1/9

Political Science Junior Qualifying Examination Handbook

Modified 2019-12-17 AHM

Table of Contents

1! Policies 1!

2! Junior Qual Website 2!

3! Components of the Research Design 2!

4! Evaluation of the Junior Qualifying Examinations 2!

5! A Step by Step Guide 3!

5.1! Some General Tips 3!

5.2! The Proposal: Choose Your Research Question Thoughtfully 4!

5.3! Research Design: Crafting a Program for Research 4!

6! Junior Qual FAQ 6!

7! Appendix: Core Source Materials for the Research Design 6!

7.1! Qualitative Methods 7!

7.2! Surveys 7!

7.3! Research 7!

7.4! Review 8!

7.5! Style 8!

7.6! Writing 8!

1 Policies

The Junior Qualifying Examination in Political Science is taken very seriously by the faculty.

It consists of two parts: passing a Junior Seminar and writing a research design over the course

of a semester with a professor in the department. The research design portion is typically based

on the subject matter in a concurrent or previously-taken 300- or 400-level course, and consists

of three parts: An initial short written proposal; a draft research design based on that review; and

the final product, a revised research design. Junior Qual Samples are accessed via the Junior

Qual Moodle.

The research design portion of the examination is typically written in conjunction with or

following completion of a 300- or 400-level course that the student is taking in Political Science

in the semester immediately preceding their senior year, but may be taken earlier as long as the

two empirical introductory courses and one 300- or 400-level course have been completed or are

in progress. In the first week of classes, students will be assigned to a faculty member from

whom they have taken or are taking a 300- or 400-level course. Designs may not ordinarily be

written based on the content of 200-level political science courses.

Students going on terms abroad must make early arrangements to complete the three

requirements of the junior qualifying examinations. This is their responsibility. Standard

accommodations can be made for students on terms abroad; however, if at all possible, students

who plan to be abroad in their second semester of their junior year should take a Junior Seminar

prior to departing.

2/9

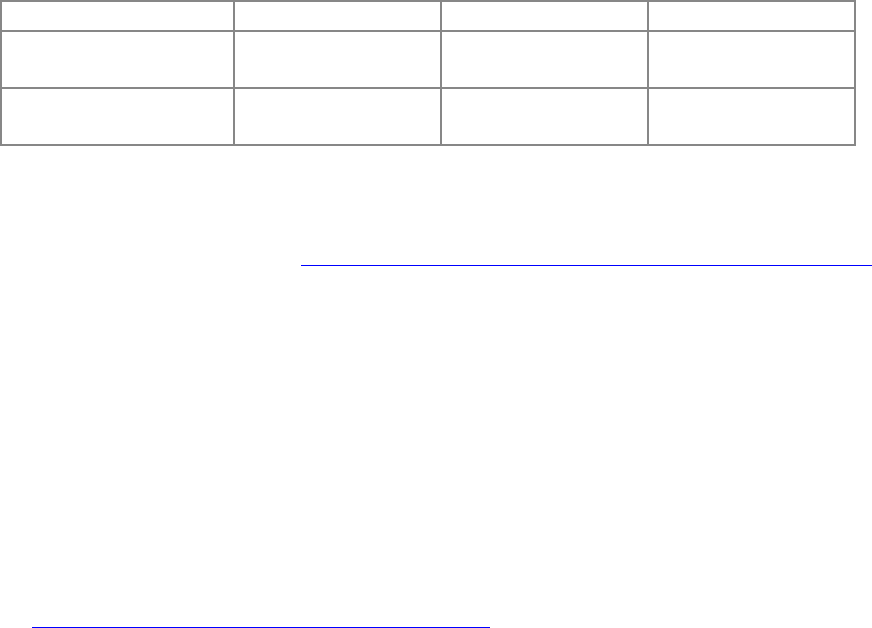

Junior Qualifying Examination Schedule

Week 3

Proposal Due

Monday at noon

Moodle

Week 12

Week 11 of instruction

Draft Research

Designs Due

Monday at noon

Moodle

Week 16

Finals week

Final Papers Due

Monday at noon

Moodle

2 Junior Qual Website

To assist you with the qual, a number of frequently-updated and electronic resources have

been placed online. Please consult: http://academic.reed.edu/poli_sci/resources/juniorqual.html.

Important resources include:

1. This Year's Deadlines. These are posted at the beginning of the academic year and are

updated to reflect any subsequent changes in dates or locations of events. The Qual Czar

will also send any updates to the Qual mailing list via Moodle.

2. Junior Qual Samples. The Qual Czar has placed sample research designs on the qual

Moodle.

3. Core Source Materials for a Literature Review. You will often write a literature

review before writing your research design. This includes specialized sources for

subfields of political science, sources for locating and borrowing books and journal

articles, databases and indexes for scholarly literature and current news, tools for locating

legal information, government publications, and statistics. See

http://libguides.reed.edu/politicalscience/psqual

3 Components of the Research Design

To clarify the process, we have broken the research design into four parts. All four must be

completed by the end of the second semester of a major's junior year, and are listed below in

chronological order.

1. Assignment. The student is assigned to qual with a professor.

2. Proposal. The proposal is a short (2-3 page, double-spaced) statement of the puzzle or

question on which a literature review could be conducted.

3. Draft Research Design. The design puts forward a hypothesis or thesis for further

research, often based on a literature review. The design should be about 5 pages. The

design states clearly the thesis or hypothesis, significance of the question, methods that

could be used, the steps to be followed, the observable outcome expected, and relative

assessment of strengths and weaknesses

4. Final Research Design. The final research design is expected to incorporate and be

responsive to feedback from faculty during the entire process.

4 Evaluation of the Junior Qualifying Examinations

A student must successfully complete the junior qualifying examination by the end of their

junior year in order to register for Pol 470, Thesis. The department as a whole evaluates the

research design. However, the Proposal, Draft Research Design, and Final Research Design must

3/9

be submitted by the specified due date to Moodle. Students who fail to submit one or more of

these materials on time will fail the Examination. The Junior Qual Czar shall set the deadlines in

with the approval of the department; particular professors may not alter these arrangements for

students. Students who miss deadlines may petition the department, though this is far from the

normal expectation of things. The Department expects all deadlines to be met in a timely fashion.

The Department would like to stress a few points on evaluation. First, and most obviously,

incorporate whatever relevant feedback or advice you heard from your professor and/or Qual

Czar into the research design. Speak about it with your professor and the Qual Czar if any input

is unclear. Failure to incorporate feedback can lead to a conditional pass.

Once your designs are in, the process from there proceeds as follows. The department will

meet and go over the research designs. We assume that your work this semester is evolving and

so the final product will represent improvements in detail, clarity and organization from the draft

design.

Our priority will be with dealing with the senior orals and grades, so we are unlikely to get

back to you sooner than a week after the end of the final examination period. As is the custom,

the Department’s assessment of your qual will be delivered by email as well as a hard copy to

your mail box.

There are three possible outcomes for the qual: pass, conditional pass, and fail. Fail happens

rarely, though it has happened. The conditional pass is more common than a fail assessment.

This means that the submitted document lacks in some respect and the department places some

conditions that you must perform to pass fully. This may include simply providing missing

material, rewriting certain elements of the design, and so forth. Obviously the ideal situation for

us and you would be if all of you passed the qual—and we certainly hope you do.

5 A Step by Step Guide

5.1 Some General Tips

In a general way, the Qual process (including both the junior seminar and the qual itself)

reproduces various kinds of assignments that you are going to have to do during thesis though

not necessarily in the sequence that it happens for thesis. The semester-long process allows you

to redo components of the design, and the design is assessed only upon final submission at the

end of the semester.

There are a number of different strategies for proposing a topic, conducting a literature

review (in the junior seminar), and writing a research design (for the qual). The junior seminar

and the qual are designed to complement each other, and most students find it advantageous to

take both in the same seminar. The samples on the website reflect some possible approaches, but

do not exhaust all valid options. Some options include:

● An empirical question (e.g., what explains the 1994 Republican Revolution?) with an

specific, empirical literature review looking at different authors' explanations for the

specific phenomenon (national disaffection with government and realignment) in

question rather than election outcomes in general; the research design then proposes

to investigate a "hole" in the empirical literature: e.g., rather than looking for national

explanations, move to the regional level and identify individual "battlegrounds."

● An empirical question (e.g., what explains the size of China's nuclear arsenal?) with a

mechanism-focused literature review investigating different general causal

mechanisms (technical, economic, political, doctrinal) for the size of nuclear arsenals

4/9

rather than explanations for China's specific arsenal; the research design lays out how

to measure relevant variables and apply the theories to China.

● A theoretical question (e.g., what lessons do the Marxist and republican traditions of

interpretation of Machiavelli have for contemporary politics?) with a literature review

that is centered around interpretations of a particular theorist; the research design

proposes to test the internal coherency of combining present-day leftist thought with

classical Marxist readings of Machiavelli.

● A theoretical question (e.g., does the civic republican theory of negative liberty

provide better guarantees of liberty?) with a literature review that looks at different

writers on positive and negative liberty as well as theorists who have spawned the

revival of civic republican notions of negative liberty; the research design proposes to

examine the internal consistency of the latter theorists' arguments as well as its

compatibility with a wider system of beliefs about liberty as non-interference.

5.2 The Proposal: Choose Your Research Question Thoughtfully

For the proposal, we would like a clearly stated question. If you think you can suggest one,

propose the broad outlines of what you're thinking of framing for your research design. We

know, of course, that your design may change. But try out what the possibilities might be for you

and get feedback from us. Please keep in mind that your first requirement as a senior will be to

submit a thesis proposal by the end of the first month to the division (not the department), so you

might as well learn how to do it now. You do not have to have any faculty member sign off on

your qual proposal before turning it in.

The way you define your question in the long run affects the number and range of sources

and the quality of the arguments you can pull together. The choice of question can therefore be

strategic. This is the first place in the assignment where your creative judgment and skill come

into play.

Some questions are simply enormous (What is the literature on revolution, terrorism or

Congress or John Rawls?) and there are many well-traveled paths. In these areas, the goal is to

narrow the topic in a way that there is a puzzle, question, proposition or hypothesis to explore.

For example, "Is a presidential system more liable to gridlock than a parliamentary system?" may

yield a variety of different positions in comparative politics. Or "Has Hobbes really solved the

"Problem of the Fool" in the Leviathan?" Each of these questions directs your attention towards a

range of different answers to this question.

A question may also be a non-starter because there is very little information on it or all the

information you can find on it is of one sort (say, journalistic coverage or by just one author).

Here you may need to think about ways to revise your question so you can grasp a variety of

research sources. Here your instructor may be able to give you good advice.

You must state in your proposal the significance of the question in political science. What is

the existing literature you have found so far on this question? While understanding "what views

of Osama bin Laden might exist in the United States?" might be a question of interest to you, you

need to explain why a political scientist might be interested in this question.

5.3 Research Design: Crafting a Program for Research

Why draft a research design now? In Thesis, your first responsibilities will be to propose a

research design and conduct a literature review, and your design must be something you can

complete within a year. So the qual tests your ability to frame that project. One common error in

the qual research design is to propose surveys or studies that would take either a portion of a

5/9

lifetime or a multimillion dollar grant to complete. If you sense that this is the case with the

strategy or question you have come up with, then you need to either rethink your strategy or

refine your question. All seniors in the Division of HSS must submit a research proposal in the

first month of thesis, so it is good to be familiar with this format. The Junior Qualifying

Examination thus includes your mastering the first skill you need to draw on for Pol 470, thesis.

Your next task is consequently to design a draft research proposal. Typically, this will be

based on a literature review you have written in junior seminar or another course. We expect the

initial research designs submitted to be drafts, just as the schedule says. That is, we expect

substantial improvement on them when they are resubmitted at the end of the semester,

incorporating faculty comments as well as other improvements along the way. Even so, if the

draft is incomplete or inadequate, we may, in some cases, ask for resubmissions.

Even though the designs are drafts at this stage, the department expects to see the following

elements incorporated into the designs.

1. You should offer a clear thesis or puzzle based on the review and state its significance to

political science (not just to politics). Why is this research question important (the inevitable

“who cares?” question)? This question should be plausible in light of the literature review you

have just conducted. Think about the literature you have read and place your design within the

framework of the literature.

2.Propose one or two ways to test, prove, or disprove your thesis, outline the stages through

which the research would proceed for each, and tell us what you expect what these ways will

yield based on the literature you have reviewed thus far (what observable implications of your

thesis might they generate, for example). Weigh their merits and promise as it pertains to the

thesis you have proposed. What would it take to convince you you've chosen an inappropriate

range of methods, or conversely these are the right methods even if the results don't support your

claim? What would it take to convince you that you should reformulate what you’re doing or

claiming (what are the truth conditions for your work)? Whether the material is empirical or

theoretical, each student must answer this question in plausible and feasible ways. Keep in mind

that if you cannot answer this question, then there is no difference between what you are doing

and mythology or rhetoric.

This document should be no longer than 5 pages and must have an acceptable system of

citation as well as a bibliography. Your literature review should be of great assistance to you, but

remember that a literature review opens the way for many research papers, not just one. If you

are uncertain on how to proceed with the literature you have read, you should speak as soon as

possible with your class instructor.

Though there is no expectation that the student will have the time to answer it, the strategy

you propose must be feasible. This means that a student could pursue and complete the strategy

you propose over the course of a year given the resources normally available to one.

This is of course not (yet at any rate) a research paper. If you did write a research paper based

on the literature review, you would need to go over your review again and delete a lot of material

as many of the sources you cover may not be directly related to your research design.

Your final task is to edit your draft research proposal and turn it in as your final research

design. We expect improvement from the draft in this submission, incorporating faculty

comments as well as other improvements along the way. Even so, if the draft is incomplete or

inadequate, we may, in some cases, give you a conditional pass and additional guidance for

completion.

6/9

6 Junior Qual FAQ

Is the junior qual a research paper? No, it is not. You are not researching a topic. In the

literature review, you are cataloging what there is that has been written about a topic. Your

review should have the capacity to identify various materials (books, articles, etc.) using various

approaches, theses, or methodologies. In the research design, you are proposing a paper, not

writing it.

How do I know if there is enough on a topic? One simple test is to go to the Library of

Congress Catalog (http://catalog.loc.gov/) and type in the two or three keywords on your topic. If

you type in “revolution,” for example, or “Marx and Weber,” you’ll get over 10,000 hits.

Obviously you can’t read 10,000 books in a semester. Rethink your proposed idea until it is both

scholarly and manageable.

How realistic should my research design be? Your research design should be something

you can complete within a year. Your qual tests your ability to frame a project of the sort your

thesis will be like. One common error is to propose surveys and studies that would take a portion

of a lifetime or a multi-million dollar grant to complete. If you sense that this is the case with the

strategy or question you are using, then you need to either rethink your strategy or refine your

question.

What happens at the end of the process? There are three possible outcomes: pass,

conditional pass, and fail. Fail means that the student must take the qual again (not necessarily

another qual paper; it may be an exam instead). Conditional means that the student’s submissions

were lacking in some respect and that the student is unprepared to start thesis until certain skills

are mastered. In this case, the department assigns some conditions that must be satisfied before

the student can register for thesis. This may include rewriting a portion of a submission or some

additional exercise. All conditions must be satisfied by the start of the next semester, and failure

to submit the condition is automatically a fail. Pass is the best result, of course, and you will

receive written notification when you can register for thesis.

When does notification happen? We notify students after the end of the semester. Keep in

mind that faculty are focused primarily on senior grades, and they may not get to reviewing the

junior quals until well after finals week, depending on the semester.

7 Appendix: Core Source Materials for the Research Design

A fundamental part of the senior thesis at Reed is learning to engage with, and conduct,

independent scholarly research. This is why we require a research design as part of our junior

qual. Without understanding the basics of social science research, you will struggle when

working on your thesis.

However, it is also true that the Political Science department does not frequently offer an

explicit course dedicated to research design; instead, these lessons are most often taught in

conjunction with substantive material. Research design and methodology questions also appear

in our introductory courses, and in some statistics courses, but often students do not recognize

the importance of these lessons at the time they are exposed to them.

As a consequence, while most of our seniors are very competent in summarizing literature

and identifying key arguments, the research design component of the junior qualifying

examination is the component that is most often misunderstood, and is the greatest cause of

conditional passes and failures.

7/9

If you feel that your understanding of what constitutes a good social science research design

is shaky, we provide to you the list of sources below. Working in partnership with your qual

supervisor, you should read one or more of these sources to help guide your thinking as you

prepare your research design.

These readings and resources are suggested by faculty. Most of the books are available in the

Reed Library. They are divided into six categories, although many of them apply to more than

one category. The texts listed under Qualitative Methods deal specifically with designing

research and selecting cases qualitatively, while the texts under Surveys will be helpful for

quantitative research designs involving fieldwork and surveys. Research texts are general guides

to writing research papers, while Review texts deal with how to conduct a literature review.

Style guides help with citation and good writing practice, while Writing guides deal with

writing projects more generally. This annotated bibliography was done using Endnote; the

Endnote file and styles are available on the web page.

7.1 Qualitative Methods

Brady, Henry E., and David Collier, eds. Rethinking Social Inquiry : Diverse Tools, Shared

Standards. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004. An important and

very useful guide to conducting case studies and comparative research.

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. Designing Social Inquiry : Scientific

Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton University Press, 1994. A book on

comparative social inquiry written from the perspective of quantitative research; for a

good companion piece, see the Brady and Collier book.

Ragin, Charles C., and Howard Saul Becker. What Is a Case?: Exploring the Foundations of

Social Inquiry. Cambridge University Press, 1992

Skocpol, Theda, and Margaret Somers. “The Uses of Comparative History in Macrosocial

Inquiry.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 22, no. 2 (April 1980): 174–97.

Van Evera, Stephen. Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science. Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press, 1997. Case study methods and comparative politics.

7.2 Surveys

Fenno, Richard F. Home Style: House Members in Their Districts. Little, Brown, 1978. See

especially the appendix that deals with elite interviewing.

Huff, Darrell, and Irving Geis. How to Lie with Statistics. New York: Norton, 1954.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/225473 It is a delightful little book. His examples are

dated, but charmingly so (it was published in 1952). But his points are still as well-taken

as ever. Huff was one of the premier statisticians of the mid twentieth century.

Kingdon, John W. Congressmen’s Voting Decisions. University of Michigan Press, 1989. A

good guide to case selection and elite interviewing.

Miller, Delbert C., and Neil J. Salkind. Handbook of Research Design and Social Measurement.

Sage Publications Inc, 2002. Especially good for finding established measurement scales

which can be used for original survey research purposes.

7.3 Research

Booth, Wayne C., Joseph M. Williams, and Gregory G. Colomb. The Craft of Research, 2nd

Edition (Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing). University Of Chicago

Press, 2003. This is a concise, practical guide to mastering the art of research which helps

one plan, carry out, and report on research in any field, at any level.

8/9

Johnson, Janet Buttolph, Richard A. Joslyn, and H. T. Reynolds. Political Science Research

Methods. 4th ed. CQ Press, 2001. On reserve of PS 210 and also a copy in the PPW; see

the first few chapters that deal with question formulation, hypothesis generation, and

concept formulation.

Rodrigues, Dawn. The Research Paper and the World Wide Web. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Prentice Hall, 1997. A comprehensive guide to writing research papers for students in all

fields; it helps researchers navigate through print and online sources by providing

explanatory chapters on the research process, search strategies, source evaluation and

documentation.

7.4 Review

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. Sage

Publications, 2004. This reference guide focuses on the “scientific” style but the sections

on the internet as well as the first part on literature reviews and why they are important

and useful; also, she covers a special kind of lit review called a “meta analysis,” which is

essentially using the data from several studies as a new database.

Hayes, John R., ed. Reading Empirical Research Studies: The Rhetoric of Research. Hillsdale,

N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc, 1992.

Light, Richard J., and David B. Pillemer. Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984. This book discusses “meta analysis”

which is a form of literature review, but one based on re-analyzing massive amounts of

combined empirical data from a number of independent studies, hence “summing up;”

the Research Bureau of the National Association of Science does a lot of this, check their

website for examples; the kind of literature reviews done for theses are what they call

“traditional literature reviews.”

.

7.5 Style

Staff, University of Chicago Press. Chicago Manual of Style. University Of Chicago Press, 2003

Strunk, William, Jr., and E.B. White. The Elements of Style. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1999

Turabian, Kate L, John Grossman, and Alice Bennett. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers,

Theses, and Dissertations. 6th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996

7.6 Writing

Baglione, Lisa A. Writing a Research Paper in Political Science: A Practical Guide to Inquiry,

Structure, and Methods. Belmont, CA: Thomson Higher Education, 2006.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/70691921. This is a “how-to” cookbook that addresses

everything from finding a question to some easy stats.

Ballenger, Bruce. The Curious Researcher: A Guide to Writing Research Papers. Longman,

2006. Features plenty of material on the conventions of research writing–citation

methods, organizational approaches, evaluating sources, and how to avoid plagiarism;

emphasizes introducing students to the spirit of inquiry.

Becker, Howard Saul, and Pamela Richards. Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and

Finish Your Thesis, Book, Or Article. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. All

the nuts and bolts, just as the title implies.

Dunn, William N. “The Policy Issue Paper.” In Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction, 423–31.

Prentice-Hall, 1981. Outlines a policy paper and even has a checklist to be sure one has

done everything.

9/9

Lipson, Charles. How to Write a BA Thesis : A Practical Guide from Your First Ideas to Your

Finished Paper. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip053/2004026816.html Intended as a guide to the whole

thesis process, the first seven chapters (120 pages) do a nice job laying out the basic

process of identifying an area of research and asking the “thesis” of a thesis.

Weidenborner, Stephen, and Domenick Caruso. Writing Research Papers: A Guide to the

Process. 4th ed. St. Martin’s, 1994. A step-by-step student guide to every aspect of the

research process, from finding a topic to formatting the final manuscript.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. The Clockwork Muse: A Practical Guide to Writing Theses (Harvard

University Press: 1999.