Estimating the Costs and Benefits of

Rendering an Opinion on Internal Control

over Financial Reporting

A Joint Study by the

Chief Financial Officers’ Council

and the

President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency

2

Table of Contents

Page

Reason for Survey and Recommendations………………...…. 3

Executive Summary…………………………………………. … 3

Introduction…………………………………………………. … 6

Where We Are Today……………………………………….. … 6

The Federal Environment…………………………………… 6

New Efforts to Improve Internal Control…………………… 7

Survey Results…………………………………………………. 8

Estimating the Cost to Render an Opinion on Internal Control.. 8

Identifying the Benefits of Rendering an Opinion on Internal

Control………………………………………………………… 10

Experiences of Publicly-Traded Companies……………………… 12

Experience Estimating the Cost……………………………….. 12

First Year Benefits Realized………………………………….. 13

Conclusion……………………………………………………….. 14

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology……………………………… 15

Attachment A………………………………………………………. 16

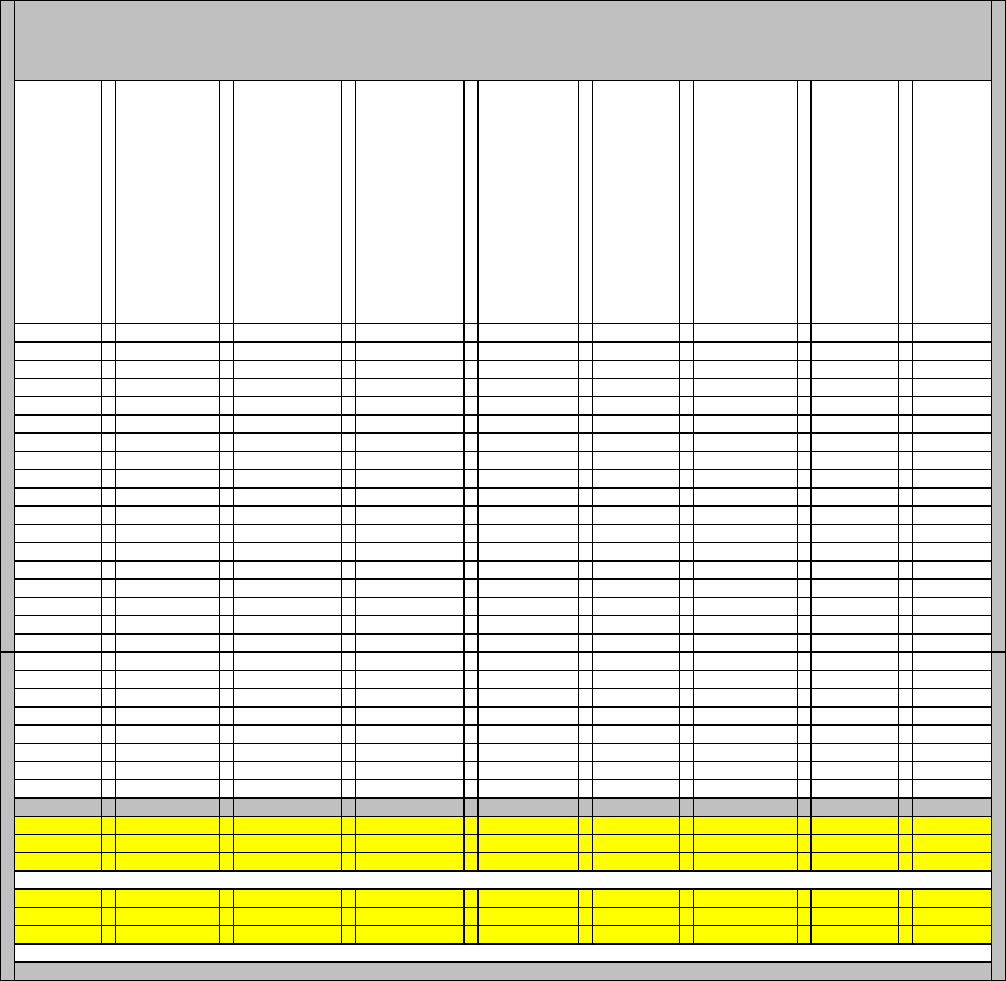

Table A: Estimated Audit Costs of Opining on Internal Control over

Financial Reporting……………………………………. 18

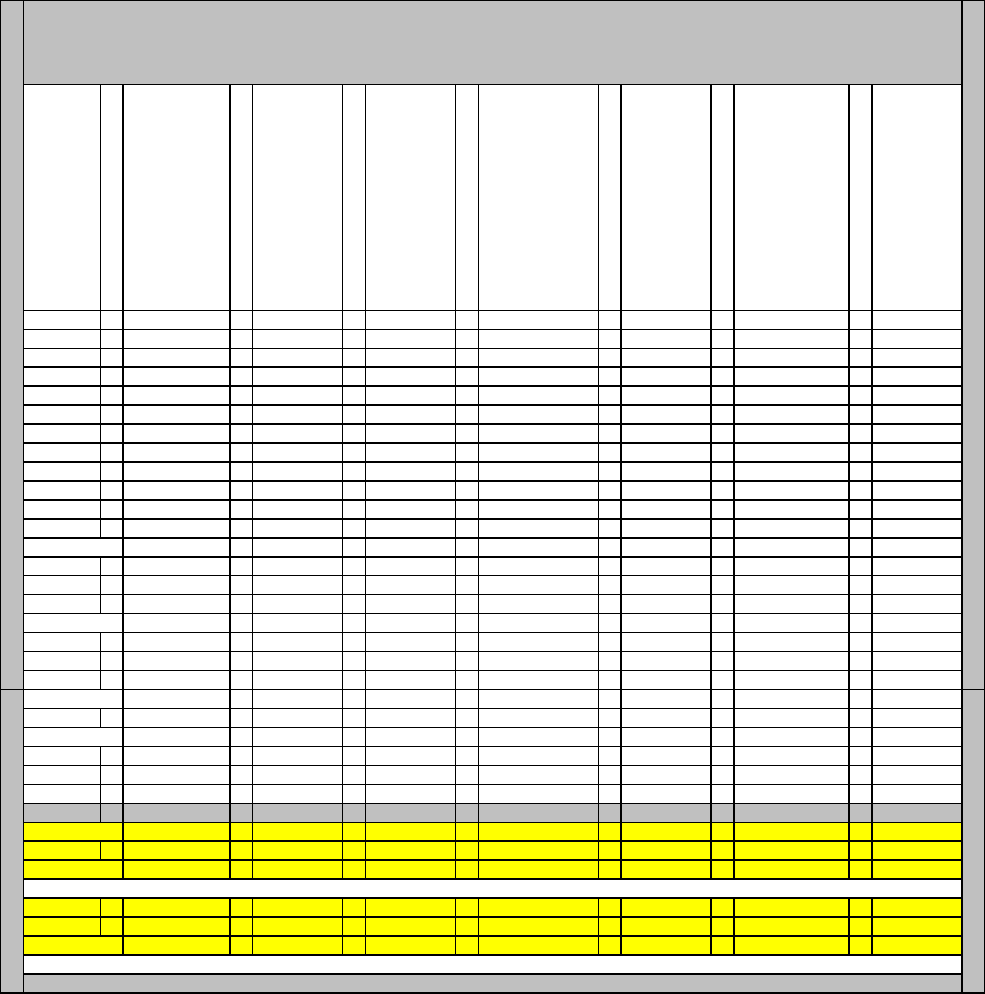

Table B: Additional Work Required to Render an Opinion on Internal

Control over Financial Reporting…………………….. 19

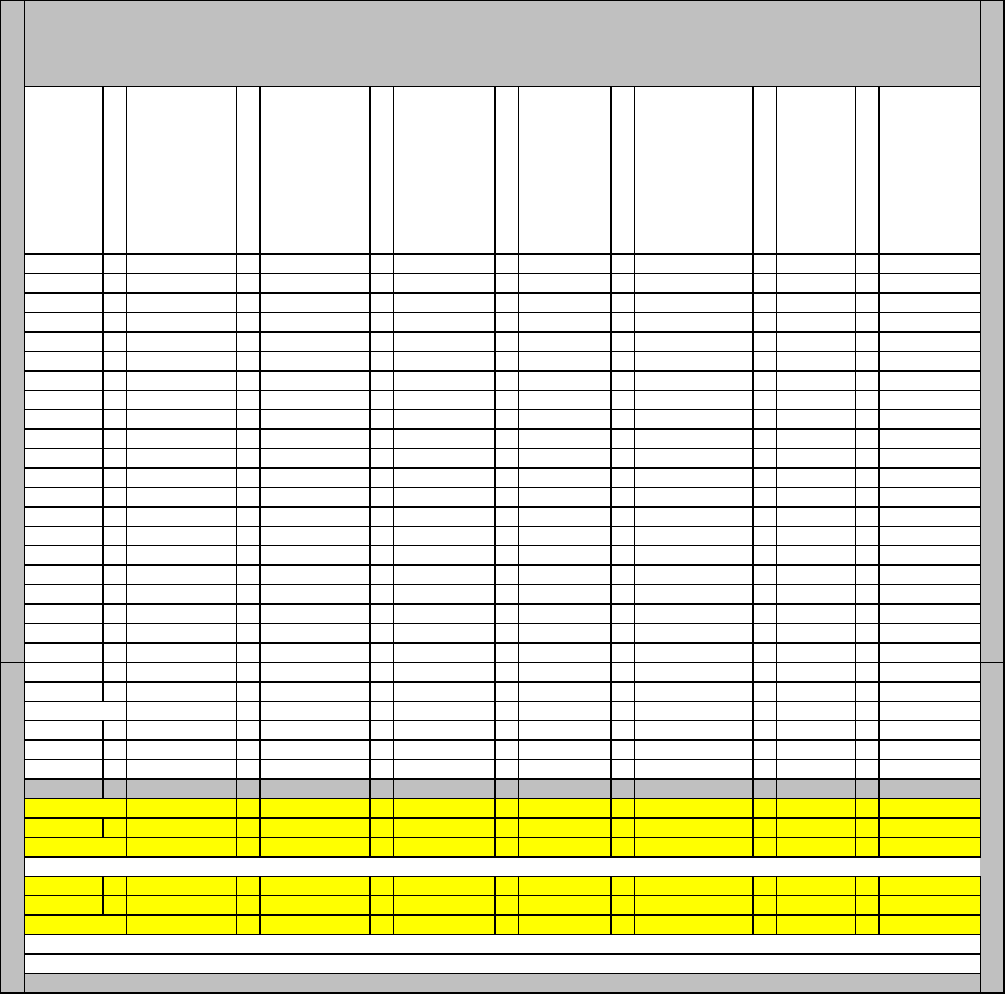

Table C: Disadvantages of Opinion on Internal Control over Financial

Reporting………………………………………………. 20

Table D: Benefits of Opining on Internal Control over Financial

Reporting………………………………………………. 21

3

Reason for Survey and Recommendations

The Department of Homeland Security Financial Accountability Act, P.L. 108-330,

directs the Chief Financial Officers Council (CFOC) and the President's Council on Integrity and

Efficiency (PCIE) to conduct a joint study on the potential costs and benefits of requiring the

Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) Act agencies to obtain audit opinions on internal control over

financial reporting. This report contains the results of that joint study. Because the estimates to

render an opinion on internal control are so substantial, both CFOs and Inspectors General (IGs)

recommend that all CFO Act agencies should not be required to conduct such an audit at this

time. Rather, agencies should be given the opportunity to implement the revised Office of

Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Internal

Control, (A-123) and obtain an internal control audit only where particular circumstances

warrant such an audit.

Executive Summary

Much of the debate on the internal control provisions of Section 404 of the Sarbanes-

Oxley Act (Section 404) (which requires management to provide an assessment on the

effectiveness of internal control and the auditor to attest to, and report on, the assessment made

by management) centers around the costs and related benefits of the additional audit assurance.

The value and benefit of rendering a separate opinion on internal control over financial reporting

must be balanced against the added costs. Estimating these added costs, however, is challenging

given the lack of hard data and the number of factors that go into developing a reliable estimate.

Similarly, measuring the benefits of the independent audit assurance is equally difficult since

ongoing and new management initiatives and existing audit coverage also contribute to

strengthening internal control in the Federal Government. Chief among the management

initiatives expected to significantly contribute to improved internal control are the recent

revisions to A-123.

The cost information provided in this report was developed using estimates and should

not be considered “hard” numbers. Moreover, quantifying the incremental benefits of obtaining

an audit opinion on the internal control over financial reporting, and hence performing any sort

of meaningful cost/benefit analysis, has proven elusive. How does one, for example, assign a

dollar value to preventing a misstatement or fraud of an unknown amount that may or may not

occur, or may occur with unknown frequency?

Federal IGs estimate that the incremental costs of the audit work needed to render an

opinion on internal control for all 24 CFO Act agencies would be more than $140.6 million.

Approximately 60 percent of this total, or $84.4 million, is the estimate to render an opinion on

internal control for the Department of Defense (DoD). For the 24 CFO Act agencies, the average

estimated incremental audit cost is approximately 51 percent of the financial statement audit

costs, or more than $5.8 million per reporting entity. Excluding the costs to audit DoD’s internal

control, the average estimated incremental audit cost is reduced to $2.4 million per reporting

entity.

Although these estimates are not hard numbers and could be less over time as auditors

gain more experience developing a fully integrated audit approach, these costs are significant.

These numbers also represent only the increased costs directly attributable to the requirement to

4

render an opinion on internal controls. Several Offices of the Chief Financial Officers (OCFOs)

believe they also will incur additional costs to support the audit effort. The additional costs that

management must incur to support this effort are not part of this report.

A majority of the OIGs and OCFOs believe that some benefits may be derived from this

type of audit. They cited (1) improved internal control and reduced material weaknesses, (2)

reduced errors and improved data integrity, documentation reliability and reporting, and (3)

improved agency focus and oversight as the top three potential benefits that may be gained from

an opinion on internal control. They also believe that identifying new material weaknesses and

reportable conditions are possible benefits.

Both groups, however, believe that these benefits should largely be achieved when

agencies effectively implement the revisions to A-123. The revisions strengthened the

requirements for management’s assessment of internal control over financial reporting. Because

the IGs assisted OMB in revising A-123, along with the CFOs, there is a level of confidence that,

if agencies properly implement A-123, the result should be an effective internal control review

and testing program. Therefore, except for the additional assurance provided by an opinion on

internal control, the benefits can already be realized from an internal control review program

implemented by management (similar to Section 404).

An effective and meaningful cost/benefit analysis should not compare the incremental

audit costs to all of the benefits that could be achieved through a process similar to that under

Section 404. The true benefit of the auditor’s opinion on internal control is the added

independent assurance it provides that management’s assessment of its internal control is fairly

presented. It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the incremental benefit of the auditor’s

opinion without first knowing how well management does in performing its assessment under

the revised A-123. That knowledge will come, at least in part, through the financial statement

audit process, as auditors are required to report on an agency’s compliance with laws and

regulations. While not a formal opinion, it will be a useful tool in helping OMB and other

stakeholders assess the implementation effort on the part of federal managers.

Based on cost data currently available from the private sector (which is significantly

higher than originally projected) and the estimates that are beginning to be developed for the

public sector, most industry experts agree that there are significant incremental costs associated

with obtaining an opinion on internal control over financial reporting. In addition, there is a

general consensus that, at least in the early stages of implementing Section 404, it is difficult to

determine the incremental benefits that might be gained from the additional work. Before

incurring these additional costs in the Federal sector, the OIGs and OCFOs believe that it would

be prudent to take a less costly approach and allow Federal managers to first implement the

revised A-123, and then evaluate that effort, along with the private sector’s implementation of

Sarbanes-Oxley, as additional information becomes available.

And even then, given the inherent differences between agencies, it might be judicious to

follow the same logic that forms the basis for A-123, and implement any incremental work on a

case-by-case basis. The decision to obtain an audit opinion must be decided initially by each

agency, and other knowledgeable parties, based on the condition of its financial management

program. Agencies that already have problems obtaining a clean opinion on their financial

statements do not need to obtain an opinion on internal control to tell them they have material

5

weaknesses. On the other hand, some agencies may want the added assurance that is achieved

by obtaining an opinion on internal control.

6

Introduction

The Department of Homeland Security Financial Accountability Act, P.L. 108-330,

directs the CFOC and the PCIE to conduct a joint study, and to report to the Congress and to the

Comptroller General of the United States, on the potential costs and benefits of requiring

agencies subject to the CFO Act to obtain audit opinions of their internal control over financial

reporting. This report contains the results of that joint effort.

Working under the leadership of OMB who chairs both councils, we surveyed the IGs for

their estimate of the costs of the incremental audit work and asked the IGs and the CFOs for their

input on the challenges and benefits of obtaining an opinion on internal control. In addition, we

looked at the experiences of publicly-traded companies which, at this point, have had a year of

experience implementing Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. We also considered the

environment in which the Federal Government operates which differs considerably from the one

in which publicly-traded companies operate. Finally, we considered the anticipated benefits that

are expected to be achieved through the revisions to A-123 which become effective in fiscal year

2006.

Where We Are Today

The Federal Environment

Unlike the private sector, the Federal Government operates in an environment that is

subject to more legislative and regulatory requirements designed to promote and support

effective internal control. Although these laws and regulatory requirements have not proven

fully effective in establishing a strong system of internal control by themselves, taken as a whole,

they have created an environment in which accuracy, timeliness, and accountability have become

a maxim for many Federal agencies. Also contributing to this robust control environment are the

rigorous existing auditing requirements relating to internal control and the many initiatives

implemented by the Administration through the President’s Management Agenda (PMA).

While the Sarbanes-Oxley Act created a new requirement for managers of publicly-

traded companies to report on internal controls over financial reporting, Federal managers have

been subject to similar internal control reporting requirements for many years as well as other

numerous legislative and regulatory requirements that promote and support effective internal

control. The Federal Managers’ Financial Integrity Act (FMFIA) of 1982 provides the statutory

basis for management’s responsibility for and assessment of internal control. In addition, the

CFO Act, which was passed in 1990, requires agency CFOs to, “develop and maintain an

integrated agency accounting and financial management system, including financial reporting

and internal controls, which … complies with applicable … internal control standards….” The

Federal Financial Management Improvement Act (FFMIA) of 1996 and OMB Circular No. A-

127, Financial Management Systems, instructed agencies to maintain an integrated financial

management system that complies with Federal system requirements, Federal accounting

standards, and the U.S. Standard General Ledger at the transaction level. The Federal

Information Security Management Act of 2002 requires agencies to provide information security

controls proportionate with the risk and potential harm of not having those controls in place. The

Improper Payments Information Act of 2002 requires agencies to review and “…identify

programs and activities that may be susceptible to significant improper payments.” The

7

Inspector General Act (IG Act) of 1978, as amended, requires that IGs submit semiannual reports

to the Congress on significant abuses and deficiencies identified in their audits, and to

recommend actions to correct those deficiencies.

Just as Federal agency management has been subject to more stringent internal control

requirements than private sector entities, auditors of Federal entity financial statements have

traditionally been subject to more rigorous auditing requirements relating to internal control than

their counterparts in the private sector. Before the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and its

increased audit requirements, auditing standards in the private sector did not require auditors to

test internal control if they did not plan to rely on the internal control in performing their audit.

These standards also did not require auditors to publicly report, in writing, internal control

deficiencies found during the audit. In contrast, the auditing requirements issued by OMB for

audits of agency-wide financial statements under the CFO Act have always required the auditor

to perform sufficient tests of internal control to support a low assessed level of control risk for

those internal controls that have been properly designed and placed in operation. And since

1981, Government Auditing Standards have required auditors to publicly report, in writing,

deficiencies in internal control found during financial statement audits.

In addition to legislative and regulatory requirements, initiatives implemented by the

Administration have also strongly impacted the Federal control environment. Under the PMA,

OMB monitors internal control weaknesses regularly. To receive green, or a successful rating,

on the PMA scorecard, agencies must eliminate all internal control weaknesses. Quarterly, OMB

monitors agency performance in meeting corrective action plan targets established under the

PMA scorecard. Agencies are required to submit corrective action plans to OMB to resolve

internal control weaknesses reported. Quarterly, agencies are graded on their progress in

achieving the corrective action milestones contained in their plans. Across the government, a

total of 13 new weaknesses were reported in FY 2004 – a net increase of two new weaknesses

from FY 2003. This increase, albeit small, may be attributed to the accelerated reporting

requirement mandated by OMB, which placed greater emphasis on the need for effective

financial reporting controls. However, as internal control is strengthened at agencies to routinely

meet accelerated reporting dates, internal control weaknesses should be reduced. Total FMFIA

material weaknesses and nonconformances decreased by nearly 11 percent.

New Efforts to Improve Internal Control

In light of the new requirements for publicly-traded companies contained in the Sarbanes-

Oxley Act, OMB re-examined the existing internal control requirements for Federal agencies.

As a result, A-123, which implements FMFIA, has been revised to strengthen the requirements

for conducting management’s assessment of internal control over financial reporting. The

circular is effective beginning in fiscal year 2006.

A-123 recognizes that there is an appropriate balance between controls and risk in an

agency’s programs and operations. Too many controls can result in inefficient and ineffective

government. The benefit should outweigh the cost. Under A-123, agencies are required to

integrate their internal control efforts to meet the requirements of FMFIA with other efforts to

improve effectiveness and accountability. Internal control should be an integral part of the entire

cycle of planning, budgeting, management, accounting, and auditing. It should support the

effectiveness and the integrity of every step of the process and provide continual feedback to

8

management. Thus the revisions to A-123 require management to strategically evaluate internal

control risks and directly test, document, and report on the effectiveness of financial controls.

Additionally, existing audit requirements in OMB Bulletin 01-02, Audit Requirements for

Federal Financial Statements, require the auditor to obtain an understanding of the process by

which the agency identifies and evaluates weaknesses reported under FMFIA, and to report

instances where the agency’s FMFIA process failed to detect and report material weaknesses.

In keeping with the balance between controls and risk, under A-123 agencies may, at

their discretion, elect to receive an audit opinion on internal control over financial reporting.

Also, if an agency cannot meet the deadlines outlined in its approved corrective action plan,

OMB may, at its discretion, require the agency to obtain an independent audit opinion of the

agency’s internal control over financial reporting as part of its financial statement audit.

Today, three

1

of the 24 CFO Act agencies have subjected their internal control over

financial reporting to examination. In the most recent report on internal control over financial

reporting, one agency received an unqualified opinion, and the other two received qualified

opinions because of material weaknesses. The agency that received an unqualified opinion

identified reportable conditions.

Survey Results

Estimating the Cost to Render an Opinion on Internal Control

Given the IGs’ responsibility to audit the financial statements, or to determine the

independent external auditor, we asked them to provide an estimate of the cost to render an

opinion on internal control over financial reporting. It is important to recognize, however, that

estimating the cost to render an internal control opinion is challenging given the lack of hard data

and the number of unknown factors that go into developing a strong estimate. While we provide

estimated cost information in this report, these estimates should not be considered hard numbers.

In a number of responses, the OIGs reported a range for the cost estimate rather than a

single dollar amount. In these cases, the cost estimate that we included in our totals and averages

reflects the middle of the range provided by the OIGs. These estimates are only for the

incremental cost of the additional internal control work required to render an opinion on internal

control. They exclude management’s cost to support the audit effort, or to implement the new

requirements in A-123, Appendix A. Although we did not collect cost estimates for

management’s activities, some CFOs believe that additional costs would be incurred. See Table

A for information on the estimated incremental audit costs.

In addition, to avoid skewing the overall and agency totals, we also provide estimates that

exclude the audit costs for DoD. These alternative numbers are useful since there may be limited

utility in obtaining an opinion on internal control given the material weaknesses at DoD, and the

1

The General Services Administration (GSA), the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the Social Security

Administration have obtained an opinion on internal control over financial reporting for 12 years, 10 years, and 8

years, respectively. GSA, however, has not subjected its internal control over financial reporting to an audit since

fiscal year 2003.

9

great uncertainty in developing a cost estimate for a department that has not yet established a

baseline cost to audit its financial statements.

The estimated costs to render an audit opinion on internal control for all 24 CFO Act

agencies is more than $140.6 million, of which $56.2 million, or 40%, is for the 23 civilian CFO

Act agencies. The average estimated incremental audit costs are estimated to be approximately

51 percent of the financial statement audit costs, or more than $5.8 million per reporting entity.

Excluding DoD, the cost per reporting entity is $2.4 million. The incremental cost estimates

ranged from as low as 6.5 percent to more than 100 percent of the cost of the financial statement

audit. In dollar terms, these costs ranged from $38,000

2

to $84.4 million. The wide range of

costs reflects the relative size and complexity of the entity being audited.

Driving these costs are the additional work that the auditor would need to perform

beyond the requirements of OMB Bulletin 01-02, Audit Requirements for Federal Financial

Statements, and the PCIE/Government Accountability Office Financial Audit Manual, in order to

render an opinion on an agency’s internal control. In general, OIGs believe a substantial amount

of additional work would need to be performed in order to render an opinion on internal control,

but noted that the extent of additional testing necessary is subject to auditor judgment.

Additional or different controls would have to be tested based on management’s assessment of

those controls and risk factors associated with the entity. In this regard, the auditor would need

to evaluate management’s own testing and documentation of the controls, assess the criteria

used, review the internal control documentation, identify missing controls, test the identified

controls, and report on the effectiveness of those controls. See Table B for OIG responses on the

additional work needed to render an opinion on internal control.

Observation

A number of OIGs and CFOs believe that significant audit costs are a major deterrent to

requiring an opinion on internal control. This is especially true when one considers A-123 since

the benefits realized by the Federal sector after implementing the revised circular may not be as

dramatic as in the private sector, where companies have gone from virtually no internal control

reporting to the requirements of Section 404. See Table C for disadvantages reported by the

OIGs. Many OIGs and OCFOs commented that the costs associated with obtaining the audit

opinion may exceed the benefit that would be derived from the process. As reported above, the

OIGs estimated that the additional work could increase the audit fees by more than 50 percent.

Although the costs in the later years may drop, the incremental audit costs are expected to be

substantial, costing an estimated average of more than $2.4 million. It is questionable whether

the benefits from obtaining an audit opinion are substantial enough, beyond those derived from

implementing the revised A-123, to justify the incremental audit cost and the costs to support the

audit.

The OIGs also identified budget constraints as another disadvantage to requiring an

opinion on internal control. OIGs commented that some agencies may not be able to obtain the

resources, both staff and funding, needed to prepare for a successful audit, let alone the resources

2

The actual costs, however, could be higher than the estimates which were reported. One agency reported a cost of

$38,000 but they qualified the amount, noting that it was the amount bid five years ago before the Sarbanes-Oxley

Act was implemented. The agency believes that these costs would be significantly higher in the outgoing years.

10

needed to perform the audit. One OIG noted that strong performance measures, such as a

reduction in financial management costs and improved reporting, be in place to ensure the

efficient use of resources before an opinion on internal control is required.

Some OIGs commented that their budgets barely cover their costs to meet existing audit

requirements. These OIGs felt that if an opinion on internal control is mandated, it must also be

funded. They noted that unfunded mandates would be difficult to absorb and would require them

to divert resources and funds from other audit areas that could provide far greater benefits than

what an opinion on internal control over financial reporting would provide.

Some OIGs and OCFOs also questioned the need to obtain an opinion on internal control

in certain circumstances. For example, if an agency is reporting material weaknesses through its

financial statement audit process, there is a high likelihood that the auditors would issue a

qualified, or disclaimer of, opinion on internal control, adding little benefit for an opinion. Also,

if an agency effectively implements the revised requirements of A-123, there may be little value

in requiring an opinion on internal control.

Several OIGs commented that any new requirements to obtain an opinion on internal

control over financial reporting should be implemented gradually, if at all. It should not be a

“one size fits all.” Any requirement to obtain an opinion on internal control should strike a

reasonable balance between the costs and benefits, recognizing the strengthened controls and

oversight that already exist in the Federal Government.

Identifying the Benefits of Rendering an Opinion on Internal Control

Unlike costs, which to some degree can be estimated, benefits can only be described in

general terms, making a cost/benefit analysis difficult. The most easily identifiable benefit is the

further independent assurance. Specific OIG responses on the benefits of obtaining an opinion

varied, and not all benefits identified are captured in this report. For purposes of effectively

analyzing and reporting on the OIG responses, we summarized their responses into seven

categories. The seven categories and OIG responses are included in Table D.

The OIGs for the three agencies that already provide an opinion on internal control over

financial reporting identified several benefits to obtaining an opinion on internal control over

financial reporting. Specifically, all three reported (1) improved internal control and reduced

material weaknesses, and (2) reduced errors and improved data integrity, documentation

reliability and reporting as benefits of the additional work. Two of the OIGs also reported

identifying new material weaknesses and reportable conditions as benefits from this process.

One OIG reported improved agency focus and oversight as an additional benefit. None of the

three OIGs could quantify the benefits realized.

Most of the OIGs of agencies that do not provide an opinion on internal control over

financial reporting believe that benefits may be derived from this type of audit. Their answers

were similar to answers provided by their counterparts at agencies that do provide an opinion on

internal control. They also cited a third benefit -- improved agency focus and oversight. Six

OIGs also reported the detection of new material weaknesses and reportable conditions as

possible benefits.

11

Four OIGs reported that there is little or minimal benefit in obtaining an opinion on

internal control over financial reporting. For example, if an agency receives a clean opinion, has

no material weaknesses or reportable conditions, and actively corrects the identified internal

control deficiencies; new material weaknesses may not be identified. Conversely, in situations

where an agency has existing material weaknesses, it may not be an efficient use of resources to

require an opinion on internal control over financial reporting until the material weaknesses are

resolved.

Observation

The benefits identified above should largely be achieved by a number of management

and audit initiatives that are currently underway, and cannot be attributed solely to an opinion on

internal control. Specifically, many of these benefits should be achieved when agencies

effectively implement the revisions to A-123

3

which strengthened the requirements for

management’s assessment of internal control over financial reporting. Because the IGs assisted

OMB in revising A-123, along with the CFOs, there is a level of confidence that, if agencies

properly implement A-123, the result should be an effective internal control review and testing

program. Therefore, except for the additional assurance provided by an opinion on internal

control, the benefits can already be realized from an internal control review program

implemented by management (similar to Section 404). In addition, the financial statement audits

as currently conducted include tests of compliance with laws and regulations, which will provide

an independent check on agencies’ A-123 implementation efforts.

In addition, as part of the financial statement audit, the auditor must already (1) obtain an

understanding of the process by which the agency identifies and evaluates weaknesses required

to be reported under FMFIA and related agency implementing procedures, and (2) compare

material weaknesses disclosed during the audit with those material weaknesses reported in the

agency’s FMFIA report that relate to the financial statements and document material weaknesses

disclosed by the audit that were not reported in the agency’s FMFIA report. The auditor must

also consider whether the failure to detect and report material weaknesses constitutes a

reportable condition or material weakness in the entity’s internal control.

Other initiatives currently underway that contribute to the achievement of the above

benefits include the process and control improvements resulting from accelerated reporting, and

the focus on internal control in the Executive Scorecard that rates agencies’ performance in

meeting the PMA initiative on improving financial management.

3

The revised A-123 now requires Federal managers, as a subset of FMFIA Section 2 reporting, to provide an

assurance statement on internal control over financial reporting. To make this assurance statement, the agency must

establish a senior assessment team to ensure that staff or contractors carry out the assessment in a thorough,

effective, and timely manner. If A-123 is effectively implemented, the assessment team will be able to conclude

whether the design and operation of the internal controls over financial reporting were effective or whether material

weaknesses exist in the design or operation of internal control over financial reporting. To evaluate internal control

at the process, transaction or application level, the assessment team must: (1) determine significant accounts; (2)

identify and evaluate major classes of transactions; (3) understand the financial reporting process; (4) gain an

understanding of control design to achieve management’s assertions; and (5) test controls and assess compliance to

support management’s assertions.

12

An effective and meaningful cost/benefit analysis should not compare the incremental

audit costs reported above to all of the benefits that could be achieved through a process similar

to that done under Section 404. The real benefit of the auditor’s opinion on internal control is

the added independent assurance it provides that management’s assessment of its internal control

is fairly presented. It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the incremental benefit of the

auditor’s opinion without first knowing how effectively management performs on its assessment

under the revised A-123.

To some extent, this assessment will be done under the current requirements for Federal

financial statements since the auditor must obtain an understanding of the process by which the

agency identifies and evaluates weaknesses required to be reported under FMFIA and to report

instances where the reporting entity’s FMFIA process failed to detect and report material

weaknesses. Beginning in fiscal year 2006, this process will be done using the revised A-123

which strengthened management’s assurance statements process.

Experiences of Publicly-Traded Companies

In addition to surveying the OIGs and OCFOs, we also reviewed information about the

private sector to provide additional insight on the costs, benefits, and challenges of obtaining an

opinion on internal control over financial reporting. The information is drawn from articles on

the costs, and associated benefits, of complying with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and statements

made by representatives of public companies, members of audit committees, and auditors who

testified before the Securities and Exchange Commission on their experiences implementing the

Act. We did not corroborate this information.

Experience Estimating the Cost

Initial cost estimates to comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act were low. Studies

conducted by an association for financial executives

4

found that total costs, including the costs of

management’s assurance assessment, averaged $4.36 million. These costs were up 39 percent

from the $3.14 million they expected to pay initially. Total cost of compliance averaged $1.34

million for internal control, $1.72 million for external costs, and $1.30 million for auditor fees.

The auditor fees are in addition to companies’ financial statement audit fees, on average 57

percent higher.

Data in another study

5

from 90 Fortune 1000 companies

6

who are audited by the nation’s

four largest accounting firms

7

shows that issuers spent substantial sums to comply with the new

4

Financial Executives International (FEI) Survey: Section 404 Costs Exceed Estimates. Copyright 2005 FEI.

http://www.fei.org/404_survey_3_21_05.cfm

.

5

Charles River Associates, Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 Costs and Remediation of Deficiencies: Estimates From a

Sample of Fortune 1000 Companies, CRA No. D06155-00. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/soxcomp/soxcom-all-

attach.pdf.

6

The average company revenues were $8.1 billion.

7

Deloitte & Touche LLP, Ernst & Young LLP, KPMG LLP, and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

13

reporting requirements. On average, the companies in the sample each spent $7.8 million to

implement Section 404 overall. Audit fees accounted for approximately one quarter of the total

compliance costs, or an average of $1.9 million.

Some have suggested that Section 404 compliance costs will decline over time, pointing

to one-time start-up expenditures and “learning curve” costs that typically occur with any new

reporting requirement. Others have suggested that first year costs include deferred maintenance

of internal control systems that have been allowed to degrade. If these views are correct,

compliance costs would be expected to decline over time. Survey responses by audit firms

support this hypothesis. On average, audit firm respondents believe that the total 2005

compliance costs of the clients in the sample, including Section 404 audit fees, will average $4.2

million – 46 percent less than the estimated 2004 costs.

First Year Benefits Realized

A primary benefit cited by many observers is that the heightened attention to internal

control will enhance the reliability of financial statements by helping companies to identify

internal control deficiencies and remediate these deficiencies in a timely manner. To assess the

full effects of the new reporting requirement, Charles River Associates

8

, a consulting firm,

sampled 90 Fortune 1000 companies to gather information about the total number of deficiencies

identified by the issuer or the auditor in the Section 404 process regardless of whether the

deficiency was remediated prior to the year-end assessment date.

9

On average, for year-end 2004, management and the independent auditor identified 348

deficiencies per company. Of these, management remediated an average of 271 deficiencies

prior to their year-end assessment date. The remaining 77 deficiencies are expected to be

remediated in the future. Of the unremediated deficiencies, almost 96 percent were classified as

control deficiencies not rising to the level of a significant deficiency or material weakness. The

data showed an average of 74 control deficiencies and three significant deficiencies per company

still existed at year-end. A total of five material weaknesses were unremediated as of the year-

end assessment date across the 90 companies for which data was available.

10

8

Charles River Associates, Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 Costs and Remediation of Deficiencies: Estimates From a

Sample of Fortune 1000 Companies, CRA No. D06155-00. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/soxcomp/soxcom-all-

attach.pdf.

9

For Section 404 purposes, management and the independent auditor are required to disclose in their public reports

only material weaknesses that exist as of the year-end assessment date. Whether deficiencies are identified by

management or the auditor, management may implement new controls or strengthen existing procedures to correct

deficiencies before the company’s year-end assessment date, in effect remediating these potential problems. By

identifying and remediating control deficiencies during the year, fewer material weaknesses are likely to be reported.

10

If a deficiency was remediated prior to the year-end assessment date, management and the auditors would not

necessarily have evaluated whether it would have been a significant deficiency or a material weakness as defined by

the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board Auditing Standard No. 2. Therefore, the number of deficiencies

remediated prior to the year-end assessment date was collected in the aggregate without determination as to whether

some would have been classified as significant deficiencies or material weaknesses.

14

Observation

Recognizing that the number of the findings per company is quite substantial, the number

of material weaknesses for 90 companies was low, with only five unremediated material

weaknesses at the end of the assessment period. The cost for 90 companies to identify these

material weaknesses, however, was significant, totaling $702 million

11

.

Also, on the whole, it is difficult to imagine that Federal agencies would identify the

same number of deficiencies that publicly-traded companies identified in their first year of

implementing Section 404. Although companies in the private sector have been required to

maintain effective internal controls under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, many

behavioral changes did not occur until the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The same cannot be said of the

Federal Government, which has seen tremendous improvements in financial management

practices in the past 15 years. Passage of key legislation, more congressional oversight on

financial management matters, hiring highly recognized CFOs from the corporate world, and the

PMA have all contributed toward creating an environment that supports strong internal control.

Many of the articles and links that we used in conducting this study are included in

Attachment A.

Conclusion

Based on data currently available from the private sector and the estimates that are

beginning to be developed for the public sector, most industry experts agree that there are

significant incremental costs to obtaining an opinion on internal control over financial reporting.

In addition, there is a general consensus that, at least in the early stages of implementing Section

404, it is difficult to determine the incremental benefits that might be gained from the additional

work.

The critical question which needs to be addressed in assessing the benefits of obtaining

an audit opinion on internal controls is whether the benefits derived significantly exceed the

results of agencies’ implementation of the revised A-123. Before incurring these additional

costs, it would be prudent to see how Federal managers implement the revised A-123 and

evaluate the private sector’s implementation of Sarbanes-Oxley when additional information

becomes available.

And even then, given the inherent differences between agencies, it would be judicious to

implement the incremental work on a case-by-case basis. The decision on whether to obtain an

opinion needs to be decided by each agency, and other knowledgeable parties, depending on the

condition of its financial management program. Agencies that already have problems obtaining

a clean opinion on their financial statements do not need to obtain an opinion on internal control

to tell them they have material weaknesses. On the other hand, agencies that believe they are

11

Charles River Associates, Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 Costs and Remediation of Deficiencies: Estimates From a

Sample of Fortune 1000 Companies, CRA No. D06155-00. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/soxcomp/soxcom-all-

attach.pdf.

15

leading organizations may want the added assurance that can be achieved by obtaining an

opinion on internal control.

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

The objective of our study was to gather information on the potential costs and benefits

of requiring the CFO Act agencies to obtain audit opinions on internal control over financial

reporting. To accomplish this objective, the CFOC and the PCIE, under the leadership of OMB,

who chairs each council, canvassed the Federal community for their input.

OMB requested that the PCIE Audit Committee coordinate the collection of cost and

benefit information from the IG community. The Audit Committee Chair sent a questionnaire to

the IG community to gather data on the estimated audit costs and the benefits of performing an

examination under the standards of AT § 501, Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over

Financial Reporting. The Audit Committee received responses from each of the IGs at the 24

CFO Act agencies and then summarized the information. We shared the summary with the

respondents to ensure that we had accurately captured their comments.

To gather input from the CFOs on the challenges and benefits of obtaining an opinion on

internal control, we shared the results of the IG survey with the CFOC’s Policies and Practices

Committee and incorporated their comments. We then shared the draft study with the full PCIE

and CFOC whose comments and insights were also subsequently incorporated. During this final

comment period, we also asked the members to respond to two questions about the expected

benefits of A-123 and obtaining an opinion on internal control.

Because publicly-traded companies had one year of experience implementing Section

404, we also looked at their experiences. We considered these experiences in light of the

different environments in which the Federal Government and publicly-traded companies operate.

We also considered the revisions to A-123, effective beginning in fiscal year 2006, which has

many similarities to Sarbanes-Oxley.

We did not ask for supporting documentation on how the OIGs developed the cost

estimates and we made some interpretation in analyzing the results. We reviewed numerous

articles, surveys, and statements made before regulatory bodies relating to the implementation of

Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. We did not, however, review all statements made before

regulatory bodies.

16

Attachment A

Below are some of the links to articles or studies that we used that provide cost/benefit

information related to implementation of Sarbanes-Oxley or similar requirements related to

reporting on internal control over financial reporting.

1. http://www.nysscpa.org/cpajournal/2004/1104/perspectives/p6.htm

2. http://www.404institute.com/docs/SOXSurveyJuly.pdf

3. http://www.managementconsultancy.co.uk/news/1137963

4. http://www.usatoday.com/money/companies/regulation/2003-10-19-sarbanes_x.htm

5. http://www.auditnet.org/articles/Sarbanes-Oxley_Implementation_Costs.pdf

6. http://www.cfo.com/index.cfm/l_emailauthor/3661477/c_3661527/2984986

7. http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3010299/1/c_3046597?f=TIFarticle021105

8. http://searchcio.techtarget.com/originalContent/0,289142,sid19_gci1031357,00.html

9. http://www.404institute.com/archived_results.aspx

10.

Sarbanes-Oxley for

Feds.doc

SO Act Section 404

Practical Guide July 2

0

Federal Agencies -

Will Sarbanes-Oxley

F

SOX 404.doc

Audit Fees Double

Due to Sarbox.doc

11. http://accounting.smartpros.com/x46291.xml

12. http://accounting.smartpros.com/x42491.xml

13. http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,4149,1238790,00.asp

14. http://techupdate.zdnet.com/techupdate/stories/main/Sarbanes_Oxley_Compliance_Spen

ding.html?tag=tu.fd.css.link

15. http://www.cfodirect.com/

16. http://www.amrresearch.com/content/resourcecenter.asp?id=429#

17. http://www.fei.org/ (numerous Sarbanes-Oxley articles and resources)

18. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/soxcomp.htm

17

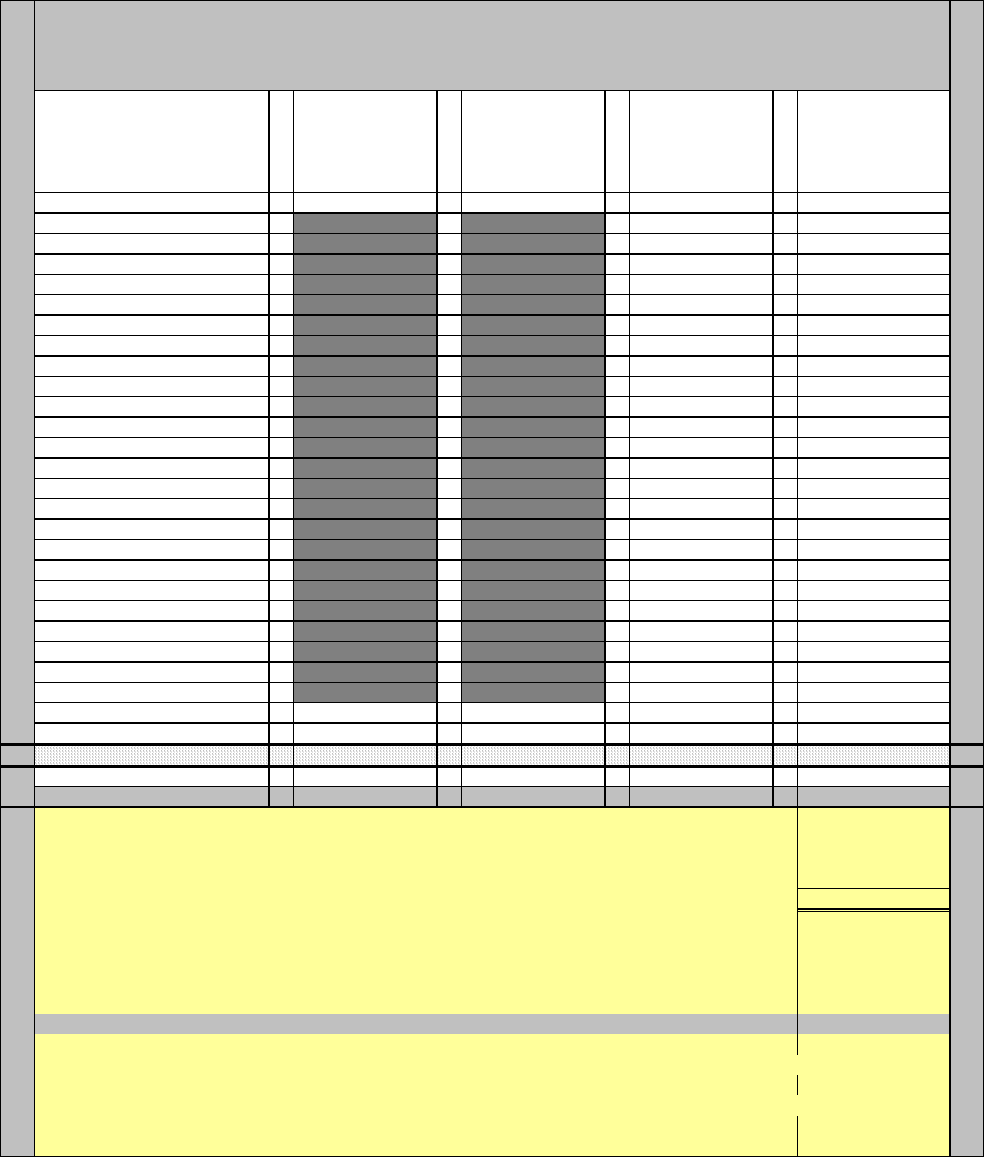

Estimated Audit Costs of Opining on Table A

Internal Control Over Financial Reporting

CFO Act Agency

Cost of the

Financial

Statement Audit **

Additional

Cost/Estimate for

the Internal

Control Opinion ***

Percent Estimate

of Internal Control

Opinion Cost to

Total Audit Cost

***

Extent of Additional

Work

AID 37.9% substantial

DHS 40.0% substantial

DOC 40.0% minimal

DOD 51.0% substantial

DOE 30.0% substantial

DOI 85.7% substantial

DOJ 62.5% substantial

DOL 10.0% moderate

DOT 40.0% substantial

ED 100.0% substantial

EPA 112.5% substantial

GSA * 14.3% moderate

HHS 62.5% substantial

HUD 24.0% moderate

NASA 47.1% substantial

NSF 6.5% minimal

NRC * 18.0% moderate

OPM 100.0% substantial

SBA 37.5% substantial

SSA * 35.0% moderate

STATE 25.0% substantial

TREASURY 62.5% substantial

USDA 50.0% substantial

VA 87.5% substantial

Total $275,707,15

8

$140,637,98

0

51.0

%

Total Cost for 24 CFO Act Agencies $140,637,980 17 substantial

Total Cost for 23 Civilian CFO Act Agencies $56,287,980 5 moderate

2 minimal

Average Cost Per Agency to Render an Opinion on Internal Control: Total 24

24 CFO Act Agencies $5,859,916

23 Civilian CFO Act Agencies $2,447,303

* = Agency previously has obtained an opinion on internal controls

** = Audit Costs include significant OIG and/or Independent Public Accountant costs to conduct the financial statement

audit but exclude CFO preparation costs related to the audits

*** = When an agency provided a range of the cost estimate or percent, the mid-level range was used to calculate the

cost or the percent amounts

18

Additional Work Required to Render Table B

an Opinion on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting

Agency

Test Additional/

Different

Controls Based

On

Management's

Assessments

More Planning

and Coverage Of

Cycles,

Understanding,

Identifying,

Documenting,

Reviewing

Internal Control

and Activities/

Other

Components Of

Internal Control

Management

Must

Document/Test

Internal Control;

Inadequate

Documentation/

Testing May

Cause Rework

Or Increase In

Scope

Number/

Severity Of

Control

Deficiencies

And Evaluation

And

Classification Of

Control

Deficiencies Will

Increase Level

Of Work

Won't Be

Able To

Rotate

Testing Of

Controls Or

Totally Rely

On Other

Firm's Work,

Thus

Increasing

The Amount

Of Testing

New Or Modified

Systems

Processes;

Controls Can

Increase the

Scope Of Work;

Will Have To

Document/Test

IT/General And

Application

Controls Testing

Increase

Reporting -

Extra Time

Needed To

Complete

Auditor's

Report,

Including

Consultation

Of Wording

Of Report.

Minimal

Additional

Testing/ Or

No Answer

AID x xx

DHS x x x

DOC x

DOD x

DOE x x

DOI x x

DOJ x x x

DOL x x

DOT x

ED x x x x x xx

EPA x x x

GSA * x

HHS x x x x

HUD x x

NASA x x

NRC * x x x

NSF x

OPM x

SBA x x x x

SSA * x x x

STATE x x

TREASURY x x x

USDA x x

VA x

Sum Totals 18 13 6 2 2 9 5 2

Opinion 2 2 0 1 0 2 0

No Opinion 16 11 6 1 2 7 5 2

All- 2

4

75.0

%

54.2

%

25.0

%

8.3

%

8.3

%

37.5

%

20.8

%

8.3

%

Opinion 8.3

%

8.3

%

0.0

%

4.2

%

0.0

%

8.3

%

0.0

%

0.0

%

No Opinion 66.7

%

45.8

%

25.0

%

4.2

%

8.3

%

29.2

%

20.8

%

8.3

%

* Agency previously has obtained an opinion on internal controls

19

Disadvantages of Opining on Table C

Internal Control Over Financial Reporting

Agency

Contentious

Dealings With

Management/

Management

Only Focused

On

Compliance/

Short Term

Fixes

Not Aware

Of Any/Not

Apparent/

Did Not

Identify Any

Increased

Audit

Costs/Cost

Exceed

Benefit

More Funding

Needed/Inability

To Fix

Weaknesses/

Budget

Constraint/Lack

Of Staff

Other Than

Clean

Opinions

Rendered

On Internal

Controls

While

Receiving

Clean F/S

Opinions/Or

Just

Disclaimer

Increased

Agency Costs

Documentation/

Testing/

Implementing

Controls/Time

To Put Internal

Control In Place

First

Would Not

Identify New

or

Significant

Findings/

Issues

AID x x x

DHS x x x

DOC x x xx

DOD x x x

DOE x x x

DOI x

DOJ x x

DOL x x x

DOT x

ED x x x

EPA x

GSA * x

HHS x

HUD xx

NASA x

NRC * x x

NSF x

OPM

x

x

SBA x x x

SSA * x

STATE x x x

TREASURY x x x

USDA x

VA x

Sum Totals 2 1 17 11 5 11 2

Opinions 1 0 1 0 0 0 0

No Opinion 1 1 16 11 5 11 2

All- 24 8% 4% 71% 46% 21% 46% 8%

Opinions 33.3% 0.0% 33.3% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

No Opinion 4.8% 4.8% 76.2% 52.4% 23.8% 52.4% 9.5%

* Agency previously has obtained an opinion on internal controls

20

Benefits of Opining on Table D

Internal Control Over Financial Reporting

Agency

Improved

A

gency Focus/

Oversight/

Assessment/

Management/

Ensure

Compliance

Improved

Internal

Controls/

Reduced

Weaknesses/T

ake Corrective

Action

Decreased

Processing

Time/

Increase in

Efficiency or

Production

Better Use

of Funds/

Saved

Money/

Reduced

Audit Costs

Reduced

Errors/Improved

Data Integrity,

Reliability,

Documentation,

& Reporting/

Enhance Public

Confidence

Limited/

Minimal

Benefits

Identify New

Material

Weaknesses

or Reportable

Conditions/

Deficiencies

AID xx

DHS x x x x x

DOC x

DOD x x x xx

DOE x

DOI x x

DOJ x

DOL x

DOT x

ED x x x

EPA x x

GSA * x x

HHS x

HUD x

NASA x x

NRC * x x x x

NSF x x

OPM x

SBA x x x

SSA * x x x

STATE x x x x

TREASURY x xx

USDA x x

VA x x x

Sum Totals 11 13 2 4 13 4 8

Opinion 1 3 0 0 3 0 2

No Opinion 10 10 2 4 10 4 6

All 2

4

45.8% 54.2% 8.3% 16.7% 54.2% 16.7% 33.3%

Opinion 33.3% 100.0% 0.0% 0.0% 100.0% 0.0% 66.7%

No Opinion 47.6% 47.6% 9.5% 19.0% 47.6% 19.0% 28.6%

* Agency previously has obtained an opinion on internal controls

21