August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

1

HP-2022-20

Unwinding the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision:

Projected Enrollment Effects and Policy Approaches

KEY POINTS

• After expiration of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), Medicaid’s continuous

enrollment provision will come to an end. Using longitudinal survey data and 2021 enrollment

information, we currently project that 17.4 percent of Medicaid and Children’s Health

Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollees (approximately 15 million individuals) will leave the

program based on historical patterns of coverage loss.

• Approximately 9.5 percent of Medicaid enrollees (8.2 million) will leave Medicaid due to loss of

eligibility and will need to transition to another source of coverage. Based on historical

patterns, 7.9 percent (6.8 million) will lose Medicaid coverage despite still being eligible

(“administrative churning”), although HHS is taking steps to reduce this outcome.

• Children and young adults will be impacted disproportionately, with 5.3 million children and 4.7

million adults ages 18-34 predicted to lose Medicaid/CHIP coverage. Nearly one-third of those

predicted to lose coverage are Latino (4.6 million) and 15 percent (2.2 million) are Black.

• Almost one-third (2.7 million) of those predicted to lose eligibility are expected to qualify for

Marketplace premium tax credits. Among these individuals, over 60 percent (1.7 million) are

expected to be eligible for zero-premium Marketplace plans under the provisions of the

American Rescue Plan (ARP). Another 5 million would be expected to obtain other coverage,

primarily employer-sponsored insurance.

• An estimated 383,000 individuals projected to lose eligibility for Medicaid would fall in the

coverage gap in the remaining 12 non-expansion states – with incomes too high for Medicaid,

but too low to receive Marketplace tax credits. State adoption of Medicaid expansion in these

states is a key tool to mitigate potential coverage loss at the end of the PHE.

• States are directly responsible for eligibility redeterminations, while CMS provides technical

assistance and oversight of compliance with Medicaid regulations. Eligibility and renewal

systems, staffing capacity, and investment in end-of-PHE preparedness vary across states. HHS

is working with states to facilitate enrollment in alternative sources of health coverage and

minimize administrative churning. These efforts could reduce the number of eligible people

losing Medicaid compared to the estimates above.

• The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 extends the ARP’s enhanced and expanded Marketplace

premium tax credit provisions until 2025, providing a key source of alternative coverage for

those losing Medicaid eligibility.

August 19, 2022

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

2

INTRODUCTION

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) mandated continuous Medicaid enrollment throughout

the federal COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) period for nearly all of those enrolled in Medicaid on or

after the date of enactment on March 18, 2020, through the end of the month in which the PHE declaration

ends. In exchange for meeting these and other provisions, the FFCRA temporarily increased the federal

medical assistance percentage (FMAP) by 6.2 percentage points, which all states received. The continuous

enrollment provision suspended Medicaid’s regular eligibility renewal and redetermination process by

prohibiting termination of ineligible individuals as a condition of receiving the temporary increased FMAP

except for those who voluntarily disenroll or are no longer a state resident.

*

A temporary increase in federal

matching also applies to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) during the PHE, and the continuous

enrollment provision applied to states running CHIP as part of combined Medicaid/CHIP programs.

†

At the end

of the PHE states will have 12 months to initiate redeterminations of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility for all

enrollees and two additional months (14 months total) to complete all pending actions. State Medicaid

programs vary with respect to their staffing, administrative capacity, and sophistication of enrollment and

renewal systems.

The nation’s uninsured rate declined to a historic low of 8.0% in the first quarter of 2022, due in part to the

continuous enrollment provision in Medicaid as well as strong enrollment outreach efforts and expanded

Marketplace subsidies under the American Rescue Plan (ARP).

1

Between February 2020 and December 2021,

Medicaid enrollment grew by approximately 15.5 million individuals, from 71.2 million to 86.7 million (a 21.8

percent increase).

2

Many of these individuals gained Medicaid eligibility due to pandemic-related changes in

income and employment, while others may have enrolled in Medicaid during this time due to a change in

family composition (e.g., the addition of a child), disability, or pregnancy status. Research indicates that

Medicaid enrollment growth during the pandemic was primarily driven by increased retention of existing

enrollees rather than new applications.

3

,

4

Coverage changes in Medicaid are common, and even short gaps in insurance can have negative effects on

access to care.

5

,

6

A recent analysis found that 21 percent of Medicaid enrollees changed coverage within one

year, with 8 percent disenrolling and reenrolling in Medicaid within the year.

7

Changes in Medicaid coverage

occur for several reasons, including loss of Medicaid eligibility due to income fluctuations or changes in family

circumstances, becoming eligible for a different source of coverage (e.g., through an employer ), or

administrative churning. Administrative churning refers to the loss of Medicaid coverage despite ongoing

eligibility, which can occur if enrollees have difficulty navigating the renewal process, states are unable to

contact enrollees due to a change of address, or other administrative hurdles.

Based on typical coverage changes in Medicaid that would have occurred without the continuous enrollment

provision, and the economic and labor market fluctuations that occurred during the PHE, many current

enrollees will no longer be eligible for Medicaid after the PHE ends and will need to transition to a different

source of coverage (sometimes referred to as “unwinding” the coverage protections of the COVID-19 PHE).

Additionally, some enrollees may be at risk of Medicaid coverage loss due to administrative reasons. The risk

of administrative churning may be particularly high after the PHE due to the volume of redeterminations states

must conduct and the time since Medicaid agencies last communicated with many beneficiaries. Previous

_______________________

*

States are required to review eligibility only once every 12 months for beneficiaries whose eligibility is based on Modified Adjusted

Gross Income (MAGI) methodologies and at least once every 12 months for non-MAGI beneficiaries.

†

The enhanced federal match rate for CHIP is the result of the standard calculation of CHIP’s FMAP, which is based on Medicaid’s

FMAP. The continuous enrollment provision does not apply to people enrolled in separate CHIP programs. See:

https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-faqs.pdf

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

3

analyses have projected the estimated number of individuals likely to lose Medicaid coverage at the end of the

PHE, with one study predicting a range of 5 to 14 million individuals and another predicting 12.9 to 15.8 million

individuals leaving Medicaid.

8

,

9

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is leveraging all of

its programs and divisions in a robust stakeholder engagement strategy to ensure individuals remain

connected to coverage. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is working closely with state

Medicaid agencies, Marketplaces, navigators, health plans, and many others. These efforts are outlined later

in the Discussion section.

This issue brief presents current HHS projections of transitions in coverage due to the sunset of the continuous

enrollment provision at the end of the PHE; describes administrative actions underway to mitigate coverage

losses; and highlights legislative approaches including the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 that could help

promote seamless coverage transitions at the end of the PHE.

METHODS

The objectives of this analysis were to predict the range of estimates for how many Medicaid enrollees are

likely to lose coverage when the PHE ends, assess whether coverage loss is likely to be due to loss of eligibility

or due to administrative churning, and identify alternative coverage options available to those who lose

Medicaid.

This analysis used the Survey for Income and Program Participation (SIPP), based on data from March 2015 to

November 2016. The SIPP is a nationally representative, longitudinal panel survey in which respondents are

followed across multiple years (4 years in total for each panel) and income and health insurance enrollment

information is collected monthly. In our analysis, the 21-month timespan from March 2015 to November 2016

was treated as an analogous period to the PHE lasting March 2020 through December 2021. Based on the

2015-2016 data, we estimated Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in December 2016 (analogous to December

2021, the projected end of the PHE) among those enrolled in Medicaid for at least one month between March

2015 and November 2016, the 21-month PHE simulation period. Once someone enrolled in Medicaid during

the PHE, we treated them as enrolled until the end of the PHE.

We classified our study sample of those “ever in Medicaid” during the 21-month period from March 2015

through November 2016 into three categories at the end of the PHE: (1) those still eligible and enrolled in

Medicaid; (2) those eligible for Medicaid but no longer enrolled (i.e., not enrolled due to administrative

churning); and (3) those no longer eligible for Medicaid (i.e., not eligible due to income or a change in

categorical status).

‡

In addition to enrollment, we also estimated eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP based on

January 2021 modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) percent-of-poverty limit rules, which captures variation

by state and eligibility group (infants, children 1-5, children 6-18, pregnant beneficiaries, adult

parents/caregivers, other adults, and beneficiaries 65 or older). We assume individuals receiving

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) remained automatically enrolled in Medicaid.

§

For all SIPP estimates,

references to Medicaid include CHIP except where otherwise noted.

Among those ineligible for Medicaid at the end of the PHE, we assessed enrollment and eligibility for

subsidized Marketplace coverage, employer-sponsored insurance (ESI), and other coverage based on 2021 ARP

eligibility criteria. Individuals were deemed eligible for subsidized Marketplace coverage if they were not

_______________________

‡

In this brief, the term “eligible” refers to individuals that could obtain Medicaid coverage based on the Medicaid eligibility

requirements in their state but does not mean that an individual is enrolled in Medicaid coverage.

§

Eligibility predictions do not account for medically needy pathways or other optional pathways for seniors or those with disabilities.

Those who reported being enrolled in Medicaid in December 2016 were classified as eligible for Medicaid regardless of whether they

were predicted to be eligible based on these rules.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

4

eligible for Medicaid, had incomes above 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL), and did not have access to

minimum essential coverage (MEC).

**

To calculate zero-premium Marketplace coverage options under the

ARP among subsidy-eligible individuals, we applied estimates of the proportion of the uninsured population

eligible for zero-premium plans based on American Community Survey data and county-level premium rates.

10

Medicaid coverage enrollment and eligibility estimates were calculated by Medicaid expansion status, age,

race and ethnicity, income, and sex.

We consider several alternative scenarios and time frames for coverage changes, depending on the rate of

administrative churning compared to historical rates, and how quickly states choose to conduct their

redeterminations after the expiration of the PHE.

All estimates presented in this brief have been projected forward to account for the difference in Medicaid

enrollment between December 2016 and December 2021. The primary limitation of this analysis is that the

data are based on historical data. Although differences in Medicaid enrollment are accounted for, differences

in population changes or economic conditions between 2014-2016 and now are not. Therefore, estimates may

not reflect the present-day distribution of income or rates of administrative churning. Also, due to the

unknown expiration date of the PHE, our analysis, which is based on an end date of the PHE of December

2021, will slightly underestimate the total population affected by the end of the continuous enrollment

provision. In addition, while the SIPP data shows actual insurance enrollment in December 2016, in the post-

PHE period, it is likely to take recently-disenrolled people time to identify and enroll in other available

coverage options. Estimates of zero-dollar premium availability were based on population-level averages for

the subsidy-eligible uninsured population as a whole, rather than based on individual income and premiums;

accordingly, these projections are not precise estimates and should be interpreted with caution. Finally, all

references to Medicaid eligibility or enrollment in the SIPP analysis include CHIP. However, while many

children continue to be eligible for CHIP after losing Medicaid, our analysis did not separately estimate

eligibility for CHIP versus Medicaid at the end of the PHE, or distinguish between states with separate CHIP

programs and those that are combined with Medicaid, since the SIPP did not have adequate sample size for

reliable state estimates.

RESULTS

An estimated 80.1 million individuals were enrolled in Medicaid at some point during the 21-month study

period (2015-2016). This estimate is lower than actual December 2021 Medicaid/CHIP enrollment of 86.7

million, but all remaining estimates in this report were adjusted to account for this difference in enrollment.

Total Medicaid Disenrollment

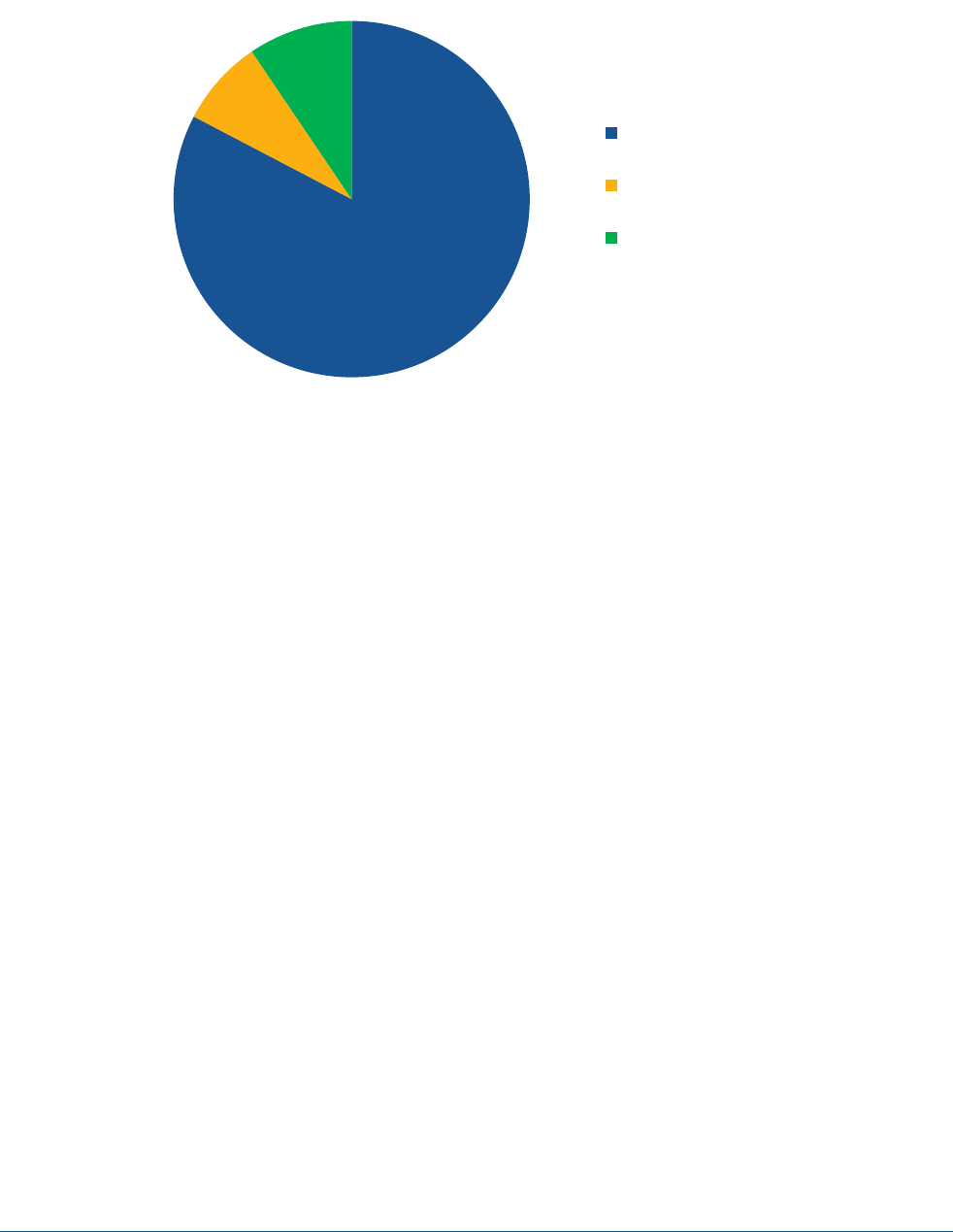

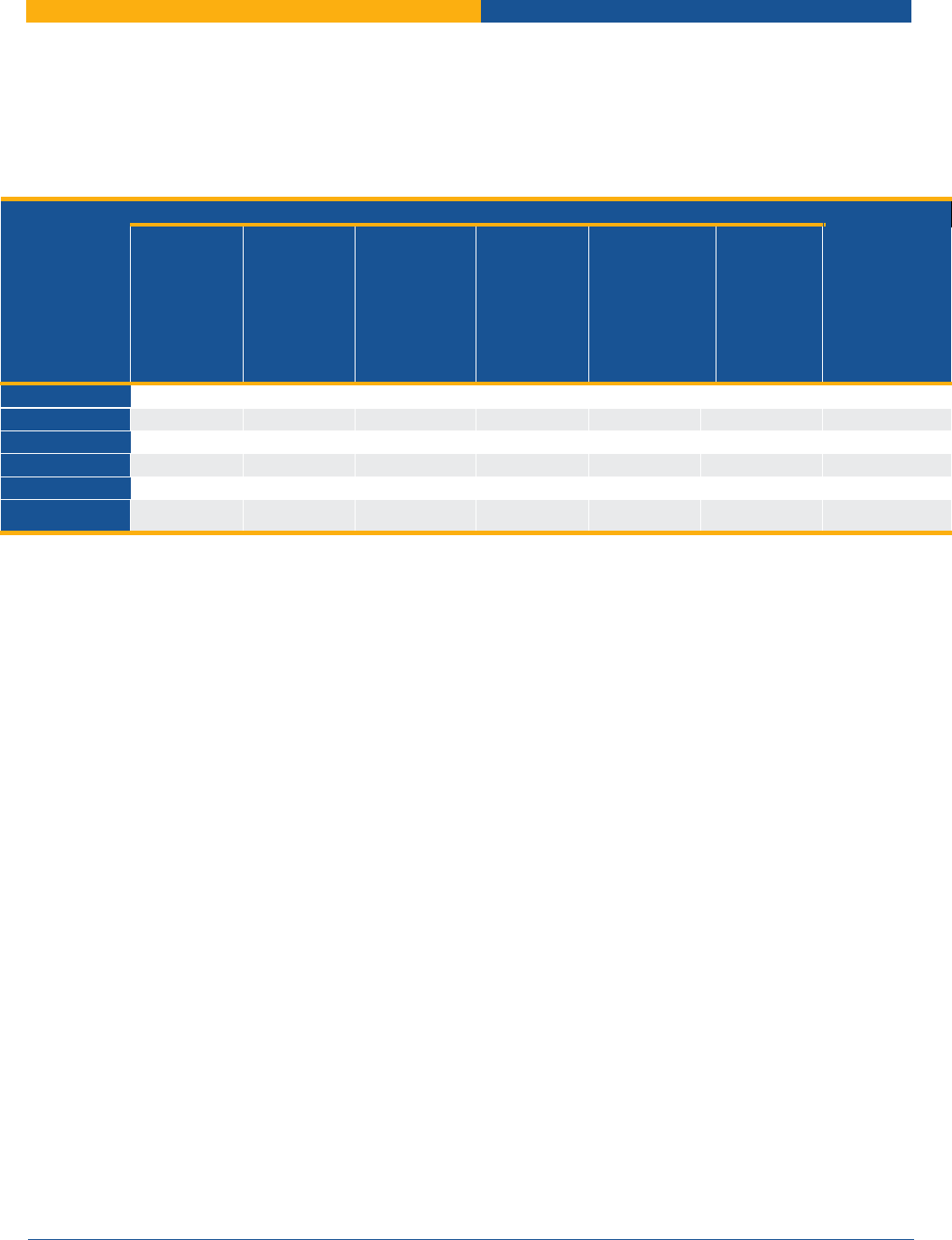

Figure 1 shows the predicted proportion of Medicaid enrollees that maintained Medicaid enrollment, were

ineligible for Medicaid, or experienced administrative churning (i.e., were eligible for Medicaid but not

enrolled) based on 2015/2016 SIPP data. Approximately 9.5 percent of enrollees (8.2 million of 86.7 million)

were predicted to be ineligible for Medicaid after the PHE, while 7.9 percent (6.8 million of 86.7 million) were

predicted to lose coverage despite being eligible for Medicaid. Combined, this leaves 82.7 percent (or 71.7

million people) predicted to be eligible and maintain enrollment in Medicaid post-PHE, and 15 million total

_______________________

**

MEC was defined as coverage as of December 2016 in Medicare, CHAMPUS, VA, TRICARE, or health insurance provided by someone

outside of the household. Coverage provided through “other” insurance or the Indian Health Service were not classified as MEC.

Income determinations were based on December 2015 MAGI rules.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

5

predicted to leave the program from loss of eligibility or administrative churning. The primary reasons for

Medicaid eligibility loss were changes in income, changes in family composition, or moving to another state.

Figure 1. Predicted Eligibility, Ineligibility, and Administrative Churn Among Medicaid Enrollees at End of PHE

Source: Analysis of SIPP treating March 2015-Nov. 2016 as analogous to March 2020-Dec. 2021 PHE, among enrollees ever-

enrolled in Medicaid during the 21-month period.

Potential Trajectories of Administrative Churning

We estimated five different scenarios based on varying degrees of administrative churning and

redetermination time frames to estimate how disenrollment will be impacted. Scenarios 1-4 assume an even

rate of redeterminations processed over the 12 months of 2021, while scenario 5 assumes states process

redeterminations over a six-month timeframe. The scenarios were:

1. A “no churning” scenario in which only those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid are disenrolled.

While this scenario is not realistic since it assumes zero percent administrative churning among still-

eligible individuals, it provides a sense of how many people are likely to lose Medicaid even if renewal

were fully optimized and no eligible individuals left the program. In this scenario, a total of 8.2 million

individuals will lose Medicaid coverage at the end of the PHE due to a change in Medicaid eligibility

and 684,000 individuals would leave Medicaid each month during the first year after the PHE

expiration.

2. A “low churning” scenario in which those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid are disenrolled (8.2

million), and administrative churning is half of the 2016 historical rate. This scenario would result in

total disenrollment (administrative churning plus eligibility loss) of 11.6 million individuals and monthly

disenrollment of 968,000 individuals over 12 months.

3. A “typical churning” scenario in which the 8.2 million individuals who are no longer eligible for

Medicaid are disenrolled and churning rates match the historical average in 2016 SIPP data. This

scenario reflects the primary estimates (“Base Case”) presented throughout this brief. Under this

scenario, a total of 15 million individuals are predicted to leave Medicaid, with monthly disenrollment

of 1.3 million individuals over 12 months.

4. A “high churning” scenario in which we assume those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid are

disenrolled, as well as 50 percent excess administrative churning above historical rates. This scenario

could occur if there is substantial beneficiary confusion, high rates of moving or changes in residence,

and/or overloaded state Medicaid eligibility systems. This scenario would result in total disenrollment

of 18.4 million individuals, with monthly disenrollment of 1.5 million individuals over 12 months.

71.7M

(82.7%)

8.2M

(9.5%)

6.8M

(7.9%)

Still Enrolled in Medicaid

Not Eligible for Medicaid

Administrative Churning

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

6

5. A “high churning” six-month redetermination scenario in which we assume those who are no longer

eligible are disenrolled as well as 50 percent excess administrative churning processed over a six-

month timeframe. This would result in the same total disenrollment as in scenario 4 (18.4 million

individuals) but monthly disenrollment of 3.1 million individuals over six months.

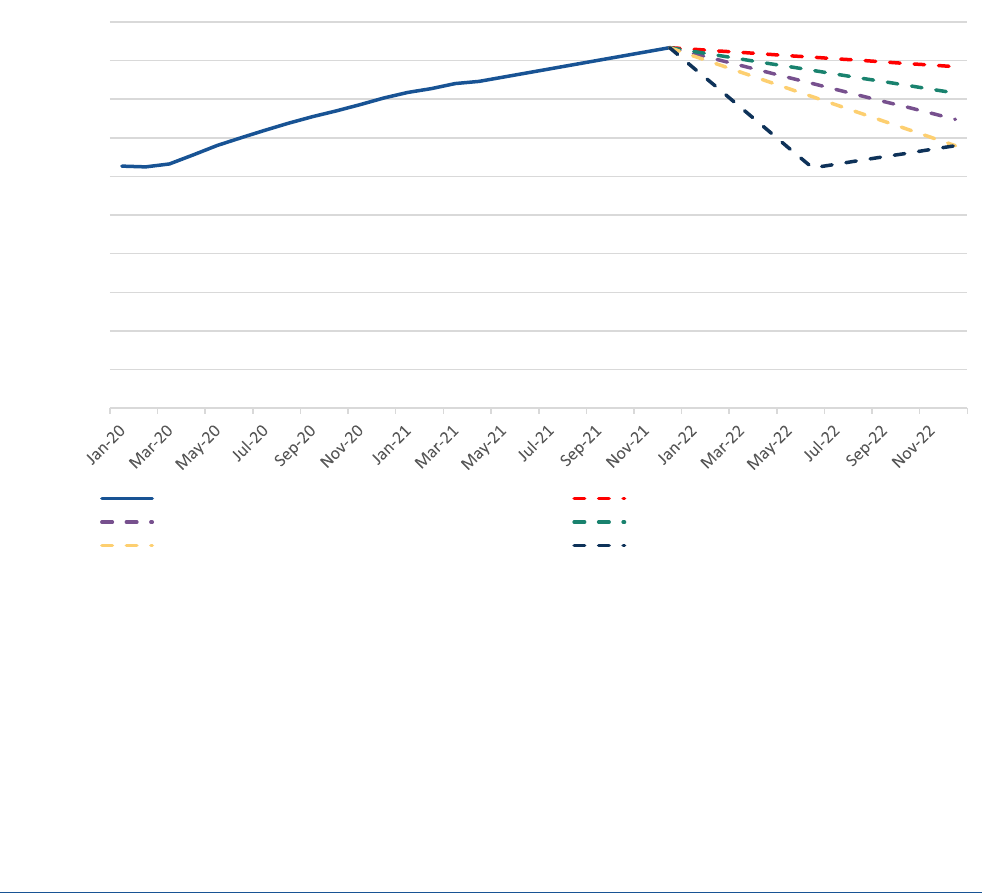

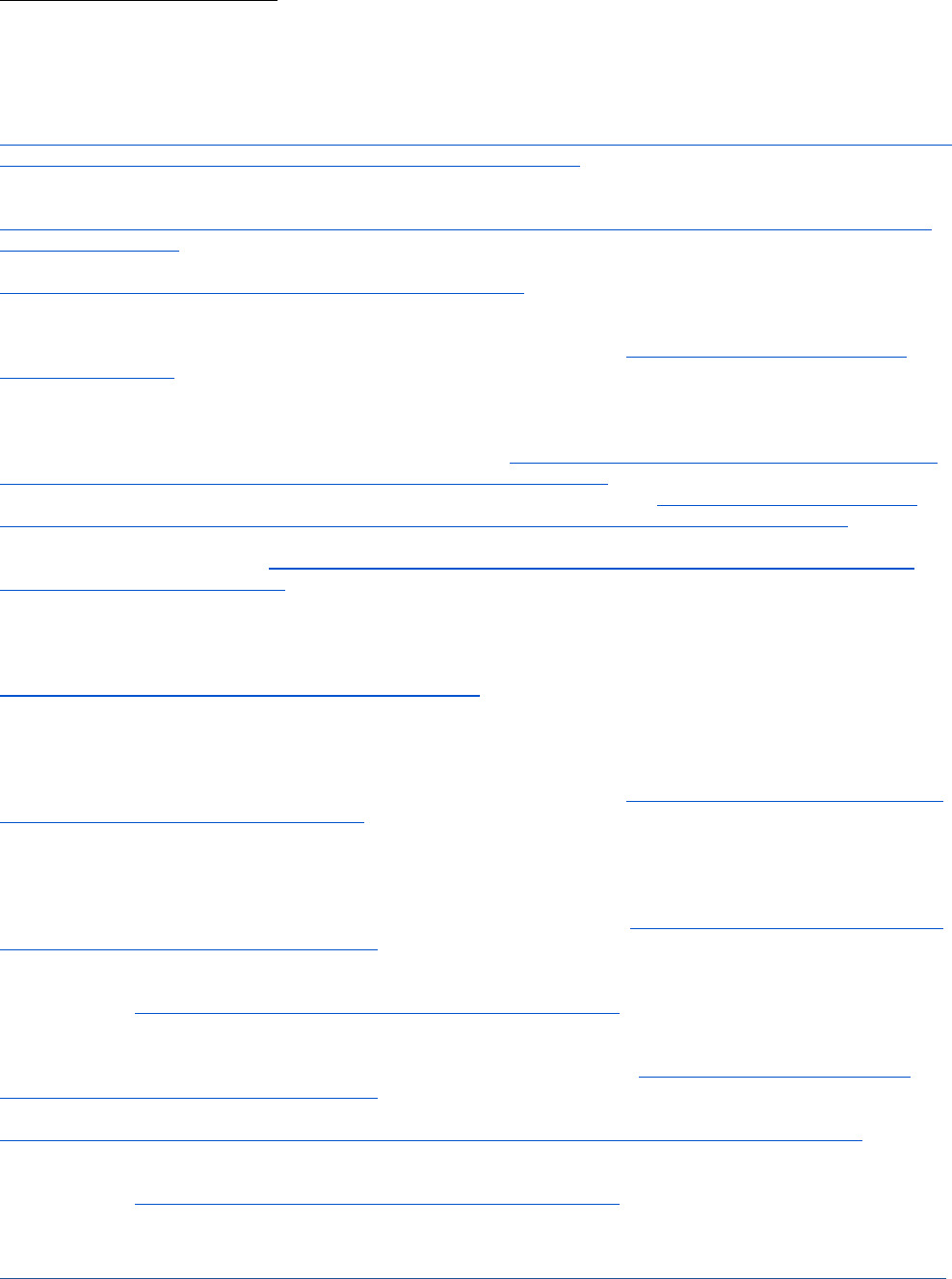

Figure 2 plots actual monthly Medicaid enrollment from January 2020 – December 2021 and projects total

Medicaid eligibility loss during 2022 under the above five scenarios. The projections in Figure 2 account for

new monthly enrollment (based on January-April 2021 enrollment rates), but do not account for individuals

who were disenrolled from Medicaid at the end of the PHE who may re-enroll over the course of 2022. The

scenarios shown in Figure 2 result in a range of total Medicaid enrollment estimates by December 2022, from

74 million under a high churning scenario to 84 million under a scenario with a zero rate of churning.

Accounting for new enrollment, we predict that net totals of 5.8 million, 9.3 million, and 12.7 million would

leave the program from loss of eligibility or administrative churning across low, medium, and high levels of

historical churning, respectively.

Figure 2. Projected Medicaid Coverage Loss During 12 Months of 2022 Under Alternative Assumptions About

Rates of Administrative Churning

Demographics

Demographics and State Patterns of Individuals Leaving Medicaid

Among the 8.2 million individuals predicted to be ineligible for Medicaid in the post-PHE period, 5.4 million (66

percent) resided in states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as of 2021, while 2.8

million (34 percent) resided in non-expansion states (Table 1). Among the 6.8 million individuals predicted to

be disenrolled despite being eligible for Medicaid, 4.7 million (69%) resided in expansion states and 2.1 million

(31%) resided in non-expansion states (Table 1).

84M

77M

81M

74M

71M

40,000,000

45,000,000

50,000,000

55,000,000

60,000,000

65,000,000

70,000,000

75,000,000

80,000,000

85,000,000

90,000,000

Actual Enrollment No churning - only loss of eligibility

Typical churning Low churning

High churning High churning - 6 months

Source: Analysis of SIPP treating March 2015-Nov. 2016 as analogous to March 2020-Dec. 2021 PHE, among enrollees

ever-enrolled in Medicaid during the 21-month period. New monthly Medicaid enrollment in 2021 based on monthly

enrollment January-April 2021.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

7

Table 1. Predicted Medicaid Coverage Loss at the end of the PHE by Medicaid Expansion Status

Characteristic

Loss of Medicaid Eligibility

Disenrolled Despite Being Eligible

for Medicaid

(Administrative Churning)

State Expansion Status

N

%

N

%

Expansion

5,400,000

66%

4,700,000

69%

Non-Expansion

2,800,000

34%

2,100,000

31%

Children and young adults, as well as Latino and Black individuals, are predicted to be impacted

disproportionately. Children ages 0-17 make up nearly one in five of the individuals predicted to be ineligible

for Medicaid and over half of the 6.8 eligible but disenrolled individuals (i.e., administrative churning), while

young adults ages 18-34 comprise more than one in three of those predicted to lose Medicaid eligibility and

nearly one-quarter of those predicted to experience administrative churning (Table 2). Further, Latino

individuals comprise over one quarter of those predicted to be ineligible for Medicaid and over one-third of

those predicted to experience churning, while Black individuals comprise fourteen percent of those predicted

to lose Medicaid eligibility and 15 percent of those predicted to experience churning (Table 2). Those with

incomes 138-250% FPL comprise nearly 40% of those predicted to be ineligible for Medicaid, while those with

incomes less than 100% FPL comprise over half of those predicted to experience administrative churning.

Table 2. Predicted Medicaid Coverage Loss at the end of the PHE by Age, Race, Sex, and Income

Characteristic

Loss of Medicaid Eligibility

Disenrolled Despite Being Eligible

for Medicaid

(Administrative Churning)

Age

N

%

N

%

0-17

1,399,000

17.1%

3,896,000

57.1%

18-24

1,387,000

16.9%

823,000

12.1%

25-34

1,763,000

21.5%

737,000

10.8%

35-44

1,120,000

13.7%

511,000

7.5%

45-54

967,000

11.8%

390,000

5.7%

55-64

777,000

9.5%

288,000

4.2%

65+

791,000

9.6%

173,000

2.5%

Race/Ethnicity

Latino

2,190,000

26.7%

2,409,000

35.3%

White non-Latino

3,967,000

48.4%

2,648,000

38.8%

Black non-Latino

1,125,000

13.7%

1,027,000

15.1%

Asian/Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Isl.

501,000

6.1%

394,000

5.8%

Multi-racial, other

420,000

5.1%

342,000

5.0%

Sex

Male

4,298,000

52.4%

2,880,000

42.2%

Female

3,906,000

47.6%

3,937,000

57.8%

Income*

<100% FPL

691,000

8.4%

3,761,000

55.2%

>100-138% FPL

555,000

6.8%

1,077,000

15.8%

>138-250% FPL

3,038,000

37.0%

1,714,000

25.1%

>250-400% FPL

2,032,000

24.8%

264,000

3.9%

>400% FPL

1,889,000

23.0%

2,000

0.0%

*Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) in December 2016 as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL).

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

8

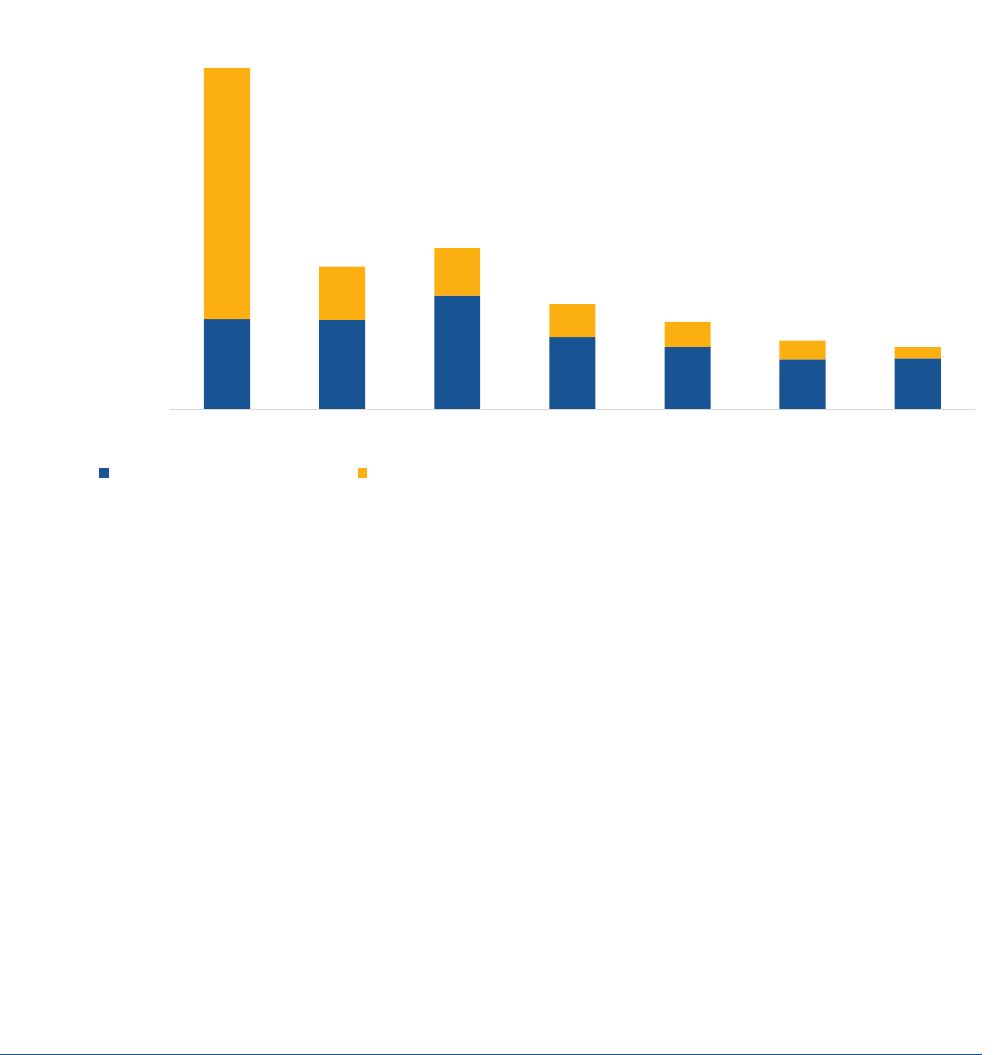

Figures 3 and 4 show rates of Medicaid eligibility loss and administrative churning within each age, income,

and racial and ethnic group. As evident in Figure 3, the majority of children losing coverage are likely still

eligible for Medicaid or CHIP. State-level CHIP policies may play a role in how many children lose Medicaid

coverage at the end of the PHE. Fewer children will become ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP at the end of the

PHE in states with more generous CHIP eligibility limits. Additionally, more children are likely to experience

churning in states where there are greater administrative barriers to transitioning from Medicaid to CHIP. For

example, thirteen states have a separate CHIP, and 26 states charge an enrollment fee or premiums in CHIP. In

these states, children are less likely to be automatically enrolled in CHIP compared to states that operate joint

programs or don’t charge premiums or fees, increasing the risk of administrative churning among children. In

states with combined Medicaid/CHIP programs, coverage transitions should be more seamless.

Figure 3. Predicted Medicaid Coverage Loss Due to Eligibility Loss versus Administrative Churning, by Age

Note: Each bar adds to 100%, showing the breakdown of predicted Medicaid coverage loss due to administrative churning versus loss

of eligibility.

Source: Analysis of SIPP treating March 2015-Nov. 2016 as analogous to March 2020-Dec. 2021 PHE, among enrollees ever-enrolled in

Medicaid during the 21-month period. Projections are from the Base Case scenario.

27.8%

60.0%

72.6%

69.5%

69.6%

67.3%

78.6

72.2%

40.0%

27.4%

30.5%

30.4%

32.7%

21.4%

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

0-17 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+

Number of Individuals Predicted to Lose

Medicaid

Loss of Medicaid Eligibility Disenrolled Despite Being Eligible for Medicaid (Administrative Churning)

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

9

Figure 4. Predicted Medicaid Coverage Loss Due to Eligibility Loss versus Administrative Churning, by Race

and Ethnicity

Note: Each bar adds to 100%, showing the breakdown of predicted Medicaid coverage loss due to administrative churning

versus loss of eligibility.

Source: Analysis of SIPP treating March 2015-Nov. 2016 as analogous to March 2020-Dec. 2021 PHE, among enrollees ever-

enrolled in Medicaid during the 21-month period. Projections are from the Base Case scenario.

Loss of Medicaid Eligibility and Alternative Coverage Options

Alternative health insurance options are available for the majority of individuals who become ineligible for

Medicaid or CHIP after the end of the PHE (Figure 5). In our study population, approximately 3.6 million of the

individuals predicted to be ineligible for Medicaid at the end of the PHE were enrolled in ESI and 1.4 million

individuals were enrolled in other insurance, including Marketplace coverage without Advanced Premium Tax

Credits (APTCs), Medicare, military health insurance, non-Marketplace nongroup coverage, and insurance

classified as “other” in SIPP after losing Medicaid. Another one-third of the individuals ineligible for Medicaid

at the end of the PHE (2.7 million of 8.2 million) were potentially eligible for post-ARP premium tax credits

(Table 3).

††

Of this group, 1.6 million were eligible for APTCs and cost-sharing reductions (incomes 100-250%

FPL), and 1.7 million were eligible for APTCs and also likely eligible for a zero-premium Marketplace plan.

An estimated 383,000 individuals ineligible for Medicaid at the end of the PHE fell in the coverage gap and

were not enrolled in or eligible for any insurance (Figure 5 and Appendix Table 1). These individuals earned less

than 100% FPL and resided in the 12 non-expansion states, meaning that their incomes were too high for their

state’s Medicaid program but too low (<100% FPL) to qualify for subsidized Marketplace coverage. Under the

_______________________

††

Under the ARP, ACA marketplace premium subsidies are substantially enhanced for people at every income level and offered to

those with income above 400% FPL for the first time. These enhanced and expanded premium tax credits will expire at the end of

2022.

36.0%

82.8%

60.4%

49.5%

51.9%

64.0%

17.2%

39.6%

50.5%

48.1%

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

Latino White non-Latino Black non-Latino Asian/Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Isl.

Multi-racial, other

Number of Individuals Predicted to Lose

Medicaid

Loss of Medicaid Eligibility Disenrolled Despite Being Eligible for Medicaid (Administrative Churning)

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

10

ARP the only individuals not potentially eligible for some type of subsidized coverage are generally those in the

Medicaid coverage gap.

‡‡

Figure 5. Predicted Health Coverage Enrollment and Eligibility among those Predicted to Lose Medicaid

Eligibility after the PHE

Source: Analysis of SIPP treating March 2015-Nov. 2016 as analogous to March 202-Dec. 2021 PHE, among enrollees ever enrolled in

Medicaid during the 21-month period. Projections are from the Base Case scenario.

Table 3. Marketplace Eligibility among those Predicted to Lose Medicaid Eligibility after the PHE

Income

Potentially Eligible for

APTCs*

Eligible for Zero-Premium

Marketplace Plan**

Eligible for APTCs and

CSRs

<100%

0

0

0

100 - 138%

259,000

259,000

259,000

>138 - 250%

1,306,000

1,156,000

1,306,000

>250 - 400%

552,000

219,000

0

>400% FPL

573,000

22,000

0

TOTAL

2,689,000

1,656,000

1,565,000

APTCs = Advanced Premium Tax Credits. CSRs = Cost Sharing Reductions.

* Under the ARP, there is no upper income limit on APTC availability, though in practice some higher income individuals may

not receive any APTCs because their premiums are below the required income share under the ACA even without an APTC.

**Based on applying the zero-premium eligibility proportion among uninsured non-elderly adults using CPS data in ASPE brief

“Access to Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform Part II: Availability Among Uninsured Non-Elderly

Adults Under the American Rescue Plan” to the number of individuals predicted to lose Medicaid eligibility but be eligible for

Marketplace premiums within each income band. This group overlaps with those eligible for cost-sharing reductions (CSRs)

and both groups are a subset of those potentially eligible for APTCs.

_______________________

‡‡

Under the ARP, there is no upper income limit on APTC availability, though in practice some higher income individuals may not

receive any APTCs because their premiums are below the required income share under the ACA even without an APTC

229,000

383,000

1,418,000

2,689,000

3,595,000

Affordable ESI Offer but Not Enrolled

Medicaid Coverage Gap

Changed to Non-Marketplace Coverage that Precludes APTCs

Eligible for APTCs

Changed to ESI

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

11

DISCUSSION

Using pre-pandemic Medicaid enrollment from national survey data as an approximation for the PHE, we

currently project that 9.5 percent (8.2 million) of individuals enrolled in Medicaid as of December 2021 will

lose Medicaid eligibility at the end of the PHE and need to transition to another source of coverage. An

additional 7.9 percent (6.8 million) are projected to lose Medicaid coverage despite still being eligible, due to

administrative churning. In our analysis, two-thirds of those predicted to lose Medicaid eligibility (5.0 million

of the 8.2 million) were projected to enroll in ESI or other non-Marketplace coverage. Among those without

ESI, the majority would be eligible for low or no-cost coverage through the Marketplace, with the exception of

those who fall in the Medicaid coverage gap in states that have not expanded Medicaid. Children and young

adults, as well as Latino and non-Latino Black populations, are expected to be disproportionately affected by

Medicaid coverage loss once the PHE ends, and seamless transitions to CHIP will play an important role for

many in maintaining coverage.

Overall, this means that while our model projects that as many as 15 million individuals could leave Medicaid

after the PHE, approximately one third (5 million) are likely to obtain other coverage outside the Marketplace

(primarily ESI) and nearly 3 million (20 percent) would have a subsidized Marketplace option. Additionally,

some individuals who lose Medicaid eligibility at the end of the PHE may regain it during the unwinding period

and some individuals who lose coverage despite being eligible (i.e., experience churning) may re-enroll.

These findings highlight the importance of administrative and legislative actions to reduce the risk of coverage

losses after the continuous enrollment provision ends. Successful policy approaches must address the

different reasons for coverage loss. Broadly speaking, one set of strategies is needed to increase the likelihood

that those losing Medicaid eligibility acquire other coverage, and a second set of strategies is needed to

minimize administrative churning among those still eligible for coverage. Importantly, some administrative

churning is expected under all scenarios, though reducing the typical churning rate by half would result in the

retention of 3.4 million additional enrollees. The next section discusses some of the administrative actions the

CMS is currently taking, as well as opportunities for legislation that can reduce the risk of coverage loss after

the PHE.

Administrative Actions

CMS is working closely with state Medicaid agencies, Marketplaces, navigators and assisters, beneficiary and

consumer advocates, health plans, agents and brokers, departments of insurance, and many others as part of a

robust stakeholder engagement strategy to ensure individuals remain connected to coverage.

Working with State Medicaid Agencies to Reduce Churning: States are directly responsible for eligibility

redeterminations for Medicaid beneficiaries, while CMS provides oversight of compliance with Medicaid

regulations and technical assistance. For over a year, CMS has coordinated with state Medicaid and CHIP

agencies to develop state unwinding plans that will minimize churning and maximize coverage retention. CMS

has hosted regular workgroups, bi-weekly and individual calls with states, and developed a variety of guidance

documents, tools, and resources for state use in planning efforts. In March 2022, CMS released a new suite of

guidance and planning and communications tools that offer states a roadmap to restore routine eligibility and

enrollment operations after the PHE ends and promote continuity of coverage.

11

This guidance includes

outlining strategies for working with managed care plans such as working with plans to obtain and update

beneficiary contact information; sharing renewal files with plans to conduct outreach and provide support to

individuals enrolled in Medicaid during their renewal period; enabling plans to conduct outreach to individuals

who have recently lost coverage for procedural reasons; and permitting plans to assist individuals to transition

to and enroll in ACA Marketplace coverage if ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

12

When the PHE ends, states will have a 12-month unwinding period to initiate renewals of eligibility for all

individuals enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP. The Administration has committed to providing states with 60 days

advanced notice before the expiration of the PHE to support state planning. States are expected to prioritize

eligibility and enrollment work in a manner that prevents inappropriate terminations and promotes smooth

transitions to other coverage for individuals no longer eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, or a Basic Health Program

(BHP).

§§

CMS has also strongly encouraged states to spread their eligibility redeterminations over the full 12-

month unwinding period to help achieve manageable workloads, reduce the risk of administrative churning,

and achieve a renewal schedule that is sustainable in future years.

There are many actions states can take to minimize churning during unwinding, including adopting strategies

to streamline enrollment and renewal processes, investing in resources and staff to process the volume of

eligibility determinations, and implementing additional efforts to update enrollee contact information. States

can expand the number of data sources used at redetermination to increase the number of individuals

renewed based on available information. For example, Medicaid enrollees who also receive Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits often have recent verified information on file that could assist in

approving and renewing Medicaid coverage. State Medicaid agencies could use SNAP data to expedite

application processing. For non-MAGI beneficiaries who must complete a renewal form, states can use pre-

populated renewal forms to reduce the burden on enrollees. States can also extend the period for enrollees to

provide information needed to redetermine their eligibility and provide beneficiaries with the same minimum

of 30 days to return the form that is required for MAGI beneficiaries. For the unwinding period, states may

seek time-limited authority under section 1902(e)(14)(A) of the Social Security Act to pursue strategies to

streamline the renewal process, reduce churning, and ease the administrative burden states may experience in

light of challenges including that many enrollees have moved during the pandemic and a significant time has

passed since agencies last communicated with many of them. This will not only support state efforts to

promote continuity of coverage in Medicaid/CHIP but also facilitate seamless coverage transitions, particularly

for Medicaid-enrolled children who become eligible for coverage in a separate CHIP.

Finally, among the 12 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid, Medicaid expansion to low-income adults is

another critical tool to reducing the risk of coverage losses after the PHE. A recent ASPE report documented

the coverage gains in states that recently expanded Medicaid since 2019,

1

and if the remaining non-expansion

states were to follow suit, this would provide a needed alternative form of coverage for the estimated 383,000

individuals in the coverage gap who are projected to lose insurance after the PHE. More broadly, 3.8 million

uninsured nonelderly adults with incomes below 138% FPL would become newly eligible for Medicaid if their

states were to expand the program.

12

Outreach to Those Losing Medicaid Eligibility: CMS, in partnership with state Medicaid agencies and state-

based Marketplaces, is deploying a multifaceted strategy to facilitate continuity of coverage for consumers

who are no longer eligible for Medicaid/CHIP coverage. CMS is examining a variety of improvements to federal

Marketplace policies and systems to streamline the consumer experience in transitioning from Medicaid/CHIP

coverage to private insurance, such as improving the notices consumers receive in the mail and streamlining

verification processes to limit the number of people required to provide additional paper documentation

during the application process.

_______________________

§§

Section 1331 of the Affordable Care Act gives states the option of creating a Basic Health Program (BHP), a health benefits coverage

program for low-income residents who do not qualify for Medicaid, CHIP, or other minimum essential coverage and have income

between 133 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Two states, New York and Minnesota, have implemented

BHPs which together cover approximately 1 million individuals.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

13

Medicaid and CHIP agencies can also help people who are no longer eligible start the process of transitioning

to other health insurance by providing information about coverage options and linking people to enrollment

assistance. CMS is working with state Medicaid agencies to ensure states that use the federal platform are

securely sending the Marketplace accurate and complete contact information to allow CMS to effectively

increase outreach to individuals no longer eligible for Medicaid/CHIP coverage.

Additionally, navigators and other assistance personnel will maintain a critical physical and virtual presence in

communities across the U.S. to help consumers understand basic concepts and rights related to health

coverage, provide enrollment assistance, and work with individuals to link coverage to care. CMS is

broadening pathways for enrollment assistance and increasing funding to navigator grantees to support new

requirements during unwinding. Specifically, CMS allocated a total of $100M to federal Marketplace navigator

grantee organizations for the 2022-2023 budget period, including $12.5M in support of additional direct

outreach, education, and enrollment activities for unwinding.

CMS is also providing information to people with Medicaid coverage to prepare for the restart of yearly

Medicaid/CHIP eligibility reviews, including on the importance of updating contact information and checking

the mail for renewal forms, and coverage options in the event a beneficiary is no longer eligible for

Medicaid/CHIP.

More broadly, HHS is leveraging all of its programs and divisions – including the Indian Health Service, the

Community Health Center Program, regional offices, and public affairs – to inform and engage external

stakeholders. This includes creating a website (Medicaid.gov/unwinding) where stakeholders can access an

unwinding toolkit printed in multiple languages and template social media graphics to use in outreach to

beneficiaries, among other resources; a website (Medicaid.gov/renewals) where beneficiaries can get

connected to their state’s eligibility website in order to update their contact information; and hosting monthly

information calls for beneficiaries, consumer advocates, providers, state officials, and other stakeholders

where they can learn about new resources related to the unwinding process.

Legislative Opportunities

In addition to administrative actions, there are also legislative opportunities to help mitigate coverage loss at

the end of the PHE:

Extend the ARP’s Marketplace subsidies past 2022: The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 extends the ARP’s

enhanced and expanded subsidies to individuals obtaining Marketplace coverage. These subsidies were

previously scheduled to expire at the end of 2022. The law is projected to save 13 million Marketplace

enrollees an average of $800 per year on health insurance costs.

13

Prior ASPE analyses have shown the impacts

of the ARP on lowering Marketplace premiums and improving plan affordability. The ARP subsidy provisions

enable three in five uninsured consumers and four in five current Marketplace enrollees to find a zero-

premium plan (after premium tax credits) on HealthCare.gov.

14

The 2022 Open Enrollment Period resulted in

the highest-ever Marketplace enrollment of 14.5 million,

15

and surveys indicate that an additional 2 million

adults reported Marketplace enrollment in early 2022 compared to 2020, accounting for approximately half of

the 4 million total adults who gained health coverage during this period.

1

This extension of the ARP’s premium

tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act will allow millions of people, including newly disenrolled Medicaid

beneficiaries, to continue to benefit from the enhanced and expanded premium subsidies and maintain access

to zero- and low-premium Marketplace plans.

16

Expand Twelve-Month Continuous Eligibility Provisions in Medicaid: Continuous eligibility policies can

mitigate both Medicaid coverage loss and administrative churning by guaranteeing continued eligibility for

Medicaid over a 12-month period regardless of changes in income or circumstances. States currently have the

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

14

option of providing 12-months of continuous eligibility for children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP, and over half

of states have done so.

17

Currently, 12 months of continuous eligibility for Medicaid-enrolled adults is only

available via section 1115 demonstrations, and only two states have done so to date (New York, which still

maintains the policy, and Montana, which no longer has this policy in effect). The process for states to provide

12 months of continuous eligibility for adults could be streamlined through new legislation creating a state

plan option. Alternatively, legislation could mandate that states provide 12-month continuous Medicaid/CHIP

eligibility for adults and children. To promote continuous eligibility for the pregnant population enrolled in

Medicaid, the American Rescue Plan (ARP) included a temporary option for states to use federal matching

funds to extend continuous Medicaid and CHIP eligibility for pregnant beneficiaries from 60 days up to 12

months postpartum. This option became available to states on April 1, 2022, and will last five years.

CONCLUSION

Unwinding the PHE’s continuous enrollment provision in Medicaid will lead to millions of current enrollees no

longer being eligible for the program, and administrative churning could put millions of additional people at

risk for losing Medicaid coverage even though they are still eligible. HHS is taking a wide range of proactive

steps to reduce the number of individuals who are at risk of becoming uninsured due to the unwinding of the

PHE. Facilitating enrollment in alternative health insurance coverage among those determined ineligible for

Medicaid through coordination with state and federal Marketplaces and enhanced outreach and education

efforts will help minimize potentially harmful gaps in health insurance coverage. Efforts by states and

community groups, in collaboration with CMS, can reduce the risk of administrative churning among those still

eligible for Medicaid coverage. Finally, the extension of the enhanced ARP premium subsidies in the Inflation

Reduction Act will increase affordability and access to alternative health insurance at the end of the PHE,

helping preserve the historic coverage gains in ACA-related coverage in 2021 and 2022.

1,

18

In the post-PHE

period, tracking enrollment will be critical to monitoring progress and directing resources to minimize

interruptions in coverage.

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

15

APPENDIX

Appendix Table 1. Enrollment and Eligibility in Alternative Health Insurance among Those Predicted to Lose

Medicaid Eligibility after the PHE

Income (%

FPL)

Not APTC Eligible

APTC Eligible

Ineligible for

Medicaid or

Marketplace

APTCs

(Coverage

Gap) ***

Affordable

ESI Offer

but not

enrolled

Enrolled in

ESI

Enrolled in

other non-

Marketplace

coverage

that

precludes

APTCs

Potentially

Eligible for

APTCs*

Eligible for

Zero Premium

Marketplace

Plan**

Eligible for

APTCs and

CSRs

<100%

78,000

164,000

177,000

0

0

0

383,000

100 - 138%

0

82,000

214,000

259,000

259,000

259,000

>138 - 250%

85,000

1,105,000

540,000

1,306,000

1,156,000

1,306,000

>250 - 400%

37,000

1,156,000

288,000

551,000

219,000

0

>400% FPL

29,000

1,088,000

199,000

573,000

22,000

0

TOTAL

229,000

3,595,000

1,418,000

2,689,000

1,656,000

1,565,000

383,000

Notes:

** Under the ARP, there is no upper income limit on APTC availability, though in practice some higher income individuals may not

receive any APTCs because their premiums are below the required income share under the ACA even without an APTC.

**Based on applying the zero-premium eligibility proportion among uninsured non-elderly adults using CPS data in ASPE brief

“Access to Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform Part II: Availability Among Uninsured Non-Elderly Adults

Under the American Rescue Plan” to the number of individuals predicted to lose Medicaid eligibility but be eligible for Marketplace

premiums within each income band. This group overlaps with those eligible for cost-sharing reductions (CSRs).

*** Some of these categories are partially overlapping and therefore sum to greater than the total.

HP-2022-20

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

16

REFERENCES

1

Lee A, Ruhter J, Peters C, De Lew N, Sommers BD. National Uninsured Rate Reaches All-Time Low in Early 2022. (Issue Brief No. HP-

2022-23). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. August 2022.

2

Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Application, Eligibility Determination, and Enrollment Reports & Data. Accessed at:

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-medicaid-

chip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-reports-data/index.html

3

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Releases August Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Trends Snapshot Showing Continued

Enrollment Growth. June 21, 2021. Accessed at:

https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/new-medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-snapshot-shows-almost-10-million-americans-

enrolled-coverage-during

4

Khorrami P and Sommers BD. Changes in US Medicaid Enrollment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. May 5, 2021. Accessed at:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2779458

5

Sugar S, Peters C, DeLew N, Sommers BD. Medicaid Churning and Continuity of Care: Evidence and Policy Considerations Before and

After the COVID-19 Pandemic (Issue Brief No. HP-2021-10). Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 12, 2021. Accessed at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/medicaid-

churning-continuity-care

6

Abdus, S. Part-year Coverage and Access to Care for Nonelderly Adults https://journals.lww.com/lww-

medicalcare/Fulltext/2014/08000/Part_year_Coverage_and_Access_to_Care_for.6.aspx

7

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. An Updated Look at Rates of Churn and

Continuous Coverage in Medicaid and CHIP. October 2021. Accessed at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/An-

Updated-Look-at-Rates-of-Churn-and-Continuous-Coverage-in-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf

8

Williams E, Rudowitz R and Corallo B. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 10, 2022. Accessed at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-

brief/fiscal-and-enrollment-implications-of-medicaid-continuous-coverage-requirement-during-and-after-the-phe-ends/

9

Buettgens M and Green A. What Will Happen to Medicaid Enrollees’ Health Coverage after the Public Health Emergency? Urban

Institute. March 9, 2022. Accessed at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/what-will-happen-medicaid-enrollees-health-

coverage-after-public-health-emergency

10

Branham, D.K, Conmy, A.B., DeLeire, T., Musen, J., Xiao, X., Chu, R.C., Peters, C., and Sommers, B.D. (March 29, 2021). Access to

Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform, Part I: Availability Among Uninsured Non-Elderly Adults and

HealthCare.gov Enrollees Prior to the American Rescue Plan (Issue Brief No. HP-2021-07). Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant

Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed at:

https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdfreport/access-to-low-premiums-issue-brief.

11

Medicaid.gov. Unwinding and Returning to Regular Operations after COVID-19. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-

states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/index.html.

12

Rudich J, Branham DK, Peters C, and Sommers BD. Estimates of Uninsured Adults Newly Eligible for Medicaid If Remaining 12 Non-

Expansion States Expand Medicaid: 2022 Update (Data Point No. HP-2022-06). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. February 2022. Accessed at: https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/reports/updated-

estimates-medicaid-eligibility-non-expansion-states

13

Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget. Statement of Administrative Policy H.R. 5376 – Inflation

Reduction Act of 2022. August 6, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SAP-H.R.-5376.pdf.

14

Branham DK, Eibner C, Girosi F, Liu J, Finegold K, Peters C, and Sommers BD. Projected Coverage and Subsidy Impacts If the American

Rescue Plan’s Marketplace Provisions Sunset in 2023 (Data Point No. HP-2022-10). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. March 23, 2022 Accessed at: https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/reports/impacts-

ending-american-rescue-plan-marketplace-provisions

15

Lee A, Chu RC, Peters C, and Sommers BD. Health Coverage Changes Under the Affordable Care Act: End of 2021 Update. (Issue Brief

No. HP-2022-17). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April

2022. Accessed at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-coverage-changes-2021-update

16

Branham DK, Eibner C, Girosi F, Liu J, Finegold K, Peters C, and Sommers BD. Projected Coverage and Subsidy Impacts If the American

Rescue Plan’s Marketplace Provisions Sunset in 2023 (Data Point No. HP-2022-10). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. March 23, 2022. Accessed at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/impacts-

ending-american-rescue-plan-marketplace-provisions

17

Medicaid.gov. Continuous Eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP Coverage. September 2021. Accessed at:

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/enrollment-strategies/continuous-eligibility-medicaid-and-chip-coverage/index.html.

18

Lee A, Chu RC, Peters C, and Sommers BD. Health Coverage Changes Under the Affordable Care Act: End of 2021 Update. (Issue Brief

No. HP-2022-17). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April

2022. Accessed at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-coverage-changes-2021-update

August 2022

ISSUE BRIEF

17

HP-2022-20

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

200 Independence Avenue SW, Mailstop 447D

Washington, D.C. 20201

For more ASPE briefs and other publications, visit:

aspe.hhs.gov/reports

SUGGESTED CITATION

Unwinding the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision:

Projected Enrollment Effects and Policy Approaches (Issue Brief

HP-2022-20) Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary

for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services. August 19, 2022

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and

may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to

source, however, is appreciated.

___________________________________

Subscribe to ASPE mailing list to receive

email updates on new publications:

aspe.hhs.gov/join-mailing-list

For general questions or general

information about ASPE:

aspe.hhs.gov/about