Japan

THE JAPANESE CHILD PROTECTION

SYSTEM: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE LAWS

AND THE ISSUES LEFT UNSOLVED

Ayako Harada

*

Résumé

Au Japon, depuis le début des années 1990, on assiste à une augmentation sensible

du nombre de cas d’enfants maltraités dont s’occupent les centres locaux d’aide

sociale à l’enfance. Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho, une nouvelle loi relative à la

prévention des mauvais traitements dont sont victimes les enfants, a été adoptée

en 2000 en réponse à ce phénomène. Depuis, cette loi ainsi que d’autres lois

relatives à la protection de l’enfance, ont fait l’objet de révisions successives visant

à remédier aux difficultés que pose leur mise en oeuvre. C’est ainsi que s’est

graduellement développé le système de protection de l’enfance au Japon. Le

présent texte s’intéresse au fonctionnement actuel du système de protection de

l’enfance et illustre quelques difficultés concrètes qu’il rencontre. Il commence par

une brève description du contexte social dans lequel s’inscrit cette augmentation

des cas de maltraitance des enfants. Ensuite, il examine les règles régissant chaque

phase de l’intervention de protection et il fait état de leur application concrète sur

le terrain. Finalement, ce texte analyse les problèmes institutionnels et juridiques

auxquels le système est confronté et qui nécessitent un effort soutenu de réforme.

I INTRODUCTION

The number of child abuse and neglect cases in Japan has been dramatically

increasing since the early 1990s. In 2000, the Child Abuse Prevention Act, an

Act created to deal with the child abuse problem, was enacted. Since then, this

Act and another law deeply related to the child protection system have been

revised with the intention of fixing the problems that had occurred within the

system.

This chapter first describes the social background of the rapid increase in the

number of child abuse and neglect cases in Japan. Then it examines how the

rules and regulations are provided by the laws and how they are implemented in

* Research Associate, Institute of Comparative Law, Waseda University; LLD, Kyoto

University, 2007.

practice at each phase of the child protection proceedings. And, finally, it

discusses the issues still left unsolved, which require us to continue our intensive

reform efforts.

II THE INCREASE IN CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

CASES AND ITS SOCIAL BACKGROUND

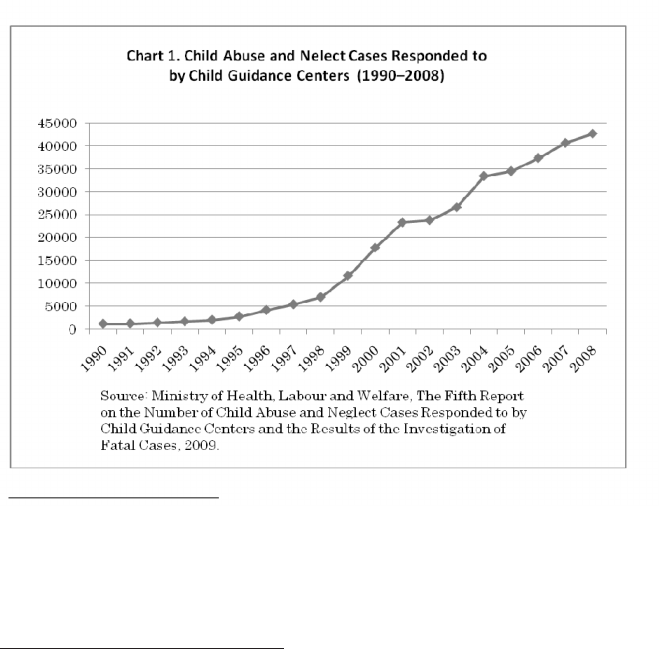

Let us begin with a brief discussion of the rapid increase in the number of child

abuse and neglect cases in Japan. As seen in Chart 1, there has been a steep rise

in the number of child abuse and neglect cases that are responded to by child

guidance centres, the public agencies in charge of child protection services. In

1990, child guidance centres responded to 1,100 cases; this rose to 42,662 in

2008.

1

(Note that the total Japanese population was approximately 128 million

in 2008.)

1

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2009) The Fifth Report on the Number of Child Abuse

and Neglect Cases Responded to by Child Guidance Centre and the Results of the Investigation of

Fatal Cases [Jido Sodansho ni Okeru Jido Gyakutai Sodan Taio Kensu Oyobi Kodomo Gyakutai

ni Yoru Shibo Jirei To no Kensho Kekka To no Dai 5 Ji Hokoku ni Tsuite], available at:

www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2009/07/h0714-1.html (accessed 28 February 2010).

218 The International Survey of Family Law

There are two plausible explanations for the sharp increase in the number of

child abuse and neglect cases. First, the incidence of child abuse and neglect

may actually have increased due to the social circumstances that negatively

affect the parenting abilities of contemporary families. As a result of rapid

urbanisation after World War II, family ties and community relationships have

become weaker than before. However, social support for families, particularly

for families with children, has not been developed well in Japan. Without

sufficient support, many families are struggling with economic hardships,

unstable employment, destruction of the marital relationship, single

parenthood, family members’ health problems, social isolation, and other

hardships that jeopardise their parenting abilities. While families with child

abuse problems usually face more than one of these hardships, economic

hardships seem to be especially common among them.

2

Their hardships have

been becoming more serious due to economic downturn in Japan since the

early 1990s.

Secondly, the increase in the number of abuse and neglect cases may reflect a

change in social attitudes toward child abuse and neglect. It is only recently that

child abuse and neglect have become recognised as serious social problems in

Japan. Concerned professionals and citizens started child abuse prevention

activities, such as telephone counselling services, in the mid-1980s. The national

government officially started to count the number of child abuse cases in 1990

and, 10 years later, enacted the Child Abuse Prevention Act, an independent

Act created to deal with child abuse and neglect problems. The developments in

social activities and public policy have changed our attitude toward child abuse:

we now feel that child abuse is a serious social problem that we have to deal

with. As a result, more and more cases are now being discovered in our society

and reported to the public agencies.

Though it is difficult to tell exactly how valid each of the explanations may be,

it seems both of them have contributed, at least to some extent, to the dramatic

increase in the number of child abuse and neglect cases in the last two decades.

III BASIC STRUCTURE OF THE JAPANESE CHILD

PROTECTION SYSTEM AND PROCEEDINGS PROVIDED

BY THE LAWS

The Japanese child protection system is structured according to the provisions

of several related laws. The Child Welfare Act (Jido Fukushi Ho),

3

the Child

2

See Ryoichi Yamano The Poorest Country for Children, Japan – Effects of Child Poverty on

Children’s Learning Abilities and Emotional/Physical Developments and its Impact on Society

[Kodomo no Saihinkoku, Nihon – Gakuryoku, Shinshin, Shakai ni Oyobu Shoeikyo] (Kobunsha,

Tokyo, 2008) pp 106–111.

3

Law No 164, 12 December 1947.

219The Japanese Child Protection System

Abuse Prevention Act (Jido Gyakutai no Boshi To ni Kansuru Horitsu,

so-called ‘Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho’),

4

and the Civil Code (Mimpo)

5

are

particularly important.

The Child Welfare Act (CWA) provides the general regulations on public child

welfare services. The Act empowers prefectural governments and child

guidance centres to take administrative measures to meet the needs of children

and their parents, including social care of the children. This Act has been

amended several times since the late 1990s to clarify or expand the

administrative authority and responsibilities in relation to child protective and

social care services.

The Child Abuse Prevention Act (CAPA) is an Act that lays out the

responsibilities of the national government and the prefectures in preventing

child abuse and neglect and protecting children from harm. This Act was

amended in 2004 and in 2007.

The Civil Code (CC) is a law that provides the basic rules for relationships

between private individuals. Part 4 of the Civil Code, entitled ‘Relatives

[Shinzoku]’, provides for legal family relationships and the rights and

responsibilities among family members. Several articles of Part 4 stipulate the

relationships between parents and children, define parental authority, and

provide requirements for forfeiting parental authorities. These articles are

especially relevant to child protection proceedings.

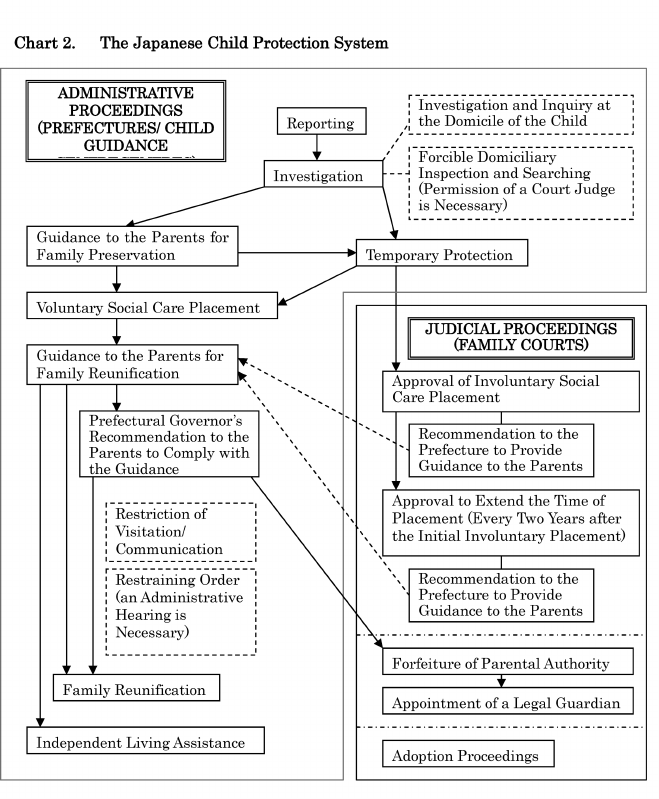

Chart 2 visualises the basic structure of the Japanese child protection system.

The rest of this section examines how the proceedings are framed by the laws

and how they are implemented in practice.

4

Law No 82, 24 May 2000.

5

Law No 89, 27 April 1896.

220 The International Survey of Family Law

221The Japanese Child Protection System

(a) Reporting

The Child Welfare Act provides that any person shall report to a child guidance

centre or other public offices when he or she finds that a child is without any

guardian or when he or she finds it is inappropriate to leave a child in the

custody of the child’s guardian. A child under such situations is defined as ‘the

child in need of protection’ (CWA, arts 6-2(8) and 25). The Child Abuse

Prevention Act clarifies that any child under the age of 18 who is abused or

neglected by his or her guardian falls within the definition of ‘the child in need

of protection’ who needs to be reported (CAPA, arts 2 and 6). The Child Abuse

Prevention Act also provides that any person shall report when he or she

suspects child abuse or neglect, clarifying that we should report even when we

are not completely sure that abuse or neglect has actually occurred (CAPA,

art 6).

CAPA, art 5 states that teachers and other school personnel, workers at child

welfare institutions, physicians, public health nurses, lawyers, and other

individuals whose professions are related to the welfare of children should be

committed to early discovery of child abuse. The 2004 revision of this article

provided that not only these professional individuals but also organisations

(eg schools) should be committed to early discovery of child abuse. This

clarification was introduced to avoid inner-organisational disputes over the

necessity of early discovery and reporting.

Although there has been controversy over whether reporting responsibility

should be mandatory for professionals,

6

the current laws do not provide

criminal punishment for their failure to report. The legal scheme for reporting

does not involve immunity for good-faith wrong reports either, which is

criticised as a deficiency of our reporting law.

7

However, the Child Abuse

Prevention Act does at least provide a couple of measures that help promote

reporting. First, the Act requires officials to keep secret the identity of the

person who reported (CAPA, art 7). And secondly, the Act requires

professionals not to interpret the laws that criminalise the unlawful disclosure

of confidential information as preventing the compliance of their responsibility

to report child abuse (CAPA, art 6(2)).

The Child Abuse Prevention Act defines the four categories of child abuse that

should be reported: physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect and emotional abuse

(CAPA, art 2). The 2004 revision of this article clarified that the guardian’s

failure to protect a child from abuse by a non-parent adult falls within the

definition of neglect. The revision also clarified that incidents of domestic

violence at the domicile of a child are regarded as emotional abuse to the child.

6

See Minoru Ishikawa ‘Legal Policies for Child Abuse and the Problems to be Solved [Jido

Gyakutai o Meguru Hoseisaku to Kadai]’ (2000) 1188 Jurist [Jurisuto] 2–10 at 6.

7

See, eg, Hiroko Goto ‘The Revision of the Child Abuse Prevention Act and its Shortcomings

[Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho no Kaisei to Sono Mondaiten]’ (2004) 6(9) Contemporary Criminal

Law [Gendai Keiji Ho] 54–61 at 57.

222 The International Survey of Family Law

The Child Abuse Prevention Act prohibits child abuse and neglect by any

persons (CAPA, art 3), but provides only for proceedings that deal with cases of

child abuse by ‘guardians’, defined as persons who exercise parental authority

over the child, who are the legal guardians of the child or who currently have

physical custody of the child (CAPA, art 2). The Child Welfare Act uses the

same definition of ‘guardians’ and lays out the services available to the child

and his or her guardians (CWA, art 6). In practice, most of the ‘guardians’

involved in the child protection system are the birth parents of the child.

According to the report of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, of all

the child abuse and neglect cases that were responded to by child guidance

centres in 2006 (37,323 cases), the birth mother was the primary perpetrator in

62.8% (23,442 cases) and the birth father was the primary perpetrator in 22.0%

(8,219 cases).

8

(b) Investigation

CAPA, art 8 states that directors of the child guidance centres shall try to verify

the safety of a child in a timely manner when a report has been received. The

prefectural governor may have officials enter the domicile of the child and

conduct necessary investigations and inquiries, if there is a suspicion that the

child is abused or neglected in the domicile (CAPA, art 9).

9

Support from police

officers shall be requested when necessary (CAPA, art 10). In 2006, child

guidance centres conducted 238 investigations and inquiries at the domicile of

the child.

10

If the child’s guardian does not co-operate with the investigation and inquiry at

the domicile of the child, the guardian may be punished by a fine (CAPA,

art 9(2), CWA, art 61-5). However, the possibility of a fine may not be

sufficient to affect the attitude of the guardian. For example, the guardian may

firmly refuse to co-operate with the investigation, completely shutting the door

to prevent investigators’ contact with the child. To prevent delay in the

confirmation of the child’s safety in such a situation, the 2007 revision of the

Child Abuse Prevention Act introduced the measure of forcible domiciliary

inspection and searching. To invoke this measure, the required steps have to be

taken as follows.

First, the prefectural governor shall issue a summons that requires the guardian

to appear with the child (CAPA, art 8-2). If the guardian refuses to appear with

the child, the governor may issue a second summons (CAPA, art 9-2). If the

guardian refuses a second time, and if there is a suspicion of child abuse or

8

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2007) The Number of Child Abuse and Neglect Cases

Responded to by Child Guidance Centres in 2006 [Heisei 18 Nendo Jido Sodansho ni Okeru Jido

Gyakutai Sodan Taio Kensu To] (hereinafter, Child Abuse Cases in 2006), available at:

www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kodomo/dv16/index.html (accessed 28 February 2010).

9

According to CWA, art 12(3), directors and social workers of the child guidance centres are

regarded as the assisting officials of the prefectural governor. In practice, investigations and

inquiries are conducted by social workers of the child guidance centres.

10

See Child Abuse Cases in 2006,aboven8.

223The Japanese Child Protection System

neglect, the governor obtains the permission of a court judge to have officials

conduct forcible domiciliary inspection and searching (CAPA, art 9-3). The

permission of a judge empowers the officials to forcibly enter the domicile by

breaking the door locks if necessary (CAPA, art 9-7). During the fiscal year of

2008, there were 28 cases of the first summons, 3 cases of the second summons,

and 2 cases of forcible domiciliary inspection and searching. As a result of the

two cases of domiciliary inspection and searching, four children were found

endangered and removed from their domiciles through the measure of

temporary protection.

11

(c) Temporary protection

The Child Abuse Prevention Act and the Child Welfare Act require directors of

the child guidance centres to pursue temporary protection of a child when

necessary (CAPA, art 8, CWA, art 33(1)). Temporary protection shall not

exceed 2 months, but directors of the child guidance centres may extend the

term of protection if necessary (CWA, art 33(3) and (4)). There were 10,221

cases of temporary protection due to child abuse or neglect in 2006.

12

Most of

the protected children are placed in temporary protection shelter facilities in

the buildings of the child guidance centres.

Under the Child Welfare Act, temporary protection is regarded as an

administrative measure that may be pursued without providing the guardian

any opportunities to be heard by a court, even when he or she is against it.

Although administrative appeal and administrative litigation are available for

the guardian who wants to raise an objection to temporary protection of his or

her child, the administrative appeal and administrative litigation seem to be

insufficient to provide due process of law for the guardian. Administrative

appeal, on the one hand, does not necessarily provide a neutral forum since the

investigation is conducted by an official of the prefecture.

13

Administrative

litigation, on the other hand, is conducted in a court, but the issues of child

protection may not be properly dealt with in this type of litigation for several

reasons: not the prefecture but the guardian has to bear the economic burden

of filing a petition as well as the burden of proof as a plaintiff; the case is not

heard by a family court that has expertise in dealing with family issues;

administrative litigation usually takes a long period of time, and so on.

14

From

11

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2009) Report on Summons and Other Measures

Conducted in 2008 [Heisei 20 Nendo ni Oite Jisshi Sareta Shutto Yokyu To ni Tsuite], available

at: www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2009/07/dl/h0714-1b.pdf (accessed 28 February 2010).

12

See Child Abuse Cases in 2006, aboven8.

13

See Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2007) Guideline for Managing Child Abuse Cases

[Kodomo Gyakutai Taio no Tebiki], chapter 10.

14

See Hirohito Suzuki et al ‘Proposal for the Revision of the Law on Parental Authority and the

Related Laws [Shinken Ho Oyobi Kanren Ho Kaisei Teian]’ (2010) 650 Journal of Family

Register [Koseki Jiho] 4–13 at 10–11; see also Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2009)

Opinion for the Reform of the System of Parental Authority for the Prevention of Child Abuse

[Jido Gyakutai Boshi no Tame no Shinken Seido Minaoshi ni Kansuru Ikensho], pp 22–23,

available at: www.nichibenren.or.jp/ja/opinion/report/data/090918.pdf (accessed 28 February

2010).

224 The International Survey of Family Law

the perspective of procedural due process, many commentators argue that there

should be at least a post facto court hearing to authorise temporary

protection.

15

It should also be noted that the lack of a court hearing to

authorise the separation of a child from his or her guardian may be contrary to

Art 9 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which requires the State

Parties to ‘ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents

against their will, except when competent authorities subject to judicial review

determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such

separation is necessary for the best interests of the child’ (emphasis added).

The current laws are unclear about whether and to what extent the guardian’s

parental authority is restricted when the child guidance centre conducts

temporary protection. According to the Civil Code, a child who has not

attained the age of majority (20 years of age) shall be subject to the parental

authority of his or her parents (CC, art 818), and a person who exercises

parental authority holds the rights and owes the responsibilities to care for and

educate the child (CC, art 820). Since there is no court authorisation to suspend

the guardians’ parental authority when temporary protection is conducted, the

guardians tend to think that their parental authority is intact and, therefore,

they are entitled to visit, communicate with their child or even get their child

back anytime they want to. When their requests are rejected, some of them

become furious and violent to the social workers and the staff members at the

temporary protection shelter.

To deal with this problem, the 2007 revision of the Child Abuse Prevention Act

introduced a new provision that empowers directors of the child guidance

centres to restrict the guardian’s visitation or communication with the child

who is under temporary protection, if it is necessary for the protection of the

child (CAPA, art 12). The restriction of visitation or communication can be

pursued without any court hearings. It is true that the child guidance centres

have to deal with many parents whose behaviour is uncontrollable without such

a restriction, but there remains a question of procedural due process in

restricting the contact between a child and his or her guardians.

(d) Social care placement of the child

Out-of-home care provided through the public child welfare system is called

‘social care’ in Japan. Social care may be provided by a child welfare institution,

a group home, or a foster family home. In Japan, most of the children who

need social care are placed in child welfare institutions due to lack of sufficient

15

See, eg, Tsuneo Yoshida ‘Toward the Revision of the Child Abuse Prevention Act – An

Examination from the Legal Perspective [Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho no Kaisei ni Mukete –

Hoteki Shiten kara no Kento]’ in Tsuneo Yoshida (ed) Legal System for the Prevention of Child

Abuse – Issues and Directions for the Law Revision [Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho Seido – Kaisei no

Kadai to Hokosei] (Shogakusha, Tokyo, 2003) pp 3–32 at p 19; see also Ishikawa, above n 6 at

p 8 and Suzuki et al, above n 14 at pp 9–10.

225The Japanese Child Protection System

number of foster family homes and group homes. Among the 4,125 social care

placements due to child abuse or neglect in 2006, 93.9% were placements in

child welfare institutions.

16

Under the Child Welfare Act, prefectures may place a child in social care based

on the recommendation of the child guidance centre, unless such a placement is

not against the will of the person who exercises parental authority over the

child (CWA, art 27(1), (3), and (4)). In other words, as long as the parent is not

against the social care placement of his or her child, the prefecture may

conduct the placement as an administrative measure, without any court

involvement. In practice, social workers at the child guidance centres offer the

option of social care to the parents and convince them to give consent to the

placement while the child is protected in a temporary protection shelter.

If the parent does not accept the social worker’s offer of the social care

placement, the prefecture may pursue the placement through the approval of a

family court. A family court may issue the approval when it finds that the

guardian abuses his or her child or significantly fails to care for the child, or if

there is any other situation where the welfare of the child is extremely harmed

under the custody of the guardian (CWA, art 28(1)).

Social care placements by a court approval (ie involuntary social care

placements) were quite rare until the mid-1990s. The national total number of

court approvals was less than 20 in each year from 1989 to 1995.

17

The number

has gradually increased since then. In 2006, there were 170 approvals.

18

Nevertheless, the tradition of pursuing voluntary placements is still intact. As

mentioned above, there were 4,125 social care placements due to child abuse or

neglect in 2006, whereas there were only 170 court approvals for involuntary

placement in the same year. This data indicates that only about 4% of the

placements were involuntary in 2006. The preference for voluntary placement

may be appropriate when child abuse is not severe and the parent is

co-operative, but if voluntary placement is pursued in severe child abuse cases

or when the parent is not co-operative at all, it raises a concern of delay or

abandonment of a placement necessary to protect children.

19

16

See Child Abuse Cases in 2006,aboven8.

17

Supreme Court of Japan, General Secretariat, Family Bureau (2005) Trends in the Cases of

Article 28 of the Child Welfare Act and Actual Conditions in the Management of the Cases [Jido

Fukushi Ho 28 Jo Jiken no Doko to Jiken Shori no Jitsujo] (20 November 2003–19 November

2004) Monthly Bulletin on Family Courts [Katei Saiban Geppo] Vol 57 No 8, pp 133–143 at

p 134.

18

Supreme Court of Japan, General Secretariat, Family Bureau (2009) Trends in the Cases of

Article 28 of the Child Welfare Act and Actual Conditions in the Management of the Cases [Jido

Fukushi Ho 28 Jo Jiken no Doko to Jiken Shori no Jitsujo] (January–December 2008) Monthly

Bulletin on Family Courts [Katei Saiban Geppo] Vol 61 No 8, pp 141–159 at p 143; hereinafter,

CWA Art 28 Cases in 2008.

19

There is a statistic that demonstrates this concern. The child guidance centres of Tokyo

Prefecture reported that among the cases in which centres considered a social care placement

to be necessary for the child, parental consent was quickly or fairly easily obtained in 49.6% of

cases. However, it reported that the consent was obtained only after intensive efforts to

convince parents in 31.0% of the cases. In addition, the plan of placement was abandoned

226 The International Survey of Family Law

There is no legal time limitation of voluntary social care. Therefore, the child

may stay in social care for many years, as long as the parents are not against the

placement. On the other hand, if the placement is involuntary, the placement

may not exceed 2 years, unless the prefecture obtains the approval of a family

court to extend the time of placement. To pursue the extension of the

placement, the prefecture has to show that the child will be abused, significantly

neglected or extremely harmed by the parent unless the social care placement is

continued (CWA, art 28(2)).

The Child Welfare Act empowers directors of the child welfare institutions and

foster parents to take the necessary measures in relation to the care, education

and discipline of the child (CWA, art 47(2)). Although the parent of the child

retains the parental authority to care for and educate the child unless his or her

parental authority is forfeited through an independent legal proceeding

provided by the Civil Code, the parent cannot intervene into said measures

taken by the director of the child welfare institution or the foster parent.

However, the current laws do not provide any rules to allocate the rights and

responsibilities in making specific decisions for the care and education of the

child in social care. In addition, family courts do not have jurisdictions over

disputes related to the care and education of the child in social care, which

occur among the parent, the social care provider and the child guidance centre.

The lack of rules and court proceedings raises serious confusion and

inconvenience in the care of children in social care. For example, the parent

may refuse to give consent to the medical care that the social care provider and

the child guidance centre find necessary for the child. In such a situation, the

medical care may be given up due to a concern that the parent still holds the

right to make all the medical decisions for the child.

The Child Abuse Prevention Act provides several measures to control contact

between the child and the parent while the child is in social care. First, directors

of the child guidance centres and directors of the child welfare institutions may

restrict parental visitation or communication if it is necessary for the protection

of the child (CAPA, art 12). The 2007 revision of the Child Abuse Prevention

Act provided that directors of the child guidance centres and directors of the

child welfare institutions may prohibit parental visitation and communication

not only when the social care placement is involuntary but also when it is

voluntary. Secondly, according to CAPA, art 12(4), prefectural governors may

issue a restraining order that completely prohibits the parent’s access to the

child for up to 6 months. To take this measure, all the following requirements

must be met: (1) the child has been placed in social care by court approval

(ie the placement is involuntary); (2) parental visitation and communication

because parental consent was not obtained or because the social workers could not even talk to

the parents in 14.9% of the cases. The centres filed a petition for court approval of an

involuntary placement in only 4.5% of the cases. Tokyo Prefecture, Department of Welfare and

Health (2005) The Current Status of Child Abuse [Jido Gyakutai no Jittai] (Part 2), available at:

www.fukushihoken.metro.tokyo.jp/jicen/gyakutai/files/hakusho2.pdf (accessed 28 February

2010).

227The Japanese Child Protection System

have been completely restricted by the director of the child guidance centre or

by the director of the child welfare institution; and (3) a restraining order is

necessary to prevent child abuse or to protect the child from harm. The

governor must conduct an administrative hearing before issuing the order. If

the parent does not comply with the restraining order, the parent may be

punished by imprisonment or a fine (CAPA, art 17). These provisions were also

introduced in the 2007 revision of the Child Abuse Prevention Act.

Prohibition of parental contact or communication may be necessary to protect

the child from harm, but it would have a strong impact on the relationship

between the parent and the child. To strike a balance between protecting

children’s safety and maintaining family relationships, family courts may have

to be involved in deciding whether and how the parent may contact their child

while the child is placed in social care.

Children in social care are supposed to be taken care of in a safe and nurturing

environment, but this assumption may be untrue in reality. In Japan, most of

the children in social care are placed in child welfare institutions rather than

foster family homes, as already described. Unfortunately, many incidents of

institutional abuse have been reported so far. There are also incidents of child

abuse or neglect by foster parents. In order to prevent and respond to the

incidents of child abuse and neglect in social care, the 2008 revision of the

Child Welfare Act provided the responsibilities of the prefectures to take

necessary measures to collect reports, investigate the reported cases and protect

the children from harm (CWA, art 33-10 through 33-17).

20

(e) Guidance for the parents and family reunification

Prefectures may, as an administrative measure, have child guidance centre

social workers or other designated professionals provide guidance to the

parents and the child (CWA, art 27(1) and (2)). The guidance to the parents

shall be provided appropriately with due consideration to family reunification

and other necessary measures to provide a favourable family environment for

the child (CAPA, art 11(1)).

When a prefecture takes the administrative measure of providing guidance to a

parent, the parent is obliged to comply with the guidance (CAPA, art 11(2)). If

the parent fails to comply with the guidance, the prefectural governor may

formally recommend that the parent comply (CAPA, art 11(3)). If the parent

still fails to comply with the guidance and the director considers the parent’s

exercise of his or her parental authority to be extremely harmful to the welfare

of the child, the director of the child guidance centre may file a petition to

20

For a detailed analysis of the current legal scheme to prevent child abuse in social care, see

Kohei Yokota ‘The Legislation to Revise a Part of the Child Welfare Act – Social Care:

Focusing on the Prevention of Institutional Abuse [Jido Fukushi Ho no Ichibu o Kaisei Suru

Horitsu – Shakaiteki Yogo: Shisetsu Nai Gyakutai no Boshi o Chushin ni]’ (2009) 1374 Jurist

[Jurisuto] 39–47.

228 The International Survey of Family Law

forfeit the parental authority of the parent (CAPA, art 11(5)). As discussed

below, however, it is fairly rare for the directors to pursue the forfeiture of

parental authority.

In the current child protection system, the involvement of family courts in the

family reunification services is quite limited. Family courts may recommend

that the prefecture provide guidance to the parents when the courts issue the

approval of involuntary social care placement or extension of the placement

(CWA, art 28(6)), but it is under the discretion of the courts whether they issue

a recommendation or not. In practice, the courts do not issue such

recommendations very often.

21

In addition, the courts do not have jurisdiction

to periodically review the effects of the guidance they recommended or to order

the parents to comply with such guidance.

Practitioners and researchers point out that guidance to the parents fails very

often due to a serious conflict between the social workers and the parents,

especially when the child’s social care placement is involuntary. Although the

Child Abuse Prevention Act empowers prefectural governors to issue formal

recommendations to parents to comply with the guidance as explained above,

social workers do not regard such recommendations as an effective measure for

encouraging parents to comply with the guidance, because the governor’s

recommendation does not legally bind the parents to do so. Some

commentators argue that family courts should have the authority to directly

recommend or order the parents to comply with the guidance or to utilise the

services that the courts authorise as necessary for the parents.

22

According to the Child Welfare Act, the prefectural governor may decide

whether and when the social care placement should be over (CWA, art 27(5)).

When the governor decides to end the placement, the governor must hear the

opinion of the child guidance centre, and of the social worker who provided

guidance to the parent, and consider the effects of the guidance and the

measures to be taken to prevent abuse or neglect after the child is reunified with

the parent (CAPA, art 13). Family courts do not touch on the prefectural

governor’s decision of family reunification, except when the prefecture pursues

family court approval to extend the placement every 2 years after the initial

involuntary placement, where the court must consider the possibility of family

reunification in deciding whether the court should approve the extension of the

placement. In a great majority of the cases, family reunification is completed

without any court involvement, no matter whether the placement was

voluntary or involuntary.

21

Family courts issued recommendations to the prefecture to provide guidance to the parents in

only 16 out of 145 approvals of involuntary placement in 2008. (The total number of

approvals was 169 in 2008, but the data of only 145 approvals was available). See CWA Art 28

Cases in 2008, n 18 above at p 151.

22

See, eg, Japan Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2009) Opinion for the

Reform of the System of Parental Authority in Relation to Child Abuse [Jido Gyakutai o Meguru

Shinken Seido Minaoshi ni Tsuite no Ikensho], pp 9–10, available at: www.jaspcan.org/

20091126JaSPCAN_shinken.pdf (accessed 28 February 2010).

229The Japanese Child Protection System

As a whole, there seem to be two inherent problems in the Japanese family

reunification scheme. First, there is no court review to assure the safety of the

child before the child is returned to the parents. There is a possibility for the

child guidance centre to rush into a wrongful family reunification decision that

is harmful to the child. Sadly to say, there are reports of children who were

severely harmed or killed after they were reunified with their parents.

23

Secondly, the parent and the child do not have any opportunity to be heard in a

family court, even when they are against the decision of the child guidance

centre about their reunification.

(f) Forfeiture of parental authority

The Civil Code provides that family courts may, upon the petition of a relative

of the child or a public prosecutor, authorise the forfeiture of parental

authority, if the parent abuses their parental authority or there is gross parental

misconduct (CC, art 834). Forfeiture of parental authority does not mean a

permanent termination of parental authority or complete deprivation of the

legal status as a parent. When the cause of the forfeiture is eliminated, the

family court may, upon the petition of the parent or a relative, revoke the

authorisation of the forfeiture of parental authority (CC, art 836). According

to the Child Welfare Act, the director of a child guidance centre may also file a

petition for the forfeiture of parental authority to a family court (CWA,

art 33-8). The Child Abuse Prevention Act provides that the forfeiture of

parental authority should be appropriately pursued to prevent child abuse or to

protect abused children (CAPA, art 15).

In the context of child protection proceedings, directors of the child guidance

centres may pursue forfeiture of parental authority if a parent severely abuses

or neglects the child and administrative measures are not sufficient to change

the behaviour or attitude of the parent. But in practice, directors of the child

guidance centres rarely pursue forfeiture of parental authority. In 2006, there

were only three petitions from directors of the child guidance centres and two

of them were authorised in the court.

24

There are several reasons for the infrequent use of forfeiture of parental

authority in the Japanese child protection system. First, there is a technical

difficulty in pursuing this measure. The director of the child guidance centre

has to find someone who is willing to become the legal guardian of the child if

there is no one who holds parental authority over the child as the result of the

forfeiture of parental authority. The Civil Code requires that the guardian of a

child must be a private individual, which prevents the director of the child

guidance centre from serving as the legal guardian of the child. Some

23

During the period between January 2007 and March 2008, at least four children died due to

abuse by their parents after they were reunified with their parents. See Social Security Council

of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2009) Report on the Results of the Investigation

of Fatal Child Abuse Cases [Kodomo Gyakutai ni Yoru Shibo Jirei To no Kensho Kekka ni

Tsuite], pp 6–7, available at: www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kodomo/dv37/dl/10.pdf.

24

See Child Abuse Cases in 2006,n8above.

230 The International Survey of Family Law

commentators argue that we should introduce new legal rules to enable the

directors of the child guidance centres to become the legal guardian of the

child when no one holds parental authority for the child.

25

Secondly, there is a structural difficulty in pursuing the forfeiture of parental

authority. The child guidance centre is in charge of providing guidance and

support to the parent for family reunification. Pursuing forfeiture of parental

authority will destroy the relationship with the parent, as forfeiture of parental

authority is regarded as placing strong moral blame on the parent. If the child

guidance centre’s relationship with the parent is destroyed, reunification will be

impossible, since there is no effective measure to encourage the parent to

co-operate with the centre’s services, as discussed above. Therefore, the child

guidance centres recognise forfeiture of parental authority as ‘the last resort’,

26

to be invoked only when they have to deal with parents who are extremely

abusive and uncontrollable without invoking such a strong measure.

(g) Independent living assistance for the child

The laws do not describe when prefectures can, or should, terminate their

efforts to reunify the child with the parent. Therefore, the child in social care

and his or her parent retain a possibility of reunification until the child is too

old for social care.

27

Unless the parent attempts to intervene in the child’s life in

social care in an extremely harmful manner, his or her parental authority

remains intact, because the child guidance centre almost never files a petition

for forfeiture of parental authority when the parents are not harmful to the

child, as discussed above.

Generally speaking, child guidance centres do not attempt to find an adoptive

family for children in social care, even when family reunification is deemed

impossible. Neither the Child Welfare Act nor the Child Abuse Prevention Act

requires child guidance centres to initiate adoption services for the child who

cannot be reunited with his or her parents. It seems that child guidance centres

provide adoption services only when the parents express a wish to place their

child for adoption. Adoption may be legally finalised according to the Civil

Code, which provides the legal requirements and outlines the court proceedings

for adoption.

25

See Japan Federation of Bar Associations, above n 14 at pp 13–14.

26

See Yoshida, above n 15 at p 21.

27

According to the CWA, the national and prefectural governments are responsible for the

welfare of children under the age of 18 (CWA, art 4(1)). Therefore, a child’s maximum age for

social care placement is 18, but prefectures may extend their placement until they turn 20

(CWA, art 31(2)). In practice, however, children may have to leave social care before they turn

18, since child guidance centres may end the social care of the children who finish compulsory

education at the age of 15 (elementary and junior high school education is compulsory in

Japan) without a plan to enter high school or who drop out of high school while in social care.

These children are usually assisted to find a job and leave social care.

231The Japanese Child Protection System

The Child Abuse Prevention Act provides that the national and prefectural

governments are required to provide services not only to protect children from

abuse and neglect but also to support them in becoming independent

individuals (CAPA, art 4(1)). This provision indicates that if the children

cannot be reunified with their parents, the governments are responsible for the

care and support of them until they start living independently. The 2008

revision of the Child Welfare Act expanded the responsibilities of prefectures

to provide independent living assistance for the children who have left social

care (CWA, art 33-6). Unfortunately, however, many practitioners argue that it

is difficult to provide sufficient care and support to prepare the children for

independent living due to lack of resources. They express a concern that many

adolescents may have a difficult time in society after they leave social care.

28

IV ISSUES YET TO BE SOLVED

The Japanese child protection system has been developed through the efforts of

practitioners, researchers and policy makers, mostly since the mid-1980s. The

legal structure for the child protection system has also been developed thanks

to the enactment and the revisions of the related laws mostly since 2000.

However, many issues are still left unsolved. There are some areas where

intensive reform efforts are necessary.

First, we should develop sufficient child welfare service resources to protect all

endangered children, to facilitate safe and nurturing social care for them, and

to provide adequate support for their parents to fix their problems. Lack of

resources is a very serious deficiency of our system. Especially problematic are

the lack of a sufficient number of social workers in the child guidance centres

and their heavy caseloads. According to research, the average caseload of child

guidance centre social workers was 107, which was significantly higher than

their counterparts in other developed countries.

29

This problem has occurred

due to the delay in increasing the number of social workers. Although child

abuse cases increased by more than 30 times during the last 15 years, the

number of social workers to respond to them has not even doubled during the

same period.

30

Without a sufficient number of professional social workers, it is

impossible to protect children in a timely manner or provide adequate guidance

and support for parents, as the laws require them to do.

28

See, eg, Tetsuro Tsuzaki ‘The System to Provide Support for Child Abuse Cases and its

Problems to be Solved [Jido Gyakutai ni Taisuru Enjo no Shikumi to Sono Kadai]’ in Tetsuro

Tsuzaki and Kazuaki Hashimoto (eds) Current Situation of Child Abuse – Toward the

Establishment of a Collaborative System [Jido Gyakutai wa Ima – Renkei Shisutemu no Kochiku

ni Mukete] (Minerva Shobo, Kyoto, 2008) pp 16–26 at pp 24–25.

29

Jun Saimura ‘The Directions the Japanese Child Abuse System Should Proceed Toward

[Korekara Nihon ga Susumu beki Hoko towa]’ in Tetsuro Tsuzaki and Kazuaki Hashimoto

(eds) Current Situation of Child Abuse – Toward the Establishment of a Collaborative System

[Jido Gyakutai wa Ima – Renkei Shisutemu no Kochiku ni Mukete] (Minerva Shobo, Kyoto,

2008) pp 203–217 at pp 205–206.

30

Ibid, p 205.

232 The International Survey of Family Law

Secondly, we should reform the legal provisions on parental authority in order

to better protect the interests of abused and neglected children. Under the Civil

Code currently in effect, parental authority is regarded as the power stemming

from a person’s status as a biological or an adoptive parent to a child rather

than the privilege obtained through his or her role in caring for the child in

accordance with the best interests of the child. Some researchers recommend

that the phrase ‘parental authority’ in the Civil Code should be replaced by

‘parental obligation’ to emphasise that parents have responsibilities as well as

rights to care for and educate their children in accordance with their best

interests.

31

On the basis of the new philosophy of parental rights and

responsibilities, we should re-establish the legal scheme to regulate parental

rights and responsibilities in the specific context of the child protection

proceedings. For example, we should clarify how the parental rights and

responsibilities are restricted or allocated when the child guidance centre

conducts temporary protection of the child or when the child is placed in social

care. In addition, we may have to introduce a new legal framework to suspend

parental rights and responsibilities, either temporarily or partially, to enable

prefectures or child guidance centres to make decisions for the care and

education of a child when the parent’s decisions would be harmful for the child.

The Ministry of Justice has recently begun considerations on these issues as

preparation for the revision of the legal provisions on parental authority. There

is a possibility that the provisions of the Civil Code and other related laws on

parental authority will be revised in the near future.

32

Thirdly, we should expand the jurisdiction of family courts to cover the

important stages in child protection proceedings. The jurisdiction of family

courts over child protection proceedings as provided by the current laws seems

to be too limited to ensure the safety and welfare of children. In expanding the

family court jurisdiction, we will have to overcome many challenges, both

technical and philosophical, since our child welfare system has been operating

without court authority for many years. Before the dramatic increase in child

abuse cases already described, the child welfare system provided services to

parents who understood their problems and asked for guidance and support on

their own; therefore, there was basically no demand for court involvement in

child welfare services. However, the situation surrounding child welfare has

completely changed since child guidance centres started to respond to child

abuse cases. The child guidance centres now deal with more and more parents

who neither admit their problems, nor accept the social workers’ guidance, nor

easily provide consent to the social care placement of their children. Without

31

Suzuki et al, above n 14 at p 6.

32

A study group formed by the Ministry of Justice in June 2009, consisting of leading

researchers and practitioners in the fields of family law and child welfare, issued a report in

January 2010 that discussed the necessity of the reforms of the legal provisions on parental

authority and argued possible directions of such reforms (available at: www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/

minji191-1.pdf, accessed 28 February 2010). Upon the completion of this report, the Minister

of Justice requested the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice to draft an outline of the

revision of the Civil Code’s parental authority provisions. On 5 February 2010, the Legislative

Council decided to form a new subcommittee to conduct preparatory discussion for the

revision.

233The Japanese Child Protection System

well-structured legal proceedings in which the courts conduct hearings and

issue necessary decisions and orders, the child guidance centres face enormous

difficulty both in intervening and in supporting the family. Although it is

arguable how far the jurisdiction of family courts should extend, it could

include post facto authorisation of temporary protection, adjudication of the

fact of child abuse, approval of social care placement, authorisation and

periodical review of service plans, management of parental visitation, decisions

about reunification, suspension and forfeiture of parental authority and

planning for a substitute family when reunification is impossible.

And fourthly, we should consider how we can ensure there is procedural due

process for the parent and the child. Their views and opinions should be heard

and respected in decisions that affect their family relationships. Especially when

a child is separated from his or her parent, the parent and the child shall be

given an opportunity to participate in the proceedings and make their views

known, in accordance with Art 9(2) of the Convention on the Rights of the

Child. Participation in the proceedings would be promoted through the help of

an independent representative. Currently, the child guidance centres are

represented or supported by lawyers more often than not, but the parents and

the children are usually unrepresented. Some practitioners suggest that the

parents should be supported to obtain adequate legal advice and assistance

from a lawyer when they are involved in the child protection system.

33

The

lawyer would help the parents see their situations objectively, make sound

decisions about their options and communicate their views in a legally

appropriate manner. We should also recognise the importance of an

independent representative for the children, as some commentators suggest.

34

The independent representative would help the children understand what the

proceedings mean to them and form their own views and advocate their views

and interests in the proceedings.

V CONCLUSION

The Japanese child protection system has been gradually developed thanks to

enormous practical and legislative efforts over the last few decades. However,

we still have many issues to overcome in order to better serve the interests of

abused and neglected children. Reform efforts should be continued, both in

developing social welfare resources sufficient to meet the needs of the children

and their parents, and in establishing a legal system responsible for making

33

See, eg, Yoshihiko Iwasa ‘Child Abuse Cases from a Lawyer’s Perspective (2) – After the Two

Revisions of the Child Abuse Prevention Act [Bengoshi kara Mita Jido Gyakutai Jiken (2) –

Jido Gyakutai no Boshi To ni Kansuru Horitsu no Nido ni Wataru Kaisei o Hete]’ (2009)

Monthly Bulletin on Family Courts [Katei Saiban Geppo], Vol 61 No 8, pp 1–48 at pp 42–43.

34

See, eg, Ryoko Yamaguchi ‘The American Legal System for Child Abuse and Issues in the

Japanese System [Amerika no Jido Gyakutai Ho Seido to Nihon no Kadai]’ in Tsuneo Yoshida

(ed) Legal System for the Prevention of Child Abuse – Issues and Directions for the Law Revision

[Jido Gyakutai Boshi Ho Seido – Kaisei no Kadai to Hokosei], (Shogakusha, Tokyo, 2003) pp

188–224 at pp 219–220.

234 The International Survey of Family Law

decisions about what should be done for the safety and interests of the children

in each stage of the child protection proceedings.

235The Japanese Child Protection System