1

The State of Global

Learning Poverty:

2022 Update

In partnership with

2

The State of Global

Learning Poverty:

2022 Update

CONFERENCE EDITION

June 23, 2022

3

Cover photo: © Liderina - stock.adobe.com

4

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, the World Bank, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development

Office (FCDO), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Bill & Melinda

Gates Foundation (BMGF) would like to recognize all the ministries of education, teachers, communities,

and families that have worked tirelessly to protect the learning of millions of students during the

pandemic.

This report was prepared by a core team consisting of the following colleagues: João Pedro Azevedo,

Halsey Rogers, Ellinore Ahlgren, Maryam Akmal, Marie-Helene Cloutier, Elaine Ding, Ahmed Raza, and Yi

Ning Wong (World Bank); Silvia Montoya (UIS); Borhene Chakroun, Gwang-Chol Chang, and Sonia

Guerriero (UNESCO Headquarters); Pragya Dewan, Suguru Mizunoya, Nicholas Reuge, Kenneth Russell,

and Haogen Yao (UNICEF Headquarters); Rona Bronwin (FCDO); Joanie Cohen-Mitchell (USAID); and Clio

Dintilhac and Izzy Boggild-Jones (BMGF). The work was carried out under the overall guidance of Mamta

Murthi, Alberto Rodriguez, Jaime Saavedra, and Omar Arias (World Bank); Stefania Giannini (UNESCO);

Robert Jenkins (UNICEF); Alicia Herbert (FCDO); LeAnna Marr (USAID); and Benjamin Piper (BMGF).

The team is extremely grateful to Luis Crouch (RTI International) and to Gabriel Demombynes, Deon

Filmer, Laura Gregory, Alaka Holla, and Yevgeniya Savchenko (World Bank) for serving as peer reviewers.

The team would also like to thank Kevin Carey, Maria Marta Ferreyra, Andrea C. Guedes, Keith E.

Hansen, Auguste Tano Kouame, Martin Raiser, and Seynabou Sakho for their comments and

suggestions.

The invaluable support of the communication and advocacy teams of our institutions—Kristyn Schrader-

King, Karolina Ordon, Stefano De Cupis, David Moore, and Diana Styvanley (World Bank); Cynthia

Guttman (UNESCO); Ann Marie Wilcock, Anja Nielsen, and Georgina Diallo (UNICEF); Kate McGeown

(FCDO); Ashley Massey (USAID); and Izzy Boggild-Jones (BMGF)—is greatly appreciated.

We apologize for any omissions and express our sincerest thanks to everyone, whether named here or

not, who graciously gave their time and expertise.

5

Foreword

The deep pre-COVID learning crisis has been made even more severe by the pandemic. One of the

most intuitive indicators of the learning crisis is the learning poverty rate, which measures the share of

children who cannot read a simple text with comprehension by age 10. Widespread learning poverty

predated the pandemic: this report shows that in 2019, before the pandemic hit, the learning poverty

rate was already estimated at 57 percent in low- and middle-income countries, and that in Sub-Saharan

Africa it was 86 percent. Moreover, global progress against learning poverty had already stalled:

between 2015 and 2019, there was no reduction in global learning poverty. Reading, together with

writing, numeracy, and socioemotional skills, is a building block for all the other education outcomes

that societies care about. The very high level of global Learning Poverty is a signal that many education

systems, despite their progress in the recent decades at improving access to schools, have not delivered

learning. The magnitude of the learning challenge in the developing world is immense, and it is now

even larger than before as a consequence of the pandemic.

Since the onset of COVID-19, the school closures and disruptions caused by the pandemic have likely

driven learning poverty rate much higher still. The 2022 simulations presented in this report that build

on the most up-to-date data and evidence on learning and the impacts of the pandemic suggest global

learning poverty in low- and middle-income countries has surged to an estimated 70 percent. The

increases have been especially large in South Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean, the regions

where schools have been closed the longest. Because universal foundational skills are essential to the

flourishing of individuals and societies, this widespread learning poverty threatens to undermine the

future of today’s children and the economic prospects of their countries.

Concerted action against learning poverty is urgently needed now, with every society prioritizing the

welfare of today’s children and youth. To safeguard the future, it is essential to make this a turning

point. We need to ensure a sharp acceleration of learning, starting in the short term with a robust

recovery from the COVID shock. There will be nothing automatic about this recovery and acceleration.

Just reopening schools does not heal the scars of the pandemic, let alone solve the problems that

caused such high levels of learning poverty even before COVID. Policymakers, schools, teachers, and

families will need better strategies, bolstered by additional financing and support, to recover and

accelerate learning, especially for those most harmed by the school closures. In most countries, those

most harmed are not only marginalized minorities or the very poor; despite efforts in many countries to

reach students with some type of remote learning, the vast majority have seen their learning process

seriously impacted. The stagnation of global progress since 2015 shows that education systems were

already failing in reducing learning poverty. To provide opportunity for all children, this has to change—

and change will require both political and technical advances that ensure effective approaches for

promoting foundational learning reach all children and youth. This report lays out a menu of policy

options for doing this. It is essential for governments to set clear priorities for tackling learning poverty

and figuring out which approaches work best in their countries.

Fighting this learning crisis is the challenge of our times if we do not want to lose this generation of

children and youth. Investing in their education is a precondition to avoid a future negative shock to

productivity, earnings, and welfare; is essential for social stability, peace, and security; is critical for

building fairer societies and ensuring equality of opportunities for all; and is essential to change

6

mindsets regarding the urgency of climate change. This is a global challenge, and a collective effort is

needed to raise awareness and support national efforts.

A global coalition can support these national efforts, which is why our six organizations are working

together very closely on the agenda of foundational learning. This coalition is advancing on various

fronts. First, we are speaking with one voice on the vital importance of foundational skills to the SDGs.

Learning poverty is one key indicator of this, as it stands in for a broader set of foundational skills that all

children need for further education, employment, and citizenship. At the same time, we are working

closely together on other fronts—closing the learning data gap, building evidence on how to promote

foundational learning for all children, and providing coordinated financial and technical support to

countries that show real commitment to reducing learning poverty. We are confident that countries can

turn the tide on reducing learning poverty, accelerating learning, and building the foundations for more

prosperous and equitable societies.

Jaime Saavedra

Stefania Giannini

Robert Jenkins

Alicia Herbert

LeAnna Marr

Benjamin Piper

World Bank

UNESCO

UNICEF

FCDO

USAID

Bill & Melinda

Gates Foundation

7

Executive Summary

• Even before COVID-19, the world was facing a learning crisis, with nearly 6 out of every 10 ten-

year-olds in low- and middle-income countries suffering from learning poverty—meaning they

were unable to read and understand a simple story.

• Now COVID-19 pandemic school closures and disruptions have deepened the crisis, sharply

increasing learning poverty and exacerbating the inequalities in education.

• Without urgent action to reduce learning poverty, we face a learning and human capital

catastrophe.

• If children do not acquire the basics of literacy—together with numeracy and other foundational

skills—the futures of hundreds of millions of children around the world, and their societies, are at

grave risk.

• There is a narrow window to act decisively to recover and accelerate learning.

• This will require firm political commitment and implementation of evidence-based approaches for

rapid impact.

• The good news is that the core policies that can help recover learning lost to the pandemic will

also address the deeper underlying learning crisis that predated COVID-19, accelerating learning

and delivering long-term benefits for economies and societies.

Global learning poverty is at crisis levels and continues to worsen in the wake of the worst shock to

education and learning in a century. The learning poverty indicator was launched by the World Bank

and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics in 2019 to spotlight the global learning crisis. High rates of

learning poverty are an early signal that education systems are failing to ensure that children develop

critical foundational skills and thus are far from reaching, and in many cases are not on track to reach,

the SDG 4 target of universal quality education for all by 2030. This makes it much harder for children to

acquire the technical and higher-order skills needed to thrive in increasingly demanding labor markets,

and for countries to develop the human capital needed for sustained, inclusive economic growth.

The learning crisis long predated COVID-19. New data presented in this report confirms that learning

poverty was very high even before the pandemic hit: in 2019, the average global learning poverty rate

in low- and middle-income countries was 57 percent. In other words, nearly 6 out of 10 children were

not acquiring even minimal proficiency in literacy by age 10 before the pandemic hit. And in Sub-

Saharan Africa, 86 percent of children already suffered from learning poverty in 2019.

Even more concerning, progress against learning poverty had already stalled before COVID-19. The

new data shows that between 2015 and 2019, global learning poverty rose further from 53 percent—

the baseline estimate when the learning poverty indicator was launched—to 57 percent. This stagnation

marks a change from the 2000-2015 period, when global learning poverty had fallen from 61 to 53

percent.

1

Since then, the pandemic has led to an unprecedented disruption of schooling and learning around

the world. Globally, between February 2020 and February 2022, education systems were fully closed for

8

in-person schooling for about 141 days on average. In South Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean,

children lost on average 273 and 225 full days of school, respectively. As a response to the school

closures, almost all countries implemented different strategies of remote learning. As countries realized

that, due to the lack of connectivity and the existence of a wide digital divide, it was not possible to rely

only on the internet to provide learning materials or any type of interaction between students and

teachers, they relied on TV and radio, which expanded quickly across the globe. However, these efforts

were very heterogenous across regions in terms of strategies, depth of supply, and usage. Evidence is

accumulating that the capacity of these remote learning efforts to substitute for in-person learning is

very low. As a result, in many countries the school closures led to large learning losses. This is true even

in countries with high internet penetration and higher levels of digital skills among the teaching force.

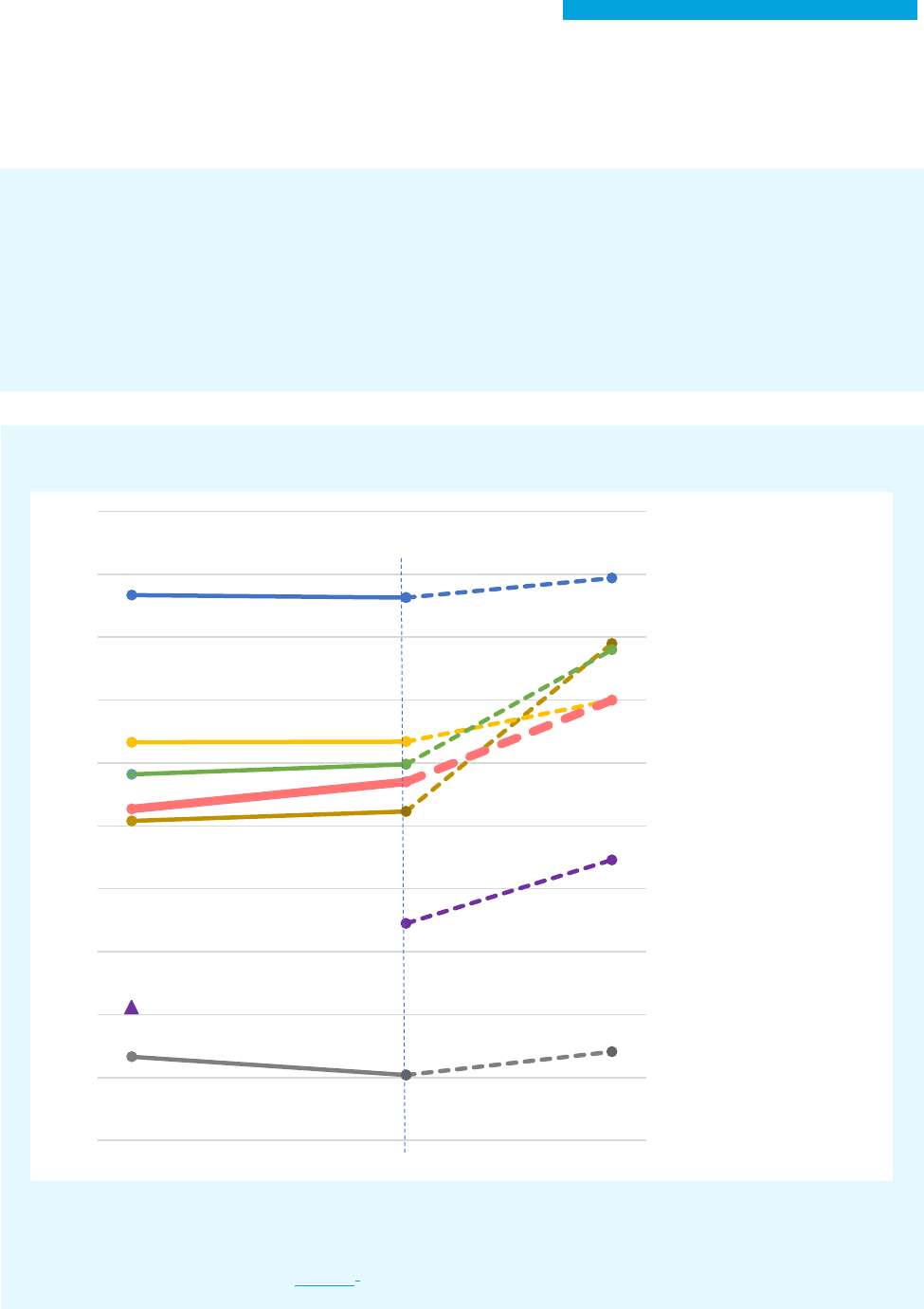

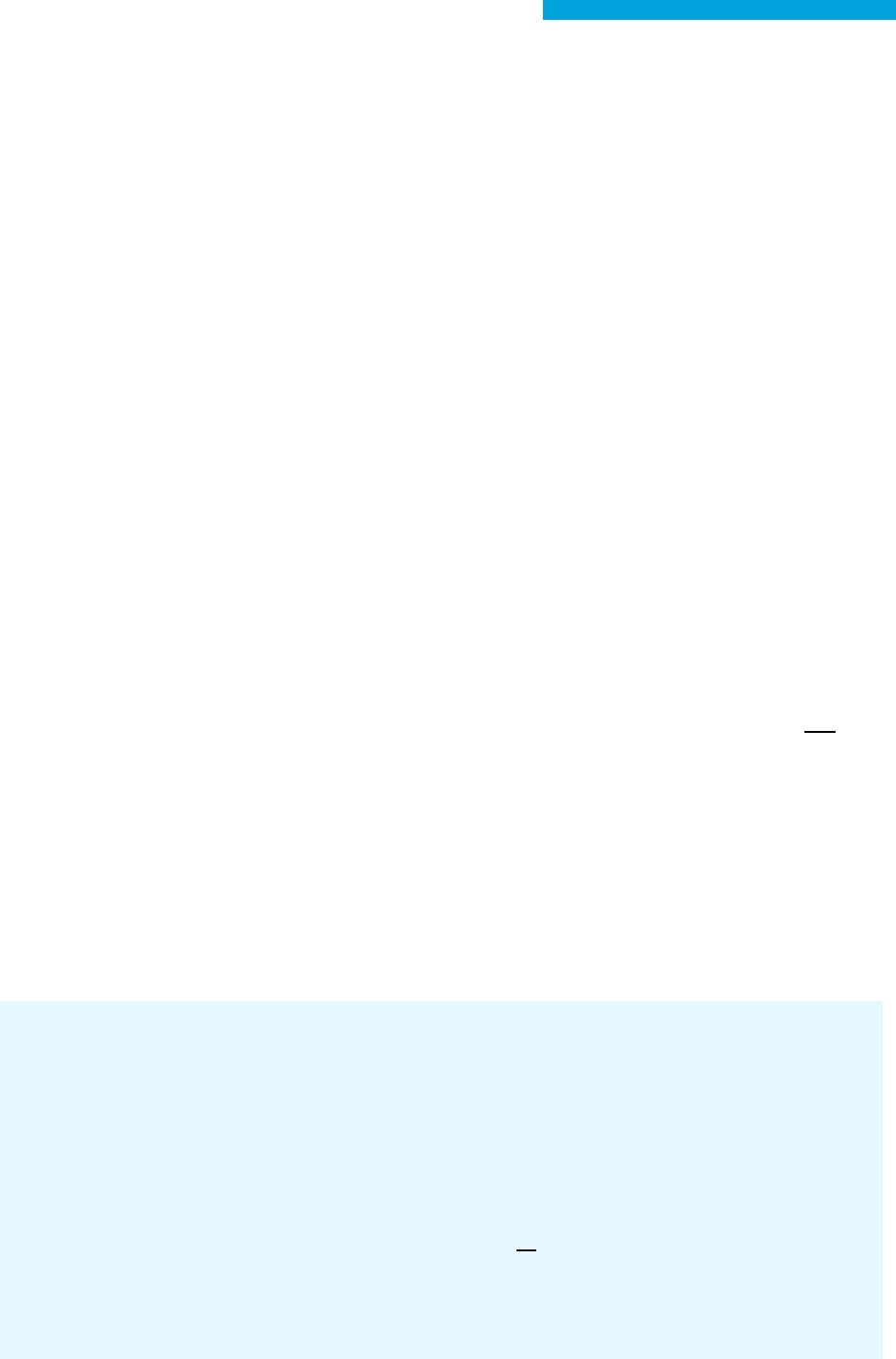

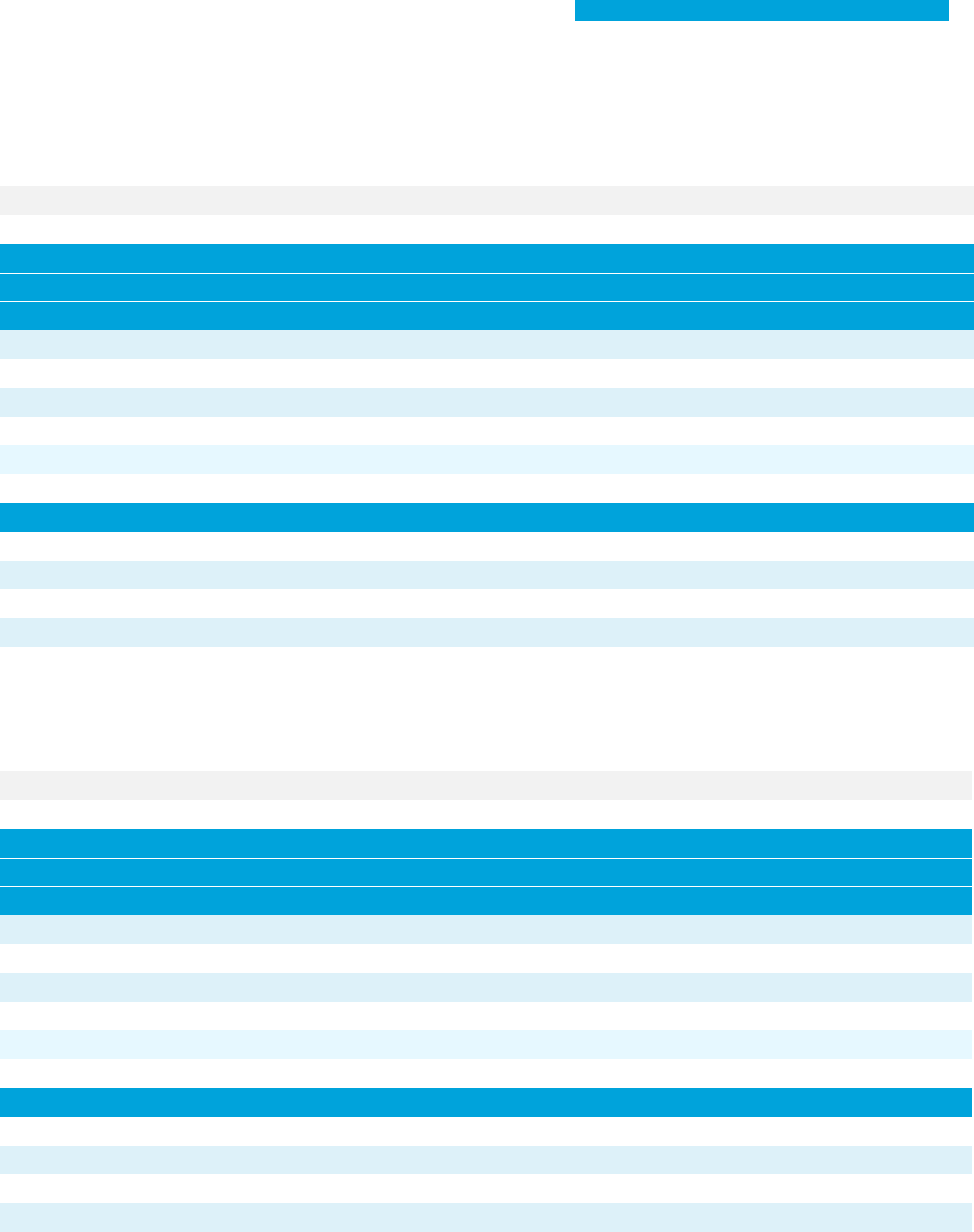

The simulation results based on the latest available data and evidence indicate that the pandemic has

likely caused a sharp increase in global learning poverty, to an estimated 70 percent (Figure 1), and

exacerbated inequalities in education. To assess the potential impact of the pandemic in education we

simulate possible changes in Learning Poverty. The simulation modeling for this report shows that 7 out

of 10 children in low- and middle-income countries could now be suffering from learning poverty. This

means that an additional 1 out of every 8 children in low- and middle-income countries is now in

learning poverty, and that all of the gains in learning poverty that low- and middle-income countries

recorded since 2000 have been lost The increases in learning poverty have likely been largest in South

Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean, due to the very long school closures in those regions. In

both regions, school closures were long and widespread across the territory, and schools were kept

shuttered even after economies started to gradually open and even after vaccines started to be

available for large segments of the population. In both regions, lack of connectivity for about half of the

population precluded the use of internet for remote learning or to distribute learning material. Use of

TV and radio for remote learning expanded quickly in many countries, but that was not enough to

provide meaningful learning to most students. Only the richer segments of the population—those with

broadband connectivity, access to devices for the use of each family member, a place to study,

availability of books and learning material, and a conducive home environment, among other

conditions—were able to maintain a reasonable level of education engagement. On the other hand, in

Sub-Saharan Africa and in East Asia and the Pacific, with the exception of a few specific countries, school

closures were much shorter. Comparing across income levels, in middle-income countries the likely

increases in learning poverty were generally much larger than in low-income countries. This pattern

stems largely from the longer school closures in middle-income countries and their higher levels of in-

school learning during normal times. In all these countries, the efforts to expand remote learning were

insufficient to compensate for the impacts of school closures.

9

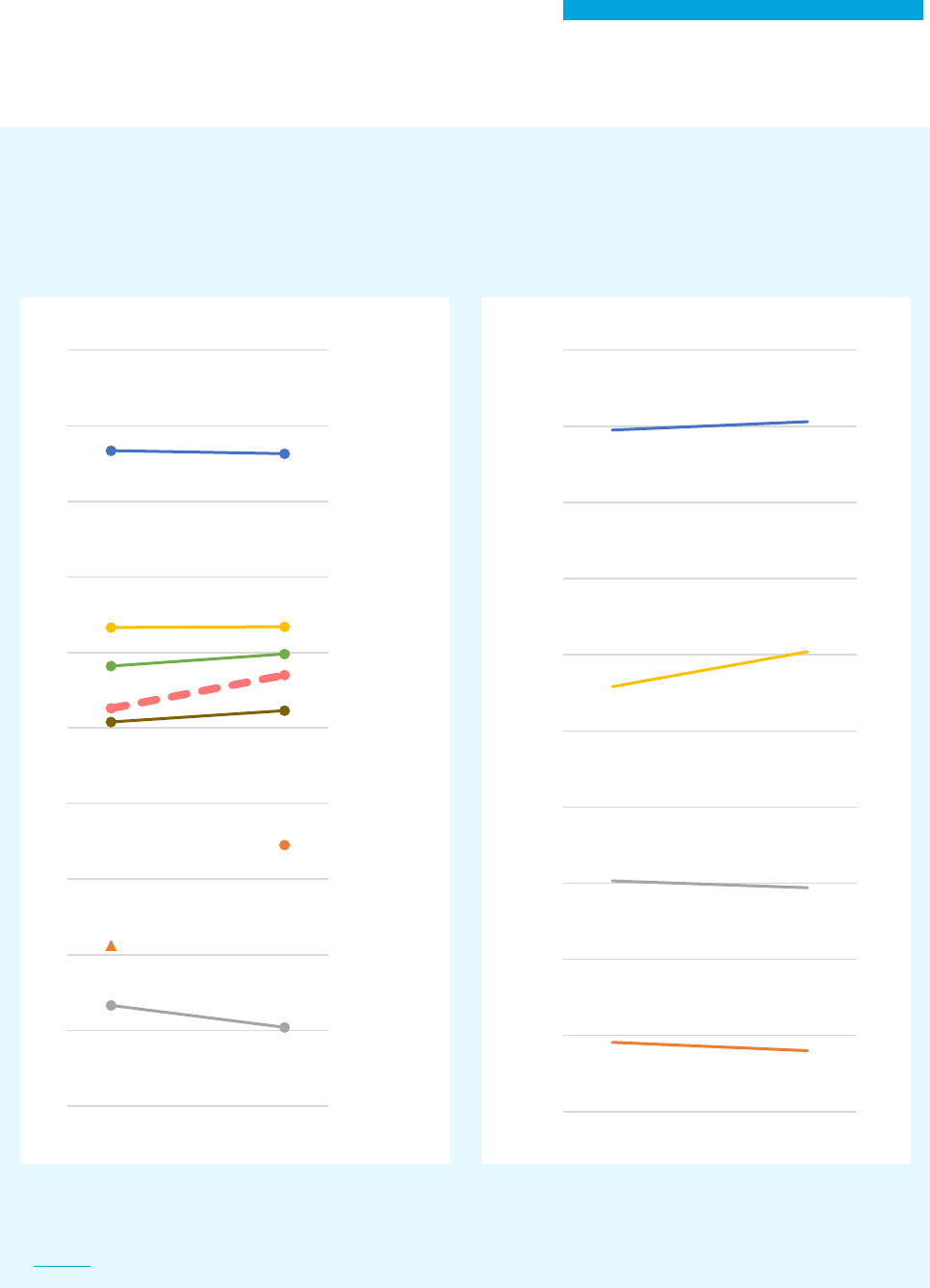

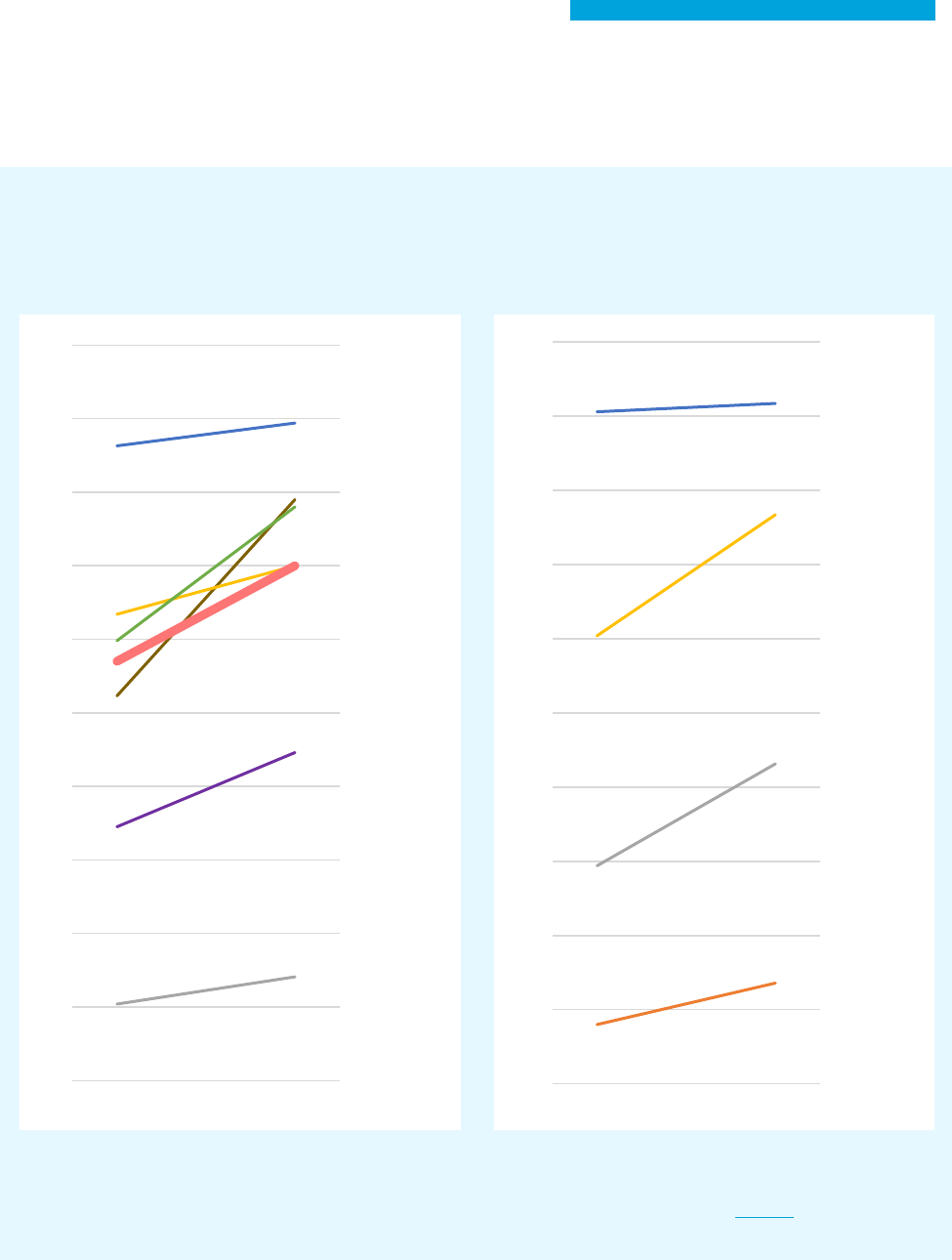

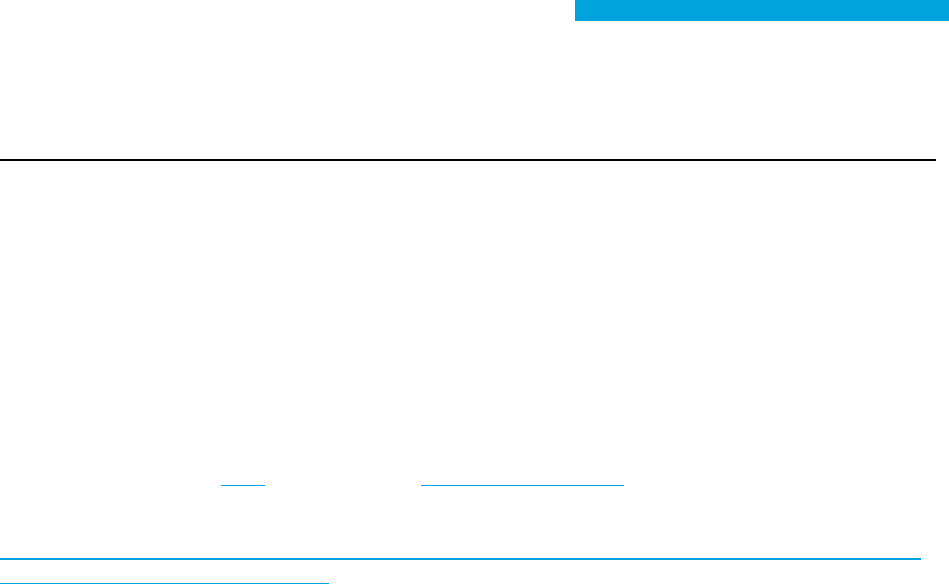

Figure 1. Learning Poverty Globally and by Region—2015 and 2019, with 2022 Simulation Estimates

Note: Numbers for 2022 are simulations. The global figure is for all low- and middle-income countries. Regional and global figures are all

population-weighted averages. For the East Asia and Pacific region, the 2015 and 2019 averages are not directly comparable, due to major

improvements in data quality and availability and new assessments recently available for the two years. This report follows the World Bank

regional classification; for details, please see this page.

2

For methodological details and all other simulation results, see Azevedo et al. 2022.

0.0

10.0

20.0

30.0

40.0

50.0

60.0

70.0

80.0

90.0

100.0

2015 2019* 2022**

Learning crisis

(Pre-pandemic)

Learning crisis

(Simulation)

The simulation model shows that because of the long school closures and the ineffectiveness of

remote learning attempts during the pandemic, 7 out of 10 children in low- and middle-income

countries could now be suffering from learning poverty. That would mean that due to this

shock, an additional 1 out of every 8 children in low- and middle-income countries are now in

learning poverty, and all of the gains in learning poverty that low- and middle-income countries

recorded since 2000 have been lost. But this is a simulation. Learning losses can be reversed if

urgent action is taken.

Europe and Central Asia

Global

South Asia

Latin America and Caribbean

Sub-Saharan Africa

East Asia and Pacific

Middle East and North Africa

10

Recent data available for a few countries corroborates the expectation that learning losses might be

very large. Emerging data that measures actual learning levels of children in reopened school systems

around the world in many cases corroborates the predictions of large learning losses.

3

For example, data

available for the State of São Paulo in Brazil (one year after the onset of the pandemic), for the state of

Karnataka in India, and for a few states in Mexico shows learning losses equivalent to the extent of the

school closure—meaning that one year of school closures maps to roughly one year of normal learning

that was not achieved or was forgotten.

The very high levels of learning poverty, both before COVID and now, violate children’s right to

education. After all the hard work by so many families and educators to provide education for all,

manifested in rising enrollments, it is unacceptable that 70 percent of children in low- and middle-

income countries may not be reading with comprehension at even a minimally adequate level.

Moreover, parents are often not aware of how little their children are learning, because of the lack of

effective use of learning assessments. This violates the trust that families have placed in education—

trust that has led to 90 percent enrollment at primary level in the low- and middle-income countries—

and it undermines realizing the high returns that investments in education can deliver to children and

their communities

Coming on top of the widespread pre-COVID learning poverty, the learning losses from the pandemic

could generate a major shock to human capital accumulation and productivity. Lost foundational

learning will translate into lower levels of skills, which in turn will reduce productivity and earnings of

today’s children once they enter the workforce. Research using systematic measures of adult skills

shows that even among those with the same level of schooling, those with better literacy and numeracy

skills earn substantially more.

4

Lost foundational learning due to the shock will ultimately translate into

lower levels of adult skills, which in turn will reduce productivity and earnings of today’s children once

they enter the workforce. These human capital impacts from disruptions can have substantial effects on

the affected generation; in Zimbabwe, children whose schooling was reduced by a drought in the 1980s

saw their lifetime earnings fall by 14 percent.

5

During the Ebola outbreak, teenage pregnancies

increased in some communities by as much as 65 percent,

6

and some girls never returned to the

classroom after schools reopened, due to increased rates of sexual abuse and exploitation, as well as

teenage pregnancies.

7

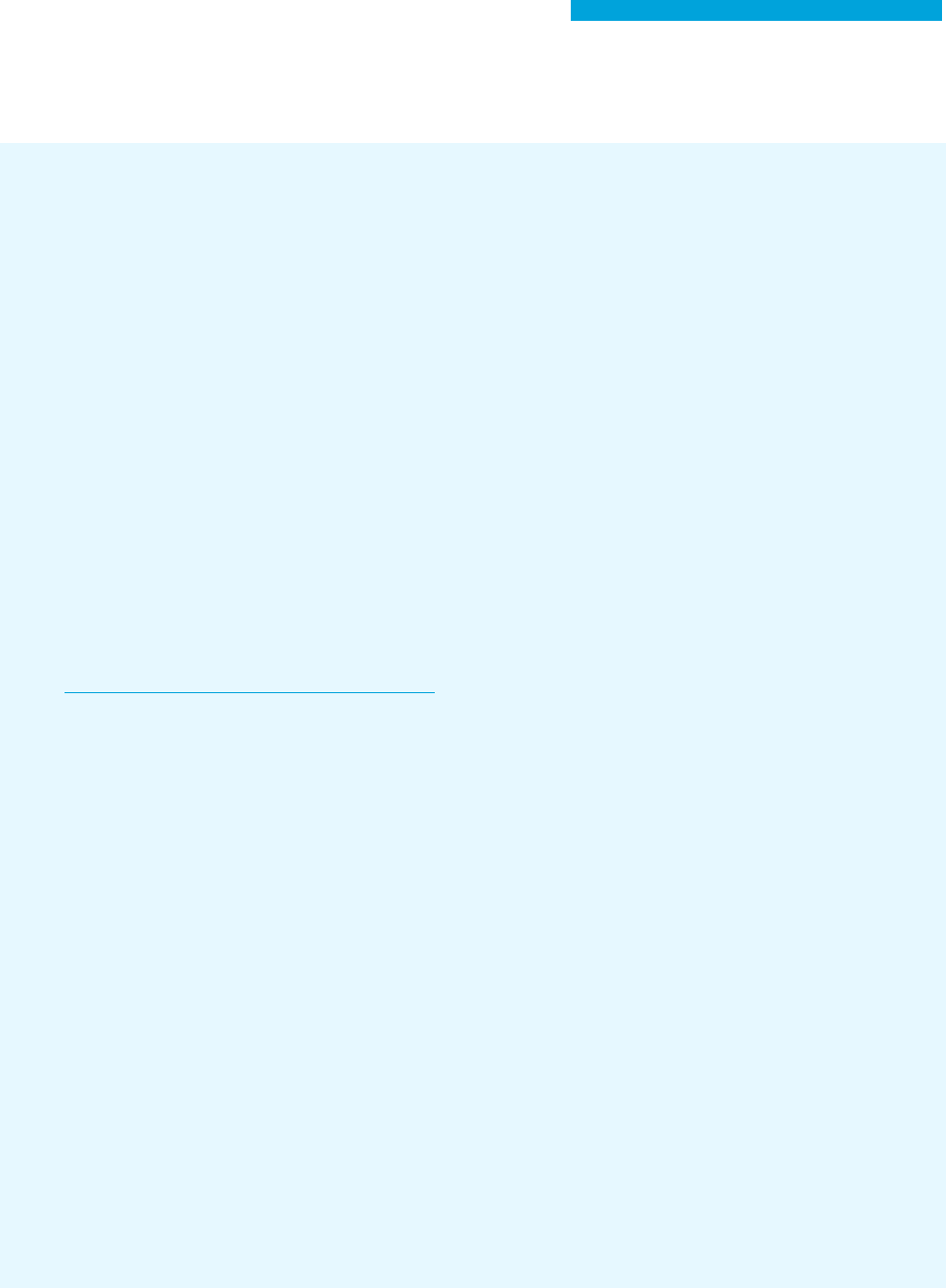

A swift response is essential: not only was learning poverty already high, but the recent learning

losses could be compounded over time, making the cost of inaction especially high. Many education

systems were already unable to ensure learning, and now students are returning to school with even

less of the foundations needed to benefit from instruction. Evidence from past disruptions to education,

such as the 2005 Pakistan earthquake, shows that without recovery measures, learning losses may grow

even more after children return to school, if the curriculum and teaching do not adjust to meet

students’ learning needs.

8

As students fall further behind the curriculum, the risk grows that many will

The very high levels of learning poverty, both before COVID and now,

violate children’s right to education.

11

become disengaged and ultimately drop out of school. Even if they remain in school, this dynamic could

lead to a much greater range of learning levels in the classroom, which makes it even more challenging

for teachers to meet the needs of their students. Actions that countries take in the short term—even

over just the next year—could therefore make a big difference for the longer-term learning trajectory of

a generation at risk.

Without action, the current generation of students now risks losing $21 trillion in lifetime earnings in

present value, or the equivalent of 17 percent of today’s global GDP. Relative to current incomes, this

economic cost is disproportionately borne by low- and middle-income countries, in which this

generation of students could lose $11 trillion of lifetime earnings.

9

In addition to this intergenerational

inequality shock, evidence is mounting that the shock has worsened inequality within the current

generation of children, as those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and other disadvantaged

groups have suffered larger learning losses.

10

Putting this as annual earnings equivalent, in low- and

middle- income countries, this implies that the average person of the school-age generation might see a

reduction in annual income of $975.

Recovery from this major blow to human capital requires national political commitment at all levels,

from the highest political offices to all members of society. A key first step is for political leaders to

highlight to the public the serious threat that the learning crisis poses, the extent it has worsened due to

disruptions in schooling and learning during the pandemic, and to make solving it a top priority. But

commitment at the top levels of government is not enough. Recovering from this massive shock, and

then turning the tide against the longer-term learning crisis that predated COVID, will also require

broader national coalitions for learning recovery and acceleration—coalitions that include families,

educators, civil society, the business community, and other ministries. And this commitment needs to be

further translated into concrete actions at the national and sub-national levels, with better learning

measurement to end the learning data crisis, clear targets for progress, and evidence-based plans

supported by adequate financing and good implementation. National commitments to education

require that all actors align in the design and implementation of reforms with the sole objective of

improving the education and wellbeing of children and youth—not the positions or interests of political

parties or unions, nor the interest of suppliers, vendors, or providers, or any other education

stakeholders, but only the interest of students.

The good news is that there are policies to recover learning losses in the short term, and that these

policies will also allow countries to accelerate learning and take on the deeper pre-pandemic learning

crisis. The RAPID framework for learning recovery and acceleration (recently formulated by the UNICEF,

What to do in the next few months?

It is not enough for children to return to school. The curriculum and teaching must adjust to

meet students’ learning needs. As students fall further behind the curriculum, the risk grows

that many will become disengaged and ultimately drop out of school. Many countries are

already implementing several of the policies in the RAPID framework, but scaling them up to

all children in all countries is urgently needed.

12

UNESCO, and the World Bank) synthesizes the menu of policy interventions that countries could

consider and adapt to their local context—many of which are already being implemented at the country

level, although in different combinations and with varying reach. These interventions also coincide

substantially with those that were most effective at accelerating learning before COVID, based on

evidence from high-performing education systems and rigorously evaluated programs.

11

These are

short-term interventions that must be complemented with many other reforms in teachers’ careers and

incentives, curriculum, instructional methods, safety, infrastructure, and management, among others, in

order to sustain acceleration. RAPID focuses on what countries must do—and what many already

doing—during the next few years. The five elements of RAPID are:

• Reach every child and keep them in school: As schools reopen, it is crucial to monitor children’s

enrollment, attendance, and grade progression; understand why some children have not returned

to school; and support them to return and to stay in school. Back-to-school campaigns, family

outreach and early warning systems can help keep children in school, as can removing school

fees, as well as introducing or expanding cash transfers and school feeding programs.

• Assess learning levels regularly: Measuring children’s current learning levels after their return to

school is essential, to help teachers target instruction in the classroom to each child’s starting

point. This requires providing teachers with formative assessment tools that they can easily apply

in the classroom. Regular system assessments of learning are also needed to guide system-level

decisions on how to continue to reduce to learning poverty and dropout..

• Prioritize teaching the fundamentals: Learning recovery efforts should focus on essential missed

content and prioritize the most foundational skills and knowledge, particularly literacy and

numeracy, that students need for learning within and across subjects and for more advanced

learning in the future. This focus is especially important, given the dense and overreaching

curricula implemented in many countries, and it is essential to free teachers from the excessive

burden of having to cover too much material. Learning recovery programs should also help

teachers to improve their teaching of foundational skills, notably through specific and practical

training and teacher guides connected to well-designed student textbooks. Pre-COVID evidence

from countries like Brazil and Kenya showed that a greater focus on foundational learning, with

practical tools to support it, is central to successful learning acceleration as well.

• Increase the efficiency of instruction, including through catch-up learning: To recover missed

learning, school systems need to adopt effective teaching practices that support teachers in their

immediate classroom challenges, as they are receiving children with larger and more varied

learning deficits. These practices include learner-focused recovery strategies such as structured

pedagogy programs, instruction targeted to students’ current learning levels, individualized self-

learning programs, tutoring, and catch-up programs for out-of-school children. In tandem with

these strategies, extending instructional time by modifying the academic year or offering summer

school can further accelerate learning recovery. Several of these interventions, too, were

identified as cost-effective approaches to learning acceleration before COVID.

12

13

• Develop psychosocial health and well-being: The pandemic has harmed the mental health and

psycho-social wellbeing of both learners and teachers, compounding risks for those who are

already marginalized. It is crucial to ensure that schools are safe and that children are healthy and

protected from violence and can access basic services—such as nutrition, counselling, water,

sanitation, and hygiene services. Promoting children’s welfare is inherently of great value, and it

also has the benefit of promoting learning: children learn best when they experience joy and a

sense of belonging at school.

13

To lead to broad, sustained acceleration of learning, these short-term interventions must be

implemented at scale, and this implementation must be part of a national strategy of structural

reforms over the longer term. Some countries are adopting some of these interventions for learning

recovery—but to avoid huge losses to productivity and inclusion of today’s children, this now needs to

happen much more widely, and it needs to serve as the basis for learning acceleration. While the

interventions can make a substantial difference in the short run even where policy frameworks are

weaker, sustained progress will depend on reforms like ensuring a professionalized teaching career and

ongoing teacher support, providing well-designed textbooks and teaching and learning materials for all,

closing the digital divide, ensuring that schools are safe and inclusive, and investing in managing schools

and the system in a professional way that focuses relentlessly on improving education outcomes.

With the urgent implementation of these policies, it is possible to recover and accelerate learning and

to build more effective, equitable, and resilient education systems. This is what is needed to increase

learning by as much as possible by 2030—and continue that work beyond 2030—and to ensure that all

children and youth have the opportunity to shape the future they deserve.

A key step for political leaders is to highlight for the public the serious threat that the

learning crisis poses and the extent it has worsened due to disruptions in schooling and

learning during the pandemic, and to make solving it a top priority.

14

Contents

Acknowledgments.................................................................................................................................... 4

Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 5

Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 7

Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 14

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 15

Part I: Learning Poverty, pre- and post-COVID ......................................................................................... 18

Learning poverty: What it is and why it matters ............................................................................................ 19

Learning poverty was already very high and not improving before COVID-19 .............................................. 22

The crisis within a crisis: COVID-19 has now made the challenge even greater ............................................ 26

Countries have set very ambitious targets for reducing learning poverty ..................................................... 32

Part II: Ending learning poverty: commitment, recovery, and acceleration, guided by better data ............. 35

The first step toward learning recovery and acceleration: Political commitment ......................................... 38

The short-term agenda: Recovering and accelerating learning with the RAPID framework ......................... 40

The longer-term agenda: Sustaining learning acceleration beyond the recovery period .............................. 47

Spotlight: Deep dive on data and measures for fighting learning poverty ................................................. 49

Better data and indicators are crucial for accelerating the fight against learning poverty ............................ 49

Better data is needed to fight learning poverty ............................................................................................. 50

Better indicators are needed to fight learning poverty .................................................................................. 52

International coalitions for learning can support and be supported by better data and indicators.............. 54

Conclusion: the urgency for learning recovery and acceleration ............................................................... 55

References ............................................................................................................................................. 57

Annexes ................................................................................................................................................. 62

Annex 1: List of new international and regional assessments used in the learning poverty update ............. 62

Annex 2: COVID-19 Learning Loss Simulation Analytical Framework ............................................................. 62

Annex 3: Key simulation assumptions ............................................................................................................ 63

Annex 4: Learning poverty by region and income level (2015 and 2019) and simulation results (2022) ...... 66

Annex 5: Detailed 2019 country learning poverty data.................................................................................. 66

Annex 6: Change in learning poverty gap by region and income level........................................................... 72

Annex 7: Change in learning poverty severity by region and income level .................................................... 72

Annex 8: Global economic cost by region and income level .......................................................................... 73

Annex 9: Per-student average earnings loss (annual) by region and income level ........................................ 73

Annex 10: Per-student average earnings loss (lifetime) by region and income level .................................... 74

Annex 11: Earnings loss as share of average earnings (annual) by region and income level ......................... 74

Endnotes ............................................................................................................................................... 75

15

Introduction

”A world where every child could read is definitely a goal worth pursuing.”

Ayomide Olawale

19-year-old student, Nigeria

All children should be able to read with comprehension by age 10. Reading is a gateway for learning as

the child progresses through school—and conversely, an inability to read slams that gate shut. Beyond

this, when children cannot read, it is usually a clear indication that school systems aren’t well organized

to help children learn in other areas such as math, science, and the humanities. And although it is

possible to learn later in life with enough effort, children who don’t read by age 10—or at the latest, by

the end of primary school—usually fail to master reading later in their schooling career.

14

Even before COVID-19, it had become clear that many children around the world were not learning to

read proficiently. While most children were in school, a majority were not acquiring foundational skills.

Moreover, even before the pandemic-driven school disruptions, nearly 260 million children and youth

were not in school.

15

This is the leading edge of a learning crisis that threatens countries’ efforts to build human capital and

shared prosperity, and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Without foundational

learning, students often fail to thrive later in school or when they join the workforce. They don’t acquire

the human capital they need to power their careers and economies once they leave school, or the skills

that will help them become engaged citizens and nurture healthy, prosperous families. When young

people lack these skills, it threatens equity and stability of a nation. And as a major contributor

to human capital deficits, the learning crisis undermines sustainable green growth, poverty reduction,

and shared prosperity at a global and national level. The impacts of schooling and learning on growth

can be very large: Recent research estimates that three-quarters of differences in long-term growth

across countries can be explained by differences in levels of learning of the population.

16

To acutely spotlight the learning crisis, in October 2019 the World Bank and the UNESCO Institute for

Statistics launched the concept and indicator of learning poverty,

17

drawing on new data produced in

the context of SDG 4. Learning poverty means being unable to read and understand a simple text by age

10. This indicator brings together schooling and learning indicators: it begins with the share of children

who haven’t achieved minimum reading proficiency (as measured in schools) and is adjusted by the

proportion of children who are out of school (and are assumed not able to read proficiently).

This report provides the first update of the global and regional learning poverty numbers, and it

reaffirms that even before COVID, learning poverty was very high and progress in reducing it had

stalled. The average global learning poverty rate was 57 percent in low- and middle-income countries in

2019, with the rate reaching 86 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa. Even more concerning, after significant

global progress in reducing learning poverty between 2000 and 2015, progress had stalled between

2015 and 2019.

16

Since then, COVID has likely sharply increased learning poverty: simulations of the impacts of the

COVID-driven school disruptions and ensuing economic shocks clearly point to an amplification of the

severe pre-pandemic learning crisis. Our best estimate is that the global learning poverty rate may now

have reached 70 percent, with especially large increases in South Asia and in Latin American and the

Caribbean, the regions where schools have been closed the longest. Action is urgently needed now—

business as usual is not sufficient to heal the scars of the pandemic, and it will certainly not accelerate

progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4.

This report adds to other recent evidence presented on the impacts of the pandemic. With

Mission:

Recovering Education, UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank joined forces in early 2021 to provide

guidance and support to countries navigating the crisis. Several joint public goods have been produced

aligning messages, surveys, and protocols to help countries respond to the dramatic consequences of

COVID on this generation of students. In December 2021, the World Bank, UNESCO, and UNICEF warned

in

The State of the Global Education Crisis that the pandemic was leading to unprecedented losses in the

human capital of the current generation of students, and that governments had to act quickly to reverse

the damage. Then in March 2022, the

Where Are We in Learning Recovery? report (UNICEF, UNESCO,

and the World Bank) laid out a strategy, the RAPID framework, that could help countries guide the

learning recovery. This report reinforces those messages with the first update of the global and regional

learning poverty rates, together with updated simulations showing a substantial surge in learning

poverty since the pandemic. It also lays out an agenda for action, built around political commitment and

interventions to recover and accelerate learning. This report expands the partnership of co-signers to

include other major actors in international education and development—UK’s FCDO, USAID, and the Bill

& Melinda Gates Foundation. By aligning around a unified message on the importance of recovering and

accelerating foundational learning, the co-signing organizations seek to highlight the need for countries

to act urgently and decisively. Finally, this report is accompanied by a companion Guide for Learning

Recovery and Acceleration, also co-signed by all six institutions, that provides detailed guidance and

concrete country examples on interventions for learning recovery and acceleration.

Rapid learning recovery is indeed possible. There are resources and concrete actions—summarized in

the RAPID framework—available for every education system to help their children recover lost

learning, and to use the recovery to reduce learning poverty and accelerate long-term progress. The 5-

part RAPID framework captures essential policy actions of a learning recovery and acceleration program,

and its acronym conveys a sense of the urgency required to meet the challenges brought by this global

shock to education—and by the pre-COVID learning crisis. Recovery and acceleration require improving

instruction at scale, for all children, by making sure that education systems: (i) Reach every child and

keep them in school; (ii) Assess learning levels regularly; (iii) Prioritize the fundamentals; (iv) Increase

the efficiency of instruction, including through catch-up learning; and (v) Develop the psychosocial

health and well-being of children and teachers. A robust learning recovery program built around these

approaches, sustained over time, can serve as a springboard for also tackling the pre-pandemic learning

crisis and giving all children the opportunity to achieve the future they deserve.

This report expands on each of these key points. Part I presents the latest data on global and regional

learning poverty rates, both just before COVID hit and today, to map out the scale of the global learning

crisis. Part II summarizes how countries can recover and accelerate learning with political commitment

and an evidence-based RAPID-informed strategy. Finally, taking a deeper look at the learning poverty

data, the report argues that behind the learning crisis there is a learning data gap. Without timely data,

17

it is impossible to get an accurate understanding of the magnitude of the challenge and institute

effective policies to accelerate the fight against learning poverty. The report therefore includes a

Spotlight deep dive into the data and indicators needed to inform the fight against learning poverty,

and more broadly to monitor whether countries are on track to meet their broader education and

learning goals.

18

Part I: Learning Poverty, pre- and post-COVID

"When I was at the age of 12, I was unable to read and write nor spell my own name, and because

of this, communication became harder by the day… No one should have to experience the same

shame and embarrassment I constantly felt as a child due to my incapacity/incapability to read

and write well. If I became the minister of education in my country, I would see to it that every

child by the age of 10 is able to read and write well."

Grace Erika Meki Jumah

16-year-old student, Malawi

• Even before COVID-19, the world was facing a learning crisis, with nearly 6 of every 10 children in

low- and middle-income countries suffering from learning poverty—meaning they were unable to

read and understand a simple text.

• Pandemic-driven school closures have deepened the crisis, sharply increasing learning poverty to

an estimated 70 percent and exacerbating the inequalities in education.

• Without urgent action to reduce learning poverty, we face a learning catastrophe.

COVID-19 has caused unprecedented disruptions to schooling. At the peak of the COVID-related school

closures, 1.6 billion children in 188 countries were impacted. Globally, between February 2020 and

February 2022, education systems were fully closed for in-person schooling for about 141 days on

average. While some countries quickly reopened schools, the closures were especially long in South Asia

(273 days on average), Latin America and the Caribbean (225 days), and the Middle East and North

Africa (183 days).

While recent data on academic learning, school participation, socioemotional wellbeing, and

enrollment remains patchy, evidence is mounting from many countries that these closures

substantially reduced learning and increased learning inequality around the world. In many

countries—and especially in low- and middle-income countries—data from new measurements of

student learning is confirming that remote learning was largely ineffective and a poor substitute for in-

person schooling.

18

Most countries did not have well-designed remote learning systems at scale set up

before the pandemic, and despite great efforts and investments, the systems hastily constructed as

school closed did not have the necessary reach or quality. Moreover, the closures led to or exacerbated

deep inequalities in learning outcomes, along dimensions of geography, gender, age/grade,

socioeconomic status, ability, and more. For example, there is evidence that the decline in learning

resulting from limiting the school experience to only remote schooling, is likely greater for younger

children, who benefit most from quality in-person interactions, and whose families are less likely to

prioritize their learning during school closures. There is also evidence that widespread school closures

have disproportionally affected students from disadvantaged backgrounds, who are less likely than their

peers to have the necessary connectivity, books, instructional material, and physical space to work and

study at home and to be strongly supported to learn at home.

19

19

This section provides an update on one important global indicator for measuring the learning losses

due to the pandemic: the rate of learning poverty. The learning poverty rate is a signal of how far a

system is from reaching the SDG 4 target of universal quality education for all by 2030. The new

evidence on learning poverty reveals both the pre-pandemic learning crisis in basic education and the

damage done by the pandemic.

Learning poverty: What it is and why it matters

Children have a human right to quality education, and foundational skills are essential to fulfilling that

right. SDG 4 commits all signatories to ensure that, by 2030, “all girls and boys complete free, equitable

and quality primary and secondary education.” At the primary level, this means that every child should

both complete primary school and achieve at least minimum proficiency in reading and numeracy (and

other skills). Moreover, foundational skills power individual careers as well as the social and economic

prosperity of nations. Reducing learning poverty, and improving all educational outcomes in general, is

central to improving health, peace, security and stability, equality of opportunity, and the mindsets

change needed to address the climate change challenges at a local and global level.

The learning poverty rate measures the proportion of children who are unable to read a simple text

with comprehension by age 10. Launched in 2019 by the World Bank and the UNESCO Institute for

Statistics, the learning poverty rate is calculated by combining the share of primary-age children who are

out of school with the share who are in school but have not achieved this minimum proficiency in

reading by the end of primary. In other words, it captures both schooling and learning, and it is aligned

with the SDG 4 indicators measuring whether all primary-age children are in school (SDG 4.1.4) and

acquiring meaningful skills by the end of primary (SDG 4.1.1b). Box 1 gives more detail on how learning

poverty and other related indicators are calculated.

Of course, learning how to read is only an early milestone, albeit an important one, for a good quality

education. The pandemic has shown the role of schools as a central part of the social fabric of society,

providing children with knowledge and cognitive skills, socioemotional skills, and executive function

development. Schools provide children an opportunity to learn subjects as diverse as mathematics,

science, arts, and citizenship and to develop socioemotional skills and physical and mental health, and

so much more.

Why does reading with comprehension matter?

Learning Poverty serves as a useful early signal of risks to broader education quality.

• Reading is such a foundational skill for higher levels of learning and for most of the

educational outcomes that societies care about.

• Systems that ensure that all children learn to read tend to do well in promoting other

domains of learning too—so high learning poverty signals other weaknesses.

• The Learning Poverty rate measures what share of all children are not able to read with

comprehension, including both those who are in school and not learning and those who are

not even in school. It therefore indicates the society’s failure to give children the

fundamental skills they need for life.

20

Yet learning poverty can be a useful early warning measure of how deep the learning crisis was before

the pandemic, and of how the pandemic has deepened this crisis. Some of the main reasons that

learning poverty serves as a useful early signal of broader education quality are: first, reading is such a

foundational skill for other subjects and for higher levels of learning; second, systems that ensure that

all children learn to read tend to do well in promoting other domains of learning too; and third, the

learning poverty rate combines schooling and learning in a single easy-to-understand indicator. For all

these reasons, this report focuses on learning poverty, but always as a stand-in for the deeper learning

and schooling crisis.

21

Box 1. Learning poverty and related concepts explained

Learning poverty means being unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10. The indicator

combines the share of primary-aged children out of school, who are defined as schooling-deprived

(SD), and the share of pupils below a minimum proficiency in reading, who are defined as learning-

deprived (LD).

Learning poverty = Schooling deprivation + [(1- Schooling deprivation) x Learning deprivation]

Learning deprivation is defined as the share of children at the end of primary who read below the

minimum proficiency level, as defined by the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (GAML) in the

context of the SDG 4.1.1b monitoring for reading. This is calculated for those children who are

attending school.

Schooling deprivation is defined as the share of primary-aged children who are out of school. All out-

of-school children are assumed to be below the minimum proficiency level in reading. This dimension

is linked to SDG 4.1.4 (the out-of-school rate).

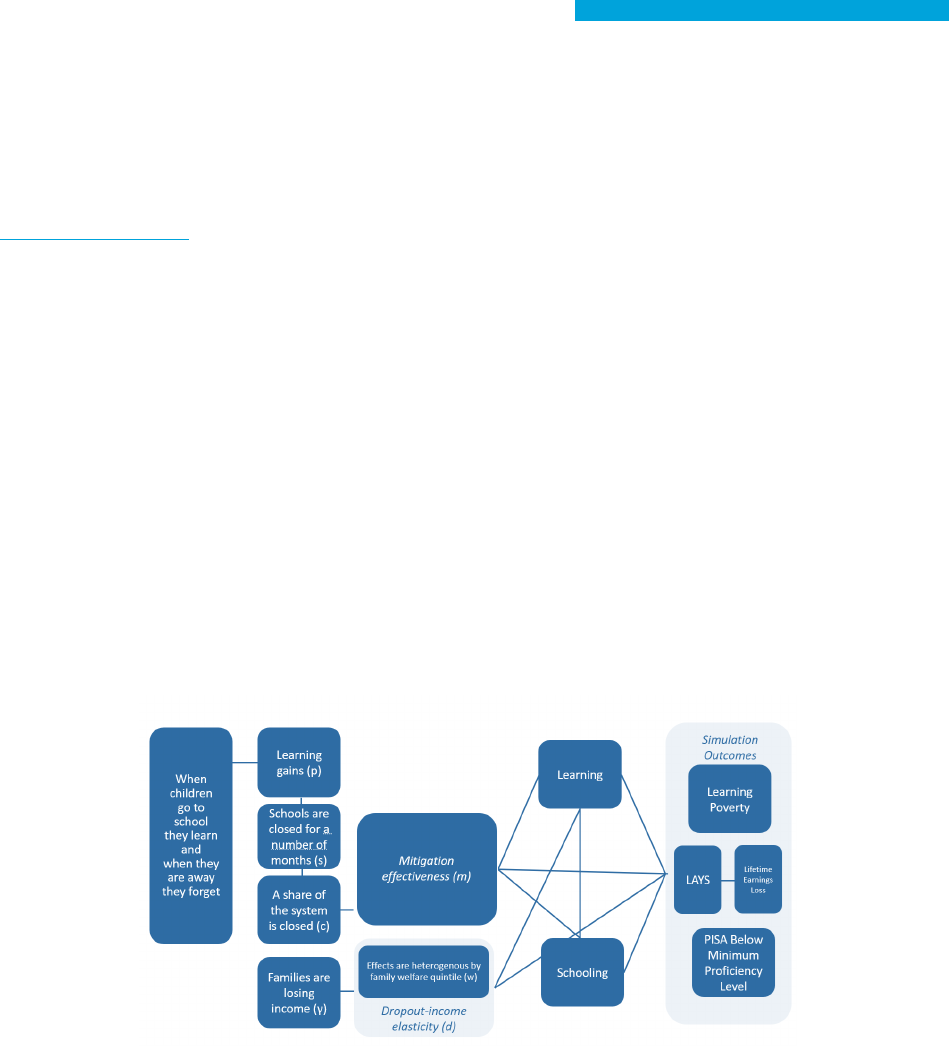

This figure shows a hypothetical example of how learning poverty is calculated using data on learning

deprivation and schooling deprivation.

Figure 2. How Learning Poverty is Calculated

Beyond learning poverty and its constituent indicators, there are two other learning indicators that

measure the learning status of children who are below the minimum proficiency level in reading:

Learning poverty gap captures the average distance of a learning-deprived child to the minimum

proficiency level and indicates the average increase in learning required to eliminate learning poverty.

It helps capture the average learning shortfall among children under the minimum proficiency level.

Learning poverty severity captures the inequality of learning among the learning-poor population. The

severity measure can distinguish between an increase in the learning gap driven by students near the

threshold and one driven by those at the very bottom of the learning distribution.

For more information, see Azevedo 2020 and Azevedo et al 2021.

22

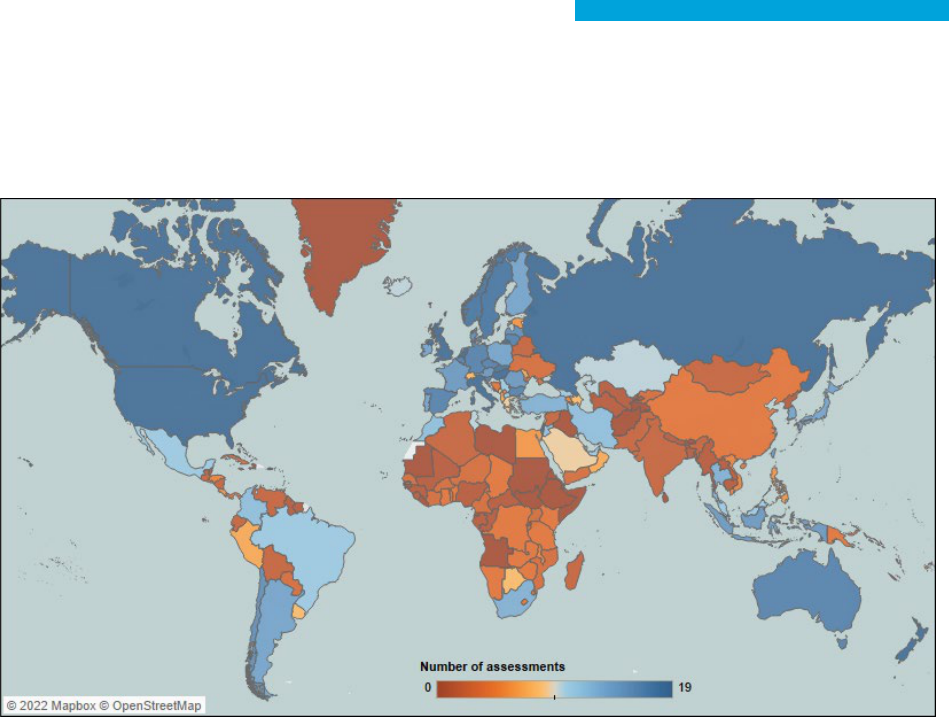

This next section presents new estimates of learning poverty in 2019, just before COVID-19 hit, and

compares them with comparable estimates from 2015, and then discusses simulations of how much

learning poverty is likely to have increased during the pandemic. These new statistics on the state of

learning poverty are meant to inspire and guide country policy responses, which will be discussed in Part

II of the report.

Learning poverty was already very high and not improving before COVID-19

When the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the World Bank first launched the learning poverty

measure in 2019, the global 2015 estimate was 53 percent.

20

In other words, over half of all 10-year-old

children in low- and middle-income countries had not acquired even the minimum reading skills

necessary for all subsequent learning. In fact, the situation is even worse than this indicates. While the

concept aims to capture learning of 10-year-olds, due to shortcomings in available data, many of the

children covered by the data were not tested until at least age 12—yet they had not yet acquired

foundational reading skills even at that point.

New data presented in this report show that in 2019, the global learning poverty rate was even higher

than previously thought: 57 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries were living in

learning poverty. Since the original learning poverty estimates were produced three years ago, new

internationally comparable assessments of student learning have been carried out in several regions—

Latin America and Caribbean, East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. This new data thus gives us a more

recent global and regional picture of the learning crisis on the eve of the pandemic, and also one with

somewhat better country coverage. Out of 144 low- and middle-income countries, we now have data

within the Learning Poverty reporting window for 69 countries and for approximately 81 percent of the

relevant school-age population, compared with 62 countries and a population coverage of 80 percent in

the original report. The number of reporting countries has increased in all regions except in the Middle

East and North Africa and in South Asia, where the number remained constant.

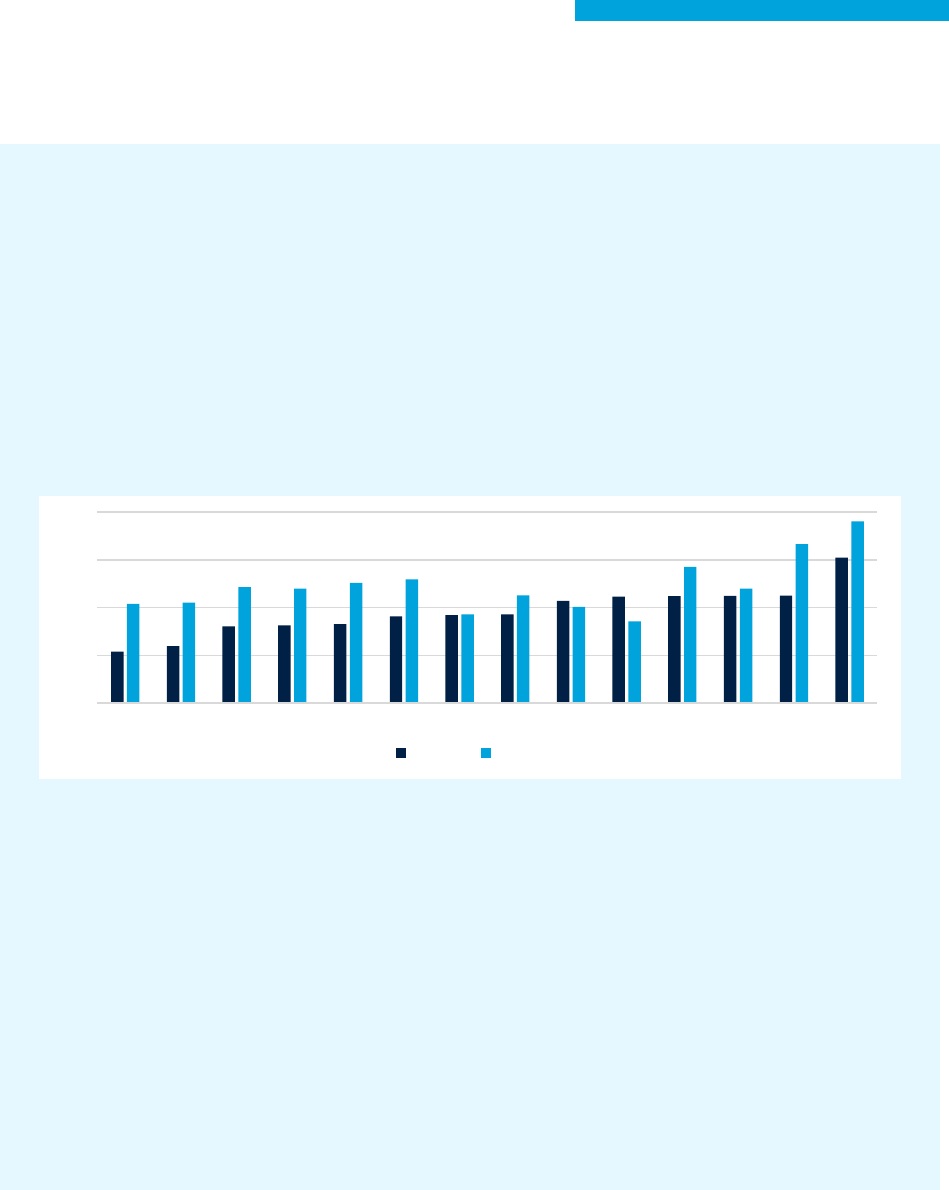

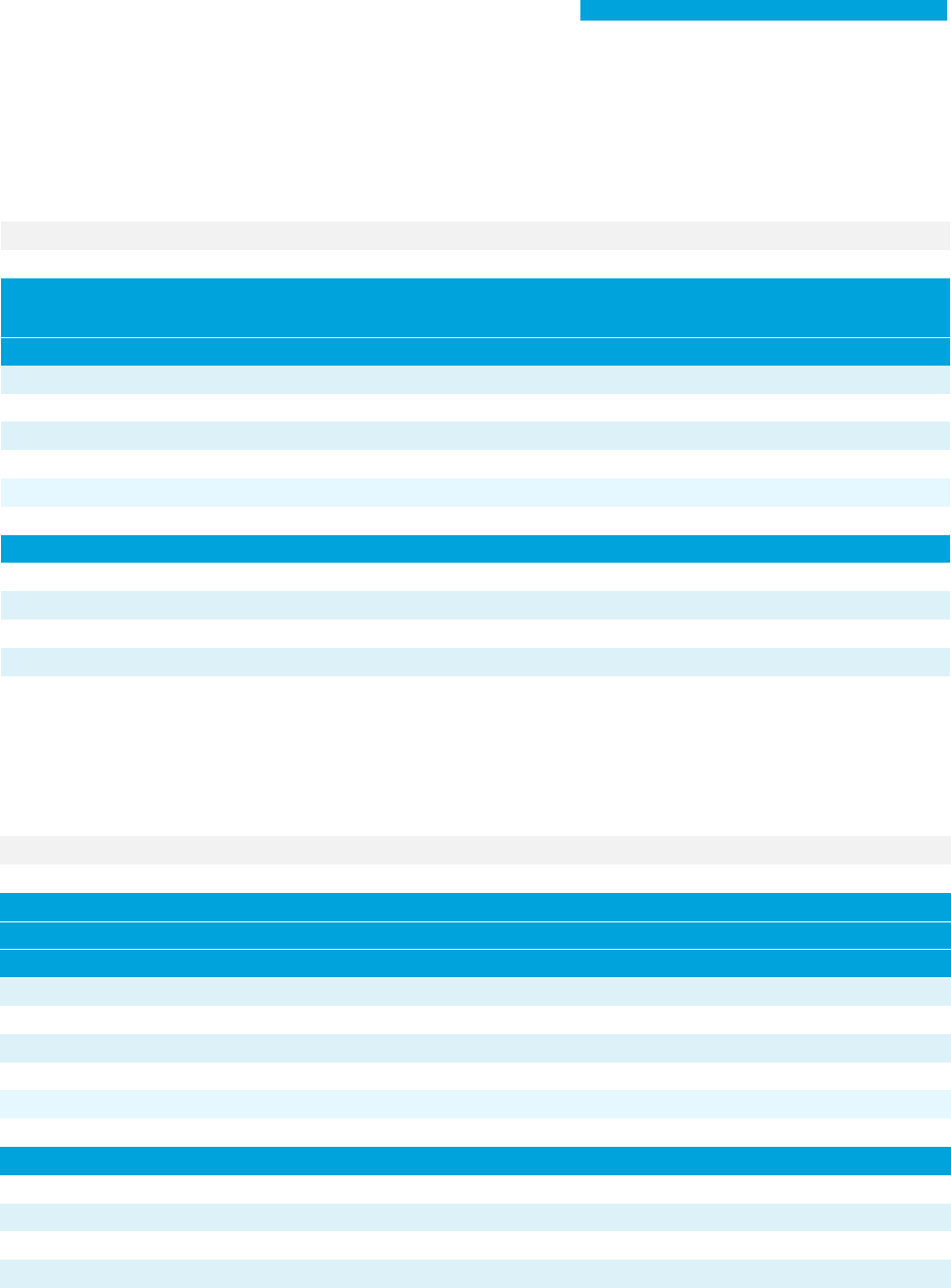

Children in Sub-Saharan Africa suffered from the worst learning poverty by far even before the

pandemic, but learning poverty was very high in other regions too. In 2019, the learning poverty rate

was 86 percent in Africa and above 50 percent in three other regions—the Middle East and North Africa

(63 percent), South Asia (60 percent), and Latin America and the Caribbean (52 percent) (Figure 3a).

Disturbingly, progress against learning poverty had stalled even before COVID-19. There had been

improvement before 2015, as global learning poverty fell from 61 to 53 percent between 2000 and

2015.

21

Against this backdrop, the increase in learning poverty between 2015 and 2019, from 53 to 57

percent, is especially concerning. While there are issues with precise comparability because of improved

measurement, including better learning assessments (as explained in Box 2), it is clear that there was no

progress at the global level during this period. For the two regions—Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin

American and the Caribbean—that repeated earlier regional assessments in 2019, the results showed

little or no improvement, as Figure 3a shows.

22

The increase in the global learning poverty rate is also

driven partially by continuing demographic shifts, such as Sub-Saharan Africa’s increasing share of the

world’s school-age children. While some countries in the region, such as Kenya and South Africa, have

had programs that succeeded in improving literacy at significant scale, Sub-Saharan Africa remains the

23

region with the highest learning poverty, and population growth in the region has contributed to driving

up the global learning poverty rate.

Box 2: What is behind the new (higher) estimates of pre-COVID global learning poverty?

There are three factors underlying the higher estimate of global learning poverty in 2019 (compared

with 2015): changes driven by better measurement using new data sources, actual changes captured by

updated learning or schooling deprivation measures, and demographic shifts.

• The first factor is changes due to better measurement using new data sources. Improvements in

learning measurement occurred mainly in East Asia and the Pacific. When the learning poverty

measure was first calculated, most countries in the region relied on learning estimates from their

National Learning Assessments. Since then, SEAMEO and UNICEF have released the results for the

first round of the Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics (SEA-PLM), which offers far greater

comparability with the proficiency standards determined by the Global Proficiency Framework.

This improvement in measurement led to higher rates of learning poverty in the East Asia and the

Pacific region in 2019. While it is not possible to pinpoint exactly how learning poverty changed in

the region, it is clear that the rate is higher than previously estimated. In addition, the 2019

estimates incorporate improved measures of enrollment in 41 countries where learning

deprivation estimates have not changed. While the net effect of those revisions on the global and

regional aggregates is negligible in most cases, in South Asia they result in an increase in the

regional learning poverty estimate from 58 to 60 percent.

• The second factor is actual increases as captured by consistent movements in the components of

the learning poverty indicator—that is, changes in either learning or schooling deprivation. For the

most part, the lack of progress in learning poverty between 2015 and 2019 can be ascertained

most clearly by observing changes captured by the temporally comparable learning assessments

in Latin America and the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa (LLECE and PASEC, respectively). Both

assessment programs show virtually no improvement in the respective region during this period.

• The third factor contributing to the 2015-2019 changes is the demographic shifts in the relevant

school-age populations. Most notably, the population weight of Sub-Saharan Africa, a region with

extremely high learning poverty, increased over this period.

While better measurement is behind the higher estimates of global learning poverty, we can safely

conclude that global progress against learning poverty stalled during the period just before the

pandemic. A simple decomposition suggests that changes associated to better measurement (new sources

of data) account for about 50 percent of the overall observed change in the global learning poverty rate

between 2015 and 2019, from 53 to 57 percent, while actual changes and demographic shifts account for

the remaining 50 percent. Thus, while better measurement is behind part of the higher global learning

poverty rate, it is clear that there has not been global progress against learning poverty in the years before

COVID-19 hit. In any case, we now also have a better measure of the deep pre-COVID learning crisis than

we did before. With consistent effort to keep improving data availability and quality (as the Spotlight

section of this report emphasizes), it will be possible to track learning poverty trends consistently in more

and more countries.

24

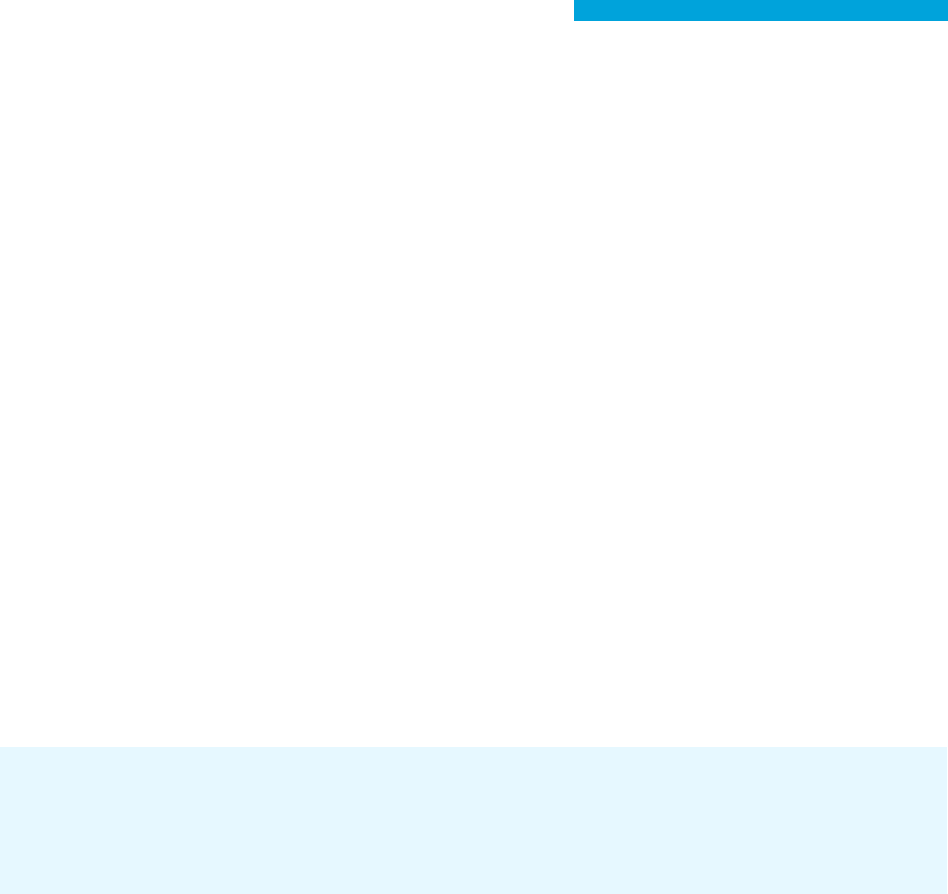

Figure 3 Learning Poverty (Pre-Pandemic)

(a) By Region (Low- and Middle-Income

countries only)

(b) By Income group (including High-Income

countries)

Note: The global figure (a) is for low- and middle-income countries. Regional and global figures are all population-weighted averages. For the

East Asia and Pacific region and Lower-middle-income countries, the 2015 and 2019 averages are not directly comparable, due to major changes

in the country composition and assessments used for the two years. This report follows the World Bank regional classification; for details, please

see this page.

23

For methodological details and all other simulation results, see Azevedo et al. 2022.

21

35

13

10

51

52

63

63

58

60

87

86

53

57

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2015 2019*

9

8

30

29

56

60

90

91

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2015 2019*

Europe and

Central Asia

Global (LICs+MICs)

South Asia

Latin America

and Caribbean

Sub-Saharan

Africa

East Asia

and Pacific

Middle East

and North Africa

Low-income

Lower-middle-income

Upper-middle-income

High-income

25

Results by income groups show extremely high and persistent learning poverty rates among low-

income countries. The learning poverty estimates for 2019 show that 9 out of 10 children in low-income

countries remained in learning poverty (Figure 3b). Results for lower-middle income countries also show

a significant increase; however, this is mostly driven by the relatively high population weight of East Asia

and the Pacific lower-middle-income countries, which saw improvements in learning data, as discussed

in Box 2.

Beyond the high levels of learning poverty, the high levels of inequality in learning are a serious

concern. High levels of learning inequality can reflect the inequality of opportunities in the access to

good quality of education. High learning inequality has implications for the effectiveness of instruction in

the classroom, as it impacts how teachers teach to students of varying learning levels in their

classrooms. It requires teachers to further adapt instruction to meet students’ learning levels to prevent

low-performing students from falling further behind. There is emerging evidence that even before

COVID, learning inequality was on the rise in regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean (Box 3).

The pre-COVID changes in learning poverty make it very clear that just returning to business as usual

after school reopening cannot be the goal of education systems in low and middle-income countries.

Even before the pandemic, education systems were in a deep crisis of low learning and substantial

learning inequality. To safeguard the future of children and their societies as a whole, education systems

must therefore not only recover lost learning, but also continue to accelerate learning to end the

learning crisis.

26

The crisis within a crisis: COVID-19 has now made the challenge even greater

How much has COVID-19 worsened the learning poverty problem globally? The update of the learning

poverty data can give us only a pre-COVID baseline because no learning data is yet available from

internationally comparable learning assessments carried out since the start of the pandemic.

24

To allow

targeting of resources and measurement of progress, improving the availability of learning data needs to

be a priority going forward, as discussed below. For now, it is important to gauge the likely magnitude of

the pandemic’s impacts through simulations. The results from those simulations are deeply concerning.

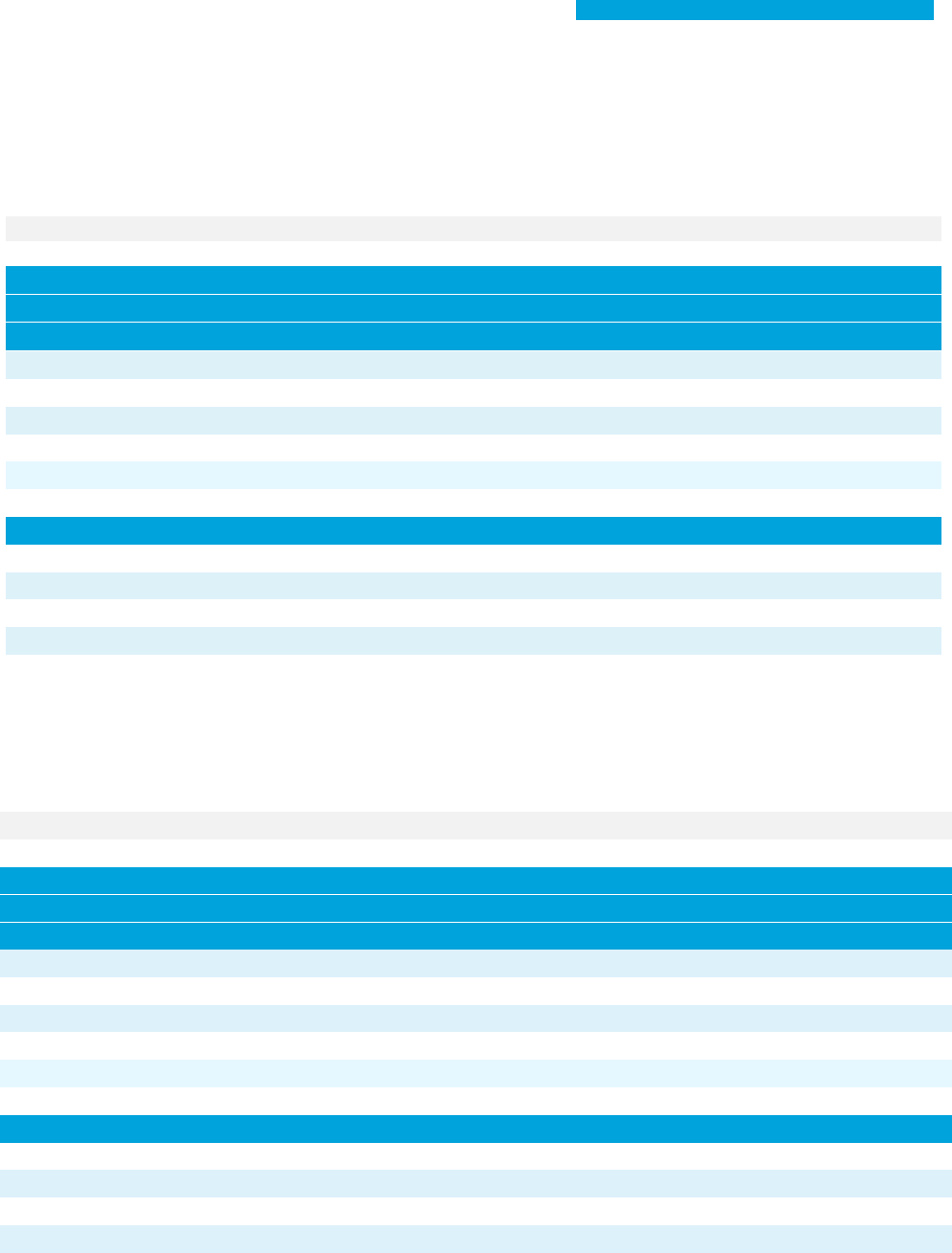

Box 3. Learning inequality was on the rise even before COVID-19:

Evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean and implications for instruction

Beyond high overall levels of learning poverty in Latin American and the Caribbean, learning inequality was increasing

in the region prior to the pandemic. The Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (ERCE) assessment results shown

in Figure 4 below illustrate that learning inequality was on the rise in the region prior to the pandemic. Between 2013

and 2019, learning inequality in math and reading for students in grade 6 increased in all countries in the region. On

average, learning inequality increased by 38 percent in math and 49 percent in reading. The countries with the largest

increases in inequality during the period were the Dominican Republic, where learning inequality increased by 61

percent for math and 76 percent for reading, followed by Guatemala, with 45 percent for math and 67 percent for

reading.

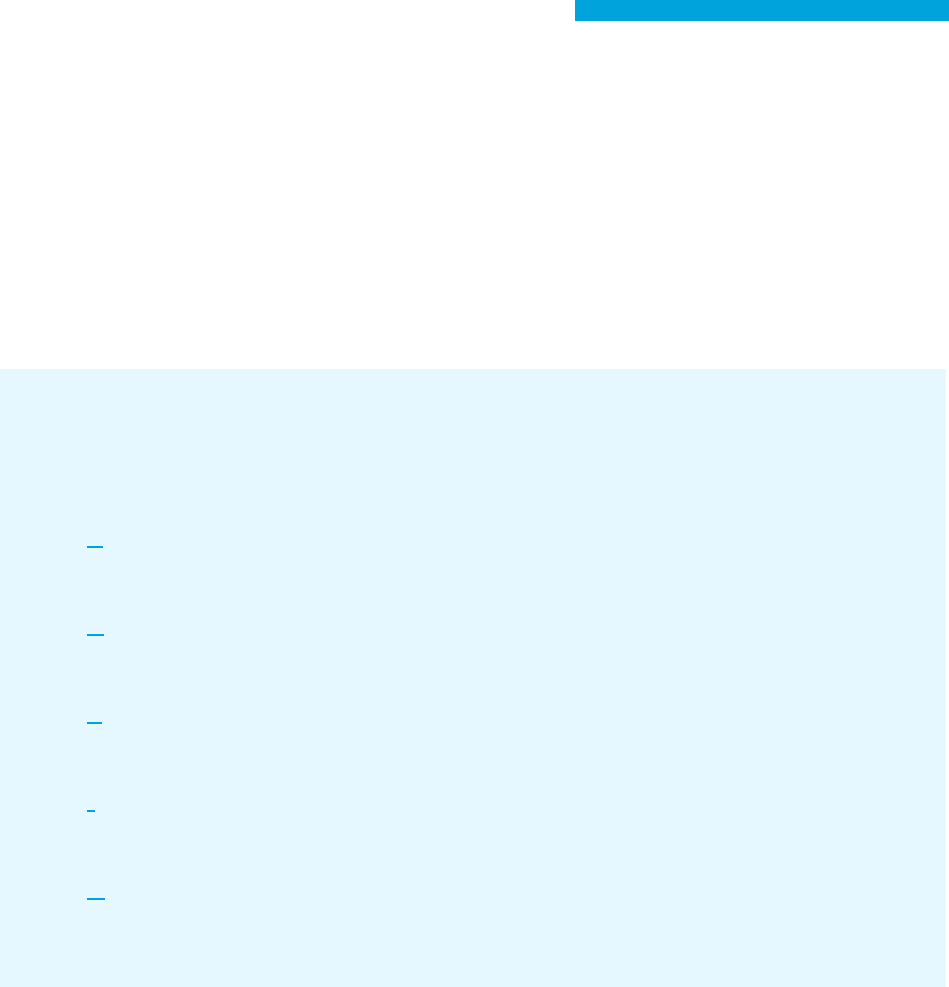

Figure 4. Increase in learning inequality between 2013 and 2019 for grade 6, by country and subject

Note: Changes in inequality are measured using changes in the Gini index of the distribution of test scores in each year.

Source: Own calculations based on the Global Learning Assessment Database (GLAD).

There is evidence that school closures during the COVID-19 crisis may have further increased learning inequality in

Latin America and the Caribbean and beyond. Students in hard-to-reach areas, students with disabilities, and socio-

economically disadvantaged students often had limited access to effective remote learning. For example, research

indicates that socio-economically disadvantaged students were disproportionately affected by learning losses during the

pandemic compared to their peers, as seen in the United States, the Netherlands, Pakistan, and Mexico, among other

countries.

The increase in inequality of learning has implications for the effectiveness of instruction in the classroom. The

increase exacerbates a pre-pandemic problem in education: how teachers instruct students of varying learning levels at

the same time. Higher learning inequality among students means teachers must cater to a larger spread of learning

levels within their classrooms. When teachers do not adjust to students’ learning levels, their instruction becomes less

effective and poor educational outcomes persist, as students are left behind.

Sources: Muralidharan, Singh, and Ganimian 2019; UNICEF, UNESCO, and World Bank 2021

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

PER MEX CRI ARG NIC PAN PRY URY ECU BRA HND COL GTM DOM

Maths Reading

27

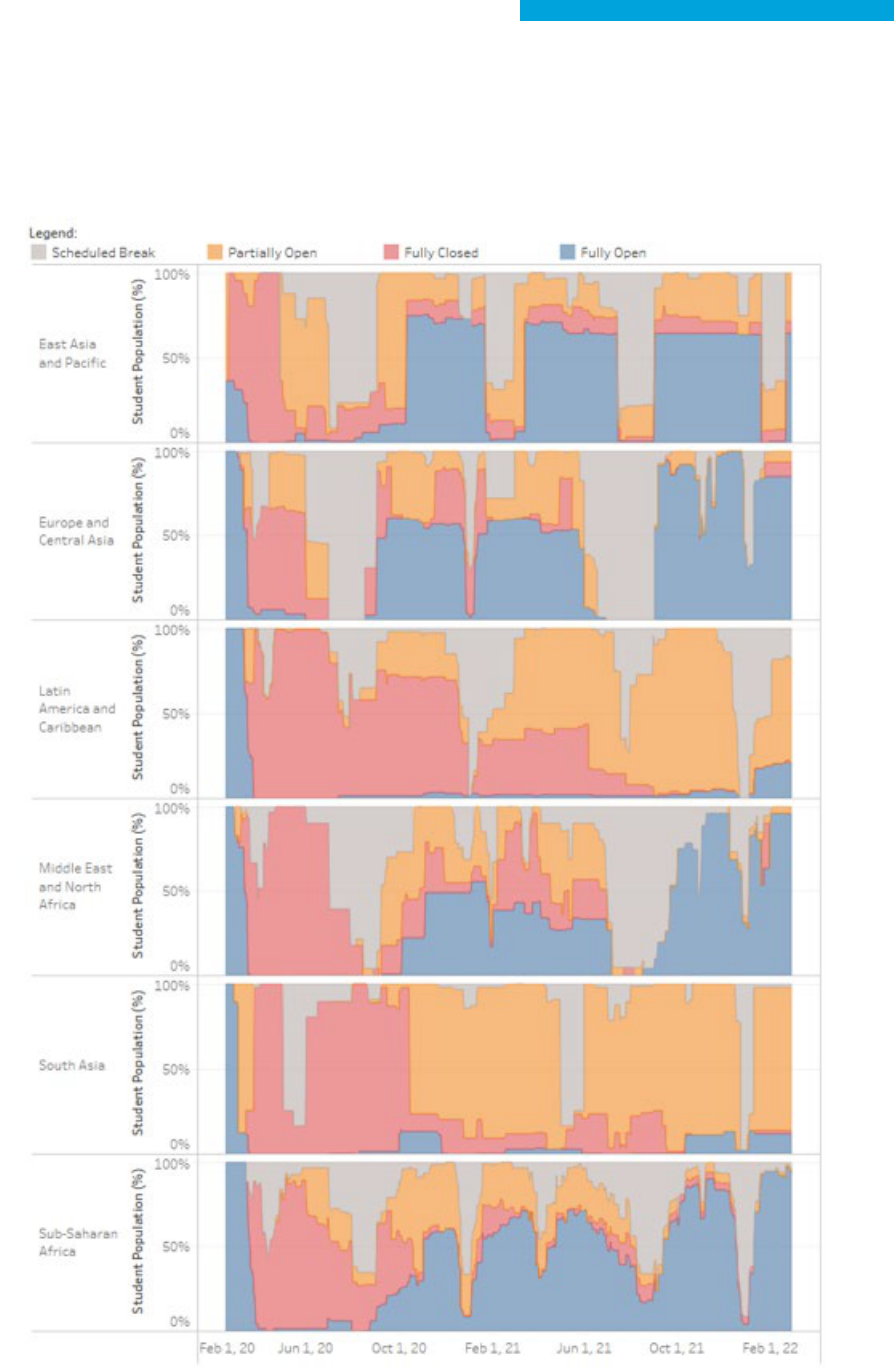

Figure 5. Share of the student population by national school closure status

according to UNESCO school monitoring calendar by region

Source: UNESCO School Closure Calendar as of June 2022.

28

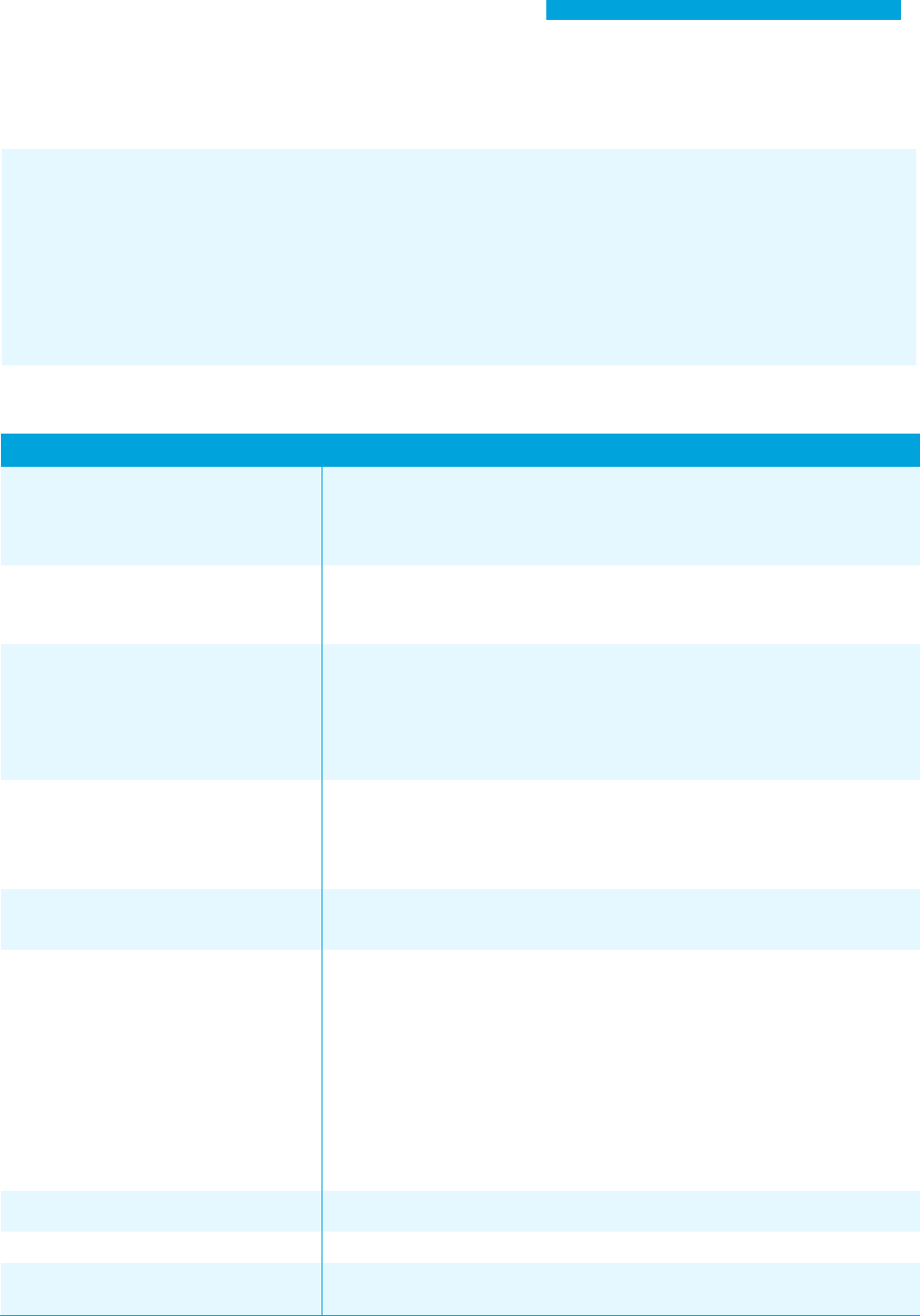

The learning poverty simulations estimate how COVID-driven school closures have affected learning

poverty and what the global learning poverty rate is in 2022. To this end, we build on the most recent

pre-pandemic learning data, using evidence on the expected learning gain, data on the length of school

closures, and the impacts of shocks on school dropouts, among other relevant data (see Annex 2 for a

summary of the simulation conceptual model and Annex 3 for definitions and main assumptions and

parameters used in the simulations).

25

The use of scenario-based simulations is not new, but it gained

prominence during the pandemic as a tool to help governments assess the potential consequences of a

shock of unprecedent magnitude. The main parameters of the simulation model are the following:

• Learning gains normally achieved during a regular school year before COVID. The higher the rates

of expected learning gains observed when schools are open, the higher the learning losses when

schools close. These expected learning gains vary across country income levels and remain

constant across scenarios (see Annex 3).

• Income shocks’ impact on enrollments. Simulations also partially capture the (much smaller)

potential cumulative effects of household income shocks over the past two years on student

school enrollment in primary education. This effect is negligible because evidence from both

before and during COVID shows that at the primary-school level, income shocks typically have

small effects on enrollment.

26

This component varies across countries based on country-specific

enrollment-income elasticities and growth projections and remains constant across scenarios.

• Observed duration of school closures, which ranged from a few weeks in some countries to

nearly two years in others. We incorporate the latest country-specific school closure data, which

covers two full years of schooling during COVID, from February 2020 to February 2022. As Figure

5 shows, there are significant differences in the school-opening policies of governments around

the world. This component varies across countries and remains constant across scenarios.

• Partial closure estimates, the share of students in a school system who are assumed to be

affected by partial closures. Partial closures can be by geographic location or by certain grades or

can cover all students if a hybrid model is adopted. Very few countries have been able to monitor

the share of their system partially closed. This parameter varies across scenarios.

• Effectiveness of mitigation strategies during school closures, the country’s ability to ensure

some learning continuity while schools were closed; this parameter varies by country’s income

level and across scenarios (see below).

Evidence so far on the last of these factors indicates that mitigation strategies, and remote learning in

particular, were typically not effective. The simulations therefore assume that during school closures,

children in low- and middle-income countries learned on average only 5 to 20 percent of what they

usually learn while schools were open. While some governments were able to respond swiftly to school

closures by providing a variety of effective remote learning modalities, many were not. Most notably, 40

percent of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa did not provide any remote learning strategy despite full or

partial school closures of about one year.

27

Even in countries that did provide remote learning solutions,

provision of remote learning did not always result in take-up by students. Surveys of schools

28

and

households reveal that many children, especially in low-income countries, were not able to engage in

remote learning at all.

29

Some countries experienced a “remote learning paradox” where the chosen

remote learning approach was not suitable to the needs of the majority of the students, contributing to

uneven take-up.

30

According to a survey of education ministries by UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank and

OECD (2021), over a third of low- and lower-middle income countries that provided lessons through

29

radio or TV reported that less than half of primary school students were reached by radio or TV.

31

Even

students who were able to receive some distance education often spent much less time learning than if

they would have during in-person instruction, and they were exposed to pedagogies and curricula that

had been hurriedly adapted to remote learning. Moreover, teachers often did not receive adequate

training in remote instruction and digital skills.

32

In several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, fewer than 1

in 5 primary school students maintained contact with their teacher during school closures.

33

Finally, as

discussed below, data from actual measurement of learning losses support the assumption that

mitigation was not effective: newly collected data on learning levels emerging from some low- and

middle-income countries shows major learning losses across a range of contexts.

34

For purposes of illustration, we focus our discussion based on outcomes from the intermediate

scenario. The results in terms of global and regional learning poverty levels do not vary dramatically

across the scenarios (Annex 4). Our preference for the intermediate scenario in the narrative builds on

our understanding of the evidence to date, which suggests that: the mitigation strategies put in place

have largely been ineffective (as discussed above); and many countries with educational systems that

reported partial closures (on average for the last two years) were largely fully closed. The parameter

choices under the intermediate scenario reflect that evidence. As more and better data becomes

available, we will be able to continuously improve these estimates.

According to the latest simulations,

35

the global learning poverty rate among low and middle-income

countries is expected to have risen to 70 percent, based on data up to February 2022. This is a massive

increase from the 57 percent rate of 2019. That is, as a result of the pandemic, the learning poverty rate

is likely 13 percentage points higher, and an additional 1 out of every 8 children in low- and middle-

income countries is now in learning poverty. This means that all of the gains in learning poverty that

low- and middle-income countries recorded since 2000 have been lost.

36

Moreover, the damage may be

even larger than these simulated figures suggest. In the regions and countries with very high pre-

pandemic learning poverty, the pandemic-related shocks could have pushed children who were already

below the minimum proficiency level in reading further behind.

South Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean are likely to have suffered the largest increases in

learning poverty.

37

Both regions have seen very long school closures, of at least 273 and 225 days on

average, respectively. These two regions also had the largest share of students affected by partial school

closures as of early 2022 (Figure 5). As a result, children have missed out on a substantial amount of in-

person learning. Learning poverty is estimated to have risen from 52 to 79 percent in Latin America and

the Caribbean, and from 60 to 78 percent in South Asia (Figure 6a). That is, in both regions the share of

children in learning poverty may have increased by around twenty percentage points or more in just the

past two years. This means that after nearly two years without in-person schooling, children who, for

instance, are returning to Grade 4 would have to rely mostly on whatever learning foundations they had

acquired by Grade 2. Beyond basic education, learning-adjusted years of schooling—meaning the

number of years of schooling that, adjusted for quality, a child born today can expect to complete—are

expected to have fallen from 7.8 to 6.0 in LAC and from 6.5 to 4.9 in South Asia.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the region that already suffered from the highest levels of pre-pandemic

learning poverty, the biggest impact will be to cause children who are already learning-poor to fall

further behind.

38

In many Sub-Saharan African countries, school closures lasted only a few months, and

the resulting increase in the learning poverty rate is likely to be smaller (from 86 to 89 percent; see

30

Figure 6a). Yet this increase will be accompanied by a further deepening of learning poverty for children

below the minimum reading proficiency threshold. Children with the weakest foundational literacy

before school closures are most likely to have suffered learning loss, especially if their families are not

literate.

39

These losses in the region come on top of a severe pre-COVID learning crisis. Before the

pandemic, the average child in the region could expect to complete only 5 learning-adjusted years of

schooling by age 18. With learning outcomes already so poor and many children, especially girls, already

buffeted by conflict and poverty, the projected loss of 0.6 years will be another blow to the region’s

prospects to build human capital if learning is not recovered and accelerated quickly.

In low-income countries, learning poverty is likely to have remained extremely high, while in all other

country-income groups, especially lower-middle-income countries, it likely deteriorated. The

simulation results indicate that in 2022, 9 out of 10 primary-age children in low-income countries remain

in learning poverty. In lower-middle-income countries, in contrast, learning poverty is likely to have

increased sharply, by an estimated 16 percentage points (Figure 6b). While high-income countries also

saw a significant relative increase, given their low baselines, they have stronger capacity and readiness

to respond to the shock. The challenge is especially great in low-income countries, given that even

before COVID, education systems failed to achieve even minimal levels of reading proficiency.

Actual learning data now emerging from numerous countries supports the conclusion that there have

been very large learning losses. Systematic measurement of learning losses typically could not happen

while schools remained closed, but new learning results have appeared from a growing number of

systems as schools reopened. Early findings from high-income countries showed that most had suffered