ABSTRACT

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2270 American Journal of Public Health

Jac J. L. van der Klink, MD, MSc, Roland W. B. Blonk, PhD,

Aart H. Schene, PhD, MD, and Frank J. H. van Dijk, PhD, MD

Jac J.L. van der Klink, Roland W.B. Blonk, and Frank

J. H. van Dijk are with Coronel Institute, Academic

Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amster-

dam, the Netherlands. Jac J. L. van der Klink is also

with the Foundation for Quality in Occupational

Health, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Roland W.B.

Blonk is also with TNO Work and Employment,

Hoofddorp, the Netherlands. Aart H. Schene is with

the Department of Psychiatry, Academic Medical

Center, University of Amsterdam.

Requests for reprints should be sent to Jac J. L.

van der Klink, MD, MSc, Coronel Institute, Acade-

mic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, PO

Box 22660, 1100 DD Amsterdam, the Netherlands

(e-mail: [email protected]).

This article was accepted May 12, 2000.

Objectives. This quantitative meta-

analysis sought to determine the effec-

tiveness of occupational stress–reducing

interventions and the populations for which

such interventions are most beneficial.

Methods. Forty-eight experimental

studies (n = 3736) were included in the

analysis. Four intervention types were

distinguished: cognitive–behavioral in-

terventions, relaxation techniques, mul-

timodal programs, and organization-

focused interventions.

Results. A small but significant

overall effect was found. A moderate ef-

fect was found for cognitive–behavioral

interventions and multimodal interven-

tions, and a small effect was found for

relaxation techniques. The effect size for

organization-focused interventions was

nonsignificant. Effects were most pro-

nounced on the following outcome cate-

gories: complaints, psychologic resources

and responses, and perceived quality of

work life.

Conclusions. Stress management

interventions are effective. Cognitive–

behavioral interventions are more effec-

tive than the other intervention types. (Am

J Public Health. 2001;91:270–276)

The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of in-

terventions designed for patients with emo-

tional difficulties is a relevant topic in general

practice.

1

Such considerations also apply in oc-

cupational health care. With the increases in

workloads of the past decades, the number of

employees experiencing psychologic problems

related to occupational stress has increased rap-

idly in Western countries.

2

At the societal level,

costs are considerable in terms of absenteeism,

loss of productivity, and health care consump-

tion. In Britain, it is estimated that 40 million

workdays are lost to the nation’s economy

owing to mental and emotional problems.

3

At

the individual level, there are costs in terms of

high rates of tension, anger, anxiety, depressed

mood, mental fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

These problems, usually referred to in aggre-

gate as distress, are often classified as neuras-

thenia, adjustment disorders, or burnout. Inci-

dence rates in the Netherlands vary from 14 to

50 cases per year per 1000 patients.

4

Interventions designed to reduce occu-

pational stress can be categorized according

to focus, content, method, and duration. In re-

gard to focus, interventions can be categorized

as (1) aiming to increase individual psycho-

logic resources and responses (e.g., coping) or

(2) aiming to change the occupational context.

The first category of intervention is usually

referred to as stress management training.

However, stress management is the common

denominator of an assortment of interventions

ranging from relaxation methods

5

to cognitive–

behavioral interventions

6,7

and client-centered

therapy.

8

The second category refers to inter-

ventions such as organizational development

9,10

and job redesign.

11

We distinguished 4 intervention types ac-

cording to categorizations used in previous re-

views

12–14

: cognitive–behavioral approaches,

relaxation techniques, multimodal interven-

tions, and organization-focused interventions.

Cognitive–behavioral approaches aim at chang-

ing cognitions and subsequently reinforcing

active coping skills.

6,7

Relaxation techniques

focus on physical or mental relaxation as a

method to cope with the consequences of stress.

Multimodal interventions emphasize the ac-

quisition of both passive and active coping

skills. The fourth intervention type involves a

focus on the organization as a whole.

Several reviews have been conducted of

interventions designed to reduce occupational

stress.

2,5,12,14–16

The general finding of these re-

views is that such interventions are effective.

However, the reviews have been qualitative in

nature and thus provide limited information on

which type of intervention is most effective

and for whom. Recently, Bamberg and Busch

conducted the first meta-analysis on occupa-

tional stress–reducing interventions.

17

How-

ever, they included only cognitive–behavioral

interventions in their quantitative analyses.

In the present quantitative review, the fol-

lowing research questions were posed: (1) Are

stress interventions effective, as suggested by

qualitative reviews of the literature? (2) If so,

which type of stress intervention is most effec-

tive, and on which outcome measures? In ad-

dition to these research questions, exploratory

analyses were conducted to determine what

moderator variables (e.g., job characteristics,

preventive/remedial nature of interventions,

length of treatment) were related to the effec-

tiveness of the interventions.

The Benefits of Interventions for

Work-Related Stress

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2 American Journal of Public Health 271

Methods

Search and Inclusion Criteria

Two strategies were used to locate appro-

priate studies. First, 4 databases—Medline

(1966–1996), ClinPsych (1980–1996), Cur-

rent Contents (1997), and Nioshtic (1970–

1996)—were used to conduct a computerized

search. Three groups of terms were composed

for this search: (1) terms linked to stress-re-

lated psychologic problems (psychologic stress,

work stress, job stress, neurasthenia, burnout,

minor psychiatric problems, mental fatigue,

minor depression, neurosis, distress, nervous

breakdown, and adjustment disorder), (2) terms

related to the intervention (therapy, treatment,

protocol, program, intervention, primary care,

prevention, and employee assistance program),

and (3) terms related to the population (em-

ployee, occupational, vocational, rehabilita-

tion, work, job, absenteeism, and sickness

leave).

Within each group of terms, searches were

added. Subsequently, these searches were com-

bined. Second, a manual search of relevant re-

views, book chapters, and articles was con-

ducted, with the objective of finding relevant

references missed in the computerized search.

To be included in our database, a study

had to meet several criteria. First, the inter-

vention was required to be specifically designed

to prevent or reduce psychologic complaints

related to occupational stress. Second, in terms

of the target population, participants had to be

recruited from the working population because

of imminent or already-manifested stress-

related psychologic problems not diagnosed

as involving a major psychiatric disorder (e.g.,

depression or posttraumatic stress disorder) or

a stress-related somatic disorder (e.g., hyper-

tension, coronary heart disease). Third, an ex-

perimental or quasi-experimental design in-

volving a no-treatment control group had to

be used. Within the quasi-experimental studies,

we required that the experimental group and

the control group be recruited from identical

populations and have identical baseline values

on dependent variables. In this high-quality

group of primary studies, we applied no rank-

ing for methodological quality aspects because

the consequent choice of a weighting factor in

the quantitative analyses would introduce an

element of subjectivity. Fourth, outcome vari-

ables had to be well defined and of sufficient

reliability. Finally, we required that the study be

published as a journal article in English.

Definitions

The variables used in the meta-analysis

included intervention-related variables, out-

come variables, and population characteristics.

Intervention-related variables were (1) type of

intervention, (2) total number of hours, (3) num-

ber of weeks, and (4) number of sessions. The

latter 3 variables could be considered indexes

of the intensity and extent of the intervention.

Because they were relevant in assessing the

cost-effectiveness and practical applicability

of a program, we used these variables as mod-

erators in the exploratory analyses.

As described earlier, 4 intervention types

were included; 3 involved a focus on individ-

uals and 1 involved a focus on the organiza-

tion. In several reviews, a third focus has been

discerned: the interaction between the indi-

vidual and the organization.

14,18

Thus far, how-

ever, intervention studies conducted with this

focus have been uncontrolled.

19

The outcome variables included were

placed into 5 categories: (1) quality of work

life, including such aspects as job demands,

work pressure, job control, working conditions,

and social support from management and col-

leagues; (2) psychologic resources and re-

sponses, including measures of self-esteem,

mastery, beliefs, and coping skills

20

; (3) phys-

iology, including measures such as tension,

electromyographic activity, (nor)adrenaline,

and cholesterol level; (4) complaints, including

stress or burnout rates or symptoms, somatic

symptoms, and mental health status and symp-

toms (because of their significance in general

health practice, depressive symptoms and anx-

iety symptoms were considered as separate

subcategories); and (5) absenteeism.

A number of population characteristics,

such as sex, age, years of employment, occu-

pational status, and baseline stress level, may

be important moderators of treatment effects

and thus may provide information on which

types of interventions are effective and for

whom. However, for most of these character-

istics, the specific information required was

not available in the studies; the exceptions were

baseline stress level and occupational status.

The predictive influence of these characteris-

tics on treatment effects was investigated in a

number of exploratory analyses.

In line with Newman and Beehr

12

and

with Murphy,

2

2 baseline stress level categories

were distinguished, preventive and remedial.

In the present meta-analysis, a study was con-

sidered preventive if no participant selection

had taken place in regard to stress levels. A

study was considered remedial if participants

were selected by means of a criterion.

As noted by Karasek and Theorell, occu-

pational status may be indicative of level of job

control.

20

On the basis of Karasek and Theo-

rell’s ratings, we categorized study samples as

“high control” or “low control.” Two studies

involving samples with mixed occupations

were classified as low control because most of

the participants in these studies had low-control

jobs

.21,22

Two studies were excluded from these

exploratory analyses because of a lack of suf-

ficient information.

23,24

Statistical Analysis

The Advanced BASIC Meta-Analysis

program

25

was used in conducting statistical

analyses. In this program, several statistics

(e.g., F, t, r, and P) can be entered, and a

product–moment correlation is obtained. These

effect size correlations are transformed to

Fisher z scores. Subsequently, mean Fisher z

scores are calculated and transformed back to

effect size (r) values.

If F or t values were reported, we used

these values; if such values were not reported,

they were computed if the required informa-

tion was available. If this computation was not

possible, P values were used; effects reported

as nonsignificant were rated as P=0.5.

26

A problem in meta-analyses is that stud-

ies with a relatively large number of outcome

measures disproportionately affect the meta-

analytic results. To counteract this problem,

Rosenthal and Rubin

27

proposed a method of

computing a mean effect size in which the in-

tercorrelation of outcome measures is taken

into account.

25(pp45–47)

For all analyses, outcome

variables were combined according to this

method. We used all outcome measures re-

ported in a study in calculating effect sizes.

We report effect sizes in Cohen’s d, which

can be derived directly from r values. Cohen’s d

represents the standardized mean difference

between the intervention group mean and the

control group mean. Thus, a d value of 1 indi-

cates that the intervention group performed 1

standard deviation above the control group on

a particular outcome variable.

Results

Description of Studies

Forty-eight studies

10,21–24,28–67

conducted

between 1977 and 1996 met the inclusion crite-

ria; findings from these studies were published

in 45 different articles. None of the 48 studies

had a curative orientation in the usual sense (i.e.,

target population consisting of people seeking

help). Four studies were considered remedial,

because there was selection in regard to baseline

stress level. Forty-one studies involved employ-

ees with jobs categorized as high in job control.

Five studies evaluated an organization-

focused intervention, 18 evaluated a cognitive–

behavioral intervention, 17 evaluated a relax-

ation technique, and 8 evaluated a multimodal

approach. In all studies, several outcome analy-

ses were conducted. The result was 99

intervention–outcome combinations.

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2272 American Journal of Public Health

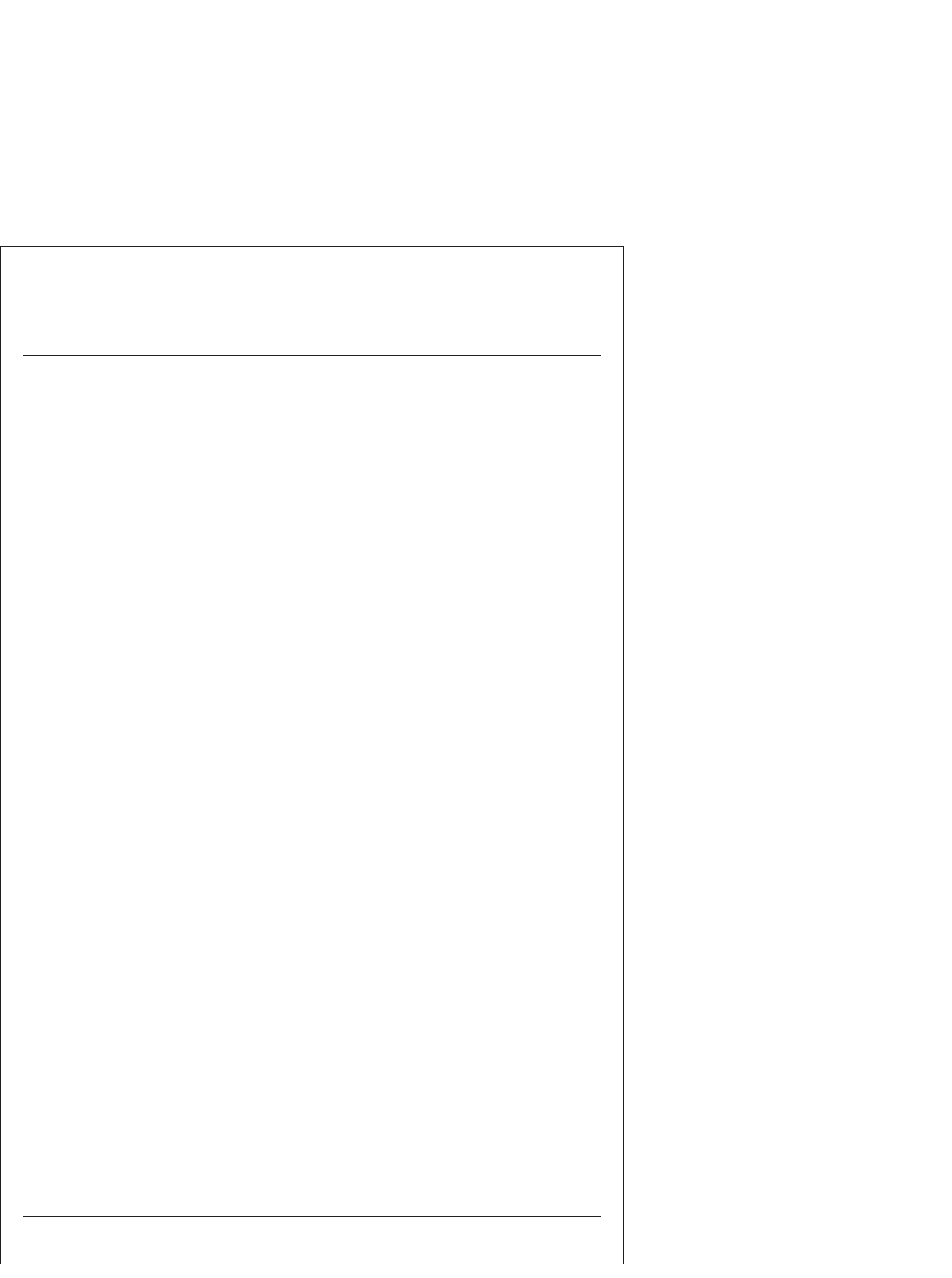

TABLE 1—Effect Sizes per Study Expressed in Cohen’s d and 95% Confidence

Intervals: Meta-Analysis of Occupational Stress-Reducing

Interventions, 1977–1996

Category d 95% Confidence Interval

Organizational

Heaney et al. (1995) 0.06 –0.11, 0.23

Jackson (1983) 0.12 –0.43, 0.67

Jones et al. (1988) 0.5* 0.01, 0.99

Landsbergis & Vivona-Vaughan (1995, 1) –0.2 –0.86, 0.46

Landsbergis & Vivona-Vaughan (1995, 2) –0.04 –0.7, 0.62

Cognitive–behavioral

Bruning & Frew (1986) 0.1 –0.6, 0.8

Cecil & Forman (1990) 0.58 –0.08, 1.24

Curtis (1992) 1.98* 1.32, 2.64

Fava et al. (1991) 1.09* 0.4, 1.78

Forman (1981) 1.62* 0.49, 2.75

Freedy & Hobfoll (1994) 0.26 –0.17, 0.69

Gray-Toft (1980) 0.8 –0.23, 1.83

Grønningsæter et al. (1992) 0.0 –0.55, 0.55

Higgins (1986) 0.39 –0.28, 1.16

Keyes & Dean (1988) 0.87* 0.48, 1.3

Kushnir & Malkinson (1993) 0.41 –0.29, 1.11

Kushnir et al. (1994) 1.43* 0.91, 1.95

Lee & Swanson Crockett (1994) 0.8* 0.26, 1.34

Long (1988) 0.26 –0.22, 0.74

McCue & Sachs (1991) 0.41 –0.12, 0.94

Sharp & Forman (1985) 0.98* 0.42, 1.54

von Baeyer & Krause (1983) 2.2* 0.82, 3.58

West et al. (1984) 0.28 –0.35, 0.91

Relaxation

Aderman & Tecklenburg (1983) 0.72* 0.04, 1.4

Alexander et al. (1993) 0.54* 0.0, 1.08

Arnetz (1996) 0.04 –0.4, 0.48

Bruning & Frew (1986) 0.35 –0.36, 1.06

Carrington et al. (1980) 0.47* 0.07, 0.87

Fiedler et al. (1989) 0.35 –0.17, 0.87

Higgins (1986) 0.3 –0.36, 0.96

Murphy (1983) 0.32 –0.48, 1.12

Murphy (1984) 0.1 –0.74, 0.94

Peters et al. (1977; 2 studies) 0.3 –0.12, 0.72

Toivanen et al. (1993, 1a) 0.28 –0.29, 0.85

Toivanen et al. (1993, 2) 0.45 –0.12, 1.02

Toivanen et al. (1993, 1b) 0.32 –0.25, 0.89

Tsai & Swanson Crockett (1993) 0.43* 0.09, 0.77

Tunnecliff et al. (1986) 0.0 –1.05, 1.05

Vaughn et al. (1989) 1.71* 0.63, 2.79

Vines (1994) 0.0 –0.5, 0.5

Multimodal

Bertoch et al. (1989) 1.15* 0.35, 1.95

Friedman et al. (1983) 0.7* 0.24, 1.16

Ganster et al. (1982) 0.28 –0.23, 0.75

Johanson (1991) 0.82* 0.35, 1.29

Larsson et al. (1990) 0.24 –0.19, 0.67

McNulty et al. (1984) 0.45 –0.15, 1.05

Norvell et al. (1987) 0.26 –0.88, 1.4

Pruitt (1992) 0.37 –0.13, 0.87

*P < .05.

Twenty of the studies involved a follow-

up assessment. In most cases, follow-up was ei-

ther uncontrolled or reported in a way that al-

lowed no retrieval of statistical metrics.

Therefore, only the first postintervention as-

sessment was included in the meta-analysis.

The mean interval between preintervention and

postintervention assessment was 9 weeks for

interventions that focused on individuals (SD=

6 weeks). This deviation was merely due to dif-

ferences in intervention duration. Differences

in interval between intervention types were not

significant. The interval for organization-

focused programs was considerably longer (38

weeks) owing to longer program durations and

longer postintervention assessment intervals.

Pretest-to-posttest dropout rates varied from

0% to 40%. The mean dropout rate for pro-

grams that focused on individuals was 11%;

differences between intervention types were

nonsignificant. Organization-focused programs

had a mean dropout rate of 26%.

Effect Sizes

Effect sizes were calculated as described in

the Methods section.A combined analysis of ef-

fect sizes yielded a significant effect size across

all studies (d= 0.34, 95% confidence interval

[CI]=0.27, 0.41).According to Cohen’s criteria

68

(small effect: d<0.5; medium effect: 0.5<d<0.8;

large effect: d>0.8), however, this effect size was

small. Examination of the data indicated that 17

studies yielded a significant overall effect size,

all in the expected (positive) direction. Of these

17 studies, 2 (both focusing on relaxation tech-

niques) revealed a small effect, 4 (1 organization

focused, 2 relaxation, and 1 multimodal) revealed

a medium effect, and 11 (8 cognitive–behavioral,

1 relaxation, and 2 multimodal) revealed a large

effect. In the 31 remaining studies, overall effects

were nonsignificant; effect sizes for these stud-

ies were small and negative (d≤ –0.2; 1 study),

nonrelevant (–0.2<d≤0.2; 9 studies), small (0.2<

d≤0.5; 19 studies), and medium (0.5<d≤0.8; 2

studies). It should be noted that these 31 studies

yielded many specific outcomes that were sig-

nificant. Table 1 shows effect sizes and confi-

dence intervals for the 48 studies.

Type of Intervention

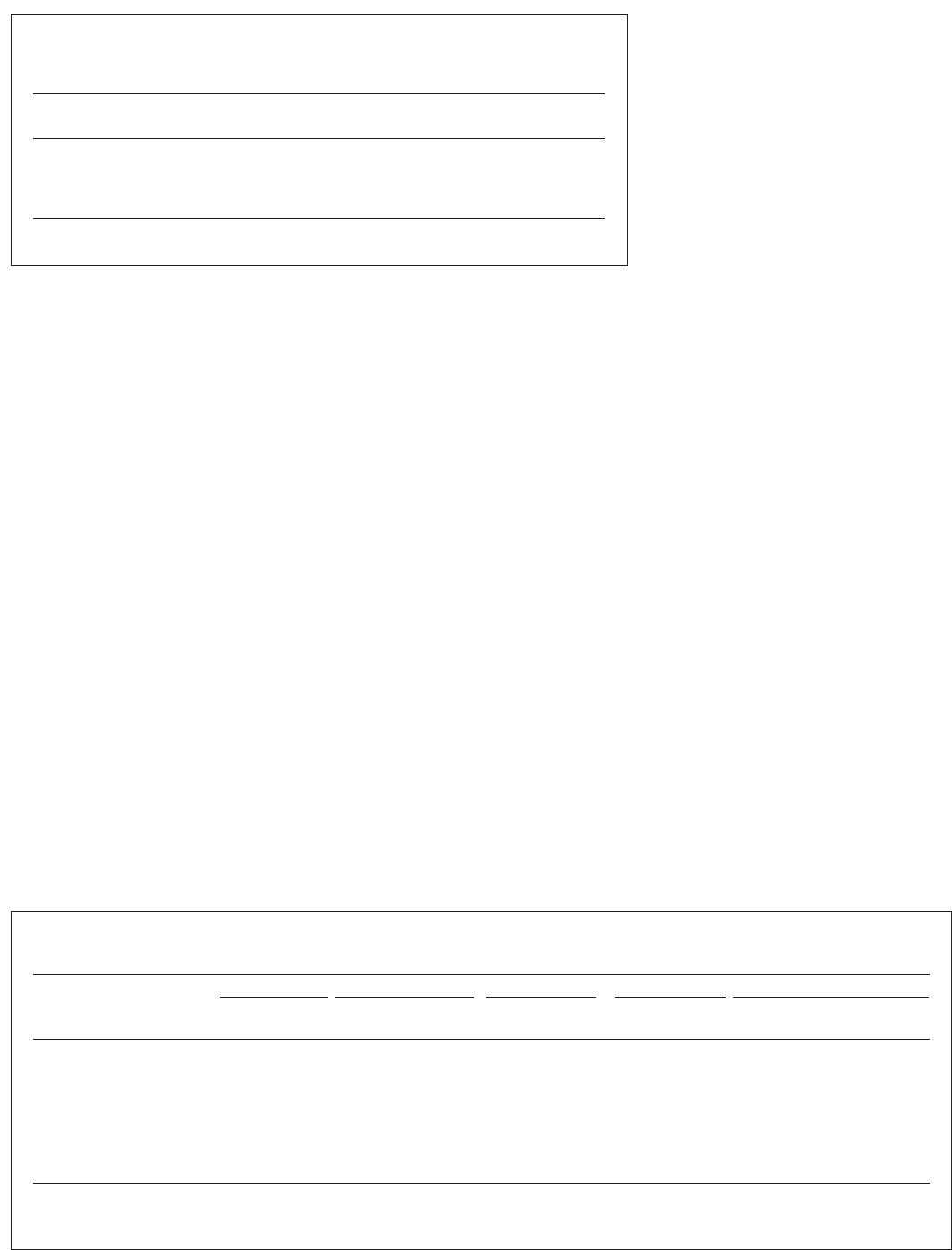

Effect sizes were calculated for the 4 dif-

ferent types of interventions. These effect sizes

are shown in Table 2.

The combination of the effect sizes for

interventions that focused on individuals

yielded a significant Cohen’s d of 0.44 (95%

CI=0.36, 0.52; heterogeneous effect). The ef-

fect size difference between interventions fo-

cusing on individuals (combined as well as

separate) and those focusing on the organiza-

tion was significant (P < .05). Furthermore,

cognitive–behavioral interventions were sig-

nificantly more effective than relaxation tech-

niques (P< .005); the difference in effect be-

tween cognitive–behavioral and multimodal

interventions was marginally significant (P=

.06). There were no significant effect size dif-

ferences between relaxation and multimodal

interventions. Cognitive–behavioral interven-

tions yielded heterogeneous effects, indicating

divergent levels of effectiveness among these

studies.

Outcome Variables

Effect sizes were calculated for the 5 out-

come categories across intervention types. As

noted earlier, organization-focused interven-

tions were less effective than interventions fo-

cusing on individuals. Outcome studies on or-

ganizational interventions usually involve

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2 American Journal of Public Health 273

TABLE 2—Cohen’s d and Confidence Intervals for the 4 Intervention

Categories: Meta-Analysis of Occupational Stress–Reducing

Interventions, 1977–1996

No. of No. of 95% Confidence

Category Studies Participants d Interval

Organizational 5 1463 0.08 –0.03, 0.19

Cognitive–behavioral 18 858 0.68* 0.54, 0.82

Relaxation 17 982 0.35* 0.22, 0.48

Multimodal 8 470 0.51* 0.33, 0.69

*P < .05.

TABLE 3—Effect Sizes, by Intervention, Expressed in Cohen’s d and Weighted for Sample Size: Meta-Analysis of

Occupational Stress-Reducing Interventions, 1977–1996

Organizational Cognitive–Behavioral Relaxation Multimodal Individual Focus (Summation)

No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of No. of

Outcome d Studies d Studies d Studies d Studies d Studies Participants

Quality of work 0.05 4 0.48*** 7 0.29** 8 0.59** 2

a

0.41*** 17 708

Psychologic responses

and resources 0.14** 1 0.65*** 10

a

0.26* 5 0.22 1 0.48*** 16

a

915

Physiology . . . 0 0.11 2 0.31*** 10 0.36* 3 0.30*** 15 808

Complaints 0.05 4 0.52*** 14

a

0.31*** 14 0.48*** 6 0.42*** 34

a

1923

Anxiety symptoms ... 0 0.70*** 7 0.25* 7 0.50*** 4 0.54*** 18 871

Depressive symptoms 0 1 0.23 2 0.11 2 0.59*** 2 0.33** 6 392

Absenteeism 0 1 –0.18 1 –0.09 2 . . . 0 –0.12 3 121

a

Heterogeneous effect.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

significantly larger sample sizes than studies on

individual interventions. As a consequence, ef-

fect sizes for outcome categories may be dis-

proportionately affected by the small effect

sizes found within organization-focused inter-

ventions. Therefore, we analyzed separately

the effect sizes for outcome variables across

all intervention types and across interventions

focusing on individuals only. Across all inter-

vention types, the effect sizes found for the

outcome categories quality of work, psycho-

logic responses and resources, physiology, com-

plaints, and absenteeism were 0.17, 0.28, 0.30,

0.27, and –0.03, respectively. The correspon-

ding effect sizes for interventions focusing on

individuals were 0.41, 0.48, 0.30, 0.42, and

–0.12. With the exception of absenteeism, all

effect sizes were significant at P< .05.

Interactions Between Intervention Types

and Outcome Variables

Table 3 presents results by outcome cat-

egory and intervention type. The overall picture

that emerges from Table 3 is that interventions

involving a cognitive–behavioral approach ap-

pear to be the preferred means of reducing em-

ployees’stress-related complaints. However, it

should be noted that the results were hetero-

geneous for 2 outcome categories, indicating

divergent effects. With regard to psychophys-

iologic outcomes, interventions in which re-

laxation was part of the program appeared to

be most effective. The effect of organization-

focused interventions was small and non-

significant, except for the psychologic re-

sponses and resources category.

Psychophysiologic measures were used

as outcomes only in studies evaluating inter-

ventions that focused on individuals. Relax-

ation techniques and multimodal interventions

appeared to be effective in reducing psy-

chophysiologic stress measures. Absenteeism

was measured in 4 studies; neither the cogni-

tive approach nor relaxation training appeared

to be successful in regard to this outcome vari-

able. Noteworthy is that 1 study included med-

ical malpractice as an outcome variable. The

results of this study, in which an organization-

focused intervention was conducted in hospi-

tals, indicated a significant postintervention

decrease in medical practice failures (d=0.50,

P< .05).

46

Exploratory Analyses

An examination of intervention-related

characteristics (number of weeks, number of

contact hours, number of sessions) across the

4 intervention types revealed no significant

predictive influence of these characteristics on

the overall effect size. Separate analyses for

the intervention types revealed that for

cognitive–behavioral interventions, there was

an inverse correlation between number of ses-

sions and effect size (r=–0.27, P< .05). This

indicates that shorter programs were more ef-

fective. Furthermore, organization-focused pro-

grams were significantly longer than cognitive–

behavioral programs (16.4 vs 6.8 weeks; P<

.05, 2-tailed).

The differential effects of preventive vs re-

medial programs and high vs low job control

both appeared to be marginally significant (P<

.10). Larger effect sizes were found for remedial

programs (n =4, d= 0.59, P<.10) than for pre-

ventive programs (n = 44, d = 0.32, P< .001).

Stress-reducing interventions revealed the largest

effect sizes among employees with high-control

jobs. This latter finding can, however, be attrib-

uted to the fact that all but 1 cognitive–behavioral

intervention and all multimodal interventions

concerned employees with such jobs.

Only relaxation techniques were used with

employees in both types of jobs (low or high in

job control); effect sizes were not significantly

different. For high-control employees, cognitive–

behavioral interventions (n=17, d=0.69, P<.001)

were significantly more effective (P<.001) than

relaxation techniques (n =9, d=0.30, P<.001);

the difference in effect between cognitive–

behavioral and multimodal interventions (n=8,

d=0.51, P<.001) was also significant (P<.05).

The difference between relaxation and multi-

modal interventions was marginally significant

(P<.10). The single cognitive–behavioral study

involving a population with jobs classified as low

in job control did not yield a significant result.

48

Discussion

In the present study, we quantitatively

evaluated the effects of interventions designed

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2274 American Journal of Public Health

to reduce occupational stress. Forty-eight stud-

ies met our inclusion criteria of an appropri-

ate design and reliable measures. This is a rel-

atively large number of studies with

methodological rigor, considering the lack of

such studies in the early days of stress inter-

vention research.

5,12

However, despite the con-

siderable increase in methodologically sound

studies in this field, there is a relative lack of

studies with clinically referred employees. Fur-

thermore, the few methodologically rigorous

studies that have been conducted with patients

have not included no-treatment control groups

but have compared 2 treatment types (e.g., Firth

and Shapiro

69

); as a result, these studies could

not be included in our meta-analysis.

Most studies were conducted with vol-

unteer samples rather than clinically referred

samples. Research with clinically referred sam-

ples in settings where treatment is ordinarily

provided is needed to test the generalizability

of the results found in this meta-analysis. Pre-

liminary support was found in the present meta-

analysis: interventions conducted with em-

ployees at high levels of baseline stress

appeared to be at least as effective as inter-

ventions conducted with employees at low lev-

els of baseline stress. However, only 4 studies

involved participant selection in regard to high

baseline stress levels. Furthermore, develop-

ment of treatments that meet the needs of clin-

ically referred employees may generate new

hypotheses and procedures that address clini-

cal exigencies more fully and effectively.

In concordance with earlier qualitative re-

views, the present meta-analysis provides reli-

able evidence that employees benefit from

stress-reducing interventions. Although small

according to Cohen’s criteria,

68

a significant

effect size was found across 48 studies repre-

senting 3736 participants.

In the present study, 4 different types of

stress-reducing interventions were distin-

guished. Three types were considered as fo-

cusing on individuals, and 1 was considered as

focusing on the organization. The analyses

clearly demonstrated that the former were more

effective than the latter. We conclude that an in-

tervention that focuses on individual employees

is the first choice in the case of employees with

stress-related complaints. The rather surpris-

ing lack of a significant effect for organizational

interventions is elaborated on subsequently.

A comparison between interventions that

focused on individuals revealed that cognitive–

behavioral approaches are more effective than

relaxation techniques and tend to be more ef-

fective than multimodal programs. The effect

size found for the cognitive–behavioral inter-

ventions was comparable to those reported in

2 recent meta-analyses on the effectiveness of

such interventions

17

and the effectiveness of

stress inoculation training, a specific form of

cognitive–behavioral intervention.

70

This sup-

ports the robustness of the present finding.

The effectiveness of cognitive–behavioral

interventions has also been shown in compar-

ative treatment outcome studies conducted in

psychotherapeutic settings (e.g., Firth and

Shapiro

69

). This may indicate that interventions

conducted by general practitioners or occupa-

tional physicians or referred by them to psy-

chologists or psychotherapists should be

cognitive–behavioral in nature. However, a het-

erogeneous effect was found for cognitive–

behavioral interventions, which implies that

some interventions were very effective and oth-

ers were not. Future research should be directed

at predictors of treatment effects. Furthermore,

a cautionary note is necessary here because

differential effects in regard to outcome vari-

ables were found for the different interventions

that focused on individuals.

With respect to outcome variables,

cognitive–behavioral interventions appeared to

be effective in improving perceived quality of

work life, enhancing psychologic resources and

responses, and reducing complaints. Multimodal

programs showed similar effects; however, they

appeared to be ineffective in increasing psycho-

logic resources and responses. In terms of psy-

chophysiologic outcomes, relaxation techniques

(whether pure or embedded in a multimodal pro-

gram) appeared to be effective. However, the ef-

fectiveness of cognitive–behavioral programs in

the area of psychophysiologic outcomes was ex-

amined only in 2 studies that yielded no posi-

tive outcomes. The finding that different inter-

ventions resulted in different levels of

effectiveness for specific outcomes indicates that

choice of intervention for a particular individ-

ual or group may be determined by the outcome

sought.

In contrast to the consensus among re-

searchers on the content of interventions, there

was considerable diversity in the outcome vari-

ables used.As a result, some of our outcome cat-

egories were broadly defined.As noted earlier, the

robustness of our findings was supported by com-

parisons with findings from 2 more restricted

meta-analyses, and the pattern of results was con-

firmed as well when we narrowed our outcomes

(to anxiety and depression symptoms). In 18 stud-

ies, anxiety was an outcome variable. In 8 stud-

ies, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was used.

There were no differences in effect sizes or sig-

nificance levels between analysis with this in-

strument and those using other anxiety measures.

Regarding cognitive–behavioral inter-

ventions, we found an inverse relation between

number of sessions and effect size. Effect size

plotted against number of sessions showed no

optimum number. The mean number of ses-

sions for the 9 cognitive–behavioral interven-

tion studies with large effect sizes was 6.8; the

mean number of sessions for all cognitive–

behavioral interventions was 7.6. The inverse

relationship found cannot be attributed to a

planned relationship between number of ses-

sions and severity of symptoms. All programs

had a fixed number of sessions, and, because

there were only 2 cognitive–behavioral stud-

ies involving participant selection on baseline

values (both with 8 sessions), there was no

planned relationship at the program level. This

result is in accordance with the finding of Bar-

kum and Shapiro

71

concerning the effective-

ness of brief therapeutic interventions.

Another interesting issue is that of the

marginally significant effect of occupational

status on treatment outcome. Occupational sta-

tus may be indicative of level of job control.

13

Stress-reducing interventions appeared to be

effective for populations at high levels of job

control, in contrast to populations at low lev-

els. Although caution should be exercised here

because level of job control is inferred from

occupational status, and job control can ap-

parently vary extensively within a particular

type of occupational status, elaboration of this

effect may generate new hypotheses.

The difference between employees with

high job control and those with low job control

may be attributed to the fact that all cognitive–

behavioral and multimodal interventions in-

volved the former group. Because cognitive–

behavioral interventions produced the largest

effects, the effect found for occupational status

may be confounded. However, the relatively

large effect size found for cognitive–behavioral

interventions with employees with high job

control may also be explained by the fact that

employees profit most when they are provided

with individual coping skills in a job that allows

them to exercise those skills. If so, these inter-

ventions may be less effective for employees

working in a constrained environment. Unfor-

tunately, this hypothesis could not be tested,

because only 1 study was conducted in which

the effect of a cognitive–behavioral intervention

was investigated with employees with low job

control.

The idea that, in addition to the pattern of

symptoms, the type of work patients do is in-

dicative of the type of intervention that should

be used is in line with the recommendations of

Kahn and Byosiere

72

and, more recently, Kom-

pier et al.

73

In stress reduction programs, the

type of intervention used should be based on

systematic identification of stress risk factors

and risk groups. Without such a systematic risk

assessment, there will be no optimal fit between

intervention and individual, which may result in

the absence of an effect. However, this hypoth-

esis needs to be addressed in future research.

Surprisingly, no effect was found for

organization-focused interventions. This lack

of effect is remarkable in that successes have

been reported in (uncontrolled) evaluations of

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2 American Journal of Public Health 275

organization-focused interventions.

73

A num-

ber of factors may explain this lack of effect.

First, with the exception of absenteeism,

all outcomes were assessed at an individual

level. The primary outcomes of organizational

interventions involve aspects of the workplace.

Thus, individual-level outcomes with this kind

of intervention depend on an intermediate ef-

fect. Therefore, it may take time to produce

measurable effects at the individual level.

Second, organization-focused interven-

tions lack an individually tailored focus. Many

organization-focused programs aim at en-

hancing job control. However, individual per-

ception and coping skills are necessary if one

is to use this extra control and make it prof-

itable. Support for this hypothesis may be found

in the Jones et al.

46

study. Of the organization-

focused interventions included in our sample,

only that study incorporated training in per-

ception and coping skills at an individual level.

Contrary to the other organizational studies,

that study yielded a significant effect. Although

such research on the effectiveness of combined

interventions was recommended years ago by

Murphy,

16

this area clearly remains an issue

for future research.

The preceding considerations are in op-

position to the broadly shared vision that there

is a hierarchy of interventions in which pri-

mary prevention should prevail over interven-

tions that focus on individuals in efforts to re-

duce work-related stress.

5,12,50,74

In jobs that

already involve a high degree of decision lati-

tude, cognitive–behavioral interventions seem

to be most effective. These interventions, in

such an environment, can influence individual

variations in perception and use of coping

skills. In jobs with a low degree of decision

latitude, organization-focused interventions

aimed at increasing control potentials should

prevail, accompanied by cognitive–behavioral

interventions. If this strategy is not possible,

interventions that focus on enhancing passive

coping (relaxation techniques) have a moder-

ate but proven effect.

The present study aimed at investigating

the evidence concerning the effectiveness of

stress-reducing interventions. As noted earlier,

support was found for the benefits of such pro-

grams. However, a number of intriguing issues

remain to be addressed in future research.

Among these issues are the evaluation of oc-

cupational stress interventions with patients

treated by occupational physicians or general

practitioners and the development and con-

trolled evaluation of interventions involving a

combined individual and organizational focus.

Research on predictors of treatment effects

(e.g., job control) will be important in terms

of enhancing effects and processes of change.

Insight into the conditions under which an in-

tervention is most effective may enhance the

development of more effective intervention

strategies. We also recommend that a controlled

follow-up of at least 12 weeks be part of the

design of intervention studies.

Finally, we noted considerable diversity

in the outcome variables used, apparently rooted

in conceptual ambiguity about the core dimen-

sions of stress outcomes. Research on the core

dimensions of stress outcomes, which will lead

to more consensus about outcomes and instru-

ments used, is indispensable for the further de-

velopment and evaluation of interventions.

Contributors

All of the authors participated in planning the study,

in interpreting the analysis outcomes, and in writing

the paper. J. J. L. van der Klink and R.W.B. Blonk con-

ducted the analyses.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the

Occupational Health Service of Royal PTT Neder-

land (KPN) and the Netherlands Organisation of Sci-

entific Research (NWO).

References

1. Friedli K, King MB, Lloyd M, Horner J. Ran-

domised controlled assessment of non-directive

psychotherapy versus routine general-practi-

tioner care. Lancet. 1997;350:1662–1665.

2. Murphy LR. Stress management in working set-

tings: a critical review of the health effects. Am

J Health Promotion. 1996;11:112–135.

3. Cartwright S, Cooper CL. Managing Workplace

Stress. London, England: Sage Publications;

1997.

4. Terluin B. Nervous Breakdown Substantiated:

A Study of the General Practitioner’s Diagno-

sis of Surmenage [in Dutch] [thesis]. Zeist, the

Netherlands: Kerckebosch; 1994.

5. Murphy LR. Occupational stress management:

a review and appraisal. J Occup Psychol. 1984;

57:1–15.

6. Roskies E. Stress Management for the Healthy

Type A: Theory and Practice. New York, NY:

Guilford Press; 1987.

7. Meichenbaum DH, Cameron R. Stress inocula-

tion training. In: Meichenbaum DH, Jarenko

ME, eds. Stress Reduction and Prevention. New

York, NY: Plenum Press; 1983:115–154.

8. Cooper CL, Sadri G. The impact of stress coun-

seling at work. In: Crandall R, Perrewé PL, eds.

Occupational Stress: A Handbook. Washington,

DC: Taylor & Francis; 1995:273–282.

9. Golembiewski RT, Hilles R, Daly R. Some ef-

fects of multiple OD interventions on burnout

and work site features. J Appl Behav Sci. 1987;

23:295–313.

10. Heaney CA, Price RH, Rafferty J. Increasing

coping resources at work: a field experiment to

increase social support, improve work team

functioning, and enhance employee mental

health. J Organ Behav. 1995;16:335–352.

11. Schurman SJ, Israel BA. Redesigning work sys-

tems to reduce stress: a participatory action re-

search approach to creating change. In: Murphy

LR, Hurrell JJ Jr, Sauter SL, Keita GP, eds. Job

Stress Interventions. Washington, DC: Ameri-

can Psychological Association; 1995:235–261.

12. Newman JE, Beehr TA. Personal and organiza-

tional strategies for handling job stress: a review

of research and opinion. Personnel Psychol.

1979;32:1–43.

13. DeFrank RS, Cooper CL. Worksite stress man-

agement interventions: their effectiveness and

conceptualisation. J Manage Psychol. 1987;2:

4–10.

14. Ivancevich JM, Matteson MT, Freedman SM,

Phillips JS. Worksite stress management inter-

ventions. Am Psychol. 1990;45:252–261.

15. McLeroy KR, Green LW, Mullen KD, Foshee V.

Assessing the effects of health promotion in

worksites. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:379–401.

16. Murphy LR. Workplace interventions for stress

reduction and prevention. In: Cooper CL, Payne

R, eds. Causes, Coping, and Consequences of

Stress at Work. Chichester, England: John Wiley

& Sons Inc; 1988:301–339.

17. Bamberg E, Busch C. Employee health im-

provement by stress management training: a

meta-analysis of (quasi-)experimental studies

[in German]. Z Arbeits Organisationspsychol.

1996;40:127–137.

18. van der Hek H, Plomp HN. Occupational stress

management programs: a practical overview of

published effect studies. Occup Med. 1997;47:

133–141.

19. Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping.

J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:2–21.

20. Karasek RA, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress,

Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Work-

ing Life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990.

21. Aderman M, Tecklenburg K. Effect of relax-

ation training on personal adjustment and per-

ceptions of organizational climate. J Psychol.

1983;115:185–191.

22. Carrington P, Collings GH Jr, Benson H, et al.

The use of meditation-relaxation techniques for

the management of stress in a working popula-

tion. J Occup Med. 1980;22:221–231.

23. Vaughn M, Cheatwood S, Sirles AT, Brown KC.

The effect of progressive muscle relaxation on

stress among clerical workers. Am Assoc Occup

Health Nurs J. 1989;37:302–306.

24. Vines SW. Effects on employees’ psychological

distress and health seeking behaviors. Am Assoc

Occup Health Nurs J. 1994;42:206–213.

25. Mullen B. Advanced Basic Meta-Analysis.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;

1989.

26. Mullen B, Rosenthal R. BASIC Meta-Analysis:

Procedures and Programs. Hillsdale, NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum Associates; 1985.

27. Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Meta-analytic proce-

dures for combining studies with multiple ef-

fect sizes. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:400–406.

28. Alexander CN, Swanson GC, Rainforth MV,

Carlisle TW, Todd CC, Oates RM Jr. Effects of

the transcendental meditation program on stress

reduction, health, and employee development:

a prospective study in two occupational settings.

Anxiety Stress Coping. 1993;6:245–262.

29. Arnetz BB. Techno-stress: a prospective psy-

chophysiological study of the impact of a con-

trolled stress-reduction program in advanced

telecommunication systems design work. J

Occup Environ Med. 1996;38:53–65.

30. von Baeyer C, Krause L. Effectiveness of stress

February 2001, Vol. 91, No. 2276 American Journal of Public Health

management training for nurses working in a

burn treatment unit. Int J Psychol Med. 1983;

13:113–125.

31. Bertoch MR, Nielsen EC, Curley JR, Borg WR.

Reducing teacher stress. J Exp Educ. 1989;57:

117–128.

32. Bruning NS, Frew DR. Can stress intervention

strategies improve self-esteem, manifest anxi-

ety, and job satisfaction? A longitudinal field

experiment. J Health Hum Resources Adm.

1986;9:110–124.

33. Cecil MA, Forman SG. Effects of stress inocu-

lation training and co-worker support groups on

teachers’ stress. J Sch Psychol. 1990;28:

105–118.

34. Curtis KA. Altering beliefs about the impor-

tance of strategy: an attributional intervention. J

Appl Soc Psychol. 1992;22:953–972.

35. Fava M, Littman A, Halperin P, et al. Psycho-

logical and behavioral benefits of a stress/type A

behavior reduction program for healthy middle-

aged army officers. Psychosomatics. 1991;32:

337–342.

36. Fiedler N, Vivona-Vaughan E, Gochfeld M.

Evaluation of a work site relaxation training pro-

gram using ambulatory blood pressure moni-

toring. J Occup Med. 1989;31:595–602.

37. Forman SG. Stress-management training: eval-

uation of effects on school psychological serv-

ices. J Sch Psychol. 1981;19:233–241.

38. Freedy JR, Hobfoll SE. Stress inoculation for

reduction of burnout: a conservation of resources

approach. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1994;6:

311–325.

39. Friedman GH, Lehrer BE, Stevens JP. The ef-

fectiveness of self-directed and lecture/discus-

sion stress management approaches and the

locus of control of teachers. Am Educ Res J.

1983;20:563–580.

40. Ganster DC, Mayes BT, Sime WE, Tharp GD.

Managing organizational stress: a field experi-

ment. J Appl Psychol. 1982;67:533–542.

41. Gray-Toft P. Effectiveness of a counseling sup-

port program for hospice nurses. J Counseling

Psychol. 1980;27:346–354.

42. Grønningsæter H, Hytten K, Skauli G, Chris-

tensen CC, Ursin H. Improved health and cop-

ing by physical exercise or cognitive behavioral

stress management training in a work environ-

ment. Psychol Health. 1992;7:147–163.

43. Higgins NC. Occupational stress and working

women: the effectiveness of two stress reduc-

tion programs. J Vocational Behav. 1986;29:

66–78.

44. Jackson SE. Participation in decision making as

a strategy for reducing job-related strain. J Appl

Psychol. 1983;68:3–19.

45. Johanson N. Effectiveness of a stress manage-

ment program in reducing anxiety and depres-

sion in nursing students. J Am Coll Health. 1991;

40:125–129.

46. Jones JW, Barge BN, Steffy BD, Fay LM,

Kunz LK, Wuebker LJ. Stress and medical

malpractice: organizational risk assessment

and intervention. J Appl Psychol. 1988;73:

727–735.

47. Keyes JB, Dean SF. Stress inoculation training

for direct contact staff working with mentally

retarded persons. Behav Residential Treatment.

1988;3:315–323.

48. Kushnir T, Malkinson R. A rational-emotive

group intervention for preventing and coping

with stress among safety officers. J Rational

Emotive Cognitive Behav Ther. 1993;11:

195–206.

49. Kushnir T, Malkinson R, Ribak J. Teaching stress

management skills to occupational and envi-

ronmental health physicians and practitioners.

J Occup Med. 1994;36:1335–1340.

50. Landsbergis PA, Vivona-Vaughan E. Evaluation

of an occupational stress intervention in a pub-

lic agency. J Organ Behav. 1995;16:29–48.

51. Larsson G, Setterlind S, Starrin B. Routiniza-

tion of stress control programs in organizations:

a study of Swedish teachers. Health Promotion

Int. 1990;5:269–278.

52. Lee S, Swanson Crockett M. Effect of as-

sertiveness training on levels of stress and as-

sertiveness experienced by nurses in Taiwan,

Republic of China. Issues Ment Health Nurs.

1994;15:419–432.

53. Long BC. Stress management for school per-

sonnel: stress-inoculation training and exercise.

Psychol Schools. 1988;25:314–324.

54. McCue JD, Sachs CL. A stress management

workshop improves residents’coping skills. Arch

Intern Med. 1991;151:2273–2277.

55. McNulty S, Jefferys D, Singer G, Singer L. Use

of hormone analysis in the assessment of the

efficacy of stress management training in po-

lice recruits. J Police Soc Adm. 1984;12:

130–132.

56. Murphy LR. A comparison of relaxation meth-

ods for reducing stress in nursing personnel.

Hum Factors. 1983;25:431–440.

57. Murphy LR. Stress management in highway

maintenance workers. J Occup Med. 1984;26:

436–442.

58. Norvell N, Belles D, Brody S, Freund A. Work-

site stress management for medical care per-

sonnel: results from a pilot program. J Special-

ists Group Work. 1987;12:118–126.

59. Peters RK, Benson H, Porter D. Daily relaxation

response breaks in a working population, I: ef-

fects on self-reported measures of health, per-

formance, and well-being. Am J Public Health.

1977;67:946–953.

60. Peters RK, Benson H, Peters JM. Daily relax-

ation response breaks in a working population,

II: effects on blood pressure. Am J Public Health.

1977;67:954–959.

61. Pruitt RH. Effectiveness and cost efficacy of in-

terventions in health promotion. J Adv Nurs.

1992;17:926–932.

62. Sharp JJ, Forman SG. A comparison of two ap-

proaches to anxiety management for teachers.

Behav Ther. 1985;16:370–383.

63. Toivanen H, Länsimies E, Jokela V, Hänninen

O. Impact of regular relaxation training on the

cardiac autonomic nervous system of hospital

cleaners and bank employees. Scand J Work En-

viron Health. 1993;19:319–325.

64. Toivanen H, Helin P, Hänninen O. Impact of reg-

ular relaxation training and psychosocial work-

ing factors on neck-shoulder tension and ab-

senteeism in hospital cleaners. J Occup Environ

Med. 1993;35:1123–1130.

65. Tsai S, Swanson Crockett M. Effects of relax-

ation training, combining imagery, and medita-

tion on the stress level of Chinese nurses work-

ing in modern hospitals in Taiwan. Issues Ment

Health Nurs. 1993;14:51–66.

66. Tunnecliff MR, Leach DJ, Tunnecliff LP. Rela-

tive efficacy of using behavioral consulting as

an approach to teacher stress management. J Sch

Psychol. 1986;24:123–131.

67. West DJ, Horan JJ, Games PA. Component

analysis of occupational stress inoculation ap-

plied to registered nurses in an acute care hos-

pital setting. J Counseling Psychol. 1984;31:

209–218.

68. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Be-

havioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic

Press Inc; 1988.

69. Firth J, Shapiro DA. An evaluation of psycho-

therapy for job-related distress. J Occup Psy-

chol. 1986;59:111–119.

70. Saunders T, Driskell JE, Hall Johnston J, Salas

E. The effect of stress inoculation training on

anxiety and performance. J Occup Psychol.

1997;70:170–186.

71. Barkum M, Shapiro DA. Brief psychotherapy

interventions for job-related distress: a pilot

study of prescriptive and exploratory therapy.

Counseling Psychol Q. 1990;2:133–147.

72. Kahn RL, Byosiere P. Stress in organizations.

In: Dunette MD, Hough LM, eds. Handbook of

Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd

ed. Vol 3. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychol-

ogists Press; 1992:571–650.

73. Kompier MAJ, Geurts SAE, Gründemann

RWM, Vink P, Smulders PGW. Cases in stress

prevention: the success of a participative and

stepwise approach. Stress Med. 1998;14:

155–168.

74. Baker DB. The study of stress at work. Annu

Rev Public Health. 1995;6:367–381.