This Issue

Volume 5, Number 5

May 2014

Creating an Accurate Cause

of Death Statement on a

Death Certificate

1

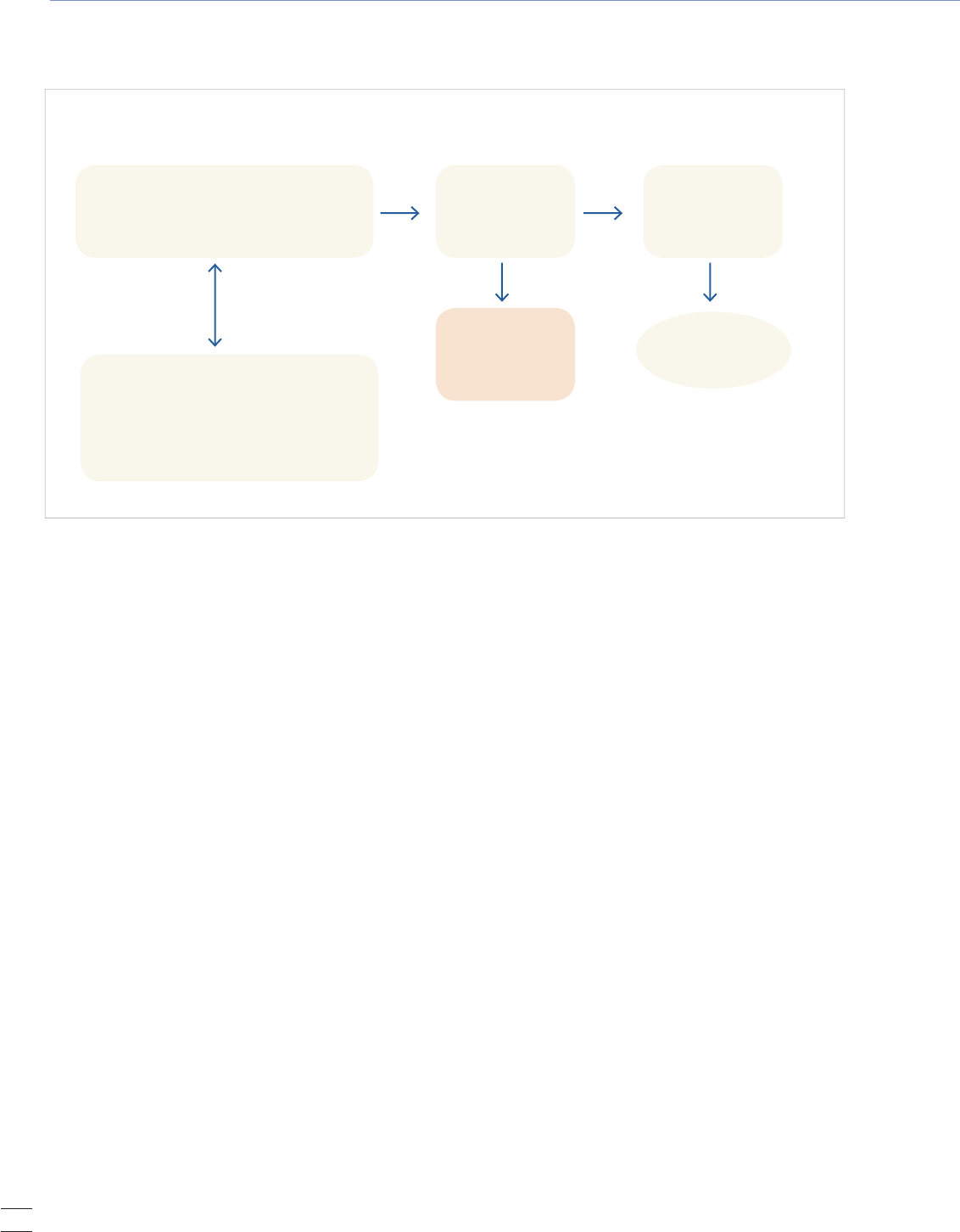

Figure 1. Death

Registration Process

2

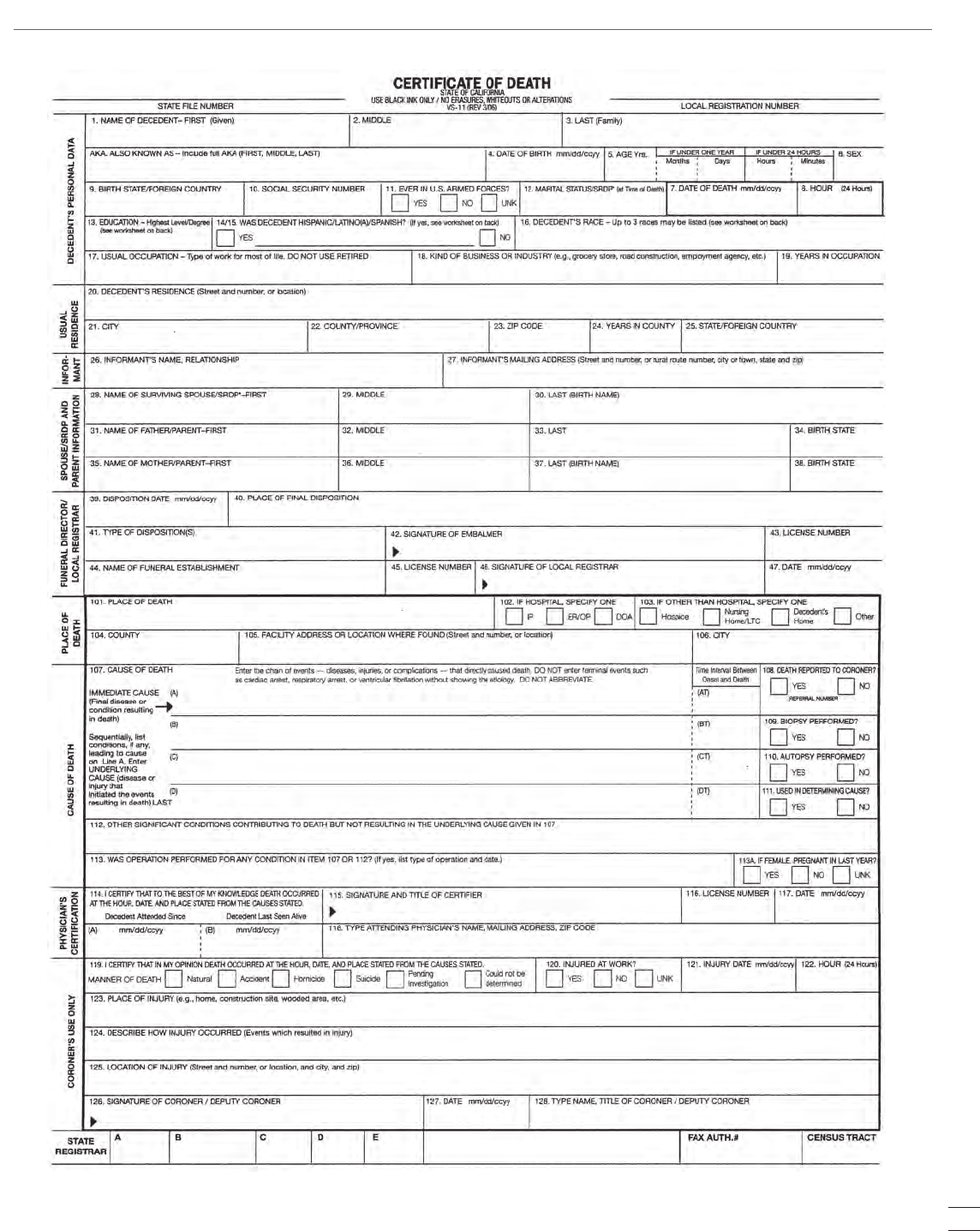

Figure 2. Sample Form of

California Certificate of Death

3

Electronic Cigarettes:

What Health Care

Providers Should Know

6

Figure 1. Diagram of

an Electronic Cigarette

6

Upcoming Training

8

Index of Disease

Reporting Forms

8

Death certificates are important

legal documents. Physicians play

a vital role in ensuring that the

medical information is accurate,

timely, and complete.

Natalia E. Sejbuk, MPH

Elizabeth Friedman, MPH

Loren Lieb, MPH

A

death certificate is a vital legal

document that contains the date,

location, and cause of a person’s

death. The information provided on

the death certificate is as important to

families and the health of the population

as the information entered in medical

records is to individuals. Even so,

physicians, who have primary

responsibility for determining the cause

and manner of death, often receive

little formal training in completing the

death certificate.

A death certificate is vital not only for

settling estates, closing bank accounts,

determining insurance and pension

benefits, and providing evidence

in court, it is also important for

monitoring mortality trends, providing

outcome data for research studies, and

for setting priorities for health-related

funding, research, and interventions. In

some circumstances, death certificates

may also be used for surveillance

of unusual health conditions and

conditions of public health significance.

In most cases, the attending physician

is responsible for determining and

completing the cause-of-death section

on the death certificate. Since

statistical data are derived from this,

it is important to complete the death

registration process as accurately and

promptly as possible.

The Process

On October 1, 2007, Los Angeles County

implemented the web-based California

Electronic Death Registration System

(CA-EDRS) to expedite the death

registration process. This paperless

Creating an Accurate Cause of Death

Statement on a Death Certificate

system enables funeral directors,

physicians, coroners, and hospitals to

submit electronic death certificates

for registration 24 hours per day. This

around-the-clock access assures that

death registration can occur within the

8 days required by California law and

that the cause of death can be reported

by the physician within the required

15 hours (California Health and

Safety Code, Chapter 6, Article 1,

§102775-102805).

The funeral director initiates the

death registration process by gathering

personal and demographic information

about the deceased—this responsibility

makes the funeral director the anchor

of the death registration system. Next,

the attending physician or coroner

completes the medical portion of the

death certificate to determine the

manner in which the individual died.

Medical examiners or coroners are re-

sponsible for investigating any cause of

death that is unexpected, unexplained,

or resulting from injury, poisoning,

or a public health threat. If a case is

referred to the coroner, the coroner

enters cause-of-death information

directly into CA-EDRS under the

“Coroner’s use only” section.

In most cases, however, the attending

physician is responsible for determin-

ing the cause of death. The physician

continued on page 2 >

2

Rx for Prevention LA County Department of Public Health May 2014

CREATING AN ACCURATE CAUSE OF DEATH STATEMENT from page 1

receives a cause-of-death worksheet provided by the funeral

director; once completed, he or she returns it to the funeral

director. The death certificate is then forwarded to the local

Department of Public Health; in LA County, it is the Registrar

for the LA County Department of Public Health. The death

certificate is reviewed and the cause of death is checked for

compliance with the International Classification of Diseases

10th revision (ICD-10) rules and for acceptance of the death

certificate in accordance with state guidelines. Once the death

certificate is accepted by the local Registrar, the physician

must attest to the accuracy of the cause-of-death information

on the certificate. This is done remotely using either a fax

machine to send the physician’s signed attestation to the

funeral home or by telephone, which requires the physician

to dial a toll-free number to provide a voice attestation. The

death certificate can then be submitted to the Public Health

Registrar by the funeral director for legal registration.

Throughout the death registration process, information is

entered directly into CA-EDRS. Los Angeles County data are

incorporated into both state and national databases, which are

used to describe the characteristics of those who died, to

determine life expectancy, and to compare mortality trends

and patterns with other jurisdictions. Mortality data for

Los Angeles County residents are summarized annually in

a report that describes the leading causes of death and pre-

mature death and that examines 10-year mortality trends.

1

Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) compiles data

for the United States that are also published annually.

2

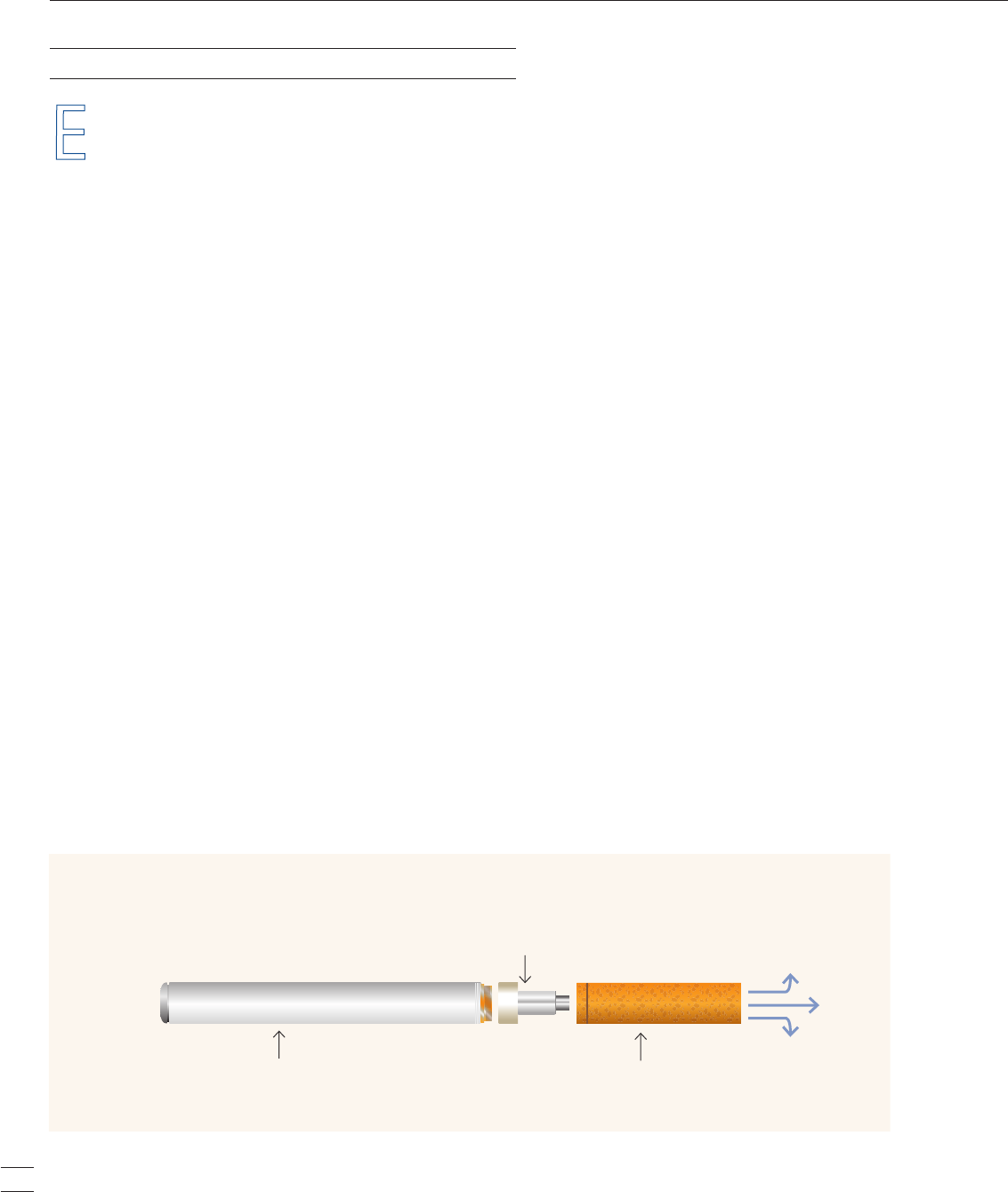

Figure 1 depicts the sequence of events that occur throughout

the course of the death registration process.

The Cause-of-Death Section: Instructions for Physicians

Section 107 of the California Certificate of Death (Figure 2)

is the most difficult section to complete. It is the physician’s

responsibility to report the cause of death as correctly as pos-

sible based on his or her best medical opinion. The section

consists of two parts. Part I is a sequential list of conditions

leading to the immediate cause of death and the time intervals

between their onset and the death. Part II is a list of other

conditions contributing to, but not directly causing, death.

PART I

Immediate cause of death: Item 107(A) is for the immediate

cause of death. This should be a disease, condition, or injury

that directly resulted in death. A common error is to list a

mechanism of death (for example, cardiac arrest) rather than

a disease (myocardial infarction). Vague terms such as “brain

dead” or “pulmonary arrest” cannot be used on the death

certificate. If cancer is the immediate cause of death, the pri-

mary site, cell type, and specific organ or lobe affected must

be listed. Examples are “adenocarcinoma of sigmoid colon” or

“squamous cell cancer of the breast.” Terms such as “old age”

or “senescence” are not acceptable since they do not actually

cause death. Autopsy cases must always be referred to the

coroner (with the exception of a few teaching medical facili-

ties) and, in some cases, it is appropriate for the coroner to list

the cause of death as “deferred” while waiting for the cause of

death results. If a death certificate is registered as “deferred,”

an amendment needs to be filed by the coroner in CA-EDRS

as soon as the results are available. In rare circumstances,

after investigation, the coroner may list the cause of death as

Figure 1. Death Registration Process

FUNERAL DIRECTOR

• Coordinates the death certicate processing

• Collects personal and demographic data

about decedent

CA State Office of

Vital Records

National Vital

Statistics System

(NVSS)

LOCAL REGISTRAR

Legal registration

MEDICAL CERTIFIER

• Licensed Physician

• Coroner

• Determines and certies the "Cause of

death" as being correct

Certied copy of

death certificate

available to family

SAMPLE

3

May 2014 LA County Department of Public Health Rx for Prevention

Figure 2. Sample Form of California Certificate of Death

4

Rx for Prevention LA County Department of Public Health May 2014

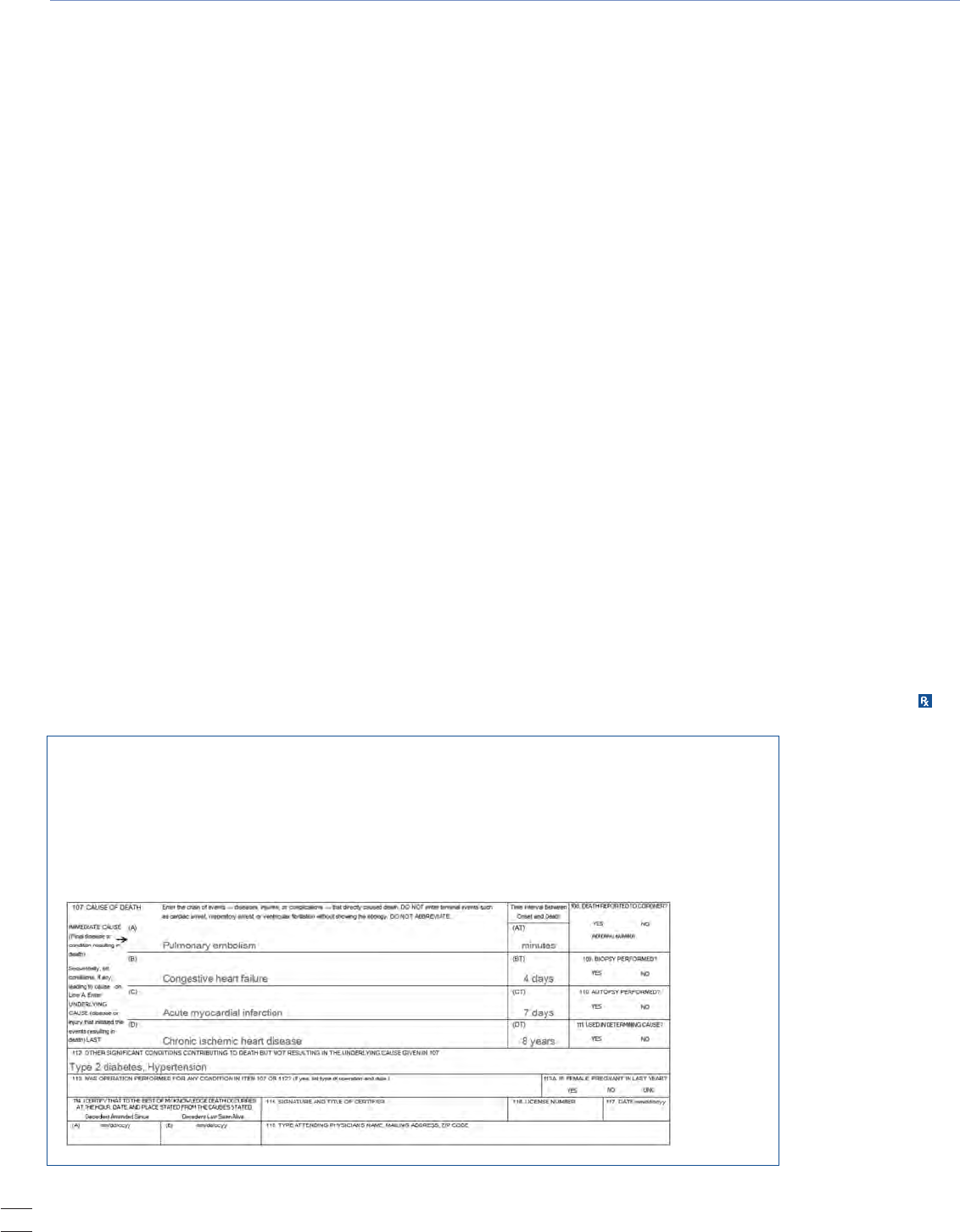

Case Study 1

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the ICU because of acute chest pain. She has Type 2 diabetes,

hypertension, obesity, and angina. Over the next 24 hours, an acute myocardial infarction is

confirmed. Heart failure develops but improves with management. The woman then experiences a

pulmonary embolus, confirmed by ventilation-perfusion lung scan and blood gases; over the next

2 hours she becomes unresponsive and dies. What should be written in the cause of death section?

“Could not be determined” in Section 119. Abbreviations

must never be used in section 107, and line 107(A) should

never be blank.

Underlying cause of death: Items 107(B-D) are for the

intermediate and underlying causes of death. This is the most

significant piece of information on the certificate since most

mortality analyses are based on the underlying cause of death.

Every condition listed should cause the one above it. Thus,

entering conditions in an illogical order will prompt the

Public Health Registrar to question the cause of death and

the certificate will be returned to the funeral director for

revision. A useful way to make sure the order of the causes

makes sense is to say the phrase “due to” or “as a consequence

of,” moving from line A down to the last filled-in line. For

instance, a death may be due to a pulmonary embolus, as a

consequence of hip surgery, resulting from an injury from a

fall, resulting from a cerebral infarction. Cerebral infarction

is the underlying cause of death. Multiple conditions cannot

be listed on 1 line in this section.

Time intervals: To the right of lines 107(A-D) are items

107(AT-DT) where the time intervals between the conditions

listed and the time of death are to be listed. The more precise

the time the better, but it is acceptable to estimate and

use terms such as “approximately.” If the time interval is

unknown and cannot be estimated, “unknown duration”

can be listed. Something must always be entered on these

lines next to the corresponding conditions; they cannot

be left blank.

PART II

Other significant conditions: Item 112 is where other ill-

nesses or conditions that may have contributed to the death,

but were not the direct cause of it, can be listed. Multiple

conditions may be listed here. There may be uncertainty as

to the direct or contributing causes of death, so it is up to the

physician to use his or her best medical judgment as to the

most likely causes and sequences contributing to death.

The Big Picture

Most physicians at some point in their careers will complete

a death certificate. The cause of death information from each

death becomes a permanent legal record and part of our state

and national mortality databases; therefore, it is important

that physicians, together with all those involved in the death

registration process, make every effort to complete each death

certificate as accurately and completely as possible. Mortality

data are important to physicians since they influence fund-

ing for medical and health research and can influence clinical

practice. They are also critical for establishing public health

priorities. The county’s annual mortality summary provides

information about the leading causes of death and premature

death. For example, in 2010, an average of 155 people died

each day in Los Angeles County, including 35 from coronary

heart disease, 9 from injuries, and 9 from stroke.

1

The remain-

ing deaths resulted from such causes as emphysema, diabe-

tes, pneumonia, liver disease, and cancer. Without properly

completed death certificates, we would not be able to analyze

mortality patterns and make them widely available. Addition-

al resources and contact information are listed on page 5 for

any questions regarding the death registration process.

5

May 2014 LA County Department of Public Health Rx for Prevention

Additional Resources for Physicians

CDC Physician Handbook on Death Certication

www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf

Improving Cause of Death Reporting (online tutorial)

http://www.cdc.gov/primarycare/materials/online-trainings/icdr/player.html

CDC NCHS Mortality Data from the National Vital Statistics System

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/deaths.htm

California Electronic Death Registration System Website

http://www.edrs.us/edrs/index.jsp

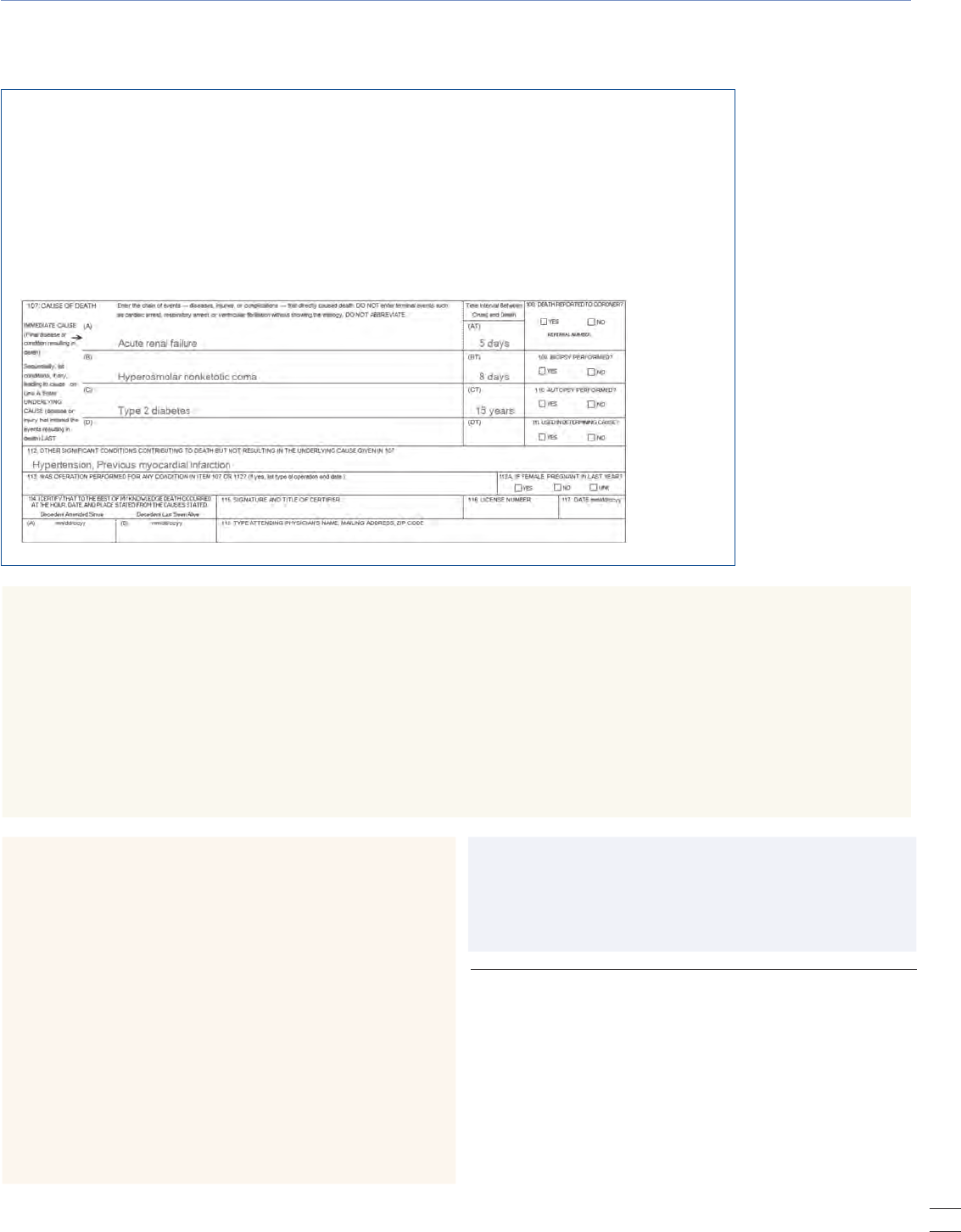

Case Study 2

A 75-year-old female has a 15-year history of Type 2 diabetes, history of hypertension, and an

uncomplicated myocardial infarction 6 years prior. Her daughter found her disoriented in her home

and brought her to the hospital. On admission, she was unresponsive. Laboratory tests disclosed

severe hyperglycemia, hyperosmolarity, azotemia, and mild ketosis without acidosis. A diagnosis

of hyperosmolar nonketotic coma was made. She was vigorously treated, and within 72 hours her

hyperosmolar and hyperglycemic state was resolved. However, she remained anuric with progressive

azotemia. Attempts at renal dialysis were unsuccessful. The patient died 8 days later in severe renal

failure. What should be written in the cause of death section?

Contacts

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health,

Public Health Registrar

Gustavo Feregrino (213) 240-8029

Roland Carrillo (323) 869-8510

Alma Ortega (323) 869-8512

Gregory Mercado (213) 989-7073

LA County Department of Coroner

Dr. Mark A. Fajardo, Chief Medical Examiner Coroner,

(323) 343-0512; After hours, (323) 343-0714

CA-EDRS Help Desk

(916) 552-8123

Natalia E. Sejbuk, MPH, is an Epidemiology Analyst, Office of Health

Assessment and Epidemiology; Elizabeth Friedman, MPH, is an

Epidemiology Analyst, Community Health Services; and Loren Lieb,

MPH, is a Supervising Epidemiologist, Ofce of Health Assessment and

Epidemiology, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

REFERENCES

1. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Ofce of Health

Assessment and Epidemiology. Mortality in Los Angeles County

2010: Leading causes of death and premature death with trends for

2001-2010. October 2013. Available online at http://publichealth.

lacounty.gov/dca/data/documents/2010MortalityReport.pdf. Print

copies are available from the Ofce of Health Assessment and Epide-

miology at (213) 240-7785.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statis-

tics Reports, Deaths: Final Data for 2010. May 2013.

6

Rx for Prevention LA County Department of Public Health May 2014

Susan Bradshaw, MD, MPH, ABIHM

Tonya Gorham Gallow, MSW

E

lectronic cigarettes, or e-cigarettes, are battery-operated

devices designed to create a vapor that is inhaled by

the user (“vaping”). The vapor is produced by heating

an internal cartridge that is typically filled with a solution

of nicotine, flavors, and other chemicals. The inhaled

vapor produces a sensation similar to that of inhaled tobacco

smoke.

1-3

E-cigarettes are being widely marketed as a healthier

alternative to conventional cigarettes and as a “safe” smoking-

cessation aid. Although there are anecdotal reports of smokers

who have found e-cigarettes to be helpful in their efforts to

quit smoking, the efficacy of e-cigarettes as an aid in smoking

cessation has not been demonstrated. These products are cur-

rently unregulated and their benefits as well as risks among

youth and adults have not been well-studied.

4

In recent years, there has been an explosion in the popular-

ity of e-cigarettes. Created in China, e-cigarettes became read-

ily available internationally in 2006. Since then, the industry

has grown from a few thousand users to several million

worldwide. In the United States, retail sales of e-cigarettes

doubled from $250 million to $500 million between 2011 and

2012, and sales are expected to quadruple by 2014.

5-6

Of particular concern is the rapid rise in use among youth.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC), the percentage of high-school students in the U.S. who

had ever used e-cigarettes doubled from 4.7% to 10% between

2011 and 2012. During the same 2-year period, the percent-

age of middle-school students who had ever used e-cigarettes

doubled from 1.4% to 2.7%. In 2011, about 21% of adults who

smoked traditional cigarettes had used electronic cigarettes,

up from about 10% in 2010.

7-8

This is unfortunate because

some tobacco control researchers believe e-cigarettes may be

a socially acceptable gateway to nicotine addiction and the

renormalization of tobacco use.

Electronic Cigarettes

What Health Care Providers Should Know

E-cigarette Products

E-cigarettes come in many varieties, including e-pens,

e-cigars, and e-hookah products. They contain e-cigarette

liquid, also known as e-liquid, generally a solution of pro-

pylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and/or polyethylene glycol

mixed with concentrated flavors; and a variable concentration

of nicotine, including nicotine-free versions. E-liquid is

available in a variety of flavors.

Recent studies have identified serious problems associated

with the lack of product standards and regulation. Manufac-

turers do not always accurately label the amount of nicotine in

their products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

found that certain cartridges labeled as “No nicotine” actu-

ally contained nicotine, and that other cartridges labeled as

containing identical amounts of nicotine contained markedly

different amounts of nicotine. One study examined 6

brands of products for design, content, quality, and product

information, including warnings. Most of the products

leaked when handled, creating the potential for dermal

nicotine exposure and potential nicotine poisoning.

Health and Safety Risks

The rise in consumption of e-cigarettes is very worrisome

because early studies indicate these products may not be safe.

At least 10 chemicals identified in e-cigarette aerosol (or the

vapor) are on California’s Proposition 65 list of carcinogens

and reproductive toxins.

The compounds that have been identified in e-cigarette

aerosol include acetaldehyde, benzene, cadmium, formalde-

hyde, isoprene, lead, nickel, nicotine, N-nitrosonornicotine,

and toluene. Chemicals found in e-cigarette aerosol include

metals, such as chromium and tin nanoparticles; tobacco-

specific nitrosamines, chemicals known to cause cancer; and

diethylene glycol, a substance commonly found in antifreeze.

The concentrations for most of the above elements in

e-cigarette aerosol were higher or equal to the corresponding

concentrations in conventional cigarette smoke.

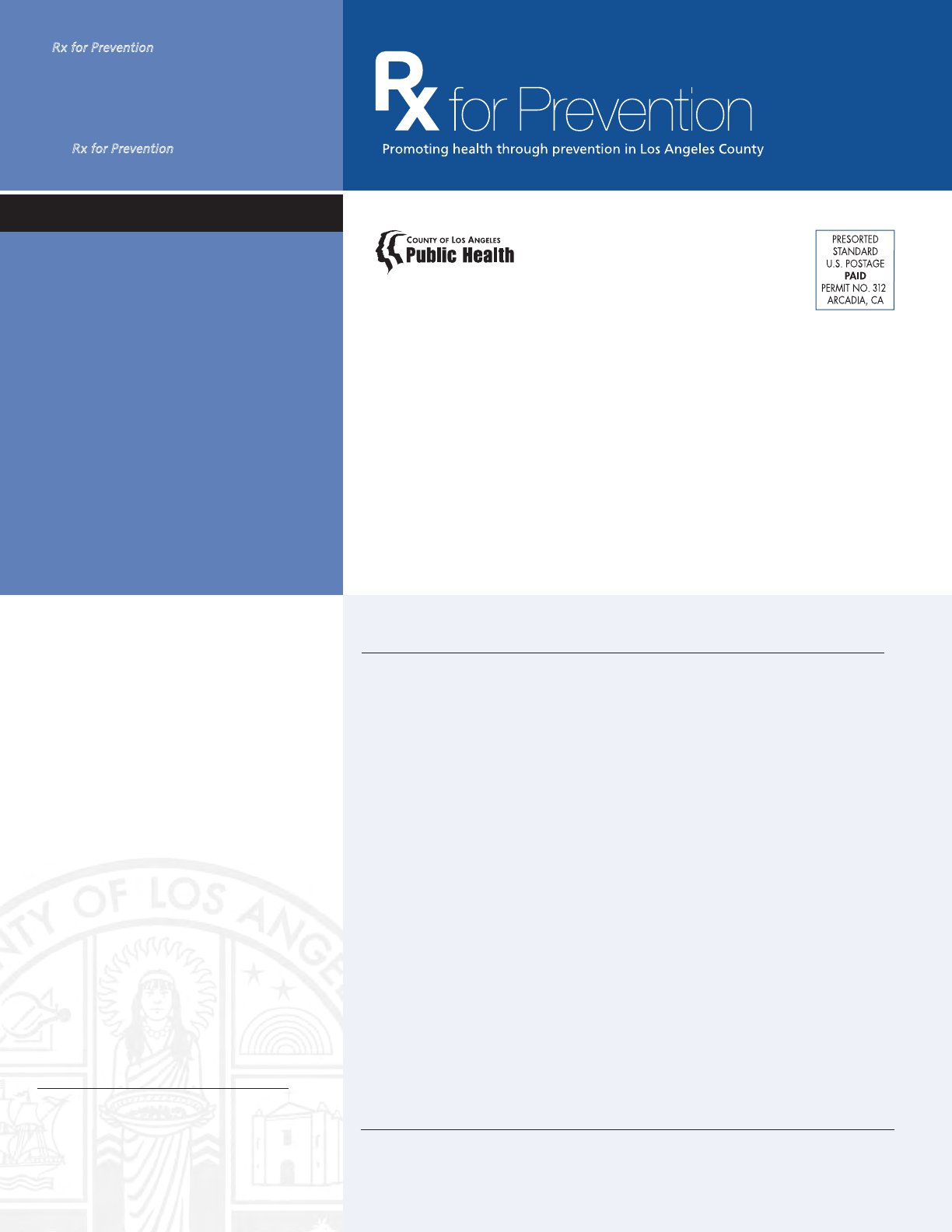

Battery

Vapor

Atomization Chamber

Heats the solution, vaporizing it

Nicotine Cartridge

Holds a solution, which may

or may not contain nicotine

Diagram of an Electronic Cigarette

7

May 2014 LA County Department of Public Health Rx for Prevention

Another health concern is the chronic inhalation of pro-

pylene glycol, the main ingredient in e-liquid. Even though

propylene glycol is FDA-approved for oral consumption, the

inhalation of vaporized nicotine in propylene glycol is not.

Short-term exposure causes eye, throat, and airway irrita-

tion, and long-term exposure can result in children develop-

ing asthma. Some studies show that heating propylene glycol

changes its chemical composition, producing small amounts

of propylene oxide, a known carcinogen.

Nicotine toxicity is a significant health concern, given

reports of accidental poisonings from e-cigarette products on

the rise, particularly among children. E-cigarette-related calls

to poison control centers tripled between 2012 and 2013, and

the number of poisonings jumped to 1,351 in 2013, a 300%

increase from 2012. The CDC reported a dramatic rise in the

number of e-cigarette-related phone calls to poison control

centers, from just 1 call per month on average in 2010 to

nearly 200 calls per month in early 2014. More than 50% of

the calls involved children aged 5 and under.

Signs of Nicotine Toxicity

Liquid nicotine is far more dangerous than that found in other

tobacco products because it is absorbed more quickly. Toxi-

cologists identify potential dangers of e-liquids because of

their neurotoxicity and ability to be lethally absorbed quickly

through the skin.

Health care providers should be familiar with signs and

symptoms related to nicotine toxicity. Mild symptoms include

nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, increased heart rate,

and increased blood pressure. More severe symptoms include

seizures, decreased heart rate, and decreased blood pressure.

Symptoms from skin or eye exposure include irritation,

redness, severe pain, and inflammation, and may result in

whole-body toxicity.

Recommendations

Given the unknown public health impact and the current

lack of regulation, the Los Angeles County Department of

Public Health recommends a precautionary approach regard-

ing the use of e-cigarettes until further research is available.

The CDC, along with other health agencies, recommend that

health care providers consider the following actions:

• Be well-informed and vigilant that e-cigarettes have the

potential to cause acute adverse health effects and represent

an emerging public health concern.

• Inform patients of potential dangers of e-cigarettes and

encourage parents to talk to their children and to discour-

age use. Advise patients to keep e-cigarettes out of reach of

children, preferably locked in a secure place.

• Inform patients that e-cigarettes have not been approved by

the FDA as a quit-smoking aid. Encourage the use of FDA-

approved smoking-cessation medication among patients

who want to quit. Additional information on strategies and

support for quitting smoking can be found online at

www.LAQuits.com or by calling 1-800-NO-BUTTS.

Update

At press time, the FDA proposed rules to strictly regulate

electronic cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, nicotine gels, water

pipe tobacco, and hookahs. After a 75-day public comment

period (starting April 25, 2014), the proposed rules include

the following:

• Setting the age limit to buy the products to be at least

18 years (states can set it higher)

• Health warnings required on all products

• Sale of the products in vending machines

would be prohibited

• Manufacturers would be required to register all of their

products and ingredients with the FDA

• Manufacturers would only be able to market new products

after an FDA review

• Manufacturers would need to provide scientic evidence

before making any claims of risk reduction tied to use of

their product.

Susan Bradshaw, MD, MPH, ABIHM, is a Physician Specialist, and

Tonya Gorham Gallow, MSW, is Director, Tobacco Control and Preven-

tion Program, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

REFERENCES

1. Tobacco Fact Sheet–Electronic Cigarettes (E-Cigarettes). (June

2013). American Legacy Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.

legacyforhealth.org/content/download/ 582/6926/le/LEG-Fact-

Sheet-eCigarettes-JUNE2013.pdf.

2. Questions and answers on electronic cigarettes or electronic

nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). (July 2013). World Health Organi-

zation, Tobacco Free Initiative. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/

tobacco/communications/statements/eletronic_cigarettes/en/.

3. E-Cigarettes [fact sheet]. (Oct 2013). American Academy of Pediat-

rics–Julius B. Richmond Center of Excellence. Retrieved from: http://

www2.aap.org/richmondcenter/ pdfs/ECigarette_handout.pdf.

4. Food and Drug Administration. News and events—electronic

cigarettes (e-cigarettes). Silver Spring, Maryland: US Department of

Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2014.

Available at http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/publichealthfocus/

ucm172906.htm.

5. Herzog B.E- Cigs Revolutionizing The Tobacco Industry; Wells Far-

go Security Equity Research, June 12, 2013. (Email Correspondence).

6. Mangan D. “E-cigarette sales are smoking hot, set to hit

$1.7 billion.” CNBC. 28 August 2013. Available at: http://

www.cnbc.com/id/100991511.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortal-

ity Weekly Report: Notes from the Field: Electronic Cigarette Use

Among Middle and High School Students – United States, 2011-

2012. MMWR 2013;62:p729-830.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Press Release: About

one in ve U.S. adult cigarette smokers have tried an electronic

cigarette. CDC. 28 February 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/

media/releases/2013/ p0228_electronic_cigarettes.html.

Index of Disease Reporting Forms

All case reporting forms from the LA County Department of Public Health are

available by telephone or Internet.

Rx for Prevention is published 10 times a year

by the Los Angeles County Department of

Public Health. If you would like to receive this

newsletter by e-mail, go to www.publichealth.

lacounty.gov and subscribe to the ListServ

for

Rx for Prevention.

Office of the Medical Director

241 N. Figueroa St., Suite 275

Los Angeles, CA 90012

Use of trade names and commercial sources in Rx for Prevention is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Los Angeles

County Department of Public Health (LACDPH).References to non-LACDPH sites on the Internet are provided as a service to Rx for Prevention

readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by LACDPH. The Los Angeles County Department of

Public Health is not responsible for the content of these sites. URL addresses listed in Rx for Prevention were current as of the date of publication.

Reportable Diseases & Conditions

Confidential Morbidity Report

Morbidity Unit (888) 397-3993

Acute Communicable Disease Control

(213) 240-7941

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/

reports/CMR-H-794.pdf

Sexually Transmitted Disease

Confidential Morbidity Report

(213) 744-3070

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/dhsp/

ReportCase.htm (web page)

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/dhsp/

ReportCase/STD_CMR.pdf (form)

Adult HIV/AIDS Case Report Form

For patients over 13 years of age

at time of diagnosis

Division of HIV and STD Programs

(213) 351-8196

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/dhsp/

ReportCase.htm

Pediatric HIV/AIDS Case Report Form

For patients less than 13 years of age

at time of diagnosis

Pediatric AIDS Surveillance Program

(213) 351-8153

Must first call program before reporting

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/dhsp/

ReportCase.htm

Tuberculosis Suspects & Cases

Confidential Morbidity Report

Tuberculosis Control (213) 745-0800

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/tb/forms/

cmr.pdf

Lead Reporting

No reporting form. Reports are

taken over the phone.

Lead Program (323) 869-7195

Animal Bite Report Form

Veterinary Public Health (877) 747-2243

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/vet/

biteintro.htm

Animal Diseases and Syndrome

Report Form

Veterinary Public Health (877) 747-2243

www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/vet/

disintro.htm

LOS ANGELES COUNTY

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS

Gloria Molina, First District

Mark Ridley-Thomas, Second District

Zev Yaroslavsky, Third District

Don Knabe, Fourth District

Michael D. Antonovich, Fifth District

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Jonathan E. Fielding, MD, MPH

Director and Health Officer

Cynthia A. Harding, MPH

Chief Deputy Director

Jeffrey D. Gunzenhauser, MD, MPH

Medical Director

Steven Teutsch, MD, MPH

Chief Science Ofcer

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Jeffrey D. Gunzenhauser, MD, MPH

jgunzenhauser@ph.lacounty.gov

Steven Teutsch, MD, MPH

steutsch@ph.lacounty.gov

MEDICAL COMMUNITY ADVISER

Thomas Horowitz, DO

EDITORIAL BOARD

Melanie Barr, RN, MSN

Stephanie Caldwell, MPH

Kevin Donovan, MPH

Julia Heinzerling, MPH

Christina Jackson, MPH

Anna Long, PhD, MPH

Paula Miller, MPH, CHES

Sadina Reynaldo, PhD

Carrie Tayour, MPH

Rachel A. Tyree, MPH

Summer Nagano,

Managing Editor

Alan Albert & Kathleen Pittman,

Graphic Designers

Maria Ojeda, Administration

Comments or Suggestions? If so, or if you

would like to suggest a topic for a future issue,

e-mail Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, co-editor, at

jgunzenhauser@ph.lacounty.gov.

Upcoming Training

Immunization Training:

2014 Adult Immunization Schedule

The Los Angeles County Department of

Public Health Immunization Program is

offering a 2-hour CEU training titled

"2014 Adult Immunization Schedule" at

no charge to providers. Topics include adult

immunization schedule updates and recommen-

dations for vaccinating medically high-risk adults

and health care personnel.

To register or learn more about other trainings

sponsored by the Immunization Program,

visit www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/ip/

trainconf.htm or call (213) 351-7800.