Publication 5464 (Rev. 1-2021) Catalog Number 75086E Department of the Treasury

Internal Revenue Service www.irs.gov

Conservation

Easement

Audit Technique Guide

This document is not an official pronouncement of the law or the position of the Service and cannot be

used, cited, or relied upon as such. This guide is current through the revision date. Since changes may

have occurred after the revision date that would affect the accuracy of this document, no guarantees are

made concerning the technical accuracy after the revision date.

The taxpayer names and addresses shown in this publication are hypothetical.

Audit Technique Guide Revision Date: 1/21/2021

2

Table of Contents

I. Overview .............................................................................................. 13

A. Statement of Purpose ................................................................... 13

B. Generally ........................................................................................ 13

C. Background / History .................................................................... 14

D. Relevant Terms ............................................................................. 15

D.1. Conservation Easement ..................................................... 15

D.2. Charitable Contribution ...................................................... 15

D.3. Qualified Conservation Contribution ................................ 15

D.4. Conservation Purpose ........................................................ 16

D.5. Fair Market Value ................................................................. 16

E. Law / Authority .............................................................................. 16

E.1. Exhibit 1-1 Conservation Easement Legal Authority ....... 16

E.2. Tax Issues ............................................................................ 17

E.3. Resources ............................................................................ 17

II. Statutory Requirements for All Charitable Contributions .............. 18

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 18

B. Charitable Contribution Definition .............................................. 18

B.1. Qualified Organization ........................................................ 18

B.2. Charitable Intent .................................................................. 18

C. Real Estate Contributions ............................................................ 18

D. Partial Interest Rule ...................................................................... 19

3

E. Conditional Gifts ........................................................................... 19

F. Earmarking .................................................................................... 19

G. Year of Donation ........................................................................... 19

H. Substantiation of Noncash Contributions .................................. 20

I. Amount of Deduction ................................................................... 21

III. Qualified Conservation Contribution ................................................ 22

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 22

B. Qualified Real Property Interest .................................................. 22

C. Qualified Organization .................................................................. 22

D. Conservation Purpose .................................................................. 23

E. Perpetuity ...................................................................................... 23

E.1. Reserved Rights .................................................................. 24

E.2. Recording Easements ......................................................... 25

E.3. Amendment Clauses in Easement Deeds ......................... 25

E.4. Subordination of Mortgages in Lender Agreements ........ 26

E.5. Extinguishment ................................................................... 26

E.6. Allocation of Proceeds in Deed and Lender Agreements 26

IV. Qualified Organization ....................................................................... 28

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 28

B. Qualified Organization .................................................................. 28

C. Commitment and Resources ....................................................... 28

D. Special Rules for Buildings in a Registered Historic District ... 29

4

E. Cash Contributions ....................................................................... 29

E.1. Quid Pro Quo Contribution ................................................ 30

V. Conservation Purpose ....................................................................... 30

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 30

B. Land for Outdoor Recreation or Education ................................ 31

C. Relatively Natural Habitat or Ecosystem .................................... 31

D. Open Space ................................................................................... 33

D.1. Scenic Enjoyment ............................................................... 33

D.2. Governmental Conservation Policy ................................... 34

D.3. Significant Public Benefit ................................................... 34

E. Historically Important Land or Structure .................................... 36

E.1. Historically Important Land ................................................ 36

E.2. Certified Historic Structure ................................................ 36

E.3. Special Rules for Buildings in Registered Historic

Districts .................................................................................... 37

F. Public Access ................................................................................ 38

G. Inconsistent Uses ......................................................................... 38

H. Baseline Study .............................................................................. 39

VI. Substantiation ..................................................................................... 39

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 40

B. Contemporaneous Written Acknowledgment ............................ 40

C. Form 8283, Noncash Charitable Contributions .......................... 42

5

C.1. Generally .............................................................................. 42

C.2. Declaration of Appraiser ..................................................... 43

C.3. Donee Acknowledgment ..................................................... 44

C.4. Failure to Attach Form 8283 ............................................... 44

D. Qualified Appraisal ....................................................................... 44

D.1. Qualified Appraisal Under Regulations ............................. 44

D.2. Generally Accepted Appraisal Standards ......................... 45

D.3. Reasonable Cause .............................................................. 45

E. Façade Easement Filing Fee (Registered Historic District Only)

45

F. Baseline Study .............................................................................. 45

G. Additional Donor Recordkeeping Requirements ....................... 46

H. Exhibit 6-1 - Substantiation Requirements ................................. 46

VII. Qualified Appraisal Requirements .................................................... 47

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 47

B. Qualified Appraisal ....................................................................... 47

B.1. Reasonable Cause Exception ............................................ 49

C. Qualified Appraiser ....................................................................... 50

D. Generally Accepted Appraisal Standards ................................... 51

D.1. Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice ... 51

E. Appraisal Fees .............................................................................. 53

VIII. Amount of Deduction ................................................................... 53

6

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 53

B. Percentage Limitations ................................................................ 53

B.1. Individuals ............................................................................ 53

B.2. Corporations ........................................................................ 54

B.3. Special Rules for Qualified Farmers and Ranchers ......... 54

B.4. Carryovers ........................................................................... 55

C. Contributions of Appreciated Property ....................................... 55

C.1. Ordinary Income and Short-Term Capital Gain Property 55

C.2. Long-Term Capital Gain Property ...................................... 56

D. Bargain Sale .................................................................................. 57

D.1. Taxable Gain ........................................................................ 57

D.2. Federal and State Easement Purchase Programs ........... 57

E. Quid Pro Quo or Substantial Benefit and Charitable Intent ...... 58

F. Rehabilitation Tax Credit .............................................................. 58

F.1. Recapture of Rehabilitation Tax Credit ............................. 59

IX. Valuation of Conservation Easements ............................................. 59

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 59

B. Valuation Process ......................................................................... 60

C. Valuation Date ............................................................................... 61

D. FMV ................................................................................................ 61

D.1. Before and After Method .................................................... 61

7

D.2. Use of Flat Percentage Cannot Be Applied to Before Value

62

D.3. Contiguous Parcels ............................................................. 62

D.4. Enhancement Rule .............................................................. 62

E. Market Analysis ............................................................................. 63

F. Highest and Best Use ................................................................... 64

G. Methodology .................................................................................. 65

G.1. Sales Comparison Approach ............................................. 66

G.2. Cost Approach ..................................................................... 67

G.3. Income Capitalization Approach ........................................ 67

G.4. Subdivision Development Method ..................................... 67

G.5. Aggregate Partnership Interest .......................................... 69

H. Transferable Development Rights ............................................... 69

X. Partnership Anti-Abuse Rules, Judicial Doctrines, and Codified

Economic Substance Doctrine .......................................................... 70

A. Partnership Anti-Abuse Rules ..................................................... 70

B. Judicial Doctrines ......................................................................... 72

B.1. Bona Fide Partner and Partnership ................................... 72

B.2. Substance Over Form ......................................................... 73

B.3. Step Transaction Doctrine .................................................. 74

C. Codified Economic Substance Doctrine ..................................... 76

XI. Preplanning the Examination ............................................................ 77

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 77

8

B. Review of Return ........................................................................... 77

B.1. Form 8283 – Appraisal Summary ....................................... 78

B.2. Signature Requirements ..................................................... 79

B.3. Return Attachments ............................................................ 79

B.4. Other Tax Issues ................................................................. 80

B.5. TEFRA Considerations ....................................................... 80

B.6. BBA Considerations (Taxable Years Beginning on or After

January 1, 2018) ...................................................................... 81

C. Internal Sources of Information ................................................... 81

C.1. IRS Intranet .......................................................................... 81

C.2. Program Analysts ................................................................ 81

C.3. Integrated Data Retrieval System – IDRS .......................... 81

C.4. Façade Filing Fee Verification ............................................ 82

C.5. Tax Exempt Organization Search ...................................... 82

C.6. Office of Professional Responsibility ................................ 82

D. External Sources of Information.................................................. 83

D.1. Internet Research ................................................................ 83

D.2. Taxpayer............................................................................... 83

D.3. Donee Organization ............................................................ 83

D.4. Appraiser .............................................................................. 84

D.5. Public Records .................................................................... 84

D.6. National Park Service .......................................................... 85

9

E. Interviews ...................................................................................... 86

F. Information Document Requests ................................................. 86

G. Valuation Expert Involvement ...................................................... 86

G.1. Referral to LB&I Engineering ............................................. 87

G.2. Referral Outcomes .............................................................. 87

G.3. LB&I Engineering Products ................................................ 88

G.4. Outside Experts ................................................................... 88

H. Consultation with Counsel ........................................................... 88

I. Coordination with TEGE ............................................................... 88

XII. Conducting the Examination ............................................................. 89

A. Overview ........................................................................................ 89

B. Interviews ...................................................................................... 90

C. Property Inspection ...................................................................... 91

D. Review of Documents ................................................................... 92

D.1. Deed of Conservation Easement ....................................... 92

D.2. Perpetuity ............................................................................. 93

D.3. Conservation Purpose ........................................................ 93

D.4. Reserved Rights .................................................................. 94

D.5. Lender Agreements ............................................................. 94

D.6. Subordination Agreements ................................................ 94

D.7. Allocation of Proceeds ....................................................... 95

10

D.8. Baseline Study ..................................................................... 95

D.9. Taxpayer’s Appraisal .......................................................... 97

D.10. Donee Organization ............................................................ 97

D.11. Commitment and Resources .............................................. 97

D.12. Cash Payments .................................................................... 98

D.13. Contemporaneous Written Acknowledgment................... 99

D.14. National Park Service – Form 10-168 ................................ 99

D.15. Partnership Documents .................................................... 101

E. Third-Party Contacts .................................................................. 101

E.1. Donee Organizations ........................................................ 102

E.2. Mortgage Lenders ............................................................. 102

E.3. Appraiser ............................................................................ 103

E.4. Federal and State Conservation Agencies ..................... 103

E.5. Local Government Officials .............................................. 103

E.6. Real Estate Agents ............................................................ 104

E.7. Property Owners ............................................................... 104

XIII. Concluding the Examination...................................................... 104

A. Overview ...................................................................................... 104

B. Issue Identification ..................................................................... 105

B.1. Substantial Compliance .................................................... 105

C. Report Writing ............................................................................. 106

11

C.1. Job Aids ............................................................................. 107

C.2. Valuation Expert Reports ................................................. 108

C.3. Penalties............................................................................. 108

C.4. Technical Assistance ........................................................ 109

D. Closing Conference .................................................................... 109

E. Taxpayer Protests ....................................................................... 109

E.1. Rebuttals to Taxpayer Protest ......................................... 109

F. Exhibit 13-1 Conservation Easement Issue Identification

Worksheet .................................................................................... 110

XIV. Penalties ...................................................................................... 114

A. Overview ...................................................................................... 114

B. Introduction to Penalty Approval .............................................. 115

C. Accuracy-Related Penalties ....................................................... 117

C.1. Section 6662(b)(1) and (c) Negligence or Disregard of

Rules or Regulations ............................................................. 117

C.2. Section 6662(b)(2) and (d) Substantial Understatement of

Income Tax ............................................................................. 118

C.3. Section 6662(b)(3) and (e) Substantial Valuation

Misstatement and Section 6662(h) Gross Valuation

Misstatement ......................................................................... 118

C.4. Section 6662(b)(6) and (i) Codified Economic Substance

Doctrine .................................................................................. 119

D. Section 6663 Civil Fraud Penalty ............................................... 120

E. Section 6664 Reasonable Cause Exception ............................. 120

12

E.1. Special Rule for Overvaluation of Charitable

Contributions ......................................................................... 120

E.2. Reliance on Professionals ................................................ 121

F. Section 6694 Understatement of Taxpayer’s Liability by Tax

Return Preparer ........................................................................... 122

G. Sections 6700 and 6701 Penalty for Promoting Abusive Tax

Shelters and Aiding and Abetting Understatements of Tax ... 122

H. Section 6695A Substantial and Gross Valuation Misstatements

Attributable to Incorrect Appraisals .......................................... 123

H.1. Office of Professional Responsibility Sanctions............ 124

I. Penalties Specifically Related to Reportable Transactions .... 124

I.1. Section 6662A Accuracy-Related Penalty on

Understatements with Respect to Reportable Transactions

125

I.2. Section 6707A Penalty for Failure to Include Reportable

Transaction Information with Return ................................... 126

I.3. Section 6707 Failure to Furnish Information Regarding

Reportable Transaction ........................................................ 126

I.4. Section 6708 Failure to Maintain Lists of Advisees with

Respect to Reportable Transactions ................................... 127

XV. State Tax Credits ......................................................................... 127

A. Overview ...................................................................................... 127

B. State Tax Credit Programs ......................................................... 127

C. Receipt of State Tax Credits ...................................................... 128

D. Sale of State Tax Credits ............................................................ 129

13

I. Overview

A. Statement of Purpose

(1) The purpose of this audit techniques guide (ATG) is to provide guidance for the

examination of charitable contributions of conservation easements. Users of

this guide will learn about the general requirements for charitable contributions

and additional requirements for contributions of conservation easements.

(2) This ATG includes examination techniques and an overview of the valuation of

conservation easements. It also includes a discussion of penalties, which may

be applicable to taxpayers and others involved in the conservation easement

transaction.

(3) This guide is not designed to be all-inclusive. It is not a comprehensive training

manual for conservation easements.

B. Generally

(1) To be deductible, donated conservation easements must be legally binding,

permanent restrictions on the use, modification and development of property

such as farmland, forest land, scenic areas, historic land or historic structures.

The restrictions on the property must be in perpetuity. Current and future

owners of the easement and the underlying property must all be bound by the

terms of the conservation easement deed.

(2) The general rule is that no charitable contribution deduction is allowed for a

transfer of property of less than the taxpayer’s entire interest in the property.

IRC § 170(f)(3). Section 170(f)(3)(B)(iii) provides an exception to the partial

interest rule for qualified conservation contributions.

(3) Section 170(h)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) states that a qualified

conservation contribution is a contribution of a qualified real property interest

(i.e., a restriction granted in perpetuity on the use which may be made of the

real property) to a qualified organization exclusively for conservation purposes.

The IRC and accompanying Treasury Regulations outline the requirements that

must be met before a charitable contribution is deductible.

(4) Qualified organizations that accept conservation easements must have a

commitment to protect the conservation purposes of the donation in perpetuity

and must have sufficient resources to enforce compliance with the terms of the

easement deed.

(5) Section 170(h)(4)(A) specifies the four conservation purposes:

• Preservation of land areas for outdoor recreation by, or the education of,

the general public.

• Protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar

ecosystem.

14

• Preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land), where

such preservation is for the scenic enjoyment of the general public or

pursuant to a clearly delineated federal, state, or local governmental

conservation policy and, for both purposes, will yield a significant public

benefit.

• Preservation of a historically important land area or a certified historic

structure.

(6) The donation of a conservation easement that meets all statutory and

regulatory requirements, including specific substantiation requirements, can be

claimed as a charitable contribution deduction.

(7) The value of a conservation easement must be determined in a qualified

appraisal prepared and signed by a qualified appraiser. The value of the

contribution is the fair market value (FMV) of the conservation easement at the

time of the contribution. To the extent there is a substantial record of sales of

conservation easements comparable to the donated easement, the FMV is

based on the sales price of such comparables. If there is no substantial record

of marketplace sales, the value is generally the difference between the FMV of

the underlying property before and after the easement is granted to the donee.

Because there is usually no substantial record of comparable sales, a before

and after valuation is used in most cases.

(8) To conduct a quality examination, in-depth development of facts is necessary.

Examiners have primary responsibility for addressing the taxpayer’s compliance

with all statutory and regulatory requirements.

(9) Valuation is also an important component of this tax issue. A multi-divisional

approach, working with LB&I Engineering, Counsel, and Tax Exempt and

Government Entities (TEGE), may be needed to properly develop tax issues in

a conservation easement examination.

(10) Taxpayers, return preparers, appraisers, and others involved with an improper

or overvalued conservation easement may be subject to various penalties.

(11) While the charitable contribution of a conservation easement may be the most

significant issue on the tax return, Examiners should be alert to other related tax

issues such as a sale of state tax credits, basis adjustments, or a recapture of

rehabilitation tax credits.

C. Background / History

(1) In recognition of our need to preserve our heritage, Congress allowed an

income tax deduction for owners of significant property who give up certain

rights of ownership to preserve their land or buildings for future generations.

(2) The IRS has seen abuses of this tax provision that compromise the policy

Congress intended to promote. We have seen taxpayers, often encouraged by

promoters and armed with questionable appraisals, take inappropriately large

15

deductions for easements. In some cases, taxpayers claim deductions when

they are not entitled to any deduction at all (for example, when taxpayers fail to

comply with the law and regulations governing deductions for contributions of

conservation easements). Also, taxpayers have sometimes used or developed

these properties in a manner inconsistent with section 501(c)(3). In other cases,

the charity has allowed property owners to modify the easement or develop the

land in a manner inconsistent with the easement’s restrictions.

(3) Another problem arises in connection with historic easements, particularly

façade easements. Here again, some taxpayers are taking improperly large

deductions. They agree not to modify the façade of their historic house and they

give an easement to this effect to a charity. However, if the façade was already

subject to restrictions under local zoning ordinances, the taxpayers may, in fact,

be giving up nothing, or very little. A taxpayer cannot give up a right that he or

she does not have.

D. Relevant Terms

D.1. Conservation Easement

(1) “Conservation easement” is the generic term for easements granted for

preservation of land areas for outdoor recreation, protection of a relatively

natural habitat for fish, wildlife, or plants, or a similar ecosystem, preservation of

open space for the scenic enjoyment of the public or pursuant to a federal,

state, or local governmental conservation policy, and preservation of a

historically important land area or historic building.

(2) Conservation easements permanently restrict how land or buildings are used.

The “deed of conservation easement” describes the conservation purpose, the

restrictions and the permissible uses of the property. The deed must be

recorded in the public record and must contain legally binding restrictions

enforceable by the donee organization.

(3) The donor gives up certain rights specified in the deed of conservation

easement, but retains ownership of the underlying property. The extent and

nature of the donee organization’s control depends on the terms of the

conservation easement deed. The organization has an interest in the

encumbered property that runs with the land, which means that its restrictions

are binding not only on the landowner who grants the easement but also on all

future owners of the property.

D.2. Charitable Contribution

(1) A charitable contribution is a contribution or gift to or for the use of a qualifying

organization. See Chapter 2.

D.3. Qualified Conservation Contribution

16

(1) Section 170(h)(1) defines a qualified conservation contribution as a contribution

of a qualified real property interest to a qualified organization to be used

exclusively for conservation purposes.

D.4. Conservation Purpose

(1) Section 170(h)(4)(A) defines “conservation purpose” as one of the following:

• Preservation of land for outdoor recreation by, or the education of, the

general public.

• Protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar

ecosystem.

• Preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land) either for

the scenic enjoyment of the general public or pursuant to a clearly

delineated governmental conservation policy (both purposes must yield a

significant public benefit).

• Preservation of a historically important land area or a certified historic

structure.

(2) The easement must be created by deed and be exclusively for conservation

purposes. Donations of conservation easements may meet more than one

conservation purpose.

D.5. Fair Market Value

(1) The value of the donated easement must meet the definition of FMV as defined

by Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-1(c)(2): The FMV is the price at which the property

would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being

under any compulsion to buy or sell and both having reasonable knowledge of

relevant facts.

E. Law / Authority

E.1. Exhibit 1-1 Conservation Easement Legal Authority

(1) NOTE: This exhibit is not an all-inclusive list of potential issues for donations of

conservation easements. Users should review IRC § 170, DEFRA § 155, the

corresponding Treasury Regulations, Notice 2006-96 and case law.

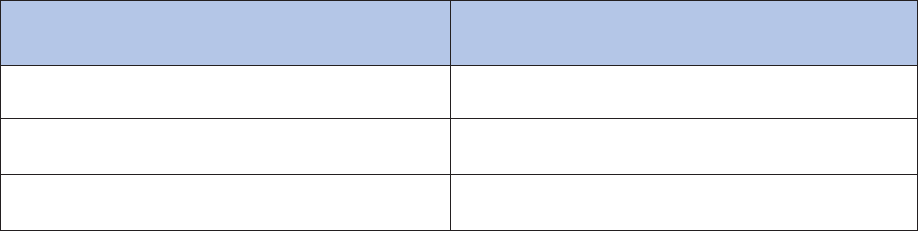

Code/Regs/Other

Title

IRC § 170

Charitable, etc., contributions and gifts

DEFRA § 155

Deficit Reduction Act of 1984

Notice 2006-96

Guidance Regarding Appraisal

Requirements for Noncash Charitable

17

Contributions

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-1

Charitable, etc., contributions and gifts;

allowance of deduction

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-13

Recordkeeping and return requirements for

deductions for charitable contributions

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14

Qualified conservation contributions

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-16

Substantiation and reporting requirements

for noncash charitable contributions

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-17

Qualified appraisal and qualified appraiser

E.2. Tax Issues

(1) Taxpayers must satisfy numerous statutory provisions in order to claim a

noncash charitable contribution deduction for the donation of a conservation

easement. Some deficiencies revealed in examinations of conservation

easements include:

• Failure to meet charitable contributions rules, for example the easement

was granted in exchange for a change in zoning by the county (a quid pro

quo).

• Noncompliance with substantiation requirements.

• Inadequate documentation of or lack of conservation purpose.

• Lack of perpetuity evidenced by terms in the deeds.

• Reserved property rights inconsistent with conservation purpose.

• Failure to comply with subordination rules.

• Failure to provide the donee organization with the specified proportionate

share of the proceeds in the event of extinguishment.

• Use of improper appraisal methodologies.

• Failure to report income from the sale of state tax credits.

• Overvalued conservation easements.

(2) The IRS has identified some promoters and appraisers involved in conservation

easement tax schemes.

E.3. Resources

(1) Information about conservation easements, including contacts, job aids, and

other reference materials are on the IRS Virtual Library, Form 1040 Knowledge

Base.

18

II. Statutory Requirements for All Charitable Contributions

A. Overview

(1) In order to claim a charitable contribution deduction for a conservation

easement, taxpayers must meet the statutory requirements applicable to all

charitable contributions, as well as the specific requirements for conservation

easement donations.

(2) See Publication 526, Charitable Contributions (PDF), Publication 561,

Determining the Value of Donated Property (PDF), and Publication 1771,

Charitable Contributions - Substantiation and Disclosure Requirements (PDF).

B. Charitable Contribution Definition

(1) A charitable contribution is a contribution or gift to or for the use of a qualifying

organization. It is a transfer of money or property made with charitable intent

and without receipt of adequate consideration. IRC § 170(c); Treas. Reg. §

1.170A-1(h).

(2) Section 170 contains the rules that govern income tax deductions for charitable

contributions, including donations of conservation easements.

B.1. Qualified Organization

(1) A taxpayer can only deduct contributions made to organizations eligible to

accept tax-deductible contributions, which are organizations described in IRC §

170(c).

(2) An organization accepting tax-deductible contributions of conservation

easements must meet additional requirements to be a qualified organization.

See Chapter 4 for additional guidance on qualified organizations.

B.2. Charitable Intent

(1) A charitable contribution is a donation or gift to, or for the use of, a qualified

organization. It is voluntary and made without receipt, or the expectation of

receipt, of anything of economic value.

(2) A transfer of money or property is not voluntary if it is required or is made with

the expectation of a direct or indirect benefit. A benefit received or expected to

be received in connection with a payment or transfer by the taxpayer is called a

quid pro quo.

(3) See Chapter 8 for additional discussion of charitable intent and quid pro quo.

C. Real Estate Contributions

(1) For a contribution of real estate, including a contribution of a conservation

easement, there is no “transfer,” and therefore no deductible charitable

contribution, unless there is:

19

• A deed signed by the donor transferring the property and

• Acceptance by the qualified organization.

(2) Conservation easement deeds must be recorded in the public record.

D. Partial Interest Rule

(1) Generally, in order to have a deductible contribution, a taxpayer must contribute

the entire interest in the property. A partial interest is generally not deductible.

This is known as the "partial interest" rule. IRC § 170(f)(3)(A).

(2) A qualified conservation contribution is deductible even though it is a partial

interest. It is an exception to the partial interest rule. IRC §§ 170(f)(3)(B)(iii) and

(h).

E. Conditional Gifts

(1) If the contribution is a conditional gift, the donor cannot take a deduction.

• Example: If Justin transfers land in Maine to a city on the condition that

the land is used by the city for an unlikely use (e.g., alligator habitat), there

is no deductible charitable contribution before the time that the specified

use actually occurs.

(2) However, if there is only a negligible chance that the gift will be defeated, the

deduction is allowed. Treas. Reg. §§ 1.170A-1(e) and 1.170A-7(a)(3).

• Example: Susan transfers land to a city on the condition that the land is

used by the city for a public park. If, on the date of the gift, the city plans to

use the property as a park, and the possibility that it will not be used as a

park is so remote as to be negligible, the deduction is allowable at the time

of the transfer to the city.

F. Earmarking

(1) A taxpayer may not deduct earmarked contributions (e.g., for the benefit of a

particular individual or family). Earmarked amounts are treated as transfers to

the earmarked beneficiary and not as transfers to the IRC § 170(c)

organization.

• Example: Steven made payments to his church. He earmarked the

payments for John, a needy individual. Steven cannot deduct the amount

of the payments since he earmarked the funds for John. The church was

merely a conduit for Steven’s gift to John.

G. Year of Donation

(1) A taxpayer may deduct contributions paid within the taxable year. IRC §

170(a)(1) and Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-1(a) and (b).

20

(2) A promise to pay cash or transfer property in the future is not deductible. The

taxpayer may deduct payments made by check when the check is mailed or

delivered to the IRC § 170(c) organization. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-1(b).

(3) For conservation easements, the year of the deduction is the year of

recordation. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(1).

• Example: A conservation easement was granted to a qualified

organization on December 20, 2007, as evidenced by the dated

signatures on the conservation easement deed. However, the easement

was not recorded in the public records until March 12, 2008. The year of

donation is 2008.

H. Substantiation of Noncash Contributions

(1) A charitable contribution is not deductible unless it is properly substantiated in

accordance with the IRC and the regulations. The documentation requirements

vary depending on the date of contribution, nature of the contribution (noncash

in the case of a conservation easement), type of property contributed, and

dollar amount claimed. For a conservation easement, the following documents

are required:

(2) Contemporaneous written acknowledgment from the donee organization. IRC §

170(f)(8). The contemporaneous written acknowledgment must meet the

acknowledgment requirement and the contemporaneous requirement.

• The acknowledgment must:

• Be in writing,

• Describe the property received by the donee,

• Contain a statement of whether the donee provided any goods or

services in consideration, in whole or in part, for the gift, and

• Provide a description of and a good faith estimate of the goods or

services, other than intangible religious benefits, provided to the

taxpayer.

• The contemporaneous requirement provides:

• The taxpayer must get the acknowledgment on or before the earlier

of:

• The date the taxpayer files a return for the year in which the

contribution was made, or

• The due date (including extensions) for filing such return.

(3) Form 8283, Section B, with supplemental statement.

(4) Deed (should be stamped with the recording date).

(5) Qualified Appraisal (for contributions of more than $5,000).

21

(6) Baseline study.

(7) The tax court has considered a number of cases in which taxpayers argued that

the deed of easement satisfied the contemporaneous written acknowledgment

requirement. In French v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2016-53, and Schrimsher

v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2011–71, the deed did not satisfy the

contemporaneous written acknowledgment requirement. In Big River

Development, LP v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2017-166; 310 Retail, LLC v.

Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2017-164; RP Golf, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C.

Memo. 2012-282; and Averyt v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012–198, the

deed did satisfy the contemporaneous written acknowledgment requirement.

(8) Examiners should contact Counsel for assistance if a taxpayer contends that

the deed of easement satisfies the contemporaneous written acknowledgment

requirement.

(9) In Belair Woods, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2018-159, a Form 8283

that omitted the cost basis of the subject property, with an attachment indicating

that it was not necessary to disclose it, neither strictly nor substantially complied

with the regulatory requirement to include such information on the form. See

also RERI Holdings v. Commissioner, 149 T.C. 1 (2017); Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-

13(c)(2)(i)(B) and (4)(ii)(E). Taxpayers are afforded the opportunity to

demonstrate reasonable cause for omitting the information. IRC §

170(f)(11)(A)(ii)(II).

(10) See Publication 526, Charitable Contributions (PDF), and Publication 1771,

Charitable Contributions - Substantiation and Disclosure Requirements (PDF)

and Chapter 6 for additional guidance on substantiation requirements.

(11) See IRC § 170(f)(8)(A)-(D), Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-13(f) (effective for

contributions made on or after December 16, 1996 and on or before July 30,

2018) and Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-16(a) (effective for contributions made after

July 30, 2018).

(12) See also Section 155 of the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 (DEFRA), Pub. L. 98-

369, 98 Stat. 691, Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-13(c)(2)(i)(B) (effective for contribution

made after December 31,1984, and on or before July 30, 2018) and Treas.

Reg. § 1.170A-16(c)-(e) (effective for contributions made after July 30, 2018).

I. Amount of Deduction

(1) Factors that may affect the amount a taxpayer may claim as a charitable

contribution deduction for a conservation easement include:

• FMV

• Quid pro quo and charitable intent

• Bargain sale

22

• Type of property (ordinary income, short-term capital gain, long-term

capital gain)

• Basis

• Percentage limitations

• Type of donee organization

(2) See Chapter 8 and Publication 526, Charitable Contributions (PDF) for

additional guidance on specific limitations on charitable contributions.

III. Qualified Conservation Contribution

A. Overview

(1) Section 170(h)(1) defines a qualified conservation contribution as a contribution

of a qualified real property interest to a qualified organization to be used

exclusively for conservation purposes.

B. Qualified Real Property Interest

(1) A qualified real property interest is any of the following interests in real property:

• The entire interest of the donor, other than a qualified mineral interest.

• A remainder interest.

• A restriction on the use of the real property granted in perpetuity (often

referred to as a conservation easement).

(2) See IRC § 170(h)(2).

C. Qualified Organization

(1) The recipient of a deductible conservation easement donation must be a

qualified organization and also an eligible donee. IRC §§ 170(h)(1)(B) and

170(h)(3); Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1).

(2) Qualified organizations include:

• The federal government, a United States (U.S.) possession, the District of

Columbia, a state government, or any political subdivision of a state or

U.S. possession.

• An organization described in IRC § 170(b)(1)(A)(vi).

• A charity described in IRC § 501(c)(3) that meets the public support test of

IRC § 509(a)(2).

• An IRC § 501(c)(3) organization that meets the requirements of IRC §

509(a)(3) and is controlled by one of the organizations described above.

(3) Note: See Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1) for the requirements to qualify as an

eligible donee.

23

(4) See IRC § 170(h)(3) and Chapter 4 for additional information on qualified

organizations.

D. Conservation Purpose

(1) Section 170(h)(4)(A) defines “conservation purpose” as one of the following:

• Preservation of land for outdoor recreation by, or the education of, the

general public.

• Protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar

ecosystem.

• Preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land) either for

the scenic enjoyment of the general public or pursuant to a clearly

delineated governmental conservation policy (both purposes must yield a

significant public benefit).

• Preservation of a historically important land area or a certified historic

structure.

(2) The easement must be created by deed and be exclusively for conservation

purposes. Donations of conservation easements may meet more than one

conservation purpose.

(3) See Chapter 5 for additional information on conservation purpose.

E. Perpetuity

(1) A deductible conservation easement must be made in perpetuity, permanently

restricting the use of the property. Section 170(h)(2)(C) requires that the interest

in real property be subject to a use restriction granted in perpetuity, and IRC §

170(h)(5)(A) requires that the conservation purpose be protected in perpetuity.

See also Treas. Reg. §§ 1.170A-14(b)(2) and 1.170A-14(g)(1).

(2) This means that the deed of conservation easement must indicate that the

restriction remains on the property forever and is binding on current and future

owners of the property.

(3) If a deed of conservation easement does not meet the perpetuity requirements,

the contribution of a conservation easement is not deductible.

(4) If the conservation easement deed imposes restrictions for a specific period

such as ten years, it is not in perpetuity and is not deductible. An easement is

not enforceable in perpetuity if it ends after a period of years or if it can revert to

the donor or to another private party. However, if a remote future event, like an

earthquake, can extinguish the easement, the donation could nevertheless be

treated as enforceable in perpetuity. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(3).

(5) In Carpenter v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012-1, a conservation easement

was not enforceable in perpetuity because it allowed for the extinguishment of

the easement by mutual consent of the parties if circumstances arose in the

24

future that would render the purpose of the conservation easement impossible

to accomplish.

(6) In Belk v. Commissioner, 140 T.C. 1 (2013), motion for reconsideration denied,

T.C. Memo. 2013-154, aff’d 774 F.3d 1243 (4th Cir. 2014), the deed of

easement allowed the taxpayers and donee to change the property subject to

the easement by substituting other property owned by the taxpayers for the

property originally subject to the easement. The tax court ruled that the

provision caused the easement to fail the requirements of IRC § 170(h)(2)(C),

as the donated property interest was not subject to a use restriction granted in

perpetuity.

(7) In Pine Mountain Preserve, LLLP v. Commissioner, 151 T.C. 247 (2018), and

Pine Mountain Preserve, LLLP v. Commissioner, 116 T.C. Memo. 214, rev’d in

part, aff’d in part, vacated and remanded, 2020 WL 6193897 (11th Cir. Oct. 22,

2020), the 2005 deed of easement set out boundaries for ten building areas, but

allowed the boundaries to be modified by mutual agreement of the donor and

NALT, the donee. The 2006 deed of easement allowed the designation of six

building areas within the conservation area, but with no other restriction on

location except that the locations must be approved in advance by NALT. The

tax court, following Belk, ruled that these provisions caused the easement to fail

the grant in perpetuity requirements of IRC § 170(h)(2)(C). In so doing, the

court explicitly rejected the holding in BC Ranch II, L.P. v. Commissioner, 867

F.3d 547 (5th Cir. 2017), where the Fifth Circuit ruled that the so-called floating

homesites did not defeat perpetuity. The Eleventh Circuit, in Pine Mountain,

ruled that the moveable building areas do not violate the “granted in perpetuity”

requirement under § 170(h)(2)(C), but remanded the issue of whether they

violate the “protected in perpetuity” requirement under § 170(h)(5)(A). The

Eleventh Circuit agreed with the tax court that the amendment clause did not

violate the protected in perpetuity requirement of IRC § 170(h)(5)(A). Lastly, the

Eleventh Circuit held that when determining the fair market value of the

easement, the tax court should value the easement using the standards set

forth in the governing regulations.

(8) Agents should note that under Golsen v. Commissioner, 54 T.C. 742, 756-57,

aff’d, 445 F.2d 985 (10th Cir. 1971), the tax court is bound by an appellate

court’s opinions in cases appealable to that appellate court’s circuit. We

recommend that all floating homesite/moveable building area clause cases and

amendment clause cases be referred to the assigned LB&I and SB/SE

Counsel.

E.1. Reserved Rights

(1) In Hoffman Props. II, LP v. Commissioner, 956 F.3d 832 (6th Cir. 2020), a

façade easement case, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the tax

court’s holding that the automatic approval clause in the deed rendered the

easement nondeductible because the clause was inconsistent with the

easement being enforceable in perpetuity under IRC § 170(h)(5)(A). The clause

25

reserved to the donor rights to modify the building façade if the donor obtained

the prior approval of the easement holder, but if the holder failed to respond to a

request for approval within 45 days, the request was automatically considered

approved. The court of appeals explained that a failure of the donee to act

within 45 days would foreclose its ability to prevent the proposed modification.

For a CCA containing an acceptable “constructive denial” clause, see CCA

202002011 (released Jan. 10, 2020).

E.2. Recording Easements

(1) The deed of conservation easement must be recorded in the appropriate

recordation office. See generally Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(1).

(2) In a federal tax controversy, state law controls the determination of a taxpayer’s

interest in property while the tax consequences are determined under federal

law. United States v. Nat’l Bank of Commerce, 472 U.S. 713, 722 (1985);

Woods v. Commissioner, 137 T.C. 159, 162 (2011). An easement is not

enforceable in perpetuity before it is recorded.

(3) In addition to the deed, all exhibits or attachments to the deed, such as a

description of the easement restrictions, maps, and lender agreements, may

need to be recorded. In Herman v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2009-205, the

taxpayer recorded a “Declaration of Restrictive Covenant” for a donation of

unused development rights above a building in New York City. The covenant

referred to an attached architectural drawing, which described the easement

restrictions, but the drawing was not recorded. The court ruled that because the

attached drawing was not recorded, it could not bind subsequent purchasers,

did not protect the conservation purpose of preserving the building “in

perpetuity,” and failed to meet the requirements of IRC § 170(h)(5)(A). But see

Butler v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012-72, holding that documents

incorporated into the deed by reference do not have to be recorded with the

deed under Georgia law.

E.3. Amendment Clauses in Easement Deeds

(1) The restriction on the use of the real property must be enforceable in perpetuity,

meaning that it lasts forever and binds all future owners. An easement deed

may fail the perpetuity requirements of IRC § 170(h)(2)(C) and (h)(5)(A) if it

allows any amendment or modification that could adversely affect the perpetual

duration of the deed restriction.

(2) In Pine Mountain Preserve, LLLP v. Commissioner, 151 T.C. 247 (2018), rev’d

in part, aff’d in part, vacated and remanded, 2020 WL 6193897 (11th Cir. Oct.

22, 2020), the deed of easement allowed the donor and the donee to amend

the deed by agreement so long as the amendment was not inconsistent with the

conservation purposes. The tax court ruled that such an amendment clause

does not violate the enforceable in perpetuity requirements of IRC §

26

170(h)(5)(A). See discussion of amendment clauses and the Pine Mountain

case above under the heading “Perpetuity.”

(3) The issue of Amendment Clauses is different than the issue of Reserved

Rights. See Chapter 12 for information on Reserved Rights in an easement

deed.

E.4. Subordination of Mortgages in Lender Agreements

(1) If the property has a mortgage or lien in effect at the time the easement is

recorded, the easement contribution is not deductible unless the mortgagee or

lien holder subordinates its rights in the property to the rights of the donee

organization to enforce the conservation purposes of the easement in

perpetuity. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(2).

(2) The subordination agreement must be recorded in a timely manner.

(3) In Minnick v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012‐345, aff’d, 796 F.3d 1156 (9th

Cir. 2015), the tax court held that petitioners were not entitled to a charitable

contribution deduction because they failed to meet the subordination

requirements (i.e., the mortgagor and petitioners had not entered into a

subordination agreement at the time the easement was donated, rather, it was

entered into after the donation). See also Mitchell v. Commissioner, 138 T.C.

324 (2012), supplemented by T.C. Memo. 2013-204, aff’d, 775 F.3d 1243 (10th

Cir. 2015); RP Golf, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2016‐80, aff’d 860

F.3d1096 (8th Cir. 2018); Palmolive Building Investors v. Commissioner, 149

T.C. 380 (2017).

E.5. Extinguishment

(1) Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(6)(i) generally provides that if a subsequent

unexpected change in the conditions surrounding the property that is the

subject of a donation can make impossible or impractical the continued use of

the property for conservation purposes, the conservation purpose can

nonetheless be treated as protected in perpetuity if the restrictions are

extinguished by judicial proceeding and all of the donee’s proceeds (determined

under Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(6)(ii)) from a subsequent sale or exchange of

the property are used by the donee organization in a manner consistent with the

conservation purposes of the original contribution.

E.6. Allocation of Proceeds in Deed and Lender Agreements

(1) In order to claim a charitable contribution deduction for the donation of a

conservation easement, the donor, at the time of the gift, must agree that the

donation of the perpetual conservation restriction gives rise to a property right,

immediately vested in the donee organization, with a FMV that is at least equal

to the proportionate value that the perpetual conservation restriction at the time

of the gift bears to the value of the property as a whole. The proportionate value

27

of the donee’s property rights must remain constant. The donee organization

must be entitled to a portion of the proceeds at least equal to that proportionate

value of the perpetual conservation restriction. The requirements of Treas. Reg.

§ 1.170A-14(g)(6)(i) and (ii) are strictly construed. If a grantee is not absolutely

entitled to the proportionate share of extinguishment proceeds, then the

conservation purpose of the contribution is not protected in perpetuity. The only

exception is if state law provides that the donor is entitled to the full proceeds

from the conversion without regard to the terms of the prior perpetual

conservation restriction. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(6)(ii) (last clause).

(2) Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(6)(ii) requires the donee’s proportionate interest

upon extinguishment of a conservation easement to be a percentage

determined by (1) the FMV of the conservation easement on the date of the gift

(numerator), over (2) the FMV of the property as a whole on the date of the gift

(denominator).

(3) In Carroll v. Commissioner, 146 T.C. 196 (2016), petitioners’ deed of

conservation easement instead used a ratio of the charitable contribution

deduction allowable over the value of the property as a whole on the date of the

gift. Thus, the deed failed to satisfy Treas. Reg. § 1.170A- 14(g)(6)(ii) because it

did not guarantee the donee a proportionate share of the extinguishment

proceeds based on the FMV of the conservation easement at the time of the

gift.

(4) In PBBM-Rose Hill, Ltd. v. Commissioner, 900 F.3d 193 (5th Cir. 2018), the

deed of easement provided that in case of extinguishment, the donee would

receive the proportionate value required by the regulation less the expenses of

the sale and the amount attributable to improvements constructed after the

easement. The court disallowed the deduction because any reduction to the

proportionate value required by the regulation failed to satisfy its requirements.

(5) In Coal Property Holdings, LLC v. Commissioner, 153 T.C. 126 (2019), the

deed of easement provided that in case of extinguishment, the donee would

receive the proportionate value required by the regulation “after the satisfaction

of prior claims” and less any increase in value attributable to improvements.

The court, following PBBM-Rose Hill, disallowed the deduction because any

reduction to the proportionate value required by the regulation failed to satisfy

its requirements.

(6) See also Plateau Holdings, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-93; Belair

Woods, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-112; Village at Effingham, LLC

v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-102; Riverside Place, LLC v.

Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-103; Maple Landing, LLC v. Commissioner,

T.C. Memo. 2020-104; Englewood Place, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo.

2020-105; Hewitt v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-89; Woodland Property

Holdings, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-55; Oakbrook Land

Holdings, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-54; Cottonwood Place, LLC

v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-115; Red Oak Estates, LLC v.

28

Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2020-116; Smith Lake, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C.

Memo. 2020-107; Lumpkin One Five Six, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo.

2020-94.

(7) Examiners should contact Counsel for assistance in review of deeds and lender

agreements to determine if the documents satisfy the allocation of proceeds

requirements of Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(6)(ii).

IV. Qualified Organization

A. Overview

(1) A taxpayer must transfer the conservation easement to an eligible donee to

qualify for a contribution deduction. An eligible donee:

• Is a qualified organization,

• Must have the commitment to protect the conservation purpose(s) of the

donation, and

• Must have the resources to enforce the conservation restrictions.

(2) See IRC § 170(h)(3); Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1).

B. Qualified Organization

(1) A qualified organization is one of the following:

• A governmental unit, including the U.S. government, a U.S. possession,

the District of Columbia, a state government, or any political subdivision of

a state or U.S. possession so long as the contribution is made for

exclusively public purposes.

• A public charity described in IRC § 501(c)(3) that meets the public support

test of IRC § 509(a)(2) or a public charity described in 170(b)(1)(A)(vi).

• A public charity described in IRC § 501(c)(3) that meets the requirements

of IRC § 509(a)(3) and is controlled by one of the organizations described

above. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1).

C. Commitment and Resources

(1) The qualified organization must have the commitment to protect the

conservation purpose(s) of the donation Treas. Reg. § 1.170A- 14(c)(1). An

entity organized or operated for one of the conservation purposes in IRC §

170(h)(4)(A) is considered to have the commitment required to protect the

conservation purposes of the donation. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1).

(2) Qualified organizations that accept easement contributions and are committed

to conservation will generally have an established monitoring program, such as

annual property inspections to ensure compliance with the conservation

easement terms and to protect the easement in perpetuity. The terms of the

29

easement contribution must permit the qualified organization access to the

property for inspection. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(5)(ii).

(3) The qualified organization must also have the resources to enforce the

restrictions of the conservation easement. Resources do not necessarily mean

cash. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(c)(1). Resources may be in the form of the

volunteer services of lawyers who provide legal services or conservationists

who inspect the property and prepare monitoring reports.

(4) See Chapter 12 for suggestions on how to evaluate the organization’s

commitment and resources.

D. Special Rules for Buildings in a Registered Historic District

(1) For a contribution made after July 25, 2006, of a qualified real property interest

with respect to a building in a registered historic district, an additional

requirement must be met to satisfy the commitment and resources test. Section

170(h)(4)(B)(ii) requires the taxpayer and the donee organization to execute a

written agreement certifying, under penalty of perjury, that the donee is a

qualified organization with a purpose of environmental protection, land

conservation, open space preservation, or historic preservation, and that the

donee has the resources to manage and enforce the restriction and a

commitment to do so. The taxpayer is also required to attach to its return a

copy of the qualified appraisal for the qualified property interest, photos of the

entire exterior of the building and a description of all restrictions on the

development of the building. IRC § 170(h)(4)(B)(iii)(I-III).

(2) Note: This special rule does not apply to properties listed on the National

Register.

(3) See Chapter 5 for a complete discussion of the special rules for buildings in

registered historic districts.

E. Cash Contributions

(1) A common practice for qualified organizations is to request a cash contribution

(sometimes referred to as a “stewardship fee”) from donors of conservation

easements. To be deductible as a charitable contribution, the cash payment

must be a voluntary transfer made with charitable intent to a qualified

organization. IRC § 170 (a) and (c). All cash contributions, regardless of

amount, must be substantiated with a bank record or a receipt from the donee.

The record or receipt must show the name of the donee, the date of the

contribution, and the amount of the contribution. IRC § 170(f)(17); Treas. Reg.

§ 1.170A-15.

(2) Charitable intent exists if the transfer is made without the receipt of, or the

expectation of receiving, a quid pro quo for the transfer. Generally, if the

benefits the transferor receives or expects to receive are substantial, rather

than incidental to the transfer, the transfer does not satisfy the charitable intent

30

requirement under IRC § 170. Hernandez v. Commissioner, 490 U.S. 680, 691

(1989); United States v. American Bar Endowment, 477 U.S. 105, 117-118

(1986); Wendell Falls Development, LLC v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2018-

45, at *10-13; Singer Co. v. United States, 196 Ct. Cl. 90, 106 449 F.2d 413,

422-423 (1971).

(3) If a direct or indirect economic benefit (other than a tax deduction) is received or

is expected to be received as a result of making a contribution, the deduction

may be limited or disallowed. See generally § 1.170A-1(h)(3), which was

published on June 13, 2019. A state or local tax credit is a direct or indirect

economic benefit that reduced the amount of a taxpayer’s charitable

contribution deduction.

E.1. Quid Pro Quo Contribution

(1) A quid pro quo contribution is a transfer of money or property made to a

qualified organization partly in exchange for goods or services in return from the

charity or a third party. A quid pro quo may also be in the form of an indirect

benefit from a third party.

• Example: A land developer agrees to grant a conservation easement to

the county or other qualified organization in exchange for the approval of a

proposed subdivision. See Triumph Mixed Use Investments III, LLC v.

Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2018-65. *31-42.

(2) If a taxpayer receives a quid pro quo, the transfer to the charity may be

deductible as a charitable contribution, but only to the extent the amount

transferred exceeds the FMV of the quid pro quo, and only if the excess amount

was transferred with charitable intent. United States v. American Bar

Endowment, 477 U.S. 105, 117 (1986).

(3) The burden is on the taxpayer to show that all or part of a payment is a

charitable contribution or gift. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-1(h)(1) and (2); United

States v. American Bar Endowment, 477 U.S. 105, 116-118 (1986); and Rev.

Rul. 67-246, 1967-2 C.B. 104.

V. Conservation Purpose

A. Overview

(1) A contribution of a conservation easement to a qualified organization must be

made for one of the following conservation purposes:

• Preservation of land areas for outdoor recreation by, or the education of,

the general public.

• Protection of a relatively natural habitat for fish, wildlife, or plants, or a

similar ecosystem.

• Preservation of open space for the scenic enjoyment of the general public,

or pursuant to a federal, state, or local governmental conservation policy,

both yielding a significant public benefit.

31

• Preservation of historically important land area or certified historic building.

(2) IRC § 170(h)(4)(A).

(3) The conservation easement must be transferred by deed (or other legal

instrument as appropriate under the law of the relevant State) and recorded

where the property is located, be exclusively for conservation purposes,

protected in perpetuity, and meet at least one of the above conservation

purposes.

(4) Any required access to the land by the general public depends on the

conservation purpose of the conservation easement. If the claimed

conservation purpose is for the preservation of open space under IRC §

170(h)(4)(A)(iii), the contribution must yield a significant public benefit which is

usually by visual access from a public highway. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-

14(d)(4)(ii)(B).

(5) The deed of conservation easement must prohibit inconsistent use of the

property that could permit destruction of a significant conservation interest,

even if the easement accomplishes an enumerated conservation purpose.

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(e)(2).

(6) A baseline study is used to identify the conservation attributes and to establish

the condition of the property at the time of the conservation easement donation.

Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(5).

B. Land for Outdoor Recreation or Education

(1) This category includes the donation of a qualified real property interest to

preserve land for outdoor recreation by, or for the education of, the general

public. IRC § 170(h)(4)(A)(i).

(2) Substantial and regular physical access by the general public to the preserved

land is required. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(d)(2)(ii).

• Examples: A donation to preserve a lake for use by the general public for

boating or fishing, or to preserve land for a hiking trail.

(3) See Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(d)(2) for additional guidance.

(4) See also PPBM-Rose Hill, Limited v. Commissioner, 900 F.3d 193 (5th Cir.

2018). In denying the charitable contribution deduction because the taxpayer

failed to comply with the extinguishment clause requirements in Treas. Reg. §

1.170A-14(g)(6)(ii), the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the tax court on

the issue of whether the conservation easement met the outdoor recreation

conservation purpose. The court determined that the easement met the outdoor

recreation conservation purpose because the terms of the deed stated that the

property was being protected for outdoor recreation “for use by the general

public.”

C. Relatively Natural Habitat or Ecosystem

32

(1) This conservation purpose is satisfied if the conservation easement protects a

significant relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife or plants, or similar

ecosystem. IRC § 170(h)(4)(A)(ii). An ordinary tract of land where a common

fish, wildlife or plant community, or similar ecosystem normally lives does not

satisfy this conservation purpose. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A- 14(d)(3)(ii).

(2) Significant habitats and ecosystems include, but are not limited to:

• Habitats for rare, endangered, or threatened species.

• Natural areas that are relatively intact and are considered high quality

examples of land or aquatic communities.

• Natural areas that are in or contribute to the ecological viability of a park,

preserve, wildlife refuge, wilderness area, or other similar conservation

area.

(3) For this conservation purpose, limitations on public access are allowable. For

example, a restriction on all public access to the habitat of a threatened native

animal species would not defeat the claimed deduction. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-

14(d)(3)(iii). The taxpayer’s documentation, called a baseline report, as required

by Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(g)(5)(i), should clearly describe and identify the

relative natural habitat or ecosystem being protected on the property.

(4) The determination of what specifically meets this conservation purpose test is

based on the facts and circumstances of the specific case. In Glass v.

Commissioner, 124 T.C. 258 (2005), aff’d, 471 F.3d 698 (6th Cir. 2006), the

taxpayer donated two easements that restricted the development of a fraction of

a 10-acre parcel of residential property. The tax court held that the conservation

purpose of natural habitat was satisfied because the conservation easements

were placed on property that had possible places to create or promote a

relatively natural habitat of plants or wildlife.

(5) In Atkinson v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2015-236, taxpayer claimed

deductions for conservation easements encumbering non-contiguous tracts of

land on and adjacent to golf courses located in a gated and guarded residential

community. The tax court distinguished the Glass case and held that the

easements did not protect a relatively natural habitat. In so holding, the tax

court reasoned, among other things, that the golf courses’ use of pesticides

could destroy the ecosystem of the encumbered property. The tax court’s

reliance on the Service’s expert reports and testimony in Atkinson demonstrates

the importance of expert evidence in “protecting natural habitat” cases.

(6) In Champions Retreat Golf Founders, LLC. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2018-

146, taxpayer claimed a deduction for an easement on approximately 350 acres

that encumbered most of a golf course scattered among houses in a gated

residential community. Taxpayer argued the easement satisfied conservation

purposes by preserving habitat for "species of conservation concern," and

providing open space for scenic enjoyment of the general public and pursuant

to a clearly delineated governmental policy. The court sustained the

33

disallowance, finding that that the easement failed to satisfy either the habitat

purpose or the open space purpose. The court held there was an insufficient

presence of rare, endangered, or threatened species, and the encumbered land

was in a non-natural state. Finally, the court held that open space conservation

purpose was not met because there was insufficient physical and visual access

for the public to enjoy the encumbered land in the gated community. Moreover,

the court held that the easement did not satisfy a clearly delineated

governmental policy since the state statute cited by the taxpayer did not support

a determination that the encumbered property was a part of an “identified

conservation project.” As in the Atkinson case, the tax court relied on expert

reports and testimony to determine that the taxpayer failed to satisfy the

conservation purposes of IRC § 170(h). On appeal, the Eleventh Circuit Court

of Appeals disagreed with the tax court and vacated and remanded the tax

court opinion. Champion’s Retreat Golf Founders, LLC v. Commissioner, 959

F.3d 1033 (11th Cir. 2020). A Motion to Amend the Opinion, filed in the 11th

Circuit Court of Appeals on behalf of the Commissioner, is currently pending.

D. Open Space

(1) The donation of a qualified real property interest to protect open space

(including farmland and forest land) must be (1) for the scenic enjoyment of the

general public, or (2) pursuant to a clearly delineated federal, state, or local

governmental conservation policy. This type of conservation easement must

preserve open space and must yield a significant public benefit. IRC §

170(h)(4)(A)(iii).

D.1. Scenic Enjoyment

(1) Preservation of open space may be for the scenic enjoyment of the general

public if development of the property would impair the scenic character of the

local rural or urban landscape or interfere with a scenic panorama that can be

enjoyed by the public. Treas. Reg. § 1.170A- 14(d)(4)(ii)(A).

(2) Whether the easement provides scenic enjoyment to the general public is

evaluated based on all the facts and circumstances. The burden of proof is on

the taxpayer to show the scenic characteristics of the property.

(3) Treas. Reg. § 1.170A-14(d)(4)(ii)(A) lists factors to consider:

• The compatibility of the land use with other land in the vicinity.

• The degree of contrast and variety provided by the visual scene.

• The openness of the land (which would be a more significant factor in an

urban or densely populated setting or in a heavily wooded area).

• Relief from urban closeness.

• The harmonious variety of shapes and textures.

34

• The degree to which the land use maintains the scale and character of the

urban landscape to preserve open space, visual enjoyment and sunlight

for the surrounding area.

• The consistency of the proposed scenic view with a methodical state

scenic identification program, such as a state landscape inventory.

• The consistency of the proposed scenic view with a regional or local