it

is important to develop funding strategies to enhance access to day reporting

centers.

Problem Solving Courts in Nebraska Should Develop Practices to

Enhance Services to Racial Minorities

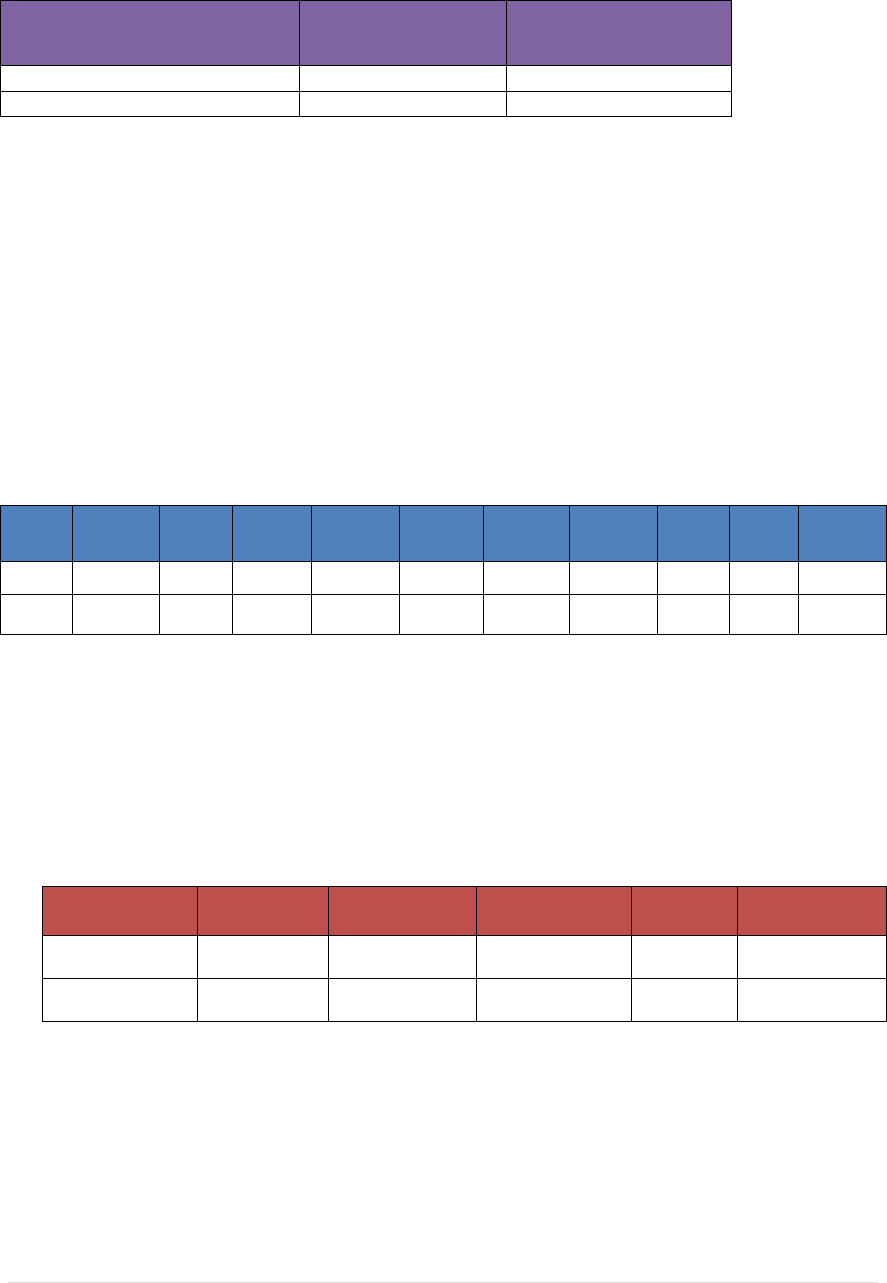

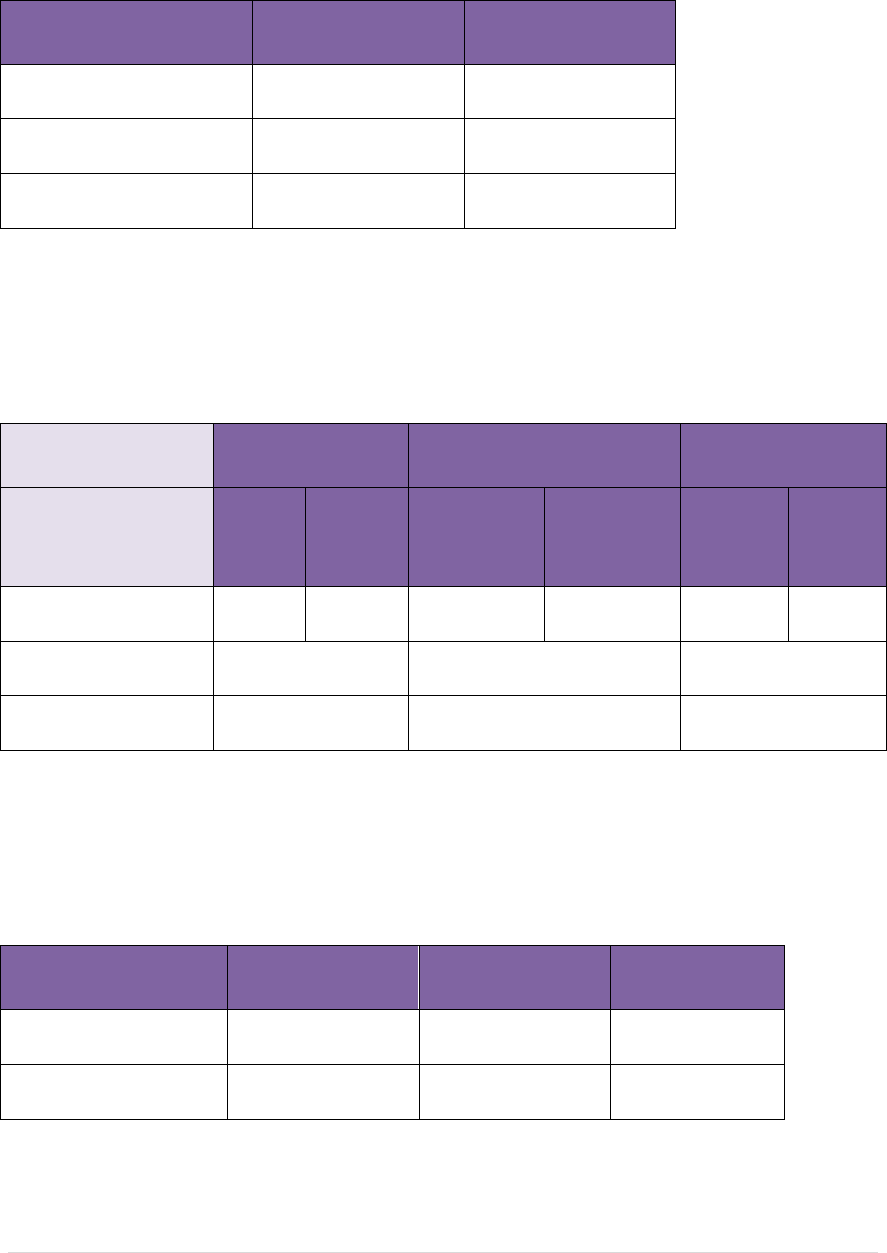

For adult courts, African Americans and Native Americans were found less likely to

graduate than other populations. For juvenile courts, African Americans were also found

less likely to graduate than other groups. This finding is not unique to Nebraska and is

consistent with other studies indicating racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African

Americans, do less well in problems solving courts than white/Caucasians (see Finigan

(2009) for a summary of studies). Culturally competent approaches include matching

evidence based practices to populations being served, conducting training in cultural and

linguistic competence, and tailoring services and strategies to the unique cultural needs of

participants. Unique culturally competent approaches for Native Americans have been

developed that can be used as a resource (Tribal Law Institute, 2003). The evaluation also

revealed racial disparities in one adult drug court; efforts should be made to assess

systems and processes that may be contributing to this disparity.

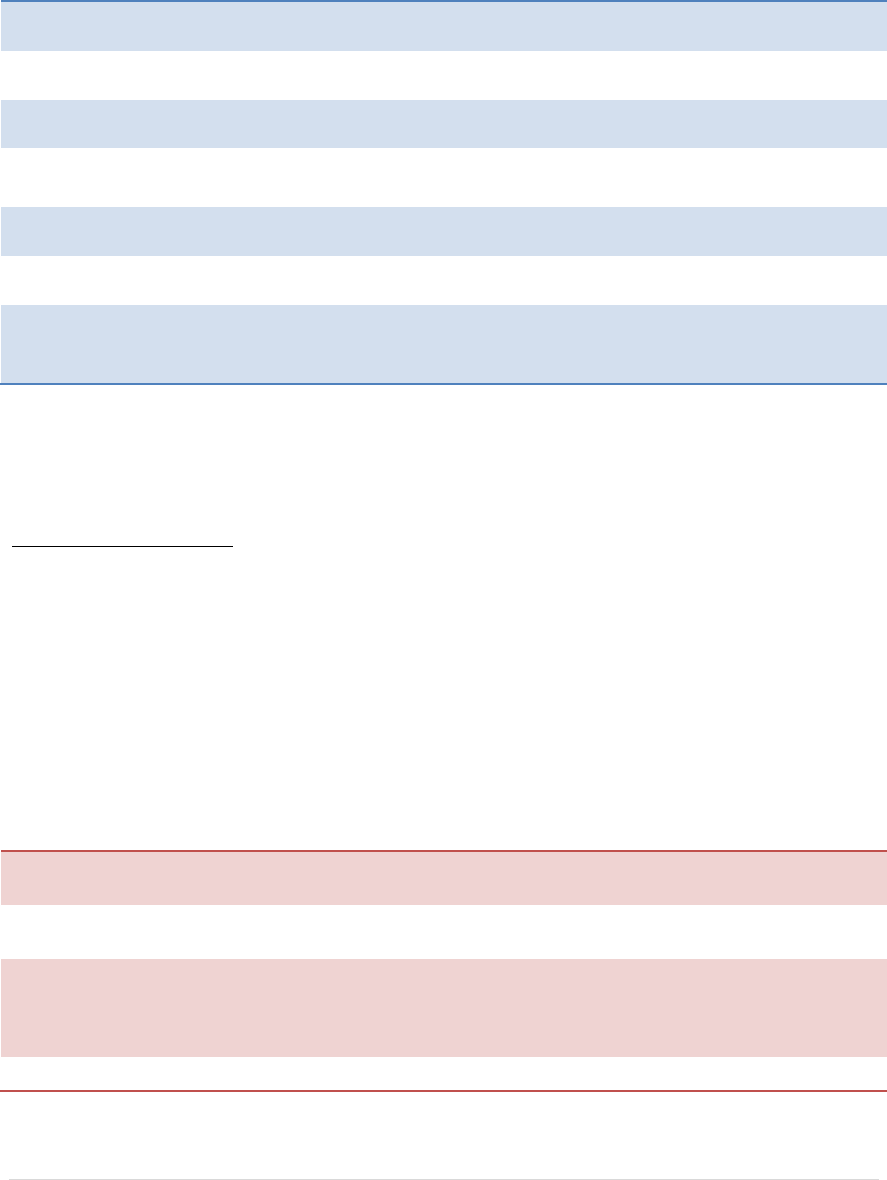

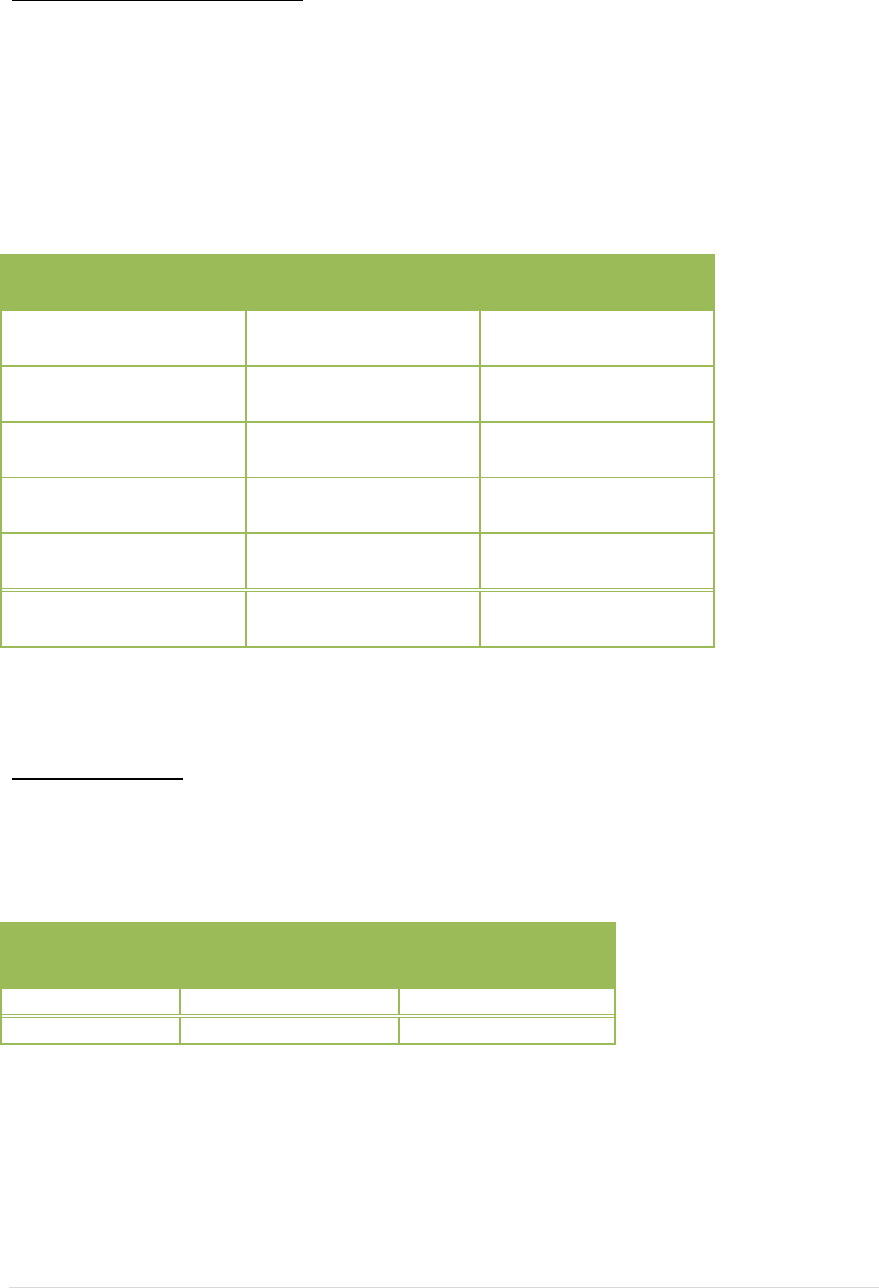

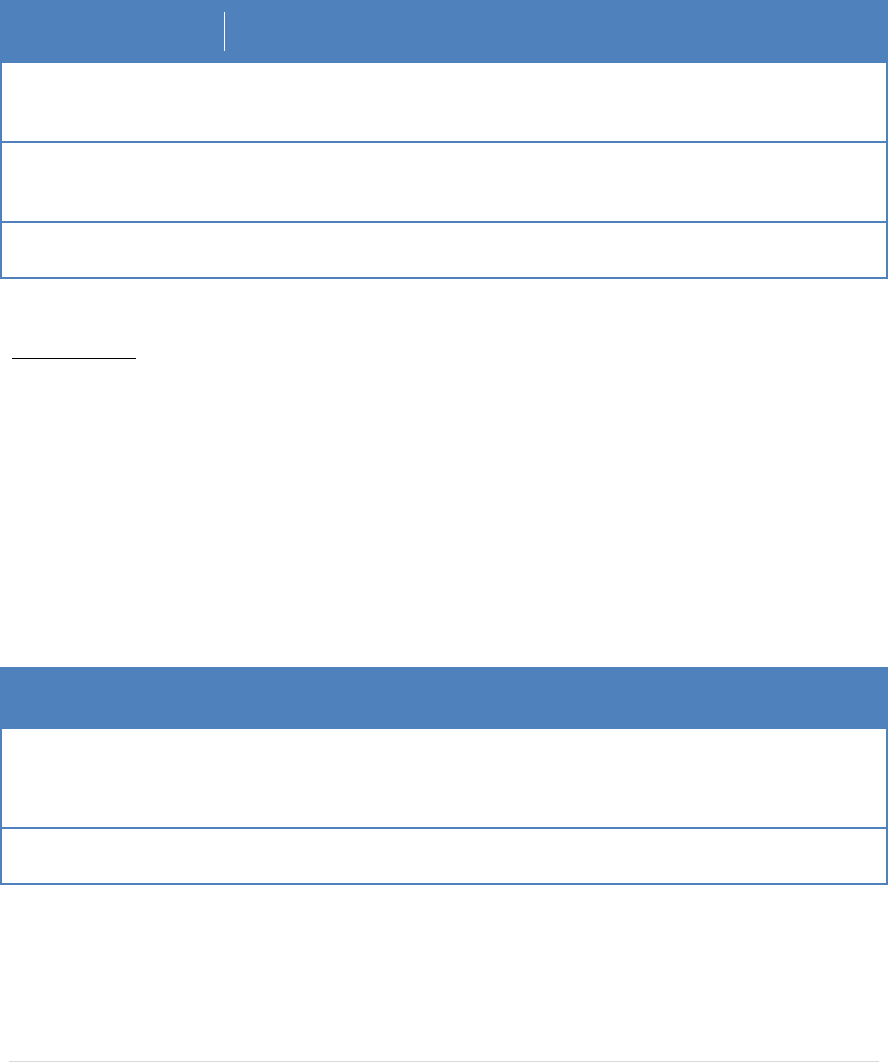

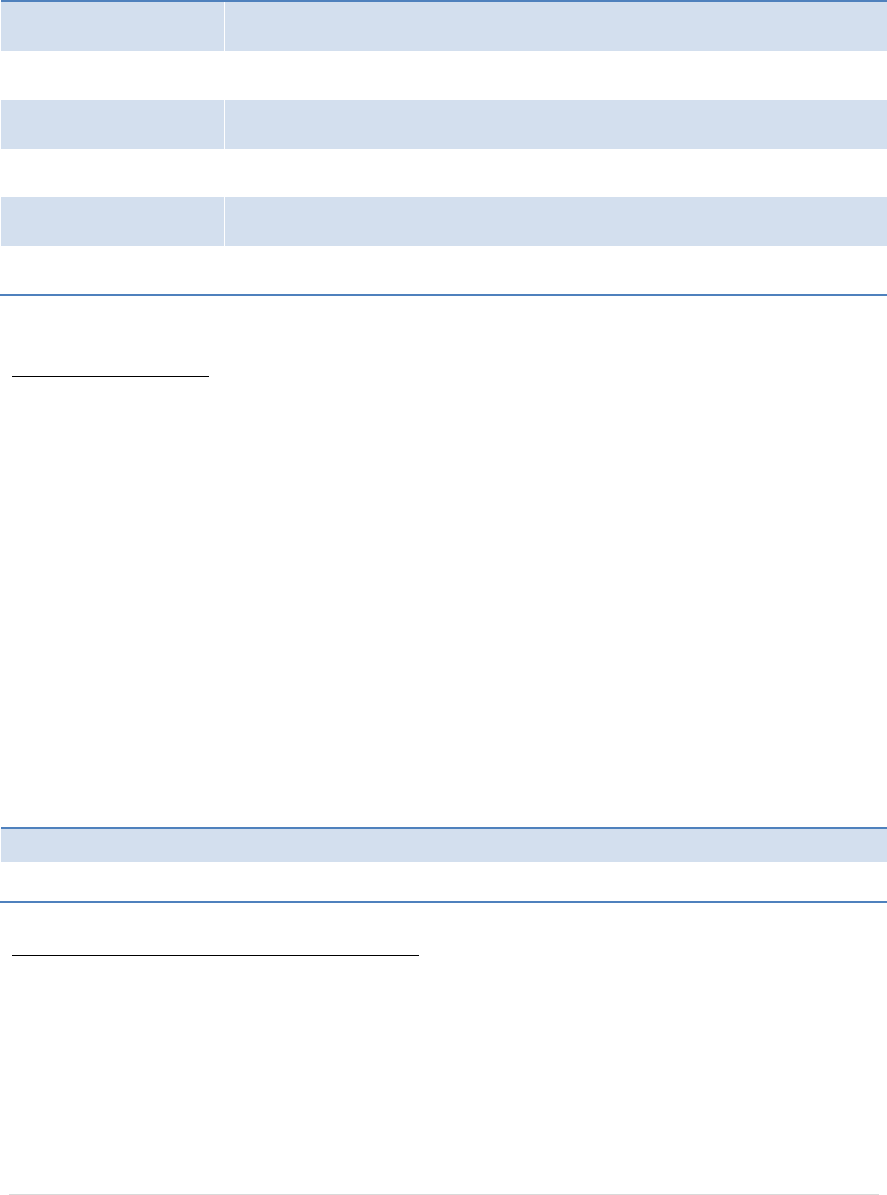

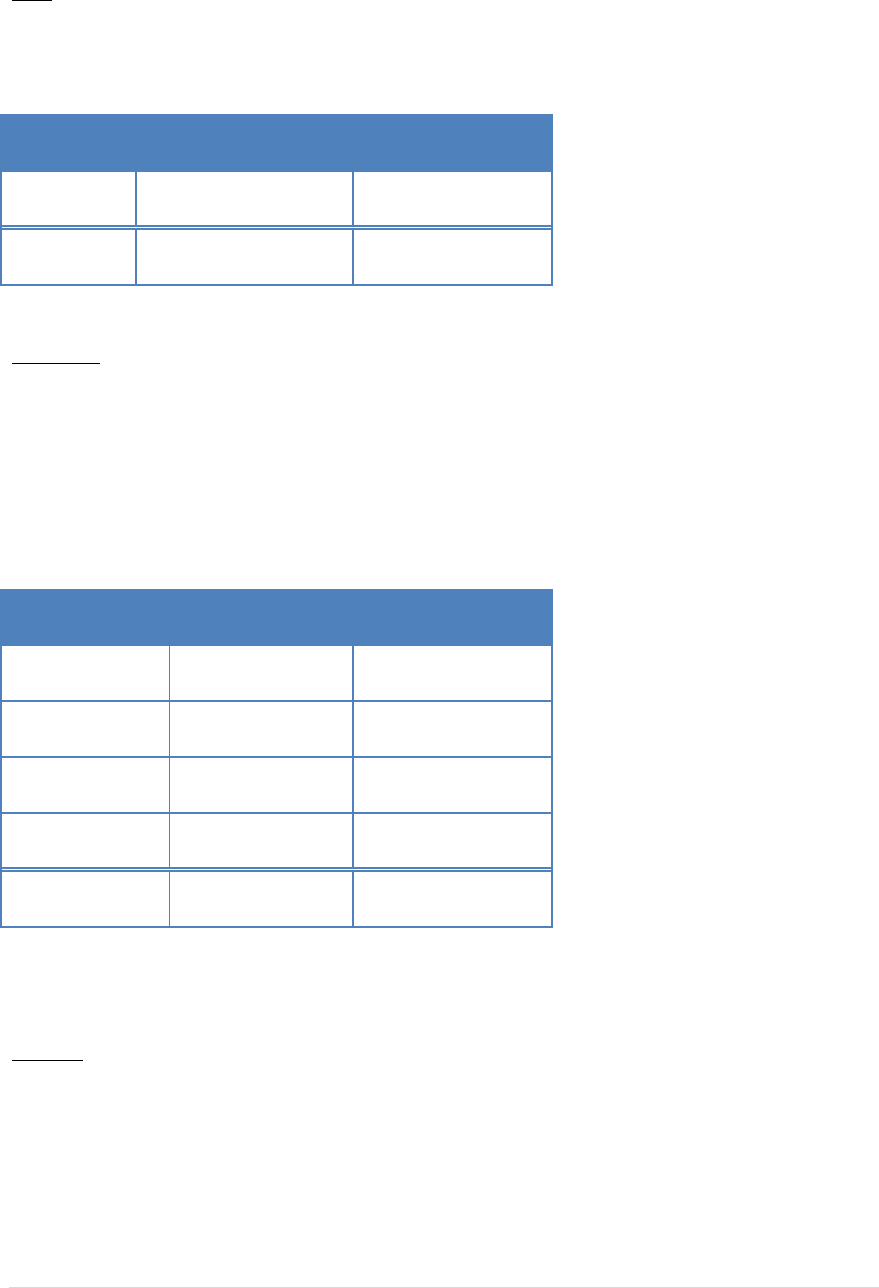

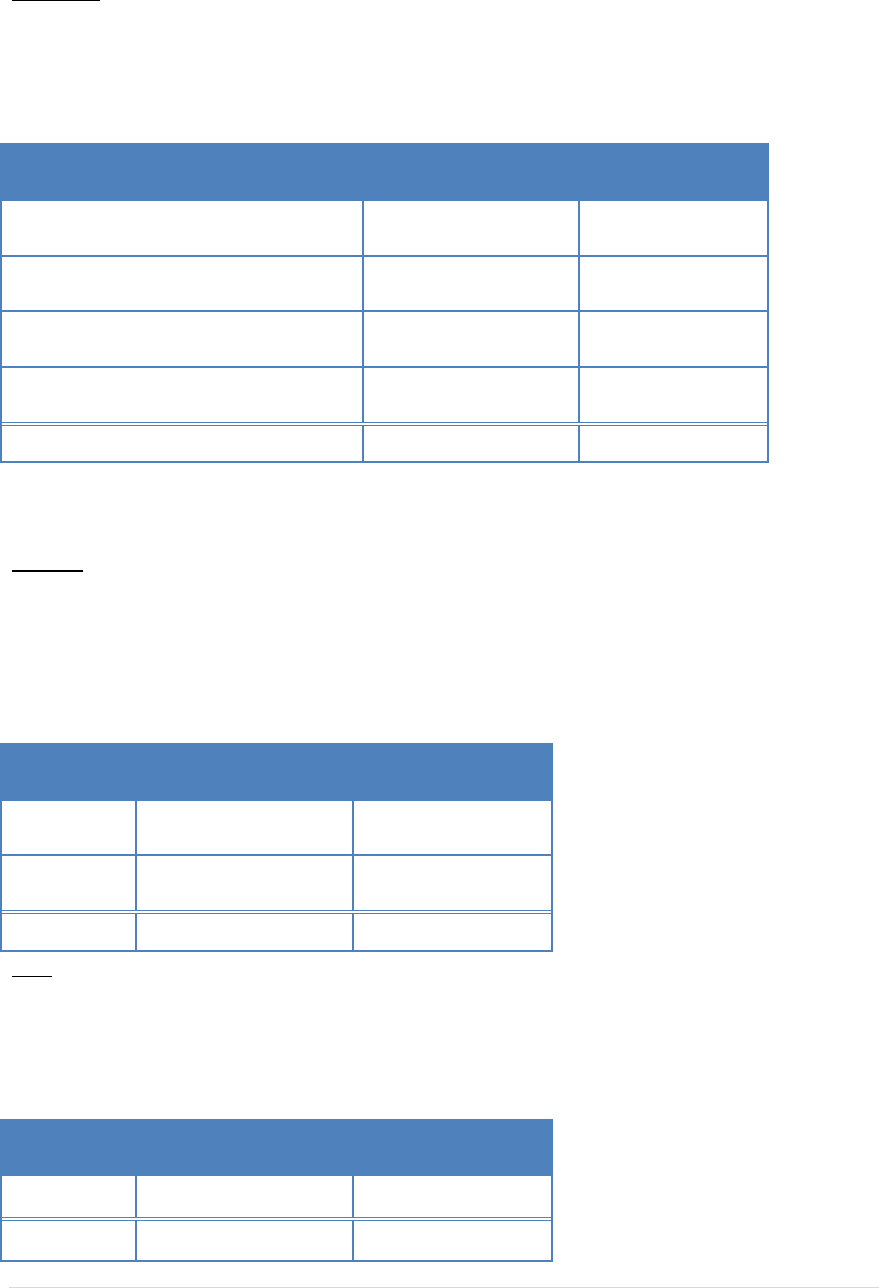

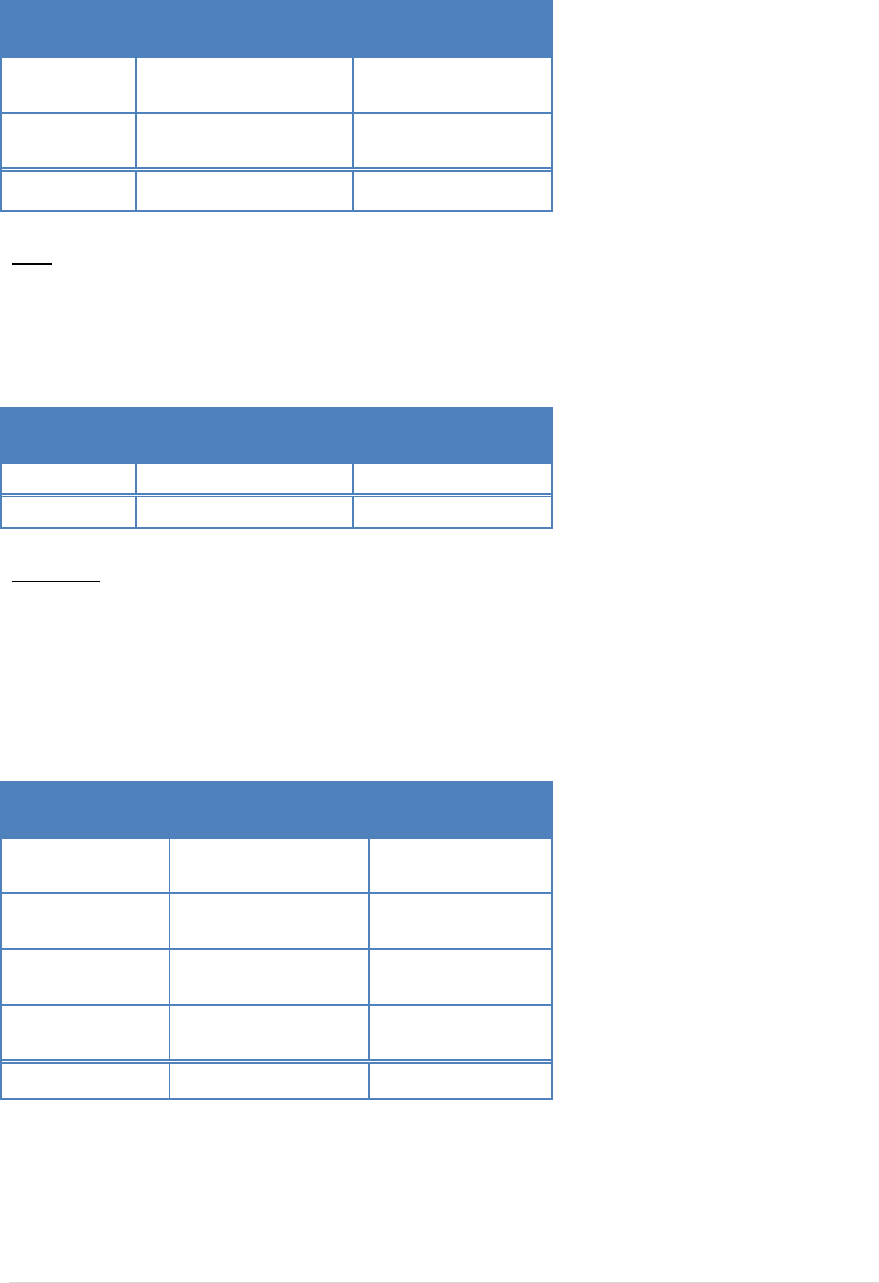

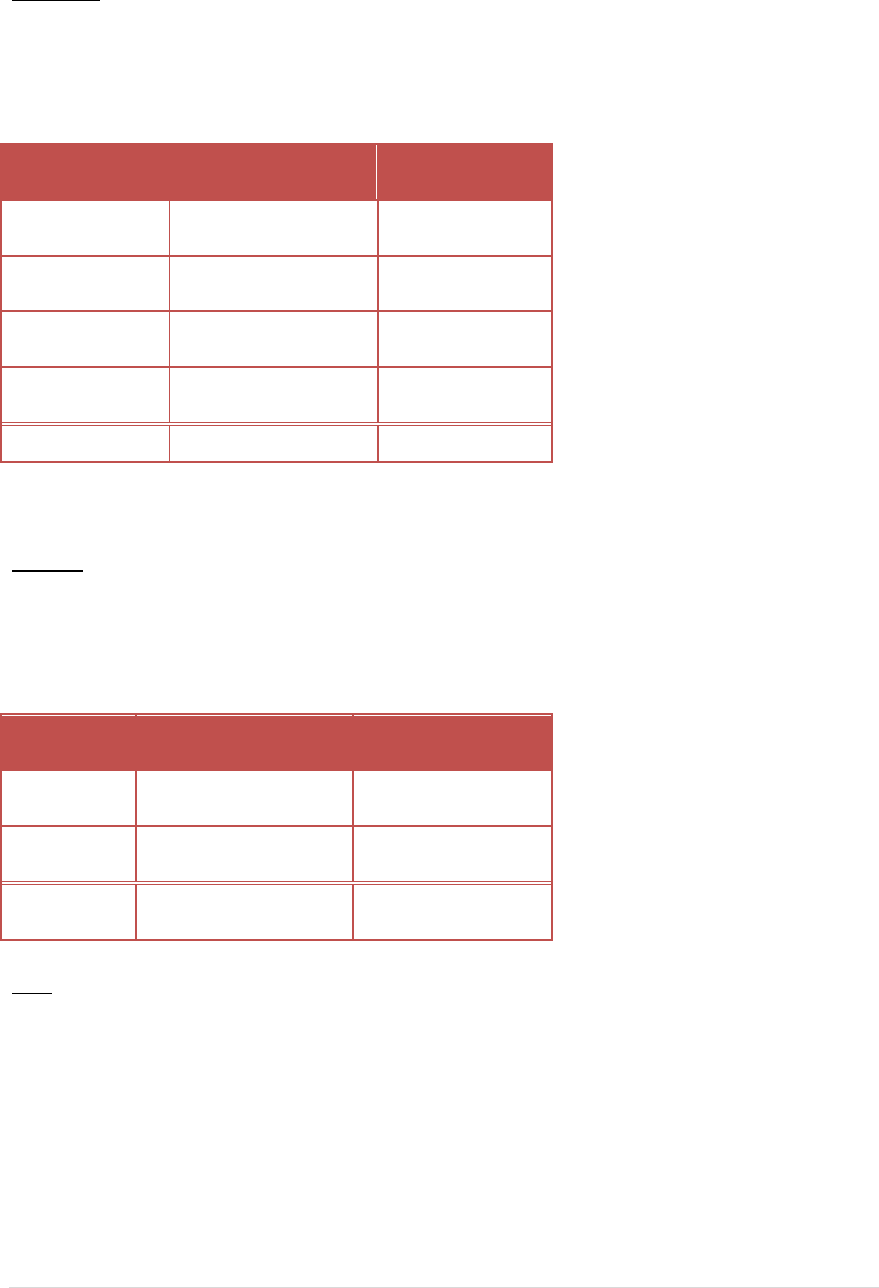

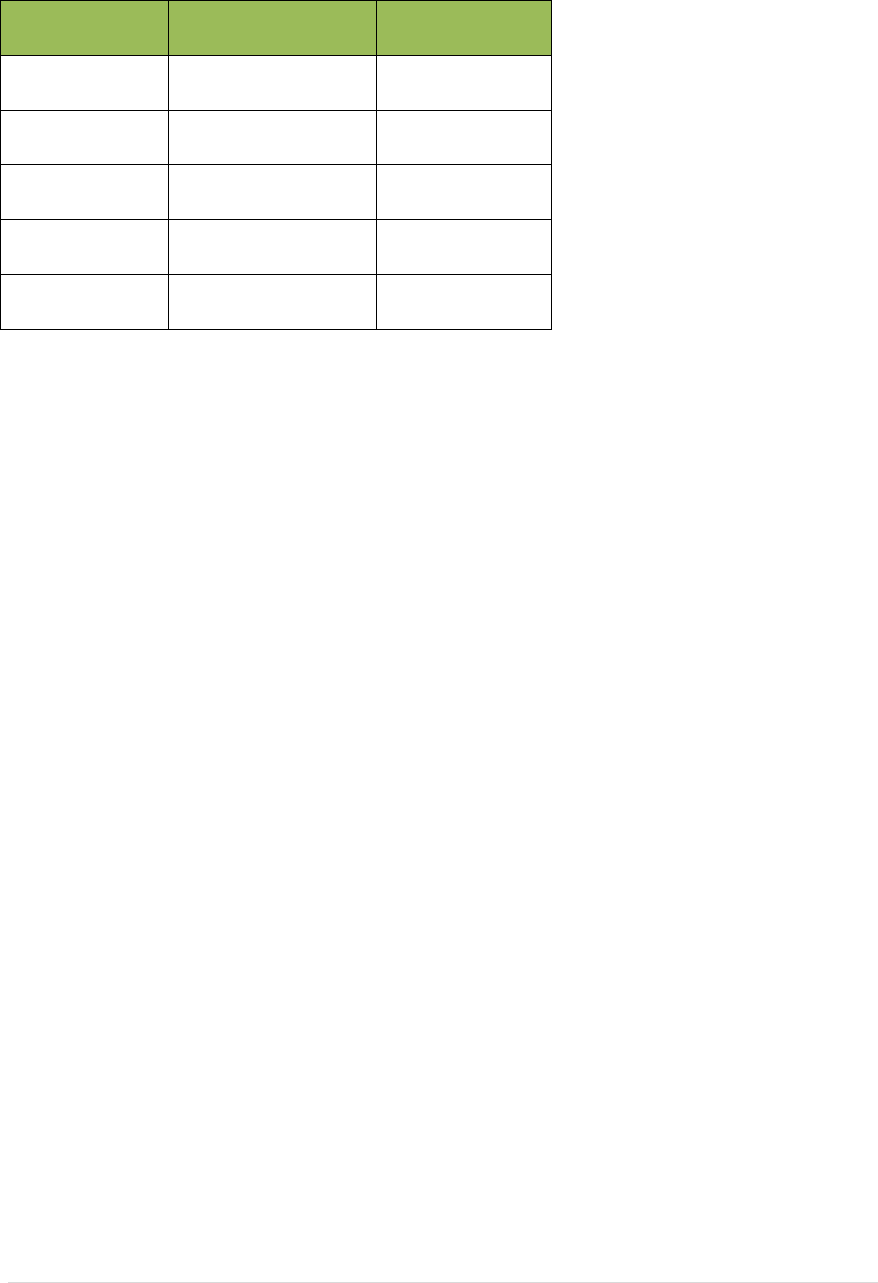

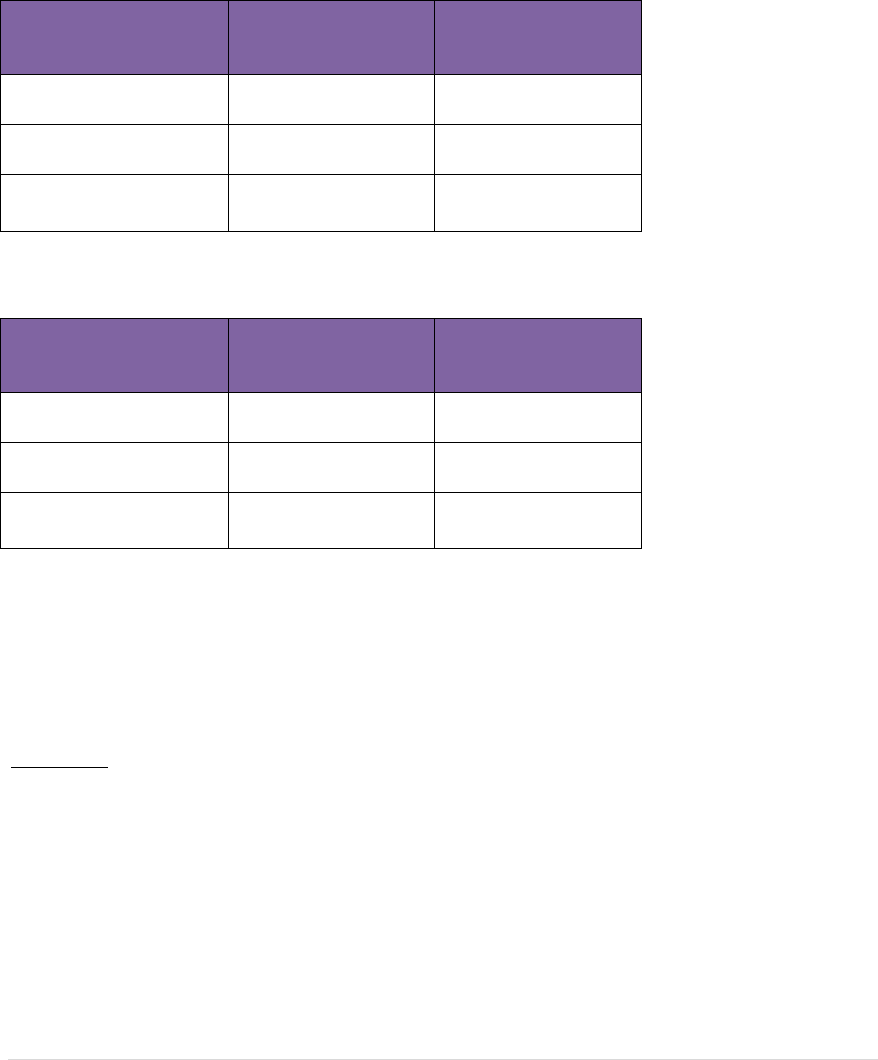

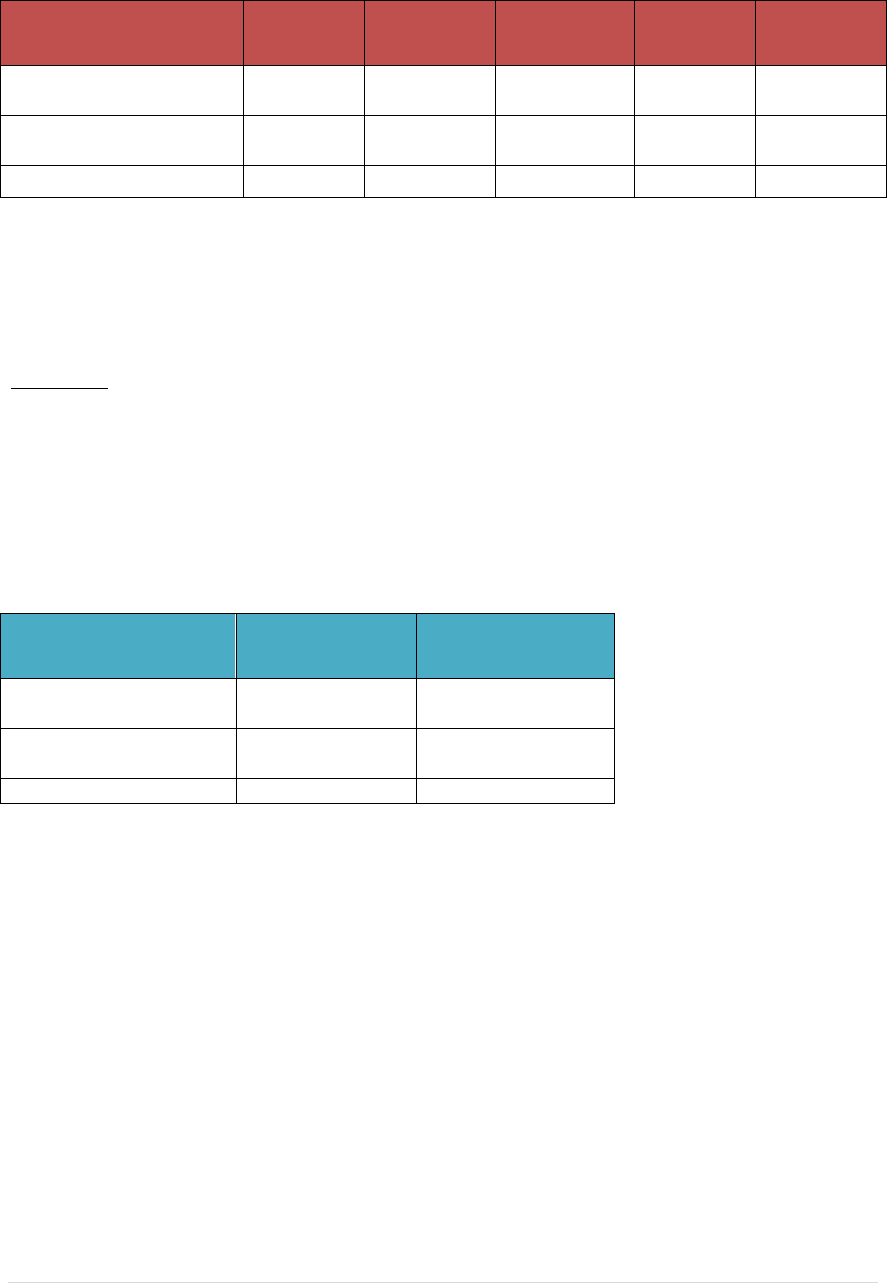

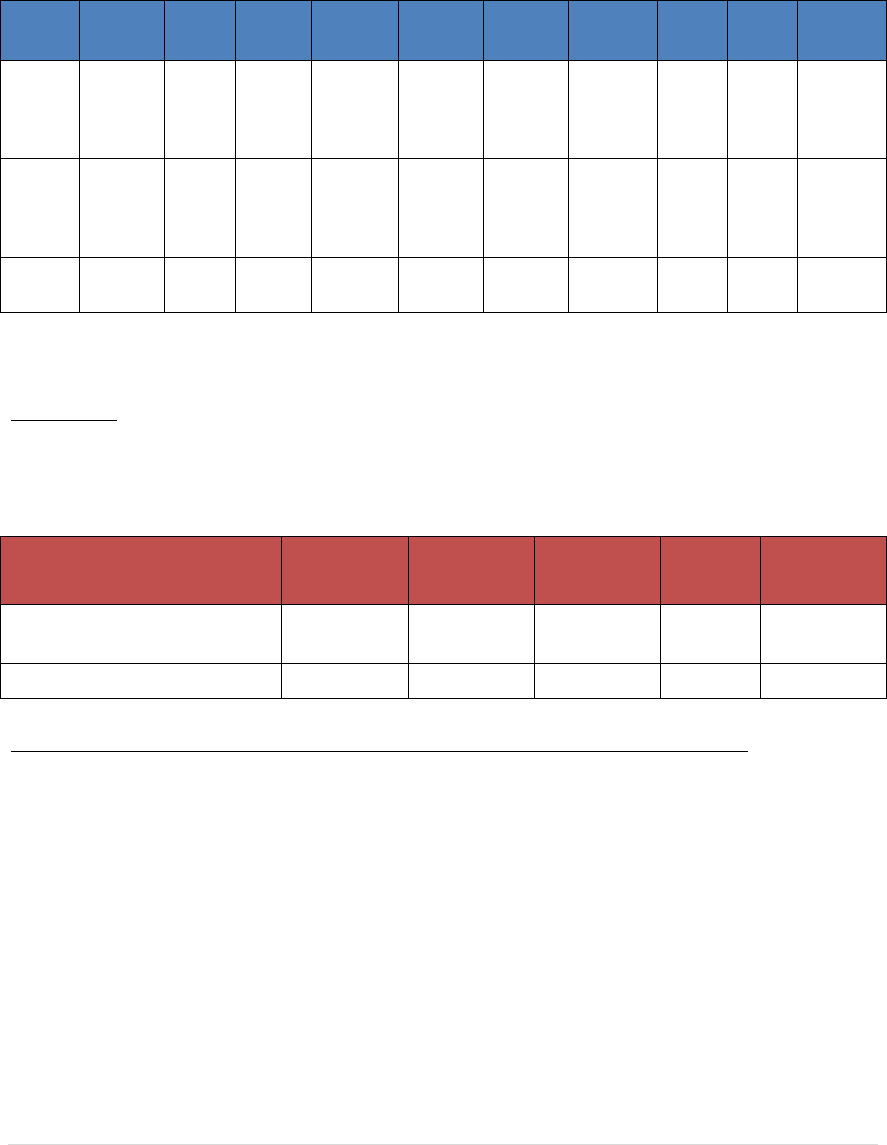

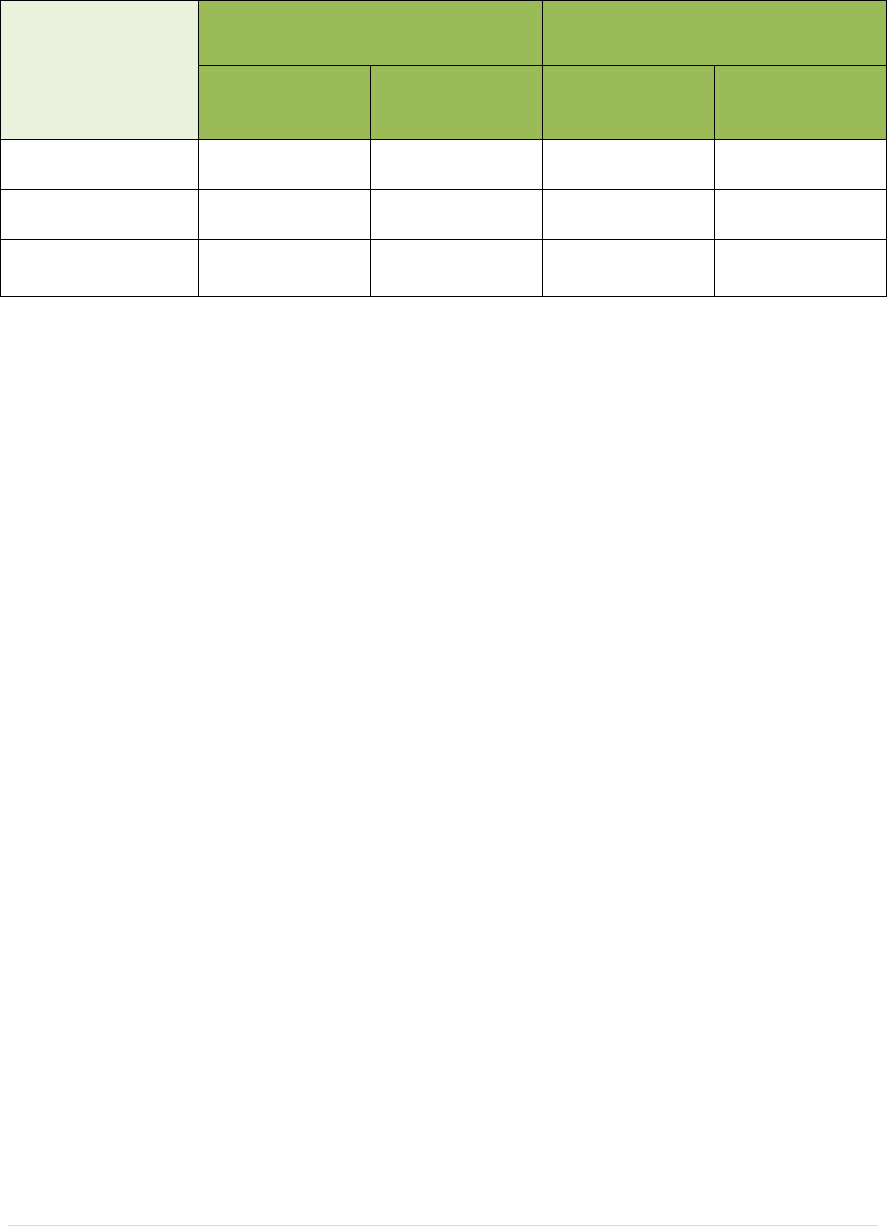

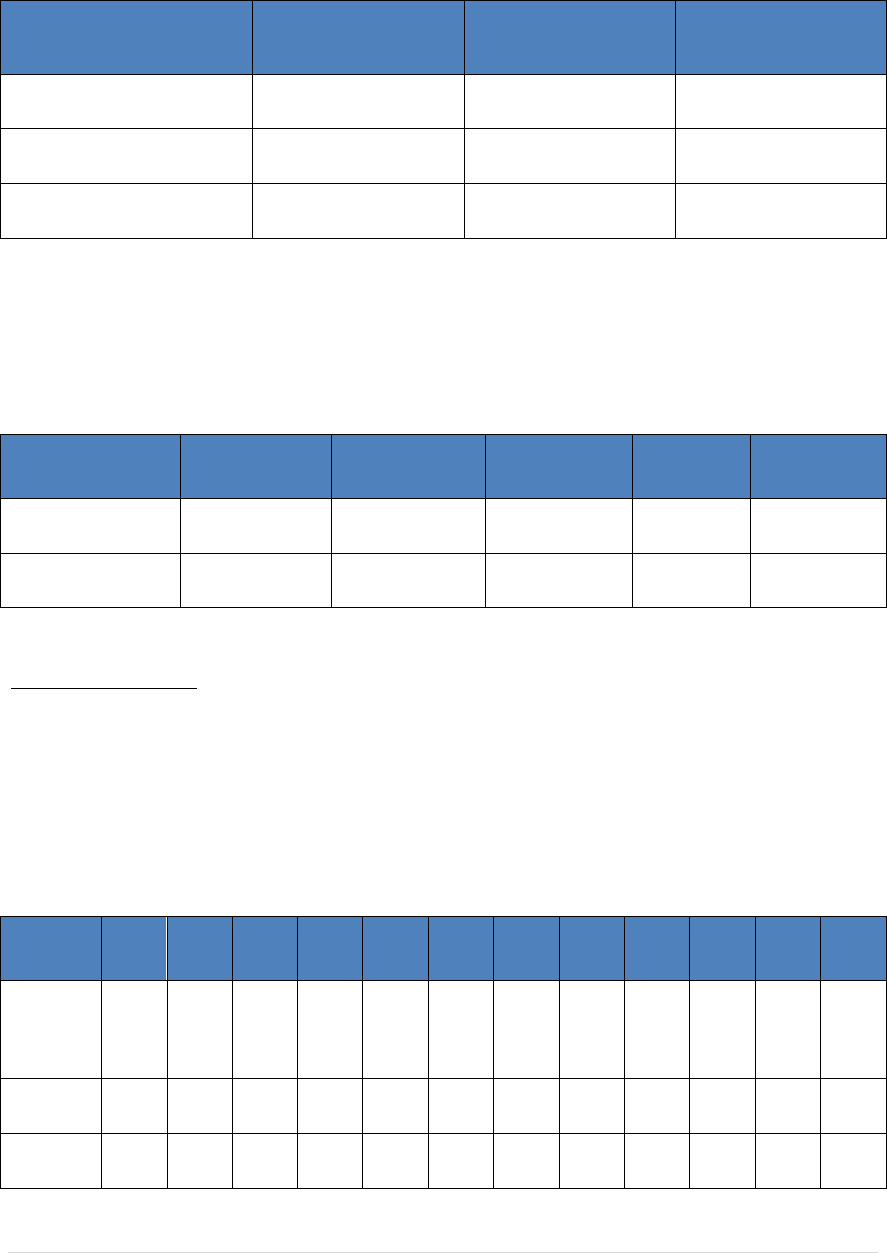

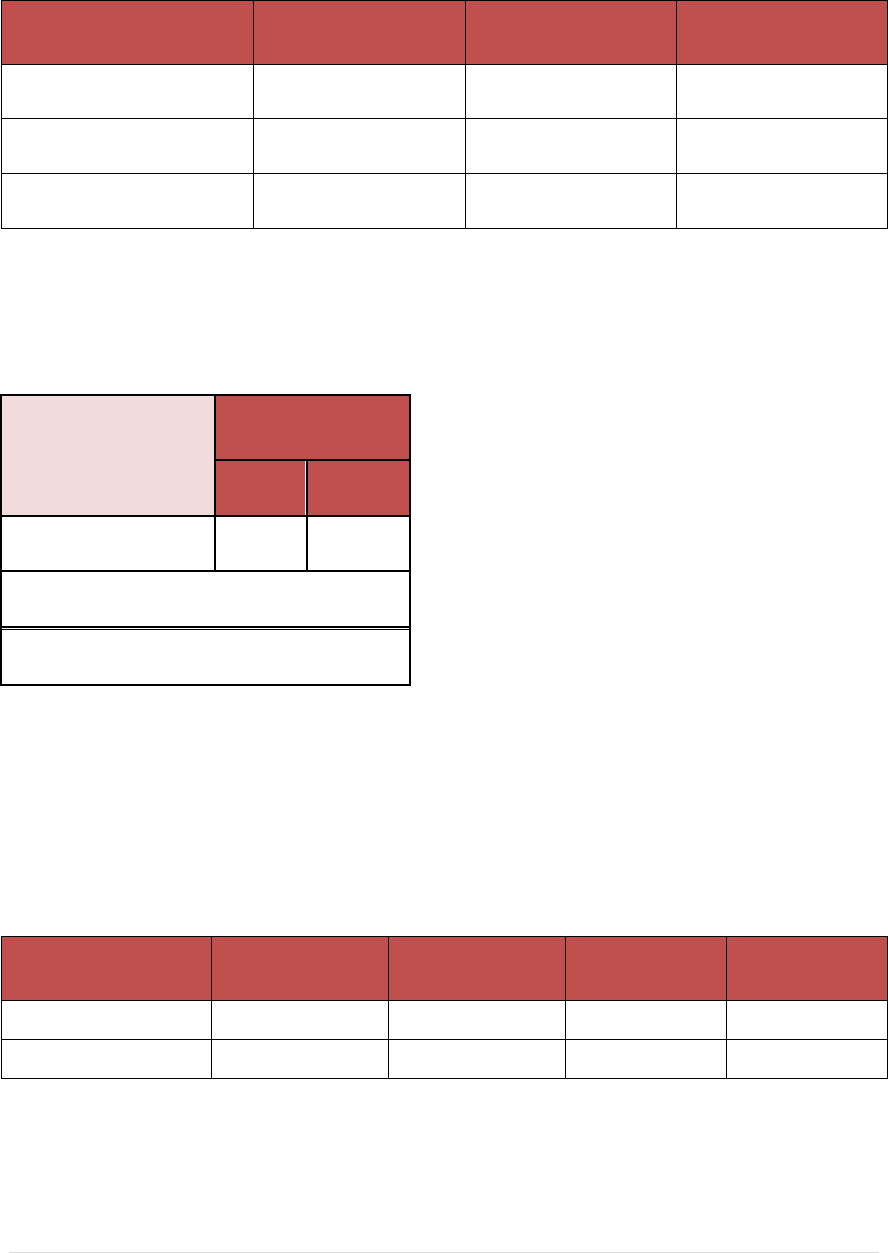

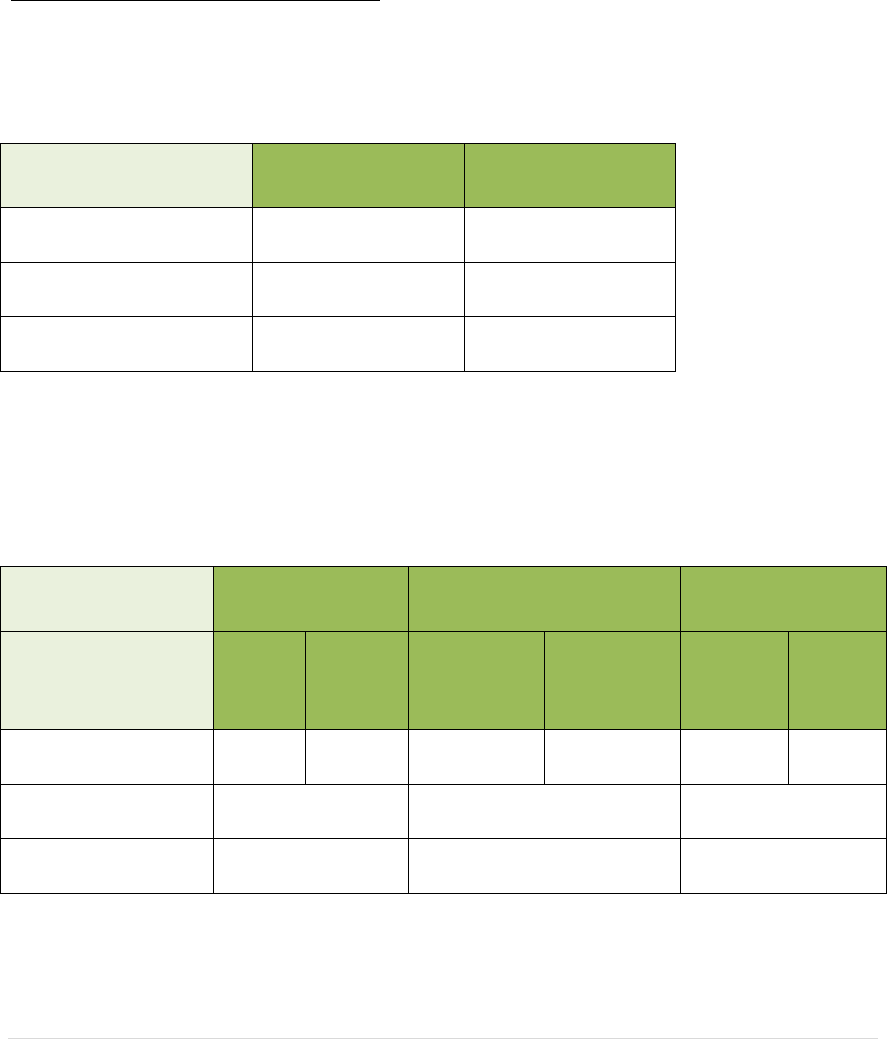

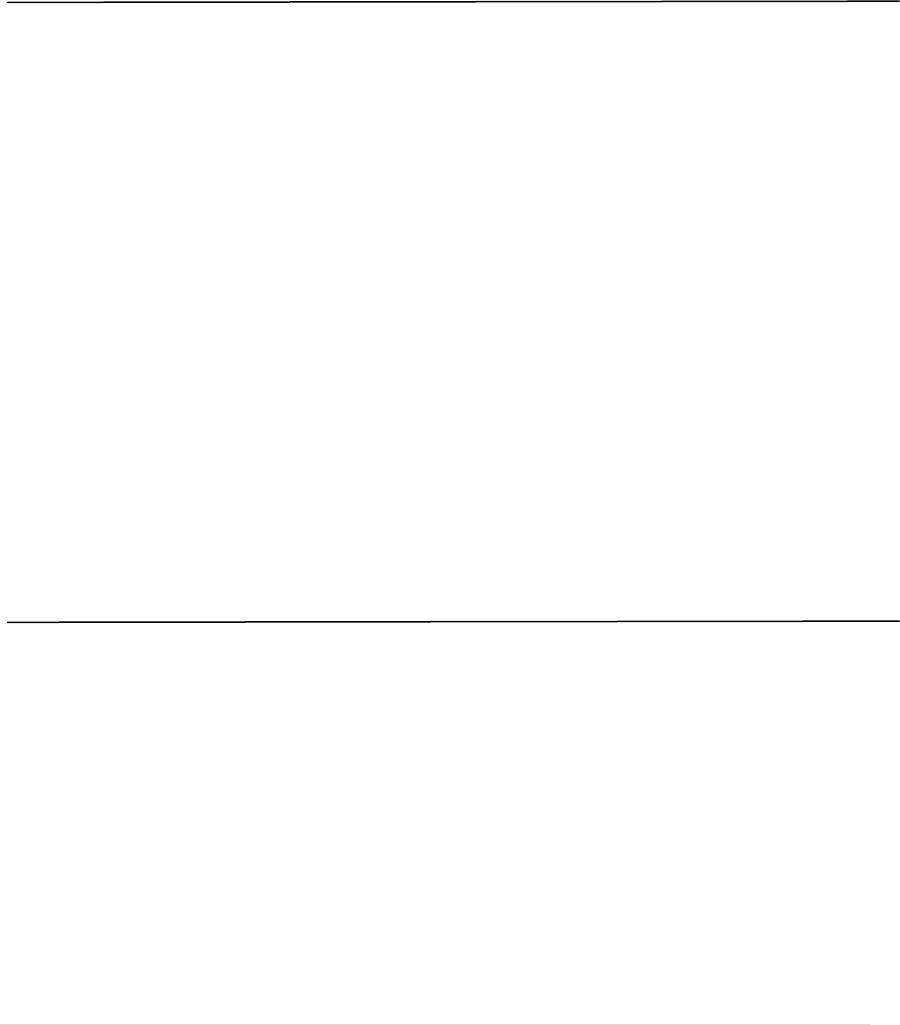

Relationship of Race/Ethnicity to Graduation for Adult Drug Courts

Adult Drug Court

White/ Caucasian

Black/ African -

American

Hispanic

Other

Percent

Graduating

61.6%

40.9%

65.5%

44.9%

Group Size

760

193

58

49

F(3,1056) = 10.778, p < .001

Relationship of Race/Ethnicity to Graduation for Juvenile Drug Courts

Juvenile Drug

Court

White/ Caucasian

Black/ African -

American

Hispanic

Other

Percent

Graduating

45.7%

18.8%

23.5%

33.3%

Group Size

151

32

17

15

F(3,211) = 3.527, p = .016

Nebraska Problem Solving Courts Should Enhance Program Evaluation

Capacity and Quality Enhancement

We were able to access useful data for this evaluation, and we believe the analysis

provides important direction for Nebraska problem solving courts. However, enhancing

the program evaluation capacity will allow additional questions to be answered such as

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

18 | P a g e

the relationship between costs and outcomes and the effectiveness of family dependency

drug courts. Ongoing program evaluation allows programs to improve the quality of their

operations and to make informed policy and programmatic decisions leading to better

lives for participants.

Recommendations for increasing the evaluation capacity for problem solving courts

include the following:

Implement periodic peer practice reviews and a formal process for ongoing

fidelity measurement and analysis

Develop a data dictionary for the current Problem Solving Court Management

Information System (PSCMIS)

Provide additional resources to enhance the PSCMIS such as building in

automated calculators and reports, adding fields to allow data collection over

time, and reducing the number of fields for text information, and developing

protocols to ensure the quality of data

Work with family dependency drug courts to participate in the PSCMIS and to

enhance their operations

Continue the valuable statewide collaboration of problem solving court

coordinators and increase training for local drug court teams and other

stakeholders

Ensure judges, law enforcement, treatment providers, and other key participants

are actively involved on problem solving court teams

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

19 | P a g e

This evaluation is designed to examine problem solving courts in Nebraska. The

Nebraska Problem Solving Courts are shown in Figure 1.1.

Project Design and Implementation

The evaluation was conducted by the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center under

contract with the Administrative Office of the Courts. The Public Policy Center is a

nationally recognized unit that regularly works with the judicial system in Nebraska (e.g.,

since 2001 it has served as the research lead and coordinator of the state’s Minority

Justice initiative), collaborates with the National Center for State Courts (e.g., How the

Public Views the State Courts, 1999) and serves as national evaluator on such diverse

projects as the Centers for Disease Control’s Public Engagement Pilot Project on

Pandemic Influenza (2005, chap. 6). The evaluation included a participatory program

evaluation design, which is particularly useful for complex projects that are collaborative

in nature (Greene, 1988; Mark & Shotland, 1985). Participatory evaluations provide

stakeholders a greater role in the evaluation process, thus ensuring a greater

understanding of the benefits of evaluation in the early stages of implementation. In

addition, participation allows stakeholders to influence and share control over the

implementation by influencing the parameters that guide the processes, decisions, and

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

20 | P a g e

resources. Stakeholder participation helps with the interpretation of data in the context of

the system’s actual work, and may generate additional evaluation questions based on the

needs of the participating organizations. The Evaluation Team included problem solving

court coordinators, judges, court administrative personnel, and service providers. The

team assisted with development of protocols and selection of data collection procedures

that maximize the utility of the information collected while minimizing the burden of

data collection. The Evaluation Team also assisted in generating additional evaluation

questions and interpreting data.

Evaluation Questions

The evaluation was both formative – designed to examine and improve current practices,

and summative – designed to determine program outcomes. The evaluation attempted to

answer the following major questions:

Questions related to participant characteristics:

1. How do offender characteristics compare to admission criteria, sentencing

guidelines, and offenders not admitted to drug court (e.g., disparity in minority

access)?

2. What are the issues related to accessing drug courts/substance abuse services?

Questions related to program implementation:

3. What are the program components (e.g., types and amounts of

services/sanctions/court procedures) for each court, and how do they compare

across courts?

4. How does practice compare to designed procedures (fidelity) and best practices?

Questions related to outcomes:

5. How do participant outcomes (e.g., post-program recidivism) match up to

comparison group outcomes?

6. How are outcomes associated with client characteristics (e.g., severity of offense,

demographics, treatment needs, sentencing guidelines), program implementation

(e.g., treatment dosage), and costs?

Question related to evaluation capacity:

7. What is the increase in evaluation capacity at the state and local levels?

Evaluation Design

To answer these questions, we used a mixed methods design including qualitative and

quantitative approaches. Quantitative data was accessed through the Nebraska Problem

Solving Court Management Information System. All quantitative information was stored

and analyzed using SPSS, a statistical software package for the social sciences. The

evaluation also included qualitative information related to program access, process, and

perceived outcomes. Qualitative information included reviews of each court’s policies

and procedures, direct observation of drug court proceedings, and interviews or focus

groups with drug court coordinators. All tools and protocols (e.g., data collection,

analysis scripts, interview questions) are made available and accessible to local and state

court officials via inclusion in the evaluation report and through a toolkit developed as

part of the evaluation.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

21 | P a g e

Participant Information

The information examined pertaining to participants (and family members, where

relevant) included characteristics such as demographics, needs, criminal history,

eligibility factors, and risk factors. This information was acquired from the existing

PSCMIS. A discrepancy analysis was used to compare participant demographic

information (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, age,) with demographics of the comparison

group. This analysis was intended to identify whether racial/ethnic minorities and other

demographic groups are being differentially served by Nebraska drug courts. We also

examined education levels, employment levels, types of crimes committed, and types of

substances abused to better understand the populations served by problem solving courts

and to determine if there are differences across courts

Outcome Information

Criteria related to program success included number of participants successfully

completing drug court, employment status upon program completion, educational

attainment upon program completion, improvement in risk scores and post-program

recidivism. The evaluation will identify outcomes by program (e.g., graduation versus

termination) and conduct multivariate analyses to explore associations between outcomes

and participant characteristics (e.g., demographic information, criminal offenses, Level of

Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI) information), and program

characteristics (e.g., number of sanctions number of court hearings). The outcome

analysis was conducted for graduates of drug courts, and for the comparison groups.

Program Information

Process variables that could be quantified include such factors as frequency of drug tests,

number of court hearings, number of incentives, and number of sanctions imposed.

Program information was compared across courts. Actual court practices were compared

to evidence-based or promising practices as they are articulated in available literature.

Qualitative data, including interviews with drug court participants, drug court staff, and

treatment professionals and drug court observations, were used to understand how the

processes function in the field. Interview questions and observation criteria were based

on the 10 key drug court components and best practice guidelines. The observations of

court proceedings and team meetings serve as a way to validate or explain court

functions.

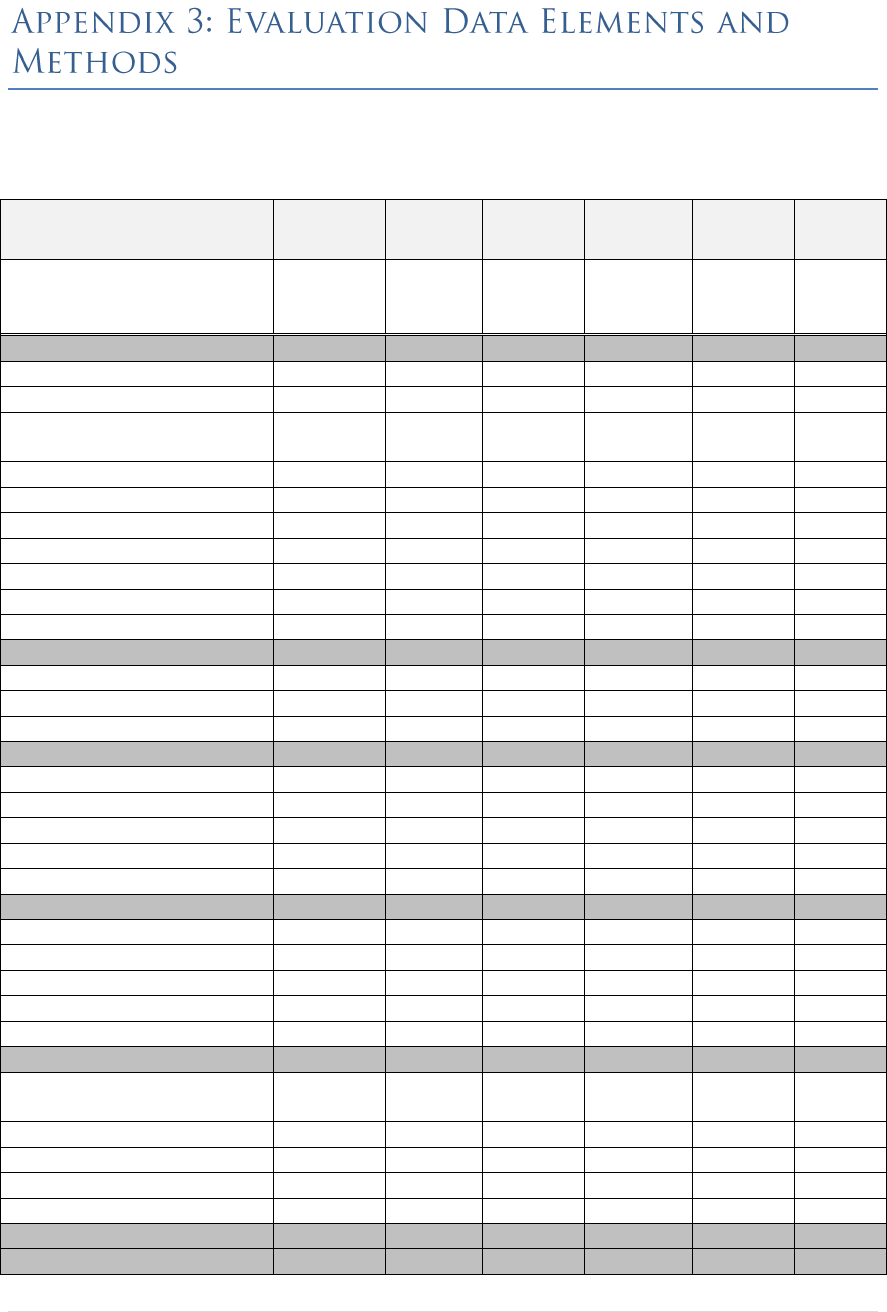

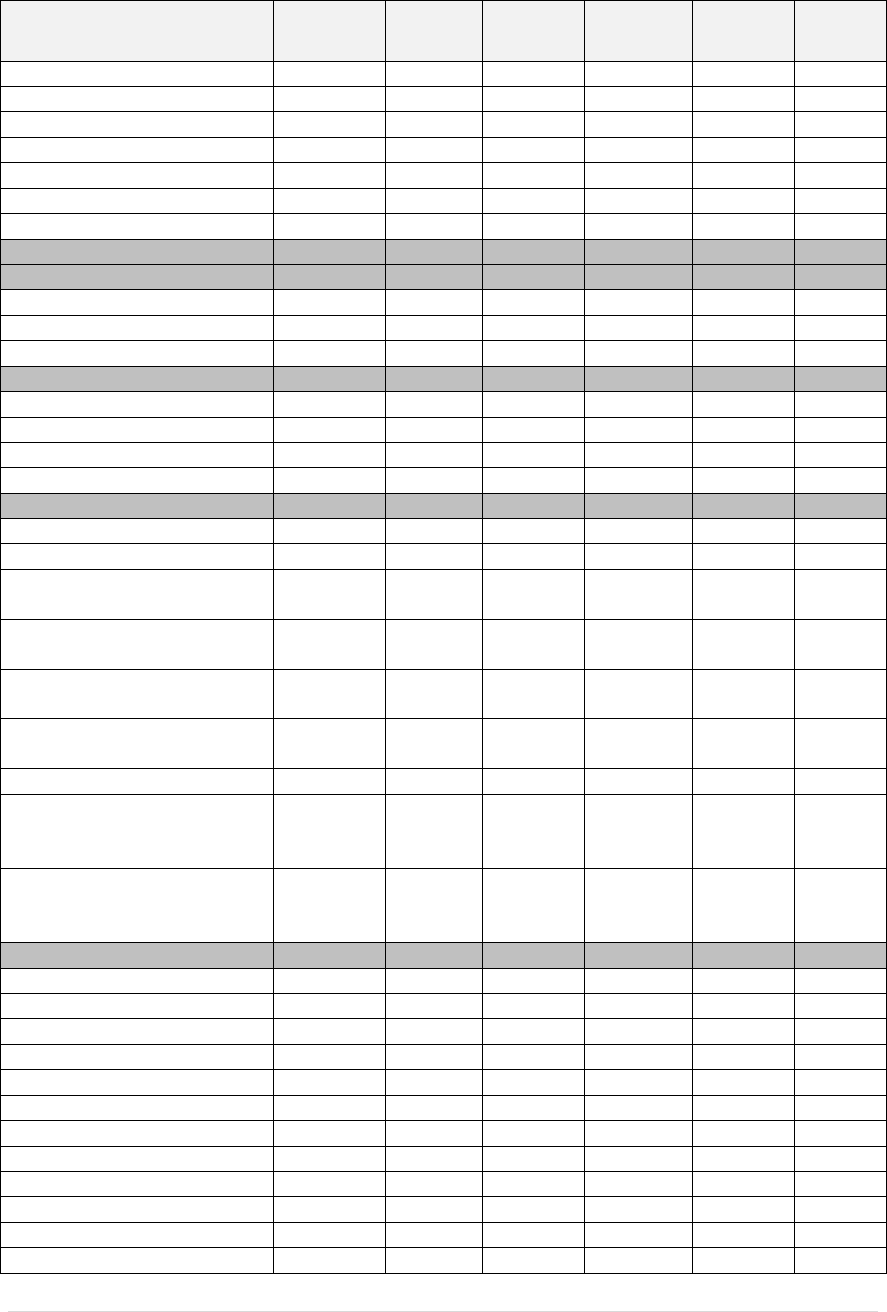

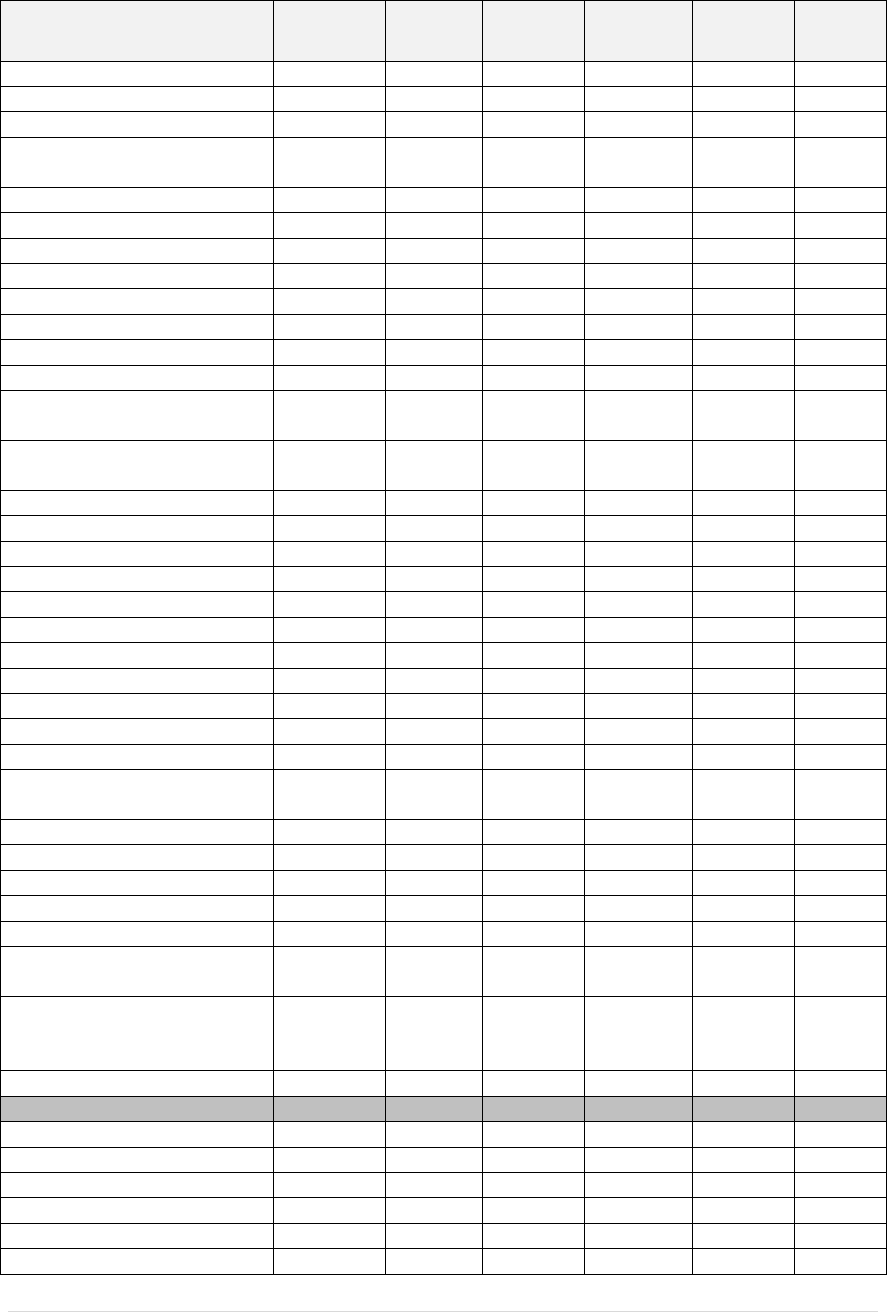

Data Elements

The evaluation included a review of the completeness and quality of information in the

PSCMIS database. The primary focus of the quantitative analysis included the Statewide

Performance Measures which were in the PSCMIS system, data was complete, and

captured in a manner that allowed meaningful analysis. We worked with problem

solving court coordinators to understand what types of data they were entering in the data

fields and, in the absence of a standard statewide data dictionary, what definitions they

were using for the data.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

22 | P a g e

Through both examination of the database and discussions with PSC Coordinators, some

modifications were identified which could make future evaluation and ongoing tracking

of Statewide Performance Measures easier. Much of the data in the PSCMIS had to be

recoded to be of use in the analysis. Data for comparison groups was obtained from the

probation database. A summary of the data used in the quantitative analysis and a

description of the methodology can be found in Appendix 3. There are some caveats to

the data analysis. For some of the variables, the sample size was too low to analyze

statistically. In many of these cases, we included the data in the tables so the reader could

see the descriptive information; however, the these low number variables were not

included in the analysis. For all pairwise analyses, the level of significance we used is a p

value less or equal to .05.

Report Structure

Following are the evaluation questions and where to find the results pertaining to

those questions:

1. How do offender characteristics compare to admission criteria, sentencing

guidelines, and offenders not admitted to drug court (e.g., disparity in minority

access)?

2. What are the issues related to accessing drug courts/substance abuse services?

To understand the admission criteria of courts, we reviewed policies and procedures and

conducted site visits to each court (see Chapter 3). To help understand who Nebraska

problem solving courts are serving, we reviewed data pertaining to participant

characteristics from the Problem Solving Court Management Information System

((PSCMIS), comparing participant characteristics across courts, to the literature and to

admission criteria (see Chapter 4). To assess access to problem solving courts, we

conducted a disparity analysis to determine whether certain groups were under-

represented in each court (see Chapter 4), and examined length of time between arrest

and admission into problem solving courts (see Chapter 5).

3. What are the program components (e.g., types and amounts of

services/sanctions/court procedures) for each court, and how do they compare

across courts?

4. How does practice compare to designed procedures (fidelity) and best practices?

To understand the programs and their components, we reviewed policies and procedures

and conducted site visits for each court (see Chapter 1). To understand best practices, we

reviewed the problem solving court literature (see Chapter 2). To understand the

differences across courts, we used data from the PSCMIS to compare the different

programs (see Chapter 5).

5. How do participant outcomes (e.g., post-program recidivism) match up to

comparison group outcomes?

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

23 | P a g e

6. How are outcomes associated with client characteristics (e.g., severity of offense,

demographics, treatment needs, sentencing guidelines), program implementation

(e.g., treatment dosage), and costs?

To assess outcomes of problem solving court participants, we selected individuals who

had successfully graduated from programs across the state and worked with the Nebraska

Crime Commission to determine recidivism using a standard definition. We used a

matched comparison of individuals on probation and compared these two groups. The

data for this component of the evaluation are still being analyzed and will be reported

when the analysis is complete (see Chapter 8).

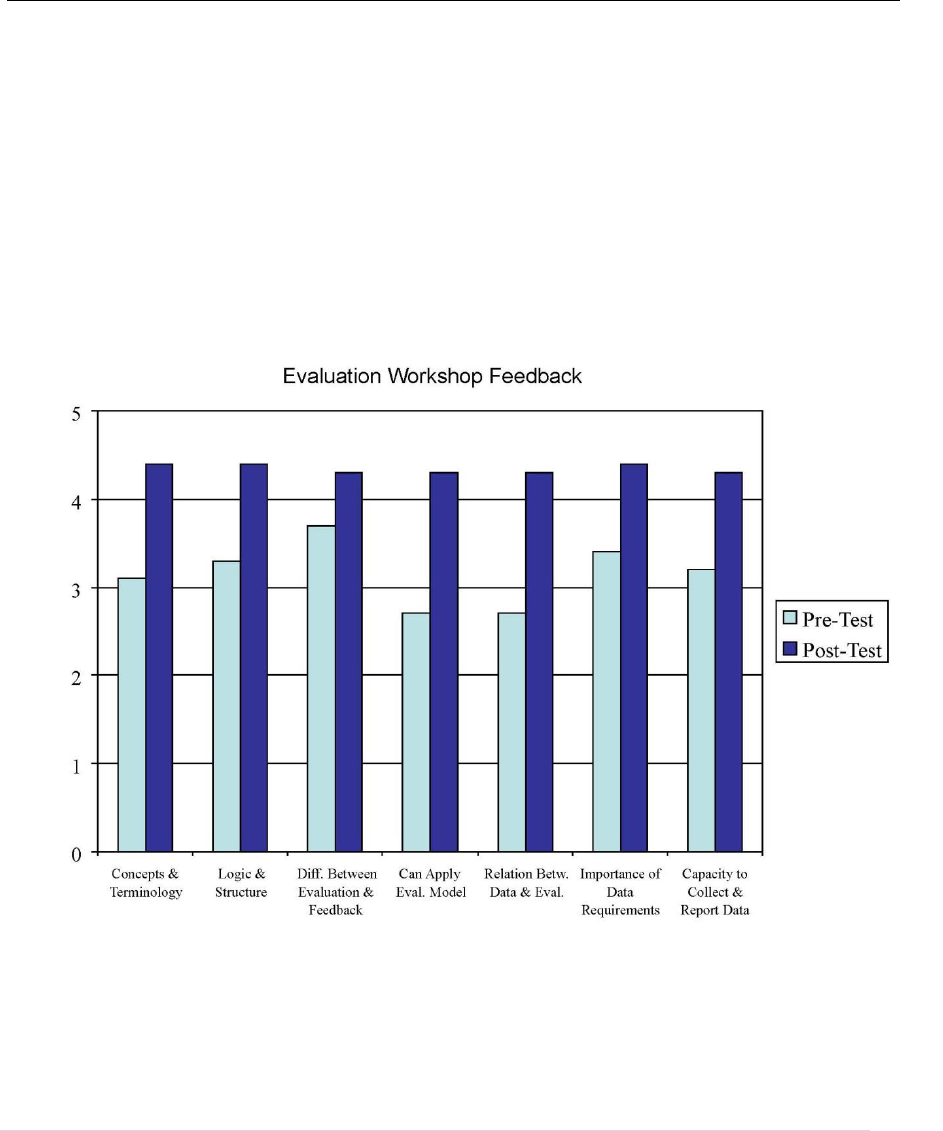

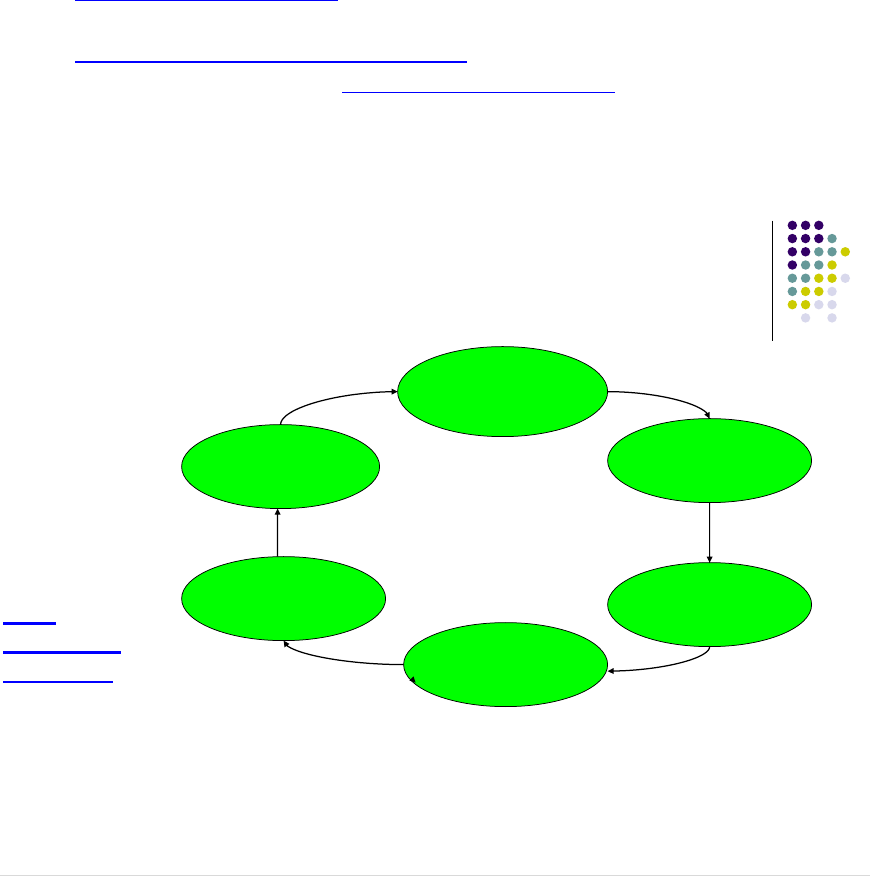

7. What is the increase in evaluation capacity at the state and local levels?

To assess and enhance evaluation capacity at the state and local levels, we conducted a

number of activities. During the site visits, we asked coordinators about their program

evaluation efforts to better understand their knowledge and capacity (see Appendix 1).

We also conducted two workshops on program evaluation, in which we examined a logic

model framework and discussed how the logic model could be applied to the evaluation

of individual problem solving courts in Nebraska. We reviewed the PSCMIS data system

through a program evaluation lens, and provided recommendations below for

enhancements that would improve the ability of the state and individual program to

conduct program evaluations. Also, to allow replication of the current evaluation, we

provide the evaluation tools (see Appendix 2) and a description of the methodology,

which can be used for future evaluations (see Appendix 3). Finally, we developed a

program evaluation tool kit which can be used by Nebraska problem solving courts (see

Appendix 4).

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

24 | P a g e

Drug Courts and Best Practices

Since their inception, drug court programs have grown tremendously in the past two

decades, and there are now over 2,100 such programs currently operating in the nation

(Huddleston, Marlowe, & Casebolt, 2008). A number of studies have emerged indicating

that drug courts are an effective intervention to reduce crime and improve addiction and

substance abuse outcomes (Finigan, Carey, & Cox, 2007; GAO, 2005; Marlowe,

DeMatteo, & Festinger, 2003). However, demonstrating the effectiveness of drug courts

has been a development in progress. Earlier studies that featured randomized treatment

and control groups were relatively rare (Whiteacre, 2004a). As more rigorous evaluation

methodology has been employed with greater frequency, evidence has grown from

randomized or quasi-experimental studies which does indicate the efficacy of drug court

programming (Breckenridge, Winfree, Maupin, & Clason, 2000; Gottfredson & Exum,

2002; Gottfredson, Najaka, & Kearley, 2003; Gottfredson, Najaka, Kearley, & Rocha,

2006; Perry et al., 2009). However, there are also experimental or quasi-experimental

studies which have shown no or minimal differences between treatment and control

groups in drug court programs (Hepburn & Harvey, 2007; MacDonald, Morral,

Raymond, & Eibner, 2007), and some commentators continue to question the

methodological soundness of drug court evaluations generally (Gutierrez & Bourgon,

2009; Merrall & Bird, 2009). Additionally, some drug court studies have found that

African Americans and other minorities, and certain types of drug users, are more likely

to experience negative outcomes or fail than others (Banks & Gottfredson, 2003; Hickert,

Boyle, & Tollefson, 2009; Listwan, Sundt, Holsinger, & Latessa, 2003; Roll,

Prendergast, Richardson, Burdon, & Ramirez, 2005). Thus, although a significant weight

of research does support the notion that drug court programs can and do work, there are

at least areas for improvement in drug court programming, and a clear need to identify

best practices (Lutze & van Wormer, 2007).

Drug Courts: A Basic Review

Drug court programs operate by using a court’s legal authority to treat and change a

participant’s substance abuse behavior in exchange for dismissed or reduced criminal

charges or sentences. The basis for this approach is grounded in the belief that drug

and/or alcohol abuse is both a health and criminal justice problem, and that effective

treatment of an underlying drug/alcohol problem will or might reduce criminal behavior

(Lurigio, 2000; Vigdal, 1995). A typical drug court program involves the active

participation of a judge who regularly monitors a participant’s progress and dispenses

sanctions or rewards with input from a prosecutor, defense attorney, and probation

officials and treatment providers (GAO, 2005; Lowenkamp, Holsinger, & Latessa, 2005;

NDCI & NCJFCJ, 2003). Although there is significant variation in drug court operations

by jurisdiction and target population, the success of drug court programs has led to the

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

25 | P a g e

standardization of operating principles across drug courts, and a call for the use of

evidence-based or evidence-informed practices in daily activities and provision of

treatment.

Significant variation and trial-and-error characterized the experiences of earlier drug

court programs. Courts experimented with drug case dockets in large cities starting in the

1950s, and limited forms of diversion programs or court processes existed, which

emphasized screening, expedited processing, and other practices which laid the

foundations for modern drug court programs (Belenko, 1998; Mahoney, 1994). In the

first wave of modern drug courts in the early 1990s, most programs were mainly

diversionary in nature, worked primarily with lower-level offenders in a pre-plea model,

and operated without the benefit of knowing long-term recidivism rates (Cooper &

Trotter, 1994; Huddleston, Marlowe, & Casebolt, 2008).

Since then, researchers have investigated programmatic components of drug courts to

determine which aspects of the drug court process are most responsible for disposition

and positive outcomes among participants. Studies have examined the role of the judge

and judicial hearings (Festinger et al., 2002; Marlowe, Festinger, Dugosh, & Lee, 2005;

Marlowe et al., 2003), drug or alcohol treatment (Banks & Gottfredson, 2003; Taxman &

Bouffard, 2003), employment or other social support factors (Leukefeld et al., 2003;

Mateyoke-Scrivner, Webster, Staton, & Leukefeld, 2004) and personal characteristics of

offenders (Garrity et al., 2008; Gray & Saum, 2005; Hartman, Listwan, & Shaffer, 2007;

Roll, Prendergast, Richardson, Burdon, & Ramirez, 2005). Research has arrived at mixed

results. Importantly, drug court professionals have begun moving towards developing

best practices based on both the research evidence as well as from general principles of

practice.

The Ten Key Components of Drug Courts

In 1997, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) established its

10 key components for drug courts, a move which drove national momentum towards

standardizing operational principles for drug courts across the country (NADCP, 1997).

The NADCP work identified the key components, their purposes, and a series of core

benchmarks for achieving each component.

Key Component #1: Drug courts integrate alcohol and other drug treatment services with

justice system case processing.

Key Component #2: Using a non-adversarial approach, prosecution and defense counsel

promote public safety while protecting participants’ due process rights.

Key Component #3: Eligible participants are identified early and promptly placed in the

drug court program.

Key Component #4: Drug courts provide access to a continuum of alcohol, drug, and

other related treatment and rehabilitation services.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

26 | P a g e

Key Component #5: Abstinence is monitored by frequent alcohol and other drug testing.

Key Component #6: A coordinated strategy governs drug court responses to participants’

compliance.

Key Component #7: Ongoing judicial interaction with each drug court participant is

essential.

Key Component #8: Monitoring and evaluation measure the achievement of program

goals and gauge effectiveness.

Key Component #9: Continuing interdisciplinary education promotes effective drug court

planning, implementation, and operations.

Key Component #10: Forging partnerships among drug courts, public agencies, and

community-based organizations generates local support and enhances drug court program

effectiveness.

Generally, the components can be categorized as principles that address either drug court

team dynamics (components 2, 6, 9, 10) or offender identification and screening

processes (components 1, 3, 4, 5, 7) (Olson, Lurigio, & Albertson, 2001). Finally, there is

also a key component (8) which specifically calls for integrating monitoring and

evaluation mechanisms into overall court operations as well.

Case studies of the extent to which drug courts have effectively implemented the 10 key

components into daily practices are mixed but largely positive. Whereas sentencing and

other dispositional issues may have previously been determined by sentencing guidelines,

criminal history, and the nature of the offense, drug court program decisions are based on

a much larger scope of information. Drug court teams often review a wide range of

information, including the offender’s urine analysis results, treatment progress, mental

health status, housing or community environment, education and employment, and family

situation. This results in a greater amount of information that the team processes, and

increased amounts of time, communication, and coordination among all drug court team

members (Olson, Lurigio, & Albertson, 2001). Administering drug court programs are

demanding and complex, and fully implementing all key components to an ideal level is

often difficult to achieve. Challenges facing drug courts come from all directions. In a

five-state survey of drug court judges and administrators, Nored and colleagues found

that besides securing operating funds, the biggest perceived obstacles to administering

drug court programs were lack of belief in drug courts by both offenders and law

enforcement, lack of political support, and lack of interagency cooperation and

communication (Nored, Carlan, & Goodman, 2009).

Still, drug courts have achieved significant levels of success despite challenges. Carey,

Finigan, and Pukstas (2008) evaluated eighteen drug court programs and found that all 10

key components were implemented in some form in all programs. However, certain

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

27 | P a g e

specific forms of implementation were more common than others, and could thus be

considered core practices of operational drug court programs (Carey, Finigan, & Pukstas,

2008). Other commentators have also identified core elements of drug court

programming and areas of variation across jurisdictions (Casey and Rottman, 2005),

prevalence and type of treatment services in drug courts (Taxman & Bouffard, 2002), and

key functions of case management within the drug court program environment

(Monchick, Scheyett, & Pfeifer, 2006).

Best Practices: Specific Areas

Overall Structural Administration of Programs

Because drug court programs span the criminal justice and health professions, finding

areas in which there is successful communication and shared assumptions and objectives

may be difficult to obtain in drug court programs (Olson, Lurigio, & Albertson, 2001).

Drug court team members need to speak a shared language that will help them identify

needs of offenders and coordinate effective strategies, and identify appropriate times to

meet on a regular basis. Best practices that can be particularly effective for streamlining

and improving team performance among drug court professionals include maintaining

high staff to participant ratios, maintaining small caseloads for staff members, providing

continual training and education for drug court personnel, and implementing

individualized case management and treatment (Peters & Osher, 2004). These standards

are, however, difficult to obtain and/or maintain in the context of most drug court

programs and associated service providers. Treatment staff are often over-worked,

underpaid, and experience high levels of stress and burn-out that can lead to high turn-

over rates (Gallon, Gabriel, & Knudsen, 2003; Woltmann et al., 2008). Drug court

program coordinators should be prepared to continually seek funding streams that support

a fully-functional program, and engage in ancillary activities that demonstrate program

efficacy to potential supporters in the policymaking and philanthropic arena.

A comprehensive screening system should be developed at the point of entry, followed

by continuing assessment and monitoring for participants. Principal screening criteria

should be for drug use severity, mental health problems, motivation for treatment, and

criminal thinking patterns (Knight, Flynn, & Simpson, 2008). Studies have indicated,

generally, that drug courts are more successful for some types of offenders over others –

with outcomes varying on criminal history, type and frequency of drug use, social and

demographic characteristics, and other factors (Butzin, Saum, & Scarpitti, 2002; Hartley

& Phillips, 2001; Schiff & Terry, 1997). Using standardized intake and assessment

mechanisms, a proper screening and assessment system will either divert-out offenders

who are likely to fail in drug court to more appropriate programs, or properly match

incoming offenders into the most suitable drug court treatment track after entry (Johnson,

Hubbard, & Latessa, 2000).

Cultural competency education should be integrated into trainings for drug court staff and

associated service providers. Program coordinators should regularly assess cultural

competency strengths and weaknesses. Although many drug court participants may share

some socio-economic characteristics such as low levels of education and poverty-related

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

28 | P a g e

circumstances, studies have shown that African Americans and other minorities may have

less positive drug court outcomes than whites (Brewster, 2001; Butzin, Saum, &

Scarpitti, 2002; Dannerbeck, Harris, Sundet, & Lloyd, 2006). Women and young

offenders also experience particular circumstances that might impose barriers to

successful drug court outcomes. Women offenders may be more likely than men to have

child care-taking responsibilities, less education, more employment problems, high rates

of mental health problems, and be victims of sustained physical, emotional, or sexual

abuse as adults or children (Dannerbeck, Sundet, & Lloyd, 2002; D’Angelo, & Wolf,

2002; Grella, 2008). Juvenile offenders may have motivational or anti-social problems

that impede willingness to follow drug court orders and work with staff (Lutze & van

Wormer, 2007; Whiteacre, 2004b; Winters, 1999). Drug court staff should regularly

assess how a participant’s cultural characteristics might impact their behavior and

performance in the program (Osborne, 2008). Additionally, drug court staff, including

judges, must be cognizant of the possibility that employing standard treatment regimens

across populations with varying characteristics and backgrounds may lead to disparate

results.

Role of the Judge and Issuing of Rewards/Sanctions

The judge plays a key role in drug court programming by regularly interacting with and

monitoring the offender through treatment progress and drug monitoring, and issuing the

applicable rewards or sanctions. Much research has been conducted on the importance of

the judge and judicial hearings on drug court outcomes. Findings have been mixed in

regards to the frequency with which judicial interaction or the number of judges involved

in a single offender’s case impacts outcomes (King & Pasquarella, 2009; National

Institute of Justice, 2006). Nonetheless, there is a general consensus that frequent and

regular involvement of a judge in monitoring offender progress and serving a leadership

position within drug court teams is essential to programming success (Marlowe,

Festinger, & Lee, 2004; Marlowe et al., 2003, 2008; National Institute of Justice, 2006).

As the most visible and powerful authority figure within the drug court setting, the judge

plays the critical role of issuing sanctions or rewards based upon the flow of information

provided by treatment providers, probation officers, prosecutors, and defense attorneys.

Positive reinforcement offered by judges is an important counterforce to relapse. Judges

should strive to offer positive reinforcement when due, as well as recognize

unsatisfactory behavior and areas that need improvement in judicial hearings. Praise from

a judge can be particularly effective with individuals who have low self-esteem or have

experienced hardships in their lives, and serves as a model for the rest of the drug court

team (Stitzer, 2008). In addition, research indicates judicial involvement is particularly

important for high risk participants (Marlowe, Festinger, & Lee, 2004).

In issuing positive reinforcement, judges should clearly 1) identify target behaviors for

the offender in question (i.e., regularly attend treatment or UA appointments, refrain from

relapse, comply with probation orders); 2) identify reinforcements to incentivize

improvements or positive behavior (i.e. verbal praise, gift cards); and 3) escalate

schedules of incentives if warranted. Tangible incentives such as vouchers or prizes are

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

29 | P a g e

recommended and have been shown to support positive behavior change (Lussier, Heil,

Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006; Stitzer, 2008; Stitzer & Petry, 2006).

Judges should also be equally clear in the issuing of sanctions. A lack of clarity or

ambiguity in informing offenders about the consequences of negative behaviors in drug

court can lead to misinterpretation or frustration that might undermine program

objectives. Violations should be defined in as tangible a way as possible, such as in

positive UA results, non-attendance of appointments or treatment sessions, failure to

appear, etc. Clear notification of sanctions being issued for identified infractions will

serve as a guide for offenders to improve their behavior (Marlowe, 2008; Marlowe,

Festinger, Foltz, Lee, & Patapis, 2005; Marlowe & Kirby, 1999). Issuing of sanctions

must be immediate upon awareness of violations. Thus, it is incumbent upon drug court

staff to systematically monitor and document an offender’s behavior and communicate

progress to the rest of the drug court team. Regular UA procedures are essential for

monitoring substance abuse, and procedures should be created for both regular and

random, unexpected UA (Marlowe, 2008).

In the issuing of sanctions, it should be noted that offenders will react best when they

understand why sanctions were administered and that they were administered as part of a

fair process. Offenders should be treated with dignity, and given an opportunity to air

their voice in response (Lindquist, Krebs, & Lattimore, 2006; Marlowe, 2008). This again

illustrates the importance with which interaction with a judge is a critical component of

the drug court process. Judges should be cognizant that some infractions may be

deliberate violations with court orders, whereas others may be related to poor treatment

progress. Judges should be prepared to make this distinction when considering sanctions

and how to best respond to program violations (Arabia, Fox, Caughie, Marlowe, &

Festinger, 2008; Marlowe, 2008).

Treatment

Drug courts should employ treatment programs known to have a theoretical and

evidence-based basis for effectiveness. The employment of cognitive-behavioral

approaches in treatment is one example of a treatment regimen commentators have

recommended for use in drug court programs (Johnson, Hubbard, & Latessa, 2000). The

National Institute of Justice specifically recognizes cognitive behavioral therapy as an

effective approach for use in drug court programs (National Institute of Justice, 2006).

Cognitive-behavioral approaches are widely varying and easily adaptable, and aim to

build an offender’s cognitive skills in areas that may contribute or lead to criminal or

substance abuse behavior (Lipsey, Landenberger, & Wilson, 2007).

Studies have found that cognitive-behavioral strategies are effective in working with drug

and alcohol abusers (Bouffard & Taxman, 2004; Taxman, & Bouffard, 2003). A

particular variant – Relapse Prevention Therapy – is recommended as a theory-based

form of treatment that has been successfully employed among offender populations

(Marlatt, Parks, & Kelly, 2008; Porporino, Robinson, Millson, & Weekes, 2002).

Cognitive-behavioral approaches might be particularly effective for certain types of

populations, such as methamphetamine users (Lutze & van Wormer, 2007) and high-risk

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

30 | P a g e

offenders (Marlowe, D., 2003). They have also been shown to be generally effective in

reducing recidivism and anti-social behavior (Beck & Fernandez, 1998; Welsh &

Farrington, 2006). An NIJ assessment analyzing components of successful drug court

programming concluded that cognitive skills-based treatment should be employed, and

that programs which use incompatible forms of treatment, or a “scatter-shot” form of

treatment (e.g. combining a 12-step approach with cognitive behavioral therapy), without

a theoretical and evidence-based basis may be ineffective (National Institute of Justice,

2006).

Providing a continuum of care in court-ordered treatment is essential to drug court

programming success. Treatment should be integrated into court operations, and

treatment staff should consider providing training sessions to judges, prosecutors, public

defenders, and probation officers so they have an understanding of the treatment process.

Tying court room procedures to treatment outcomes is critical because program fidelity is

structured around progress in treatment and the subsequent issuing of court-ordered

rewards of sanctions (National Institute of Justice, 2006). Although flexibility should

exist for individual offenders, general principles and guidelines should exist on a formal

basis for courts to issue rewards or sanctions based on treatment outcomes. Formal

agreements between drug court programs, treatment providers, and providers of ancillary

services (vocational skills training, etc.) are helpful to institutionalize regular

communication and tracking of program participants through treatment (National

Institute of Justice, 2006).

Investigations into treatment efficacy continue. Henggeler and colleagues evaluated

outcomes among juvenile offenders in four randomly assigned conditions to assess the

effectiveness of evidence-based treatments: family court, drug court, drug court with

multi-systemic therapy (MST), and drug court with multi-systemic therapy combined

with contingency management (CM). They found that outcomes for criminal behavior

were mixed, but that the drug court treatments combined with the increased use of

evidence-based treatment regimens were most effective for reducing substance abuse. In

other words, drug court with MST and CM was most effective, followed by drug court

with MST, drug court, and finally, family court (Henggeler et al., 2006).

It should be noted that research does exist which supports the notion that gender-based

treatment approaches may be successful for women. Women offenders often have high

rates of co-occurring disorders, and/or have experienced significant levels of violence,

abuse, or other forms of trauma which contribute to substance abuse and criminal

behavior (Dannerbeck, Sundet, & Lloyd, 2002; D’Angelo, & Wolf, 2002; Grella, 2008).

Women-centered treatment programs need to integrate pregnancy and child-caring needs,

and address histories of trauma or abuse into programming and services. Additionally,

because women may often have less education or employment-related skills than men, it

is important that adequate educational and vocational skill trainings be integrated into

treatment programs for female offenders (Bloom, Owen, & Covington, 2003; Fallot, &

Harris, 2002; Grella, 2008).

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

31 | P a g e

Co-occurring disorders

Studies have indicated that individuals entering the criminal justice system have much

higher levels of co-occurring disorders than the general population, which in turn can

serve to inhibit compliance with legal orders, participation in treatment programs, and

successful re-entry into communities (Abrams, & Teplin, 1991; Chandler, Peters, Field,

& Juliano-Bult, 2004; Steadman et al., 1999). This heightens the importance with which

drug court teams are able to understand the complex, and often highly-individualized

relationships between an offender’s substance abuse behavior, mental or emotional health

state, criminal behavior or post-criminal behavior, and overall social situation (Peters &

Osher, 2004). As many as a third of drug court participants may have co-occurring

disorders (Peters, 2008).

Peters and Hills (1997) have suggested that screening for key mental health criteria are an

important first step for determining whether or not an offender with co-occurring

disorders should be admitted into a drug court program. Drug court programs may not be

appropriate for offenders with delusions or paranoia, suicidal thoughts, inability to

interact in group treatment environments, inability to comply with treatment regimens,

and inability to interact effectively with drug court team members. However, drug courts

can also be appropriate for some offenders with co-occurring disorders if the correct

resources exist for them (Peters & Hills, 1997). Peters and Bartoi (1997) suggest

bifurcating screening of participants into drug court programs and assessment after entry.

At the point of screening for entry, drug court personnel should consider an offender’s

type and severity of co-occurring disorders, severity of criminal charges and criminal

history, motivation for recovery and change, and availability of internal and external

resources that would assist an offender to participate effectively in a drug court program,

such as access to mental health services, case management, material needs, and social

support (Peters & Bartoi, 1997; Peters & Osher, 2004). Continual assessment after entry

gauges an offender’s abilities to effectively participate in drug court programming, and

what special needs or services are or are not required. Peters (2008) has recommended

specific evidence-based instruments for both screening and assessment of co-occurring

disorders for drug court participants.

Although individuals with co-occurring disorders may pose extra challenges for drug

courts, drug court programs may be optimal environments for some offenders with co-

occurring disorders, and many such offenders have successfully graduated from drug

court programs (Peters, 2008). Drug courts should expect offenders with co-occurring

disorders to form a significant portion of their program population, and adopt suitable

guidelines and practices for them. Drug court programming has been established for such

offenders (Redlich, Steadman, Monahan, Robbins, & Petrila, 2006; Sage, Judkins, &

O’Keefe, 2004). Recommendations for drug courts include specialty training and

education about mental health and co-occurring disorders to all staff; establishing

communications with community mental health practitioners, agencies, and emergency or

transitional housing agencies that work with mentally ill offenders; and a willingness to

allow flexibility in the application of sanctions and rewards to individuals with co-

occurring disorders.

Nebraska Problem Solving Court Evaluation

32 | P a g e

An Overview of Problem-Solving Courts in Nebraska

Methods for approaching program review

The evaluation team conducted individual reviews of all operational problem solving

court programs in Nebraska from October 2010 to February 2011. A total of 22 programs