2021 Trade Policy Agenda

and 2020 Annual Report

OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

ON THE TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM

UNITED STATES TRADE REPRESENTATIVE

FOREWORD

The 2021 Trade Policy Agenda and 2020 Annual Report of the President of the United States on the Trade

Agreements Program are submitted to the Congress pursuant to Section 163 of the Trade Act of 1974, as

amended (19 U.S.C. § 2213). Chapter IV and Annex III of this document meet the requirements of Sections

122 and 124 of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act with respect to the World Trade Organization. The

discussion on the Generalized System of Preferences in Chapter II satisfies the reporting requirement

contained in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (Pub. L. 115-141, div. M, title V, § 501(c)). This

report includes an annex listing trade agreements entered into by the United States since 1984. Goods trade

data are for full year 2020. Full-year services data by country are only available through 2019.

The Office of the United States Trade Representative is responsible for the preparation of this report and

gratefully acknowledges the contributions of all USTR staff to its writing and production. We note, in

particular, the contributions of Julie McNees and Spencer Smith. Appreciation is extended to partner Trade

Policy Staff Committee agencies.

March 2021

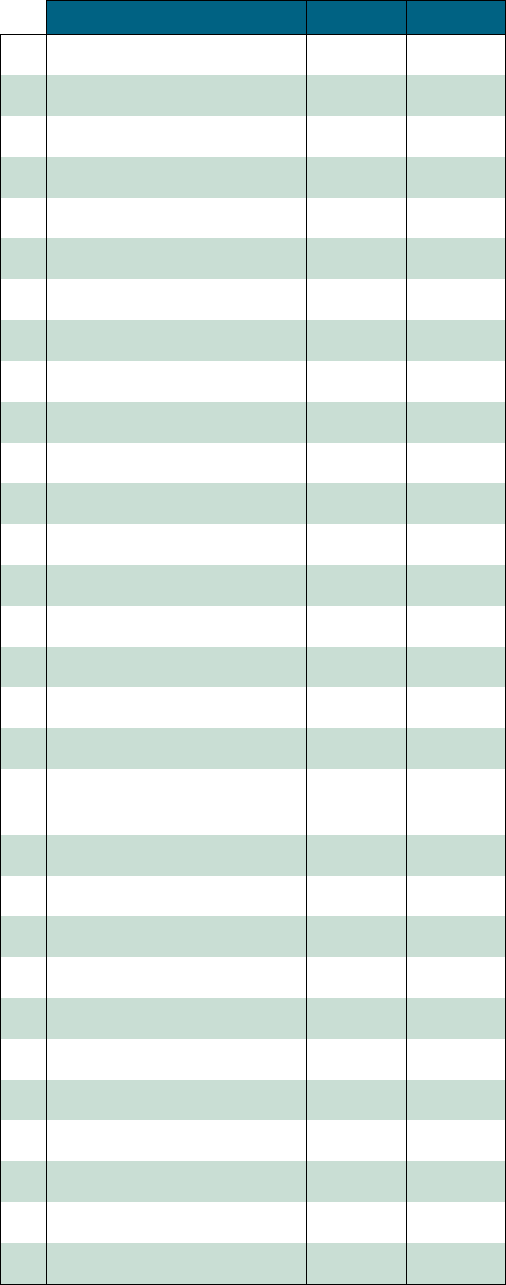

LIST OF FREQUENTLY USED ACRONYMS

AGOA .......................................................................... African Growth and Opportunity Act

APEC ........................................................................... Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

ASEAN ........................................................................ Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CAFTA–DR ................................................................. Dominican Republic–Central America–United

States Free Trade Agreement

CBERA......................................................................... Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act

CBI…............................................................................ Caribbean Basin Initiative

CVD ............................................................................. Countervailing Duty

DOL ............................................................................. U.S. Department of Labor

DSB .............................................................................. WTO Dispute Settlement Body

DSU ............................................................................. WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding

EU

1

............................................................................... European Union

FOIA ............................................................................ Freedom of Information Act

GATT ........................................................................... General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

GATS ........................................................................... General Agreement on Trade in Services

GDP ............................................................................. Gross Domestic Product

GI ................................................................................. Geographical Indications

GPA ............................................................................. WTO Agreement on Government Procurement

GSP .............................................................................. Generalized System of Preferences

ICTIME ........................................................................ Interagency Center on Trade Implementation,

Monitoring, and Enforcement

ILO ............................................................................... International Labor Organization

IP .................................................................................. Intellectual Property

ITA ............................................................................... WTO Information Technology Agreement

KORUS ........................................................................ United States–Korea Free Trade Agreement

MFN ............................................................................. Most-Favored-Nation

MOU ............................................................................ Memorandum of Understanding

NAFTA ........................................................................ North American Free Trade Agreement

OECD ........................................................................... The Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development

SBA .............................................................................. U.S. Small Business Administration

SME ............................................................................. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise

SPS ............................................................................... Sanitary and Phytosanitary

TAA ............................................................................. Trade Adjustment Assistance

TBT .............................................................................. Technical Barriers to Trade

TFA .............................................................................. WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement

TIFA ............................................................................. Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

TPSC ............................................................................ Trade Policy Staff Committee

TRIPS ........................................................................... Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property

Rights

1

Unless specified otherwise, all references to the European Union refer to the EU-28.

TRQ ............................................................................. Tariff-Rate Quota

USAID ......................................................................... U.S. Agency for International Development

USDA ........................................................................... U.S. Department of Agriculture

USMCA ....................................................................... United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement

USTR ........................................................................... United States Trade Representative

WTO ............................................................................ World Trade Organization

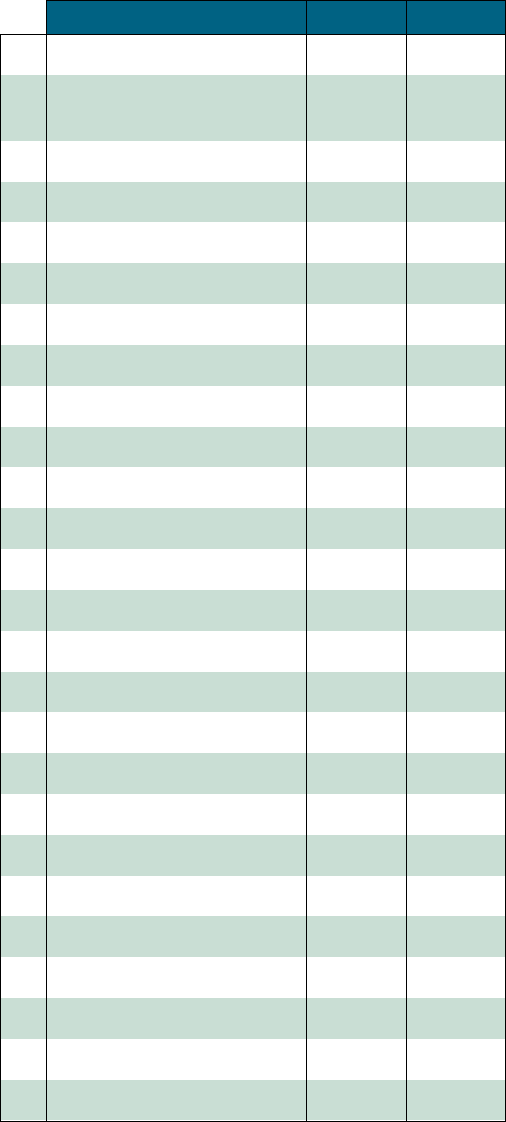

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA

THE PRESIDENT’S TRADE POLICY AGENDA ..................................................................................... 1

THE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT ON THE TRADE

AGREEMENTS PROGRAM

THE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT ON THE TRADE AGREEMENTS

PROGRAM................................................................................................................................................... 1

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS ............................................................................................. 1

A. Agreements Notified for Negotiation ................................................................................................... 1

1. United States–European Union Trade Agreement ............................................................................ 1

2. United States–Japan Trade Agreement and United States–Japan Digital Trade Agreement ............ 1

3. United States–Kenya Trade Agreement ............................................................................................ 1

4. United States–United Kingdom Trade Agreement ........................................................................... 2

B. Concluded Agreements ........................................................................................................................ 3

1. United States–China Economic and Trade Agreement ..................................................................... 3

2. United States and European Union Trade Agreement Regarding Tariffs on Certain Products ........ 3

3. United States–Brazil Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation ........................................... 3

4. United States–Ecuador Protocol to the Trade and Investment Council Agreement Relating to

Trade Rules and Transparency .............................................................................................................. 3

5. United States–Fiji Trade and Investment Framework Agreement .................................................... 4

C. Free Trade Agreements in Force .......................................................................................................... 4

1. Australia ............................................................................................................................................ 4

2. Bahrain .............................................................................................................................................. 4

3. Central America and the Dominican Republic ................................................................................. 5

4. Chile .................................................................................................................................................. 9

5. Colombia ......................................................................................................................................... 10

6. Israel ................................................................................................................................................ 11

7. Jordan .............................................................................................................................................. 12

8. Korea ............................................................................................................................................... 13

9. Mexico and Canada ......................................................................................................................... 14

10. Morocco ........................................................................................................................................ 17

11. Oman ............................................................................................................................................. 19

12. Panama .......................................................................................................................................... 19

13. Peru ............................................................................................................................................... 20

14. Singapore ...................................................................................................................................... 22

D. Other Negotiating Initiatives .............................................................................................................. 22

1. The Americas .................................................................................................................................. 22

2. Europe and the Middle East ............................................................................................................ 24

3. Japan, Republic of Korea, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum ............................ 27

4. China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mongolia .................................................................................... 29

5. Southeast Asia and the Pacific ........................................................................................................ 31

6. Sub-Saharan Africa ......................................................................................................................... 32

7. South and Central Asia ................................................................................................................... 34

II. TRADE ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITIES ........................................................................................ 37

A. Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 37

B.

Section 301 ......................................................................................................................................... 39

1. China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and

Innovation ........................................................................................................................................... 40

2. European Union – Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products (Hormones) ........................... 42

3. Digital Services Taxes .................................................................................................................... 44

4. Enforcement of U.S. WTO Rights in European Union Large Civil Aircraft Dispute .................... 47

5. Vietnam’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to the Import and Use of Illegal Timber ............. 49

6. Vietnam’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Currency Valuation ........................................ 49

C.

Section 201 ......................................................................................................................................... 49

D. WTO and FTA Dispute Settlement .................................................................................................... 50

E.

Other Activities ................................................................................................................................... 97

1. Generalized System of Preferences ................................................................................................. 97

2. The African Growth and Opportunity Act .................................................................................... 100

3. Other Monitoring and Enforcement Activities ............................................................................. 101

4. Special 301 .................................................................................................................................... 103

5. Section 1377 Review of Telecommunications Agreements ......................................................... 105

6. Antidumping Actions .................................................................................................................... 105

7. Countervailing Duty Actions ........................................................................................................ 106

8. Section 337 .................................................................................................................................... 107

III. OTHER TRADE ACTIVITIES ...................................................................................................... 111

A. Agriculture and Trade ...................................................................................................................... 111

1. Opening Export Markets for American Agriculture ..................................................................... 111

2. Negotiating Trade Agreements for American Agriculture ........................................................... 115

3. Bilateral and Regional Activities .................................................................................................. 117

3. Agriculture in the World Trade Organization ............................................................................... 120

4. Enforcing Trade Agreements for American Agriculture .............................................................. 120

B. Digital Trade .................................................................................................................................... 121

C. Intellectual Property ......................................................................................................................... 121

D. Manufacturing and Trade ................................................................................................................. 123

E.

Small and Medium-Sized Business Initiative ................................................................................... 124

F. Trade and the Environment ............................................................................................................... 128

1. Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Activities ........................................................................... 128

2. Regional Engagement and Multilateral Fora ................................................................................ 133

G.

Trade and Labor ............................................................................................................................... 134

1. Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Activities ........................................................................... 134

2. Preference Programs ..................................................................................................................... 138

3. International Organizations ........................................................................................................... 140

4. Trade Adjustment Assistance ........................................................................................................ 141

H. Trade Capacity Building .................................................................................................................. 142

1. The Enhanced Integrated Framework ........................................................................................... 142

2. U.S. Trade-Related Assistance under the World Trade Organization Framework ....................... 143

3. TCB Initiatives for Africa ............................................................................................................. 144

4. Free Trade Agreements ................................................................................................................. 145

5. Standards Alliance ........................................................................................................................ 145

I. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development .............................................................. 146

1. Trade Committee Work Program .................................................................................................. 146

2. Trade Committee Dialogue with Non-OECD Members ............................................................... 147

3. Other OECD Work Related to Trade ............................................................................................ 147

IV. THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION ................................................................................... 149

A. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 149

B. WTO Negotiating Groups ................................................................................................................ 150

1. Committee on Agriculture, Special Session ................................................................................. 150

2. Council for Trade in Services, Special Session ............................................................................ 151

3. Negotiating Group on Rules ......................................................................................................... 151

4. Dispute Settlement Body, Special Session ................................................................................... 151

5. Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Special Session ................... 152

6. Committee on Trade and Development, Special Session ............................................................. 153

7. Negotiating Group on Non-Agricultural Market Access .............................................................. 154

C. Work Programs Established in the Doha Development Agenda ...................................................... 154

1. Working Group on Trade, Debt, and Finance ............................................................................... 154

2. Working Group on Trade and Transfer of Technology ................................................................ 154

3. Work Program on Electronic Commerce ...................................................................................... 155

D. General Council Activities ............................................................................................................... 155

E. Council for Trade in Goods .............................................................................................................. 155

1. Committee on Agriculture ............................................................................................................ 156

2. Committee on Market Access ....................................................................................................... 156

3. Committee on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures ...................................... 157

4. Committee on Trade-Related Investment Measures ..................................................................... 157

5. Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures ................................................................ 158

6. Committee on Customs Valuation ................................................................................................ 158

7. Committee on Rules of Origin ...................................................................................................... 159

8. Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade ................................................................................... 159

9. Committee on Antidumping Practices .......................................................................................... 160

10. Committee on Import Licensing ................................................................................................. 160

11. Committee on Safeguards ........................................................................................................... 161

12. Committee on Trade Facilitation ................................................................................................ 161

13. Working Party on State Trading Enterprises .............................................................................. 162

F. Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ................................................. 162

G. Council for Trade in Services .......................................................................................................... 162

1. Committee on Trade in Financial Services ................................................................................... 163

2. Working Party on Domestic Regulation ....................................................................................... 163

3. Working Party on General Agreement on Trade in Services Rules .............................................. 164

4. Committee on Specific Commitments .......................................................................................... 164

H. Dispute Settlement Understanding ................................................................................................... 164

I. Trade Policy Review Body ................................................................................................................ 166

J. Other General Council Bodies and Activities ................................................................................... 168

1. Committee on Trade and Environment ......................................................................................... 168

2. Committee on Trade and Development ........................................................................................ 168

3. Committee on Balance-of-Payments Restrictions ........................................................................ 169

4. Committee on Budget, Finance and Administration ..................................................................... 169

5. Committee on Regional Trade Agreements .................................................................................. 169

6. Accessions to the World Trade Organization ............................................................................... 170

K. Plurilateral Agreements .................................................................................................................... 171

1. Committee on Trade in Civil Aircraft ........................................................................................... 171

2. Committee on Government Procurement ..................................................................................... 172

3. The Information Technology Agreement and the Expansion of Trade in Information Technology

Products ............................................................................................................................................ 172

V. TRADE POLICY DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................... 175

A. Policy Coordination ......................................................................................................................... 175

B. Public Input and Transparency ......................................................................................................... 176

1. Transparency Guidelines and Chief Transparency Officer ........................................................... 176

2. Public Outreach ............................................................................................................................. 177

3. The Trade Advisory Committee System ....................................................................................... 178

4. State and Local Government Relations ......................................................................................... 181

5. Freedom of Information Act ......................................................................................................... 182

C. Congressional Consultations ............................................................................................................ 182

ANNEX I: U.S. TRADE IN 2020 .......................................................................................................... 185

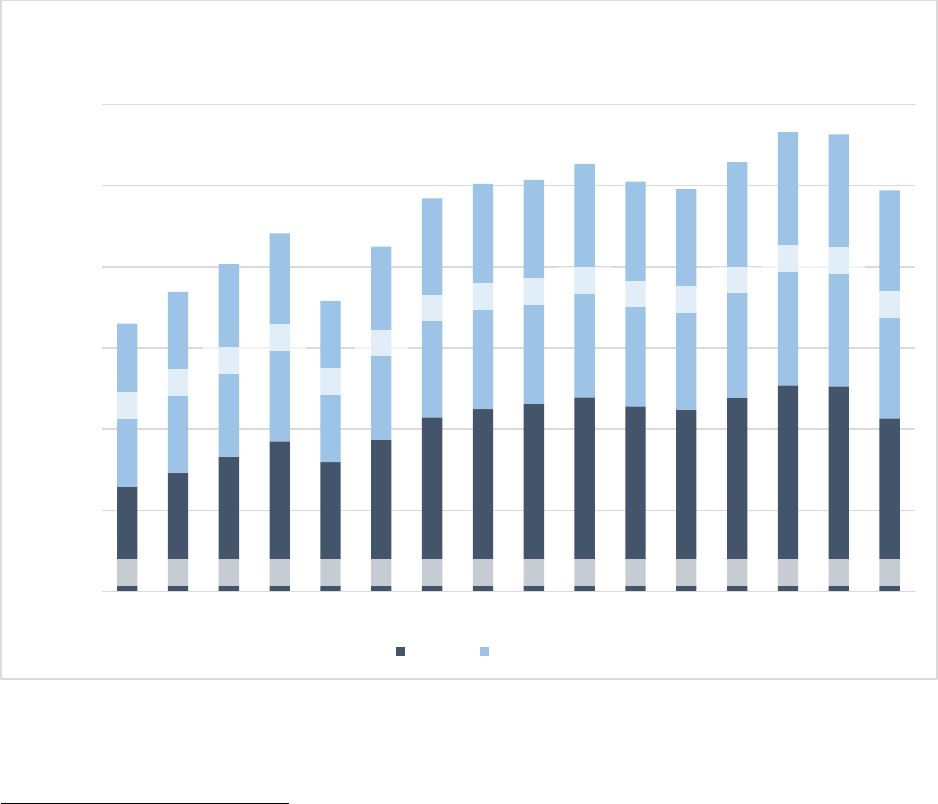

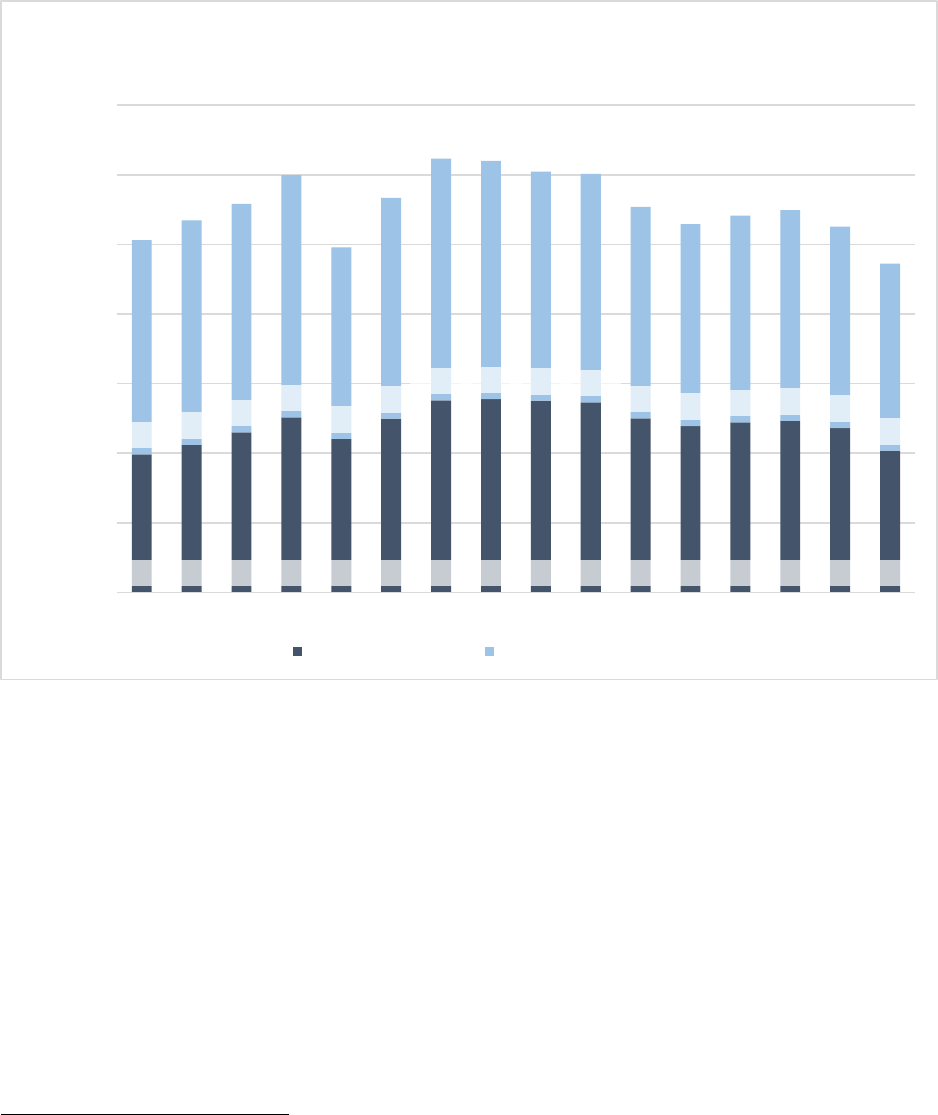

I. 2020 Overview .................................................................................................................................. 187

II. Export Growth .................................................................................................................................. 189

A. U.S. Goods Exports ...................................................................................................................... 189

B. U.S. Services Exports ................................................................................................................... 191

III. Imports ............................................................................................................................................ 192

A. U.S. Goods Imports ...................................................................................................................... 192

B. U.S. Services Imports ................................................................................................................... 193

IV. The U.S. Trade Balance .................................................................................................................. 194

ANNEX II: U.S. TRADE-RELATED AGREEMENTS AND DECLERATIONS .......................... 195

I. Agreements That Have Entered Into Force ....................................................................................... 197

II. Agreements That Have Been Negotiated, But Have Not Yet Entered Into Force ........................... 223

III. Other Trade-Related Agreements, Understandings and Declarations ............................................ 225

ANNEX III: BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE WTO .................................................... 237

THE PRESIDENT’S

2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA

THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA | 1

THE PRESIDENT’S TRADE POLICY AGENDA

INTRODUCTION

President Biden is focused on ending the COVID-19 pandemic and strengthening the economy by taking

bold steps to increase vaccine production and delivery, re-open our schools, and make landmark

investments in our economy to put people back to work and deliver immediate relief to American families.

The President’s Build Back Better agenda will create millions of good-paying jobs and support America’s

working families by tackling four national challenges: building a stronger industrial and innovation base

so the future is made in America; building sustainable infrastructure and a clean energy future; building a

stronger, caring economy; and, advancing racial equity across the board.

The President’s trade agenda is an essential component of the fight against COVID-19, the economic

recovery, and the Build Back Better agenda. President Biden seeks a fair international trading system that

promotes inclusive economic growth and reflects America’s universal values. The President knows that

trade policy should respect the dignity of work and value Americans as workers and wage-earners, not only

as consumers. The President’s trade agenda will restore U.S. global leadership on critical matters like

combatting forced labor and exploitative labor conditions, corruption, and discrimination against women

and minorities around the world. Through bilateral and multilateral engagement, the Biden Administration

will seek to build consensus on how trade policies may address the climate crisis, bolster sustainable

renewable energy supply chains, end unfair trade practices, discourage regulatory arbitrage, and foster

innovation and creativity.

Central components of the 2021 trade agenda will be the development and reinforcement of resilient

manufacturing supply chains, especially those made up of small businesses, to ensure that the United States

is better prepared to confront future public health crises. Additionally, trade policies will thoughtfully

address the opportunities and challenges posed by the digital economy and prepare for any potential future

disruptions to the global trading system.

Opening markets and reducing trade barriers are fundamental to any trade agenda. This will be a priority

for the Biden Administration, particularly since export-oriented producers, manufacturers, and businesses

enjoy greater than average productivity and wages. Market opportunities reap the greatest economic

benefits when they are pursued in alignment with the interests of American workers and innovators,

manufacturers, farmers, ranchers, fishers, and underserved communities. Under the Biden Administration,

trade policy will encourage domestic investment and innovation and increase economic security for

American families, including through combatting unfair practices by our trading partners.

President Biden’s comprehensive trade agenda will contribute to a strong domestic recovery and ensure

future opportunities for American workers and businesses, including through opening international

markets. The prioritized trade policies below support the President’s work to end the pandemic and

strengthen the economy, while looking toward a more sustainable future by tackling unfair trade practices,

creating and retaining good-paying American jobs, implementing labor practices that protect workers, and

promoting policies that protect our environment.

2 | THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA

PRESIDENT BIDEN’S POLICY PRIORITIES

Tackling the COVID-19 Pandemic and Restoring the Economy

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to be the greatest threat to the U.S. economy. President Biden is

pursuing domestic policies that will help to stop the spread of the virus, safely re-open the economy, and

invest in a nationwide recovery. The Biden Administration is focused on increasing vaccine production

and distribution so that every American can be vaccinated as soon as possible. In addition, the Biden

Administration is committed to making the necessary long-term investments to strengthen domestic

production of essential medical equipment that will expand industrial capacity and bolster preparation to

tackle future public health crises. The trade agenda will support these domestic investments with the goal

of ensuring that frontline workers have immediate access to necessary personal protective equipment and

promoting long-term supply chain resiliency for equipment and supplies critical to protecting public health

in the United States. Trade policy will also support the broader economic recovery by helping companies,

including small businesses and entrepreneurs, put Americans to work by building world-class products for

export to foreign markets.

The Biden Administration is also committed to advancing global health security to save lives, promote

economic recovery, and develop resilience against future global pandemics or crises. It looks forward to

working with trading partners to collaborate on initiatives to address the global health and humanitarian

response.

Putting Workers at the Center of Trade Policy

The Biden Administration recognizes that trade policy is an essential part of the Build Back Better agenda,

and the trade agenda must protect and empower workers, drive wage-driven growth, and lead to better

economic outcomes for all Americans. A worker-centered trade policy requires extensive engagement with

unions and other worker advocates. Under the Biden Administration, workers will have a seat at the table

in the development of trade policies.

The Biden Administration will review past trade policies for their impacts on, and unintended consequences

for, workers. Labor obligations under existing agreements will be fully enforced. The Biden

Administration is committed to self-initiating and advancing petitions under the new Rapid Response

Mechanism in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to ensure workers receive relief

through efficient, facility-level enforcement when there are violations of the USMCA.

New trade policies will be crafted to promote equitable economic growth through the inclusion in trade

agreements of strong, enforceable labor standards that protect workers’ rights and increase economic

security. Trading partners will not be allowed to gain a competitive advantage by violating workers’ rights

and pursuing unfair trade practices. In addition, the Biden Administration will engage with allies to achieve

commitments to fight forced labor and exploitative labor conditions, and increase transparency and

accountability in global supply chains. President Biden opposes attempts by foreign countries to artificially

manipulate currency values to gain unfair advantage over American workers. The Biden Administration

will examine how Treasury, Commerce and USTR can work together to put effective pressure on countries

that are intervening in the foreign exchange market to gain a trade advantage. The Biden Administration

is prepared to use the full range of trade tools at its disposal to ensure that products that use forced labor

and exploitative labor conditions are not imported into the United States, and fight back against other unfair

labor practices.

THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA | 3

Putting the World on a Sustainable Environment and Climate Path

The United States and the global community face a profound climate crisis, and the Biden Administration

is committed to pursuing action at home and abroad to avoid the increasingly disruptive and potentially

catastrophic impact of climate change. The United States will work with other countries, both bilaterally

and multilaterally, toward environmental sustainability.

As part of this whole-of-government effort, the trade agenda will include the negotiation and

implementation of strong environmental standards that are also critical to a sustainable climate pathway.

These standards will include promoting sustainable stewardship of natural resources, such as sustainable

fisheries management, and preventing harmful environmental practices, such as illegal logging and wildlife

trafficking. This comprehensive approach may also entail leveraging our strong bilateral and multilateral

trade relationships to raise global climate ambition.

The Biden Administration will work with allies and partners that are committed to fighting climate change.

This will include exploring and developing market and regulatory approaches to address greenhouse gas

emissions in the global trading system. As appropriate, and consistent with domestic approaches to reduce

U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, this includes consideration of carbon border adjustments. Additionally, the

Biden Administration will work with allies as they develop their own approaches and act against trading

partners that fail to meet their environmental obligations under existing trade agreements.

The trade agenda will support the Biden Administration’s comprehensive vision of reducing greenhouse

gas emissions and achieving net-zero global emissions by 2050, or before, by fostering U.S. innovation and

production of climate-related technology and promoting resilient renewable energy supply chains.

Advancing Racial Equity and Supporting Underserved Communities

The Biden Administration is committed to advancing racial equity and supporting underserved

communities as part of the mission of all federal government agencies and offices. The trade agenda will

support domestic initiatives that eliminate social and economic structural barriers to equality and economic

opportunity and pursue the same objectives in negotiations with our trading partners.

In the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the devastating effect of persistent economic disparities

on communities of color. The Biden Administration is committed to a trade agenda that acknowledges this

grave reality and ensures that the concerns and perspectives of Black, Latino, Asian American and Pacific

Islander (AAPI), and Native American workers, their families, and businesses are a cornerstone of proposed

policies.

Through thoughtful, sustained engagement, and innovative data collection and sharing, the Biden

Administration will seek to better understand the projected impact of proposed trade policies on

communities of color and to ensure those impacts are considered before pursuing such policies. The trade

agenda will be shaped by meaningful outreach to and engagement with community-based stakeholders,

such as minority-owned businesses, business incubators, Historically Black Colleges and Universities

(HBCUs), Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs), other minority serving institutions (MSIs), and local and

national civil rights organizations.

4 | THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA

Addressing China’s Coercive and Unfair Economic Trade Practices Through a

Comprehensive Strategy

The Biden Administration recognizes that China's coercive and unfair trade practices harm American

workers, threaten our technological edge, weaken our supply chain resiliency, and undermine our national

interests. Addressing the China challenge will require a comprehensive strategy and more systematic

approach than the piecemeal approach of the recent past. The Biden Administration is conducting a

comprehensive review of U.S. trade policy toward China as part of its development of its overall China

strategy.

The Biden Administration is committed to using all available tools to take on the range of China’s unfair

trade practices that continue to harm U.S. workers and businesses. These detrimental actions include

China’s tariffs and non-tariff barriers to restrict market access, government-sanctioned forced labor

programs, overcapacity in numerous sectors, industrial policies utilizing unfair subsidies and favoring

import substitution, and export subsidies (including through export financing). They also include coercive

technology transfers, illicit acquisition and infringement of American intellectual property, censorship and

other restrictions on the internet and digital economy, and a failure to provide treatment to American firms

in numerous sectors comparable to the treatment Chinese firms receive in those sectors in the United States.

The Biden Administration will also make it a top priority to address the widespread human rights abuses of

the Chinese Government’s forced labor program that targets the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious

minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and elsewhere in the country. Americans and

consumers around the world do not want products made with forced labor on store shelves, and workers

should not be disadvantaged by competing with a state sponsored regime of systematic repression. The

trade agenda will consider all options to combat forced labor and enhance corporate accountability in the

global market.

The Biden Administration will pursue strengthened enforcement to ensure that China lives up to its existing

trade obligations. Where gaps exist in international trade rules, the United States will work to address them,

including through enhanced cooperation with our partners and allies. At the same time, the Biden

Administration will make transformative investments at home in American workers, infrastructure,

education, and innovation necessary to enhance U.S. competitiveness and put the United States in a stronger

position to address the challenges arising out of Chinese economic policies.

Partnering with Friends and Allies

The Biden Administration will seek to repair partnerships and alliances and restore U.S. leadership around

the world. The Biden Administration will reengage and be a leader in international organizations, including

the World Trade Organization (WTO). The United States will work with Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-

Iweala and like-minded trading partners to implement necessary reforms to the WTO's substantive rules

and procedures to address the challenges facing the global trading system, including growing inequality,

digital transformation, and impediments to small business trade. The Biden Administration will also work

with allies and like-minded trading partners to establish high-standard global rules to govern the digital

economy, in line with our shared democratic values.

The Biden Administration will also coordinate with friends and allies to pressure the Chinese Government

to end its unfair trade practices and to hold China accountable, including for the extensive human rights

abuses perpetrated by its state-sanctioned forced labor program. In addition, the trade agenda will seek to

collaborate with friends and allies to address global market distortions created by industrial overcapacity in

THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA | 5

sectors ranging from steel and aluminum to fiber optics, solar, and other sectors to which the Chinese

Government has been a key contributor.

Standing Up for American Farmers, Ranchers, Food Manufacturers, and

Fishers

U.S. farmers, ranchers, food manufacturers, and fishers compete in global markets, and expanded market

access raises incomes, expands employment, and lets their farms, ranches, manufacturing plants, and

fishing operations thrive. America’s agricultural communities have been burdened in recent years by erratic

trade actions that were taken without a broader strategy. These actions triggered retaliation by our trading

partners, leading to billions of dollars in lost exports and precipitating unprecedented mitigation payments.

The Biden Administration is committed to standing up for American farmers, ranchers, food manufacturers,

and fishers by pursuing smarter trade policies that are inclusive and work for all producers. The trade

agenda will seek to expand global market opportunities for American farmers, ranchers, food

manufacturers, and fishers and will defend our producers by enforcing global agricultural trade rules.

Promoting Equitable Economic Growth Around the World

The Biden Administration is committed to leveraging the global leadership of the United States to promote

economic stability and alleviate poverty in developing countries. The trade agenda plays an important role

in creating economic opportunities abroad, but the Biden Administration knows that simply granting greater

market access for corporations will not alone result in equitable economic growth or worker empowerment

in our trading partners. Policies that promote equitable global economic growth and increase global demand

benefit American workers, manufacturers, farmers, ranchers, fishers and service providers by expanding

the customer base, and increasing global demand helps support better prices.

The trade agenda will include a review of existing trade programs to evaluate their contribution to equitable

economic development, including whether they reduce wage gaps, increase worker unionization, promote

safe workplaces, tackle forced labor and exploitative labor conditions, and lead to the economic

empowerment of women and underrepresented communities. As part of this review, the Biden

Administration will seek to incorporate corporate accountability and sustainability into trade policies. In

addition, the Biden Administration is committed to engaging in robust technical assistance and trade

capacity building with trading partners to ensure workers and small and medium-sized enterprises around

the world benefit from U.S. trade policy.

Making the Rules Count

The Biden Administration will act when our trading partners break the trade rules. Strong trade

enforcement is essential to making sure our trading partners live up to their commitments and that U.S.

trade policy benefits American workers, manufacturers, farmers, businesses, families, and communities.

President Biden will not hesitate to bring trade cases against trading partners that discriminate against

American businesses or deny our producers market access. The trade agenda will include comprehensive

enforcement of labor and environmental standards of existing trade agreements and will consider new ways

of addressing the suppression of wages and workers’ rights in other countries to the detriment of U.S.

workers. Although unilateral action may be necessary in some instances, President Biden will make it a

priority to work with friends and allies on trade enforcement and pursue meaningful change for U.S.

workers and businesses in the global trading landscape.

6 | THE PRESIDENT’S 2021 TRADE POLICY AGENDA

CONCLUSION

The Biden Administration will pursue a trade policy that helps the U.S. economy recover from the COVID-

19 pandemic and reinforces investments our country is making in the domestic economy. In addition, the

President's trade agenda will be a critical component of the Biden Administration’s plan to Build Back

Better. Through a review of existing policies, negotiations of new standards, enforcement of our trade

agreements, and partnership with our friends and allies, President Biden’s trade agenda will support all

workers, combat climate change, advance racial equity, increase supply chain resiliency, and expand market

opportunities for American manufacturers, producers, farmers, fishers, and businesses of all sizes. The

Biden Administration will prioritize trade policies that have tangible benefits for all working Americans,

families, and communities.

THE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE

PRESIDENT ON THE TRADE AGREEMENTS

PROGRAM

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS | 1

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS

A. Agreements Notified for Negotiation

1. United States–European Union Trade Agreement

On October 16, 2018, at the direction of the President, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

notified Congress that the United States intended to enter into negotiations on a trade agreement with the

European Union (EU). On November 15, 2018, USTR issued a Federal Register notice seeking public

comment on a proposed U.S.–EU trade agreement, including U.S. interests and priorities, in order to

develop U.S. negotiating positions. The period for submission of public comments closed on December

10, 2018. On December 14, 2018, USTR held a public hearing on the proposed U.S.–EU trade agreement.

USTR also consulted extensively with relevant congressional and trade advisory committees on U.S.

negotiating objectives and positions. On January 11, 2019, USTR published detailed negotiating objectives

for a U.S.–EU trade agreement.

For further discussion on the United States–European Union Trade Agreement, see Chapter I.D.2 Europe

and the Middle East.

2. United States–Japan Trade Agreement and United States–Japan Digital

Trade Agreement

On October 16, 2018, at the direction of the President, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

notified Congress that the United States intended to enter into negotiations on a trade agreement with Japan.

On October 26, 2018, USTR issued a Federal Register notice seeking public comment on a proposed United

States–Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA) including U.S. interests and priorities, in order to develop U.S.

negotiating positions. The period for submission of public comments closed on November 26, 2018. On

December 10, 2018, USTR held a public hearing on the proposed USJTA. USTR also consulted extensively

with relevant congressional and trade advisory committees on U.S. negotiating objectives and positions.

On December 21, 2018, USTR published detailed negotiating objectives for the USJTA.

The United States and Japan began negotiations for a phase-one agreement in April 2019, reached

agreement in principle on early achievements in the areas of market access and digital trade in August 2019,

and announced that the final agreements in these two areas had been reached in September 2019. On

October 7, 2019, the United States and Japan signed the USJTA and the United States–Japan Digital Trade

Agreement, reflecting those early achievements. Following the completion of respective domestic

procedures, both agreements went into effect on January 1, 2020. The United States and Japan announced

plans for additional negotiations for a phase-two agreement in September 2019.

For further discussion on the United States–Japan Trade Agreement and United States–Japan Digital

Trade Agreement, see Chapter I.D.3 Japan, Korea, APEC and Chapter III.A Agriculture.

3. United States–Kenya Trade Agreement

In August 2018, the United States and Kenya established the U.S.–Kenya Trade and Investment Working

Group in order to, inter alia¸ explore ways to deepen the trade and investment ties between the two countries

2 | I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS

and lay the groundwork for a stronger future trade relationship, including by pursuing exploratory talks on

a potential future bilateral trade and investment framework.

On February 6, 2020, the President announced that the United States intended to initiate trade agreement

negotiations with Kenya following a meeting at the White House with Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.

On March 17, 2020, at the direction of the President, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

notified Congress that the United States intended to enter into negations on a trade agreement with Kenya.

On March 23, 2020, USTR issued a Federal Register notice seeking public comment on a proposed United

States–Kenya trade agreement, including U.S. interests and priorities in order to develop U.S. negotiating

positions. The period for submission of public comments initially closed on April 15, 2020. On April 13,

2020, USTR issued a separate Federal Register notice announcing the cancellation of a public hearing on

the proposed United States–Kenya trade agreement, consistent with guidance issued by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, and extended the deadline for

submission of public comments to April 28, 2020. USTR also consulted extensively with relevant

congressional and trade advisory committees on U.S. negotiating objectives and positions. On May 22,

2020, USTR published detailed negotiating objectives for a United States–Kenya Trade Agreement.

On July 8, 2020, the United States formally launched trade agreement negotiations with Kenya. U.S. and

Kenyan negotiators held two sets of negotiating sessions in 2020.

For further discussion on the United States–Kenya Trade Agreement, see Chapter I.D.6 sub-Saharan

Africa.

4. United States–United Kingdom Trade Agreement

Following a national referendum in 2016, the United Kingdom (UK) notified the European Union (EU) in

March 2017 of its intention to leave the EU (known as “Brexit”).

In July 2017, the United States and the UK established the United States–United Kingdom Trade and

Investment Working Group in order to, inter alia, lay the groundwork for a potential future free trade

agreement once the UK has left the EU.

On October 16, 2018, at the direction of the President, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

notified Congress that the United States intended to enter into negotiations on a potential trade agreement

with the UK after the UK had left the EU. On November 16, 2018, USTR issued a Federal Register notice

seeking public comment on a proposed U.S.–UK trade agreement, including U.S. interests and priorities,

in order to develop U.S. negotiating positions. The period for submission of public comments closed on

January 15, 2019. On January 29, 2019, USTR held a public hearing on the proposed U.S.–UK trade

agreement. USTR also consulted extensively with relevant congressional and trade advisory committees

on U.S. negotiating objectives and positions. On February 28, 2019, USTR published detailed negotiating

objectives for a U.S.–UK trade agreement. On May 5, 2020, the U.S. Trade Representative and UK

Secretary of State for International Trade announced the formal launch of trade agreement negotiations

between the United States and the UK. U.S. and UK negotiators held five sets of negotiating sessions in

2020 and made considerable progress towards a comprehensive, ambitious trade agreement.

For further discussion of the United States–United Kingdom Trade Agreement, see Chapter I.D.2 Europe

and Middle East.

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS | 3

B. Concluded Agreements

1. United States–China Economic and Trade Agreement

On January 15, 2020, the United States and China signed an historic economic and trade agreement, known

as the “Phase One Agreement.” This Phase One Agreement requires structural reforms and other changes

to China’s economic and trade regime in the areas of intellectual property, technology transfer, agriculture,

financial services, and currency and foreign exchange. The Phase One Agreement also includes a

commitment by China to make substantial additional purchases of U.S. goods and services in calendar years

2020 and 2021. Importantly, the Phase One Agreement establishes a strong dispute resolution system that

ensures prompt and effective implementation and enforcement.

2. United States and European Union Trade Agreement Regarding Tariffs on

Certain Products

On August 21, 2020, the United States and the European Union (EU) announced a trade agreement

regarding reductions on tariffs on certain products of interest to each side. The agreed tariff modifications

entered into effect on December 18, 2020 for the EU, with the publication in the Official Journal of the EU

of Regulation (EU) 2020/2131 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and on December 22 for the

United States, with the issuance of a proclamation by the President. Under the agreement, the EU

eliminated tariffs on imports of certain live and frozen lobster products on a Most-Favored-Nation (MFN)

basis, retroactive to August 1, 2020. The EU tariffs will be eliminated for a period of five years, and the

European Commission will initiate procedures aimed at making the tariff elimination permanent. The

United States reduced by 50 percent its tariff rates on prepared meals, certain crystal glassware, surface

preparations, propellant powders, cigarette lighters, and lighter parts. The U.S. tariff reductions are also on

an MFN basis and retroactive to August 1, 2020.

For further discussion on the U.S. and EU reductions on tariffs on certain products, see Chapter I.D.2

Europe and the Middle East.

3. United States–Brazil Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation

On October 19, 2020, the United States and Brazil signed a Protocol Relating to Trade Rules and

Transparency. The new Protocol is an update to the Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation

(ATEC) of 2011, and is an integral part of that agreement. The Protocol with Brazil, the first of its kind,

highlights the importance of openness and procedural fairness in trade rules. It comprises three annexes,

each with state-of-the art provisions for trade agreements: Trade Facilitation and Customs Administration,

Good Regulatory Practices, and Anti-Corruption.

For further discussion on Brazil, see Chapter I.D.1 The Americas.

4. United States–Ecuador Protocol to the Trade and Investment Council

Agreement Relating to Trade Rules and Transparency

On December 8, 2020, the United States and Ecuador signed a Protocol on Trade Rules and Transparency.

The new Protocol is an update to the United States–Ecuador Trade and Investment Council Agreement

(TIC) of 1990, and is an integral part of that agreement. The Protocol establishes high-standard trade rules

with Ecuador, based on the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement and a similar Protocol with Brazil.

It comprises four annexes, each with state-of-the-art provisions for trade agreements: Customs

4 | I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS

Administration and Trade Facilitation, Good Regulatory Practices, Anti-Corruption, and Small and

Medium-Sized Enterprises.

For further discussion on Ecuador, see Chapter I.D.1 The Americas.

5. United States–Fiji Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

On October 15, 2020, the United States signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) with

Fiji. The TIFA establishes a framework for discussing trade and investment issues to expand and deepen

bilateral ties between the two countries. This is the United States’ first TIFA with a small island developing

state in the Pacific, and it provides the opportunity, in select circumstances, for other small Pacific Island

states to join as observers in TIFA discussions. This TIFA will help strengthen the United States’ economic

commitment to the Indo-Pacific region.

For further discussion on the Indo-Pacific, see Chapter I.D.5 Southeast Asia and Pacific.

C. Free Trade Agreements in Force

1. Australia

The United States–Australia Free Trade Agreement (FTA) entered into force on January 1, 2005.

Operation of the United States–Australia Free Trade Agreement

The United States–Australia Joint Committee is the central oversight body for the FTA. The United States

met regularly with Australia throughout 2020 to monitor implementation of the FTA and review concerns

about market access. In April 2020, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and the U.S. Department

of Agriculture engaged Australia under the United States–Australia FTA Sanitary and Phytosanitary

Committee to discuss a range of issues, including U.S. market access for pork, turkey, beef, and horticulture

products. The United States continued to work closely with Australia to deepen the bilateral trade

relationship and coordinate on issues of regional and international importance.

Agriculture

For a discussion on agriculture-related activities, see Chapter III.A.3 Bilateral and Regional Activities.

2. Bahrain

The United States–Bahrain Free Trade Agreement (FTA) entered into force on August 1, 2006. Under the

FTA, as of August 1, 2006, Bahrain provides duty-free access to 100 percent of the two-way trade in

industrial and consumer products, and trade in most agricultural products. In addition, Bahrain opened its

services market, creating important new opportunities for U.S. financial services providers and U.S.

companies that offer telecommunication, audiovisual, express delivery, distribution, health care,

architecture, and engineering services. Under the 2018 United States–Bahrain Memorandum of

Understanding on Trade in Food and Agriculture Products, Bahrain continues to accept existing U.S. export

certifications for food and agricultural products.

The United States–Bahrain Bilateral Investment Treaty, which took effect in May 2001, covers investment

issues between the two countries.

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS | 5

Operation of the United States–Bahrain Free Trade Agreement

The United States–Bahrain Joint Committee (JC) is the central oversight body for the FTA. Meetings of

the JC have addressed a broad range of trade issues, including: (1) efforts to increase bilateral trade and

investment levels, (2) efforts to ensure effective implementation of the FTA’s customs, investment, and

services chapters, (3) possible cooperation in the broader Middle East and North Africa region, and (4)

additional cooperative efforts related to labor rights and environmental protection.

Labor

During 2020, USTR and the U.S. Department of Labor continued to monitor labor rights in Bahrain, in

particular with respect to employment discrimination and freedom of association related concerns that had

been highlighted initially during consultations that began in 2013 under the United States–Bahrain FTA.

For further discussion on labor-related activities, see Chapter III.G.1 Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral

Activities.

3. Central America and the Dominican Republic

On August 5, 2004, the United States signed the Dominican Republic–Central America–United States Free

Trade Agreement (CAFTA–DR) with five Central American countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador,

Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) and the Dominican Republic. The Agreement has been in force

since January 1, 2009 for all seven countries that signed the CAFTA–DR. It entered into force for the

United States, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua in 2006, for the Dominican Republic on

March 1, 2007, and for Costa Rica on January 1, 2009.

The CAFTA–DR eliminates tariffs, opens markets, reduces barriers to services, and promotes transparency,

prosperity, and stability throughout the region. U.S. export and investment opportunities with Central

America and the Dominican Republic have continued to grow under the CAFTA–DR. All the CAFTA–

DR Parties have committed to strengthening trade facilitation, regional supply chains, and implementation

of the Agreement. U.S. consumer and industrial goods may enter duty free in all of the other CAFTA–DR

member country markets. Nearly all U.S. textile and apparel goods meeting the Agreement’s rules of origin

enter the other CAFTA–DR countries’ markets duty free and quota free. Under the CAFTA–DR, one-third

of U.S. agricultural exports to the region are currently subject to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs). However, these

TRQs will increase annually through 2025, after which the TRQs will be eliminated and the affected

products will enter other CAFTA–DR countries duty free.

Operation of the Dominican Republic–Central America–United States Free Trade Agreement

The CAFTA–DR Free Trade Commission (FTC) is the central oversight body for the CAFTA–DR. The

CAFTA–DR Coordinators, who are technical level staff of the Parties, maintain ongoing communication

to follow up on agreements reached by the FTC, to advance technical and administrative implementation

issues under the CAFTA–DR, and to define the agenda for meetings of the FTC.

Agriculture

For a discussion on agriculture-related activities, see Chapter III.A.3 Bilateral and Regional Activities.

6 | I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS

Environment

For a discussion on environment-related activities, see Chapter III.F.1 Free Trade Agreements and

Bilateral Activities.

Labor

Ongoing labor capacity building activities, including the exchange of views on best practices, support

efforts to promote labor rights and improve the enforcement of labor laws in the CAFTA–DR countries. In

2020, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) continued to fund technical assistance projects under the

CAFTA–DR Labor Cooperation and Capacity Building Mechanism, the U.S. Agency for International

Development continued to support activities focused on freedom of association and labor relations as part

of its Global Labor Program, and the U.S. Department of State continued funding a program to combat

labor violence in Guatemala and Honduras.

Dominican Republic

During 2020, the United States continued to engage with the Government of the Dominican Republic, the

sugar industry, and civil society groups on the concerns identified in a 2013 DOL report. The report

responds to allegations in a public submission that the Government of the Dominican Republic had failed

to enforce the country’s labor laws in the sugar sector. Sugar producers have engaged in the process to

varying degrees and have implemented some of the reforms raised in the public submission and

recommended in the DOL report. The Dominican Ministry of Labor continued its direct outreach on labor

rights to sugarcane cutters at all three major Dominican sugar companies and expanded the program to

include the state-run sugar company. Additionally, the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Labor discussed

more formal collaboration to help build Creole language capacity in the labor inspectorate. Although

progress has been made, procedural and methodological shortcomings in the labor inspections process still

remain. Through a DOL-funded $5 million technical assistance project designed to improve working

conditions and address child labor in the Dominican agriculture sector, the Minister of Labor committed to

sustaining an electronic case management system that could help systematize inspections, in line with the

DOL report recommendations.

Honduras

In 2015, a DOL report issued in response to a 2012 public submission under the CAFTA–DR led to the

signing of a Labor Rights Monitoring and Action Plan (MAP). Since that time, the United States and the

Government of Honduras have been working together to fulfill commitments Honduras made in the MAP,

including addressing legal and regulatory frameworks for labor rights, undertaking institutional

improvements, intensifying targeted enforcement, and improving transparency. Honduras has made some

significant progress in implementing the MAP over the past five years, including convening numerous

tripartite meetings with private sector and labor stakeholders to discuss progress under the MAP, passing a

comprehensive new labor inspection law in January 2017, issuing an implementing regulation for the law

in July 2019, and adopting a child labor referral mechanism in August 2019. In 2020, the U.S. Government

conducted one mission to Honduras to follow up on the MAP, with further missions postponed to 2021 as

a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the U.S. Government and Government of Honduras agreed

to extend the MAP for a period of nine months, once Honduras lifts its COVID-19 state of emergency. This

should help ensure that required actions to improve Honduras’ capacity for collecting fines assessed under

the new inspection law and resolving freedom of association cases in the melon and automotive parts sectors

are completed before the MAP concludes.

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS | 7

The U.S. Government is providing a number of technical cooperation projects in Honduras to support

employment and labor rights, including the Department of State-funded program to combat labor violence

mentioned above. The DOL funds an $11.6 million project to reduce child labor and improve labor rights

in support of the Government of Honduras’ implementation of MAP commitments, a $2 million project to

improve and expand a new electronic case management system for the labor inspectorate and to improve

Honduras’ technical capacity to collect fines, as well as a $2 million project with the International Labor

Organization to combat child labor in the coffee sector.

Costa Rica and El Salvador

In support of a recent labor law reform in Costa Rica, the DOL continued to fund a $2 million technical

assistance project to build the capacity of key Costa Rican agencies responsible for enforcing labor laws,

particularly the labor inspectorate and the labor courts, with respect to minimum wages, hours of work, and

occupational safety and health in the agricultural export sector. The project promotes access to labor rights

by workers in the agricultural sector through new mechanisms to file complaints before national

administrative and labor courts. The DOL continues to fund two technical assistance projects in Costa Rica

that support vulnerable and marginalized youth in acquiring the skills to enter the job market, help

companies develop apprenticeship or workplace-based training programs for vulnerable youth, and support

efforts to strengthen the laws and policies for these programs. With support provided by the DOL, the

Government of Costa Rica enacted legislation to align age requirements for employment programs with the

legal age for employment.

In November 2020, the U.S. Government held a technical exchange between the Ministry of Labor of El

Salvador and DOL’s Bureau of Labor Statistics on labor market intelligence. This was the first technical

exchange under the Labor Cooperative Dialogue, which seeks to design and implement cooperative

activities such as technical exchanges on key topics of interest as a way to advance compliance with labor

commitments under the CAFTA–DR, particularly effective enforcement of labor laws.

The DOL continued to fund labor capacity-building projects implemented by IMPAQ International, a

research institute headquartered in Washington, DC. These projects included a $4 million project on labor

market information systems in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and a $17 million technical

assistance project to support vocational training and skill-building for at-risk youth and to prevent

exploitative child labor practices in El Salvador and Honduras.

For further discussion on labor-related activities, see Chapter III.G.1 Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral

Activities.

Other Implementation Matters

The CAFTA–DR mechanisms continue to strengthen our trading relationships as we monitor and enforce

the Agreement with Central America and the Dominican Republic and build U.S. export opportunities.

During 2020, the United States held follow-on discussions on issues addressed during July and November

2019 meetings of CAFTA–DR Coordinators and other technical committees. Engagements have addressed

issues related to the Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Matters; the Committee on Technical

Barriers to Trade (TBT); and customs- and border-related matters to improve transparency, efficiency, and

the operation of the Agreement to facilitate trade. Bilateral discussions during 2020 advanced the CAFTA–

DR Parties’ agreement from 2019 to further address SPS and TBT issues of priority interest to U.S.

exporters and manufacturers.

In 2020, the CAFTA–DR Parties completed notifications that they had taken the respective domestic actions

to implement the modifications to the product-specific rules of origin, which reflect the 2017 changes to

8 | I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS

the Harmonized System (HS) nomenclature. The United States announced in the Federal Register the

effective date of modifications to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States concerning the

CAFTA–DR, which became applicable on November 1, 2020. These steps satisfy administrative

requirements and facilitate customs processing for member countries.

During 2020, the CAFTA–DR Parties exchanged trade data reports under the Agricultural Review

Commission (ARC) that was established in November 2019, in accordance with Article 3.18 of the

CAFTA–DR, to review implementation and operation of the Agreement as it relates to trade in agricultural

goods. The ARC is comprised of members of the Committee on Agricultural Trade under the CAFTA–

DR.

In 2020, the United States also continued to work closely with CAFTA–DR Parties on bilateral and regional

matters related to implementation of the Agreement. For example, the U.S. Government continued to work

with several CAFTA–DR partners on implementation of agricultural and SPS trade matters. The U.S.

Government worked to improve the transparency and effectiveness of regulatory and TRQ administration

procedures, which has resulted in enhanced market access for U.S. exporters of several agricultural

products, including U.S. dairy products and table eggs in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

During 2020, the United States finalized a bilateral agreement with Costa Rica recognizing the U.S.

Department of Transportation’s “Blue Ribbon” program as satisfying Costa Rica’s tire regulations,

facilitating U.S. exports.

The U.S. Government also worked with several countries to ensure implementation of the Agreement’s

provisions on intellectual property (IP), including those related to notice and takedown and safe harbor for

Internet service providers, government use of unlicensed software, geographical indications, and IP

enforcement, achieving comprehensive progress in Costa Rica.

Through the FTC, the CAFTA–DR Parties committed to addressing inefficiencies and obstacles to cross-

border trade in the region to increase the transparency and predictability of trade and doing business. The

CAFTA–DR Parties are poised to benefit from trade facilitation, and continue to make progress in this area,

including reforms to customs practices that reduce the cost and time of transporting goods across borders

within the region’s highly integrated manufacturing and supply-chain networks.

The FTC further emphasized the need for greater regional integration and agreed to support supply-chain

systems in the region through several initiatives. The United States is supporting advances in this area

through various trade capacity building efforts to promote economic prosperity. These initiatives include

efforts to support the U.S. textile and apparel industry by strengthening utilization of the Agreement and

regional supply chains.

Trade Capacity Building

Trade capacity building programs and planning in other areas continued throughout 2020 to promote

economic prosperity to mitigate migration from Central America.

During 2020, USTR, along with USAID and other U.S. Government trade and donor agencies, such as the

U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA), State, and Commerce, carried out bilateral and regional projects

with the CAFTA–DR partner countries to promote economic prosperity and trade facilitation in the region

and increase trade capacity within the CAFTA–DR countries.

During 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce implemented the Central America Customs, Border

Management, and Supply Chain trade facilitation program, which provides technical assistance to the

I. AGREEMENTS AND NEGOTIATIONS | 9

governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras on implementing transparency reforms to improve

and simplify customs clearance procedures. The program promotes economic prosperity objectives and