BURDEN SHARING

Benefits and Costs

Associated with the

U.S. Military Presence

in Japan and South

Korea

Report to Congressional Committees

March 2021

GAO-21-270

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-21-270, a report to

congressional

committees

March 2021

BURDEN SHARING

Benefits and Costs Associated with the U.S. Military

Presence in Japan and South Korea

What GAO Found

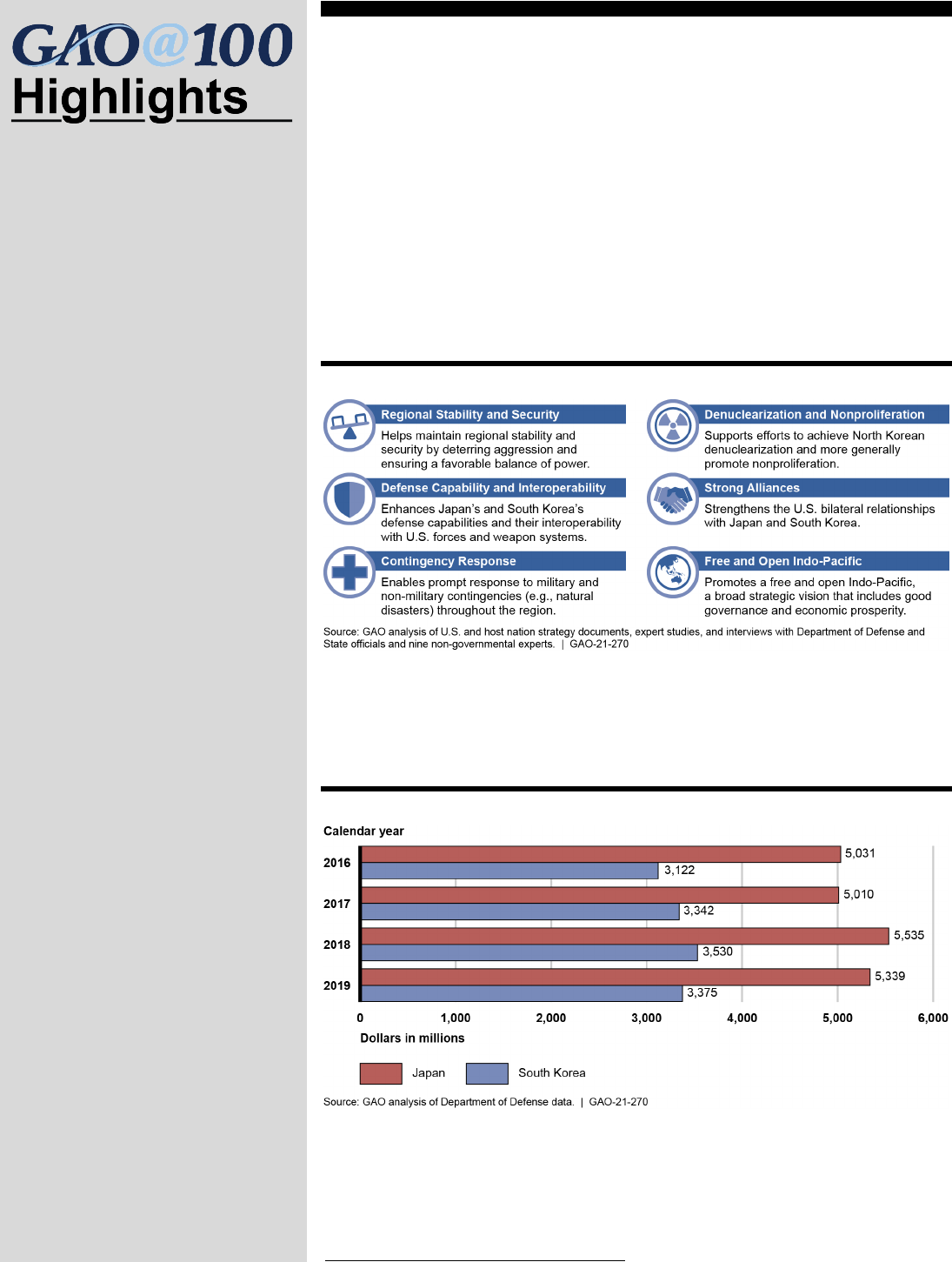

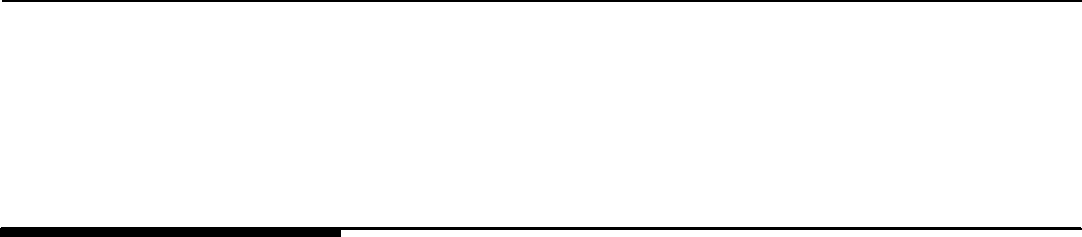

GAO identified six benefits to U.S. national and regional security derived from the

U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea (see fig.1). U.S. officials and

strategy documents cited them, and non-governmental experts generally agreed.

Identified Benefits to U.S. National Security Derived by the American Military Presence in

Japan and South Korea

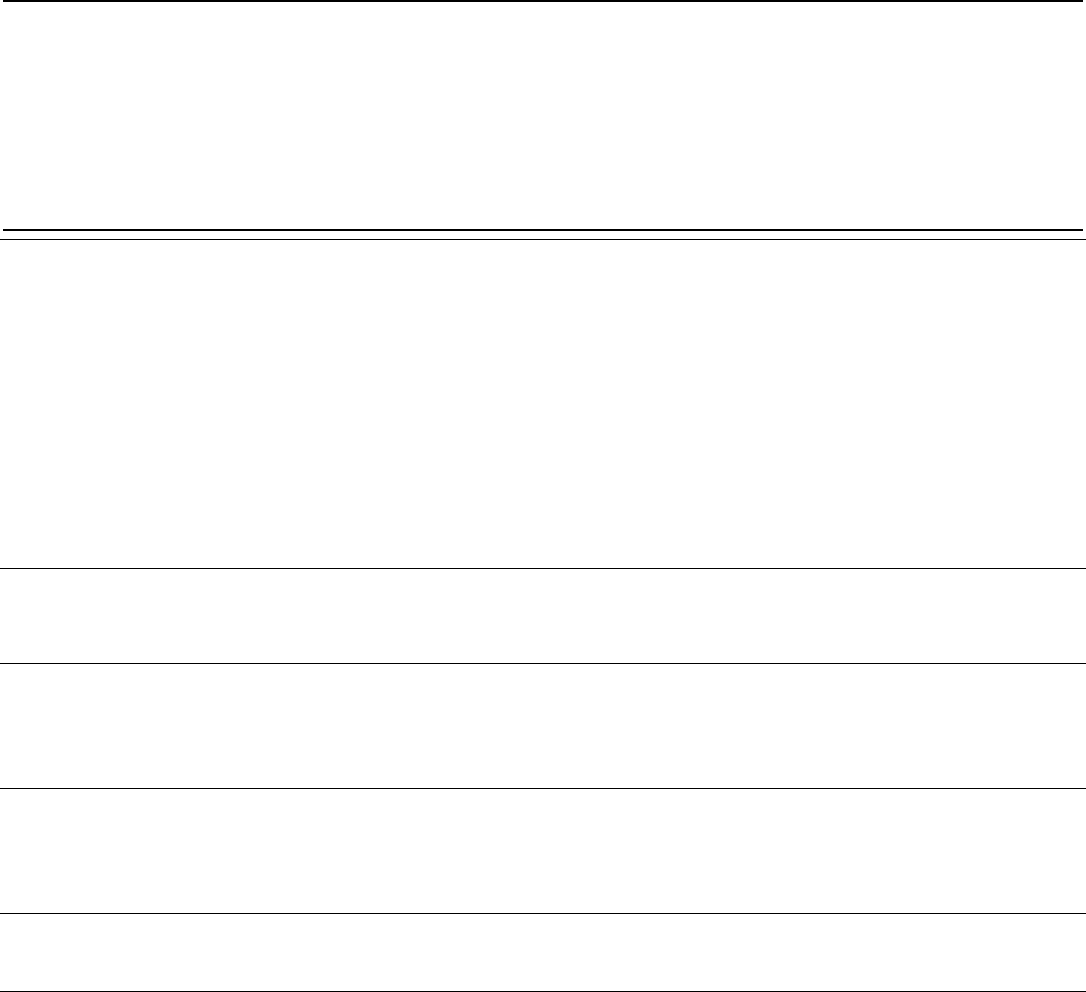

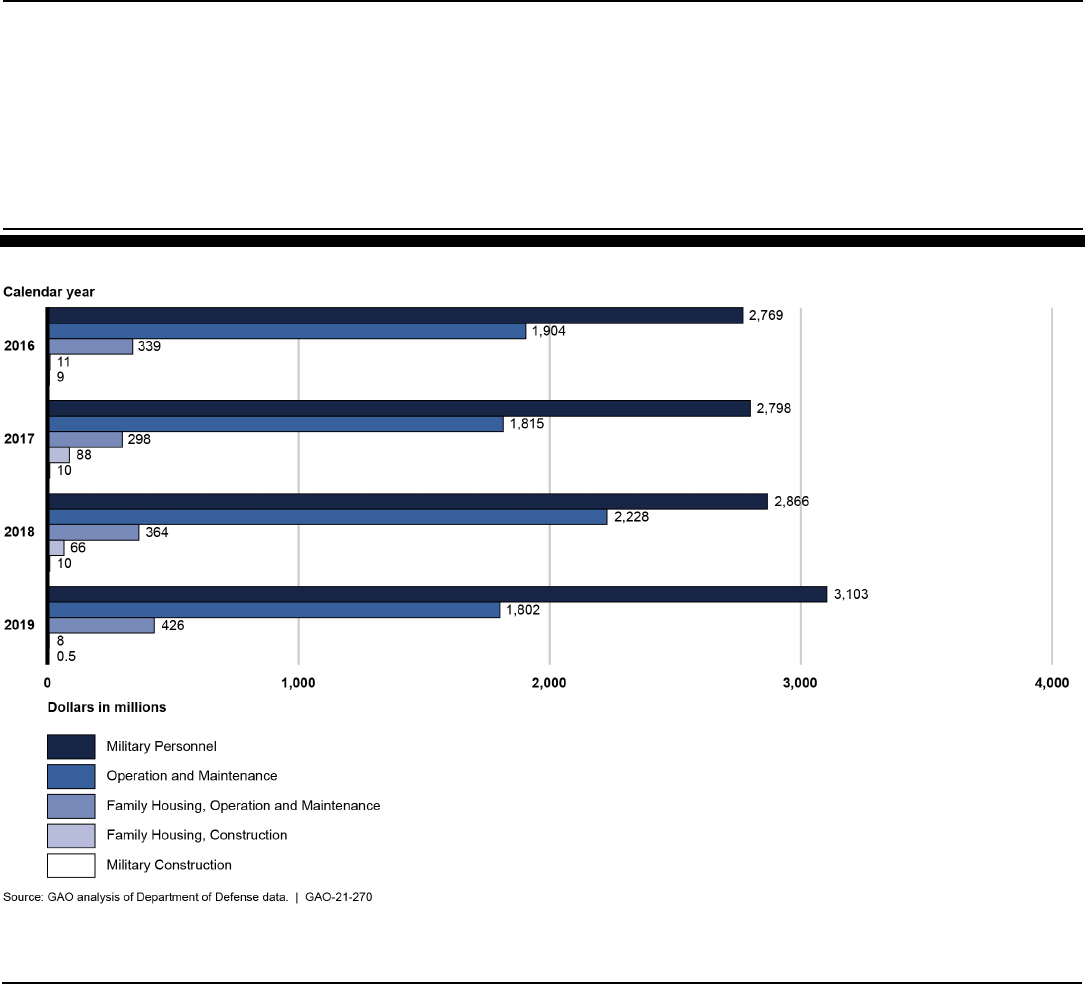

The Department of Defense (DOD) obligated $20.9 billion for its presence in

Japan and $13.4 billion for its presence in South Korea from 2016 through 2019

from funds available to the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps (see fig. 2).

The military services obligated these funds from five categories, in order of size:

military personnel, operation and maintenance, family housing operation and

maintenance, family housing construction, and military construction.

Department of Defense Obligations to Support the Military Presence in Japan and South

Korea, 2016—2019

According to data obtained from DOD, Japan provided $12.6 billion and South

Korea provided $5.8 billion from 2016 through 2019 in cash payments and in-

kind financial support. This direct financial support paid for certain costs, such as

labor, construction, and utilities. In addition to direct financial support, Japan and

South Korea provided indirect support, such as forgone rents on land and

facilities used by U.S. forces, as well as waived taxes, according to DOD officials.

View GAO-21-270. For more information,

contact

Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or

and Jason Bair at (202)

512

-6881 or [email protected].

Why GAO Did This Study

Both DOD and the Department of State

(State) report that c

ooperation

between

the U.S. and

its allies

Japan and South

Korea

is essential for confronting

regional and global challenges

. The

decades

-long forward presence of the

U.S. military in

those countries has

under

girded these security alliances.

DOD

has about 55,000 troops in

Japan

, its largest forward-deployed

force in the world. DOD has about

28,500

troops in South Korea. It

spends billions of dollars annually and

maintains dozens of facilities in both

countries

, ranging from tens of

thousands of acres for training sites to

single antenna outposts

, in support of

this presence

.

The Nat

ional Defense Authorization

Act

for Fiscal Year 2020 included a

provision for GAO to report on the

security benefits derived from th

e

forward presence of the U.S.

military

in

Japan and South Korea and the costs

associated with

it for calendar years

2016 through 2019.

This report

describes (1) the identified benefits to

U.S. national and regional security

derived from the U.S. military presence

in Japan and South Korea, (2) the

funds obligated by the U.S. military for

its presence in Japan and South Korea

for 2016 through 2019, and (3) the

direct and indirect burden

sharing

contributions

made by Japan and

South Korea for 2016 through 201

9.

To

address these objectives, GAO

interview

ed DOD and State officials

and nine

non-governmental experts;

reviewed various strategy documents

and expert studies

; and analyzed

relevant cost data obtained from DOD.

Letter 1

Background 4

U.S. Military Presence in Japan and South Korea Enhances U.S.

National Security by Maintaining Regional Stability, Among

Other Benefits Identified from Relevant Sources 7

DOD Obligated $20.9 Billion in Japan and $13.4 Billion in South

Korea for Its Permanent Military Presence in 2016 through 2019 14

Japan and South Korea Provided Direct and Indirect Financial

Support for the U.S. Military Presence from Calendar Years

2016 through 2019 20

Agency Comments 30

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 33

Appendix II DOD Obligations to Support Its Presence in Japan and South Korea,

in Dollars (2016—2019) 42

Appendix III Japan and South Korea’s Direct Financial Support for the U.S.

Military Presence in Those Countries (2016—2019) 47

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 54

Tables

Table 1: Appropriation Accounts Used to Support U.S. Permanent

Military Presence in Host Countries 6

Table 2: Department of Defense Obligations to Support Its

Presence in Japan, 2016—2019 42

Table 3: DOD Obligations to Support Its Presence in South Korea,

2016—2019 43

Table 4: Japan’s Direct Financial Support for the U.S. Military

Presence under the Special Measures Agreement,

2016—2019 47

Table 5: Japan’s Direct Financial Support for the U.S. Military

Presence from Other Initiatives, in Dollars, 2016—2019 48

Contents

Table 6: Japan’s Direct Financial Support for the Defense Policy

Review Initiative, in Dollars, 2016—2019 48

Table 7: Japan’s Direct Financial Support for the Special Action

Committee on Okinawa, in Dollars, 2016—2019 49

Table 8: South Korea’s Direct Financial Support for the U.S.

Military Presence, in Dollars, 2016—2019 50

Table 9: South Korea’s Direct Financial Support for the Yongsan

Relocation Plan, in Dollars, 2016—2019 50

Figures

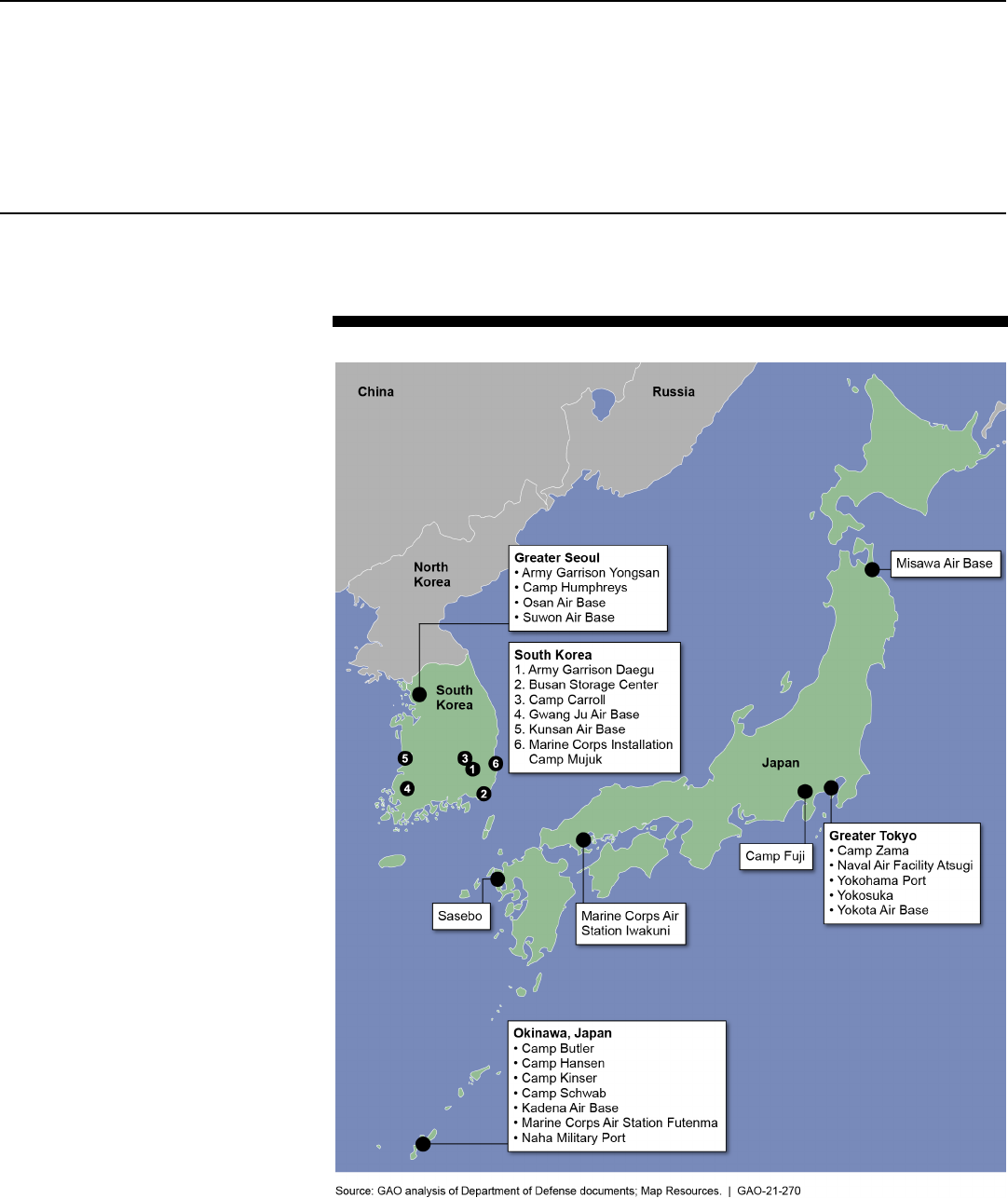

Figure 1: Selected U.S. Military Installations in Japan and South

Korea 5

Figure 2: Benefits of the U.S. Military Presence in Japan and

South Korea Identified from Strategy Documents, Expert

Studies, and Interviews with Officials and Non-

Governmental Experts 8

Figure 3: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in Japan,

by Military Service, Calendar Years 2016—2019 15

Figure 4: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in Japan,

by Appropriation Account, Calendar Years 2016—2019 17

Figure 5: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in South

Korea, by Military Service, Calendar Years 2016—2019 18

Figure 6: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in South

Korea, by Appropriation Account, Calendar Years 2016—

2019 19

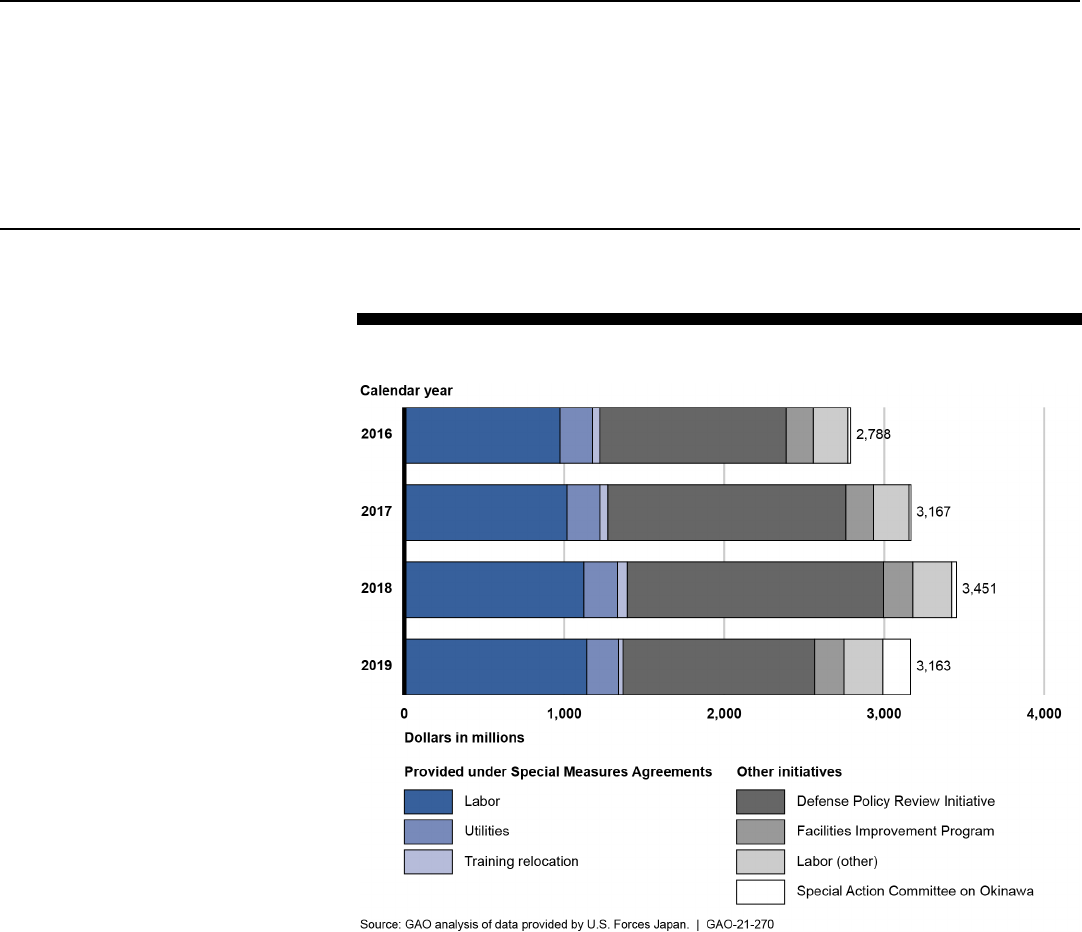

Figure 7: Direct Cash and In-Kind Financial Support by Japan for

the U.S. Military Presence, Calendar Years 2016—2019 21

Figure 8: Direct Cash and In-Kind Financial Support by South

Korea for the U.S. Military Presence, Calendar Years

2016—2019 26

Figure 9: Examples of Potential Indirect Financial Support by

Japan and South Korea 29

Abbreviations

DEAMS Defense Enterprise Accounting and Management

System

DOD Department of Defense

SABRS Standard Accounting, Budgeting, and Reporting

System

SMA Special Measures Agreement

State Department of State

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

March 17, 2021

Congressional Committees

Both the Department of State (State) and Department of Defense (DOD)

state that cooperation between the United States and its allies Japan and

South Korea is essential for confronting regional and global challenges,

and the decades-long forward presence of the U.S. military in Japan and

South Korea has undergirded these security alliances. According to State,

the U.S. relationship with Japan is a cornerstone of peace in East Asia,

and Japan works with the United States to pursue common approaches

to regional and global challenges. State also says that the U.S.

relationship with South Korea is a linchpin of peace and security on the

Korean peninsula, reduces the threat posed by North Korea, and works to

achieve North Korean denuclearization. According to officials at State and

DOD, the U.S. military presence in those countries is key to maintaining

peace in the region and protecting U.S. national security.

The U.S. military has had a presence in Japan and South Korea for

decades, and it currently has about 55,000 troops in Japan—the largest

forward-deployed force in the world—and about 28,500 troops in South

Korea. The dollar costs associated with this presence are in the billions

annually, and they cover DOD activities and dozens of facilities that range

in size from tens of thousands of acres for training sites to single antenna

outposts.

This presence is governed by a series of treaties and agreements under

which the governments of Japan and South Korea provide both direct and

indirect financial support for the U.S. military stationed in those countries.

The United States signed mutual defense and cooperation treaties with

South Korea in 1953 and with Japan in 1960. Subsequently, the United

States complemented its mutual defense and cooperation treaties with

both countries by completing Status of Forces Agreements with Japan in

1960 and South Korea in 1966.

1

Since then, the United States has also

agreed to a series of Special Measures Agreements (SMA) with Japan

1

The respective Status of Forces Agreements generally govern the status of U.S. defense

personnel stationed in each country, as well as the facilities and areas to which they have

access. The Status of Forces Agreement between the United States and Japan is

associated with the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. The Status of Forces

Agreement between the United States and South Korea is associated with the Mutual

Defense Treaty between the two nations.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

and South Korea. The SMAs generally cover multi-year terms and

describe costs to which the host nations have agreed in order to support

the presence of U.S. troops. According to State officials, Japan and South

Korea have also agreed to pay for some one-time costs outside of the

SMAs, such as those associated with the relocation and realignment of

U.S. forces at the request of the host nation, which can sometimes be

substantial.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 included a

provision for us to report on matters related to the security benefits

derived from the forward presence of the U.S. military in Japan and South

Korea and the costs associated with that presence for calendar years

2016 through 2019.

2

This report describes (1) the identified benefits to

U.S. national and regional security derived from the U.S. military

presence in Japan and South Korea; (2) the funds obligated by the U.S.

military for its presence in Japan and South Korea for calendar years

2016 through 2019; and (3) direct and indirect burden sharing

contributions made by Japan and South Korea for calendar years 2016

through 2019.

3

To identify the benefits of the U.S. military presence in Japan and South

Korea, we identified and conducted a review of selected national security

and defense strategy documentation from the U.S. and host nation

governments.

4

We also reviewed 20 selected expert studies that discuss

the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. We identified these

studies through a literature search and selected them for their relevance

and recent publication, among other criteria. In addition to our review of

these strategy documents and studies, we conducted interviews with

officials from DOD and State, as well as with non-governmental experts

from various think tanks and universities. From our examination of

strategy documents, expert studies, and interviews, we identified six

broad categories of benefits to U.S. national security derived from the

U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. We then selected and

conducted semi-structured interviews with nine non-governmental experts

2

See Pub. L. No. 116-92, § 1255 (2019). Unless otherwise specified, years in this report

are calendar years, not fiscal years. Numbers are not adjusted for inflation.

3

For a summary of this report in Japanese, see GAO-21-425. For a summary of this report

in Korean, see GAO-21-424.

4

Some of these documents were global in scope. For example, see, White House, 2017

National Security Strategy (Dec. 18, 2017). Other documents were specific to the region

or host nations. For example, see, Department of Defense, Indo-Pacific Strategy Report:

Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region (June 1, 2019).

Page 3 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

based on their relevant expertise and institutional and geographic

diversity. We asked these experts to rank the six identified benefits on a

scale reflecting the range of strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree or

disagree, agree, and strongly agree, with regard to the extent to which

those benefits are derived from the U.S. military presence in Japan and

South Korea. We also asked these experts for their perspectives on any

potential challenges or drawbacks associated with the U.S. military

presence in Japan and South Korea.

To identify funds obligated by the U.S. military, we obtained and analyzed

obligations data from the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force for

calendar years 2016 through 2019, in the following five appropriation

accounts: military personnel, operation and maintenance, military

construction, family housing operation and maintenance, and family

housing construction.

5

We also reviewed DOD guidance, such as relevant

financial management regulations, to identify the methodology and

accounting procedures used to track these costs.

To identify host nation financial support for the U.S. military presence, we

analyzed the SMAs and other host nation support agreements and

arrangements with Japan and South Korea. Additionally, we interviewed

DOD officials regarding various forms of Japan’s and South Korea’s host

nation support. We also obtained and analyzed data from U.S. Forces

Japan and U.S. Forces Korea on the direct financial support provided by

Japan and South Korea within, and outside of, SMAs for calendar years

2016 through 2019.

To assess the reliability of the data sources used to conduct our

analyses, we conducted interviews with officials from the four relevant

military services—Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force—as well as

with officials at the headquarters of U.S. Forces Japan and U.S. Forces

Korea, to determine their data quality assurance procedures. We also

reviewed their written responses to a data reliability questionnaire

focused on the controls used to ensure that the data they provided were

reliable. We found the data we used to be sufficiently reliable for the

purposes of our reporting objectives. See appendix I for more information

on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2020 to March 2021

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

5

These were the most recent calendar years available during our review.

Page 4 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The U.S.-Japan alliance is a cornerstone of peace and prosperity in the

Indo-Pacific, and U.S. forces in Japan are an essential component of the

military’s posture there, according to DOD. As of 2019, the United States

had about 55,000 military personnel in Japan. The majority of the U.S.

presence is concentrated on the island of Okinawa, Japan’s

southernmost prefecture and, according to a senior State official, a

strategically valuable location for the United States. According to DOD

and State officials, the Japanese public are broadly supportive of the U.S.

military presence in their country, but this presence is a more contentious

issue in Okinawa, in part because of the history of U.S. occupation of the

island at the end of World War II.

To reduce the footprint of the U.S. military presence in Japan, the United

States and Japan are implementing the 2012 revision to a 2006 roadmap

that would relocate some U.S. forces in Japan, especially within Okinawa

and would move other forces off of Okinawa entirely. Specifically, 9,000

Marines will relocate to Guam, Hawaii, the continental United States, and

Australia (on a rotational basis), according to DOD officials. These

initiatives have sometimes encountered significant delays, such as the

construction of the replacement facility for U.S. Marine Corps Air Station

Futenma. That project has encountered local opposition as well as

complications arising from environmental analyses, according to DOD

and Japanese officials.

South Korea is considered one of the United States’ most important

strategic and economic allies in Asia and is a linchpin of peace and

security on the Korean Peninsula and the region. The United States has

maintained some degree of military presence in South Korea since the

end of World War II. As of 2020, the United States had about 28,500

military personnel in South Korea. The Army has the most significant

presence, and the majority of its soldiers there are based at Camp

Humphreys—the largest U.S. overseas military base in the world. In

addition to the protection afforded by the forward presence of U.S. forces,

South Korea, like Japan, benefits from the extended deterrence derived

Background

U.S. Military Presence in

Japan and South Korea

Page 5 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

from the U.S. armed forces, including the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Figure 1

below depicts the location of selected U.S. military installations in Japan

and South Korea.

Figure 1: Selected U.S. Military Installations in Japan and South Korea

Page 6 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

The U.S. military primarily obligates funds associated with five

appropriation accounts to support its forward presence in Japan and

South Korea, as detailed in table 1 below.

6

Table 1: Appropriation Accounts Used to Support U.S. Permanent Military Presence in Host Countries

Appropriation account

Description

Military personnel

Pay, allowances, individual clothing, subsistence, interest on

deposits, gratuities, permanent change of station travel, and

expenses of temporary duty travel between permanent duty

stations for active duty military personnel

Operation and maintenance

Includes expenses associated with the current operations of the

force and maintenance of equipment and vehicles, as well as

civilian salaries; also, certain minor military construction, facilities

repair, and purchases of items below a threshold

Family housing operation and maintenance

Operation and maintenance expenses associated with family

housing, including debt payment, leasing, minor construction,

principal and interest charges, and insurance premiums

Family housing construction

Construction—including acquisition, replacement, addition,

expansion, extension, and alteration—of family housing units

Military construction

Acquisition, construction, installation, and equipment of temporary

or permanent public works, military installations, facilities, and real

property

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documents and relevant statutes. | GAO-21-270

6

According to DOD officials, DOD also incurs costs related to rotational forces that rotate

into Japan and South Korea. These costs can include transportation, training, and

sustainment costs for equipment maintained in Japan and South Korea. These costs are

outside the scope of this report.

U.S. Military Spending

Categories

Page 7 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

From our examination of U.S. and host nation strategy documents and

expert studies, as well as interviews with officials at DOD and State and

with non-governmental experts, we identified six important benefits

derived from the U.S. presence in Japan and South Korea, as shown in

figure 2. The nine non-governmental experts we interviewed largely

agreed that these benefits derive from the U.S. military presence in Japan

and South Korea.

U.S. Military

Presence in Japan

and South Korea

Enhances U.S.

National Security by

Maintaining Regional

Stability, Among

Other Benefits

Identified from

Relevant Sources

Page 8 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Figure 2: Benefits of the U.S. Military Presence in Japan and South Korea Identified from Strategy Documents, Expert Studies,

and Interviews with Officials and Non-Governmental Experts

Note: This list is not necessarily exhaustive of all identified benefits of the U.S. military presence in

Japan and South Korea, and the order in which the six benefits are presented is not intended to

signify ranking.

Several experts noted that, collectively, all six benefits contribute to U.S.

national security in addition to the regional security of the Indo-Pacific.

Additionally, one expert and several DOD and State officials noted that

these six benefits overlap and are mutually reinforcing. For example,

DOD and State officials said that the U.S. military presence in Japan and

South Korea helps to maintain regional stability and security and to

strengthen alliances. In turn, both of these benefits promote a free and

open Indo-Pacific. While experts broadly agreed that these six benefits

derive from the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea, some

experts noted that certain benefits are more relevant for a particular host

Page 9 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

nation, and that there are sometimes challenges associated with the U.S.

military presence. Below we examine and provide details about each of

the six benefits in greater depth.

Regional Stability and Security. Various national strategy documents

we reviewed, as well as DOD and State officials and experts we

interviewed, identified regional stability and security as a benefit deriving

from the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. For example,

DOD’s 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report indicates that the forward

posture of the U.S. military has been a robust deterrent to aggression and

contributes to regional stability and security.

7

Officials at Embassies

Tokyo and Seoul said that the U.S. military presence has enabled the

United States to project power throughout the region and to deter

adversaries such as China, Russia, and North Korea. DOD officials

added that this military presence has also preserved a favorable balance

of power in the region.

All nine experts we interviewed agreed—and eight of them strongly

agreed—that the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea helps

maintain regional stability and security. Additionally, seven of the nine

experts identified regional stability and security as the most important of

the six identified benefits. One expert reported that the U.S. military

presence has deterred not only adversaries, but also allies, from taking

destabilizing actions. This expert said that, for example, the U.S. military

presence in South Korea gave the United States leverage to dissuade

South Korea from retaliating against North Korea’s sinking of a South

Korean naval ship in 2010.

Although they agreed that the U.S. military presence in Japan and South

Korea helps maintain regional stability and security, several experts said

that there are nonetheless some challenges associated with having U.S.

troops stationed overseas. Specifically, two experts said that forward-

deployed troops are at increased vulnerability to a potential first strike

from an adversary, such as China or North Korea. One expert added,

however, that ultimately the United States is nevertheless committed to

having troops in the region, a commitment that deters U.S. adversaries

and reassures U.S. allies.

7

DOD, Indo-Pacific Strategy Report (June 1, 2019).

Regional Stability and Security

Department of Defense and Department of

State officials and all nine non-governmental

experts agreed that the U.S. military presence

helps maintain regional stability and security

by deterring aggression and ensuring a

favorable balance of power in the region.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

Page 10 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Defense Capability and Interoperability. DOD’s 2019 Indo-Pacific

Strategy Report indicates that the forward presence of the U.S. military

enables the United States to undertake joint and combined training with

Japan and South Korea and to enhance those countries’ defense

capabilities and interoperability (i.e., the ability to act together to achieve

objectives).

8

DOD and State officials agreed, with officials at Embassy

Tokyo noting that the U.S. presence facilitates foreign military sales to

Japan because Japan sees firsthand the effectiveness of U.S. equipment.

For example, Japan has procured F-35 and Osprey aircraft to mirror U.S.

capabilities and ensure interoperability with U.S. forces. Similarly, officials

at Embassy Seoul said that the combined command structure between

U.S. Forces Korea and the South Korean military has resulted in strong

interoperability.

All nine experts agreed—and eight of them strongly agreed—that

improving U.S. allies’ defense capabilities and interoperability is a benefit

deriving from the U.S. presence in Japan and South Korea. For example,

the United States and Japan participate in joint exercises (such as Keen

Sword) that involve tens of thousands of participants from both countries

and are designed to increase the combat readiness and interoperability of

the Japanese Self Defense Forces and the U.S. military.

9

According to

three experts we interviewed, the forward presence of the U.S. military

makes such exercises possible, and these exercises serve to build the

defense capabilities of the host nations and their interoperability with the

United States. Several experts also noted that the U.S. military presence

facilitates intelligence sharing between the United States and Japan and

between the United States and South Korea.

8

DOD, Indo-Pacific Strategy Report (June 1, 2019).

9

Keen Sword is a joint biennial exercise involving U.S. and Japanese forces. In 2020,

approximately 9,000 U.S. forces and 37,000 Japanese forces participated in Keen Sword.

Defense Capability and Interoperability

Department of Defense and Department of

State officials and all nine non-governmental

experts agreed that the U.S. military presence

enhances Japan's and South Korea's defense

capabilities and interoperability with U.S.

forces and weapon systems.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

Page 11 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Contingency Response. The White House’s 2017 National Security

Strategy indicates that the forward posture of the U.S. military is

necessary to respond to and shape events quickly.

10

DOD and State

officials we spoke with reiterated this point, with one official noting that the

forward deployment of troops and resources shortens U.S. supply lines

by thousands of miles, thus enabling the U.S. forces to respond more

quickly to evolving threats and contingencies. Another official said that the

U.S. forward presence in Japan has been valuable in responding to non-

military contingencies, citing examples of humanitarian crises and natural

disasters throughout the region. These examples include the December

2004 earthquake in Indonesia, the March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and

tsunami disaster in Japan, and the November 2013 Typhoon Hainan in

the Philippines.

All nine experts agreed—and seven of them strongly agreed—that the

U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea enables prompt

response to military and non-military contingencies. One expert said that

U.S. Forces Korea’s motto, “Fight Tonight,” reflects the importance of

military readiness to respond to contingencies. With respect to non-

military contingencies, two experts said that U.S. forces in Japan are well

positioned to respond to contingencies throughout the region. For

example, several experts noted that the U.S. forces in Japan were

integral in quickly assisting with disaster relief efforts following the 2011

earthquake and tsunami. Another expert said that absent the forward

presence of the U.S. military in Japan and South Korea, China might fill

this vacuum and respond more quickly than the United States to regional

contingencies. Two experts said that, in addition to enabling a more

prompt response, the U.S. forward presence makes it more cost-effective

to respond to contingencies.

While all nine experts agreed that prompt contingency response is a

benefit of the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea generally,

two experts said that the U.S. presence in South Korea specifically is less

able to respond to regional non-military contingencies. They noted that

because U.S. forces in South Korea serve primarily to deter North Korea,

those forces are less flexible to respond to non-military contingencies

elsewhere, as doing so could risk diminishing their deterrent effect.

10

White House, 2017 National Security Strategy (Dec. 18, 2017).

Contingency Response

Department of Defense and Department of

State officials and all nine non-governmental

experts agreed that the U.S. military presence

in Japan and South Korea enables prompt

responses to military and non-military

contingencies throughout the region.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

Page 12 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Denuclearization and Nonproliferation. The White House’s 2017

National Security Strategy and DOD’s 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report

identify the final and fully verifiable denuclearization of North Korea and

the promotion of nonproliferation more generally as goals.

11

DOD and

State officials we spoke with said that the U.S. military presence in Japan

and South Korea helps support these strategy goals.

Six of the nine experts agreed—with four strongly agreeing—that the U.S.

military presence in Japan and South Korea helps support U.S. efforts to

achieve denuclearization (i.e., removal of nuclear weapons) and

nonproliferation (i.e., reduction in the increase or spread of nuclear

weapons). With respect to denuclearization, two experts said that the

U.S. forward presence along with the U.S. nuclear umbrella makes our

allies in the region less likely to pursue development of their own nuclear

weapons. Two experts said that the U.S. presence is helpful in

nonproliferation efforts with respect to North Korea.

However, three of the nine experts neither agreed nor disagreed that

denuclearization and nonproliferation constituted a benefit derived from

the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. Two of these

experts said that the U.S. military presence may assist with

nonproliferation efforts, but they were more skeptical as to whether the

U.S. military presence helps achieve denuclearization—at least with

respect to North Korea. One expert said that North Korea is unlikely to

denuclearize, as the regime views its nuclear weapons as a deterrent in

the face of the U.S. military presence on the Korean peninsula.

11

White House, 2017 National Security Strategy (Dec. 18, 2017); DOD, Indo-Pacific

Strategy Report (June 1, 2019).

Denuclearization and Nonproliferation

Department of Defense officials and some

Department of State officials and six non-

governmental experts said that the U.S.

military presence in Japan and South Korea

supports efforts to achieve denuclearization

and promote nonproliferation.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

Page 13 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Strong Alliances. State’s 2019 A Free and Open Indo-Pacific states that

the enduring commitment of the United States to the Indo-Pacific is

demonstrated by the forward presence of the U.S. military in the region,

and DOD and State officials we spoke with said that the U.S. military

presence strengthens U.S. bilateral relationships with Japan and South

Korea.

12

All nine experts we spoke with agreed—with eight strongly agreeing—that

the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea strengthens the

United States’ bilateral alliance with both host nations. One expert said

the willingness of the United States to place its troops in harm’s way

reassures allies. In addition to strengthening the U.S. bilateral

relationships with Japan and South Korea, two experts said that the U.S.

military presence has helped normalize and stabilize the historically

fraught relationship between Japan and South Korea.

However, six experts said that local opposition to and complaints about

the U.S. military presence among some residents who live in the vicinity

of bases present a challenge for alliance management. Several experts

said that, given the extent of opposition in localities such as Okinawa, the

U.S. military presence in those places might not be politically sustainable.

More generally, one expert said that while the U.S. military presence is a

necessary component of our strong alliances with Japan and South

Korea, it is not uniquely responsible for those alliances—that is, other

political and economic factors also contribute to these relationships.

12

State, A Free and Open Indo-Pacific (Nov. 4, 2019).

Strong Alliances

Department of Defense and Department of

State officials and all nine non-governmental

experts agreed that the U.S. military presence

strengthens U.S. bilateral relationships with

Japan and South Korea.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

Page 14 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Free and Open Indo-Pacific. State’s 2019 A Free and Open Indo-Pacific

outlines a strategic vision that includes the promotion of good governance

and economic prosperity.

13

The 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report

specifically identifies the U.S. forward posture in the region as important

to upholding a free and open Indo-Pacific.

14

DOD and State officials we

spoke with similarly identified this as a benefit, with one official stating

that the U.S. military presence specifically facilitates free commerce and

upholds the rules-based order.

All nine experts agreed—with six strongly agreeing—that the forward

presence of the U.S. military in Japan and South Korea helps promote a

free and open Indo-Pacific. For example, one expert said that the U.S.

military presence in Japan and South Korea is important to protecting

supply lines and trade routes that facilitate economic prosperity.

While all nine experts agreed that the U.S. military presence promotes a

free and open Indo-Pacific, two experts said that this benefit is not

necessarily or exclusively a function of the military. For example, one of

these experts said that the alliance more generally promotes a free and

open Indo-Pacific. Two experts noted that South Korea is less aligned

with the United States on the concept of a free and open Indo-Pacific than

is Japan. They explained that South Korea is more reliant on China

economically and is therefore more reticent to antagonize China by

aligning itself too closely with the strategic vision of the United States for

the region.

DOD obligated a total of $20.9 billion for its permanent military presence

in Japan and a total of $13.4 billion for its permanent military presence in

South Korea in 2016 through 2019, from funds available to the Army,

13

State, A Free and Open Indo-Pacific (Nov. 4, 2019).

14

DOD, Indo-Pacific Strategy Report (June 1, 2019).

Free and Open Indo-Pacific

Department of Defense and Department of

State officials and all nine non-governmental

experts agreed that the U.S. military presence

in Japan and South Korea promotes a broad

strategic vision that includes good

governance and economic prosperity.

Source: GAO. | GAO-21-270

DOD Obligated $20.9

Billion in Japan and

$13.4 Billion in South

Korea for Its

Permanent Military

Presence in 2016

through 2019

Page 15 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

15

The military services obligated

these funds from the following five appropriation accounts: (1) military

personnel, (2) operation and maintenance, (3) family housing operation

and maintenance, (4) family housing construction, and (5) military

construction. For detailed information on DOD’s obligations by service

and by appropriation account, see appendix II.

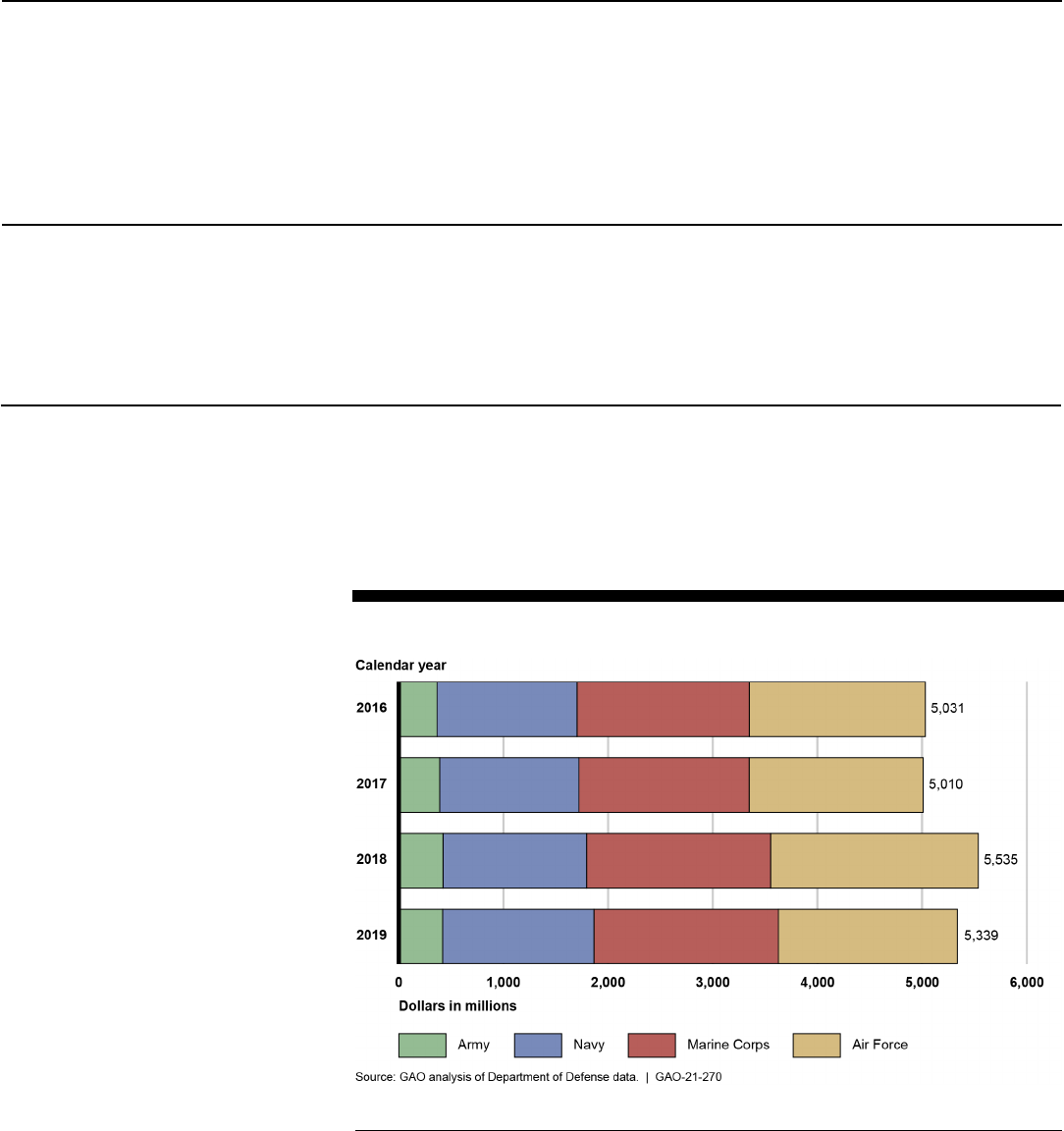

According to DOD data, DOD obligated a total of $20.9 billion for the U.S.

military presence in Japan in calendar years 2016 through 2019. Annual

obligations remained relatively consistent during this time, peaking in

2018. DOD obligated about $5.0 billion in 2016, $5.0 billion in 2017, $5.5

billion in 2018, and $5.3 billion in 2019. Figure 3 displays the funds

obligated by military service and year.

Figure 3: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in Japan, by Military

Service, Calendar Years 2016—2019

15

An agency incurs an obligation when, for example, it places an order, signs a contract,

awards a grant, purchases a service, or takes other actions that require the government to

make payments to the public or from one government account to another. Obligated

amounts were identified by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force. DOD also

obligates from funds available to the Defense Commissary Agency and Defense Logistics

Agency, among others, to support its military presence in Japan and South Korea. Those

agencies were outside the scope of this report, and those funds are not included in the

total herein presented. DOD obligations for its military presence in Japan and South Korea

in this section may not add due to rounding.

DOD Obligations for the

U.S. Military Presence in

Japan

Page 16 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Note: Obligated amounts were identified by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

Collectively, from 2016 through 2019, the Air Force obligated $7.0 billion

to support its forces in Japan—the largest of the four U.S. military

services’ obligations there. The Marine Corps has a significant presence

in Okinawa and obligated $6.8 billion in that time period. The Navy

obligated $5.5 billion to support about 20,000 Navy personnel in Japan.

The Army obligated $1.6 billion, the smallest of the services’ obligations.

In total, from 2016 through 2019, DOD obligated about 92 percent ($19.3

billion) of these funds in Japan for military personnel and operation and

maintenance. Specifically, from 2016 through 2019, DOD obligated $11.5

billion in Japan for military personnel and $7.7 billion for operation and

maintenance. During that time DOD also obligated $1.4 billion for family

housing operation and maintenance, $173.0 million for family housing

construction, and $29.8 million for military construction. Figure 4 displays

the funds obligated by appropriation account and year.

Page 17 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Figure 4: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in Japan, by Appropriation Account, Calendar Years 2016—2019

Note: Obligated amounts were identified by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

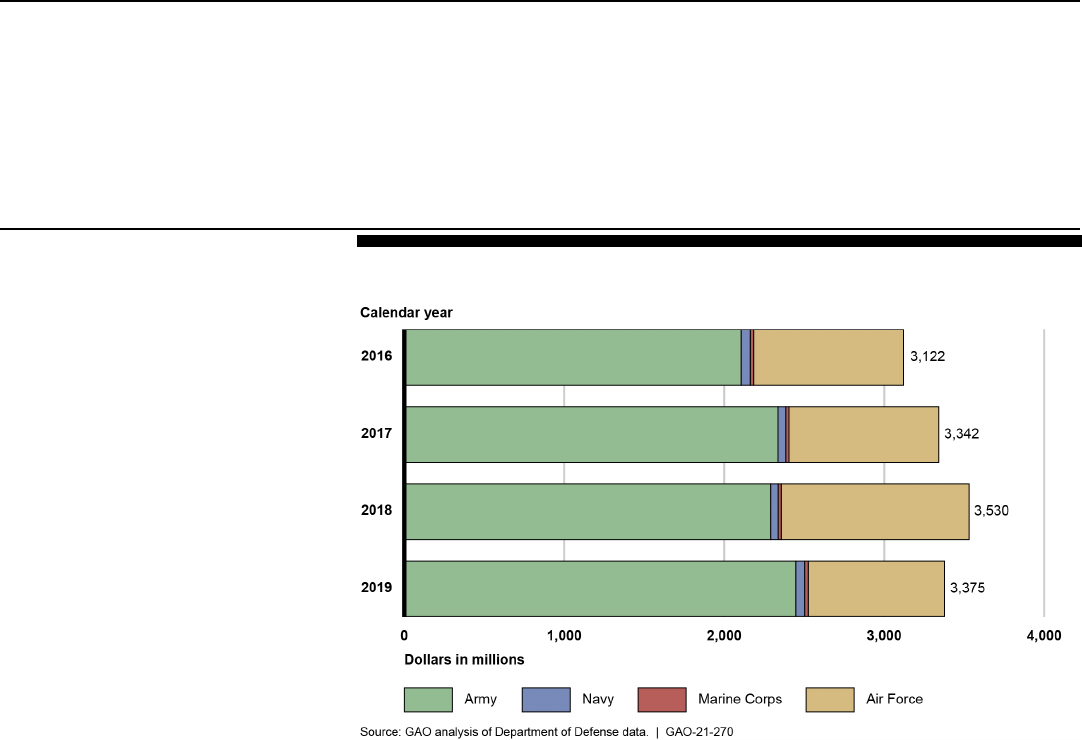

According to DOD data, DOD obligated a total of $13.4 billion for the U.S.

military presence in South Korea in 2016 through 2019. DOD obligations

in South Korea remained relatively constant during this time, peaking in

2018. Specifically, DOD obligated $3.1 billion in 2016, $3.3 billion in 2017,

$3.5 billion in 2018, and $3.4 billion in 2019. Figure 5 displays the funds

obligated by service and year.

DOD Obligations for the

U.S. Military Presence in

South Korea

Page 18 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Figure 5: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in South Korea, by Military

Service, Calendar Years 2016—2019

Note: Obligated amounts were identified by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

DOD obligated about 98 percent of these funds from amounts available to

the Army and the Air Force. The Army obligated $9.2 billion in South

Korea from 2016 through 2019—the largest of the four military services’

obligations there. The majority of U.S. servicemembers in South Korea

are Army personnel and are based at Camp Humphreys. During this time

period, the Air Force obligated $3.9 billion, supporting its presence at two

air bases in South Korea: Osan Air Base and Kunsan Air Base. The Navy

and Marine Corps have a significantly smaller presence in South Korea.

The Navy obligated $208.7 million in South Korea from 2016 through

2019. The Marine Corps obligated $82.8 million, the smallest of the

services’ obligations. According to DOD officials, the Marine Corps

presence in South Korea consists of approximately 280 Marines primarily

located at Camp Humphreys and Camp Mujuk.

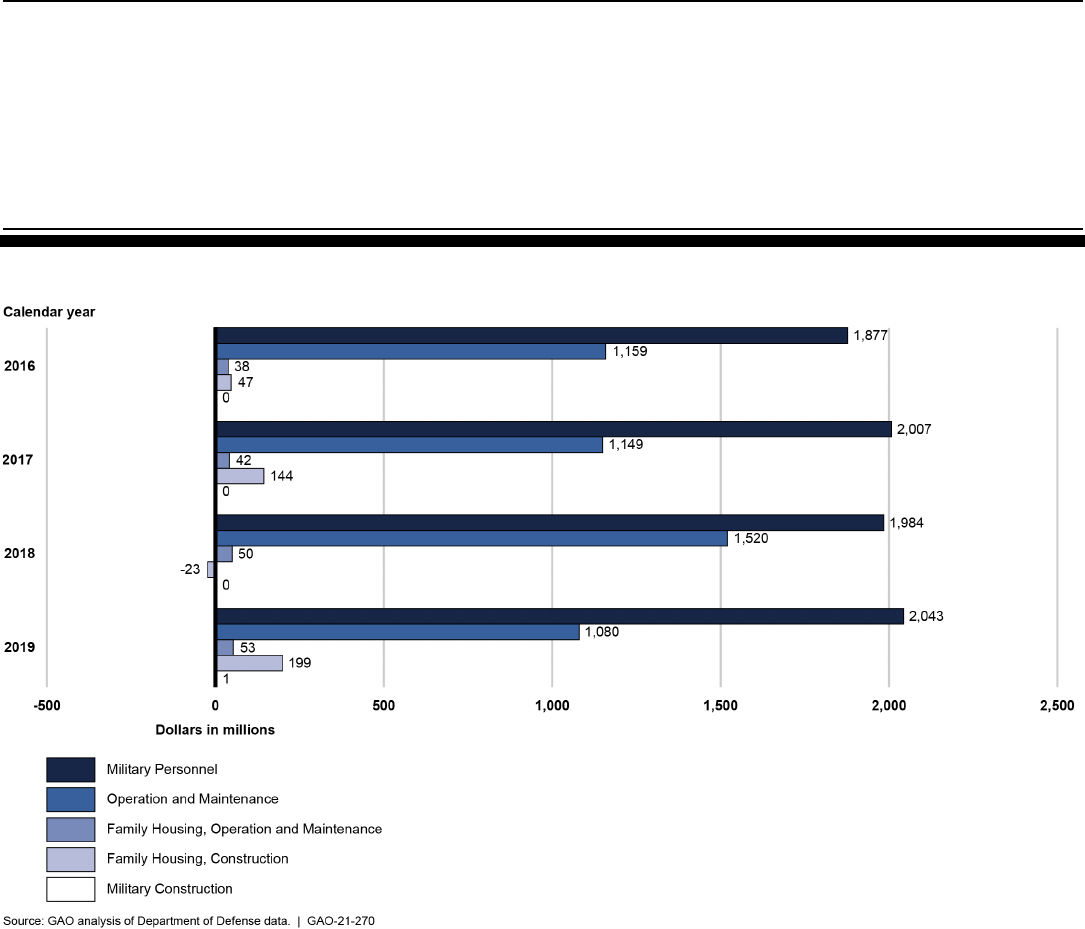

In total, from 2016 through 2019, military personnel and operation and

maintenance obligations accounted for the majority of DOD’s obligations

in South Korea. Figure 6 displays the funds obligated by appropriation

account and year.

Page 19 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Figure 6: Funds Obligated for the U.S. Military Presence in South Korea, by Appropriation Account, Calendar Years 2016—

2019

Note: Obligated amounts were identified by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force. According

to Army officials, in 2017 the Army awarded a family housing construction project at Camp Walker to

a contractor. The officials stated, however, that in 2018 the project was terminated and funds de-

obligated after the contractor defaulted, resulting in the data showing a negative obligation of $23

million for family housing construction in 2018. Army officials stated that the project was re-awarded

and funds were re-obligated in 2019.

Page 20 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

For calendar years 2016 through 2019, Japan provided $12.6 billion (¥1.6

trillion) and South Korea provided $5.8 billion (₩6.6 trillion) in direct

financial support for the U.S. military presence in those countries. Direct

financial support includes (1) cash payments provided by the

governments of Japan and South Korea and (2) in-kind financial

support.

16

The governments of Japan and South Korea provided these

cash payments and in-kind financial support to pay for expenses such as

facilities construction, labor, and services to support the U.S. military

presence. Additionally, some DOD officials noted several forms of

potential indirect financial support provided by Japan and South Korea, to

include forgone revenues and rents on lands and facilities used by U.S.

forces, as well as various taxes, tolls, and duties waived by the host

nation governments.

17

See appendix III for a detailed breakdown of Japan

and South Korea’s direct financial support.

As outlined in the 2011 and 2016 SMAs with Japan, Japan agreed to

provide both cash and in-kind financial support for the following three cost

categories: labor, utilities, and training relocation.

18

Across these

categories, Japan provided cash and in-kind financial support totaling

$5.3 billion (¥609.1 billion) in calendar years 2016 through 2019.

19

In

addition to assistance provided under the SMAs, Japan also provided

$7.3 billion (¥953.9 billion) of direct financial support for the Defense

Policy Review Initiative, the Facilities Improvement Program, non-SMA

labor, and the Special Action Committee on Okinawa initiatives, as

16

For the purposes of this report, in-kind financial support refers to the provision of goods

or services instead of money. For example, Japan provides in-kind financial support for

labor by directly paying Japanese nationals to work on U.S. military installations in support

of the U.S. presence there.

17

According to DOD officials, DOD does not formally track or estimate the value of

Japan’s and South Korea’s indirect financial support, and that support is not reflected in

the total amount of direct financial support provided by host nation governments.

18

See Agreement Concerning New Special Measures Relating to Article XXIV of the

Agreement under Article VI of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the

United States of America and Japan, Regarding Facilities and Areas and the Status of

United States Armed Forces in Japan, U.S.-Japan, Jan. 22, 2016, T.I.A.S. No. 16-401.3.

For the previous SMA, see Agreement Concerning New Special Measures Relating to

Article XXIV of the Agreement under Article VI of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and

Security between the United States of America and Japan, Regarding Facilities and Areas

and the Status of United States Armed Forces in Japan, U.S.-Japan, Jan. 21, 2011,

Temp. State Dep’t No. 11-67.

19

This total primarily reflects Japan’s direct financial support under the current SMA, which

is effective from April 1, 2016, through March 31, 2021; but it also includes direct financial

support from the final quarter of the previous SMA, which was in effect from April 1, 2011

through March 31, 2016.

Japan and South

Korea Provided Direct

and Indirect Financial

Support for the U.S.

Military Presence

from Calendar Years

2016 through 2019

Japan Provided $12.6

Billion in Direct Financial

Support from 2016

through 2019

Page 21 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

discussed below. Figure 7 displays all direct cash and in-kind financial

support provided by Japan for calendar years 2016 through 2019.

Figure 7: Direct Cash and In-Kind Financial Support by Japan for the U.S. Military

Presence, Calendar Years 2016—2019

Notes: GAO converted the data from Japanese fiscal years to calendar years. The Japanese fiscal

year begins on April 1 and ends on March 31; for example, Japanese fiscal year 2016 began on April

1, 2016, and ended on March 31, 2017. We also converted Yen to U.S. Dollars. This figure does not

include certain training relocation costs in Japanese fiscal year 2019 because the data were not

available at the time of our review.

Under the SMAs for calendar years 2016 through 2019, Japan provided

the following:

• Labor: Japan provided salaries and benefits for Japanese nationals

working on U.S. bases as in-kind financial support. For 2016 through

2019, Japan’s in-kind labor financial support totaled $4.3 billion. As of

2020, Japan was responsible under the SMA for paying for no more

than 23,178 Japanese employees. This cap is determined in

Japan’s Direct Financial

Support und

er the Special

Measures Agreements

Page 22 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

arrangements implementing the SMA, and it varies from year to

year.

20

• Utilities: Japan pays for a portion of utilities consumed at U.S.

facilities, including electricity, gas, and water supply.

21

Japan provided

$819.8 million as a direct cash payment to the United States to offset

utility costs from 2016 through 2019.

• Training relocation: Japan provided the United States $184.1 million

in direct cash payments to relocate U.S. training exercises, such as

live-fire artillery training, away from populated areas.

20

According to DOD officials, the United States is responsible for paying for any additional

Japanese employees, known as “overhires.” The officials stated that the United States is

currently paying for approximately 3,000 overhires.

21

Under the current implementing arrangement, Japan calculates its initial draft budget

request for each fiscal year by multiplying the average of expenditures during the prior 3

fiscal years by 61 percent. The arrangement also includes an annual cap (¥24.9 billion) on

the total utility expenditures Japan will bear.

Page 23 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

In addition to the direct financial support Japan provides under the SMA,

Japan provided $7.3 billion (¥953.9 billion) in 2016 through 2019 in

support of other initiatives, including those focused on relocating and

realigning forces within and from Japan (see sidebar). This was

composed of $5.4 billion (¥738.6 billion) to support the Defense Policy

Review Initiative, $710.7 million (¥82.4 billion) for the Facilities

Improvement Program, $922.4 million (¥106.9 billion) for certain labor

costs not covered by the SMA, and $230.5 million (¥26 billion) on

initiatives related to the Special Action Committee on Okinawa.

Japan provided direct financial support totaling $5.4 billion (¥738.6 billion)

to offset U.S. costs associated with the Defense Policy Review Initiative,

a series of 19 realignment initiatives through which the United States and

Japan’s Direct Financial

Support as Part of Other

Initiatives

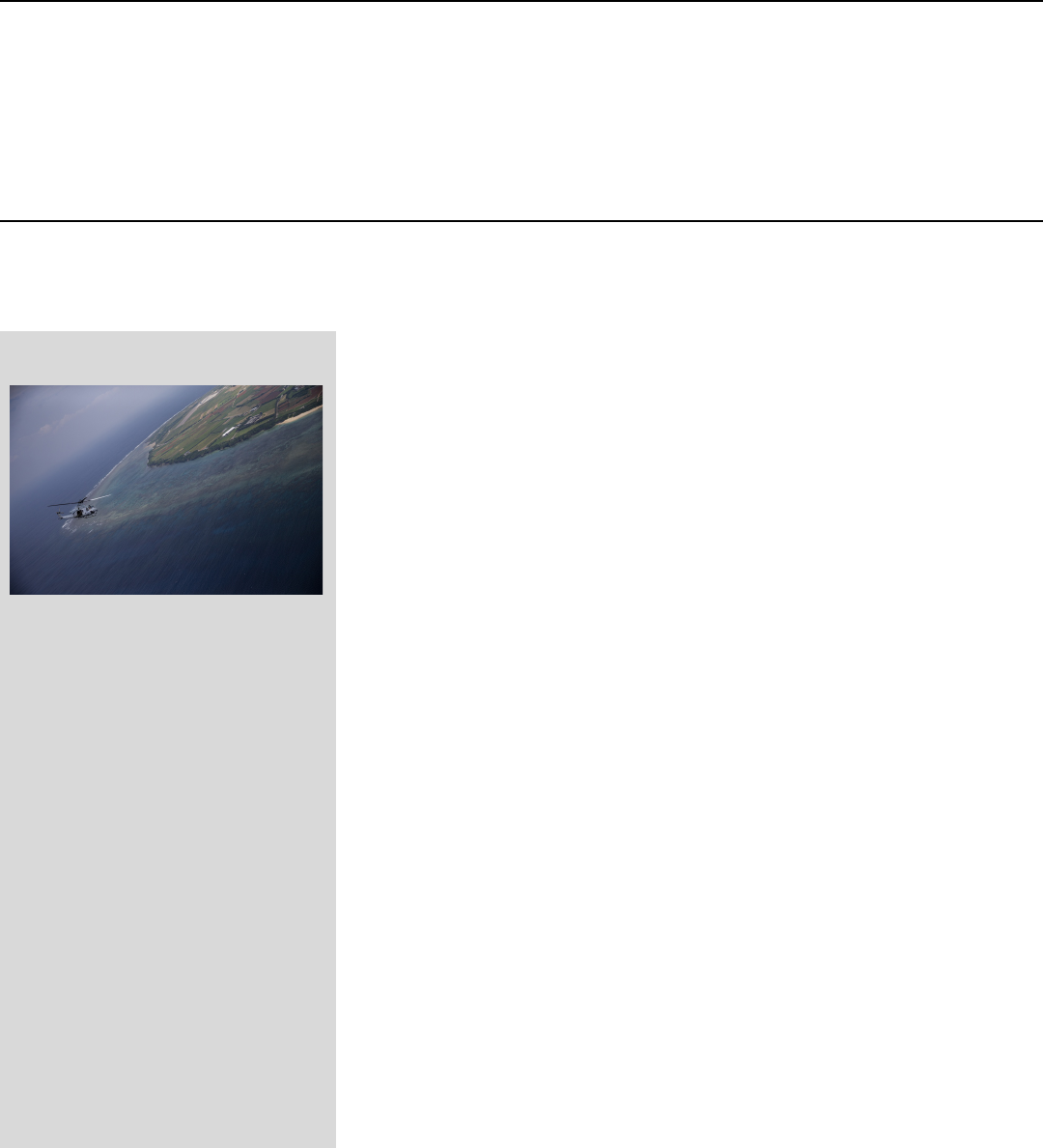

Initiatives to Relocate and Realign U.S.

Forces within and from Japan

Aerial view of the coast of Okinawa.

In 1995 the United States and Japan

established the Special Action Committee on

Okinawa, under which they developed

initiatives to reduce the impact of the U.S.

military presence on Okinawa, such as

returning land used by U.S. forces to

Okinawa. The two nations outlined additional

initiatives in the 2006 U.S.-Japan Roadmap

for Realignment Implementation, in which the

United States planned to move roughly 8,000

Marines from Okinawa to Guam. These more

recent initiatives are known collectively as the

Defense Policy Review Initiative.

One component of the realignment from

Okinawa is to replace Marine Corps Air

Station Futenma with the construction of a

new base in a less congested area of

Okinawa. The plan was initially to be

completed by 2014, but local opposition as

well as environmental analyses have

contributed to significant delays.

Other initiatives include the relocation of

tanker aircraft and a Navy carrier wing to

Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni and the

consolidation of U.S. facilities on Okinawa.

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documents.

U.S. Marine Corps photo/Sgt. Wesley Timm. | GAO-21-270

Page 24 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Japan seek to reduce the U.S. footprint in Okinawa, among other goals.

22

Japan’s most significant costs associated with the Defense Policy Review

Initiative from 2016 through 2019 included in-kind construction projects at

the Futenma Replacement Facility in Okinawa ($2.1 billion), the relocation

of carrier fixed-wing aircraft from Naval Air Facility Atsugi to Marine Corps

Air Station Iwakuni ($1.6 billion), and direct cash financial support to

support the realignment of Marines from Okinawa to Guam ($1 billion).

Japan also provided $710.7 million in in-kind financial support to the

Facilities Improvement Program, a voluntary program that funds U.S.

infrastructure and facilities in Japan. According to DOD officials, the

Facilities Improvement Program had 104 ongoing projects throughout

Japan as of July 2020. Under the program, U.S. Forces Japan submits a

priority list of projects each year for Japan to consider, and Japan has

discretion as to which projects to fund. DOD officials said that one such

priority project that Japan selected to fund was runway repairs at Misawa

Air Base. They added that these repairs also benefit Japan, as the

runways are jointly used by U.S. and Japanese forces and they support

commercial flights that service the local community. According to DOD

officials, U.S. Forces Japan has submitted construction of a new hangar

at Kadena Air Base as another priority project, but Japan has declined to

fund it, citing local concerns about noise pollution.

In addition to Japan’s in-kind financial support for labor costs under the

SMA ($4.3 billion) that was previously discussed, Japan provided in-kind

financial support totaling $922.4 million for certain labor costs not covered

under the SMA. Specifically, these non-SMA labor costs include health

checks, immunizations, uniforms, social insurances, and other costs

associated with Japanese nationals working on U.S. bases in Japan.

According to a State official, Japanese law requires these costs.

Japan also provided $230.5 million to several realignment initiatives

related to the Special Action Committee on Okinawa, a U.S.-Japan

bilateral process established in 1995. Similar to the Defense Policy

Review Initiative, these initiatives aim to reduce the U.S. footprint in

22

The major realignment initiatives under the Defense Policy Review Initiative were

outlined in the 2006 U.S.-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation and were

subsequently adjusted by more recent joint statements and agreements. See, e.g., U.S.-

Japan Security Consultative Committee, Joint Statement of the Security Consultative

Committee (Apr. 26, 2012). We previously reported on the Defense Policy Review

Initiative in GAO, Marine Corps Asia Pacific Realignment: DOD Should Resolve Capability

Deficiencies and Infrastructure Risks and Revise Cost Estimates, GAO-17-415

(Washington, D.C.: Apr. 5, 2017).

Page 25 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Okinawa. These initiatives include the return of land used by U.S. forces

to Okinawa and projects to reduce the noise pollution resulting from the

U.S. military presence.

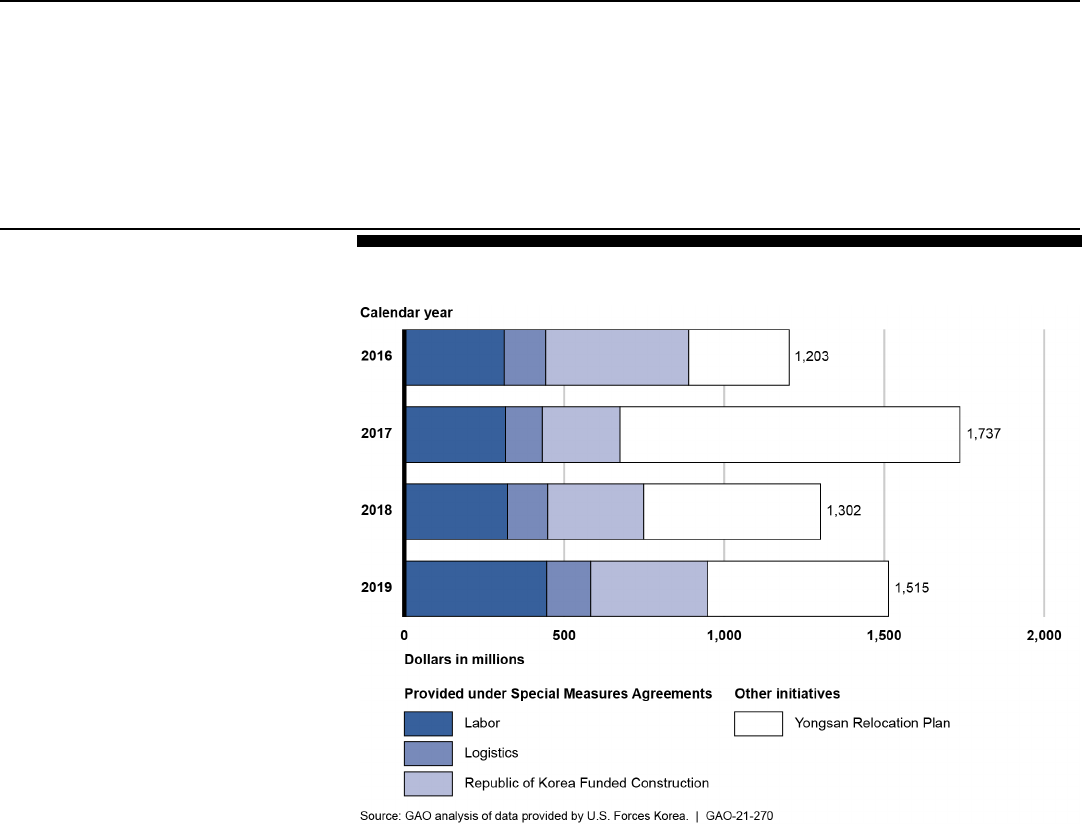

From 2016 through 2019, South Korea provided $3.3 billion (₩3.8 trillion)

in both cash and in-kind financial support under two SMAs—one covering

the years 2014 through 2018, and the other covering 2019 only.

23

In both

SMAs, South Korea agreed to provide direct cash and in-kind financial

support for the following three cost categories: construction, logistics, and

labor. In addition to direct financial support provided via the SMAs, South

Korea provided $2.5 billion (₩2.9 trillion) in facilities to the United States

associated with the Yongsan Relocation Plan.

24

Figure 8 displays all the

direct financial support provided by South Korea for calendar years 2016

through 2019.

23

For the SMA covering 2019, see Agreement Concerning Special Measures Relating to

Article V of the Agreement under Article IV of the Mutual Defense Treaty between the

United States of America and the Republic of Korea Regarding Facilities and Areas and

the Status of United States Armed Forces in the Republic of Korea, U.S.-S. Korea, Mar. 8,

2019, T.I.A.S. No. 19-405. This 10

th

SMA expired at the end of 2019, and State confirmed

that as of January 2021 the United States and South Korea are currently in negotiations to

reach another agreement. For the previous SMA, see Agreement Concerning Special

Measures Relating to Article V of the Agreement under Article IV of the Mutual Defense

Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of Korea Regarding

Facilities and Areas and the Status of United States Armed Forces in the Republic of

Korea, U.S.-S. Korea, Feb. 2, 2014, T.I.A.S. No. 14-618.

24

According to DOD officials, as part of the Yongsan Relocation Plan requested by South

Korea, South Korea provided facilities for U.S. use. South Korea did not provide some

unique facilities such as Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities.

South Korea Provided

$5.8 Billion in Direct

Financial Support from

2016 to 2019

Page 26 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Figure 8: Direct Cash and In-Kind Financial Support by South Korea for the U.S.

Military Presence, Calendar Years 2016—2019

Under the SMAs for calendar years 2016 through 2019, South Korea

provided the following:

• Labor: South Korea provided a direct cash payment for some salaries

and benefits of Korean nationals working for U.S. Forces Korea,

totaling $1.4 billion from 2016 through 2019.

• Logistics: South Korea’s in-kind financial support for logistics totaled

$507.5 million from 2016 through 2019. Through contracts with South

Korean firms, South Korea provided a variety of equipment, supplies,

and services to support the U.S. forward presence, including the

storage, transportation, and maintenance of ammunition; distribution

and storage of fuels; and facility sustainment services.

South Korea’s Direct Financial

Support under the Special

Measures Agreements

Page 27 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

• Construction: South Korea provided $1.4 billion from 2016 through

2019 in construction costs under the SMA, most of which was

provided as in-kind financial support.

25

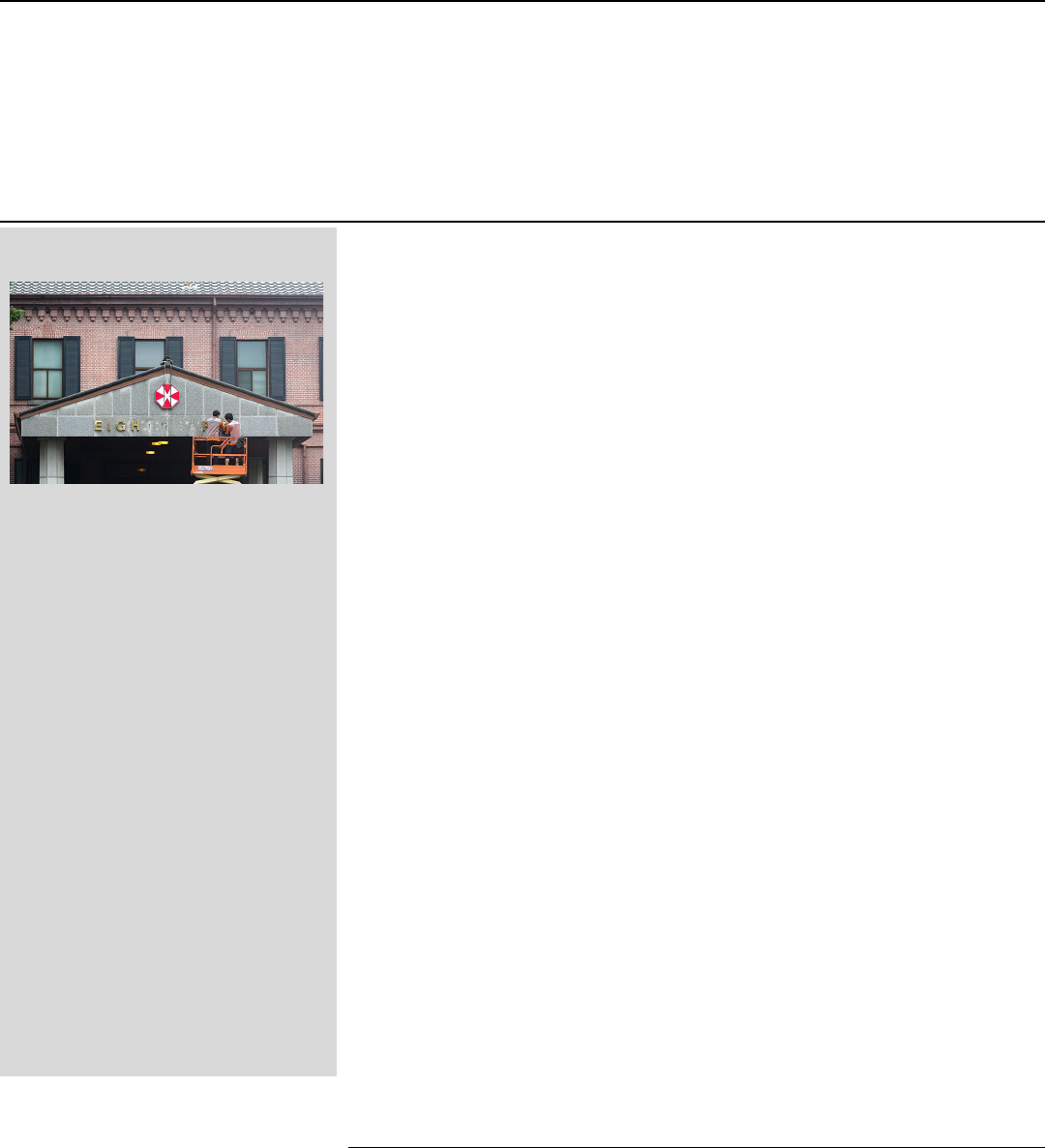

Separate from the SMAs, from 2016 through 2019 South Korea provided

$2.5 billion in facilities to the United States associated with the Yongsan

Relocation Plan, one of two relocation initiatives that DOD officials

identified within South Korea during this time—the other being the Land

Partnership Plan (see sidebar).

26

25

While South Korea provides most of its direct financial support for SMA construction

costs in-kind, South Korea provides a smaller portion (12 percent) of the total construction

project costs as cash payments for design and construction oversight costs.

26

The two nations signed the Yongsan Relocation Plan agreement in 2004, along with an

associated memorandum of agreement. Agreement on the Relocation of United States

Forces from the Seoul Metropolitan Area, U.S.-S. Korea, Oct. 26, 2004, T.I.A.S. No. 04-

1213.

South Korea’s Support as Part

of the Yongsan Relocation

Plan

Page 28 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

South Korea requested and funded the Yongsan Relocation Plan to

relocate U.S. forces from Yongsan Garrison in Seoul primarily to Camp

Humphreys, approximately 40 miles south of Seoul, thereby returning real

estate to South Korea. To this end, South Korea provided $2.5 billion in

in-kind support from 2016 through 2019. The estimated lifetime cost of

the Yongsan Relocation Plan is $7.4 billion.

Conversely, the Land Partnership Plan is a U.S.-driven initiative that

consolidated U.S. installations north of Seoul and relocated those forces

to Camp Humphreys, among other locations.

27

DOD officials said that,

because it is a U.S. initiative, South Korea did not provide financial

support for this relocation from 2016 through 2019. However, according to

DOD officials, U.S. Forces Korea used residual funds provided under

prior SMAs to offset U.S. costs associated with the Land Partnership

Plan. The estimated lifetime cost of the Land Partnership Plan is $3.3

billion.

27

The two nations signed the Land Partnership Plan agreement in 2002 and amended it in

2004. Agreement for the Land Partnership Plan, U.S.-S. Korea, Mar. 29, 2002, Temp.

State Dep’t No. 04-652; Agreement Amending the Agreement between the United States

of America and the Republic of Korea for the Land Partnership Plan of March 29, 2002,

U.S.-S. Korea, Oct. 26, 2004, Temp. State Dep’t No. 05-016. U.S. Forces Korea also used

$157.8 million in U.S. funds from 2016 through 2019 to fund the Land Partnership Plan.

Initiatives to Relocate U.S. Forces within

South Korea

Eighth Army signage removal at Yongsan

Garrison.

In 2002, the United States and South Korea

signed the Land Partnership Plan, a U.S.

initiative to consolidate and relocate U.S.

forces from various camps north of Seoul to

two principal hubs in Pyeongtaek and Daegu.

In 2004, the United States and South Korea

signed the Yongsan Relocation Plan, a South

Korean initiative to relocate U.S. Forces from

the Yongsan Garrison and the Seoul

metropolitan area to Camp Humphreys,

approximately 40 miles south of Seoul.

Both initiatives were driven by a desire to

return land used by U.S. forces to South

Korea, among other reasons. For the Land

Partnership Plan specifically, the United

States also wanted to consolidate U.S. forces

onto fewer and more permanent bases to

improve the quality of life for U.S. personnel

stationed in South Korea.

The bulk of unit relocations occurred between

2016 and 2019, though DOD expects that

some relocations will occur beyond 2022. The

original goal was to complete the Land

Partnership Plan and the Yongsan Relocation

Plan by the ends of 2011 and 2016,

respectively.

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documents.

U.S. Army photo/Sgt. 1st Class Sean Harp. | GAO-21-270

Page 29 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

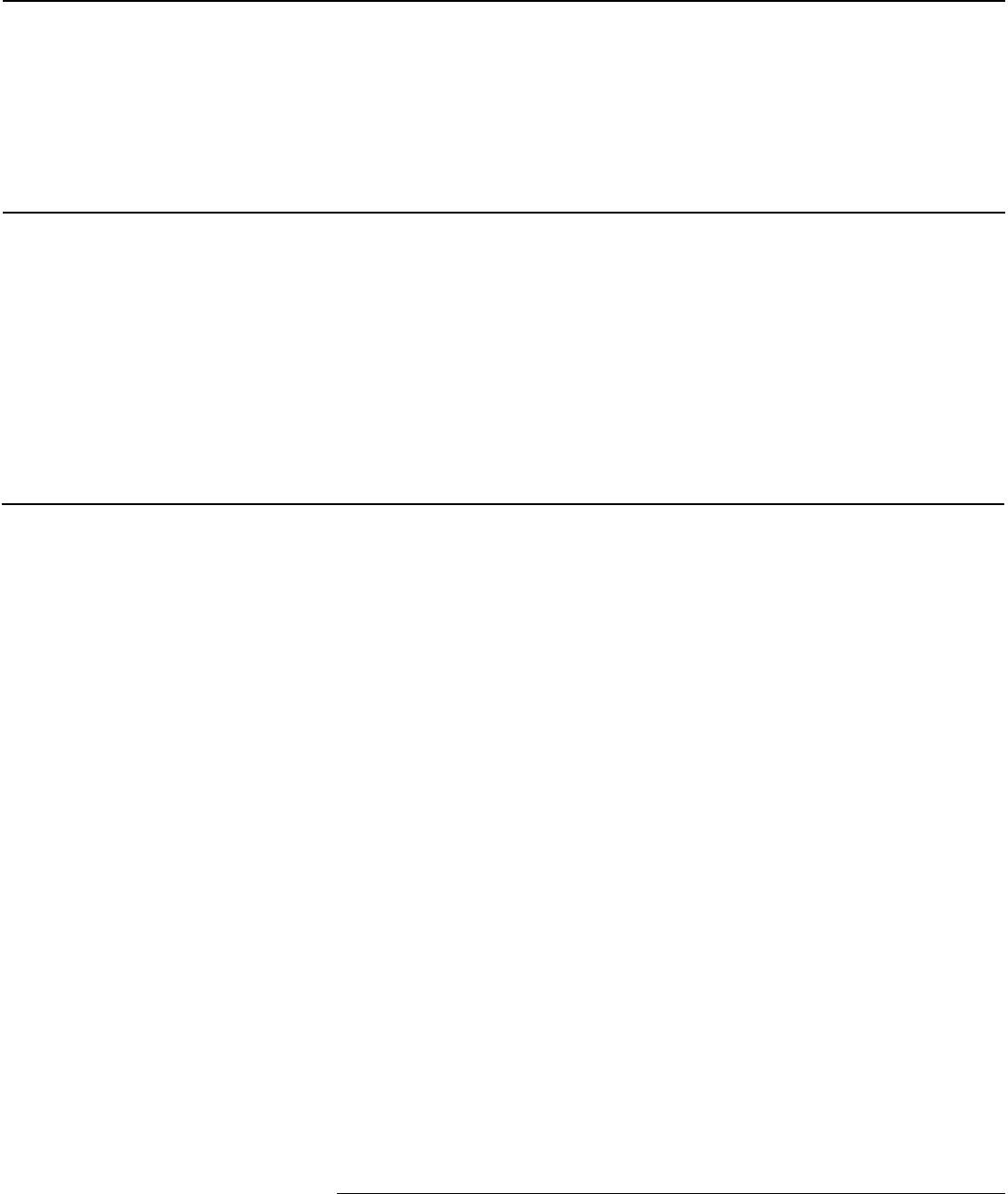

DOD officials we spoke with noted that Japan and South Korea provide

various forms of indirect financial support for the U.S. military presence,

such as forgone rents and revenues on land and facilities used by U.S.

forces that the host nations could otherwise lease and develop. Japan

and South Korea also waive various taxes and fees for U.S. forces

stationed in their countries. See figure 9 for additional examples of what

may be considered as these countries’ indirect financial support. DOD

officials said that tax waivers and other potential examples of indirect

support are covered by the Status of Forces Agreements with both

countries, as distinct from host nation support. As such, one DOD official

said that they should not count toward these host nations’ burden sharing

totals.

28

Figure 9: Examples of Potential Indirect Financial Support by Japan and South

Korea

Note: This list is not exhaustive of all potential or claimed indirect financial support by Japan and

South Korea. Additionally, DOD officials said that the United States does not consider several of the

above examples to be indirect financial support for the purpose of burden sharing negotiations. For

example, officials said that tax and fee waivers are covered by the Status of Forces Agreements the

United States has with Japan and South Korea, as well as, generally, any nation in which the U.S.

military has a presence.

a

According to data obtained from U.S. Forces Japan, Japan provided $947 million in subsidies to its

base-hosting communities from 2016 through 2019. DOD and State officials said that Japan has

claimed that the subsidies increase domestic political support for the alliance, but officials noted that

these costs to Japan are self-imposed.

b

The Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army is a branch of the Republic of Korea Army that

augments the Eighth United States Army by having Korean personnel serve alongside their U.S.

counterparts. According to the Eighth Army, the Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army Soldier

Program offsets U.S. military personnel costs and reflects U.S.-South Korean cooperation and

friendship.

28

Status of Forces Agreements are bilateral or multilateral agreements that, among other

things, establish the framework under which U.S. military personnel operate in a foreign

country.

Japan and South Korea

Have Provided Some

Indirect Financial Support

for the U.S. Military

Presence in Those

Countries

Page 30 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

According to DOD officials, the indirect financial support these countries

provide is more difficult to quantify than is direct cash financial support.

Officials explained that the United States lacks insight into the host

nations’ methodologies and accounting procedures for accurately tracking

these indirect costs. For example, one official said that the United States

cannot track how often U.S. military personnel access a toll road, and that

the host nation governments—to the extent that they track such costs—

do not proactively share this information with the United States.

We provided a draft of this report to DOD and State for review and

comment. DOD and State provided technical comments, which we

incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional

committees, the Secretaries of Defense and State, and other interested

parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO

website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact

[email protected]. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations

and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff

who made significant contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Diana Maurer,

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Jason Bair,

Director, International Affairs and Trade

Agency Comments

Page 31 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

List of Committees

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable James M. Inhofe

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Robert Menendez

Chairman

The Honorable James E. Risch

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Jon Tester

Chair

The Honorable Richard Shelby

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Martin Heinrich

Chair

The Honorable John Boozman

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related

Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Adam Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gregory Meeks

Chairman

The Honorable Michael McCaul

Ranking Member

Page 32 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Chair

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Debbie Wasserman-Shultz

Chairwoman

The Honorable John Carter

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related

Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 33 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 included a

provision for us to report on matters related to the security benefits

derived from the forward presence of the U.S. military in Japan and South

Korea and the costs associated with that presence for calendar years

2016 through 2019.

1

This report describes (1) the identified benefits to

U.S. national and regional security derived from the U.S. military

presence in Japan and South Korea; (2) the funds obligated by the U.S.

military for its presence in Japan and South Korea for calendar years

2016 through 2019; and (3) direct and indirect burden sharing financial

support that Japan and South Korea have made for calendar years 2016

through 2019.

To identify the benefits of the U.S. military presence in Japan and South

Korea, we reviewed relevant expert studies and national security and

defense strategy documentation from the U.S. and host nation

governments. We conducted a literature search to identify relevant expert

studies to review, such as white papers published by foreign policy

experts that provided narrative discussions of potential impacts of the

U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. The parameters of the

literature search included journal articles, dissertations, working papers,

and think tank documents from 2010 through May 2020, when we

conducted the literature search. The literature search identified 88 studies

from various countries, experts, and institutions. We then reviewed the

abstracts and other information (e.g., title, author, and publication year) of

all 88 studies and eliminated those we determined were less relevant,

such as U.S. public opinion research about the U.S. military’s overseas

presence. Of these 88 studies, we selected 20 for additional review based

on their relevance to the U.S. military presence in Japan and/or South

Korea and on their having been published within the past 10 years, as

well as on having variation in institutions, to include think tanks and

universities.

With respect to the strategy documents we reviewed, some were global in

scope (e.g., the 2017 National Security Strategy), while others were

specific to the region or host nations (e.g., the 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy

1

See Pub. L. No. 116-92, § 1255 (2019).

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Identifying Benefits to U.S.

National Security Derived

from the U.S. Presence in

Japan and South Korea

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 34 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

Report).

2

To identify any benefits stated in the expert studies or strategy

documents, two analysts separately read the expert studies and strategy

documents and highlighted text that referred to benefits derived from the

U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. We then grouped

individual expert studies and strategy documents based on the benefits

each identified to determine which benefits of the U.S. military presence

in Japan and South Korea were cited frequently across both expert

studies and strategy documents. In addition to our review of these studies

and strategy documents, we interviewed officials from the Departments of

Defense (DOD) and State (State), as well as non-governmental experts

from various think tanks and universities. From these interviews and our

review of the expert studies and strategy documentation, we identified six

broad benefits.

To provide further context about the extent to which these identified

benefits apply to Japan, South Korea, and the larger Indo-Pacific region,

we also obtained diverse expert perspectives about these identified

benefits. We conducted targeted web searches and a literature search to

identify relevant experts to interview. We developed criteria such as

relevant expertise and geographic and institutional diversity to select a

non-generalizable sample of 11 non-governmental experts in this field.

Two experts declined to participate, so we interviewed nine experts.

These experts included senior fellows and political scientists affiliated with

think tanks, universities, and research institutes in the United States and

in Asia. While our findings from these interviews are not generalizable,

the sample of experts nonetheless reflected our selection criteria and

interest in obtaining diverse perspectives.

These expert interviews were semi-structured. We asked experts to

indicate the extent to which the identified benefits were a consequence of

the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea. The experts used a

five-point scale in their responses that ranged from “strongly agree” to

“strongly disagree.”

3

We used these interviews to obtain additional

2

Specifically, we reviewed the following U.S. strategy documents: the White House’s 2017

National Security Strategy; the Department of Defense’ 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report

and 2018 National Defense Strategy; and the Department of State’s 2018 Joint Regional

Strategy, 2018 Integrated Country Strategy: Japan, 2019 Integrated Country Strategy:

Republic of Korea, and 2019 A Free and Open Indo-Pacific. We also reviewed the

following host nation strategy documents: South Korea’s 2018 Defense White Paper; and

Japan’s 2018 Defense Program Guidelines, 2018 Medium Term Defense, 2019 Defense

of Japan, and 2020 Defense of Japan.

3

The following Likert scale responses were available to experts: “strongly disagree,”

“disagree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “agree,” and “strongly agree.”

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 35 GAO-21-270 Burden Sharing

examples of how the identified benefits applied in the region or to the

specific host nations. We also asked these experts for their perspectives

on any potential challenges or drawbacks associated with the U.S.

military presence in Japan and South Korea. In addition to these expert

interviews, we interviewed officials from DOD and State about the

identified benefits, though we did not prompt officials to respond using

this scale. Specifically, we spoke with officials from the Office of the

Secretary of Defense, the Japan and South Korea desks at State, U.S.

Embassy Tokyo, U.S. Embassy Seoul, and the U.S. Consulate General to

Naha, Okinawa.

To identify funds obligated for the U.S. military’s presence in Japan and

South Korea, we obtained and analyzed obligated funding data from the

Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force for calendar years 2016

through 2019.

4

Specifically, we sent a request for obligated funding data

to the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force for their military presence

in Japan and South Korea associated with the following five appropriation

accounts: (1) military personnel, (2) operation and maintenance, (3)

family housing operation and maintenance, (4) family housing

construction, and (5) military construction. Each service submits

obligations data for these five appropriation accounts to the Office of the

Under Secretary of Defense Comptroller for each country in which the

service has a permanent presence that costs greater than $5 million to

maintain per year. Then, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense

Comptroller combines the data from each service and prepares the

Overseas Cost Report, which includes the OP-53 budget exhibit, which