Economic Aspects of the Opioid Crisis

Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee of the United States Congress

Sir Angus Deaton

1

June 8, 2017

Thank you, Chairman Tiberi, Ranking Member Heinrich, Vice Chairman Lee, and the mem-

bers of the committee for holding this hearing on economics and the opioid crisis.

Deaths from legal and illegal drugs are contributing to an almost unprecedented increase in

overall mortality among middle-aged white non-Hispanics. A century of mortality decline

came to a halt at the end of the 20

th

century and mortality rates for this group were higher

in 2015 than in 1998. Driven by these developments, life expectancy at birth, a key indica-

tor of how well a society is doing, fell for white non-Hispanics from 2013 to 2014, and for

the whole population from 2014 to 2015.

Rising life expectancy in America, and around the world, is one of several key indicators

that life today is so much better than 50 or 100 years ago. That this measure should go into

reverse is both stunning and devastating. No such reversal has taken place in other rich

countries, though there are warning signs in other English-speaking countries, such as Brit-

ain, Ireland, Canada, and Australia. Nor is it happening for Hispanics in the US, nor for Afri-

can Americans, whose mortality rate remains higher than that for whites, but is rapidly de-

clining.

Opioids are a big part of this story. Supplies of opioids—the new forms of heroin, of fenta-

nyl, and prescription opioids—have stoked and maintained the epidemic. Selling heroin is

profitable and illegal. Selling prescription drugs is profitable and legal. Pharmaceutical

companies have made tens of billions on prescription opioids alone while life expectancy

has fallen. Our health care system has sometimes been better at generating wealth than at

generating health.

Opioids have a legitimate if limited role in treating pain. But a case can be made that it

would have been better if they had never been approved; physicians are far from infallible

in deciding which patients are likely to become addicted and, once patients are addicted,

treatment is difficult and often unsuccessful. A stronger case can be made against the wide-

spread prescription of opioids within the community, by general practitioners and dentists.

Enough opioids are prescribed each year to give every American adult a month’s supply.

Other countries restrict opioid use more carefully, for example to acute hospitalization or

end of life care. It is estimated that the US, with 5 percent of the world’s population, con-

sumes 80 percent of the world’s opioids.

1

Sir Angus Deaton, a Laureate of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, is Senior Scholar and the Dwight D.

Eisenhower Professor of Economics and International Affairs Emeritus, Woodrow Wilson School of Public

and International Affairs and the Economics Department at Princeton University and Presidential Professor of

Economics at the University of Southern California.

My own research, with my Princeton colleague Anne Case, has looked at opioid deaths as

part of a broader epidemic of rising mortality. These are the deaths that we refer to as

“deaths of despair.” They consist of suicides and deaths from alcoholic liver disease as well

as accidental overdoses from legal and illegal drugs. The opioid deaths are the largest com-

ponent, but the other two causes are not far behind. In 2015, for white non-Hispanic men

and women aged 50 to 54 without a college degree—who are much more seriously at risk

than those with a college degree—deaths of despair are around 110 per 100,000, of which

50 are accidental overdoses, 30 are suicides, and 30 are alcoholic liver disease and cirrho-

sis.

In the last year or two, there has also been a turn-up in the mortality rate from heart dis-

ease—after many years of decline—and if obesity is the cause, as many argue, some of

these deaths might also be classed as deaths of despair, which would put the total deaths of

despair at levels approaching deaths from cancer or from heart disease, the two major kill-

ers in midlife the US today.

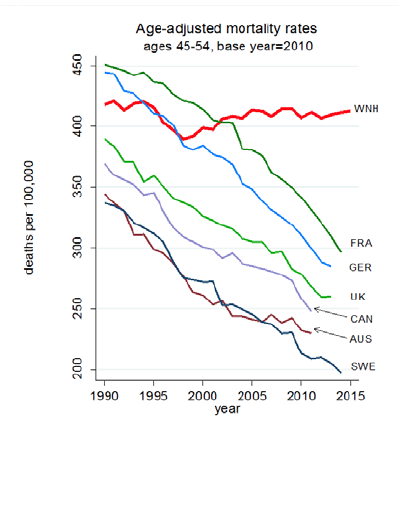

Figure 1 shows the all-cause mortality rates for the somewhat broader 45-54 group of

white non-Hispanics (WNH), together with mortality rates for selected comparison coun-

tries. The mortality rates in midlife in those other

countries continue to decline at the rates that were

standard in the US prior to 1998. This turnaround

in the US is driven by the opioid epidemic, by sui-

cides, by cirrhosis, and by the slowing (and recent

reversals) in the decline in heart disease. People

are killing themselves by drinking, by accidentally

overdosing, by overeating, or much more quickly,

by committing suicide directly.

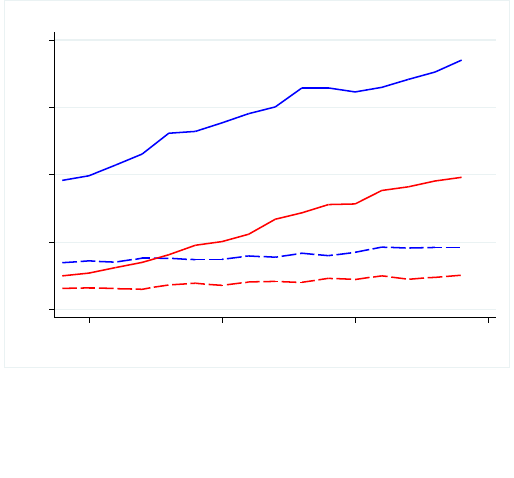

Deaths of despair have risen in parallel for men

and women, see Figure 2. Such deaths, like all sui-

cides, are lower for women than for men, but the

increases for men and women have marched in

lockstep. For all-cause mortality, there are differ-

ences that reflect the history of men’s and

women’s smoking, and the long-term effects on

lung cancer, but those are not part of my story

here. Rather, the rise in deaths of despair is a story

of contrast between those with more and those

with less education.

We note that deaths of despair among midlife whites have risen roughly in parallel for all

levels of urbanization in the US, from inner-city MSA to rural counties. The level of deaths is

lower, by about 20 per 100,000, or 70 compared with 90, in the fringe areas of large MSAs,

but the growth over time has been the same as elsewhere

Figure 1: Age-adjusted mortality rates

in midlife for the US and selected cou

n-

tries

Our work has also documented an in-

crease in morbidity—especially pain,

but also inability to function in various

capacities—in the same age and ethnic

group. Once again, people with less

than a college degree do worse than

those who have completed a four-year

BA. One might have hoped that the in-

crease in the use of opioids to combat

pain might have decreased the preva-

lence of pain, but that has not hap-

pened. Perhaps the increase in pain

would have been even larger without

opioids, but that would leave us with a

huge increase in pain to be explained.

We think of opioids, not as the funda-

mental cause of the epidemic of midlife

mortality and morbidity, but as an accelerant, a set of drugs that added fuel to the fire, and

made an already bad situation much worse. And it is in that broader context that we can

begin to see the economic underpinnings of the epidemic.

Deaths of despair cannot be readily explained by the contemporaneous state of the econ-

omy, by the Great Recession, by unemployment, or by family incomes. There are many doc-

umented links between the economy and health, not always in the same direction, but nei-

ther the opioid epidemic nor the broader epidemic of deaths of despair can be matched to

patterns of unemployment or income over the past 20 years. In particular, opioid deaths,

and deaths of despair more broadly were increasing year on year prior to the Great Reces-

sion, and continued to increase year on year afterwards. This was in spite of large fluctua-

tions in employment and in incomes. We tend to regard all of these deaths of despair as sui-

cides in one form or another, and we believe that suicides respond more to prolonged eco-

nomic conditions than to short-term fluctuations, and especially to the social dysfunctions,

such as loss of meaning in the interconnected worlds of work and family life, that come

with prolonged economic distress.

A longer-term perspective is more promising. Those who were in their early 50s in 2010

were born in the early 1960s. Raj Chetty and his collaborators have estimated that about

60 percent of this cohort had higher incomes at age 30 than did their parents at the same

age, compared with 90 percent of those born 20 years earlier. This is the group that was

first hit by the long-term decline in median earnings that set in after the early 70s, and

those without a four-year college degree would not have benefited from the rising college

wage premium.

Workers who entered the labor market before the early 70s, even without a college degree,

could find good jobs in manufacturing, jobs that came with benefits and on the job training,

and could be expected to last, and that brought annual increases in earnings, and a road to

middle class prosperity. Such jobs have become steadily less prevalent over time.

men, high school degree or less

women, high school degree or less

men, 4-year college or more

women, 4-year college or more

0 50 100 150

200

poisoning, suicide and alcohol-related liver mortality

2000

2005

2010

2015

year

White non-Hispanic mortality ages 50-54, by education

Figure 2: Deaths of despair (suicides, alcoholic

liver disease,

and accidental poisonings) by sex

and education

The loss of good jobs for people with no more than a high school degree has come with a

decline in other socially significant outcomes. There has been a decline in marriage rates,

though couples often cohabit and have children out of wedlock. These cohabiting relation-

ships are relatively unstable (more so than in Europe), so that many fathers do not live

with their children, and many children have lived with several “fathers” by their early

teens. Changing social views on marriage and out-of-wedlock childbearing have permitted

these dysfunctional outcomes.

Heavy drinking, obesity, increasing social isolation, drugs, and suicide are plausible out-

comes of these cumulative processes that deprive white working class lives of their mean-

ing.

We do not know why it is that African Americans and Hispanics are protected from these

outcomes nor why we do not see these events in Europe. The existence of more generous

social safety nets in Europe is often noted as is the greater stability of cohabitation. Tighter

control of opioids undoubtedly helps. But we do not know, and it is possible that the Euro-

pean reprieve is a temporary one.