MAY

20

23

FTA Report No. 0245

Location-Based

Service Data for

Transit Agency

Planning and

Operations

Market Scan and

Feasibility Analysis

PREPARED BY

John A. Volpe National Transportation

Systems Center

COVER PHOTO

Courtesy of Adobe Stock # 464958739

DISCLAIMER

This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of

information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States

Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because

they are considered essential to the objective of this report. The opinions and/or recommendations expressed herein do

not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Location-Based Service

Data for Transit Agency

Planning and Operations

Market Scan and Feasibility

Analysis

MAY 2023

FTA Report No. 0245

PREPARED BY

John A. Volpe National Transportation

Systems Center

U.S. Department of Transportation

55 Broadway

Cambridge MA 02142

SPONSORED BY

Federal Transit Administration

Oice of Research, Demonstration and Innovation

U.S. Department of Transportation

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

AVAILABLE ONLINE

https://www.transit.dot.gov/research-innovation/

a-reports-and-publications

Metric Conversion Table

SYMBOL WHEN YOU KNOW MULTIPLY BY TO FIND SYMBOL

LENGTH

in inches 25.4 millimeters mm

ft feet 0.305 meters m

yd yards 0.914 meters m

mi miles 1.61 kilometers km

VOLUME

fl oz fluid ounces 29.57 milliliters mL

gal gallons 3.785 liters L

ft

3

cubic feet 0.028 cubic meters m

3

yd

3

cubic yards 0.765 cubic meters m

3

NOTE: volumes greater than 1000 L shall be shown in m

3

MASS

oz ounces 28.35 grams g

lb pounds 0.454 kilograms kg

T short tons (2000 lb) 0.907

megagrams

(or "metric ton")

Mg (or "t")

TEMPERATURE (exact degrees)

o

F Fahrenheit

5 (F-32)/9

or (F-32)/1.8

Celsius

o

C

FEDERAL TR ANSIT ADMINISTRATION ii

Metric Conversion Table

Metric Conversion Table

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION v

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

Form Approved

OMB No. 0704-0188

1. REPORT DATE

May 2023

2. REPORT TYPE

Final

3. DATES COVERED

September 2021 – January 2023

The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing

instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of

information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing

the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215

Jeerson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no

person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number.

4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE

Location-Based Service Data for Transit Agency Planning and Operations:

Market Scan and Feasibility Analysis

5a. CONTRACT NUMBER

6. AUTHOR(S)

Jingsi Shaw, Lafcadio Flint, and Eric Englin

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESSE(ES)

John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center

U.S. Department of Transportation

55 Broadway

Cambridge, MA 02142

8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT

NUMBER

FTA Report No. 0245

9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Transit Administration

Oce of Research, Demonstration and Innovation

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE, Washington, DC 20590

12 . DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Available from: National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springeld, VA 22161; (703) 605-6000, Fax (703) 605-6900,

email [[email protected]v]; Distribution Code TRI-30

14. ABSTRACT

This report provides a primer on location-based service (LBS) data and its uses in public transportation. It denes LBS data, describes the

techniques for collecting and processing the data, and the key parties involved. The report highlights opportunities, limitations, and potential

risks of using LBS data, based on the literature and interviews with transit agencies, data providers, and data privacy experts. Finally, this report

provides recommendations to transit agencies on the prudent, safe, and eective use of LBS data.

15. SUBJECT TERMS

Analysis, Analytics, Data, Data Science, Location-based Services, Innovation, Planning, Privacy

a. REPORT

Unclassified

b. ABSTRACT

Unclassified

17. LIMITATION OF

ABSTRACT

Unlimited

19a. NAME OF RESPONSIBLE PERSON

5b. GRANT NUMBER

5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER

c. THIS PAGE

Unclassified

16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF:

18. NUMBER

OF PAGES

41

19b. TELEPHONE NUMBER

Standard Form 298 (Rev. 8/98)

Prescribed by ANSI Std. Z39.18

13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES [www.transit.dot.gov/research-innovation/fta-reports-and-publications] [https://www.transit.dot.gov/about/research-

innovation] [https://doi.org/10.21949/1527658] Suggested citation: Federal Transit Administration. Location-Based Service Data for Transit

Agency Planning and Operations: Market Scan and Feasibility Analysis.

Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Transportation, 2022.

https://doi. org/10.21949/1527658.

10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S)

FTA

11. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S REPORT NUMBER(S)

5d. PROGRAM NUMBER

5e. TASK NUMBER

5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 Executive Summary

3 Section 1 Introduction

8 Section 2 Methodology

10 Section 3 Key Findings

17 Section 4 Feasibility Analysis

24 Section 5 Recommendations

27 Appendix A Stakeholder Interviews

30 Acronyms and Abbreviations

31 References

LIST OF FIGURES

3 Figure 1-1 Passively Collected Mobile Device Data Sources

6 Figure 1-2 LBS Data Ecosystem

7 Table 1-1 Major Data Measures from LBS Data

8 Table 2-1 Major Transportation Planning Documents Reviewed

9 Table 2-2 Agencies Interviewed and Ailiated Role

12 Table 3-1 Major Existing/Proposed LBS Data Use Cases by Interviewed

Transit Agencies

21 Table 4-1 Comprehensive Data Privacy Laws

LIST OF TABLES

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION vii

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by the Technology, Innovation, and Policy Division

of the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) John A. Volpe National

Transportation Systems Center under sponsorship from the Federal Transit

Administration (FTA) Oice of Research, Demonstration, and Innovation. The

authors thank the project team from FTA: David Schneider, Ken Cervenka, and

Je Roux. The authors also wish to thank the individuals interviewed for this

report, who oered insights based on their experience in transit agencies across

the country, big and small.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION viii

Abstract

This report provides a primer on location-based service (LBS) data and its

uses in public transportation. It defines LBS data, describes the techniques for

collecting and processing the data, and the key parties involved. The report

highlights opportunities, limitations, and potential risks of using LBS data,

based on the literature and interviews with transit agencies, data providers, and

data privacy experts. Finally, this report provides recommendations to transit

agencies on the prudent, safe, and eective use of LBS data.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 1

Executive Summary

Anonymized and aggregated data from smart phones and other location-

aware devices can be used to infer information about people’s travel patterns,

including trip origins and destinations, modes of transportation, when trips

occurred, and overall travel times. However, most transit agencies continue

to rely on more traditional methods, such as automated passenger counter

(APC) devices, automated fare collection (AFC), ridership surveys, and census

data, to analyze travel patterns and identify potential transit riders. During

the pandemic, many transit agencies found that traditional data could not

quickly or accurately capture the disruptive impacts on ridership and are

exploring location-based service (LBS) data as a novel tool to better understand

travel patterns and travel demand going forward. This report summarizes the

experiences of transit agencies using LBS data to improve transit operations and

planning, lessons learned, key challenges and risks.

Through interviews and information reviewed, this report identifies the

following key findings:

• Transit agencies have found promising use cases for LBS data, including

bus network redesign, improving bus operations, understanding mode

share and complete trips, emergency response, prioritizing investment,

and outreach/marketing. Bus network redesign is the most common use

case among all the interviewed agencies.

• Transit agencies work closely with data vendors to improve LBS data and

explore how to use the data to guide decision making. The agencies work

with aggregated information that data vendors process and generate

based on raw LBS data. None of the agencies used disaggregated data due

to three main reasons: 1) state data privacy laws, 2) privacy concerns, and

3) technical challenges associated with making sense of the data.

• Transit agencies may find the greatest success if they use LBS data to

supplement existing data streams and take steps to “ground truth” results.

• Although no transit agencies reported any privacy concerns raised by the

public, transit agencies are aware of LBS data-related privacy concerns.

• The data used by vendors may change as novel data sources used to

examine spatial and temporal patterns become available.

Transit agencies, industry experts, and privacy advocates caution that LBS

data comes with limitations: time and expertise are required to process and

interpret the information eectively; accuracy may be diicult to verify; some

demographic groups may be underrepresented, and LBS data raises concerns

about potential violations to individual privacy and civil liberties. While LBS data

have many constructive potential uses, it should also be used prudently and

safely. The report identifies the following key questions and recommendations:

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

How can a transit agency tell if LBS is the right tool?

• Network with early adopters to identify lessons learned and determine

how transit agencies use LBS data and what it takes to successfully use LBS

data to support the needs of transit agencies.

• Evaluate internal technical capacity and consider partnerships with

state departments of transportation (DOTs), metropolitan planning

organizations (MPOs), and academia to share insights and use the data

eectively. Consider conducting a pilot or trial before entering a long-term

contract.

What precautions can agencies take when working with LBS data?

• Develop methods to “ground truth” LBS data and seek to understand

vendor data aggregation and analytical methodologies to the greatest

extent possible.

• Establish strong internal controls for data management and privacy

protection and be prepared to answer questions from the public on data

bias and privacy.

• Stay abreast of ongoing technological and legal changes.

Transit agencies using LBS data should treat it as one investment in a portfolio

of many transit data products. LBS is an emerging data source for most transit

agencies and excitement about its potential for new insights should be balanced

with a healthy skepticism. If used wisely, LBS data can be a useful tool in a

transit agency’s analytic toolbox. Transit agencies should pay attention to the

changing landscape for tools or data sources that can be used to understand

people’s movements and activities without security, legal, or ethical concerns.

Section

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 3

Introduction

Purpose and Scope

Over the past decade, location-based service (LBS) data has been used for

a variety of academic, commercial, and public-sector purposes. During the

COVID-19 pandemic, location data has helped government and health oicials

understand people’s movements and risk exposure. Around the same time,

given that traditional data could not quickly or accurately capture the disruptive

impacts on ridership, many transit agencies started exploring LBS data as a

novel tool to better understand travel demand going forward.

This report provides a primer on LBS data and its uses in public transportation. It

defines LBS data, describes the techniques for collecting and processing the data

and the key parties involved. The report highlights opportunities, limitations,

and potential risks of using LBS data, based on the literature and interviews with

data privacy experts. Finally, this report provides recommendations to transit

agencies on the prudent, safe, and eective use of LBS data.

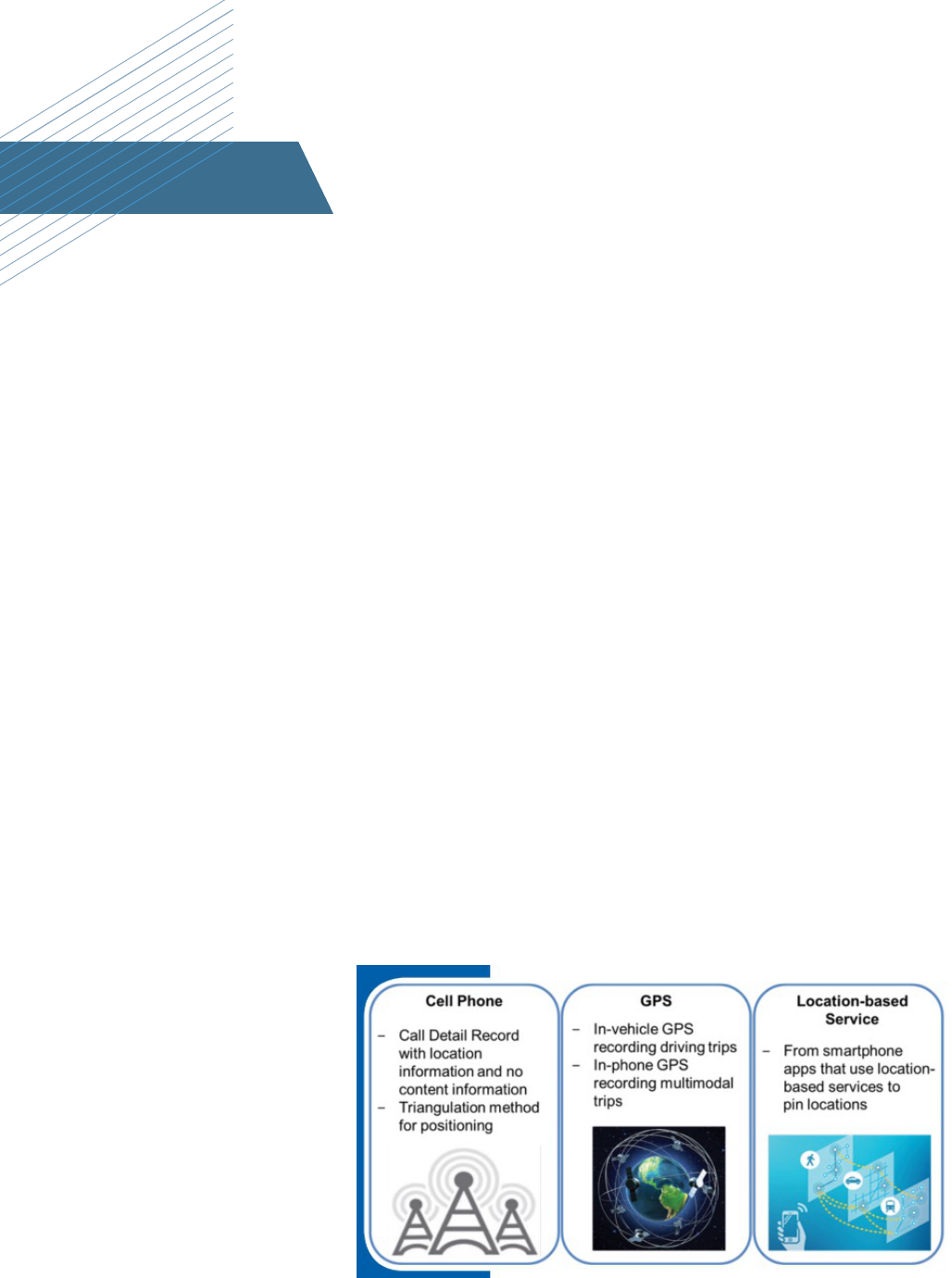

What is Mobile Device Location Data?

Mobile devices can collect data in a variety of ways. In some cases, the user

directly consents to the collection by responding to a prompt; alternatively, the

user may indirectly consent to the collection by simply using a particular app.

LBS data, similarly to cell phone and GPS data, are generated through passive

data collection. The accuracy of data varies by location data sources. The spatial

precision of in-vehicle navigation-GPS is three to five meters. LBS has five to

25 meters spatial precision, while that for cellular towers (cell phone data) is

100-2000 meters [1]. Passive data collection relies on continuous data collection

from the signals that mobile devices use. These signals are shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1 Passively Collected Mobile Device Data Sources [2]

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 4

SECTION

|

1

Location-Based Service Data

LBS data – the focus of this report – comes from a method where smartphone

providers determine the phone location using GPS, Wi-Fi, and cell phone

towers. These location data are packaged by smartphone providers for apps

– generally called Location Services on Apple and Google devices [3]. More

recently, smartphones have increasingly included more visibility for users to

know how this information is shared with dierent apps.

Raw LBS data consist of geographic coordinate locations across time for

dierent devices. Typically, these raw data are transformed into trip-level

data of origins and destinations based on when a mobile device begins to

dwell in a particular location. Private companies analyze these data to provide

information about the device user (e.g., home locations, work locations,

demographics of home location), and are increasingly able to assign the

transportation mode across trips. This is particularly relevant for transit

because it allows a better understanding of how transit relates to a person’s full

trip from origin to destination, and a person’s larger travel patterns.

Cell Phone Data

Traveler location data can be provided by cell phone carriers using triangulation

from cell towers. This provides a more generalized location than other

data types. Travel mode is diicult to infer using this data as device speed

measurements cannot be measured with detail. Cell phone carriers can supply

this data directly, but oen in a less processed format than what is available

from a third-party data vendor.

GPS Data

GPS data can be supplied from either vehicle navigation systems or mobile

devices. In general, mobile devices have their GPS data recorded by mobile

operating system developers, such as Apple and Android.

Other data sources

There are other emerging data sources that can provide location information

of travelers or vehicles which are not considered in this study. Some of these

data sources only collect data from specific modes (e.g., connected vehicles

or micromobility). Other sources include: 1) using dierent communication

technologies (e.g., Bluetooth and Wi-Fi), or 2) relying on users actively sharing

location and traic data through apps owned either by a transit agency or a

third-party company. A few examples include:

• Vehicle probe or connected vehicle data: Vehicles are increasingly able

to collect data while being driven. This can include origin-destination (O-D)

data and information on vehicle events while driving. Where vehicle trips

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 5

SECTION

|

1

are dominant in a region, vehicle data may be a substitute for LBS data, but

vehicle trips will not be able to provide information on trips taken on public

transit.

• Bluetooth and Wi-Fi data: Bluetooth Wi-Fi signals emitted by passing

devices can be collected via beacons. Devices generally change their media

access control addresses constantly, so the Bluetooth or Wi-Fi data are

not commonly used for trip-level or device-level analyses now that other

options are available.

• Fare collection apps: Some transit agencies have apps where transit

riders may pay their fares and learn more about the transit system. These

apps may be able to generate their own data from users. However, it is

not clear that any fare collection apps have demonstrated the ability to

collect suicient travel data to be useful in transit planning. This may be an

opportunity for future innovation for transit agencies.

• Active mobile device data collection: Not all smartphone apps passively

collect location information. Some apps, such as Strava and Waze, rely on

users that actively consent to their data being collected.

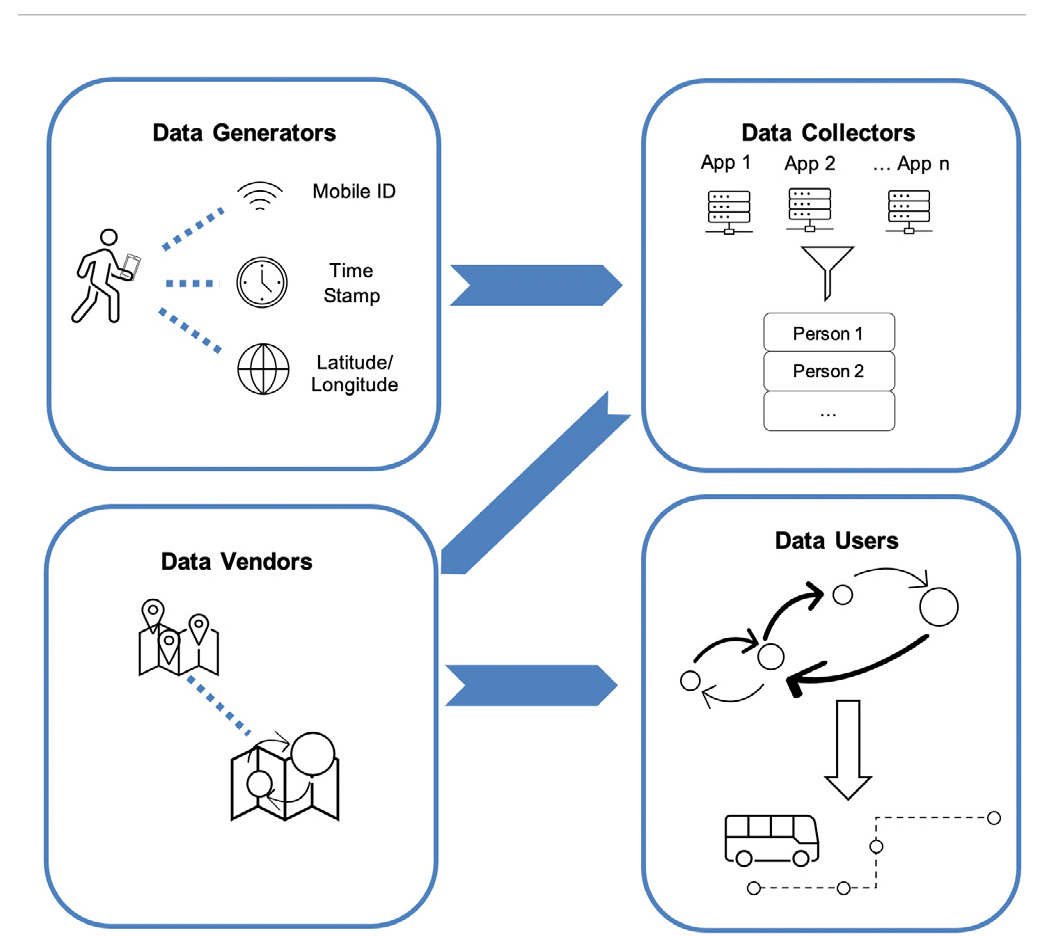

How Are LBS Data Collected?

Collecting LBS data requires an application that uses location-based service,

a position mechanism to collect geodata, a mobile network to transmit and

receive data, and soware running on a remote server to compute and deliver

relevant data to users based on geographic location. In a broad sense, the LBS

data ecosystem is composed of four parties: data generators, data collectors,

data vendors, and data users (See Figure 1-2). Data generators refer to cell

phone users whose data are passively collected by the LBS data collectors.

Data collectors (“middlemen”) combine, process, and sell the raw data to data

vendors, who then validate, analyze, and extract information on travel patterns.

Many vendors fit more than one of these supplier type categories. Data users

refer to entities, such as transit agencies, that rely on the insights generated

from the LBS data to make business decisions. Users may never touch the

disaggregated LBS data or know exactly which apps or technologies the data

are collected through.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 6

SECTION

|

1

Figure 1-2 LBS Data Ecosystem

How Are LBS Data Processed?

LBS data can be processed in various ways, depending on the data vendor

and its business model. In its most raw form, the data captures individual

coordinates from cell phone and GPS data. Another level of processing

combines these raw data with other information, such as survey data or data

from mobile applications. At the aggregated level, the data might be grouped

in an interactive dashboard that transit agencies can access to identify trends

such as O-D flows. LBS data is oen combined with other contextual data, such

as census data, ridership data, and road and transit network data, to provide

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 7

SECTION

|

1

useful insights to meet a transit agency’s needs. For instance, census data can

be combined with LBS data to analyze demographic characteristics of travelers,

and ridership data can help validate the modes assigned for dierent trips in the

LBS data.

Table 1-1 lists several key data measures derived or implied from LBS data, and

which rules are typically followed to derive those measures.

Table 1-1 Major Data Measures from LBS Data

Data Measure How Typically Calculated [4] [5]

Trips

When a mobile device remains in the same place for longer than a certain amount of time – for

example, 5-20 minutes – then a provider can generally assume that a trip has ended and the user is

now dwelling in a certain location. A new trip can be started when the user begins moving again.

Home and Work

Location

With longer periods of data, providers may be able to find patterns in where device owners spend

their nighttime and daytime hours. In general, providers can assign usual nighttime locations as

home locations and usual daytime locations as work locations.

Demographics

At a high level, providers can use two general approaches for demographics. Both begin by using

the census tract information for the device owner’s predicted home location.

1) Based on this census tract demographic information and other travel patterns, providers can

predict the device owner’s demographic information.

2) Provide the percentages of demographic information in a mobile device’s “home” census tract.

Mode Type

Providers can overlay the device’s speed and location onto a mapping service, such as

OpenStreetMap, to predict the mode type for any part of a trip. This can be aided using ridership

data from a transit agency. Mode options include bus, rail, bicycle, and pedestrian.

Section

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 8

Methodology

Literature Review

The project team reviewed literature on LBS data in transportation published

by transportation planning agencies, the private sector, and nonprofits. The

literature review included information on multiple types of mobile device data

and other sources of “big data” that could potentially complement or replace

LBS data. The project team reviewed dierent products from transportation

planning agencies, shown in Table 2-1. LBS data use cases are relatively more

established for personal vehicles, so this review included multi-modal uses.

Table 2-1 Major Transportation Planning Documents Reviewed

Title Agency Overview

Big Data for Regional

Travel and Mobility

Analyses [6]

Metropolitan

Washington Council

of Governments

(MWCOG)

MWCOG completed a study on the dierent big data available,

along with possible use cases and limitations of these data. The

evaluation included more than 20 big data products and how

they addressed the MPO’s programmatic needs.

Big Data Pilot Project

for Transportation

Planning: Replica [7]

Sacramento

Area Council of

Governments

(SACOG)

This series of documents covers SACOG’s methodology to create

the regional travel patterns based on LBS data from Replica.

Transit Bus Routing On-

Demand: Developing an

Energy-Saving System

[8]

Blacksburg Transit;

Virginia Tech

University

This report provides an analysis on reducing greenhouse gas

emissions from transit buses by using dynamic bus scheduling

and size selection. The project included creating a mobile

application that could generate data from users on rider locations

and destinations.

StreetLight Data Usage

at MnDOT [9]

Minnesota DOT

This presentation covers the major findings and use cases for

Minnesota DOT using StreetLight Data.

Comprehensive

Operations Analysis:

Existing Conditions

Technical Memorandum

[10]

Duluth Transit

Authority

Duluth Transit Authority conducted an analysis of bus operations.

The analysis used AirSage data to look at regional travel patterns,

including origin-destination of trips.

LA’s Plan to Reboot Its

Bus System-Using Cell

Phone Data [11]

Los Angeles Metro

Rail (LA Metro)

As part of the agency’s eort to boost ridership, LA Metro used

location data from 5 million cell phones to understand where

the service gaps are and how to restructure the work to attract

people who could ride a bus.

How We Used Data to

Design an Equitable Bus

Network [12]

Massachusetts Bay

Transportation

Authority (MBTA)

The Bus Network Redesign team at MBTA used LBS data, together

with other data sources (e.g., census data, rider surveys, land

use, and roadway data), to understand travel patterns and rider

needs.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 9

SECTION

|

2

Stakeholder Interviews

The project team used the results of the literature review to conduct

stakeholder interviews. Stakeholders included transit agencies, data vendors,

and data privacy experts, as shown in Table 2-2. The project team provided the

transit agencies and LBS data providers with a set of standard questions (See

Appendix B).

The project team identified transit agencies that had some previous experience

using LBS data for transit planning or operations. As of 2022, only a small

number of transit agencies have extensive experience integrating LBS data

into their planning and performance practices. These transit agencies tend to

serve larger metropolitan areas. The project team also aimed to include smaller

transit agencies that had a dierent perspective on resource constraints and

serving smaller populations or geographic areas.

The project team also interviewed other expert stakeholders to provide

additional context on LBS data. These included the major data vendors being

used by transit agencies today to understand some of the nuances in the LBS

data and analytical tools oered by each company. Expert stakeholders in

nonprofit and academia also oered a broader perspective of the potential

future risks of LBS data that transit agencies may face.

Table 2-2 Agencies Interviewed and Ailiated Role

Category Agency

Transit Agency

New Jersey Transit (Newark, NJ)

Alameda County Transit (Oakland, CA)

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (Boston, MA)

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (Washington, D.C.)

Los Angeles Metro Rail (Los Angeles, CA)

Duluth Transit (Duluth, MN)

Minneapolis Metro Transit (Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN)

King County Metro (Seattle, WA)

Data Vendor

StreetLight Data

Replica

Cambridge Systematics (Locus)

Data Privacy Expert

Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC)

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

Georgetown Law School, Center on Privacy and Technology

University of Washington, Department of Urban Design and Planning

Section

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 10

Key Findings

Data Vendors and Products

This section describes approaches to gathering, analyzing, and sharing LBS data

used by Cambridge Systematics, Replica, and Streetlight, the companies who

are the most common data suppliers to transit agencies in 2022. In addition to

the three vendors described in this section, there are other companies in the

field whose work/products are not discussed in this report.

Cambridge Systematics works with Place IQ, a location intelligence service

provider, to acquire anonymized LBS data. The company validates the data

against national-level travel behavior data [13]. It also oers consulting services,

including data acquisitions, processing, building interface, and providing

visualization. The company combines data collected through dierent sources

including data from transit agencies, such as APC and transit card data. Transit

agencies can understand trips by time of day, day of week, travel mode, trip

purposes, and traveler types via the dashboards developed by the company.

Replica is an online platform that provides granular information on travel

patterns, including network-link volumes, O-D pairs, and specific characteristics

of travelers, all of which is calibrated against “ground-truth” data to ensure

quality. The platform could help users understand travel patterns and

demographics of specific cohorts (such as transit riders, low-income residents,

or commuters), identify the characteristics of travelers who utilize certain

network segments, and monitor travel changes in near-real-time. Replica

oers data at multiple time horizons, ranging from weekly and seasonally to

long-term. Replica synthesizes a composite of data inputs, including LBS data,

connected-vehicle data from both personal vehicles and commercial freight

vehicles, points of interest (POI) and associated visits data, publicly available

and proprietary real estate data, payments data, and traic and transit

ridership counts. The company relies on the composite approach to reduce

sampling bias.

StreetLight Data provides online products to measure travel patterns of

vehicles, bicycles, transit riders, and pedestrians. StreetLight’s metrics are

primarily derived from the following data sources: LBS data, connected-vehicle

data, GPS data, data from vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian sensors, land use

data, parcel data, census characteristics (e.g., demographics, vehicle ownership,

housing density), road network, and characteristics from OpenStreetMap.

Streetlight allows users to select various types of customized zones for analysis,

such as block groups, or more specific areas like a city block or trail. Some

key industry standard metrics available in the platform are segment analysis,

routing, O-D volumes, speed, traic volumes, annual average daily traic, and

turning movement counts [5].

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 11

SECTION

|

3

Although the data vendors rely on similar sources of data, the ways that those

vendors process, analyze, and summarize the data vary in the following ways:

Data processing and analysis: Dierent data vendors combine LBS data with

dierent additional datasets and follow dierent analytical approaches to

process the data. Transit agencies can decide on customized geographic areas,

such as neighborhoods, transit hubs, or major corridors, and times to require

more specific data for their analysis. Data vendors are working with transit

agencies to continually improve their analytical process and outputs. If using

customized geographies, transit agencies might work out an agreement with

the data vendor for identifying the geographic scale for aggregating LBS data

and identifying several geographic zones for analysis. Additional variations

include:

• Time lag: some data vendors update their LBS data more frequently and

with shorter time delay compared with other vendors.

• Levels of customization: some vendors present their customized

dashboards and some of them work with transit agencies to add features

to suit their needs.

• Additional support: some vendors oer consulting services in addition

to an LBS data platform or oer access to less processed data outside of

the platform that agencies can either process on their own or work with a

contractor to process.

Transit LBS Use Cases

Transit agencies have only recently begun to use LBS data for planning and

operations. Of the transit agencies interviewed for this study, the first transit

agency began using LBS data in 2018. By comparison, in 2013, one year aer

StreetLight data became available, FHWA began its National Performance

Management Research Data Set (NPMRDS), which relies on vehicle probe data to

measure the performance of the National Highway System [14].

Several transit agencies interviewed mentioned that they first began to use LBS

data to develop a better understanding of travel patterns throughout a service

area by all transportation modes, in order to identify transit’s market size and

share (including region-wide and in specific corridors). Transit agencies also

hope to use LBS data to identify trip lengths, demographics of travelers, and

trips taken outside of a transit network. This information can help agencies

make informed planning and operations decisions.

In addition to using LBS data for exploratory analysis, agencies identified

specific use cases summarized in Table 3-1.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 12

SECTION

|

3

Table 3-1 Major Existing/Proposed LBS Data Use Cases by Interviewed Transit Agencies

Transit Use Case Description

Redesigning Bus Network

Analyze origin-destination for transit and non-transit users to understand regional

travel patterns, the impacts of disruption on the transportation network (e.g.,

COVID), emerging markets for new transit trips, and the potential to adjust bus

routes to better meet trip demands.

Improving Bus Operations

Identify on-time performance along certain bus routes or corridors throughout a

metro area. For current routes, this may be used to justify bus rapid transit (BRT) on

certain corridors. Another case is to guide transit signal priority decisions.

Improving Integration between

Transit and Other Modes (e.g.,

first-/last-service provision)

Understand market share of transit relative to other modes, such as driving and

Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) and use trip-level information to show

how transit networks relate to a person’s entire trip, including the first/last mile or

trips with multiple stops.

Prioritizing Investments

Better target investments, improve transit services at underserved communities, or

plan for last-mile trips. This would likely be used with the demographic information

generated by the data vendors.

Emergency Response

Understand incident response times and dynamics, which could be useful for power

outages, hurricanes, or other disasters.

Public Engagement/Marketing

Identify opportunities for public engagement (e.g., identifying places with large gaps

between predicted ridership and actual ridership, and then targeting these areas for

transit outreach and marketing).

Bus network redesigns are one of the primary use cases and the following

transit agencies that were interviewed have conducted or are exploring the use

of LBS data for service restructuring:

• Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA Metro) is

one of the early adopters in this area. The agency used LBS data from 5

million cell phones in LA County to understand traveler behavior. By using

the LBS data, together with fare card data, the agency identified service

gaps and supported bus route redesigns.

• The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) and

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) used a variety of data,

including LBS data and metrics, to understand where people travelled on

all modes and to design an equitable bus network.

• Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) used LBS data

to better understand non-transit travel following LA Metro’s experience of

using LBS data for bus network redesign.

• New Jersey Transit used LBS data to identify places/routes where more

resources were needed and where redesign was required.

• Minneapolis Metro used O-D patterns from LBS data to review bus service

to an area with residential and commercial properties.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 13

SECTION

|

3

Transit Agency Observations

1. Transit agencies have selected data vendors based on dierent

criteria including data ownership, transparency, specific data

elements available (e.g., mode share, demographic characteristics,

trip length), latency, and granularity.

a. Several transit agencies wanted to procure data so that the agency

can own the data and apply it to future work or share the data

internally or with peer agencies.

b. The capability to modify vendor data output and the approach taken

by vendors are both reasons for choosing a specific data vendor

versus another.

c. Some transit agencies mentioned that they were looking for specific

measures from the LBS data products, such as mode share (including

bike and pedestrian), demographic information associated with LBS

data, and trip length (especially short trips). Additional factors the

agency considered include how LBS data is processed and analyzed,

and whether it can be easily explained to the public.

d. How soon the data can be turned around and if the data are

suiciently granular to provide insights that transit agencies need are

additional key factors for selecting a data vendor.

2. Transit agencies oen access LBS data products through a

subscription. Some agencies purchase LBS data directly from a vendor,

while others go through a contractor that helps to process the data.

Some agencies partnered with neighboring agencies/MPOs/state DOTs

to secure licenses for surrounding areas. Subscriptions to LBS data and

services are oen for a one-year commitment.

Several transit agencies indicated that their MPO or state DOT also

purchased LBS data (some with the same data vendor and others with

a dierent vendor). Transit agencies may need to consider whether

they could share the subscription with other agencies or would need to

purchase their own subscription.

3. Transit agencies have worked closely with vendors. Transit agencies

reported they have worked with data vendors for help on how to use

LBS data and to ask questions about vendor methodologies. One transit

agency was able to use their own data to correct how the data vendor

defines specific concepts of race/ethnicity. Data vendors interviewed

have updated their products using transit agency feedback.

4. Processing LBS data can be time- and labor-intensive: Transit

agencies mentioned they still require sta with technical expertise to

work on LBS data even with assistance from a data vendor. Several

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 14

SECTION

|

3

transit agencies indicate that it took much longer than they planned to

process the data. Meanwhile, some agencies recognized that it requires

a bigger team to work on LBS data.

5. Transit agencies believe LBS data is a useful decision support tool.

One transit agency reported that they were able to understand travel

demand from LBS data, which helped guide their bus route redesign.

The agency was able to compare the transit service with other travel

modes and identified key turning points where transit became a less

attractive mode. Another transit agency mentioned its market vendor

was using LBS data and GTFS feeds to measure how many people in the

area could see bus ads/billboards.

6. Aggregated data can meet the needs of transit agencies. LBS data is

usually presented in a dashboard that may display zonal-level counts.

Agencies are also generally able to access deidentified data outside

of these dashboards; however, this requires additional processing

to make the data usable. Even though some transit agencies could

have access to disaggregated and anonymized LBS data through their

subscription service, interviewees reported they are not interested in

acquiring disaggregated data due to state data privacy law, privacy

concerns in general, and technical challenges associated with making

sense of the data. Agencies indicated that aggregated information can

oen suiciently answer their questions so there is no need to acquire

disaggregated data.

7. Customization may be needed. All the data vendors interviewed

provide user access via dashboards that visualize measures like O-D

patterns and allow users to download the data behind the dashboard.

Data vendors typically allow the data to be downloaded in CSV format

and viewed with visualization tools, such as PowerBI.

One data vendor mentioned that over 90 percent of projects can

be completed using the information on its platform without any

customized support from the company. However, some transit agencies

would like the data presented at additional levels of granularity and in

this case would need additional support. Agencies additionally noted

the need to process some data outside of what was displayed in the

vendor platforms, which can lead to incurring costs beyond the basic

subscription.

8. Transit agencies need LBS data to include transportation modes,

demographic characteristics of travelers, and time of day.

Identifying mode was important to several agencies. One transit

agency originally purchased O-D flow data but found it did not provide

suicient information.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 15

SECTION

|

3

9. The changing nature of the data has been an issue for some

agencies. External impacts, like term changes from mobile operating

systems, can lead to changes in how apps collect personal information

of users, which further influence vendor data outputs. One agency

mentioned that data structure changes on the vendor side could

cause the delay on utilizing LBS data. At the same time, data collection

methodology changes are usually an improvement, but need be

explained to other stakeholders.

10. There can be significant time investment to integrate LBS data

into existing systems. Several transit agencies identified having the

LBS data output to fit into the agencies’ existing workflow could be a

challenge. For instance, a transit agency may expect the LBS data being

generated at specific geographic scale to fit into their existing system.

11. Transit agencies expressed the following concerns about LBS data

validity and coverage:

a. Demographic characteristics of travelers can be challenging to

infer. Data vendors typically relate mobile device data to census

data and identify a traveler’s demographic information based

on the inferred home location (the location where the cell phone

user spends most of the nighttime). Some transit agencies raised

concerns on how demographic characteristics are assigned to

travelers. For example, if an area has a mix of households in dierent

racial or income categories, it will take additional information to

infer a traveler’s demographic information and could still be hard

to validate. Data vendors also recognized similar challenges when

identifying communities of color or tagging households with income

categories. There is a challenge in validating the inference at a very

granular level while retaining privacy.

b. Time thresholds used for determining when a trip ends may over-

represent short trips. One transit agency reported a discrepancy

between the O-D pattern for transit trips derived from LBS data

compared with the pattern the agency developed using its internal

data. The agency also raised questions about the time threshold

used to determine when a trip ends. For instance, data showing a cell

phone stopping in one place for a few minutes could mean that the

trip is complete, or it might mean that a traveler is waiting for a bus

or rail transfer.

12. Agencies reported that LBS data is still useful despite demographic

coverage caveats. Most transit agencies acknowledge that certain

demographic groups are under-represented or even excluded

from the LBS data, such as travelers over 85 or under 16. However,

some agency representatives noted that LBS data still provides a

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 16

SECTION

|

3

more comprehensive view of people’s travel patterns compared to

conventional datasets, so the sample bias is not a significant concern

for them. Some interviewees noted that the benefits of using LBS data

products outweigh the drawbacks.

13. Transit agencies have not experienced pushback from the public

regarding privacy. No transit agencies among the group interviewed

for this report reported any privacy concerns raised to them by

members of the public. All the transit agencies and data vendors

interviewed have been open with their methodologies of using and

analyzing LBS data. To protect the privacy of travelers, some data

vendors emphasize that, not only do they share travel data at the

aggregated level, but they also avoid capturing people’s visits to specific

locations, such as hospitals and rehab facilities.

14. Transit agencies are sharing their experiences and are draing

guidance for future uses. Some transit agencies mentioned that they

were working on developing guidance on how the LBS data can be

used and that they plan to make their information available to other

operators. One transit agency listed a few key questions for other

agencies to consider before procuring LBS data, such as asking for data

samples, conducting spot checks, and understanding data formats.

15. In the future, LBS data products may be influenced by external

factors, such as changes to Apple or Google privacy settings and

other terms and conditions. One data vendor’s service shut down for

a short period of time when Apple’s private policy changed. Some data

vendors indicated they have started adopting strategies to plan ahead

and mitigate the potential impacts of those external changes on their

service.

Section

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 17

Feasibility Analysis

This section provides analysis, recommendations, and other information for

transit agencies that are considering using LBS data.

Advantages

Transit agencies identified several key advantages of LBS data compared with

more traditional data. LBS data is good for understanding high-level traic

volumes across various modes. The data has more spatial coverage and better

temporal resolution. Compared with traditional travel survey data, which could

take up to five or 10 years to update, LBS data updates more frequently and can

capture disruptive changes in a timely fashion. LBS data is also available for

historical time periods, generally starting around 2017.

Relationship between LBS and Traditional

Transit Data

Some interviewees are optimistic that LBS data will eventually be able

to accurately identify trips made on dierent transportation modes and

dierent trip segments. However, none of the transit agencies or data vendors

interviewed consider LBS data as a replacement to travel surveys or passenger

counting systems, nor can LBS data provide information on trips not taken.

Travel surveys still provide key information for a number of other operations

and planning processes.

Technical Challenges

Despite rapid advances in the field of LBS, many challenges still exist,

including analysis of LBS, applications, evaluation, and privacy concerns [15].

The literature review and interviews highlighted the following key technical

challenges:

1. Transit agency interviewees and other stakeholders described LBS data

as a “black box,” where complex algorithms are used to combine many

data sources in dierent formats to calculate key statistical summaries

on trips and mode share.

2. Even though data vendors have been open and transparent about

the methods they use to identify individual trips and travel modes

associated with each trip, the information is still inferred from the data,

based on assumptions. Those assumptions could have caveats under

specific circumstances. For example, trips are generally determined by

the movement of the cell phone user. If the user remains in the same

place for longer than a certain amount of time, it will be treated as

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 18

SECTION

|

4

the end of a trip. Transit agencies found this could be problematic for

determining transit trips because transit users could be transferring

between vehicles.

3. Specific modes of interests to transit agencies, like walking and biking,

do not have suicient representation in the LBS data.

4. LBS data modelers combine the cell phone-based data with other

information (such as land uses, POI, census data, APC, and road and

transit networks) to understand travel patterns and make sense of what

the LBS shows in comparison to what transit agencies already know.

Data from dierent sources oen are collected at dierent points in time

and could lag behind the LBS data. In addition, delays between when

the datasets are prepared and when they are purchased can lead to out-

of-date information. One transit agency used 2019 data in 2022, which

le post-pandemic travel patterns out of the picture.

5. Transit agencies found that it is hard to determine which geographic

areas to designate for analysis. One transit agency noticed that

conventionally used geographic areas (e.g., census tracts or traic

analysis zones) dier from the actual transit layout in its region. The

agency provided the example of a bus stop that may serve the people

in a specific census tract, but the geographic location of the stop falls

outside of the census tract.

6. Evolving data sources and algorithms for analyzing LBS data make it

diicult to make year-over-year comparisons of the data.

Organizational Challenges

1. Transit agencies face challenges when choosing between data

providers. Transit agencies found it hard to compare the benefits and

costs of contracting with a specific data vendor because each vendor

has a dierent set of products and data processing procedures.

2. Transit agencies need sta with technical expertise to work

directly with LBS data. Although some agencies reported procuring

consulting services to use LBS data, interviewees mentioned that

sta with data science backgrounds or training for sta with more

traditional experience was necessary to use LBS data eectively. Transit

agencies whose sta have greater technical expertise could conduct

more exploratory work, whereas agencies with more limited technical

experience and resources would need to choose use cases with a limited

scope and more established history.

3. The cost-benefit tradeos of using LBS data are not well defined.

Although all transit agency representatives interviewed in this study

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 19

SECTION

|

4

reported that they found LBS to be a useful tool, no interviewee put a

dollar value or otherwise quantified the insights that the data provided.

The cost of using the data also varies, and includes sta time spent using

the data as well as the cost of a subscription. Smaller agencies who

find the cost of purchasing LBS data (which can run into the hundreds

of thousands) to be prohibitive may find a more aordable option in

partnering with a state DOT or MPO that has access to the data.

Bias, Misuse, and Privacy Concerns

Data from smart phones and other location-aware devices make it possible

to track the precise movements of millions of people. At the same time, not

all people use cell phones, either because of age, aordability, or personal

preferences. Critics of LBS data have expressed two major concerns about the

practice: 1) the data may not be a representative sample of the population being

analyzed, and policy decisions based on LBS data may be biased against people

without cell phones; and 2) using LBS data supports an industry that poses

serious threats to privacy and civil liberties, even if the end user does not have

access to personal information. Privacy risks may vary depending upon which

LBS data have been acquired, how the data are used, and what constraints (e.g.,

regulations/laws on data privacy) are in place that transit agencies must take

into consideration.

Data Bias

LBS data captures travel behavior of cell phone users. Several prerequisites

include owning a smart phone, paying for cell phone/internet service that

provide full time service, and a good connection to a cell phone tower or

Wi-Fi network. This means specific demographic groups, such as school-aged

children or elderly, low-income, and rural residents, could be underrepresented

or ignored. The vendors interviewed in this study described methods to adjust

their results to account for under-represented populations. Transit agency

representatives interviewed did not raise demographic coverage as a major

concern. However, transit agencies using LBS data should be aware of the

perception of data bias.

Data Privacy and Misuse

LBS datasets may contain sensitive information and are at risk for misuse

and abuse by individuals that have access to the data. Data privacy experts

emphasized that, while raw data pose a direct and significant privacy risk,

data that have been processed may pose the same or greater privacy risk.

Companies processing LBS data to determine home and/or work location data,

and then appending additional data to the records such as demographics,

are re-identifying the individual and increasing privacy risk. Although transit

agencies may not have purchased disaggregated data, privacy experts

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 20

SECTION

|

4

cautioned that supporting the LBS industry over time could increase the odds

that abuse would occur “upstream.” Several data privacy experts interviewed

highlighted the potential risk that malicious actors may use LBS data for

harassment or stalking.

Data privacy experts also cautioned that aggregation itself can be challenging.

For example, areas with dierent population densities or neighborhoods with

specific demographic groups may require dierent levels of aggregation.

Households living in low-density areas require a higher level of aggregation

because there might be only a few households at a disaggregated geospatial

scale. Households from lower-income neighborhoods may also need a higher

level of aggregation. Their travel patterns are more uniquely identifiable

because they face more constraints on traveling; for instance, they may be

more likely to travel long distances, work late hours, and travel to particular

destinations for work or socializing.

In order to avoid misuse of the data to identify a specific household, larger

samples will be required to share similar travel attributes in order to protect

the activity patterns of low-income travelers. Privacy advocates noted that

re-identification of individuals in previously aggregated data is possible and

that even aggregated data can contain information to sensitive destinations

such as hospitals, drug rehabilitation centers, and abortion clinics. Data privacy

researchers pointed out that there is currently no assured way to anonymize

LBS data, because the geo-spatial traces of people over time provide enough

information to personally re-identify more than 95 percent of the population,

even when aggregated per hour and at the spatial level of cell tower [16]. With

this level of re-identification possible just from geo-spatial locations over time,

the privacy risk is high and prevalent, even if so-called 'personally identifiable

information' such as name or birthdate have been removed.

Public Perceptions and a Changing Legal Landscape

The Public is Concerned about Data and Privacy

The public is generally concerned with their online and oline activities being

tracked and monitored by companies and the government. A study conducted

by the Pew Research Center found that most Americans feel “their personal

data is less secure now, that data collection poses more risks than benefits, and

believe it is not possible to go through daily life without being tracked” [17]. The

major concerns that Americans have regarding personal data being collected

include:

• Lack of control over which data are being collected,

• Lack of understanding of who can access their online and oline data and

how data are being used, and

• Risks outweigh the benefits to an individual.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 21

SECTION

|

4

For LBS data, an earlier Pew study shows that as of April 2012, over 35 percent

of adult cell phone app users said they have turned o the location-tracking

feature on their cell phone due to privacy concerns [18]. These users were

worried about other people or companies being able to access their location

information. Public perception toward privacy is inherently dynamic because it

can change over time at the individual and societal levels. As people’s lives are

increasingly disrupted by personal information leaks, how privacy is defined

and evaluated may continue to change [19].

State- and Federal-Level Data Privacy and Consumer

Protection Laws

Studies tracking the state-level data privacy laws in the U.S. identified that,

as of 2022, five U.S. states had comprehensive data privacy laws in place [20],

including:

Table 4-1 Comprehensive Data Privacy Laws

State State Laws

California Cal. Civ. Code §§ 1798.100 et seq. (California Consumer Privacy Act

of 2018 (CCPA))

California Consumer Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

Proposition 24, approved Nov. 2020, eective January 1, 2023

Colorado Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1301 et seq. (2021 S.B. 190)

Connecticut 2022 S.B. 6 (Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring)

Utah 2022 S.B. 227 (Utah Consumer Privacy Act)

Virginia 2021 H.B. 2307/2021 S.B. 1392 (Consumer Data Protection Act)

Comprehensive state-level data privacy laws generally give residents the right

to know about what personal information is collected by a company and how it

is used and shared. The laws also generally allow for residents to request their

personal information from companies, request to have their data deleted, and

opt out of having their data sold to third parties.

California has led the establishment of consumer data privacy laws in the

country. The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) applies to

information that identifies, relates to, describes, and is (or could be) linked

with a particular consumer. De-identified data, publicly available data, and

aggregated data are exempt from CCPA. The law applies to businesses that

meet specific thresholds, such as processing data of 50,000 or more consumers,

and at least 50 percent of revenue coming from selling data. Under CCPA,

penalties for violators could be up to $7,500 per intentional violation or $2,500

per unintentional violation. Following the CCPA, the California Privacy Right Acts

(CPRA) has gone into eect on January 1, 2023. The CPRA include new rights,

such as giving consumers the right to correct inaccurate personal information

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 22

SECTION

|

4

that a company collected about them, and limiting the use and disclosure of

sensitive personal information [21, 22].

Some states have data privacy laws with moderate protective measures in

place, such as Nevada. The law generally mandates that websites must allow

Nevada consumers to opt out of having their personal information sold to third

parties. There are also states with even more limited restrictions for businesses

collecting personal information, including Vermont, Minnesota, Maine,

Delaware, Arizona, Missouri, Oregon, Hawaii, New York, and Tennessee. The

laws in those states may only focus on data collected on specific subgroups of

people, such as children [23].

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a data privacy law that

impacts all organizations that sell products and services to people in

the European Union, including American businesses. The GDPR requires

compliance by any entity that processes personal information of consumers,

with no revenue threshold, processing threshold, or broker threshold. The

consequences of non-compliance with the GDPR could be up to $20M or 4

percent of total annual turnover of the preceding financial year worldwide,

whichever is higher [24].

Although there is no data privacy and protection law enacted at the federal

level, H.R. 8152, the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA),

represents the latest attempt by Congress to introduce comprehensive federal

legislation regarding data privacy. The proposed ADPPA adopts a “data

minimization” strategy and lists 17 acceptable purposes for data collection and

usage. Moreover, using data for targeted advertising is subject to restrictions,

including:

• Sensitive data (e.g., health information, location, private messages) cannot

be used,

• Companies will be prohibited from tracking consumers using third-party

sites, and

• An opt-out process will be universally implemented.

If passed, it could require uniform compliance for all companies conducting

business in the U.S. On July 22, 2022, the House Energy and Commerce

Committee approved the proposed ADPPA. It is currently under discussion by

members of Congress [25].

Impacts of Term Changes by Apple and Android

to Limit LBS Data and Protect Privacy

Third-party trackers rely on an identifier (also known as an “ad ID”) associated

with each cell phone to collect location data. The identifier was unique,

permanent, and was frequently accessed by third parties without user

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 23

SECTION

|

4

knowledge or consent. Following lawsuits and investigations, companies like

Android and Apple started restricting the use of those unique identifiers. In

2021, Apple introduced App Tracking Transparency, which led to a significant

drop in the number of users opting in for tracking. Androids started rolling out a

way for users to turn o their ad ID. However, Android’s ad ID was still in use and

based on an opt-out basis as of April, 2022 [26]. Disabling ad ID makes it harder

for advertisers and data brokers to track an individual cell phone user. Although

removing ad ID will not stop all tracking, this is moving in the right direction to

protect individual privacy.

Section

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 24

Recommendations

Transit agencies who are considering using LBS data for the first time or who

are in the early stages of using the data may want to consider the following

approaches:

1. Learn from the “early adopters.” A growing number of transit

agencies, including those listed in this report, may be good sources of

lessons learned and these lessons will proliferate as use expands over

time. Studies such as the ones cited in this report’s literature review and

those published in connection with the Transportation Research Board

(TRB) may also be helpful sources of impartial information.

2. Develop internal technical capacity to evaluate and use the data

eectively. Although data vendors can provide technical assistance to

their clients, using LBS data involves some investment in information

technology resources, sta with data analytics or data science

backgrounds, and/or training for sta who lack these skill sets. Agencies

should consider whether they have the internal resources available and,

if necessary, make plans to invest in their technical capacity and/or work

with consultants.

3. Determine if LBS data is a priority for your agency and weigh the

costs of implementation. Understand the costs and benefits of using

LBS data and determine whether there is/are a specific problem(s) that

LBS data would help your agency solve.

4. Consider partnering with State DOTs, MPOs, and academia. Agencies

that lack extensive technical experience or financial resources to

purchase LBS resources directly may find it helpful to share a license

with a nearby MPO, state DOT, or colleges and universities to explore

transit use cases of LBS data.

5. Consider using LBS data on a limited basis or for a pilot project

before entering a longer-term arrangement. Agencies may want to

request a sample of the data and/or a trial period to better understand

how the data are organized and how they can be used. Using data for a

discrete pilot project, such as understanding travel along a particular

corridor instead of across the entire transit system, may be a useful first

step.

6. Seek to understand data vendor aggregation and analytical

methodologies to the greatest extent possible. Although some

LBS collection and aggregation methods are considered confidential

business information, important details (such as the methodology

used to split trips among modes, how LBS data is validated, how

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 25

SECTION

|

5

demographic information is inferred, and how vendors adjust their data

to compensate for underrepresented groups) are publicly available or

can be clarified in conversations with vendors.

7. Develop methods to “ground truth” LBS data, especially if using the

data to evaluate transportation mode splits. Agencies seeking to use

LBS data as a proxy for transit ridership should develop an approach

for comparing the LBS results against internal data, such as information

from APCs. Agencies may also want to share their results with LBS

vendors where discrepancies exist so that vendors can adjust their

models to improve accuracy.

8. Establish strong internal controls for data management and privacy

protection. Steps could include developing a privacy risk assessment

and protocol that evaluates an agency’s existing privacy policies and

strengths, as well as the risks that personally identifiable information

could be misused by agency sta or transmitted outside the agency.

Other risk mitigation measures include documenting which individual(s)

will have access to LBS data and for which projects the data will be used

before an agency begins working with the data, and having a dedicated

privacy oicer who can evaluate the benefits and risks of any data the

agency is using. Protecting LBS data can take place within an agency’s

comprehensive data management framework, which identifies and

classifies the datasets it uses; the data owners or stewards; access

rights; policies for sharing information externally; and procedures for

data storage, archiving, and preservation. Additional recommendations

for transit data privacy protection can be found in the Transportation

Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) report Data Sharing Guidance

for Public Transit Agencies Now and in the Future (2020). In addition, the

TCRP report The Transit Analyst Toolbox: Analysis and Approaches for

Reporting, Communicating, and Examining Transit Data (2021) includes

information and case studies on data management and governance.

In addition, agencies may want to reach out to privacy experts in

the academic community for advice or for assistance with further

anonymizing data. Privacy experts recommended using dierential

privacy tools to inject “noise” into the data as an additional preventive

measure. This approach has been adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

However, employing dierential privacy requires trained professionals

spending a significant amount of time and energy to process the data.

Also, there is a tradeo between privacy and accuracy when applying

dierential privacy to data.

9. Be prepared to answer questions about data bias and privacy.

Agency sta may encounter questions from agency leadership, board

members, or members of the public regarding whether LBS data

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 26

SECTION

|

5

excludes underrepresented groups or whether the agency has access

to the travel history of individuals. Agencies should be prepared to

describe how the data are being used, as well as the steps they have

taken to protect privacy and guard against data bias.

10. Stay abreast of ongoing technological and legal changes. Agencies

should seek legal counsel regarding any federal, state, or local laws

that govern the use of LBS data. Agencies should also bear in mind

that location-based privacy measures are being debated at the state

and national levels, and that technology companies are responding by

making changes to how they collect location data. Agencies working

with data vendors on an ongoing basis should consult with their vendor

on how new laws or technology company processes may have changed

the data they are receiving and how the data have changed over time.

11. Treat LBS data as one investment in a portfolio of many transit data

products. LBS data and more traditional sources of information are

not mutually exclusive. In fact, since agencies are interested in verifying

LBS data against internal records, they should strive to maintain and

improve their conventional sources of data. Agencies may also want to

consider developing (or taking advantage of) their own fare payment

and travel planning apps that could be used to gather location-based

data from riders who opt into sharing their information. These apps

could be a useful source of information if privacy considerations further

limit LBS data.

Appendix A

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 27

Stakeholder Interviews

Interview Guide for Transit Agencies

Context Framing Questions

1. What is your overall impression of the state of LBS data, particularly with

regard to its use in transit?

2. Are you using LBS data?

3. IF SO

Product(s)/Vendors

a. What product(s) are you using?

i. How did you select that vendor(s)?

ii. To what extent did you validate their data against alternatives

and/or existing/traditional data? What QA/QC have you

performed? How have you evaluated the data with respect to

equity/representation?

iii. What was the process for procuring and implementing LBS data

into your workflow? Timeline? Roadblocks?

Utilizing data

b. How are you using them?

i. Do you use the LBS data for service planning, scheduling,

performance monitoring or other purposes?

ii. What role does LBS data play? Does it replace existing data? Or

supplementing existing data?

c. What have been the results?

i. Advantages

1. Quantifiable benefits?

ii. Challenges/Limitations

1. What mitigation strategies have you considered/used?

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 28

APPENDIX

|

A

Recommendations/Lessons Learned

d. Recommendations to other agencies

i. What would you advise other agencies to do as part of their

market research? What questions should they ask of vendors?

What expectations should they have in approaching LBS data (in

terms of both capabilities and limitations)?

ii. What internal resources (sta, hardware/soware, data, etc.)

have been important?

Closing Remarks

e. Closeout/Next Steps

i. What resources and/or information would/could be useful from

FTA on this topic?

ii. Who else should we contact for this project (agencies, vendors,

experts)?

If Not Using LBS Data

a. Experience:

i. To what extent have you explored/evaluated its use?

ii. What platforms have you looked into?

b. Purposes of exploring LBS data: What needs/gaps were you looking

to address?

c. Challenges: What has kept you from investing in LBS data?

d. Closing remark:

i. What resources and/or information would/could be useful from

FTA on this topic?

ii. Who else should we contact for this project (agencies, vendors,

experts)?

Interview Guide for LBS Data Providers

Product(s)

1. What types of LBS-related products does your company oer (e.g., LBS

data only, data analysis, etc.)? What capabilities are you oering?

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 29

APPENDIX

|

A

2. How mature are those capabilities (i.e., are they available commercially

now or available more for beta testing/development now)? How do

capabilities evolve over time?

3. What is your goal for this product (in the next 5 years)?

Advantages/Use Cases

4. What advantages can transit agencies expect over conventional/existing

data sources?

5. Can you share examples of transit agencies using your data? If so, how

are they using it? What types of output metrics/insights can users

expect to extract?

6. What data sources are reflected in your product(s)? Where does your

company purchase LBS data and what level of process is the data in?

7. How are transit agencies and your company working together to

improve the quality and usefulness of the data provided?

8. What have you learned from your interaction with transit agencies?

What would be helpful from the agencies?

9. To what extent have you run into challenges working with transit

agencies (agency-based technical challenges, terms of use challenges,

skepticism/change management)?

Technical Questions

10. To what extent can agencies validate the accuracy of the data?

11. How do you protect privacy?

12. (How) do you account for representation among travelers who may not

own a smartphone?

Challenges/Concerns

13. What terms/limitations are typically applied to your product(s)?

14. What changes in technology may aect your ability to continue oering

LBS products? (e.g., changes to terms of service)

15. What do partnerships look like with customers?

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 30

Acronyms and Abbreviations

AFC Automated Fare Collection

APC Automated Passenger Counter

ADPPA American Data Privacy and Protection Act

CCPA California Consumer Privacy Act

CPRA California Privacy Rights Act

CSV Comma Separated Value

DOT Department of Transportation

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

FTA Federal Transit Administration

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation

GPS Global Positioning System

GTFS General Transit Feed Specification

LBS Location-Based Service

MPO Metropolitan Planning Organization

NPMRDS National Performance Management Research Data Set

O-D Origin-Destination

POI Points of Interest

TCRP Transit Cooperative Research Program

TNC Transportation Network Company

TRB Transportation Research Board

USDOT United States Department of Transportation

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 31

References

[1] StreetLight Data, "StreetLight InSight Metrics: Our Methodolody and Data Sources," 10 2018.

[Online]. Available: https://www.streetlightdata.com/wp-content/uploads/StreetLight-Data_

Methodology-and-Data-Sources_181008.pdf.

[2] FHWA Exploratory Advanced Research Program, "The Exploratory Advanced Research Program