Roger Williams University Roger Williams University

DOCS@RWU DOCS@RWU

Arts & Sciences Faculty Publications Arts and Sciences

2007

Effects of Expert Testimony and Interrogation Tactics on Effects of Expert Testimony and Interrogation Tactics on

Perceptions of Confessions Perceptions of Confessions

Morgan Moffa

Roger Williams University

Judith Platania

Roger Williams University

Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/fcas_fp

Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Effects of expert testimony and interrogation tactics on perceptions of confessions.

Psychological

Reports,

100(2), 563-570.

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at DOCS@RWU. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For

more information, please contact [email protected].

Psychologzcal

Report\,

2007, 100, 563-570.

0

Psychological Reports 2007

EFFECTS OF EXPERT TESTIMONY AND INTERROGATION

TACTICS ON PERCEPTIONS

OF

CONFESSIONS

'

MORGAN

S.

MOFFA AND JUDITH PLATANIA

Roger Williams

Univev.rity

Summary.-Evidence obtained through the process of interrogation is frequently

undermined

by what can be perceived as overzealous interrogation tactics. Although

the majority of psychologically oriented tactics are

legally permissible, they nonetheless

contribute to innocent suspects confessing to crimes they did not commit. The pres-

ent study examined the effect of expert testimony and interrogation tactics on percep-

tions of a confession. 182 undergraduates read a transcript of a homicide trial that

varied based on interrogation tactic: implicit threat of punishment (maximization) or

leniency (minimization) and expert witness testimony (presence or absence of expert

testimony). Analysis indicated that the type of interrogation tactic used in obtaining

the confession affected participants' perceptions of the coerciveness of the interroga-

tion process.

The process of interrogation to elicit a confession is an essential process

in our system of jurisprudence. The conventional wisdom has been and con-

tinues in part to be that an innocent person would never confess to a crime

he did not commit (Kassin

&

Wrightsman, 1981). Such self-incrimination is

typically considered irrational (Colorado v. Connely, 1986) or perhaps an

attempt to gain notoriety, as in the infamous kidnapping case of the

Lind-

bergh baby in which 200 people falsely confessed (Bernstein, 2006). Not only

are confessions sometimes unrelated to guilt, at times they have been obtain-

ed through bargaining or negotiating with a suspect. Considering the variable

nature of the interrogation process, as many as 20% of all confessions are

recanted (Wrightsman

&

Fulero, 2005). Regardless of whether a confession is

voluntary or coerced, confession evidence can be so persuasive to a jury that

its presence during trial renders all other trial aspects meaningless

(McCor-

mick, 1972).

There are several legal protections that apply to confessions, some in-

volving case law and some evolving out of the United States Constitution.

The cause and remedy for obviously coerced confessions is illustrated in

Brown v. Mississippi (1936). As a result of interrogators' use of physical tor-

ture or "third-degree" tactics, the Brown court vacated the defendants' con-

viction. This decision was based on the Constitution's provision of due pro-

cess, as codified in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Fifth

-

~-~~p-~~~p

'Address correspondence to Morgan Moffd c/o Judlth Platanla, Roger

Williams

Univerwy,

One Old Ferry Road, Brlstol, RI 02809, or e mall (m~moffa@~ahoo com and jpldtan~d@rwu

edu)

M.

S.

MOFFA

&

J.

PLATANIA

Amendment also protects every defendant from acting as a witness against

himself. No government agent can lawfully compel a suspect to make any in-

voluntary statement at any time during interrogations. In Miranda v. Arizona

(19661, the court interpreted and applied the Fifth Amendment to provide a

fundamental right to all suspects to remain silent. These safeguards exist to

protect the suspect's rights, as well as to ensure the validity of the confes-

sions.

Social science research in the area of confessions is necessary to evaluate

the psychological implications of legally permissible practices used in inter-

rogations (Royal

&

Schutt, 1976; O'Hara

&

O'Hara, 1980; Macdonald

&

Michaud, 1987; Walkley, 1987; Inbau, Reid, Buckley,

&

Jayne, 2001). One

term with much significance for social psychology in the evaluation of a

Mi-

randa waiver is "voluntariness." In order for a valid law enforcement appli-

cation of Miranda protections, a suspect's waiver must be "knowing, volun-

tary, and intelligent"

(Melton, Petrila, Poythress,

&

Slobogin, 1997, p. 158).

The court is required to evaluate the context of the waiver in terms of the

"totality of the circumstances" (Columbe v. Connecticut, 1961; Samaha,

2002, p. 385). The 1991 decision in Arizona v. Fulminante created a

per

se

rule for confessions and a limitation on the exclusionary rule of evidence. If

sufficient evidence existed to convict a defendant in addition to a disputed

confession, the confession itself was considered to be harmless error, and

thus admissible. Before this case, a coerced confession was grounds for auto-

matic reversal.

Suspects waive their Miranda rights at an alarming rate of approximate-

ly

80% (Grisso

&

Pomicter, 1977). Given this, researchers need to under-

stand the details of when Miranda rights are invoked and the value of exam-

ining the many factors that affect the interrogation process. According to

Leo

(1996b), 4 out of

5

suspects waived their rights and submitted to ques-

tioning. Kassin, Meissner, and

Norwick (2005) found college students per-

formed significantly better than police investigators when evaluating confes-

sions as either true or false. In a series of experiments, undergraduates and

detectives viewed or heard prisoners confess to either fabricated or factual

crimes. College students were more accurate than detectives in evaluating the

truthfulness of the confession. This study provides empirical support for ad-

dressing the consequences of waiving Miranda rights.

The use of interrogation tactics

by police is intended to lawfully commu-

nicate a threat (maximization) or a promise (minimization) to a suspect to

elicit a confession. Explicit threats and promises are not always avoided; the

nature of the confession and how it is obtained must be within certain legal

boundaries in order to be admissible at trial. The communication of a threat

or promise in the interrogation process lends itself to empirical investigation,

and therefore is one focus of the present investigation. Jurors' perceptions of

M.

S.

MOFFA

&

J.

PLATANIA

on their own perceptions of maximization and minimization as well as testi-

mony provided

by an expert regarding confessions when evaluating coer-

cion. In addition, verdict preference was examined as a function of each of

the independent variables. Finally, there is a question of the moderating ef-

fect (if any) of expert testimony on the dependent variables. In order to al-

low meaningful comparisons, a no-coercion condition was included as a con-

trol condition.

Hypothesis 1: Jurors' perceptions of "pressure on defendant to confess"

and "fairness of the police interrogation" would be a function of interroga-

tion tactic (maximization vs minimization) and the presence or absence of

testimony by an expert. Maximization would be associated with increased

ratings of pressure and decreased ratings of fairness. These effects should be

moderated by the presence or absence of testimony

by an expert.

Hypothesis 2: There would be a significant interaction of expert testi-

mony and interrogation tactic on jurors' decisions of voluntary vs coerced

confessions, and verdict.

Hypothesis

3: There would be a significant interaction of expert testi-

mony and interrogation tactic on perceptions of accuracy of the testimony

by the interrogator.

Participants

One hundred eighty-two undergraduates participated in this study as

part of a research requirement or for extra credit. Fifty-one percent were

women (n

=

92) and 49% were men (n

=

90). All participants were between

the ages of

18

and 24 years. Ninety-five percent were Euro-American, unmar-

ried, and reported no prior jury experience. All participants were treated in

accordance with

APA's ethical principles (2002). In all instances, participa-

tion took place during a class period, in a group setting.

Materials

Participants read a

10-page transcript of a homicide trial. After reading

the transcript,

they responded to

a

45-item questionnaire measuring demo-

graphics and attitudes toward the trial scenario. Seventeen items measuring

attitudes toward the trial scenario had internal consistency of Cronbach

a=

.92.

All judgments were made on a scale of 0: Not at all important/accurate,

etc. to

6:

Very important/accurate, etc. See Appendix (p. 570) for examples

of key attitudinal items. The entire study took 30 to 45 minutes to complete

-

'American Psychological Association. (2002) Ethical principles of

ps

chologists and code of

conduct. Retrieved January

8,

2007 from

http://~~~.apa.org/ethi~s/~odk~0022Pdf.

EFFECTS OF EXPERT TESTIMONY

Design and Procedure

All participants who

agreed to participate gave their consent and were

administered a homicide trial transcript to read. In this case, the State al-

leged that the victim was stabbed to death outside of a bar by her

ex-

boyfriend. Transcripts varied based on the type of interrogation tactic used

with the ex-boyfriend in order to elicit a confession (maximization or mini-

mization) and testimony

by an expert (presence or absence of expert testi-

mony) only; all other trial aspects remained constant,

i.e., opening and clos-

ing statements of the defense and prosecution and general judge's instruc-

tions.

Both types of interrogation tactic were based on researchers' descrip-

tions (Inbau,

et al., 2001; Costanzo, 2004; Wrightsman

&

Fulero, 2005). For

example, for Maximization the following statements were used: "We have an

eyewitness that says you did this," and "Your prints are on the murder

weapon." For Minimization the following statements were used: "Look, you

did this in the heat of passion, so you're not in that bad of shape," and

"Morally, you're practically justified." Transcripts represented a

2

(Expert

Testimony: expert, no expert)

x

3 (Interrogation Tactic: maximization, mini-

mization, control) between-subjects factorial design. At the completion of

the study, participants were verbally debriefed and thanked.

RESULTS

Manipulation Check

A

one-way analysis of variance was conducted to assess if participants

were aware of the presence of expert testimony (expert vs no expert). Re-

sults indicated the manipulation was effective

(F,

,,,,

=41.62, p

<

.001; Ms

=

3.61 and 1.88, respectively).

A

2 (Expert Testimony: expert, no expert)

x

3

(Interrogation Tactic:

maximization, minimization, control) analysis of variance on jurors' percep-

tions of the amount of pressure placed on the defendant to confess in-

dicated a significant main effect of interrogation tactic

(F,

,7,

=

7.55, p

=

.OOI;

q2=

.O8). Scheffk's test of multiple comparisons indicated Maximization dif-

fered significantly from Minimization

(p

<

.001; Ms

=

5.10 and 4.15, respec-

tively). Participants exposed to implicit communication of threats or harsh

punishment (maximization) were significantly more likely to perceive greater

pressure to confess compared to those exposed to implied communications

of lenience or justification (minimization). No significant effect of expert tes-

timony was found and no significant Expert Testimony

x

Interrogation Tactic

interaction. A

2

(Expert Testimony: expert, no expert) ~3 (Interrogation

Tactic: maximization, minimization, control) analysis of variance on jurors'

perceptions of the fairness of the police interrogation did not indicate signif-

icant main effects or interaction.

M.

S.

MOFFA

&

J.

PLATANIA

Hypothesis

2

was not supported. Results of separate log-linear analyses

found no significant associations between expert testimony and interrogation

tactic as independent variables and perceptions of confession (coerced vs not

coerced) or verdict (guilty vs not guilty) as dependent variables.

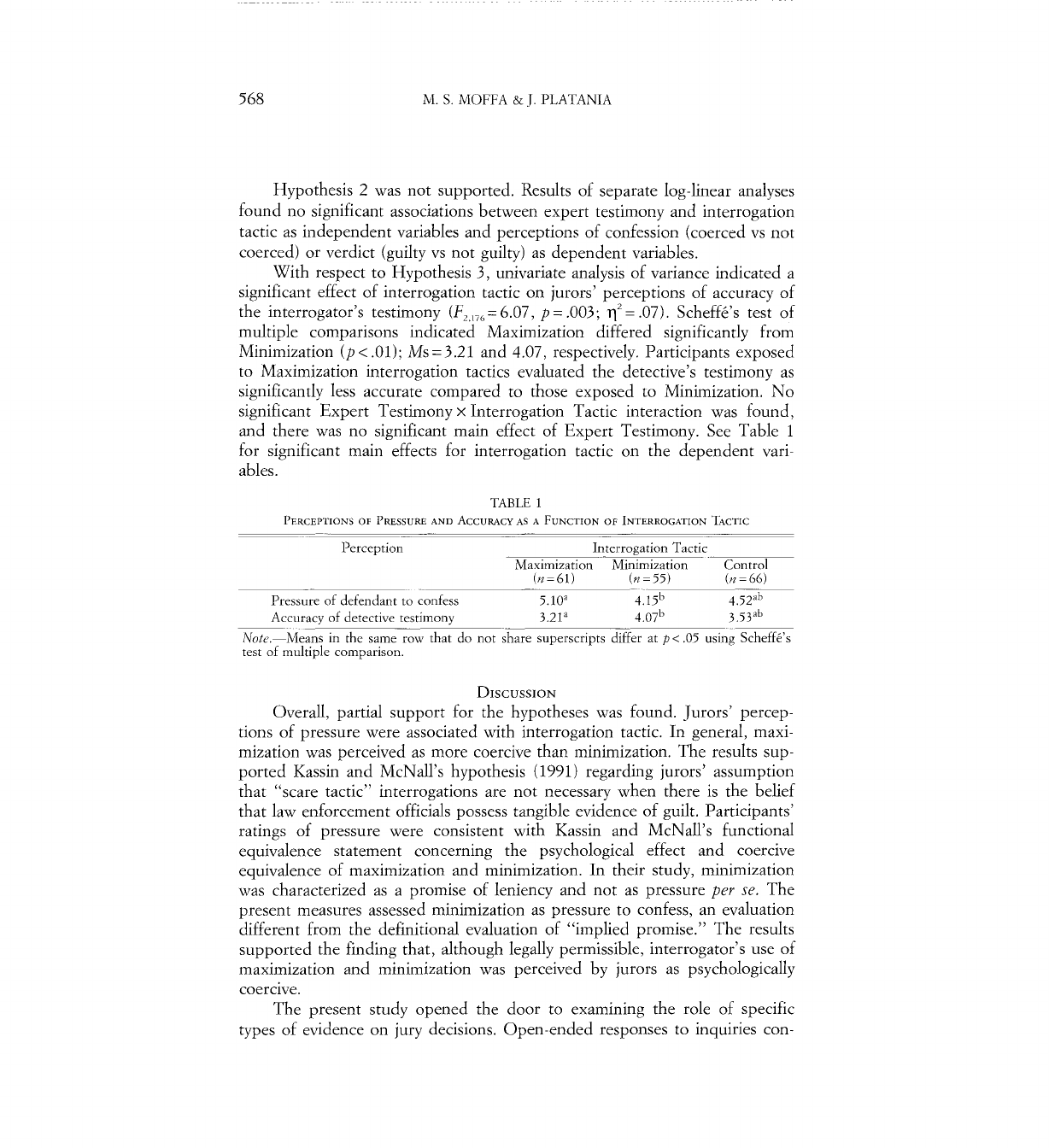

With respect to Hypothesis

3,

univariate analysis of variance indicated a

significant effect of interrogation tactic on jurors' perceptions of accuracy of

the interrogator's testimony

(F,

,i,=

6.07,

p

=

.003;

q2

=

.07). Scheffk's test of

multiple comparisons indicated Maximization

differed significantly from

Minimization

(p <

.01); Ms

=

3.21

and 4.07, respectively. Participants exposed

to Maximization interrogation tactics evaluated the detective's testimony as

significantly less accurate compared to those exposed to Minimization. No

significant Expert Testimony

x

Interrogation Tactic interaction was found,

and there was no significant main effect of Expert

Testimony. See Table 1

for significant main effects for interrogation tactic on the dependent vari-

ables.

TABLE

1

PERCEPTIONS

OF

PRESSURE

AND

ACCURACY

AS

A

FUNCTION

OF

INTERROGATION TACTIC

--

Perception Interrogation Tactic

Maximization Minimization Control

(n=61) (n

=

55)

(n

=

66)

Pressure of defendant to confess

5.10a 4.15~ 4.52"b

Accuracy of detective testimony

3.21' 4.07" 3.53""

Note.-Means in the same row that do not share superscripts differ at

p<

.05

using Scheffk's

test of multiple comparison.

DISCUSSION

Overall, partial support for the hypotheses was found. Jurors' percep-

tions of pressure were associated with interrogation tactic. In

general, maxi-

mization was perceived as more coercive than minimization. The results sup-

ported Kassin and McNall's hypothesis (1991) regarding jurors' assumption

that "scare tactic" interrogations are not necessary when there is the belief

that law enforcement officials possess tangible evidence of guilt. Participants'

ratings of pressure were consistent with Kassin and

McNall's functional

equivalence statement concerning the psychological effect and coercive

equivalence of maximization and minimization. In their study, minimization

was characterized as a promise of leniency and not as pressure

per

se.

The

present measures assessed minimization as pressure to confess, an evaluation

different from the definitional evaluation of "implied promise." The results

supported the finding that, although legally permissible, interrogator's use of

maximization and minimization was perceived

by jurors as psychologically

coercive.

The present

study opened the door to examining the role of specific

types of evidence on jury decisions. Open-ended responses to inquiries

con-

EFFECTS OF EXPERT TESTIMONY

569

cerning the most important factors in reaching a verdict pointed to the im-

portance of evidence either directly or indirectly,

i.e., "no murder weapon";

"no physical evidence"; and

"only circumstantial evidence of guilt." Partici-

pants consistently referred to the absence of this type of forensic evidence in

the trial transcript, suggesting a possible moderating effect of evidence on

decision-making. The inclusion and manipulation of testimony regarding fo-

rensic evidence may improve understanding the effects of testimony

by ex-

pert witnesses. Subsequent research on the effects of interrogations, confes-

sions, and expert testimony should examine their associations with other

types of forensic evidence.

Although the expert testimony condition alone did not show significant

effects, there is the possibility that it had some effect on decision-making.

Based on the present results, it seems that expert testimony

by itself is nec-

essary but not sufficient to modify jurors' perceptions. Conversely, percep-

tions of interrogator were not a function of the combined effects of expert

testimony and interrogation tactic, unexpectedly. Although a moderating ef-

fect was not found, there was a main effect of Interrogation Tactics on per-

ception of the accuracy of the interrogator. Participants exposed to maximi-

zation interrogation tactics evaluated the detective's testimony as less accu-

rate compared to those exposed to minimization. Forensic-type evidence

may have a moderating effect on perceptions of the interrogator's testimony

as well.

One limitation of the study was the written presentation of the stimulus

materials. Video stimulus materials are the most favorable experimental

method to approximate actual courtroom experience. Enhanced presentation

of expert testimony, either via video or

in vivo

exposure, would probably fa-

cilitate a more accurate and complex perceptual process for participants,

leading to more ecologically and externally valid results. In addition, it is im-

portant to stress the issue of generalizing from simulation-type research with

undergraduate students to the behavior of actual jurors. This is particularly

important considering how infrequently students serve as jurors compared

with community members. The value of this study, however, is the insight

offered into factors affecting perceptions of interrogation tactics in a confes-

sion scenario. Researchers should examine the relation between perceptions

and expectations of forensic-type evidence and expert testimony on jurors'

decision-making in criminal trials.

REFERENCES

Arizona

v.

Fulminantc,

499

U.S.

279 (1991).

BERNSTEIN,

L.

(2006)

The

case that

never

dies: the

Lindbergh kidnapping.

lournal of American

History,

92, 1477.1478.

Brown

Y.

MississLpp~

297

U.S.

278 (1936).

Colorado

v

Connely,

479

U.S.

157 (1986).

Colz~mbe

v.

Connecticut,

367

U.S.

568 (1961).

M.

S.

MOFFA

&

J. PLATANlA

COSTANZO, M. (2004)

P.sychology applied to law.

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

GRISSO,

T.,

&

POMICTER, C. (1977) Interrogation of juveniles: an empirical study of procedures,

safeguards, and rights waiver.

Law and Human Behavior,

1, 321-339.

GLJOJONSS~N, G.

H.

(2003) Psycholo y brings justice: the science of forensic psychology.

Crim-

inal Behavior and Mental

~ealtt

13, 159-167.

INBAU,

F.

E.,

REID,

J.

F.,

BUCKLEY,

J.

P.,

&

JAYNE,

B.

(2001)

Criminal

interrogation^

and confes-

sions.

Baltimore,

MD:

Williams

&

Wilkins.

KASSIN, S. M. (1997)

The psychology of confession evidence.

American I'.sychologist,

52, 221-

122

LII.

KASSIN, 5. M. (2005)

On the psychology of confessions: does innocence put innocents at risk?

Amerzcan Psychologi.st,

60, 215-228.

KASSIN,

5.

M., &GUDJONSSON,

G.

H.

(2004) The psychology of confessions:

a

review of the lit-

erature and issues.

Psychological Science in the Public lnterelt,

7, 33-68.

KASSIN, S. M.,

&

MCNALL,

K.

(1991)

Police interrogations and confessions: communicating

promises and threats by pragmatic implication.

Law and Human Behavior,

15, 233-251.

KASSIN,

S.

M., MEISSNER,

C.

A.,

&NORWICK,

R.

J.

(2005)

"I'd know a false confession if 1 saw

one": a comparative study of college students and police investigators.

Law and Human

Behavzor,

29, 21 1-227.

KASSIN,

5.

M.,

&

WRIGHTSMAN,

L.

S.

(1981)

Coerced confessions, judicial instructions, and

mock juror verdicts.

Journal of

flp

lied Soczal Psychology,

11, 489-506.

1x0, R. (195'6a) Miranda's revenge: pice interrogation as a confidence game.

Law and 5ociety

Review,

50, 259-288.

LEO, R. (1996b) Inside the interrogation room.

The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology,

86, 266-303.

LEO,

R.

A,,

&OFSHE,

R.

J.

(1996)

The consequences of false confessions: deprivations of lib-

erty and miscarriages of justice in the age of psychological interrogation.

The Journal of

Criminal Law and Criminology,

55, 429-496.

MACDONALD,

J.

M.,

&MICHAUD,

D.

L. (1987)

The confession: interrogation and criminal profiles

for police

offi'cerc-.

Denver,

CO:

Apache.

MCCORMICK,

C.

T.

(1972)

Handbook of the law of evidence.

(2nd ed.) St. Paul, MN: West.

MELTON, G.

B.,

PETRILA,

J.,

POYTHRESS,

N.

G., &SLOBOGIN,

C.

(1997)

Psychological evaluations

for the courts.

(2nd ed.) New York: Guilford.

Miranda v, Arizona,

384

U.S.

436 (1966).

O'HARA,

C.

E.,

&

O'HARA,

G.

L.

(1980)

Fundamentals of criminal z'nvestigatlon.

(5th ed.)

Springfield, IL: Charles

C.

Thomas.

ROYAL,

R.

F.,

&

SCHUTT, S.

R.

(1976)

The gentle art

of

intewzcwing and interrogatzon: a profes-

sional manual and guide.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Russ~~o, M.

B.,

MEISSNER,

C.

A,,

NARCI~ET,

F.

M.,

&

KASSIN,

S.

M. (2005) Investigating true

and false confessions within a novel experimental paradigm.

Psychological Science,

12,

481-486.

SAMAHA,

J.

(2002)

Crimznal procedure.

(5th ed.) Belmont,

CA:

Wadsworth.

WALKLEY,

-

1.

(1987)

Police intcrrogatzon: handbook for invcstigatorc.

London: Police Review

lJubl.

WRIGHTSMAN, L. S.,

&

FIJLERO, S. M. (2005)

Forensic p.rychology.

Belmont,

CA:

Thompson/

Wadsworth.

Accepted February

20,

2007

APPENDIX

1. Please rate the importance of the confession expert's testimony to your verdict.

2.

How

accurate was Detective Fuller's testimony?

3. Please rate the fairness of the

policc interrogation process described in the trial

4. How much pressure was the defendant under to confess?

Note.-

Judgments were made on 7-point scales (0: Not at all lmportant/accurate to 6: Very

important/accurate).