1

CLIMATE TRANSPARENCY POLICY PAPER:

ENERGY TRANSITION IN BRAZIL

AUTHORS: WILLIAM WILLS, FERNANDA FORTES WESTIN

PRESENTATION

This document provides a qualitative analysis of the context and

policies of the Energy Transition developments in Brazil in order

to subsidize the preparation of a comparison paper on Energy

Transition in three Latin America G20 countries: Brazil, Argentina

and Mexico.

ABOUT CLIMATE TRANSPARENCY

Climate Transparency is a global partnership with a shared mis-

sion to stimulate a ‘race to the top’ in G20 climate action and to

shift investments towards zero carbon technologies through en-

hanced transparency.

Climate Transparency brings together the most authoritative cli-

mate assessments and expertise of stakeholders from G20 coun-

tries. Jointly, these experts develop a credible, comprehensive

and comparable picture on G20 climate performance: The Brown

to Green Report covers easy-to-use information on all major areas

such as mitigation and climate fi nance and includes detailed fact

sheets on all G20 countries. It is published on an annual basis on

the eve of the G20 Summit. Climate Transparency is made possi-

ble through support from the Federal Ministry for Environment,

Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) through the In-

ternational Climate Initiative, ClimateWorks Foundation and the

World Bank Group.

ABOUT CENTROCLIMA

CentroClima/LIMA, linked to the Energy Planning Program (PPE),

is part of COPPE, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Since 1997 CentroClima/LIMA was responsible for the execution

of around 250 research projects, many of which for international

institutions. Throughout this period, agreements, partnerships,

cooperation agreements and contracts were signed with pub-

lic bodies of the federal, state and municipal administration, as

well as companies and non-governmental organizations. These

research activities led to the publication of approximately 320 sci-

entifi c papers, 75 articles in national and international journals,

70 books or book chapters, 140 papers in Annals of Congresses

and 25 articles in magazines and newspapers. In addition, they

provided material for the preparation of more than 50 Master’s

dissertations and 30 PhD thesis.

KEY POLICY INSIGHTS

• Energy effi ciency and change of consumption patterns must

play a major role in decarbonization, contributing to a very

signifi cant decrease in energy demand by 2050.

• Brazil must avoid the lock-in in carbon-intensive technolo-

gies, especially in long lifespan infrastructures as refi neries,

fossil-fuel fi red power plants, and interrupt fossil fuel subsidies

as soon as possible.

• Prepare a comprehensive energy effi ciency program to foster

investments in this area.

• To foster the energy transition in Brazil, and to meet the tar-

gets of the Paris Agreement, it is necessary to redirect invest-

ments, reduce subsidies to fossil fuels, and create a long-term

low carbon strategy.

1. INTRODUCTION

Brazil stands out with one of the world’s cleanest energy matrix,

with great use of hydropower plants. Low-interest incentive and fi -

nancing policies, as well as fair prices made possible by electric po-

wer auctions, have led the wind power industry to grow signifi cant-

ly recently. Currently, the insertion of the solar source for distributed

generation is getting stronger, but there is still a concern about the

regulation of these new sources, especially in the free market. The

large use of fl ex-fuel cars makes ethanol widely used (27,5% blend

mandate on the gasoline plus the possibility of running on 100%

ethanol), and biodiesel blending policies already reached 10% in

2018. Studies show that natural gas might be a transition fossil fuel

by 2050, aiming to reduce the use of coal and other fossil fuels in

the country. Thus, this document presents the general framework

on Brazil and identifi es drivers, challenges and opportunities to

achieve GHG mitigation goals, presenting policies and legislation

to support a robust transition of the energy sector.

Renewable energy sources in Brazil accounts for about 42% of to-

tal primary energy supply and 85% of the power sector producti-

on. There is a great potential of renewable sources such as hydro-

power, wind, biomass, and solar, which begins to be exploited for

electricity generation. Non-renewable sources account for about

57.2% of total primary energy supply, and an important part of it

is used in the transport sector (32.7%), (EPE, 2018a). Brazilian ener-

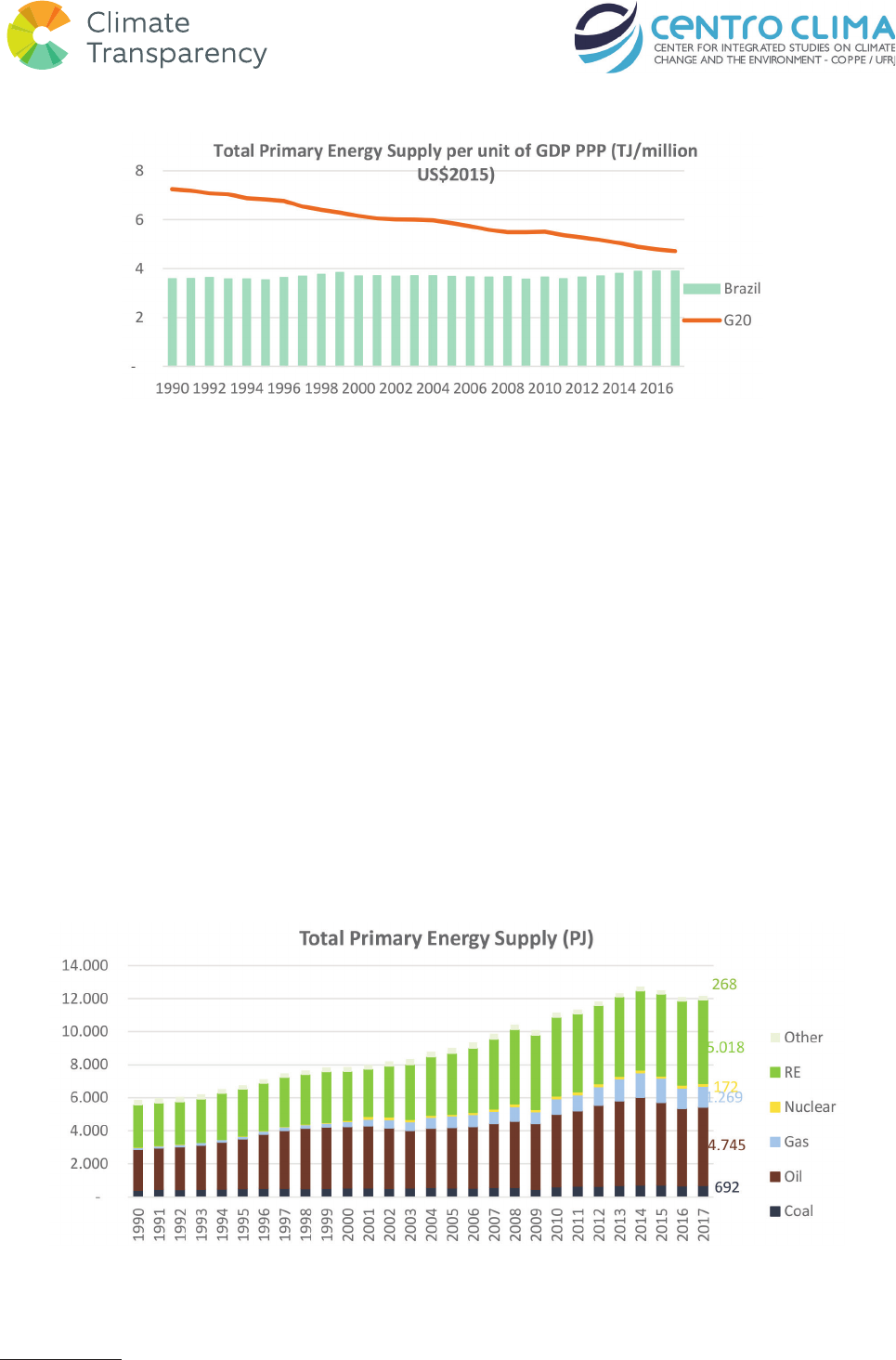

gy intensity has remained practically stable since 1990, below 4 TJ

/ million US$ according to the IEA cited by B2G (2018), (Figure 1).

2

Even though Brazilian energy intensity is about 20% below the

average of other G20 countries, the gap has reduced a lot since

1990. Thus, to direct the country towards the desired trend follo-

wed by other G20 countries, not only energy effi ciency policies

should be implemented, but also, for economic and social rea-

sons, the country must review its economic policies in order to

produce and export products with more value added. Brazilian

total GHG emissions are around 1.6 billion tons of CO

2

eq. The

energy sector appears only in third place in total emissions, after

land use change and agriculture sectors, however, to avoid lock-

in, the energy sector must start its transition now.

Due to its extensive territory and natural resources, for a long

time, Brazil relies on an important part of its energy mix in re-

newables, mainly hydropower, biomass and biofuels, and wind.

With the invention of the fl ex-fuel

1

car, ethanol production re-

gained importance after 2004. Today, fl ex-fuel cars represent

about 90% of the new sales and around 80% of the light vehicles

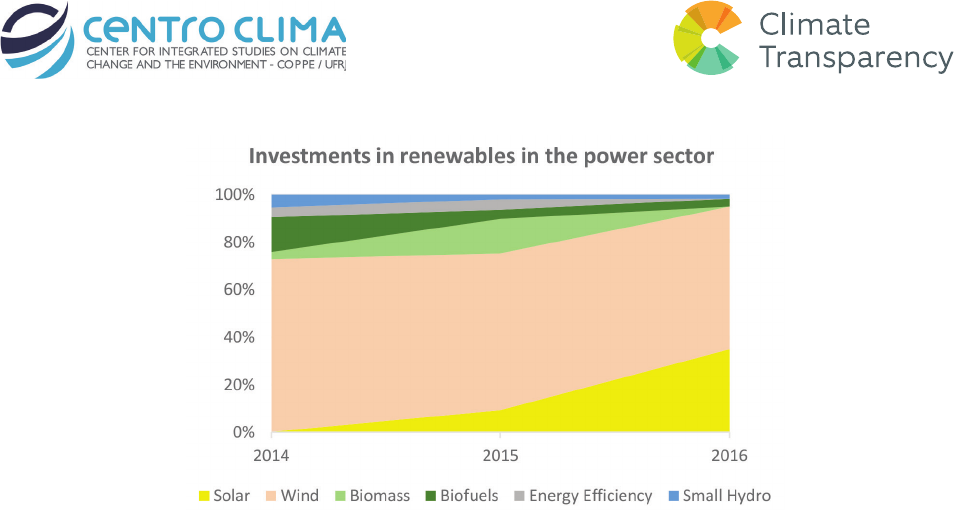

fl eet. But after the discovery of large oil reserves in the pre-salt

layer (2007), the federal government redirected its eff orts in in-

vestments in E&P, and subsidized oil derivatives consumption

to reduce infl ation at the beginning of the 2010s. As a result, oil

consumption grew fast after 2010, and the share of renewables

was kept stable (Figure 2).

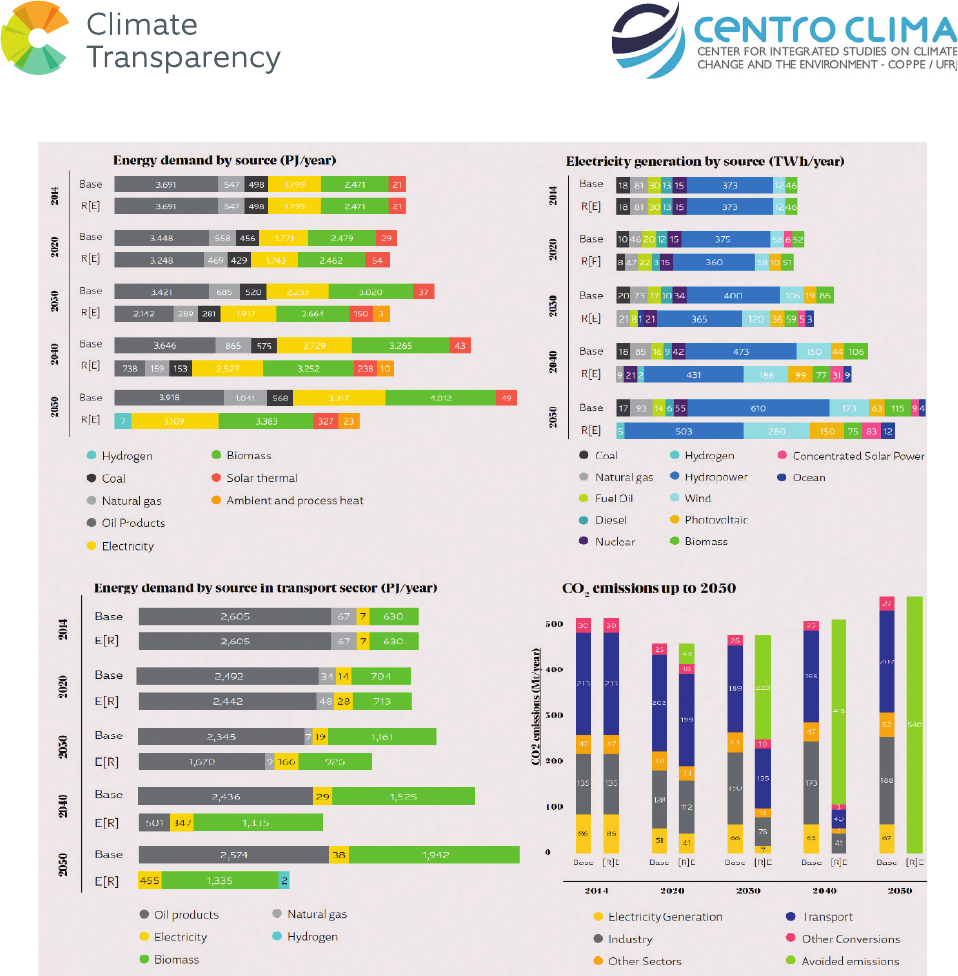

With greater political support and the launch of the PROINFA pro-

gram, more than 40% of the total investments in the power sec-

tor were in renewable energy between 2000 and 2013. Between

2014 and 2016, the highest share of investments in the power

sector was in wind power. In 2016, investments in solar energy

increased signifi cantly to around 35% of total investments in the

power sector (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Energy intensity in Brazil compared to G20 average

Source: B2G (2018)

1

Flex-fuel cars can run either with ethanol or gasoline, or any mix between the two fuels.

Figure 2: Total Primary Energy Supply in Brazil

Source: B2G (2018)

3

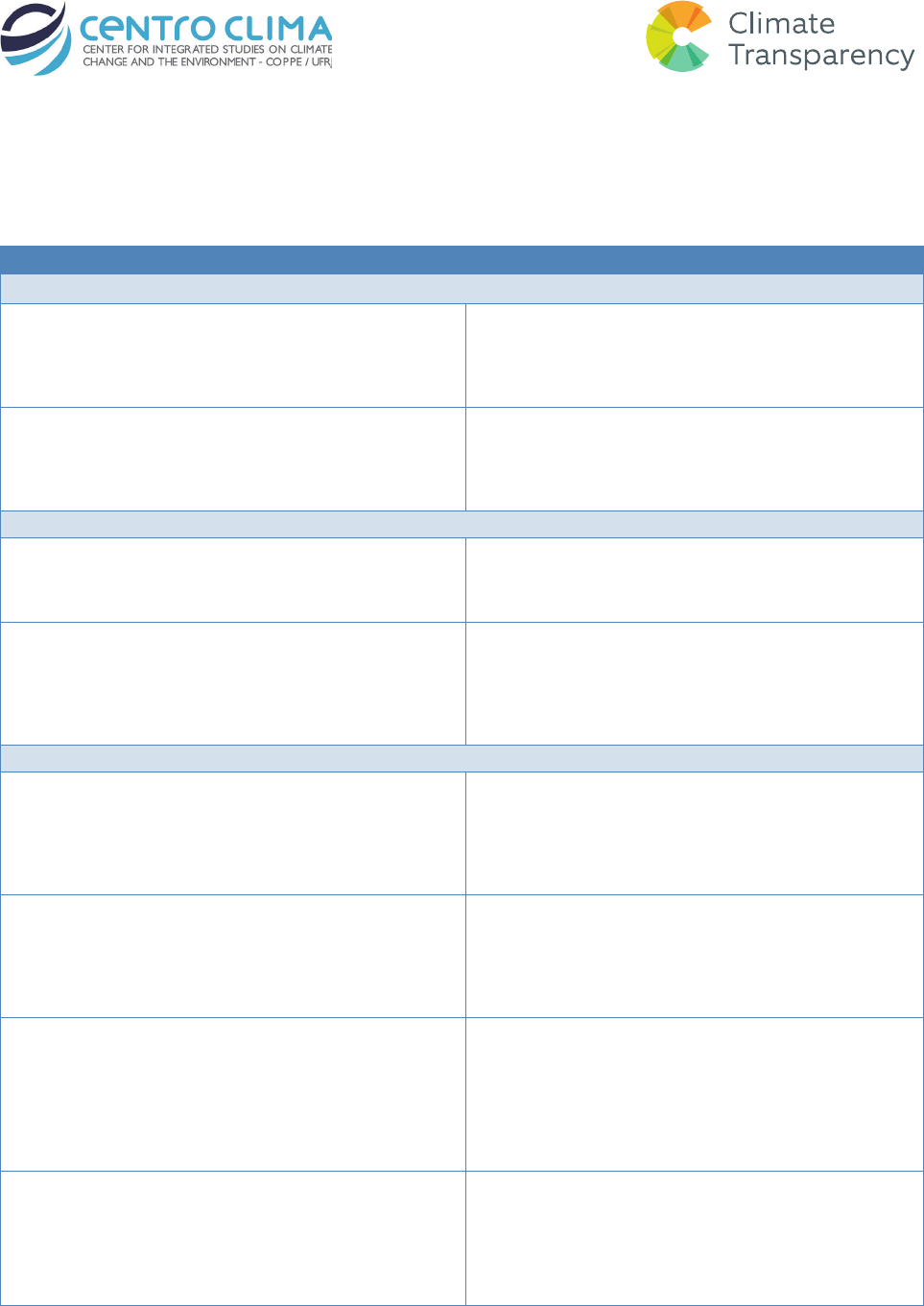

One of the most comprehensive studies in Brazil regarding an

ambitious Energy Transition was the “Energy [R]Evolution”, pre-

pared by Greenpeace (2016) with the participation of the German

Aerospace Center and COPPE, at the Federal University of Rio de

Janeiro. In the study, researchers developed two scenarios: a con-

ventional reference scenario (Base) and the progressive Energy

Revolution scenario - E[R]. The reference scenario refl ects current

developments in the energy industry and policies. In contrast, the

Energy Revolution scenario simulates an energy sector that does

not use any nuclear power and fossil fuels by 2050.

It is important to highlight that the study is very ambitious re-

garding technological development, and energy effi ciency gains,

decreasing GHG emissions from the energy sector to zero by

2050. Figure 4 presents total energy demand by source, electricity

generation by source, energy demand by energy source in the

transport sector, and GHG emissions by source, for both scenarios.

Among the main fi ndings of the study, we can cite:

• Energy effi ciency and change of consumption patterns must

play a major role in decarbonization, contributing to a 47%

decrease in energy demand by 2050.

• The electrifi cation of the energy mix, along with the diversi-

fi cation and decentralization of power generation is also key

to the E[R] scenario.

• Among other benefi ts, 12% more jobs will be created in the

energy sector in Brazil in the E[R] scenario.

Figure 3: Investments in renewables in the power sector

Source: Adapted from UN Environment and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (2018)

4

Figure 4: Energy sector according to Energy [R]Evolution

Source: Adapted from Greenpeace (2016)

5

2. KEY POLICIES TO FOSTER THE ENERGY TRANSITION IN BRAZIL

Political and fi nancial incentives are key to the energy transition. Some selected initiatives in Brazil are presented below.

Policies to foster renewable energy

Policies or initiatives Comments

Renewable Energy in Power Generation

Program for the Incentive of Alternative Energy Sources - PROINFA -

Decree nº 5.025, of March 30, 2004. Predicted the expansion of alter-

native sources (wind, SHP, solar and biomass) with priority dispatch

for wind energy. Guarantee of purchase of energy by Eletrobrás

(Feed-In tari ).

Despite delays due to the lack of adequate infrastructure at the time, it

was an important initial impulse for investments in alternative energy in

the country.

New Energy Auctions and Alternative Energy Auctions - de ne the

prices of the contracts, as well as the value of the tari s paid by con-

sumers, and the participation of the energy sources used (Brasil En-

ergia, 2018)

The Installed Capacity contracted in the period from 2009 to 2023, is of

7,568 MW for Biomass thermoelectric plants, 4,033 MW for Solar energy

and 16,739 MW for Wind energy (Instituto Acende Brasil, 2018). In 2018

there will be the 1st auction of biogas plant (cane residues) of 21 MW, to

start operation until 2021 (Canal Energia, 2018).

Distributed Generation

Law 5.163 / 2004 updated by Decree 786/2017. The DG can be con-

nected to the distribution network or be in the consumption centre,

which reduces the need for power transmission structure and avoid

losses;

Improved regulation of the market after the Energy Reform, Law 10.848 /

2004 (free and regulated markets), stimulation for energy self-producers

and special incentive to foster solar photovoltaic energy.

Program for the Development of Distributed Generation (ProGD):

aims to expand and deepen the actions to stimulate the generation

of energy by the consumers, based on renewable energy sources (in

particular solar photovoltaic), such as tax exemption for auto pro-

ducers and economic incentives (BNDES) for public buildings, hospi-

tals, etc. (MME, 2015).

Various tax incentives and special fi nancing conditions (Pronaf, Finem

BNDES, Proger (BB), Climate Fund etc.) for energy self-producers.

Biofuels

National Ethanol Program - PROALCOOL, Decree 76.593 / 1975: It

aimed to intensify the production of ethanol fuel to replace gasoline

in Brazil after the rst oil crisis in the 1970s.

Proalcool increased the production of ethanol from 0.9 billion litres in

1975 to 27.8 billion litres in 2017 (Nova Cana, 2018a). The replacement

of gasoline with alcohol saved US$ 61 billion and created about 1 million

direct jobs and a few million indirect ones in 30 years (Bertelli, 2016). Cur-

rently, Brazilian regular gasoline contains 27.5% ethanol. Ethanol can also

be used directly in fl ex-fuel cars, which are 80% of the fl eet.

National Program for the Production and Use of Biodiesel - PNPB

(2004): aims to introduce biodiesel into the Brazilian energy matrix

through (1) social inclusion of family farmers (social seal); (2) guar-

antee competitive prices, quality and supply; (3) produce biodiesel

from di erent oil sources, strengthening the regional potentialities

for the production of raw material (SEAD, 2018).

Law 11,097 / 2005 - Introduces the biodiesel in the Brazilian ener-

gy matrix, stipulating the minimum percentage of 5% in the diesel

mixture.

As a result, 59 auctions were carried out and 31.6 billion litres of biodiesel

were sold, avoiding the importation of 27 billion litres of diesel equiva-

lent, or 30% of diesel imports (Coelho, 2018).

The National Energy Policy Council (CNPE) anticipated the increase of

biodiesel blend in diesel to 10% in March 2018 (Agência Brasil, March

2018). Scenarios of PNE 2050, from EPE, estimate a 20% mix of biodiesel

in the diesel (B20) until 2030.

Law 13,576 / 2017 - Establishes the National Biofuels Policy (Renov-

aBio) and encourages the production of ethanol and biodiesel: Es-

tablishes annual greenhouse gas reduction targets.

After its regulation, decarbonisation credits (CBIOs) will be issued

by producers and importers that operate with biofuel (Nova Cana,

2018c).

The National Energy Policy Council (CNPE) will defi ne a series of criteria

and a value for companies for environmentally correct production, after

analyzing the entire production chain (Royal FIC, 2018).

6

Policies to reduce fossil fuel consumption

In the power sector, the use of fossil fuels will still be essential in Brazil until at least 2035 (Chambriard, 2017) due to economic and tech-

nological issues. However, in order to comply with the Paris Agreement (Cop-21), important steps are already being taken to discourage

the use of fossil fuels in the sector, as shown in the following table.

Policies or initiatives Comments

Increase the use of Natural Gas

In 2016, BNDES, the Brazilian Development Bank, announced that it

will no longer nance fuel oil and coal thermopower plants, direct-

ing investments with the long-term interest rate for projects with

high social and environmental returns (BNDES, 2016).

For the peak-load service, the trend is to use more natural gas from the

pre-salt (Goldemberg and Lucon, 2007).

Law 12.351 / 2010, called the “pre-salt regulatory framework”, estab-

lishes the end of Petrobras’ natural monopoly and allows the partic-

ipation of private agents in oil and gas exploration in these areas.

With this initiative, the government looks, among other objectives, to in-

crease the feasibility of exploration and transportation of natural gas to

the shore.

GHG emissions control of fossil-fuel- red power plants

Normative instruction by IBAMA in 07/2009 Links the previous environmental license (LP) of new projects of coal or oil

thermopower plants to the Carbon Dioxide Emission Mitigation Program,

requiring the planting of trees to mitigate emissions or investments in

renewable energy or energy effi ciency.

Policies to promote energy e ciency and research and development

Since the 1980s, Brazil has been encouraging energy effi ciency measures. Although there is a National Energy Effi ciency Plan since 2011,

Brazil has diffi culties in making it happen, and should invest more in energy effi ciency programs and focus on: the modernization of

industry, the diversifi cation of the transportation network, the implementation of policies to combat energy wastage and establish more

stringent energy effi ciency standards (Altoé et al., 2017).

Policies or initiatives Comments

Energy E ciency (EE) Incentives

Law 10.295 / 2011 (EE Law): provides the National Policy on the Con-

servation and Rational Use of Energy and establishes maximum lev-

els of energy consumption or of EE for machinery and in the country.

Procel - National Energy Conservation Program: Since 1985, it works

on several fronts: information, education, industries, public build-

ings, energy e ciency labelling, appliances, banning of incandes-

cent lamps etc.

With the various Procel actions, from 1986 to 2017, approximately 2 mil-

lion tons of CO

2

were avoided, generating savings of R$ 3.8 billion. The

Program cost R$ 2.97 billion and saved 128 billion kWh (PROCEL / Eletro-

bras, 2018).

Research and Development

Law 9,991 / 2000 - Compulsory investments in Research and Devel-

opment: 1.0% of Net Operating Revenue (ROL) of companies in the

electricity sector. As of 2016, the distributors must allocate 0.75% to

R&D and 0.25% for Energy E ciency.

The average annual investment of these companies for R&D is R$ 380 mil-

lion and for Energy Effi ciency is 420 million (ANEEL, 2015).

7

Financing and other incentive mechanisms to

promote renewable energy

The Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) is the main financier

of alternative energy projects in the country, with specific fi-

nancing conditions with long-term interest rates, being able

to finance up to 80% of the renewable energy project at an

annual interest rate of about 10% (or 0.97% per month), th-

rough its subsidiary Special Agency for Industrial Financing

(FINAME). Starting in 2016, the alternative energy line finances

projects that worth more than R$ 20 million. BNDES provides

other special funds for alternative energy sources, which sup-

port small-scale projects in isolated areas and for residential

use (Rennkamp and Westin, 2017).

Recently the BNDES decided to increase its participation in fi -

nancing the generation of solar energy (from 70% to up to 80%).

For energy effi ciency projects, participation continues to be 80%.

For wind power plants, biomass, cogeneration and small hydro-

electric plants, the share is 70%. Investments in coal and oil fuels,

which are more polluting, will not be supported and the partici-

pation limit in large hydroelectric plants has decreased from 70%

to 50%. The bank will also subscribe up to 50% of the value of the

debentures.

CPFL Renováveis was certifi ed by the Climate Bonds Initiative by

the wind power criterion to issue debentures in the amount of

R$ 200 million. It is the fi rst company in South America to issue

a green bond with international certifi cation and the fi rst in the

power sector to issue a certifi cate (CPFL Energia, 2017).

Demand for Renewable Energy Certifi cates (RECs) also skyrocke-

ted in 2016, and according to the Totum Institute, which coordi-

nates the Renewable Energy Certifi cation Program, in one year,

demand rose from 13.4 thousand to 107.5 thousand certifi cates.

The idea of the certifi cation is to receive energy in the traditional

way and to acquire the equivalent energy volume through these

Certifi cates (each certifi cate equals 1 MWh generated from clean

sources), (ABRAGEL, 2018).

3. ECONOMIC CHALLENGES AND

OPPORTUNITIES

3.1. Opportunities

According to the MME cited by Ambiente Energia (2018), invest-

ments that are already authorized for 2021 includes 14 solar pho-

tovoltaic plants (Ceará), 8 wind farms, 2 hydroelectric plants and

a biomass-fi red thermopower plants (bagasse), adding 883 MW

to the National Integrated System (SIN). Investments are of R$ 4.5

billion and 4,040 direct Jobs are expected to be created.

Wind power value chain

Wind power emerged as an alternative for the diversifi cation of

the electrical matrix after the 2001 energy crisis and today is the

ninth largest global capacity (13GW), an average capacity factor

of 40%, representing today about 8% of the Brazilian power ma-

trix in terms of installed power. Total potential in the country is

around 300 GW. The Ministry of Mines and Energy forecasts an ex-

pansion of 125% by 2026 when 28.6% of the electricity produced

in Brazil will be from a wind power source. The Brazilian Industrial

Development Agency (ABDI) estimates that by 2026 the wind po-

wer chain could generate approximately 200,000 new direct and

indirect jobs (ABDI apud ABEEólica, 2018).

The value chain of wind energy has been growing with the incen-

tives provided by the federal and state governments (Tax exemp-

tion, long-term fi nancing, etc.). In recent years, Brazil has evolved

signifi cantly its industrial model of the wind power sector. Cur-

rently, the wind turbine assembly and the manufacture of various

components (towers, blades, subcomponents of the hub and na-

celle) are carried out in Brazil, with a reduction in the number of

imported items compared to previous years. It should be noted,

however, that progress in local knowledge does not follow this

same pace. The knowledge that is most widespread in the coun-

try covers mainly the technology for the processing of goods: the

assembly of wind turbines, the steel making (cutting, bending,

welding and painting), concrete manufacturing processes and

the manufacturing processes of large components. The specifi c

knowledge for the design development of most of these com-

ponents is still small and, given the potential for technology ge-

neration in the country, could considerably increase (ABDI, 2014).

Wind energy has decreased costs in Brazil since the beginning

of the expansion cycle and the revision of the nationalization

content requirements of the Development Bank (BNDES) that

was fundamental to accelerate the implementation times of

wind turbines in the country.

The metal-mechanical industrial base already established in the

Southeast region was of great importance in the process of es-

tablishing the wind turbine industry in Brazil. After the national

content requirements were implemented, there was a regional

deconcentration of manufacturing, and some companies started

to settle in the Northeast and South regions. There are currently

more than 100 companies in the supply chain, six major wind tur-

bine manufacturers with established manufacturing plants and

one national wind turbine manufacturer. The Brazilian production

stands out for the components of low and medium technology

like towers, shovels, nacelle etc. There was also a great evolution

in logistics infrastructure in the last decade.

However, by 2021 a signifi cant drop in the demand for wind tur-

bines is estimated and the production chain will have to adjust

itself, trying to be more competitive in the international market,

and investing in export of components to Latin America, etc.,

despite the high industrial cost in Brazil and the existing export

diffi culties (logistics, for example). The repowering of parks and

the O&M industry could provide support for companies as well as

the start of off shore exploration of wind power in the northeast

region (Schaff el, Westin and La Rovere, 2017).

8

Solar power value chain

Brazil has high solar potential throughout the year and has reser-

ves of important raw material for the solar industry (silicon) and

some materials (aluminium and acrylic), as well as components

and equipment already established, depending on the importati-

on of few components (cells, thin fi lms etc.).

However, to face the technological and economic barriers, it will

depend on a large-scale production. According to SEBRAE (2017),

it is still about 60% more expensive to produce the photovoltaic

modules in Brazil than it imports them, besides it is necessary to

improve the productivity of the Brazilian workforce and reduce

the average cost of electricity to the industry. Despite those dif-

fi culties, more than 7,500 distributed solar generation plants in

companies and industries were built by the end of 2016 to meet

part of their electricity consumption, and the trend is that this

value chain will multiply. Today more than 1,600 companies

(small and medium installers) already operate in this segment in

the country. Through mergers and acquisitions, solar companies,

energy distribution concessionaires and international investors

are entering the solar generation market in Brazil, driven by the

energy auctions and in the Free Contracting Environment.

The forecast of a new policy with fl exibilization of nationalization in-

dex announced for the photovoltaic industry by BNDES should fa-

vour the expansion and consolidation of the national photovoltaic

production chain. It is estimated that around 30% of the electrical

matrix will be of solar photovoltaic energy in 2040 (SEBRAE, 2017).

ABDI (2014) provided several suggestions to foster the develop-

ment of the productive chain of wind power in Brazil, the ones

cited below are also applicable to the solar photovoltaic gene-

ration:

• Development of a broader industrial policy, covering aspects

of competitiveness, productivity and with emphasis on tech-

nological development.

• Better connect industrial policy with the country’s energy po-

licy, in order to give better conditions (security) for companies

to make their investments.

• Encouraging the adoption of collaborative Supply Chain stra-

tegies, establishing partnerships and long-term contracts.

• Adequacy of the metalworking chain in order to meet the

high levels of quality and productivity demanded by the solar

sector.

3.2. Barriers

Between 2013 and 2017 subsidies in the area of fossil fuels rea-

ched R$ 342 billion related to subsidies and tax exemptions to

direct expenses for the production of oil, natural gas and coal,

as well as for the final consumption of gasoline, diesel and

cooking gas representing in average 1% of GDP (INESC, 2018).

About 8% of this amount refers to financial support and 92%

of tax exemptions. Although the themes of fiscal reform and

the reduction of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies have been dis-

cussed since Rio + 20 as one of the Sustainable Development

Objectives, there is currently the permanence and expansion

of subsidies, such as the extension of REPETRO until 2040 and

creation of the Special Tax Regime (MP 795/17). According to

the INESC adviser, there is no transparency regarding the in-

vestments, since these are not registered as official tax expen-

ditures by the federal revenue as the Repetro (Special Customs

Regime), (Radio Brasil Atual, 2018).

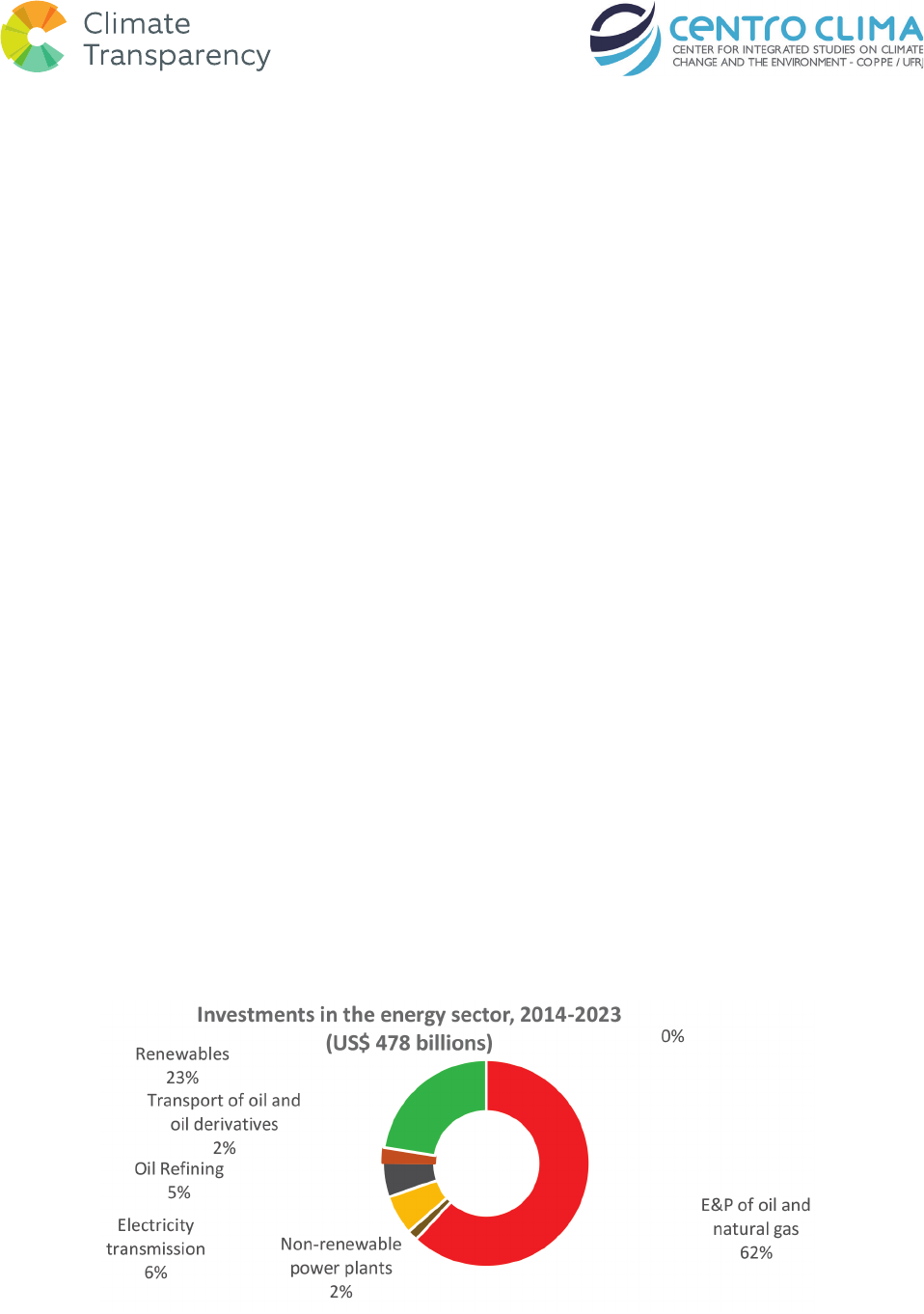

According to the World Resources Institute - WRI Brasil Report

(Lucon, Romeiro and Fransen, 2015), the 62% of the invest-

ments in the Brazilian energy sector from 2014 to 2023 will be

directed at fossil fuels, against 23% for renewables, as present-

ed in figure 5.

Figure 5: Investments in the Brazilian energy sector from 2014 to 2023

Source: Adapted from Lucon, Romeiro and Fransen (2015)

9

The Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology (MCTIC) stated

that the low competitiveness of biomass compared to imported

coal, high access costs and lack of knowledge of the option of

cogeneration with sugarcane bagasse are important barriers to

a more comprehensive use of biomass in the power sector. To

transpose them, a series of measures must be taken, starting with

specifi c auctions with diff erentiated price-ceiling for plants ope-

rating with renewable fuels. MCTIC also suggests to change the

regulation for thermoelectric plants to biomass up to 30MW, the

creation of cooperatives to collect biomass and the holding of

events for the sector in order to discuss renewable generation

and carbon pricing schemes (MCTIC, 2017).

The most recent offi cial plan of the energy sector (EPE, 2017),

estimates that until 2026, the largest share of investments in the

energy sector will still be directed to the oil and natural gas sec-

tor (71.4%), while the power sector will receive 26.2% (including

renewable and non-renewable) and the liquid biofuels sector will

receive only 2.4% of total investments, that is estimated at US$

423 billion from 2017 to 2026.

• To foster the energy transition in Brazil, and to meet the tar-

gets of the Paris Agreement, it is absolutely necessary to redi-

rect investments and reduce subsidies to fossil fuels.

4. SOCIAL ANALYSIS

Despite the large share of renewable sources in the power sector,

there are still social and environmental confl icts with respect to

large hydropower plants. The still available hydraulic potential are

in areas of great ecological and social relevance (legal Amazon),

where the criticism is with respect to the loss of terrestrial ecosys-

tems and fi shing resources and losses of fertile lands, historically

inhabited by traditional populations.

In this regard, new renewable sources such as wind and solar have

gained more empathy, however, problems related to the alterati-

on of coastal dune dynamics, landscape interference of wind tur-

bines and privatization of land near the beach were reasons for

discontent among the local population (Porto and Ferreira, 2013).

Assessment on just transition

The debate around just transition in Brazil is not very popular yet,

despite the importance of this topic in a developing country.

From the government perspective, the Ministry of Environment

published the National Adaptation Plan to Climate Change in

2016 (MMA, 2016), which recognized the challenge to achieve a

just transition; however, the report did not present any clear strat-

egy to achieve it.

Green jobs are jobs created in a variety of activities that have di-

rect or indirect positive impacts on the environment, with objec-

tives to achieve sustainable development goals from economic

practices with lower environmental risks and poverty reduction

(UNEP, 2008 apud Ansanelli and Santos, 2016). In Brazil, about 2.5

million jobs in 2008 were considered green (6.73% of total jobs),

according to the ILO. There was a 22% increase in the number of

green jobs from 2009 to 2015, according to the Brazilian Ministry

of Labor (Ministério do Trabalho, 2017).

International Labour Organization (ILO, 2018) stated that if ap-

propriate policies are adopted, the transition of the world econ-

omy to a greener and more sustainable model should create 620

thousand new jobs in Brazil, which more than compensates for

the 180 thousand jobs that could be lost. ILO recommends that

countries should adopt with urgency a policy mix that includes

income transfers, stronger social security, limits on the use of fos-

sil fuels, and off er new training programs to anticipate the skills

needed for the transition.

Investment in renewable energy sources, associated with in-

centive policies (tax reductions and attractiveness in fi nancing)

in addition to reducing GHG emissions, can create an important

number of jobs. In the wind power sector alone, 150,000 direct

jobs were criticized in 2016, currently counting 13 GW, or 8.6% of

the national electricity matrix (ABDI cited by ABEEOLICA, 2018).

Regarding the eradication of poverty, the “Light for All” program

stands out with success in seeking the universalization of access

to electricity in rural areas, prioritizing traditional populations and

areas of extreme poverty. Launched in 2003, it benefi ted more

than 16 million people and was invested by 2016, about R$ 23

billion so far, using funds from the Energy Development Account

(CDE), as well as state resources and concessionaires (Drummond,

2016). In 2019, an investment of more than 250 million USD is

planned to install 95,540 new electric power connections in 17

states (Agência Brasil, April 2018). Resources will be used to install

photovoltaic systems. The Program was extended until 2022 and

aims to reach another 500 million USD for full.

Wind power also contributes to increasing the income of land-

owners in poor regions. The contracts provide fi xed payments for

more than 20 years and are renewable. Some “wind farms” can

earn 15,000 USD per month. Many apply the income in agricul-

ture, generating more jobs and productivity in places that were

not very productive or for sale. In addition, there is a compen-

sation for the passing of the Transmission Lines (Cerne cited by

Gibson and Carvalho, 2015).

Environmental bene ts

The reduction of fossil fuel consumption will be of great value for

the improvement of the quality of the air, especially in big cities.

To address this serious problem that is the main cause of respira-

tory diseases in major cities in Brazil, the energy transition should

also encourage greater use of public transportation, bike paths

and electric cars.

In addition, a smaller participation of thermopower plants in

the power sector would contribute to the improvement of air

and water quality. As a recent example, the thermopower plant

“Pecém II” had to remove the surrounding population because

of the poor air quality due to the coal dust, aff ecting even the

quality of the water in the surroundings (Assembleia Legislativa

do Estado do Ceará, 2015).

10

Distributed generation and the free energy market will contrib-

ute greatly to the power supply of basic sanitation systems, which

is defi cient in sewage treatment, for example. Currently, Brazil

consumes 12.1 TWh of electricity to move the machines and

equipment for water and sanitation companies and current ex-

penditure is estimated at almost 1 billion USD per year. One of the

reasons of such high energy costs is that the Brazilian system was

basically designed in the 1970s and 1980s when there was a huge

subsidy on electricity for basic sanitation (of the order of 75%) and

no concern about energy effi ciency and costs (Corrêa, 2001).

Distributed generation

With almost 8,000 connections in the country at the beginning

of 2017, it is estimated that by 2030 around 2.7 million consumer

units may produce their own energy, including households, busi-

nesses, industries and the agricultural sector, which could result

in 24 GW installed of clean and renewable energy (MME, 2015).

Among current investment initiatives for distributed generation

are solar energy fl oating in hydroelectric lakes (25 million USD in

research and development from 2016 to 2019) and complemen-

tary power generation in public buildings (more than 100 thou-

sand kWh / year), (MME, 2015). However, most of the distributed

generation facilities are in the residential sector.

By 2050, photovoltaic generation capacity is expected to become

thousands of times bigger, reaching an installed capacity be-

tween 78 and 128GW, as the cost of production is becoming in-

creasingly competitive. EPE predicts that 78 GWp will be installed

in distributed generation systems by 2050, with a strong focus on

residential microgeneration (Portal Solar, 2018).

Barriers to a fair energy transition

Planning processes are not always transparent. Many develop-

ments are decided before a public hearing has been held about

possible alternatives, what is required by law. However, the ten-

dency is to decentralize energy planning, with greater social par-

ticipation and transparency, at the municipal level, despite the

diffi culty of funding (Collaço and Bermann, 2017).

Recently, projects such as small hydropower plants and some

wind farms considered to be of small environmental impact po-

tential, are able to obtain a simplifi ed environmental license, car-

ried out in a single phase, without the need to develop detailed

environmental studies. Also, the public hearing is replaced by an

informative technical meeting (CONAMA Resolution 279/2001).

The development of decentralized alternative energy enables the

supply of energy in isolated areas of the country, not having to

invest in costly transmission and distribution lines. Thus, millions

of families were benefi ted, as well as health, education and sani-

tation institutions, bringing a greater quality of life with the arrival

of electric light.

Some cases of corruption can be found in the country in con-

nection with the payment of bribes and to third parties to ob-

tain illegal benefi ts. An example in the state of Mato Grosso was

related to 12 sugar and ethanol companies that were processed

by the State Finance Secretariat (SEFAZ), based on the Anti-Cor-

ruption Law (Federal Law 12,846 / 2013) for alleged payment of 5

million USD of bribes to state public agents for the reduction of

tax burdens from 2010 to 2015. As a consequence, if convicted,

those companies will have to pay a fi ne of 20% of gross revenue in

the year prior to the proceeding, full compensation for damages

caused to the public administration, as well as the restriction of

the right to participate in bids and to enter into contracts with

the public administration (Silveira quoted by Nova Cana, 2018b).

Corruption schemes related to the company Oderbrecht through

plea bargains also show that to build a large hydroelectric plant

in Brazil it was suffi cient that there were bribe payments and be-

hind-the-scenes actions, making this development “much more

relevant than effi cient and economically viable projects.” Aiming

to accelerate the release of funds from the Brazilian Development

Bank or the granting of environmental licenses, infl uential poli-

ticians requires “tips” at the national congress, as, for example, in

the case of UHEs of the Madeira River (Jirau and Santo Antônio),

according to a report by Calixto (2017). Thus, it is argued that this

acceleration of the licensing process is the “need of the electric

sector on pain of the risk of lack of energy” (MPF, n / d);

In order to reduce problems of this nature, the new energy model

foresees the obligatoriness of the new generation projects only

to go to the bid after having the previous environmental license

- PL 401/2013 that aims to change the Bidding Law n. 8666/1993,

making the annexe to the bidding notice mandatory with the

prior environmental license or required by applicable legislation.

Another bill, PL 3729/04, calls for simplifi cation of the licensing

process (greater legal certainty is expected for entrepreneurs and

more investments), (Senado Federal, 2017).

For greater transparency in the planning of the electricity sector,

it is necessary according to the MME (2017):

• Foster access to information.

• The regulation should lead to the establishment of the fair

and equitable competition of economic agents and of dif-

ferent energy sources, also evaluating the electrical and so-

cio-environmental externalities.

• The isonomic treatment should require the modernization

of the incentives policies or subsidies for a given technology,

and these incentives must have clear and limited objectives,

with transparent mechanisms.

11

CONCLUSION

Brazil is one of the countries with the cleanest energy matrix in

the world and its energy intensity has remained stable since the

1990s. It was one of the main G20 countries investing in renew-

able energy in the last decade. However, more than half of its

energy matrix is still represented by fossil fuels, far from what is

needed to maintain climate change under control.

Many programs were created in Brazil in order to diversify the Bra-

zilian energy matrix, with Proalcool and Proinfa as its main mile-

stones. These programs allowed the success of the country’s bio-

fuels and wind energy sector respectively. Fiscal incentives and

public funding of alternative energy sources played a crucial role

in the growth of the sector and in establishing the country’s wind

energy value chain. Now, similar measures would be important

for the growth of the solar energy value chain, coupled with a

greater investment in research and development.

Brazil, as a country of continental dimensions, needs comprehen-

sive social policies that promote the universalization of access to

electricity and has been fulfi lling its goals with the “Light for All”

Program. The energy sector reform in 2004 brought the fi gures

of the free and regulated market, which was important for the

expansion and planning of new sources, especially for Distributed

Generation, and a greater incentive in energy effi ciency programs

such as PROCEL is necessary, given the low investment verifi ed in

EE in recent years.

Regarding the energy sector, the Brazilian NDC is a bit shy, as most

of the GHG emissions reduction will come from the reduction in

deforestation and agriculture. For 2030 it is fairly enough, but for

the long-term, a low-carbon strategy should be developed as en-

ergy is key for economic development.

As a sum-up, renewable energies in Brazil are advancing rapidly

and the energy transition will inevitably take place along with the

country’s technological-economic evolution, but the question

that remains is: Will it be fast enough?

Policy Recommendations

• Avoid the lock-in in carbon-intensive technologies, especial-

ly in long lifespan infrastructures as refi neries, fossil-fuel fi red

power plants, etc.

• Start to redirect investments from E&P in the oil sector to

other promising renewable energy sources.

• Increase solar distributed generation through a comprehen-

sive national plan that addresses regulation and taxes issues,

and helps the poor population to invest in its own solar gene-

ration with facilitated fi nancing conditions.

• Prepare a comprehensive energy effi ciency program to foster

investments in this area.

• Implement economic instruments, either a carbon tax, a car-

bon market, or a hybrid instrument to accelerate the energy

and economic transition to a low carbon society.

• To foster the energy transition in Brazil, and to meet the tar-

gets of the Paris Agreement, it is absolutely necessary to redi-

rect investments and reduce subsidies to fossil fuels.

• To sum up, Brazil needs to create a long-term low carbon stra-

tegy in order to meet the targets of the Paris agreement

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has been produced as part of the eff orts of Climate

Transparency, an international partnership of Centro Clima/

COPPE/UFRJ and 13 other research organizations and NGOs com-

paring G20 climate action – www.climate-transparency.org. The

paper is fi nanced by the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The

Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and

Nuclear Safety (BMU) supports this initiative on the basis of a de-

cision adopted by the German Bundestag.

12

REFERENCES

ABEEólica. Energia eólica deve gerar mais de 200 mil empre-

gos no Brasil até 2026. (News) Avaiable at: http://abeeolica.org.

br/noticias/estudo-abdi-ventos-que-trazem-empregos/. Accessed

in: Sep., 13, 2018.

ABDI – Agência Brasileira de Desenvolvimento Industrial. Mape-

amento da Cadeia Produtiva da Indústria Eólica no Brasil.

Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior.

2014. 152 p. (pdf). Avaiable at: http://investimentos.mdic.gov.br/

public/arquivo/arq1410360044.pdf

ABRAGEL – Associação Brasileira de Geração de Energia Limpa.

Certi cado de Energia Renovável. (News) Avaiable at: http://

www.abragel.org.br/energia-renovavel/. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Agência Brasil. Aumento para 10% do percentual de bio-

diesel no diesel entra em vigor. March, 01, 2018. Avaiable at:

http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/economia/noticia/2018-03/aumen-

to-para-10-do-percentual-de-biodiesel-no-diesel-entra-em-vigor

Agência Brasil. Temer assina decreto que prorroga Luz para

Todos. Portal ISTOÉ. April, 27, 2018. (News) Avaiable at: https://

istoe.com.br/temer-assina-decreto-que-prorroga-luz-para-todos/.

Accessed in: Aug. 2018.

Altoé, Leandra et al. Políticas Públicas de Incentivo à E ciên-

cia Energética. Estudos Avançados. Vol 31, no. 89. São Paulo.

Jan/Apr. 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0103-40142017.31890022.

Avaiable at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid

=S0103-40142017000100285. Accessed in: Aug. 2018.

Ambiente Energia. MME autoriza instalação de 25 usinas de

energia limpa para geração de 883 MW. 13 de setembro de

2018. (News) Avaiable at: https://www.ambienteenergia.com.br/

index.php/2018/09/governo-autoriza-instalacao-de-25-usinas-ge-

radoras-de-energia-limpa/34721#.W5r1BOhKiUk

ANEEL – Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica. P&D no setor

elétrico. Programa de P&D regulado pela ANEEL. P&D ANEEL. Su-

perintendência de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento e Efi ciência Ener-

gética – SPE. Brasília, DF, 2015. (ppt). Avaiable at: http://www.aneel.

gov.br/documents/656831/14942679/ANEEL-PeD-ABAQUE-Novem-

bro2015.pdf/4a06dfa3-9b41-47b0-a4d6-19550027650d

Ansanelli, Atela Luiza de Mattos and Santos, Luiz Henrique Bispo.

Empregos verdes no Brasil: Uma análise da dinâmica regional

entre 2007 e 2014. 5º Congresso Internacional de Tecnologi-

as para o Meio Ambiente. Bento Gonçalves – RS. April, 2016.

(Paper) Avaiable at: https://siambiental.ucs.br/congresso/getArtigo.

php?id=539&ano=_quinto. Accessed in: Sep., 12, 2018.

Assembleia legislativa do Estado do Ceará. Autoridades pedem

providências para poluição causada pela termoelétrica.

July, 8, 2015. Avaiable at: https://www.al.ce.gov.br/index.php/ulti-

mas-noticias/item/42986-0807_df_audi%C3%AAncia-esteira. Ac-

cessed in: Sep., 15, 2018.

B2G – Brown to Green. The G20 transition to a low-carbon

economy. Report. Climate Transparency, 2018. (pdf). Avaiable at:

https://www.climate-transparency.org/g20-climate-performan-

ce/g20report2018

Bertelli, Luiz Gonzaga. A verdadeira história do Proalcool. Por-

tal Biodieselbr, jan., 29, 2016. (News). https://www.biodieselbr.com/

proalcool/historia/proalcool-historia-verdadeira.htm

BNDES. BNDES divulga novas condições de nanciamento

à energia elétrica. October, 03, 2016. (News) Avaiable at: htt-

ps://www.bndes.gov.br/wps/portal/site/home/imprensa/noticias/

conteudo/bndes-divulga-novas%20condicoes-de-financiamen-

to-a-energia-eletrica. Accessed in: Aug, 29, 2018

Brasil Energia. O negócio é diversi car. n. 452, aug, 1, 2018.

(News)

Calixto, Bruno. O que as delações da Odebrecht dizem sob-

re corrupção nas hidrelétricas da Amazônia. Época. 13 de

abril de 2017. (News) Avaiable at: https://epoca.globo.com/cien-

cia-e-meio-ambiente/blog-do-planeta/noticia/2017/04/o-que-de-

lacoes-da-odebrecht-dizem-sobre-corrupcao-nas-hidreletri-

cas-da-amazonia.html. Accessed in set. 2018.

Canal Energia. Raízen inicia obras da primeira usina de bio-

gás viabilizada no ACR. 23 de agosto de 2018. (News) Avaia-

ble at: https://www.canalenergia.com.br/noticias/53072780/raizen-

inicia-obras-da-primeira-usina-de-biogas-viabilizada-no-acr?utm_

source=Assinante+CanalEnergia&utm_campaign=2bc9f-

27bac-NewsDiaria&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_e9f71a-

dea7-2bc9f27bac-153925341

Chambriard, Magda. Tendências de E&P no brasil e no mun-

do e o excedente da cessão onerosa. FGV Energia. Caderno

Opinião. Aug. 2017. (pdf) Avaiable at: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.

br/dspace/bitstream/handle/10438/19275/Coluna%20Opiniao%20

Magda-AGOSTO-2017_v4.pdf

Coelho, Mauro. Projeções de oferta e demanda de etanol,

gasolina, biodiesel e diesel - O planejamento Energético

da Matriz veicular do Brasil até 2030. Sindaçucar-PE. EPE/

MME, 2018. (pdf). Avaiable at: http://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/

sala-de-imprensa/noticias/Documents/EPE_Jos%C3%A9%20Mau-

ro_Proje%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20de%20Oferta%20e%20Demanda_

26mar.pdf

Collaço, Flávia Mendes de Almeida and Bermann, Célio. Per-

spectivas da Gestão de Energia em âmbito municipal no Brasil.

Dilemas ambientais e fronteiras do conhecimento II. Estudos

Avançados. vol.31 no. 89. São Paulo. Jan/Apr. 2017. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1590/s0103-40142017.31890018

Corrêa, Maurício. Setor de água e saneamento quer mais e -

ciência em energia. Paranoá Energia. Brasília. April, 28, 2001.

(News). Avaiable at: http://www.paranoaenergia.com.br/noti-

cias/2017/04/28/3858/. Accessed in set. 2018.

CPFL Energia. CPFL Renováveis é a primeira empresa da

América do Sul a emitir título verde com certi cação inter-

nacional. São Paulo, march, 29, 2017. (News). Avaiable at: https://

www.cpfl.com.br/releases/Paginas/cpfl-renovaveis-e-a-primei-

ra-empresa-da-america-do-sul-a-emitir-titulo-verde-com-certifi -

cação-internacional.aspx

Drummond, Carlos. Entenda como funciona o Luz para Todos.

Carta Capital. Feb., 22, 2016. Avaiable at: https://www.cartacapital.

com.br/especiais/infraestrutura/entenda-como-funciona-o-luz-pa-

ra-todos

EPE - Empresa de Pesquisa Energética. Balanço Energético Na-

cional 2018 – Ano base 2017. 2018a. (pdf) Avaiable at: http://

www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/

PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-303/topico-397/Relatório%20Sín-

tese%202018-ab%202017v .pdf#search=ben

13

EPE - Empresa de Pesquisa Energética. Plano Decenal de Ex-

pansão de Energia 2026. Ministério de Minas e Energia/ Secre-

taria de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento Energético. Brasília -

DF: MME/EPE, 2017. Avaiable at: http://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/

publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/

publicacao-40/PDE2026.pdf

Gibson, Felipe and Carvalho, Fred. “O vento me dá dinheiro”, diz

dono de fazenda com torres de energia eólica. Portal G1. 25 de

jan. 2015. (News) Avaiable at: http://g1.globo.com/rn/rio-grande-

do-norte/noticia/2015/01/o-vento-me-da-dinheiro-diz-dono-de-fa-

zenda-com-torres-de-energia-eolica.html. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Goldemberg, José and Lucon, Oswaldo. Energia e meio ambien-

te no Brasil. Estudos avançados. Vol. 21. N. 59. São Paulo, Jan/

Apr. 2007. Dossiê Energia. ISSN 0103-4014 (Print version). Avai-

able at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid

=S0103-40142007000100003 Accessed in: set. 2018.

Greenpeace. [R]evolução Energética – Rumo a um Brasil com

100% de energias limpas e renováveis. 2016. 95 pgs. (pdf)

Avaiable at: https://storage.googleapis.com/planet4-brasil-state-

less/2018/07/Relatorio_RevolucaoEnergetica2016_completo.pdf

ILO - International Labor Organization. Greening Jobs. World

Employment Social Outlook – WESO 2018. 189 p. (pdf)

INESC – Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos. Subsídios aos

combustíveis fósseis no Brasil – Conhecer, avaliar, refor-

mar. Brasília, Jun. 2018. Avaiable at: le:///C:/Users/Admin/App-

Data/Local/Packages/Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe/

TempState/Downloads/Estudo_completo_Inesc%20(3).pdf

Instituto Acende Brasil. Programa Energia Transparente – Mo-

nitoramento Permanente da Operação e Comercialização

de Energia no Brasil. 12ª ed. Jul. 2018. Avaiable at: http://www.

acendebrasil.com.br/media/estudos/ppt_energiatransparente_edi-

cao12_acendebrasil_rev12.pdf. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Lucon, Oswaldo; Romeiro, Viviane and Fransen, Taryn. Oportun-

idades e desa os para aumentar sinergias entre as políti-

cas climáticas e energéticas no Brasil. WRI Brasil Cidades

Sustentéveis. WRI Ross Center, 2015. (pdf). Avaiable at: https://

wribrasil.org.br/sites/default/fi les/bridging-the-gap-energy-cli-

mate-pt-es_1.pdf

MCTIC – Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comuni-

cações. Trajetórias de mitigação e instrumentos de políti-

cas públicas para alcance das metas brasileiras no acor-

do de Paris. Secretaria de Políticas e Programas de Pesquisa e

Desenvolvimento – SEPED/ Coordenação Geral do Clima – CGCL.

May, 2017. 38 p. (pdf) Avaiable at: http://sirene.mcti.gov.br/do-

cuments/1686653/2098519/Contribuic%CC%A7a%CC%83o+M-

CTIC+II_NDC_1.pdf/8db5a027-ccd3-4f1c-af01-23dacbd6d6a9

SEAD – Secretaria Especial de Agricultura Familiar e do Desenvol-

vimento Agrário. O que é o Programa Nacional de Produção

e Uso do Biodiesel. (Website) Avaiable at: http://www.mda.gov.

br/sitemda/secretaria/saf-biodiesel/o-que-%C3%A9-o-programa-

nacional-de-produ%C3%A7%C3%A3o-e-uso-do-biodiesel-pnpb.

Accessed in: Aug. 2018.

Ministério do Trabalho. Ministro rea rma compromisso com

a sustentabilidade em conferência da OIT, em Genebra.

Jun. 14, 2017. (News) Avaiable at: http://trabalho.gov.br/notici-

as/4679-ministro-reafirma-compromisso-com-a-sustentabilida-

de-em-conferencia-da-oit-em-genebra

MMA – Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Plano Nacional de Ad-

aptação à Mudança do Clima: sumário executivo / Ministério

do Meio Ambiente. BRASIL. Brasília: MMA, 2016. Avaiable at:

http://www.mma.gov.br/images/arquivo/80182/LIVRO_PNA_Re-

sumo%20Executivo_.pdf

MME - Ministério de Minas e Energia. Princípios para atuação

governamental no setor elétrico. March, 03, 2017. Avaiable at:

http://www.mme.gov.br/web/guest/consultas-publicas?p_au-

th=TheH3uoF&p_p_id=consultapublicaexterna_WAR_consul-

tapublicaportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_

mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_count=1&_con-

sultapublicaexterna_WAR_consultapublicaportlet_consultaId-

Normal=32&_consultapublicaexterna_WAR_consultapubli-

caportlet_javax.portlet.action=downloadArquivo

MME - Ministério de Minas e Energia. Brasil lança Programa

de Geração Distribuída com destaque para energia solar.

Dec., 15, 2015. http://www.mme.gov.br/web/guest/pagina-inicial/

outras-noticas/-/asset_publisher/32hLrOzMKwWb/content/progra-

ma-de-geracao-distribuida-preve-movimentar-r-100-bi-em-investi-

mentos-ate-2030

MPF – Ministerio Público Federal. Aspectos polêmicos do

Licenciamento Ambiental. Ministério Público e Licencia-

mento Ambiental. (n/d) Avaiable at: http://www.mpf.mp.br/

atuacao-tematica/ccr4/dados-da-atuacao/grupos-de-trabalho/

gt-licenciamento/documentos-diversos/palestras-docs/4_as-

pectos.pdf. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Nova Cana. Geração de energia com o aumento da produção

de etanol. 2018a. (News) Avaiable at: https://www.novacana.

com/usina/geracao-energia-aumento-producao-etanol/. Acces-

sed in: Sep., 2018.

Nova Cana. Mato Grosso processa 12 empresas do setor

sucroenergético por corrupção. Governo do Mato Grosso.

August, 08, 2018b. (News) Avaiable at: https://www.novacana.

com/n/industria/usinas/justica-mato-grosso-processa-12-se-

tor-sucroenergeticas-corrupcao-080818/. Accessed in: Sep., 14,

2018.

Nova Cana. Os CBios são um novo produto para setor de bio-

combustíveis, garante Paulo Costa do MME. Notícias agríco-

las. August, 07, 2018c. Avaiable at: https://www.novacana.com/n/

etanol/mercado/regulacao/paulo-costa-mme-cbios-novo-pro-

duto-setor-biocombustiveis-070818/. Accessed in: Sep., 15, 2018.

Portal Solar. O que é Geração Distribuída – GD. n/d. (Website)

https://www.portalsolar.com.br/o-que-e-geracao-distribuida.html.

Accessed in: Aug., 19, 2018.

Porto, Marcelo Filipo de Souza; Finamore, Renan and Ferreira,

Hugo. Injustiças da sustentabilidade: Con itos ambientais

relacionados à produção de energia “limpa” no Brasil. 2013:

Crise ecológica e novos desafi os para a democracia. Revista Críti-

ca de Ciências Sociais, 2013. P. 37-64. Avaiable at: https://journals.

openedition.org/rccs/5217. Accessed in: Aug. 2018.

PROCEL – Programa Nacional de Conservação de Energia. Re-

sultados PROCEL 2018. Ano base 2017. Eletrobras, 2018. (pdf).

Avaiable at: http://www.procelinfo.com.br/resultadosprocel2018/

docs/Procel_rel_2018_web.pdf. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Radio Brasil Atual. Estudo do Inesc revela gastos do governo

com combustíveis fósseis. Política. Jun. 20, 2018. (News). Avaiable

at: https://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/politica/2018/06/estudo-do-in-

esc-revela-que-valores-gastos-com-subsidio-pelo-governo-federal-po-

deriam-ser-aplicados-em-programas-sociais. Accessed in ago. 2018.

14

Rennkamp, Britta and Westin, Fernanda Fortes. Local content re-

quirements and nancial incentive measures in emerging

wind energy markets: Brazil and South Africa cases. Energy

Research Centre – ERC/ University of Cape Town - UCT, South Af-

rica, 2017. (Report)

Royal FIC. Lei dos Biocombustíveis estabelece política de in-

centivo para o setor. March, 29, 2018. (News) https://www.roy-

al c.com.br/lei-dos-biocombustiveis-estabelece-politica-de-in-

centivo-para-o-setor/. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

Schaff el, Silvia Blajberg; Westin, Fernanda Fortes and La Rovere,

Emílio Lèbre. Sinergias entre Geração Eólica O shore e Ex-

ploração Marítima de Petróleo e Gás. XVII Congresso Brasi-

leiro de Energia 2017. Rio de Janeiro, nov., 2017.

SEBRAE – Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empre-

sas. Cadeia de valor da energia solar fotovoltaica no Brasil.

Projeto Plataforma. Brasília – DF. 2017. (pdf ) Avaiable at: http://m.

sebrae.com.br/Sebrae/Portal%20Sebrae/Anexos/estudo%20ener-

gia%20fotovolt%C3%A1ica%20-%20baixa.pdf

Senado Federal. Projeto de Lei do Senado n. 401, de 2013.

Portal do Senado Federal – Atividade Legislativa. Avaiable at:

https://www25.senado.leg.br/web/atividade/materias/-/mate-

ria/114580. Accessed in: Sep. 2018.

UN Environment and Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Global

Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2018. Frankfurt

School-UNEP/BNEF. 2018. Available at: http://fs-unep-centre.org/

sites/default/ les/publications/gtr2018v2.pdf