A surgery trainee's guide to writing a manuscript

Tiffany W. Liang, David V. Feliciano, Leonidas G. Koniaris

*

Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

article info

Article history:

Received 31 July 2016

Received in revised form

20 November 2016

Accepted 21 December 2016

Keywords:

Scholarly writing

Surgery training

Writing guide

Academic productivity

Research

Publishing

abstract

Publishing clinical and research work for dissem ination is a critical part of the academic process.

Learning how to write an effective manuscript should be a goal for medical students and residents who

hope to participate in publishing. While there are a number of existing texts that address how to write a

manuscript, there are fewer guides that are specifically targeted towards surgery trainees. This review

aims to direct and hopefully encourage surgery trainees to successfully navigate the process of con-

verting ideas into a publication that ultimately helps understanding and improves the care of patients.

© 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

One of the core purposes of physicians and surgeons is to

improve human life through the application and advancement of

medical science. This can be done not only by treating patients in

the clinical setting, but also by contributing to the fund of medical

knowledge through innovative research that can lead to improved

future therapies. Innovations in research, however, are not mean-

ingful until they are shared with the general scientific community,

such as through publication.

The objective of this article is to provide surgery trainees with

an overview of how to report to the scien tific literature through

peer-reviewed publications. While there are many p ublished

manuscripts that address paper writing in general, there is less

information that specifically ta rgets the surgery train ee. Those

who would like a more comprehensive guide on this subject are

directed to a book ed ited by Schein and colleagues.

1

Publications

are expected and required for competitive residencies and fel-

lowships, academic jobs, and ultimately promotion and tenure at

academic institutions. While it can be extremely challenging for

surgeons to find the time to perform research, write and suc-

cessfully publish papers, the authors would argue that academic

work in conjunction with direct patient care is essential to a sur-

geon's professional development. While there a re other forms of

academic work (e.g., b ook chapters, presentations at conferences),

the focus here is on writing for publication in peer-reviewed

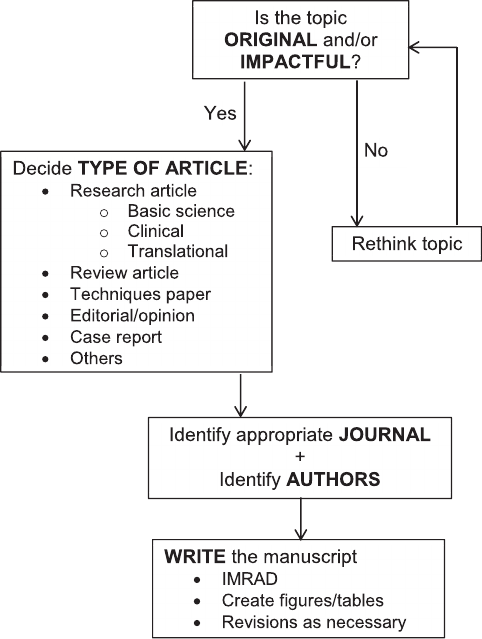

journals. Fig. 1 serves as a general flowchart guide to the creative

writing process. As many of the points are based upon the empiric

experiences of the authors, the article potentially may present

biases of the authors.

2. Before beginning to write

Before starting the actual writing process, there are certain

preliminary considerations. First, the ideas and data that will be

presented in the manuscript should generally be original and im-

pactful. For research articles, this step should ideally be considered

prior to beginning the data collection process. Recognizing if a

project represents a new direction or a less interesting confirma-

tion of existing ideas is important as one decides if a particular

project is worth pursuing and for what journals it may be appro-

priate. The benefit of investing the time and effort required to

publish a study that represents only confirmatory information

should be carefully considered. Next, determining the type of

article that best presents the finding(s) to the reader will direct its

* Corresponding author. Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of

Medicine, 550 N. University Blvd., UH 1295, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

The American Journal of Surgery

journal homepage: www.americanjournalofsurgery.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.12.010

0002-9610/© 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563

style and content. Deciding the target journal and authors would

then follow. These steps are essential for building the foundation of

the manuscript and will be described in further detail below.

2.1. Ensure originality and impact of research

If others have already reported what one plans to write, the first

question to answer is what value is there in publishing the same

findings? If there would be considerable value gained in a confir-

matory paper, or if disagreement exists in the literature, this would

support the undertaking of such a project. For example, if one has

the opportunity to report a very large series regarding the treat-

ment of a particular condition with multiple therapies, this

frequently is of broad interest. Reporting complication rates and

potential pitfalls of this condition related to different therapies will

help guide treatment and should be well received. Furthermore,

even if a topic is already discussed in the literature, there may be a

certain aspect of the research that may be novel, providing new

insights. This innovative “angle” of the research should be high-

lighted in the manuscript as well as in the correspondence to the

journal where the manuscript will be submitted.

2.2. Decide on type of article

There are a variety of article types, depending on the type of

information to be conveyed. These include research articles, review

articles, techniques papers, letters to the editor, opinions, case re-

ports or series, and other journal-specific formats, such as a quiz or

interesting image. Each journal has a different profile of article

types that it accepts. Usually this has to do with the scope of the

journal e if its main purpose is to showcase the newest techniques

in vascular surgery (i.e., techniques papers), then it will likely not

accept a manuscript discussing a newly discovered biomarker in

pancreatic cancer (i.e., research article), no matter how significant

the findings are.

Research articles are generally considered the most difficult to

complete, since these require experimentation and/or data collec-

tion and analysis prior to writing. Both basic science and clinical

papers fall into this category. These articles will generally be par-

titioned into introduction, methods, results, and discussion/

conclusion sections. Research articles and clinical reviews remain

the mainstay of surgical journals. These articles are generally

considered the most significant contributions any individual makes

in their academic career.

Review articles are a good way for researchers to analyze the

literature and develop a solid fund of knowledge in an area of in-

terest. The information obtained through this process can often be

used as a foundation for the background when composing related

grants, lectures, theses, and research articles. Reviews will also help

others unfamiliar with the subject get a quick overview of existing

knowledge in that area.

2,3

Techniques papers are used to showcase and describe a pro-

cedure or novel operative approach or, occasionally, an entirely

new type of operation. While a well-written manuscript is a must

for any type of paper, a clear description of how to perform the

particular technique is invaluable in this type of article. Images,

either photographs or well-drawn illustrations, are often better

than text when describing a procedure. As retold by others, “Great

paper, poor art e reject. Poor paper, great art e accept!” The

emphasis in these articles is the technical approach, with a limited

presentation of complications and long-term outcomes. Presenta-

tion format and appropriateness for specific journals should be

considered carefully, as not all journals accept these types of

articles.

Letters to the editor are written in response to an article pub-

lished in a particular journal. They usually question the interpre-

tation of a study or offer an alternative viewpoint. Furthermore,

they can be used to disseminate data and ideas that otherwise

might not be published.

4

Finally, letters to the editor also allow an

opportunity to cite relevant literature that the initial article may not

have sufficiently referenced. Regarding promotion and tenure,

however, many reviewers will not consider letters to the editor as

equivalent to independent research articles. Thus, these articles can

be an excellent adjunct to one's record of scholarly publication but,

like case reports below, should be used judiciously.

Case reports and related article types are written for interesting

and unusual disease presentations, remarkable images that provide

an excellent teaching opportunity, and/or some novel aspect of

management. They can be single-patient reports, a small series of

two or more similar cases, or include a more extensive review of

cases previously reported in the literature.

5

Regardless, case re-

ports, in the authors' experience, can be difficult to publish, as

numerous case reports may have already been written that

encompass what one might think is novel, and reviewers may not

consider the report interesting. Nonetheless, a case report that in-

troduces a new idea that will contribute to better management of

patients is more likely to be accepted.

Rather than considering only a case report as a way to share an

interesting clinical case, there are numerous other article types,

including opinion or editorial-type articles, image reports, and quiz

articles that may be easier to publish and will allow the case to be

presented. These are journal-specific and are not discussed in

further detail here. Nonetheless, the reader is encouraged to review

Fig. 1. How to write an article.

T.W. Liang et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563 559

different journals and potentially consider these article types to

report their case. Finally, the authors would stress that case reports

and similar manuscripts, although potentially of interest, should

generally not constitute the majority of one's academic produc-

tivity. Authors should try and focus on the other article types that

are more highly regarded.

2.3. Identify the ideal journal(s)

When deciding which journal is best suited for a potential

manuscript, three considerations are the scope, readership, and

scholarly metrics of the journal. The scope of a journal refers to

what types of articles and the topics the journal aims to publish.

Often, the scope is linked to the aims, mission, or purpose of the

journal. The readership is largely determined by the scope and

should be taken into account when choosing a journal in order to

ensure that one reaches the intended audience. Besides ensuring

that the intended type of audience is reached e for example, sur-

geons instead of pediatricians e the size of the audience can be

important as well. Journal citation metrics are one method of

gauging the importance of a journal via a measure of the average

number of times other articles have referenced articles in a specific

journal. Journals with higher citation metrics are generally

considered more prestigious and, therefore, reach a larger audi-

ence. Thus, it is desirable to publish one's article in a journal with a

higher impact factor. The top 20 relevant journals in the surgical

field are listed in order of ranking by impact factor in Table 1,as

reported by the 2014 Journal Citation Reports

®

(Thomson Reuters,

2015). The Eigenfactor score is another method used to rank the

significance of a journal and is also shown in this table. Eigenfactor

is determined by not only taking into account the number of times

a journal is cited by another journal, but also by the influence and

prestige of the citing journal.

6

A good rule of thumb in considering a journal is to determine if it

is indexed by Journal Citation Reports and recognized by the United

States National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of

Health shared website, PubMed commons (http://www.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/pubmed). Another factor suggestive of quality is if a jour-

nal is supported by a scientific, medical or surgical society. While it

may be more difficult to publish a manuscript in one of these peer-

reviewed or refereed journals that are listed on PubMed and the

Journal Citation Reports, the end result of the peer-review process

in these journals will likely be a better paper that will be accessed

more by other researchers.

Many new journals will not be listed by PubMed or have a

Journal Citation Report listing, as a journal must be out for at least a

few years to generate such metrics. The Journal Citation Report

provides metrics for approximately 11,700 journals. Thus, there

arguably is not a need to publish in unlisted journals unless a

particular project has been rejected from a number of journals

listed. In some instances, the term “predatory journal” has been

introduced for unlisted journals that have little or no peer-review

process, are not indexed in these databases, and may offer publi-

cation for a fee. Publishing in such journals may prevent wide-

spread dissemination of the manuscript and, therefore, fail to

promote the goals of academic work.

7

2.4. An algorithm for choosing appropriate journals

How does one go about finding the right journal? Considering a

top journal, such as listed in Table 1, would certainly be a good first

choice. Another efficient method to search for a suitable journal is

through search engine sites. A sample of such sites that are free of

charge to the general public can be found in Table 2. These search

engines are also good for identifying multiple candidate journals, in

case one's first choice does not pan out. The journals identified by

these sites, however, should always be further investigated to

ensure suitability for the manuscript being submitted. Another

caution is that some journal finder sites are geared only to journals

affiliated with a particular publishing company. Therefore, their

search results may not represent all possible relevant journals. In

any case, consulting with a mentor and/or senior author is usually

warranted for novice researchers. The authors' bias is also to use

only journals that are referenced by Journal Citation Reports

®

(Thomson Reuters), which allows sorting of journals by topic and

impact factor.

2.5. Identifying the author(s)

Authorship is important to determine early in the writing pro-

cess, and it is suggested to be inclusive.

8

The senior author should

ultimately be responsible for who the authors are and the order in

which their names are listed. If there is no senior author, then all

co-authors should come to an agreement on the final decision. The

Table 1

Top 20 surgical journals ranked by impact factor (2014 Journal Citation Reports

®

, Thomson Reuters, 2015).

Rank Journal Total cites Impact factor Eigenfactor score

1 Annals of Surgery 41,468 8.327 0.07481

2 Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 25,650 6.807 0.03499

3 Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 8562 6.650 0.02437

4 American Journal of Transplantation 18,092 5.683 0.05320

5 British Journal of Surgery 20,540 5.542 0.03445

6 Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery e American Volume 37,434 5.280 0.04747

7 American Journal of Surgical Pathology 18,910 5.145 0.03022

8 Journal of the American College of Surgeons 13,352 5.122 0.03631

9 Endoscopy 8546 5.053 0.01610

10 Archives of Surgery 13,280 4.926 0.01880

11 Liver Transplantation 9357 4.241 0.01762

12 Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 23,757 4.168 0.05431

13 Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 3158 4.066 0.00940

14 JAMA Surgery 785 3.936 0.00371

15 Annals of Surgical Oncology 19,490 3.930 0.05779

16 Annals of Thoracic Surgery 32,052 3.849 0.06305

17 Transplantation 24,021 3.828 0.03823

18 Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 13,256 3.749 0.01911

19 Obesity Surgery 9098 3.747 0.01661

20 Journal of Neurosurgery 29,516 3.737 0.03310

T.W. Liang et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563560

first author(s) typically earns the title by contributing the most

effort into developing the project, performing the data collection

and analysis process, and/or writing the manuscript. The senior

author, if different from the first author, is usually the person who

takes responsibility for the paper overall and might be the mentor

for the more junior first author. The corresponding author is

responsible for communicating with the journal as well as with

readers with questions or comments after publication. The senior

and corresponding authors are often the same person. All authors

should agree on the order of middle authors, which may be

determined by order of contribution. A potentially useful scoring

system to determine order of authorship has been proposed by

Petroianu.

9

It involves more heavily weighted criteria such as cre-

ation of the original idea and method as well as less heavily

weighted items such as study funding and provision of materials.

9

Authorship can be a difficult issue. Familiarity with criteria for

authorship is suggested and reviewed by the International Com-

mittee of Medical Journal Editors. Briefly, according to this com-

mittee, meeting the criteria for authorship requires that all authors

have made considerable contributions to the following

1

: the

conception and design of the work or to the collection, analysis, and

interpretation of the generated data

2

; writing the manuscript or

critically reviewing and revising it for intellectual content; and

3

approving the final version of the manuscript for publication.

10

Some journals will require a description of each author's contri-

butions. Any individual who does not meet all the criteria, but has

contributed to the work, could alternatively be acknowledged at

the end of the article.

10

Simply having contributed cases or funding

to a study, or providing materials or reagents for an experiment

generally is considered insufficient to warrant authorship.

3. Writing

Composing and refining the manuscript can be an intimidating

undertaking, especially for the novice author. Over time, the pro-

cess becomes easier. Initially, it is useful to focus one's thoughts and

to approach writing the paper in manageable sections. The stan-

dardized format for research articles is discussed below in section

titled “Parts of the Paper,” as well as general guidelines for article

sections. Finally, a review by a professional editor may be worth-

while to ensure that the information is presented in the most un-

derstandable way.

3.1. Focus your thoughts

It is essential to discuss and critically review data and ideas with

co-authors and mentors. The paper's main point and how the

findings and paper will impact the field of interest should be

identified so that this might be more clearly conveyed in the

manuscript. Authors should consider what to present and keep

focused on a particular topic. Separating a paper with too broad of a

scope into two or more focused papers should be considered.

Similarly, authors should be clear regarding the type of article they

are targeting; for example, authors should avoid combining a

research article with a techniques or review paper.

3.2. Parts of the paper

Most papers have abstracts at the beginning that convey the

main points of the article. The abstract structure may differ by

journal and article type. For structured articles presenting original

Table 2

Journal search engines.

Search engine Website(s) Input options Output

Edanz journal selector http://www.edanzediting.com/journal_selector General

information

Journal name

Publisher

Field of study

Abstract, keywords

Journal name

Scope and related information

Publisher

Impact factor

Frequency

Open access

Elsevier journal finder http://journalfinder.elsevier.com/ Title

Abstract

Fields of research

Open access filter

Journal name

Confidence of match

Impact factor

Open access, fee

Editorial time

Acceptance rate

Production time

Embargo period

Scope and related information

Journal/author name estimator (JANE) http://biosemantics.org/jane/index.php Title

Abstract

Keywords

Language

Publication type

Open access options

PubMed Central

filter

Confidence of match

Journal name

Open access

Article Influence score

Similar articles

Springer/BioMed central/Chemistry central journal

selector

http://www.springeropen.com/authors/authorfaq/

findout

http://www.biomedcentral.com/authors/authorfaq/

findout

http://www.chemistrycentral.com/authors/authorfaq/

findout

Abstract

Impact factor filter

Open access filter

Confidence of match

Journal name

Impact factor

Frequency

Publishing model (e.g. open

access)

Web of science™ Journal Citation Reports

®

http://about.jcr.incites.thomsonreuters.com/ Journal category

Impact factor range

Publisher

JCR year

Open access filter

Journal name

Total cites

Impact factor

Eigenfactor score

JCR, Journal Citation Reports.

T.W. Liang et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563 561

research, the abstract is generally composed of four sections:

background and objectives, methods, results, and conclusions. Such

distinct sections may not be appropriate for reviews or case re-

ports; rather, a summary is adequate in these types of articles.

Research articles tend to follow the traditional introduction,

methods, results, and discussion/conclusion sections format,

otherwise known as “IMRAD.

11e18

” Other article types may not

follow the typical IMRAD format, but usually have introduction,

body, and discussion/conclusion sections. Generally, the introduc-

tion consists of a few paragraphs that briefly describe the back-

ground of the project and why the paper is written. All manuscripts

should ideally include how the work is novel and/or how it hopes to

impact patient care. The methods section describes the approach of

the project and how the data collection and analyses were per-

formed, as well as details of any relevant procedures and materials.

The results section describes the information that is generated from

data collection and analyses and may include the initial interpre-

tation of this information. The discussion section consolidates the

project's findings and interpretations of its results, and it might

include suggestions on how these findings can impact patient care.

The conclusion section should also discuss how the study findings

should be incorporated into models of current understanding as

well as discuss limitations around the interpretation of the data

presented. Future directions of research are also generally included

in this section. Finally, the discussion might end with a take-home

message.

Most scholarly articles reference other publications and, there-

fore, will have a reference or bibliography section at the end. The

number of references and its citation style will be dictated by the

journal that the article will be submitted to. Using a reference

manager (i.e., a software program that automates organization of

citations) is helpful, as it can usually automatically format the ref-

erences to journal-specific requirements. This feature is especially

useful when resubmitting the same article to a different journal.

Additional items include tables and figures that are referenced

in the manuscript or supplementary material (usually additional

figures and tables, or miscellaneous methods that further clarify

those mentioned in the main text) that could not be included in the

main article. Authors can always consider hiring a professional ar-

tist or using computer software to generate informative, profes-

sional appearing illustrations. All photos should be of high quality.

It is worth mentioning that the order of writing may not follow

the order in which the sections of the paper were described above.

It might make more sense to start with writing the methods and

results, then move on to the introduction and discussion, possibly

after discussions with co-authors and others regarding the study's

significance. Completion of the abstract may be considered once all

the sections are relatively finalized. Alternatively, the abstract may

actually be the first item that one writes as it will then serve as a

guide for the rest of the paper, especially if submitting an abstract to

a conference prior to the actual writing of the manuscript.

4. Ethics of writing

As with all academic endeavors, one should abide by a basic

code of ethics when writing a manuscript. Most would agree that

plagiarism, or reproducing others' work (their ideas even more so

than merely their words

19

) as your own, is a blatant violation of

ethical conduct.

Self-plagiarism, however, appears to be less commonly defined

and is often misunderstood. Having more than 30% of two or more

of your own published works matching in text is one useful defi-

nition of self-plagiarism.

20

This concept, however, also involves

more nuanced characterizations. Mohapatra and Samal have sug-

gested that there are 3 types of self-plagiarism

1

: publishing two (or

more) manuscripts that have the same data but with different

words

2

; splitting up one larger study into separate publications in

order to increase the number of publications, even though the larger

study would make more sense or better support the findings (i.e.,

“salami publications”); and

3

using text from one's own previously

published work in a new work.

21

To further clarify the second point,

the key is whether the intent is merely to obtain more publications

or if it is to improve the paper. For example, the authors of this

manuscript would argue that dividing up a manuscript because a

topic is too broad is not an example of ethical misconduct, since a

large combined manuscript would add unnecessary confusion to

the reader and does not add value to the results. In any case,

deception is the distinguishing factor of self-plagiarism,

20,22

as it is

for any form of plagiarism.

In order to screen for possible cases of plagiarism, many journals

use software services such as iThenticate (http://www.ithenticate.

com/). For a fee, authors themselves can also access this service,

as it is useful to check even for unintentional plagiarism or self-

plagiarism.

Dealing with a conflict of interest is a separate ethical issue. As

one section editor of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology wrote

in an editorial, it is defined as having “a set of conditions [that] is

operating that could have a marked influence on behavior.

23

”

Having a conflict of interest by itself is not necessarily problematic,

but rather it is the failure to disclose that has ethical implica-

tions.

15,23

Transparency, disclosure, and peer review are good ways

to address conflicts of interest, whether financial or personal in

nature.

24

Lastly, the topic of self-citation should be mentioned. It is

certainly acceptable and even required when referring to previous

relevant work (to avoid deception in self-plagiarism), but authors

should exercise restraint. This practice can artificially give the

appearance of increased academic productivity and, therefore, be

an ethical dilemma. Moreover, excess self-citations may not be well

received by reviewers and are improper if the citation of work of

others may be more appropriate.

5. Conclusion

Everyone from students to senior surgeons should advance their

personal and professional development as well as the field of sci-

ence and medicine at large. Even if a trainee decides not to be

involved in research in the future, at least he or she is familiar with

the process of writing and has the ability to more critically assess

the scientific literature. It can be argued that it makes one a better

physician and surgeon over time.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding

agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Schein M, Farndon JR, Fingerhut A. A Surgeon's Guide to Writing and Publishing.

Shropshire, UK: TFM Publishing Ltd; 2001:288.

2. McKillop IH, Moran DM, Jin X, Koniaris LG. Molecular pathogenesis of hepa-

tocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2006 Nov;136(1):125e135. PubMed PMID:

17023002. Epub 2006/10/07. eng.

3. Koniaris LG, McKillop IH, Schwartz SI, Zimmers TA. Liver regeneration. J Am Coll

Surg. 2003 Oct;197(4):634e659. PubMed PMID: 14522336. Epub 2003/10/03.

eng.

4. Zimmers TA, Pierce RH, McKillop IH, Koniaris LG. Resolving the role of IL-6 in

T.W. Liang et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563562

liver regeneration. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2003 Dec;38(6):1590e1591. author

reply 1. PubMed PMID: 14647070. Epub 2003/12/03. eng.

5. Altinors N. The structure of a neurosurgical manuscript. Acta Neurochir Suppl.

2002;83:115e120. PubMed PMID: 12442631. Epub 2002/11/22. eng.

6. Bergstrom C. Eigenfactor. College Res Libr News. 2007;68(5):314e316.

7. Moher D, Srivastava A. You are invited to submit. BMC Med. 2015;13:180.

PubMed PMID: 26239633. Pubmed Central PMCID: Pmc4524126. Epub 2015/

08/05. eng.

8. Koniaris LG, Coombs MI, Meslin EM, Zimmers TA. Protecting ideas: ethical and

legal considerations when a Grant's principal investigator changes. Sci Eng

Ethics. 2016 Aug;22(4):1051e1061.

9. Petroianu A. Distribution of authorship in a scientific work. Arquivos brasileiros

de cirurgia Dig ABCD ¼ Braz Arch. Dig Surg. 2012 Jan-Mar;25(1):60e64. PubMed

PMID: 22569982. Epub 2012/05/10. Eng Por.

10. UNiform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. Jama.

1997;277(11):927e934.

11. Baker PN. How to write your first paper. Obstetrics Gynaecol Reprod. Med.

2012;22(3):81e82.

12. Cetin S, Hackam DJ. An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1.

J Surg Res. 2005;128(2):165e167.

13. Davidson A, Delbridge E. How to write a research paper. Paediatr Child Health.

2012;22(2):61e65.

14. El-Serag HB. Scientific manuscripts: the fun of writing and submitting.

Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(6, Supplement):S19eS22.

15. Johnson TM. Tips on how to write a paper. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):

1064e

1069.

16. Manske PR. Structure and format of peer-reviewed scientific manuscripts.

J Hand Surg. 2006;31(7):1051e 1055.

17. Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV. How to write and publish an original research

article. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2010;202(4), 344.e1-.e6.

18. Singer AJ, Hollander JE. How to write a manuscript. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(1):

89e93.

19. Bouville M. Plagiarism: words and ideas. Sci Eng Ethics. 2008 Sep;14(3):

311e322. PubMed PMID: 18368537. Epub 2008/03/28. eng.

20. Marik PE. Self-plagiarism: the perspective of a convicted plagiarist. Eur J Clin

Investig. 2015 Jun 25. PubMed PMID: 26110581. Epub 2015/06/26. Eng.

21. Mohapatra S, Samal L. The ethics of self-plagiarism. Asian J Psychiatry. 2014

Dec;12:147. PubMed PMID: 25466781. Epub 2014/12/04. eng.

22. Bonnell DA, Hafner JH, Hersam MC, et al. Recycling is not always good: the

dangers of self-plagiarism. ACS Nano. 2012 Jan 24;6(1):1e4. PubMed PMID:

22268423. Epub 2012/01/25. eng.

23. Williams HC. Full disclosureenothing less will do. J Investig Dermatol. 2007

Aug;127(8):1831e1833. PubMed PMID: 17632552. Epub 2007/07/17. eng.

24. Caplan AL. Halfway there: the struggle to manage conflicts of interest. J Clin

Investig. 2007 Mar;117(3):509e510. PubMed PMID: 17332876. Pubmed Cen-

tral PMCID: Pmc1804343. Epub 2007/03/03. eng.

T.W. Liang et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 558e563 563