Public

Records

Act

for Washington Cities,

Counties, and Special

Purpose Districts

Last Updated:

March 2019

Public Records Act

Copyright © 2019 by MRSC. All rights reserved. Except as permit-

ted under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication

may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means or

stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior written

permission of the publisher; however, governmental entities in the

state of Washington are granted permission to reproduce and dis-

tribute this publication for ocial use.

MRSC

2601 Fourth Avenue, Suite 800

Seattle, WA 98121-1280

(206) 625-1300

(800) 933-6772

www.MRSC.org

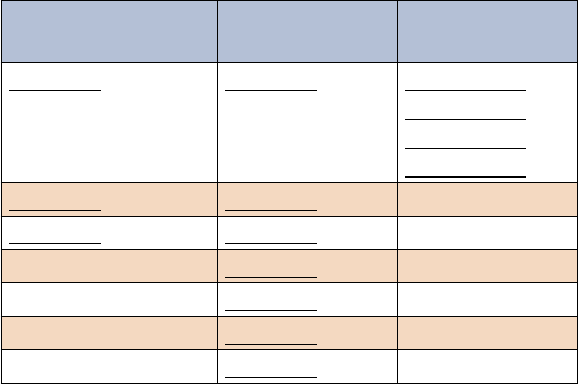

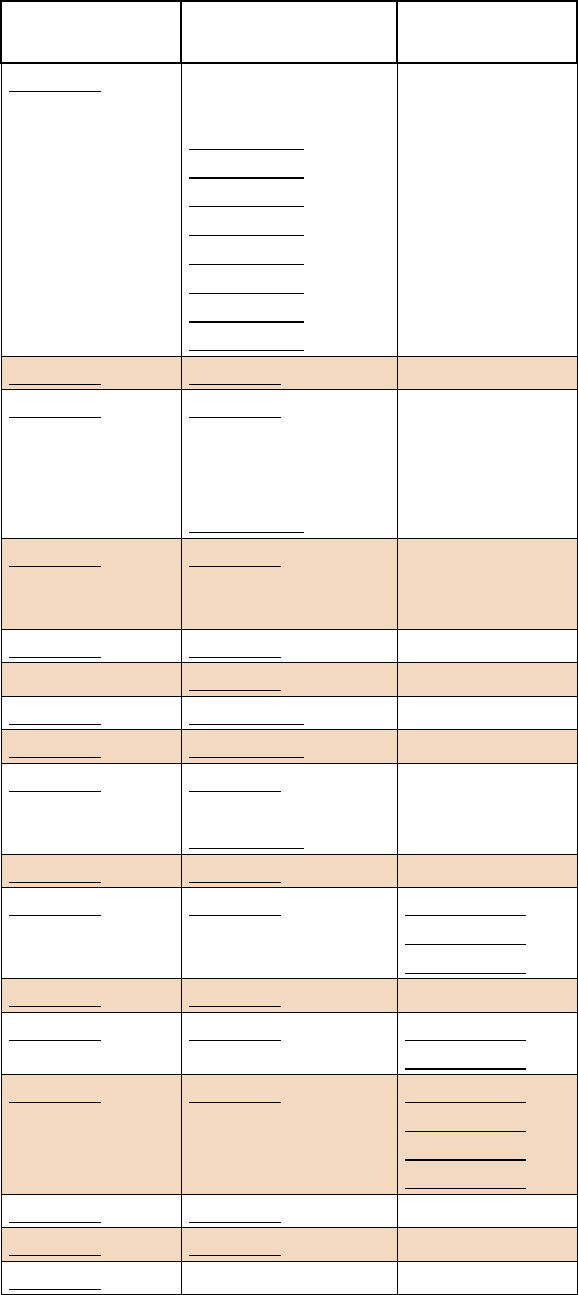

Revision History

March 2019

• Exemptions and Prohibitions: Updated list of common prohibitions and exemptions relevant

to local governments outside the PRA

• Appendix A: Added PRA related online resources

• Appendix C: Updated lists of state and federal exemptions and prohibition statutes not listed

in the PRA

Foreword

Because the legislature routinely updates the Public Records Act

statutes, and because the courts issue many decisions each year

interpreting the statutes, MRSC has chosen to update this publica-

tion as needed. e electronic version available here is our latest

version. If you like to use a printed copy, we recommend that you

print a new copy periodically, so that you have the benet of the

most recent updates.

Washington’s public disclosure laws apply to all Washington gov-

ernments, including counties, cities, towns, and special purpose

districts. We rst produced this publication in 1996 due to the

large volume of inquiries that the Municipal Research and Services

Center (MRSC) received over the years concerning public disclo-

sure. Since that time, numerous exemptions have been added to the

public disclosure statutes and the courts have issued many deci-

sions which aect the application of the statutes. We updated this

publication in 2004 to reect those changes.

Eective July 1, 2006 almost all of the public records disclosure

statutes, now called the Public Records Act, were recodied, neces-

sitating another revision of this publication in 2006. e disclosure

statutes used to be codied in chapter 42.17 RCW, but were recodi-

ed to a new chapter 42.56 RCW. Conversion tables for the statutes

are in Appendix B of this publication and will help you understand

references to the statutory numbering you might come across in

earlier court decisions and other documents discussing the public

records laws. Also included in the conversion tables, and in the

main text of this publication, are citations to the Public Records

Act Model Rules (which now include rules specically related to

electronic records). ose Model Rules are located in chapter 44-14

of the Washington Administrative Code.

is material is intended for use by local government employees

and ocials, and we have presented it in a format that we hope

will be easy to use and understand. For further research, we have

provided the reader with footnotes and appendices.

Special acknowledgment is given to Jim Doherty, Legal Consultant,

who prepared the original publication and oversaw this revision.

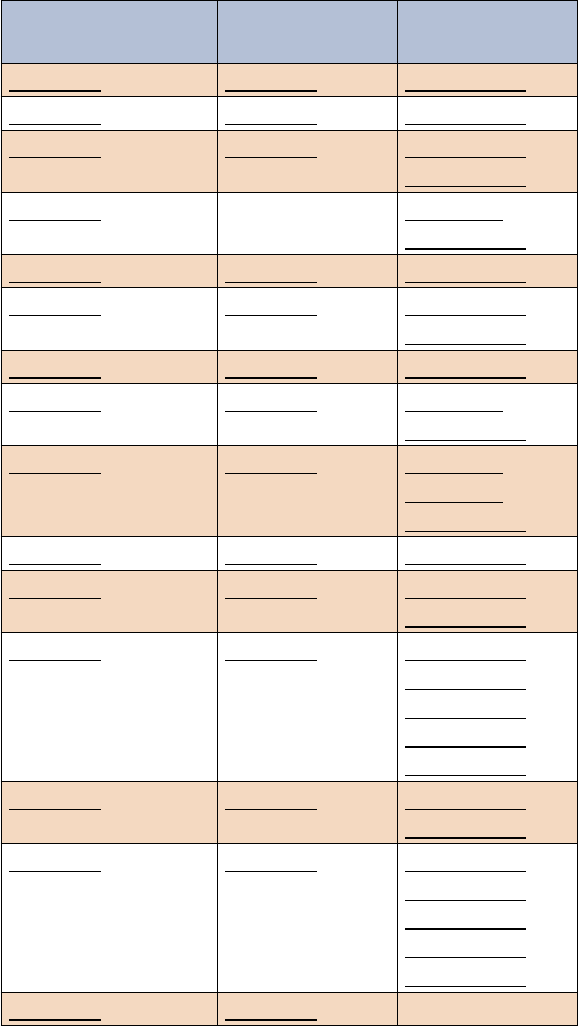

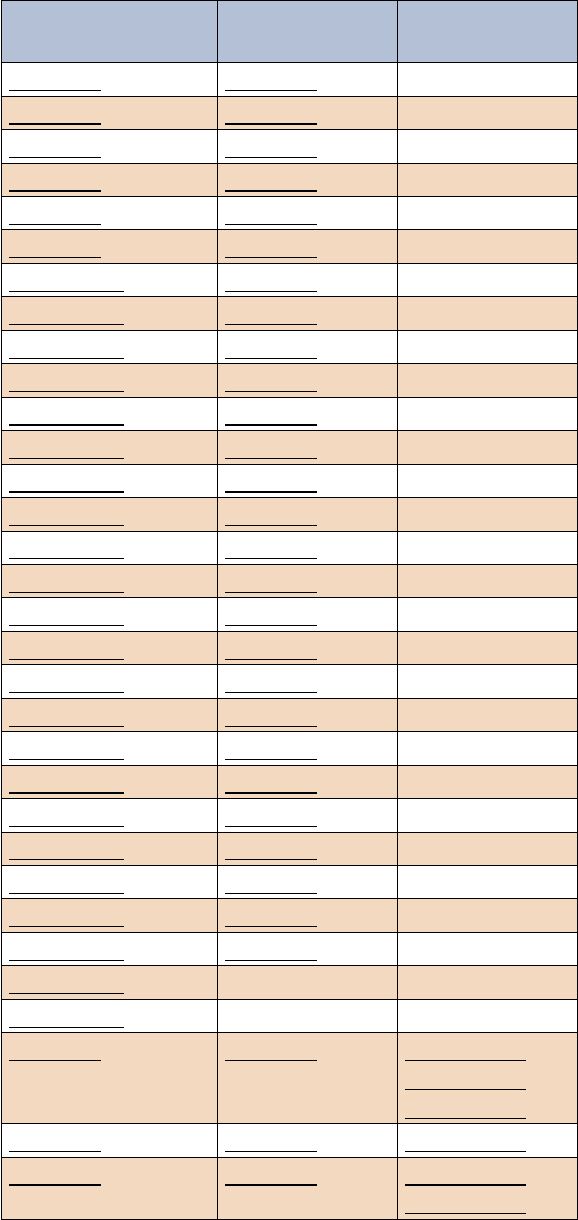

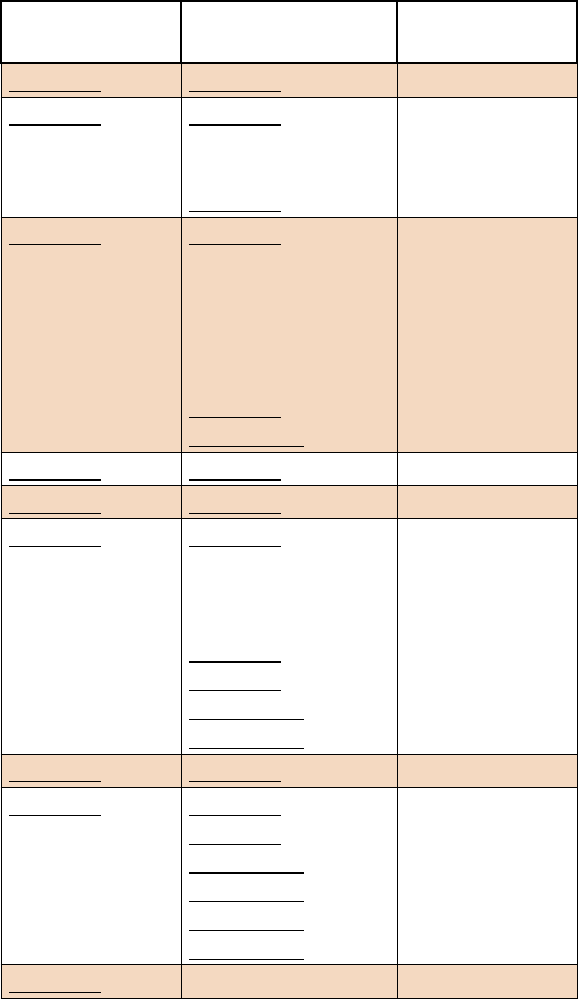

Contents

Introduction 7

Concerning the Public Records Act Model Rules 8

Public Records Exemption Accountability Committee 9

Government Records: Local Government’s Duty to Provide Access 10

Acting in Good Faith – Disclosing a Record in Error 11

Acting in Good Faith – Penalties, Attorney’s Fees, and Costs 12

What Are Public Records? 13

Electronic Data and Records 14

Determining What Must Be Disclosed Under the Public Records Act 16

Specific Exemptions and Prohibitions 16

Exempt Records and Redaction 28

Redacting Information in Records Made Available to the Public 31

Exemptions and Prohibitions Outside the Public Records Act 33

Criminal History, Juvenile, Sexual Offense, Jail and Inmate, and Law Enforcement Records 36

Criminal History Records – Chapter 10.97 RCW 36

Juvenile Records – Chapter 13.50 RCW 36

Sexual Offender Information – Chapter 4.24 RCW 36

Jail and Inmate Records – Chapter 70.48 RCW 37

Law Enforcement Records 37

Personnel Records 39

Inspection by Local Government Officials and Employees 41

Employee Inspection of Personnel File 41

Identity and Motivation of Persons Requesting Records or Lists – Does it Matter? 42

Prisoner Injunction Provision – 2009 Legislation 42

Lists of Individuals Requested for Commercial Purposes 42

Electrical Utility Records Sought by Police 44

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Data Requested for Commercial or Non-commercial Purposes 45

Procedures for Making Records Available for Public Inspection 46

Public Records Officer – RCW 42.56.580 46

Index of Records – RCW 42.56.070 46

List of Exemption and Prohibition Statutes Not Contained in Chapter 42.56 RCW 46

Form of Request – RCW 42.56.100 47

Protection of Public Records and Agency Functions – RCW 42.56.100 47

Times for Inspection and Copying – RCW 42.56.090 48

Charges for Copying – RCW 42.56.070(7), (8) and RCW 42.56.120 48

Deposits and Responding in Installments – RCW 42.56.120 49

Prompt Responses Required – RCW 42.56.520 49

Additional Time for Response – RCW 42.56.520 50

Unclear Request for Information – RCW 42.56.520 50

Denial of Request for Records Disclosure – RCW 42.56.520 50

Local Government-Initiated Court Action to Prevent Disclosure – RCW 42.56.540 51

Judicial Review of Local Agency Action – RCW 42.56.550 52

Penalties, Attorney’s Fees, and Costs If Local Government Loses in Court – RCW 42.56.550(4) 52

Retention and Destruction of Public Records 54

Preservation of Electronic Public Records 54

Appendix A: Recommended Resources 56

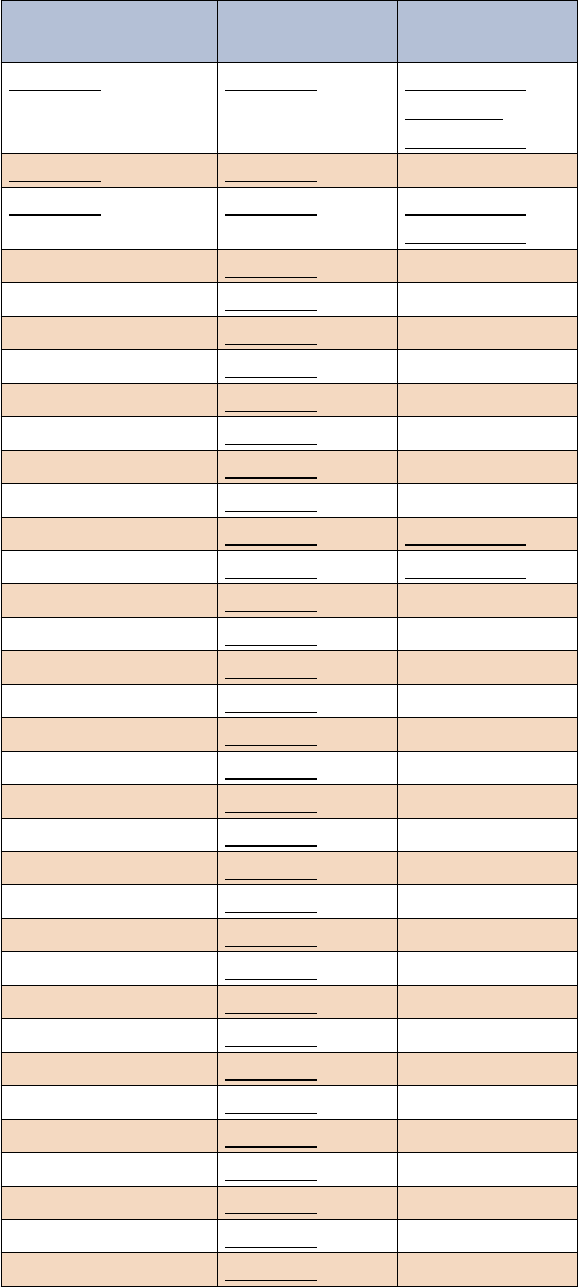

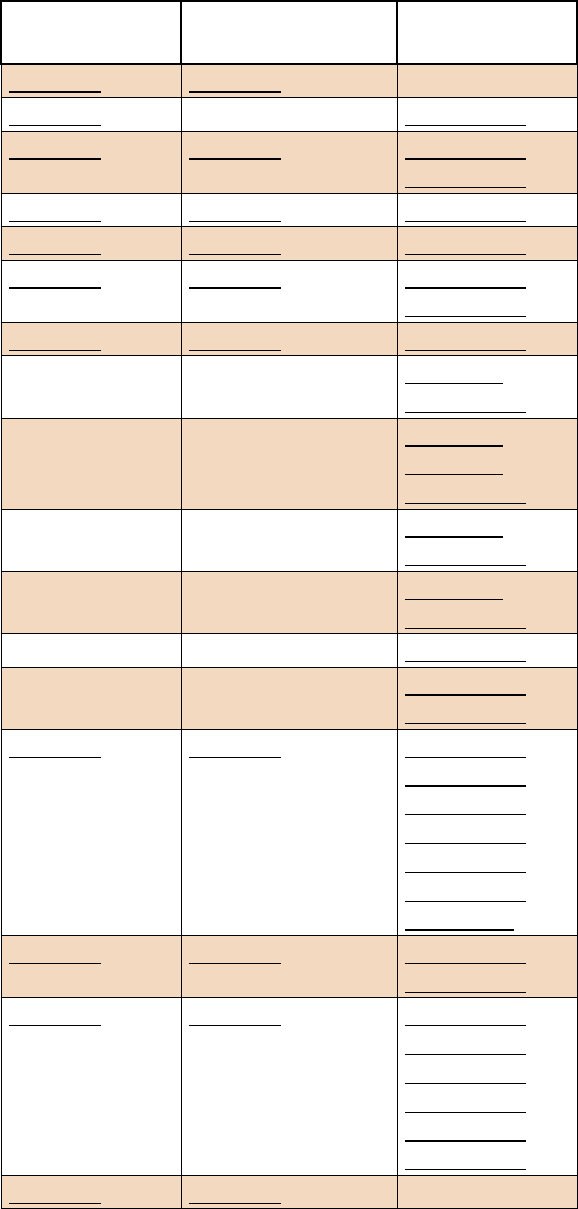

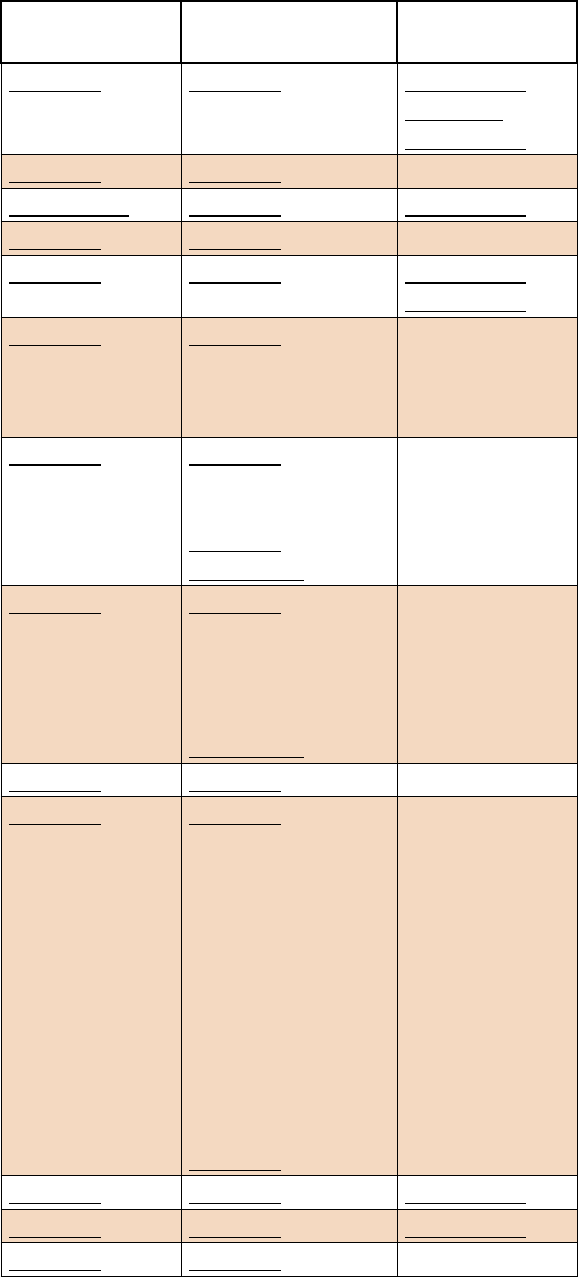

Appendix B: Cross-Reference Guide for 2006 Recodification 57

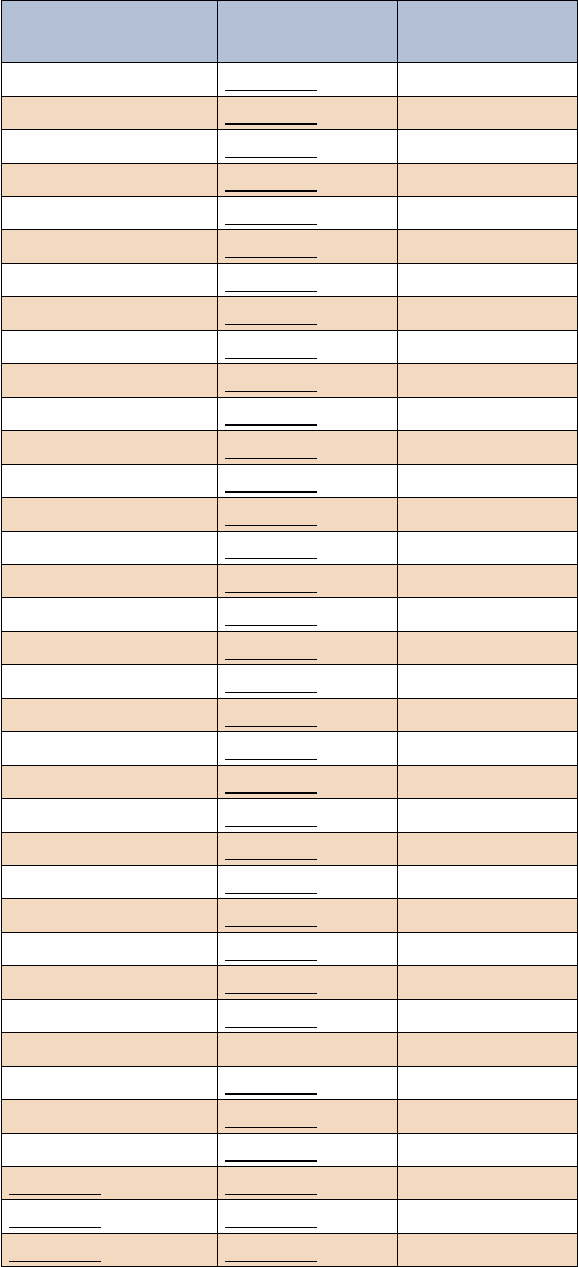

Appendix C: Exemption and Prohibition Statutes Not Listed in Chapter 42.56 RCW 67

7Public Records Act

Introduction

In 1972 the voters in state of Washington adopted Initiative 276,

which required that most records maintained by state, county, and

city governments be made available to members of the public. e

public disclosure statutes have been frequently revised over the

past three decades. e latest revision of the disclosure statutes are

found in chapter 42.56 RCW, and are referred to as the Public Re-

cords Act.

1

Although the public records disclosure statutes do not

apply to judicial records (case les),

2

the legislature has specically

extended their coverage to state legislative records.

3

In addition, the

public records disclosure statutes apply equally to “every county,

city, town, municipal corporation, quasi-municipal corporation,

or special purpose district” or “any oce, department, division,

bureau, board, commission, or agency thereof, or other local public

a g e n c y.”

4

is publication will refer to these units of government

collectively as “local government” or “local agency.”

is publication discusses all of the statutory disclosure exemptions

which are relevant to local governments, as well as the mandatory

procedures for responding to a public records disclosure request.

roughout the text are questions and answers relating to diverse

public disclosure issues; they reect the broad range of public dis-

1

See RCW 42.56.020.

2

See Nast v. Michels, 107 Wn.2d 300 (1986) (holding that the Public Disclosure

Act did not provide access to court case les, instead, the public disclosure of court case

les is governed by other Washington statutes and past court decisions, i.e., common law);

accord Beuhler v. Small, 115 Wn. App. 914, 918 (2003) (nding that the trial court prop-

erly concluded that the PDA did not grant the plainti a right to access a judge’s computer

les); see also, In re Personal Restraint of Gentry, 137 Wn.2d 378, 389–90 (1999) (holding

that under GR 15(c)(2)(B), case records would not be sealed from the public, because the

defendant’s right to a fair trial was not imperiled nor was sealing the motions necessary

to prevent a serious and imminent threat to any compelling interest). Also see Dreiling v.

Jain, 151 Wn.2d 900 (2004) and WAC 44-14-01001 and Spokane & E. Lawyer v. Tomp-

kins, 136 Wn. App. 616 (2007) and WAC 44-14-01001. On 10/15/2009 the Washington

Supreme Court upheld the Nast decision in City of Federal Way v. Koenig.

3

RCW 42.56.010(2).

4

Telford v. urston County Bd. of Comm’rs, 95 Wn. App. 149, 152 (1999), review

denied 138 Wn.2d 1015 (1999). In determining whether an organization is a public agen-

cy under the PDA, the appeals court has adopted a four factor balancing test: “e factors

are: (1) whether the entity performs a governmental function; (2) the level of government

funding; (3) the extent of government involvement or regulation; and (4) whether the en-

tity was created by government.” See also Michael R. Kenyon and Stephen R. King, “Gov-

ernment Contractors and the Washington Public Disclosure Act: When Private Docu-

ments Become Public Records,” Legal Notes Information Bulletin No. 509 (2001) (analysis

of public agency determinations). See also WAC 44-14-01001.

1

CHAPTER ONE

8Public Records Act

closure questions answered by MRSC over the years. Because this publication is directed toward a

wide audience of local government ocials and employees, many of the citations to legal author-

ity are located in the footnotes, rather than in the body of the text.

Appendix A has sample local government policies, ordinances, and forms related to public dis-

closure. Appendix B has the RCW conversion tables that will assist with the 2006 statutory re-

numbering (included with the conversion tables are citations to the corresponding sections of the

Public Records Act Model Rules). Appendix C is a list of state laws, other than those in chapter

42.56 RCW, aecting condentiality and disclosure of public records.

Do not be surprised if you have a public disclosure question which is not discussed in this pub-

lication. Disclosure issues are almost as numerous as the public records in your custody. MRSC

also has helpful Public Records Act information on our website, including:

• Public Records Act Court Decision,

• OPMA and PRA Practice Tips and Checklists.

If you need additional assistance when analyzing disclosure questions, please contact your legal

counsel or MRSC.

Question: Does the federal Freedom of Information Act govern public access to any local govern-

ment records?

Answer: No. The federal Freedom of Information Act applies only to federal agencies and the records

maintained by those agencies. However, state courts will, in appropriate situations, look to the fed-

eral Freedom of Information Act and case law interpreting that act when interpreting similar provi-

sions in the state public disclosure statutes.

5

Concerning the Public Records Act Model Rules

In 2005, the state legislature directed the Attorney General to adopt advisory “model rules” for

state and local agencies.

6

ese Model Rules are now published in the Washington Administrative

Code at chapter 44-14. ough the current version of the Model Rules deals mostly with disclo-

sure procedures, there are instructive comments regarding some specic disclosure exemptions,

such as the right to privacy, the attorney-client privilege, and the deliberative process exemption.

e legislature granted the Attorney General the discretion to periodically revise the Model Rules.

Cities and counties should review the Model Rules and determine whether they wish to incorporate

some or all of the Model Rules into their own local disclosure procedures or policies.

e WAC sections quoted below are taken from the “Introductory Comments” to the Model

Rules, and provide some explanation for their purpose and role.

5

Servais v. Port of Bellingham, 127 Wn.2d 820, 835 (1995); see also PAWS v. UW, 125 Wn.2d 243, 265 (1994).

6

RCW 42.56.570.

9Public Records Act

WAC 44-14-00001 - Statutory Authority and purpose.

. . . e overall goal of the model rules is to establish a culture of compliance among

agencies and a culture of cooperation among requestors by standardizing best practices

throughout the state. e attorney general encourages state and local agencies to adopt the

model rules (but not necessarily the comments) by regulation or ordinance.

WAC 44-14-00002 - Format of model rules.

We are publishing the model rules with comments. e comments have ve-digit WAC

numbers such as WAS 44-14-04001. e model rules themselves have three-digit WAC

numbers such as 44-14-040.

e comments are designed to explain the basis and rationale for the rules themselves as

well as to provide broader context and legal guidance. . . .

WAC 44-14-00003 - Model rules and comments are nonbinding.

e model rules, and the comments accompanying them, are advisory only and do not

bind any agency. Accordingly, many of the comments to the model rules use the word

“should” or “may” to describe what an agency or requestor is encouraged to do. e use of

the words “should” or “may” are permissive, not mandatory, and are not intended to cre-

ate any legal duty.

While the model rules and comments are nonbinding, they should be carefully considered

by requestors and agencies. e model rules and comments were adopted aer extensive

statewide hearings and voluminous comments from a wide variety of interested parties.

Public Records Exemption Accountability Committee

In 2007 the legislature created a public records exemption accountability committee.

7

is broad-

based group is charged with reviewing the existing exemptions and annually submitting their rec-

ommendations to the governor, attorney general, and to the appropriate committees of the house

of representatives and the senate.

10Public Records Act

Government Records: Local

Government’s Duty to Provide Access

Local government agencies are required, within ve days of receiv-

ing a public disclosure request, to respond by (1) providing the

requested record; (2) providing an internet address and link on

the agency’s website to the specic records requested, except that

if the requestor noties the agency that he or she cannot access the

records through the internet, then the agency must provide copies

of the record or allow the requestor to view copies using an agency

computer; (3) acknowledging receipt of the request and providing

a reasonable estimate of the time required to ll the request; or (4)

denying the request.

8

Given limited budgets and sta, local agencies

tend to have all available resources invested in day-to-day running

of the agency. Requests for disclosure of public records oen occur

at inconveniently busy times. Despite the extra burden that disclo-

sure requests place on busy agency sta, every government ocial

and employee should be reminded of the strongly-worded language

that was incorporated into the public disclosure act:

e people of this state do not yield their sovereignty to the

agencies that serve them. e people, in delegating author-

ity, do not give their public servants the right to decide what

is good for the people to know and what is not good for

them to know. e people insist on remaining informed so

that they may maintain control over the instruments they

have created. e public records subdivision of this chapter

shall be liberally construed and its exemptions narrowly

construed to promote this public policy.9

When passed in 1972, Initiative 276 contained a similar public

policy statement:

It is hereby declared by the sovereign people to be the public

policy of the state of Washington: . . . (11) at, mindful

of the right of individuals to privacy and of the desirability

of the ecient administration of government, full access

to information concerning the conduct of government on

2

CHAPTER TWO

11Public Records Act

every level must be assured as a fundamental and necessary precondition to the sound

governance of a free society.

10

Both the state legislature and the voters of Washington are clear about their position on public

disclosure: the citizens of this state have a right to know almost all of the details of how local and

state governments are run. e courts have enforced this policy by liberally construing the Act’s

disclosure provisions and narrowly construing its exemptions.

11

Working for local government is like working inside a goldsh bowl. Almost everything is open

to public scrutiny. It is the duty of agency sta to respond to public disclosure requests eciently

and graciously since the public is not only your client, but also your employer. Although agency

sta may become annoyed at a disclosure request because of the time it takes to locate records, or

because the records may disclose a mistake or improper action, the following statutory provision

should serve as a reminder of the importance of open government:

Courts shall take into account the policy of this chapter that free and open examination of

public records is in the public interest, even though such examination may cause inconve-

nience or embarrassment to public ocials and others.

12

From a practical standpoint, dealing with requests in a responsive and courteous manner mini-

mizes public distrust of government, thus preventing a public disclosure request from escalating

into an expensive and time consuming legal event.

Question: Must the city disclose a letter of resignation from a disgruntled employee when the

letter consists of a rambling tirade in which the employee criticizes his supervisor, the mayor and the

council for a number of decisions?

Answer: The letter must be disclosed. The city may redoct from the letter only information which is

covered by a specic statutory exemption.

Acting in Good Faith – Disclosing a Record in Error

All requests for public records must be examined carefully, and all requested records must be

provided except for those records which are clearly exempt from disclosure. A court will look fa-

vorably on a good faith attempt to comply with the public disclosure act if an employee discloses

a public record, and later analysis or court decision shows it should not have been disclosed. In

such a circumstance, a local government may be immune from liability:

No public agency, public ocial, public employee, or custodian shall be liable, nor shall

a cause of action exist, for any loss or damage based upon the release of a public record if

the public agency, public ocial, public employee, or custodian acted in good faith in at-

tempting to comply with the provisions of this chapter.

13

10

RCW 42.17.010.

11

Limstrom v. Ladenburg, 136 Wn.2d 595, 604 (1998) (citing RCW 42.17.251).

12

RCW 42.56.550(3).

13

RCW 42.56.060.

12Public Records Act

In order to act in good faith, local government employees and ocials making disclosure deci-

sions must be familiar with the public disclosure requirements and the many exemptions con-

tained in the statutes.

Acting in Good Faith – Penalties, Attorney’s Fees, and Costs

Acting in “good faith” will not absolve an agency from the imposition of court costs, attorney fees,

and potential penalties for erroneously withholding public records, but can be taken into consid-

eration by a judge when determining the amount of penalties. RCW 42.56.550(4) provides:

Any person who prevails against an agency in any action in the courts seeking the right

to inspect or copy any public record or the right to receive a response to a public record

request within a reasonable amount of time shall be awarded all costs, including reason-

able attorney fees, incurred in connection with such legal action. In addition, it shall be

within the discretion of the court to award such person an amount not to exceed one hun-

dred dollars for each day that he or she was denied the right to inspect or copy said public

record.

Note that prior to July of 2011 the above statute required that the minimum penalty for wrong-

fully withholding a record was $5 per day. Many of the court decisions dealing with penalties

stressed that mandatory provision. Keep that statutory amendment in mind if you review prior

court decisions or articles dealing with PRA penalties.

Legal advice should be sought in situations where statutory requirements seem unclear. Fortu-

nately, court decisions and attorney general opinions are available for guidance in this complex

eld. e Public Records Act statutes, along with the Open Public Meetings Act,18 provide the

foundation for open government. Such openness encourages public participation and awareness,

and helps dispel fears that local governments are not responsible or responsive to the people.

Question: Must local government agencies disclose copies of their bank records?

Answer: Yes. Bank records concern public funds and should be disclosed upon request. There is one

exception: If the agency’s bank accounts are kept in such a way that disclosure of a particular account

record would reveal exempt tax information, then that data should not be disclosed. For instance, if a

jurisdiction has only two or three motels, disclosure of hotel/motel tax revenue could enable a person

to estimate the income of a particular taxpayer.

13Public Records Act

What Are Public Records?

A “public record” is dened to include,

. . . any writing containing information relating to the

conduct of government or the performance of any govern-

mental or proprietary function prepared, owned, used, or

retained by any state or local agency regardless of physical

form or characteristics.

14

“Writing” is also dened in the disclosure statutes:

“Writing” means handwriting, typewriting, printing, photo-

stating, photographing, and every other means of recording

any form of communication or representation, including,

but not limited to, letters, words, pictures, sounds, or sym-

bols, or combination thereof, and all papers, maps, mag-

netic or paper tapes, photographic lms and prints, motion

picture, lm and video recordings, magnetic or punched

cards, discs, drums, diskettes, sound recordings, and other

documents including existing data compilations from which

information may be obtained or translated.

15

Whether private business records can relate to “conduct of govern-

ment” has not been addressed by Washington courts.

16

However,

the Washington Supreme Court has held that where “records relate

to the conduct of . . . [a public agency] . . . and to its governmental

function. . . . [T]he records are ‘public records’ within the scope of

the public records act.”

17

Local governments are not required to create documents in order

to comply with a request for specic information.

18

Rather, they

must produce existing records for review and copying. Also, local

governments are not obligated to compile information from various

records so that information is in a form that is more useful to the

requestor. For example, if someone wants records concerning the

time it took the city re department to respond to residential res

occurring between midnight and 6:00 a.m. over a two-year period,

18

Citizens for Fair Share, 117 Wn. App. at 435 (citing Smith v. Okanogan County,

100 Wn. App. 7, 13–14 (2000)). See also WAC 44-14-04003(6).

3

CHAPTER THREE

14Public Records Act

the city only needs to provide copies of existing records.

19

City employees are not required to do

research for private individuals.

20

Question: Is the city clerk required to provide information over the phone to a newspaper reporter

who is asking “what occurred at the council meeting last night?”

Answer: This is not a public disclosure request, because the caller is not asking to review or copy a

public record. There is no legal obligation to provide oral information concerning what occurred at

the meeting. However, the reporter may request a copy of the minutes of the meeting after they are

prepared. It is an administrative decision whether city sta should answer oral requests for non-

record information. See also WAC 44-14-04002(2).

Electronic Data and Records

Increasing amounts of public information are now contained in electronic format, rather than on

paper. Public disclosure laws apply to electronic data.

21

e state legislature formed a Public Infor-

mation Access Policy Task Force in 1994 to examine the issue of providing broad public access to

government records by electronic means. Aer reviewing the recommendations of the task force,

the legislature passed legislation strongly encouraging expansion of electronic access to public

records:

Broad public access to state and local government records and information has potential

for expanding citizen access to that information and for improving government services.

Electronic methods for locating and transferring information can improve linkages be-

tween and among citizens, organizations, businesses, and governments. Information must

be managed with great care to meet the objectives of citizens and their governments.

It is the intent of the legislature to encourage state and local governments to develop,

store, and manage their public records and information in electronic formats to meet their

missions and objectives. Further, it is the intent of the legislature for state and local gov-

ernments to set priorities for making public records widely available electronically to the

public.

22

E-mail in particular has been the topic of many questions regarding public records. According to

the State Archivist, who is responsible for creating public record retention guidelines,

Individual E-mail messages may be public records with legally mandated retention re-

quirements, or may be information with no retention value. E-mail messages are public

records when they are created or received in the transaction of public business and re-

19

Smith, 100 Wn. App. at 18.

20

Bonamy v. City of Seattle, 92 Wn. App. 403, 409 (1993).

21

See Isabel R. Safora, “Municipal Policies on Internet Usage & E-mail Document Retention,” Legal Notes Information

Bulletin No. 497, §§ VI–VII (1997) (discussing application of the PDA to e-mail and retention).

22

RCW 43.105.250.

15Public Records Act

tained as evidence of ocial policies, actions, decisions, or transactions. Such messages

must be identied, led, and retained just like records in other formats.

23

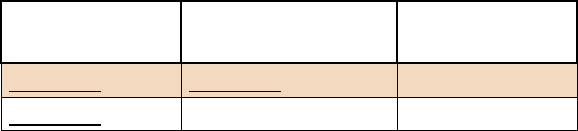

For guidance, the State Archivist lists the following e-mail messages that are usually public re-

cords and must be retained:

• Policy and procedure directives.

• Correspondence or memoranda related to ocial public business.

• Agendas and minutes of meetings.

• Documents relating to legal or audit issues.

• Messages which document agency actions, decisions, operations and responsibilities.

• Documents that initiate, authorize or complete a business transaction.

• Dras of documents that are circulated for comment or approval.

• Final reports or recommendations.

• Appointment calendars.

• E-mail distribution lists.

• Routine information requests.

• Other messages sent or received that relate to the transaction of local government

business.

24

Conversely, the State Archivist lists the following e-mail messages which are usually administra-

tive materials with no retention value:

• Information-only copies, or extracts of documents distributed for reference or conve-

nience, such as announcements or bulletins.

• Phone message slips that do not contain information that may constitute a public record.

• Copies of published materials.

• Informational copies.

• Preliminary dras.

• Routing slips.

25

Additional information and guidance for determining whether e-mail is a public record can be

found in Records Management Guidelines for All Local Government Agencies, a publication by the

State Archives Division of the Washington Secretary of State, and available online at

http://www.secstate.wa.gov/archives/gs.aspx.

e Model Rules have been amended to include a section on electronic records. See WAC 44-14-

050, and the comments to that provision found at WAC 44-14-05001 through WAC 44-14-05005.

We recommend that you read those provisions carefully. e same basic requirements for re-

sponding to paper records also apply to electronic records.

23

Wash. Secretary of State, Local Government Agencies of Washington State: Records Management Guidelines, p. S-62,

updated 1/05, available at http://www.secstate.wa.gov/archives/gs.aspx.

24

Id.

25

Id.

16Public Records Act

Determining What Must Be Disclosed Under the Public

Records Act

ere are three questions a local agency must consider when responding to a request for disclo-

sure. First, are the requested records exempt from disclosure or prohibited from being disclosed?

Second, if they are exempt, can information be deleted from the record so it might still be re-

leased? ird, if the records are not exempt, should information be deleted that would constitute

an unreasonable invasion of privacy if disclosed?

Specific Exemptions and Prohibitions

All agency records are available for review by the public unless they are specically exempted

26

or

prohibited from disclosure by the statutes. If no statutory exemption or prohibition covers the re-

quested record, it must be disclosed.

27

is section discusses exemptions listed in RCW 42.56.230

through 42.56.480. However, there are numerous other exemptions and disclosure prohibitions

located elsewhere in the statutes that are relevant for local governments. Appendix C of this publi-

cation contains a listing of the many disclosure exemptions and prohibitions that are not located

in the Public Records Act (chapter 42.56 RCW). Some of those additional exemptions and prohi-

bitions are discussed in chapter 5 of this publication.

e public disclosure act provides that exemptions are to be narrowly construed; consequently,

the courts have consistently ruled that only information specically exempted can be withheld

from public disclosure.

28

Note: If, aer reviewing the statutes, you are unsure whether a document meets the exemption

criteria, consult with your department head or legal counsel.

e italicized statutory sections below are taken directly from the statutes and pertain to local

governments. e records designated below are exempt from disclosure.

RCW 42.56.230 Personal information.

e following personal information is exempt from public inspection and copying under this chapter:

(1) Personal information in any les maintained for students in public schools, patients

or clients of public institutions or public health agencies, or welfare recipients.

(2) Personal information, including but not limited to, addresses, telephone numbers,

personal electronic mail addresses, social security numbers, emergency contact and date of

birth information for a participant in a public or nonprot program serving or pertaining

to children, adolescents, or students, including but not limited to early learning or child care

26

Exemptions are permissive, not mandatory. WAC 44-14-06002(1) and AGO 1980 No. 1.

27

RCW 42.56.070; see also PAWS, 125 Wn.2d at 257-61.

28

RCW 42.56.030; Brouillet v. Cowles Pub., 114 Wn.2d 788, 793 (1990). (“e public disclosure act mandates disclosure

of all public records not falling under specic exemptions delineated in the act. In keeping with the act’s policy, we construe ex-

emptions from mandatory disclosure narrowly.”)

17Public Records Act

services, parks and recreation programs, youth development

programs, and aer-school programs. Emergency contact

information may be provided to appropriate authorities and

medical personnel for the purpose of treating the individual

during an emergency situation;

is exemption, which became eective in January 2012, applies to

contact information for minors who may be participating in pro-

grams oered by local government agencies. In the past such infor-

mation (except for social security numbers) had to be disclosed.

(3) Personal information in les maintained for employ-

ees, appointees, or elected ocials of any public agency to the

extent that disclosure would violate their right to privacy.

is “personal information” exemption concerns personnel les.

Since some of the information in employee personnel les may be

protected by the employee’s right to privacy, careful scrutiny should

precede any decision to disclose those records. Files of retired em-

ployees are also covered by this provision.

29

Additional analysis of

personnel records disclosure and right to privacy issues are found

later in this chapter and in chapter 7.

Question: Must a local agency disclose, upon request, copies of

phone bills, which contain unlisted phone numbers placed on the

bills as a result of personal calls made by local agency employees?

Answer: Yes. No exemption applies. The phone calls may be

personal or private, but because billing records of the calls are not

part of the employees’ personnel les, neither RCW 42.56.230 or

42.56.250(3) apply. This is the case even if the phone bills include

unlisted phone numbers of local agency employees. Many cities

and counties allow employees to make personal calls from their

work phones, but there is no exemption which allows the local

governments to delete unlisted numbers from their phone bills. If

a city or county employee wishes to maintain condentiality of an

unlisted phone number, calls to that number should not be made

29

Seattle Fire Fighters v. Hollister, 48 Wn. App. 129, at 134 (1987).

4

CHAPTER FOUR

18Public Records Act

from their work phone phone.

(4) Information required of any taxpayer in connection with the assessment or collection

of any tax if the disclosure of the information to other persons would (i) be prohibited to such

persons by RCW 84.08.210, 82.32.330, 84.40.020, or 84.40.340 or (ii) violate the taxpayer’s

right to privacy or result in unfair competitive disadvantage to the taxpayer.

Agencies should be very cautious about the release of any taxpayer information. is exemption

does not prohibit disclosure of basic tax information such as the totals of various tax revenues; it

only prohibits disclosure of information which can be identied with a particular taxpayer.

(5) Credit card numbers, debit card numbers, electronic check numbers, card expira-

tion dates, or bank or other nancial account numbers, except when disclosure is expressly

required by government or other law.

RCW 42.56.240 Investigative, law enforcement, and crime victims.

e following investigative, law enforcement, and crime victim information is exempt from public

disclosure and copying under this chapter:

(1) Specic intelligence information and specic investigative records compiled by inves-

tigative, law enforcement, and penology agencies, and state agencies vested with the respon-

sibility to discipline members of any profession, the nondisclosure of which is essential to

eective law enforcement or for the protection of any person’s right to privacy;

e Washington Supreme Court has held that an active police investigation le, in its entirety, is

exempt from disclosure under the Act’s “eective law enforcement” exemption, unless the law en-

forcement agency decides that specic information is not essential to solving the case.

30

e court

will not second guess a law enforcement agency’s decision not to disclose information contained

in an open investigation le. is eectively bars challenges to law enforcement agency disclo-

sure determinations with respect to such materials. Some factors the prosecutor should consider

include whether disclosure might inadvertently compromise apprehension of a suspect, divulge

sophisticated police investigative techniques, or disrupt the sharing of information between law

enforcement agencies.

31

However, if a suspect has already been arrested and the matter referred to the prosecutor for a

charging decision, information contained in the investigative le is disclosable unless disclosure

would impede eective law enforcement. Under these circumstances, the court is more willing to

look at what should be disclosed to the public.

As with any disclosable record, information concerning sexual oenses, some health matters, and

certain other private details can be deleted when disclosing police investigation reports in order

30

Newman v. King County, 133 Wn.2d 565, 574 (1997).

31

Cowles Pub. Co. v. Spokane Police Dept., City of Spokane, 139 Wn.2d 472, 478 (1999).

19Public Records Act

to protect a person’s right to privacy. See the information concerning redaction later in this chap-

ter.

(2) Information revealing the identity of persons who are witnesses to or victims of crime

or who le complaints with investigative, law enforcement, or penology agencies, other than

the public disclosure commission, if disclosure would endanger any person’s life, physical safe-

ty, or property. If at the time a complaint is led the complainant, victim or witness indicates

a desire for disclosure or nondisclosure, such desire shall govern. However, all complaints

led with the public disclosure commission about any elected ocial or candidate for public

oce must be made in writing and signed by the complainant under oath;

e exemption listed here, allows agencies to delete details from police investigation reports

which identify witnesses or victims of crimes, but only if disclosure would endanger any person’s

life, physical safety, or property.

(3) Any records of investigative reports prepared by any state, county, municipal, or

other law enforcement agency pertaining to sex oenses contained in chapter 9A.44 RCW or

sexually violent oenses as dened in RCW 71.09.020, which have been transferred to the

Washington association of sheris and police chiefs for permanent electronic retention and

retrieval pursuant to RCW40.14.070(2)(b);

(4) License applications under RCW 9.41.070; copies of license applications or informa-

tion on the applications may be released to law enforcement or corrections agencies, and

e above exemption refers to concealed pistol licenses.

(5) Information revealing the identity of child victims of sexual assault who are under

the age of eighteen. Identifying information means the child victim’s name, address, location,

photograph, and in cases in which the child victim is a relative or stepchild of the alleged

perpetrator, identication of the relationship between the child and the alleged perpetrator.

32

e intent of this exemption is to allow witnesses and victims of crimes to make statements to po-

lice ocers without fear that their identity will be made available to the public. A related statute,

RCW 10.97.130, prohibits the release of the names of juveniles who are victims of sex crimes.

RCW 42.56.250 Employment and licensing.

e following employment and licensing information is exempt from public inspection and copy-

ing under this chapter:

(1) Test questions, scoring keys, and other examination data used to administer a license,

employment, or academic examination;

32

See Koenig v. City of Des Moines, 158 Wn.2d 173.

20Public Records Act

is exemption enables local governments to keep private their employment testing materials,

questions and answers. is is crucial for local governments which use standardized tests for civil

service or other city recruitment.

(2) All applications for public employment, including the names of applicants, resumes,

and other related materials submitted with respect to an applicant;

is exemption enables individuals to apply for local government employment without worrying

about disclosure of their application, or of the fact that they are seeking employment. is exemp-

tion applies to all non-elective local government positions, including administrative positions,

such as city manager, or professional positions, such as city attorney or city engineer.

e broad wording of this exemption appears to cover not only resumes or application materials

of current job applicants, but also such materials submitted to the local government in connection

with current or past local government employees. ere is no case law conrming whether the

exemption should be interpreted so expansively. If the resume and other materials are in a current

employee’s personnel le, RCW42.56.230(2) would also apply. However, it would be rare that the

“right to privacy” protection of that subsection would apply to the types of information typically

contained in resumes and related documents.

is statutory section also protects from disclosure employment application records which con-

tain information submitted to a local government by prior employers in response to requests for

information about an applicant.

33

Question: If requested, must a local government disclose a record containing the names of those

who have notied the local government that they would like to be considered for appointment to a

vacant council position?

Answer: The names should probably be disclosed. The individuals are not applying for “local govern-

ment employment” as that would normally be understood.

(3) e residential addresses, residential telephone numbers, personal wireless telephone

numbers, personal electronic mail addresses, social security numbers, and emergency contact

information of employees or volunteers of a public agency, and the names, dates of birth,

residential addresses, residential telephone numbers, personal wireless telephone numbers,

personal electronic mail addresses, social security numbers, and emergency contact informa-

tion of dependents of employees or volunteers of a public agency that are held by any public

agency in personnel records, public employment related records, or volunteer rosters, or are

included in any mailing list of employees or volunteers of any public agency. For purposes of

this subsection, “employees” includes independent provider home care workers as dened in

RCW 74.39A.240;

33

See RCW 4.24.730, enacted in 2005, regarding an employee’s or former employee’s right to inspect written records of

their employer or former employer indicating to which prospective employers they have provided employment information.

21Public Records Act

is is the only disclosure exemption specically referring to individuals who are working with

the local government in a volunteer capacity. It is conceivable that a court interpreting other dis-

closure statutes, that are applicable to records relating to employees, might apply those statutes to

volunteers.

(4) Information which identies a person who, while an agency employee: (i) Seeks ad-

vice, under an informal process established by the employing agency, in order to ascertain his

or her rights in connection with a possible unfair practice under chapter 49.60 RCW against

the person; and (ii) requests his or her identity or any identifying information not be dis-

closed;

(5) Investigative records compiled by an employing agency conducting a current inves-

tigation of a possible unfair practice under chapter 49.60 RCW or of a possible violation of

other federal, state, or local laws prohibiting discrimination in employment; and

(6) [is subsection is not relevant for local government agencies.]

RCW 42.56.260 Real estate appraisals.

Except as is provided by chapter 8.26 RCW, the contents of real estate appraisals, made for

or by any agency relative to the acquisition or sale of property, until the project or prospective

sale is abandoned or until such time as all of the property has been acquired or the property

to which the sale relates is sold, are exempt from disclosure under this chapter. In no event

shall disclosure be denied for more than three years aer the appraisal.

is exemption allows local governments to keep appraisal information away from public scruti-

ny while negotiating a potential purchase or sale. Local government legislative bodies may review

and discuss condential appraisal information in an executive session,

34

and the councilmembers

or commissioners are prohibited from disclosing that information.

35

RCW 42.56.270 Financial, commercial, and proprietary information.

e following nancial, commercial, and proprietary information is exempt from disclosure under

this chapter:

(1) Valuable formulae, designs, drawings, computer source code or object code, and

research data obtained by any agency within ve years of the request for disclosure when

disclosure would produce private gain and public loss;

Several cases have interpreted this exemption. In one, the Washington Supreme Court found

that the cash ow analysis of port properties prepared for a port’s sole use in negotiations with

34

RCW 42.30.110(1)(b), (c).

35

RCW 42.23.070(4).

22Public Records Act

prospective joint venture partners was within the research data exemption.

36

In another case, the

court found that a university’s research data relating to intellectual property was exempt from dis-

closure.

37

In both decisions, the requesting party was denied his public disclosure request, because

he would have proted and the government would have incurred a loss.

By contrast, in a court of appeals decision the court found that documents used by professors and

accountants hired by the city, to perform credit and nancial analysis for the city’s loan guarantee

for private shopping center development, were not exempt.

38

e city was unable to show a public

loss resulting from the disclosure of the requested research.

MRSC has been asked whether this exemption applies to blueprints or other architectural draw-

ings submitted to a city’s building department for review. It is doubtful that the exemption would

oen apply, because disclosure would not necessarily cause both “private gain and public loss.”

Also, even though the person who submitted the materials has a copyright interest in the docu-

ments, disclosure is not automatically prohibited. A court has held that an individual with a

copyright interest in public records is not an indispensable party in an action to compel disclo-

sure, and those requesting copies of the materials may be entitled to the records if the facts meet

the “fair use doctrine.”

39

Consequently, MRSC has recommended that when there is a disclosure

request for these types of materials, the agency should immediately notify the person who sub-

mitted the documents or architectural drawings to allow the person with a copyright interest the

option of seeking a court order prohibiting disclosure.

40

In connection with the public bidding process, local governments oen obtain information which

bidders would not voluntarily divulge to their competitors. Such information may be exempt, if

the “public loss” factor can be met.

41

In any event, it would be wise to promptly notify a bidder if

the city receives a request for such records.

[e exemptions listed in subsections 2 through 11 of RCW 42.56.270 have limited applicability

to local government records.]

RCW 42.56.280 Preliminary dras, notes, recommendations, intra-agency memorandums.

42

Preliminary dras, notes, recommendations, and intra-agency memorandums in which opin-

ions are expressed or policies formulated or recommended are exempt under this chapter,

36

Servais v. Port of Bellingham, 127 Wn.2d 820 (1995).

37

PAWS, 125 Wn.2d at 243.

38

Spokane Research & Defense Fund v. City of Spokane, 96 Wn. App. 568, 575-77 (1999), rev. denied, 140 Wn.2d 1001

(2000).

39

Lindberg v. County of Kitsap, 133 Wn.2d 729, 745 (1997) (holding that “[a] copyright interest in the documents does

not of itself make the owner an indispensable party to a lawsuit demanding under a public disclosure statute the right to have cop-

ies or to make copies of them”).

40

e procedure for such court review is outlined in RCW 42.17.540.

41

See generally, Rocco N. Treppiedi, “Disclosing Proprietary Information Obtained in Competitive Bidding,” Legal Notes

Information Bulletin No. 432 (1985); Kyle J. Crews, “Second Update on Public Disclosure, Public Bidding Documents,” Legal

Notes Information Bulletin No. 491 (1995).

42

See WAC 44-14-06002(4) in the Model Rules for comments on this “deliberative process” exemption.

23Public Records Act

except that a specic record shall not be exempt when publicly cited by an agency in connec-

tion with any given action.

is exemption applies to records connected with the deliberative process. Only records contain-

ing opinions or recommendations are exempt. Factual materials which are being considered as

background material on a particular issue or problem are not exempt. For example, if a city trea-

surer or nance ocer prepares a nancial report for the mayor detailing the status of the city’s

expenditures for the current budget year, that document is not exempt from disclosure. Con-

versely, if that report contains recommendations for scal policy changes, any portions contain-

ing the recommendations would be exempt from disclosure. Also, memos concerning possible

scal policy changes written between a mayor, nance ocer, or department heads are exempt.

is exemption does not apply aer the policies or recommendations set forth in the requested

document(s) have been implemented.

43

e Washington Supreme Court has determined that before an agency is entitled to rely on this

exemption, it must show (1) that the records contain pre-decisional opinions or recommenda-

tions of subordinates expressed as part of a deliberative process; (2) that disclosure would be inju-

rious to the deliberative or consultative function of the process; (3) that disclosure would inhibit

the ow of recommendations, observations, and opinions; and (4) that the materials covered

by the exemption reect policy recommendations and opinions and not the raw factual data on

which a decision is based.

44

A subsequently decided case has discussed how this “deliberative process” exemption would apply

to a preliminary list of issues to be addressed in collective bargaining negotiations.

45

Question: Are a clerk’s handwritten notes, which are used to prepare the formal council minutes,

exempt from disclosure? How about unapproved drafts of the minutes?

Answer: Neither are exempt. The clerk is merely making notes of what is said and done by the coun-

cil at an open, public meeting. We recommend that any preliminary drafts of council minutes which

are provided to the public be clearly labeled as preliminary drafts.

RCW 42.56.290 Agency party to controversy.

46

Records which are relevant to a controversy to which an agency is a party but which records

would not be available to another party under the rules of pretrial discovery for causes pend-

ing in the superior court are exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

43

Dawson, 120 Wn.2d at 793.

44

PAWS, 125 Wn.2d at 256.

45

ACLU v. City of Seattle, 121 Wn. App. 544 (2004), and the subsequent unreported decision with the same name, de-

cided by the Court of Appeals on 7/20/2009.

46

See WAC 44-14-06002(3) in the Model Rules for comments on the attorney-client privilege.

24Public Records Act

is exemption concerns attorney work product. e term “controversy” refers to pending litiga-

tion, threatened litigation, and completed litigation.

47

Whenever a local government is involved in

a current or potential legal controversy, disclosure of any related documents should be discussed

and reviewed carefully with the local government attorney.

Some attorneys provide detailed billing statements that may include entries that show an attor-

ney’s “work product” or litigation strategy. e legislature adopted an “intent” statute providing

guidance on billing statements sent to public agencies by their legal counsel, whether in-house or

not – see RCW 42.56.904.

48

e Attorney General has posted a “guidance document” concerning the attorney-client privilege

and the work product doctrine on the Attorney General’s web page dealing with the Model Rules

– see www.atg.wa.gov/records/modelrules.

Question: Must a local government disclose a “separation agreement” entered into with an em-

ployee in order to settle a claim and avoid litigation? (The terms of the agreement were worked out

by the council in an executive session, with the assistance of the local government attorney.)

Answer: The agreement must be disclosed. The relevant controversy exemption does not apply

in this situation, because this document would be available to a party under the rules of pretrial

discovery. Furthermore, the public has a legitimate interest in the details of a settlement agreement

involving the government’s conduct of its aairs and the expenditure of public funds.

49

RCW 42.56.300 Archeological sites.

Records, maps or other information identifying the location of archaeological sites in order to

avoid the looting or depredation of such sites are exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.310 Library records.

Any library record, the primary purpose of which is to maintain control of library materials,

or to gain access to information, that discloses or could be used to disclose the identity of a

library user is exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.320 Educational information. [Not relevant for cities and counties.]

RCW 42.56.330 Public utilities and transportation.

47

Dawson, 120 Wn.2d at 791; see also O’Connor v. Wash. State Dept. of Social & Health Services, 143 Wn.2d 895, 912

(2001) (holding that records relevant to a controversy to which an agency is a party are exempt if those records would not be avail-

able to another party under superior court rules of pretrial discovery).

48

See also, West v. urston County, 144 Wn. App. 573 (2008) and Yakima County v. Herald-Republic, 170 Wn.2d 775

(2011).

49

See Yakima Newspapers v. Yakima, 77 Wn. App. 319 (1995).

25Public Records Act

e following information relating to public utilities and transportation is exempt from disclosure

under this chapter: [Subsection (1) is not relevant for local government agencies.]

(2) e residential addresses and, telephone numbers, electronic contact information, and

customer-specic utility usage and billing information in increments less than a billing cycle

of the customers of a public utility contained in the records or lists held by the public utility

of which they are customers, except that this information may be released to the division of

child support or the agency or rm providing child support enforcement for another state un-

der Title IV-D of the federal social security act, for the establishment, enforcement, or modi-

cation of a support order.

Question: Must the city disclose the amount owed by a utility customer, and whether the account is

delinquent or not?

Answer: Yes. Records showing the amount owed by a utility customer, and whether the account is

delinquent must be produced in response to a public records request; however, customer-specic

utility usage and billing information in increments less than a billing cycle is exempt. As well, the

customer’s residential address, phone numbers and email address are also exempt.

Question: Would the RCW 42.56.330 exemption prohibit a city from providing a mailing list of its

utility customers to the directly adjacent city? (The neighboring city is going to be undertaking some

major utility construction which will temporarily impact utility customers in the other city. It wants

to mail out notices to the impacted residents of that city.)

Answer: This is not a request for public disclosure, but disclosure to another municipality. Conse-

quently, there is no statutory reason to prevent one city from providing this information to another

city.

(3) e names, residential addresses, residential telephone numbers, and other individu-

ally identiable records held by an agency in relation to a vanpool, carpool, or other ride-

sharing program or services; however, these records may be disclosed to other persons who

apply for ride-matching services and who need that information in order to identify potential

riders or drivers with whom to share rides;

(4) e personally identifying information or current or former participants or applicants

in a paratransit or other transit service operated for the benet of persons with disabilities or

elderly persons;

(5) e personally identifying information of persons who acquire and use transit passes

….;

(6) [Deals with motor carrier intelligent transportation system information - not rel-

evant for local government agencies.]

26Public Records Act

(7) e personally identifying information of persons who acquire and use transponders

or other technology to facilitate payment of tolls ....

RCW 42.56.335 Public utility districts and municipally owned utilities – Restrictions on ac-

cess by law enforcement authorities.

e above subsection concerns police agencies’ inspection of electrical consumption records that

might indicate a drug growing operation in a particular residence or structure.

RCW 42.56.340 Timeshare, condominium, etc. owner lists.

is exemption relates to information held by the state department of licensing.

RCW 42.56.350 Health professionals.

is exemption deals with information about health care professionals held by the state depart-

ment of health.

RCW 42.56.360 Health care.

(1) e following health care information is exempt from disclosure under this chapter:

[Subsections (a) through (e) and (g) deal with information held by the state board of health or

state board of pharmacy, and are not relevant for local governments.]

(f) Except for published statistical compilations and reports relating to infant mortality re-

view studies that do not identify individual cases and sources of information, any records

or documents obtained, prepared, or maintained by the local health department for the

purposes of an infant mortality review conducted by the department of health under

RCW 70.05.170. . . .

(2) Chapter 70.02 RCW applies to public inspection and copying of health care information of pa-

tients.

RCW 42.56.370 Domestic Violence Program, rape crisis center clients.

Client records maintained by an agency that is a domestic violence program as dened in

RCW70.123.020 or 70.123.075 or a rape crisis center as dened in RCW 70.125.030 are exempt

from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.380 Agriculture and livestock.

is exemption deals with information held by state agencies, not local governments.

27Public Records Act

RCW 42.56.390 Emergency or transitional housing.

Names of individuals residing in emergency or transitional housing that are furnished to the de-

partment of revenue or a county assessor to substantiate a claim for property tax exemption under

RCW84.36.043 are exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.400 Insurance and nancial institutions.

is exemption concerns records held by state agencies, not local governments.

RCW 42.56.410 Employment security department records.

Records maintained by the employment security department and subject to chapter 50.13 RCW if

provided to another individual or organization for operational, research, or evaluation purposes are

exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.420 Security.

e following information relating to security is exempt from disclosure under this chapter:

(1) ose portions of records assembled, prepared, or maintained to prevent, mitigate,

or respond to criminal terrorist acts, which are acts that signicantly disrupt the conduct of

government or of the general civilian population of the state or the United States and that

manifest an extreme indierence to human life, the public disclosure of which would have a

substantial likelihood of threatening public safety, consisting of:

(a) Specic and unique vulnerability assessments or specic and unique response or

deployment plans, including compiled underlying data collected in preparation of or

essential to the assessments, or to the response or deployment plans; and

(b) Records not subject to public disclosure under federal law that are shared by

federal or international agencies, and information prepared from national security

briengs provided to state or local government ocials related to domestic prepared-

ness for acts of terrorism.

(2) ose portions of records containing specic and unique vulnerability assessments or

specic and unique emergency and escape response plans at a city, county, or state adult or

juvenile correctional facility, the public disclosure of which would have a substantial likeli-

hood of threatening the security of a city, county, or state adult or juvenile correctional facil-

ity or any individual’s safety;

(3) Information compiled by school districts or schools in the development of their com-

prehensive safe school plans pursuant to RCW 28A.320.125, to the extent that they identify

specic vulnerabilities of school districts and each individual school;

28Public Records Act

(4) Information regarding the infrastructure and security of computer and telecommu-

nications networks, consisting of security passwords, security access codes and programs,

access codes for secure soware applications, security and service recovery plans, security risk

assessments, and security test results to the extent that they identify specic system vulner-

abilities; and

(5) e security section of transportation system safety and security program plans

required under RCW 35.21.228, 35A.21.300, 36.01.210, 36.57.120, 36.57A.170, and

81.112.180.

RCW 42.56.430 Fish and wildlife.

is exemption mostly concerns records held by state agencies and is not relevant for local gov-

ernments, except for subsection (2), dealing with information regarding sensitive wildlife data,

such as data concerning the nesting sites of endangered species, or information concerning spe-

cies that are threatened but have a commercial or black market value.

RCW 42.56.440 Veterans’ discharge papers – Exceptions.

County auditors dealing with veterans’ discharge papers need to read this statue carefully.

RCW 42.56.450 Check cashers and sellers licensing applications.

is exemption deals with records held by the state director of nancial institutions and is not

relevant for local governments.

RCW 42.56.460 Fireworks.

All records obtained and all reports produced as required by state reworks law, chapter 70.77 RCW,

are exempt from disclosure under this chapter.

RCW 42.56.470 Correctional industries workers.

is exemption is not relevant for local governments.

RCW 42.56.480 Inactive programs.

is exemption is not relevant for local governments.

Exempt Records and Redaction

e preceding section looked at specic records that are exempt from disclosure. Once a record

is found to be exempt, the local agency must determine whether personal information can be

deleted from the exempt record so that it might still be released.

29Public Records Act

e requirement that exempt material be deleted and the rest of the record disclosed, is some-

times referred to as redaction.

50

is section deals only with redaction pertaining to the exemp-

tions listed in the Public Records Act.

Having determined that a record is exempt from disclosure under the Public Records Act,

RCW42.56.210(1) provides that “the exemptions of this section are inapplicable to the extent that

information, the disclosure of which would violate personal privacy or vital government interests,

can be deleted from the specic record sought (emphasis added).” erefore, exemptions will not

bar disclosure of records, where the local agency can delete information that would violate (1)

personal privacy or (2) vital government interests.

1. Redacting Information, Disclosure of Which Would Violate Personal Privacy

e terms “right to privacy,” “right of privacy,” “privacy,” or “personal privacy,” are found through-

out the Public Records Act.

51

In 1978 the state supreme court dened the right to privacy in

Washington to be coincident with the common law:

One who gives publicity to a matter concerning the private life of another is subject to

liability if the matter publicized is of a kind that (a) would be highly oensive to a reason-

able person, and (b) is not of legitimate concern to the public.

52

e court cited the following explanation as illustrative of the type of facts protected by the right

to privacy:

Every individual has some phases of his life and his activities and some facts about himself

that he does not expose to the public eye, but keeps entirely to himself or at most reveals

only to his family or to close personal friends. Sexual relations, for example, are normally

entirely private matters, as are family quarrels, many unpleasant or disgraceful illnesses,

most intimate personal letters, most details of a man’s life in his home, and some of his

past history that he would rather forget. When these intimate details of his life are spread

before the public gaze in a manner highly oensive to the ordinary reasonable man, there

is an actionable invasion of his privacy, unless the matter is one of legitimate public inter-

est.

53

In 1987 the legislature adopted this statement of the law, and it is now codied as RCW 42.56.050:

A person’s “right to privacy” . . . is invaded or violated only if disclosure of information

about the person: (1) Would be highly oensive to a reasonable person, and (2) is not of

legitimate concern to the public.

50

e Model Rules discuss redaction at WAC 44-14-04004(b)(i).

51

ere is no general “privacy” exemption. See WAC 44-14-06002(2).

52

Hearst v. Hoppe, 90 Wn.2d 123, 135-36 (1978) (adopting Restatement (Second) of Torts § 652D, at 383 (1977)).

53

Hearst, 90 Wn.2d at 136.

30Public Records Act

Both the “oensiveness” and “legitimate concern” elements must be met before information may

be redacted from a record.

e Washington courts have applied this rule on several occasions. In one case the court held that

“under Washington’s public records act, the names of police ocers, without simultaneous release

of other identifying information such as home addresses, residential telephone numbers, and

social security numbers cannot be considered “highly oensive.” . . . ”

54

Additionally, a legitimate

public concern existed because “. . . police ocers are public employees, paid with public tax dol-

lars. ey are granted a great deal of power, authority, and discretion in the performance of their

duties.”

55

In 2005 the court of appeals provided a wide-ranging analysis of the right to privacy in regard

to public employee personnel records when it examined disclosure issues involving teachers and

records of allegations of misconduct of a sexual nature.

56

In another appeals case regarding employee identication numbers, the appeals court held that

the “. . . release of employees’ identication numbers would be highly oensive, because disclosure

could lead to public scrutiny of individuals concerning information unrelated to any governmental

operation and impermissible invasions of privacy. . . .”

57

However, the release of employee names

would not be similarly oensive or lead to such invasions of privacy; rather, disclosure of employ-

ee names would “allow public scrutiny of government.”

58

In general, performance evaluations of public employees that do not contain particular incidents

of misconduct are presumed to be highly oensive and of small public concern.

59

However, this

does not apply to the position of city manager, because the “. . . performance of the City Manager’s

job is a legitimate subject of public interest . . . [he or she] . . . cannot reasonably expect that evalu-

ations of the performance of his or her public duties will not be subject to public disclosure.”

60

erefore, while the courts generally view non-particularized evaluations as highly oensive,

there is an overriding legitimate public concern in the case of city managers.

Question: Are public employee time sheets (time cards) public records which must be disclosed?

Answer: Yes, but any personal information such as social security numbers, addresses, or phone

numbers should be deleted before release.

61

54

King County v. Sheehan, 114 Wn. App. 325, 346 (2002).

55

Id. at 347.

56

Bellevue John Does 1-11 v. Bellevue School District #405, 129 Wn. App. 832.

57

Tacoma Pub. Library v. Woessner, 90 Wn. App. 205, 221-22 (1998) (emphasis added).

58

Id.

59

Dawson, 120 Wn.2d at 797; accord Spokane Research & Defense Fund v. City of Spokane, 99 Wn. App. 452, 456 (2000).

60

Spokane Research & Defense Fund, 99 Wn. App. at 457.

61

See RCW 42.56.230(3) and 42.56.250(3); Woessner, 90 Wn. App. at 224 (holding that it was permissible to redact em-

ployee identication numbers from a report but employee names should not have been redacted).

31Public Records Act

Question: Are the salaries of local government employees a public record which must be disclosed?

Answer: Yes, there is no exemption which applies to such information. The public has a right to know

how its monies are spent.

62

Data regarding tax deductions or other voluntary deductions should be

deleted before disclosure.

Comment: is provision is not a general privacy exemption. e private information protected

under RCW 42.56.050 is limited to “the right to privacy in certain public records” and the provi-

sion does not “create any right of privacy beyond those rights that are specied in this chapter

[the Public Records Act] as express exemptions.”

2. Redacting Information, Disclosure of Which Would Violate a Vital Government Interest

e term “vital government interest” is not dened in the Public Records Act. A helpful discus-

sion of that term is contained in a 1976 attorney general letter opinion,

63

which opined that the

descriptive term “vital” gives a more restrictive meaning to the phrase than if the legislature had

used the term “important.”

A similar term “vital government functions” is used in RCW 42.56.540, and it may be useful by

analogy. at statute authorizes a superior court to prohibit disclosure of public records if the

court nds

“. . . that such examination would clearly not be in the public interest and would substan-

tially and irreparably damage any person, or would substantially and irreparably damage

vital government functions.”

Comment: A local agency may be exposed to liability for violating an individual’s privacy rights

if it makes the wrong determination about whether private information should be redacted. As a

precaution, an agency should contact the individual who is the subject of the records request. is

notication will provide an opportunity for that individual to seek a court order prohibiting the

disclosure.

Redacting Information in Records Made Available to the Public

When a public record is not exempt under the specic provisions in the Public Records Act, a lo-

cal agency must still examine the document to see if any portions are exempt or prohibited from

disclosure.

ough there is no general privacy exemption, a few specic exemptions incorporate privacy

as one of the elements, such as personal information in employee les.

64

If some information is

clearly exempt or prohibited from disclosure, that information must be redacted from the record.

62

See AGO 1973 No. 4. For a discussion of an opposing view, see pp. 12-8 through 12-10 in the article by Kyle J. Crews

cited in Appendix A.

63

AGLO 1976 No. 47, at p. 6.

64

See WAC 44-14-06002(2) and AGO 1998 No. 12.

32Public Records Act

is redaction provision is similar to that provided in RCW 42.56.210(1) except that it applies to

all public documents. If a record contains both information which should be disclosed, and some

which is exempt from disclosure, a local government is generally required to delete the exempt

information from the record and disclose the rest. For example, if there is a request for records

concerning the hours worked during a certain month by a particular local government employee,

the local government should redact all exempt, personal information which might also be con-

tained in the records, such as the home phone number or home address, personal e-mail address,

personal wireless phone number, and social security number – the rest of the record must be

disclosed.

65

e redaction requirement applies to all but a few specically excepted public records. e state

supreme court has held that if another statute “(1) does not conict with the Act [Public Records

Act], and (2) either exempts or prohibits disclosure of specic records in their entirety, then (3)

the information may be withheld in its entirety notwithstanding the redaction requirement.”

66

As

an example, an agency may refuse to disclose employee medical records which it has on le, in

its entirety.

67

No redaction requirement applies here because of the specic statutory prohibition

provided for medical records.

65

RCW 42.56.250.

66

PAWS, 125 Wn.2d at 262.

67

See chapter 70.02 RCW.

33Public Records Act

Exemptions and Prohibitions Outside the Public

Records Act

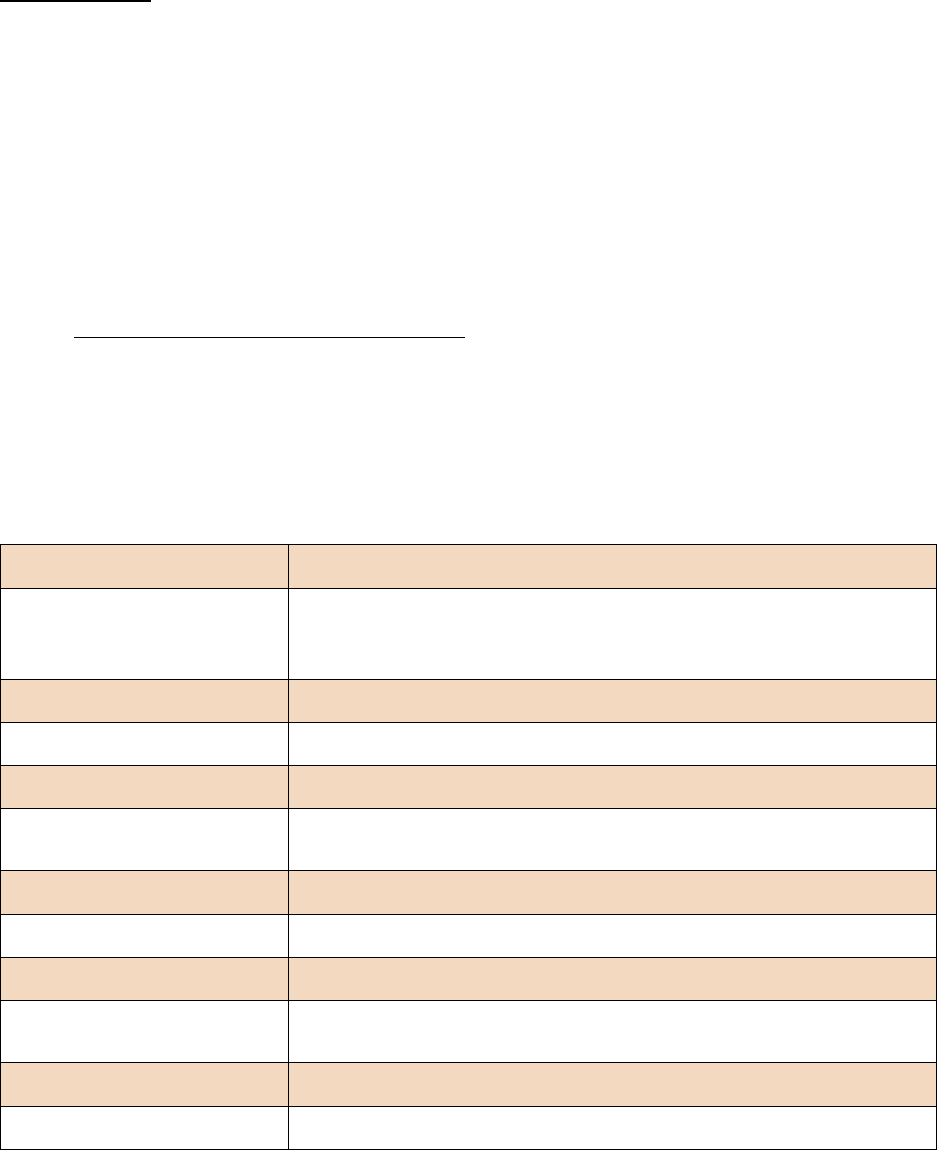

In addition to the many exemptions provided in the Public Records Act, chapter 42.56 RCW, the

legislature has enacted numerous laws which prohibit or exempt the disclosure of other classes of

information. e prohibitions and exemptions relevant to local governments include:

• Addresses of victims of domestic violence. Chapter 40.24 RCW.

• Medical records. Chapter 70.02 RCW.

68

is exemption applies to medical records in an

employee’s personnel le,

69

and also to medical records prepared by ambulance EMTs,