DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Intenonally le blank.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Analytica

POB 998 352-339-6090 Voice

Newberry, FL 32669 888-287-3959 Fax

Herb@analyca-group.com www.analyca-group.com

February 5, 2020

Mr. Glen Salyer

Assistant County Manager

Lee County, Florida

Dear Glen:

Enclosed are the ndings of the Gap Analysis of Human Services in Lee County. Per your

direcon, this report is intended to be of value to the community focusing on a range of

services, not solely on the responsibilies of the Lee Board of County Commissioners (BoCC).

Consistent with that direcon, these ndings incorporate the perspecves of many human

service providers in the County. There has been a high level of parcipaon through various

means by people too numerous to thank personally. They have demonstrated in this study

what I believe to be one of the strengths of the County’s human services community a high

level of cooperaon focused on their clients’ and the community’s best interests.

This study was only possible in this meframe with the extensive support provided by County

sta. Please contact me if you have quesons or comments. It was a pleasure to work with

you on this project.

Cordially,

Herbert A. Marlowe, Jr., Ph.D.

Principal

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Intenonally le blank.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

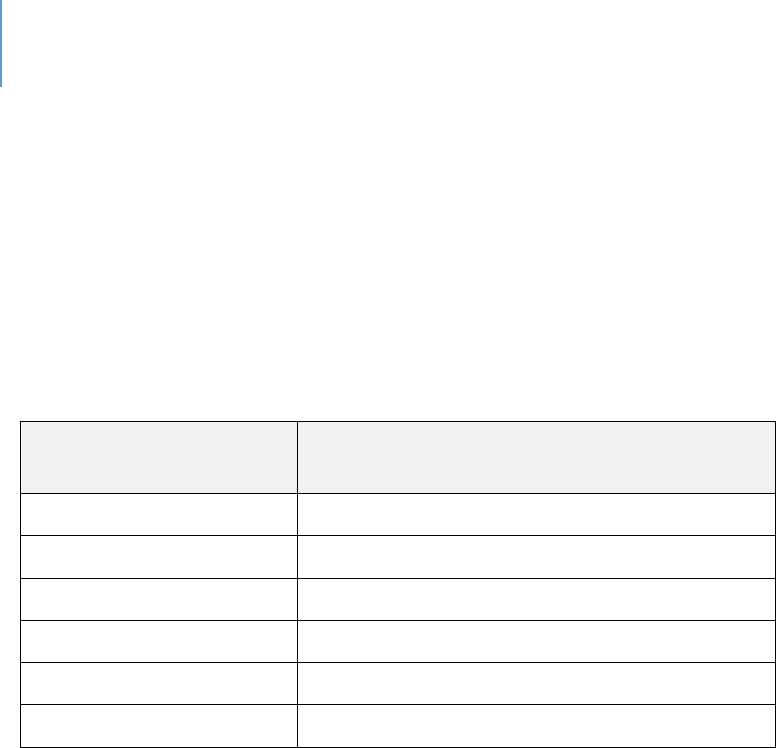

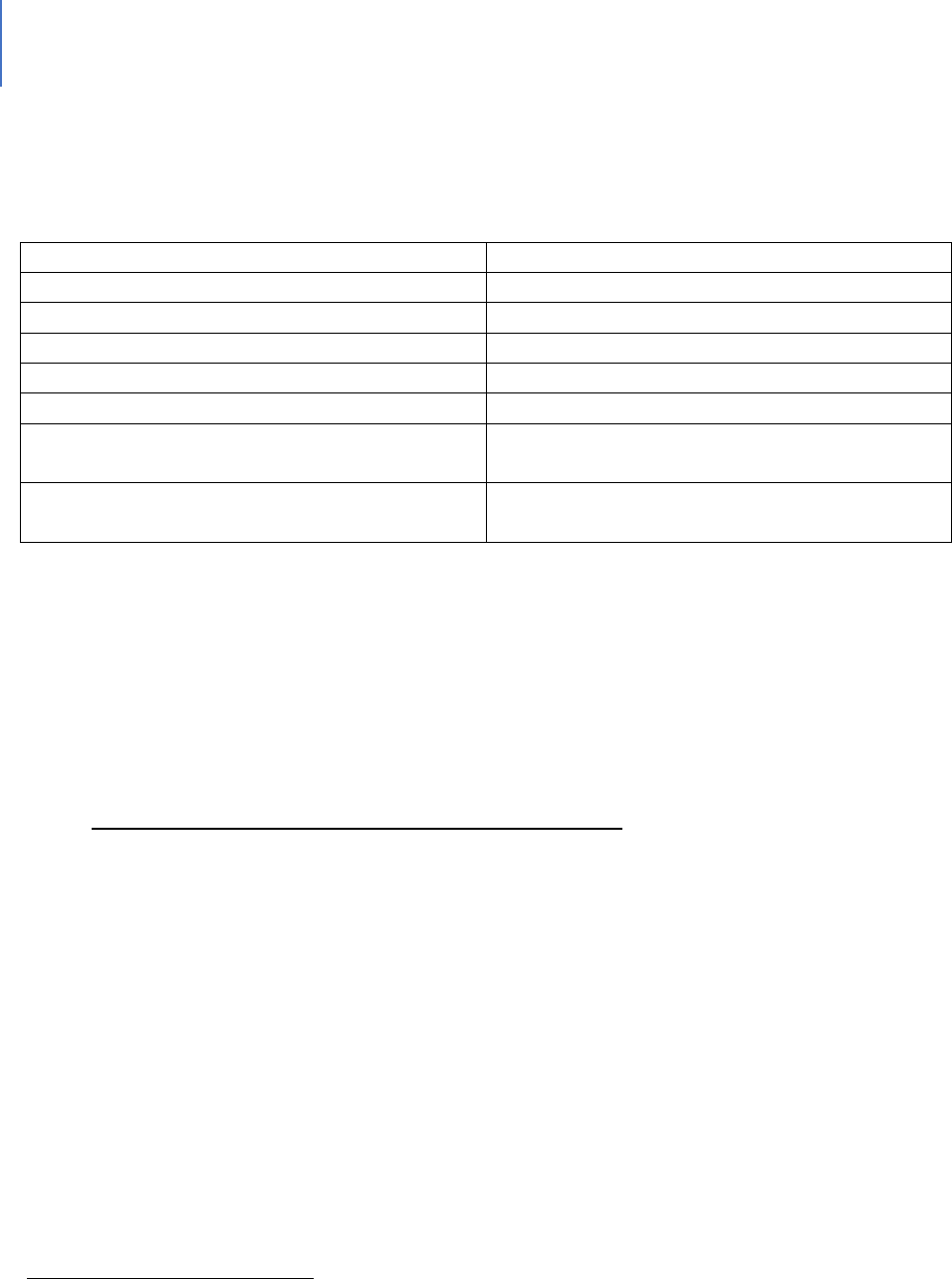

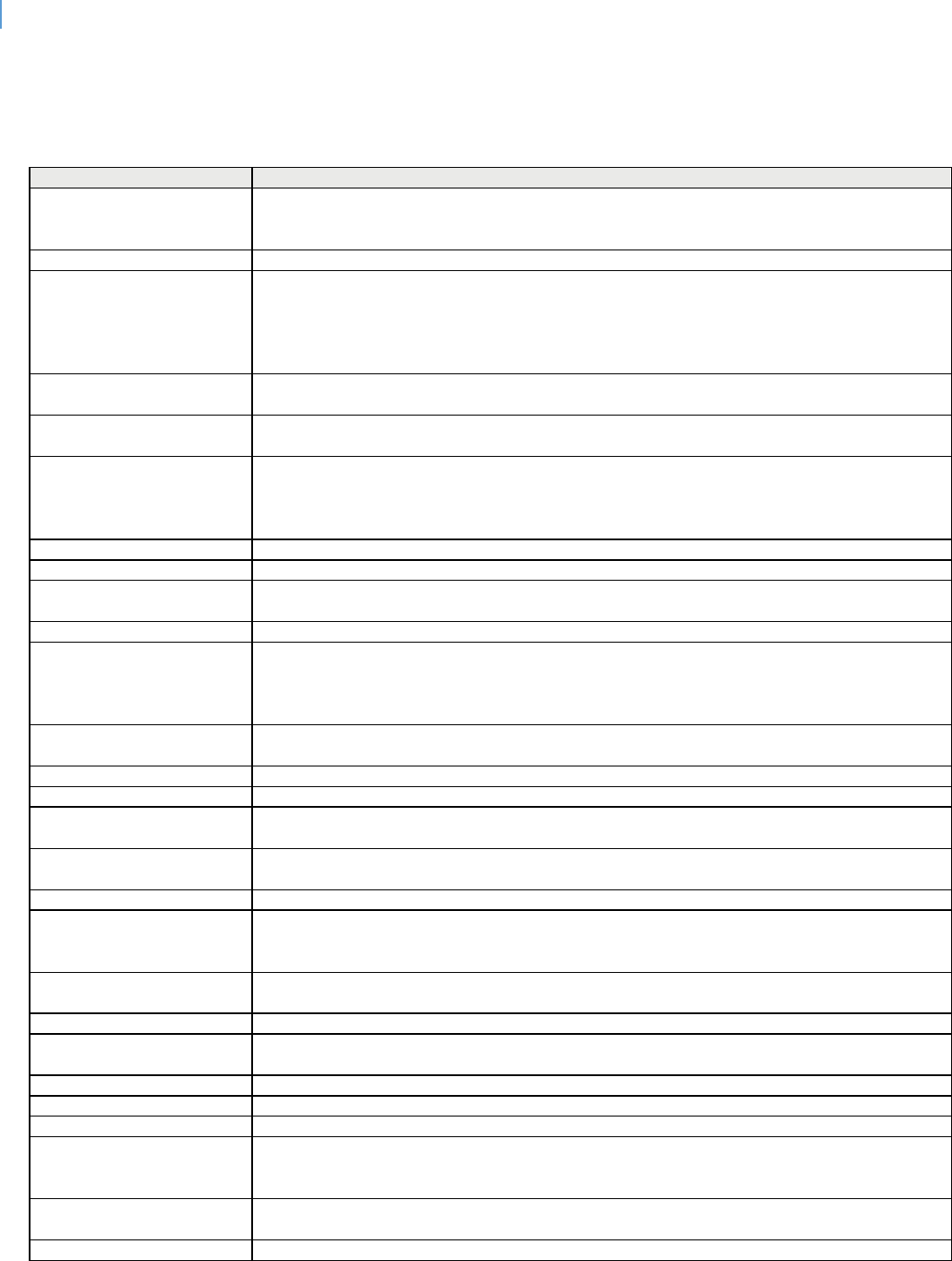

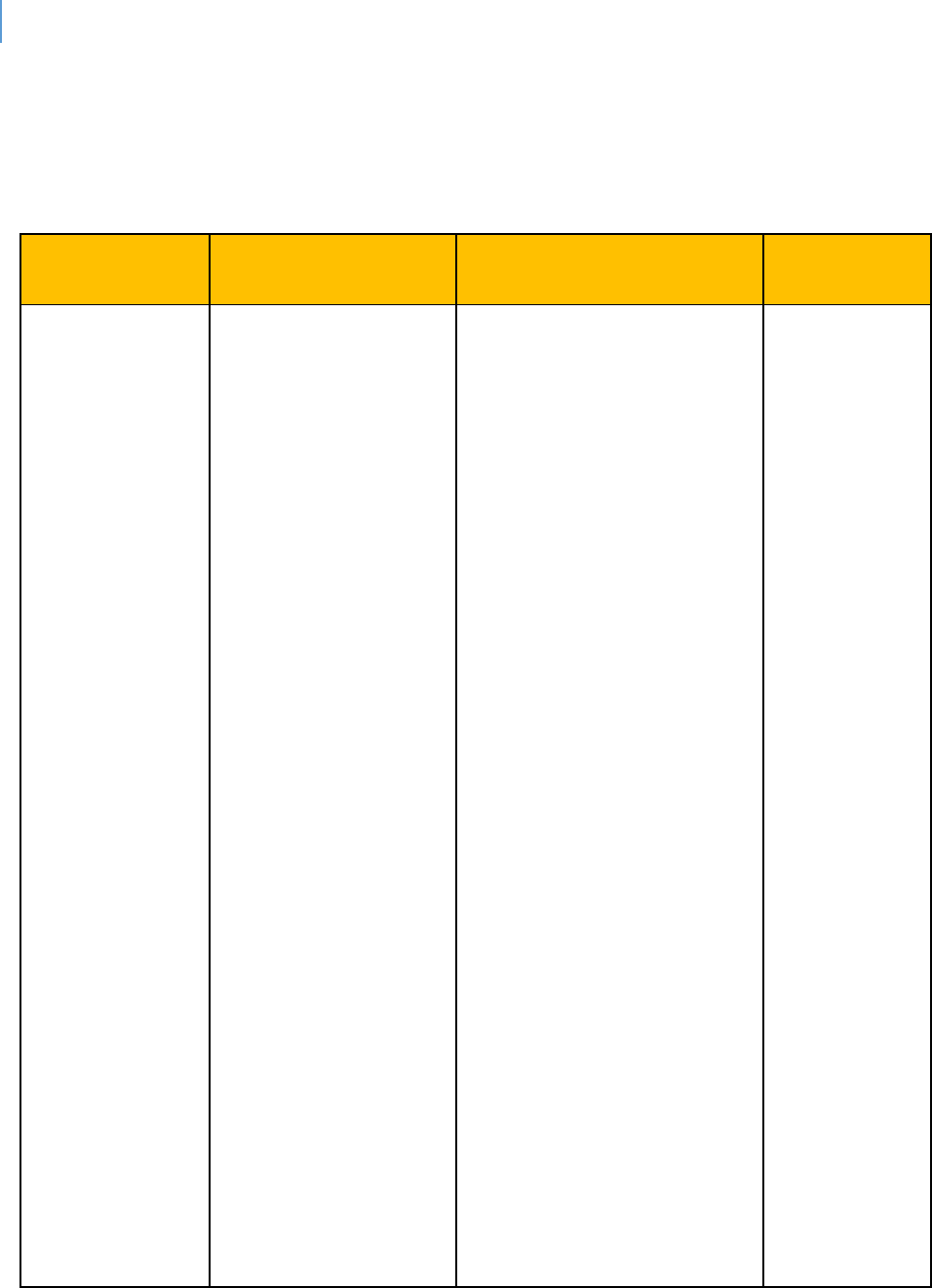

Table of Contents

Transmial Leer

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 1 - Introducon ................................................................................................................ 9

SECTION ONE: QUANTITATIVE DATA ............................................................................................ 15

Chapter 2 - Lee County Descripon and Demographics ............................................................. 17

Chapter 3 - Behavioral Outcomes ................................................................................................ 31

Chapter 4 - Comparison of Recent Community Surveys ............................................................. 79

SECTION TWO: INFRASTRUCTURE ............................................................................................... 89

Chapter 5 - Housing ..................................................................................................................... 91

Chapter 6 - Transportaon ........................................................................................................ 105

Chapter 7 - Food Security and Nutrion ................................................................................... 111

Chapter 8 - Employment ........................................................................................................... 131

Chapter 9 - Stang .................................................................................................................... 135

Chapter 10 - County Facilies .................................................................................................... 153

Chapter 11 - Organizaonal Capacity ........................................................................................ 155

Chapter 12 - Informaon Technology ........................................................................................ 161

SECTION THREE: DEVELOPMENT - THE FOUNDATION .............................................................. 165

Chapter 13 - Children and Youth Development ........................................................................ 167

SECTION FOUR: SYSTEMS OF CARE ........................................................................................... 197

Chapter 14 - Behavioral Health ................................................................................................. 199

Chapter 15 - Criminal Jusce and Behavioral Health ................................................................ 217

Chapter 16 - Child Abuse and Neglect, Foster Care and Adopon ........................................... 241

Chapter 17 - Domesc Violence ................................................................................................ 255

Chapter 18 - Elder Abuse, Neglect and Exploitaon ................................................................. 259

Chapter 19 - Sexual Violence and Stalking ................................................................................ 269

Chapter 20 - Trauma and Eects of Violence Exposure ............................................................ 277

Chapter 21 - Suicide and Self-harm ........................................................................................... 289

Chapter 22 - Juveniles ............................................................................................................... 297

Chapter 23 - Homelessness ....................................................................................................... 307

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

SECTION FIVE: SPECIAL POPULATIONS ...................................................................................... 325

Chapter 24 - Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilies ................................... 327

Chapter 25 - Deafness and Blindness: Birth or Early Childhood Development......................... 353

Chapter 26 - Persons with other Physical Disabilies ............................................................... 361

Chapter 27 - Seniors .................................................................................................................. 373

Chapter 28 - Veterans ................................................................................................................ 385

SECTION SIX: GEOGRAPHY......................................................................................................... 391

Chapter 29 - Spaal Match Analysis .......................................................................................... 393

SECTION SEVEN: FUNDING ........................................................................................................ 397

Chapter 30 - Funding Responsibilies ....................................................................................... 399

Chapter 31 - Equity Funding ...................................................................................................... 403

Chapter 32 - County Funding ..................................................................................................... 405

SECTION EIGHT: CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................. 413

Chapter 33 - Core Drivers .......................................................................................................... 415

Chapter 34 - Board of County Commissioners - Specic Issues ................................................ 445

Chapter 35 - Conclusions ........................................................................................................... 449

APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................... 457

Appendix A - Human Services Gap Survey ................................................................................ 459

Appendix B - Comprehensive Health Needs Assessment ......................................................... 467

Appendix C - Needs Assessment for CSBG Work Plan ............................................................... 467

Appendix D - 2019 - 2023 Consolidated Plan HUD.................................................................... 467

Appendix E - Connuum of Care Plan ....................................................................................... 467

Appendix F - Impediments to Fair Housing Choice ................................................................... 467

Appendix G - Lee County Parks and Recreaon CIP .................................................................. 469

Appendix H - Lee Count Library CIP ........................................................................................... 473

Appendix I - Child Well-Being Index Summary .......................................................................... 475

Appendix J - Calculang Household Income ............................................................................. 491

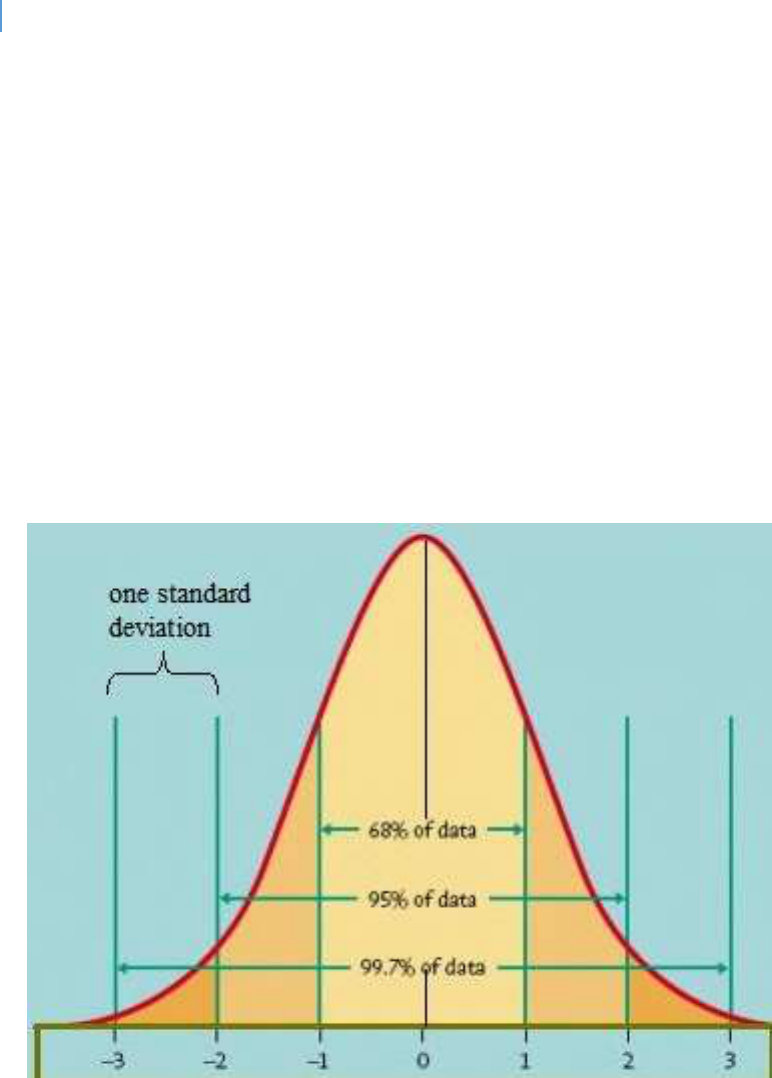

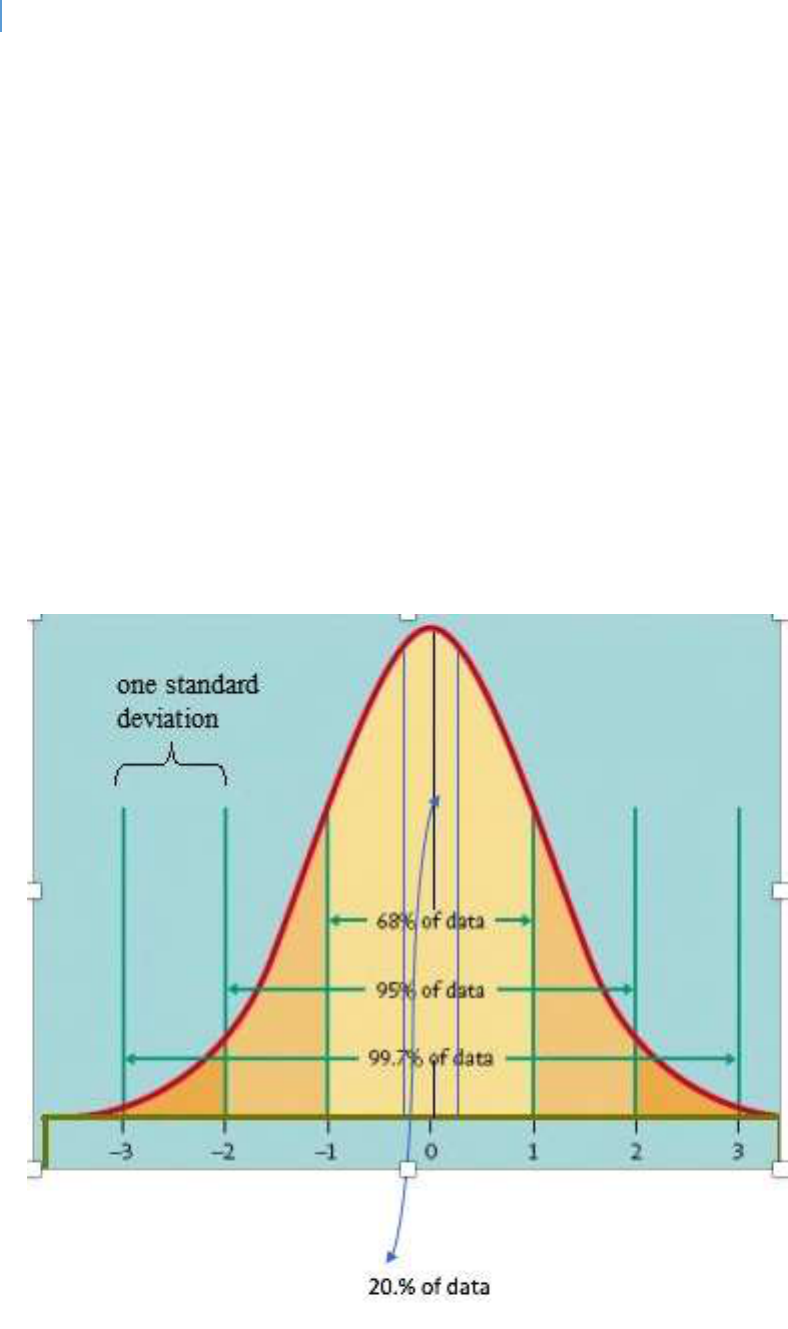

Appendix K - The Bell Curve and Smoothing Data .................................................................... 495

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

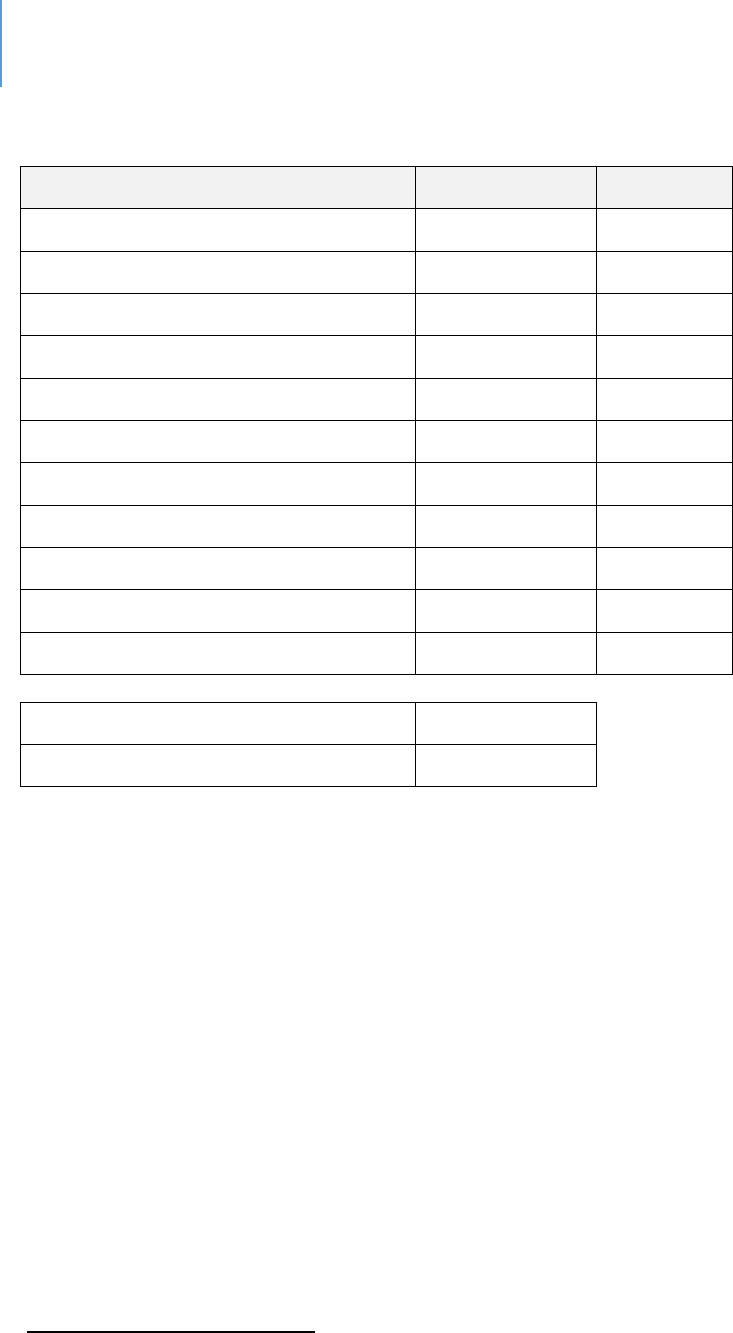

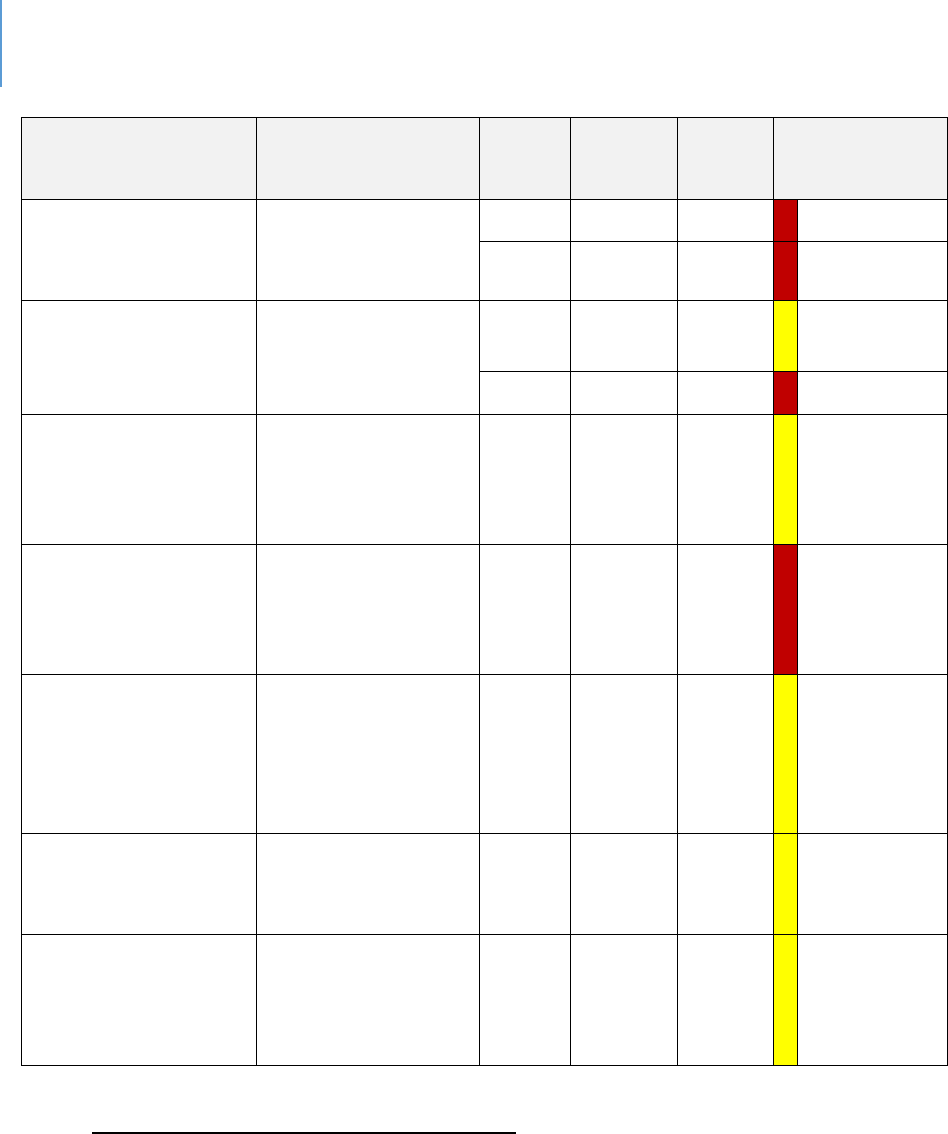

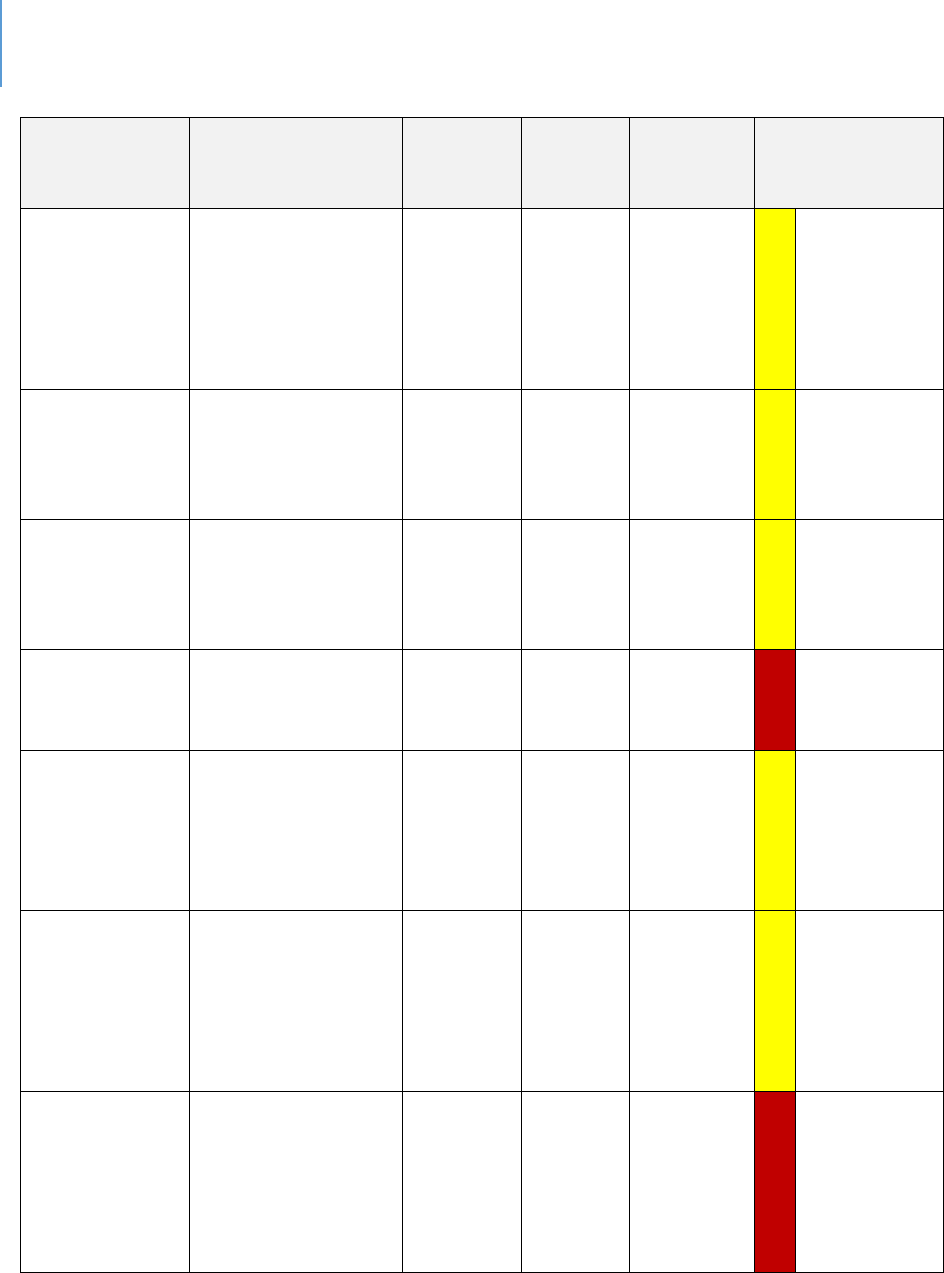

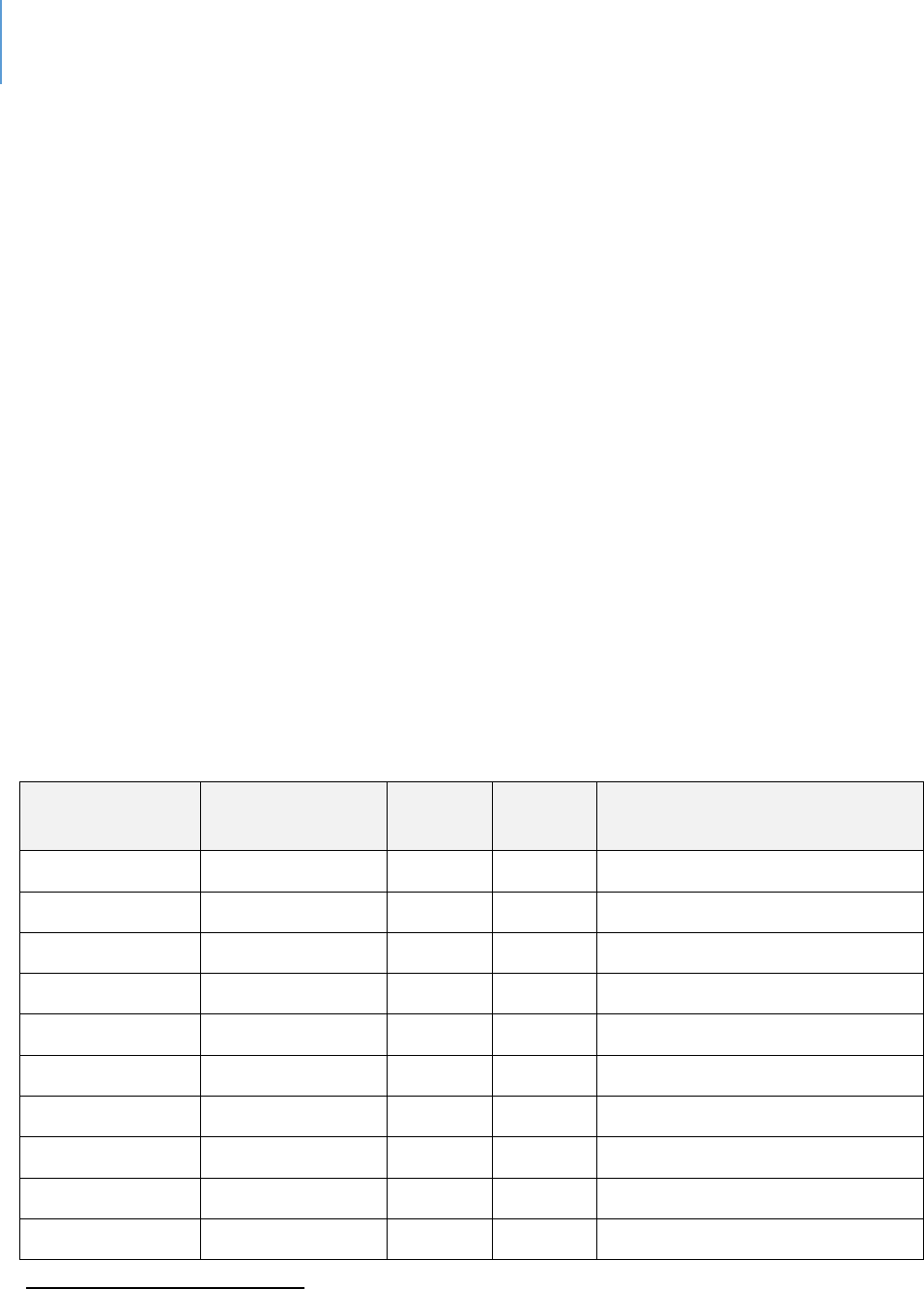

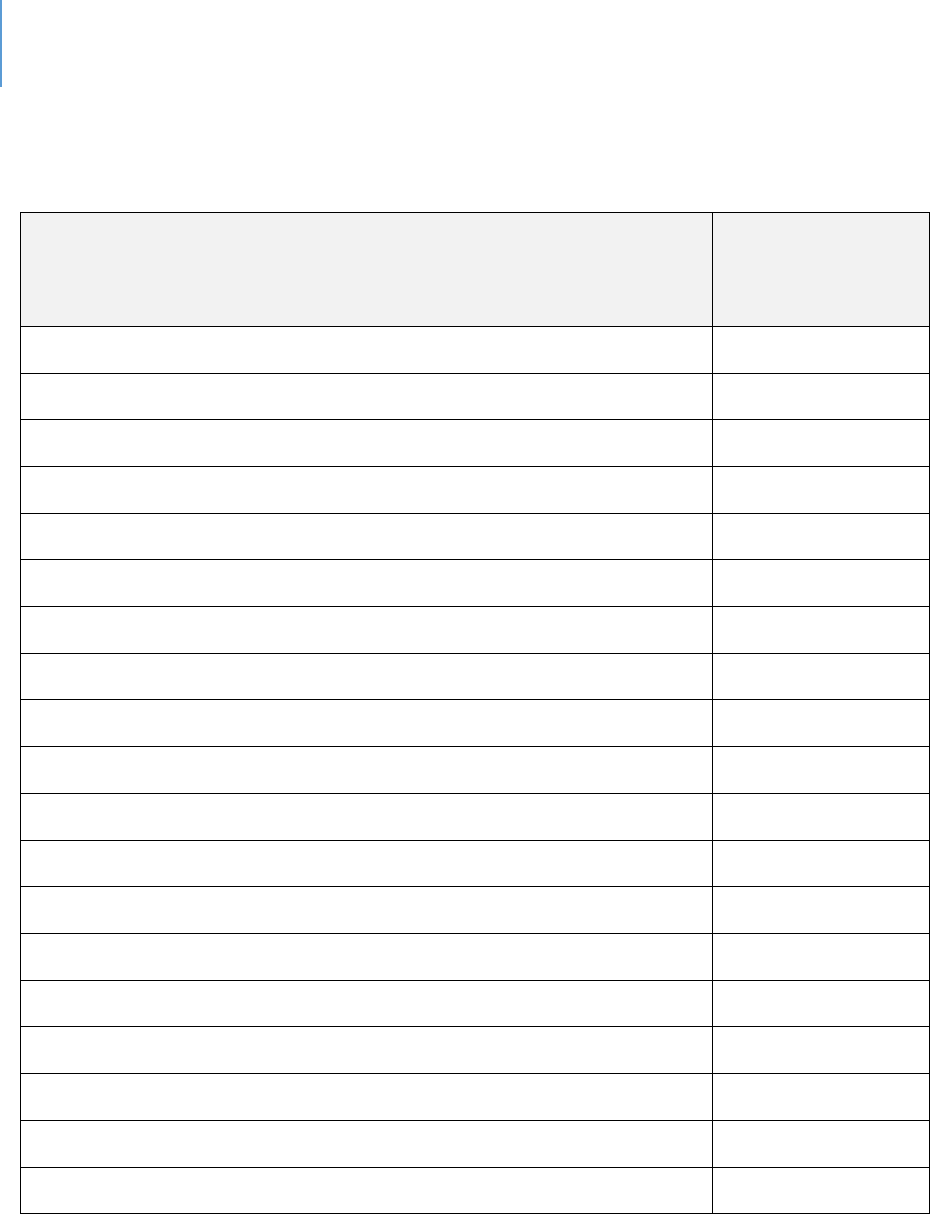

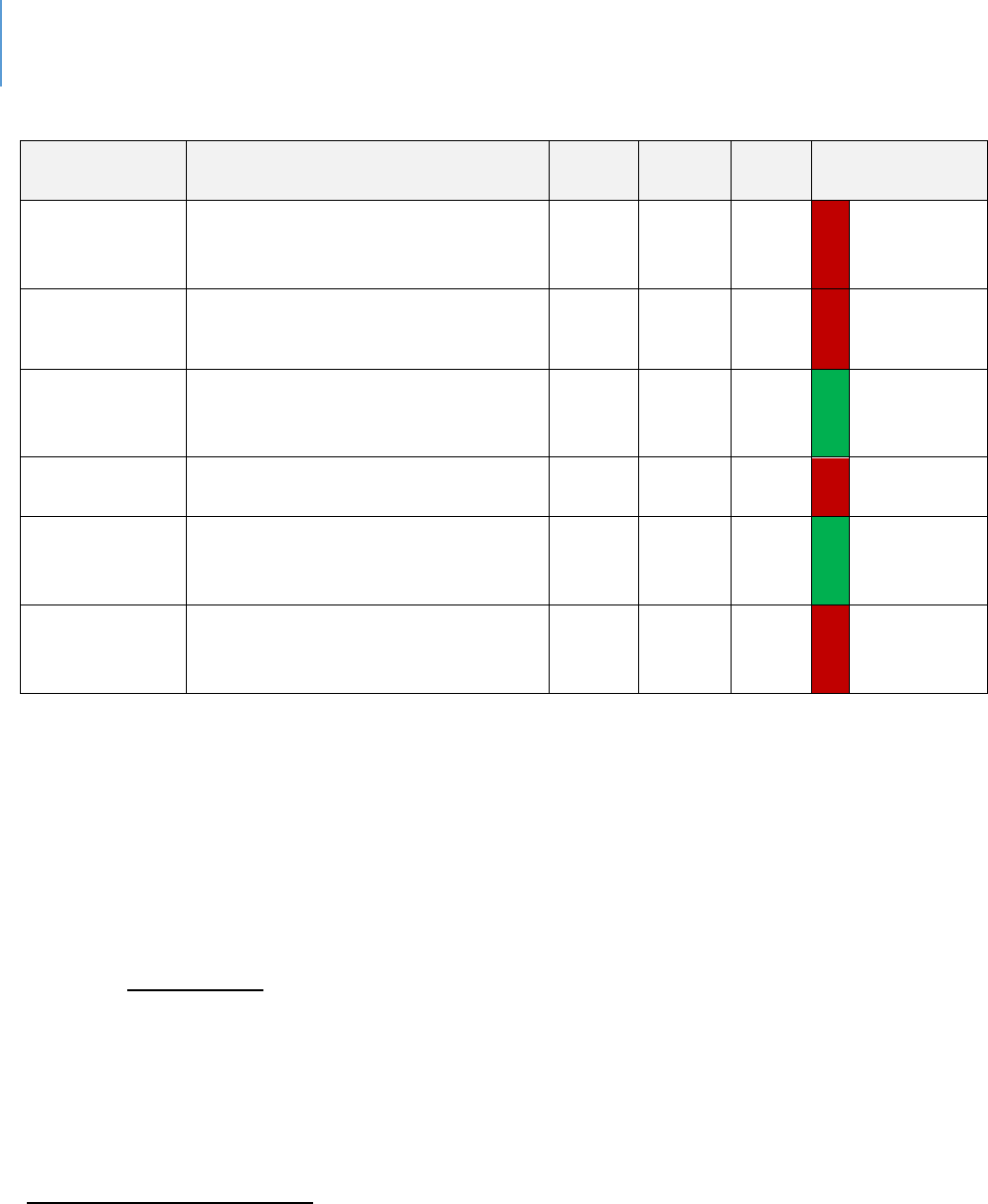

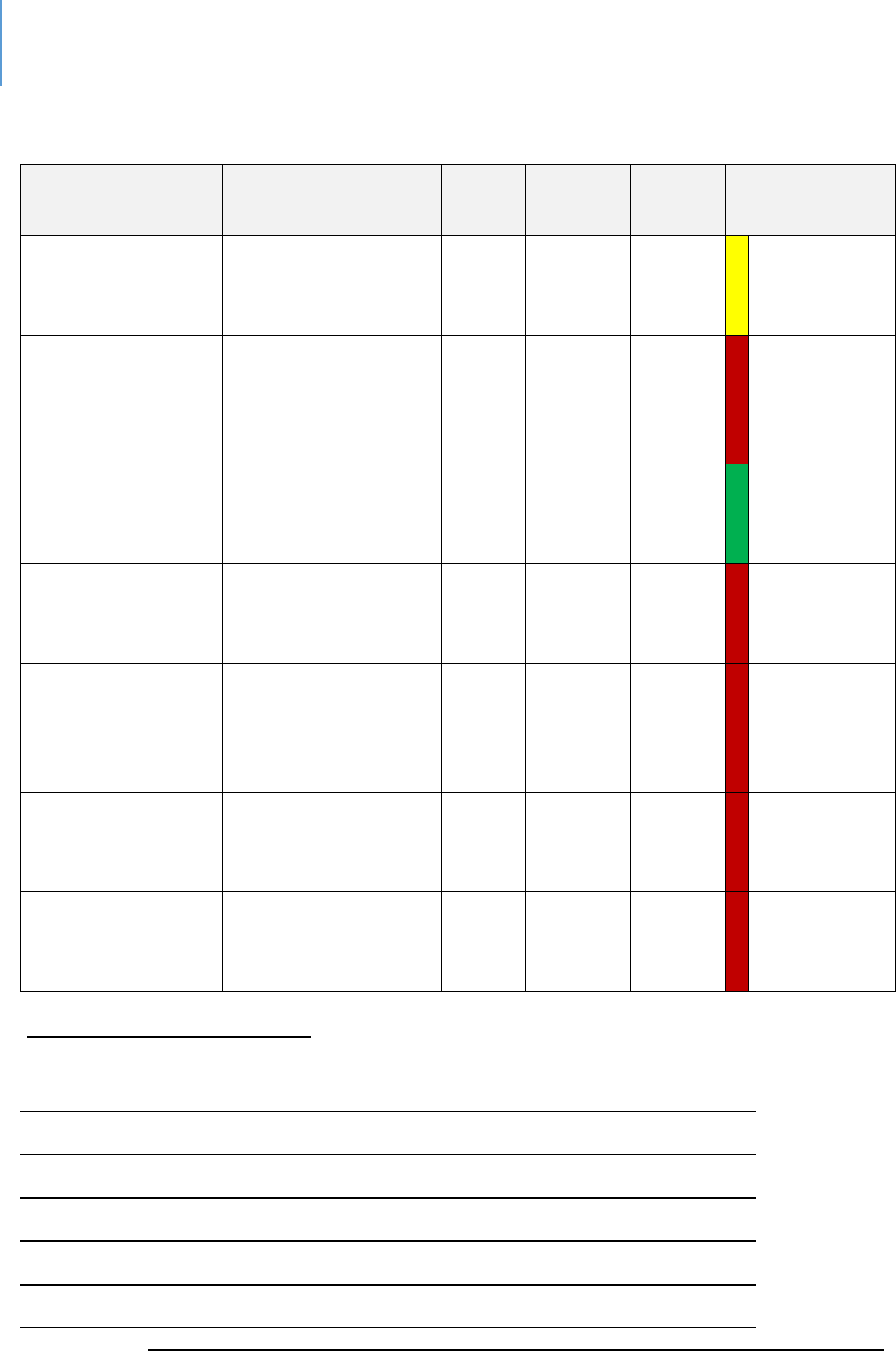

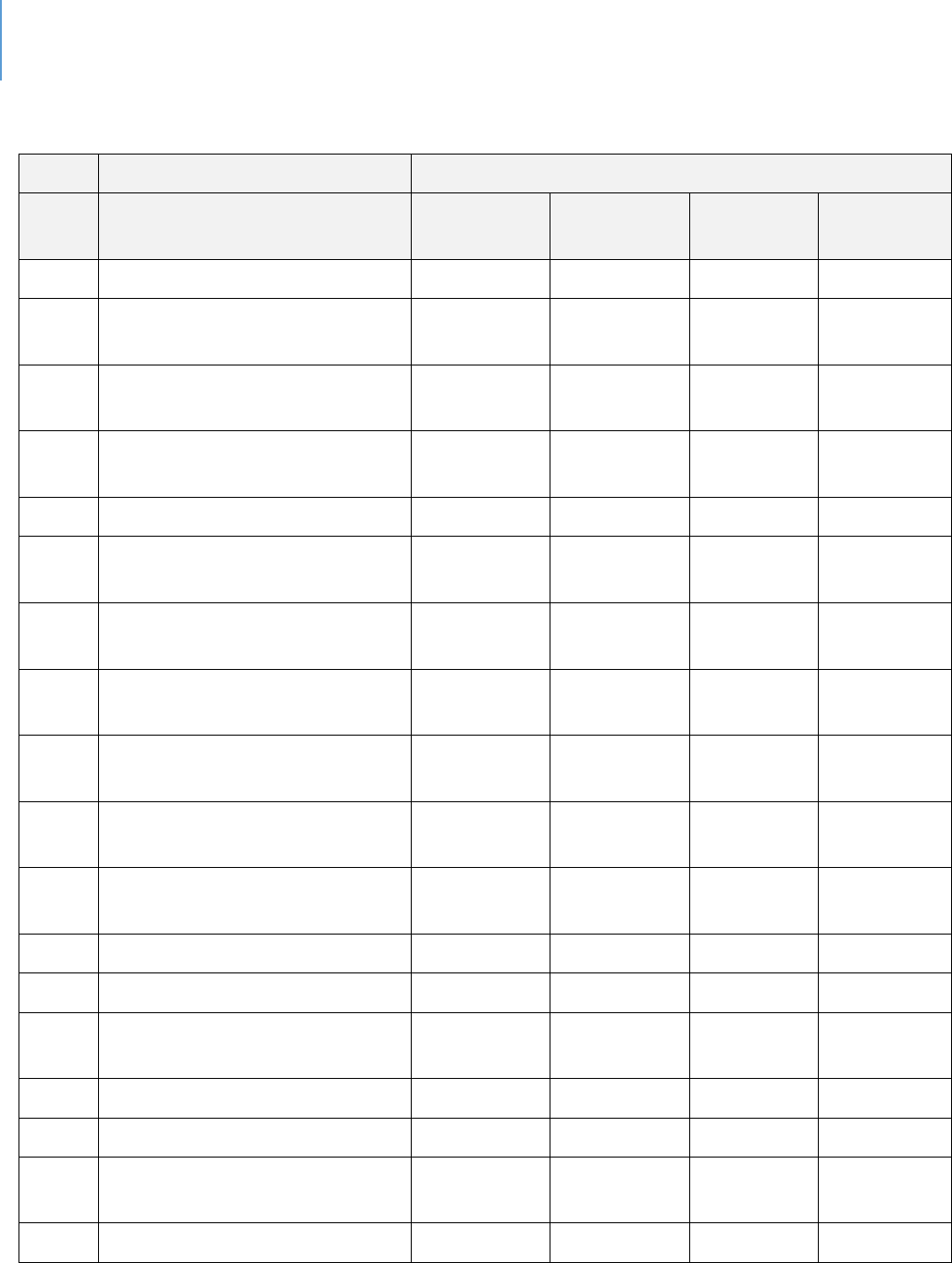

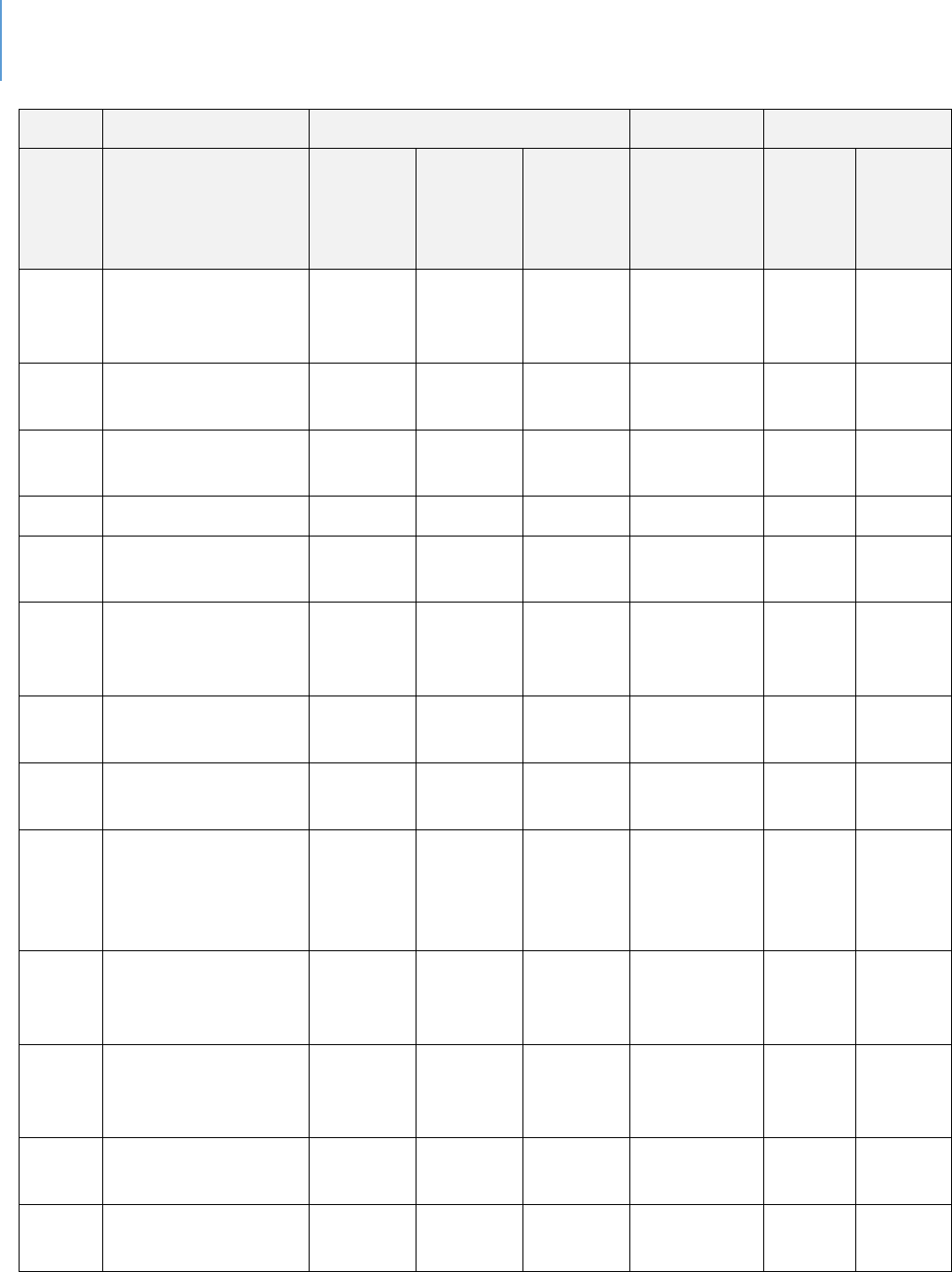

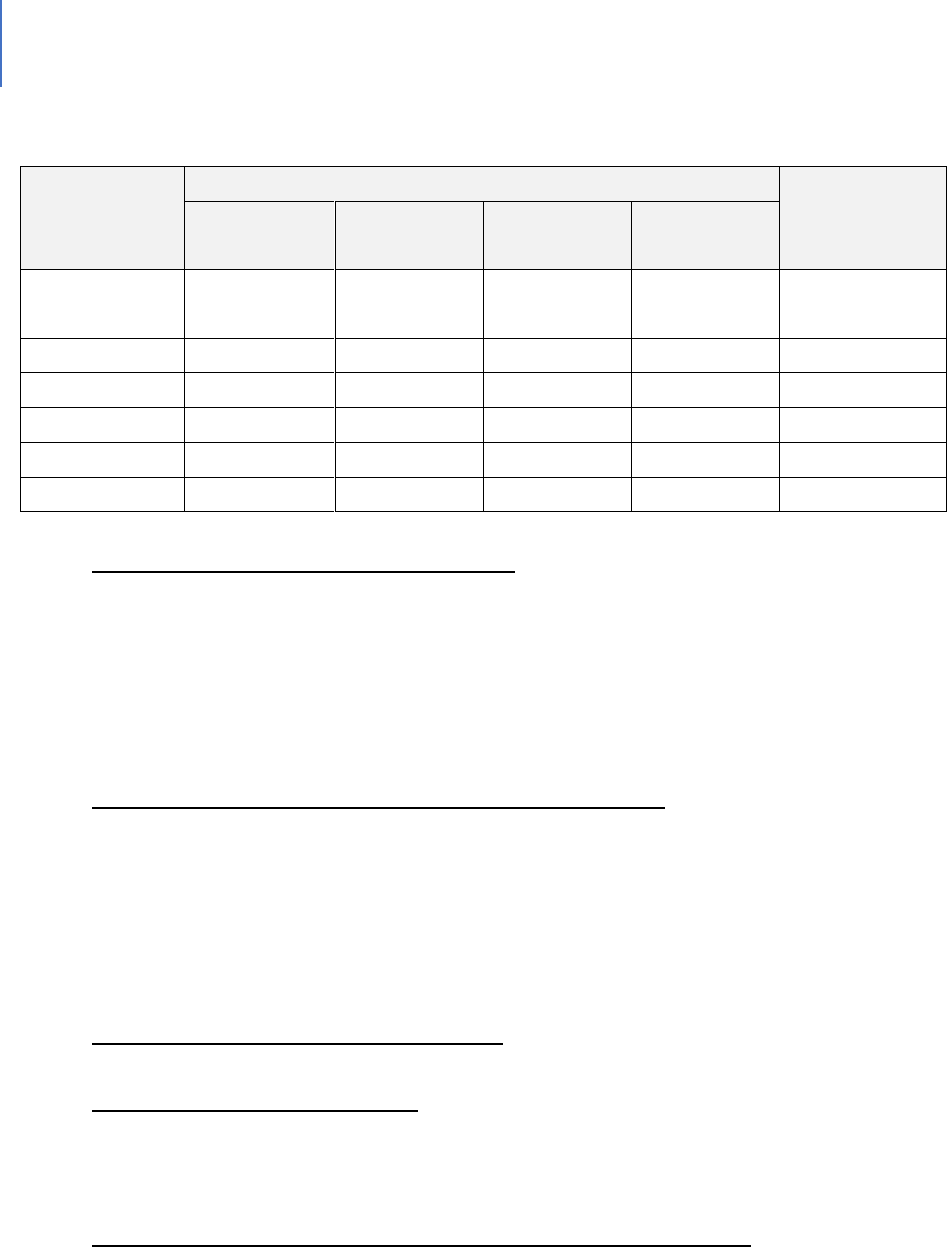

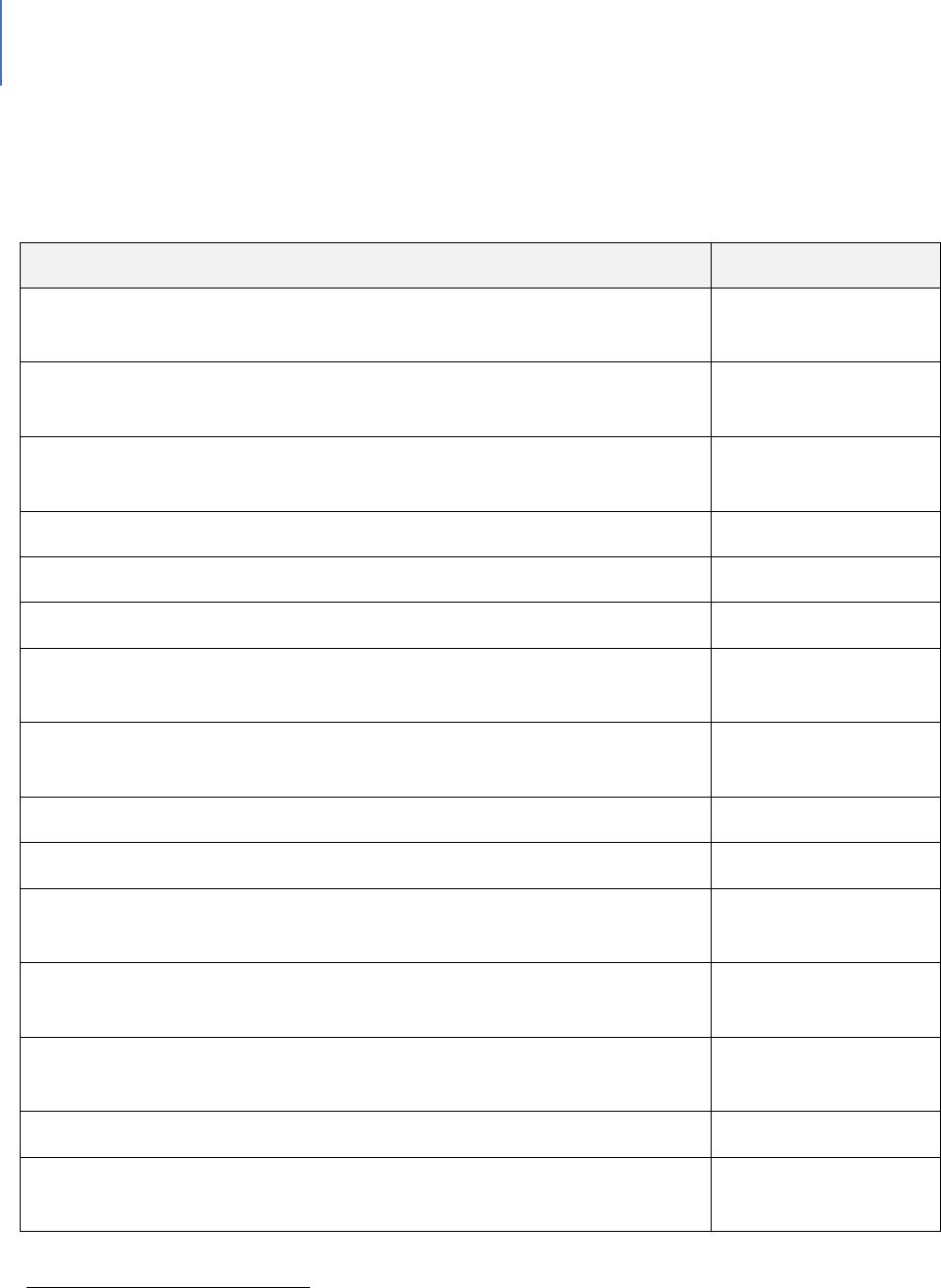

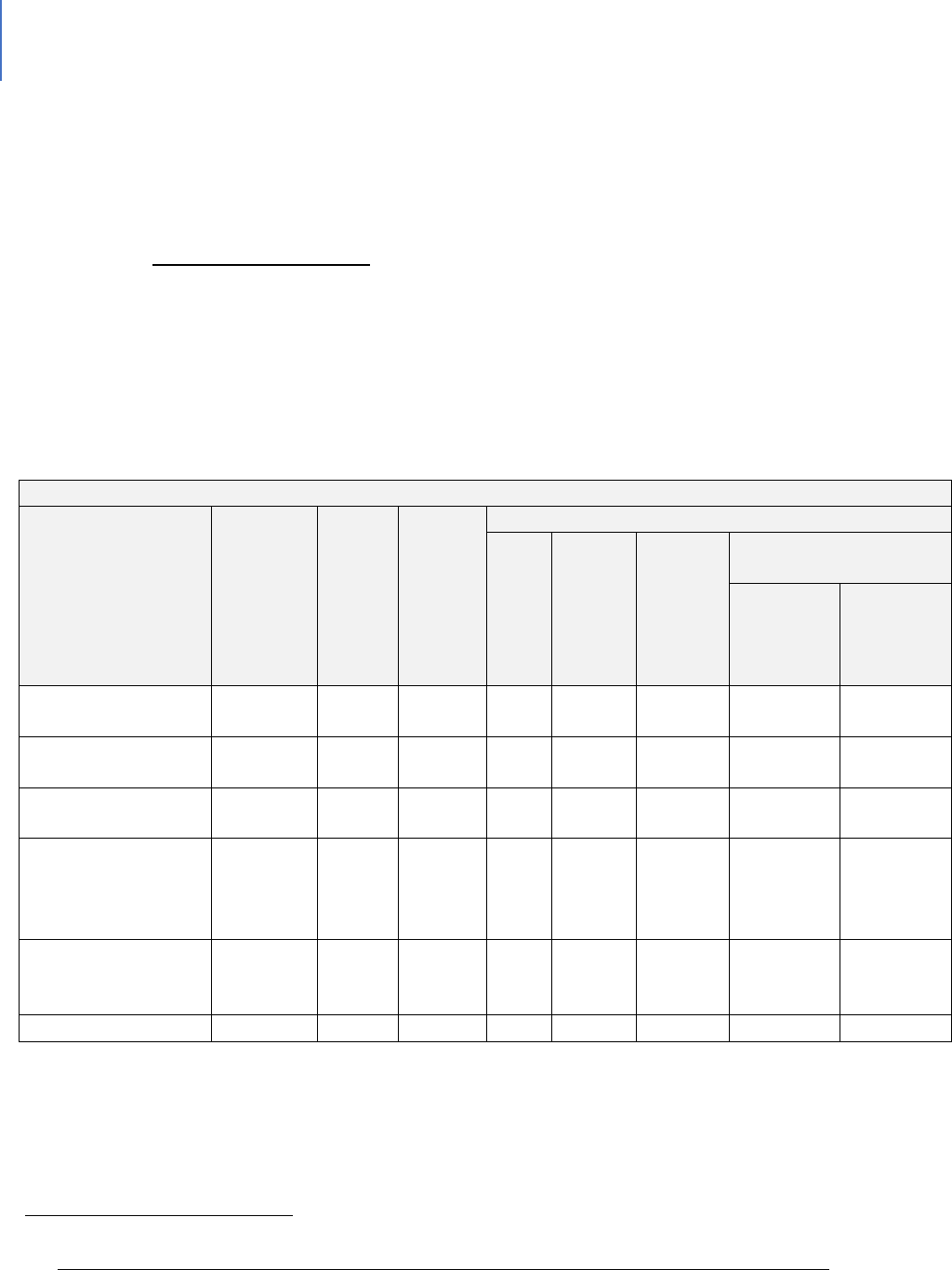

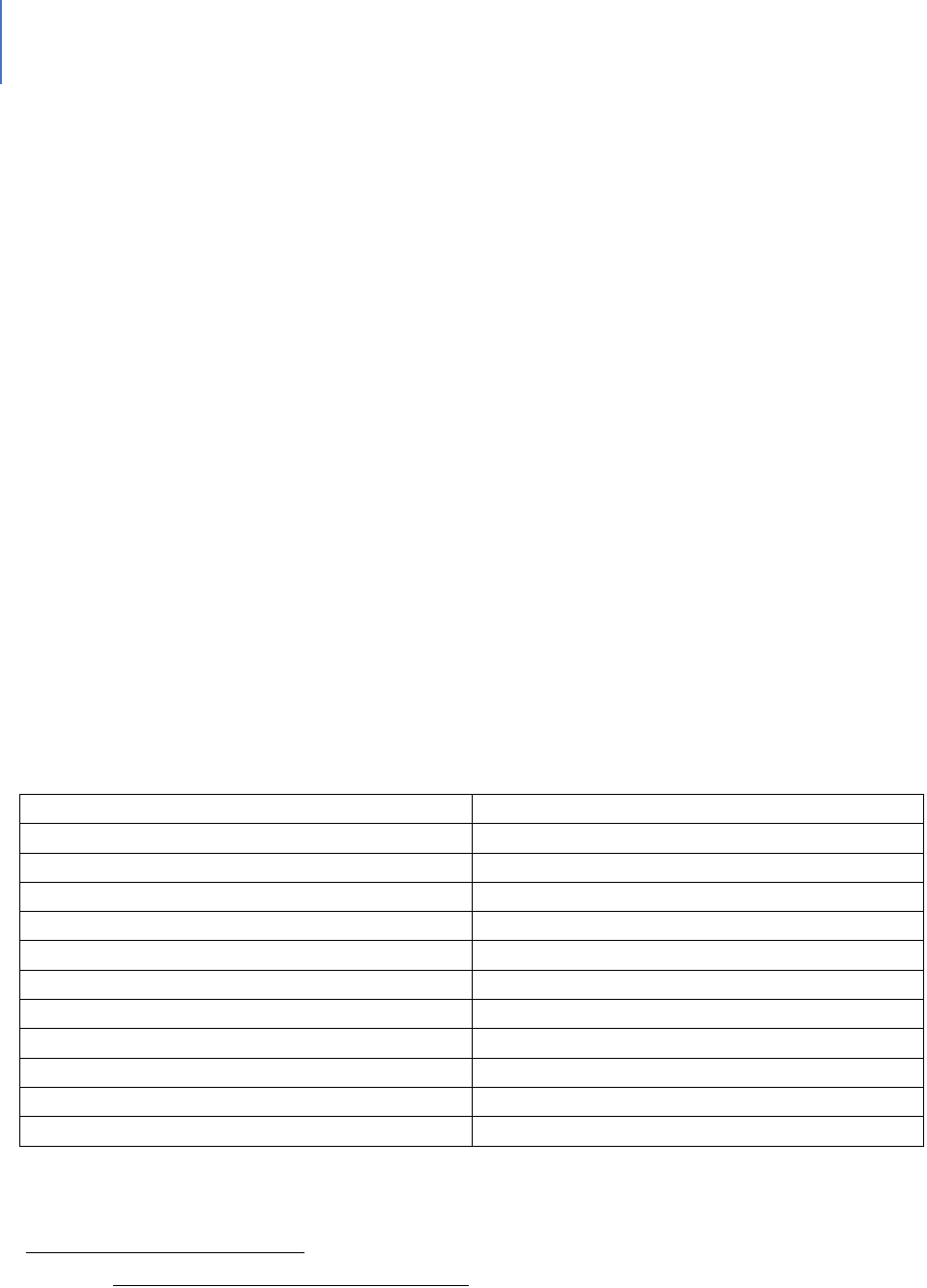

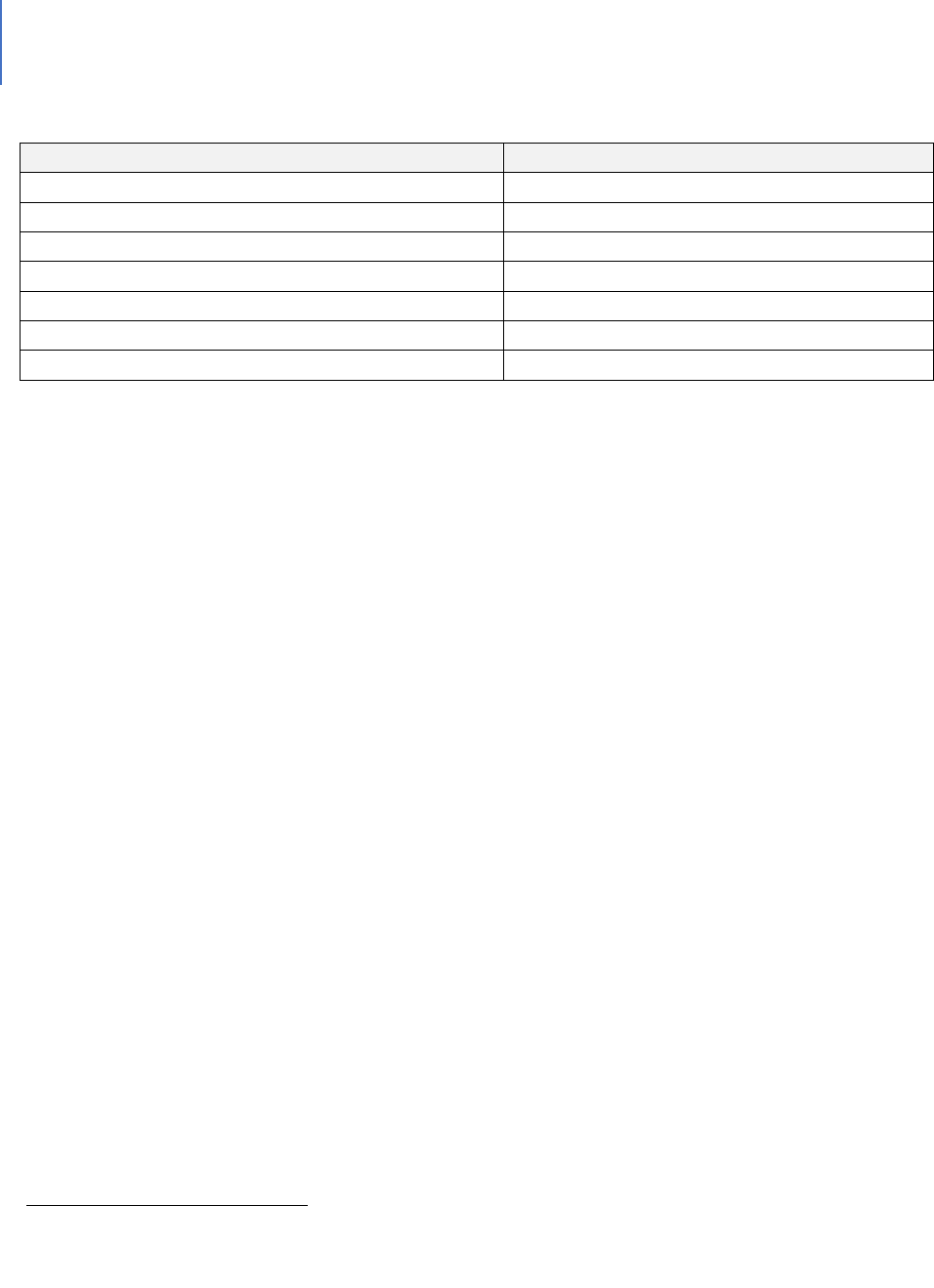

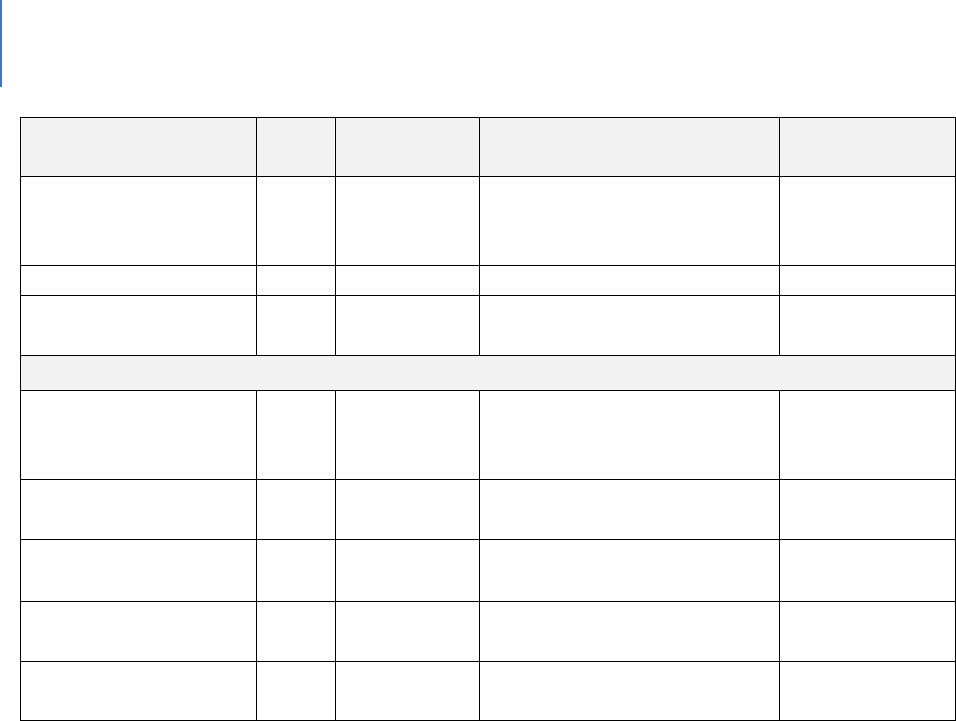

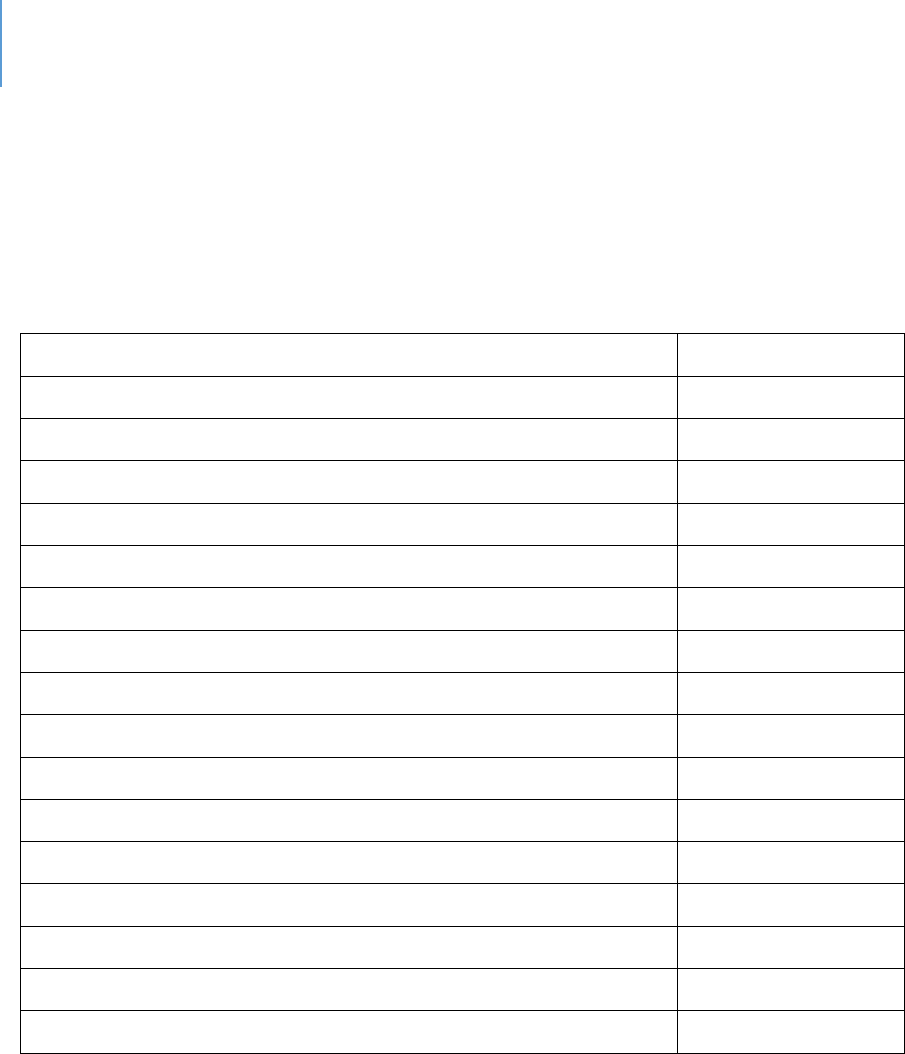

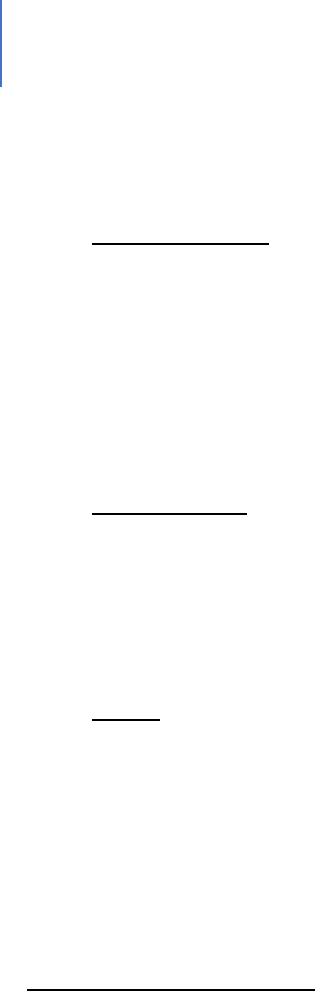

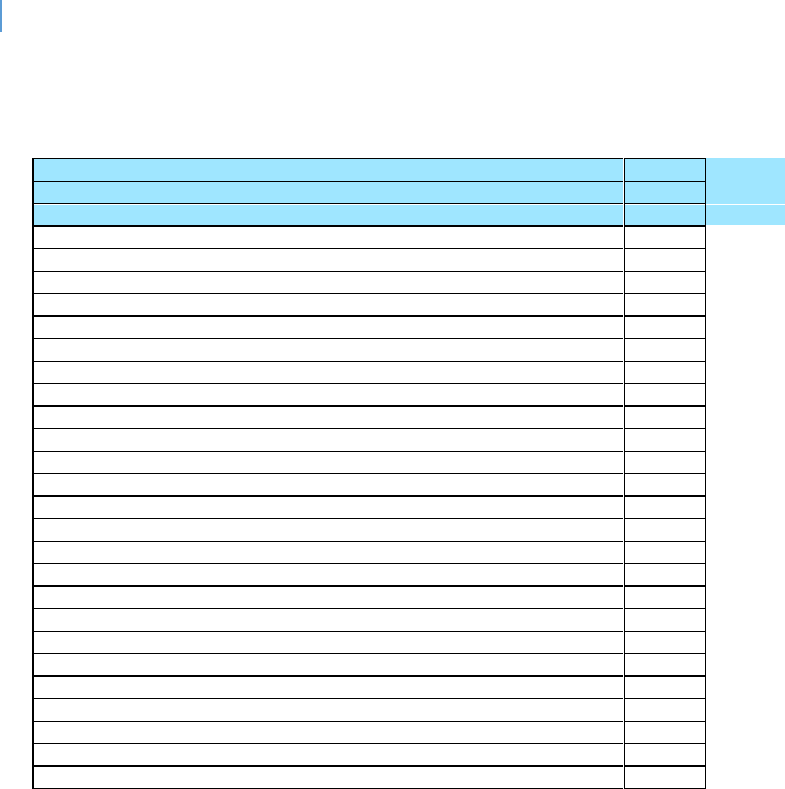

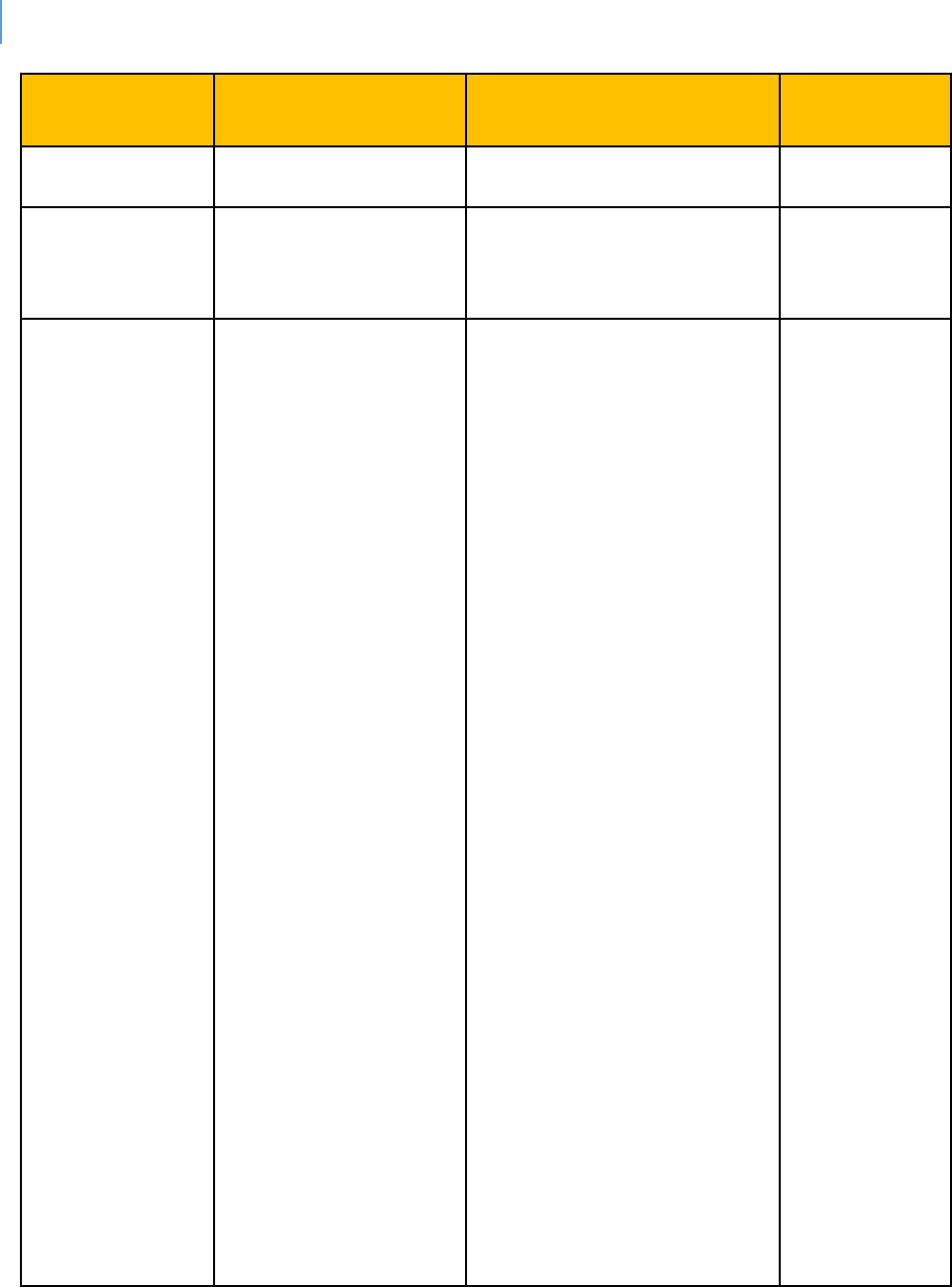

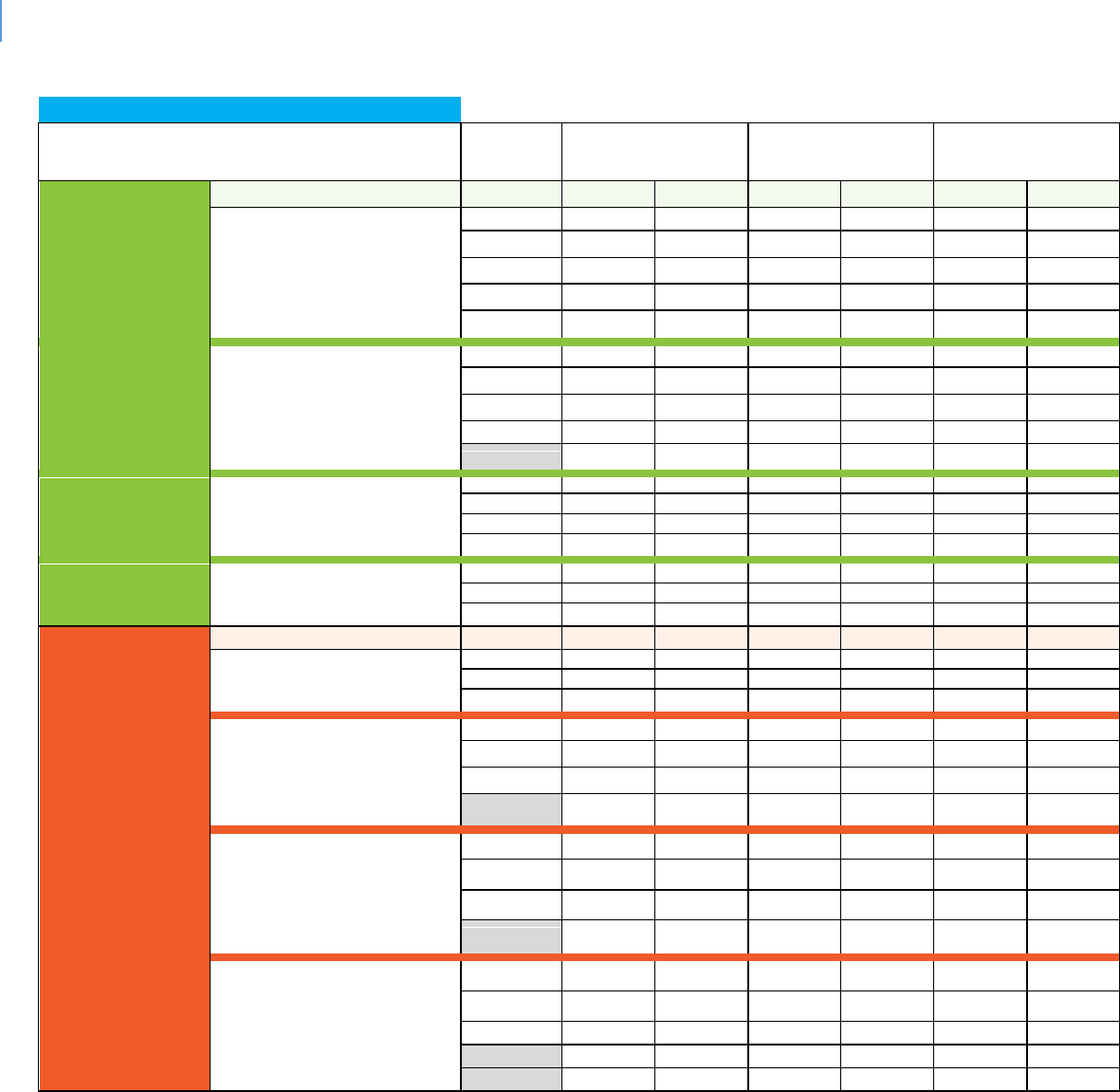

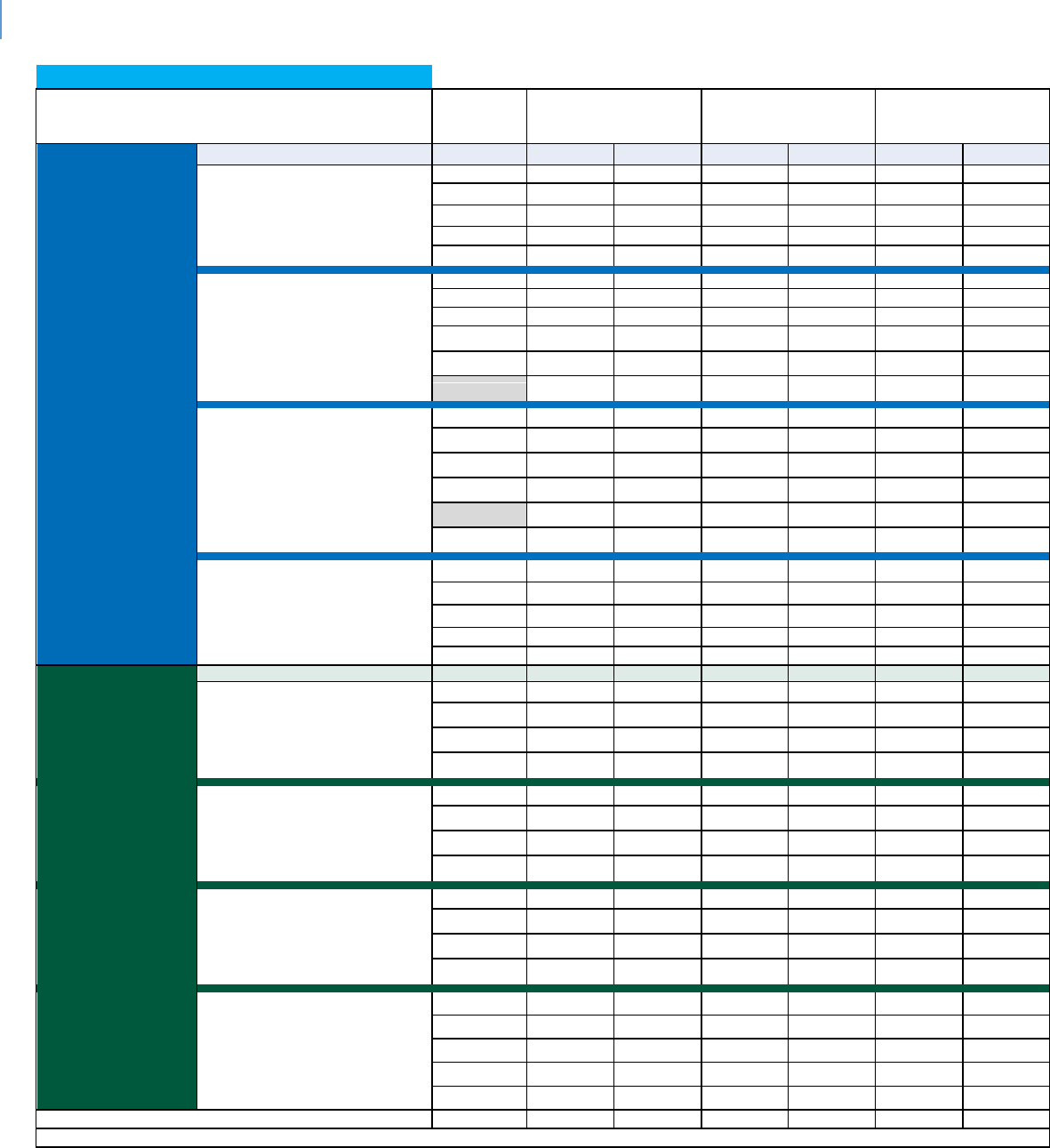

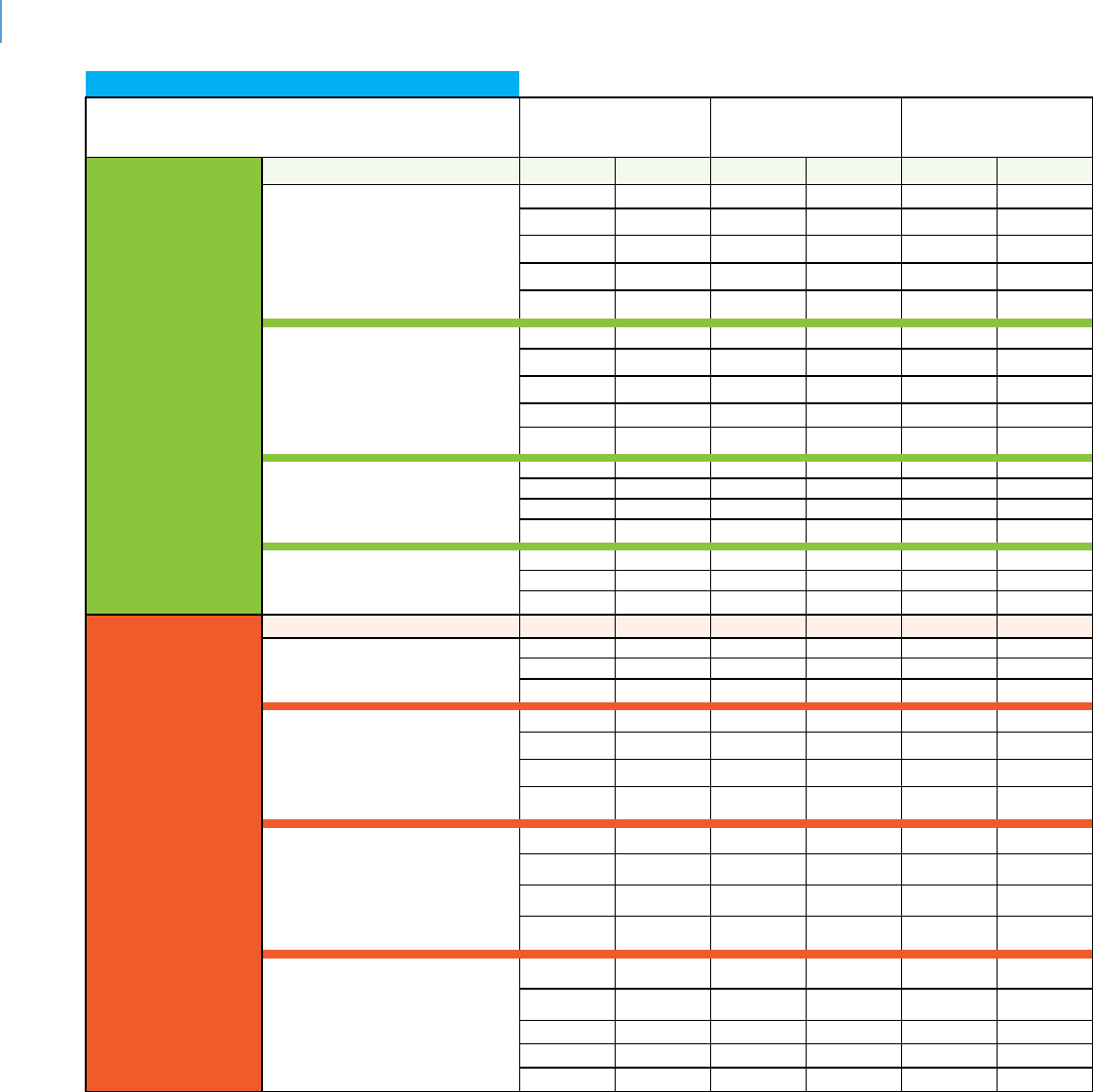

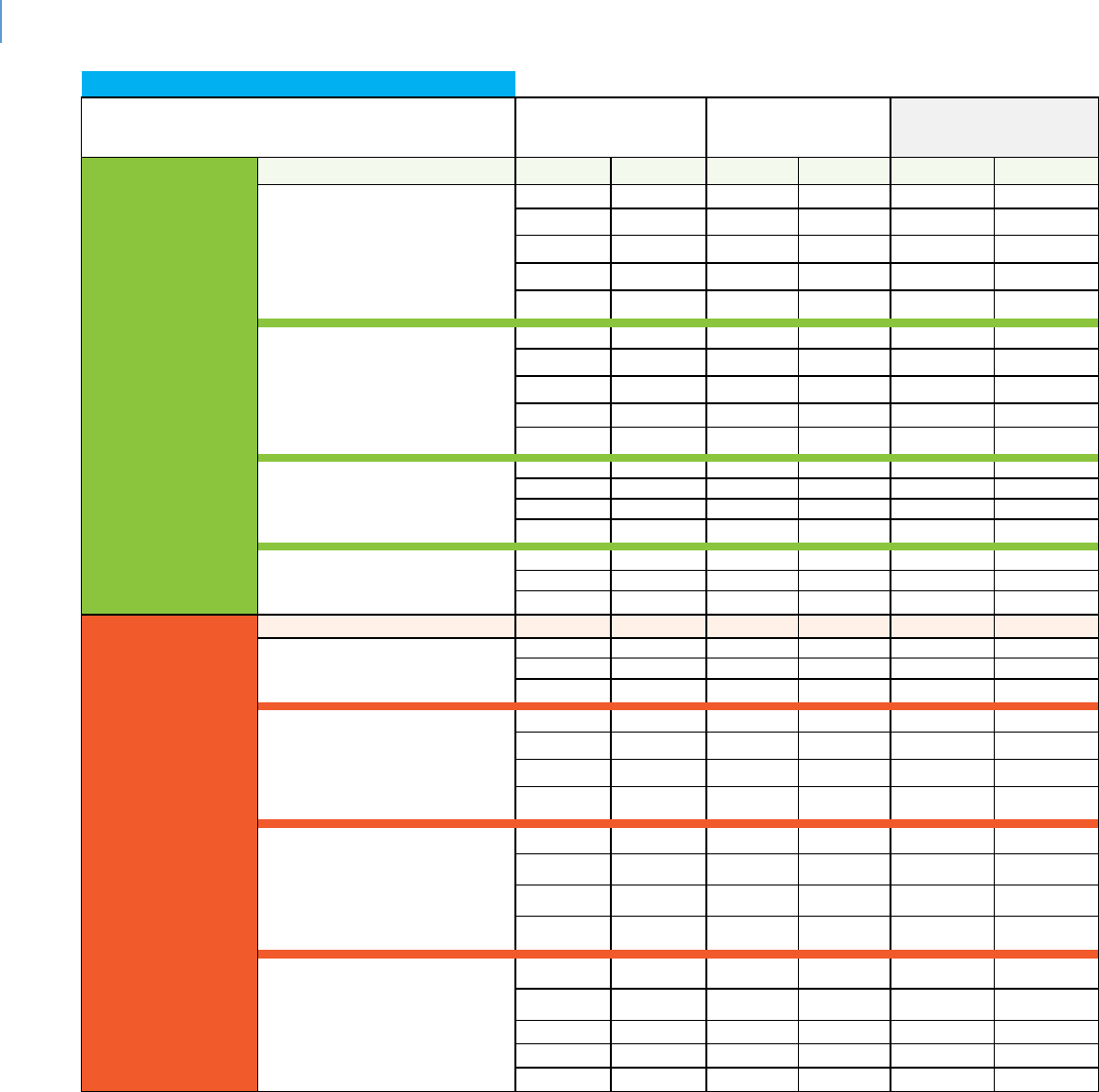

Index of Data Tables

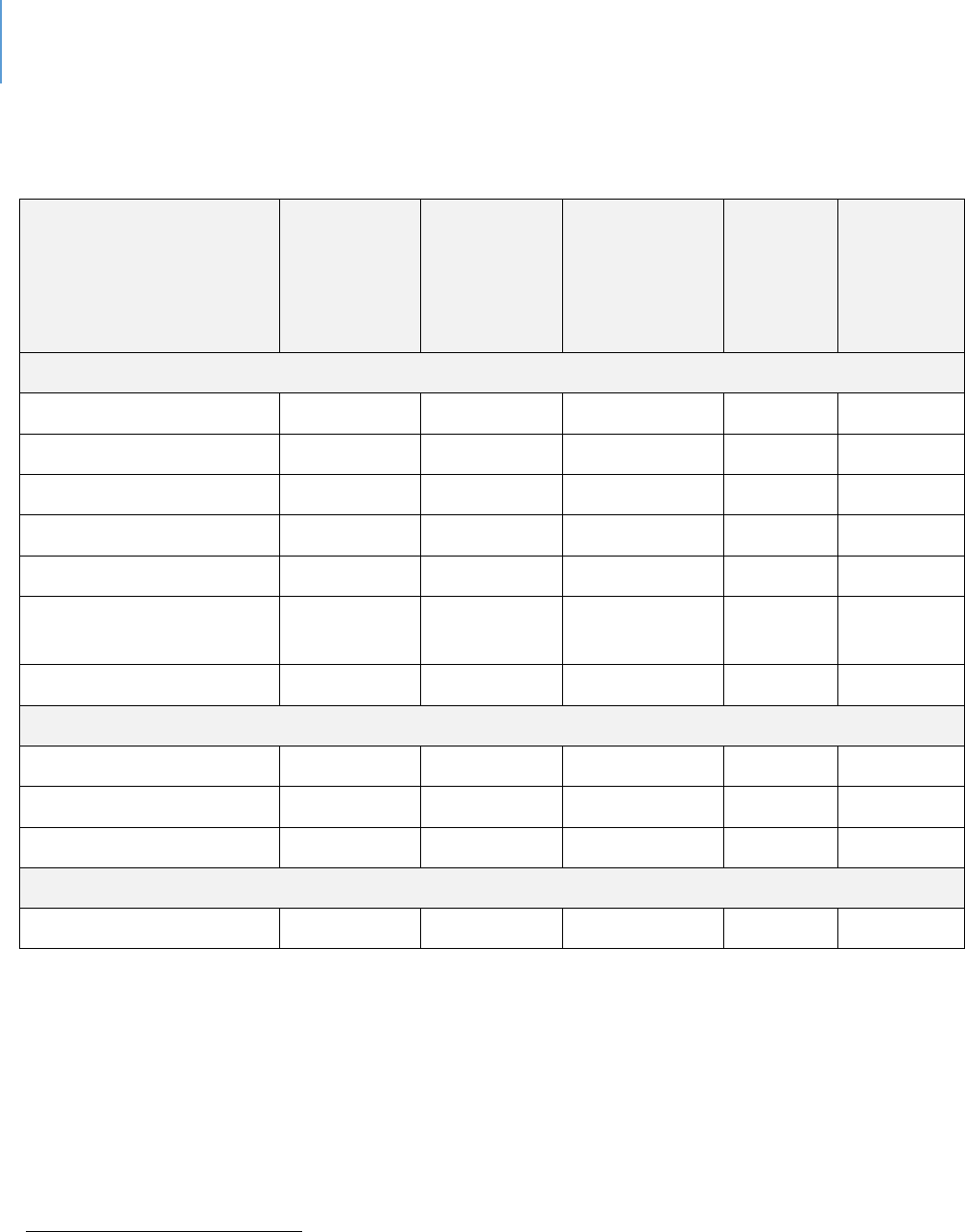

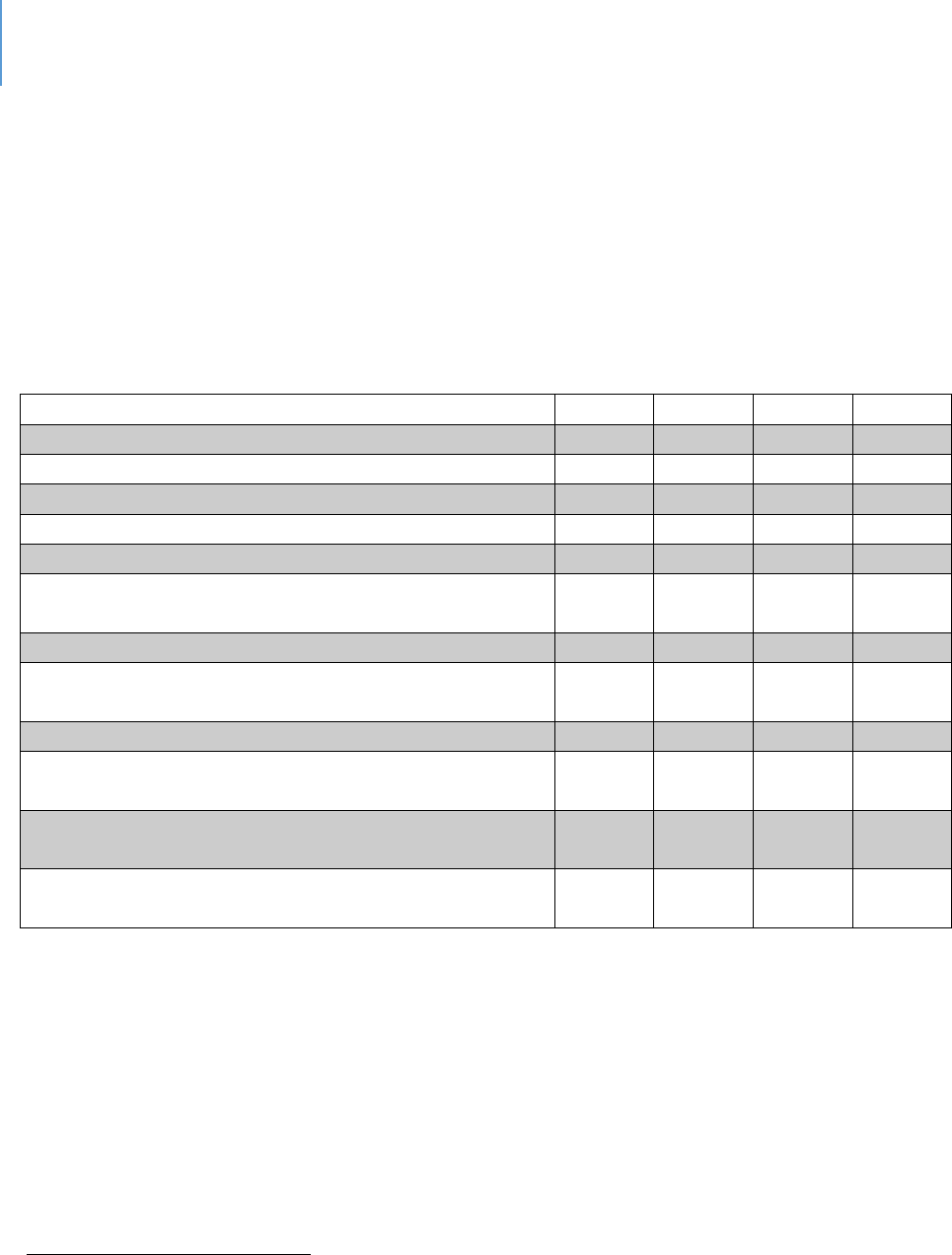

Table 1. Populaon Change Countywide ..................................................................................... 19

Table 2. Limited English Prociency Language Group, 2017 ........................................................ 20

Table 3. Lee County Race/Origin ................................................................................................... 22

Table 4. Income and Benets (In 2018 Inaon Adjusted Dollars) ............................................... 24

Table 5. Percentage Below Poverty Level in the Last 12 Months ................................................. 25

Table 6. Florida Occupaonal Employment and Wages; Cape Coral-Fort Myers MSA ................. 27

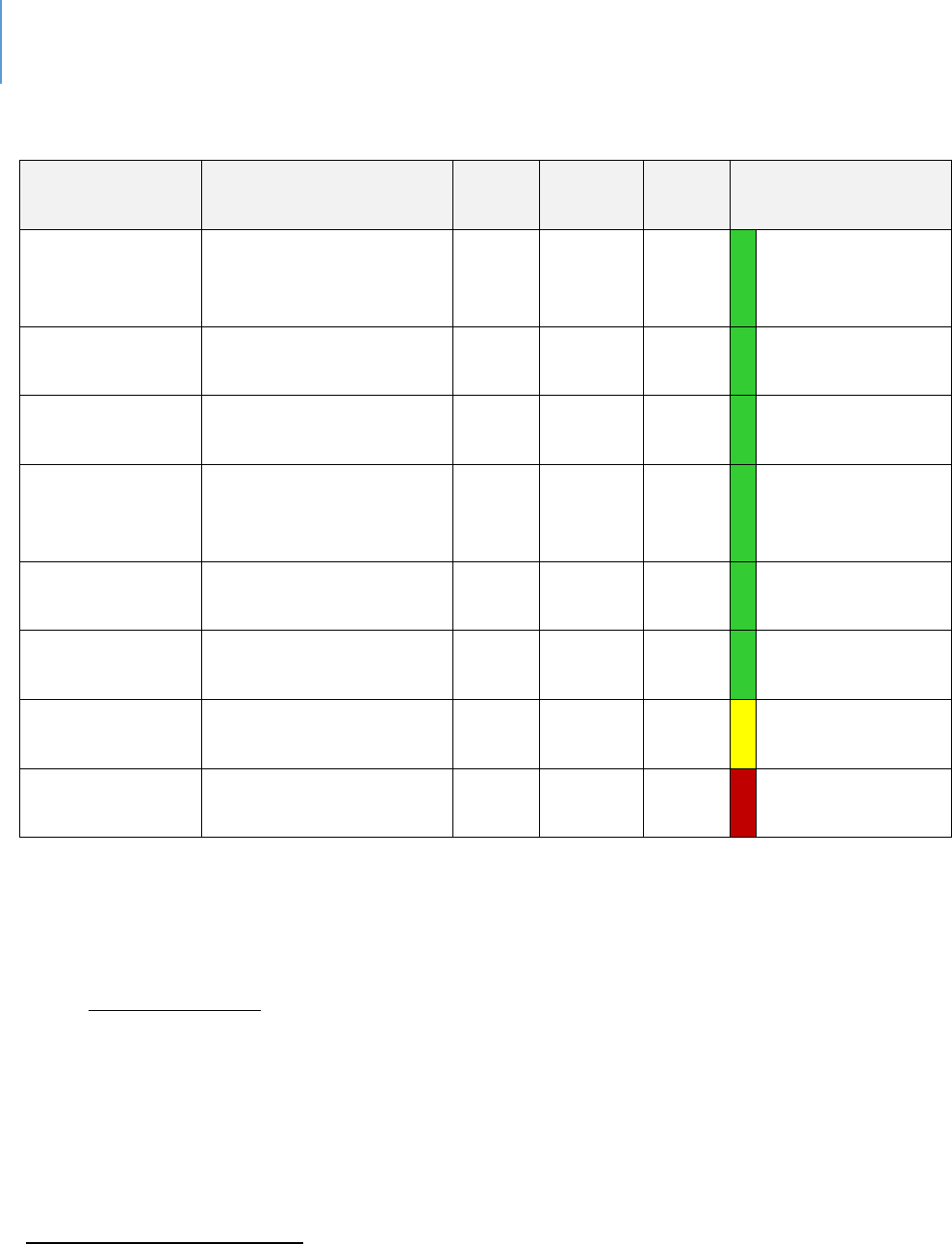

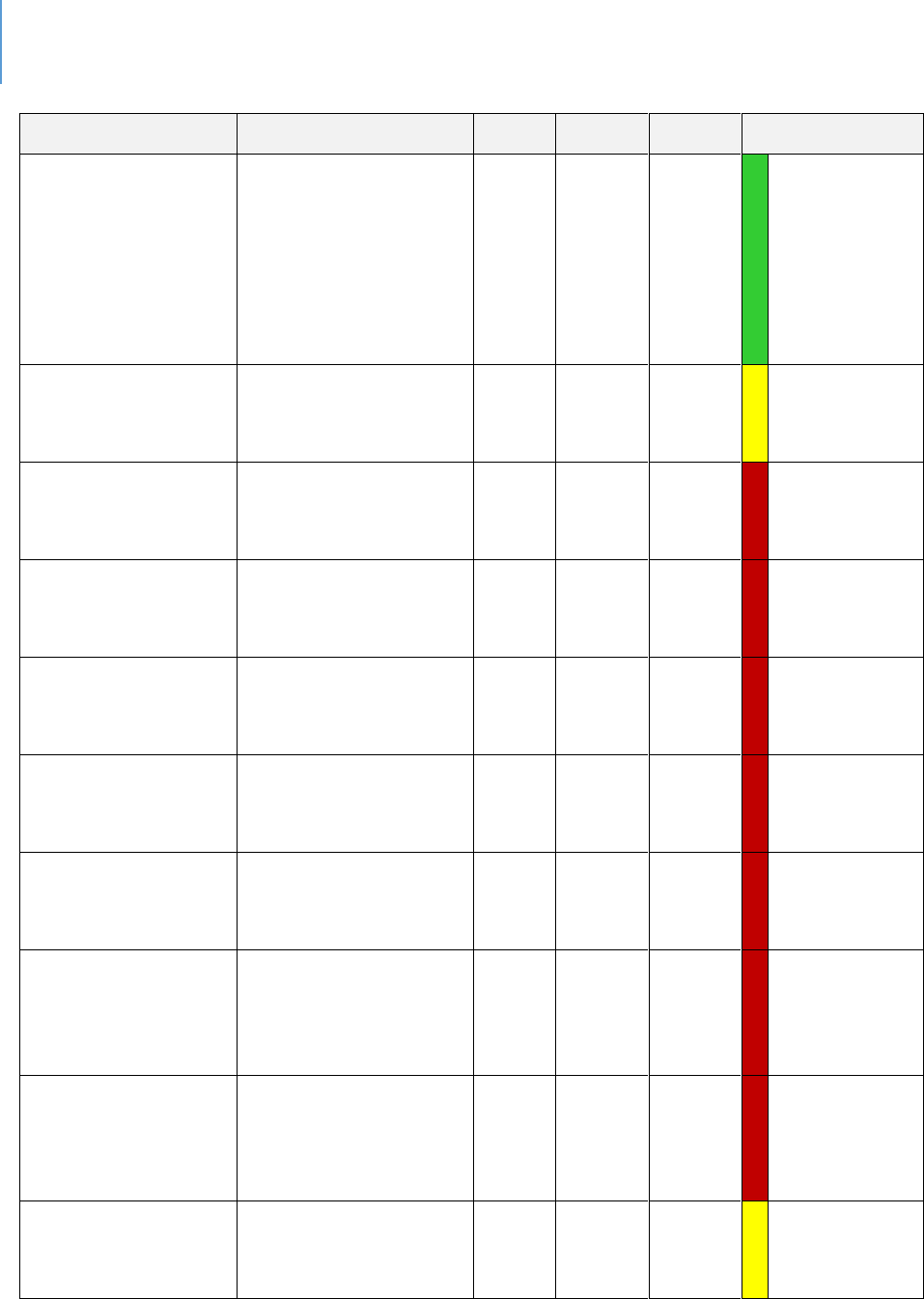

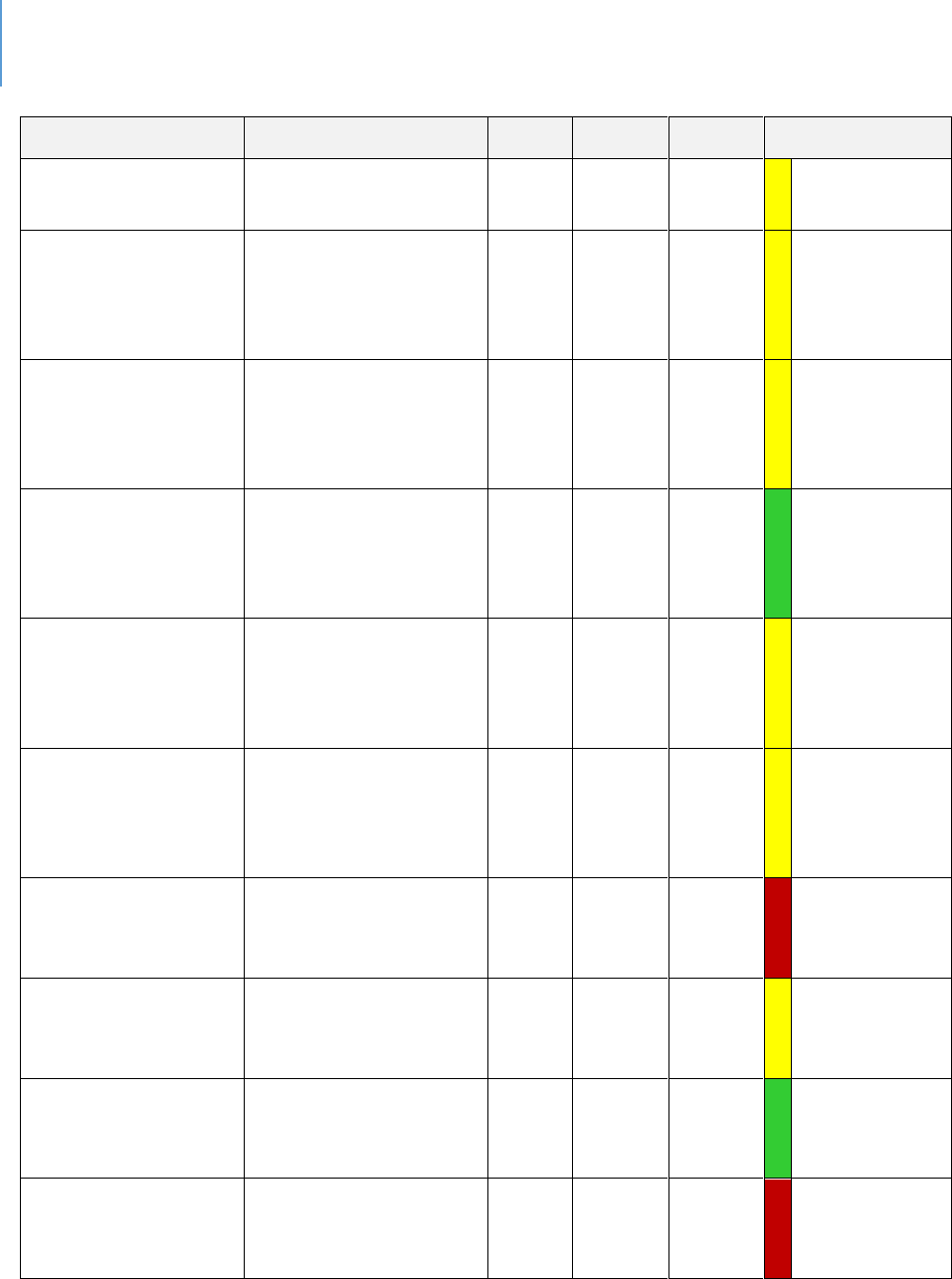

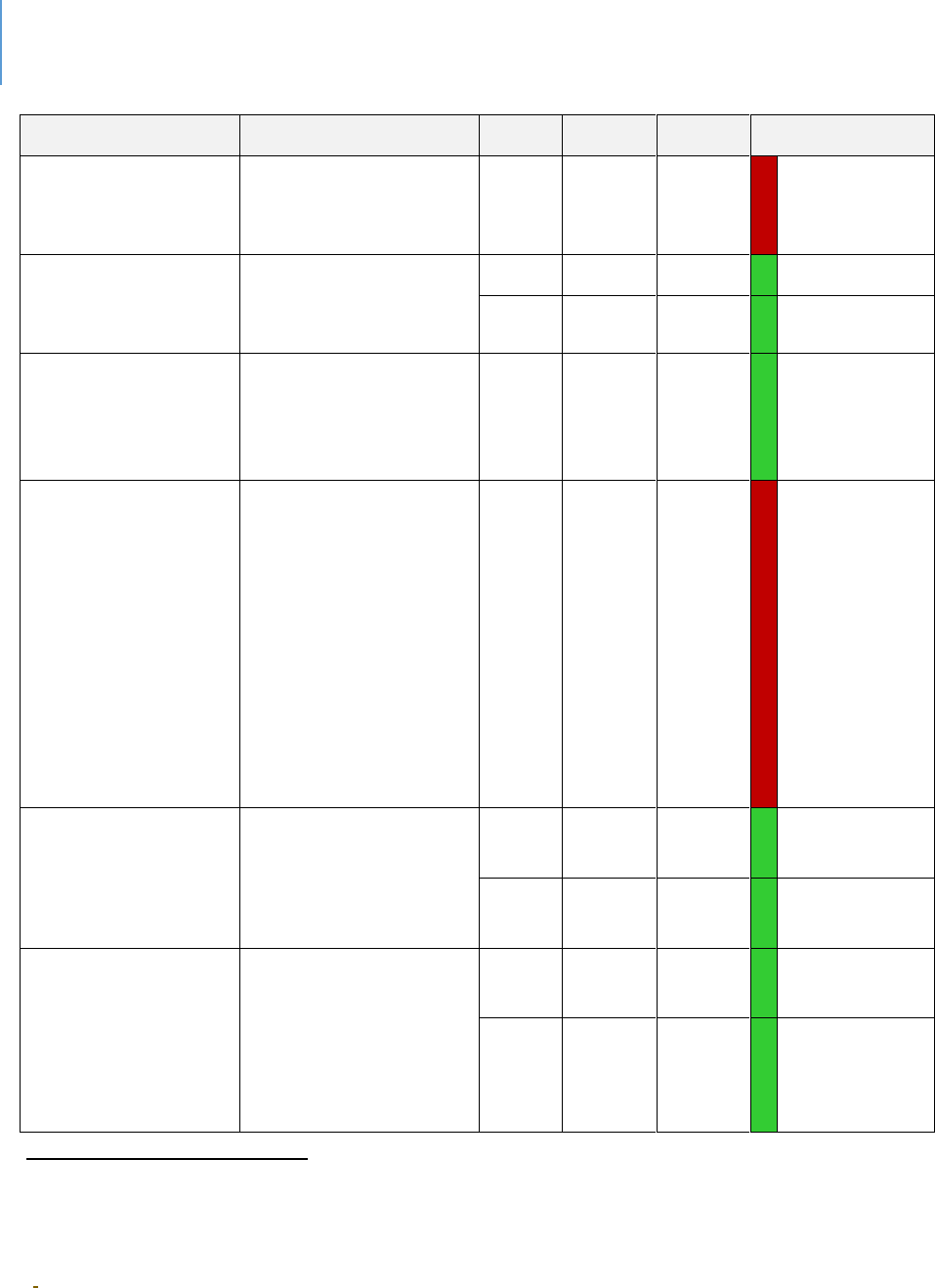

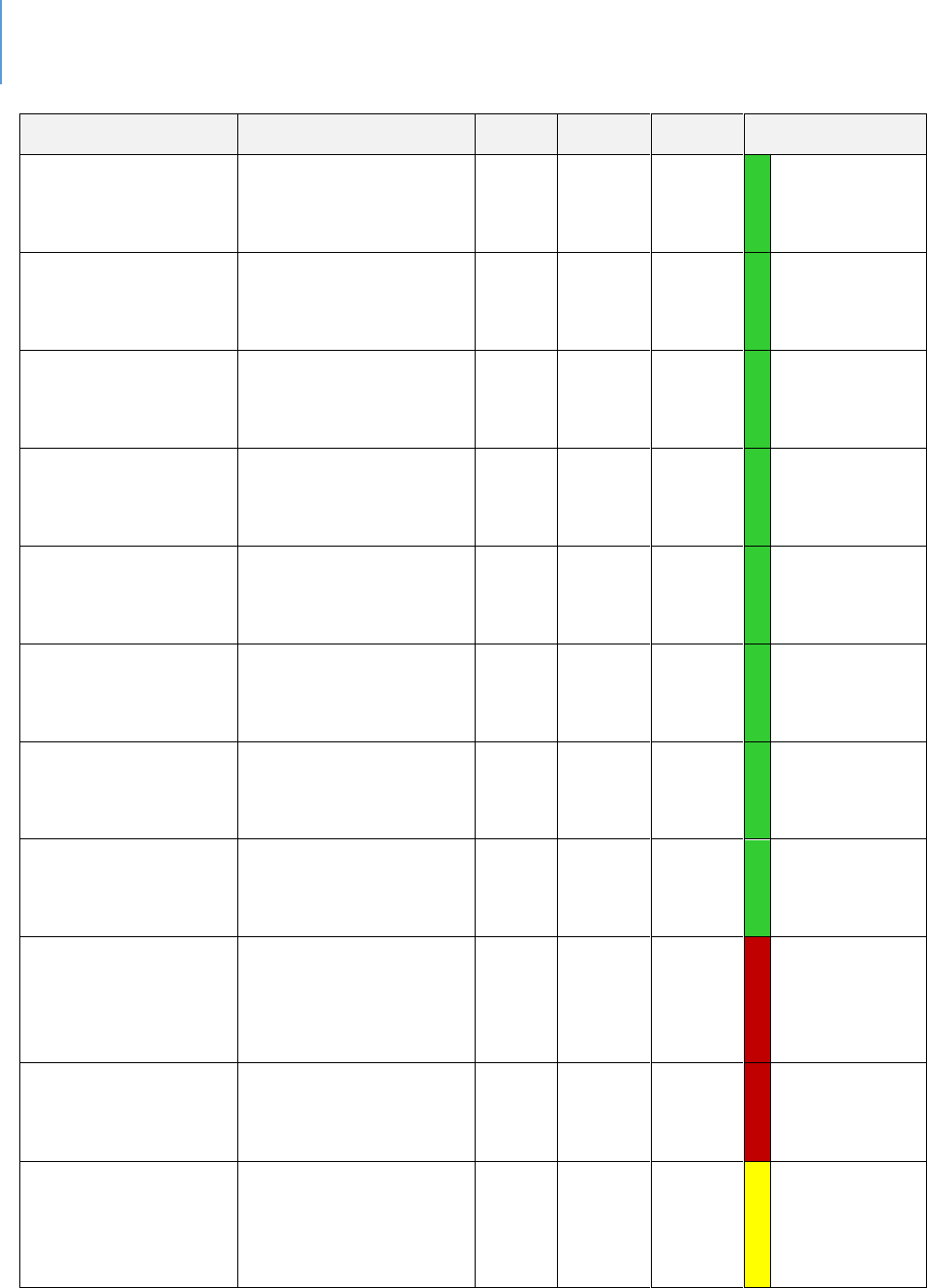

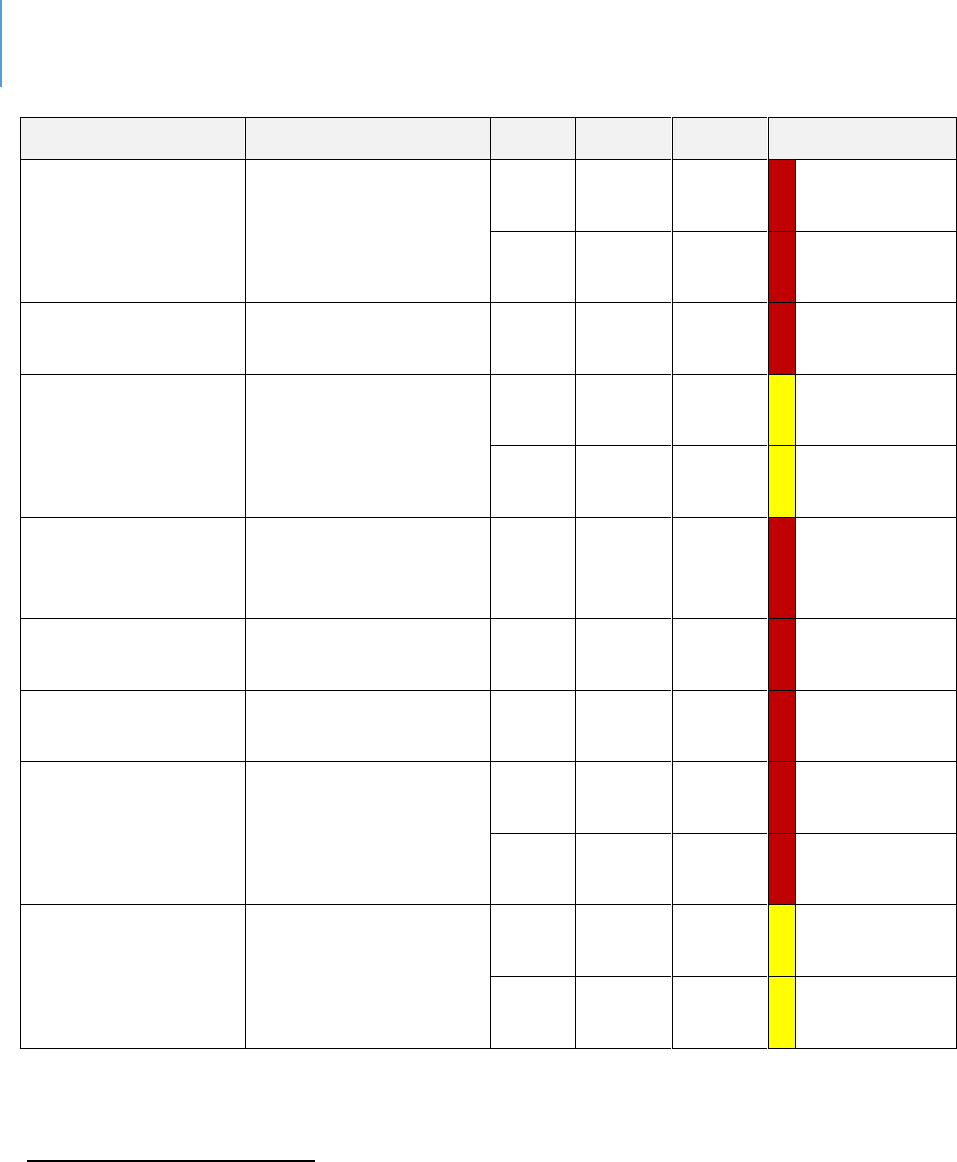

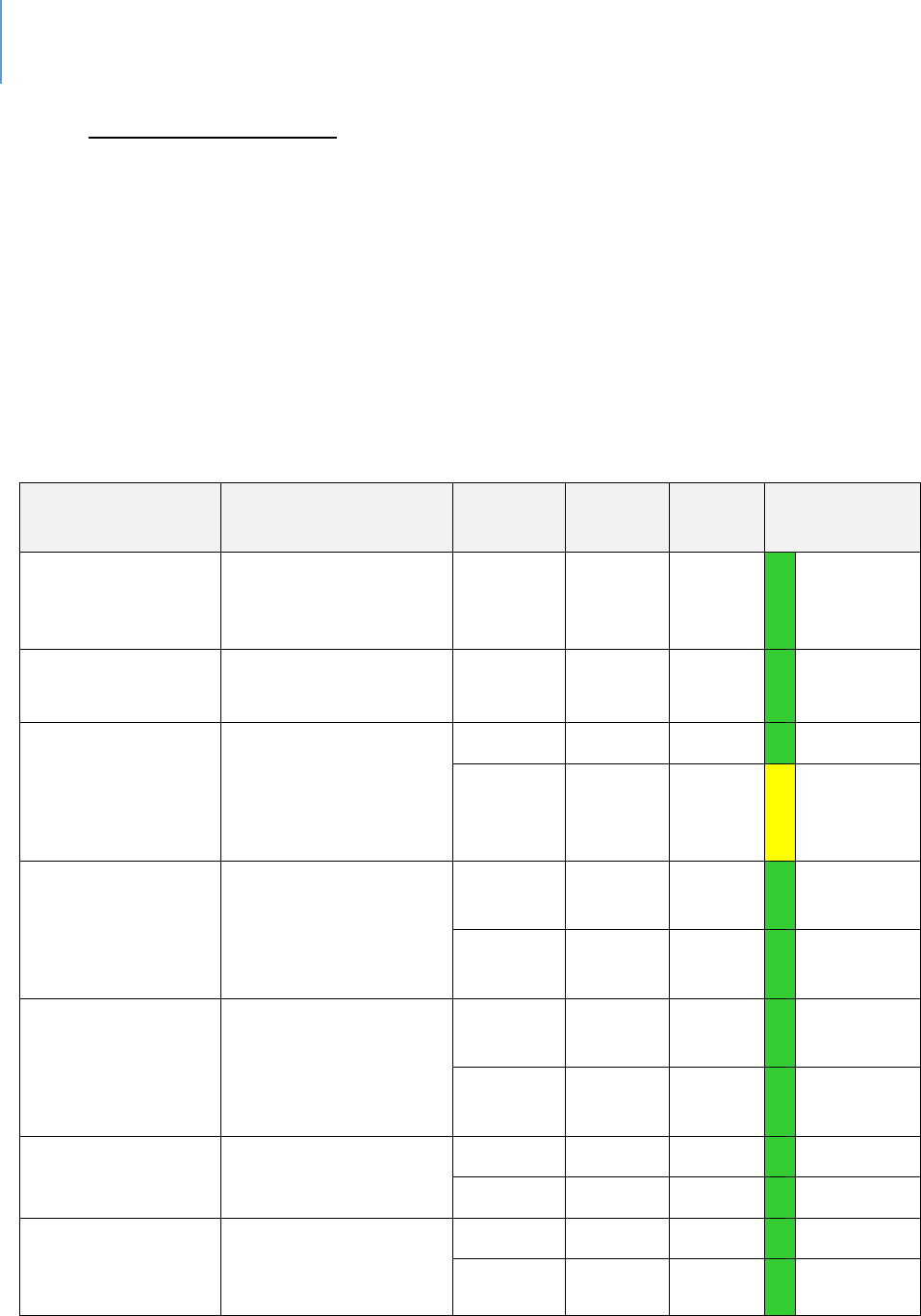

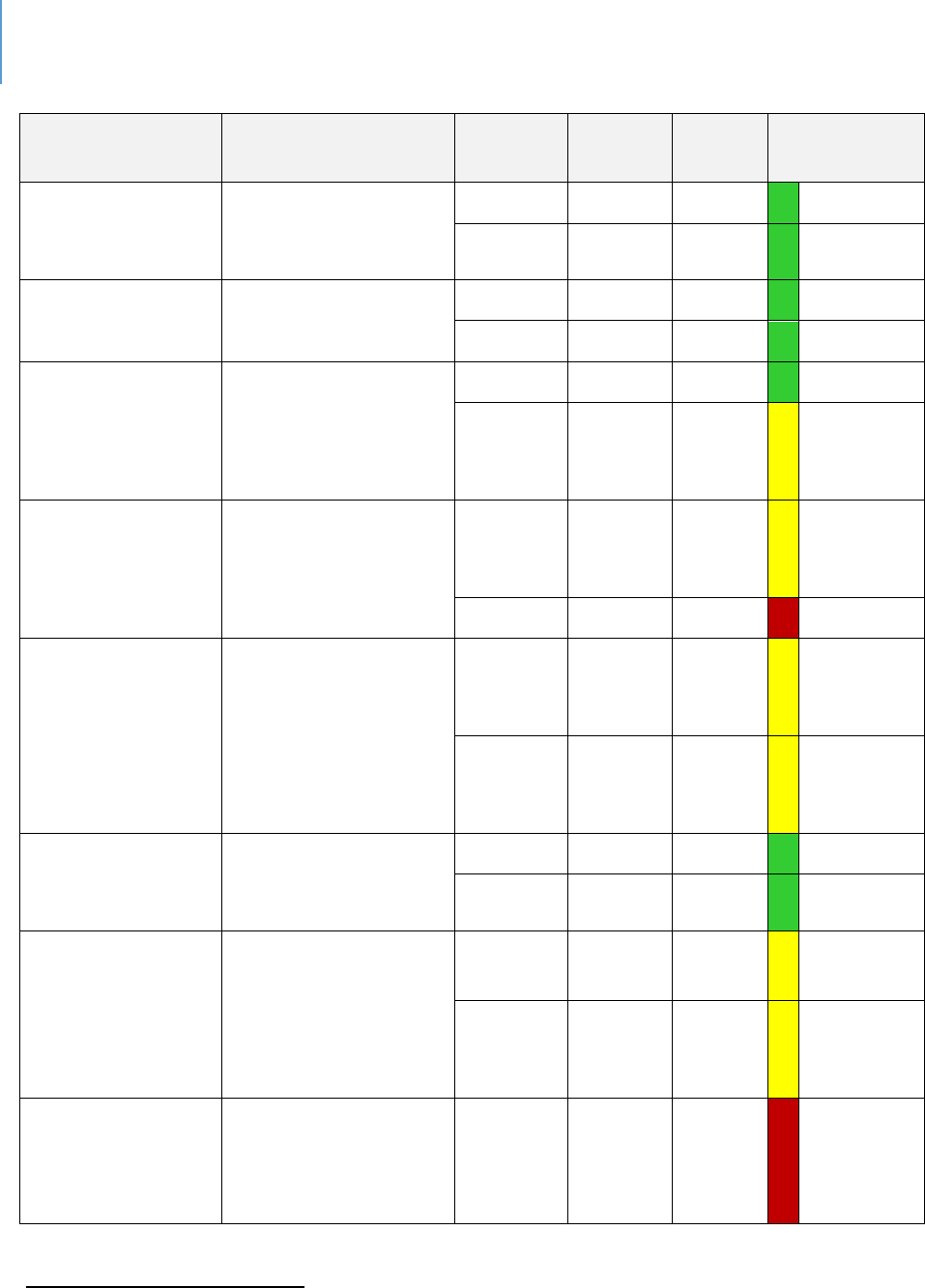

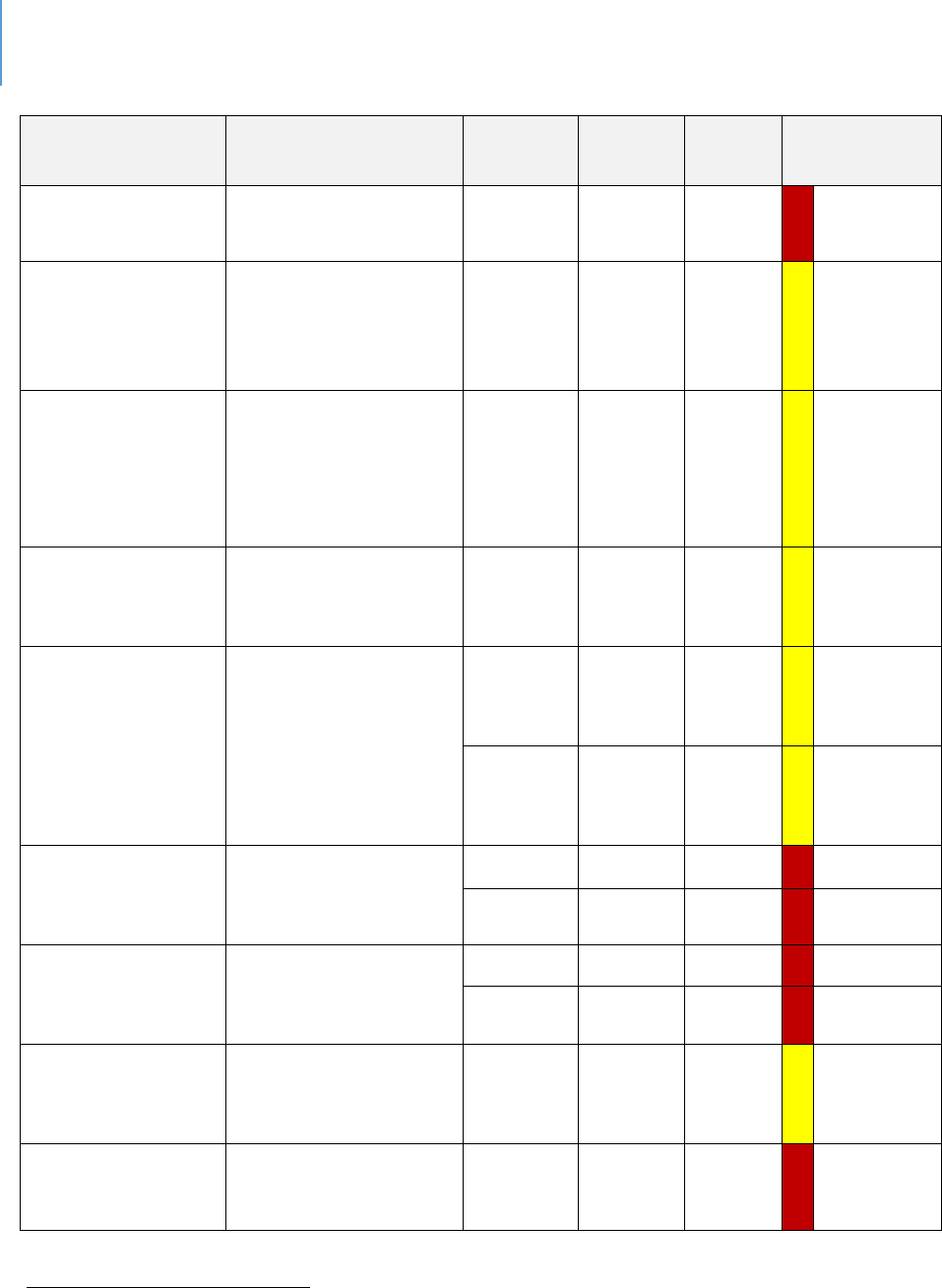

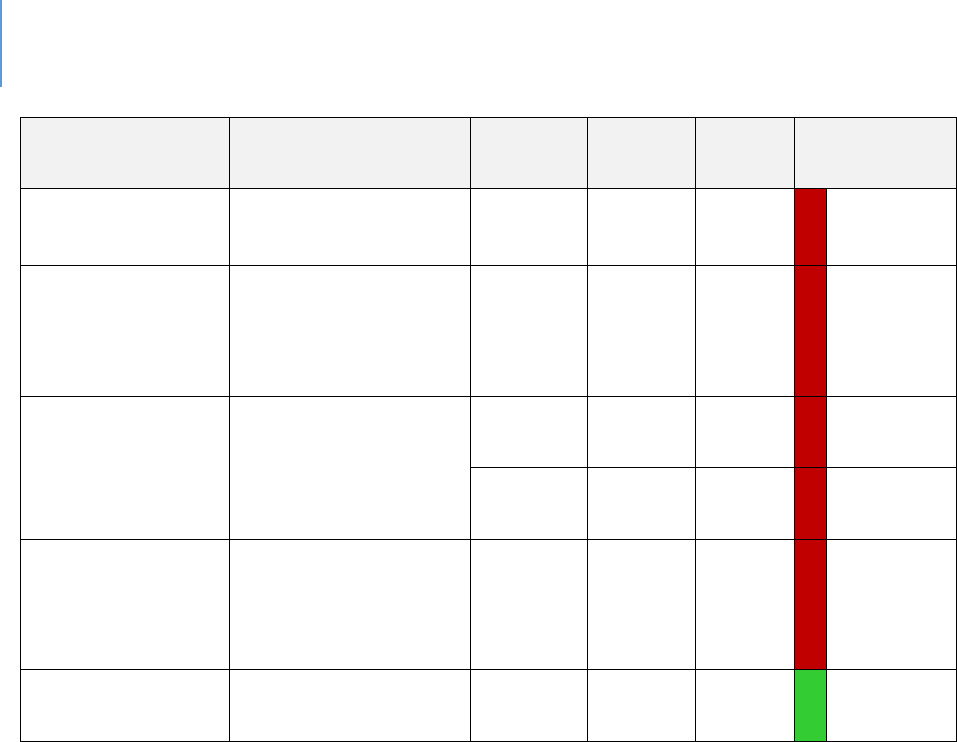

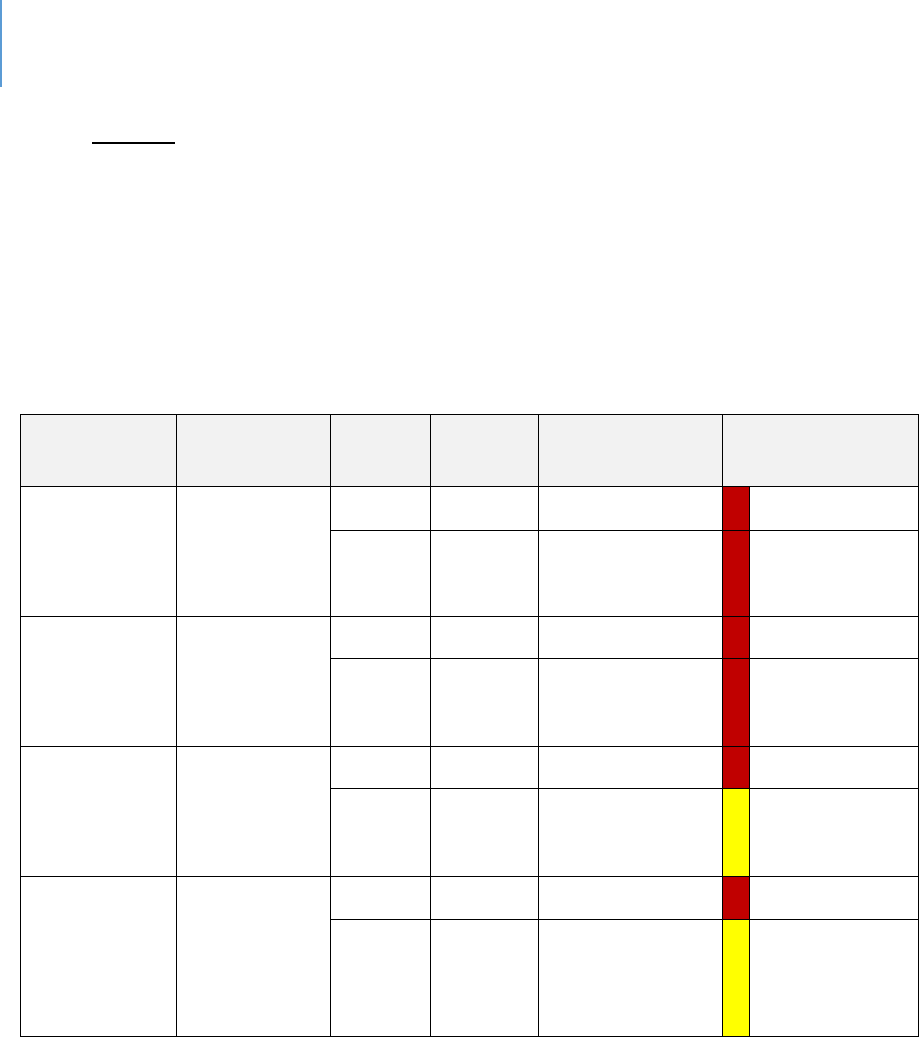

Table 7. Comparison of Aggregated Data ..................................................................................... 34

Table 8. Behavioral Health Outcomes ........................................................................................... 35

Table 9.Comparison of Violence related Behaviors ...................................................................... 41

Table 10. Comparison of Nutrional Related Outcomes .............................................................. 45

Table 11. Comparison of Alzheimer’s and HIV Outcomes ............................................................ 47

Table 12. Comparison of Health Pracces .................................................................................... 48

Table 13. Access to Services .......................................................................................................... 50

Table 14. Facilies ......................................................................................................................... 53

Table 15. Comparave Housing Data ............................................................................................ 54

Table 16. Birth Data ....................................................................................................................... 55

Table 17. Health Indicators for Children and Youth ...................................................................... 56

Table 18. Violence Outcomes regarding Children and Youth ........................................................ 58

Table 19. Foster Care Outcomes ................................................................................................... 59

Table 20. Home Status of Children and Youth .............................................................................. 59

Table 21. Overall Child Wellbeing Rankings: Top 10 Counes 3-Year Average ............................. 62

Table 22. Comparison of Overall CSC Counes and Lee County Ranks on Child Wellbeing ......... 63

Table 23. County Rankings on Specic Child Wellbeing Variables ................................................ 64

Table 24. Ranked Comparison Results for Lee County on Specic Kids Count Metrics ................ 66

Table 25. Comparison of Average County Scores ......................................................................... 69

Table 26. CSC Funding and Per Capita (Youth) .............................................................................. 70

Table 27. Poverty ........................................................................................................................... 73

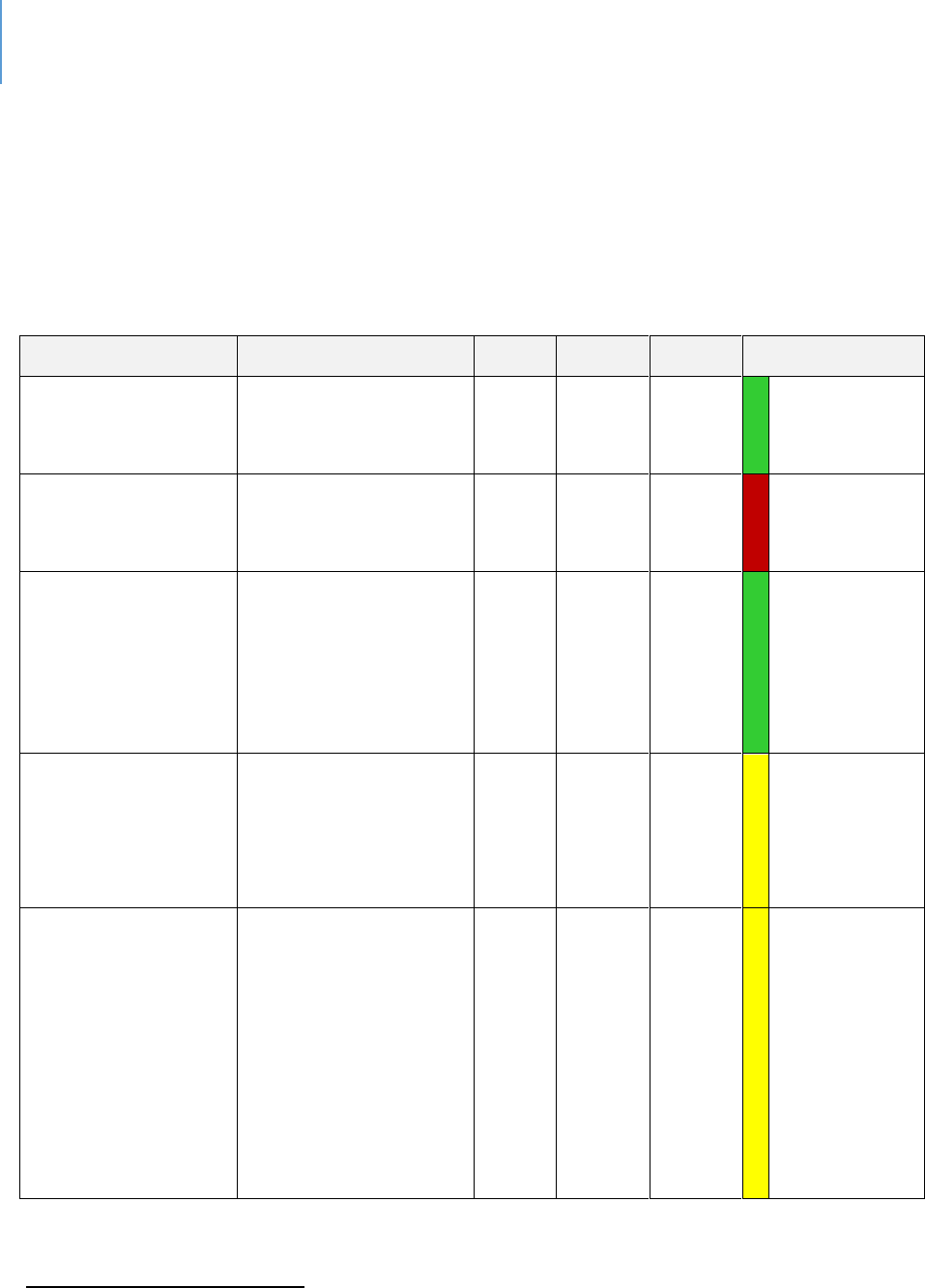

Table 28. Mental Health Services .................................................................................................. 80

Table 29. Housing .......................................................................................................................... 82

Table 30. Transportaon ............................................................................................................... 84

Table 31. Child-care ....................................................................................................................... 85

Table 32. Homelessness ................................................................................................................ 86

Table 33. Special Populaons ........................................................................................................ 87

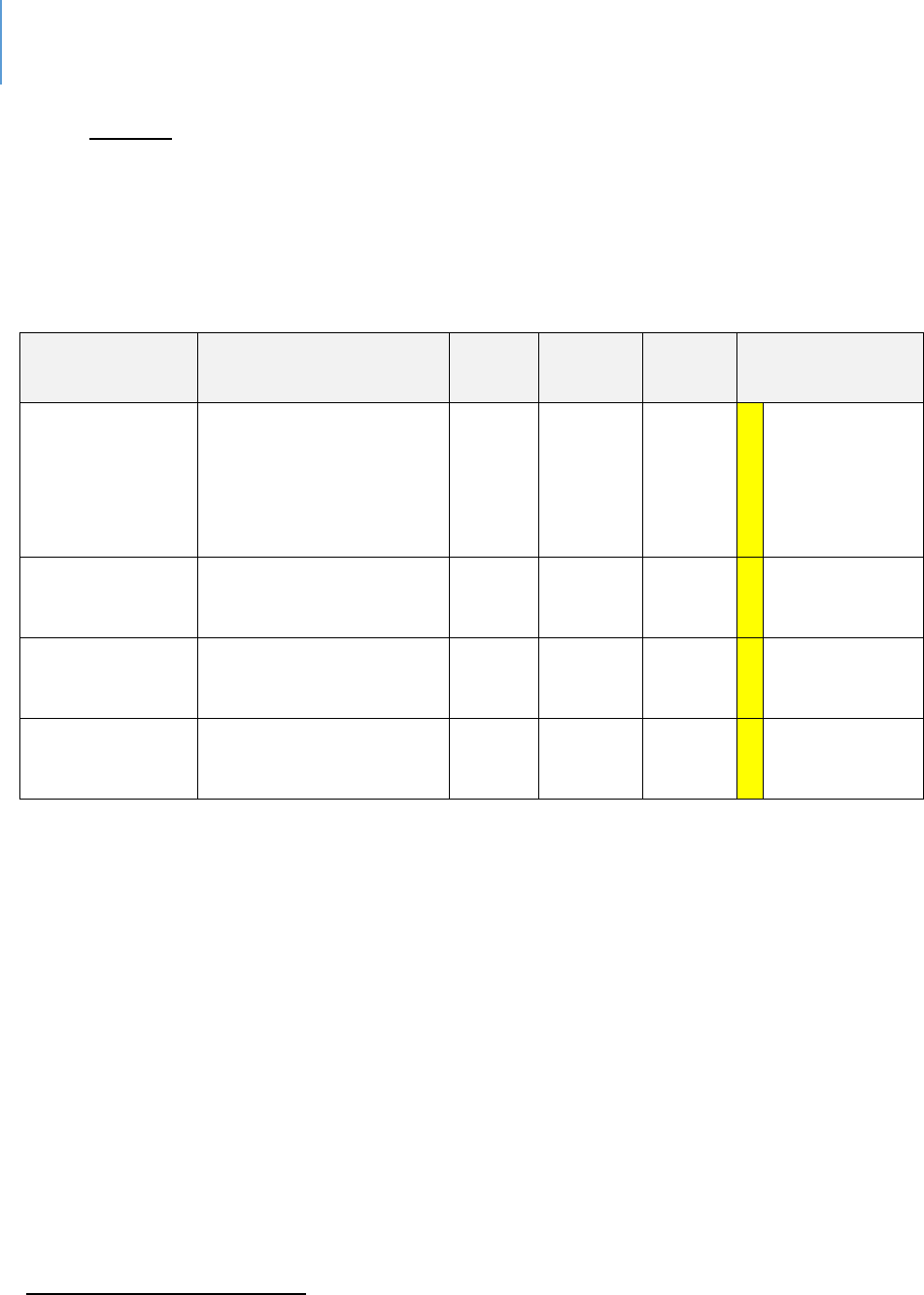

Table 34. Comparave Housing Data ............................................................................................ 92

Table 35. Lee County Renter Household Income .......................................................................... 93

Table 36. Lee County Distribuon of Paid Rent Ranges ................................................................ 93

Table 37. Annotated Distribuon of Paid Rent Ranges ................................................................. 94

Table 38. Aordable Rent Income (@30%) vs Available Units at that Income ............................. 94

Table 39. Low Income Housing in Lee County .............................................................................. 95

Table 40. Rental Cost-burden in Lee County ................................................................................. 97

Table 41. Comparison of Various Access Indicators ...................................................................... 98

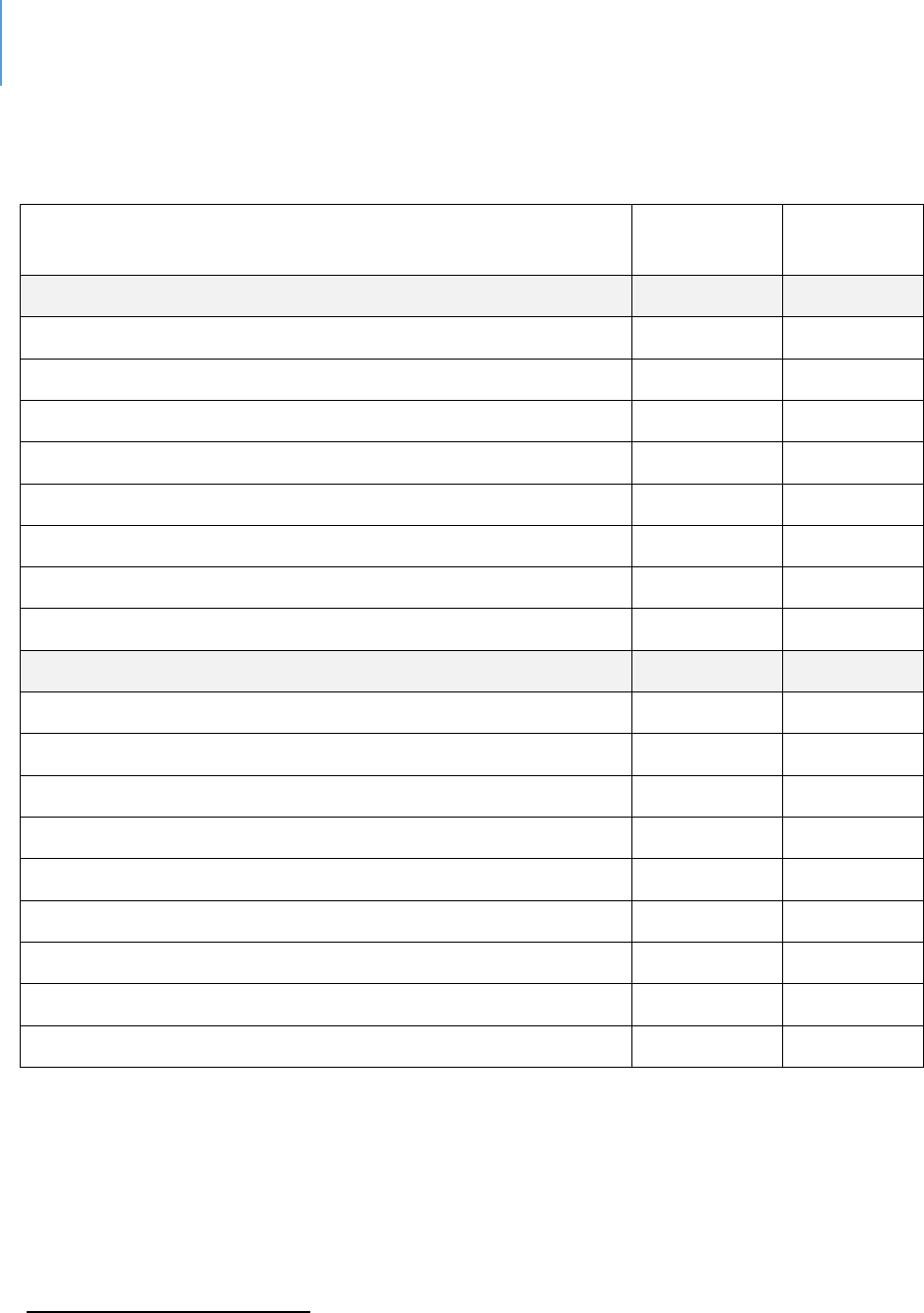

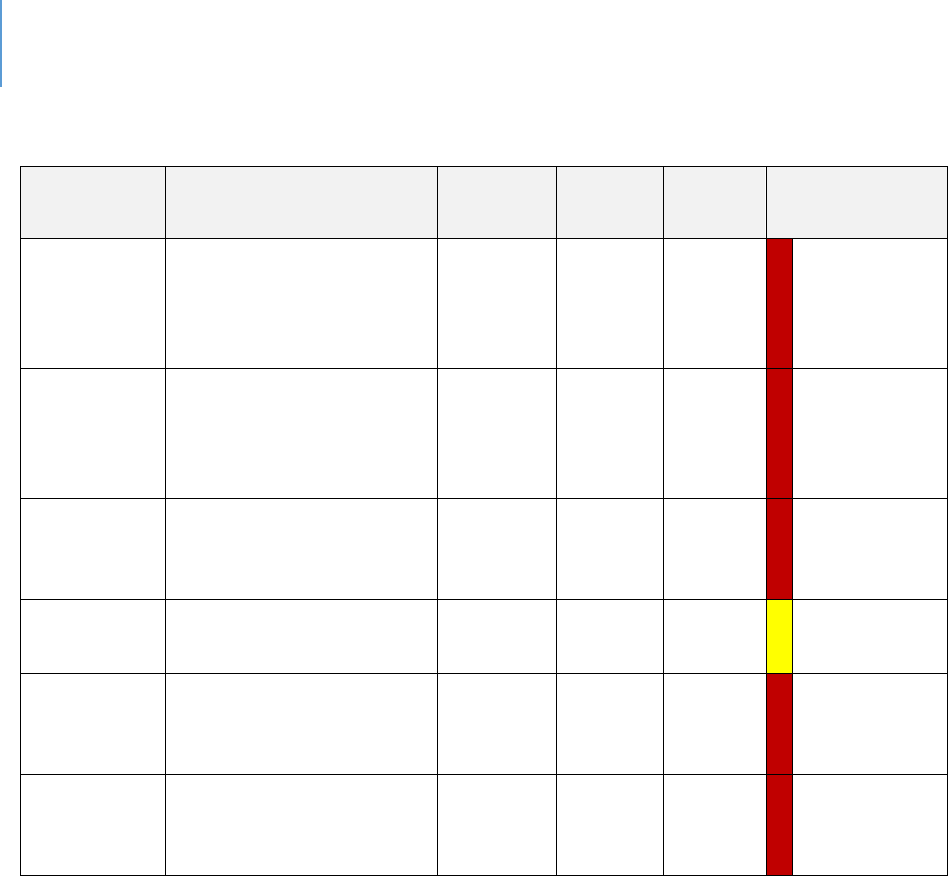

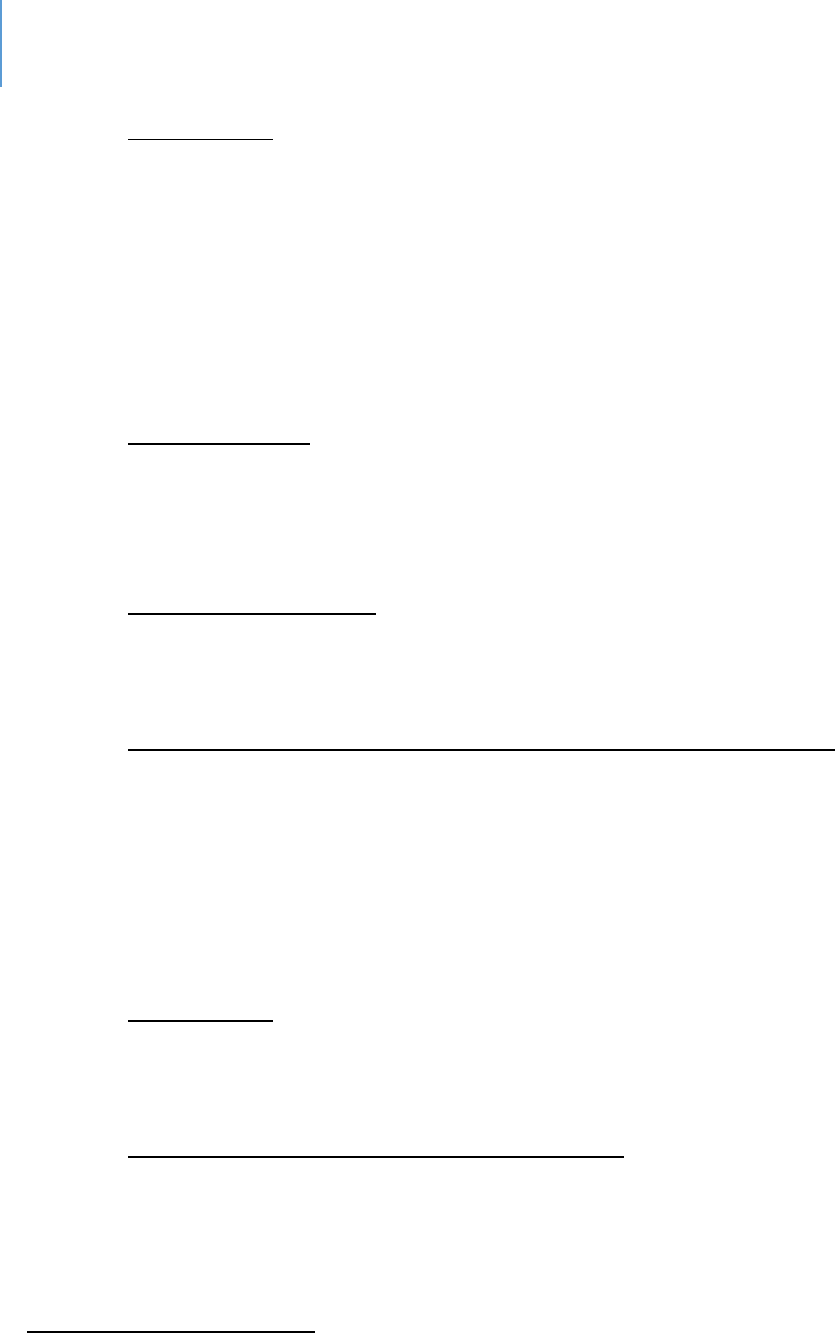

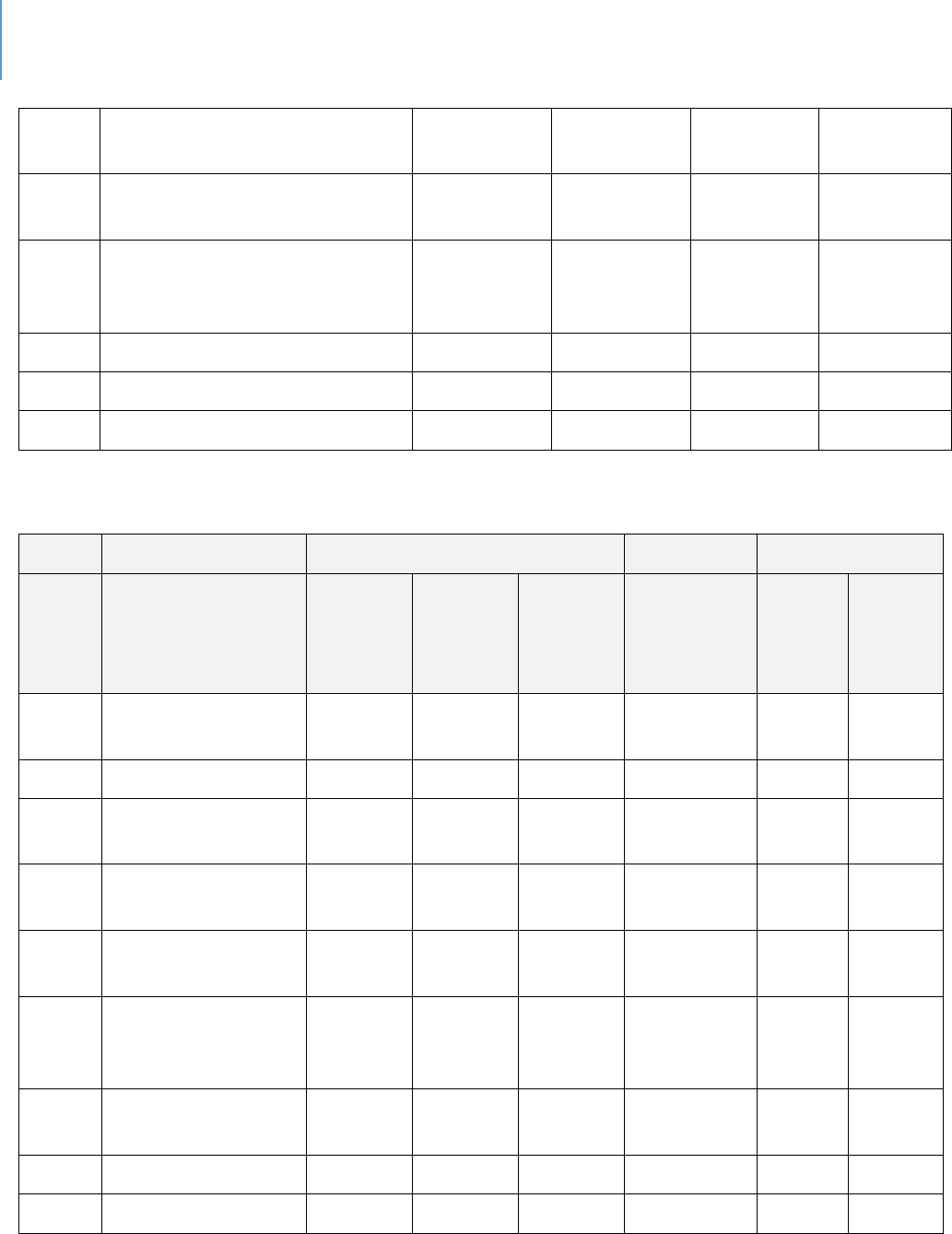

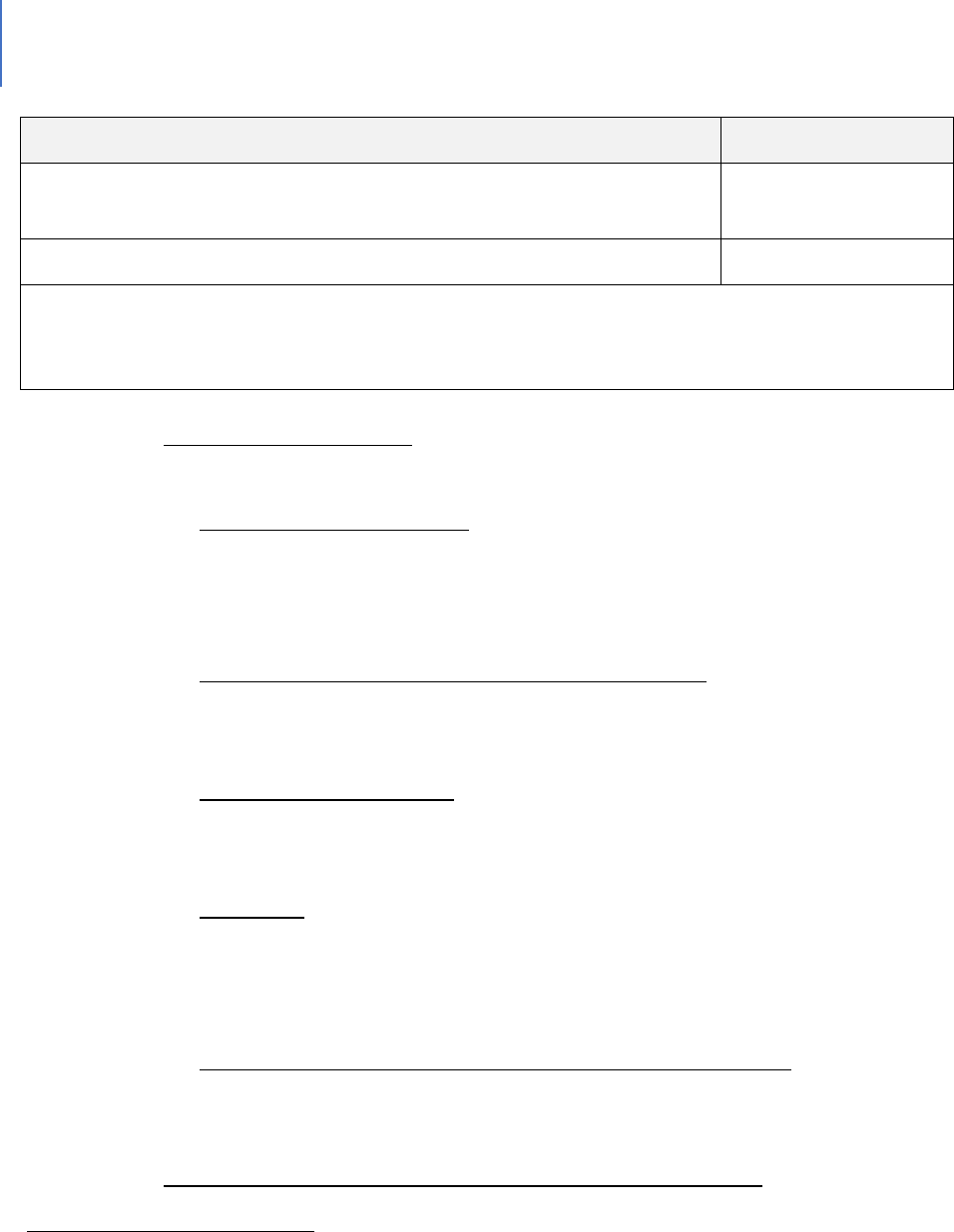

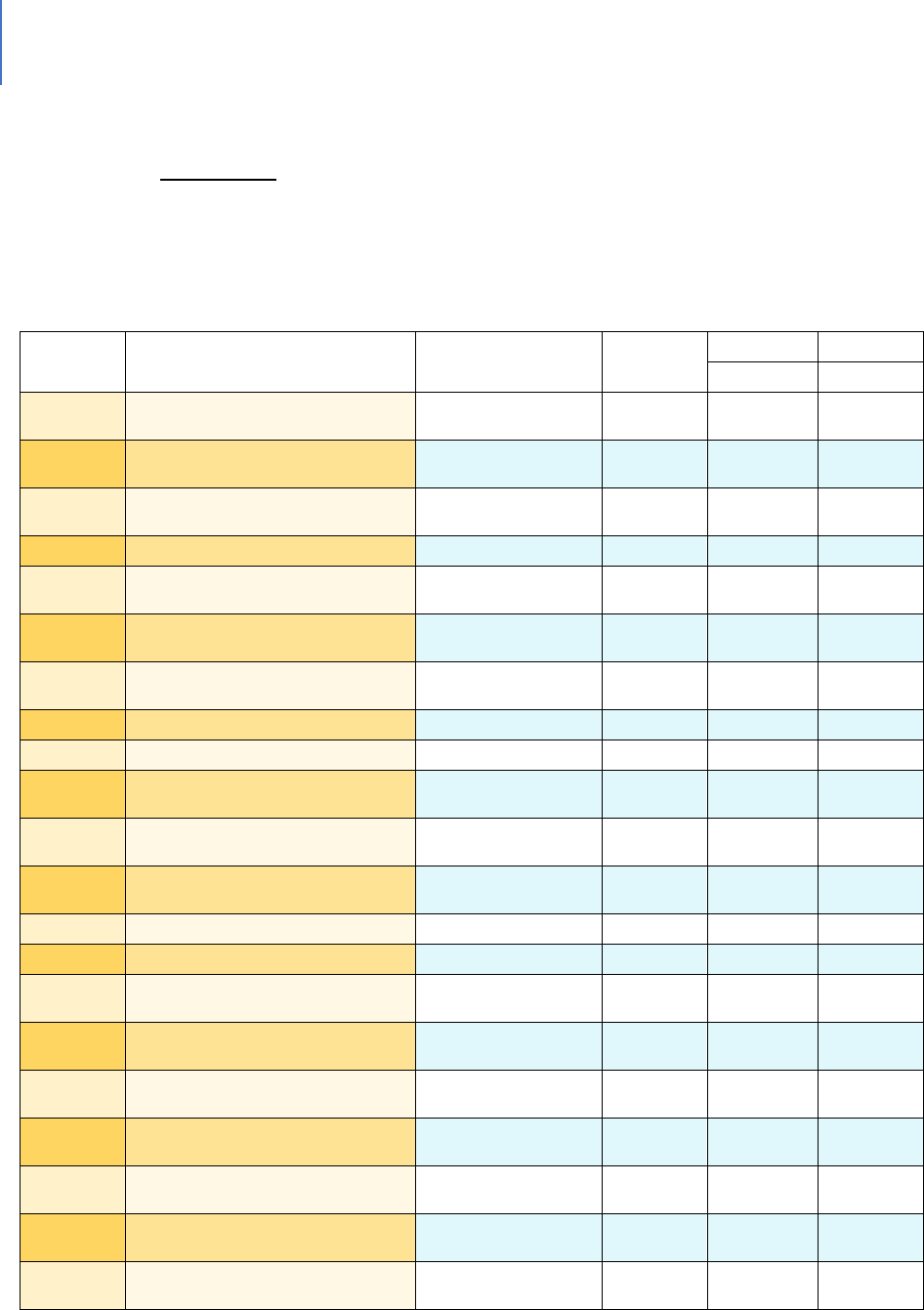

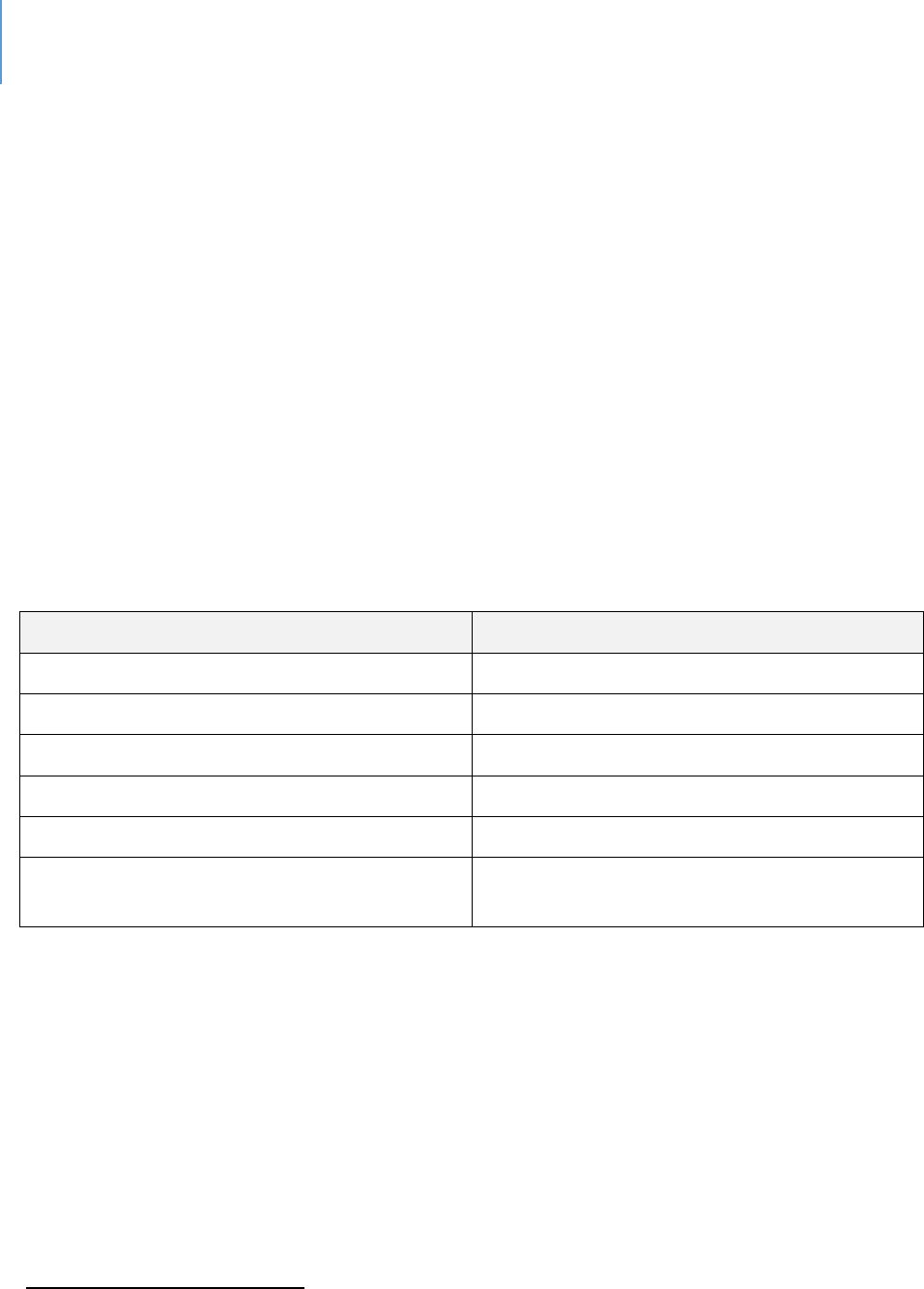

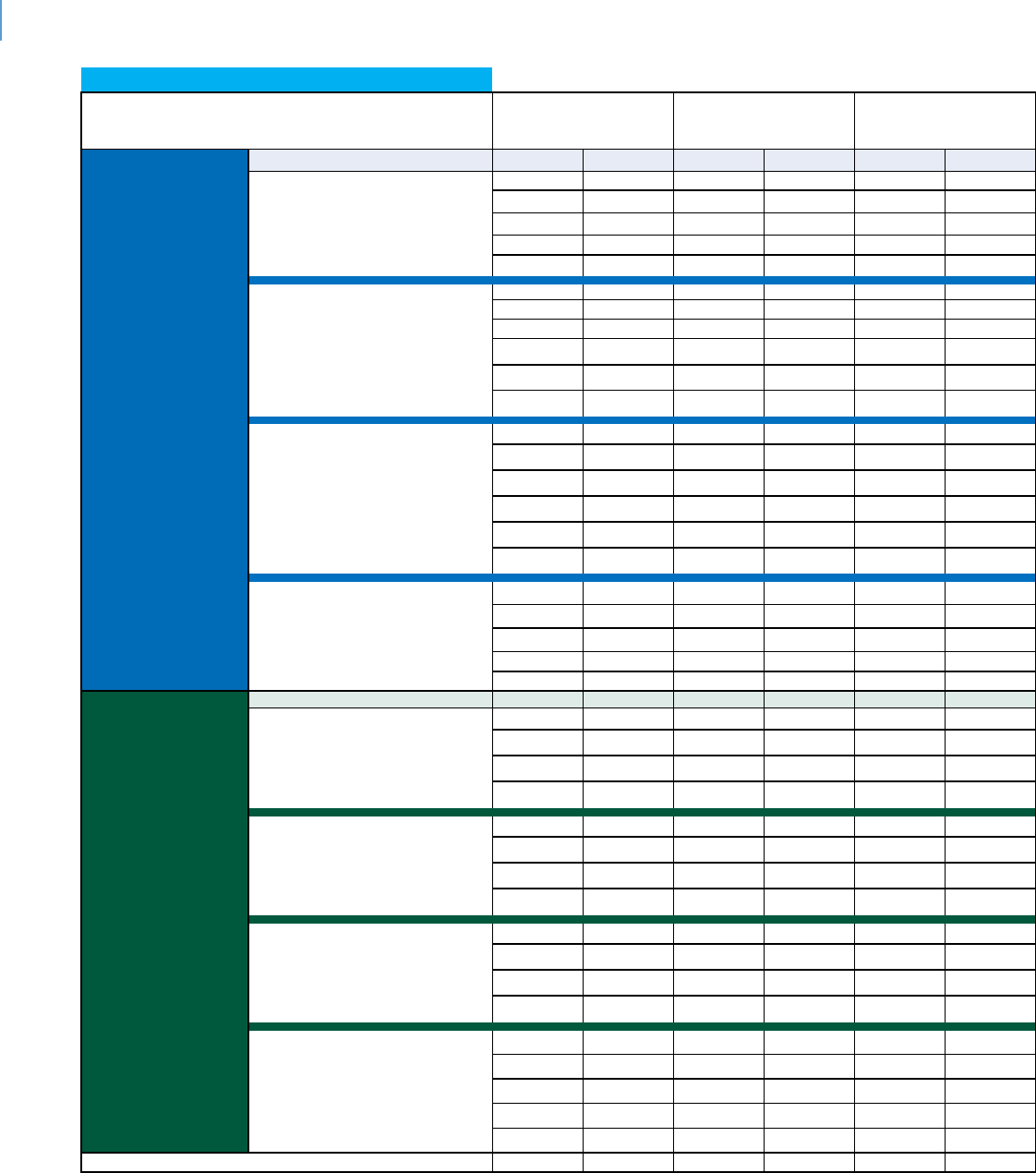

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Table 42. Cost Burden for Households in Florida Including at Least One Person with a Disability

(Age 5+) ....................................................................................................................................... 102

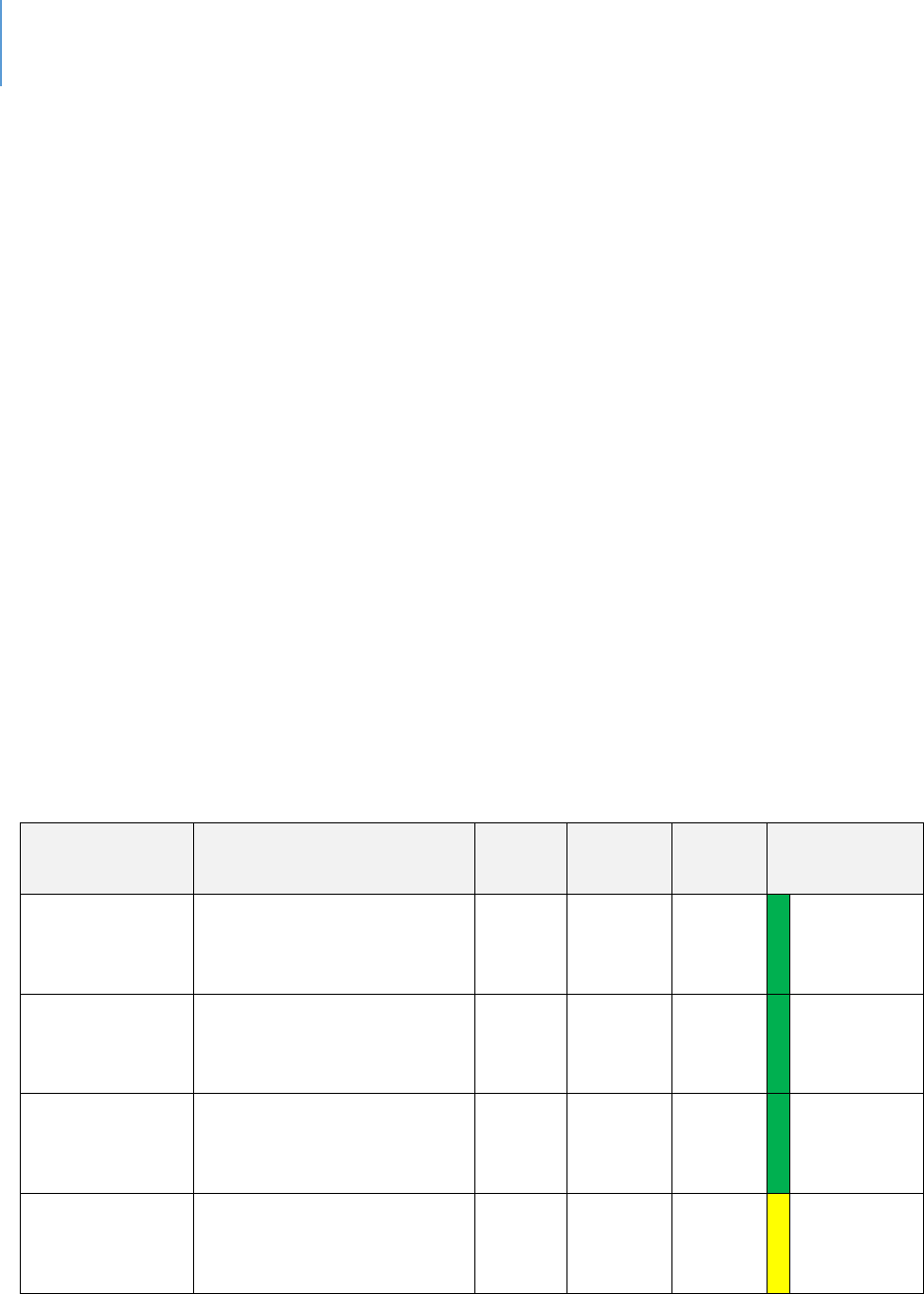

Table 43. Comparison of Nutrional Related Outcomes ............................................................ 114

Table 44. Food Insecurity in Lee County ..................................................................................... 116

Table 45. Percentage of Income Spent on Food by Quinles ..................................................... 123

Table 46. Esmaon of Severe Financial Constraint* ................................................................. 124

Table 47. Health Care Stang Comparison Data ........................................................................ 138

Table 48. Lee County Fastest Growing Industries by NAICS Title (PROJECTIONS ....................... 142

Table 49. Lee County Industries Gaining the Most New Jobs (PROJECTIONS) ........................... 143

Table 50. Lee County Fastest-Growing Occupaons (PROJECTIONS) ......................................... 144

Table 51. Lee County Occupaons Gaining the Most New Jobs (PROJECTIONS) ....................... 148

Table 52. Community Demographics .......................................................................................... 173

Table 53. 2018 Unemployment and Income by Educaon Level ................................................ 184

Table 54. Kindergarten Readiness Scores ................................................................................... 189

Table 55. Educaon ..................................................................................................................... 190

Table 56. Violence Outcomes Regarding Children and Youth ..................................................... 191

Table 57. Median and Mean Hourly Wages for Selected Jobs in Florida .................................... 192

Table 58. 2015 Poverty Guidelines for the 48 Conguous States and the District of Columbia 195

Table 59. Child Poverty in Lee County ......................................................................................... 196

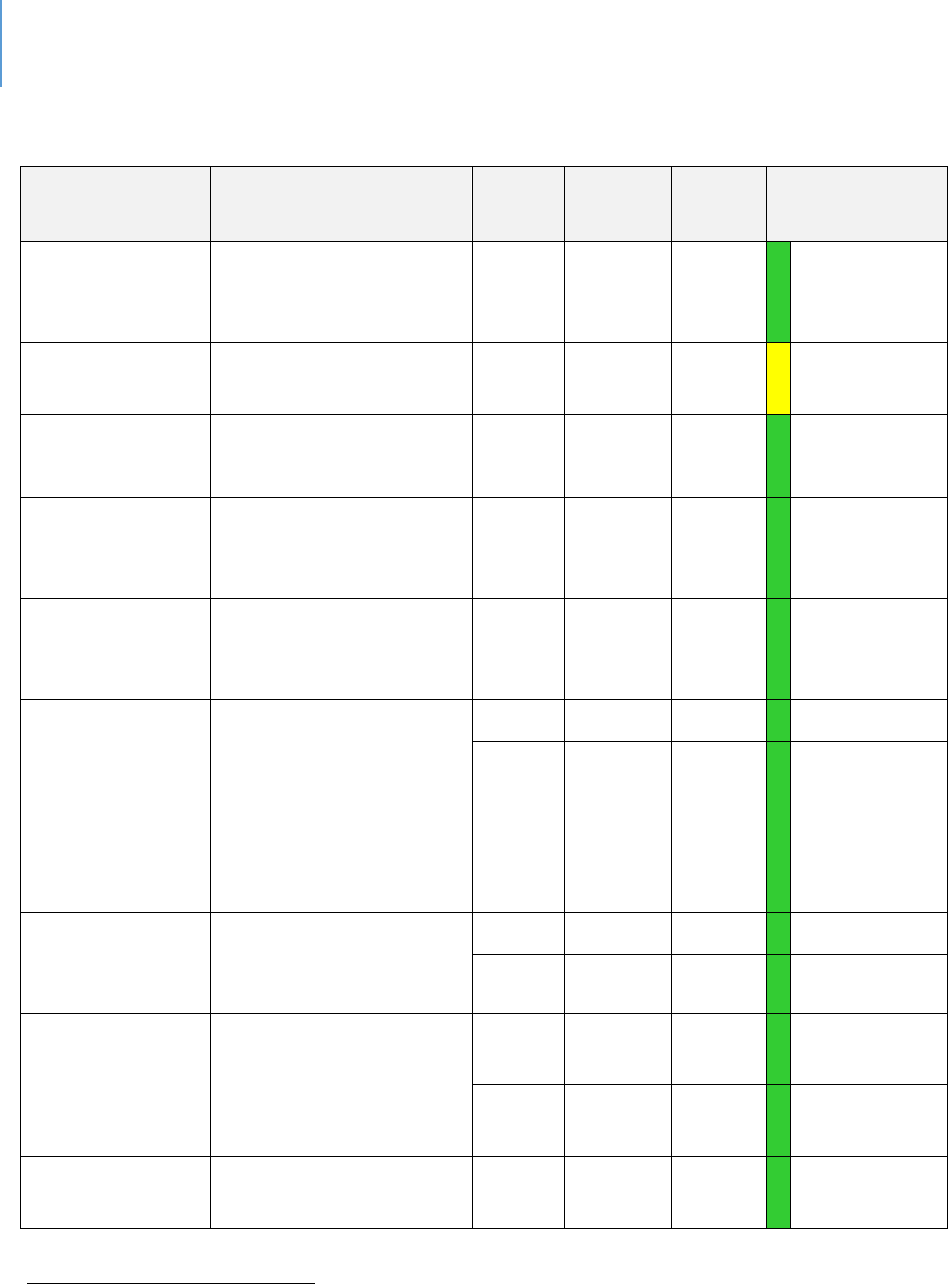

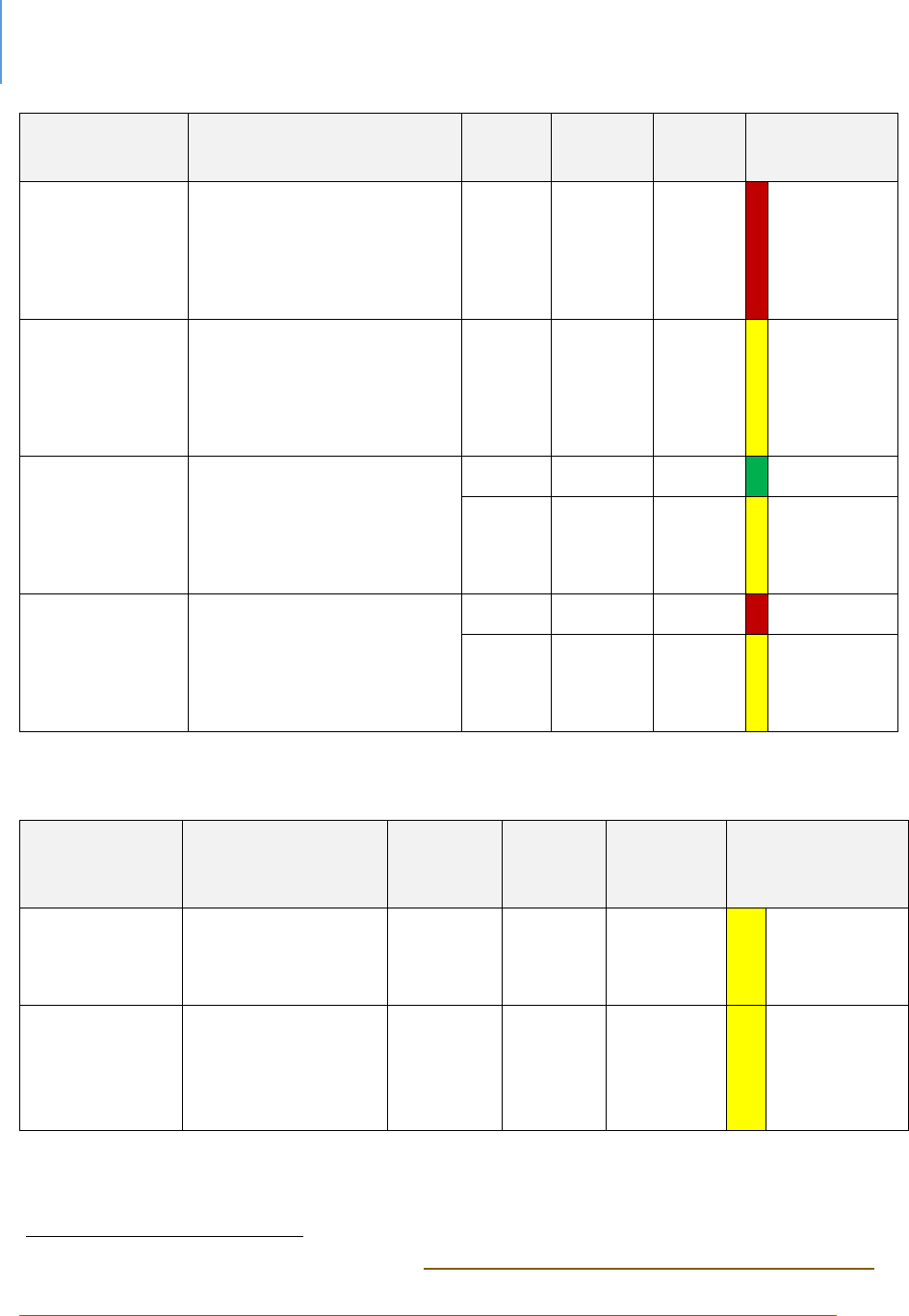

Table 60. Behavioral Health Indicators - Lee County .................................................................. 203

Table 61. State Rankings: Mental Health Expenditures as a Percentage of Total State

Expenditures, Average of FY 2012 and 2013 .............................................................................. 208

Table 62. Funding Equity ............................................................................................................. 211

Table 63. Child Abuse and Neglect Indicators in Lee County ...................................................... 243

Table 64. Domesc Violence in Lee County ................................................................................ 257

Table 65. Rates of Domesc Violence – Lee County, FDLE Data ................................................. 257

Table 66. Dependency Rao Over Time ...................................................................................... 260

Table 67. Elderly Abuse Cases in Florida per 1,000 Persons ....................................................... 261

Table 68. Adult Protecon Scorecard Department of Children and Families Suncoast Region:

20th Circuit (Lee, Collier, Charloe, Hendry, Glades) ................................................................. 262

Table 69. Adult Protecve Invesgators Workload ..................................................................... 263

Table 70. Suicide Rates Adults 60+.............................................................................................. 263

Table 71. Comparison Data ......................................................................................................... 271

Table 72. Rates of Forcible Sexual Oences in Lee County Compared to the State of Florida

Average, 2018 ............................................................................................................................. 271

Table 73. Rates of Rape and Forcible Sex Oences, FDLE data ................................................... 271

Table 74. Child Abuse and Neglect Indicators in Lee County ...................................................... 281

Table 75. Domesc Violence in Lee County ................................................................................ 284

Table 76. Rates of Domesc Violence – Lee County, FDLE Data ................................................. 284

Table 77. Rates of Forcible Sexual Oences in Lee County Compared to the State of Florida

Average, 2018 ............................................................................................................................. 284

Table 78. Rates of Rape and Forcible Sex Oences, FDLE Data .................................................. 285

Table 79. Comparave Data on Rape and Violent Crime ............................................................ 285

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Table 80. Young Adults Aging Out of Out-of-Home Care who did not Perpetrate Abuse by their

25th Birthday by County ............................................................................................................. 286

Table 81. Suicide Rates in Lee County, FL .................................................................................... 286

Table 82. Suicide rates in Lee County .......................................................................................... 293

Table 83. Risk and Protecve Factors by Domain ....................................................................... 297

Table 84. School Data .................................................................................................................. 301

Table 85. Family History with Criminal Jusce System ............................................................... 301

Table 86. Peer Associaons ......................................................................................................... 301

Table 87. Mental Health History ................................................................................................. 301

Table 88. Alcohol Usage .............................................................................................................. 301

Table 89. Drug Usage .................................................................................................................. 302

Table 90. History of Physical Abuse ............................................................................................. 302

Table 91. History of Sexual Abuse ............................................................................................... 302

Table 92. Connuum of Care, Lee County 2018 Funding............................................................ 314

Table 93. Client Age Ranges Receiving Homelessness Prevenon Services (2013 – 2018) ........ 315

Table 94. Elderly Clients Served by HVS ...................................................................................... 315

Table 95. Income Level of Persons Receiving Homelessness Prevenon Assistance ................. 316

Table 96. Emergency Response Funding by Households ............................................................ 318

Table 97. Volunteer Summary ..................................................................................................... 319

Table 98. Percepons of Barriers to Hiring Persons with Disabilies (PWD) .............................. 334

Table 99. Cost Burden for Households in Florida Including At Least One Person with a Disability

(Age 5+) ....................................................................................................................................... 343

Table 100. Other HACFM data: Characteriscs of Residents ...................................................... 344

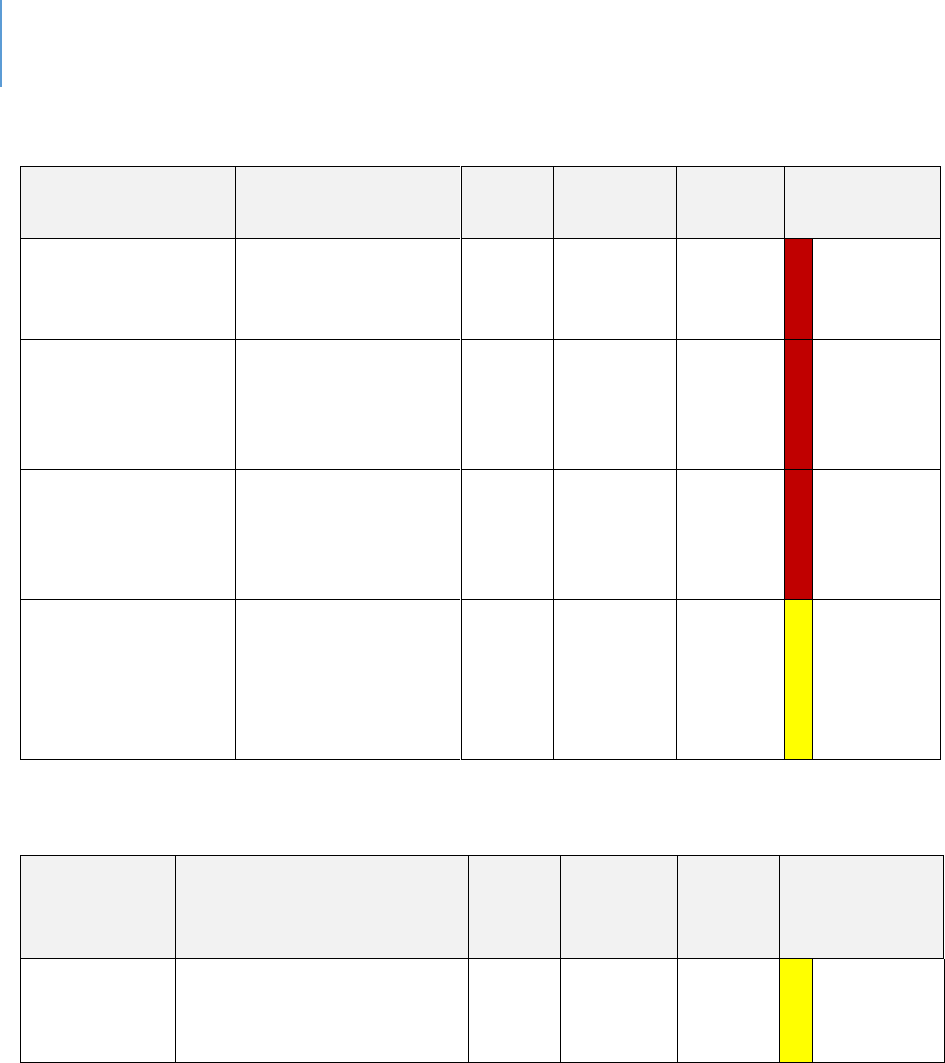

Table 101. Disability Status of Seniors ........................................................................................ 365

Table 102. Age Group Populaon Esmates for Lee County ...................................................... 374

Table 103. Financial Status of Seniors ......................................................................................... 375

Table 104. Elder Households with Cost Burden .......................................................................... 376

Table 105. Food Insecurity in Lee County ................................................................................... 376

Table 106. Seniors and SNAP 2017 ............................................................................................. 376

Table 107. Medically Underserved (65+) .................................................................................... 376

Table 108. Disability Status of Seniors ........................................................................................ 377

Table 109. Health Care Facilies for Seniors ............................................................................... 380

Table 110. Fiduciary Responsibilies and Other Roles ............................................................... 400

Table 111. Non-Acute Funding for Mental Health Services, Central Florida Behavioral Network

..................................................................................................................................................... 403

Table 112. Mandated Services .................................................................................................... 407

Table 113. Policy Choice funding FY 18-19 Actuals ..................................................................... 408

Table 114. Court System FY 18-19 Actuals .................................................................................. 409

Table 115. Discreonary Grants/Donaons ................................................................................ 410

Table 116. Total Human Services Expenditure ............................................................................ 411

Table 117. Cost-burdened Data ................................................................................................... 427

Table 118. Shares of average expenditures on selected major components by composion of

consumer unit, 2018 ................................................................................................................... 428

Table 119. Moderate and Severe Housing Cost-Burden ............................................................. 429

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

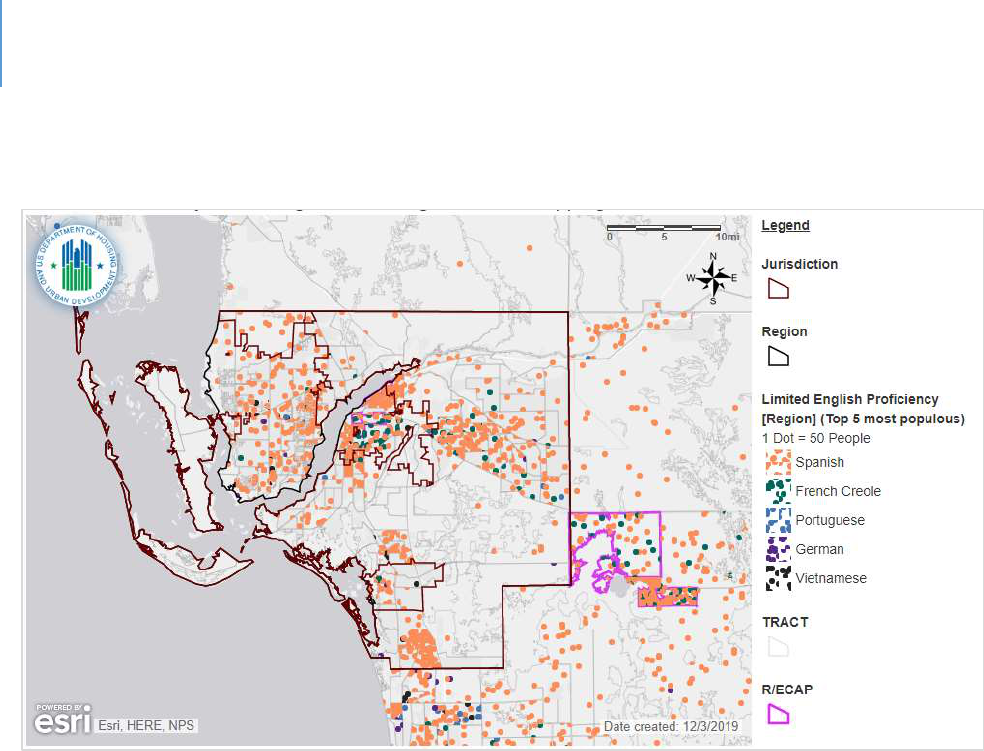

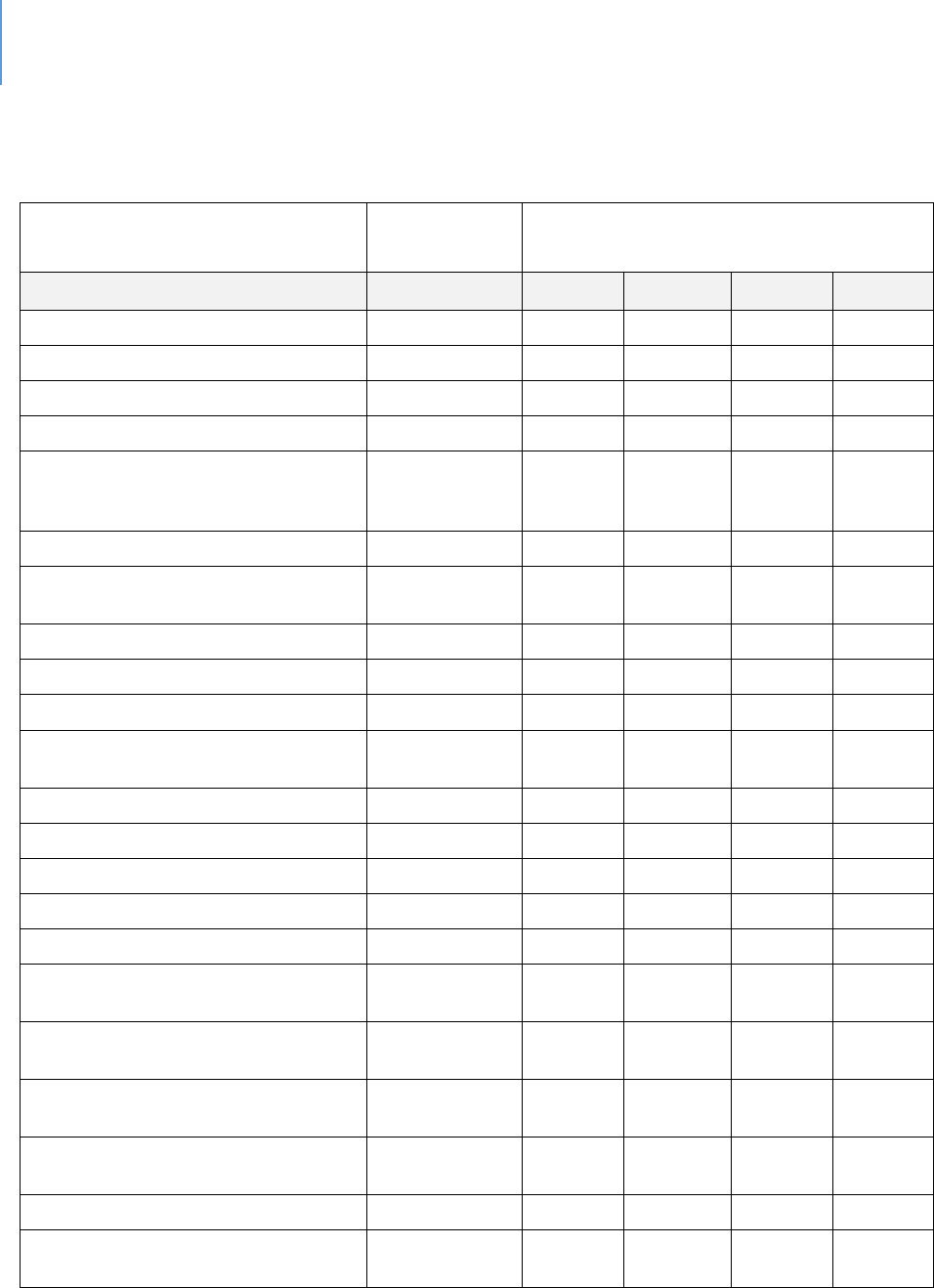

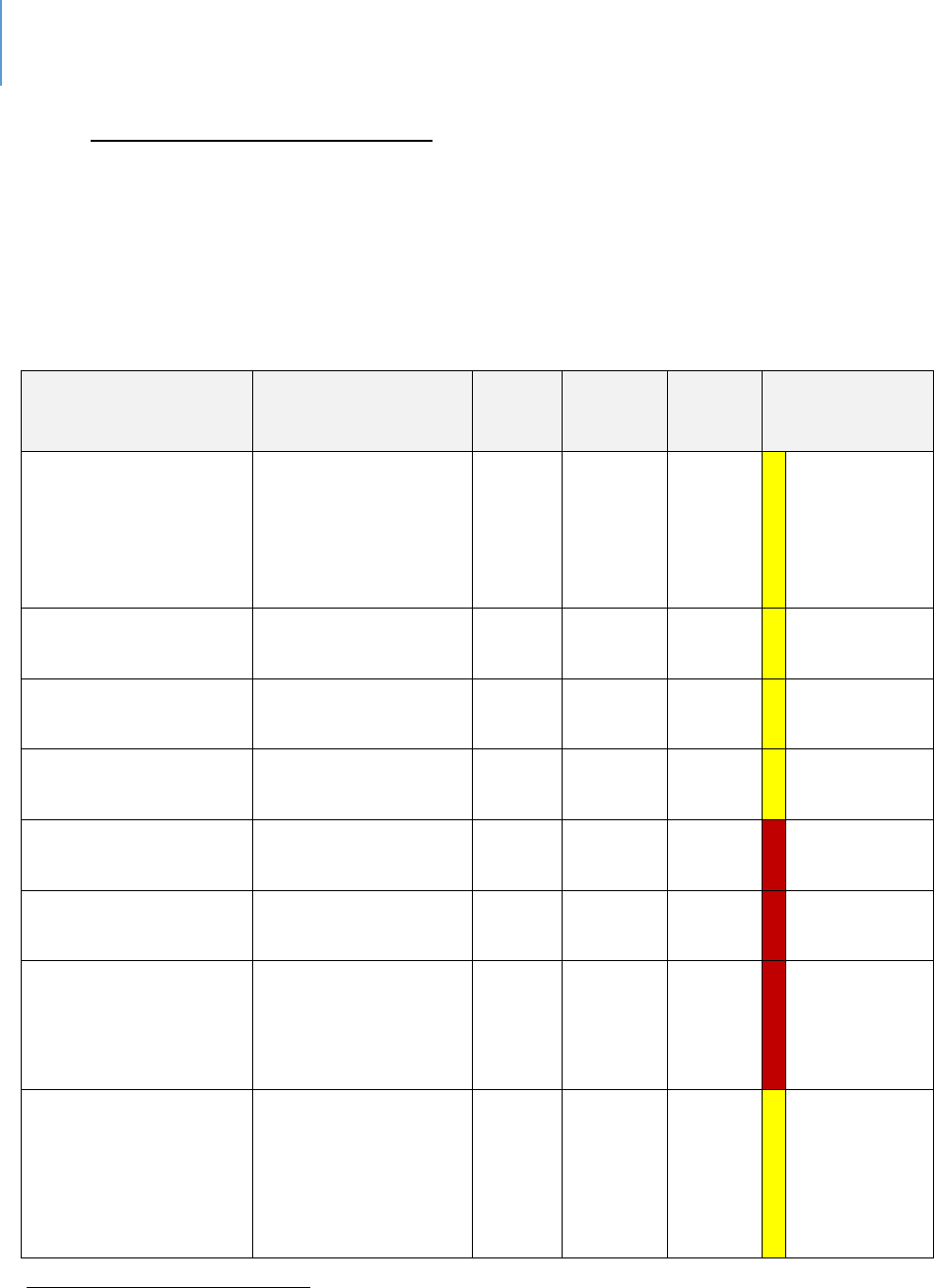

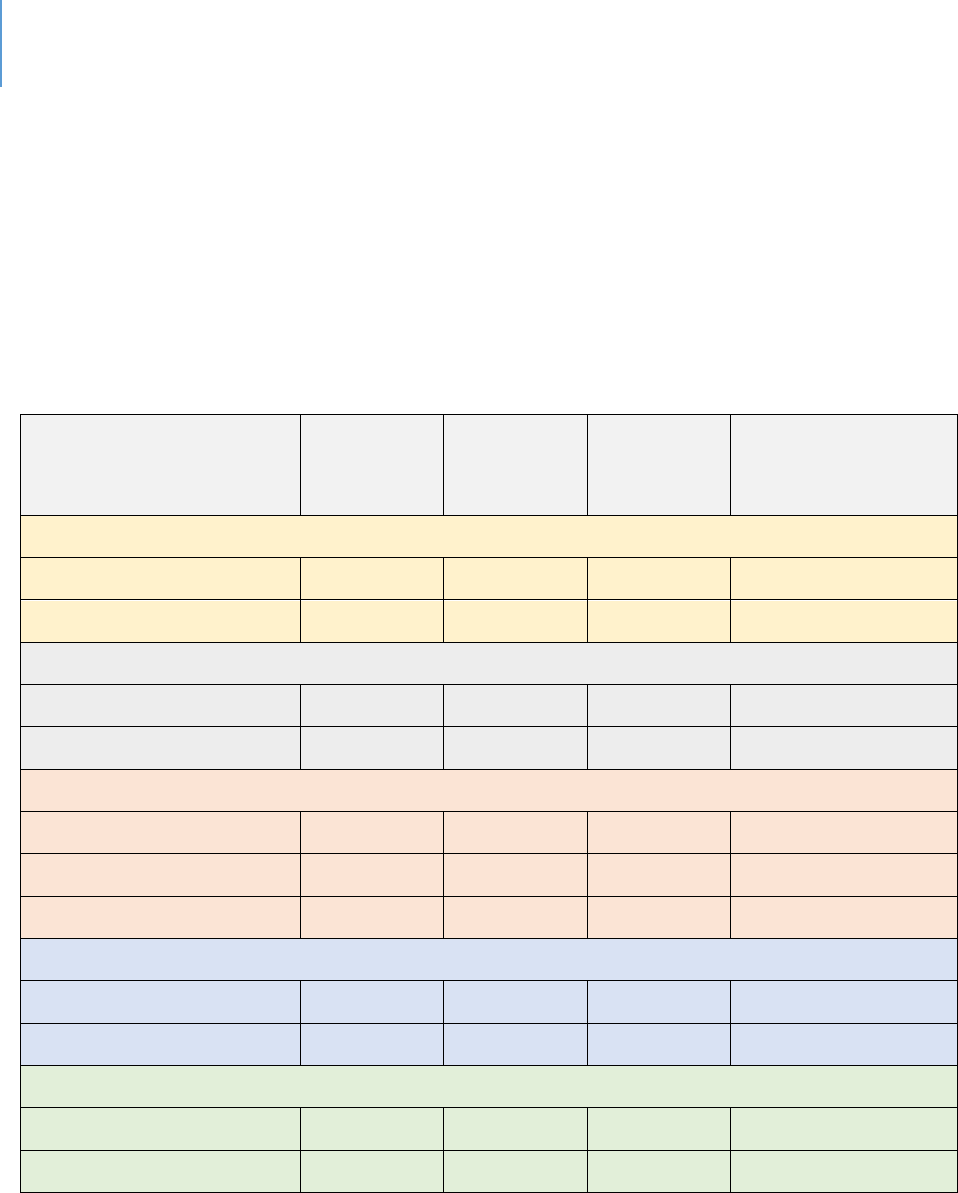

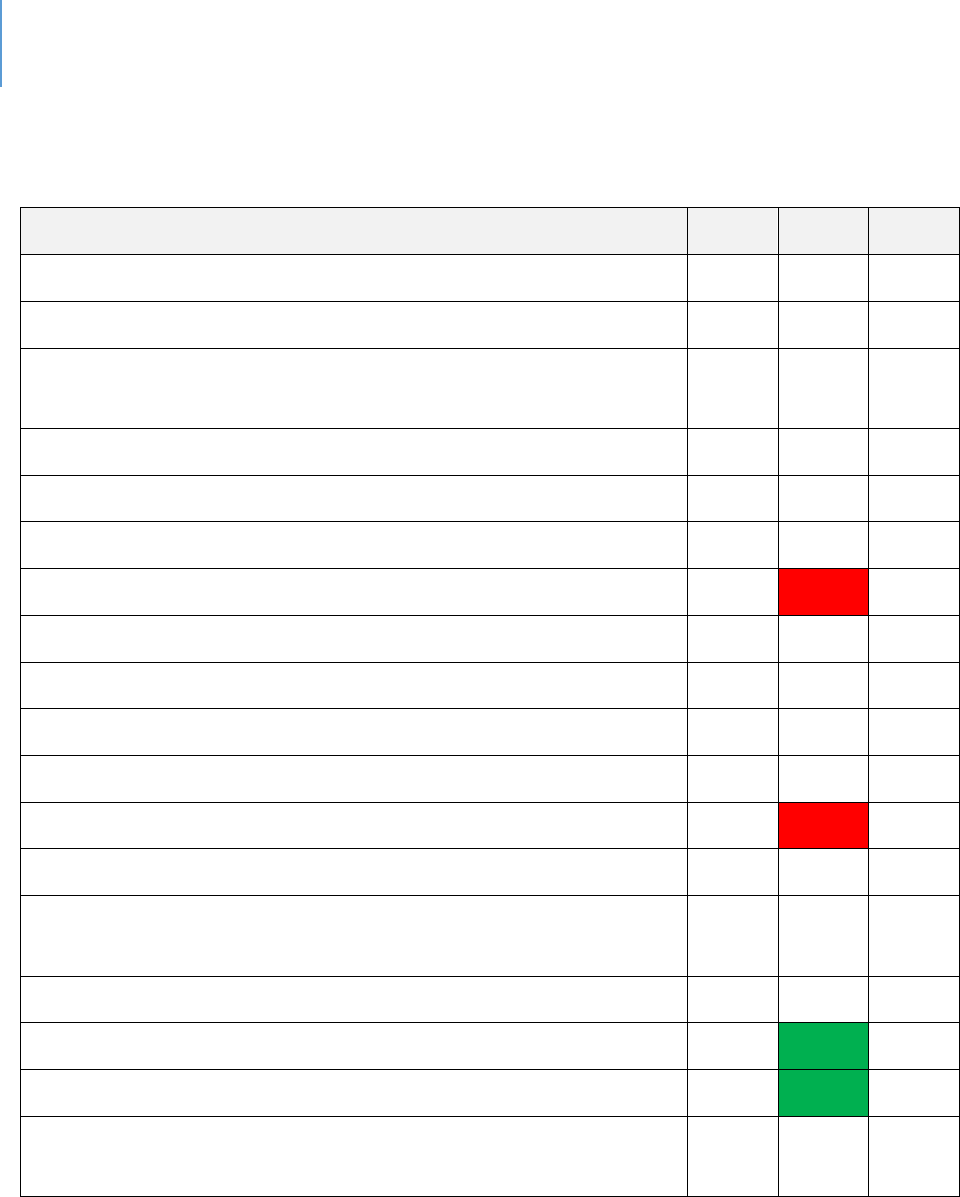

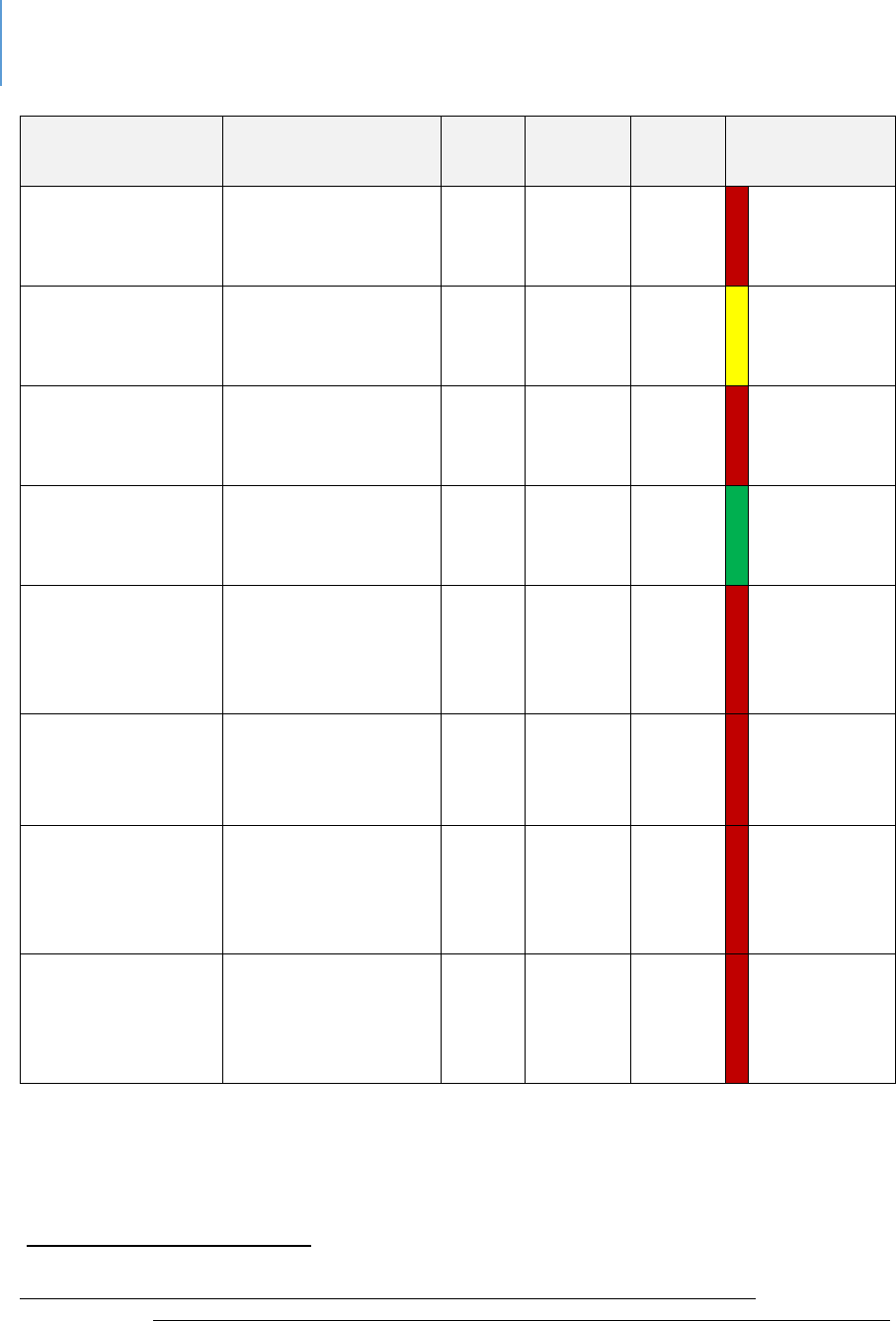

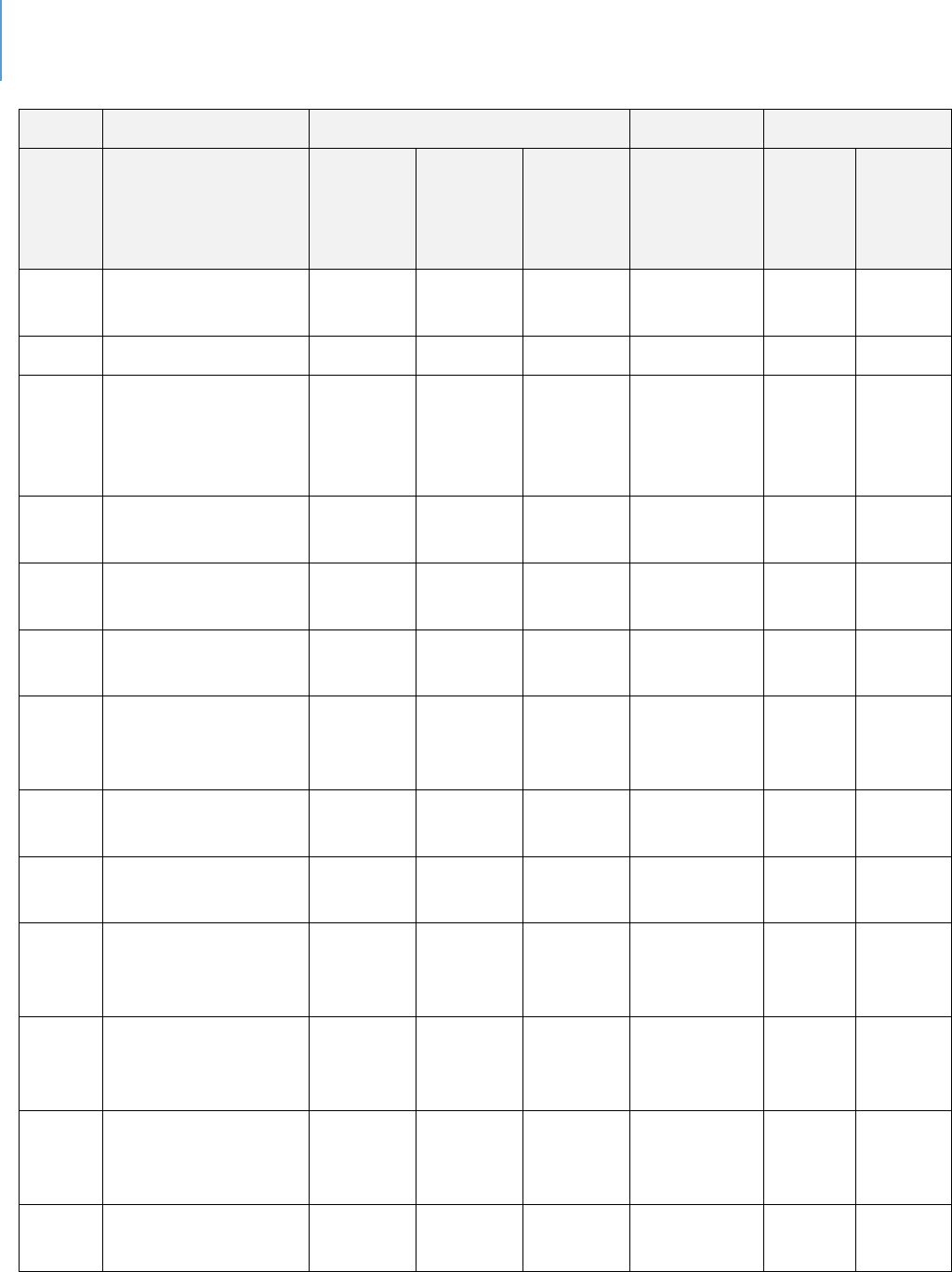

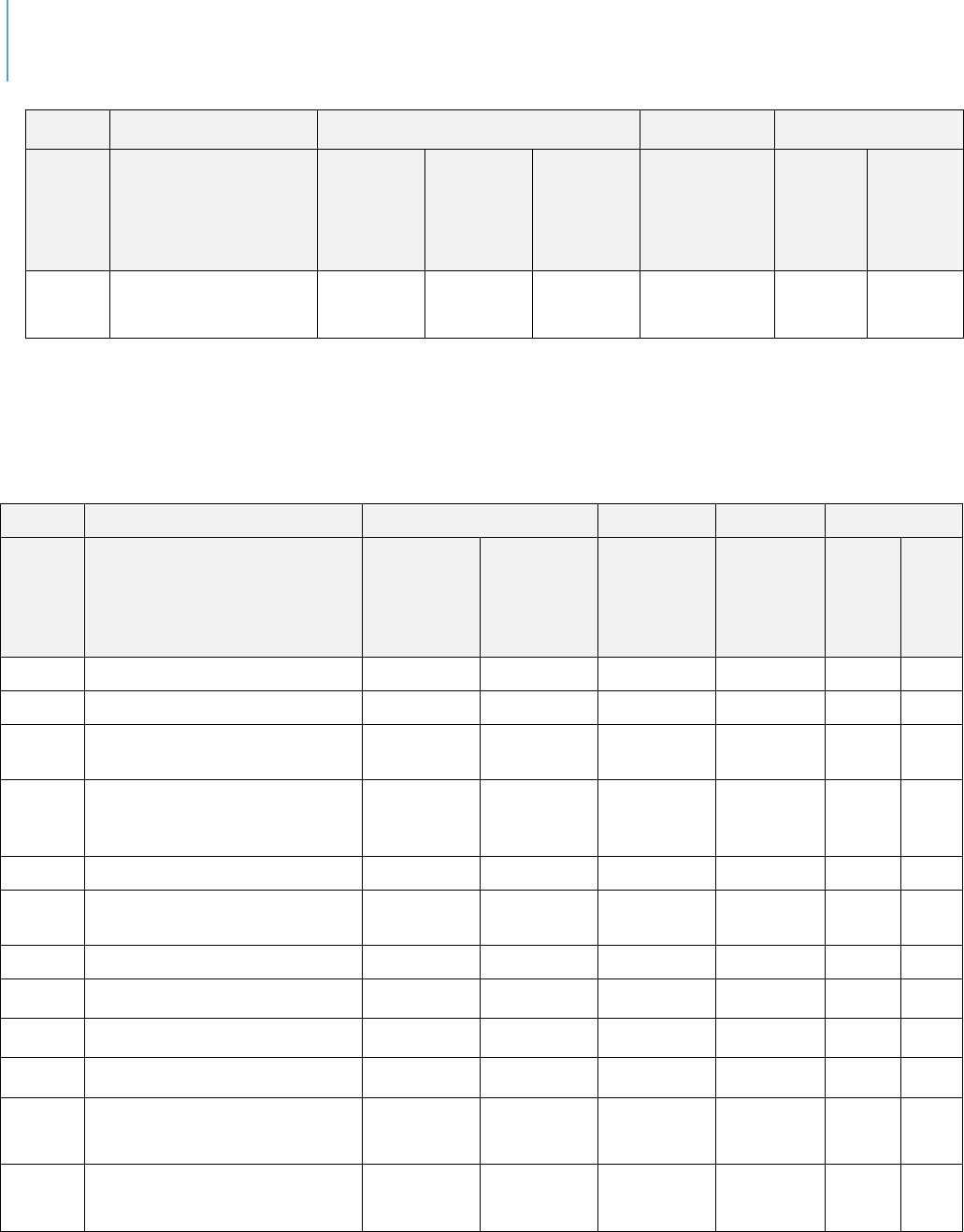

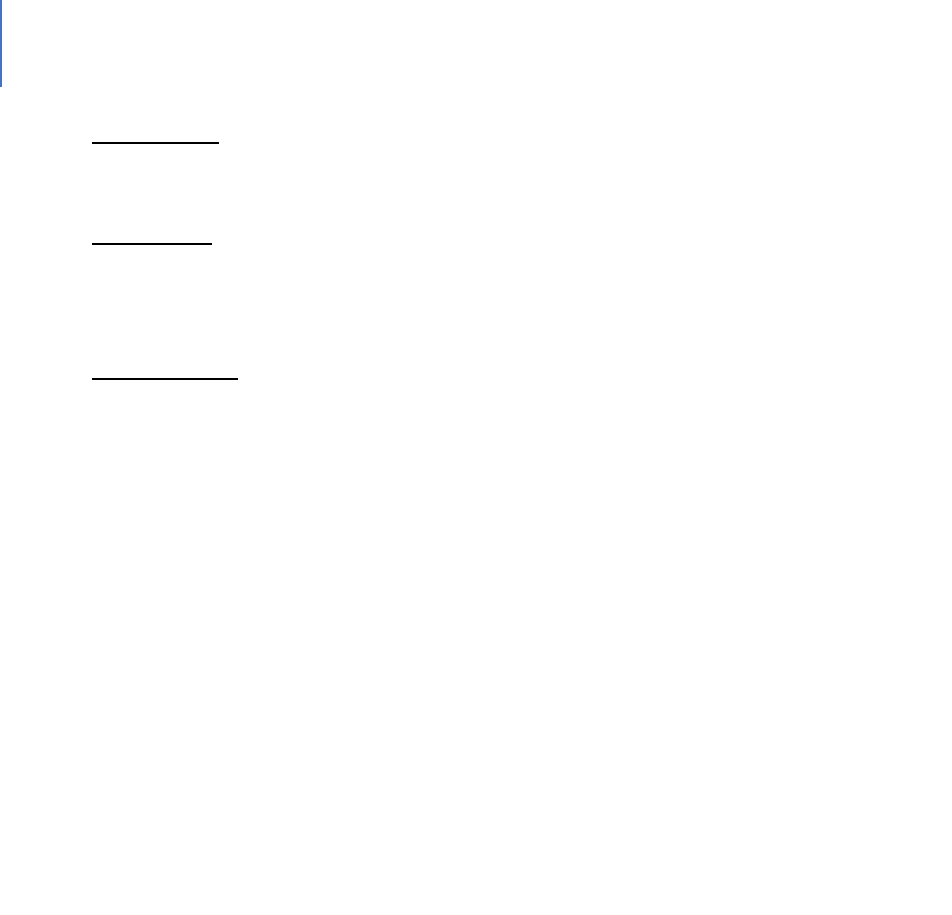

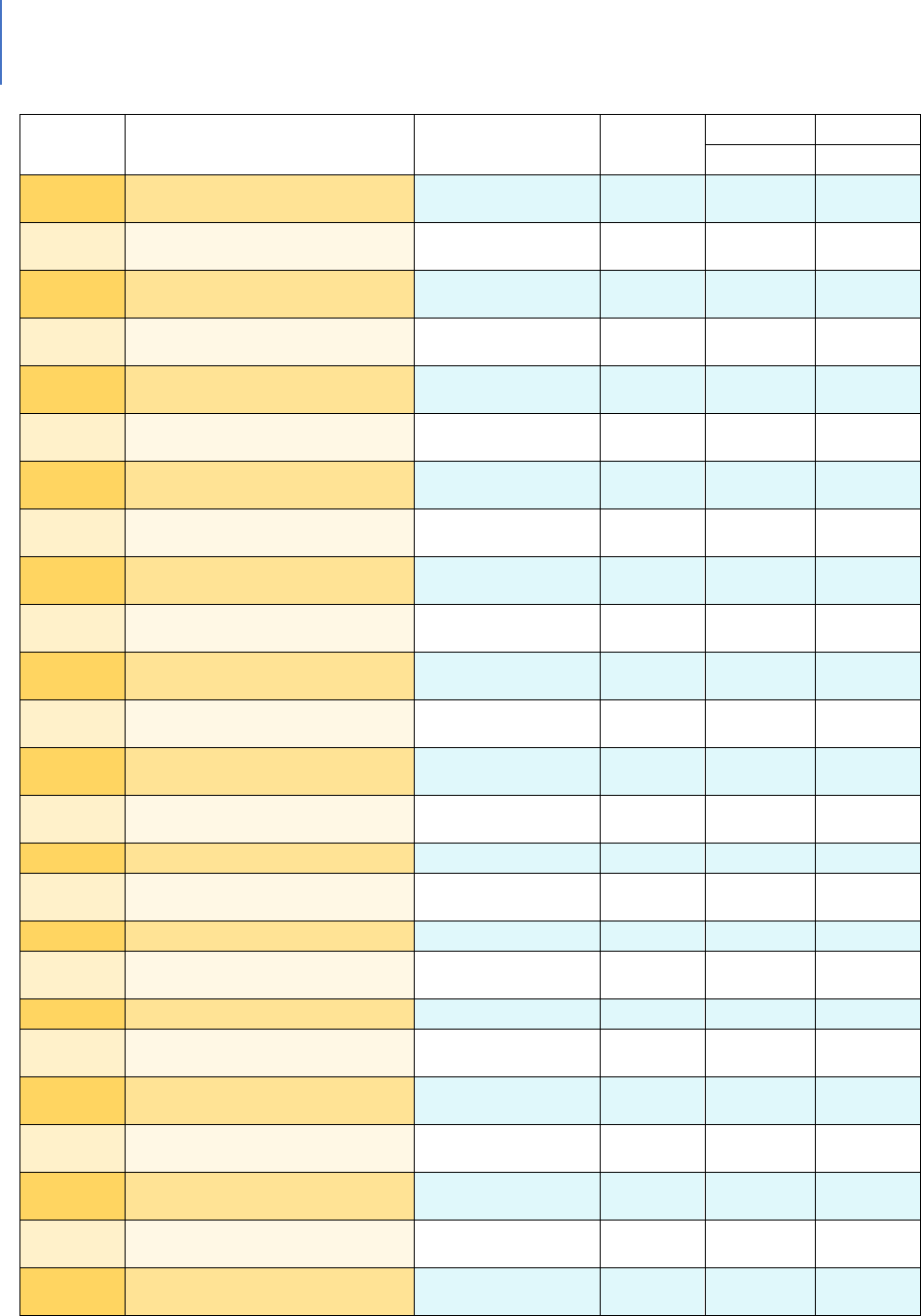

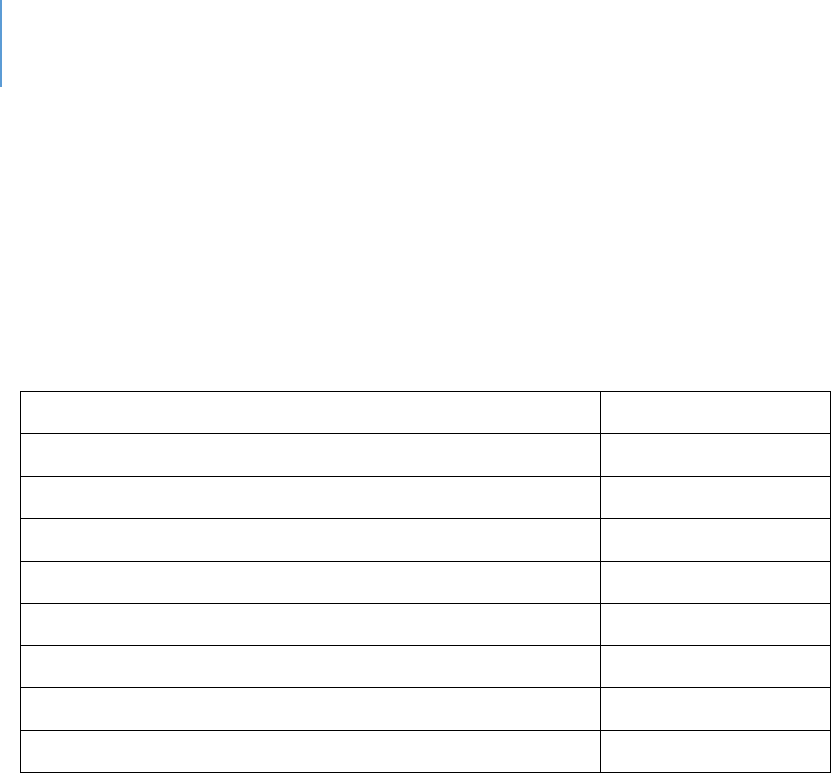

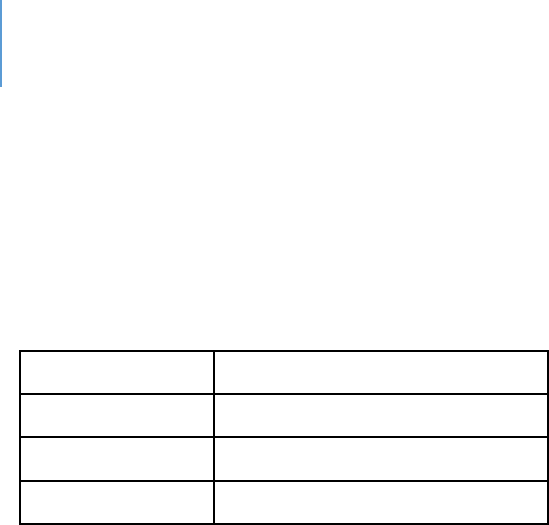

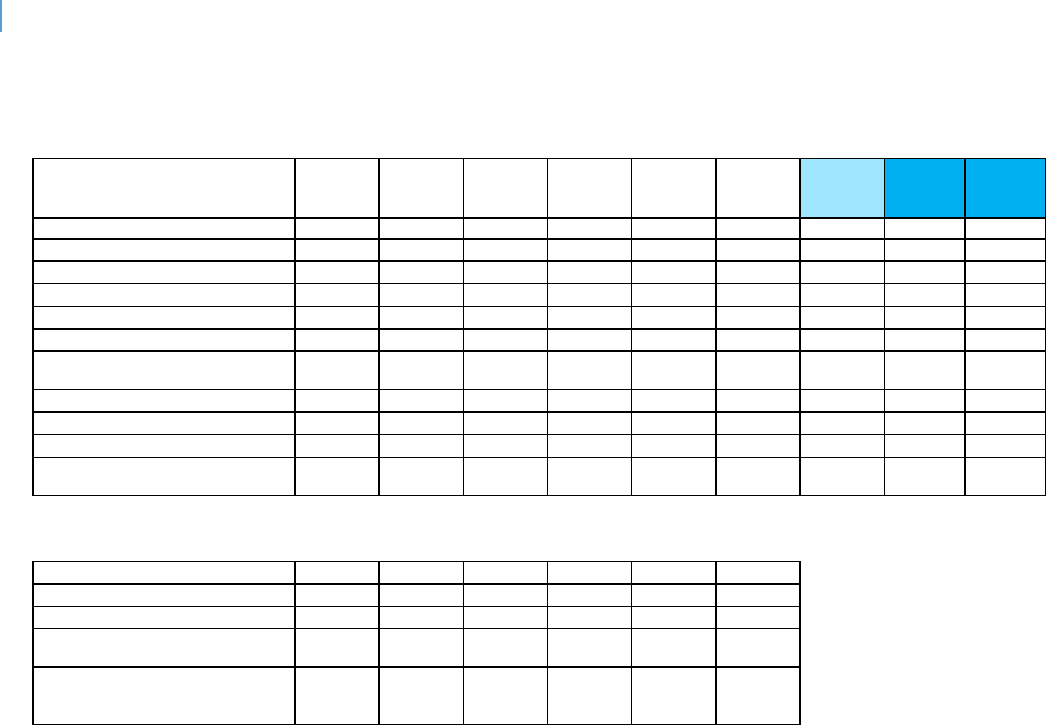

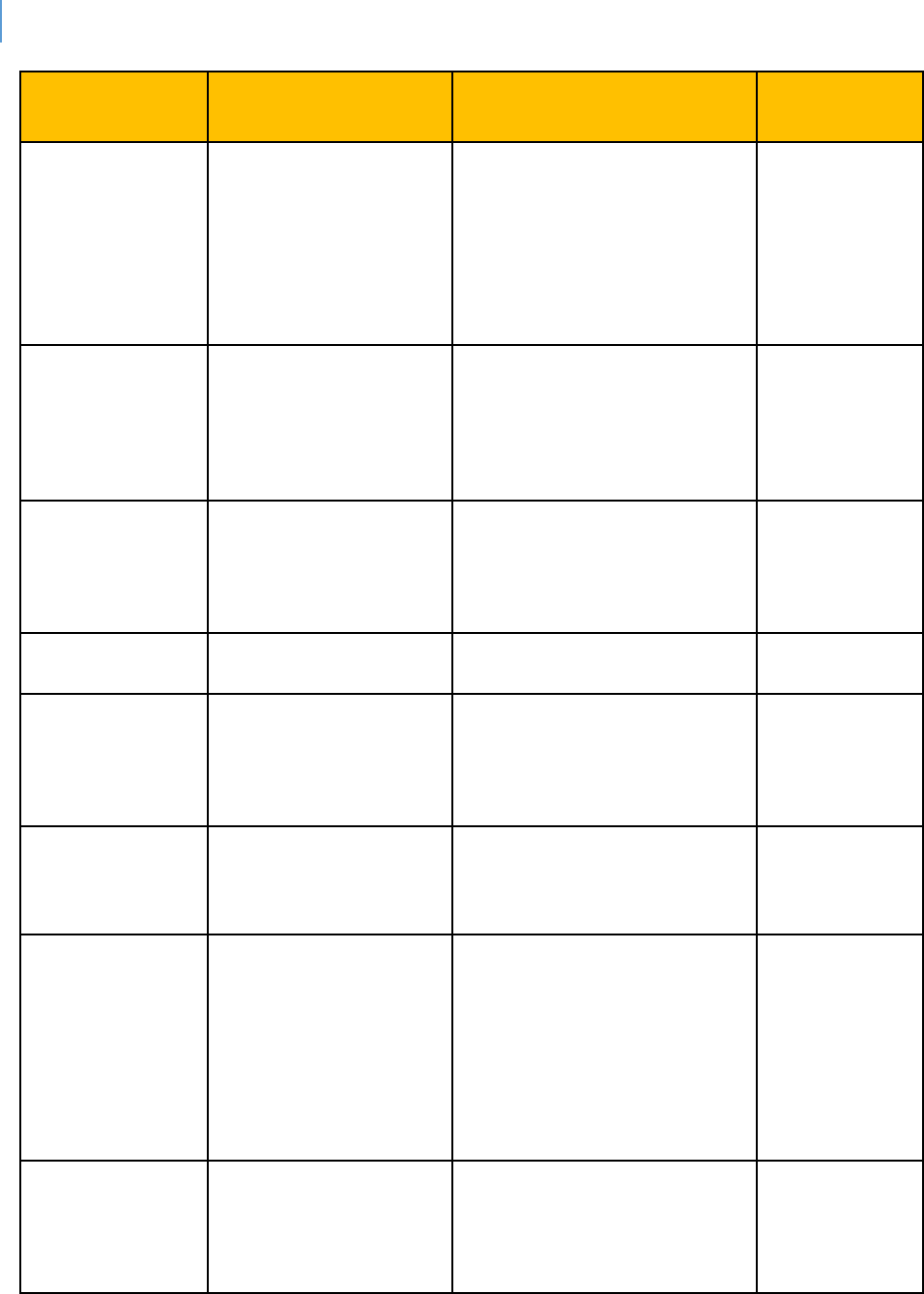

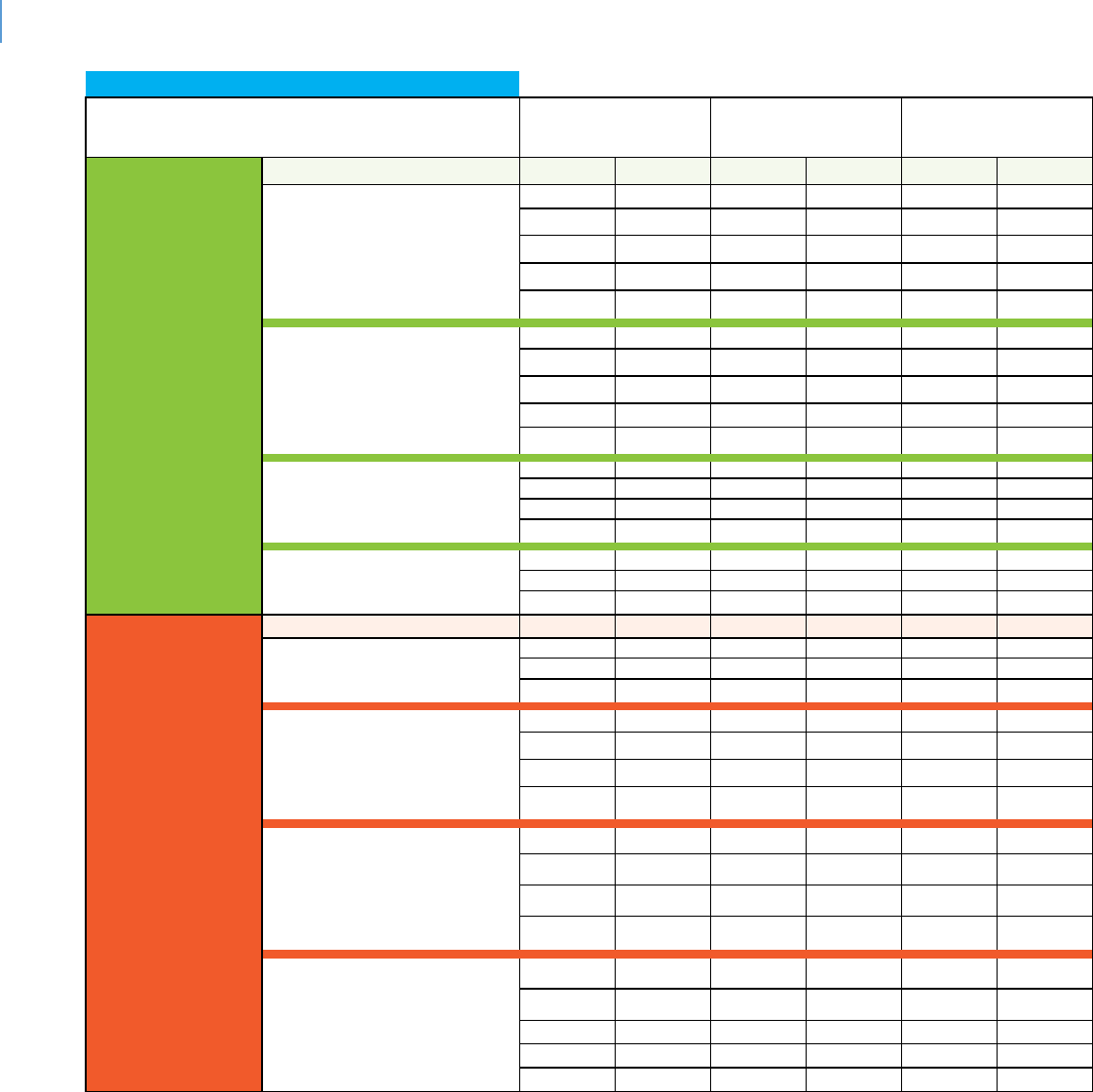

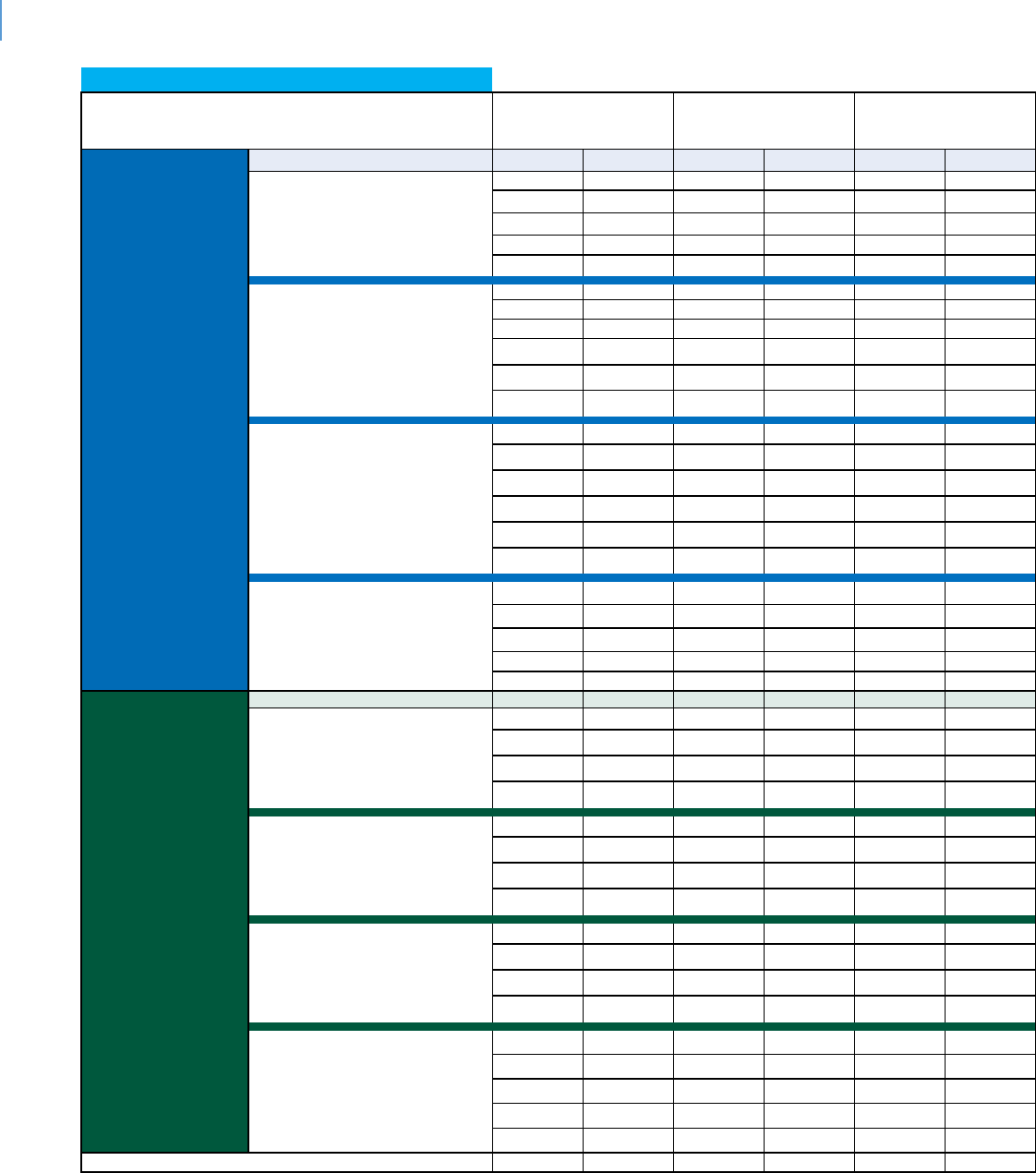

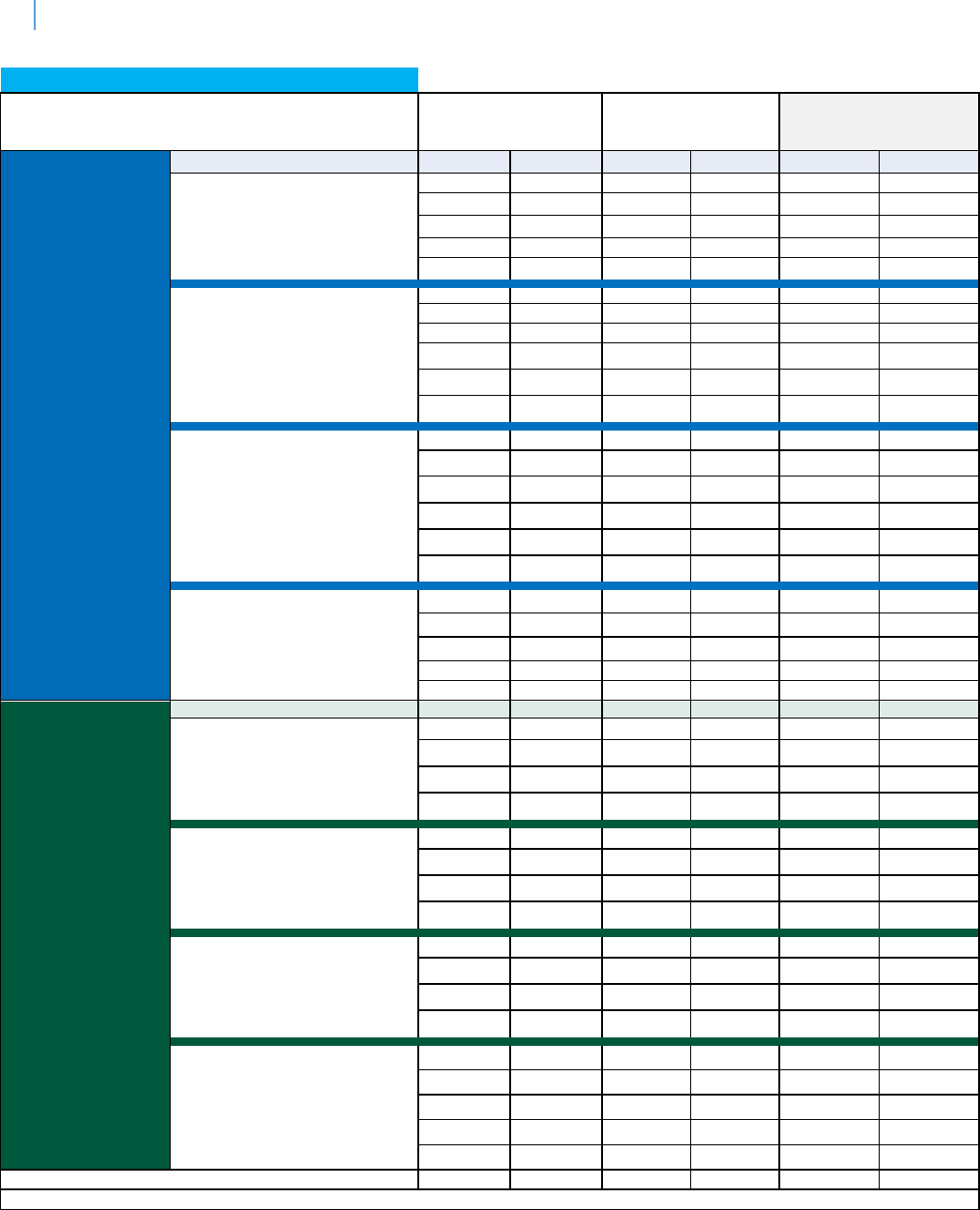

Index of Figures

Figure 1. Lee County, Florida Locaon .......................................................................................... 17

Figure 2. Populaon Growth Esmates ........................................................................................ 18

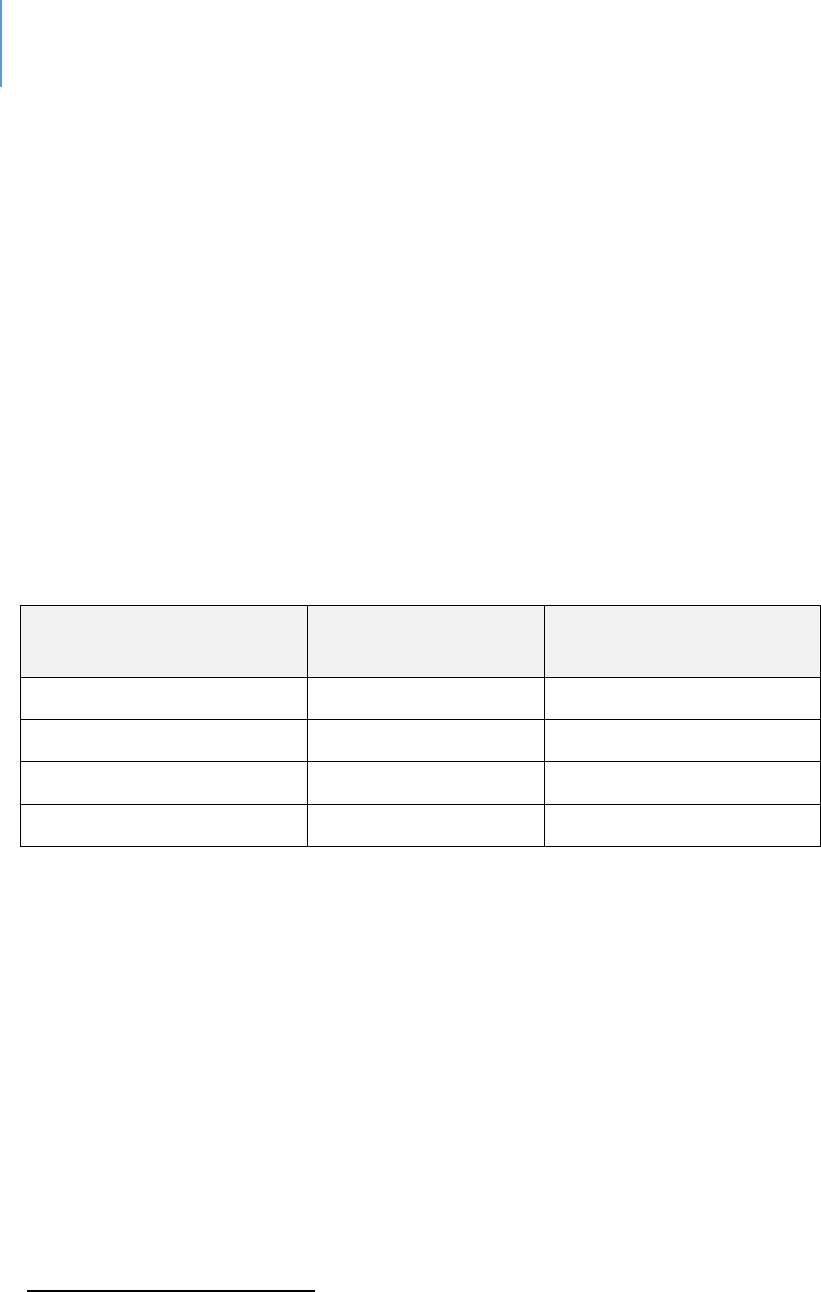

Figure 3. Map of Limited English Prociency Language Group, 2017 .......................................... 21

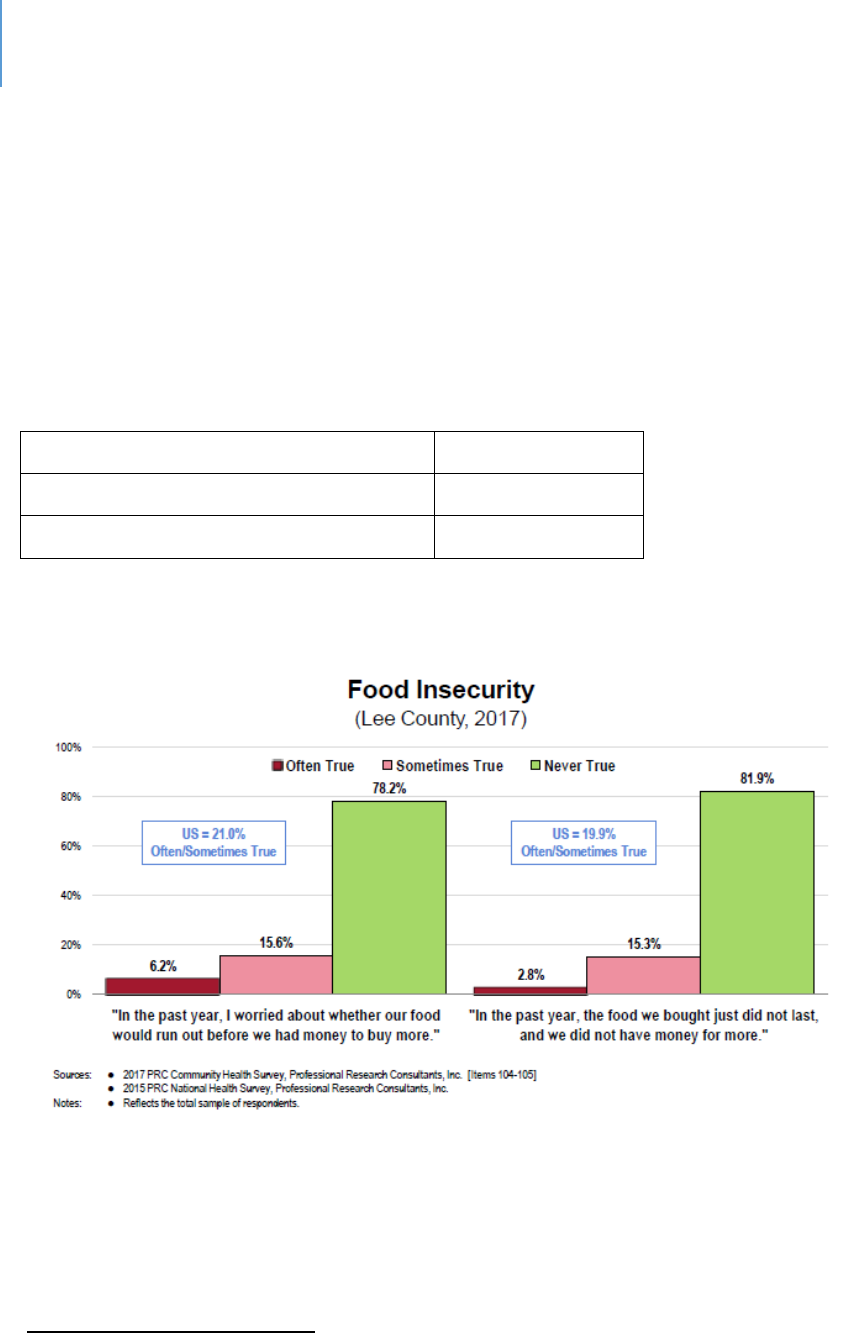

Figure 4. Food Insecurity ............................................................................................................. 116

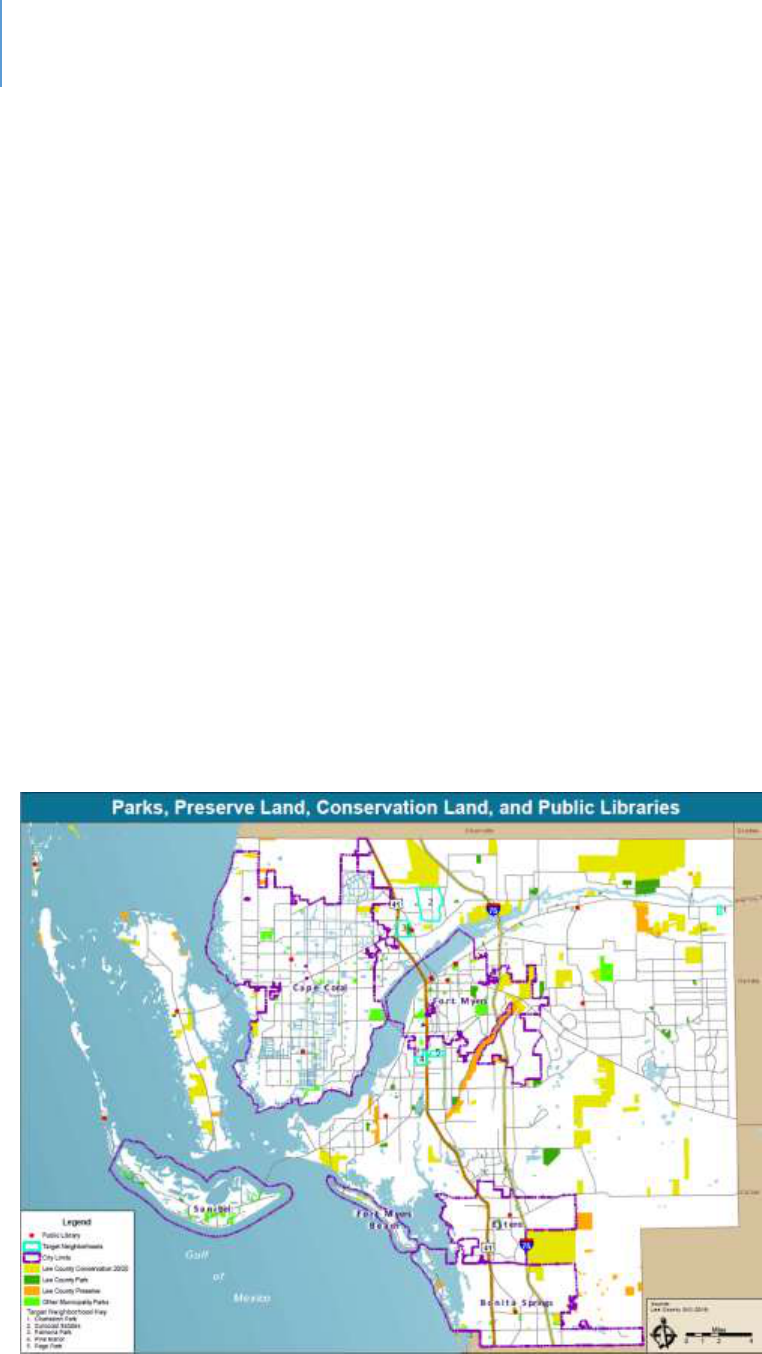

Figure 5. Map of Lee County Parks, Conservaon Lands and Libraries ...................................... 153

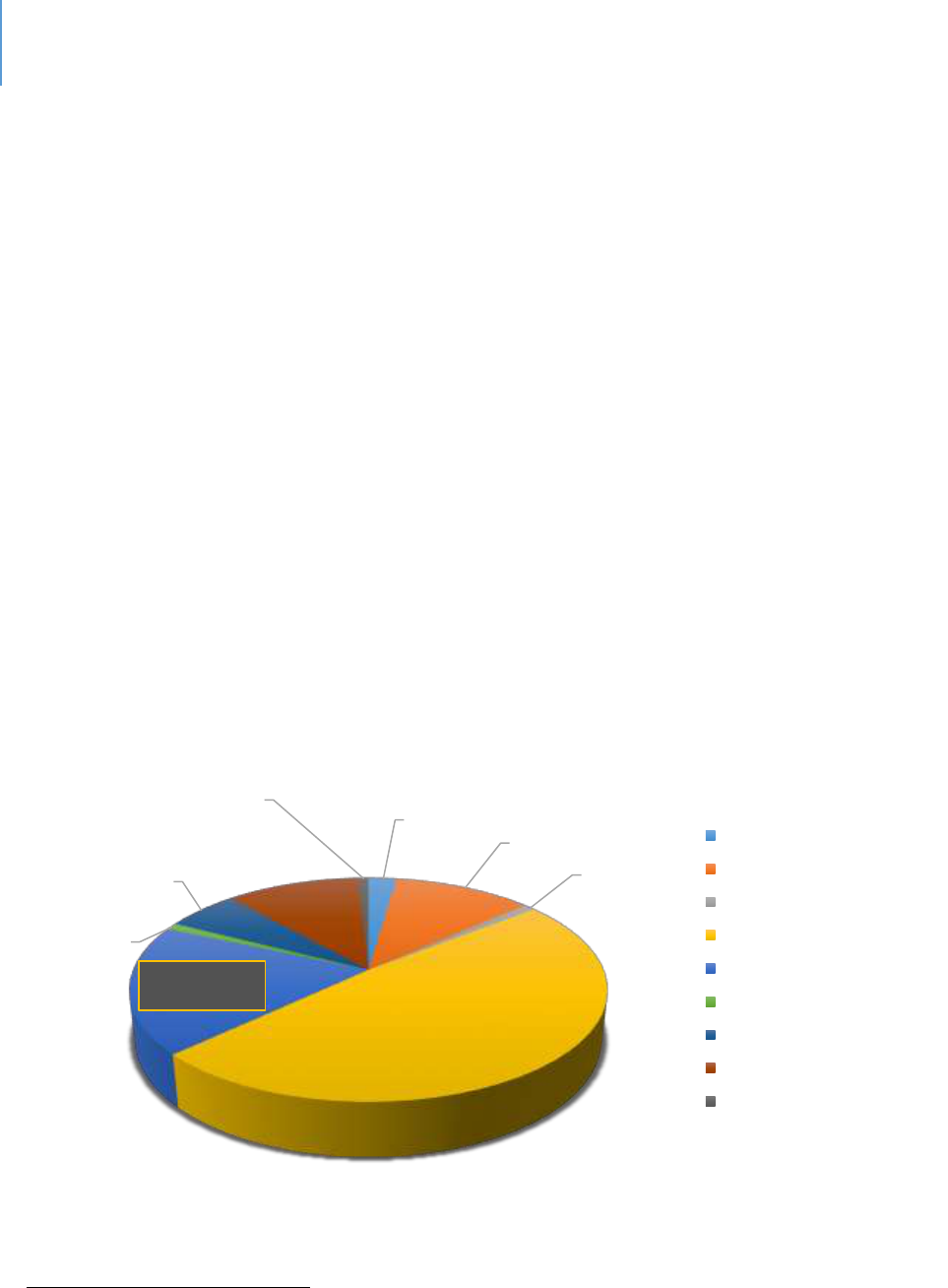

Figure 6. Revenue Collected by Tax Exempt Organizaons in Lee County, Florida ..................... 155

Figure 7. Number of Births in each County, Rolling Three-year Average .................................... 174

Figure 8. Percentage of Live Births under 2,500 grams, Rolling Three-year Average ................. 174

Figure 9. Infant Death Rate per 1,000 Live Births, Rolling Three-year Average .......................... 175

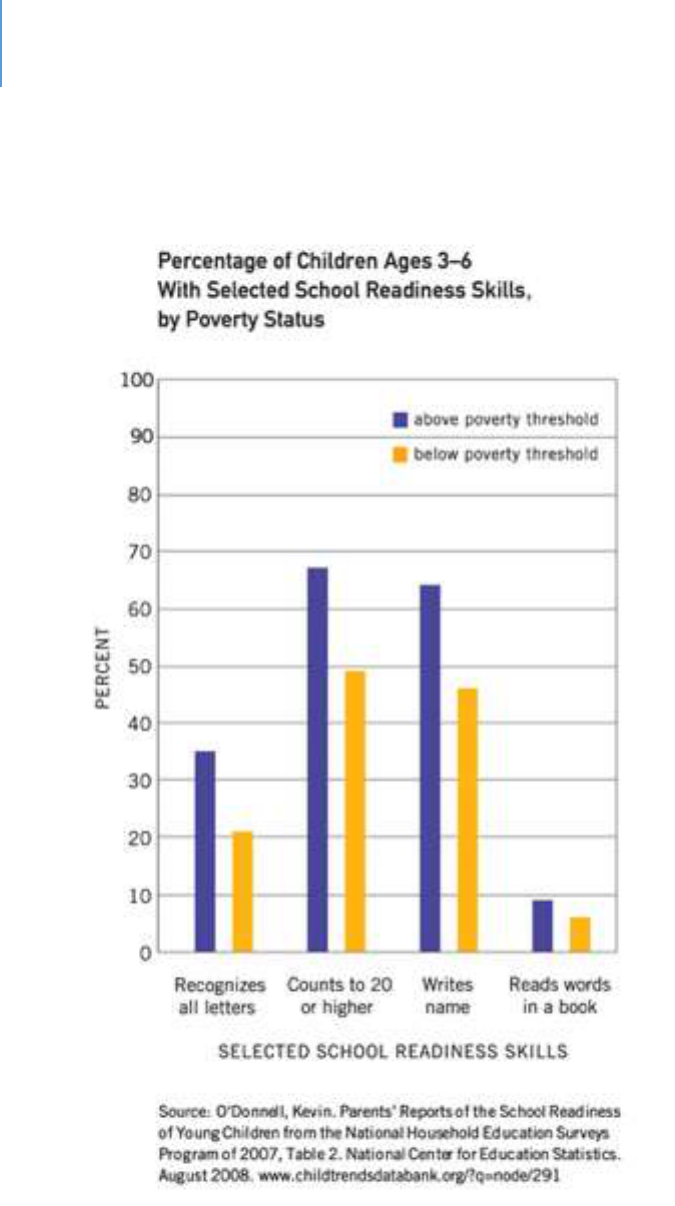

Figure 10. Percentage of Children Ages 3-6 with Selected School Readiness Skills by Poverty

Status........................................................................................................................................... 178

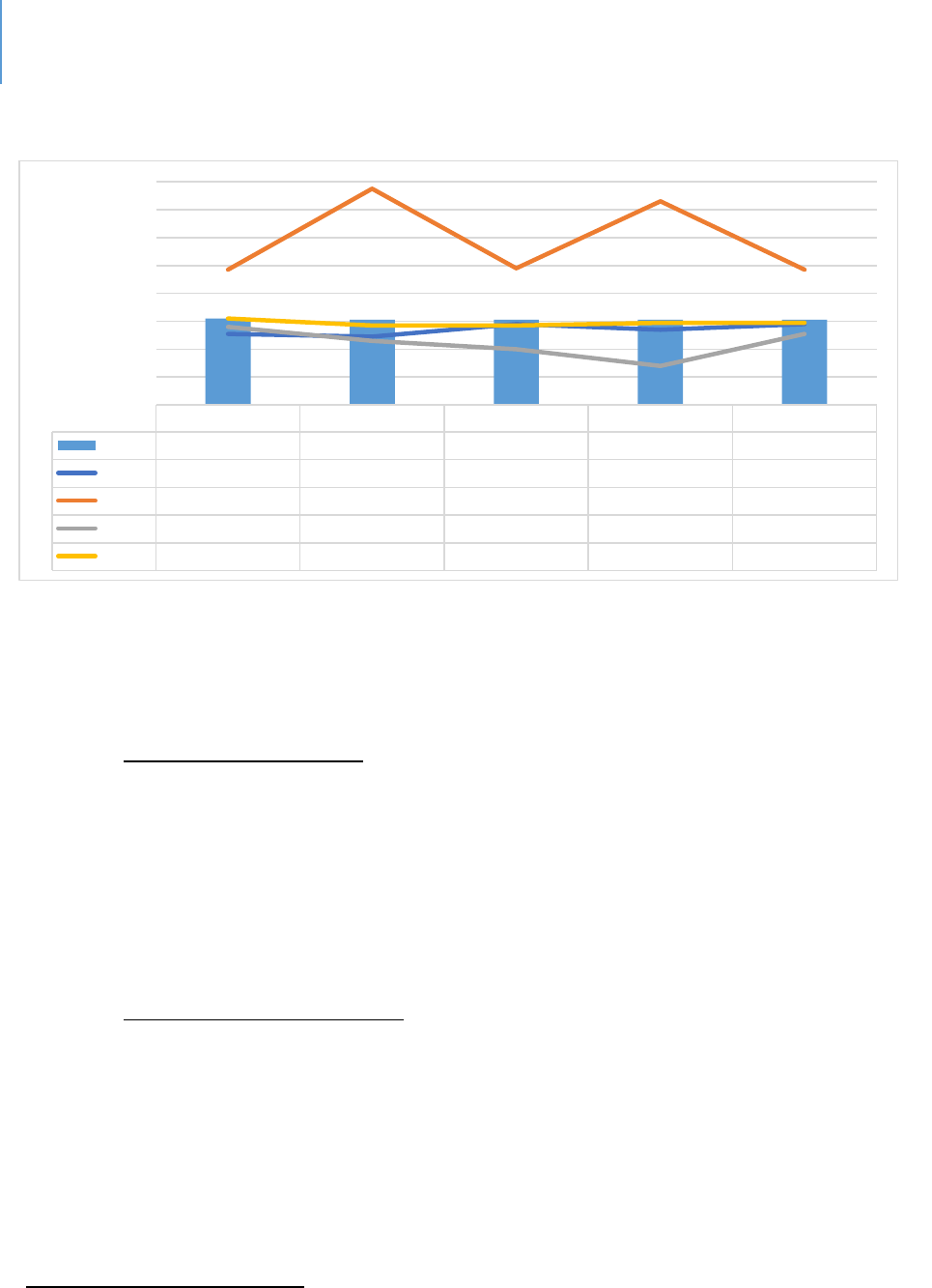

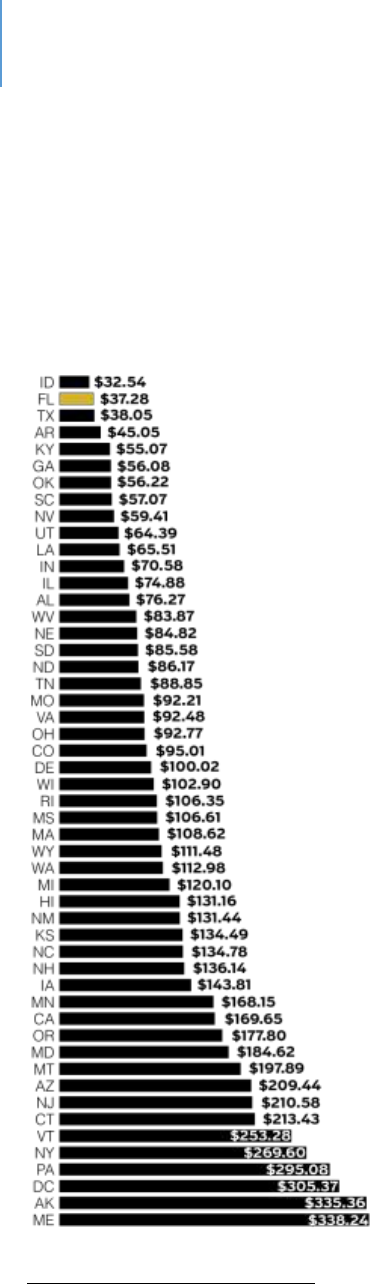

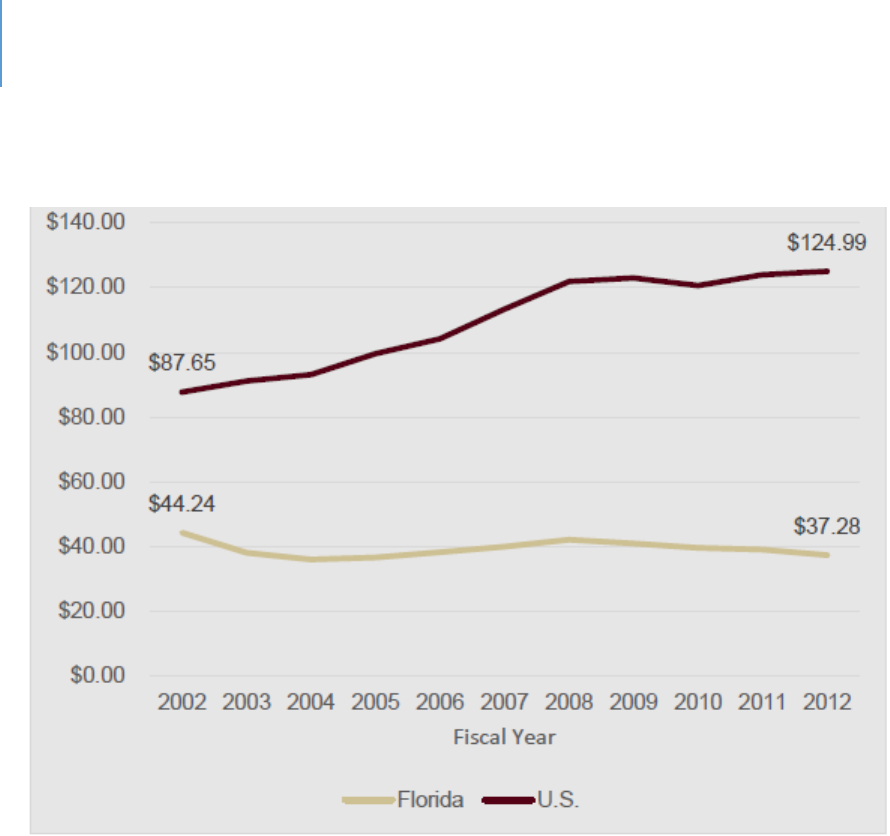

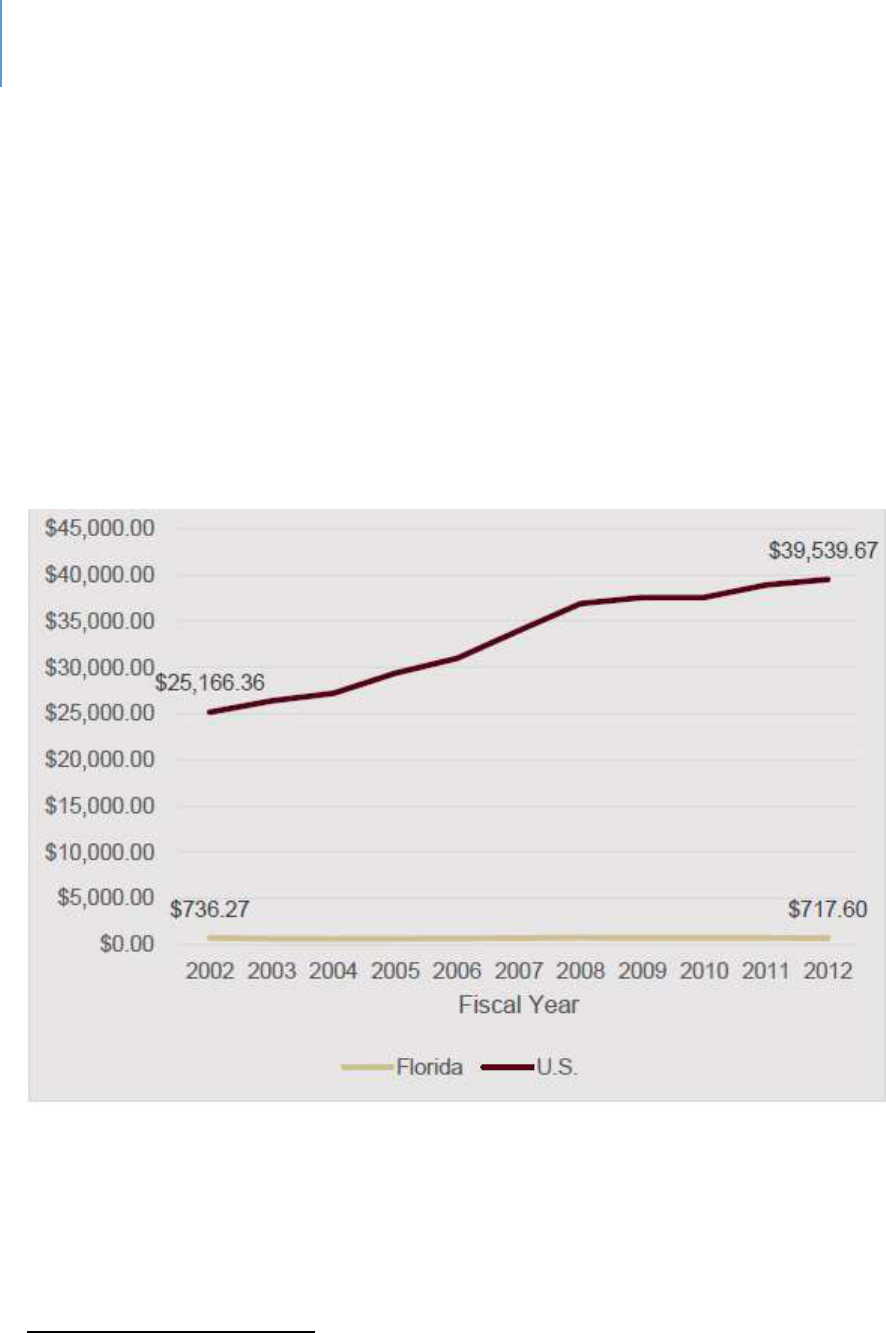

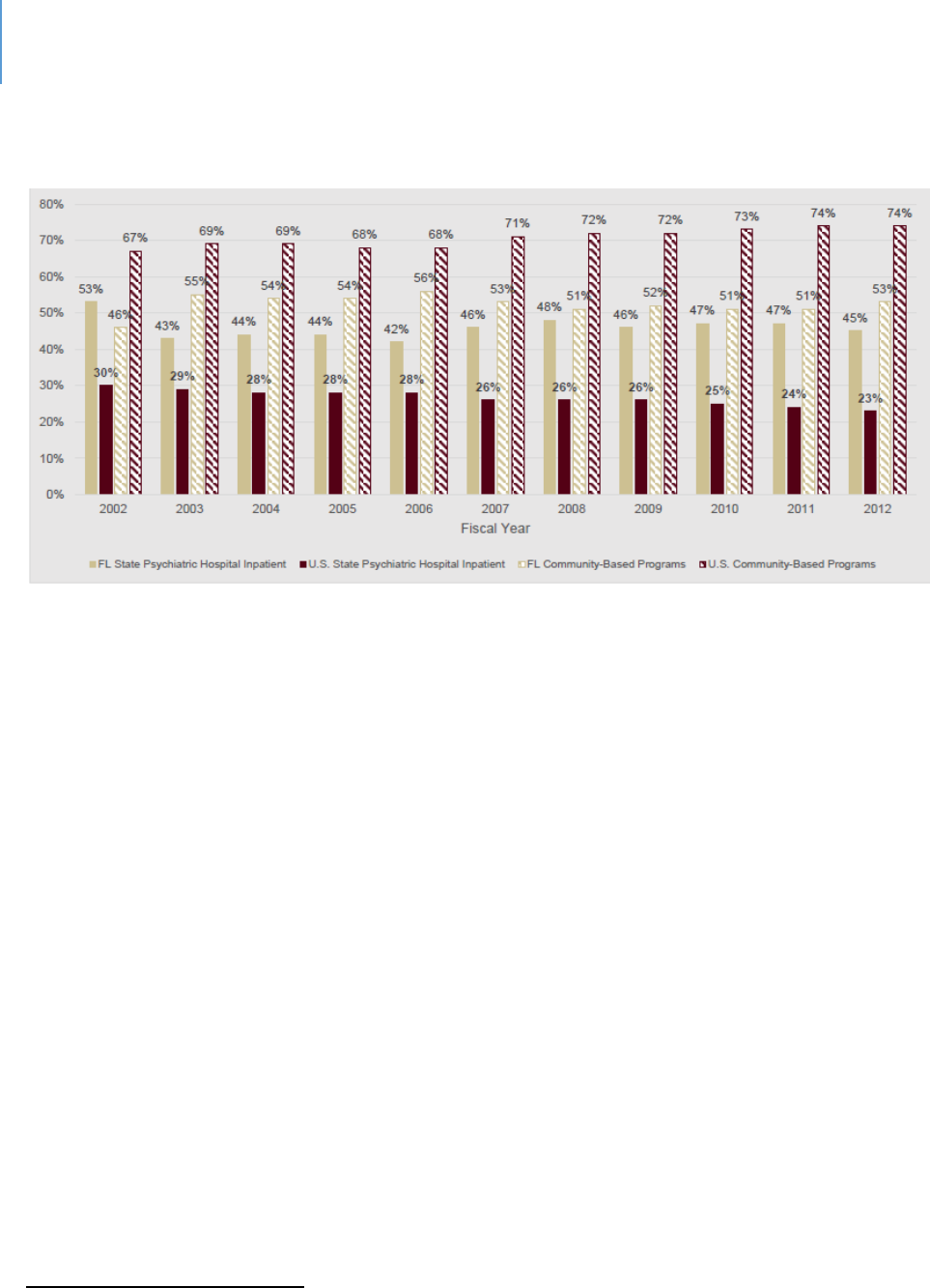

Figure 11. Florida Per Capita Funding for Mental Health Services Compared to Other States .. 205

Figure 12. State Mental Health Agencies per Capital Expenditure ............................................. 206

Figure 13. Comparison of State of Florida Funding Trends for Behavioral Health Compared to

Naonal Trends ........................................................................................................................... 207

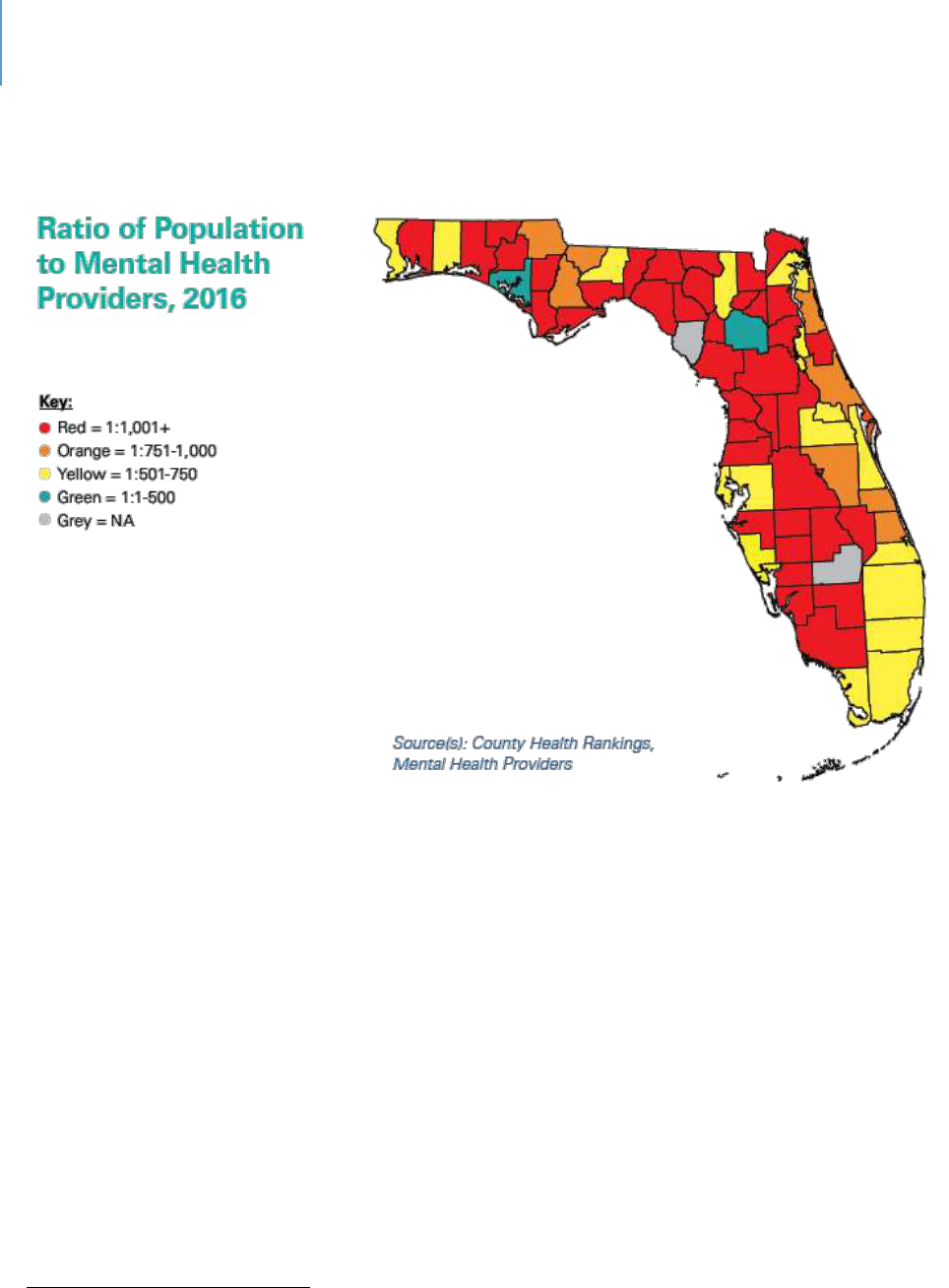

Figure 14. Rao of Populaon to Mental Health Providers, 2016 .............................................. 210

Figure 15. State Mental Health Agency Expenditures by Type of Program as a Percent of Total

Expenditures ............................................................................................................................... 212

Figure 16. Jails and Mental Disorders ......................................................................................... 220

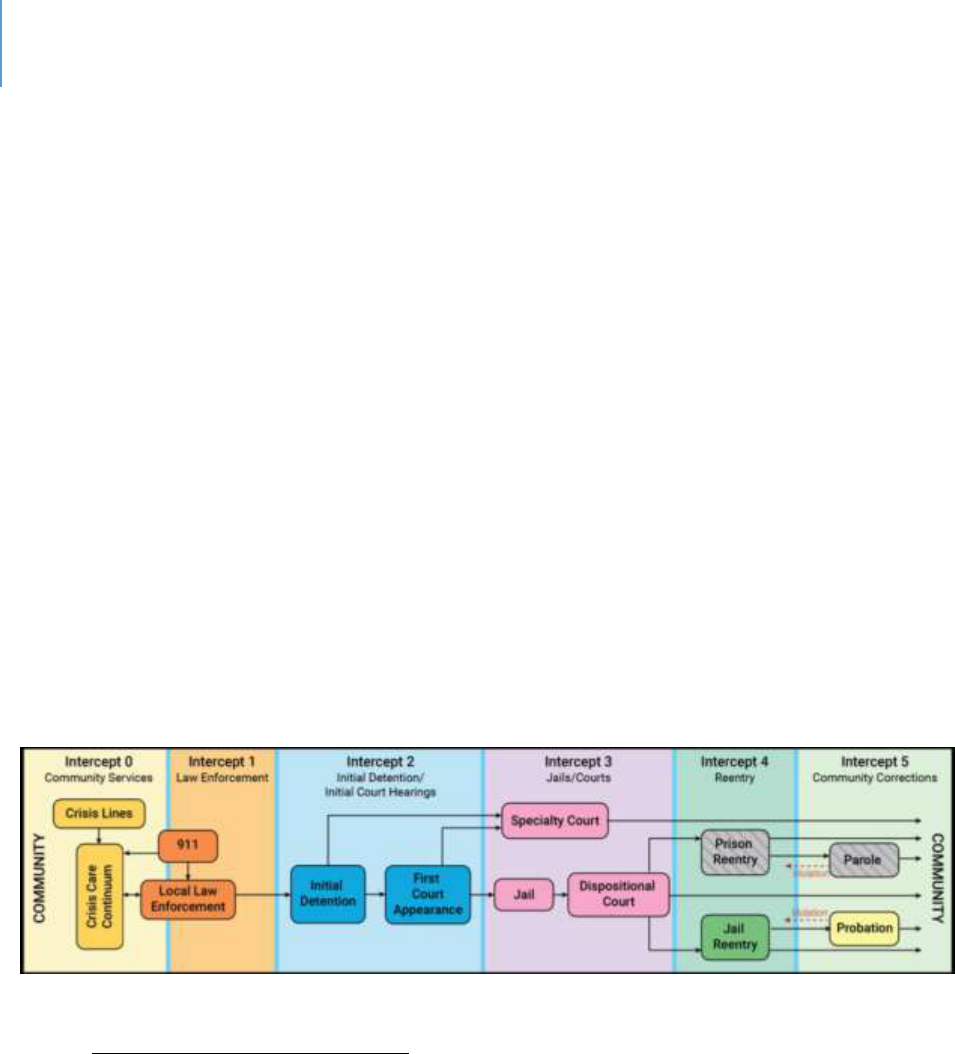

Figure 17. The Sequenal Intercept Model ................................................................................ 223

Figure 18. Children and Young Adults Receiving DCF Services in Lee County ............................ 245

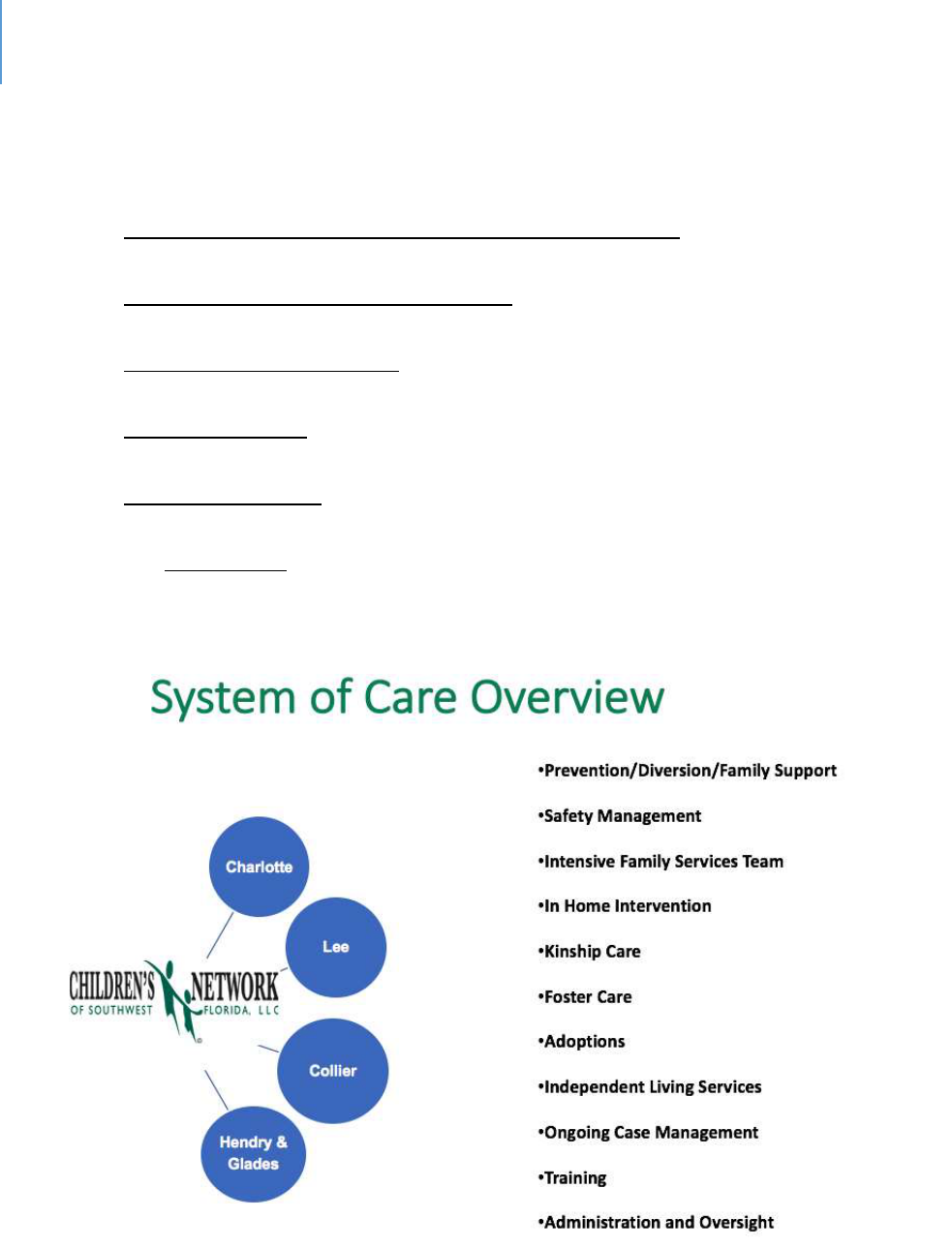

Figure 19. Children’s Network of SWFL System-of-Care Overview ............................................. 246

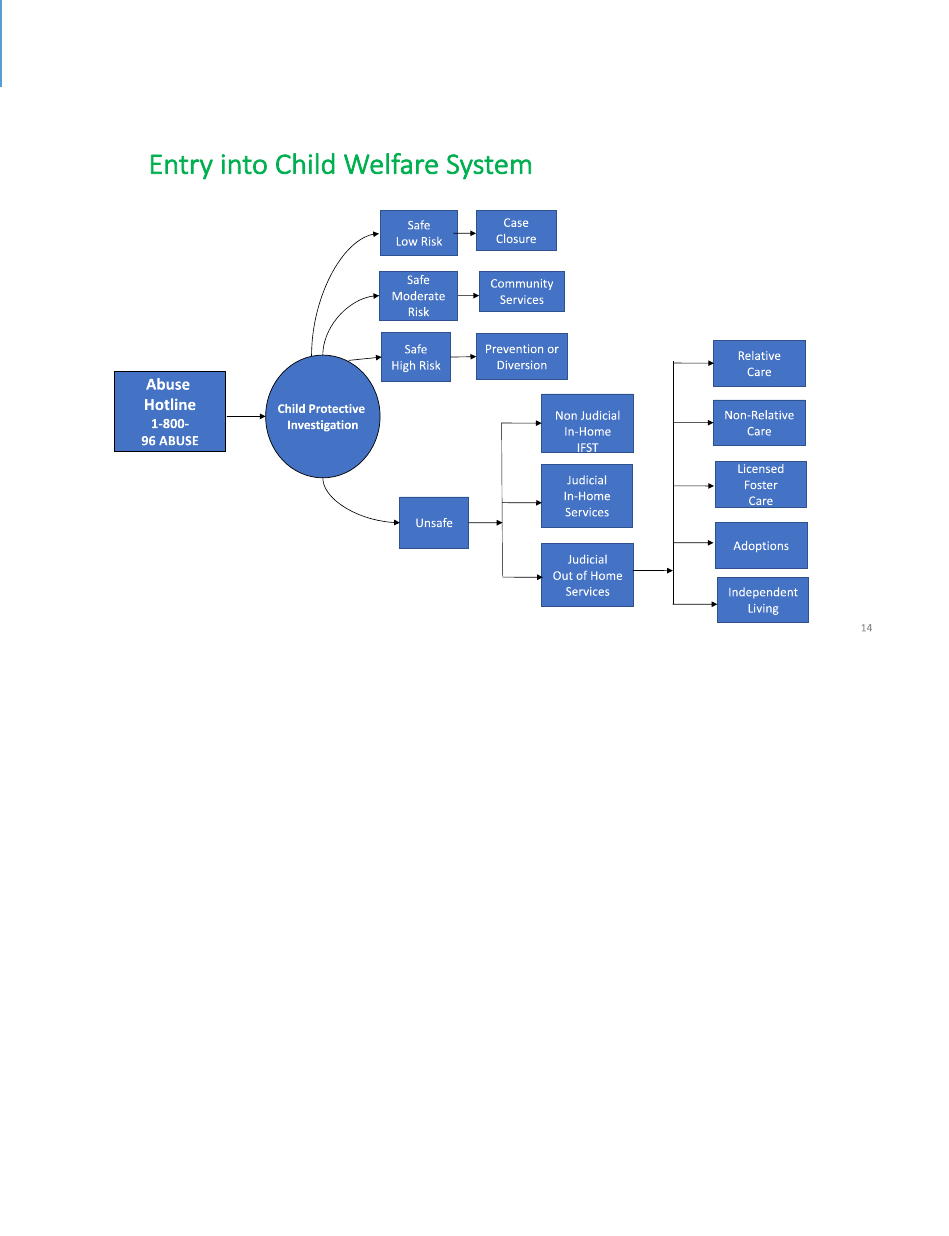

Figure 20. Illustrates the Process Stages of the System-of-Care ................................................. 247

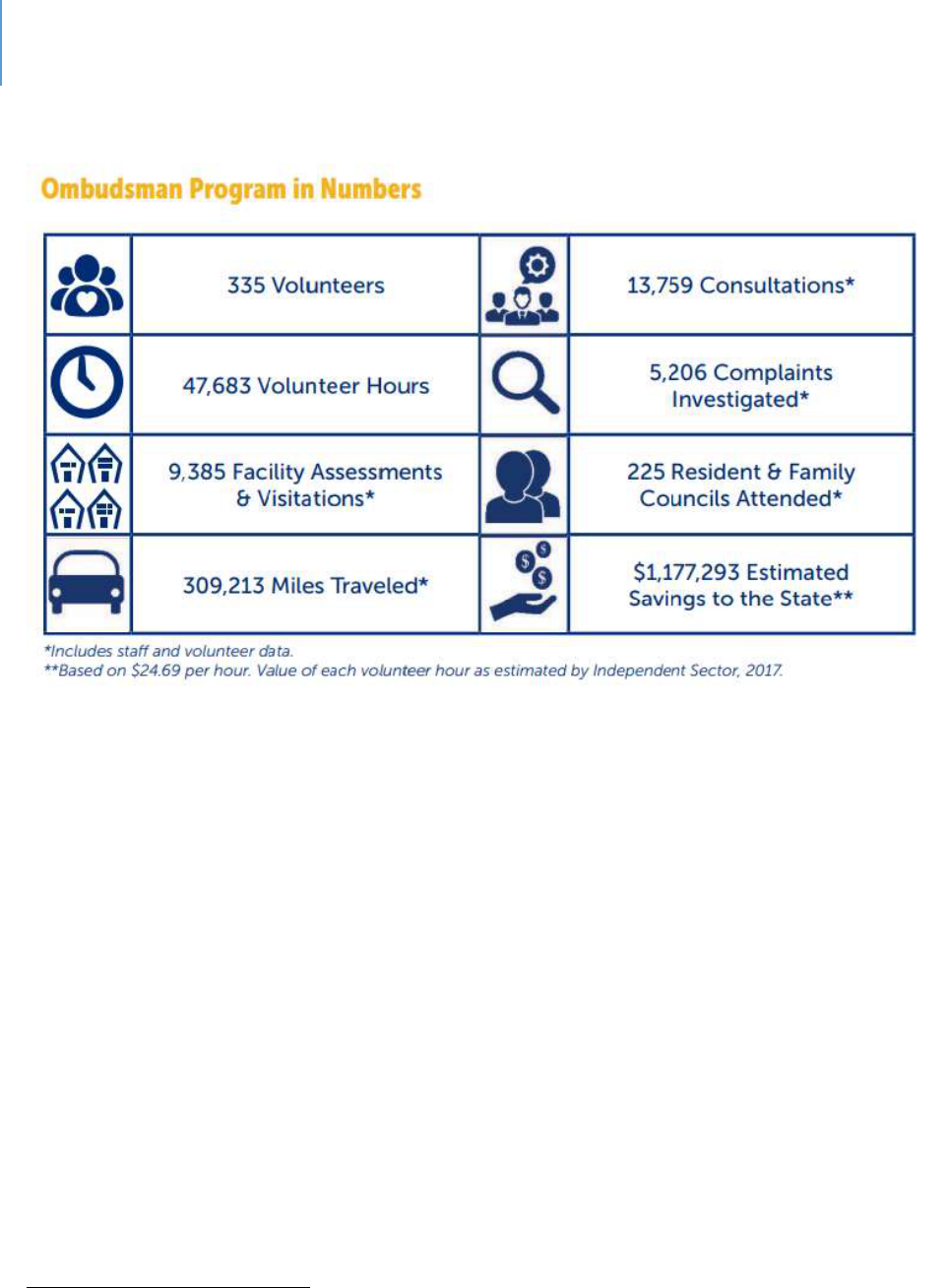

Figure 21. State of Florida Ombudsman 2017-2018 Annual Report .......................................... 265

Figure 22. Children and Young Adults Receiving DCF Services in Lee County ............................ 283

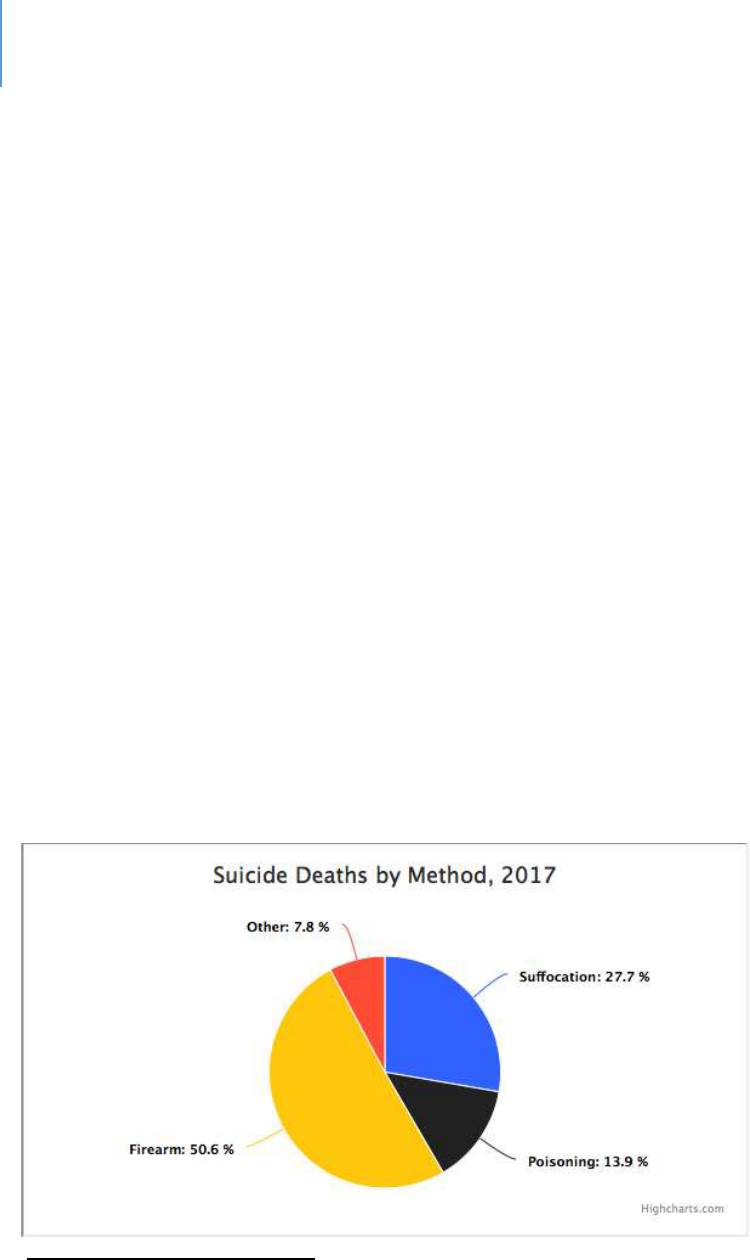

Figure 23. Suicide Deaths by Method ......................................................................................... 290

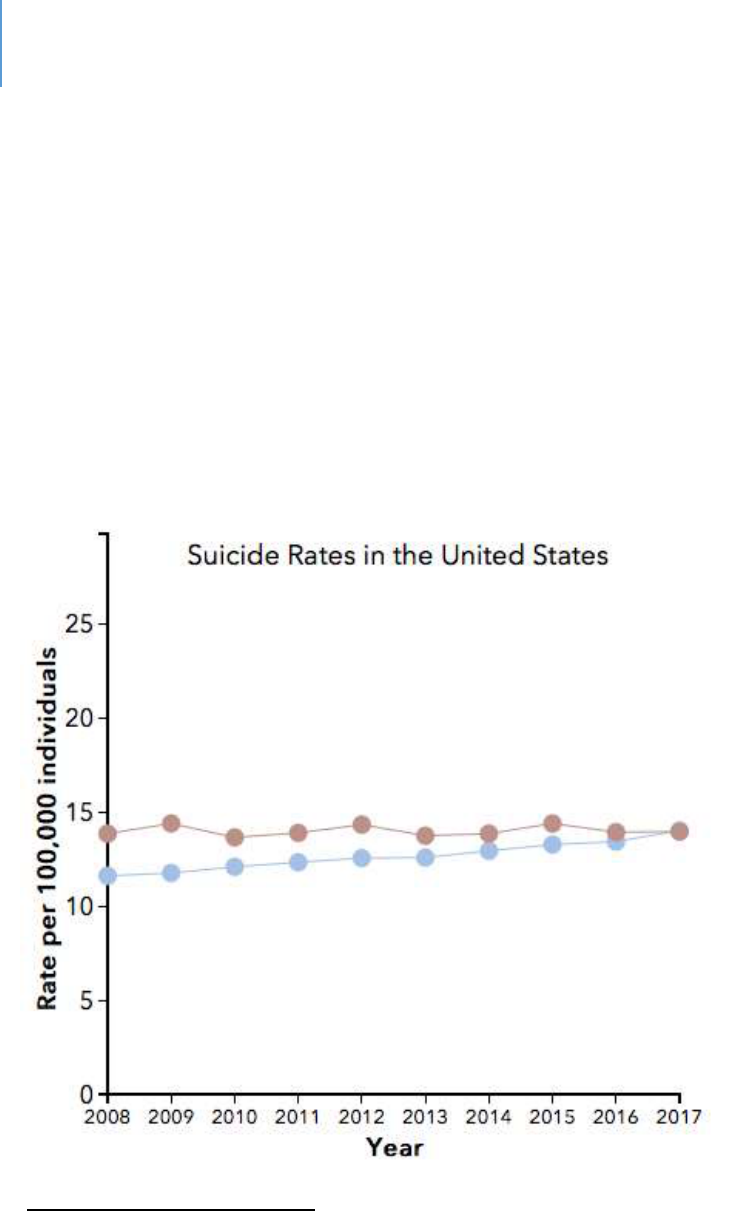

Figure 24. Suicide Rates in the United States ............................................................................. 292

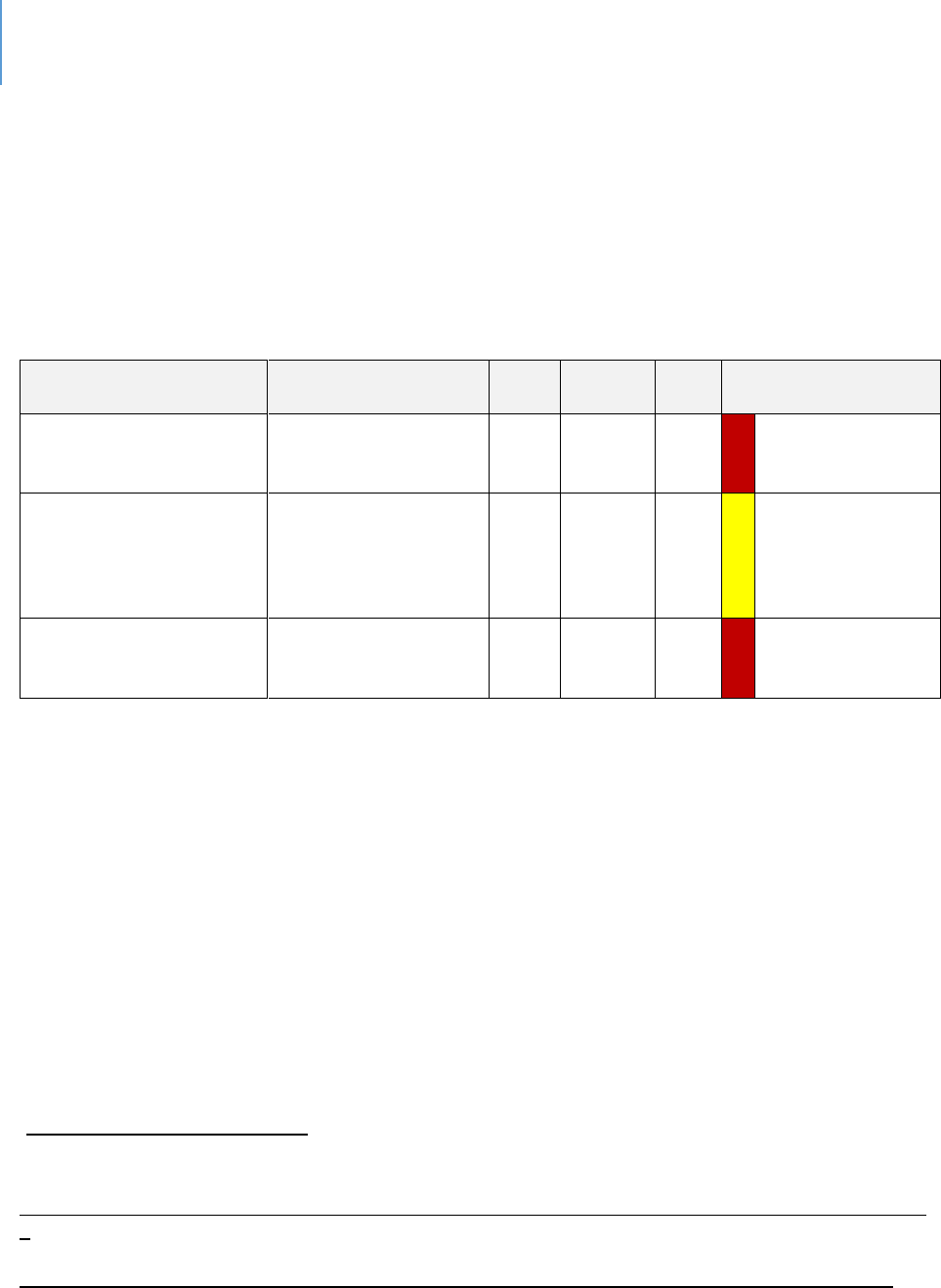

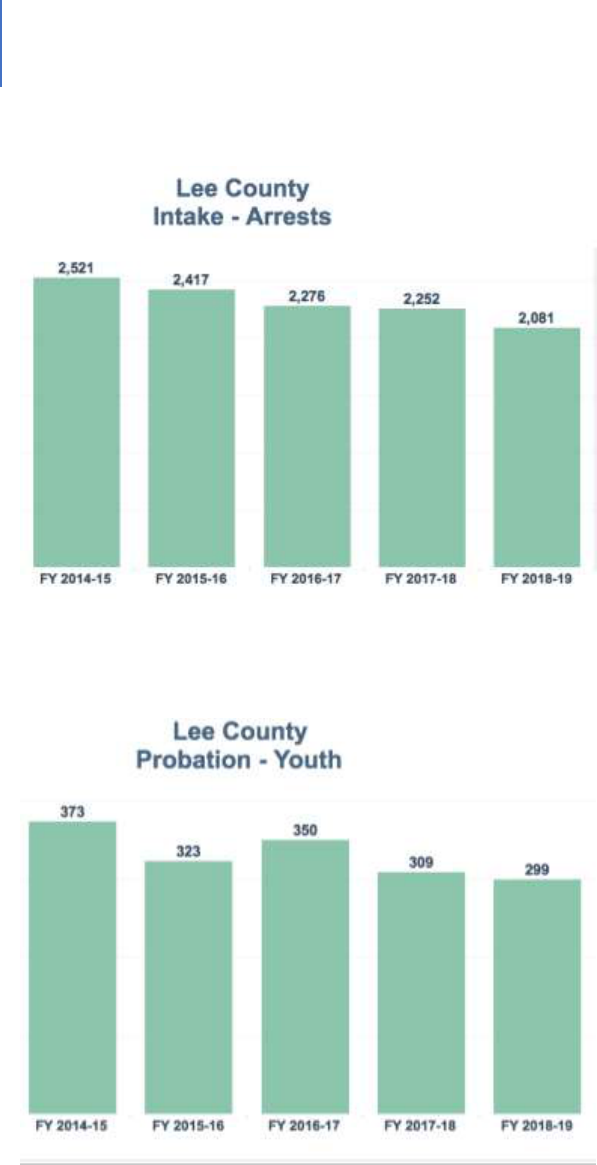

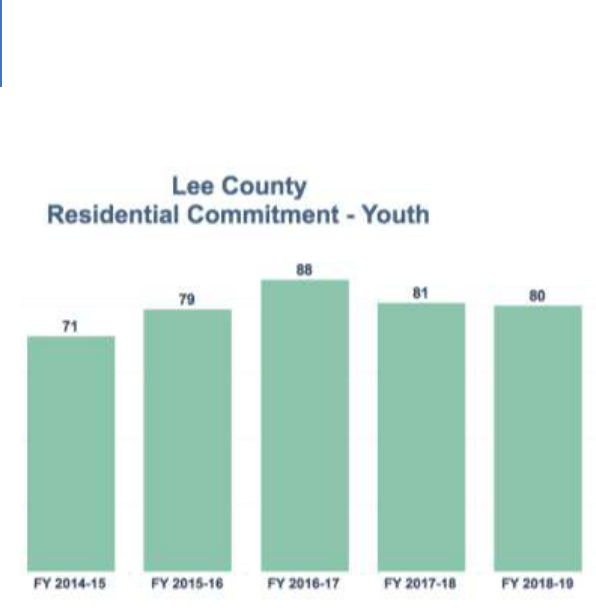

Figure 25. Declining Rate of Arrests for Juvenile Oenses ......................................................... 299

Figure 26. Decline in the Number of Juveniles on Probaon ..................................................... 299

Figure 27. The Number of Lee County Children in Some Form of Residenal Restricon ......... 300

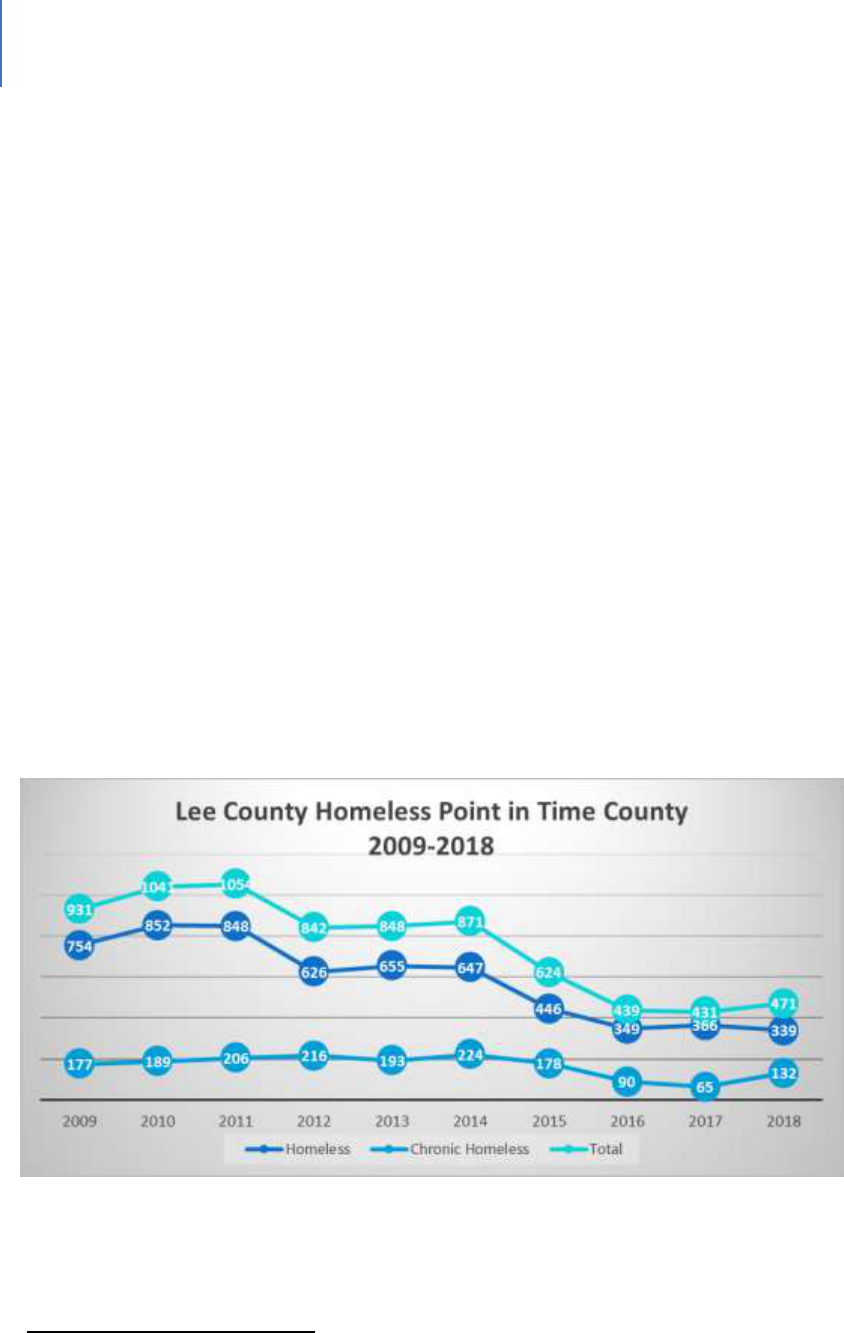

Figure 28. Lee County Homeless Point in Time 2009-2018 ........................................................ 313

Figure 29. Coordinated Entry Homeless Households and Income Reporng............................. 316

Figure 30. Employment First ....................................................................................................... 332

Figure 31. Housing Components ................................................................................................. 341

Figure 32. NED/Mainstream Housing Vouchers for Individuals with Disabilies in Florida ....... 345

Figure 33. Lee County Populaon Projecons ............................................................................ 375

Figure 34. Dependency Rao Projecons ................................................................................... 377

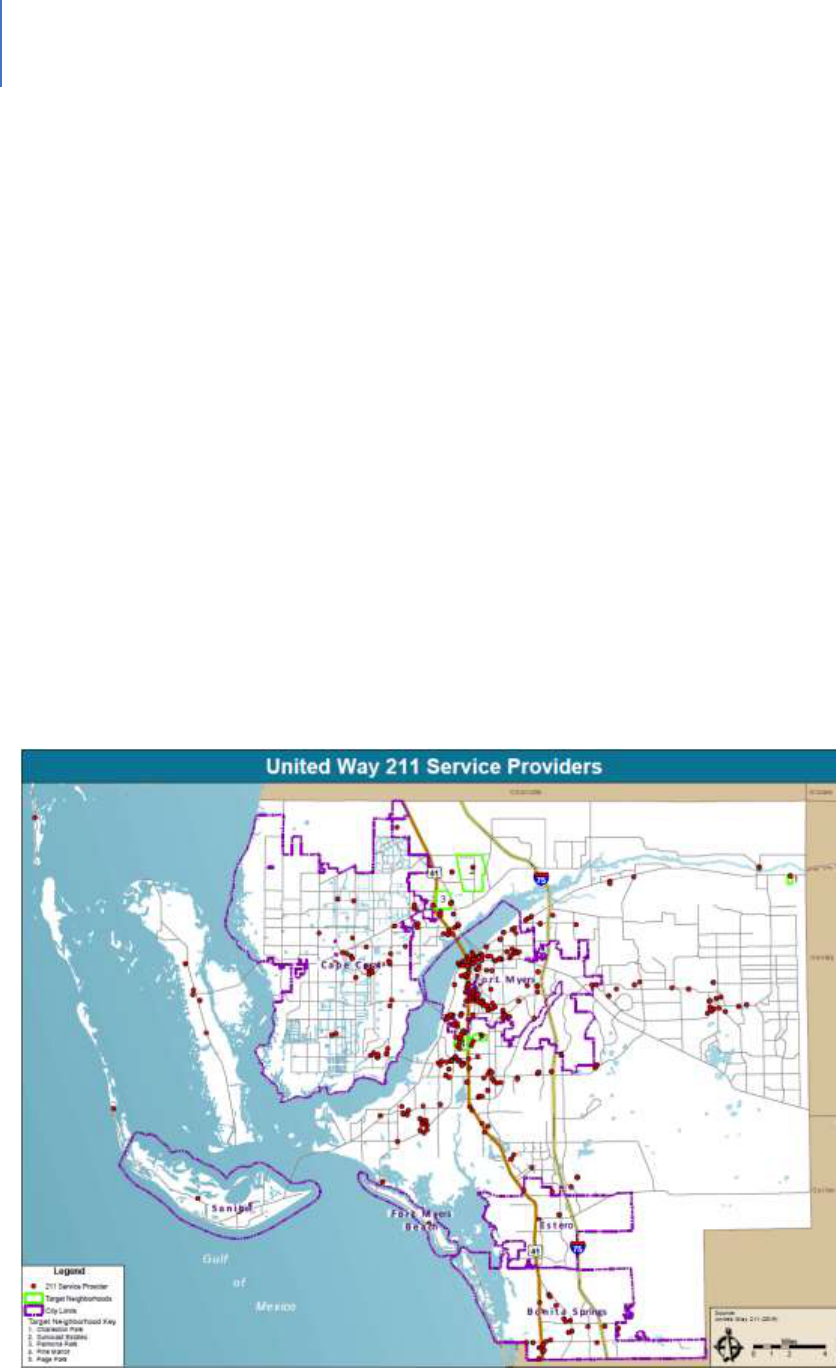

Figure 35. Map United Way 211 Providers ................................................................................. 393

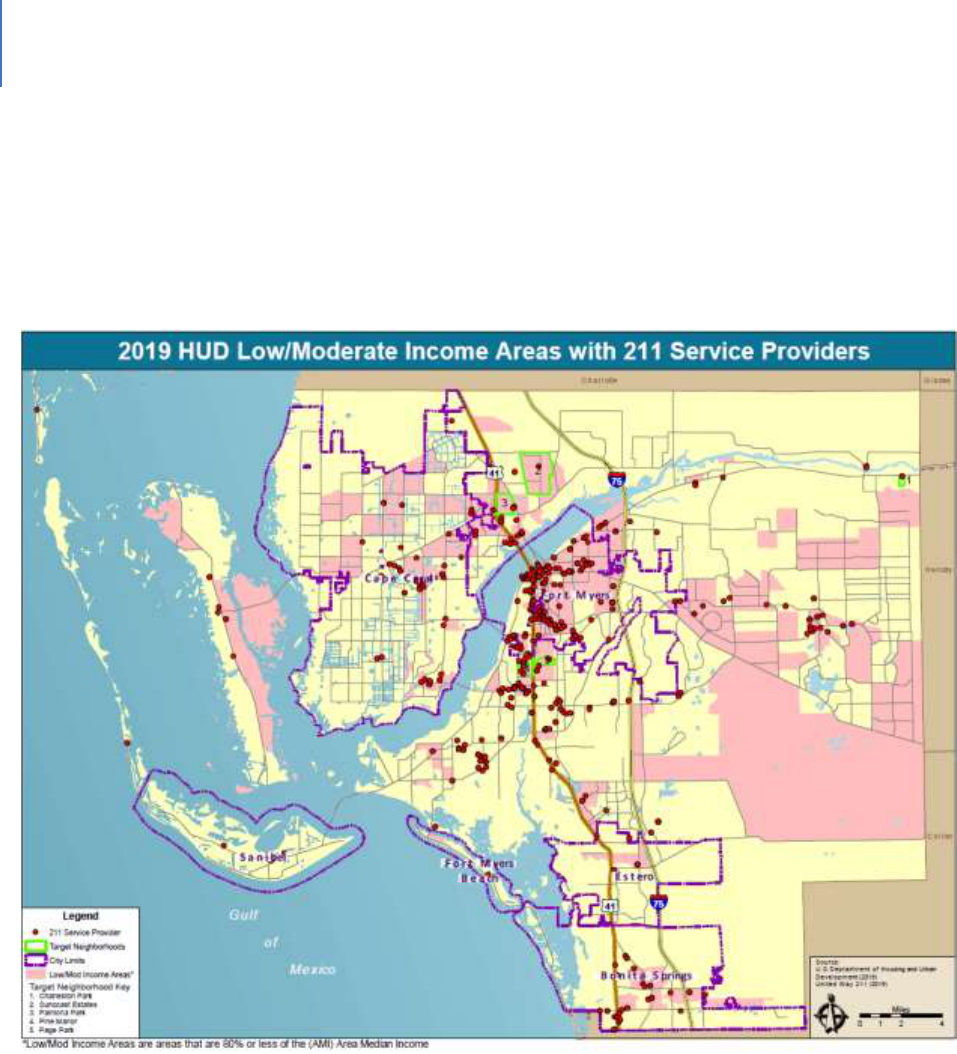

Figure 36. Map HUD Low/Mod Income Areas with 211 Service Providers ................................ 394

Figure 37. Map Parks, Preserves, Conservaon Land and Public Libraries................................. 395

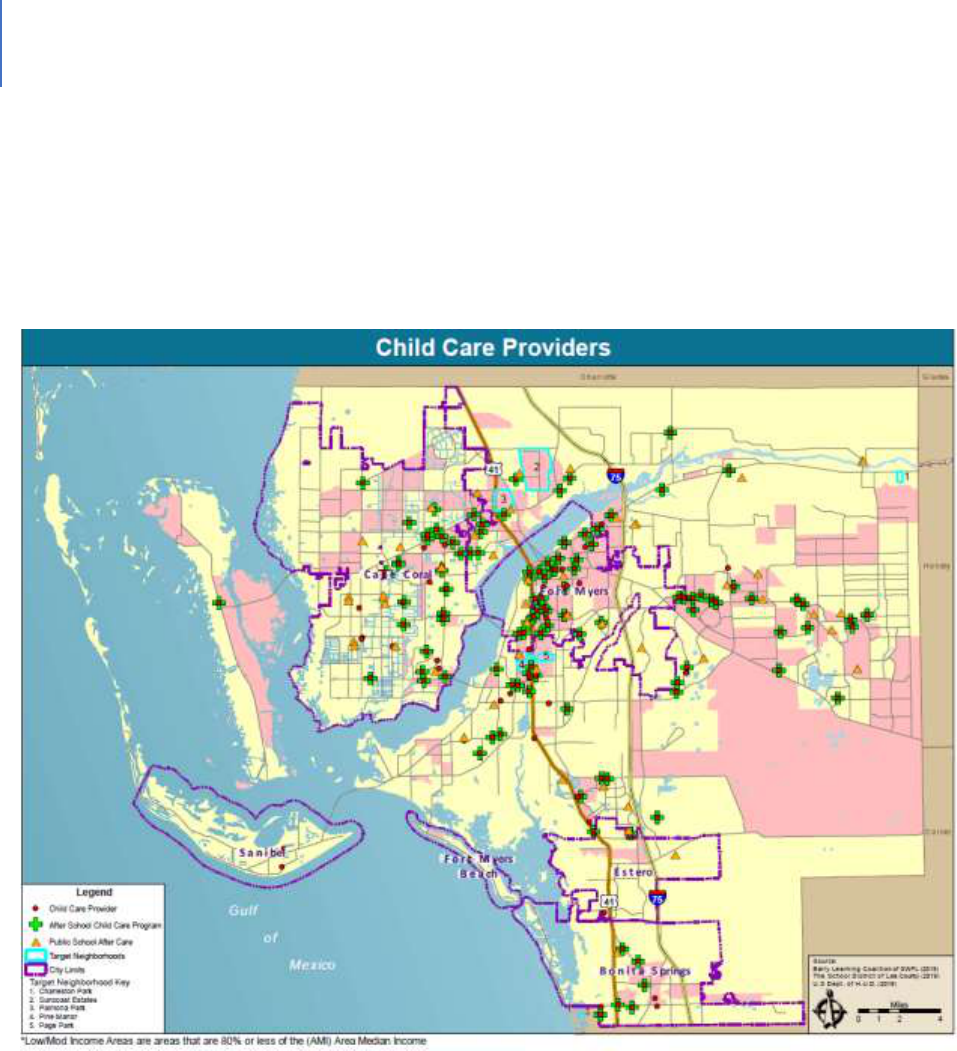

Figure 38. Map Childcare Providers ............................................................................................ 396

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introducon

The Lee Board of County Commissioners directed sta to idenfy gaps in the public and

private systems of delivering vital human services in Lee County. The results of this Gap

Analysis are reported here.

This comprehensive assessment addresses mulple services, including those that may

not be under the purview of County Commissioners. This report, which idenes gaps

but does not recommend specic soluons, is intended by design to be of value to the

enre community rather than to be used specically as an internal County document.

The Gap Analysis ulizes a system model that incorporates tradional needs assessment

– a focus on the gap between an idened need and the capacity of exisng services to

meet that need – as only one of a set of analycal methods. The full set of analyses are

summarized below.

Gap Analysis: The Analycal Methodology

Gaps in this assessment are examined from mulple perspecves. These include:

Need/Capacity. This is the most common understanding of “gap,” in that the number of

people needing a service is greater than the level of services that can be provided.

Behavioral Outcomes. The ulmate test of the value and validity of any human service

program is its impact on behavior and/or life condion. To assess this gap perspecve,

databases reporng various populaon-correlated stascs on behaviors such as drug

use per capita rates or homeless persons who were housed in permanent housing were

used to compare Lee County with other counes in the state.

Evidence-Based Pracces. Known as evidence-based pracces, these programs have

been evaluated by academic researchers and found to be eecve. All human service

programs are well intenoned. However, intenons do not always result in posive or

long-term change. Evidence-based programs, or “best pracces,” have been found to

eecvely turn intenon into posive impacts.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 2

Policy/Process. In some cases, regulaons or organizaonal processes inadvertently

result in service gaps. For example, this may result from eligibility restricons or

communicaon gaps.

Access/Geography. This examines whether a gap exists between where people who

need services reside and the locaon where those services are provided.

Equity Funding. There are variees of funding streams involved in the human services

eld. Various formulas exist that underlie those funding streams. The queson here is

whether Lee County is funded equitably when compared with other counes in the

state.

Scope of the Analysis

The assessment examined the various dimensions of the human services system. This

included:

Systems of Care. These systems range in formality from highly linked to a loose network

of providers. They focus on a set of issues or behaviors that are problemac from some

perspecve. The following systems were analyzed:

Behavioral health;

Behavioral health and criminal justice interface;

Child abuse and neglect;

Domestic violence;

Elder abuse, neglect and exploitation;

Sexual violence and stalking;

Trauma and effects of violence exposure;

Suicide and self-harm;

Juvenile delinquency; and,

Homelessness.

Special Populaons. These are persons who are grouped by either age, disability, or life

status and who also share a common set of issues. While they are likely served in

mulple systems of care, they bring their own issues, which are best idened in

separate discussions. The issues of the following special populaons were examined:

Intellectual and developmental disabilities;

Congenital hearing and visual disabilities;

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 3

Persons with other physical disabilities;

Senior citizens; and,

Veterans.

Development. The systems of care and special populaons are characterized by some

diculty, or risk, that require an extra level of aenon and intervenon. Development

is concerned with normal development paerns and tasks and how they can be

fostered for everyone. The perspecve examined child and youth development.

Infrastructure. This dimension encompasses the basic human needs of housing,

transportaon, food and employment. It also encompasses the organizaonal

infrastructure needed to deliver services such as sta, facilies, organizaonal structure

and technology.

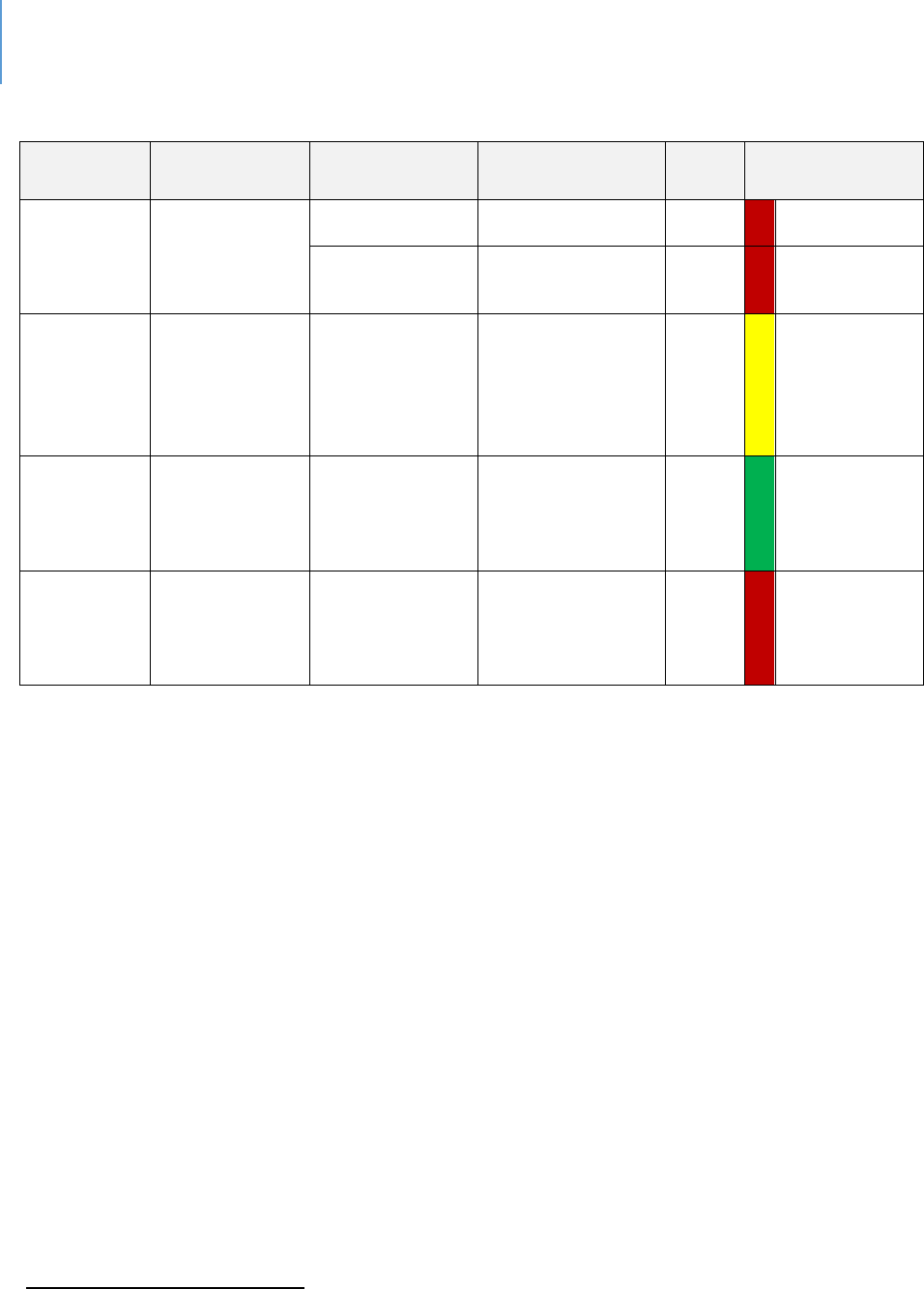

Findings

When compared to either naonal, state or local data or to accepted best pracces,

there are gaps of varying degrees of signicance in each system-of-care as well as in the

services provided to various special populaons, child and youth development and

infrastructure. The three most crical of these are:

Behavioral Health. Consistently, the data-collecon tools used for this analysis point to

behavioral health services as having the most serious gaps in the County. These data-

collecon tools included various surveys that have been conducted in Lee County, the

perspecves of professionals, comparave nancial data showing that Florida ranks

anywhere from 48

th

to 50

th

in terms of per-capita funding for mental health services,

and the fact that behavioral health problems are found to be factors in almost all the

systems of care assessed in this analysis.

Housing. With the same consistency across the methods used, housing for special-

needs clients (supporve housing) and housing for workers (aordable housing using

HUD denions) were idened as one of the three most signicant gaps from a

countywide perspecve. From a clinical perspecve, the eecveness of any treatment

intervenon is weakened if the person is in an unstable, unsafe or otherwise poor

housing situaon. If people are homeless, in highly transitory housing or in housing

that is stressful because of crime, violence or poor quality, the resultant stressors can

become overwhelming. These stressors can lead to relapse into more problemac

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 4

behavior or regression. From a system-of-care perspecve, housing is a crical

component to overall success.

Transit. Just as housing was consistently idened as a dominant gap, so was transit.

While not as crical to posive outcomes as housing, transit remains a key component

for the success of systems of care. Being able to access care and support, employment

or basic-life necessies are all elements needed by system-of-care plans. This gap is

crical for residents dependent upon public transportaon to access support services

and/or the employment and educaonal opportunies required to address their needs.

Other common issues. Variees of services were examined in this analysis. Several

gaps, in addion to the above three, were found to exist across the various services.

These are detailed in the “Conclusions” chapter.

Staffing. There is a significant shortage of professionals in the various fields such as

nursing, psychiatry, psychology and social work. Low-compensation issues make

retention of technicians, first-line or direct care workers, whose salaries are most

often in the $10-$12 an hour range, difficult.

The increasing complexity of the work. Increased knowledge of the human brain,

the growing body of evidence-based practices that require specialized training, and

the diversity of clients, make the work of delivering outcome-based human services

increasingly complex. For example, child-care workers would ideally have at least an

Associate’s degree in child development. Early childhood educators are discussing

Bachelor degrees as the minimum standard.

The need for more integrated service delivery systems. Clients overlap various

systems of care, particularly physical and mental health, which are strongly linked. A

more integrated approach is needed. There has been an emphasis on greater

integration of physical and mental health services among professionals, but for a

variety of factors that has not yet been achieved.

Evidence-based practices. Many providers in the area use a variety of evidence-

based practices. Continuing to emphasize the use of such practices should be

encouraged by all funders. An example of evidence-based practice is various forms

of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which has been studied with control groups and

found to be effective. Providing the training required to use these practices is

challenging due to costs and limited staffing.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 5

More coordinated and flexible funding streams. Local decision-making would be

strengthened if there were a greater opportunity to target external funds in ways

more consistent with local needs. For example, the eligibility requirements for

Healthy Start funding leaves parents who would benefit ineligible because their

income is slightly above eligibility limits while being insufficient to pay for these

services.

Prevention and early intervention. Widely recognized as the most effective long-

term strategies, finding the means to dedicate funds to these interventions would

bring long-term benefit to the community.

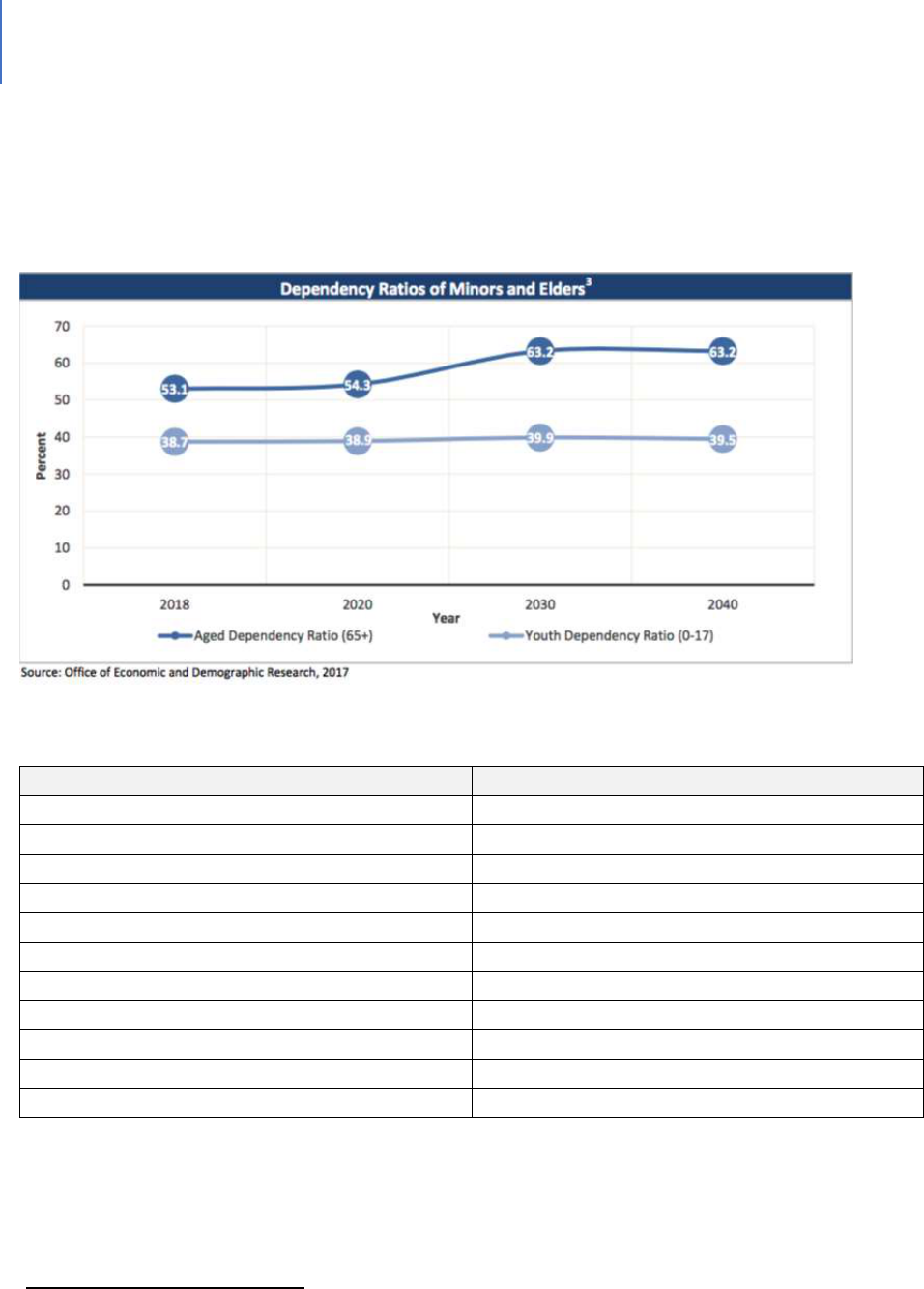

The Silver Wave. The proportion of Lee County residents who are elderly will

continue to increase. Preparing to address the human service issues that will arise is

a key future task. Various programs define the age that constitutes an elderly status

as 55, 60, 62 or 65. For data analysis purposes, the age that was used was whatever

age criterion the program being examined used.

Public understanding and education. Some people are not aware of services for

which they are eligible. There can be prejudice or bias toward certain groups of

people for whom human services is a necessity.

Data gaps. The need for greater information collection and sharing, especially across

systems, will grow. For example, real-time data about the psychiatric status of jail

inmates would be beneficial to those agencies responsible for mental health

planning. Many of these systems of care have high-demand users who often cycle

through their services. Between systems, interagency information sharing on high-

demand users could be helpful to provide actions that are more effective.

Affordability. As communities become more economically dynamic and diverse,

they become more expensive. Housing, transportation and food comprise a larger

proportion of their living costs than considered reasonable. For example, housing

affordability is worse in the larger and more economically diverse counties of

Florida, affordability challenges also exist in Lee. As noted in the report, it is

estimated that 22% of children in the county live in poverty and 37% of households

are cost-burdened for housing.

1

1

This data will be found in chapter 3.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 6

For approximately 44% of the households, only 16% of the rental housing stock is

affordable.

2

Transportation costs are considered affordable if they are 15% or less

of household income. This would be $7,281 per year for the average Lehigh Acres

household. The estimated driving costs for Lehigh Acres are $12,822 per year.

3

According to a USDA survey, 18.1% of Lee County adults report a time in the past

year (“often” or “sometimes”) when the food they bought just did not last, and they

did not have money to get more.

4

For 8% of the senior population (65 or older), or

slightly more than 19,000 persons, their household income falls below the federal

poverty guideline.

5

In-home services. For reasons of transportation and clinical benefit, greater delivery

of services in-home is needed. These in-home services have been found to be highly

beneficial because they allow the clinician to observe the family in a natural setting

and remove some of the barriers to accepting interventions.

Trauma. People who are exposed to violence, natural or manmade disaster, feel at

risk of harm or seeing others harmed can be traumatized by the event. If this

exposure is repeated or occurs with regularity, the likelihood some of one being

traumatized increases. The experience of trauma has both physical, physiological

and psychological effects. Both victims and those working with victims can

experience trauma. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the military is one example of

the impacts of experiencing or observing traumatic events. There is a need for a

broader understanding of trauma by behavioral health professionals as well as other

professionals who deliver human services.

Education for non-behavioral health disciplines. There is a need for other

professionals who interact with the various systems of care to have a better

understanding of various behaviors associated with differing conditions. There has

been a recent emphasis on more training on mental health issues or developmental

disability issues for law enforcement personnel as one example. These same

recommendations can be made for other elements of the criminal justice system.

2

This data will be found in chapter 5.

3

www.esri.com/software/american-community-survey

4

Lee County Health Needs Assessment, Lee Health

5

This data will be found in chapter 27.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 7

Assessment. An improved ability to assess individuals and families would be of value

across the various systems of care. For example, a greater ability to more fully

assess the mental status of people who are homeless or entering jail could lead to

better decisions about interventions. Being able to better assess potential elder

abuse is another example of improvement potential.

Employment. For the adult-oriented human service systems of care, employment is

a consistent concern. The benefits of employment are obvious. Barriers include

transportation, employer bias, the need for some special accommodations and

training. People with developmental disabilities, histories of drug abuse or mental

illness, or people with jail or prison records face employment challenges of differing

types.

Language and cultural diversity. As the County becomes more culturally and

linguistically diverse, demands are being placed upon the human service field to

respond with bi- or multi-lingual staff and more culturally sensitive interventions or

services.

Growing service demand in Lehigh Acres. The demographics are becoming more

diverse and households are cost-burdened from a combination of housing and

transportation costs. Services are currently limited as the chapter on spatial

matching demonstrates.

Technology. As with the rest of society, technology is changing how work is done.

There are potential benefits for service provision. Telepresence, in which services

could be delivered remotely through the internet, is one example of how technology

could improve access to services.

Chapter 34 addresses those services for which the BoCC has certain responsibilies

and/or which are of the most signicant nancial impact. This chapter addresses topics

such as:

Behavioral health and criminal jusce. The County funds the jail and other

criminal jusce components. A signicant proporon of jail inmates have

mental health or substance- abuse issues that are a cost-burden to the County.

Examining alternave or addional approaches could have a nancial impact.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Executive Summary Page | 8

Performance-For-Results Funding. The County funds various nonprots.

Examining these programs from a system-of-care approach and evidence-based

pracces perspecves could enhance their value.

Homelessness. The County serves as the lead agency for the Connuum of Care.

There has been an increased emphasis on diversion and prevenon. Addional

resources on those points could be cost-eecve.

Housing. While the County is not a housing developer, it has several tools that

could assist the development community to respond to the need for supporve

and aordable housing.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 1 | Introduction Page | 9

CHAPTER 1

Introducon

Purpose of the Study

This report addresses potenal gaps in the human services system in Lee County,

Florida. It is a comprehensive assessment covering not only those services provided by

the Lee Board of County Commissioners, but also services provided through federal and

state governments, as well as those provided through private means. It is intended to

be of use to the community in determining priories and investments.

The Denion of Human Services in this Assessment

Human services are dened in this study as:

Development services. These are eorts intended to strengthen, enrich or improve the

quality of life for members of the community through developing resiliency, social skills

and development of the whole person. Excluded from the denion for the scope of

this study are arts and culture acvies (except those designed for therapeuc

purposes), general educaon and the acvies of civic and faith communies. Included

in this denion are recreaon programs for persons of any age and quality child-care

programs.

Prevenon services. Certain behaviors can be harmful to self or others, regardless of

any demographic or socio-economic category. Communies wish to prevent those

behaviors from developing in the rst place. Programs and eorts to prevent the

development of problemac behavior, such as an-smoking campaigns, are examples of

programs that would be covered in this assessment. These services are targeted to the

community at-large.

Early Intervenon services. These are services that are targeted to more specic groups

that are deemed to be at a higher level of risk. This risk may have been determined by

research studies that have found a certain category of people to be more likely to

develop a problemac behavior or that face a challenging situaon requiring addional

support. The risk may also be determined by an early set of behaviors that have been

shown to be related to the development of more serious problems. For example,

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 1 | Introduction Page | 10

children who enter school without a certain level of reading skill are challenged and

may have greater dicules in school.

Intervenon and Treatment. These are services designed to intervene to:

Modify problematic behavior;

Address a complex social condition that results from a combination of personal

behavior, social and economic forces and/or geographic factors;

Address issues that arise from physical or personal disaster, victimhood, loss of

support systems or relationships;

Provide basic needs such as housing, food, and transportation.

What is excluded from this study are any comprehensive assessments of the following

systems:

The public education system, at any level, except where there are direct linkages to

social services such as addressing the needs of homeless children;

Private elementary, middle, high school, vocational or higher education services.

Child-care and pre-K programs are examined;

The public and private physical health care systems of the community, except for

physical disabilities that have significant social service implications such as people

whose disability requires personal care;

The arts and culture entities.

Gap Analysis: A Mul-dimensional Perspecve

Gaps in this assessment are examined from mulple perspecves. These include:

The gap between need and capacity. This is the most common understanding of “gap”

in that the number of people needing a service is greater than the level of services that

can be provided. This gap is referred to as the Needs / Capacity Gap.

Behavioral outcomes. The ulmate test of the value and validity of any human service

program is its impact on behavior (such as no use of drugs) or life status or condions

(such as being in permanent housing). To assess this gap perspecve, several data-

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 1 | Introduction Page | 11

bases reporng various populaon-level stascs on behaviors were used to compare

Lee County with other counes in the State.

Best pracces. Known as evidence-based pracces, these are programs that have been

evaluated and found to be eecve. All human service programs are well intenoned.

However, intenons do not always result in posive or long-term change. Evidence-

based programs, or best pracces, have been found to eecvely turn intenon into

posive impacts.

Policy/Process. In some cases, regulaons or organizaonal processes inadvertently

result in service gaps. This may be due to eligibility restricons, communicaon gaps or

other sources.

Access and Geography. This gap examines whether a gap exists between where the

people needing services reside and the locaon in which those services are provided.

Equity Funding. There are a variety of funding streams involved in the human services

eld. Various formulas exist that underlie those funding streams. The queson here is

whether Lee County is funded equitably when compared with other counes in the

State.

Methodology

This assessment used a variety of data sources to idenfy gaps. When mulple sources

idened a gap, the conclusion was determined to be more reliable and valid than if

the gap was only idened by one source. The data sources for the assessment

included:

Populaon Data. This data came from both public and private databases that reported

prevalence of certain behaviors or condions. Data gathered included a variety of

metrics, such as per-capita raos or percentages. Wherever possible, data specic to

Lee County was used and compared with the State of Florida averages, raos,

percentages, etc. It is considered populaon data because it is measuring a condion in

a populaon, such as seniors in Lee County, rather than an individual’s status.

Research Studies and Expert Opinion. The topics addressed in this study do not solely

exist in Lee County. These are issues every community in the naon faces to some

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 1 | Introduction Page | 12

degree. For most of these issues, there is a long history of eorts and intervenons

intended to address the issue or problem. For many of these topics, there is a research

base that seeks to determine scope, causality, eecveness of various soluons and

implicaons. In addion to research and evaluaon studies, professional associaons

have developed a process in which knowledge is shared and skills and soluons are

promoted. This results in a body of expert opinion of people who have worked in the

eld for years and understand its strengths and weaknesses. This informaon was

gathered by the means listed below:

Surveys

Focus groups

Interviews

Literature reviews

Program Data. Each service program maintains some level of data about their services.

These vary in comprehensiveness, detail, length of data collecon, reliability and

validity. Whatever the varying quality, this is sll a source of informaon. Some of the

data types examined here include:

Outputs

Financials

Staffing

Report Format

The report is organized in eight secons as described below:

Secon One: Descripve and Quantave data. This secon uses various quantave

data sources to examine potenal gaps in human services. It consists of three chapters

as listed below:

Lee County Demographics

Behavioral Outcomes

Comparison of Surveys

Secon Two: Infrastructure. This secon addresses basic needs such as housing,

transportaon, employment and food, as well as the organizaonal infrastructure

needed to provide services such as stang, facilies, organizaonal capacity and

technology.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 1 | Introduction Page | 13

Housing

Transportation

Food

Employment

Staffing

Facilities

Organizational Capacity

Information and Technology

Secon Three: Development. This chapter addresses the rst element of a service

system – development. It consists of one chapter on child and youth development.

Secon Four: Systems of Care. These are systems designed to address a specic issue,

such as homelessness or domesc violence. There are 10 chapters in this secon and

they are organized in the chapter format presented below. They may cover prevenon,

early intervenon or treatment services from both a Needs / Capacity perspecve

and/or a Best Pracce perspecve. Each concludes with a lisng of gaps.

Secon Five: Special Populaons. This secon addresses four populaons for which

there are disncve issues as well as disncve funding sources. These populaons are

persons with intellectual and developmental disabilies, persons with congenital deaf

and blind issues, persons with disabilies and veterans.

Secon Six: Geography. This secon consists of one chapter that examines spaal

mismatch.

Secon Seven: Financial. This secon examines which enes are responsible for

funding the various services, funding equity issues and a determinaon of the Lee

Board of County Commissioners’ current human services related expenditures.

Secon Eight: Conclusions. This secon examines the core drivers underlying the

human services issues such as behavioral health, trauma and cost-burdened

households. It concludes with an examinaon of the Lee County strategy.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Section One: Quantitative Data Page | 14

Intenonally le blank.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Section One: Quantitative Data Page | 15

Secon One: Quantave Data

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Section One: Quantitative Data Page | 16

Intenonally le blank.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 17

CHAPTER 2

Lee County Descripon and Demographics

County Descripon

Assessment of demographic characteriscs can indicate the need for access to a variety

of services in a community. Factors such as populaon growth, age trends and

economy help to shape regional needs and also play a role in idenfying potenal gaps

in available services and resources.

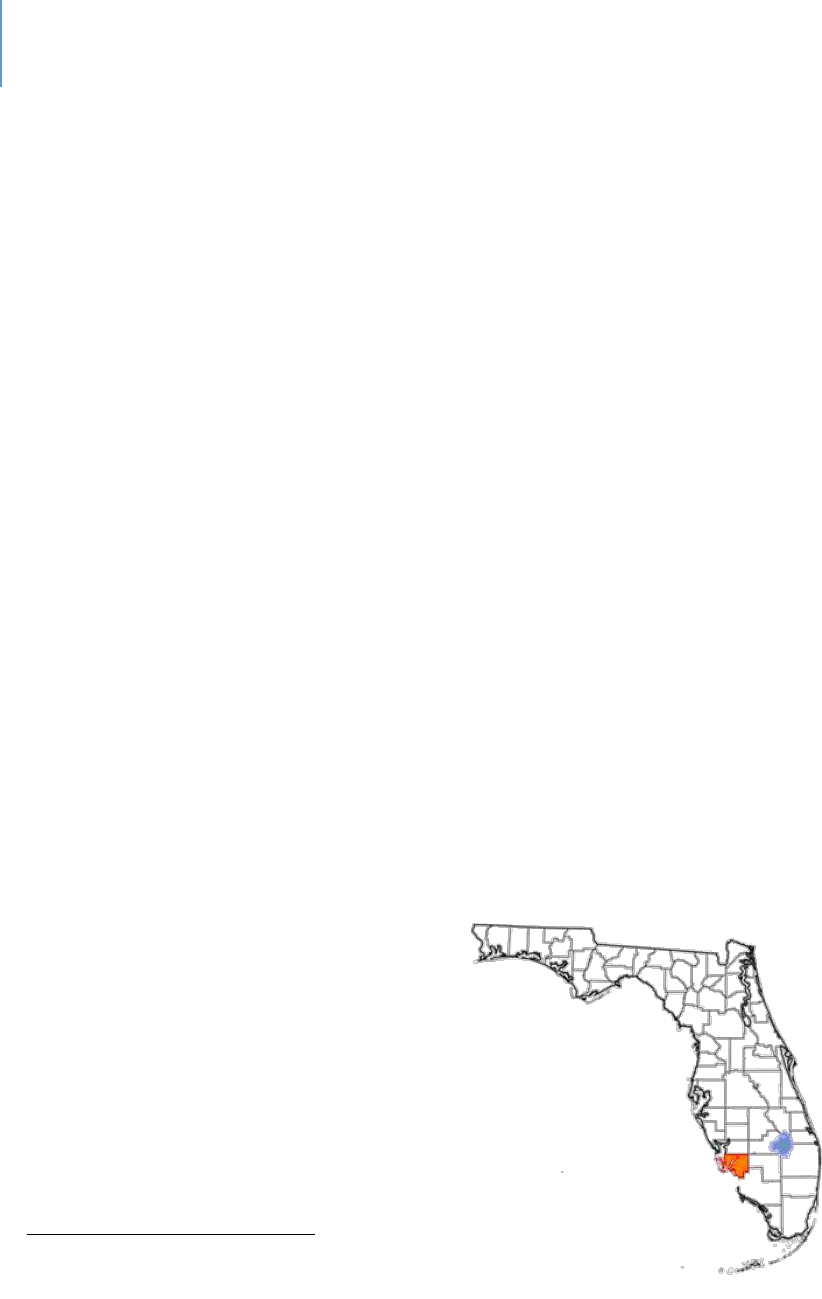

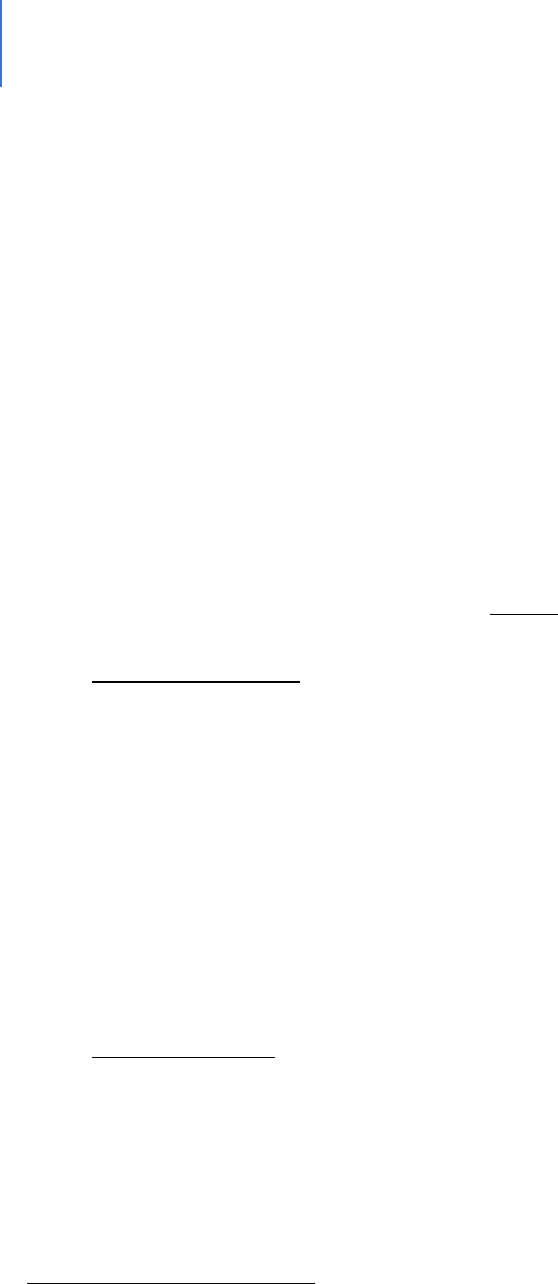

Lee County is the eighth most populated county in the State of Florida. Located on the

Gulf Coast of Florida, Lee County encompasses approximately 813 square miles of land

including several small islands in the Gulf of Mexico. The County is bordered by

Charloe County to the north, Hendry County to the east and Collier County to the

south. Lee County comprises the Cape Coral – Fort Myers, FL Metropolitan Stascal

Area (MSA). The City of Cape Coral is the largest City within the MSA. Other units of

local government within the MSA are the City of Bonita Springs, the City of Fort Myers,

the Town of Fort Myers Beach, the Village of Estero, and the City of Sanibel.

Unincorporated areas of the County are mostly divided into named communies.

These include: Bayshore, Boca Grande, Buckingham, Caloosahatchee Shores, Olga,

Capva, Greater Pine Island, Matlacha, Lehigh Acres, Northeast Lee County, Alva, North

Olga, North Fort Myers, Page Park, San Carlos Island, Southeast Lee County, Tice and

others.

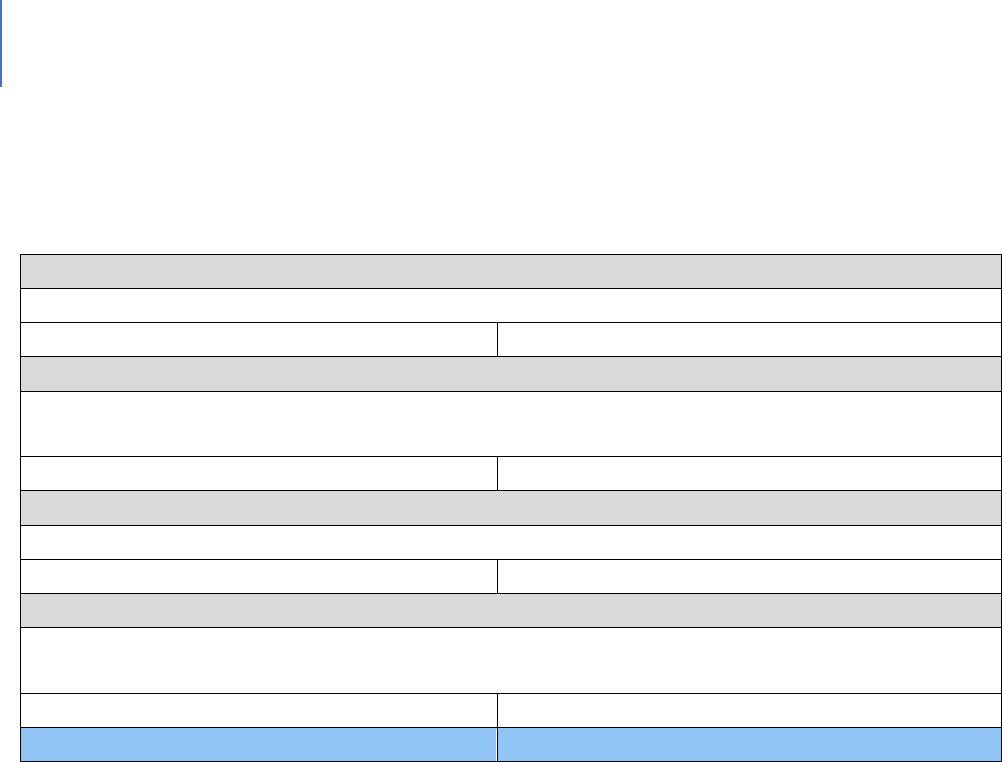

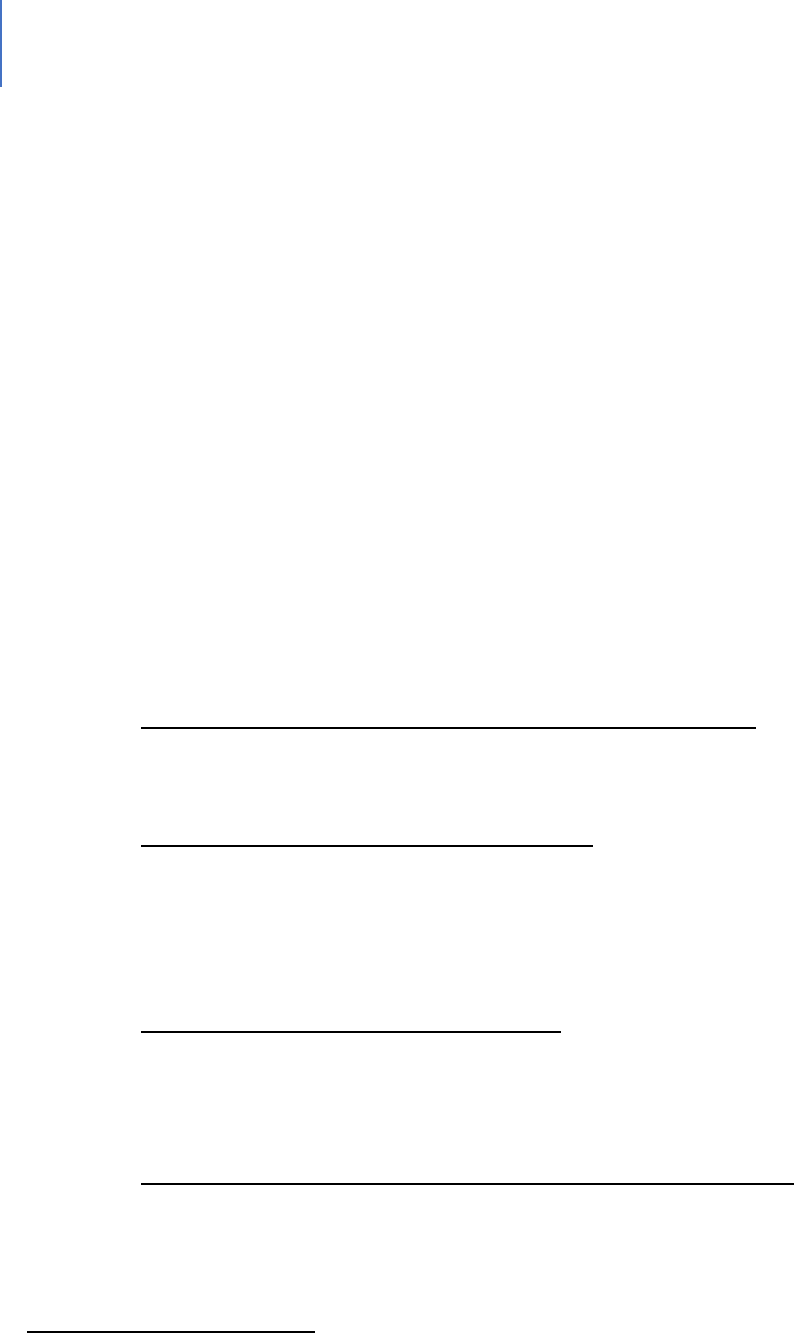

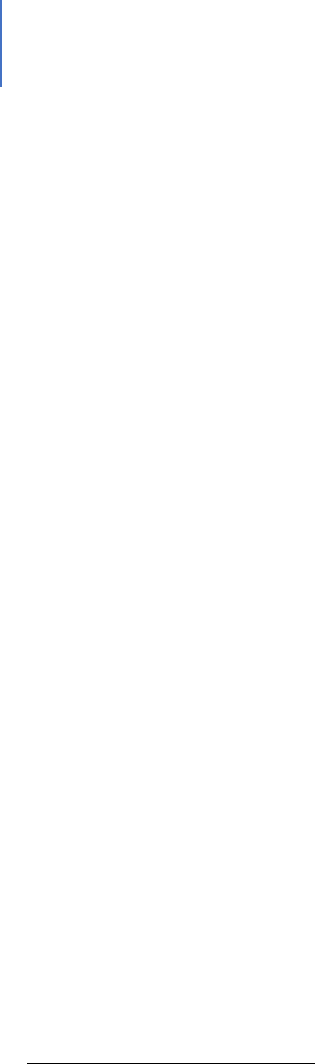

Figure 1. Lee County, Florida Location

Lee County, Florida

Populaon 754,610

6

Number of Households 281,222

7

Median Age is 48.8

8

Median Household Income $56,129

9

Poverty Rate 12.2

10

6

American Community Survey, Quick Facts, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/leecountyflorida

7

American Community Survey, DP03, 2018 1-Year Estimates

8

American Community Survey, S0101: 2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates

9

American Community Survey, DP03, 2018 1-Year Estimates

10

American Community Survey, S1701, 2018 1-Year Estimates

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 18

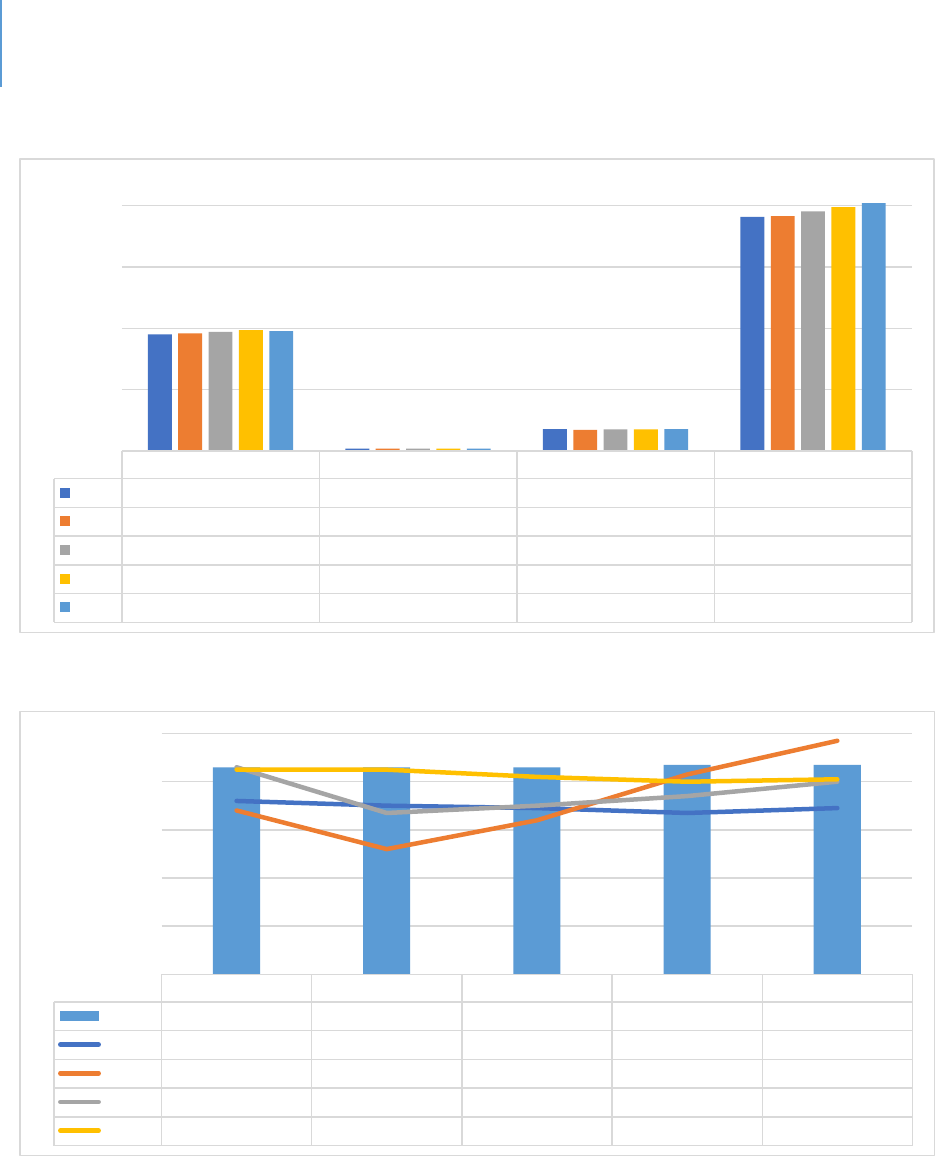

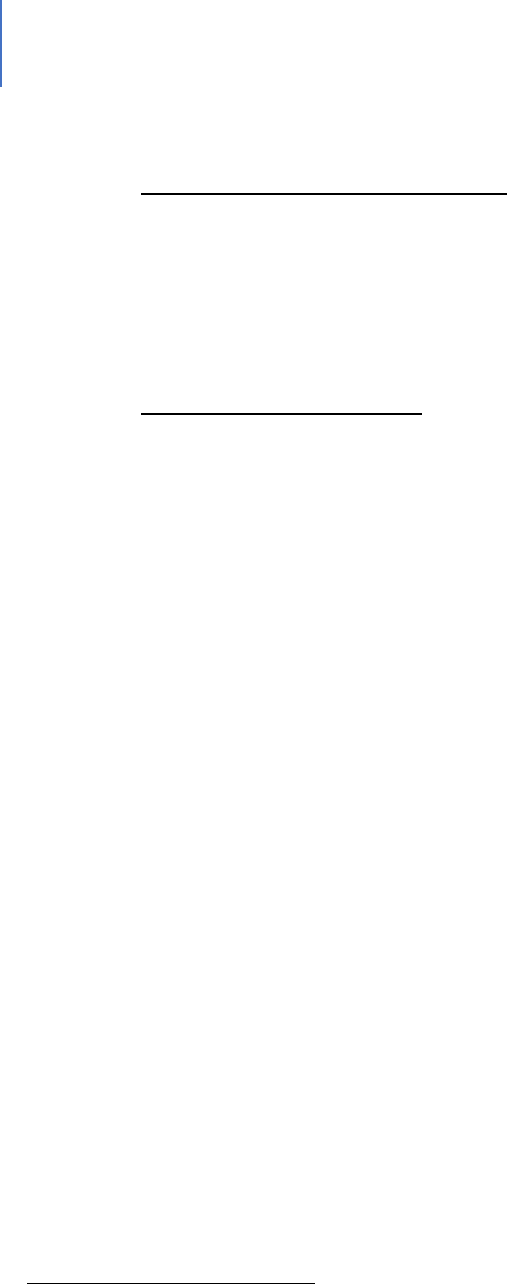

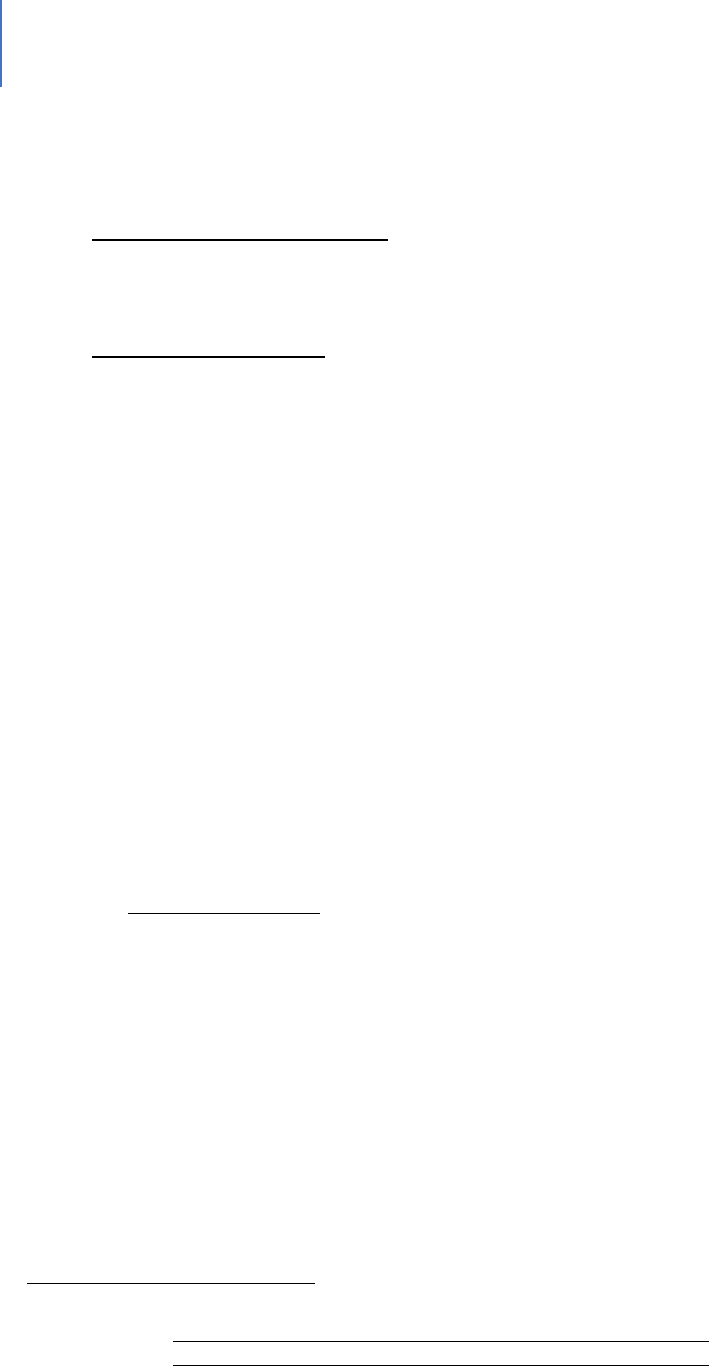

Populaon Growth

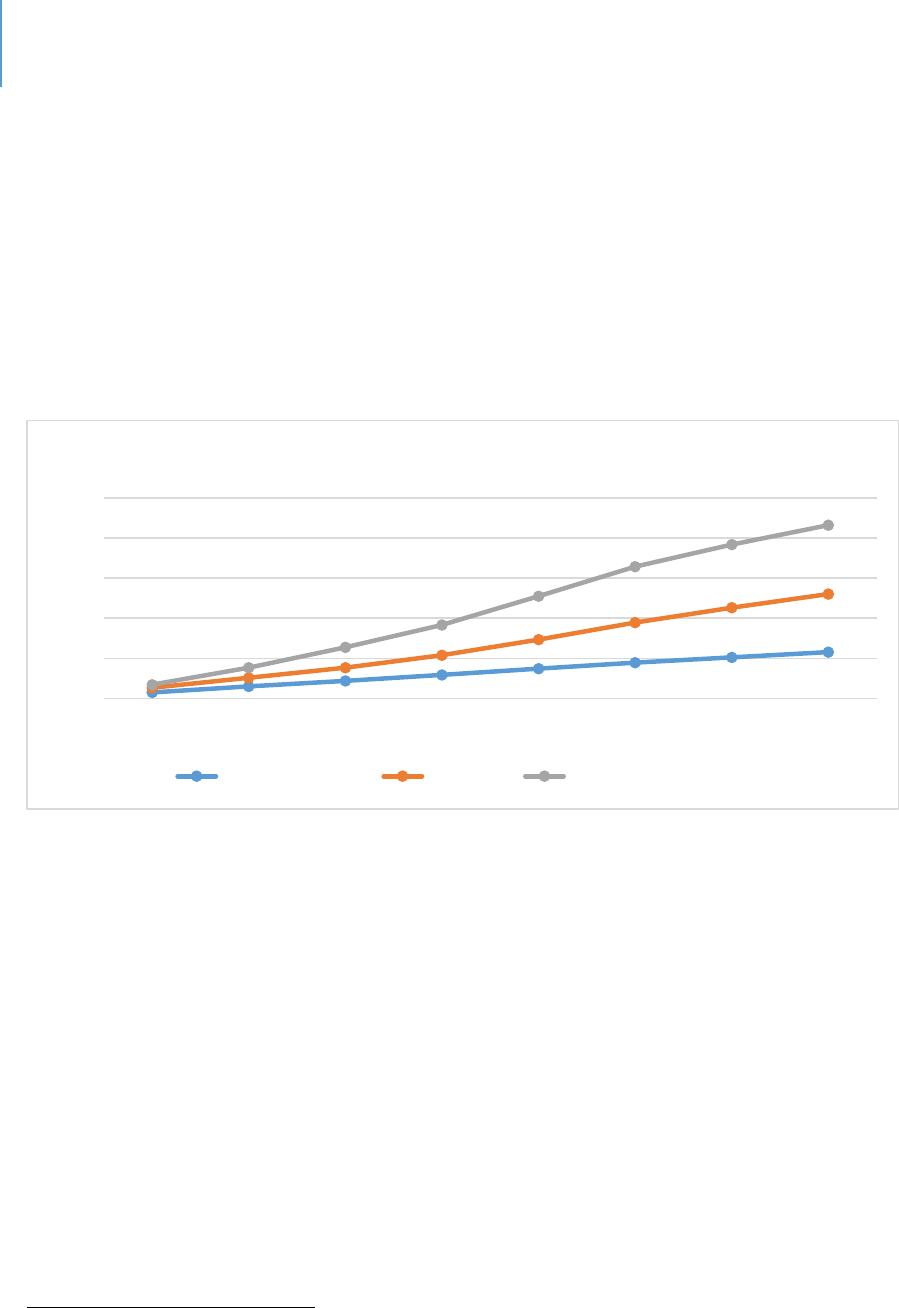

The 2018 American Community Survey One-Year Populaon Esmate indicates a total

populaon of 754,610 in Lee County, a 22% increase over the 2010 census of 620,454.

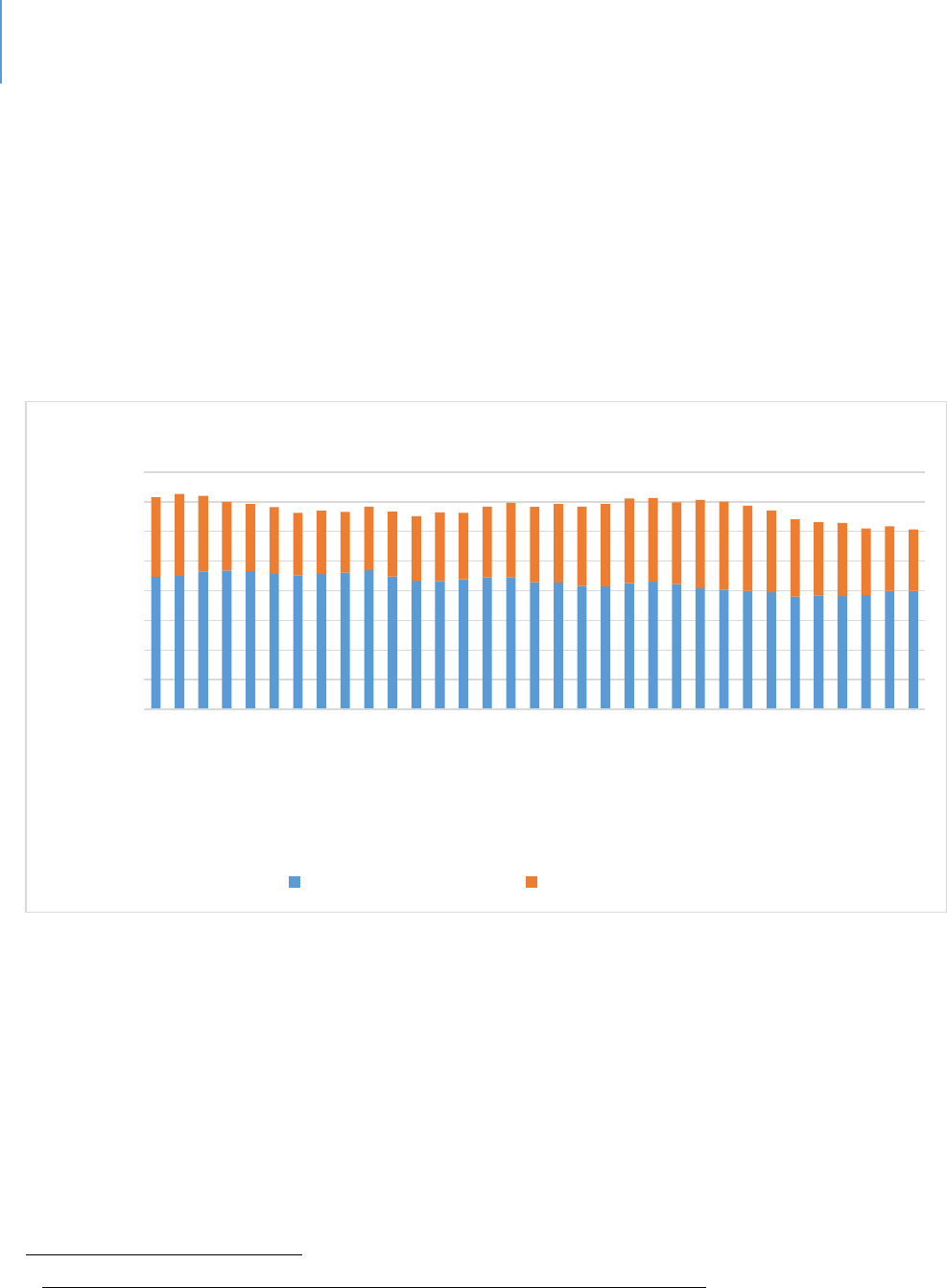

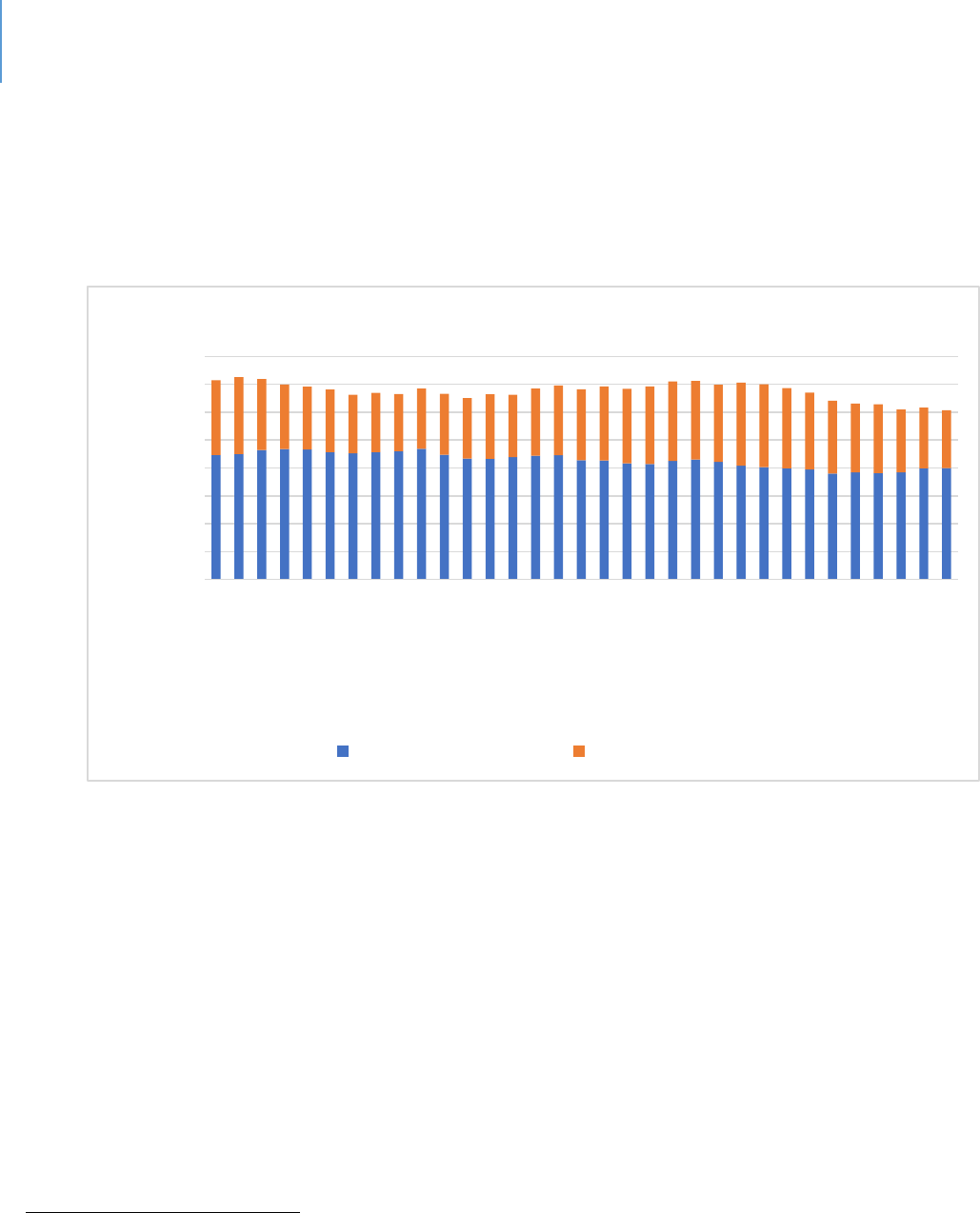

Figure 2 displays a comparison of Lee County to the populaon growth in Florida and

the United States.

Figure 2. Population Growth Estimates

11

In addion to the growth of the permanent residents, Lee County has a cyclical,

seasonal populaon increase of 18% in standard dwelling units.

12

Data from the Bureau of Economic and Business Research at the University of Florida

indicates a projected populaon growth for 2030. Projecons ancipate that

unincorporated Lee County will experience the greatest growth at 140,000 or 38%. The

City of Cape Coral will see an inux of populaon, growing 34.5% by 2030. The enre

Lee County populaon is ancipated to grow by more than 240,000, or 32.8% by 2030;

18% over the ancipated State populaon growth rate.

11

American Community Survey, B01003: 2018 ACS 1-Year Esmates

12

Lee County Community Development

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Population Growth Estimates, 2010 - 2018

United States Florida Lee County, Florida

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 19

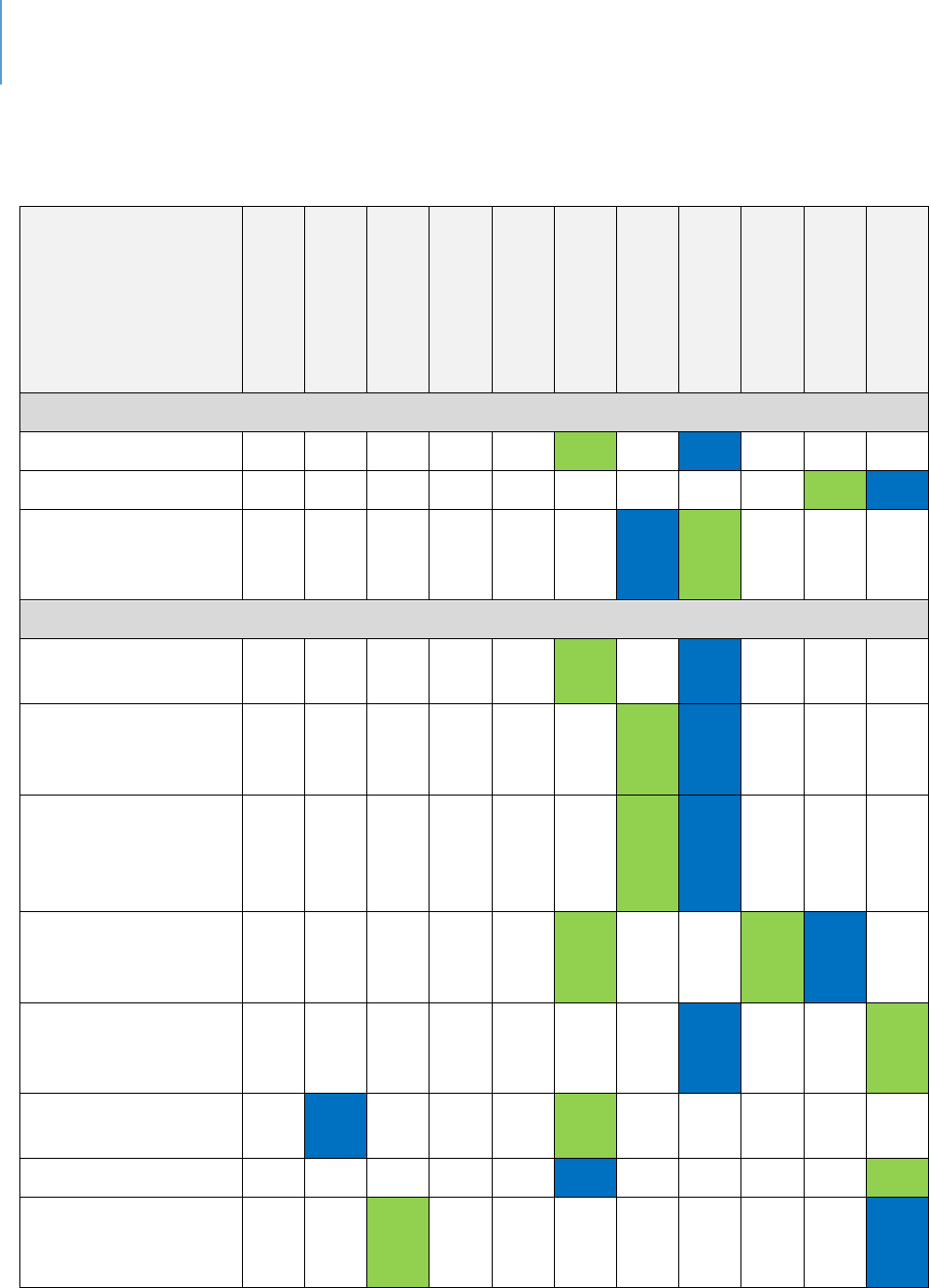

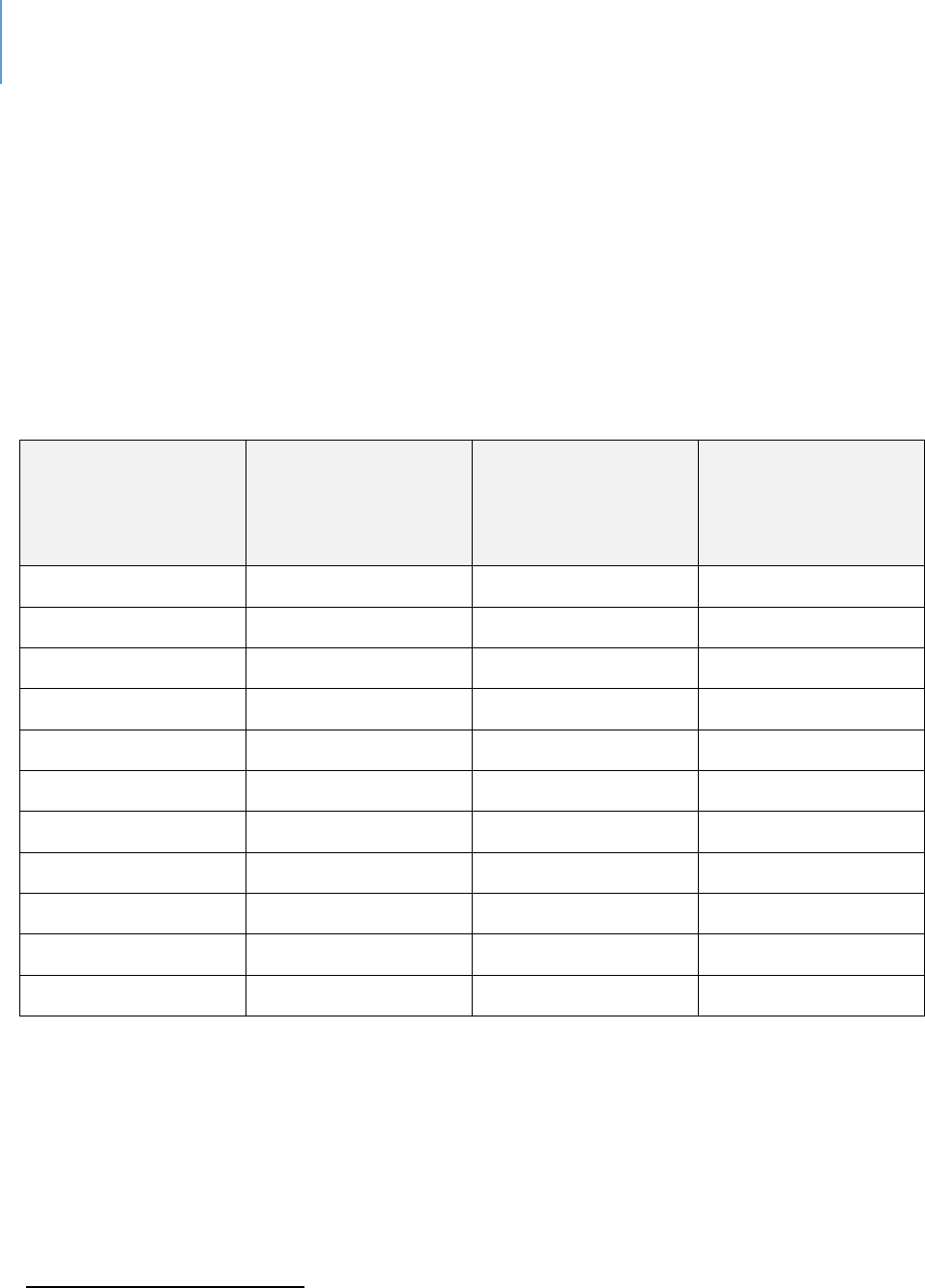

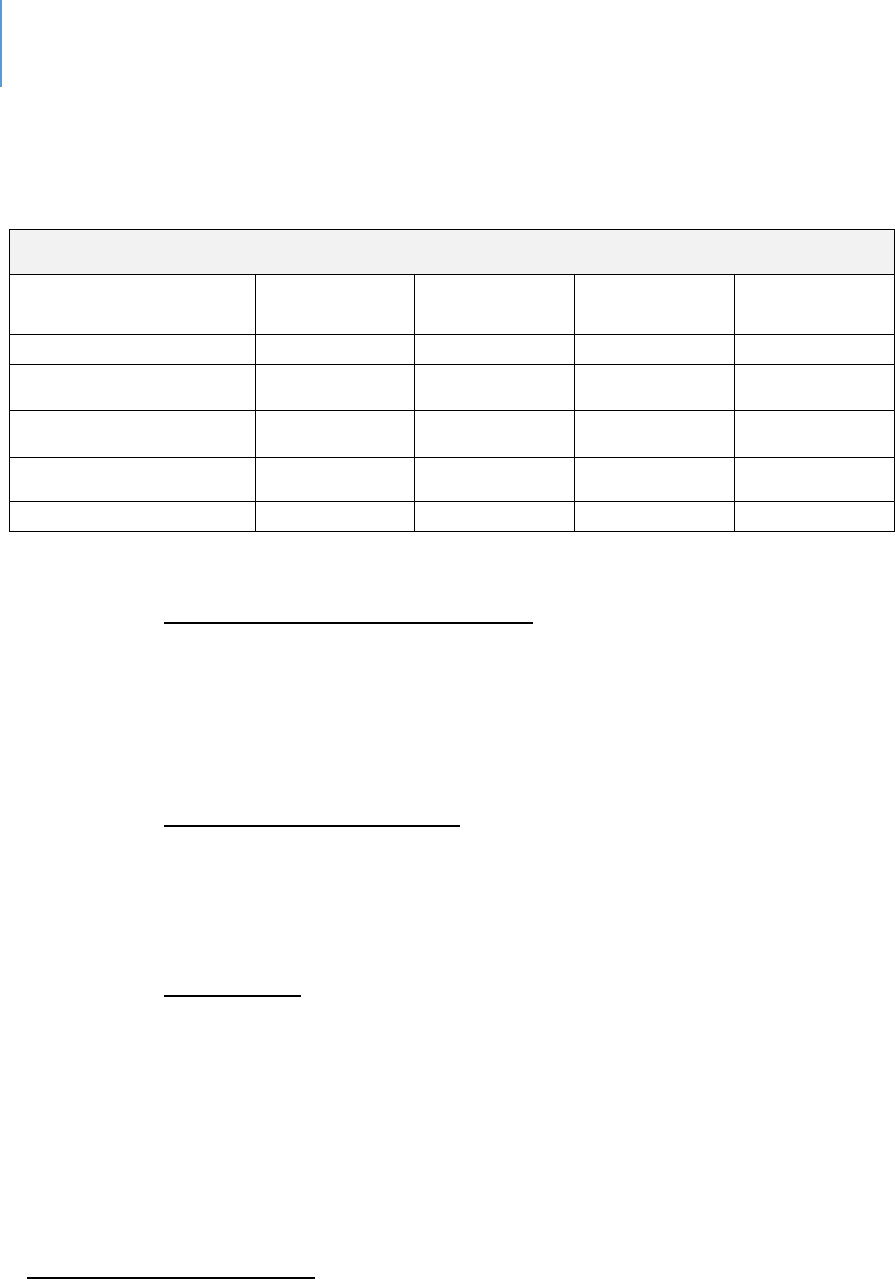

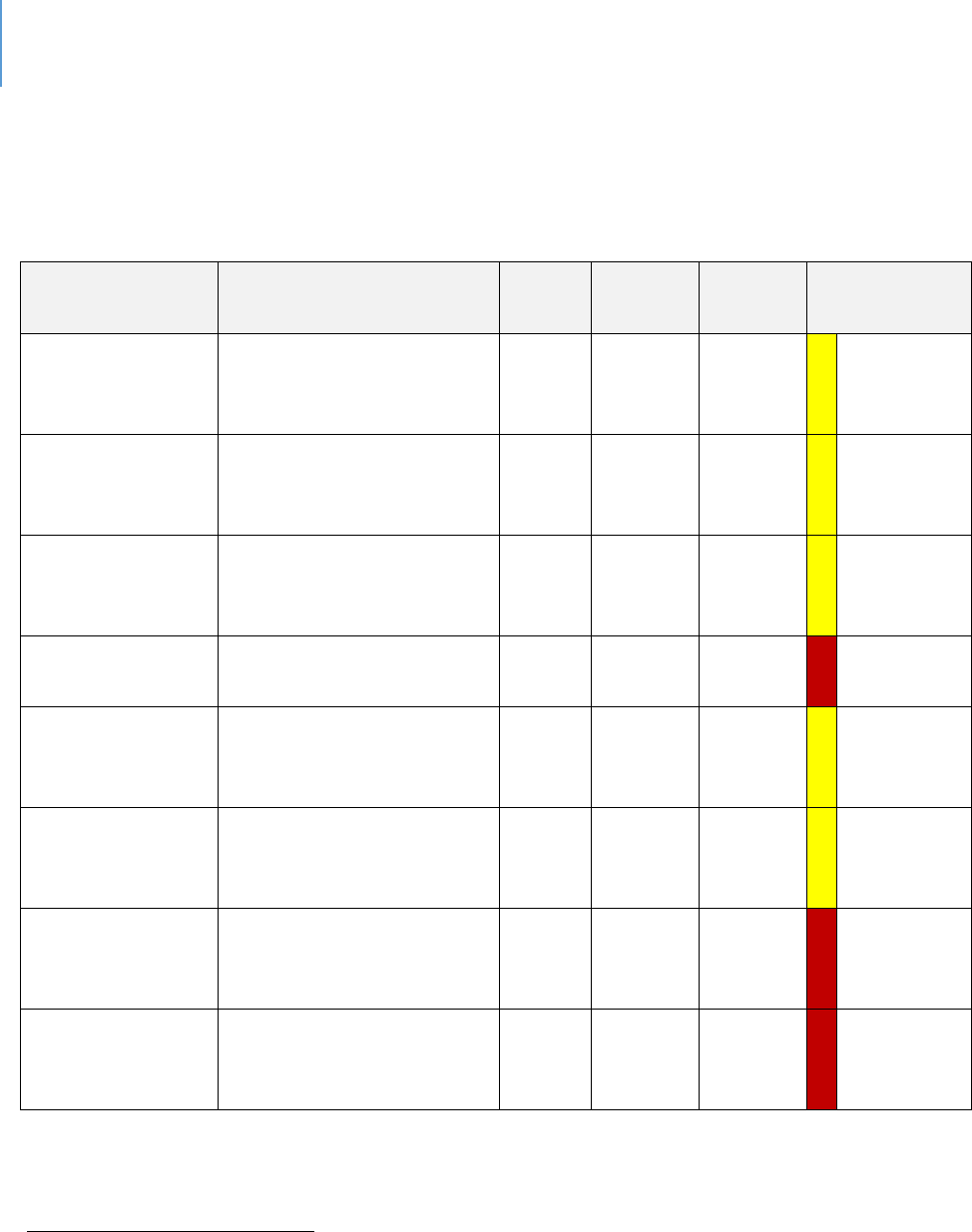

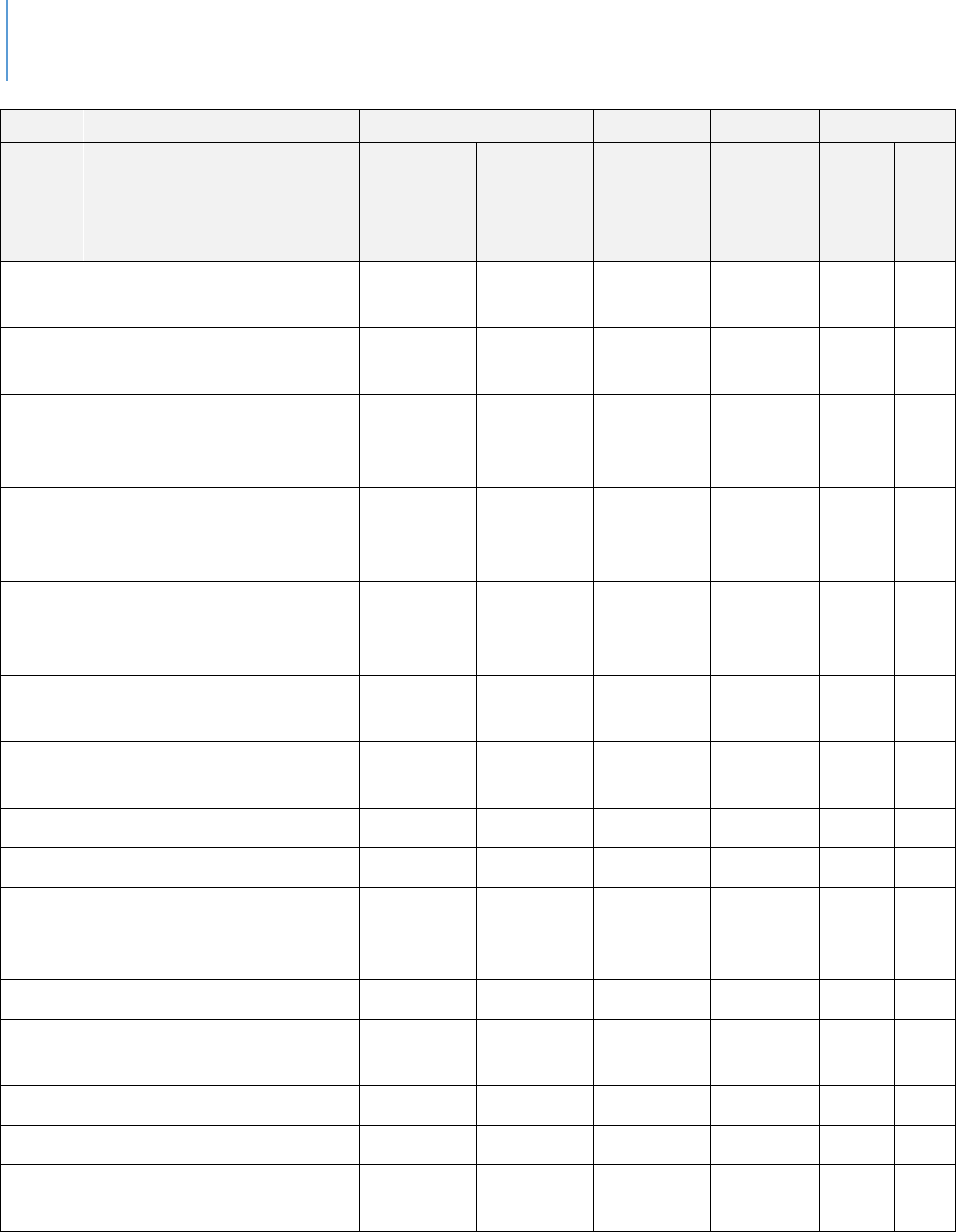

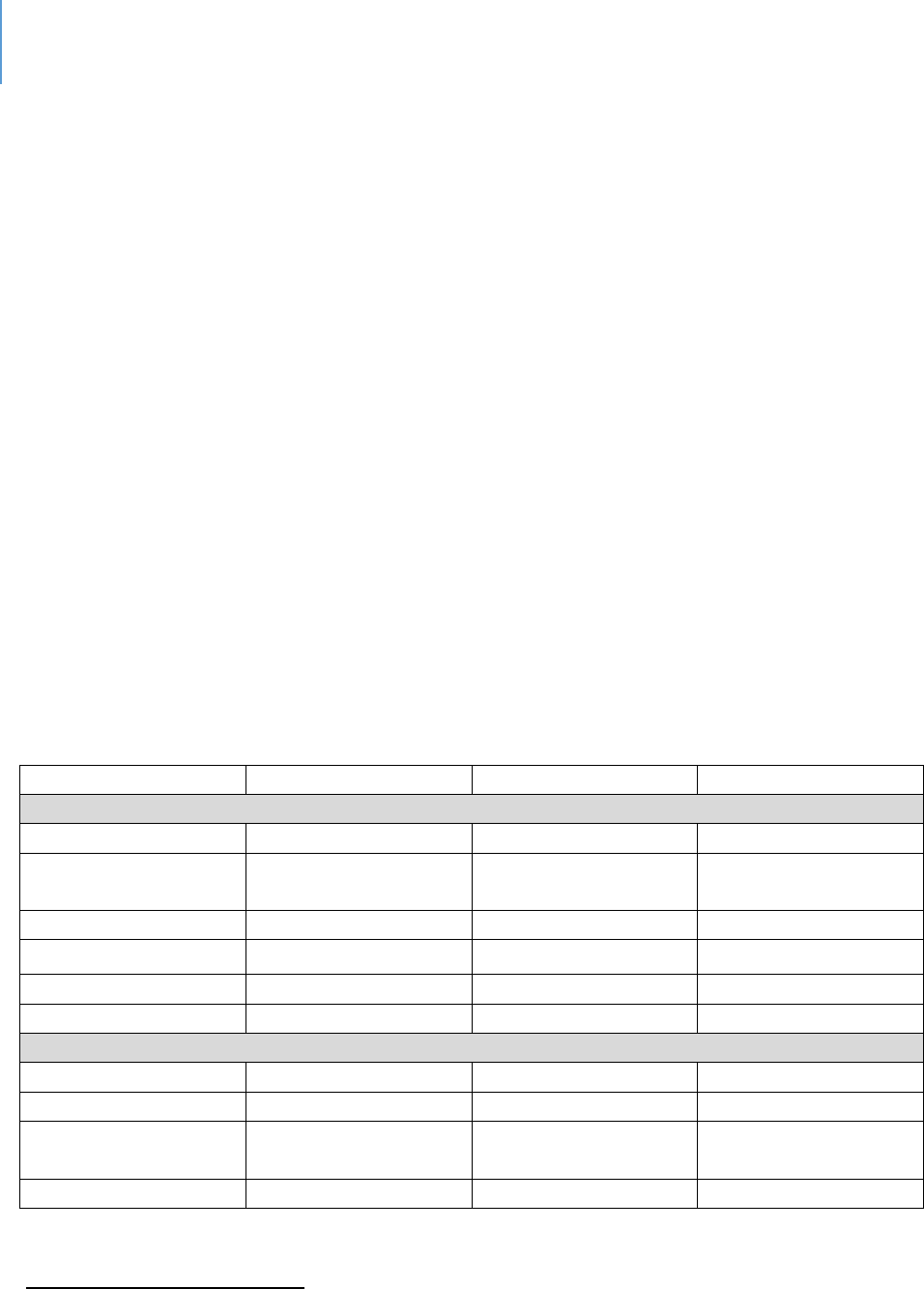

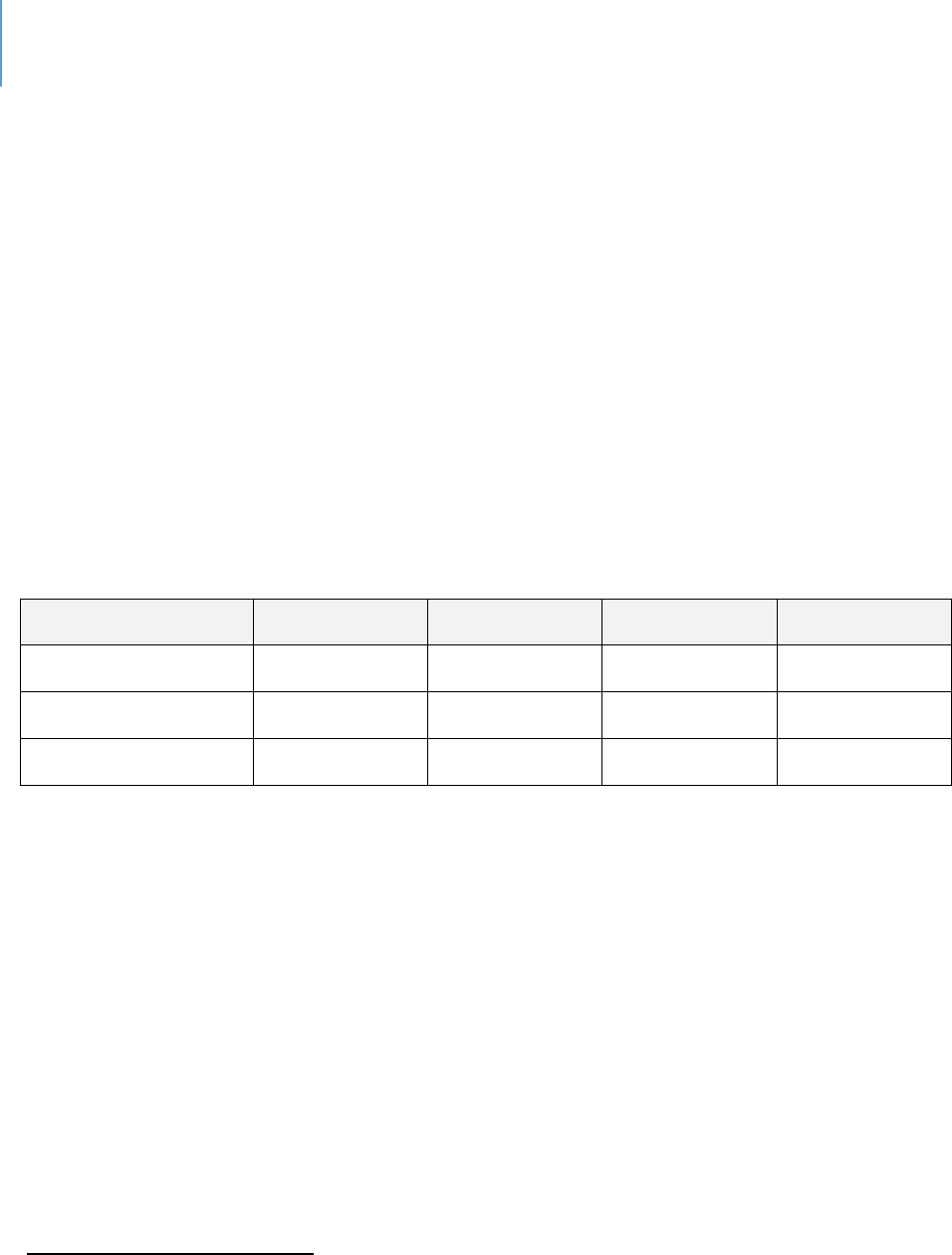

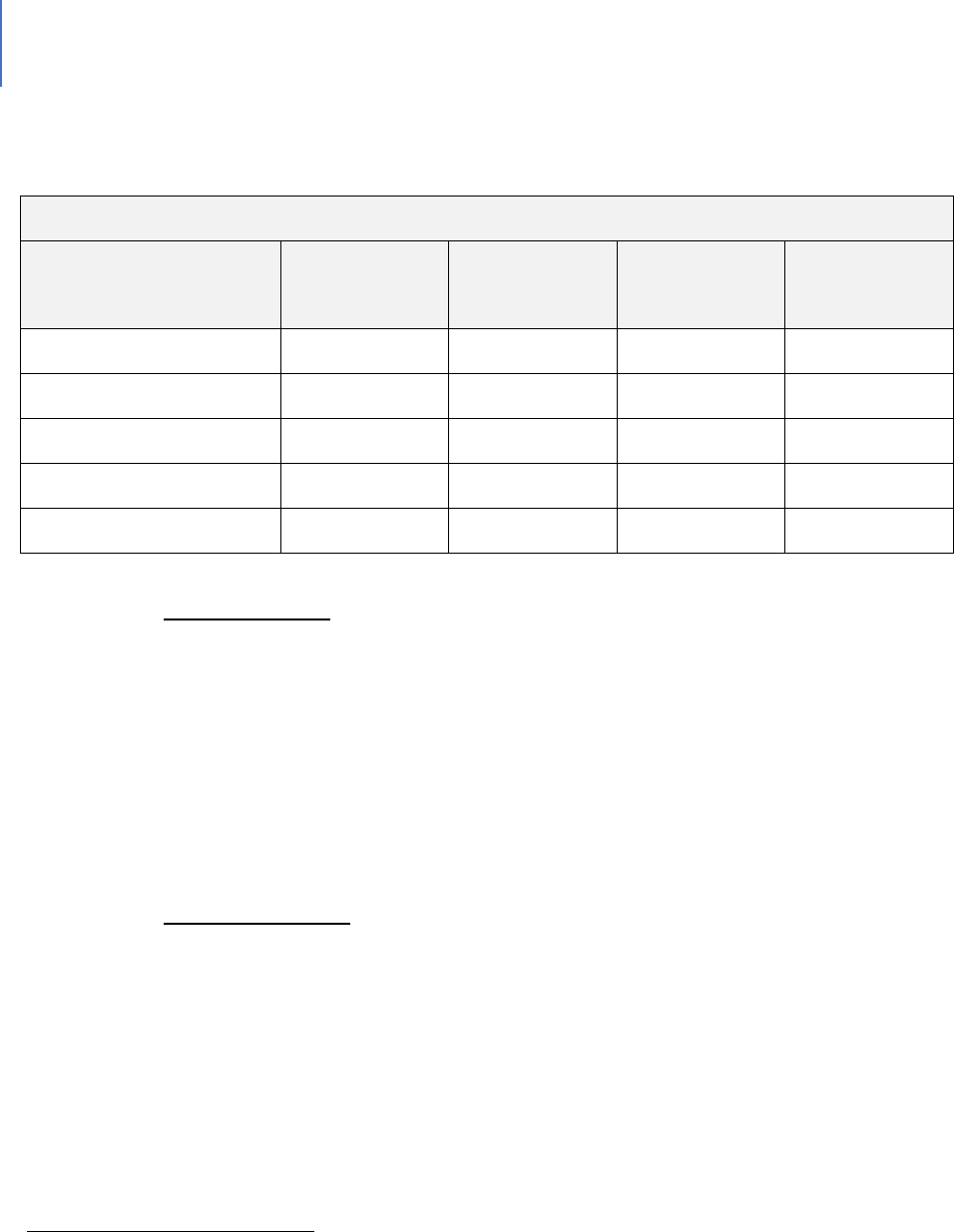

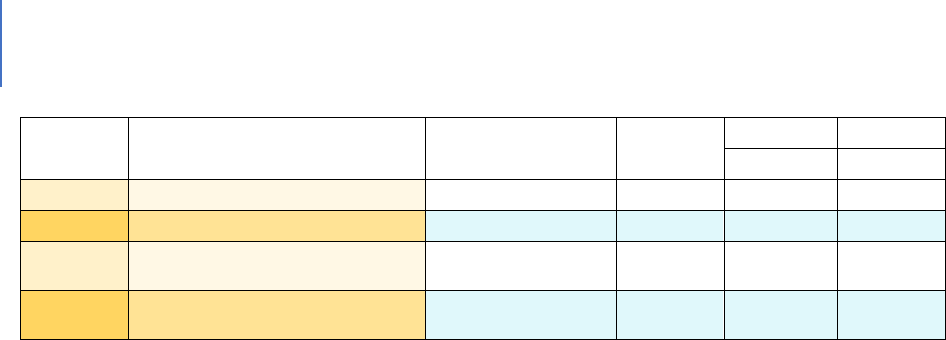

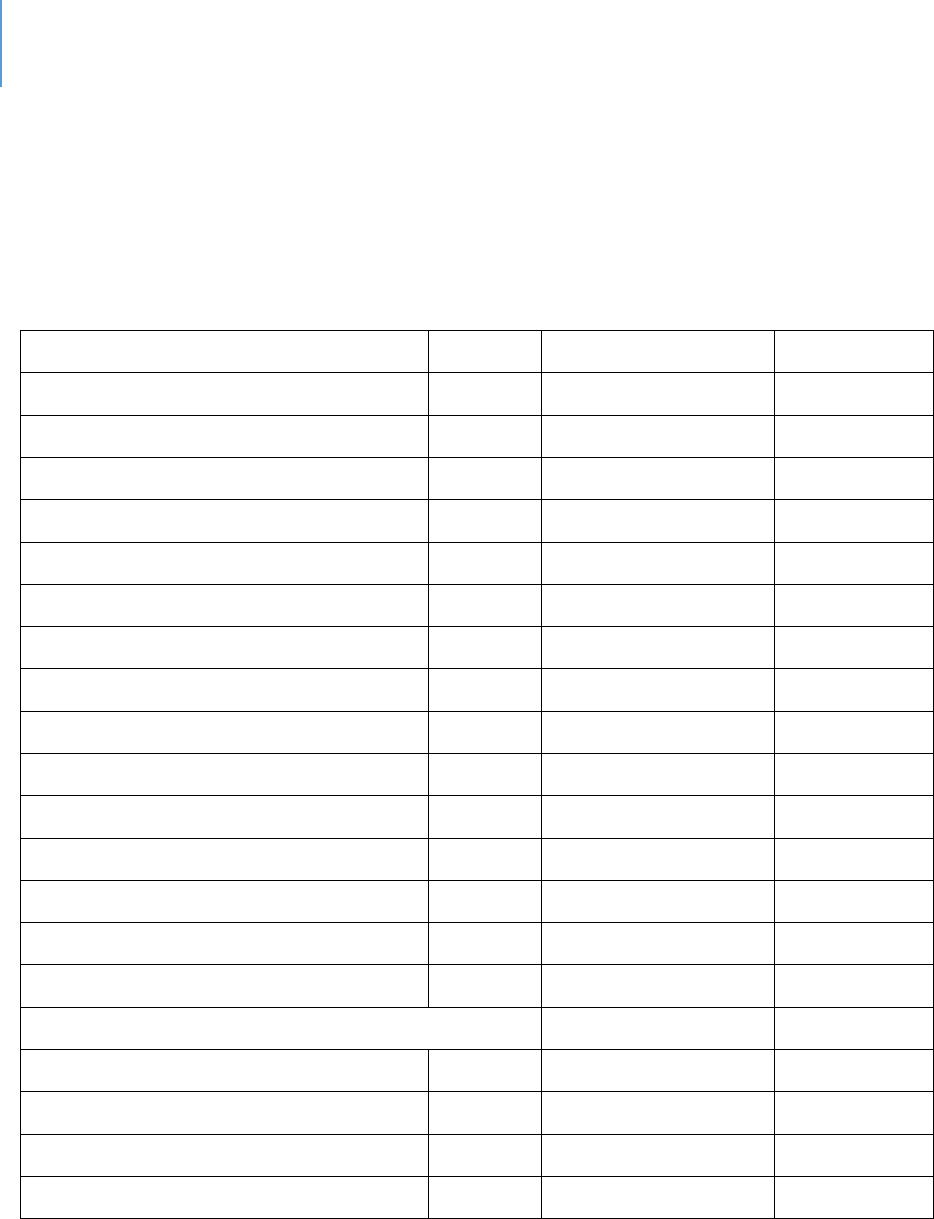

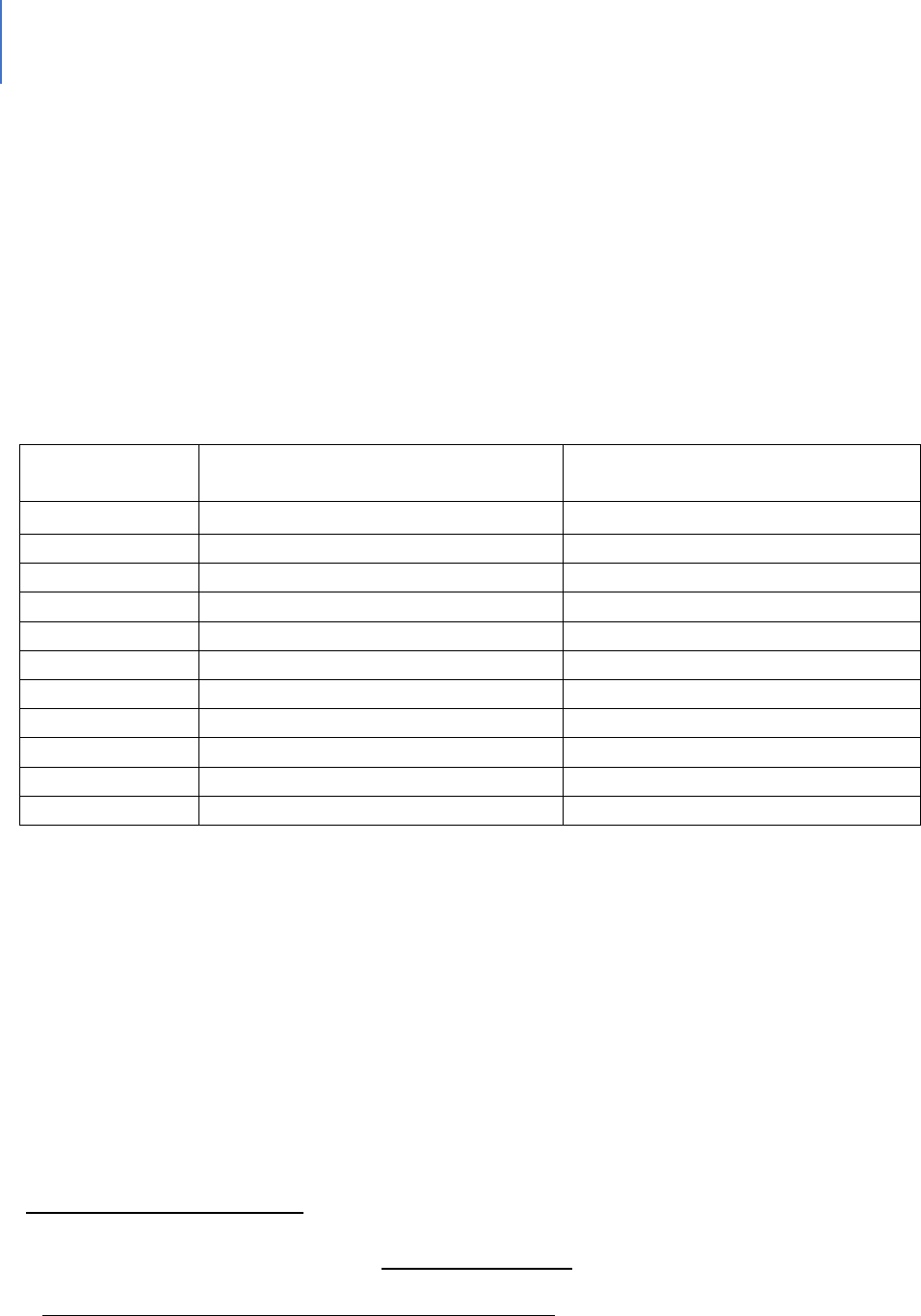

Table 1. Population Change Countywide

13

University of Florida, Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR)

Jurisdicon

Total

Populaon

2010

Esmated

Populaon

2019

Total

Populaon

2030

(Projecon)

14

Percent

Change

2010 -

2019

Projected

Percent

Change

2019 -

2030

Urban County

Bonita Springs

43,857

54,437

62,645

24.1%

15.1%

Fort Myers Beach

6,277

6,520

5,818

3.9%

-10.8%

Sanibel

6,469

6,756

6,920

4.4%

2.4%

Estero*

0

32,412

48,125

15

N/A

48.5%

Unincorporated

345,548

361,315

501,646

4.6%

38.8%

Unincorporated (Plus

Estero)*

345,548

393,727

549,771

13.9%

Total Urban County

402,151

461,440

625,154

14.7%

35.5%

Entlement Jurisdicons

Cape Coral

154,305

185,837

249,942

20.4%

34.5%

Fort Myers

62,298

87,871

101,525

41.0%

15.5%

Total Lee County

618,754

735,148

976,621

18.8%

32.8%

State of Florida

State of Florida

18,801,332

21,208,589

24,340,500

12.8%

14.8%

*Estero Incorporated in December 2014.

13

Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR), University of Florida 201

14

2030 City projections from Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR), University of Florida 2017

15

Metro Forecasting Models projections, The Village of Estero Comprehensive Plan

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 20

Limited English Prociency

People with Limited English Prociency (LEP) are dened by the federal government as

those with a limited ability to read, write, speak or understand English. American

Community Survey data reports on households in which English is not spoken at home.

In 2017, the Census Bureau reported that 147,361 people across Lee County (21.1

percent of the populaon) spoke at least one language other than English. Of these,

62,713 (9.4 percent of the populaon) spoke English less than “very well.” Translaon

of vital documents is required for HUD entlement communies if the number of LEP

persons in a single language group constutes 5% or 1,000, whichever is less. The

language group to qualify according to this threshold is Spanish.

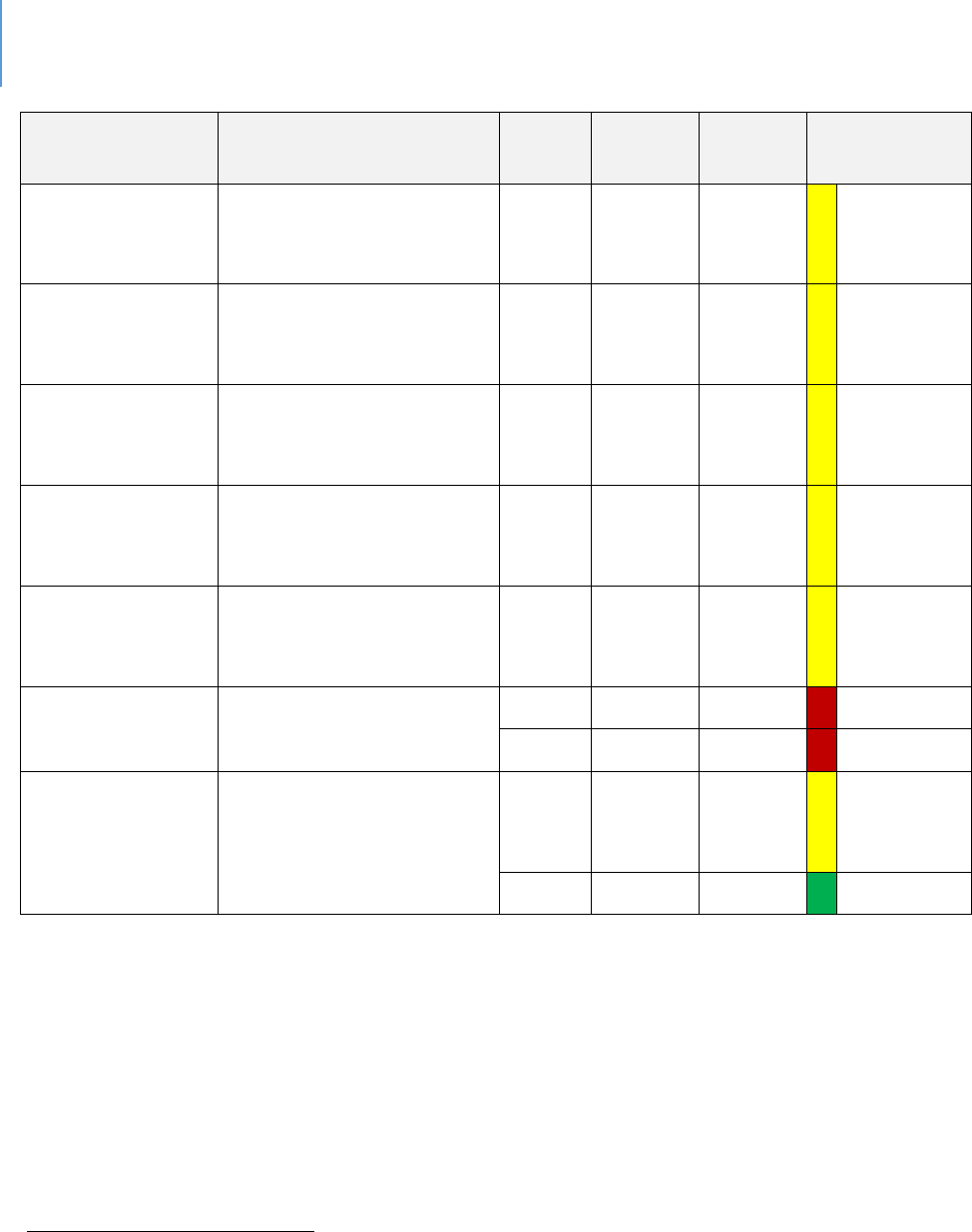

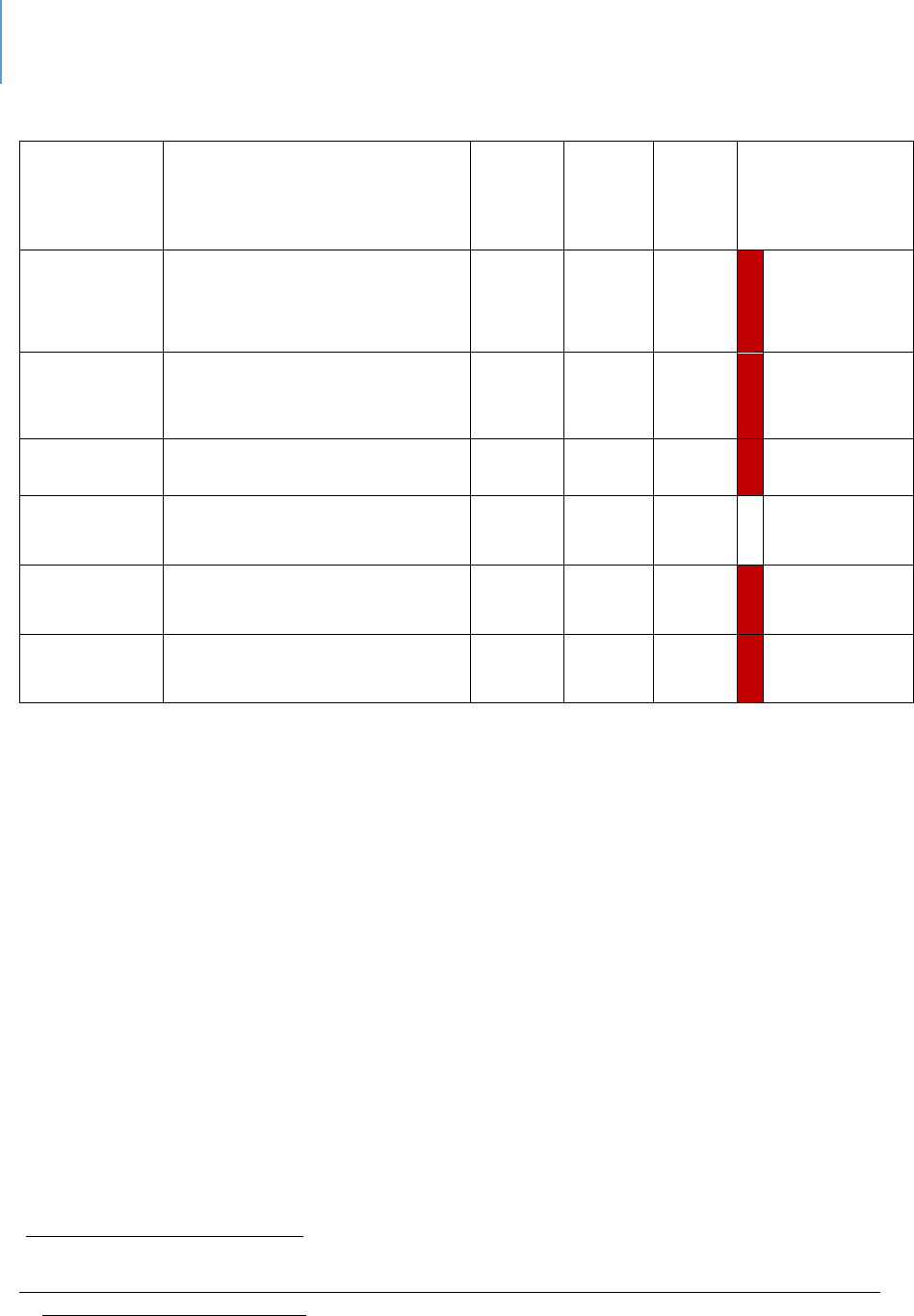

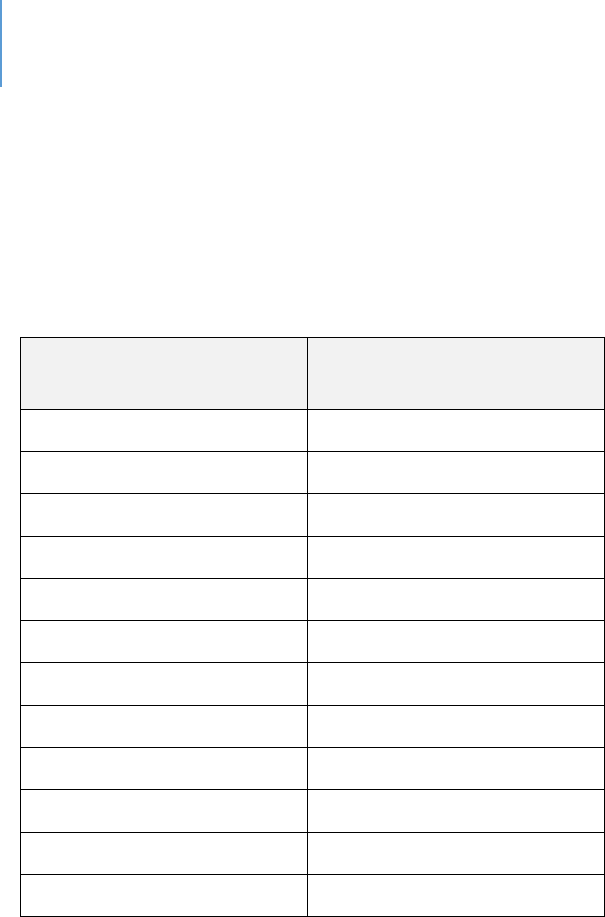

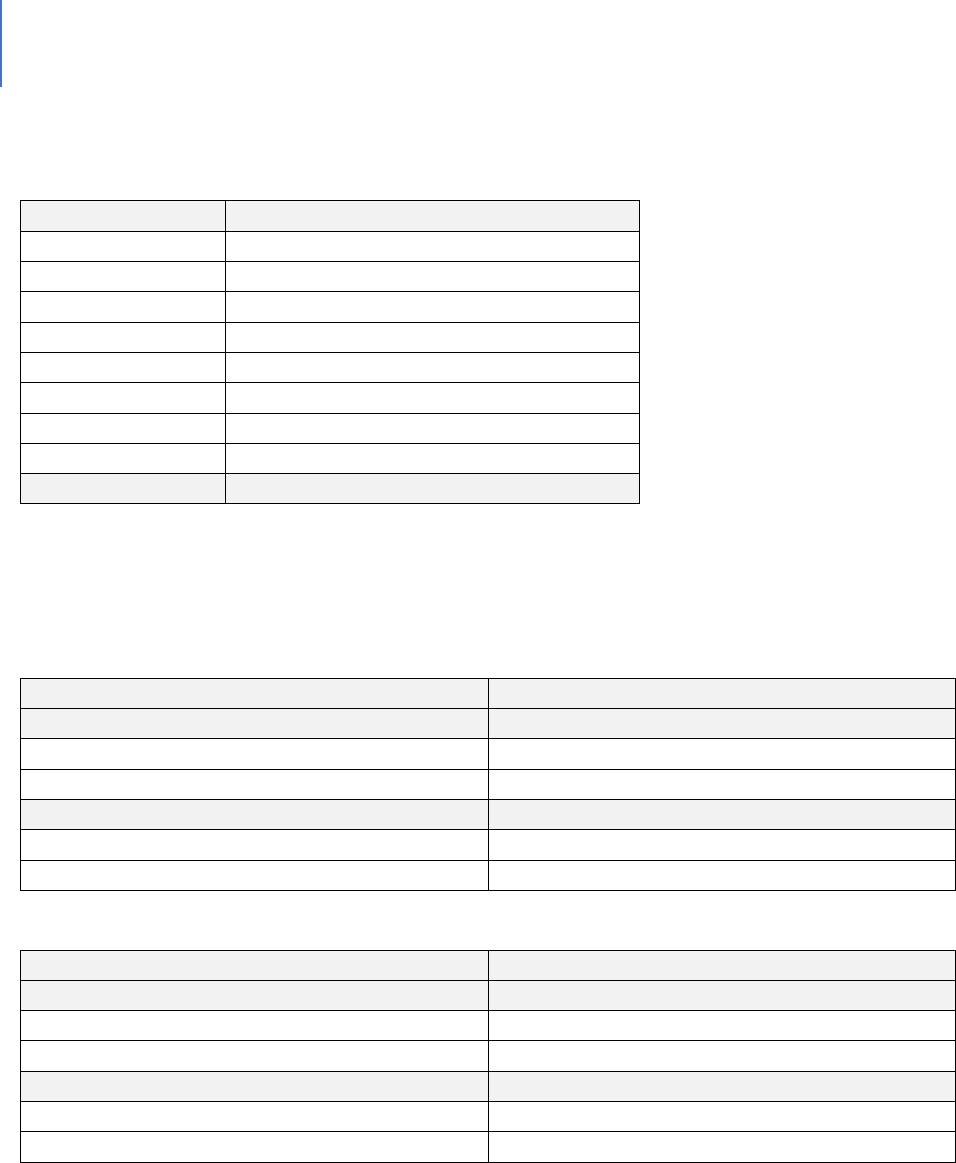

Table 2. Limited English Proficiency Language Group, 2017

16

Language Group

Number of LEP

Speakers

Percent of Total

Populaon

Spanish

47,083

7.83%

French Creole

4,633

0.77%

Portuguese

1,130

0.19%

German

1,049

0.17%

16

HUD AFFH Data (AFFHT0004) Released November 17, 2017.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 21

Figure 3. Map of Limited English Proficiency Language Group, 2017

Race, Ethnicity and Naonal Origin

Overall, Lee County has become more diverse since 2010. This is due to two factors: an

increase in racial and ethnic minority populaon and a decrease in the percentage of

white populaon. Aer white residents, the largest racial/ethnic group in Lee County is

Hispanic. Hispanic or Lano is an ethnic classicaon by the U.S. Census Bureau.

However, Hispanic individuals can be of any race.

The 2018 Census esmates indicated a major shi in populaon composion from

2010, which showed a 70.8% white (not Hispanic or Lano) and Hispanic or Lano (any

race) populaon, comprising 18.4% of the County’s total populaon. In 2018, 66.3% of

the populaon idened as white (not Hispanic or Lano) and Hispanic or Lano (any

race) populaons, comprised 21.9% of the County’s total populaon.

The County’s populaon that is Hispanic or Lano increased from 114,098 to 165,233

people from 2010 and 2018, an increase of 45%.

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 22

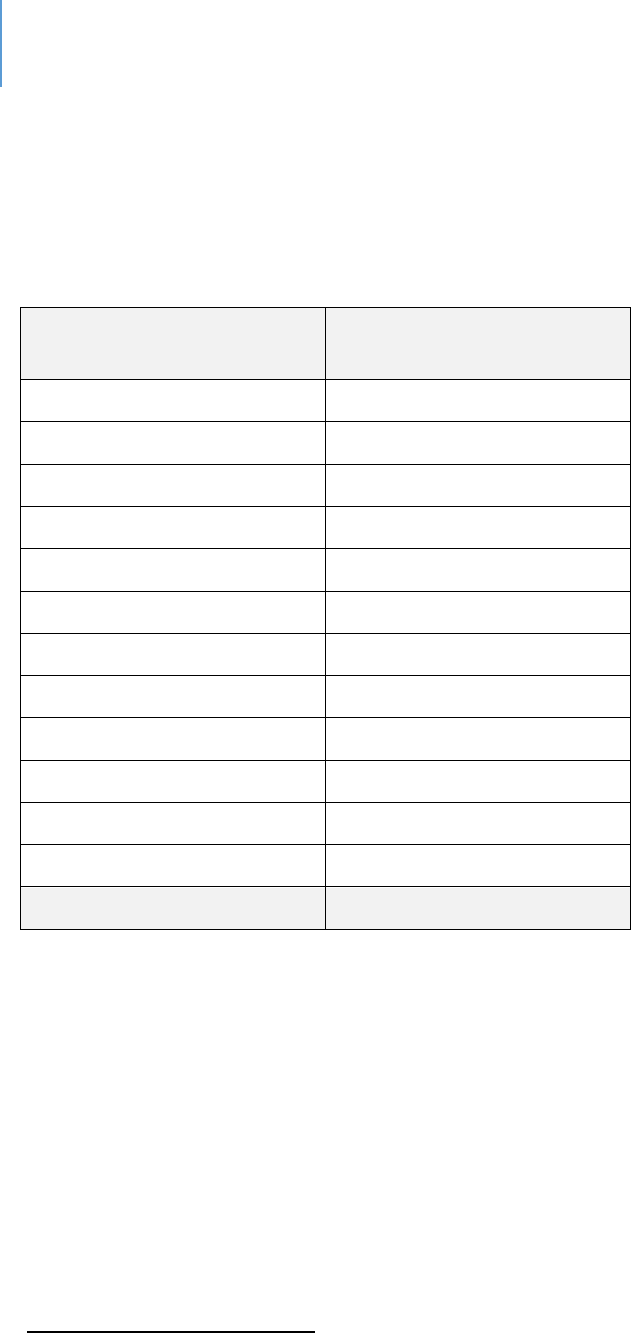

Table 3. Lee County Race/Origin

17

US Census American Community Survey, 2018.

Race/Origin

2018

2010

#

%

#

%

Not Hispanic or Lano

589,377

78.1%

506,053

81.6%

White alone

500,358

66.3%

438,950

70.8%

Black or African American alone

64,553

8.6%

48,326

7.8%

American Indian and Alaska Nave alone

487

0.1%

680

0.1%

Asian alone

12,098

1.6%

8,631

1.4%

Nave Hawaiian and Other Pacic Islander alone

272

0.0%

0

0.0%

Some other race alone

3,730

0.5%

1,970

0.3%

Two or more races:

7,879

1.0%

7,496

1.2%

Hispanic or Lano - All Races

165,233

21.9%

114,098

18.4%

TOTAL

754,610

620,151

Age

The age characteriscs of a community give insight into current and future demand for

resources. The age composion of a community aects housing and service demands

since dierent age groups have very dierent needs. Seniors may seek healthcare

services, community acvies and nancial assistance to manage budgeng on a xed

income.

Lee County’s overall median age of 48.8 years old is six years greater than the State’s

median age of 42.2 years old.

18

The proporon of residents over 65 years of age has increased 5% since 2010.

17

American Community Survey, B03002: 2018 ACS 1-Year Esmates

18

American Community Survey, S0101: 2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 23

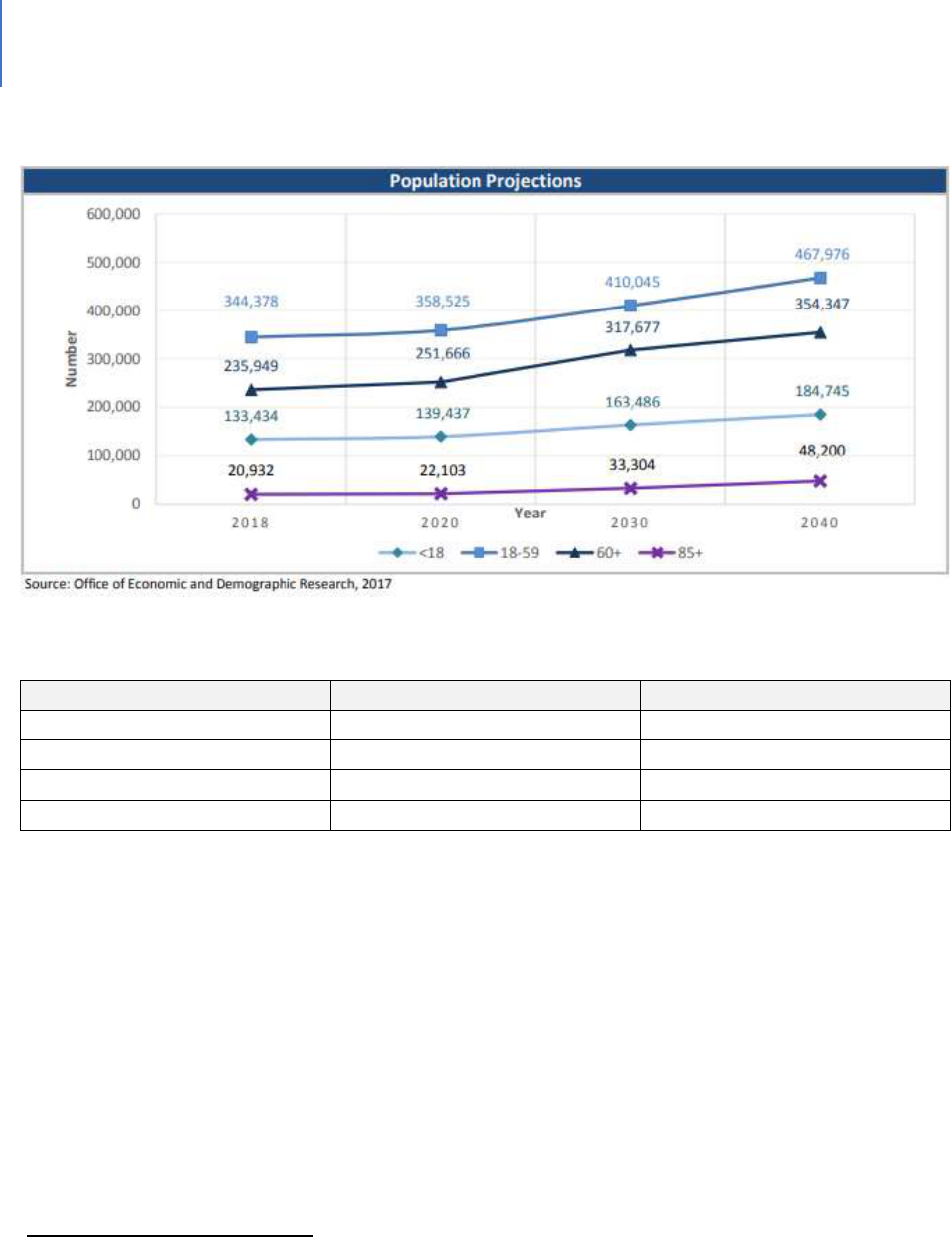

The populaon projecon by BEBR indicates that between 2020 through 2030, Lee

County’s populaon of 65 and older residents will increase by 44%; and between 2020

through 2045 that populaon is projected to increase by more than 54%.

19

Poverty, Employment, and Economy

Household income, employability and economy are potenally the most important

factors in determining the resources needed in a community. Economic factors play an

important role in a household’s health, housing stability, educaonal opportunies,

transportaon opons and the ability to engage in community acvies.

Area Median Income and Poverty Level

In 2012, the median household income (MHI) in Lee County was $46,278 (in 2012

inaon adjusted dollars). In 2018, the esmated median family income was $56,129,

an increase of $9,851 from 2012.

More than 30% of the County households earned less than $35,000 in 2018, and 36.4%

earned more than $75,000 in 2018. Those with household income of $35,000 to

$74,999 represented 33.5% of all income groups.

19

hps://www.bebr.u.edu/populaon

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 24

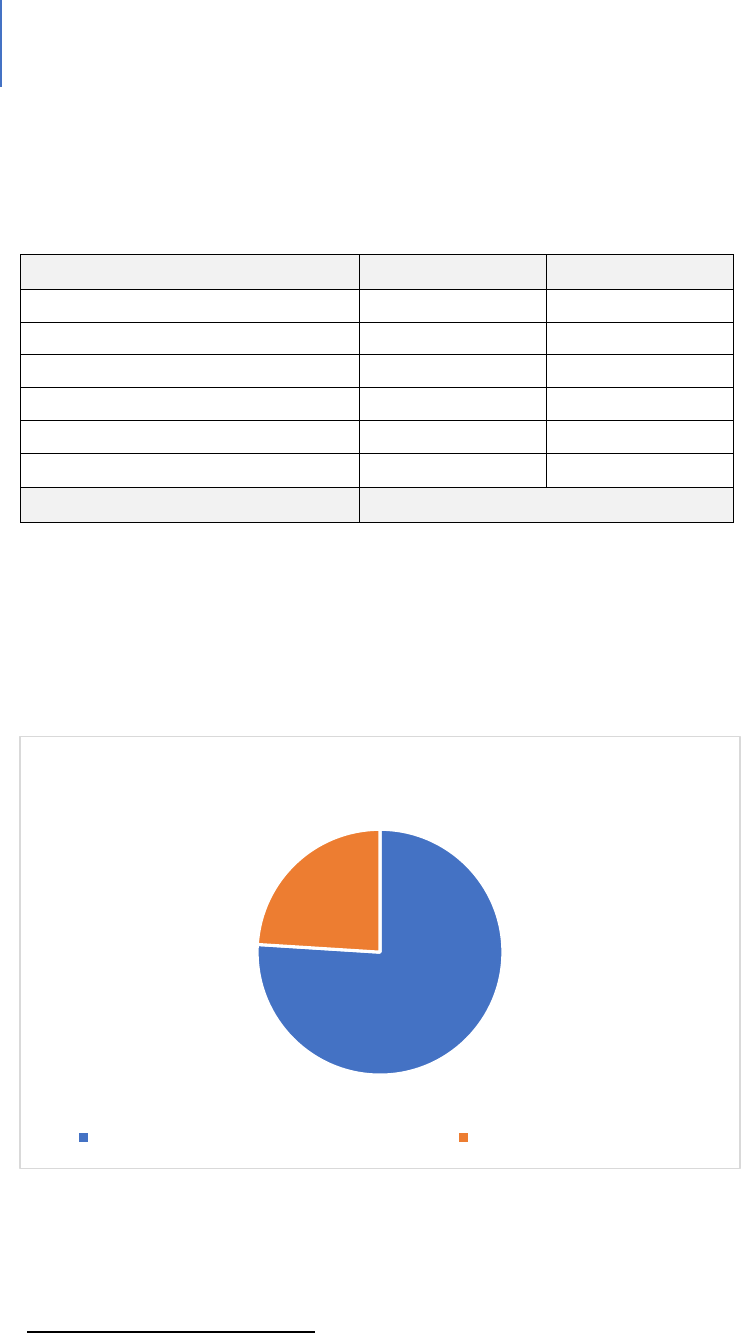

Table 4. Income and Benefits (In 2018 Inflation Adjusted Dollars)

20

#

%

Total Households

281,222

100%

Less than $10,000

17,520

6.20%

$10,000 to $14,999

12,359

4.40%

$15,000 to $24,999

28,058

10.00%

$25,000 to $34,999

26,702

9.50%

$35,000 to $49,999

40,002

14.20%

$50,000 to $74,999

54,356

19.30%

$75,000 to $99,999

32,815

11.70%

$100,000 to $149,999

38,900

13.80%

$150,000 to $199,999

14,006

5.00%

$200,000 or more

16,504

5.90%

Median Household Income

$56,129.00

Mean Household Income

$80,438.00

Based on ve-year esmates, approximately 10.2% of all families and 14.9% of all

individuals in Lee County had an income below the poverty level. Overall, Lee County’s

poverty rates are lower than the statewide rate. However, disparies exist for female-

headed households, especially those with children under the age of 18.

20

American Community Survey, DP03: 2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 25

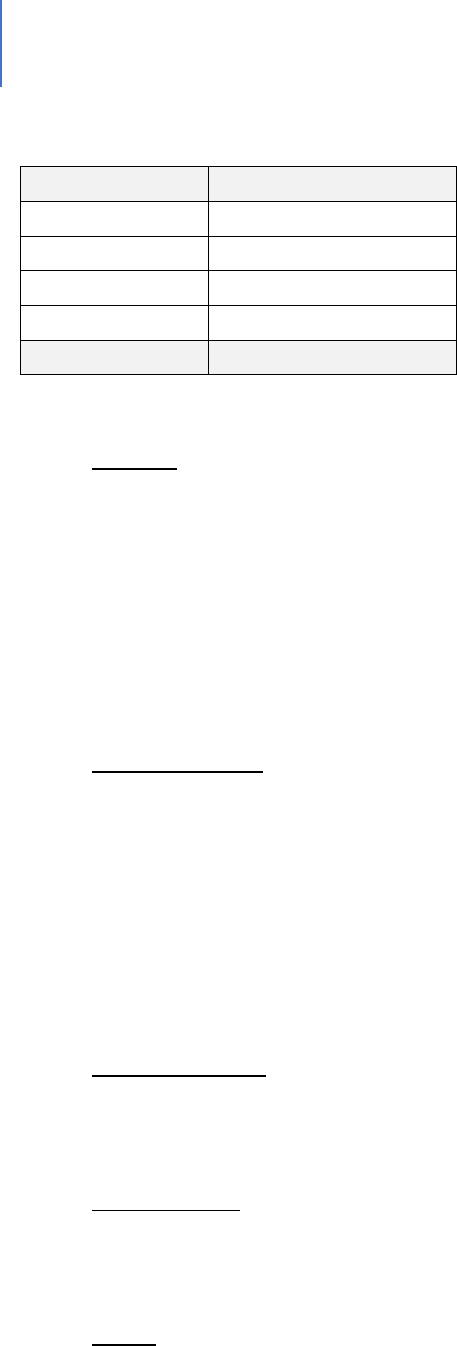

Table 5. Percentage Below Poverty Level in the Last 12 Months

(ACS 5-year Esmates 2013-2017)

21

Florida

Lee

County

All families

11.10%

10.20%

With related children of the householder under 18 years

18.20%

19.80%

With related children of the householder under 5 years only

17.00%

17.30%

Married couple families

6.30%

5.90%

With related children of the householder under 18 years

8.90%

9.90%

With related children of the householder under 5 years only

7.00%

7.20%

Families with female householder, no husband present

26.80%

28.90%

With related children of the householder under 18 years

36.50%

39.20%

With related children of the householder under 5 years only

39.10%

40.40%

All people

15.50%

14.90%

Under 18 years

22.30%

24.90%

Related children of the householder under 18 years

22.00%

24.60%

Related children of the householder under 5 years

24.60%

27.00%

Related children of the householder 5 to 17 years

21.00%

23.70%

18 years and over

13.70%

12.60%

18 to 64 years

14.80%

15.00%

65 years and over

10.30%

7.80%

People in families

12.60%

12.40%

Unrelated individuals 15 years and over

26.60%

24.90%

21

American Community Survey, S1702 and S1701: 2013-2017 ACS 5-Year Estimates

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 26

Employment and Other Sources of Income

Employment is the primary source of income for most Lee County residents. More than

265,000 residents in Lee County are employed. A key factor in determining the needs

of Lee County residents is determining if they have enough income to maintain a

normal standard of living.

According to data from the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity, the

occupaons with the most employment are as follows:

22

22

Florida Department of Economic Opportunity, Wage Estimates, http://www.floridajobs.org/workforce-

statistics/data-center/statistical-programs/occupational-employment-statistics-and-wages

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 27

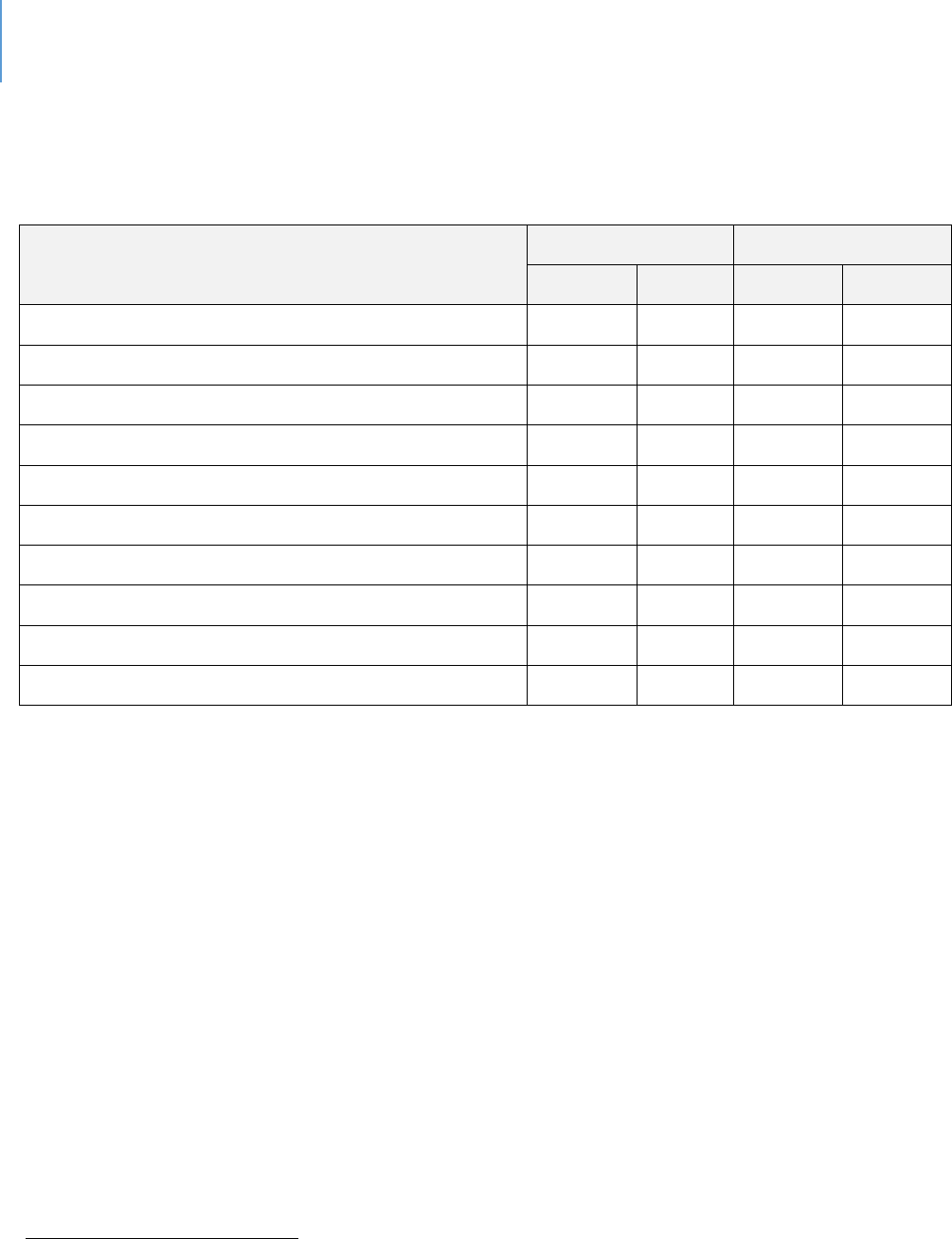

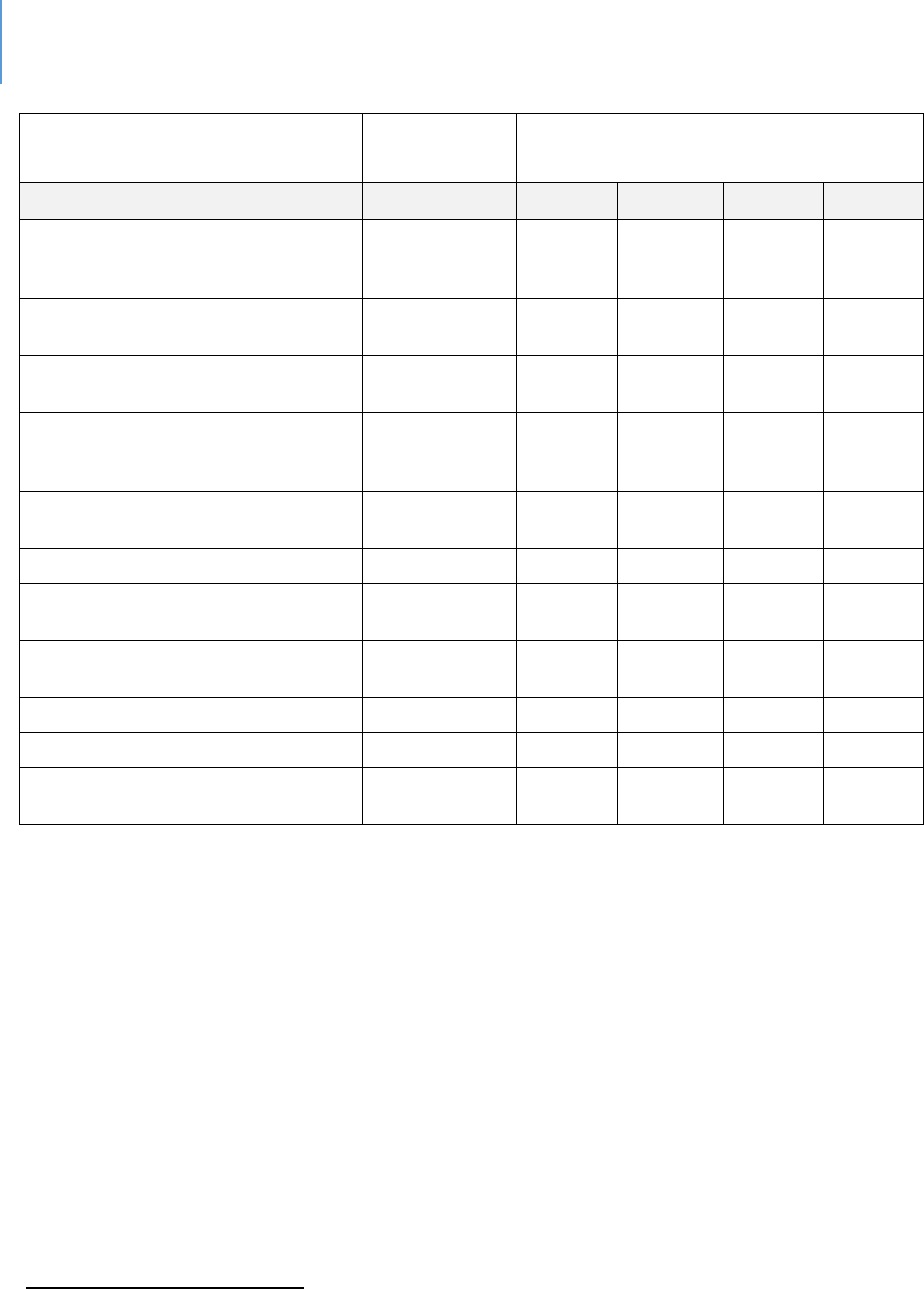

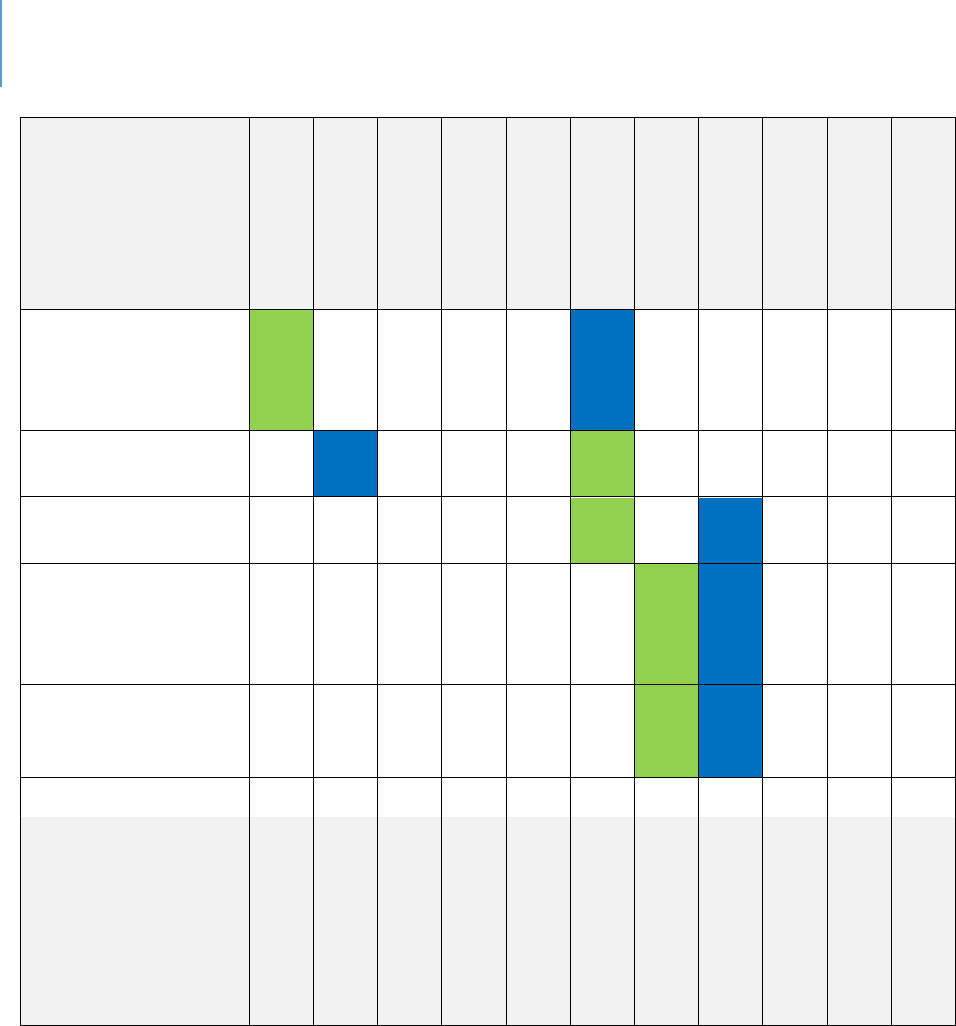

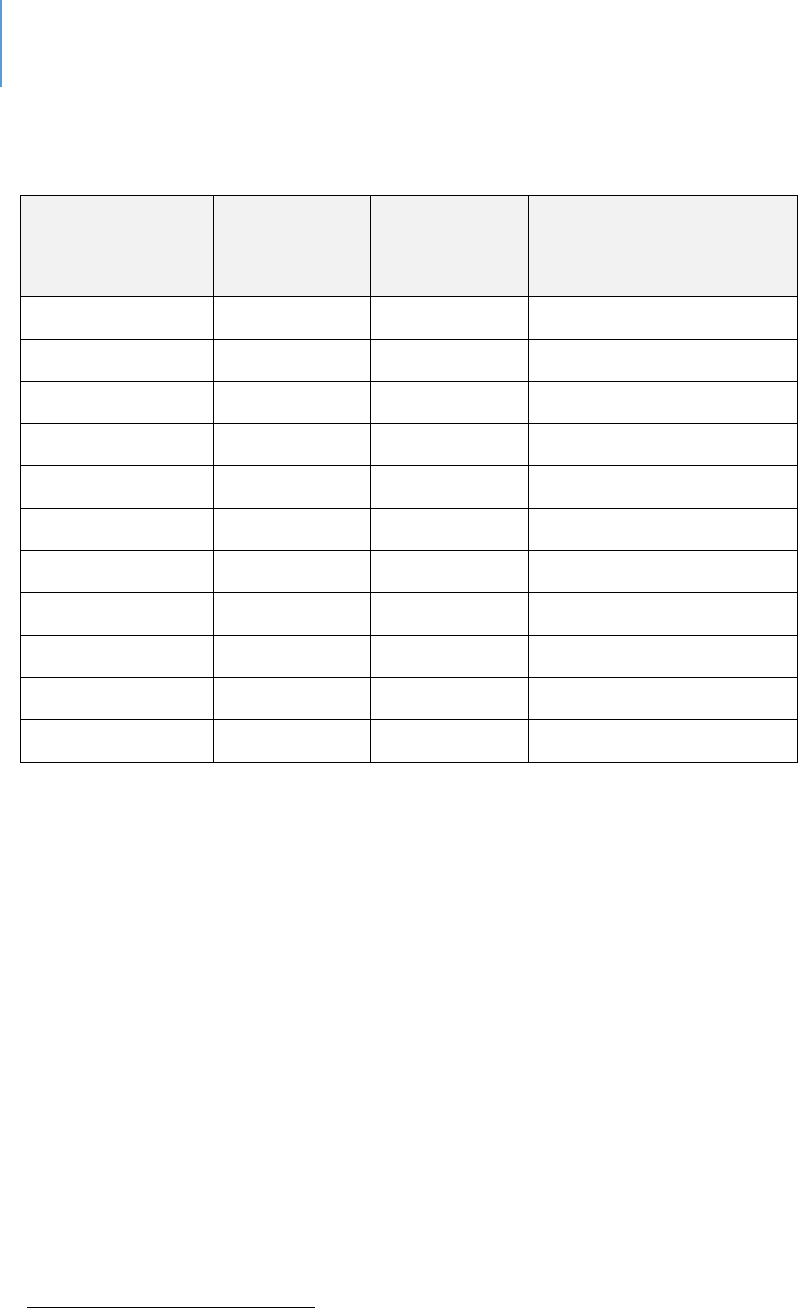

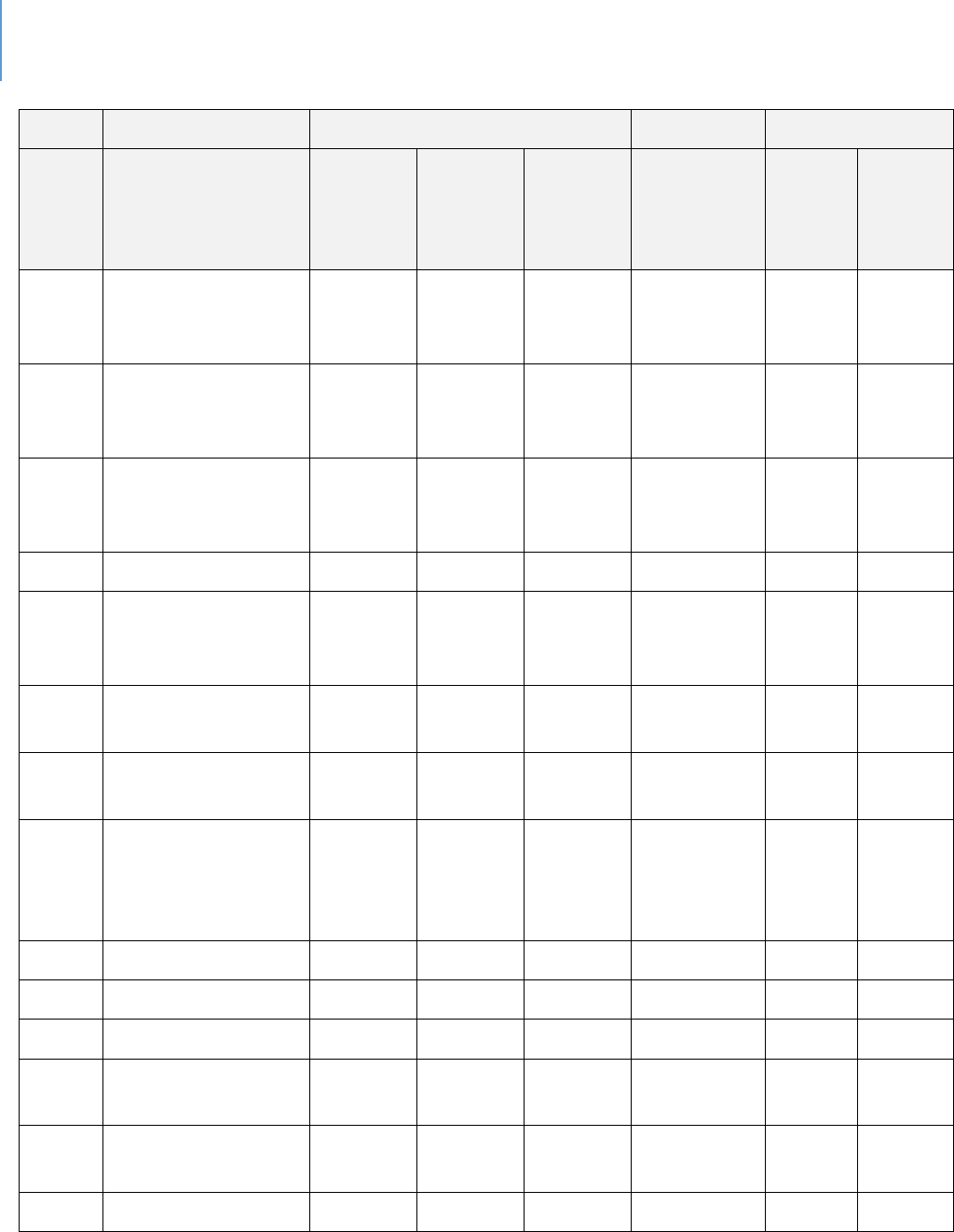

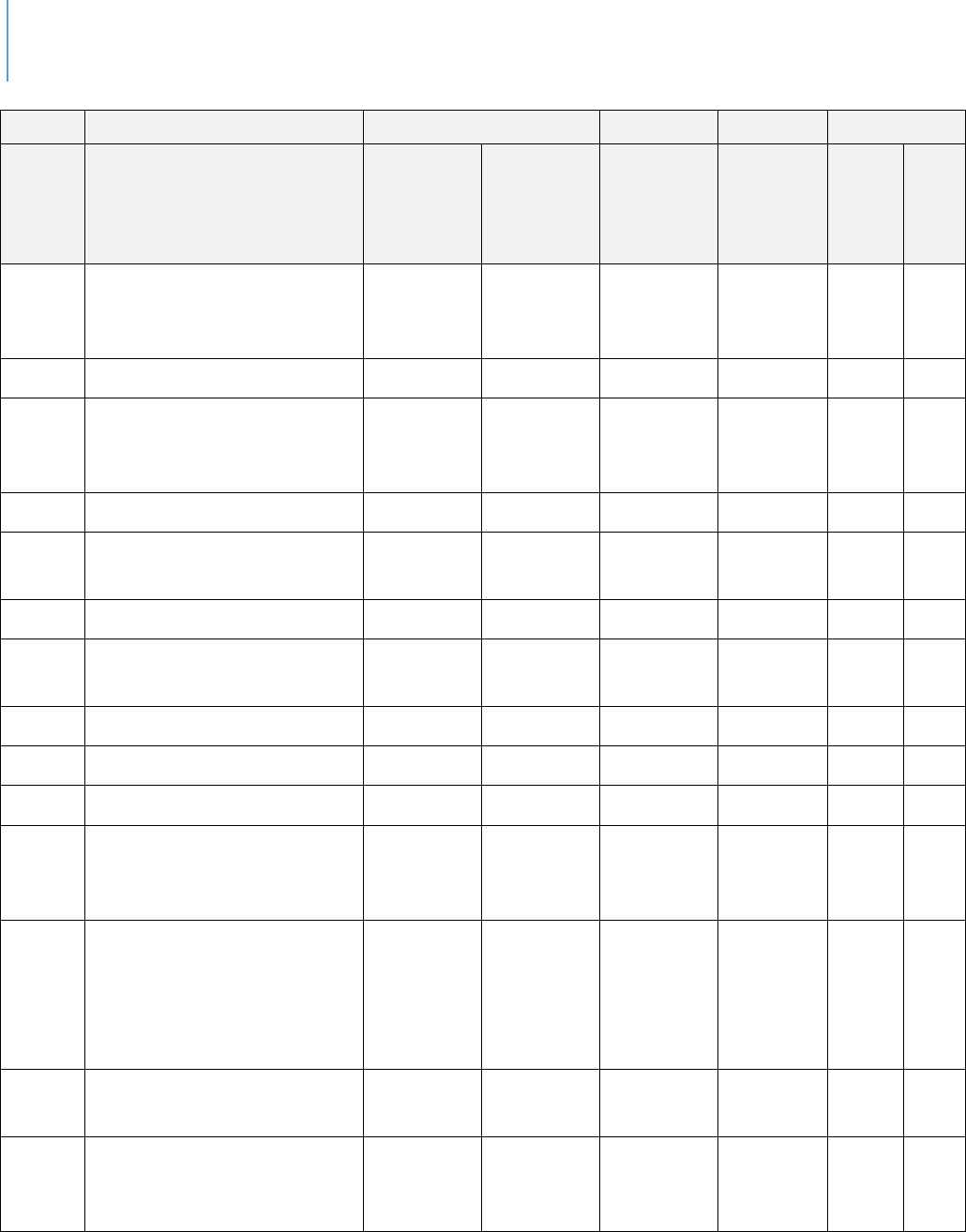

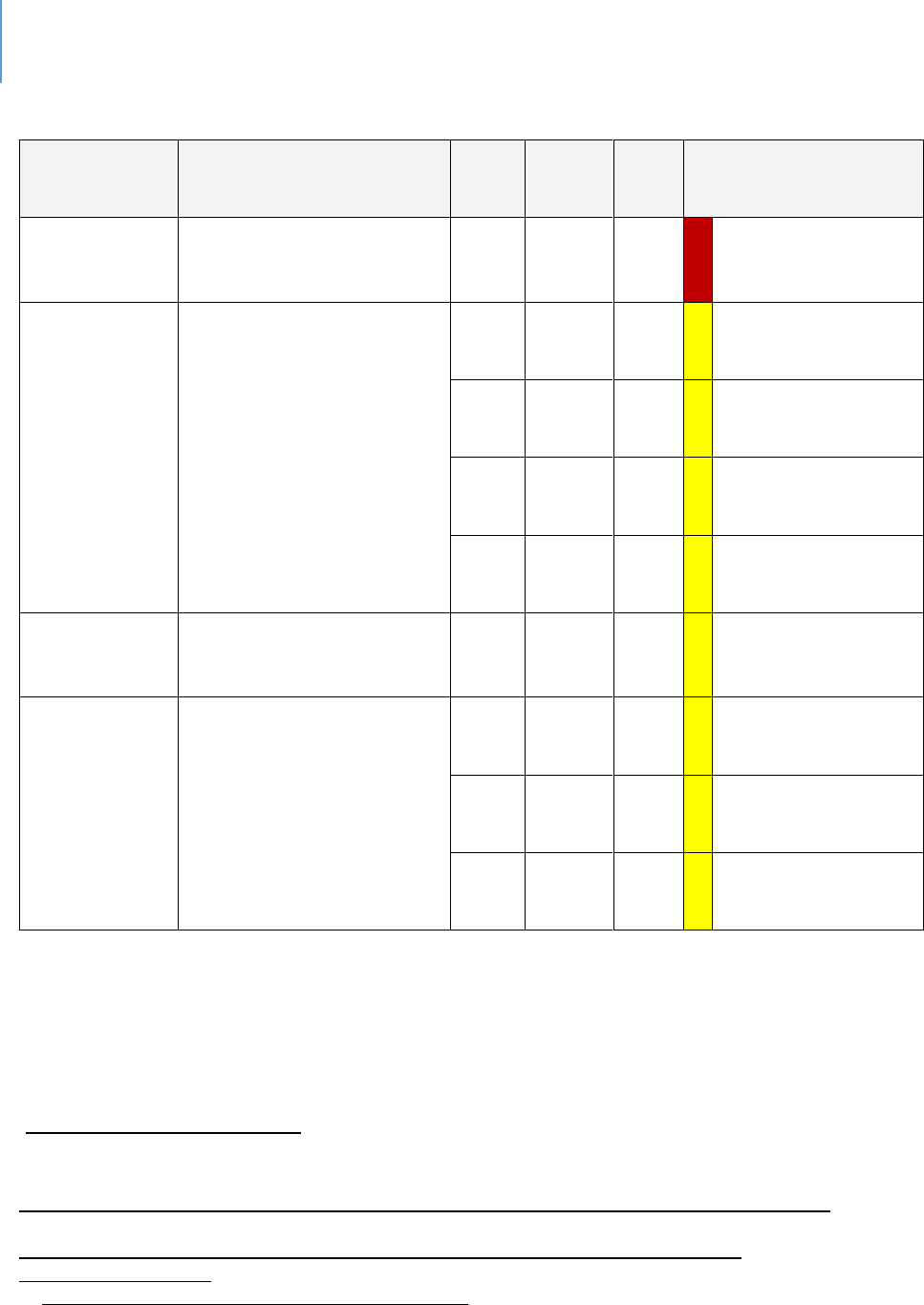

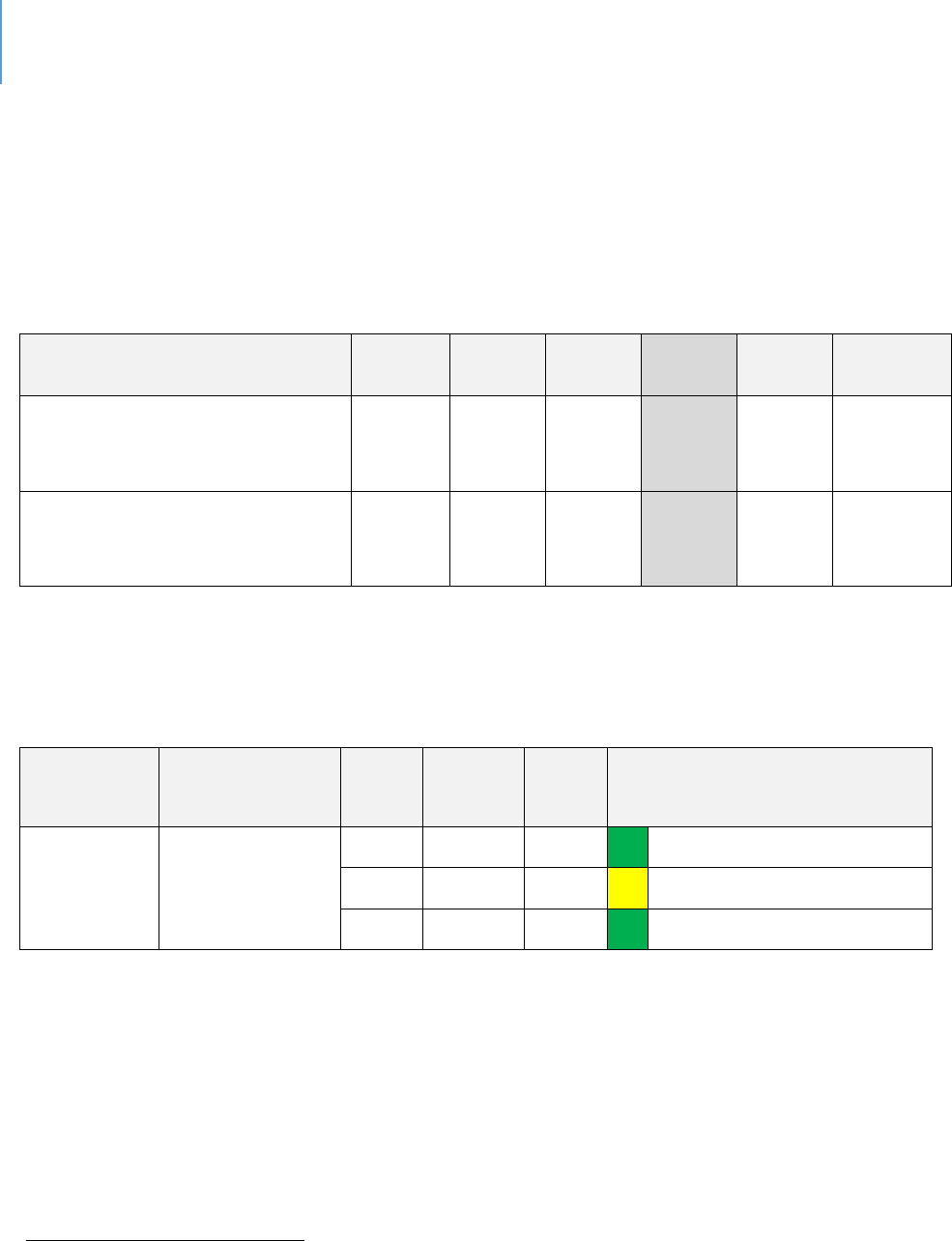

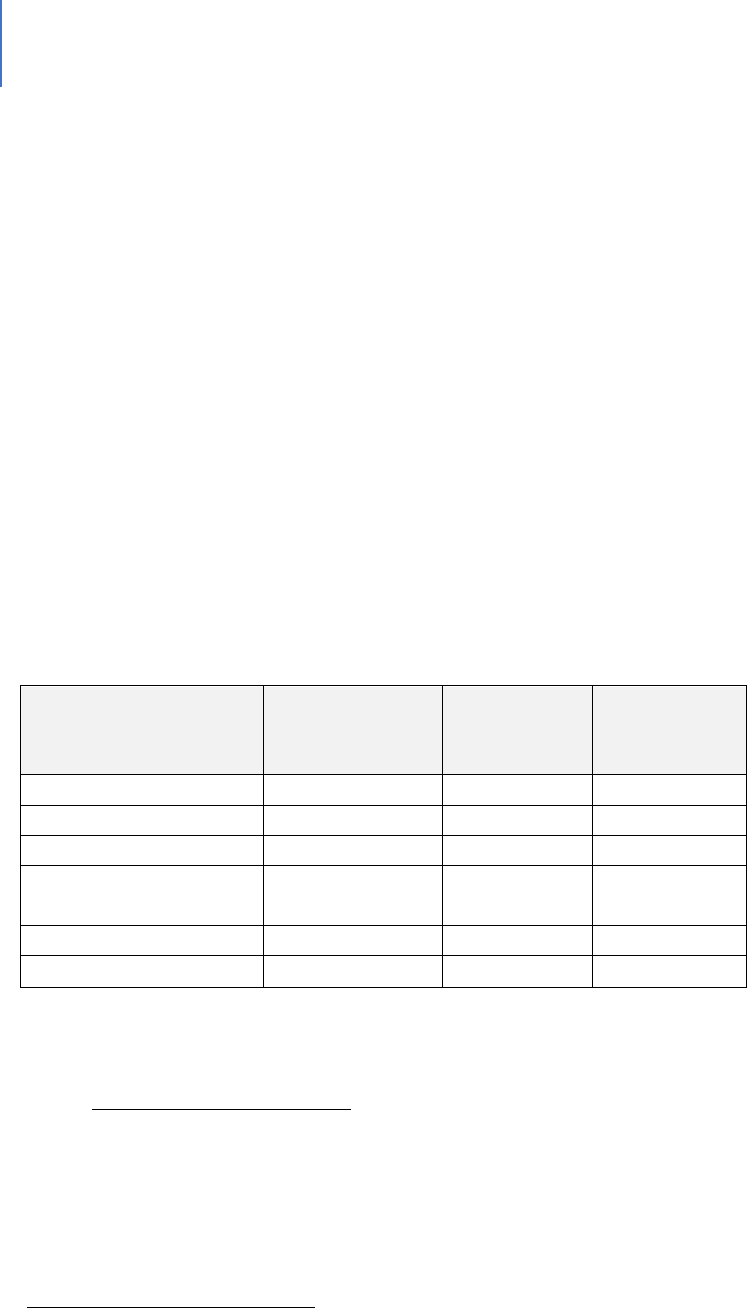

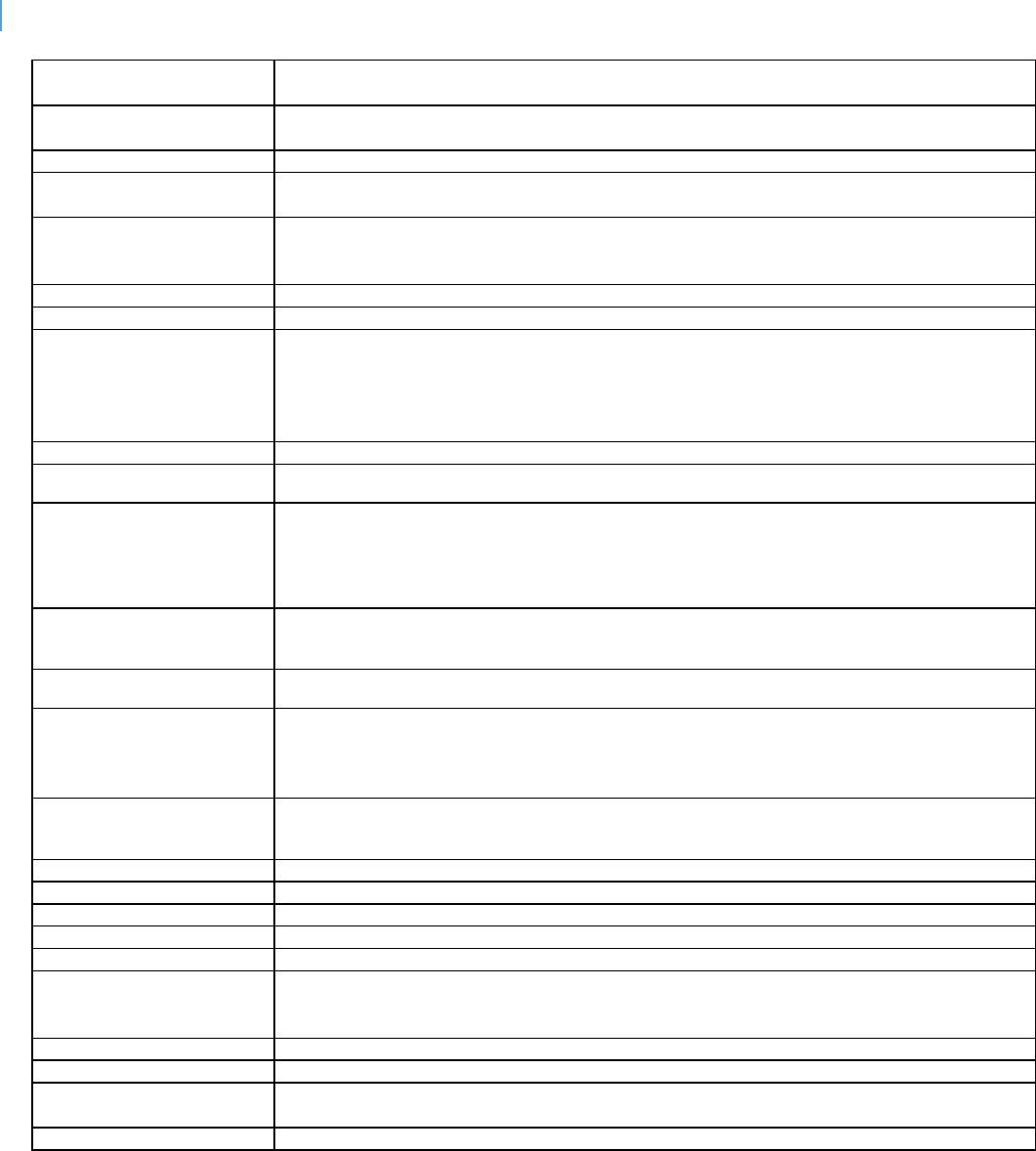

Table 6. Florida Occupational Employment and Wages; Cape Coral-Fort Myers MSA

(Released.)

2018

Hourly Wage

(2018 wage estimates in dollars)

Title

Employment

Mean

Median

Entry**

Exp***

Total all occupations

265,780

20.67

15.83

10.36

25.83

Retail Salespersons

14,150

12.50

10.64

8.97

14.27

Waiters and Waitresses

8,290

11.21

9.33

8.85

12.40

Cashiers

7,880

11.00

10.39

9.04

11.99

Combined Food Preparation and

Serving Workers, Including Fast

Food

6,780

10.36

9.88

8.87

11.11

Customer Service Representatives

6,650

14.88

13.61

10.77

16.94

Landscaping and Grounds-keeping

Workers

5,940

13.07

12.29

10.60

14.31

Office Clerks, General

5,900

15.52

14.59

10.41

18.07

Registered Nurses

5,660

32.26

31.66

25.76

35.51

Construction Laborers

4,480

15.63

15.12

11.16

17.87

Secretaries and Administrative

Assistants, Except Legal, Medical,

4,330

17.13

16.36

12.37

19.51

Stock Clerks and Order Fillers

4,290

12.91

12.00

10.08

14.32

Cooks, Restaurant

4,100

13.74

13.57

10.65

15.28

General and Operations Managers

3,680

49.58

38.47

22.47

63.13

Carpenters

3,360

18.98

18.57

13.96

21.49

Nursing Assistants

3,350

14.13

13.90

11.46

15.47

Receptionists and Information

Clerks

3,000

14.32

14.16

11.58

15.69

First-Line Supervisors of Retail

Sales Workers

2,990

22.75

21.07

13.93

27.17

First-Line Supervisors of Office and

Administrative Support Worker

2,960

26.77

24.76

16.77

31.78

Janitors and Cleaners, Except

Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners

2,900

12.61

11.75

10.13

13.86

Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners

2,870

11.52

11.21

9.57

12.49

Bookkeeping, Accounting, and

Auditing Clerks

2,650

18.62

18.31

12.92

21.48

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 28

2018

Hourly Wage

(2018 wage estimates in dollars)

Title

Employment

Mean

Median

Entry**

Exp***

Sales Representatives, Wholesale

and Manufacturing, Except

Technical and Scientific Products

2,640

32.35

28.31

15.99

40.53

Laborers and Freight, Stock, and

Material Movers, Hand

2,630

14.34

13.85

10.88

16.07

Maintenance and Repair Workers,

General

2,630

17.57

16.93

12.45

20.14

First-Line Supervisors of

Construction Trades and Extraction

Work

2,530

28.17

27.22

19.70

32.40

First-Line Supervisors of Food

Preparation and Serving Workers

2,510

21.29

15.07

11.13

26.37

Food Preparation Workers

2,500

11.78

11.12

9.24

13.04

Elementary School Teachers,

Except Special Education

2,370

63,684

*

64,661*

49,469

*

70,791

*

Heavy and Tractor-Trailer Truck

Drivers

2,260

18.91

17.82

13.51

21.61

Security Guards

2,200

13.10

12.68

10.14

14.58

Medical Assistants

2,120

15.96

15.47

13.05

17.41

Light Truck or Delivery Services

Drivers

2,040

15.75

13.89

9.93

18.66

* Annual Wage.

** Entry Wage - This is the wage an entry-level worker might expect to make. It is dened as the average (mean)

wage earned by the lowest third of all workers in a given occupaon.

*** Experienced Wage - This wage represents what an experienced worker might expect to make. It is dened as

the average (mean) wage earned by the upper two-thirds of all workers in a given occupaon.

Wages based on 2nd qtr. 2018 survey.

In addion to income from employment, there are other sources from which

households can gain income. Social Security and rerement income are the largest

non-employment income sources in Lee County. The percent of the populaon that

receives public assistance and / or Food Stamps / SNAP is lower in Lee County (11.6%)

than statewide (15%).

23

23

American Community Survey, B19058: 2017 5-Year Estimates

DRAFT Lee County Human Services Gap Analysis

Secon One: Quantave Data

Chapter 2 | Lee County Description and Demographics Page | 29

Labor Force

Labor is dened as members of the populaon who are available and willing to work,

and who are currently employed or have recently looked or a job. Lee County’s labor

force parcipaon rate is 52.9%, indicang that approximately 337,314 individuals over