National Response

Framework

Third Edition

June 2016

National Response Framework

i

Executive Summary

The National Response Framework is a guide to how the Nation responds to all types of disasters and

emergencies. It is built on scalable, flexible, and adaptable concepts identified in the National

Incident Management System to align key roles and responsibilities across the Nation. This

Framework describes specific authorities and best practices for managing incidents that range from

the serious but purely local to large-scale terrorist attacks or catastrophic natural disasters. The

National Response Framework describes the principles, roles and responsibilities, and coordinating

structures for delivering the core capabilities required to respond to an incident and further describes

how response efforts integrate with those of the other mission areas. This Framework is always in

effect and describes the doctrine under which the Nation responds to incidents. The structures,

roles, and responsibilities described in this Framework can be partially or fully implemented in the

context of a threat or hazard, in anticipation of a significant event, or in response to an incident.

Selective implementation of National Response Framework structures and procedures allows for a

scaled response, delivery of the specific resources and capabilities, and a level of coordination

appropriate to each incident.

The Response mission area focuses on ensuring that the Nation is able to respond effectively to all

types of incidents that range from those that are adequately handled with local assets to those of

catastrophic proportion that require marshaling the capabilities of the entire Nation. The objectives of

the Response mission area define the capabilities necessary to save lives, protect property and the

environment, meet basic human needs, stabilize the incident, restore basic services and community

functionality, and establish a safe and secure environment to facilitate the integration of recovery

activities.

1

The Response mission area includes 15 core capabilities: planning; public information

and warning; operational coordination; critical transportation; environmental response/health and

safety; fatality management services; fire management and suppression; infrastructure systems;

logistics and supply chain management; mass care services; mass search and rescue operations; on-

scene security, protection, and law enforcement; operational communications; public health,

healthcare, and emergency medical services; and situational assessment.

The priorities of the Response mission area are to save lives, protect property and the environment,

stabilize the incident, and provide for basic human needs. The following principles establish

fundamental doctrine for the Response mission area: engaged partnership; tiered response; scalable,

flexible, and adaptable operational capabilities; unity of effort through unified command; and

readiness to act.

Scalable, flexible, and adaptable coordinating structures are essential in aligning the key roles and

responsibilities to deliver the Response mission area’s core capabilities. The flexibility of such

structures helps ensure that communities across the country can organize response efforts to address

a variety of risks based on their unique needs, capabilities, demographics, governing structures, and

non-traditional partners. This Framework is not based on a one-size-fits-all organizational construct,

but instead acknowledges the concept of tiered response, which emphasizes that response to incidents

should be handled at the lowest jurisdictional level capable of handling the mission.

1

As with all activities in support of the National Preparedness Goal, activities taken under the response mission

must be consistent with all pertinent statutes and policies, particularly those involving privacy and civil and human

rights, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and Civil Rights Act of

1964.

National Response Framework

ii

In implementing the National Response Framework to build national preparedness, partners are

encouraged to develop a shared understanding of broad-level strategic implications as they make

critical decisions in building future capacity and capability. The whole community should be

engaged in examining and implementing the strategy and doctrine contained in this Framework,

considering both current and future requirements in the process.

National Response Framework

iii

Table of Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1

Framework Purpose and Organization .................................................................................1

Evolution of the Framework ...................................................................................................3

Relationship to NIMS ..............................................................................................................3

Intended Audience ...................................................................................................................4

Scope ............................................................................................................................. 4

Guiding Principles ...................................................................................................................5

Risk Basis ..................................................................................................................................7

Roles and Responsibilities ........................................................................................... 8

Individuals, Families, and Households ..................................................................................8

Communities .............................................................................................................................9

Nongovernmental Organizations ............................................................................................9

Private Sector Entities ...........................................................................................................10

Local Governments ................................................................................................................11

State, Tribal, Territorial, and Insular Area Governments ................................................12

Federal Government ..............................................................................................................15

Core Capabilities ......................................................................................................... 20

Context of the Response Mission Area.................................................................................20

Response Actions to Deliver Core Capabilities ...................................................................28

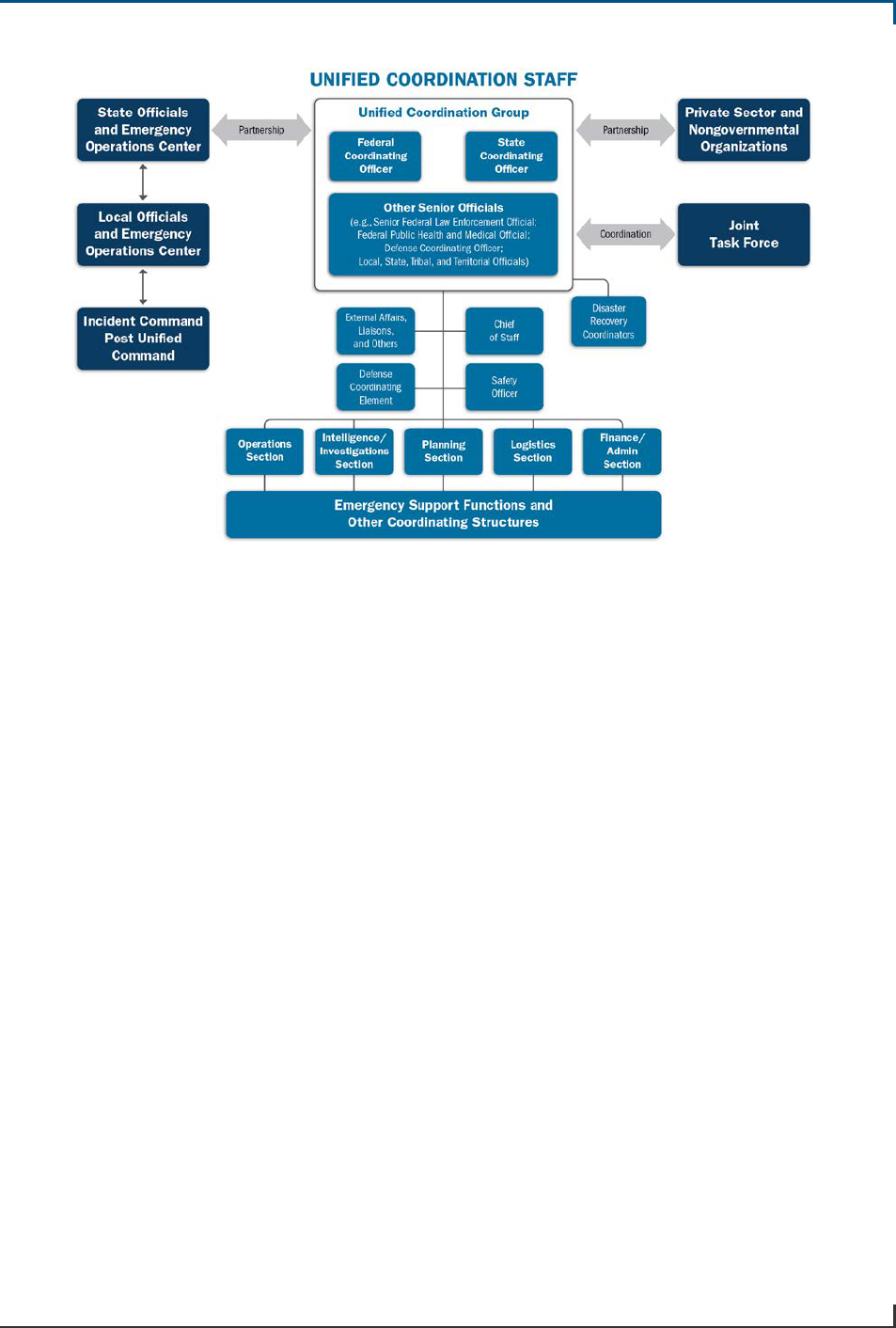

Coordinating Structures and Integration .................................................................. 32

Local Coordinating Structures .............................................................................................32

State and Territorial Coordinating Structures ...................................................................32

Tribal Coordinating Structures ............................................................................................32

Private Sector Coordinating Structures ..............................................................................33

Federal Coordinating Structures..........................................................................................33

Operational Coordination .....................................................................................................39

Integration ..............................................................................................................................45

National Response Framework

iv

Relationship to Other Mission Areas ......................................................................... 47

Operational Planning .................................................................................................. 47

Response Operational Planning ...........................................................................................48

Planning Assumptions ...........................................................................................................51

Framework Application ........................................................................................................51

Supporting Resources ................................................................................................ 51

Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 52

National Response Framework

1

Introduction

The National Preparedness System outlines an organized process for the whole community to move

forward with their preparedness activities and achieve the National Preparedness Goal. The National

Preparedness System integrates efforts across the five preparedness mission areas—Prevention,

Protection, Mitigation, Response, and Recovery—in order to achieve the goal of a secure and

resilient Nation. The National Response Framework (NRF), part of the National Preparedness

System, sets the strategy and doctrine for how the whole community builds, sustains, and delivers the

Response core capabilities identified in the National Preparedness Goal in an integrated manner with

the other mission areas. This third edition of the NRF reflects the insights and lessons learned from

real-world incidents and the implementation of the National Preparedness System.

Prevention: The capabilities necessary to avoid, prevent, or stop a threatened or actual

act of terrorism. Within the context of national preparedness, the term “prevention” refers

to preventing imminent threats.

Protection: The capabilities necessary to secure the homeland against acts of terrorism

and manmade or natural disasters.

Mitigation: The capabilities necessary to reduce loss of life and property by lessening

the impact of disasters.

Response: The capabilities necessary to save lives, protect property and the

environment, and meet basic human needs after an incident has occurred.

Recovery: The capabilities necessary to assist communities affected by an incident to

recover effectively.

Framework Purpose and Organization

The NRF is a guide to how the Nation responds to all types of disasters and emergencies. It is built

on scalable, flexible, and adaptable concepts identified in the National Incident Management System

(NIMS)

2

to align key roles and responsibilities across the Nation. The NRF describes specific

authorities and best practices for managing incidents that range from the serious but purely local to

large-scale terrorist attacks or catastrophic

3

natural disasters.

This document supersedes the NRF that was issued in May 2013. It becomes effective

60 days after publication.

The term “response,” as used in the NRF, includes actions to save lives, protect property and the

environment, stabilize communities, and meet basic human needs following an incident. Response

also includes the execution of emergency plans and actions to support short-term recovery. The NRF

describes doctrine for managing any type of disaster or emergency regardless of scale, scope, and

complexity. This Framework explains common response disciplines and processes that have been

2

http://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system

3

A catastrophic incident is defined as any natural or manmade incident, including terrorism, that results in

extraordinary levels of mass casualties, damage, or disruption severely affecting the population, infrastructure,

environment, economy, national morale, or government functions.

National Response Framework

2

developed at all levels of government (local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area,

4

and Federal) and

have matured over time.

To support the Goal, the objectives of the NRF are to:

Describe scalable, flexible, and adaptable coordinating structures, as well as key roles and

re

sponsibilities for integrating capabilities across the whole community,

5

to support the efforts of

l

ocal, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and Federal governments in responding to actual and

potential incidents

.

Describe, across the whole community, the steps needed to prepare for delivering the response

core capabilities

.

Foster integration and coordination of activities within the Response mission area.

Outline how the Response mission area relates to the other mission areas, as well as the

re

lationship between the Response core capabilities and the core capabilities in other missi

on

ar

eas

.

Provide guidance through doctrine and establish the foundation for the development of the

Response Federal Interagency

Operational Plan (FIOP).

Incorporate continuity operations and planning to facilitate the performance of response core

capabilities during all hazards emergencies or other situations that may disrupt normal

operations

.

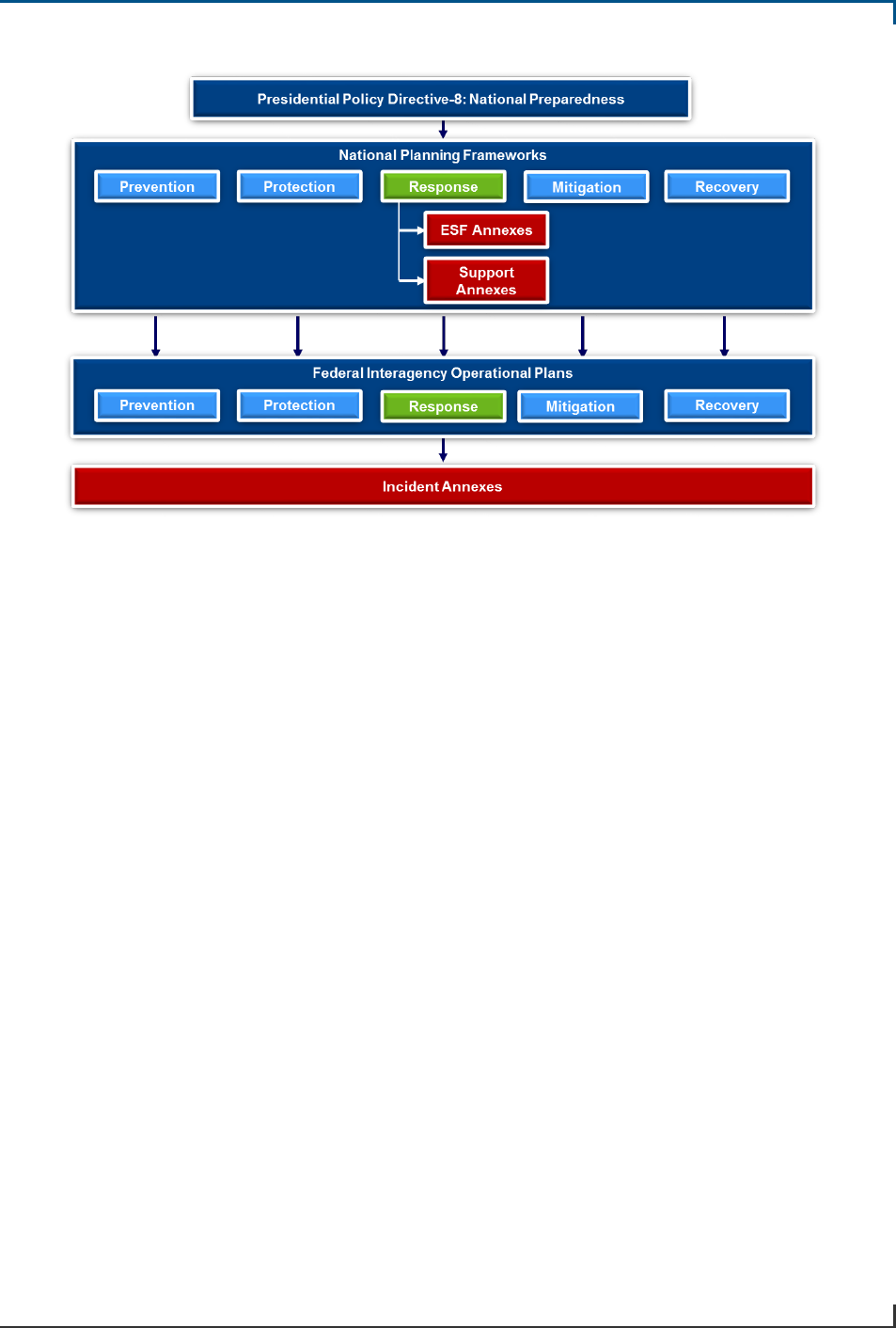

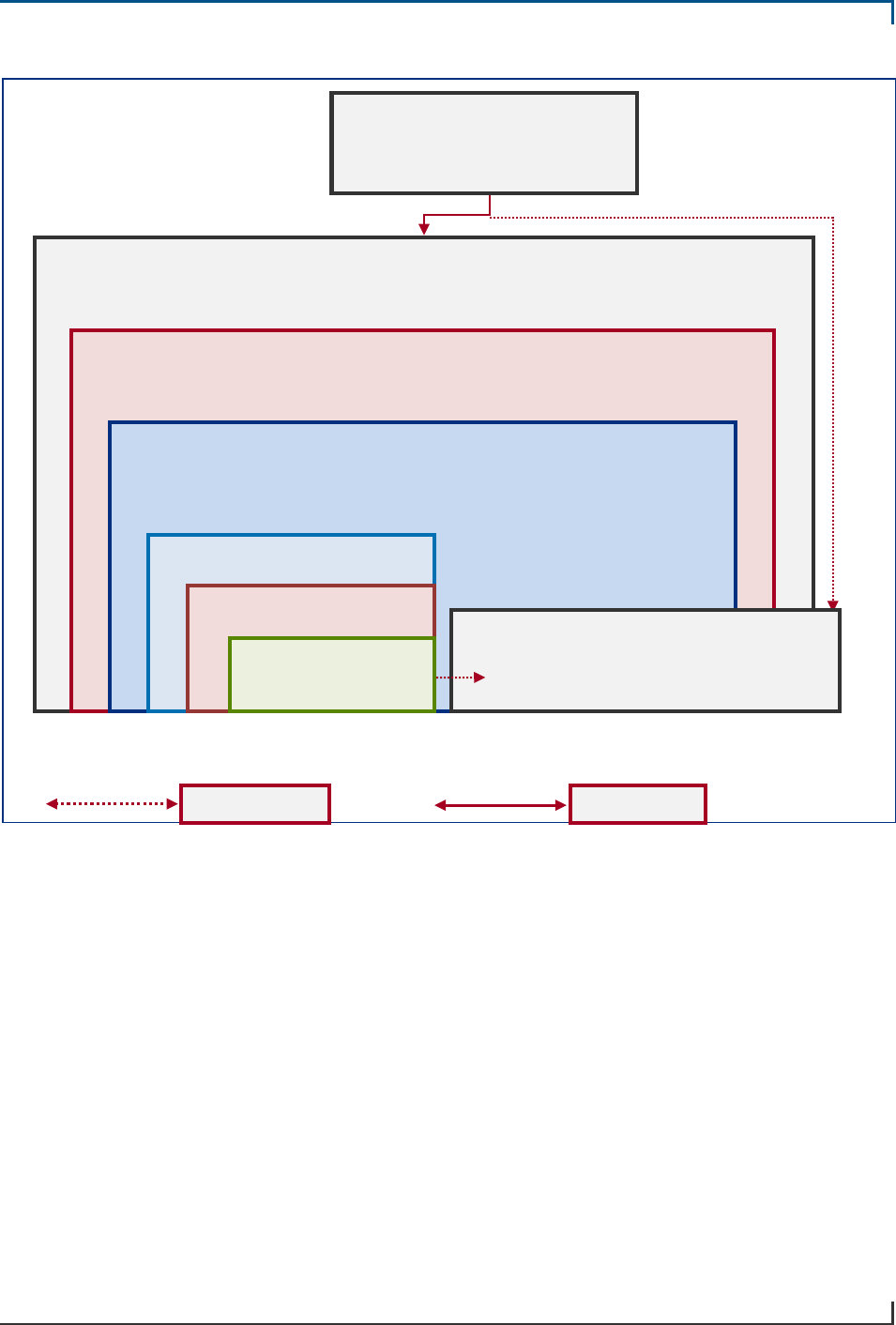

T

he NRF is composed of a base document, Emergency Support Function (ESF) Annexes, and

Support Annexes. The annexes provide detailed information to assist with the implementation of the

NRF.

ESF Annexes describe the Federal coordinating structures that group resources and capabilities

into functional areas that are most frequently needed in a national response.

Support Annexes describe the essential supporting processes and considerations that are most

common to the majority of incidents.

Note that the incident annexes, which address response to specific risks and hazards, can now be

found as annexes to the Response FIOP rather than as supplements to the NRF. This change is

consistent with guidance in the National Preparedness System.

4

Per the Stafford Act, insular areas include Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American

Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Other statutes or departments and agencies may define the term insular area

differently.

5

Whole community includes individuals and communities, the private and nonprofit sectors, faith-based

organizations, and all levels of government (local, regional/metropolitan, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and

Federal). Whole community is defined in the National Preparedness Goal as “a focus on enabling the participation in

national preparedness activities of a wider range of players from the private and nonprofit sectors, including

nongovernmental organizations and the general public, in conjunction with the participation of all levels of

governmental in order to foster better coordination and working relationships.” The National Preparedness Goal may

be found online at http://www.fema.gov

.

National Response Framework

3

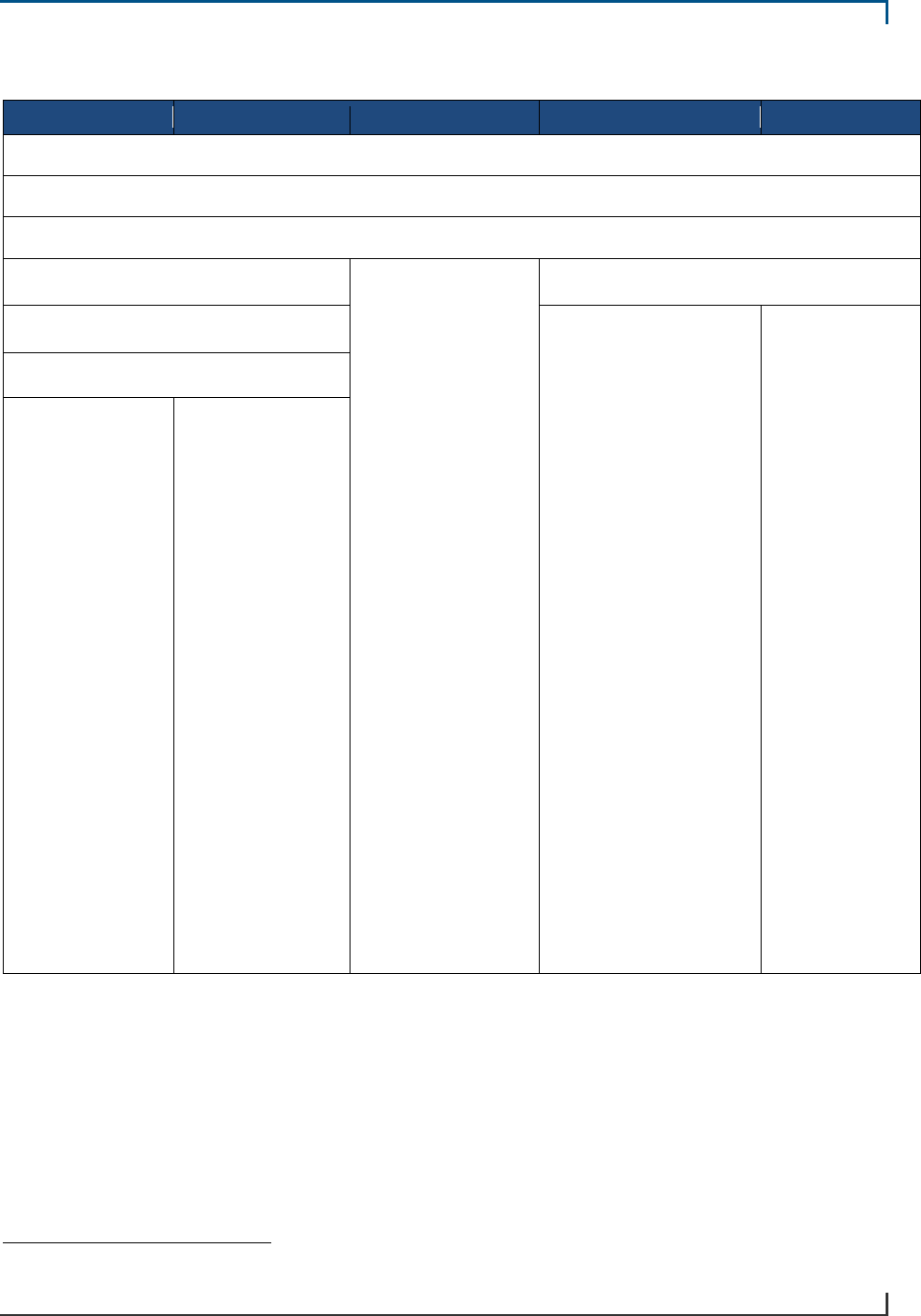

Figure 1: NRF and FIOP Structure

Evolution of the Framework

The NRF builds on over 20 years of Federal response guidance beginning with the Federal Response

Plan published in 1992, which focused largely on Federal roles and responsibilities. The

establishment of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the emphasis on the development

and implementation of common incident management and response principles led to the development

of the National Response Plan (NRP) in 2004. The NRP broke new ground by integrating all levels

of government, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations (NGO) into a common

incident management framework. In 2008, the NRP was superseded by the first NRF, which

streamlined the guidance and integrated lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and other incidents.

This NRF reiterates the principles and concepts of the 2013 version of the NRF and implements the

new requirements and terminology of the National Preparedness System. By fostering a holistic

approach to response, this NRF emphasizes the need for the involvement of the whole community.

Along with the National Planning Frameworks for other mission areas, this document now describes

the all-important integration and inter-relationships among the mission areas of Prevention,

Protection, Mitigation, Response, and Recovery.

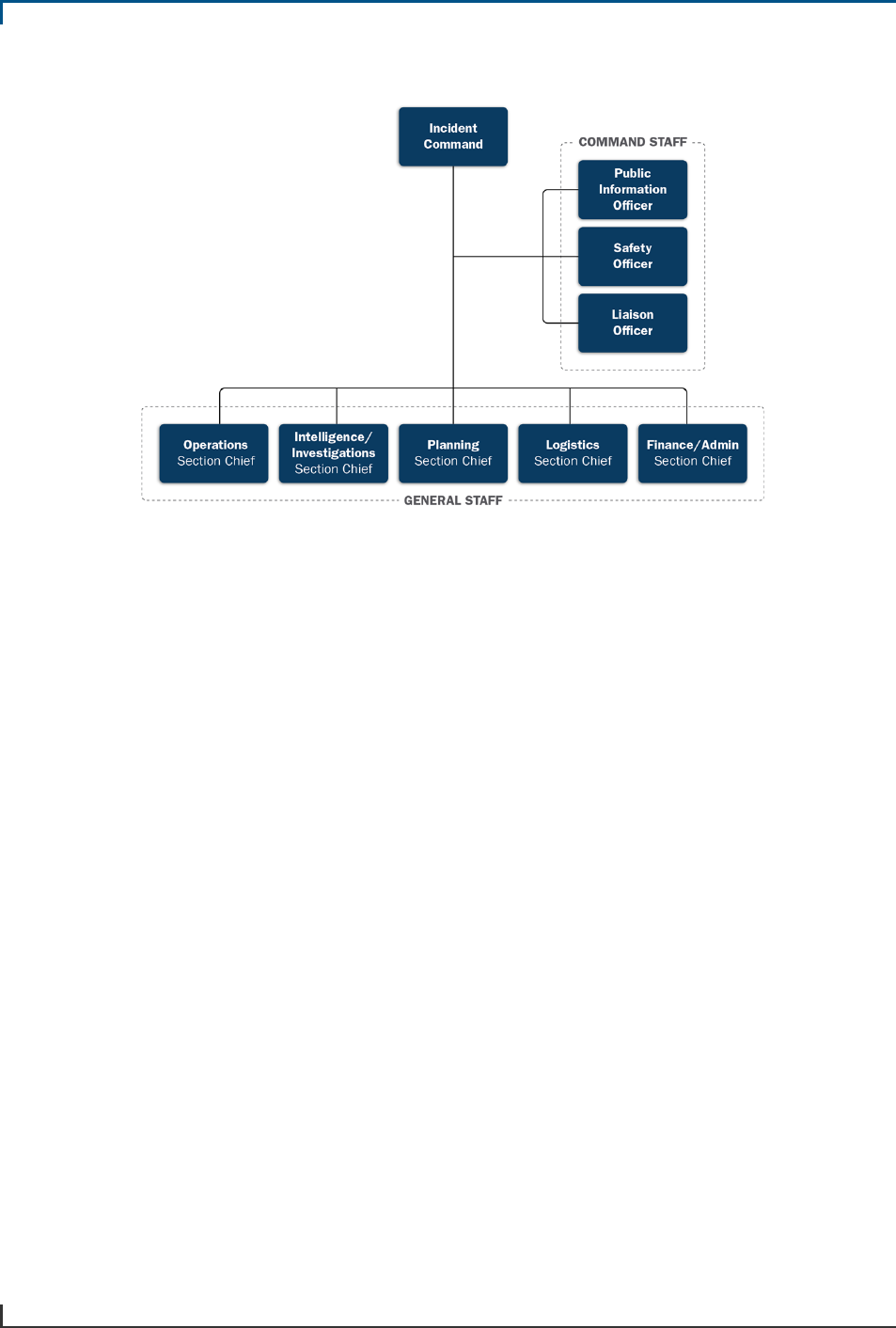

Relationship to NIMS

The response protocols and structures described in the NRF align with NIMS. NIMS provides the

incident management basis for the NRF and defines standard command and management structures.

Standardizing national response doctrine on NIMS provides a consistent, nationwide template to

enable the whole community to work together to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and

recover from the effects of incidents regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity.

All of the components of the NIMS—including preparedness, communications and information

management, resource management, and command and management—support response. The NIMS

concepts of multiagency coordination and unified command are described in the command and

management component of NIMS. These two concepts are essential to effective response operations

National Response Framework

4

because they address the importance of: (1) developing a single set of objectives, (2) using a

collective, strategic approach, (3) improving information flow and coordination, (4) creating a

common understanding of joint priorities and limitations, (5) ensuring that no agency’s legal

authorities are compromised or neglected, and (6) optimizing the combined efforts of all participants

under a single plan.

Intended Audience

Although the NRF is intended to provide guidance for the whole community, it focuses especially on

the needs of those who are involved in delivering and applying the response core capabilities defined

in the National Preparedness Goal. This includes emergency management practitioners, first

responders, community leaders, and government officials who must collectively understand and

assess the needs of their respective communities and organizations and determine the best ways to

organize and strengthen their resilience.

The NRF is intended to be used by the whole community. The whole community includes

individuals, families, households, communities, the private and nonprofit sectors, faith-based

organizations, and local, state, tribal, territorial, and Federal governments. This all-inclusive

approach focuses efforts and enables a full range of stakeholders to participate in national

preparedness activities and to be full partners in incident response. Government resources alone

cannot meet all the needs of those affected by major disasters. All elements of the community must

be activated, engaged, and integrated to respond to a major or catastrophic incident.

Engaging the whole community, particularly with regards to developing individual and community

preparedness, is essential to the Nation’s success in achieving resilience and national preparedness.

By providing equal access to acquire and use the necessary knowledge and skills, this Framework is

intended to enable the whole community to contribute to and benefit from national preparedness.

This includes children

6

; older adults; individuals with disabilities and others with access and

functional needs

7

; those from religious, racial, and ethnically diverse backgrounds; people with

limited English proficiency; and owners of animals, including household pets and service and

assistance animals. Their contributions must be integrated into the Nation’s efforts, and their needs

must be incorporated as the whole community plans and executes the core capabilities.

8

Scope

The NRF describes structures for implementing nationwide response policy and operational

coordination for all types of domestic incidents.

9

This section describes the scope of the Response

6

Children require a unique set of considerations across the core capabilities contained within this document. Their

needs must be taken into consideration as part of any integrated planning effort.

7

Access and functional needs refers to persons who may have additional needs before, during and after an incident

in functional areas, including but not limited to: maintaining health, independence, communication, transportation,

support, services, self-determination, and medical care. Individuals in need of additional response assistance may

include those who have disabilities; live in institutionalized settings; are older adults; are children; are from diverse

cultures; have limited English proficiency or are non-English speaking; or are transportation disadvantaged.

8

For further information, see the Core Capabilities section.

9

A domestic incident may have international and diplomatic impacts and implications that call for coordination and

consultations with foreign governments and international organizations. The NRF also applies to the domestic

response to incidents of foreign origin that impact the United States. See the International Coordination Support

Annex for more information.

National Response Framework

5

mission area, the guiding principles of response doctrine and their application, and how risk informs

response planning.

The Response mission area focuses on ensuring that the Nation is able to respond effectively to all

types of incidents that range from those that are adequately handled with local assets to those of

catastrophic proportion that require marshaling the capabilities of the entire Nation. The objectives of

the Response mission area define the capabilities necessary to save lives, protect property and the

environment, meet basic human needs, stabilize the incident, restore basic services and community

functionality, and establish a safe and secure environment to facilitate the integration of recovery

activities.

10

The NRF describes the principles, roles and responsibilities, and coordinating structures for

delivering the core capabilities required to respond to any incident and further describes how

response efforts integrate with those of the other mission areas. The NRF is always in effect, and

elements can be implemented at any time. The structures, roles, and responsibilities described in

the NRF can be partially or fully implemented in the context of a threat or hazard, in anticipation of a

significant event, or in response to an incident. Selective implementation of NRF structures and

procedures allows for a scaled response, delivery of the specific resources and capabilities, and a

level of coordination appropriate to each incident.

In this Framework, the term ‘incident’ includes actual or potential emergencies and disasters

resulting from all types of threats and hazards, ranging from accidents and natural disasters to cyber

intrusions and terrorist attacks. The NRF’s structures and procedures address how Federal

departments and agencies coordinate support for local, state, tribal, territorial, and insular area

governments.

Nothing in the NRF is intended to alter or impede the ability of any local, state, tribal, territorial,

insular area, or Federal government department or agency to carry out its authorities or meet its

responsibilities under applicable laws, executive orders, and directives.

Guiding Principles

The priorities of response are to save lives, protect property and the environment, stabilize the

incident, and provide for basic human needs. The following principles establish fundamental doctrine

for the Response mission area: (1) engaged partnership, (2) tiered response, (3) scalable, flexible, and

adaptable operational capabilities, (4) unity of effort through unified command, and (5) readiness to

act. These principles are rooted in the Federal system and the Constitution’s division of

responsibilities between state and Federal governments. These principles reflect the history of

emergency management and the distilled wisdom of responders and leaders across the whole

community.

Engaged Partnership

Effective partnership relies on engaging all elements of the whole community, as well as

international partners in some cases. This also includes survivors who may require assistance and

who may also be resources to support community response and recovery.

10

As with all activities in support of the National Preparedness Goal, activities taken under the response mission

must be consistent with all pertinent statutes and policies, particularly those involving privacy and civil and human

rights, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and Civil Rights Act of

1964.

National Response Framework

6

Those who lead emergency response efforts must communicate and support engagement with the

whole community by developing shared goals and aligning capabilities to reduce the risk of any

jurisdiction being overwhelmed in times of crisis. Layered, mutually supporting capabilities of

individuals, communities, the private sector, NGOs, and governments at all levels allow for

coordinated planning in times of calm and effective response in times of crisis. Engaged partnership

and coalition building includes ongoing clear, consistent, accessible, effective,

11

and culturally and

linguistically appropriate communication and shared situational awareness about an incident to

ensure an appropriate response.

Tiered Response

Most incidents begin and end locally and are managed at the local or tribal level. These incidents

may require a unified response from local agencies, the private sector, and NGOs. Some may require

additional support from neighboring jurisdictions or state governments. A smaller number of

incidents require Federal support or are led by the Federal Government.

12

National response

protocols are structured to provide tiered levels of support when additional resources or capabilities

are needed.

Scalable, Flexible, and Adaptable Operational Capabilities

As incidents change in size, scope, and complexity, response efforts must adapt to meet evolving

requirements. The number, type, and sources of resources must be able to expand rapidly to meet the

changing needs associated with a given incident and its cascading effects. As needs grow and change,

response processes must remain nimble and adaptable. The structures and processes described in the

NRF must be able to surge resources from the whole community. As incidents stabilize, response

efforts must be flexible to facilitate the integration of recovery activities.

Unity of Effort through Unified Command

Effective, unified command is indispensable to response activities and requires a clear understanding

of the roles and responsibilities of all participating organizations.

13

The Incident Command System

(ICS), a component of NIMS, is an important element in ensuring interoperability across multi-

jurisdictional or multiagency incident management activities. Unified command, a central tenet of

ICS, enables organizations with jurisdictional authority or functional responsibility for an incident to

support each other through the use of mutually developed incident objectives. Each participating

agency maintains its own authority, responsibility, and accountability.

11

Information, warnings, and communications associated with emergency management must ensure effective

communication, such as through the use of appropriate auxiliary aids and services (e.g., interpreters, captioning,

alternate format documents) for individuals with disabilities, and provide meaningful access to limited English

proficient individuals.

12

Certain incidents such as a pandemic or cyber event may not be limited to a specific geographic area and may be

managed at the local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, or Federal level depending on the nature of the incident.

13

The ICS’s “unified command” concept is distinct from the military use of this term. Concepts of “command” and

“unity of command” have distinct legal and cultural meanings for military forces and military operations. Military

forces always remain under the control of the military chain of command and are subject to redirection or recall at

any time. Military forces do not operate under the command of the incident commander or under the unified

command structure, but they do coordinate with response partners and work toward a unity of effort while

maintaining their internal chain of command.

National Response Framework

7

Readiness to Act

Effective response requires a readiness to act that is balanced with an understanding of the risks and

hazards responders face. From individuals and communities to the private and nonprofit sectors,

faith-based organizations, and all levels of government (local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area,

and Federal), national response depends on the ability to act decisively. A forward-leaning posture is

imperative for incidents that may expand rapidly in size, scope, or complexity, as well as incidents

that occur without warning. Decisive action is often required to save lives and protect property and

the environment. Although some risk to responders may be unavoidable, all response personnel are

responsible for anticipating and managing risk through proper planning, organizing, equipping,

training, and exercising.

Risk Basis

The NRF leverages the results of the Strategic National Risk Assessment (SNRA), contained in the

second edition of the National Preparedness Goal, to build and deliver the response core capabilities.

The results indicate that a wide range of threats and hazards continue to pose a significant risk to the

Nation, affirming the need for an all-hazards, capability-based approach to preparedness planning.

The results contained in the Goal include:

Natural hazards, including hurricanes, earthquakes, tornados, drought, wildfires, winter storms,

and floods, present a significant and varied risk across the country. Climate change has the

potential to cause the consequence of weather-related hazards to become more severe.

A virulent strain of pandemic influenza could kill hundreds of thousands of Americans, affect

millions more, and result in economic loss. Additional human and animal infectious diseases,

including those undiscovered, may present significant risks.

Technological and accidental hazards, such as transportation system failures, dam failures, or

chemical spills or releases, have the potential to cause extensive fatalities and severe economic

impacts. In addition, these hazards may increase due to aging infrastructure.

Terrorist organizations or affiliates may seek to acquire, build, and use weapons of mass

destruction (WMD). Conventional terrorist attacks, including those by “lone actors” employing

physical threats such as explosives and armed attacks, present a continued risk to the Nation.

Cybersecurity threats exploit the increased complexity and connectivity of critical infrastructure

systems, placing the Nation’s security, economy, and public safety and health at risk. Malicious

cyber activity can have catastrophic consequences, which in turn, can lead to other hazards, such

as power grid failures or financial system failures. These cascading hazards increase the potential

impact of cyber incidents.

Some incidents, such as explosives attacks or earthquakes, generally cause more localized

impacts, while other incidents, such as human pandemics, may cause impacts that are dispersed

throughout the Nation, thus creating different types of impacts for planners to consider.

No single threat or hazard exists in isolation. As an example, a hurricane can lead to flooding, dam

failures, and hazardous materials spills. The Framework, therefore, focuses on core capabilities that

can be applied to deal with cascading effects. Since many incidents occur with little or no warning,

these capabilities must be able to be delivered in a no-notice environment.

Effective continuity planning helps to ensure the uninterrupted ability to engage partners; respond

appropriately with scaled, flexible, and adaptable operational capabilities; specify succession to

National Response Framework

8

office and delegations of authority to protect the unity of effort and command; and to account for the

availability of responders regardless of the threat or hazard.

In order to establish the basis for these capabilities, planning factors drawn from a number of

different scenarios are used to develop the Response FIOP, which supplements the NRF. Refer to the

Operational Planning section for additional details on planning assumptions.

Roles and Responsibilities

Effective response depends on integration of the whole community and all partners executing their

roles and responsibilities. This section describes those roles and responsibilities and sharpens the

focus on identifying who is involved with the Response mission area. It also addresses what the

various partners must do to deliver the response core capabilities and to integrate successfully with

the Prevention, Protection, Mitigation, and Recovery mission areas.

An effective, unified national response requires layered, mutually supporting capabilities. Individuals

and communities, the private and nonprofit sectors, faith-based organizations, and all levels of

government (local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and Federal) should each understand their

respective roles and responsibilities and how to complement each other in achieving shared goals. All

elements of the whole community play prominent roles in developing the core capabilities needed to

respond to incidents. This includes developing plans, conducting assessments and exercises,

providing and directing resources and capabilities, and gathering lessons learned. These activities

require that all partners understand how they fit within and are supported by the structures described

in the NRF.

Emergency management staff in all jurisdictions have a fundamental responsibility to consider the

needs of all members of the whole community. The potential contributions of all these individuals

toward delivering core capabilities during incident response (e.g., through associations and alliances

that serve the people identified above) should be incorporated into planning efforts.

Emergency management staff must also consider those who own or have responsibility for animals,

both as members of the community who may be affected by incidents and as a potential means of

supporting response efforts. This includes those with household pets, service and assistance animals,

working dogs, and agricultural animals/livestock, as well as those who have responsibility for

wildlife, exotic animals, zoo animals, research animals, and animals housed in shelters, rescue

organizations, breeding facilities, and sanctuaries.

Individuals, Families, and Households

Although not formally part of emergency management operations, individuals, families, and

households play an important role in emergency preparedness and response. By reducing hazards in

and around their homes by efforts such as raising utilities above flood level or securing unanchored

objects against the threat of high winds, individuals reduce potential emergency response

requirements. Individuals, families, and households should also prepare emergency supply kits and

emergency plans, so they can take care of themselves and their neighbors until assistance arrives.

Information on emergency preparedness can be found at many community, state, and Federal

emergency management Web sites, such as http://www.ready.gov.

Individuals can also contribute to the preparedness and resilience of their households and

communities by volunteering with emergency organizations (e.g., the local chapter of the American

Red Cross, Medical Reserve Corps, or Community Emergency Response Teams [CERT]) and

completing emergency response training courses. Individuals, families, and households should make

National Response Framework

9

preparations with family members who have access and functional needs or medical needs. Their

plans should also include provisions for their animals, including household pets or service and

assistance animals. During an actual disaster, emergency, or threat, individuals, households, and

families should monitor emergency communications and follow guidance and instructions provided

by local authorities.

Communities

Communities are groups that share goals, values, and institutions. They are not always bound by

geographic boundaries or political divisions. Instead, they may be faith-based organizations,

neighborhood partnerships, advocacy groups, academia, social and community groups, and

associations. Communities bring people together in different ways for different reasons, but each

provides opportunities for sharing information and promoting collective action. Engaging these

groups in preparedness efforts, particularly at the local and state levels, is important to identifying

their needs and taking advantage of their potential contributions.

Nongovernmental Organizations

NGOs play vital roles at the local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and national levels in

delivering important services, including those associated with the response core capabilities. NGOs

include voluntary, racial and ethnic, faith-based, veteran-based, and nonprofit organizations that

provide sheltering, emergency food supplies, and other essential support services. NGOs are

inherently independent and committed to specific interests and values. These interests and values

drive the groups’ operational priorities and shape the resources they provide. NGOs bolster

government efforts at all levels and often provide specialized services to the whole community.

NGOs are key partners in preparedness activities and response operations.

Examples of NGO contributions include:

Training, management, and coordination of volunteers and donated goods.

Identifying and communicating physically accessible shelter locations and needed supplies to

support people displaced by an incident.

Providing emergency commodities and services, such as water, food, shelter, assistance with

family reunification, clothing, and supplies for post-emergency cleanup.

Supporting the evacuation, rescue, care, and sheltering of animals displaced by the incident.

Providing search and rescue, transportation, and logistics services and support.

Identifying those whose needs have not been met and helping to provide assistance.

Providing health, medical, mental health, and behavioral health resources.

Assisting, coordinating, and providing assistance to individuals with access and functional needs.

At the same time when NGOs support response core capabilities, they may also require government

assistance. When planning for local community emergency management resources, government

organizations should consider the potential need to better enable NGOs to perform their essential

response functions.

Some NGOs are officially designated as support elements to national response capabilities:

The American Red Cross. The American Red Cross is chartered by Congress to provide relief

to survivors of disasters and help people prevent, prepare for, and respond to emergencies. The

National Response Framework

10

Red Cross has a legal status of “a federal instrumentality” and maintains a special relationship

with the Federal Government. In this capacity, the American Red Cross supports several ESFs

and the delivery of multiple core capabilities.

National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (National VOAD).

14

National VOAD is

the forum where organizations share knowledge and resources throughout the disaster cycle—

preparation, response, recovery, and mitigation—to help disaster survivors and their

communities. National VOAD is a consortium of approximately 50 national organizations and 5

5

t

erritorial and state equivalents.

Volunteers and Donations. Incident response operations frequently exceed the resources of

government organizations. Volunteers and donors support response efforts in many ways, a

nd

g

overnments at all levels must plan ahead to incorporate volunteers and donated resources int

o

re

sponse activities. The goal of volunteer and donations management is to support jurisdictions

affected by disasters through close collaboration with the voluntary organizations and agencies

.

The objective is to manage the influx of volunteers and donations to voluntary agencies and all

levels of government before, during, and after an incident. Additional information may be f

ound

i

n the Volunteers and Donations Management Support Annex.

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). Within the NCMEC, the

National Emergency Child Locator Center (NECLC) facilitates the expeditious identification a

nd

r

eunification of children with their families.

Private Sector Entities

Private sector organizations contribute to response efforts through partnerships with each level of

government. They play key roles before, during, and after incidents. Private sector entities include

large, medium, and small businesses; commerce, private cultural and educational institutions; and

industry; as well as public/private partnerships that have been established specifically for emergency

management purposes. During an incident, key private sector partners should have a direct link to

emergency managers and, in some cases, be involved in the decision making process. Strong

integration into response efforts can offer many benefits to both the public and private sectors.

Private sector organizations may be affected by direct or indirect consequences of an incident. Such

organizations include entities that are significant to local, regional, and national economic recovery

from an incident. Examples include major employers and suppliers of key commodities or services.

As key elements of the national economy, it is important for private sector organizations of all types

and sizes to take every precaution necessary to boost resilience, the better to stay in business or

resume normal operations quickly.

Unique private sector organizations including critical infrastructure and regulated entities may

require additional efforts to promote resilience. Critical infrastructure—such as privately owned

transportation and transit, telecommunications, utilities, financial institutions, hospitals, and other

health regulated facilities—should have effective business continuity plans.

Owners/operators of certain regulated facilities or hazardous operations may be legally responsible

for preparing for and preventing incidents and responding when an incident occurs. For example,

Federal regulations require owners/operators of nuclear power plants to maintain emergency plans

and to perform assessments, notifications, and training for incident response.

14

Additional information is available at http://www.nvoad.org.

National Response Framework

11

Private sector entities may serve as partners in state and local emergency preparedness and response

organizations and activities and with Federal sector-specific agencies. Private sector entities often

participate in state and local preparedness activities by providing resources (donated or compensated)

during an incident—including specialized teams, essential services, equipment, and advanced

technologies—through local public-private emergency plans or mutual aid and assistance agreements

or in response to requests from government and nongovernmental-volunteer initiatives.

A fundamental responsibility of private sector organizations is to provide for the welfare of their

employees in the workplace. In addition, some businesses play an essential role in protecting critical

infrastructure systems and implementing plans for the rapid reestablishment of normal commercial

activities and critical infrastructure operations following a disruption. In many cases, private sector

organizations have immediate access to commodities and services that can support incident response,

making them key potential contributors of resources necessary to deliver the core capabilities. How

the private sector participates in response activities varies based on the type of organization and the

nature of the incident.

Examples of key private sector activities include:

Addressing the response needs of employees, infrastructure, and facilities.

Protecting information and maintaining the continuity of business operations.

Planning for, responding to, and recovering from incidents that impact their own infrastructure

and facilities.

Collaborating with emergency management personnel to determine what assistance may be

required and how they can provide needed support.

Contributing to communication and information-sharing efforts during incidents.

Planning, training, and exercising their response capabilities.

Providing assistance specified under mutual aid and assistance agreements.

Contributing resources, personnel, and expertise; helping to shape objectives; and receiving

information about the status of the community.

Local Governments

The responsibility for responding to natural and manmade incidents that have recognizable

geographic boundaries generally begins at the local level with individuals and public officials in the

county, parish, city, or town affected by an incident. The following paragraphs describe the

responsibilities of specific local officials who have emergency management responsibilities.

Chief Elected or Appointed Official

Jurisdictional chief executives are responsible for the public safety and welfare of the people of their

jurisdiction. These officials provide strategic guidance and resources across all five mission areas.

Chief elected or appointed officials must have a clear understanding of their emergency management

roles and responsibilities and how to apply the response core capabilities as they may need to make

decisions regarding resources and operations during an incident. Lives may depend on their

decisions. Elected and appointed officials also routinely shape or modify laws, policies, and budgets

to aid preparedness efforts and improve emergency management and response capabilities. The local

chief executive’s response duties may include:

Obtaining assistance from other governmental agencies.

National Response Framework

12

Providing direction for response activities.

Ensuring appropriate information is provided to the public.

Emergency Manager

The jurisdiction’s emergency manager oversees the day-to-day emergency management programs

and activities. The emergency manager works with chief elected and appointed officials to establish

unified objectives regarding the jurisdiction’s emergency plans and activities. This role entails

coordinating and integrating all elements of the community. The emergency manager coordinates the

local emergency management program. This includes assessing the capacity and readiness to deliver

the capabilities most likely required during an incident and identifying and correcting any shortfalls.

The local emergency manager’s duties often include:

Advising elected and appointed officials during a response.

Conducting response operations in accordance with the NIMS.

Coordinating the functions of local agencies.

Coordinating the development of plans and working cooperatively with other local agencies,

community organizations, private sector entities, and NGOs.

Developing and maintaining mutual aid and assistance agreements.

Coordinating resource requests during an incident through the management of an emergency

operations center.

Coordinating damage assessments during an incident.

Advising and informing local officials and the public about emergency management activities

during an incident.

Developing and executing accessible public awareness and education programs.

Conducting exercises to test plans and systems and obtain lessons learned.

Coordinating integration of the rights of individuals with disabilities, individuals from racially

and ethnically diverse backgrounds, and others with access and functional needs into emergency

planning and response.

Helping to ensure the continuation of essential services and functions through the development

and implementation of continuity of operations plans.

Other Local Departments and Agencies

Department and agency heads collaborate with the emergency manager during the development of

local emergency plans and provide key response resources. Participation in the planning process

helps to ensure that specific capabilities are integrated into a workable plan to safeguard the

community. These department and agency heads and their staffs develop, plan, and train on internal

policies and procedures to meet response needs safely. They also participate in interagency training

and exercises to develop and maintain necessary capabilities.

State, Tribal, Territorial, and Insular Area Governments

State, tribal, territorial, and insular area governments are responsible for the health and welfare of

their residents, communities, lands, and cultural heritage.

National Response Framework

13

States

State governments

15

supplement local efforts before, during, and after incidents by applying in-state

resources first. If a state anticipates that its resources may be exceeded, the governor

16

may request

assistance from other states or the Federal Government through a Stafford Act Declaration.

The following paragraphs describe some of the relevant roles and responsibilities of key officials.

Governor

The public safety and welfare of a state’s residents are the fundamental responsibilities of every

governor. The governor coordinates state resources and provides the strategic guidance for response

to all types of incidents. This includes supporting local governments as needed and coordinating

assistance with other states and the Federal Government. A governor also:

In accordance with state law, may make, amend, or suspend certain orders or regulations

associated with response

.

Communicates to the public, in an accessible manner (e.g., effective communications to address

all members of the whole community), and helps people, businesses, and organizations cope wit

h

t

he consequences of any type of incident.

Coordinates with tribal governments within the state.

Commands the state military forces (National Guard personnel not in Federal service and state

militias)

.

Coordinates assistance from other states through interstate mutual aid and assistance agreements,

s

uch as the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC).

17

State Homeland Security Advisor

Many states have designated homeland security advisors who serve as counsel to the governor on

homeland security issues and may serve as a liaison between the governor’s office, the state

homeland security structure, and other organizations both inside and outside of the state. The advisor

often chairs a committee composed of representatives of relevant state agencies, including public

safety, the National Guard, emergency management, public health, environment, agriculture, and

others charged with developing prevention, protection, mitigation, response, and recovery strategies.

State Emergency Management Agency Director

All states have laws mandating the establishment of a state emergency management agency, as well

as the emergency plans coordinated by that agency. The director of the state emergency management

agency is responsible for ensuring that the state is prepared to deal with large-scale emergencies and

15

States are sovereign entities, and the governor has responsibility for public safety and welfare. Although U.S.

territories, possessions, freely associated states, and tribal governments also have sovereign rights, there are unique

factors involved in working with these entities. Federal assistance is available to states and to the District of

Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern

Mariana Islands. Federal disaster preparedness, response, and recovery assistance is available to the Federated States

of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands pursuant to Compacts of Free Association. The extent to

which Federal response or assistance is provided to tribes, territories, and insular areas under other Federal laws is

defined in those laws and supporting regulations.

16

“Governor” is used throughout this document to refer to the chief executive of states, territories, and insular areas.

17

A reference paper on EMAC is available at http://www.emacweb.org.

National Response Framework

14

coordinating the statewide response to any such incident. This includes supporting local and tribal

governments as needed, coordinating assistance with other states and the Federal Government, and,

in some cases, with NGOs and private sector organizations. The state emergency management

agency may dispatch personnel to assist in the response and recovery effort.

National Guard

The National Guard is an important state and Federal resource available for planning, preparing, and

responding to natural or manmade incidents. National Guard members have expertise in critical

areas, such as emergency medical response; communications; logistics; search and rescue; civil

engineering; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear response and planning; and

decontamination.

18

The governor may activate elements of the National Guard to support state domestic civil support

functions and activities. The state adjutant general may assign members of the Guard to assist with

state, regional, and Federal civil support plans.

Other State Departments and Agencies

State department and agency heads and their staffs develop, plan, and train on internal policies and

procedures to meet response and recovery needs. They also participate in interagency training and

exercises to develop and maintain the necessary capabilities. They are vital to the state’s overall

emergency management program, as they bring expertise spanning various response functions and

serve as core members of the state emergency operations center (EOC) and incident command posts

(ICP). Many of them have direct experience in providing accessible and vital services to the whole

community during response operations. State departments and agencies typically work in close

coordination with their Federal counterpart agencies during joint state and Federal responses, and

under some Federal laws, they may request assistance from these Federal partners.

Tribes

The United States has a trust relationship with federally-recognized Indian tribes and recognizes their

right to self-government. Under the Stafford Act, federally-recognized Indian tribes may directly

request their own emergency and major declaration, or they may request assistance under a state

request. In addition, federally-recognized Indian tribes can request Federal assistance for incidents

that impact the tribe, but do not result in a Stafford Act declaration.

In accordance with the Stafford Act, the Chief Executive

19

of an affected Indian tribal government

may submit a request for a declaration by the President.

Tribal governments are responsible for

coordinating resources to address actual or potential incidents.

Tribes are encouraged to build relationships with local jurisdictions and their states as they may have

resources most readily available. The NRF’s Tribal Coordination Support Annex outlines processes

and mechanisms that tribal governments may use to request Federal assistance during an incident.

18

The President may call National Guard forces into Federal service for domestic duties, including pursuant to

under section 12406 of Title 10 (providing such authority e.g., in cases of invasion by a foreign nation, rebellion

against the authority of the United States, or where the President is unable to execute the laws of the United States

with regular forces) under 10 U.S. Code § 12406). When called into Federal service, National Guardsmen are

employed under Title 10 of the U.S. Code and are no longer under the command of the governor. Instead, they

operate under the Secretary of Defense.

19

The Stafford Act uses the term “Chief Executive” to refer to the person who is the Chief, Chairman, Governor,

President, or similar executive official of an Indian tribal government.

National Response Framework

15

Chief Executive

The Chief Executive is responsible for the public safety and welfare of his or her respective tribe.

The Chief Executive:

Coordinates resources needed to respond to incidents of all types.

In accordance with the law, may make, amend, or suspend certain orders or regulations

associated with the response.

Communicates with the public in an accessible manner and helps people, businesses, and

organizations cope with the consequences of any type of incident.

Negotiates mutual aid and assistance agreements with other local jurisdictions, states, tribes,

territories, and insular area governments.

Can request Federal assistance.

Territories/Insular Area Governments

Territorial and insular area governments are responsible for coordinating resources to address actual

or potential incidents. Due to their remote locations, territories and insular area governments often

face unique challenges in receiving assistance from outside the jurisdiction quickly and often request

assistance from neighboring islands, other nearby countries, states, private sector or NGO resources,

or the Federal Government.

Territorial/Insular Area Leader

The territorial/insular area leader is responsible for the public safety and welfare of the people of

his/her jurisdiction. As authorized by the territorial or insular area government, the leader:

Coordinates resources needed to respond to incidents of all types.

In accordance with the law, may make, amend, or suspend certain orders or regulations

associated with the response.

Communicates with the public in an accessible manner and helps people, businesses, and

organizations cope with the consequences of any type of incident.

Commands the territory’s military forces.

Negotiates mutual aid and assistance agreements with other local jurisdictions, states, tribes,

territories, and insular area governments.

Can request Federal assistance.

Federal Government

The Federal Government maintains a wide range of capabilities and resources that may be required

to deal with domestic incidents in order to save lives and protect property and the environment while

ensuring the protection of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties. To be successful, any approach to

the delivery of Response capabilities will require an all-of-nation approach. All Federal departments

and agencies must cooperate with one another, and with local, state, tribal, territorial, and insular

area governments, community members, and the private sector to the maximum extent possible.

The Federal Government becomes involved with a response when Federal interests are involved;

when state, local, tribal, or territorial resources are overwhelmed and Federal assistance is requested;

National Response Framework

16

or as authorized or required by statute, regulation, or policy. Accordingly, in some instances, the

Federal Government may play a supporting role to state, local, tribal, or territorial authorities by

providing Federal assistance to the affected parties. For example, the Federal Government provides

assistance to state, local, tribal, and territorial authorities when the President declares a major

disaster or emergency under the Stafford Act. In other instances, the Federal Government may play a

leading role in the response where the Federal Government has primary jurisdiction or when

incidents occur on Federal property (e.g., National Parks, military bases).

Regardless of the type of incident, the President leads the Federal Government response effort to

ensure that the necessary resources are applied quickly and efficiently to large-scale and

catastrophic incidents. Different Federal departments or agencies lead coordination of the Federal

Government’s response depending on the type and magnitude of the incident and are also

supported by other agencies that bring their relevant capabilities to bear in responding to the

incident. For example, FEMA leads and coordinates Federal response and assistance when the

President declares a major disaster or emergency under the Stafford Act. Similarly, the Department

of Health and Human Services (HHS) leads all Federal public health and medical response to

public health emergencies and incidents covered by the NRF.

Secretary of Homeland Security

In conjunction with these efforts, the statutory mission of the Department of Homeland Security is to

act as a focal point regarding both natural and manmade crises and emergency planning. Pursuant to

the Homeland Security Act and Presidential directive, the Secretary of Homeland Security is the

principal federal official for domestic incident management. The Secretary of Homeland Security

coordinates preparedness activities within the United States to respond to and recover from terrorist

attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies. The Secretary coordinates with Federal entities to

provide for Federal unity of efforts for domestic incident management.

As part of t

hese responsibilities, the Secretary provides the Executive Branch with an overall

architecture for domestic incident management and coordinates the Federal response, as required.

The Secretary of Homeland Security may monitor activities and activate specific response

mechanisms to support other Federal departments and agencies without assuming the overall

coordination of the Federal response during incidents that do not require the Secretary to coordinate

the response or do not result in a Stafford Act declaration. Other Federal departments and agencies

carry out their response authorities and responsibilities within this overarching construct of DHS

coordination.

Unity of effort differs from unity of command. Various Federal departments and agencies may have

statutory responsibilities and lead roles based upon the unique circumstances of the incident. Unity of

effort provides coordination through cooperation and common interests and does not interfere with

Federal departments’ and agencies’ supervisory, command, or statutory authorities. The Secretary

ensures that overall Federal actions are unified, complete, and synchronized to prevent unfilled gaps

or seams in the Federal Government’s overarching effort. This coordinated approach ensures that the

Federal actions undertaken by DHS and other departments and agencies are harmonized and

mutually supportive. The Secretary executes these coordination responsibilities, in part, by engaging

directly with the President and relevant Cabinet, department, agency, and DHS component heads as

is necessary to ensure a focused, efficient, and unified Federal preparedness posture. All Federal

departments and agencies, in turn, cooperate with the Secretary in executing domestic incident

management duties.

The Secretary’s responsibilities also include management of the broad “emergency management” and

“response” authorities of FEMA and other DHS components. DHS component heads may have lead

National Response Framework

17

response roles or other significant roles depending on the type and severity of the incident. For

example, the U.S. Secret Service is the lead agency for security design, planning, and implementation

of National Special Security Events (NSSE) while the Assistant Secretary for Cybersecurity and

Communications coordinates the response to significant cyber incidents.

FEMA Administrator

The Administrator is the principal advisor to the President, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and

the Homeland Security Council regarding emergency management. The FEMA Administrator’s

duties include assisting the President, through the Secretary, in carrying out the Stafford Act,

operation of the National Response Coordination Center (NRCC), the effective support of all ESFs,

and more generally, preparation for, protection against, response to, and recovery from all-hazards

incidents. Reporting to the Secretary of Homeland Security, the FEMA Administrator is also

responsible for managing the core DHS grant programs supporting homeland security activities.

20

Attorney General

Like other Executive Branch departments and agencies, the Department of Justice and the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI) will endeavor to coordinate their activities with other members of the

law enforcement community, and with members of the Intelligence Community, to achieve

maximum cooperation consistent with the law and operational necessity.

The Attorney General has lead responsibility for criminal investigations of terrorist acts or terrorist

threats by individuals or groups inside the United States, or directed at United States citizens or

institutions abroad, where such acts are within the Federal criminal jurisdiction of the United States,

as well as for related intelligence collection activities within the United States, subject to the National

Security Act of 1947 (as amended), and other applicable law, Executive Order 12333 (as amended),

and Attorney General-approved procedures pursuant to that Executive Order. Generally acting

through the FBI, the Attorney General, in cooperation with other Federal departments and agencies

engaged in activities to protect our national security, shall also coordinate the activities of the other

members of the law enforcement community to detect, prevent, preempt, and disrupt terrorist attacks

against the United States. In addition, the Attorney General, generally acting through the FBI

Director, has primary responsibility for searching for, finding, and neutralizing WMD within the

United States.

The Attorney General approves requests submitted by state governors pursuant to the Emergency

Federal Law Enforcement Assistance Act for personnel and other Federal law enforcement support

during incidents. The Attorney General also enforces Federal civil rights laws, such as the Americans

with Disabilities Act of 1990, Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Further

information on the Attorney General’s role is provided in the National Prevention Framework and

Prevention FIOP.

Secretary of Defense

The Secretary of Defense has authority, direction, and control over the Department of Defense

(DOD).

21

DOD resources may be committed when requested by another Federal agency and

approved by the Secretary of Defense, or when directed by the President. However certain DOD

20

See the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act, enacted as part of the FY 2007 DHS Appropriations

Act, P.L. 109-295.

21

10 U.S.C. §113.

National Response Framework

18

officials and organizations may provide support under the immediate response authority,

22

a mutual

aid agreement with the local community,

23

or pursuant to independent authorities or agreements.

24

When DOD resources are authorized to support civil authorities, command of those forces remains

with the Secretary of Defense. DOD elements in the incident area of operations coordinate closely

with response organizations at all levels.

Secretary of State

A domestic incident may have international and diplomatic implications that call for coordination

and consultation with foreign governments and international organizations. The Secretary of State is

responsible for all communication and coordination between the U.S. Government and other nations

regarding the response to a domestic crisis. The Department of State also coordinates international

offers of assistance and formally accepts or declines these offers on behalf of the U.S. Government

based on needs conveyed by Federal departments and agencies as stated in the International

Coordination Support Annex. Some types of international assistance are pre-identified, and bilateral

agreements are already established. For example, the USDA/Forest Service and Department of the

Interior have joint bilateral agreements with several countries for wildland firefighting support.

Director of National Intelligence

The Director of National Intelligence serves as the head of the Intelligence Community, acts as the

principal advisor to the President for intelligence matters relating to national security, and oversees

and directs implementation of the National Intelligence Program. The Intelligence Community,

comprising 17 elements across the Federal Government, functions consistent with laws, executive

orders, regulations, and policies to support the national security-related missions of the U.S.

Government. It provides a range of analytic products, including those that assess threats to the

homeland and inform planning, capability development, and operational activities of homeland

security enterprise partners and stakeholders. In addition to intelligence community elements with

specific homeland security missions, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence maintains a

number of mission and support centers that provide unique capabilities for homeland security

partners.

Other Federal Department and Agency Heads

Various Federal departments or agencies play primary, coordinating, or support roles in delivering

response core capabilities. In some circumstances, other Federal agencies may have a lead or support

role in coordinating operations, or elements of operations, consistent with applicable legal

authorities. Nothing in the NRF precludes any Federal department or agency from executing its

22

In response to a request for assistance from a civilian authority, under imminently serious conditions, and if time

does not permit approval from higher authority, DOD officials may provide an immediate response by temporarily

employing the resources under their control, subject to any supplemental direction provided by higher headquarters,

to save lives, prevent human suffering, or mitigate great property damage within the United States. Immediate

response authority does not permit actions that would subject civilians to the use of military power that is regulatory,

prescriptive, proscriptive, or compulsory. (DOD Directive 3025.18)

23

DOD installation commanders may provide support to local jurisdictions under mutual aid agreements (also

known as reciprocal fire protection agreements), when requested.

24

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has independent statutory authorities regarding emergency management, such

as Section 5 of the Flood Control Act of 1941 (Public Law 84-99) (e.g., providing technical assistance; direct

assistance such as providing sandbags, pumps, and other types of flood fight materials, emergency contracting; and

emergency water assistance due to contaminated water source). Also, the Defense Logistics Agency has an

interagency agreement with FEMA to provide commodities including fuel to civil authorities responding to

disasters.

National Response Framework

19

existing authorities. For all incidents, Federal department and agency heads serve as advisors for the

Executive Branch relative to their areas of responsibility.

When the Secretary of Homeland Security is not coordinating the overall response, Federal

departments and agencies may coordinate Federal operations under their own statutory authorities, or

as designated by the President, and may activate response structures applicable to those authorities.

The head of the department or agency may also request the Secretary of Homeland Security to

activate NRF structures and elements (e.g. Incident Management Assistance Teams and National

Operation Center elements) to provide additional assistance, while still retaining leadership for the

response.

Several Federal departments and agencies have authorities to respond to and declare specific types of

disasters or emergencies. These authorities may be exercised independently of, concurrently with, or

become part of a Federal response coordinated by the Secretary of Homeland Security, pursuant to

Presidential directive. Federal departments and agencies carry out their response authorities and

responsibilities within the NRF’s overarching construct or under supplementary or complementary

operational plans. Table 1 provides examples of scenarios in which specific Federal departments and

agencies have the responsibility for coordinating response activities. This is not an all-inclusive list.

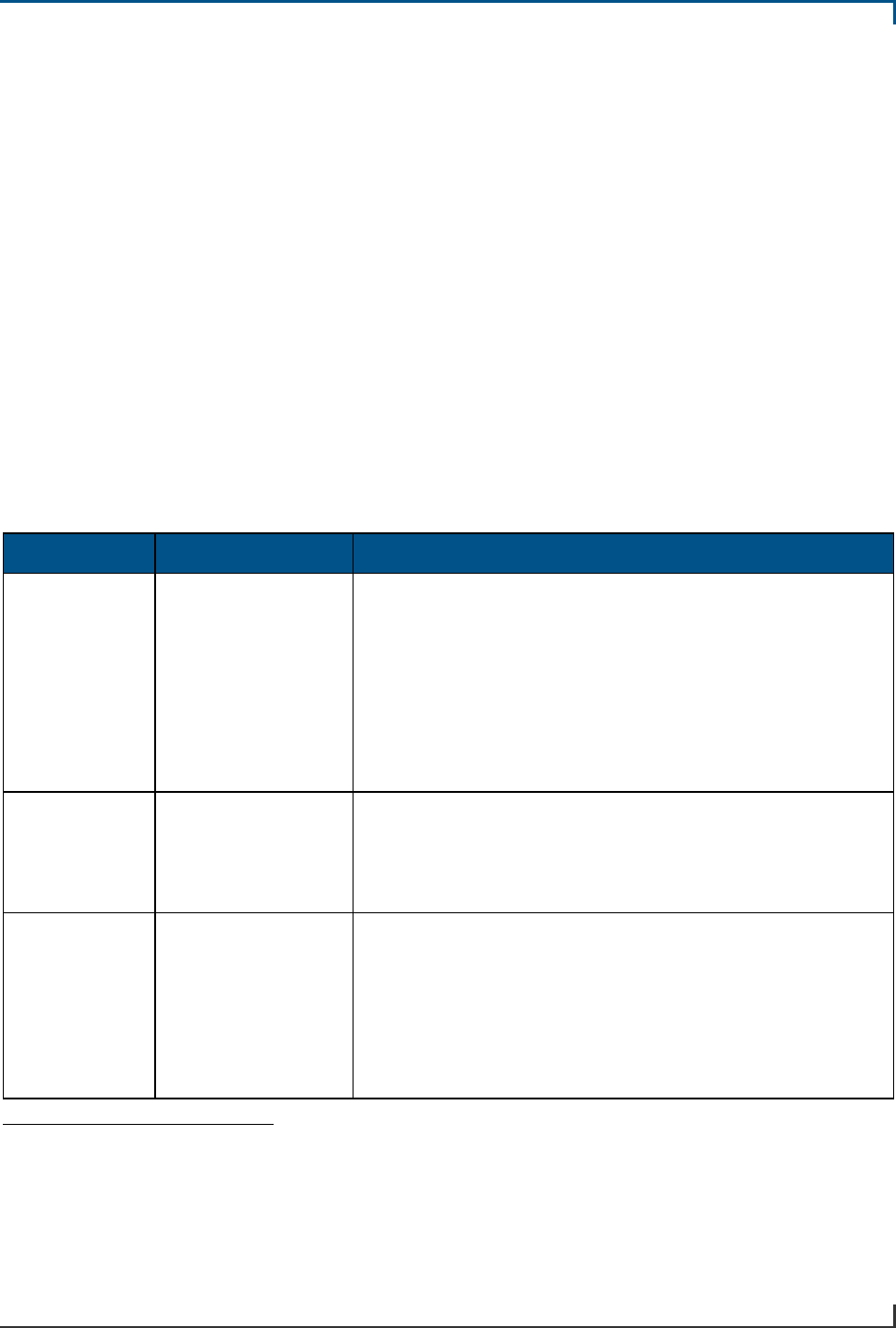

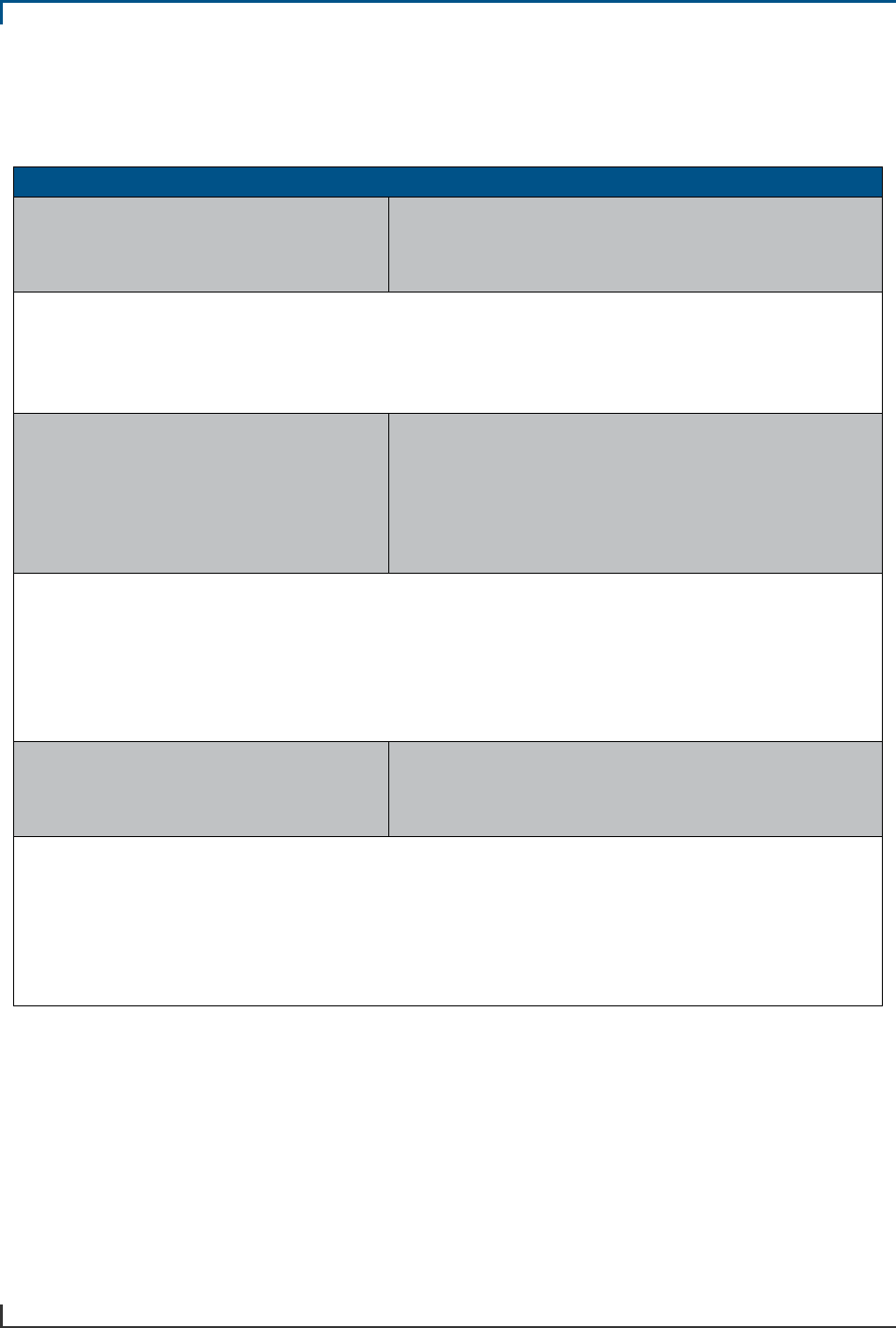

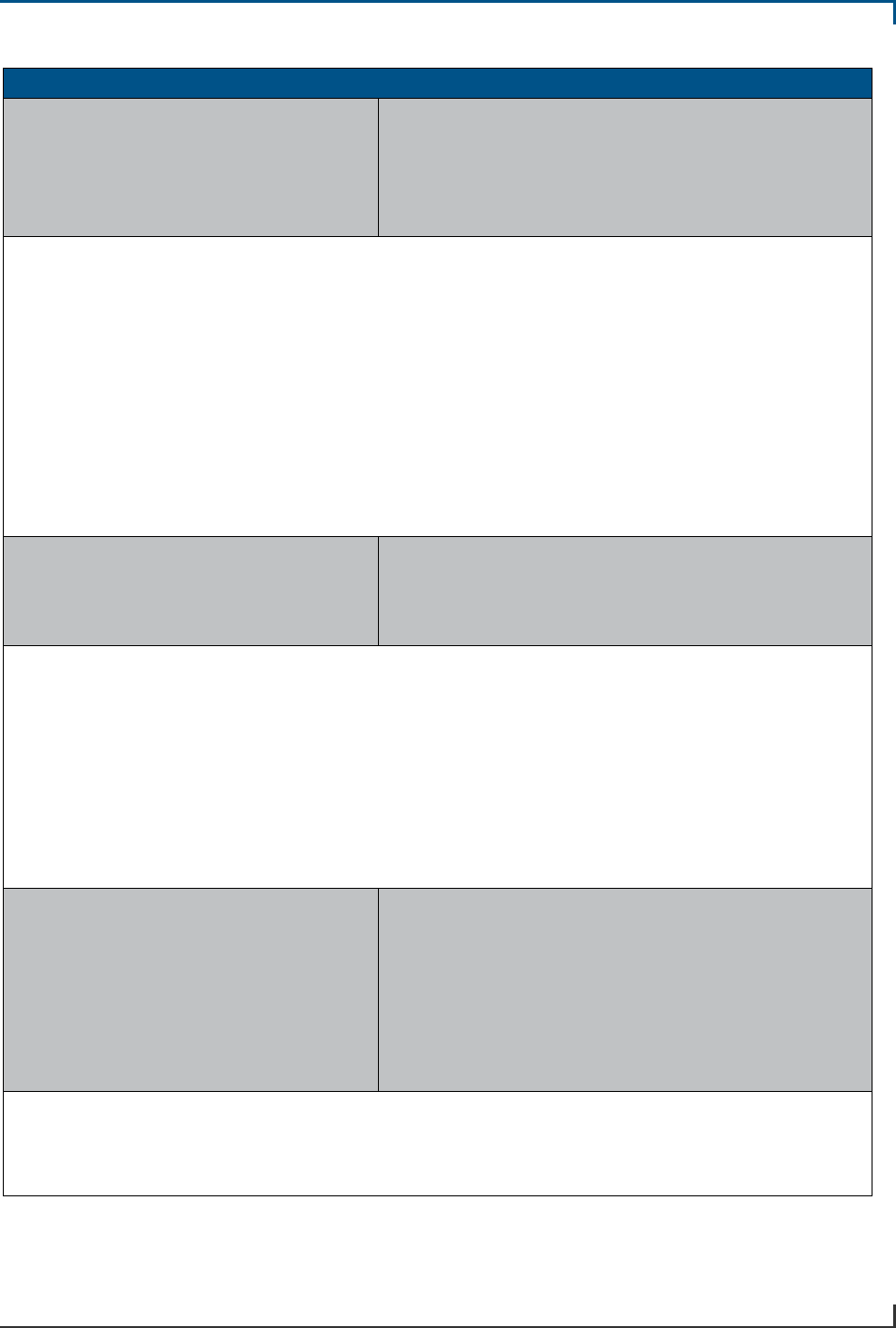

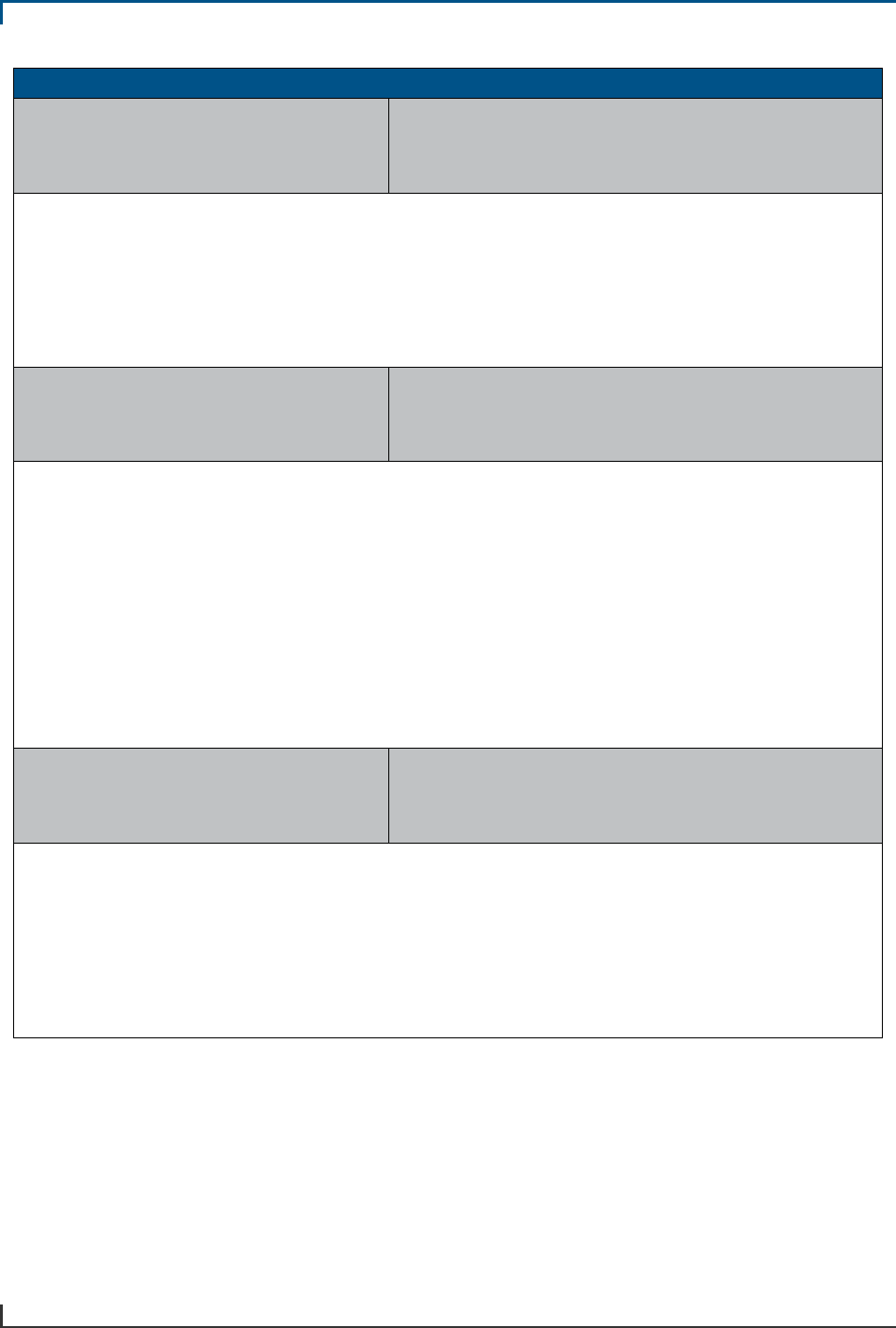

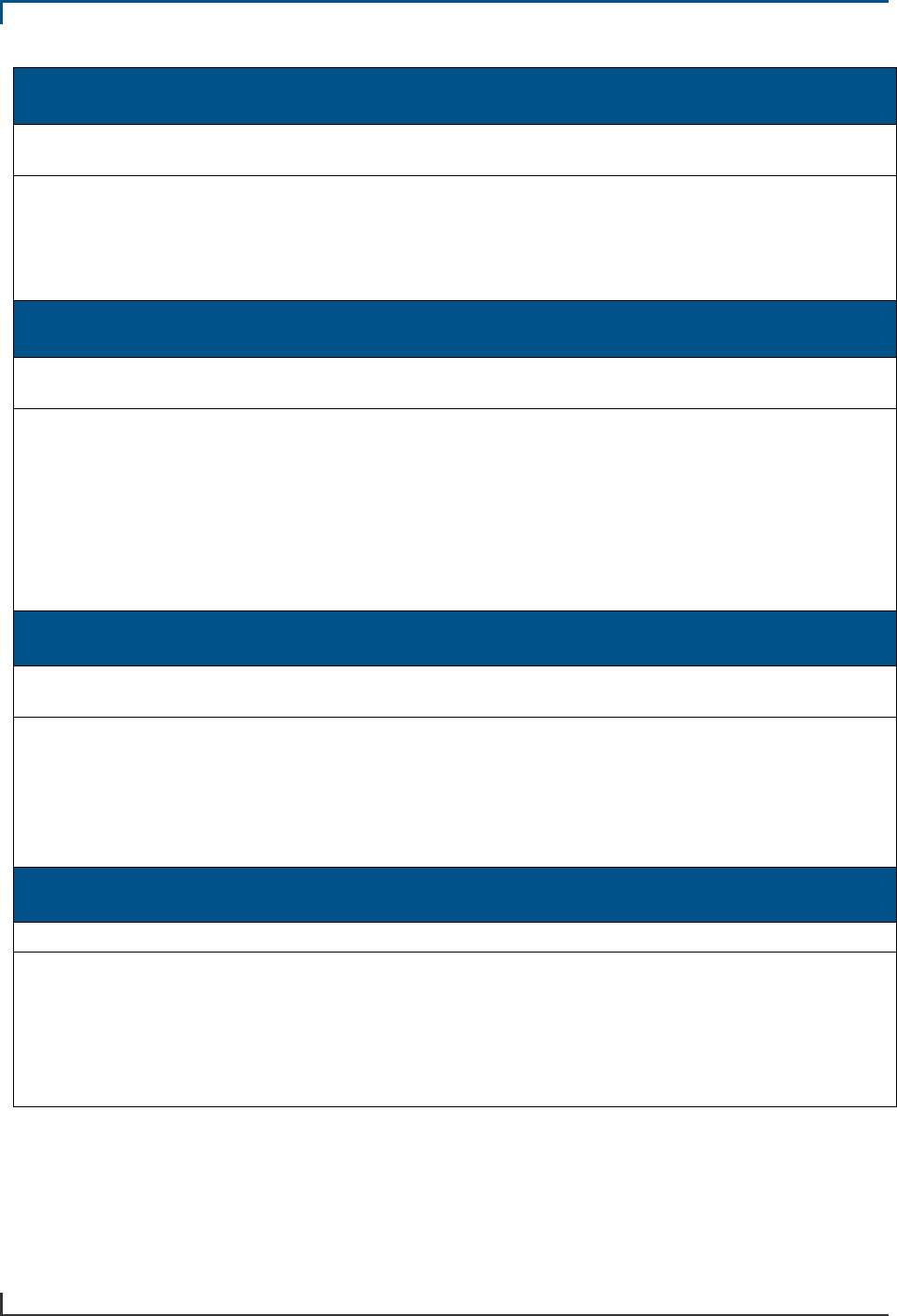

Table 1: Examples of Other Federal Department and Agency Authorities

25

Scenario Department/Agency Authorities

Agricultural and

Food Incident

Department of

Agriculture (USDA)

The Secretary of Agriculture has the authority to declare an

extraordinary emergency and take action due to the

presence of a pest or disease of livestock that threatens

livestock in the United States. (7 U.S. Code § 8306 [2007]).

The Secretary of Agriculture also has the authority to declare

an extraordinary emergency and take action due to the

presence of a plant pest or noxious weed whose presence

threatens plants or plant products of the United States. (7 U.S.

Code § 7715 [2007]).

Public Health

Emergency

26

Department of

Health and Human

Services

The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human

Services has the authority to take actions to protect the public

health and welfare, declare a public health emergency, and

to prepare for and respond to public health emergencies.

(Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S. Code §§ 201 et seq.).

Oil and

Hazardous

Materials Spills

EPA or USCG

The EPA and USCG have the authority to take actions to

respond to oil discharges and releases of hazardous

substances, pollutants, and contaminants, including leading

the response. (42 U.S. Code § 9601, et seq., 33 U.S. Code §

1251 et seq.) The EPA Administrator and Commandant of the

USCG

27

may also classify an oil discharge as a Spill of

National Significance and designate senior officials to

participate in the response. (40 CFR § 300.323).

28

25

These authorities may be exercised independently of, concurrently with, or become part of a Federal response