1

Cornel Stanciu, MD, CPE, MRO, FASAM, FAPA

Director of Addiction Services at New Hampshire Hospital

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

May 16, 2024

Understanding Kratom: Consumption

Patterns and Treatment Strategies for

Kratom Addiction

2

Housekeeping

• This event is brought to you by the Providers Clinical Support System

– Medications for Opioid Use Disorders (PCSS-MOUD). Content and

discussions during this event are prohibited from promoting or selling

products or services that serve professional or financial interests of

any kind.

• The overarching goal of PCSS-MOUD is to increase healthcare

professionals' knowledge, skills, and confidence in providing evidence-

based practices in the prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm

reduction of OUD.

3

AAAP is committed to presenting learners with unbiased, independent,

objective, and evidence-based education in accordance with accreditation

requirements and AAAP policies.

Presenter(s), planner(s), reviewer(s), and all others involved in the planning

or content development of this activity were required to disclose all

financial relationships within the past 24 months

All disclosures have been reviewed, and there are no relevant financial

relationships with ineligible companies to disclose.

All speakers have been advised that any recommendations involving clinical medicine must be based on evidence that is

accepted within the profession of medicine as adequate justification for their indications and contraindications in patient

care. All scientific research referred to, reported, or used in the presentation must conform to the generally accepted

standards of experimental design, data collection, and analysis.

Disclosure to Learners

4

Educational Objectives

• At the conclusion of this activity participants should be able to:

Understand Kratom’s literature, covering its uses, risks (overdose,

addiction), and product toxicities.

Evaluate Kratom’s role in harm reduction, distinguishing between

evidence-based practices and misconceptions.

Implement evidence-based treatments for Kratom addiction,

facilitating informed discussions and effective interventions with

patients.

5

INTRODUCTION

6

• Tropical evergreen

tree/shrub related to the

coffee plant.

• Native to Southeast Asia

• Indigenous to Thailand,

Indonesia, Malaysia and

Papua New Guinea.

• First formally described in

1839 by Dutch colonial

botanist Pieter Korthals.

The Plant - Mytragyna Speciosa Korth

7

• Used for centuries by the indigenous

population to enhance stamina and

combat physical ailments from hard

labor.

• Not regarded as “drug use”, but rather

as a way of life, embedded in

traditions and customs.

• Therapeutically also used for self-

managing pain, cough and diarrhea.

• Leaves are chewed, brewed as tea, or

to a lesser degree smoked, producing

a complex stimulant and opioid-like

effect.

Traditional Use

8

• In time it has also gained popularity as an

opioid substitute.

• Its potential for tolerance and

dependence has long been apparent.

• Reports of significant adverse effects or

mortality in Asia are not extensively

documented.

• A recent trend in the region is its use in

urban settings by young individuals as

part of polydrug concoctions for euphoric

effects.

Use in Southeast Asia

9

• Dry or crushed leaves;

concentrated extracts, powders,

capsules; tablets, liquids, and

gum/resin.

• Readily available at smoke shops

or through online vendors with no

quality control.

• Dramatic increase in importation

since 2016.

Use in the West

10

• Kratom is increasingly used by people who advocate for it as a plant-based

remedy to self-manage pain, mental health symptoms, and opioid withdrawal.

• Growth of Kratom use in the Western world also parallels increasing concerns

over adverse effects, abuse, and addictive potential.

• Adverse effects associated with Kratom products span multiple organ systems

including hepatic, renal, cardiac, endocrine, and neurological.

• Fatalities involving kratom are increasingly documented, however involve co-

ingestions, or polydrug combinations.

Use in the West

11

• The prevalence of Kratom

use in the United States is

not well defined, with

lifetime estimates ranging

from 0.9 to 6.1%

versus 2.9 to 12% in

Thailand.

Epidemiology

12

Epidemiology

• Association data supports a greater burden of mental health and

substance use disorders, especially opioids, among users.

• Lifetime nonmedical opioid use is also associated with a greater

likelihood of Kratom use.

• In SE Asia:

Tolerance occurs within 3 months, and some escalate use 4-10x

within the first few weeks.

55% of regular users become dependent, with some reports

suggesting a relapse rate of 78-83% at 3 months.

13

• Demographics:

Middle-aged (31-50 years of

age), white male.

Married, employed, and insured.

Some college education with an

income of over $35,000 / year.

Duration of use >1 year but < 5

years.

• Reasons for use

Self-manage chronic pain (68%),

anxiety, or depression (65%) and

as an opioid replacement.

40% of users endorse the use of

Kratom to reduce/stop opioid

use, with 74% claiming >6mo

success in abstinence.

41% disclosed use to healthcare

providers.

• Ratings of improvements show a

majority of consumers rate overall

health as “good”.

Survey of consumers

14

Distribution of Consumers

• Heavily concentrated in the South, followed by West and Midwest, and few in

the Northeast

15

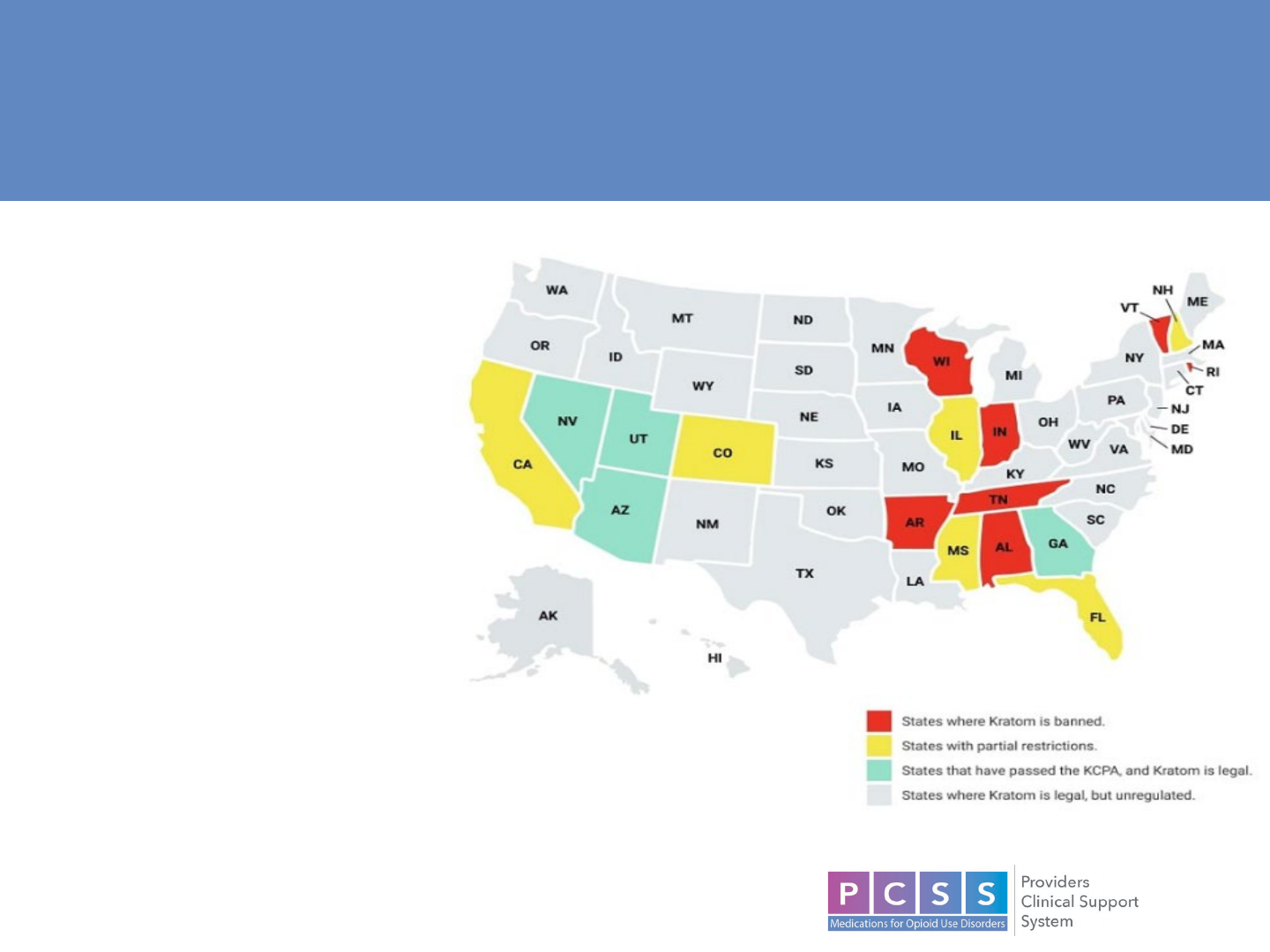

• Malaysia, Vietnam – illegal.

• Thailand – illegal until 2021.

• In the US it was legal to grow and

purchase in all states until 2015.

• Uncontrolled under federal

regulation.

• In 2016 the DEA submitted an

intent to schedule under the CSA,

but later that year withdrew.

• The Kratom Consumer Protection

Act exists in some states as

legislation to ensure consumer

access to Kratom with a framework

for regulatory oversight.

Legal Status and Regulation on Sales

16

PHARMACOLOGY

17

• The effects in humans have historically been described as dose-dependent:

Small doses (1-5g)

Stimulatory, caffeine-like, effects.

Larger dosages (>5g)

Sedative, analgesic effects.

Behavioral Pharmacology

18

• Leaf analysis

40 structurally related alkaloids,

flavonoids, terpenoid saponins,

polyphenols, and various glycosides.

• >25 indole alkaloids

− 1-2% by weight

Mitragynine (MG)

− ~60%

7-hydroxymitragynine (7OHMG)

− Extremely small representation of

plants

− Metabolic product of MG

(CYP3A4)

Complex Composition

19

• White vein – stimulating, to help with concentration.

• Green vein – improves mood, and depression.

• Red vein – calming effects, to help relax/sleep.

• Commercial products differ in composition.

“Potency”

20

Phase Model

21

Opioid Receptors

22

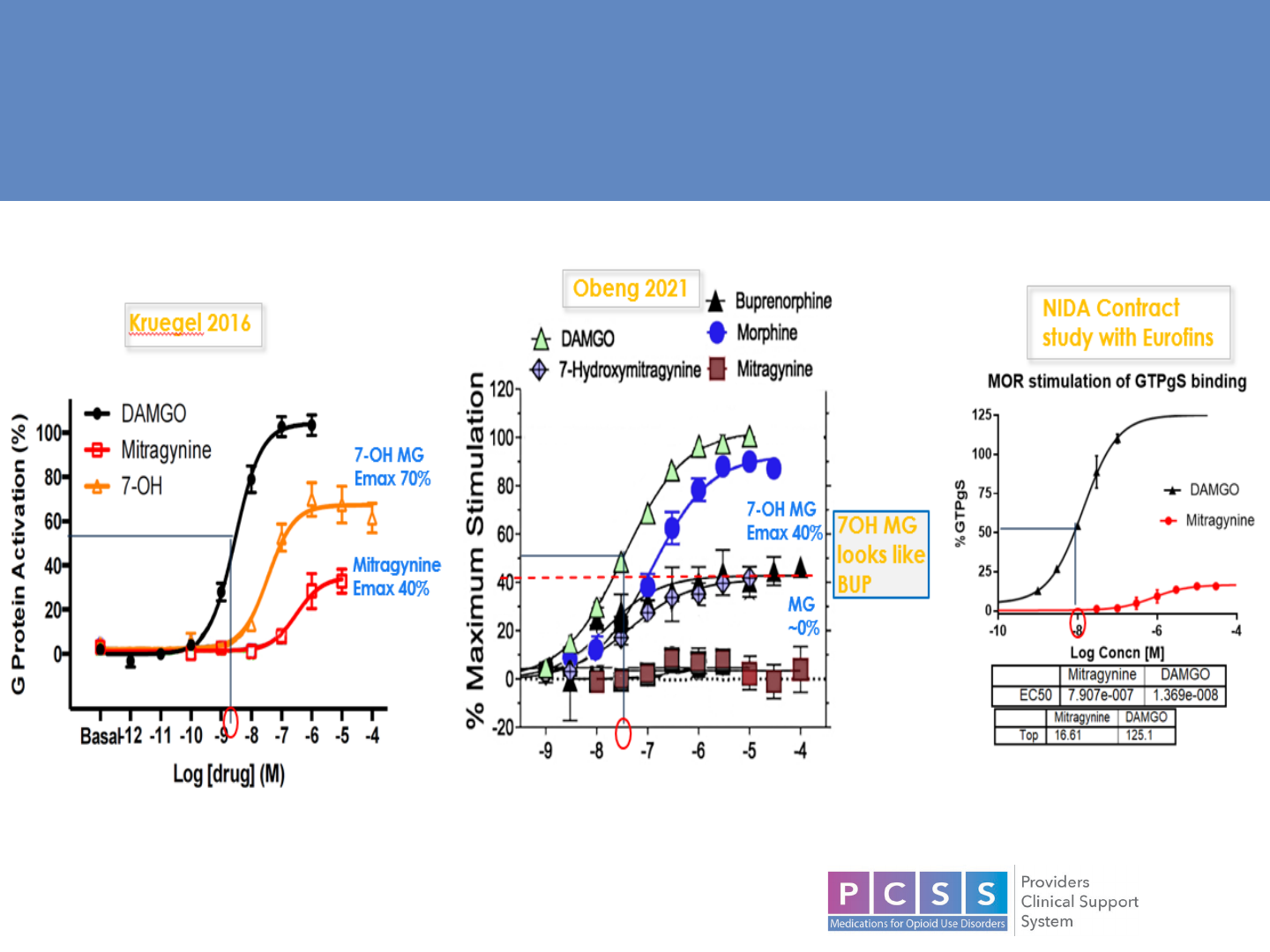

Opioid Receptor Efficacy

23

• Similarities to opioids:

Partial agonism at mu

receptors

Binding to opioid Rs initiates G-

protein-coupled receptor

(GPCR) signaling.

• Differences from opioids:

GPCR activation by indole

alkaloids does not initiate the β

-

arrestin pathway

− “biased agonism”

• MG also exerts non-opioid

receptor pain-relieving effects by

stimulating alpha-2 and inhibiting

cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA and

protein expression.

Atypical Interactions with Opioid Receptors

24

Other Receptor Systems

25

• MG relieves neuropathic

pain.

Relief blocked by both

opioid and adrenergic

blockers.

MG

YOH = Yohimbine

26

ADVERSE EFFECTS

27

• Ascending doses of Kratom alkaloids result in an increase in:

− Blood pressure

− Liver function tests

− Creatinine

− Death preceded by convulsions, not respiratory depression

• Herb: drug interactions:

MG inhibits CYP 2C9, 2D6, 3A4 as well as glucuronidation by UDP-

glucuronosyltransferases.

• Labilities:

MG less reinforcing than morphine and may be tolerance-sparing when

co-administered.

7OHMG substitutes for morphine, re-institutes conditioned place

preference (CPP, measure of rewarding effects in animal models).

Animal Studies

28

Human Case Reports

• After > 1 year of regular use:

Weight loss; Insomnia; Constipation; Skin hyperpigmentation; Extreme fatigue.

29

• Kratom overdoses resemble adrenergic toxicity more so than opioids:

Nausea and tachycardia predominate.

Respiratory depression is rare.

Clinical effects

Total

n (%

a

)

Clinical effects

Total

n (%

a

)

Single-substance exposure total 1174

Neurological

Gastrointestinal

Agitated/irritable 269 (22.9) Nausea 171 (14.6)

Drowsiness/lethargy 168 (14.3) Vomiting 155 (13.2)

Confusion 125 (10.6) Abdominal pain 76 (6.5)

Seizures (single/multiple) 113 (9.6)

Respiratory

Tremor 79 (6.7) Respiratory depression 42 (3.6)

Dizziness/vertigo 62 (5.3)

Hematologic/hepatic

Hallucinations/delusions 61 (5.2) AST, ALT > 100 59 (5.0)

Cardiovascular

Tachycardia 251 (21.4)

Hypertension 119 (10.1)

Poison Control Centers

30

Kratom-Related Deaths

• Co-ingestions and other active use disorders predispose patients to death

(found in 87% of cases).

• It is challenging to identify which deaths are attributed to kratom alone.

Stanciu, C.N., et al. (2023). "Kratom Overdose Risk:

A Review." Curr Addict Rep, 10(1), 9–28. DOI:

10.1007/s40429-022-00464-1

31

MANAGEMENT

32

• ~41% of Kratom consumers disclose consumption to healthcare providers.

In assessments, use non-judgmental, non-stigmatizing, questions

− “Do you use any herbal medicines, like valerian root or kratom?”

• Not detected by routine toxicology or conventional confirmatory drug

screening tests.

• HPLC or Mass spectrometry is required for detection & identification.

Detection

33

• Toxicity -- supportive management in most cases.

Acute hepatitis -- N-acetylcysteine (as in any other drug-induced hepatitis).

Seizures or neurological symptoms -- anti-epileptics.

Kidney injury, cardiovascular events, or other emergency presentations

addressed with appropriate measures.

• Overdose

Kratom-only overdoses resemble stimulant overdoses (cardiovascular,

seizure).

− Poison Control Center reports show low levels of meiosis, sedation, and

respiratory depression.

Co-ingestions are common

− Reports describe mixed outcomes with reversal agents (naloxone); no

clinical trials exist.

Toxicity

34

• Mimics opioid withdrawal, but milder:

Withdrawal intensity positivity correlated to:

− Daily amount consumed.

− Duration and frequency of use.

Starts ~12-24 hours from last use, can last

up to 4 days

− Symptomatic management of a

hyperadrenergic state (i.e.. Clonidine).

− Good response to opioid receptor agonists

(Methadone), or partial agonists

(Buprenorphine).

Cravings and relapse risk is high.

Withdrawal

35

“Kratom Use Disorder”

• ~25.5% of consumers, however mild-mod severity (tolerance, withdrawal) and

no functional impact.

• Vulnerability factors: male, young, consuming Kratom frequently, and having

psychiatric and substance use disorders.

36

• Our team’s efforts to establish a “standard of care”.

• Since 2021 several reports emerged.

Mixed evidence of amount used, and Buprenorphine dose needed.

• Those requiring MOUD for maintenance could represent a small

group.

Maintenance Treatment

37

CASES

38

Case 1 - Andrew

• 33yo Caucasian male h/o anxiety, depression (on Escitalopram 20mg and

Propranolol 10mg BID), OUD in sustained remission x 12 y

• Started 2.5y ago, initially 2 caps per dose, progressively increased to 8 caps

within a few weeks to manage various mood states.

• Distinct effects from kratom vs. Percocet: increased energy, uplifted mood, and

motivation.

• Diminishing effects over time, he continued to consume 12-15 caps daily,

transitioning to powdered kratom washed with water 1.5 y ago.

• Significant lifestyle disruptions in the last year, including marital strain, work

interference, and financial burden.

• Struggled with increasing intervals between doses, experiencing withdrawal

symptoms (cold sweats, "brain zaps", and cravings after 6-7 hr. abstinence).

• Detox and eventually transitioning to naltrexone using SOWS alongside

clonidine, loperamide and gabapentin failed - could not abstain for >12 hr.

• Successfully transitioned to buprenorphine - 2mg daily with an additional 2mg

dose as needed in the evening for craving management.

39

Case 2 - Fred

• 37yo Caucasian male h/o OUD in sustained remission admitted to inpatient

psych due to depression, SI.

• General workup was unremarkable (EKG, labs, vs); Urine tox + THC.

• Disclosed a 6-mo h/o Kratom use, escalating to 11 capsules daily (3 in AM, 3

mid-day, 5 in PM), supplemented with an unknown quantity powder in water.

• Introduced to it as an antidepressant and had initially started with 1 cap in the

morning however within days he increased his dosage to 3 caps to combat

decreased effectiveness and maintain energy levels.

• Constipation is the only side effect, recent attempts to quit after learning about

reports on the Internet of various adverse effects were hindered by cravings and

"rebound depression.”

• Last use 24hr prior to admission and he experienced progressively worsening

nausea and flu-like symptoms which were first noticed 6 hours ago.

• COWS = 11, Methadone 5mg x1 administered, COWS = 2.

• Next day COWS remained 2, Clonidine 0.1mg x1 for anxiety, (HR 87 and BP

142/95).

• Aripiprazole 5mg (past response), fifth day he underwent a naltrexone challenge

and received a monthly long-acting injectable.

40

Case 3 - Mark

• 43yo Caucasian male h/o anxiety, chronic pain, ADHD

• Anxiety is generalized with occasional panic attacks, has a therapist

• Past injuries, and back pain necessitating spinal fusion.

• Self-medicating for pain with kratom (~5 g of powder daily) for >5 years.

• Improves pain allowing him to be mobile without the use of any pharmacotherapies –

which his orthopedic surgeon has discussed in the past.

• In addition to the pain benefit he also has noticed that kratom ingestion also tends to

“bring the temperature down” on his anxiety.

• No adverse effects and his dose and frequency have remained the same as when

he initiated.

• Has had stretches of up to 1wk of no kratom and never experienced withdrawal, or

cravings despite pain exacerbation.

• Trintellix 20mg and Vyvanse 30mg

• Organic evaluation unremarkable (CMP, CBC, TSH), MG level 133 ng/mL was

quantified.

*psychoeducation, motivational enhancement ongoing

41

• The exact prevalence of kratom use is unknown, however clinicians

are encountering more and more consumers.

• Despite consumers claiming benefits/harm reduction, it is possible for

some to meet DSM criteria for a “use disorder” diagnosis.

• Kratom is a complex botanical, and its alkaloids interact with many

receptor systems - including opioids.

• There is a spectrum of adrenergic and opiodendric involvement

impacting each user, and withdrawal, and maintenance treatment

requires individualized treatment.

Summary

42

References

• Abuse, N. I. on D. (--). What are the long-term effects of methamphetamine misuse? National Institute on Drug Abuse.

https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/methamphetamine/what-are-long-term-effects-methamphetamine-misuse

• Akindipe, T., Wilson, D., & Stein, D. J. (2014). Psychiatric disorders in individuals with methamphetamine dependence: Prevalence and

risk factors. Metabolic Brain Disease, 29(2), 351–357.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-014-9496-5

• Chan, B., Freeman, M., Kondo, K., Ayers, C., Montgomery, J., Paynter, R., & Kansagara, D. (2019). Pharmacotherapy for

methamphetamine/amphetamine use disorder—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 114(12), 2122–2136.

https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14755

• Coffin, P. O., Santos, G.-M., Hern, J., Vittinghoff, E., Santos, D., Matheson, T., Colfax, G., & Batki, S. L. (2018). Extended-release

naltrexone for methamphetamine dependence among men who have sex with men: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction,

113(2), 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13950

• Colfax, G. N., Santos, G.-M., Das, M., Santos, D. M., Matheson, T., Gasper, J., Shoptaw, S., & Vittinghoff, E. (2011). Mirtazapine to

Reduce Methamphetamine Use: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(11), 1168–1175.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.124

• Elkashef, A., Kahn, R., Yu, E., Iturriaga, E., Li, S.-H., Anderson, A., Chiang, N., Ait-Daoud, N., Weiss, D., McSherry, F., Serpi, T.,

Rawson, R., Hrymoc, M., Weis, D., McCann, M., Pham, T., Stock, C., Dickinson, R., Campbell, J., … Johnson, B. A. (2012). Topiramate

for the treatment of methamphetamine addiction: A multi-center placebo-controlled trial: Topiramate for methamphetamine addiction.

Addiction, 107(7), 1297–1306.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03771.x

• Heinzerling, K. G., Swanson, A.-N., Hall, T. M., Yi, Y., Wu, Y., & Shoptaw, S. J. (2014). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of

bupropion in methamphetamine-dependent participants with less than daily methamphetamine use: Bupropion for methamphetamine

dependence. Addiction, 109(11), 1878–1886. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12636

• Jayaram-Lindström, N., Hammarberg, A., Beck, O., & Franck, J. (2008). Naltrexone for the Treatment of Amphetamine Dependence: A

Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(11), 1442–1448.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020304

• Kish, S. J. (2008). Pharmacologic mechanisms of crystal meth. CMAJ, 178(13), 1679–1682. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071675

• Konstenius, M., Jayaram-Lindström, N., Guterstam, J., Beck, O., Philips, B., & Franck, J. (2014). Methylphenidate for attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder and drug relapse in criminal offenders with substance dependence: A 24-week randomized placebo-controlled

trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 109(3), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12369

43

References

• Logan, B. K. (2002). Methamphetamine—Effects on Human Performance and Behavior. 19.

• Logan—2002—Methamphetamine—Effects on Human Performance and.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2021, from

http://www.biblioteca.cij.gob.mx/Archivos/Materiales_de_consulta/Drogas_de_Abuso/Articulos/methamphetamine.pdf

• Longo, M., Wickes, W., Smout, M., Harrison, S., Cahill, S., & White, J. M. (2010). Randomized controlled trial of dexamphetamine maintenance for

the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction, 105(1), 146–154.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02717.x

• Matsumoto, T., Kamijo, A., Miyakawa, T., Endo, K., Yabana, T., Kishimoto, H., Okudaira, K., Iseki, E., Sakai, T., & Kosaka, K. (2002).

Methamphetamine in Japan: The consequences of methamphetamine abuse as a function of route of administration. Addiction, 97(7), 809–817.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00143.x

• Methamphetamine Psychosis: Epidemiology and Management—ProQuest. (n.d.-a). Retrieved November 7, 2021, from

https://www.proquest.com/docview/1641841832/fulltext/C1BC91A83BD045E1PQ/1?accountid=10422

• Methamphetamine Psychosis: Epidemiology and Management—ProQuest. (n.d.-b). Retrieved November 7, 2021, from

https://www.proquest.com/docview/1641841832/fulltext/C1BC91A83BD045E1PQ/1?accountid=10422

• Meyers, R. J., Roozen, H. G., & Smith, J. E. (2011). The Community Reinforcement Approach. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(4), 380–388.

• Miller, S. (2019). The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine (6th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

• NIDA. 2021, April 13. What are the long-term effects of methamphetamine misuse?. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.go. (n.d.).

• Signs Someone is Using Methamphetamine—How to Tell | The Recovery Village. (n.d.). The Recovery Village Drug and Alcohol Rehab. Retrieved

November 21, 2021, from

https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/meth-addiction/faq/know-someone-crystal-meth/

• Snapshot. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2021, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/methamphetamine/what-are-long-

term-effects-methamphetamine-misuse

• The pattern of tissue loss in methamphetamine users whose brains were mapped by MRI scans. (n.d.). UCLA. Retrieved November 21, 2021,

from https://newsroom.ucla.edu/file?fid=52e6ed77f6091d799c00001e

• Thompson, P. M. (2004). Structural Abnormalities in the Brains of Human Subjects Who Use Methamphetamine. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(26),

6028–6036.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0713-04.2004

• Thompson—2004—Structural Abnormalities in the Brains of Human Su.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2021, from

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/24/26/6028.full.pdf

• Trivedi, M. H., Walker, R., Ling, W., dela Cruz, A., Sharma, G., Carmody, T., Ghitza, U. E., Wahle, A., Kim, M., Shores-Wilson, K., Sparenborg, S.,

Coffin, P., Schmitz, J., Wiest, K., Bart, G., Sonne, S. C., Wakhlu, S., Rush, A. J., Nunes, E. V., & Shoptaw, S. (2021). Bupropion and Naltrexone in

Methamphetamine Use Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(2), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2020214

44

PCSS-MOUD Mentoring Program

• PCSS-MOUD Mentor Program is designed to offer general information to

clinicians about evidence-based clinical practices in prescribing

medications for opioid use disorder.

• PCSS-MOUD Mentors are a national network of providers with expertise in

addictions, pain, and evidence-based treatment including

medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).

• 3-tiered approach allows every mentor/mentee relationship to be unique

and catered to the specific needs of the mentee.

• No cost.

For more information visit:

https://pcssNOW.org/mentoring/

46

PCSS-MOUD is a collaborative effort led by the

American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP) in partnership with:

_________________________________________

Addiction Policy Forum American College of Medical Toxicology

Addiction Technology Transfer Center* American Dental Association

African American Behavioral Health Center of Excellence American Medical Association*

American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry* American Orthopedic Association

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry American Osteopathic Academy of Addiction Medicine*

American Academy of Family Physicians American Pharmacists Association*

American Academy of Neurology American Psychiatric Association*

American Academy of Pain Medicine American Psychiatric Nurses Association*

American Academy of Pediatrics* American Society for Pain Management Nursing

American Association for the Treatment of Opioid

Dependence

American Society of Addiction Medicine*

American Association of Nurse Practitioners Association for Multidisciplinary Education and

Research in Substance Use and Addiction*

American Chronic Pain Association Coalition of Physician Education

American College of Emergency Physicians* College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists

Black Faces Black Voices

47

PCSS-MOUD is a collaborative effort led by the

American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP) in partnership with:

Columbia University, Department of Psychiatry*

Partnership for Drug-Free Kids

Council on Social Work Education* Physician Assistant Education Association

Faces and Voices of Recovery Project Lazarus

Medscape Public Health Foundation (TRAIN Learning Network)

NAADAC Association for Addiction Professionals* Sickle Cell Adult Provider Network

National Alliance for HIV Education and Workforce

Development

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine*

National Association of Community Health Centers Society of General Internal Medicine

National Association of Drug Court Professionals Society of Teachers of Family Medicine

National Association of Social Workers* The National Judicial College

National Council for Mental Wellbeing* Veterans Health Administration

National Council of State Boards of Nursing Voices Project

National Institute of Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network World Psychiatric Association

Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board Young People In Recovery

_________________________________________

48

Educate. Train. Mentor

www.pcssNOW.org

pcss@aaap.org

@PCSSProjects

www.facebook.com/pcssprojects/

Funding for this initiative was made possible by cooperative agreement no. 1H 79TI086770 from SAMHSA. The views expressed in written conference materials or

publications and by speakers and moderators do no t necessarily reflect the o fficial policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade

names, co mmercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.