51

Drivers of the London Housing Crisis: The Neoliberal Nexus of Ideology,

Policy, and Capital

Julia Frances Alice Everett

Abstract

For the average Londoner, the subject of housing is a bleak one. House prices in the

capital continue to rise while homelessness, displacement, and poor-quality

accommodation become increasingly pervasive and damaging, with seemingly no end

in sight. This paper is situated within a budding literature surrounding the international

political economy of housing and property and seeks to trace the root drivers of the

London housing crisis. It argues that although crises in housing are not necessarily new

phenomena, this current period of crisis is intensified by neoliberal ideology which has

justified and driven government policies which have in turn facilitated the

financialization of the London housing market. These developments have occurred

counter to the interests of ordinary Londoners through the reconceptualization housing

as an asset, as opposed to a right. The paper will examine how ideology intersects with

capital and UK government policy, in effect perpetuating the London housing crisis.

Keywords: Housing crisis, London, Neoliberalism, Political Economy, Homelessness

The question of housing is one of primary importance in the study of global political economy due

to its fundamentality in our daily lives. It is difficult to deny that the effects of the housing crisis

are felt by all Londoners, be it through profit or loss. The housing crisis takes numerous forms,

such as a lack in socially provisioned housing for the neediest in society as well as shortages of

affordable housing in London (Watt & Minton, 2016: 204). As homelessness figures in the capital

continue to rise (Fitzpatrick, et al., 2018: 48-9), it is urgent that we trace the root causes of the

dearth of available, affordable housing in London so that we may find the solutions. This paper

will argue that the crisis in housing has been intensified by neoliberal ideology which informs

government policies and in turn facilitates global investment in the London housing market at the

expense of the intee of egla Londone. Neolibealim i a loaded and coneed oic, b

it generally signifies a certain set of political and economic practices and policies such as

privatisation, deregulation, and financialization (Edwards, 2016: 224) which facilitates the

reconstruction of power dynamics in favour of international capital (Eagleton-Pierce, 2018). This

issue is one which is filled with complexity and numerous interlinking factors, not all of which

can be adequately discussed here. This paper will begin by asking whether this issue can genuinely

be considered a crisis as opposed to simply a continuing and intensifying trend. It will then turn to

the root ideology which underpins government policy and the UK economy; that of neoliberalism.

Then it will explore how this ideology has impacted government policy and how it has in turn

exacerbated the crisis. Finally, it will examine the role of international finance capital and its

contribution to the crisis.

52

Housing Crisis or Business as Usual?

Land and property have a unique role in the economy and have led to consistent conflict throughout

the history of capitalism (Clarke & Ginsburg, 1975: 1), which begs the question as to whether the

current period can even be considered a crisis at all. Housing is unique and politically important

as it represents not simply a single transaction but a contractual relationship with the state,

landlords, or financiers. Therefore, the dialectically opposed classes of worker and capitalist are

brought closer together in an ongoing and antagonistic relationship (ibid: 1). As a result, housing

struggles and crises have proven to be an enduring feature of late-capitalist society (Gallent, et al.,

2017: 2205). Paul Watt and Anna Minton (2016: 204) argue that the current era of conflict can be

traced back to the 1980s, which coincides with the rise of neoliberal ideology, and Margaret

Thache 1979 elecion a Pime Minie. Ben Fine and Alfedo Saad-Filho (2017) contend that

the neoliberal era can be considered a qualitative development in the capitalist system, and as such

could possibly mark a new stage in the housing struggle. As will be argued throughout this paper,

neoliberal policy plays a role in reinforcing the conditions which facilitate the housing crisis.

Simon Jenkin (2015, cied in Wa & Minon, 2016: 205) ak hehe hee i an cii in

housing at all, arguing that neoliberal politics and finance have normalised crisis-like conditions

in the housing market as well as actively encouraging them which is an argument to be explored

throughout this paper. This suggests that under the rubric of neoliberalism, the housing crisis we

see today is nothing more than business as usual.

But for many Londoners affected by the current situation in the housing market, it is a crisis which

is seriously affecting livelihoods around the capital. The contradictions surrounding housing and

property which arise under the capitalist mode of production can be argued to be intensifying.

There has been a seven percent decline in home ownership since 2003 despite government focus

on encoaging a oe oning democac (Gallen, e al., 2017: 2206), hich gge ha

geing on o he hoing ladde i no longe enable fo man in he caial. Fhe eidence of

intensified contradictions in housing can be seen in activist groups which are currently being

formed and gaining traction. An example of these groups is Focus E15 which was arose when

young homeless people including mothers and children were evicted from the Focus E15 hostel

after funding was cut by Newham Council. The solution provided by the council was private

housing outside of the capital as far as Manchester, uprooting young vulnerable people from any

existing support networks (Focus E15 Campaign, 2019). This squeezing out of lower income

people from the capital has been referred to by groups such as Focus E15 as a form of social

cleansing (Watt & Minton, 2016: 211), suggesting that London is gradually becoming a space

reserved for the wealthy. Therefore, it can be argued that although this may not be a crisis for the

ealh ho ae iml caing on ih bine a al, fo hoe on lo income in London

this is an intensifying crisis which is threatening livelihoods. Therefore, we must ask ourselves the

question: Why is there a housing crisis in London?

The Ideological Roots of the Crisis

Neoliberalism has been the underpinning ideology of UK governments since the 1980s, which has

been reflected in concrete policy actions as well as in terms of the popular political psyche of the

UK. A eiol efeed o, hee i he agmen ha he neolibeal ea mak a fndamenal

change in the development of capitalism. Multiple dimensions are involved in the phenomenon of

neoliberalisation as it transforms social, economic, and political spheres and as such reproduces

itself through these channels. It has been argued that this process is underpinned by

53

financialization, (Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017: 686) the meaning and significance of which will be

explored below. Ideologically and socially, neoliberalism has penetrated popular discourse and

conceptions about housing and its provision because it redefines the relationship between the

individual, society, and the state (Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017). This phenomenon can be understood

hogh he len of Gamci conce of hegemon hich age ha hegemon i eablihed b

social leadership but is then projected outwards and takes on its own momentum (Bieler & Morton,

2004: 87). Thus, political ideas are perpetuated throughout social life and as a result become self-

reproducing. Nick Gallent, Dan Durrant & Neil May, argue that ideology shapes the housing

system (2017: 2208), which is arguably dominated by neoliberal hegemony.

We can see that neoliberal hegemonic ideology has had an impact on the housing system. After

the Second World War there was an ideological and political move towards the welfare state and

the idea that housing is a social good which should be available to all through state provision

(Minton, et al., 2016: 257). This implies the idea of collectivism in which the interests of society

are elevated above those of the individual. Neoliberalisation swept away these ideas and replaced

them with individualism. In terms of housing, individualism is a factor in the public perception of

property simply being an asset for the purpose of capital accumulation (Edwards, 2016: 223). This

is the case historically under capitalism as housing is a commodity (Clarke & Ginsburg, 1975: 1),

but the idea of housing being a social good which should be provisioned by the state for the

neediest in society has to some extent evaporated. This is an example of how the relationship

between state and society have been transformed by neoliberal hegemony. Neoliberalism has

impacted popular attitudes towards housing, as it is now seen as a privilege which is worked for

as opposed to a right. Thus, the idea arises that people who cannot afford to live in London are in

such a situation as a result of their own individual failings instead of the failings of collective

society to provide for them, and as such they are left to deal with the consequences alone. These

conceptions in turn facilitate such policies which, as I argue, lead to a dialectical and mutually

reinforcing relationship between government policies and public perceptions of the housing

system.

Post-Thatcher Government Housing Policy

It has already been argued that the new stage in the capitalist economy of neoliberalism has social,

economic, and political dimensions; thus, neoliberal ideology is reflected in policy towards

housing provision and regulation. Historically speaking, the state has intervened in the provision

of housing under capitalism because as a system it fails to provide housing for the working classes

of a basic standard. The state intervenes in housing to maintain and reproduce the working class

which the capitalist system is dependent upon, so that it does not compromise its own existence

(Clarke & Ginsburg, 1975: 6). Housing policy has changed in line with neoliberal ideology since

the 1980s. Along with the ideological shift of the post-war consensus came a boost in the provision

of working-class housing as that provided by local councils became a high priority although

concil hoebilding nee eached he goenmen aim and a hen lahed afe he

dealaion cii of 1947 (ibid: 9). Hoee, Thache elecion adicall aleed he diecion of

governmental housing policy, tearing down a core pillar of the post-war welfare state (Minton, et

al., 2016: 257). To understand how neoliberal housing policy has contributed to a housing crisis

in London as well as around the UK, the rest of this section will examine certain aspects of post-

Thatcher governmental housing policy and its consequences for the London housing market.

54

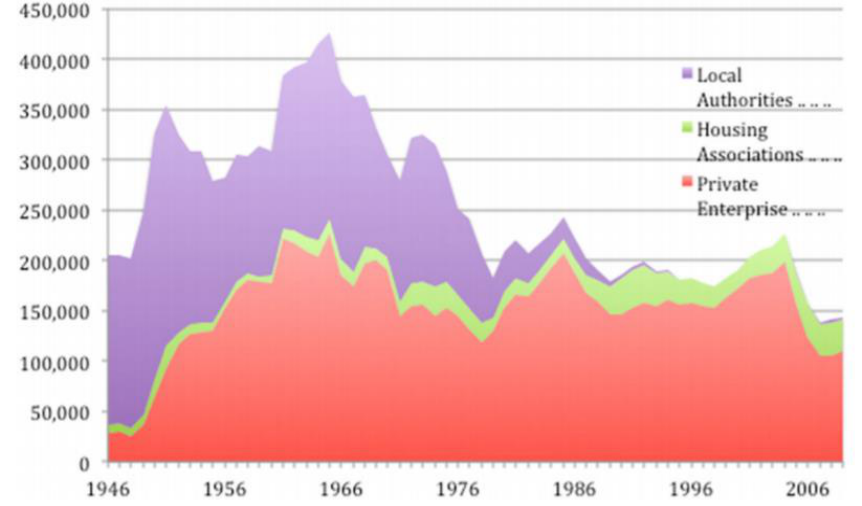

Figure 1- UK annual completions of dwellings by developer type 19462012 (Edwards, 2016, p. 226)

One of the most prominent features of neoliberalism is the importance of privatisation and

reconfiguring the role of the state away from the provision of social goods (Edwards, 2016: 224).

Housing has been no exception to this under neoliberal governmental policy since Thatcher, which

has seen much continuity in its direction. House building has been placed in private hands and

housing provision is no longer the responsibility of the local council as this task has now been

given to housing associations. Figure 1 supports this notion and demonstrates the scale of the

transformation into the neoliberal era which has brought privatisation, as housebuilding

responsibilities for local authorities have been reduced to almost nothing in recent years. Housing

associations are non-profit organisations which provide social housing in lieu of the state. Publicly

owned land is therefore seen through a neoliberal lens as a group of assets which should be

managed through financial principles rather than as a public service (Edwards, 2016: 223). The

growth of housing associations has been a result of the limitation of local councils in the provision

of ocial hoing ch a he Hoing Ac 1988 hich edced he concil oe and

responsibilities in housing (Watt & Minton, 2016: 207). However, housing associations have not

been able to fill the vacuum left by local councils and there has been a contraction in social housing

going on since 1981 (Watt & Minton, 2016: 209-210). Figure 1 supports this argument as we can

see that far fewer homes are being built since the mid-1970s by housing associations than were

being built by local councils. Therefore, because of neoliberal privatisation in terms of social

housing provision we can see that fewer social homes are being provided which is a major

conibing faco o London hoing cii.

Resulting in this shift from the public to the private spheres there is an increasing trend of

gentrification in London as there is no buffer of social housing to protect against it (Watt & Minton,

2016: 210). Genificaion i he oce of egeneaion hich i going on hogho London

boroughs which involves reconfiguring an area to suit middle class tastes whilst squeezing out the

working class further into the peripheries of the city. This process is facilitated again by neoliberal

hegemony as council estates which house the most deprived in society, are stigmatised and dubbed

55

ink eae b he media (ibid: 209). Thee conceion ae fhe eeaed b Neman

idea that tower blocks produce crime and should be replaced by low rise housing which has more

clearly defined private boundaries of ownership (Minton, et al., 2016: 257-258). This thinking

reflects neoliberal individualism and these conceptions have served to facilitate the process of

genificaion. Neman idea hae conibed o egeneaion of ceain concil eae in

London. In 2015 a Conservative housing minister stated that council estates needed to be

egeneaed, hile eaing hem o died bonfield ie (Glckbeg, 2016: 238-239). This

demolition and regeneration of housing estates can be interpreted as state-led gentrification (Watt

& Minton, 2016: 210-211) which breaks apart communities. To illustrate, the Heygate estate was

demolished in 2014 and was replaced by mostly luxury apartments which were overpriced and

therefore pushed out old tenants from the immediate area (Watt & Minton, 2016: 212). This is the

process of state-led genificaion o ocial cleaning in acion and i no a unique case. Fine and

Saad-Filho (2017) argue that a key feature of neoliberalism is that it is a class offensive against

workers in favour of global capital through its collaboration with the state. Gentrification can be

seen as an aspect of this because it benefits the upper classes at the expense of the working class.

Th, genificaion and egeneaion hich eflec neolibeal idea hae been a ke faco in

contributing to the housing crisis.

Financialization

As has been previously argued, neoliberalism as a phenomenon can be understood as a

reconfiguration of the relationships between the individual, society, and the state in favour of the

interests of global capital (Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017). Financialization can be interpreted as being

a part of this neoliberalisation process as it is argued to be a fundamental change in recent capitalist

history which has not only led to a stark growth in the financial sector but has also impacted how

non-financial firms and individuals think and behave (Edwards, 2016: 223). It has already been

said that housing is a fixed asset which has historically been used for wealth creation (Gallent, et

al., 2017: 2206). But in the past decades this has intensified as the real estate market has become

a way for global capital to find risk free investments which give back high returns. Watt and

Minton (2016: 206) argue succinctly that the London housing market has been used as a

eclaie en-eeking inemen ehicle fo global caial. London i a he cene of his

because of its status as a global city resulting in unwillingness by the state to regulate these

speculative investments for fear that it will impede investment in the country more generally; this

is an aspect of the neoliberal phenomenon of deregulation (Edwards, 2016: 224).

However, it should be noted here that other cities such as Zurich and Hong Kong do have

strategies to protect from overuse of speculation and foreign investment despite continuing to hold

hei global ci ae (Glckbeg, 2016: 245). Luna Glucksberg (2016) argues that to

understand the causes of the London housing crisis we need to look at the people at the top of the

housing market, who they are and the consequences of their involvement. Glucksberg outlines a

typology of these investors. The most relevant of those include those who buy to invest, who are

often based in the Far East and finance new build properties which are then rented out but are often

priced far above affordable levels and are usually not social housing. Furthermore, those who buy

for their children are those wealthy central London homeowners who sell up and buy smaller

properties for their children. These people are being priced out of the most elite postcodes so are

moving further out which leads to gentrification and price increases. Moreover, others buy to leave

their properties, using London real estate to protect their capital similarly to a bank. This leaves

56

many properties in central London empty with no obvious owner, meaning that it is often hard to

discern who is liable for council tax. This trend also causes price inflation as well as underuse of

desperately needed housing. Therefore, financialization and the movements of the wealthy elite

are clearly a factor in the housing crisis as prices are being pushed up, leading to gentrification and

displacement. This is because there is a mismatch in the interests of the working classes and those

of the elite in the super-prime market, the latter being favoured by neoliberal policy decisions such

as deregulation of financial markets. Thus, financialization can be viewed as a key cause of the

housing crisis.

Conclusion

In sum, the housing crisis can be interpreted as an intensification of contradictions in the housing

system which are encouraged by neoliberal policies of UK governments since around the 1980s.

Neoliberal discourses have broken down the post-war welfare state consensus and ushered in an

era of individualism and self-help. Neoliberal policies and the resulting crisis in housing are

normalised and brushed under the rug as the state pursues policies which aid global capital at the

expense of the working class. This is carried out through privatisation and reworking the role of

the state in housing provision, leading to a dearth of social and affordable housing in London. This

ie i inenified b egeneaion ojec hich genif, dilace lneable commniie and

disrupt social cohesion. Furthermore, the state has facilitated the increased financialization of the

housing market through deregulation which contributes to rising prices in the centre of the city,

gentrification and disused housing which is so desperately needed. Therefore, London has a

housing crisis because of the sway of neoliberalism which has impacted government policy which

puts global capital ahead of working-class interests, allowing the housing market to be a tool of

accumulation rather than a social good.

Bibliography

Bieler, A. & Morton, A. (2004) A critical theory route to hegemony, world order and historical

change: Neo-Gramscian perspectives in International Relations. Capital & Class, 28(1),

pp. 85-113.

Clarke, S. & Ginsburg, N. (1975) The Political Economy of Housing. University of Warwick

[Online] [Accessed 07 February 2019].

Available at: https://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~syrbe/pubs/ClarkeGinsburg.pdf.

Eagleton-Pierce, M. (2018) Neoliberalism. In: T. Shaw, et al. eds. Palgrave Handbook on

Contemporary International Political Economy. Houndmills: Palgrave.

Edwards, M. (2016) The Housing Crisis and London. City, 20(2), pp. 222-237.

Fine, B. & Saad-Filho, A. (2017) Thirteen Things You Need to Know About Neoliberalism.

Critical Sociology, 43(4-5), pp. 685-706.

Focus E15 Campaign (2019) Focus E15 Campaign Website. [Online] [Accessed 17 February

2019] Available at: https://focuse15.org/about/.

Fitzpatrick, S., Pawson, H., Bramley, G., Wilcox, S., Watts, B., and Wood, J. (2018) The

Homelessness Monitor: England 2018, London: Crisis.

57

Gallent, N., Durrant, D. & May, N. (2017) Housing Supply, Investment Demand and Money

Creation: A Comment on the Drivers of London's Housing Crisis. Urban Studies, 54(10),

pp. 2204-2216.

Glucksberg, L. (2016) A View From the Top: Unpacking Capital Flows and Foreign Investment

in Prime London. City, 20(2), pp. 238-255.

Jenkins, S. (2015) Crisis, What Housing Crisis? We Just Need Fresh Thinking. The Guardian,

[Online]. September 30. [Accessed 14 January 2020] Available at:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/ 2015/sep/30/housing-crisis-policy-myth-

realities.

Minton, A., Pace, M. and Williams, H. (2016) The Housing Crisis: A Visual Essay. City, 20(2),

pp. 256-270.

Watt, P. & Minton, A. (2016) London's Housing Crisis and its Activisms - Introduction. City,

20(2), pp. 204-221.