HARVARD JOURNAL

of

LAW & PUBLIC POLICY

VOLUME 43, NUMBER 3 SUMMER 2020

ESSAYS

T

HE ROLE OF THE EXECUTIVE

William P. Barr ........................................................................ 605

C

IVIC CHARITY AND THE CONSTITUTION

Thomas B. Griffith ................................................................... 633

ARTICLES

S

IXTH AMENDMENT FEDERALISM

Louis J. Capozzi III ................................................................. 645

T

AKING ANOTHER LOOK AT THE CALL ON THE FIELD:

R

OE, CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS, AND STARE DECISIS

Thomas J. Molony .................................................................... 733

NOTE

D

EATH QUALIFICATION AND THE RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY:

A

N ORIGINALIST ASSESSMENT

Douglas Colby ......................................................................... 815

HARVARD JOURNAL

of

LAW & PUBLIC POLICY

Editor-in-Chief

N

ICOLE M. BAADE

Articles Chair

J

ACOB THACKSTON

Senior Articles Editors

A

ARON HSU

K

EVIN KOLJACK

R

YAN MAK

J

AMES MCGLONE

J

OEY MONTGOMERY

Articles Editors

N

ICK CORDOVA

J

AMIN DOWDY

A

ARON HENRICKS

J

ASON MUEHLHOFF

A

LEX RIDDLE

O

LIVER ROBERTS

J

AY SCHAEFER

J

ESSICA TONG

T

RUMAN WHITNEY

V

INCENT WU

Website Manager

M

ARK GILLESPIE

Deputy Editor-in-Chief

R.J.

MCVEIGH

Executive Editors

A

LEX CAVE

D

OUGLAS COLBY

A

NASTASIA FRANE

J

OSHUA HA

A

DAM KING

B

RIAN KULP

W

HITNEY LEETS

A

NNA LUKINA

J

OHN MITZEL

J

ASJAAP SIDHU

B

RYAN SOHN

D

OUG STEPHENS IV

M

ATTHEW WEINSTEIN

Notes Editors

D

AVIS CAMPBELL

B

RIAN KULP

Managing Editors

H

UGH DANILACK

A

ARON GYDE

Deputy Managing Editors

M

AX BLOOM

C

HASE BROWNDORF

J

OHN KETCHAM

S

TUART SLAYTON

Chief Financial Officer

D

YLAN SOARES

Deputy Chief Financial Officer

C

OOPER GODFREY

Communications Manager

W

ENTAO ZHAI

Events Manager

T

RUMAN WHITNEY

Social Chair

J

AY SCHAEFER

Senior Editors

J

OHN BAILEY

N

ICK CORDOVA

J

AMIN DOWDY

R

OBERT FARMER

A

LEXANDER GUERIN

A

ARON HENRICKS

J

OHN MORRISON

J

ASON MUEHLHOFF

A

LEXANDRA MUSHKA

A

LEX RIDDLE

O

LIVER ROBERTS

J

AY SCHAEFER

I

SAAC SOMMERS

J

ESSICA TONG

A

ARON WARD

V

INCENT WU

W

ENTAO ZHAI

Editors

J

OHN ACTON

J

ASON ALTABET

M

ATT BENDISZ

A

UGUST BRUSCHINI

A

LAN CHAN

C

ATHERINE COLE

J

ONATHAN DEWITT

T

YLER DOBBS

R

YAN DUNBAR

J

UAN FARAH

W

ILLIAM FLANAGAN

C

ATHERINE FRAPPIER

C

HRISTOPHER HALL

J

ACOB HARCAR

C

HRISTIAN HECHT

R

OSS HILDABRAND

M

ARIA HURYN

A

LEXANDER KHAN

J

AKE KRAMER

B

ENJAMIN LEE

M

AGD LHROOB

K

EVIN LIE

P

RANAV MULPUR

D

ANIEL MUMMOLO

E

LI NACHMANY

C

ARSON PARKS

H

UNTER PEARL

B

RYAN POELLOT

N

ATHAN RAAB

J

ACOB RICHARDS

B

ENJAMIN SALVATORE

A

DAM SHARF

D

UNN WESTHOFF

A

SHLEY VAUGHAN

J

USTIN YIM

Founded by E. Spencer Abraham & Steven J. Eberhard

B

OARD OF ADVISORS

E. Spencer Abraham, Founder

Steven G. Calabresi

Douglas R. Cox

Jennifer W. Elrod

Charles Fried

Douglas H. Ginsburg

Orrin Hatch

Jonathan R. Macey

Michael W. McConnell

Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain

Jeremy A. Rabkin

Hal S. Scott

David B. Sentelle

Bradley Smith

Jerry E. Smith

THE HARVARD JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY RECEIVES

NO FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOL OR

HARVARD UNIVERSITY. IT IS FUNDED EXCLUSIVELY BY

SUBSCRIPTION REVENUES AND PRIVATE CHARITABLE

CONTRIBUTIONS.

The Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy is published three times annually by the

Harvard Society for Law & Public Policy, Inc., Harvard Law School, Cambridge,

Massachusetts 02138. ISSN 0193-4872. Nonprofit postage prepaid at Lincoln, Nebraska

and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Harvard

Journal of Law & Public Policy, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138.

Yearly subscription rates: United States, $55.00; foreign, $75.00. Subscriptions are

renewed automatically unless a request for discontinuance is received.

The Journal welcomes the submission of articles and book reviews. Each manuscript

should be typed double-spaced, preferably in Times New Roman 12-point typeface.

Authors submit manuscripts electronically to [email protected], preferably

prepared using Microsoft Word. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the Society or of its officers, directors, editors, members,

or staff. Unless otherwise indicated, all editors are students at the Harvard Law School.

Copyright © 2020 by the Harvard Society for Law & Public Policy, Inc.

PREFACE

COVID-19 has created a pandemic unprecedented in modern

times. Schools, businesses, restaurants, and even churches have

closed their doors to limit the spread of the virus. Many of life’s

most cherished events, including weddings, graduations, births,

baptisms, and, perhaps most tragically, funerals, have been

postponed, conducted virtually, or limited to only immediate

family members. It is times like these that can bring us together

as a nation in thought, prayer, word, and action. And there are

many accounts of such unity and mutual encouragement.

However, the pandemic has also highlighted the divisive parti-

san rhetoric that unfortunately characterizes this country—a

divisiveness that threatens, among other things, our constitu-

tional structure and the liberty it guards.

In this Issue of the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, we

have the honor of publishing two Essays based on speeches

addressing constitutional concerns related to partisanship in

this country. In one, Judge Thomas Griffith of the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the D.C. Circuit laments the loss of civic charity—

the “spirit of amity” and “mutual deference” as George

Washington put it—that helped forge the Constitution and is

required to maintain it. In another, Attorney General of the

United States William Barr—in the Nineteenth Annual Barbara

K. Olson Memorial Lecture at the Federalist Society’s 2019

National Lawyers Convention—condemns partisan attacks on the

executive power that the Framers enshrined in the Constitution,

particularly those directed against President Donald Trump’s

Administration. He warns, “In this partisan age, we should

take special care not to allow the passions of the moment to

cause us to permanently disfigure the genius of our constitu-

tional structure.” Special thanks are due the editors from other

law schools who volunteered to stay on for yet another issue to

prepare Attorney General Barr’s speech for publication. We

could not have published it without their outstanding work.

We are delighted to follow these Essays with two excellent

Articles on current legal issues. The first Article, by Louis

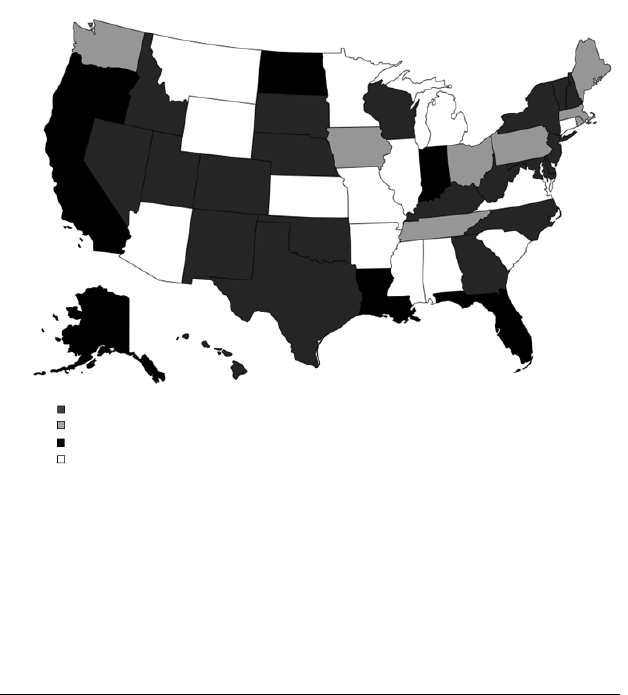

Capozzi, is a fifty-state survey of the right to appointed counsel

in misdemeanor cases and shows that many states have pro-

Preface ii

vided a broader right to counsel than that required by the Sixth

Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Capozzi provides a di-

verse array of approaches to misdemeanor justice that states

may consider instead of a one-size-fits-all approach. In the sec-

ond Article, Professor Thomas Molony traces the history of

opinions written or joined by Chief Justice Roberts in cases in-

volving stare decisis with an eye to how the Chief Justice might

rule in a case challenging Roe v. Wade. He concludes that the

Chief Justice’s devotion to judicial restraint and the rule of law

would lead him to vote in favor of overruling Roe only if a chal-

lenged abortion regulation cannot be upheld on narrower

grounds and if reaffirming Roe would cause more harm to the

Constitution than casting the abortion question out of federal

courts and back to the States.

Finally, we have the pleasure of publishing one of our own

in this Issue. In another piece on the Sixth Amendment, Douglas

Colby argues that death qualification—the process of removing

potential jurors who are unwilling to impose the death penalty—

does not violate an originalist understanding of the the Sixth

Amendment right to an impartial jury.

I end this preface of my last Issue on a more personal note. It

has been a true honor to serve as Editor-in-Chief of this excep-

tional journal. The Journal has been my home since my first

year of law school. As Editor-in-Chief, I have seen all of the

hard work and dedication that editors put into this journal at

every stage. More than that, I have the privilege of calling each

and every member of this journal not only a classmate and col-

league, but a friend. It is bittersweet to be graduating and leav-

ing behind my work on the Journal, but I am confident the next

masthead will continue its legacy of excellence, and I look for-

ward to seeing the bright futures of all of its members unfold.

Nicole M. Baade

Editor-in-Chief

THE FEDERALIST SOCIETY

presents

The Nineteenth Annual Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture

Featuring Attorney General William P. Barr

The Role of the Executive

November 15, 2019

The staff acknowledges the assistance of the following members of the

Federalist Society in preparing this speech for publication:

National Editor

Hugh Danilack

Harvard Law School

Executive Editors

Michael R. Wajda

Duke University School of Law

Timothy J. Whittle

University of Virginia School of Law

General Editors

Cameron L. Atkinson

Quinnipiac Univeristy School of Law

Sarah Christensen

George Mason University

Antonin Scalia Law School

Mary Colleen Fowler

University of Kansas School of Law

Stacy Hanson

University of Illinois College of Law

Kelly L. Krause

Marquette University Law School

Abbey Lee

University of Kansas School of Law

Cody Ray Milner

George Mason University

Antonin Scalia Law School

Ashle Page

University of North Carolina Law School

Steven M. Petrillo II

Rutgers Law School—Camden

Cynthia M. Tannar

Georgetown University Law Center

Nicholas J. Walter

Arizona State University

Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

THE ROLE OF THE EXECUTIVE

WILLIAM P. BARR

*

Good Evening. Thank you all for being here. And thank you

to Gene Meyer for your kind introduction.

It is an honor to be here this evening delivering the Nineteenth

Annual Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture. I had the privilege

of knowing Barbara and had deep affection for her. I miss her

brilliance and ebullient spirit. It is a privilege for me to partici-

pate in this series, which honors her.

The theme for this year’s Annual Convention is “Originalism,”

which is a fitting choice—though, dare I say, a somewhat “uno-

riginal” one for the Federalist Society. I say that because the

Federalist Society has played an historic role in taking original-

ism “mainstream.”

1

While other organizations have contributed

to the cause, the Federalist Society has been in the vanguard.

A watershed for the cause was the decision of the American

people to send Ronald Reagan to the White House, accompa-

nied by his close advisor Ed Meese and a cadre of others who

were firmly committed to an originalist approach to the law.

2

I

was honored to work with Ed in the Reagan White House and

be there several weeks ago when President Trump presented

him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. As the President

aptly noted, over the course of his career, Ed Meese has been

* Attorney General of the United States. This Essay is a lightly edited version of

Attorney General Barr’s remarks at the Nineteenth Annual Barbara K. Olson

Memorial Lecture on November 15, 2019, at the Federalist Society’s 2019 National

Lawyers Convention.

1.See John O. McGinnis, An Opinionated History of the Federalist Society, 7 G

EO.

J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 403, 406–07, 411 (2009); Michael Kruse, The Weekend at Yale That

Changed American Politics, POLITICO MAG. (Sept./Oct. 2018), https://www.politico.com/

magazine/story/2018/08/27/federalist-society-yale-history-conservative-law-court-

219608 [https://perma.cc/J7TW-HRLE].

2. Kruse, supra note 1.

606 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

among the nation’s “most eloquent champions for following

the Constitution as written.”

3

I am also proud to serve as the Attorney General under

President Trump, who has taken up that torch in his judicial

appointments. That is true of his two outstanding appoint-

ments to the Supreme Court, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett

Kavanaugh; of the many superb court of appeals and district

court judges he has appointed, many of whom are here this

week; and of the many outstanding judicial nominees to come,

many of whom are also here this week.

*

* * * *

I wanted to choose a topic for this afternoon’s lecture that

had an originalist angle. It will likely come as little surprise to

this group that I have chosen to speak about the Constitution’s

approach to executive power.

I deeply admire the American presidency as a political and

constitutional institution. I believe it is one of the great and re-

markable innovations in our Constitution, and it has been one

of the most successful features of the Constitution in protecting

the liberties of the American people. More than any other

branch, it has fulfilled the expectations of the Framers.

Unfortunately, over the past several decades, we have seen

steady encroachment on presidential authority by the other

branches of government.

4

This process, I think, has substantially

weakened the functioning of the executive branch, to the det-

riment of the nation. This evening, I would like to expand a bit

on these themes.

I. T

HE FRAMERS’ VIEW OF THE EXECUTIVE

First, let me say a little about what the Framers had in mind

in establishing an independent executive in Article II of the

Constitution.

3. Donald J. Trump, President, United States, Remarks by President Trump at

Presentation of the Medal of Freedom To Edwin Meese (Oct. 8, 2019), https://

www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-presentation-

medal-freedom-edwin-meese/ [https://perma.cc/CHW8-QXBH].

4. See, e.g., Common Legislative Encroachments On Executive Branch Authority,

13 Op. O.L.C. 248 (1989).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 607

The grammar school civics class version of our Revolution is

that it was a rebellion against monarchial tyranny and that, in

framing our Constitution, one of the main preoccupations of

the Founders was to keep the executive branch weak.

5

This is

misguided. By the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1689,

monarchical power was effectively neutered and had begun its

steady decline.

6

Parliamentary power was well on its way to

supremacy and was effectively in the driver’s seat. By the time

of the American Revolution, the patriots well understood that

their prime antagonist was an overweening Parliament.

7

In-

deed, British thinkers came to conceive of Parliament, rather

than the people, as the seat of sovereignty.

8

During the Revolutionary era, American thinkers who con-

sidered inaugurating a republican form of government tended

to think of the executive component as essentially an errand

boy of a supreme legislative branch. Often the executive (some-

times constituted as a multimember council) was conceived as

a creature of the legislature, dependent on and subservient to

that body, whose sole function was carrying out the legislative

will.

9

Under the Articles of Confederation, for example, there

was no executive separate from Congress.

10

Things changed by the Constitutional Convention of 1787. To

my mind, the real “miracle” in Philadelphia that summer was

the creation of a strong executive, independent of, and coequal

with, the other two branches of government.

5. Cf. Erin Peterson, Presidential Power Surges, HARV. L. TODAY (July 17, 2019),

https://today.law.harvard.edu/feature/presidential-power-surges/ [https://perma.cc/

33DU-QFMJ] (“’The starting point was that we’d gone through a revolution

against monarchial power,’ [Professor Mark Tushnet] says. ‘Nobody wanted the

chief executive to have the kinds of power the British monarch had.’”).

6. See Louis Henkin, Revolutions and Constitutions, 49 L

A. L. REV. 1023, 1027 (1989).

7. Id. (“The experience of the American colonies under British rule persuaded

them that they needed protection for rights against the legislature as well as

against the executive.”).

8. See, e.g., J

EREMY BENTHAM, A FRAGMENT ON GOVERNMENT 72 (J.H. Burns,

H.L.A. Hart & Ross Harrison eds., Cambridge Univ. Press 1981) (1776).

9. Robert N. Clinton, A Brief History of the Adoption of the United States Constitution,

75 I

OWA L. REV. 891, 895 (1990) (describing how Congress set up committees and

civil offices to serve in an executive capacity under Congress’s direction).

10. Id. at 892–93 (“Fundamentally, the Articles of Confederation created a gov-

ernment with a single branch of government—a Congress with members appointed

by and representing the state legislatures.”).

608 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

The consensus for a strong, independent executive arose

from the Framers’ experience in the Revolution and under the

Articles of Confederation.

11

They had seen that the war had al-

most been lost and was a bumbling enterprise because of the

lack of strong executive leadership.

12

Under the Articles of

Confederation, they had been mortified at the inability of the

United States to protect itself against foreign impositions or to

be taken seriously on the international stage.

13

They had also

seen that, after the Revolution, too many States had adopted

constitutions with weak executives overly subordinate to the

legislatures.

14

Where this had been the case, state governments

had proven incompetent and indeed tyrannical.

15

From these practical experiences, the Framers had come to

appreciate that, to be successful, republican government re-

quired the capacity to act with energy, consistency, and deci-

siveness.

16

They had come to agree that those attributes could

best be provided by making the executive power independent

of the divided counsels of the legislative branch and vesting the

executive power in the hands of a solitary individual, regularly

elected for a limited term by the nation as a whole.

17

As Jefferson

put it, “[F]or the prompt, clear, and consistent action so neces-

sary in an Executive, unity of person is necessary . . . .”

18

While there may have been some differences among the

Framers as to the precise scope of executive power in particular

areas, there was general agreement about its nature. Just as the

great separation-of-powers theorists—Polybius, Montesquieu,

Locke—had, the Framers thought of executive power as a dis-

11. Charles J. Cooper & Leonard A. Leo, Executive Power Over Foreign and Mili-

tary Policy: Some Remarks on the Founders’ Perspective, 16 O

KLA. CITY UNIV. L. REV.

265, 268–69 (1991).

12. Id.

13. Cooper & Leo, supra note 11, at 269–70; Bruce Stein, The Framers’ Intent and

the Early Years of the Republic, 11 H

OFSTRA L. REV. 413, 418–19 (1982).

14. T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 70, at 423 (Alexander Hamilton) (Clinton Rossiter ed.,

2003); Cooper & Leo, supra note 11, at 267–68.

15. T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 70, supra note 14, at 423 (Alexander Hamilton).

16. See, e.g., id. at 421–22.

17. See, e.g., id.

18. See Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Adams (Feb. 28, 1796), in 28 T

HE

PAPERS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON 618, 618–19 (John Catanzariti et al. eds., 2000).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 609

tinct species of power.

19

To be sure, executive power includes

the responsibility for carrying into effect the laws passed by the

legislature—that is, applying the general rules to a particular

situation.

20

But the Framers understood that executive power

meant more than this.

It also entailed the power to handle essential sovereign func-

tions—such as the conduct of foreign relations and the prosecu-

tion of war—which by their very nature cannot be directed by

a preexisting legal regime but rather demand speed, secrecy,

unity of purpose, and prudent judgment to meet contingent

circumstances.

21

They agreed that—due to the very nature of

the activities involved, and the kind of decisionmaking they

require—the Constitution generally vested authority over these

spheres in the Executive.

22

For example, Jefferson, our first

Secretary of State, described the conduct of foreign relations as

“executive altogether,” subject only to the explicit exceptions

defined in the Constitution, such as the Senate’s power to ratify

treaties.

23

A related and third aspect of executive power is the power to

address exigent circumstances that demand quick action to

protect the well-being of the nation but on which the law is

either silent or inadequate—such as dealing with a plague or

natural disaster. This residual power to meet contingency is

essentially the federative power discussed by Locke in his Second

Treatise.

24

And, finally, there are the Executive’s powers of internal

management. These are the powers necessary for the President

to superintend and control the executive function, including

the powers necessary to protect the independence of the execu-

tive branch and the confidentiality of its internal deliberations.

Some of these powers are express in the Constitution, such as

19. See ERIC NELSON, THE ROYALIST REVOLUTION: MONARCHY AND THE AMERICAN

FOUNDING 15, 17, 184–228 (2014).

20. See id. at 195.

21. See id. at 221–24.

22. See id.

23. 5 T

HOMAS JEFFERSON, Opinion on the Powers of the Senate, in THE WRITINGS OF

THOMAS JEFFERSON 161, 161 (Paul Leicester Ford ed., New York, G.P. Putnam’s

Sons 1895).

24. J

OHN LOCKE, SECOND TREATISE OF GOVERNMENT 77, § 147 (Richard H. Cox

ed., Harlan Davidson, Inc. 1982) (1690).

610 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

the appointment power,

25

and others are implicit, such as the

removal power.

26

One of the more amusing aspects of modern progressive

polemic is their breathless attacks on the “unitary executive

theory.”

27

They portray this as some new-fangled “theory” to

justify executive power of sweeping scope. In reality, the idea

of the unitary executive does not go so much to the breadth of

presidential power. Rather, the idea is that, whatever the ex-

ecutive powers may be, they must be exercised under the

President’s supervision.

28

This is not “new,” and it is not a

“theory.” It is a description of what the Framers unquestiona-

bly did in Article II of the Constitution.

29

After you decide to establish an executive function inde-

pendent of the legislature, naturally the next question is who

will perform that function? The Framers had two potential

models. They could insinuate “checks and balances” into the

executive branch itself by conferring executive power on mul-

tiple individuals (a council) thus dividing the power.

30

Alterna-

tively, they could vest executive power in a solitary individual.

31

The Framers quite explicitly chose the latter model because

they believed that vesting executive authority in one person

would imbue the presidency with precisely the attributes nec-

essary for energetic government.

32

Even Jefferson—usually

25. U.S. CONST. art. II, § 2, cl. 2–3.

26. Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52, 119, 125 (1926).

27. See, e.g., Chris Edelson, Exploring the Limits of Presidential Power, ACS:

EXPERT

F. (Dec. 2, 2013), https://www.acslaw.org/expertforum/exploring-the-limits-of-

presidential-power [https://perma.cc/6TTD-46RR] (stating that critics describe the

unitary executive theory as placing the President above the law).

28. See S

TEVEN G. CALABRESI & CHRISTOPHER S. YOO, THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE:

PRESIDENTIAL POWER FROM WASHINGTON TO BUSH 3–4 (2008).

29. See id. (“[T]he theory of the unitary executive holds that the Vesting Clause

of Article II, which provides that ‘the executive Power shall be vested in a President

of the United States of America,’ is a grant to the president of all the executive

power, which includes the powers to remove and direct all lower-level executive

officials.”).

30. See R

ICHARD J. ELLIS, FOUNDING THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY 31–43 (1999)

(discussing the early debate over having one President or multiple).

31. See T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 70, supra note 14 (Alexander Hamilton) (commenting

on how a unitary executive is more favorable than a plurality in the executive).

32. Id. at 421 (“Energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of

good government. . . . [Politicians and statesmen] have, with great propriety, con-

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 611

seen as less of a hawk than Hamilton on executive power

33

—

was insistent that executive power be placed in single hands,

and he cited America’s unitary executive as a signal feature

that distinguished America’s success from France’s failed re-

publican experiment.

34

The implications of the Framers’ decision are obvious. If

Congress attempts to vest the power to execute the law in

someone beyond the control of the President, it contravenes the

Framers’ clear intent to vest that power in a single person, the

President.

35

So much for this supposedly nefarious theory of

the unitary executive.

II. E

NCROACHMENTS ON THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH TODAY

We all understand that the Framers expected that the three

branches would be jostling and jousting with each other, as

each threatened to encroach on the prerogatives of the others.

36

They thought this was not only natural, but salutary, and they

provisioned each branch with the wherewithal to fight and to

defend itself in these interbranch struggles for power.

37

So let me turn now to how the Executive is presently faring

in these interbranch battles. I am concerned that the deck has

become stacked against the Executive. Since the mid-60s, there

sidered energy as the most necessary quality of [a single executive], and have

regarded this as most applicable to power in a single hand . . . .”).

33. See John Yoo, Jefferson and Executive Power, 88 B.U. L. R

EV. 421, 422–23 (2008).

34. See Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Destutt de Tracy (Jan. 26, 1811), in 3 T

HE

PAPERS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON, RETIREMENT SERIES 334, 335–36 (J. Jefferson Looney

et al. eds., 2006).

35. C

ALABRESI & YOO, supra note 28, at 34–35; see also 1 ANNALS OF CONG. 463

(1789) (Joseph Gales ed., 1834) (“If the Constitution has invested all Executive

power in the President, I venture to assert that the Legislature has no right to di-

minish or modify his Executive authority.”).

36. See Constitutional Amendment to Restore Legislative Veto: Hearing on S.J. Res.

135 Before the S. Subcomm. on the Constitution of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 98th

Cong. 63 (1984) (statement of Peter L. Strauss, Professor, Columbia Law School)

(“The framers expected the branches to battle each other to acquire and defend

power.”).

37. See T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 51, supra note 14, at 318–19 (James Madison) (“But

the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the

same department consists in giving to those who administer each department the

necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of

the others.”).

612 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

has been a steady grinding down of the executive branch’s au-

thority that accelerated after Watergate.

38

More and more, the

President’s ability to act in areas in which he has discretion has

become smothered by the encroachments of the other branches.

39

When these disputes arise, I think there are two aspects of

contemporary thought that tend to operate to the disadvantage

of the Executive. The first is the notion that politics in a free re-

public is all about the legislative and judicial branches protect-

ing liberty by imposing restrictions on the Executive.

40

The

premise is that the greatest danger of government becoming

oppressive arises from the prospect of executive excess. So,

there is a knee-jerk tendency to see the legislative and judicial

branches as the good guys protecting society from a rapacious

would-be autocrat.

This prejudice is wrongheaded and atavistic. It comes out of

the early English Whig view of politics and English constitu-

tional experience, where political evolution was precisely

that.

41

You started out with a king who holds all the cards; he

holds all the power, including legislative and judicial. Political

evolution involved a process by which the legislative power

gradually, over hundreds of years, reigned in the king, and ex-

tracted and established its own powers, as well as those of the

38. See, e.g., ANDREW RUDALEVIGE, THE NEW IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY: RENEWING

PRESIDENTIAL POWER AFTER WATERGATE 101, 107 (2005) (noting in 1974 Congress

substantially broadened the Freedom of Information Act to allow for judicial re-

view of executive determinations that something needed to be kept secret, even

for national security materials).

39. See, e.g., Free Enter. Fund v. Pub. Co. Accounting Oversight Bd., 561 U.S.

477, 492–508 (2010) (holding that the dual for-cause removal limitations under the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 for members of the Public Company Accounting

Oversight Board constrained presidential power in violation of the constitutional

separation of powers); Morrison v. Olson, 487 U.S. 654, 703–15 (1988) (Scalia, J.,

dissenting) (arguing that the independent counsel provisions of the Ethics in

Government Act of 1978, which the majority upheld, constrained presidential

power in violation of the separation of powers); Common Legislative Encroach-

ments On Executive Branch Authority, 13 Op. O.L.C. 248 (1989).

40. See Julian Davis Mortenson, Article II Vests the Executive Power, not the Royal

Prerogative, 119 C

OLUM. L. REV. 1169, 1210–19 (2019); Tara L. Branum, President or

King? The Use and Abuse of Executive Orders in Modern-Day America, 28 J.

LEGIS. 1,

17–21 (2002).

41. See Mortenson, supra note 40, at 1191–1201.

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 613

judiciary.

42

A watershed in this evolution was, of course, the

Glorious Revolution in 1689.

43

But by 1787, we had the exact opposite model in the United

States.

44

The Founders greatly admired how the British consti-

tution had given rise to the principles of a balanced govern-

ment.

45

But they felt that the British constitution had achieved

only an imperfect form of this model. They saw themselves as

framing a more perfect version of separation of powers and a

balanced constitution.

46

Part of their more perfect construction was a new kind of ex-

ecutive. They created an office that was already the ideal Whig

executive. It already had built into it the limitations that Whig

doctrine aspired to.

47

It did not have the power to tax and

spend;

48

it was constrained by habeas corpus and by due pro-

cess in enforcing the law against members of the body politic;

49

it was elected for a limited term of office;

50

and it was elected

by the nation as whole.

51

That is a remarkable democratic insti-

tution—the only figure elected by the nation as a whole. With

the creation of the American presidency, the Whig’s obsessive

focus on the dangers of monarchical rule lost relevance.

This fundamental shift in view was reflected in the Convention

debates over the new frame of government. Their concerns

were very different from those that weighed on seventeenth-

century English Whigs. It was not executive power that was of

so much concern to them; it was danger of the legislative

branch, which they viewed as the most dangerous branch to

liberty.

52

As Madison warned, “The legislative department is

42. Id.

43. Id. at 1196–99.

44. A

RTICLES OF CONFEDERATION of 1781 (lacking a single executive and vesting

all executive and legislative power in a congress).

45. Martin S. Flaherty, The Most Dangerous Branch, 105 Y

ALE L.J. 1725, 1756–58 (1996).

46. Victoria Nourse, Toward a “Due Foundation” for the Separation of Powers: The

Federalist Papers as Political Narrative, 74 T

EX. L. REV. 447, 474–76 (1996).

47. See Flaherty, supra note 45, at 1761–62.

48. U.S.

CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 1.

49. U.S.

CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 2; id. amend. V.

50. U.S.

CONST. art. II, § 1.

51. Id.

52. See, e.g., 1 T

HE RECORDS OF THE FEDERAL CONVENTION OF 1787, at 71, 144,

386–88

(Max Farrand ed., 1911).

614 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

everywhere extending the sphere of its activity and drawing all

power into its impetuous vortex.”

53

And indeed, they viewed

the presidency as a check on the legislative branch.

54

The second contemporary way of thinking that operates

against the Executive is a notion that the Constitution does not

sharply allocate powers among the three branches, but rather

that the branches—especially the political branches—“share”

powers.

55

The idea at work here is that, because two branches

both have a role to play in a particular area, we should see

them as sharing power in that area and that it is not such a big

deal if one branch expands its role within that sphere at the ex-

pense of the other.

56

This mushy thinking obscures what it means to say that

powers are shared under the Constitution. The Constitution

generally assigns broad powers to each of the branches in

defined areas.

57

Thus, the legislative power granted in the

53. THE FEDERALIST NO. 48, supra note 14, at 306 (James Madison).

54. See, e.g., T

HE RECORDS OF THE FEDERAL CONVENTION OF 1787, supra note 52,

at 144; T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 73, supra note 14, at 441 (Alexander Hamilton) (de-

fending the Executive’s veto power as necessary to “establish[] a salutary check

upon the legislative body, calculated to guard the community against the effects

of faction, precipitancy, or of any impulse unfriendly to the public good”).

55. See, e.g., R

ICHARD E. NEUSTADT, PRESIDENTIAL POWER AND THE MODERN

PRESIDENTS: THE POLITICS OF LEADERSHIP FROM ROOSEVELT TO REAGAN 29 (The

Free Press 1991) (1960) (presenting the view that the United States is not “a gov-

ernment of ‘separated powers’” but “a government of separated institutions shar-

ing powers”); Lloyd N. Cutler, Now Is the Time for All Good Men . . ., 30 W

M. &

MARY L. REV. 387, 387 (1989) (“[The Framers] decided the best way to maintain

checks and balances among the branches was to allow at least one other branch to

share in each power principally assigned to a different branch.”); Paul R. Verkuil,

Separation of Powers, the Rule of Law and the Idea of Independence, 30 W

M. & MARY L.

REV. 301, 301 (1989); see also THE FEDERALIST NO. 37, supra note 14, at 224 (James

Madison) (“[N]o skill in the science of government has yet been able to discrimi-

nate and define, with sufficient certainty, its three great provinces—the legislative,

executive, and judiciary . . . .”).

56. See Flaherty, supra note 45, at 1737 (“To [the functionalist], the Constitution . . .

invites[] the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary to share power in creative

ways. So long as the arrangements that emerge do not upset the specified design

at the top of the structure . . . what emerges is fair game.”).

57. See T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 48 (James Madison); Edward Susolik, Note, Separa-

tion of Powers and Liberty: The Appointments Clause, Morrison v. Olson, and Rule of

Law, 63 S.

CAL. L. REV. 1515, 1528 (1990) (noting that for a “strict separation of

powers . . . [l]egislative, executive, and judicial functions are conceptualized as

separate and distinct, and actors within each branch are not to undertake duties

allocated to another branch”).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 615

Constitution is granted to the Congress.

58

At the same time, the

Constitution gives the Executive a specific power in the legisla-

tive realm—the veto power.

59

Thus, the Executive “shares” leg-

islative power only to the extent of this specific grant of veto

power. The Executive does not get to interfere with the broader

legislative power assigned solely to the Congress.

60

In recent years, both the legislative and judicial branches

have been responsible for encroaching on the presidency’s

constitutional authority. Let me first say something about the

legislature.

A. Encroachments by the Legslative Branch

As I have said, the Framers fully expected intense pulling

and hauling between the Congress and the President. Unfortu-

nately, just in the past few years, we have seen these conflicts

take on an entirely new character.

Immediately after President Trump won election, opponents

inaugurated what they called “The Resistance,” and they rallied

around an explicit strategy of using every tool and maneuver

available to sabotage the functioning of his administration.

61

Now “resistance” is the language used to describe an insurgency

against rule imposed by an occupying military power. The

term obviously connotes that the government opposed is not

legitimate.

62

This is a very dangerous—indeed, incendiary—

58. See U.S. CONST. art. I, § 1 (“All legislative Powers herein granted shall be

vested in a Congress of the United States . . . .”).

59. See U.S. C

ONST. art. I, § 7, cl. 2.

60. See Springer v. Philippine Islands, 277 U.S. 189, 201–02 (1928) (discussing the

“generally inviolate” rule that “the executive cannot exercise either legislative or

judicial power”).

61. See David S. Meyer & Sidney Tarrow, Introduction to

THE RESISTANCE: THE

DAWN OF THE ANTI-TRUMP OPPOSITION MOVEMENT 1, 1–24 (David S. Meyer &

Sidney Tarrow eds., 2018)

(describing how a variety of social activism movements

combined to create the origins of “The Resistance”); Charlotte Alter, How the Anti-

Trump Resistance Is Organizing Its Outrage, T

IME (Oct. 18, 2018, 6:35 AM), http://

time.com/longform/democrat-midterm-strategy/ [http://perma.cc/CDD9-HBZB];

Alex Seitz-Wald, The anti-Trump ‘Resistance’ turns a year old—and grows up, NBC

N

EWS (Jan. 19, 2018, 8:53 AM), http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2018-state-of-

the-union-address/anti-trump-resistance-turns-year-old-grows-n838821 [http://

perma.cc/CPY2-4EZS].

62. See Tom Ginsburg, Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez, Mila Versteeg, When to

Overthrow your Government: The Right to Resist in the World’s Constitutions, 60

UCLA

L. REV. 1184, 1208 (2013) (describing the “right to resist” as a “necessary

616 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

notion to import into the politics of a democratic republic.

63

What it means is that, instead of viewing themselves as the

“loyal opposition,” as opposing parties have done in the past,

64

they essentially see themselves as engaged in a war to cripple,

by any means necessary, a duly elected government.

65

A prime example of this is the Senate’s unprecedented abuse

of the advice-and-consent process.

66

The Senate is free to exer-

cise that power to reject unqualified nominees, but that power

was never intended to allow the Senate to systematically oppose

and draw out the approval process for every appointee so as to

prevent the President from building a functional government.

67

Yet that is precisely what the Senate minority has done from

his very first days in office. As of September of this year, the

popular response in cases of illegitimately exercised or formulated government

authority”).

63. See Arthur Kaufmann, Small Scale Right to Resist, 21 N

EW ENG. L. REV. 571,

574 (1985–1986) (“The tragedy of resistance [is] not only its futility but also its

danger to the order of the community . . . .”); Edward Rubin, Judicial Review and

the Right To Resist, 97 G

EO. L.J. 61, 63 (2008) (“Resistance . . . is always traumatic,

typically dangerous, and often ineffective; and unsuccessful efforts generally lead

to disastrous consequences for the participants.”).

64. See George Anastaplo, Loyal Opposition in a Modern Democracy, 35 L

OY. U.

CHI. L.J. 1009, 1010 (2004) (describing the role of the “loyal opposition” as a foil

against presidency policies, used by a competing, yet cooperating, political party);

see also Jean H. Baker, A Loyal Opposition: Northern Democrats in the Thirty-Seventh

Congress, 25 C

IVIL WAR HIST. 139 (1979) (noting that even during the Civil War,

Democrats from northern states played the role of “loyal opposition” against the

Lincoln Administration).

65. Joel Kotkin, Loyal opposition versus resistance to trump, O

RANGE COUNTY REG.

(Jan. 8, 2017, 12:00 AM), http://www.ocregister.com/2017/01/08/loyal-opposition-

versus-resistance-to-trump/ [http://perma.cc/5VBF-PAN7]; Campbell Robertson,

In Trump Country, the Resistance Meets the Steel Curtain, N.Y.

TIMES (Feb. 6, 2020),

https://nyti.ms/2UqYF9n [https://perma.cc/6DQU-PHJA].

66. Compare Nominations: A Historical Overview, U.S.

SENATE, https://

www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Nominations.htm [https://

perma.cc/E9DU-U79H] (last visited May 3, 2020) and The Confirmation Process for

Presidential Appointees, H

ERITAGE FOUND., https://www.heritage.org/political-

process/heritage-explains/the-confirmation-process-presidential-appointees [https://

perma.cc/842A-RS35] (last visited May 3, 2020) (three rejections of Supreme Court

nominations and nine rejections of cabinet appointments in the past hundred

years) with Dan Cancian, Donald Trump Suffers Setback as Senate Rejects Hundreds of

Nominations, N

EWSWEEK (Jan. 5, 2019, 10:43 AM), https://www.newsweek.com/

donald-trump-judicial-nominations-116th-congress-us-senate-charles-schumer-

1280392 [https://perma.cc/7PUM-DHUD] (hundreds of nominees rejected and

increased timeframe for decisions during the Trump Administration).

67. See T

HE FEDERALIST NO. 76, supra note 14, at 455–57 (Alexander Hamilton).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 617

Senate had been forced to invoke cloture on 236 Trump nomi-

nees

68

—each of those representing its own massive consump-

tion of legislative time meant only to delay an inevitable con-

firmation. How many times was cloture invoked on nominees

during President Obama’s first term? Seventeen times.

69

The

second President Bush’s first term? Four times.

70

It is reasonable

to wonder whether a future President will actually be able to

form a functioning administration if his or her party does not

hold the Senate.

Congress has in recent years also largely abdicated its core

function of legislating on the most pressing issues facing the

national government.

71

They either decline to legislate on major

questions or, if they do, punt the most difficult and critical issues

by making broad delegations to a modern administrative state

that they increasingly seek to insulate from presidential con-

trol.

72

This phenomenon first arose in the wake of the Great

Depression, as Congress created a number of so-called “inde-

pendent agencies” and housed them, at least nominally, in the

executive branch.

73

More recently, the Dodd-Frank Act’s crea-

68. See Cloture Motions—115th Congress, U.S. SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/

legislative/cloture/115.htm [https://perma.cc/29BP-CAYD] (last visited May 3, 2020);

Cloture Motions—116th Congress, U.S.

SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/

cloture/116.htm [https://perma.cc/4MGP-EHRL] (last visited May 3, 2020).

69. See Cloture Motions—111th Congress, U.S.

SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/

legislative/cloture/111.htm [https://perma.cc/6KT5-Y33Q] (last visited May 5, 2020);

Cloture Motions—112th Congress, U.S.

SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/

cloture/112.htm [https://perma.cc/X5SM-PSAK] (last visited May 5, 2020).

70. See Cloture Motions—107th Congress, U.S.

SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/

legislative/cloture/107.htm [https://perma.cc/QX6C-ZWVH] (last visited May 5, 2020);

Cloture Motions—108th Congress, U.S.

SENATE, https://www.senate.gov/legislative/

cloture/108.htm [https://perma.cc/26AE-ZSBN] (last visited May 5, 2020).

71. See David Schoenbrod, Consent of the Governed: A Constitutional Norm that the

Court Should Substantially Enforce, 43

HARV. J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 213, 244–53 (2020);

Ethan Blevins, Ending the Administrative State is an Uphill and Necessary Battle for a

Free Nation, N

AT’L REV. (Feb. 20, 2020, 5:50 PM), https://www.nationalreview.com/

bench-memos/ending-administrative-state-uphill-necessary-battle-free-nation/

[https://perma.cc/C9PB-7JY5].

72. Schoenbrod, supra note 71, at 244–53; Blevins, supra note 71; Chuck DeVore, The

Administrative State Is Under Assault And That’s A Good Thing, F

ORBES (Nov. 27, 2017,

1:53 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckdevore/2017/11/27/the-administrative-

state-is-under-assault-and-thats-a-good-thing/#60c12ddc393c [https://perma.cc/

D825-TAUW].

73. John Yoo, Franklin Roosevelt and Presidential Power, 21 C

HAP. L. REV. 205, 227–

31 (2018).

618 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

tion of the Consumer Financial Protection Branch, a single-

headed independent agency that functions like a junior varsity

President for economic regulation, is just one of many examples.

74

Of course, Congress’s effective withdrawal from the business

of legislating leaves it with a lot of time for other pursuits. And

the pursuit of choice, particularly for the opposition party, has

been to drown the executive branch with “oversight” demands

for testimony and documents.

75

I do not deny that Congress

has some implied authority to conduct oversight as an incident

to its legislative power. But the sheer volume of what we see

today—the pursuit of scores of parallel “investigations”

through an avalanche of subpoenas—is plainly designed to in-

capacitate the executive branch, and indeed is touted as such.

76

The costs of this constant harassment are real. For example,

we all understand that confidential communications and a pri-

vate, internal deliberative process are essential for all of our

branches of government to properly function. Congress and the

judiciary know this well, as both have taken great pains to

shield their own internal communications from public inspec-

tion.

77

There is no FOIA

78

for Congress or the courts. Yet Congress

has happily created a regime that allows the public to seek

whatever documents it wants from the executive branch at the

same time that individual congressional committees spend

their days trying to publicize the Executive’s internal decisional

74. See PHH Corp. v. CFPB, 839 F.3d 1, 15–17 (D.C. Cir. 2016), rev’d en banc, 881

F.3d 75 (D.C. Cir. 2018).

75. See, e.g., Laura Blessing, Congressional Oversight in the 116th, G

OV’T AFF. INST.

AT

GEO. U. (Mar. 8, 2019), https://gai.georgetown.edu/congressional-oversight-in-

the-116th/ [https://perma.cc/7PQ5-XJDS].

76. Alex Moe, House investigations of Trump and his administration: The full list,

NBC

NEWS (May 27, 2019, 12:02 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-

trump/house-investigations-trump-his-administration-full-list-n1010131 [https://

perma.cc/SW85-2AUN] (listing fourteen different Democrat-led House commit-

tees investigating President Trump as of May 2019).

77. See, e.g., Classified Information Procedures Act, 18 U.S.C app. 3 (2018);

R

ULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, r. XVII(10), reprinted in H.R. DOC. NO.

114-192, at 788–89 (2017) (authorizing “secret sessions”); S

TANDING RULES OF THE

SENATE, r. XXI, reprinted in S. DOC. NO. 113-18, at 15 (2013) (authorizing “closed

sessions”); Supreme Court Procedures, U.S.

COURTS, https://www.uscourts.gov/about-

federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/

supreme-1 [https://perma.cc/UJ47-WM8F] (last visited May 3, 2020) (noting that

only Justices are allowed in the room when the Supreme Court holds conference).

78. 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2018).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 619

process.

79

That process cannot function properly if it is public,

nor is it productive to have our government devoting enor-

mous resources to squabbling about what becomes public and

when, rather than doing the work of the people.

In recent years, we have seen substantial encroachment by

Congress in the area of executive privilege. The executive

branch and the Supreme Court have long recognized that the

need for confidentiality in executive branch decisionmaking

necessarily means that some communications must remain off

limits to Congress and the public.

80

There was a time when

Congress respected this important principle as well.

81

But today,

Congress is increasingly quick to dismiss good faith attempts to

protect executive branch equities, labeling such efforts “obstruc-

tion of Congress” and holding cabinet secretaries in contempt.

82

One of the ironies of today is that those who oppose this

President constantly accuse this Administration of “shredding”

constitutional norms and waging a war on the rule of law.

83

When I ask my friends on the other side, what exactly are you

referring to? I get vacuous stares, followed by sputtering about

79. See ACLU v. CIA, 823 F.3d 655, 662 (D.C. Cir. 2016) (“Nevertheless, because

it is undisputed that Congress is not an agency, it is also undisputed that ‘congres-

sional documents are not subject to FOIA’s disclosure requirements.’”(quoting

United We Stand Am., Inc. v. IRS, 359 F.3d 595, 597 (D.C. Cir. 2004))).

80. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 711 (1974) (“Nowhere in the Constitution . . . is

there any explicit reference to a privilege of confidentiality, yet to the extent this

interest relates to the effective discharge of a President’s powers, it is constitution-

ally based.”).

81. In re Sealed Case, 121 F.3d 729, 740 n.9 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (“Interestingly, it

appears that Congress has at times accepted executive officers’ refusal to testify

about conversations they had with the President, even as it was insisting on access

to other executive branch documents and materials.” (citing M

ARK J. ROZELL, EX-

ECUTIVE

PRIVILEGE: THE DILEMMA OF SECRECY AND DEMOCRATIC ACCOUNTABILITY

44 (1994); Robert Kramer & Herman Marcuse, Executive Privilege—A Study of the

Period 1953–1960, 29 G

EO. WASH. L. REV. 827, 872–73 (1961))).

82. See, e.g., H.R.

REP. NO. 116-125, at 1–2 (2019).

83. Tim Ahmann, Top Democrats say Trump is shredding Constitution with emer-

gency declaration, R

EUTERS (Feb. 15, 2019, 11:25 AM), https://www.reuters.com/

article/us-usa-shutdown-democrats/top-democrats-say-trump-is-shedding-constitution-

with-emergency-declaration-idUSKCN1Q423R [https://perma.cc/36UX-FE96]; see

also Neil S. Siegel, Political Norms, Constitutional Conventions, and President Donald

Trump, 93 I

ND. L.J. 177, 191–203 (2018).

620 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

the travel ban

84

or some such thing. While the President has

certainly thrown out the traditional Beltway playbook, he was

upfront about that beforehand, and the people voted for him.

What I am talking about today are fundamental constitutional

precepts. The fact is that this Administration’s policy initiatives

and proposed rules, including the travel ban, have transgressed

neither constitutional nor traditional norms, and have been

amply supported by the law and patiently litigated through the

court system to vindication.

85

Indeed, measures undertaken by this Administration seem a

bit tame when compared to some of the unprecedented steps

taken by the Obama Administration’s aggressive exercises of

executive power—such as, under its DACA program, refusing

to enforce broad swathes of immigration law.

86

The fact of the matter is that, in waging a scorched earth, no-

holds-barred war of “Resistance” against this Administration,

it is the Left that is engaged in the systematic shredding of

norms and the undermining of the rule of law. This highlights

a basic disadvantage that conservatives have always had in

contesting the political issues of the day. It was adverted to by

the old, curmudgeonly Federalist, Fisher Ames, in an essay

during the early years of the Republic.

87

In any age, the so-called progressives treat politics as their

religion. Their holy mission is to use the coercive power of the

state to remake man and society in their own image, according

84. See Exec. Order No. 13,769, 82 Fed. Reg. 8977 (Jan. 27, 2017); Exec. Order No.

13,780, 82 Fed. Reg. 13,209 (Mar. 6, 2017); Proclamation No. 9645, 82 Fed. Reg.

45,161 (Sept. 24, 2017).

85. See, e.g., Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392, 2403–04, 2423 (2018) (upholding

the travel ban).

86. See Memorandum from Janet Napolitano, Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland

Sec., to David V. Aguilar, Acting Comm’r, U.S. Customs & Border Protection, et

al., Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to

the United States as Children (June 15, 2012), https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/

s1-exercising-prosecutorial-discretion-individuals-who-came-to-us-as-children.pdf

[https://perma.cc/JG97-XT57]; Barack Obama, President, United States, Remarks

by the President in Address to the Nation on Immigration (Nov. 20, 2014), https://

obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/11/20/remarks-president-

address-nation-immigration [https://perma.cc/7ADG-YUZB].

87. F

ISHER AMES, Laocoon No. II, in WORKS OF FISHER AMES 103, 106–08 (Boston,

T.B. Wait & Co. 1809).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 621

to an abstract ideal of perfection.

88

Whatever means they use

are therefore justified because, by definition, they are a virtu-

ous people pursing a deific end. They are willing to use any

means necessary to gain momentary advantage in achieving

their end, regardless of collateral consequences and the systemic

implications. They never ask whether the actions they take

could be justified as a general rule of conduct, equally applica-

ble to all sides.

89

Conservatives, on the other hand, do not seek an earthly par-

adise. We are interested in preserving over the long run the

proper balance of freedom and order necessary for healthy de-

velopment of natural civil society and individual human flour-

ishing.

90

This means that we naturally test the propriety and

wisdom of action under a “rule of law” standard.

91

The essence

of this standard is to ask what the overall impact on society

over the long run if the action we are taking, or principle we

are applying, in a given circumstance was universalized—that

is, would it be good for society over the long haul if this was

done in all like circumstances?

92

For these reasons, conservatives tend to have more scruple

over their political tactics and rarely feel that the ends justify

the means. And this is as it should be, but there is no getting

around the fact that this puts conservatives at a disadvantage

when facing progressive holy war, especially when doing so

under the weight of a hyper-partisan media.

88. See Jim DeMint & Rachel Bovard, Opinion, Progressive politics is the Left’s

new religion, W

ASH. EXAMINER (Sept. 24, 2019, 12:00 AM), https://

www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/progressive-politics-is-the-lefts-new-

religion [https://perma.cc/6ZA5-G3AH].

89. See, e.g., John O. McGinnis, Progressivism Is a Long-Term Threat to the Rule of

Law, L

AW & LIBERTY (July 18, 2016), https://lawliberty.org/progressivism-is-a-

long-term-threat-to-the-rule-of-law/ [https://perma.cc/GGJ5-XCDY].

90. See Lee Edwards, What Is Conservatism?, H

ERITAGE FOUND. (Oct. 25, 2018),

https://www.heritage.org/conservatism/commentary/what-conservatism [https://

perma.cc/5E5Q-JKEM]; Russell Kirk, Ten Conservative Principles, R

USSELL KIRK CTR.,

https://kirkcenter.org/conservatism/ten-conservative-principles/ [https://perma.cc/

V5U8-BPDF] (last visited May 4, 2020).

91. Calvin R. Massey, Rule of Law and the Age of Aquarius, 41 H

ASTINGS L.J. 757,

759 (1990) (book review) (“Adherence to the rule of law is truly conservative in

that it preserves the balance between majoritarian power and individual rights or

societal values, in order to permit a systemic solution to materialize.”).

92. See Antonin Scalia, The Rule of Law as A Law of Rules, 56 U.

CHI. L. REV. 1175,

1178–80 (1989).

622 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

B. Encroachments by the Judicial Branch

Let me turn now to what I believe has been the prime source

of the erosion of separation-of-power principles generally, and

executive branch authority specifically. I am speaking of the

judicial branch.

In recent years the judiciary has been steadily encroaching on

executive responsibilities in a way that has substantially under-

cut the functioning of the presidency. The courts have done this

in essentially two ways: First, the judiciary has appointed itself

the ultimate arbiter of separation-of-powers disputes between

Congress and Executive, thus preempting the political process,

which the Framers conceived as the primary check on inter-

branch rivalry. Second, the judiciary has usurped presidential

authority for itself, either (a) by, under the rubric of “review,”

substituting its judgment for the Executive’s in areas commit-

ted to the President’s discretion, or (b) by assuming direct con-

trol over realms of decisionmaking that heretofore have been

considered at the core of presidential power.

The Framers did not envision that the courts would play the

role of arbiter of turf disputes between the political branches.

As Madison explained in Federalist 51, “the great security

against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the

same department, consists in giving to those who administer

each department the necessary constitutional means and per-

sonal motives to resist encroachments of the others.”

93

By giv-

ing each the Congress and the presidency the tools to fend off

the encroachments of the others, the Framers believed this

would force compromise and political accommodation.

The “constitutional means” to “resist encroachments” that

Madison described take various forms. As Justice Scalia observed,

the Constitution gives Congress and the President many “clubs

with which to beat” each other.

94

Conspicuously absent from

the list is running to the courts to resolve their disputes.

That omission makes sense. When the judiciary purports to

pronounce a conclusive resolution to constitutional disputes

between the other two branches, it does not act as a coequal.

93. THE FEDERALIST NO. 51, supra note 14, at 318–19 (James Madison).

94. Transcript of Oral Argument at 10, Zivotofsky v. Clinton, 566 U.S. 189 (2012)

(No. 10-699).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 623

And, if the political branches believe the courts will resolve

their constitutional disputes, they have no incentive to debate

their differences through the democratic process—with input

from and accountability to the people. And they will not even

try to make the hard choices needed to forge compromise. The

long experience of our country is that the political branches can

work out their constitutional differences without resort to the

courts.

In any event, the prospect that courts can meaningfully re-

solve interbranch disputes about the meaning of the Constitution

is mostly a false promise. How is a court supposed to decide,

for example, whether Congress’s power to collect information

in pursuit of its legislative function overrides the President’s

power to receive confidential advice in pursuit of his executive

function? Nothing in the Constitution provides a manageable

standard for resolving such a question. It is thus no surprise

that the courts have produced amorphous, unpredictable bal-

ancing tests like the Court’s holding in Morrison v. Olson

95

that

Congress did not disrupt “the proper balance between the co-

ordinate branches by preventing the Executive Branch from

accomplishing its constitutionally assigned functions.”

96

Apart from their overzealous role in interbranch disputes,

the courts have increasingly engaged directly in usurping pres-

idential decisionmaking authority for themselves. One way

courts have effectively done this is by expanding both the

scope and the intensity of judicial review.

97

In recent years, we have lost sight of the fact that many criti-

cal decisions in life are not amenable to the model of judicial

decisionmaking. They cannot be reduced to tidy evidentiary

standards and specific quantums of proof in an adversarial

process. They require what we used to call prudential judg-

ment. They are decisions that frequently have to be made

promptly, on incomplete and uncertain information, and nec-

essarily involve weighing a wide range of competing risks and

making predictions about the future. Such decisions frequently

95. 487 U.S. 654 (1988).

96. Id. at 695 (alterations adopted) (quoting Nixon v. Admin. of Gen. Servs., 433

U.S. 425, 443 (1977)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

97. See, e.g., Hawaii v. Trump, 878 F.3d 662 (9th Cir. 2017), rev’d, 138 S. Ct. 2392

(2018).

624 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

call into play the “precautionary principle.”

98

This is the princi-

ple that when a decisionmaker is accountable for discharging a

certain obligation—such as protecting the public’s safety—it is

better, when assessing imperfect information, to be wrong and

safe, than wrong and sorry.

It was once well recognized that such matters were largely

unreviewable and that the courts should not be substituting

their judgments for the prudential judgments reached by the

accountable executive officials. This outlook now seems to have

gone by the boards. Courts are now willing, under the banner of

judicial review, to substitute their judgment for the President’s

on matters that only a few decades ago would have been un-

imaginable—such as matters involving national security or for-

eign affairs.

The travel ban case is a good example. There the President

made a decision under an explicit legislative grant of authority,

as well as his constitutional national security role, to temporarily

suspend entry to aliens coming from a half dozen countries

pending adoption of more effective vetting processes.

99

The

common denominator of the initial countries selected was that

they were unquestionable hubs of terrorism activity, which

lacked functional central government’s and responsible law

enforcement and intelligence services that could assist us in

identifying security risks among their nationals seeking entry.

100

Despite the fact there were clearly justifiable security grounds

for the measure, the district court in Hawaii and the Ninth Circuit

blocked this public safety measure for a year and half on the

theory that the President’s motive for the order was religious

bias against Muslims.

101

This was just the first of many immi-

gration measures based on good and sufficient security

grounds that the courts have second guessed since the begin-

ning of the Trump Administration.

102

98. Cass R. Sunstein, Beyond the Precautionary Principle, 151 U. PA. L. REV. 1003,

1003–04 (2003).

99. Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. at 2403–05.

100. Id. at 2403–04.

101. Id. at 2404, 2406–07.

102. See, e.g., E. Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Barr, 934 F.3d 1026 (9th Cir.), stay

granted, 140 S. Ct. 3 (2019); Sierra Club v. Trump, 929 F.3d 670 (9th Cir.), stay granted,

140 S. Ct. 1 (2019); Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 908

F.3d 476 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. granted, 139 S. Ct. 2779 (2019).

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 625

The travel ban case highlights an especially troubling aspect

of the recent tendency to expand judicial review. The Supreme

Court has traditionally refused, across a wide variety of con-

texts, to inquire into the subjective motivation behind govern-

mental action. To take the classic example, if a police officer has

probable cause to initiate a traffic stop, his subjective motivations

are irrelevant.

103

And just last term, the Supreme Court appro-

priately shut the door to claims that otherwise-lawful redis-

tricting can violate the Constitution if the legislators who drew

the lines were actually motivated by political partisanship.

104

What is true of police officers and gerrymanderers is equally

true of the President and senior executive officials. With very

few exceptions, neither the Constitution, nor the Administrative

Procedure Act

105

or any other relevant statute, calls for judicial

review of executive motive. They apply only to executive ac-

tion.

106

Attempts by courts to act like amateur psychiatrists at-

tempting to discern an executive official’s “real motive”—often

after ordering invasive discovery into the executive branch’s

privileged decisionmaking process—have no more foundation

in the law than a subpoena to a court to try to determine a

judge’s real motive for issuing its decision. And courts’ indul-

gence of such claims, even if they are ultimately rejected, rep-

resents a serious intrusion on the President’s constitutional

prerogatives.

The impact of these judicial intrusions on executive respon-

sibility have been hugely magnified by another judicial innova-

tion—the nationwide injunction. First used in 1963,

107

and

103. Whren v. United States, 517 U.S. 806, 813 (1996) (“Subjective intentions play

no role in ordinary, probable-cause Fourth Amendment analysis.”).

104. Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2506–07 (2019) (“[P]artisan gerry-

mandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal

courts. Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the

two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution,

and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.”).

105. 5 U.S.C. §§ 551, 553–559, 701–706 (2018).

106. See, e.g., id. § 706(2) (providing that a reviewing court shall “hold unlawful

and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions” that are arbitrary, capri-

cious, or contrary to law).

107. See Wirtz v. Baldor Elec. Co., 337 F.2d 518, 520, 536 (D.C. Cir. 1963) (up-

holding an injunction against a rule that would establish a uniform wage in the

electrical motors and generators industry); see also Samuel L. Bray, Multiple Chan-

cellors: Reforming the National Injunction, 131 H

ARV. L. REV. 417, 437–39 (2017).

626 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy [Vol. 43

sparely since then until recently, these court orders enjoin en-

forcement of a policy not just against the parties to a case, but

against everyone. Since President Trump took office, district

courts have issued over forty nationwide injunctions against

the government.

108

By comparison, during President Obama’s

first two years, district courts issued a total of two nationwide

injunctions against the government.

109

Both were vacated by

the Ninth Circuit.

110

It is no exaggeration to say that virtually every major policy

of the Trump Administration has been subjected to immediate

freezing by the lower courts.

111

No other President has been

subjected to such sustained efforts to debilitate his policy

agenda.

The legal flaws underlying nationwide injunctions are myriad.

Just to summarize briefly, nationwide injunctions have no

foundation in courts’ Article III jurisdiction or traditional equi-

table powers;

112

they radically inflate the role of district judges,

allowing any one of more than 600 individuals to singlehandedly

freeze a policy nationwide, a power that no single appellate

judge or Justice can accomplish; they foreclose percolation and

108. Tessa Berenson, Inside the Trump Administration’s Fight to End Nationwide

Injunctions, T

IME (Nov. 4, 2019, 3:12 PM), https://time.com/5717541/nationwide-

injunctions-trump-administration/ [https://perma.cc/K4EK-29GC]. As of February

2020, the number is up to fifty-five. Jeffrey A. Rosen, Deputy Attorney Gen., United

States, Opening Remarks at Forum on Nationwide Injunctions and Federal Regu-

latory Program (Feb. 12, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-

attorney-general-jeffrey-rosen-delivers-opening-remarks-forum-nationwide

[https://perma.cc/T23U-6GKF].

109. See Log Cabin Republicans v. United States, 716 F. Supp. 2d 884, 929 (C.D.

Cal. 2010), vacated by, 658 F.3d 1162 (9th Cir. 2011); L.A. Haven Hospice, Inc. v.

Sebelius, No. CV08-4469-GW (RZX), 2009 WL 5865294, at *1 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 20,

2009), aff’d in part, vacated in part, remanded, 638 F.3d 644 (9th Cir. 2011).

110. See Log Cabin Republicans, 658 F.3d at 1168; L.A. Haven Hospice, 638 F.3d at

648 (vacating “that portion of the injunction barring enforcement of the regulation

against hospice providers other than Haven Hospice”).

111. See Jordan Fabian & Jacqueline Thomsen, Courts become turbocharged battle-

ground in Trump era, H

ILL (July 22, 2019, 6:00 AM), https://thehill.com/homenews/

administration/453881-courts-become-turbocharged-battleground-in-trump-era

[https://perma.cc/D3F8-HZ6N].

112. See Memorandum from the Attorney General to Heads of Civil Litigating

Components United States Attorneys, Litigation Guidelines for Cases Presenting

the Possibility of Nationwide Injunctions 7–8 (Sept. 13, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/

opa/press-release/file/1093881/download [https://perma.cc/Y9U6-E79W]; Bray, supra

note 107, at 425–27.

No. 3] The Role of the Executive 627

reasoned debate among lower courts, often requiring the

Supreme Court to decide complex legal issues in an emergency

posture with limited briefing; they enable transparent forum

shopping,

113

which saps public confidence in the integrity of

the judiciary; and they displace the settled mechanisms for ag-

gregate litigation of genuinely nationwide claims, such as Rule

23 class actions.

114

Of particular relevance to my topic tonight, nationwide in-

junctions also disrupt the political process. There is no better

example than the courts’ handling of the rescission of DACA.

As you recall, DACA was a discretionary policy of enforcement

forbearance adopted by President Obama’s administration.

115

The Fifth Circuit concluded that the closely related DAPA policy

(along with an expansion of DACA) was unlawful,

116

and the

Supreme Court affirmed that decision by an equally divided

vote.

117

Given that DACA was discretionary—and that four

Justices apparently thought a legally indistinguishable policy

was unlawful—President Trump’s administration understand-

ably decided to rescind DACA.

118

Importantly, however, the President coupled that rescission

with negotiations over legislation that would create a lawful

and better alternative as part of a broader immigration com-

promise.

119

In the middle of those negotiations—indeed, on the

same day the President invited cameras into the Cabinet Room

to broadcast his negotiations with bipartisan leaders from both

Houses of Congress

120

—a district judge in the Northern District

113. See Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392, 2425 (2018) (Thomas, J., concurring).