Idaho| 2022

MEDICAID SUPPORTIVE HOUSING SERVICES

Crosswalk

Page 1 of 26

About The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare

The Mission of the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare (IDHW) is that the Department is dedicated to

strengthening the health, safety, and independence of Idahoans. The IDHW is organized into eight divisions

including behavioral health, family and community services, information and technology, licensing and

certification, management services, Medicaid, Public Health, and Welfare (Self-Reliance). Their 2022-2026

Strategic Plan outlines the following goals:

• Ensure affordable, available healthcare that works

• Protect children, youth, and vulnerable adults

• Help Idahoans become as healthy and self-sufficient as possible

• Strengthen the public’s trust and confidence in IDHW

About Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH)

CSH is the national champion for supportive housing, demonstrating its potential to improve the lives of highly

impacted individuals and families by helping communities create over 335,000 homes with supportive services

for people who need them. CSH funding, expertise, and advocacy have provided nearly $1 billion in direct loans

and grants for supportive housing across the country. Building on over 30 years of success developing multi and

cross-sector partnerships, CSH engages systems to invest in solutions that drive equity, help people thrive, and

harness data to generate concrete and sustainable results. By aligning affordable housing with services and

other sectors, CSH helps communities move away from crisis, optimize their public resources, and ensure a

better future for everyone. CSH advances solutions that use housing as a platform for services to improve the

lives of highly impacted people, maximize public resources and build healthy communities. Visit us at

www.csh.org.

Acknowledgments

CSH would like to acknowledge and thank The Idaho Housing and Finance Association (IHFA) and it's Home

Partnership foundation, and other funding partners for the Idaho Medicaid Crosswalk including The Idaho

Community, and St. Alphonsus Health System.

CSH would also like to acknowledge the staff at IDHW, Division of Medicaid, who provided guidance and

clarification on the Idaho state Medicaid Plan, its Waivers, Medicaid cost data, and programmatic operations.

IHFA and Our Path Home also provided direct connections to community partners and programs as well as

critical data from their Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) to inform the Medicaid Crosswalk

report. And finally, housing and service providers statewide, who provided information on the day-to-day

operations of direct healthcare and housing program services, including:

• Advocates Against Family Violence (AAFV)

• CLUB, Inc.

• Full Circle Health

• Marimn Health

• Southeastern Idaho Community Action Agency (SEICAA)

Page 2 of 26

• St. Vincent de Paul

• Terry Reilly Health Services

This report would not have been possible without input from state staff, and staff from the healthcare, housing,

and homelessness sectors who shared about the day-to-day operations of their programs across Idaho.

Introduction

The World Health Organization identifies housing as a social determinant of health, which means it is an

underlying, contributing factor to health outcomes. Yet these services are not yet part of our healthcare

response for individuals with the most complex health challenges facing housing stability. Supportive housing

services include pre-tenancy and tenancy-sustaining services which improve health and well-being, ensure

housing stability, and reduce inappropriate healthcare utilization. This Crosswalk examines the extent to which

supportive housing services do and do not align with existing benefits covered by Idaho’s Medicaid program and

other state-funded community-based services that align with housing. This report consists of four parts:

• Part One –Background and definitions for supportive housing and Medicaid

• Part Two – Brief overview of key aspects of the State’s Medicaid program and the estimated supportive

housing needs in Idaho

• Part Three – Overview of key areas of alignment and gaps in the Crosswalk of services currently covered

by Medicaid

• Part Four – CSH’s recommendations for the steps Idaho can take to maximize Medicaid to pay for

supportive housing services

Page 3 of 26

CONTENTS

Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4

Part One: Background on Supportive Housing ............................................................................ 5

I. Supportive Housing .......................................................................................................... 5

II. The Need for Supportive Housing in Idaho ....................................................................... 6

III. Housing and Service Programs in Idaho ....................................................................... 8

Part Two: Overview of Medicaid ................................................................................................. 9

I. The Medicaid Program ..................................................................................................... 9

II. Medicaid in Idaho ........................................................................................................... 10

Part Three: Crosswalk Findings and Analysis ........................................................................... 13

I. Materials Reviewed for the Crosswalk ............................................................................ 13

II. Methodology: State Plan and Document Review ............................................................ 13

III. Findings: State Plan and Document Review ............................................................... 16

IV. Findings: Medicaid Alignment with Supportive Housing Services in Idaho .................. 16

V. Findings from Provider Interviews .................................................................................. 18

Part Four: Recommendations ................................................................................................... 22

I. Prioritize the Creation of a Supportive Housing Services Benefit .................................... 22

II. Coordinate Local and State Funding for Tenancy Supports ........................................... 23

III. Weave Medically Necessary Housing Services into the Existing Health System ............ 24

IV: Ensure Quality ............................................................................................................... 25

V: Redirect Cost Avoidance Back to Behavioral Health and Housing Systems ................... 26

Page 4 of 26

Introduction

On January 7, 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sent a letter to State Health Officials

(SHO) outlining opportunities under Medicaid to better address social determinants of health (SDOH) to support

states in designing programs, benefits, and services that can more effectively improve population health, reduce

disability, and lower overall health care costs.

1

The CMS letter recognized the positive impacts of supportive

housing for a subset of Medicaid beneficiaries with complex care needs who need stable housing and better

access to quality healthcare.

Several statewide partners in Idaho, including IHFA, hospitals, and foundations saw the potential of supportive

housing to improve population health outcomes, build health equity and address homelessness and housing

instability in its communities.

IHFA and its Home Community Foundation convened partners that recognize the opportunity to further

integrate supportive housing services into Medicaid. The Home Community Foundation contracted with CSH to

complete this Medicaid Supportive Housing Services Crosswalk to determine the degree to which Idaho’s

Medicaid program currently aligns with supportive housing services in policy and practice and where gaps would

need to be addressed to ensure that the most impacted beneficiaries can live in their own homes and

communities with stability and autonomy. CSH has analyzed more than a dozen state Medicaid plans, comparing

services offered and populations covered with the services provided in high-quality supportive housing. CSH has

also assisted multiple states in creating new Medicaid benefits for supportive housing services, referred to

throughout this document as pre-tenancy and tenancy support services. The purpose of this Crosswalk is to

highlight how Medicaid and housing can provide better care while using resources more efficiently for highly

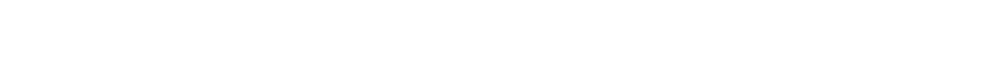

impacted Medicaid beneficiaries. The graphic in Figure 1 below, highlights what this ideal journey could look like

for these Idahoans.

1

https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21001.pdf

Page 5 of 26

PART ONE: BACKGROUND ON SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

Supportive housing combines affordable housing with intensive tenancy support services to help people who

face the most complex challenges live with stability, autonomy, and dignity. People who benefit from supportive

housing include people experiencing chronic homelessness

2

(extended periods of homelessness and one or

more disabling conditions), people who live in public institutions and licensed residential settings because of the

lack of affordable housing with tenancy supports in their communities, and people who cycle between

homelessness and these settings.

A federally recognized evidence-based practice,

3

research demonstrates that supportive housing provides

housing stability, improves health outcomes, and reduces public system costs. Supportive housing is not

affordable housing with resident services. It is a specific intervention that employs the principles of Housing First

and consumer choice in service delivery, and it provides specialized tenancy support services with low staff-to-

client ratios of 1:10 or 1:15.

The housing in supportive housing is deeply affordable. Tenants pay thirty percent of their incomes toward rent

and utilities. Subsidies pay the remaining cost of operating the housing. Supportive housing is independent like

any other rental housing and requires a lease with full tenancy rights and responsibilities. It is a platform from

which tenants can engage in health-related and other supportive services to improve their lives. The core

services in supportive housing are pre-tenancy (outreach, engagement, housing search, application assistance,

and move-in assistance) and tenancy sustaining services (landlord relationship management, tenancy rights, and

responsibilities education, eviction prevention, crisis intervention, and subsidy program adherence). In addition,

the service providers working in supportive housing connect tenants to primary and behavioral healthcare and

other community resources to help them thrive. Services such as counseling, peer supports, independent living

skills, supported employment, end-of-life planning, and crisis supports are also provided to residents by

supportive housing service providers and/or their community partners.

In June 2021, CSH coordinated and completed a FUSE effort in Multnomah County in partnership with Health

Share, the Local Public Safety Coordinating Council, the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office, and the Joint Office

on Homeless Services to determine the frequency that emergency and in-patient healthcare services and jails

were used in response to people experiencing homelessness and housing instability as compared to those living

in supportive housing. Most significantly, the findings showed that supportive housing is a game changer in its

ability to reduce crisis and institutional responses for people experiencing homelessness including:

• Over 400 fewer jail booking

• Over 500 fewer in-patient psychiatric stays

• Over 17,000 fewer Emergency Department visits

• Over 5,000 fewer avoidable Emergency Department visits

• Over 200 fewer hospitalizations

2

HUD's Definition of Homelessness: Resources and Guidance - HUD Exchange

3

SAMHSA Supportive Housing Evidence Based Toolkit. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Permanent-Supportive-Housing-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-

KIT/SMA10-4509

I. Supportive Housing

Page 6 of 26

These findings illustrate that supportive housing is one of the most effective ways to decrease avoidable

overspending on emergency health services and reduce the criminalization of people in need of accessible

housing and healthcare.

Financing supportive housing requires “three legs of a stool,” 1) capital funds to build apartment buildings, 2)

rental assistance to supplement the rents that tenants with extremely low incomes can pay, and 3) services to

support tenants in accessing housing and healthcare so that they can thrive in their communities. Most states

and localities do not have the resources to take this intervention to scale. A lack of sustainable services funding

often delays the creation of new supportive housing. Funding for services has historically come in the form of

short-term grants and contracts attempting to address long-term needs. Instead of using these funds to create

more housing, communities use a significant portion of these limited resources to pay for the tenancy supports

in supportive housing that could instead be covered by Medicaid.

In 2020, Idaho expanded its Medicaid programs as part of the federal expansion. As of March 2022, Idaho has

412,564 individuals enrolled in Medicaid.

4

Within Idaho, there is a cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries that have

critical, unmet housing and healthcare needs. Many of these highly impacted people are aging or living with co-

occurring chronic physical and behavioral health conditions, including severe mental illness, substance use

disorders, functional impairments, and other disabilities. Their incomes are below 30% of the median household

income of $17,674 (extremely low income as defined by HUD) and are unable to afford rent in Idaho without a

subsidy.

5

These beneficiaries experience housing instability, homelessness, and/or are cycling through multiple

social service systems, acute care settings, and institutions.

While significant public sector investments have been made in long-term care facilities, shelters, residential

treatment facilities, and hospitals in many cases, these individuals could benefit from the care they need in their

own homes and communities. The cost of these interventions can be the same or higher than those of housing

supports. As well, when households experience homelessness, they are at greater risk of expensive and often

preventable institutionalization, lack of access to primary care, and lack of integrated services addressing their

complex care needs. While these residents represent a small percentage of the total state population, the State

makes disproportionately large investments in the systems most accessible to them without addressing their

needs or those of their communities.

To better understand the supportive housing need in Idaho, CSH used publicly available state and local data to

predict the need across a variety of subpopulations. As of 2019, Idaho was predicted to need an additional 3,347

supportive housing apartments. The five largest populations needing supportive housing include those

returning from incarceration, older adults (65 and older), adults experiencing chronic homelessness, individuals

with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and unaccompanied and justice-involved transitional-aged

youth.

6

4

https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/stateprofile.html?state=Idaho

5

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/ID/INC110220#INC110220

6

https://cshorg.wpengine.com/supportive-housing-101/data/

II. The Need for Supportive Housing in Idaho

Page 7 of 26

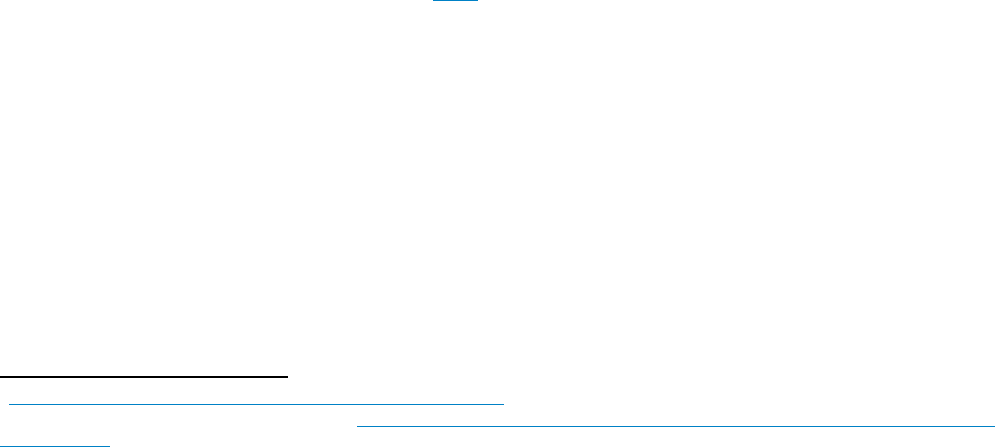

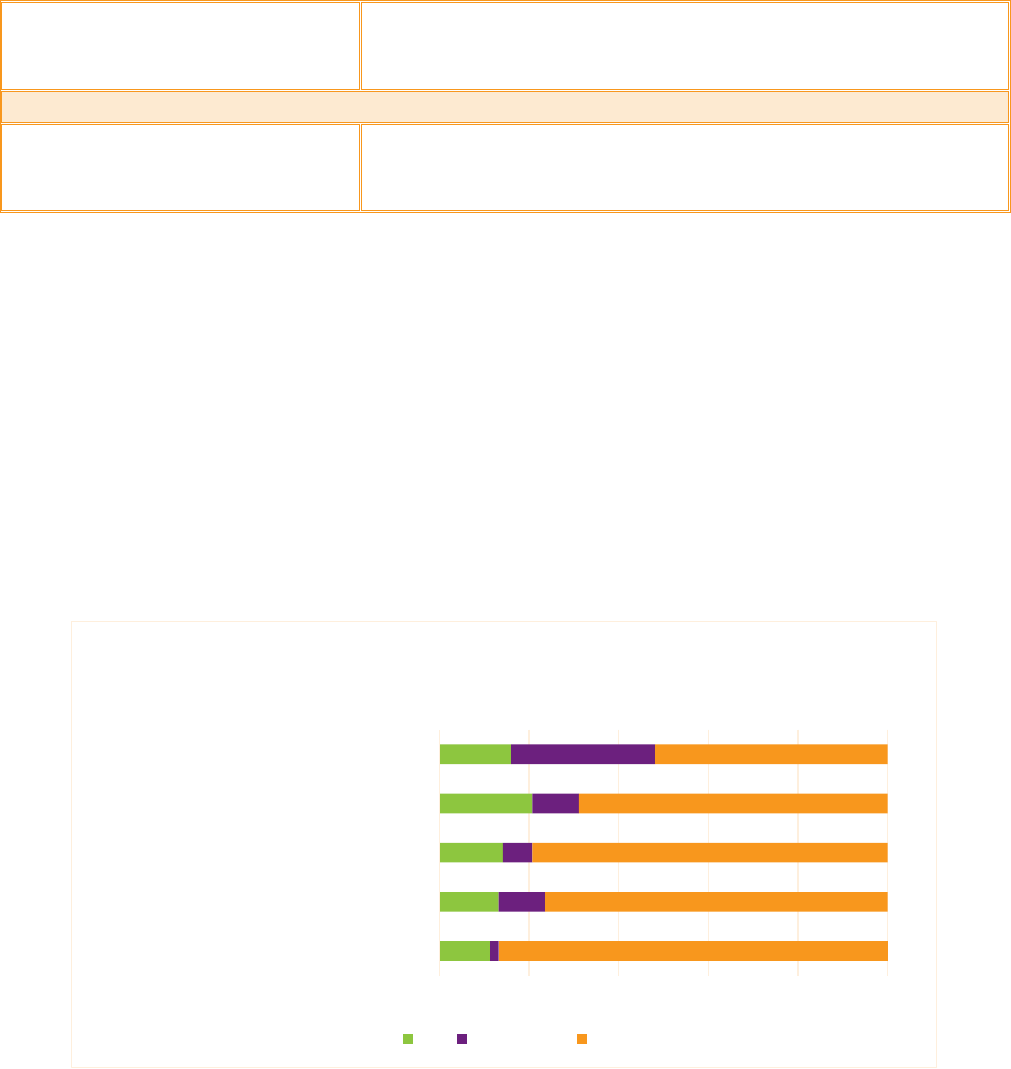

When disaggregated by race, the need for supportive housing demonstrates institutionalized racism inherent in

the barriers to affordable housing and person-centered healthcare services. CSH’s Racial Disparities and

Disproportionality Index (RDDI) shows disparity indices calculated by comparing racial groups’ rates of

representation in a public sector system with their representation in the population at large. Figure 1 below

illustrates the likelihood of a group experiencing system involvement in Idaho compared to all other groups. For

Idaho, the RDDI illustrates racial disparities in the involvement in multiple systems, especially for Black and

American Indian/Alaska Native individuals. For example, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals are

much more likely to experience chronic homelessness than all other households (with indices of 6.1 and 2.2,

respectively). Similar disparities are seen in multiple populations’ experiences of homelessness (e.g., non-

chronic, families, and youth) as well as other systems such as Child Welfare, Veterans, and Mental Health

institutions).

Figure 1: Racial Disparities and Disproportionality Index

Every year, communities across the nation that receive homelessness assistance funds from the federal

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are required to conduct a count of people experiencing

homelessness, known as the Point in Time (PIT) count. Continuums of Care (CoCs) can opt to do street counts

every other year. Some communities in Idaho did not participate in the 2021 count due to COVID. Idaho PIT

counts and national reports about the data highlight trends in the number of people experiencing homelessness.

In 2020, Idaho identified 1,668 individuals experiencing homelessness which was a 4% increase since 2019. The

number of individuals experiencing homelessness has consistently increased in Idaho year-over-year since 2017.

Of these, 235 persons were identified as chronically homeless which is a 6% increase from last year. Idaho also

identified that within the population of individuals experiencing homelessness, 78 were veterans. The impact of

a lack of affordable housing is also demonstrated in the PIT. 30% of individuals reported that the inability to find

affordable housing is the primary circumstance preventing them from procuring housing. Another 19% stated

that either evictions or inability to pay the entirety of the rent prevented them from accessing housing.

7

7

https://www.idahohousing.com/documents/point-in-time-count-2020.pdf

Page 8 of 26

People of color across various racial and ethnic groups experience homelessness disproportionately. Black Idaho

residents are .9% of the state’s population but 10.7% of those experiencing homelessness. Native Americans are

1.4% of the population but 12.5% of those experiencing homelessness.

8

When supportive housing services are

provided by culturally specific organizations and programs, they can be a powerful tool in addressing racial

disparities in health, economic mobility, and homelessness.

Several local and State initiatives are underway to make a dent in the supportive housing need in Idaho.

Following are a few key examples:

• Treatment and Transitions Program: IDHWs Treatment and Transitions Program (TNT) serves

individuals with severe mental illness and/or a co-occurring disorder who are experiencing

homelessness or housing instability. The project is funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration (SAMHSA). The TNT Program supports transition homes that provide recently

hospitalized patients with a place to live for up to six months after discharge. The program provides

participants with a stable living situation while they continue their recovery and work to attain

permanent supportive housing. Participants are also provided with coordinated care services that ease

the potential difficulty of managing the use of services on their own. The TNT Program aids participants

by providing recovery coaches, continued behavioral health services, a supportive environment in

transitional housing upon discharge, and entry into permanent supportive housing. By 2021, the

program had served 181 individuals with 88% avoiding readmission to psychiatric hospital settings

within twelve months of entry into the project and 94% receiving housing services upon discharge from

the program.

9

This pilot program has demonstrated that access to critical housing support services

reduces re-institutionalization, improves outcomes, and reduces costs; however, the scale of the pilot is

too small to meet the need in Idaho for those exiting institutions in need of supportive housing.

Additionally, the transition homes provided through TNT are not permanent housing and the supportive

services are time-limited. This pilot highlights that there is a need for a more permanent, sustainable,

and scalable solution for some of Idaho’s most vulnerable community members.

• PATH Grant from SAMHSA: SAMHSA provides community block grants each year to fund services for

people with serious mental illness (SMI) experiencing homelessness. In 2022, SAMHSA provided

$300,000 to IDHW to support Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness (PATH) Programs.

PATH funding can help support services including, outreach, screening, habilitation, community mental

health, substance use disorder treatment, referrals, and specified housing services. While PATH case

managers can provide outreach to connect unstably housed individuals with housing and services, the

level of outreach and community engagement varies based on region and the level of the initiative taken

by individual PATH case managers.

• New Path Supportive Housing: New Path Community Housing, Idaho’s first single-site, permanent

supportive housing development using the Housing First approach to helping the chronically homeless,

is a result of a comprehensive collaboration between many agencies. The community offers 40 one-

8

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/idaho-population-change-between-census-decade.html

9

https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/ipi_reports/67/

III. Housing and Service Programs in Idaho

Page 9 of 26

bedroom apartments in Boise with intensive on-site supports including social and medical services.

10

While New Path Community Housing has demonstrated positive outcomes for its tenants, particularly

related to housing stability, many more PSH units are needed in Boise/Ada County to meet the needs of

those experiencing homelessness. To create new PSH units, a permanent, sustainable funding source for

the housing support services must be identified as the project is now relying on local grant funding for

services.

• Valor Pointe Supportive Housing: Valor Pointe was the second supportive housing development in

Idaho that utilized the Housing First model. The community offers 26 one-bedroom apartments for

Idaho’s most vulnerable Veterans. Their offerings include on-site health care, mental health counseling,

and substance use treatment.

11

While this PSH project is a valuable part of the housing continuum for

those experiencing homelessness, eligibility is limited to participating Veterans and is not scalable to the

broader population experiencing homelessness in Idaho.

PART TWO: OVERVIEW OF MEDICAID

Medicaid is public health insurance that pays for essential medical and medically-related services for people

with low incomes. Statutorily, Medicaid insurance cannot pay for room and board. Medicaid’s ability to

reimburse for services starts with an eligibility determination as to whether an individual is Medicaid eligible

and, if so if they are enrolled in the Medicaid program.

The federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) oversees all state Medicaid plans. A Medicaid

“State Plan” is a contract between a state and the federal government. It defines the services, populations, and

payment rates that are part of the state’s Medicaid program. All state plans cover certain mandatory benefits as

determined by federal statute. States and CMS can also agree to cover additional benefits designated as

‘optional’ in federal statute.

12

For example, Idaho covers services for persons with intellectual and

developmental disabilities, persons who are aging, and persons with behavioral health needs via a variety of

Medicaid waivers or State Plan Amendments or SPAs.

States can make changes to their Medicaid State Plan by applying to CMS for a state plan amendment (SPA) or

to waive certain provisions of the Social Security Act that governs Medicaid regulations (a Waiver). Medicaid

authorities are commonly known by their federal statute section number. Examples of authorities that can help

states address housing as a SDOH include:

• 1115 Medicaid Waivers allow for state demonstration programs to pilot innovative services, serve new

populations, or test payment structures.

• 1915(i) SPAs: Among other benefits, States can use these authorities to provide Home and Community

Based Services (HCBS) for specific populations (older adults with functional impairments, adults with

severe physical disabilities, individuals with severe or persistent mental illness, individuals with

10

http://newpathboise.org/index.html?devicelock=desktop#about

11

https://valorpointe.nwrecc.org/

12

For more detail on mandatory and optional Medicaid benefits - https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/mandatory-optional-medicaid-

benefits/index.html

I. The Medicaid Program

Page 10 of 26

developmental disabilities, children with special health care needs and people living with traumatic

brain injuries). These services are intended to help beneficiaries remain in their own homes and

communities for as long as possible, rather than requiring that they move into institutions to receive the

level of care they need.

13

States can reimburse providers directly for services in a Fee for Service (FFS) structure or they can contract with

managed care organizations (MCOs) to establish a provider network and manage payments to those providers.

States contract with MCOs primarily on a per member, per month (PMPM) basis. This shifts the financial risk

onto the MCOs. While MCOs may have greater flexibility than state governments to contract for provider

services, they may also at times need to limit the services they cover to stay within their budget. States and

MCOs establish agency licensing and credentialing requirements and staff qualifications that determine which

providers can receive Medicaid reimbursement. In Idaho, Behavioral Health Services are managed by Optum

14

,

while Physical Health services remain in a FFS arrangement with the state.

15

Indian Health Service (IHS), another agency within the federal Department of Health and Human Services, is

responsible for providing federal health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. The federal

government provides 100% payment for services provided to American Indian and Alaska Natives receiving

healthcare in IHS facilities, which include Tribal Contract or Compact Health Centers that deliver outpatient

healthcare programs and Urban Indian Health Centers, which are designated Federally Qualified Health Centers

that provide comprehensive primary care and related services. These facilities are owned or leased by Urban

Indian organizations and receive grant and contract funding through Title V of the Indian Health Care

Improvement Act. Marimn Health, owned by the Coeur D’Alene Tribe receives IHS grant funding and was

included in the provider interviews that informed the Idaho Medicaid Crosswalk.

In November 2018, Idaho voters passed Proposition Two to expand Medicaid and provide coverage to

individuals with an annual household income at or below 133% of the Federal poverty level.

16

Additionally,

Idaho opted for Medicaid expansion that took effect in January 2020 with more than 121,000 people enrolled in

expanded Medicaid as of 2022.

17

Before Medicaid expansion, there are an estimated 78,000 residents of Idaho

who fell into the gap of having too low of an income to be eligible for subsidies in the marketplace and also too

high an income for Medicaid. Under the Medicaid expansion, these individuals became Medicaid-eligible. Of

these Medicaid beneficiaries, some are experiencing homelessness and/or living with substance use disorders,

chronic health conditions, and undiagnosed mental illness and would benefit from supportive housing services.

This Crosswalk report includes a review of the availability of supportive housing services in the Idaho Medicaid

State Plan and its State Plan Amendments (SPAs), the 1915c Medicaid Waiver for Home and Community-Based

Services (commonly called the Aging and Disabilities Waiver), and the Traditional IID/DD Home and Community

Based Services Waiver (commonly called the Traditional DD Waiver), 1115 Medicaid Waiver for Behavioral

13

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer/

14

https://www.optumidaho.com/

15

https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/services-programs/medicaid-health

16

https://ballotpedia.org/Idaho_Proposition_2,_Medicaid_Expansion_Initiative_(2018)

17

https://www.healthinsurance.org/medicaid/idaho/

II. Medicaid in Idaho

Page 11 of 26

Health Transformation, and the Optum Idaho Provider Manual. These authorities allow for the provision of

services for highly vulnerable individuals who are aging and/or living with serious mental illness or behavioral

health conditions, intellectual, developmental, or physical disabilities.

Managed Care in Idaho

In Idaho, the Idaho Behavioral Health Plan (IBHP), dual-eligible and dental services operate through

managed care. IBHP contracts with the managed care organization (currently Optum) to provide a range of

services that include adult behavioral health, behavioral health crisis resources, children’s behavioral

health, substance use services, and suicide prevention. According to the UBHP website, “Through

Expansion, all adults that obtain Medicaid eligibility are now eligible to receive behavioral health services

through the IBHP, including adults with serious mental illness (SMI) or serious and persistent mental illness

(SPMI). Members are always able to choose their provider within the Optum network and have the right to

change their provider at any time.”

18

Although Idaho is currently contracted with Optum, IBHP is currently

soliciting new contracts for negotiation in 2023.

Fee for Service Reimbursement in Idaho

In addition to managed care for behavioral health services, Idaho also operates a fee-for-service

reimbursement system payment structure that is based on the type of service provided and the duration of

the service time. The majority of the Medicaid benefits in Idaho are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis.

Additionally, most of the services delivered through Medicaid to non-dual eligible populations are offered

through a fee-for-service model including (but not limited to): transitional care management, substance use

screening and interventions, advanced care planning, and more.

19

Idaho’s Medicaid Waiver Authorities

Currently, there are two 1915(c) waivers in Idaho that most directly impact adults who need supportive

housing. The first is the Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) waiver,

often referred to as the Aging

and Disabilities Waiver, which provides services for individuals to remain in their own homes and

communities to avoid unnecessary institutionalization in long-term care facilities. The services available

under the HCBS program may include case management, homemaker services, home health aides, adult pay

programs, and more.

20

Additionally, Idaho has a separate 1915(c) waiver for HCBS for individuals with

intellectual disabilities and cognitive impairment, known as the Traditional Individuals with Intellectual

Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities (IID/DD) HCBS Waiver. The services available under the IID HCBS

waiver may include supported living (which differs from supportive housing as it focuses on activities of daily

living), chore services, supported employment, home-delivered meals, adult day programs, and more.

21

To

access the services covered by both these waivers, individuals must meet certain functional criteria that

indicate a need for institutional care as determined by a level of care assessment.

Additionally, the state has an 1115 demonstration Waiver that was implemented in April 2020 and is approved

through March 2025. The demonstration waiver “provide[s] the state with authority to provide high-quality,

18

https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/providers/managed-care-providers/behavioral-health

19

https://publicdocuments.dhw.idaho.gov/WebLink/DocView.aspx?id=22931&dbid=0&repo=PUBLIC-DOCUMENTS

20

https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/services-programs/home-and-community-based-services

21

https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/services-programs/medicaid-health/apply-adult-developmental-disabilities-programs

Page 12 of 26

clinically appropriate treatment to participants with mental health and substance use disorders.”

22

The waiver

specifically provides reimbursement for services to adults ages 21 through 64 treated in large psychiatric

hospitals. Additionally, the waiver provides a five-year road map to further develop Idaho’s behavioral health

care system including the addition of community-based Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams.

Idaho Behavioral Health Plan

Idaho provides Medicaid-funded behavioral health services through a managed care organization known as the

Idaho Behavioral Health Plan (IBHP). IBHP is undergoing significant changes right now. Currently, Optum is the

contracted provider for IBHP services, but IBHP is currently in the procurement process for a new contract.

Additionally, the Idaho Behavioral Health Council, comprised of both government staff and community

members, developed a 2021-2024 strategic plan. The strategic plan identifies a few recommendations and

action items that would benefit supportive housing tenants including expanded access to behavioral health

services and investment in the creation of new units of supportive housing.

Indian Health Services (IHS)

American Indians that meet eligibility requirements for Montana Medicaid may enroll in Medicaid and Indian

Health Services and receive coverage for the same services as individuals enrolled in Medicaid only.

Additionally, the federal government is required to match 100% of state expenditures on behalf of American

Indian Medicaid beneficiaries for services received through an Indian Health Services facility, whether operated

by IHS, a Tribe, or a Tribal Organization (I.e., Urban Indian Health Center). Of these, one is a designated Health

Station, five Health Centers and one fills both roles. Of these, six are designated as Title 6 Tribal 638 and tribally

operated. One of these is a Federally operated Health station. The providers of HIS services include Marimn

Health, Fort Hall HRSA After Hours Clinic, Not Tsoo Gah Nee Indian Health Center, Kamiah Health Center.

Kootenai Health Station, and Nimiipuu Health Center.

23

Non-Medicaid Funding for Supportive Housing Services

As mentioned previously, The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA) awarded Idaho with a $300,000 PATH block grant for substance abuse prevention and

treatment and community mental health services.

Additionally, HUD’s CoC program provides additional

funding to both nonprofit providers, as well as State and local governments. In 2021, $1.5 million was

awarded to the Boise/Ada County CoC and $3.7 million to the BoS CoC.

24

The funding for these services

helps bolster supportive housing provider capacity as well as supplement Medicaid, Medicare, and

private insurance benefits.

Additionally, four Federally Qualified Health Centers in Idaho received SAMSHA funding for $1 million

each to create four Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics across the state of Idaho. CCBHCs

offer a wide variety of services needed to improve access, assist people in crisis, and treat those with the

most serious, complex mental illnesses and substance use disorders. The Governor has also

22

https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/providers/behavioral-health-providers/idaho-behavioral-health-transformation-waiver

23

https://www.ihs.gov/

24

https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/CPD/documents/FY2021_ID_Press_Report.pdf

Page 13 of 26

recommended a total of $12 million in funding ($6 million per year for 2 years) for ARPA State funds for

2023 and 2024 to support this initiative.

25

PART THREE: CROSSWALK FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

This Crosswalk concentrates on Idaho’s Medicaid services that address the healthcare needs of beneficiaries

with functional impairments who are likely to be impacted by housing instability, homelessness, and/or

unnecessary institutionalization. The Crosswalk considers two primary sources of information in determining the

degree to which Medicaid covers supportive housing services in policy and practice: 1) A review of the State Plan

and other relevant documents, and 2) Interviews with providers who serve these populations.

For the document review, CSH reviewed the following:

1) Idaho State Medicaid Plan

2) Idaho’s 1115 Medicaid Waiver for Behavioral Health Transformation

3) Idaho’s 1915(c) Waiver for Aging and Physically Disabled

4) Idaho’s 1915(c) Waiver for Developmental Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

5) Optum Idaho Provider Manual

6) Idaho Behavioral Health Council’s 2021-2024 Strategic Action Plan

The purpose of the provider interviews is to inform where alignment and gaps exist between supportive housing

services and Medicaid in practice. CSH interviewed seven health and service providers across the state. Some

provide only supportive housing services, while some provide both services and housing and some are

healthcare providers. Four do not have experience with Medicaid, and three seek Medicaid reimbursement for

the services they provide. The interviews included a series of questions about the funding and operations of

their programs, their understanding of Medicaid reimbursement for supportive housing services, and their

perceptions of Medicaid Assistance alignment with supportive housing services. CSH also sought to understand

the array of services that supportive housing service providers are currently offering to tenants, regardless of

funding source.

To determine the degree to which Medicaid currently references one or more supportive housing services, CSH

cross-walked the services provided in quality supportive housing with key provisions of the Idaho State Medicaid

Plan and authorities described above for Idahoans experiencing housing instability with a behavioral health

disability. Figure 5 below notes where these key services are referenced in the State Plan.

Figure 5: Supportive Housing Services Mentioned in Idaho’s Medicaid Plan

Service

State Plan and Authorities Where the Service is Mentioned

Housing Stabilization and Services Coordination

25

ibhc-leading-idaho.pdf

I. Materials Reviewed for the Crosswalk

II. Methodology: State Plan and Document Review

Page 14 of 26

On-call Crisis Support/Intervention

BH Transformation Waiver, 1915 HCBS for IDD (Under Crisis Services),

State Plan Behavioral Health (Under Crisis Services)

Supportive Services

1915 HCBS for IDD (Under Community Support)

Non-Emergency Transportation

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS for Aging, 1915 HCBS for IDD, State Plan BH

Life Skills/Independent Daily Living Services

Personal Financial Management and

Budgeting

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Residential Habilitation)

Direct Provision of Health/Medical Services

Nursing/Visiting Nurse Care

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Skilled Nursing)

Medical Day Care

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Adult Day Health), 1915 HCBS for IDD

(Under Adult Day Health)

Home Health Aide Services

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Attendant Care), 1915 HCBS for IDD

(Under Residential Habilitation)

Personal Care and Personal

Assistance

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Personal Care), 1915 HCBS for IDD

(Under Residential Habilitation)

Peer Support Services or Community

Health Worker Services

BH Transformation Waiver, State Plan BH

HIV/AIDS services

State Plan (General Population), 1915 HCBS for IDD, State Plan BH

Medication Management or

Monitoring

State Plan (General Population), 1915 HCBS for Aging, 1915 HCBS for

IDD, State Plan BH (Under Medication Management)

Non-Emergency Medical

Transportation

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS for IDD, State Plan BH (Under State Plan)

Routine Medical Care

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS for Aging, 1915 HCBS for IDD, State Plan BH (Under State Plan)

Direct Provision of Mental Health Services

Page 15 of 26

Medication

Management/Monitoring

State Plan BH (Under Medication Management)

Peer Mentoring/Support

BH Transformation Waiver, State Plan BH (Under Peer Services)

Psychiatric Services (specify below)

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, State

Plan BH (Under State Plan Benefit)

Individual Psychosocial Assessment

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under Diagnostic Assessment)

Individual Counseling

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under State Plan Benefit)

Group Therapy

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under State Plan Benefit)

Direct Provision of Substance Abuse Services

Substance Abuse Counseling

(individual)

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under SUD Treatment)

Substance Abuse Counseling (group)

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under SUD Treatment)

MAT (Medication Assisted

Treatment)

State Plan (General Population), BH Transformation Waiver, 1915

HCBS Waiver for IDD, State Plan BH (Under Opioid Treatment)

Direct Provision of Employment Services

Training and Vocational Education

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment)

Job Skills Training

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment), 1915 HCBS for

IDD (Under Supported Employment)

Job Readiness Training — Resumes,

Interviewing Skills

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment), 1915 HCBS for

IDD (Under Supported Employment)

Job Retention Services — Support,

Coaching

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment), 1915 HCBS for

IDD (Under Supported Employment)

Page 16 of 26

Job Development/Job Placement

Services

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment), 1915 HCBS for

IDD (Under Supported Employment)

Direct Provision of Vocational Services

Training and Vocational Education

1915 HCBS for Aging (Under Supported Employment), 1915 HCBS for

IDD (Under Supported Employment)

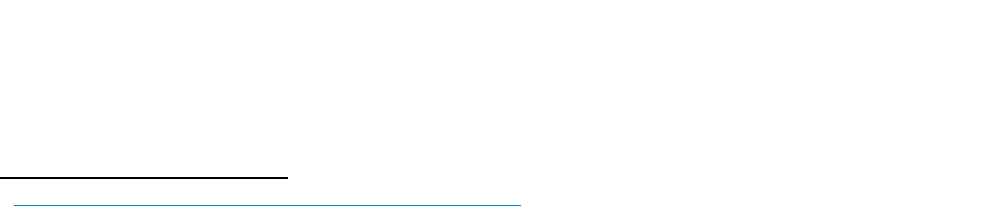

To quantify the degree to which these services are referenced in the State Plan and authorities described above,

CSH tallied the number of pre-tenancy and tenancy-sustaining services that are noted in IDHW’s policy

documents. Figure 6 below represents the percentage of coverage.

• Services that appear explicitly in policy documents and read as though they are accessible without

barriers are reflected as “covered” in green.

• Services that theoretically could be delivered as part of an existing, broadly defined Medicaid service but

are not explicitly mentioned in the service definitions are noted in purple as “inconclusive.”

• Services that are not referenced at all are depicted as orange as “not covered.”

Figure 6: Percentage of Supportive Housing Services Covered by State Plan or Authority

Following is a brief description of how each of the authorities above does or does not align with supportive

housing services.

0.0% 20.0% 40.0% 60.0% 80.0% 100.0%

State Plan (general population)

BH Transformation Waiver

1915© HCBS for Aging and Physically Disabled

1915© HCBS for IDD

State Plan BH- based on Review of the Optum

Manual

Alignment of Idaho Medicaid Services with Quality

Supportive Housing Services

Yes Inconclusive No

III. Findings: State Plan and Document Review

IV. Findings: Medicaid Alignment with Supportive Housing Services in Idaho

Page 17 of 26

Idaho State Medicaid Plan

The Idaho State Medicaid Plan covers essential health benefits such as inpatient and outpatient care and

behavioral health services. Idaho has worked over the past few years to expand access to behavioral health

services, in particular, substance use disorder services to address the opioid crisis. State plan services do include

some alignment with supportive housing services such as psychiatric services like counseling, group therapy, and

substance abuse services. However, most supportive housing services do not align with the current State Plan,

including housing stabilization services, Case Management, and Pre-Tenancy supports.

1115 Behavioral Health Transformation Waiver, Optum Provider Manual

The Behavioral Health Transformation Waiver includes the most services that align with supportive housing for

eligible Medicaid members of all authorities analyzed. To be eligible for the Behavioral Health Transformation

Waiver, Medicaid members must have a diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder (SUD), Serious Mental Illness

(SMI), or Serious Emotional Disturbance (SED); and while many supportive housing services fall into the category

of possible alignment with the Waiver, significant gaps remain for those in need of supportive housing. The

Behavioral Health Transformation Waiver was designed for Medicaid funds to reimburse for acute short-term

stays in institutional settings as well as support Medicaid beneficiaries with services to transition back into the

community from these settings and to address the SUD treatment needs of those suffering from opioid

addictions. Because the Waiver was not specifically designed to address the needs of those experiencing

homelessness with a SUD or SMI, CSH found significant gaps in coverage for pre-tenancy and tenancy-sustaining

services. The publicly facing materials also do not address how services are accessed or how a person attains a

diagnosis and this can be a significant barrier for those experiencing homelessness or housing instability.

1915(c) Waiver, HCBS for Aging and Physically Disabled

The process for an individual to receive home and community-based care services (HBCS) varies

depending on income eligibility, liquid assets, and an individual’s level of need based on a functional

assessment identifying the level of impairment and duration of impairment consistent with an

institutional level of care. Like all Waivers, The HCBS Waiver in Idaho is not an entitlement program

which means even when a Medicaid member meets eligibility requirements, it does not equate to

immediate receipt of program benefits and must still go through a lengthy application process. In

addition to meeting income and asset eligibility, Idaho Medicaid members must be sixty-five (65) or

older and require a nursing facility level of care based on a functional assessment to be deemed eligible

for 1915(c) Aging and Physically Disabled Waiver services.

CSH found very limited alignment between IDHW’s 1915(c) HCBS Waiver for the aging population and quality

supportive housing services. This benefit is primarily meant to provide an alternative to nursing home facility

admission for Idahoans that are aged, blind, or disabled and is not aligned with critical supportive housing

services like outreach to nursing home facilities by HCBS case managers or tenancy sustaining services.

1915(c) Waiver for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (I/DD).

CSH similarly found limited alignment between the state’s 1915c Waiver for individuals with intellectual and

developmental disabilities and quality supportive housing services. These services provide HCBS to individuals

who, but the provision of these services would require an institutional level of care. Idaho does not report a

Page 18 of 26

significant number of persons with ID/DD experiencing homelessness, so while these waiver services have the

most alignment with quality supportive housing, their utility in these efforts is limited.

The following gaps in quality supportive housing services exist across the State Medicaid Plan and all Waivers:

• Outreach and In-reach

• Assistance with collecting required documentation

• Assessment of housing preferences and barriers related to tenancy

• Assistance with housing search and housing applications

• Identification of resources to cover moving and start-up expenses

• Ensuring housing unit is safe and ready for move-in

• Assistance with move-in arrangements

• New tenant orientation/move-in assistance

• Tenant’s rights education/introduction to tenant’s council

• Education/training on tenant and landlord rights/responsibilities

• Ongoing training and support with activities related to household management and healthy tenant

habits

• Coaching on developing and maintaining relationships with landlord/property manager/neighbors

• Assistance resolving disputes with landlords, property management, and neighbors

• Assistance with housing recertification

• Assistance with acquiring furnishings

CSH conducted interviews with seven healthcare and/or housing providers in Idaho to learn the breadth and

depth of services that providers are currently offering to tenants and those experiencing homelessness,

regardless of funding source. Three prominent themes emerged from CSH’s interview with providers of

supportive housing services and healthcare.

o Providers of Housing and Providers of healthcare operate separately, and the two systems

are not integrated (except for small pilot projects), even in PSH-designated units and/or projects.

Housing providers:

o PSH housing providers statewide specialize in the provision of housing; specifically, the

providers interviewed have extensive experience owning and operating housing. Many of the

providers interviewed receive funding from the Balance of State CoC to provide housing and

services to a specific number of PSH tenants annually. Several housing providers interviewed

also receive CoC funding to administer the BoS Coordinated Entry System (CES) for their

designated region. CES is a community-wide process to prioritize and connect those

experiencing or at risk of homelessness with appropriate housing and resources.

o PSH providers in Idaho are currently utilizing the limited resources from CoC funding and small

state and local grants to fund rental assistance and services for tenants. Providers interviewed

reported that funding is typically used to fund case management and services provided on-site

for PSH tenants aiming to support tenants in meeting their basic needs and maintaining housing.

This may include the following support for tenants:

V. Findings from Provider Interviews

Page 19 of 26

▪ Accessing food, food stamp benefits, and other public benefits such as Medicaid.

▪ Keeping housing units clean and understanding the terms of lease/rental agreement

▪ Goal setting

▪ Referrals to other community providers

▪ Transportation/transportation assistance

Providers generally reported the goal of meeting with tenants at least monthly, but several

providers noted that this was a challenge at times if tenants did not want to meet with their

case managers or if tenants did not attend scheduled appointments with case managers.

o Case managers for PSH are working for housing services providers and are not providing

behavioral health services to tenants. If PSH tenants need to access behavioral health services,

they are referred to local providers. This was mentioned as a major gap in services by nearly all

of the providers interviewed; several reported that case managers will provide PSH tenants with

a list of local behavioral health or Substance Use Disorder (SUD) providers and that tenants

often struggle with finding a provider nearby, making and keeping appointments, and with

finding transportation to and from appointments. One PSH provider interviewed shared an

experience with a recent tenant in PSH who had lost their housing stating “this tenant fell

through the cracks; in a perfect world we would have tighter bonds with mental health agencies

to have been able to meet their needs”.

Healthcare Providers

o Several Federally qualified health centers (FQHC) statewide are working with very vulnerable

community members, many of whom experience housing instability. Except for Terri Reilly

Health, the Healthcare providers interviewed do not currently have existing partnerships with

PSH providers. Healthcare providers reported seeing many patients experiencing homelessness

and identified housing as a critical Social Determinant of Health, but providers were not clear on

how to refer patients directly to supportive housing in their region.

o Healthcare providers interviewed do provide robust SUD treatment and behavioral health

services in some cases. This includes health centers offering Medically Assisted Treatment (MAT)

and residential programs for those experiencing challenges managing their substance use

and/or behavioral health. The challenge is that healthcare providers are set up to provide office-

based care, while tenants in PSH often need to be engaged by healthcare providers in their

housing or another community setting.

o Healthcare providers interviewed are working to increase access to healthcare and have

implemented several impactful initiatives to do so. This includes mobile health clinics operated

out of vans; this is critical for community members as the mobile clinics can move around the

community and set up sites at locations like emergency shelters for those experiencing

homelessness. Marimn health, serving the Coeur D’Alene Tribal community located in Plummer,

ID can provide mobile health services for Tribal Members experiencing homelessness on

location using its van, including MAT services and is also able to transport patients that need

medical care to the clinic. Marimn Health reported that they often see patients experiencing

homelessness in the Tribal Community, which is disproportionally impacted by housing

Page 20 of 26

insecurity in Idaho and nationally.

26

While Marimn can provide some services for those

experiencing homelessness, they expressed challenges in being able to go beyond meeting the

basic needs of patients without having access to affordable, permanent housing.

o PSH units statewide are not serving Idaho’s most impacted community members, in particular,

those with the highest barriers to obtaining and maintaining permanent housing, including those

transitioning from institutions and those not currently connected with the homelessness system or

behavioral health services, are largely not the tenants that can access PSH-designated units. This

includes individuals exiting institutions, experiencing behavioral health challenges, or those with justice-

system involvement. Several supportive housing providers interviewed stated that SUD and Behavioral

health challenges were not a prominent issue among their tenants in PSH, which is meant to target

those with the longest histories of homelessness who face the most complex housing stability

challenges. Since funding for supportive housing in Idaho comes exclusively from the homelessness

system, only persons experiencing homelessness can access those community living opportunities.

o Housing providers did not report direct referrals from their CES system into PSH from

institutional settings, such as the Department of Corrections or the state psychiatric hospitals.

o Several capacity gaps emerged during interviews with supportive housing providers, regarding

specific services provided in PSH and the frequency/level of intensity of the services. Most

providers did not have experience billing Medicaid, only one provider is currently billing

Medicaid for services in a supportive housing setting. Despite the variation in providers and

regions, the following capacity gaps were consistently noted in the interviews:

▪ Understanding of pre-tenancy supports (housing search, collecting documents, etc.) is

varied and happening in an extremely limited way, if at all, among providers

▪ Understanding of ongoing tenancy sustaining services (eviction prevention, community

integration) is varied, primarily surrounding a tenant’s voluntary engagement in

services. Several providers reported eviction as an outcome for PSH tenants who were

unwilling or unable to engage in services.

▪ Finding affordable housing options, in desired locations, that will accept a client’s rental

assistance voucher and rent limits is a widespread challenge

▪ Many providers rely on and are pursuing congregate settings, such as group homes and

transitional housing for individuals with behavioral health needs, including SUD

▪ Case Management ratios vary but are consistently higher than quality standards would

require, and providers expressed concern with sustaining both high-quality services and

staff considering the high caseloads

▪ The current PSH funding model in Idaho has resulted in a low number of PSH units often

existing within a larger affordable housing development (e.g., 5% of the total units,

resulting in 4-5 PSH units in a building). This makes it challenging for providers to reach

‘economies of scale’ for case management and services since typical staffing ratios in

PSH would be 1 case manager for every 15 tenants. With only a small number of PSH

units in their portfolio, providers are not able to dedicate an entire staff person(s) for

supportive services.

26

https://www.csh.org/supportive-housing-101/data/#RDDI

Page 21 of 26

▪ Several providers are currently utilizing Peer Support Workers to provide supportive

services in PSH even though they are not billing Medicaid. Peer Services is an activity

that is eligible for Medicaid reimbursement under the state Medicaid Plan for enrolled

providers.

o Providers who are authorized to seek Medicaid reimbursement are very limited in the specific

kinds of services that are eligible for reimbursement. This included limitations that providers

reported regarding patient eligibility and billing requirements for specific patient encounters that are

difficult to meet for those experiencing homelessness and/or in supportive housing.

o For example, FQHC providers reported that it can be challenging to access Medicaid

reimbursement for patients experiencing homelessness because they tend to be more transient

and may be involved or enrolled with other providers. One FQHC provided an example of

treating patients for eligible services, but not being able to bill for the services because that

patient was enrolled with another provider as their “medical home”. Providers also shared that

those experiencing homelessness or in PSH often have myriad unmet healthcare needs that they

are not able to get reimbursed for, including:

▪ Case management provided by nurses

▪ Nutrition services

▪ Pharmacy

▪ Integrated Behavioral Health

▪ Chronic Care Management (providers reported this is difficult for patients experiencing

homelessness because often copays are required and the patient needs to actively enroll

to receive services)

o Terry Reilly Health Services was a key supportive housing provider interviewed for the Idaho

Medicaid Crosswalk because of the organization’s unique role as both a healthcare provider

(FQHC) and lead supportive housing service provider at New Path Community Housing in Boise.

Terry Reilly is authorized to bill Medicaid for services, including case management services, and

while the organization can capture some Medicaid reimbursement for services, they reported

several limitations on their ability to leverage Medicaid as a significant funding source for

services. Some of the reported barriers to accessing Medicaid reimbursement in supportive

housing include:

▪ While case management is considered a qualifying behavioral health service for

Medicaid reimbursement, providers must first complete a Comprehensive Diagnostic

Assessment (CDA) and Treatment Plan for Medicaid members to receive

reimbursement.

▪ Completing a CDA and Treatment Plan with unhoused residents can be challenging if

they are also struggling with chronic health conditions, varying levels of historical and

current trauma, substance use disorder, mental health problems, and/or other disabling

conditions. The administrative burdens of systems access are a barrier to persons

receiving the care to which they are entitled.

▪ Often, considerable time is spent in engagement and relationship building with PSH

tenants to enable them to trust providers sufficiently to consent to treatment. As a

result, staff members are often working extensively with someone providing pre-

tenancy and tenancy supports and are unable to bill for a ‘qualifying encounter.’

Page 22 of 26

▪ In addition to the initial barriers that exist within the current Medicaid structure to bill

for services, CDAs and Treatment Plans must be updated on a regular and documented

frequency with input from the resident which means the ability to bill for any encounter

could lapse based on the tenant’s level of engagement and consent to treatment.

Specifically, the CDA needs to be redone every 12 months as well for ongoing

reimbursement.

▪ Terry Reilly described the behavioral health reimbursement model under Medicaid as a

“square peg in a round hole” for supportive housing providers and tenants, providers

document many “non-billable interim encounters” with tenants, even if the encounter is

not reimbursable, to demonstrate that they are involved with tenants in an ongoing

therapeutic way. Terry Reilly expressed that a per diem or per member/per month

(PMPM) reimbursement structure for tenants in supportive housing would make their

revenue model for services more sustainable than it is currently.

PART FOUR: RECOMMENDATIONS

CSH’s recommendations aim to support Idaho in acting on recent CMS guidance to further address housing as a

SDOH to increase access to healthcare, improve health, and lower system costs.

27

The following

recommendations offer ways that Idaho can ensure increased access to quality services that will address

housing as a key Social Determinant of Health, improve care, and reduce costs.

The state of Idaho is making strides to increase access to Medicaid services (particularly behavioral

health) and create a system of care that addresses the social determinants of health, providing the

right level of care, to the right people, at the right time. IDHW is currently balancing the

implementation of several important initiatives, including Medicaid expansion and the redesign of the

Idaho Behavioral Health Plan which has required a significant amount of staff time and capacity.

However, as the state considers future healthcare innovations and state policies, the creation of

Supportive Housing Services Benefit in the state Medicaid Plan should be a top priority. Importantly,

the creation of a Medicaid Supportive Housing services benefit was explicitly prioritized as a key

strategy within the IBHCs 2021-2024 Strategic Action Plan. A Supportive Housing Services Benefit will

lead to improved care, reduce health disparities, and reduce costs when the benefit is specifically

targeted to Idahoans experiencing homelessness with a behavioral health disability. To include these

services and populations, IDHW would need to seek a new State Plan Amendment (SPA) or Waiver

from CMS. CSH recommends pursuing one of two commonly-used authorities to include pre-tenancy

services and tenancy sustaining services, the 1915(i) SPA or an 1115 Waiver.

27

https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21001.pdf

I. Prioritize the Creation of a Supportive Housing Services Benefit to Address Health-Related

Social Needs (HRSN)

Page 23 of 26

1915(i) SPA

The 1915(i) is an optional state plan benefit that allows states to provide HCBS to individuals who

meet state-defined needs-based criteria that are less stringent than institutional criteria. States may

target the benefit to a specific population based on functional impairments, age, disability, diagnosis,

and/or Medicaid eligibility. Needs-based criteria may include, but cannot only include, state-defined

risk factors, such as the risk of or experiencing homelessness. States have the option to cover any

services necessary to live in the community. Minnesota

28

and North Dakota

29

have been approved for

these services under 1915(i) SPAs, and Connecticut

30

and Illinois

31

have submitted to CMS for SPAs

that offer housing support services.

1115 Waiver

CMS requires that a demonstration project under section 1115(a) of the Act be budget neutral to the

federal government, and States are expected to conduct independent and robust evaluations of the

demonstration. It is important to note that CMS currently will not approve a demonstration providing

coverage of services consistent with those authorized under section 1915(i) unless the state agrees to

adhere to programmatic requirements of individual assessments of need for those services.

Washington State and Hawaii are examples of two neighboring states using 1115 Waivers to

implement pre-tenancy and tenancy-sustaining services through Medicaid. It is also possible that

Idaho could amend its existing 1115 waiver to add additional housing-related services and supports;

IDHW should consider this option for prioritizing the creation of a supportive housing benefit without

having to seek a completely new Waiver or SPA.

A core element of acknowledging housing-related services as healthcare services is changing the

paradigm of access to care. In traditional healthcare structures, beneficiaries are required to seek out

services and go to clinics to receive them. Individuals who need supportive housing need the opposite-

they need the services to come to them. Service delivery must be engaging and coordinated to build

trust and support major life transitions. Therefore, these services or potential funding must include an

outreach and engagement component to ensure they reach the people that need them most.

CMS requires that Medicaid resources do not duplicate other available funding streams and that

Medicaid aligns with other programs and fills gaps where appropriate. CSH estimates that robust

Medicaid-covered supportive housing services will address approximately 80% of the need for

supportive housing services. The other 20% should be covered by flexible grants and contracts to

address the clearly-delineated gaps, including:

28

https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/MN/MN-18-0008.pdf

29

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/spa/downloads/ND-20-0010.pdf

30

https://portal.ct.gov/DSS/Health-And-Home-Care/Connecticut-Housing-Engagement-and-Support/Connecticut-Housing-Engagement-and-Support-

Services---CHESS

31

https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/cc/Pages/1915iapplication.aspx

II. While implementing statewide behavioral health transformation, coordinate local and state

funding for tenancy supports that Medicaid cannot provide

Page 24 of 26

• Outreach and engagement

• Benefits navigation

• Services for people who are not able to be immediately Medicaid enrolled

• Services for people who are not eligible for Medicaid or who are working on their citizen

documentation

• Warm hand-off to ensure coordination of services and care if a person changes providers or

Medical Home

• Services provided by agencies that provide culturally-specific services that cannot become

Medicaid billing agencies and/or partner with those that are.

When it comes to Medicaid alignment with other programs, there are several high-impact opportunities

for integrating supportive housing services into the anticipated Idaho Behavioral Health Plan changes in

2023. In particular, IDHW should focus on the following priorities:

• Directly connecting ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) Teams to supportive housing

tenants. As ACT teams are transitioned to community providers, it provides an opportunity

for increased support to supportive housing tenants. Many supportive housing services can

be directly provided via Medicaid funding by an ACT team in a community setting. With the

implementation of a new managed care contract for behavioral health services in 2023,

IDHW should ensure that housing-related services are included as allowable ACT-related

activities.

• Utilize the CCBHC model to explore direct partnerships with healthcare and housing

providers. With the state's investment in CCBHCs as part of its behavioral healthcare

reform, state partners should complete a supportive housing landscape assessment with the

four participating CCBHCs. The goal of this assessment is to guide the CCBHCs to housing

partnerships in order to address the needs of those they serve.

Throughout the review of covered services, it became apparent that many Medicaid services,

including HCBS, do allow for pre-tenancy and tenancy-sustaining services. Unfortunately, services

offered aren’t often community-based, and caseloads are too high to offer the level of support

highly vulnerable people need. This system-wide movement toward best practices in the State

could be accelerated by updating the following aspects of service delivery to address housing and

care coordination needs:

Assessment questions

Housing needs and preference questions should be included in all Medicaid services

assessments, including Targeted Case Management for SMI, all HCBS programs, SUD

treatment programs, and long-term care and nursing care facilities.

Individualized service plans for all HCBS recipients to include housing crisis support planning

The aging population in Idaho has been identified as needing more supportive housing units than

III. Weave medically necessary housing services into the existing health system

Page 25 of 26

any other vulnerable population. Idaho’s home and community-based service plans vary

depending on whether or not the individual is eligible for Medicaid. All HCBS service plans should

be individualized and include a plan for addressing housing crises and promoting housing stability,

regardless of the payer source (Medicaid State Plan, Medicaid HCBS Waiver, SPED, or Ex-SPED).

Case manager job descriptions and caseloads

Whereas case manager activities surrounding community visits and addressing housing needs are

currently outlined as guidelines, these activities would be highly effective as required activities as

elements of a case manager’s job description and performance reviews. Caseload ratios should be

set with a maximum number of clients to case manager ratio that accommodates community and

in-home visits.

Outreach and in-reach formalized with shelters, long-term care facilities, nursing homes,

and hospitals

Outreach, in-reach, and referral processes should be formalized with all referring entities through

shared referral forms, common assessment questions, combined staff training, and formal data-

sharing partnership agreements for sharing protected client information to coordinate care.

Staff training in supportive housing using a housing-first lens

Supportive housing is increasingly promoted as an evidence-based health intervention through

managed care and CMS. In adopting a housing-first model of supportive housing, Idaho will see

increased success in meeting its goal of promoting evidence-based cost-effective programs, while

delivering the right care at the right time to the people who need it most. To promote this

evidence-based practice, Idaho Behavioral Health Plan providers, PATH staff, healthcare, and

housing providers across the State would benefit greatly from supportive housing training.

Beyond the Crosswalk, cross-sector opportunities exist to develop policy goals, determine

implementation priorities, develop cross-sector partnerships based upon new federal, state, and local

housing opportunities, and other next steps. CSH recommends that IDHW and IHFA develop collective

goals and standards for supportive housing service delivery and housing across state departments and in

partnership with local municipalities and providers. Providers will need training and support in learning

and measuring their work against a set of state-wide standards such as CSH’s Quality Supportive

Housing Standards. Training programs, learning circles, guidance from people with lived expertise, and

professional technical assistance will be needed to ensure successful implementation. Examples of

common measures could include:

• Need for supportive housing

• Number of persons served, disaggregated by race and ethnicity

• Length of time from referral to lease up in housing

• Impact on housing stability, reasons for exiting housing, and destinations upon exit

• Impact on standard health-related outcomes and healthcare costs

IV: Ensure quality

Page 26 of 26

• Changes in racial disparities

Another critical step that the state of Idaho should take to address the creation of more quality

supportive housing units is by creating incentives for the development of new PSH projects within its

housing finance structure. IHFA should incentivize the creation of new supportive housing at scale

through its annual Qualified Allocation Plan for Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), which is a

state-administered indirect federal subsidy used to finance the creation of low-income affordable rental

housing

32

. IFHA currently does have some incentives in place for housing developers to include PSH

units within their affordable housing development, but unfortunately, this has not allowed for the level

of scale needed to meet the needs of those experiencing homelessness statewide. CSH recommends

that IHFA increase the minimum percentage of PSH units in an overall project required for an award of

competitive LIHTCs. IHFA may also use alternative state resources to incentivize the creation of new PSH