DWI

JUDICIAL PROBLEMS AND PITFALLS

2015 New York State Magistrates Association Conference

Niagara Falls, New York

PETER GERSTENZANG, ESQ.

Introduction

Peter Gerstenzang is the senior partner in the Albany firm of Gerstenzang,

O'Hern, Sills & Gerstenzang where he focuses on Criminal Defense with an emphasis on DWI

cases and Vehicular Crimes. He commenced his legal career as a prosecutor for the United

States Army in the Republic of Vietnam. From 1972 to 1975, he was an Assistant District

Attorney for the County of Albany. Certified as a breath test operator, he taught at the New

York State Police Academy in their Breath Test Training Program for 12 years.

Mr. Gerstenzang is Board Certified by the National College for DUI Defense

(ANCDD@), and is a former Dean of that college. The NCDD is the only organization accredited

by the American Bar Association to certify attorneys as specialists in DUI law.* His book,

Handling the DWI Case in New York, published by West Group, is considered a standard

reference in the field of Driving While Intoxicated cases.

Peter Gerstenzang is a regular lecturer for the New York State Association of

Criminal Defense Lawyers, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, the New

York State Magistrates Association, the New York State Bar Association, and the New York

State Defenders Association. In addition, he lectures for numerous County Bar and Magistrates

Associations, public defense organizations and the New York State Court Clerks Association.

* The NCDD is not affiliated with any governmental authority. See Rules of Prof. Con., Rule

7.4(c)(1); Hayes v. New York Attorney Grievance Comm. of the 8th Jud. Dist., 672 F.3d 158 (2d Cir.

2012).

NEW YORK STATE MAGISTRATES ASSOCIATION

JUDICIAL PROBLEMS AND PITFALLS

September 28, 2015

Materials Prepared by

PETER GERSTENZANG, ESQ.

GERSTENZANG, O’HERN, SILLS & GERSTENZANG

210 Great Oaks Boulevard

Albany, New York 12203

Copyright © 2015

Portions Excerpted from

Handling the DWI Case in New York by

Peter Gerstenzang, Esq. and Eric H. Sills, Esq.

Reprinted with permission of West Publishing Company

All Rights Reserved

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ARRAIGNMENT ISSUES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

A. Arraignment Without Counsel.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

B. Defendant Declines Assigned Counsel.. . . . . . . . . . . . 2

C. Defendant Wishes to Proceed Pro Se. . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

D. CPL § 170.10(4)(a). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

CHAPTER 45: SUSPENSION PENDING PROSECUTION.. . . . . . . . . 5

§ 45:1 In general. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

§ 45:2 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- The prompt suspension law. . . 6

§ 45:3 ___ Suspension procedure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

§ 45:4 ___ Applicability to certain underage drivers.. . . 11

§ 45:5 ___ What if defendant appears for arraignment

without counsel?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

§ 45:6 ___ Applying Pringle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

§ 45:7 ___ What role do the People play at a Pringle

hearing?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

§ 45:8 ___ Applicability to chemical test result of

exactly .08%. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

§ 45:9 ___ Applicability to out-of-state licensees.. . . . 20

§ 45:10 ___ Hardship privilege. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

§ 45:10A ___ Hardship privilege cannot be used to operate

commercial motor vehicle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

§ 45:11 ___ Pre-conviction conditional license. . . . . . . 22

§ 45:12 ___ Applicability of pre-conviction conditional

license to commercial and taxicab drivers.. . . . . 24

§ 45:13 ___ Violation of pre-conviction conditional

license is a traffic infraction; violation of

hardship privilege constitutes AUO. . . . . . . . . 24

§ 45:14 ___ Prompt suspension law does not preclude Court

from suspending defendant's driver's license

under other laws. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

§ 45:15 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) -- Suspension pending

prosecution based upon prior conviction or

vehicular crime.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

§ 45:16 ___ Suspension procedure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

§ 45:17 ___ Effect of failure to comply with statute. . . . 27

§ 45:18 VTL §§ 1193(2)(e)(1) & (7) -- Suspension time

frame.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

§ 45:19 ___ Length of suspension. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

§ 45:20 ___ Constitutionality.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

§ 45:21 ___ Double Jeopardy and Equal Protection. . . . . . 31

§ 45:22 VTL § 1194(2)(b)(3) -- Temporary suspension of

license at arraignment in chemical test refusal

cases.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

§ 45:23 VTL § 510(3-a) -- Discretionary suspensions.. . . . 32

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Cont'd)

Page

CHAPTER 41: TEST REFUSALS (Select sections from).. . . . . 35

§ 41:35 Procedure upon arrest -- Report of Refusal. . . . . 35

§ 41:36 Report of Refusal -- Verification.. . . . . . . . . 36

§ 41:37 Report of Refusal -- Contents.. . . . . . . . . . . 36

§ 41:38 Report of Refusal -- To whom is it submitted?.. . . 36

§ 41:39 Procedure upon arraignment -- Temporary suspension

of license. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

§ 41:40 Procedure upon arraignment -- Court must provide

defendant with waiver form and notice of DMV

refusal hearing date. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

§ 41:41 Effect of failure of Court to schedule DMV

refusal hearing.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

§ 41:42 Effect of delay by Court in forwarding Report of

Refusal to DMV. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

§ 41:44 Report of Refusal must be forwarded to DMV

within 48 hours of arraignment. . . . . . . . . . . 39

§ 41:45 Forwarding requirement cannot be waived -- even

with consent of all parties.. . . . . . . . . . . . 39

§ 41:28 Chemical test refusal must be "persistent". . . . . 39

§ 41:29 What constitutes a "persistent" refusal?. . . . . . 40

§ 41:88 Admissibility of chemical test refusal evidence

in actions arising under Penal Law. . . . . . . . . 41

CHAPTER 13: (One section from)

§ 13:37 Violation of conditional license as AUO.. . . . . . 42

CHAPTER 49: THE 20-DAY ORDER.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

§ 49:1 In general. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

§ 49:2 What is a 20-Day Order?.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

§ 49:3 Purpose of a 20-Day Order.. . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

§ 49:4 Scope of a 20-Day Order.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

§ 49:5 Eligibility for a 20-Day Order. . . . . . . . . . . 46

§ 49:6 Chemical test refusals and 20-Day Orders. . . . . . 47

§ 49:7 Court's obligations upon conviction.. . . . . . . . 47

§ 49:8 Advice to defendant regarding 20-Day Order. . . . . 48

§ 49:9 20-Day Orders in certain drug-related cases.. . . . 49

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Cont'd)

Page

CHAPTER 48: IGNITION INTERLOCK DEVICE PROGRAM. . . . . . . 50

§ 48:1 In general. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

§ 48:2 What is an ignition interlock device?.. . . . . . . 51

§ 48:3 Rules and regulations regarding IIDs. . . . . . . . 51

§ 48:4 Definitions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

§ 48:5 Scope of IID program. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

§ 48:6 Who must be required to install and maintain

an IID?.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

§ 48:7 Who may not be required to install and maintain

an IID?.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

§ 48:8 Cost, installation and maintenance of IID.. . . . . 62

§ 48:9 IID installer must provide defendant with fee

schedule. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

§ 48:10 What if defendant is unable to afford cost of IID?. 63

§ 48:11 Notification of IID requirement.. . . . . . . . . . 64

§ 48:12 Defendant must install IID within 10 business

days of sentencing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

§ 48:13 Defendant must provide proof of compliance

with IID requirement within 3 business days of

installation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

§ 48:14 DMV will note IID condition on defendant's

driving record. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

§ 48:15 How often does defendant have to blow into IID?.. . 66

§ 48:16 Lockout mode. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

§ 48:17 Circumvention of IID. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

§ 48:18 Duty of IID monitor to report defendant to Court

and District Attorney.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

§ 48:19 Use of leased, rented or loaned vehicles. . . . . . 69

§ 48:20 Use of employer-owned vehicles. . . . . . . . . . . 69

§ 48:21 Pre-installation requirements.. . . . . . . . . . . 70

§ 48:22 Mandatory service visit intervals.. . . . . . . . . 71

§ 48:23 Accessibility of IID providers. . . . . . . . . . . 71

§ 48:24 Frequency of reporting by IID providers.. . . . . . 72

§ 48:25 Defendant entitled to report of his/her IID

usage history.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

§ 48:26 IID providers must safeguard personal information.. 73

§ 48:27 Post-revocation conditional license.. . . . . . . . 74

§ 48:28 Intrastate transfer of probation/conditional

discharge involving IID requirement.. . . . . . . . 78

§ 48:29 Interstate transfer of probation/conditional

discharge involving IID requirement.. . . . . . . . 79

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Cont'd)

Page

CHAPTER 48: IGNITION INTERLOCK DEVICE PROGRAM (Cont'd)

§ 48:30 VTL § 1198 does not preclude Court from imposing

any other permissible conditions of probation.. . . 80

§ 48:31 Imposition of IID requirement does not alter

length of underlying license revocation.. . . . . . 81

§ 48:32 IID requirement runs consecutively to jail

sentence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

§ 48:33 Applicability of IID requirement to parolees. . . . 84

§ 48:34 IID cannot be removed without "certificate of

completion" or "letter of de-installation". . . . . 85

§ 48:35 Constitutionality of VTL § 1198.. . . . . . . . . . 85

§ 48:36 Necessity of a Frye hearing.. . . . . . . . . . . . 85

MISTAKE OF LAW STOPS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

VEHICLE STOP DETENTION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

TABLE OF APPENDICES

Page

App.

1 Copy of Hurrell-Harring v. State of New York,

15 N.Y.3d 8 (2010). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

2 Advisory Committee on Judicial Ethics'

Opinion 14-01 dated January 30, 2014. . . . . . . . 105

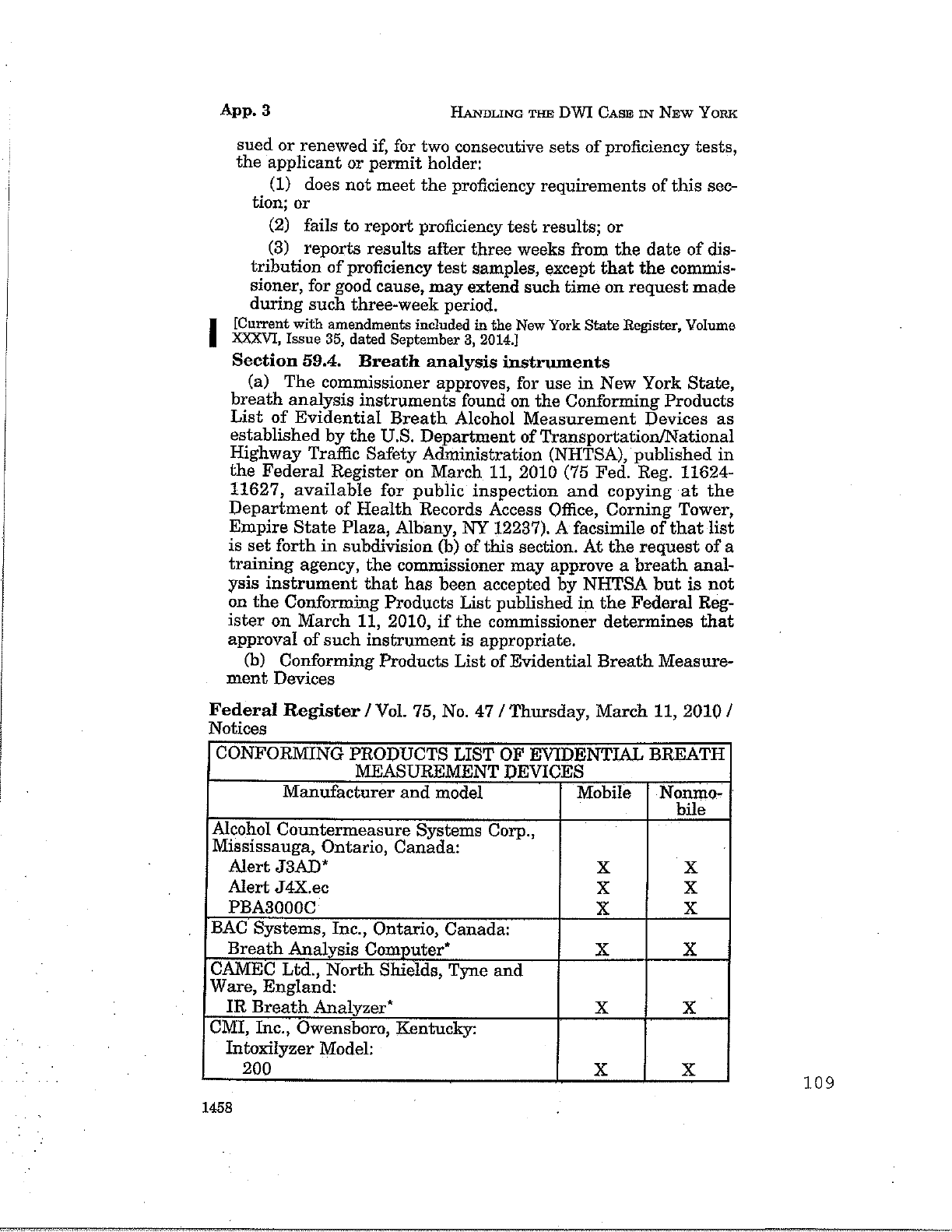

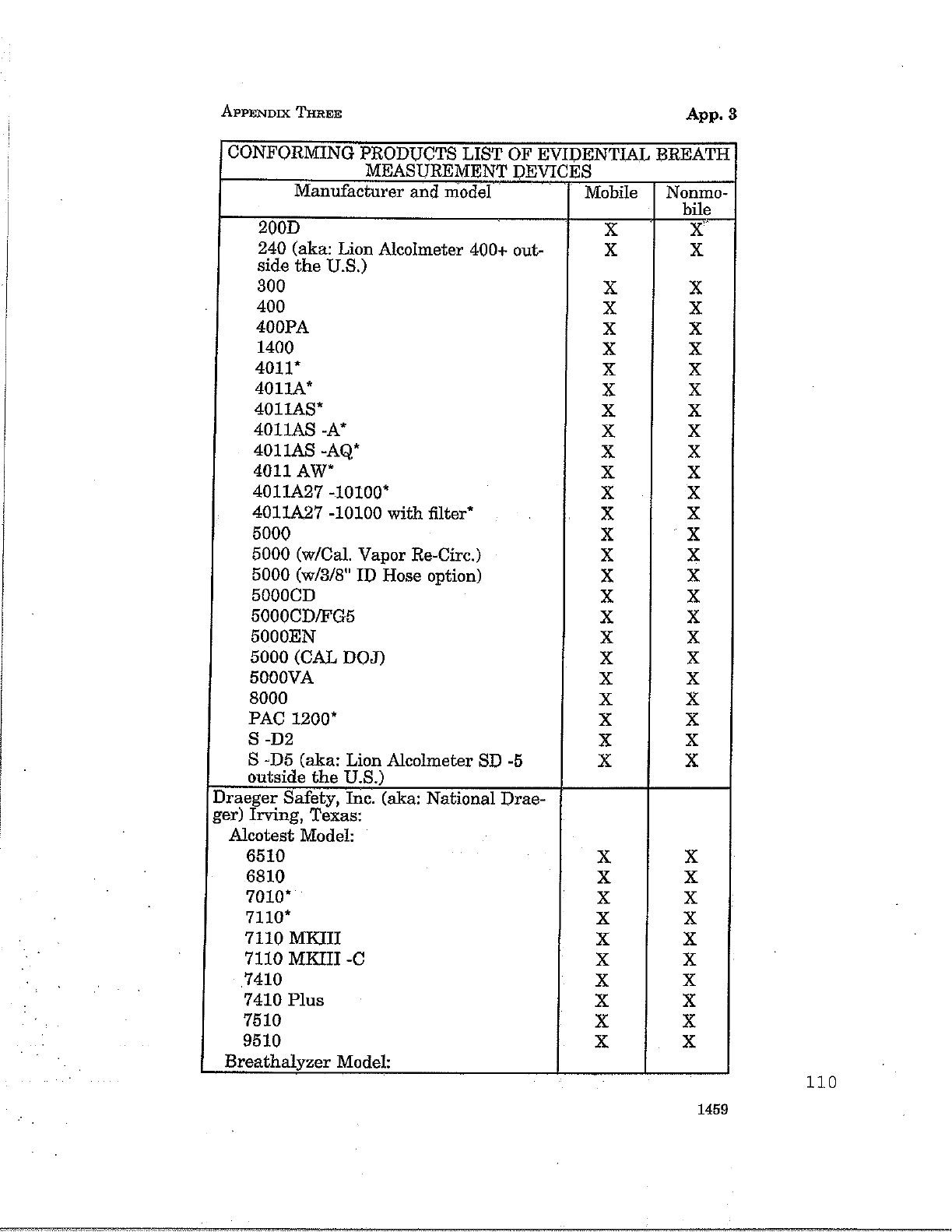

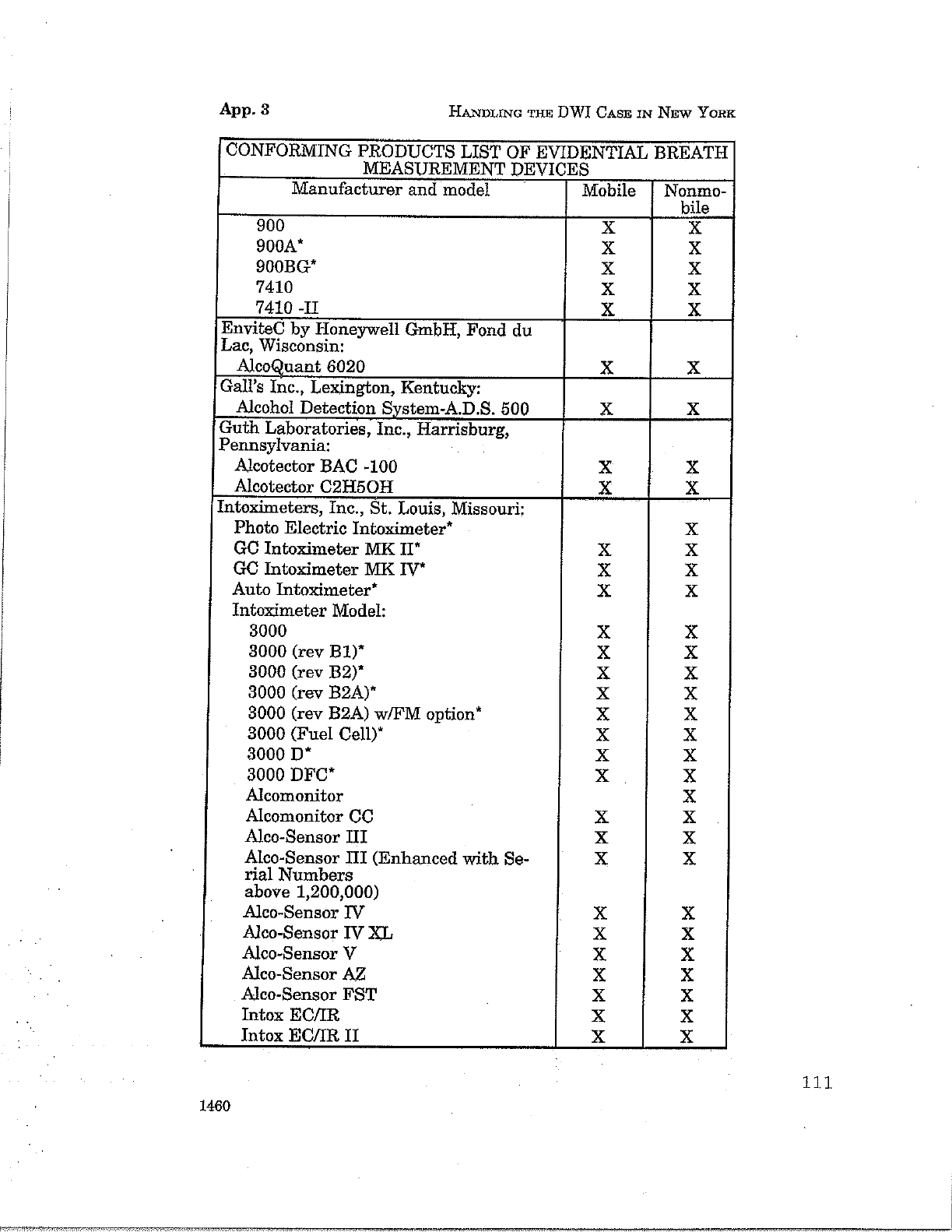

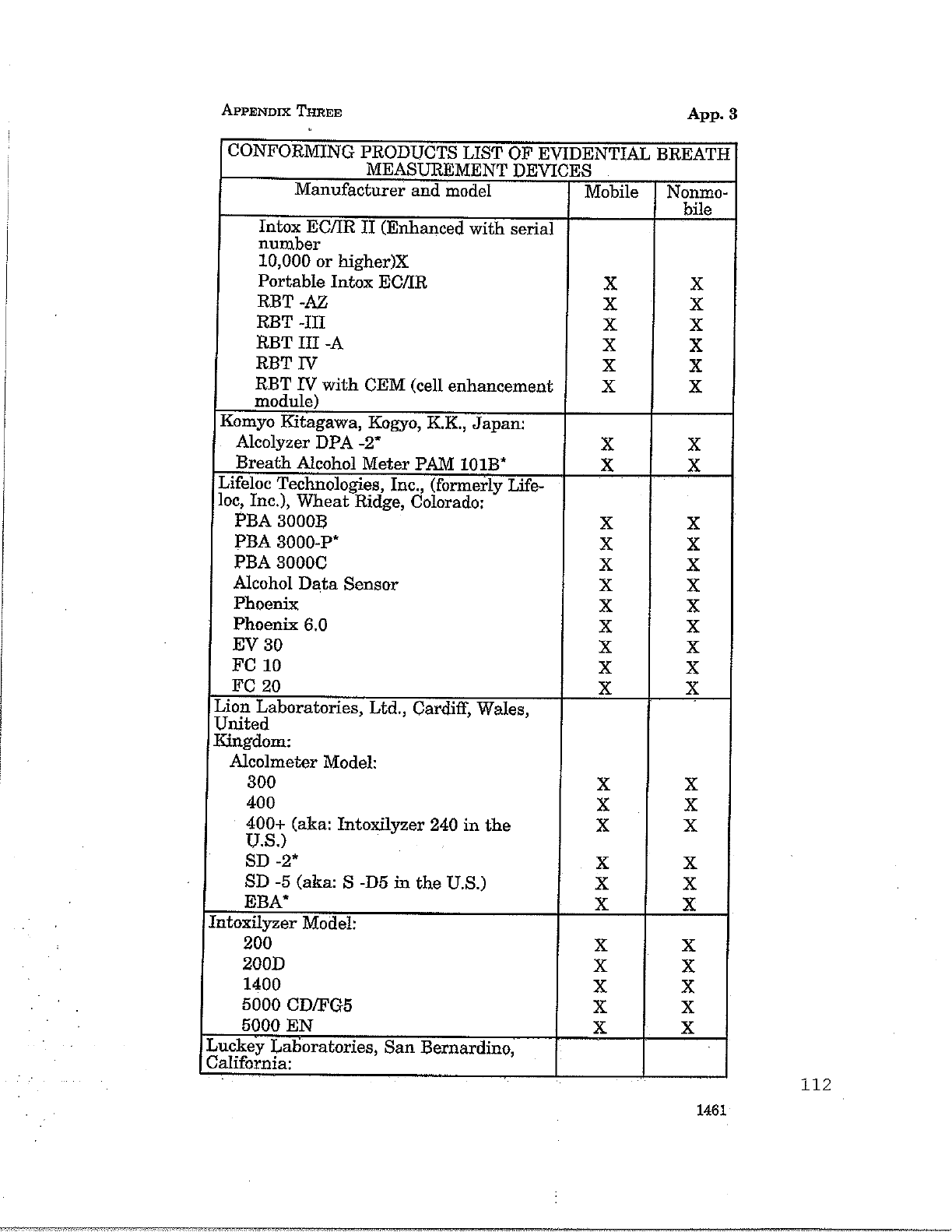

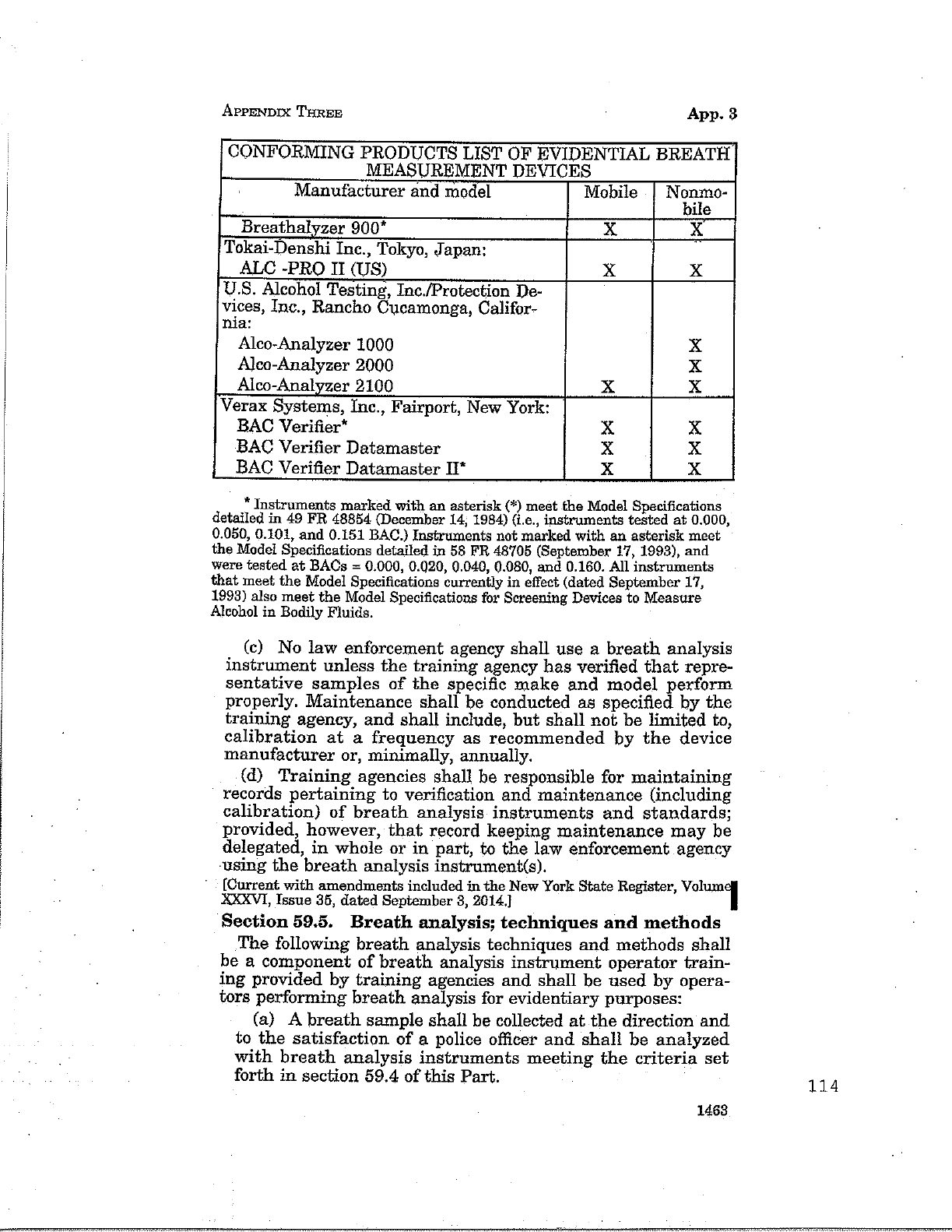

3 New York State Department of Health Rules and

Regulations for Chemical Tests (Breath, Blood,

Urine and Saliva).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

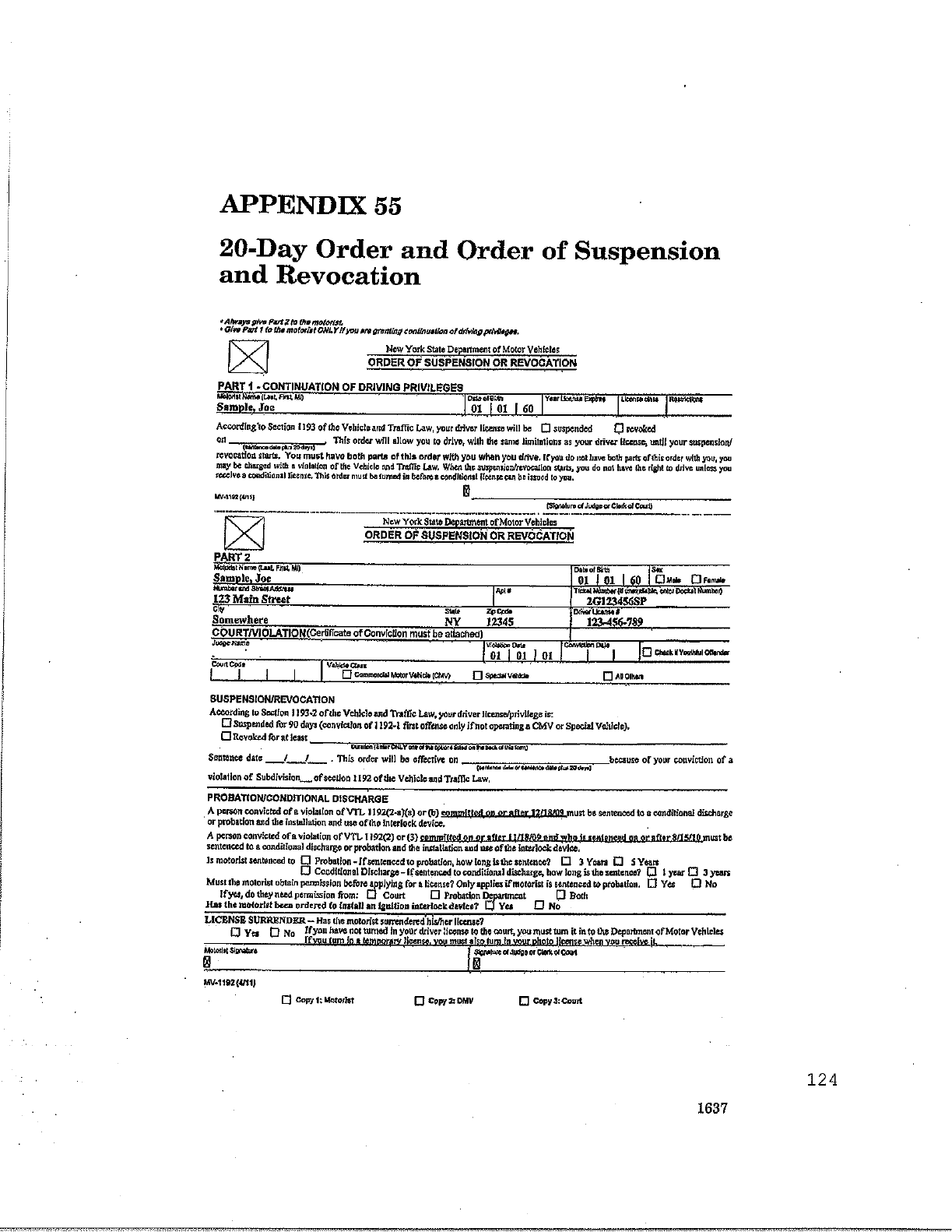

55 20-Day Order and Order of Suspension and

Revocation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

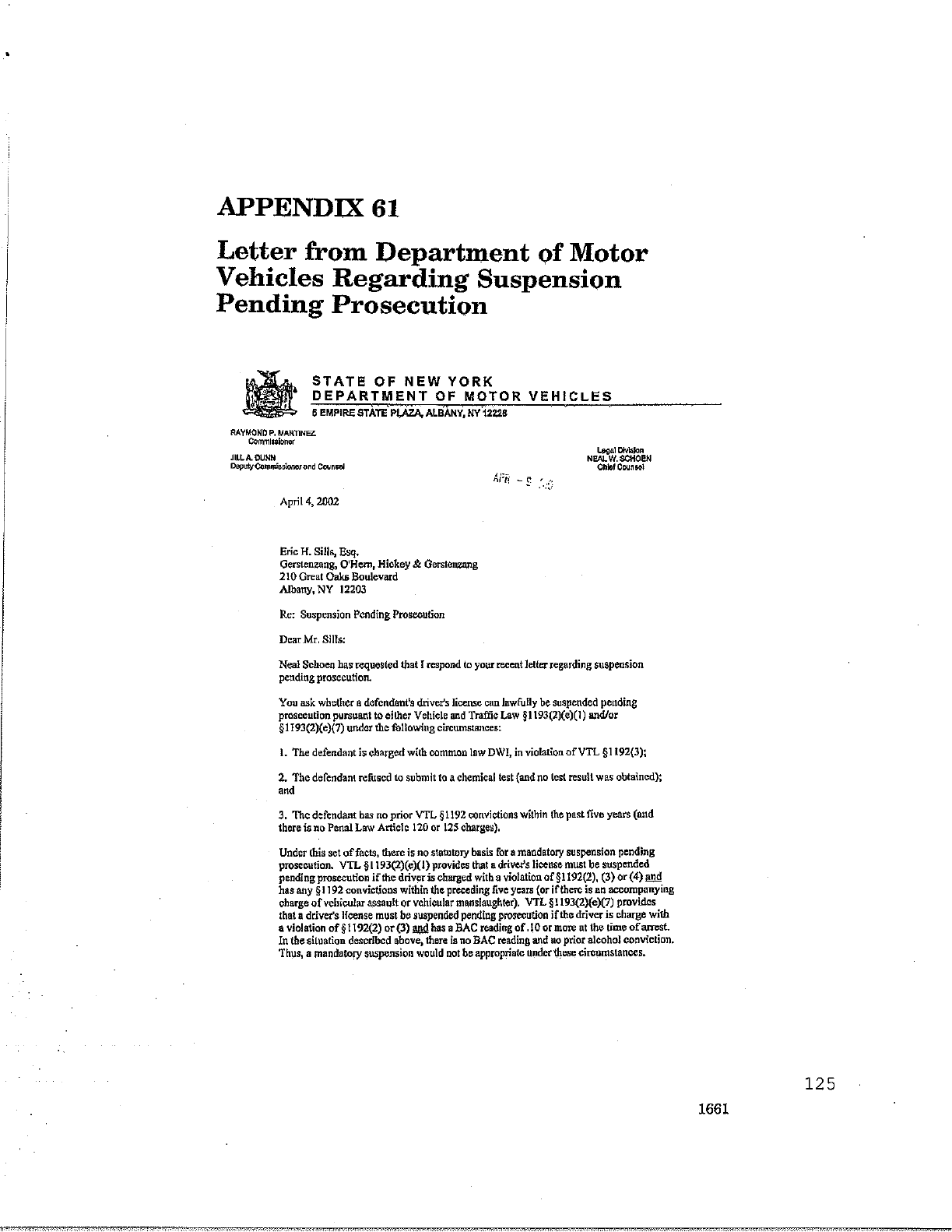

61 Letter from Department of Motor Vehicles Regarding

Suspension Pending Prosecution. . . . . . . . . . . 125

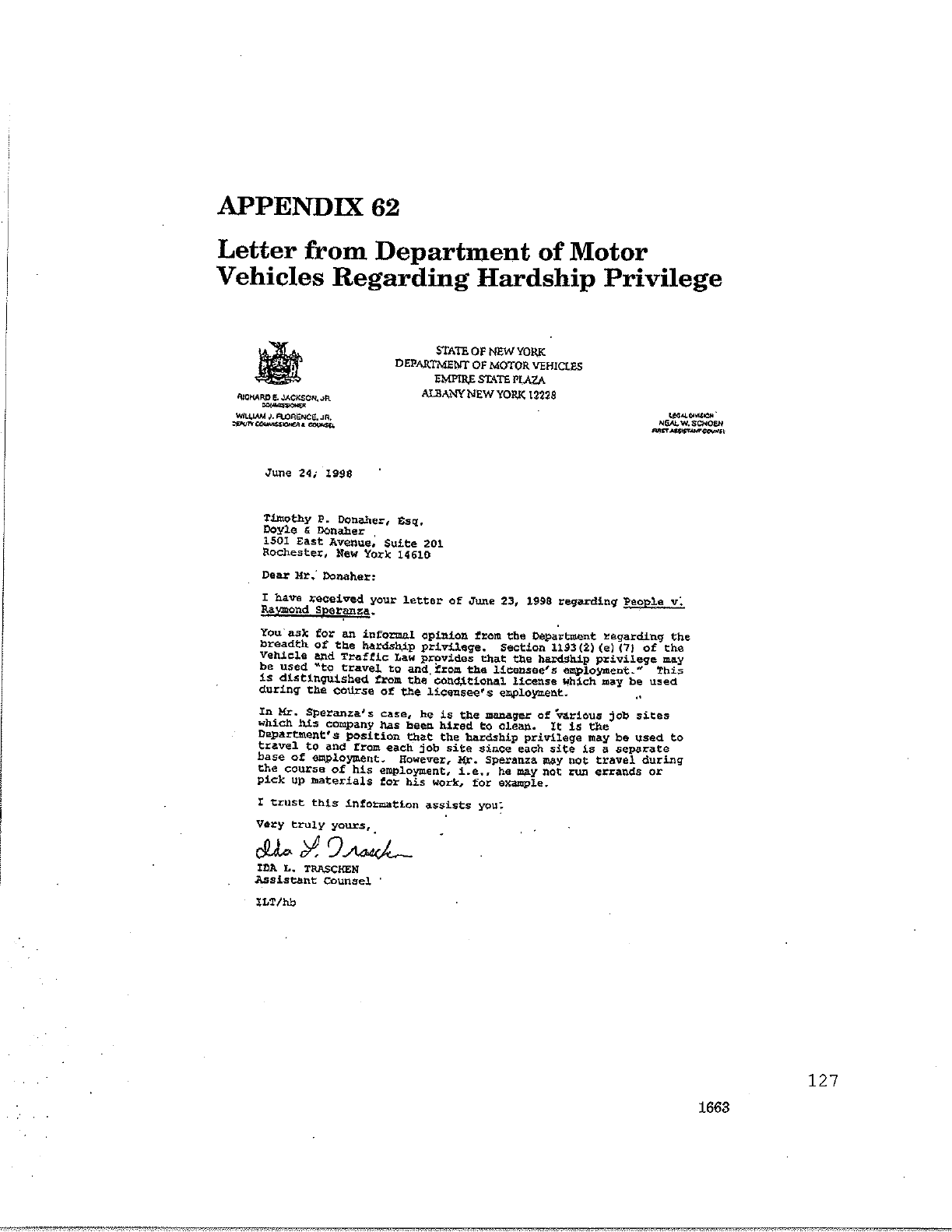

62 Letter from Department of Motor Vehicles Regarding

Hardship Privilege. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

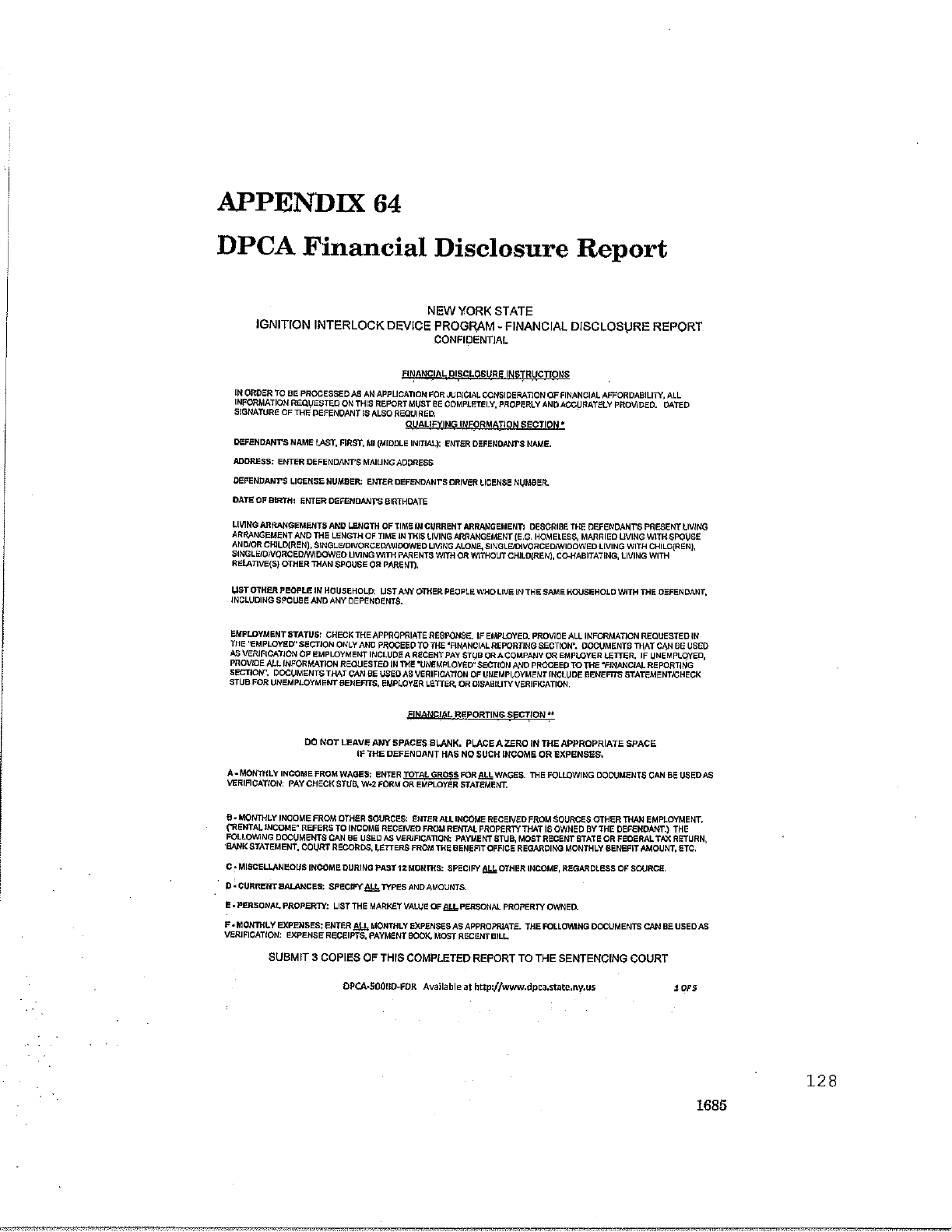

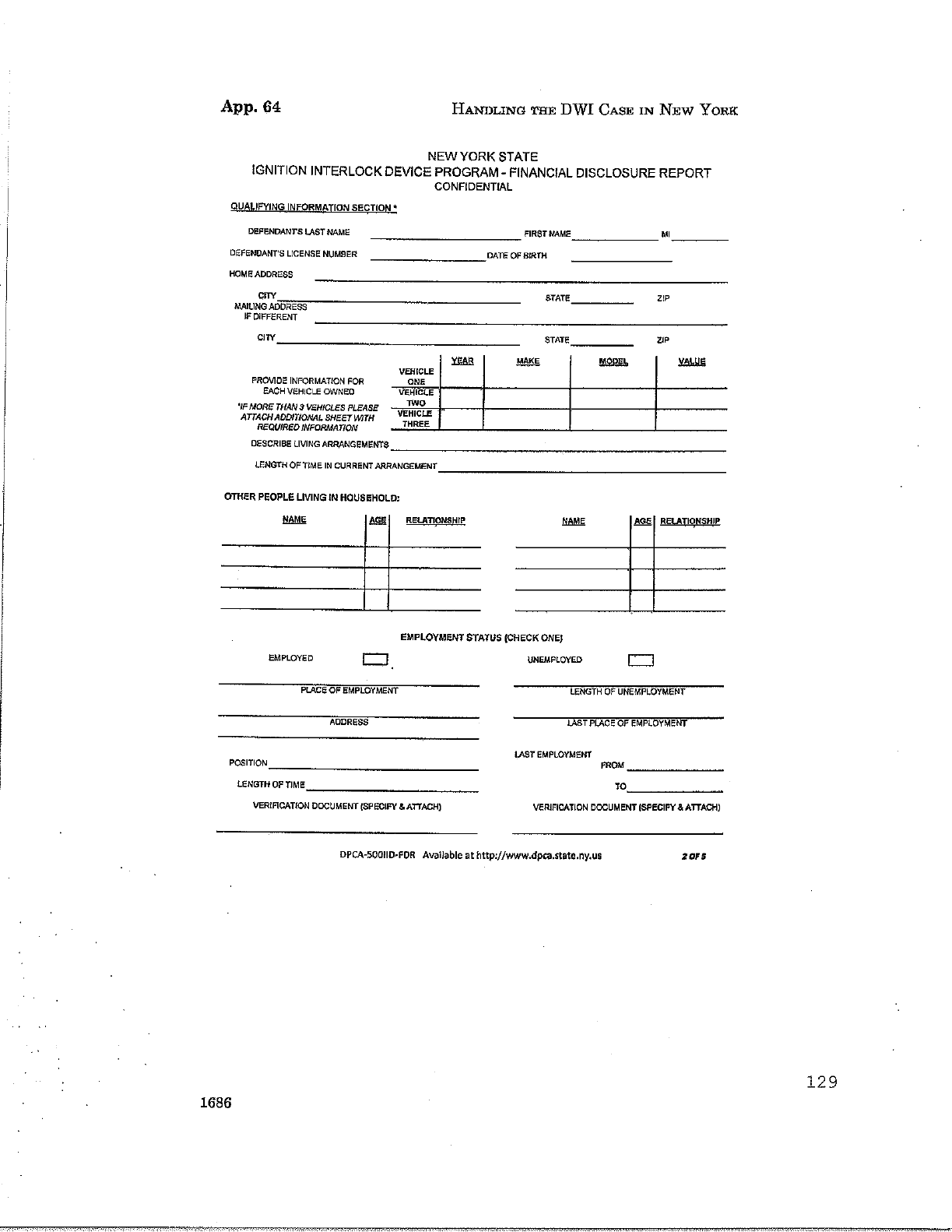

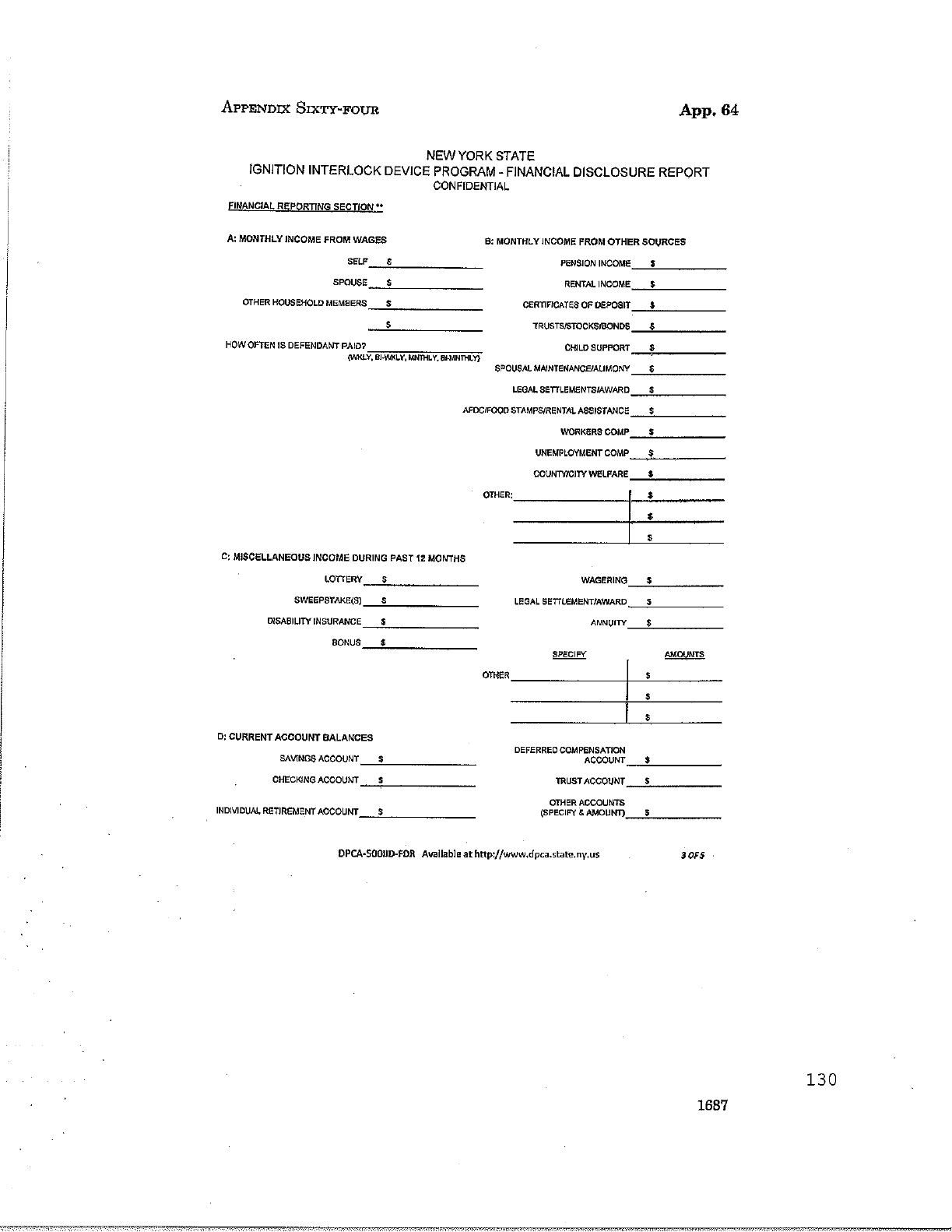

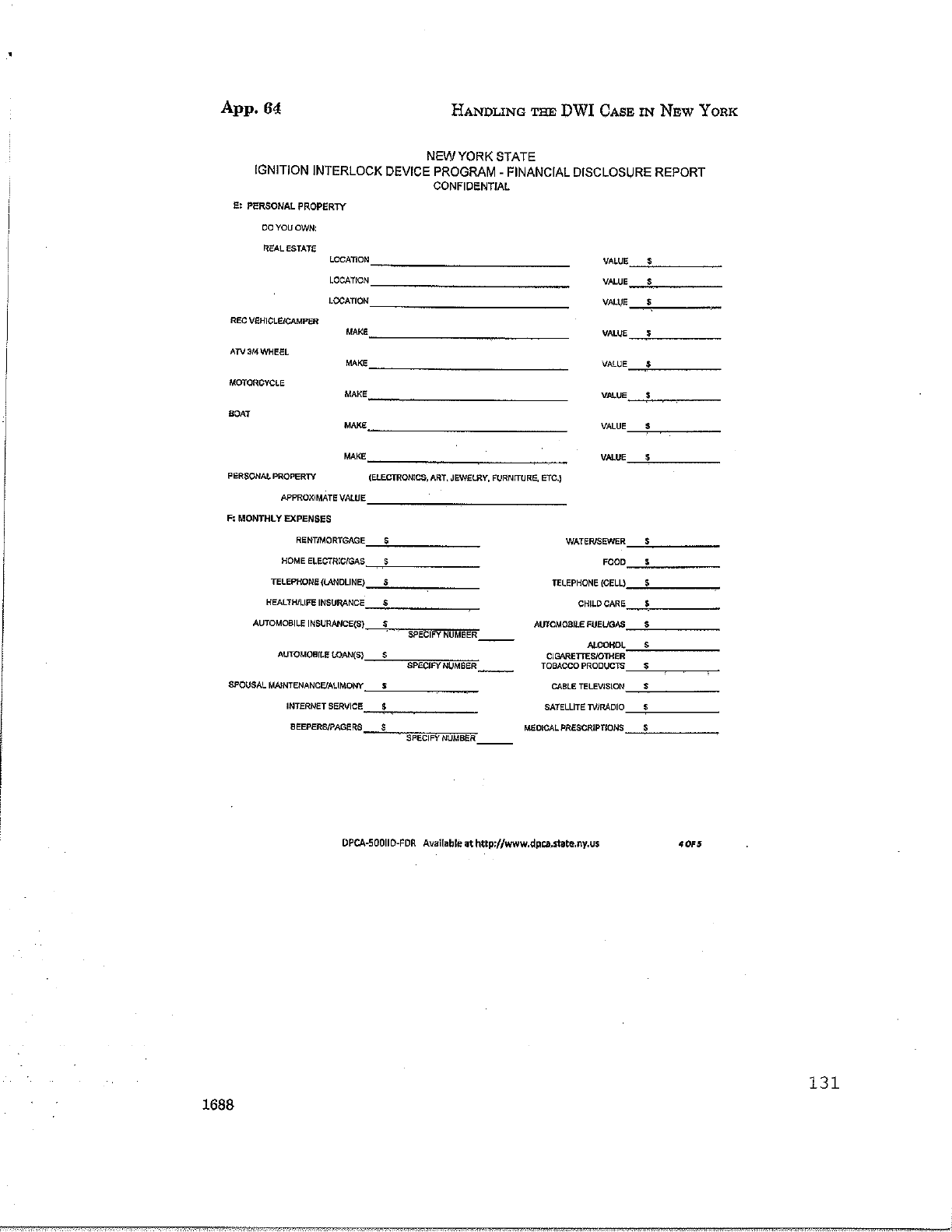

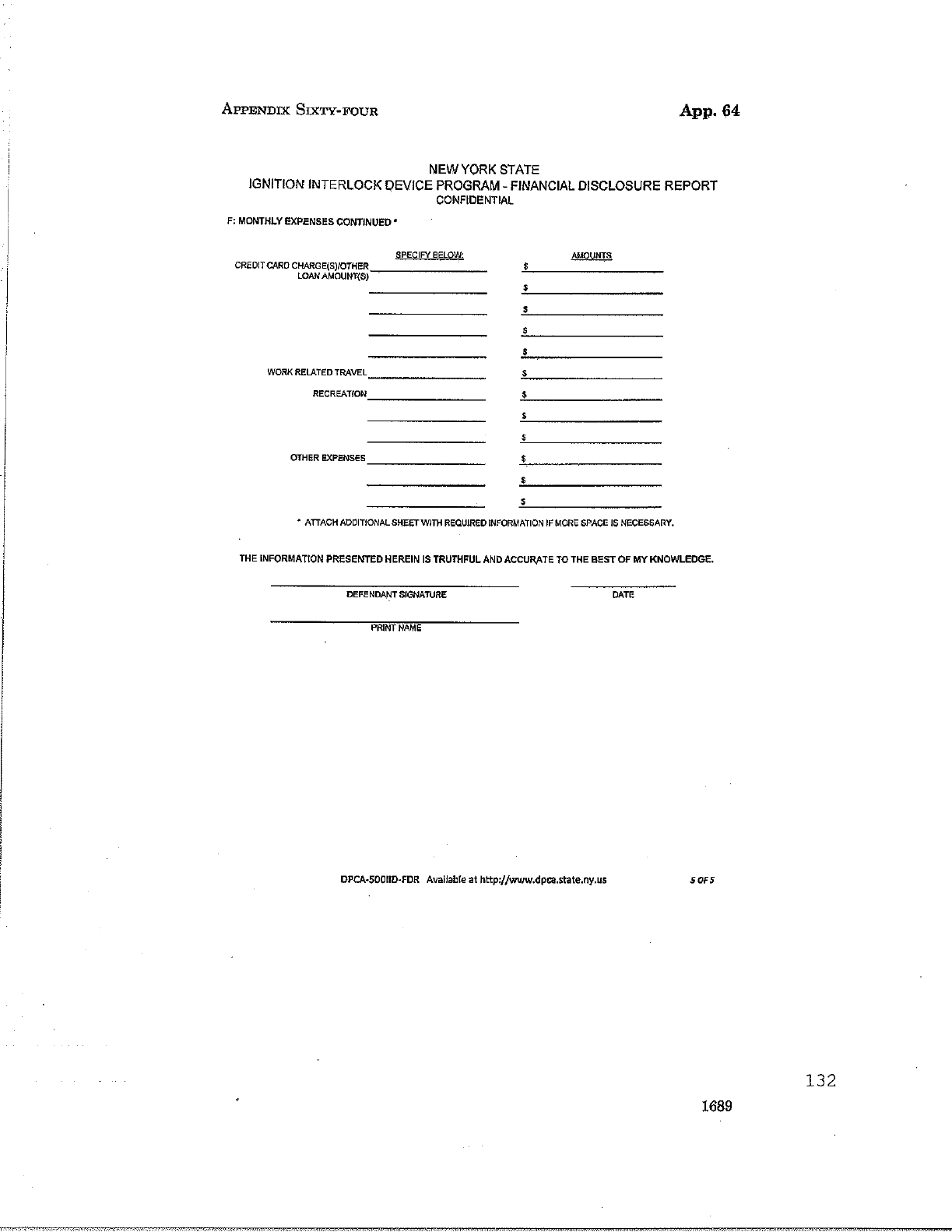

64 DPCA Financial Disclosure Report. . . . . . . . . . 128

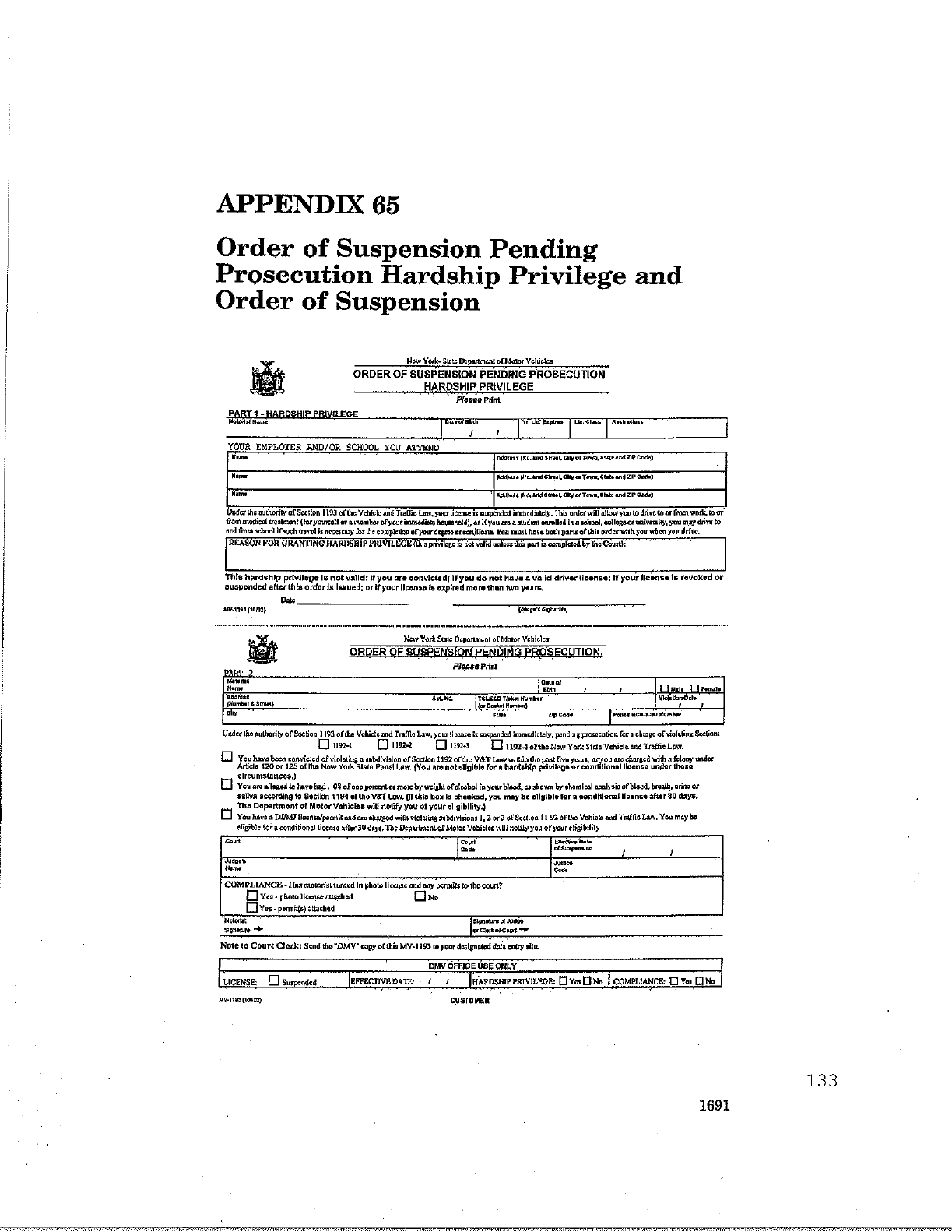

65 Order of Suspension Pending Prosecution Hardship

Privilege and Order of Suspension.. . . . . . . . . 133

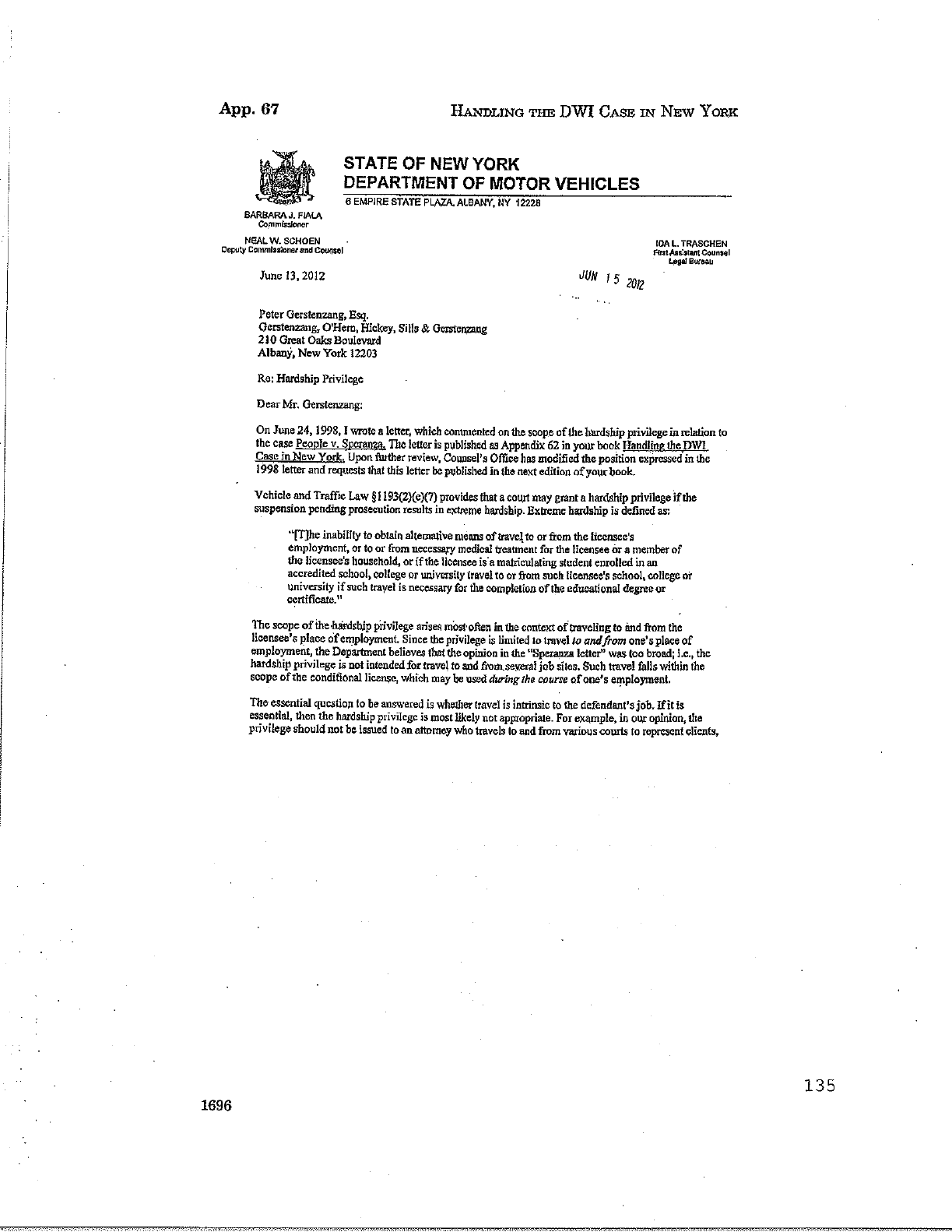

67 Letters from Department of Motor Vehicles Revising

Opinion Regarding Hardship Privilege. . . . . . . . 134

68 Copy of People v. Guthrie, 25 N.Y.3d 130 (2015).. . 137

69 Copy of Heien v. North Carolina, 135 S.Ct. 530

(2014). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

70 Copy of Rodriguez v. United States, 135 S.Ct. 1609

(2015). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

71 Copy of People v. Banks, 85 N.Y.2d 558,

626 N.Y.S.2d 986 (1995).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 184

iv

ARRAIGNMENT ISSUES

A. Arraignment Without Counsel

In Hurrell-Harring v. State of New York, 15 N.Y.3d 8 (2010),

a copy of which is attached at Appendix 1, the New York State

Court of Appeals stated a defendant charged with a crime had a

right to counsel at arraignment. While arraignments in New York

have always included advising the defendant of their right to

counsel, the Court of Appeals went further and stated that

implementation of that right required the presence of counsel at

arraignment:

Contrary to defendants' suggestion and that

of the dissent, nothing in the statute may be

read to justify the conclusion that the

presence of defense counsel at arraignment is

ever dispensable, except at a defendant's

informed option, when matters affecting the

defendant's pretrial liberty or ability

subsequently to defend against the charges

are to be decided.

Id. at 21.

The Court focuses on the fact that an arraignment includes,

among other things, the issuance of a securing order. In that

regard, the Court states: "There is no question that 'a bail

hearing is a critical stage of the State's criminal process'"

(citations omitted). Id. at 20.

The issue of bail takes center stage in the Court's

discussion of the necessity of counsel's presence at arraignment.

While it has been argued that defendants who were released in

their own recognizance with their rights reserved suffered no

detriment in the absence of counsel, that argument cannot be made

where bail is set and the defendant is remanded. Even where an

unrepresented defendant is able to "make" bail, a determination

has been made by the Court that impacts their financial

circumstances at a time when they were not represented by

counsel.

CPL § 510.30 sets forth criteria controlling the

determination on the issue of recognizance or bail. Those

criteria include matters in which the assistance of counsel could

be critical. For example, CPL § 510.30(2)(a):

(i) The principal's character,

reputation, habits and mental

condition;

(ii) His employment and financial

resources; and

1

(iii) His family ties and the length of his

residence if any in the community; and . . .

(vi) His previous record if any in

responding to court appearances when required

or with respect to flight to avoid criminal

prosecution; and . . .

(viii) If he is a defendant, the weight of

the evidence against him in the pending

criminal action and any other factor

indicating probability or improbability of

conviction.

In light of the Court's determination that the arraignment

is a critical stage of the proceeding, it appears that the Court

is saying that the arraignment of a defendant may not proceed

without counsel, absent an informed waiver of that right by the

defendant.

Recognizing the crucial importance of

arraignment and the extent to which a

defendant's basic liberty and due process *21

interests may then be affected, CPL 180.10

(3) expressly provides for the “right to the

aid of counsel at the arraignment and at

every subsequent stage of the action” and

forbids a court from going forward with the

proceeding without counsel for the defendant,

unless the defendant has knowingly agreed to

proceed in counsel's absence CPL 180.10 [5]).

Id. at 20-21.

Ethically, the only opinion that is directly on point is

Opinion 14-01 dated January 30, 2014, attached as Appendix 2.

Here, the Committee concludes their opinion stating: "Whether a

judge may preside over an arraignment, in which a defendant is

not represented by counsel, raises primarily legal questions;

however, if a judge acts in conformity with governing law the

judge will not violate the Rules Governing Judicial Conduct."

See Opinion 11-87 (emphasis added). Accordingly, if a Judge

determines that the presence of an attorney is required to

conduct an arraignment, absent defendant's waiver, then the Judge

would appear to be ethically bound to have counsel present at

arraignment.

B. Defendant Declines Assigned Counsel

While the mandate to have counsel present at the arraignment

of an indigent accused seems clear, it gets more complicated

2

where the defendant has the capability to retain private counsel.

What happens when that defendant is brought before the Court at

4:00 AM and wants to retain private counsel? Can the Court

assign a public defender to represent that defendant for purposes

of arraignment?

Clearly, a court that forces a defendant to accept the

services of assigned counsel is in as much violation of the

defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel as a court that

proceeds to determine the defendant's interests without counsel.

In addition, does a court have authority to assign counsel to

someone who does not qualify? Is such an assignment a

misappropriation of public funds?

Declining the services of assigned counsel does not

constitute a waiver of a defendant's right to counsel.

Accordingly, this situation presents an even greater challenge

than obtaining counsel for an indigent defendant who either

accepts those services, or proceeds pro se.

C. Defendant Wishes to Proceed Pro Se

It is important to note that while the law requires the

presence of an attorney at arraignment, it also recognizes

defendant's right to proceed without counsel. This is

particularly significant since there are a number of courts that

routinely advise a defendant that they will be held in custody

until the defendant either accepts the assignment of a Legal Aid

lawyer or Public Defender; or retained counsel arrives to

represent the defendant at arraignment. In these courts, the

right to counsel becomes a mandate that forces defendants to

choose between being released on a securing order, or held in

custody pending the arrival of their attorney. They are given

the alternative of accepting an assigned lawyer whom they would

otherwise not choose to represent them, and do so only under the

coercion of continued incarceration.

D. CPL § 170.10(4)(a)

Statutorily, courts are mandated to not only advise the

defendant of their rights, but to take affirmative action to

implement those rights. CPL 170.10(3) states:

The defendant has the right to the aid of

counsel at the arraignment and at every

subsequent stage of the action. If he

appears on such arraignment without counsel,

he has the following rights:

(a) to an adjournment for the purpose of

obtaining counsel.

CPL 170.10(4)(a) states:

3

Except as provided in subdivision five, the

court must inform the defendant:

(a) Of his rights as prescribed in

subdivision three; and the Court must not

only accord him opportunity to exercise such

rights but must itself take such affirmative

action as is necessary to effectuate them.

4

Copyright © 2015

West Group

PART XII

PENALTIES AND CONSEQUENCES

CHAPTER 45

SUSPENSION PENDING PROSECUTION

§ 45:1 In general

§ 45:2 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- The prompt suspension law

§ 45:3 ___ Suspension procedure

§ 45:4 ___ Applicability to certain underage drivers

§ 45:5 ___ What if defendant appears for arraignment without

counsel?

§ 45:6 ___ Applying Pringle

§ 45:7 ___ What role do the People play at a Pringle hearing?

§ 45:8 ___ Applicability to chemical test result of exactly .08%

§ 45:9 ___ Applicability to out-of-state licensees

§ 45:10 ___ Hardship privilege

§ 45:10A ___ Hardship privilege cannot be used to operate

commercial motor vehicle

§ 45:11 ___ Pre-conviction conditional license

§ 45:12 ___ Applicability of pre-conviction conditional license

to commercial and taxicab drivers

§ 45:13 ___ Violation of pre-conviction conditional license is a

traffic infraction; violation of hardship privilege

constitutes AUO

§ 45:14 ___ Prompt suspension law does not preclude Court from

suspending defendant's driver's license under other laws

§ 45:15 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) -- Suspension pending prosecution

based upon prior conviction or vehicular crime

§ 45:16 ___ Suspension procedure

§ 45:17 ___ Effect of failure to comply with statute

§ 45:18 VTL §§ 1193(2)(e)(1) & (7) -- Suspension time frame

§ 45:19 ___ Length of suspension

§ 45:20 ___ Constitutionality

§ 45:21 ___ Double Jeopardy and Equal Protection

§ 45:22 VTL § 1194(2)(b)(3) -- Temporary suspension of license at

arraignment in chemical test refusal cases

§ 45:23 VTL § 510(3-a) -- Discretionary suspensions

-----

§ 45:1 In general

A defendant charged with DWI must be aware of several statutes

which, if applicable, call for the mandatory and/or permissive

suspension of his or her driver's license pending prosecution. The

5

first statute is VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- the so-called "prompt

suspension law" -- which is generally applicable to a defendant who

is charged with DWI and who is alleged to have had a BAC of .08% or

more at the time of his or her arrest. The second statute, VTL §

1193(2)(e)(1), is applicable to a defendant who is charged with

DWI, Aggravated DWI, DWAI Drugs or DWAI Combined Influence and who

either (a) has been convicted of any violation of VTL § 1192 within

the preceding 5 years, or (b) is charged with Vehicular Assault or

Vehicular Homicide in connection with the current incident. A

third statute, VTL § 1194(2)(b)(3), is applicable to a defendant

who is charged with a violation of VTL § 1192 and who is alleged to

have refused to submit to a chemical test.

Prior to the enactment of the prompt suspension law, VTL §

510(3-a) had occasionally been used to suspend DWI defendants'

driver's licenses pending prosecution. However, in light of VTL §§

1193(2)(e)(1) and (7), as well as the Court of Appeals' decision in

Pringle v. Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d 426, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82 (1996), continued

reliance upon VTL § 510(3-a) in this regard would appear to be

unwarranted. See Matter of King v. Kay, 39 Misc. 3d 995, 963

N.Y.S.2d 537 (Suffolk Co. Sup. Ct. 2013).

§ 45:2 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- The prompt suspension law

A defendant who is charged with DWI, Aggravated DWI or DWAI

Combined Influence and who is alleged to have had a BAC of .08% or

more at the time of his or her arrest is subject to the prompt

suspension law. This law provides, in pertinent part:

(7) Suspension pending prosecution; excessive

blood alcohol content. a. Except as provided

in clause a-1 of this subparagraph, a court

shall suspend a driver's license, pending

prosecution, of any person charged with a

violation of [VTL § 1192(2), (2-a), (3) or (4-

a)] who, at the time of arrest, is alleged to

have had .08 of one percent or more by weight

of alcohol in such driver's blood as shown by

chemical analysis of blood, breath, urine or

saliva, made pursuant to [VTL § 1194(2) or

(3)].

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(a).

Notably, the prompt suspension law, by its express terms, only

applies under certain circumstances. For example, the prompt

suspension law only applies where the defendant is charged with VTL

§ 1192(2), (2-a), (3) or (4-a); it does not apply where the

defendant is charged with VTL § 1192(1) (i.e., DWAI) or (4) (i.e.,

DWAI Drugs). In addition, the prompt suspension law only applies

where a chemical test result is obtained; it does not apply where

6

the defendant is alleged to have refused to submit to a chemical

test. See Appendix 61.

Furthermore, the prompt suspension law only applies where the

defendant's BAC is .08% or more; it does not apply where the

defendant's BAC is below .08%, even if he or she is charged with

VTL § 1192(3). Moreover, the prompt suspension law only applies

where a prosecution is pending. Accordingly, a defendant who

enters a plea of guilty and is sentenced at arraignment is not

subject to the prompt suspension law. On the other hand, a

defendant who enters a plea of guilty at arraignment, but whose

sentencing is adjourned, is subject to the prompt suspension law

(because the prosecution does not terminate until the imposition of

sentence).

§ 45:3 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Suspension procedure

Pursuant to the express language of the prompt suspension law,

in order to impose a suspension thereunder the Court must make two

findings. First, the Court "must find that the accusatory

instrument conforms to the requirements of [CPL §] 100.40." VTL §

1193(2)(e)(7)(b). CPL § 100.40 sets forth the facial sufficiency

requirements for local criminal court accusatory instruments.

Second, the Court must find that "there exists reasonable cause to

believe . . . that . . . the holder operated a motor vehicle while

such holder had .08 of one percent or more by weight of alcohol in

his or her blood as was shown by chemical analysis of such person's

blood, breath, urine or saliva, made pursuant to the provisions of

[VTL § 1194]." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b).

If such tentative findings are made, the statute provides that

"the holder shall be entitled to an opportunity to make a statement

regarding these two issues and to present evidence tending to rebut

the court's findings." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b).

The Court of Appeals' decision in Pringle v. Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d

426, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82 (1996), added in several prerequisites to

suspension under the prompt suspension law that do not appear in

the statute itself. For example, Pringle adds numerous procedural

due process requirements into the prompt suspension law which must

be complied with before a suspension pending prosecution thereunder

can be imposed; and adds the threshold requirements that a "court

may not order suspension of the license unless it has in its

possession the results of the chemical test, and, as the

Commissioner concedes, these results must be presented to the court

in certified, documented form (see, CPLR 4518[c])." Id. at 432,

646 N.Y.S.2d at 85-86 (emphasis added). See also People v.

DeRojas, 180 Misc. 2d 690, ___, 693 N.Y.S.2d 404, 405 (App. Term,

2d Dep't 1999).

7

In addition, Pringle created, and granted the defendant an

absolute right to, a so-called "Pringle hearing." In this regard,

the Pringle Court held that "[u]nder the prompt suspension law, the

court must hold a suspension hearing before the conclusion of the

proceedings required for arraignment and before the driver's

license may be suspended." 88 N.Y.2d at 432, 646 N.Y.S.2d at 85

(emphasis added). At this hearing, "the court must first determine

whether the accusatory instrument is sufficient on its face and

next whether there exists reasonable cause to believe that the

driver operated a motor vehicle while having a blood alcohol level

in excess of [.08] of 1% as shown by a chemical test." Id. at 432,

646 N.Y.S.2d at 85. See also People v. Roach, 226 A.D.2d 55, ___,

649 N.Y.S.2d 607, 608-09 (4th Dep't 1996).

With regard to the opportunity to rebut, the Pringle Court

held that it would be "meaningless" to allow the defendant "to

'rebut the court's findings' after the suspension is ordered." 88

N.Y.2d at 432, 646 N.Y.S.2d at 86. Accordingly, the Court

interpreted the prompt suspension law to require both (a) that the

defendant be "entitled to present evidence to rebut the court's

tentative findings before the court may order the license

suspension," id. at 432, 646 N.Y.S.2d at 86 (emphasis added), and

(b) that it is "incumbent on the court to grant a driver's

reasonable request for a short adjournment if necessary to marshal

evidence to rebut the prima facie showing of 'reasonable cause.'"

Id. at 433, 646 N.Y.S.2d at 86.

In People v. Roach, 226 A.D.2d 55, 649 N.Y.S.2d 607 (4th Dep't

1996), the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, both (a) stated

that to invoke the prompt suspension law the Court must find, inter

alia, that "there is reasonable cause to believe that the driver

failed a properly administered and reliable chemical sobriety

test," id. at ___, 649 N.Y.S.2d at 609 (emphasis added), and (b)

made clear that the defendant's driver's license should not be

suspended pending prosecution if the driver rebuts the prima facie

showing. Id. at ___, 649 N.Y.S.2d at 609. See also People v.

Boulton, 164 Misc. 2d 604, ___, 625 N.Y.S.2d 428, 430 (Troy City

Ct. 1995) ("Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b) appears to

mandate the return of the license to the defendant whenever

evidence is presented tending to rebut the Court's findings. On

close analysis this burden is neither onerous nor cumbersome").

Despite the fact that a lawful VTL § 1192 arrest is a

prerequisite to a valid request to submit to a chemical test, see,

e.g., Matter of Gagliardi v. Department of Motor Vehicles, 144

A.D.2d 882, ___, 535 N.Y.S.2d 203, 204 (3d Dep't 1988) ("In order

for the testing strictures of Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1194 to

come into play, there must have been a lawful arrest for driving

while intoxicated"), and despite the fact that VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)

requires that the driver fail a chemical test administered pursuant

to VTL § 1194, neither VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) nor Pringle appear to

contemplate that the driver can challenge the lawfulness of his or

her arrest at a Pringle hearing.

8

Regardless, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit recently held, in a similar DWI-related civil forfeiture

case, that:

[W]e find that the Due Process Clause requires

that claimants be given an early opportunity

to test the probable validity of further

deprivation, including probable cause for the

initial seizure. * * *

As a remedy, we order that claimants be given

a prompt post-seizure retention hearing, with

adequate notice, for motor vehicles seized as

instrumentalities of crime pursuant to

N.Y.C.Code § 14-140(b). * * *

Although we decline to dictate a specific form

for the prompt retention hearing, we hold

that, at a minimum, the hearing must enable

claimants to test the probable validity of

continued deprivation of their vehicles,

including the City's probable cause for the

initial warrantless seizure. In the absence

of either probable cause for the seizure or

post-seizure evidence supporting the probable

validity of continued deprivation, an owner's

vehicle would have to be released during the

pendency of the criminal and civil

proceedings. * * *

In conclusion, we hold that promptly after

their vehicles are seized under N.Y.C.Code §

14-140 as alleged instrumentalities of crime,

plaintiffs must be given an opportunity to

test the probable validity of the City's

deprivation of their vehicles pendente lite,

including probable cause for the initial

warrantless seizure.

Krimstock v. Kelly, 306 F.3d 40, 68, 68-69, 69, 70 (2d Cir. 2002)

(footnote omitted). See also County of Nassau v. Canavan, 1 N.Y.3d

134, 144-45, 770 N.Y.S.2d 277, 286 (2003) (same).

The retention of a motor vehicle driven by an alleged drunken

driver pendente lite pursuant to N.Y.C.Code § 14-140 is analogous

to the suspension of the driver's license of an alleged drunken

driver pendente lite pursuant to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7). As such,

since the Krimstock Court expressly rejected the New York State

Courts' assessment of the Constitutional due process requirements

associated with the retention of a motor vehicle pendente lite

pursuant to N.Y.C.Code § 14-140 -- Krimstock expressly rejected,

9

and was critical of, the conclusions of Grinberg v. Safir, 181

Misc. 2d 444, 694 N.Y.S.2d 316 (N.Y. Co. Sup. Ct.), aff'd, 266

A.D.2d 43, 698 N.Y.S.2d 218 (1st Dep't 1999), see Krimstock, 306

F.3d at 53 -- it is reasonable to assume that the Second Circuit

would also disagree with the Pringle Court's apparent conclusion

that the driver need not be given an opportunity to test the

lawfulness of his or her warrantless arrest in connection with a

suspension pendente lite pursuant to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7).

Nonetheless, in Matter of Vanderminden v. Tarantino, 60 A.D.3d

55, ___-___, 871 N.Y.S.2d 760, 763-64 (3d Dep't 2009), the

Appellate Division, Third Department, without addressing Krimstock

(or other Due Process cases), had the following to say about the

scope of a Pringle hearing:

As relevant to petitioner's remaining

arguments, which pertain to the scope and

conduct of his Pringle hearing, we begin by

noting that the prompt suspension law provides

that, in order for the court to issue a

suspension order, it must find that (1) the

accusatory instrument conforms with CPL

100.40, and (2) reasonable cause exists to

believe that the driver operated a motor

vehicle with ".08 of one percent or more by

weight of alcohol in his or her blood as was

shown by chemical analysis of such person's

blood, breath, urine or saliva" (Vehicle and

Traffic Law § 1193[2] [e][7][b]). Where such

an initial determination is made, Vehicle and

Traffic Law § 1193(2)(e)(7) further provides

that the driver "shall be entitled to an

opportunity to make a statement regarding

these two issues and to present evidence

tending to rebut the court's findings"

(Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1193[2][e][7][b]).

In this case, respondent determined that the

simplified information complied with CPL

100.40 and that, based upon the certified

breath test results, as well as the arresting

officer's supporting deposition, there was

reasonable cause to believe that petitioner

had a BAC of .08% or more while operating a

motor vehicle. Therefore, respondent made the

necessary preliminary findings to issue a

suspension order.

In rebuttal, petitioner called three police

witnesses and attempted to question them

regarding the calibration of the breath test

device, the administration of the test, and

matters relating to probable cause for

10

petitioner's arrest. Respondent precluded any

questioning relating to the calibration and

maintenance of the breath device as well as to

probable cause for the arrest, concluding that

such matters were outside the scope of a

Pringle hearing.

We are not persuaded by petitioner's

contention that his due process rights were

violated by respondent's rulings. While

issues pertaining to the lawfulness of the

police stop, probable cause for arrest, and

whether the breath test device was working

properly at the time of the test are relevant

to the admissibility of breath test results at

a criminal trial, and may ultimately bear on

the determination of criminal culpability,

they are beyond the scope of a Pringle

hearing. Significantly, a Pringle hearing is

a civil administrative proceeding which runs

parallel to the criminal proceedings. It is

not a plenary hearing requiring the same level

of due process protection as a criminal trial,

nor is it "an opportunity for free-wheeling

discovery regarding the criminal matter."

Indeed, as the Court of Appeals has observed,

to "convert the license suspension proceeding

into a trial on the merits of the underlying

criminal charge . . . would be prohibitively

expensive and cumbersome, and would subvert

the State's compelling interest in promoting

highway safety." For these reasons, we agree

with Supreme Court that respondent

appropriately limited petitioner's inquiry.

(Citations omitted).

Courts will have to reconcile Vanderminden with the Court of

Appeals' holding in Pringle that "the minimal risk of an erroneous

suspension is further diminished by the driver's right to a

meaningful presuspension opportunity to rebut the chemical test

results." Pringle v. Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d 426, 434, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82,

87 (1996) (emphasis added).

§ 45:4 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Applicability to certain underage

drivers

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(a-1) applies to drivers under 18 years of

age who do not yet possess a full class D or class M driver's

license. A class D license is a regular, non-commercial driver's

license. A class M license is a motorcycle driver's license. VTL

§ 1193(2)(e)(7)(a-1) provides:

11

a-1. A court shall suspend a class DJ or MJ

learner's permit or a class DJ or MJ driver's

license, pending prosecution, of any person

who has been charged with a violation of [VTL

§ 1192(1), (2), (2-a) and/or (3)].

The "J" designation pertains to a junior learner's permit or junior

driver's license. A person between 16 and 18 years of age can

apply for a junior permit/license. A class DJ or MJ driver's

license can be converted to a class D or M driver's license if the

holder is at least 17 years of age and has, among other things,

successfully completed an approved high school or college driver

education course. See 15 NYCRR § 2.5. At age 18, a valid class DJ

or MJ driver's license automatically converts to a class D or M

driver's license.

Notably, unlike the prompt suspension law for class D or M

driver's license holders, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(a-1) applies not only

where the defendant is charged with VTL § 1192(2), (2-a) and/or

(3), but also where he or she is charged with VTL § 1192(1) (i.e.,

DWAI). In addition, unlike the prompt suspension law for class D

or M driver's license holders, no chemical test result is required.

Thus, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(a-1) can be applied to chemical test

refusal cases, and to cases where the chemical test results are not

yet available.

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b) provides that "the suspension occurring

under clause a-1 of this subparagraph shall occur immediately after

the holder's first appearance before the court on the charge which

shall, whenever possible, be the next regularly scheduled session

of the court after the arrest or at the conclusion of all

proceedings required for the arraignment."

In terms of due process, in order to impose a suspension under

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(1-a), the Court must make two findings. First,

the Court "must find that the accusatory instrument conforms to the

requirements of [CPL §] 100.40." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b). CPL §

100.40 sets forth the facial sufficiency requirements for local

criminal court accusatory instruments. Second, the Court must find

that:

[T]here exists reasonable cause to believe

either that (a) the holder operated a motor

vehicle while such holder had .08 of one

percent or more by weight of alcohol in his or

her blood as was shown by chemical analysis of

such person's blood, breath, urine or saliva,

made pursuant to the provisions of [VTL §

1194] or (b) the person was the holder of a

12

class DJ or MJ learner's permit or a class DJ

or MJ driver's license and operated a motor

vehicle while such holder was in violation of

[VTL § 1192(1), (2) and/or (3)].

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b) (emphasis added).

If such tentative findings are made, the statute provides that

"the holder shall be entitled to an opportunity to make a statement

regarding these two issues and to present evidence tending to rebut

the court's findings." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(b). In addition, the

additional procedural due process requirements set forth in the

Court of Appeals' decision in Pringle v. Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d 426, 646

N.Y.S.2d 82 (1996), apply. See § 45:3, supra.

§ 45:5 What if defendant appears for arraignment without

counsel?

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the prompt suspension

law is the way in which it is administered by many Courts where the

defendant appears for arraignment without counsel. In this regard,

many defendants who appear for arraignment without counsel in DWI

cases have their driver's licenses summarily suspended by the

Court. No findings are made; no Pringle hearing is held; no

opportunity to make a statement or present evidence is offered,

etc.

Simply stated, such Courts are both (a) flagrantly

disregarding the requirements of the statute, and (b) flagrantly

disobeying the Court of Appeals' decision in Pringle v. Wolfe, 88

N.Y.2d 426, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82 (1996). As such, they are flagrantly

disregarding defendants' Constitutional right to Due Process.

But that is not all. Such Courts are also violating one of

the most cherished Constitutional rights of all -- the right to

counsel -- which right has been zealously protected by the Court of

Appeals, and has been codified in CPL § 170.10. In this regard,

the Court of Appeals has made clear that:

The State constitutional right to counsel is a

"cherished principle" worthy of the "highest

degree of [judicial] vigilance." Our

decisional law has advanced this principle by

holding that the State constitutional right to

counsel attaches indelibly in two situations.

First, it arises when formal judicial

proceedings begin, whether or not the

defendant has actually retained or requested a

lawyer. . . . Although these principles are

similar to those developed under the Fifth and

Sixth Amendments to the Federal Constitution,

13

New York's constitutional right to counsel

jurisprudence developed "independent of its

Federal counterpart" and offers broader

protections.

People v. Ramos, 99 N.Y.2d 27, 32-33, 750 N.Y.S.2d 821, 824 (2002)

(citations and footnote omitted). See also People v. West, 81

N.Y.2d 370, 373, 599 N.Y.S.2d 484, 486 (1993); People v. Ross, 67

N.Y.2d 321, 502 N.Y.S.2d 693 (1986); People v. Cunningham, 49

N.Y.2d 203, 207-08, 424 N.Y.S.2d 421, 423-24 (1980).

This "indelible" right to counsel . . .

attaches upon defendant's request for an

attorney, at arraignment or upon the filing of

an accusatory instrument. Underlying the rule

is the concept that a criminal defendant

confronted by the awesome prosecutorial

machinery of the State is entitled, at a bare

minimum, to the advice of counsel when he is

considering surrender of his valuable legal

rights.

People v. Grimaldi, 52 N.Y.2d 611, 616, 439 N.Y.S.2d 833, 835

(1981) (emphases added) (citations omitted).

In addition, CPL § 170.10(3) provides:

3. The defendant has the right to the aid of

counsel at the arraignment and at every

subsequent stage of the action. If he appears

upon such arraignment without counsel, he has

the following rights:

(a) To an adjournment for the purpose of

obtaining counsel; and

(b) To communicate, free of charge, by letter

or by telephone, for the purposes of

obtaining counsel and informing a

relative or friend that he has been

charged with an offense; and

(c) To have counsel assigned by the court if

he is financially unable to obtain the

same; except that this paragraph does not

apply where the accusatory instrument

charges a traffic infraction or

infractions only.

(Emphases added).

14

Furthermore, CPL § 170.10(4) mandates that the Court "must

inform the defendant":

(a) Of his rights as prescribed in

subdivision three; and the court must not

only accord him opportunity to exercise

such rights but must itself take such

affirmative action as is necessary to

effectuate them.

(Emphasis added).

Numerous Court of Appeals decisions clearly establish that,

for a waiver of the fundamental Constitutional right to counsel to

be valid, the Court must conduct a "searching inquiry," on the

record, into whether the waiver is knowing, voluntary, intelligent

and unequivocal. In People v. Smith, 92 N.Y.2d 516, 683 N.Y.S.2d

164 (1998), the Court of Appeals reiterated that:

This Court has recognized that defendants may

insist on foregoing the benefits associated

with the right to counsel and proceeding on a

pro se basis. We have consistently also

cautioned, however, that the waiver of this

fundamental right to counsel requires that a

trial court must be satisfied that a

defendant's waiver is unequivocal, voluntary

and intelligent; otherwise the waiver will not

be recognized as effective.

To ascertain whether a waiver meets these

appropriately rigorous requirements, the trial

courts "should undertake a sufficiently

'searching inquiry'" in order to be

"reasonably certain" that a defendant

appreciates the "'dangers and disadvantages'

of giving up the fundamental right to

counsel." Governing principles demand that

appropriate record exploration between the

trial court and defendant be conducted, both

to test an accused's understanding of the

waiver and to provide a reliable basis for

appellate review.

When a record lacks the requisite "searching

inquiry" or fails to measure up to the

prescribed standards, a waiver of the right to

counsel will be deemed ineffective. To pass

muster, a "searching inquiry" must reflect

record evidence that defendant's know what

they are doing and that choices are exercised

"with eyes open."

15

This Court has also signified that these

record exchanges should affirmatively disclose

that a trial court has delved into a

defendant's age, education, occupation,

previous exposure to legal procedures and

other relevant factors bearing on a competent,

intelligent, voluntary waiver.

Id. at 520, 683 N.Y.S.2d at 166-67 (emphases added) (citations

omitted). See also People v. Arroyo, 98 N.Y.2d 101, 103-04, 745

N.Y.S.2d 796, 798 (2002) (same); People v. Slaughter, 78 N.Y.2d

485, 491-92, 577 N.Y.S.2d 206, 210-11 (1991) (same); People v.

Sawyer, 57 N.Y.2d 12, 21, 453 N.Y.S.2d 418, 423 (1982) (same).

In this regard, the United States Supreme Court has made clear

that "[p]resuming waiver from a silent record is impermissible.

The record must show, or there must be an allegation and evidence

which show, that an accused was offered counsel but intelligently

and understandingly rejected the offer. Anything less is not a

waiver." Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506, 516, 82 S. Ct. 884, 890

(1963). See generally People v. Nixon, 21 N.Y.2d 338, 355, 287

N.Y.S.2d 659, 672 (1967) ("In cases involving defendants without

lawyers . . . particular pains must be taken. . . . In such cases

inquiry, well beyond the standards thus far propounded, is

indicated").

The requirement of a valid waiver of the right to counsel is

also codified in CPL § 170.10(6). CPL § 170.10(6) provides, in

pertinent part, that except where the only charges are traffic

infractions:

If a defendant . . . desires to proceed

without the aid of counsel, . . . the court

must permit the defendant to proceed without

the aid of counsel if it is satisfied that he

made such decision with knowledge of the

significance thereof, but if it is not so

satisfied it may not proceed until the

defendant is provided with counsel, either of

his own choosing or by assignment.

Finally, the official Practice Commentaries to CPL § 170.10

provide, in pertinent part, that:

The statutory procedure as outlined, however,

omits an essential first step that should be

the responsibility of the court whenever the

defendant appears without counsel and there

has been no warrant of arrest. This is

scrutiny of the accusatory instrument for

legal sufficiency. The reason for immediate

initial appraisal of that instrument is of

16

course that it is the basis of the court's

jurisdiction; and, accordingly, if the

instrument is not legally sufficient, the

court has no authority at all to proceed with

the arraignment. It must dismiss the

instrument and discharge the defendant.

If the court is satisfied that it has

jurisdiction, the next step is to advise the

defendant of his or her rights. In this

respect the statute reflects New York's long-

standing policy that every effort be made for

certainty that the defendant is aware, and has

reasonable opportunity to avail himself, of

the right to representation by counsel. Thus

the court, in addition to advising an

unrepresented defendant of the rights set

forth in subdivision three, must not only

accord the defendant an opportunity to

exercise those rights, "but must itself take

such affirmative action as is necessary to

effectuate them."

A defendant has the right to the aid of

counsel at arraignment and at all subsequent

stages of the proceedings, regardless of the

gravity of the charge. Under New York

statutory law this right is broader than the

requirements of the Federal Constitution.

. . .

Note too, the clear statutory direction that,

in cases other than a traffic infraction, the

court must not permit defendant to proceed

without the aid of counsel unless it is

satisfied that the defendant made the choice

to do so with knowledge of the value of

counsel and risks inherent in self-

representation. This requires a "searching

inquiry" as to defendant's appreciation of the

"dangers and disadvantages" of attempting to

cope with the legal proceedings -- e.g.,

various motions, jury selection, introduction

of evidence, objections to same, etc. -- as

distinguished from merely advising as to the

seriousness of the charge and of the fact that

the defendant could be sentenced to

imprisonment. People v. Kaltenbach, 1983, 60

N.Y.2d 797, 469 N.Y.S.2d 685, 457 N.E.2d 791.

Preiser, Practice Commentaries, McKinney's Cons. Laws of N.Y., Book

11A, CPL § 170.10, at 12-13 (emphases added) (citations omitted).

17

Simply stated, an unfortunate byproduct of the prompt

suspension law is that it puts local criminal courts, who are often

under tremendous pressure from groups such as M.A.D.D., S.A.D.D.

and R.I.D., in a position where they are forced to balance the

fundamental need to impartially protect defendants' Constitutional

rights with the perceived need to confiscate the driver's licenses

of accused drunken drivers at any cost -- and, all too often, the

latter concern prevails.

In People v. Rios, 9 Misc. 3d 1, 801 N.Y.S.2d 113 (App. Term,

9th and 10th Jud. Dist. 2005), the defendant's convictions of

various traffic infractions were reversed for failure to properly

advise the defendant of his right to counsel.

§ 45:6 Applying Pringle

After years without any appellate guidance in the area, the

Appellate Division, Third Department, has recently issued several

decisions addressing Pringle and the prompt suspension law. The

leading case addressing the scope of a Pringle hearing is Matter of

Vanderminden v. Tarantino, 60 A.D.3d 55, 871 N.Y.S.2d 760 (3d Dep't

2009), which is discussed at length in § 45:3, supra. See also

Matter of Schermerhorn v. Becker, 64 A.D.3d 843, 883 N.Y.S.2d 325

(3d Dep't 2009); Matter of Schmitt v. Skovira, 53 A.D.3d 918, 862

N.Y.S.2d 167 (3d Dep't 2008).

One issue that is now well settled is that "a Pringle hearing

is a civil administrative proceeding separate and apart from the

underlying criminal prosecution, but which runs parallel thereto."

Schermerhorn, 64 A.D.3d at ___, 883 N.Y.S.2d at 328. See also

Vanderminden, 60 A.D.3d at ___, 871 N.Y.S.2d at 764; Schmitt, 53

A.D.3d at ___, 862 N.Y.S.2d at 170-71. As such, the results of a

Pringle hearing can be challenged via a CPLR Article 78 proceeding.

Schmitt, 53 A.D.3d at ___, 862 N.Y.S.2d at 172.

In addition, Schermerhorn addresses the People's role at a

Pringle hearing. This issue is addressed in § 45:7, infra.

Furthermore, Vanderminden addresses the applicability of the prompt

suspension law to out-of-state licensees. This issue is addressed

in § 45:9, infra.

§ 45:7 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- What role do the People play at a

Pringle hearing?

In Matter of Schermerhorn v. Becker, 64 A.D.3d 843, 883

N.Y.S.2d 325 (3d Dep't 2009), the Appellate Division, Third

Department, squarely addressed the issue of the People's role at a

Pringle hearing. The Court held that "a district attorney clearly

does not hold the status of a party in a Pringle hearing." Id. at

___, 883 N.Y.S.2d at 328-29. Nonetheless, if they so choose, the

People can play a "limited role" at the hearing. Id. at ___, 883

18

N.Y.S.2d at 328. Specifically, the People can remind the Court of

the prompt suspension law, offer to provide the Court with the

defendant's chemical test result, and "comment in the event that

defense counsel attempt[s] to markedly expand the narrow scope and

purpose of the Pringle hearing." Id. at ___ & n.2, 883 N.Y.S.2d at

328 & n.2. See generally Matter of Broome County DA's Office v.

Meagher, 8 A.D.3d 732, 777 N.Y.S.2d 567 (3d Dep't 2004); Czajka v.

Breedlove, 200 A.D.2d 263, ___, 613 N.Y.S.2d 741, 742 (3d Dep't

1994) ("The position of District Attorney is a purely statutory

office and, consequently, the only powers and duties which may be

exercised by one acting in that post are those conferred by the

Legislature, either expressly or by necessary implication").

Notably, the Schermerhorn Court made clear that the People are

not required to participate in Pringle hearings. 64 A.D.3d at ___

n.2, 883 N.Y.S.2d at 328 n.2 ("Nor do we suggest that a district

attorney's presence at a Pringle hearing is required").

§ 45:8 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Applicability to chemical test

result of exactly .08%

The express language of the prompt suspension law states that

it applies to a DWI defendant who "is alleged to have had .08 of

one percent or more by weight of alcohol in such driver's blood as

shown by chemical analysis of blood, breath, urine or saliva, made

pursuant to [VTL § 1194(2) or (3)]." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(a)

(emphasis added). Nonetheless, this State's highest Court, in

interpreting this law when the proscribed BAC was .10%, clearly and

expressly held that:

The court may not order suspension of the

driver's license unless it has in its

possession the documented results of a

reliable chemical test showing that the

driver's blood alcohol level was in excess of

.10 of 1%.

Pringle v. Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d 426, 434, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82, 87 (1996)

(emphasis added). In this regard, the "in excess of .10 of 1%"

language does not appear to be a typographical error; rather, it

appears throughout the Pringle decision. See, e.g., id. at 432,

646 N.Y.S.2d at 85 ("At the suspension hearing, the court must

first determine whether the accusatory instrument is sufficient on

its face and next whether there exists reasonable cause to believe

that the driver operated a motor vehicle while having a blood

alcohol level in excess of .10 of 1% as shown by a chemical test")

(emphasis added) (citation omitted); id. at 430, 646 N.Y.S.2d at

84; id. at 435, 646 N.Y.S.2d at 88.

19

This same rationale should apply to a chemical test result of

exactly .08% now that the statute has been amended to reflect the

change in VTL § 1192(2).

§ 45:9 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Applicability to out-of-state

licensees

In Matter of Vanderminden v. Tarantino, 60 A.D.3d 55, ___, 871

N.Y.S.2d 760, 762-63 (3d Dep't 2009), the Appellate Division, Third

Department, held as follows:

The threshold question is whether petitioner,

as the holder of a Vermont license, was

subject to the prompt suspension law.

Petitioner contends that because the statute

authorizes the suspension of a driver's

license but does not specifically refer to an

out-of-state licensee's driving privileges,

the statute applies only to holders of New

York licenses. We do not agree. As noted by

the Court of Appeals, Vehicle and Traffic Law

article 31, of which section 1193 is a part,

is "a tightly and carefully integrated statute

the sole purpose of which is to address drunk

driving." Within the statutory scheme,

section 1193 contains the exclusive criminal

penalties and civil sanctions applicable to

drunk driving offenses, including the prompt

suspension provision that is intended to keep

potentially dangerous drivers off New York's

roadways while their criminal charges are

adjudicated. The role of that provision would

be undermined, and its application rendered

arbitrary, if it is interpreted to allow the

holder of an out-of-state license to continue

driving in New York when, under the same

circumstances, the holder of a New York

license would be prohibited from driving.

Given the comprehensive nature and remedial

purpose of article 31, we do not believe the

Legislature intended such an anomalous result.

Accordingly, we construe Vehicle and Traffic

Law § 1193(2)(e)(7) as authorizing a court to

suspend the driving privileges of an out-of-

state licensee under the same circumstances as

would justify suspending a New York license.

(Citations and footnote omitted). See also People v. MacDougall,

165 Misc. 2d 991, ___, 630 N.Y.S.2d 853, 854 (Brighton Just. Ct.

1995) (same). Cf. People v. Nuchow, 164 Misc. 2d 24, ___, 623

N.Y.S.2d 1006, 1010 (Orangetown Just. Ct. 1995) (reaching opposite

conclusion).

20

Where an out-of-state licensee's New York driving privileges

are suspended pending prosecution, the Court has the power to issue

him or her a hardship privilege. See People v. Reick, 33 Misc. 3d

774, 930 N.Y.S.2d 429 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 2011). See also next

section. Similarly, DMV will issue the person a pre-conviction

conditional license if he or she is otherwise eligible therefor.

§ 45:10 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Hardship privilege

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e) provides, in pertinent part, that "[i]f

the court finds that the suspension imposed pursuant to this

subparagraph will result in extreme hardship, the court must issue

such suspension, but may grant a hardship privilege, which shall be

issued on a form prescribed by the commissioner." (Emphasis

added). The phrase "extreme hardship" as used in VTL §

1193(2)(e)(7)(e) does not take on its literal meaning. Rather, it

is defined as follows:

"[E]xtreme hardship" shall mean the inability

to obtain alternative means of travel to or

from the licensee's employment, or to or from

necessary medical treatment for the licensee

or a member of the licensee's household, or if

the licensee is a matriculating student

enrolled in an accredited school, college or

university travel to or from such licensee's

school, college or university if such travel

is necessary for the completion of the

educational degree or certificate.

Id.

In People v. Reick, 33 Misc. 3d 774, ___, 930 N.Y.S.2d 429,

430-31 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 2011), the Court held that a hardship

privilege can be granted to an out-of-state licensee.

Where the defendant requests a so-called "hardship hearing,"

the statute makes clear that the hearing must be held within 3

business days. See VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e) ("In no event shall

arraignment be adjourned or otherwise delayed more than three

business days solely for the purpose of allowing the licensee to

present evidence of extreme hardship") (emphasis added). Notably,

this section merely prohibits the adjournment of the arraignment

for more than 3 business days if the sole purpose for the

adjournment is to allow the licensee to present evidence of extreme

hardship; if an adjournment is granted for reasons other than, or

in addition to, this purpose, the 3-day limitation does not appear

to apply.

21

In terms of proving extreme hardship, the statute places the

burden of proving extreme hardship on the licensee, "who may

present material and relevant evidence." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e).

However, "[a] finding of extreme hardship may not be based solely

upon the testimony of the licensee." Id. (emphasis added). In

this regard, the author advises clients to bring proof of where

they live and proof of where they work, go to school, etc.; and, if

possible, a friend or relative who can corroborate such

information. For cases addressing factors to be considered in

determining extreme hardship, see People v. Correa, 168 Misc. 2d

309, 643 N.Y.S.2d 310 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 1996), and People v.

Bridgman, 163 Misc. 2d 818, 622 N.Y.S.2d 431 (Canandaigua City Ct.

1995). "The court shall set forth upon the record, or otherwise

set forth in writing, the factual basis for such finding." VTL §

1193(2)(e)(7)(e).

If granted, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e) provides that a hardship

privilege:

[S]hall permit the operation of a vehicle only

for travel to or from the licensee's

employment, or to or from necessary medical

treatment for the licensee or a member of the

licensee's household, or if the licensee is a

matriculating student enrolled in an

accredited school, college or university

travel to or from such licensee's school,

college or university if such travel is

necessary for the completion of the

educational degree or certificate.

(Emphasis added).

Although the statutory language omits any reference to driving

as part of (i.e., during) the licensee's employment, an informal

opinion from DMV Counsel's Office states that a person who needs to

drive to and from various job sites may do so, but he or she may

not drive for purposes such as running errands, picking up work

materials, etc. See Appendix 62. Notably, however, a more recent

informal opinion from DMV Counsel's Office states that DMV has

"retreated" from this position. See Appendix 67.

§ 45:10A VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Hardship privilege cannot be used

to operate commercial motor vehicle

"A hardship privilege shall not be valid for the operation of

a commercial motor vehicle." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e).

§ 45:11 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Pre-conviction conditional license

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(d) provides, in pertinent part:

22

[I]f any suspension occurring under [VTL §

1193(2)(e)(7)] has been in effect for a period

of [30] days, the holder may be issued a

conditional license, in accordance with [VTL §

1196], provided the holder of such license is

otherwise eligible to receive such conditional

license. . . . The commissioner shall

prescribe by regulation the procedures for the

issuance of such conditional license.

The relevant regulations are set forth at 15 NYCRR § 134.18,

which provides as follows:

Section 134.18 Conditional license issued

pending prosecution.

(a) When a driver's license is suspended

pending prosecution pursuant to section

1193(2)(e)(7) of the Vehicle and Traffic Law,

the holder of such license may be issued a

conditional license, 30 days after such

suspension takes effect, provided such person

is eligible for such a license as set forth in

section 134.7 of this Part and section 1196 of

the Vehicle and Traffic Law. Such person

shall not be required to and may not

participate in the alcohol and drug

rehabilitation program when issued a

conditional license pursuant to this section.

(b) Establishment of conditions. Each

conditional license issued under this section

shall be subject to the conditions set forth

in section 134.9(b) of this Part and section

1196 of the Vehicle and Traffic Law.

(c) Revocation of conditional license. The

provisions of section 134.9(c) of this Part

shall be applicable to a conditional license

issued under this section.

(d) Period of validity. A conditional license

issued under this section shall be valid,

unless otherwise revoked, suspended or

expired, until the prosecution for the pending

alcohol-related charge is terminated.

Simply stated, a person whose driver's license is suspended

pursuant to the prompt suspension law is eligible for a pre-

conviction conditional license if he or she would be eligible for

a conditional license if convicted of the underlying DWI charge,

and vice versa.

23

§ 45:12 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Applicability of pre-conviction

conditional license to commercial and taxicab drivers

Prior to September 30, 2005, VTL § 1196(7)(g) provided that

"[a]ny conditional license or privilege issued to a person

convicted of a violation of any subdivision of [VTL § 1192] shall

not be valid for the operation of any commercial motor vehicle or

taxicab as defined in this chapter." (Emphasis added). Since a

person whose driver's license is suspended pending prosecution

pursuant to the prompt suspension law is not convicted of a VTL §

1192 violation, VTL § 1196(7)(g) was inapplicable to a pre-

conviction conditional license issued to such person. Accordingly,

a pre-conviction conditional license could be used to operate a

commercial motor vehicle and/or a taxicab.

A 2007 amendment to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(d) provides that "[a]

conditional license issued pursuant to this subparagraph shall not

be valid for the operation of a commercial motor vehicle."

On the other hand, DMV will still issue a pre-conviction

conditional license valid for the operation of a taxicab.

§ 45:13 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Violation of pre-conviction

conditional license is a traffic infraction; violation of

hardship privilege constitutes AUO

VTL § 1196(7)(f) provides that using a pre-conviction

conditional license "for any use other than those authorized

pursuant to [VTL § 1196(7)(a)]" constitutes a traffic infraction.

See also People v. Rivera, 16 N.Y.3d 654, 655-56, 926 N.Y.S.2d 16,

17 (2011) ("a driver whose license has been revoked, but who has

received a conditional license and failed to comply with its

conditions, may be prosecuted only for the traffic infraction of

driving for a use not authorized by his license, not for the crime

of driving while his license is revoked").

By contrast, there is no comparable statute dealing with using

a hardship privilege for a use other than those authorized pursuant

to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(e). As a result, a person caught violating

a hardship privilege can be charged with AUO. See also Chapter 13,

supra.

§ 45:14 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7) -- Prompt suspension law does not

preclude Court from suspending defendant's driver's

license under other laws

Finally, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(7)(c) expressly states that

"[n]othing contained in this subparagraph shall be construed to

prohibit or limit a court from imposing any other suspension

pending prosecution required or permitted by law." This language

presumably refers to suspensions pending prosecution pursuant to

24

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1), VTL § 1194(2)(b)(3) and VTL § 510(3-a), which

are discussed in the sections that follow.

Our thanks to Neal W. Schoen, First Assistant Counsel, and Ida

L. Traschen, Associate Counsel, of DMV Counsel's Office, for their

advice and assistance with regard to the prompt suspension law.

§ 45:15 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) -- Suspension pending prosecution

based upon prior conviction or vehicular crime

A defendant who is charged with DWI, Aggravated DWI, DWAI

Drugs or DWAI Combined Influence and who either (a) has been

convicted of any violation of VTL § 1192 within the preceding 5

years, or (b) is charged with Vehicular Assault or Vehicular

Homicide in connection with the current incident, is also subject

to the suspension of his or her driver's license pending

prosecution. In this regard, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) provides, in

pertinent part:

(1) Suspension pending prosecution; procedure.

a. Without notice, pending any prosecution,

the court shall suspend such license, where

the holder has been charged with a violation

of [VTL § 1192(2), (2-a), (3), (4) or (4-a)]

and either (i) a violation of a felony under

[Penal Law Article 120 or 125] arising out of

the same incident, or (ii) has been convicted

of any violation under [VTL § 1192] within the

preceding [5] years.

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1)(a).

Notably, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1), by its express terms, only

applies under certain circumstances. For example, it only applies

where the defendant is charged with VTL § 1192(2), (2-a), (3), (4)

or (4-a); it does not apply where the defendant is charged with VTL

§ 1192(1) (i.e., DWAI). In addition, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) only

applies where the defendant either (a) has been convicted of any

violation of VTL § 1192 within the preceding 5 years, or (b) is

charged with Vehicular Assault or Vehicular Homicide in connection

with the current incident. Furthermore, unlike the prompt

suspension law, no chemical test result is required; thus, VTL §

1193(2)(e)(1) can be applied to chemical test refusal cases.

Like the prompt suspension law, VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) only

applies where a prosecution is pending. Accordingly, a defendant

who enters a plea of guilty and is sentenced at arraignment is not

subject to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1). On the other hand, a defendant who

enters a plea of guilty at arraignment, but whose sentencing is

adjourned, is subject thereto (because the prosecution does not

terminate until the imposition of sentence).

25

§ 45:16 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) -- Suspension procedure

In order to impose a suspension under VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1), the

Court must make three findings. First, the Court "must find that

the accusatory instrument conforms to the requirements of [CPL §]

100.40." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1)(b). CPL § 100.40 sets forth the

facial sufficiency requirements for local criminal court accusatory

instruments. Second, the Court must find that "there exists

reasonable cause to believe that the holder operated a motor

vehicle in violation of [VTL § 1192(2), (2-a), (3), (4) or (4-a)]."

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1)(b). Critically, this means that reasonable

cause (i.e., probable cause) to believe that the defendant is

guilty of DWI, Aggravated DWI, DWAI Drugs or DWAI Combined

Influence -- and not merely of DWAI Alcohol -- is an element of a

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) suspension. Third, the Court must find that

"there exists reasonable cause to believe . . . either (i) the

person had been convicted of any violation under [VTL § 1192]

within the preceding [5] years; or (ii) that the holder committed

a violation of a felony under [Penal Law Article 120 or 125]." VTL

§ 1193(2)(e)(1)(b).

If such tentative findings are made, the statute provides that

"the holder shall be entitled to an opportunity to make a statement

regarding the enumerated issues and to present evidence tending to

rebut the court's findings." VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1)(b).

If a suspension is imposed pursuant to VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) as

a result of the defendant being charged with a felony under Penal

Law Article 120 or 125:

[A]nd the holder has requested a hearing

pursuant to [CPL Article 180], the court shall

conduct such hearing. If upon completion of

the hearing, the court fails to find that

there is reasonable cause to believe that the

holder committed a felony under [Penal Law

Article 120 or 125] and the holder has not

been previously convicted of any violation of

[VTL § 1192] within the preceding [5] years

the court shall promptly notify the

commissioner and direct restoration of such

license to the license holder unless such

license is suspended or revoked pursuant to

any other provision of this chapter.

VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1)(b).

In light of the Court of Appeals' decision in Pringle v.

Wolfe, 88 N.Y.2d 426, 646 N.Y.S.2d 82 (1996), it seems clear both

(a) that the procedural due process requirements set forth therein

apply equally to both VTL §§ 1193(2)(e)(1) and (7), and (b) that

26

evidence of a defendant's alleged prior VTL § 1192 conviction must

be submitted to the Court in "certified, documented form." See §

45:3, supra. See also CPL § 60.60; People v. Van Buren, 82 N.Y.2d

878, 609 N.Y.S.2d 170 (1993); People v. Smith, 258 A.D.2d 245, 697

N.Y.S.2d 783 (4th Dep't 1999).

In People v. Osborn, 193 Misc. 2d 173, ___, 749 N.Y.S.2d 853,

855 (Sullivan Co. Ct. 2002), the Court held that "the principles

upon which the Court of Appeals based Pringle, supra in regard to

V & T § 1193(2)(e)(7) apply equally herein with regard to V & T §

1193(2)(e)(1)." In so holding, the Court reasoned that:

A drivers license is a substantial property

right and due process must be followed whether

that property right is sought to be taken

under V & T § 1193(2)(e)(7) or (2)(e)(1).

The statutory language of V & T §

1193(2)(e)(7) is almost exactly the same as V

& T § 1193(2)(e)(1) with the one exception

that one of the criteria for the taking under

V & T § 1193(2)(e)(7) is blood alcohol content

of [.08] or higher while one of the criteria

under V & T § 1193(2)(e)(1) is a prior

conviction of any section of V & T § 1192

within the preceding five years. This

distinction does not mollify one's Due Process

rights under Pringle.

Id. at ___, 749 N.Y.S.2d at 855.

Similarly, in People v. Giacopelli, 171 Misc. 2d 844, ___, 655

N.Y.S.2d 835, 839 (Clarkstown Just. Ct. 1997), the Court held that:

[B]oth sections 1193(2)(e)(1) and (7),

providing for pretrial suspension, have a

"deprivational" effect, and as the very same

"substantial property interest" is at issue

under both statutes, Pringle v. Wolfe must

apply to both sections equally. Perhaps more

importantly, there exists a stronger reason

for a hearing under section 1193(2)(e)(1), as

there exists no tempering of the suspension

with the grant of a "hardship license" as is

available in section 1193(2)(e)(7)(e).

§ 45:17 VTL § 1193(2)(e)(1) -- Effect of failure to comply with

statute

In Matter of Plumley v. Leuenberger, 131 Misc. 2d 543, ___,

500 N.Y.S.2d 911, 913 (Oneida Co. Sup. Ct. 1985), the Court lifted

27

the suspension of the petitioner's driver's license pending

prosecution and ordered that the license be returned where the Town

Court failed to follow the requirements of the suspension statute.

The Court held that the suspension was untimely in that it occurred

after the arraignment had been completed. Id. at ___, 500 N.Y.S.2d

at 913. In addition, "[n]o findings were made and transmitted to

petitioner. Consequently, he was not given an opportunity to rebut

them. Thus, there has been no compliance with the statute, and the

suspension should be lifted and the license returned." Id. at ___,

500 N.Y.S.2d at 912.