Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

1

A study of organic food consumers’ knowledge, attitudes and

behavior regarding labor in organic farms

Alyssa-Marie G. Tison

ABSTRACT

Buying organic is considered by consumers as a way to “vote with their dollar” and mitigate the

environmental impacts associated with conventional agricultural systems. Although large scale

certified organic farms that hire labor limit workers’ exposure to known harmful pesticides, low

farm worker wages coupled with higher labor demands, seasonal hiring and limitations of access

to health benefits still pose concerns that are not addressed through the organic certification

process. In this study, I evaluated consumer knowledge and awareness of the current organic

certification process, attitudes about buying organic, and frequency of and motives for

purchasing organic foods. I surveyed consumers online and in two farmers’ markets in Northern

California (San Francisco Ferry Plaza and Downtown Berkeley Farmers’ Market). Consumers’

lack of knowledge about organic certification standards suggests that their understanding of

organics aligns with the popular public discourse reflecting organic products marketing

strategies. Most participants value the inclusion of labor in organic certification standards,

reasoning that people should be paid fairly for their labor. However, the study suggests that

consumers do not necessarily purchase organics to support farm workers.

KEYWORDS

hired labor, organic food industry, certification standards, consumers’ perceptions, food labels

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

2

INTRODUCTION

In the 1960s and 1970s, environmentalists focused on the biophysical and human health

effects of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, leading to the popularization of alternative food

systems that take into account consumer safety and paving the way for the development of

organic farming. The alternative food movement opposed pesticide use in food production and

eventually, in the 1980s, genetically modified organisms (Reed 2010). More recently, the organic

food industry has highlighted issues concerning soil quality, food contamination, and

conservation of biodiversity (Guthman 1998, Heckman 2005). The alternative food systems

discourse has increasingly been concerned with natural products and social responsibility

(Williams and Hammitt 2001). However this discourse does not necessarily reflect the realities

behind the production of certified organic food products.

Consumers consider buying organic as a way to “vote with their dollar” and mitigate the

environmental impacts of conventional agriculture (Alkon 2008, Shreck et al. 2006). As organics

have expanded since the 1980s, agribusinesses have appropriated the imagery of organics for

profit (Williams and Hammitt 2001). Essentially, the use of the term organic in the market has

been politically constructed by regulatory agencies and the parties in control—large

agribusinesses (Guthman 2002, Guthman 2004). Today, we see how even small family owned

organic farms rely on corporate farms to obtain tax and liability privileges (Guthman 2004). This

brings up several issues related to how the organic industry moves from an alternative, counter-

conventional agriculture movement to a more industrialized system.

Many consumers assume that all organics are produced sustainably (Rigby and Caceres

2001). This, however, is not always the case because a holistic definition of sustainability must

account for the biophysical, economic, and social implications of production. Today, the

legitimized use of the term “organic” has a structured and narrower meaning. According to the

National Organics Program of the United States Department of Agriculture, the federal agency

responsible for organic certification, organic agriculture is an “ecological production

management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles and soil

biological activity. It is based on minimal use of off-farm inputs and on management practices

that restore, maintain and enhance ecological harmony (USDA 2010).” Furthermore, Guthman

(2004) discusses the dilution of organic standards for certain organic products in order to

accommodate certain businesses production. Thus, organic certification does not regulate social

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

3

factors such as farm worker labor conditions, which serve as the basis of operation and

production in organic farms (Allen and Kovach 2000).

Although large scale certified organic farms that hire labor limit workers’ exposure to

known harmful pesticides, low farm worker wages, seasonal hiring and limitations of access to

health benefits still pose concerns (Guthman 2004). In 2008, there were about 5 million acres of

land allocated for organic farming in the United States (USDA: Economic Research Service

2008). The demand for organic food products has allowed corporations to capitalize on people’s

understanding of sustainability, fostering false ideas of what organic production entails (Shreck

et al. 2006). This high demand for organics allowed agribusinesses to control the organic

industry, using their resources to leverage the politics of organics and certification standards

(Allen and Kovach 2000, Guthman 2004).

Even though most consumers perceive organic as a pesticide-free system, organic farm

workers can still be exposed to allowed synthetic and potentially dangerous substances such as

sulphur (Buck et al. 1997). Farm workers also face the high demands of complying with the

certified organic farming standards, which include crop rotation schedules that allow farms to

hire on a seasonal cycle thereby, limiting worker qualification for health care benefits , and

stringent food harvesting techniques that may require manual labor (stoop and hand harvesting)

(Strochlic et al. 2008, Walz 2004). Furthermore, most California organic growers pay minimum

wage, despite the high ratio of sales per acre of land (Guthman 2004). Some organic farms still

use piece rate payment, where farm workers get paid based on the amount of crops they harvest

rather than by the hour (US Department of Labor 2008). This poses safety concerns because it

forces workers to work more to get paid more (Strochlic et al. 2008). The lack of awareness

about these labor-related issues poses social and ethical concerns, suggesting the need of

incorporating farm labor standards into organics certification processes (CATA 2009, Newman

2009). In order to achieve regulatory reform, consumers must be made aware of the reality of

farm labor issues in organic agriculture, yet few studies have examined consumer perceptions

regarding labor practices in organic agriculture and the organic certification standards itself

(Blum 2006, Howard and Allen 2006, Allen and Perez 2007, Shreck et al. 2006). A first step in

this direction is to document how consumers perceive the current organic food movement, which

may inform political strategies to change public opinion and mobilize support for a reform of

organics certification to incorporate labor standards. Ultimately, this means aligning the public

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

4

organic food discourse, the ideologies of organic farming and the actual practices of organic

agriculture.

I examined the significance of labor practices to people who purchase organic products by

focusing on their awareness regarding the current organic food standards, perceptions of

different food issues, their consumption patterns and purchasing motives for buying organic food

products. From my findings, I suggest practical considerations that could help align consumer

attitude, knowledge and behavior regarding organics.

METHODS

Study Site

To investigate organic food consumers’ knowledge, attitude and behavior regarding farm

labor practices, I surveyed consumers who purchase organic food at the Downtown Berkeley

Farmer’s Market (Center St. and Milvia St.) and the San Francisco Ferry Plaza Farmer’s Market.

I also surveyed consumers online by distributing the identical instrument on Facebook, Tumblr

and various on-campus and off-campus listservs.

Data Collection

The three-page survey consisted of 13 questions aimed at understanding consumer

knowledge, behavior and attitude towards organic foods (Appendix I). I administered surveys in

person to anonymous participants. The entire survey took between 10 to 15 minutes to complete.

At the farmers’ markets, I randomized participants and surveyed each site around the

same hours, between 10 am and 2pm. In order reduce bias in my sample, I walked through the

farmer’s market and asked every fourth person I saw to take the survey. I collected data for 3-4

hours starting at the opening hour of each farmer’s market.

Statistics and Analyses

Variables

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

5

To determine consumers’ formal understanding of organics, I included a question that

scores consumer knowledge about the certification standards both in California (state-level) and

the United States (federal-level). I scored each participant’s response and gave them a numerical

score which I then used to get insight as to whether consumers were knowledgeable of the

organic certification standards. The survey questions, the answers to these and the reference to

the answers can be found in the Appendix. I compared the scores from the two groups using a t-

test to check for significant difference between the scores of the two groups. I also included an

open ended question that asked consumers to define organic in the context of organic foods, how

it is used in the market. Answers to this question were compared to and scored based on the

definition used by the United States National Organic Certification Standards. I outlined the

scoring rubric for this part in Table 1. Each consumer received a score based on the number of

key words found in their response that can be found in the USDA organic definition. These

knowledge-based tests helped me assess whether consumers were aware of the absence of the

labor standards in organic food certification standards.

Table 1. Scoring Rubric based on USDA Organic Food Definition question. Each consumer received a score

based on the number of keywords in their response that follow the USDA definition for “organic”.

Score

Rubric

Key Words

0

No key words found in answer.

Cycling resources

Ecological balance

Biodiversity

Production system

Legal term

Cultural

Biological

Mechanical practices

Soil management

Water management

1

1 key word found in the answer.

2

2 key words found in the answer.

3

3 key words found in the answer.

4

4 or more key words found in the answer.

To understand consumer behavior, I asked questions about what organic products

consumers usually purchase, and the frequency of purchasing organic food at different markets

(Whole Foods, Safeway, Locally owned grocery stores, Farmer’s Market). Furthermore, in order

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

6

to determine consumers’ general attitudes about organics, I asked participants to rank the

importance of the different food issues. I compared how labor ranks relative to other food issues

in order to evaluate how consumers value labor practices as a food issue or a concern compared

to other food issues such as pesticide use, incorporation of genetically modified organisms and

access for low-income people.

In addition, I asked consumers to indicate their position on different statements relating to

organic food consumption practices and production in order to understand consumer motives for

purchasing organic. To understand consumer attitudes regarding labor and motives, I asked

participants, using a Likert Scale, if they were willing to pay more to improve farm labor

conditions and to give farm workers better benefit. I also asked consumers if they believe that

labor standards should ultimately be added in the organic certification standards.

RESULTS

Survey Respondents

I collected 134 survey responses, with 34 from Downtown Berkeley Farmers’ Market, 30

from San Francisco Ferry Plaza and 70 online. I decided to aggregate the data for the Downtown

Berkeley Farmers’ Market and the San Francisco Ferry Plaza because the populations at these

sites have similar demographics. I address this set as the “Farmers’ Market” (FM) group, and

refer to the online data as the “online” (ON) group. In both groups, more females took the survey

with 53% in the Farmers’ Market group and 74% in the online group. Over half of the

respondents from the Farmer’s Market group are in the “25-30” and “over 30” age groups. These

Farmers’ Market participants have attained their Bachelor’s degree or a higher degree (Table 2).

The respondents from the online group are in the “18-21” and “22-25” age groups. Most of these

online respondents have either finished high school or are still in college.

I will address this set as the Farmers’ Market group. I refer to the online data as the

“online” group. In both groups, more females took the survey with 53% in the Farmers’ Market

group and 74% in the online group. Over half of the respondents from the Farmer’s Market

group are in the “25-30” and “Over 30” age groups. These Farmers’ Market participants have

attained their Bachelor’s degree or a higher degree (Table 2). The respondents from the Online

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

7

group are in the “18-21” and “22-25” age groups. Most of these online respondents have either

finished high school or are still in college.

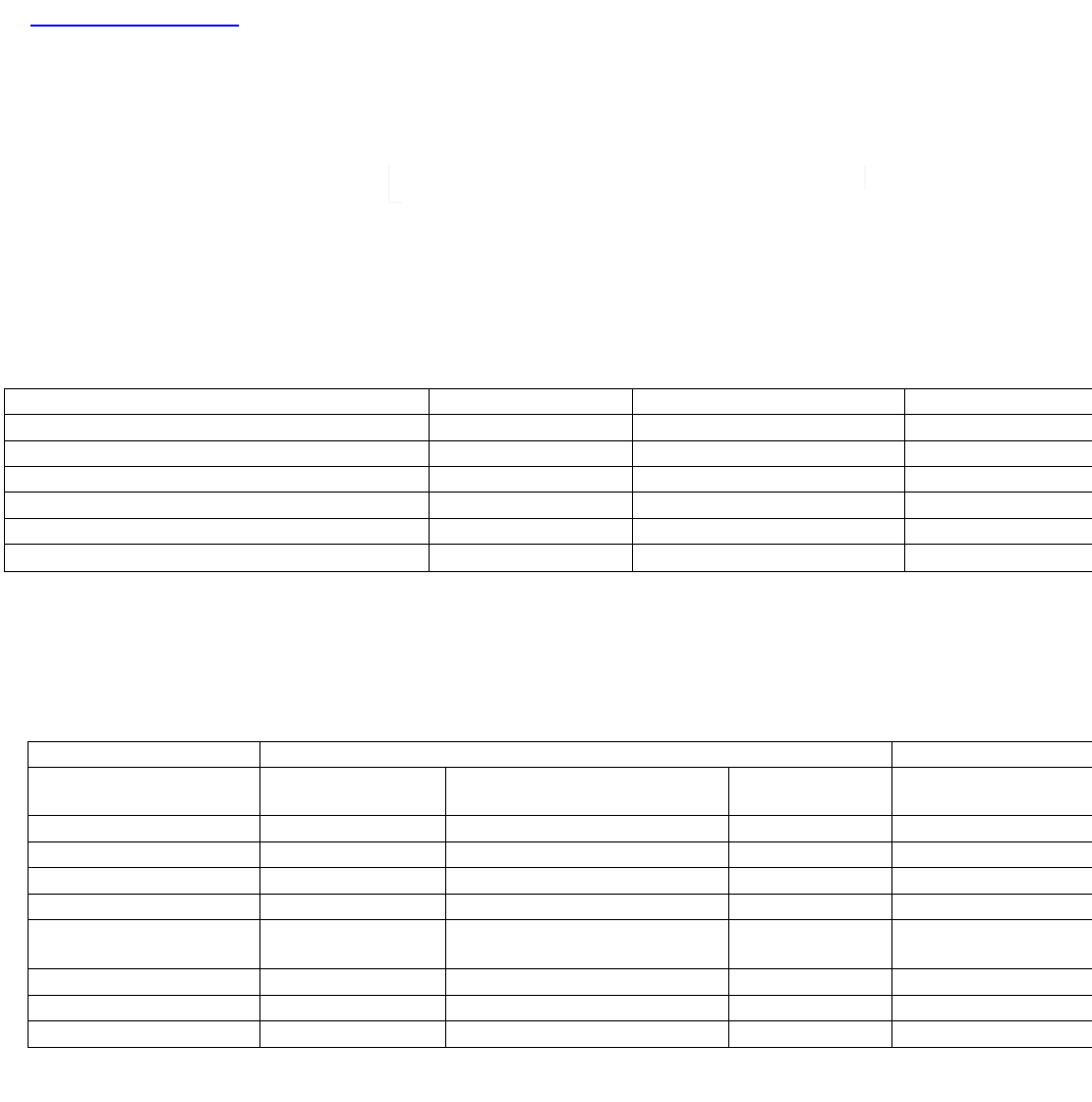

Demographic

Farmers’ Market

(n=64)

Online ( n=70)

Gender

Female

Male

Other

NA

34

25

3

2

52

18

0

0

Ethnicity

American-Indian/Native American

African American/Black

Asian/Pacific Islander(Native Hawaiian)

White (not Hispanic or Latino)

Latino/Hispanic

Other

NA

1

3

5

44

1

2

8

0

1

35

15

17

2

0

Age

18-21

22-25

26-30

Over 30

NA

10

8

12

32

2

45

17

5

3

0

Income

Less than $20,000

$20,000-$40,000

$40,000-$60,000

$60,000-$80,000

$80,000-$100,000

More than $100,000

NA

10

2

2

6

7

35

2

26

19

10

6

2

7

0

Highest Level of Education

Some High School, High School, Some College

Bachelor’s Degree

Master’s Degree, Professional Degree, PhD.

NA

14

29

17

4

42

19

6

3

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

8

Knowledge of Organic Certification

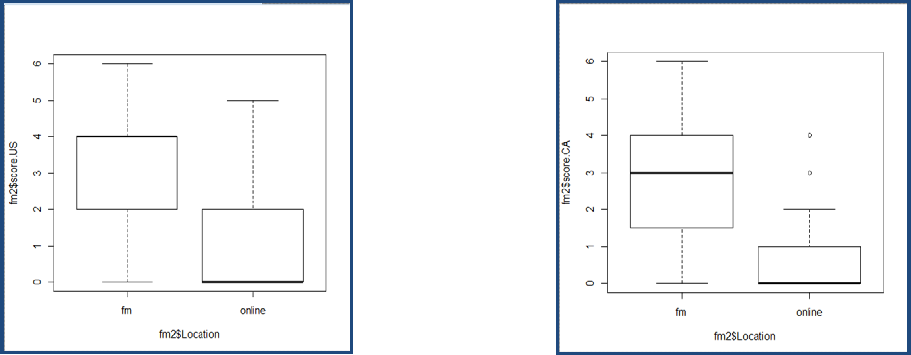

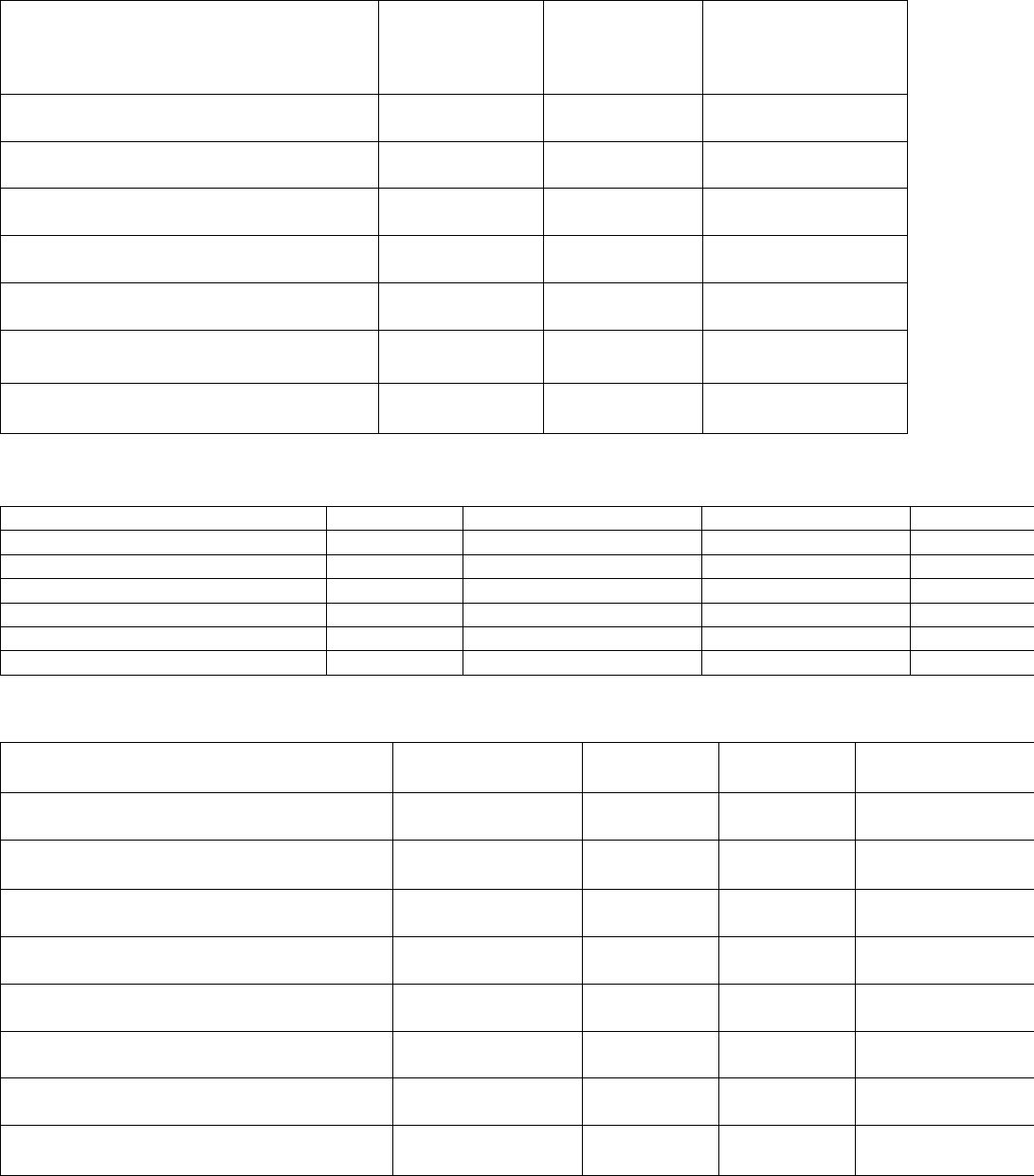

Out of 7 questions, participants in the Berkeley-San Francisco “Farmers’ Market Group”

(n=64) has a mean score of 3.22, with mode 3 and median 4 on knowledge of the federal

(USDA) organic certification standards tests. This group has a mean score of 2.75 for the

California (CCOF) organic certification standard.. Participants f or the “online” group (n=70) has

the mean score 1.1for the knowledge of US organic certification test and 0.71 for the California

organic certification test. Using t-test, it shows that there was a significant difference in the

scores between the sites for both the US and California tests (US: p-value<0.05, p=value=

4.347e-12; CA: p-value<0.05, p-value=1.673e-12) (Fig 1.) In the Farmers’ Market group, 60.9%

correctly responded “No” to the inclusion of labor regulations in the current federal organic food

certification standards. For the same set of standards, 24.3% answered correctly with 64.3% as

“unsure” from the online Group. Twenty- nine out of 70 respondents from the online Group

(41.4%) and 26 out of 64 from the Farmers’ Market group (40.6%) wrote that labor-related

certification standards should be included in the United States organic certification.

Fig1. Federal and State Certification Knowledge Scores. These boxplots show the difference in scores for the

federal (US) and state (CA) certification knowledge test between the Farmers’ Market Group and the online Group.

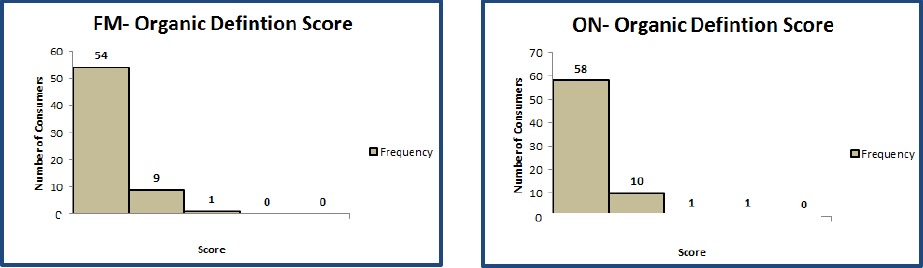

Defining Organic

When asked to define “organic” as used in the organic food context, a majority of

participants related “organic” to ideas of freshness, natural, health, lack of pesticides,

US Certification Knowledge Score

CA Certification Knowledge Score

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

9

biodiversity, and social responsibility. When I compared participant answers to the definition

used by the United States National Organic Certification Standards, 83% of the Farmers’ Market

respondents scored 0, as did 83% of the online participants. The rubric can be found in Table 1.

From both groups, no one scored over 2 (Fig 2.). The following keywords showed in the

answers but do not match the definition as defined by the USDA National Organic Program

definition: no pesticides, no synthetic substances, no chemicals, healthy, sustainable,

environmentally friendly, pure, and small-scale.

Fig 2. Distribution of consumers “Define Organic” question for both the Farmers’ Market (FM) and online

groups (ON).

Consumption Pattern

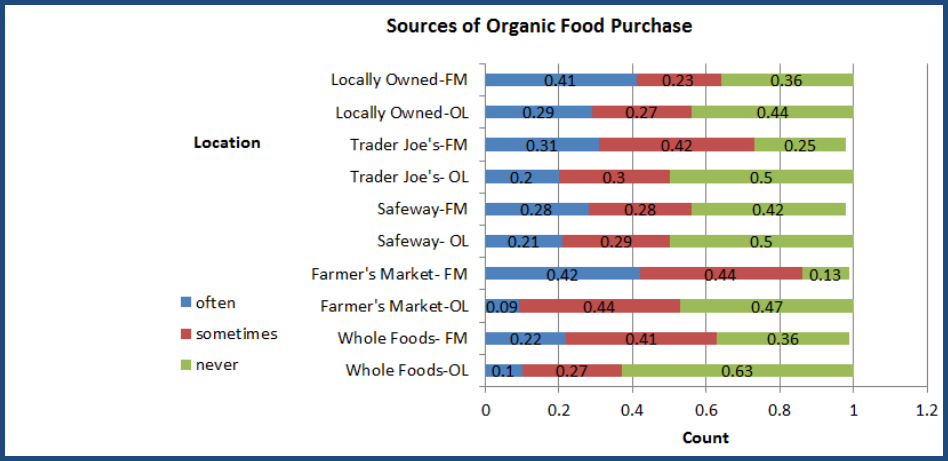

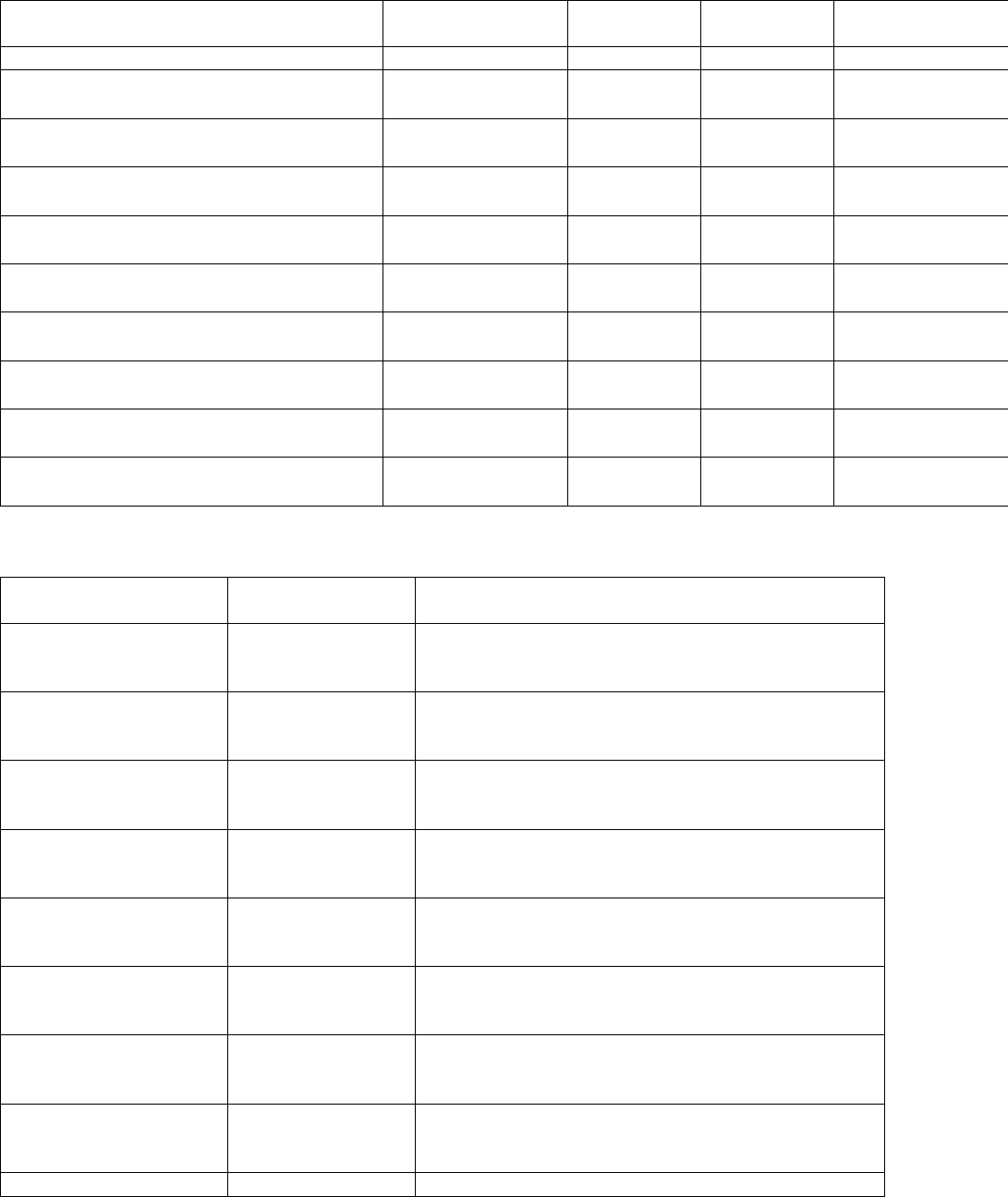

When consumers were asked to indicate which products they purchase at farmer’s

markets, 94% of the Farmers’ Market group respondents indicated buying produce (vegetables

and fruit). Sixty-one percent of the online participants buy organic produce. Consumers also

indicated the frequency of buying organic food at different markets. From the Farmer’s Market

group, 42% buy at farmer’s market ‘often’ and 44% buy “sometimes”. Nine percent of the online

participants buy from farmers’ market “often” and 44% buy sometimes. Forty-one percent of the

consumers from the Farmers’ Market group shop at locally owned stores “often”. Twenty-nine

percent of the consumers from the online group buy at locally owned grocery stores “often”.

Figure 3 outlines the summary of the frequency of shopping from different sources of organic

food purchases both for the Farmers’ Market group and the online group.

0 1 2 3 4

0 1 2 3 4

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

10

Figure 3. Frequency of Shopping at different markets that offer organic products. “Often” is defined as

purchasing organics once a week, “Sometimes” defined as a few times a month, and “Never” as not at all. FM is for

farmers’ market data and OL is for the online data.

Motives for Purchasing Organic Food

When asked to indicate their position on certain statements, 38% from the Farmers’

Market group indicated that they “Agree” and 23% said that they “Strongly Agreed” with the

statement “I buy organic food to support farm workers” (Table 3). From the online group, 21%

agreed with this statement and 11% said that they “Strongly Agree”. Nineteen percent of the

respondents from the Farmers’ Market group either Disagreed or Strongly Disagreed with this

statement. From the online group, 11% either indicated that they “Disagree” or “Strongly

Disagree” with this statement.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

11

Table 3. Percent of people who indicated “Agree” and “Strongly Agree” on statements related to labor.

Site

I buy organic to support local

farm owners.

I buy organic to support farm

workers.

Farmer’s Market

n=64

38% Agree, 38% Strongly Agree

38% Agree, 23% Strongly Agree

Online

n=70

21% Agree, 20% Strongly Agree

21% Agree, 11% Strongly Agree,

Importance of Labor

“Reduction of pesticide use in food” ranks as the highest priority for the consumers in the

Farmers’ Market group with 69% ranking this as the “Top Priority”. “Protecting farm workers’

rights by improving job conditions” was ranked the highest by the online group, with 34% of the

participants ranking this as “Top Priority” (Table 4.) Of the 6 food issues, “Food processing

techniques” and “Increasing Farm worker salary” were ranked 5

th

and 6

th

respectively by the

Farmers’ Market group. These same issues were ranked 3

rd

and 5

th

priority, respectively, by the

online group. Consumers from the Farmer’s Market group ranked labor-related issues the lowest

(bottom 3) compared to the online group, which ranked “Protecting farmworkers’ rights by

improving job conditions” as the 1

st

priority.

Table 4. Percentage of consumers who ranked these food issues as “Top Priority”. Labor issues are highlighted.

Food Issue

Farmers’ Market

Ranking

Online

Ranking

Food processing

techniques

41%

5

27%

3

Increasing farm worker

salaries

31%

6

21%

5

Limiting the number of

GMOs in food.

47%

2

26%

4

Reduction of pesticide

use in food

69%

1

33%

2

Improving food access

for low-income people.

64%

3

33%

2

Protecting farm

workers’ rights by

improving job

conditions.

45%

4

34%

1

.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

12

Including Labor in the Certification Standards

When asked which factors should ultimately be included in the organic certification

process, 33% and 54.4% of the respondents from the Farmers’ Market group and online group,

respectively, indicated that Labor should be included. Responses as to why “Labor” should be

incorporated into the standards include farm worker health and safety. Consumers also wrote

down responses pertaining to sustainability and labor equity. There is a higher number of

consumers from the online group who indicated that labor standards should be included in the

certification process (Table 5).

Table 5. Which factors should be included in the organic certification standards? This shows the percentage of

consumers from the Farmers’ Market (FM) group and the online (On) group who think that labor standards should

be included and the coded responses for their justification.

Factor

% of people who said “Yes”

Why?

Aesthetics

FM: n=13 , 20.3%

On: n=11, 15.7%

FM: marketing strategies

On: marketing strategies

Carbon Emissions

FM: n= 16, 51.5 %

On: n=31, 44.2%

FM: important

On: mitigate global warming,

sustainability

Soil Management

FM: n=54, 84.3%

On: n=48, 68.6%

FM: soil health, production benefits

On: soil health, production benefits,

sustainability, conservation,

Water Management

FM: n=51, 79.6%

On: n=41, 55.4%

FM: water quality

On: conservation, important

Labor

FM: n=21, 33%

On: n=36, 51.4%

FM: health, important, fair trade

On: equity, health, sustainability

Animal Welfare

FM: n=50, 78%

On: n=44, 62.8%

FM: animal rights

On: animal rights

Public Health

FM: n=49, 76.5%

On: n=41, 58.5%

FM: disease control

On: consumer safety, worker safety

Price Control

FM: n=29, 45.3%

On: n=30, 40.5%

FM: lower prices, accessibility

On: lower prices, accessibility

Sourcing

FM: n=29, 45.3%

On: n=37, 53%

FM: mitigate global warming

On: local, sustainability

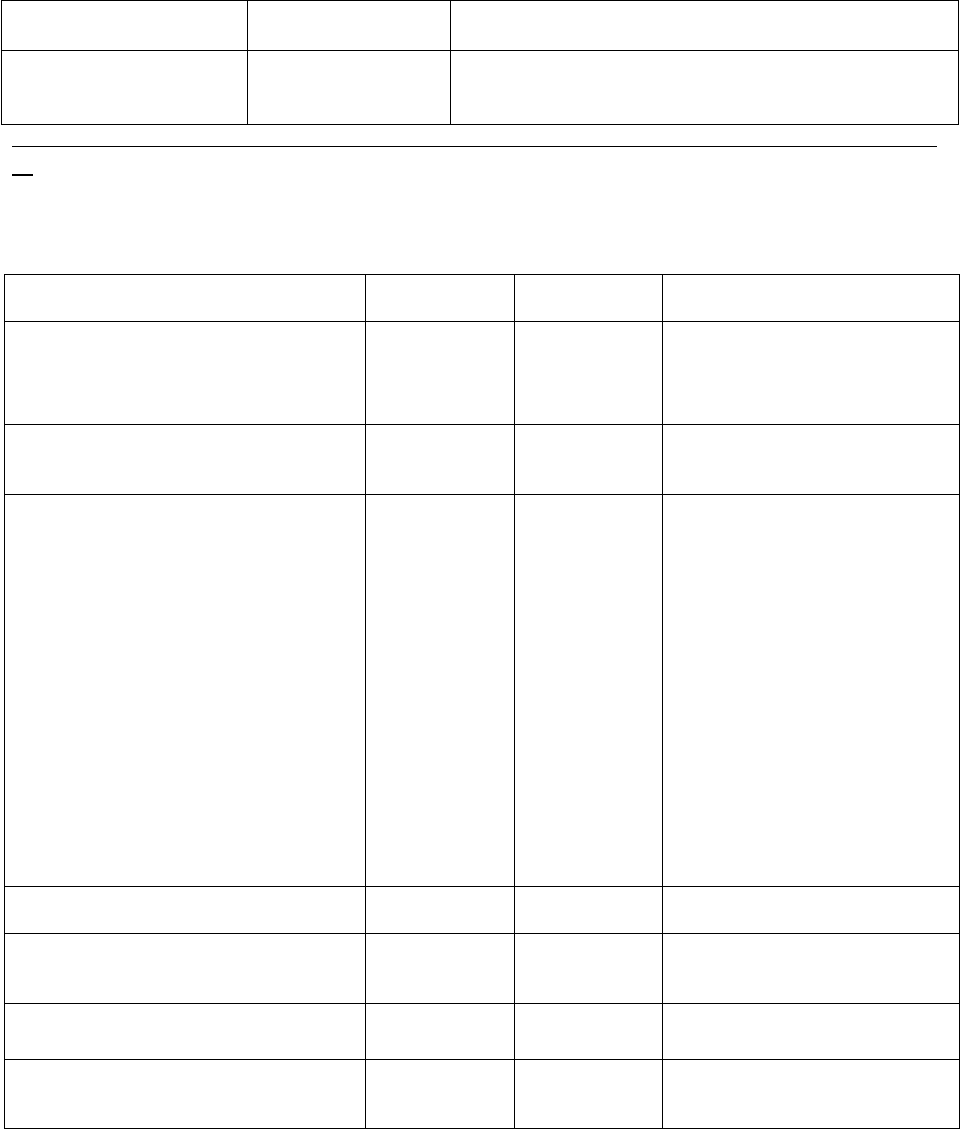

When given the statement “I am willing to pay more if I can ensure that farm labor

conditions are improved”, 55% indicated that they agree and 17% strongly agreed from the

Farmers’ Market group. From the online group, 24% agreed and 16% strongly agreed. I ran a

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

13

chi-squared test for this statement and found that there is a statistically significant difference (p-

value<0.05, p-value=1.6E-6) between these sites for the responses. There is also a statistically

significant difference (p-value<0.05, p-value=0.01) between the Farmer’s Market and online

group for the “Agreed” and “Strongly Agreed”. There were more participants from the Farmer’s

group who “Agreed” or “Strongly Agreed” with this statement. For the statement, “I am willing

to spend more if I can ensure that farm workers get health benefits”, 45% respondents agreed

and 23% strongly agreed from the Farmers’ Market group .The online group had 26% people

agree and 17% people strongly agree. A chi-squared test shows that there is a statistically

significant difference (p-value<0.05, p-value=0.006) between the Farmers’ Market group and the

online Group for the overall responses to the second statement. However, there is no statistically

significant difference between the number of respondents who agreed with the statement from

these two sites.

Table 6. Willingness to pay for improved labor practices. These two statements particularly looks at willingness

to pay to improve job conditions and for workers’ increased access to health benefits.

Site

I am willing to spend more for organic

food if I can ensure that farm labor

conditions are improved.

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure

that farm workers get health benefits.

Farmers’ Market

n=64

55% Agree, 17% Strongly Agree

45% Agree, 23 % Strongly Agree

Online

n=70

24% Agree, 16% Strongly Agree

26% Agree, 17% Strongly Agree

DISCUSSION

Organic food consumers seem to value labor highly in their attitudes toward food

purchases, but their behavior and knowledge do not align with these attitudes. Most consumers

think that all organic farming is biophysically, socially and economically sustainable, defining

“organic” as “natural,” “lacking pesticides,” “fresh” and essentially, good for the environment.

The high demands of complying with the standardized organic farming regulations require 15%

more labor in organic farms than conventional systems (Pimentel et al. 2005). Twenty four

percent of hired labor is considered year round workers while the rest work seasonally (Waltz

2004), and seasonal workers earn a dollar less than year round workers (US Department of Labor

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

14

2005). Seasonal hiring brings into question job stability and health care access for organic

farmers. Consumer attitudes, which I measured through “willingness to pay” survey responses,

prioritization of labor-related food issues, consumer willingness to include labor standards in the

organic food standards, and motives for purchasing organic food, suggest that organic food

consumers are aware of these labor concerns. However, their attitudes towards labor equity and

support for farm workers do not translate into labor conscious consumer purchasing patterns.

Increasing knowledge about what the certification actually regulates can increase consumer

awaren ess and therefore, open up dialogue about organic farm labor issues.

Knowledge

The low average scores for both the Farmers’ Market group and the online group on the

certification test suggest that consumers lack knowledge about the certification standards that

define organic foods. The USDA defines “organics” as food produced in accordance with the

organic certification standards: “Organic production refers to the production system that

integrates cultural, biological and mechanical practices that fosters cycling of resources,

promotes ecological balance and conserves biodiversity (USDA 2010, National Organics

Program 2012).” No participant scored 100% on knowledge of the organic certification process.

In the Farmers’ Market group, over half of the participants correctly answered that labor

regulations are not included in the federal certification standards. From the online group, 64.3%

(n=45) respondents did not know if labor regulations are included in these standards. No labor

standards are included in the organic certification in both the United States and California. The

fact that we, as a society, have relied on other people to produce our food have made it easier for

us to detach ourselves from the production end of the process. Unfortunately, we have forgotten

who takes part in this process and thus, consumers tend to focus more on the end results, the

actual product (Guthman 2004). This pattern was also evident in consumers’ understanding of

the use of the term organic. Consumers wrote responses such as “natural,” “no pesticides or

chemicals” and/or “environmentally friendly.” These definitions do not align with the USDA-

certification definition of organic. These popular definitions of organic can be attributed to the

lack of awareness and interaction of consumers with what is actually going on in the farm.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

15

Consumer perception of organic agriculture is mostly, if not solely, shaped by public discourse—

through media, the presentation of organic food products in grocery stores and farmers’

markets—create concepts that relate to this idea of “going back to nature” (Alkon 2008).

Defining Organic

Consumers seem to relate their ideas of organics to notions of sustainable agriculture.

However, unlike the “lite” version of organic production that is most common, “sustainable

agriculture” takes into account environmental health, economic profitability, and social and

economic equity (Feenstra 1997). The low mean scores from the certification test from both the

Farmer’s Market group and the online group show that none of the participants knew fully what

the federal and state (California) organic standards entail. Despite lack of knowledge regarding

the stipulations of the organic standards, consumers still support this industry. This may relate to

how consumers understanding of organics are heavily influenced by the public discourse, the

way that the market presents organics. Survey respondents’ definition of the term “organic”

provides further evidence for this claim. Consumers from both groups wrote down responses

including “natural”, “fresh”, “no pesticides”, “healthier”, “sustainable”. These terms relate to the

ideas of organic as either a connection to nature or an avenue for environmental justice (Alkon

2008). Although organic, during its earlier phase as an alternative food movement, embodied

these two nuances, the institutionalized meaning of the word had become regulated that the

actual use of the term of organic shifted into a narrower, more structured, regulated and “lite”

(or shallow) definition (Allen and Kovach 2000, Guthman 2004). Essentially, this

standardization of organics led to the proliferation of bigger businesses in the organic food

industry and the movement of organics into an industry that simulated conventional farming

(Guthman 2004).

Ranking Labor Issues

Participants from the Farmers’ Market group ranked labor-related issues as the last three

priorities relative to pesticide use, accessibility of healthy food for low-income people, and

limiting GMOs. Online participants ranked increasing farm worker salary as the lowest while

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

16

improving job conditions ranked first. This finding aligns with those discussed by Perez and

Allen in a survey of college students from a liberal college, University of California Santa Cruz,

in that college students ranked improving job conditions for farm workers as one of the top food

issues (Allen and Perez 2007). College students, especially those from more liberal colleges, tend

to be more exposed to liberal thinking and social justice issues. Awareness about these issues

politicizes students and helps them understand the injustices revolving around the socially

problematic conventional agricultural system. This can be related to the intergenerational gap

between the Farmers’ Market group and the online group, where there are more college aged

students currently in college who rank labor issues higher than the older respondents who have

finished college from the Farmers’ Market group.

Inclusion of Labor Standards and Willingness to Pay

Most participants valued the inclusion of labor in organic certification standards,

reasoning that people should be paid fairly for their labor. Those who said that it should not be

included reasoned that labor standards should be certified under a separate label or certification

process. This suggests that most consumers value labor but are split between wanting to include

labor standards in the current certification process and creating a new certification process purely

based on labor regulations. For consumers purchasing other “environmentally-friendly”

products, they perceive single issue certification labels as a way for them to take into account

and focus on individual issues that they value and support (through purchase) (Young et al.

2010). In a survey of 1000 households, consumers expressed interest in having standards and a

separate food label that would guarantee a living wage for farm workers (Howard and Allen

2006). Including labor standards in the organic certification standards may put pressure on these

organic farms to improve the quality of labor for their workers. It can also imply increased prices

on top of the already premium prices of organic food which brings into question accessibility for

people who cannot afford these goods. A majority of the consumers in this study, the people who

buy and therefore have access to these products, indicated their willingness to pay more to ensure

that farm workers get treated fairly through increased access to health benefits and improved job

conditions. This suggests that consumers who already purchase organic on a regular basis would

be willing to support this fair labor label.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

17

Behavior

From the Famers’ Market group and the online group, most survey respondents often

purchase produce in the Farmers’ Markets. This suggests that consumers, whether they are aware

of this or not, are buying from smaller organic farms. The study by Strochlic et al. concludes that

smaller farms with high organic production tend to have better wages and better opportunities for

their employees (Stochlic et al. 2008). This contradicts the claim that working in conventional

farms is better because there are fewer abuses (Buck et al. 1997). These contradicting notions

stems from the varying attitudes of farm owners and ultimately, the capitalist agenda of these

farms. A number of small farms rely on corporate farms for resources, subjecting them to the

stipulations of agribusinesses (Guthman 2004). This implies that produce coming from farmers’

market or smaller farms do not automatically indicate the presence of fair labor.

Attitude-Behavior Gap

I observed the attitude-behavior gap in the findings of this study. Over half of the

consumers from both the Farmers’ Market and the online group indicated that labor should be

included in the organic certification standards. However, less than half of the consumers agreed

with the statement “I buy organic to support farm workers”, suggesting that consumers do not

necessarily prioritize farm workers and thus, labor concerns when purchasing organic foods

(Hearne and Volcan 2002). This can be further observed particularly in the Farmer’s Market

group wherein consumers ranked labor-related issues as the least of their priorities relative to

other food issues. This implies that other motivations for buying organic may include mitigating

environmental issues and health and safety concerns about pesticides (Zanoli and Naspetti 2002).

Although consumers agree that labor practices should be regulated, consumers purchase organic

produce for reasons other than supporting farm workers.

This same gap can be observed through the consumer responses on the willingness to pay

statements. A higher percentage of consumers from the Farmers’ Market group were willing to

pay more to ensure that farm working conditions are improved than the consumers from the

online group (Table 6). Increased prices of organic produce by taking into account social

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

18

externalities may hinder low-income consumers from purchasing more socially responsibly

produced organic products (Vermier and Verbeke 2006, Padel and Foster 2005). Most of the

online group consumers indicated a yearly income of less than $40,000 (Table 2). This difference

between the Farmers’ Market and the online group indicates how socio-economic status can

deter labor conscious consumers from supporting a more ethical organic industry, thus,

contributing to the existence of the consumer attitude and behavior gap.

Limitations

Time, sample size, sample site and the demographic information of the participants

limited the scope and inference of this study. I was only able to go to 2 sites (San Francisco

Ferry Plaza and Downtown Berkeley Farmer’s Market) to survey participants. The rest of the

participants were recruited online through listservs and social networking sites (Facebook,

Tumblr, etc.). Furthermore, although the randomization technique mentioned in the Methods

section was implemented, the participants were mostly to older, upper middle class female, and

White/Caucasian- identified. Also, the survey findings tend to be limited to the more liberal

thinking consumers, which essentially make up a majority of the population in this study.

Future Directions

Increasing sample size, sampling in different areas, and refining the questionnaire can

help improve the study in the future. Increasing sample size can increase the power of the

analysis. Sampling in different areas can increase the diversity of the sample (demographics) and

can possibly give a better inference as to consumer behavior, knowledge and attitude towards

labor. Finally, refining the survey and making the questions more specific and less wordy can

help consumers focus more on the questions rather than on the length of the survey, which in

turn, can give more accurate responses.

Broader Implications

Production in organic farms needs change. The gaps in consumer knowledge, attitudes

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

19

and behavior may be closed through increased visibility and public awareness about the realities

of labor in organic farming. By doing so, this can open the way to the inclusion of labor

standards in the certification process and bringing consumer practices more in line with their

perceptions. Increased public awareness about labor on organic farms and its similarities with

labor on conventional farms can influence the public’s attitudes regarding the organic label.

It can bring more awareness to the politics behind the organic industry, thereby allowing

consumers to understand how their ideas about organic and sustainability do not actually follow

the shallow or “lite” definition of organic as it is used in the market (Guthman 2004). Making

organic certification more transparent may change behavior to align it with attitude by educating

the public about organic certification with attitude by educating the public about organic

certification. Changing this discourse makes it possible to change the political economy of

organics Furthermore, this increased awareness and possibly the politicization of people around

the issue of labor in organic farms can leverage reform of the current certification standards that

may close the gap between consumer attitudes and consumer knowledge. Making certification

standards more holistic, taking into account economic, social and biophysical factors, may align

consumers’ attitudes and perceptions of organics with what the standards actually includes.

Finally, the possibility of creating separate labor standards may expose the farms with fair labor

practices and those that do not. A study surveying 1000 households show that consumers would

support a label associated with giving farm workers fair living wages (Howard and Allen 2006).

By having this label, labor in farms become more transparent for consumers who actually want

to support farms that guarantee economically, socially and environmentally conscious and just

labor practices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my mentor, Kurt Spreyer, for helping me define my research and communicate this

thesis. Thank you to the other ES 196 instructors, Patina Mendez, Melissa Eitzel and Seth

Shonkoff, for guiding me through this process and for preparing workshops that helped me

construct my thesis. Finally, thank you to my friends, family and my community for continuing

to ground me in the work that I do and for inspiring me to keep on fighting for social justice.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

20

REFERENCES

Alkon, Alison. 2008. Paradise or Pavement: the Social Constructions of the Environment in Two

Urban Farmers’ Markets and their Implications for Environmental Justice and

Sustainability. Local Environment 13: 271-289.

Allen, P. and M. Kovach. 2000. The Capitalist Composition of Organic: The Potential of

Markets in Fulfilling the Promise of Organic Agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values

17: 221-232.

Allen, P. and J. Perez. 2007. Farming the College Market: Results of a Consumer Study at UC

Santa Cruz. The Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 11:1-6.

Blum, Andrea. 2006. Organic Farming’s Labor Problem. Common Ground. Columbia

Foundation. http://www.columbia.org/pdf_files/cainstituteforruralstudies.pdf

Buck, D., C. Getz, and J. Guthman. 1997. From Farm to Table: The Organic Vegetable

Commodity Chain of Northern California. Sociologia Ruralis 37: 3-20.

Allen, P. and J. Perez. 2007. Farming the College Market: Results of a Consumer Study at UC

Santa Cruz. The Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 11:1-6.

Feenstra, Gail. 1997. Locl food systems and sustainable communities. American Journal of

Alternative Agriculture 12: 28-36.

Guthman, Julie. 1998. Regulating Meaning, Appropriating Nature: The Codification of

California Organic Agriculture. Antipode30: 135-154.

Guthman, Julie. 2004. The Trouble with ‘Organic Lite’ in California: a Rejoinder to the

‘Conventionalisation’ Debate. Sociologia Ruralis 44: 301-316.

Guthman, Julie. 2004. Agrarian DreamsThe Paradox of Organic Farming in California.

University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA.

Guthman, Julie. 2004. Back to the land: the paradox of organic food standards. Environment and

Planning 36: 511-528.

Hearne, R and M. Volcan. May 2002. The Use of Choice Experiments to Analyze Consumer

Preferences for Organic Produce in Costa Rica. Journal of Environmental Management

65: 153-163.

Heckman, Joseph. 2005. A history of organic farming: Transitions from Sir Albert Howard’s

War in the Soil to the USDA National Organic Program. Renewable Agriculture and

Food Systems 21:143-150Reed, M. 2010. Rebels for the Soil: the rise of the global

organic food and farming. Earthscan, Washington, DC, USA.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

21

Howard, P. and P. Allen. 2006. Beyond organic: consumer interest in new labeling schemes in

the Central Coast of California. International Journal of Consumer Studies 30: 439-451.

Newman, Sarah.2009. Organic Consumers Association. Labor Exploitation: The Ugly Truth

Behind Organic Food. http://www.organicconsumers.org/articles/article_17971.cfm

Padel, S. and C. Foster. 2005. Exploring the Gap between Attitudes and Behavior:

Understanding why Consumers Buy or Do Not Buy Organic food. British Food Journal

107: 8 606 – 625.

Pimentel, D, P. Hepperly, J. Hanson. D. Douds and R. Siedel. 2005. Environmental, Energetic,

and Economic Comparisons of Organic and Conventional Farming Systems. BioScience

55: 573-582.

Rigby, D. and D. Caceres. 2001. Organic farming and the sustainability of agricultural systems.

Agricultural Systems 68: 21-40.

Shreck, A., C.Getz, and G. Feenstra. 2006. Social Sustainability, farm labor, and organic

agriculture: Findings from an exploratory analysis. Agriculture and Human Values 23:

439-449.

Strochlic, R., C. Wirth, A. F. Besada and C. Getz. 2008. Farm Labor Conditions on Organic

Farms in California. California Institute for Rural Studies.

Vermeir, I. and W. Verbeke. 2005. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the consumer

attitude- behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 19:

169-164.

Walz, Erica. 2004. Final Results of the Fourth National Organic Farmers’ Survey: Sustaining

Organic Farms in a Changing Organic Marketplace. Organic Farming Research

Foundation.

Williams, P. and J. Hammitt. 2001. Perceived Risks of Conventional and Organic Produce:

Pesticides, Pathogens, and Natural Toxins. Risk Analysis 21: 319-330

Young, W., K. Hwang, S. McDonald, and C. Oates. 2010. Sustainable consumption: green

consumer behavior when purchasing products. Sustainable Development 18: 20-31.

Zanoli, R. and S. Naspetti. 2002. Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food: A

means-end approach. British Food Journal 104: 643- 653

2005. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2001–2002: A

Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farm Workers. US. Department

of Labor Publication No. 9, U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, DC, USA.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

22

2008. Data Sets. Table 2. U.S. certified organic farmland acreage, livestock numbers, and farm

operations.USDA, Economic Research Service, based on information from USDA-

accredited State and private organic certifiers. [http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/organic/]

2008. Wage and Hour Division (WHD). Fact Sheet #12: Agricultural Employers Under the Fair

Labor Standards Act (FLSA). US Department of Labor.

[http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs12.htm

2010. Manual Two: USDA National Organic Program Standards. CCOF Certification Services,

LCC. [http://www.ccof.org/pdf/US%20National%20Organic%20Standards.pdf]

2012. Title 7—Agriculture, Part 205—National Organic Program. Electronic Code of Federal

Regulations. [http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-

idx?c=ecfr&sid=3f34f4c22f9aa8e6d9864cc2683cea02&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title07/7cfr205_

main_02.tpl]

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

23

APPENDIX

I.Surv ey. My name is Alyssa Tison and I am a 4

th

year undergraduate student at UC Berkeley, majoring in

Environmental Sciences. For my Senior Thesis, I aim to understand organic food consumers’ preferences and

purchasing behavior. This survey includes 3 pages, with a series of 13 questions. It will take 10-15 minutes to

complete. Please read each question thoroughly and answer each to the best of your abilities. Thank you for

participating in this study. If you would like to get more information, please feel free to email me at

alyssatison@berkeley.edu.

Age (in years): __________

Gender: Male Female Other

Race/Ethnicity:

Indicate how often you shop at the following markets.

American Indian/Native American

African-American/Black

Asian/ Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian

White (not Hispanic or Latino)

Latino/Hispanic

Other: ____________

Highest Level of Education Completed

Less than $20,000

$20,000 -$40,000

$40,000-$60,000

Detergent and other cleaning supplies

Cooked food

Other:______

Certification of the Source

Source’s Labor Practices

Packaging

Taste

Yearly Household Income:

$60,000 -$80,000

$80,000-$100,000

More than $100,000

4-year Bachelor’s Degree

Master’s Degree

Doctoral Degree (PhD)

Professional Degree (JD, MD)

Other:

Produce (Vegetables, fruit)

Dairy Products (Cheese, yogurt, milk)

Cooked food

Less than High School

Some High School

High School (Diploma, GED)

Some College/Associates Degree

2-year Associates Degree

Price

Aesthetics

Health Implications

Location of the Source

What organic products do you buy? Mark all that apply.

How often do you buy organic food with these labels important are these food labels to you? Indicate their importance to you.

Certification Label

Frequency

Importance

Often (once a week) Sometimes(Few times/ month) Not at all Is this important to

you?

Fair Trade Label

Yes

No

Certified Organic

Yes No

Locally Produced Label

Yes No

Water Quality Protection

Yes

No

Humane Animal

Treatment

Yes No

US Grown

Yes

No

Union Label

Yes No

Other:________

Yes No

What do you consider when you buy organic food? Rank these 1-8, 1 being your #1 priority. Use #1-#8 ONLY

Often (once a week) Sometimes( few times/ month) Not at all

Farmer’s Market

Whole Foods

Safeway

Trader Joe’s

Locally owned grocery stores (Berkeley Bowl, etc.)

Other (Please indicate):

Define Organic, as used in the context of organic food products. Write no more than 3 sentences to answer this.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

24

Read the question and answer Yes or No.

Question Included in US

Federal

Certification?

Included in

California

Certification?

If you answered NO,

should it be included in

the certification

standards?

Organic Food have NO contact with ANY

synthetic substances.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Pests may be controlled using synthetic

substances.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

All organic foods contain only non-organic

substances.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Organic Food standards include farm labor

practices.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Organic Food standards regulate human

health.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Organic Food standards regulate Carbon

Emissions/Footprint

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Organic Food standards consider soil quality

and management.

Yes No Yes No Yes No

Indicate how important these food issues are to you.

Top Priority

Important but low priority

Somewhat Important

Not Important

Food processing techniques

Increasing farm worker salary

Limiting the GMOs* in food

Reduction of pesticide use in food

Food access for low-income people.

Improving job conditions

*GMOs: Genetically Modified Organisms

Indicate your position about the following statements.

Question Strongly Disagree Disagree Agree Strongly Agree

Farmers meet organic food standards.

The government effectively regulates food

production.

Organic food standards help the food industry.

Organic food standards should include labor

standards.

Organic food standards should include

standards on animal welfare.

I buy organic to protect myself from consuming

pesticides.

I buy organic food to support local farm owners.

I buy organic food to oppose industrialized

conventional agriculture.

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

25

I buy organic because it is a political stand.

I buy organic to support farm workers.

I buy organic food because it is fresher than

convetionally grown food.

I buy organic to interact with people growing

my food.

Question Strongly Disagree Disagree Agree Strongly Agree

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure that

all the organic standards are met.

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure that

animals are treated humanely.

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure that

carbon emissions are regulated.

I am willing to spend more for organic food if I

can ensure that job conditions are improved.

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure that

farm workers get health benefits.

I am willing to spend more if I can ensure that

there are no GMOs in my food.

Ultimately, what do you think should be included in the organic production process? Why? Write your answer in

1-2 sentences.

Factor

Should this be

included?

Why?

Aesthetics

Yes No

Carbon Emissions

Yes No

Soil Management

Yes No

Water Management

Yes No

Labor

Yes No

Animal Welfare

Yes No

Public Health

Yes No

Price Control

Yes No

Sourcing (ie. Where items

Yes No

Alyssa Tison Consumer Knowledge of Labor in Organic Farms Spring 2012

26

are sold)

Other (Please indicate):

Yes No

Thank you for participating in this study. If you would like to get more information, please feel free to email me

at alyssatison@berkeley.

II. Answers to the Certification Knowledge Test. Citations from the USDA and CCOF Organic Certification

Standards

Regulation

Included in the

US?

Included in

CA?

Cited in the USDA/CCOF

Standards

Organic Food have NO contact with ANY

synthetic substances.

NO

NO

§ 205.105. (a) Synthetic

substances and

ingredients, except as provided in

§ 205.601 or § 205.603;

Pests may be controlled using synthetic

substances.

YES

YES

§ 205.603 Synthetic substances

allowed for use in organic

livestock production.

All organic foods contain only organic

substances.

No

No

Claims. Oral, written, implied, or

symbolic representations,

statements, or advertising or other

forms of communication

presented to the public

or buyers of agricultural products

that relate to the organic

certification process or the term,

"100 percent organic,"

"organic," or "made with organic

(specified ingredients or food

group(s))," or, in the case of

agricultural products

containing less than 70 percent

organic ingredients, the term,

"organic," on the ingredients

panel.

Organic Food standards include farm

labor practices.

No

No

None found.

Organic Food standards regulate human

health.

Yes

Yes

§ 205.236 Origin of livestock.

§ 205.238 Livestock health care

practice standard.

Organic Food standards regulate Carbon

Emissions/Footprint

No

No

None found.

Organic Food standards consider soil

quality and management.

Yes

Yes

§ 205.203 Soil fertility and crop

nutrient management practice

standard.