Addressing the Climate Crisis

An Action Plan for Psychologists

REPORT OF THE APA TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE

APPROVED BY APA COUNCIL OF REPRESENTATIVES, FEBRUARY 2022

IIMICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

Copyright © 2022 by the American Psychological Association. This material may be reproduced and distributed without permission

for educational or research purposes provided that acknowledgment is given to the American Psychological Association. This material

may not be translated or commercially reproduced without prior permission in writing from the publisher. For permission, contact APA,

Rights and Permissions, 750 First Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002–4242.

American Psychological Association (APA) reports synthesize current knowledge in a given area and may offer recommendations for

future action. They neither constitute APA policy nor commit APA to the activities described therein. This report was requested by the

APA Council of Representatives at its February 2020 meeting.

Suggested Citation:

American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Climate Change. (2022) Addressing the Climate Crisis: An Action Plan for

Psychologists, Report of the APA Task Force on Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/science/about/publications/

climate-crisis-action-plan.pdf.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS1

Addressing the Climate Crisis

An Action Plan for Psychologists

REPORT OF THE APA TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE

APPROVED BY APA COUNCIL OF REPRESENTATIVES, FEBRUARY 2022

APA Task Force on Climate Change (2020–2022)

Members

Gale M. Sinatra, Ph.D. (Chair)

Rossier School of Education

Univ. of Southern California

Los Angeles, California (USA)

Wael K. Al-Delaimy, M.B.Ch.B., D.C.M., Ph.D.

Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health

and Human Longevity Science

Univ. of California, San Diego

La Jolla, California (USA)

Nancy J. Chaney, R.N., M.S.

Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments

Moscow, Idaho (USA)

Merritt Juliano, J.D., M.S.W., LCSW

Regenerative Psychotherapy PLLC

Westport, Connecticut (USA)

Azeemah Kola, J.D., M.SC., M.A.

Dept. of Psychology

New School for Social Research

New York City, New York (USA)

Ezra M. Markowitz, Ph.D.

Dept. of Environmental Conservation

Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst

Amherst, Massachusetts (USA)

Taciano L. Milfont, Ph.D.

School of Psychology

Univ. of Waikato

Tauranga (New Zealand)

Richard Plenty, Ph.D.

This Is…

Organization and Leadership Development

Epsom, Surrey (United Kingdom)

Sarah W. Sutton, M.A.

Environment & Culture Partners

Tacoma, Washington (USA)

Sander L. van der Linden, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychology

Univ. of Cambridge

Cambridge (United Kingdom)

Sara J. Walker, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychiatry

Oregon Health & Science Univ.

Portland, Oregon (USA)

Gabrielle Wong-Parodi, Ph.D.

Dept. of Earth System Science

Woods Institute for the Environment

Stanford Univ.

Palo Alto, California (USA)

Liaisons from APA Boards

Susan D. Clayton, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychology

College of Wooster

Wooster, Ohio (USA)

Board of Directors

Kathryn H. Howell, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychology

Univ. of Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee (USA)

Board for the Advancement of Psychology in

the Public Interest

Jeanne Miranda, Ph.D.

Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human

Behavior

Univ. of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California (USA)

Board of Professional Affairs

Janet K. Swim, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychology

The Pennsylvania State Univ.

State College, Pennsylvania (USA)

Board of Scientific Affairs

Maggie Syme, Ph.D.

Center on Aging

Kansas State Univ.

Manhattan, Kansas (USA)

Board of Educational Affairs

APA Staff

Howard S. Kurtzman, Ph.D. (Liaison)

Science Directorate

Scott Barstow, MSc

Advocacy Office

Janet Johnson

Science Directorate

Joseph Keller, Ph.D.

Advocacy Office

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

The Task Force and Its Work

The Climate Crisis

Climate Change and Its Impacts

Responding to Climate Change

How Psychologists Can Address the Climate Crisis

Mitigation

Adaptation

Public Understanding and Attitudes

Social Action

Building a Stronger Role for Psychologists

APA’s Role in Addressing the Climate Crisis

APA’s Strategic Plan

APA’s Work So Far

Recommendations for APA

Research

Practice

Education

Advocacy

Communications

APA’s Energy Use and Sustainability Practices

Implementing the Recommendations

Final Comment

References

Appendix APA’s Climate Change Activities (–)

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

INTRODUCTION

Successful responses to the climate crisis require the participation of all fields and

sectors of society. Psychologists have conducted valuable work on the climate crisis

and can make even greater contributions to understanding the crisis, mitigating and

adapting to climate change, and achieving climate justice. This report from the

American Psychological Association’s Task Force on Climate Change examines the

multiple roles psychologists play in research, practice, education, advocacy, and

communications related to the climate crisis and how APA can facilitate expansion

of psychologists’ work in these domains.

The task force recommends that APA pursue a set of activities that will both

(a) strengthen the field by encouraging a larger number of psychologists, across

all specializations, to work on climate change, and (b) broaden the impact of

psychologists’ work on climate change by supporting their engagement and collab-

orations with other fields and sectors. Further, the task force offers recommenda-

tions for how APA can help mitigate climate change by improving its own energy

use and sustainability practices and encouraging improvements by other organi-

zations and the public.

Responding to the climate crisis is an essential task for the current generation

and many generations to come. Although the severity and urgency of the crisis

should not be understated, it remains within the capacity of society to reduce its

most adverse effects and to promote health, well-being, and justice for all people.

Psychologists have the knowledge and skills to design and implement strategies that

will help realize these aims. As a leading scientific and professional association, APA

can prepare, support, and organize psychologists to address the climate crisis and

amplify their work for greatest impact and visibility.

The task force presents this report not only to guide APA but also to inspire

individual psychologists, psychology groups and departments, and other psycholog-

ical associations to devote attention to the climate crisis, and to serve as a model for

people and organizations in other disciplines and professions.

4MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

THE TASK FORCE AND ITS WORK

The mission of the American Psychological

Association’s Task Force on Climate Change was to

review the progress APA has made in addressing cli-

mate change and to offer recommendations for its

future activities in the area. The task force was autho-

rized in February 2020 by the APA Council of

Representatives, the association’s highest governing

body, in a policy resolution titled APA’s Response to

the Global Climate Change Crisis. The resolution

included the following provision about the task force:

he Presiden o P shall appoin a as orce

composed o leadin inernaional epers o reie

Ps pas and curren aciiies relaed o lobal

climae chane and o recommend oals and sraeies

or uure P aciiies ha ill hae a sron impac on

he climae chane crisis. he Council o epresenaies

requess ha he as orce eep in mind he prime

imporance o issues surroundin miraion human

rihs and ssemic aspecs includin poliical

economic and corporae o climae chane as ell as

address ho P can improe is on susainabili

pracices. he as orce ill submi a repor o he

Council o epresenaies and he repor ill be

disseminaed o he membership o P.

APA issued a call for nominations for members of the

task force in July 2020. The call specified that the task

force was to “include individuals from psychology and

from other disciplines or professions, and individuals

from both within and outside the United States.” Upon

review of the nominations received, APA President

Sandra L. Shullman appointed twelve individuals to

serve on the task force in September 2020. The task

force included members with backgrounds in psychol-

ogy, medicine, epidemiology, nursing, environmental

science, local government, law, social work, museums,

and business. They were based in the United States,

the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, with several

having strong ties to other countries as well. All mem-

bers had significant expertise and experience in cli-

mate change and related topics.

The task force held twenty-six 90-minute virtual

meetings (via Zoom) between October 2020 and

January 2022. Between meetings, it engaged in discus-

sion by email and at times worked in subgroups. In

addition to task force members, participants included

liaisons from five major APA boards (Board of Direc-

tors, Board for the Advancement of Psychology in the

Public Interest, Board of Educational Affairs, Board of

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

Professional Affairs, and Board of Scientific Affairs)

and APA staff.

In their meetings, task force members reviewed,

shared, and discussed information in a variety of areas,

including:

• Ps pas and curren aciiies relaed o climae

chane.

• Ps on ener use and susainabili pracices.

his opic as addressed b he as orce as a

hole raher han b a subroup as as oriinall

announced.

• Curren direcions in pscholoical science pracice

and educaion relaed o climae chane.

• he publics undersandin aiudes and emoional

responses concernin climae chane.

• Poliical economic and socieal acors inluencin

climae chane and indiidual and collecie

responses o i.

• Inernaional naional and reional policies and

prorams relaed o climae chane.

• elaed enironmenal challenes such as polluion

and biodiersi loss.

• Human rihs enironmenal jusice and oher

social jusice issues.

• Indienous culures eperiences o and responses

o climae chane.

• Sraeies or communicain abou climae chane.

• docac and aciism on climae chane issues.

• or on climae chane conduced b indiiduals

and oraniaions in oher ields includin sciences

humaniies healhcare social jusice and public

polic.

The task force considered these areas in relation to

APA’s strategic plan and APA’s policies on human

rights, ethics, racism, multiculturalism, immigration,

socioeconomic status, global perspectives, and scien-

tific freedom as well as input received from APA

boards and divisions and information about APA’s

other current activities.

A previous APA task force, which met in 2008–09,

produced a review of psychological research on

climate change and offered recommendations for

6MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

further research (Swim et al., 2011). That work served

as the basis for a 2011 Council of Representatives

resolution on psychologists’ role in addressing climate

change. The current task force consulted with several

members of the earlier task force (Thomas J. Doherty,

Joseph P. Reser, Paul C. Stern, and Elke U. Weber) to

learn their perspectives on how the field of climate

change and psychology has developed since 2009,

current opportunities and needs in the field, and steps

APA can take to advance the field. (In addition, two

members of the earlier task force, Susan D. Clayton

and Janet K. Swim, served as liaisons from APA boards

to the current task force.)

The 2008–09 task force also produced “policy

recommendations” for APA activities on climate

change. Although not formally endorsed or adopted by

APA, these recommendations informed APA’s subse-

quent work. The recommendations were considered by

the current task force in assessing the progress APA

has made and in developing new recommendations.

The current task force focused on activities that are

managed, conducted, or directly supported by APA’s

central office in Washington, DC (including activities

of boards and the Council of Representatives). It was

not feasible to closely examine or develop specific

recommendations for APA’s 54 divisions, which vary in

size, resources, and structure and operate with a degree

of autonomy from the central office. However, the task

force suggested new activities that the central office

might pursue in collaboration with divisions (as well as

with other organizations independent of APA, includ-

ing state and regional psychological associations and

ethnic psychological associations in the U.S.).

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

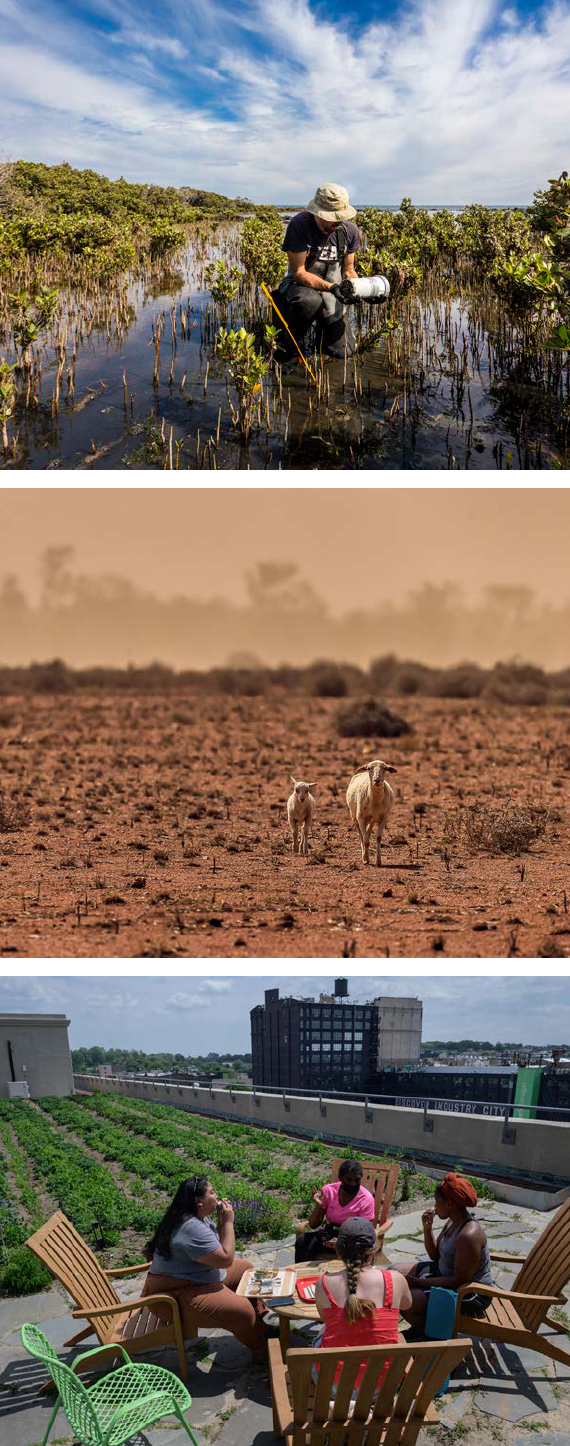

THE CLIMATE CRISIS

Changes in the climate due to emissions of gases

resulting from human energy, industrial, and agricul-

tural practices are having broad and harmful impacts

on life on our planet, including on human health and

well-being. Many of these impacts are violations of

human rights and increase disparities among popula-

tion groups. However, major actions taken now can

limit the severity of climate change and its conse-

quences. This section presents an overview of cli-

mate change and its effects and of the steps that

individuals, organizations, and governments can take

both to mitigate climate change and to enable people

to adapt to it.

Climate Change and Its Impacts

Since the late nineteenth century, the average surface

temperature of the earth has increased by about 1.1

degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit), with most of

the increase occurring since the mid-twentieth cen-

tury (IPCC, 2021). Scientists have firmly established

that this temperature change, referred to as global

warming, is primarily due to increased amounts of car-

bon dioxide and other “greenhouse” gases being emit-

ted into the atmosphere and that the increase in

emissions is due to human activities. The gases essen-

tially trap heat in the atmosphere, thus raising surface

temperature (National Academy of Sciences, 2020).

The growth of carbon dioxide emissions stems

from increased burning of fossil fuels (oil, coal, and

natural gas) as well as clearing of forests and grass-

lands (which capture and store carbon dioxide).

Although carbon dioxide comprises the largest

percentage of greenhouse gas emissions, other green-

house gases also contribute to global warming. These

include methane, which is released in the production

and transport of fossil fuels and in certain agricultural

and waste processing practices. They also include

nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases, emitted in various

industrial and agricultural activities (U.S. Environmen-

tal Protection Agency, 2021b).

Higher surface temperatures have led to changes

in the climate of every region of the planet, including

altered precipitation patterns, rising sea levels,

melting polar ice, and increases in severe storms,

flooding, heatwaves, drought, and wildfires (IPCC,

2014a, 2018; U.S. Global Change Research Program,

2017). Such changes have begun to have profound

impacts on people’s health and on the well-being of

individuals and communities. While outcomes vary

across populations and settings, climate change is

contributing to greater prevalence and severity of the

conditions and events listed below (Al-Delaimy et al.,

2020; Clayton et al., 2021; Ebi et al., 2018; Lawrance

et al., 2021; National Intelligence Council, 2021; U.S.

8MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

Global Change Research Program, 2018; Watts et al.,

2021; Xu et al., 2020):

• reme eaher and climae eens includin

ildires leadin o deahs injuries and damae o

inrasrucure buildins and proper.

• Menal healh condiions includin pos-raumaic

sress anie depression and subsance misuse.

• Inerpersonal aression and iolence.

• Impaired coniie and brain uncion.

• Premaure birhs and lo birh eih.

• Shoraes o sae aer and ood.

• Dehdraion and heasroe.

• Inecious diseases ransmied hrouh ood aer

insecs and oher animals.

• Cardioascular respiraor idne and alleric

condiions.

Climate change can also lead to job losses, economic

disruptions, interruptions in education and social ser-

vices, losses of culturally significant places and

resources, intergroup and international conflict, and

population displacements (including voluntary and

forced migrations, refugee movements, and planned

relocations, both within and across national boundar-

ies).

1

Associated with these impacts, individuals may

experience loss or alteration of identity, autonomy, or

sense of control. Further, households, social networks,

and communities may become less cohesive and

effective, and communities that undergo major disas-

ters or lose homelands may experience collective or

historical trauma. As climate change continues, these

impacts will become more severe in future years.

Many of these impacts are violations of human

rights under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

and other international agreements, including rights

concerning life, health, and culture (Feygina et al.,

2020; Gardiner, 2011; Office of the High Commissioner

for Human Rights, 2015; United Nations Environment

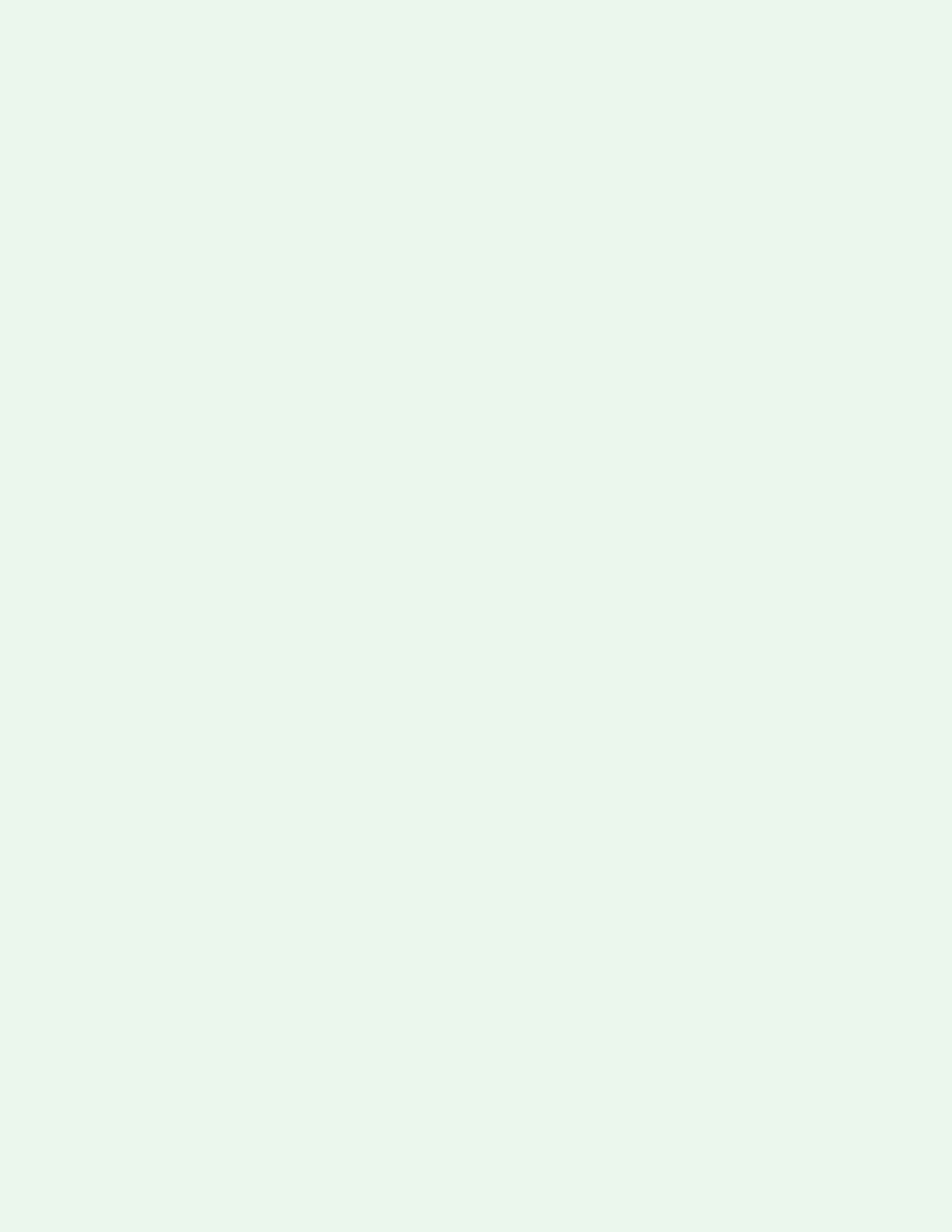

Programme, 2015). Further, some groups dispropor-

tionately bear the negative impacts of climate change,

including Indigenous peoples, communities of color,

1Two World Bank (2018, 2021) reports project that by 2050 as many as 216 million people throughout the world may be forced to

migrate within their countries due to climate change unless significant mitigation and adaptation actions are taken.

and communities that are economically disadvantaged

(Clayton et al., 2021; Jafry, 2019; Méndez et al., 2020).

These disparities can be attributed in part to the facts

that such communities are more likely to be located in

areas in which extreme weather occurs or in which

there are fewer protections against such weather, that

they face other health and economic challenges that

are exacerbated by climate impacts, and that they have

less access to resources to recover from climate

impacts. Other groups—including children, older

adults, women, persons with disabilities, and outdoor

workers—may also bear greater impacts of climate

change due to various environmental, health, economic,

and social factors. Growing recognition of these dispar-

ities has led to activism and policy efforts to achieve

climate justice, part of the broader movement for

environmental justice (Henry et al., 2020; Jafry, 2019;

Méndez, 2020; NAACP, 2021; Robinson & Shine, 2018;

Rouf & Wainwright, 2020).

Responding to Climate Change

Unless major reductions in greenhouse gas emissions

are made quickly, by about 2030, the earth’s average

surface temperature will continue to rise and climate

change will intensify, with catastrophic consequences

for human health, well-being, and equity (IPCC, 2018,

2021). The Paris Agreement, an international treaty

adopted in 2015, set a goal of limiting global warming

to below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit)

and preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees

Fahrenheit). Major shifts in policy, investments, tech-

nology, and behavior—especially in the more econom-

ically developed countries, which currently produce

most emissions—are needed to achieve either of these

targets (Pearce, 2021).

Responses to climate change are generally classi-

fied under the broad categories of mitigation or adapta-

tion (IPCC, 2014b). Mitigation refers to efforts to limit,

prevent, and counteract greenhouse gas emissions so

that human-driven climate change can be slowed and

eventually halted. Mitigation approaches can aim to

reduce overall consumption of energy as well as alter

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS9

how energy is produced and used. Critical to mitigation

is adoption of new norms, practices, and technologies

for transportation, indoor heating and cooling, diet,

land management, agriculture, industry, and waste

processing (Carmichael, 2019; Meyer & Lord, 2021;

Milfont, Satherley, et al., 2021). Mitigation also involves

the development and widespread implementation of

technologies for producing energy from sources other

than fossil fuels (e.g., solar, wind, hydropower, geother-

mal, nuclear). In addition, proposals have been made

for applying geo-engineering methods for removing

greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (e.g., large-

scale tree planting, carbon dioxide filtering devices)

and reflecting sunlight back into space (e.g., by adding

reflective particles to the upper atmosphere) (Converse

et al., 2021; Cox et al., 2022; National Academies of

Sciences Engineering & Medicine, 2019, 2021a, 2021b).

Adaptation refers to efforts to reduce the current

and future negative impacts of climate change and help

people to adjust to the impacts. These efforts are neces-

sary because, even under the most optimistic projec-

tions, the climate will continue to change through much

of this century due to the greenhouse gases that have

already been and are currently being emitted (IPCC,

2021). Adaptation can take various forms. Examples

include building seawalls, shifting to drought-resistant

food crops, improving disaster preparation and response

by households and communities, training healthcare

workers, promoting psychological and social resilience

within communities, incorporating climate risks into

financial policy and planning, relocating populations

from unsafe areas, and services for climate migrants and

refugees, as well as regenerative approaches to agricul-

ture and daily living (Clayton et al., 2021; Newton et al.,

2020; Pelling & Garschagen, 2019; U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency, 2022).

Large-scale mitigation and adaptation efforts build

on ongoing research to develop effective new norms,

practices, and technologies that will be accepted and

adopted by households, communities, institutions,

corporations, and nations. They also involve new laws,

regulations, policies, infrastructure, staffing, and

funding by governments and private entities; these can

move society forward by creating the opportunities,

supports, incentives, and requirements that will lead

organizations and individuals to participate in mitiga-

tion and adaptation initiatives (Cambridge Sustainabil-

ity Commission on Scaling Behaviour Change, 2021;

Vandenbergh & Gilligan, 2017). Although governments

around the world have taken some steps to advance

such initiatives, their efforts to this point are widely

viewed as insufficient (Plumer & Friedman, 2021).

In the U.S., a majority of the population perceives

climate change to be a significant issue and favors

government action to address it (Ballew et al., 2019;

Tyson & Kennedy, 2020; United Nations Development

Programme & Univ. of Oxford, 2021). However, individ-

uals affiliated with the two major political parties tend to

hold or express contrasting views about climate change

and policy (although these differences are moderated by

age and gender) (Doell et al., 2021; Jenkins-Smith et al.,

10MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

2020). Political leaders from the two parties are rarely

able to reach agreements on new federal policies and

programs for mitigation and adaptation, and therefore

those initiatives that are adopted tend to be limited in

impact or scope (Karapin, 2016; Mildenberger, 2020).

Another noteworthy element of the political

landscape in the U.S. is misinformation about climate

change disseminated by individuals, think tanks, and

corporations (Brulle, 2021; Brulle et al., 2020; Cook,

2020; Cook et al., 2019). Most prominent are sustained

efforts by the fossil fuel industry since the 1960s to

mislead the public and policymakers about global

warming and to lobby against changes in laws (e.g., tax

subsidies) that favor use of fossil fuels (Mann, 2021;

Oreskes & Conway, 2010; Parry et al., 2021; Skovgaard,

2021; Skovgaard & van Asselt, 2018; Supran & Oreskes,

2021). Among the industry’s strategies has been to

downplay the dangers of its greenhouse gas emissions

and the feasibility of alternative energy sources. The

industry has also suggested that responsibility for the

country’s continued reliance on fossil fuels lies with

individual customers (who usually have limited energy

use options) rather than corporations and government.

Some companies have acknowledged the need to move

away from fossil fuels (Taylor & Rankin, 2008), but their

plans are considered by many climate change observers

to be insufficient in magnitude or speed (Waldman,

2018; Worland, 2020). Various scholars and advocates

have worked to identify and counteract these and other

forms of misinformation about climate change (Climate

Social Science Network, 2022).

To be successful, mitigation and adaptation

initiatives must recognize differences among

individuals, communities, and countries in the amounts

of emissions they produce, the nature and degree of

climate change impacts they experience, and their

capacities for transitioning to new technologies and

practices. For example, wealthier people and countries

generally produce more emissions and so they are

generally expected to make greater emissions

reductions and to assist others in their mitigation and

2 The complexity of mitigating climate change increases when a broader range of environmental issues is examined. For example,

assessments of proposed projects for mining lithium, used in batteries for electric vehicles, must consider their potential negative effects

of endangering water supplies and ecosystems and disrupting the lands of Indigenous communities (Barringer, 2021; Zografos & Robbins,

2020).

adaptation efforts (Atwoli et al., 2021; Urpelainen &

George, 2021). By contrast, workers who lose their

jobs due to closures of fossil fuel facilities (e.g., coal

mines and oil refineries) may need financial and other

forms of support, as may people with low incomes in

countries in which subsidies for fossil fuel prices are

removed (Richardson, 2021; Timperley, 2021). Taking

a climate justice and human rights perspective, all

those affected by climate change and potential

responses to it in a region or community should be

represented in decision-making to ensure that their

needs and interests are addressed.

In addition, responses to climate change should take

into account its interactions with other environmental

problems, including pollution, biodiversity loss, ocean

acidification, soil depletion, deforestation, animal

diseases, and pandemics (Haines & Frumkin, 2021;

Nielsen, Marteau, et al., 2021; United Nations Environ-

ment Programme, 2019). For example, greenhouse gas

emissions contain pollutants that have adverse health

effects besides those linked to global warming (e.g.,

sulfur dioxide), and deforestation contributes to both

climate change and biodiversity loss. Climate change

can lead animals to migrate to new habitats and make

them more vulnerable to diseases, which in turn

increases the risk for cross-species transmission of

diseases to humans with potential pandemic spread

(Baker et al., 2021).

Various multidisciplinary frameworks have

emerged in recent years to capture the relationships

among the environment, human activity, and human

and animal health [e.g., One Health (Deem et al., 2018),

EcoHealth, GeoHealth, Planetary Health, the Anthro-

pocene (Zalasiewicz et al., 2019)]. These frameworks

can help guide more comprehensive mitigation and

adaptation efforts that address the full range of environ-

mental challenges. Although the scope of the task

force (and this report) is limited to climate change, the

task force encourages APA and others to address

climate and other environmental issues in this broader,

integrated fashion.

2

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS11

HOW PSYCHOLOGISTS CAN ADDRESS THE CLIMATE CRISIS

Psychologists have made significant contributions to

responding to the climate crisis (Clayton & Manning,

2018; Ferguson & Schmitt, 2021; Swim et al., 2011) and

are well positioned to contribute more. As research-

ers, practitioners, educators, consultants, communi-

cators, leaders, and advocates, psychologists have

multiple opportunities to take action to advance indi-

vidual and collective health, well-being, and justice.

Nearly all subject areas and approaches within psy-

chology (including environmental, cognitive, social,

community, developmental, educational, school,

counseling, clinical, neuroscientific, health, psychody-

namic, humanistic, industrial and organizational,

human factors, and other subfields) offer concepts,

methods, and tools that can be applied or elaborated

to address climate change.

This section describes examples of the kinds of

work that psychologists can undertake now and in

coming years to address the climate crisis and how the

role of psychologists can be strengthened. The “Recom-

mendations for APA” below include further discussion

of some of these topics. Across all areas, psychologists

would be expected to abide by principles of justice,

respect for others, and scientific integrity, as elabo-

rated in the ethics codes, standards, and guidelines of

national psychological associations and other psycho-

logical organizations.

Mitigation

As researchers and practitioners, psychologists can

contribute to the design of new technologies for resi-

dences, transportation, industry, and other settings

that will both result in reduced energy consumption or

greenhouse gas emissions and be usable and accepted

by people and organizations. Among these are new

solar energy technologies, heating/cooling technolo-

gies, electric and self-driving vehicles, and devices

regulated by artificial intelligence (Furszyfer Del Rio et

al., 2021; Stein, 2020; Viola, 2021). Psychologists can

participate as well in assessments of the potential

environmental and societal impacts (both positive and

negative) of broad application of these technologies.

For those technologies that are deemed appropriate

for application, psychologists can develop and imple-

ment methods for motivating and guiding people and

organizations to adopt them (Palomo-Vélez & van

Vugt, 2021; Verplanken & Whitmarsh, 2021). Adoption

involves integrating them with—and in some cases

modifying or replacing—other existing technologies,

behaviors, and organizational structures. Throughout

such transformations, psychologists can help people

to understand and engage in collective decision-mak-

ing and evaluation regarding changes to their environ-

ments and ways of living (Árvai & Gregory, 2021;

Orlove et al., 2020).

1MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

Further, psychologists’ perspectives and methods

can enhance efforts, now being pursued across multiple

disciplines and professions, to rethink and transform the

design of people’s environments and lives so that energy

use and emissions are reduced (Creutzig et al., 2018;

Faure et al., 2022; Nielsen, Clayton, et al., 2021; Uzell,

2018; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017). Psychologists can help

forge new approaches in such domains as residence size

and design (e.g., encouraging smaller homes that use

less energy); virtual and remote work (e.g., making such

work productive and satisfying with less need for

commuting); regional, urban, and neighborhood

planning (e.g., meeting people’s needs locally and reduc-

ing shipping and travel); transportation (e.g., public

transit, walking, cycling); diet (e.g., reducing consump-

tion of meats, the production of which involves substan-

tial greenhouse gas emissions); and agricultural, land

management, and manufacturing practices (e.g., regen-

erative agriculture, innovations in materials and

processes, recycling and reuse of materials) (Creutzig et

al., 2020; Doidge et al., 2020; Fox-Penner et al., 2021;

Mastrangelo et al., 2014; Newton et al., 2020; Nielsen,

Clayton, et al., 2021). Psychologists can ensure that new

environments, policies, and behaviors are compatible

with human cognitive, emotional, and social functioning

and with the identities, cultures, goals, and practices of

the people involved and affected by the changes, and

thereby increase the likelihood they will be adopted and

maintained (Constantino et al., 2021).

Adaptation

Psychologists have critical roles to play in helping indi-

viduals, households, communities, organizations, and

countries understand and adjust to the impacts of cli-

mate change. They can produce research and offer

interventions and services in areas such as:

• Pscholoical responses o climae e.. anie

rauma rie denial and solasalia as ell as hope

and opimism.

• Naure deelopmen and prealence o menal

healh condiions and social problems associaed

ih climae chane e.. depression anie sub-

sance use disorders demenia academic prob-

lems inerpersonal conlic and iolence.

• ecs o climae chane on healh-relaed behaiors

e.. die eercise sleep reamen adherence.

• ecs o pre-eisin menal healh condiions on

capaci o cope ih climae chane impacs.

• herapies speciicall ied o climae and he eni-

ronmen e.. ecoherap oudoor herapies.

• Suppor and uidance or people and communiies

ransiionin o ne orms o liin ha are less

ener inensie and more proecie and respecul

o he enironmen e.. reeneraie liin.

In addition to providing services to people who

experience challenges or transitions related to climate

change, psychologists can help people prepare for

climate change impacts and prevent or reduce distress

by supporting them in building their psychological and

social resilience (Clayton et al., 2021; Doppelt, 2016;

Everett et al., 2020). Resilience encompasses elements

such as positive attitudes, a sense of meaning or

purpose, coping and self-regulation skills, self-efficacy,

social connections, community cohesion, practical

preparations for disasters and other climate impacts,

and taking productive action on climate change.

Programs for developing resilience can be organized at

any level from individual to community to whole

country. Although resilience does not guarantee that

individuals and communities will escape negative

consequences of climate change or “bounce back” fully

from them, it may help them respond constructively to

current challenges and develop new skills, strategies,

and resources for moving forward.

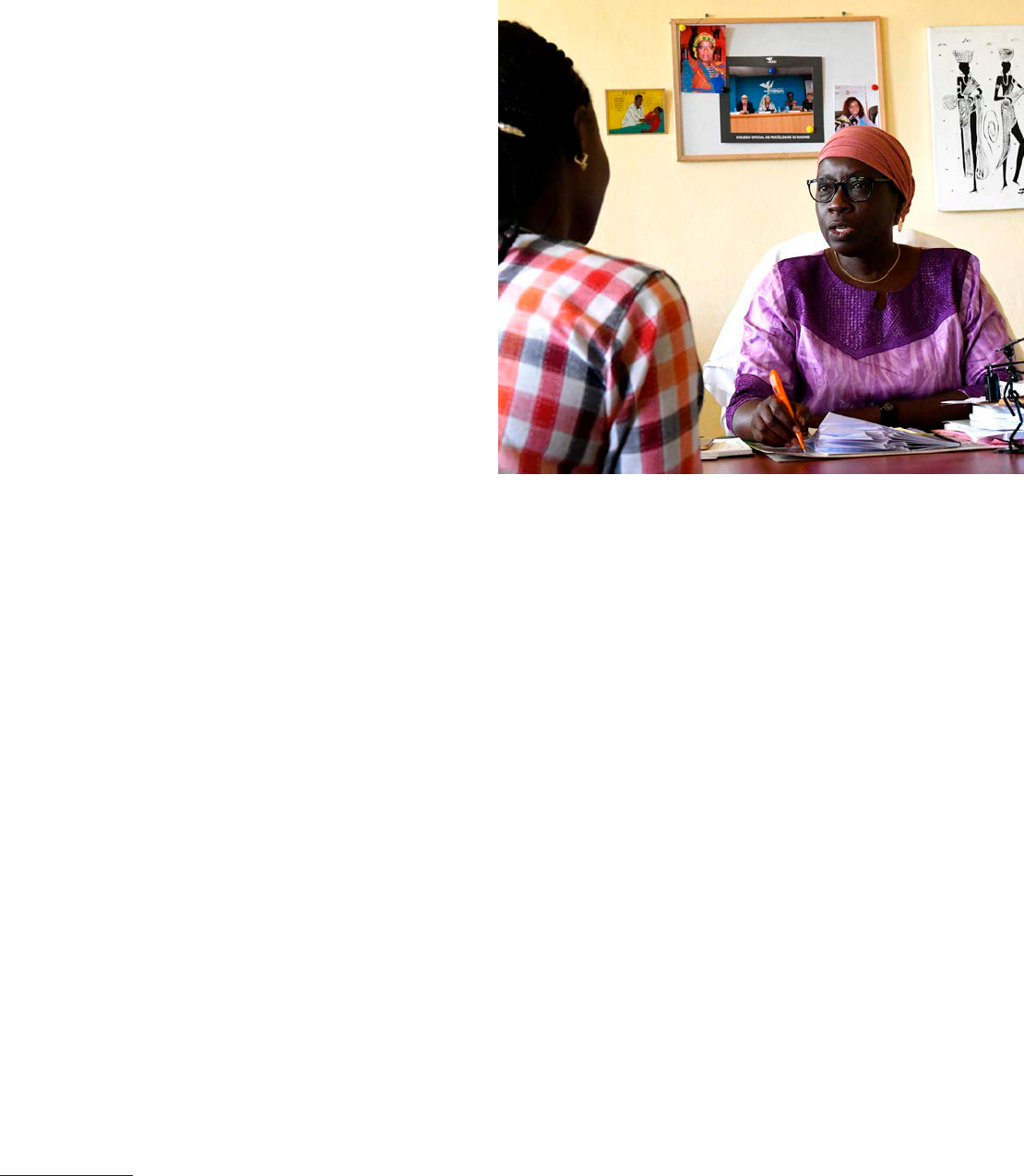

As more people migrate (including those who are

involuntarily displaced) due to climate change, it is

likely that psychologists will be called upon to work

with migrants, the communities to which they relocate

(temporarily or permanently), and government and

social service agencies to ensure that migrants’ social

and health needs are met. Psychologists can also

contribute to the design of policies and programs to

ensure that they respect migrants’ cultures, address

the needs of specific groups (e.g., children, women,

LGBT groups), and prevent or counteract discrimina-

tion and injustice toward migrants.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS1

Public Understanding and Attitudes

What people believe and think about climate change

and how to respond to it is key to the success of miti-

gation and adaptation initiatives and the adoption and

implementation of effective climate policies.

Psychologists have engaged in assessments of the

public’s understanding and attitudes regarding climate

change, how people’s views vary across demographic

groups, what factors influence their views, and how

their views are related to changes in behavior (Ballew

et al., 2019; Doell et al., 2021; Milfont, Zubielevitch, et

al., 2021; Priestley et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2016). As such

work continues, further insights can be gained by

examining how views on climate change relate to

broader understanding and attitudes concerning

nature, science, social justice, the role of government,

and other topics.

Psychologists can also help develop effective forms

of education (in schools and other settings) and public

communication about climate change and climate

policies, tailored to specific audiences and purposes.

Especially important is developing methods to help

people identify and accept accurate information about

climate change and avoid or reject misinformation,

disinformation, and misleading arguments (Compton

et al., 2021; Ecker et al., 2022; Sinatra & Hofer, 2021).

False and manipulative messages include “discourses

of delay,” by which some political and business groups

acknowledge human-driven climate change but claim

little can be done to mitigate it (Lamb et al., 2020), and

“greenwashing,” by which companies present exagger-

ated or incomplete information about their efforts to

reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Cislak et al., 2021).

More broadly, psychologists can contribute to the

design of educational and communication initiatives to

prepare people (especially young people) for a future

life in a world in which climate change and other

environmental challenges are principal features (Geiger

et al., 2019; Guzmán et al., 2021; Markowitz & Guckian,

2018). These efforts would help people to understand

the systemic relationships among climate and environ-

mental processes and human behavioral and social

processes. They would also enable people to become

informed about options for mitigation and adaptation

strategies and their implications for life in their commu-

nities and globally. Such initiatives would help individ-

uals plan their own lives and be knowledgeable

participants in public discussion and social action

around the climate crisis.

Some issues related to climate change policies can

be expected to become more widely discussed in

coming years. These include assessments of the risks

and benefits of geo-engineering technologies and

nuclear power, which are controversial (Pearce, 2019).

Proposals for achieving climate justice may also be

debated as those involve not only directing efforts and

resources to groups who historically have been disad-

vantaged and have less political power but also altering

the behaviors, lifestyles, and energy use of affluent

people and wealthier countries, which produce greater

amounts of greenhouse gas emissions (Nielsen, Nicho-

las, et al., 2021; Wiedmann et al., 2020). Psychologists

can help frame and influence public discussions of

these issues so that they are based on careful consid-

erations of evidence, values, and justice while minimiz-

ing the influences of biases and manipulation.

Social Action

Psychologists can take action themselves to establish

policies and programs for mitigating and adapting to

climate change and advancing climate justice. They

can work on the “inside” as staff members and advi-

sors to government, business, and other entities,

applying their expertise to the development and justi-

fication of new initiatives. On the “outside,” psycholo-

gists can serve as advocates and activists for policies

and programs on their own, within their local or pro-

fessional organizations (including APA), and as partic-

ipants in climate advocacy groups (e.g., the

organizations affiliated with the Climate Action

Network International and ecoAmerica).

Further, psychologists can conduct research and

offer guidance on mechanisms for successful climate

advocacy. For example, drawing on social and organi-

zational psychology, they might advise on advocacy

groups’ organization, leadership, and processes. Such

guidance preferably is developed with the members of

the groups, rather than imposed upon them, and

reflects the groups’ goals, resources, cultures, and

contexts.

14MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

In all these types of work, psychologists can apply

their knowledge of public attitudes, persuasion, and

communication (as noted above); how to motivate

people to participate in collective efforts; how to

promote sound information gathering, analysis, and

decision-making; and how to facilitate productive

interactions among stakeholders with various perspec-

tives (such as community members, scientists, and

policymakers).

Some scholars and advocates argue that new

policies and programs alone will be insufficient to

address climate change over the long term and that

fundamental changes in economic, social, and political

systems are needed (McPhearson et al., 2021; Pater-

son & P-Laberge, 2018). Proposals for new systems

that would more effectively protect the environment

and meet human needs include regulated capitalism

(Budolfson, 2021), democratic socialism (Fraser, 2021),

regenerative economics (Fath et al., 2019), circular

economics (Korhonen et al., 2018), doughnut econom-

ics (Raworth, 2017), and no-growth, degrowth, and

slow-growth economics (Jackson, 2017; Keyßer &

Lenzen, 2021). Elaboration and assessment of such

proposals calls upon the expertise and experience of

social scientists, political and cultural analysts, and

community members.

Psychologists can contribute to these efforts

through research on people’s beliefs, attitudes, and

behaviors related to prominent features of many

contemporary societies—such as materialism,

consumption, individualism, competition, hierarchy,

and disconnection from nature—and how these

psychological and behavioral characteristics are

associated with energy use as well as health, well-be-

ing, and equity (Kasser, 2016; Milfont et al., 2013;

Weintrobe, 2021). Such research could shed light on

what kinds of systemic changes are most feasible, how

to achieve them, and what their outcomes are likely to

be. Psychologists can also join in efforts to gain public

support for such systemic changes and help people

and institutions implement them and adjust to the

disruptions they may produce.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS1

Building a Stronger Role for Psychologists

For significant progress in these areas to be made,

there is a need for more psychologists across all areas

of the field to devote at least some of their efforts to

climate change topics. Today only a small number of

psychologists address climate change as a part of

their professional work.

3

It would be valuable both for

established psychologists to shift their attention to

climate change (e.g., applying methods and theories

they have used in work on other topics) and for grad-

uate students and early career psychologists to adopt

it as their focus (enabling progress to continue in

future decades). The breadth and complexity of cli-

mate change topics, along with their significance for

human health and well-being, offer many pathways

for satisfying and successful careers. (The

Recommendations sections below suggest methods

for encouraging and training psychologists to engage

in climate change work.)

To enhance the soundness and impact of their

work, psychologists must engage with other domains

that address climate change—not just other disciplines

and professions but policymaking and advocacy as

well. Psychologists also need to collaborate with and

learn from the diverse populations, within countries

and around the world, who are affected by climate

change and by mitigation and adaptation initiatives

(Nash et al., 2020; Tam & Milfont, 2020). This atten-

tion to diverse peoples and their varied experiences of

climate change will keep human rights and climate

justice concerns in the forefront of psychologists’ work

and offer psychologists new perspectives and insights.

For example, members of Indigenous communities

have important knowledge of the physical and social

impacts of climate change in their regions and valuable

perspectives on mitigation and adaptation strategies,

which they may choose to share with others in mutually

respectful settings (Cowie et al., 2016; Kimmerer, 2013;

3 An examination of scientific journals supports this point. As noted in the Appendix, across 15 years (2007–21) of APA’s 90 journals,

only 87 articles referred to “global warming” or “climate change.” Among non-APA psychology journals, few other than the Journal of

Environmental Psychology, Ecopsychology, and Environment and Behavior have published work on global warming or climate change (Swim,

2021). An inspection of the contents of the major climate change journals Nature Climate Change and Climatic Change indicates that

fewer than 5% of their articles report psychological work. Also, the annual APA convention generally has few sessions on climate change

(mainly sponsored by Division 34), and sessions on climate change are rare at other psychology conferences. In an informal census of

environmental psychologists maintained by Robert Gifford, 103 out of 1330 list themselves as interested specifically in global warming or

climate issues.

Nakashima et al., 2018; Petzold et al., 2020; UNESCO,

2020). Further, many Indigenous cultures emphasize

the interrelationships of humans, non-human living

beings, and the earth, encouraging people to treat the

environment with respect and as a partner. Indigenous

peoples also often understand themselves as closely

tied to the experiences and actions of multiple gener-

ations preceding them and following them. This type of

holistic, interactive, and long-term view of humans’

relationship with the environment can complement

and enrich other scientific and technological approaches

to the climate crisis, including those of psychologists.

Psychologists can be strong leaders in addressing

the climate crisis. They have the knowledge and skills

to help people understand the crisis and what is needed

to respond to it. They can play key roles in designing

and implementing initiatives and policies that will be

broadly accepted and effective. They can guide individ-

uals and institutions in incorporating considerations of

climate change and climate justice into their ongoing

activities. Through such work, psychologists can help

people develop confidence and hope that our society

can meet the enormous challenges of the climate crisis.

16MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

APA’S ROLE IN ADDRESSING THE CLIMATE CRISIS

Given the association’s leadership position in the field

of psychology, its current goals, and its history of work

on climate change, APA can do much to strengthen

the role of psychologists in addressing the climate cri-

sis. This section discusses the climate crisis in relation

to APA’s current strategic plan (approved by the

Council of Representatives in 2019) and reviews APA’s

previous work on climate change.

APA’s Strategic Plan

APA’s current strategic plan is organized around four

main goals. As described below, work to address the

climate crisis falls within these goals. Indeed, the goals

suggest that APA devote attention and resources to

the climate crisis.

• Uilie pscholo o mae a posiie impac on

criical socieal issues.

he climae crisis hreaens he healh and ell-be-

in o eer human bein on he plane in curren

and uure eneraions is eacerbain healh and

economic injusices and riss maniin social

conlics. I is an increasinl imporan acor in

oher socieal issues ha P is currenl address-

in such as hose surroundin human rihs

racism healh equi populaion healh immira-

ion socioeconomic saus and echnolo. I is also

a major opic in Ps or ih inernaional par-

ners includin or ihin he lobal Pscholo

lliance and eors o adance he Unied Naions

Susainable Deelopmen oals.

• Prepare he discipline and proession o

pscholo or he uure.

s concerns abou climae chane ro all secors

o socie—includin pscholoiss—ill become

inoled in he desin and implemenaion o mi-

iaion and adapaion sraeies. In ac pschol-

oiss inolemen is necessar as he success o

hese sraeies ill depend on careul consider-

aion o heir pscholoical behaioral and social

dimensions. Moreoer pscholoical approaches

can be used o help indiiduals and communiies

undersand climae chane and climae jusice

and build heir sense o aenc and capaci or

collecie acion o address hese challenes.

P can raise aareness o he muliple pes o

conribuions pscholoiss can mae o address

climae chane and help prepare pscholoiss or

hese roles.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS1

urher climae chane oers opporuniies

or pscholo o ro as a ield. I presens a

broad rane o ne opics or research pracice

educaion and adocac. Such or can build

on eisin approaches and mehods as ell as

deelop ne ones. Climae chane opics are no

onl hihl relean o healh ell-bein jusice

and social polic bu inrinsicall ineresin and

appealin o man people includin sudens.

ih suppor rom P and oher insiuions

or on climae chane and relaed enironmenal

issues can eole ino a major ocus o pscholo

and dra ne people ino he ield.

• leae he publics undersandin o reard or

and use o pscholo.

Pscholoiss conribuions o miiaion and

adapaion iniiaies can be epeced o enhance

undersandin and respec or pscholo amon

policmaers and members o oher proessions

as ell as oher members o he public. urher

pscholoiss can pla prominen public roles in

helpin people respond consruciel o disress

and anie relaed o climae chane hich are

increasinl prealen especiall amon ouh

Hicman e al. 01. P can help oranie and

suppor pscholoiss o carr ou hese inds o

or and hae an inluenial oice in public aairs.

• Srenhen Ps sandin as an auhoriaie

oice or pscholo.

s he leadin oraniaion in he U.S. represen-

in all areas o pscholo and ih a hisor o

or on climae chane P has he breadh and

saure o adance and spea or he ull rane o

pscholoical approaches o he climae crisis.

4 Related scientific and professional associations that support work on climate change include the Australian Psychological Society,

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, and Royal College of Psychiatrists. Groups with a primary focus on climate change

include the Climate Psychology Alliance, Climate Psychology Alliance North America, Climate Psychiatry Alliance, and Medical Society

Consortium on Climate and Health.

5 Although earlier discussions and efforts within APA noted the need for psychologists to address energy use, global warming, or climate

change, they did not result in sustained activity. For example, a Task Force on Psychology and Environmental Problems, organized by

Division 34 and including representatives from other divisions and APA’s central office, met in 1993–94 and produced several brief

unpublished reports and newsletter articles (Cvetkovich, 1994), but no further work from or related to that task force was found.

6 As described earlier, the task force did not systematically examine the activities of divisions, although it noted that several divisions,

including Division 34: Society for Environmental, Population, and Conservation Psychology, Division 9: Society for the Psychological Study of

Social Issues, and Division 8: Society for Personality and Social Psychology, have supported or disseminated work on climate change.

Is naional and inernaional prominence also

enables P o sere as a model and parner or

oher associaions in pscholo and relaed ields

or acion on he crisis.

4

APA’s Work So Far

As requested in the Council of Representatives resolu-

tion that established it, the task force reviewed APA’s

past and current activities on climate change. It used

2007 as the starting point, as APA’s sustained atten-

tion to climate change can be traced to that year, when

its then Science Directorate chief called on the field of

psychology to address “the human behaviors respon-

sible for global warming and energy consumption”

(Breckler, 2007).

5

The task force focused on activities

managed or supported by the APA central office,

drawing on information gathered by staff (summa-

rized in the Appendix below).

6

The task force observed that APA has regularly

conducted and sponsored work of high quality on

climate change since 2007. Of note are the 2008–09

task force report [later published as a special issue of

American Psychologist (Swim et al., 2011)], which

highlighted for a broad readership the progress and

significance of psychological research on climate

change, and APA’s three reports with ecoAmerica

(2014, 2017, and 2021), which brought the psycholog-

ical and mental health dimensions of climate change to

the awareness of environmental communities, policy-

makers, and the general public. Further, the regular

coverage of climate change in the Monitor on Psychol-

ogy has been a unique and valuable educational

resource for psychologists and students.

However, the needs and opportunities for work by

APA on climate change exceed what it has done to this

18MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

point. As discussed in previous sections, the climate

crisis is now widely recognized to be an immense and

urgent threat to human health and well-being. Psychol-

ogists’ expertise and experience are highly relevant to

many aspects of mitigation, adaptation, public

communication, and social action in response to the

crisis. However, realizing that potential fully will

require more psychologists, across the breadth of the

field, to devote their efforts to climate change work

and to engage more closely with other fields and

sectors of society. As the largest and best resourced

psychological organization in the U.S., and building on

its previous work, APA can lead in developing the

field’s capacity and enhancing its impact. Taking on

that responsibility will require a stronger and more

strategic commitment to addressing the climate crisis

than APA has made thus far.

To guide APA’s future work on the climate crisis,

the task force developed a set of twelve recommenda-

tions along with suggestions for activities to imple-

ment them (see next section). These recommendations

and activities stem from the earlier set of recommen-

dations for APA activities made by the 2008–09 task

force (which were only partially implemented and are

still relevant); recommendations and ideas in the

recent scientific, professional, and policy literature;

and the task force’s considerations of climate change

and responses to it within psychology and other fields.

Reflecting the magnitude and complexity of the

climate crisis, a great deal of work is suggested for

APA. Thus, the task force also offers comments on how

APA might implement, manage, and prioritize the

proposed activities.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS19

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR APA

7 These domains are not intended to map exactly to the organizational structure of APA’s central office. For example, the Research domain

encompasses activities in the Science Directorate, Office of Publications and Databases, and other units, and the Practice domain includes

activities in the Practice Directorate (health service psychology) and Science Directorate (applied psychology), among other units.

Building on the deliberations and observations

described in the preceding sections, the task force

developed recommendations to advance work on cli-

mate change within five primary domains of APA’s

central office programmatic activities: Research,

Practice, Education, Advocacy, and Communications.

Following its charge, the task force also developed rec-

ommendations for APA’s own energy use and sustain-

ability practices.

7

Although each domain is addressed

separately, they are interrelated. For example, research

and practice on climate change inform one another,

and education, advocacy, and communications draw

on shared approaches for conveying information and

influencing attitudes and behaviors. Moreover, APA’s

efforts to enhance its own energy use and sustainabil-

ity practices can draw on work in all these areas.

For each domain, the task force formulated a pair of

recommendations (see Table 1). One recommendation

in each pair focuses on strengthening the work of

psychologists and APA on climate change, especially

through programs and resources that will enable a

greater number and breadth of psychologists to gain

knowledge, skills, and career opportunities in the area.

The other recommendation in each pair focuses on

broadening the impact of psychologists’ work through

engagement and collaboration with people and organi-

zations in fields beyond psychology and APA.

Each recommendation is accompanied by sugges-

tions for activities that the APA central office can

undertake over the next several years to implement

them. The task force aimed to formulate these recom-

mendations with enough specificity to guide APA

leadership, members, and staff but sufficient breadth

to allow flexibility in light of new developments in

climate change and psychology and at APA.

Although listed separately, the suggested activi-

ties could be integrated into single events and

programs when implemented. For example, the

various meetings and workshops that are proposed

could be components of larger conferences. Ideally,

most activities will be held virtually, to increase access

by a broad range of participants as well as to reduce

costs and avoid greenhouse gas emissions associated

with long-distance travel.

0MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

TABLE 1

Task force recommendations for APA’s work on climate change

STRENGTHENING THE FIELD BROADENING IMPACT

Research

Advance research on climate change

across all areas of psychological

science.

Promote engagement of

psychological scientists with

policymakers, practitioners, and

community members on climate

change issues.

Practice

Build psychologists’ capacities to

support people in mitigating and

adapting to climate change.

Enlarge the range of settings and

partnerships in which psychology

practitioners address climate change.

Education

Incorporate coverage of climate

change into all levels of psychology

education.

Promote coverage of the

psychological dimensions of climate

change in the education of other

professionals and the public.

Advocacy

Engage in sustained advocacy on

climate change to government at all

levels and to business and non-profit

organizations.

Partner on climate advocacy with

other scientific, professional, social

justice, environmental, and health

organizations.

Communications

Serve as an important channel of

information to psychologists about

climate change and how they can

contribute to effective climate action.

Educate the public about the

psychological dimensions of climate

change and effective climate action.

APA’s Energy Use/

Sustainability

Implement a strategic approach to

reduce greenhouse gas emissions

and improve sustainability across all

of APA’s operations and in the

psychological community.

Engage with other organizations and

the public to reduce greenhouse gas

emissions and improve sustainability

practices.

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS1

Research

Psychological research has produced important find-

ings on a variety of topics, including public understand-

ing and attitudes about climate change (Hoggett, 2019;

Hornsey et al., 2018; Milfont, Abrahamse, et al., 2021),

motivations to engage in mitigation and adaptation

efforts (Brick et al., 2021; Sparkman et al., 2021; Truelove

et al., 2015), factors shaping behaviors related to cli-

mate change (Lacroix & Gifford, 2018; Milfont &

Markowitz, 2016), the design of interventions to help

people alter their behaviors (Capstick et al., 2014; Karlin

et al., 2015; Marghetis et al., 2019), and the mental

health impacts of climate change (Burke et al., 2018;

Clayton et al., 2021; Vergunst & Berry, 2021). However,

as noted in previous sections, the field’s full potential to

respond to the climate crisis will not be realized until a

greater number and broader range of psychologists

address it. Research questions bearing on climate

change can be formulated and investigated in virtually

every area of basic and applied psychological research

(as represented, for example, by APA’s 54 divisions and

other psychology organizations). Many current lines of

research could be extended to address climate change

topics, including work in such areas as science educa-

tion, decision-making, organizational behavior, and

disaster response, to name a few.

Expanded psychological research on climate

change can lead to more effective interventions and

services advancing mitigation and adaptation and to a

stronger role for psychology in shaping local, national,

and international policies and programs on climate

change and environmental justice. To have these

impacts, researchers must formulate questions that

address major practical issues related to climate

change and consult with the communities most

involved with or affected by these issues when design-

ing, conducting, and disseminating the research. A line

of research might start with studies in highly controlled

settings or with limited participant samples. It then

may need to be scaled up to determine whether the

results are replicable and meaningful in the real world

(including across populations and cultures) and are

translatable into applications with significant effects

on the trajectory of climate change or its consequences.

Then, as research applications are implemented, further

research is often needed to evaluate their effectiveness,

identify unanticipated outcomes, and design improved

applications. Successful research programs on climate

change require that scientists have ongoing communi-

cations and cooperation with community members,

practitioners, and/or policymakers.

As they investigate climate change, psychologists

can take advantage of the field’s position as a “hub

science” (Cacioppo, 2007) to facilitate the sharing and

integration of research findings and approaches across

disciplines and the formation of multidisciplinary

collaborations. For example, psychologists’ engagement

with researchers in other social science disciplines can

help ensure that all levels of analysis—individual, family,

organizational, community, national, international—are

considered in addressing human behavior related to

climate change (Dietz et al., 2020; Nielsen, Clayton, et

al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2019). Collaborations with

medical, epidemiological, and public health researchers

can produce more sophisticated accounts of the mental,

behavioral, and physical health effects of climate change

and their interactions. And psychological research that

engages with work in biology, environmental sciences,

and agriculture can reveal how the human behavioral

dimensions of climate change are also linked to

pollution, biodiversity loss, land use, and the survival

and health of other species (Inauen et al., 2021).

In addition, fields outside of standard scientific

disciplines offer perspectives and insights that can

enrich psychological science. As noted earlier, the

cultures and knowledge of Indigenous peoples offer

important perspectives for the study of humans’

relationship with nature. Psychologists can also draw

from, and potentially contribute to, scholarship and

creative work in the humanities, arts, design, engineer-

ing, and planning that address climate and the natural

environment (Adamson & Davis, 2018; Baucom, 2020;

Degroot et al., 2021; Holm & Brennan, 2018).

Climate change interacts with other health, social,

and economic challenges as well. Throughout the world,

populations already disadvantaged or discriminated

against often bear the greatest adverse impacts of

climate change (IPCC, 2014a; U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency, 2021a). Increasingly, groups will be

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

displaced or choose to migrate due to climate change

in concert with other socioeconomic factors; these

groups will face risks of social disruption and health

problems as well as discrimination and conflicts in the

regions to which they move (Carrico & Donato, 2019;

Hauer et al., 2020; White House, 2021; World Bank,

2018, 2021). Overall, researchers must attend to the

experiences and needs of diverse populations to under-

stand climate change and its consequences adequately

and to design mitigation and adaptation strategies that

will be accepted, implemented, and effective (Bradley

et al., 2020; Charlson et al., 2021; Nash et al., 2020;

Pearson & Schuldt, 2018; Tam & Milfont, 2020).

Cross-cultural research, international collaborations,

and direct engagement of researchers with the affected

communities will be valuable for much of this work.

In conducting research to advance mitigation and

adaptation, it will be useful to examine other cases in

which substantial modifications of individual and

collective behavior have been achieved. These include

bans and regulations on various pollutants, adoption of

seatbelts, reductions in tobacco use, and responses to

the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the broader literatures

in such areas as disasters, migration, civil rights, and

war may contain insights regarding how people think

about and respond to environmental and social change

that can inform mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The task force offers the following recommenda-

tions to guide APA’s efforts to enhance psychological

research on climate change:

RECOMMENDATION 1

STRENGTHENING THE FIELD

Advance research on climate change across all

areas of psychological science.

APA can implement this recommendation through

activities such as the following:

FACILITATING NEW RESEARCH

• Sponsor inernaional research orshops reies

and hie papers in muliple areas o pscholoical

and mulidisciplinar research o assess he sae o

nolede ideni he research needs o

praciioners policmaers and communiies and

deermine hih-priori opics or ne pscholoi-

cal research on climae chane.

• Deelop join iniiaies ih P diisions ehnic

pscholoical associaions scieniic and scholarl

socieies in pscholo and oher disciplines aca-

demic insiuions museums oos and oher

research oraniaions o plan sponsor conduc and

disseminae pscholoical and mulidisciplinar

research on climae chane.

• Oranie and help obain undin or mulidisci-

plinar research neors and research eams on

speciic hih-priori opics.

• docae or undin o research on pscholo and

climae chane b oernmen and priae bodies

and oer uidance o researchers seein undin.

See also docac recommendaions.

PUBLICATIONS

• or ih ediors o include climae chane in he

scopes o all P journals deelop special journal

secions on climae chane and solici submissions

on climae chane or P journals and boos.

• plore deelopmen o a ne journal on he ps-

choloical dimensions o climae chane ha ould

sere as a major oule or hih-quali research and

inormaion across he breadh o pscholo and

relaed mulidisciplinar areas. o enhance impac

he journal mih adop such eaures as open

access rapid reie polic bries educaional

maerials and summaries or non-specialiss.

• im o mae aricles abou climae chane in all

P journals open access o all readers.

• Build and mainain a reposior o aricles daases

and relaed maerials on pscholoical research on

climae chane rom boh P and non-P sources.

MEETINGS

• Mae climae chane research includin mulidis-

ciplinar or one o he recurrin hemes o Ps

annual conenion and is oher scieniic eens.

• Sponsor irual inernaional meeins o scieniss

praciioners and policmaers o disseminae

MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

research indins eamine he pracical applica-

ions o curren pscholoical and mulidisciplinar

research on climae chane and deelop approaches

or increasin he uili o research or pracice and

polic deelopmen.

• Oranie irual presenaions discussions and

rainins on pscholoical research on climae

chane aimed a mulidisciplinar and inernaional

audiences includin researchers praciioners and

policmaers. lso promoe and mae aailable o

pscholoiss similar resources rom oher disci-

plines and proessions ha can enhance pscholo-

ical research.

RECOMMENDATION 2

BROADENING IMPACT

Promote engagement of psychological

scientists with policymakers, practitioners, and

community members on climate change issues.

APA can implement this recommendation through

activities such as the following:

EXPANDING SCIENTISTS’ REACH

• rain pscholoical scieniss on ho o presen

heir climae research eeciel o policmaers

and arrane opporuniies or pscholoical scien-

iss o ie esimon and mee ih oernmen

oicials o adocae or science-based climae poli-

cies. See also docac recommendaions.

• Sponsor inernships elloships and oher place-

mens o pscholoical scieniss ho or on cli-

mae opics ihin oernmen polic and

adocac oraniaions.

• docae or and encourae reaer paricipaion

b pscholoiss in he or o he Ineroernmenal

Panel on Climae Chane and oher naional and

inernaional climae research bodies.

FOSTERING COOPERATION

• Conene irual meeins ha brin pscholoical

scieniss oeher ih U.S. and inernaional lead-

ers on climae issues rom non-research ields e..

praciioners communi roups enironmenal

jusice oraniaions oundaions businesses

non-oernmenal oraniaions aih roups

adocaes aciiss ariss polic specialiss o-

ernmen oicials o ideni research prioriies

co-desin research projecs and discuss he iner-

preaion o research indins and ho o appl

indins or reaes impac.

• Sponsor aherins o scieniss and members o

arious secors o he eneral public o share nol-

ede and eperiences relaed o climae ideni

research needs plan research projecs and discuss

eecie and equiable as o appl indins rom

research.

• Proide rainin and uidance o boh scieniss and

non-scieniss on ho he can successull com-

municae and or oeher in he plannin con-

duc disseminaion and applicaion o research.

Practice

Psychological practice on climate change encom-

passes both mitigation of and adaptation to climate

change. For mitigation, psychologists’ work includes

helping individuals, households, organizations, and

communities alter the types and amounts of energy

they use; contributing to the development and imple-

mentation of new technologies that produce lower

levels of greenhouse gas emissions; and working with

governments, businesses, and other institutions to

design policies, environments, and processes that

lead to lower emissions (Lutzke & Árvai, 2021; Sintov

& Schultz, 2015; Whitmarsh et al., 2021; Wolske &

Stern, 2018). Such efforts may involve, for example,

working with communities to modify the opportuni-

ties and incentives in people’s environments that

influence their patterns of energy use, or helping to

plan and manage organizational change to support

new work or travel patterns or adoption of new tech-

nologies (Cambridge Sustainability Commission on

Scaling Behaviour Change, 2021; Unsworth et al.,

2021). Psychologists are increasingly interested in

mitigation actions that result in rapid, large-scale

decreases in emissions, which require consideration

of a broad range of behaviors and of the social, cul-

4MICN PSCHOOIC SSOCIIONDDSSIN H CIM CISIS: N CION PN O PSCHOOISS

tural, and economic contexts of behavior (Nielsen,

Clayton, et al., 2021).

Successful mitigation will require systemic changes

at the organizational, community, national, and inter-

national levels. Psychologists can help design and

implement mechanisms for bringing together stake-

holders in ways that allow all relevant perspectives and

interests to be represented in the development of new

missions and organizational structures aimed at reduc-