Children’s Specialist Program

Reference Guide

ProfessionalSkiInstructorsofAmerica

AmericanAssociationofSnowboardInstructors

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 1 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

CHIL

DREN’S SPECIALIST REFERENCE GUIDE

This R

eference Guide is intended to be an additional resource for the Children’s Specialist (CS)

assessment based certificate program. Snowsports School trainers and instructors are welcome to refer

to this Guide to enhance their children’s education knowledge base.

At the PSIA/AASI 2013 Fall Conference, the National Children’s Task Force (NCTF) recommended that

the “Study Guide” nomenclature be changed to “Reference Guide”. The NCTF also wanted this Guide to

be updated on an ongoing basis with new or updated information. Revisions will be noted in the “Revision

History” section.

Many people and groups contributed to making this guide a success, including the ASEA National Board

of Directors, PSIA/AASI Intermountain Board of Directors, the (former) PSIA Junior Education Team

(JETS), the PSIA/AASI National Teams, Alexandra Smith Boucher, Marie Russell-Shaw, Amy Zahm,

Carol Workman, and Grant Nakamura. Thanks also to Patti Olsen, John Musser and Maggie Loring for

their assistance in preparing and reviewing the guide.

Mark Nakada, Editor

PSIA/AASI-I Children’s Program Manager

November 2013

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 2 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Revisi

on History ....................................................................................................................................... 4

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 5

The CAP Model ....................................................................................................................................... 5

Cognitive Development ........................................................................................................................... 5

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development ......................................................................................... 5

Some Practical Considerations of Piaget’s Stages ............................................................................. 6

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences .......................................................................................................... 7

Affective Development ............................................................................................................................. 9

Humor ................................................................................................................................................. 9

Moral Development (Kohlberg) ......................................................................................................... 10

Physical Development ........................................................................................................................... 11

Visual Development .......................................................................................................................... 11

Auditory Development ....................................................................................................................... 12

The Perceptual Motor System ............................................................................................................... 12

Some Basic Movement Concepts ......................................................................................................... 13

Phases of Motor Skill Acquisition ...................................................................................................... 14

Motor Skill Acquisition: Initial Stage, Elementary Stage & Mature Stage .......................................... 14

Real vs. Ideal ......................................................................................................................................... 15

The Teaching Cycle - P-D-A-S .............................................................................................................. 16

Parents in the Learning Partnership ...................................................................................................... 17

The Parent Trap .................................................................................................................................... 19

Problem Solving With Children .............................................................................................................. 20

Tough Kids ............................................................................................................................................ 21

What is ADHD? ..................................................................................................................................... 21

The Coercive Cycle (or how to make it worse!) ..................................................................................... 24

Positive and Negative Reinforcement ................................................................................................... 24

How to Use Positive Reinforcement Effectively - IFEED-AV ........................................................... 25

Variables That Affect Compliance ..................................................................................................... 26

Spider Webbing ..................................................................................................................................... 28

APPENDICES ....................................................................................................................................... 29

APPENDIX 1 - Piaget’s Stages & Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development ................................... 29

APPENDIX 2 – Building Solid Movement Patterns With The Game Toolkit ..................................... 32

References, Resources and Recommended Reading .......................................................................... 35

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 3 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

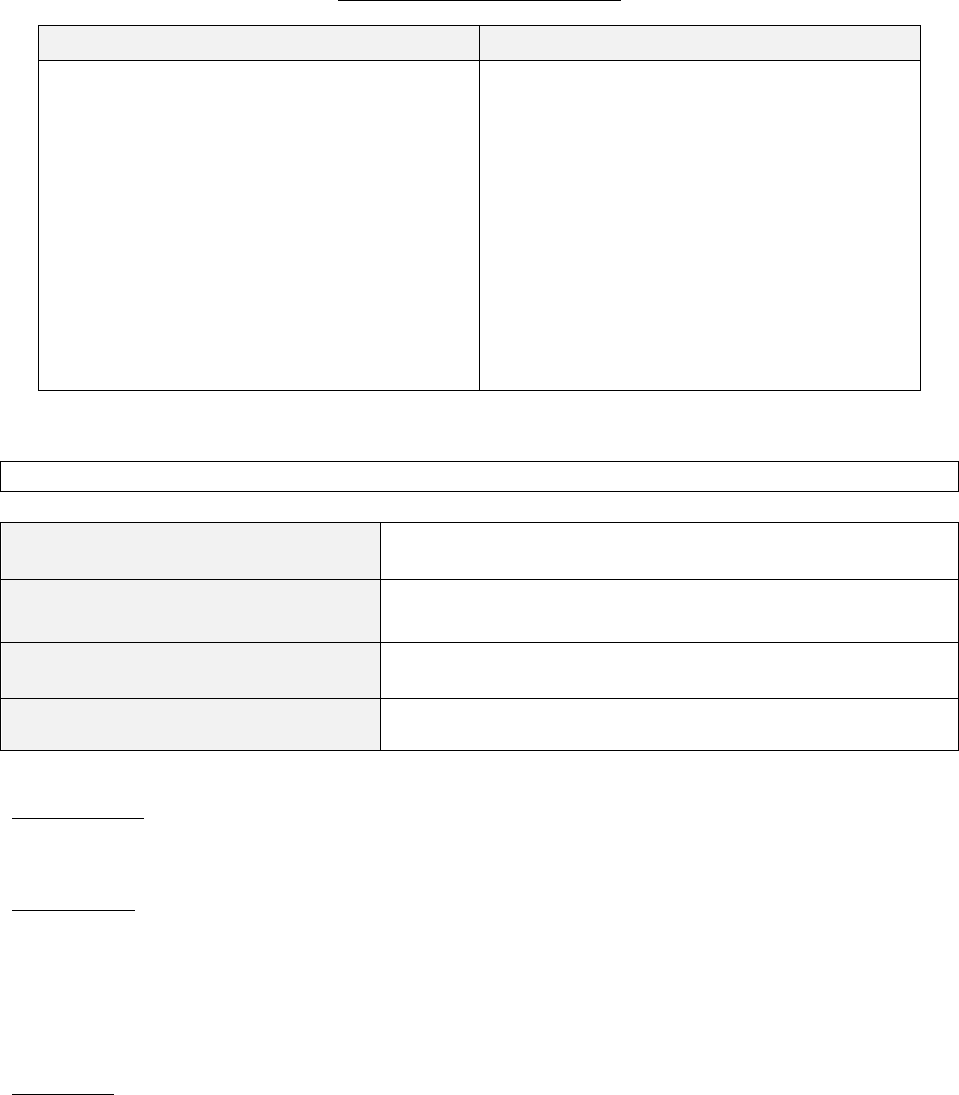

Revision History

Version

Date

Notes

1.0 1990

Materials presented at the Children’s National Symposium

(Park City, UT)

2.0–4.0 2000, 2001 & 2005 Materials updated

5.0.0 Nov/Dec 2012 Study Guide edited and reformatted for easier review

5.0.1 Nov 2013 “Study Guide” nomenclature changed to “Reference Guide”

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 4 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Introduction

This gui

de is designed to present Snowsports instructors with specific information that can help them to

be more effective instructors for children. The models, theories, and tools presented herein can help the

instructor to better understand what children bring to a lesson, and the specific behaviors and ways that

impact learning at different stages of development.

Understanding the developing child will help you make appropriate decisions regarding what you need to

do to help children progress and develop toward desired outcomes in the mountain environment.

The CAP Model

“How

development affects learning and performance”

CAP stands for Cognitive, Affective, and Physical. The CAP model was designed to give instructors

insight into how children think, behave, and move. This model is a tool instructors can use to determine

the level of development in any student, and guide the process of selecting goals and presenting

information to the student. These ideas can also help to guide practice tasks, check that the child

understands, and summarize the lesson.

“Some kids are late bloomers while others grow like weeds!”

Cognitive Development

Piage

t’s Theory of Cognitive Development

In general

, Piaget’s “stage” theory is a good way to begin to understand children’s cognitive development.

Piaget’s four stages are often used to roughly determine a child’s level of cognitive development. Piaget

proposed that cognitive development occurs in specific stages:

The Sensorimotor stage, from birth to 2 years, is when the child transitions from strictly

reactive/reflexive to intentional behavior

The Pre-Operational stage, from 2 to 6 years, is when the child begins to develop reasoning and

classification skills and also begins to be able to see things from others’ perspectives

Concrete Operations, from 6 to 10 years, is the time when the child has more advanced mental tools

at his disposal, and marks the beginning of more abstract reasoning

Formal Operations, from age 10 up, is the time when problems are approached more systematically,

deductive logic is used, and abstract thought and reasoning are fully developed. (Bee; The

Developing Child; Harper & Row, 1989).

It should be noted that Piaget’s theory, although influential and useful, has some problems: (1) children

generally develop signs of complex thinking earlier than Piaget suspected; (2) children definitely exhibit

more complex level of thinking in areas in which they are more familiar - than in areas in which they are

less knowledgeable, and (3) children are not consistent in their performance of tasks that allegedly

require the same level of cognitive development. (Bee; The Developing Child; Harper & Row, 1989)

“Children view the world differently than adults”

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 5 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

AGE

STAGE

CHARACTERISTICS

0-2 Sensorimotor

Active experimentation and coping through the 5 senses. Examples:

eating snow, putting everything in the mouth

The child is learning to differentiate him/herself from others and the

environment

2-6 Pre-Operations

Language and communication skills are growing as evidenced by the

increased vocabulary, yet children often don’t understand the words

they are using

Although the thought process is egocentric, the child is beginning to see

that others have feelings as well

These children still have difficulty paying selective attention

These children are beginning to differentiate between thoughts and

actions

6-10+

Concrete

Operations

With this stage comes better memory, reversibility, expanding mind and

vocabulary

“Concrete” refers to ideas that are based on things one can see, feel, or

touch

10+

Formal

Operations

Children in this stage begin to relate consequences-to-actions they take

Abstract thinking, the world of ideas, becomes accessible

Logic is more mature.

Piaget

pointed to the age of seven (7) as a time for major cognitive changes. Piaget said, “Around this

age, children make the critical transition from pre-operations to more advanced concrete operations.”

Transition: “An increased understanding of classification skills, an understanding of conservation

concepts, and a marked increase in memory abilities.” (Stroufe, Child Development: Its’ Nature and

Course; McGraw-Hill, 1992)

Some Practical Considerations of Piaget’s Stages

Sensor

imotor Stage: (The 5 Senses)

This s

tage includes children up to around age 2. Children at this stage need to learn about their

environment through the five senses, and learn almost solely through experimentation. The key to

success at this stage is allowing the child to experiment while keeping them safe and happy.

Pre-Operations Stage: (The Word)

This s

tage includes children around ages 2 - 6. Children at this stage tend to have egocentric behaviors,

and are beginning to learn to see things from others’ perspectives. Vocabulary and memory are

developing every day, but are still more general and limited. The keys to success with this “stage” child

are to keep verbal directions clear and simple, and to use the child’s own words to describe things.

Children at this stage will be confused by receiving too many directions or too much information!

Games that involve fantasizing, imagination or pretending can be fun, but “real” situations should still be

pointed out to these children (for safety concerns). Children at this stage need ample personal attention.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 6 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Concrete Operations Stage: (The Mind)

From

ages 6 to 10 years old, children’s minds evolve even more. Memory and the ability to communicate

become more sophisticated. Kids at this stage can benefit from learning to visualize themselves skiing or

riding.

Pretending and imagining games may become less desirable, while competition becomes more obvious

in some children at this stage. Children in this stage might be taught to compete against their own

performance. For example, an instructor may say,” Good - Ashley, you made 8 turns on that run; now see

if you can do more than 8 here.”

Prior to this stage, children need simple instructions and cannot reverse them. In this stage, children

begin to show the ability to accept more complex or detailed instructions - and can even reverse the order

of a set of instructions.

Formal Operations Stage: (Consequences)

This

stage is Piaget’s last stage of cognitive development in humans, and is characterized by highly

developed logic and reasoning skills. People at this stage are aware how their actions may have some

consequences, and how these actions may affect others.

Interestingly, Piaget theorized that not all individuals attain this final stage, and the age at which different

individuals enter this stage is highly variable. It is important for instructors to tactfully remind students of

all ages of consequences, especially teens.

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

Howar

d Gardner’s theory of “multiple intelligences” can be a useful tool to determine a child’s “talents”,

other interests, and learning preferences. The theory of multiple intelligences deals with how the mind

processes information and solves problems – and proposes that there are more forms of intelligence than

just reading and arithmetic comprehension. Each of the multiple intelligences can be looked at as an area

of proficiency that children exhibit at a young age. As we develop, we gain more proficiency in all of the

intelligences. However, even as adults, we may tend to prefer certain ways of receiving information to

others. The intelligences Gardner proposed are:

Linguistic (word smart)

Spatial (visual smart)

Music (auditory smart)

Math (number & logic smart)

Intrapersonal (self-smart)

Interpersonal (social smart)

Kinesthetic (body smart)

Nature (nature smart)

Perhaps the best thing about the ‘Multiple Intelligences’ theory is that it is easy to understand and use in

any learning environment. Gardner gives us practical tools to help “tailor” a lesson to the student.

Instructors can use the various “intelligences” to categorize the different types of analogies or games that

they use to appeal to different kids. The ‘Multiple Intelligences’ theory can also enhance an instructor’s

ability to teach to the four learning styles: Watcher, Thinker, Feeler, and Doer. Because students usually

begin to combine intelligences and learning styles - especially as they get older, the most effective

instructors always do things in a lesson that appeal to all of the intelligences. An excellent example of

this is this excerpt from the PSIA Children’s Instruction Manual (1997):

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 7 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

“Consider teaching a child to tie Nordic boot or snowboard boot laces as the objective of the

lesson. You can use words to describe the shapes needed to create the bow strings (word and

picture smart); count the number of steps needed to complete the task (number-smart); guide the

child’s hand and fingers going through the movements (word and body-smart); help the child

recognize the rhythm of the movements – i.e., making a loop is slow, wrapping the lace around is

fast (music-smart); and do the task together (people-smart) - until the child is ready to do it alone

(self-smart).” (PSIA, “Children’s Instruction Manual;” 1997).

The below chart is the result of brainstorming from a group of instructors discussing the Multiple

Intelligences:

Linguistic

Verbal, talks a lot

Tells stories

Uses words, place names

Make up your own language

Poems, riddles, and rhymes

Spatial

Visual

Shapes of clouds

Drawing

Shapes in the snow

Colors

Look where you want to go

Music

Rhythm to a song

Make up your own song

Sound of your skis or ride

Nursery rhymes

Bodily Kinesthetic

NOT a good listener

Physical

Throws snowballs

Just wants to ski or ride

More coordinated

Natural athlete

Sensations, feelings

Math

Logic

Talks about numbers

Loves numbers on chair lifts & towers

Uses number games for turns or skills

Interpersonal

Socialite

Groups & pairs

Team name

Special role in group

Sensitive to others’ feelings

Intrapersonal

Thinks about things a lot

Guided discovery

Doer

Likes to be alone or on their own

Knows their own feelings

Nature

Aware of surroundings

Relates to nature when processing info

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 8 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Instructors need to be very observant of their students’ characteristics, and listen to what the students

and their parents tell them. One of the best ways to identify a child’s most developed intelligence is to

observe what they do when they’re “off-task” (no longer responding to a specific question or instruction).

You can also simply ask the child and the parent about the child’s gifts or learning preferences.

“What is your favorite thing to do when you are not skiing?”

For more information about Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences, please refer to PSIA/AASI’s Core Concepts

Manual and Children’s Instruction Manual (2

nd

edition).

Affective Development

Humor

“Hum

or develops as the child grows and matures. It may be a solo activity or it may involve others. The

main idea is that at each stage of development the things that cause laughter can be extremely different.

Being a stand-up comic is not a prerequisite for teaching, but it helps to have an understanding of what

makes kids laugh.” (Smith-Boucher, ATS: Children’s Development; PSIA, 1994)

STAGE

Type of Humor

Sensorimotor

Pre-Operations

Concrete Operations

Formal Operations

Peek-a-boo

Slapstick

Knock-knock, jokes, riddles and toilet talk

Sarcasm, laughing at self

In 1976,

Paul McGhee did a study entitled “Children’s Appreciation of Humor.” The following three jokes

are similar to those used in his study:

Mr. Jones went to a pizzeria and ordered a whole pizza for lunch. When the waiter asked if he wanted

it cut into six or eight pieces, Mr. Jones said, “Please make it six. I could never eat eight.”

“Please stay out of the house today,” Janie’s mother said.” I have too much work to do.” “Okay,”

replied Janie as she walked to the stairs. “Where do you think you’re going?” her mother asked.

“Well,” said Janie, “if I can’t stay in the house, I’ll just play in my room instead.”

Mr. Wheatley teaches first grade. One day his class was learning about religion, so Mr. Wheatley

asked how many children were Catholic. When Billy didn’t raise his hand, the teacher said, “Well Billy,

I thought you were Catholic too.” “Oh, no,” said Billy. “I’m not Catholic, I’m American.”

Adults generally do not find these jokes as funny as 8 or 9 year olds do. Each of these jokes deals with an

error in reasoning that is conquered in middle childhood - conservation and classification. 8 and 9 year

olds have just developed these reasoning skills, which is why children that age find them funny.

Preschoolers, on the other hand, would not understand the punch lines as errors in reasoning.

Joke telling and riddles can be fascinating for children between the ages of 5 and 8. It is evidence of their

cognitive, affective and social development. It’s not too difficult to find out what various kids think is funny.

Listen as they interact, and discuss with your peers.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 9 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Riddles can also be very amusing to youngsters in middle childhood and may even aid cognitive and

social development.

Q: Why should you always wear a watch in the desert?

A: Because a watch has springs in it.

Again, younger children would not understand this riddle - as the child must be able to consider the dual

meaning of the word “springs”.

Moral Development (Kohlberg)

Moral

development has to do with the child’s concept of “right” and “wrong”.

Piaget and Kohlberg studied and described moral development. Piaget addressed the early stages of

moral reasoning for children aged 2-6, while Kohlberg extended Piaget’s work and described moral

reasoning into adolescence and adulthood. These theories can help the instructor to better understand a

child’s perspective when giving reasons for instructions or rules. They also may be useful in

understanding reward and punishment for behavior modification. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development

are presented in more detail in APPENDIX 1.

7 to 12+ year old children (in general) are highly motivated by EXTRINSIC rewards, while snow sports are

full of INTRINSIC rewards for them to discover through exploration. With this age group, use plenty of

experiential learning and POSITIVE reinforcement.

“Young people need models, not critics”

Below are four sayings to remind you of the more common stages of moral development for children in

ski school:

APRROXIMATE STAGE

Moral Behavior

Pre-Operational

Concrete Operational

Teens (and many adults)

Formal Operations

“Good is good, bad is bad”

“Clever as a fox”

All in favor, say “aye”’

Listen to your conscience

Age r

anges are approximate for these stages - as they are highly variable. It is possible to have several

children the same age at different stages of moral development.

In Kohlberg’s first stage, he describes children that equate “what is bad” to “what is punished”. Eventually,

children evolve to the second stage when they equate “what is good” to “what feels good and to what is

not punished”. Children in these first two stages of moral development are looking for their parents to tell

them “what is good” and “what is bad”, and they soon learn that their behavior can please or displease

others (i.e., good boy, nice girl).

Children next begin to see adult rules as something to challenge. They still respect adults as the

authority, but begin to believe in their own cleverness at staying one step ahead of the rules. Children at

this stage are developing their sense of self-identity and often will test “the letter of the law” - or to what

extent it will be enforced. Teenagers, as well as younger children, will often exhibit the behaviors

associated with this stage.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 10 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Beginning in the pre-teen years, young people develop their sense of self-identity even further, and often

recognize the importance of “fitting in” to a group or cultural identity. With this stage comes a sense of

individual rights or beliefs based on what is seen to be socially acceptable by their group - and “peer

pressure” enters the picture.

Finally, the abstract concepts of fairness, justice, dignity, and equality all become important and help

guide the individual’s ideas about right and wrong. Some adults never really attain this stage, while

others may reach it in their teens.

Physical Development

Duri

ng childhood, growth is happening every day. A child’s physical growth determines their experience,

makes new behaviors possible, and is an important factor in motor skill development. By knowing what

the student is capable of, the instructor is able to establish realistic lesson goals that set the student up

for success. “An awareness of children’s physical development will help to explain why and how children

move the way they do.” (PSIA, “Children’s Instruction Manual;” 1997).

Children are not just miniature adults, they are proportioned differently. In general, younger children are

“top heavy.” They have a higher center of mass than adults, because a child’s head is larger in proportion

to the rest of their body. Because of this “top heavy” body shape, a child’s balanced stance can look

awkwardly “low” or “back”. As children develop physically, their center of mass moves downwards

towards the abdomen and hips. Recognizing this characteristic will aid in the understanding of a child’s

stance and movement.

Another interesting point is that most children under the age of 4 cannot reach their arm over their head

and touch the opposite side ear – as their arms are simply not long enough.

Muscular and skeletal development occurs constantly throughout childhood. The increase in size,

strength, control and coordination of muscles is a determining factor in what the child will be able to

accomplish on skis or a snowboard.

Although the rate varies at which children mature, development still occurs in stages for all children. “By

paying attention to the stages, you will be able to attain realistic goals on the hill.” (Smith-Boucher, ATS:

Children’s Development; PSIA, 1994).

Visual Development

Vis

ual acuity in children improves over the first 8-14 years of life. The average child with normal visual

development attains ‘standard’ 20/20 vision around age 10 or 11. 20/20 vision means that the person can

properly identify an object at twenty feet. Children under 2 have relatively poor visual acuity (20/800 at

birth, 20/100 by about 4 months), but acuity improves steadily thereafter.

Some other skills related to visual development:

The ability to follow a moving object smoothly

The ability to fix eyes on a series of stationary objects

The ability to change focus quickly

The ability to team the eyes together

The ability to see over a large area (in the periphery)

The ability to see and know (recognize) in a short look

The ability to see in depth

(Orem, Learning to See Seeing to Learn; Mafex Associates, 1971)

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 11 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Auditory Development

In new

borns, auditory acuity is much better than visual acuity. Although the auditory sense is well

developed some weeks before birth, it continues to improve up to adolescence. Auditory acuity in

newborns - in regards to general range of pitch or loudness, is as good as adults. However, adults show

an increased acuity in hearing low-pitched or quiet sounds.

Newborns have a very limited ability to determine the locations of sounds (direction and distance).

However, this skill improves greatly over the first 6 months of life, and continues to improve throughout

childhood into adolescence.

One thing that many children and adults have difficulty with - is discriminating one voice out of many or

hearing instructions given to them when there is general background noise. When giving instructions, it is

important for instructors to stay close enough to their students and speak clearly - with eye contact - to be

sure that they are being heard.

The Perceptual Motor System

Firs

t, we perceive information through our senses. Then, we receive this information through our senses:

sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. This is called sensory input - or reception. Next, our brain

interprets this information.

We can perceive the information kinesthetically, through feeling tactile pressure, from balance or

proprioception.

We can process information through our visual sense, which is fully developed somewhere between 8

and 14 years of age. Visual processing is made up of acuity (sharpness & clarity), discrimination

(perceiving details), constancy (brightness, color & shape), figure/ground (perceiving figures separate

from the background), and localization (orientation of people & objects in space).

We can also use our auditory sense. Full maturity of auditory functioning does not occur until nearly 7

years of age, although hearing is one of the first senses to develop in the womb. We perceive and

process sound through our perception of direction, distance, and discriminating between separate

sounds.

Lastly, we respond to the perception we have arrived at through our motor system. For example, this

may take the form of a scream, if we conclude there is a spider crawling on our arm, or we may stop our

car, if we determine there is a red light ahead of us. These reactions are usually orderly and predictable,

based on the common perception of the input we receive.

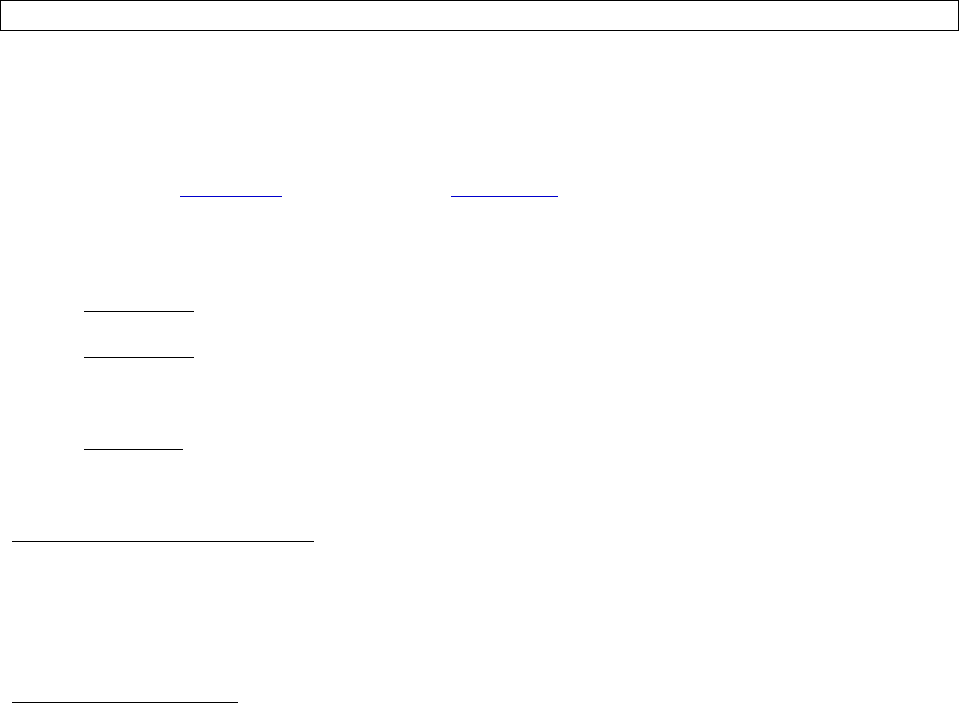

…the brain sorts

& organizes the

information…

…and produces

a physical/motor

response.

Information

comes in

through the

senses…

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 12 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Some Basic Movement Concepts

(From B

ode, Peterson & Workman, Child Centered Skiing; Publisher’s Press, 1988)

There are several developmental factors which relate to motor skill performance:

One-sided movements are easier than two-sided movements

o It’s easier to move one body part at a time, and it’s easier for body parts on the same side to

do the same movements.

Cross-lateral and oppositional movements are more difficult

o If two sides of the body are moving at the same time, it’s easier to keep all the extremities

doing the same thing. Examples: For skiers, work with one foot at a time. For snowboarders,

traversing/forward sideslips are easier, because you're focusing on one foot instead of

balancing on both.

Motor control develops in a cephalo-caudal and a proximo-distal direction

o Cephalo-caudal means head-to-feet and proximo-distal means from the inside-outwards.

Humans develop motor control starting from the head first - then down to the feet, and from

the center of the body, then out to the extremities.

o In both skiing and snowboarding, the upper body’s movements must be separated (or

controlled independently) from the lower body. In addition, one side of the body experiences

different movements and sensations than the other side. Examples: For skiers, it is easier to

learn a wedge, than it is to learn to sideslip on both skis. For snowboarders, actively twisting

the board can be a difficult move - as children tend to pivot around one foot instead of around

the center of the board.

Large muscles groups are controlled before the small ones

o At any age, the large muscles are easier to move into proper body alignment before

coordinating the smaller muscle groups - such as those that move the ankle (dorsiflexion and

plantar flexion movements)

Movements will also be gross and general before becoming more refined and specific.

o Coordination develops in specific stages

o Balance improvement occurs by developing the body’s balance receptors (proprioception)

while approximating a centered stance

The center of mass moves from higher in the body to lower in the body.

o Younger kids will bend at the waist to balance

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 13 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Phases of Motor Skill Acquisition

Motor Skill Phase Approximate Age of Child Stage of Motor Skill Development

Reflexive Movement

0 - 4 months Information encoding stage

4 months - 1 year Information decoding stage

Rudimentary Movement Birth - 2 years Pre-control stage

Fundamental Movement

2 - 3 years Initial stage

4 - 5 years Elementary stage

6 - 7 years Mature stage

Sport-related Movement

7 - 10 years General (transitional) stage

11 - 13 years Specific stage

14 and up Specialized stage

Motor Skill Acquisition: Initial Stage, Elementary Stage & Mature Stage

The IN

ITIAL stage of motor skill acquisition begins with increased awareness of what the body is doing.

Young children will often look at their body parts or skis to help connect what is happening to them with

what they are feeling.

The ELEMENTARY stage of motor skill acquisition is characterized by attention on the environment. Kids

at this stage gain more control to avoid objects or others around them. The perceptual motor system and

eye movements are becoming more sophisticated related to physical or athletic sports.

The MATURE stage is marked by more fluid and elegant movements - that appear easy. Movements

become more coordinated, accurate, rhythmical, and consistent.

# # #

There are three sensory receptors which work to balance - the eyes, the soles of the feet, and the inner

ear (cochlea). Basic balance concepts to consider: (1) a wider stance (base of support) is more stable; (2)

the closer the center of mass is to the ground - the greater the stability, and (3) the more centered the

center of mass is over the base of support - the greater the stability.

The ideal balanced position in skiing or riding is an upright, tall stance with the center of mass centered

fore and aft over the feet. The joints are slightly flexed in an athletic stance and allow for the body to be

aligned over the outside ski (or over the board) in turns. Learning how to move the ankles properly in all

skiing or riding maneuvers will increase the ability to maintain balance. Having a good balanced stance

and learning to direct movements of the body in the intended direction of travel will enable more efficient

and fluid skiing or riding.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 14 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Real vs. Ideal

Here ar

e some things to think about regarding “ideal” sport-specific movements vs. “real” movements - as

seen in children - using the CAP Model:

We are always striving to develop ideal movements in our students whether they are adults or

children

It is important for children’s instructors to understand how children are physically different from adults,

so they can understand why they see different movements or stances from children at a given stage

Instructors should not simply “give up” because they know that a child is not physically mature

enough to move ideally on their skis or board. Instead, we want to “plant the seed” for good

movements by always encouraging the “ideal”, in hopes that when the child is physically ready, they

will be able to better approximate the ideal. Young children can develop very strong and efficient

movement patterns and balance, and they will adapt and evolve their movements as they develop

physically.

When instructors recognize what is “ideal” and what is “real”, they find it less frustrating to work with

smaller, younger children, because the focus is more on the process than the outcomes. As we all know,

skiing and riding are great ways to help develop and promote balance and strength in adults and children.

We also know that children develop at different rates, and some children will be capable of more ideal

movements at much younger ages than others.

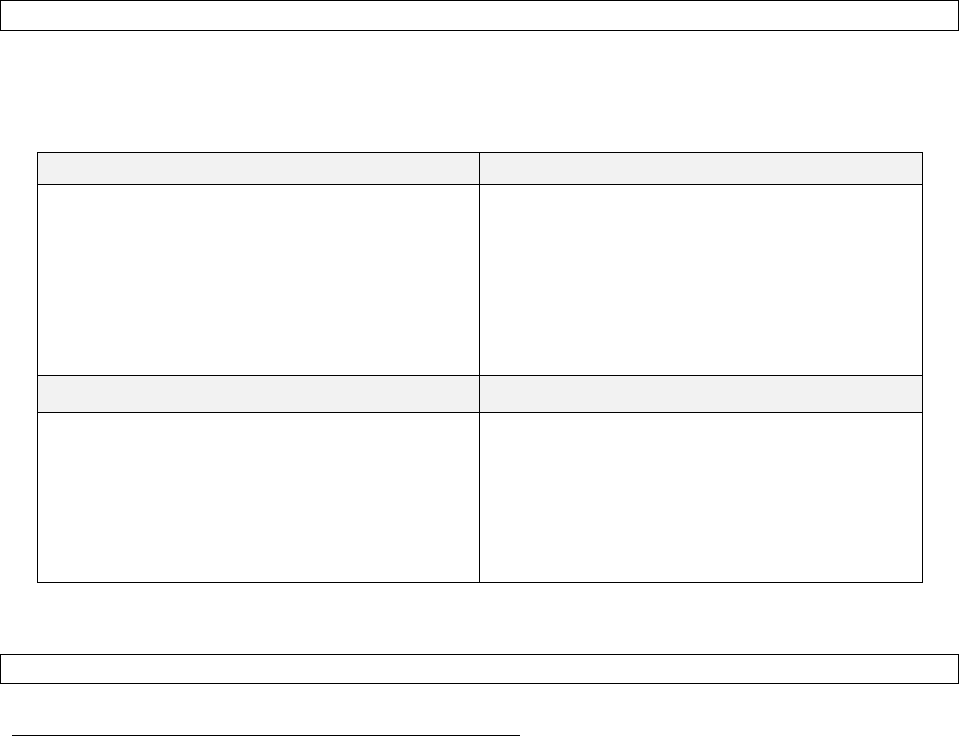

Real vs. Ideal - Skiing

REAL IDEAL

Children flex more in the hips and knees -

and tend to work the back of the boot and

tail of the ski more

Children tend to move their whole body

and legs in a more gross way

Edging movements tend to be more harsh

and bracey

Balance may or may not be well directed

to the outside ski in the turn

Children generally lack upper/lower body

separation - and tend to turn their whole

bodies

Children under 7 usually don’t use poles

and generally lack upper body discipline

The ankles, knees, and hips flex and

extend to maintain balance and pressure

control over the skis

Directional movements of the feet, legs,

and hips release and engage the edges at

the turn transition

Balance is directed to the outside ski in

the turn

The legs and feet turn under the upper

body to guide the skis

Movements of the upper body, arms,

hands and pole usage are disciplined and

directed to flow with the skis through turns

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 15 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Real vs. Ideal - Snowboarding

REAL IDEAL

Children tend to flex more in the hip than

lower in the body, levering off the binding

backs

It is difficult for children to work the legs

in opposition; they tend to use the legs

more as a unit

Children have an easier time controlling

the trunk, and try to use the upper body

before the legs

The ankles, knees & hips flex and extend

to maintain balance and pressure over

the board

The legs and feet work independently or

oppositionally - to torsionally flex or twist

the board

Movements of the upper body, arms and

hands are disciplined and compliment

the action of the legs

Movements to toe and heel sides are

used equally and toe/heel symmetry

results

The Teaching Cycle - P-D-A-S

PLAY

Introduce the Learning Segment

Assess the Student

DRILL

Determine Goals & Plan Objectives

Present & Share Information

ADVENTURE

Practice

Check for Understanding

SUMMARY

Summarize the Learning Segment

PLAY & DR

ILL: Children need to SEE, FEEL and HEAR; they need to explore through their senses.

Meaningful activities and games develop balance awareness and movements that can help you learn

about each child (or your group). Remember to keep it fun and use plenty of positive reinforcement.

ADVENTURE: Children need to experience certain aspects of the sport on their own and gain mileage

while truly enjoying themselves. The “adventure” phase appeals to the affective aspects of the child’s

development in skiing or riding - as well as providing valuable practice time.

NOTE: The instructor can learn a lot about the child’s learning preferences by simply observing the child

at play during “free time”. The activities that the child chooses to participate in (when given a choice) are

meaningful to the way the child learns.

SUMMARY: Summarize the learning segment for the children and their parents in a clear, honest, and

memorable way. Throughout the lesson constantly remind the child “what” the child has done well and

“what” they have learned in terms that appeal to them. At the end of the lesson, touch base with the

parents and explain your focus and methods, so they will be able to continue to reinforce the desired

behaviors. Give the parents a good understanding of the level of their child’s skiing and the process

involved with skill improvement and development. Use the CAP model, and give specific examples that

apply to their child.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 16 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Parents in the Learning Partnership

Parent

s are a partner in the “Learning Partnership” - as they are usually responsible for the child’s

involvement in winter sports. Parents may have many roles, such as the child’s transportation system,

equipment supplier, food service provider, lesson and ticket purchasing agent, tear wipers, and

cheerleaders for their child’s participation in skiing and/or snowboarding.

“Parents are the customers; Children are the consumers” - John Alderson, JETS former member

Parent

s need to know that the service they have purchased is of value to their child. The CAP model can

be used to address parents’ needs as follows:

o COGNITIVE: Parents need to know that we will help their child with the process of learning

o AFFEC

TIVE: Parents need to trust that we care for their child and will take care of the child’s

sense of comfort and well being. Opportunities for developing a sense of competence will be

provided through the child’s experiences with us.

o PHYSICAL: Parents need to feel that we will help their child develop movement skills that will

make it possible for them to explore and enjoy the mountain environment.

Parents and the Teaching Cycle

Parent

s have an expertise and experience that can be a valuable resource for the instructor to use to help

meet the child’s needs. We should seek and incorporate the parents' help - and let them know how we

will meet (or have met) their child’s needs by involving them in the teaching cycle.

Introducing The Lesson

Est

ablishing and building rapport with a child’s parents is key to the success of any lesson. Instructors

should run a Pre-Flight Checklist with parents - before taking off with their kids:

o Check the child’s clothing and equipment before the parent leaves

o Where and when can the parent meet the child at the end of the lesson?

o Who will be meeting the child? What is the plan, if the child is to be on their own?

o Will the child be joining the Snowsports school for lunch? Is there anything they shouldn’t eat?

o Is a drink or snack appropriate at a break? Is there anything the child should not eat?

o Let the parent know if there is a “PLAN B” for a child who has just had enough

o Is there anything else that would be helpful to know about the child? (i.e., meds)

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 17 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Determining Appropriate Goals For The Student

Parent

s can provide information about their child that will help us determine goals, and plan the content of

the lesson:

o ASK what the parents would like their child to receive from the lesson. Both the parent’s desires

and the child’s help can guide our decisions concerning lesson goals and content

o ASK about the child’s previous experiences and accomplishments

o LISTEN AND LOOK for clues about the child’s motivations and learning preferences

Summarizing The Lesson

Let the par

ent(s) and the child know what was accomplished during the lesson. The CAP model can once

again be used a guide:

o Cognitive accomplishments might include: “John followed directions well or solved a problem.”

o Affective accomplishments may be: “Suzy made a new friend or helped other children in the

group.

o Physical accomplishments are: The terrain and conditions that the child skied or rode – and the

movements that the child learned or improved on.

Other things to consider:

o Relate how the child’s accomplishments met the parent’s desires and child’s needs – and make a

“next step” recommendation for the child (or other needs)

o For the “assistant mileage” coach, we need to make recommendations that will help the parents

provide beneficial practice experiences for their child

o The comfort, challenge, and “Yikes” zones: Let the parent know where their child will be

comfortable and where they will be unsafe

o Provide cues you used to help refine movements. Cues shared with parents need to be

movements that the parent can easily observe and determine if their child is accomplishing the

desired movements.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 18 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

The Parent Trap

Par

ents As Consultants In The Learning Partnership

Somet

imes a child will have a need that we can’t find a way to meet. Asking parents for their ideas -

based on their expertise and experience - can help the instructor discover how to provide what the child

needs. Although the instructor may feel his/her own expertise is vulnerable in admitting that help is

needed, our concern for the child will be recognized over any lack of expertise. Being a professional

doesn’t mean we need to know everything, but it does mean that we will find the answer if we don’t have

one.

If the parent’s expectations (or actions) do not match what the instructor feels the child needs, the

following dilemmas may ensue:

o The “Shadow” Parent: This parent can be your worst nightmare! They will stick around the whole

lesson and distract their child (not to mention the rest of the class).

o “Level 3 at Buffalo Mountain / Level 2 at Honest Peak”: This is the parent who is either unaware

of the true ability of their child - or just has too much pride to be honest. This causes trouble not

only for the entire class, but also for the eventual loss of face when the child must move to a

lower level.

o “Ski/Ride with Big Bro/Sis or Best Buddy”: If a parent insists that their child must be with a friend

or sibling, it is always best to move both children to a lower level. Even then, the two may become

disruptive or be unable to cope with each other in this new environment.

o “My Child is the next Lindsey or Shawn”: Such pressure on a child makes for unstable emotions,

not to mention huge crashes when the expectations are not met.

o “My parents think this is a good idea, but I’m not too sure”: When children do not want to be

there, not only do you have issues assimilating them into the class, but you have unrealistic

expectations on the part of the parent.

Releasing The Parent Trap

o Be Hones

t: Explore the situation together. LISTEN to the parent - then discuss options

o Define the problem or issue as you see it

o Generate possible solutions together

o Choose a solution

o Implement a course of action

o Evaluate whether the chosen solution is working

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 19 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Problem Solving With Children

Def

inition

Probl

em solving is a technique that instructors use to help children deal with problems, and develop skills

to solve problems on their own. Problem solving skills enable children to:

o Be more independent

o Express their individuality

o Be more self-reliant

o Gain a sense of responsibility

o Build self-esteem

Negotiation

There ar

e six (6) basic steps in the negotiation process:

o Help the child clearly identify the problem

o Encourage the child to contribute possible solutions to the problem and accept any ideas. Even

outlandish ideas can be respected for the contribution, and will also get the child involved and

perhaps willing to contribute further

o Review the child’s ideas positively

o Help the child decide upon the idea they prefer

o Help the children implement the preferred solutions

o Reinforce the process by describing how well they solved their problems

CAUTION! The instructor is NOT the authority figure solving the conflict!

The instructor DOES NOT:

o Place blame

o Try to figure out what is fair

o Order the children to take turns

o Separate the children, scold them, or lecture them about sharing

Helpful Tips:

o Establish good EYE CONTACT

o Kneel down to the child’s level

o Speak in a NEUTRAL and CALM tone of voice - and don’t become emotional

o Have each child express their opinion

“There are no problems, only solutions”

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 20 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Tough Kids

To help i

nstructors be more effective at teaching children with learning differences (such as ADD or

ADHD, et al.), it is important to understand the characteristics of a “tough” kid:

Noncompliant

Aggressive

Does not do what is requested

Breaks rules

Argues

Makes excuses

Delays

Does the opposite of what is asked

Throws tantrums

Fights

Destroys property and/or vandalizes

Teases

Verbally abuses

Is vengeful

Is cruel to others

Poor Self-Management Skills Poor Social Skills

Cannot delay rewards

Acts before thinking

Shows little remorse of guilt

Will not follow rules

Cannot foresee consequences

Has few friends

Non-cooperative and bossy

Does not know how to reward others

Lacks affection

Has few problem-solving skills

Constantly seeks attention

What is ADHD?

Atten

tion Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD or AD/HD) is a neurological disorder. A landmark study by

Alan Zemetkin at the National Institute of Health in 1990 used a Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

scanning device to study the brain’s use of glucose (the brain’s main energy source). The study described

a significant difference between glucose metabolism in individuals with a history of ADHD and those

without such a history. Adults with ADHD utilize glucose at a lesser rate than adults without ADHD. This

reduced rate is mostly evident in the portion of the brain that is important for attention, handwriting, motor

control, and inhibition of responses.

ADHD is one of the most common reasons a child is referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist. The

consensus is that it occurs in 3-5% of the population. About 1 child in 20 will have ADHD. The ratio of

males to females is said to be 6 to 1; however, [this author] believes females are probably under-

identified and undiagnosed. Some research suggests that the ratio is closer to 3 to 1. Girls are more often

identified with the type of ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) that does not exhibit symptoms of

hyperactivity/impulsivity, and thus are probably not as easily recognized as having the disorder.

It is suggested to use the phrase “a child with ADHD” - rather than “an ADHD child”, because it

communicates an important concept. The child is first and foremost a child, a unique and special human

being. Try not to get caught in the trap of defining the child by their abilities or disabilities. ADD/ADHD is a

syndrome - rather than a disease.

A syndrome is more difficult for professionals to diagnose, because it must be determined if a collection of

symptoms exhibited by an individual genuinely characterize the syndrome. Thus, it is likely that up to 50%

of children with ADHD are never properly diagnosed.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 21 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) describes three types of this

disorder:

o Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, combined type: Includes symptoms of both inattention

and hyperactivity

o Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, predominantly inattentive type: Includes symptoms of

inattention only or primarily

o Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type: Includes those

with symptoms primarily related to hyperactivity and impulsivity

Psychologists usually want to see the individual and study their particular collection of symptoms for at

least six months before being able to give an accurate diagnosis. From Russell A. Barkley's article

published in Scientific American Magazine in 1998:

"As I watched 5-year old Keith in the waiting room in my office, I could see why his parents said

he was having such a tough time in kindergarten. He hopped from chair to chair, swinging his

arms and legs restlessly, and then began to fiddle with the light switches, turning the lights on and

off again to everyone's annoyance - all the while talking nonstop. When his mother encouraged

him to join a group of other children busy in the play room, Keith butted into a game that was

already in progress and took over, causing the other children to complain of his bossiness and

drift away to other activities. Even when Keith had the toys to himself, he fidgeted aimlessly with

them and seemed unable to entertain himself quietly. Once I examined him more fully, my

suspicions were confirmed: Keith had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).” (Barkley,

Russell A., "Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder", Scientific American, Sept. 1998).

Recent research suggests that ADD/ADHD may result from a failure of self-control. The disorder may

actually arise when certain brain circuits do not develop normally, perhaps due to genetics.

Some researchers had originally theorized that ADD/ADHD was a problem in attention, suggesting that it

stems from an inability of the brain to filter various competing sensory inputs. However, new research

conducted by Joseph A. Sergeant of the University of Amsterdam shows that children with the disorder

do not have that problem. Instead, these kids cannot inhibit their impulsive motor responses to such input.

Even more interesting to physical education teachers is research that shows “that children with ADHD are

less capable of preparing motor responses in anticipation of events, and are insensitive to feedback about

errors make in those reactions." (Barkley) The example given is a commonly used test of reaction time in

which children with ADD/ADHD are less proficient than other children to ready themselves to press a key

when they see a flashing light. It was also observed that they did not slow down in order to improve their

accuracy even after several mistakes.

Obviously, this is relevant to teaching motor skills or sports to kids with the disorder. In addition to

commonly prescribed drug therapies, Barkley recommends parents and teachers be trained “in specific

and more effective methods for managing behavioral problems of children with the disorder.” Barkley also

reports "that children with ADHD might also be helped by a more structured environment."

ADD/ADHD Success Stories

Ben F

ranklin and Thomas Edison are somewhat different examples of people with ADD. It has been

theorized that both men had the disorder. They have been termed as ADD/ADHD "success stories". Both

men were known to be highly impulsive and sometimes prone to uncontrollable bursts of emotion. But

somehow these men found ways to become highly successful and influential individuals in society despite

the notion that they had the disorder. The key here is that the disorder is not necessarily related to

intelligence or trainability and does not mean that children with the disorder cannot learn to function in

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 22 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

society and even become very successful. For more information on this aspect of ADD read the book,

"ADD Success Stories" by Thom Hartmann (1995).

ADD has become the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorder in children in the United States.

The National Institute of Mental Health has accepted the theory that the brains of people with ADD/ADHD

have a different type of glucose metabolism, or at least a different rate of blood flow, from those without

ADD/ADHD. At its core, ADD is generally acknowledged to have three components:

o Distractibility: It is not that the child cannot pay attention to anything, it is that they pay attention to

everything

o Impulsivity: Interrupts others, has little emotional control, impatient and restless

o Risk taking

Desirable Traits of ADHD

RESILIENCY

INGENUITY

CREATIVITY

SPONTAINEITY

BOUNDLESS ENERGY

SENSITIVITY TO THE NEEDS OF OTHERS

ACCEPTING & FORGIVING

RISK TAKERS

INTUITIVE

INQUISITIVE

IMAGINATIVE

INVENTIVE

INNOVATIVE

RESOURCEFUL

EMPATHETIC

GOOD-HEARTED

GREGARIOUS

OBSERVANT

FULL OF IDEAS AND SPUNK

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 23 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

The Coercive Cycle (or how to make it worse!)

Teacher

Student

“Wouldn’t you like to….” Ignores

“Come on, please…” Delays

“You had better….” Makes excuses, argues

“Now you’ve had it!” Tantrums, aggression

“OK OK!” Stops tantrum

At t

his rate, the child should have the instructor trained soon!

How to Intervene, Manage and Survive!

Use ve

ry few specific rules and stick to them!

Keep the number of rules to a minimum (max. 5)

Have rules represent basic expectations

Keep wording positive+

Make rules describe behavior that is observable and measurable

Tie following rules to consequences

Give choices or options

Only say what you really mean

Positive and Negative Reinforcement

How

does using positive or negative reinforcement affect how a child learns?

Positive reinforcement is said to occur when something a person desires is presented after

appropriate behavior has been exhibited. The reinforcement is only given after an appropriate

behavior is exhibited.

Negative reinforcement is said to occur when a person engages in a behavior to avoid or escape

something they dislike.

Punishment is said to occur when something the person does not like or wishes to avoid is applied

after the ‘inappropriate’ behavior has occurred, resulting in a decrease in the behavior.

Both positive and negative reinforcement increase behavior - while punishment decreases behavior.

REMEMBER: Nothing is more important than reinforcing to all kids - especially Tough Kids.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 24 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

How to Use Positive Reinforcement Effectively - IFEED-AV

I Reinforce IMMEDIATELY

F Reinforce FREQUENTLY

E Reinforce ENTHUSIASTICALLY

E Reinforce With EYE CONTACT

D DESCRIBE The Behavior

A Use ANTICIPATION

V Use VARIETY

Rein

force Immediately: The longer an instructor waits to reinforce a student, the less effective the

reinforcer will be. This is particularly true of younger students or students with severe disabilities.

Reinforce Frequently: It is especially important to reinforce frequently, when a student is learning a

new behavior or skill. If reinforcers are not given frequently enough, the student may not produce

enough of the new behavior for it to become well established. The standard rule is three or four

positive reinforcers for every one negative consequence (including negative verbal comments) an

instructor delivers.

If, in the beginning, there is a great deal of inappropriate behavior to which the teacher must attend,

positive reinforcement and recognition of appropriate behavior must be increased accordingly to

maintain the desired three or four positives to each negative. An example of a simple social reinforce:

“Good job, you finished your six turns.”

Reinforce Enthusiastically: It is easy to simply hand an edible reinforcer to a student; it takes more

effort to pair it with an enthusiastic comment. Modulation in the voice and excitement with a

congratulatory air conveys that the student has done something important. For most teachers, this

seems artificial at first. However, with practice, enthusiasm makes the difference between a reinforcer

delivered in a drab, uninteresting way - and one that indicates that something important has taken

place.

Reinforce With Eye Contact: It is also important for the instructor to look the student in the eyes

when giving a reinforcer - even if the student is not looking at him/her. Like enthusiasm, eye contact

suggests that a student is special and that the student has the instructor’s undivided attention. Over

time, eye contact may become reinforcement in and of itself.

Describe the Behavior: The younger the student or the more severely disabled, the more important

it is to describe the appropriate behavior that is being reinforced. Instructors often assume that

students know what it is they are doing right - that has resulted in the delivery of reinforcement.

However, this is often not the case. The student may not know why reinforcement is being delivered,

or think that it is being delivered for some behavior other than what the instructor intended to

reinforce. Even if the student does know what behavior is being reinforced, describing it is important.

Anticipation: Building excitement and anticipation for the earning of a reinforcer can motivate

students to do their very best. The more “hype” the teacher uses, the more excited students become

to earn the reinforcer. Presenting the potential reinforcer in a “mysterious” way will also build

anticipation.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 25 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Variety: Just like adults, students - and particularly Tough Kids - get tired of the same things. A

certain reinforcer may be highly desired, but after repeated exposure, it loses its effectiveness.

Variety is the spice of life for non-disabled and disabled alike. Generally, when teachers are asked

why they do not vary their reinforcers, they indicate that it worked very well once. It is necessary to

change reinforcer frequently to make the reinforcement more effective.

Variables That Affect Compliance

Giv

e commands in the form of statements not questions

o Watc

h out for statements asked as questions like: “Isn’t it time to do your work?” or “Wouldn’t

you like to start to work?” Instead, make the request a polite command, such as “Please start

your work now” or "Let's get started."

Give commands from close proximity

o Get close to the student when giving a command. The optimal distance for giving a command

is approximately three (3) feet.

Use a quiet voice, do not yell

o When giving a command, give it in a quiet voice, up-close - with eye contact.

Be non-emotional

o Be calm, not emotional. Yelling, threatening gestures, ugly faces, guilt inducing statements,

rough handling, and deprecating comments about the student or his/her family only reduce

compliance.

Look the student in the eyes

o Request eye contact when giving a student a command. For example, “John, please look me

in the eyes. Now, I want you to...”

Give the student time

o When giving a student a command, give them from 5 to 10 seconds to respond before (1)

giving the command again, or (2) giving a new command.

Watch out for “the Nag”

o Issue a command only twice - then follow through with a preplanned consequence. The more

you request, the less likely you are to gain compliance.

Watch out for multiple requests

o Make only one request at a time. Do not string requests together.

Describe the behavior you want

o It helps to give specific and well-described requests rather than global requests.

o Make more start requests than stop requests. Requests that start behaviors (i.e., “Do”

requests) are more desirable than requests that inhibit behaviors (i.e., “Don’t” requests).

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 26 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Verbal

ly reinforce compliance

o It is easy to forget and not socially reward a student when they comply with your request. If

you do not reward the student, compliance will decrease.

To Motivate and Encourage:

Tell

the students what you want them to do and make certain they understand

Tell them what will happen, if they do what you want them to do

When the student does what you want them to do, give them immediate positive feedback in ways

that are direct and meaningful to them.

Some Tools You Can Use:

Prec

ision commands

Group contingencies (limited use) and team play

Tokens

Time out (limited use)

Positive Reductive Techniques:

Differ

ential Attention: Ignore misbehavior; Pay attention to appropriate behavior

“Sure I Will” program

Direct instruction

Public posting

Contracts

Home note

Self-monitoring

Try these, too:

Antec

edent strategies

Natural positive reinforcement

Edible reinforcement

Social reinforcement

Mystery motivators

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 27 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Spider Webbing

Spider

webbing is a way of generating connections in order to solve problems. You can take a resource

and connect it with something else (i.e., transforming resources into ideas) – or you can explore possible

solutions by making connections. First, select a word and connect it to a problem. Then expand upon the

words/problems until you come to a solution. By making connections, you can arrive at a solution that is

fun and effective.

Example: A group is working on making very round turns. The instructor may choose a “trigger word”

such as “Circle”.

The instructor says, “See if you can ski and make a turn like a circle, just as though you were skiing

around a lady bug. Now, let’s make turns around a big, rolled up potato bug. How about some turns

around a huge juicy caterpillar?”

Following another branch of the spider web, the instructor may say, “What if we made “C” turns? Or “J”

turns? Or linked turns together like “S” shapes?”

For small children, the instructor may follow another branch of the web. Make turns around cones, and

then around “hula hoops” on the ground, and then around balls.

The Spider Web Logic:

CIRCLE > LADYBUG > POTATO BUG > CATERPILLAR

CIRCLE > “C” > “J” > “S”

CIRCLE > BALLS > HULA HOOPS > CONES

Begin with one “trigger” word and grow it. Sometimes the children will help the connections grow. Solving

problems through creativity adds a great deal of fun to the lesson.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 28 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

APPENDICES

APPENDIX 1 - Piaget’s Stages & Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Piag

et’s Stages

Senso

ri-motor Stage

The inf

ant uses their senses to find out about the world, relying on touching, seeing, tasting, etc.

The infant learns to differentiate herself from others and the environment

The Pre-Operational Stage

The begi

nning of this stage is marked by language use

The toddler differentiates between thought and action

Thought is egocentric: They can control nature, nature is alive, thinking is not reversible, thinking is

centered on one aspect of a situation at a time, following a series of instructions is difficult, concepts

of left and right are not understood, play relates to all aspects of development.

The Concrete Operations Stage

This

stage is defined by the ability to differentiate appearance from reality

Reasoning is justified in a logical manner:

o Identity

o Compensation

o Reversibility

Mental images are dynamic, because children can reverse actions and mentally manipulate objects:

o Able to see the world from more than one perspective

o Cooperation with others

o Understands the reasons for rules

o Can differentiate reality from fantasy

o Mental faculties are still developing

o Child begins to understand and relate speed, time and distance

o The child acts first and then deals with results

o The child sees adult rules as challenges to their cleverness

Competition and the Concrete Child:

o Children gain status from sports

o Athletics can create an artificial focus for the ego and can cause severe stress

o The child is in a critical period for absorbing cultural information, values and peer group

influence

o The child can understand another’s point of view and is interested in outcomes

o Competition should be carefully monitored and controlled

o Feelings on competence and success are essential to continued maximum growth toward

potential

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 29 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Resear

ch shows that rewards reduce enjoyment, decrease persistence on task, and may retard

moral development.

Instructing the Concrete Operational Child:

o Skiing safety is the priority

o Visualizations are appropriate

o Movement sequences can be performed when children can perform individual motor tasks

o The most common cause of lesson failure is too much information

o The children, the process, and participation are more important than the product

o The concept of right and left is still developing, colors can avoid confusion

o Cooperation is part of play

o Children should be encouraged to compete against their own performance and not against

others.

The Formal Operations Stage

The for

mal thinker can hypothesize and consider consequences and what “might be” rather than

being limited to what they have experienced

Use of higher reasoning (i.e., inductive and deductive)

Formal thought is potentially at the level of adult thought

Koh

lberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Level

1: Pre-Conventional Morality

Stage 1: Obedience orientation and punishment. “Good is good, and bad is bad”. Child decides what

is wrong based on what is punished.

Stage 2: Individualism and instrumental purpose. “Clever as a fox”. The child equates what is good

with what is rewarded and avoids punishment. If it feels good, it is good.

Level 2: Conventional morality

Stage 3:

Mutual interpersonal expectations, relationships, and interpersonal conformity. The family

becomes important and moral actions must live up to others’ expectations. Certain behaviors can

please people. At this stage, children begin to learn the value of respect, trust, gratitude, loyalty, and

the Golden Rule.

Stage 4: Social system and conscience (law and order). Young person’s focus shifts from family to

large social groups or institutions. Duty, law and contributing to society are seen as good.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 30 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Level

3: Post conventional morality (“Principled Morality”)

Stage 5:

Social contract or utility and individual rights. This stage recognizes: “Greatest good for the

greatest number,” the importance of each person’s life and liberty, and rule and law ensures fairness.

People in this stage can also see when rules or laws should be ignored or changed.

Stage 6: Universal Ethical Principles. The individual has developed and follows “self-chosen ethical

principles.” If there is a difference between law and conscience, conscience wins. Individuals at this

stage accept outright responsibility for their own actions; their morals are based on universal ethics. It

is estimated that less than 10-15% of the population progresses past stage 5.

Kohlberg proposed that not everyone progresses through all the six stages - nor are the stages specific to

certain ages. He does argue that each stage follows and grows from the previous one.

It can be extrapolated from the 1983 Colby and Kohlberg study that around age 15, about half (50%) of

teens progress to Level 2; Conventional morality around age 24, and 50% of individuals will move to

Stage 4 (Law and Order). At age 36, 35% of the study participants were at Stage 3, over 60% was at

Stage 4, and only 10% were at Stage 5 (Bee; The Developing Child, Harper and Row, 1989).

What becomes relevant to [children’s] instructors is the transition from Pre-Conventional Morality to

Conventional Morality; or the transition from “rules are just rules” to understanding the reasons for the

rules. The implications on teaching ‘Your Responsibility Code’ become thought provoking.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 31 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

APPENDIX 2 – Building Solid Movement Patterns With The Game Toolkit

(By

Grant Nakamura)

The Game Toolkit

The Gam

e Toolkit is a collection of techniques that we can use as instructors and coaches to build

movement patterns through play. We've all used games to invigorate our lessons. Our students

unconsciously learn very quickly when the learning environment is playful. Their attention span is

increased during fun and playful times. A child's avocation is playing and since learning is their vocation,

merging the two is a highly successful teaching method. The Toolkit provides a framework with which we

can design a blueprint and eventually develop a new game or exercise.

There are literally hundreds of games used by instructors all over the country. They have been shared

and modified for years. So why the Toolkit? Why the need to develop new games?

Games get old. You and/or your students get tired of playing them. There may be no game you know of

that works on a specific skill or movement pattern. Or worse, some games are just plain wrong! But the

most compelling reason: once you develop a game that works, you have the pride of knowing that it's

your game. Underlying the whole process is the Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA) Teaching

Model: the Toolbox that holds our tools. The Teaching Model gives us an overall framework for our

lessons. The Teaching Model is described as part of the American Teaching System (ATS) in the PSIA

Alpine Manual (1996):

Creativity Model

The pr

imer for your creativity is another tool: the Creativity Model. This tool in the Toolkit prepares your

creative side by providing a loose structure or framework that you can use to keep the creativity juices

flowing. Roger von Oech describes four facets or personalities of creativity in his book, “A Kick in the Seat

of the Pants”: Use your Explorer, Artist, Judge, and Warrior to be more creative. During the creative

process you will assume each of these personalities to build you game from the blueprint.

The Explorer

The Expl

orer is the mask you put on which encompasses your past and present experiences, your

curiosity, courage, and open-mindedness. It's the part of you that says, “We don't have to do things the

way we've always done it.” This isn't rocket science; it's just the willingness to look at things in a different

way. Hopefully, this is an ongoing process: a lifelong adventure into the unknown.

The Artist

The Ar

tist makes use of the information compiled during the Explorer's lifetime. The Artist is not

comfortable with familiarity and certainty doesn’t do things the same way every time. As an Artist, we

need tools or a palette to take the blueprint and all this other information and put it into a usable form.

CS Reference Guide

PSIA/AASI Intermountain - Page 32 of 36

Last Updated: November 2013

Von O

ech's Artist Palette:

o Adapt - What different contexts can you put your concept?

o Imagine - What unusual “what-if” questions can you make up involving your idea? How “far-out”

can you go?

o Reverse - Look at your concept backwards. How does it look upside down? Or inside out?

o Connect - What can you combine with your concept? What similarities does it share with [your

concept]?

o Eliminate - What rules can you break? What's obsolete? What's taboo? What's no longer

necessary?

o Parody - Make fun of your concept. How silly can you be? How outrageous? What jokes can you

think up involving your concept?