DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 283 152

CS 210 489

AUTHOR

Smith, Michael W.

TITLE

Reading and Teaching Irony in Poetry: Giving Short

People a Reason To Live.

PUB DATE

[85]

NOTE

52p.

PUB TYPE

Reports - Research/Technical (143) --

Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC03 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

Comparative Analysis; Educational Research; *English

Instruction; High Schools; *Irony; Learning

Processes; *Metacognition; *Poetry; *Research

Methodology; Teaching Methods

IDENTIFIERS

Direct Instruction; Rasch Model

ABSTRACT

Because so little research has been conducted on

methods of teaching literature, two separate but related studies were

conducted to (1) examine what it means to understand stable irony,

and (2) to compare two methods, direct and tacit, of teaching stable

irony. A 36-item test, comprised of questions about 7 ironic poems

and 2 nonironic poems, calibrated for difficulty according to Rasch

analysis, was administered to 514 students. In addition, 4

experienced high school English teachers and 12 students were

interviewed and asked to respond to 2 other ironic poems. Results of

the written test showed that the ironic items were in general more

difficult to explicate than the nonironic items. The interviews

suggested that the students had difficulty detecting the presence of

irony. Four high school teachers and their classes participated in

the second study comparing the direct method of teaching irony, based

on metacognition and Booth's (1974) four steps of reconstructing

irony, and the tacit method, which gives students more exposure to

ironic poems. Control groups were given no specific instruction on

irony. Results showed that the direct and tacit methods achieved

a

statistically significant difference in comparison with the control

groups, but that there is little statistical significance between

direct and tacit methods. The study suggests that college bound high

school students need to be instructed in reading skills, to prevent

misreading, and researchers might look into the effectiveness of

small group work versus large group work. The test used in the study

is appended. (sC)

************************************************k**********************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.

***********************************************************************

U.S. OEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

*This document has been reproduced as

received from the person or organiration

originating it.

O Miner changes have been made to improve

reproductiOn duality

Points of view or opinions stated in this doCu-

ment do not necessarily represent official

OERI position or policy

READING AND TEACHING IRONY IN POETRY:

GIVING SHORT PEOPLE

A REASON TO LIVE

Michael W. Smith

4242 N. Kedvale

Chicago, Illinois 60641

Teacher:

Elk Grove High School

Elk Grove Village, Illinois

Degree:

University of Chicago

Phones:

vvtirk: 439-4800

home: 286-3799

"PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

Michael W. Smith

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)."

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

Squire and Applebee (1986) report that over one-hffif of the time

spent in English classes is spent studying literature. Unfortunately for

teachers, however, there is little research on teaching literature to guide

them as they devise this instruction.

In fact, Purves and Beach (1972) note that there are few studies

which consider classroom or curricular treatment. They note the need for:

... the investigation of what the teacher does.

"Teaching" literature, intervening in the natural

response processes of young people, seems to have

an e.ffect on them, on their cognitive performance,

on their attitudes, and perhaps on their interest

patterns. This sort of intervention seems to have

more effect than does the manipulation of the materiffi

thught or the structure and sequence of material.

The nature and effect of different kinds of intervention

need to be explored, particularly the relation between

the type of intervention and the kinds of outcomes that

are sought or measured. (p. 182)

Researchers have not heeded their cali.

In the 1984 and 1965 reviews

of studies in Research in the Teaching of English done by Dietrich and

Behms and by Durst and Marshffil, only one of the few studies on literature

considered a treatment, and that study was not experimenthl.

Cooper (1985) argues that one promising approach for ekmluating the

results of classroom literary study is to focus specificaliv on one

literary skill. This research follows Cooper's suggestion and focuses on

understhnding sthble irony in poetry in two distinct studies. The first

study considers what it means to understhnd sthble irony in poetry. The

second study compares two methods of teaching students to interpret

stable irony in poetry.

3

2

A Definition of Stable Irony

Any discussion of irony must begin with a definition, for there are

few, if any, literary terms that have meant so much to so many. Muecke

(1969) writes that:

[Irony's] forms and functions are so diverse

as to seem scarcely amenable to a single

definition: Anglo-Saxon understhtement,

Eighteenth-century raillery, Romantic Irony,

and schoolboy sarcasm are ell forms of irony;

Sophocles and Chaucer, Shakespeare and Kafka,

Swift and Thomas Mann are all ironists; for

Socrates irony was a standpoint, the governing

principle of his intellectual activity; to Quintilthn

irony was a figure in rhetoric; to Karl Solger

irony was the very principle of art; and to Cleanth

Brooks irony is, "the most general term we have for

the kind of qualification which the various elements

in a ccntext receive from the context." (p. 3)

To study irony effectively, then, one must narrow the focus.

In my

research I am concerned with what is, perhaps, the most basic form of

irony. Muecke calls it simple irony. He explains:

The more familiar kind of irony is Simple Irony,

in which an apparently or ostensibly true

s.thtement, serious question, valid assumption,

or legitimate expecthtion is corrected, invalidated,

or frustrated by the ironist's real meaning, by the

true sthte of affairs, or by what actually happens. (p. 23)

Booth (1974) calls simple irony "stable irony." He defines sthble

ironies by noting their chief features:

1. They are pll intended, deliberately created

by human beings to be heard or read and understood

with some precision by other human beings; they are

not mere openings, provided unconsciously, or accidenthl

4

3

sthtements &lowing the confirmed pursuer of ironies

to read them as reflections against the author.

2. They are all covert, intended to be reconstructed

with meanings different from those on the surface,

not merely overt sthtements that "It is ironic that ..."

or direct assertions that "things" are or "the universe"

is ironic.

3. They are &1 nevertheless stable or fixed, in the

sense that once the reconstruction of meaning has

been made, the reader is not then invited to undermine

it with further demolition and reconstruction.

4. They are &1 finite in application

The reconstructed

meanings are in some sense loc&, limited. (pp. 5-6)

Booth recognizes the wide variety of ironies, but he begins his

discussion with stable ironies, for understanding sthble ironies is

a

fundament& literary skin. He notes: "Every good reader must be,

among

other things, sensitive in detecting and reconstructing ironic meanings."

Kennedy (1976) corroborates the importance of this ability: "We had

best

be &ert for irony on the printed page, for if

we miss it, our interprethtion

of a poem may go wild." (p. 19)

Those who are able to detect and reconstruct ironic meanings

share a

unique literary experience. Booth explains: "...

we should marvel, in a

time when everyone t&ks so much about the breakdown of values

and the

widening of communication gaps, at the astonishing agreements

stable

ironies can produce among us." (p. 62) He explains further:

I spend a great deal a of my professional life

deploring "polar" thinking, reductive dichothrnies,

either-or disjunctions. And here ! find mgself

saying that only in strict polar decisions can

one

kind of reading be properly performed. On the

one

hand, some of the greatest intellectu& achievements

seem to come when we learn how to say both-and

not either-or, when we see that people and works

5

4

of art are too complex for simple true-false.

tests.

Yet here I am saying that some of

our most important

literary experiences are designed precisely to

demand

flat and absolute choices, saying that the sudden

plain irreducible "no" [rejecting the surface

meaning

of a text] of the first step in ironic

reconstruction is

one of our most precious literary moments. (pp. 128-129)

The Detection and Reconstruction of Stable

Ironies

Booth argues that stable ironies produce

astonishing agreements

among readers. If that is so, it seems reasonable to

presume that readers

must interpret stable ironies in similar

ways. Booth and Muecke agree

that the first step toward understanding is

to recognize that an author is

being ironic. They quote Quintilian, who

argues that irony

...

is made evident to the understanding either

by the delivery, the character of the speaker

or

the nature of the subject. For if

any of these

three is out of keeping with the words, it

at

once becomes clear that the intention of the

speaker is other than what he actually

says.

Muecke's analysis is quite similar. He

argues that the contradiction

between the surface meaning and the context

suggests irony. According to

Muecke, the context is made up of what

we know about the writer and the

subject, what the writer tells

us about himself or herself above the

pretended meaning, and finally, what

we are told by the style.

Booth's analysis is much more specific and,

consequently, more

useful. He argues that an author can signal irony through

the use of one or

more of five clues. The first is a straightforward warning in the

author's

own voice. He cites three basic ways authors can give these

warnings: in

titles, in epigraphs, and in other direct clues.

A second clue occurs when

6

5

an author has his or her speaker proclaim a known

error, perhaps the

misstatement of a popular expression,

an error in historical fact, or a

rejection of a conventional judgment. Though

Booth does not discuss them,

illogical expressions would also be subsumed

by this clue. A third clue is

the existence of conflicts within

a work. Booth cites The Rape of the

Lock:

Now lap-dogs give themselves the rousing

shake,

And sleepless lovers, just at twelve, awake.

Unless Pope is unaware of the contradiction (a

possibility we cannot

accept), he must be being ironic. A fourth

clue is a clash of style. Booth

explains that whenever the language of

a speaker is clearly not the same

as the language of the author, we must be alert for the

presence of irony.

For example, from the first sentence of The

Adventures of Huckleberry

Finn, we are aware of the distance between Twain

and Huck. Consequently,

we attend to Huck's words with some suspicion. Other examples of

this

clue would be understatements and exaggerations.

The final clue, Booth

explains, is a conflict of belief. That is, vlienever

the speaker espouses a

belief that the author could not endorse,

we percuive irony. This is the

clue that most clearly informs "A Modest Proposal."

While he does not

discuss it in A Rhetoric of Irony, Booth believes that

this clue also

includes behavior by a speaker that the author could

not endorse. (1985,

personal communication) In each case the reader

must bring to bear

standards from outside the text onto the world of the

text, proceeding

from the belief that the author does not hold alien values.

Suspecting the presence of irony is not the

same as reconstructing

meaning. Booth is unique among theorists in that he

tries to explain the

7

6

process of reconstruction, a process that other theorists

appear to believe

is natur&. Booth argues that reconstructing meaning involves

four steps:

rejecting the surface meaning, trying out alternative

meanings, applying

one's knowledge of

iior, aril selecting arnag alternatives:

In this case I find L.Lloth's arguments less

satisfying, for he does not

explain how the alternative meanings

are generated.

I agree that in "the

usual case of quick recognition" these meanings

come "flooding in." (p. 11)

However, since the meanings that flood in

are not random, something must

control them, and it has to be more than knowledge of the

author, for one

can understand the irony of unknown authors. I suggest that

once one

rejects the surface meaning, one must consider what

in the work (or

situation) is not under dispute. For example, in

Browning's "My Last

Duchess" we reject the Duke's assessment of his wife's death

on the basis

of a conflict of belief. Browning simply could not endorse the Duke's

behavior. However, in my experience of this poem, alternative

meanings

did not come flooding in. Instead I had to consider carefully

on what I

could base a reconstructed meaning. While the Duke's attitude

towards his

wife is suspect, I have no reason to believe that her

easy smile and joy in

life are his fabrications. While his defense of his actions

is suspicious, I

do not believe that he is lying or being ironic when he explains

that he

would not "stoop" to speak with her about her behavior.

I can &so clearly

understand his enormous pride in his title. Further, the

situation is not

under dispute; the Duke is talking to an emissary from

a count about a

proposed marriage. With these and other such facts in

hand, I apply my

knowledge of the world. The Duchess seems wonderful; I

would rejoice in

such a match. The Duke behaves like other self-centered

people I have

8

7

known, though, of course, none of my acquaintances have gone to such

extremes to satisfy wounded pride. People do not allude to illegal acts

unless they have a motive for so doing. The Duke is willing to expose his

guilt to make his expectations of the Count's daughter clear.

Putting it

all together, I believe that Browning must be criticizing this murderous

egotist. Now I check this meaning to see if it jibes with my understanding

of Browning. It does. Browning's monologues often reveal

a speaker who

is blind to his own vices.

To replace Booth's four steps of reconstruction, then, I offer four of

my own.

I believe that readers:

1. Reject the surface meaning

2. Decide what is not under dispute in the work

3. Apply their knowledge of the world to generate

a reconstructed meaning

and., if possible,

4. Check the reconstructed meaning against their

knowledge of the author.

Study I: A Consideration of What It Means to Understand !rony in Poetry

Of course, Booth's self-study is of little use to teachers if the

interpretive strategies that he.identifies are just idiosyncratic. This

study attempts to investigate Booth's theories empirically by considering

what it means to understand irony in poetry in two ways. First, it

attempts to define the variable through the analysis of test results.

Second, it attempts to understand the interpretive strategies experienced

and inexperienced readers use when they encounter stable irony in poetry.

Designing the Test

One of the major problems that plagues research in the social

sciences is the absence of effective instruments.

If we are to learn

9

8

anything about a variable or an individual,

we must have some objective

way to measure that variable or individual. Wright gives

an illustration.

(1986, personal communication) When

we read that a high jumper has

jumped seven feet, we never ask how it

was measured. We understand the

variable height because we

can measure it objectively. When we are

assessing the medal chances of a jumper who has

never performed in the

United States, we look at how high he has jumped.

We don't say, "Well, he

jumped 7 3" over in China. Lets see how he does with

our rulers." That

would be silly, but it's the sort of silliness that

confounds much social

science research. For example, researchers suggest

that IQ is an index of

intelligence, yet an individuals score

on an 10 test may vary markedly

depending on the test he or she takes. Unless

we believe that intelligence

fluctuates from day to day, and, of

course, we don't, we should recognize

that 10. tests don't give us reliable information about

how intelligent

individuals are or even what intelligence is.

An effective instrument is necessary f

or meaningful research results.

To consider what it means to understand irony

in poetry, I developed a

thirty-six item test. (See appendix.) The test makes

four statements

about each of nine poems and asks readers to

agree or- disagree with each

of the statements. The true/false format reflects the

belief that a

normative understanding of stable irony is possible.

Seven of the nine

poems contain irony. Some of the items on these ironic

poems make

statements about information that is not under dispute.

In all, the test

includes fifteen items that address non-ironic information

and twenty-one

items that address ironic information.

I piloted a first draft of this test with

seven graduate students in

1 0

9

English.

I &so asked them to write a justification for each of their

responses. Most of the variation in response was due to ambiguities in the

questions.

I then revised the test trying to eliminate the ambiguities.

Three experienced English teachers and

one graduate student in English

took this second draft of the test. They

were unanimous in their

responses.

I piloted this revised version of the test with twenty-eight

freshmen

in the honors track, nineteen freshme.n in the

average track, and a class of

sixteen juniors and seniors.

I did a Rasch an&ysis of the results to

ev&uate its effe.ctiveness as an instrument.

More specifically, Rasch analysis fit statistics enable test

designers

to see if their items are independent of each other and of other variabths.

In addition, Rasch an&ysis allows test designers to examines whether

their items are functioning as they intended. Wright and Stone (1979)

explain, "that a more able person should always have

a greater probability

of success on any item than a less able person." (p. 69) If this

is not the

case then the item does not measure ability &ong th

varthble. Not only

does Rasch anal yis &low one to examine the effective of each item

for the

entire group, it &so enables test designers to examine whether

each

individu& is using the items as they were intended. Wright and

Stone note

that, "... before we c.an use any person's

score as the basis for their

measure, we must determine whether or not their particular pattern of

responses is, in fact, consistent with our expecthtions." (p. 4) That is,

students must perform in a pattern that approximates a Guttman (1950)

sc&e. They must tend to get the easy questions correct and

then miss

most of the questions that are beyond their ability.

10

On the basis of the pilot results., 1

further revised the test. The

revised test was administered to the

five hundred and fourteen students

who were part of my second study. (Two

hundred and fifty-three students

took the test twice. Eight students

who took the pretest did not take the

posttest. The first administration of

the test included only seven

poems,

five of which contained irony. The

second administration included two

additional ironic poems.) Rasch analysis

of these results showed that the

revised test approximates objectivity

well enough to use it with

confidence as a measuring device.

Interpreting Test Results

Rasch analysis assigns questions and

individuals a value that locates

their position along a variable. This 6alibration

is reported in logits, the

log of the probability that

an individual with ability at the origin of the

scale will get a question right divided

by the probability that he

or she will

get the item wrong. The meaning of

a logit is always the same. An

advantage of 1.1 logits always

means that the student has a 75% chance to

answer an item correctly. Locating items along

a variable on a linear scale

gives meaning to the variable. As Wright

and Stone explain,

once a test's

items have been validated,

...

it becomes practical to turn

our attention to

a far more important activity, namely,

a critical

examination of the calibrated items

to see what

they imply about the possibility of

some variable

of useful generality. We want to find

out whether our

calibrated items spread out in

a way that shows a

coherent and meaningful direction. (p.E13)

12

11

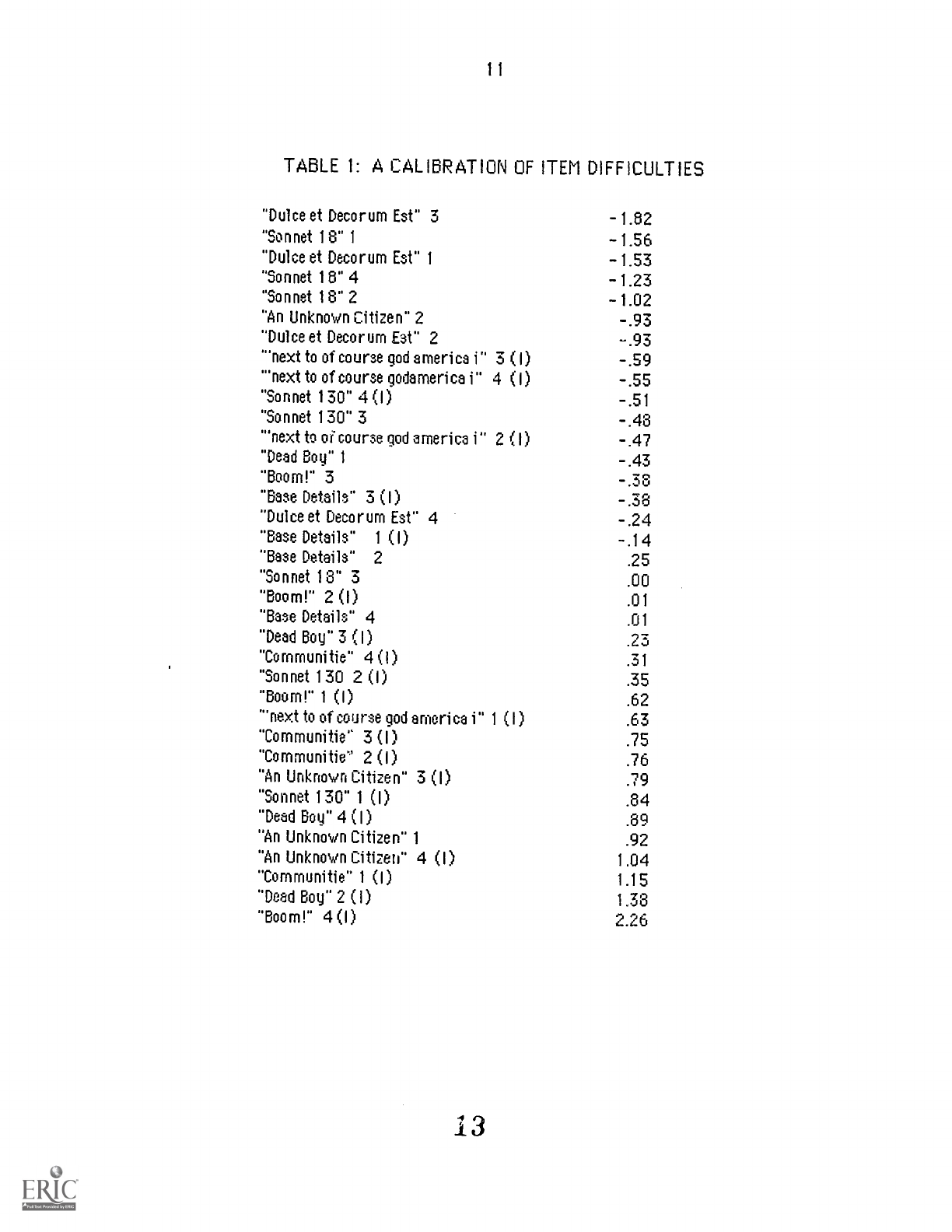

TABLE 1: A CALIBRATION OF ITEM DIFFICULTIES

"Du lce et Decorum Est" 3

-1.82

"Sonnet 18" 1

-1.56

"Duke et Decorum Est" 1

-1.53

"Sonnet 18" 4

-1.23

"Sonnet 18" 2

-1.02

"An Unknown Citizen" 2

-.93

"Dulce et Decorum Est" 2

-.93

"'next to of course god america i" 3 (I)

-.59

"'next to of course godamerica i" 4 (I)

-.55

"Sonnet 130" 4 (I)

-.51

"Sonnet 130" 3

-.48

"'next to of course god arnerica i" 2 (1)

-.47

"Dead Bog" 1

-.43

"Boom!" 3

-.38

"Base Details" 3 (I)

-.38

"Duke et Decorum Est" 4

-.24

"Base Details"

1 (I)

-.14

"Base Details"

2

.25

"Sonnet 13" 3

.00

"Boom!" 2 (I)

.01

"Base Details" 4

.01

"Dead Boy" 3 (I)

23

"Cornrnunitie" 4 (I)

.31

"Sonnet 130 2 (I)

.35

"Boom!" 1 (I)

.62

"'next to of course god arnorica i" 1 (I)

.63

"Communitie" 3 (I )

.75

"Comrnunitie" 2 (I)

.76

"An Unknown Citizen" 3 (I)

.79

"Sonnet 130" 1 (I)

.84

"Dead Boy" 4 (I)

.89

"An Unknown Citizen" 1

.92

"An Unknown Citizen" 4 (I)

1.04

"Communitie" 1 (I)

1.15

"Dead Boy" 2 (I)

1.38

"Boom!" 4 (I)

2.26

13

12

Table 1 displays the item calibrations. The easiest items

have the

most negative values. The most difficult questions have the

highest

positive values. The mean error for these calibrations is .12.

I have

ordered the items from the easiest to the most difficult.

The I

in

parentheses indicates that the item is ironic. The 1-4

indicates to which

of the poem's four items the calibration refers. The

mean of all item

difficulties is 0.00.

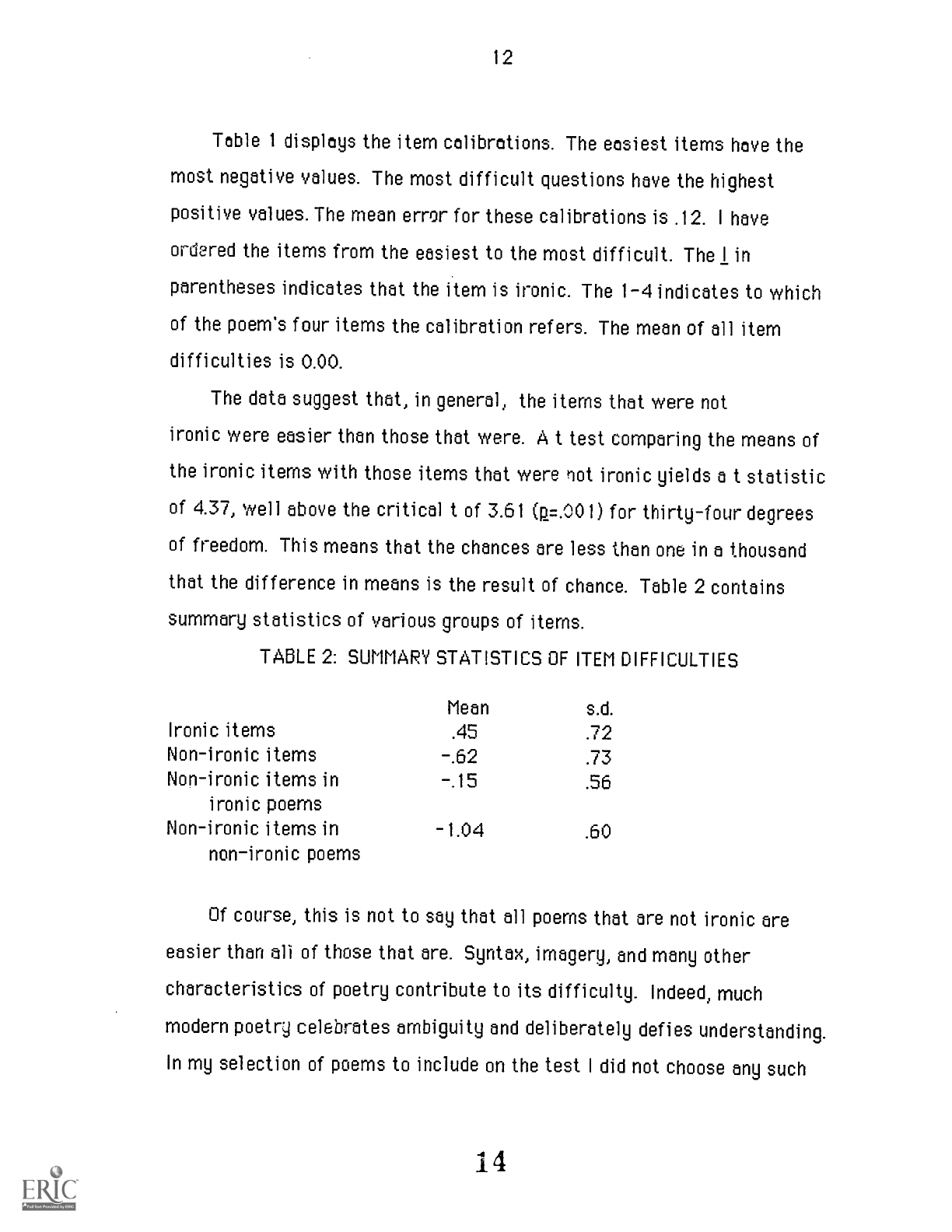

The data suggest that, in general; the items that

were not

ironic were easier than those that

were. A t test comparing the means of

the ironic sterns with those items that

were not ironic yields a t statistic

of 4.37, well above the critical t of 3.61 (p=.001)

for thirty-four degrees

of freedom. This means that the chances

are less than one in a thousand

that the difference in means is the result of chance.

Table 2 conthins

summary statistics of various groups of items.

TABLE 2: SUMMARY STATISTICS OF ITEM DIFFICULTIES

Mean

s.d.

Ironic items

.45

.72

Non-ironic items

-.62

.73

Non-ironic items in

ironic poems

-.15

.56

Non-ironic items in

non-ironic poems

-1.04

.60

Of course, this is not to say that all poems that

are not ironic are

easier than ali of those that are. Synthx, imagery, and

many other

characteristics of poetry contribute to its difficulty. Indeed,

much

modern poetry celebrates ambiguity and deliberately defies understhnding.

In my selection of poems to include on the test I did not

choose any such

.14

13

poems. Since I have argued that authors use sthble irony intending it to be

understood, I selected non-ironic poems that are straightforward, so that I

could make reasonable comparisons.

Ironic items appear, in general, to be more difficult than non-ironic

items. However, the item calibrations establish that within the ironic

items there is substantial variations in difficulty. Initially, I theorized

that the difficulty of ironic items would depend on the nature of the poem,

its syntax, imagery, etc. However, I underestimated the importance of

another major factor, the belief the irony atthcks. Booth explains that

"Every reader will have the greatest difficulty in detecting irony that

mocks his own beliefs or characteristics." (p. 81)

I believed that Auden's "An Unknown Citizen" would be a relatively

easy poem because its syntax and vocabulary are relatively easy. However,

the final question, "The author believes that the reader should approve the

kind of life the citizen led," was the second most difficult on the pretest.

To check to see if students prior beliefs could explain this,

I asked

one class each of ninth, tenth, and eleventh graders who did not

participate in the study to respond to this statement: "Living

a

comfortable life without controversy is desirable." This statement is

one

of the ideas that Auden attacks in his poem. Nine students strongly agreed

with this statement. Thirty-eight agreed. Twenty-one disagreed, and

no

one strongly disagreed.

I also asked students to respond to this statement:

"In a war the officers who plan the strategy are the true heroes, not the

soldiers who carry it out."

Sassoon attacks this position in "Base

Details." Only one student strongly agreed, four agreed, thirty-five

disagreed, and twenty-eight strongly disagreed.

15

14

Assuming that the students in my study had similar views,

majority went into "An Unknown Citizen" holding a belief that is a subject

of Auden's irony. That could.explain why the question was more difficult

than I anticipated.

Again assuming that the students in my study held

similar beliefs, they were predisposed to be sympathetic to Sassoon's

position, and this predisposition may have contributed to making the

item relatively easy to understand.

Of course, the belief being attacked is not the only factor that

contributes to making irony difficult to understand. The final question to

Nemerov's "Boom!" was by far the most difficult on the test. This question

reads: "7

'7' author believes that if people are fortunate it is because God

is watchihy out for them." When I asked the ninth, tenth, and eleventh

grade students who did not participate in this study to respond to the

statement: "If people are fortunate it is because God is watching out for

them," four strongly agreed, thirty agreed, twenty-six disagreed, and eight

strongly disagreed.

Assuming that the students in my study held similar beliefs, slightly

more than half of them were predisposed to accept Nernerov's irony. Many

fewer were prepared to accept Auden's irony, yet the item on "Boom!" was

much more difficult than the item on "An Unknown Citizen." Nernerov's

allusions could explain the difficulty of the item on "Boom!" To understand

Nemerov's belief, one must understand the significance of Job and Demian

and Karnak and Nagasaki. While I gave a note to each of these allusions,

the note alone cannot explain all of the associations these allusions have

for an experienced reader.

It appears, then, that the belief that is the subject of the irony and

16

15

the intrinsic difficulty of the poem are the factors that make irony

difficult to understhnd.

The non-ironic items &so conthin

substhntial variation of

difficulty. The data support my theory that it is easier to understand

non-ironic items in poems that contain no irony than it is to understand

non-ironic items in poems that contain some irony. The mean level of

difficulty for the items in poems that featured no irony was -1.04. A t

test comparing this mean with the mean of non-ironic items in poems that

contain irony (-.15) results in a t statistic of 2.76, well above the critic&

t of 2.16 (p =.05) for thirteen degrees of freedom. This means that the

chances are less than five in a hundred that the difference in means is the

result of chance.

On balance, it appears that an understhnding of irony begins by

recognizing what is not ironic. As the ability to understhnd irony

increases., readers are better able to reconstruct ironic meanings in

increasingly difficult poems and to reconStruct ironic meanings that

ch&lenge their own beliefs and behaviors.

An An&ysis of Experienced and Inexperience.d Readers

Procedures

To examine more carefully the interpretive strategies readers use

when they encounter irony, I interviewed four skilled readers., each one of

them an experienced high school English teacher, and one student randomly

selected from each of the twelve classes that that participated in my

second study.

I interviewed the students before and after they received

their treatments. However, in this study I am reporting only the

pre-treatment interviews as I am interested in the students natural

17

16

responses. (I will report on the effect of the treatments on the interviews

in the second study.)

The two poems I used in the interviews are Sterling Brown's

"Southern Cop" and Robert Browning's "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister."

I

asked one qestion after reading the title and author. After each stanza I

asked one question that corresponds to one of the five clues that Booth

identifies.

I also asked the respondents to define irony. In each interview,

then, the subjects responded to twenty questions, six on "Southern Cop,"

eleVen on "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister," and three definitions.

After the interviews had been typed and coded, two raters rated each

of the twenty responses on the following four point scale:

1

Clearly shows no recognition of irony

2 Probably shows no recognition of irony

3 Probably shows some recognition of irony

4 Clearly shows a recognition of irony

The raters agreed or were only one point apart on over 92% of the

responses. On the twenty-one responses on which the raters scoring

differed by more than one point, a third rater scored the response.

I

eliminated the odd response.

If the third rating was between the other

two, I read the response to decide whether to omit the higher or lower

rating.

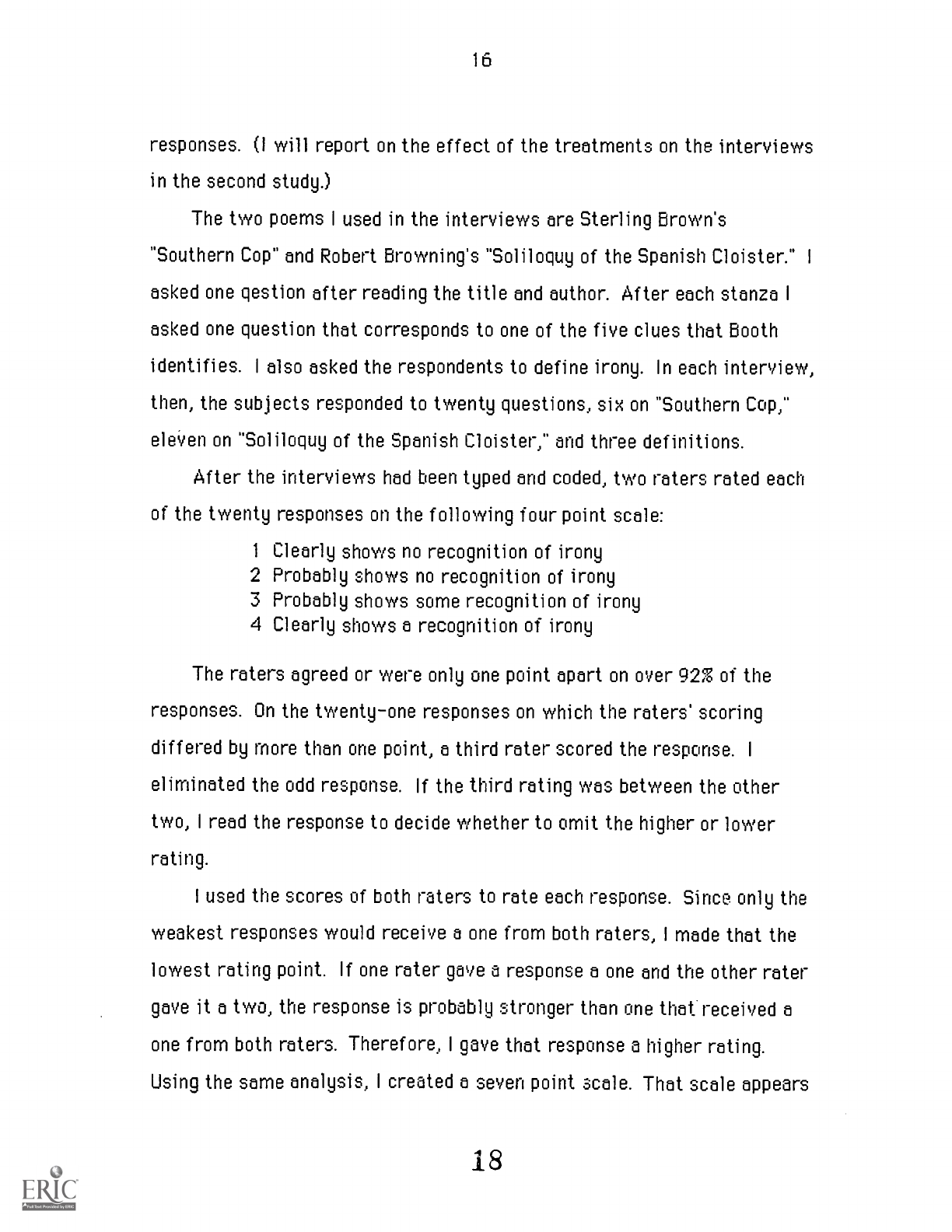

I used the scores of both raters to rate each response. Since only the

weakest responses would receive a one from both raters, I made that the

lowest rating point.

If one rater gave a response a one and the other rater

gave it a two, the response is probably stronger than one that received a

one from both raters. Therefore.. I gave that response a higher rating.

Using the same analysis, I created a seven point scale. That scale appears

18

17

below:

rater 1

rater 2

final score

1

1 1

1

2

2

2

2

3

2

3

4

3

3

5

4

3

6

4

4

7

I did a Rasch analysis of both the experts and the students' responses.

Results and Discussion

The Experts

The experts responded to all five of the clues that Booth identifies,

though clearly some were more suggestive than others. In general, the

position of the clue determined how suggestive it was. That is, the ironic

readings of the skilled readers evolved. They added each new clue to the

previous ones in order to generate their readings.

It is not surprising, then, that the straightforward warnings in the

titles were not very suggestive. Only one skilled reader clearly responded

to the negative connotations in the title "Southern Cop." (For the

discussion of both the experienced and inexperienced readers I will

consider only those responses that received a score of five or above as

clearly demonstrating a recognition of irony.) He noted that the title

"probably implies a negative feeling towards, let's say, abusive authority."

Also, only one skilled reader clearly responded to the explicit distancing

move that Browning makes in his title "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister."

As that reader explained:

Well, I know Browning often uses irony. There's often

an implied criticism of the speaker. The title doesn't do

19

18

much for me, though I see this as another dramatic

monologue.

The fact that it is a dramatic monologue does not

carry the weight for this

reader that it would for Booth, who argues that

any time the author thkes

pains to point out that he or she is not the speaker

we need to be alert for

the possibility of irony.

In fact, were Browning not the author, it appears

that the title would have carried little weight at all for this reader.

As a group, the experienced readers did not

appear to see a dramatic

monologue as a strong signal of the presence of irony. While the title

clearly establishes that the author was not the speaker, the experienced

readers withheld their judgment on the author's attitude to the speaker's

words. Perhaps because the experienced readers went into the

poem with

the understhnding that the speaker of the poem is not the

same as the

author, clues that highlight this distinction did not appear to significantly

affect their interpretations. This is not to say that other types of

straightforward warnings such as epigraphs would not

carry more force.

The speaker's proclamation of known errors was

a far more

significant signal of irony for the skilled readers.

In "Southern Cop" three

of the readers saw the speaker's faulty logic as an indictment. As

one

explained, "He's setting up a premise that on the one hand he wants

us to

accept because it seems logical; however, on closer inspection it's

obviously a fallacy." In "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" the speaker's

error in the fifth sthnza was a telling clue. All of the readers clearly saw

it as an indication of irony. As one reader explained, "The author feels

that the speaker is a phony, and all of these phony rnanifesthtions of

the

fork crosswise and the three sips to honor the Trinity are embellishments

...The author is really cutting into the speaker." However, not all known

2 0

19

errors are the same. The experienced reader who had been

reading the

Browning poem as ironic from its title

on did not respond to the mistake

the speaker made in his prayer in the final

stanza. This shows that it is

difficult to generalize about the force of the

clues, for they are context

specific.

This point is also made clear by the experienced

readers' response to

clashes in style. All four readers received

a seven on the response to the

understatement in the third stanza of "Southern Cop."

As one explains,

"What the speaker says is an understatement;

it's not necessarily the

reaction one would expect, and because of that I think

there's a criticism

of the speaker implied by the author." Interestingly,

the experienced

readers responded to this clue more strongly than

they did to the conflict

of facts in the final stanza. However, only

one experienced reader

responded to the violence of the language in the first

stanza of Browning's

work. He explained, "I'm surprised by

some of the choice of words

...

and

just the vehemence of the language." The

other readers noted only that the

stanza establishes the extent of the speaker's

dislike of Brother Lawrence.

Their response to this stanza evidences their

caution in jumping into an

ironic reading. The difference in

response to these clues suggests the

extent to which the position of

a clue in a text determines its weight. In

'Southern Cop" the clash of style was the clinching piece

of evidence. In

"Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" the clash of style

became significant

after the readers understood the irony through the other

clues.

The conflicts of fact were also important clues. Three

of the

experienced readers clearly recognized that the final stanza

of "Southern

Cop" indicated that the poem is ironic. As

one experienced reader

21

20

commented: "[Ty has] hod on unfortunate

experience in accidentally

shooting the man, but his tragedy isn't nearly

as great as that of the dead

Negro." However, one experienced reader

did not perceive this stanza as a

conflict of facts. Rather he saw it

as "a pretty clear shift of the poet's

description of Ty

... a more explicitly sympcithetic look at him for being

so stupid and ignorant." Three of the experienced readers

also clearly

recognized the conflict of facts in the fourth

stanza of "Soliloquy of the

Spanish Cloister" as a signal of irony. One

reader noted, "I think I'm

beginning to feel an attitude of hypocrisy here.

He speaks of the women in

very sensuous terms himself." Another simply stated, "The

author feels

the speaker is guilty of lust also."

The experienced readers seemed

more reluctant to respond to the

conflicts of belief than they did the other clues.

Even Ty Kendrick's

unjustified shooting of the Negro

was not enough to commit two of the

readers to an ironic interpretation. One reader

explained that she would

"have to wait and find out" about the author's

attitude toward these

events. Another explained that the validity of

the excuses "are the

questions I'm asking myself at this point." The

same hesistance marked

many of the responses to "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister."

On the third

stanza one reader commented, "The speaker is

very gleeful at any

perceived flaws in Brother Lawrence, and it's not

apparent yet whether

that is a criticism of the speaker." Another

says, "He seems so filled with

hate and sour grapes towards [Brother Lawrence],

you have to be a little

suspicious of his ire.

I want to know more at this point." By

the seventh

and eighth stanzas, though, all of the experienced

readers clearly

recognized that the speaker's actions were

a signal of irony. Indeed all

22

21

four readers received a seven for their responses to stanzas seven and

eight.

These responses indicate that the experienced readers saw

interpretation as an evolving process. They made hypotheses on the basis

of the clues, but wanted to wait to commit themselves to the hypotheses.

In fact, all four of the readers alluded to the dynamic aspect of

interpretation. One said about the second stanza that, "I can't tell if

there's sympathy for the speaker or not... I'm inclined to think so, but I'm

going to hold off judgment on that." Three of the readers made the point

clear in their response to the the seventh stanza.

One said, "By this time

we know that we've got a really spiteful, vindictive monk on our hands."

Another said, "It seems each stanza gets worse and worse in what the

speaker wants to do to Brother Lawrence." A third noted: "We're definitely

moving into an interpretation that revolves around the narrator's being

petty ..."

In each case it is clear that an interpretation developed through

the course of the poem. The conflicts in beliefs aided in that development,

but by itself a conflict of belief tended not to be enough to commit the

experienced reader to an ironic interpretation.

It is notable, however, that once the experienced readers perceived

the irony within the stanzas, they offered an ironic interpretation of the

whole poem. They did not fluctuate between ironic and non-ironic

readings. This behavior was only one of those that distinguished them

from the inexperienced readers.

The Inexperienced Readers

As I explained above. I analyzed the pre-treatment interview of one

student from each of the twelve classes that participated in the study.

23

22

Unlike the experienced readers who had

a firm grasp of the concept of

irony, the students I interviewed

seemed unfamiliar with irony. Before

the instruction, ten of the students

were unable to define irony. One

thought it might mean "to be

on a ship with pirates." Another thought it

might mean "kind of tough...bars of steel

or something." The two students

who were able to define irony

gave a definition of situational irony. None

of the students gave a definition that would

include stable irony. Readers

may not recognize stable irony if they are unaware that it

is an option that

writers exercise.

It is not surprising, then, that the

inexperienced readers

were much less responsive to the clues than the experienced

readers. In

fact, in seven of the pre-treatment interviews,

students did not make a

single response that received a final rating

of five or above.

None of the students perceived the straightforward

warning in the

titles. Those students who discussed the title

at all tended to see it as a

means to establish a setting. On "Southern Cop"

a typical response was

"Southern police, that's what I get...maybe

something racial, I'm not sure."

On "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" only six

students made any inference

at all. A typical response of those who did

was, "Maybe it means this

Spanish monastery where this guy makes

a speech."

The interviews contained three examples of known

error proclaimed.

On the second stanza of "Southern Cop" and the fifth

stanza of "Soliloquy

of the Spanish Cloister" only one of the twelve

r6zponses clearly

recognized the proclamation of a known error

as a signal of irony. On the

ninth stanza of "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" two

students responded

to this clue. The student who recognized the known

error proclaimed in

the second stanza of "Southern Cop" commented, "Makes

the Negro look

24

23

like he's innocent. Just 'cause he

ran doesn't mean he should have shot

him and Ty was looking for

a basic chance to make himself look better."

This student realized Brown's intention

in directing our sympathy to the

Negro. A far more common

response was one that confused the speaker and

the author. For example, one student reponded,

"The person who wrote it

might be prejudice against black people,

'cause he thinks he was

dangerous." lt is clear that this student rejects

the speaker's

characterization, yet she does not recognize that the

author shares her

view. Several students volunteered that they

thought that Ty was clearly

in the wrong, but they, too, gave

no indication that the author intended

that effect.

In "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister" most simply

paraphrased the action of the stanza. A typical

response to the fifth

stanza was, "The speaker's trying to show that he's

a better person than

the brother."

There was a similar pattern of

responses to the conflict of facts in

the two poems. Only one response clearly recognized

the conflict of facts

as a signal of irony in the fourth stanza of "Southern Cop." No

students

recognized the conflict of facts in the fourth

stanza of "Soliloquy of the

Spanish Cloister." The strongest response

on the final stanza of "Southern

Cop" explained that, "He deserves worse,

or whatever...again it seems

like he's criticizing him, or sarcasm... 'Let

us pity Ty'--we should not

pity Ty." On the other hand, the majority of

students once again tended to

paraphrase. As one explained, "Ty feels bad 'cause

he's standing there

wondering whether he's made the right choice and

now he knows he didn't,

and now the Negro's sitting there complaining to Ty

or making Ty feel bad."

This same tendency to paraphrase marked the

students' responses to the

25

24

fourth stanza of "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister." One typical

response

notes that, "The speaker thinks... or the other

guys in the monastery think

that he's lusting after women and everything and that he's

not worthy for

the church..."

The majority of the students also did not clearly recognize the

clashes of style in the poems as a clue to irony. Only

one of the twelve

responses clearly noted the irony of the understatement in sthnza three of

"Southern Cop." That student explained that, "He's criticizing--or

not

criticizing, but sort of sarcastic about Ty, using 'unfortunate

hich, you

know... it's unfortunate for the Negro, and the

use is a South-...

;e." A

far more characteristic response argued that, "He's kind of

prejudice--the

speaker--because he's trying to condone what Ty did..." Once

again the

respondent disagreed with the speaker's assessment of the situation

yet

failed to understhnd that Brown shared that disagreement.

The most compelling clue for the students was the conflict of

belief

in the eighth sthnza of "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister."

In fact, the

measure of this item was more than two standard errors lower than the

measure of the next easiest item. This is a sthtistically significant

difference. Four responses clearly recognized the irony of this sthnza.

As

one student explains, "The author thinks that the speaker is kind of corrupt

too, because he has this novel, and maybe Brother Lawerence is

not as bad

as he says." Several students realized that it was odd that the speaker had

such a novel, but they seemed unable to give an ironic interprethtion.

One

noted, "First he was saying Brother Lawrence was bad, and

then he's saying

he has this novel, and this novel is like bad,

so

...

I dunno."

In general,

though, this clue was the most evocative for two

reasons. First, the other

2 6

25

clues in the previous stanzas may have aided students in realizing the

irony of this stEnza. Second, the irony of the eighth stanza may be

apparent in a paraphrase or plot summary of the stanza, which, as I have

explained above, is a primary move for many of the inexperienced readers.

Realizing the behavior of the speaker does not require the attention to the

details of the poem as do the other clues. The inexperienced readers did

not respond as well to other conflicts of beliefs. Only one student

recognized the conflict of belief in the first stanza of "Southern Cop" and

the seventh stanza of "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister." No students

recognized the conflict of belief in the second and sixth stanzas of

"Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister."

Even when the inexperienced readers recognized irony within the

stanza, they did not always use their realization in their overall reading of

the poem. In fact, of the five s...idents who clearly recognized irony within

at least one of the poems, only one maintained ell ironic reading. For

example, consider the student whose response to the eighth stanza of

"Soliloquy of the E.., 3nish Cloister" I cited above. To my question on the

final stanza, he noted, "it makes the author think that the speaker talks

about Satan i,

his prayer, and he could be bad, too, and Brother Lawrence

would not be as bad." This student appears to realize that the speaker is

the target of Browning's poem. However, when I asked him to explain

BruNning's purpose in writing the poem, he said, "It illustrates why he

hatc

Brother LLwrence." This student appeared not to put the parts

together into a ,3herent whole. He was not alone in this tendency. The

transcripts reveal that many students appeared to see the stanzas as

discrete rather than as parts of a unified whole.

26

In general, the experienced readers made use of all of the clues that

Booth cited, though the straightforward warning contained in each

title

had little impact on most of their readings. For the experienced

readers

the interpretation of irony was an evolving

process. The clues that had the

most impact were those found late in the poem. These clues provided the

final pieces of evidence that caused the experienced readers to commit

to

an ironic reading. The experienced readers were cautious about making

such a commitment, especially when they had to apply standards from

outside the poem, as they would when they recognized

a conflict of belief.

However, once they made such a commitment they did not

waver from it.

The inexperienced readers, on the other hand, tended not to recognize

the clues. In fact, when I asked about each stanza, the most

common

response was to offer something of a paraphrase. Even when the students

recognizu, the irony within the poems, they sometimes failed to

use their

insights in their final interpretations.

Further study of different groups of readers interpreting different

types of ironic texts would be useful. However, the interviews strongly

suggest that Booth's analysis is applicable to experienced

reauers. The

readings of the students suffered because they did not recognize the

five

clues.

What can a classroom teacher do with an understhnding of huw ironic

meanings are detected and reconstructed? Researchers in the field of

metacognition in reading instruction would argue that this understanding

could be the basis of a successful instructional program.

Study II: A Comparison of the Effects of Direct. Tacit, and No Instruction

on High School Students Comprehension of Irony in Poetry

28

27

The purpose of the second study is to examine two methods of

improving students ability to interpret irony in poetry. One method of

instruction, the direct method, follows the lead of the research

on

metacognition and attempts to give students conscious control

over the

strategies that Booth identifies. The other method, the tacit method,

follows the f,i,oestions of English education theorists like Beach and

Hillocks who beli.-Ive that students will develop effective strategies for

interpreting different kinds of texts if they have extended practice with

those types of texts.

I compared the effect of the direct and tacit

treatments to each other and to no treatment groups.

Subjects

Four teachers from two suburban Chicago high schools agreed to

participate in the study. One of these teachers presented the material to

ninth graders, one presented the materials to eleventh graders, and two

presented the materials to tenth graders. In all, two hundred and

fifty-three students took both the pretest and the posttest. This number

includes seventy-two ninth graders, one hundred and nine tenth graders,

and seventy-two eleventh graders.

Procedures

I randomly assigned the experimental, control, and no instruction

treatments to the two teachers who had three similar classes. The other

two teachers had only two similar classes.

I also randomly assigned the

experimental and control treatments to these teachers. Each of these

teachers arranged for another class of the same course and level to act

as

a no treatment group.

The Treatments

29

28

The direct method of instruction thkes its inspiration from the

findings reading researchers have made on the powerful effects that

developing methcognitive understhndings of reading strategies have

on

comprehension. These researchers have considered the impact of

explicitly teaching the rules or skills

necessary to complete a reading

thsk successfully. Raphael and Pearson (1982); Raphael, Wonnecott,and

Pearson (1983); Brown, P&incsar, and Armbruster (1984); and Paris, Oka,

and De Brito (1983) are among those who have shown the

power of this

type of instruction.

Brown, Bransford, Campione, and Ferrara (1983) summarize key

findings in this area:

...

if we consider a number of instruction&

experiments that have included groups of students

differing in age or ability and that have involved

manipulation of the complexity of the skills being

taught, a gener& pattern begins to emerge. The

most basic point is that poor performance often

results in a f&lure of the learner to bring to bear

specific routines or skills importhnt for optimal

performance. In this case, readers need to be

thught explicitly what those rules are. This, in turn,

requires a dethiled theoretic& an&ysis of the

domain in question; otherwise, we cannot specify the

skills in sufficient detail to enable instruction. (pp. 140-141)

In brief, the direct instruction seeks first to build students'

awareness of the five clues that Booth identifies as the way authors

sign& that their work might be ironic by examining five cartoons by James

Thurber, each of which makes its irony clear through the use of a different

clue. In the discussion of these cartoons, the instruction also highlights

and makes explicit the three steps that readers go through in

3 0

29

reconstructing mening of Ler they have rejected the surface meaning of a

text.

With this background, students examine five to ten examples of each

clue in separate worksheets. Then students focus on the steps of

reconstruction in two worksheets. After this preparation, students begin

applying the principles they have learned to popular songs. Only after the

students should have become thoroughly familiar with the five clues and

the steps of reconstruction does the instruction proceed to actual poetry.

Students analyze the first four poems with the aid of worksheets, the

questions on which highlight the clues and aid students in reconstructing

meaning.

After students write an ironic monologue, they analyze four poems on

their own without the aid of supporting questions, relying only on their

understanding of the clues and the steps of reconstruction. This should

ensure that students monitor their understanding of the unit concepts.

After writing an essay on understanding irony, students will be given two

poems that consider man's relationship to others, only one of which is

ironic. Students will be asked to explain how they recognized the

difference between the poems.This exercise should help them develop

a

final key skill to understanding irony: knowing when to stop. That is, the

exercise should help students discriminate between what is and what is

not ironic. The direct instruction places an almost equal emphasis on

small and large group work.

The tacit method of instruction is based on the idea espoused by

Beach and Hillocks that students will develop their own strategies for

dealing with a certain type of text if they have extended practice with

31

30

that type of text. They would argue that tacit knowledge is equally

effective. Beach and Appleman (1984) explain:

From extensive reading of a certain text type,

readers acquire thcit knowledge of different text

structures. The fact that readers perceive a certain

text in terms of a certain text structure means

that they can derive meaning from that text. (p.

118)

Among English educators Hillocks has been perhaps the most

outspoken proponent of developing units of literature around works that

share similar structures.

In his The Dynamics of English Instruction

(1971, written with McCabe and McCampbell), he explains his rationale:

If a student is confronted with a series of

related literary situations that require similar

(but not the same) inferences, he will learn

what to observe and how to make the necessary

inferences. (p. 254)

To aid students in their observations, he suggests that units of

related pieces of literature be developed around a series of key questions.

Hillocks argues that repeated practice answering these focused questions

will help students develop the interpretive strategies they need to answer

them. An outstanding example of his approach is his book Satire (1974).

The two types of experimental instruction share many of the same

features. The tacit method uses all of the texts that the direct method

does. However, because the initial work in the direct instruction with the

cartoons and the worksheets takes time, the tacit method uses additional

poems. All four of the teachers of the tacit method presented five

additional ironic poems. Two teachers presented the tacit instruction

more quickly than the other teachers. These teachers also included a

culminating activity that called for students to evaluate Masters's

32

31

attitude to eight of his speakers from Spoon River Anthology. By including

these addition& poems the teachers all spent the same number of

classroom periods on the two methods of instruction.

Also, the thcit instruction does not explicitly mention irony, although

the notion is explained without the use of the term. Like the direct

instruction, the thcit instruction stresses both small and thrge group

work. The small group worksheets in the thcit instruction on poems that

have worksheets in the direct instruction are slightly modified versions of

the direct instruction worksheets that eliminate only references to the

clues and the steps of reconstruction. The worksheets on those poems

that have no worksheets in the direct instruction and the worksheets of

poems not included in the direct instruction were thken from lite.rature

texts, with the exception of the assignment on Spoon River Anthology.

with only explicit references to irony omitted. The worksheet on Spoon

River Anthology simply asked students to rank the speakers of eight poems

according to how positively Masters felt about them. Explicit references

to irony were omitted so that control teachers who were asked to explain

the term did not include any of the substance of the experiment&

instruction in their answers.

In the tacit instruction students did two similar writing assignments.

The sequence of the control instruction is slightly different to

accommodate the additional poems in a sensible format.

Each teacher spent the same number of class periods for both the direct

and thcit instruction. Teachers administered the posttest without

informing their students of the format or date of the test.

33

32

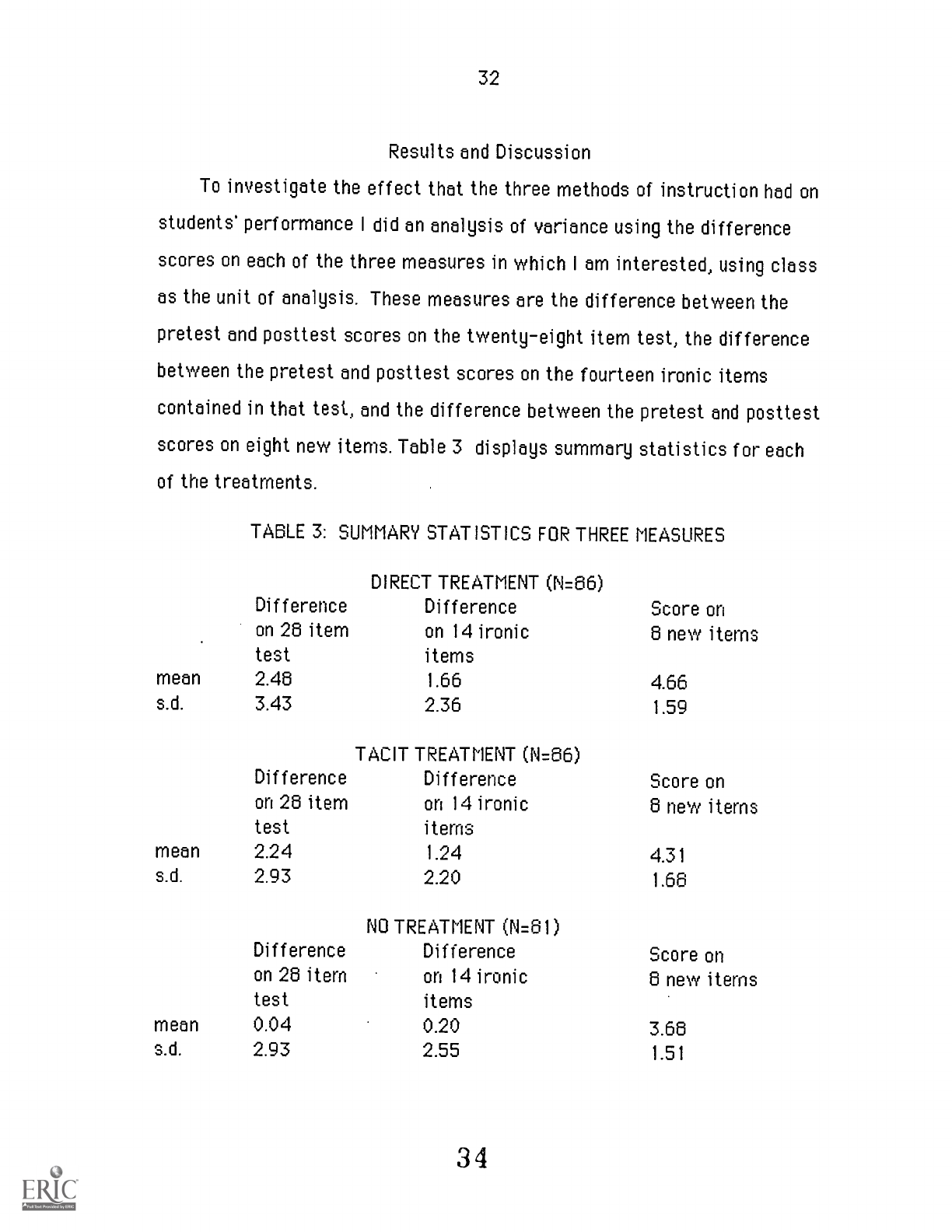

Results and Discussion

To investigate the effect that the three methods of

instruction had on

students' performance I did an analysis of variance using

the difference

scores on each of the three measures in which I am interested, using class

as the unit of analysis. These measures are the difference between

the

pretest and posttest scores on the twenty-eight item

test, the difference

between the pretest and posttest scores

on the fourteen ironic items

contained in that test, and the difference between the pretest

and postte.st

scores on eight new items. Table 3 displays summary statistics for each

of the treatments.

TABLE 3: SUMMARY STATISTICS FOR THREE MEASURES

DIRECT TREATMENT (N=66)

Difference

Difference

Score on

on 28 item

on 14 ironic

8 new items

test

items

mean

2.48

1.66

4.66

s.d.

3.43

2.36

E59

TACIT TREATMENT (N=86)

Difference

Difference

Score on

on 28 item

on 14 ironic

8 new items

test

items

mean

2.24

1.24

4.31

s.d.

2.93

2.20

E68

NO TREATMENT (N=61)

Difference

Difference

Score on

on 28 item

on 14 ironic

8 new items

test

items

mean 0.04

0.20

3.68

s.d.

2.93

2.55

1.51

3 4

33

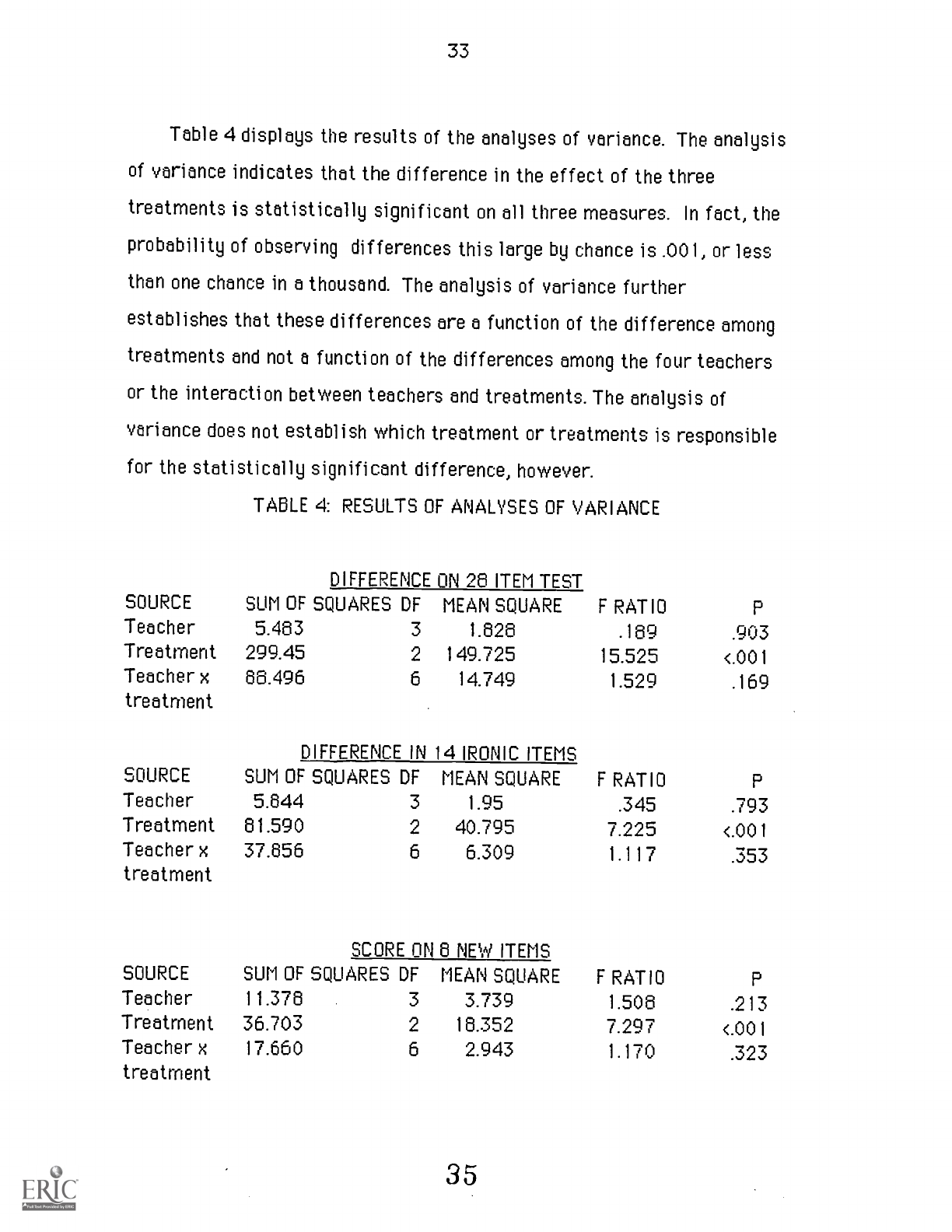

Table 4 displays the results of the analyses

of variance. The analysis

of variance indicates that the difference

in the effect of the three

treatments is statistically significant

on all three measures. In fact, the

probability of observing differences this large by

chance is .001, or less

than one chance in a thousand. The analysis of

variance further

establishes that these differences

are a function of the difference among

tre.atments and not a function of the differences

among the four teachers

or the interaction between teachers and treatments. The analysis

of

variance does not establish which treatment

or treatments is responsible

for the stati sti cal 1 y signifi cant difference,

however.

TABLE 4: RESULTS OF ANALYSES OF VARIANCE

DIFFERENCE ON 28 ITEM TEST

SOURCE

SUM OF SQUARES OF

MEAN SQUARE

F RATIO

Teacher

5.483

3

1.828

.189

.903

Treatment

299.45 2

149.725

15.525

<.001

Teacher x

treatment

88.496

6

14.749

1.529

.169

DIFFERENCE IN 14 IRONIC ITEMS

SOURCE

SUM OF SQUARES DF

MEAN SQUARE

F RATIO

Teacher

5.844 3

1.95

.345

.793

Treatment

81.590

2

40.795

7.225

<.001

Teacher x

treatment

37.856

6

6.309

1.117

.353

SCORE ON 8 NEW ITEMS

SOURCE

SUM OF SQUARES DF

MEAN SQUARE

F RATIO

Teacher

11.378 3

3.739

1.508

.213

Treatrnent

36.703 2

18.352

7.297

<.001

Teacher x

treatment

17.660

6

2.943

1.170

.323

35

34

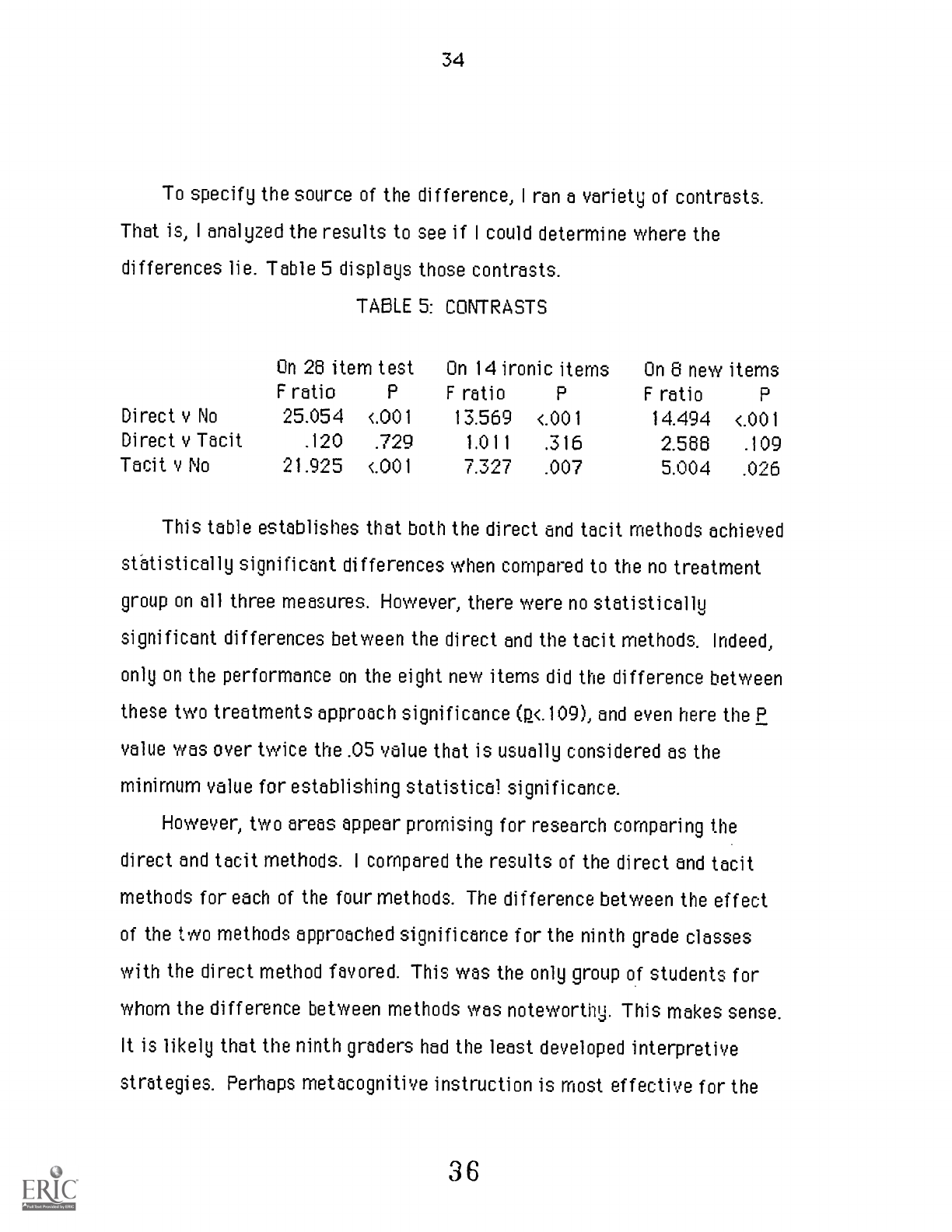

To specify the source of the difference, I ran

a variety of contrasts.

That is,

I analyzed the results to see if I could determine where the

differences lie. Table 5 displays those contrasts.

TABLE 5: CONTRASTS

On 28 item test

On 14 ironic items

On 6 new items

F ratio

P

F ratio

P

F ratio

Direct v No

25.054

<.001

13.569

<.001

14.494

<.001

Direct v Tacit

.120

.729

1.011

.316

2.588

.109

Tacit v No

21.925

(001

7.327

.007

5.004

.026

This table establishes that both the direct and thcit methods achieved

statistic&ly significant differences when compared to the

no treatment

group on all three measures. However, there were no statistically

significant differences between the direct and the tacit methods. Indeed,

only on the performance on the eight new items did the difference between

these two treatments approach significance (p<.109), and even here the P

value was over twice the .05 value that is usually considered es the

minimum value for establishing statistic& significance.

However, two areas appear promising for research comparing the

direct and tacit methods.

I compared the results of the direct and tacit

methods for each of the four methods. The difference between the effect

of the two methods approached significance for the ninth grade classes

with the direct method favored. This was the only group of students for

whom the difference between methods was noteworthy. This makes

sense.

It is likely that the ninth graders had the least developed interpretive

strategies. Perhaps metacognitive instruction is most effective for the

3 6

35

least experienced readers. In addition, the direct instruction appeared to

have a greater impact on the students' ability to

answer the interview

questions. For this an&ysis I compared the differences between the

students' pretreatment and posttreatment interviews

as calculated by

Rasch analysis. Three of the students who received the direct instruction

improved by more than two sthndard errors and the fourth improved by

more than one sthndard error. In contrast, although one individu& who

received the thcit instruction improved more than two standard

errors, the

other three individuals did not dernonstrate a noteworthy change. One

student who received no treatment improved one standard

error while the

other two received scores that were one standard error

worse.

Because the sample is so small it is risky making any

generalizations. However, the data are suggestive. The interview

questions were more difficult than the test questions. The data suggest

that the direct method is more useful than the tacit method in helping

students cope with more difficult thsks. This &so makes

sense.

If a task

is easy, one can do it naturally. Reflection on the

process is not

necessary. However, when a task is problematic, it may be important to

have conscious control of the strategies one may

use to accomplish it.

Studies that use tests that are thrgeted above the population's ability

would help investigate this hypothesis.

Though much addition& study is needed, the results

are promising.

The data strongly suggest that both methods of instruction

can help

students significantly improve their interpretive skills in particular

genre

in a relative1:j short period of time. Both methods were statistic&ly

superior to no treatment on each of the measur6s I considered. However,

37

36

the study does not suggest the superiority

of either the direct or tacit

method. Further research should consider the effect

of these methods in

other reading situations and with other populations

of readers.

These findings are particularly interesting

because of the little

research on effective methods of teaching literature.

They provide a

challenge to literature teachers because both

methods are substantially

different from current instructional practice,

at least as it is reflected in

literature textbooks. No text that I have

seen specifies the interpretive

strategies that skilled readers bring to

a particular task, though Hillocks

takes a step in this direction by arranging literature

units around a few

key questions. No major anthology has followed

the suggestions of Beach

or the example of Hillocks and offered units in well-defined

genre. Genre

divisions as broad as "poetry" or "the short story" give readers

little

sense of direction instead of locating them in what Booth calls

a "fairly

narrow groove."

(p. 99)

Additional Implications

One implication of my work is that we need not do research

on

teaching literature in a vacuum. While little research exists

that

evaluates methods of instruction, there are developed research

traditions

that can provide a guide. One is reading research. To this point

little has

been done to apply the findings of reading research to literature

instruction. In high schools reading is what is taught to remedial

students; literature is what is taught to the college-bound.

And never the

twain shall meet. Literature teachers seem to believe that

their business

is not the business of reading teachers. "Reading

teachers seek to build

comprehension skills," they might say. "Our students

already have them."

38

But as I have pointed out, this positini

J. Students do misread.

Reading research can help suggest methods that

may help students avoid

misreadings.

The direct method of instruction in

my study was inspired by the

work that reading researchers did on metacognition.

Future researchers

may wish to investigate other areas of reading research, for example,

questioning strategies or the use of advanced organizers.

Reading

research is a fruitful source of inspiration and guidance;

my work

suggests that researchers on teaching literature will profit if

they

consi der it.

In planning their work researchers also should consider

the body of

theory that already exists. For years, methods texts have

advocated

presenting coherent units of instruction

as an effective way to teach

literature. My work was one attempt to test this premise. Other

premises

abound. They should be tested before they

are accepted. Is small group

work more effective than large group discussions? We

pretend that it is,

but empirical support would allow teachers to

use it with more

confi dence.

In addition, researchers should look to the work of literary

critics in

planning their studies. Their theories can often be examined

empirically.

My work was inspire.d by the work of Booth, and, at least

to some extent,

supports his insights. The work of other critics has

an influence on how

teachers teach. We need to test these theories and their effects

before we

accept them.

If we are to do this, we must have instruments. My

work convinces

me that Rasch analysis is an invaluable tool for designing and validating

3 9

38

tests. As researchers develop more and

more reliable instruments, future

research will be facilitated.

In the past decade we have made great

strides in our understhnding

of how students compose and what

instruction is most effective in helping

them compose better. We need

now to direct the same energy towards

understhnding how students interpret literature

and how we can help them

do it better.

4 0

APPENDIX

41

Each of the following syen poems is followed by four statements. Please indicate whether

you

believe each statement is true (T) or false '(F). Ple.ise respond to

every statement. Circle onl

one response to each statemt:.

1.

BASE DETAILS

If I were fierce and bald and short of breath,

I'd live with scarlet Majors at the Base.

And speed gl urn heroes up the line to death.

You'd see me with my puffy, petulant face,

Guzzling and gulping in the best hotel,

Reading the Roll of Honor. "Poor young chap,"

I'd say- -"I used to know his father well;

Yes, we've lost heavily in this last scrap."

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I'd toddle safely home and die-

bed.

SieQiried Sassoon

The author admires officers. T

F

The author believes thot enlisted men feel honored to fight in wars.

T

F

The author believes that officers have a genuine concern for their

men.

T

F

The author believes that war is equally dangerous for officers and enlisted

men. T

F

2.

THE UNKNOWN CITIZEN

(To JS/07/M/378

This Marble Monument

Is Erected by the State)

He was found by the bureau of statistics to be

One against whom there was no official complaint,

And all reports on his conduct agree

That, in the modern sense of an old-fashioned word, he was a saint,

For in everything he did he served the Greater Community.

Except for the War till the day he retired

He worked in a factory and never got fired,

But satisfied his employers, Fudge Motors Inc.

Yet he wasn't a scab or odd in his views,

For his Union reports that he paid his dues,

(Our report on his union shows it was sound)

And our Social Psychology workers found

That he was popular with his mates and liked a drink.

The press are convinced that he bought a paper every day

And that his reactions to advertisements were normal in every

way.

42

40

Policies taken out i n his name prove that he was fully insured,

And his Health-card shows he was once in a hospital but left it cured.

Both his producers research and High-Grade living declare

He was full y sensible to the advantages of the Installment Plan

And had everything necessary to the Modern Man,

A phonograph, a radio, a car and a frigidai

re.

Our researchers Into Public Opinion are content

That he had the proper opinions for the time of

year;

When there was peace, he was for peace; when there

was war, he

went.

He was married and added five children to the population,

Which our eugenist says was the right number for a parent of his

generation,

And our teachers report that he never interfered with their education.

Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd:

Had anything been wrong, we would certainl y have heard.

W. 11. Auden