e Basic Law of

BUDGETING

A Guide for Towns, Village Districts and School Districts

2022

2

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

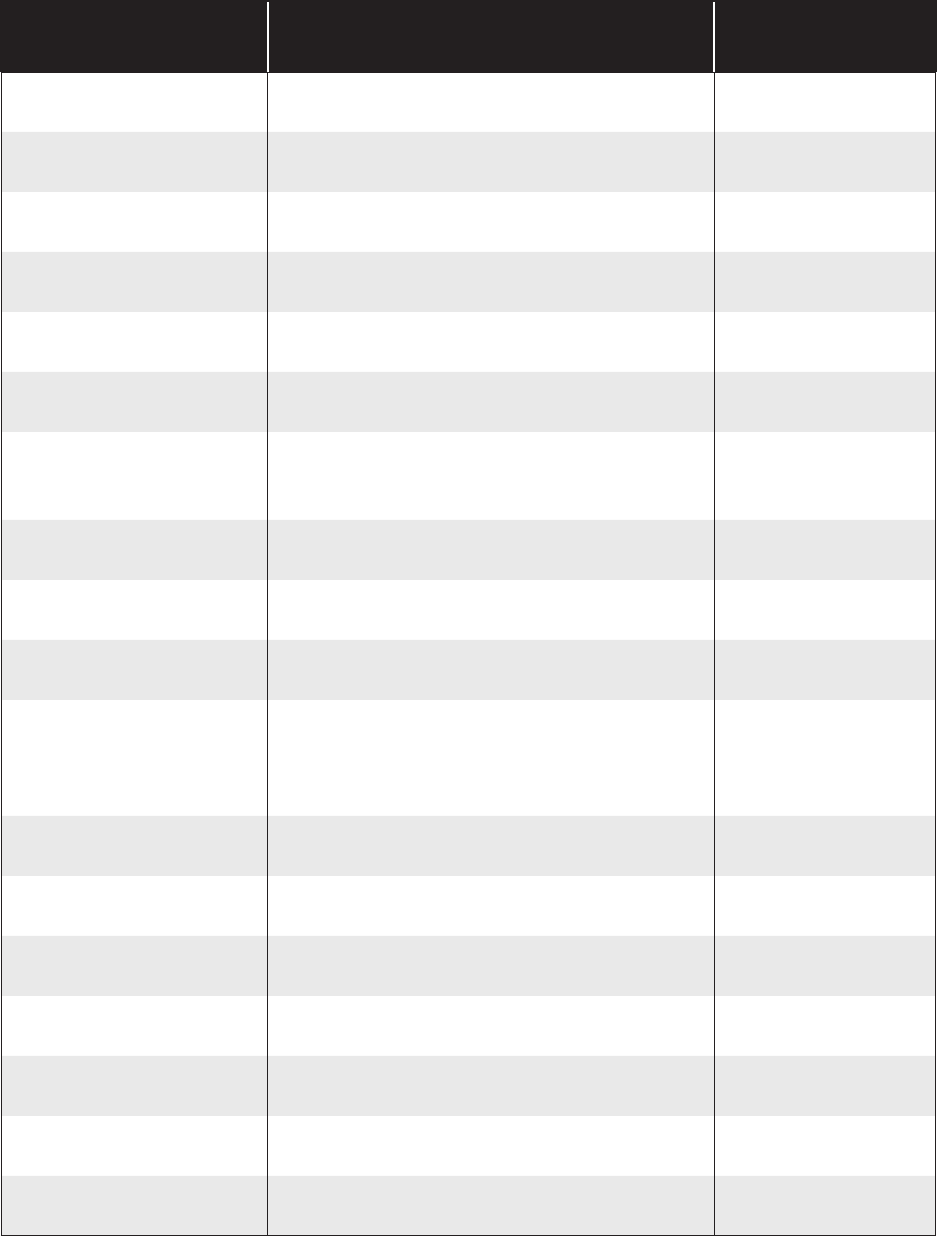

TABLE OF CONTENTS

About this Publication ............................................................................................................. 6

Introduction to the Municipal Budget Law.......................................................................... 7

Glossary of Terms ...................................................................................................................... 9

Seven Key Concepts

Chapter 1. Appropriations

First Key Concept 15 ....................................................................................................12

A. Appropriations Create Guiding Values ................................................................................ 12

B. Appropriations Are Acts of Legislative Policy .................................................................... 12

C. e Proper Purposes of Appropriations .............................................................................. 13

D. e Meaning of RSA 31:4 – Home Rule .............................................................................. 13

E. A Power to Act Implies a Power to Appropriate ................................................................. 14

F. Public Purposes Only ............................................................................................................. 14

G. How Specic Should a Proposed Appropriation Be? ......................................................... 16

H. Contingency Funds ................................................................................................................ 16

I. Tax/Spending Caps ................................................................................................................. 17

J. Procedural Requirements for Valid Appropriations .......................................................... 17

K. Inter-Municipal Agreements, Shared Services, and Voluntary Contributions .............. 19

Chapter 2. ‘Gross Basis’ Budgeting

Second Key Concept ....................................................................................................21

A. Care in Draing Warrant Articles ........................................................................................ 21

B. Examples of Mistakes ............................................................................................................. 21

C. Comparative Columns ........................................................................................................... 22

D. Individual Versus Special Articles ........................................................................................ 23

E. Special Articles and Recommendations .............................................................................. 23

F. Numeric Tallies and Recommendations on Other Warrant Articles

if Authorized by Town Meeting or Governing Body ......................................................... 23

G. Multi-Year Appropriations for Capital Projects ................................................................. 24

H. Estimated Tax Impact ............................................................................................................. 25

3

New Hampshire Municipal Association

Chapter 3. Warrant Notice and Permissible Amendments

Third Key Concept .......................................................................................................26

A. Voters’ Ability to Amend Amounts ...................................................................................... 26

B. Later Transfers Cannot Be Restricted from the Floor ....................................................... 26

C. Amendment by Altering Mode of Funding ........................................................................ 27

D. ‘Stay-at-Home Test’ ................................................................................................................. 27

E. Appropriating Money at Special Meetings: e Requirement of ‘Emergency’ .............. 27

Chapter 4. No Spending Without an Appropriation

Fourth Key Concept .....................................................................................................29

A. Basic Rule of Budget Accounting ......................................................................................... 29

B. Exceptions to the Rule ............................................................................................................ 29

C. What About Spending Prior to Town Meeting? ................................................................. 30

D. Other Statutory Exceptions to No-Spending-Without-Appropriation Rule .................. 31

E. Multi-Year Contracts .............................................................................................................. 32

Chapter 5. When Do Appropriations Lapse?

Fifth Key Concept ....................................................................................................... 35

A. Source of the ‘Lapse’ Rule ...................................................................................................... 35

B. Don’t Confuse Appropriation Accounting with Cash Accounting or Tax Accounting ............. 35

C. Lapsing to ‘Fund Balance’ – Not ‘Surplus’ ........................................................................... 35

D. Unanticipated Revenue Is Not ‘Lost’ .................................................................................... 37

E. Exceptions to the ‘Lapse’ Rule: RSA 32:7 ............................................................................. 37

F. Statutorily Nonlapsing Funds................................................................................................ 40

Chapter 6. Transfers of Appropriations During the Year

Sixth Key Concept ....................................................................................................... 45

A. Special Warrant Articles Nontransferable ........................................................................... 45

B. Maintaining Records of Transfers ........................................................................................ 45

C. Line Item Voting? ................................................................................................................... 46

D. Failed Separate Article: ‘No Means No’’ ............................................................................... 47

Chapter 7. The Budget Committee

Seventh Key Concept.................................................................................................. 48

I. Composition and Creation of the Ocial Budget Committee ........................... 48

A. Ocial v. Advisory Budget Committee .................................................................................. 48

B.

Adoption of an Ocial Budget Committee ............................................................................ 48

C.

Membership .............................................................................................................................. 49

II. Role and Authority of the Budget Committee .....................................................50

A. Ocial v. Advisory Budget Committee .................................................................................. 50

B.

Adoption of an Ocial Budget Committee ............................................................................ 50

4

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

C. “e Budget” ........................................................................................................................... 51

D. Acquiring Information for Budget Preparation.................................................................. 51

E. e Default Budget ................................................................................................................. 52

F. Reviewing (Not Controlling) Expenditures ........................................................................ 52

G. Special Article Recommendations........................................................................................ 53

H. Failure of Budget Committee to Propose a Budget ............................................................ 53

I. Limit on Appropriations ........................................................................................................ 54

J. Right to Know Law ................................................................................................................. 56

Chapter 8. Appropriations under the Ocial Ballot

Referendum (SB 2) System .......................................................................................... 57

A. ‘Standardized’ Referendum System Versus ‘Customized’ Charter ................................... 57

B. Description of the SB 2 System ............................................................................................. 57

C. Dierent Deadlines................................................................................................................. 58

D. Default Budget ........................................................................................................................ 58

E. Recommendations/Altering Recommendations ................................................................ 62

F. Voting Issues ............................................................................................................................ 62

G. Special Meetings ..................................................................................................................... 64

Chapter 9. Basic Town, Village District and School District

Meeting Procedures ....................................................................................................65

A. Rules of Procedure ........................................................................................................... 65

B. Wording of Articles, Motions and Amendments ......................................................... 66

C. Dividing a Question ......................................................................................................... 67

D. Reconsideration and Limits on Reconsideration ......................................................... 67

E. Preventing Disorder ......................................................................................................... 69

F. Separating Voters from Nonvoters ................................................................................. 69

G. How Votes Are Counted and Declared ......................................................................... 69

H. Requests for Secret Yes/No Ballot .................................................................................. 69

I. Questioning a Vote ........................................................................................................... 70

Chapter 10. Capital Improvements Plans: An Important Financial

Planning Tool ...............................................................................................................71

A. Why Do We Need a Capital Improvements Program? ............................................... 71

B. Where Does the CIP Fit Into Local Government? ...................................................... 72

C. Where Do We Begin? ...................................................................................................... 73

D. What is a “Capital Improvement”? ................................................................................ 73

E. What Goes Into a Capital Improvements Program? ................................................... 74

F. Draing, Revising and Adopting the CIP ..................................................................... 77

G. Next Steps: Begin Again! ................................................................................................ 78

5

New Hampshire Municipal Association

Chapter 11. Understanding the Property Tax System ....................................... 79

A. Property Taxes Based on Appropriations ............................................................................ 79

B. Valuing Property: e Appraisal Process ............................................................................ 79

C. Increased Assessed Value Does Not Necessarily Mean Increased Taxes ........................ 80

D. Proportionality ........................................................................................................................ 80

E. e Assessing Process ............................................................................................................ 81

F. e Equalization Process ....................................................................................................... 82

G. Setting the Tax Rate ................................................................................................................ 82

H. Property Tax Bill ..................................................................................................................... 83

I. How Much Will at Add to the Tax Rate? ........................................................................ 83

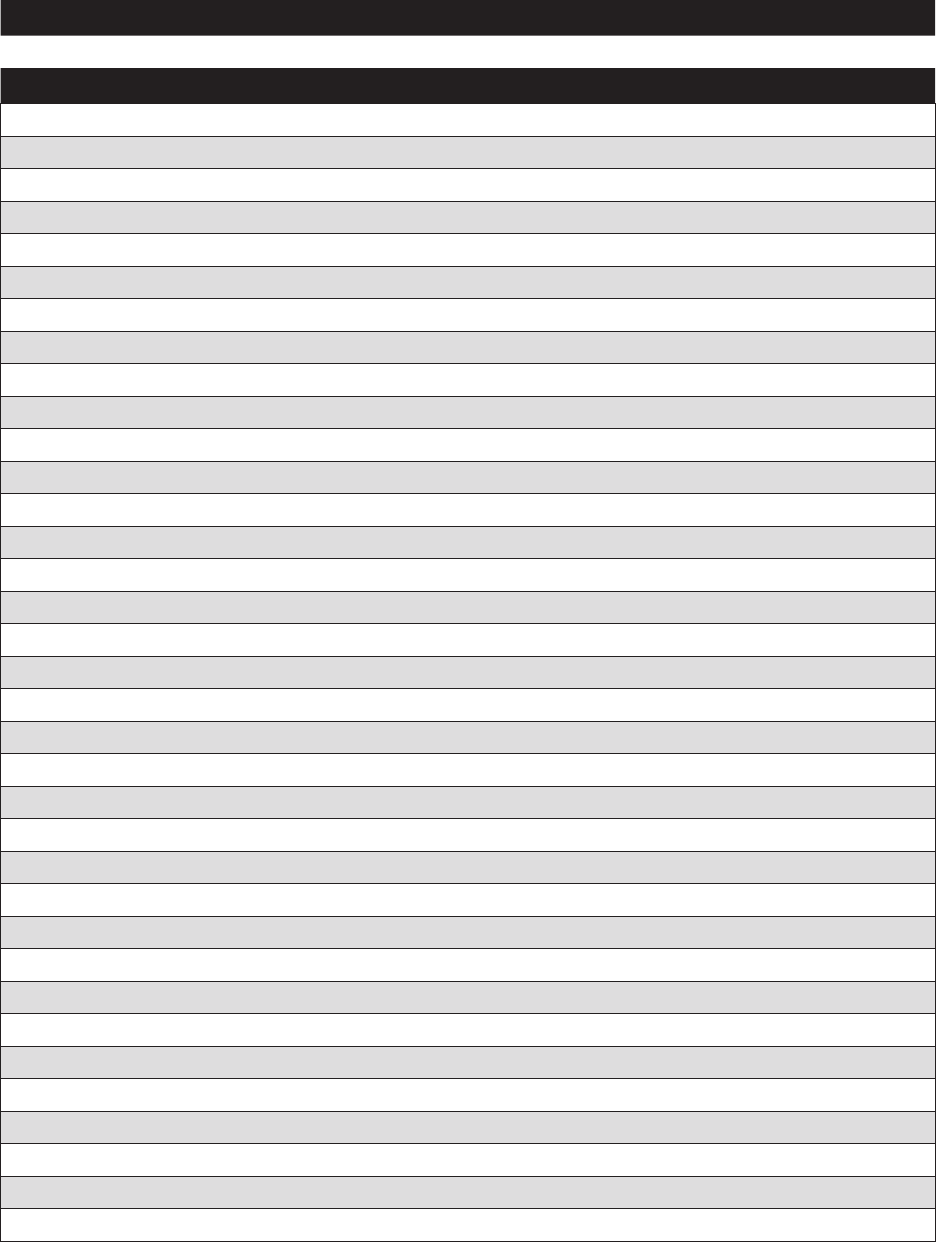

Appendix A: Custody and Expenditure of Common Town Funds ........................... 85

Appendix B: Fees, Licenses, Permits & Penalties ..................................................... 86

Appendix C: Financing Options ................................................................................. 89

Appendix D: Assessed Value Illustrations ................................................................ 93

Appendix E: Tax Rate Impact Worksheet .................................................................. 95

Appendix F: Timetable for Special Town Meeting.................................................... 96

Appendix G: Due Dates for Municipal, School & Village District Forms ................. 98

Appendix H: Default Budget FAQ ........................................................................... 102

Table of Statutes ....................................................................................................... 107

6

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION

is publication is intended for use in conjunction with the New Hampshire Municipal Association’s

(NHMA) Budget and Finance Workshops and as a reference throughout the year. We hope you nd

this survey of the Municipal Budget Law helpful as you carry out your duties as a municipal ocial.

Other NHMA publications are available to provide more in-depth information on town meeting and

other municipal law issues, including the Town Meeting and School Meeting Handbook and Knowing the

Territory: A Survey of Municipal Law for New Hampshire Local Ocials.

NHMA’s Legal Services attorneys focus on the laws of towns, cities, and village districts, but the scope of

their legal advice does not include school-specic issues. However, we recognize that in a town with an

ocial budget committee, that committee also serves the local school district. erefore, with the help of

Attorney William J. Phillips of the New Hampshire School Boards Association, we have included some

school- specic information, including information relevant to cooperative school districts, and we note

that in many cases school budgeting laws are similar to town, city, and/or village district budgeting laws.

For school tips, look for this icon throughout the book:

is edition also features a glossary to help you understand the “language” of budgeting law. e

information presented is not intended as legal advice and is not a substitute for consulting your municipal

attorney or calling on NHMA’s Legal Services attorneys. Local ocials in New Hampshire Municipal

Association-member municipalities may contact NHMA’s Legal Services attorneys with questions

and to receive general legal assistance. Attorneys are available by phone at 603-224-7447or by email at

legalinquiries@nhmunicipal.org.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

including but not limited to photocopying, recording, posting on a website, or other electronic or

mechanical methods, without prior written permission of the New Hampshire Municipal Association,

except in the case of quotations that cite the publication as the source or other non-commercial uses

permitted by law. e forms contained in this publication are available for your use

7

New Hampshire Municipal Association

INTRODUCTION TO

THE MUNICIPAL BUDGET LAW

e information in this survey, in general, applies to the budget process in all towns, village districts

and school districts governed by the Municipal Budget Law, RSA chapter 32. All principles covered here

also apply to those towns and districts that have adopted the ocial ballot referendum system under

RSA 40:13 (SB 2), except for some special considerations under SB 2 that are covered in Chapter 8. In

general, the word “meeting” is used to mean action by the legislative body under either the traditional

town meeting or the ocial ballot referendum system. e special provisions of municipal charters and

cities are not covered in this publication.

RSA Chapter 32 Applies to All Annual Meeting Forms of Government

e Municipal Budget Law governs in every town, village district and school district with an annual meeting

form of government, including those with the ocial ballot referendum form of meeting (SB 2). e rst

half of the chapter, RSA 32:1 – :13, applies to all such towns and districts. See RSA 32:2, Application.

RSA 32:14 – :24 apply only in the towns and districts that have established an ocial budget committee by

vote of the legislative body under RSA 32:14. RSA 32:5-b applies only to those towns and districts which

have adopted that section pursuant to RSA 32:5-c.

Advisory Committees

e Municipal Budget Law explicitly recognizes unocial or advisory budget and nance committees

that exist in many municipalities. e law does not require any town or district without an ocial budget

committee to have one. RSA 32:24. In this publication, the term “budget committee” means an ocial

Municipal Budget Law budget committee adopted according to RSA 32:14, not an advisory nance/ budget

committee. e role of the budget committee is covered in Chapter 7.

Removal from Oce

RSA 32:12 states that anyone who violates the provisions of the Municipal Budget Law may be removed

from oce by the superior court upon petition. is rule has been upheld in case law. For example, the New

Hampshire Supreme Court held that a police chief who overspent his budget was properly dismissed under

a “for cause” dismissal standard. Blake v. Pittseld, 124 N.H. 555 (1984).

If the town has an ocial budget committee, the budget committee can le the removal petition. RSA 32:23.

Removal is not automatic. In a case involving the Merrimack Village District, a superior court judge ruled

that where an over expenditure of the budget’s bottom line occurred as a result of good faith ignorance

and did not cause harm to the district, the court has discretion not to order removal. e New Hampshire

Supreme Court summarily armed this ruling.

Biennial Budgeting

Cities and towns can budget on a two-year cycle under the provisions of RSA 32:25. e idea is to reduce the

amount of time local ocials spend preparing budgets. e law must be adopted by vote of the legislative

body. If adopted, the following year the legislative body enacts a budget for two distinct 12-month scal

years or a single 24-month scal period. Each year’s budget has the same legal eect as a normal annual

8

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

budget, but the governing body can carry over appropriations from the rst budget year to the second.

Key Concepts

Some ocials, particularly those new to municipal budgeting, nd the Municipal Budget Law to be a

complicated set of unrelated rules. e key to understanding the municipal budget process centers on seven

fundamental budgeting and nance concepts. is survey highlights those seven concepts.

9

New Hampshire Municipal Association

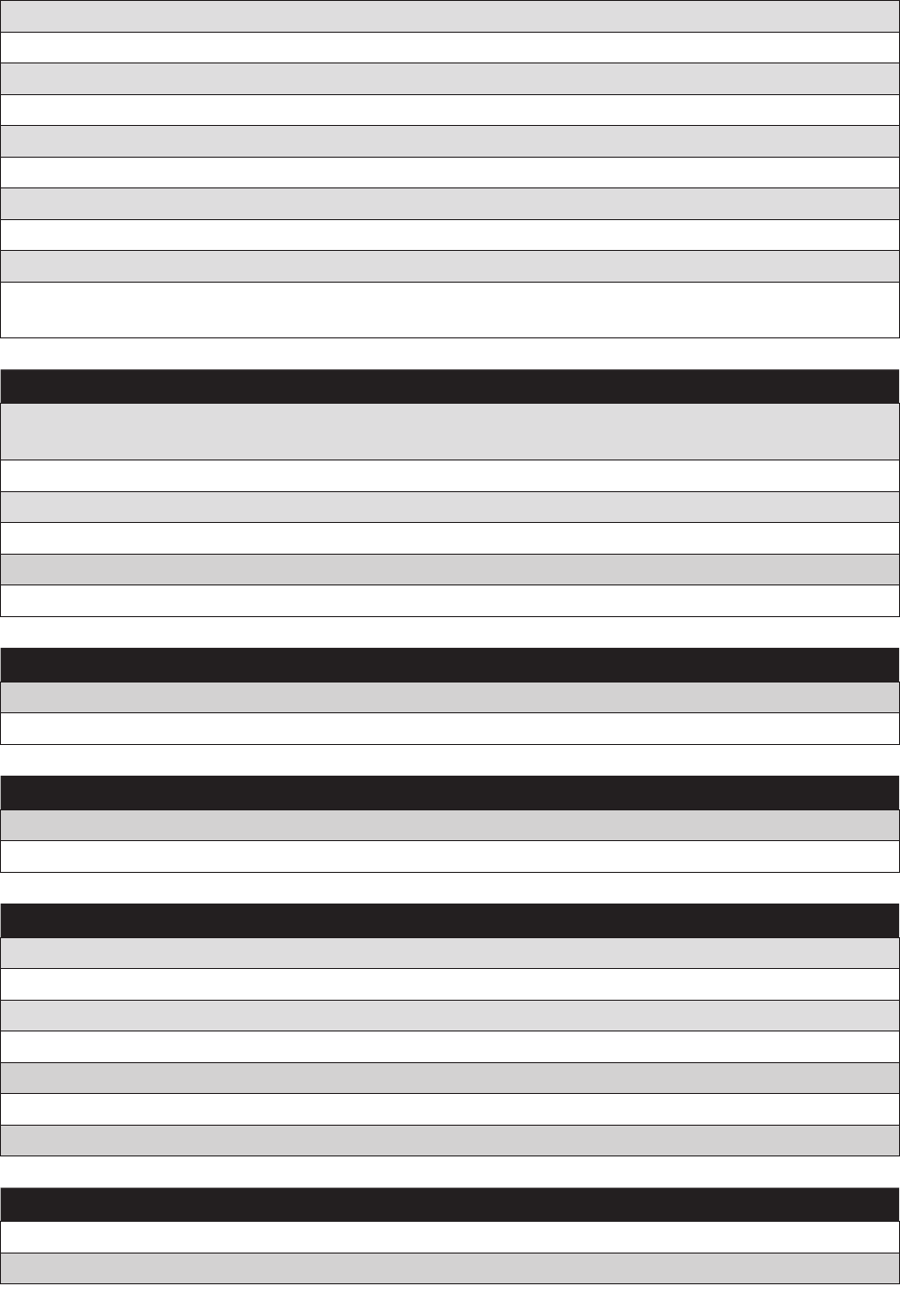

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Appropriate: To set apart from the public revenue of a municipality a certain sum for a specied purpose

and to authorize the expenditure of that sum for that purpose.

Appropriation: An amount of money appropriated for a specied purpose by the legislative body.

Agents to expend: A public body or public ocial, usually the select board, given the authority to expend

funds without further legislative body approval.

Bottom line: e total amount of all appropriations for the scal year.

Budget: A statement of recommended appropriations and anticipated revenues submitted to the legislative

body by the budget committee, or the governing body if there is no budget committee, as an attachment to,

and as part of the warrant for, an annual or special meeting.

Contracts for Default Budget Purposes: As used in RSA 40:13, contracts previously approved, in the

amount so approved, by the legislative body in either the operating budget authorized for the previous

year or in a separate warrant article for a previous year.

Default budget: e amount of the same appropriations as contained in the operating budget authorized

for the previous year, reduced and increased, as the case may be, by debt service, contracts, and other

obligations previously incurred or mandated by law, and by reduced one-time expenditures contained in the

operating budget and by salaries and benets of positions that have been eliminated in the proposed budget.

Capital improvement: A high cost improvement with a useful life of several years, such as infra-

structure projects, land acquisition, buildings, or engineering studies for any of those projects, as well as

vehicles or highway maintenance equipment in some municipalities.

Capital improvements program: A planning tool used to aid the mayor or select board and the budget

committee in considering the annual budget. e program must classify projects according to the

urgency and need for realization, recommend a time sequence for their implementation, be based on

information submitted by the departments and agencies of the municipality, and take into account public

facility needs indicated by the prospective development shown in the master plan of the municipality

or as permitted by other municipal land use controls. e program may also contain the estimated cost

of each project and indicate probable operating and maintenance costs and probable revenues, if any, as

well as existing sources of funds or the need for additional sources of funds for the implementation and

operation of each project.

Capital reserve fund: A savings account established to fund a particular capital project or projects.

Emergency (under RSA 31:5): A sudden or unexpected situation or occurrence, or combination of

occurrences, of a serious and urgent nature, that demands prompt, or immediate action, including an

immediate expenditure of money. is denition, however, does not establish a requirement that an

emergency involves a crisis in every set of circumstances.

10

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

Encumbered funds: Funds that a municipality has a legal obligation to pay, created by contract or

otherwise, to any person for the expenditure of that amount.

Escape clause: See nonappropriation clause.

Fiscal year: For towns, January 1st to December 31st (RSA 31:94), unless the town has adopted the

optional July 1st to June 30th scal year in accordance with RSA 31:94-a – :94-e; for school districts, the

scal year begins on July 1st (RSA 194:15).

Fixed charges: Includes appropriations for principal and all interest and principal payments on bonds

and notes, except tax anticipation notes, as well as mandatory assessments imposed on town by the

county, state, or federal governments.

Fund balance: An account on the town’s balance sheet, accounting for lapsed appropriations, assets, and

liabilities; may be retained, used to reduce the tax rate, or appropriated by the legislative body.

Gross basis budgeting: e requirement that all anticipated revenue from all sources, not just tax money,

must be shown as osetting revenues to the amounts appropriated for specic purposes in the annual budget.

Lapse: e time at which an appropriation may no longer be spent, typically at “year’s end” unless the

appropriation is nonlapsing.

Line Item: A purpose for which money may be spent in the budget.

Nonappropriation clause: A provision in a contract that terminates the agreement automatically without

penalty to the municipality if the requisite annual appropriation is not made. Commonly referred to as an

“escape clause.”

Ocial budget committee: A budget committee adopted by the legislative body according to RSA 32:14

with the duties and authority set forth in RSA Chapter 32.

One-Time Expenditures: Expenditures not included in the default budget because they are

appropriations not likely to recur in the succeeding budget, as determined by the governing body, unless

the town meeting votes to delegate determination of the default budget to the budget committee.

Operating budget: e “budget,’’ exclusive of “special warrant articles,’’ as dened in RSA 32:3, VI, and

exclusive of other appropriations voted separately.

Purpose: A goal or aim to be accomplished through the expenditure of public funds. In addition, as

used in RSA 32:8 and RSA 32:10, I(e), concerning the limitation on expenditures, a line on the budget

form posted with the warrant, or form submitted to the department of revenue administration, or an

appropriation contained in a special warrant article, shall be considered a single “purpose.”.

Public purpose: As applied to appropriations, any purpose for which a municipality may act if such

appropriation is not prohibited by the laws or the New Hampshire Constitution.

Raise: To collect or procure a supply of money for use; the source from which an appropriation is made.

Revolving fund: A fund established pursuant to RSA 31:95-h, into which fees and charges for certain

services and facilities may be deposited and from which expenses for those services and facilities may be

expended by a board or body

designated by the legislative body at the time the fund is created.

11

New Hampshire Municipal Association

Sanbornizing: A term of art derived from the case of Appeal of the Sanborn Regional School Board, 133

N.H. 513 (1990), meaning sucient disclosure to the legislative body of the cost items in a collective

bargaining agreement, such that the multi-year costs of the agreement become binding on the municipality.

Separate warrant article: An article containing an appropriation that is set apart from the operating budget.

Special revenue fund: A nonlapsing fund established pursuant to RSA 31:95-c, restricting revenues from

specic sources to be expended for specic purposes by the legislative body.

Special warrant article: Any article in the warrant for an annual or special meeting which proposes an

appropriation by the meeting and which (a) is submitted by petition; (b) calls for an appropriation of an

amount to be raised by the issuance of bonds or notes pursuant to RSA 33; (c) calls for an appropriation

to or from a separate fund created pursuant to statute, including but not limited to a capital reserve

fund under RSA 35, or trust fund under RSA 31:19-a; (d) is designated in the warrant, by the governing

body, as a special warrant article, or as a nonlapsing or nontransferable appropriation; or (e) calls for an

appropriation of an amount for a capital project under RSA 32:7-a.

Surplus: See fund balance.

Tax year: April 1

st

– March 31

st

.

Ten percent rule: In towns and districts with an ocial budget committee, the total amount

appropriated, including amounts appropriated in separate and special warrant articles, cannot exceed

the total recommended by the budget committee by more than 10 percent. e 10 percent calculation is

computed on the total amount recommended by the budget committee, less that part of any appropriation

item which constitutes “xed charges.”

Town-funded trust fund: A “savings account” established pursuant to RSA 31:19-a for the maintenance

and operation of the town and for any other valid public purpose.

Unanticipated revenue: Revenue from an unexpected source, i.e., a source of money the municipality did

not anticipate it would receive any funds from.

Year’s end: e end of the scal year.

12

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

CHAPTER ONE

First Key Concept

APPROPRIATIONS

Once an understanding of the concept of an appropriation is mastered, the municipal budget process is

easier to understand. e words “appropriate” and “appropriation” are dened in RSA 32:3, as follows:

I. “Appropriate” means to set apart from the public revenue of a municipality a certain

sum [of money] for a specied purpose and to authorize the expenditure of that sum

for that purpose.

II “Appropriation” means an amount of money appropriated for a specied purpose by

the legislative body.

A. Appropriations Create Guiding Values

An appropriation is a fundamental exercise of governmental power. Both taxing power and spending

power ow directly from the power to make appropriations. Appropriations give a governmental unit

purpose and direction. ey form the guiding values of the governmental entity. When local ocials

make spending decisions, they are carrying out those policy values.

B. Appropriations Are Acts of Legislative Policy

An appropriation is a policy decision to set aside a specic amount of public money, which typically has

not been collected yet, for a specic stated governmental purpose. It is a legislative act. RSA 32:6 provides

that appropriations can be made only by vote of the legislative body (the voters) at a properly noticed

annual or special meeting.

Appropriation and spending should not be confused. An appropriation is not the actual spending

of money. It is the underlying authorization to spend money. An appropriation is also different

from the authorization to tax (raising money). “Raising” indicates the source of the revenue;

“appropriating” indicates how the money will be spent. The New Hampshire Supreme Court has

described the difference:

To ‘raise’ money, as the word is ordinarily understood, is to collect or procure a supply of money for

use…. To ‘appropriate’ is to set apart from the public revenue a certain sum for a certain purpose.

Frost v. Hoar, 85 N.H. 442 (1932).

A vote of the legislative body (assembled meeting or ocial ballot referendum vote) is required for a valid

appropriation. A proposed budget or warrant article presented to the voters by the governing body or budget

committee is only advisory. It is not nal, and it is not an appropriation. Indeed, the only legally binding

eect of a proposed budget or warrant article is that the warrant notice requirement does not permit any

13

Chapter 1. Appropriations

new subject matter to be added by the voters (see Section J.) e budget prepared by the governing body or

budget committee is similar to a legislative bill that has been introduced but not voted on yet.

C. The Proper Purposes of Appropriations

“Purpose” means a goal or aim to be accomplished through the expenditure of public funds. RSA 32:3, V.

1. SCHOOL DISTRICTS

e state law setting the proper purposes of school appropriations, RSA 198:4, is an old statute. It

limits school appropriations to “the support of the public schools, for the purchase of textbooks,

scholars’ supplies, ags and appurtenances, for the payment of tuition of the pupils in the district

in high schools and academies in accordance with law, and for the payment of all other statutory

obligations of the district.”

2. VILLAGE DISTRICTS

A village district or precinct must be explicitly created for one or more of the specic purposes

found in RSA 52:1, such as “the supply of water.” Once that happens, the district has “all the

powers in relation to the objects for which it was established that towns have or may have in

relation to like objects, and all that are necessary for the accomplishment of its purposes.”

RSA 52:3, II.

3. TOWNS

While the purposes to which school district and village district money may be appropriated are

limited, the statute governing town appropriations is broader. RSA 31:4 authorizes a town to

appropriate money “for any purpose for which a municipality may act if such appropriation is not

prohibited by the laws or by the constitution of this state.” However, as explained in the sections

below, towns have only the powers that the State gives them. erefore, it is important to nd

authorization somewhere in the law for a purpose, as well as to understand whether and how the

state laws and/or Constitution limit the purposes for which towns may appropriate public funds.

It is also useful to note that towns are not limited to the purposes printed on the MS-636 and

MS-737 budget forms. e town budget forms required by the New Hampshire Department of

Revenue Administration (DRA) contain line items for most valid public purposes. ese items

now correspond to the “uniform system of accounts” developed by DRA. It is, however, possible

to insert numbered line items for purposes that are not on this chart of accounts, so long as the

purposes are otherwise legal and are not prohibited by state law or the state constitution.

D. The Meaning of RSA 31:4 – Home Rule

New Hampshire is not a home rule state in the constitutional sense. We have a long tradition of local

control, but unlike many state constitutions, the New Hampshire Constitution does not grant power

directly to towns and cities. It grants power only to the legislature. In New Hampshire, towns have “home

rule” only if the legislature gives it to them, and the legislature is free to decline to grant that authority at

any time.

Towns have only such powers as are expressly granted to them by the legislature and such as are

necessarily implied or incidental thereto. Girard v. Allenstown, 121 N.H. 268 (1981).

Under the ruling in cases like Girard, the most basic rule of local government in New Hampshire is

that a town cannot undertake any action unless a statute authorizes that action. With that rule in

mind, the legislature has granted authority for towns to appropriate money “for any purpose for which

a municipality may act….” RSA 31:4. is means that a town may only appropriate money if there is

14

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

authority somewhere in the law for that purpose, and only if there is no law or constitutional principle

that prohibits it.

e pre-1983 version of RSA 31:4 contained 43 separate paragraphs of permitted types of appropriations.

is list is still found in the older, pre-1988 hardbound edition of the statute book. e legislature got

tired of adding to the list to keep up with town needs. Now the list is open-ended. For example, can towns

appropriate money to help with the expansion of a local nonprot private hospital? e answer is yes.

First, running a hospital is something the town or city itself could do, and many municipalities across the

country do so. Second, the old version of RSA 31:4 contained a specic paragraph (VI) that allowed aid to

hospitals and clinics. However, even this broad power to appropriate money has its limits. As explained in

Section F, our state constitution requires public money to be appropriated only for “public purposes.”

E. A Power to Act Implies a Power to Appropriate

Any statute granting authority to municipalities also impliedly authorizes municipalities to appropriate

money to carry out that action. For example, RSA 31:39 authorizes a town to pass ordinances. e power

to appropriate money to enforce those ordinances is implied.

F. Public Purposes Only

Receipt of public money entails an obligation to benet the public. Under the New Hampshire

Constitution, public money can be appropriated only for valid public purposes, but not to create a purely

private benet. is issue can be confusing at times because even something that may have a “public

benet” does not always constitute a “public purpose” as required by the New Hampshire Constitution.

While the public might benet from the use of municipal appropriations to a private entity, such as a

private ambulance service, the “public purpose” requirement means that municipalities have to go one

step further and secure the ability to enforce or obtain that benet for the public. As a general rule, town

money cannot be granted to a private person, company or organization unless that private person takes

on some obligation to benet the town. Opinion of the Justices, 88 N.H. 484 (1937). In other words, there

must be a quid pro quo (literally, “this for that”). Oen the obligation is contractual, as in the purchase of

goods or services. Even where there is no express contract, the obligation must exist. For example, a grant

to a private ambulance service is usually permitted under the law because the ambulance service knows

and agrees that it is expected to use that money to provide a public service.

A written contract is not always necessary. Some legally enforceable obligations are not in writing, but

a written agreement is a good idea. e governing body (select board, school board or village district

commissioners) is responsible to the voters for making sure money is used for the appropriated purpose.

If money does go to private parties or organizations, the governing body must do whatever is necessary to

be assured that the voters’ directives are carried out and the money is not diverted to other purposes.

In draing warrant articles for appropriations to private organizations, state the purpose of the money in

the warrant article. Doing so creates an implied contract if a private organization accepts the money. e

private organization becomes obligated to use it for the purpose stated in the article.

In a few specic cases, the legislature has carved out particular purposes of appropriation which

may appear to benet private parties, but which a statute declares to be a proper public purpose for

which towns or cities may appropriate money. For example, if the legislative body votes to adopt

the provisions of RSA 36-A:4-a, the conservation commission may expend funds to facilitate a

conservation easement transaction, even if the municipality will not hold any interest in the property

or the easement. RSA 36-A:4-a; RSA 36-A:5, II.

15

Chapter 1. Appropriations

1. INCIDENTAL PRIVATE BENEFIT IS PERMITTED

e legal validity of an appropriation is not defeated if a private person incidentally benets,

so long as the main purpose of an appropriation is to promote the public welfare. Hampton v.

Hampton Beach Improvement Co., 107 N.H. 89 (1966). In Hampton, the town had granted a 99-year

lease on town-owned beach land in 1897 to a private company because the land was otherwise

not yielding any income to the town. e lease included an agreement that the town would pay

the taxes on the leased land during the lease. By the 1960s the land had been improved and was

extremely valuable, but the town was obligated to abide by the very low 1897 lease amount and its

promise to pay the taxes. e lease was held valid, however, because at the time it was made, it was

projected to serve a proper public purpose over its life, with private prot merely incidental.

2. SPECIAL TAX TREATMENT

e Hampton case implies that contracts for special tax treatment may be legal if a town (a)

agrees to pay the tax and (b) is getting some benet as quid pro quo. erefore, giving a tax

abatement to a particular prot-making business just to aid the local economy clearly violates the

constitution because the town is not paying the tax and there is no specic quid pro quo benet to

the town.

RSA chapter 79-E was enacted to encourage the revitalization of downtown municipal areas. If

the legislative body votes to adopt the program, a municipality may oer property tax incentives

by not increasing taxes for a certain amount of time if a property owner substantially rehabilitates

a structure in a downtown, central business district or town or village center area. “Substantial”

rehabilitation costs at least 15 percent of the assessed value prior to the rehab, or $75,000,

whichever is less. In certain cases, this tax relief may also be available for the replacement of

under-utilized structures in these areas. See RSA 79- E:1, II-a. is tax relief can remain in eect,

at the discretion of the governing body, for up to ve years with provisions for extensions for

certain types of projects. Tax relief is granted only to assessment increases attributable to the

rehabilitation of the property and is not available when more than 50 percent of construction

costs are being funded through grant programs.

As of July 5, 2011, municipalities may also decide to extend the tax incentive to include the

rehabilitation of buildings that have been destroyed by re or act of nature, including buildings

destroyed up to 15 years before the municipality adopts this incentive. RSA 79-E:2, II. In

these cases, for the incentive period designated by the governing body, the property tax on the

structure will not exceed the tax on the assessed value of the structure that would have existed

if it had not been destroyed. RSA 79-E:13, I (b). Eective October 9, 2021 municipalities may

designate a “residential property revitalization zone” and grant community revitalization tax

relief under RSA 79-E to the owner of a residential property in the zone with not more than four

units if the structure is at least 40 years old and if the owner signicantly improves the quality,

condition, or use of the structure. Eective April 1, 2022, municipalities may create “housing

opportunity zones” and apply the community revitalization tax relief incentive to housing units

constructed within a housing opportunity zone. To be eligible, at least one-third of the housing

units constructed must be designated for households with an income of 80 percent or less of

the area median income, or the housing units in a qualifying structure must be designated for

households that are deemed to be of “very low, low, or moderate income” under RSA 204-C:57, IV.

e governing body must determine, for each property for which an exemption is sought, that

there is a public benet to granting the tax relief, that the public benet is preserved through

a covenant, and that the proposed use is consistent with the master plan or development

regulations. e purpose of the covenant is to ensure that the structure is maintained and used in

a way that furthers the public benet for which the tax relief was granted. e covenant must be

16

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

at least coextensive with the tax relief period but can be up to twice the duration of that period.

It must include provisions requiring the owner to maintain certain insurance coverage and can

include a lien against the proceeds from insurance claims. All transferees and assignees are

subject to the provisions of the covenant, so it is recorded in the registry of deeds and runs with

the property. e applicant for tax relief is charged with the reasonable expenses in draing,

reviewing, and executing the covenant and there are provisions to protect the municipality

should the property owner not live up to the agreement. A municipality’s denial of the application

for this tax relief is discretionary and may not be set aside by the Board of Tax and Land Appeals

(BTLA) or a court except for bad faith or discrimination.

3. REIMBURSEMENT FOR PURELY PRIVATE BENEFIT

If the town spends money in a way that benets only private individuals (for example, plowing

private roads or private driveways), the town’s costs must be reimbursed by those who benet

so that no burden falls on the taxpayers. In addition, such work on behalf of private individuals

is permissible only if it is incidental to work performed primarily for a public purpose. Clapp v.

Jarey, 97 N.H. 456 (1952).

G. How Specic Should a Proposed Appropriation Be?

When preparing the budget or separate warrant articles, always be sure the wording of an appropriation is

clear enough to let the governing body know how much exibility it has. e degree of specicity is up to

the legislative body and is oen based on political considerations. e amount of freedom the governing

body has depends on how specic the purposes in the warrant article or on the budget form are.

For example, consider a special article which states: “… to raise and appropriate $____for a new grader

to be purchased from Town Graders, Inc. of Concord.” is wording is probably too specic because it

limits the options of the ocials making the purchase. It could be construed to prohibit purchasing from

another dealer. What if that vendor does not have any graders at that price? What if can be obtained for

less money from another vendor? On the other hand, an article that says “equipment” instead of “grader”

may not be specic enough and may lead voters to amend the article to more specically dene the action

that may be taken by the governing body, thus keeping the reins on their ocials.

As a general rule, a warrant article should be draed to be specic enough to set the policy but broad

enough to allow the governing body discretion on the details of carrying out that policy. e dollar

amount must always be exactly specied, but it serves as an upper limit, not as a mandate for spending

the entire amount.

It is also important to consider who legally is required to have custody of the funds being appropriated

and which ocial(s) or board will have legal authority to spend those funds. See Appendix A for a chart

outlining some of the more common types of funds created by towns, who may have custody of the funds

and who may authorize expenditures of those funds.

H. Contingency Funds

As of August 24, 2013, towns may establish a contingency fund by an article separate from the budget

and all other articles in the warrant for the annual meeting. e fund may be used by the governing body

during the year to meet the cost of unanticipated expenses that may arise during that year. e fund may

not exceed one percent of the amount appropriated by the town during the preceding year, excluding

capital expenditures and debt service. A detailed report of all expenditures from the contingency fund

must be made each year by the select board and published in the annual report. RSA 31:98-a; RSA 32:11, V.

17

Chapter 1. Appropriations

RSA 198:4-b, I authorizes school districts to establish contingency funds in like manner as towns.

However, school contingency funds are not subject to the one percent rule that applies to towns.

I. Tax/Spending Caps

Towns and cities (as well as school districts) may adopt limits on spending or tax increases. For a city,

or for a town with a town council form of government, the charter may be amended to include a limit

on annual increases in the amount raised by taxes in the city or town budget. e limit must include

a provision allowing for override of the cap by a supermajority vote as established in the charter.

RSA 49-C:12, III; RSA 49-C:33, I(d); RSA 49-D:3, I(e). Amendments eective August 20, 2021 provide

that city and town charter exclusions, ordinances and accounting practices that have the eect of an

override of a tax cap require a supermajority vote of the legislative body.

In other towns with traditional town meeting or ocial ballot referendum town meeting (SB 2), and

other political subdivisions adopting a budget at an annual meeting of the voters, the voters may adopt

a limit on annual increases in the estimated amount of local taxes in the governing body’s or budget

committee’s proposed budget. RSA 32:5-b; RSA 32:5-c. e cap must be either a xed dollar amount or a

xed percentage. If the taxes raised for the prior year were reduced by the use of fund balance (explained

in Chapter 5), the amount of the reduction is added back and included in the amount to which the tax

cap is applied. RSA 32:5-b, I-a (eective August 5, 2013). If a cap is adopted, the estimated amount to

be raised by local taxes as shown on the proposed budget certied by the governing body or budget

committee and posted with the warrant may not exceed the local taxes actually raised for the prior

scal year by more than the cap. e cap does not, however, limit the amount the voters may actually

appropriate at the meeting; it is only a limit on the budget submitted to the voters for consideration. In a

traditional town meeting, the voters may still amend the proposed budget up or down in the same way

they ordinarily would. In a town using the SB 2 form of town meeting, adoption of a cap does not prevent

the voters at the deliberative session from amending one or more warrant articles (or all of them) to

increase the amount of a proposed appropriation or the total amount of all proposed appropriations. It is

important to note, of course, that in a town with an ocial budget committee, the ten percent limitation

(explained in Chapter 7) will still apply and eectively cap the total amount that may be appropriated.

A cap can be adopted by a town with either traditional town meeting or an SB 2 meeting. In either case,

the question of adopting a cap must be placed on the warrant by the governing body or by citizen petition

under RSA 39:3. In a town with traditional town meeting, voting on the question is by ballot conducted

at the business session of the meeting, not by ocial ballot with the election of ocers. In an SB 2 town,

the question is voted upon on the ocial ballot with all other questions. In either case, adoption of the

cap requires a three-hs majority of those voting. If a cap is adopted, it takes eect beginning with the

subsequent scal year. A cap can be repealed in the same manner in which it is adopted.

e law also raties all tax or spending cap provisions previously adopted in any city or town charter.

RSA 49-B:13, II-a.

J. Procedural Requirements for Valid Appropriations

An appropriation must comply with several procedural requirements to be valid. Each procedural

requirement is explained in more detail throughout this book. ey include:

• a public budget hearing;

• disclosure of all purposes and amounts at the hearing;

• budgeting on a gross basis (See Chapter 2);

18

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

• recommendations of the governing body and, if there is one, the budget committee (See Chapter 2,

sections D, E and F);

• warrant notice (See Chapter 3); and

• listing of all appropriations and separate warrant articles on the posted budget.

1. BUDGET HEARING

All towns and districts must hold at least one public hearing on each budget not later than 25 days before

any annual or special meeting. Additional hearings may be held fewer than 25 days before the meeting.

RSA 32:5, I. In ocial ballot referendum (SB 2) towns and districts, the 25-day requirement does not

apply; instead, the budget hearing is held on or before the third Tuesday in January for a March annual

meeting. (See RSA 40:13, II-b and II-c for SB 2 hearing requirements for April and May town meetings.)

If there is a budget committee, that committee conducts the public hearing(s); otherwise, the governing

body (select board, school board or village district commissioners) does so. RSA 32:5, I. Public notice

of each hearing must be given at least seven days in advance, not counting the date of the hearing.

e statute does not specify how the notice must be given, but the best practice is to give notice by

both posting in two public places and publishing. If a public hearing is recessed to a later date or time,

additional notice is not required for the next session if the date, time and place are made known at the

original session. RSA 32:5, I.

2. DISCLOSURE OF ALL PURPOSES AND AMOUNTS AT HEARING

Aer the public budget hearing, no new purpose or amount can be added to the proposed budget unless

that purpose or amount was “discussed or disclosed” at that hearing, or unless a further hearing is held.

RSA 32:5, II. is statute prevents the budget committee or governing body from adding new purposes

to, or increasing amounts in, the proposed budget that were not discussed or disclosed at the hearing. e

legislative body (the voters), however, may increase or decrease proposed amounts or delete (but not add)

purposes of appropriation at the meeting. is topic is covered in more detail below.

e law does not require the proposed budget to be posted with the notice of the budget hearing, but

without at least a dra proposal, the public has no realistic opportunity for input. Also, while the law does

not technically require the proposed budget to be prepared in time for distribution at the hearing, all line

items and amounts must be “disclosed or discussed” at the hearing. Having a prepared form helps ensure

all items will be “disclosed.” However, eective September 21, 2021, if a town or district uses subaccounts to

budget or track nancial data it shall make that data available for public inspection at the public hearing.

e hearing requirement also applies to appropriations included in petitioned warrant articles. erefore,

at least one budget hearing must be scheduled aer the nal day for submitting petitioned articles. is

is the h Tuesday prior to the meeting in traditional meeting towns (RSA 39:3), the second Tuesday in

January for March SB 2 meeting towns (RSA 40:13, II-a), or 30 days prior to the meeting in traditional

school districts (RSA 197:6). at leaves a very narrow window within which at least one of the budget

hearings must be held.

e governing body or the budget committee, if there is one, is not required to vote on the nal proposed

budget at the public hearing. e law says the budget must be nalized “aer the conclusion of public

testimony.” at could mean immediately aer, or several days later at a properly noticed public meeting.

If a member of the public, at the public hearing, makes a suggestion for a new appropriation, the

governing body or budget committee can add it to the proposed budget without a second hearing because

it was “discussed” at that rst hearing.

RSA 32:5, IV specically requires all appropriations to be listed on the posted budget, which includes

special warrant article appropriations and other warrant article appropriations not included in the

19

Chapter 1. Appropriations

operating budget. e DRA will invalidate any appropriation not included on the posted budget

form (MS-636 and MS-737). Special warrant articles also require a notation of whether or not

they are recommended by the governing body and, if there is one, the budget committee.

3. COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENTS

RSA 32:19-a creates a submission date aer which the cost items of a collective bargaining

agreement (CBA) reached between employee unions and the governing body may not be included

in the proposed budget. RSA 32:5-a requires a negotiated agreement on cost items by the nal

date for submitting petitioned warrant articles. Cost items not negotiated by that date cannot

be submitted to the legislative body at the annual meeting, but may be submitted later at a

special meeting held under RSA 31:5 or RSA 197:3. e law also allows a special town or district

meeting, without the requirement of superior court permission, to consider CBA cost items

rejected by the annual meeting, if authorization is included in the original warrant in the form

of a contingent warrant article, inserted by petition or by the governing body, as follows: “Shall

[name of municipality], if article ___ is defeated, authorize the governing body to call one

special meeting, at its option, to address article ___ cost items only?” RSA 31:5, III and

RSA 197:3, III. Cost items are dened by RSA 273-A:1, IV.

In budget committee towns, RSA 32:19 exempts CBA cost items from the 10 percent rule, but

only that portion of the CBA cost items that is not recommended by the budget committee. See

Chapter 7 for more information about budget committees and the 10 percent rule.

K. Inter-Municipal Agreements, Shared Services, and Voluntary Contributions

RSA chapter 53-A authorizes municipalities to enter into agreements with other municipalities, counties,

school districts, school administrative units (SAU’s), and village districts for the purpose of providing

services and facilities in a cooperative manner that is mutually advantageous to all parties. It also

authorizes the appropriation of funds necessary to carry out the contractual obligations that are incurred.

Any powers, privileges, or authority exercised, or capable of being exercised, by a municipality may be

exercised jointly with any other public agency of the state, such as providing water and sewer services or

entering into public works mutual aid agreements. Several laws enacted in 2016 claried and expanded

this “joint exercise of powers,” granting specic authority to do the following:

• cooperate with school districts and SAU’s for activities such as, but not limited to, conducting

nancial, human resources, information technology, and other managerial and administrative

functions. RSA 53-A:2, 53-A:3;

• enter into agreements with adjacent municipalities and nonprot entities to provide suitable

cemeteries. RSA 289:2; and

• voluntarily contribute funds, services, property, or other resources toward any county or state

project, program or plan, subject to annual renewal of the voluntary contribution by the legislative

body. RSA 44:1-b, RSA 31:103-a.

In 2019, the legislature passed legislation to allow two or more municipalities to enter into an agreement

under RSA 53-A to issue bonds for any purpose permitted under RSA 33 as well as claried that

municipalities may enter into an agreement under RSA 53-A to jointly establish a tax increment nancing

district under RSA 162-K (regardless of a climate emergency).

RSA chapter 53-A outlines the statutory requirements and procedures for an inter-municipal

agreement, including the purpose; duration and termination; creation of an administrative entity,

administrator, or joint board; manner of nancing; indemnication; manner of acquiring, holding, and

20

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

disposing of real and personal property used in the cooperative undertaking; ling requirements; and

state agency approvals.

An important cautionary note is that the New Hampshire Retirement System (NHRS) strongly

encourages participating employers to call for guidance with respect to enrollment, eligibility,

creditable service, and earnable compensation for “shared personnel” in agreements with both other

NHRS participating employers, as well as non-participating employers. NHMA is aware of at least one

inter-municipal entity that has contacted NHRS and received guidance on this issue.

21

Chapter 2. ‘Gross Basis’ Budgeting

CHAPTER TWO

Second Key Concept

‘GROSS BASIS’ BUDGETING

RSA 32:5, III requires all appropriations to be stated on a “gross basis,” meaning that all anticipated

revenue from all sources, not just tax money, must be shown as osetting revenues to the amounts

appropriated for specic purposes. Revenues other than taxes raised may include grants, gis, bond issues

and proceeds of the sale of municipal property. With a few exceptions revenues not appropriated cannot

be spent. is rule follows logically from the principle that all expenditures—not just tax expenditures—

must be supported by legislative body appropriations RSA 32:8.

A. Care in Drafting Warrant Articles

If the town wants to buy a new re truck for $360,000 and intends to pay for it with $280,000 of tax

money and $80,000 from selling the old re truck, the total amount of $360,000 must be appropriated,

disclosing both sources of revenue. In other words, always set forth the grand total in the “raise and

appropriate” clause, and then go on to break it down by listing the amount to be drawn from each

separate revenue source, including any non-tax revenue that is to be used. When draing warrant

articles, care should be taken to observe this requirement because DRA has the authority to invalidate

appropriations that fail to follow it. It is helpful to have dra warrant articles reviewed well in advance by

DRA and/or the town’s attorney.

B. Examples of Mistakes

Here are some examples of votes taken in recent years, collected by the DRA (names omitted to protect

the innocent):

1. TOTAL AMOUNT

“To see if [the town] will vote to raise and appropriate the sum of $75,000 to renovate [a

particular building] and to authorize the withdrawal of $75,000 from the Capital Reserve Fund

created for this purpose; and further to combine this $150,000 with the $20,600 appropriated last

year for [another purpose] and to authorize the select board to apply for a matching amount from

the CDBG program.”

Problems: First, the total amount of the appropriation was never stated. It is impossible to

determine the total cost of the renovation project, and we cannot determine how much in

matching CDBG funds to anticipate. Gross basis budgeting requires all anticipated revenues,

whether from grants or other sources, to be included in the total amount appropriated. Second,

DRA disallowed the $20,600. e fact that it was appropriated last year for another purpose does

not exempt it from the requirement of being appropriated this year for this new purpose (and

the language that was used did not do this clearly enough). Remember that an appropriation

22

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

normally “lapses” at the end of the year. (Lapse is covered in more detail in Chapter 5.) e belief

that a prior year’s appropriation has a continuing existence and need not be included in the new

total appropriation is a common mistake.

2. APPROPRIATE REVENUES, TOO

“I move to raise and appropriate a supplemental appropriation of $20,000 for the cost of replacing

[the roof of a certain building]; and further to authorize the withdrawal of $4,000 from the

Building Capital Reserve Fund; the balance of $14,500 is to be funded by current excess revenues

received in the current year [an insurance settlement].”

Problem: Again, the total amount of this appropriation is impossible to determine. e $14,500

insurance settlement may be revenue already received, but it must be appropriated to meet

the gross basis appropriation requirement. Is the total amount of the appropriation $34,500?

$20,000? $18,500? e total amount of the appropriation should be stated rst, so there is no

misunderstanding. If the numbers within the article do not add up to the total stated at the

beginning, there will be a problem.

3. INCLUDE THE APPROPRIATION, NOT JUST THE PURPOSE

“To see if the Town is in favor of the select board conducting a local resident survey on the

manner and quality of street maintenance in the town, to assist the select board’s operation of the

public works department.” e article was then amended on the oor of the meeting, so that the

end of the last sentence said, “and to raise and appropriate the sum of $10,000 for the cost of the

resident survey.”

Problem: e original article contained no appropriation. Although the voters attempted to

amend the article on the oor of the meeting to include an appropriation, it was not proper

because all purposes of appropriation must be disclosed or discussed at the budget hearing,

and all proposed purposes of appropriation must be included with the warrant that is posted

before the meeting. In this case, it is likely that DRA would disallow the $10,000 attempted

appropriation in the amendment. Had the original article included an appropriation amount, the

meeting could have amended that amount up or down.

4. PROPER WARRANT ARTICLE DRAFTING

Always set forth the grand total amount in the “raise and appropriate” clause, including any

amount from trusts or capital reserve funds and any amount from anticipated revenue or existing

fund balance. en break it down. Be certain that the math works; all the component parts of

the appropriation should add up to the grand total amount at the beginning of the article. An

example of a well-worded article is as follows:

“To see if the town will raise and appropriate the sum of $100,000 to repair the town’s war

memorial statue; of this amount $20,000 is authorized to be withdrawn from the War Memorial

Statue Trust Fund, $30,000 is anticipated revenue from a settlement with War Memorial

Insurance Company, and the balance of $50,000 is to be raised from general taxation.”

C. Comparative Columns

RSA chapter 32 requires the budget to include comparative columns showing the prior year’s

appropriations and prior year’s expenditures. DRA forms contain the information for the comparative

columns. RSA 32:5, III and IV.

23

Chapter 2. ‘Gross Basis’ Budgeting

D. Individual Versus Special Articles

Appropriations may be made in a variety of ways. Many appropriations are part of the line-item operating

budget (that is, what appears on the MS-636 and MS-737 forms). Others may be part of warrant articles

that propose an appropriation. ese are referred to as individual or separate warrant articles because

they separate out a proposed appropriation from the line item budget. Generally, the governing body may

choose to propose an appropriation that would otherwise appear in the line item budget as an individual

appropriations article instead.

ere are ve specic types of individual appropriations articles that are treated in a special way, and

those are referred to as “special warrant articles.” Under RSA 32:3, VI, special warrant articles are dened

as follows:

• petitioned warrant articles;

• articles calling for issuing bonds or notes;

• appropriations into or out of separate funds, such as capital reserves or trust funds;

• any other separate article designated and labeled by the governing body as “special,” “nonlapsing”

o

r “nontransferable;” and

• an appropriation of an amount for a capital project under RSA 32:7-a.

us, all “special” warrant articles are separated out from the operating budget, but not all of these

individual warrant articles are considered “special.”

Appropriations in special warrant articles are treated as nonlapsing at the end of the year. ey cannot be

transferred to other purposes under the transfer power of the governing body. (See Chapter 6.)

E. Special Articles and Recommendations

All special warrant articles require a notation of whether or not they are recommended by the governing

body. In budget committee towns and districts, special articles should contain both governing body and

budget committee recommendations. RSA 32:5, V. Articles regarding cost items for collective bargaining

agreements also require a statement of the recommendation or non-recommendation of the governing

body and budget committee. RSA 32:19. However, RSA 32:5, V provides that “defects or deciencies in

these notations shall not aect the legal validity of any appropriation otherwise lawfully made.”

ese statutes do not (nor does any other statute) expressly extend the recommendation requirements

to non-money articles, and there has been debate over whether the select board has such authority.

At least one superior court judge has determined that a select board does have the authority to place

recommendations on non-money articles. Olson v. Town of Graon, 168 N.H. 563 (2016). In Olson, the

Superior Court sided with the town and decided that RSA 32:5, V-a gives a governing body the authority

to insert recommendations aer any warrant articles, not just non-budgetary articles. e N.H. Supreme

Court agreed that the language in the statute permits the select board to place its recommendations on

the warrant for any warrant article including non-money articles.

F. Numeric Tallies and Recommendations on Other Warrant Articles if Authorized by

Town Meeting, Governing Body or Ocial Budget Committee

RSA 32:5, V-a allows any town operating by traditional town meeting to require that the numeric tally of

all votes of an advisory or ocial budget committee and all votes of the governing body be printed in the

24

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

warrant next to that article. A vote to include the numeric tally under this law also authorizes a town to

include these recommendations on individual warrant articles, not just special warrant articles and those

relating to cost items in a collective bargaining agreement.

RSA 40:13, V-a allows any town operating under the ocial ballot referendum (SB 2) town meeting to

require that the numeric tally of all votes of an advisory or ocial budget committee and all votes of the

governing body be printed on the ballot next to the aected article. A vote to include the numeric tally

under this law also authorizes a town to include these recommendations on separate warrant articles

as well as ballot questions, in addition to special articles and those relating to cost items in a collective

bargaining agreement.

In either case, the town may authorize this by a vote of town meeting, or if the town has not voted to do

so, the governing body or an ocial budget committee may take a vote at a public meeting on their own

initiative. RSA 32:5, V-a. e “numeric tally” means the total result of the vote on the item, such as “Budget

Committee recommends this article by a vote of 9 to 2. Select board does not recommend this article

by a vote of 3 to 2.” Unless and until such a vote of town meeting or the governing body has occurred,

recommendations should continue to appear without the numeric tally and only with special articles and

cost items of collective bargaining agreements.

G. Multi-Year Appropriations for Capital Projects

As of August 23, 2013, towns may make multi-year appropriations for “capital project.” RSA 32:7-a.

A capital project for this purpose is one for which bonds could be issued under RSA 33:3 or RSA 33:3-a.

ese include:

the acquisition of land;

planning relative to public facilities;

the construction, reconstruction, alteration and enlargement or purchase of public buildings;

for other public works or improvements of a permanent nature including broadband

infrastructure;

for the purchase of departmental equipment of a lasting character;

for the payment of judgments;

for economic development (including public-private partnerships involving capital

improvements, loan and guarantees); and

preliminary expenses associated with proposed public work or improvement of a permanent

nature (including public buildings, water works, sewer systems, solid waste facilities and

broadband infrastructure).

e article authorizing the appropriation must (a) identify the specic project, (b) state the term of years

of the appropriation (up to ve years), (c) state the total amount of the appropriation, and (d) state the

amount to be appropriated in each year of the term. e article must pass by a 2/3 vote (3/5 vote in ocial

ballot referendum towns).

For each year aer the rst year, the amount designated for that year as provided in the original warrant

article shall be deemed appropriated without further vote by the legislative body. In other words, once

town meeting has authorized a capital project multi-year appropriation, no warrant article is needed in

25

Chapter 2. ‘Gross Basis’ Budgeting

any other year of the term; each year’s amount will be treated as appropriated automatically in the future

years of the term. In ocial ballot referendum towns, that year’s amount is also automatically included in

the default budget.

If the amount appropriated in any year is not spent in that year, it will not lapse. e money will

remain available for use for the project during the term stated in the warrant article. However, a capital

project appropriation does not create a capital reserve fund. It is simply accounted for as a nonlapsing

appropriation from year to year. At the end of the term stated in the original warrant article, any unspent

amounts will lapse into the fund balance.

At any annual meeting before the end of the term of the project, the legislative body may rescind the

appropriation by a simple majority vote on a warrant article. If the project is rescinded, any unexpended

appropriations for the project will lapse into fund balance immediately.

H. Estimated Tax Impact

e legislative body (town, school or village district meeting) may vote to require that the annual budget

and all special warrant articles having a tax impact include a statement of the estimated tax impact of that

appropriation. RSA 32:5, V-b. e law species that it is up to the governing body (select board, school

board, or village district commissioners) to determine whether an article has a tax impact. In addition,

the determination of the estimated tax impact is subject to approval by the governing body, even if

someone else actually performs the initial calculations.

It is important to remember that the estimated tax impact will always be just that: an estimate. e tax

rate is set in the fall, many months into the scal year and many months aer the annual meeting. During

that time, several issues will be at play. Property tax rates are based on the amount of appropriations

approved, less non-tax revenues that are received, divided by the equalized property value of the

municipality. However, the municipality’s property value is based on an assessment that does not occur

until April 1 (and is not fully compiled for several months aer that). e actual revenues received from

sources other than taxes may be greater or less than the estimates on the budget forms voted on at the

annual meeting. All of this means that the true amount to be raised by taxes, and the total property

values on which the tax rate will be determined, may be quite dierent from the estimates used in March

to determine the estimated tax rate.

erefore, if the estimated tax impact is going to be included in the warrant and/or ballot, it is strongly

advisable to explain to voters that it is only an estimate based on the information available at the time.

Having said that, however, it can be useful to know if a particular proposed appropriation might have an

impact of pennies, dimes, or dollars on the tax rate, even if the actual impact varies slightly.

26

The Basic Law of Budgeting – 2022 Edition

CHAPTER THREE

Third Key Concept

WARRANT NOTICE AND

PERMISSIBLE AMENDMENTS

RSA 32:6 and RSA 39:2 prohibit an annual or special meeting from appropriating any amount for any

purpose unless that purpose appears in the warrant or in the posted budget (whether as a line item in

the budget or as a separate article). e posted budget can be thought of as part of the warrant for notice

purposes. New line items — “purposes” — cannot be added from the oor of town meeting or under an

“other business” article.

For traditional meetings, the warrant and budget must be posted in two public places in the town or