Sacred Heart University Sacred Heart University

DigitalCommons@SHU DigitalCommons@SHU

WCBT Faculty Publications Jack Welch College of Business & Technology

2014

The Interaction Between Learning Styles, Ethics Education, and The Interaction Between Learning Styles, Ethics Education, and

Ethical Climate Ethical Climate

Leanna Lawter

Sacred Heart University

Tuvana Rua

Sacred Heart University

Chun (Grace) Guo

Sacred Heart University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac

Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Educational Assessment,

Evaluation, and Research Commons, Human Resources Management Commons, and the Organizational

Behavior and Theory Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Lawter, Leanna; Rua, Tuvana; and Guo, Chun (Grace), "The Interaction Between Learning Styles, Ethics

Education, and Ethical Climate" (2014).

WCBT Faculty Publications

. 347.

https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac/347

This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jack Welch College of Business &

Technology at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in WCBT Faculty Publications by an

authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact santoro-

dillond@sacredheart.edu.

For Peer Review

The Interaction betwee

n Learning Styles, Ethics Education,

and Ethical Climate

Journal:

Journal of Management Development

Manuscript ID:

Draft

Manuscript Type:

Original Article

Keywords:

Learning styles, deep learning, ethics education, ethics climate

Journal of Management Development

For Peer Review

Article ID : 04

The Interaction between Learning Styles, Ethics Education, and Ethical Climate

ABSTRACT

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to investigate how learning styles and learning spaces

interact to stimulate deep learning. Specifically we investigated the interaction of learning styles

with ethics education and the ethical climate to influence the likelihood of engaging in ethical

behavior.

Design/methodology/approach –Data was collected from two groups of students—those who

had completed a business ethics course and those who had not completed a business ethics

course. The sample consisted of 180 undergraduate students at a private university in the United

States. Data was analyzed using regression analysis to test the hypotheses. A scenario-based

measure of the likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior was developed and implemented in the

study.

Findings –Both ethics education and ethical climate had a direct impact on a student’s likelihood

of engaging in ethical behavior. The interaction between learning style and business ethics class

significantly impacted experiential learners’ likelihood of engaging in ethical behaviors. Results

for non-experiential learners as relates to ethical climate were non-significant, but ad hoc

analysis indicates ethical climate significantly impacted likelihood to engage in ethical

behaviors.

Practical Implications –The findings have practical implications for how universities should

utilize learning spaces both inside and outside the classroom to be stimulate deep learning and be

more effective in sensitizing students to ethical behavior.

Originality/Value –Our results support using formal and informal learning spaces to stimulate

deep learning as it relates to ethics education in universities.

Page 1 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Article ID : 04

Keywords – learning styles, deep learning, ethics education, ethical climate

Paper Type – Research paper

Page 2 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 1

Introduction

As business educators, one of our challenges is to develop more ethical managers. The

solution to this challenge has been at most universities to require students to complete a course in

business ethics (Givens, 2004). While ethics education in the form of a business ethics course

may heighten a student’s sensitivity to particular ethical situations, ethics education may in fact

fall short of its main objective—creating ethical managers (Smith and Oakley, 1996). In fact,

business schools are notorious for high levels of cheating (Bowers, 1964; McCabe 1997;

McCabe, Butterfield & Trevino, 2006) and may actually be creating an ethical climate where

observed cheating fosters de-sensitivity to ethical situations and encourages unethical behavior in

order to get ahead (McCabe and Trevino, 1995).

Although explanations of unethical behavior have long been attributed to individual

factors, previous research has shown that contextual factors can interact with individual factors

in influencing moral reasoning and important organizational outcomes (e.g. Adam, Tashchian

and Shore, 2001; Dickson, Smith, Grojean and Ehrhard, 2001; Weber, 1990). Researchers

(Adam et al. 2001; Dickson et al., 2001; Victor and Cullen, 1988) note that the perceived

consequences of behavior, the perceived conformity to group expectations, and the individuals’

economic dependence on the employing organization can exert powerful influence on individual

decisions as well as business unit readiness, success and cohesiveness. Following this logic, we

expect that in an educational setting, students’ ethical behavior can be shaped by individual

factors as well as contextual factors such as the ethical climate of the university and ethics

education in influencing their moral reasoning and individual behavior.

Traditionally, researchers and educators argue that teaching styles should fit and reflect

students’ learning preferences and needs (Kolb, 1984). However, a drastic different approach

Page 3 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 2

recently proposed by Kolb and Kolb (2009) suggests that in order to activate deep learning, the

student must engage in types of learning which are less frequently used and, in a sense, get out of

their comfort zone. For example, while experiential learners are adept at using tacit knowledge,

they may benefit more from business ethics class that facilitates reflective learning and thereby

helps them reframe past events (Lawter, Guo, Rua, 2011). However, to our knowledge, little

research is done on investigating the approach developed by Kolb and Kolb (2009).

Puzzled by these different perspectives, in the present study, we investigate how students’

learning styles, an individual level variable, when interacting with ethics education and the

ethical climate of the university, two context level variables, influence the likelihood of

engaging in ethical behavior. Our primary assertion is that both the classroom and the general

ethical climate of a university act as learning spaces for students. Thus we posit that both the

formal learning space of the business ethics classroom and the informal learning space of the

ethical climate of the university will influence a student’s likelihood of engaging in ethical

behavior.

Deep learning theory (Kolb and Kolb, 2009) suggests that for experiential learners and

non-experiential learners deep learning is stimulated in different learning spaces. Following this

line of reasoning, we would expect that for experiential learners formal learning spaces where

learning occurs primarily through vicarious learning would stimulate deep learning. Similarly,

we would expect that for non-experiential learners informal learning spaces where learning

occurs primarily through experiential learning would stimulate deep learning.

Based on deep learning theory, we posit that for the experiential learner the formal

classroom will have a stronger influence on the likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior, as

business ethics class will activate reflective learning and the reframing of experiences gained

Page 4 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 3

from informal learning spaces. We also predict that for the non-experiential learner the ethical

climate will have a stronger influence on the likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior, as the

experience of seeing students caught cheating will reinforce vicarious learning from formal

learning spaces.

To test these hypotheses we conducted a survey among 180 undergraduate students and

the findings of our data analysis provide initial support to our speculations. We found that

students who took a business ethics class were more likely to engage in ethical behavior. We

also found that students who perceived higher percentages of students caught cheating were

more likely to engage in ethical behavior. Additionally we found some support for the

interactive effects of learning style and learning spaces. Our study makes three major

contributions to theory and practice. First our findings support the theory that deep learning

occurs when students engage in learning outside of their preferred learning style. Empirically,

we found statistical support for the interaction between experiential learning style and formal

learning space. Additionally, ad hoc analysis suggests that further investigation into the

interaction between non-experiential learning styles and informal learning space is needed.

Lastly, the practical implications for our study is that in sensitizing our students to ethical

behaviors, as institutions we need to employ both formal learning spaces and informal learning

spaces as important avenues of learning.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Learning Spaces and Its Influence on Learning

Learning spaces are generally defined as places where formal, or informal learning takes

place (Marsick & Watkins, 2001; Milne, 2006). More specifically, formal learning takes place in

highly structured settings (Marsick & Watkins, 1990) whereas informal learning can take place

Page 5 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 4

anywhere in an organization in an unstructured manner. Accordingly, different learning spaces at

a university can lead to different types of learning: classrooms being highly structured will lead

to formal learning (Marsick & Watkins, 1990), while interactions with peers outside the

classroom and contextual cues from the overall sense of the university climate lead to informal

learning (Marsick & Watkins, 2001; Wenger, 1998).

Bronfrenbrenner (1977) described learning/development spaces as a “topologically

nested arrangement of structures each contained within the next” (p. 514). Kolb and Kolb (2005)

further defined learning spaces within the university setting as a three tiered system of spaces

such that the immediate setting such as the classroom or course is the microsystem of the

individual, whereas the other concurrent settings in the person’s life such as other courses,

dorms, or fraternities serve as the mesosytem, while the overarching institutional patterns and

values of the wider culture in an organization would serve as the macrosystem. Accordingly,

these three levels of the system (micro, meso or macro) would generate distinct learning

opportunities for the learner as each of these levels will present unique experiences. Within the

current study two levels of learning spaces are compared—business ethics class as an example of

the microsystem, which provides formal learning, and ethical climate of the university as an

example of the macrosystem, which provides informal learning.

Business Ethics Class as a Learning Space

Business ethics class acts as a formal learning space where students are sensitized to

types of ethical dilemmas in organizations and societies. The main objective of business ethics

education is to generate a higher level of moral awareness and moral maturity in our graduates.

The expectation is to enable the student to engage their own personal values when they are

Page 6 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 5

confronted with an ethical dilemma once they enter the business world (Lowry, 2003). The

format of most business ethics courses involves sensitizing the student to types of ethical

dilemmas in organizations by teaching ethics theories as frameworks to evaluate possible

outcomes and then having the student practice their newly developed awareness through the

extensive use of case-based examples (Gentile, 2010). This traditional approach to teaching

business ethics has been criticized for relying on vicarious learning and the lack of transferability

from the academic setting to the student’s work experiences after university (McDonald and

Donleavy, 1995).

Yet, business ethics class can have a positive impact on student awareness of ethical

situations and increase the ability to reframe past experiences. Lawter, Guo, and Rua (2011)

found that students believed that a business ethics class was beneficial as it allowed them

reframe past experiences and reflect on the ethical nature of past actions. Additionally, students

who had also engaged in some form of experiential learning coupled with the business ethics

course reported a higher likelihood of acting ethically when confronted with an ethical dilemma.

Gentile (2010) also supported the positive effects of business ethics education on students’

ability to engage in ethical behaviors. By coupling vicarious learning activities and experiential

learning activities within a formal learning space, Gentile found that students felt more prepared

when confronted with an ethical dilemma outside the classroom.

By integrating both experiential and vicarious learning activities, business ethics class

acts as a valuable learning space for reflection and reframing of past experiences for students.

Therefore, we speculate that business ethics education is successful in students’ heightening

sensitivity to ethical situations and encourage them to engage in ethical behavior. As such, we

predict that:

Page 7 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 6

Hypothesis 1: Students who take a business ethics class will be more likely to engage in

ethical behavior.

Ethical Climate as a Learning Space

Passarelli and Kolb (2011) suggest that learning extends beyond the classroom and

involves a socialization process via membership and identity formation because students also

learn from others in their community. Situated learning theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991) provides

support for the ethical climate as a learning space as it defines learning as a transaction between

the person and the social environment, where learning is extended beyond the physical classroom

into the process of a becoming a member of a community of practice. Students develop

experiences and share those experiences within their communities creating a climate based on

those shared experiences (Passarelli & Kolb, 2011). Climate is one of the most infuential

contextual factors that can either facilitate or impede effective teaching and learning that take

place in the classroom setting through interpersonal interactions (Marsick and Watkins, 2001).

Climate acts as a learning space as “karma in the walls and halls” by informing the learners

about how to make sense of what they observe and how to interpret what they experience

(Callahan, 1999).

Victor and Cullen (1987) defined ethical climate as “the shared perception of what is

ethically correct behavior and how ethical issues should be handled” within an organization

(pp.51-52). Research has shown that situational factors, such as presence of codes of ethics,

obedience to authority or conformity to the group and shared perceptions of the organization’s

policies and practices, can have a strong impact on individual ethical behaviors (Adams et al.,

Page 8 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 7

2001; Trevino, 1992; Weber, 1990). These previous studies suggest that organizational context

has an overriding influence on individual moral decisions made in an organizational context.

In a university setting, cheating has long been noted as one of the most frequently

occurring unethical behaviors (McCabe, 2005). McCabe and Trevino (1993) observed that

observing peers cheating without consequences can lead others to cheat, as observing this type of

unethical behavior in one’s immediate surroundings can be viewed as an acceptable way of

behaving and getting ahead within that culture. On the contrary, students who perceive strong

disapproval of cheating among their peers, which would signify a culture intolerance of this type

of unethical behavior, report consistently lower levels of cheating

(

McCabe and Bowers, 1996).

Based on the findings of two experiments, Gino, Ayal and Ariely (2009) note that individuals’

unethical behavior depends on the social norms implied by dishonesty of other members.

Accordingly, we argue that peer conduct and perceptions of cheating behavior, can contribute to

the perceived general ethical climate or the macro-system of the learning space of the university,

which will influence students’ likelihood of engaging in academic dishonesty. As such, we

hypothesize that ethical climate acts as an informal learning space such that:

Hypothesis 2a: Students who perceive higher percentages of students cheating at

university will be less likely to engage in ethical behavior.

Similarly, in an education setting, empirical findings indicate that in universities, which

have honor codes and academic integrity policies that are widely known and accepted by the

members of these communities and in which there are clearly stated consequences for not

conforming to these standards, students display lower levels of cheating (McCabe and Trevino,

1993). More specifically, the prevalence of cheating and the subsequent consequences will

create an ethical climate, which acts as an informal learning space for the student whereby the

Page 9 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 8

student learns whether unethical behavior is socially acceptible and whether there are

consequences for engaging in unethical behavior. In essence, students engage the experiential

learning process of ethical behavior within this informal learning space (macro-system) as a

member of the university’s ethical climate other than their immediate learning from the

microsystem, which is the business ethics courses.

In our view, university policies and practices supporting ethical behaviors (and

specifically those which demonstrate an intolerance of academic cheating of all kinds) create an

ethical climate and can serve as a macro-system of student learning spaces in the domain of

academic integrity. This type of learning space constitutes the immediate ethical climate for

students and provides a set of expected ethical behaviors prescribed for all members of these

communities within this domain. Therefore we predict:

Hypothesis 2b: Students who perceive higher percentages of students caught cheating at

university will be more likely to engage in ethical behavior.

Learning Styles and Learning Spaces

Matching the method of teaching with the learning style of the learner has been shown to

have a significant influence on academic success (Kolb, 1984). Experiential learning is described

as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Kolb,

1984, p. 41). Vicarious learning, on the other hand, is achieved through observing either first

hand or through others accounts with no active involvement in the experience (Bandura, 1977;

Gholson and Craig, 2006; Rosenthal and Zimmerman, 1978). Research shows that individuals

differ in terms of their preference for employing learning styles due to hereditary equipment,

particular life experiences and the demand of the present environment, which generates different

Page 10 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 9

learning styles for different learners (Kolb and Kolb, 2005; 2009). The traditional perspective on

learning style is that matching the method of teaching with the learning style of the learner is the

best means of positively impacting academic success (Kolb, 1984).

However, there is opposing views to this perspective. Kolb and Kolb (2005) suggests

that the different levels of the learning spaces also impact different levels of learning. When it

comes to ethics, it is highly possible that these different levels have different perpectives to

provide, and then the question becomes whether individuals’ preferences in regards to learning

styles impact the way they absorb and use these conflicting and competing teachings they receive

from these different learning spaces. Kolb and Kolb (2009) suggest that when the learner is

forced to activate types of learning which are less frequently used by the learner, the process of

deep learning is stimulated. The implication of this is that learners develop a comfort zone of

learning where they become adept at using a particular learning style. As such, experiential

learners become adept at using experiences as the basis of their learning, just as non-experiential

learners become adept at using vicarious learning as the basis of their learning. In order to

stimulate deep learning, students must be forced out of their comfort zones and learning styles,

and encouraged to engage in the other parts of the learning cycle which they are less adept at

using.

Within the context of teaching business ethics in a university setting, experiential learners

are adept at using the ethical climate as an experiential learning space. They experience acting in

an unethical manner and the possible consequences of that behavior. However, for the

experiential learners, there is enormous value in using vicarious learning in a classroom setting

as this method of teaching stimulates and engages abstract thinking and reflection, which

supports and activates their deep learning. Therefore, we predict:

Page 11 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 10

Hypothesis 3: Experiential learners will be more likely to engage in ethical behavior if

they have taken a business ethics class.

On the other hand, non-experiential learners are adept at using vicarious learning, which

best translates to the traditional classroom experience. In order for concrete experience to be

activated and deep learning to be stimulated, non-experiential learners need to observe what they

have learned vicariously being enacted within their experiential learning space—the university

ethical climate. For the non-experiential learners, observing the enforcement of academic

integrity policies in the university ethical climate reinforces the lessons learned from their

vicarious learning. Therefore, we predict:

Hypothesis 4: Non-experiential learners will be more likely to engage in ethical behavior

if they perceive higher percentages of students caught cheating.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The study was conducted by surveying undergraduate business students at a private

university in the United States. Students were asked to complete two surveys at two points in

time. The first survey asked students about preferred learning styles, perceptions about ethical

climate of the university, whether they had completed a business ethics course, and

demographics. The second survey administered two weeks later measured students’ likelihood

of engaging in ethical behavior using a scenario-based approach. Surveys were matched based

on the subject’s name. The matched survey yielded data from 180 respondents.

Participants were age 18 to 24. Fifty five percent of respondents were female, and eighty

four percent identified themselves as Caucasian. Participants represented all business majors

Page 12 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 11

across the university—Business Administration major (31.5%), Marketing (18.8%), Sports

Management (13.9%), Finance/Economics (13.8%), and Accounting (15.6%). Approximately

40% had completed a business ethics class.

Measures

Data on learning styles was collected using the VARK, a 16 item scale which was

customized for university aged students (Fleming and Mills, 1992; Leite, Svinicki, and Shi,

2010). The VARK consists of four sub-scales each measuring four styles of learning:

kinesthetic, aural, visual, read/write. Students were then classified into two groups based on

their highest score on the VARK: experiential learners (those with kinesthetic learning style as

the highest score) and non-experiential learners (those with either aural, visual, read/write

learning styles as the highest score). Ethical climate was captured by asking students what

percentage of students at the university cheat and what percentage of students at the university

are caught cheating

Scenario-based surveys are commonly used in the ethics literature to test for likeliness to

engage in ethical behavior, allowing for the description of a scenario with response questions

which ask the participant how likely they would be to engage in a particular behavior. Each

subsequent behavior in the response question escalates the behavior based on decreasing

likelihood of engaging in the behavior (Shu, Gino, and Bazerman, 2011; Zhong, Ku, Lount, and

Murnighan, 2010). In the current study, likelihood of engaging in ethical behaviors was

measured using a scenario-based survey. Three scenarios were developed by the authors based

on five semesters of a term project in which students were asked to identify a situation from their

work history in which they encountered an ethical dilemma. The three most frequently

mentioned ethical dilemmas—stealing from work, sexual harassment, and covering up wrong-

Page 13 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 12

doing of a friend—were used to develop three amalgamated scenarios. The three scenarios were

tested for content validity using a sample of 23 students. A full scenario-based instrument was

developed where participants were then ask how likely they would be engage in two behaviors,

the second being an escalation of involvement. Participants were asked 1) how likely they would

be to approach one or more of the people involved in the scenario and 2) how likely they would

be to report the incident to a higher authority. A five-point Likert response was used ranging

from “not at all” to “definitely” for each response (see Appendix A). The finalized scenario-

based instrument was pilot tested on an independent sample of 68 students followed up by a

debriefing.

Results

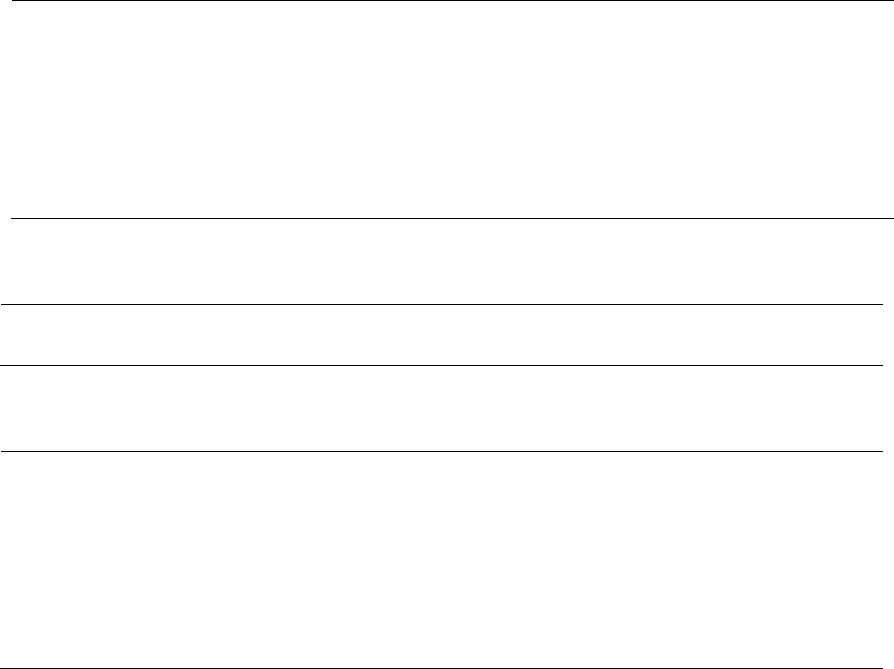

Descriptive statistics and correlations were calculated for the dependent and independent

measures (Table 1).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Insert Table 1 about here

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Regression analysis was used to test the hypotheses. Per Aiken and West (1991) direct

effects were entered into the model first to test for significance and effect size; interaction terms

were entered into the model in the second stage. Three direct effects were hypothesized.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that students who took a business ethics course would have a higher

likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior. This hypothesis was supported and found to be

significant (β = 1.678, t = 2.746, p = .007). Hypothesis 2a predicted that students who perceived

higher percentages of students cheating would have a lower likeliness to engage in ethical

behavior. This was not supported (β = .002, t = .241, p = .809). Hypothesis 2b predicted that

Page 14 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 13

students who perceived higher percentages of students caught cheating would have a higher

likeliness to engage in ethical behavior. This hypothesis was also supported and found to be

significant (β = .038, t = 2.739, p = .007) (See table 2).

Two interactive effects were hypothesized. Hypothesis 3 predicted that experiential

learners would have a higher likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior if they have taken a

business ethics class. This hypothesis was supported (β = 2.662, t = 2.064, p = .04). Hypothesis

4 predicted that non-experiential learners would have a higher likelihood of engaging in ethical

behavior if they perceived higher percentages of students caught cheating. This hypothesis was

not supported (β = .004, t = .145, p = .885) (see Table 2).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Insert Table 2 about here

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Discussion

For those of us in business ethics education, the hope is that our classes have a positive

impact on increasing the sensitivity of our students to the nuances of ethical situations and

engaging in ethical behaviors. Our findings show support that taking a business ethics class

positively impacts the likelihood of a student engaging in ethical behavior. This is most likely

due to increased sensitivity to ethical situations, and a better understanding why specific

behavior would be considered unethical. Additionally, our findings show support for the impact

of the ethical climate of the university on our students. Our results show that students who

perceive higher percentages of students caught cheating are more likely to engage in ethical

behavior. The implication for both these findings is that formal and informal learning spaces are

important as environments in instructing our students, particularly as they pertain to ethics

Page 15 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 14

education. Our teachings in the classroom need to align with our policies and practices outside

the classroom.

It is of interest to note that our hypothesis on the effect of observing other students

cheating on likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior was not significant. Based on a large

body of literature on cheating (e.g., McCabe, 2005; McCabe and Trevino, 1995) we expected

students who perceived higher levels of cheating would be less likely to engage in ethical

behavior. Our speculation on the prevalence of cheating as a factor in the ethical climate is that

cheating is so widespread (students reported a mean of 66%) that students are accustomed to

seeing people cheat. Our students’ assumption is that a large majority of their peers are cheating

as they are most likely observing widespread cheating with little consequences. However, when

students observe that there are potential consequences for cheating (i.e., being caught), this

hopefully reinforces the message that if you do something that is against the rules, there will be

consequences.

Our findings on the interaction between learning styles and learning spaces as it relates to

deep learning are intriguing. When we examined the interaction with learning style (experiential

versus non-experiential) and having taken a business ethics class, we found that business ethics

class had a larger impact on the perspective of experiential learners than non-experiential

learners. This finding is in sync with Kolb and Kolb’s (2009) theorizing of deep learning.

Specifically, experiential learners are already adept at using contextual cues from the

climate as a means of learning—in a sense, they have already gleaned the lessons about

acceptability of cheating and the likelihood of getting caught from the ethical climate. The

classroom experience, on the other hand, engages abstract learning and solicits reflective

learning as it applies to previous experience by forcing experiential learners out of their comfort

Page 16 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 15

zone and (hopefully) reframing their previous experiences. This eventually leads to deep

learning (Kolb & Kolb, 2009) for these individuals, which results in higher likelihood for

engaging in ethical behavior.

Although our initial analysis did not reveal a significant interaction effect of percentage

caught cheating and learning styles on likelihood of ethical behavior, a closer look at the data

indicated that among non-experiential learners, there was a significant difference between

students who perceived above average percentages of students caught cheating and below

average percentages of students caught cheating and their mean likelihood of engaging in ethical

behavior. Non-experiential learners who perceived below average percentages had a mean

likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior of 21.9; non-experiential learners who perceived

above average percentages had a mean likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior of 23.1 (F =

5.25, p = .024). On the other hand, for experiential learners the means were very similar: 22.8

for those who perceived above average percentages of students caught cheating and 22.7 for

those who perceived below average percentages of students caught cheating (See Table 3a). A

similar pattern existed among experiential and non-experiential learners as related to taking a

business ethic class. The difference between the means for experiential learners of likelihood of

engaging in ethical behavior was 3.42 points (out of 30) (F = 10.02, p = .003); the difference

between the means for non-experiential learners of likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior

was .8 (out of 30) (F = 1.05, p = .307) (see Table 3a).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Insert Table 3a about here

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

In order to further investigate the differences between experiential and non-experiential

learners as it related to the interaction between learning spaces (taking a business class and the

Page 17 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 16

ethical climate as measured by percentage of students caught cheating) and likeliness to engage

in ethical behavior, we split the data set into two sub-samples—experiential and non-

experiential. Regression equations were then used to test the effects of the two learning spaces.

The results from the regression analysis after splitting the data based on learning styles

suggest for experiential learners taking a business ethics class was a more impactful than ethical

climate on likelihood of engaging in ethical behavior. The results suggest a reverse pattern for

non-experiential learners as the perception of the percent of students caught cheating was a

significant predictor for likelihood of ethical behavior and the effect size for taking a business

ethics class was much smaller than for experiential learners (see table 3b).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Insert Table 3b about here

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Our findings support the deep learning theorizing suggested by Kolb and Kolb (2009).

Different learning styles interact with different levels of learning space in a manner which can

stimulate deep learning. More specifically, experiential learners are adept at using experience-

based learning within informal learning spaces to learn. Thus, the formal learning space of the

classroom situation which fosters vicarious learning skills of reflection encourages deep learning.

Our findings also suggest that non-experiential learners, who are adept at vicarious learning, are

able to engage in active learning by experiencing unethical behavior and its consequences as a

member of the community. The ethical climate of the university acts as an informal learning

space fosters active learning and stimulates deep learning.

Page 18 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 17

Implications for Ethics Education

Ethics education does not happen in a vacuum. It is critical that those of us in business

education recognize that business education is two pronged. The classroom experience as a

formal learning space is where students can engage in abstract and reflective learning. This is

where the concepts, theories, and their applications can be used to for vicarious learning. The

ethical climate of the university as an informal learning space is where students can act as a

member of the climate and gain concrete experiences—in a sense the practical application of the

vicarious learning. In order for any ethics education to be successful, universities must view

ethics education holistically and recognize that at all three levels of the university learning

space—micro, meso, and macro—act on our students’ perceptions to stimulate deep learning.

We must practice what we preach. Our students learn both by engaging in vicarious learning in

the classroom and by experiencing those lessons as real life consequences outside the classroom.

The other implication from our findings is that for our students, their experiences outside

the classroom are potentially more important than their experiences inside the classroom. For

both experiential and non-experiential learners, the ethical climate positively impacts their

perceptions of ethical behavior. Based on our findings, we suggest more research into the

interaction of ethical climate and learning styles as it relates to a number of outcomes linked to

developing more ethical students and more ethical managers.

Page 19 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 18

References

Adams, J.S., Tashchian, A. and Shore, T. H. (2001), “Codes of ethics as signals for ethical

behavior”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp.199-211.

Aiken, L. S. and West, S. G. (1991), Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions,

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bandura, A. J. (1977), Social learning theory, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall.

Biberman, N. J. and Buchanan, J. (1986), “Learning style and study skills differences across

business and other academic majors”, Journal of Education Business, Vol. 67 No. 7, pp.

303-307.

Bowers, W. J. (1964), Student dishonesty and its control in college, Bureau of Applied Social

Research, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Bronfrenner, U. (1977), “Toward an experimental ecology of human development”, American

Psychologist, Vol. 7, pp. 513-530.

Callahan, M.H.W. (1999), Case Study of an Advanced Technology Business Incubator as a

Learning Environment, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Georgia,

Athens, GA.

Dickson, M.W., Smith, D. B., Grojean, M. W. and Ehrhart, M. (2001), “An organizational

climate regarding ethics: the outcome of leader values and the practices that reflect

them”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 12 No.2, PP. 197-217.

Fleming, N. D. and Mills, C. (1992), “Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflection”, To

Improve the Academy, Vol.11, pp. 137-155.

Gentile, M. C. (2010), Giving Voice to Values: How to Speak Your Mind When You Know What's

Right, Yale Univeristy Press, New Haven, CT.

Page 20 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 19

Gholson, B. and Craig, S. D. (2006), “Promoting constructive activities that support vicarious

learning during computer-based instruction”, Educational Psychology Review, Vol. 18

No.2, pp. 119-139.

Gino, F., Ayal, S. and Ariely, D. (2009), “Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior the

effect of one bad apple on the barrel”, Psychological Science, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp.393-398.

Givens, K. (2004), “A Call for Ethics Education”, BizEd, Vol. 3 No. 5, p. 8.

Gopinah, C. and Sawyer, J. E. (1999), “Exploring the learning from an enterprise simulation”,

Journal of Management Development, Vol. 18 No. 5, pp. 477-489.

Kolb, D. A. (1984), Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and

development, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Kolb, A. Y. and Kolb, D. A. (2005), “Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing

experiential learning in higher education”, Academy of Management Learning and

Education. Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 193-212.

Kolb, A. Y. and Kolb, D. A. (2009), “Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach

to management learning, education and development”, Handbook of Management

Learning, Education and Development, Armstrong, S. J. and Fukami, C. (Eds.), Sage

Publications, London, UK, pp. 42-68.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1990), Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation,

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.

Lawter, L., Guo, G. and Rua, T. (2011), “The Disconnect Between Business Ethics Education

and Putting it Into Practice: How Do We Fix It?”, Effectively Integrating Ethical

Dimensions into Business Education , Wankel, C., and Stachowicz-Stanusch, A. (Eds),

Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, NC.

Page 21 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 20

Leite, W. L., Svinicki, M. and Shi, Y. (2010), “Attempted Validation of the scores of the VARK:

Leaning Styles Inventory with Multitrait-Multimethod Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Models”, Educational and Psychological Measurement, Vol.70, pp. 323-339.

Lowry, D. (2003), “An Investigation of Student Moral Awareness and Associated Factors in

Two Cohorts of an Undergraduate Business Degree in a British University: Implications

for Business Ethics Curriculum Design”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp.

7-19.

McCabe, D. L. (1997), “Classroom cheating among natural science and engineering majors”,

Science and Engineering Ethics, Vol. 3, pp. 433–445.

Marsick, V. J. and Watkins, K. E. (1990), Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace,

London and New York: Routledge.

Marsick, V. J. and Watkins, K. E. (2001), “Informal and incidental learning”, New directions for

adult and continuing education, Vol. 89, pp. 25-34.

McCabe, D. L. (2005), “Cheating Among College and University Students: A North American

Perspective”, International Journal for Academic Integrity, Vol. 1, No. 1.

McCabe, D. L. and Bowers, W. J. (1996), “The Relationship Between Student Cheating and

College Fraternity or Sorority Membership”, NASPA Journal, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 280-91.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D. and Trevino, L. K. (2006), “Academic dishonesty in graduate

business programs: Prevalence, causes and proposed action”, Academy of Management

Learning and Education, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 294-305.

McCabe, D. L. and Trevino, L. K. (1993), “Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other

contextual influences”, Journal of Higher Education. Vol. 65 No. 5, pp. 522-538.

Page 22 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 21

McCabe, D. L. and Trevino, L. K. (1995), “Cheating among business students: A challenge for

business leaders and educators”, Journal of Management Education, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp.

205-218.

McDonald, G. M. and Donleavy, G. D. (1995), “Objections to the teaching of business ethics”,

Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 14 No. 10, pp. 839-853.

Milne, A. (2006). Designing blended learning space to the student experience. In D. G. Oblinger

(Ed.), Learning spaces. Chapter 11. EDUCAUSE.

http://www.educause.edu/LearningSpaces/10569

Passarelli, A. M., & Kolb, D. A. (2011). The Learning Way: Learning from Experience as the

Path to Lifelong. The Oxford Handbook of Lifelong Learning, 70.

Rosenthal, T. L. and Zimmerman, B. J. (1978), Social learning and cognition, New York:

Academic Press, p. 338.

Shu, L. L., Gino, F. and Bazerman, M. H. (2011), “Dishonest deed, clear conscience: When

cheating leads to moral disengagement and motivated forgetting”, Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin. Vol. 37 No. 3, pp. 330-349.

Smith, P. L. and E. F. Oakley (1996), “The value of ethics education in business school

curriculum”, College Student Journal, Vol. 30 No. 3, p. 274.

Trevino, L. K. (1992). Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education

and management. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5,6): 445-459.

Victor, B. and Cullen, J.B. (1987), "A theory and measurement of ethical climate in

organizations", Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, Vol. 9, pp.51-71.

Victor, B. and Cullen, J.B. (1988), “The organizational bases of ethical work climates”,

Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 33, Nov. 1, pp.101-125.

Page 23 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 22

Weber, J. (1990), “Managers’ moral reasoning: assessing their responses to three moral

dilemmas”, Human Relations, Vol. 43, No. 7, PP.687-702.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Zhong, C. B., Ku, G., Lount, R. B. and Murnighan, J. K. (2010), “Compensatory ethics”,

Journal of Business Ethics. Vol. 92 No. 3, pp.323-339

Page 24 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 23

Table1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Mean

SD

1 2 3 4

1. Engage in Ethical Behavior 22.29

3.47

2. Took Business Ethics Class

0.23

0.42

0.18

*

3. Experiential Learner 0.29

0.45

0.01 0.09

4. Percent Cheating 66.26

27.75

-0.01 0.17

*

-0.01

5. Percent Caught Cheating 22.09

18.49

0.18

*

-0.09 -0.06

0.32

**

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Page 25 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 24

Table 2. Regression Analysis of Likelihood of Engaging in Ethical Behavior

B

Std. Error

t

Sig

Step 1:

Took a Business Ethics Class 1.678

.611

2.746

.007

Step 2:

Took a Business Ethics Class .760

.750

1.014

.312

Experiential Learner -.526

.661

-.796

.427

Experiential X Class 2.662

1.290

2.064

.040

B

Std. Error

t

Sig

Step 1:

Percent Cheating .002

.009

.241

.809

B

Std. Error

t

Sig

Step 1:

Percent Caught Cheating .038

.014

2.739

.007

Step 2:

Percent Caught Cheating .037

.016

2.277

.024

Experiential Learner .326

.871

.375

.708

Experiential X Caught Cheating .004

.031

.145

.885

Page 26 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 25

Table 3a. Means of Learning Styles by Direct Effects

Grouped By:

Mean

sd

F Sig

Experiential Learner

Business Ethics class 24.87

3.54

10.02

.003

No Business Ethics Class

21.44

3.38

Non-Experiential

Learner Business Ethics Class 23.00

4.07

1.05

.307

No Business Ethics Class 22.20

3.46

Grouped By:

Mean

sd

F Sig

Experiential Learner High Percentage Caught

*

22.83

3.42

.64

.428

Low Percentage Caught 22.56

4.28

Non-Experiential

Learner High Percentage Caught 23.06

3.30

5.23

.024

Low Percentage Caught 21.89

3.71

*High and low defined as above or below the mean

Table 3b. Regression Analysis by Learning Style of Direct Effects

t Sig

Grouped By:

Beta

Std. Error

Experiential Learner Took Business Ethics Class

3.344

1.072

3.118

.003

Percent Caught .037

.027

1.398

.169

Non-Experiential Learner

Took Business Ethics Class

1.001

.731

1.368

.174

Percent Caught .040

.016

2.536

.012

Page 27 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 26

Appendix A. Scenario-based Survey for Likelihood of Engaging in Ethical Behavior

Below are three situations which a person observe or experience in an internship or in a

job. Indicate how likely you would be to report the situation to a supervisor.

1. You have been working part-time at Joe’s Pizzeria and Restaurant as a waiter/waitress for

about six months. One night while working you observe that one of the bartenders has not been

putting all the cash from the checks in the register. Twice you have handed him a check with

cash, and it seems that he is pocketing the cash and ripping up the check.

How likely would you be to say something to the bartender about what you observed?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

How likely would you be to say something to Joe the owner about what you observed?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

2. Your dad put you in touch with a friend of his who is the president of a marketing firm

that specializes in exactly what you want to do after college. The interview went well, and you

were offered a paid internship at the company. The group that you work in has about 20 people,

and you really like your job. There is another intern who works in the same department. You

have only been there for about 2 weeks, but you notice that the guy who is in charge of your

group is always hitting on the other intern-- making sexually related comments about her and to

her. She is really uncomfortable with the situation, but does not know what to do.

How likely would you be to say something to your father about what you observed?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

How likely would you be to say something to human resources about what you observed?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

3. You and your friend were both hired for summer jobs at a local golf course doing grounds

work. The head grounds keeper has a board of what you are supposed to be doing each day, and

usually checks on you two or three times a day. Otherwise you and your friend are on your own

and just expected to get the work done. Your hours are 8am to 3pm every day for the summer.

Your friend is continually late for work. He asks you to punch him in at 8am so he does not get

into trouble. He is a good friend so you just do. One Sunday morning you punch him in at 8 as

always, but it is 11am and he still hasn’t shown up. You get a text from him that he is with his

girlfriend at the beach and wants you to cover for him for the day.

Page 28 of 29Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

For Peer Review

Learning Styles Interaction 27

How likely would you be to say something to your friend about what has happened?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

How likely would you be to say something to the head grounds keeper about what has happened?

_____Not at all ____Probably not _____Possibly _____Probably ____Definitely

Page 29 of 29 Journal of Management Development

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60