REPORT TO THE LEGISLATURE

Innovative Learning Pilot

Program

2022

Authorizing Legislation: RCW 28A.300.810

Rebecca Wallace

Assistant Superintendent of

Secondary Education and Pathway Preparation

Prepared by:

• Liz Quayle, Manager, Mastery-based Learning

• Rhett Nelson, Director, Learning Options

rhett.nelson@k12.wa.us | 360-819-6204

Page | 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 4

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5

Implementing the Pilot Legislation ........................................................................................................................... 5

Participants in the Pilot .................................................................................................................................................. 6

Data Collection ................................................................................................................................................................. 6

Program Interviews ......................................................................................................................................................... 7

Description of the Pilot Programs ............................................................................................................................. 7

Comparison Models ........................................................................................................................................................ 8

CEDARS Reporting and Transcripts .......................................................................................................................... 9

Required Reporting Topics ............................................................................................................................................. 10

Efficiency .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10

Cost .................................................................................................................................................................................... 10

Additional and Targeted Resources .................................................................................................................. 12

Impacts of Different Funding Models .............................................................................................................. 12

Staffing ......................................................................................................................................................................... 15

Impacts of These Programs on Students ............................................................................................................. 17

State Standards & Attendance ........................................................................................................................... 17

Success Rates ............................................................................................................................................................. 18

Internships .................................................................................................................................................................. 18

Equity ............................................................................................................................................................................ 19

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................................. 20

Ongoing Questions ...................................................................................................................................................... 21

Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Benefits ............................................................................................................................................................................. 22

Concerns ........................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Next Steps ........................................................................................................................................................................ 22

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................................... 23

References ............................................................................................................................................................................ 24

Laws and Rules ............................................................................................................................................................... 24

Data Resources .............................................................................................................................................................. 24

Appendices ........................................................................................................................................................................... 25

Appendix A: Innovation Learning Pilot Approvals ............................................................................................ 25

Appendix B: Sample Report Card Data ................................................................................................................. 26

Page | 3

Appendix C: Program Models .................................................................................................................................. 27

Appendix D: Survey to the Pilots ............................................................................................................................ 28

Survey Questions to the Innovative Learning Pilot Programs ................................................................ 28

Responses to the Innovative Learning Pilot Survey June/July 2022 ..................................................... 29

Appendix E: Sample Forms ........................................................................................................................................ 40

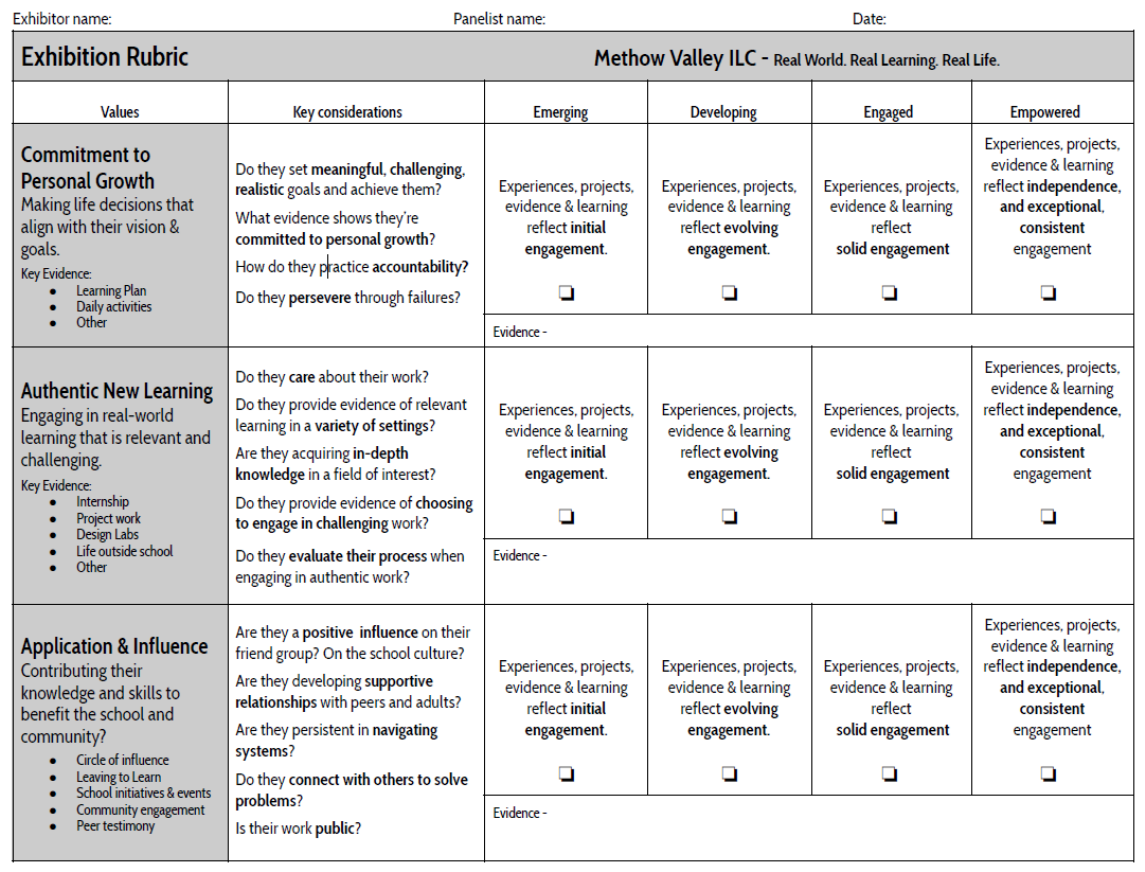

Methow Valley Exhibition Rubric Form ............................................................................................................ 40

Gibson Ek Competency Achievement Chart .................................................................................................. 41

Legal Notice ......................................................................................................................................................................... 42

Page | 4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The 2020 Legislature approved an innovative learning pilot program. This program is intended to

explore options to break away from traditional credits and course requirements and to provide new

and more equitable access to learning options that prepare students for post-high school

pathways. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), in collaboration with the State

Board of Education (SBE), must report to the Legislature regarding the efficiency, cost, and impacts

of the funding model or models used under the pilot program.

The research indicated that costs of the programs had many similarities to traditional education

models. Some costs needs were highlighted, many of which are experienced in other educational

models. These include addressing needs of specific populations such as students who arrive off-

track for graduating, providing smaller class sizes, coordination and management of off-campus

activities, and covering additional costs of running one or more unique programs in a small district.

OSPI reviewed school report card data on state assessments, attendance, and graduation rates.

While performance on these varied between pilots, analysis suggests that these were even with or

improved from programs serving similar populations of students. The pilot also identified

challenges to reporting data points that are used by OSPI to recognize and disaggregate student

performance, growth toward graduation, and the accountability measure of 9th grade on-track.

Long term impact is unknown.

A few risks were identified about reporting and instructional time that is off-campus and

unsupervised by district staff. These risks are similar to those found in Alternative Learning

Experiences (ALE), cooperative worksite learning, and instruction provided under contract. OSPI

believes these can be best addressed through rule making, identifying when these settings would

qualify as a regular classroom, establishing minimum expectations and clarifying responsibilities.

Page | 5

INTRODUCTION

The 2020 Legislature approved a pilot for innovation in learning, which allowed participants to

break away from traditional credits and course requirements, exploring new and more equitable

access to learning options that prepare students for post-high school pathways, including careers,

higher education, and civic engagement. This legislation directed the Office of Superintendent of

Public Instruction (OSPI) to oversee this pilot and report on its efficiency, cost, and impact.

In providing this pilot opportunity, the Legislature, OSPI, and State Board of Education (SBE)

explored innovation in education and funding models to support it. In a digital era where a one-

size-fits-all model no longer applies to students’ career paths, this model encourages career

exploration, draws on students’ interests and goals, and provides skills in the work and college

environment that will best serve our future citizens.

Seven schools are actively participating in the pilot. In addition to reviews of existing data,

members of the OSPI Learning Options department and mastery-based learning staff from SBE met

regularly with members of the Innovative Learning Pilot programs through the 2021–22 school

year. This allowed for learning about their practices, with a focus on evaluating efficiency, cost, and

impact.

The programs all practice a similar model of instruction that includes classroom instruction plus

off-campus learning experiences described as job shadowing and internships. A key element of this

is student-led development of learning plans focusing on interests, internships, project-based

learning, critical thinking, and post high school goals. Teachers work with the students’ plans to

meet competencies and state standards, providing personalized onsite learning using various

instructional methods. According to reports from the pilots, the students are more engaged in their

learning.

Implementing the Pilot Legislation

Beginning in the 2020–2021 school year, schools who had received a waiver of the credit-based

graduation requirements from the SBE, were encouraged to apply for the innovative learning pilot

program as described in Revised Code of Washington (RCW) 28A.300.810 and Senate Bill (SB) 6521

(2020).

The state defined “mastery-based learning” in House Bill (HB) 1599 (2019) as an educational

program where:

• Students advance upon demonstrated mastery of content

• Competencies include explicit, measurable, transferable learning objectives that empower

students

• Assessments are meaningful and a positive learning experience for students

• Students receive rapid, differentiated support based on their individual learning needs

Page | 6

• Learning outcomes focus on competencies that include application and creation of

knowledge along with the development of important skills and outlooks

In order to participate, the school district must have applied for and received a waiver (Washington

Administrative Code (WAC) 180-18-055) from the credit unit graduation requirements as granted

by SBE for the 2019–20 school year. The purpose of the waiver is to implement a local restructuring

plan to enhance the educational program for high school students by waiving one or more of the

requirements of WAC Chapter 180-51. Eligible programs applied and completed the attestation

and participation for the innovative learning pilot program, and seven that used mastery-based

learning models as defined above were approved.

OSPI, together with SBE staff, collaborated to meet with these programs regularly throughout

2021–22 for the purpose of evaluating practices, activities, policies; to develop and adopt rules for

the effective and efficient implementation of these programs; and to clarify reporting practices for

full-time equivalent students in an approved mastery-based learning programs for general

apportionment funding.

As authorized by the Legislature in HB 1599 and SB 5429, Washington had a Mastery-based

Learning Work Group, staffed by the SBE, from 2019–2021. Additional background information

about mastery-based learning can be found on the Mastery-based Learning Work Group webpage,

particularly the 2020 and 2021 Reports.

Participants in the Pilot

Approved pilots participated in monthly information-finding meetings with OSPI and SBE staff

throughout the 2021–22 school year. A detailed list of the participating pilots is available in

Appendix A.

These pilots are:

• Swiftwater Learning Center, Cle Elum-Roslyn School District

• Highline Big Picture School, Highline School District

• Gibson Ek High School, Issaquah School District

• Chelan School of Innovation, Lake Chelan School District

• Independent Learning Center, Methow Valley School District

• Quincy Innovation Academy, Quincy School District

• Selah Academy Big Picture Learning, Selah School District

Data Collection

For this report, OSPI used data from the Comprehensive Education Data and Research System

(CEDARS) related to student enrollment and school report card data for progress/accountability

Page | 7

metrics the state collects for all schools. In addition to these, OSPI conducted regular interviews

with the pilot leadership.

Program Interviews

From April 2021 through June 2022, representatives from OSPI and SBE met with representatives

from the innovative learning programs selected to participate in this pilot. Representatives from

five of the programs completed a survey (see the survey) in June 2022.

The purpose of these meetings was to learn more from the pilot sites about their programs and

how the basic education was provided, identify challenges or conflicts in meeting state education

and reporting regulations, and provide information relevant to the report of the pilot.

Monthly attendance at the meetings was not required, although most participated each month.

Topics addressed at these meetings included:

• Learning plan and standards

• Project-based learning

• Objective measures

• Special populations

• Internship

• Career and Technical Education (CTE) & dual credit options

• Graduation pathways

• Transfers & transcripts

• Staffing

• Successes & challenges

• Recommendations

Description of the Pilot Programs

The schools that participated in the pilot all utilized a specific and proprietary model called Big

Picture Learning. Big Picture Learning is one of several mastery-based educational models that

have applied for and have received a credit waiver from SBE.

Pilots use an interest-driven learning model, which includes a mix of classroom instruction, project-

based learning, and other strategies guided by the teacher and individual learning plan. These are

connected to and supported by job shadow and internship experiences. The learning from these

experiences is related back to the classroom learning and is shared with peers in the learning

environment.

Page | 8

Competencies focus on blending state learning standards in core subjects with real-life application.

Teachers and students work together to create a learning plan that includes expectations toward

content mastery, personal qualities toward self-directed learning, and application to career goals.

For students who require differentiated supports in the area of special education, programs

incorporate the application of specific learning goals from the student’s special education

Individualized Education Plan (IEP) to the student’s overall educational plan. For students who need

more direct instruction, this is provided either by program special education teachers or staff or

through the local comprehensive school.

There are some similarities between these pilot Big Picture competencies and the skills established

in the Profile of a Graduate recommendations created by the Mastery-based Learning Work Group.

These competencies are key skills identified primarily by Big Picture schools to recognize that the

student is prepared to graduate and be successful in their next stages of college, career, and life.

The work of the state Mastery-based Learning Work Group’s Profile of a Graduate is reflected in

the Five Learning Goals, or Competencies, in the pilots’ learning plans.

Figure 1: Comparison of Pilot Competencies and the skills of the Profile of a Graduate

Big Picture Five Learning Goals /

Competencies

Washington State Profile of a Graduate

Personal Qualities

Master Life Skills/Self-agency; Sustains Wellness

Quantitative Reasoning

Cultivates Personal Growth & Knowledge

Social Reasoning

Embraces Differences/Diversity

Communication

Communicates Effectively

Empirical Reasoning

Solves Problems

Source: SBE Profile of a Graduate

What is unique about the design of participating schools:

1. Most schools do not track student progress through individual credits.

2. Student progress is based on students meeting competencies, identified by the school, which

together are equivalent to the 24-credit framework per the SBE waiver.

3. Student schedule is not primarily based on individual courses.

4. Regular significant off-campus learning takes place through internships, job shadow, and other

career exploration-related activities.

Comparison Models

Pilots operate on a model that blends full-day classroom time with off-site internships or job

shadow opportunities. Much of the learning takes place through onsite project-based or place-

Page | 9

based learning, which is integrated with an internship experience taking place offsite half of a day

to two days per week. This is different from the general in-person model, which requires daily full-

day onsite attendance; a more structured Career and Technical Education (CTE) worksite learning

(WSL) model where worksite learning occurs at a qualified worksite outside the classroom in

fulfillment of a student’s career and educational plan, while applying skills and knowledge obtained

in a qualifying class; or from Alternative Learning Experiences (ALEs), where some or all of the

learning take place away from campus. Find a chart of comparison models in Appendix C.

Unlike ALEs regulated by WAC 392-550, the student learning plans used in the pilots are student-

developed, teacher-reviewed for meeting state requirements, and are project-based, not course-

based. ALEs require written student learning plans (WSLPs) that are developed by the certificated

teacher, are course- and credit-based (for high school), and identified as either site-based, remote

(offsite, but not online), or online.

Unlike CTE WSL, internships in the pilots are generally not arranged by a CTE-endorsed teacher

certificated in WSL; they are not monitored using the same process; and the student is generally

not paid.

CEDARS Reporting and Transcripts

All courses must be entered into the district student information system to report to the CEDARS

system. In an in-person school, student schedules are developed per content-based course and

assigned to teachers with corresponding endorsements. These courses are graded and linked to a

transcript.

For project-based learning in the pilots, a single project may represent several content areas and

may be facilitated by multiple teachers. The pilots use a narrative-based transcript with a

translation document that explains how credits may be transferred to an in-person school.

The difference between this model and a traditional individual course model makes CEDARS course

reporting more challenging for these pilots, with many reporting few courses or using vague titles

such as “advisory.” As a result, OSPI could not effectively compare student course participation,

credit attempt/attainment, or grades as indicators of student progress. If these models continue to

expand, there would be value in identifying and establishing how to best capture student

performance and progress in such programs.

Page | 10

REQUIRED REPORTING TOPICS

According to SB 6621(2020) (5), by December 1, 2022, OSPI, in collaboration with SBE, must report

to the legislature regarding the efficiency, cost, and impacts of the funding model or models used

under the pilot program.

Efficiency

Students in the pilots focus on their interests while teachers work with them to build a learning

plan that meets the student’s individual needs, setting clear goals to achieve all areas of the

competencies. This is measured through a combination of results, including increased graduation

rates, post-high school career application, minimal staffing and curriculum expense, and systems

that are well-organized and competent.

This allows the student to build their academic strengths without the distraction of other students,

while giving them space to develop knowledge and skills for collaboration on joint projects. This

also provides students with the opportunity to access instruction when they need it, and to either

move more quickly or more slowly as best fits their learning mode.

For teachers, they are able to focus their attention on students when the individual student or small

group needs it, providing the right resources at the right time, limiting the additional time often

spent in other schools on classroom management.

Cost

School districts are funded primarily through reported student full-time-equivalent (FTE). This

funding is designed to support adequate staffing for the number of students, as well as materials,

supplies, and operatic costs (MSOC). While these rates are designed with student to staff ratios in

mind, schools are funded at the district level, not the school level. The district makes decisions to

direct these funds to schools and programs how they believe will best meet their goals and

priorities. As a result, actual staffing and how these funds are used varies both from district to

district and school to school. While this flexibility is useful for school districts, it also makes it

challenging to make any definitive comparisons on costs. This project was able to identify some

specific costs the pilots highlighted.

Based on the pilot conversations, some specific costs that were recognized as impacts to these

programs that were identified include:

• Small class sizes: The districts prioritized small class sizes in many of these settings. This comes

at a cost and may have pulled funding from other activities, services, materials, or staffing.

Several pilots identified district prioritizing these small class sizes for their program. Values they

found in small class sizes include:

o Improved ability to develop relationships between the teacher and the students.

o Addressing individualized learning needs for students who are often not working with

common curriculum.

Page | 11

• Student populations:

o Almost all programs’ enrollments reflected higher percentages of students with

disabilities. While the presence of a disability does not always indicate a specific

higher cost, it often involves recognizing an increased need, and therefore cost, for

accommodations and services.

o Many of the pilots reported serving high percentages of students who struggled in

more regular settings. These programs had some unique costs and time allocations

addressing the causes of these struggles, and the impacts these struggles have had.

For example, Selah Big Picture identified a need to reengage students and develop

executive skills. To address these needs, they devoted additional resources to social

and emotional learning that were not as intentional or targeted in the other schools.

o There is no requirement that a district allocate their resources to increase services

for students who are struggling or off-track for graduation.

• Coordination of the off-campus internship and job shadowing: With all students

participating in these off-campus activities, staff time was required to maintain relationships

with these outside organizations, develop and coordinate agreements, visit locations, and

ongoing communications. Most pilots described these activities as the responsibility of the

teacher. Teachers often maintained these during the time when students were scheduled at

these off-site locations and the teacher had fewer or no students in the classroom. One pilot

had designated staffing to help support coordination activities.

• Small program costs: All the pilots were an option in their district, meaning that the districts

were all running traditional high school programs in addition to the pilot. While larger districts

had enough students to provide these options without impact, smaller districts often did not.

There were impacts to having similar qualified and endorsed staff spread between both

settings, which limited varieties of academic offerings. Additional resources may benefit these

smaller districts and programs.

• Transportation: The pilots addressed transportation differently, often depending on when the

student would participate in their internships. Programs in which students participated in an all-

day internship would expect the student to get to the location independently. Some students

may have access to public transportation either locally or through school provided bus passes,

while some programs reported that they provided staff drivers in school vehicles to transport

the students to the internship location.

These identified costs are not exclusive to the pilots. As mentioned above, school districts have a

lot of flexibility in how they locally allocate state apportionment. This ideally allows them to better

meet the unique needs of their community and provide targeted resources and supports as they

choose. There are no mandated priorities, and while this does allow these local decisions, there is

also no requirement they use equity as a lens in their decision-making.

Page | 12

The pilot legislation allowed all programs to be funded at the prototypical school funding rate for

the duration of the pilot, meaning that the state is paying the same per-student FTE as they would

for a student in the traditional in-person school. The pilot project found this was appropriate and

allowed them to maintain adequate staff to support the students in all their learning settings. OSPI

did not recognize any efficiencies that would reduce the amount of staffing or MSOC needed to

serve students while maintaining the level of connection and oversite with the off-campus facility

and mentor. In order to continue this level of funding following the pilot, OSPI recommends the

creation of some additional regulations to maintain high expectations and reduce risk when the

school is treating these off-campus activities as regular instructional time.

Districts receive additional funding for providing services for student with disabilities as defined in

the student Individualized Education Program (IEP). These additional funds are allocated per

student, based the district’s basic education allocation rate times a multiplier of 1.0075 for students

with disabilities who participate in a basic education classroom at least 80% of the time and a

multiplier of 0.9950 for all other students with disabilities. These formula funds are capped at 13.5%

of a district’s basic education population. Additional Special Education safety net funding is

provided to districts that can demonstrate financial need due to high-cost individual students.

Additional and Targeted Resources

Schools and teachers often seek additional resources to support their priorities and projects. Pilots

reported accessing additional revenue sources including applying for and using Elementary and

Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) grants, and Learning Assistance Program (LAP)

funding, while one pilot reported using an ALE model to support lower teacher-student ratios. Two

pilots reported a district commitment to supporting the model and its lower teacher-student ratio.

Impacts of Different Funding Models

These are the primary questions OSPI wanted to answer regarding funding for the significant hours

these students are involved in off-campus internships:

1. Do these hours meet the definition of instructional time?

Based on the definition of instructional hours in RCW 28A.150.205, these off-campus instructional

hours appear to align with the concept that these are “hours students are provided the opportunity

to engage in educational activity planned by and under the direction of school district staff”

2. If these are instructional hours, what funding model do these align to?

State regulations provide different funding models instructional hours based on different criteria

and accountability requirements. The primary ones investigated for these pilots were the in-person

seat-time model (prototypical), ALE, and cooperative work-site learning.

Prototypical In-Person Seat Time Model

Prototypical funding recognizes students’ on-campus instructional time through the school

calendar, student schedule, and regular attendance. For pilots, a majority of the instructional time is

on-campus, classroom- and attendance-based, and aligned to the expectation of a traditionally-

funded setting. However, for pilots, a significant and regular amount of instructional time (between

Page | 13

10%-40% of the weekly time) was scheduled off-campus attending internship and job shadowing

activities, which may not meet the expectations of the in-person model and creates confusion with

other off-campus funding models.

• Benefits of this funding model:

o The funding model is consistent with the traditional education, so there is no financial

difference, additional regulations, or stigma.

• Barriers of this funding model:

o Differing funding and regulations from other offsite learning models

o Inconsistent or possibly inadequate regulations to ensure accountability to student

safety and appropriate settings for students in their offsite learning activity.

o Inconsistent or possibly inadequate regulations to ensure that this off-campus

instruction time is connected to the expectations of K-12 learning standards.

• To make this funding model work:

o Establish criteria to recognize these instructional hours as in-person settings similar to a

regular classroom.

o Set consistent accountability parameters to ensure the safety and appropriateness of

the settings for students, and the connection to K-12 instruction and student learning.

Alternative Learning Experience (ALE) Courses

The ALE funding model applies when some or the instruction for a course is independent of the

regular classroom. This is the primary funding model for students learning off-campus, not directly

supervised by school staff. ALE is funded at a fixed rate, calculated based on the estimated

statewide annual average allocation per full-time equivalent student in grade 9 through grade 12 in

general education. This is the same formula that creates the Running Start Rate. Depending on the

district, this may be higher or lower than the prototypical funding rate.

Of the nine district programs that qualified for the pilot, the three largest district programs would

receive an average reduction of $533 per full time equivalent (FTE) funding by moving to an ALE

rate, and the six smaller programs would receive an average of $549 in increased funding per FTE.

• Benefits of this funding model:

o Establishes consistent accountability to instruction, planning, and evaluation of student

learning when students are offsite and not directly supervised by their teacher.

• Barriers to this funding model:

o ALE is a course-level funding model, and these internships are not independent courses,

nor do they neatly fit into an individual course.

Page | 14

o Programs believe these regulations do not align with or adequately support their model,

as the pilots’ structure includes onsite time and an internship offsite activity that does

not correspond with either ALE or CTE course requirements.

o Anecdotal information that the different funding amount creates a stigma or financial

incentive of one model over another rather than a student-centered decision.

• To make this funding model work:

o To address the issue related to a “course,” there could be a new ALE course type

developed and established in RCW to recognize these unique settings.

o OSPI does not recommend this as a funding model for these settings at this time.

▪ This would not address the funding difference and that could incentivize some

districts to increase or decrease the amount of time devoted to these internships

based on financial decisions.

▪ Modifying the ALE funding model in legislation would create significant impacts

to existing ALE apportionment.

▪ This also would not be able to address the perceived stigma, nor the

documentation of ALE accountability requirements. This is an ongoing challenge

that OSPI continues to investigate.

Work-based Learning (WBL) and Worksite Learning (WSL)

Courses receive vocational funding per course, based on student enrollment. Cooperative worksite

learning which most resembles this model is funded at half the rate of prototypical funding with

two hours of worksite learning recognized as one hour of instructional time. A state auditor’s office

audit highlighted that this appears to be most closely aligned with the internship component of

these schools. However, based on interviews with these programs, the programs believe these

experiences from these internships are more integrated into the instructional program than a

traditional cooperative worksite learning experience.

• Benefits of this funding model:

o CTE cooperative worksite requirements ensure that CTE and Labor and Industries

standards are met when students are on a worksite. These practices help to ensure

accountability to a safe and appropriate setting for students.

• Barriers of this funding model:

o The purpose of these settings is described differently than the purpose of cooperative

worksite learning.

o The CTE regulations particularly connecting the student to a qualifying CTE course of

study, and a certificated CTE teacher create barriers to qualifying as cooperative

worksite learning.

Page | 15

o The funding for cooperative worksite learning does not recognize that the teachers do

not have a reduced workload.

o Requirements include an endorsed CTE teacher with specific worksite learning

credentials, 360 logged hours per 180-hour course, background checks, contract

approvals, and pre-WSL preparatory courses.

• To make this funding model work:

o OSPI does not recommend this as a funding model for these programs.

▪ Without meeting the criteria of CTE, these programs would be unable to comply

with the funding model. These pilots acknowledge that these are not work

environments and provide more academic support and connection than is

expected in a WSL setting.

▪ Additionally, the funding for WSL would significantly impact these programs’

ability to provide the staffing and support to students and ensure that these

internships are recognized as academic learning settings.

Staffing

Pilots have specific and varied requirements for their instructional staff. Due to the nature of the

model, pilots have stated that they seek teachers who are more flexible in instructional methods

and have multiple endorsements. Pilots work to keep all teacher-student ratios low to best meet

the needs of individual students. With a higher-than-average enrollment of students with

disabilities, teachers with special education endorsements are needed. In one program, the special

education teacher is shared with the local school’s kindergarten and all the district’s alternative

programs; in another program, the Special Education director oversees the IEPs and 504 plans.

Counselors and Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)/mental health specialists are also often shared with

other campuses.

• Qualifications of “Advisors” and their responsibilities:

o “Advisor” is the term these programs use for their certificated teachers and internship

supervisors. Advisors are often endorsed in multiple subject areas or paired with another

teacher with complementary endorsements. Advisors work with the student to develop their

learning plan and verify that state standards are being met.

• Teacher qualifications:

o According to the Education and Research Data Center (ERDC) reporting for the 2019–20

school year, teachers in the pilots have a minimum average of 10 years’ experience, with

some programs averaging 20 years’ experience.

o In seeking teachers for these programs, the pilots identified qualifications that best meet

the culture of their programs.

Page | 16

▪ They often recruit teachers from alternative programs who are able to develop

relationship with students and think creatively with the students in developing their

learning goals.

▪ According to one administrator, when hiring, “It’s more about mind-set – growth &

open, renaissance people. They want them to be adult learners, vulnerable, people

who understand childhood adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and are trauma

informed. Teachers must be calm, and able to work with kids when they’re riled up.

They provide lots of SEL support.”

▪ Another program director added, “Teachers must have the ability to have authentic

relationships with students, really listen to the students’ interests, life experiences,

and provide high expectations.”

• Challenges:

o Sufficient program funding to hire needed staff for all student services, including internship

coordination, enrollment reporting, and instruction.

o Piecing together part-time staff to meet endorsement expectations and still provide a

consistent and solid program

o Some programs have as few as one or two teachers who must cover all subject areas.

o Lack of access to counseling and mental health staff

o Certification wish list for programs lacking certain endorsements among their teachers:

▪ CTE endorsements – especially for worksite learning

▪ Math-endorsed teachers

▪ Teachers with multiple endorsements for providing project-based learning when

paired teaching is not available

▪ Special education endorsements

▪ Additional endorsement options that recognize the model of instruction rather than

limited to content area expertise.

• Teacher-student ratios:

o Pilots reported a range of 12 to 18 students per certificated teacher, with one smaller

program reporting up to 33 students per certificated staff member. School report card data

showed that while most of these pilots showed smaller class sizes than other high schools

in their district, these numbers reflect a similar variance to other schools in the state.

o Programs with lower ratios may also include staff with specialized certifications, including

principals, part-time counselors, specialists, and teachers providing special education

services.

Page | 17

• Special education staffing:

o Each of the programs interviewed stated that the special education teacher or director

overseeing the student IEPs and 504 plans is shared with other district schools or programs.

• Funding to implement lower ratios:

o Programs reported using grants, and other funding sources to support lower teacher-

student ratios, including districts that choose to allocate additional resources to these

programs.

• Internship coordinators:

o One pilot reported that a support staff member arranges internships, then passes the

follow-up to the certificated teacher-advisor. In all other pilots, the certificated teacher

provides the additional time and effort in arranging for and following up with the

employer/mentor for the internship in addition to their on-campus instructional

responsibilities.

o Multiple programs reported having good connections in the community, an application and

interview process for prospective mentors, and regular communication with the mentor or

jobsite.

Impacts of These Programs on Students

The pilots are choice programs where students and families self-select to enroll. For this report,

OSPI examined the impacts of these programs on school accountability measures— including

attendance rates, graduation rates, and state test scores—compared with the prototypical school.

In addition, the pilots report increased student engagement in learning, acquisition of life and

career skills, and improved connections between content knowledge and real-world applications.

State Standards & Attendance

SBE has approved the credit waiver for these schools. The waiver requires assurance that these

schools are addressing the expectations of the state graduation requirements and college

admission requirements through these models.

In addition, districts are required to report annually on a set of indicators designed to demonstrate

that the students are meeting the purpose of the diploma to be ready for success in postsecondary

education, gainful employment, and citizenship, and are equipped with the skills to be a lifelong

learner. The focus on competencies allows for a personalized path toward each goal, incorporating

various content standards in the process, and flexibility in time to complete instruction. By

developing higher level competencies (which may encompass multiple standards) based on the

existing state learning standards and implementing this model broadly, the state can continue to

support interdisciplinary opportunities that improve student engagement and success and connect

students to post-high school careers.

Page | 18

Students in these programs participate in on-campus learning including project-based learning and

specific instruction for content areas. As part of students’ instructional hour schedules, they also

participate in regular and significant offsite learning through coordinated internships and other

similar activities. These offsite settings are coordinated by the district, are part of the student’s

schedule, and attendance is tracked and supervised by an assigned “mentor” at the site.

Success Rates

Where data was obtained, student performance was as good or better than average for the

populations these pilots were serving but this difference varied based on the specific population

being served.

The increased success rate of students who participate in these programs, compared to

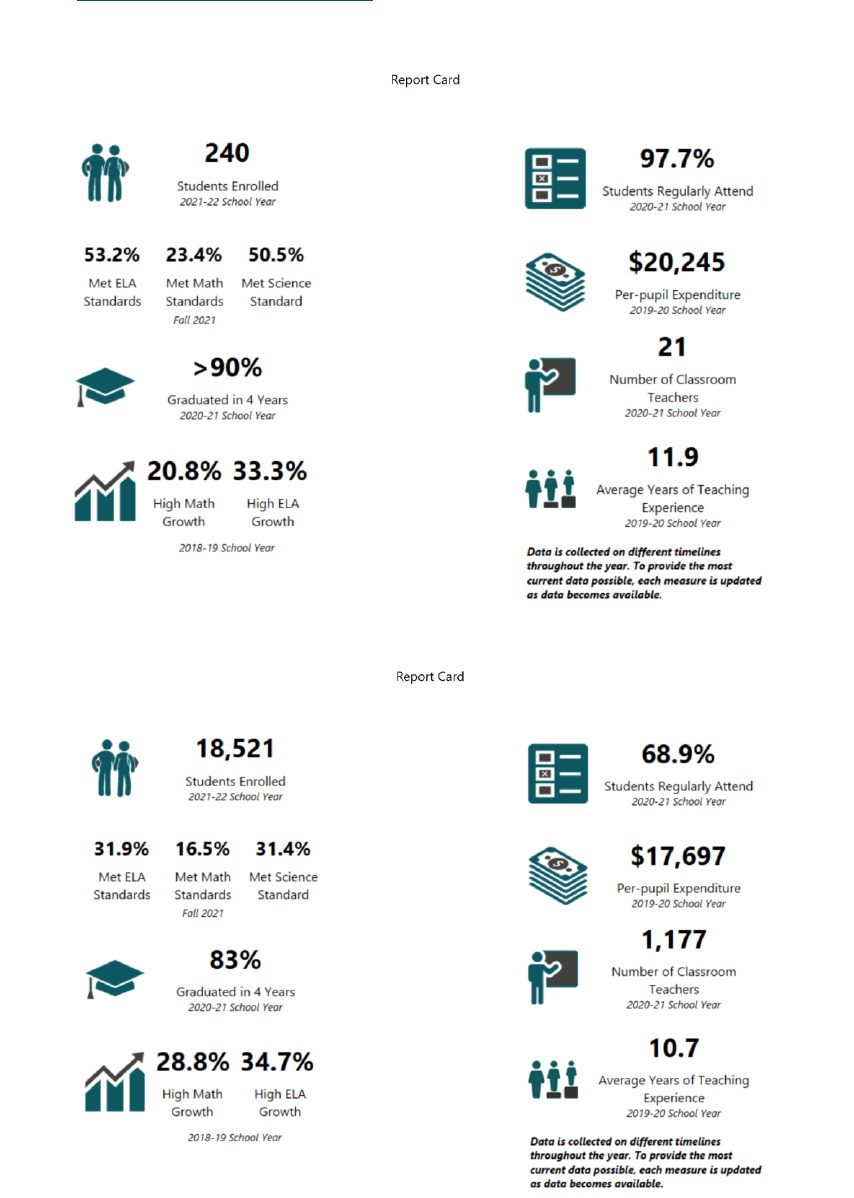

neighboring prototypical schools, is demonstrated in Appendix B through the Washington State

Report Card for selected schools in Highline School District. This sample data, unavailable for the

smaller programs due to size, show that students in the Highline Big Picture School had 97.7%

attendance, compared to 68.9% district-wide; more than 90% graduated in 4 years, compared to

83% as the district average; and state testing scores were 7–21% higher than the district averages.

According to the Washington State Report Card for 2021–22, an average of 17.63% of the pilots’

student population have IEPs, compared to an average of 13.16% for their districts. The state

average for students with disabilities is 14.5%. The pilots reported greater student engagement and

student-led goal setting than in prototypical models, resulting in a higher graduation rate for this

population. Due to low enrollment figures, only one district showed this data on the state report

card. For 2020–21, Gibson Ek High School showed a graduation rate for students with disabilities at

76.9% with 15.4% continuing, compared to a state average of 63.9% graduating and 21.5%

continuing.

Due to the nature of being a non-credit program, 9th grade on-track data is not available.

According to the pilots, High School and Beyond Plans (HSBPs) showed a connection to post-high

school plans that include work-related goals stemming from the students’ internships.

Programs described how students enrolled in pilots have a greater voice in their learning and focus

on real-world application through the student-led learning plan. Each student works with their

advising teacher to develop a learning plan designed to address the required competencies, state

standards, potential internships, and their personal goals.

Internships

By participating in internships, programs described how students are able to gain skills and

characteristics that will apply after graduation, including practical work skills and communication

skills with adults. Students are able to see and experience a variety of work settings and are able to

make connections between content knowledge and real-world opportunities. Through this process,

students are able to make decisions for continued self-directed learning and long-term goals.

For students who are not able to continue throughout high school in one pilot program, there may

be a challenge in translating and transferring their experiences to a credit-based transcript. Pilots

Page | 19

shared their documentation practices and “crosswalks” to translate and recommend credits to the

incoming school, per WAC 180-18-055.

Equity

The pilots have reported an enrollment diversity of race and poverty levels that reflects the rest of

their district, according to their district enrollment demographics. One of the districts that is seeing

greater enrollment among student from higher income families noted this disproportionality and is

looking at strategies to achieve a more equitable enrollment, consistent with the district

populations.

One exception is in the area of special education, where many of the pilots report a higher

percentage of students requiring IEP and 504-plan services. Of the seven active pilots in the

interviews, the Washington State Report Card shows an average of 6.6% higher enrollment of

students with disabilities and 11.5% higher enrollment of students with 504 plans (not including the

one district that did not report 504 plan enrollment) than their district averages.

Pilots report minimal support for students who need mental health and/or SEL. Additional

counselors are not available, and space size and/or pandemic requirements limits large group

social activities. These limitations and barriers are often reported by staff in other choice programs,

such as ALE, as well.

Page | 20

RECOMMENDATIONS

To continue providing and supporting these and other related innovative programs, this report

recommends the following:

• Reporting Student Performance and Progress: Identify and establish how to best capture

student performance and progress in these new models. This may include updates to

CEDARS reporting options, reporting guidance, or other strategies determined by OSPI.

• Teacher Qualifications: The Professional Educator Standards Board is exploring additional

endorsements or structures that recognize teacher expertise in additional instructional

contexts such as teaching through project-based learning, blended content learning, and

supervision of offsite internship experiences.

• Supervision in Assigned Off-Campus Settings: Determine responsibilities and processes

for supervision by the school and teacher when a student is at an off-campus instructional

setting. Define or standardize what must be in place for the school to address risks and

remain accountable to the student learning and student safety.

• Funding Model: Recognize and fund these off-campus instruction components as in-

person prototypical instructional time. This will be supported by OSPI developing rules,

similar to WAC 392-121-188, articulating the expectations and responsibilities of the school

district and the organization where the student is placed. OSPI and the State Auditor’s

Office identified these models as including instruction outside of the regular classroom, and

possibly not eligible for state apportionment without compliance to ALE regulations or

Cooperative Worksite Learning regulations. Through this pilot, OSPI staff recognizes that

these activities meet the definition of instructional hours, but do not quite fit into either

category of ALE or worksite learning.

• Regulations: In addition to many of the existing contracted instruction regulations, which

focus on the compliance to state and federal education laws, OSPI recommends regulations

to mitigate some risks that were identified in the pilot These regulations will need to be in

place by August 2023 in preparation for the 2023–24 school year. This includes:

o Clarify how these settings meet the definition for a regular classroom and are not an

ALE or worksite learning setting.

o Establish minimum criteria of the agreement between the district and the

organization.

o Clarify district and organization responsibility for a safe and appropriate

instructional setting.

o Clarify the responsibilities of the assigned certificated teacher when the instructional

activities are provided by a contractor and not directly supervised by the teacher.

This would support the supervision section above.

Page | 21

• Career and Technical Education Enhancement: The pilots clearly stated that these jobsite

activities are exploration and learning settings, not work settings. This instructional time

would not be eligible for the Career and Technical Education enhancement allowed in

worksite learning unless it also complies the requirements of worksite learning. The

apportionment would also be limited to the parameters of worksite learning and the

district’s CTE program approval.

• Transportation: No revision to existing transportation to funding regulations is

recommended. Transportation time would not be included as instructional time. This aligns

with existing regulations in Running Start and traditional learning settings.

Ongoing Questions

• Inconsistent data: Pilots were able to identify data for student achievement and equity.

There were challenges to reporting information into CEDARS, as this system is based upon

credit reporting for individual subjects. Course level data provides the state information on

which subjects students are receiving instruction in, who is responsible for the instruction

(and their qualifications), and course outcomes. This data gap reduces the ability for OSPI

and other data users to see relevant information about the school and students. There is a

need to identify and establish how to best capture student performance and progress in

these new models. This may include updates to CEDARS reporting options, reporting

guidance, or other strategies determined by OSPI.

• No consistent guidance on teacher or school responsibilities for offsite activities: The pilots

were clear about teacher and district responsibilities for student safety and learning content

connections for the internships. There is a need for consistent guidance or regulation to

reduce risk for school districts and their students, as is in place for other offsite learning in

ALE and worksite learning.

• No limit to offsite activities: There is no state limit on the amount of instructional time

devoted to internships. Pilots reported that students were spending 5-40% of their school

week in these internship settings. As mentioned earlier in this report, internships are not

traditional teacher-led instructional settings, although the activities do align to state

learning standards and school competencies. The time in these settings may have a direct

impact on the student’s academic choices, and ability to complete academic goals or

coursework.

• Need for a long-term funding solution: Participation in the pilot allowed districts to claim

full apportionment even when they did not align with the expectations of the in-person

seat-time model. Without adjustments to apportionment regulations, these programs will

continue to find themselves at a financial disadvantage or at risk for audit findings.

Page | 22

CONCLUSIONS

Benefits

The innovative learning pilot programs have shown through multiple student examples—through

data and anecdotal stories—that they meet the needs of their students, providing engagement and

opportunities to explore content area, careers, and interests through learning and field experiences.

Teachers and staff who are drawn to these programs often have industry or field experience,

multiple years of teaching, and/or experience in various types of alternative programs. They are

focused on student-led learning and can provide resources to connect multiple content areas.

As a leading example, pilots may influence local prototypical schools to expand work-based

learning opportunities and create more mastery-based and project-based learning opportunities

for groups of students that incorporate multiple content areas, critical thinking, and student-led

learning.

Concerns

This pilot began in response to funding concerns raised by these programs because they did not fit

into the existing structures and models, including the prototypical school, alternative learning

experience, or career-technical education. Due to comparatively low student enrollment numbers

and lack of comparative data due to COVID-19 disruptions, there is an inability to fully see what the

students are doing, and how they are progressing, as shown in CEDARS, and equity implications

associated with existing reporting systems.

There were also concerns about consistency in student learning regarding the equivalency of the

diploma of a student in one of these programs versus that of a student who went through a more

traditional course and credit-based program. While some of the pilots have been able to clearly

translate their competencies to credits, much of the student learning activities do not make clear or

consistent connections with graduation credits or content area standards across all programs. This

is especially the case where content requirements are split over the student’s years of enrollment

through themes and are not split out into sequential year-defined credits. Each program has its

approach to tracking and documenting how students meet the learning standards and

requirements.

Next Steps

Through interviews, surveys, and onsite visits, this work was meant to accomplish several goals,

including a review of areas that may not meet state expectations or have increased barriers in the

areas of data; consistency vs prototypical or ALE model programs; teacher qualifications; funding;

accountability for state standards; and student safety.

While pilots were already actively considering the primary noted areas, there would be a benefit for

OSPI and SBE to collaborate in developing state level guidance and accountability systems to

better address the unique needs of these programs as determined through this pilot.

Page | 23

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

State Board of Education:

• Alissa Muller, Director of the Mastery-based Learning Collaborative

• Seema Bahl, Senior Policy Analyst

• Randy Spaulding, Executive Director

Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction:

• Rhett Nelson, Director, Learning Options

• Liz Quayle, Mastery-based Learning Program Manager

• Samantha L. Sanders, Director, Career & Technical Education

• Kim Reykdal, Director, Graduation and Pathway Preparation

• Cindi Rockholt, Assistant Superintendent, Educator Growth & Development

Innovative Learning Pilot Program Representatives:

• Sarah Houseberg, Director, Swiftwater Learning Center, Cle Elum-Roslyn SD

• Jeff Petty, Principal, Highline Big Picture School, Highline SD

• Julia Bamba, Principal, Gibson Ek High School, Issaquah SD

• Erik Peterson, Director, Chelan School of Innovation, Lake Chelan SD

• Sara Mounsey, Principal, Independent Learning Center, Methow Valley SD

• Kathleen Brown, Principal, Quincy Innovation Academy, Quincy SD

• Joe Coscarat, Principal, Selah Academy Big Picture Learning, Selah SD

Page | 24

REFERENCES

Laws and Rules

• INNOVATIVE LEARNING PILOT PROGRAM

EFFECTIVE DATE: April 3, 2020

• Senate Bill 6521

• Chapter 353, Laws of 2020

• 66th Legislature

• 2020 Regular Session

• RCW 28A.300.810 Innovative Learning Pilot Program

• WAC 180-18-055 Alternative high school graduation requirements.

• WAC 180-51-051 Procedure for granting students mastery-based credit.

• WAC 392-121-182 Alternative learning experience requirements [for state funding].

Data Resources

• Washington State Report Card

• Education Research & Data Center (ERDC)

• High school graduate outcomes

• Innovative Learning Pilot Programs: interviews and survey

Page | 25

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Innovation Learning Pilot Approvals

Fourteen programs were approved for the Innovative Learning Pilot Program. Of these 14, seven

chose to participate actively in the monthly information-finding meetings with OSPI and SBE staff.

Active participation in these meetings was optional. Surveys were sent to the participants of these

meetings.

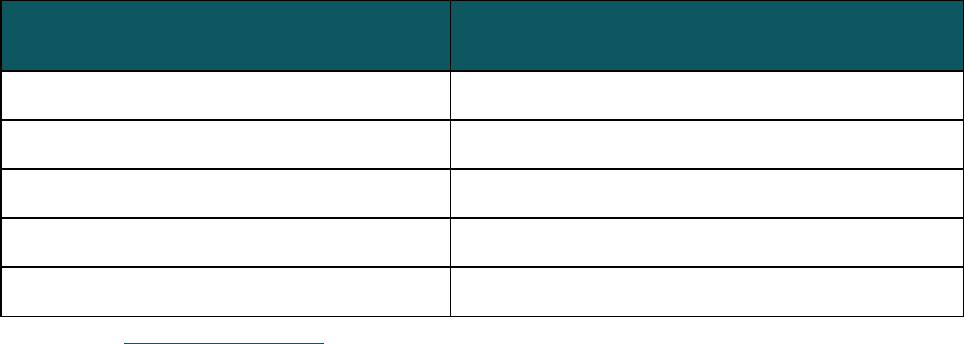

Figure 2: Participating pilot participation

Mtgs

Survey

District

School

active

Yes

Cle Elum-Roslyn

Swiftwater Learning Center

active

No

Highline

Big Picture High School

active

Yes

Issaquah

Gibson Ek High School

active

Yes

Lake Chelan

Chelan School of Innovation

active

Yes

Methow Valley

Independent Learning Center

active

Yes

Quincy

Quincy Innovation Academy

active

No

Selah

Selah Academy BPL

Source: OSPI Innovative Learning Program Pilot Minutes

Page | 27

Appendix C: Program Models

Figure 3: Program model comparisons

Pilots

On-site schools with

CTE programs

ALE

Attendance

requirements

3-5 days onsite + 1/2-2

days offsite internship

Daily onsite attendance

Weekly direct personal

contact: no onsite

attendance required by

the state, may be

required by the local

program

CTE: Vocational

funding, CTE

credit

Limited CTE staffing.

CTE credit must be

separately defined

from the pilot’s non-

credit bearing

competencies.

Coordinated at the

district level; available

to all students; funding

per student enrolled in

course(s); oversight by

CTE-certificated

teacher

Vocationally enhanced

funding for CTE

courses is not available;

limited CTE staffing

Graduation

Pathways

Limited access to Dual

Credit, CTE, Bridge to

College courses;

Advanced Placement

(AP)/International

Baccalaureate (IB)

Fewer barriers to

delivering each

pathway

Limited access to Dual

Credit, CTE, Bridge to

College courses;

Advanced Placement

(AP)/International

Baccalaureate (IB)

Documentation

(not including

attendance)

Student-led Learning

Plan; 2-3 interim

exhibitions per year

Detailed forms for WSL;

hours log for credits;

Teacher-developed

WSLP, monthly

progress review

Community

connections

Integral to internships,

project resources,

community service

Community service

requirements (some)

Community-based

instructors (some),

project resources

Sources: Pilot interviews, 9/2021-6/2022; pilot documentation samples, 4/2022; WBL WAC 392-

121-124, Worksite Learning Manual; ALE WACs 392-121-182, 392-550, Guide to Offering

Alternative Learning Experiences; 2021–22 Enrollment Reporting Handbook.

Page | 28

Appendix D: Survey to the Pilots

Survey Questions to the Innovative Learning Pilot Programs

We have appreciated the time you have given for participating in the Innovative Learning Pilot

Program Conversations this year. We have learned a lot about your programs, and hope that they

have provided insight from other programs for you as well.

In accordance with our timeline for reporting to the Legislature, we will be compiling our notes

from this survey, and from the conversations, to complete our draft. We will be sending that draft

to you in the fall, accompanied by invitations for individual videoconference meetings to review

and discuss your program’s information.

We understand that not all of these questions may pertain directly to your program; please answer

as many as you can. We are providing a Word version for your draft. You are welcome to either

submit your answers via the Alchemer survey link, or by sending the doc or pdf back to us

(liz.quayle@k12.wa.us).

The survey will be open through Friday, July 15. If you are emailing a doc or pdf, please send it by

July 15. Thank you again for your time!

1. What are successes that you have had through mastery-based learning this past school year?

2. What have been non-pandemic-related challenges this year for your program or for your

students?

3. What are highlights or structures in your program that you haven’t previously shared that we

can include in our report to the legislature?

4. How do you communicate the curriculum available to students and adoption processes to the

district, board, and community?

5. What drives your curricular choices and who makes the decisions?

6. In considering your practices this year, what are some changes you might make to the

internship process next year in:

a. Staff oversight,

b. Amount of time in the week students are away from campus,

c. How internship learning is connected to the on-site learning,

d. Impact on students’ ability to access other course opportunities at the school or at other

locations (Skill Center, Running Start, local High School)?

7. What would be the impact to your program if there were restrictions on time allowed for

students to be off campus for internships?

8. What would be the impact to your program if there were a different funding calculation for

your school due to the off-campus time?

Page | 29

9. If the funding difference was not a factor, what do you see as barriers to using an ALE

framework for your program? (Link to ALE WAC & Guide)

10. What data do you use to inform the public and the district/board about the progress of the

school and its students?

11. How is equity demonstrated in your data?

12. What are key tips and suggestions that you would like to pass along to future mastery-based

learning programs?

13. How has been part of the Innovative Learning Pilot affected your program development?

14. What are some specific resources or needs that we can address in the continued pilot meetings

through next year?

15. How can we as state agencies (OSPI, SBE) support your program or other innovative programs?

Responses to the Innovative Learning Pilot Survey

June/July 2022

Q – Quincy Innovation Academy, Quincy

CH – Chelan School of Innovation, Lake Chelan

CER – Swiftwater Learning Center, Cle Elem-Roslyn

MV – Independent Learning Center, Methow Valley

IS – Gibson Ek High School, Issaquah

1. What are successes that you have had through mastery-based learning this past school

year?

Q - We have refined our competency-based evidence method by building upon a portfolio. We

have also expanded our community engagement since being shut down by the pandemic.

CH - Students are less stressed, as traditional assessment practices often measure compliance

rather than growth and learning. Students are able to work at their own pace.

CER - Students are excited to come to school. We have high engagement and students are actively

participating in the development of their learning.

MV - Students have achieved competency growth through interest-based exploration in the form

of projects, internships, and real-world experiences.

-We have engaged students who were otherwise disengaged in the traditional program, several of

whom were on a path to dropping out or not graduating on time. Others who were simply

uninspired and found inspiration through our program.

-Students have been exposed to post high school options they would not have known about or

considered without our internship program. Those opportunities have motivated students to

change post high school plans.

Page | 30

-We have strengthened connections with community assets, including organizations, businesses,

and individuals which enriches our program as well as adding value to those assets.

IS - Ability to meet students where they are; engage them through relevant and interest-based

learning; and help them demonstrate growth in academic and personal skills. Additionally, having

students be able to engage in learning through project-based learning helps them to enjoy their

learning and find ways to deepen their learning while also connecting their learning to the

competencies, identifying ways they can grow as a learner.

Compare this to more traditional settings where students are told the skills they are being taught

and then given specific assignments that are supposed to help students learn, practice and

develop. However, if a student is not ready for this learning or these skills then they are unable to

demonstrate the mastery or growth that is important to them personally.

2. What have been non-pandemic-related challenges this year for your program or for your

students?

Q - Teachers and staffing to really do the necessary community outreach and professional

development.

CH - Finding a solution for P.E. time in a district with limited facilities. Managing online/credit

retrieval students.

CER - There are still students who think we are a credit retrieval program and have a hard time

getting on board. Students have a hard time really thinking about what it is that they want to learn

because they have never been part of the process. We are also still navigating around how to

communicate mastery to other schools if a student moves out of district. We also struggle with

transportation, having our own school vehicle would be ideal so we could transport students to

internships.

MV - We have seen a significant increase in need for mental health support.

-Our limited physical space has limited our ability to host larger group activities.

-The culture war issues within the community have impacted our students.

IS - This is probably somewhat related to the pandemic in many ways, but something that we have

to focus on no matter what the cause. We have seen a drop in the ability of students to socialize

with one another and follow some simple expectations in a school setting.

3. What are highlights or structures in your program that you haven’t previously shared that

we can include in our report to the Legislature?

Q - Making sure that all this work is communicated to all stakeholders, including higher education

and business leaders.

CH - Our students participate in frequent community service projects with organizations in our

community, such as Thrive Chelan Valley, the U.S. Forest Service, and Historic Downtown Chelan

Association.

Page | 31

CER - One of our students is a youth school board rep for the Cle Elum Roslyn School District. This

year she presented alongside our superintendent at the WASA Small Schools conference, and it

was amazing to hear her insight on the education system. School leaders from across the state

were shocked that an “alternative” student was capable of presenting at that level and were even

more shocked that it was her idea to attend and present at the conference.

MV - A few highlights from this year included the addition of small group projects aimed to

promote positive changes in our community. These projects were unique to our program because

they were student led, arising from a need identified by students, with adult support in

implementing aspects of Design Thinking for problem solving.

Some brief descriptions of these projects follow:

Advocating for needs of teens

This small group conducted several listening sessions with teens in the community to learn more

about the unmet teens in the community. They met with teens from the ILC and Liberty Bell as well.

The result of their learning was a realization that they needed to better inform the community

about the desire for a recreational space for teens to gather. They produced a pamphlet with their

findings to inform the community.

They also attended a community meeting regarding a proposed new pool facility to share their

findings and advocate for a teen center component to be included. Their work continues to provide

a teen perspective to adult community organizers in discussions around improving opportunities.

Combating social isolation

This small group recognized that following the pandemic, social isolation was an issue. They

brainstormed specific demographic groups who might have been significantly impacted. Youth

recognized that they had been particularly isolated from their grandparents throughout the

pandemic. Thus, they chose to reach out to elders in the community to find out if social isolation is

an issue for them. They invited a few experts in the field: the executive director for Methow At

Home (nonprofit organization empowering elders to age in place) and a person associated with

Jamie's Place (local elder care home). After interviewing these experts, they asked for ideas of how

to have a positive impact on the problem of social isolation. Both of the experts stated that elders

want connection, to be seen and heard, and to tell their stories.

The group of students landed on the idea of creating a podcast that recorded interviews with

elders. This, coupled with portraits that artists would paint of the elders during the interviews.

The group ended up interviewing six people and recording the interviews. A local podcaster came

into the school and taught the students to edit and produce the podcasts. They edited the hour

and a half long recordings. The students created an intro and outro to the podcast. After listening

to many different podcasts, they created a script, edited it, and added it to the end of each

episode. They then published the podcasts on YouTube and the Methow At Home and Jamie's

Place websites. The Methow Valley Newspaper also produced a piece on the student's project.

Page | 32

The culminating event was a tea with the elders. Here, the students and elders reflected on the

experience. Both students and elders were significantly impacted by the project. Both groups felt a

huge amount of gratitude for the experience. Students presented the portraits to the elders. One

pair, an elder and a student, went on to record another podcast together, with the elder

interviewing the teen about contemporary issues faced by teens.

IS – N/A

4. How do you communicate the curriculum available to students and adoption processes to

the district, board, and community?

Q - We do a yearly board work session, and students and parents through quarterly exhibitions and

school activities. We also can post updates, on our website.

CH - Students are made aware of curriculum options at the beginning of the school year during

Advisory and on an ongoing basis as they work with their Advisors to develop their Learning Plans.

CER - We are very transparent about our program. In the early stages we worked side by side with

the district and school board to determine what was the best option for our school. Once we had

board approval, our next step was sharing with the community. We hit the pavement and

introduced ourselves and our students to businesses to create partnerships and spread the word

about Big Picture Learning.

MV - Instead of a traditional curriculum, we use Big Picture Learning design principals to guide

teaching and learning. These have been adopted by our school board, are included on our website,

and are regularly reported to the community through our district’s quarterly publication, Methow

Pride.

IS - We communicate in several ways including our website, short videos, extensive student/family

handbook that covers more than just behavior expectations and regulations, School Improvement

Plan and meeting with the school board, data and program details as they relate to our school

board’s end monitoring, ongoing bulletins to family and community.

5. What drives your curricular choices and who makes the decisions?

Q – These are local building recommendations, and then our directors, and then board and

superintendent final decision.

CH - Student needs and interests, as well as high-priority goals listed on our school improvement

plan. Staff and administration make the decisions. Students also have a voice in some of the

curriculum they select.

CER - Students, everything we do is based on the students’ wants and needs.

MV - We use competencies to guide the adult led learning in our school. Other learning is initiated

by students based upon their interest, often (but not always) supported by internships.

Page | 33

IS - Our competencies are the foundation to the learning that happens in our program. How

students demonstrate these skills and grow in these areas can vary depending on the personalized

needs of these students. Students engage in the following ways to demonstrate evidence of

learning and growth over 4 years in the areas of academic learning, personal characteristics,

community engagement, and social emotional learning. Experiences for learning and growth

happen in advisory, independent projects, collaborative projects, internships, math courses, design

labs, outside of school experiences, travel and field trips, core foundation workshops.

6. In considering your practices this year, what are some changes you might make to the

internship process next year in:

a. Staff oversight,