University of Richmond

UR Scholarship Repository

Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science

Spring 2013

University of Richmond, md[email protected]du

Follow this and additional works at: h8p://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications

Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Economic Policy

Commons, International Business Commons, and the Models and Methods Commons

7is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in

Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact

scholarshiprepository@richmond.edu.

Recommended Citation

Da8a, Monti Narayan, and Kevin Bales. "Slavery Is Bad for Business: Analyzing the Impact of Slavery on National Economies." e

Brown Journal of World Aairs 19, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2013): 205-23.

205

S/S

2013

• ,

205

Copyright © 2013 by the Brown Journal of World Aairs

Slavery is Bad for Business:

Analyzing the Impact of Slavery on

National Economies

Assistant Professor

M N D

University of Richmond

P and modern-day slavery is reach-

ing a tipping point—it is coming to be understood as a global problem with

economic and policy implications far beyond simple reports of cross-border

human tracking. A decade ago most educated citizens considered slavery a

phenomenon of the past, relegated to history textbooks. Today a strong narra-

tive has reached global proportions: activists, epistemic communities, NGOs,

IGOs, and governments are acknowledging the scope and extent of slavery in

the twenty-rst century. One need only point to Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl

Wu Dunn’s bestseller Half the Sky, President Barack Obama’s 2012 speech at the

Clinton Global Intiative, or the awareness that celebrities such as Mira Sorvino

and Jada Pinkett Smith are raising about the subject to illustrate how far the

antislavery movement has progressed.

1

Yet despite such civic mindedness, surprisingly little data and empirically

driven research exist on slavery today. Although some headway has been made

in estimating its prevalence—most notably in the form of contributions by

Kevin Bales and by the International Labor Organization (ILO)—apart from a

Professor

K B

University of Hull

M N D is assistant professor of political science at the University of Richmond. He is

the author of Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the U.S. National Interest

(Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). He is developing several projects on human tracking and

modern-day slavery with Kevin Bales of Free the Slaves and Helen Sworne and Siobhan Miles of Chab Dai.

K B is professor of contemporary slavery at the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and

Emancipation at the University of Hull. He is the author of Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global

Economy (University of California Press, 1999) and a number of other books on contemporary slavery.

He is currently completing a book on the relationship between slavery and environmental destruction

and global warming and a project on global forced marriage with Jody Sarich.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

206

207

as jus cogens, a norm from which no derogation is ever permitted. As an illegal

economic activity, it is restricted, at least nominally, in all nation-states. On a

moral level, no rational politician would condone slavery today. Indeed, nor-

matively, the twenty-rst century is an age in which it is socially fashionable to

wear T-shirts or display bumper stickers that promote the antislavery movement.

On the other hand, contemporary slavery, like its historical antecedent,

yields certain economic benets, albeit for a very small portion of the global

economy. e ILO estimates that about $44 billion USD per year is made in

slavery-derived prots. Although this is a drop in the bucket of global economic

output, valued at $74 trillion, it suggests that, at least for illicit markets, there

are incentives to perpetute slavery.

7

e prots of slavery ow primarily to

slaveholders, who benet from global markets and global prices. For example,

a criminal who uses slaves to produce a cotton crop will sell his cotton at the

same price as his neighbor who does not exploit slaves. ey both receive the

market price, one which is ultimately set in the global commodity exchanges.

While both farmers receive the same price for their cotton, the slave-using farmer

will have a higher prot margin due to his much lower labor cost, amounting

to bare subsistence for his workers. With a guaranteed market price, he has no

incentive to sell at a lower rate. As with many other criminal enterprises such

as drug tracking, the estimated prot margins found in contemporary slavery

are sometimes astoundingly high.

8

Prot margins vary in contemporary slavery. At one end of the spectrum

is the commercial sexual exploitation of enslaved women. Such an illegal—and

extremely brutal—working-class brothel business has been found to generate

prot margins in the order of 850 percent in the booming economy of ailand,

a locality with high levels of demand.

As Table 1 shows, the monthly prots from slavery in a working-class

brothel in a small town in western ailand are about $72,000. Annually, this

yields a net prot of $864,000. Brothels serving richer clients or sex tourists

might be expected to fare better. e fact that there are dozens of brothels in

this small town alone suggests that enslavement for sexual exploitation is a

multimillion-dollar business in the region.

At the other end of the spectrum are traditional forms of enslavement that

tend to be part of a country’s local economy. Brick kilns that rely on slave labor

in rural Pakistan, for example, generate around 25 percent prot, compared to

10–15 percent for those kilns that pay their workers. At the same time, hereditary

forms of collateral debt bondage with similar prot margins, practiced in agricul-

tural slavery in northern India, remain extensive.

9

Adding to the protability of

rough estimate of how many slaves exist in the world today (21 to 27 million),

scholars and policy makers know little about the risk factors—let alone the busi-

ness impact—that contemporary slavery has on the global community.

2

Indeed,

most extant research, athough useful, is qualitative, not allowing for statistical

models.

3

To what extent is slavery empirically bad for business? For whom is

the business of slavery protable, and for whom is it economically burdensome?

is article, using a novel dataset, demonstrates that slavery is empirically

bad for business. Building upon the work of Robert Smith, our analysis exam-

ines the relationship between the prevalence of slavery in a country (in terms of

the proportion of the population enslaved) and several economic measures (the

United Nations Human Development Index,

growth domestic product in terms of purchas-

ing power parity, access to nancial services,

and the Gini coecient).

4

In each instance,

controlling for alternative explanations, greater

levels of slavery are associated with a decline in economic growth and human

development. e ndings imply that beyond the morality of the issue, slavery

is objectively harmful for total economic output and social development. is

article begins with a discussion of how slavery is protable for slaveholders and

then proceeds with a discussion of how it undermines social and economic

output at the macro level.

conteMPorary slavery: ProfitaBle for slaveholders

A signicant amount of historical and economic research has examined the

slavery of the past and clearly demonstrates its protability for slaveholders.

5

As a legal enterprise, slavery in the past generated ancillary economic activity in

the form of insurance, transport, advertising, loans, credit, mortgages, and so

on. Governments could also tax proceeds from slave-trading and slave use and

regulate the activities and procedures of slavery. Although a moral evil, histori-

cally slavery was good for business.

6

Contemporary slavery, primarily due to its universal illegality, is a far dif-

ferent creature. e fundamental nature of slave work has not changed dramati-

cally; it is still dirty, dangerous, and demeaning. Most slaves work in agriculture,

mining or other such extractive industries, assembly, food processing, manu-

facturing, or what might be called “personal (forced) services” such as domestic

service or commercial sexual exploitation. It is a type of work that tends to be

hidden because it is illegal in all countries and condemned in international law

Slavery is objectively harmful

for total economic output

and social development.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

206

207

as jus cogens, a norm from which no derogation is ever permitted. As an illegal

economic activity, it is restricted, at least nominally, in all nation-states. On a

moral level, no rational politician would condone slavery today. Indeed, nor-

matively, the twenty-rst century is an age in which it is socially fashionable to

wear T-shirts or display bumper stickers that promote the antislavery movement.

On the other hand, contemporary slavery, like its historical antecedent,

yields certain economic benets, albeit for a very small portion of the global

economy. e ILO estimates that about $44 billion USD per year is made in

slavery-derived prots. Although this is a drop in the bucket of global economic

output, valued at $74 trillion, it suggests that, at least for illicit markets, there

are incentives to perpetute slavery.

7

e prots of slavery ow primarily to

slaveholders, who benet from global markets and global prices. For example,

a criminal who uses slaves to produce a cotton crop will sell his cotton at the

same price as his neighbor who does not exploit slaves. ey both receive the

market price, one which is ultimately set in the global commodity exchanges.

While both farmers receive the same price for their cotton, the slave-using farmer

will have a higher prot margin due to his much lower labor cost, amounting

to bare subsistence for his workers. With a guaranteed market price, he has no

incentive to sell at a lower rate. As with many other criminal enterprises such

as drug tracking, the estimated prot margins found in contemporary slavery

are sometimes astoundingly high.

8

Prot margins vary in contemporary slavery. At one end of the spectrum

is the commercial sexual exploitation of enslaved women. Such an illegal—and

extremely brutal—working-class brothel business has been found to generate

prot margins in the order of 850 percent in the booming economy of ailand,

a locality with high levels of demand.

As Table 1 shows, the monthly prots from slavery in a working-class

brothel in a small town in western ailand are about $72,000. Annually, this

yields a net prot of $864,000. Brothels serving richer clients or sex tourists

might be expected to fare better. e fact that there are dozens of brothels in

this small town alone suggests that enslavement for sexual exploitation is a

multimillion-dollar business in the region.

At the other end of the spectrum are traditional forms of enslavement that

tend to be part of a country’s local economy. Brick kilns that rely on slave labor

in rural Pakistan, for example, generate around 25 percent prot, compared to

10–15 percent for those kilns that pay their workers. At the same time, hereditary

forms of collateral debt bondage with similar prot margins, practiced in agricul-

tural slavery in northern India, remain extensive.

9

Adding to the protability of

rough estimate of how many slaves exist in the world today (21 to 27 million),

scholars and policy makers know little about the risk factors—let alone the busi-

ness impact—that contemporary slavery has on the global community.

2

Indeed,

most extant research, athough useful, is qualitative, not allowing for statistical

models.

3

To what extent is slavery empirically bad for business? For whom is

the business of slavery protable, and for whom is it economically burdensome?

is article, using a novel dataset, demonstrates that slavery is empirically

bad for business. Building upon the work of Robert Smith, our analysis exam-

ines the relationship between the prevalence of slavery in a country (in terms of

the proportion of the population enslaved) and several economic measures (the

United Nations Human Development Index,

growth domestic product in terms of purchas-

ing power parity, access to nancial services,

and the Gini coecient).

4

In each instance,

controlling for alternative explanations, greater

levels of slavery are associated with a decline in economic growth and human

development. e ndings imply that beyond the morality of the issue, slavery

is objectively harmful for total economic output and social development. is

article begins with a discussion of how slavery is protable for slaveholders and

then proceeds with a discussion of how it undermines social and economic

output at the macro level.

conteMPorary slavery: ProfitaBle for slaveholders

A signicant amount of historical and economic research has examined the

slavery of the past and clearly demonstrates its protability for slaveholders.

5

As a legal enterprise, slavery in the past generated ancillary economic activity in

the form of insurance, transport, advertising, loans, credit, mortgages, and so

on. Governments could also tax proceeds from slave-trading and slave use and

regulate the activities and procedures of slavery. Although a moral evil, histori-

cally slavery was good for business.

6

Contemporary slavery, primarily due to its universal illegality, is a far dif-

ferent creature. e fundamental nature of slave work has not changed dramati-

cally; it is still dirty, dangerous, and demeaning. Most slaves work in agriculture,

mining or other such extractive industries, assembly, food processing, manu-

facturing, or what might be called “personal (forced) services” such as domestic

service or commercial sexual exploitation. It is a type of work that tends to be

hidden because it is illegal in all countries and condemned in international law

Slavery is objectively harmful

for total economic output

and social development.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

208

209

of enslaved people since replacement can be more cost eective than care. e

cost of slaves is now so low that they are often seen as disposable inputs into

criminal enterprises rather than as capital investments.

tainted Goods

Although slavery might benet slaveholders, it negatively aects everyone else—

ranging from slaves to the global consumer—in dierent ways. e negative

impact for global consumers is not economic but moral and political. Slavery does

not reduce or increase prices but does involve consumers in illegal and immoral

activities. Many countries including the United States prohibit the importation

of slave-made goods, and case law going back to the eighteenth century allows

the conscation of goods that circumstantially may have been involved in the

slave trade. Adding to this is the repugnance expressed by most consumers at the

idea of buying goods made by slaves, especially child slaves—and that repugnance

is hard to avoid. Slaves are used in the production of many basic commodities

that ow from the poor Global South to the rich North, as well as of some

goods, such as tomatoes and oranges, produced and consumed in the North.

12

Originating from numerous countries, documented cases of slavery exist in the

production of textiles, gemstones, apparel, and agricultural products.

13

Coee

is sometimes grown using slave labor, and some sugar is harvested by slaves. In

the Congo, for example, armed gangs enslave local people and force them to dig

minerals such as coltan, cassiterite, wolframite, and tungsten. ese minerals

are then sold to exporters who send them to Europe and Asia where they are

used to make components needed for the production of cell phones, comput-

ers, and other electronics.

14

Slavery also creeps into nancial investments when

pension funds or mutual funds carry stock in companies that subcontract other

companies that use slave labor.

15

ese modern, scattered, small-scale, and criminal slave-based enterprises

contrast markedly with the relatively much larger economic organization of

historical slavery, in which, as evil as it was, the economic benets of the legal

slave trade were diused throughout local and regional economies. In the past,

it could be assumed that a sizable proportion of commodities such as sugar and

cotton was produced by slaves and that the prots from such enterprises would

be cycled back through local, regional, and national economies along with the

prots from other legitimate businesses.

16

Today, however, the situation is more complicated in that it is slaveholders

who primarily benet from contempary slavery. Consider the cocoa industry

contemporary slavery, regardless of the type of slavery, is the exceptionally low cost

of acquiring slaves.

10

For most of human history, slaves were expensive. In 1850,

for example, the average price of an “average” slave in the American South (a

“prime eld hand” meaning a young man capable of heavy agricultural work) was

between $1,000 and $1,200 in 1850 dollars, which equates to around $45,000

in 2013 dollars.

11

Today it could be argued that slaves are less expensive today

than at any time in the past. In a marketplace in the central region of the Ivory

Coast, one researcher easily purchased two 19-year-old agricultural workers for

about $30 each. In India, bonded laborers are able to report precise sums that

represent the acquisition cost required to enslave their family (often the debt

being taken some generations previously and passed down)—ranging from as

little as $10 to over $100. In Brazil desperate urban workers place themselves

in the hands of recruiters only to nd themselves held under violence far in the

forests and charged with a “debt” amounting to a few hundred dollars. Even in

ailand, where teenagers are sold into prostitution and a premium is charged

for their virginity and attractiveness, prices rarely go over $1000.

Table 1. Monthly income and expenditures (in baht) for the always prospering

brothel.U.S. gures adjusted for ination for 2012. Source: Kevin Bales, Disposable

People: New Slavery in the Global Economy (University of California Press, 1999).

Low initial acquisition costs means that slave owners neglect the welfare

Table 1. Monthly Income & Expenditure (in Baht) for the Always Prospering Brothel

Costs (per month)

Income (per month)

Rent

5,000

Commercial sex*

1,050,000

Utilities & bills

2,000

Rent paid by prostitutes

600,000

Food & drink

45,000

Sale of condoms

70,000

Pimp’s salary

7,000

Sale of drinks

672,000

Cashier

7,000

Virgin premium

50,000

Cook

5,000

“Interest” on debt-bond

15,000

Bribes

6,000

Payments to taxis etc.

12,000

Beer & whisky

168,000

TOTAL COSTS

257,000

TOTAL INCOME

2,457,000

(In US dollars)

($8,389)

MONTHLY PROFIT

2,200,000

(In U.S. dollars)

($71,813)

*Average 14 clients per day at 125 baht per client for 20 prostitutes for 30 days.

Source: Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, University of California

Press, 1999. U.S. figures adjusted for inflation for the year 2012.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

208

209

of enslaved people since replacement can be more cost eective than care. e

cost of slaves is now so low that they are often seen as disposable inputs into

criminal enterprises rather than as capital investments.

tainted Goods

Although slavery might benet slaveholders, it negatively aects everyone else—

ranging from slaves to the global consumer—in dierent ways. e negative

impact for global consumers is not economic but moral and political. Slavery does

not reduce or increase prices but does involve consumers in illegal and immoral

activities. Many countries including the United States prohibit the importation

of slave-made goods, and case law going back to the eighteenth century allows

the conscation of goods that circumstantially may have been involved in the

slave trade. Adding to this is the repugnance expressed by most consumers at the

idea of buying goods made by slaves, especially child slaves—and that repugnance

is hard to avoid. Slaves are used in the production of many basic commodities

that ow from the poor Global South to the rich North, as well as of some

goods, such as tomatoes and oranges, produced and consumed in the North.

12

Originating from numerous countries, documented cases of slavery exist in the

production of textiles, gemstones, apparel, and agricultural products.

13

Coee

is sometimes grown using slave labor, and some sugar is harvested by slaves. In

the Congo, for example, armed gangs enslave local people and force them to dig

minerals such as coltan, cassiterite, wolframite, and tungsten. ese minerals

are then sold to exporters who send them to Europe and Asia where they are

used to make components needed for the production of cell phones, comput-

ers, and other electronics.

14

Slavery also creeps into nancial investments when

pension funds or mutual funds carry stock in companies that subcontract other

companies that use slave labor.

15

ese modern, scattered, small-scale, and criminal slave-based enterprises

contrast markedly with the relatively much larger economic organization of

historical slavery, in which, as evil as it was, the economic benets of the legal

slave trade were diused throughout local and regional economies. In the past,

it could be assumed that a sizable proportion of commodities such as sugar and

cotton was produced by slaves and that the prots from such enterprises would

be cycled back through local, regional, and national economies along with the

prots from other legitimate businesses.

16

Today, however, the situation is more complicated in that it is slaveholders

who primarily benet from contempary slavery. Consider the cocoa industry

contemporary slavery, regardless of the type of slavery, is the exceptionally low cost

of acquiring slaves.

10

For most of human history, slaves were expensive. In 1850,

for example, the average price of an “average” slave in the American South (a

“prime eld hand” meaning a young man capable of heavy agricultural work) was

between $1,000 and $1,200 in 1850 dollars, which equates to around $45,000

in 2013 dollars.

11

Today it could be argued that slaves are less expensive today

than at any time in the past. In a marketplace in the central region of the Ivory

Coast, one researcher easily purchased two 19-year-old agricultural workers for

about $30 each. In India, bonded laborers are able to report precise sums that

represent the acquisition cost required to enslave their family (often the debt

being taken some generations previously and passed down)—ranging from as

little as $10 to over $100. In Brazil desperate urban workers place themselves

in the hands of recruiters only to nd themselves held under violence far in the

forests and charged with a “debt” amounting to a few hundred dollars. Even in

ailand, where teenagers are sold into prostitution and a premium is charged

for their virginity and attractiveness, prices rarely go over $1000.

Table 1. Monthly income and expenditures (in baht) for the always prospering

brothel.U.S. gures adjusted for ination for 2012. Source: Kevin Bales, Disposable

People: New Slavery in the Global Economy (University of California Press, 1999).

Low initial acquisition costs means that slave owners neglect the welfare

Table 1. Monthly Income & Expenditure (in Baht) for the Always Prospering Brothel

Costs (per month)

Income (per month)

Rent

5,000

Commercial sex*

1,050,000

Utilities & bills

2,000

Rent paid by prostitutes

600,000

Food & drink

45,000

Sale of condoms

70,000

Pimp’s salary

7,000

Sale of drinks

672,000

Cashier

7,000

Virgin premium

50,000

Cook

5,000

“Interest” on debt-bond

15,000

Bribes

6,000

Payments to taxis etc.

12,000

Beer & whisky

168,000

TOTAL COSTS

257,000

TOTAL INCOME

2,457,000

(In US dollars)

($8,389)

MONTHLY PROFIT

2,200,000

(In U.S. dollars)

($71,813)

*Average 14 clients per day at 125 baht per client for 20 prostitutes for 30 days.

Source: Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, University of California

Press, 1999. U.S. figures adjusted for inflation for the year 2012.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

210

211

Slavery generates a downward spiral of social and economic stuntedness. It is a

social and economic cancer.

Only very recently did scholars begin to examine the impact of slavery on

human development. In 2009 Robert Smith was among the rst to analyze a

number of factors that were thought to aect social and economic development

as measured by the United Nations Human Development Index; these factors

included corruption, regime type, internal conict, national debt, geography,

and culture.

20

For the rst time in a study of contemporary nation-states, Smith

included measures of slavery in the analysis of human development using an

earlier version of data from Kevin Bales of Free the Slaves, the center for the

modern abolitionist movement.

21

Smith’s study explored the impact that slavery might have on human de-

velopment and provided insight as to how slavery might t with other factors

that are known to aect development. Given the large amount of work that

has been done to explore determinants of development in the Global South, it

was remarkable that, as Smith explains, “When the full range of the covariates

are retained, and when the four categories of slavery are used to classify the re-

gions, the resulting ... statistics imply that slavery explains much of the regional

variability in the Human Development Index rank scores.”

22

Smith went on to

identify the policy implications:

Among the covariates studied here, slavery (debt bondage, forced labor,

forced prostitution, chattel slavery) and the lack of political freedom

explain much of the variability that is between regions and corruption

explains much of the variability among countries within a region.

Additionally, countries with higher values of conict and social unrest

and higher values of national debt have signicantly worse Human

Development Index rank. To enhance human development countries

should eliminate debt bondage and other forms of slavery, move toward

fully democratic political systems, and eliminate corruption.

23

Clearly there can be mutually reinforcing relationships among these factors.

ese interrelationships point to the circular and reinforcing nature of human

rights violations. In terms of human development and economic development,

the result from Smith’s analysis is clear: slavery impedes economies and societ-

ies even though the proportion of slaves in the global population is small, their

productive capacity is small, and their economic value, as measured by price,

has reached an all-time low.

in the twenty-rst century. In the Ivory Coast, there are about 600,000 small

family farms that grow cocoa, producing just under half of the world’s supply.

17

Young men, normally from neighboring countries such as Mali, migrate looking

for work. In remote rural areas, some are tricked and enslaved into working on

farms that grow a range of crops, including cocoa for export. While no one knows

for certain how many of these farms use slaves, the percentage of farms using

slaves is likely to be in the single digits.

18

When the farmers sell their cocoa to

wholesalers, the slave-grown cocoa is mixed with the free-labor cocoa, and there

is currently no way to tell the two apart.

e farmer who exploits slaves and the

farmer that does not will receive exactly

the same price for their cocoa at the farm

gate. In this way, the prots of slavery

are retained by the slaveholder and are not passed up along the product chain.

e cocoa that is exported from the Ivory Coast to Europe and North America

to be made into chocolate, used in other foodstus, or made into cosmetics is

also mixed with cocoa from other countries; thus, it becomes even harder to

distinguish the fraction that is tainted by slavery.

19

is concealment of slave-

made commodities, made possible through blending in global supply chains, also

applies to cotton, sugar, gold, shrimp, and a host of other products. What the

case of cocoa illustrates, and what applies to virtually all slave-based businesses,

is that prots from slavery tend to accrue solely to the criminal slaveholder and

are not passed up the product chain in the form of lower prices to consumers.

the effects of slavery on huMan develoPMent

Contemporary slavery yields a number of negative social and economic eects.

Slaves, subjects of violence and intimidation on a systematic basis, are unwilling

agents of economic stagnation. From a scal perspective, slave labor tends to

pull down the wages of free labor in the same area, thus lessening the disposable

incomes of free families. At the same time, slaves are not able to play a full role

in their local economy in that they have little or no purchasing power and so

they subsist on the barest necessities.

More generally, slaves, by the nature of their social position, have no means

to contribute to the economy except in minimal ways. ey are not at liberty to

purchase anything in a country’s markets. erefore, slaves, as a group—denied

the benets of human development in the form of education, access to politi-

cal participation, and self-direction—remain an untapped economic resource.

The prots of slavery are retained

by the slaveholder and are not

passed up along the product chain.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

210

211

Slavery generates a downward spiral of social and economic stuntedness. It is a

social and economic cancer.

Only very recently did scholars begin to examine the impact of slavery on

human development. In 2009 Robert Smith was among the rst to analyze a

number of factors that were thought to aect social and economic development

as measured by the United Nations Human Development Index; these factors

included corruption, regime type, internal conict, national debt, geography,

and culture.

20

For the rst time in a study of contemporary nation-states, Smith

included measures of slavery in the analysis of human development using an

earlier version of data from Kevin Bales of Free the Slaves, the center for the

modern abolitionist movement.

21

Smith’s study explored the impact that slavery might have on human de-

velopment and provided insight as to how slavery might t with other factors

that are known to aect development. Given the large amount of work that

has been done to explore determinants of development in the Global South, it

was remarkable that, as Smith explains, “When the full range of the covariates

are retained, and when the four categories of slavery are used to classify the re-

gions, the resulting ... statistics imply that slavery explains much of the regional

variability in the Human Development Index rank scores.”

22

Smith went on to

identify the policy implications:

Among the covariates studied here, slavery (debt bondage, forced labor,

forced prostitution, chattel slavery) and the lack of political freedom

explain much of the variability that is between regions and corruption

explains much of the variability among countries within a region.

Additionally, countries with higher values of conict and social unrest

and higher values of national debt have signicantly worse Human

Development Index rank. To enhance human development countries

should eliminate debt bondage and other forms of slavery, move toward

fully democratic political systems, and eliminate corruption.

23

Clearly there can be mutually reinforcing relationships among these factors.

ese interrelationships point to the circular and reinforcing nature of human

rights violations. In terms of human development and economic development,

the result from Smith’s analysis is clear: slavery impedes economies and societ-

ies even though the proportion of slaves in the global population is small, their

productive capacity is small, and their economic value, as measured by price,

has reached an all-time low.

in the twenty-rst century. In the Ivory Coast, there are about 600,000 small

family farms that grow cocoa, producing just under half of the world’s supply.

17

Young men, normally from neighboring countries such as Mali, migrate looking

for work. In remote rural areas, some are tricked and enslaved into working on

farms that grow a range of crops, including cocoa for export. While no one knows

for certain how many of these farms use slaves, the percentage of farms using

slaves is likely to be in the single digits.

18

When the farmers sell their cocoa to

wholesalers, the slave-grown cocoa is mixed with the free-labor cocoa, and there

is currently no way to tell the two apart.

e farmer who exploits slaves and the

farmer that does not will receive exactly

the same price for their cocoa at the farm

gate. In this way, the prots of slavery

are retained by the slaveholder and are not passed up along the product chain.

e cocoa that is exported from the Ivory Coast to Europe and North America

to be made into chocolate, used in other foodstus, or made into cosmetics is

also mixed with cocoa from other countries; thus, it becomes even harder to

distinguish the fraction that is tainted by slavery.

19

is concealment of slave-

made commodities, made possible through blending in global supply chains, also

applies to cotton, sugar, gold, shrimp, and a host of other products. What the

case of cocoa illustrates, and what applies to virtually all slave-based businesses,

is that prots from slavery tend to accrue solely to the criminal slaveholder and

are not passed up the product chain in the form of lower prices to consumers.

the effects of slavery on huMan develoPMent

Contemporary slavery yields a number of negative social and economic eects.

Slaves, subjects of violence and intimidation on a systematic basis, are unwilling

agents of economic stagnation. From a scal perspective, slave labor tends to

pull down the wages of free labor in the same area, thus lessening the disposable

incomes of free families. At the same time, slaves are not able to play a full role

in their local economy in that they have little or no purchasing power and so

they subsist on the barest necessities.

More generally, slaves, by the nature of their social position, have no means

to contribute to the economy except in minimal ways. ey are not at liberty to

purchase anything in a country’s markets. erefore, slaves, as a group—denied

the benets of human development in the form of education, access to politi-

cal participation, and self-direction—remain an untapped economic resource.

The prots of slavery are retained

by the slaveholder and are not

passed up along the product chain.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

212

213

the 0.001-level and explains about 55 percent of the variance we observe (R

2

=

0.55). is nding substantiates Smith’s reasoning that slavery is a useful factor in

understanding variation in social and economic development around the globe.

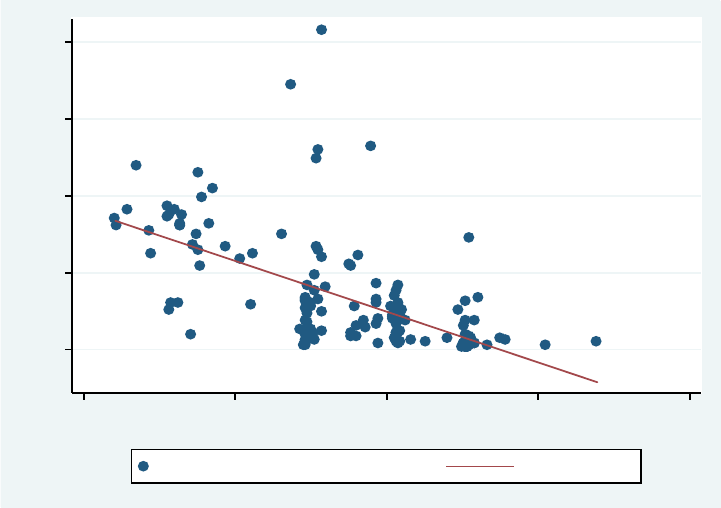

Figure 1. e relationship between the Human Development Index and slavery.

Of course, correlation does not imply causation. Simply because there is

a strong bivariate relationship between HDI and slavery does not mean that

the latter causes the former. Indeed, the relationship may be spurious. In this

instance, to control for the possibility of a spurious relationship, it is important to

account for other competing explanations that may shed light on cross-national

variation in HDI, independent of slavery. If, while holding these other factors

constant, the relationship between slavery and HDI maintains statistical signi-

cance, then we have greater support for our hypothesis. In this light we include

three control variables, the rst of which accounts for cross-national variation

in literacy rates, given that scholarship suggests that education is a powerful

predictor of human development and economic growth.

28

We measure education

in terms of literacy (on a scale from 0 percent to 100 percent) from the United

Nations Development Program.

29

e second variable examines cross-national

variation in regime type, given that some scholars argue that higher levels of

democratization lead to greater levels of productivity and growth.

30

We obtain

data for this measure from Freedom House, which ranks all the countries of

the relationshiP BetWeen slavery and the huMan develoPMent index

e next step in this research agenda is to explore the empirical relationship be-

tween slavery and human development. A challenge arises, however, in obtaining

data to approximate the prevalence of slavery around the globe. Estimates vary

based on diering approaches that use secondary source estimates and country-

level, random sample surveys. e ILO estimates that there are 21 million

slaves in the world today. Based on the data used by this article, however, this

gure is somewhat higher, upwards of 27 million.

24

Part of the reason for the

discrepancy is in the transparency of the research methods made available.

25

As

scholarship on human tracking and modern-day slavery develops over time,

the complete sharing of data and methods used will help resolve the dierence

observed in the number of slaves.

We begin by exploring the relationship between the prevalence of slavery

and the UN Human Development Index (HDI). e HDI, as the UN reports,

“is a summary measure of human development. It measures the average achieve-

ments in a country in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and

healthy life (health), access to knowledge (education), and a decent standard of

living (income).”

26

HDI is measured on an interval scale, from zero (represent-

ing “low development”) to one (indicating “high development”). We use data

from the year 2012. For the 162 countries in our dataset for which we have a

corresponding measure of slavery prevalence, we nd that the measure of HDI

has considerable range, with a minimum value of 3.04 percent (for the country

of Somalia) and a maximum value of 95.5 percent (for Norway). Countries on

average have an HDI score of 66.7 percent, which indicates “reasonably high

development.”

27

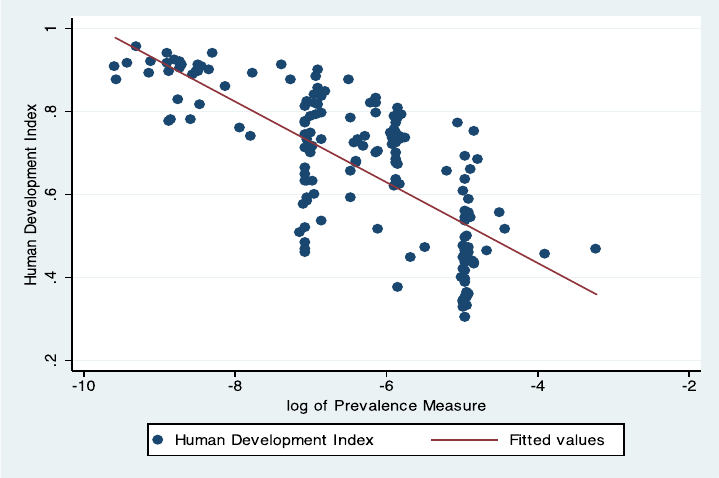

Our rst hypothesis is higher levels of the prevalence of slavery lead to lower

levels of HDI, all else being equal. In other words, we believe that slavery is a

powerful predictive factor in understanding cross-national variation in human

development. We test this in two ways, rst by observing the graphical relation-

ship between the two variables (HDI and Prevalence) as Figure 1 illustrates.

In Figure 1, our measure of slavery is on the x axis (in which we have

taken the log of this measure so as to normalize its distribution) and the HDI

measure is on the y axis. Each dot in Figure 1 represents one of the countries

in our dataset. Note the downward sloping shape of the graph, which suggests

that, as we hypothesized, higher levels of slavery correlate with lower levels of

HDI. Conversely, lower levels of slavery correspond to higher levels of HDI. A

bivariate regression analysis yields that this nding is statistically signicant at

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

212

213

the 0.001-level and explains about 55 percent of the variance we observe (R

2

=

0.55). is nding substantiates Smith’s reasoning that slavery is a useful factor in

understanding variation in social and economic development around the globe.

Figure 1. e relationship between the Human Development Index and slavery.

Of course, correlation does not imply causation. Simply because there is

a strong bivariate relationship between HDI and slavery does not mean that

the latter causes the former. Indeed, the relationship may be spurious. In this

instance, to control for the possibility of a spurious relationship, it is important to

account for other competing explanations that may shed light on cross-national

variation in HDI, independent of slavery. If, while holding these other factors

constant, the relationship between slavery and HDI maintains statistical signi-

cance, then we have greater support for our hypothesis. In this light we include

three control variables, the rst of which accounts for cross-national variation

in literacy rates, given that scholarship suggests that education is a powerful

predictor of human development and economic growth.

28

We measure education

in terms of literacy (on a scale from 0 percent to 100 percent) from the United

Nations Development Program.

29

e second variable examines cross-national

variation in regime type, given that some scholars argue that higher levels of

democratization lead to greater levels of productivity and growth.

30

We obtain

data for this measure from Freedom House, which ranks all the countries of

the relationshiP BetWeen slavery and the huMan develoPMent index

e next step in this research agenda is to explore the empirical relationship be-

tween slavery and human development. A challenge arises, however, in obtaining

data to approximate the prevalence of slavery around the globe. Estimates vary

based on diering approaches that use secondary source estimates and country-

level, random sample surveys. e ILO estimates that there are 21 million

slaves in the world today. Based on the data used by this article, however, this

gure is somewhat higher, upwards of 27 million.

24

Part of the reason for the

discrepancy is in the transparency of the research methods made available.

25

As

scholarship on human tracking and modern-day slavery develops over time,

the complete sharing of data and methods used will help resolve the dierence

observed in the number of slaves.

We begin by exploring the relationship between the prevalence of slavery

and the UN Human Development Index (HDI). e HDI, as the UN reports,

“is a summary measure of human development. It measures the average achieve-

ments in a country in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and

healthy life (health), access to knowledge (education), and a decent standard of

living (income).”

26

HDI is measured on an interval scale, from zero (represent-

ing “low development”) to one (indicating “high development”). We use data

from the year 2012. For the 162 countries in our dataset for which we have a

corresponding measure of slavery prevalence, we nd that the measure of HDI

has considerable range, with a minimum value of 3.04 percent (for the country

of Somalia) and a maximum value of 95.5 percent (for Norway). Countries on

average have an HDI score of 66.7 percent, which indicates “reasonably high

development.”

27

Our rst hypothesis is higher levels of the prevalence of slavery lead to lower

levels of HDI, all else being equal. In other words, we believe that slavery is a

powerful predictive factor in understanding cross-national variation in human

development. We test this in two ways, rst by observing the graphical relation-

ship between the two variables (HDI and Prevalence) as Figure 1 illustrates.

In Figure 1, our measure of slavery is on the x axis (in which we have

taken the log of this measure so as to normalize its distribution) and the HDI

measure is on the y axis. Each dot in Figure 1 represents one of the countries

in our dataset. Note the downward sloping shape of the graph, which suggests

that, as we hypothesized, higher levels of slavery correlate with lower levels of

HDI. Conversely, lower levels of slavery correspond to higher levels of HDI. A

bivariate regression analysis yields that this nding is statistically signicant at

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

214

215

variables, literacy and regime type, also hold statistical signicance.

Yet HDI does not capture total economic output, which prompts another

question: What is the relationship between slavery and overall economic output?

at is, to what extent does slavery inuence the average person’s ability to make

a decent living on the macro level?

An excellent measure for economic output is gross domestic product (GDP)

per capita in terms of purchasing power parity.

33

Countries vary considerably

in terms of how much the average citizen makes. Following the logic of Smith,

we argue that higher levels of slavery predict lower levels of GDP, all else being

equal. is is our second hypothesis. We obtain data for GDP per capita from

the World Bank’s “World Development Indicators” using data from the year

2011.

34

GDP per capita varies considerably, with a minimum value of $277 (for

Somalia), a maximum value of $82,978 (for Qatar), and a standard deviation

of $14,537. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between slavery and GDP and

casts support for our second hypothesis.

Figure 2. e relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and slavery.

Like the information presented in Figure 1, the data in Figure 2 illustrates

a downward-sloping, negative relationship between the outcome we seek to

understand (GDP per capita) and the key explanatory variable of interest (the

0 20000 40000 60000 80000

Gross Domestic Product

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2

log of Prevalence Measure

GDP (purchasing power parity) Fitted values

the globe on a linear scale from 2 (“highly free”) to 14 (“not free).

31

e third

variable captures cross-national variation in geography, given that dierences

in human development and productivity may be explained at least in part by

geographic diversity.

32

We account for this with dummy variables for Western

Europe, North America, Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and

the Middle East, using Sub-Saharan Africa as our baseline.

Slavery (log) -4.487***

(0.532)

Literacy 0.546***

(0.0343)

Regime Type -0.615***

(0.176)

Western Europe -2.698

(1.750)

North America -4.395

(13.85)

Central and Eastern Europe -2.293

(1.945)

Asia 1.926

(1.688)

Latin America -1.334

(1.756)

e Middle East -1.295

(1.682)

Constant -2.232

(4.014)

N 160

R

2

0.84

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 2. Human development indicators (robust standard errors in parentheses).

Table 2 presents the results of our rst multivariate model, in which

we regress HDI on our slavery measure while controlling for literacy rates,

regime type, and geographic variation. e results of Table 2 lend support for

our hypothesis. Holding literacy rates, regime type, and geography constant,

a one-percent increase in the prevalence of slavery is associated with a 0.045

percent decrease in human development, other things being equal. is nding

is signicant at the 0.001-level and lends credence to Smith’s claims. Two other

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

214

215

variables, literacy and regime type, also hold statistical signicance.

Yet HDI does not capture total economic output, which prompts another

question: What is the relationship between slavery and overall economic output?

at is, to what extent does slavery inuence the average person’s ability to make

a decent living on the macro level?

An excellent measure for economic output is gross domestic product (GDP)

per capita in terms of purchasing power parity.

33

Countries vary considerably

in terms of how much the average citizen makes. Following the logic of Smith,

we argue that higher levels of slavery predict lower levels of GDP, all else being

equal. is is our second hypothesis. We obtain data for GDP per capita from

the World Bank’s “World Development Indicators” using data from the year

2011.

34

GDP per capita varies considerably, with a minimum value of $277 (for

Somalia), a maximum value of $82,978 (for Qatar), and a standard deviation

of $14,537. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between slavery and GDP and

casts support for our second hypothesis.

Figure 2. e relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and slavery.

Like the information presented in Figure 1, the data in Figure 2 illustrates

a downward-sloping, negative relationship between the outcome we seek to

understand (GDP per capita) and the key explanatory variable of interest (the

0 20000 40000 60000 80000

Gross Domestic Product

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2

log of Prevalence Measure

GDP (purchasing power parity) Fitted values

the globe on a linear scale from 2 (“highly free”) to 14 (“not free).

31

e third

variable captures cross-national variation in geography, given that dierences

in human development and productivity may be explained at least in part by

geographic diversity.

32

We account for this with dummy variables for Western

Europe, North America, Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and

the Middle East, using Sub-Saharan Africa as our baseline.

Slavery (log) -4.487***

(0.532)

Literacy 0.546***

(0.0343)

Regime Type -0.615***

(0.176)

Western Europe -2.698

(1.750)

North America -4.395

(13.85)

Central and Eastern Europe -2.293

(1.945)

Asia 1.926

(1.688)

Latin America -1.334

(1.756)

e Middle East -1.295

(1.682)

Constant -2.232

(4.014)

N 160

R

2

0.84

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 2. Human development indicators (robust standard errors in parentheses).

Table 2 presents the results of our rst multivariate model, in which

we regress HDI on our slavery measure while controlling for literacy rates,

regime type, and geographic variation. e results of Table 2 lend support for

our hypothesis. Holding literacy rates, regime type, and geography constant,

a one-percent increase in the prevalence of slavery is associated with a 0.045

percent decrease in human development, other things being equal. is nding

is signicant at the 0.001-level and lends credence to Smith’s claims. Two other

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

216

217

ing our understanding of the inuence of slavery on GDP? ere is no perfect

answer to this question given the lack of data on the size of untraceable criminal

economic activity in each country, but in the case of slavery this uncounted

output should not dramatically alter the results

presented for two reasons. First, in virtually all

economies, the estimated value of slavery within

the criminal economy is much lower than the

sums generated by drugs, weapons, gambling,

and general corruption. Second, a signicant

part of slave-produced goods and economic activity are counted in GDP, but

without the fact of slave origin being known. Note that cocoa, cotton, iron,

shrimp and sh, and minerals for electronics can all have slave origin and still

be counted in national output. e key point here is that it is the slavery that

is hidden, not the export goods or the prots made on them.

Regardless of whether HDI or GDP per capita is used, a story begins to

emerge: slavery is associated with outcomes that are harmful not only for eco-

nomic and social development (as HDI illustrates) but also for economic output

per citizen (as GDP per capita illustrates). ese are macro estimates. We are not

arguing that the lives of most families and individuals are directly aected by

slavery—far from it. However, from a systemic perspective, the evidence suggests

that slavery signicantly depresses social and economic output at the aggregate

level. Based on these data, we nd further reason to substantiate Smith’s logic that

slavery yields serious negative outcomes of global proportions despite the small

ancillary benets that a small population of contemporary slaveholders reap.

Let us press on with Smith’s logic by exploring two more indicators of so-

cial productivity. One measure of interest is the access to nancial services that

the average citizen can obtain in a given country. Access to nancial services

is crucial for upward social mobility. Without access to credit, there is often

little the average family can do to improve its lot in life. We obtain data for this

measure from scholarship by Patrick Honohan, aliated with the World Bank,

Trinity College Dublin, and the Center for Economic and Political Research.

35

Honohan’s research has generated a cross-national measure of access to nancial

services that ranks on a scale from 0 (no access) to 100 (full access). e de-

scriptive statistics for this measure are interesting. e country with the lowest

ranking is Kyrgyzstan (which received a 1), and the country with the highest

is the Netherlands (which received a 100). e standard deviation is about 28

points, indicating a great deal of cross-national variation in this measure.

Our third hypothesis is higher levels of slavery will be correlated with lower

The key point here is that it

is the slavery that is hidden,

not the export goods or

the prots made on them.

prevalence of slavery by country). A bivariate regression analysis reveals that

the nding is statistically signicant at the 0.001-level and explains about 39

percent of the variance we observe (R

2

= 0.39). A multivariate regression analysis

(using the same control variables as we did for the HDI hypothesis) yields the

following output.

Slavery (log) -5260.3***

(734.8)

Literacy 143.0***

(41.38)

Regime Type -148.8

(364.4)

Western Europe 2753.9

(3429.1)

North America -3239.6

(2187.6)

Central and Eastern Europe 1475.0

(2631.1)

Asia -2496.7

(2249.3)

Latin America -3109.1

(2531.4)

e Middle East 204.8

(4837.5)

Constant -31747.7***

(7178.9)

N 160

R

2

0.44

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 3. Gross domestic product (robust standard errors in parentheses).

Table 3 sheds light on the extent to which the prevalence of slavery is asso-

ciated with GDP per capita. Holding literacy rates, regime type, and geography

constant, a one-percent increase in the prevalance of slavery is associated with

a $52.6 decrease in per capita GDP. us, a 10-percent increase corresponds to

a $526 decrease in GDP per capita—not a small sum.

At this point, it would be fair to ask if the measurement of slavery’s impact

on GDP is suciently robust given that the criminal market is not normally

included in any computation of GDP. Since the proceeds of the underground

economy are untraceable and thus untaxable, how might their existence be alter-

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

216

217

ing our understanding of the inuence of slavery on GDP? ere is no perfect

answer to this question given the lack of data on the size of untraceable criminal

economic activity in each country, but in the case of slavery this uncounted

output should not dramatically alter the results

presented for two reasons. First, in virtually all

economies, the estimated value of slavery within

the criminal economy is much lower than the

sums generated by drugs, weapons, gambling,

and general corruption. Second, a signicant

part of slave-produced goods and economic activity are counted in GDP, but

without the fact of slave origin being known. Note that cocoa, cotton, iron,

shrimp and sh, and minerals for electronics can all have slave origin and still

be counted in national output. e key point here is that it is the slavery that

is hidden, not the export goods or the prots made on them.

Regardless of whether HDI or GDP per capita is used, a story begins to

emerge: slavery is associated with outcomes that are harmful not only for eco-

nomic and social development (as HDI illustrates) but also for economic output

per citizen (as GDP per capita illustrates). ese are macro estimates. We are not

arguing that the lives of most families and individuals are directly aected by

slavery—far from it. However, from a systemic perspective, the evidence suggests

that slavery signicantly depresses social and economic output at the aggregate

level. Based on these data, we nd further reason to substantiate Smith’s logic that

slavery yields serious negative outcomes of global proportions despite the small

ancillary benets that a small population of contemporary slaveholders reap.

Let us press on with Smith’s logic by exploring two more indicators of so-

cial productivity. One measure of interest is the access to nancial services that

the average citizen can obtain in a given country. Access to nancial services

is crucial for upward social mobility. Without access to credit, there is often

little the average family can do to improve its lot in life. We obtain data for this

measure from scholarship by Patrick Honohan, aliated with the World Bank,

Trinity College Dublin, and the Center for Economic and Political Research.

35

Honohan’s research has generated a cross-national measure of access to nancial

services that ranks on a scale from 0 (no access) to 100 (full access). e de-

scriptive statistics for this measure are interesting. e country with the lowest

ranking is Kyrgyzstan (which received a 1), and the country with the highest

is the Netherlands (which received a 100). e standard deviation is about 28

points, indicating a great deal of cross-national variation in this measure.

Our third hypothesis is higher levels of slavery will be correlated with lower

The key point here is that it

is the slavery that is hidden,

not the export goods or

the prots made on them.

prevalence of slavery by country). A bivariate regression analysis reveals that

the nding is statistically signicant at the 0.001-level and explains about 39

percent of the variance we observe (R

2

= 0.39). A multivariate regression analysis

(using the same control variables as we did for the HDI hypothesis) yields the

following output.

Slavery (log) -5260.3***

(734.8)

Literacy 143.0***

(41.38)

Regime Type -148.8

(364.4)

Western Europe 2753.9

(3429.1)

North America -3239.6

(2187.6)

Central and Eastern Europe 1475.0

(2631.1)

Asia -2496.7

(2249.3)

Latin America -3109.1

(2531.4)

e Middle East 204.8

(4837.5)

Constant -31747.7***

(7178.9)

N 160

R

2

0.44

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 3. Gross domestic product (robust standard errors in parentheses).

Table 3 sheds light on the extent to which the prevalence of slavery is asso-

ciated with GDP per capita. Holding literacy rates, regime type, and geography

constant, a one-percent increase in the prevalance of slavery is associated with

a $52.6 decrease in per capita GDP. us, a 10-percent increase corresponds to

a $526 decrease in GDP per capita—not a small sum.

At this point, it would be fair to ask if the measurement of slavery’s impact

on GDP is suciently robust given that the criminal market is not normally

included in any computation of GDP. Since the proceeds of the underground

economy are untraceable and thus untaxable, how might their existence be alter-

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

218

219

Slavery (log) -10.54***

(1.515)

Literacy 0.123

(0.0891)

Regime Type -2.514***

(0.428)

Western Europe 2.675

(4.213)

North America 20.83*

(10.33)

Central and Eastern Europe 5.492

(4.690)

Asia -3.856

(5.112)

Latin America -9.024

(5.099)

e Middle East -7.879

(5.356)

Constant -17.56*

(8.821)

N 139

R

2

0.64

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 4. Access to nancial services (robust standard errors in parentheses).

e last measure we explore is the level of economic equality/inequality in

the world today. ere is evidence of a growing gap between the Global South

and the North. As the rich countries get richer, the poor countries get poorer. Our

fourth hypothesis is that greater levels of slavery should be correlated with higher

levels of global inequality. e measure we use to test this is the Gini coecient,

the data for which we obtain from the World Bank.

36

e Gini coecient is a

measure of income inequality, on a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 represents

perfect inequality and 0 signies perfect equality. us, a lower score on the

Gini coecient scale is better than a higher score. Among the data we have,

the country with the highest amount of income inequality is Namibia (a score

of 63.9) and the country with the lowest income inequality is Denmark (24.7).

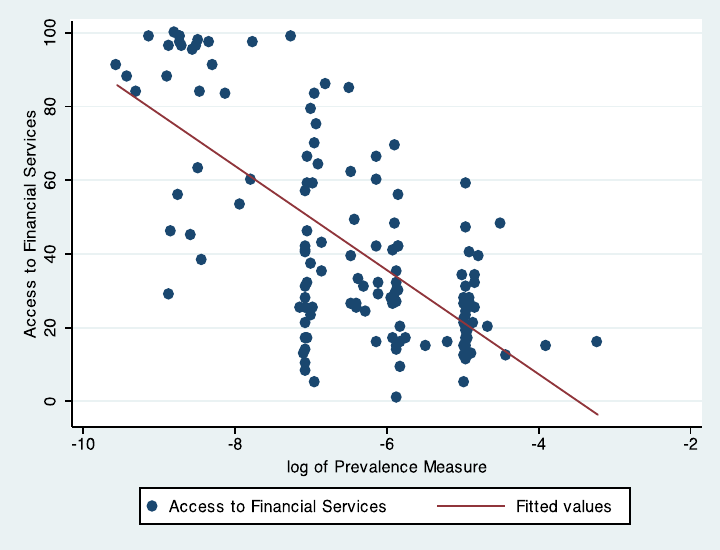

levels of access to nancial service. We nd graphical evidence of this in Figure 3.

Figure 3. e relationship between access to nancial services and slavery.

Similar to Figures 1 and 2, Figure 3 illustrates a downward-sloping, nega-

tive relationship between access to nancial services (on the y axis) and the

prevalence of slavery (on the x axis). A bivariate regression analysis informs us

that this nding is also statistically signicant at the 0.001-level and explains

about 49 percent of the variance we observe (R

2

= 0.49). A multivariate analysis,

as seen in Table 4, reveals that a one-percent increase in the prevalence of slavery

is associated with about a tenth of a unit decrease in access to nancial services.

us, a ten-percent increase in slavery corresponds to about a one-unit decrease in

access to nancial services, other things being equal.

Once again, the data points to the destructive social and economic conse-

quences of contemporary slavery, but it is important to reect on the circular

nature of this particular relationship as well—lack of access to credit can place

poor families in extreme vulnerability to enslavement in times of crisis, in which

individuals and families are removed from the credit market, cut o from ever

being credit consumers.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

218

219

Slavery (log) -10.54***

(1.515)

Literacy 0.123

(0.0891)

Regime Type -2.514***

(0.428)

Western Europe 2.675

(4.213)

North America 20.83*

(10.33)

Central and Eastern Europe 5.492

(4.690)

Asia -3.856

(5.112)

Latin America -9.024

(5.099)

e Middle East -7.879

(5.356)

Constant -17.56*

(8.821)

N 139

R

2

0.64

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 4. Access to nancial services (robust standard errors in parentheses).

e last measure we explore is the level of economic equality/inequality in

the world today. ere is evidence of a growing gap between the Global South

and the North. As the rich countries get richer, the poor countries get poorer. Our

fourth hypothesis is that greater levels of slavery should be correlated with higher

levels of global inequality. e measure we use to test this is the Gini coecient,

the data for which we obtain from the World Bank.

36

e Gini coecient is a

measure of income inequality, on a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 represents

perfect inequality and 0 signies perfect equality. us, a lower score on the

Gini coecient scale is better than a higher score. Among the data we have,

the country with the highest amount of income inequality is Namibia (a score

of 63.9) and the country with the lowest income inequality is Denmark (24.7).

levels of access to nancial service. We nd graphical evidence of this in Figure 3.

Figure 3. e relationship between access to nancial services and slavery.

Similar to Figures 1 and 2, Figure 3 illustrates a downward-sloping, nega-

tive relationship between access to nancial services (on the y axis) and the

prevalence of slavery (on the x axis). A bivariate regression analysis informs us

that this nding is also statistically signicant at the 0.001-level and explains

about 49 percent of the variance we observe (R

2

= 0.49). A multivariate analysis,

as seen in Table 4, reveals that a one-percent increase in the prevalence of slavery

is associated with about a tenth of a unit decrease in access to nancial services.

us, a ten-percent increase in slavery corresponds to about a one-unit decrease in

access to nancial services, other things being equal.

Once again, the data points to the destructive social and economic conse-

quences of contemporary slavery, but it is important to reect on the circular

nature of this particular relationship as well—lack of access to credit can place

poor families in extreme vulnerability to enslavement in times of crisis, in which

individuals and families are removed from the credit market, cut o from ever

being credit consumers.

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

220

221

utes little to national production. Slaves are normally not able to acquire assets

or access credit and just as it is for the free working poor, credit access and asset

acquisition are key determining factors for achievement of economic autonomy.

Except in the way they benet criminals, we assert that slaves, though practically

invisible, exert a strong, negative pull on local and national economies through

their lack of full economic participation.

At the same time, there is a fruitful area for future research in the posi-

tive impact on local, regional, and national economies that coincides with the

liberation of those in slavery. Recent longitudinal research by Free the Slaves

among villages in northern India that have high levels of hereditary debt-bondage

slavery demonstrates a dramatic increase in economic activity (as well as human

development measures) following liberation.

37

e eradication of slavery has

long been sought on moral and philisophical grounds; this new research suggests

that the rationale for liberation might be extended to economic ends as well.

While slavery tends to deaden economic activity, it appears that liberation may

be an important economic stimulus. is is important because the resources

needed to reduce global slavery, while relatively small when compared to other

social problems, are not forthcoming.

38

e idea that the eradication of slavery

might ultimately pay for itself through economic growth is one that needs

demonstration. If “slavery is bad for business” is a hypothesis worth exploring,

how much more so is its mirror assertion that freedom from slavery generates

economic growth?

notes

1. “President Barack Obama speech to Clinton Global Initiative,” Politico, September 25, 2012; “Human

tracking: Mira Sorvino ghts against modern-day slavery,” Politico, December 6, 2012; “Jada Pinkett

Smith Hosts Sex-Tracking Awareness Party,” CBS News, October 30, 2012.

2. For example, see: Kevin Bales, “International Labor Standards: Quality of Information and Measures

of Progress in Combating Forced Labor,” Comparative Labor Law and Policy 24, no. 2 (2004); “21 Million

People are Now Victims of Forced Labour, ILO says,” International Labour Organization, June 1, 2012.

3. For example, see: Elżbieta M. Goździak and Micah N. Bump, “Data and Research on Human

Trafcking: Bibliography of Research-Based Literature,” October 2008.

4. Robert B. Smith, “Global human development: accounting for its regional disparities,” Quality and

Quantity 43, no. 1 (2009).

5. For example, see: Robert Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: e Rise and Fall of American Slavery:

Evidence and Methods (New York: Norton, 1992); Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, Time on the Cross:

e Economics of American Slavery (New York: Norton, 1974).

6. Of course, in no way do we condone the slavery of the past, as we see the morality of the issue as

the most important consideration. Slavery is a bloody and costly issue over the long term and can destroy

the fabric of a nation.

7. If these estimates are correct, the monetary value of slavery represents 0.00059 percent of the global

economy.

A

W

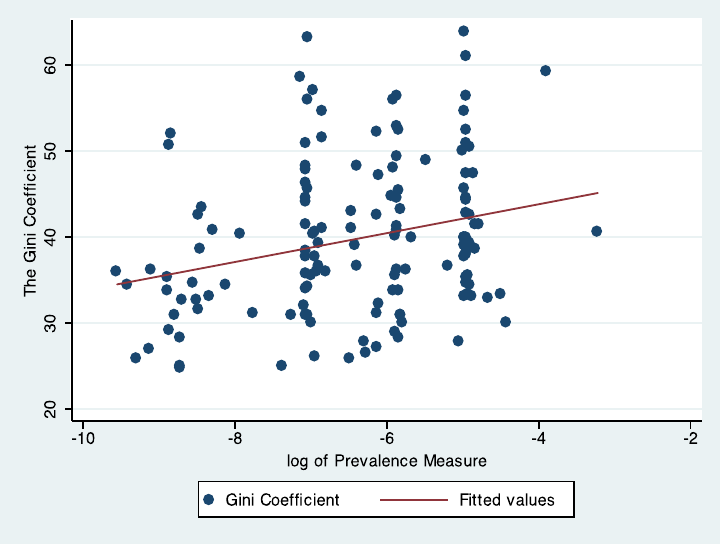

Figure 4. e relationship between the Gini coecient and slavery.

Figure 4 suggests that Smith’s thinking bears out: there is an upward-

sloping, positive relationship between the Gini coecient (on the y axis) and

our measure of the prevalence of slavery (on the x axis). Higher levels of slavery

correlate with greater levels of economic inequality. Although this nding is

signicant at the 0.001-level, the R

2

compared to those of the other models is

quite modest, explaining only about seven percent of the variance we observe.

A multivariate analysis, similar to the results of Tables 2, 3, and 4, reveals that

our measure of slavery prevalence is signicant at the 0.10-level in its association

with the Gini coecient, holding literacy, regime type, and geography constant.

conclusion

While slavery may make high prots for a small number of slaveholders, we argue

that the practice tends to disproportionately depress a country’s economy. Since

the work of slaves is generally concentrated at the lowest end of the economic

ladder in basic, low-skill jobs that are dirty and dangerous, slave output contrib-

M N D K B

Slavery is Bad for Business

S/S

2013

• ,

220

221

utes little to national production. Slaves are normally not able to acquire assets

or access credit and just as it is for the free working poor, credit access and asset

acquisition are key determining factors for achievement of economic autonomy.

Except in the way they benet criminals, we assert that slaves, though practically

invisible, exert a strong, negative pull on local and national economies through

their lack of full economic participation.

At the same time, there is a fruitful area for future research in the posi-

tive impact on local, regional, and national economies that coincides with the

liberation of those in slavery. Recent longitudinal research by Free the Slaves

among villages in northern India that have high levels of hereditary debt-bondage

slavery demonstrates a dramatic increase in economic activity (as well as human

development measures) following liberation.

37

e eradication of slavery has

long been sought on moral and philisophical grounds; this new research suggests

that the rationale for liberation might be extended to economic ends as well.

While slavery tends to deaden economic activity, it appears that liberation may

be an important economic stimulus. is is important because the resources

needed to reduce global slavery, while relatively small when compared to other

social problems, are not forthcoming.

38

e idea that the eradication of slavery

might ultimately pay for itself through economic growth is one that needs

demonstration. If “slavery is bad for business” is a hypothesis worth exploring,

how much more so is its mirror assertion that freedom from slavery generates

economic growth?

notes

1. “President Barack Obama speech to Clinton Global Initiative,” Politico, September 25, 2012; “Human

tracking: Mira Sorvino ghts against modern-day slavery,” Politico, December 6, 2012; “Jada Pinkett

Smith Hosts Sex-Tracking Awareness Party,” CBS News, October 30, 2012.

2. For example, see: Kevin Bales, “International Labor Standards: Quality of Information and Measures

of Progress in Combating Forced Labor,” Comparative Labor Law and Policy 24, no. 2 (2004); “21 Million

People are Now Victims of Forced Labour, ILO says,” International Labour Organization, June 1, 2012.

3. For example, see: Elżbieta M. Goździak and Micah N. Bump, “Data and Research on Human

Trafcking: Bibliography of Research-Based Literature,” October 2008.

4. Robert B. Smith, “Global human development: accounting for its regional disparities,” Quality and

Quantity 43, no. 1 (2009).

5. For example, see: Robert Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: e Rise and Fall of American Slavery:

Evidence and Methods (New York: Norton, 1992); Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, Time on the Cross:

e Economics of American Slavery (New York: Norton, 1974).

6. Of course, in no way do we condone the slavery of the past, as we see the morality of the issue as

the most important consideration. Slavery is a bloody and costly issue over the long term and can destroy

the fabric of a nation.

7. If these estimates are correct, the monetary value of slavery represents 0.00059 percent of the global

economy.

A

W