18 Journal of Nursing Regulation

Nurse Practice Acts Guide and Govern:

Update 2017

Kathleen A. Russell, JD, MN, RN

The state’s duty to protect those who receive nursing care is the basis for a nursing license. That license is an authorization

or permission from state government to practice nursing. The guidelines within the state nurse practice act and the state

nursing regulations provide the framework for safe, competent nursing practice. All nurses have a duty to understand their

nurse practice act and regulations, and to keep up with ongoing changes as this dynamic document evolves and the scope

of practice expands.

Keywords: Board of nursing, education standards, licensure, nurse practice act, nursing regulation, public protection, scope of practice

Learning Objectives

⦁

Recall the history of nurse practice acts (NPAs).

⦁

Describe the eight elements of an NPA.

⦁

Discuss disciplinary action, including grounds and possible

actions.

⦁

Name the ways that licensure status and board of nursing

(BON) actions are communicated to the public.

⦁

Identify the purpose of state involvement in the regulation of

nursing practice.

P

ermitting a new driver to get behind the wheel of a car

requires the driver to know the laws governing driving;

however, the laws do not tell the whole story. For example,

what is a driver to do when entering an unprotected intersection?

What governs the driver’s movement into the intersection? How

does the driver account for the weather, vehicle, and road condi

-

tions? What is the driver’s knowledge and experience level? Any

new driver needs guidance or rules to manage the inherent risks.

Inherent risks are also a part of nursing. Patients are ill;

medications and treatments have benefits and adverse effects; clini

-

cal situations are undetermined, open ended, and highly variable

(Benner, Malloch, & Sheets, 2010, p. 6). Providing nursing care

sometimes feels like the new driver navigating that unprotected

intersection. As with the new driver, education and standards pro

-

vided by laws and regulations designed to protect the public pro-

vide guidance in nursing practice.

Nursing requires specialized knowledge, skill, and indepen

-

dent decision making:

The practice of nursing involves behavior, attitude and judg

-

ment, and physical and sensory capabilities in the applica-

tion of knowledge, skills, and abilities for the benefit of the

client. Nursing careers take widely divergent paths—prac

-

tice focus varies by setting, by types of clients, by differ-

ent disease, therapeutic approach or level of rehabilitation.

Nurses work at all points of service in the health care system

(Sheets, 1996).

A layperson does not necessarily have access to health profes

-

sional credentials and he or she does not ordinarily judge whether

the care received is delivered according to standards of care.

Because health care poses a risk of harm to the public if practiced

by professionals who are unprepared or incompetent, licensed pro

-

fessionals are governed by laws and regulations designed to mini-

mize the risk.

Additionally, nurses are mobile and sophisticated, and they

work in a society that is changing and asymmetrical for consum

-

ers. The result is that the risk of harm is inherent in the intimate

nature of nursing care. Thus, the state is required to protect its

citizens from harm (Sheets, 1996). That protection comes in the

form of reasonable laws to regulate occupations such as nursing.

Consequently, these laws include standards for education, scope of

practice, and discipline of professionals.

History of Nurse Practice Acts

Before the Industrial Revolution, individuals could evaluate the

quality of services they received. Many communities were small,

and everyone knew everyone. Basic needs were met mostly by each

family, and when people turned to others, they knew the reputa

-

tions of those who provided services. At that time, anyone could

call themselves a nurse. However, as technology and knowledge

advanced, a variety of people and groups began to provide services

(Sheets, 1996). Individuals were no longer good arbiters of the

quality of a provider or a service:

The Progressive Era (1890–1920) in the United States was

a wellspring of innovative ideas and industrialization. The

era saw advancements in science, urbanization, education,

Continuing Education

www.journalofnursingregulation.com 19Volume 8/Issue 3 October 2017

and law, which in turn led to remarkable social, economic,

and political reform; however, it was the confluence of these

factors that led to the modernization of the professions and

the idea of professional regulation and licensing (Alexander,

2017).

Regulation implies government intervention to accom

-

plish an end beneficial to its citizens. Because the United States

Constitution does not include provisions to regulate nursing, the

responsibility falls to the states. Under a state’s police powers, it

has the authority to make laws to maintain public order, health,

safety, and welfare (Guido, 2010, p. 34). In addition to the state’s

need to protect the public, nursing leaders wanted to:

legitimize the profession in the eyes of the public, limit the

number of people who hired out as nurses, raise the quality

of professional nurses, and improve educational standards in

schools of nursing (Penn Nursing Science, 2012).

The first nurse registration law was enacted in 1903 in

North Carolina, and it was written to do just that—protect the

title of nurse and improve the practice of nursing. Developing

nursing examinations and issuing licenses was entrusted to the

North Carolina Board of Nursing (North Carolina Nursing

History, 2017). New Jersey, New York, and Virginia passed regis

-

tration laws later that same year. These early acts did not define the

practice of nursing; however, in 1938, New York defined a scope

of practice for nursing (NCSBN, 2010). By the 1970s, all states

required licensure for registered and practical nurses.

Advanced practice nurses can be traced to the Civil War,

when nurses assisted with anesthesia services during surgery

(Hamric, Spross, & Hanson, 2005, p. 4). Advanced practice reg

-

istered nurse (APRN) roles and specialization have continued to

this day, as has the evolution of formal scope of practice language

within legislative statutes.

Nurse’s Guide to Action

How could a law function as a guide to action if almost no one

knows it (Howard, 2011, p. 30)? The laws and regulations for

the nursing profession can only function properly if nurses know

the current laws and regulations governing practice in their state.

Laws governing individual health care providers are enacted

through state legislative action. Regulatory authority is derived

from legislative action. Whereas a state constitution forms the

framework for state governments, legislatures enact laws that grant

specific authority to regulatory agencies. For example, a state leg

-

islature enacts an NPA to regulate nursing and delegates author-

ity to the state boards of nursing (BONs) to enforce the NPA.

The mission or purpose of the BON is to protect the public. State

legislatures delegate many enforcement activities to state admin

-

istrative agencies. This delegation of regulatory authority allows

the legislature to use the expertise of the administrative agencies

in the implementation of statutes.

All states and U.S. territories have an NPA and a set of

regulations or rules that must be considered together. The broad

nature of the NPA is insufficient to provide the complete guidance

for the nursing profession. Therefore, each state develops rules or

regulations that seek to clarify or make the NPA more specific.

Regulations and rules must be consistent with the NPA and can

-

not extend beyond it. These regulations and rules undergo a pro-

cess of public review before enactment (NCSBN, 2011a; Ridenour

& Santa Anna, 2012, p. 504). Once enacted, regulations and rules

have the full force and effect of law.

Although the specificity of NPAs varies among states, all

NPAs include:

⦁

definitions

⦁

authority, power, and composition of a BON

⦁

educational program standards

⦁

standards and scope of nursing practice

⦁

types of titles and licenses

⦁

protection of titles

⦁

requirements for licensure

⦁

grounds for disciplinary action, other violations, and possible

remedies.

Specific NPA and regulations may be located on the BON

website. Additionally, the NCSBN Nurse Practice Act Toolkit

(NCSBN, 2017a) includes a Find Your Nurse Practice Act tool that

provides links to each state’s NPA and regulations. The NPA is

found as chapters in the state law or state statute. Regulations are

found in the state administrative code. Additionally, at least 18

BONs have created Nurse Practice Acts/Jurisprudence online, self-

paced continuing education courses (NCSBN Learning Extension,

2017).

Definitions

Terms or phrases used in statutes must be clear and unambiguous

for the intent of a law to be useful to legislators and citizens. A law

does not need to define terms that are commonly understood; how

-

ever, definitions are often included to avoid ambiguity about word

meanings. For example, encumbered, reinstatement, and reactivation are

often defined in NPAs. An encumbered license is defined as a license

with current discipline, conditions, or restrictions. Reinstatement is

different from reactivation in that reinstatement refers to reissuance

of a license following disciplinary action, whereas reactivation is

a reissuance not related to disciplinary action (NCSBN, 2012a).

Authority, Power, and Composition of a BON

The NPA grants authority to regulate the practice of nursing

and the enforcement of law to an administrative agency or BON,

which is charged with maintaining the balance between the rights

of the nurse to practice nursing and the responsibility to protect

the public health, safety, and welfare of its citizens (Brous, 2012,

p. 508). The membership and qualifications of the BON, terms of

office, meetings, and election of officers are specified in the NPA.

The BON is usually composed of registered nurses (RNs), licensed

20 Journal of Nursing Regulation

practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs), advanced practice nurses,

and members representing the public.

How BON membership is constituted depends on state

statute. Some states give the governor authority to appoint mem

-

bers to the BON after reviewing suggestions from professional

nursing organizations. Other states require nominations from pro

-

fessional organizations with appointment by the director or head of

the regulatory agency. Only in North Carolina are BON members

elected by the general public. In still other states, the legislature

appoints public members (Brent, 2012, p. 2). The BON typically

hires an executive officer, who has the authority to staff the office

with nurses, attorneys, investigators, and administrative staff.

Typically, the powers and duties of BONs include:

⦁

making, adopting, amending, repealing, and enforcing rules

⦁

setting nursing education standards

⦁

setting fees for licensure

⦁

performing criminal background checks

⦁

licensing qualified applicants

⦁

maintaining database of licensees

⦁

ensuring continuing competence

⦁

developing nursing standards of practice

⦁

collecting and analyzing data

⦁

implementing discipline process

⦁

regulating registered nurses

⦁

regulating unlicensed assistive personnel

⦁

hiring BON employees.

Educational Program Standards

Most U.S. BONs set standards for prelicensure nursing educational

programs and clinical learning experiences and approve such pro

-

grams that meet requirements of the NPA. These standards are

reflected in the rules that accompany the NPA. The prelicensure

program standards include accreditation, curriculum specifics,

administrator and faculty qualifications, continuing approval,

and approval of new, or withdrawal of approved, nursing educa

-

tion programs.

Specific curriculum rules often include necessary standards

of evidence-based clinical judgment; skill in clinical management;

biological, physical, social, and behavioral science requirements;

professional responsibilities; legal and ethical issues; patient safety;

and best practices of nursing.

Standards and Scope of Nursing Practice

Nursing care is both directed and evaluated by the NPA and regu-

lations/rules. The standards and scope of nursing practice within

an NPA are aligned with the nursing process. For example, com

-

prehensive nursing assessment based on biological, psychological,

and social aspects of the patient’s condition; collaboration with the

health care team; and patient-centered health care plans, includ

-

ing goals and nursing interventions, can all be language within

the NPA. Further standards include decision making and critical

thinking in the execution of independent nursing strategies, provi

-

sion of care as ordered or prescribed by authorized health care pro-

viders, evaluation of interventions, development of teaching plans,

delegation of nursing intervention, and advocacy for the patient.

Rules are often more specific and inclusive than the act. The

NPA may require safe practice, whereas the rules may specify a plan

for safe practice, requiring orientation and training for competence

when encountering new equipment and technology or unfamiliar

care situations; communication and consultation with other health

team members regarding patient concerns and special needs, sta

-

tus, or changes; response or lack of response to interventions; and

significant changes in patient condition (NCSBN, 2012a, 2012b).

The NPA typically identifies delegating and assigning nursing

interventions to implement the plan of care as within an RN’s scope of

practice (NCSBN, 2012a). The rules, however, spell out the RN’s

responsibility to organize, manage, and supervise the practice of

nursing. Indeed, the rules can delineate the specific steps for effec

-

tive delegation by an RN as ensuring:

⦁

unlicensed assistive personnel have the education, legal author-

ity, and demonstrated competency to perform the delegated

task

⦁

tasks are consistent with unlicensed assistive personnel’s job

description

⦁

tasks can be safely performed according to clear, exact, and

unchanging directions

⦁

results of the task are reasonably predictable

⦁

tasks do not require assessment, interpretation, or independent

decision making

⦁

patient and circumstance are such that delegation of the task

poses minimal risk to the patient

⦁

consequences of performing the task improperly are not life

threatening

⦁

RNs provide clear directions and guidelines regarding the task

(NCSBN, 2012b).

Title and Licensure

NPA language generally includes a statement regarding the title of

RN and LPN/VN. By specifying that the title of RN is “given to

an individual intended to practice nursing” and LPN/VN is “given

to an individual licensed to practice practical/vocational nursing,”

the NPA protects these titles from being used by unauthorized

persons and thereby protects the public (NCSBN, 2012a).

Each state’s NPA also includes statements regarding exami

-

nation for licensure as RNs and LPN/VNs, including frequency

and requisite education before examination and reexamination.

Additional requirements of licensure by examination typically

include:

⦁

application and fee

⦁

graduation from an approved prelicensure program or a pro-

gram that meets criteria comparable to those established by

the state

⦁

passage of the professional examination

⦁

attestation of no report of substance abuse in the last 5 years

www.journalofnursingregulation.com 21Volume 8/Issue 3 October 2017

⦁

verification of no report of actions taken or initiated against a

professional license, registration, or certification

⦁

attestation of no report of acts or omissions that are grounds for

disciplinary action as specified in the NPA.

The majority of jurisdictions include criminal background

checks as an additional requirement for licensure (NCSBN,

2012c).

Further requirements are also included in NPAs for licen

-

sure by examination of internationally educated applicants, licen-

sure by endorsement, as well as licensure renewals, reactivation,

and continuing education. Endorsement is an approval process for

a nurse who is licensed in another state. Obtaining licensure by

endorsement often includes prelicensure requirements and verifi

-

cation of licensure status from the state where the nurse obtained

licensure by examination (NCSBN, 2012a).

Although statutory language varies from state to state

regarding the licensure of APRNs, most states recognize clini

-

cal nurse specialist, nurse midwife, nurse practitioner, and regis-

tered nurse anesthetist as APRN roles and require certification by

a national nurse certification organization. Education and specific

scope of practice for APRNs varies from state to state.

Grounds for Disciplinary Action, Violations, Statute of

Limitations, Possible Remedies, and Reciprocal Discipline

The majority of nurses are competent and caring individuals who

provide a satisfactory level of care; however, when a nurse deviates

from the standard of care or commits an error, a complaint may

be filed with the BON. The BON, through its statutory author

-

ity specified in the NPA, is responsible for reviewing and acting

on complaints. A BON can take formal action only if it finds suf

-

ficient basis that the nurse violated the NPA or regulations. Each

case varies and needs to be considered on its own merits (Brous,

2012, pp. 510–511; NCSBN, 2012d). Since BONs take dis

-

ciplinary action in order to protect the public by ensuring that

only properly qualified and ethical individuals practice nursing,

this public safety objective is not time-limited. Therefore, in the

absence of a specific statute to the contrary, statutes of limitations

are inapplicable to BON license revocation and other disciplinary

proceedings (NCSBN, 2017b).

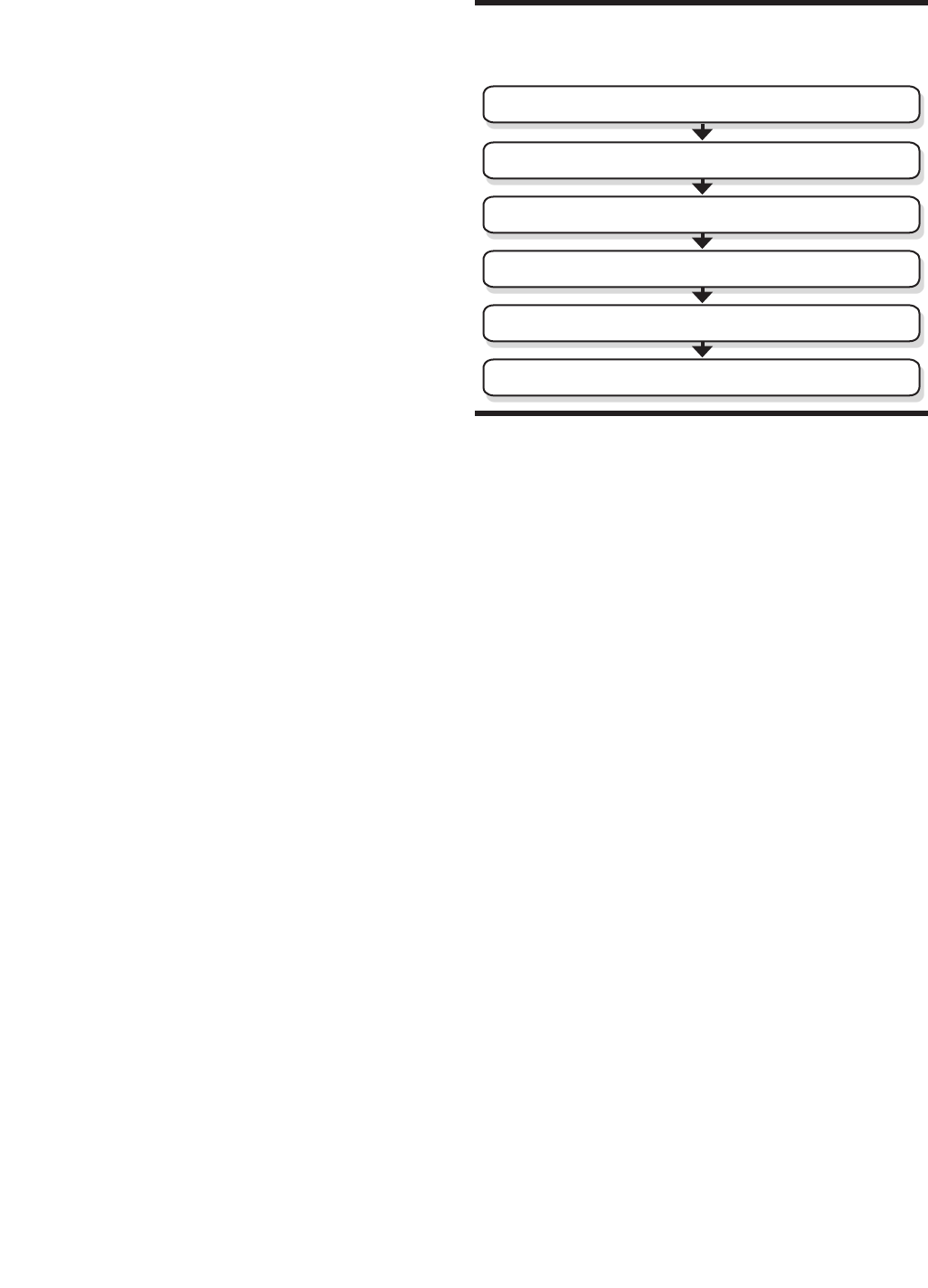

For an overview of the disciplinary process from receipt of

complaint to resolution, see Figure 1. Complaints about nursing

care are often grouped into the following categories:

⦁

Practice-related: breakdowns or errors during aspects of the nurs-

ing process (Wade, 2015)

⦁

Drug-related: mishandling, misappropriation, or misuse of con-

trolled substances

⦁

Boundary violations: nontherapeutic relationships formed

between a nurse and a client in which the nurse derives a ben

-

efit at the client’s expense (NCSBN, 2009)

⦁

Sexual misconduct: inappropriate physical or sexual contact with

a client

⦁

Abuse: maltreatment of clients that is physically, mentally, or

emotionally harmful (Russell & Wade, 2015)

⦁

Fraud: misrepresentation of the truth for gain or profit (usually

related to credentials, time, or payment)

⦁

Positive criminal background checks: detection of reportable crim-

inal conduct as defined by statute (NCSBN, 2011b, 2012e;

Russell & Beaver, 2013; Russell, 2016).

If a substance use disorder is suspected from the evidence,

some BONs may offer the nurse a nondisciplinary alternative-to-

discipline program. These programs are monitoring programs, not

treatment programs. The possibility of avoiding the public noto

-

riety of discipline can be a driving factor in breaking through the

nurse’s denial of substance use disorder and movement to a pro

-

gram that will assist in retaining her or his license. These programs

refer nurses for evaluation and treatment, monitor the nurse’s com

-

pliance with treatment and recovery recommendations, monitor

abstinence from drug or alcohol use, and monitor their practice

upon return to work. Alternative-to-discipline programs aim to

return nurses to practice while protecting the public. Various mod

-

els of alternative-to-discipline programs exist, and their use varies

among BONs (NCSBN, 2017c). Some programs provide services

via the BON, a contracting agency, a BON special committee,

a peer-assistance program of a professional association, or a peer-

assistance employee program (NCSBN, 2012f).

Some states have incorporated an alternative-to-discipline

program for practice-related complaints (NCSBN, 2016). These

programs seek to provide patient safety through timely education

and oversight (Holm & Emrich, 2015). This type of program shifts

the focus to improving practice and professional responsibility. To

participate in a practice-related alternative-to-discipline program,

the practice by the nurse must not pose a threat to patient safety.

These programs vary by state.

FIGURE 1

Board of Nursing Complaint Process

Filing a complaint

Initial review of complaint

Investigation

Board proceedings

Board actions

Reporting and enforcement

22 Journal of Nursing Regulation

For all other grounds, the final decision reached by the BON

is based on the findings of an investigation and the results of the

board proceedings. The language used to describe the types of

actions available to BONs varies according to each state’s statute.

Although terminology may differ, board action affects the

nurse’s licensure status and ability to practice nursing in the state

taking action. BON actions may include the following:

⦁

fine or civil penalty

⦁

referral to an alternative-to-discipline program for prac-

tice monitoring and recovery support for those with drug- or

alcohol-dependence or some other mental or physical condition

⦁

public reprimand or censure for minor violation of the NPA,

often with no restrictions on license

⦁

imposition of requirements for monitoring, remediation, edu-

cation, or other provision tailored to the particular situation

⦁

limitation or restriction of one or more aspects of practice, such

as probation with limits on role, setting, activities, or hours

worked

⦁

separation from practice for a period (suspension) or loss of

license (revocation or voluntary surrender)

⦁

other state-specific remedies (NCSBN, 2012g).

An attempt to evade disciplinary action merely by flee

-

ing the state does not protect the public. Therefore, a state board

of nursing is well within its legitimate authority to take action

against a licensee on the basis of another state’s disciplinary action

that implicates the individual’s ongoing ability and likelihood to

practice professionally and safely. This reciprocal or retained juris

-

diction action serves to assist the BON to fulfill the legislature’s

charge to protect the public (NCSBN, 2017b).

Public Access to Licensure Status and Board Actions

Licensure status and BON actions are public information, and

BONs use a variety of methods to communicate this information,

including newsletters, database and websites. Licensure infor

-

mation and board action for most states are also available to the

public via Nursys QuickConfirm License Verification

©

(Nursys

QuickConfirm

©

, 2017). Any individual or entity may use this ser-

vice free of charge.

Federal law requires that state adverse actions taken against

a health care professional’s license be reported to the federal data

bank. The National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) was estab

-

lished in 1986 by Congress as a workforce tool to “prevent prac-

titioners from moving from state-to-state without disclosure or

discovery of previous damaging performance” (U.S. Department of

Health & Human Services, 2017a). As such, the NPDB is a reposi

-

tory of reports containing information on certain adverse actions

related to health care practitioners, providers, and suppliers. The

data bank also includes information on medical malpractice pay

-

ments. Information housed within NPDB is not available to the

general public. Only authorized eligible entities may query the

NPBD. The NPDB Guidebook (U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services & Health Resources and Services Administration,

2015) contains specific information regarding authorized queri

-

ers, which generally includes hospitals, other health care entities,

professional societies, licensing boards, attorneys, and the licensee.

There is a nominal charge for an authorized individual or entity to

query the NPDB (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services,

2017b).

Being Informed About Your NPA

Ignorance of the law is never an excuse! The NPA and state regu-

lations are not resources one can study in a prelicensure nursing

education program and then put aside. The act and the regulations

are dynamic documents that evolve and are updated or amended as

changes in law or rules are made:

Inherent in our current healthcare system are changes which

relate to demographic changes (such as the aging of the

“baby boomers”); advances in technology; decreasing health

-

care dollars; advances in evidence-based healthcare proce-

dures, practices and techniques; and many other societal and

environmental factors (NCSBN, 2012h).

State BONs are resources for the NPA and regulations.

Links to NPAs are available on most state BON websites. Some

BONs attempt to provide new information to nurses via their web

-

site or newsletter (Tedford, 2011). For example, the Virginia BON

posts a list of frequently asked questions to help nurses navigate

the various aspects of licensure and posts announcements regard

-

ing practice or licensing changes on their homepage (Virginia

Board of Nursing, 2017). Use the Find Your Nurse Practice Act

tool (NCSBN, 2017a) or take your jurisdiction’s Nurse Practice

Act/Jurisprudence online, self-paced continuing education course

(NCSBN Learning Extension, 2017).

The state’s duty to protect those who receive nursing care is

the basis for a nursing license. That license is an authorization or

permission from state government to practice nursing. The guide

-

lines within the state NPA and the state nursing regulations pro-

vide the framework for safe, competent nursing practice. All nurses

have a duty to understand their NPA and regulations and to keep

up with ongoing changes as this dynamic document evolves and

the scope of practice expands. The guidelines of the NPA and the

regulations provide safe parameters within which to work and

protect patients from unprofessional and unsafe nursing practice

(Brent, 2012, p. 5; Mathes & Reifsnyder, 2014). More than 100

years ago, state governments established BONs to protect the pub

-

lic’s health and welfare by overseeing and ensuring the safe practice

of nursing. Today, BONs continue their duty, but the law cannot

function as a guide to action if almost no one knows about it. “To

maintain one’s license in good standing and continue practicing,

nurses must understand that rights are always accompanied by

responsibilities” (Brous, 2012, p. 506). It is your responsibility to

know your state’s NPA and rules before you enter that unprotected

intersection of nursing care.

www.journalofnursingregulation.com 23Volume 8/Issue 3 October 2017

References

Alexander, M. (2017). The evolution of professional regulation. Journal of

Nursing Regulation, 8(2), 3.

Benner, P. E., Malloch, K., & Sheets, V. (Eds.). (2010). Nursing pathways for

patient safety. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nurs

-

ing.

Brent, N. J. (2012). Protect yourself: Know your nurse practice act [Online CE].

Retrieved from https://www.nurse.com/ce/protect-yourself-know-

your-nurse-practice-act

Brous, E. (2012). Nursing licensure and regulation. In D. J. Mason, J. K.

Leavitt, & M. W. Chaffee (Eds.). Policy & politics in nursing and health

care (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

Guido, G. W. (2010). Legal & ethical issues in nursing (5th ed.). Boston, MA:

Pearson.

Hamric, A. B, Spross, J. A., & Hanson, C. M. (2005). Advanced practice nurs

-

ing: An integrative approach. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Holm, M., & Emrich, L. (2015). Justice with dignity alternative to discipline for

nurses with practice errors. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/2015_

DCM_Holm_Emrich.pdf

Howard, P. K. (2011). The death of common sense: How law is suffocating Amer

-

ica. New York, NY: Random House.

Mathes, M., & Reifsnyder, J. (2014). Nurse’s law: Legal questions & answers for

the practicing nurse. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International,

Center for Nursing.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2009). Professional boundaries:

A nurse’s guide to the importance of appropriate professional boundaries [Bro

-

chure]. Chicago, IL: Author.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2010). Nurse practice act—

Arkansas v4 [Online course]. Retrieved from http://learningext.com/

hives/c3ce5f555a/summary

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2011a). What you need to know

about nursing licensure and boards of nursing [Brochure] Chicago, IL:

Author.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2011b). State and territorial

boards of nursing: What every nurse needs to know [Brochure]. Chicago, IL:

Author.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012a). Model act. Chicago,

IL: Author.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012b). Model rules. Chicago,

IL: Author.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012c). The 2011 Uniform

Licensure requirements. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/

12_ULR_table_adopted.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012d). Filing a complaint.

Retrieved from www.ncsbn.org/163.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012e). Initial review of a com

-

plaint. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/1616.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012f). Board proceedings.

Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/672.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012g). Board action.

Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/673.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2012h). Changes in healthcare

professions’ scope of practice: Legislative considerations [Brochure]. Retrieved

from www.ncsbn.org/Scope_of_Practice_2012.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2016). Member board profile -

discipline, delegation, telenursing mbp 2016. Retrieved from https://www.

ncsbn.org/MBPD_D_TelehealthLinks.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2017a). Nurse practice act tool

-

kit. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/npa-toolkit.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2017b). Statute of Limitations

and Retained Jurisdiction. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/

Statute_of_Limitations_and_Retained_Jurisdiction.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2017c). Alternative to disci

-

pline programs for substance use disorder. Retrieved from https://www.

ncsbn.org/alternative-to-discipline.htm

NCSBN Learning Extension. (2017). Nurse practice acts/jurisprudence.

Retrieved from https://learningext.com/nurses/p/nurse_practice_acts

North Carolina Nursing History. (2017). A century of caring video. Retrieved

from https://nursinghistory.appstate.edu/century-caring-video

Nursys QuickConfirm

©

. (2017). QuickConfirm License Verification

©

.

Retrieved from https://www.nursys.com/LQC/LQCSearch.aspx

Penn Nursing Science. (2012). History of nursing timeline. Retrieved from

www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/Pages/timeline_1900-1929.

aspx?slider1=1#chrome

Ridenour, N., & Santa Anna, Y. (2012). An overview of legislation and reg

-

ulation. In D. J. Mason, J. K. Leavitt, & M. W. Chaffee (Eds.). Policy

& politics in nursing and health care (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

Russell, K. A. (2012). Nurse practice acts guide and govern nursing prac

-

tice. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 3(3), 36–42.

Russell, K. A. (2016). Due process and right-touch regulation strengthen

regulatory decision making. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 7(2), 39–42.

Russell, K. A. & Beaver, L. K. (2013). Professionalism extends beyond the

workplace. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 3(4), 15–18.

Russell, K. A. & Wade, A. (2015). When the court interprets legislative

intent: mandatory reporting of child abuse. Journal of Nursing Regula

-

tion, 6(1), 39–42.

Sheets, V. (1996). Public protection or professional self-preservation?

Unpublished manuscript, National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

Tedford, S. A. (2011, October). When was the last time you read the nurse

practice act? ASHN update. Retrieved from http://epubs.

democratprinting.com/publication/index.php?i=83957&m=&l=&

p=4&pre=&ver=swf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & Health Resources and

Services Administration. (2015). National practitioner data bank guide

-

book. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Ser-

vices. Retrieved from https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/resources/

aboutGuidebooks.jsp?page=DOverview.jsp

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2017a). NPDB national

practitioner data bank - about us. Retreived from https://www.npdb.

hrsa.gov/topNavigation/aboutUs.jsp

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2017b). NPDB national

practitioner data bank - Querying the NPDB. https://www.npdb.hrsa.

gov/hcorg/aboutQuerying.jsp

Virginia Board of Nursing. (2017). Board home. Retrieved from https://

www.dhp.virginia.gov/nursing/default.htm

Wade, A. (2015). The BON’s authority to interpret regulations, negli

-

gence, and nurse practice act statutes. Journal of Nursing Regulation,

6(3), 25–28.

Kathleen A. Russell, JD, MN, RN, is a Senior Policy Advisor,

Nursing Regulation, National Council of State Boards of Nursing,

Chicago, Illinois.

This continuing education article is an important update of the reasons for

and the significance of state nurse practice acts and associated regulations

originally published in 2012 (Russell, K. A. [2012]. Nurse practice acts

guide and govern nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Regulation,

3(3), 36–42).