a

GAO

United States Government Accountability Office

Report to Congressional Committees

January 2006

INTERNET ACCESS

TAX MORATORIUM

Revenue Impacts Will

Vary by State

GAO-06-273

What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

Januar

y

2006

INTERNET ACCESS TAX MORATORIUM

Revenue Impacts Will Vary by State

Highlights of

GAO-06-273, a report to

congressional committees

According to one report, at the end

of 2004, some 70 million U.S. adults

logged on to access the Internet

during a typical day. As public use

of the Internet grew from the mid-

1990s onward, Internet access

became a potential target for state

and local taxation.

In 1998, Congress imposed a

moratorium temporarily preventing

state and local governments from

imposing new taxes on Internet

access. Existing state and local

taxes were grandfathered. In

amending the moratorium in 2004,

Congress required GAO to study its

impact on state and local

government revenues. This

report’s objectives are to determine

the scope of the moratorium and its

impact, if any, on state and local

revenues.

For this report, GAO reviewed the

moratorium’s language, its

legislative history, and associated

legal issues; examined studies of

revenue impact; interviewed people

knowledgeable about access

services; and collected information

about eight case study states not

intended to be representative of

other states. GAO chose the states

considering such factors as

whether they had taxes

grandfathered for different forms

of access services and covered

different urban and rural parts of

the country.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is not making any

recommendations in this report.

The Internet tax moratorium bars taxes on Internet access services provided

to end users. GAO’s interpretation of the law is that the bar on taxes

includes whatever an access provider reasonably bundles to consumers,

including e-mail and digital subscriber line (DSL) services. The moratorium

does not bar taxes on acquired services, such as high-speed communications

capacity over fiber, acquired by Internet service providers (ISP) and used to

deliver Internet access. However, some states and providers have construed

the moratorium as barring taxation of acquired services. Some officials told

us their states would stop collecting such taxes as early as November 1,

2005, the date they assumed that taxes on acquired services would lose their

grandfathered protection. According to GAO’s reading of the law, these

taxes are not barred since a tax on acquired services is not a tax on Internet

access. In comments, telecommunications industry officials continued to

view acquired services as subject to the moratorium and exempt from

taxation. As noted above, GAO disagrees. In addition, Federation of Tax

Administrators officials expressed concern that some might have a broader

view of what could be included in Internet access bundles. However, GAO’s

view is that what is included must be reasonably related to providing

Internet access.

The revenue impact of eliminating grandfathering in states studied by the

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) would be small, but the moratorium’s

total revenue impact has been unclear and any future impact would vary by

state. In 2003, when CBO reported how much states and localities would

lose annually by 2007 if certain grandfathered taxes were eliminated, its

estimate for states with grandfathered taxes in 1998 was about 0.1 percent of

those states’ 2004 tax revenues. Because it is hard to know what states

would have done to tax access services if no moratorium had existed, the

total revenue implications of the moratorium are unclear. In general, any

future moratorium-related impact will differ by state. Tax law details and

tax rates varied among states. For instance, North Dakota taxed access

service delivered to retail consumers, and Kansas taxed communications

services acquired by ISPs to support their customers.

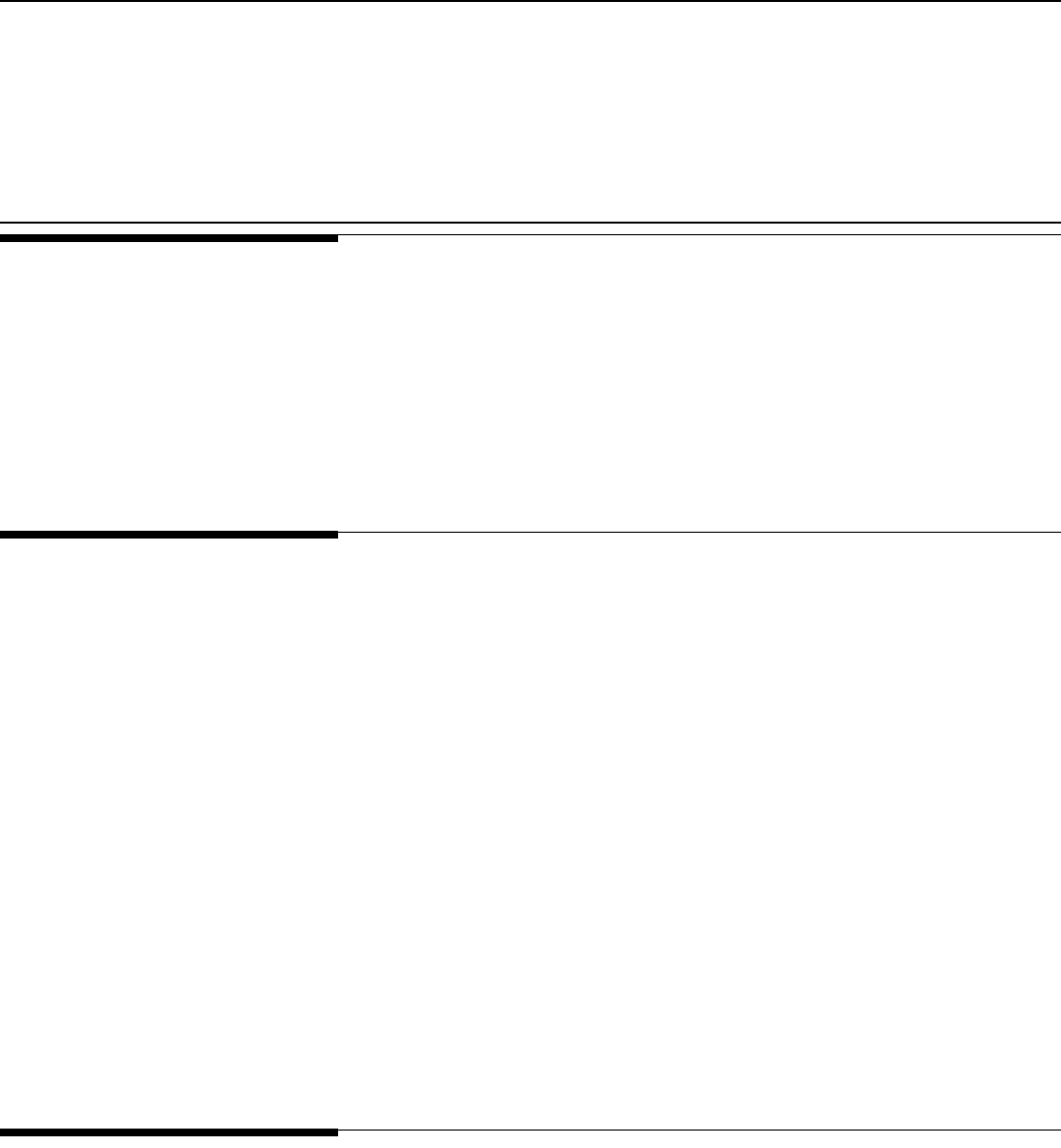

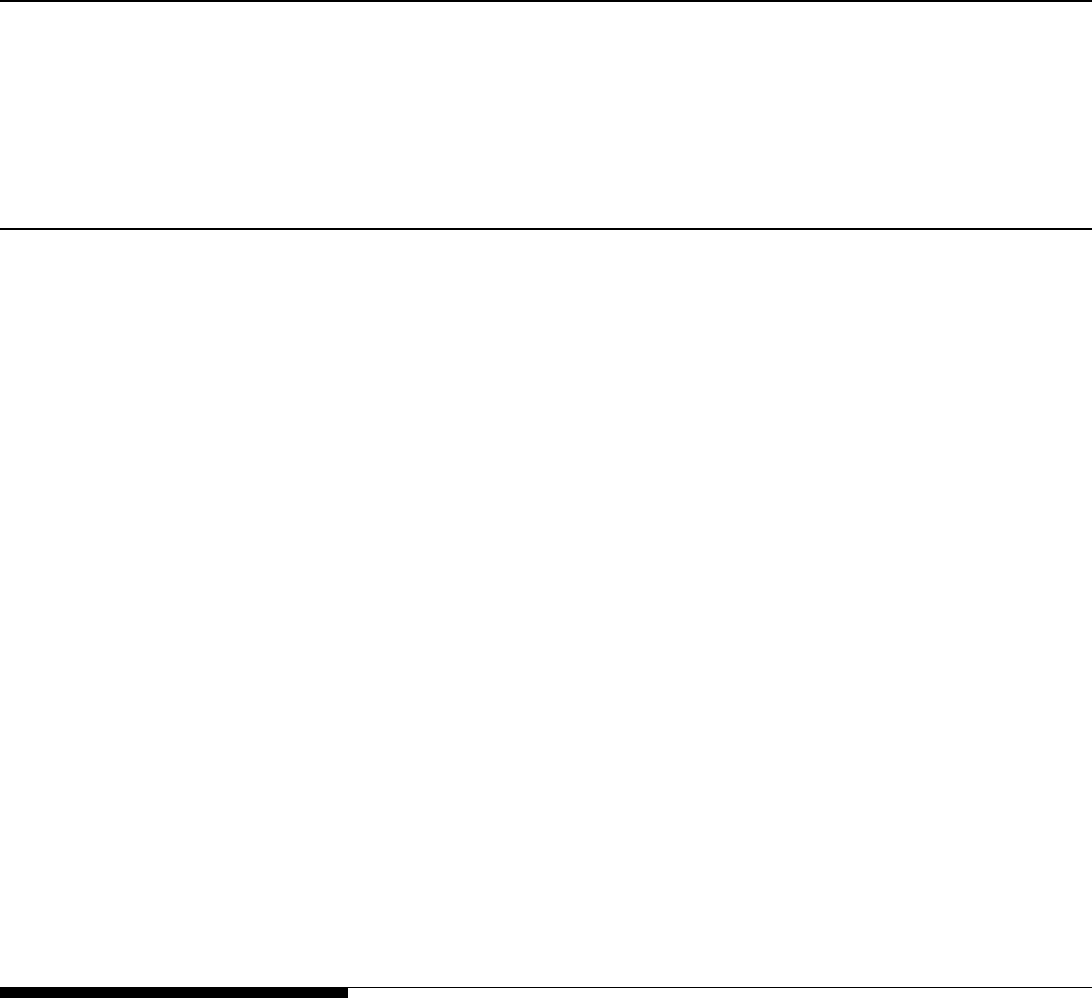

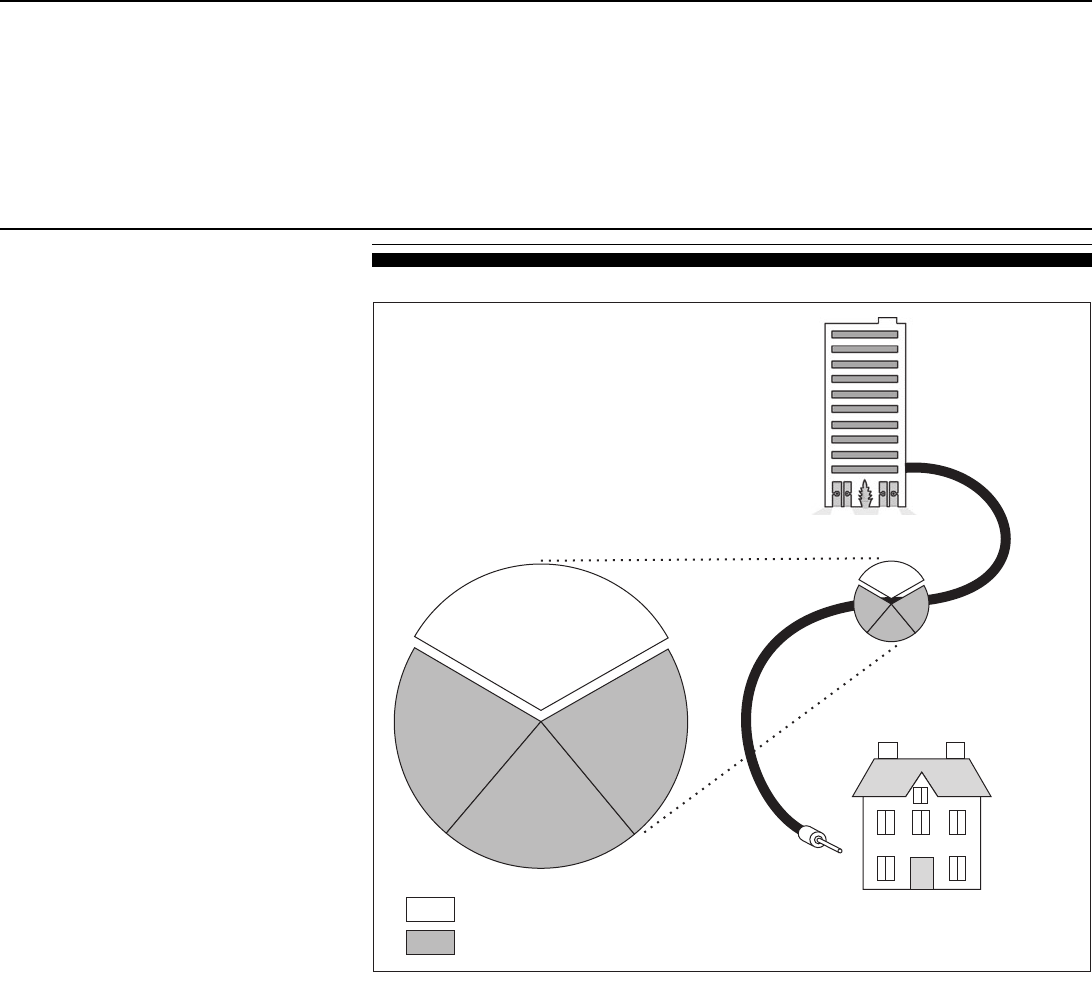

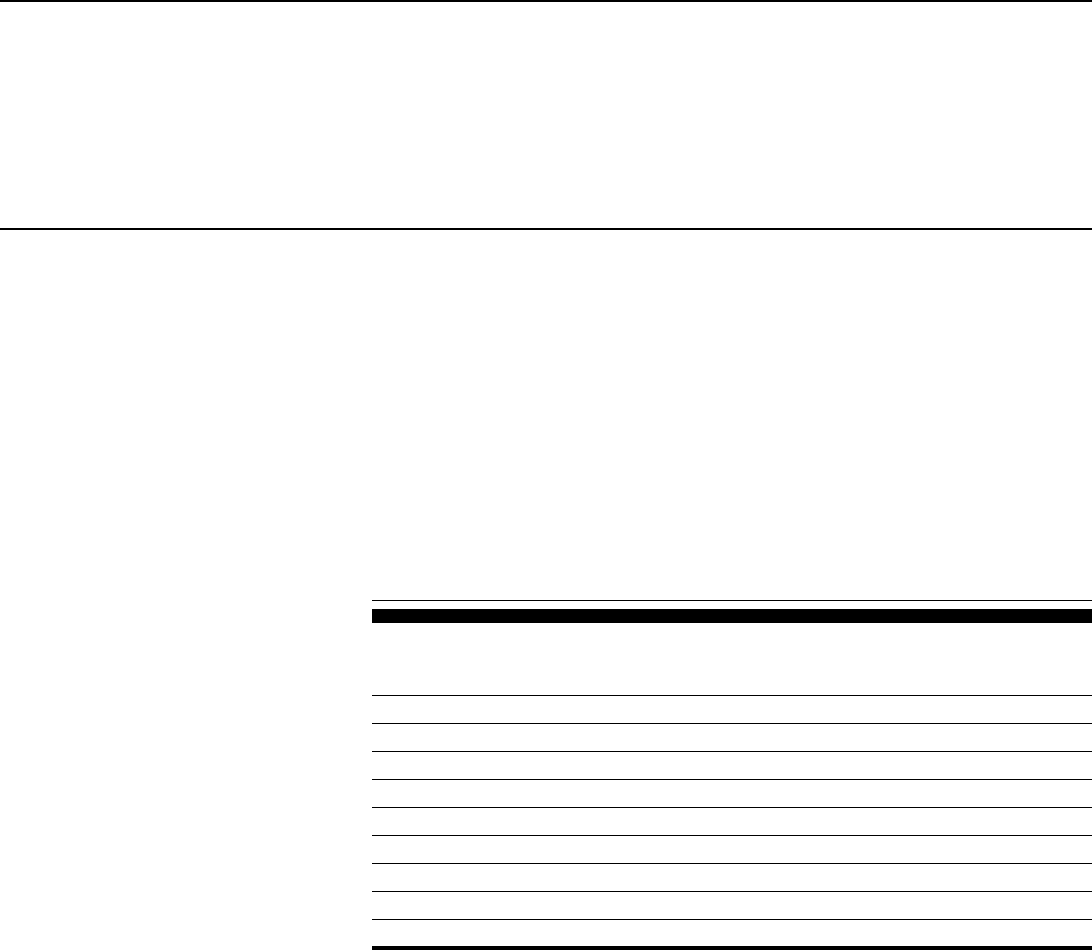

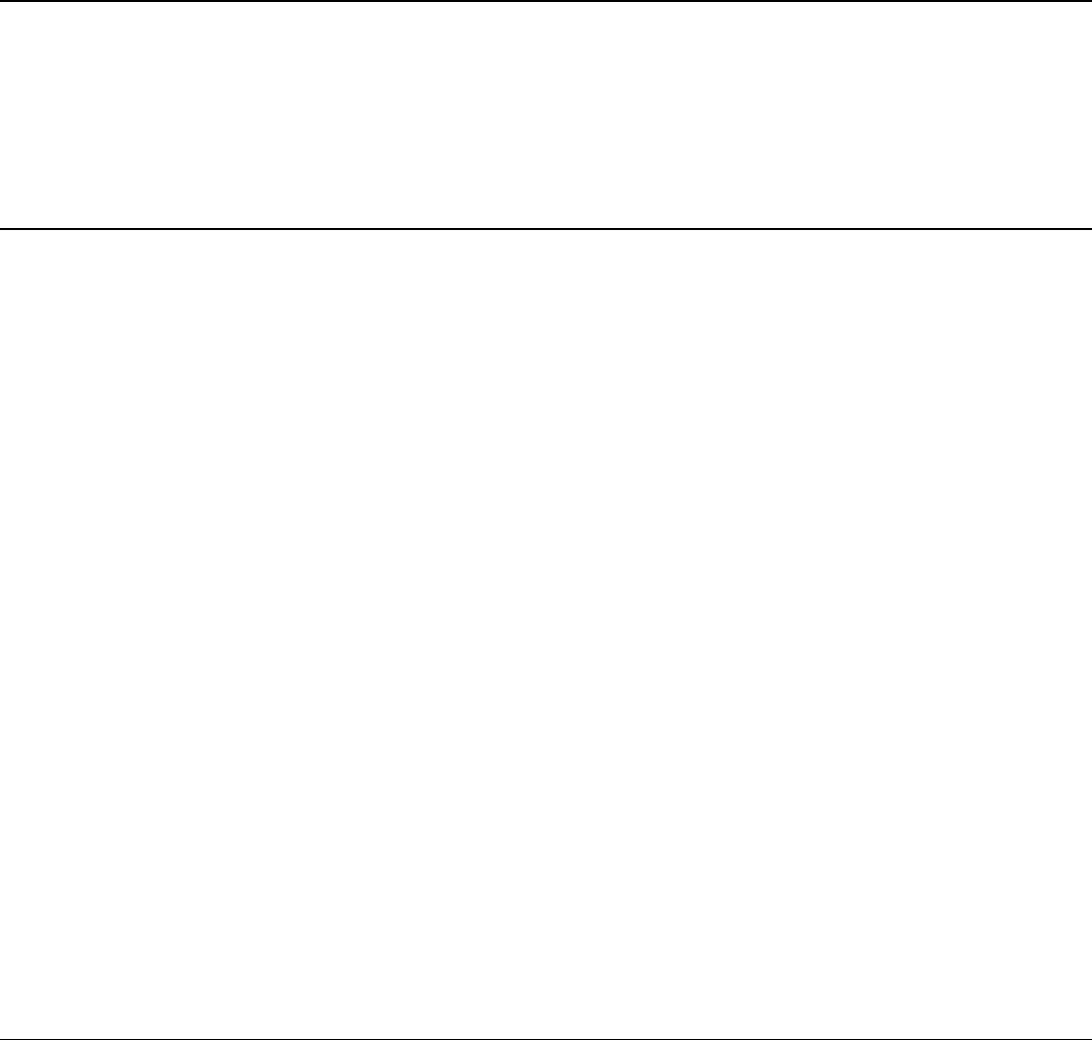

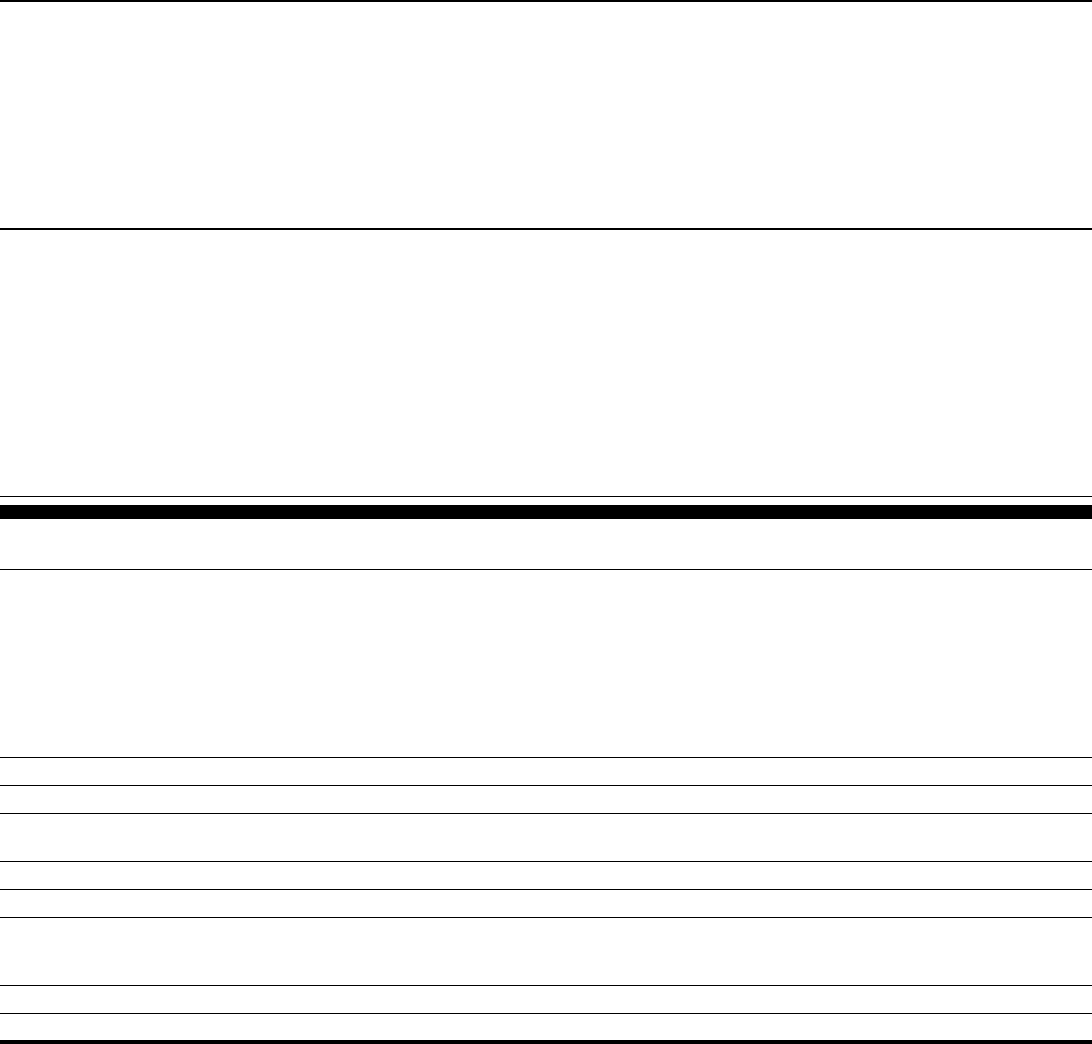

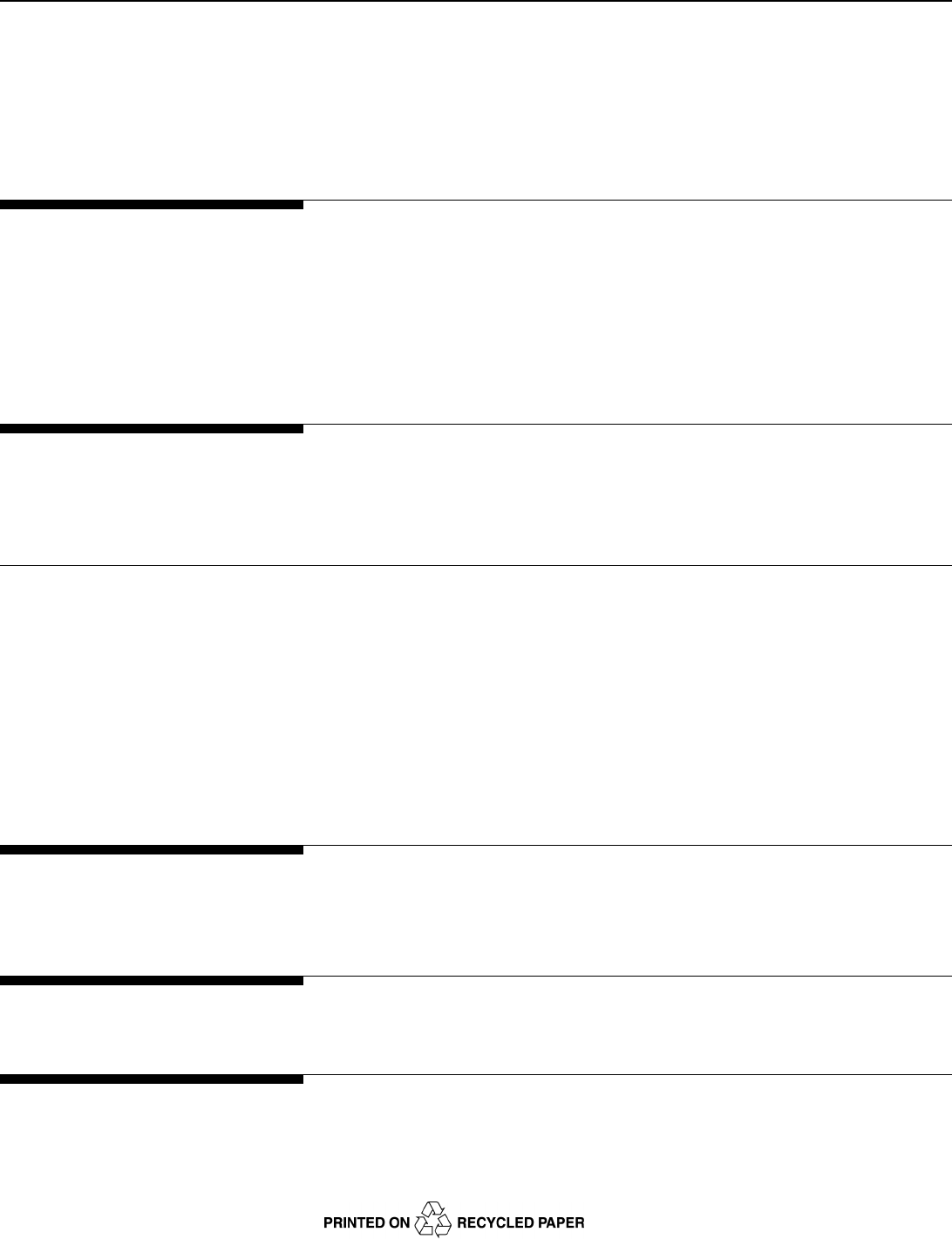

Simplified Model of Tax Status of Services Related to Internet Access

Source: GAO and PhotoDisc (images).

Sell acquired

services to ISP

Sells bundled

access services

to end user

End user

ISP

Providers of

acquired services

Tax exempt

Subject

to taxation

a

a

Depends on state law.

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-06-273.

To view the full product, including the scope

and methodology, click on the link above.

For more information, contact James R. White

at (202) 512-9110 or [email protected].

Page i GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Contents

Letter 1

Results in Brief 3

Background 4

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 7

Internet Access Services, Including Bundled Access Services, May

Not Be Taxed, but Acquired Services May Be 8

While the Revenue Impact of Eliminating Grandfathering Would Be

Small, the Moratorium’s Total Revenue Impact Has Been Unclear

and Any Future Impact Would Vary by State 13

External Comments 20

Appendixes

Appendix I: Bundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed, but Acquired

Services Are Taxable 23

Bundled Services, Including Broadband Services, May Not Be

Taxed 23

Acquired Services May Be Taxed 24

Appendix II: CBO’s Methodology for Estimating Costs Relating to Taxing

Internet Access Services 28

Appendix III: Case Study States’ Taxation of Services Related to Internet

Access 30

California 31

Kansas 31

Mississippi 31

North Dakota 32

Ohio 32

Rhode Island 33

Texas 34

Virginia 35

Appendix IV: Comments from Telecommunications Industry Officials 36

Appendix V: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 50

Tables

Table 1: Summary of Case Study State Rough Estimates of 2004 Tax

Revenue from Acquired Services 12

Table 2: Case Study State Officials’ Rough Estimates of Taxes

Collected for 2004 Related to Internet Access 15

Table 3: Characteristics Showing Variations among Case Study

States 19

Contents

Page ii GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Table 4: Characteristics of Case Study States 30

Figures

Figure 1: Hypothetical Internet Backbone Networks with

Connections to End Users 5

Figure 2: Simplified Illustration of Services Purchased by

Consumers 9

Figure 3: Simplified Model of Tax Status of Services Related to

Internet Access 11

Abbreviations

AOL America Online

CBO Congressional Budget Office

DSL digital subscriber line

FTA Federation of Tax Administrators

ISP Internet service provider

POP point of presence

POTS plain old telephone service

VoIP Voice over Internet Protocol

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

Page 1 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

A

January 23, 2006 Letter

The Honorable Ted Stevens

Chairman

The Honorable Daniel K. Inouye

Co-Chairman

Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Joe Barton

Chairman

The Honorable John D. Dingell

Ranking Minority Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

According to one study, at the end of 2004 some 70 million U.S. adults

logged on to the Internet during a typical day.

1

As Internet usage grew from

the mid-1990s onward, state and local governments imposed some taxes on

it and considered more. Concerned about the impact of such taxes,

Congress extensively debated whether state and local governments should

be allowed to tax Internet access. The debate resulted in legislation setting

national policy on state and local taxation of access.

In 1998, Congress enacted the Internet Tax Freedom Act,

2

which imposed a

moratorium temporarily preventing state and local governments from

imposing new taxes on Internet access or multiple or discriminatory taxes

on electronic commerce. Existing state and local taxes were

“grandfathered,” allowing them to continue to be collected. Since its

enactment, the moratorium has been amended twice, most recently in

2004, when Congress included language requiring that we study the impact

of the moratorium on state and local government revenues and on the

deployment and adoption of broadband technologies.

3

Such technologies

permit communications over high-speed, high-capacity media, such as that

1

Pew Research Center, Trends 2005 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 25, 2005).

2

Pub. L. 105-277, 112 Stat. 2681-719 (1998), 47 U.S.C. § 151 Note.

3

Internet Tax Nondiscrimination Act, Pub. L. 108-435, § 7, 118 Stat. 2615, 2618 (2004).

Page 2 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

provided by cable modem service or by a telephone technology known as

digital subscriber line (DSL).

4

This report focuses on the moratorium’s impact on state and local

government revenues. Its objectives are to determine (1) the scope of the

moratorium and (2) the impact of the moratorium, if any, on state and local

revenues. In determining any impact on revenues, the report explores what

would happen if grandfathering of access taxes on dial-up and DSL services

were eliminated, what might have happened in the absence of the

moratorium, and how the impact of the moratorium might differ from state

to state. This report does not focus on taxing the sale of items over the

Internet. A future report will discuss the impact that various factors,

including taxes, have on broadband deployment and adoption.

To prepare this report, we reviewed the language of the moratorium, its

legislative history, and associated legal issues; examined studies of revenue

impact done by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and others;

interviewed representatives of companies and associations involved with

Internet access services; and collected information through case studies of

eight states. We chose the states to get a mixture of those that did or did

not have taxes grandfathered for different forms of access services, did or

did not have local jurisdictions that taxed access services, had high and low

state tax revenue dollars per household and business entity with Internet

presence, had high and low percentages of households online, and covered

different urban and rural parts of the country. We did not intend the eight

states to represent any other states. In the course of our case studies, state

officials told us how they made the estimates they gave us of tax revenues

collected related to Internet access and how firm these estimates were. We

could not verify the estimates, and, in doing its study, CBO supplemented

estimates that it received from states with CBO-generated information.

Nevertheless, based on other information we obtained, the state estimates

we received appeared to provide a sense of the order of magnitude of the

dollars involved. We did our work from February through December 2005

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. A

later section of this report contains a complete discussion of our

objectives, scope, and methodology.

4

DSL is a high-speed way of accessing the Internet using traditional telephone lines that

have been “conditioned” to handle DSL technology.

Page 3 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Results in Brief

The Internet tax moratorium bars taxes on Internet access, meaning taxes

on the service of providing Internet access. In this way, it prevents services

that are reasonably bundled as part of an Internet access package, such as

electronic mail and instant messaging, from being subject to taxes when

sold to end users. These tax-exempt services also include DSL services

bundled as part of an Internet access package. Some states and providers

have construed the moratorium as also barring taxation of what we call

acquired services, such as high-speed communications capacity over fiber,

acquired by Internet service providers and used by them to deliver access

to the Internet to their customers. Because they believed that taxes on

acquired services are prohibited by the 2004 amendments, some state

officials told us their states would stop collecting them as early as

November 1, 2005, the date they assumed that taxes on acquired services

would lose their grandfathered protection. However, according to our

reading of the law, the moratorium does not apply to acquired services

since, among other things, a tax on acquired services is not a tax on

“Internet access.” Nontaxable “Internet access” is defined in the law as the

service of providing Internet access to an end user; it does not extend to a

provider’s acquisition of capacity to provide such service. Purchases of

acquired services are subject to taxation, depending on state law.

The revenue impact of eliminating grandfathering in states studied by CBO

would be small, but the moratorium’s total revenue impact has been

unclear and any future impact would vary by state. In 2003, CBO reported

that states and localities would lose from more than $160 million to more

than $200 million annually by 2008 if all grandfathered taxes on dial-up and

DSL services were eliminated, although part of this loss reflected acquired

services. It also identified other potential revenue losses, although

unquantified, that could have grown in the future but that now seem to

pose less of a threat. CBO’s estimated annual losses by 2007 for states that

had grandfathered taxes in 1998 were about 0.1 percent of the total 2004

tax revenues for those states. Because it is difficult to know what states

would have done to tax Internet access services if no moratorium had

existed, the total revenue implications of the moratorium are unclear. The

1998 moratorium was considered before connections to the Internet were

as widespread as they later became, limiting the window of opportunity for

states to adopt new taxes on access services. Although some states had

already chosen not to tax access services and others stopped taxing them,

other states might have been inclined to tax access services if no

moratorium were in place. In general, any future impact related to the

moratorium will differ from state to state. The details of state tax law as

Page 4 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

well as applicable tax rates varied from one state to another. For instance,

North Dakota taxed access service delivered to retail consumers. Kansas

taxed communications services acquired by Internet service providers to

support their customers. Rhode Island taxed both access service offerings

and the acquisition of communications services. California officials said

their state did not tax these areas at all.

We are not making any recommendations in this report.

In oral comments on a draft of this report, CBO staff members said we

fairly characterized CBO information and suggested clarifications that we

have made as appropriate. Federation of Tax Administrators (FTA)

officials said that our legal conclusion was clearly stated and, if adopted,

would be helpful in clarifying which Internet access-related services are

taxable and which are not. However, they expressed concern that the

statute could be interpreted differently regarding what might be reasonably

bundled in providing Internet access to consumers. A broader view of

what could be included in Internet access bundles would result in potential

revenue losses much greater than we indicated. However, as explained in

appendix I, we believe that what is bundled must be reasonably related to

accessing and using the Internet. In written comments, which are reprinted

in appendix IV, company representatives commented that the 2004

amendments make acquired services subject to the moratorium and

therefore not taxable, and that the language of the statute and the

legislative history support this position. While we acknowledge that there

are different views about the scope of the moratorium, our view is based on

the language and structure of the statute.

Background

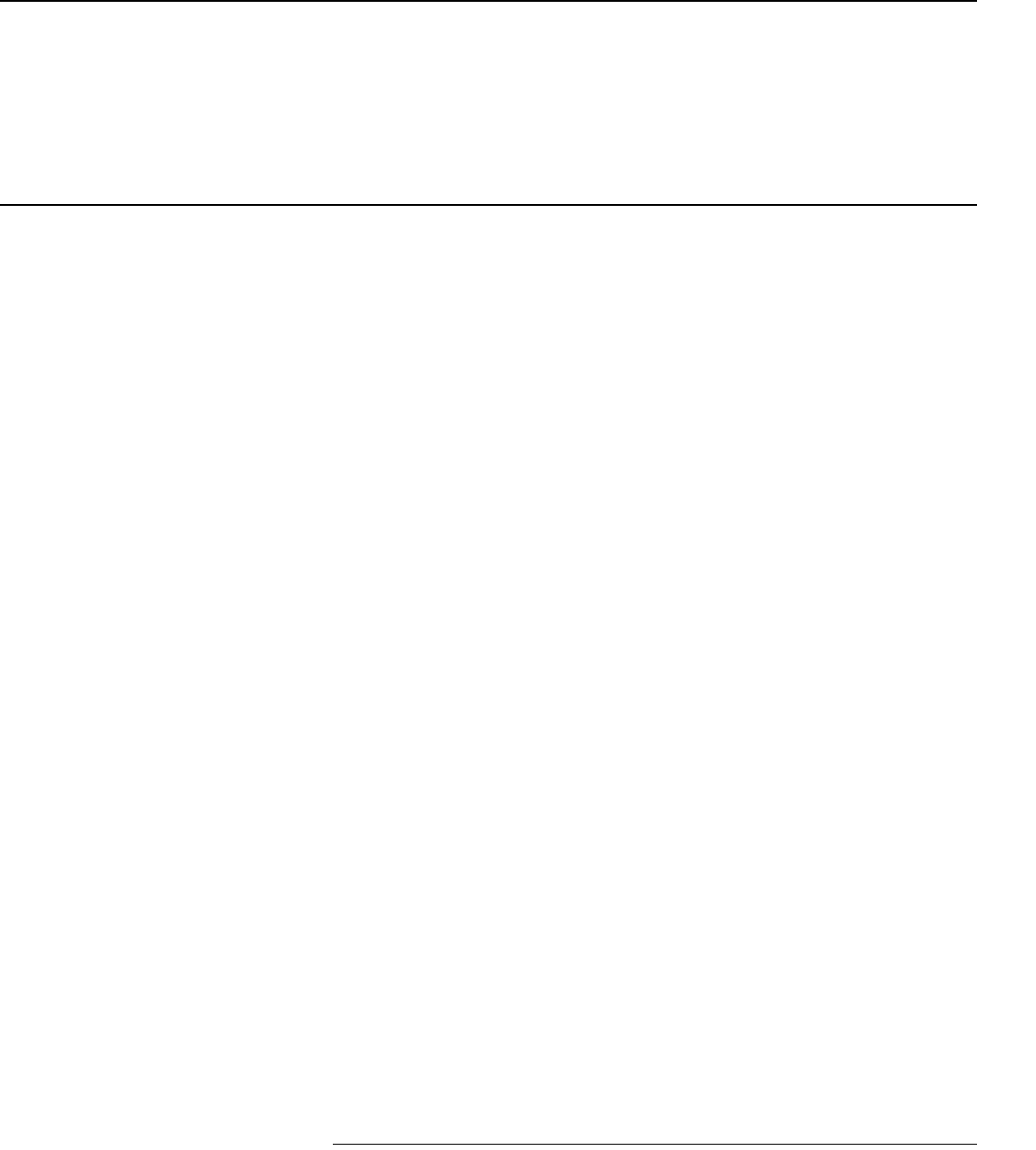

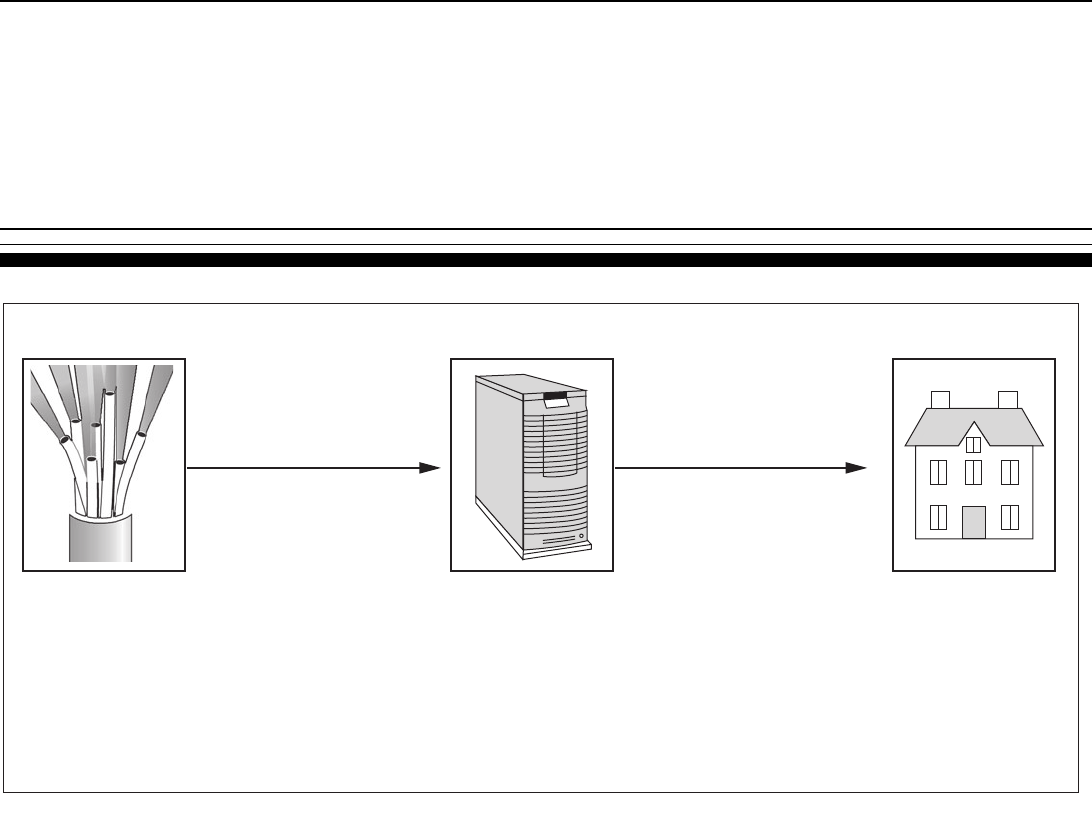

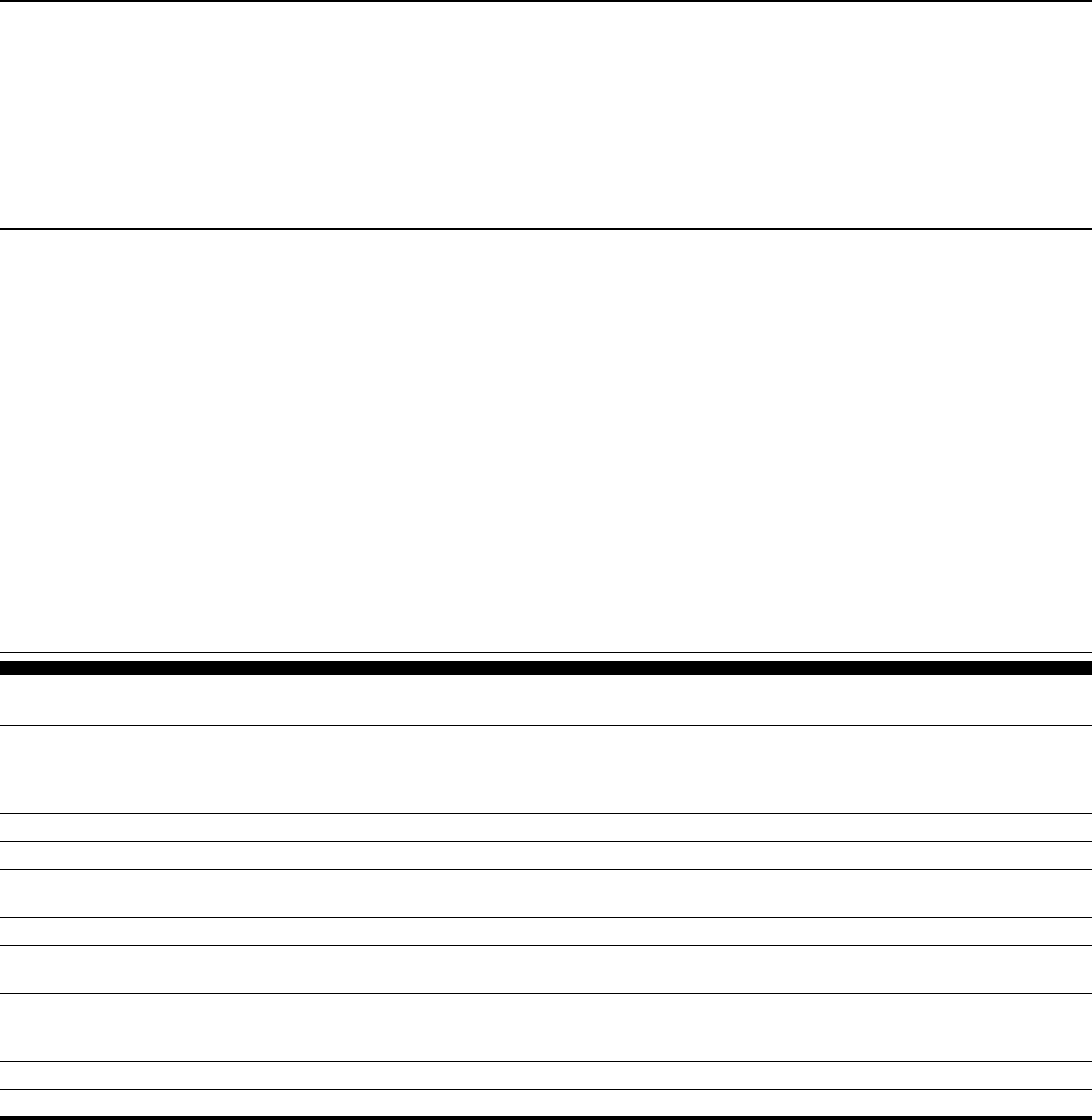

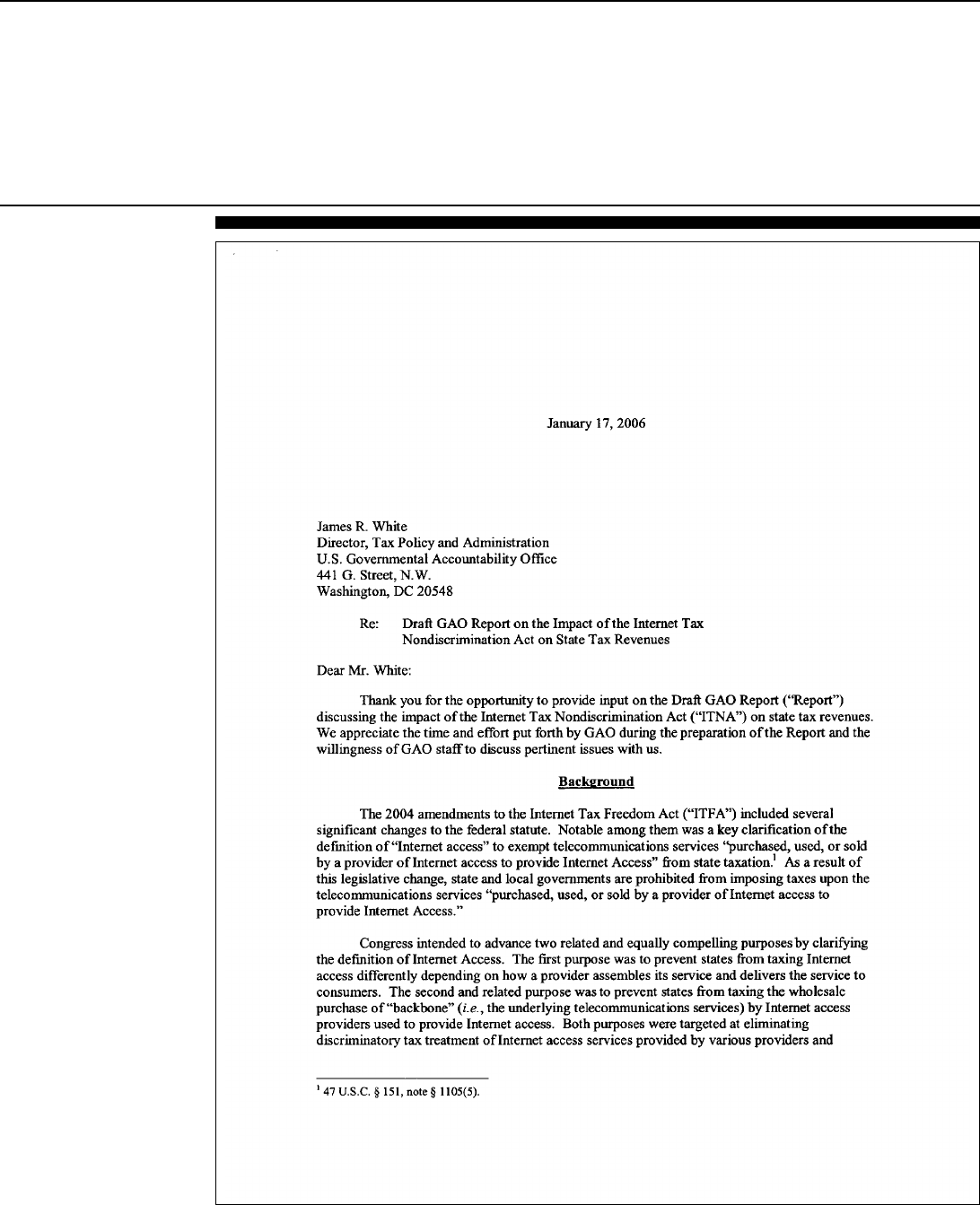

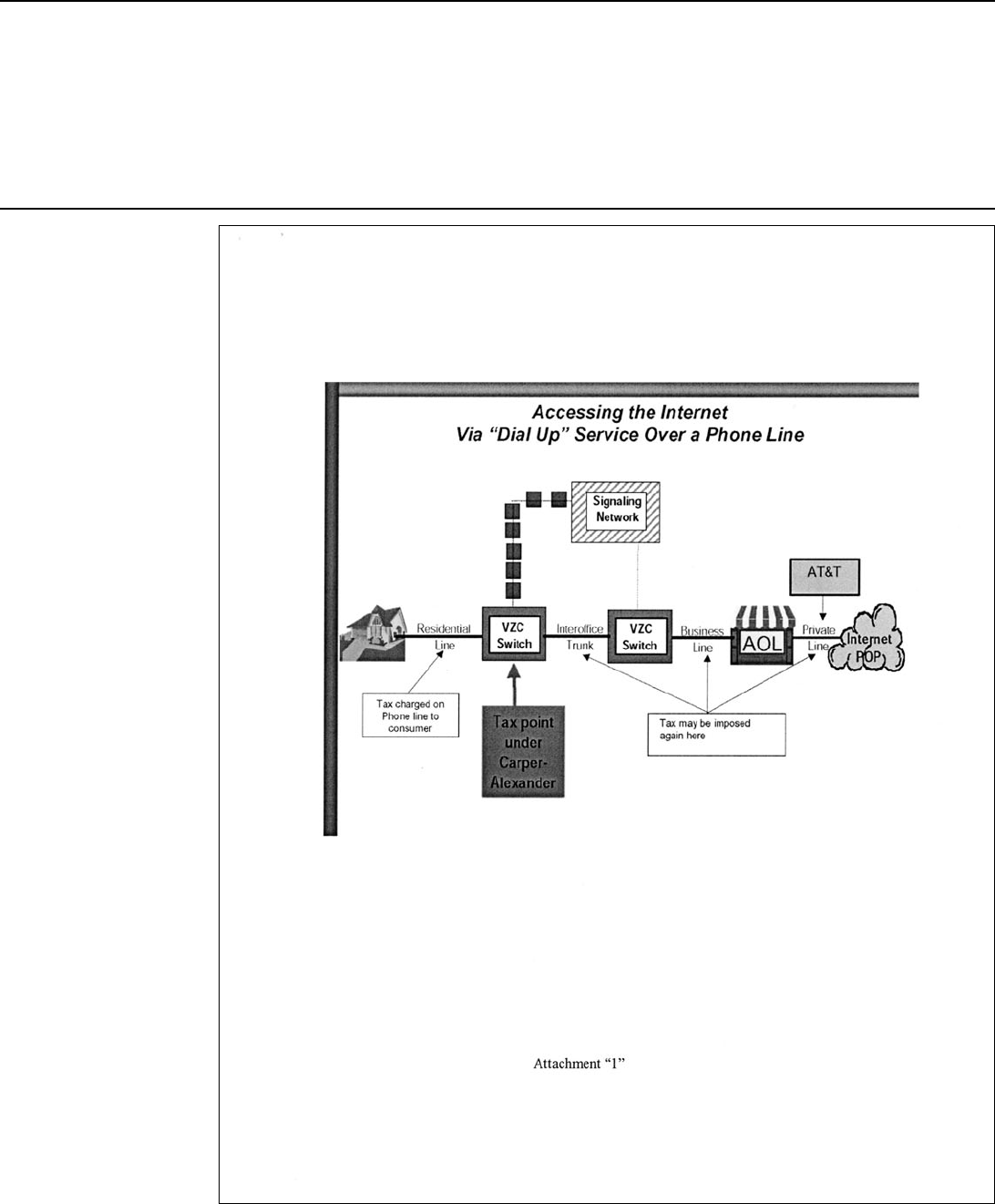

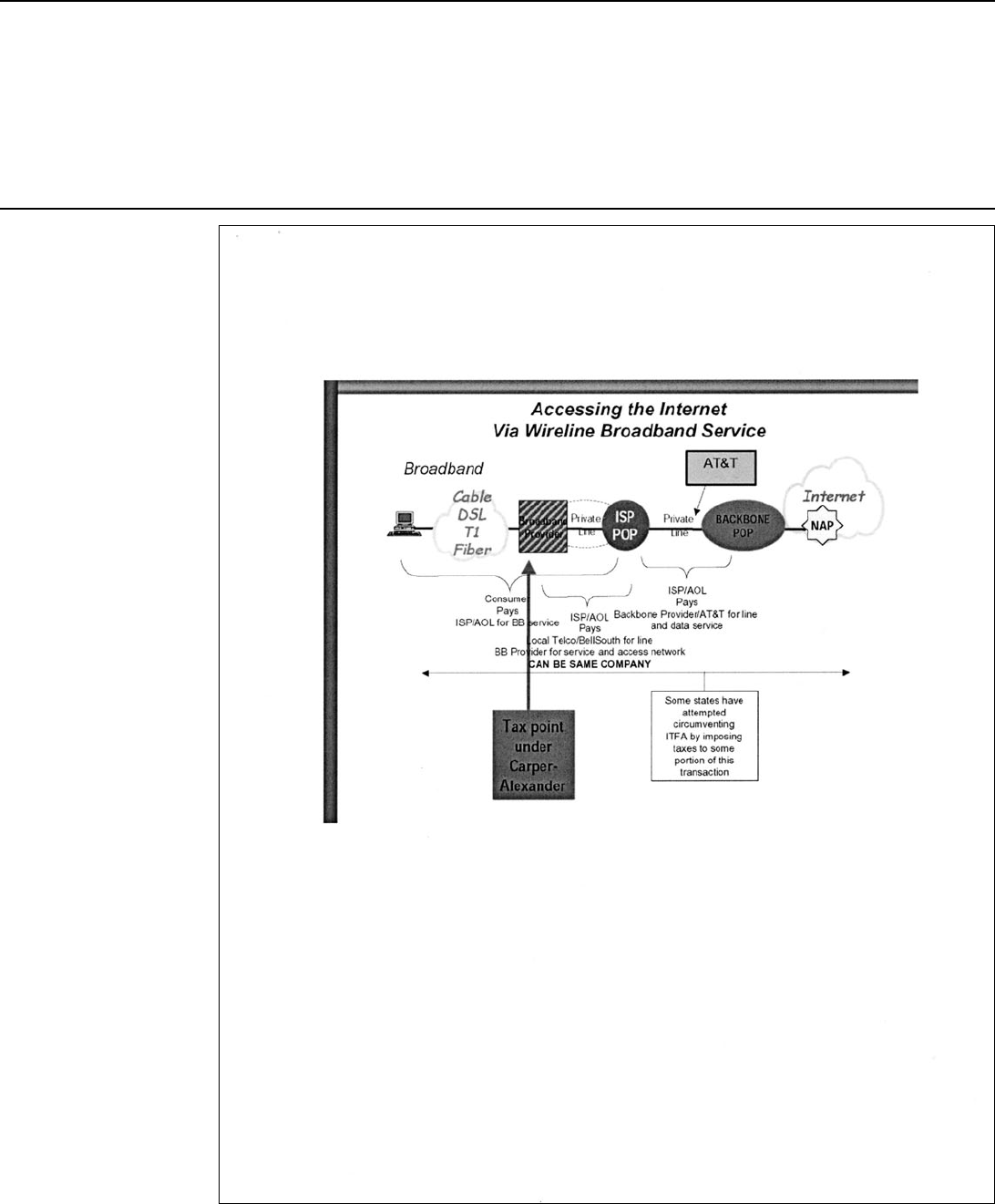

As shown in figure 1, residential and small business users often connect to

an Internet service provider (ISP) to access the Internet. Well-known ISPs

include America Online (AOL) and Comcast. Typically, ISPs market a

package of services that provide homes and businesses with a pathway, or

“on-ramp,” to the Internet along with services such as e-mail and instant

messaging. The ISP sends the user’s Internet traffic forward to a backbone

network where the traffic can be connected to other backbone networks

and carried over long distances. By contrast, large businesses often

maintain their own internal networks and may buy capacity from access

providers that connect their networks directly to an Internet backbone

network. We are using the term access providers to include ISPs as well as

providers who sell access to large businesses and other users. Nonlocal

traffic from both large businesses and ISPs connects to a backbone

Page 5 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

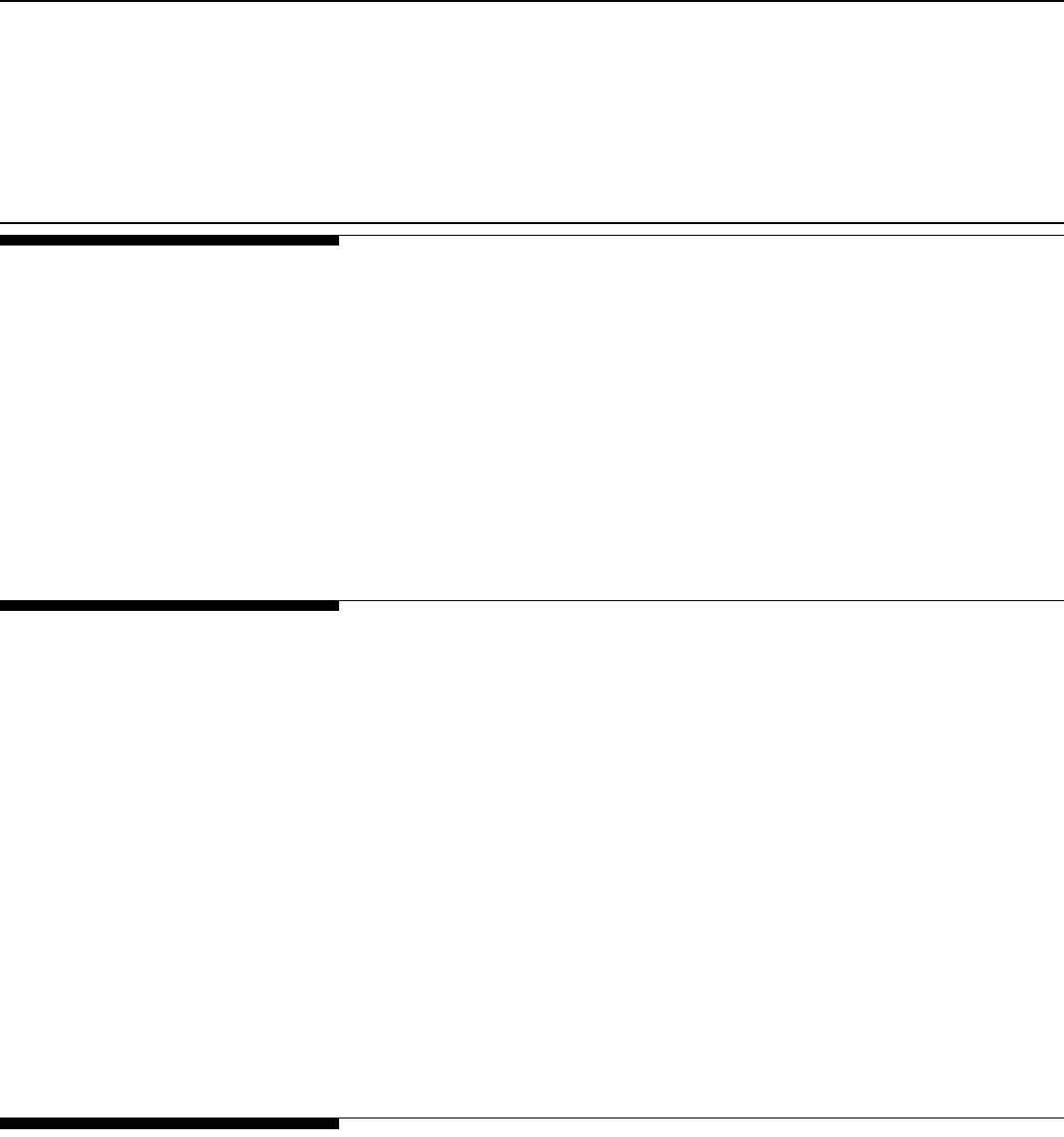

provider’s network at a “point of presence” (POP). Figure 1 depicts two

hypothetical and simplified Internet backbone networks that link at

interconnection points and take traffic to and from residential units

through ISPs and directly from large business users.

Figure 1: Hypothetical Internet Backbone Networks with Connections to End Users

As public use of the Internet grew from the mid-1990s onward, Internet

access and electronic commerce became potential targets for state and

local taxation. Ideas for taxation ranged from those that merely extended

existing sales or gross receipts taxes to so-called “bit taxes,” which would

measure Internet usage and tax in proportion to use. Some state and local

governments raised additional tax revenues and applied existing taxes to

POP

POP

POP

POP

POP

New York

Denver

Seattle

Backbone A

Backbone B

Point of presence

Point of interconnection

Dallas

Atlanta

Los Angeles

Large business

and institutional

users

Large business

and institutional

users

Residential, small

business, and other

users

ISP

ISP

Large business

and institutional

users

Residential, small

business, and other

users

Chicago

San

Francisco

Source: GAO and PhotoDisc (images).

Page 6 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Internet transactions. Owing to the Internet’s inherently interstate nature

and to issues related to taxing Internet-related activities, concern arose in

Congress as to what impact state and local taxation might have on the

Internet’s growth, and thus, on electronic commerce. Congress addressed

this concern when, in 1998, it adopted the Internet Tax Freedom Act, which

bars state and local taxes on Internet access, as well as multiple or

discriminatory taxes on electronic commerce.

5

Internet usage grew rapidly in the years following 1998, and the technology

to access the Internet changed markedly. Today a significant portion of

users, including home users, access the Internet over broadband

communications services using cable modem, DSL, or wireless

technologies. Fewer and fewer users rely on dial-up connections through

which they connect to their ISP by dialing a telephone number. By 2004,

some state tax authorities were taxing DSL service, which they considered

to be a telecommunications service, creating a distinction between DSL

and services offered through other technologies, such as cable modem, that

were not taxed.

Originally designed to postpone the addition of any new taxes while the

Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce studied the tax issue and

reported to Congress, the moratorium was extended in 2001 for 2 years

6

and again in 2004, retroactively, to remain in force until November 1, 2007.

7

The 2001 extension made no other changes to the original act, but the 2004

act included clarifying amendments. The 2004 act amended language that

had exempted telecommunications services from the moratorium.

5

A tax is a multiple tax if credit is not given for comparable taxes paid to other states on the

same transaction; a tax is a discriminatory tax if e-commerce transactions are taxed at a

higher rate than comparable nonelectronic transactions would be taxed, or are required to

be collected by different parties or under other terms that are more disadvantageous than

those that are applied in taxing other types of comparable transactions. Generally, states

and localities that tax e-commerce impose comparable taxes on nonelectronic transactions.

States that have sought at one time to require that access providers collect taxes due—a

process that might been thought to have been discriminatory—have backed away from that

position. Moreover, although interstate commerce may bear its fair share of state taxes, the

interstate commerce clause of the Constitution requires there to be a substantial nexus, fair

apportionment, nondiscrimination, and a relationship between a tax and state-provided

services that largely constrains the states in imposing such taxes. Quill Corp. v. North

Dakota, 504 U.S. 298, 313 (1992). In any case, our report does not focus on taxing the sale of

items over the Internet.

6

Internet Tax Nondiscrimination Act, 2001, Pub. L. 107-75, § 2, 115 Stat. 703.

7

Internet Tax Nondiscrimination Act, 2004, Pub. L. 108-435, §§ 2 to 6A, 118 Stat. 2615 to 2618.

Page 7 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Recognizing state and local concerns about their ability to tax voice

services provided over the Internet, it also contained language allowing

taxation of telephone service using Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP).

Although the 2004 amendments extended grandfathered protection

generally to November 2007, grandfathering extended only to November

2005 for taxes subject to the new moratorium but not to the original

moratorium.

Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

To determine the scope of the Internet tax moratorium, we reviewed the

language of the moratorium, the legislative history of the 1998 act and the

2004 amendments, and associated legal issues.

To determine the impact of the moratorium on state and local revenues, we

worked in stages. First, we reviewed studies of revenue impact done by

CBO, FTA, and the staff of the Multistate Tax Commission and discussed

relevant issues with federal representatives, state and local government

and industry associations, and companies providing Internet access

services. Then, we used structured interviews to do case studies in eight

states that we chose as described earlier. We did not intend the eight states

to represent any other states.

For each selected state, we focused on specific aspects of its tax system by

using our structured interview and collecting relevant documentation. For

instance, we reviewed the types and structures of Internet access service

taxes, the revenues collected from those taxes, officials’ views of the

significance of the moratorium to their government’s financial situation,

and their opinions of any implications to their states of the new definition

of Internet access. We also learned whether localities within the states

were taxing access services. When issues arose, we contacted other states

and localities to increase our understanding of these issues.

We discussed with state officials how they derived the estimates they gave

us of tax dollars collected and how firm these numbers were. We could not

verify the estimates, and CBO supplemented estimates that it received from

states. Nevertheless, based on other information we obtained, the state

estimates appeared to provide a sense of the order of magnitude of the

numbers compared to state tax revenues.

We did our work from February through December 2005 in accordance

with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Page 8 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Internet Access

Services, Including

Bundled Access

Services, May Not Be

Taxed, but Acquired

Services May Be

The moratorium bars taxes on the service of providing access, which

includes whatever an access provider reasonably bundles in its access

offering to consumers. On the other hand, the moratorium does not

prohibit taxes on acquired services, referring to goods and services that an

access provider acquires to enable it to bundle and provide its access

package to its customers. However, some providers and state officials have

expressed a different view, believing the moratorium barred taxing

acquired services in addition to bundled access services.

Internet Access Services,

Including Bundled

Broadband Services, May

Not Be Taxed

Since its 1998 origin, the moratorium has always prohibited taxing the

service of providing Internet access, including component services that an

access provider reasonably bundles in its access offering to consumers.

However, as amended in 2004, the definition of Internet access contains

additional words. With words added in 2004 in italics, it now defines the

scope of nontaxable Internet access as

“a service that enables users to access content, information, electronic mail, or other

services offered over the Internet, and may also include access to proprietary content,

information, and other services as part of a package of services offered to users. The term

‘Internet access’ does not include telecommunications services, except to the extent such

services are purchased, used, or sold by a provider of Internet access to provide Internet

access.”

8

(italics provided)

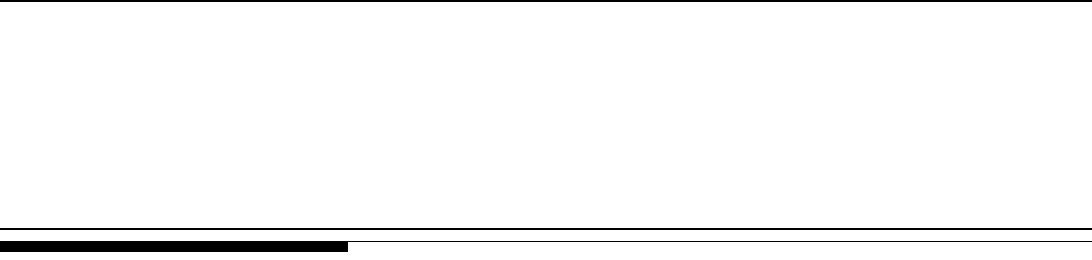

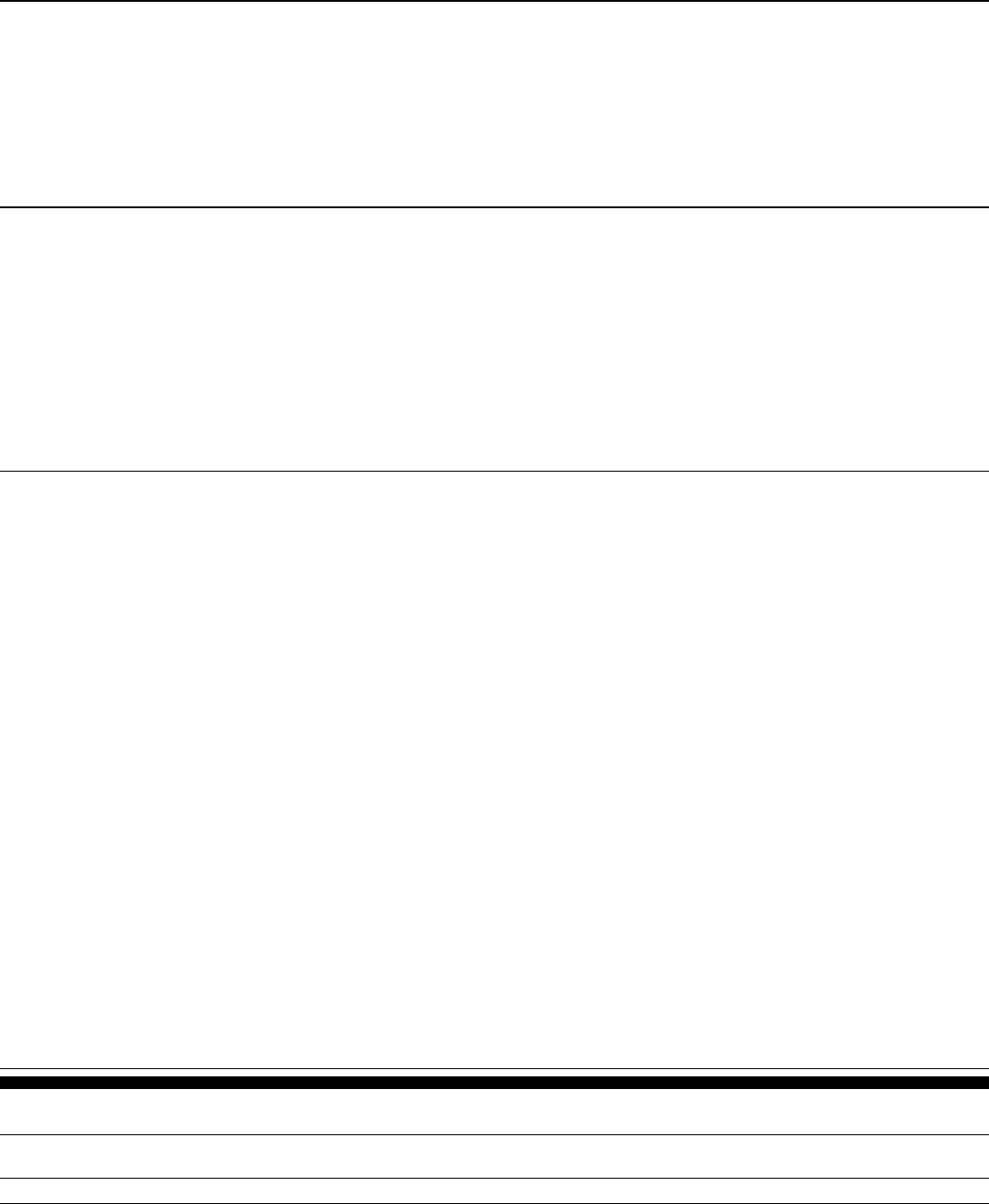

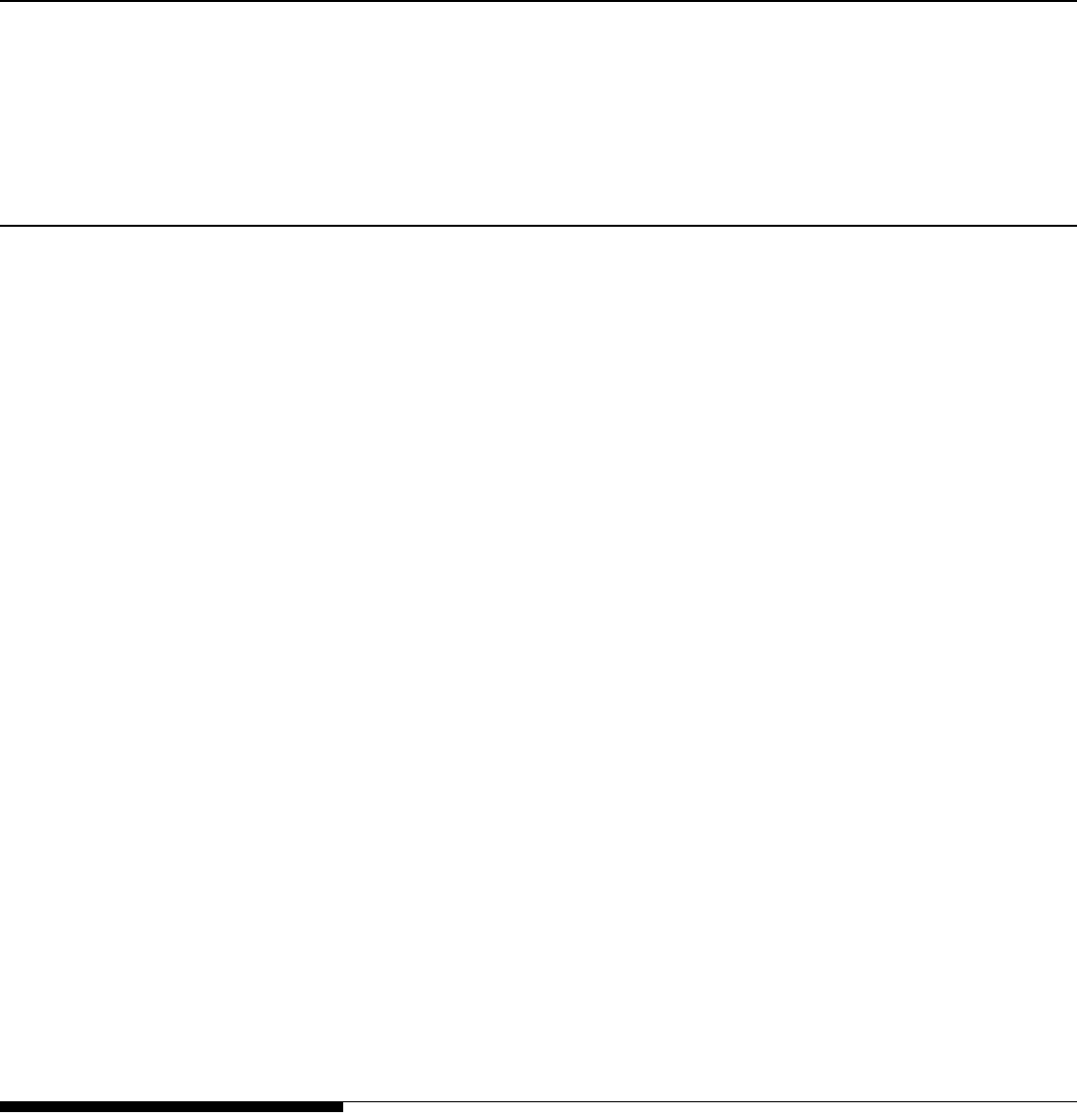

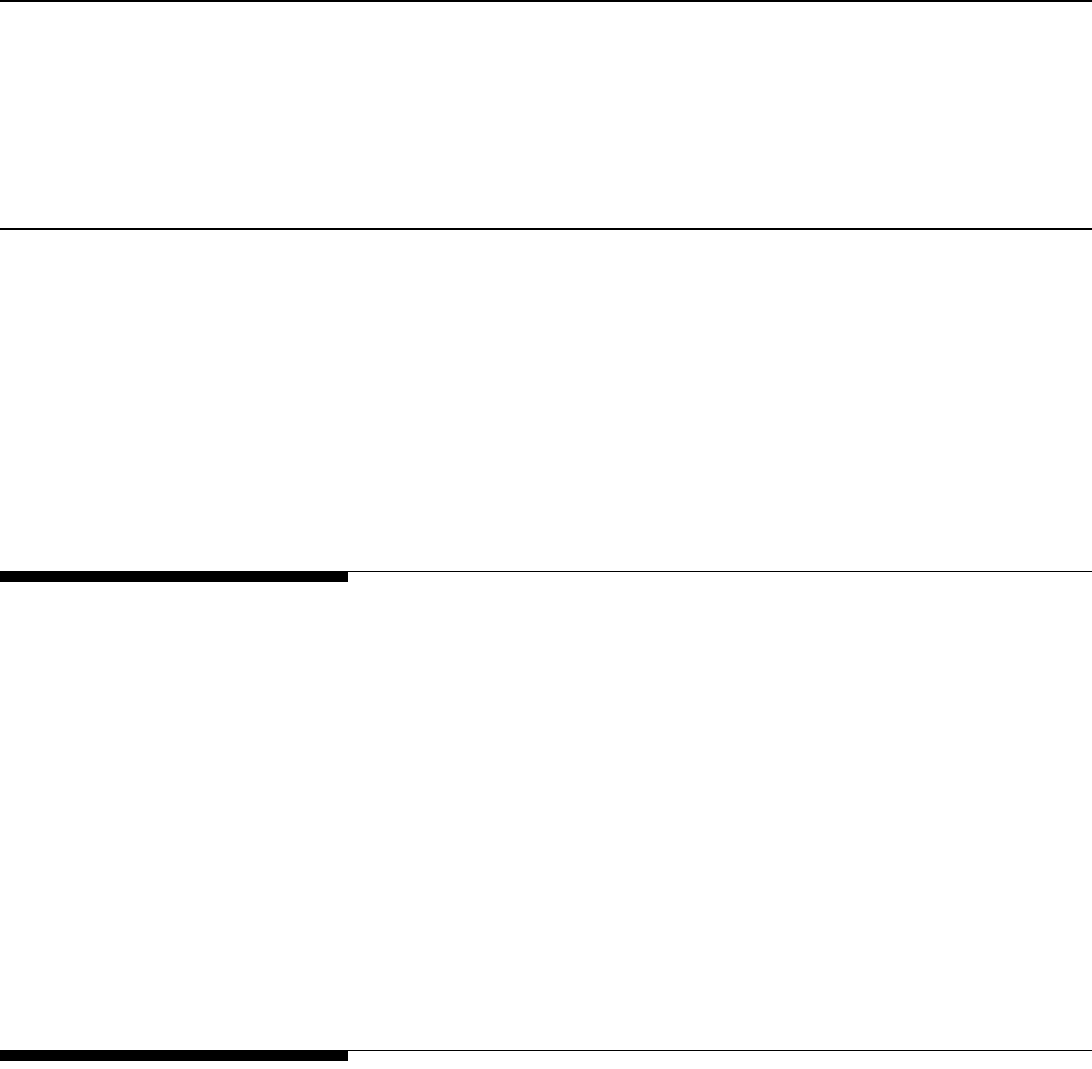

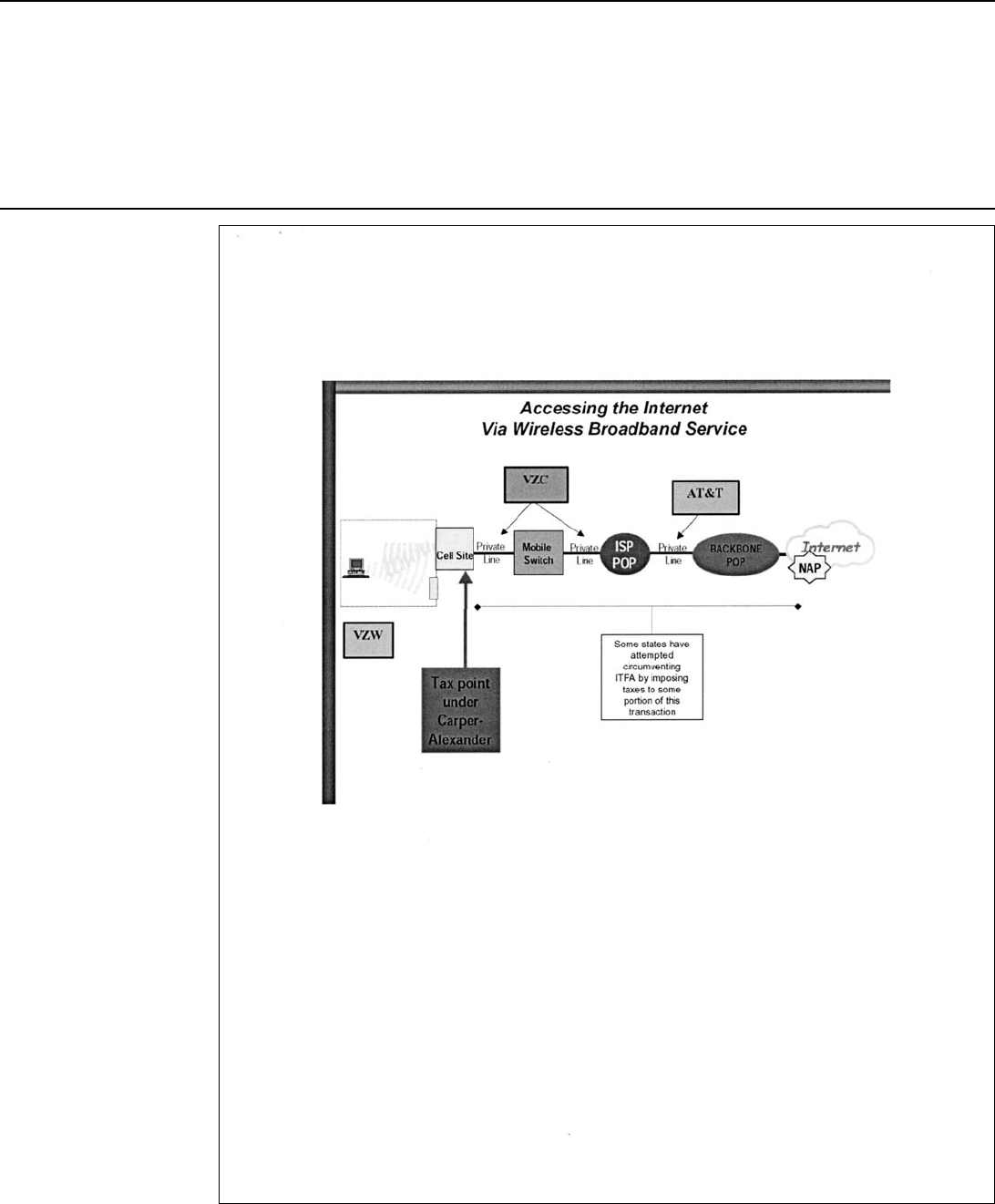

As shown in the simplified illustration in figure 2, the items reasonably

bundled in a tax-exempt Internet access package may include e-mail,

instant messaging, and Internet access itself. Internet access, in turn,

includes broadband services, such as cable modem and DSL services,

which provide continuous, high-speed access without tying up wireline

telephone service. As figure 2 also illustrates, a tax-exempt bundle does

not include video, traditional wireline telephone service referred to as

“plain old telephone service” (POTS), or VoIP. These services are subject to

tax. For simplicity, the figure shows a number of services transmitted over

one communications line. In reality, a line to a consumer may support just

one service at a time, as is typically the case for POTS, or it may

simultaneously support a variety of services, such as television, Internet

access, and VoIP.

8

47 U.S.C. § 151 Note § 1105(5).

Page 9 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Figure 2: Simplified Illustration of Services Purchased by Consumers

a

Traditional wireline telephone service, commonly referred to in the communications industry as “plain

old telephone service” (POTS).

b

May become taxable if not capable of being broken out from other services on a bill.

Our reading of the 1998 law and the relevant legislative history indicates

that Congress had intended to bar taxes on services bundled with access.

However, there were different interpretations about whether DSL service

could be taxed under existing law, and some states taxed DSL. The 2004

amendment was aimed at making sure that DSL service bundled with

access could not be taxed. See appendix I for further explanation.

Source: GAO and PhotoDisc (images).

Home, business, or

other user

Tax-exempt

b

Subject to taxation

Providers including

telephone, cable,

and wireless

companies

Internet access

package

(may include e-mail, Internet

access, and instant

messaging)

Video

POTS

a

VoIP

Page 10 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Acquired Services May Be

Taxed

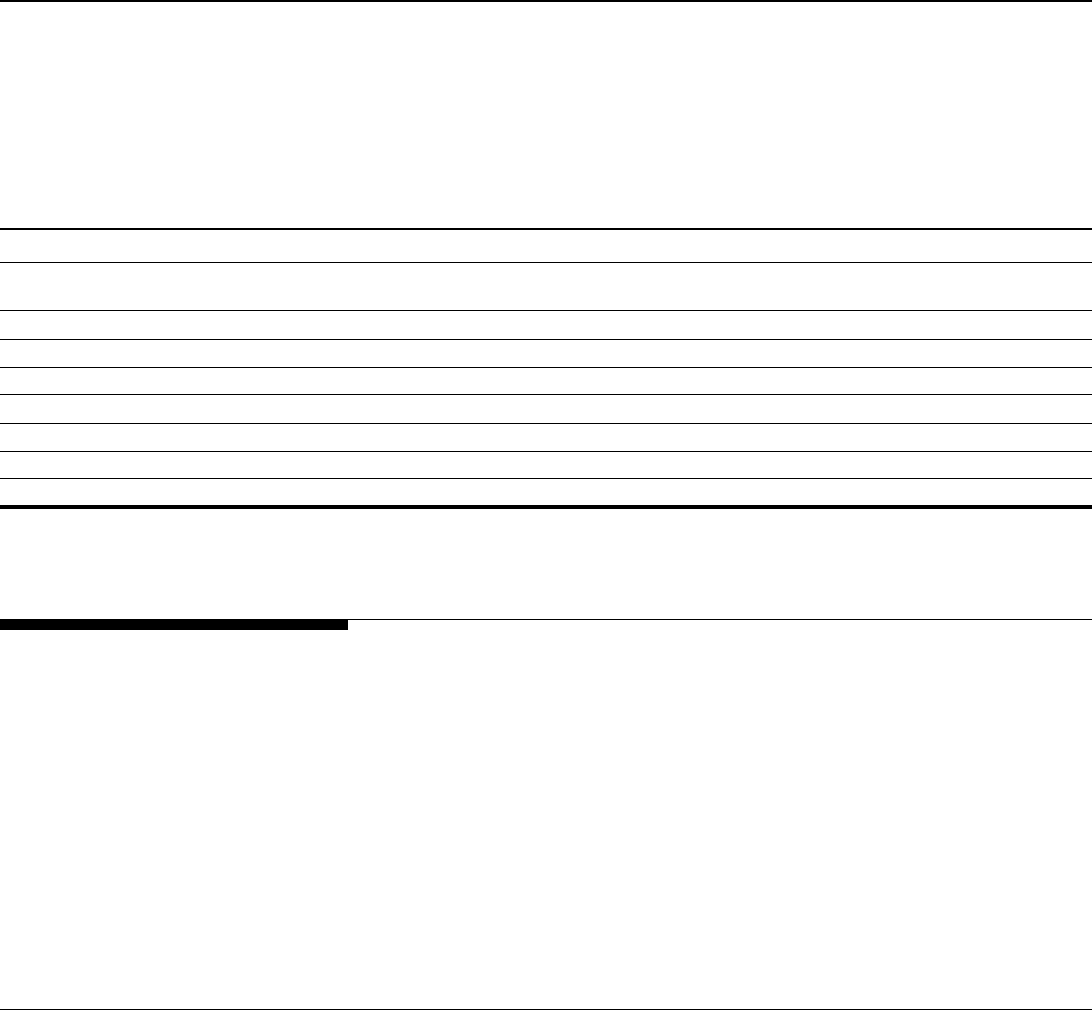

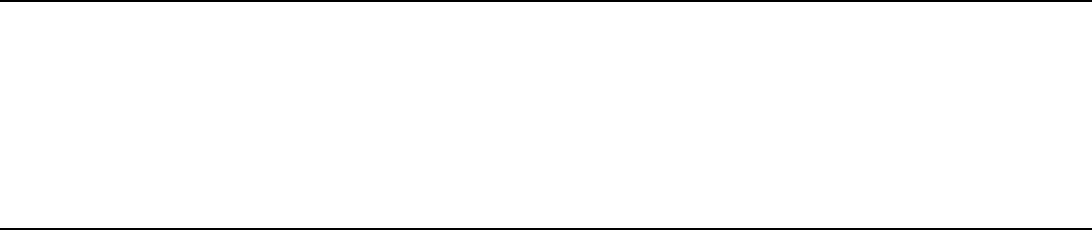

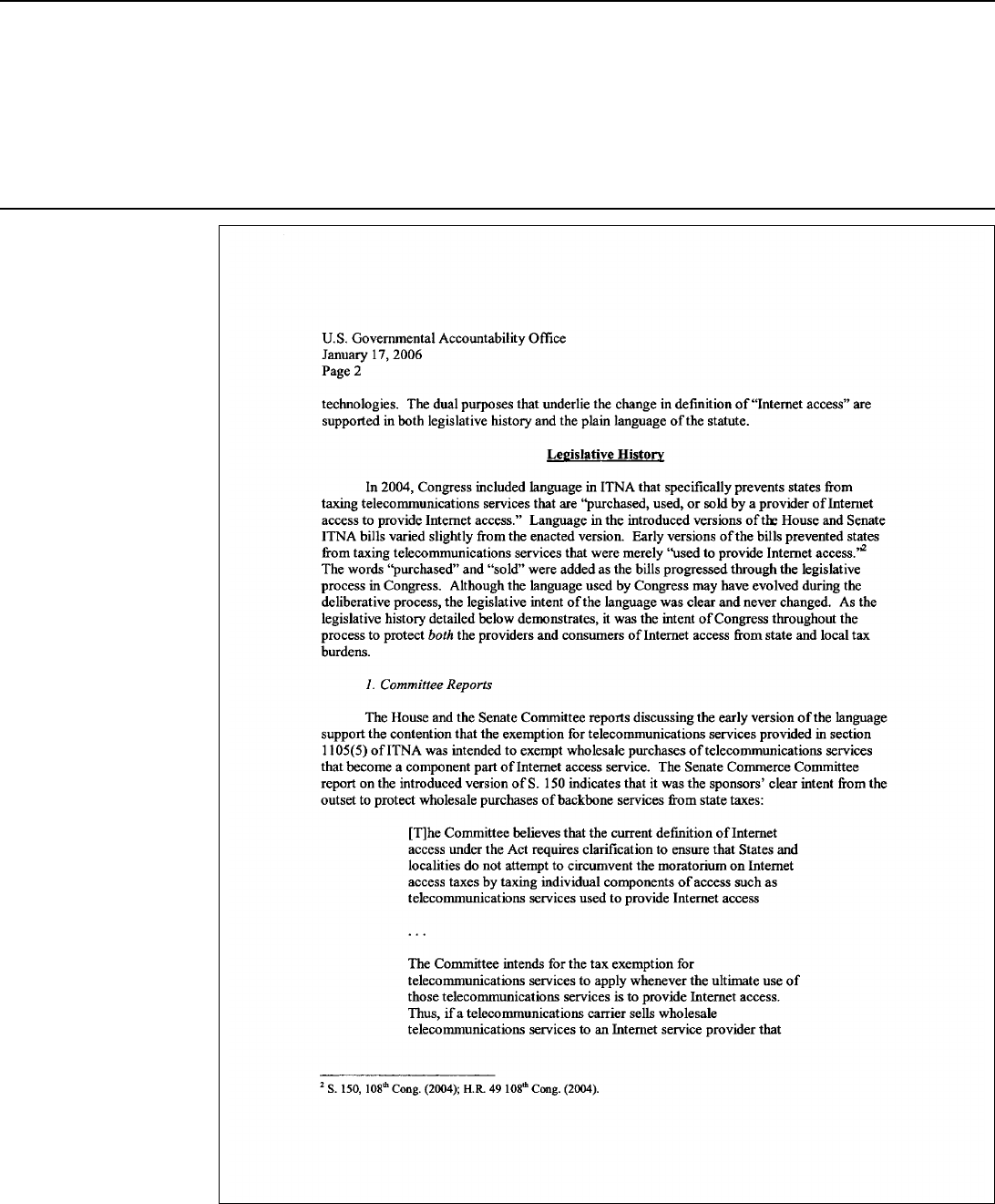

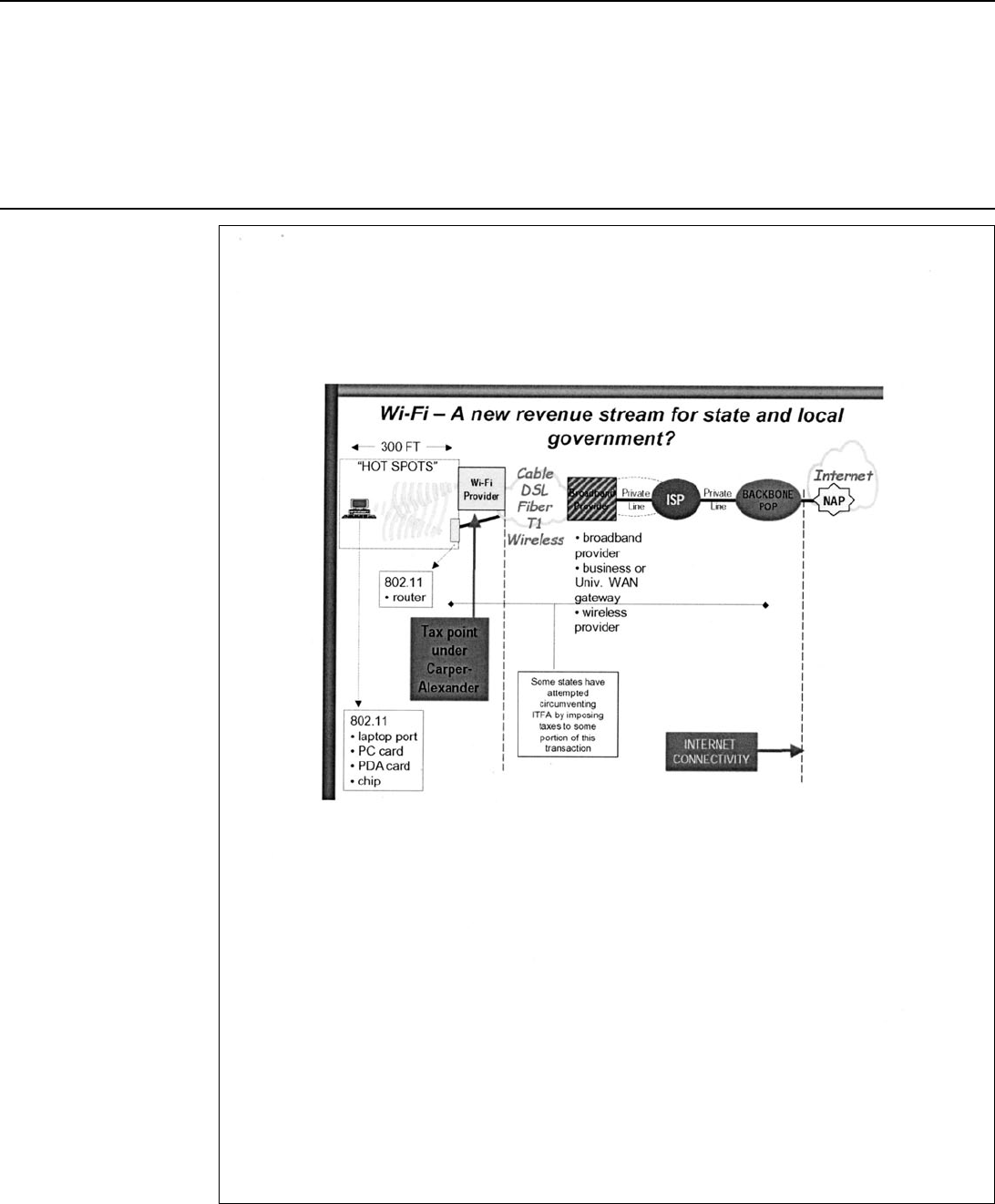

Figure 3 shows how the nature and tax status of the Internet access

services just described differ from the nature and tax status of services that

an ISP acquires and uses to deliver access to its customers. An ISP in the

middle of figure 3 acquires communications and other services and

incidental supplies (shown on the left side of the figure) in order to deliver

access services to customers (shown on the right side of the figure). We

refer to the acquisitions on the left side as purchases of “acquired

services.”

9

For example, acquired services include ISP leases of high-speed

communications capacity over wire, cable, or fiber to carry traffic from

customers to the Internet backbone.

9

Some have also used the term wholesale to describe acquired services. For example, the

New Millennium Research Council in Taxing High-Speed Services (Washington, D.C.,

Apr. 26, 2004) said that “wholesale services that telecommunications firms provide ISPs can

include local connections to the customer’s premise, high-capacity transport between

network points and backbone services.” We avoid using the term, however, because it

suggests a particular sales relationship (between wholesaler and retailer) that may be

limiting and misleading.

Page 11 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Figure 3: Simplified Model of Tax Status of Services Related to Internet Access

a

“Sell acquired services” refers to selling services, either to a separate firm or to a vertically-integrated

affiliate.

b

Depends on state law.

Purchases of acquired services are subject to taxation, depending on state

law, because the moratorium does not apply to acquired services. As noted

above, the moratorium applies only to taxes imposed on “Internet access,”

which is defined in the law as “a service that enables users to access

content, information, electronic mail, or other services offered over the

Internet.…” In other words, it is the service of providing Internet access to

the end user—not the acquisition of capacity to do so—that constitutes

“Internet access” subject to the moratorium.

Some providers and state officials have construed the moratorium as

barring taxation of acquired services, reading the 2004 amendments as

making acquired services tax exempt. However, as indicated by the

language of the statute, the 2004 amendments did not expand the definition

of “Internet access,” but rather amended the exception from the definition

to allow certain “telecommunication services” to qualify for the

moratorium if they are part of the service of providing Internet access. A

Examples of services

provided:

• E-mail

• Internet access

• Instant messaging

Examples of end users:

• Home

• Business

• Government

• Education

Source: GAO and PhotoDisc

(

ima

g

es

)

.

Sell acquired

services

a

to ISP

Sells bundled

access services

to end user

End userISP

Examples of services

provided:

• Capacity over a medium

(copper wire, coaxial cable,

fiber, wireless, satellite)

• Hardware to connect to capacity

(modem or equivalent)

• Server capacity and other

capabilities to create own Web

presence (e-mail, Web site, Web

hosting, etc.)

Providers of

acquired services

Tax exempt

Subject

to taxation

b

Page 12 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

tax on acquired services is not a tax directly imposed on the service of

providing Internet access.

Our view that acquired services are not subject to the moratorium on

taxing Internet access is based on the language and structure of the statute,

as described further in appendix I. We acknowledge that others have

different views about the scope of the moratorium. Congress could, of

course, deal with this issue by amending the statute to explicitly address

the tax status of acquired services.

Some States Have Applied

the Moratorium to Acquired

Services

As noted above, some providers and state officials have construed the

moratorium as barring taxation of acquired services. Some provider

representatives said that acquired services were not taxable at the time we

contacted them and had never been taxable. Others said that acquired

services were taxable when we contacted them but would become tax

exempt in November 2005 under the 2004 amendments, the date they

assumed that taxes on acquired services would no longer be grandfathered.

As shown in table 1, officials from four out of the eight states we studied—

Kansas, Mississippi, Ohio, and Rhode Island—also said their states would

stop collecting taxes on acquired services, as of November 1, 2005, in the

case of Kansas and Ohio whose collections have actually stopped, and later

for the others. These states roughly estimated the cost of this change to

them to be a little more than $40 million in revenues that were collected in

2004. An Ohio official indicated that two components comprised most of

the dollar amounts of taxes collected from these services in 2004:

$20.5 million from taxes on telecommunications services and property

provided to ISPs and Internet backbone providers, and $9.1 million from

taxes for private line services (such as high-capacity T-1 and T-3 lines) and

800/wide-area telecommunications services that the official said would be

exempt due to the moratorium. The rough estimates in table 1 are subject

to the same limitations described in the next section for the state estimates

of all taxes collected related to Internet access.

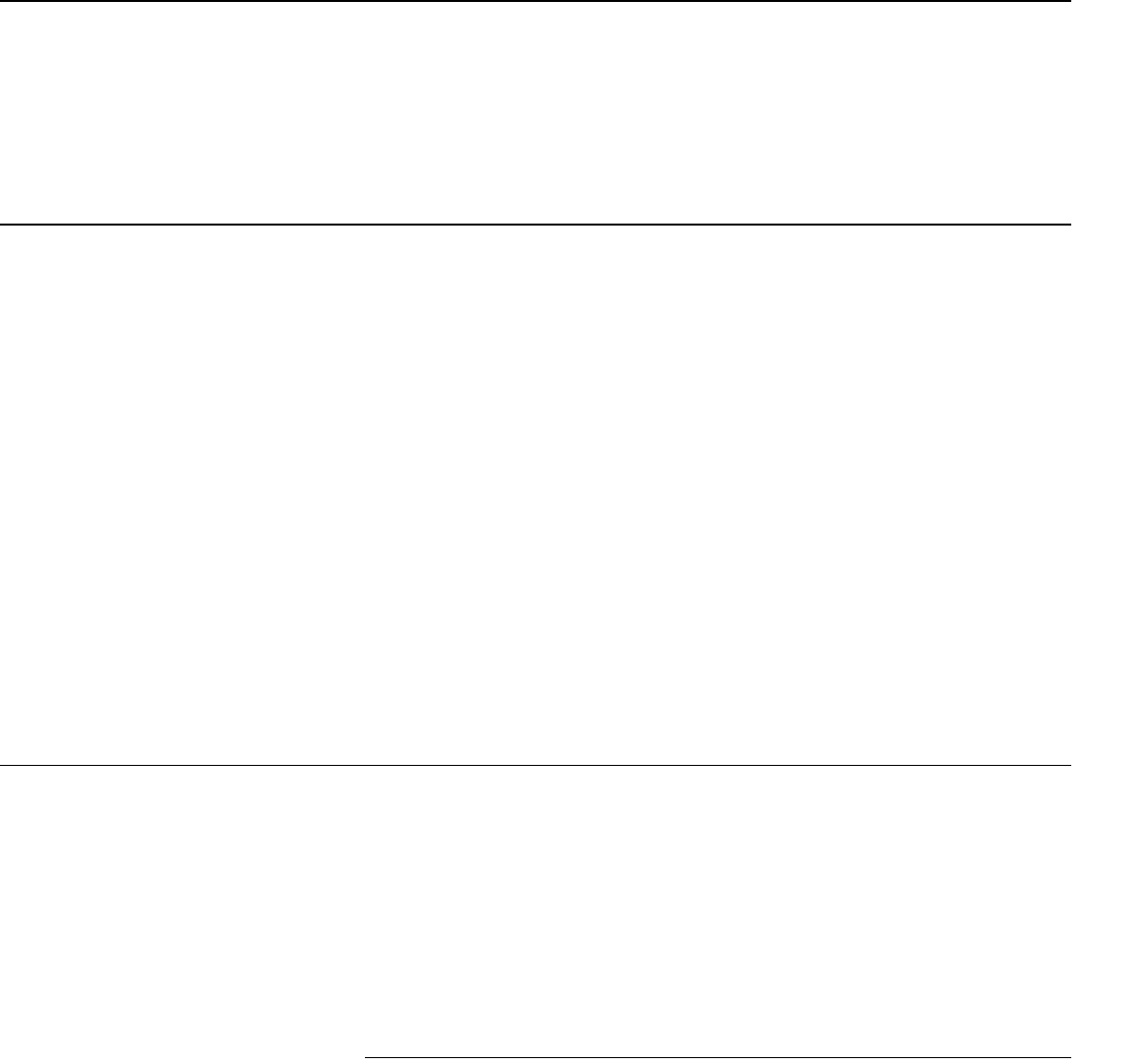

Table 1: Summary of Case Study State Rough Estimates of 2004 Tax Revenue from Acquired Services

State

Collected taxes paid on

acquired services

2004 revenue from taxes paid on acquired services (dollars in

millions)

California $0

Page 13 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Source: State officials.

Note: The next section contains a discussion of general limitations of the state estimates of revenue

from taxes.

While the Revenue

Impact of Eliminating

Grandfathering Would

Be Small, the

Moratorium’s Total

Revenue Impact Has

Been Unclear and Any

Future Impact Would

Vary by State

According to CBO data, grandfathered taxes in the states CBO studied

were a small percentage of those states’ tax revenues. However, because it

is difficult to know which states, if any, might have chosen to tax Internet

access services and what taxes they might have chosen to use if no

moratorium had ever existed, the total revenue implications of the

moratorium are unclear. In general, any future impact related to the

moratorium will differ from state to state.

According to Information in

CBO Reports, States Would

Lose a Small Fraction of

Their Tax Revenues If

Grandfathered Taxes on

Dial-up and DSL Services

Were Eliminated

In 2003, CBO reported how much state and local governments that had

grandfathered taxes on dial-up and DSL services would lose in revenues if

the grandfathering were eliminated. The fact that these estimates

represented a small fraction of state tax revenues is consistent with other

information we obtained. In addition, the enacted legislation was narrower

than what CBO reviewed, meaning that CBO’s stated concerns about VoIP

and taxing providers’ income and assets would have dissipated.

CBO provided two estimates in 2003 that, when totaled, showed that no

longer allowing grandfathered dial-up and DSL service taxes would cause

state and local governments to lose from more than $160 million to more

than $200 million annually by 2008. According to a CBO staff member, this

Kansas x 9-10

Mississippi x At most, 1

North Dakota 0

Ohio x 32.3

Rhode Island x Insignificant compared to total telecommunications tax revenues

Texas 0

Virginia 0

(Continued From Previous Page)

State

Collected taxes paid on

acquired services

2004 revenue from taxes paid on acquired services (dollars in

millions)

Page 14 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

estimate included some amounts for what we are calling acquired services

that, as discussed in the previous section, would not have to be lost. CBO

provided no estimates of revenues involved for governments not already

assessing the taxes and said it could not estimate the size of any additional

impacts on state and local revenues of the change in the definition of

Internet access. Further, according to a CBO staff member, CBO’s

estimates did not include any lost revenues from taxes on cable modem

services. In October 2003, around the time of CBO’s estimates, the number

of cable home Internet connections was 12.6 million, compared to 9.3

million home DSL connections and 38.6 million home dial-up connections.

CBO first estimated that as many as 10 states and several local

governments would lose $80 million to $120 million annually, beginning in

2007, if the 1998 grandfather clause were repealed. Its second estimate

showed that, by 2008, state and local governments would likely lose more

than $80 million per year from taxes on DSL service.

10

CBO’s estimates resulted from systematic, detailed analyses of information

from state and national sources and involved assumptions to deal with

uncertainties. In arriving at these estimates, CBO asked each state with

grandfathered taxes for information on how much it collected in taxes

related to access services. In addition, it estimated each state’s access

service-related taxes by using such data as the number of Internet users in

the state, the average fees that users paid to providers, applicable state tax

rates, expected amounts of dial-up versus broadband usage, and estimates

of possible noncompliance with tax assessments. See appendix II for

further information on the CBO methodology and associated limitations.

Rather than again doing what CBO had done and gathering information on

all 50 states, we tried to supplement what we learned from CBO by

exploring more in-depth information in case studies of eight states.

The CBO numbers are a small fraction of total state tax revenue amounts.

For example, the $80 million to $120 million estimate for the states with

originally grandfathered taxes for 2007 was about 0.1 percent of tax

revenues in those states for 2004—3 years earlier.

10

The more than $80 million per year is the amount of revenue that CBO expected state and

local governments to collect on DSL service and some acquired services by 2008. If the

jurisdictions had recognized that the reason for the 2004 amendments was largely moot, and

if they had not been collecting taxes on DSL service in the first place, they would not have

had part of the $80 million to lose.

Page 15 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

The fact that CBO estimates are a small part of state tax revenues is

consistent with information we obtained from our state case studies and

interviews with providers. For instance, after telling us whether various

access-related services, including cable modem service, were subject to

taxation in their jurisdictions, the states collecting taxes gave us rough

estimates of how much access service-related tax revenues they collected

for 2004 for themselves and their localities, if applicable. (See table 2.) All

except two collected $10 million or less. Even the largest state tax amount

reportedly collected in 2004 for Internet access revenues, excluding

collections for localities—$50 million in Texas—was only about one-sixth

of 1 percent of the state’s tax revenues for that year; the largest percentage

for any of our case study states was about 0.2 percent.

Table 2: Case Study State Officials’ Rough Estimates of Taxes Collected for 2004

Related to Internet Access

Source: State officials.

Note: The accompanying text contains a discussion of general limitations of the state estimates of

revenue from taxes.

a

According to a Mississippi official, although estimating a dollar amount would be extremely hard, the

state believes the amount collected was at most $1 million.

b

Rhode Island officials told us that taxes collected on access were taxes paid on services to retail

consumers, and Rhode Island did not have an estimate for taxes collected on acquired services.

c

Texas officials did not provide us with an estimate of taxes collected for Texas localities.

The states made their estimates by assuming, for instance, that access

service-related tax revenues were a certain percentage of state

telecommunications sales tax revenues, by reviewing providers’ returns, or

by making various calculations starting with census data. Most estimates

provided us were more ballpark approximations than precise

computations, and CBO staff expressed a healthy skepticism toward some

state estimates they received. They said that the supplemental state-by-

State Estimated taxes collected (dollars in millions)

California N/A

Kansas $9-10

Mississippi At most, 1

a

North Dakota 2.4

Ohio 52.1

Rhode Island Less than 4.5

b

Texas 50

c

Virginia N/A

Page 16 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

state information they developed sometimes produced lower estimates

than the states provided. According to others knowledgeable in the area,

estimates provided us were imprecise because when companies filed sales

or gross receipts tax returns with states, they did not have to specifically

identify the amount of taxes they received from providing Internet access-

related services to retail consumers or to other providers. As discussed

earlier, sales to other providers remain subject to taxation, depending on

state law. Some providers told us they did not keep records in such a way

as to be able to readily provide that kind of information. Also, although

states reviewed tax compliance by auditing taxpayers, they could not audit

all providers.

The dollar amounts in table 2 include amounts, where provided, for local

governments within the states. For instance, Kansas’s total includes about

$2 million for localities and North Dakota’s about $400,000 for localities. In

these states as well as in others we studied, local jurisdictions were

piggybacking on the state taxes, although the local tax rates could differ

from each other. For example, according to a state official, in Kansas the

state tax was 5.3 percent, and the state collected an average of another 1.3

percent for local jurisdictions. While we did encounter localities outside

our case study states that taxed access services under their own authority,

almost all the collections for local jurisdictions that we came across were

amounts collected by the states that were sent back to the localities.

State tax officials from our case study states who commented to us on the

impacts of the revenue amounts did not consider them significant.

Similarly, state officials voiced concerns but did not cite nondollar specifics

when describing any possible impact on their state finances arising from no

longer taxing Internet access services. However, one noted that taking

away Internet access as a source of revenue was another step in the

erosion of the state’s tax base.

11

Other state and local officials observed

that if taxation of Internet access were eliminated, the state or locality

would have to act somehow to continue meeting its requirement for a

balanced budget. At the local level, officials told us that a revenue decrease

would reduce the amount of road maintenance that could be done or could

adversely affect the number of employees available for providing

government services.

11

In the debate leading to the 2004 amendments’ passage, critics had expressed concern that

the federal government was interfering with state and local revenue-raising ability.

Page 17 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Because of the provisions in the enacted 2004 law, some unquantified

revenue losses noted by CBO in its 2003 study that could have grown to be

large no longer seem to pose the threat that some feared. For example,

CBO mentioned the possibility of state and local governments being unable

to tax customers’ telephone calls over the Internet. However, as enacted,

the 2004 amendments differed from the version reviewed by CBO and

contained language excluding Internet-based telephone service, known as

VoIP, from the moratorium.

12

In addition, CBO expressed concern that providers could bundle products

containing content, such as books and movies, call the product Internet

access, and have the whole bundle be exempt from taxes. Although some

people we interviewed still feared bundled content and information might

become tax free, they and others indicated they were aware of no court

cases in which this argument has been asserted.

13

The 2004 amendments also included a provision specifically allowing states

to tax Internet providers’ net income, capital stock, net worth, or property

value, addressing another concern raised by some parties.

Timing of Moratorium Might

Have Precluded Many States

from Taxing Access

Services, with Unclear

Revenue Implications

Because it is difficult to predict what states would have done to tax

Internet access services had Congress not intervened when it did, it is hard

to estimate the amount of revenue that was not raised because of the

moratorium. For instance, at the time the first moratorium was being

considered in 1998, the Department of Commerce reported Internet

connections for less than a fifth of U.S. households, much less than the half

of U.S. households reported 6 years later. Access was typically dial-up. As

states and localities saw the level of Internet connections rising and other

technologies becoming available, they might have taxed access services if

12

In our case studies, we found that even though the 2004 amendments did not affect the

taxation of VoIP, some state and local officials were still very concerned about VoIP’s

taxability. When questioned about the impact of the moratorium on his state’s financial

situation, one official noted that the state was more concerned about what will happen with

VoIP than about the current provisions of the 2004 amendments. Some local officials we

interviewed were concerned that legislation like the 2004 amendments is a step toward

eroding their ability to tax utilities such as telephone services. City officials were

apprehensive that additional legislation will “piggyback” on the 2004 amendments, exclude

services from state taxation, and eventually define VoIP as Internet access, having a severe,

detrimental effect on revenues.

13

Also see the first footnote in appendix I.

Page 18 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

no moratorium had been in place. Taxes could have taken different forms.

For example, jurisdictions might have even adopted bit taxes based on the

volume of digital information transmitted.

The number of states collecting taxes on access services when the first

moratorium was being considered in early 1998 was relatively small, with

13 states and the District of Columbia collecting these taxes, according to

the Congressional Research Service. Five of those jurisdictions later

eliminated or chose not to enforce their tax. In addition, not all 37 other

states would have taxed access services related to the Internet even if they

could have. For example, California had already passed its own Internet

tax moratorium in August 1998.

Still, after the moratorium began, other states showed an interest in taxing

Internet access services. Although the 1998 act precluded those

jurisdictions from taxing Internet access, it included language stating that

access services did not include telecommunications services. States

seeking to take advantage of this provision taxed parts of DSL service they

considered a telecommunications service and not an Internet access

service. If taxing DSL service shows a desire to tax access services in

general, many states not taxing dial-up or cable modem service

14

might

have done so but for the moratorium.

Given that some states never taxed access services while relatively few

Internet connections existed, that some stopped taxing access services,

and that others taxed DSL service, it is unclear what jurisdictions would

have done if no moratorium had existed. However, the relatively early

initiation of a moratorium reduced the opportunity for states inclined to tax

access services to do so before Internet connections became more

widespread.

Any Future Impact of the

Moratorium Will Vary by

State

Although as previously noted the impact of eliminating grandfathering

would be small in states studied by CBO or by us, any future impact related

to the moratorium will vary on a state-by-state basis for many reasons.

State tax laws differed significantly from each other, and states and

14

Care must be taken not to confuse cable television service and cable modem service,

which is used to deliver Internet access. Cable television service providers may also

provide cable modem service. Only cable modem service is subject to the moratorium.

Page 19 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

providers disagreed on how state laws applied to the providers. Appendix

III summarizes information we gathered about our case study states.

As shown in table 3, states taxed Internet access using different tax

vehicles imposed on diverse tax bases at various rates. The tax used might

be generally applicable to a variety of goods and services, as in Kansas,

which did not impose a separate tax on communications services. There,

the state’s general sales tax applied to the purchase of communications

services by access providers at an average rate of 6.6 percent, combining

state and average local tax rates. As another example, North Dakota

imposed a sales tax on retail consumers’ communications services,

including Internet access services, at an average state and local combined

rate of 6 percent. Rhode Island charged a 5 percent tax on companies’

telecommunications gross receipts.

Table 3: Characteristics Showing Variations among Case Study States

Source: State officials and laws.

a

For purposes of this report, a reference to a sales tax includes any ancillary use tax. Also for our

purposes, the difference between a sales and a gross receipts tax is largely a distinction without a

difference since the moratorium does not differentiate between them.

b

Rhode Island retail consumers did not pay this tax directly, but rather through the gross receipts tax

paid by their providers.

Our case study states showed little consistency in the base they taxed in

taxing services related to Internet access. States imposed taxes on

State Type of tax

a

Taxing retail

consumer

Internet access

services

Taxing acquired

services

State tax rate

(percentage)

Local tax rate

(percentage)

Exemptions of

customer types or

payment amounts

California N/A N/A N/A

Kansas Sales x 5.3 1.3 on average

Mississippi Gross

income

x 7.0 N/A

North Dakota Sales x 5.0 1.0-2.0

Ohio Sales x x 5.5 1.0 on average Residential

consumers

Rhode Island Gross

receipts and

sales

x

b

x 5.0,

6.0

N/A

Texas Sales x 6.25 2.0 limit First $25 of services

Virginia N/A N/A N/A

Page 20 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

different transactions and populations. North Dakota and Texas taxed only

services delivered to retail consumers. In a type of transaction which, as

discussed earlier, we do not view as subject to the moratorium, Kansas and

Mississippi taxed acquired communications services purchased by access

providers. Ohio and Rhode Island taxed both the provision of access

services and acquired services, and California and Virginia officials told us

their states taxed neither. States also provided various exemptions from

their taxes. Ohio exempted residential consumers, but not businesses,

from its tax on access services, and Texas exempted the first $25 of

monthly Internet access service charges from taxation.

Some state and local officials and company representatives held different

opinions about whether certain taxes were grandfathered and about

whether the moratorium applied in various circumstances. For example,

some providers’ officials questioned whether taxes in North Dakota,

Wisconsin, and certain cities in Colorado were grandfathered, and whether

those jurisdictions were permitted to continue taxing. Providers disagreed

among themselves about how to comply with the tax law of states whose

taxes may or may not have been grandfathered. Some providers told us

they collected and remitted taxes to the states even when they were

uncertain whether these actions were necessary; however, they told us of

others that did not make payments to the taxing states in similarly

uncertain situations. In its 2003 work, CBO had said that some companies

challenged the applicability of Internet access taxes to the service they

provided and thus might not have been collecting or remitting them even

though the states believed they should.

Because of all these state-by-state differences and uncertainties, the impact

of future changes related to the moratorium would vary by state. Whether

the moratorium were lifted or made permanent and whether

grandfathering were continued or eliminated, states would be affected

differently from each other.

External Comments

We showed staff members of CBO, officials of FTA, and representatives of

telecommunications companies assembled by the United States Telecom

Association a draft of our report and asked for oral comments. On

January 5, 2006, CBO staff members, including the Chief of the State and

Local Government Unit, Cost Estimates Unit, said we fairly characterized

CBO information and suggested clarifications that we have made as

appropriate. In one case, we have noted more clearly that CBO

supplemented its dollar estimates of revenue impact with a statement that

Page 21 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

other potential revenue losses could potentially grow by an unquantified

amount.

On January 6, 2006, FTA officials, including the Executive Director, said

that our legal conclusion was clearly stated and, if adopted, would be

helpful in clarifying which Internet access-related services are taxable and

which are not. However, they expressed concern that the statute could be

interpreted differently regarding what might be reasonably bundled in

providing Internet access to consumers. A broader view of what could be

included in Internet access bundles would result in potential revenue

losses much greater than we indicated. However, as explained in appendix

I, we believe that what is bundled must be reasonably related to accessing

and using the Internet. FTA officials were also concerned that our reading

of the 1998 law regarding the taxation of DSL services is debatable and

suggests that states overreached by taxing them. We recognize that

Congress acted in 2004 to address different interpretations of the statute,

and we made some changes to clarify our presentation. We acknowledge

there were different views on this matter, and we are not attributing any

improper intent to the states’ actions.

When meeting with us, representatives of telecommunications companies

said they would like to submit comments in writing. Appearing in appendix

IV, their comments argue that the 2004 amendments make acquired

services subject to the moratorium and therefore not taxable, and that the

language of the statute and the legislative history support this position. In

response, we made some changes to simplify appendix I. That appendix,

along with the section of the report on bundled access services and

acquired services, contains an explanation of our view that the language

and structure of the statute support our interpretation.

We are sending copies of this report to interested congressional

committees and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be

available at no charge on GAO’s Web site at

http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staffs have any questions about this report, please contact

me at (202) 512-9110 or

[email protected]. Contact points for our Offices of

Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page

Page 22 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are

listed in appendix V.

James R. White

Director, Tax Issues

Strategic Issues

Page 23 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Appendix I

AppendixesBundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed,

but Acquired Services Are Taxable

Appendix I

The moratorium bars taxes on the service of providing access, which

includes whatever an access provider reasonably bundles in its access

offering to consumers.

1

On the other hand, the moratorium does not bar

taxes on acquired services.

Bundled Services,

Including Broadband

Services, May Not Be

Taxed

As noted earlier, the 2004 amendments followed a period of significant

growth and technological development related to the Internet. By 2004,

broadband communications technologies were becoming more widely

available. They could provide greatly enhanced access compared to the

dial-up access technologies widely used in 1998. These broadband

technologies, which include cable modem service built upon digital cable

television infrastructure as well as digital subscriber line (DSL) service,

provide continuous, high-speed Internet access without tying up wire-line

telephone service. Indeed, cable and DSL facilities could support multiple

services—television, Internet access, and telephone services—over

common coaxial cable, fiber, and copper wire media.

The Internet Tax Freedom Act bars “taxes on Internet access” and defines

“Internet access” as a service that enables “users to access content,

information, electronic mail, or other services offered over the Internet.”

The term Internet access as used in this context includes “access to

proprietary content, information, and other services as part of a package of

services offered to users.” The original act expressly excluded

“telecommunications services” from the definition.

2

As will be seen, the act

barred jurisdictions from taxing services such as e-mail and instant

messaging bundled by providers as part of their Internet access package;

however, it permitted dial-up telephone service, which was usually

provided separately, to be taxed.

1

Notwithstanding fears expressed by some during consideration of the 2004 amendments,

this does not mean that anything may be bundled and thus become tax exempt. Clearly,

what is bundled must be reasonably related to accessing and using the Internet, including

electronic services that are customarily furnished by providers. In this regard, it is

fundamental that a construction of a statute cannot be sustained that would otherwise

result in unreasonable or absurd consequences. Singer, 2A Sutherland Statutory

Construction, § 45:12 (6

th

ed., 2005).

2

The 1998 act defined Internet access as “a service that enables users to access content,

information, electronic mail, or other services offered over the Internet, and may also

include access to proprietary content, information, and other services as part of a package

of services offered to users. Such term [Internet access] does not include

telecommunications services.”

Appendix I

Bundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed,

but Acquired Services Are Taxable

Page 24 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

The original definition of Internet access, exempting “telecommunications

services,” was changed by the 2004 amendment. Parties seeking to carve

out exceptions that could be taxed had sought to break out and treat DSL

services as telecommunications services, claiming the services were

exempt from the moratorium even though they were bundled as part of an

Internet access package. State and local tax authorities began taxing DSL

service, creating a distinction between DSL and services offered using

other technologies, such as cable modem service, a competing method of

providing Internet access that was not to be taxed. The 2004 amendment

was aimed at making sure that DSL service bundled with access could not

be taxed. The amendment excluded from the telecommunications services

exemption telecommunications services that were “purchased, used, or

sold by a provider of Internet access to provide Internet access.”

The fact that the original 1998 act exempted telecommunications services

shows that other reasonably bundled services remained a part of Internet

access service and, therefore, subject to the moratorium. Thus,

communications services such as cable modem services that are not

classified as telecommunications services are included under the

moratorium.

Acquired Services May

Be Taxed

As emphasized by numerous judicial decisions, we begin the task of

construing a statute with the language of the statute itself, applying the

canon of statutory construction known as the plain meaning rule. E.g.

Hartford Underwriter Insurance Co. v. Union Planers Bank, N.A., 530

U.S. 1 (2000); Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337 (1997). Singer, 2A

Sutherland Statutory Construction, §§

46:1, 48A:11, 15-16. Thus, under the

plain meaning rule, the primary means for Congress to express its intent is

the words it enacts into law and interpretations of the statute should rely

upon and flow from the language of the statute.

As noted above, the moratorium applies to the “taxation of Internet

access.” According to the statute, “Internet access” means a service that

enables users to access content, information, or other services over the

Internet. The definition excludes “telecommunications services” and, as

amended in 2004, limits that exclusion by exempting services “purchased,

used, or sold” by a provider of Internet access. As amended in 2004, the

statute now reads as follows:

“The term ‘Internet access’ means a service that enables users to access content,

information, electronic mail, or other services offered over the Internet….The term

Appendix I

Bundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed,

but Acquired Services Are Taxable

Page 25 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

“Internet access” does not include telecommunications services, except to the extent such

services are purchased, used, or sold by a provider of Internet access to provide internet

access.” Section 1105(5).

The language added in 2004--exempting from “telecommunications

services” those services that are “purchased, used, or sold” by a provider in

offering Internet access--has been read by some as expanding the “Internet

access” to which the tax moratorium applies, by barring taxes on “acquired

services.” Those who would read the moratorium expansively take the

view that everything acquired by Internet service providers (ISP)

(everything on the left side of figure 3) as well as everything furnished by

them (everything in the middle of figure 3) is exempt from tax.

In our view, the language and structure of the statute do not permit the

expansive reading noted above. “Internet access” was originally defined

and continues to be defined for purposes of the moratorium as the service

of providing Internet access to a user. Section 1105(5). It is this

transaction, between the Internet provider and the end user, which is

nontaxable under the terms of the moratorium.

3

The portion of the

definition that was amended in 2004 was the exception: that is,

telecommunication services are excluded from nontaxable “Internet

access,” except to the extent such services are “purchased, used, or sold by

a provider of Internet access to provide Internet access.” Thus, we

conclude that the fact that services are “purchased, used, or sold” by an

Internet provider has meaning only in determining whether these services

can still qualify for the moratorium notwithstanding that they are

“telecommunications services;” it does not mean that such services are

independently nontaxable irrespective of whether they are part of the

service an Internet provider offers to an end user. Rather, a service that is

“purchased, used, or sold” to provide Internet access is not taxable only if it

is part of providing the service of Internet access to the end user. Such

services can be part of the provision of Internet access by a provider who,

for example, “purchases” a service for the purpose of bundling it as part of

an Internet access offering; “uses” a service it owns or has acquired for that

purpose; or simply “sells” owned or acquired services as part of its Internet

access bundle.

3

As noted previously, the moratorium applies to “taxes on Internet access.” Related

provisions defining a “tax on Internet access” for purposes of the moratorium focus on the

transaction of providing the service of Internet access: such a tax is covered “regardless of

whether such tax is imposed on a provider of Internet access or a buyer of Internet access.”

Section 1105(10).

Appendix I

Bundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed,

but Acquired Services Are Taxable

Page 26 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

In addition, we read the amended exception as applying only to services

that are classified as telecommunications services under the 1998 act as

amended. In fact, the moratorium defines the term “telecommunications

services” with reference to its definition in the Communications Act of

1934,

4

under which DSL and cable modem service are no longer classified

as telecommunications services.

5

Moreover, under the Communications

Act, the term telecommunications services applies to the delivery of

services to the end user who determines the content to be communicated;

it does not apply to communications services delivered to access service

providers by others in the chain of facilities through which Internet traffic

may pass. Thus, since broadband services are not telecommunications

services, the exception in the 1998 act does not apply to them, and they are

not affected by the exception.

6

The best evidence of statutory intent is the text of the statute itself. While

legislative history can be useful in shedding light on the intent of the statute

or to resolve ambiguities, it is not to be used to inject ambiguity into the

statutory language or to rewrite the statute. E.g., Shannon v. United States

512 U.S. 573, 583 (1994). In our view, the definition of Internet access is

unambiguous, and, therefore, it is unnecessary to look beyond the statute

to discern its meaning from legislative history. We note, however, that

consistent with our interpretation of the statute, the overarching thrust of

changes made by the 2004 amendments to the definition of Internet access

was to take remedial correction to assure that broadband services such as

DSL were not taxable when bundled with an ISP’s offering. While there are

some references in the legislative history to “wholesale” services,

4

47 U.S.C. §153(46).

5

DSL and cable modem services are now referred to as “information services with a

telecommunications component,” under the Communications Act of 1934. See In the

Matter of Appropriate Framework for Broadband Access to the Internet over Wireline

Facilities, FCC 05-150, (2005), and related documents, including In the Matter of

Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act and Broadband Access and

Services, FCC 05-153, 2995 WL 2347773 (F.C.C.) (2005). Although FCC announced its

intention as early as February 15, 2002, to revisit its initial classification of DSL service as a

telecommunications service under the Communications Act (In the Matter of Appropriate

Framework for Broadband Access to the Internet over Wireline Facilities, FCC 02-42, 17

F.C.C.R. 3019, 17 FCC Rcd. 3019), it was not until after the Supreme Court’s decision in

National Cable & Telecommunications Ass'n v. Brand X Internet Services, 125 S.Ct. 2688

(2005), that it actually did so.

6

There was some awareness during the debate that the then pending Brand X litigation

(“Ninth Circuit Court opinion affecting DSL and cable”) could affect the law in this area.

See comments by Senator Feinstein, 150 Cong. Rec. S4666.

Appendix I

Bundled Access Services May Not Be Taxed,

but Acquired Services Are Taxable

Page 27 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

backbone, and broadband, many of these pertained to earlier versions of

the bill containing language different from that which was ultimately

enacted.

7

The language that was enacted, using the phrase “purchased,

used, or sold by a provider of Internet access” was added through the

adoption of a substitute offered by Senator McCain, 150 Cong. Rec. S4402,

which was adopted following cloture and agreement to several

amendments designed to narrow differences between proponents and

opponents of the bill. Changes to legislative language during the

consideration of a bill may support an inference that in enacting the final

language, Congress intended to reject or work a compromise with respect

to earlier versions of the bill. Statements made about earlier versions carry

little weight. Landgraf v. USI Film Products, 511 U.S. 244, 255-56 (1994).

Singer, 2A Sutherland Statutory Construction, §

48:4. In any event, the

plain language of the statute remains controlling where, as we have

concluded, the language and the structure of the statute are clear on their

face.

7

For example, proponents of giving the statute a broader interpretation cite S. REP. 108-155,

108

TH

CONG., 1

ST

SESS. (2003), which includes the following statement.

“The Committee intends for the tax exemption for telecommunications services to apply whenever the

ultimate use of those telecommunications services is to provide Internet access. Thus, if a

telecommunications carrier sells wholesale telecommunications services to an Internet service

provider that intends to use those telecommunications services to provide Internet access, then the

exemption would apply.”

At the time the 2003 report was drafted, the sentence of concern in the draft legislation read,

“Such term [referring to Internet access] does not include telecommunications services,

except to the extent such services are used to provide Internet access.” As adopted, the

wording became, “The term 'Internet access' does not include telecommunications services,

except to the extent such services are purchased, used, or sold by a provider of Internet

access to provide Internet access.” The amended language thus focuses on the package of

services offered by the access provider, not on the act of providing access alone.

Page 28 GAO-06-273 Internet Access Tax Moratorium

Appendix II

CBO’s Methodology for Estimating Costs

Relating to Taxing Internet Access Services

Appendix II

According to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) staff, CBO estimated

revenue losses to states and localities from changing how Internet access

was taxed by using two independent methodologies and comparing their

results. First, it collected information directly from the states. Using data

from the Federation of Tax Administrators and the Multistate Tax

Commission to identify states taxing access and their related tax

collections, CBO discussed with state officials what the dollar amounts

included and what they did not. It then reduced the state loss estimates by

various percentages to get a sense of the ranges possible by assuming, for

instance, that providers were not always paying the taxes states thought

they should pay.

To estimate from a second direction, CBO compiled its own state-by-state

information. It multiplied the number of Internet users by state times an

average access fee for each user times the state’s applicable tax rate. It

then discounted each state total based on assumptions about

noncompliance with tax assessments.

To arrive at the number of users, according to CBO staff, CBO consulted

the Department of Commerce, the Federal Communications Commission,

and studies of Internet usage. From these sources, it obtained historical

numbers of users and trends that it could project showing the number of

users growing over time, and how usage was changing between dial-up and

high-speed.

Finally, according to the staff members, CBO gathered the other

information for its state-by-state estimate from other sources. It obtained

state tax rates from Council on State Taxation information and computed a

weighted average access fee after calling access providers about their

current rates. It assumed that any change in revenues brought on by

changes in technology and markets would offset each other. It estimated

noncompliance to cover both tax avoidance and nexus

1

issues by using