Replication and Extension of the Early Childhood

Friendship Project: Effects on Physical and

Relational Bullying

Jamie M. Ostrov, Stephanie A. Godleski, Kimberly E. Kamper-DeMarco,

Sarah J. Blakely-McClure, and Lauren Celenza

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Abstract. A replication of a preventive early childhood intervention study for

reducing relational and physical aggression and peer victimization was conducted

(Ostrov et al., 2009). The present study expanded on the original 6-week program,

and the revised Early Childhood Friendship Project (ECFP) 8-week program

consisted of developmentally appropriate puppet shows, active participatory

activities, passive activities, and in vivo reinforcement periods. Both teacher and

observer reports were obtained at pretest and posttest for relational and physical

bullying, as well as relational and physical peer victimization, for each partici-

pating child. The initial sample (N ⫽ 141; age M ⫽ 45.53 months; age SD ⫽ 7.29)

included 80 children randomly assigned to the intervention group (six classrooms)

and 61 children randomly assigned to the control group (six classrooms). The

present study found that the ECFP reduced relational bullying in the intervention

group relative to the control group and reduced relational and physical victim-

ization for girls in the intervention group relative to the control group. The

importance of early intervention and implications for educators and clinicians are

discussed.

A developmental psychopathology per-

spective emphasizes the importance of early

childhood peer relationships and the skills ac-

quired during this key developmental period

for setting the stage for later peer interactions

and relationships (Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson,

1999). Therefore, intervening with preschool-

aged children to help them begin on a positive

trajectory of interpersonal relationships is of

critical importance. However, little research to

date has investigated intervention programs

for reducing aggressive behavior in typically

developing preschoolers. Other intervention

work with younger children, such as the In-

credible Years Dina Dinosaur Classroom

(Reid & Webster-Stratton, 2001; Webster-

We acknowledge the many research assistants in the University at Buffalo Social Development Laboratory

who have contributed to the collection and management of the data reported in this article. Thanks to Emily

J. Hart for her assistance with intervention components of this project. We acknowledge Drs. Greta

Massetti and Kirstin Gros for intellectual contributions in the development of the initial ECFP program.

Special thanks to the families, teachers, and school directors for their participation and support of our

research.

Correspondence regarding this article should be directed to Jamie M. Ostrov, Department of Psychology,

Copyright 2015 by the National Association of School Psychologists, ISSN 0279-6015, eISSN 2372-966x

School Psychology Review,

2015, Volume 44, No. 4, pp. 445– 463

445

Stratton, Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008), has pri-

marily addressed physically aggression (i.e.,

using physical force to harm others, including

hitting and kicking; Dodge, Coie, & Lynam,

2006). When relational aggression (i.e., using

removal or the threat of removal of the rela-

tionship to harm, including performing social

exclusion, making friendship withdrawal

threats, ignoring, and spreading malicious ru-

mors, gossip, secrets, and lies; Crick & Grot-

peter, 1995) is addressed (for review, see Leff,

Waasdorp, & Crick, 2010), the work has pri-

marily been conducted with older children

(e.g., Leadbeater, Hoglund, & Woods, 2003;

Leff, Goldstein, Angelucci, Cardaciotto, &

Grossman, 2007; Leff et al., 2009). Finally,

when negative peer behaviors in young chil-

dren are targeted, mixed results have been

demonstrated (Harrist & Bradley, 2003). Spe-

cifically, Harrist and Bradley (2003) found

some success in their intervention “You can’t

say you can’t play” but also reported difficulty

in changing the targeted behavior. Peer accep-

tance rates improved in the intervention class-

rooms relative to the control classrooms, but

the children did not like the new rule, social

dissatisfaction was higher among the interven-

tion classrooms, and rates of social exclusion

did not significantly change (Harrist & Brad-

ley, 2003). These mixed findings indicate the

need for early childhood programs to highlight

how to interact with peers rather than prohibit

exclusion.

EARLY CHILDHOOD FRIENDSHIP

PROJECT

The primary impetus for the develop-

ment of the Early Childhood Friendship Proj-

ect (ECFP) was to design a classroom-based

intervention program for early childhood to

reduce physical and relational forms of both

aggression and victimization. Early childhood

was targeted given the notion that the earlier

we intervene for aggression, the greater the

probability there is for adaptive outcomes

(Sroufe, 2013). This initial work was also

conducted given the growing literature doc-

umenting that physical aggression and rela-

tional aggression are uniquely associated

with significant social–psychological adjust-

ment problems across development (e.g.,

peer rejection) and are associated with

symptoms of psychopathology (for review,

see Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, &

Crick, in press).

The ECFP was developed based on the

available evidence-based literature and prior

programs (see Ostrov et al., 2009) designed to

reduce aggression and conduct problems

among young children (e.g., Reid & Webster-

Stratton, 2001; Webster-Stratton et al., 2008),

as well as several core principles (see Ostrov

& Kamper, 2015). These principles include

the following: (a) Social modeling of problem-

solving and conflict-resolution strategies in a

developmentally appropriate manner (e.g.,

puppets and stories) should decrease bullying

and peer victimization subtypes; (b) reduc-

tions in classroom-level bullying and victim-

ization behavior would result from modifying

reinforcement contingencies within the peer

context; and (c) social and emotional skills

training would reduce bullying and peer vic-

timization. Moreover, a key belief was that the

program should explicitly address both phys-

ical and relational forms of aggression to ef-

fect change in both behaviors. A focus on

reducing both aggression and victimization

subtypes was adopted rather than assuming

that a reduction in aggression would in turn

produce a reduction in peer victimization. In

addition, we balanced our program between

positive (e.g., inclusion) and negative (e.g.,

friendship withdrawal) themes (see Table 1) to

Table 1. Weekly Program Themes

Week Content

1 Introduction and physical aggression

2 Relational aggression: Social exclusion

3 Prosocial behavior: Social inclusion

4

Relational aggression: Friendship

withdrawal

5 Friendship formation

6 Reporting versus tattling (mean names)

7 Prosocial behavior: Sharing and helping

8 Conclusions, review, and graduation

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

446

reduce the aggressive behavior and avoid

iatrogenic effects (i.e., modeling novel aggres-

sive interactions could unintentionally in-

crease aggressive behavior; see Ostrov, Gen-

tile, & Mullins, 2013). A number of these

principles are reflected in other school-based

bullying and peer victimization intervention

programs, and these programs have been

found to be efficacious for older samples (e.g.,

Espelage, Low, Polanin, & Brown, 2013;

Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2006; Lochman &

Wells, 2004; van Schoiack-Edstrom, Frey, &

Beland, 2002).

BULLYING IN EARLY CHILDHOOD

In addition to distinguishing between

the general forms of aggression (i.e., physical

or relational), we may also make distinctions

between general aggression and bullying. Bul-

lying is a subtype of aggression so that all

bullying is aggression but not all aggression is

bullying (see Leff et al., 2010; Ostrov & Kam-

per, 2015). The current Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) uniform defi-

nition of bullying highlights components of

power imbalance and repetition or the likeli-

hood of repetition as the primary distinguish-

ing factors (Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Ham-

burger, & Lumpkin, 2014). This definition is

important to obtain valid prevalence rates and

has numerous clinical and legal implications

given the zeitgeist. Thus, aggressive behavior

among equal-status friends would not be con-

sidered bullying, and even though, as aggres-

sion, it should be taken seriously, it would not

currently trigger mandated reporting to legal

authorities within the United States. We also

acknowledge that bullying is an interpersonal

relationship process (Pepler, 2006) that in-

volves a focus greater than the sole bully and

thus our school-based intervention addresses

the peer relations of the entire classroom to

address concerns specific to both bullies and

victims, which is a common approach in the

recent literature (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). It

is important to note that bullying may present

in multiple forms (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, &

Lindstrom Johnson, 2015; Gladden et al.,

2014; Low & Espelage, 2013), and in the

present study, both physical and relational

forms of bullying were examined. Investigat-

ing bullying during early childhood may be

particularly important given that it is under-

studied (for review, see Vlachou, Andreou,

Botsoglou, & Didaskalou, 2011). The research

that has been conducted has shown not only

that bullying is prevalent during this period

(Vlachou et al., 2011) but also that experienc-

ing bullying during early childhood is associ-

ated with negative social outcomes, such as

unhappiness at school (Arseneault et al.,

2006).

CURRENT STUDY AND

HYPOTHESES

The current randomized controlled trial

(RCT) serves as an opportunity for replication

and extension of the initial trial of the ECFP

program. The initial 6-week trial showed that

intervention classrooms had large reductions

in relational aggression and physical victim-

ization relative to control classrooms. Inter-

vention rooms also showed moderate reduc-

tions in physical aggression and increases in

prosocial behavior relative to randomly as-

signed control classrooms. Only small de-

creases were documented for relational vic-

timization (Ostrov et al., 2009). Although an

important first step in creating an intervention

that addresses relational and physical aggres-

sion and victimization, the initial findings

were only reported at the level of the class-

room (Ostrov et al., 2009). The current study

addresses the efficacy of an expanded program

at the individual child level in a new sample,

as suggested by Leff, Waasdorp, and Crick

(2010) in their evaluation of the ECFP for

reducing relational aggression and peer vic-

timization. The core principles and features of

the program are similar to the initial trial (Os-

trov et al., 2009), but several additional sub-

stantive changes were adopted for the present

study. First, on the basis of prior feedback

from our key stakeholders, we expanded the

program from 6 to 8 weeks to add two new

social skills lessons (i.e., 1 week focusing on

tattling versus reporting and 1 week empha-

sizing sharing and helping). Second, to ad-

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

447

dress the aforementioned key limitation (see

Leff, Waasdorp, & Crick, 2010), we collected

our data in a manner that permitted the indi-

vidual child to serve as the unit of analysis.

Third, we examined whether the intervention

was effective at reducing bullying behavior.

To this end, we developed a new measure of

bullying subtypes for this developmental pe-

riod, and the present study is one of the first to

examine both physical and relational subtypes

of bullying among 3 to 5 year olds. That is, a

few prior studies have purported to examine

the presence of bullying behaviors among

young children (e.g., Monks et al., 2009), but

prior studies have rarely adopted the present

definition of bullying and, thus, the current

study is one of the first known studies to

examine the presence of bullying among very

young children using a specific definition of

bullying rather than a general aggression–vic-

timization construct (Gladden et al., 2014).

The psychometric properties of this measure

will be introduced and present an additional

contribution of our study independent of the

intervention goals. Fourth, in the present

study, we examined the moderating influence

of gender, which has rarely been examined in

this developmental period and with similar

intervention programs. Therefore, the present

study provided an opportunity to extend the

literature by examining the impact of an ex-

panded ECFP on physical and relational bul-

lying (as well as peer victimization) for boys

and girls in preschool.

Given the success of the initial RCT, we

anticipated confirmation of our two specific

hypotheses representing the extension of the

program to the study of bullying behaviors.

First, we hypothesized that children in the

intervention classrooms would show a signif-

icant reduction in physical bullying relative to

children in the control classrooms. Second, we

hypothesized that children in the intervention

classrooms would show a significant reduction

in relational bullying compared with children

in the control group. Finally, we examined the

moderating role of gender. Given significant

within-gender differences for aggression sub-

types during early childhood (i.e., the modal

form of aggression is relational for girls; Os-

trov, Kamper, Hart, Godleski, & Blakely-Mc-

Clure, 2014), we anticipated the possibility of

gender moderation. However, given the lack

of prior work and theory regarding bullying

behaviors during early childhood, these ques-

tions were exploratory.

METHOD

Children were recruited from six

schools that were recently accredited or are

currently accredited by the National Associa-

tion for the Education of Young Children (12

classrooms) throughout the western New York

area. These schools serve children from pri-

marily middle-class families and comprise

four schools associated with universities and

two institutions with religious affiliations.

These schools are located in urban areas (two

schools) and suburban areas (four schools).

Schools were selected to represent the larger

diverse community, but to reduce confounding

variables, only centers deemed above average

in quality (i.e., as indexed by their current or

recent national accreditation status and infor-

mal observations made by the first author)

were invited to participate. In addition, all

schools had previously participated in prior

basic or applied research by the research team,

but no active intervention work had occurred

within the schools for roughly five years and

three schools (eight classrooms) had not

participated in prior intervention research.

Schools were contacted directly by the princi-

pal investigator and invited to participate in

the study. All of the schools and classrooms

that were contacted participated in the study.

Participants and Measures

Recruitment yielded an initial sample of

141 participants (67 girls) (age M ⫽ 45.53

months; age SD ⫽ 7.29). The participating

families represented diverse ethnic back-

grounds (3% African American, 11% Asian,

69% White, 2% Hispanic, 14% biracial, 1%

other). Randomization occurred at the level of

the classroom, with each classroom being as-

signed a number and those numbers being

randomized (with a random number generator)

to either intervention or control. Six class-

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

448

rooms were randomized to the intervention

group (n ⫽ 80; 57%), and six classrooms were

randomized to the control group (n ⫽ 61;

43%). There were a few schools that contained

both an intervention classroom and a control

classroom, but concerns about contamination

were low given that the children and staff did

not interact during the day and had different

playground times. There were two cases in

which classrooms were next to each other with

a partitioning divider between the rooms.

These rooms were known to have joint free-

play periods and shared staff during the day;

therefore, these rooms were combined prior to

randomization. One classroom was a multiage

room (i.e., 3 to 5 years), whereas the others

were designated for 3 or 4 year olds. There

were equal numbers of girls (n ⫽ 40) and boys

(n ⫽ 40) assigned to the intervention but

slightly (although not statistically significant)

more boys (n ⫽ 34) than girls (n ⫽ 27) in the

control group. Classroom size was not signif-

icantly different between the intervention

(M ⫽ 13.33, SD ⫽ 4.68) and control

(M ⫽ 10.17, SD ⫽ 2.23) groups, but the effect

size was large, t(10) ⫽ 1.50, p ⫽ .17,

d ⫽ 0.86. There were no group differences in

demographic information such as ethnicity,

highest parent occupation level (used as a

proxy for socioeconomic status and based on

the index of Hollingshead, 1975), and gender.

Even though there was randomization at the

level of the classroom, there was a significant

difference between the intervention and con-

trol groups regarding age such that children in

the intervention group (M ⫽ 43.47 months,

SD ⫽ 6.96) were significantly younger than

children in the control group (M ⫽ 47.99

months, SD ⫽ 6.97), t(116) ⫽ –2.30, p ⫽

.023, d ⫽ – 0.65. Over the course of the school

year, attrition within the study was low (eight

children [four girls] within intervention group

and two children [one girl] within control

group), with 92.7% of the sample continuing

their participation at Time 2. However, there

were some missing data resulting from teacher

packets that were not returned at the posttest

and were excluded from the study, which re-

sulted in a reduction in the intervention sample

by 16 children (10 girls). Ultimately, this re-

sulted in a final study sample of 56 children

(26 girls) in the intervention group and 59

children (26 girls) in the control group. Those

children who dropped out of the study did not

significantly differ on any key study variables.

General Aggression Subtypes

Relational and physical aggression was

measured using the Preschool Proactive and

Reactive Aggression (PPRA) scale (Ostrov &

Crick, 2007). The Preschool Proactive and

Reactive Aggression–Teacher Report (PPRA-

TR), originally based on the Forms and Func-

tions of Aggression Measure (Little, Jones,

Henrich, & Hawley, 2003), includes 14 items

used to assess aggressive behavior. Subscales

include three items to assess both forms and

functions (i.e., proactive physical aggression,

reactive physical aggression, proactive rela-

tional aggression, reactive relational aggres-

sion) of aggressive behavior in early child-

hood and two positively toned items. This

measure was completed by teachers as well as

by observers (i.e., PPRA–Observer Report;

see Ostrov, Murray-Close, Godleski, & Hart,

2013). Previous research has supported the use

and validity of observer reports of aggressive

behavior (e.g., Murray-Close & Ostrov, 2009;

Ostrov et al., 2013). A composite of both

teacher and observer reports was used to as-

sess general aggressive behavior for validity

purposes. Observers were given the same in-

structions as teachers when completing all of

the observer report forms. Because it was im-

possible to conceal the group status (i.e., in-

tervention versus control) from the teachers

whereas observers were blind to intervention

status throughout the entire study, observer

report was used to better account for any bias

that teachers might have. Teachers were un-

aware of the study hypotheses, which pro-

vided more reassurance that a composite was

the best solution to incorporate teachers—the

typical informants when reporting on aggres-

sion in early childhood—and observers. Ob-

servers included nine female undergraduate

and three graduate students.

To inform observer reports, trained ob-

servers conducted a series of eight 10-min

observations using focal child sampling with

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

449

continuous recording procedures over a

2-month period to record physical and rela-

tional aggression, as well as physical and re-

lational victimization (see Ostrov & Keating,

2004). Observations were similar in length of

time and setting across the schools, with minor

variations in length based on the number of

participants in a given classroom. These struc-

tured observations were not used in the present

study and were only designed to familiarize

observers with the children and their behavior

prior to completion of the observer reports that

were adopted in the present article. On com-

pletion of all of the observations, one observer

from each classroom was randomly selected to

complete the reports for each participant.

Within the current study, each of the four

subscales was internally consistent at both

time points (Cronbach’s ␣s ⬎ 0.87) and the

correlation between teacher and observer re-

ports was moderate and significant at Time 1

(i.e., for relational aggression, r ⫽ 0.35, p ⬍

.001; for physical aggression, r ⫽ 0.52, p ⬍

.001). For ease of communication, only

Time 1 findings are presented for all validity

analyses; Time 2 findings are available on

request by contacting the first author.

Bullying Subtypes

Both teachers and observers also com-

pleted a newly revised rating of bullying that

expands on the PPRA scale (see above) orig-

inally developed by Ostrov and Crick (2007).

This adapted measure, the Preschool Bullying

Subscales Measure (PBSM; Ostrov & Kam-

per, 2012), uses the aforementioned CDC

definition to distinguish it from items measur-

ing aggressive behavior. Wording from the

PPRA-TR was modified to include repetition

and power imbalance [e.g., “to get what this

child wants, s/he repeatedly will take things

(e.g., toys) away from others with less power

(e.g., smaller, younger, or has fewer

friends)”]. The measure has 18 items evaluat-

ing the forms and functions of bullying on a

5-point Likert scale from 1 (never or almost

never)to5(always or almost always). Specif-

ically, the measure includes four subscales:

proactive physical bullying (four items; e.g.,

“this child repeatedly hits, kicks, or punches

others with less power to get what s/he

wants”); reactive physical bullying (four

items; e.g., “if other children make this child

mad, s/he will often physically hurt those with

less power”); proactive relational bullying

(four items; e.g., “this child repeatedly keeps

other with less power from being in her/his

group of friends to get what s/he wants”); and

reactive relational bullying (four items, e.g.,

“if other children hurt this child, s/he often

keeps those with less power from being in

his/her group of friends”). Two positively

toned filler items were also included. For the

current study, function (e.g., proactive and

reactive) was not analyzed separately and

physical and relational bullying composites

were made by summing those items from both

teacher and observer reports. Teacher (PBSM-

TR) and observer (PBSM-OR) reports were

significantly correlated at Time 1 for relational

bullying (r ⫽ 0.27, p ⫽ .002) and physical

bullying (r ⫽ 0.46, p ⬍ .001). These compos-

ites showed high reliability for physical bul-

lying at Time 1 (Cronbach’s ␣⫽0.94) and

Time 2 (Cronbach’s ␣⫽0.91) and for rela-

tional bullying at both time points (Cronbach’s

␣s ⫽ 0.93 and 0.91, respectively).

As part of the measurement revision for

assessing bullying subtypes, the PBSM was

evaluated by several aggression and bullying

experts at a national research conference. Ini-

tially, the content experts evaluated the mea-

sure for content validity and provided ample

feedback and ideas to improve the measure.

Feedback was integrated to address all aspects

of the definition of bullying. Pilot work re-

garding the measure has shown good reliabil-

ity (Cronbach’s ␣s ⬎ 0.80) and validity (e.g.,

significant associations between teacher and

observer ratings). In addition, the physical and

relational subscales of the PBSM were signif-

icantly correlated with the physical and rela-

tional subscales of the PPRA (rs ranged

from 0.54 to 0.67). These correlation coeffi-

cients show significant ( ps ⬍ .01) association

between aggression and bullying behavior but

highlight that the PBSM captures a subset of

aggressive behavior different than general

physical and relational aggression.

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

450

Peer Victimization

For each time point, both teachers and

observers completed a revised version (see

Godleski, Kamper, Ostrov, Hart, & Blakely-

McClure, 2015) of the Preschool Peer Victim-

ization Measure (PPVM)–Teacher Report

(Crick et al., 1999). The revised measure used

in the present study contained twelve items,

which included four items assessing relational

victimization (e.g., “This child gets left out of

the group when someone is mad at them or

wants to get back at them”) and four items

assessing physical victimization (e.g., “This

child gets pushed or shoved by peers”). There

were also four positively toned filler items. On

a 5-point scale from 1 (never to almost never

true)to5(always or almost always true), both

teachers and observers rated how frequently

the focal children experienced physical or re-

lational victimization. Past research has shown

acceptable reliability for this measure (God-

leski et al., 2015; Ostrov, 2010). Teacher and

observer report measures on the PPVM were

significantly and moderately correlated at

Time 1 for both subscales (e.g., physical vic-

timization at Time 1, r ⫽ 0.30, p ⬍ .001).

Each subscale was summed across both infor-

mants, and a composite of teacher and ob-

server reports was created. For the current

study, Cronbach’s ␣s were 0.83 for relational

victimization and 0.80 for physical victimiza-

tion at Time 1 and 0.82 for relational victim-

ization and 0.81 for physical victimization at

Time 2.

Program Implementation

To assess the fidelity and integrity of

program implementation, the interventionists

maintained weekly logs, which were reviewed

by the first and second authors and discussed

during weekly supervision meetings. Further-

more, during implementation, each of the in-

terventionists met together for small-group

weekly supervision with the first and second

authors to address any ethical or clinical con-

cerns, including any potential issues brought

up in the weekly interventionist logs, as well

as to practice upcoming lessons and activities

in the program manual. The first and second

authors each conducted observations of the

interventionists implementing the weekly les-

son using a randomly generated schedule.

These observations formally assessed the fi-

delity of the implementation by each interven-

tionist at least twice. A checklist was used to

verify completion of required program com-

ponents (e.g., the interventionist introduced

the puppet and conducted the puppet show, the

interventionist asked at least two comprehen-

sion questions). This checklist comprised the

content component of the fidelity assessment.

In addition, the first and second authors com-

pleted a series of ratings of the implementation

style used by the interventionist on the following

domains: interventionist warmth, communica-

tion style (pacing and modulation), developmen-

tal appropriateness, and child engagement and

interest. A 7-point rating scale from 1 (superior)

to7(inappropriate) comprised the process com-

ponent of this assessment.

Teacher Evaluations

At the conclusion of the intervention,

teachers were given evaluation forms. For

each question (e.g., “The children in my class-

room benefited from the program”), a 5-point

Likert rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree)

to5(strongly agree) was used. All head teach-

ers completed the evaluation form.

Interventionist Evaluations

At the conclusion of the intervention,

the interventionists completed an evaluation

of the intervention. The interventionists re-

sponded to several questions (e.g., “Teachers

were actively engaged in the program”) on a

5-point rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree)

to5(strongly agree).

Procedure

The study was approved by the univer-

sity’s social and behavioral sciences institu-

tional review board (IRB), and parents pro-

vided written consent prior to participation.

For children to participate in the study and to

receive the intervention, consent forms were

sent home for each student within all 12 class-

rooms and parents were required to complete

and return the written consent forms. Given

the nature of the classroom intervention, ef-

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

451

forts were made to recruit all children within

each classroom; however, a small number of

children (⬍10%) did not receive parental con-

sent. During the implementation of the inter-

vention, in accordance with local IRB stipula-

tions, these children would often engage in

another activity with a teacher rather than par-

ticipate in the intervention (described below).

Children’s head teachers also provided written

informed consent prior to completing reports.

Teacher reports were always distributed when

approximately half of the observations were

completed. Teachers were provided an hono-

rarium ($10 to $25 gift certificate depending

on class size) after completing packets at each

time point. Participants and school personnel

received newsletters summarizing the major

results of the project.

Observer Training

Observers were trained to recognize

physical and relational aggression and victim-

ization in early childhood (Ostrov & Keating,

2004). They went through training consisting

of in-depth readings, coding of videotaped ag-

gressive and nonaggressive interactions, dis-

cussion with the principal investigator, and

practice observations within the classroom

(see Crick et al., 2006). After completing six

standard observation sessions using video-

tapes (without pausing or rewinding) from

prior studies, as well as passing a multiple-

choice and matching examination testing un-

derstanding of the definitions of the constructs

and appropriate use of the observation codes

(with discussion regarding any errors or omis-

sions), observers spent a minimum of 2 days

within the classroom to decrease reactivity and

allow the participants to acclimate to the ob-

servers’ presence.

Intervention Details

The intervention comprised 8 weeks of

lessons and activities designed to address

physical and relational aggression, physical

and relational victimization, and prosocial be-

havior among 3 to 5 year olds. Each week

involved 4 intervention blocks: an interven-

tionist-led lesson facilitated by puppets, in

vivo practice through reinforcement during

free play, a passive participatory activity (e.g.,

craft), and an active participatory activity

(e.g., game). For the group lessons, develop-

mentally appropriate animal puppets were

used to aid discussion and learning about the

week’s topic (e.g., physical aggression, exclu-

sion, inclusion, friendship withdrawal, and

friendship loss; see Table 1), through either

puppet shows or positive role-playing, to help

children practice appropriate skills with the

puppets. The interventionist and puppets then

actively positively reinforced the targeted

skills during free play. Active and passive

activities were meant to solidify the week’s

lesson with the preschoolers while also facil-

itating teacher collaboration. The activities

were tailored to the teacher’s needs and class-

room structure and function, which allowed

for flexibility in implementation within differ-

ent classroom settings. That is, the core of the

program (i.e., puppet shows, reinforcement

periods) was identical across classrooms.

Slight variations were occasionally offered

(e.g., passive activities could be modified such

that students in one classroom could make

their own puppets and practice the weekly

lesson and participants in another room could

read a book created for the project that rein-

forced the lesson of the week). As mentioned

earlier, the intervention manual was updated

and revised from the pilot study (Ostrov et al.,

2009) to include additional lessons: a lesson

focusing on helping and sharing behavior as

well as a lesson on verbal aggression with an

emphasis on understanding the difference be-

tween tattling and reporting.

Interventionists were all PhD students in

child clinical psychology or early childhood

education with extensive knowledge of child

development. They were trained prior to im-

plementation through readings, in vivo train-

ing, demonstrations, and guided practice and

role-playing of skills. Training generally fo-

cused on knowledge of the lessons and man-

ual, use of the puppets as part of the lessons

and reinforcement periods, and use of devel-

opmentally appropriate labeled praise. Weekly

training sessions with the puppets were video-

taped for review and later discussion. Prein-

tervention and postintervention reports of

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

452

child behavior were assessed to document

change over the course of the intervention;

baseline (Time 1) data were collected 2 to 3

weeks before the intervention, and follow-up

(Time 2) was conducted 2 to 3 weeks after

implementation of the intervention concluded.

Teachers and interventionists completed eval-

uations of the program once all program and

formal assessments were finished. Control

classrooms operated as they typically would.

For ethical reasons, classrooms that were ini-

tially assigned to the control condition were

given the intervention a few months later, but

no outcome data were collected.

RESULTS

First, preliminary analyses (i.e., descrip-

tive statistics, stability, correlations between

study variables) were conducted. Less than

1% of subscale items were missing, and mean

imputation was used when 75% of the partici-

pant’s responses were available for a given scale.

Second, analyses of fidelity and acceptability, as

well as teacher engagement, were run. Third, the

key study models were run with a series of

analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs).

Preliminary Analyses

First, descriptive statistics were calcu-

lated; these are found in Table 2. Outliers (⬎3

SDs above the mean) were reduced to the

value of 3 SDs above the mean (Kline, 2011).

Skew was less than 3 (range ⫽ 0.31 to 2.30)

and kurtosis was less than 8 (range ⫽ –1.18

to 6.2), suggesting that nonnormality of the

data was not a concern (Kline, 2011) for all

variables.

Second, attrition analyses (a series of

independent-group t tests) did not indicate any

significant differences between children who

stayed in the study and those who left the

study (n ⫽ 10) on any of the key study vari-

ables, ts ⬍ 1.40, ps ⬎ 0.16. Third, correlations

between study variables were conducted; these

are presented in Table 2. They are separated

by intervention status to examine differential

associations at pretest (see Table 2), and

Fisher r-to-z tests were conducted comparing

the groups for all intercorrelations at pretest.

Only one of the six associations was signifi-

cantly different. That is, the intercorrelation

between physical and relational victimization

at pretest was significantly higher for the con-

trol group relative to the intervention group,

z ⫽ –2.46, p ⬍ .05. In general, the groups

displayed similar patterns of association for all

behaviors of interest at pretest.

Fourth, a series of independent-group t

tests was run to compare initial levels of the

four main dependent variables (i.e., physical

and relational bullying as well as physical and

relational victimization). Only one difference

emerged between the intervention and control

groups at pretest, and this was found for phys-

ical victimization, t(137) ⫽ –2.51, p ⫽ .013,

d ⫽ –0.43, suggesting that despite our ran-

domization procedures, the intervention group

(M ⫽ 11.83, SD ⫽ 3.67) started off lower on

the level of physical victimization than the

control group (M ⫽ 13.52, SD ⫽ 4.22). This

finding underscored the importance of control-

ling for initial levels of the outcome in all

subsequent models.

Fidelity and Acceptability

The content checklists indicated that the

interventionists covered all key program re-

quirements as dictated in the program manual

for each weekly lesson (i.e., 100% of material

covered in each session). The process ratings

indicated that the average rating was 1.44

(SD ⫽ 0.63), suggesting superior perfor-

mance. The interventionists were rated as be-

ing warm, being developmentally appropriate,

having good pacing and communication style,

providing praise to the children, and being

engaged in the task.

The evaluations from teachers were pos-

itive as the mean response was above 4.5 (on

a 5-point scale) on all items. The findings

suggest that the teachers believed the interven-

tionists were effective and the program was

beneficial, supporting the acceptability of the

program (see Table 3). Although there was

variability with the interventionist evaluations

suggesting some differences in teacher en-

gagement across the classrooms, the interven-

tionists indicated that, on average, the teachers

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

453

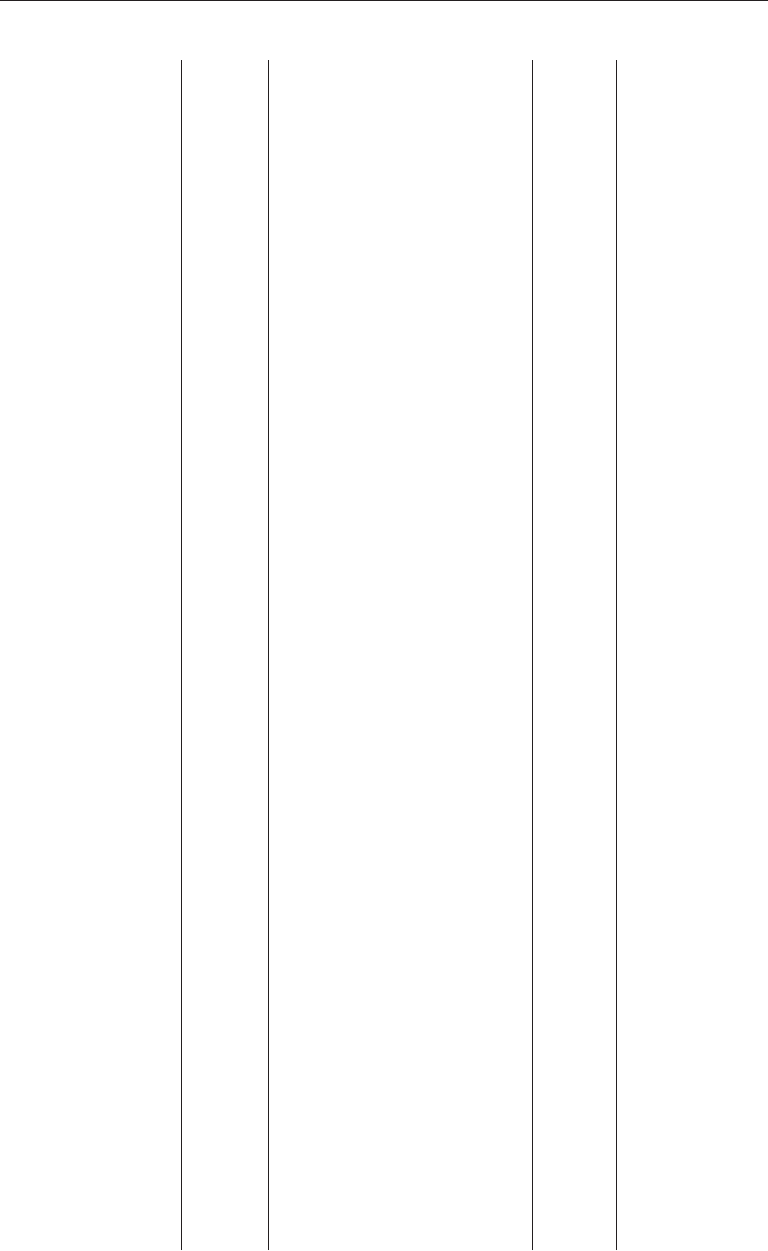

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Key Study Variables

Physical

Bullying

at T1

Physical

Bullying

at T2

Relational

Bullying

at T1

Relational

Bullying

at T2

PVICT

at T1

PVICT

at T2

RVICT

at T1

RVICT

at T2 MSD Range

Physical bullying at T1 — .51*** .44*** .14 .54*** .36** .57*** .34** 23.21 10.69 16.00–66.00

Physical bullying at T2 .75*** — .42** .68*** .12 .43*** .28* .53*** 21.80 7.80 16.00–52.00

Relational bullying at T1 .70*** .57*** — .59*** .24* .13 .68*** .48*** 26.41 10.06 16.00–48.00

Relational bullying at T2 .46*** .65*** .62*** — ⫺.09 .32* .35** .61*** 24.17 9.58 16.00–49.00

PVICT at T1 .48** .47** .35** .18 — .44*** .41*** .12 11.83 3.67 8.00–22.00

PVICT at T2 .18 .48*** .09 .29* .52*** — .25 .65*** 12.29 3.22 8.00–18.00

RVICT at T1 .46*** .45*** .64*** .35** .71*** .22 — .56*** 15.22 5.42 8.00–29.00

RVICT at T2 .23 .48*** .26* .56*** .09 .64*** .16 — 15.58 5.74 8.00–30.00

M 22.86 23.74 25.44 28.58 13.52 13.84 14.84 17.25

SD 10.16 8.53 9.72 9.62 4.22 4.34 4.31 5.14

Range 16.00–59.00 16.00–55.00 16.00–63.00 16.00–55.00 8.00–24.00 8.00–26.00 8.00–26.00 8.00–31.00

Note. All variables represent composites of observer and teacher reports. Above the diagonal is the intervention group, and below the diagonal is the control group. PVICT ⫽ physical

victimization; RVICT ⫽ relational victimization; T1 ⫽ Time 1 (pretest); T2 ⫽ Time 2 (posttest).

*p ⬍ .05, **p ⬍ .01, ***p ⬍ .001.

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

454

were engaged and supportive of the program

and that the children seemed engaged with the

content and, in the interventionists’ view, ben-

efited from the program (see Table 3).

Key Study Models

A series of 2 (Intervention status) ⫻ 2

(Gender) ANCOVA models with baseline lev-

els of the outcome variable serving as the

covariate was conducted. In addition, each

model controlled for baseline levels of the

alternative subtype of bullying or victimiza-

tion. The dependent variable was the posttest

assessment. Four main models were exam-

ined, and three follow-up models were run for

comparison purposes with the prior trial. For

ease of interpretation and comparison with

prior studies, Time 2 estimated marginal

means are provided and Cohen’s d statistics

are reported as a measure of the magnitude of

the effect (see Table 4). Cohen’s (1988) effect

size recommendations define d ⫽ 0.2 as small,

d ⫽ 0.5 as medium, and d ⫽ 0.8 as large

effects. Given the variability in class size

(M ⫽ 11.75, SD ⫽ 3.86, range ⫽ 7 to 18) and

the aforementioned significant difference be-

tween the intervention and control groups with

respect to age of the participants, we ran all

models controlling for age and class size and

the overall pattern of effects was similar; thus,

for ease of communication and parsimony, the

models without these covariates are shown.

In the first model, physical bullying at

posttest was the dependent variable. A nonsig-

nificant main effect for intervention status was

revealed, F(1, 101) ⫽ 1.78, p ⫽ .185,

p

2

⫽ 0.017. The effect size suggests a small

effect. The intervention group did not show

lower levels of posttest physical bullying com-

pared with the control group, controlling for

initial levels of bullying behavior.

In the second model, relational bullying at

posttest was the dependent variable. A signifi-

cant main effect for intervention status emerged,

F(1, 100) ⫽ 7.03, p ⫽ .009,

p

2

⫽ 0.07 (see

Table 4). The effect size suggests a medium

effect. The children in the intervention group

had significantly lower levels of relational bul-

lying at posttest compared with the control

group, controlling for initial levels of bullying

behavior. An inspection of the means (see

Table 2) indicates that those in the interven-

tion group decreased in their rates of relational

bullying compared with the control group,

which increased in their rates of relational

bullying.

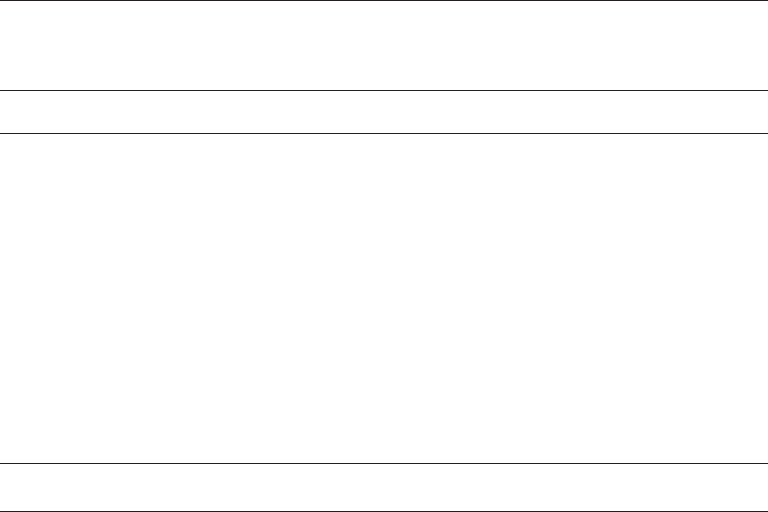

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for Teacher and Interventionist Evaluations

MSD

Teacher evaluations

The program was entertaining for the children. 5.00 0.00

The interventionist was knowledgeable and skilled in handling program topics

and content. 4.83 0.41

The program was developmentally appropriate for my classroom. 5.00 0.00

The children in my classroom benefited from the program. 4.67 0.52

I would recommend this program to other teachers in my school. 4.83 0.41

Interventionist evaluations

Teachers were supportive of the program and provided classroom management

when needed. 3.83 0.75

Teachers were actively engaged in the program. 3.50 0.84

Children in the classroom benefited from the program. 4.17 0.75

Children actively attended and participated in weekly intervention tasks. 4.33 0.82

Children in the classroom were engaged with the program components. 4.33 0.52

Note. Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree)to5(strongly agree).

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

455

The third model tested for intervention

effects with physical victimization at posttest

as the dependent variable, and a significant

two-way interaction between intervention sta-

tus and gender emerged, F(1, 105) ⫽ 4.37,

p ⫽ .039,

p

2

⫽ 0.04. Follow-up tests showed

a significant simple effect of intervention status

for girls, F(1, 47) ⫽ 6.96, p ⫽ .011,

p

2

⫽ 0.13,

but no effect for boys, F(1, 57) ⫽ 0.18, p ⫽ .67,

p

2

⫽ 0.003. The effect size indicates a medium

effect. An examination of the means (see Table

4) shows that girls in the intervention group

showed a significantly lower level of physical

victimization relative to girls in the control

group, controlling for initial levels. Moreover, an

inspection of the pretest and posttest means for

girls (see Table 4 for posttest) indicates that

those in the intervention group (M

pretest

⫽ 11.46,

SD

pretest

⫽ 3.48) decreased in their rates of phys

-

ical victimization whereas those in the control

group (M

pretest

⫽ 12.35, SD

pretest

⫽ 3.79) in

-

creased in their rates of physical victimization.

The fourth model tested for intervention

effects with relational victimization at posttest

as the dependent variable. A significant main

effect for intervention status emerged, F(1,

107) ⫽ 3.94, p ⫽ .050,

p

2

⫽ 0.035, but this

effect was qualified by a significant two-way

interaction between intervention status and gen-

der, F(1, 107) ⫽ 4.55, p ⫽ .035,

p

2

⫽ 0.041.

Follow-up tests indicated a significant simple

effect of intervention status for girls, F(1,

48) ⫽ 6.25, p ⫽ .016,

p

2

⫽ 0.12, but no effect

for boys, F(1, 57) ⫽ 0.02, p ⫽ .880,

p

2

⬍ 0.001. The effect size indicates a me

-

dium effect for girls. An inspection of the

means (see Table 4) shows that girls in the

intervention group had significantly lower lev-

els of relational victimization at posttest than

girls in the control group, controlling for initial

levels of victimization. Moreover, an inspection

of the pretest and posttest means for girls (see

Table 4 for posttest) indicates that those in

the intervention group (M

pretest

⫽ 15.03,

SD

pretest

⫽ 5.10) decreased in their rates of re

-

lational victimization whereas those in the con-

trol group (M

pretest

⫽ 14.26, SD

pretest

⫽ 3.98)

increased in their rates of relational

victimization.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to

replicate and extend the initial ECFP program.

As previous research had identified, there was

a need to examine the efficacy of the program

at an individual level (Leff, Waasdorp, &

Crick, 2010) because the initial results were

reported with only the classroom as the unit of

analysis (Ostrov et al., 2009). The present

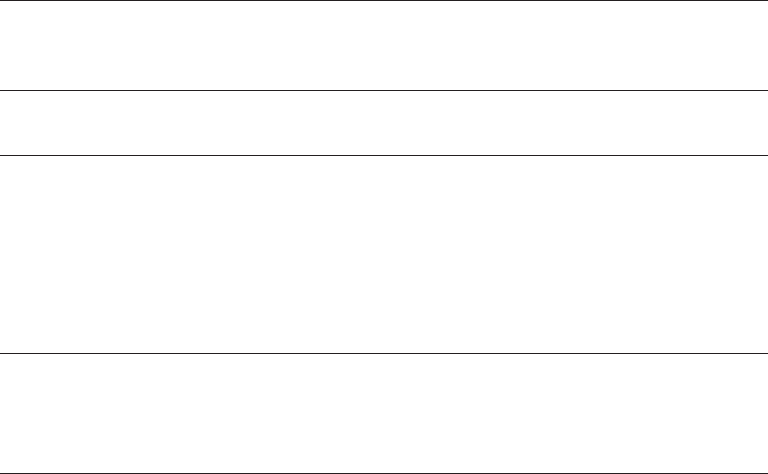

Table 4. Summary of Intervention Effects and Effect Sizes

Model (Dependent Variable) Key Finding M

INT

(SD)

M

CON

(SD)

Effect Size

(Cohen’s d)

Physical bullying at T2 Main effect for intervention status 21.83 (6.26) 23.48 (6.39) ⫺0.26

Relational bullying at T2 Main effect for intervention status 24.41 (7.86) 28.45 (7.86) ⫺0.51

Physical victimization

at T2

Gender ⫻ Intervention status

Simple effect for girls 11.21 (2.91) 13.35 (2.89) ⫺0.74

No effect for boys 14.01 (3.76) 13.60 (3.73) 0.11

Relational victimization

at T2

Gender ⫻ Intervention status

Simple effect for girls 14.33 (5.72) 18.29 (5.70) ⫺0.69

No effect for boys 16.74 (4.50) 16.56 (4.48) 0.04

Note. All dependent variables represent composites of observer and teacher reports. All models controlled for pretest

(baseline) levels of the outcome variable, and estimated marginal means at Time 2 are presented. Standard deviations

and Cohen’s d values were calculated for ease of communication and for comparison purposes with the initial Early

Childhood Friendship Project trial. The full analysis of covariance findings are reported within the text. CON ⫽ control

group; INT ⫽ intervention group; T2 ⫽ posttest.

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

456

study examined the efficacy of an expanded

version of the ECFP, an 8-week randomized

trial (expanded from the original 6-week trial)

to address physical and relational bullying, as

well as physical and relational victimization,

among 3 to 5 year olds.

First, the present RCT showed appropri-

ate levels of fidelity and acceptability. Second,

in support of our hypotheses, the program was

found to be effective at significantly lowering

relational bullying in the children receiving

the intervention relative to the control group.

These findings were robust to age differences

between the intervention and control groups at

Time 1 because controlling for age did not

change the pattern of effects. Moreover, these

reductions were considered medium effects.

Nonsignificant reductions were documented

for physical bullying among the intervention

group participants relative to the control group

participants, who appeared to increase in their

rates of physical bullying. This pattern of ef-

fects was in the predicted direction, but the

effect size suggested only a small effect.

Third, for both physical and relational victim-

ization, there was a significant interaction of

gender and intervention status. Significant dif-

ferences were found in relation to physical and

relational victimization levels in the interven-

tion and control classrooms only for girls, but

not for boys. That is, for girls in the interven-

tion classrooms, there were significantly lower

levels of receiving physical aggression and

receiving relational aggression compared with

girls in the control classrooms. It is important

to note that the intervention group also had

significantly lower levels of physical victim-

ization at baseline, or Time 1; however, the

findings were based on changes in physical

victimization given initial levels. Thus, despite

this initial difference, the level of change was

significantly different between the groups over

the course of the intervention. Specifically,

girls in the intervention group had signifi-

cantly lower levels of physical victimization

and showed decreases in their physical victim-

ization levels over time compared with girls in

the control group, whose physical victimiza-

tion levels increased. It is not entirely clear

why the program decreased peer victimization

only for girls and not for boys. Past programs

with older children have shown similar find-

ings regarding boys. A study of the Preventing

Relational Aggression in Schools Everyday

(PRAISE; Leff et al., 2010) program, a 20-

session classroom-based universal prevention

program for use within urban school contexts,

also found that the program was not as effec-

tive for boys relative to girls. Leff et al. (2010)

reported that boys found the materials and

concepts to be engaging, but the authors ar-

gued that additional generalization strategies

and supports, especially for high-risk boys,

may be needed for the boys to benefit from the

school-based program. In addition, they pos-

ited that for programs such as PRAISE to be

more effective for boys, it may need to be

focused on problem-solving strategies within

the context of competitive sport activities

(Leff et al., 2010). It is conceivable that sim-

ilar approaches would be helpful and should

be considered when implementing future pro-

grams for young boys.

In contrast to the original investigation

of the ECFP, the effect sizes were generally

lower in our study. That is, the initial trial

showed that intervention classrooms had large

reductions in relational aggression relative to

control classrooms, whereas the present trial

showed significant but medium effects for re-

lational bullying. Intervention rooms also

showed moderate reductions in physical ag-

gression relative to randomly assigned control

classrooms in the initial study, whereas the

present trial yielded small and nonsignificant

effects for physical bullying. It is notable that

we saw reductions in bullying behavior in the

current trial, which may be more difficult to

change given the lower base rate of bullying

experiences relative to general aggressive be-

havior. The initial trial showed large reduc-

tions in physical victimization for intervention

classrooms relative to control classrooms,

whereas the current study showed moderate

effects only for girls. Only small decreases

were documented for relational victimization

in the initial trial (Ostrov et al., 2009), and

moderate effects were found in the present

RCT but only for girls. In general, it is hard to

compare the two RCTs because measuring at

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

457

the individual child level instead of the class-

room level, as well as accounting for more

fine-grained analyses of peer behavior (i.e.,

including bullying as well as victimization),

may account for the slightly different effect

sizes in the current RCT. The focus of our

intervention was more so on relational aggres-

sion (i.e., 2 weeks are dedicated to the topic)

relative to physical aggression (i.e., only 1

week explicitly addresses physical aggression;

see Table 1). Future trials should expand the

coverage of physical aggression, and perhaps

with a greater dosage, the magnitude of the

effects will improve. However, despite the

small to medium effects in the current trial, we

assert that the findings have clinical signifi-

cance. It is notable that we saw significant

reductions in relational bullying, which is per-

haps a more insidious form of aggression

relative to general relationally aggressive be-

havior. Moreover, for relational bullying, the

documented average drop for children in the

intervention classrooms coupled with an aver-

age increase for children in the control class-

rooms suggests that the program leads to

meaningful changes. Bullying behavior has

serious legal and clinical implications for chil-

dren and families (see Lovegrove, Bellmore,

Green, Jens, & Ostrov, 2013), and this sup-

pression or reduction in the behavior has the

potential to help children avoid most bullying

behavior.

The present study makes several impor-

tant contributions to the developmental,

school psychology, and clinical science liter-

ature. First, this study is a replication and

extension of the first preliminary ECFP study.

The current trial of the ECFP showed efficacy

in reducing negative peer behaviors at the

level of the child. This extends on the past

research that found positive effects at the

classroom level (Ostrov et al., 2009). It is

important to note that the present study is also

the first known study to investigate both rela-

tional and physical forms of bullying with an

early childhood sample. Furthermore, the

study measure developed for the assessment of

multiple forms of bullying during the early

childhood period conforms to the current CDC

definition of bullying (Gladden et al., 2014)

instead of assessing general aggression or vic-

timization. The introduction of the PBSM was

another contribution of the present study. The

PBSM was determined to be valid (i.e., based

on significant moderate associations across in-

formants) and internally consistent but also

showed sensitivity to change over the course

of the intervention. The PBSM is based on

existing early childhood aggression methods

with strong psychometric properties (e.g., Os-

trov & Crick, 2007), and with parallel teacher

and observer report options, it should be use-

ful to school-based scholars and practitioners.

In particular, the ECFP program facilitated a

reduction in relational bullying in intervention

classrooms whereas control classrooms exhib-

ited an increase in relational bullying. Given

the differing implications for and definitions

of general aggression versus bullying,itis

important to consider forms of both types of

peer behavior. This is especially the case be-

cause children who are bullied may be at par-

ticularly greater risk of negative outcomes

than children who experience aggression with-

out chronicity or the power imbalance and, as

such, these children may warrant an increased

urgency to intervene (Hunter, Boyle, & War-

den, 2007; Solberg & Olweus, 2003).

Limitations

Although the current study addressed a

number of weaknesses articulated in prelimi-

nary work conducted using the ECFP (Ostrov

et al., 2009), including conducting analyses at

the level of the child, there are still several

limitations that should be focused on in future

work. First, although naturalistic observations

would be the best measure of our outcome

variables, because our observers were un-

aware of classroom condition and were well

trained in observing aggression and victimiza-

tion, our secondary analysis designed to ex-

plicitly code for bullying behaviors resulted in

a relatively small number of behaviors and

could not be used in the present study because

of restricted range concerns, as well as reli-

ability problems. In the future, if a new system

is developed that explicitly trains observers to

recognize power differentials and repetition,

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

458

some of the concerns might be avoided. A

number of significant obstacles (and threats to

validity and reliability) are present in this

work, including a decision regarding how to

properly operationalize and document repeti-

tion (i.e., Should repetition occur only within

the 10-min observational sampling session, or

might it be based on prior knowledge or ob-

servation of repetition?).

It is important to note that the current

intervention is only a short, 8-week interven-

tion conducted by study staff in the classroom.

As previously mentioned, the staff conducting

the intervention were trained in the procedures

and reinforcement strategies thought to be

most effective in the intervention. Teachers

did not receive any additional training regard-

ing the lessons or reinforcement strategies im-

plemented by the staff throughout the week.

This decreased the likelihood that teachers

were engaging in reinforcement and interven-

tion strategies aimed at reducing bullying and

victimization within these classrooms. Future

work should consider including seminars to

help teachers engage in similar reinforcement

strategies when program staff are not in the

classroom. This would likely help increase

teacher engagement in the program as well as

help yield general reductions in levels of bul-

lying, aggression, and victimization over the

course of the intervention. In turn, teachers

might feel more connected to the program as

well as change the overall classroom climate

to encourage friendship formation and be

more vigilant concerning problem behaviors.

For the ECFP to be disseminated on a larger

scale, teachers need to be involved throughout

the intervention.

Similarly, there was no emphasis on be-

havior change outside of the classroom. Given

that many empirically supported behavioral

treatments in early childhood often focus on

parent training or training within the home,

incorporation of these treatment packages may

increase behavior change. In line with these

articulations, interventions with a focus on

changing social behaviors are often examined

among peers. Interventions incorporating peer

relations outside of the classroom environment

might help children generalize these outcomes

and help influence behavior more globally.

In terms of methodology, there are a few

considerations that need to be raised. First, we

did lose 10% (eight individuals) of the sample

within the intervention group because of attri-

tion and an additional 16 children because of

missing teacher packets from one intervention

classroom. We also had fewer than 60 partic-

ipating children in the control group. This

reduced sample size does increase concern

that our study was underpowered for the anal-

yses conducted. This could help to explain the

limited findings concerning physical bullying

and victimization for boys. Increased sample

sizes in the future would likely help account

for this limitation. Second, the overall effect

sizes were small to medium and were smaller

than those in the initial ECFP trial. We attri-

bute these small effect sizes to our use of the

child as our unit of analysis, something not

done in the prior trial with the ECFP. It is

important to acknowledge that this community

sample from high-quality early childhood pro-

grams is not likely to be engaging in high

levels of aggressive or bullying behavior,

making large effect sizes harder to establish.

This study might have shown different out-

comes if examined in a more at-risk popula-

tion in which aggression and bullying are

more prevalent. Classroom size may also be

an important factor to consider when imple-

menting intervention strategies. On average,

the sizes of the classrooms were not signifi-

cantly different from one another, but the

magnitude of the effect size suggested a mean-

ingful difference. Intervention rooms tended

to have a larger number of children in them.

The larger class size may have facilitated

greater peer interactions and the potential for

more friendship dyads emerging over the

course of the trial, which might have facili-

tated the intervention effects, but these spec-

ulations cannot be formally tested in the

current study. Lastly, it is important to ac-

knowledge that the participants in the current

study were nested within classrooms. Because

the data are hierarchically structured, it may

be beneficial to examine these results using

multilevel modeling in future work with a

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

459

larger sample to more fully understand what

components of the classroom are most influ-

ential for behavior change within the

intervention.

Future Directions

The present study introduces a number

of questions and aims to be addressed in future

studies. Even though the observers spent

months engaged in formal and informal obser-

vation and the use of observer reports has been

successful in prior studies (e.g., Murray-Close

& Ostrov, 2009), future attempts should be

made to design a new naturalistic observa-

tional system that reliably captures bullying

behavior. That is, the use of systematic obser-

vations would provide a relatively unbiased

assessment of bullying behaviors. Second,

greater attention is needed on identifying other

individual differences that may moderate the

intervention effects. For example, are the chil-

dren who are the most aggressive benefiting

from the program in the same way that the

children who are victimized may benefit? It is

also conceivable that older children (4 and 5

year olds) may have benefited more from the

program than younger preschoolers (3 year

olds), who might have had a more difficult

time remembering the weekly social skill

steps. Our study was not powered for testing

these developmental differences, and future

work should examine these questions. In ad-

dition, given that the focus of the program is to

change the reinforcement contingencies in the

peer group and classroom, the program may

benefit children who primarily engage in pro-

active or goal-oriented aggression or bullying,

but without an explicit program emphasis on

emotion regulation, we may not be targeting

reactive functions of aggression (see Ostrov et

al., 2013) in the same way that other programs

might (e.g., Coping Power, Lochman & Wells,

2004; Friend2Friend, Leff et al., 2009). Third,

although the initial version of the program was

replicated by an independent research group at

the University of Nebraska at Omaha (Moody,

Casas, & Kelly-Vance, 2012), further replica-

tion of the intervention effects by an indepen-

dent research laboratory is needed to support

the program as an evidence-based interven-

tion. Fourth, future work is needed to add a

teacher training component that might en-

hance the amount of behavioral reinforcement

that occurs beyond that conducted by program

staff. These efforts might also help to enhance

teacher engagement, which is a possible mod-

erator not explicitly tested in the present study

but should be the focus of future research.

Fifth, a parent training and home component

might also enhance the efficacy of the program

and should be examined in the future. Finally,

the program only lasted 8 weeks, and teachers

indicated that a greater dosage and an ex-

panded program that further emphasized prac-

tice and repetition of the core social skills

would have helped those children most in need

of the program.

Implications for Educators and

Clinicians

Young children benefit from consis-

tency, and the messages being conveyed re-

garding bullying behaviors are not always

consistent across contexts. The present pro-

gram offers teachers a possibility—a curricu-

lum that they could be trained to use and

implement in their own classrooms to help

their students understand the social world

around them, as well as how each of them

plays a role in the classroom community as

they build it together. The program could be

easily taught to teachers through training and

teaching of the dynamics of the program, as

well as the potential benefits, as illustrated by

this study. Having teachers implement the pro-

gram consistently and efficiently in their own

classrooms could potentially be more effective

than having outside staff do so because these

teachers are with their students on a daily

basis. Teachers spend significantly more time

with their students than the interventionists

were able to, allowing these teachers the op-

portunity to teach, observe, reinforce, and as-

sess the content of the program on a more

comprehensive level. The potential benefit of

sending a consistent, uniform message to chil-

dren through their teachers regarding friend-

ship and social behaviors related to changes in

School Psychology Review, 2015, Volume 44, No. 4

460

bullying and victimization is an empirical

question that has yet to be explored within this

project. However, as we look to the future,

the impact of incorporating school-wide

teacher training programs will be important

to explore.

The present study also has implications

for clinicians, especially school-based practi-

tioners. School psychologists and school-em-

ployed mental health professionals may be

able to help to shape educators’ and parents’

beliefs and attitudes about the importance of

addressing multiple forms of aggression and

bullying (Espelage & Swearer, 2003). Further-

more, clinicians can implement or support the

implementation of the ECFP in preschool

classrooms to help reduce negative social

behaviors, such as bullying and aggression,

and potentially prevent future social– em-

otional maladjustment for both aggressors

and victims.

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, the current study showed signif-

icant decreases in bullying behavior and vic-

timization for children participating in the

ECFP. This project extends previous work

(Ostrov et al., 2009) examining a similar in-

tervention by examining changes at the indi-

vidual level rather than using general class-

room-wide analyses. The findings also support

the psychometric properties of the PBSM in-

strument. Overall, these results support the use

of early intervention in community classrooms

to reduce aggression and bullying behavior

and help children learn to cultivate friendships

at an early stage in development. The ECFP

gives young children the opportunity to ask

questions in a safe environment, in motivating,

developmentally appropriate ways, through

the use of puppets, stories, and play. Future

randomized studies are needed to provide ad-

ditional empirically supported evidence of the

efficacy of the ECFP and the proliferation of

the intervention as a tool for teachers to help

foster social development in early childhood.

REFERENCES

Arseneault, L., Walsh, E., Trzesniewski, K., Newcombe, R.,

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2006). Bullying victimization

uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young

children: A nationally representative cohort study. Pedi-

atrics, 118, 130 –138. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2388

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Lindstrom Johnson,

S. (2015). Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and

electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: Influence

of school context. Journal of Clinical Child and

Adolescent Psychology, 44, 494 –508. doi:10.1080/

15374416.2014.893516

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behav-

ioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Academic

Press.

Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Mosher, M. (1997). Rela-

tional and overt aggression in preschool. Developmen-

tal Psychology, 33, 579 –587.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggres-

sion, gender, and social-psychological adjustment.

Child Development, 66, 710 –722.

Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., Burr, J. E., Cullerton-Sen, C.,

Jansen-Yeh, E., & Ralston, P. (2006). A longitudinal

study of relational and physical aggression in pre-

school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychol-

ogy, 27, 254 –268. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.006

Dodge, K. A., Coie, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2006). Aggres-

sion and anti-social behavior in youth. In W. Damon

(Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of

child psychology: Volume 3. Social, emotional, and

personality development (6th ed., pp. 719 –788). New

York, NY: Wiley.

Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Polanin, J. R., & Brown, E. C.

(2013). The impact of a middle school program to

reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence.

Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 180 –186. doi:

10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.021

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on

school bullying and victimization: What have we

learned and where do we go from here? School Psy-

chology Review, 32(3), 365–383.

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E.,

& Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance

among youths: Uniform definitions for public health

and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta,

GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Con-

trol, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and

U.S. Department of Education.

Godleski, S. A., Kamper, K. E., Ostrov, J. M., Hart, E. J.,

& Blakely-McClure, S. J. (2015). Peer victimization

and peer rejection during early childhood. Journal of

Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 380 –

392. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.940622

Harrist, A. W., & Bradley, K. D. (2003). “You can’t say

you can’t play”: Intervening in the process of social

exclusion in the kindergarten classroom. Early Child-

hood Research Quarterly, 18, 185–205.

Hollingshead, A. A. (1975). Four-factor index of social

status. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University, New

Haven, CT.

Hunter, S., Boyle, J., & Warden, D. (2007). Perceptions

and correlates of peer-victimization and bullying. Brit-

ish Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 797– 810.

doi:10.1348/000709906X17046

Kamper, K. E., & Ostrov, J. M. (2014). Relational bully-

ing and deception in early childhood. Poster presented

at the Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse Prevention’s

2014 Annual Conference, Buffalo, NY.

Early Childhood Friendship Project on Bullying

461

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural

equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Leadbeater, B., & Hoglund, W. (2006). Changing the

social context of peer victimization. Journal of the

Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychia-

try, 15, 21–26.

Leadbeater, B., Hoglund, W., & Woods, T. (2003).

Changing contents? The effects of a primary preven-

tion program on classroom levels of peer relational and

physical victimization. Journal of Community Psychol-

ogy, 31, 397– 418.

Leff, S. S., Goldstein, A. B., Angelucci, J., Cardaciotto,

L., & Grossman, M. (2007). Using a participatory

action research model to create a school-based inter-

vention program for relationally aggressive girls: The

friend to friend program. In J. E. Zins, M. J. Elias, &

C. A. Maher (Eds.), Bullying, victimization, and peer

harassment: A handbook of prevention and interven-

tion (p. 199 –218). New York, NY: Haworth Press.