Financial Reporting Standards:

Global Or International?

By Frederick Lindahl and Hannu

Schadewitz

Peer Reviewed

2

Frederick Lindahl is an Associate

Professor of Accountancy, The George

Washington University.

Hannu Schadewitz is a Professor of

Accounting, Turku School of

Economics, University of Turku,

Finland.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Huihong Tan, Yinka Dare, Jianing Liu,

Rami Katajisto, and Atte A. Salminen for their able research assistance.

This research has benefited from funding by the OP Bank Group

Research Foundation and the Turku School of Economics.

Abstract

Purpose – This paper studies quantitative, monetary information about

differences between IFRS and US GAAP in the three principal financial

statements.

3

Design/methods/approach – Comparative data from the same company

are compared. The explanations of differences are found in lengthy end

notes. The sample is from civil law countries with reputations for high

integrity, which reduces the possible confounding effects of legal systems

or earnings management. Sample countries are highly economically

developed, thereby reducing distortions that would result from different fair

value conditions.

Findings – A few key standards account for most of the monetary

differences between the accounting standards. In some cases large

differences in one direction offset large differences in the other direction,

reducing the insights obtainable from only comparing income.

Research limitations/implications – The window of data availability for

single company reporting under both standards was narrow. However,

because of convergence activities, these differences are likely slowly to

decline.

Originality/value – This is the only paper to examine the footnote

disclosure in sufficient detail to accurately measure differences. It is also

the only paper to analyze the cash flow statement. It is valuable for

financial analysts and academic researchers who study accounting quality

and make international comparisons.

I. INTRODUCTION

The world of corporate governance was radically changed when the

European Union, Australia, and New Zealand adopted IFRS applicable to

financial reports from 2005. EU adoption created a massive economic

bloc that used a common “language” to report financial results. For the

first time, those countries spoke the same “language”, and reports from

their companies were comparable with each other and with many other

IFRS countries throughout the world. It is largely agreed that IFRS is a set

of high quality accounting standards replacing local standards of varying

quality. Thus, these countries joined the US in using uniformly high quality

accounting. An important question is, “Are these two sets of high quality

standards comparable with each other?” While IFRS had some of its

origins in US standards, it is not clear how similar are final IFRS to US

standards.

4

This paper addresses that question. If US and IFRS standards

are similar, it can be said that standards are “global”; and that financial

reporting is comparable around the world. The comparability of reporting

would be increased if the US were to adopt IFRS. The US Securities and

Exchange Commission is studying whether to adopt IFRS as the US

standard (SEC 2012). The likelihood of this depends on the similarity of

the two sets of standards.

Motivated by these two crucial questions—the global character of

accounting standards and the likelihood of future uniformity--this study

offers evidence on the quantitative differences at the time of IFRS

adoption based on information available around the time of the change.

Convergence—increasing similarity—of accounting standards is an

expressed goal (“Norwalk Agreement” in 2002). However, progress has

been slow since the choice of accounting standards involves legal,

economic, political, and cultural factors. This paper addresses the core

issue: do IFRS and US GAAP provide similar accounting figures for the

same firm? We analyze this issue from the perspectives of (1) investors,

(2) financial analysts, and (3) academic researchers who investigate the

quality of financial reporting. We show the degree of similarity in these

data, which are the raw material for these three groups of users. Since

the needs for these three constituencies are not the same, we treat them

separately.

We know from many sources (e.g., KPMG, 2014; Baudot, 2014)

that the standards say different things. We know much less about whether

in practice these differences occur often and when they do occur, if they

lead to material differences in monetary amounts. Our contribution is to

measure, rather than verbally describe, differences between IFRS and US

GAAP.

There is vigorous debate among academics (Albrecht, 2008; Dye

and Sunder, 2001; Sunder, 2009), practitioners (Selling 2008), standard

setters, and regulators (Niemeier, 2008) about the relative strengths of US

GAAP and IFRS. For example, some argue that IFRS is the stronger set

because it is “principles-based” (Tweedie, 2007). Others argue that US

GAAP is equally “principles-based” (Kershaw, 2005) or that GAAP is

better because it has more “bright line” rules that limit earnings

management (Bratton and Cunningham 2009). Furthermore, accounting

5

research shows that IFRS is better than GAAP (e.g., Ashbaugh and

Olsson, 2002), and that GAAP is better than IFRS (e.g., Bradshaw and

Miller 2008). Much of the disagreement comes from the imprecision of

“better.” Some base their view on smaller analyst forecast errors, some

on “value relevance”, and some on “accounting quality” metrics (Dechow

et al., 2010).

Perhaps this debate has not reached consensus because the

participants in the debates have too little data, as mainly they have verbal

descriptions of differences. In this context, this research asks whether the

representations based upon IFRS and US GAAP deliver the same

mapping of economic events onto financial reports.

Contributions

The first contribution shows the degree of difference using actual

reported data. Investors often use numbers standing alone: “Has net

income increased?” We look at reported data from all three primary

financial statements, the income statement, the balance sheet, and the

statement of cash flows. We use the best information available: financial

statements for the period 2004 to 2006 that reconcile the two sets of

numbers. (The last year that the SEC required reconciliation was 2006.)

Secondly we contribute to financial analysis. Users often use

numbers in combination, e.g., as ratios, to assess profitability, liquidity and

risk. One can reach one conclusion based on analysis of the primary

numbers but a different conclusion from ratios. There are an infinite

number of ratios that could be computed. We choose from standard

textbooks a few important, widely used ratios to analyze differences

between the standards.

We also make a third contribution. Studies of “accounting quality”

draw judgments about the adequacy of standards. Much research

analyzes international quality differences. This research is built on the

premise that the properties of accounting numbers in different countries

can reveal underlying country differences in quality. It is important to know

if the premise is warranted, because this literature is often cited to support

quality differences between IFRS and GAAP (Hail et al., 2010; Kothari et

al., 2009). We contribute to the research on international accounting

differences by providing empirical evidence on the comparability of data

that researchers commonly use.

6

We do not judge which standards are better, or conclude on the

merits of harmonization. We offer new quantitative information that will

help others reach those conclusions.

Modes of analyses

In this section we explain the three modes of analysis that

constitute our research approach.

Reported data

This section addresses the reported data. It is important in

debating whether IFRS is better than GAAP to understand detailed, written

descriptions of differences (e.g., KPMG 2014). It is equally important to

see quantitative evidence about the importance of the different data in

practice.

Hail et al. (2010), in considering the choice of IFRS vs. GAAP, state

“proponents argue that … the remaining differences are small” (p.368).

However, this is based on qualitative differences and convergence

activities, as they do not cite numbers. Our study analyzes the remaining

differences from a quantitative viewpoint. We analyze the reported data

resulting from the two sets of accounting standards for the same

companies, one set prepared under IFRS and one under US GAAP.

We analyze the data reported in the three main financial

statements, including the cash flow statement. Cash flow reporting under

the two systems must be understood. It is one of the primary financial

statements. We first analyze the primary results such as net income.

Second, we analyze the data line by line. As we show, reading only the

line item labels in the reconciliation leads to misinterpretation of the

underlying accounting differences. Third, we choose a sample of

countries where there is a tradition of high quality accounting (as

described below) and where economic conditions are similar. In this way

we hope to avoid differences in accounting that may result from different

traditions of accounting quality (Bozzollan et al., 2009; Cascino and

Gassen, 2015) and different economic conditions that can affect, for

example, fair value accounting.

Financial analysis

7

The reason to compare financial ratios based upon alternative sets

of accounting standards is that, while the reported data are important in

themselves, they are often interpreted in relation to other data in the

financial statements. For instance, it is important to know net income, but

it is also important to know what resources were used to generate that

income; that is, “return on equity” tells users more than just earnings: the

former, how management used the assets entrusted to it, and the latter,

how effectively financial management engaged leverage.

Investment decisions are based on financial analyses applied

across firms. To interpret the results correctly, one must know whether

differences in the computed results reflect different economic performance

or differences due to accounting rules. Lev and Thiagarajan (1993) show

that fundamental information analysis, which rests heavily on financial

statement numbers, can have a substantial role in explaining excess

returns. We measure some differences that arise through the standards,

which can be isolated from financial performance because our comparison

is intra-company. This gives insight into the importance of the rule

differences.

Many financial ratios assess profitability using net income (Wahlen

et al., 2011), so valid comparisons require that the net income numbers be

comparable. In this paper we compare income, computed according to

IFRS and US GAAP. Since other ratios use line items (e.g., sales and

inventory to detect sales decreases or obsolete inventory), we analyze the

line items that lead to differences in net income. Further, we compare

shareholders’ equity (another measure common in financial analysis) and

cash flow (often an element of ratio analysis). It is indisputable that

different standards generate different numbers. Our question is “How

big?”

Accounting research studies

The third reason to compare the accounting numbers generated by

alternative sets of accounting standards is that accounting research often

uses reported data that are created according to different sets to assess

which countries’ financial reporting environments are better. The studies

use reported data to compare countries using different approaches such

as “value relevance” and “earnings quality.”

8

What are the potential pitfalls in these studies that stem from the

reported data? Researchers have increasingly conducted studies in the

area of international accounting using financial reports from many

countries (e.g., Barth et al., 2008; Ball et al., 2000; Brüggmann et al.,

2012; DeFond and Hung, 2007; Hail, 2007; Leuz et al., 2003; Pope et al.,

2011; Wysocki, 2005). In conducting studies of accounting quality, there

should be a clear understanding of the role of the reported data. When

one studies quality in different countries, one should not compare the level

of accruals as a measure of “earnings management” without

understanding that different accounting standards almost surely use

different accrual methods. Without making an adjustment for the different

methods, the researcher would attribute differences to “earnings

management” when in fact what he or she might have observed were

different accounting methods.

We find that studies often implicitly assume that differences

between systems are small enough that they do not require adjustments.

Our study shows that many of the differences are not small. Researchers

may consider whether empirical validity can be achieved if the differences

are ignored.

Our analysis may be useful in (a) assessing the strength of

conclusions drawn from past studies, and (b) designing future tests that

may better measure quality.

1

Some researchers have noted that there was a reconciliation

requirement, and then there wasn’t (e.g., Tang et al., 2012; Kim et al.,

2012). They investigate changes from the “before” to the “after” period.

They could make much better interpretation of the results if they knew

more than just that the reconciliation disappeared, and knew in addition

exactly what information—items and amounts—ceased with the

reconciliation.

Because researchers often pool cross-sectional with time series

data, there is a potential pitfall to using numbers from transition years and

treating them as if they were from a “steady state” application of different

accounting standards. Our study, done year by year, shows the extent of

this distortion.

9

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section we consider papers that analyze IFRS-GAAP

differences. Only a few studies have examined whether there are

significant IFRS vs. US GAAP differences that might result in non-

comparable measurements and interpretations of data from the separate

accounting regimes.

2

Ucieda Blanco and García Osma (2004) examined SEC filings and

found a number of material differences between IAS and US GAAP.

3

They used data from 1995-2001, so their findings are stale in light of the

IOSCO project (Flower 2004, chap. 7), recent changes in IAS, and the

process of convergence since Norwalk Agreement.

Street et al. (2000) analyze violations of IFRS. This was informative

about how indiscriminately “IFRS” was used among issuers. Many

companies that stated that their reports were in accordance with IFRS did

not follow those standards. Adherence to standards was problematic

during an earlier period and today´s standards are much changed. To

answer questions about size and magnitude, one cannot rely too much on

studies that used earlier data.

Henry et al (2009) describe differences between US GAAP and

IFRS net income and shareholders´ equity. They access the first three

years (2004-2006) of EU adoption data from the European companies that

file Forms 20-F. The basis for their sample (n=75) is that their firms are at

a “comparable stage of economic development to the United States” (p.

122). This is a desirable attribute for the study design, though it seems a

stretch to say that Hungary (a country in their sample) is at a stage

comparable with the US or that the level of accounting integrity is the

same.

4

Their sample is heterogeneous, drawn from northern and southern

European countries, and even from eastern Europe.

They classify line items by the label they find in the 20-F “rather

than the more in-depth, typically multi-page footnoted explanations” (p.

133). They present the line items on a before-tax basis and classify “tax”

10

on the reconciling item list as a separate adjustment, when in fact it is the

tax effect of all the other reconciling items.

5

They find higher net income under IFRS and lower shareholders´

equity. They analyse net income and stockholders´ equity, but not cash

flow. They find marginally significant evidence that net income differences

between 2004 and 2006 decrease, which they take as evidence of

convergence. Two data points are not strong evidence of convergence,

especially since they do not find a significant decrease between 2004 and

2005 or between 2005 and 2006. They also find that shareholders´ equity

is getting closer between 2004 and 2006, citing this as further evidence of

convergence. It is in fact the same evidence. Equity becomes closer when

retained earnings become closer; that is, converging net income

automatically converges the equity accounts in the long run, assuming

clean surplus equation. IFRS allows “first time adoption” provisions. It is

not really possible to judge whether a measured difference between net

income between 2004 and 2006 is convergence in the underlying

standards or the one-time effect of first-time adoption amounts.

Plumlee and Plumlee (2008) describe 100 IFRS-GAAP

reconciliations, measuring frequency and size of the individual line item

categories and the overall effects on profits and book value of equity. The

sample is a “random” (method not described) selection. They group the

line items into 22 classes of their own construction. They do industry

analysis and find differences in the reconciling items, as one would expect;

for example, firms in finance businesses have reconciling items related to

hedging more often than firms doing manufacture.

Gray et al. (2009) compare net income and shareholders’ equity for

2004-2006 and find IFRS income higher than GAAP and equity lower.

Gordon et al. (2013) use 156 Forms 20-F that reconcile IFRS and

GAAP for three years, 2004-2006. They evaluate accounting quality and

value relevance. They conclude that GAAP still differs from IFRS,

showing “incremental informativeness” over and above the IFRS numbers.

They also state that GAAP has higher “cash persistence” and value

relevance. They use cash flow measures, but do not adjust for differences

in reporting between GAAP and IFRS. They establish that differences

11

exist, and in that sense complements the first of our three research

contributions.

In sum, while all these studies contribute to proving that differences

exist between IFRS and US GAAP, our work explores how and why the

differences exist.

III. SAMPLE

We measure the dollar differences between GAAP and IFRS

uncontaminated by differences in national implementations of IFRS. To

achieve that, we use a sample of countries where there is a tradition of

sophisticated accounting, good enforcement, and similar conditions of

development (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany Luxembourg, the

Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland). Dissimilar conditions would result

in non-comparable numbers even with complete compliance. Fair value

accounting requires the use (when available) of similar assets traded in

active markets. But markets for traded assets vary around the world, so

“level 1” may be chosen in one country while “level 2” might be appropriate

elsewhere. Even if level 1 is feasible in both countries, different market

conditions might give different values.

To find countries with high quality accounting, one possibility would

be to rely on studies of “accounting quality.” However, many of these

studies are plagued by problem that they assume, without checking, that

data from different accounting standards are directly comparable. The

point of our paper is that it is necessary to validate that assumption before

drawing conclusions. It would be possible to rely on direct ratings of

accounting, but these are very old and are based on different regimes

(e.g., CIFAR (1995) is based on 1993 data).

By limiting the number of sample countries, we have the resources

to analyze every word of the reconciliation notes, which sometimes

exceed 20 pages. Nevertheless, we have a sample large enough for

reliable statistical inference. Our design emphasizes depth rather than

breadth.

We study all the U.S.-listed companies from our sample countries

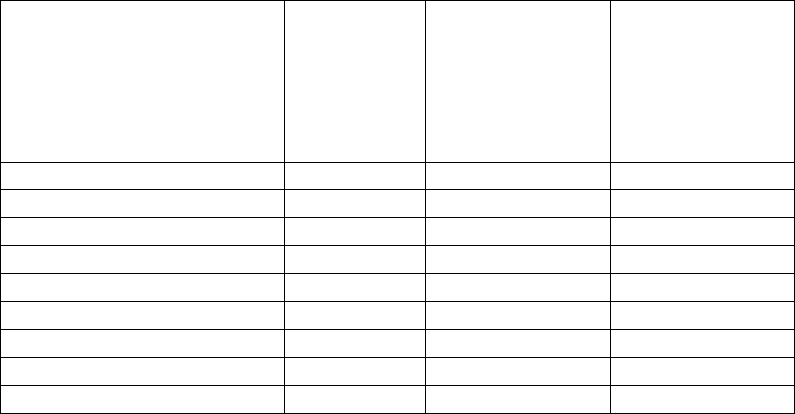

covering years 2004 though 2006. Table 1 below supports the quality

criterion. Table 2 below shows countries and sample size.

12

Table 1. Ranking of business integrity: proxies for accounting

excellence

Rank

4

Corruptions

Perception

Index

1

Global

Competitiveness

Report

2

(“ethical

behavior of

firms”)

World

Competitiveness

Yearbook

3

(“management

practices: ethical

practices”)

Belgium

20

21

17

Denmark

4

1

5

Finland

1

3

3

Germany

16

15

17

Luxembourg

11

11

12

The Netherlands

9

16

11

Sweden

6

18

9

Switzerland

7

10

13

Total countries in rating

163

117

117

Notes:

1. Corruptions Perceptions Index (Transparency International, 2006; McAdam and

Rummel, 2004)

2. Global Competitiveness Report (Ochel and Röhn, 2006; Lopez-Claros et al.,

2005)

3. World Competitiveness Yearbook (Garelli, 2004, p. 593)

4. Lower numbers are higher ratings.

Table 2. Sample description

Country

Number of

firms

Belgium

1

Denmark

3

Finland

4

Germany

8

Luxembourg

4

The Netherlands

8

Sweden

8

Switzerland

6

Total firms in sample

42

Notes:

1. The sample consists of all companies from the sample countries that report on

SEC Form 20-F.

2. Because of de-listings and mergers, year 2006 has 31 firms.

IV. RESEARCH METHODS

Our research method compares net income, shareholder equity,

and cash flow prepared under IFRS that also show reconciliation to US

GAAP. We compare absolute money amounts and relative figures

between IFRS and US GAAP. We also test the statistical significance of

the differences.

We collected data from SEC Form 20-F on every firm in our sample

countries that reconciles IFRS to US GAAP, 2004 to 2006. The SEC

requires this of all foreign private issuers, which either trade their shares in

the US or have certain types of American Depositary Receipts. Form 20-

F includes, as a note to the financial statements, the differences between

net income and shareholders’ equity under IFRS and under US GAAP.

The presentation starts with IFRS income (or equity), then shows the

reconciling amounts, and arrives at net income (or equity) under GAAP.

The reconciling amounts are also explained in written text, which is key to

understanding the differences.

One problem with relying on the label to the reconciling item, as

done in other studies, is that some line items include more than one

difference. Deutsche Telekom lists “Mobil Communications Licenses.”

Without reading the associated note, one cannot know that this includes

two IFRS-GAAP differences, one for recording impairment and one for

14

recording capitalized interest cost. In the same report is a line item called

“Fixed Assets.” This item includes both a capitalized interest difference

and an exception allowed by IFRS 1 for “deemed cost” of the assets.

Another factor that requires reading is that some items are labeled

as “other.” In sum, labels are not enough; to find the standards that differ

and by how much requires thorough analysis of the disclosure.

We report the net income difference and disaggregate it into its line

item components, both the relative and absolute importance of each. We

use the five largest items for each company. In cases where there are

fewer than five major items, we use them all. Nevertheless, in any case

we exclude an item less than ½% of IFRS net income. This captures all

reconciling items that are at least 1% of net income.

No prior research has compared cash flow statements. Cash flow

from operations (CFO) is a fundamental disclosure in financial reporting

(e.g., Fama and French, 1995). It is used in ratio analysis (e.g., Wahlen et

al., 2011, chapter 5), and in studies of IFRS value relevance (e.g., Gordon

et al., 2013; Banker et al., 2009). CFO is subject to classification

differences between US GAAP and IFRS (Stolowy et al., 2013). We

measure these differences to see whether CFO under GAAP is close

enough to CFO under IFRS that differences can be ignored.

V. RESULTS

We report first on whether there are material monetary differences

between IFRS and US GAAP. We take several approaches to measuring

the differences.

Reported data

Net income

Because many managers and analysts use earnings as a measure

of financial performance, we examine the income statement for differences

between IFRS and US GAAP.

Panel A of Table 3 below reports the aggregate dollar effects of

adjusting from IFRS to GAAP. In 2005 the mean is $2,180 million and the

15

median is $521 million.

6

The incomes for 2004 are smaller and for 2006

are larger under IFRS. Net income is positively skewed for the sample

under both accounting regimes.

Table 3. Income effects of reconciling items, IFRS to US GAAP

Panel A: Statistics compiled for whole sample

2006

2005

2004

(in $ millions)

Mean

%

med.

%

mean

3

%

med.

%

mean

3

%

med.

%

Net income, IFRS

2,971

100%

969

100%

2,180

100%

521

100%

1,628

100%

477

100%

Net income, US GAAP

2,664

89.7%

797

82%

1,983

91.0%

513

98.6%

1,635

100.4%

454

88.3%

Total of all reconciling

items

2

(difference in

rows above)

-307

-

10.3%

-196

-9.0%

6.5

-0.0%

Total of 5 largest

reconciling items

1

-123

-4.1%

-127

-5.8%

-55.7

-3.4%

Total of absolute mean

value of 5 largest

reconciling items

5

310

10.4

237

10.9%

308

19%

Panel B: US GAAP divided by IFRS net income, compiled firm-by-firm

2006

2005

2004

Average among firms, US GAAP / IFRS

98.6%

106%

4

105%

Standard error

34%

24%

4

38%

Median

98%

94%

97%

First quartile

88%

84%

92%

Third quartile

98%

99%

115%

Sample size

4

: 31, 42 and 42 for years 2006, 2005, and 2004.

Notes: This table shows the differences between net incomes compiled under IFRS and

US GAAP. Panel A shows the statistics for all firms in the sample combined. Panel B

computes the statistics for each firm, then shows the average across firms. Panel B

removes the possibility that one or two very large firms might be “driving” the results. It

shows that the reconciling items are pervasive throughout the sample.

1. The “5 largest reconciling items” refers to the five largest items for the

individual firm, not the five most frequent ones overall. For every sample firm

these five (or less) items include all reconciling items that are at least 1% of net

income.

2. The reconciling items are “after tax” numbers, directly comparable with net

income. The amount reported on Form 20-F is multiplied by (1-statutory tax

rate). The differences in net incomes under the two standards arise from the

net effect of the individual reconciling items.

3. The Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxin t-test rejects equality of IFRS and GAAP

distributions at a p-value less than 0.01 for the 2005 and 2006 samples, but does

not reject equality at the 0.10 level for 2004.

4. One firm is removed because a “small denominator” distorts the overall pattern.

This firm had net income close to zero. If that firm were included, the mean

would be 265% and standard error 102%.

5. The absolute value is computed by taking the algebraic mean of all firms for a

particular line item, then transforming that to an absolute value. It is not taking

the absolute value at the firm level, then averaging. The average value for a

firm of the five largest reconciling items as a percentage of IFRS income are 29%

for 2004, 45% for 2005, and 16% for 2006.

For the sample as a whole, we find that GAAP net income is lower

by 9.0% in 2005.

7

IFRS and GAAP mean earnings are statistically

different in 2005 and 2006 (p<.01), but the null of equality is not rejected

for 2004.

On the basis that the null of equality is not rejected, one might be

tempted to think that for 2004, IFRS and GAAP are so close that,

regardless of what the underlying standards say, the differences in

application have no economic significance. This is true only on average,

and only when looking at the “bottom line.” Table 3 shows the absolute

value of the five largest differences. The averages (e.g., 0.4% in net

income for 2004) hide big positive adjustments that are offset by big

negative adjustments. The absolute values of the adjustments are about

19% of net income in 2004 and 10-11% in 2005 and 2006.

18

Averages hide differences in line items, and they also hide

differences among firms. Figure 1 below shows large variation among

individual firms.

This analysis shows that the different accounting rules under GAAP

and IFRS create substantial differences in financial reports. Those who

argue about which system is better are addressing a relevant question

since the amounts differ substantially.

Frequency of income statement adjustments

“The reliability of an aggregated number, such as net income, is

likely to be a complicated function of the separate reliability of each of its

components” (Schipper, 2007, p.316). There are many possible causes

for line item differences, as found in the written comparisons of IFRS and

GAAP (e.g., KPMG, 2014). Table 4 below shows where the most

common differences occur in practice. A handful of differences accounts

for almost the entire amount of earnings differences.

Table 4. Frequency of occurrence of reconciling items among the

sample firms

2006

2005

2004

Pensions

17

Pensions

22

Goodwill

24

Goodwill

17

Financial instruments

22

Financial instruments

20

19

Financial instruments

13

Goodwill

18

Pensions

19

Impairments

11

Revenue recognition

16

Share-based

compensation

16

Revenue recognition

8

Share-based

compensation

12

Revenue recognition

13

Share-based

compensation

8

Restructuring

10

Restructuring

12

Restructuring

5

Impairments

10

Intangible assets

1

11

Debt

5

Intangible assets

(note 3)

9

Impairments

8

Fixed assets

5

Fixed assets

6

Deferred taxes

5

Interest capitalization

5

Debt

6

Acquisitions

5

Intangible assets

(note 3)

4

Acquisitions

5

Debt

5

Acquisitions

4

Interest capitalization

4

Development costs

4

Totals

102

140

142

Sample size 31, 42 and 42 respectively in 2006, 2005, and 2004. Because of de-listings

and mergers, year 2006 has 31 firms.

Notes:

1. All reconciling items that occur for at least 10% of the sample are reported here.

2. The table is compiled from the largest five reconciling items for each sample

firm. Every reconciling item for every firm is included if it is at least 1% of net

income.

3. “Intangible assets” does not include accounting for development costs, a

separate category for which we observed four reconciling items in 2005 and, as

shown, five in 2004.

Pension, financial instruments, and goodwill accounting are the

most common reconciling items, recorded by around half the firms. Many

of the items appear in all years.

Table 4 also reveals: (a) The top three or four items are all common

(no dominant adjustment); and (b) the same items appear in roughly the

same order of frequency in all three years, which is not surprising since

they are the same companies. The rank correlations for the items that

appear in both years are 0.93 for 2004-2005, and 0.90 for 2005-2006.

Dollar amounts of income statement adjustments

20

It is important to know not just frequency of differences, but their

magnitudes. Even if the differences are common, they do not matter if

they are small.

Tables 4 above and 5 below show that the frequency of items is not

highly correlated with the dollar amount. For example, for an individual

firm the pension adjustment is either the biggest or second biggest in 14 of

the 24 firms that made the reconciliation in 2005. By contrast, although

share-based compensation is ranked #5 in frequency in 2005, for only one

firm is it the largest.

Pensions, the most frequent item in 2005, have large dollar effects:

almost 1% of net income in 2005. But other items do not follow the same

pattern. Goodwill, for example, is the most frequent item in 2004, but the

magnitude is only 40% of what it is in 2005, when the frequency rank

drops to 3

rd

. These are sign reversals; the process that generates

accounting numbers for similar accounts in consecutive years is not a

stationary process.

Table 5. Largest reconciling items, as a percentage of IFRS

net income

2006

2005

2004

Derivatives and

hedging

-2.7%

Goodwill

-2.2%

Impairments

-2.3%

Intangible assets

1

1.5%

Derivatives and

hedging

2.0%

Pensions

-1.7%

Impairments

-1.3%

Financial instruments

-1.0%

Goodwill

0.9%

Pensions

-1.2%

Pensions

-0.9%

Intangible

assets

1

-0.9%

Deferred taxes

0.5%

Intangible assets

1

-0.8%

Restructuring

0.6%

Share-based

compensation

0.6%

Deferred taxes

0.6%

Interest capitalization

0.5%

Debt

-0.5%

Foreign

currency

-0.5%

Sample size 31, 42 and 42 respectively in 2006, 2005 and 2004

Notes:

1. The table is compiled from the largest five reconciling items for each sample

firm. Every reconciling item for every firm is included if it is at least 1% of net

income.

2. The minus number indicates that the item is reduced under U.S. GAAP relative

to IFRS.

3. All adjustments equal to at least 0.1% of IFRS net income are shown.

4. The reconciling items are “after tax” numbers, directly comparable with net

income. The amount reported on Form 20-F is multiplied by (1-statutory tax

rate).

Some items may occur rarely, and they are not big on the average,

but may be very significant for individual firms. Comparability, an objective

of the framework, is a firm-to-firm characteristic, not an average result.

Firm differences

As shown above in Table 3, there was a 9.0% mean reduction and

1.4% median reduction going from IFRS to GAAP in 2005. This does not

22

show how large the adjustments were for individual firms. In both 2005

and 2004, two different firms had reductions going from IFRS to GAAP

income of 50% or more.

Interest costs incurred in construction are an example. While for

the 42 firms, the effect is small, only 0.3% of earnings, for those firms that

experience borrowing in connection with large scale construction, the

average effect is +4.6%.

Equity values

The book value of equity accumulates all current and previous

income differences. It is the net of the assets and liabilities and may also

include adjustments that do not pass through the income statement.

If net income differs, then retained earnings differ. These are early

years of IFRS use, so there has not been time for IFRS-GAAP differences

to have become a large effect. Another difference can be IFRS No. 1.

This standard permits, under some conditions, “deemed costs” of assets,

which are not the same as costs that would normally be applied under

IFRS. Goodwill accounting under IFRS and US GAAP has been different.

Any adjustment of the asset accounts affects the equity accounts.

Impairment of goodwill affects asset balances for years or decades.

Those differences cumulate over years, so balances can become quite far

apart.

As Table 6 below shows, there are major differences in equity

values under the two sets of standards.

Table 6. Book Values of Shareholders’ Equity

1

2006

2005

2004

US GAAP

IFRS

US GAAP

IFRS

US GAAP

IFRS

Average

($ million)

2

16,739

15,936

12,970

11,825

11,913

10,263

Median ($ million)

5,001

5,175

4,364

4,269

3,624

3,838

Average ratio

(GAAP to IFRS)

1.11

1.10

1.15

Median

1.00

1.02

1.05

1

st

quartile

0.97

1.09

0.97

1.13

1.00

1.19

3

rd

quartile

Sample size

31

42

42

Notes:

1. Source of information is the reconciliation reported on Forms 20-F.

2. The Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxin t-test for equality of the IFRS and GAAP

distributions is rejected at the p=0.01 level for all samples.

We show that in equity, as well as earnings, there are considerable

differences, both at the firm and at the aggregate level. This is one more

reason why the choice between IFRS and GAAP matters, and invites

attention to the underlying reasons

Cash flow

The last element of the study is the classification of cash flows.

SEC policy did not require that IFRS cash flow reporting be reconciled to

GAAP. We took cash flow data from annual reports.

IFRS and GAAP differ in the allowable classifications, specifically

for interest paid and received, dividends paid and received and taxes paid

(Stolowy et al., 2013). IFRS, but not GAAP, allows alternatives.

Although the average effect is small, the averages mask substantial

effects for individual firms. More than 15% of firms in our sample use an

IFRS classification that does not match GAAP. The effect is understated

since not every firm reports these adjustable items separately, so they are

not always identifiable.

In this section we have reported on differences in all three primary

income statements, and we have done a “by firm” analysis. The

differences in the aggregate and at the firm level show that the choice

between IFRS and GAAP is meaningful.

Financial analysis

This section discusses our second analysis: whether the choice of

GAAP or IFRS makes a difference for financial analysis. If the choice

does create differences, then a considering which set of standards is more

reliable is important.

Net income

Net income is an element of most financial analysis. Measures

such as return on assets, return on equity, and return on sales are primary

measures of performance. We have shown that these amounts vary

considerably, the use of IFRS or GAAP may influence performance

evaluation.

Frequency and dollar amounts of income statement

adjustments

Large line item differences between IFRS and GAAP may offset

each other. For example, ROA for a particular firm may be very nearly the

same under either set of standards. This does not imply that the question

of “which is better” is moot. The “DuPont” formula points to different

elements having different significance.

8

Return on sales multiplied by

asset utilization equals ROA. If revenue recognition rules give higher

revenue from IFRS at the same time that fair value rules give a higher

asset base, then ROA might be close under the two standards. But the

two components could differ and lead to different conclusions about

“product profitability” (return on sales). Thus, a careful consideration of

which system gives the better analytical result can rest on individual line

items. Table 4 above shows that the differences caused by revenue

recognition principles are common and are large for some firms.

Financial analysis is done at the firm, not the aggregate level.

Variation of the individual items, not the average, matters in analyzing

firms.

Shareholders’ equity adjustments

As is the case of income, this measure is used in performance

evaluation. In some cases, the differences in net income and equity might

even accentuate the need for close evaluation of which set of standards is

better. For instance, net income (x) may be higher under one standard but

equity (y) is lower. The percentage differences in ROE measures (x/y)

exceeds the percentage differences of both x and y.

To see whether this is just conjecture or whether it is observed, we

compute the difference. Figure 2 below shows a substantial difference in

this performance ratio. Note that only about 20% of the firms are within

5% of each other, and a quarter differ by more than 15%.

Another common use of equity in financial analysis is in leverage

characteristics (Lantto and Sahlström, 2009). Having shown how widely

equity varies under IFRS in comparison with GAAP, it is probable that

IFRS and GAAP do not deliver comparable leverage measures.

Cash flow

Cash flow is used in financial analysis (e.g., Lev and Thiagarajan,

1993). For example, a measure like how many times cash flow covers

interest obligations approximates the risk of default on debt. It seems a

reasonable question to ask, for example, whether it is better to classify

dividends paid as operational or financing. We add to that the evidence

that the classifications are empirically different (Table 7 below), and that

they are significant for some firms.

Academic research

Net income

Measures of “earnings management” are used in a large area of

accounting (Dechow et al., 2010). A favorite measure is accruals, on the

belief that higher the correlation between a firm’s cash flows and its

income, the less use is being made of accruals as a means to manage

earnings.

Since accruals are the difference between income under IFRS and

GAAP, in measuring earnings quality with accruals, one must recognize

that the level of accruals is a matter of both discretionary adjustments to

manage earnings, and different accounting standards. Unless this is

understood, the researcher may mistake different accrual standards for

deliberate actions to mislead investors.

Frequency and dollar amounts of income statement

adjustments

Many accounting studies make use of line items to test their “value

relevance.” One research question might be whether the IFRS values are

more value relevant than the GAAP numbers. This study has been done

for income (Gordon et al., 2013), but not for line items. The value

relevance of items can differ only if the accounting numbers differ. Table 5

above indicates which items it might be candidates for value relevance

tests.

Shareholders’ equity adjustments

Accounting researchers believe that the ratio of book value of

equity to market value of equity measures future growth opportunities

(Collins et al., 1989; Kothari, 2001; Roychowdhury and Watts, 2007). If a

study combines firms that use IFRS with firms that use GAAP, the ratio will

be affected by (a) different growth opportunities and (b) different

accounting standards. So, once again, the question is whether the equity

figures differ enough so that (b), which is not controlled for, will distort

conclusions about (a)? This is addressed in Figure 3 below.

We present book to market ratio under the two sets of standards.

As shown in Fgure 3, they are not likely even to be close.

9

The researcher

is confronted with a dilemma. “Market” is the same in both cases, so if the

book-to-market ratio really does measure growth opportunities, then either

“book value” under IFRS or else “book value” under GAAP captures this

growth element better. For a large segment of firms the book-to-market is

larger under IFRS, and for another large segment it is smaller. It supports

the debate about which is better.

Cash flow

McGinnis and Collins (2011) study the role of analysts’ cash flow

forecasts in curbing earnings management. This study utilizes entirely US

data, but it would be natural to test the same thing using international data.

IFRS (but not GAAP) allows discretionary choices for classification of

some cash flow items (See Table 7 below.) In an international comparison,

the question may be: “What are analysts forecasting? Do they use the

companies’ conventions or do they use uniform classification?” For this

purpose, it is arguable that “GAAP is better” since it excludes discretion

and gives comparability in large data set studies where hand-collecting is

not done. Our evidence shows considerable differences among firms.

That fact should be addressed in designing research.

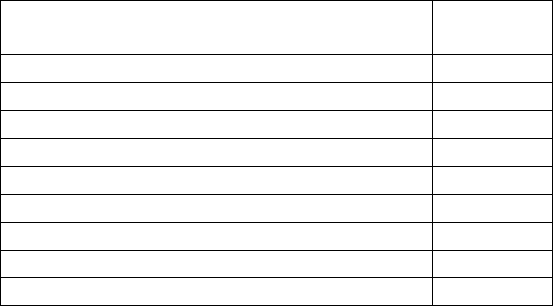

Table 7. Cash Flow from Operations, IFRS compared with US

GAAP

2006

2005

2004

Mean Ratio: US GAAP / IFRS

.973

.967

.995

Range: Low

.694

.750

.804

High

1.08

1.00

1.20

Number of observations

39

42

42

With differences

7

7

7

Note: Three of the original firms in the sample merged in 2006.

Some research studies make use of cash flow from

operations (CFO) as an input to measuring “accounting quality.” As

Gordon et al. (2013) show (using Dechow and Dichev, 2002),

discretionary accruals, a principal input to the earnings quality measure,

are calculated by subtracting CFO from net income. Clearly, if cash flow

from operations differs between IFRS and GAAP, then different

conclusions are possible. They are more likely the farther apart are the

CFO measures. Gordon et al. perform an international “accounting

quality” study, comparing earnings management results based on the

IFRS vs. GAAP viewpoint. They take the necessary step of basing the

accrual computation on two methods, one using net income from IFRS

and one using net income from GAAP. But they do not account for

different rules for measuring CFO.

Banker et al. (2009) measure the association of cash flows with

pay-for-performance and value relevance.

10

An interesting extension

would be to investigate whether the same associations are detected

outside the US. Since compensation policies in the US tend to differ from

those in Europe (e.g., more US use of stock options), the relation might be

expected to differ. But in an international comparison the conclusions

could be robust only if CFO were measured on a consistent basis.

CFO has an important role in financial analysis, so it is

important to know that the measures can differ, as table 7 above shows.

VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Here we summarize the three concerns that motivated this study.

First, we contribute to the policy debate over whether the US should

change to international standards. The farther apart the standards are,

the more important is this choice. If harmonization and convergence have

reached their goal, then the benefits from the US changing are small since

GAAP largely replicates IFRS. But the standards are still far apart, so the

decision is more complex. The comparability from a single set of

standards is an advantage, but if the quality is lower, then the higher costs

to investors is a disadvantage. This study does not attempt to assess

which standards are better, only to show that they are not very

comparable yet.

The detail shows that a handful of accounting principles drive a

significant difference in income and net assets. That handful causes large

differences on average. The differences are even more significant when

considered firm-by-firm. This is important since it is not an “aggregate”,

but firm level comparability that is the goal of accounting convergence.

We consider the GAAP-IFRS differences from the viewpoint of the

financial analyst who does analysis on a firm-by-firm basis. Even where

there are small average differences (e.g., in net income), those small

averages often hide a wide variability among firms. The goal of financial

reporting is to provide information for investors. Investors examine results

at the firm level. GAAP-IFRS differences have significant effects at the

firm level on indicators of financial performance and position such as

shareholder equity, net income, return on equity, and book to market ratio.

Academic research is often cited in policy deliberations (e.g.,

Niemeier, 2008). Research studies often involve items where there can

be large differences—income, line items, equity, and cash flows. In

summary, the line item differences can be large and occur frequently, but

there are not very many of these line items. For any one firm, five or fewer

of the differences explain almost the whole GAAP-IFRS reconciliation.

Since only a few standards cause most of the differences, then only

a few standards must be harmonized for the average numbers to become

comparable (though there may be other standards with big effects only on

a few firms).

Researchers can look at a few, known differences, and adjust them.

Even if making the appropriate adjustment is not feasible, at least the

direction of the bias in the results can be addressed. This study allows the

researcher to understand the most important differences in financial

reporting and representation. For example, a test of the hypothesis that

European companies invest less in product development would be biased

against rejecting the null. The future investigator must be aware that

changes in standards will reduce the longitudinal consistency of the

numbers. Users of data from these years should be mindful that a non-

stationary process generated these data, and the time series is unstable

(Box and Jenkins, 1976).

1

We use the term “accounting quality” as a blanket to cover studies of

“earnings management,” “earnings quality,” “information content,”

“conservatism,” and “timely recognition.”

2

Because of the small number of foreign private issuers that used IFRS

before 2005, there are many more studies that compare US GAAP with

local GAAP.

3

Foreign private issuers reconcile on SEC Form 20-F the accounting

results in accordance with the basis of preparation (e.g., IFRS) with what

the corresponding accounting results would have been under US GAAP.

The SEC required this for net income and shareholders’ equity until

November 2007.

4

In 2005, GDF per capita in the US was $44,308. In Hungary it was

$11,092 (World Bank, 2013).

5

“[T]axes, which require adjustment for nearly all sample countries” (134).

6

We convert everything to dollars at the rates prevailing in October 2006.

7

Net income is after tax, and we have tax-adjusted each line item. For

companies with net losses, we do not apply any tax adjustment.

8

Soliman (2008) shows that this is an important tool in financial analysis.

9

A test of means rejects the null of equality of book values at the p=0.003

level.

10

They use earnings as well as cash flows, so the points raised here also

apply to the “net income” section, above.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, D., 2008. Schedule for Against IFRS for the USA, The Summa–

Debits and Credits of Accounting. Available at:

http://profalbrecht.wordpress.com/2008/10/04/publishing-schedule/

Ashbaugh, H. and P. Olson, 2002. An exploratory study of the valuation

properties of cross-listed firms’ IAS and U.S. GAAP earnings and

book values. The Accounting Review 77 (1): 107–126.

Ball, R., S. P. Kothari, and A. Robin, 2000. The effect of international

institutional factors on properties of accounting earnings. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 29 (1): 1–51.

Banker, R. D., R. Huang, and R. Natarajan, 2009. Incentive contracting

and value relevance of earning and cash flows. Journal of

Accounting Research 47 (3): 647–678.

Barth, M. E., W. R. Landsman, and M. H. Lang, 2008. International

Accounting Standards and accounting quality. Journal of

Accounting Research 46 (3): 467–498.

Baudot, L., 2014. GAAP convergence or convergence Gap: unfolding ten

years of accounting change. Accounting, Auditing and

Accountability Journal 27 (6): 956–994.

Box, G. E. P. and G. Jenkins, 1976. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting

and Control. Holden-Day, San Francisco.

Bozzolan, S., M. Trombetta, and S. Beretta, 2009. Forward-looking

disclosures, financial verifiability and analysts’ forecasts: a study of

cross-listed European firms. European Accounting Review 18 (3):

435–473.

Bradshaw, M. T. and G. S. Miller, 2008. Will harmonizing accounting

standards really harmonize accounting? Evidence from Non-U.S.

firms adopting US GAAP. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and

Finance 23 (2): 233–269.

Bratton, W.W. and L.A. Cunningham, 2009. Treatment differences and

political realities in the GAAP-IFRS debate. Virginia Law Review 95

(4): 989-1023.

Brüggemann, U., J.-M. Hitz, and T. Sellhorn, 2012. Intended and

unintended consequences of mandatory IFRS adoption: A review of

extant evidence and suggestions for future research, European

Accounting Review 21 (1): 1-37.

Cascino, S. and J. Gassen, 2015. What drives the comparability effect of

mandatory IFRS adoption? Review of Accounting Studies 20: 242-

282.

Center for International Financial Analysis and Research (CIFAR), 1995.

International accounting and auditing trends. Center for

International Financial Analysis and Research Publications,

Princeton, NJ.

Collins, D. W. and S. P. Kothari, 1989. An analysis of intertemporal and

cross-sectional determinants of earnings response coefficients.

Journal of Accounting and Economics 11 (2-3): 143–181.

Dechow, P. M. and I. D. Dichev, 2002. The quality of accruals and

earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting

Review 77: 35–59.

Dechow, P.M., W. Ge, and C. M. Schrand, 2010. Understanding earnings

quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their

consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2-3):

344-401.

DeFond, M. and M. Hung, 2007. Investor protection and analysts’ cash

flow forecasts around the World. Review of Accounting Studies 12

(2-3): 377–419.

Dye, R. A. and S. Sunder, 2001. Why not allow FASB and IASB Standards

to compete in the U.S.? Accounting Horizons 15 (3): 257–271.

Fama, E. F. and K. F. French, 1995. Size and book-to-market factors in

earnings and returns, Journal of Finance 50 (1): 131–155.

Flower, J., 2004. European Financial Reporting, New York: Palgrave.

Garelli, S., 2004. World competitiveness yearbook 2004. International

Institute of Management Development (IMD), Lausanne.

Gordon, E. A., B. N. Jorgensen, and C. Linthicum, 2013. Are IFRS - US

GAAP reconciliations informative? Working paper, University of

Texas – San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Gray, S.J, C.L. Linthicum, and D.L. Street, 2009. Have “European” and US

GAAP measures of income and equity converged under IFRS?

Evidence from European companies listed in the US. Accounting

and Business Research 39 (5): 431-447.

Hail, L., 2007. Discussion of investor protection and analysts’ cash flow

forecasts around the World. Review of Accounting Studies 12: 421-

441.

Hail, L., C. Leuz, and P. Wysocki, 2010. Global accounting convergence

and the potential adoption of IFRS by the United States:

Conceptual Underpinnings and Economic Analysis. Accounting

Horizons 24 (3): 355-394.

Henry, E., S. Lin, and Y.-w. Yang, 2009. The European-U.S. ‘GAAP gap’:

IFRS to U.S. GAAP Form 20-F reconciliations. Accounting Horizons

23 (2): 121–150.

Hickey, A., 2011. US decision could make or break IFRS. GFS News,

available at http://www.gfsnews.com/article/2790/1/

IAS Plus, 2006. Deloitte website for global accounting news. Deloitte.

Available at http://www.iasplus.com/standard/ias01.htm

IASB (International Accounting Standards Board), 2004. Framework for

the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements, London.

Kershaw, D., 2005. Evading Enron: Taking principles too seriously in

accounting regulation. The Modern Law Review 68 (4): 594–625.

Kim, Y., H. Li, and S. Li, 2012. Does eliminating the Form 20-F

reconciliation from IFRS to U.S. GAAP have capital market

consequences? Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1-2):

249-270.

Kothari, S. P., 2001. Capital markets research in accounting. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 31 (1-3): 105–231.

Kothari, S.P., K. Ramanna, and D. J. Skinner, 2009. Implications for

GAAP from an analysis of positive research in accounting. Journal

of Accounting and Economics 50 (2-3): 246–286.

KPMG, 2014. IFRS compared to U.S. GAAP: An overview. Available at:

http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublicati

ons/IFRS-GAAP-comparisons/Documents/IFRS-compared-to-US-

GAAP-2014.pdf

Lantto, A-M. and P. Sahlström, 2009. Impact of International Financial

Reporting Standard adoption on key financial ratios. Accounting

and Finance 49 (2): 341–361.

Leuz, C. D., D, Nanda, and P. Wysocki, 2003. Earnings management and

investor protection: an international comparison. Journal of

Financial Economics 69 (3): 505–527.

Lev, B. and S. R. Thiagarajan, 1993. Fundamental information analysis.

Journal of Accounting Research 31 (2): 190–215.

Lopez-Claros, A., M. E. Porter, and K. Schwab, 2005. The global

competitiveness report 2005-2006. World Economic Forum,

Geneva.

McAdam, P. and O. Rummel, 2004. Corruption: a non-parametric analysis.

Journal of Economic Studies 31 (5-6): 509–523.

McGinnis, J. and D. W. Collins, 2011. The effect of cash flow forecasts on

accrual quality and benchmark beating. Journal of Accounting and

Economics 51 (3): 219-239.

Niemeier, C. D., 2008. Keynote address on recent international initiatives.

2008 Sarbanes-Oxley, Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC) and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)

Conference, New York State Society of Certified Public

Accountants (CPAs), New York City, Sep. 10.

Ochel, W. and O. Röhn, 2006. Ranking of countries—the WEF, IMD,

Fraser and Heritage Indices. The Center for Economic Studies, the

Ifo Institute for Economic Research (CESifo) Database for

Institutional Comparisons in Europe (DICE) Report 4, 48–61.

Pope, P.F. and S.J. McLeay, 2011. The European IFRS experiment:

Objectives, research challenges and some early evidence.

Accounting and Business Research 41 (3): 233-266.

Plumlee, M. and R. D. Plumlee, 2008. Information lost: a descriptive

analysis of IFRS firms’ 20-F reconciliations. Journal of Applied

Research in Accounting and Finance 3 (1):15–31.

Roychowdhury, S. and R. L. Watts, 2007. Asymmetric timeliness of

earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting.

Journal of Accounting and Economics 44 (1-2): 2–31.

Schipper, K., 2007. Required disclosures in financial reports. The

Accounting Review 82 (2): 301–326.

SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), 2010. Commission

Statement in Support of Convergence and Global Accounting.

Division of Corporate Finance, Office of the Chief Accountant, 24

Feb.

SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), 2011. Work Plan for the

Consideration of Incorporating International Financial Reporting

Standards into the Financial Reporting System for U.S. Issuers.

Division of Corporate Finance, Office of the Chief Accountant, 16

Nov.

SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), 2012. Work Plan for the

Consideration of Incorporating International Financial Reporting

Standards into the Financial Reporting System for U.S. Issuers:

Final Staff Report. Division of Corporate Finance, Office of the

Chief Accountant, 13 Jul.

Selling, T., 2008. Top ten reasons why U.S. Adoption of IFRS is a terrible

idea, The Accounting Onion. Available at:

http://accountingonion.typepad.com/theaccountingonion/2008/09/to

p-ten-reasons.html.

Soliman, M. T., 2008. The use of DuPont analysis by market participants.

The Accounting Review 83 (3): 823–853.

Stolowy H., M. J. Lebas, and Y. Ding, 2013. Financial accounting and

reporting: A Global Perspective (4

th

Ed.). Cengage, Singapore.

Street, D.L., N. B. Nichols, and S. J. Gray, 2000. Assessing the

acceptability of International Accounting Standards in the US: An

empirical study of the materiality of US GAAP reconciliations by

non-US companies complying with IASC Standards. The Journal of

International Accounting 35 (1): 27–63.

Sunder, S., 2009. IFRS and the accounting consensus. Accounting

Horizons 23 (1): 101–110.

Tang, T., G.V. Krishnan, M.C. Wolfe, and H.S. Yi, 2012. The impact of

eliminating the 20-F reconciliation requirement for IFRS filers on

earnings persistence and information uncertainty. Accounting

Horizons 26 (4): 741-765.

Transparency International, 2006. Corruption Perception Index 2005.

Available at:

http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2

005

Tweedie, D., 2007. Can Global Standards Be Principle Based? Journal of

Applied Research in Accounting and Finance 2 (1): 3–8.

Ucieda Blanco, J.L. and B. García Osma, 2004. The comparability of

International Accounting Standards and US GAAP: an empirical

study of Form 20-F reconciliations. International Journal of

Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation 1 (1): 5–36.

Wahlen, J.M., S.P. Baginski and M. T. Bradshaw, 2011. Financial

Reporting, Financial Statement Analysis and Valuation, 7th ed.

Thomson South-Western, Mason.

World Bank, 2013. World Development Indicators database.

Wysocki, P.D., 2005. Assessing earnings and accruals quality: U.S. and

international evidence. Working paper, MIT.

Source of title photo: By Hansjorn, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2424536