Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation

Volume 26 Article 19

2021

Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for

Resolving Problems of Practice Resolving Problems of Practice

Craig A. Mertler

Arizona State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare

Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Teacher Education

and Professional Development Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Mertler, Craig A. (2021) "Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for Resolving Problems of

Practice,"

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation

: Vol. 26 , Article 19.

Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass

Amherst. For more information, please contact scholarworks@library.umass.edu.

Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for Resolving Problems of Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for Resolving Problems of

Practice Practice

Cover Page Footnote Cover Page Footnote

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Craig A. Mertler, Division of Educational

Leadership & Innovation, PO Box 37100, Mail Code 3151, Phoenix, AZ 85069. Email:

This article is available in Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/

vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 1

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

A peer-reviewed electronic journal.

Copyright is retained by the first or sole author, who grants right of first publication to Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. Permission

is granted to distribute this article for nonprofit, educational purposes if it is copied in its entirety and the journal is credited. PARE has the

right to authorize third party reproduction of this article in print, electronic and database forms.

Volume 26 Number 19, August 2021 ISSN 1531-7714

Action Research as Teacher Inquiry:

A Viable Strategy for Resolving Problems of Practice

Craig A. Mertler, Arizona State University

Teacher inquiry is the process of applying action research to educational problems of practice, carried

out by educational practitioners. The value of teacher inquiry—and all applications of action

research—is that the research is being conducted by insiders, those who work directly with the

problem being studied. It is based upon critical reflection and investigation into one’s own

professional practice. This paper presents discussion of teacher inquiry as a viable approach to

resolving practitioner-based problems of practice in a process that also affords teachers the operation

to generate their own knowledge about classroom practices. The process of conducting action

research, along with its applications and benefits, are reviewed and contextualized within the work of

classroom teachers. Perspectives held by educators regarding teacher inquiry are also discussed. The

paper closes with a discussion of ways in which teacher inquiry can be highly beneficial as a means of

professional growth during and following the COVID-19 global pandemic and includes a concrete

example of teacher inquiry during the pandemic.

Introduction

Action research has been a respected and widely

used approach for conducting applied research in

educational settings for decades but continues to suffer

from general misunderstandings among researchers and

practitioners alike (Mertler, 2020a). While there are

numerous similarities between action research and more

traditional forms of educational research, the important

distinguishing characteristics of action research (Mertler,

2020a)—it is a process that improves education by

incorporating change and involving educators working

together to improve their own practices; it is

collaborative and participative, since educators are

integral members of the research process; it is practical

and relevant, allowing educators direct access to research

findings; and, it focuses on critical reflection about

professional practice—are what make it an ideal

approach to systematic inquiry for the educational

practitioner, specifically in the form of teacher inquiry. The

main goal of action research is to address local-level

problems in practice with the anticipation of finding

immediate answers to questions or solutions to those

problems (Mertler, 2018). The purpose of this paper is

to shed light on the process of conducting teacher

inquiry in the form of action research—including its

benefits and applications—to facilitate applied research

in contextualized and practical settings, conducted by

practitioners who are focused on solving their own, self-

identified problems of practice.

1

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 2

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

Teacher Inquiry as Applied

Educational Research for Practitioners

Dana and Yendol-Hoppey (2019) define teacher

inquiry as “systematic, intentional study of one’s own

professional practice” (p. 6). There exists a great deal of

overlap between the concepts of action research and

teacher inquiry. In fact, the literature contains numerous

terms used synonymously with “teacher inquiry,”

including “teacher research,” “classroom research,”

“classroom inquiry,” and “practitioner inquiry.” In

essence, teacher inquiry consists of the application of

action research to classroom problems, conducted by

professional educators (e.g., classroom teachers,

counselors, special educators, and administrators).

Regardless of the term that we might use to describe

this practice, all the above refer to the act of professional

educators not only being involved in the research

process, but actually leading that process. They are

responsible for identifying the problem, specifying its

scope and breadth, making informed decisions about

appropriate data to collect and analyze, and then actually

collecting and analyzing those data, for purposes of

drawing conclusions and addressing their initially-stated

problem under investigation.

When we talk about teacher inquiry, we are referring

to a type of applied research in education that is entirely

about the practitioner and her desire and need to study

her own practice. We are not talking about university

professors and researchers or staff from a national

research firm going into schools and conducting

research on topics that they are interested in studying.

Applied research is educational research that is focused

on solving a specific problem. Teacher inquiry could be

considered the epitome of applied educational research

(Mertler, 2013, 2020a).

The Nature of ‘Problems of Practice’ and the

Appropriateness of Teacher Inquiry

When we talk about topics appropriate for teacher

inquiry, we often refer to them as problems of practice. A

problem of practice is just that—a problem faced by a

practitioner in her professional practice. Further, it is a

problem that she wants to try to resolve through the

application of a strategic, systematic, and scientific

approach. Oftentimes, educators mistakenly equate

educational problems with problems of practice (Mertler,

2020a). As we all know, problems are extremely

abundant in educational settings. However, the difficulty

here is that problems—in and of themselves—are not

directly “solvable.” For example, in speaking with a

classroom teacher, you might become aware of the

following problem in a school or district: “there is clearly

an achievement gap in our district.” By definition, this

would not be considered a problem of practice because

it is simply too large and too complex to be investigated

and solved. Henriksen, Richardson, and Mehta (2017)

have described a “problem of practice” as follows:

The term ‘problem of practice’ is common in

education, but it has no single, common scholarly

definition… We suggest that a problem of practice

is: a complex and sizeable, yet still actionable,

problem which exists within a professional’s sphere

of work. Such problems connect with broad or

common educational issues but are also personal

and uniquely tied to an educational context and its

variables; thus, they must be navigated by

knowledgeable practitioners. (p. 142)

Note several important features of their definition.

First, the problem of practice must be complex and

sizable, but must still be actionable. In other words, it

must be solvable, to some degree. Second, they clearly

note that the problem of practice should exist within a

professional’s sphere of work and must be specific to a

particular context, setting, group of students, etc. Simply

put, this means that the practitioner must have control

over the entity under investigation. She must be able to

change her practice, to try something new, to assess how

well it works, and then to make changes in an effort to

move her practice forward.

There may literally be no better or more appropriate

way to investigate specific problems of practice than to

do so through the process of teacher inquiry (Mertler,

2020a). The application of action research by

practitioners in their own settings investigating their own

problems of practice is the most appropriate way to

address those problems (Mertler, 2013). It could be

argued that literally no one else has the insight and levels

of experience necessary to understand and to solve a

particular context-specific problem of practice than the

practitioners who are involved in that setting and with

that problem on a daily basis (Mertler, 2013). Mertler

continues by stating that problems of practice are so

inextricably context-specific that outsiders would have a

difficult time fully understanding and grasping the

2

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 3

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

impact of the problem and any potential solution. The

specificity may center around a specific teacher’s style of

instruction, a mix of student personalities in a classroom,

a particular curriculum that is used only in that district,

or perhaps even the cultural makeup of the local

community. The types of experiential knowledge

requisite to study a particular problem of practice should

not be overlooked or diminished when we talk about

teacher inquiry as an applied approach to conducting

research in educational settings.

In turn, this helps to establish one of the most

critical ways in which teacher inquiry and action research

are important to the broader field of educational

research. Specifically, teacher inquiry gives voice to the

professional educator, allowing that educator to identify

and investigate problems with which she has first-hand

knowledge. In essence, the broader result of this process

is that teachers have the capacity to become what Dana

and Yendol-Hoppey (2019) refer to as “knowledge

generators.” Teachers have been historically seen as

“dispensers of knowledge,” as opposed to “generators

of knowledge.” Teacher inquiry is the systematic process

that allows educators to create original knowledge about

educational practice. It could be argued that, from an

historical perspective, educational research has relied on

outsiders who are studying PK-12 classrooms to

generate that knowledge. The collective voice,

experiences, and knowledge of the professionals “on the

ground”—immersed in that particular setting each and

every day—were typically not considered. The

knowledge that can be generated by considering and

valuing the perspectives of educational practitioners

through the application of teacher inquiry has the

potential to alter that landscape.

Overview of Action Research

Since it has been alluded to earlier, an overview of

action research is warranted. Action research is any sort

of systematic inquiry conducted by those with a direct,

vested interest in the teaching and learning process in a

particular setting; by definition, it is truly systematic

inquiry into one’s own practice (Johnson, 2008). In

educational settings, it is a process that “allows teachers

to study their own classrooms…in order to better

understand them and to be able to improve their quality

or effectiveness” (Mertler, 2020a, p. 6). Action research

provides a structured process for customizing research

findings, enabling educators to address specific

questions, concerns, or problems within their own

classrooms, schools, or districts. The best way to know

if something will work with your students or in your

classroom is to try it out, collect and analyze data to

assess its effectiveness, and then make a decision about

your next steps based on your direct experience. It is

arguably the most effective and practical approach to

solving contextualized organizational problems and

answering related questions (Mertler, 2020b).

Action research is conducted by practitioners for

themselves; their problems and unanswered questions

provide the impetus for situated and contextualized

action research. Action research occurs in a manner

completely opposite to more traditional forms of

educational research, where it is typical to have the focus

of some sort of research imposed upon educators by

another individual or a team of researchers. Of course,

this also means that the onus for developing those ideas

for action research rest with the practitioners, as well.

It is important to note that action research is not a

haphazard trial-and-error exercise or “stabs in the dark.”

Like any other approach to conducting research, action

research is a scientific and systematic process consisting

of a set of procedures designed to help professionals and

other practitioners—or groups of practitioners—

identify a problem, design and implement an

intervention or other innovative approach to the

problem, assess the effectiveness of the proposed

solution, and then develop a plan for where to proceed

next.

Applications and Benefits of Action Research

Mertler (2020a) cited six ways in which action

research and teacher inquiry are critical to the teaching

profession. Key among these are (1) the improvement

of educational practice, (2) professional growth, and (3)

teacher empowerment (Vaughan & Mertler, 2020). First,

professional inquiry of this type can directly lead to the

improvement of educational practice. During this

process, educators are studying their own practice by

reflectively and critically examining their own problems

of practice, as they are situated within their specific

context. This includes the identification of specific

problems (i.e., the aforementioned “problems of

practice”) to which they seek answers, the collection of

observational and other key data, and finally,

engagement in a process that facilitates meaningful, data-

3

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 4

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

informed, and practical decision making. Action

research and teacher inquiry provide a process that

affords professional educators opportunities to seek out

and actually find those answers that they know will work

in their schools and classrooms and with their students.

Second, action research and teacher inquiry have

been shown to lead to highly effective professional

growth (Vaughan et al., 2019; Mertler, 2013). For

decades, the approach to professional development in

education has been a “one-size-fits-all” model. The basic

logic behind this approach is that every professional

educator can somehow benefit from professional

development on the same topic. This simply is not the

case. Since the early 1980s (Oliver, 1980), action research

has been promoted as a meaningful alternative to more

“typical” professional development opportunities for

educators. Oliver (1980) argued that the major benefit of

action research as inservice training for educators is that

it promotes a continuing process of professional

development in a climate where professional educators

not only pose the research questions, but also test their

own solutions, as well. More “enlightened” forms of

professional learning (McNiff, 2002) operate on the

assumption that educators already possess a good deal

of professional knowledge, and are highly capable of

furthering their own learning by focusing on specific

aspects of their practice that they want to improve.

These types of professional learning capitalize on a more

appropriate form of support to help educators celebrate

what they already know, but also encourage them to

develop new knowledge. Action research and teacher

inquiry lend themselves very nicely to this process, in

that they require educators to evaluate what they are

doing and further to assess how effectively they are

doing so.

Third, teacher inquiry serves as an extremely

effective and efficient means for teachers to experience

professional empowerment. In an educational climate

that is growing more and more data-driven all the time,

and when teachers assume responsibility for collecting

their own data—and making subsequent decisions from

those data—they tend to experience a higher level of

professional empowerment. This allows educators to

bring their own expertise, talents, creativity, and

innovations into their schools and classrooms. They

then can design and implement instructional programs,

lessons, and activities that will best meet the needs of

their students (Mertler, 2020a). In addition, this type of

empowerment allows—and, in fact, promotes—a sense of

professional risk-taking, provided the goal is based in the

improvement of educational practice.

The true benefit of action research and teacher

inquiry is that educators can focus and direct their own

professional growth and development in specific areas

that they want to target, as opposed to having

professional development topics thrust upon them. This

allows for the emergence of professional development

activities that are customizable in order to fit the needs of

an individual educator, or perhaps even collaborative

teams of educators (e.g., teachers of the students in the

same grade, or teachers of the same content area).

Specific areas identified and targeted for improvement

can serve as the focus of the personalized and

customized professional growth and development

through action research (Mertler, 2013).

To extrapolate this notion a bit, if we accept the

premise that action research can serve as a basis for

meaningful professional development, then it would

make sense that it could be part of a system of annual

teacher evaluation (Mertler, 2013). For example,

educators could begin an academic year by developing

specific professional development goals for themselves

that they would pursue through a systematic teacher

inquiry approach. If educators were permitted—

perhaps, even encouraged—to develop their own

professional development goals, and to systematically

collect data and investigate their own practice, and

provided they were held accountable for the degree of

their successes (or at least for what they learn because of

reflection on the engagement in such a process), systems

of teacher evaluation could see the addition of this

critical piece of teaching effectiveness and its impact on

student learning—from the perspective of the educator,

herself. Incorporating teacher inquiry into teacher

evaluation processes would add to teachers’ sense of

empowerment, and to a general sense of ownership over

their own teacher evaluation processes (Mertler, 2013).

The Process of Action Research

Action research is typically described as a cyclical

process, whereby a complete cycle of research (i.e., one

actual research study) builds on and extends any cycles

of action research into the same or closely-related

problem that preceded it. A single cycle, then, consist of

four stages of research activities. Those stages are:

4

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 5

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

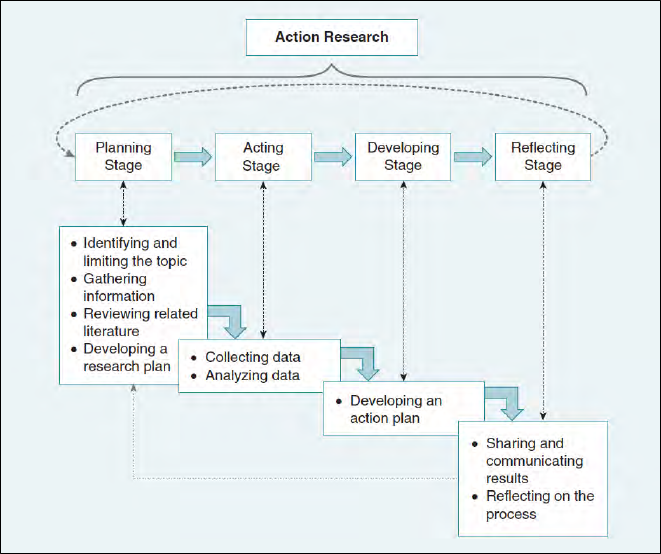

• The planning stage,

• The acting stage,

• The developing stage, and

• The reflecting stage.

The four stages of the action research cycle—along

with specific research activities to be carried out in each

stage—are depicted in Figure 1.

The first of these stages—the planning stage—

consists of preliminary activities related to the

development and implementation of an action research

study. During this stage, the educational practitioner

begins by initially identifying a topic. Oftentimes, the

topic must be limited or expanded, depending on the

initial scope of the potential problem under

investigation. The practitioner also gathers information

related to the topic. This related information would

obviously include a small-scale review of related

literature to discover what existing research work may

have already been done on the problem of interest.

However, the search for this related information

should not be limited to just published research. Since

action research is practitioner-focused, related

information that is both practical and experiential can

also be extremely important in guiding the development

of an action research study. This means that educators

can look to colleagues—both internal and external to

their own organizations—for guidance and practical

suggestions for approaches, interventions, or innovative

approaches to solving the problem that they may have

tried and with which they may have experienced some

degree of success. Both formal and informal sources of

information related to the identified problem can be

important in terms of helping to guide the development

and structure of an action research study.

Figure 1. The Four Stages and Specific Activities of a Single Cycle of Action Research

Note. From “Overview of the Action Research Process,” in Action Research: Improving Schools and Empowering Educators (6

th

ed.),

by C. A. Mertler, 2020, p. 37, SAGE Publications.

5

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 6

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

Also important during this stage of the action

research cycle is the statement of formal research

questions that will serve to guide the conduct of the

action research, as well as the development of a specific

research plan for the study. Action research can use any

design or approach to implementing an innovative

approach, collecting data, and analyzing those data that

may be used in more formal qualitative, quantitative, or

mixed-methods research studies. Therefore, it is

common to see approaches for data collection

including, but not limited to, interviews, observations,

focus groups, surveys, questionnaires, assessments,

pretest-posttest measures, as well as any combination

of the preceding.

The second stage—the acting stage—is where the

actual conduct of the study occurs. This is the point in

the action research process where the practitioner

physically collects and analyzes all data to be used in

attempts to provide answers to the guiding research

questions. Once again, all strategies or approaches to

data collection and analysis are appropriate at this stage

of the action research process. That being said,

however, it is probably most typical that practitioners

rely on the use of thematic analysis and coding for the

analysis of any qualitative data and descriptive

statistics—and, possibly, t-tests or analysis of

variance—for the analysis of quantitative data.

As mentioned above, virtually any strategy or

approach to data collection and analysis are

appropriate in an action research study. The key is

alignment between the data (and subsequent analyses)

and the guiding research questions. The practitioner-

researcher must ensure that the data and associated

analyses will provide answers to those questions. In

cases where the research questions call for open-ended,

non-structured narrative data—in the form of

perceptions, beliefs, or feelings—then qualitative data

would be the most appropriate form of data for

answering the research questions. Alternatively, in

situations where the research questions might require

participants to rate their perceptions on a

predetermined response scale, quantitative data and

analyses would be the appropriate strategy. However,

many researchers tend to see the best alignment with

the process and goals of action research to be a mixed-

methods approach to inquiry (Creswell, 2005; Mertler,

2020b). The belief here is that the combination

qualitative and quantitative data will enable the

practitioner-researcher to answer the guiding research

questions in the most comprehensive and thorough

manner.

The third stage of the process—the developing

stage—is comprised of the development of an action

plan for moving forward in the process of conducting

action research. The action plan is the ultimate goal of

any action research study—it is the action part of action

research (Mertler, 2020a). This typically consists of two

different aspects: an action plan for practice and an

action plan for future cycles of action research. Since this

action research is being conducted by practitioners, it

is of utmost importance that the practitioner-

researcher use the results and conclusions from a cycle

of action research to impact and change current and

future practice. After all, this is the main reason that a

practicing educator makes a conscious and

professional decision to use action research as a means

of solving various educational problems. Secondly, it is

important to develop plans for the continuation and

exploration of the problem using an action research

approach. The logic here is that seldom is a problem

solved after a single cycle of action research. Aspects of

the problem may experience improvement, but in all

likelihood, there is still more improvement and change

that could and should occur.

The final stage of the action research process—

the reflecting stage—provides the opportunity to reflect

not only on the context and results of the action

research study at hand, but also on the action research

process as a whole. Since, at its core, action research is

about critical examination of one’s own professional

practice, reflection on the process of conducting action

research is a critical step in the process. It is important

to note that the act of professional reflection often

leads directly into the next cycle of action research, by

providing the foundation for the nature of the next

stages of investigating the same problem or, perhaps,

the next problem to be investigated. This is the basis

for the way in which one cycle of action research

logically and practically leads into the next cycle.

It is also crucial to note that, although this final

stage of the process is labeled the “reflecting” stage and

the expectation is that a teacher would use this

opportunity to reflect on the overall process, reflection

is an integral part of the action research process.

Critical, professional reflection must span the entire

action research process. In other words, professional

6

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 7

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

educators who engage in the action research process in

the form of teacher inquiry are engaging in critical

reflection during each of the four stages of the process

shown in Figure 1. For example, to accurately frame

the problem of practice during the planning stage,

teachers would need to reflect on their past experiences

and struggles that they may have had with that specific

problem. They would also reflect on approaches that

they may have tried in the past, to identify aspects of

them which may have been beneficial and that they

would want to continue. During the acting stage, they

might reflect on previous data that they have collected,

or strategies for analysis with which they are most

comfortable. During the developing stage, they would

want to reflect on the knowledge that they had gained

up to this point in the cyclical process, since that

knowledge would be used to develop a plan for their

next steps in trying to resolve their identified problem

with practice.

Research of any kind involves systematic and

scientific investigation, and quality research must meet

standards of sound practice (Mertler, 2022). Action

research is no exception to this rule of thumb. The

basis for establishing the quality of traditional research

lies in the concepts of validity and reliability. Action

research typically relies on a different set of standards

for determining quality and credibility (Stringer, 2013).

Because action research adheres to the standards of

quality and credibility rather than validity and

reliability, it has sometimes been criticized for being an

inferior approach to research as well as for being of

lesser quality. Rather than being considered lesser or

inferior, action research should be viewed as being

different from traditional research. Nevertheless, it is

critical for action researchers to ensure that their

research is sound (Mertler, 2022).

The extent to which action research reaches an

acceptable standard of quality is directly related to the

usefulness of the research findings for the intended

audience (Mertler, 2022). This general level of quality

in action research is referred to as rigor—the quality,

validity, accuracy, and credibility of action research and

its findings. Rigor is typically associated with the terms

validity and reliability in quantitative studies—referring

to the accuracy of instruments, data, and research

findings—and with accuracy, credibility, and dependability

in qualitative studies (Melrose, 2001). Melrose (2001)

has suggested that the term rigor be used in a broader

sense, encompassing the entire research process, and

not just aspects of data collection, analysis, and

findings.

Rigor in action research is typically based on

procedures used to ensure that the procedures and

analyses of the action research project are not biased,

or reflective of only a very limited view from the

researcher’s perspective (Stringer, 2013). There are

numerous techniques that can be used to help provide

evidence of rigor within the parameters of practitioner-

led action research studies (Melrose, 2001; Stringer,

2013). Among these techniques are:

• Repeating the cycle. Most action researchers tend

to believe that one cycle of action research is

simply not enough. Rigor can be enhanced by

engaging in a number of cycles of action

research into the same problem or question,

where the earlier cycles help to inform how to

conduct later cycles, as well as specific sources

of data that should be considered. In theory,

with each subsequent cycle of action research,

more is learned, and greater credibility is

added to the findings.

• Prolonged engagement and persistent observation. For

participants to fully understand the outcomes

of an action research inquiry and process, the

researcher should provide them with extended

opportunities to explore and express their

experiences within the study (Stringer, 2013)

as it relates specifically to the problem under

investigation. However, it is important to note

that simply spending more time in the setting

is not enough. It is not about the quantity of

time spent in the setting, but rather it is about

the quality of the time spent.

• Experience with the action research process. As with

virtually any type of research, experience with

the process is invaluable. Rigor, itself, can be

highly dependent on the experiences of the

action researcher. If a professional educator

had conducted previous action research

studies—or even previous cycles within the

same study—he or she can perform more

confidently and have greater credibility with

respective audiences (Melrose, 2001).

• Triangulating the data. Rigor can also be

enhanced during the action research process

7

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 8

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

by including multiple sources of data and

other information. Using multiple sources of

data allow the action researcher to verify the

accuracy of the overall data and clarify

meanings or misconceptions held by those

participating in the study (Stringer, 2013).

Accuracy of data and credibility of findings go

hand in hand (Mertler, 2022). In addition, this

is another good reason for using a mixed-

methods approach to data collection an

analysis in action research.

• Member checking. Depending on the purposes of

the study, participants should be provided

with the opportunity to review raw data,

analyses, and final reports resulting from the

action research process (Stringer, 2013). This

process can be very influential in terms of

validating the findings resulting from any

action research study (although, it is important

to note that this procedure may not be

appropriate in all action research projects).

Rigor is enhanced by allowing participants to

verify that various aspects of the research

process have adequately and accurately

represent their beliefs and perspectives. It also

gives them the opportunity to further explain

or expand on information previously

provided.

• Participant debriefing. Similar to member

checking, debriefing provides another

opportunity to participants to provide insight

into the conduct of the action research study.

In contrast to member checking, the focus of

debriefing is on their emotions and feelings, as

opposed to factual information they may have

provided.

Educator Perspectives on Teacher

Inquiry

Admittedly, it is one thing to promote the idea of

teacher inquiry in schools and classrooms, but

professional educators who have been involved in the

process of conducting their own teacher inquiry have

experienced a sense of professionalism that they might

not have realized other word otherwise, had they not

participated in teacher inquiry and action research in

their own settings (Vaughan & Mertler, 2020).

Vaughan and Mertler provided a summary of the

perceptions held by many educators who have

participated in the teacher inquiry process. Included in

their summary was the fact that, for many practitioner-

researchers, gaining an understanding of research

afforded them opportunities to make connections with

and to name their practice as research. This, in turn,

bolstered their self-perceptions as professional

educators, as well as researchers. Educators often

discussed the fact that involvement in the teacher

inquiry process helped them to redefine their own

practice in new ways. It gave them fresh perspectives

on what it meant to teach, and it also demystified the

research process.

Once they had been exposed to the action

research process, many teachers felt that they had been

doing action research all along as part of their daily

work; respectfully, this was likely not the case

(Vaughan & Mertler, 2020). While teachers routinely

use data to help guide decisions that they make in their

classrooms, many do not engage in a systematic, step-

by-step process such as action research to reflect on

their practice, consider alternative approaches to

address problems they face, develop and implement

some sort of an innovative approach, collect and

analyze data, develop a plan for next steps, all the while

engaging in critical professional reflection. However, it

does serve to reinforce the idea that the work that

teachers often engage in daily can be a wonderful

“launching-off point” to get them started in the formal

conduct of teacher inquiry in their classrooms. This

will lead them to a systematic process, whereby the

decisions that they make in their daily practice will truly

become researched-based decisions, thus helping to

foster the develop of educational “knowledge

generators.”

Oftentimes in educational settings, research has

power in decision making and those who have access

to research typically have more power than those who

do not (Vaughan & Mertler, 2020). Being involved in

and having some sense of ownership over the research

process into their own problems of practice provided

teachers with the language necessary to discuss

research and to become integral players in the decision-

making processes in their schools. This, then, often

lead teachers to experience greater confidence when

trying to be innovative in their classrooms, and also

8

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 9

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

fostered their enthusiasm to share their research

practices with colleagues in meaningful and influential

ways. Teachers have often commented that engaging

in teacher inquiry on a regular basis each academic year

has helped them to learn and grow as professional

educators (Mertler & Hartley, 2017).

Teacher Inquiry During a Global

Pandemic

If becoming immersed in the global COVID-19

pandemic has taught us nothing else—at least from an

educational perspective—we have learned just how

professional teachers can be (Vaughan & Mertler, 2020).

Through professional as well as personal experiences,

we have seen teachers who never received training in

how to deliver instruction virtually, let alone offer

emotional and social support to students and families

in their charge. Across our country, as well as around

the world, we saw professional educators rise to an

occasion that they had no way of anticipating.

Certainly, there were naysayers, but most teachers

around the world stepped up when they knew they

needed to do so (Vaughan & Mertler, 2020). Virtually

all of them were trying new things, experimenting with

activities, implementing new ways of trying to keep

first graders, teenagers, and young adults engaged in

the teaching and learning process. Although many of

them were likely unaware of it at the time, it could be

argued that a vast majority of them were engaging in

the process of teacher inquiry without realizing it. They

were trying to solve problems that were being thrown

at them. They were constantly assessing how well those

strategies worked and then how to proceed moving

forward. It is very likely that many of them created

strategies that they might very well continue to use

once schooling returns to normal and students are

once again in their classroom seats.

My sincere hope for the educational community is

that this process created meaning and value for

professional educators everywhere. Exposure to and

involvement in the process of conducting

contextualized teacher inquiry is something that will

likely have a lasting impact on their collective

professional practice. While it is incredibly unfortunate

that it took a global pandemic for many professional

educators to realize their potential when it comes to

teacher inquiry and the process of solving their own

problems of practice, there is a silver lining associated

with it. Professional educators now could continue to

move their practice forward in incredibly meaningful

and insightful ways by engaging in the process of

teacher inquiry, either individually or collaboratively in

teams. Doing so will undoubtedly help them grow as

professional educators, provide opportunities to

experience levels of professional empowerment that

they may not have experienced up to this point in their

careers, and provide for themselves a data-informed

“voice at the table” when it comes to research-based

educational decision making.

A Brief Example of Teacher Inquiry during the

COVID-19 Global Pandemic

Ashlene is a sixth-grade teacher who was in the

middle of her eighth year of teaching when the

COVID-19 pandemic hit. During the 2019-2020

school year, she had 24 students in her class. In the

spring of 2020, when all instruction moved to an online

format, things started out okay, but Ashlene soon

found herself struggling to keep all her students

actively engaged in their virtual classroom

environment. Trying to manage 24 participants in a

virtual video meeting proved to be quite challenging.

She tried a couple of large-group activities with her

entire class, but they still were not working. As she

reflected on her own teaching practices, she decided to

do a little searching online and came across a handful

of journal articles that talked about small group

learning and peer feedback in a virtual environment.

Initially, she liked the idea, so she asked a couple of her

colleagues if they had ever tried anything like that. Only

one had ever tried it and was currently doing it with her

students. She shared with Ashlene that it was fairly

successful in terms of helping with the issue of a lack

of student engagement.

Even though Ashlene knew that she would have

to hold many more virtual class sessions that she had

been since she wasn’t working with her entire class at

a given time, she wanted to try this approach to see if

it helped, not only with student engagement but also

with student learning. She divided her class of 24 into

four groups of six students each. She knew this meant

that she would now have four times as many virtual

class meetings as she had been doing previously, but

she felt it was something that she needed to try.

Additionally, she decided to pose the following

9

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 10

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

questions that she would attempt to answer with her

inquiry approach to her classroom problem:

• To what extent are my students more engaged in the

virtual learning process when I use small-group

instruction and peer feedback?

• To what degree do small-group instruction and peer

feedback impact my students’ academic performance?

She tried this approach in her virtual classroom for

three weeks and she began to notice a difference in

how students were behaving and interacting with each

other online. However, she knew that this was purely

anecdotal information, and she needed some

additional, formal data to guide where she would go

next. She decided to create a small survey for students

consisting of eight questions, asking their opinions of

the smaller groups and peer feedback process, what

they liked and didn’t like about it, and if they would

want to keep doing it. She also took a close look at the

student work that had been submitted to her over the

last three weeks.

To Ashlene’s surprise, the student survey data

were overwhelmingly positive. The students seemed to

like the smaller groups, felt that they had more of an

opportunity to speak during class sessions, and liked

the fact that they got to work closer with a smaller

number of their classmates. They did suggest, however,

that in the future, they be allowed to pick the members

of their small groups. Ashlene was very happy with her

data, but also knew that she would have to take the

responsibility for placing students into their smaller

groups. She was also very pleased with student work.

They had been doing a unit on plants and the

environment and had been required to prepare a short

research paper, for which Ashlene used an analytic

rubric to evaluate their work. Over the last few years,

she had noticed that students struggled on a couple of

the criteria addressed by the rubric. However, student

performance in those areas over the last three weeks

had improved quite a bit. She attributed this, at least in

part, to the peer feedback aspect that she had

incorporated into her virtual instruction, along with the

fact that students were preparing drafts of their papers

using Google Docs and could share them with the

other members of their small groups. Ashlene decided

that she would continue to use this approach for the

remainder of the school year and then spend some time

during the summer break re-evaluating what she had

done and deciding what changes she would want to

make for next year.

When the 2020-2021 school year arrived and

instruction was continuing to take place virtually,

Ashlene was very excited because she knew that she

would have an opportunity to implement her new

teaching strategies with a different set of students to

continue to assess how well they were working. She

decided to make a few minor changes to her peer

feedback model, including a more thorough

introduction to it for her students, which she believed

she had not taken the time to do during the previous

school year. Toward the end of the first half of the

school year, she collected data like those she had

collected the previous year. She was not surprised to

find that the results were quite similar. After two cycles

of implementing her innovative strategy, she was quite

happy with the results and planned to continue with

these strategies moving forward.

In fact, when late winter of 2021 arrived, and her

school’s instruction returned to an in-person format,

she felt so confident in her new strategies that she

continued to use small groups and peer feedback

within her physical classroom space and face-to-face

instruction. Students had been informally letting her

know that they really liked working with their small

groups and they liked being able to use the technology

to help them with their work and the feedback they

were providing to their classmates.

Ashlene was so pleased with the results of her

three cycles of teacher inquiry that she decided to share

what she had done with her building principal. Her

principal was equally impressed and asked her if she

would be willing to share her inquiry process with the

other teachers in their school at an upcoming faculty

meeting. The principal felt that there was a great deal

of potential for other teachers in the school to grow

and develop professionally by implementing

continuing cycles of teacher inquiry.

Conclusions

Action research is admittedly not a new approach

to applied research and solving context-specific

problems. However, many professional educators lack

familiarity with action research and teacher inquiry as a

process. The concept of research is often so foreign to

10

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 11

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

them that they feel believe that it is not something that

they are capable of doing (Mertler, 2013). In contrast

to those opinions, many teachers are well versed in

processes that involve trial and error. The difference

between trial-and-error efforts and the systematic

process of teacher inquiry is the fact that action

research and teacher inquiry are more structured, more

systematic, and more sequential. The four-step process

to conducting applied inquiry studies as presented in

this paper can provide a great deal of guidance and

structure to these efforts undertaken by professional

educators in their settings. In addition, the idea that

one cycle feeds into and informs subsequent cycles—

all of which are built upon continual and critical

professional reflection—strongly supports the idea of

career-long learning and professional growth for

educators everywhere.

It is important to note that undertaking these kind

of initiatives in school settings—while straightforward

and systematic—are not necessarily nor inherently

easy. One requisite criterion that should be in place is

some sort of collegial or supervisory support in school

settings (Mertler 2013). Whether it be a mentorship

relationship or a collegially-supportive relationship,

professional educators need to know that their efforts

in implementing teacher inquiry do not go unnoticed.

In addition, it is sometimes reasonable to expect that

the process of teacher inquiry may oftentimes lead

those who conduct it to come up against hurdles or

unanticipated consequences of their work. Mentoring

and supportive relationships can go a long way to help

professional educators brainstorm, problem solve, and

continue their forward momentum in efforts to

improve their practice. Action research in the form of

teacher inquiry is a process that can facilitate the

realization of those types of professional goals by

giving teachers voice and by helping to create

“knowledge generators.”

References

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning,

conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research

(2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice

Hall.

Dana, N. F., & Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2019). The reflective

educator’s guide to classroom research: Learning to teach and

teaching to learn through practitioner inquiry (3rd ed.).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Henriksen, D., Richardson, C., & Mehta, R. (2017). Design

thinking: A creative approach to educational

problems of practice. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 26,

140-153.

Johnson, A. P. (2008). A short guide to action research (3rd

ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

McNiff, J. (2002). Action research for professional development:

Concise advice for new action researchers (3

rd

ed.). Dorset,

England: Author. Retrieved from

http://www.jeanmcniff.com/userfiles/file/Publicatio

ns/AR%20Booklet.doc

Melrose, M. J. (2001). Maximizing the rigor of action

research: Why would you want to? How could you?

Field Methods, 13(2), 160-180.

Mertler, C. A. (2013). Classroom-based action research:

Revisiting the process as customizable and

meaningful professional development for educators.

Journal of Pedagogic Development, 3(3), 39-43. Available

online: http://www.beds.ac.uk/jpd/volume-3-issue-

3/classroom-based-action-research-revisiting-the-

process-as-customizable-and-meaningful-

professional-development-for-educators

Mertler, C. A., & Hartley, A. J. (2017). Classroom-based,

teacher-led action research as a process for enhancing

teaching and learning. Journal of Educational Leadership

in Action, 4(2). Available online:

http://www.lindenwood.edu/academics/beyond-the-

classroom/publications/journal-of-educational-

leadership-in-action/all-issues/volume-4-issue-

2/faculty-articles/mertler/

Mertler, C. A. (2018). Action research communities: Professional

learning, empowerment, and improvement through collaborative

action research. London/New York: Routledge.

Mertler, C. A. (2020a). Action research: Improving schools and

empowering educators (6

th

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

SAGE.

Mertler, C. A. (2020b). Action research. In G. J.

Burkholder, K. A. Cox, L. M. Crawford, & J. H.

Hitchcock (Eds.), Research design and methods: An applied

guide for the scholar-practitioner (pp. 275-291). Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Mertler, C. A. (2022). Introduction to educational research (3rd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Oliver, B. (1980). Action research for inservice training.

Educational Leadership, 37(5), 394-395.

11

Mertler: Action Research as Teacher Inquiry...

Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2021

Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Vol 26 No 19 Page 12

Mertler, Action Research as Teacher Inquiry

Stringer, E. (2013). Action research (4th ed.). Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Vaughan, M., Cavallaro, C., Baker, J., Celesti, C.,

Clevenger, C., Darling, H., Kasten, R., Laing,

M., Marbach, R., Timar, A., & Wilder, K. (2019).

Positioning teachers as researchers: Lessons in

empowerment, change, and growth. Florida

Educational Research Association Journal, 57(2), 133-139.

Vaughan, M., & Mertler, C. A. (2020). Re-orienting our

thinking away from “professional development for

educators” and toward the “development of

professional educators.” Journal of School Leadership.

Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/1052684620969926

Citation:

Mertler, C.A. (2021). Action Research as Teacher Inquiry: A Viable Strategy for Resolving Problems of

Practice. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 26(19). Available online:

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19/

Corresponding Author

Craig A. Mertler

Division of Educational Leadership & Innovation

Arizona State University

PO Box 37100

Mail Code 3151

Phoenix, AZ 85069

email: craig.mertler [at] asu.edu

12

Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol. 26 [2021], Art. 19

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/19