The IMPROVE Act, or the Improving Manufacturing, Public Roads and

Opportunities for a Vibrant Economy Act, was signed into law on April 26,

2017. Also called the “2017 Tax Cut Act,” it has been described as the largest

tax cut in Tennessee history. The IMPROVE Act does four main things:

1. Enhances existing revenue sources for the highway fund by

increasing fuel taxes and annual vehicle registration fees, and

identifies over 900 transportation projects to be paid for with the

increase;

2. Allows local governments to increase revenue for public

transit by levying surcharges on a variety of local taxes, such as the

sales tax, business tax, and rental car tax, after a local referendum;

3. Cuts three taxes, including the state sales tax on food, the Hall

income tax on investment income, and franchise and excise taxes on

manufacturers; and

4. Enhances property tax relief payments for low-income elderly

homeowners, low-income disabled homeowners, and service-disabled

veterans and their surviving spouses.

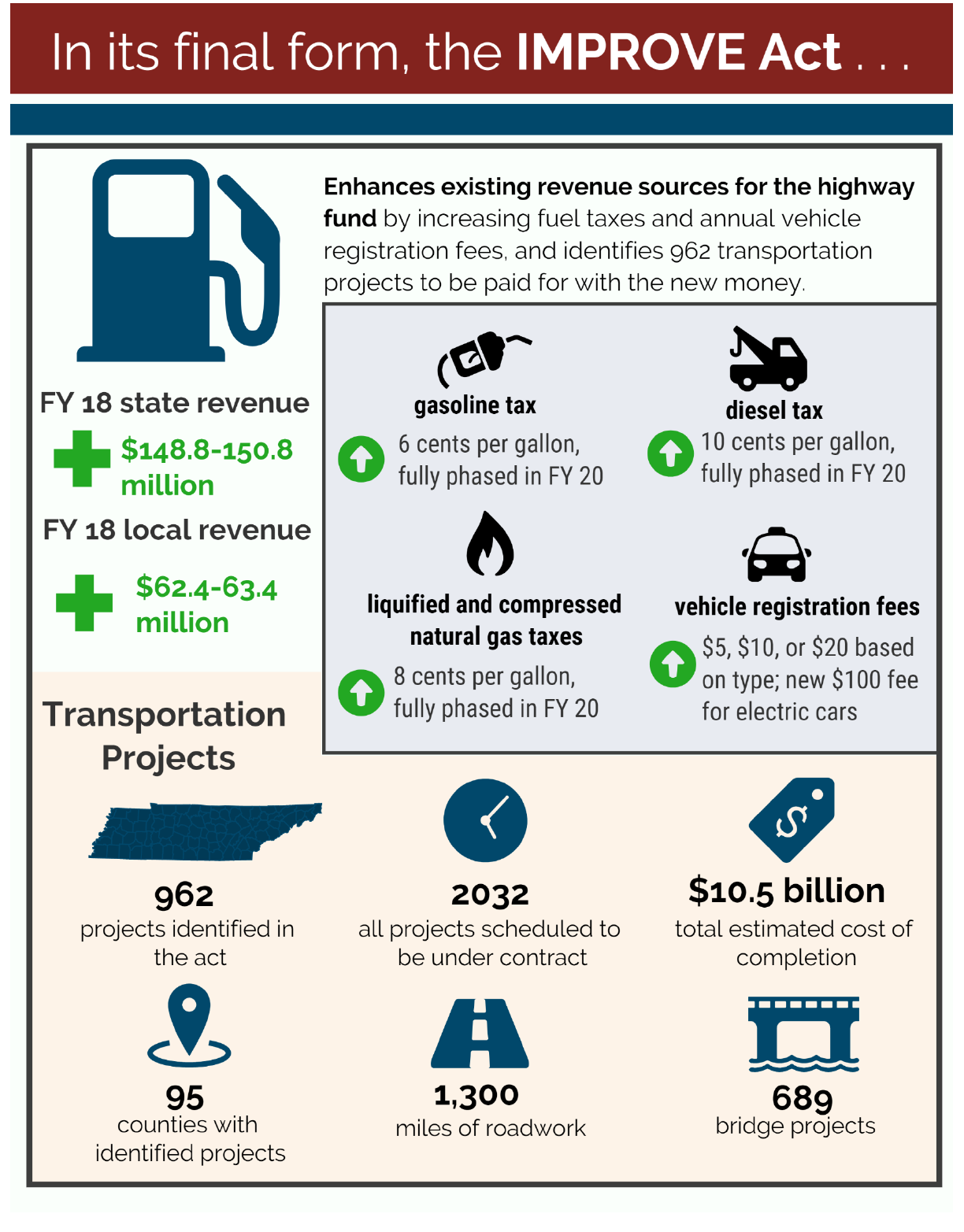

The IMPROVE Act increases fuel taxes and vehicle registration fees

Money for building and maintaining roads and bridges

comes from three main sources: state taxes on fuel,

including gasoline and diesel; motor vehicle registration

fees; and federal revenue. Fuel taxes and registration fees

are sometimes referred to as “user fees,” meaning that

users, or the people driving cars and trucks, pay for using

the roads.

The IMPROVE Act enhances taxes on fuel – phased in over

a period of three years – and increases annual registration

fees beginning July 1, 2017. While some of the increased

revenue goes to cities and counties, the state’s portion of

the new money goes to the highway fund and is intended to

fund 962 transportation projects identified in the act.

The Comptroller’s Office has

estimated the impact of these

changes using a range of fiscal

year 2017-18 revenue

estimates presented to the

State Funding Board by the

Tennessee Department of

Revenue, Fiscal Review

Committee staff, the Boyd

Center for Business and

Economic Research at the

University of Tennessee, and

East Tennessee State

University.

What can one cent do?

A one-cent increase in fuel taxes results in

about . . .

+$34 million in gas tax revenue, or roughly:

+$21.1 million to the state highway fund;

+$8.6 million to counties; and

+$4.3 million to cities.

+$10.6 million in diesel tax revenue, or about:

+$7.8 million to the state highway fund;

+$1.9 million to counties; and

+$0.9 million to cities.

July 2017

2

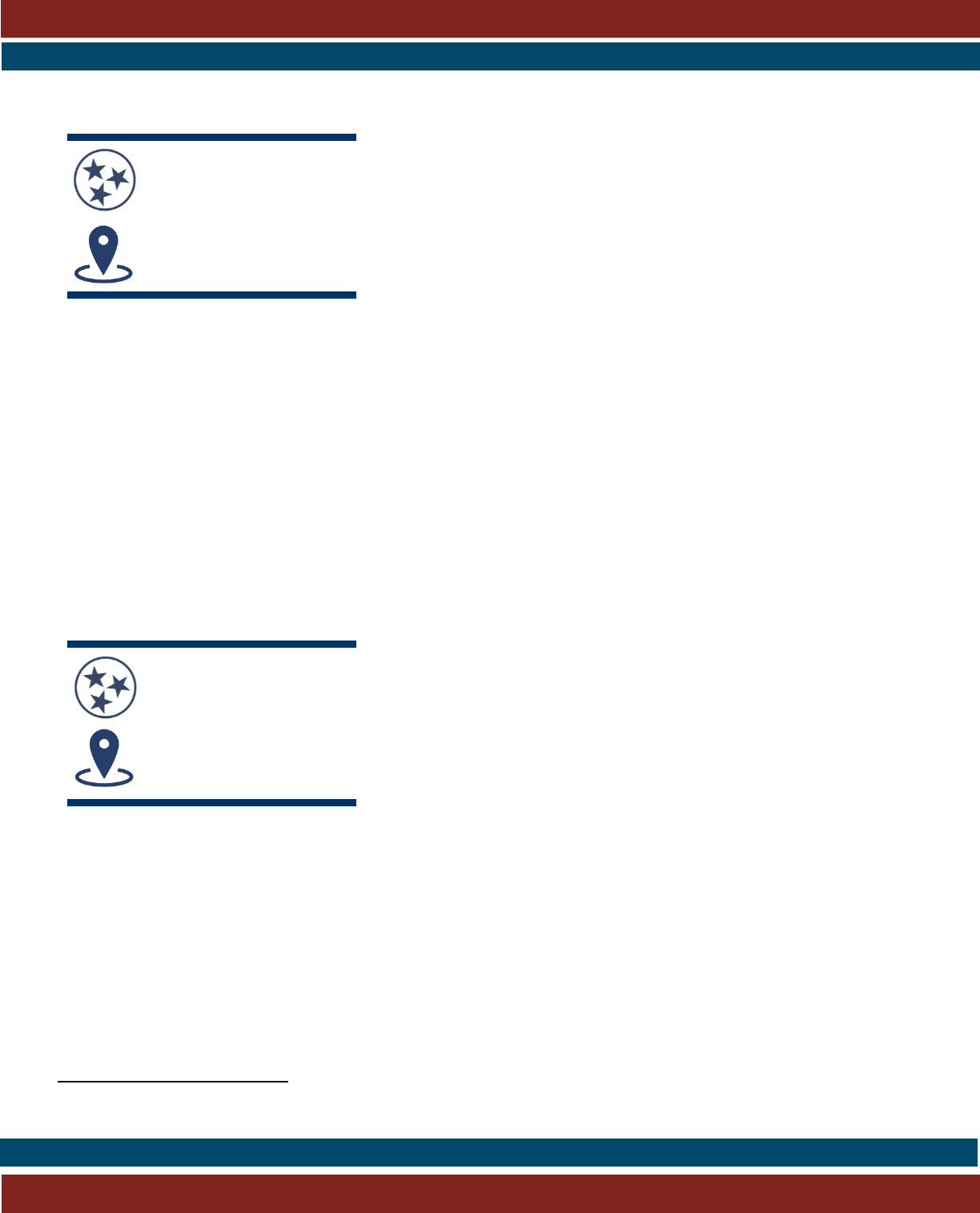

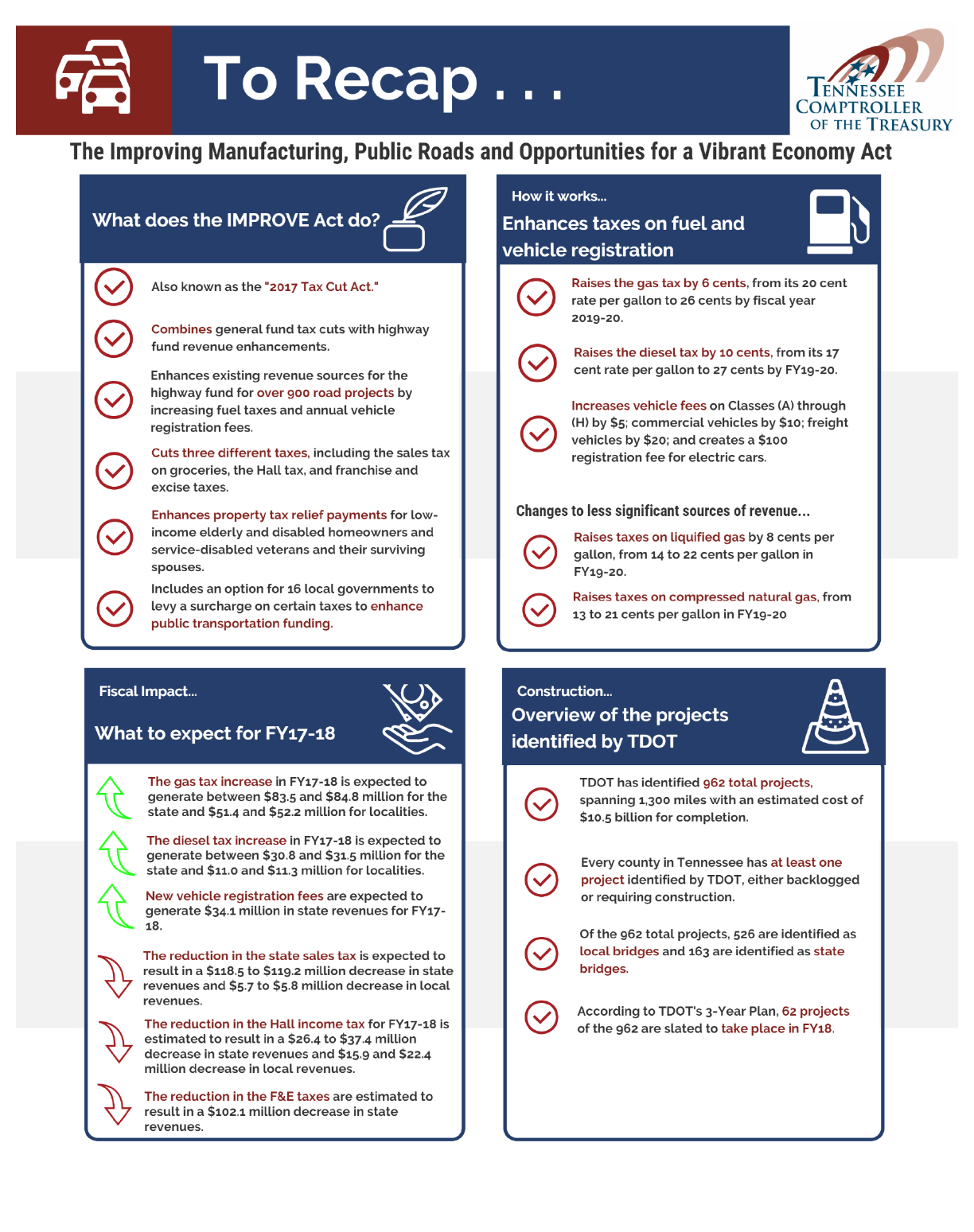

The IMPROVE Act increases the gas tax by 6 cents, phased in over three years

The gasoline tax is Tennessee’s main source of state transportation

funding: in fiscal year 2015-16, the gas tax alone accounted for 55

percent of all transportation-related revenue collected by the state.

The gas tax was set at 20 cents per gallon in 1989. Gas tax revenues

increased during the 1990s with the new rate, but have been

relatively flat since the early 2000s, partly due to inflation and more

efficient vehicles consuming less fuel.

The IMPROVE Act increases the tax from 20 cents to 26 cents per

gallon by fiscal year 2019-20. The initial increase, beginning in fiscal

year 2017-18, increases the tax by 4 cents and is expected to generate between $134.8 and $137.0 million in

new money. Of that, the state highway fund will receive 61.9 percent, or about $83.5 to $84.8 million. Local

governments will receive between $51.4 and $52.2 million – $34.2 to $34.8 million for counties, and $17.1 to

$17.4 million for cities.

The tax increases another cent to 25 cents per gallon in fiscal year 2018-19. Assuming consumers buy roughly

the same amount of gas, the tax will generate an additional $202.2 to $205.5 million over the original 20-cent

rate by the time it is fully implemented in fiscal year 2019-20. In other words, the state will bring in between

$125.2 and $127.2 million, counties about $52 million, and cities about $26 million more that year than they

would have if the tax had remained at 20 cents per gallon. Cumulatively in those three years, the state will have

collected over half a billion dollars in additional revenue: $313 to $318 million for the state highway fund, $128

to $131 million for counties, and about $64.5 million for cities.

The IMPROVE Act increases the diesel tax by 10 cents over a period of three years

Under the IMPROVE Act, the diesel tax increases from its current 17

cents per gallon rate to 27 cents per gallon beginning in fiscal year

2019-20. The initial 4-cent increase will generate between $41.8 and

$42.7 million in new revenue. Roughly $30.8 to $31.5 million, or 73.7

percent, will go to the highway fund; about $7.3 to $7.5 million will

flow to counties, and $3.7 to $3.8 million to cities.

By the time the 10-cent increase is fully phased in, the diesel tax will

generate anywhere between $104.6 million and $106.8 million over

its original 17-cent rate – about $77.1 to $78.7 million for the highway

fund, $18.3 to $18.7 million for counties, and $9.2 to $9.4 million for cities. Cumulatively, the state highway

fund will receive $161.9 to $165.3 in additional funding, along with $38.4 and $39.2 million for counties and

$19.3 to $19.7 million for cities.

The IMPROVE Act increases taxes on liquified gas and compressed natural gas by 8 cents,

phased in over three years

Taxes on liquified gas – propane and butane – and compressed natural gas used for fuel will both increase 8

cents over three years: propane from 14 to 22 cents per gallon, and compressed natural gas from 13 to 21 cents

per gallon.

A

Neither propane nor compressed natural gas are a significant source of revenue; in fiscal year

2015-16, they generated about $97,000 and $1.4 million, respectively. Because of low propane collections and

A

Although not specifically mentioned in statute, the Department of Revenue taxes liquified natural gas at the same rate as

compressed natural gas (currently 13 cents per gallon, and increasing to 21 cents per gallon).

FY 18 state impact

+$83.5-84.8M

FY 18 local impact

+$51.4-52.2M

FY 18 state impact

+$30.8-31.5M

FY 18 local impact

+$11.0-11.3M

3

volatile natural gas revenues, the Comptroller’s Office did not attempt to estimate the increased collections

from increasing the tax rate.

Fiscal Review cited an increase of $21,429 in fiscal year 2017-18, $35,714 in fiscal year 2018-29, and $57,143 in

fiscal year 2019-20 for propane; compressed natural gas collections were projected to increase by $319,385,

$532,308, and $851,692 in the same years.

Although current revenues from both of these taxes are shared with

local governments, increases under the IMPROVE Act are not shared and go entirely to the state highway fund.

The IMPROVE Act increases vehicle registration fees by $5, $10, or $20 depending on

vehicle type

Tennessee has three main tiers of vehicle registrations: private

vehicles, including motorcycles, cars, and trailers; private or

commercial vehicles that transport passengers, such as buses or vans;

and freight vehicles.

Beginning July 1, 2017, the IMPROVE Act increases the annual

registration fee for all three tiers. Altogether, the change in fees for

vehicle registrations will generate roughly $34.1 million in state

money each year.

B

All of the resulting money goes into the state

highway fund, but local governments can and do impose additional

local fees, though such local fees may not go toward transportation. Fees increase across the board from $5 to

$20, depending on the type of vehicle:

• Private vehicle fees increase by $5, and will generate an additional $26.1 million for the

highway fund based on Department of Revenue data, assuming the number of such

B

All registered freight vehicles except for logging trucks and trucks that transport farm products directly from farms to

market are subject to an additional 2.5 percent safety inspection fee. This money goes to the Department of Safety’s motor

vehicle account, rather than the state highway fund. The Department of Revenue estimates that 282,000 vehicles are

subject to this fee – the 2.5 percent fee, applied to the $20 registration fee increase in the IMPROVE Act, will generate an

additional $141,000 for the motor vehicle account.

20¢

17¢

14¢

13¢

4¢

4¢

3¢

3¢

1¢

3¢

2¢

2¢

1¢ 3¢

3¢

3¢

gas diesel liquified gas compressed

natural gas

Changes in fuel taxes by year

FY 17

FY 18 state impact

+$34.1M

FY 18 local impact

N/A

FY 20

FY 17

FY 17

FY 17

FY 20

FY 20

FY 20

4

vehicles remains stable. The new rate varies depending on the type of vehicle – trailer registrations,

for example, increase from $9.50 to $14.50, while fees for private buses increase from $200 to $205.

• Fees for private and commercial vehicles transporting passengers increase by $10 and

will bring in an estimated $51,600 in additional recurring revenue. Such fees are based on

the number of seats in the vehicle. On the low end, the fee for a bus or van with fewer than seven seats

increases from $37.13 to $47.13; fees for buses with more than 35 seats increase from $317.63 to

$327.63.

• Registration fees for freight vehicles increase by $20 each and will increase revenue by

$7.7 million. Freight fees are determined by weight. For example, the fee for a truck with a maximum

gross weight under 9,000 pounds increases from $48.50 to $68.50; the fee for a semi truck with a

maximum weight up to 80,000 pounds changes from $1,332.50 to $1,352.50.

In addition, the IMPROVE Act creates a $100 registration fee for electric cars. Currently, while electric cars

must be registered as private vehicles – $18.75 currently and increasing to $23.75 under the act – they do not

use gas and do not pay fuel taxes. Compared with the new gas tax rate of 26 cents per gallon, the $100

registration fee is equal to the gas tax revenue generated from about 385 gallons of gas. Taking the average fuel

efficiency of 23.9 miles per gallon for light-duty vehicles in 2015, the annual $100 fee is equivalent to the

revenue from driving about 9,200 miles a year, less than the 11,600 miles driven per capita in Tennessee in

2015. In other words, even with the new $100 fee, electric cars may not pay the same share for using the roads

as their gas-fueled counterparts. The Department of Revenue estimates there are approximately 2,500 electric

cars in the state, which will bring in about $250,000 from the new registration fee.

How are increased gas and diesel revenues shared with local governments?

Tennessee law requires that portions of current fuel tax revenues from gasoline, diesel, propane, and

compressed natural gas are shared with local governments. Additionally, a small percentage of those

revenues goes to the state general fund.

The IMPROVE Act specifies that increases in gas and diesel tax revenues will also be shared with

local governments; new money from propane and compressed natural gas taxes will not.

Furthermore, none of the additional money will go to the state general fund. The majority of

increased gas tax revenues, or 61.9 percent, goes to the state highway fund. Another 25.4 percent is

distributed to counties, and the remaining 12.7 percent is passed to cities. Similarly, most of the

increased diesel tax revenue – 73.7 percent – goes to the state highway fund, while 17.5 percent is

given to counties and the final 8.8 percent goes to cities.

State law sets formulas for sharing these funds among local governments:

▪ Of the 25.4 percent of increased gas tax revenue and 17.5 percent of increased diesel tax

revenue given to counties:

o 50 percent is shared evenly between all 95 counties;

o 25 percent is distributed based on area; and

o The remaining 25 percent is distributed based on population.

▪ The entirety of increased gas and diesel tax revenues given to cities – 12.7 and 8.8 percent,

respectively – is distributed based on population.

5

Local funding options for public transportation

The IMPROVE Act completely repeals Tennessee Code Annotated Title 67, Chapter 3, Part 10, which allowed

counties and cities to levy an additional one cent per gallon tax on gasoline following a local referendum. Money from

the additional local tax had to be used for public transportation services. No local government had used the

authority.

The IMPROVE Act creates additional local funding options for public transit. Currently, local governments may levy a

variety of local taxes, including the local option sales tax, city business taxes on retailers and wholesalers, and hotel-

motel taxes. Maximum rates for these taxes are capped in law, however, and may have statutory earmarks for the

resulting revenue, potentially limiting a local government’s ability to increase revenues for certain types of programs.

For example, if a county’s local option sales tax rate is set at 2.50 percent, the county cannot increase the rate

beyond an additional 0.25 percent because of the statutory maximum of 2.75 percent. By law, half of all local option

sales tax revenue must go toward education; accordingly, a county that increases the tax by 0.25 percent must

dedicate another 0.125 percent of revenue to education, with the remaining 0.125 percent of the total rate available

to spend at its discretion. Thus, the county may have limited ability to bring in new revenue for certain programs.

The IMPROVE Act allows local governments an option to generate new revenue specifically for public transit

programs. Following a local referendum, counties with populations over 112,000 and cities with more than 165,000

people may levy a surcharge on top of several current local taxes, including the sales tax, business tax, motor vehicle

tax, and rental car tax. The surcharge is collected in addition to current local tax revenues. For example, a county

could collect an additional 2.75 percent on sales on top of the underlying sales tax rate – in total, consumers could

pay up to 5.50 percent on their purchases in local taxes, and up to 12.50 percent when including the state sales tax

rate. The IMPROVE Act also outlines parameters and maximum rates for the surcharges (e.g., motor vehicle taxes

and surcharges combined cannot exceed $200).

Based on current population estimates, 12 counties are eligible to use this option: Shelby, Davidson, Knox, Hamilton,

Rutherford, Williamson, Montgomery, Sumner, Sullivan, Wilson, Blount, and Washington. The four largest cities –

Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga – may also potentially do so at the municipal level.

6

7

8

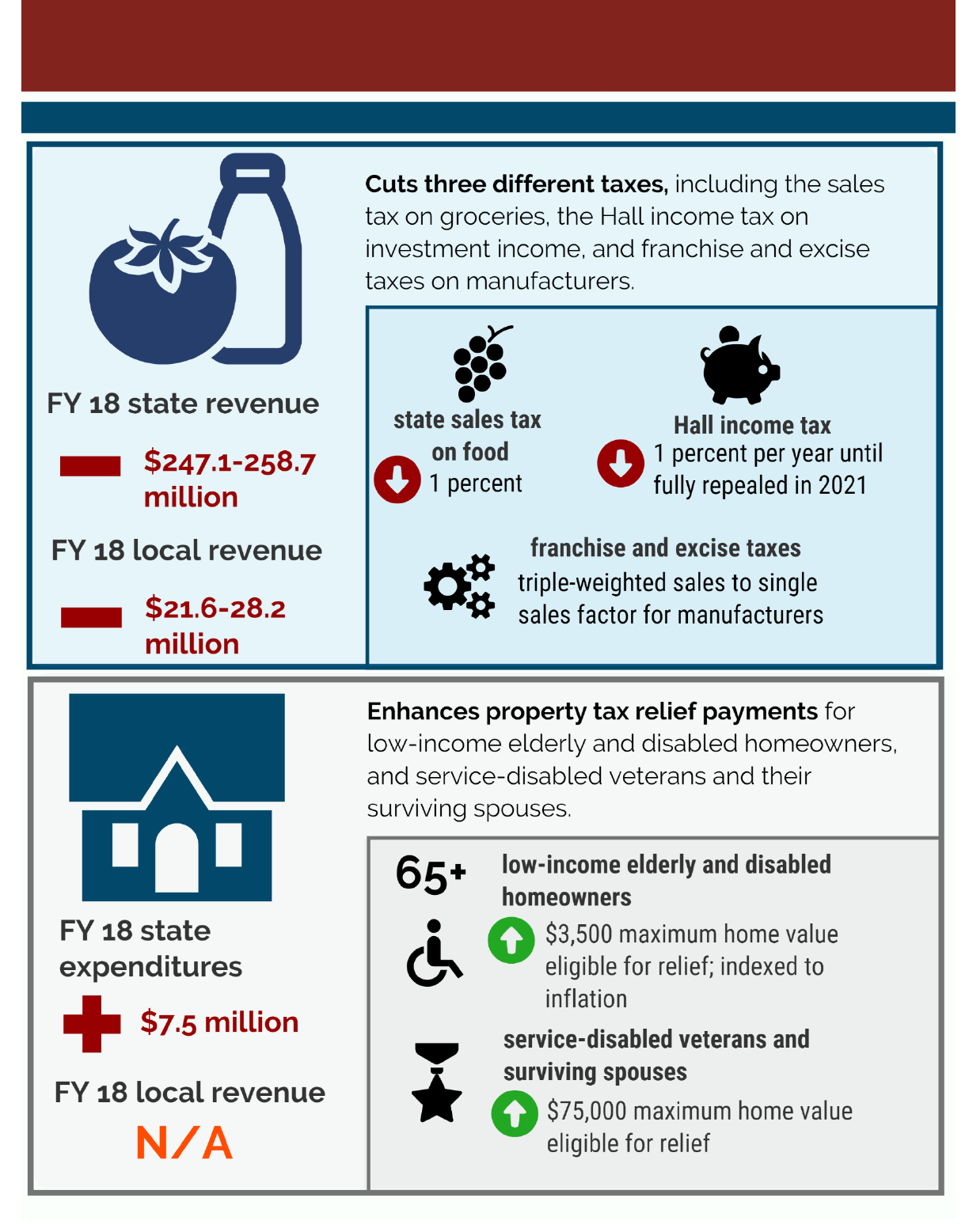

The IMPROVE Act cuts three types of taxes

The IMPROVE Act cuts the state sales tax on food and gradually phases out the Hall income tax until its

complete repeal. The new law also offers manufacturers an option that could potentially reduce their franchise

and excise tax burden.

The IMPROVE Act cuts the state sales tax on food from 5 to 4 percent

The majority of goods sold in Tennessee are taxed at 7 percent at the

state level, and local governments have the option to levy a local sales

tax up to 2.75 percent. “Food and food ingredients for human

consumption,” or groceries, however, are taxed at a lower state rate,

although they are still subject to up to a 2.75 percent tax at the local

level. In 2002, the state rate was set at 6 percent; it was reduced to

5.5 percent in 2007, 5.25 percent in 2012, and 5 percent, its current

rate, in 2013.

The IMPROVE Act further

cuts the tax on food from 5 percent to 4 percent. Based on revenue

projections for fiscal year 2018-19, taxpayers will save between $124.2

to $124.9 million in total. State revenues will decrease by about $118.5

to $119.2 million. In addition to the local option sales tax, the state

shares a small portion of state revenues with local governments; based

on the reduction in the state rate, revenue shared with local

governments will decrease by about $5.7 million.

C

Although local

governments are not held harmless for the loss of state-shared revenue,

the IMPROVE Act does not affect their ability to levy a local option tax

up to 2.75 percent on groceries.

The IMPROVE Act reduces the Hall income tax 1 percentage

point each year until full repeal in 2021

While Tennessee does not

have a general income tax, the

Hall tax is levied on

investment income, including

dividends from stocks and

interest on bonds. In 2016, the

Hall tax was reduced from 6

percent to 5 percent, and the

legislature expressed an intent to continue cutting the rate in future

years. The IMPROVE Act puts the phaseout schedule in law, and reduces the rate 1 percent each year so that

the tax will be completely repealed beginning January 1, 2021.

Based on projected collections for fiscal year 2017-18, a 1 percent cut in the Hall tax will save taxpayers between

$42.3 and $59.8 million. Statutory formulas set the local share at 3/8, or 37.5 percent, of total revenue, with

C

One percent of the 4.603 percent of state sales tax revenues shared with local governments is given to the Municipal

Technical Advisory Service (MTAS) at the University of Tennessee. In conjunction with the reduction of state-shared sales

tax revenue, annual MTAS funding will decrease by approximately $57,000.

Where does state revenue

from food sales go?

Revenue from 0.5 percent of the

sales tax rate goes toward K-12

education, or the BEP. The

remaining revenue is divided up as

follows:

▪ 29.0141 percent to the

general fund;

▪ 65.0970 percent to the

education fund;

▪ 4.6030 percent to local

governments;

▪ 0.3674 percent to the

Department of Revenue for

administrative purposes; and

▪ 0.9185 percent to the debt

service fund.

FY 18 state impact

-$118.5-119.2M

FY 18 local impact

-$5.7-5.8M

FY 18 state impact

-$26.4-37.4M

FY 18 local impact

-$15.9-22.4M

9

the state receiving 5/8, or 62.5 percent. Thus, for every 1 percent cut in the Hall tax, city and county revenue

will decrease between $15.9 and $22.4 million; state revenue will decrease by $26.4 to $37.4 million.

In 2021 when the tax is fully repealed, taxpayers will save between $132.2 and $186.9 million in the state’s

share of Hall tax payments that would have been collected if the tax had remained at 5 percent.

Correspondingly, local revenue will decrease by $79.3 to $112.1 million. Cumulatively over the six-year

phaseout, this amounts to between $396.7 and $560.6 million in decreased state revenue, and $238.0 and

$336.4 million in decreased local revenue.

The IMPROVE Act offers manufacturers an alternative calculation for franchise and excise taxes

Manufacturing is one of Tennessee’s biggest industries – according to

the Department of Economic and Community Development, the

percentage of Tennessee manufacturing workers is 1.38 times greater

than the national average. The IMPROVE Act attempts to make

Tennessee more attractive to manufacturers by offering them an

alternative way to calculate their franchise and excise taxes and

potentially reduce their tax burden.

Franchise and excise, while technically two separate taxes, are both

levied on the privilege of doing business in Tennessee. The franchise

tax is based on a business’s net worth, and the excise tax depends on

income. The calculation of tax is relatively straightforward in theory

for entities that do business entirely in Tennessee, but becomes more complicated for multi-state businesses.

Multi-state businesses are subject to tax on a portion, rather than the entirety, of their net worth and net

earnings. Net worth and net earnings are multiplied by a fraction

based on property, payroll, and sales – for tax years beginning on

or after July 1, 2016, the sales factor is now weighted three times as

heavily as the others (a “triple-weighted sales factor”).

For manufacturers – defined as companies that make more than

50 percent of their Tennessee revenue from manufacturing – the

IMPROVE Act creates an option to use a different apportionment

ratio for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2017. Rather

than taking into account property, payroll, and sales, the new ratio

includes sales only: total receipts from Tennessee divided by total

receipts. That is, if 55 percent of the manufacturer’s sales are made

in Tennessee, 55 percent of its net worth and net earnings will be

subject to franchise and excise taxes. In many cases, manufacturers

may have a substantial amount of property and payroll in

Tennessee, but may make many sales out of state. Consequently,

eliminating the property and payroll factor and only taking into

account Tennessee sales may reduce their franchise and excise tax

burden, as Tennessee receipts may make up a relatively small

portion of their total sales.

Franchise and excise collections are volatile; additionally, the

Department of Revenue cannot conclusively determine the number

of manufacturers who will use the alternative calculation until

businesses file their tax returns and elect to use the new option. As

Other recent changes in franchise

and excise taxes

In 2015, the General Assembly passed the

“Revenue Modernization Act,” which

addressed franchise and excise taxes.

Among other things, it created new

guidelines for taxing out-of-state

businesses that have no physical presence

in the state. Previously, although such

businesses earned revenue from

Tennessee customers (through online

purchases, for example), they did not pay

Tennessee taxes.

The act also changed the apportionment

ratio for net worth and net earnings from

a double-weighted to triple-weighted sales

factor. By reducing the weight of the

other two factors, property and payroll,

the act intended to encourage businesses

to physically relocate to Tennessee by

potentially reducing their tax burden.

FY 18 state impact

-$102.1M

This figure is provided by the Department

of Revenue. Due to the difficulty of

estimating franchise and excise taxes, the

Comptroller’s Office cannot provide an

independent estimate.

10

a result, the Comptroller’s Office cannot estimate the potential impact of the IMPROVE Act’s changes to

franchise and excise taxes. The Department of Revenue projects that revenue will decrease by $102,122,000 in

fiscal year 2017-18 and $113,300,000 in fiscal year 2018-19 and beyond.

The IMPROVE Act enhances property tax relief payments for elderly, disabled,

and service-disabled veteran homeowners

Local governments, rather than the state, impose property taxes. All

95 counties set a county tax rate; other entities – such as a city, a

special school district, or a fire district – may levy property taxes in

addition to the county rate for properties within that specific

boundary.

The state constitution provides for property tax relief for certain

elderly and disabled homeowners who meet income requirements, as

well as certain service-disabled veterans and their surviving spouses.

Property tax relief reduces the homeowner’s property tax bill because

the state, rather than the homeowner, pays all or a portion of the tax

to the local government.

As such, local revenue is not affected by changes in property tax relief eligibility

requirements.

In tax year 2016, homeowners age 65 or older or those with qualifying

disabilities were eligible for property tax relief on the first $23,500 of

market value of their homes, so long as total qualifying income was no

more than $29,180. There is no income limit for disabled veterans or

their surviving spouses, and property tax relief applied to the first

$100,000 of market value of their homes that same year.

The IMPROVE Act increases value limits for all three categories of

property tax relief. The value limits for elderly and disabled

homeowners increase from $23,500 to $27,000 beginning in tax year

2017, and veterans from $100,000 to $175,000. The act also ties this

value figure for elderly and disabled homeowners to the Consumer Price

Index, so that the limits may be adjusted by up to 3 percent each year

for inflation.

Based on projected enrollment, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that

state expenditures for property tax relief will increase $7.5 million: $2.7

million for elderly and disabled homeowners, and $4.8 million for

service-disabled veterans and their surviving spouses.

Recipient

FY 16-17

FY 17-18

Low-income elderly

(65+) and disabled

Income limit

$29,180

$29,180

Maximum market value for

which tax relief is paid

$23,500

$27,000, indexed in

future years

Disabled veterans/

surviving spouse

Income limit

none

none

Maximum market value for

which tax relief is paid

$100,000

$175,000

Who gets property tax relief?

In fiscal year 2015-16, the state

spent about $25.5 million on

property tax relief payments for

nearly 104,000 people. The majority

of recipients, or almost 92,000, were

elderly or disabled. Roughly 12,000

recipients were service-disabled

veterans or surviving spouses.

Although property tax rates and bills

vary widely from county to county,

the average payment to elderly and

disabled recipients was $137; the

average for veterans was $536.

FY 18 state impact

+$7.5M state

expenditures

FY 18 local impact

N/A

11

Contact Information

Justin P. Wilson

Comptroller of the Treasury

Jason Mumpower

Chief of Staff

Comptroller of the Treasury

State Capitol

Nashville, Tennessee 37243

(615) 741-2501

www.comptroller.tn.gov

To report fraud, waste, or abuse of government funds and

property, contact the Comptroller’s toll-free hotline at

1-800-232-5454 or www.comptroller.tn.gov/hotline.