[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Assurance review of the operation of the

Accredited Employer Work Visa scheme

February 2024

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 4

Context .............................................................................................................................................................. 4

Is the Scheme being administered appropriately? ........................................................................................... 5

What are the next steps for improvement? ..................................................................................................... 9

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 10

Context for this Review ................................................................................................................................... 10

IRREGULAR MIGRATION AND MIGRANT EXPLOITATION .............................................................................. 11

What Constitutes Irregular Migration and Migrant Exploitation? .................................................................. 11

How does Migrant Exploitation manifest? ..................................................................................................... 11

Indicators of the Extent of Migrant Exploitation in New Zealand .................................................................. 13

Changes to Migration Patterns ....................................................................................................................... 14

THE IMMIGRATION SYSTEM – ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ......................................................................... 15

THE POLICY AND DESIGN OF AEWV ...................................................................................................... 17

The Policy Design ............................................................................................................................................ 17

THE OPERATIONALISATION OF AEWV ................................................................................................... 24

Decisions made at the launch of AEWV .......................................................................................................... 24

Policy changes impacting Immigration Instructions for AEWV ....................................................................... 25

Decision to amend risk tolerances .................................................................................................................. 26

General Instructions ........................................................................................................................................ 27

Managing risk .................................................................................................................................................. 31

The introduction of the ADEPT IT System ....................................................................................................... 33

Constantly changing AEWV operating procedures ......................................................................................... 35

Immigration Officers’ discretion to conduct manual checks .......................................................................... 36

Employer Reaccreditation ............................................................................................................................... 38

Post-decision assurance through AERMR ....................................................................................................... 38

Declines, Suspensions and Revocations .......................................................................................................... 40

Quality Assurance and Control........................................................................................................................ 41

Success Measures and processing targets and their impacts ......................................................................... 42

Concerns raised internally post-implementation of AEWV ............................................................................ 45

Public-facing evidence of risks emerging post-implementation of AEWV...................................................... 47

FINDINGS - WAS MBIE’S ADMINISTRATION OF AEWV CARRIED OUT APPROPRIATELY........................................ 49

Main findings ................................................................................................................................................... 49

Detailed findings ............................................................................................................................................. 50

RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................................................ 53

APPENDIX A – TERMS OF REFERENCE .................................................................................................... 57

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

APPENDIX B- METHODOLOGY / APPROACH FOLLOWED ............................................................................. 60

Interviewee identification ............................................................................................................................... 60

Information gathering ..................................................................................................................................... 60

Numbers of submitters/interviewees ............................................................................................................. 61

Data analysis ................................................................................................................................................... 61

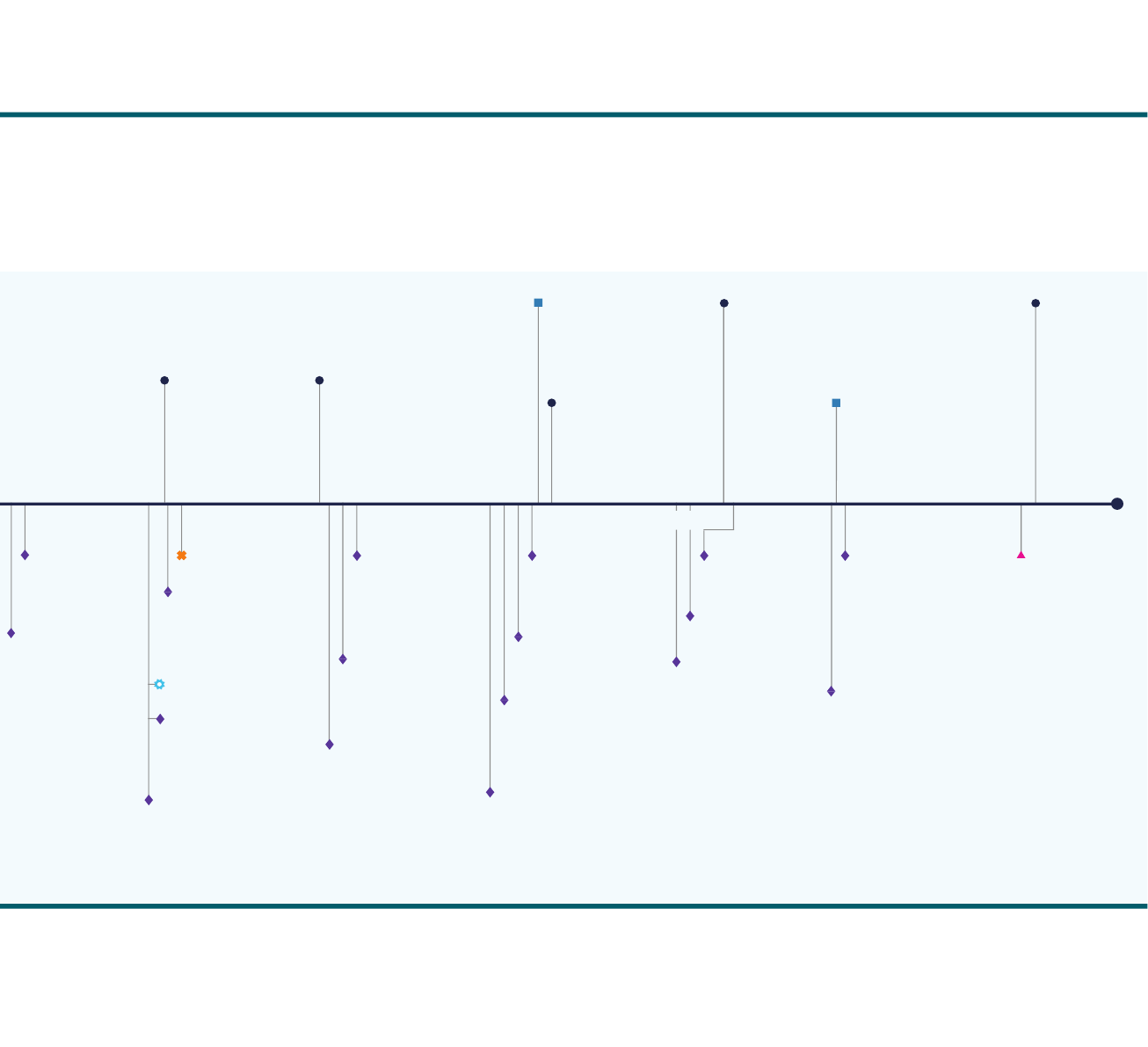

APPENDIX C - AEWV TIMELINE .......................................................................................................... 62

APPENDIX D - DETAILED ANALYSIS OF GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS .................................................................... 64

GI 1 – To Clear Current Job Check Queue ....................................................................................................... 66

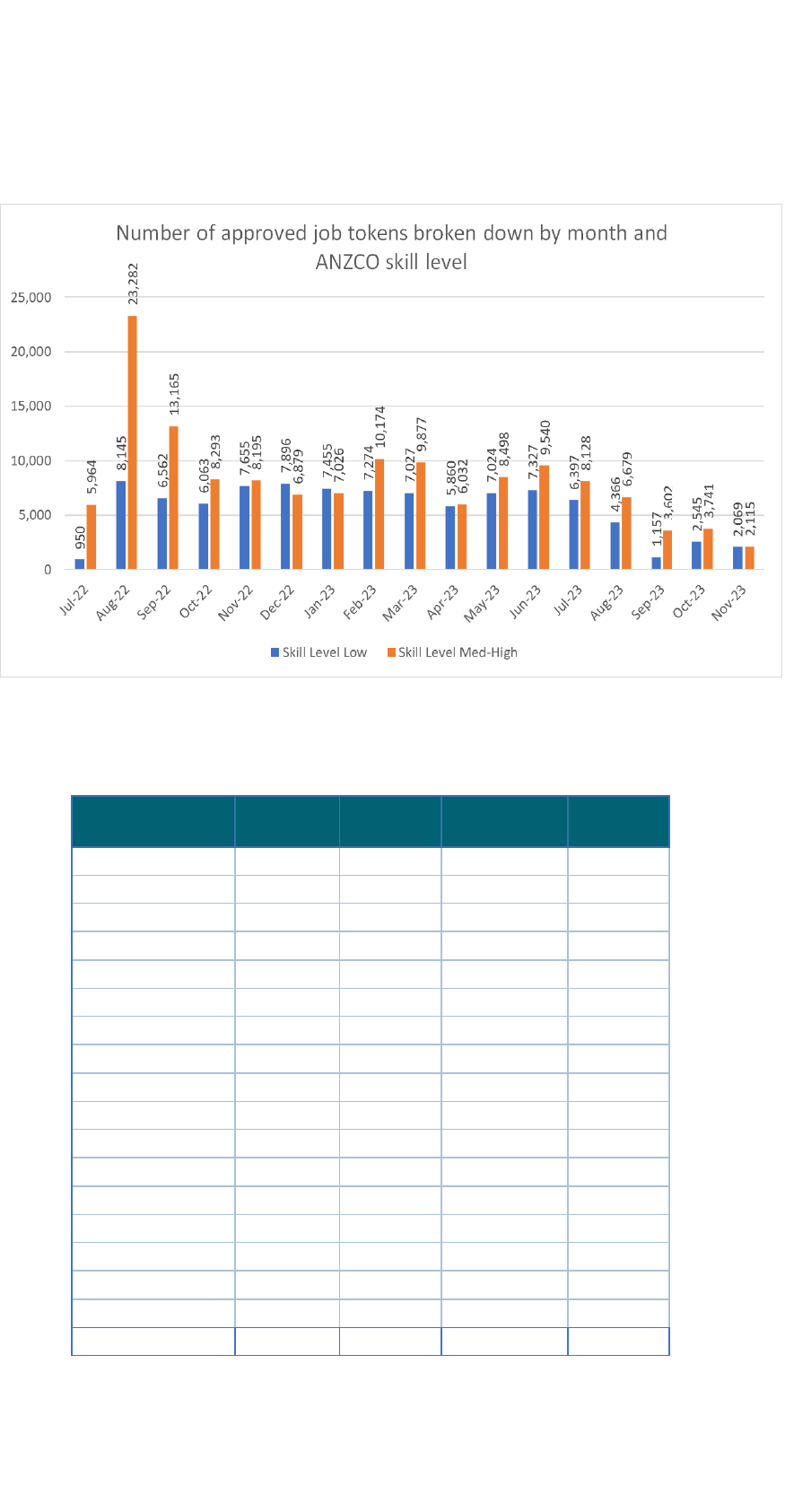

GI 2 - TO ENHANCE ACCREDITED EMPLOYER WORK VISA PROCESSING ........................................................ 69

Proposed Approach ......................................................................................................................................... 69

APPENDIX E - AEWV PROCESSING VOLUMES TO DATE ............................................................................... 75

GLOSSARY OF TERMS ........................................................................................................................ 78

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Executive Summary

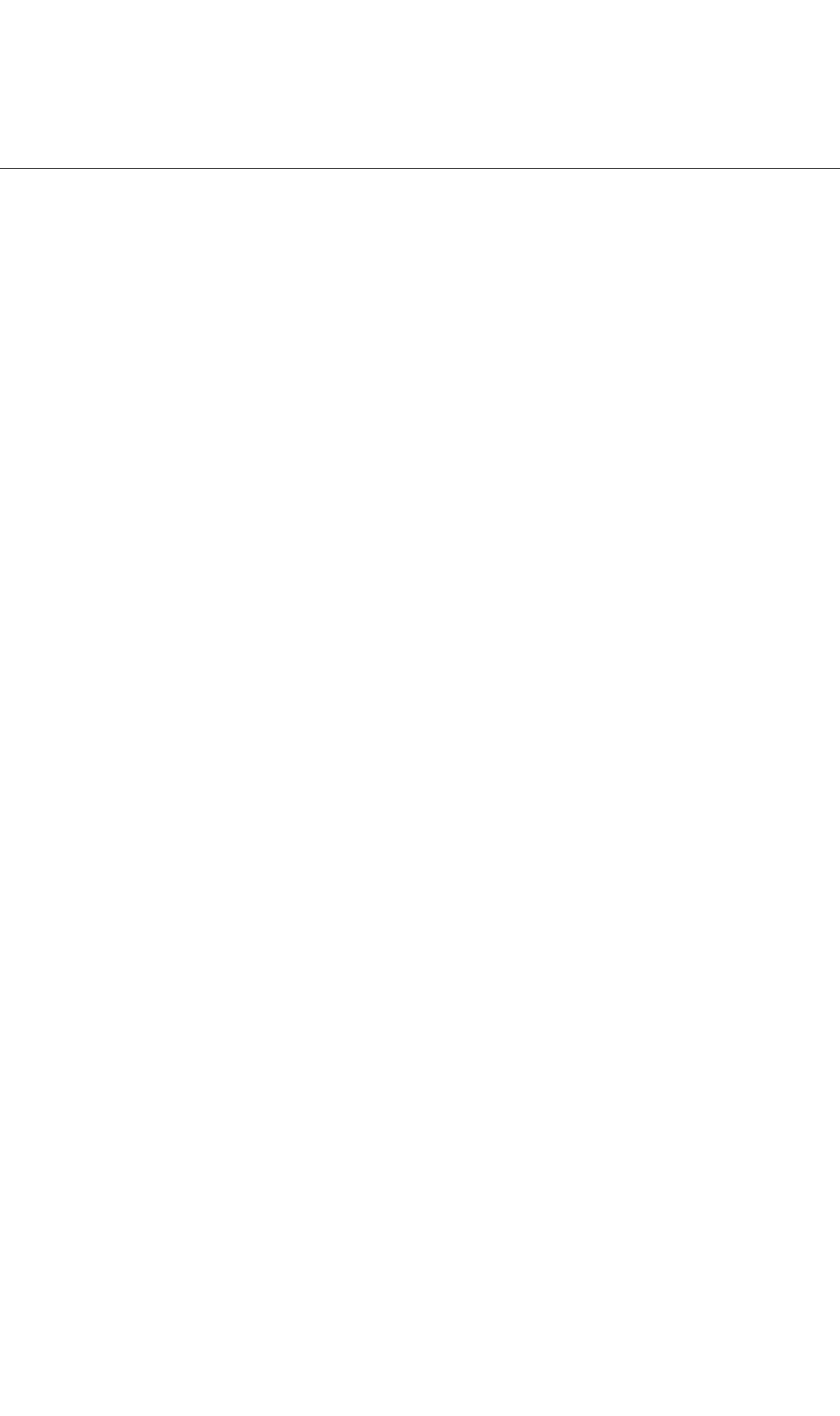

Context

1. In March 2020 New Zealand closed its borders due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Immigration New

Zealand (INZ) made a number of operational changes in response to the border closures, including

reducing its visa processing capability largely through the closure of some of its offshore offices.

2. The Government announced a phased re-opening of the borders in February 2022, and subsequently

announced the acceleration of the same bringing the full opening forward to July 2022 from the

originally planned October 2022 date. At the time of re-opening, there were unprecedented labour

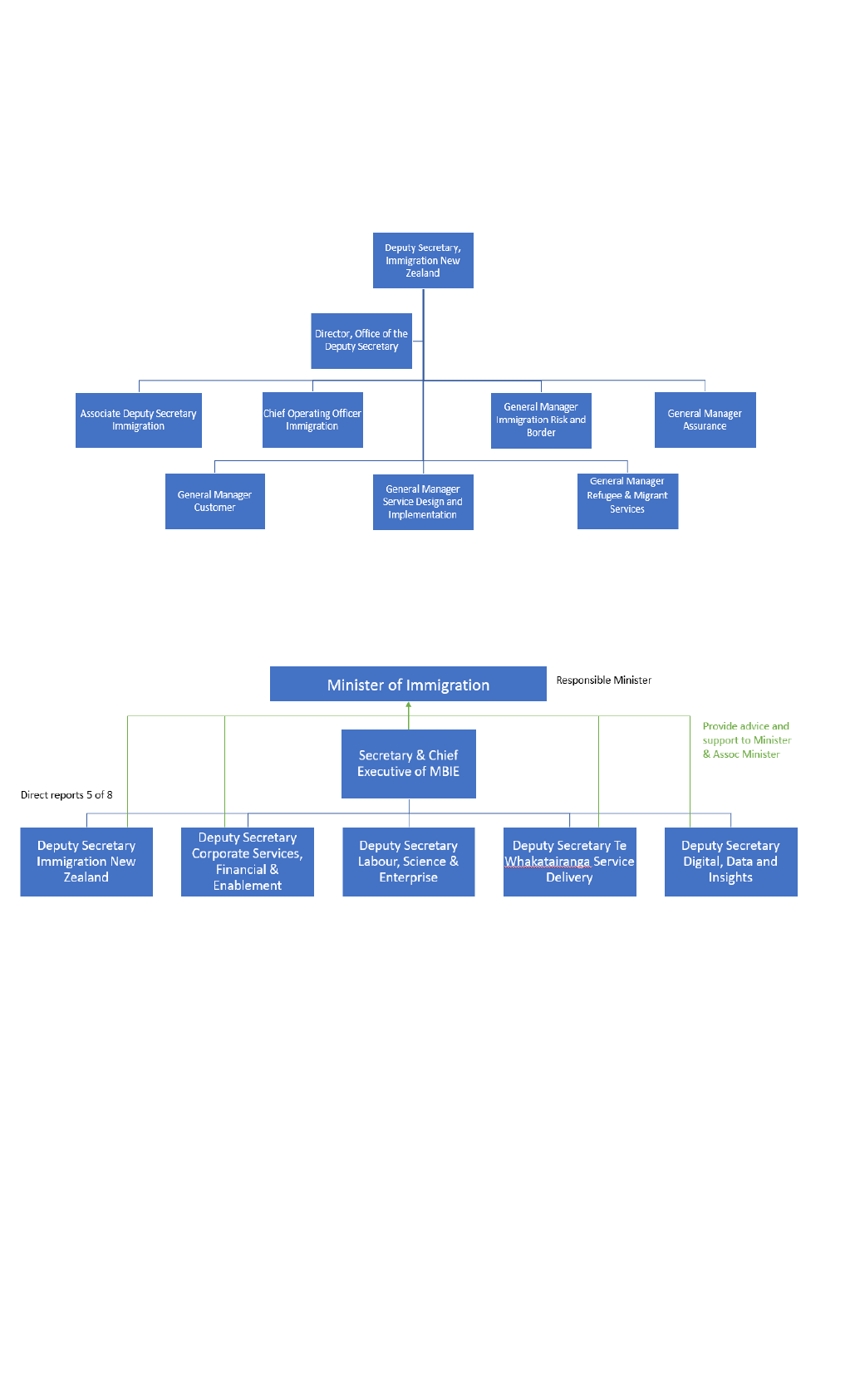

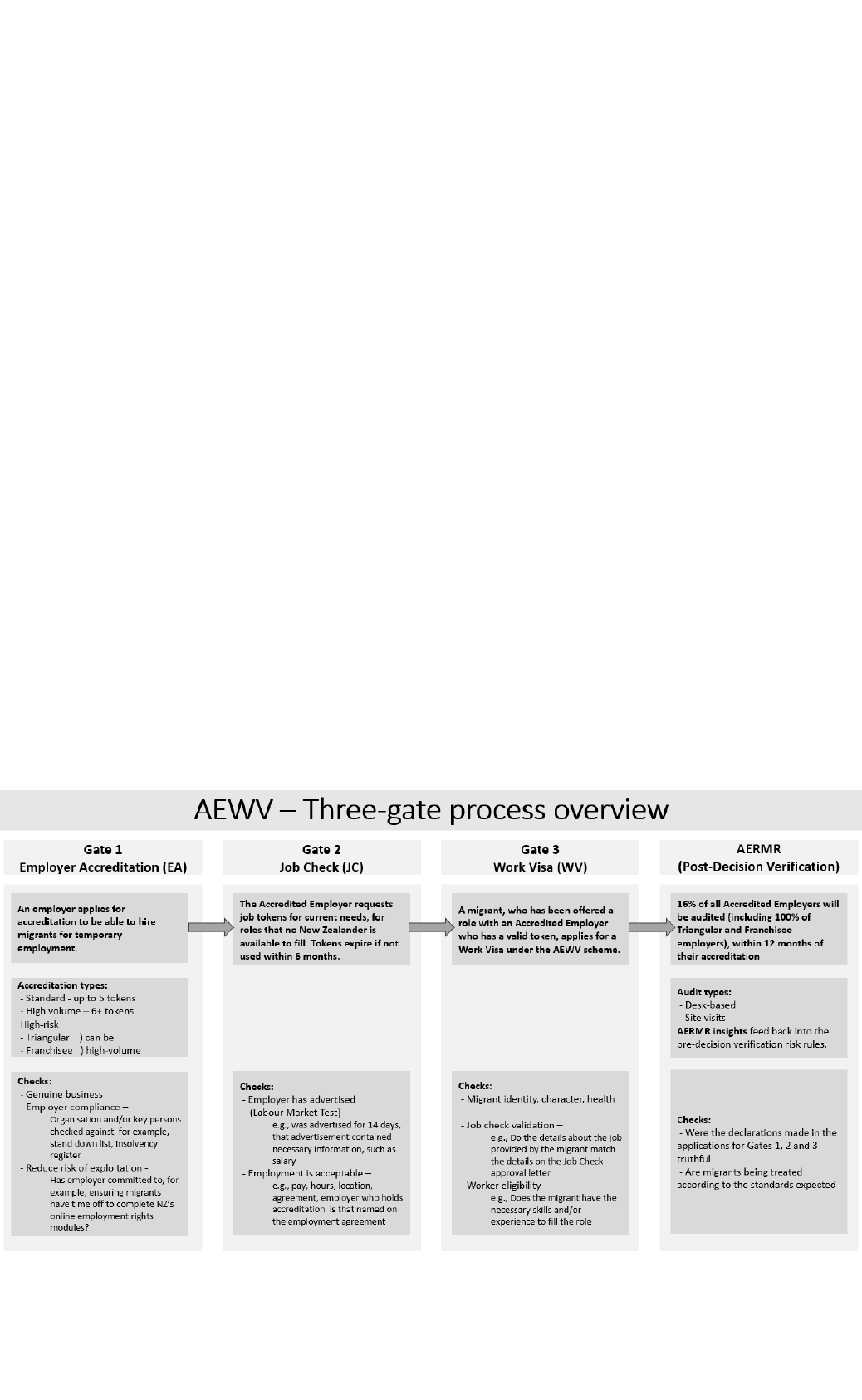

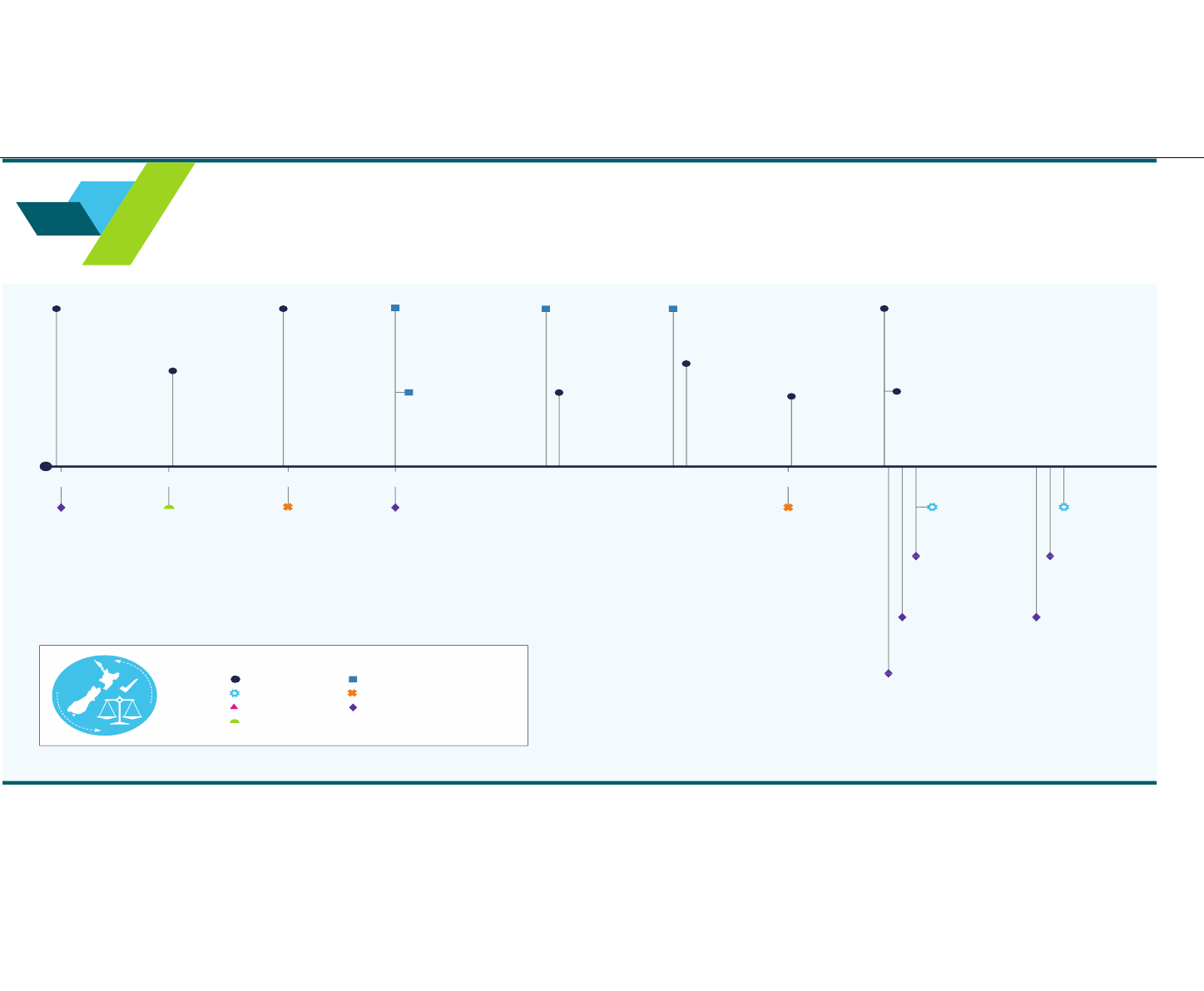

shortages in New Zealand with very low unemployment, a shortage of skilled workers across many

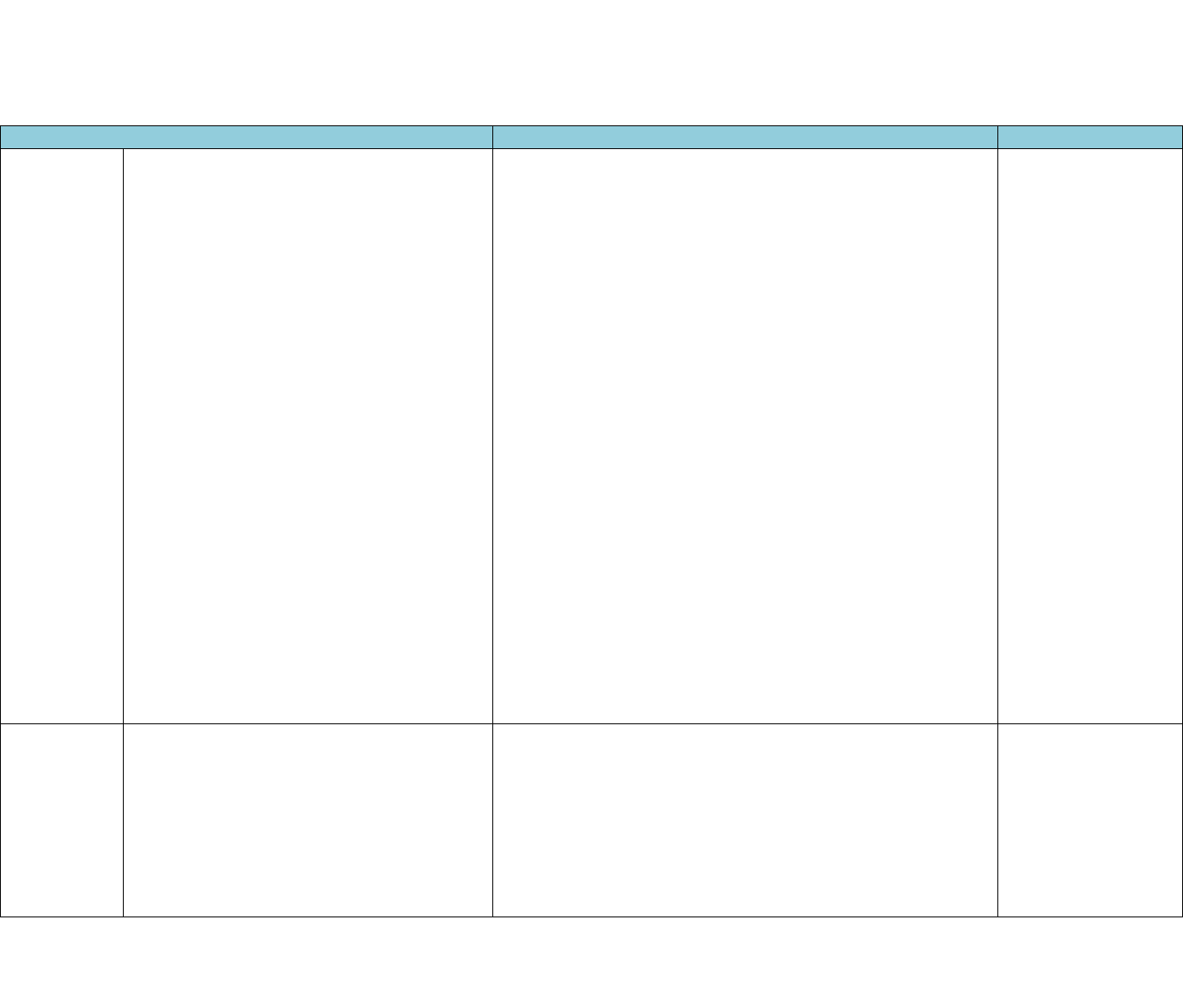

occupations, and pent-up demand for migrant labour resulting from the border closure. Enabling an

increase in the available workforce was a priority for the government and for employers.

3. Contemporaneously, and in that context, the Government introduced its new temporary work visa: The

Accredited Employer Work Visa (AEWV), which sought to bring the previous 6 work-related visa

categories into a single visa product. The policy development work on the AEWV scheme had been

undertaken between 2017 and 2019, prior to the pandemic, with planning for the implementation

occurring while the borders were closed. The Scheme was designed to reorient the focus of

employment visas from a migrant led system, which relied on aspirant migrants to collate the relevant

material and submit applications, to an employer led system. Under the new system the onus would be

on the aspirant employer to provide assurance that they operated a financially sustainable business

able to offer genuine employment, and that the need for the migrant worker was genuine. The migrant

worker would then be required to provide assurance that they were of good character and health, and

appropriately skilled/qualified to perform the job offered. The design of the Scheme included three

processing gateways:

a. The Employer Accreditation gateway, which required employers to provide declarations relating

to basic requirements associated with being a valid business and a good employer. A successful

application resulted in them being accredited to use the AEWV scheme to hire migrant workers.

b. The Job Check gateway, which checked the job requirements of applications received from

accredited employers to ensure that no New Zealander was available to fill the position being

recruited to, and that the terms and conditions of employment were consistent with

Immigration Rules; and

c. The Work Visa gateway, which checked that the migrant was of good character and health and

was suitably qualified to do the job offered by the accredited employer.

4. A key feature of the policy design of the AEWV Scheme was that it was to be a “high trust” model. This

meant that the front-end of the application process (that is, the first two gateways), was designed to

rely heavily on the declarations made by employers. The main mechanism for checking the validity of

those assurances was through system rules and risk integration functions built into the visa processing

technology platform called Advanced Digital Employer-led Processing and Targeting (ADEPT), and

through post-decision checks. Checks were to occur through:

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

a. Accredited Employer Risk Monitoring and Review (AERMR). This involved conducting desk and

site-based checks of a percentage of accredited employers, some targeted and some randomly

selected, to identify and address non-compliance; and

b. Re-accreditation. Employers were required to renew their accreditation status after a certain

period of time. The reaccreditation process involved checking that accredited employers were

acting consistently with the declarations and commitments they had previously made.

5. In addition to informing the accreditation decisions in individual cases, AERMR and the reaccreditation

process were designed to generate robust intelligence and feed into a continuous learning system.

6. The AEWV scheme went live in three stages between May and July 2022 and has now been operational

for almost two years.

7. The AEWV scheme is administered by INZ, which is a business unit within the Ministry of Business,

Innovation and Employment (MBIE). To process AEWV applications, Immigration Officers at INZ have

been using the automated visa processing platform, ADEPT. ADEPT automates the initial process of

checking employer declarations using several system rules. Where ADEPT identifies risk factors or

possible areas of concern, Immigration Officers are alerted to the issue. The system is designed to allow

Immigration Officers to take a light touch approach to checking aspects of applications, taking much

information at face value whilst targeting their attention towards higher risk applications.

8. From April 2023 concerns were raised with MBIE, the Minister of Immigration, and through the media,

about the operation of the AEWV scheme. At a high level the concerns related to how the Scheme was

being administered by INZ, particularly at the first two gateways, potentially resulting in opportunities

for misuse and exploitation by third parties. To provide independent assurance as to the operation of

the Scheme, the former Minister of Immigration asked the Public Service Commissioner to undertake

this review.

9. This review took place between August 2023 and February 2024 (with the investigation phase of the

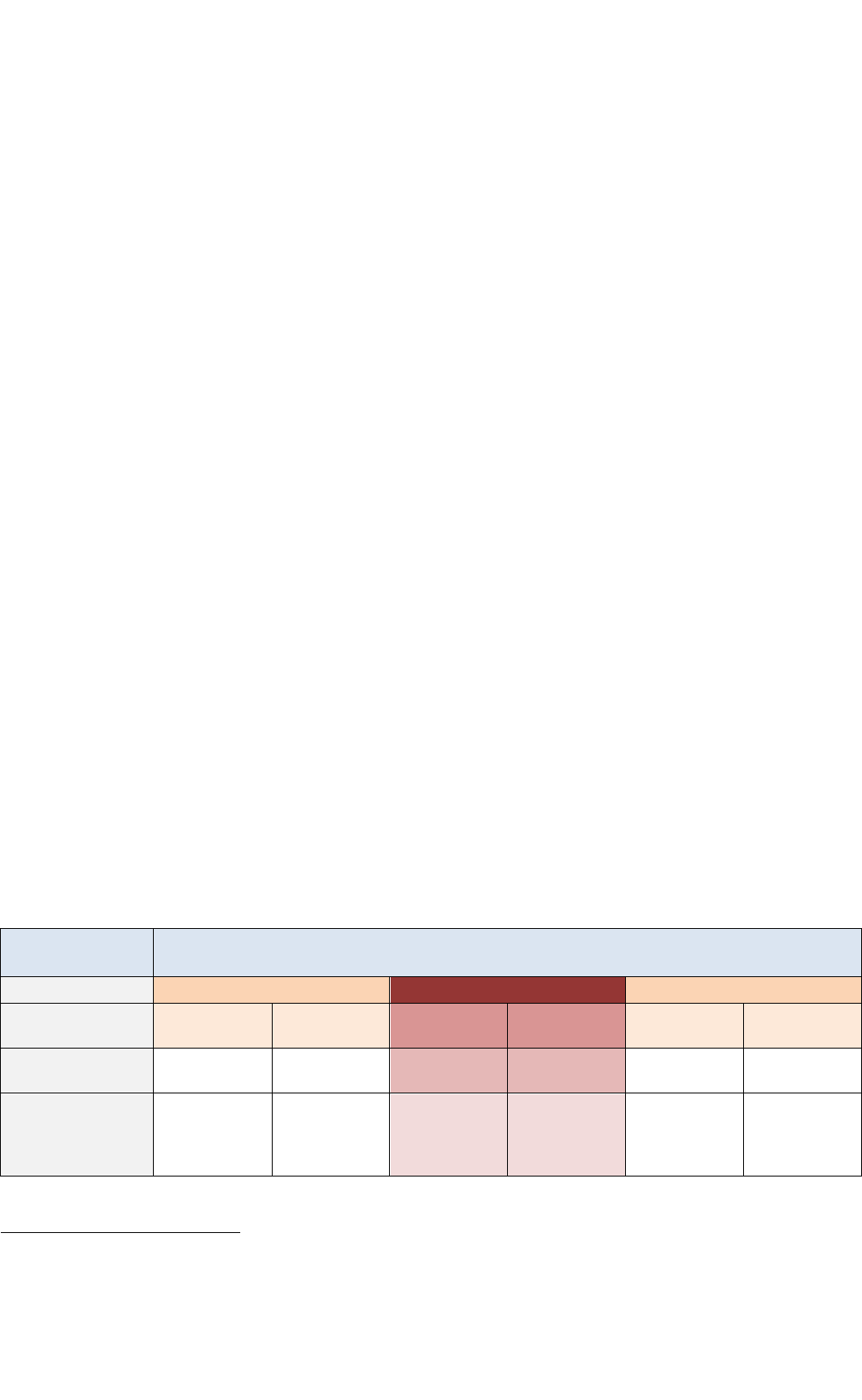

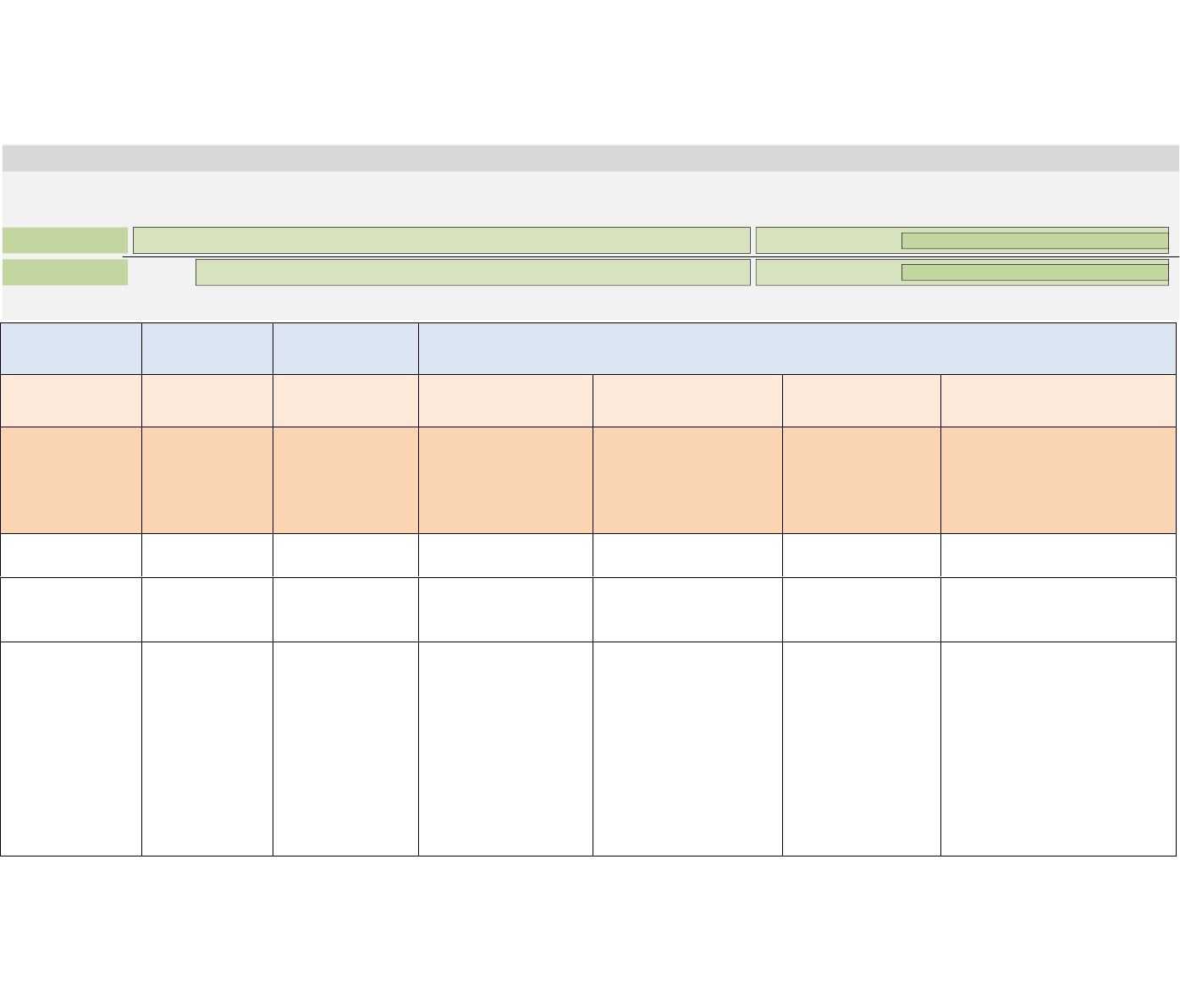

Review being undertaken between September and December 2023). Its purpose has been two-fold:

a. To consider whether Immigration New Zealand’s administration of the AEWV scheme is being

carried out appropriately, including but not limited to, consideration of operational efficiency,

risk management, and the external post-COVID context; and

b. To identify any appropriate next steps for improvement in the administration of the AEWV

scheme, with a focus on mitigating the risk of migrant exploitation and irregular migration.

Is the Scheme being administered appropriately?

10. To answer this question, it is necessary to look back at the circumstances surrounding the initial

implementation of the AEWV scheme. As a result of the unusual circumstances eventuating from COVID-

19, the new scheme went live in extremely challenging circumstances. There was a “perfect storm” of

adverse conditions, namely:

a. The implementation of a new policy that merged 6 previous employer visas into one new

scheme.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

b. Implementing necessarily new business processes (the three gateways, plus the post-decision

checks).

c. The introduction of a new technology platform, ADEPT, that was not fully operational at the time

of launch and had not been subject to user-testing resulting from resourcing challenges and the

acceleration of the border opening.

d. Adopting published standard processing times that could not been tested for operational

feasibility prior to go-live.

e. Implementation by an almost entirely new visa operations team (200 people were recruited in

2022 to process AEWV applications); and

f. Under immense pressure from the Government, employers, and the New Zealand community

more generally, to get migrant workers into the country quickly.

11. Considering these unique and challenging circumstances, INZ executed the initial establishment of

processing operations and commencement of processing AEWV applications well.

12. Perhaps not surprisingly given the circumstances, a number of issues emerged almost immediately. Of

particular note, it quickly became apparent that the volumes of applications were exceeding INZ’s

capacity to process them in accordance with the published timeframes. In response to this situation, to

increase the volume of applications able to be processed and to bring visa application processing

within published processing timeframes, INZ gave General Instructions that modified the order and

manner of application processing by Immigration Officers for the second and third gateways reducing

the amount of checking of applications Immigration Officers were required to undertake. The initial

intention of the General Instructions was that they were to be an interim approach, would be

reassessed four weeks from implementation, and adjusted as appropriate. They remained in place and

largely intact until mid 2023.

13. Following the identification of abuse being observed in the Scheme from April 2023, in June and August

2023, INZ made operational changes to tighten up on how applications were being processed in the

final two gates of AEWV. INZ advise they have continued to make operational changes to strengthen the

Scheme subsequently.

14. It is critical that New Zealanders have trust and confidence in the AEWV scheme and its administration.

Its integrity is of high public importance, given the potential impact on vulnerable migrants.

15. The majority of New Zealand businesses are good employers seeking and offering genuine employment

to migrant workers. Unfortunately, the relatively small proportion of bad actors in the system, both off-

and on-shore, will always seek and exploit weakness in immigration systems and policy. The Review

accepts that no immigration system can mitigate all risk to migrants, but there are additional steps that

INZ should take to minimise the risks of irregular migration and migrant exploitation, and to ensure

trust and confidence in New Zealand’s immigration system. Further action is required as described in

the section on recommendations below.

16. In terms of whether the AEWV scheme is being administered appropriately, the review makes a series of

general and detailed findings and recommendations. Consistent with the timeframe of the

investigation phase of the Review being undertaken, the Review has focused largely on the period the

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

launch of AEWV to December 2023 to inform its findings and recommendations. The findings include

that:

a. During the period July 2022 – June 2023 changes made to operational settings did not include

sufficient risk assessments.

b. The immigration risk associated with the operation of the AEWV scheme increased between 27

July 2022 and 30 June 2023. This was the result of General Instructions 1, 2, 3 and 4. General

Instructions 1 and 2 (given by INZ in July and August 2022), had the effect of temporarily limiting

several application checks by Immigration Officers undertaken at the Job Check and Work Visa

Gateways, thereby exposing the Scheme to increased risk of abuse. This situation was extended

through General Instructions 3 and 4, which were given by the Incident Management Team (IMT)

in November 22 and February 2023. General Instruction 5 (given in June 2023) re-introduced

some checks to reduce the risk exposure to the Scheme in response to multiple examples of

immigration risks materialising and being observed by INZ. General Instruction 6 continued the

re-introduction of checks in August 2023.

c. The Review considers the giving of General Instructions 1 and 2 were reasonable in the

circumstances, given the need to increase processing volumes and reduce visa processing times

to alleviate the pressure on the border at the time of re-opening. When approved and given, the

intention was that the General Instructions would be introduced for a short period of time and

their use reviewed before consideration of their extension. In approving the General Instructions

INZ accepted the changes would increase the immigration risks. However, prior to their approval

INZ did not undertake a structured risk assessment to fully understand the impact of the change

on the overall risk profile and to ensure that key people could be made aware of the impact prior

to the decisions being made. In future, if similar changes to the operational settings are

required, structured risk assessments including establishing risk tolerances and mitigations

should be undertaken. Similarly, and consistent with the original approval, the IMT operating at

the time should have undertaken a structured review and risk assessment to understand the

specific risks being accepted before extending the General Instructions alongside the limited risk

and verification activity that was undertaken at the time. Again, there is a need for decision-

makers and Ministers to be fully appraised of the shifting immigration risks and any limitations

around their assessment, particularly when changes to the risk settings are being made.

Concerns raised by staff have not been given adequate attention

17. Immigration staff spoken to by the Review indicated they raised concerns with INZ senior leadership

from April 2023 regarding the observed risk presenting at the various gateways (but in particular at Job

Check and Work Visa), and indicated they felt responses by senior INZ leadership did not adequately

address those concerns.

18. Discussions with INZ leadership indicate that, at the time,there was limited evidence of visa system

abuse presenting through INZ’s risk monitoring activity, which was consistent with their belief that

nothing in the General Instructions given required immigration officers to ignore risk, and that concerns

were largely reflective of some staff not necessarily understanding the policy and operational settings

relating to the Scheme.

19. As well as this disconnect above being demoralising for some staff, this was a missed opportunity for

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

the system to learn, improve, and mitigate further harm, based on the intelligence gathered at the

frontline.

20. The Review acknowledges that since September 2023, INZ leadership has made a number of changes to

its staff communication and engagement and that this continues to be a priority.

Post-Decision Verification & Review checks are not fully operational yet

21. The AEWV Scheme was designed to be a learning system implemented over three years. It was

designed to utilise intelligence and insights from post-decision verification and review to inform future

changes to the Scheme design and operations in response to both changes in the external policy

environment and operational learnings observed.

22. The de-scoping of the development of ADEPT’s business analytics and intelligence modules has

reduced the ability of the AEWV operations team to analyse system and scheme performance and to

inform operational decision-making and review.

23. The Cabinet-delayed employer reaccreditation process means that verification of employer measures

to minimise migrant exploitation have not yet been carried out, including for high-risk employers. It is

scheduled to commence in the second quarter of 2024.

24. The diversion of AERMR resources to manage immigration risk in other areas of the immigration system

during the second half of 2022 and early 2023 resulted in significant delays to the implementation of

AERMR and post-decision review. This compromised INZ’s understanding of the performance of the

visa scheme and, whilst aspects of AERMR implementation are nearing completion, some aspects

remain behind schedule.

25. The Review understands INZ has continued to make operational changes to its administration of AEWV

consistent with the Scheme’s design as a learning system in the period post when the Review’s

investigative work was conducted. The Review acknowledges INZ has a number of changes underway

to continue to improve many of the issues identified and discussed since this review began in August

2023.

There is no clear picture of the extent of possible system abuse

26. It is difficult to compare trends of complaints and investigations between years, due to changed visa

products, effects of COVID-19 and border closures, however the increase in the number of complaints

and investigations relating to AEWV in recent months, may be possible indicator of increased system

abuse. It also needs to be acknowledged that work being done by MBIE to make it easier to report

migrant exploitation since 2020, the significant increase in working migrant numbers since the borders

reopened, as well as the financial incentives resulting from the financial support package agreed by the

former Minister, may be influencing the number of complaints received.

27. MBIE do not appear to have a methodology or approach through which they regularly are able to

calibrate the extent or nature of migrant exploitation, relying largely on lag indicators of system

abuse/non-compliance. Whilst reliance on their internal Risk and Verification activity is useful to

determine the extent of non-compliance detected through review, the need to develop a wider

intelligence model with greater lead indicators seems evident and would provide wider insights and

intelligence than appears to be the case currently.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Key communications with frontline staff have been confusing

28. The numerous changes to General Instructions, Standard Operating Processes (SOPs) and Immigration

Guidelines, coupled with complex documentation, and the lack of integration into a single set of

operating instructions increased complexity for Immigration Officers and created confusion regarding

the correct and current interpretation and processing practice.

29. The focus on visa processing standard timeframes, and the lack of focus on changed risk profile,

resulted in undue emphasis on visa processing volumes and approvals, which was experienced by visa

processing staff spoken to by the Review as disempowering and frustrating.

30. The introduction of ADEPT, the three-gateway system, and the inclusion of automation of a number of

risk rules represented a significant change in visa processing practice in INZ. This change was not well

communicated, and inadequate change management support was provided to visa processing staff to

operate in the new system.

31. The full set of main and detailed findings is set out at the back of this report, grouped with reference to

the topics that the terms of reference required this Review to consider.

What are the next steps for improvement?

32. As indicated above, AEWV is designed to operate as a learning system with operational scrutiny, risk

tolerance and policy requirements constantly being adjusted to respond to environmental changes and

competing priorities, including improving the experience for customers paying for INZ’s services whilst

minimising risks to migrants. In line with this model, and in response to issues identified by this Review,

MBIE and INZ have made a number of changes to improve the administration of the AEWV scheme.

33. The recommendations section at the end of this report begins with a summary of work underway

grouped into three main objectives:

a. Reduce the risk of migrant exploitation and improve immigration system responsiveness

through the development of an integrated compliance and system monitoring model that

balances employer, migrant and workforce needs.

b. Improve intelligence gathering and system learning opportunities; and

c. Work under way to reset the relationship between INZ’s senior leaders and frontline staff.

34. The Review recommends MBIE continue to progress work planned and underway towards achieving

these three objectives and makes 10 specific recommendations for areas of focus. Recognising that a

number of the changes recommended require a dedicated programme of work which will take time to

implement, the Review considers both work already underway and the changes once implemented, will

strengthen the performance of the Scheme, enabling MBIE and INZ to provide the necessary assurances

to the public and Ministers and further reduce the risk of harm to migrants.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Introduction

Context for this Review

35. The Review wishes to acknowledge the extraordinary challenge that the Ministry of Business,

Innovation and Employment (MBIE) faced in reopening the borders post COVID-19. With New Zealand’s

borders having been closed to non-nationals for approximately 2 years, the demand for visas to work,

study and visit was extreme. The demand from employers for migrant workers, from educational

institutions to allow international students to return, and from the tourism and wider New Zealand

community to allow visitors into the country, placed MBIE under extreme pressure to process an

unprecedented number of visas in short timeframes, post opening of the borders. MBIE and

Immigration New Zealand (INZ) also experienced direct operational impacts from COVID-19, with

revenue significantly reduced due to fewer applications, and staff levels impacted by the effects of

lockdown and mandatory isolation requirements.

36. At the time of reopening, there were unprecedented labour shortages in New Zealand with very low

unemployment, a shortage of skilled workers across many occupations, and pent-up demand for

migrant labour resulting from the border closure. Enabling an increase in the available workforce,

international students, as well as visitors and family, to flow into the country was a priority for the

government, and for New Zealanders

37.

In September 2023 concerns were raised with the

then

Minister of Immigration about the operation

of the Accredited Employer Work Visa scheme (AEWV), which was launched contemporaneously

with the border re-opening. At a high level, the concerns related to the Scheme’s administration by

Immigration New Zealand (INZ) and the potential resultant opportunities

for misuse and

exploitation of migrants by third parties.

38.

It is critical that New Zealanders have trust and confidence in the AEWV scheme and its

administration. Its integrity is of high public importance, given the potential impact on vulnerable

migrants. To provide independent assurance as to the operation of the Scheme, the Minister asked

the Public Service Commissioner to undertake a review.

39. The objective of the Review is to determine whether INZ’s administration of the Scheme is being carried

out appropriately and to identify any possible improvements, with a focus on mitigating the risk of

migrant exploitation and irregular migration.

40. The full Terms of Reference for the Review are included in Appendix A of the Report.

41. The Methodology applied, including written submissions and interviews between September and early

November 2023, is outlined in Appendix B of the Report.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Irregular Migration and Migrant Exploitation

What Constitutes Irregular Migration and Migrant Exploitation?

42. Irregular migration is considered to be “the movement of persons that takes place outside the laws,

regulations, or international agreements governing the entry into or exit from the State of origin, transit

or destination”

1

. In the context of this review, this would include persons who, by way of deception or

fraudulent activity either by them, the proposed employer, or an agent working on either theirs or the

employer’s behalf, obtained a Work Visa that permitted entry to New Zealand.

43. Migrant exploitation is considered to have occurred when harm is caused, or the risk of harm is

increased, to the economic, social, and physical well-being of a migrant worker. Migrant workers are

considered vulnerable to exploitation because they may be less aware of their rights, may have limited

English language skills, can lack independent financial or other means of support, face high

expectations from family members back in their home country, and are often reluctant to report

exploitation for fear of losing their job, visa, and/or risk deportation. Consequently, it is understood that

the extent of migrant exploitation is under-reported globally.

44. The nature of exploitation experienced by migrants in New Zealand takes many forms - from workplace

exploitation, which involves breaches of minimum standards and entitlements under employment and

immigration legislation, to serious workplace exploitation, which involves coercion or deception and

abuses of power. At its most extreme, migrant exploitation relates to offences under the Immigration

Act (2009) and the Crimes Act (1961), which include forced labour where victims are trapped in jobs that

they were coerced or deceived into, and trafficking in persons, which is the recruitment, transportation,

transfer, harbouring, or receipt of a person through coercion or deception

2

.

45. Irregular migration and migrant exploitation are not mutually exclusive and in fact have a high degree

of intersect. The Review heard numerous reports of migrants who had paid offshore agents large

amounts of money to secure a Work Visa, which itself is illegal and constitutes irregular migration.

Those people have often secured visas with employers who go on to exploit migrants, potentially by

either not offering employment consistent with the contracts committed to as part of the visa

application process, and/or failing to provide employment at all. It cannot be assumed that a migrant

realises that their actions result in activity considered to be irregular migration in the New Zealand

context. For example, in many source countries, the payment of large fees for jobs may be considered

normal practice and so an individual may not realise that in a New Zealand context this falls foul of

immigration rules and regulation and employment law.

46. Regrettably, irregular migration and migrant exploitation are not new problems in New Zealand or

globally and certainly not something that has resulted from the introduction of the AEWV Scheme.

While historical evidence indicates that it applies to only a small percentage of the migrants who

choose to travel to work in New Zealand, the impacts on the individual being exploited are potentially

profound and should not be under-estimated.

How does Migrant Exploitation manifest?

47. While not unique to migrant workers who hold an Accredited Employer Work Visa (AEWV), the following

types of exploitation have been described to the Review in association with the AEWV scheme:

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

a. On arriving in New Zealand, or soon after arrival, the migrant’s employment may not exist. This

may be because the job never existed, is no longer available, employment documents were

falsified, or exploitation of the 90-day rule whereby employers can terminate employment of a

new employee, by employers.

b. Offshore agents, potentially aided by on-shore actors, commanding significant fees for migrant

workers ($14,000-$50,000 NZD), causing heavy debt and increased vulnerability (and which

constitutes irregular migration).

c. Migrant workers being under-or-not paid (for example work for free, extended hours, or paying

money back to the employer).

d. Instances of culturally integrated migrant exploitation where migrants from the same home

country as the employer are subject to exploitation resulting from strong dependency and

vulnerability for the migrant worker. This is particularly prevalent where the migrant cannot

speak English, has low or no skills, and or cultural settings that prevent the migrant speaking out

against their employer.

e. Migrant workers not being offered employment that is consistent with the employment contract

provided by the employer as a requirement of visa.

f. Employers controlling living conditions, movement, and communication; and

g. Migrant workers being forced to work illegally as part of organised crime networks, either in

breach of their visa, or in unlawful activities.

48. By the time a migrant worker has entered New Zealand, they may have invested heavily, both

financially and emotionally, potentially having disposed of property, borrowed to fund their migration

(either legal or illegal costs) and given up employment in their home country. They may be proposing

to be separated from family and friends for considerable periods of time to realise the benefits available

from migrant work.

1

Irregular Migration International Organisation for Migration (IOM) definition of Irregular Migration relied upon by INZ.

2

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2020). Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (Cabinet paper

proactively released) Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (mbie.govt.nz)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Indicators of the Extent of Migrant Exploitation in New Zealand

49. Gaining an accurate picture of the extent of migrant exploitation is difficult. In 2018 and 2019 the

Labour Inspectorate and INZ reported that they were seeing increasingly complex cases of migrant

exploitation, and evidence suggested that exploitation is a serious issue in New Zealand. In 2018, 8

percent of temporary migrants who responded to New Zealand’s Migrant Survey said they had not

received one or more of their minimum employment rights or had been asked to pay money to their

employer to get or keep their job (a “job premium”). Extrapolated out this was estimated to mean

around 20,000 temporary workers may be being exploited

3

. The same survey found that some

industries present a higher risk of exploitation than others, for example nearly one in five migrants

working in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and retail industries indicated they had not received at least

one of their minimum employment rights or had been asked to pay a job premium. This correlates with

lower-skilled workers from low-income source countries being more vulnerable to exploitation, or

migrant workers who have significant debt.

50. In 2011/12, INZ received exploitation allegations involving 31 individuals and businesses. In 2018/19 this

had increased to 390

4

, indicating an increase in the level of exploitation. The number of allegations

involving at least one employer has been climbing, with 421 in 2020, 590 in 2021, 467 in 2022, and as of 4

December 2023, 1552, complaints against Accredited Employers where one or more migrants have

reported instances of migrant exploitation.

51. In August 2020 the Government announced new measures to better protect temporary migrant workers

from exploitation. The measures included the creation of the Migrant Exploitation Protection Visa

(MEPV) to support migrants to leave an exploitative situation quickly and remain lawfully in New

Zealand. The visa is valid for up to six months to allow the migrant to find alternative employment. Also

included in the measures were:

a. a dedicated 0800 number and web form to make it easier to report migrant worker exploitation.

b. increased funding for a joint compliance and enforcement approach through Employment New

Zealand and INZ to better respond to reports of exploitation.

c. a liaison service to support exploited migrant workers; and

d. proactive information and education to prevent exploitation.

3

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2020). Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (Cabinet paper

proactively released) Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (mbie.govt.nz)

4

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2020). Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (Cabinet paper proactively

released) Temporary migrant worker exploitation review – final proposals (mbie.govt.nz)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

52. The final piece of the 2020 Temporary Migrant Worker Exploitation Review to be implemented is

legislative change through the Worker Protection (Migrant and Other Employees) Bill. This will amend

the Immigration Act 2009, the Employment Relations Act 2000 and the Companies Act 1993 by

introducing an offence and penalty regime including disqualifying people convicted of migrant

exploitation and people-trafficking, from managing or directing a company. This legislation came into

effect on 6 January 2024 and is expected to be in force by the end of March 2024. The level of

applications and approvals for eligibility of the MEPV is another indicator of exploitation. In 2021 when

it was first introduced (for a half year – July-December), 63 MEPVs were issued. A further 125 were

issued in 2022, and in the first ten months of 2023, 652 MEPVs were issued. The measures to better

protect temporary migrant workers from exploitation, including the MEPV, means that there is now a

means for increased reporting of migrant exploitation. However, even with the MEPV available, for

those workers in exploitative positions it can be difficult to come forward and many people choose to

stay in their current situation rather than register for the MEPV. Reasons include fear of losing their visa,

facing deportation or other barriers, or concern regarding being unable to find alternative employment

during the 6-month term of the visa. This means that the number of MEPVs issued cannot be taken as a

measure of the extent of migrant exploitation in New Zealand, however, the increase in the number of

people applying for the MEPV can be seen as an indicator of a wider picture of migrant exploitation in

New Zealand.

Changes to Migration Patterns

53. The fact that over 236,000 Job Tokens have been issued over 15 months to the end of October 2023,

representing almost 3 times the regular annualised rate of migration, and with approximately 130,000

of those Job Tokens yet to be redeemed/converted into Working Visas and/or expiring unfilled,

suggests the potential for unusual migration activity, even when considering the pent-up demand as a

consequence of border closures and the exit of migrant labour over the Covid period. It’s unclear

what’s driving the increase in job token numbers however, it may be reflective the newness of the policy

and a tendency of employers to over-estimate the number of migrant workers required and therefore

increase the number of job tokens being sought to provide greater flexibility to respond to pressures

within their business.

54. The economic downturn experienced, and recent early indications of increasing unemployment rates

tend to indicate that the labour market demand is currently saturated in certain areas/sectors,

particularly relating to low/no skilled workers.

55. INZ have confirmed that the percentage of Work Visas granted to low/no skilled workers under AEWV

has significantly increased when compared to the previous work visa categories AEWV replaced and is

currently at 62% of Work Visas granted. This is approximately 20% higher than under the previous work

visas in place.

56. Post-COVID 19 pandemic, New Zealand continues to be a desirable destination for migrant workers and

is promoted as a safe country with good pay rates and the ability to get permanent residence quickly.

Early indications suggest a post-COVID pattern of a greater number of applicants with higher-risk

profiles applying for visas now than before as nationals from several countries experience a range of on-

going impacts post COVID-19, cost of living crises, and other pressures in their home country.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

The Immigration system – roles and responsibilities

The Minister of Immigration

57. The Minister of Immigration (and associate Minister(s) of Immigration under delegation from the

Minister) is responsible for the development of all immigration policy and legislation. Unlike most other

areas of government, the Minister also has decision-making powers about individual non-citizens.

58. The Immigration portfolio includes two pieces of primary legislation:

a. The Immigration Act 2009, which covers the immigration regulatory system; and

b. The Immigration Advisers Licensing Act 2007, which governs occupational licensing for providers

of immigration advice.

59. The legislation relevant to this review is the Immigration Act 2009 (the Act), which amongst other things

provides for “the development of immigration instructions (which set rules and criteria for the grant of

visas and entry permissions) to meet objectives determined by the Minister.”

5

MBIE and INZ

60. The administration and regulation of New Zealand’s immigration system is separated into multiple

units within MBIE. INZ is one of eight business units within MBIE. INZ administers the core operational

functions for visa processing. INZ is led by the Deputy Secretary Immigration, who reports to the

Secretary and Chief Executive of MBIE and is a member of the MBIE Senior Leadership Team.

61. The structure of the immigration system at MBIE is as follows:

a. INZ administers the core operational function.

b. The Employment Skills and Immigration Policy Branch within the Labour, Science and Enterprise

group, provides policy advice across the Immigration Policy teams.

c. The Immigration Advisers Authority within the Te Whakatairanga Service Delivery group provides

services to license people who provide New Zealand immigration advice and immigration

compliance and investigations, and includes the Labour Inspectorate, which enforces and

monitors minimum employment standards and the MBIE Customer Service Centre.

d. Lawyers from Legal, Ethics, and Privacy Team provide specialist first instance legal advice to

support immigration decision-making; and

e. The Digital, Data and Insights branch lead IT systems including ADEPT.

5

Immigration Act 2009 s3(b)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

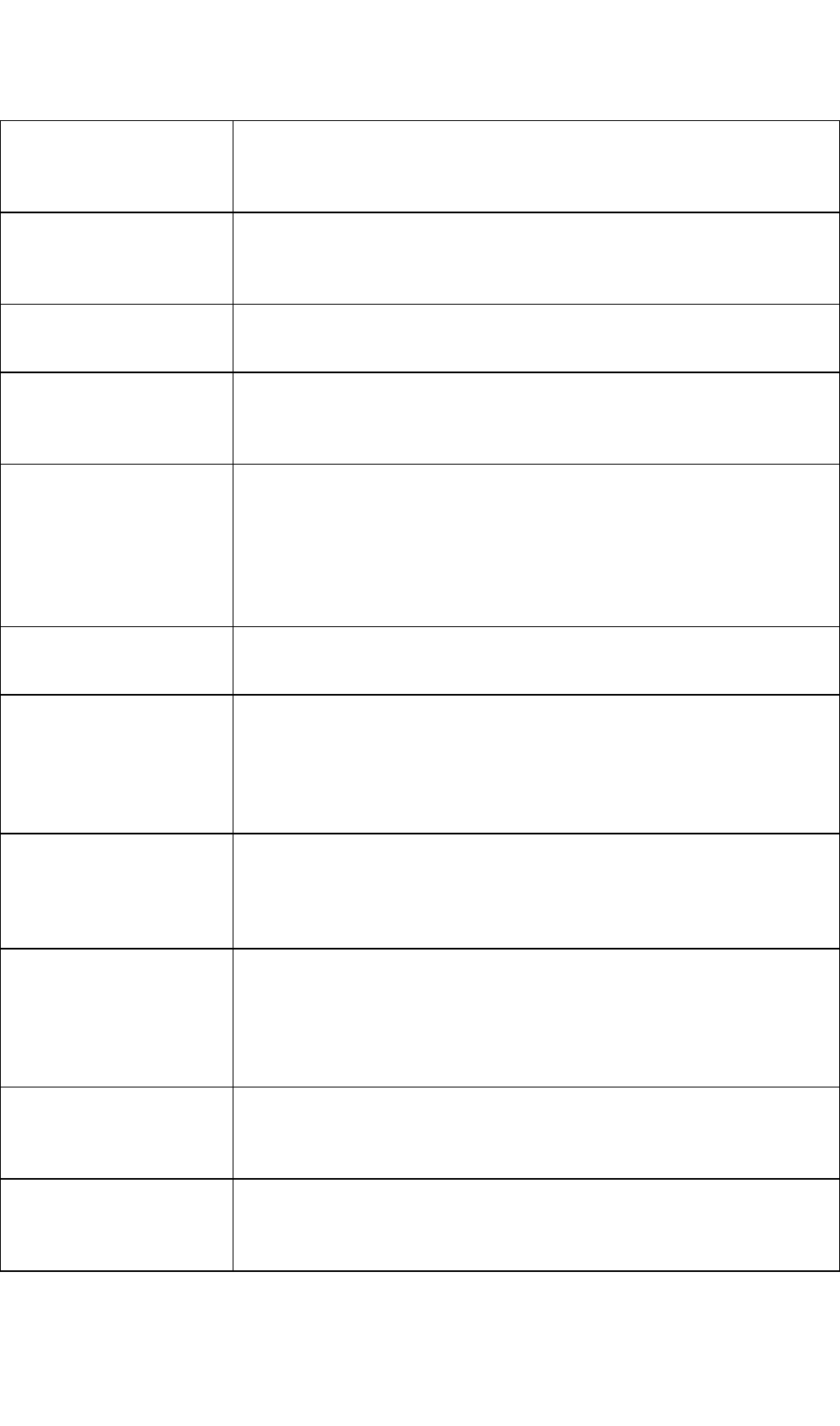

The following diagram represents the organisational structure of MBIE and INZ:

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

The policy and design of AEWV

62. As outlined in the Terms of Reference for this review (Appendix A), the policy underpinning the

development of the AEWV Scheme is outside of the scope of the Review and consequently the focus of

the Review has been on the implementation of the policy. However, for the purposes of discussing the

implementation of the Scheme, the policy objectives and settings are outlined below, including the

history and timeline of its development. A full timeline for the development and implementation of

AEWV is included in Appendix C.

63. Work on the development of a new working visa scheme commenced in 2017. The work was intended

to bring together the six existing visa categories into one: Essential Skills Work Visa; Essential Skills

Work Visa – approved in principle; Talent (Accredited Employer) Work Visa; Long Term Skill Shortage

List Work Visa; Silver Fern Job Search Visa (closed 7 October 2019); and Silver Fern Practical Experience

Work Visa.

64. Key policy objectives approved by Cabinet

6

underpinning the design of the Scheme were:

a. To provide increased certainty for employers in exchange for upfront checks.

b. Streamlined processes for genuine higher skill shortages.

c. A simplified system achieved through a reduction in visa categories.

d. Recognition that regions and sectors have different labour market needs.

e. An overall lift in the minimum standards for employing foreign workers.

f. Improved incentives on employers to recruit and train New Zealanders and to respond to skill

and labour shortages; and

g. Improved compliance and treatment of foreign workers and reduced exploitation risk.

The Policy Design

65. Following policy development work by MBIE Immigration Policy between 2017 and 2019, Cabinet

approved the design of a scheme to meet the policy objectives above, in August 2019. The Scheme was

known as the Accredited Employer Work Visa (AEWV) Scheme.

6

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2019). A new approach to employer-assisted work visas and regional workforce planning: Paper

One – Employer Gateway system and related changes (Cabinet paper proactively released). A new approach to employer-assisted work visas and

regional workforce planning: paper one - employer gateway system and related changes (mbie.govt.nz)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Employer-Led Scheme

66. The AEWV Scheme reoriented the focus of employment visas from migrant-led systems, which placed

responsibility on the aspirant migrant worker to collate and complete the visa application, to an

employer-led system where the onus is on the employer to provide assurance that they are a sound

business and that the need for a migrant is genuine, and in doing so requiring employers to provide

additional information about their businesses.

Three Gateway System

67. The AEWV Scheme design introduced three sequential processing gateways: the Employer

Accreditation gateway, the Job Check gateway, and the Work Visa gateway:

a. The Employer Accreditation gateway is where employers are required to satisfy basic

requirements associated with being a valid business and good employer, resulting in them being

accredited to hire migrants.

b. The Job Check gateway checks the job requirements of applications from accredited employers

to ensure that no New Zealander can fill the position being recruited to and that the terms and

conditions of employment are consistent with the Immigration Rules; and

c. The Work Visa gateway is where checks are made that the migrant is of good character and

health and is suitably qualified to do the job offered by the accredited employer.

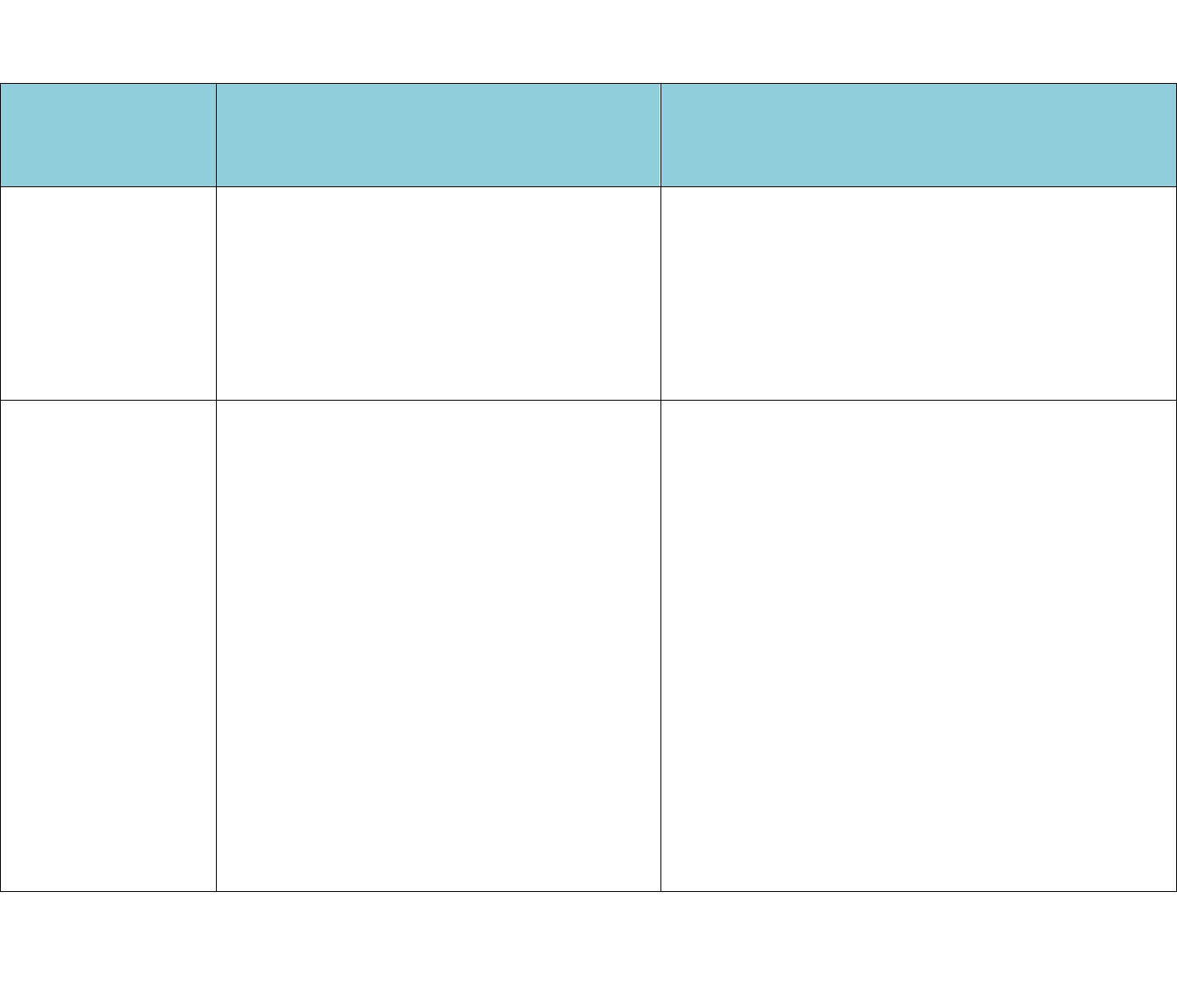

68. The following diagram outlines the Three Gateway System and the information required at each phase,

complete with the linkage to the Accredited Employer Risk and Monitoring Review activity described in

later sections.

Table 1 – AEWV Gateway process overview

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Gate 1 – the Employer Accreditation Gateway

69. The Employer Accreditation gateway was designed to achieve the following three standards:

a. That an employer must be operating a genuine business or other legitimate organisation.

b. The employer and key officers must have no recent history of regulatory non-compliance; and

c. The employer must take steps to minimise the risk of migrant exploitation. This includes

declaring they will: provide information to migrant workers about living and working in New

Zealand; provide migrants with time during paid work hours to complete online modules on

employment rights; pay all costs and fees for the recruitment of migrant workers both in and

outside of New Zealand; and not charge any fees to migrants outside of the country that would

be unlawful if charged in New Zealand.

7

It was intended that assurance activity to determine the

level of compliance with these requirements would be undertaken post-decision.

70. As part of the approval of the three gateways, in 2019 Cabinet also approved the establishment of three

categories of Accredited Employer, recognising the different labour market needs and risk profiles

associated with different employer groupings, namely:

a. Standard Employers – employers seeking five or fewer migrant workers in a twelve-month

period.

b. High-Volume Employers – employers seeking more than five migrant workers in a twelve-month

period and subject to further scrutiny as opposed to Standard Employers; and

c. High-Risk Employers – to cover Labour Hire companies with no limit on the number of migrants

an employer may seek to employ but with the greatest involved scrutiny required in the

accreditation process.

71. In 2021 the Minister agreed to a range of considerations that were required to be taken into account in

considering an employer’s ability to meet the standards outlined above. This included that INZ will

primarily rely on declarations from employers, supported by automated checks where possible, for

example, if organisation or key people are on the employer stand-down list, or if key people have been

banned from being involved with the management of a business in New Zealand. In meeting the

standard of a genuine employer, where specific risk indicators are flagged (e.g., the business has been

trading for less than 12 months), further documentation may be requested to verify that the employer is

a genuinely operating business. Other verification was to be carried out as part of post-decision

assurance.

72. Employers falling into the high-risk business model definition, which was expanded in 2021 to include

all triangular employment arrangements and franchisees, were subject to further scrutiny that included

their accreditation only lasting for 12 months, being subject to site visits, greater up-front verification

scrutiny, and more post-decision verification.

7

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (23 March 2021). Briefing to Minister of Immigration – Employer Assisted Temporary Work Visa

Reforms – Employer Gateway proposals.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

73. High-risk employers additionally had to demonstrate that they were only contracting migrant workers

to compliant businesses (i.e. those who meet employment standards consistent with those committed

to by the accredited employer), that they have good systems in place to monitor employment and

safety conditions on site, and that they have a history of contracts for placing New Zealand workers

8

.

Gate 2 - Job Check Gateway

74. The design intention underpinning the Job Check gateway was that migrant labour was only to be used

to supplement the available New Zealand labour market and that labour market risks, such as

underinvestment in training, displacement of New Zealanders, and wage suppression, be reduced.

75. The Job Check gateway design incorporated a requirement that a labour market check be undertaken

to ascertain whether a New Zealander was available to do the work. The design involved both a

requirement that the job be advertised, and that the employer provide evidence that no suitable New

Zealander was available. Initially it was contemplated that where the employment involved lower-

skilled roles, information from the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) was required to ensure that

the role was not suitable for clients under its Job Seeker category.

9

In December 2021 Cabinet

introduced the median wage threshold for AEWV visas. This higher threshold meant MSD’s role was

redundant as it was intended MSD would only be reviewing roles below the median wage. A decision

was taken to exclude sector agreement roles below the median wage as well as these were areas of

agreed shortage.

76. Under the 2019 Cabinet paper

10

three pathways were to be available under the Job Check gateway: The

Highly Paid Migrant pathway, the Regionalised Labour Market pathway, and the Sector Agreement

pathway. Regardless of pathway, employers were expected to ensure that the job being offered paid at

least the current market rate.

77. The Highly Paid pathway would apply where the remuneration for the job being sought was over 200%

of the median wage and as a result an exemption from labour market testing would apply. The key

principle behind this was that high remuneration rates generally reflect a genuine skills shortage. Later

in 2022, the Green List (priority occupations for New Zealand) was created and effectively added to this

pathway.

78. The Sector Agreements pathway sought to acknowledge that certain sectors systemically have a high

reliance on migrant workers. This pathway was intended to provide a basis for recruitment of migrant

workers based on agreed and standardised conditions between government and sectors to meet policy

objectives such as:

a. improving wages and conditions.

b. reducing reliance on lower-skilled migrant workers; and

8

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2019). (Cabinet paper proactively released). A new approach to employer-assisted work visas and

regional workforce planning: paper one - employer gateway system and related changes (mbie.govt.nz)

9

www.workandincome.govt.nz/products/a-z-benefits/jobseeker-support.html

10

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2019). (Cabinet paper proactively released). A new approach to employer-assisted work visas

and regional workforce planning: paper two - the job gateway (mbie.govt.nz)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

c. incentivising the employment, training, and upskilling of domestic workers in order to provide a

balance between employing New Zealanders and migrant workers.

79. The Regionalised Labour Market test pathway was intended to provide greater opportunities to

potential New Zealand workers, whilst at the same time easing restrictions on employers employing

migrant workers, where the risk of domestic job displacement through wage suppression was small.

80. This pathway was intended to be coupled with a strengthened Labour Market Test that included

ensuring that the employer is accredited, has met obligations under sector agreements, advertised the

role sufficiently, committed to paying market rates, and have verification from MSD that no New

Zealander was available to fill the role. As noted above, in December 2021 the median wage threshold

was introduced, making the MSD check redundant.

81. Accordingly, a Briefing was provided to the Minister and Associate Minister of Immigration outlining key

criteria

11

.

82. Any employer applying for a Job Check was required to provide key information about the job, for

example:

a. minimum and maximum pay rate for the job.

b. proposed employment agreement.

c. evidence of advertising and a declaration only from the employer that no/not enough suitable

New Zealanders applied.

d. MSD vacancy number (if below median wage) – this requirement was removed under the

Immigration Rebalance in December 2021 (see below paras 83-84); and

e. A Job Check application might include an application for multiple roles and/or positions.

Assuming a Job Check application is approved, a Job Token or multiple Job Tokens may be

issued allowing the employer to progress to recruit a suitable migrant worker.

83. As referenced above, in December 2021, Cabinet agreed to an Immigration Rebalance, with changes for

employer-assisted workers and partners.

12

These changes were designed to ensure immigration

settings were balanced correctly as the country moved from near-zero inward migration through the

COVID-19 pandemic to open borders.

84. Perhaps the most significant change made under the Immigration Rebalance was the introduction of

the requirement that AEWV roles be paid above the median wage. This effectively removed the need for

the involvement of MSD in consideration of whether a New Zealander was available for a role as they

were only checking roles under the median wage.

11

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (22 June 2021). Briefing to the Minister of Immigration and Associate Minister of Immigration:

Employer-assisted temporary work visa reforms – job and migrant worker check proposals.

12

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (Dec 2021). (Cabinet paper proactively released). Immigration Rebalance: options for employer-

assisted workers and partners (mbie.govt.nz)

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

Gate 3 – Work Visa Gateway

85. The Work Visa gateway was designed to verify the identity, health status, and character of the migrant

and validate their ability to meet the qualifications and experience requirement for the role where

applicable.

86. The AEWV Scheme design contemplated that should a Work Visa holder wish to change their employer,

subject to the new employer being accredited and having a valid Job Token approved, the migrant

worker could apply to vary employment conditions on their visa

13

.

High Trust Model

87. A key feature of the policy design of the AEWV Scheme was that it was to be a “high trust” model.

88. The high trust model contemplated that the Employer Accreditation and Job Check gateways relied

significantly on employer declaration-based information for visa processing considerations. Assurance

relating to the validity of employer declarations was designed to be obtained through a post-decision

process called the Accredited Employer Risk Monitoring and Review (AERMR), which would in turn

inform the Employer Re-accreditation process. The review understands the high trust model differed

from previous work visa categories in this regard and was a significant departure from previous visa

category designs requiring a different approach to implementation of the policy.

Reaccreditation and Accredited Employer Risk Monitoring and Review (AERMR)

89. AEWV was designed with the need to carry out employer reaccreditation to provide INZ with assurance

that employers’ declarations were compliant with the declaration commitments made. For example,

the completion of employment standards, learning modules and settlement support activities.

Reaccreditation is an important aspect of the AEWV’s assurance designed to minimise migrant

exploitation.

90. The policy intent was for most employers to have a shorter first accreditation period of 12 months, with

renewals every 24 months after that for compliant employers. High-risk employers (franchisees and

those using triangular employment arrangements) would be required to renew their accreditation every

12 months, reflecting the historically higher risk of migrant exploitation associated with these business

models.

91. The initial policy intent as outlined to Cabinet

14

was for employers operating high-risk business models

to have upfront site visits as part of the employer accreditation process, and for this to also be a

requirement for any employers identified as higher risk under the standard and high-volume categories.

During more detailed design in 2021, the then Minister for Immigration agreed to remove this

requirement, noting instead that INZ will develop a risk-based prioritisation process that priorities

higher risk employers for more robust assessment and more site visits.

13

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (22 June 2021). Briefing to the Minister of Immigration and Associate Minister of Immigration:

Employer-assisted temporary work visa reforms – job and migrant worker check proposals

14

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2019). (Cabinet paper proactively released). A new approach to employer-assisted work visas

and regional workforce planning: paper one - employer gateway system and related changes (mbie.govt.nz).

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

92. Treatment of risks for AEWV were operationalised into pre-decision and post-decision. The pre-decision

risk and verification activities that INZ traditionally deploys during a visa assessment were limited in the

Employer Accreditation gateway because INZ held limited data on employers to inform employer risk

identification and analysis.

93. The AEWV Scheme design therefore relies on post-decision checks to ensure employers are complying

with accreditation requirements, with the ability to revoke accreditation if they are not. As well as

reaccreditation, the intent was to use post-decision risk monitoring through AERMR and other risk

monitoring and review to collect data and intelligence in the first year to build the data INZ holds on

employers.

94. AERMR activities were designed to be a combination of desk-based and site-based checks. Desk-based

checks leverage MBIE’s information holdings and open-source information to assess the accuracy of

employer declarations provided through the employer accreditation gateway and identify any

additional indicators of immigration risk.

95. The desk-based checks included information relating to the viable and genuinely operating business or

operational criteria, as well as compliance with specific employment, immigration and business

standards and settlement support activities. AERMR would also conduct site-based checks either from a

recommendation from a desk-based check, or by prescription for Triangular and Franchisee accredited

employers.

96. This Risk Monitoring and Review model was intended to ensure monthly post-decision reviews of

employers by INZ’s Risk and Verification function to ensure that data was captured to inform ongoing

risk analysis and findings and reported through to INZ’s risk governance groups to inform risk tolerance

and controls.

15

This approach was intended to ensure a circular risk management approach was

embedded into the system, in other words, a ‘learning system’.

97. INZ designed the AERMR process to conduct post-decision checks on 16 percent of employers in the

first year. Checks were specified as a combination of desk -based checks across a random selection of

employers as well as targeted site based checks on a sample of all accredited employer types with a

focus on franchisee and triangular employers and any business that have been referred through a

complaint or issue raised. The implementation of AERMR was deferred for six months as an operational

decision to move resources to address risk presenting elsewhere in the immigration system.

15

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (10 May 2022). (Internal memorandum). Risk Monitoring and Review Governance Group

Submission Paper: Pre-decision Immigration Risk Management Approach to the Accreditation Gateway for the Accredited Employer Work Visa.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

The Operationalisation of AEWV

Decisions made at the launch of AEWV

98. INZ made final operational policy decisions in the weeks before implementation, including decisions on

the visa processing standards for each gate. Visa processing standards were set at:

a. 10 working days for the Employer Accreditation gateway.

b. 10 working days for the Job Check gateway; and

c. 20 working days for the Working Visa gateway.

99. One of the key features of the AEWV system consistent with the High Trust design was an automated

visa processing platform called Advanced Digital Employer-led Processing and Targeting (ADEPT). The

system was designed to automate checking of employer declarations through several system rules

described in further detail below. This allowed for low touch where appropriate while allowing targeted

scrutiny and challenge where there were risk factors or concerns. However, because the development

of ADEPT was not completed sufficiently in advance of the commencement of AEWV operations,

processing times outlined above were not able to be tested and as such the operational impacts of

meeting the processing standards could not be understood by INZ.

Opening the Christchurch office

100. The launch of AEWV occurred at a time when MBIE, and within it INZ, were under immense pressure to

enable movement of people across the New Zealand border post the COVID-19 border closure.

Pressure on the Government and subsequently on MBIE, not only from the business community but

also from the wider New Zealand community, to allow migrant workers, students, and visitors to travel

to New Zealand was extreme. This translated into a requirement for urgency and timeliness of visa

processing, and also unprecedented volumes as a result of pent-up demand.

101. Due to the pandemic, and the Government’s decision to close the borders, INZ made the decision to

close additional offshore offices responding to the flow-on impacts of border closures and reduction in

revenue. This resulted in a loss of visa processing capability and capacity and created further pressure

on the operations as it planned to support the reopening of the border. Consequently, to operationalise

AEWV, and as part of its response to reopening the border, INZ made the decision to establish a new

Visa operations team in Ōtautahi Christchurch, to be ready for the launch of the Employer Accreditation

gateway.

102. During the period from March 2022 to November 2022, 200 people were recruited into the Christchurch

offices to process AEWV applications.

What happened when AEWV was launched?

103. On 23 May 2022, the first gateway for Employer Accreditation was launched at which time only the front

end of the system of ADEPT, the part that received and lodged the application was operational.

104. Within three days of opening 1,151 Employer Accreditation applications were received. The back end of

the system, where the application is processed, was not operational for another week.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

105. The Job Check gateway opened to applications on 20 June 2022. The design of this gateway required

several activities to be undertaken by Immigration Officers, a key feature of which was new for INZ. The

issuing of job tokens in response to an approved Job Check application was an entirely new activity.

This resulted in delays in processing times as Immigration Officers were required, under the policy

settings, to complete extensive assessment of draft employment agreements. This compounded

processing time delays. These issues, coupled with the high volume of applications, resulted in

significant slowing of visa processing beyond the 10-day commitment.

106. The Work Visa gateway was launched on 4 July 2022. There was a deliberate decision to allow migrants

to apply with their job token through ADEPT, but to operate a hybrid model of processing in AMS for a

short period of time. This was to ensure that full development of functionality and testing of the

solution was undertaken before going live and that customers had a seamless interaction with the

system. This is more fully outlined below.

107. Due to the challenges and delays outlined above, initial processing times for AEWV were slow and did

not meet the published processing standards. As of 27 July 2022, the Job Check gateway had been

operational for just over 5 weeks. In that time 2896 Job Check applications had been received but only

329 (11%) had been completed. Similarly, as of 23 August 2022, the Work Visa gateway had been open

for just over 7 weeks with 2284 applications received, of which only 139 (6%) had been completed.

Policy changes impacting Immigration Instructions for AEWV

108. Visa processing relies on a range of tools and instruments, some of which are statutory while others are

operational.

109. Immigration Instructions are the statutory tool whereby the rules associated with a Visa Product are set

and give effect to the policy setting for the visa product. Immigration Instructions are established under

section 22 and 23 of the Immigration Act 2009. They are certified by the Minister of Immigration and

must be published and publicly available. The changes documented below respond to policy changes

approved either by Cabinet or by the Minister. To support the launch of AEWV, Immigration Instructions

relating to the Scheme were made publicly available prior to go-live. They became operational on the

date of issue, indicated below:

a. Employer Accreditation Gateway 23/05/2022

b. Job Check Gateway 20/06/2022

c. Work Visa Gateway 04/07/2022

110. The Immigration Instructions relating to the Job Check gateway were amended on 31 October 2022, to

reflect the first six sector agreements (for care workforce, construction and infrastructure, meat

processing, seafood, seasonal snow, and adventure tourism).

111. On 5 December 2022 the Job Check Immigration Instruction was introduced so that migrant workers

who wished to change their employer were not tied to their original employer.

112. A further amendment to the Job Check Immigration Instruction was issued on 26 April 2023 reflecting

the seventh sector agreement (transport).

113. In October 2023, an amendment to the Job Check Immigration Instructions reflected the ban of the 90-

day trial period being included in employment contracts for migrant workers under AEWV.

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

114. Despite these changes, the three substantive Immigration Instructions issued for each of the gateways

remain largely unchanged.

Decision to amend risk tolerances

115. Given the pressure to allow workers into New Zealand and challenges being experienced by INZ in

meeting published visa processing time standards resulting in delays in visa approvals, it quickly

became apparent that further changes were needed. Three options for resolution of these delays were

considered by INZ:

16

a. further automation in the ADEPT system.

b. additional processing resource; and

c. changes to risk tolerance.

116. Documents provided to the Review indicate that INZ considered neither automation nor increasing

resources to be practical options within the required timeframes. For further automation to be

developed into ADEPT additional data to support the development of risk rules was required. Given the

short operating time of the system there was deemed to be insufficient data to proceed with this

option. In addition, the lack of availability of technical resources to undertake any development in the

system meant that further automation was not a viable option.

117. The option of increasing processing resources was also dismissed due to the lead times resulting from

recruitment and training requirements and the demand on the other parts of the immigration system

associated with reopening the border.

118. Consequently, the option left to INZ, to adjust the risk tolerance to accept more risk, was deemed the

most pragmatic option available at the time. This was enabled through the giving of General

Instructions.

119. In selecting this option, INZ considered that the risk trade-off from reducing the extent of Immigration

Officer scrutiny of applications across the Job Check and Work Visa gates could be mitigated as follows:

a. by the post-decision reviews (AERMR), designed to identify risk trends and inform risk settings

over time, which were to commence as soon as possible.

b. by increased Risk Management and Review to be undertaken by INZ’s Risk & Verification Team.

c. by the reaccreditation of employers, which was to be undertaken after the first 12 months; and

d. by the proposed reduction in processing scrutiny being in place for only a short period of time,

namely two months per the original proposal.

17

16

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (25 July 2022) Internal Memo: Operational Levers to Clear Current Job Check Queue

17

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (30 September 2022) Internal Memo: Review of Operational Levers to Enhance Accredited

Employer, Job Check and Work Visa Processing

[UNCLASSIFIED]

[UNCLASSIFIED]

120. While the immediate solution applied by INZ was to change risk tolerances, additional solutions were

pursued in the following months, including moving additional staff from other visa category processing.

General Instructions

121. Under Section 26(4) of the Immigration Act 2009, the Chief Executive may give General Instructions. The

Chief Executive has the ability to delegate this action and has established delegations to the Deputy

Secretary of INZ and the Chief Operating Officer, INZ.

122. In accordance with the Act the Chief Executive or delegate may give General Instructions to Immigration

Officers on the order and manner of processing any visa application. The intention behind the

introduction of the General Instructions of AEWV applications was to improve processing times by

reducing some of the manual checking required, to focus the attention of immigration officers to areas

where risk was thought most likely to be present, and to make operational changes to better

manage risk following the first few weeks of processing.

123. The six General Instructions given for AEWV to date are outlined in Table 2 below:

Table 2- Summary of General Instructions given

General Instruction

No. and Gateways

impacted

Summary of the eect of the General Instruction

Period over which the General

Instruction was in place

Changes to settings

1 – Job Check Gateway

This General Instruction limited, for some cases:

checking of the employer regarding acceptability

of the employment; the requirement to calculate

remuneration; the requirement to determine the

genuineness of the vacancies; and the

requirement to determine that suitable labour

market testing had been undertaken.

Authorised by the Deputy