The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: The Shifting Structure of Chicago’s Organized

Crime Network and the Women It Left Behind

Author(s): Christina M. Smith

Document No.: 249547

Date Received: December 2015

Award Number: 2013-IJ-CX-0013

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally

funded grant report available electronically.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

THE SHIFTING STRUCTURE OF CHICAGO’S ORGANIZED CRIME

NETWORK AND THE WOMEN IT LEFT BEHIND

A Dissertation Presented

by

CHRISTINA M. SMITH

Submitted to the Graduate School of the

University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

September 2015

Sociology

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

© Copyright by Christina M. Smith 2015

All Rights Reserved

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

DEDICATION

For my sister, who wanted me to write a dissertation about gender.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing a dissertation does not take a village. It takes a social network—

especially a social network of durable professional and personal ties. First and foremost, I

thank Andy Papachristos for his incredible mentorship, investment, training, creativity,

sense of humor, and support. Social ties predict outcomes, and Andy made the process

toward the outcome fun, engaging, fruitful, and inspiring. Don Tomaskovic-Devey has a

high degree of mentorship ties to some of my favorite sociologists. I am fortunate that

Don shared his relational resources, friendship, and mentorship with me. Bob Zussman

thinks creatively and relationally. He convinced me that there was something in this

dissertation topic when I could not see it, and he continued to push me to see it. Jen

Fronc’s period expertise, historian’s voice, and writing inspired me to not neglect the

historical narrative. It has been a pleasure and an inspiration to work with these four

intellectual giants.

University of Massachusetts Amherst Sociology is a dense section of my social

network full of amazing people. I owe many thanks to Beth Berry, Roland Chilton, David

Cort, Christin Glodek, Rob Faulkner, Naomi Gerstel, Sanjiv Gupta, Sandy Hundsicker,

Janice Irvine, James Kitts, Jen Lundquist, Karen Mason, Joya Misra, Wenona Rymond-

Richmond, Laurel Smith-Doerr, Millie Thayer, Barbara Tomaskovic-Devey, Maureen

Warner, Wendy Wilde, and Jon Wynn. UMass Sociology became increasing multiplex

through friendships with my brilliant fellow graduate students. Thank you Dustin Avent-

Holt, Irene Boeckmann, Laura Heston, Missy Hodges, Ken-Hou Lin, Elisa Martinez,

Sarah Miller, Mary Scherer, Eiko Strader, Mahala Stewart, and Ryan Turner. Melinda

Miceli was my broker to UMass, and I thank her for my introduction to sociology at the

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

vi

University of Wisconsin- Eau Claire, mentoring me through graduate school applications,

encouraging me to apply to UMass, and for friendship throughout the years.

I received assistance from archivists and research coordinators at the Chicago

Crime Commission, Chicago History Museum, and the National Archives Great Lakes

Region—special thanks to Scott Forsythe and Matt Jacobs for their assistance in the

archives. This dissertation received support from the National Science Foundation under

Grant number 1302778, the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S.

Department of Justice under Award number 2013-IJ-CX-0013, the University of

Massachusetts Amherst Graduate School, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Department of Sociology.

Personal ties brought balance and support during graduate school. Thank you

Soha Achi, the Alegria family, Jess Barrickman, Eric Burri, Tesa Z. Helge, the Hill

family, the Jensen family, Amanda Lincoln, Katie Trujillo, Rachel Weber, and Nicole

Wilson. My siblings, Amber and Matt Smith, have been with me on this journey since

they were too young to remember. Much of what I do is for them. Sharla Alegria brings

joy, adventure, and brilliance to our home every day. Thank you, Sharla, for this

wonderfully multiplex social tie.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

vii

ABSTRACT

THE SHIFTING STRUCTURE OF CHICAGO’S ORGANIZED CRIME

NETWORK AND THE WOMEN IT LEFT BEHIND

SEPTEMBER 2015

CHRISTINA M. SMITH, B.A., UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- EAU CLAIRE

Ph.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST

Directed by: Professor Andrew V. Papachristos and

Professor Donald Tomaskovic-Devey

Women are underrepresented in crime and criminal economies compared to men.

However, research on the gender gap in crime tends to not employ relational methods and

theories, even though crime is often relational. In the predominantly male world of

Chicago organized crime at the turn of the twentieth century existed a dynamic gender

gap. Combining social network analysis and historical research methods to examine the

case of organized crime in Chicago, I uncover a group of women who made up a

substantial portion of the Chicago organized crime network from 1900 to 1919. Before

Prohibition, women of organized crime operated brothels, trafficked other women, paid

protection and graft fees, and attended political galas like the majority of their male

counterparts. The 1920 US prohibition on the production, transportation, and sale of

alcohol was an exogenous shock which centralized and expanded the organized crime

network. This organizational restructuring mobilized hundreds of men and excluded

women, even as women’s criminal activities around Chicago were on the rise. Before

Prohibition, women connected to organized crime primarily through the locations of their

brothels, but, during Prohibition, relationships to associates of organized crime trumped

locations as the means of connection. Relationships to organized crime were much more

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

viii

accessible to men than to women, and consequently gender inequality increased in the

network. The empirical foundation of this research is 5,001 pages of archival documents

used to create a relational database with information on 3,321 individuals and their

15,861 social relationships. This research introduces a unique measure of inequality in

social networks and a relational theory of gender dynamics applicable to future research

on organizations, criminal or otherwise.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................v

ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vii

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. xi

LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... xii

CHAPTER

1. LOCATING WOMEN IN ORGANIZED CRIME NETWORKS ..........................1

Gender & Crime .......................................................................................................6

Women & Organized Crime ..................................................................................10

Research Questions ................................................................................................13

Social Network Analysis ........................................................................................14

Historical Methods .................................................................................................16

Data ........................................................................................................................18

Sample ....................................................................................................................24

Chapter Outline ......................................................................................................31

Notes ......................................................................................................................36

2. WOMEN IN CHICAGO ORGANIZED CRIME, 1900-1919 ..............................40

The Laws ................................................................................................................41

The Sex Economy ..................................................................................................46

The Three Levees ...................................................................................................53

The Corruption .......................................................................................................59

The Vice Syndicate ................................................................................................66

The Women of the Syndicate .................................................................................70

The Closing of the Levees .....................................................................................74

Conclusion .............................................................................................................80

Notes ......................................................................................................................82

3. WOMEN IN CHICAGO ORGANIZED CRIME, 1920-1933 ..............................92

The Amendments ...................................................................................................94

The Women of Prohibition ....................................................................................98

The Syndicate .......................................................................................................104

The Associates .....................................................................................................114

The Women of Organized Crime .........................................................................117

The End of Prohibition .........................................................................................129

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

x

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................132

Notes ....................................................................................................................134

4. THE SHIFTING STRUCTURES OF ORGANIZED CRIME ............................143

Chicago Organized Crime Network, 1900-1919 .................................................147

Chicago Organized Crime Network, 1920-1933 .................................................163

Increasing Inequality ............................................................................................174

The Criminal Elite ................................................................................................179

Discussion ............................................................................................................188

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................191

Notes ....................................................................................................................194

5. CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................195

Limitations ...........................................................................................................198

Contributions .......................................................................................................202

Implications & Future Directions ........................................................................205

Notes ....................................................................................................................208

BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................209

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1. Primary and secondary sources ........................................................................... 21

2. Capone Database totals ....................................................................................... 23

3. Sample totals, 1900-1919 and 1920-1933 .......................................................... 30

4. Structural properties of Chicago organized crime network, 1900-1919 ........... 147

5. Organized crime network properties by gender, 1900-1919 ............................ 151

6. Structural properties of Chicago organized crime networks compared,

1900-1919 and 1920-1933 .......................................................................... 164

7. Organized crime network properties by gender, 1920-1933 ............................ 166

8. Degree for elite men, non-elite men, and women in Chicago organized

crime, 1900-1919 and 1920-1933 ............................................................... 180

9. Gender inequality in two organizational structures .......................................... 192

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Page

1. All Capone Database criminal ties from 1900-1919 and 1920-1933 ................. 27

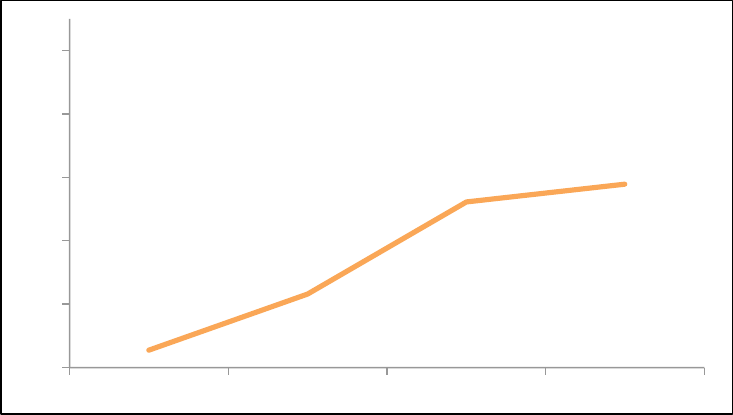

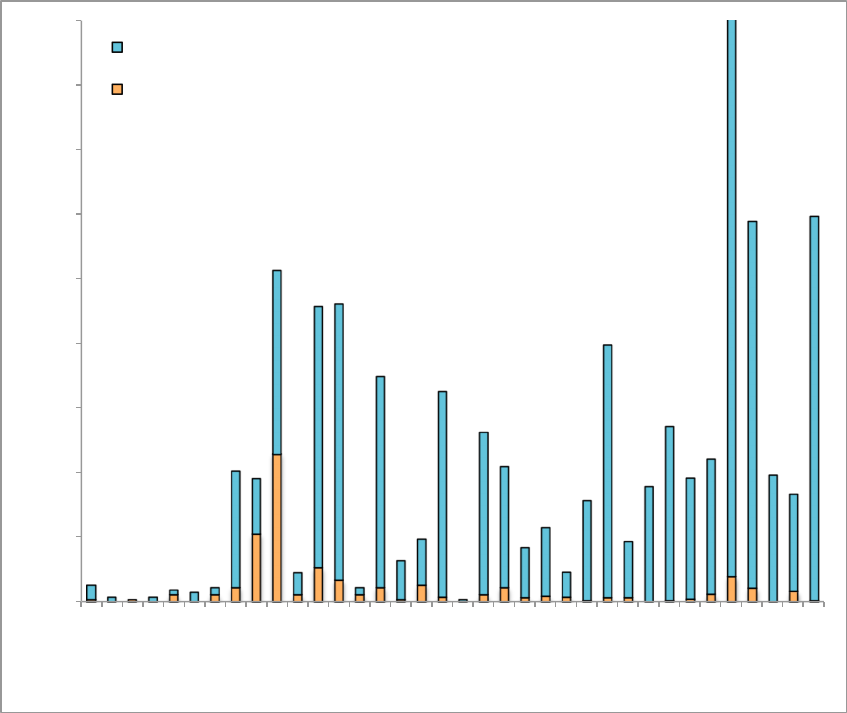

2. Women’s percent of alcohol related addresses in Chicago, 1900-1933 ........... 102

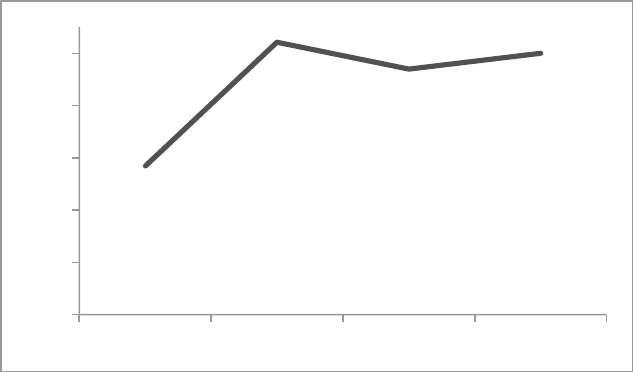

3. Women’s percent of prostitution related addresses in Chicago, 1900-1933 .... 128

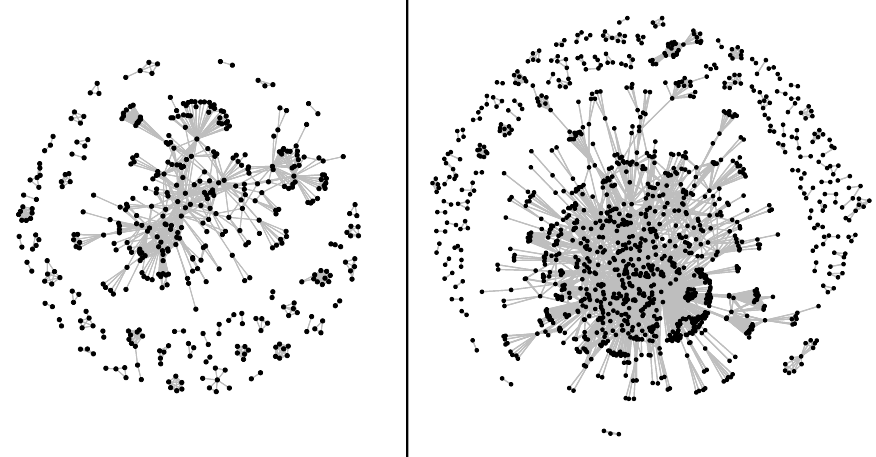

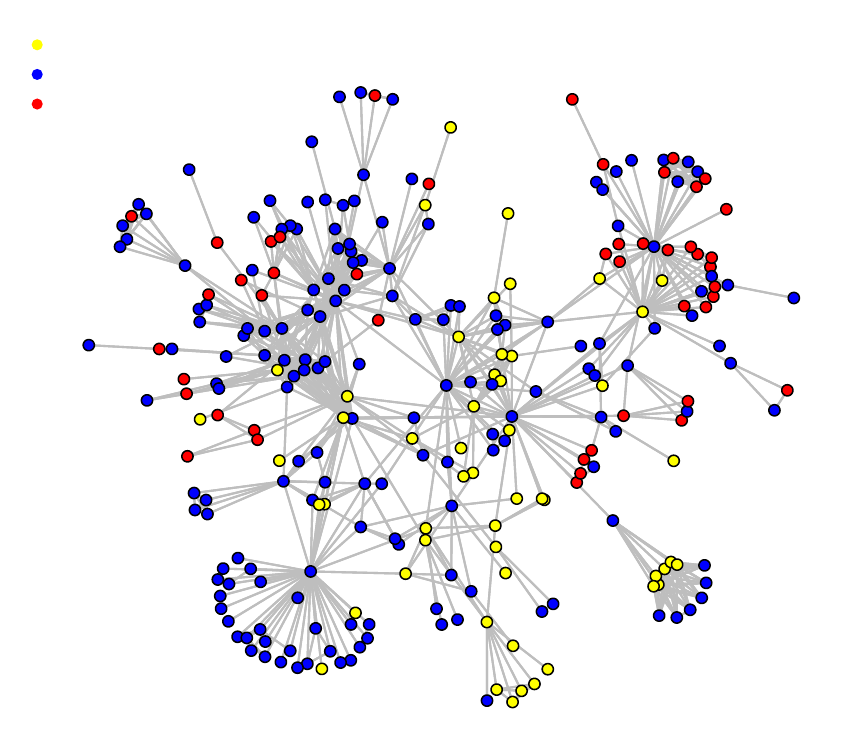

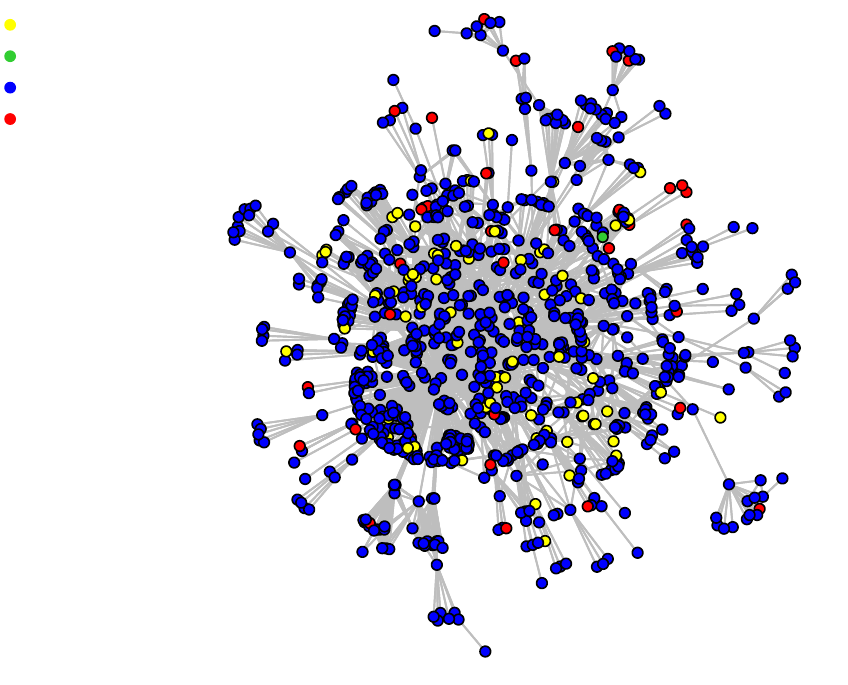

4. Chicago organized crime network, 1900-1919 (n=267) ................................... 148

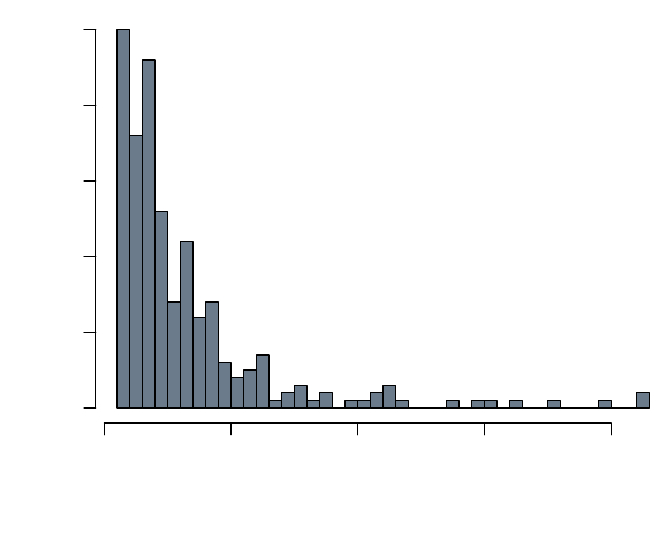

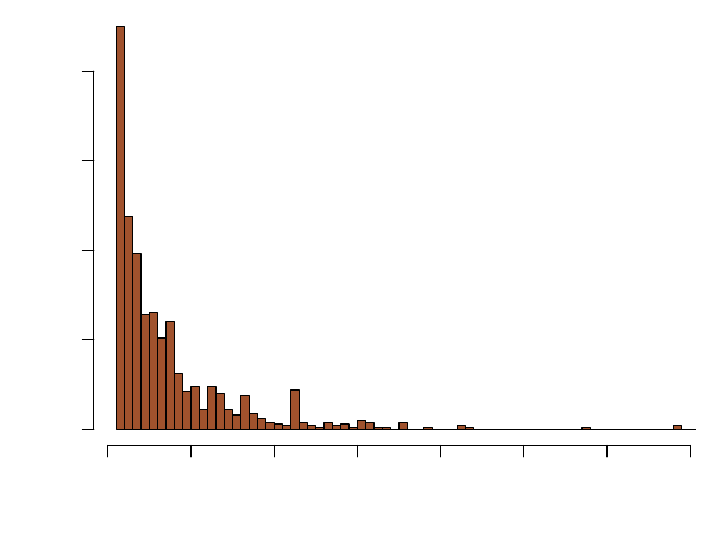

5. Histogram of degree distribution in Chicago organized crime, 1900-1919 ...... 154

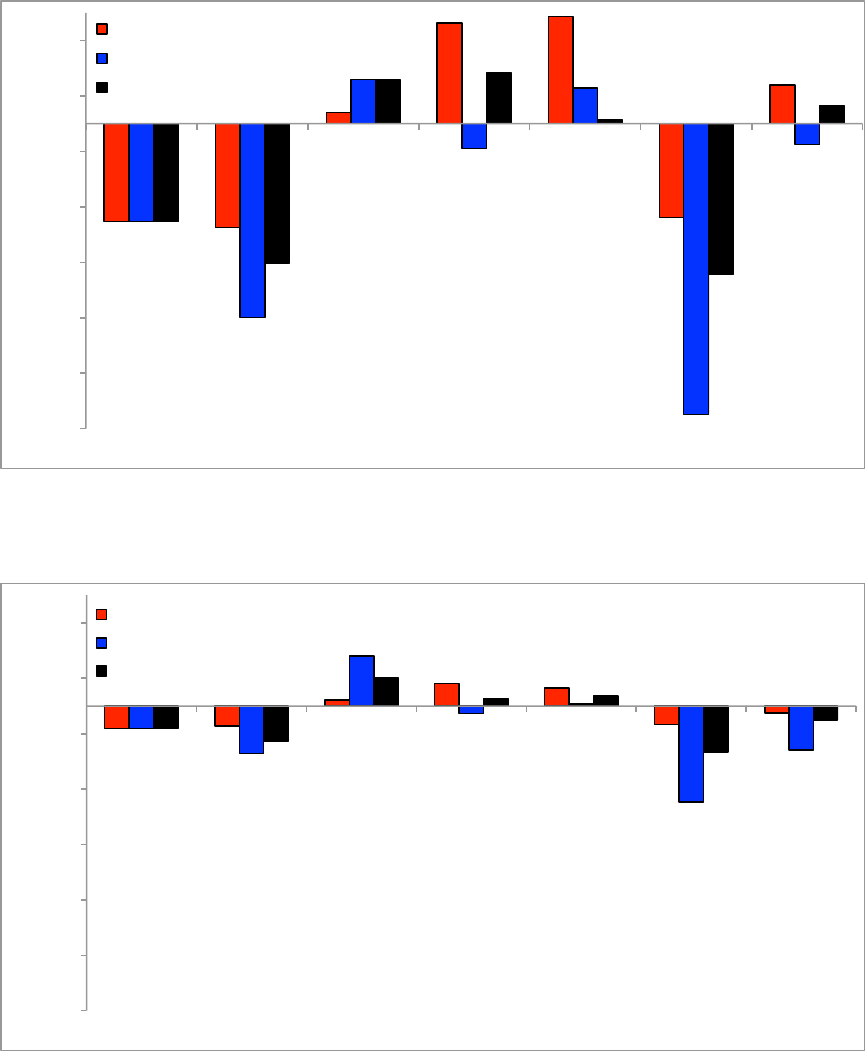

6. Change in structural properties of the Chicago organized crime network

after deletion techniques, 1900-1919 .......................................................... 159

7. Chicago organized crime network, 1920-1933 (n=937) ................................... 165

8. Histogram of degree distribution in Chicago organized crime, 1920-1933 ...... 168

9. Change in structural properties of Chicago organized crime network after

deletion techniques, 1920-1933 .................................................................. 173

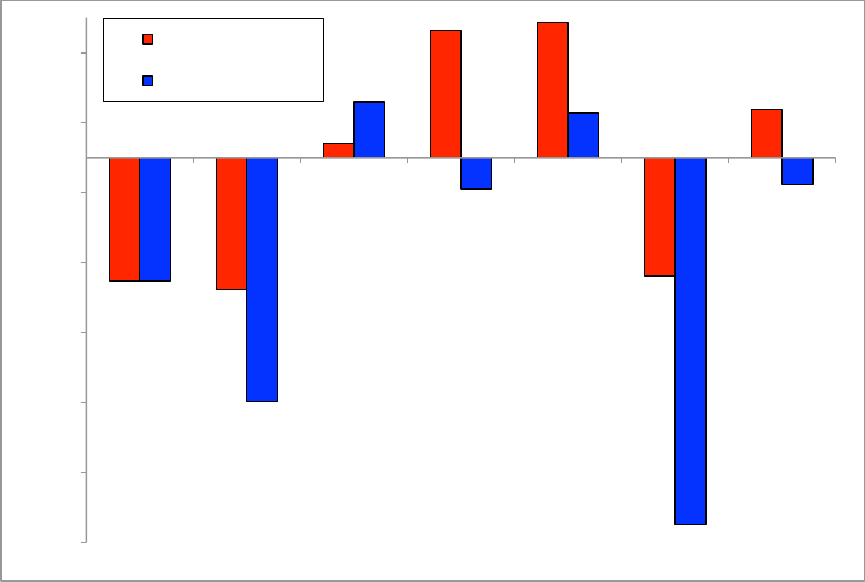

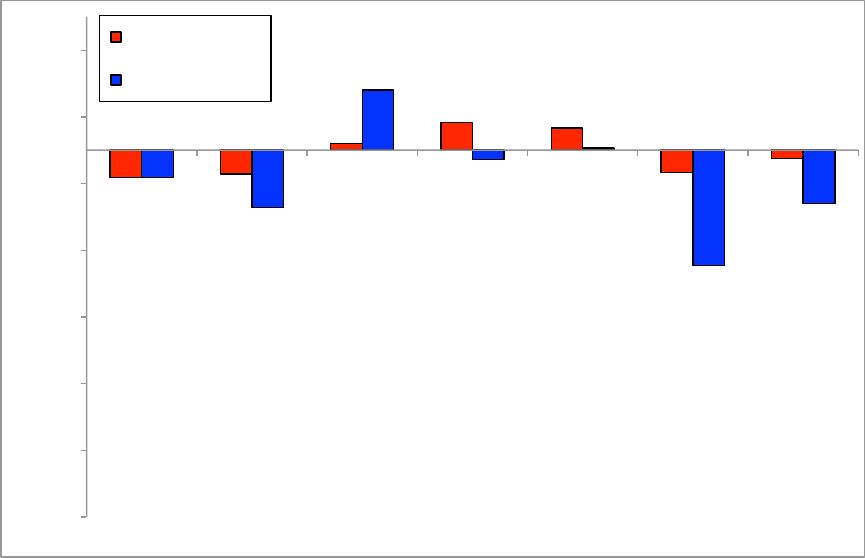

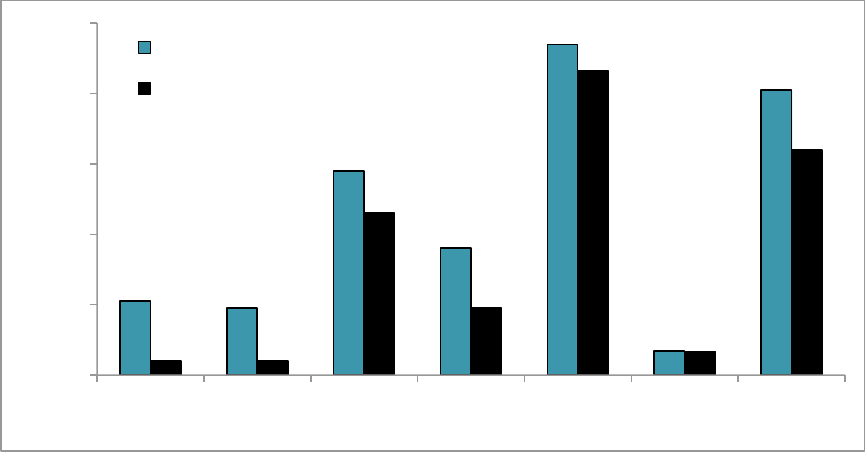

10. Bar chart comparing the gender gaps, 1900-1919 and 1920-1933 ................... 175

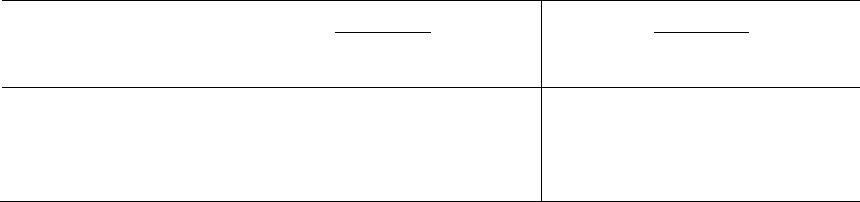

11. Bar chart comparing the elite gaps between elite and non-elite men, 1900-

1919 and 1920-1933 ................................................................................... 181

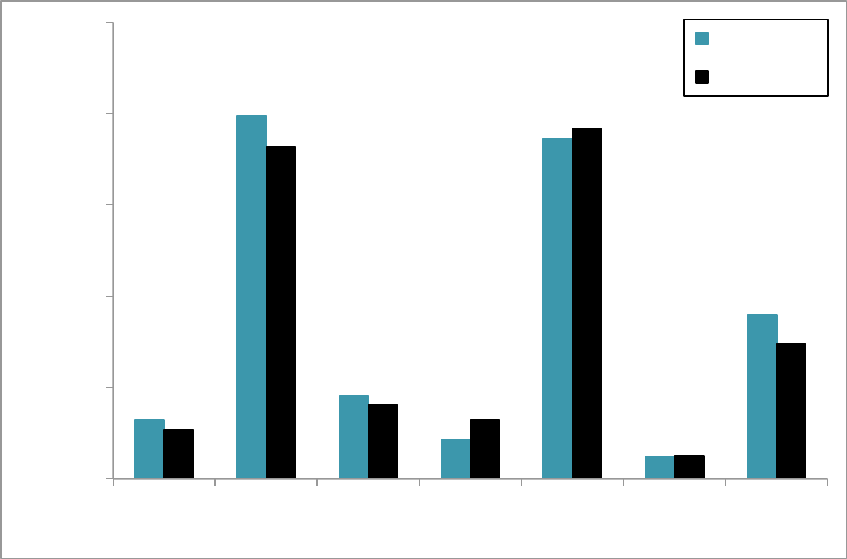

12. Bar chart comparing the gender gaps between non-elite men and women,

1900-1919 and 1920-1933 .......................................................................... 182

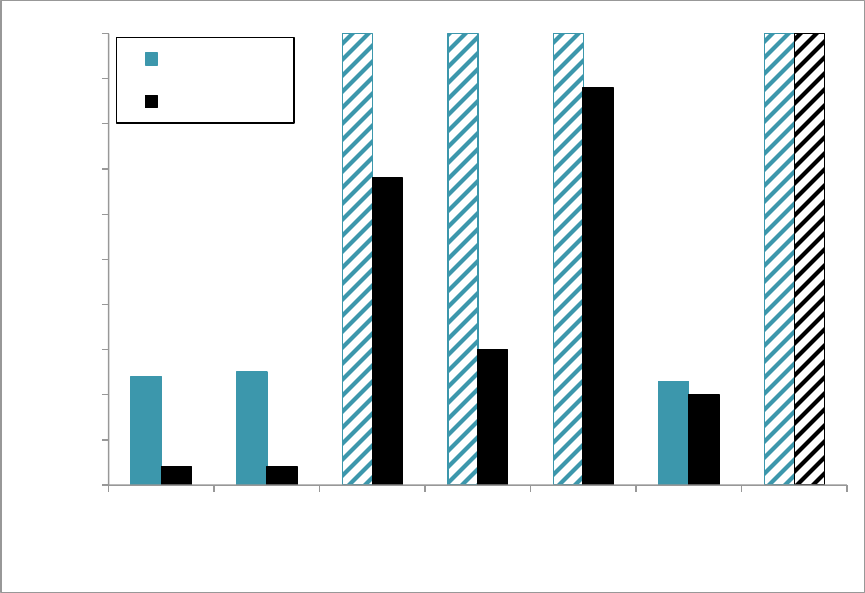

13. Change in structural properties of the Chicago organized crime network

after deletion techniques, 1900-1919 .......................................................... 186

14. Change in structural properties of the Chicago organized crime network

after deletion techniques, 1920-1933 .......................................................... 186

15. Percent of organized crime dyads per year, 1900-1933 .................................... 190

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

1

CHAPTER 1

LOCATING WOMEN IN ORGANIZED CRIME NETWORKS

Vic Shaw was a woman of Chicago’s underworld for nearly 50 years. Shaw was a

successful woman in Chicago’s organized crime network before Prohibition through her

brothels located in Chicago’s red-light district, her friendships with corrupt politicians,

and her marriage to a gangster. However, as Prohibition caused the structure of organized

crime to shift in ways that excluded women, organized crime left Shaw behind. Shaw

sold booze, sex, and narcotics in isolation from the organized crime network but her

businesses suffered.

Vic Shaw arrived in Chicago at the age of 13 around the time of the 1893 World’s

Columbian Exposition.

1

Her real name was Emma Fitzgerald, and she had run away from

her parents’ home in Nova Scotia. As her first job in Chicago, she became a burlesque

dancer. One night after her performance, a socialite named Ebie, whose parents were

Chicago millionaires, ran away with Shaw to Michigan where he convinced her that they

had gotten married. Ebie’s family lawyer caught up with the young couple posing as

newlyweds and informed them that they were indeed not legally married and that Ebie

had committed a crime, as Shaw was a juvenile. Upon their return to Chicago, the lawyer

arranged a large payout to Shaw in exchange for her leaving Ebie and Ebie’s family

alone.

2

Shaw suddenly had more money than she knew what to do with, and her friends

advised her to use it to open brothels—so she did. In the beginning, Shaw was not a great

entrepreneur, as she was “more interested in men than the business,” but by the turn of

the twentieth century Shaw was operating two successful luxury brothels in Chicago’s

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

2

red-light district.

3

She had little competition in the luxury brothel market and good legal

and political protection arranged through her corrupt friends and organized crime

associates, Aldermen Michael Kenna and John Coughlin. According to Chicago’s

organized crime world, Shaw was their “queen.”

4

Reporter Norma Lee Browning interviewed Vic Shaw at the age of 70 to reflect

on her 50 plus-year career in Chicago’s underworld.

5

The Chicago Tribune published

Shaw’s interview in a three part series in 1949 just a few years before her death.

6

Shaw

confessed to Browning her one regret, “‘Listen, chicken,’ [Shaw said] philosophically, ‘I

wouldn’t trade places with anybody. If I had it to do over again, I’d live every day just

the same except for one thing. The only regret I have is giving up a good man like

Charlie to marry Roy Jones.’”

7

Charlie was one of Shaw’s lovers, a hotelman who bought

Shaw her brownstone at 2906 Prairie Avenue, where she ran a brothel during Prohibition

and where she spent her later years running a hotel for transients.

8

When Shaw expressed regret over losing Charlie, she was referring to when she

eloped to New York City with Roy Jones, another Chicago brothel keeper. Jones was one

of several men of Chicago organized crime who married a successful brothel madam,

greatly increased his own income and influence, and eventually divorced the madam for a

younger woman—who, in Roy’s case, was a sex worker and Shaw’s employee.

9

However, the case of Vic Shaw and Roy Jones is much more than a tragic tale of a man

building his career through his wife and then leaving her. Tracing Vic Shaw and Roy

Jones’s paths within organized crime highlights the particular dynamics of gender

inequality in organized crime networks during Prohibition, leaving formerly successful

women like Shaw behind. This introduction will use the contrast between Shaw and

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

3

Jones and their relationships to organized crime to summarize the central argument of

this dissertation about organizational change and increasing gender inequality.

From 1900 to 1919, Chicago organized crime was a loose, decentralized

syndication of politicians, police officers, collectors, and gambling and prostitution

business owners. Coordinating collection of protection and bribery fees and the

corruption of legitimate offices, organized crime was largely territorial, focusing on

geographically concentrated districts of illicit businesses. Entrepreneurial women

connected rather easily to the specialized market of organized crime through the location

of their brothels. Location mattered for both Shaw’s and Jones’s early connections to

organized crime before their marriage.

During their marriage, while Jones’s connections

to organized crime grew as he developed new relationships and expanded business,

Shaw’s connections shrank. She continued to draw her benefits from organized crime, but

now through Jones.

10

When Illinois state’s attorney John Wayman forced the closing of the Chicago

red-light districts in 1912, organized crime shifted to opening and protecting new

unsanctioned red-light districts—a transition which included Jones, but excluded Shaw.

Structurally organized crime remained small and decentralized, and the specialized

protection market still focused on specific territories in the city. The need for protection

increased with new laws and regulations challenging the sex work economy. Around this

time, Shaw and Jones divorced. Following the closing of the red-light district and her

divorce, Shaw opened a more discreet brothel on Michigan Avenue and expanded

business into the distribution of narcotics. Shaw was unable to connect her new business

to the protection offered by organized crime and, as a result, faced regular raids by police

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

4

and morals inspectors. During a 1914 raid on her resort led by morals inspector

Dannenberg, Shaw was so fed up with Inspector Dannenberg that she refused to leave her

bed and held a revolver threatening to shoot Dannenberg if he tried to get her.

11

Meanwhile, Roy’s businesses thrived—even the ones located in a formally closed red-

light district—because of his strong connections to organized crime. This transition

period slightly shifted the locations of organized crime’s territories, but women with

brothels in the new districts could still get protection and connect to organized crime.

12

The major structural reorganizing that excluded many women would come in 1920 with

the passage of Prohibition.

The US Prohibition of the production, transportation, and sale of intoxicating

beverages dramatically altered the structure of organized crime. Organized crime tripled

in size, became a more centralized organization, spread geographically into the

neighboring villages, and surged in profits and influence. During Prohibition, organized

crime’s market became less territorial and less specialized. Gambling and prostitution

were still an important part of organized crime, generating even greater profits with the

additional sales of bootleg booze. At the same time, organized crime diversified its

overall portfolio to include bootlegging, labor racketeering, political corruption, and

racetracks in addition to multiple legitimate businesses.

The consequence of this restructuring was that the locations of individual

businesses mattered less as a means of connecting to organized crime. Entrée to the

restructured organization required relationships to crime bosses or associates rather than a

having a business in a particular territory. These relationships tended to be between men

and men excluded women from these relationships—a process that began with and

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

5

produced greater gender inequality. For example, following Prohibition, Shaw moved her

own business into bootlegging where she exploited the underground passages of her

brothels to move and store booze.

13

But even with her prime location in the central city,

she was not able to connect to organized crime during Prohibition. While her ex-husband

Roy ran a protected Al Capone brothel during Prohibition, Vic encountered police raids

and charges of violating Prohibition laws.

14

In this dissertation I argue that from 1900 to 1919 the Chicago organized crime

network was small, sparse, and decentralized, operating a territorial and specialized

market of protecting illicit businesses through the corruption of legitimate offices. This

organizational structure provided some limited opportunities for women. During this

period, women made up a substantial portion of the organized crime network (18 percent)

when they could connect to organized crime based on the location of their illicit

businesses and ran their prostitution establishments relatively autonomously.

This all changed in 1920 when Prohibition criminalized the desired and profitable

product of alcohol. The Chicago organized crime network responded to the new

criminalized market by multiplying in size, centralizing around a core of gangsters and

politicians, and spreading geographically to villages outside the city. This revamped

market was less territorially concentrated because the demand for booze spread much

farther geographically than the boundaries of the red-light districts. This organizational

structure excluded women who dropped to only 4 percent of organized crime associates

during Prohibition—a 14 percent decrease. Connecting to organized crime during

Prohibition required relationships to organized crime associates more so than illicit small

business locations. Relations trumped locations, exacerbating gender inequality in

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

6

organized crime because women could not access the relationships to associates like men

could. Organized crime required trusting and instrumental relationships between criminal

associates when it engaged in riskier markets, like bootlegging. Men in organized crime

sought these relationships with other men and not women. Even though the proportion of

women’s criminal establishments in booze and prostitution were increasing during

Prohibition, men excluded women from the protection offered by organized crime. The

organization had gotten too big and the market too spread out for entrepreneurial

women’s small businesses to be included.

Organizations, whether formal, informal, licit, or illicit, unequally distribute

relationships and the resources afforded by those relationships. Organizational inequality

is dynamic and can worsen when exogenous shocks force restructuring and redistribution.

In the predominantly male world of Chicago organized crime existed moments of less

and greater gender inequality; this shift in the gender gap in crime in the Chicago

organized crime network deserves interrogation. Vic Shaw and Roy Jones started at

similar points in the Chicago underworld, but once in the organized crime network

women and men did not form new relationships equally. When relationships produce

outcomes such as jobs, political affiliations, country club memberships, promotions, and

access to organized crime, we need to consider the inequality not just in the outcomes,

but also in the inequality residing between relationships.

Gender & Crime

Men dominate crime and criminal economies. According to the Bureau of Justice

Statistics, 75 percent of all arrests in 2010 were men, and men accounted for 93 percent

of the prison population (state and federal).

15

As gender gaps go in the US, the gender

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

7

gap in crime is among the largest. Research shows that men and women often have

similar motivations for committing crimes—e.g., money, respect, safety, and status—but

that gender greatly impacts the various ways crimes are enacted and completed.

16

For

example, research on home burglars and street robbers show that both men and women

offenders equally commit crimes for money, but gender influences their decisions on

weapons, co-offenders, targets, and risk.

17

The gender gap in crime is largely a phenomenon of the past 200 years. Legal

scholars Malcolm Feeley and Deborah Little’s research on the gender gap in crime

examined 226 years of British court data from 1687 to 1912.

18

They found that that 30 to

40 percent of convictions from the late 1600s to the late 1700s were women, and it was

not until the 1800s that the gender gap began increasing toward its present-day rates.

Feeley and Little argued that the dramatic gender gap in crime was largely a product of

historical and cultural shifts around the ideals of womanhood.

The gender gap in crime is also partly explained by the fact that relationships are

gendered and give differential access to crimal activities. Initiation to crime is an

interactional process between people that transfers the knowledge and skills to commit

crime and the values to support crime in contrast to the law.

19

Compared to men, women

tend to be in weak criminal networks with less access to criminal initiation and less

access to relationships containing skills and influence. Men tend to access crime through

their family, peers, and mentors—almost all of whom are other men.

20

When women

engage in criminal activity, research shows that women’s entrance to offending is

frequently through their husbands and romantic partners.

21

Romantic partners and

husbands become the gatekeepers, or brokers, of women’s access to crime. Research on

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

8

legitimate workplaces shows that for women to improve their positions in firms they

must rely on or borrow social capital from men in the workplace.

22

Women also borrow

men’s social capital when it comes to crime. Research on co-offending shows the pattern

of women’s lack of social capital in crime: men tend to co-offend with men, women co-

offend with men, but seldom do women co-offend with women.

23

When criminals access

their social networks for co-conspirators, they access relationships with men and ignore

their relationships with women.

Criminology lacks a strong theory as to why criminal relationships tend to

exclude women with such regularity. One possible inequality-producing mechanism is

the trust and concealment required in these relationships, but the results from research on

crime, trust, and gender are mixed. Some research has found that men of the underworld

unabashedly admit that they think women cannot be trusted, and they categorically

exclude women from illicit economies and underworld organizations.

24

Men’s accounting

for women’s exclusion relays stereotypes of women as weak, gossips, or opportunistic

gold-diggers.

25

In contrast, other scholars have found that criminally involved men

consider the women in their lives, especially their wives, most trustworthy.

26

Sociological and criminological research show that particular organizational

forms constrain women’s opportunities more than other organizational forms. Flat team-

based organizations provide better conditions for women’s careers than large, durable,

and hierarchical institutions.

27

A small but excellent literature on criminal markets and

gender consistently shows that women have greater crime opportunities when markets are

more open, flat, and decentralized rather than closed and hierarchal. This is especially the

case in drug markets.

28

Patricia Adler described drug dealing and smuggling at her

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

9

research site in the Southwest as a market of free enterprise, entrepreneurialism,

disorganization, short-term deals, and high turnover.

29

Women could participate as high-

level dealers in this type of market with the knowledge and connections gained from their

dealer boyfriends and ex-husbands—although women dealers struggled if men refused to

deal with or didn’t trust them.

30

In contrast, Lisa Maher found that the drug markets in New York City were

vertical hierarchies with tiers of “well-defined employer-employee relationships.”

31

In

this criminal market, women, with one exception, were completely absent from the boss

and management tiers of the hierarchy, and a very small number of women worked in the

lowest levels of street dealing and only on a temporary basis.

32

Instead, women found

work in the peripheral sex market, a market so intrinsically connected to the drug market

that as the drug economy grew, the profits for sex work lowered and violence against sex

workers increased.

33

This gendered pattern of organizational structure is not just applicable to drug

markets as research on Chinese human smugglers finds this same pattern of women’s

increased participation in flatter organizations. Chinese human smuggling operations are

sporadic and completely decentralized, relying on a long chain of one-on-one interactions

between individuals who fill only a single role in the smuggling process.

34

Women fill

some of these roles, and women’s presence alleviates some families’ concerns for safety

while negotiating the smuggling of women and children.

35

If we are going to find

increased opportunities for women in criminal organizations in a society with high gender

barriers in interaction and expectations, we need to look to flat decentralized

organizations that create the structural space for women to prosper.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

10

Women & Organized Crime

Scholars have been debating the usefulness of the term “organized crime” for

decades.

36

Criminologist Klaus von Lampe traced the history of the term’s origin and

found that the Chicago Crime Commission coined the term “organized crime” in 1919 in

reference to Chicago’s estimated 10,000 professional criminals who conducted crime in

an orderly, business-like fashion.

37

The term “organized crime” went dormant for a

while, but we have Senator Estes Kefauver’s Senate Committee of the 1950s and Mario

Puzo’s 1969 novel The Godfather to thank for the more mainstream conceptualizations of

organized crime as a national hierarchical syndicate imported with Sicilian blood oaths.

38

In some organized crime groups, a defining feature of organized crime by

members, especially mafia members, is its complete absence of women.

39

While there

certainly is no argument against organized crime as being dominated by men, it is

illogical to assume a complete absence of women in an organization that centers on

family and kin.

40

Needless to say, research, especially feminist research, complicates the

notion of organized crime as only masculine by uncovering cases of women connected to

organized crime. Women’s presence and importance in organized crime is more of a

question for the empirical networks than an abstract definition generated by mafia men.

It is no easy task for law enforcement or researchers to specify the boundaries of

the label of organized crime: on who to include and who not to include. When applying

the label, researchers’ judgment is often clouded by preconceived notions of organized

crime as only masculine, when in reality women have always been involved. Historical

research has challenged preconceived notions that women were not involved in organized

crime and instead revealed the connection between organized crime and work for poor,

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

11

often immigrant, women at the turn of the twentieth century in New York. Alan Block

identified over 300 women in New York organized crime rings involved in prostitution,

theft, drug dealing, and managing brothels and gambling dens.

41

Rona Holub’s research

uncovered an organized crime ring led by “Queen of Fences” Fredericka “Marm”

Mandelbaum, who syndicated a network of men and women thieves and amassed

approximately $1 million from stolen goods.

42

Research on contemporary cases of mafia-

like organizations shows a range of women’s involvement from silent complicity to

collecting money for and relaying messages to their incarcerated partners.

43

The

‘Ndrangheta mafia group in Milan has a kinship structure that assumes women in

leadership and work positions.

44

These women in organized crime were not just

exceptions to some masculine organization rule or dismissible anecdotes.

Since the 1970s, empirical research on organized crime has focused on (a) the

social system of overlapping kinship, neighborhood, and village ties, or (b) the

coordination between illegal enterprises and legitimate society.

45

For the purposes of this

research, organized crime was the largest constellation of connected criminal ties

between gangsters, politicians, law enforcement, and other associates embedded in

Chicago’s criminalized markets of protection, sex, gambling, and alcohol. At the level of

the dyads, most criminal relationships were not terribly interesting, such as co-offenses or

exchanges of money for illegal products and services. However, there were hundreds of

these seemingly minor criminal relationships that revolved around prominent actors

whose influence on these relationships imposed an organizational structure. The criminal

relationships of organized crime were not just a random smattering of co-offenses, they

contributed to the larger structure of control and access to criminal, political, and legal

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

12

resources. I am agnostic to the theories implying a particular organized crime structure—

e.g., patriarchal patrimonialism, illegal enterprise, patron-client models—because the

network itself reveals the structure and how that structure changes over time.

46

Additionally, the network reveals women’s proportions and positions in organized crime.

Generally, academics and policymakers are comfortable arguing for women’s

equality in wages or promotions within formal organizations, but this is not necessarily

the case when applying the logic of women’s equality in organized crime or equality in

offending more generally. Locating women in organized crime or identifying contexts in

which the gender and crime gap is lower is not the same as saying we need more women

criminals. For decades, feminist criminology has been dismantling the trope of “bad

girls” that equates women offenders with failed traditional gender performance.

47

The

goal of research on the gender crime gap is to dismantle law enforcement, courts,

archives, and, more broadly, society’s essentializing assumptions about women as

peaceful, maternal, and pro-social. In doing so, we can interrogate if and how these

essentializing gender assumptions interact with processes of recruitment, segregation, or

exclusion in crime. If the gender gap in crime is because of women’s unequal access to

criminal relationships, then the gender gap theory is not about some difference between

men and women. It is about relational inequality. Feminist researchers should attend to

the relational preconditions, not only for exclusion, erasure, and, subordination, but also

for inclusion, prominence, and respect. Moving to the roots of unequal relationships is an

important theoretical direction for criminology.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

13

Research Questions

When I first began coding the early twentieth century Chicago organized crime

network, I routinely came across vague mentions of women engaged in a variety of

organized crime activities. This dissertation started from a rather simple two-part

question: Were women important to the organized crime network, and, if so, in what

ways? But this simple question did not have a simple answer. Throughout my analysis I

found notable variation in women’s participation in organized crime over time warranting

additional consideration, specifically around the changes accompanying Prohibition.

Women were more present in pre-Prohibition organized crime than during Prohibition. I

shifted the project to a more nuanced and sequential set of research questions grounded in

the theories of organizations and relational inequality: (1) What was the structure of

Chicago organized crime before Prohibition, and how did women fit into that structure?

(2) How did the shock of Prohibition, and accompanying legal changes, change the

structure of organized crime in Chicago, and how did women fit into this revised

structure? From these questions I have come to document increasing gender inequality

across the two points in time, which produced my third and final research question: (3)

Why did gender inequality increase so dramatically in organized crime? To document

change over time I needed precise measurements of organizational structure plus

measures and statistics to calculate and compare gender gaps. To understand why

organized crime and gender inequality changed so dramatically, I needed historical detail

and historical causality. I concluded that these research questions would be unanswerable

without the mixed methods of social network analysis and historical narrative.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

14

Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis is the growing field of theory and method that centers on

the social relationships among sets of actors and analyzes how the patterns of

relationships affect various outcomes.

48

Social network research gathers, compares, and

analyzes multiple network properties at the individual, group, and system level in order to

describe organizational types, structural changes over time, and patterns of behavior,

influence, and interaction. Historians and social scientists have been plowing forward

with the tools and theories of social network analysis, but the same has not held true for

feminist scholars. Additionally, social network scholarship has tended to be weak on

gendered and intersectional analyses; the scholarship has been largely stuck on treating

gender as little more than an attribute variable failing to recognize the larger theoretical

potential of gendered relationships. Computational advances have driven many social

network research questions, but less work has rigorously applied these new methods to

classic sociological questions of inequality.

Criminologists have employed formal social network analysis to examine the

structure of street and motorcycle gangs, organized crime syndicates, narcotics

distribution, terrorist organizations, and white-collar conspiracies.

49

New criminological

research is exploring the theoretical and empirical benefits of moving social network

analysis into prison research.

50

In some cases, social network analysis may be the only

way to study criminal groups. Ethnographic and survey based studies require a level of

detail and personal information that is not easily tapped when studying crime. It is

comparatively easier to get information on how people are connected (e.g., wiretaps, co-

arrests, gang affiliation, and who is hanging out with whom) than completed surveys or

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

15

interviews with crime-involved individuals. For example, analyses of wiretap data have

revealed many individuals who are not law enforcement targets or even known criminals

make up substantial portions of criminal communication networks, and in some cases

these non-targets hold important structural positions of reciprocity and brokerage in the

network.

51

Researchers have also used relational data from police field observations to

examine young men’s risk of violence across their gang networks in Boston’s Cape

Verdean neighborhoods.

52

These examples show that in contrast to cases of thin

individual-level data pertaining to the offenders, thick data on relationships has the

potential to reveal much about crime groups’ actions and outcomes.

My approach to social network analysis is to start with a classic sociological

question about gender inequality and use social network analysis to map out inequality

within an organization. The implicit assumption is that the category of difference

produces the network, but that the network perpetuates the category. This approach also

assumes that the network itself contains and distributes resources. The resources

contained in the relationships of the organized crime network are access to crooked

politicians, police officers, judges, fixers, and influential gangsters. Not being connected

to or near these individuals is a disadvantage for both women and men leading to

exclusion from the protection afforded by organized crime as well as the relatively high

income associated with this form of criminal activity.

There is an epistemological debate in social networks on context versus structure.

Emily Erikson summarized this debate as “relationalism versus formalism,” and

explained that the divide in social networks comes from differing theoretical assumptions

on issues of content, meaning, interaction, and agency.

53

On the relationalism side of the

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

16

debate, the interactions between actors situated in their historical and cultural context

generate meaning. On the formalism side of the debate, network structure predicts action

and this linkage permits generalizability, a priori categories, and theory testing. Erikson

proposed that empirical research has the potential to provoke a rich middle ground

between the two traditions.

54

Given the mixed methods approach to this project, I tend to side with the

relationalism stance in this debate because it provides the intellectual room to interrogate

the meaning of the social relationships in the networks and to examine closely the

historical moment in which the networks occurred. However, I also acknowledge that

generic network processes—such as homophily, status, power, and influence—are at play

and measuring and comparing these processes can provide insight to a variety of

contexts. I adhere to a dialectical approach between the networks and the historical

narrative and context to evolve meaning and develop theory. Inherent to this is that I treat

social network analysis as a logic of discovery for a particular set of events, group of

people, and historical moment more so than a logic of proof.

Historical Methods

The task for historical research is to master a particular moment and place and

read through the records of that moment in search of interpreting events, reinterpreting

received narratives, and uncovering new perspectives.

55

Historical researchers must read

records in their contexts, document and organize content, and constantly pose questions

as to the origin and purpose of the documents themselves.

56

Historical research methods

are not uncommon in sociology. Criminology, in contrast, has been reluctant to adopt

historical research methods. Robert Bursik used his 2008 presidential address at the

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

17

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology to remind criminologists to

remember the classics, to stop reinventing the wheel, and to return to the dusty shelves of

libraries and archives.

57

Historical methods allow social scientists to reveal process,

events, and even intentions, while applying the powerful analytical tool of time ordering

and causal process tracing.

Archives are not neutral spaces. They house the records of powerful families,

churches, and states, privilege institutional histories over individual and household

histories, silence historically marginalized groups, and wield the power to shape

memories and index collective histories.

58

Archives have often obscured women’s history

through male-dominated archiving efforts that ignored women’s contributions, physically

separating repositories for women’s records, and women’s own consideration of their

writings as inconsequential and not worthy of storage.

59

While the historical record will

always be incomplete, this is especially true for women’s histories.

Feminist historians bring a critical lens to institutional archives in order to locate

where women’s voices were intentionally or unintentionally buried. Jennifer Fronc

interrogated the records of private surveillance firms from the early 1900s in New York,

which included thousands of pages of reports written by undercover investigators.

60

Fronc explains the need to read between the lines and read the silences in these reports in

order to reveal how these organizations practiced and produced surveillance that in turn

developed cultural space for a more repressive state through targeting the working class,

women, African Americans, immigrants, and anarchists.

61

Cynthia Blair uncovered the

history of black women’s sex work in early 1900s Chicago through official Census

records, insurance papers, court documents, church records, city guidebooks, and songs,

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

18

but these sources did not foreground the voices of African American sex workers.

62

Blair’s critical lens on institutional archives acknowledged women’s lost voices, but

simultaneously recognized the available documentation of women’s activities.

63

These

historians demonstrate that the gender problem in history is not only in what is in the

archive, but in the gendered bias in what is retrieved from them.

Data

Organized crime constitutes a hidden population. Hidden populations are hidden

because their total population is unknown to the public, and the activities of the group are

largely unknown.

64

Hidden populations are difficult to study because entering institutions

as members of a hidden population, whether for medical treatment or filling out a survey,

unveils individuals’ previously hidden activities and identities. Strategies that have been

used to sample hidden populations include snowball sampling, respondent-driven

sampling, and targeted sampling.

65

A snowball sample is a chain of referrals that begins

with the informant or initial seed and multiplies as referrals from referees move farther

from the informant.

66

There is no population list of organized crime members from which

I could draw a truly random sample, so this project employed two snowball sampling

approaches, initially using Al Capone as the seed from which I grow the network of

affiliations. The first snowball sample was via sources and the second was via associates.

As a source-based seed, I used Al Capone as a search term to locate primary and

secondary sources, and then I coded the sources beyond their sections on Al Capone. This

is how I came across John Landesco’s Illinois Crime Survey of 1929 for example.

67

While searching for archival sources pertaining to Al Capone, I located a reference to the

Illinois Crime Survey. I ended up coding this source in its entirety even though Capone

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

19

appeared on only 40 of the 146 coded pages. This source-based snowball began with one

seed, Al Capone, but in this source I located 660 individuals other than Capone who were

also mentioned.

The origin of this project was also a source-based sample. The Chicago Crime

Commission (CCC) is a watchdog organization founded in 1919 by business leaders

concerned with corruption in Chicago. The organization still exists today and houses a

large card catalogue linking organized crime individuals through archive folders.

Requesting a random selection of consolidation files and public enemy files created a

random seed from which to start building the database. The CCC’s random selection of

files included many folders pertaining to Al Capone but also included consolidation

folders on a variety of major crime activities from the early 1900s and the CCC’s original

public enemy reports. The CCC folders contained mostly newspaper clippings, but there

were also some investigator notes, legal documents, letters to CCC members, arrest

records, and reports. This source-based snowball approach expanded the network beyond

Al Capone without having to manually locate and code every document from Prohibition

Era Chicago.

The second type of snowball sampling came via associates. For an associate-

based snowball, I used the list of names generated from Capone’s archives as a starting

point for new searches. Online access to the Chicago Tribune provided a search function

for some of these names. Due to time constraints I could not exhaust the list of Al

Capone’s associates. However, I strategically targeted certain associates on the list (e.g.,

public enemies and women) and reached saturation around prominent historical events

and the individuals involved. Overall, this project required creative approaches to

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

20

snowball sampling a hidden population because I could not ask informants for a list of

referrals, instead I snowballed within the archives chasing leads and digging through

boxes.

A major concern for sampling hidden populations is avoiding bias introduced

through the initial seed or informant. Al Capone was by no means normal in terms of his

social position in Chicago. In fact, what makes Al Capone a useful informant is that he

had hundreds of discrete documented ties. From Al Capone’s not-so-normal point of

view we get a picture of the largest organized crime network in Chicago during this

period. Using Al Capone as the informant introduces bias to the sample, but it is that very

bias that is of interest in social network research. The Al Capone bias in the data captures

the reality that friends and bootlegging partners were not random events. In traditional

statistical linear modeling, Al Capone would be an elephant-sized sampling challenge;

however, social network tools are designed for exploring non-random aspects of social

life.

If archives have obscured women’s history, this is even truer for criminal

women’s history. Locating women in the archives required a relational approach by

relying on the publicly available cases of the criminal men in their lives. In other words,

women’s criminal and noncriminal events and relationships are in the archives, but they

are filed and preserved through men’s archives. In the folders and boxes dedicated to Al

Capone, his cronies, and other public enemies, I found names of women and descriptions

of their criminal and non-criminal activities. At the Chicago History Museum, I read

young men’s life histories that occasionally referenced the women in their lives.

Returning to the CCC archives with a list of women’s names connected to organized

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

21

crime permitted a card catalogue search and resulted in several cases of women who had

CCC investigation folders of their own.

Table 1: Primary and secondary sources

!

Physical Archives

Pages

1

Chicago Crime Commission

2,081

2

Chicago History Museum

178

3

National Archives—Great Lakes Region

1,072

4

Newberry Library

6

Online Archives

5

Internal Revenue Service

86

6

FBI FOIA Electronic Reading Room

6

7

Northwestern’s History of Homicide in Chicago, 1870-1930

130

8

Proquest Newspapers Chicago Tribune

788

Historical Secondary Sources

9

Asbury, Herbert. 1940. Gem of the Prairie.

172

10

Landesco, John. 1929. Organized Crime in Chicago.

231

11

Pasley, Fred. 1930. Al Capone: The Biography of a Self-made Man.

23

12

Reckless, Walter. 1933. Vice in Chicago.

12

Contemporary Secondary Sources

13

Abbott, Karen. 2007. Sin in the Second City.

3

15

Eig, Jonathan. 2010. Get Capone.

159

16

Russo, Gus. 2001. The Outfit.

45

17

Stelzer, Patricia. 1997. An Examination of the Life of John Torrio.

9

Total

5,001

To build a relational database on organized crime, I accessed files and boxes at

four physical archives located in Chicago, downloaded files from four online archives,

and coded pages from a selection of historical and contemporary secondary sources.

Table 1 presents an exhaustive list of all the sources and the distribution of the 5,001

pages of documents coded to create the database. The types of documents in the physical

and online archives vary greatly ranging from newspaper clippings and obituaries to

details of police investigations, bail bond cards, tax documents, and court testimony.

Together these documents provide an outsider perspective of organized crime that was

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

22

recorded concurrently with the organized crime activities. For the insider perspective, I

typed 178 pages of notes from the Institute for Juvenile Research Life Histories

Collection located at the Chicago History Museum. I was unable to identify individuals

or code these life histories for relational data due to the nearly 100-year-old

confidentiality protections, but these life histories provided context and voice to some of

the activities within organized crime.

Across these sources were 3,321 individuals who were in some way connected to

organized crime in Chicago in the early 1900s, some 15,861 social relationships between

them, and 1,540 locations where they spent time. I organized these individuals,

relationships, and addresses in a relational database called the Capone Database. Most

social science lacks any information on the relationships between actors, but relationships

were central to the design of this database. The Capone Database is unique in its scope,

detail, size, and historical moment. It contains detailed information on over 100 different

types of relationships. Each relationship is linked to its original source for purposes of

triangulation and reliability. Data on criminal networks are rare, and, to the best of my

knowledge, the Capone Database is the largest and most complete database on a

historical criminal organization albeit admittedly with some missing data.

Table 2 presents counts on some of the content in the Capone Database. Note that

not every person, address, or tie in the database was part of organized crime, rather these

were the people, locations, and relations that appeared in the sources as possible

organized crime activity and its take down. Social network analysis is required to sort out

these distinctions.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

23

Table 2: Capone Database totals

!

Individuals

Total

Men

Women

3,321

2,988

333

(100%)

(90%)

(10%)

Addresses

Total

Women Involved

Ownership Missing

1,540

254

578

(100%)

(16%)

(38%)

Relationships

Total

Man and Man

Man and Woman

Woman and Woman

15,861

14,544

1,148

169

(100%)

(92%)

(7%)

(1%)

Individuals in the database include attorneys, judges, police officers, and, of course,

criminals (i.e., folks who committed crimes) and gangsters (i.e. criminals who were

associated with gangs). Ten percent of the individuals in the database are women.

Addresses in the database include alcohol, prostitution, and gambling establishments, as

well as hotels and restaurants. Almost 40 percent of the addresses in the Capone Database

had no information on owners or managers, and ownership and management changed

over time. About 16 percent of the addresses in the database at some point had women

owners or managers, and this count includes women who co-owned or co-managed

properties with men. There are over 100 different types of relationships in the Capone

Database such as business associations, criminal associations, family members, romantic

partners, friendships, financial exchanges, funeral attendance, legal charges and rulings,

courtroom witnesses, travel, political associations, rivalries, union associations, and

violence. The majority of these relationships occurred during Prohibition. Each

relationship in the Capone Database counts a connection between two individuals, which

is also called a dyad. Dyads have three categories when analyzing gender composition:

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

24

dyads that connect two men, dyads that connect a man and a woman, and dyads that

connect two women. The vast majority, 92 percent, of relationships in the Capone

Database are between two men, 7 percent of the relationships are between a man and a

woman, and 1 percent of the relationships are between two women. The gender

distribution of percentages varies depending on the type of tie.

The Capone Database is complex. Some of the ties are directed, such as paying

someone’s bail or shooting someone, while others ties are undirected, like being brothers

or traveling to the Bahamas together. Some ties are negative such as rivalries and

violence, whereas others ties are positive like friendships and political campaign

contributions. For these reasons, it would be awkward to analyze the Capone Database as

a whole. Instead, analyses require subsets from the database in order to generate samples

that are of theoretical interest.

Sample

This dissertation utilizes two subsets from the Capone Database: one on

relationships and one on addresses. In this section, I describe each subset in detail and

explain its relevance to my analysis. I extracted all of the criminal ties occurring during

two time periods for the first subset: 1900 to 1919 and 1920 to 1933. This restricted

timeline required me to drop all criminal ties that did not have approximate years from

the sample, but I attempted to approximate a year whenever possible. I also dropped other

types of relationships, such as family, friendships, legitimate ties, rivalries, violence, etc.,

from the sample in order to focus solely on the criminal network. I do rely on details from

these other types of relationships when available to contextualize individuals’ entrance

into and access to organized crime. All of the criminal relationships in this subset are

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

25

undirected, which means that there is no distinction between who sends and who receives

the criminal tie.

Criminal ties in this subset include general criminal associations, co-owners of or

co-workers in illegitimate business, making graft or protection payments, co-arrests,

criminal mentorships, political corruption, etc. The value and variation in the criminal

ties get reduced in this analysis as I treat each criminal relationship as equal. For purposes

of the analysis, a $50 payment to a graft collector is equal to corruption of the Mayor’s

office. The benefit of flattening the criminal ties is that the value and variation arise

through the configuration of relationships within the networks, focusing on each person’s

count of criminal ties, the number of ties to central figures, and the number of

relationships that individuals brokered in the network—properties that shed insight on the

organizational structure of organized crime.

Sociologists have leveraged social networks to build organizational theory and

map organizational structure. The concepts of markets and organizations have a

tendency, in theory, to become rather abstract even though markets and organizations

would not exist without actors and their exchanges. Social networks make markets and

organizations less abstract and more social by populating them with actors and actors’

routines and interactions. For example, Donald Tomaskovic-Devey conceptualizes labor

markets as a network of employees moving between employers.

68

Lazega and Pattison’s

research on a law firm finds that cooperation and exchange relationships clustered within

levels of the organization but not up the organizational chain, a cooperation pattern

consistent with the bureaucratic structure of the law firm organization.

69

This type of

research assumes that organizations and markets at their core are social networks, and the

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

!

26

social networks are maps of the structure of the organization. Similarly, criminal network

researchers assume this logic in mapping the structure of criminal organizations—

networks can define the structure of organizations. Wayne Baker and Robert Faulkner’s

research on price-fixing conspiracy networks is one of the best examples of this.

70

They

conceptualize the criminal organization not as the separate companies involved in the

conspiracies but as a larger conspiracy network.

71

It is certainly challenging to map the structure of informal and illicit

organizations, but patterns emerge in social network data that point toward organizational

structures. In the Capone Database, a criminal relationship between two individuals, such

as an owner of a speakeasy buying booze from a bootlegger, does not equal organized

crime; this relationship is just a criminalized employment or market tie. Rather the

constellation of how these criminal relationships come together and center on particular

individuals within particular markets reveals the larger structure in which this single co-